FÒGLIE

It All Starts with a Seed

In questi mesi stiamo lavorando a un nuovo progetto a cui teniamo molto.

Al centro ci sono i semi: non solo come base per un nuovo modello di agricoltura, ma come simbolo di una visione più ampia, che partendo da un passato sapiente ci guida verso il futuro con più fiducia.

Perché un seme porta con sé memoria, saperi, possibilità. E ci ricorda che per far crescere qualcosa servono cura, tempo e una direzione chiara.

Da lì nasce tutto: il cibo che ci nutre, ma anche la cultura che ci ispira. Coltivare non vuol dire solo lavorare la terra, ma anche mettere radici, generare valore, costruire futuro.

L’estate è il momento in cui tutto questo prende vita: la terra dà i suoi frutti, le persone si incontrano, le idee si accendono. Nei campi, ma anche nei festival, nelle piazze, nei luoghi dove la cultura si fa esperienza condivisa. Agricoltura e cultura si intrecciano, offrendo nutrimento a corpo, mente e anima.

E allora vi invitiamo a uscire, a vivere “fuori” per stare bene “dentro”, a scoprire il mondo rurale e lasciarvi sorprendere da tutta la cultura che fiorisce in questa stagione.

In the last few months, we’ve been working on a new project that we care about a great deal.

It all revolves around seeds: not just as the basis for a new approach to agriculture, but also as a symbol of a broader vision that will see past wisdom guiding us more confidently into the future.

Seeds embody memories, knowledge and possibilities. They remind us that if something is to grow, it must be given care, time and clear guidance.

Everything comes from them, not only the food that nourishes us, but also the culture that inspires us. To cultivate means not only to work the land, but also to put down roots, create value and build a future.

Summer is the time when all of this comes to life: the land yields its fruits, people meet, and ideas take shape. This is true not only in fields, but also at festivals and in squares and everywhere cultural experiences are shared. Agriculture and culture are intertwined, nourishing the body, mind and soul.

Head “outside” and you’ll feel better “inside”. Explore the rural world and prepare to be amazed by all the culture that blooms at this time of year.

¬ Aldo Melpignano Co-Owner of Borgo Egnazia Buona lettura!

Racconti di Puglia attraverso i luoghi, i riti, le persone e la cultura di questa terra Stories about Puglia through the places, traditions, people and culture of this land

06. I CUSTODI DELLE SEMENTI Guardians of the Seeds

16. TALES - L’AIA DI PEPP U CUDICCH Pepp u Cudicch’s Threshing Floor

18. GROUND CONTROL

26. IMAGERY - MAI ABBASTANZA Never Enough

28. BOOKS - STORIE DI LIBERTÀ Tales of Freedom

30. A PRANZO TRA I CHIOSCHI Lunch Served from Stalls

36. ANDAR PER VERDURE A Fondness for Foraging

40. THE SHOW - SPETTACOLO DA BRIVIDO A Hell of a Show

42. MARE, MARE E ANCORA MARE Sea, Sea and more Sea

49. FÒGLIE IN MOVIMENTO

50. WORDS - A LALLÀ

¬ Raffaele Panizza

A farm-to-fork talk between an agronomist and a chef

Angelo, cacciatore di semi, rabdomante di tesori sottoterra, scopritore di nicchie agroecologiche. E Domingo, alchimista di radici e ortaggi rustici e rari, trasformati da cenerentole in pepite d’oro. S’incontrano nell’orto di Borgo Egnazia e insieme immaginano, in piedi su questa terra di tufo che in genere non è buonissima per l’agricoltura ma in Puglia invece buona lo diventa. Perché il vento porta i pollini coadiuvato dai bombi e dalle api bottinatrici che, agli ordini della regina, non smettono mai di bisbigliare ai fiori il loro incoraggiamento e ai frutti le loro formule magiche. «Le arnie le sistemeremo qui!» dice Domingo Schingaro, indicando

l’angolo più propizio con vista sul mare, che oggi è imbizzarrito sotto la frusta della tramontana.

Così come propizia è l’acqua che scorre nel sottosuolo e sparge i nutrimenti insinuandosi in ogni anfratto del fondo roccioso: «I fiumi carsici che attraversano questa terra chissà da dove diavolo arrivano», racconta Angelo Giordano, vestito come Indiana Jones, mentre Domingo non abbandona neppure in campagna il candido camice da chef del ristorante Due Camini. «Esattamente come succede a un viaggiatore, l’acqua più viaggia più fa incontri, e facendo incontri, s’arricchisce».

Le sementi che hanno sparso nelle campagne di Ostuni e Savelletri, tra Masseria Le Carrube, Masseria Cimino e Borgo Egnazia, presto si trasformeranno in frutta e verdura. E il ristorante avrà nuovo materiale per sperimentare, cosi come già fa portando in tavola una degustazione fantasmagorica che estrae dai prodotti della terra tutto il midollo, scomponendo ogni fibra nelle sue inattese possibilità: «Mettiamo in tavola otto vegetali su un totale di 15, a seconda di ciò che si trova in stagione», spiega Domingo mentre osserva, attento come un archeologo, un ciuffo di cavolo riccio che Angelo gli ha portato dall’orto di casa. «Ogni ingrediente CONTINUA >

Angelo is a seed hunter, dowser for underground treasures and discoverer of agroecological niches. Domingo is an alchemist who magically turns rare and rustic vegetables and roots into gold. They meet in the Borgo Egnazia vegetable garden and set their minds to work. The limestone soil beneath their feet might not normally be great for agriculture, but in Puglia it comes to be that way. That’s partly thanks to the pollen carried by the wind, with the help of bumble bees and foraging bees. Obeying their queen’s orders, the latter never stop whispering encouragement to flowers and magic spells to fruit. “We’ll put the hives here!” says Domingo, pointing to the best spot. It looks out over the

sea, which is being whipped up by the tramontane today.

An equally important part is played by the water flowing underground, which spreads nutrients as it works its way into every nook and cranny of the rocks: “Goodness knows where on earth the area’s karst rivers come from,” says Giordano. He’s dressed like Indiana Jones, while even out in the countryside Domingo is still wearing his spotless chef’s coat from the Due Camini restaurant. “Just like a traveller, the further water roams, the more encounters it has. Every encounter is enriching.”

The seeds that they have sown in the Ostuni and Savelletri countryside –

between Masseria Le Carrube, Masseria Cimino and Borgo Egnazia – will soon grow into fruit and vegetables. And the restaurant will be able to experiment with even more ingredients. It already offers breathtaking taste sensations by squeezing every last drop out of its produce, really making the most of it in original ways: “We serve eight out of a total of 15 vegetables, depending on what’s in season,” explains Domingo, looking like an archaeologist as he casts his eye over some crinkly cabbage that Angelo has brought from his vegetable garden at home. “Every single part of every ingredient is used – including the leaves and knobbly parts, to make elixirs, kombucha and essences.” Instead of a traditional menu, there CONTINUES >

Esattamente come succede a un viaggiatore, l’acqua più viaggia più fa incontri, e facendo incontri, s’arricchisce

Just like a traveller, the further water roams, the more encounters it has.

Every encounter is enriching

are cards arranged in a bunch, each with a photo of the main ingredient and a mystery title: Peas, Chicory, Roots, Wild. Once a card has been chosen, on the back are descriptions of the three creations that unleash all of the flavour: rhubarb, vanilla and tonka bean cordial; zeppola with cauliflower, sour cherry, mustard and verjuice; spaghetti with goat cacioricotta and prickly pear roots. And for dessert, amazing fried tassel hyacinths with farinella (chickpea and barley flour) and fermented chocolate. “However, now we want to do more: we’ve decided to plant varieties with unique umami,” exclaims the rapturous chef. He’s already fallen in love with so many weird and wonderful things that have been brought to him, such as Cima di Cola, a ferrous, rather sweet local cauliflower, and Tiggiano parsnips. And then there are smooth red chickpeas, grown from seeds that were found in an old farmer’s house in Santeramo in Colle, in the heart of the Murge. “That’s exactly what a seed hunter does: I scour the countryside, listening to people, collecting reports, sharing tip-offs, and finally going wherever necessary to find new seeds to save and reintroduce into the area,” explains Giordano, who works with countless associations and the most prestigious Puglian universities. As well as ecological and agricultural reasons, he also does it for political ones: “The seeds for everything that we eat are now controlled by a very small number of multinationals, which have

viene utilizzato per intero, comprese le foglie e le parti nodose, per estrarre elisir, kombucha ed essenze». E al posto del classico menù ci sono delle carte che compongono un mazzo, ciascuna con la foto dell’ingrediente principale e il titolo del suo mistero: Piselli, Cicoria, Radici, Selvatico. E descritte dietro, una volta scelta la carta, le tre preparazioni in cui tutto il sapere è declinato: cordiale di rabarbaro e vaniglia e fava tonca, zeppola con cavolfiore e amarena, senapi e agresto, spaghetto con cacioricotta di capra e radici di opunzia. E per dessert, la meraviglia dei lampascioni fritti con farinella e cioccolato fermentato. «Ora però vogliamo fare di più: abbiamo deciso di piantare varietà che abbiano cioè un umami irripetibile», decanta lo chef, già sedotto da tante stranezze che gli sono state portate al cospetto: la Cima di Cola, un cavolfiore locale ferroso e dolciastro. La pastinaca di Tiggiano. E il cece rosso liscio, il cui seme è stato ritrovato in una scatoletta custodita a casa di un anziano contadino di Santeramo in Colle, nel cuore delle Murge. «Ed è proprio questo che un seed hunter fa: perlustra le campagne, ascolta le voci, raccoglie segnalazioni, si scambia soffiate e infine viaggia fin dove è necessario per trovare un nuovo seme da salvare e reintrodurre nel territorio» spiega Giordano, che collabora con mille associazioni e con le più prestigiose università pugliesi. E lo fa non solo per ragioni ecologiche e CONTINUES > CONTINUA >

Ed è proprio questo che un seed hunter fa: perlustra le campagne, ascolta le voci, raccoglie segnalazioni, si scambia soffiate e infine viaggia fin dove è necessario per trovare un nuovo seme da salvare e reintrodurre nel territorio

That’s exactly what a seed hunter does: I scour the countryside, listening to people, collecting reports, sharing tip-offs, and finally going wherever necessary to find new seeds to save and reintroduce into the area

agrarie, ma anche per motivi politici: «I semi di tutto ciò che mangiamo sono ormai in mano a pochissime multinazionali che pian piano hanno spinto a produrre frutta e verdura ibridata artificiosamente che impoverisce sia i contadini sia il paesaggio. Un tempo si coltivava il cibo, mentre ora, si producono alimenti, e la differenza è sostanziale. Un pomodoro ibrido consuma mari d’acqua mentre un pomodoro di Ceglie Messapica, o uno di Fasano, o quello di Mola che va irrigato con l’acqua salmastra, non solo ne chiede pochissima, ma crescendo irrobustisce la terra con i suoi cicli naturali».

gradually pushed people to grow artificially hybridised fruit and vegetables, impoverishing both farmers and the landscape. People used to grow food and now they produce foodstuffs. There’s a big difference between the two. Hybrid tomatoes suck up so much water, whereas those from Ceglie Messapica, Fasano or Mola – which are irrigated with brackish water – not only require very little, but also strengthen the soil with their natural cycles as they grow.”

In Puglia, from Gargano to Santa Maria di Leuca, an informal and often unwitting network of farmers has saved dozens of threatened plant species over the centuries. Seeds stored in liquorice tins were passed down from father to son, with labels written half in dialect and half in Italian. For example, one reads Marangiana chiara cumbare Pietto di lusso, which means that a friend called Pietto passed on treasured seeds for “deluxe” (i.e. delicious) lightly coloured aubergines

In Puglia, dal Gargano fino a Santa Maria di Leuca, una rete informale e spesso inconsapevole di coltivatori diretti ha salvato nei secoli decine di specie vegetali a rischio. Ne ha custodito i semi dentro scatolette delle liquirizie e le ha tramandate di padre in figlio, contrassegnate da etichette scritte metà in dialetto e CONTINUES > CONTINUA >

Come l’astronomo scopritore di una stella la ribattezza col suo nome, allo stesso modo il contadino che salva una varietà diventa eterno insieme a essa: il pomodoro Petruccia o il cavolfiore Cumbare Pietro, se protetti, splenderanno in eterno

Just like astronomers who discover stars and name them after themselves, farmers who save varieties of crops live on forever with them: if they are protected, the Petruccia tomato and the Cumbare Pietro cauliflower will shine for all eternity

metà in italiano: “Marangiana chiara cumbare Pietto di lusso” si legge su una di esse, dove Pietto è l’amico che ha passato il tesoro e “di lusso” indica il sapore strepitoso della melanzana. Esattamente come l’astronomo scopritore di una stella la ribattezza col suo nome, allo stesso modo il contadino che salva una varietà diventa eterno insieme a essa: il pomodoro Petruccia o il cavolfiore Cumbare Pietro, se protetti, splenderanno in eterno.

Just like astronomers who discover stars and name them after themselves, farmers who save varieties of crops live on forever with them: if they are protected, the Petruccia tomato and the Cumbare Pietro cauliflower will shine for all eternity.

The University of Bari is on the front line in this battle and it has come up with a lofty name to describe these agroecological defenders: Biopatriarchs. However, at Borgo Egnazia they prefer to call them “Agricultural guardians”, because at the end of the day they are grandparents who have fed their grandchildren and great-grandchildren with these crops. In doing so, they have saved an entire civilisation. “The aim is not to say to our guests ‘Look, we’re the only ones who have these exquisite items.’ On the contrary, we’ll use cuisine to spread knowledge and make the heritage available to everyone,” says chef Domingo. He’s near the corner of the vegetable garden where wild amaranth grows. It was specially planted to attract parasites, so they would leave alone the gagliubbo melons: sweet treats to eat with a spoon, like ice cream. “This is regenerative agriculture, which feeds water tables and promotes spontaneous hybridisation, letting nature take its course during countless attempts. It’s an art that offers not only goods, but also services. The latter take the form of physical and mental wellbeing for people, and the universal wellbeing of all creation,” says Angelo with feeling. In the vegetable gardens by the sea, he is helping to

L’università di Bari, in prima linea nella battaglia, ha trovato un titolo nobiliare per questi difensori agroecologici: biopatriarchi. Ma a Borgo Egnazia preferiscono chiamarli “agricoltori custodi”, perché altro non sono che nonni e nonne che con questi prodotti hanno nutrito nipoti e pronipoti. E facendolo, hanno salvato un’intera civiltà. «L’intento non è dire ai nostri ospiti guardate, queste prelibatezze le abbiamo soltanto noi. Al contrario, useremo la cucina come piattaforma di conoscenza per rendere il patrimonio disponibile a tutti», dice chef Domingo, vicino all’angolo dell’orto dove cresce l’amaranto selvatico, che è stato piantato apposta per attirare su di sé i parassiti e far crescere in pace i meloni gagliubbo, dolci come gelati e da mangiare col cucchiaio. «Questa è l’agricoltura rigenerativa, che nutre le falde acquifere e promuove ibridazioni spontanee, lasciando che la natura faccia i suoi infiniti tentativi. Un’arte che sa donare non solo beni ma anche servizi. E CONTINUES > CONTINUA >

A Borgo Egnazia li chiamano “agricoltori custodi”. Perché altro non sono che nonni e nonne che con questi prodotti hanno nutrito nipoti e pronipoti. E facendolo, hanno salvato un’intera civiltà

At Borgo Egnazia they prefer to call them “agricultural guardians”. Because at the end of the day they are grandparents who have fed their grandchildren and great-grandchildren with these crops. In doing so, they have saved an entire civilisation

il servizio è il benessere psicofisico dell’uomo. E il benessere universale del creato», si emoziona Angelo. Che in questi orti sul mare sta aiutando a impiantare la lombricompostiera che genererà humus dai rifiuti organici. E a Borgo Egnazia contribuirà a creare la Casa delle Sementi, un archivio vivo dove il sapere dei biocustodi verrà protetto per le generazioni a venire. «Ci siamo abituati a pensare che le banane non abbiano semi, quando invece dovrebbero averli eccome, e belli grossi pure», s’infiamma a un certo punto. «Per tornare a essere individui, come Petruccia e cumbare Pietto, dobbiamo smettere di nutrirci di cloni».

set up a worm compost bin, which will produce humus from organic waste. At Borgo Egnazia he will help to create the Casa delle Sementi (Seed Bank), a living archive where the knowledge of the bio-guardians will be protected for future generations. “We’ve grown used to thinking that bananas don’t have seeds, but they really should have them, and big ones at that,” he says passionately. “If we want to go back to being individuals, like Petruccia and Cumbare Pietto, we need to stop eating clones.”

Pepp u Cudicch’s Threshing Floor

¬ Clara D’Aprile

This special place conjures up countless memories on summer evenings, when people cook, eat and sing together again, like in the old days

C’è un luogo, tra ulivi antichi e trulli silenziosi, dove le sere d’estate non si dimenticano e rinascono ogni volta nelle storie di famiglia e nei rituali di sapori, suoni, voci e volti amici.

È l’aia di Pepp u Cudicch – così chiamavano tutti il bisnonno – che scelse questo spiazzo circolare nel punto più ventilato della sua terra per battere il grano e far respirare i legumi appena raccolti.

Oggi, quello spazio non serve più all’agricoltura. Le macchine hanno preso il posto delle mani, e i raccolti si fanno altrove.

Ma lo spirito è rimasto lo stesso: quello del capcanal, la festa di fine stagione, che un tempo riuniva operai, parenti, vicini di casa e zii con la fisarmonica in mano.

L’aia di Pepp u Cudicch è cambiata, ma non ha perso la sua anima. E ogni estate continua a riempirsi della fragranza dei panzerotti fumanti, delle parmigiane preparate con la ricetta di nonna, di risate piene, chitarre che accompagnano la voce di chi ha voglia di cantare, lo stridore delle sedie di chi si alza per ballare, mani che battono a ritmo, tintinnio di bicchieri, e racconti. Tanti racconti.

È una festa circolare, proprio come l’aia, dove nessuno è ai margini e tutti si sentono parte di qualcosa. Circolare come un abbraccio antico, accogliente come le braccia che in quel gesto si sono strette, tutte le braccia che in quell’aia si sono incrociate.

C’è qualcosa di materno in quella forma rotonda. E forse è per questo che, anche quando le luci si spengono, nessuno ha davvero voglia di andare via. Si resta lì, sotto il cielo trapunto di stelle, con la brezza che attenua il caldo, gli occhi e il cuore pieni e le parole che scivolano leggere, come se il tempo si fosse fermato.

La vita all’aperto non è solo una necessità nei giorni di afa: è scegliere di vivere insieme e di sentirsi vivi nella semplicità. Come succede nell’aia di Pepp u Cudicch, dove ogni estate torna a raccontare chi siamo.

Among venerable olive trees and peaceful trulli, there is a place where summer evenings are never forgotten. They live on in family lore and rituals involving sounds, flavours, voices and friendly faces.

The place in question is a round yard that Pepp u Cudicch – as everyone called my great-grandfather –built on the windiest part of his land, for threshing grain and airing freshly picked legumes.

The space no longer serves an agricultural purpose. Machines have replaced manual labour and the harvesting is done elsewhere.

However, it is still steeped in the spirit of capcanal: the party at the end of the season, which used to bring together workers, relatives, neighbours and uncles wielding accordions.

Pepp u Cudicch’s threshing floor has changed, but its essence remains the same. Every summer, the air is still filled with the aroma of piping hot panzerotti, parmigiane made using our grandma’s recipe, bursts of laughter, guitars playing as people sing, chairs scraping as people stand up to dance, hands clapping in time, glasses clinking, and stories being shared. So many stories.

The round shape of the threshing floor is apt, because at the parties everyone is made to feel part of the circle. They are wrapped in a warm embrace as welcoming as all the arms that have encircled an abundance of bodies over the years.

There’s something maternal about that circular shape. Perhaps that’s why no one really wants to leave, even after the lights go out. Everyone stays there under the star-studded sky, enjoying the breeze on hot nights and savouring the sights, with a warm feeling in their hearts. Conversation comes easily, as if time were standing still.

People might sometimes be driven outdoors by muggy weather, but they also choose to spend time together there and really feel alive, savouring simple delights. That’s exactly what happens on Pepp u Cudicch’s threshing floor, where the story of who we are is told every summer.

¬ Gaia Baldini

The “local Avengers” by photographer Roselena Ramistella at the 10th edition of PhEST

PUGLIA. Queste lande aride punteggiate di qualche olivo non sono così desolate quanto si immagina. Si trova sempre qualcuno immerso nella polvere del western: una sagoma in lontananza. Per Roselena Ramistella sono le fondamenta per l’elevazione: uomini e donne eroi del “prendersi cura”. Hanno i corpi giusti, questi Avengers locali. Immersi in un passato che ritorna, nel mondo che rischia l’estinzione e che, proprio per questo ha imparato a scegliere a chi affidarsi per evitare l’oblio. Ecco la fotografia di un luogo cosciente, di colori bruni, animali ieratici e sguardi profetici, propri della vita umile e per questo ferocemente bella e veritiera.

Tutto si rifà al modulo periodico di nascita-riproduzione-morte-rinascita, rudimento dell’esistenza a cui per ora non è dato sfuggire e che richiede la pazienza cucita sulle labbra strette, negli occhi socchiusi meditabondi.

Resta, unico rifugio possibile dal Koyaanisqatsi che tutto inghiotte e tutto può sedurre, la terra sola.

PUGLIA. Even though this wasteland is only dotted with some olive trees, it isn’t as bleak as you would imagine. There always is a silhouette to be detected which dives into the dust of the western. The photographer Ramistella pictured these life forms as the local Avengers: they are kind of heroes equipped with the right bodies and relentlessly taking care of the world. They are immersed in a past that always comes back, in a planet risking its own extinction. It is precisely for this reason that the world surrounding our heroes has learned to choose who to rely on to avoid oblivion. Ramistella shows us the picture of this conscious place, filled with brownish colors, hieratic animals and prophetic glances - those typical of a humble life, therefore fiercely truthful and beautiful.

Everything adheres to the periodic form involving birth-reproduction-death-rebirth. The rudiment of existence which is impossible to escape (for now) and that requires the same patience sewn into the heroes’ tight lips, into their brooding eyes left ajar.

Since Koyaanisqatsi can swallow and seduce everything, the only remaining refuge is the earth.

Le immagini di queste pagine sono tratte da “Ground Control”, un progetto di Roselena Ramistella scattato tra Monopoli e le Murge durante una residenza d’artista in Puglia. Nata a Gela nel 1982, Ramistella ha ricevuto diversi premi di fotografia, tra i quali il prestigioso Sony Awards 2018, nella categoria Natural World & Wildlife.

Collabora con L’Uomo Vogue, La Repubblica, Internazionale, Wordt Vervolgd Amnesty, Io Donna. I suoi lavori sono stati pubblicati su The Guardian, BBC, The Times e The British Journal of Photography.

È Ambassador e docente di Leica.

These images are part of Ground Control, a project by Roselena Ramistella , photographed between Monopoli and the Murge region during an art residency in Puglia. Born in Gela, Sicily, in 1982, Ramistella has received national and international recognition, including the prestigious 2018 Sony Awards in the Natural World & Wildlife category.

She collaborates with L’Uomo Vogue, La Repubblica, Internazionale, Wordt Vervolgd Amnesty, Io Donna, as well as The Guardian, BBC, The Times e The British Journal of Photography.

She is Leica Ambassador and teacher.

“Ground Control” di Roselena Ramistella è una delle mostre di PhEST, il festival internazionale di fotografia e arte che, per il decimo anno, torna a Monopoli dall’8 agosto al 16 novembre 2025 con il titolo “This Is Us – A Capsule to Space”. Tra gli autori, Martin Parr, Alexey Titarenko, Phillip Toledano, Zed Nelson, Rhiannon Adam, Lorenzo Poli, più due esposizioni uniche: “Los Caprichos – La ragione dei mostri” di Francisco Goya (in collaborazione con il Museo de Bellas Artes de València) e “Jitter Period” di Yorgos Lanthimos (in collaborazione con Fotofestiwal Łódz).

“Ground Control” by Roselena Ramistella is one of the exhibitions featured at PhEST, the international festival of photography and art, which returns to Monopoli for its tenth edition from August 8 to November 16, 2025, under the theme “This Is Us – A Capsule to Space.” Among the featured artists are Martin Parr, Alexey Titarenko, Phillip Toledano, Zed Nelson, Rhiannon Adam, and Lorenzo Poli. Special exhibitions for this year: Francisco Goya with “Los Caprichos – The Reasons of Monsters” (in collaboration with the Museo de Bellas Artes de València) and Yorgos Lanthimos with “Jitter Period” (in collaboration with Fotofestiwal Łódz).

¬ Carmen Borrelli

Yeast Photo Festival is back in Salento and contemplating insatiability in the world today

C’è una fame che non si vede, eppure resiste ovunque. Una fame che convive con la pancia piena, con la dispensa ordinata, con lo scaffale del supermercato che trabocca colori. È quella fame di giustizia che attraversa anche i luoghi dove il cibo non manca. La fotografia, quando è vera, sa cogliere queste contraddizioni. Le guarda con attenzione. Le mette a fuoco.

A raccontare questo squilibrio ci pensa la quarta edizione di Yeast Photo Festival, in programma dal 25 settembre al 9 novembre 2025, tra Matino, Lecce, Castrignano de’ Greci, Gallipoli e Galatina. Il titolo scelto, “(N)ever Enough”, dice tutto: mai abbastanza o sempre troppo? Il confine tra eccesso e mancanza si fa sottile, e il festival lo esplora attraverso immagini che riflettono su consumo, accesso alle risorse, sostenibilità e desideri che cambiano.

There’s a hunger that can’t be seen, but it endures everywhere. It can coexist with full stomachs, neatly stocked pantries and supermarket shelves packed with colourful products. It’s a hunger for justice, which can be found even where there’s no shortage of food. Photography –in the true sense of the term – is capable of capturing these contradictions. Real photographers look at them carefully and bring them into focus.

This imbalance will be highlighted by the fourth edition of Yeast Photo Festival, which will take place from 25 September to 9 November 2025 in Matino, Lecce, Castrignano de’ Greci, Gallipoli and Galatina. The title says it all: “(N)ever Enough”. The festival will explore the fine line between surfeit and shortage, with images reflecting on consumption, access to resources, sustainability and changing desires.

Tra gli ospiti di questa edizione spicca il fotografo inglese Martin Parr. Le sue immagini mettono in scena abitudini e simboli della società contemporanea, lasciando spazio a letture personali. Parr è protagonista di una mostra personale a Palazzo Marchesale del Tufo di Matino e di un talk aperto al pubblico, con una preview anche a Gallipoli. La sua presenza in Puglia è frutto della collaborazione tra Yeast e PhEST – Festival Internazionale di Fotografia e Arte, una sinergia che unisce due realtà capaci di raccontare il presente da prospettive complementari.

Accanto al lavoro di Parr, il festival ospita progetti che parlano di terra, memoria e identità. La fotografa salentina Sara Scanderebech presenta un lavoro inedito sul territorio, mentre Lucas Foglia, fotografo americano, torna nel Salento con “A Natural Order” alla masseria Le Stanzie. Una riflessione visiva sulla relazione tra ordine naturale e costruzione sociale, che trova nel paesaggio agricolo salentino una nuova risonanza.

yeastphotofestival.it

One particularly prominent guest at the festival this year will be British photographer Martin Parr. Depicting modern habits and symbols of contemporary society, his pictures provide the scope for personal interpretations. As well as putting on a solo exhibition at Palazzo Marchesale del Tufo in Matino, Parr will give a public talk and appear in a preview in Gallipoli. Yeast and PhEST International Photography and Art Festival – which portray the present from complementary perspectives –have joined forces to bring him to Puglia.

Alongside Parr’s work, the festival will host projects about land, memory and identity. Salento-born photographer Sara Scanderebech will present previously unseen work about the area, while American photographer Lucas Foglia will be back in Salento with A Natural Order at Le Stanzie. His visual reflection on the relationship between natural order and social construction finds fresh resonance in the agricultural landscape of Salento.

Tales of Freedom

¬ Nando Cannone

Writers and journalists meet in Locorotondo to discuss the present

Ci sono luoghi che non devono raccontare nulla di sé, posti nei quali un colore si è impadronito di tutto, despota e cicerone insieme. Sono spazi assoluti, negli orizzonti, nei suoni, nella meraviglia. Sono così i luoghi di mare. L’azzurra palette, declinata dal mare al cielo, avvolge, incanta e racconta. Le storie che vengono a cercarti sono più di quelle che devi scovare. Sono storie di mare, di partenze e ritorni, di equipaggi persi e di affetti ritrovati, di estati accecanti e promesse non mantenute. Ma se decidi di allontanarti e intraprendere un piccolo viaggio, perché anche le piccole distanze sono portatrici di grandi cambiamenti, se quel mare decidi di guardarlo dall’alto, di navigare direzione cielo, può capitarti di sbarcare in Valle d’Itria, un territorio dai confini labili come i sogni e i racconti. Inerpicandoti per strade che cambiano continuamente orizzonte, il tuo sguardo sostituirà l’azzurro con il bianco. Bianco accecante della luce, della pietra, bianco delle pagine intonse prima di essere scritte. Il bianco è un colore che devi proteggere, interpretare, inseguire e corteggiare. Delicato e potente come le parole.

There are places that have no need to say anything about themselves; places where colour prevails, overwhelming and accommodating at the same time. There’s an absoluteness to these places and their horizons, sounds and wonders. For instance, take locations by the sea. The enveloping, enchanting light blue hues of the sea and sky have tales to tell. The stories that you stumble across outnumber those you have to unearth. These accounts are about the sea; about leaving and returning; losing crews and finding love; dazzling summers and unkept promises. However, if you decide to move away and take a little trip, you’ll see that even short distances can bring big changes. If you choose to look down on the sea from above and head towards the sky, you might find yourself in Valle d’Itria: an area with blurred boundaries, like dreams and stories. Moving upwards on roads with constantly changing horizons, you’ll see light blue make way for white: the blinding white of light, stone and pristine pages, with no writing on them yet. White is a colour that must be protected, interpreted, pursued and courted. It’s as delicate and powerful as words.

Tra questo bianco immenso, a Locorotondo, trova la sua casa “Libri nei vicoli del borgo”, che da quattordici anni racconta la grande letteratura italiana. Lo fa abbinando storie e luoghi, autori e atmosfere, lettori e meraviglia. Non è un festival e non è una rassegna, bensì un’ibrida manifestazione letteraria di comunità. Sottotitolata “Una storia alla volta”, perché tutte le cose belle si fanno una a una. Una sera, un libro, un luogo, un autore e un’affezionata comunità di lettori. Come un romanzo, Libri nei vicoli del borgo si snoda lungo il corso dell’anno, e le stagioni sono i suoi capitoli. L’estate che accompagna l’autunno, l’inverno che racconta la primavera. Insieme alle quattro librerie partner, avamposti della lettura in Valle d’Itria, sempre accanto ai lettori. Se avete avuto la fortuna di amare qualcuno, lo avete fatto senza assenze, vuoti, interruzioni, senza lasciare la luce spenta. Ci siete stati sempre. Un sottilissimo filo conduttore lega le stagioni letterarie, ma ogni stagione ha un tema con infinite prospettive, senza assoluti e giudizi, e ogni lettore si lascia illuminare dalla luce che lo emoziona. Questa XIV edizione trova il suo filo rosso in Le libertà, perché in quel foglio bianco da riempire ci sono tutte libertà del mondo. Liberi sono i protagonisti dei libri che amiamo e che popolano le nostre vite. Perché solo la libertà di scegliere con cura le parole fa sì che la vita sia la nostra vita, che la storia sia la nostra storia.

Fabio Genovesi, Paolo Giordano, Cecilia Sala, Annalisa Cuzzocrea, Ghemon, Daniele Raineri, Alessandro Piperno, Luca Mastrantonio, Anna Dalton sono solo alcuni degli ospiti invitati a raccontare storie. Storie di libertà letterarie nelle calde sere d’estate, tra le bellezze architettoniche di strade e piazze, sotto un cielo di stelle da interrogare. Lontano dall’azzurro assoluto del mare, viva presenza in un luogo che non vuole rinunciare ai suoi sogni e alle storie da cercare. Quello che non esiste, lo si immagina, come un lungomare senza il mare. Citando Garcia Lorca, in fondo è anche questo la poesia: Occhi d’infinito che guardano il bianco infinito che le generò.

librineivicolidelborgo.it

Amid these vast expanses of white, Locorotondo is home to “Libri nei vicoli del borgo” (Books in the narrow village streets), which has been showcasing great Italian literature for 14 years. It does so with a blend of stories, sites, authors, readers, awe and atmospheres. It is neither a festival nor an exhibition, but a hybrid community literary event. It has the subtitle “Una storia alla volta” (One story at a time), because all the best things are done one by one. One evening, one book, one place, one author and one devoted community of readers. Like a novel, Libri nei vicoli del borgo winds its way through the year. The seasons are its chapters. Summer accompanies autumn, and winter tells the story of spring. The initiative’s four partner bookshops are outposts for readers in Valle d’Itria and always alongside them. If you’ve ever been lucky enough to love someone, you’ll have done so without any breaks, time off or interruptions, never leaving the light off. You’ll have always been there. There’s a very fine common thread running through the literary seasons, but each season has its own theme with endless perspectives. Nothing is absolute, no judgement is passed and all readers step into the light that moves them most. The core theme of the 14th edition is Freedoms, because all the freedoms in the world await on that blank page. Freedom is enjoyed by the characters in the books we love, who are part of our lives. Only the freedom to choose words carefully can ensure that lives are our lives, and stories are our stories. Fabio Genovesi, Paolo Giordano, Cecilia Sala, Annalisa Cuzzocrea, Ghemon, Daniele Raineri, Alessandro Piperno, Luca Mastrantonio, and Anna Dalton are just some of the guests who’ve been invited to tell stories. Accounts of literary freedom are given on hot summer nights, among the beautiful architecture of streets and squares, under stars that can be consulted. Far from the all-encompassing blue of the sea, its presence is felt in a place with no intention of forgoing its dreams or its search for stories. That which doesn’t exist can be imagined, like a seafront without the sea. At the end of the day, this too is poetry, so to quote Garcia Lorca: Eyes of infinity which gaze at the white infinity which served them as mother.

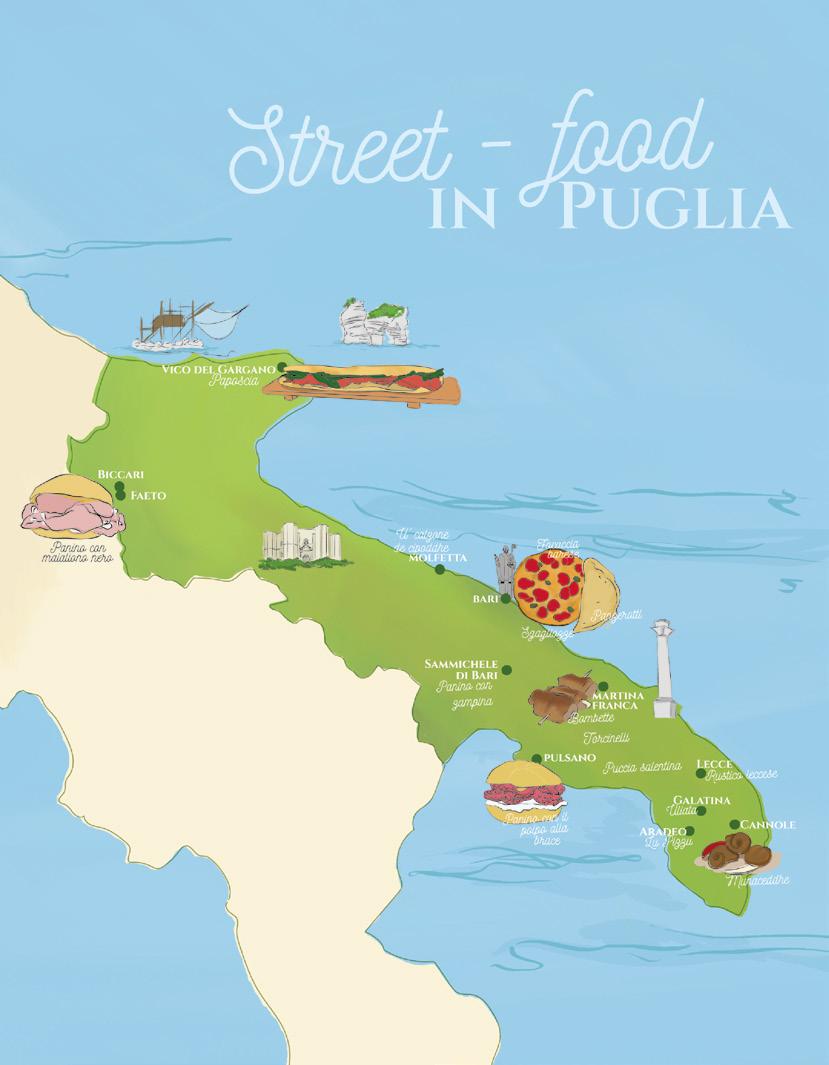

¬ Francesca D’Agnano

Discover Puglian street food, from Gargano downwards

Intraprendere un viaggio alla scoperta delle origini dello street food significa immergersi in un fiume di informazioni, storie e tradizioni che si intrecciano tra loro. Un flusso torrenziale di luoghi, date e aneddoti ci racconta di un cibo consumato per strada, nato più per necessità che per piacere: economico, veloce, spesso indispensabile per ristorarsi dopo giornate di lavoro estenuante.

Dal pesce fritto nell’Antica Grecia al thermopolium di Pompei, riportato alla luce nel 2020, il passo è lungo ma affascinante. Questa piccola rivendita di cibi e bevande, affacciata sulla strada ai tempi dell’Impero Romano, è considerata l’antenata diretta dei moderni chioschi e food truck.

È sorprendente osservare come, nei secoli e nei diversi angoli del mondo,

il cibo di strada abbia accompagnato l’evoluzione della società: in silenzio, con garbo. Ha lentamente abbandonato quella connotazione negativa che lo legava al cibo povero, di scarsa qualità riservato alle classi meno abbienti. Oggi è riconosciuto come parte integrante del patrimonio gastronomico e identitario di un territorio.

Sto per condividere con voi non un semplice itinerario culinario, ma una vera e propria peregrinazione gastronomica, dal nord al sud della Puglia. Una regione dove lo street food si declina in mille forme: celebri o sconosciute, sempre autentiche.

La prima tappa ci porta nel cuore del Gargano, tra le colline di Vico del Gargano. Qui, un tempo, i contadini impastavano gli avanzi del pane casereccio per creare un panino dalla

forma allungata e schiacciata, simile a una pantofola: la Paposcia. Pochi ingredienti: farina, acqua, lievito, sale, olio extravergine e una cottura rigorosamente nel forno a legna, per ottenere una crosta croccante e un cuore morbido. Viene ancora oggi farcita con le specialità locali: pomodori freschi, verdure sott’olio, acciughe, salumi e formaggi artigianali. Un concentrato di ingredienti genuini, sapori decisi e profumi vivaci.

Restando nel nord della regione, nei borghi di Faeto e Biccari spopola un altro simbolo della tradizione: il panino con il maialino nero dei Monti Dauni. La carne di questa razza autoctona, allevata allo stato semibrado, è cotta alla brace e servita senza ulteriori aggiunte all’interno di un morbido pane, per esaltarne il gusto autentico.

Embark on a voyage of discovery into the origins of street food and you’ll soon be inundated with interwoven information, stories and traditions. Oceans of details about places, dates and anecdotes paint a picture of food that was initially created out of necessity rather than for pleasure: quick and cheap, it was often an essential source of nourishment after days of hard toil.

From fried fish in Ancient Greece to the thermopolium unearthed in Pompeii in 2020, it’s a long but fascinating journey. The small shop, which sold food and drink by the side of the road in Roman times, is considered a direct ancestor of modern food trucks and stalls.

It’s surprising to note that over the centuries, all over the world, street food has quietly, discreetly developed side by side with society, as it has evolved. Once

deemed inferior, low in quality and only for poor people, it has gradually shaken off this negative reputation. Nowadays, it’s recognised as a key part of any area’s identity and culinary heritage.

I’d like to tell you about something that’s more than just a simple food route: it’s a genuine culinary pilgrimage, from the North to the South of Puglia. The region’s street food takes countless forms: some are famous and some less so, but all are authentic.

Our first stop is in the heart of Gargano, in the Vico del Gargano hills. Here in the countryside, people used to take leftover dough from home-made bread and shape it into a type of long, flat roll resembling a slipper, known as a Paposcia. Flour, water, yeast, salt and extra virgin olive oil are the only ingredients you need, but the rolls should always be baked in

a wood-fired oven, to ensure they have a crisp crust but are soft in the middle. Still today, they’re filled with local specialities, such as fresh tomatoes, vegetables in oil, anchovies, cured meats and artisan cheeses. They’re packed with wholesome ingredients, forthright flavours and vibrant aromas.

Elsewhere in the North of the region, the towns of Faeto and Biccari are home to another popular, iconic traditional creation: panini filled with the meat of native, semi-wild black pigs from the Daunian Mountains. The pork is barbecued and served by itself in a soft bread roll, to bring out its authentic flavour.

Moving down towards the Murge, another great classic awaits in the shape of Sgagliozze: polenta slices fried in plenty of hot oil, then sprinkled with fine salt. They’re usually served CONTINUES >

Scendendo verso le Murge, incontriamo un grande classico: le Sgagliozze. Sono tranci di polenta fritta in abbondante olio bollente e conditi con una spolverata di sale fino. Solitamente vengono servite in coni di carta, che ricordano i cuoppi del fritto a Napoli. Le storie che ne ripercorrono l’origine sono numerose: c’è chi sostiene che l’uso della polenta in Puglia sia frutto dell’importazione da parte dei contadini veneti emigrati in Gargano nel XIX secolo e chi, invece, ne attribuisce i natali alla signora Giuseppina Amoretto, che aveva scoperto la bontà della polenta a Milano durante la seconda guerra mondiale, riproponendola fritta una volta rientrata a Bari, nel cuore della città vecchia.

A Molfetta ci aspetta U calzone de cipoddhe, un calzone ripieno di sponsali (cipollotti lunghi tipici pugliesi) e merluzzo, reperibile nei panifici locali solo durante la Quaresima, per rispettare il precetto cristiano che vieta il consumo di carne.

A Bari, la protagonista indiscussa è la focaccia barese: alta, soffice, cosparsa di pomodorini, origano e olio extravergine d’oliva. Cotta in teglie ben unte nel forno a legna, è uno degli emblemi più amati della città. Ma è facile imbattersi anche in panini con polpo alla brace o con la celebre zampina di Sammichele, una salsiccia fresca arrotolata a base di vitello e maiale.

Proseguendo verso la Valle d’Itria, il paesaggio cambia ma il profumo di brace resta protagonista. Le Bombette di Martina Franca, involtini di capocollo ripieni di formaggio canestrato, e i Torcinelli, ottenuti con interiora di agnello, arrostiti su lunghi spiedi, rappresentano l’anima carnivora dello street food locale. Molte macellerie offrono la possibilità di scegliere tagli e cottura, servendo il tutto in cartocci da gustare per strada. CONTINUA >

Nei secoli e nei diversi angoli del mondo, il cibo di strada ha accompagnato l’evoluzione della società, in silenzio, con garbo

Over the centuries, all over the world, street food has quietly, discreetly developed side by side with society, as it has evolved

in paper cones that call to mind fried cuoppi in Naples. There are all sorts of theories about their origins. For instance, some claim that polenta was brought to Puglia by emigrants from Veneto who came to Gargano in the 19th century, whereas others say that a certain Giuseppina Amoretto discovered the delights of polenta in Milan during the Second World War and put her own twist on it once she got back to her home in the middle of Bari’s old town, by frying it.

Molfetta has U’ calzone de cipoddhe to offer: calzone filled with sponsali (typical Puglian spring onions) and cod. It can only be found in local bakeries during Lent, when Christians are not supposed to eat meat.

In Bari, star billing unquestionably goes to thick, soft focaccia barese, with cherry tomatoes, oregano and extra virgin olive oil on top. Baked in well-greased tins in wood-fired ovens, it’s one of the most cherished emblems of the city. However, you’ll also be spoilt for choice when it comes to grilled octopus panini and the famous zampina di Sammichele, a fresh veal and pork spiral sausage.

As you head towards Valle d’Itria, the landscape might change but the smell of barbecues still fills the air. The stars of the local meat-based street food scene are Bombette from Martina Franca (capocollo rolls filled with canestrato cheese) and Torcinelli, which are made from lamb offal and grilled on long spits. Many butchers let customers choose their cuts and say how they want the meat done, then wrap the food so it can be eaten on the street. CONTINUES >

Lo street food pugliese non può essere identificato semplicemente come cibo, senza aggiungere ulteriori connotazioni. È racconto, memoria, quotidianità

There is much more to Puglian street food than something to simply fill your stomach. It embodies stories, memories and everyday life

Il nostro viaggio si conclude tra le province di Brindisi, Lecce e Taranto, dove la Puccia salentina, pane tondo a base di semola e senza mollica, viene farcita con tutto quello che la fantasia suggerisce: tonno, verdure grigliate, formaggi, salumi. Impossibile non citare il celebre panzerotto con mozzarella e pomodoro o il raffinato rustico leccese, pasta sfoglia ripiena di besciamella, mozzarella e un cucchiaio di sugo. A Galatina si gusta l’Uliata, focaccina con olive nere leccine o cipolla. Ad Aradeo si trova Lu pizzo, molto simile a quest’ultima, ma arricchito da pomodoro e capperi. La specialità di Cannole sono le Munaceddhe, chiocciole di terra cucinate in diversi modi, che sono anche il cuore di una festa estiva molto sentita. Un piatto antico, rustico, di grande dignità gastronomica, da provare nei chioschi che le preparano ancora come una volta.

Infine, a Taranto e Pulsano, trionfa il panino con polpo alla brace, insaporito con olio, limone e un filo di prezzemolo, spesso venduto nei pressi dei mercati o sul lungomare.

Dopo aver attraversato l’intera regione e aver passato in rassegna città e piccoli borghi, è chiaro che lo street food pugliese non può essere identificato semplicemente come cibo, senza aggiungere ulteriori connotazioni. È racconto, memoria, quotidianità. È la risposta più autentica al bisogno di qualità accessibile, semplicità, identità. Non più relegato alla “fame di strada”, oggi è espressione gastronomica universalmente riconosciuta, orgogliosa e finalmente libera dai pregiudizi.

Our journey comes to an end among the provinces of Brindisi, Lecce and Taranto, where the Puccia salentina – a type of round bread roll which is all crust, with no soft part inside – can be filled with anything you like, such as tuna, grilled vegetables, cheese or cured meats. It would be remiss of me not to mention the famous mozzarella and tomato panzerotti, or refined rustico leccese: layers of puff pastry filled with béchamel sauce, mozzarella and a spoonful of sauce. In Galatina, you can enjoy an Uliata: a bread roll containing black Leccino olives or onions. Lu Pizzo from Aradeo is very similar, but flavoured with tomatoes and capers instead. In Cannole, there are a number of traditional local ways of cooking land snails, which are known as Munaceddhe and take centre stage in a very popular summer festival. An ancient, rustic dish with superb culinary credentials, it is best bought from stalls that still serve it the old-fashioned way.

Finally, in Taranto and Pulsano, there’s nothing quite like grilled octopus panini seasoned with oil, lemon and a sprinkle of parsley, which are often sold near markets and on the seafront.

Our trip all through the region, via various villages, towns and cities, has made one thing clear: there is much more to Puglian street food than something to simply fill your stomach. It embodies stories, memories and everyday life. Nothing offers a more authentic response to the need for accessible quality, simplicity and identity. No longer dismissed as “a bite to eat on the move”, it has finally cast off people’s preconceptions to become a proudly embraced, widely praised form of cuisine.

¬ Francesca D’Agnano

LO FACEVANO LE NONNE PER INSAPORIRE I LORO PIATTI.

OGGI GLI CHEF LO CHIAMANO FORAGING

An age-old way of enriching dishes, foraging is now increasingly popular among chefs espousing conscientious cuisine

C’è un sapere che cresce ai margini dei campi, che profuma di terra e libertà: è il foraging, l’antica arte di raccogliere erbe e piante spontanee nel loro ambiente naturale. Un sapere che si è fatto pratica, arricchendo i piatti delle tavole più consapevoli. Non come moda effimera, ma come gesto autentico di ritorno alla stagionalità e a un rapporto più profondo con il cibo e la natura.

conoscevano ogni segreto della cicorietta, della borragine, delle puntarelle, lo chiamavano “andar per verdure”. Oggi, quel gesto antico diventa anche innovazione gastronomica, restituisce dignità a ciò che la terra offre spontaneamente.

A Ruvo di Puglia ci sono Francesco e Vincenzo Montaruli che, nella cucina di Villa Fenicia e di Mezza Pagnotta, non trasformano semplicemente la materia prima, ma restituiscono dignità a tutto ciò che cresce fuori

dai confini dell’agricoltura convenzionale. La raccolta di ingredienti spontanei che prima veniva divulgata solo oralmente, oggi ha una dimora. I due giovani fratelli, conosciuti per Cucina Villana, hanno reso prezioso l’insegnamento del padre, che fin da bambini li ha guidati nei campi tra le erbe e le verdure. Quelle che non si addomesticano, che decidono da sole quando e dove crescere. I loro piatti nascono tra sentieri, muretti a secco e silenzi di campagna, dove il tempo si misura in germogli e lune.

In Puglia, terra aspra e generosa, il foraging non è mai scomparso: ha solo cambiato nome. Le nonne, che CONTINUA >

Foraging – the ancient art of gathering wild plants and herbs wherever they grow naturally – is steeped in a sense of freedom and connection with the Earth. Conscientious cooks put knowledge into practice in order to enrich dishes. More than just a passing fad, the renewed popularity of foraging heralds a return to a seasonal approach and a more profound relationship with food and nature.

In the rugged but bounteous land of Puglia, foraging never went away: it just used to be known by a different

name. Our grandmothers – who knew everything there was to know about wild chicory, borage and puntarelle – used to go “gathering vegetables”. This age-old practice has now become a form of culinary innovation that underlines the value of the Earth’s natural resources.

In the Villa Fenicia and Mezza Pagnotta kitchen near Ruvo di Puglia, Francesco and Vincenzo Montaruli do more than simply use ingredients: they restore the respectability of everything that grows outside the confines of conventional

agriculture. The secrets to gathering wild ingredients were once only passed on orally, but now they have a home. The two young brothers – known as the people behind Cucina Villana – have harnessed the invaluable lessons of their father. When they were little, he started taking them into the fields to learn about wild plants and herbs, which decide by themselves when and where to grow. Their dishes begin to take shape among paths, dry-stone walls and peaceful countryside, where buds and moons mark the passing of time. CONTINUES >

Raccogliere le erbe spontanee non è solo una pratica gastronomica: è un gesto etico, un atto poetico e politico al tempo stesso. È un invito a rallentare, ad abbassare lo sguardo, a riconnettersi con la terra scegliendo di ascoltarla. E di rispettarla

Foraging is more than just a culinary practice: it’s an ethical approach that shows both shrewdness and sensitivity. It encourages people to slow down, take a look around, and reconnect with the Earth, by choosing to listen to it and respect it

La cicorietta che resiste tra le pietre, il finocchietto che danza al vento, la portulaca che sfida l’asfalto, i lampascioni nascosti nella terra rossa, i cardi spinosi che crescono dove il caldo è più feroce: ogni pianta ha un carattere, una voce, una memoria.

Tra i cuochi che credono nel valore dell’etnobotanica in cucina c’è anche Domingo Schingaro, chef dei Due Camini, il ristorante stellato di Borgo Egnazia. Qui non ci si limita a rivolgersi a esperti raccoglitori: si sperimenta anche la coltivazione di specie selvatiche come tarassaco, calendula, portulaca e cardi, nell’orto del resort, accanto alle varietà antiche già presenti. È un esperimento ambizioso: se in questa estate 2025 avrà successo, garantirà continuità stagionale alle ricette e materia prima per conserve e trasformazioni.

Il foraging, in Puglia, non è solo una pratica gastronomica: è un gesto etico, un atto poetico e politico al tempo stesso. È un invito a rallentare, ad abbassare lo sguardo, a riconnettersi con la terra scegliendo di ascoltarla. E di rispettarla.

Wild chicory that survives among stones, fennel swaying in the wind, asphalt-defying purslane, tassel hyacinth hidden in the red earth, thistles that thrive in the scorching sunshine: every plant has its own personality, voice and memory.

Another big believer in ethnobotany in the kitchen is Domingo Schingaro, the chef at Borgo Egnazia’s Michelin-starred Due Camini restaurant. As well as working with expert foragers, the resort has launched a trial scheme: growing wild species such as dandelions, marigolds, purslane and thistles alongside the ancient varieties in its vegetable garden. If this ambitious experiment proves to be a success in summer 2025, it will provide a reliable source of ingredients for seasonal recipes, preserves and other products.

In Puglia, foraging is more than just a culinary practice: it’s an ethical approach that shows both shrewdness and sensitivity. It encourages people to slow down, take a look around, and reconnect with the Earth, by choosing to listen to it and respect it.

A Hell of a Show

¬ Raffaele Panizza

Cirque du Soleil performers bring the most torrid tales from the Divine Comedy to the Castellana Caves

Prima di scendere negli inferi le guide ti convincono che sei Dante invece non è vero: sei uno dei dannati e ciò che ti aspetta è l’Inferno. O almeno, questo è il gioco della mente che si può fare partecipando a Hell in the Cave, l’esperienza di teatro totale e immersivo, che per tutta l’estate, ogni sabato notte, va in scena nell’antro grande delle Grotte di Castellana, vicino a Putignano. Una fossa profonda 60 metri che i contadini da sempre chiamano la Grave, con l’apertura verso il cielo da cui al crepuscolo sciamano i pipistrelli per cacciare gli insetti tra gli alberi. Unico e irraggiungibile sbocco verso la salvezza dal quale un tempo si credeva uscissero le anime mentre ora le anime vi entrano: talune di giorno, per visitare i tre chilometri di corridoi e stanze monumentali in cui i millenni, goccia dopo goccia, hanno disegnato stalattiti e stalagmiti dalle forme fantasmagoriche (la visita completa alle Grotte di Castellana dura circa due ore). Altri invece di notte, per emozionarsi e volendo spaventarsi un po’, frastornati ed elevati dai versi della Divina Commedia che tuonano dagli altoparlanti nascosti nel buio. E da decine di danzatori, attori e performer che appaiono e scompaiono in ogni angolo della Grave, arrampicati alle rocce scivolose o calati giù dall’apertura principale, come se Dio in persona avesse giudicato peccatori gli artisti migliori del Cirque du Soleil.

Before you descend into the underworld, the guides make you think you are Dante, but in actual fact you are one of the damned and Hell awaits you. Or at least that is how it can feel during Hell in the Cave, a total, immersive theatre experience that is staged every Saturday night throughout the summer, in a large cavern in the Castellana Caves, near Putignano. Reaching a depth of 60 metres, it has always been known to local country folk as “la Grave” (“the Abyss”). At dusk, bats swarm through a hole at the top and hunt insects among the trees. The inaccessible opening was the only way out and it was once thought that souls left through it. Now people pour in through the entrance. Some come during the day to look around three kilometres of caves and monumental caverns, where stalactites and stalagmites with phantasmagoric shapes have been formed over thousands of years, drop by drop. A full tour of the Castellana Caves takes about two hours. Other visitors come at night in search of thrills and the occasional scare: hearing lines from the Divine Comedy booming out of speakers hidden in the dark can be a bewildering but elevating experience. Dozens of dancers, actors and performers pop up and then vanish all over the Grave, climbing on the slippery rocks or dropping down from the main opening, as if God himself had sent Cirque du Soleil’s finest artists to the fiery depths.

Alle nove in punto si aprono i cancelli ed ecco i quasi trecento gradini verso la pancia della grotta, che è tutta illuminata di rosso e già così fa sobbalzare il cuore. Se non fosse che appesi alle ringhiere come ragni ci sono già ad accogliere gli attori, che ringhiano e fanno roteare gli occhi, strisciano tra il pubblico che urla di meraviglia e sorpresa, compresi i bambini che come fossero nel tunnel degli orrori s’abbandonano senza freni a queste emozioni contrastanti. I canti più potenti dell’Inferno di Dante Alighieri, sommo poeta dell’umanità intera, vengono trasformati in quadri viventi che per oltre un’ora si susseguono: compare il gigante Minosse, che impugna lunghi guinzagli e tiene le anime mal nate al cappio: «LASCIATE OGNI SPERANZA O VOI CH’ENTRATE!» Tuona una voce d’attore giunta chissà da dove. Poi si scatenano i lussuriosi, che l’uno sull’altro brulicano cercando un piacere che invece è eterna condanna. Quindi i golosi, che s’ingozzano masticando le rocce calcaree poi si contorcono e sussultano. Il Conte Ugolino che narra la sua storia tremenda e infine, sospesi nel vuoto come farfalle, ecco Paolo e Francesca. Che in un silenzio incantato narrano della loro sfortunata unione, di un sentimento che sopravvive persino quaggiù, e della mano vigliacca che li uccise: «Caina attende chi a vita ci spense», dicono fluttuando a venti metri d’altezza. Le stelle intanto si affacciano sull’occhio scuro della Grave e i dannati tutto intorno cessano di strepitare. E come risuscitati, per la sorte dei due amanti, piangono a dirotto.

www.grottedicastellana.it

The gates open at nine o’clock on the dot and the visitors head down nearly 300 steps into the depths of the cave, which is all lit up in red. That alone is enough to get their hearts racing. What’s more, the actors are already waiting for them, hanging from the railings like spiders. Growling and rolling their eyes, they brush past the crowds, who scream with wonder and surprise. The children really get into it all, embracing the contrasting emotions as if they were in a fun house. The most powerful cantos from the Inferno by Dante Alighieri – the supreme poet of all humankind – are transformed into a series of live portrayals lasting more than an hour. A giant Minos appears, holding long leads and noosing ill-born souls. “ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER HERE!” bellows a voice out of nowhere. The place is soon crawling with the lustful, who sought pleasure in each other but only found eternal damnation. Next come the gluttonous, who guzzle down the limestone rocks then writhe and shake. Count Ugolino tells his dreadful story and then finally, floating like butterflies, come Paolo and Francesca. In spellbinding silence, they tell the tale of their ill-fated affair, feelings that live on even down here, and the coward who killed them: “Caina awaits him who extinguished our life,” they say, hovering at a height of 20 metres. Meanwhile, the stars start to shine in the dark eye of the Grave and the damned all around stop yelling. Seeming like they have been resurrected, they weep profusely at the fate of the two lovers.

¬ Roberta Genghi

In Puglia, it’s everywhere. In memories, rituals, history, recipes, prescriptions and lunch breaks. A common blue thread ties everything together

«Mamma, andiamo al mare dei paguri?». Francesca Mia me lo chiede tutte le volte che io e il papà le annunciamo che stiamo per andare al mare. «Sì, amore, andiamo al “nostro” mare». Nemmeno tre anni e ha già il “suo” mare. Ogni pugliese ha un mare del cuore, che spesso ha a che fare con i ricordi dell’infanzia o quelli dell’adolescenza che sanno di primi baci sugli scogli, con il rumore delle onde a cullare sogni, desideri, segreti. Guardo Francesca mentre cammina sicura nelle conchette della spiaggia di San Giovanni, a una manciata di chilometri da Polignano a Mare, alla ricerca di granchi e paguri da salutare. I suoi riccioli bagnati, così selvaggi e ostinati mi fanno pensare a quanto il mare abbia plasmato a sua immagine e somiglianza noi pugliesi, a quanto gli siamo intimamente legati. È il “nostro” mare, il più pulito d’Italia da cinque anni. Lo dice il monitoraggio del Sistema nazionale per la protezione dell’ambiente: il 99% delle acque che bagnano gli oltre novecento chilometri di costa è eccellente. E i “nostri” due mari – l’Adriatico e lo Ionio – con le loro acque cristalline, grotte nascoste e calette misteriose, identificano da millenni le tradizioni, la cultura, i rituali, vecchi e nuovi, sacri e profani.

“Mummy, are we going where the hermit crabs are?” Francesca Mia asks the same question every time her father and I tell her we’re going to the beach. “Yes, darling. We’re going to ‘our’ beach.” She isn’t even three yet, but she already has a beach she considers “hers”. All Puglians have a spot by the sea with a special place in their hearts, often due to memories from their childhoods or teenage years, such as a first kiss on the rocks and waves lapping against the shore as they nurtured hopes, dreams and secrets. I watch Francesca as she walks confidently along San Giovanni beach, a few miles from Polignano a Mare, saying hello to all the crabs she sees. As I look at her wet, unruly curly hair, I think about how much the sea has shaped the people of Puglia in its own image, and what a strong bond we feel with it. “Our” sea has been the cleanest in Italy for five years. Those are the findings of the Italian National Environmental Protection System (SNPA). According to its monitoring programme, 99% of the water around the region’s more than 900 km of coast is excellent. With their crystal-clear water, hidden caves and mysterious coves, for thousands of years “our” two seas – the Adriatic and the Ionian – have been a distinctive part of traditions, culture and rituals: both old and new, sacred and profane.

Accoglie, ascolta, abbraccia. Il mare è un richiamo. Per chi sul mare ci vive, e per chi viene dall’entroterra. Il mare è dappertutto. Sulla nostra pelle, nella nostra anima, nei nostri piatti, nel nostro modo di essere e di stare al mondo. È un filo blu che ci tiene insieme, che lega tutto. Il mare ci conosce sempre, nei momenti più felici e in quelli più cupi. Davanti al mare la felicità è – davvero! – una cosa semplice. Lo sappiamo bene ed è per questo che ce lo teniamo stretto, a tutte le stagioni (della vita).

«San Nicola che viene dal mare» è una delle frasi che meglio rappresenta il legame antico tra il santo di Myra e Bari. La devozione dei baresi attraversa confini generazionali e classi sociali. È soprattutto un “fatto” di orgoglio cittadino. E nella festa in suo onore che si svolge ogni anno dal 7 al 9

maggio, si rievoca l’impresa dei marinai baresi che nel 1087 portarono le spoglie del santo dalla Turchia a Bari, cambiandone per sempre il destino della città. L’8 maggio la statua del Santo viene portata in corteo fino al porto, imbarcata su un peschereccio (sorteggiato mesi prima) e portata in mare, seguita da una flotta di imbarcazioni e circondata dal calore di migliaia di baresi e pellegrini che arrivano da tutta Italia e dall’estero (dalla Russia in particolare). «San Nicola proteggici da le rizz vacand», metaforicamente dalle persone vuote che, proprio come i ricci di mare, possono essere belli fuori ma vuoti dentro. La scritta a caratteri cubitali campeggia davanti al tempio della baresità per eccellenza: “nderr alla lanz”, luogo iconico senza tempo tra il Teatro Margherita e il molo di San Nicola che di giorno è mercato del pesce all’aperto e di sera si trasforma in

ritrovo della movida. Che ci sia il sole o la luna, poco importa: “nderr alla lanz” ogni momento è buono per bere una birra croccante (ghiacciata in gergo) e mangiare ricci, cozze crude e focaccia.

Il mare è il nostro porto sicuro e il suo richiamo lo sentiamo anche nell’entroterra: quando cambiamo strada o itinerario pur di ritrovarcelo di fianco anche solo cinque minuti. Quando il venerdì pomeriggio, lasciamo l’ufficio e scappiamo a farci il bagno al tramonto. Quando abbiamo un’ora di pausa pranzo e, non importa i chilometri, andiamo a prendere una granita al caffè e doppia panna “‘ngann a màr”. Quando in estate ritorniamo nelle case che ci hanno lasciato i nonni, ignari di quello che la Puglia sarebbe diventata oggi. Apriamo quelle stanze che trasudano amore e nostalgia e ci ritroviamo CONTINUA >

It welcomes, listens and embraces. Everyone feels the call of the sea: both those who live by it and those who come from inland. The sea is everywhere. It’s on our skin and in our souls, dishes, lifestyles and whole approach to the world. It’s a common blue thread that ties everything and all of us together. Throughout our happiest and darkest times, the sea is always there. There’s something so simple about being happy by the sea. We’re well aware of this, which is why we cherish it so much, in all seasons (of our lives).

“Saint Nicholas who comes from the sea” is one of the sayings that best sums up the age-old ties between the saint from Myra and Bari. The devotion of the people from Bari spans generations and social classes. The whole city is proud of it. During the feast of Saint Nicholas, which takes place from 7 to 9 May every year, they commemorate the feat of the sailors

from Bari who took the relics of the saint from Turkey to their home city in 1087, changing its fate forever. On 8 May, the statue of the saint is carried to the port during a procession, loaded onto a fishing boat (chosen by lot months earlier) and taken out to sea, followed by a fleet of boats and enthusiastically surrounded by thousands of people from Bari and pilgrims from all over Italy and other countries (especially Russia). “Saint Nicholas, protect us from le rizz vacand”: literally meaning “empty sea urchins”. This is a metaphorical reference to people who might look good on the outside, but are empty inside. It can be seen in block capitals outside a place that epitomises what it means to be from Bari: nderr alla lanz, a timeless, iconic spot between the Teatro Margherita and the San Nicola wharf, which is an outdoor fish market during the day and hub of the local night-life later on. No matter whether the sun or

the moon is in the sky, nderr alla lanz is always a great place to drink a croccante (ice-cold) beer and eat sea urchins, raw mussels and focaccia.

The sea is like a safe harbour for us and we feel its pull even when we’re inland. We always hear its call: when we take a detour or change routes just to travel alongside it for five minutes; when we finish work on Friday afternoon and race down to the shore for a sunset swim; when we don’t care how many miles we have to drive during our lunch breaks to get a coffee granita with double cream ‘ngann a màr (right next to the sea); when summer comes around and we go back to the houses our grandparents left us, little suspecting what Puglia would be like today. As we open the doors to rooms steeped in a sense of love and nostalgia, all of a sudden we feel like children again, in white CONTINUES >

tutto a un tratto bambini in mutandine bianche e canottiera con la pelle abbronzatissima a fare merenda con pane e pomodoro e a rubare un pezzo di percoca dal bicchiere pieno di vino del nonno.

Il mare previene e cura insieme. È questo il senso più profondo del bagno all’alba del primo settembre sulla spiaggia di Porta Vecchia a Monopoli. Un antico rituale di purificazione e buon auspicio per l’autunno e per l’inverno, ormai un evento che richiama migliaia di cittadini e turisti. Un momento catartico profondo in cui bambini, giovani, adulti e anziani, prima che il sole albeggi, si ritrovano fianco a fianco con i piedi in acqua pronti a tuffarsi.

Il mare è anche la nostra medicina. Ad Acquaviva delle Fonti, un pediatra lo prescrive nelle ricette, insieme a gelati e biscotti. Una trovata geniale per placare la preoccupazione dei genitori e rendere e meno spaventosa la visita. Ogni giorno, nel suo studio pieno di luce e di libri, parla ai suoi piccoli pazienti delle magie del mare, e insegna loro che «i suoi colori sono la vera medicina».

pants and vests that set off our stunning tans. Snacking on bread and tomatoes, we steal a piece of percoca (peach) from our grandfather’s glass of wine.

The sea can prevent and cure at the same time. On the most profound level, that is the meaning of the dawn swim on 1 September at Porta Vecchia beach in Monopoli. An old purification ritual that is supposed to bring good luck for the autumn and winter, the event now attracts thousands of locals and tourists. Before the day breaks, a highly cathartic experience is shared by children, teenagers, adults and old people, who stand side by side with their feet in the water, ready to take the plunge.

The sea also serves medicinal purposes. A paediatrician in Acquaviva delle Fonti writes prescriptions for it, along with biscuits and ice cream. It’s an ingenious way of calming nervous parents and making a trip to the doctor’s seem less scary. In a bright surgery full of books, every day he tells his young patients about the magic of the sea and teaches them that “its colours are where the real medicine lies”.

Accoglie, ascolta, abbraccia. Il mare è un richiamo. Per chi sul mare ci vive, e per chi viene dall’entroterra. Il mare è dappertutto

It welcomes, listens and embraces. Everyone feels the call of the sea: both those who live by it and those who come from inland. The sea is everywhere

C’è una Puglia che si muove al ritmo di tamburi e tramonti, tra vicoli accesi dalle luminarie e piazze che diventano palcoscenici. È la Puglia degli eventi culturali, musicali, artistici e tradizionali: un patrimonio vivo che merita di essere raccontato e seguito giorno per giorno.

“Fòglie in movimento” è la nuova guida digitale che raccoglie gli eventi imperdibili della regione. Dai festival internazionali ai mercatini artigianali, dalle feste patronali alle mostre nei centri storici, ogni appuntamento è scelto per raccontare l’anima autentica del territorio.

Una raccolta sempre aggiornata, pensata per chi viaggia, esplora o resta, e vuole scoprire qualcosa di nuovo, lasciandosi guidare dal proprio ritmo o dall’istinto del momento.

Scopri gli eventi inquadrando il QR code.

There’s a part of Puglia that moves to the beat of drums, among sunsets, narrow streets lit up by luminarie, and squares that are transformed into stages. It’s the Puglia of cultural, musical, art and traditional events: living heritage that deserves to be showcased – and experienced – day after day.

“Fòglie in movimento” is a new digital guide to unmissable events in Puglia. From international festivals to craft fairs, patronal feasts and exhibitions in historic centres, each initiative has been selected to reflect the authentic essence of the region.

The constantly updated collection has been put together for people travelling and exploring – or staying – in Puglia who want to discover something new, moving at their own pace or acting on the spur of the moment.

Scan the QR code to discover our events.

¬ Mari Lacedra

Puglian-English Dictionary

Ci sono parole che suonano come una carezza, altre come una risata. E poi c’è A lallà, che suona come una ninnananna, un’onda che dondola, un piccolo canto mentre si passeggia con lo sguardo rivolto verso il mare e la testa tra le nuvole. Ma attenzione: non è un invito a perdere tempo — è un’istituzione.

In dialetto pugliese, A lallà è l’arte di passeggiare col cuore leggero, in quella fascia oraria dorata in cui il sole non scotta più e le nonne escono in processione con il passeggino come se stessero guidando una carrozza regale.

È la socialità a passo lento, il momento sacro del tramonto in cui tutto il paese sembra rallentare, solo per osservare i bambini che ancora non sanno parlare ma già dettano l’agenda familiare.

C’è chi pensa che a lallà sia un modo per “smaltire la pasta al forno” o per far digerire alle creature la razione di orecchiette alle cime di rapa (che anche a sei mesi, qui, si fanno assaggiare). Ma noi sappiamo la verità: a lallà è un rito di passaggio, un piccolo pellegrinaggio nei vicoli, tra anziani seduti sull’uscio a prendere il fresco e saluti lanciati dal balcone.

C’è sempre un po’ di messa in scena in questa passeggiata: la nonna con la borsetta a tracolla e i fazzolettini sempre pronti, il nonno che accompagna per “controllare il vento” (maisia che il piccolo si raffreddi), il bambino tutto agghindato, anche se l’unica destinazione è la panchina di sempre, accanto all‘albero che fa ombra.

E poi ci sono loro, i piccoli protagonisti, che da quella carrozzina interagiscono con il mondo: ricevono sorrisetti, pizzicotti sulle guance e qualche «quanto sei fatto grande!». Perché in Puglia a lallà non è solo camminare: è mostrare alla comunità che la vita continua, che le nuove generazioni crescono nutrite a latte e complimenti, e buonissime merende davanti al mare.

E ricordate: chi cammina a lallà, non ha fretta. Quindi meglio non chiedere di farsi da parte per farvi passare.

Some words feel like a gentle caress, whereas others are more like laughter. And then there’s A lallà, which sounds like a lullaby, with the rocking motion of a wave. It’s the soft song of someone looking out to sea as they stroll, with their head in the clouds. But don’t be fooled into thinking it’s all about idling away the hours, because it’s a real institution.

A lallà is the name in Puglian dialect for the art of taking a carefree walk at the delightful time of day when the blazing sun starts to cool and a procession of pushchairs appears, propelled by grandmothers who look like they’re at the reins of state carriages.

It’s a leisurely form of sociality at sunset: a sacred time when whole towns and villages seem to slow down, simply to savour the sight of children who might not be able to talk yet, but already set the family agenda.

Some might think that a lallà is a way to “walk off your pasta al forno” or help a dish of orecchiette alle cime di rapa (which children as young as six months get to enjoy here) go down. In actual fact, a lallà is a ritual that takes you on a little pilgrimage through the narrow streets, where old folk sit in the cool shade outside their doors and greetings rain down from balconies.

A lallà is always a rather theatrical affair: the grandmother with her bag over her shoulder, always ready with a tissue; the grandfather there to “keep an eye on the wind” (they wouldn’t want the little one to catch a cold); the child all dressed up, even if they’re only going to the usual bench, in the shade by a tree.

The stars of the show are the children, looking out at the world from their prams. People stop to smile at them, pinch their cheeks and occasionally exclaim “Look how big you’ve got!” After all, there’s more to a lallà in Puglia than just walking: it shows the community that life goes on and the next generation is growing, on a diet of milk, warm praise and delicious snacks by the sea.

One last thing: people out enjoying a lallà will never be in a hurry, so don’t expect them to move aside to let you past.

Raffaele Panizza

Gaia Baldini

Francesca D’Agnano

Roberta Genghi

Nando Cannone

Clara D’Aprile

Mari Lacedra

TRANSLATION

STUDIO TRE Società Benefit S.p.A.

MAP ILLUSTRATED BY Marianna Casafina

EDITORIAL PROJECT & COORDINATION

Sara Magro

AI ILLUSTRATIONS & GRAPHIC DESIGN

Mendo

PHOTO

Roselena Maristella (Courtesy PhEST International Phtography & Art Festival)

Martin Parr (Courtesy Yeast Photo Festival)

Cosimo Rubino

Lara Mayorano

Simone Valenzano

Alfredo Neglia

Alessio Riso

BORGO EGNAZIA TEAM & FRIENDS

Aldo & Camilla Melpignano, Lisa Nitti, Carmen Borrelli, Martina Papagni, Cosimo Rubino, Simone Valenzano, Elena Dell’Aquila, Lara Mayorano and the whole team.

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Associazione Clara, PhEST International Phtography & Art Festival, Yeast Photo Festival, Libri nei Vicoli del Borgo, Grotte di Castellana, Francesco Montaruli, Angelo Giordano, Domingo Schingaro

06 I custodi delle sementi – 18 Ground Control – 30 A pranzo tra i chioschi

36 Andar per verdure – 42 Mare, mare e ancora mare

STORIES ABOUT PUGLIA THROUGH THE PLACES, TRADITIONS, PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THIS LAND

06 Guardians of the Seeds – 18 Ground Control – 30 Lunch Served from Stalls

36 A Fondness for Foraging – 42 Sea, Sea and more Sea