I am convinced that a systemtic program for political education, ranging from the simplest to the highest level, is imperative for any successful organization or movement for Black liberation in this country.

- Assata Shakur

I am convinced that a systemtic program for political education, ranging from the simplest to the highest level, is imperative for any successful organization or movement for Black liberation in this country.

- Assata Shakur

Value #1: We Are Critical Thinkers

Week One

• Robert Allen, “The Dialectics of Black Power” Part I

• Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, Conclusion

• Fred Hampton, “On Political Education” (video)

• Excerpts from Consolidation, Ideology and Organization, A Discussion Paper

• Ed Whitfield, “The Power of Ideas and the Idea of Power” (video)

Value #2: We are Curious About This Moment

Week Two

• CLR James, A History of Pan-African Revolt (Ch 1 - 3)

• Robert Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America - Introduction

• Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America, Introduction

Week Three

• Huey P. Newton, “Functional Definition of Politics” (1969)

• The New Afrikan Prison Movement, “The Black Men Missing in Our Communities”

• Soledad Brother 1971 (video)

• Assata Shakur, “Women in Prison: How It Is With Us”

Week Four

• Muhammad Ahmad, “ Synthesis: Resurgence of The Black Liberation Movement and the Future” in RAM: A Case Study

• General Baker at League of Revolutionaries for a New America (video)

Value #3: We are coming together to take an active, responsible role in freeing our community

Week Six

• Fredrick Harris, “The Price of the Ticket - Clash of Ideas”

• The Negro Voter (1964) (28 mins)

• Kwame Ture, Black Power: The Politics of Black Liberation, “Afterword”

• Walter Rodney, “Black Power, A Basic Understanding”

• James and Grace Lee Boggs, “The City is the Black Man’s Land”

• George Jackson, Blood In My Eye (American Justice + Fascism)

1) What does Fanon mean when he speaks of the crimes of Europe?

Value #4: We are transforming to meet the moment

2) If we are not simply to mimic, or to catch up, but rather to “walk in the company of man, every man, night and day, for all times” -- how would this idea influence a revolutionary culture?

3) What goes into the creation of a new man?

Week Seven

• James Boggs, “The Myth and Irrationality of Black Capitalism”

• Russell Maroon Shoatz, “Black Fighting Formations”

• Atiba Shana, On Transforming the Colonial and Criminal Mentality

• Safiya Bukhari, “Coming of Age: A Black Revolutionary”

• Dhoruba Bin Wahad, Assata Shakur, and Mumia Abu-Jamal, Still Black, Still Strong, “The Man Malcolm”

• Malcolm X's Legacy — Charlie Rose Show May 1992

A concise definition of Culture as “socially transmitted behaviors” is offered, as well as a framework for thinking through Ideology. We don’t talk enough about Ideology (Identity, Analysis, Purpose and Values ), although it is our worldview that, ultimately, determines our course of action. A reactionary culture breeds reactionary behaviors.

Value #5: We are bonded with Black women and all Black people in the fight for true freedom

Week Eight

• Audre Lorde, “Hierarchy of Oppression” (audio)

• People’s College, Abdul Alkalimat et al, “Black Women in the Family”

• Farah Jasmine Griffin, “Ironies of the Saint”

Fred Hampton, On Political Education (video)

• Huey P. Newton, “The Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements”

• Russell Maroon Shoatz, “Respect Our Mothers; Stop Hating Women”

Chairman Fred doing what he does. In this video he underscores the importance of political education in developing community programs. “With no education you’ll have neo-colonialism instead of colonialism”. He explains here, too, the prerequisite that members of the party must go through an 8-week political education.

1)What’s the danger of developing programs without political education?

Week Nine

WWW.BLACKMEN.BUILD

• Combahee River Collective Statement (1977)

2)Chairman Fred said, “we don’t hate white people. we hate the oppressor” -- what is he saying and why is it important for us?

• Claudia Jones, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman”

3)What separates neo-colonialism from colonialism?

• Marsha P. Johnson and the Stonewall Rebellion: Crash Course Black American History #41

• Sylvia Rivera “Y’all Better Quiet Down”1973 Gay Pride Rally NYC

Ed Whitfield, “The Power of Ideas and the Idea of Power” (video)

• Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), “Introduction: Queens Against Society - Rapping with a Street Transvestite Revolutionary: An Interview With Marsha P. Johnson”

Glossary

Ed Whitfield describes a few fundamental ideas; 1) the relationship between resistance, advocacy and do-ityourself; 2) the community as developers; and 3) SASH (spirit, art, science and habits) of Democracy.Each of these concepts is useful in thinking through the difference between reactionary and revolutionary culture. Ed underscores the importance of thinking together.

1) Ed says there ought to be more democracy -- that people have the capacity and the right to make decisions that affect their lives; can we build a revolutionary culture without democracy?

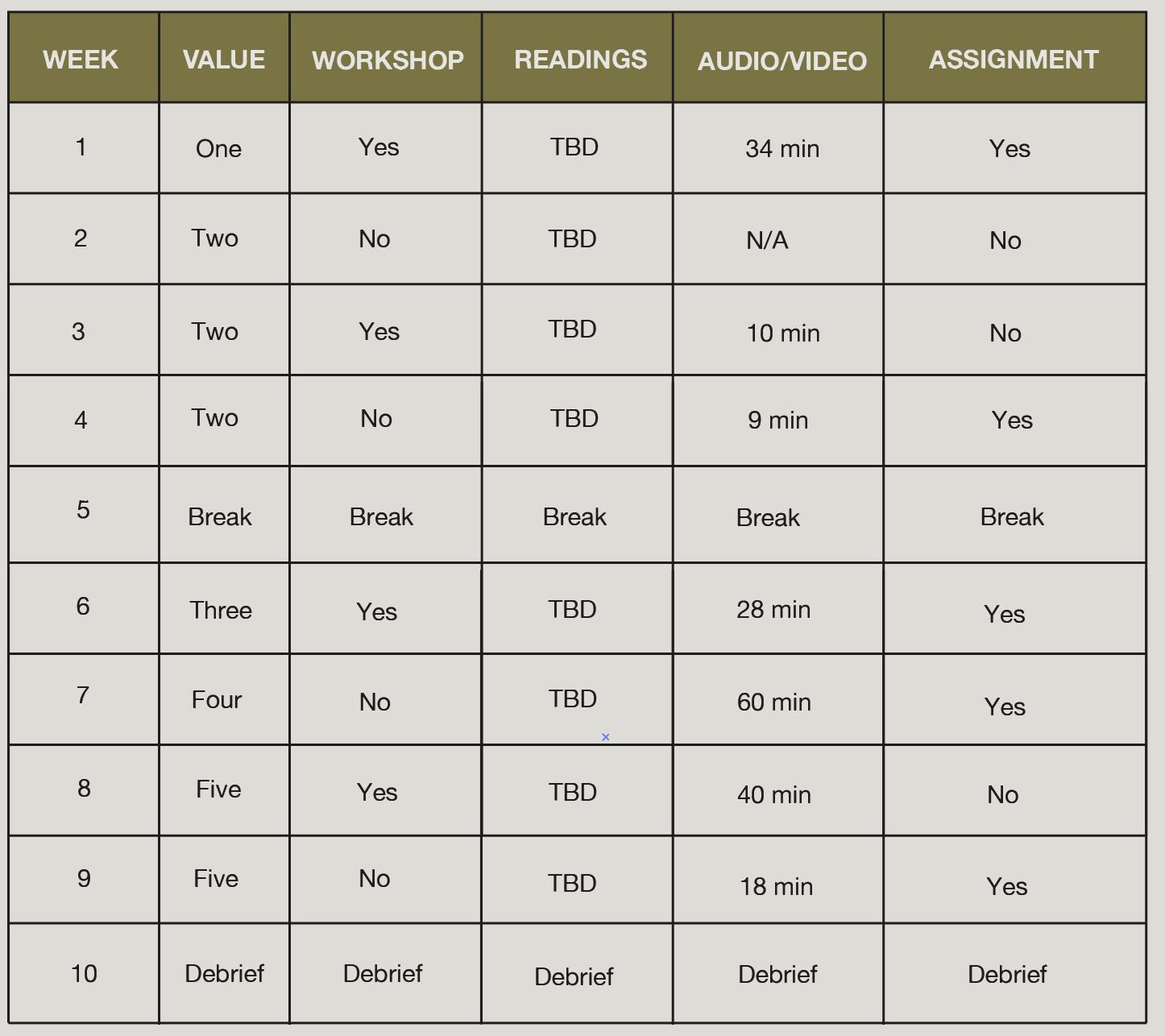

** ere will be a break during Week 5 of the Crow Reader Program**

2) How much of your work is focused on resistance? How much is advocacy?

3) How about do-it-yourself?If democracy is thinking together, what would we need to create more democratic communities?

The Crow Reader is a 9-week political education intensive for Black Men Build organizers and member-leaders.

The Crow Reader is more than a study program—it’s a disciplined practice of revolutionary learning. Over nine weeks, we engage in a structured, collective study of Black revolutionary ideas, theories, and practices that have shaped liberation movements across generations. This program is designed to deepen our political clarity, sharpen our organizing skills, and strengthen our capacity to build power in our communities.

Every movement that has transformed the material conditions of our people has been rooted in study, strategy, and collective discipline.

Fred Hampton:

Understood this when The Black Panther Party made political education a mandatory requirement for membership, because revolutionaries must be thinkers as much as fighters.

Malcolm X:

Used study as a weapon, transforming prison libraries into classrooms for liberation, mosques, ballrooms, and the street corner into learning labs.

Martin Luther King Jr:

Grounded his organizing in deep theological and philosophical study, proving that movements need both heart and analysis.

Queen Mother Moore:

She believed that true education was revolutionary and necessary for Black liberation. She encouraged independent study outside of Eurocentric institutions and emphasized learning from African scholars and activists.

Black August:

We commemorate our fallen comrades and political prisoners during the month of August by studying, training, fighting, and fasting.

The Crow Reader continues this legacy. This is not just about reading—it’s about applying knowledge in service of our struggle. Each week, we engage with texts, discuss their meaning for our work today, and commit to turning theory into action.

Member-leaders who are ready to strengthen their political foundation

Those committed to the long-term study necessary for liberation

This is for those who understand: Freedom doesn’t come by chance, it’s built through study, struggle, and strategy.

This curriculum should be approached alongside a group of comrades, within a BMB Hub-however, rigorous self-study is the foundation for meaningful engagement. The curriculum is meant as an introduction. For many, the ideas and sources will be new, but even the most veteran organizer should find value in the curriculum.

We do not endeavor to teach you what to think. Rather, this curriculum may be thought of as an orientation to how to think about history, culture, and politics.

Throughout this curriculum there are critical questions and key concepts which you are encouraged to reflect upon. We value the adage that, “practice without theory is blind,” and that, “theory without practice is sterile.” In addition to critical questions and key concepts, there are field assignments which should be carried out alongside the curriculum. This is not an extra or optional piece of the curriculum; it is the essence.

Topics and areas of study include: Philosophy, history, imprisoned intellectuals and revolutionaries, political economy, organizational theory, and organizing methods.

Pre-Brief

Before the 9-week sessions begin, the Director of Political Education and Culture will conduct a pre-brief and initial assessment with participants.

Pre-Recorded Workshops

Each of the four values in the Crow Reader has a pre-recorded workshop (theory as a weapon, historical materialism, dialectics, and popular education). These workshops should be viewed every other week during the 9 week program.

Mid-Point Check in

At week 5, we will do a check in with all participating hubs. We want to ensure the material’s quality and effectiveness and members’ clarity and understanding of the content.

Debrief

At the end of the 9 weeks, a final debrief and assessment will be held with the National PE Caucus.

Curriculum

Weekly readings, videos/audios and assignments. See tentative schedule on next page.

Group Composition & Formation

• Study groups will consist of 3–9 members each.

• The Political Education Chair will oversee the creation of additional study groups.

• Within the group, each person should identify a buddy/accountability partner.

• Roles:

▪ Co-Facilitators

▪ Notetakers

▪ Timekeeper

• Balanced Composition of Participants (Experience, Knowledge, Background)

Meeting Frequency & Expansion

• Groups should meet weekly for at least 90 minutes for consistent engagement.

• After completing a cycle, each group will identify 1–3 members to lead the next iteration.

• The goal is for each hub to facilitate 2–4 study group cycles per year, ensuring ongoing political education.

• This structure ensures sustainable, scalable learning, building leadership at every level while deepening collective revolutionary analysis.

Necessary: Making time for study is very difficult for most of us.A schedule is necessary to develop our capacity to study and turn it into a habit. At the beginning of the week, make a schedule and think carefully about what time that week you could fit in any amount of studying.

Consider things like, when you are likely to achieve better focus (for some people the early morning hours are ideal because a busy home is quiet and still), the times of the day when you are most productive and awake, moments of the day or the week where you can be undisturbed and have access to places in your home that others won’t be using, etc. Consistency is important; if you set a routine, do your best to stick to your schedule.

Have a clear objective

Necessary: Knowing your study goals boosts motivation and commitment. Unlike academic pursuits, political education serves community development. Remember your community relies on your knowledge and contribution as an educator to the movement.

Optional: Setting specific study goals (e.g., hours/minutes per week, pages read) can aid program adherence. Daily, weekly, or monthly trackers can also be encouraging. Dense subjects like economics or philosophy demand endurance, similar to exercise. Initial concentration may be brief (under 10 minutes), but endurance will improve with practice, allowing longer focus on difficult reading.

Create the necessary conditions for focused study

Necessary: A dedicated study space is crucial for focus. Ensure comfort with good seating and lighting to avoid discomfort. Eliminate distractions by silencing your phone, closing email, and avoiding domestic interruptions.

Optional: For some people, creating a “study ambience” by playing music, having a clutterfree space, and even some form of decoration, can really help to make study a pleasant experience.

Necessary: Effective understanding and retention of study material necessitate organized note-taking and a systematic approach. Few individuals can recall theoretical text well enough to explain, teach, reference, or dispute its arguments without such a system. There are many note-taking methods, so find the one(s) that works best for you.

Some basic ideas to get started:

Theoretical texts present a main argument supported by others. Identify these by highlighting the main argument in one color and supporting arguments in another. In your notes, state the author's question and outline key arguments, distinguishing them from supporting evidence. Always head your notes with the text's name, author, and date. Organize your notes for future use, as they can be valuable for writing, teaching, or related readings, saving you from rereading. Filing your notes in a way that they are easy to find is key because it saves you all the effort of having to re-read something you already read just because you can’t remember where your notes are.

Optional: As you progress, build a personal glossary of new terms and concepts, expanding on existing definitions with examples (use the glossary provided as a starting place). Also, create a topic-organized list of additional readings. Theoretical texts often build on prior knowledge or engage with other ideas. Footnotes and bibliographies can help you discover more sources on topics of interest, ensuring you deepen your knowledge base.

By Assata Shakur

Carry it on now.

What is the role of ideology in the transformation of

In newspapers. In meetings. In arguments and street ghts. We carried it on.

Carry it on.

Carry it on now.

How do we understand the intricacies of systems of exploitation and oppression? 1

Carry it on.

Carry on the tradition.

2 3

In tales told to children. In chants and cantatas.

In poems and blues songs and saxophone screams, We carried it on.

What can be learned from the “Black Radical Tradition”?

eir were Black People since the childhood of time who carried it on.

In Ghana and Mali and Timbuktu

We carried it on.

Carried on the tradition.

In classrooms. In churches. In courtrooms. In prisons. We carried it on.

These questions and this curriculum should be approached alongside a group of comrades, within a BMB Hub or Chapter -- however, rigorous self-study is the foundation for meaningful engagement. The curriculum is meant as an introduction. For many, the ideas and sources will be new, but even the most veteran organizer should find value in the curriculum.

We hid in the bush.

When the slave masters came holding spear

And when the moment was ripe, leaped out and lanced the lifeblood of our would-be masters. We carried it on.

On soapboxes and picket lines. Welfare lines, unemployment

Our lives on the line, We carried it on.

This curriculum follows five core workshops, which will be offered throughout by BMB. In its design, the curriculum will ideally take ten weeks to complete -- however, a hub may decide longer is needed. The reading is meant to be manageable. It breaks down to an average of less than 50 pages per week; one should, realistically, expect to commit at least two hours of reading per week. Each workshop is also two hours. At minimum, you’ll dedicate forty hours -- including workshops, study groups and field assignments -- to the completion of this curriculum.

In sit-ins and pray ins

And march ins and die ins, We carried it on.

Our understanding begins with a question. Throughout this curriculum there are critical questions and key concepts which you are encouraged to reflect upon. These questions can be the basis for group disussions, inspiration for a field assignment, or a prompt for personal reflection. Take the time to consider the questions; consider how each question might shape or shift your commitment and your practice.

On slave ships, hurling ourselves into oceans.

Slitting the throats of our captors. We took their whips.

On cold Missouri midnights

Pitting shotguns against lynch mobs

We value the adage that, “practice without theory is blind,” and that, “theory without practice is sterile.” Indeed, in addition to critical questions and key concepts there are field assignments which should be carried out alongside the curriculum. This is not an extra or optional piece of the curriculum; it is the essence.

And their ships

Blood owed in the Atlantic and it wasn't all ours. We carried it on.

On burning Brooklyn streets

Pitting rocks against ri es, We carried it on.

You’ll also notice excerpts from interviews, quotes, poems and narratives which are meant to offer context, perspective and insight. These should be considered part of your personal toolkit, which you will add to throughout this curriculum. A living glossary is at the end; some terms, as used in BMB and throughout the curriculum are defined. Here, too, you’re expected to continue to add to the glossary as your understanding grows.

Fed Missy arsenic apple pies.

Stole the axes from the shed. Went and chopped o master's head. We ran. We fought. We organized a railroad. An underground. We carried it on.

Against water hoses and bulldogs. Against nightsticks and bullets.

Against tanks and tear gas. Needles and nooses.

Bombs and birth control. We carried it on.

The purpose is to invite folks into a crash course on systems thinking, critical analysis and Black radical politics -- where we are each both student and teacher. We do not endeavor to teach you what to think. This is not the same as a course in Black History, though we will need to think historically. Nor is this a course on Black Sociology or Theory, though we, most certainly, will look at different theories about society. Rather, this curriculum may be thought of as an orientation tohow to think through the Values of Black Men Build. As an orientation, the process is designed around elaborating upon and making connections to our Values. As is, our Values represent the most forward facing reflection of what distinguishes Black Men Build from any other organization.

In Selma and San Juan. Mozambique, Mississippi.

In Brazil and in Boston, We carried it on.

So, we begin with values.

Maria Mies and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen summarize some of the “main features of a new subsistence paradigm”:

rough the lies and the sell-outs, e mistakes and the madness. rough pain and hunger and frustration, We carried it on.

1. How would work change? There would be a change in the secular division of labour: Men would do as much unpaid work as women [childcare, elderly care, care for the sick and infirm, household duties]. Instead of wage work, independent self-determined socially and materially useful work would be at the centre of the economy. Subsistence production would have a priority over commodity production.

Carried on the tradition.

Carried a strong tradition.

2. What are the characteristics of subsistence technology? It must be regained as a tool to enhance life, nurture, care, share, not to dominate nature but to cooperate with nature. . . . Technology should be such, that its effects could be “healed” and repaired.

Carried a proud tradition.

Carried a Black tradition.

Carry it on.

Pass it down to the children.

3. What are the “moral” features of subsistence economy? The economy respects the limits of nature. The economy is just one subsystem of the society, not the reverse . . . The economy must serve the core life system [which militates against the patriarchal capitalist—unspoken—morality that says: “War is an extension of politics, and politics is the tool best suited to increase one’s economic worth short of war”; thus anti-core life system—RMS]. It is a decentralized, regional economy.

Pass it down.

Carry it on.

4. How would trade and markets be different? Local and regional markets would serve local needs. . . . Local markets would also preserve the diversity of products and resist cultural homogenization. Long distance trade would not be used for meeting subsistence needs. Trade would not destroy biodiversity.

Carry it on now. Carry it on

TO FREEDOM!

Assata Shakur

5. Changes in the concepts of need and sufficiency. A new concept of satisfaction of needs must be based on direct satisfaction of all human needs and not the permanent accumulation of capital and material surpluses by fewer and fewer people. A subsistence economy requires new and reciprocal relations between rural and urban areas, between producers and consumers, between cultures, countries and regions. The principle of self-reliance with regard to food security is fundamental to a subsistence economy. . . . Money would be a means of circulation but cease to be a means of accumulation.²²

It is imperative that this new vision not be lumped in with the talk about “green energy” and the other fashionable ideas about saving the planet from global warming. In none of these schemes do the advocates make the bottom line what it needs to be: the absolute destruction of the ideals and institutions that define and help patriarchy to continue its exploitation and brutality toward women that has been going on for thousands of years. We must even reject some of those ideas that claim to put destruction of capitalism up front, patriarchal socialism included.

Conclusion

e liberation of women is not an outcome of revolution. It is the precondition for it.

—Stan Goff ²³

By now some of you men will be saying, “Yeah, Maroon, you make some good points. I’ll have to check out what you’re saying. But what has all of this got to do with “Respect our mothers”? You’re totally out of order to suggest that we don’t respect our moms! Forget about all those other BI_____ (I mean women). I’ve always respected my mom! In fact, I think you and Stan Goff done got y’alls in, now in y’alls old age, y’all are feeling all guilty and shit. Fall back on us young brothers. It takes time to digest and adjust to all these changes. Plus, how do we know that women ain’t gonna act crazy too?”

Let me end by saying everything written here speaks to ways that women have always—as a whole, all of our mothers for sure—been forced to the bottom of the bowels of patriarchal capitalism’s Matrix-like slave ship. So if you and I are not working to destroy that setup, then we cannot really say we respect our mothers.

We are critical thinkers

“The ruling clique approaches its task with a ‘what to think’ program; the vanguard elements have the more difficult job of promoting ‘how to think’.”

- George L. Jackson, Field Marshal of the Black Panther Party

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

- Steve Biko, South African anti-apartheid activist

Critical Question(s):

Concepts

What is Ideology?

What does it mean to build a revolutionary culture?

Materialism - Idealism - Dialectics - Contradictions - Conditions - Political Spectrum (Left to Right).

We become critical thinkers by using a scientific approach to understanding the world and engaging in political education.

Without political education, our analysis will remain underdeveloped; this is because the forces of capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy are actively limiting our capacity as Black men and Black people to think about what it takes for us to be free.

Critical thinking opposes those forces–it builds our capacity to assess the material world and our ideas so that we can distinguish between conditions that tend to liberate us and conditions that tend to oppress us. This method is called dialectics. With this knowledge, we can expand our collective imagination and build an ideology that we choose, not one that has been chosen for us.

The Crow Reader is designed to challenge us as Black men to reassess our conditions. It equips us to analyze the oppression that capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy produce in our lives and communities. The goal is to take ownership of our actions and ideology in ways that we believe will liberate us.

First, write about your own political transformation: when did you first become politically conscious?

What were the major influences? What did you believe then and what do you believe now?

Then, interview or have a discussion with two people about their politics and political development.

By Robert Allen

Reading Questions:

• What are the five formulations of Black power that Allen identifies?

• Name at least one example (historical or present-day) of each formulation.

• Which one of these formulations would be most revolutionary, and why?

• What obstacles exist for the formulation of Black power that you identified as most revolutionary?

By the time of the Newark Black Power Conference in July, 1967, it was clear that black power meant different things to different people, and the divisions in the political spectrum which black power represented became manifest at that historic meeting.

Within this spectrum five different formulations of black power can be roughly distinguished. All of them are permeated by varying degrees of cultural nationalism, and there is a good bit of overlapping between categories. In addition, orthodox black nationalists, being a political potpourri, can be found in all five categories. Moving from the political right to the political left in this spectrum, we can distinguish:

1. Black power as black capitalism. This is espoused, for example, by the nationalist Black Muslims who urge blacks to set up businesses, factories and independent farming operations. Whitney Young, executive director of the National Urban League, essentially endorsed this formulation in his recent call for "ghetto power." Another exponent is Dr. Thomas W. Matthew, a black neurosurgeon and president of the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO), who in a speech Feb. 1, 1968, before a Young Americans for Freedom audience eschewed government handouts and called instead for whites to provide capital to black businessmen through loans. The most recent supporter of black capitalism is presidential aspirant Richard M. Nixon. In a speech April 25, 1968, Nixon called for a move away from massive government-financed social welfare programs to "more black ownership, black pride, black jobs ... black power in the most constructive sense." Black militants, according to Nixon, should seek to become capitalists—"to have a share of the wealth."

2. Black power as more black politicians. Several years ago electoral politics was endorsed by SNCC as a means to achieving power. SNCC urged that black people organize independent parties, such as the Lowndes County (Alabama) Freedom party, which can place in office black men who will remain responsible to their people. This was ethnic politics. But it soon was distorted into integration politics. For example, the January, 1968, issue of Ebony magazine, which is integration-oriented and aimed at the black middle class, described the election of Negro mayors in Gary, Ind., and Cleveland, Ohio, as "Black power at the polls." But in those elections and their aftermaths the essential ingredients of ethnic group loyalty were missing. As militants have said time and again, "A black face in office is not black power."

In addition to these examples, electoral politics as a means of realizing black power has taken some unexpected turns, particularly in Newark. In a city with a growing black majority population but run by an Italian minority government, one has a situation comparable with the classic colonial model.

LeRoi Jones, well-known black nationalist and member of the United Brothers, Newark's black united front which is seeking control of the city, actively sought to cool out the riots which developed after the murder of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Jones believes that control can be won through the ballot, not the bullet.

On April 12, 1968, Jones participated in an interview with Newark police captain Charles Kinney and Anthony Imperiale, leader of a local right-wing white organization. During the interview Jones suggested that white leftists were responsible for instigating the riots. The policeman then named Students for a Democratic Society and the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) as being behind the riots. Jones did not make this specific charge but the inference was that he agreed. Later in the interview it was suggested that Jones and Imperiale would be working together with the cops to maintain the peace.

A week later Jones elaborated on his position in an interview with the Washington Post. "Our aim is to bring about black self-government in Newark by 1970," Jones said:

“We have a membership that embraces every social area in Newark. It is a wide cross-section of business, professional and political life."I'm in favor of black people taking power by the quickest, easiest, most successful means they can employ. Malcolm X said the ballot or the bullet. Newark is a particular situation where the ballot seems to be advantageous. I believe we have to survive. I didn't invent the white man. What we're trying to do is deal with him in the best way we can ... Black men are not murderers ... What we don't want to be are die-ers."

Jones added that he had "more respect for Imperiale, because he doesn't lie, like white liberals." Imperiale, he said, "had the mistaken understanding that we wanted to come up to his territory and do something. That was the basic clarification. We don't want to be bothered and I'm sure he doesn't want to be bothered." White Provocateurs?

From other such fragmentary evidence the explanation of Jones's new tactics appears to be complex but instructive. It should be noted parenthetically that a factor which confuses the matter further is found in unconfirmed reports, originating with neither the police, right wingers or nationalists, that certain whites actually were attempting to distribute molotov cocktails to blacks during the riots.

In Newark the opportunity exists for militant black nationalists to gain control of the city, assuming that they can avoid being wiped out by the police or right wingers. From their point of view, then, it is of crucial importance to buy time and maintain the peace until a nonviolent transfer of power can be effected, hopefully in the 1970 municipal elections. A violent confrontation right now, the nationalists might argue, would be disastrous for their young and still relatively weak organization.

In the meantime, during this period of stalemate, and with the real power of the city government and right-wing whites on the wane as their supporters emigrate from the city, every effort would be made to unify the black community around the aspiring new leaders and to eliminate potentially "disruptive" elements. Such elements may derive from two sources: independent political operations which have some black support, particularly one such as NCUP which also controls one of the city's eight antipoverty boards, and, on the other hand, groups which advocate arming and what may be regarded as premature violence against the establishment. Both sources exist in Newark and the essential question at issue is not that they are white or black; right, left or apolitical. The point is that they're working in the black community but are independent of the group which is seeking control, and because they, too, may grow in strength, unlike the white establishment, they could pose a long-term, even immediate threat.

Of course, as far as the police and Imperiale were concerned, Jones's statements were very useful since they publicly set one group of militants in the black community against another. The cops and Imperiale are also playing a waiting game: waiting to exploit what they hope is a growing rift among Newark's militant groups. But the situation is very much in flux, and it remains to be seen whether Jones will maintain the position he has taken.

What is strongly suggested when this dynamic is examined is that problems such as this may be expected to arise in other metropolitan areas as more and more U.S. cities find themselves with black majority populations, and the struggle for power is transformed from militant rhetoric into actual practice.

Since 1968 is a presidential election year it is natural to ask what kind of policy black militants have adopted. The answer is that no uniform strategy has been agreed upon. Some groups advocate abstention, others support Socialist Workers party candidates and still others are allied with the various Peace and Freedom party campaigns. The Black Panther party is running Eldridge Cleaver for President. Assorted nationalist groups have called for a write-in vote for exiled militant Robert F. Williams, and to top matters off, comedian-activist Dick Gregory is running his own spirited campaign.

All of this adds up to a lack of political direction which may well make it easier for establishment politicians to co-opt many black militants. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy was successful in getting militants in Indiana to campaign for him, and it is not beyond the realm of possibility that one of the major party candidates may receive the tacit or explicit support of one of the militant national organizations.

Richard Nixon, for example, recently proclaimed a new political alignment which includes Republicans, the "new South," "new liberals" and black militants. According to The New York Times of May 17, Roy Innis, associate national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, described Nixon as the only presidential candidate who understood black aspirations.

3. Black power as group integration. Nathan Wright, chairman of the Newark Black Power Conference, expressed this view most clearly in his book, "Black Power and Urban Unrest." Wright urges black people to band together as a group to seek entry into the American mainstream. For example, he calls for organized efforts by blacks "to seek executive positions in corporations, bishoprics, deanships of cathedrals, superintendencies of schools, and high-management positions in banks, stores, investment houses, legal firms, civic and government agencies and factories." Wright's position differs from black capitalism or integration politics in that he calls for an organized group effort, instead of individual effort, to win entry into the American system. This might be regarded as simply another version of ethnic politics.

4. Black power as black control of black communities. This is the political center of the black power spectrum and the most widely accepted formulation. It is what SNCC, in part, originally meant by the term and how the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) views black power today. It implies a group effort to seize total control of black communities from the white governing structure and business interests.

"Black people," said Floyd McKissick, national director of CORE in a speech July 31, 1967, outlining the group's program, "seek to control the educational system, the political-economic system and the administration of their own communities. They must control their own courts and their own police ... Ownership of businesses in the ghetto must be transferred to black people—either individually or collectively." The difficulty with this program is that it overlooks conflicting interests within the black community. It doesn't specify who is to control or in whose interest. Thus, it is open to co-optation by the power structure or may degenerate into black capitalism.

In the 1930s and '40s the Communist party supported black separatism under the slogan, "Self-determination in the black belt areas of Negro majority." Party theorists argued that black people formed a colony and that the fundamental task of the black liberation movement was to "complete the bourgeois-democratic revolution" (i.e., the Civil War) by forming a separate black nation in the Southern states, thus ending white domination and the semi-feudal status of Southern blacks. The party recognized that the Negro petty-bourgeois class, attempting to play the role of a black bourgeoisie or ruling class, has traditionally been the "most aggressive carrier of nationalism," but it thought that the proletarian and nationalist revolutions could occur simultaneously, resulting in the creation of a separate proletarian black state. At the time this might have been termed working class control of the black community. The party later changed its line and became integrationist.

The underlying logic of the Communists' arguments, however, appears to be motivating white ruling-class efforts to co-opt black power and forestall further urban revolts. The power structure has apparently concluded that direct white rule of the ghettos, at least in some instances, is no longer operating satisfactorily. It is instead seeking out appropriate black groups to administer the colonies. Traditional Negro leaders are not acceptable, having been discredited both within and without the black communities and obviously exercising no real control.

Therefore it is the new black elite, which ironically was created by both the successes and failures of the civil rights movement, to which the power structure must now turn. Some of the members of this group are militant nationalists, even separatists. They tend to be drawn from the traditional black petty-bourgeois class or to be upwardly mobile members of the working class whose mobility in some measure was made possible by early civil rights victories.

But they share a common frustration with the failures of the civil rights movement and often exhibit a genuine desire to improve the lot of black people. Because they are committed militants they also enjoy a certain credibility and acceptance in the ghetto.

It is these factors which make this group ideal administrators of the ghetto. They seek improvement, not revolution. Having moved up on the social ladder they do not share the nihilism of the youthful ghetto resident. Because they are accepted, they also have the potential to restore ghetto peace and tranquility. Even the more opportunistic members of this group have their use since they will work for "law and order" in return for the right to control and exploit the ghetto.

In short, black control of the black community is slowly being transformed into black elite control of the black community, and the bourgeois-democratic revolution is being completed, but in a manner designed to buttress the power of the white establishment over the black ghettos.

5. Black power as black liberation within the context of a U.S. revolution. This wing of the black power movement, represented by the Black Panthers, many members of SNCC and various local groups, views black people as a dispersed internal colony of the U.S., exploited both materially and culturally. It advocates an anticolonial struggle for self-determination which must go hand-in-hand with a general revolution throughout the U.S. It urges alliances with white radicals and other potentially revolutionary segments of the white population since, according to its analysis, genuine self-determination for blacks cannot be achieved in the framework of the present capitalist imperialism and racism which characterize the U.S. Links with the revolutionary third world are also stressed since the black struggle will supposedly be anticolonialist like other national liberation movements, and directed against a common enemy: U.S. imperialism.

But the black radicals, with some exceptions, have been unable to apply this analysis concretely or transform it into a program for struggle. There is a widespread feeling among militants that this is the way things ought to be, but few are sure as to why or how to make it reality.

For example, there has been no elaboration of the relationship between a general U.S. revolution and the black national liberation struggle. Only the theories of the orthodox white left are available, but these are explicitly rejected by black militants.

The question of third world link-ups has also presented difficulties. Aside from trips to third world countries or meetings with third world representatives, the only program developed for a direct link-up is found in the Panthers' call for a UN-supervised black plebiscite and the stationing of UN observers in U.S. cities. And even this is simply a variation on Malcolm X's plan in 1964 to secure UN intervention.

An indirect link to the third world exists in the black antiwar movement. Most militant black antiwar activists openly endorse revolutionary liberation struggles around the world while opposing imperialist wars of aggression. These activists also have a potential base from which to operate. For example, two days before President Johnson announced his noncandidacy, the Philadelphia Tribune, a black community newspaper, completed a seven-week "Vietnam Ballot" in which 84.5% of those polled favored a "get out of Vietnam" position. Only 11% favored a "stop the bombing-negotiate" position, and fewer than 5% supported what was then U.S. policy.

Unfortunately, this sentiment by and large has not been transformed into organization or action. The black antiwar movement has suffered from opportunism and weak or ineffective organizing efforts. A new group, the National Black Antiwar Antidraft Union, headed by SNCC's John Wilson, hopes to solve some of these problems, but it is still too young to have had any noticeable effect.

Aside from these problems the pressure of events is also overtaking black radicals. On the one side they are facing the prospect of increasing repression, on the other there is the escalating anger and nihilism in the ghettos. Black power did in some sense speak to the anger and frustration of urban masses and increased their militance. Their response has been bigger and better rebellions. The outbreaks are political in that they clearly challenge property rights, but black power militants have not brought this political undertone into conscious focus, except among black students, nor have they been able to deal with the resulting repression and co-optation. Instead, those who have not been co-opted, jailed or killed have tended to yield to nihilism and fatalism.

The inability of the white left to seriously deal with racism and repression has accelerated this process. Many black militants increasingly believe that there simply are no effective revolutionary elements in the white population. White students have largely confined themselves to the campuses, where the left has grown stronger, and have not organized poor whites or white workers, groups which have simply persisted in their support of U.S. racism and imperialism. The older middle-class white left has opted out by joining with itself in a middle-class antiwar movement or thrown in with the liberals in supporting McCarthy. A handful of white leftists maintain the proper rhetorical posture vis-a-vis the blacks, but they aren't able to produce the goods.

So, Stokely Carmichael, under these conflicting pressures, announces that whites are the enemy or, at best, irrelevant. He organizes black united fronts, whose unity consists in shared blackness and concern for survival. And survival quickly becomes the uppermost concern.

Socialism becomes irrelevant for Carmichael because he foresees a race war: black against white. He does not anticipate any class struggle in the orthodox sense, hence class analysis has no use. To Carmichael all blacks form one class: the hunted. All whites form another class: the hunters and their accomplices.

Not all militant leaders have yielded to these pressures. Even within the same organization there are differences. H. Rap Brown, present chairman of SNCC and a veteran of white America's jails, contends that it is not possible to judge a revolutionary by the color of his skin. At last October's Guardian meeting Brown expressed his position: "We don't need [white] liberals, we need revolutionaries ... So the question really becomes whether you choose to be an oppressor or a revolutionary. And if you choose to be an oppressor then you are my enemy. Not because you are white but because you choose to oppress me."

Brown, a man who has ample reason to be bitter against whites, has nevertheless frequently contended, and still does, that the revolutionary forces and their allies must be judged by the same standards: commitment and action. But these are tough standards to meet and Brown, too, is known to have growing doubts about the existence of revolutionary forces both within and without the black communities.

By Frantz Fanon

Reading Questions:

• What does Fanon mean when he speaks of the crimes of Europe?

• Fanon wrote, “What we want to do is to go forward all the time, night and day, in the company of Man, in the company of all men.” How can we connect this to collective critical thinking?

• Fanon wrote, “[W]e must make a new start, develop a new way of thinking, and endeavor to create a new man.” What goes into the creation of a new man?

Now, comrades, now is the time to decide to change sides. We must shake off the great mantle of night which has enveloped us, and reach for the light. The new day which is dawning must find us determined, enlightened and resolute.

We must abandon our dreams and say farewell to our old beliefs and former friendships. Let us not lose time in useless laments or sickening mimicry. Let us leave this Europe which never stops talking of man yet massacres him at every one of its street corners, at every corner of the world.

For centuries Europe has brought the progress of other men to a halt and enslaved them for its own purposes and glory; for centuries it has stifled virtually the whole of humanity in the name of a so-called "spiritual adventure." Look at it now teetering between atomic destruction and spiritual disintegration.

And yet nobody can deny its achievements at home have not been crowned with success.

Europe has taken over leadership of the world with fervor, cynicism, and violence. And look how the shadow of its monuments spreads and multiplies. Every movement Europe makes bursts the boundaries of space and thought. Europe has denied itself not only humility and modesty but also solicitude and tenderness. Its only show of miserliness has been toward man, only toward man has it shown itself to be niggardly and murderously carnivorous.

So, my brothers, how could we fail to understand that we have better things to do than follow in that Europe's footsteps?

This Europe, which never stopped talking of man, which never stopped proclaiming its sole concern was man, we now know the price of suffering humanity has paid for every one of its spiritual victories.

Come, comrades, the European game is finally over, we must look for something else. We can do anything today provided we do not ape Europe, provided we are not obsessed with catching up with Europe.

Europe has gained such a mad and reckless momentum that it has lost control and reason and is heading at dizzying speed towards the brink from which we would be advised to remove ourselves as quickly as possible. It is all too true, however, that we need a model, schemas and examples. For many of us the European model is the most elating. But we have seen in the preceding pages how misleading such an imitation can be. European achievements, European technology and European lifestyles must stop tempting us and leading us astray.

When I look for man in European lifestyles and technology I see a constant denial of man, an avalanche of murders.

Man's condition, his projects and collaboration with others on tasks that strengthen man's totality, are new issues which require genuine inspiration.

Let us decide not to imitate Europe and let us tense our muscles and our brains in a new direction. Let us endeavor to invent a man in full, something which Europe has been incapable of achieving.

Two centuries ago, a former European colony took it into its head to catch up with Europe. It has been so successful that the United States of America has become a monster where the flaws, sickness, and inhumanity of Europe have reached frightening proportions.

Comrades, have we nothing else to do but create a third Europe? The West saw itself on a spiritual adventure. It is in the name of the Spirit, meaning the spirit of Europe, that Europe justified its crimes and legitimized the slavery in which it held four fifths of humanity.

Yes, the European spirit is built on strange foundations. The whole of European thought developed in places that were increasingly arid and increasingly inaccessible. Consequently, it was natural that the chances of encountering man became less and less frequent.

A permanent dialogue with itself, an increasingly obnoxious narcissism inevitably paved the way for a virtual delirium where intellectual thought turns into agony since the reality of man as a living, working, self-made being is replaced by words, an assemblage of words and the tensions generated by their meanings. There were Europeans, however, who urged the European workers to smash this narcissism and break with this denial of reality.

Generally speaking, the European workers did not respond to the call. The fact was that the workers believed they too were part of the prodigious adventure of the European Spirit.

All the elements for a solution to the major problems of humanity existed at one time or another in European thought. But the Europeans did not act on the mission that was designated them and which consisted of virulently pondering these elements, modifying their configuration, their being, of changing them and finally taking the problem of man to an infinitely higher plane.

Today we are witnessing a stasis of Europe. Comrades, let us flee this stagnation where dialectics has gradually turned into a logic of the status quo. Let us reexamine the question of man. Let us reexamine the question of cerebral reality, the brain mass of humanity in its entirety whose affinities must be increased, whose connections must be diversified and whose communications must be humanized again.

Come brothers, we have far too much work on our hands to revel in outmoded games. Europe has done what it had to do and all things considered, it has done a good job; let us stop accusing it, but let us say to it firmly it must stop putting on such a show. We no longer have reason to fear it, let us stop then envying it. The Third World is today facing Europe as one colossal mass whose project must be to try and solve the problems this Europe was incapable of finding the answers to.

But what matters now is not a question of profitability, not a question of increased productivity, not a question of production rates. No, it is not a question of back to nature. It is the very basic question of not dragging man in directions which mutilate him, of not imposing on his brain tempos that rapidly obliterate and unhinge it. The notion of catching up must not be used as a pretext to brutalize man, to tear him from himself and his inner consciousness, to break him, to kill him.

No, we do not want to catch up with anyone. But what we want is to walk in the company of man, every man, night and day, for all times. It is not a question of stringing the caravan out where groups are spaced so far apart they cannot see the one in front, and men who no longer recognize each other, meet less and less and talk to each other less and less.

The Third World must start over a new history of man which takes account of not only the occasional prodigious theses maintained by Europe but also its crimes, the most heinous of which have been committed at the very heart of man, the pathological dismembering of his functions and the erosion of his unity, and in the context of the community, the fracture, the stratification and the bloody tensions fed by class, and finally, on the immense scale of humanity, the racial hatred, slavery, exploitation and, above all, the bloodless genocide whereby one and a half billion men have been written off.

So comrades, let us not pay tribute to Europe by creating states, institutions, and societies that draw their inspiration from it.

Humanity expects other things from us than this grotesque and generally obscene emulation.

If we want to transform Africa into a new Europe, America into a new Europe, then let us entrust the destinies of our countries to the Europeans. They will do a better job than the best of us

But if we want humanity to take one step forward, if we want to take it to another level than the one where Europe has placed it, then we must innovate, we must be pioneers.

If we want to respond to the expectations of our peoples, we must look elsewhere besides Europe.

Moreover, if we want to respond to the expectations of the Europeans we must not send them back a reflection, however ideal, of their society and their thought that periodically sickens even them.

For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must make a new start, develop a new way of thinking, and endeavor to create a new man.

Reading Questions:

• What’s the danger of developing programs without political education?

• Chairman Fred said, “We don’t hate white people. We hate the oppressor.” What does he mean by this, and why is it important for us?

• Chairman Fred spoke of colonialism and neo-colonialism. What are some of the examples he mentioned? Can you think of any additional examples?

Reading Questions:

• Why is it important to have a solid ideological foundation?

• What sort of principles does BMB ideology contain? Refer to past and contemporary Black history and movement history, the 9 bars, and BMB principles of Unity for support.

• How does the author explain the philosophical understanding of the world as materialist and dialectical?

In essence, an ideology is a set of principles drawn from the historical experience of a given people, a people submitted to the same general social, economic and cultural realities, in a common historical situation. An ideology can also have revolutionary or reactionary aims; it can be for oppression or for liberation from oppression. If it is revolutionary, the aims of this set of principles is to explain to this given people the causes of their past situation and their present situation, and the ways and means to bring about a future situation consistent with their desire of an independent and free existence. Ideological principles come about through research. Once they have emerged through research and are correctly put together in a coherent whole, they serve for action. Brie y, then, an ideology is a set of principles drawn from the historical experience of a particular people; as such it provides the guidelines for action, for change, in the direction desired by that people.

— Sister Shawna Maglanbayan, Garvey, Lumumba, Malcolm: Black Nationalist Separatists (Third World Press)

All ideologies arise from the historical experience of a given people, which means ideologies are indigenous, and not importable. And, any given ideology can be revolutionary or reactionary. The ideology explains causes and puts forth ways and means. The development of an ideological framework demands research, study, analysis. In seeking ideological consolidation for the organization, the Movement and the entire nation, We seek a particular, a specific order for ourselves, as We struggle for independence and, after independence, as We further consolidate and develop the new socialist society.

We understand that We struggle to liberate New Afrika - not 19th century Germany or France - not 1917 Russia. We struggle to liberate New Afrika, not China, Angola, Vietnam or Guinea-Bissau, Cuba, Brazil or Zimbabwe. We understand relationships that exist in the world, and We also understand that ideological/theoretical principles coming from other places may be useful to us - but the ideology that will successfully guide us in the process of liberating New Afrikans must be an indigenous creation of New Afrikan people.

Our ideological formulation is New Afrikan Revolutionary Nationalist. Before We can reach the point of more clearly articulating and practicing our ideology, We must become more familiar with ideology in general, and with the ideo-theoretical formulations that have come to us from other places. And, at bottom, We must get deeper into the study and analysis of our own history - the history of New Afrika.

Ideology: generally speaking, and its philosophical foundation.

..political, social and moral behavior, such that unless behavior of this sort fell within the established range, it would be incompatible with the ideology...The ideology of a society is total. It embraces the whole life of a people, and manifests itself in their class structure, history, literature, art, religion...If an ideology...seeks to introduce a certain order which will unite the actions of millions towards speci c and de nite goals, then its instruments can also be seen as instruments of social control, because "the notion of a society implies organized obligation."

— Nkrumah, Consciencism

To some bloods, all this sounds very elementary, something they "already know." To other bloods, it sounds "too academic," unrelated to their urge to "get down." But any bloods with eyes and ears will be able to relate this to the state of the nation fifteen years after the death of Malik, as We find it hard to arouse the enthusiasm of the masses because "the $ ain't what it used to be."...

Bloods who regard all talk about ideology as elementary and/or academic, who spend the bulk of their time body-building and quoting dogmas, have and will continue to fail until We learn that the strategy of armed struggle must be able to guide us in developing consciousness and uniting our people around programs which will aid us in building the New Society politically, economically, and socio-culturally - as We fight.

"The struggle for national liberation must transform the masses from their present passivity and dependence on others. It must develop in them and through them the power, the will, the capacity, and the structure to govern their own accelerated development. The masses must begin to see themselves as making their own history. Only through this fundamental transformation in attitudes, and through the creation of new infrastructures by the people themselves, can the social productive forces of the people be liberated."

We feel the need to have a clear understanding about ideology because We must have such an understanding in order to put ideology into practice. In many respects, the importance of ideology as the guide to all our actions evades us because ideology is "largely implicit," e.g., each of the principles are not entirely and immediately capable of being compiled into "handbooks" - especially when the ideology is emerging in the course of revolutionary struggle, simultaneously opposing an oppressive, reactionary order, and raising a new, revolutionary one.

Although "largely implicit," the instruments of ideology are very pervasive and concrete in their expression.

"Every society stresses its permissible ranges of conduct, and evolves instruments whereby it seeks to obtain conformity to such a range. It evolves these instruments because the unity out of diversity which a society represents, is hardly automatic, calling as it does for means whereby unity might be secured and, when secured, maintained. Though in a formal sense, these means are means of 'coercion,' in intent, they are means of cohesion. They become means of cohesion by underlining common values, which themselves generate common interests, and hence common attitudes and common reactions. It is this community, this identity in the range of principles and values, in the range of interests, attitudes, and so of reactions, which lies at the bottom of social order. It is also this community which makes social sanction necessary, which inspires the physical institutions of society, like the police force, and decides the purposes for which they are called into being."

The ideology is the foundation, and the ideology itself has a foundation. The ideology presents us with a set of principles drawn from our historical experience, and these principles ultimately rest upon a particular analysis of "the way the world works." In other words, We say, the ideology has a particular philosophical foundation.

We've said that the ideology explains the causes of the present situation, and points out the ways and means of changing the present and creating a specific future situation. We've said that the ideology uses political, social and moral theory, and establishes a particular range of political, social and moral behavior; that it manifests itself in class structure, history, literature, art and religion; that its instruments become means of cohesion by underlining common values, interests and reactions, and that it "inspires the physical institutions of society, like the police force, and decides the purposes for which they are called into being." How are all these things done, and why?

The ideology gives us our beliefs about the nature of the individual, the relationship between individuals, between individuals and the society, between individuals/society and nature, and it does these by having a philosophical foundation which provides a general analysis or description of the basis for such beliefs. Just as the ideology is drawn from particular historical experience, ultimately, the philosophical foundation also has its roots in particular social experiences, and particular interpretations of those experiences, based on how We think "the world works" - how We believe things develop, how things relate to each other.

Revolutionaries, in particular, cannot afford to take for granted the ways in which the masses conceive natural and social development. It is precisely these conceptions which are the basis for the ways in which the people will respond to efforts of agitation, education, organization and mobilization.

In 1980 We find that as We approach the masses with talk about police repression, POW's, and national independence, in many instances the "money fetish" is an obstacle blocking our progress. The masses have no idea about the actual workings of the capitalist production and distribution process. The people don't know what it means that "the cost of money has risen." The myth of amerikkkan "democracy" and the feeling of powerlessness and total inability to confront and overcome those who rule, are the dominant attitudes among our people.

We have to understand that simply pointing and saying "that is the enemy" will not suffice. We can't organize workers at the point of production if we can’t help them to first understand the production process and the ways that our exploitation is conducted in the real, day-to-day world. We can’t organize the tenants in the rat-infested buildings if they are in awe of private property, if they fear the landlord and police more than they love and respect their revolutionary vanguard, or if they regard city hall as more of a legitimate authority than their “provisional government.”

Fifteen years after the death of Malik, and We still hear our people say “but what can I do” or “it’s always been this way” - expressing a particular conception of how the world works as their reason for not involving themselves in a struggle to change the present situation.

Our ideology contains principles regarding the spirituality, humanity, and dignity of our people; a belief in the Community as a Family, and a belief that the Community is more important than the individual. These are principles that We are struggling to make live, and in the present situation We are confronted by a complex set of opposing beliefs and principles which are based, ultimately, upon a philosophy of the world which is antagonistic to ours.

The belief that our own oppression continues because We lack the power to control our own lives, rests upon a particular understanding of the world as it really is, as it really has been, and as it can be.

We believe that We can win because we understand the world as a material force, and that everything which exists in both nature and society comes into being and passes away on the basis of interconnected change and development.

So, when We see that We have an ideology which puts forth certain beliefs about the U.S. police force, as well as certain beliefs about our national reality and the war We’re engaged in, how people make change and make revolution, We understand that these beliefs rest on a philosophical understanding of the world and society that is materialist and dialectical. This philosophical understanding underlies our agitation, education and organizing round acts of U.S. police aggression, calls for "community control” of U.S police, and calls for the “disbanding” of same. Since our struggle is both against the dominating power of the oppressive U.S. Imperialist state - which the police force is an organ of - and a struggle to establish a “state of a new type,” a call to “disband” the police stems from our revolutionary ideology and its philosophical foundation.

Therefore, as We work to promote and realize the aims of our revolution…We will be able to respond to the feelings of powerlessness and inability expressed by our people. We will be able to respond, in part, because our understanding of the world as it really is and as it really works, informs us that:

the world is, by its very nature, material, and everything which exists comes into being on the basis of material causes, arises and develops in accordance with the laws of the motion of matter; activity - part of the subjective conditions that must exist before We can entertain thoughts of victory.

Raising consciousness means more than calling a pig a pig... We have to understand that even "generalizing support for armed struggle" involves a total process of changing minds, of altering the presently held assumptions regarding the nature of the oppressive state, its law, and the explicit and implicit ideological/philosophical beliefs that allow these to stand in the face of mounting genocide.

By Ed Whit eld

• Whitfield says there ought to be more democracy -- that people have the capacity and the right to make decisions that affect their lives; can we build a revolutionary culture without democracy?

• How much of your work is focused on resistance? How much is advocacy?

• How about “Do For Ourselves?” If democracy is thinking together, what would we need to create more democratic communities?

By Mari Evans

Who can be born black and not sing the wonder of it the joy the challenge And/to come together in a coming togetherness vibrating with the res of pure knowing reeling with power ringing with the sound above sound above sound to explode/in the majesty of our oneness our coming together in a comingtogetherness

Who can be born black and not exult!

Value #2:

We are curious about this moment

“We suffer political oppression, economic exploitation and social degradation. All of 'em from the same enemy.”

- Malcolm X

"You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect with other people’s pain...as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less."

- James Baldwin

Critical Question(s):

What are the dominant ideologies of those currently in power in the US and across the globe?

What does history tell us about the current political, cultural/social and economic context of Black struggle?

Who are the enemies of Black people, specifically?

Field Assignment:

Concepts

Ideology - Capitalism - Patriarchy - Domination - Exploitation - Alienation – the tactics of an oppresive society.

We must analyze the current political moment by examining its historical roots, material conditions, and ideological conflicts. This means studying contemporary movements which include protests, policies, and compounding crises as part of ongoing struggles, not isolated events. Key players include the state, capitalists, the left, and the reactionary right, but we must also expose how their actions reinforce empire (U.S. hegemony, militarized borders, neocolonialism) and racial capitalism (exploitation built on racial hierarchy). Only by understanding these systems can we move with strategic action.

Top Five - ask five people to name the top five reasons why their life, their neighborhood, this country, our people, and the world is the way it is?

Write each response on an index card; on the back of the index card write if their explanation is material or idealist.

By CLR James

Reading Questions:

• What are the reasons that CLR James gives for Haiti being the site of the first successful slave revolt?

• What do Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser and Nat Turner have in common? How were they different?

• Why is it important to study the historical significance of Haiti, particularly its revolution and postcolonial struggles, alongside the slaveholding colonies and early territories of the United States prior to the Civil War?

The history of the Negro in his relation to European civilization falls into two divisions, the Negro in Africa and the Negro in America and the West Indies. Up to the 'eighties of the last century, only one-tenth of Africa was in the hands of Europeans. Until that time, therefore, it is the attempt of the Negro in the Western World to free himself from his burdens which has political significance in Western history. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century European civilization turned again to Africa, this time not for slaves to work the plantations of America but for actual control of territory and population.

Today (1938) the position of Africans in Africa is one of the major problems of contemporary politics. An attempt is made here to give some account and analysis of Negro revolts through the centuries; in the days of slavery; in Africa during the last half-century; and in America and the West Indies today. It is impossible in this space to deal with the slave-trade and slavery; the same consideration has made it necessary to omit accounts of the early revolts in the West Indies and the incessant guerrilla warfare carried on in all the islands by the maroons (or runaway slaves) against their former masters. Negroes have continually revolted and once in Dutch Guiana the revolting slaves held almost the entire colony for months. But in the eighteenth century the greatest colony in the West Indies was French San Domingo (now Haiti) and there took place the most famous of all Negro revolts. It forms a useful starting point.

1789 is a landmark in the history of Negro revolt in the West Indies. The only successful Negro revolt, the only successful slave revolt in history, had its roots in the French Revolution, and without the French Revolution its success would have been impossible.

During the eighteenth century French San Domingo developed a fabulous prosperity and by 1789 was taking 40,000 slaves a year. In 1789 the total foreign trade of Britain was twenty-seven million pounds, of which the colonial trade accounted for only five million pounds. The total foreign trade of France was seventeen million pounds, of which San Domingo alone was responsible for eleven millions. "Sad irony of human history," comments Jaures, "the fortunes created at Bordeaux, at Nantes, by the slave-trade gave to the bourgeoisie that pride which needed liberty and contributed to human emancipation." But the colonial system of the eighteenth century ordained that whatever manufactured goods the colonists needed could be bought only in France.

They could sell their produce only to France. The goods were to be transported only in French ships. Colonial planters and the Home Government were thus in bitter and constant conflict, the very conflict which had resulted in the American War of Independence. The American colonists gained their freedom in 1783, and in less than five years the British attitude to the slave-trade changed. Previous to 1783 they had been the most successful practitioners of the slave-trade in the world. But now not only was America gone, but it was British ships which were supplying a large proportion of the 40,000 slaves a year which were the basis of San Domingo's prosperity.

The trade of San Domingo almost doubled between 1783 and 1789. The British West Indian colonies were in comparison poor, and with the loss of America, were of diminishing importance. The monopoly of the West Indian sugar planters galled the rising industrial bourgeoisie, potential free-traders. Adam Smith and Arthur Young, economists of the coming industrial age, condemned the expensiveness of slave labor. India offered the example of a country where the laborer cost only a penny a day, did not have to be bought, and did not brand his master as a slave-owner.

In 1787 the Abolitionist Society was formed and the British Government, which only a few years before had threatened to sack a Governor of Jamaica if he tampered with the slave-trade in any shape or form, now changed its mind. If the slave-trade was brought to a sudden close, San Domingo would be ruined. The British islands would lose nothing, for they had as many slaves as they seemed likely to need. The abolitionists, it is true worked very hard, and Clarkson, for instance, was a very honest and sincere man. Many people were moved by their propaganda. But that a considerable and influential section of British men of business thought that the slave-trade was not only a blot on the national name but a growing hole in the national pocket, was the point that mattered. The evidence for this is given in detail in the writer's Black Jacobins published in 1938 with a revised edition in 1963.

The Abolition Society was formed in 1787. France at that time was stirring with the revolution, and the French humanitarians formed a parallel society, "The Friends of the Negro." They preached the abolition not only of the slave-trade but of slavery as well, and Brissot, Mirabeau, Condorcet, Robespierre, many of the great names of the revolution, were among the members. They ignored or minimized the fact that, unlike Britain, two-thirds of France's overseas trade was bound up with the traffic. Wilberforce and Clarkson encouraged them, gave the society money, and did active propaganda in France. This was the position in Europe when the French Revolution began.

San Domingo possessed at that time 500,000 slaves, and only 30,000 Mulattoes and about the same number of whites. But the slave-owners of San Domingo at once embraced the revolution, and as each section interpreted liberty, equality and fraternity to suit itself, civil war was soon raging between them. Some of the rich whites, especially those who owed debts to French merchants, wanted to follow the example of America and virtually rule themselves.

The Mulattoes wanted to be rid of their disabilities, the poor whites wanted to become masters and officials like the rich whites. These classes fought fiercely with one another. The white colonists lynched and murdered Mulattoes for daring to claim equality. But the whites themselves were divided into royalists and revolutionaries. The French revolutionary legislatures first of all evaded the question of Mulatto rights, then gave some of the Mulattoes rights, then took the rights away again. Mulattoes and whites fought, and under the stress of necessity began to arm their slaves. The news from France, the slogans of liberty, equality and fraternity, the political excitement in San Domingo, the civil war between rich whites, poor whites and Mulattoes, it was these things which after two years awoke the sleeping slaves to revolution. By July, 1791, in the thickly populated North they were planning a rising.

The slaves worked on the land, and, like revolutionary peasants everywhere, they aimed at the extermination of their masters. But, working and living together in gangs of hundreds on the huge sugar-factories which covered the North Plain, they were closer to a modern proletariat than any group of workers in existence at that time, and the rising was, therefore, a thoroughly prepared and organized mass movement. On a night in August a tropical storm raged, with lightning and gusts of wind and heavy showers of rain. Carrying torches to light their way, the leaders of the revolt met in an open space in the thick forests of the Morne Rouge, a mountain overlooking Cap François, the largest town.

There Boukman, the leader, after Voodoo incantations and the sucking of the blood of a stuck pig, gave the last instructions. That very night they began. Each slave-gang murdered its masters and burnt the plantation to the ground. The slaves destroyed tirelessly. They knew that as long as those plantations stood, their lot would be to labor on them until they dropped. They violated all the women who fell into their hands, often on the bodies of their still bleeding husbands, fathers and brothers. But they did not maintain this vengeful spirit for long. As the revolution gained territory they spared many of the men, women and children whom they surprised on plantations. To prisoners of war alone they remained merciless. They tore out their flesh with red-hot pincers, they roasted them on slow fires, they sawed a carpenter between his boards. Yet on the whole, they never approached in their tortures the savageries to which they themselves had been subjected.