IT’S A WHOLE NEW SEASON FOR TURKEY

TURKEY FARMERS OF CANADA IS EXCITED TO ANNOUNCE OUR NEW CANADIAN TURKEY ™ BRAND INITIATIVE.

In the coming weeks, we will be launching a national social media communications program to promote our new brand to Canadians. Working with online influencers, we will be able to share our news with broad audiences of engaged consumers who are ready to talk about turkey, their favourite turkey recipes and everyday dining experiences. The campaign will include extensive social media support on Twitter, Facebook and the web.

We’re hoping make some noise across a wide segment of Canadians and drive deep engagement in our brand messages. We’re also aligned with key partners for in-store retail presence and a quick service restaurant promotion.

Stay tuned…………..there’s much more to come from Canadian Turkey™.

MANAGEMENT: Reducing Antibiotics Management is key by Blake Wang, PhD, Senior Poultry Nutritionist, Wallenstein Feed and Supply

16

SUSTAINABILITY: More Eggs, Smaller Footprint

Major study shows huge environmental gains have been made at the same time productivity has risen in the Canadian egg industry over the past 50 years by Treena Hein

21

PRODUCTION: 10 Years of RWA Production

A producer’s experience by Kristy Nudds

25

PRODUCTION: Results from the 39th Layer Management Test

NCSU examines effect of layer strain, management system and housing by Dr. Peter Hunton

29

KNOWLEDGE: Helping Africans Farm Eggs

Eggs’ environmental footprint

Egg Farmers of Canada is helping make a successful multi-faceted facility in Swaziland become self-sufficient by Treena Hein 31

NUTRITION: Camelina: Potential New Feed Ingredient?

The “rediscovered” mustard plant is experiencing a resurgence due to high omega-3 and energy levels compared to canola by Karen Dallimore

FROM THE EDITOR

BY KRISTY NUDDS

Level the Playing Field for RWA

Concern over the use of antibiotics for growth promotion in livestock has been growing steadily, with consumer and healthcare groups pressuring livestock producers and food retailers to commit to raising animals without their use. The concern, as we know, has been over the development of antibiotic resistant strains being transferred to humans, as well as the possibility that antibiotics will no longer work against many common infections in the future.

But it’s not just a concern amongst consumers and healthcare providers anymore – now investment bankers are sounding the alarm. A large investment group, Farm Animal Investment Risk & Return (FAIRR) and the responsible investment charity ShareAction announced in early April that they have launched an “engagement campaign” with 10 of the biggest restaurant chains in the U.S. and the U.K. to end the non-therapeutic use of antibiotics important to human health in their global meat and poultry supply chains (see page 6). In a press release, the groups state they are “responding to warnings from the World Health Organization (WHO) that irresponsible antibiotics practices are leading the world towards a “post-antibiotic era” where routine operations will no longer be possible and many infections no longer treatable.” With $1 trillion in investments at stake, the investors feel not addressing antibiotic use in livestock is a risk that needs to be mitigated, now.

Many of the targeted companies in the U.S. have made some sort of public “commitment” and given a timeline for buying poultry and other meat products raised without the use of antibiotics (RWA) from their suppliers. Canadian companies have also made similar commitments.

However, the RWA classification is not the same in the U.S., Canada, and the EU. In Canada, the RWA definition set forth

by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) requires that for a product to be labeled RWA, no antibiotics (used for prevention of disease or to treat sick birds), ionophores or coccidiostats are allowed. Yet, in the U.S. and Europe, coccidiostats are allowed in RWA protocols, giving producers in these countries an unfair advantage.

To level the playing field, the Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) is currently working on a strategy to further reduce the preventative use of antibiotics of human importance, yet allow the preventative use of ionophores and chemical coccidiostats, which are not used in human medicine. CFC says the strategy responds to the call for reduced antibiotic use in poultry while maintaining antibiotic availability and efficacy for the benefit of animal health.

It calls for elimination of the preventative use of Category II and III antibiotics (preventative use for Category I antibiotics came into effect last year), yet allows an antibiotic to be used to treat acute disease. CFC would like to see the regulatory hurdle of allowing alternative products into the Canadian marketplace diminished, and for these products to have efficacy claims –something the CFIA currently does not allow. Also, CFC plans to incorporate the costs of using alternative products into the live price wants to harmonize the definition between the RWA in Canada versus the U.S.

It will take an industry–wide commitment to achieve this goal. This issue features two articles on the management changes and challenges associated with reducing or eliminating the use of antibiotics (see pages 10 and 21). Achieving the goal can be done, but management of the birds and the barn will be key and the cooperation between producer, veterinarian and nutritionist paramount. n

JUNE 2016 Vol. 103, No.5

Editor

Kristy Nudds – knudds@annexweb.com 519-428-3471 ext 266

Digital Editor – AgAnnex Lianne Appleby – lappleby@annexweb.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly – cconnolly@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext 231 Cell: 289-921-6520

National Account Manager

Sarah Otto – sotto@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext 237 Cell: 519-400-0332

Account Coordinator

Mary Burnie – mburnie@annexweb.com 519-429-5175 • 888-599-2228 ext 234

Media Designer Gerry Wiebe

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden – amadden@annexbizmedia.com 416-442-5600 ext 3596

VP Production/Group Publisher Diane Kleer – dkleer@annexweb.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation email: blao@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3552 Fax: 416-510-5170

Mail: 80 Valleybrook Drive, Toronto, ON M3B 2S9

Subscription Rates

Canada - 1 Year $ 30.95 (plus applicable taxes)

U.S.A. - 1 Year $ 66.95 USD Foreign - 1 Year $ 70.95 USD

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer

privacy@annexbizmedia.com

Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2016 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

www.canadianpoultrymag.com

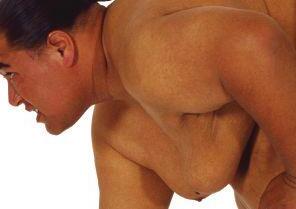

Sumo-Size your Line. Bottom

Customers struggling to get weights on their birds made the switch to OptiGROW Broiler Nipple Drinkers and immediately realized the difference it made on their Return On Investment. Make the change to OptiGROW Drinkers and OptiMIZE YOUR PROFITS!

To find out more about the new OptiGROW Nipple Drinking System please contact your local Lubing Distributor or visit our website at www.lubingusa.com. Heavy

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Tel: (519) 657.5231

Fax: (519) 657.4092

A Investors Weigh In on Antibiotics WHAT’S HATCHING HATCHING

$1 trillion coalition of 54 institutional investors has launched an engagement campaign with 10 of the biggest U.S. and U.K. restaurant chains, to call for an end to non-therapeutic use of antibiotics important to human health in their global meat and poultry supply chains.

The companies include J D Wetherspoon, McDonald’s and Domino’s Pizza Group. The coalition has been brought together by the Farm Animal Investment Risk & Return (FAIRR) Initiative and responsible investment charity ShareAction, with the support of U.S. investor group ICCR and U.S. non-profit As You Sow.

The investors are responding to warnings from the World Health

Organization (WHO) that irresponsible antibiotics practices are leading the world towards a “post-antibiotic era” where routine operations will no longer be possible and many infections no longer treatable. Academic research has established that the use of antibiotics in livestock is causing the development of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria that can spread to humans, and that antibioticresistant bacteria are transferring between humans and animals more frequently than initially thought.

The investors have written to 10 companies and asked them to set appropriate timelines to prohibit the use of all medically important antibiotics in their global meat and poultry supply chains. According to a new report – The restaurant sector and antibiotic risk – released April 11 by investor group FAIRR and responsible investment charity

ShareAction, half of the 10 global restaurant chains have no publicly available policies in place to manage or mitigate antibiotic overuse in their supply chains. None of the companies currently have a fully comprehensive policy on tackling antibiotic overuse.

The investors are concerned that a failure to confront irresponsible antibiotic use poses significant risks to their investments. These include the substantial risk of regulation as antibiotic overuse has increasingly become a target for stricter regulation in both the EU and U.S.; further regulation is highly likely. There is also the reputational risk of contributing to a global threat to human health, which currently kills an estimated 700,000 people per year.

A full list of investors signing the letter can be found at: www.fairr.org.

Broiler Producers Wanted for Trial

AUniversity of Guelph

M.Sc. candidate is looking for broiler farms willing to participate in on-farm research examining coccidiosis in broiler operations. The purpose of the research is to better understand coccidiosis caused by Eimera sp. The student is looking for 24 commercial broiler farms in southwestern Ontario, preferably in Niagara, Haldimand, Norfolk, Brant, Oxford, Middlesex, Wellington, Waterloo, Elgin, and Perth counties.

The farms must be registered with the Chicken Farmers of Ontario (CFO), and comply with OFFSAP. Participating farms can use either live coccidiosis vaccine or in-feed anticoccidials for control; no changes to existing coccidiosis control program are required.

Samples of chicken feces will be collected from inside

Cara Acquires St-Hubert Group

The managements of St-Hubert Group and Cara recently announced the signing of an agreement that will make Cara the owner of St-Hubert Group.

St-Hubert Group owns the St-Hubert Rotisserie chain, with 120 restaurants, primarily in Quebec, Ontario and New Brunswick, as well as St-Hubert

barns during chicken growout. The researcher will collect weekly samples from one flock at one through five weeks of age, once in summer (JuneAugust) and once in winter (December-February). The maximum number of on-farm visits is 14 (seven visits during two flocks).

Two brief surveys (optional), one before and one after each grow-out period, will be filled out with the assistance of a representative (less than 30 minutes to

Retail, the agrifood division that produces and distributes several food products in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. Cara manages a number of restaurant chains in Quebec and across Canada, including Swiss Chalet, Milestones and Harvey’s.

The deal, announced March 31, will enable both companies to realize their full potential. The current St-Hubert Group management team will continue to oversee operations, ensuring market practices are respected, both for customers and for employees

complete). Factors such as operations, practices and individual flock performances will be combined with the fecal test results to better understand coccidiosis in commercial broiler operations.

A summary of the study will be provided at completion of research that will outline the parasites identified in participating facilities.

Confidentiality is assured – each farm will be given an unrecognizable farm ID and participation in the study will not be made public/industry knowledge.

The researcher also assures that all farm-specific biosecurity protocols will be followed and full disinfection will take place before and after entering farms.

If interested in participating, please contact: Ryan Snyder, M.Sc. candidate, pathobiology, Ontario Veterinary College; phone: (905) 520-2066; email: snyderr@uoguelph.ca

and franchise owners. In addition, St-Hubert will maintain its head office in Quebec.

Jean-Pierre Léger, chairman and CEO of St-Hubert Group said this acquisition will create one of the largest restaurant and food-processing companies in Canada. It is part of a process aimed at ensuring the growth and sustainability of St-Hubert Group. He added that he will continue to be available to advise and support existing teams to ensure a smooth transition over the next few months.

Andrew Campbell of Strathroy has been named the 2016 recipient of the Farm & Food Care Ontario Champion Award. He was nominated for the award by the Middlesex Federation of Agriculture for his leadership in the social media movement in Canadian agriculture.

Joel Sappenfield will become the next president of CobbVantress. He will succeed Jerry Moye, who has been president since 2007 and announced earlier this year that he will be retiring in 2017. Sappenfield has held numerous poultry leadership roles with Tyson Foods since joining the company 1990.

Marla Robinson, Aviagen’s former marketing manager for North America, has been promoted to the position of global marketing director. In this role, Robinson will be responsible for promoting global consistency in communications and marketing strategies.

JOEL SAPPENFIELD

MARLA ROBINSON

ANDREW CAMPBELL

WHAT’S

HATCHING HATCHING

Walmart to Switch to Cage-Free by 2025

Walmart announced that it’s aiming to phase out the sale of eggs from caged hens by 2025, becoming the largest and most influential food retailer in the U.S. to set a deadline for switching to cage-free eggs.

The statement came two weeks after its Canadian group made an identical announcement with other Canadian grocery retailers.

Walmart, the largest grocer in the U.S., said it would require that egg suppliers adopt an industry standard for treatment of hens by 2025 and have their compliance monitored by a third party.

The new guidelines will apply to the discount retailer’s more than 5,000 stores in the United States, including its Sam’s Club warehouse chain.

Hendrix Genetics Concludes Coolen Hatchery Acquisition

HFrom LtoR: Albert van Driel (legal counsel, Hendrix Genetics), Antoon van den Berg (CEO, Hendrix Genetics), Henk Coolen (owner, Coolen Turkey Hatchery) and Wim Lemmens (corporate project manager)

endrix Genetics has concluded its agreement to purchase 100 per cent of turkey distributor Coolen Hatchery, the largest turkey hatchery in the Netherlands. Hendrix Genetics announced in October 2015 that it would be taking a controlling interest in Coolen.

Henk Coolen will continue on with Hendrix Genetics for the coming years in support of Hendrix Genetics Turkeys’ activities in the Netherlands. Future plans for the hatchery include the development of the traditional and bronze turkey markets.

JUNE 2016

June 15-17, 2016

Canada’s Farm Progress Show, Evraz Place, Regina. For more information, visit: www.myfarmshow.com

JULY 2016

July 11-14, 2016

Poultry Science Association Annual Meeting, Hilton New Orleans Riverside, New Orleans. For more information, visit: www.poultryscience.org

SEPTEMBER

September 5-9, 2016

XXV World’s Poultry Congress, China National Convention Center, Beijing, China. For more information, visit: www.wpc2016.cn

September 13-15, 2016

Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show, Canada’s Outdoor Park, Woodstock, Ont. For more information, visit: www.outdoorfarmshow.com

OCTOBER

October 4-6, 2016

Dave Libertini, managing director of Hendrix Genetics’ Turkeys Business Unit, said, “The addition of the Coolen hatchery strengthens our global network of turkey distribution.”

Antoon van den Berg, CEO of Hendrix Genetics, said, “Our organization is committed to the success of our clients around the world. This includes access to our genetics and the after sales support to help them reach the full genetic potential. This acquisition allows us to continue to serve the important grower base in the Netherlands.”

Poultry Service Industry Workshop, Banff Centre, Banff, Alta. For more information, www.poultryworkshop.com

We welcome additions to our Coming Events section. To ensure publication at least one month prior to the event, please send your event information at least eight to 12 weeks in advance to: Canadian Poultry, Annex Business Media, P.O. Box 530, 105 Donly Dr. S., Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5; email knudds@annexweb.com; or fax 519-429-3094.

Cover Story

Reducing Antibiotics Management is key to success

by Blake Wang, PhD, Senior Poultry Nutritionist, Wallenstein Feed & Supply Ltd.

Decades ago when the scientific community had concerns about bacterial resistance to antibiotics, the agricultural industry started to produce antibiotic-free (ABF) flocks. Generally speaking, all chicken is antibiotic-free, because there are no antibiotic residues in the meat due to the withdrawal periods in broiler production. So in the U.S., “antibiotic-free” is not allowed to be used on a label but may be found in marketing materials not regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In recent years, the term “raised without antibiotics” (RWA) is widely used for the flocks that are raised without the use of products classified as antibiotics for animal health maintenance, disease prevention or treatment of disease. However, it can mean different things depending on the country in which you are producing chickens. Table 1 below shows the different meaning of an RWA flock in Canada, U.S. and Europe.

Nutritionist Blake Wang writes that to successfully grow RWA flocks, one should provide good management and superior conditions by reducing stocking density, increasing downtime between crops, acidifying litter, and providing high-quality water

In Canada, absolutely no antibiotics, ionophores, or chemical coccidiostats are allowed in RWA production, whereas in the U.S., chemical coccidiostats are allowed for RWA flocks. This poses

Table 1. Medications and chemicals used in RWA flocks by country

even more challenges for Canadian RWA producers.

There are many factors that can affect broiler flock performance ranging from nutrition and health status of breeder flocks, hatchery operations, chick quality, nutrition and water quality to flock management. To successfully grow RWA flocks, one should not only provide good management and environmental conditions as for regular broiler flocks, but should create superior conditions such as reducing stocking density, increasing downtime between crops, acidifying litter, and providing high quality water. Nutritionally, well balanced rations formulated with high quality ingredients are crucial for RWA flocks.

CHICK QUALITY

A great flock starts with good quality chicks, and chick quality is even more important for broiler RWA production due to the lack of antibiotic protection. The feeding and management of broiler breeders can play an important part in the offspring’s health and performance. The breeder farms should follow strict biosecurity protocols, and breeders should receive a well-balanced and nutritionally adequate diet. Eggs should be handled in a professional

RWA MANAGEMENT

A

manner and stored in ideal conditions.

Hatcheries should follow a strict biosecurity program, with regimented cleaning and disinfection procedures. Chick boxes and hatcher trays have to be washed with correct temperatures. Good maintenance of hatching temperature and ventilation equipment is critical, as it has been shown that stress from late stage over-heating may result in leg problems and performance issues. Transport can be stressful for chicks. The temperature should be tightly regulated in the compartments with proper ventilation. To ensure uniform chick quality, there should be no over-heating in some areas while dead spots exist in others.

COCCIDIOSIS VACCINATION

Unlike RWA producers in the U.S., Canadian RWA producers cannot use chemicals to control coccidiosis, so the only option is vaccination. Coccidiosis control is key for successful RWA production, because it impacts intestinal integrity, gut health and is correlated to the risk of necrotic enteritis. Uniform vaccine application and uptake are essential for successful protection from a coccidiosis vaccine. The stocking density for the first seven days should be controlled at a half square foot per chick (or 465 cm2/bird), and litter moisture kept higher than normal at 30 to 35 per cent. The higher density and litter moisture will encourage oocyst sporulation and the opportunity to re-infect each other from their droppings. Thus, the immunity to coccidiosis will be developed earlier, and the flock will be better protected from coccidiosis.

FLOCK MANAGEMENT

Stocking density after 10 days of age is also one of the most

important factors that affect RWA flock performance. A minimum density of one square foot per bird is ideal. When the density is reduced, birds have more water line and feeder space, less competition for feed and water, better litter conditions and fewer pathogen challenges.

For RWA broiler production, the litter quality is crucial. The wetter the litter, the more likely it will promote the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and moulds. Wet litter is also the primary cause of ammonia emissions, one of the most serious performance and environmental factors affecting broiler production today. Controlling litter moisture is the most important step in avoiding ammonia problems. There are many factors that can affect litter conditions, such as leaking water lines, various diseases, improper rations, and ventilation.

Ventilation removes combustion waste by brooders, ammonia, and moisture produced by birds while continually replenishing oxygen. Broiler genetics keep improving, and broilers grow faster every year, so their demand for oxygen is increasing all the time while their output of moisture is also increasing. Thus, producers should not use the ventilation rate of 10 years ago to grow today’s birds. Adequate and effective ventilation is critical for litter management and coccidiosis control, especially for RWA production.

Producers should check and manage watering systems to prevent leaks that would increase litter moisture. Furthermore, producers should adjust drinker height and water pressure as birds grow to avoid excessive water wastage into the litter.

Chick growth rate should be moderately controlled to avoid fast weight gain. This is particularly important in a flock that is 10 to 30 days of age, when there is more challenge from coccidiosis,

great flock starts with good quality chicks, and chick quality is even more important for broiler RWA production due to the lack of antibiotic protection

Cover Story

thus a higher risk of necrotic enteritis. Producers should modify the lighting program, by slightly increasing dark hours to nine or even 10 hours, in order to improve the health condition and immunity of the birds. This modification is even more necessary for RWA flocks than for regular flocks.

NUTRITION FOR RWA FLOCKS

Sound nutrition starts with a good selection of high-quality ingredients. Composition of feed ingredients should be consistent, and all grains should be free from toxin contamination. This is critical for the first four weeks of age. Nutritionally, all ingredients should be highly digestible, since the nondigested portions might enhance unwanted microbial growth and increase the chance for necrotic enteritis. The maximum inclusion rate for some ingredients such as wheat and corn distiller grains must be closely monitored, if not eliminated. There is evidence that suggests a strong relationship between higher inclusions of these ingredients with necrotic enteritis. Some reports suggest that animal protein may increase the risk for necrotic enteritis. It is generally accepted that lower crude protein levels should be fed to RWA flocks, because higher protein may increase the chance for necrotic enteritis. Mineral balance is vital for RWA rations. Mineral levels that are either too high or too low will not only affect broiler body weight

gain and feed conversion ratio (FCR), but also impact litter quality, gut health, and hence flock performance.

With reduced growth and high-quality ingredients, the RWA feeds can cost more than the regular feeds. Together with a higher FCR for RWA flocks, it will result in a higher feed cost per kilogram of body weight gain.

ALTERNATIVE FEED ADDITIVES

Over the last few decades, there has been a lot of research to explore alternatives for antibiotics in broiler production. Generally, these alternatives are categorized into feed enzymes, phytogenic additives, probiotics, prebiotics and symbiotics (a probiotic and prebiotic combination). Feed enzymes which help improve the digestion and nutrient utilization, and in some cases improve gut health, are widely used by nutritionists in both regular feeds and RWA feeds.

Phytogenic additives (herbs, spices, essential oils or extracts) that originate from plants have been used in human food and medicine for thousands of years. Among these phytogenic products, essential oils have received considerable attention. Their active ingredients such as carvacrol, thymol, eugenol, alicin and cinnamaldehyde have been evaluated extensively as alternatives for antibiotics to improve animal health and performance. Some phytogenic products have direct antimicrobial effects, and other products show their effects on immune-regulation.

Probiotics are also called direct fed microbial (DFM) in the U.S. The mode of action is to compete for available receptor sites and nutrients with pathogens, and produce or secrete metabolites (such as short chain fatty acids and bacterocin), thus changing the gut microflora and bird performance.

Prebiotics are feed components that are not digested by host animals but selectively promote beneficial bacterial growth, hence improving animal performance. In this category, some commonly used products are mannan-oliglosaccharides (MOS) and fructooliglosaccharides (FOS).

There has been considerable research done to investigate the effects of these alternative products on animal performance and health. Yet, the responses are quite variable due to the purity and concentration of these products, how they interact with flock management and health conditions, as well as the nutritional status of the birds.

SUMMARY

To date, there is no silver bullet as an alternative to antibiotics. In conclusion, a decent RWA flock relies on the following factors:

1. Good quality chicks that come from a healthy breeder flock and well managed hatchery;

2. A successful coccidiosis vaccination program with higher stocking density and higher litter moisture for the first 10 days;

3. Sound management practices with an emphasis on improving ventilation and reducing litter moisture;

4. An RWA ration formulated with highly digestible ingredients and optimized mineral levels;

5. Moderately reduced growth by providing more dark hours. n

CPRC Update Poultry Research Strategy Evolving

BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHANGES

CPRC held its Annual General Meeting in March followed by a meeting of the board of directors. Two new directors joined the board replacing longtime directors who had decided to step down. Roelof Meijer, an eightyear board member representing Turkey Farmers of Canada (TFC) and chair for the past three years, was replaced by Brian Ricker from Ontario. Cheryl Firby, the Canadian Hatching Egg Producers (CHEP) board member has been replaced by Murray Klassen from Manitoba.

Tim Keet (Chicken Farmers of Canada) was elected chair with Helen Anne Hudson (Egg Farmers of Canada) elected vice-chair. Erica Charlton (Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council) was elected as a member of the executive committee along with the chair and vice-chair.

POULTRY SCIENCE CLUSTER

The Poultry Science Cluster, co-funded between industry, provincial governments and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) has completed year three of its five-year research plan. The cluster, the second that CPRC has administered, is a $5.6 million program with $4 million from AAFC and the balance from industry and provincial governments. Seventeen research projects in four categories make up the cluster, details of which can be found at www. cp-rc.ca/poultry-science-cluster-2/.

The Poultry Science Cluster runs from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2018 and some research projects are being completed. Two projects were scheduled to be completed by March 31, 2016, and are winding up with final

analysis and reporting underway. Ten projects are scheduled to be complete by the end of March 2017 with the final five projects being completed by the end of the cluster in March 2018.

POULTRY RESEARCH STRATEGY UPDATE

CPRC has begun a process to update the 2012 document National Research Strategy for Canada’s Poultry Sector , which formed the basis for much of the research structure of the Poultry Science Cluster. While much of the strategy remains relevant many of the research priorities identified have evolved and new issues have become important to the poultry industry. Two new priority areas, climate change impacts and precision agriculture, were added to this year’s CPRC call for Letters of Intent.

The strategy update is designed to validate and/or amend priorities from the 2012 document and to identify new priority areas since 2012. Issues that may be on the horizon but have not yet become poultry research initiatives will also be identified. The update will seek input from producers through the national and provincial representative organizations, scientific community including university and government, and other industry stakeholder organizations representing a broad range of value-chain members. Consultations will include surveys and webinars to gather information as well as to seek feedback on the updated strategy as it is developed. Target completion of the research strategy is early in 2017 so it can be used as the basis for a new application if a third science cluster program is included in the next federal-provincial agreement upon the expiry of the current Growing Forward 2 initiative.

NEW CPRC WEBSITE

The April CPRC Update announced that CPRC has a new website. Changing a website is a lot more than having someone do a new design. All of the material on the website has to be reviewed and decisions made on what should stay, what should go and new material that should be added. An important part of the CPRC website is the research summaries that are posted on all CPRC co-funded projects. A review of those summaries indicated that there were several formats being used, particularly during the last several years, and some project summaries had been missed. A format was adopted, very similar to one of those that had been used, and CPRC has reviewed all summaries, and edited them as necessary, to ensure consistency in presentation.

CPRC, its board of directors and member organizations are committed to supporting and enhancing Canada’s poultry sector through research and related activities. For more details on these or any other CPRC activities, please contact The Canadian Poultry Research Council, 350 Sparks Street, Suite 1007, Ottawa, Ontario, K1R 7S8, phone: (613) 566-5916, fax: (613) 2415999, email: info@cp-rc.ca, or visit us at www.cp-rc.ca. n

The membership of the CPRC consists of Chicken Farmers of Canada, Canadian Hatching Egg Producers, Turkey Farmers of Canada, Egg Farmers of Canada and the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors’ Council. CPRC’s mission is to address its members’ needs through dynamic leadership in the creation and implementation of programs for poultry research in Canada, which may also include societal concerns.

Sustainability More Eggs, Smaller Footprint

Major study shows huge environmental gains have been made at the same time productivity has risen in the Canadian egg industry over the past 50 years

BY TREENA HEIN

Fifty years of sustainability analysis and insight – that is what Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) recently commissioned Canadian consulting firm Global Ecologic to produce. The report is entitled: “Environmental Footprint of Canadian Eggs: 1962 versus 2012.”

EFC CEO Tim Lambert says the study results demonstrate the way Canadian egg farmers have been, and still are, constantly looking for new ways to make egg production more efficient and environmentally sound. “While egg production increased by more than 50 per cent between 1962 and 2012 [from about 43 million dozen to 66 million dozen eggs per year],” he notes, “the industry’s overall environmental footprint decreased across all emissions and resource use domains.” Indeed, Nathan Pelletier (president of Global Ecologic) found the average environmental impact for eggs produced in conventional housing systems in 2012 was roughly one-third of what it was in 1962.

To begin the study, Pelletier identified the average conditions that existed in the egg production supply chains of 2012 and 1962, and measured supply chain water, land and energy use, as well as greenhouse gas, acidifying and eutrophying emissions.

While egg production increased in Canada by more than 50 per cent between 1962 and 2012, the industry’s overall environmental footprint decreased across all emissions and resource use domains by one-third

For this, he relied on recent environmental life cycle analysis done for EFC that outlined the state of the industry in 2012, and also drew from various sources to gain insights into the realities of 1962. Taking these conditions, uses and emissions, he then evaluated the resource and environmental performance gains linked to specific advancements over the past five decades, differentiating between changes attributed to supply chain versus farm-

level activities.

However, any study that involves gathering and analyzing data from decades ago has potential challenges. “Important to conducting an analysis such as this is to know in advance which variables really matter, and to focus data collection activities accordingly,” Pelletier explains. “For example, having previously evaluated contemporary egg production systems in both the US and Canada, as well as a

MORE WITH LESS

variety of other livestock production systems, I knew that gathering representative data for variables such as feed composition, feed conversion efficiency, rate of lay, and mortality rates in the early 1960s would be quite important for the overall results. Fortunately, 1960s data for these variables are available in peer-reviewed literature, Canadian random sample egg production test data and from Statistics Canada.” Pelletier also found good information on such factors as fertilizer production, and inputs and yields for feed production.

Pelletier found that compared to 1962, Canadian egg industry acidifying emissions (those that cause acidification of freshwater systems, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) of 2012 were a whopping 61 per cent lower. Eutrophying emissions (those that lead to excessive nutrients in waterways, resultant explosive plant growth such as algal blooms and death of animal life due to lack of oxygen; sulfur

dioxide, nitrogen oxides and ammonia) were even lower (68 per cent). Greenhouse gas emissions were 72 per cent lower. The energy, land and water use in the entire supply chain decreased by 41, 81 and 69 per cent respectively.

Pelletier notes the Canadian egg industry was in transition to cage-based production during the 1960s, and explains that the specific mix of housing systems does not really matter for an analysis such as this. “What is important are hen performance data (e.g. rate of lay, mortality, etc.), whatever the housing system employed. Quite good data are available for these variables.”

REASONS FOR IMPROVED PERFORMANCE

As you can imagine, the Canadian egg industry’s much-diminished environmental footprint compared to fifty years ago is

due to several factors. The most important of these is changes, for both layer and pullet feeds, in feed composition, feed conversion efficiency, and the environmental footprints of specific feed inputs. Layer feeds in 2012 had, on average, just 38 per cent of the overall environmental impact of those of 1962, and pullet feeds 69%. This is because the average impact per tonne of production of feed ingredients improved, such as a 43 per cent decrease for corn in 2012 compared to 1962. It’s also because general inputs for field crops also dropped. Pelletier found, for example, that the energy required for ammonia synthesis (used to make nitrogen fertilizer) was cut by half over the study period. Improved crop yields and higher fuel efficiencies in freight transport also contributed. In addition, the amount of meat/bone/feather meals and fats in feed has dropped over the last 50 years, and these inputs have a much higher environmental impact compared to

Watering Wisdom u

STANDARDIZING WATER COLUMN PRESSURES FOR ALL DRINKER MODELS DOES NOT WORK. SEE VIDEO THAT PROVES IT.

Some think you can establish specific column pressure settings that work for all brands and models of poultry drinkers.

Sustainability

ingredients whose use has risen over the decades, such as soy meal.

Other important industry improvements include improved animal health and higher productivity in pullet and egg production. Production per hen has improved by almost 50 per cent and feed conversion efficiency by 35 per cent, while the combined mortality rate for pullets and layers declined by 63 per cent.

See a video at poultrywatering.com that shows how the same water column pressure can result in wet litter under one drinker model and potentially too little water discharge with another drinker model. The take away is that column pressure settings cannot be standardized across all brands and models. Each model requires it own unique column pressure settings throughout the production cycle to ensure ample water discharge without creating wet litter.

For a complete understanding of important concepts in poultry watering watch all the videos at poultrywatering.com

www.PoultryWatering.com

• How-to videos

• Poultry Watering U news

• Management downloads

Energy use, however, was the least improved factor, and Pelletier says this is because current energy production involving fossil fuels requires more input energy (for extraction and processing, etc.) than it did 50 years ago. “Without the changes we’ve seen in feed composition and efficiencies at the level of pullet and egg production,” he notes, “contemporary egg production would be considerably more energy intensive, simply due to the declining efficiency of fossil energy provision over time.”

U.S. RESULTS

Several years ago, Pelletier and colleagues from other organizations conducted a similar 50-year comparison of life cycle environmental impacts for egg production in the U.S. (1960 compared to 2010). Feed efficiency was the biggest factor. “The feed conversion ratio for egg production improved from 3.44 kg/kg in 1960 to 1.98 kg/kg — a gain of 42 per cent,” he notes. “Nonetheless, achieving feed use efficiencies comparable to the best performing contemporary facilities [the range reported by survey respondents was 1.76-2.32 kg/kg] industry-wide would do much to further reduce overall impact.”

As it has in Canada, differing feed composition has also played an important role in reducing impacts — in particular, both reduction in the total amount of animal-derived materials used, as well as increased use of porcine and poultry materials in place of ruminant materials.

Sustainability

OVERALL USE OF STUDY

Pelletier sees several uses to which the study results can be put. “First, they help us to understand the relative importance of specific variables in changing the environmental footprint of Canadian egg production,” he notes. “This knowledge will inform

future efforts to continue to improve the sustainability of Canadian eggs in terms of priority areas for targeted management initiatives.” The results, in Pelletier’s view, also provide valuable benchmarks. He says looking forward individual producers as well as the industry as a whole will be able to measure their sustainability performance

and track their progress relative to these benchmarks.

Finally, the study results provide solid evidence of the progress that the Canadian industry has achieved. “The results are also a source of inspiration for the future,” Pelletier says. “When I think about what has been accomplished over the past 50 years, I’m excited to imagine what will be possible over the next 50! The next steps, I believe, are for the industry to collaborate in defining a sustainability agenda, along with metrics, targets and milestones for sustainability initiatives looking forward.”

Lambert agrees. “Egg Farmers of Canada is becoming recognized as a global leader in agriculture for its commitment to society through its sustainability initiatives and dedication to social responsibility,” he says. “This 50-year study provides a firm foundation for the industry’s sustainability initiatives going forward, setting out benchmarks by which we can continue to measure progress. Understanding the components of the industry’s environmental footprint ensures that we can work with our producers and stakeholders to make sound, sustainable choices for the future.” n

PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN CANADIAN EGG PRODUCTION FROM 1962 TO 2012, PER TONNE OF EGGS PRODUCED

• Acidifying emissions 61% lower

• Eutrophying emissions 68% lower

• GHG emissions 72% lower

• Energy use 41% lower

• Land use 81% lower

• Water use 69% lower

• Feed conversion rate 35% increase

• Production per hen housed 50% increase

• Mortality rate (pullets) 21% lower

• Mortality rate (layers) 75% lower

Percentage change between 1962 and 2012, industry-wide

• Acidifying emissions 41% lower

• Eutrophying emissions 51% lower

• GHG emissions 57% lower

• Energy use 10% lower

• Land use 71% lower

• Water use 53% lower

• Egg production 51% higher

Production

10 Years of RWA Broiler Production

A producer’s experience

BY KRISTY NUDDS

While antibiotics and anticoccidials have been very effective in managing coccidiosis and clostridium, broiler growers are now faced with learning how to maintain production efficiencies without them.

It can be done, says Jefo technical services manager Derek Detzler. He grows about 90,000 birds/cycle in “normal” two-story barns in Ontario and started raising them without antibiotics a decade ago. But when he started the path to antibiotic reduction, there was no demand for antibiotic-free chicken. So why change?

Prior to joining Jefo, Detzler was manager of research and development of Fischer Feeds, a privately owned, independent feed

manufacturer near Listowel. “We started to see coccidiosis outbreaks in some of the flocks I was working with,” he told growers in a well-attended seminar during the B.C. Poultry Conference in Vancouver. “The drugs we were using were losing efficacy and we expected we wouldn’t get any new products.”

Wanting to restore sensitivity to the anticoccidials that were being used, Detzler says in 2004 they opted to trial a coccidiosis vaccine, applied at the hatchery, for three continuous cycles, as U.S. data showed that would be enough to repopulate the barn with Eimera oocysts not resistant to the anticoccidials. The first flock, as expected, had reduced ADG and an increased FCR. The next two flocks “did OK, not spectacular, but OK,” Detzler says.

clean-out of barns in Canada meant oocysts were removed from the barn, which could prove counter-productive to “seeding” the strains, and they didn’t change the nutrition – feeds were formulated based on the use anticoccidials, not taking in to account a potential challenging cycling period of the vaccine.

“We were very curious to know how the vaccine worked,” says Detzler. In theory, the four to six days after the vaccine is applied, the chicks should shed oocysts, pick these up again from the barn a few more times, and develop immunity to coccidiosis by days 26-30. But Detzler says they didn’t know if this was happening, so they made the “big commitment” to learn how to count oocysts.

15HY010-HybridDramaticAds_1/4page(4)_CanadianPoultry_vf_3.pdf 1 2015-07-28 11:23 AM

Surprisingly, when an anticoccidial was used again, lack of efficacy was observed due to persistent coccidiosis breaks. They wondered why, and then realized they hadn’t given the vaccine a fair chance. Mandatory

For five years, feces were collected from each barn every three days from day five onwards and oocyst counts recorded. The data was “fascinating” and after two to three years, Detzler says they had a great handle on when and how coccidiosis would

cycle in the barns based on standard management SOPs.

With complete control of coccidiosis, the next step was to try and reduce the use of AGPs, with the eventual goal of eliminating them, he says. They knew clostridium didn’t play a role until about day 12 (when they would start to see necrotic enteritis, or NE), so they first removed the AGP in the starter feed, and used an alternative product instead in what he calls “a strategically defined antibiotic reduction program” and achieved results that were equal to AGP use in the same period. With success in the starter, “we targeted the same strategy in the finisher/withdrawal phase and observed the same thing – no loss of performance.”

The next step proved to be the toughest – removal of the AGP during the challenge time of coccidiosis cycling. They knew that the chances of NE were greater during the time of oocyst cycling, so they looked at

Production

how to optimize or limit cycling. They knew they had a low number of oocysts being shed in the barn at a time when it was critical for the bird to reingest them.

Even application of vaccine at the hatchery is key, he says. They also looked at adding moisture to the barn during brooding to help oocysts sporulate. Although they had no idea how much moisture to use, Detzler says they used existing misting systems to create a moist area. Chicks were also kept confined within brood guards to increase density while shedding. By doing this, they “saw a huge shift in oocyst cycle patterns,” he says. It was concluded that proper cycling of the vaccine was “paramount” for removing AGPs.

To address other challenges associated with coccidiosis, they looked at the feed. Protein levels were reduced, and vegetarian sources increased, as there is evidence that undigested protein and animal proteins increase the risk of NE.

They tried playing with different density levels but Detzler cautions that whatever density is used, “don’t vary from it. If you do, it will affect vaccine cycling.”

If birds are breaking with NE, he says, it’s happening for a reason and what’s key is to observe, learn and benchmark. “It’s not easy to figure out, but persistence and commitment will get you through it.”

Supplemental feeding in the first five days is also used to promote gut and immune health. In addition to vaccination, probiotics, organic acids and essential oils are used instead of AGPs. “As of today, the mortality in our RWA flocks closely mirror conventionally raised birds,” he says.

Detzler admits the changes have added costs, noting his FCR can be four to eight points higher.

He says there is no “silver bullet, but if you’re committed, benchmark, and willing to learn to adopt new management techniques, it’s certainly possible.” n

Production Layer Management Test Results

The 39th NCSU test examines effect of layer strain, management system and housing

BY DR. PETER HUNTON

North Carolina State University (NCSU) is the only remaining venue in North America at which comparative testing of egg laying stocks takes place. At one time in the mid 1960s, there were more than twenty locations in the U.S. and Canada where Random Sample Laying Tests were conducted. Instead of abandoning testing altogether, NCSU chose to superimpose a variety of management systems, cage sizes and configurations on top of the strain comparisons.

In the 39th test, stocks were exposed to the following: conventional cages, enrich-

able cages, enriched colony housing, cagefree and range.

A total of 20 strains from six different breeding companies were included. Of the 20 strains, 14 have wide commercial distribution in the southeast U.S., while the other six are either experimental or have limited or no distribution. With respect to Canadian distribution, most of the stocks available here are included in the test. Dayold chicks were supplied either by breeders or commercial distributor hatcheries.

CONVENTIONAL CAGE RESULTS

Two cage densities were used: 69 sq. in. (445 cm2) and 120 sq. in. (774 cm2). The higher density (445 cm2) approximates to commercial practice, although space allowances are progressively increasing.

Comparing the cage densities showed that in white-egg hens housed at 774 cm2/ hen, feed intake was higher by 10 g/bird/ day, eggs per hen housed was higher by 7 eggs/hen and mortality lower by 0.86%.

Comparing the strains is complex. Table 1 shows some key data for all 12 white-egg strains tested. Feed intake varied from 96 to 110 g/hen/d. This is, of course reflected in the feed cost data. The strain with the lowest feed intake (Hy-Line CV26) also had comparatively low egg production and egg weight, and thus low value of eggs minus feed. However, the strain with the next lowest feed intake (Shaver White) had much higher egg production, modestly higher egg weight, and very favourable value of eggs minus feed.

15HY010-HybridDramaticAds_1/4page(4)_CanadianPoultry_vf_3.pdf 2 2015-07-28 11:23 AM

Summaries of the data were prepared from 119 to 483 days of age. The flocks were then moulted and data was again summarized at 763 days of age. Only the first cycle (to 483 days) data are reviewed here.

what does trust mean?

With two exceptions, the numbers of eggs per hen housed were quite uniform. Statistical analysis showed that most of the strain differences were not significant. Those with production >317 eggs/hen housed were significantly different from those with production <300. Mortality data are not shown, but mortality was low,

averaging 3.9%, and no significant strain differences were observed.

Egg weight was also quite uniform. The average of 60.1 g/egg leads to size categories of approximately 63% extra large, 22% large and 8% medium. For each 1.0 g increase in average egg weight, approximately 5% of the large size move to extra large. In the test situation, extra large eggs were priced approximately three cents per dozen more than large. In most Canadian situations, this premium does not exist. However, when egg weight falls 1.0 g below average, the number of medium size eggs increases two to three per cent, which causes a significant financial penalty.

Turning to the nine brown-egg strains, the first thing to note is the difference in performance between the two cage densities. Brown-egg hens given more space (774 cm2 versus 445 cm2) consumed 11 g more

1.

Production

feed/d, and laid 16 more eggs/hen housed. Mortality was 2.5% less in the larger space, although this difference was not statistically significant. The data, when combined, showed an extra $1.00 in egg value minus feed cost for the higher space allowance. For the white-egg strains, the difference was only $0.28.

The brown-egg strains feed consumption varied from 103 to 110 g/hen/d, and hen-housed production from 304 to 314 eggs. Few of these differences were statistically significant. With one exception, the values for egg income minus feed cost were also quite uniform. One is impressed by the relatively small differences between the white and brown-egg strains in these comparisons. Feed intake was actually lower among the brown-egg strains; egg numbers and egg weight were only marginally lower. Traditionally, one would expect higher feed

intake and egg size for the brown strains.

ALTERNATIVE HOUSING

Enrichable cages (EC) are 66 cm x 61 cm with 9 birds/cage (447cm2/hen). The cages are belt cleaned. Enriched colony housing (ECS) is the same style of cage but 244 cm wide and includes a nesting area and a scratching area of 1.85 m2 each, plus two perches each 123 cm long. Two bird densities were compared in this system: 36 hens/cage (447 cm2 each) and 18 hens/ cage (897 cm2 each).

Cage-free housing consists of a combination of slat floor and litter, with nest boxes and perches. Each pen is 7.4 m2 and holds 60 hens in the adult phase (8.1 birds/ m2). Birds in this system were grown in the same pens used for the laying phase. The range system, used for only three

Table 3. Comparison of mortality under different housing systems, 119-623 d of age

Table 2. Data from 9 brown-egg strains tested at the North Carolina 39th Egg Production and Management Test. (data for the two cage densities are combined)

Table

Data from 12 white-egg strains tested at the North Carolina 39th Egg Production and Management Test. (data for the two cage

strains, consists of pens 3.7 m x 2.0 m holding 60 hens. They have access to 334 m2 of grass pasture. The pasture is divided in two

Production

and rotated every four weeks.

Not all strains were exposed to all of these environments. For example, only two

10

8

8

7

8

2

8

Table 5: Highest egg value minus feed cost datum for each management system

10 white strains, enrichable cages, 447 cm2

10 white strains, enriched large colony, 447 cm2

10 white strains, enriched large colony, 897 cm2 Babcock White 28.38

8 brown strains, enrichable cages, 447 cm2 Lohmann LB-Lite 26.09

8 brown strains, enriched large colony, 447 cm2 ISA Brown 24.55

8 brown strains, enriched large colony, 897 cm2 Lohmann LB-Lite 26.40

7 white strains, cage-free system Lohmann LSL-Lite 26.29

8 brown strains, cage-free system Lohmann LB-Lite 26.80

brown-egg strains and one white-egg strain were tested on range. All except two strains experienced the enrichable cages and the enriched colony system. This makes it hard to compare both the strains and the environmental systems, but we can draw a few conditional conclusions.

All birds were moulted during the test, which lasted until 623 days of age.

COMPARING ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS

Ten white egg strains were exposed to both EC and ECS systems. The most striking difference between these was with respect to laying house mortality. When hens were housed at 69 sq. in./hen, the ECS system showed 23% laying house mortality compared with 16% for the hens in smaller cages, but the same space allowance. While both values are extremely high for contemporary laying flocks, the larger colonies were clearly at a disadvantage. Mortality for the same strains in conventional cages in a different building was 4.3%. Brown-egg strains compared in the same conditions showed overall lower mortality and no differences between ECS and EC. Among the white-egg strains, only Hy-Line W36 had relatively low mortality (6.0% and 7.4% in

15HY010-HybridDramaticAds_1/4page(4)_CanadianPoultry_vf_3.pdf 3 2015-07-28 11:23 AM

Table 4: Feed intake and egg production in different management systems, 119-623 d of age

ECS system at two different densities (447 cm2 versus 897 cm2) showed a definite benefit to the lower density. Mortality was only 9.9% versus 23%. Brown egg strains also benefited from the more generous space allowance, although to a lesser extent: 7.1% mortality versus 10.9%.

Seven white egg strains housed in the cage-free system showed mortality of 14.3%; eight brown egg strains had 15.6%. On free range, the one white egg strain tested had 13.3% mortality, while two brown egg strains averaged 3.75%.

While there were some strain differences in mortality within management systems, the general conclusion must be that large colonies and higher densities are associated with higher mortality. This is not a new discovery but one that is not encouraging for those producers planning on meeting the demand for cage-free or even furnished cage management systems.

Feed intake and egg production were also affected by management system, as shown in Table 4. In general, birds in larger colonies tended to consume more feed. This may be because of perceived increased competition in the larger colonies. Feed consumption was also higher in the cage-free and free range systems. As to egg production data, there were no real trends and the figures for the brown strains kept at 447 cm2 do not appear to be consistent with the other data.

Because of the fact that not all strains were tested in all environments, it is not possible to make realistic comparisons between them. Presented in Table 5 are the highest ranked “Egg value minus feed cost” data for each of the environmental systems.

Most notable among these data are the low values for the freerange flocks. These reflect relatively low egg production and high feed cost. As in conventional cages, the greater space allowance in the enriched cages resulted in higher values for egg income minus feed cost. Whether this would offset the higher cost associated with the extra space is doubtful.

All told, these data from the North Carolina Laying Test are of interest but this is limited by the very high mortality experienced in all but the conventional cage systems. Causes of mortality are not reported. As noted above, higher mortality is frequently associated with large colonies and with non-cage systems. This runs counter to the popular belief among consumers that bird welfare is improved in such systems. Until the systems can be improved, or consumers become more accepting of small colonies or conventional cages (unlikely in this writer’s opinion) industry will be faced with higher costs while producing eggs to meet the demand for cage-free eggs.

For those interested in the complete data from the test, they are available online at https://poultry.ces.ncsu.edu/layerperformance/ n

Knowledge Helping Africans Farm Eggs

Egg Farmers of Canada is helping make a successful multi-faceted facility in Swaziland become

self-sufficient

BY TREENA HEIN

It’s an amazing thing to be a part of an initiative that’s already making a significant difference, to be able to help take it to the next level and make further progress. That’s what Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) is achieving, having spearheaded and funded the addition of an egg farm to “Project Canaan,” a sustainable farming and economic development initiative in Swaziland, Africa. Project Canaan was started by an Ontario couple in 2009 under their charity “Heart for Africa.” Although Janine and Ian Maxwell had no farming

background, they enlisted the help of experienced folks and turned 2,500 acres of empty land into a thriving mixed farm and rural community.

The site boasts dairy cow and goat operations, along with cultivation of fruit, vegetables and cash crops and creation of hand-made items. The farm feeds the 86 orphans who make a home there, the 220 local employees and thousands of people through local church-sponsored food programs. The egg farm is the next step in making the charity’s farm, orphanage, schools, women’s shelter and medical clinic self-sustaining by 2020.

EFC’S INVOLVEMENT

pendent charitable actions being taken by IEC members (such as EFC) into a cohesive strategy, forming the International Egg Foundation. It now works with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Health Organization and other groups. For the Project Canaan egg farm, the fundraising, expertise and training is being provided by EFC, and the IEC is providing supports such as the technical services of Ontario poultry vet (and IEC scientific advisor) Dr. Vincent Guyonnet.

EFC chair Peter Clarke has visited Project Canaan several times, most recently in December 2015. He’s been involved from the start, ever since Janine presented the project to the IEC many years ago. He and others looked into the initiative in detail, were satisfied with its legitimacy, and presented it to the EFC board. There was unanimous support, and a project team then was formed to make egg production on the farm a reality.

15HY010-HybridDramaticAds_1/4page(4)_CanadianPoultry_vf_3.pdf 4 2015-07-28 11:23 AM

IN YOUR WORLD

EFC has long been involved in food assistance programs around the world, for example, sending over 16 metric tonnes of egg powder per year to feed children in developing countries over the last 20+ years. In 2014, the International Egg Commission (IEC) brought various inde-

what does perspective mean?

“We put the call out to our industry

last year, and our partners and Canadians responded with compassion and generosity,” says EFC CEO Tim Lambert. “Much of the funding for the project was the result of donations and in-kind contributions. The outcome of this collective effort yielded truly amazing results - more than $700,000 has been raised to date to support the construction of the operation and help with operating costs. We remain committed to fundraising to support the ongoing costs of operating the farm until it reaches self-sufficiency.”

The layer operation at Project Canaan welcomed its first flock of 2,500 hens in January and a second flock of 2,500 will arrive in July. The design of the two barns had to account for the extreme heat the country is exposed to. “The buildings are higher than normal,” Clarke explains, “so that the heat rises and goes out the vents, and there are also fans that help with that. The buildings are also open-sided, with

Knowledge

curtains that can be opened or closed to let the breeze blow through. The birds are doing extremely well.” The two-tier Big Dutchman cage system that was chosen is made for remote areas and has a simple design so it can be operated with little or no electricity, Lambert explains. “Feeding, egg collection and manure removal is carried out manually,” he says. “More staff will be hired to manage and operate the farm over time. This fits Heart for Africa’s philosophy that providing employment creates a ripple effect within the community.”

In addition to EFC board members, several other Canadian egg farmers have volunteered to work hand-in-hand with local Swazis to share knowledge and build an understanding of best practices. “This has become a unique opportunity for some of the young leaders in our industry,” Lambert notes. “New Brunswick egg farmer Aaron Law spent much of January in Swaziland, followed by Ontarians Isaac

Pelissero in February, and Megan Veldman and Lydia DeWeerd in March. All of these young people have shown a tremendous amount of leadership and compassion, and we are very proud that they stepped up to share their expertise.”

EFC intends to implement the Project Canaan model in other areas of Swaziland as well as other African countries. “It is part of our belief that the egg can and will play a major role in the world’s approach to hunger and malnutrition, helping children and families in developing countries where diets are deficient in protein,” Lambert says.

What stood out for Clarke on his visit was the impressive agricultural expertise that exists in Swaziland. He notes the team made a connection with a large poultry operation nearby to deliver both pullets and feed. They are currently working with a local nutritionist and veterinarian as well. For Clarke, motivation to be involved in Project Canaan is all about the huge difference it is making. “From hearing Janine’s presentation to our board, getting support from producers coast-to-coast and then going there and seeing what they’re doing with orphans, seeing the connection with 30 churches in the outlying areas and knowing just how fantastic a source of protein is an egg to a child or to any individual, it makes you want to buy in and be a part of something that can make that much of a difference,” he says. “You see the results.”

Roger Pelissero, EFC director from Ontario and father to Isaac, is another Project Canaan team member. When he visited in fall of 2014, he and others also went to Mozambique to visit the “Eggs for Africa” project there, where he says they gathered a lot of valuable information. What impresses Pelissero most about the whole project is the dedication of Janine and Ian Maxwell, whom Pelissero says started this humanitarian work in a search for meaning after 9/11 happened. “They’ve made a total change in their lives and it’s quite a commitment,” he says. “They know they can’t change the whole world, but they can made a difference in some children’s lives and they are doing that.” n

Nutrition Camelina: Potential New Feed Ingredient?

The “rediscovered” mustard plant is experiencing a resurgence due to high omega-3 and energy levels compared to canola

BY KAREN DALLIMORE

The hardy properties of Camelina sativa give it lots of potential for growing in Canada. It’s tolerant to frost and drought, doesn’t mind cool germination temperatures, thrives in marginal soils, and matures in a short 85 to 100 days, ideal even for northern Saskatchewan or Alberta.

Also known as “false flax” or “wild flax,” camelina is most wanted for its oil but now, 100 years after being introduced

to North America, the mustard plant is being re-discovered and re-evaluated as livestock feed, fuelled by close to $3.7 million in funding initiatives to develop market ready varieties.

Rob Patterson is the technical director for Canadian Bio-Systems Inc., a company that researches, develops and manufactures a wide range of products used in food, feed, industrial and environmental applications. Speaking to the Poultry Industry Council (PIC) Innovations Symposium, Patterson explained how camelina had historically been replaced in modern poultry diets by rapeseed and canola but is now experiencing a resurgence due to its multiple uses as a source of omega-3 oil as well as its potential in biofuels, high-end bio-lubricants and plastics and even jet fuel.

Several recent studies have been conducted to re-establish baseline feeding levels and nutritional recommendations for camelina meal in poultry diets. Cold

YOU IS ALL ABOUT OUR WORLD

pressed, non-solvent extracted oil cake was approved by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) in 2015 for use in feed up to 12 per cent for broilers only; camelina is not yet approved for use in layers or pigs.

How does camelina meal compare to canola meal? Using numbers from the canola feeding guide, Patterson pointed to camelina having a higher Neutral Detergent Fibre (NDF) and Acid Detergent Fibre (ADF) value than canola, but a comparable amino acid spectrum. At 12 per cent fat, camelina meal was a good energy source, compared to canola meal at 3 per cent fat due to oil extraction. The percentage of favorable linoleic and linolenic acid (omega-3) is quite high (39 per cent), but there are also some glucosinolate compounds present, similar to those in rapeseed, that are common to the brassica family and may cause feed refusals. Patterson suggested that more research and breeding work

Nutrition

is needed to ensure this issue doesn’t put constraints on the diet.

One study at the Atlantic Poultry Research Centre in Truro, N.S., found that gain in broilers dropped off as camelina inclusion reached 15 per cent of the diet, suggesting the defining line was somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent. Feed refusal resulted in less feed being consumed and therefore less growth, but feed conversion rates stayed the same. Patterson suggests that the 12 per cent cap on camelina inclusion may be unrealistic, recommending somewhere between five and 10 per cent.

As an omega-3 enrichment factor, camelina meal has potential but it’s not there yet, especially with the 12 per cent inclusion rate cap. To label a product as omega-3 enriched requires a level of 300 milligrams per 100 grams of meat. Even with enzyme supplementation, one study in 2015 by Nairn et al. at the University of Alberta could not reach that level with 12 per cent inclusion of camelina, although they did reach the enrichment level in thigh meat by day 42 with 16 per cent inclusion. In the U.S., camelina can be included up to 10 per cent on broiler and layer diets in omega-3 enriched programs but the U.S. omega-3 level of claim is lower.

Camelina oil has higher vitamin E levels than flax oil, meaning a longer shelf life, and it could be more effective than flax for meat enhancement, but Patterson doesn’t see camelina as a viable alternative to flax at this time. The caps to the usage of camelina in poultry diets as he sees them are with the limit to the level of inclusion and regulatory constraints at this time.

While he hopes to explore new opportunities with layers within the next year, indicating there is potential there, he regards it as a niche with limited opportunity that is not set to grow much unless producers are spurred by market demand to use camelina as a replacement for flax or genetically modified canola. n

TARA MOLLOY, TRADE AND POLICY ANALYST, CHICKEN FARMERS OF CANADA

Crying Foul Over Spent Fowl Imports PERSPECTIVES

Most people don’t know the difference between a broiler chicken and spent fowl. But the readership of Canadian Poultry magazine is likely well aware of what spent fowl is, and understands the significant differences between the two birds. Spent fowl are laying hens that have reached the end of their production cycle: a byproduct of egg and broiler hatching egg production. Fowl meat is much tougher than broiler chicken meat, partially because of genetics, and partially because of the age of the hens at the time of slaughter. While broiler chickens have been bred for meat consumption, spent fowl hens have been bred for their egg laying capacity and these birds are slaughtered at around 60 weeks old, whereas broiler chickens are slaughtered at around six weeks of age. Broiler chickens have never laid an egg in their lifetimes, but spent fowl carry within their meat traces of egg residue, which poses a risk to consumers who suffer from egg allergies.

Another significant difference between spent fowl and broiler meat is that while broiler chicken is subject to import controls, spent fowl is not; unlimited amounts of it can be imported into Canada. While imports of spent fowl had been stable for many years, since 2012 there has been a massive surge of imports, increasing from 47 million kg (eviscerated weight) in 2005 to 103 million kg (eviscerated weight) in 2016, more than doubling in 10 years.

Evidence suggests that this increase is at least in part due to the smuggling of broiler meat, which is being fraudulently declared as spent fowl at the border in order to bypass import controls. Once in the country, the smuggled broiler meat loses its “spent fowl” label and is sold to unsuspecting Canadian further processors, food service and retailers – and ultimately the Canadian public – as domestically-produced chicken. Consider for instance that based on production and trade statistics, in 2012 Canadian imports represented the equivalent of 101 per cent of the United States’ entire spent fowl production. Obviously, this is impossible. Though there was a slight decline during the following two years, spent fowl imports have again returned to suspiciously high levels and imports in the first quarter of 2016 are the highest ever with 29 million kg in just three months. In 2015, Canada appears to have imported the equivalent of 95.6 per

cent of the United States’ entire spent fowl production despite the fact the United States exports spent fowl to countries other than Canada and there is also a substantial American domestic demand for spent fowl meat. Clearly something is amiss.

Fraud such as this robs Canada’s chicken farmers and processors of jobs and revenue that could – and should – benefit the Canadian economy. Not only has the tariff evasion directly deprived the public coffers of at least $66 million, the impact of these excessive imports have further deprived the Canadian economy of 8,900 jobs and $600 million in contributions to the GDP.

Since evidence of this smuggling was uncovered, Canadian poultry producers and processors have been working with the federal government to find ways to stop it. On Oct. 5, 2015, the Canadian government included a pledge to implement a mandatory certification requirement on spent fowl imports. A governmental inter-department working group involving the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canada Border Services Agency, Global Affairs Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has been formed to move this pledge forward. This is an important first step, and the poultry sector eagerly awaits the working group’s action plan for instituting this mandatory import certification.

Spent fowl imports have again returned to suspiciously high levels and imports in the first quarter of 2016 are the highest ever.

One reason the smuggling has been able to go undetected for so long is due to how difficult it is to distinguish between spent fowl meat and broiler meat, particularly when it comes to inspecting shipments of boneless cuts. Chicken Farmers of Canada has worked with researchers at Trent University to find a way to address this challenge. The result is the successful development of a forensic DNA test that can verify whether a given product contains chicken, spent fowl or a combination of both. In this way, the chicken portion of even blended products, such as nuggets that may contain both broiler meat and spent fowl meat, can be subject to the appropriate import control. This test is quick and easy to administer, and provides a level of meat traceability that meets the forensic standards required for potential legal action. It is vital that this DNA test becomes part of the verification process to ensure the validity of spent fowl import certifications and put an end to the illegal smuggling of broiler meat once and for all. n

RODENT CONTROL trapped like rats » They’ll be «

These are some of the products eligible for the Vetoquinol Club points program. Sign up today at vetoquinolclub.ca and reap the benefits. club

GREAT PALATABILITY BAITS

• Low or no wax formulations

• Grains and food grade oils ingredients

• Greater acceptance for better results

• Different actives for rotation

GIVE THEM BAITS THAT THEY WILL LIKE!

Featured Turkey Products

• Free swinging design

• Robust drop tube and wear plates for added longevity

• Durable heavy duty shields

• 4-hook support strap design provides rigid support

• Feed-saving deep “V” bottom pans and steep-inward swept lips

• Heavy duty 2” ribbed tube design provides added strength

• Easy installation of flood winch cables

• User friendly feed level adjustment

• Available with galvanized steel pan and red or green plastic pan

• Easy cleaning between flocks

• Self-cleaning built to survive drinker

• Designed to dispense fresh water with each drinking action while minimizing spillage

• Ideally suited to the adult turkey environment and the way turkeys drink

• Flexible, shock-absorbing stem prevents breakage

• Twin lock design keeps the drinker secure in the pipe saddle

• Corrosion-resistant stainless steel components for long life

• T-Max tips and rotates so water swishes it clean as birds drink

• Made from long lasting heavy-duty materials and designed to prevent spillage

Ziggity T-Max Drinkers

Cumberland Turkey Feeder