RECENT media reports have highlighted something few expected to see in Somalia this soon: tourists are returning — not in droves, but in numbers significant enough to challenge the country’s long-standing reputation for danger. Stories of visitors wading into the blue waters off Mogadishu’s Lido Beach, or wandering Somaliland’s markets without escorts, are now appearing alongside the usual conflict-heavy coverage. And that shift, subtle as it may seem, matters far more than the raw numbers. Somalia received around 10,000 tourists in 2024 — a 50 per cent increase on the previous year. In any other country, such a statistic would barely register. But Somalia is not any other country. This is a nation that has spent three decades cast as a global byword for instability. For travellers to return at all is remarkable; for the numbers to rise so clearly suggests a deeper change in perception.

What makes this moment encouraging is that the shift is bottom-up as much as top-down. Yes, the government has pushed reforms, including the launch of a national eVisa system in September 2025 — a symbolic step toward projecting normality and openness. But the real shift is happening in the minds of the travellers themselves. People are beginning to consider Somalia not only in terms of risk, but also possibility.

www.africabrie

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor Desmond Davies

Contributing Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Kennedy Olilo

Consider the scene so often captured in recent photographs: families swimming at Lido Beach, fishing boats bobbing just offshore, children darting through the sand, and a lone soldier patrolling without theatrics. It is a peaceful tableau sitting atop a tense reality — yet it also reflects a Somalia that is undeniably, if cautiously, living.

Publisher

Gorata Chepete

In 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa.

What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

Jon Offei-Ansah

Desmond Davies Editor

This is where the value of tourism becomes clear. It is not simply about foreign exchange, hotel bookings or guided tours. It is about narrative power. Every visitor who returns home describing Somali generosity, vibrant coastal life or the resilience of ordinary people chips away at the hardened, one-note image of a country defined only by conflict. These stories spread quietly but widely — and eventually help reframe global expectations.

Deputy Editor

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Country Representatives

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

Angela Cobbinah

Contributing Editor

Stephen Williams

Director, Special Projects

Michael Orji

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chuks Iloegbunam

The travellers who do come tend to be motivated by curiosity, challenge or a desire to see places the world misunderstands. Many are “country counters” completing global quests. Others are drawn by the thrill of stepping into a place few outsiders visit. But what they leave with is often more profound: an appreciation of Somalia’s humanity beneath the headlines. Their presence also supports Somalia’s long-term ambition to normalise itself in the eyes of the world. Tourism encourages government ministries to invest in infrastructure, streamline procedures and strengthen state capacity. It creates jobs that are immediate and visible: drivers, guides, cooks, vendors, small-business owners. These are the kinds of livelihoods that help rebuild confidence from the ground up.

Joseph Kayira

Yet the optimism should be cautious, not naive. Somalia still faces formidable challenges. Al Shabab remains active in central and southern areas, and its threat has not receded. Millions remain displaced by conflict and climate shocks. Western governments still issue maximumlevel travel warnings. The eVisa system, though symbolically important, is not recognised by Somaliland or Puntland, revealing deep political fractures.

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Designer

Gloria Ansah

But acknowledging these realities should not obscure the signs of momentum. Somalia’s progress is not linear, but it is real. Security has improved in some corridors. Urban reconstruction is visible. And more importantly, everyday Somali life continues — families at the beach, traders in the market, children playing football on the sand. For a country so long associated with conflict, that day-to-day normalcy is itself a form of resistance.

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Country Representatives

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co.

Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Somaliland’s emergence as a calm alternative within the wider Somali cultural sphere further enriches this story. In Hargeisa, visitors wander through markets without escorts, explore ancient rock art, and engage freely with local communities. This contrast between Mogadishu’s caution and Somaliland’s relative ease demonstrates the diversity within a region often painted with a single brush. It also offers regional leaders a model of what stability can look like. Somalia’s growing tourism figures may be small, but they are symbolically powerful. They signal a shift in how the world perceives the country — and how the country perceives itself. Against the backdrop of Somalia’s well-documented struggles, even a modest upswing in tourism is a statement of resilience.

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

If Somalia can build on this fragile momentum — improving safety in key corridors, harmonising its visa regime, investing in hospitality training and strengthening community-based tourism — it could carve out a niche as a destination for culture-seekers, history enthusiasts and adventure travellers.

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

Kenya

The point is not that Somalia is suddenly safe. It is that Somalia is changing. And for the first time in a long time, the world is noticing. The beaches of Mogadishu, dotted with families and curious foreign visitors, are beginning to tell a different story: one of recovery, resistance and possibility.

Nnenna Ogbu #4 Babatunde Oduse crescent Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

Kenya

Patrick Mwangi Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

©Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Sudan, yet another blot on the African landscape

Silencing the Guns? They are getting louder ECOWAS: people power on the rise

The Economic Community of West African States, founded 50 years ago, has lost its way, as political leaders and functionaries within the organisational structure struggle to meet the aspirations of young and vibrant West Africans who want to shape their own future, concluded a recent conference in Abuja. Desmond Davies, who was in Nigeria, reports

Leaders have failed to deliver

The current state of the regional body underscores the need for deep reflection on how it can move beyond being an elite-driven institution to one that truly represents and serves its people, argues Kayode Fayemi

Tanzania’s democracy crisis deepens under Samia

Africa’s restless Gen Z forces a democratic reckoning 6 07 08 14

Tanzania’s 2025 election lays bare rising repression, regional anxiety and the strain on President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s reformist promise, writes Valerie Msoka

Jon Offei-Ansah examines how a digitally connected generation—from Nairobi to Rabat—is challenging entrenched power, demanding economic justice, and reshaping the future of democracy across Africa

Nations move past the aid era

RMB’s Where to Invest in Africa 2025/26 report, analysed by Jon Offei-Ansah, explores how the continent is shedding decades of aid dependency to embrace trade, industrial value addition and private-sector investment as the real engines of growth

38 46 20 22

Businesses struggling to keep up with modern work culture

While the ongoing battle between return to work and work from home is a misguided attempt to diffuse this tension, organisations should evolve to accommodate the new workplace

Cities failing Africa’s young dreamers

Thembisile Simelane warns that chronic underinvestment and poor planning are trapping Africa’s youth in broken cities

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

TWENTY years ago, members of the Janjaweed militia, a force made up of so-called Arabs, were wreaking havoc in the western Sudanese region of Darfur – massacring hundreds, if not thousands, of ethnic Africans. The world raised its voice, but nothing changed for the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa ethnic groups.

The International Criminal Court issued a few warrants of arrests for the atrocities being committed in Darfur. Two were specifically issued for then Sudanese President Omar al Bashir in 2009 and 2010.

Today, the Janjaweed has transformed itself into the Rapid Support Forces fighting the Sudanese army in the country’s destructive civil war. Members of the paramilitary RSF have made it again into Darfur and are continuing what they began 20 years ago. El Fasher is now the epicentre of the emerging genocide in Darfur being carried out by the RSF.

A recent Special Session of the Sudan Core Group at the UN was told that the atrocities reported after the fall of El Fasher to the RSF were “horrific: summary executions, sexual violence, abductions”. The meeting attempted to focus global attention on the horrors unfolding in El Fasher.

As the Core Group noted, support for holding the Session “shows staying silent is not an option”. Indeed, the African Union Special Envoy for the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng, and his UN counterpart, Chaloka Beyani, have added their voices to the campaign to alleviate the excruciating suffering of the people of Darfur.

Their recent joint statement at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva was unequivocal in its condemnation of the atrocities being committed by the RSF in El Fasher. “This is, unfortunately a humanitarian and human rights catastrophe unfolding before our eyes,” Dieng and Beyani said.

“The situation in Sudan, particularly in El Fasher and the wider Darfur and Kordofan regions, has reached a critical and tragic juncture. Since the outbreak of conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in April 2023, the civilian population has endured unimaginable suffering.

“Over 14 million people have been forcibly displaced, more than 40,000 killed and countless others subjected to summary executions, mass killings, abductions, torture, rape and attacks on humanitarian workers.”

But would the people of Darfur still be facing this desperate stage in their lives if African leaders and institutions such as the AU had taken strong steps to deal with the problem in the region from the outset? They cannot argue that they were not aware of the seriousness of the situation.

After all, the ICC took the matter very seriously, hence the warrants for the arrest of al Bashir. Despite the indictments, al-Bashir continued to serve as president and was involved in various political activities. The ICC's efforts to bring him to justice faced significant challenges, including the Sudanese government's refusal to hand him over to the court. When he was overthrown in 2019, he was not sent to The Hague to face trial.

But what was the African response to al Bashir as a president wanted by the ICC? South Africa, under President Jacob Zuma, welcomed al Bashir when he visited in June 2015, failing to arrest him in accordance with the Rome Statute that established the ICC.

South Africa, under Zuma, breached its international and domestic legal obligations. The ICC ruled against South Africa accordingly.

Now, it is the same South African government, albeit under a new President, Cyril Ramaphosa, that has referred Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to the ICC for alleged genocide in Gaza. How ironic.

The flow of weapons to Sudan, coming from countries such as the United Arab Emirates, must be stemmed. Indeed, this is the right time for a pan-African force to be mustered to go into Darfur to create safe spaces for the population.

Dieng and Bayela have called for action that will ensure justice and accountability for all violations, addressing impunity at every level. They want robust protection of civilians and the upholding of humanitarian law, prioritising access to life-saving aid and the restoration of basic services.

The current situation in Darfur is yet anther blot on the African landscape when it comes to preventing violent armed conflicts on the continent. Although hundreds of thousands of Sudanese have died since the civil war began in April 2023, the incursion of the RSF into Darfur is a major disaster.

Now is the time for the African Union to take the lead in bringing an end to the conflict not just in Darfur but in Sudan as a whole. There have always been half-hearted attempts by the AU to end violent conflicts in Africa. Now is the time for action.

So, apart from the strong statements coming from the AU and UN that impunity will not be tolerated, Africa, with the backing of the international community, must now act to end the war in Sudan that is looking increasingly that genocide is being committed in Darfur, leaving an indelible stain on the world’s conscience yet again when it comes to halting atrocities being committed in Africa.

SILENCING the Guns – the African Union’s ambitious initiative to end armed conflict on the continent – does not seem to be going anywhere. It is just not working.

Remember, the initial target date was 2020. But with the increase in terrorist activities in the Sahel, unconstitutional political activities and the huge flow of licit and illicit arms into the continent, a new deadline of 2030 was set.

The situation in Sudan is deteriorating fast. In Tanzania, after the October elections, soldiers were accused of opening fire on unarmed civilians, with the death toll close to 1,000.

Many of those killed were innocent people going about their daily business when the trigger-happy soldiers let loose with their weapons. Most of the bodies have not been recovered.

This is the Tanzania of Julius Nyerere, who fashioned a united nation. He must be turning in his grave after President Samia Suluhu Hassan unleashed violence against her citizens because she wanted to hang on to power at all costs.

A southern African friend of mine who is an academic in the US was outraged by “tone deaf African leaders” such as Hassan. “First, she tears her country apart with a fraudulent electoral victory. And now she appoints her family members to the cabinet. Shameless!” He was referring to the announcement that Hassan had not just appointed her daughter to the Cabinet but had included her son-in-law.

Even her inauguration riled my friend. “After claiming a 98 per cent win based on electoral figures that did not correspond to the registered voting population given out earlier by her own government, she then went on to be inaugurated at a military barracks [in Dodoma] with a few invited guests only, upending the tradition of a public swearing-in in a stadium. Was she scared of the 98 per cent who had supported her?”

You might be wondering why I am focusing on Hassan when I am talking about Silencing the Guns. Well, in my experience as a journalist covering Africa, I have noted so many times how political jiggery pokery has eventually led to armed conflicts –sooner or later, West Africa being a major case in point, as I write in my article on ECOWAS @50 in this edition.

Dr Mohamed Ibn Chambas, the current African Union High Representative for Silencing the Guns, must have his work cut out. In 2019, when he was head of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), he reported: “Preelectoral and post-electoral periods…continue to be characterised by tensions, antagonistic contests and disputes, including around non-consensual constitutional amendments.

“Addressing such potential sources of conflict remains a major priority ahead of the upcoming cycle of high-stake presidential elections in West Africa … Furthermore, tensions around electoral periods derail the necessary attention to the pressing need to address questions of development and inequality,” he added.

These recurring problems highlighted by Chambas are the bane of the move to silence the guns on the continent. The AU declared the whole of September each year as Africa Amnesty

Desmond Davies

Month that calls “for the surrender and collection of illicit small arms and light weapons without fear of arrest or prosecution”.

A worthy idea. But the problem is that how widely known is Africa Amnesty Month on the continent? More so among those caught up in armed conflicts.

Even the AU itself is in sixes and sevens when it comes to organising the event. It proposes the states and dates for the continental launch, with the UN Office for Disarmament Affair providing technical and financial assistance.

But guess what? This year, after several consultations, the AU Peace and Security Council proposed October 2 and 3 (not September!) for the continental event in Uganda. This was, my contact told me, “for various reasons including availability of officials and other engagements in their calendar both from the AU and host country, Uganda’s side”.

Mali was the other country that had requested support for the commemoration of the activities. While the AU was going round in circles, other states, including Mali and Kenya, launched their activities.

Since 2020, under the AU–UNODA Africa Amnesty Month project, UNODA, in cooperation with the AU Commission and with implementation support from the Regional Centre on Small Arms (RECSA), has assisted 16 African states in commemorating Africa Amnesty Month and assisted in the voluntary surrender of illicit arms. So far, the project has collected and destroyed more than 22,000 illicit weapons, according to AU-UNODA.

Overall, it is an uphill task for Silencing the Guns if the underlying causes that make the guns getting louder and louder are not directly addressed. These include political intolerance, discrimination, exclusion and economic deprivation. To silence the guns, Africa needs inclusive governance and sustainable development for all.

Crucially, Silencing the Guns must also apply to soldiers who shoot and kill innocent civilians exercising their democratic right to demonstrate against their governments.

We have seen what happened in Tanzania. With prospects of turbulent elections in Uganda next year and Kenya in 2027, Silencing the Guns will be sorely tested. AB

The Economic Community of West African States, founded 50 years ago, has lost its way, as political leaders and functionaries within the organisational structure struggle to meet the aspirations of young and vibrant West Africans who want to shape their own future, concluded a recent conference in Abuja. Desmond Davies, who was in Nigeria, reports

IN 1990, the project of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) – that of a socioeconomic regional grouping – was confidently chugging along when it was derailed. When 15 leaders established ECOWAS in 1975, they had high hopes of making regional integration in the lives of their citizens a reality through structures such as free movement of people, a single market and a common currency.

But 36 years ago, these aims were put to one side as the Liberian civil war, which erupted at the end of 1989, forced ECOWAS leaders to take steps to bring peace and stability to the country and the region. It was easier said than done.

Since then, ECOWAS has been busy firefighting, as conflicts erupted also in Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau and continue today. Right now, ECOWAS is caught in a bind with three members – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – who have opted out of the regional body to form the Association of Sahelian States (AES).

Their beef? They are not happy with the lack of support from ECOWAS in their fight against Islamist militants in their region.

Looking back at the history of conflict in West Africa, it was a miracle that it took 15 years after the formation of ECOWAS before the first flames of rebellion were lit. Indeed, from the outset, some of the founding leaders of the regional body never believed in political pluralism. They were authoritarians who were soon to plunge their countries into one-party states (de jure or de facto).

Sekou Toure in Guinea was a despot. General Gnassingbe Eyadema in Togo was a military dictator. Siaka Stevens in Sierra Leone was a strong-arm leader who used his paramilitary State Security Division (SSD) to cow citizens into accepting his authority. The activities of the notorious SSD undoubtedly formed the basis for the country’s bloody civil war from 1991 to 2002.

In Liberia, William Tolbert and his Americo-Liberian descendants had ruled the roost since 1847. They thought they would be in control forever until Master Sergeant Samuel Doe and his men upended the system violently. Their coup of 1980 was a bloody affair. Tolbert was killed at the Executive Mansion while other top leaders were executed on the beach.

Of the 15 ECOWAS founding leaders, six were military rulers, including General Yakubu Gown of Nigeria (the sole survivor of this group) and Ghana’s General Ignatius Kutu Acheampong.

Considering the ongoing shenanigans, it is understandable why young West Africans are now demanding a re-ordering of the ECOWAS project, They want to have more say in its future. After all, they are the ones who are soon going to take control of leadership roles in their countries.

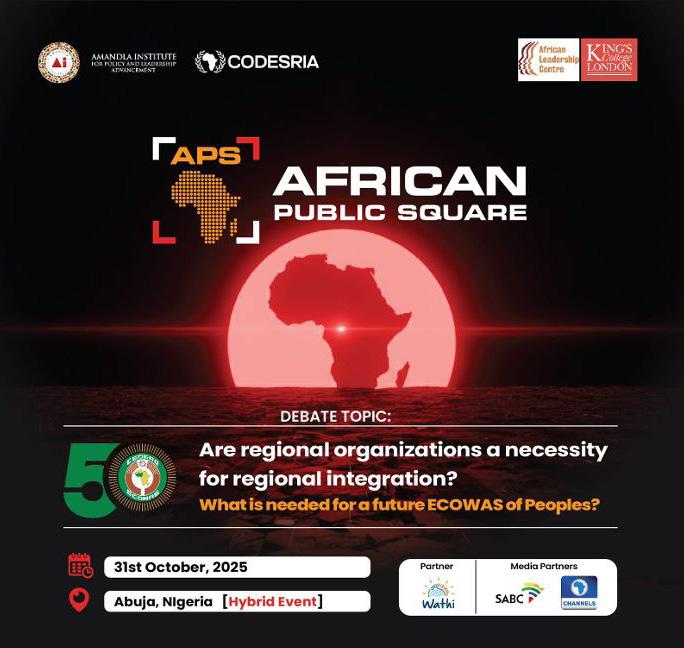

For two days (October 31 and November 1) ECOWAS headquarters in Abuja hosted the African Public Square (APS) and a meeting of experts on ECOWAS @50 that looked at the future of regional integration. It was the second gathering of the APS, which was established by the African Leadership Centre at King’s College London in 2023 as a continental platform to “facilitate transformative dialogue on peace, security and development in Africa”. The high-level public debate posed the question: Are Regional Organisations a Necessity for Regional Integration? What is Needed for a Future ECOWAS of the People?

Organised in partnership with the Amandla Institute, the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) and the West African Think Tank Initiative (WATHI), the event reflected on ECOWAS’s journey over the past five decades.

The overwhelming view was that ECOWAS was no longer fit for purpose in its current form because the political leaders had lost the plot. Participants called for an

ECOWAS of the People to help drive regional integration faster.

During the APS, young Africans had their say. Professor ‘Funmi Olonisakin, Vice President, International, Engagement and Services at King’s College London, welcomed their presence. “The promise of an ECOWAS of the People is under threat,” she said, but noted that young Africans, given the chance, were the ones who could move integration in Africa faster. She pointed out that state-led initiatives of integration in Africa were failing.

Prof Olonisakin founded the African Leadership Centre (ALC) at King’s College London 15 years ago. It has trained over 250 young Africans during this period.

With a West African population of over 400 million, 65 per cent of whom are under the age of 24, Prof Olonisakin said that it was obvious that it now had to be ECOWAS of the People for the next generation. “ECOWAS at 50 gives us the chance to look back in looking forward,” she added.

But in looking forward, there is the small matter of getting ECOWAS top brass on side. There has been fierce

criticism from civil society groups of ECOWAS officials such as its President, Dr Omar Alieu Touray, and AbdelFatau Musah, Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security.

This is understandable because they bear the brunt of the confusion that has engulfed ECOWAS. Their critics have not been too happy with the manner in which they appeared to have danced to the tune of the US and France by threatening to place sanctions on Niger with a further threat of invasion. This came even though it was obvious

that Nigeriens fully backed the coup that turfed out the Americans and French from the country.

Michael Amoah, a UK-based Ghanaian academic, was scathing in his criticism of Touray and Musah in his recent book. Decolonizing African Politics; Bridging the Contours of Debate. After excoriating Nigerian President Bola Tinubu’s “subservient and ignorant foreign minister”, Amoah writes: “… the equally subservient top brass at the ECOWAS Commission in Abuja were totally irresponsible in the way they heeded so eagerly to the United States and France whose foreign policy interests in the form of mines,

military bases and drones in Niger were at risk because of the Niger coup”. He adds: “These foreign powers egged on ECOWAS to invade Niger, while Tinubu and ECOWAS were prepared to assemble the intervention force regardless of the prevailing analysis that such an invasion would turn West Africa into a security hazard.

“It beggars belief that ECOWAS could not protect the foreign policy interests of its member-states against

neocolonial presidents and puppets, but had been hoodwinked by the interests of foreign powers to want to fight its own member-states.”

Continuing, Amoah writes: “It became the prevailing public opinion that ECOWAS should metamorphose and recalibrate as a matter of urgency. Among the strong feelings floating around [was] that both Omar Alieu Touray, the President of the ECOWAS Commission, and AbdelFatau Musah, the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security, at the time of the Niger crisis should be fired or made to resign; and certainly, Tinubu should not have been re-elected as Chair of ECOWAS for another term.”

This, though, did not happen. Given this harsh criticism of the two top officials at the ECOWAS Commission, it was not surprising that during the two-day meeting, ECOWAS bigwigs kept a low profile.

Indeed, at the end of the Abuja meeting, Musah told participants that ECOWAS had kept “a strategic silence… to give the people of West Africa their say on regional

integration”. He said that by mid-2026, an ECOWAS Social, Economic and Cultural Council would be in place “to give the people of West Africa more say about how ECOWAS functions”. He added: “We want ECOWAS citizens to take the lead in member states.”

This could make the difference that young West Africans are hoping for. Of course, it is a big ask. After all, are young West Africans fully cognisant of the overarching aims of ECOWAS when it was established in 1975?

For many young West African men and women who want to create a fully integrated community, they are still

hampered by the mind-boggling bureaucracy that makes intra-West African travel and trade such a minefield.

But one thing is clear: there is no stopping the rise of people power among the young, vibrant and tech-savvy West Africans. So, as the region marks half a century of ECOWAS’s existence, the Abuja meeting underscored a growing call among African thinkers and institutions to reimagine regionalism from the ground up – one that is participatory, equitable and responsive to West Africa’s diverse realities., and being led by young people.

The current state of the regional body underscores the need for deep reflection on how it can move beyond being an elite-driven institution to one that truly represents and serves its people, argues Kayode Fayemi

THIS is a timely and critical conversation taking place on the shifting dynamics of change within ECOWAS, the deepening security and governance challenges in the sub region and the future of regional integration in West Africa. It follows the meeting of ECOWAS founding leaders that we convened in June chaired by the only living founding father of ECOWAS, Nigeria’s General Yakubu Gowon, and attended by the Commission’s President, Dr Ali Oumar Touray, and most of his living predecessors in office.

ECOWAS is in danger of being reduced to an inchoate bureaucratic juggernaut

This important gathering presents us with an opportunity to reimagine the regional integration project in all its dimensions, including economic, security, political and structural. In doing this, we must acknowledge the significant contributions of ECOWAS in shaping regional peace and development.

From inception, ECOWAS has been a pacesetter among the regional economic communities on the continent. ECOWAS pioneered norms and standards on peace and security as well as on democracy and good governance. It also provided the models of managing international peacekeeping operations with its laudable rescue missions in Liberia and Sierra Leone and later in Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia and Guinea Bissau.

Under normal circumstances, even without its current challenges, a strong case could be made for a reinvention of the West African integration project. The grounds for such a reinvention are many, and they were already a source of discussions well before the 50th anniversary of ECOWAS.

At one level, there were strong concerns that the promised transition from the ECOWAS of rulers – an elite club of incumbent political leaders – to a Community of the people, centred on citizens was not happening, at least not as quickly and effectively as was wished. At another level, concerns were cumulating that the much-promised internal reforms designed to make the Community more agile had stalled, with the consequence that the organisation was becoming much more remote from the peoples of West Africa it was meant to serve, and in danger of being reduced to an inchoate bureaucratic juggernaut.

Furthermore, for all the efforts that had been made in adopting various inter-West Africa trade promotion policies, progress was far from being optimal. And on such critical matters as the ECOWAS single currency, its promised launch had become an endless wait as the target date kept being shifted on account of various technicalities. Obstacles to intra-West African investments and the flow of services have persisted beyond what can be easily explained, suggesting a deficit of political will among leaders. While steps were taken to improve the internal finances of the Community, the problem of inadequate funding of many of its programmes and agencies remains a huge challenge, a situation which exposed the Community to external manipulation by various donors who have not lost any opportunity to embed themselves in its structures and processes.

The uncoordinated response of West Africa to the European Union’s free trade proposals, packaged as the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) is a case in point.

Clearly, the current state of the regional body underscores the need for deep reflection on how ECOWAS can move beyond being an elite-driven institution to one that truly represents and serves its people. The challenges of poverty, inequality,

reality, in all

governance deficits and insecurity cannot be effectively addressed by ECOWAS in its current form. There is an urgent need for a new, citizen-centred approach that responds to the real concerns of ordinary West Africans, rather than focusing solely on the priorities of political leaders.

It is also my hope that a key part of our discussion will focus on security and the role of the military in addressing instability in the region. It is now evident that traditional military strategies alone are inadequate in tackling the complex threats posed by insurgent and terrorist groups. Many of these groups are deeply embedded within communities and even, in some cases, within the military itself.

What is needed is a more sophisticated intelligence-based approach, combined with efforts to address the underlying social and economic drivers of insecurity. We need a comprehensive human security strategy that deals with issues of poverty, inequality and governance failures, which extremist groups continue to exploit.

While it is understandable that many citizens are frustrated with civilian governments that have failed to deliver on governance and security, we should also not mince words that military rule is not a viable alternative in tackling governance deficits. History has shown that military regimes do not provide sustainable solutions.

In fact, in the three countries that have now exited ECOWAS, terrorism and insecurity have worsened since the military took over. The challenge for ECOWAS is how to engage these regimes

while also ensuring a pathway back to credible democratic governance.

It is crucial that ECOWAS continues to leverage diplomatic efforts in finding pragmatic ways that do not alienate the breakaway states further but instead brings them back into a cooperative regional framework. The current effort of the Commission in this regard is noted.

ECOWAS has always been a flexible and adaptive regional body, accommodating different sub-regional groupings like UEMOA, CENSAD, the Mano River Union, and others. There is no reason why AES (the putative Sahelian bloc of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger) cannot continue to be part of ECOWAS, even if they insist on maintaining a distinct identity. The goal should be to preserve regional cooperation, stability and development, rather than encouraging further divisions.

All of the issues confronting the region collectively reinforce the urgency of rethinking and reimagining ECOWAS’s role in a changing West Africa. The regional body cannot continue business as usual. It must evolve to reflect the realities on the ground and to rebuild trust with its citizens.

Fifty years is a significant milestone in which ECOWAS has accomplished a lot, but it must also serve as a moment of reckoning: a time for deep reflection, bold reforms, and a renewed commitment to the principles of regional integration, security and inclusive governance. The future of West Africa depends on the choices we make today, and it is clear that ECOWAS must embrace change if it is to remain relevant in the years ahead. AB

Dr Kayode Fayemi is Founder of the Abuja-based Amandla Institute for Policy and Leadership Advancement (www.amandlainstitute.org).The above was his presentation at the African Public Square and ECOWAS @50 meetings in Abuja on October 31 and November 1.

ECOWAS should no longer be seen as a distant monument but an integral part of each member state for mutually prosperous interaction regardless of what geopolitical changes may transpire in the future, writes Gabriel Eke

ANYTHING that is not properly designed eventually collapses under the weight of its own flaws. Institutions, like buildings, require strong foundations, sound architecture and regular maintenance to stay fit for purpose. When these are absent, decay sets in.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is now facing this moment of reckoning. For too long, it has felt like a distant bureaucracy – a club of politicians and technocrats detached from the daily realities of ordinary West Africans.

Yet, the organisation was founded in 1975 with a bold promise: to integrate the economies and destinies of the region’s people. If that vision is to survive, ECOWAS must be redesigned – not as an elite project, but as a people’s project.

First, ECOWAS must shed its static headquarters mentality. Instead of being anchored to one city, its operations should rotate across member states. This symbolic and practical shift would remind every citizen that ECOWAS belongs to them, not to a few bureaucrats in Abuja. Each member nation should feel the presence of the organisation – hosting meetings, driving initiatives and shaping the agenda. Regional integration cannot thrive if it feels foreign to the people it claims to serve.

To stay relevant, ECOWAS must adopt what can be called twinning of agendas: a unified set of regional priorities that all member states pursue within clear timeframes. Imagine all ECOWAS nations focusing, for two years, on one concrete goal: say, achieving food security, or strengthening local governance, or boosting digital connectivity. This would foster both accountability and healthy competition, uniting the region through shared purpose rather than rhetoric.

To measure progress, ECOWAS must embrace clarity on what truly constitutes governance, development and infrastructure. Governance means ensuring citizens have access to food, water, healthcare, security and justice, the basic pillars of statehood.

Development means that most citizens can afford food, shelter and clothing. Infrastructure means the collective ability to build and maintain the physical and technological systems that sustain a modern society. When these standards are met, integration becomes meaningful.

Reform must also happen from the ground up. A biannual ECOWAS People’s Forum – where communities

share success stories of resilience and innovation – could serve as a new engine of regional solidarity. From womenled farming cooperatives in Mali to youth tech hubs in Ghana, the lessons of local excellence can guide regional policy more effectively than any consultant’s report.

Ultimately, ECOWAS must confront a deeper truth: its borders, governance structures and even its political logic are still haunted by the legacy of colonialism. The arbitrary borders drawn at the Berlin Conference of 18841885 fractured natural communities and imposed alien systems of power.

This historical disfigurement continues to undermine unity and accountability. To move forward, West Africa must reclaim its own design, one rooted in indigenous models of cooperation, justice and shared prosperity.

Young West Africans – most of the population – are impatient for change. They want jobs, safety, freedom to move and dignity. They are no longer inspired by slogans or summits. ECOWAS can either evolve into a true platform for regional empowerment or fade into irrelevance.

It is time for an ECOWAS of the people – mobile, democratic, visionary and grounded in the daily lives of its citizens. The future of West Africa depends on it.

Gabriel Eke is a surgeon, poet, strategist and a member of the Fatherland Group, “a global network of forward-thinking Nigerians armed with a new understanding of our past, our present and our future”. www.fatherlandgroup.org

West African economic integration is impossible in a context of coups, insurgencies and fractured governance, writes Theodora

WEST Africa has grappled with violent conflicts, insecurity and political instability since the early 1970s, around the time the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) was established. Conceived as an economic bloc to advance the collective interests of its member states, ECOWAS would soon discover that peace and security are not peripheral concerns but central to its very survival and success.

The bold vision of regional economic power, prosperity and influence cannot be realised without the foundational assurance of peace, whether within individual states or across the region. Economic integration is impossible in a context of coups, insurgencies and fractured governance.

Fifty years on, the question is: how has ECOWAS fared in delivering the peace necessary for sustainable economic development and how does the future look like?

Since 1970, Africa has witnessed approximately 13 major wars and insurgencies. West Africa alone accounts for four of these, a little over 30 per cent, underscoring the region’s disproportionate burden of violence and instability. These conflicts have not only devastated lives but have also tested the limits of ECOWAS’s peace and security mechanisms.

The Liberian Civil Wars (1989–1997, 1999–2003). These were two extremely bloody conflicts that claimed over 250,000 lives and displaced more than one million people. ECOWAS’s ECOMOG intervention marked its first major peacekeeping deployment.

The Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002) was a brutal conflict infamous for the use of child soldiers and widespread atrocities, often fuelled by the illicit trade in “blood diamonds”. ECOWAS played a critical role in supporting disarmament and post-war recovery.

The Boko Haram Insurgency (2009–present) is an ongoing conflict centred in northeastern Nigeria but spilling into Niger, Chad and Cameroon. It involves an Islamist militant group and has triggered a regional military response, with ECOWAS coordinating humanitarian aid.

The Jihadist Insurgency in the Central Sahel (2012–present). This is a severe and escalating crisis affecting Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Over the past decade, violence has intensified, destabilising governments and prompting successive coups.

These figures do not even account for the dozens of coup d’états, electoral violence and political transitions that have further strained the region’s stability. From Guinea to Niger, democratic reversals have become alarmingly frequent, challenging ECOWAS’s normative frameworks and its ability to enforce constitutional order.

ECOWAS significantly rose to the occasion in several of these key moments of regional crisis. Its rapid deployment of peacekeepers under the ECOMOG banner in Liberia and Sierra Leone played a decisive role in ending brutal civil wars and stabilising political transitions.

In 2016, ECOWAS demonstrated its diplomatic strength by preventing post-election violence in The Gambia, ensuring a peaceful transfer of power through strategic mediation. The bloc also exerted sustained diplomatic pressure during the Ivorian crisis and post-electoral violence between 2002 and 2011, contributing meaningfully to conflict resolution and national reconciliation.

In response to decades of conflict and instability, ECOWAS has transformed from a purely economic bloc into one of Africa’s most assertive regional actors in peace and security. This evolution is anchored in a robust legal and institutional framework known as the ECOWAS Peace and Security Architecture (EPSA), designed to prevent, manage and resolve conflicts across the region. The Architecture includes:

• Revised ECOWAS Treaty (1993). This expands the bloc’s mandate to include political stability, conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

• The 1999 Protocol on Conflict Prevention established ECOWAS’s legal right to intervene in member states during crises, including unconstitutional changes of government.

• ECOMOG (ECOWAS Monitoring Group): A regional peacekeeping force deployed in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea-Bissau and Côte d’Ivoire.

• ECOWARN (Early Warning and Response Network): A system for monitoring and analysing conflict indicators across member states.

• Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance (2001): Codified democratic norms and zero tolerance for military coups.

Together, these instruments reflect ECOWAS’s commitment to a proactive, rules-based approach to regional peace and stability.

Despite its significant strides in promoting peace across the sub-region, ECOWAS has also exhibited notable weaknesses and persistent challenges. These include inconsistent enforcement of its protocols, limited investment in preventive diplomacy and the exclusion of civil society – particularly women and youth – from peace processes.

The bloc’s overreliance on external funding, growing perceptions of political bias and a tendency toward elitist decision-making have further eroded public trust and undermined its legitimacy.

These shortcomings have not only weakened ECOWAS’s credibility but also threaten the very foundation of regional integration. When peacebuilding is driven by elite interests and disconnected from grassroots realities, the vision of a united and peaceful West Africa becomes increasingly fragile.

The recent exit of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger from ECOWAS is a direct consequence of these unresolved challenges and systemic weaknesses. Their withdrawal under the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) reflects deep-seated frustrations with what many perceive as inconsistent enforcement of protocols, exclusionary decision-making and a regional architecture that prioritises elite interests over grassroots realities. It is a stark reminder that legitimacy cannot be sustained through sanctions and treaties alone.

Clearly, ECOWAS and its member states must do far more to foster a peaceful, secure and politically stable sub-region. These conditions are indispensable for meaningful economic development.

The events of recent years have made it evident that regional integration cannot thrive amid persistent insecurity and fractured

ECOWAS: how it all began

THE idea of a West African economic community began to take shape during the 1960s following the wave of independence across the region. Newly sovereign states faced similar challenges: fragile economies, heavy reliance on former colonial powers and limited trade links with one another. In response, regional leaders began advocating for closer economic cooperation as a path to collective strength.

In 1964, a meeting of West African states held in Accra explored the possibility of establishing a regional economic union. Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah strongly promoted the idea of a political federation. However, many other leaders favoured a more gradual, economically driven

governance. The lessons of the past five decades, and especially the recent rupture with the Alliance of Sahel States, underscore the urgency of reform.

This reflection echoes several critical recommendations as ECOWAS commemorates 50 years of regional integration. To reclaim its legitimacy and fulfil its founding promise, ECOWAS must strengthen and invest in preventive diplomacy by supporting local peace infrastructures and community-based mediation networks; and reform decision-making structures to reflect the diversity of West African societies and dismantle elitist barriers to participation.

It must also invest in regional self-reliance by reducing dependence on external funding and building sustainable, homegrown peace mechanisms; institutionalise inclusive governance by involving citizens especially women and youth and strengthening the ECOWAS Parliament as a relevant decision-making body; and ensure accountability and consistency in enforcing protocols and democratic norms, regardless of political or geopolitical interests.

It is crucial that ECOWAS takes a hard look in the mirror, confronts its shortcomings, and learn from its missteps. This means revisiting past interventions, listening to the voices that were excluded, implementing its protocols equally and rebuilding trust from the ground up. Only by doing so – through inclusive governance, consistent leadership and a renewed commitment to its founding principles – can the bloc reclaim its legitimacy and fulfil its promise as a true community of peoples, not just states.

approach, which caused the initiative to stall.

The idea was revived in 1972 when General Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria and President Gnassingbe Eyadema of Togo embarked on a joint diplomatic mission to rally support across West Africa. They engaged heads of state directly, presenting the case for a regional economic community.

This led to a series of meeting and technical consultations held in Lome and Accra where government representatives worked to design the proposed community. They agreed on principles such as free movement of people and goods, harmonised tariffs and economic integration.

On May 28, 1975, 15 West African countries convened in convened in Lagos and signed the Treaty of

Lagos, which formally established the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The core objective was to create a unified regional market that would allow west African nations to trade, move and develop together.

A draft treaty had been prepared earlier in Ghana during the previous year and was subsequently endorsed by foreign ministers at a preparatory meeting in Liberia. This version was formally launched at the Lagos summit and became known as the Treaty of Lagos.

It became the organisation’s founding document and ECOWAS was formally established with institutional structures, including a Council of Ministers and an Executive Secretariat, laying the groundwork for what would become one of Africa’s most enduring regional bodies.

TANZANIA’S 2025 general election, delivered as a near-total victory for President Samia Suluhu Hassan, was meant to seal her political authority. Instead, it jolted the country and unsettled its neighbours. What should have affirmed democratic legitimacy instead became a symbol of exclusion, intimidation, and declining political freedoms. Observers from the African Union (AU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) publicly concluded that the vote failed to meet democratic standards. Civil-society coalitions went further, urging the AU and SADC to reject the results entirely and press for new elections.

For Samia, once celebrated as a reformist and unifying presence, the disputed poll marks a defining moment. Her political blueprint — the 4Rs of Reconciliation, Resilience, Reforms, and Rebuilding — now faces its most serious test. The events around the election force a difficult question: can a leader who came into office promising openness and inclusion survive within a party system built on control, not competition?

This article explores Tanzania’s contested election through four lenses: the evolution of the 4Rs, the stalled constitutional agenda, the shadow of abductions and disappearances, and the entrenched power dynamics within CCM.

From the beginning, the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) shaped the electoral environment. Two major opposition parties, CHADEMA and ACT-Wazalendo, were disqualified on technicalities, removing meaningful competition before the campaign began. The 98 per cent victory Samia eventually secured resembled Tanzania’s one-party era, not the multiparty democracy restored in the 1990s.

AU observers reported irregularities ranging from ballotstuffing and unexplained delays to a heavy security presence at polling stations. The government also ordered an internet shutdown, which crippled communication on polling day. Multiple activists and journalists were arrested prior to the vote, with reports of enforced disappearances.

Government officials dismissed the allegations as foreign meddling, portraying the measures as necessary for stability.

But the contradiction was impossible to ignore: a leader who championed reconciliation appeared presiding over an election shaped by repression. What was meant to consolidate authority ended up fuelling concern that Tanzania’s democratic experiment is in regression.

Tensions erupted even before the results were announced. Protests in Dar es Salaam, Arusha, and Mbeya were met with tear gas and live ammunition, leaving several dead and dozens injured. Hundreds were arrested. The scale and speed of the violence shocked a nation long considered one of East Africa’s most stable.

But these riots were not spontaneous. They were the culmination of months of intimidation: the prosecution of opposition figure Tundu Lissu on treason charges, renewed pressure on civil-society organisations, and the quiet suffocation of independent media that had briefly enjoyed a revival under Samia’s early tenure.

The state’s refusal to engage with dissent created a vacuum quickly filled by anger. Citizens were not only rejecting the election results but demanding recognition in a political process that had excluded them. The violence reflected the breaking of a social contract long strained by distrust and manipulation.

The AU’s declaration that the election ‘fell short of democratic standards’ was unusually direct. SADC echoed similar concerns, citing harassment and intimidation. But many doubt that their statements will yield concrete action.

Africa’s civil society delivered the strongest response. Thirteen organisations urged the AU and SADC not to recognise Samia’s new term, warning that the erosion of democracy in one country weakens the entire continent.

The East African Community, however, was conspicuously muted. Its limited observer mission praised Tanzania’s ‘peace and stability’, downplaying credible reports of abuse. This silence reflects a wider regional trend in which stability is prized above democracy, even at the cost of legitimacy.

When Samia became president in 2021, she was celebrated as a breakthrough figure — Tanzania’s first woman president and one of Africa’s few female heads of state. Her early steps backed that optimism: unfettering the media, meeting with opposition leaders, and signalling a more open political direction.

But Tanzania’s political environment is shaped by entrenched patriarchal norms and dominated by CCM elites, former security chiefs, and conservative powerbrokers. To secure her place within this hierarchy, Samia has often mirrored the coercive instincts of her predecessors.

Her 4Rs, once a symbol of national healing, now risk being reduced to political branding. The challenge lies not in her gender but in the nature of CCM: a party whose DNA equates dissent with disloyalty and central authority with political survival.

Samia’s historic role remains significant, but the limits of any individual leader within such a system have become painfully evident. The real question is whether any president — man or woman — can democratise a party designed to rule indefinitely.

Samia’s 4Rs were conceived as a roadmap for national recovery after the divisive rule of the late John Magufuli. Each pillar represented a specific ambition:

• Reconciliation: restoring dialogue and political participation.

• Resilience: strengthening institutions to withstand turbulence.

• Reforms: updating restrictive laws and expanding civic space.

• Rebuilding: restoring both domestic and international confidence.

Yet each pillar has been strained.

Reconciliation faltered as opposition figures were barred, detained, or silenced.

Resilience weakened as institutions acted more as extensions of CCM than guardians of democratic norms. Reforms stalled, leaving restrictive media, assembly, and electoral laws intact.

Rebuilding suffered as donor confidence wavered and regional condemnation mounted.

Restoring credibility to the 4Rs requires political courage. Reconciliation must be more than a slogan. Resilience must involve genuine institutional independence. Reforms must be anchored in constitutional change. Rebuilding must prioritise trust, not control.

At the centre of Tanzania’s democratic malaise lies the unfinished business of constitutional reform. Civil-society groups, religious institutions, and opposition parties have long demanded a new constitution to curb presidential powers, ensure judicial independence, and protect political pluralism.

The process launched under President Jakaya Kikwete stalled under Magufuli’s authoritarian turn and has remained stagnant under Samia. But the disputed 2025 election has reignited calls for change.

A new constitution would rebalance power between citizens and the state and establish the legal backbone for free and fair elections. Yet inside CCM, many see such reform as a threat to the party’s dominance.

Samia faces a difficult choice: revive the constitutional agenda and risk alienating powerful internal constituencies, or maintain the status quo and deepen the crisis of legitimacy.

The violence reflected the breaking of a social contract long strained by distrust and manipulation

Her leadership moment demands a decision.

Among the most disturbing developments of Tanzania’s recent political landscape is the resurgence of abductions and enforced disappearances. Human-rights organisations have documented more than 200 such cases since 2019, a trend that persisted into the 2025 election period.

Victims include activists, journalists, and political organisers. Some reappear after days or weeks, traumatised but silent. Others remain missing.

The security apparatus enjoys near-total impunity. Abductions serve as a tool of repression, instilling fear and suppressing mobilisation. The long-term consequences are corrosive: civic participation declines, journalists self-censor, and trust in the state collapses.

The 4Rs cannot succeed without confronting this machinery of fear.

Beyond formal institutions, Samia must navigate the informal power networks within CCM — the real guardians of the party’s authority. These networks of regional barons, business interests, security veterans, and ideological loyalists shape the decisionmaking environment.

Their priority is continuity, not reform. Any agenda that threatens the established balance is resisted, often subtly but decisively.

Samia must balance appeasing these forces while pushing for the changes necessary to restore Tanzania’s democratic health. This is a political tightrope with high stakes: too much compromise risks further regression, while open confrontation could destabilise her position.

Tanzania now stands at a historic crossroads. Samia Suluhu Hassan’s disputed re-election has strained her reformist image and shaken public confidence. Yet the very philosophy she championed — reconciliation, resilience, reforms, and rebuilding — could still chart a way out of crisis if restored with sincerity and urgency.

Reclaiming the 4Rs would require freeing political prisoners, reopening civic space, depoliticising institutions, advancing constitutional reform, and establishing accountability for abuses. It would also involve confronting the entrenched power networks within CCM that have long equated political control with national stability.

Regionally and internationally, Samia retains symbolic significance as a trailblazing woman leader. But symbolic capital fades quickly when repression mounts.

Whether she becomes a transitional figure presiding over democratic decline or a decisive leader who confronts the machine that constrains her will define her legacy — and Tanzania’s democratic future.

Jon

Offei-Ansah

examines how a digitally connected generation—from Nairobi to Rabat—is challenging entrenched power, demanding economic justice, and reshaping the future of democracy across

FROM Antananarivo to Rabat, Nairobi to Lagos, a generational awakening is transforming African politics.

The continent’s Gen Z — born between the late 1990s and early 2010s — has emerged as a restless political force, unwilling to inherit the failures of its elders. Over the past 18 months, protests led by young Africans have overturned governments, forced policy U-turns, and redefined the relationship between citizens and the state.

These movements are not commanded by political parties, trade unions, or charismatic opposition figures. Instead, they are decentralised, digitally coordinated and defiantly post-ideological. What unites these protesters is not a single manifesto but a shared sense of betrayal — a conviction that democracy has become hollow, and that leaders elected to serve have instead governed to survive.

We still believe in democracy — we just don’t believe in their version of it

In Kenya, months of protests under the hashtag #RejectFinanceBill2024 forced President William Ruto to withdraw unpopular tax proposals. In Madagascar, student-led demonstrations over crumbling dormitories and frequent power cuts escalated into a national uprising that ended with President Andry Rajoelina’s removal from office. In Morocco, youth anger at lavish World Cup spending while hospitals and schools languish has spurred the country’s largest protests in over a decade.

This generational wave of rebellion, stretching from North to Southern Africa, represents more than isolated grievances. It signals a fundamental rupture in the social contract between governments and governed — one where promises of democracy are no longer enough without delivery.

The economic context behind this revolt is as urgent as its political dimension. Africa’s youth have borne the brunt of global economic shocks over the past five years. The Covid-19 pandemic

Morocco’s ‘GenZ 212’ collective is using memes and quick-hit videos to mock official propaganda and spark sudden street protests

decimated tourism, trade, and informal employment — lifelines for millions. When the war in Ukraine disrupted global food and energy markets, the impact reverberated across the continent, which depends heavily on grain and fuel imports from Russia and Ukraine.

Inflation surged while debt levels soared. Sub-Saharan Africa’s average debt-to-GDP ratio climbed from around 35 percent in 2013 to nearly 60 percent by 2022. As interest payments consumed national budgets, governments slashed subsidies and raised taxes, often under the guidance of the International Monetary Fund.

The outcome was a perfect storm of economic austerity and social frustration. Kenya’s proposed taxes on essentials such as bread and sanitary pads ignited outrage. Nigeria’s abrupt removal of fuel subsidies pushed transport and food prices beyond reach.

In Angola, a 33 percent fuel price hike triggered nationwide protests, while in Ghana, frustration with debt restructuring and youth unemployment has stirred renewed activism online.

Morocco’s crisis epitomises the contradictions of economic modernisation without social justice. Despite billions poured into hosting the 2030 FIFA World Cup, hospitals in rural areas remain understaffed, and public schools overcrowded. When eight women died in childbirth in Agadir in August, the tragedy became a national symbol of skewed priorities. Chants of ‘Stadiums are here, but where are the hospitals?’ echoed across cities, capturing a wider continental sentiment: that governments celebrate prestige projects while neglecting basic human needs.

Beneath these protests lies a deeper paradox. Young Africans overwhelmingly endorse democracy in principle but reject it in practice. According to Afrobarometer, nearly two-thirds of youth across 39 countries prefer democracy to any other form of government. Yet 60 percent are dissatisfied with how it works in their own countries, and more than half say they would accept a military takeover if elected leaders abuse power.

This signals not a rejection of democracy itself but disillusionment with its performance. Voter turnout among young Africans is declining sharply — barely two-thirds voted in their last elections compared to over 80 percent of older citizens. But in every other form of civic engagement, from protests to online activism, the young lead.

“We still believe in democracy,” a Kenyan protester told Africa Briefing. “We just don’t believe in their version of it.”

This sentiment reflects a profound legitimacy crisis. For decades, Africa’s democracies have emphasised elections as the ultimate test of accountability. But for Gen Z, legitimacy comes from delivery — jobs, education, and basic services — not ballots alone.

The architecture of today’s Gen Z protests mirrors the technology that raised them. They are horizontal, fast-moving, and visually powerful. Platforms like TikTok, Discord, and X (formerly Twitter) act as both organising tools and narrative battlegrounds.

In Kenya, viral videos of police violence during the June 2024 protests triggered a public backlash that forced Ruto to back down. In Nigeria, the hashtag #EndBadGovernance built on the legacy of the 2020 #EndSARS movement, expanding its critique from police brutality to corruption and inflation. Morocco’s “GenZ 212” network uses memes and short videos to ridicule official propaganda and mobilise flash protests.

This digital fluidity gives the movements tactical advantages. They can mobilise thousands without a central command, making it difficult for governments to infiltrate or suppress. Yet it also limits their staying power. Without leaders or negotiating structures, they often struggle to transform street energy into institutional reform.

Madagascar’s experience offers a cautionary tale. When Rajoelina’s government collapsed, the military swiftly filled the void, promising order but entrenching its power. The youth movement that had catalysed change found itself sidelined — a

reminder that spontaneous revolt, without political infrastructure, risks being co-opted.

What makes this moment distinct is its cross-border resonance. A protest in Nairobi trends in Accra within hours; a Moroccan activist’s video is subtitled and shared in Dakar. The grievances differ — taxes, fuel prices, or corruption — but the narrative is shared: Africa’s youth are tired of waiting for change.

This digital solidarity has created what analysts call a “protest contagion”, where civic mobilisation in one country inspires others. The collapse of Madagascar’s government reverberated across the region, emboldening activists in Zambia and Ghana.

However, as recent coups in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger illustrate, frustration with civilian rule can also breed nostalgia for strongmen who promise stability. Gen Z’s disillusionment risks feeding both democratic renewal and authoritarian regression. The line between reform and rupture has never been thinner.

The Gen Z uprising represents the most significant test for African democracy since the 1990s transition wave. Its demands are not revolutionary in the old sense — they are moral and material. Young Africans are asking for accountability, opportunity, and dignity.

Governments that ignore them do so at their peril. Repression, as history shows, only postpones reckoning. Yet to sustain its impact, the youth movement must evolve from street-level reaction to structured engagement — building civic organisations, policy agendas, and alternative leadership pipelines.

If Africa’s Gen Z can channel their defiance into constructive politics, they could yet renew the democratic project that their parents began. If not, the continent risks drifting into cycles of protest and populist authoritarianism.

As one Senegalese activist put it recently: “We are the democracy our leaders failed to build.”

Africa’s Gen Z revolt is not a rejection of democracy — it is its wake-up call. It demands that democracy become more than ritual elections and empty slogans. It insists that freedom must come with fairness, and legitimacy with service delivery.

Across the continent, leaders face a choice: rebuild trust through inclusive governance, or confront an increasingly radicalised generation with little patience left.

The energy, creativity, and digital power of Africa’s youth could either become the engine of reform or the fuel of instability The outcome depends on whether governments respond with empathy and action, or repression and denial.

For now, the message from Africa’s young protesters rings clear: democracy must deliver — or risk losing its generation. AB

Young protesters are bringing to the fore a deep anger over the lack of opportunities and political exclusion, thus forcing governments and older generations to rethink how they are governed, writes Crystal Orderson

WATCHING live images on social media of the Gen Z protests in Madagascar’s capital, Antananarivo, alongside President Andry Rajoelina fleeing the country, underscores a critical point: African leaders who ignore the socio-economic issues facing young people will provoke anger that could ultimately lead to their removal from office.

The significant Malagasy youth population called for change similar to that seen in other parts of Africa and Asia. The protests have also revealed how Gen Z is challenging traditional power structures, questioning political elites, confronting corruption and poor governance.

Furthermore, this generation has lost trust in ruling political parties and their leaders and is not shy in expressing frustration over the lack of opportunities. This growing discontent has ignited a wave of local grassroots activism and has reshaped the political landscape in some countries.

Over the past few months, we have witnessed young people challenging dominant political powers across various regions, from Kenya to Nepal, Morocco to Indonesia, and now in Madagascar. They have effectively utilised social media as a tool for mass mobilisation, confronting traditional media and political elite power structures.

In Madagascar, where the median age is just 19, protests erupted, primarily led by Generation Z. Initially focused on the pressing issue of electricity and water shortages, the demonstrations then broadened to encompass a range of critical

concerns. These included unemployment, corruption, poor governance and inadequate basic services for millions of people.

In a bid to appease the protesters, Rajoelina responded with some promises and reform. He fired his Cabinet and appointed a new Prime Minister, Ruphin Fortunat Dimbisoa Zafisambo. At the time, Rajoelina said the new premier must be “capable of restoring order and regaining the people's trust, with a focus on improving living conditions and advancing key national priorities”. Rajoelina also made a set of promises that would bring change, but it seemed it was a little too late for people.

High unemployment and growing inequality have been some of the major drivers of change in countries across the Global South. Madagascar is one of the world's poorest countries. The World Bank estimates that three-quarters of the population live below the $2.15-a-day poverty line, and that the average annual income is about $600.

It also ranks in the bottom 20 of the UN Human Development Index. These stark statistics indicate a pressing need for economic reforms and development initiatives.

Rajoelina miscalculated the support of the army, who later joined the mass protests. Ironically, they are the ones who helped the former DJ and mayor of the capital come to power. During his DJ days, Rajoelina was once nicknamed “TGV” after the French fast train, for his energy and enthusiasm. He took power in a 2009 coup, making him the country’s youngest head of state in history at the age of 34.

At the time, his ascent was an important turning point in the country’s political landscape, as Rajoelina promised to bring change and development. However, his tenure was also marred by controversy, with critics questioning his governance and the sustainability of his reforms. Now, years later, it has come back to haunt him.

In a statement, the African Union called on all Malagasy parties to act with “responsibility and patriotism to safeguard unity, stability and peace, in full respect of the constitution and established institutional frameworks”.

Peter Mutharika, the newly elected Malawian President and Chair of the Southern African Development Community’s Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation, said SADC stood in “solidarity with the government and people of Madagascar during this challenging time.” He called on all stakeholders in

Madagascar to “exercise maximum calm and restraint, safeguard the rights, freedoms and dignity of all citizens, respect the rule of law and uphold constitutional governance”. The statement added that it was ready to assist the country; however, with Mutharika still settling into his new role as head of State, I do wonder what else SADC will do for the country.

The opposition in parliament told media outlets that Rajoelina had fled the country on October 12 after soldiers defected and joined the protesters. It has been reported that a French aircraft flew Rajoelina out of the country. He later took to social media platform Facebook, where he said he had to "move to a safe location to protect his life" and that he would not “allow Madagascar to be destroyed”.

Following Rajoelina's flight from the country, parliament voted to impeach him. The new regime then announced that it had stripped Rajoelina of his citizenship.

Africa has a massive youth population, which has implications for health, education and employment. African leaders seem to be out of touch with this generation.

The UN says there are more than 1.22 billion young people in the world. Africa is home to nearly 400 million young people between the ages of 15-35 and 60 per cent of the continent's population is under the age of 25. According to the UN population fund, young people (10-24) make up 32 per cent or 208 million of the population in East and Southern Africa.