AFRICA is standing on a seismic fault line—not of destruction, but of industrial rebirth. The 2025 Special Mining Report by African Mining Week and Moore Global reads not just as a snapshot of Africa’s resource potential but as a blueprint for rewriting the continent’s economic story.

For centuries, Africa’s minerals were carted off—gold, copper, bauxite, cobalt—traded for promises, not prosperity. But the energy transition is flipping that script. As the world pivots to clean power, Africa has gone from being a pit stop in global supply chains to a pivotal power in the mineral economy. And this time, it's not just about extraction. It's about transformation.

From ore to opportunity

The industrial commodities of tomorrow—lithium, cobalt, graphite—are now found in abundance in Africa. Zimbabwe, Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Tanzania hold the keys to the global energy puzzle. But for the first time, the world’s thirst for these minerals is being met with a new kind of African demand: value retention.

Gone are the days when raw ore was simply exported. Across the continent, gigafactories are rising, smelters are expanding, and the very idea of local beneficiation is no longer aspirational—it’s operational. Morocco’s $6.3bn gigafactory and Zambia’s refined copper projects aren’t isolated miracles; they are early signs of industrial intentionality.

www.africabrie

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor Desmond Davies

Contributing

Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Kennedy Olilo

Gorata Chepete

Corridors and carbon credits

IJon Offei-Ansah Publisher

Desmond Davies Editor

Yet Africa's ambitions are bottlenecked by the arteries that carry its minerals. Dilapidated railways and slow ports still haunt many countries. But the Lobito Corridor—a trilateral project backed by the US, EU and African Development Bank—is a striking exception. It’s not just infrastructure; it’s strategy. By slashing export times and lowering costs, it proves that Africa’s industrialisation can be accelerated by smart, integrated logistics.

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Country Representatives

Angela Cobbinah Deputy Editor

Equally compelling is the emergence of carbon markets as a new revenue stream. African mines are beginning to see themselves not only as resource hubs but as climate assets. From methane capture at Beatrix to Morocco’s renewable energy certificates, a new paradigm is emerging—one where sustainability pays.

Stephen Williams Contributing Editor

Director, Special Projects

Michael Orji

But the market is fragile. The ECOTRUST backlash in Uganda showed that if equity and transparency aren’t prioritised, carbon credits risk becoming the next extractive trap. Africa must lead with integrity, or risk losing this opportunity.

n 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa. What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

Regulation: the double-edged sword

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887

Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

The junior miner’s dilemma

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Corinne Soar Contributors

A modern mining sector also demands regulatory clarity. Encouragingly, Zambia’s Integrated Mining Information System and Rwanda’s Inkomane platform show how digitalisation can create trust and attract investment. But the rise of resource nationalism— Zimbabwe’s lithium export ban, Namibia’s rare earth pause, Mali’s equity grabs— underscores a delicate balancing act.

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Oladipo Okubanjo

Gloria Ansah Designer

These are not expropriations. They are recalibrations. Africa is no longer begging for a seat at the table; it’s rearranging the chairs. Global investors must adjust their expectations: high returns must come with high local value retention.

Country Representatives

South Africa

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Not everything is bullish. Early-stage explorers—the lifeblood of mineral discovery—are starved of capital. Their survival now depends on new financing models and partnerships with majors. Without them, the future pipeline may dry up. Discovery, after all, is the start of delivery.

Edward Walter Byerley Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Nnenna Ogbu

#4 Babatunde Oduse crescent

Turning leverage into leadership

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Technology is the final accelerator. From blockchain tracing cobalt in real time to AI improving worker safety, digital tools are levelling the playing field. But geopolitics looms large. Trump’s tariffs and the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act are re-routing global supply chains away from China—and toward Africa. The Lobito Corridor isn’t just logistics; it’s leverage.

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

Kenya

Patrick Mwangi

Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

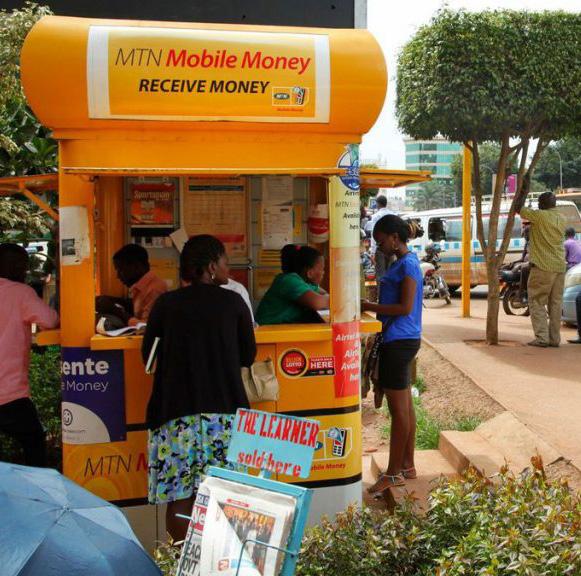

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

That leverage, however, is only as powerful as Africa’s leadership. The continent must rise not just as a supplier but as a shaper. It has the minerals. It has the momentum. But without infrastructure, skilled labour, regulatory consistency and community engagement, Africa risks letting this moment slip into history like so many others.

Kenya

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

The future isn’t just in the ground. It’s in how Africa moves, processes, governs—and dreams. The next five years will decide whether the continent is merely part of the clean energy future—or defining it.

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

©Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Critical minerals: a case for better control now

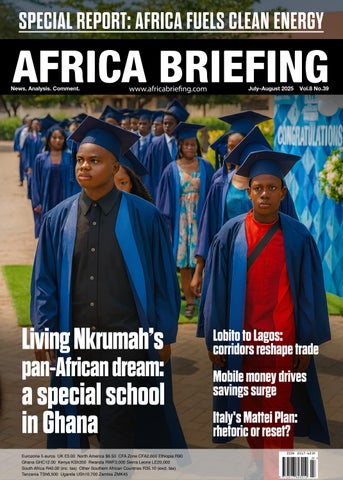

A special institution in Ghana Living Nkrumah’s pan-African dream

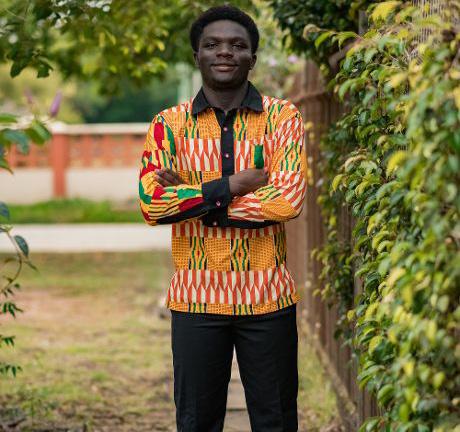

Inspired by the visionary ideals of Ghana’s leader at independence, the SOS-Hermann Gmeiner International College in Tema seeks to foster unity, intellectual empowerment and a sense of shared destiny among Africa’s youth. Desmond Davies looks at how the institution is nurturing leaders not just to excel academically, but also to adopt the responsibilities of citizenship in an interconnected continent

Voices of the future

Five students from across the African continent tell Africa Briefing about their experiences at SOS-HGIC and how the institution has prepared them for university and life beyond

6 07 08 11 16

Africa fuels the clean energy age

Africa’s mineral fortunes are being reimagined in the age of climate action. Jon Offei-Ansah explores how clean energy demand, ESG reform and digital transformation are turning the continent into a critical mineral powerhouse.

South Sudan on a slippery slope to renewed violence

The security situation in the beleaguered country is deteriorating in the midst of a worsening economic crisis, as ordinary citizens in the embattled regions struggle to survive, according to Concerned Citizens’ Network for Peace

30 32 22

Lobito to Lagos: corridors reshape trade Africa's dollar break-up starts with yuan

African retailers must prepare for next wave of cyberattacks

From the Dangote refinery scale-up to the Lobito railway, WAGP gas link and EAC’s digital customs, new corridors are cutting costs, speeding clearance and shifting market power across the region, writes Dorothy George

As the continent’s merchants accelerate digital transformation, the recent assault on the computer networks of two of the UK’s biggest retailers should serve as a crucial case study on what can go wrong when uptime – not just data – is under attack

Cairo’s yuan pact with Beijing signals a seismic shift in Africa’s currency politics — and China’s quiet campaign to dislodge the dollar is picking up speed, writes Brendan Odoi

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

AS the global economy undergoes a rapid transition – driven by the green energy revolution, digitalisation and rising technological demand – critical minerals have emerged as strategic assets that are highly sought by states and corporations alike. These resources, essential for batteries, renewable energy technologies and advanced manufacturing, have become focal points not only for industrial development but also for geopolitical competition.

The complexity of these supply chains and the diversity of actors involved – from miners and traders to manufacturers and end-users – demand integrated approaches. Stakeholders are calling for greater transparency, collaborative monitoring and the adoption of new technologies to trace minerals from extraction to final product. At the same time, there is heightened awareness of the social and environmental costs that can result from poor regulation or unchecked competition.

Such concerns have spurred calls for greater international coordination and dialogue, particularly as mineral-rich regions in Africa, South America and Asia face mounting external pressures. The link between resource governance, security and sustainable development is especially acute in areas where state authority is weak and conflict dynamics are complex. Here, the challenge is not only to improve oversight and regulation, but also to empower local communities and ensure that the benefits of mineral wealth are distributed equitably. Increasingly, there is recognition that effective mineral governance must address both global market forces and on-the-ground realities, including human rights protections, anticorruption measures, and investment in local capacity-building.

In response, international organisations and national governments have begun to pilot new frameworks for cooperation, data sharing and enforcement. Mechanisms for certification and traceability – often implemented in partnership with industry and civil society – are gaining traction as tools to counter illicit flows and build consumer trust. Yet, these efforts must overcome significant obstacles: fragmented legal regimes, limited

technical capacity and the persistent influence of non-state actors who profit from opaque trade networks.

In African countries rich in such minerals, questions of ownership, extraction and oversight are increasingly central to debates on sustainable development, security and international cooperation.

In this mix, US President Donald Trump is playing a cat-and-mouse game with African countries over control of critical minerals that American industries need desperately. On the one hand, he is pushing for a peace deal in the embattled eastern region of the critical mineral-rich Democratic Republic of Congo. The hope is that if Trump can swing it, he will use the opportunity to open the doors for US companies to exploit the DRC’s critical minerals.

On the other hand, he is antagonising the same African countries whose minerals he has his eyes on. By slapping visa bans and restrictions on 36 countries, including 25 in Africa, he has caused Africans to ponder why the US should have easy access to their critical minerals to fuel its tech, energy and defence industries.

In this light, it would make sense for critical mineral-rich African countries to now start taking control of the extraction of their resources and how much they earn from them. They need to collectively

It is now time for African countries to do the same. And it is not just about controlling the prices for their critical minerals. They must ensure that they do not just export raw material to be used in producing goods that are sold to Africa costing 10 times or more than the money African countries made from their natural resource exports.

Indeed, African governments have been seeking to maximise revenues and economic benefits from the extractive sector through measures such as increased taxes, export bans, investment incentives, state participation and local content policies. However past commodity booms have yielded limited benefits for many countries due to corruption and weak governance, highlighting the need for stronger safeguards.

Opaque agreements remain a major risk, facilitating illicit financial flows that cost Africa an estimated $90 billion annually. Undisclosed value addition agreements, resource-backed loans and mineral-for-infrastructure deals can further undermine good governance and efforts to sustainably manage debt. These are issues that an African-led critical minerals body should be able to tackle so that its members get the best deal – just as OPEC member countries.

The urgency to establish robust frameworks for the management of

African critical minerals producers must collectively control global market prices of their resources ‘ ’

negotiate better terms that would put them in control of global market prices of their critical minerals.

This is now an opportune time for African countries to come together and form a cartel – along the lines of OPEC – to start benefiting a lot more from their natural resources. The world saw how OPEC – after the Arab-Israel war of 1973 – transformed the way the oil-rich Arab nations took charge of their resource and have never looked back.

Africa’s critical minerals has only intensified. For African countries that have huge critical mineral reserves, they should be resilient and coordinate their plans to ensure that they get the best deal.

Thus, a united front of African critical mineral producers is the best way to maximise the benefits. There will be resistance from Western countries, but there are other nations that will step in and work with a united Africa trying to finally make the most of its natural resources. AB

THE SOS-Hermann Gmeiner

International College (SOSHGIC) in Tema, Ghana, is an institution that has bucked the trend in Africa since it took off in 1990. Over the last 35 years it has produced a great number of pupils who have made good in life; many of whom came from socially disrupted backgrounds.

The first batch of students came from Ethiopia. They were the traumatised survivors of the devastating famine that engulfed their country in 1984. It left many children orphaned and stuck in camps. The global response to the famine – Band Aid, Live Aid and all that – was tremendous.

That was when the Tema institution quietly stepped in – bringing in orphans from the SOS Children’s Village in Ethiopia to provide them with education and, more importantly, a stable environment.

Forty years on, while there has been a Live Aid revival in the UK, SOS-HGIC, Tema is still providing succour for students from Ethiopia and, of course, other parts of Africa. It has come a long way.

I am told that in its earliest days, the College faced daunting odds. Resources were scarce, expectations were high, and each day presented fresh challenges. Staff improvised with what little they had, often working late into the night to prepare lessons, organise activities and ensure the well-being of each student.

Students, in turn, learned to be resilient and adaptable, helping to forge a community spirit that would become the bedrock of the institution. Stories abound of those early cohorts huddled over books in dimly lit rooms, sharing laughter and anxiety in equal measure and forging bonds that would last a lifetime.

Out of this adversity, a distinctive identity began to emerge.

Margaret Nkrumah epitomised the spirit of Pan-Africanism. She was principal of the College from 1990 until 2008 and now chairs the board of the institution.

Under her, the College matured, its reputation for tenacity grew, drawing the

attention of families seeking a nurturing but challenging environment for their children. Innovations in teaching and mentorship took root and the bonds between staff and students deepened.

She ensured that the College’s commitment to holistic education meant that academic lessons were often woven together with practical life skills and character-building experiences. Slowly, stories of perseverance gave way to stories of quiet triumphs: the first cohort’s academic successes, the launch of new traditions and the sense that, together, they were building something enduring and remarkable.

This is quite obvious from the responses that Africa Briefing got from five members of the Class of 2025, which you can read in this edition. They are clearly focused on what they want to do with their lives and how to make Africa better in the future.

They speak of “effective communications”, “thinking critically” and

The

of SOS-HGIC imbibing the ethos of effective communications. My hope is that they are not frustrated by systems that are not moving Africa forward.

After all, these students are supposed to direct the future of the continent. They should be given free rein to put their learning to effective use.

Indeed, SOS-HGIC has been doing sterling work in preparing leaders that will fit into the Africa Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We want. The AU sees this as a “blueprint and masterplan for transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future”.

Formulated in May 2013, the AU noted that “the declaration marked the re-dedication of Africa towards the attainment of the Pan African Vision of an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens”.

The big question is: who are the citizens who will drive this reform forward? Naturally, it is the young

how “to grow as a leader”. They are on the right path. They have pointed out what I see as the failings of most of the current crop of African leaders.

Communicating effectively with citizens is the basis of strong leadership. How can a leader nudge his people to follow the right path if no relevant information is coming from the leadership?

And when I talk about effective communication, I do not mean banal social media postings. Serious leaders know this, and they are now turning again to traditional media to do the job.

Communications officers who feel that they have achieved something by shielding African politicians from the media are doing their countries a great disservice. One, though, is happy to see the products

Africans of today who are receiving the sort of education, training and preparation from institutions such as SOS-GHIC in Tema.

Africa has the youngest population in the world with more than 400 million young people aged between the ages of 15 to 35 years. In this regard, the AU has developed several youth development policies and programmes at continental level aimed at ensuring the continent benefits from its demographic dividend. The policies include the African Youth Charter, Youth Decade Plan of Action and the Malabo Decision on Youth Empowerment, all of which are implemented through various AU Agenda 2063 programmes.

Thus, SOS-HGIC is moving in the right direction to foster Agenda 2063. AB

Inspired by the visionary ideals of Ghana’s leader at independence, the SOSHermann Gmeiner International College in Tema seeks to foster unity, intellectual empowerment and a sense of shared destiny among Africa’s youth. Desmond Davies looks at how the institution is nurturing leaders not just to excel academically, but also to adopt the responsibilities of citizenship in an interconnected continent

SINCE its inception in 1990, the SOS-HGIC has absorbed a community of students who come from diverse backgrounds, brought together by a common goal: to uplift Africa through education and collaboration. The College has fostered a vibrant and inclusive learning environment where students are encouraged to strive for personal growth, intellectual curiosity and a sense of responsibility toward their communities.

The College embraces cultural diversity and encourages students to develop a keen sense of identity and leadership. By fostering a nurturing environment and promoting global citizenship, it aims to cultivate responsible individuals equipped with the values and skills needed to contribute meaningfully to their communities and the wider world.

Addressing the graduation of the Class of 2025 on June 7, SOS-HGIC Principal Eliz Dadson, captured the moment when she noted: “As you step into a rapidly changing world shaped by artificial intelligence, remember: it’s not the technology that defines the future — it’s how we choose to use it.”

Although the students should engage with new technology, they should do so “with wisdom, integrity, and heart. The skills you have honed here, curiosity, ethical thinking, and self-discipline, will serve you far beyond the classroom”.

Dadson added: “Although this is a graduation, it is not the end. Learning does not stop at the gates of HGIC. In fact, in a world that won’t remain still, learning becomes your superpower. Go forward boldly.”

Dr Margaret Nkrumah, who chairs the College’s board, has been there from the start. Looking back, she noted that “this school is unique”. She explained: “It is a completely African school in nature and content, run by Africans and doing one of the most rigorous courses in the world.

‘it

“There are not many international schools of this nature. Secondly, our students are carrying our name with them everywhere they go because of the way they comport themselves.”

The genesis of the institution, though, is not in Ghana. It materialised from SOS Kinderdorf International, the worldwide private welfare organisation dedicated to providing a family life and education for orphaned and destitute children. It was established in Austria in 1949 by Hermann Gmeiner to provide for children orphaned by World War II in Europe. There are now over 130 SOS Villages around the world.

SOS-HGIC Ghana was established in 1990 to provide a school of academic excellence for students from SOS Children's Villages from all over Africa and from Ghana itself. This was done in the “spirit of Pan-Africanism and an awareness of the social needs of society and to help them gain admission into the best universities”.

Rooted in its pan-African ethos and commitment to service, the College continually reviews and refines its strategic aims to align with the evolving needs of

its student body and the demands of a globalised society. The deliberate focus on nurturing talent from diverse backgrounds ensures a vibrant learning community, where students build lasting connections and broaden their horizons beyond academic pursuits.

The College’s core objectives guide all operations, including teaching, extracurricular activities and community partnerships. With a strong emphasis on inclusion, academic integrity and leadership development, the College remains steadfast in its pursuit of excellence and its dedication to empowering future changemakers.

Driven by a spirit of inclusivity and academic ambition, the objectives emphasise the identification and cultivation of talent – regardless of students’ backgrounds – ensuring that every child with the potential for advanced learning is given robust opportunities to thrive. In addition to academic rigour, the objectives highlight the necessity of preparing students for admission to leading universities worldwide, equipping them with the skills and confidence required to excel in competitive environments.

At the heart of these objectives was a commitment to building not just academic proficiency, but character, vision and a sense of purpose. The founders believed that education should not merely fill minds with knowledge but ignite within each student the confidence and curiosity to shape the world around them. The College was established as a diverse community where students from various backgrounds could learn and grow together.

In its formative years, the College attracted families and educators who shared a belief in the transformative power of learning. There was a palpable sense of pioneering spirit: staff and students alike accepted the challenges of establishing new traditions and setting standards of excellence. The vision was ambitious, but the determination to see it realised was unwavering. Every classroom discussion, extracurricular activity and community service project was seen as a building block towards a brighter future for Africa and beyond.

For Dr Nkrumah, it has not been all plain sailing for the College. But through sheer determination, it has now established itself as an educational institution that places equal weight on academic achievement, leadership growth, ethical conduct and social responsibility.

“Looking through the objectives for which this college was established, I could confidently say we have achieved each and every one of them,” she said, noting that it started off as a pilot project that had led to similar establishments, such as in Costa Rica, “as the direct result of the success of this one”.

How did the institution weather the storm in the early days? Dr Nkrumah spoke of the support SOS-HGIC Tema received from the log-serving President of SOS Children’s Village, Helmut Kutin, who died in April 2024. “The confidence of Mr Kutin in this College, and the unwavering support we received from him in those crucial teething years were of significant importance to our survival.

“Also, there was a tenacity of purpose and a clear vision of what I wanted to achieve. I was under no pressure to keep my job by pleasing someone, so I could fight for what I believed was right.

“It was important to establish procedures based on principles and hold on to those standards in the face of pressure. This proved extremely helpful to other staff,” she added.

The Tema institution noted that its “journey was, in many ways, inseparable from the larger aspirations and struggles of its parent organisation”. It added: “The vision that had taken root in local soil was echoed by a broader movement, as champions within SOS Kinderdorf International considered how best to serve the unfolding needs of children across the continent.

“At times, this meant contending with scepticism from those unaccustomed to such ambitious undertakings or navigating prolonged periods where bold ideas were set aside in the face of daunting logistical and financial barriers.”

The founders believed that education should not merely fill minds with knowledge but ignite within each student the confidence and curiosity to shape the world around them. Thus, the College was conceived as more than just a place of instruction – it was to be a living community, rich in diversity, where students from different backgrounds could learn from one another and grow together.

In its formative years, the College attracted families and educators who shared a belief in the transformative power of learning. There was a palpable sense of pioneering spirit: staff and students alike accepted the challenges of establishing new traditions and setting standards of excellence. The vision was ambitious, but the determination to see it realised was unwavering. Every classroom discussion, extracurricular activity and community service project was seen as a building block towards a brighter future for Africa and beyond.

Yet, as the seeds of this bold vision were sown, the path ahead was anything but smooth. The dream faced formidable

obstacles – doubts from established institutions, practical constraints and the perennial challenge of securing resources to sustain such an ambitious undertaking. Early champions of the College found themselves not only architects of a new educational ethos, but also tireless advocates, working to rally support among local communities and international partners alike.

The College has come a long way since the first batch of students would start in in September 1991. But this was not to be. In October 1990, a telephone call alerted the team to expect 12 “selected” Ethiopian students who were arriving to start the college. No interviews had been conducted, and no one was aware of their academic standards.

It was a mixed ability group. Some spoke little English while others had no knowledge of the language. Many of these students could not write properly in English. Other groups followed them from Liberia and Sierra Leone. Later, a few Ghanaians, whose parents were adventurous (or maybe foolhardy) enough to take a risk with the new school, were admitted. Among these pioneers was Abeye Mamo, who became the first SOS child from Ethiopia to hold a master’s degree.

But for Dr Nkrumah, it was the collective conviction, day after day, that had breathed life into the school’s vision – a vision now realised in the promise and poise of its graduates. Students, she explained, were not only excelling academically, but were becoming ambassadors of the school’s ethos, carrying its values with them into the world. With each success story, it is clear that something truly special is unfolding within the school’s walls, she noted.

‘An

TODAY, we gather to celebrate not just an academic milestone, but a journey – a journey defined by growth, grit and the power of community. And to honour the incredible support system that has carried us here.

To our teachers, thank you for your patience, your tough love and your belief in our potential, even when our missions tested your faith. To our parents and guardians, thank you for your endless encouragement, prayers and late-night motivational messages. And to our fellow students, you have been teammates, motivators and sometimes even therapists.

We are gathered here to celebrate the defining years that have shaped you into the resilient individuals sitting before us. It’s been a journey of unpredictable trials.

At the time, these moments felt like mountains. But looking back, they became turning points, proof of our resilience and our ability to rise above the chaos.

And it was not all stress and deadlines. We had laughter; laughter that echoed through campus corridors, water fights that soaked away the pressure and long walks filled with conversations that forged bonds we will carry with us forever.

That is the essence of the Class of 2025. We were more than just classmates – we were a family. A family that thrived not because we were the same, but because we chose to embrace our differences. We transcended labels – nationality, religion, background – and held fast to the values of empathy, inclusion and unity that SOSHGIC has imbued in us.

As we step out into the world, we do so not as finished products, but as works in progress – curious, determined and deeply aware of the world’s complexities. Whether we go on to study medicine, engineering, the arts, economics, or anything in between, we carry with us not only the knowledge

of the IB [International Baccalaureate], but the spirit of SOS-HGIC: the belief that education is a tool for change.

Looking back, there is so much we think we could have done differently –lessons we learnt, mistakes we made – but somehow, it has all come together. Better

your experience here but will carry you far beyond these walls.

Today’s gathering is more than just a ceremony; it is a testament to our spirit, determination and unwavering efforts throughout these transformative years. It stands as a moment of pride not only for

Let us be the generation that reimagines the world ‘ ’

than we could have ever imagined.

To future students, take full advantage of the opportunities that will be placed in your path. It is easy to sit back and observe but remember, you miss 100 per cent of the shots you do not take. Be bold. Your network of new people will not only enrich

ourselves, but for our families, friends and everyone who has supported us along the way.

As we go forth, let us remember our school’s motto: Knowledge in the Service of Africa. It is not just a phrase, but a call to action. It reminds us that the true value of education lies not merely in what we know, but in how we use that knowledge to uplift others, to lead with integrity and to make a meaningful difference in the world around us.

The future may seem uncertain –filled with AI revolutions, climate crises and shifting global dynamics – but we are not afraid. Why? Because we have already faced adversity and learned how to adapt. Because we have learned to ask questions, to seek truth and to lead with compassion. And because we have seen that when people come together, even in their differences, powerful things happen.

So let us go forward boldly – into universities, into careers, into service. Let us be the generation that does not just inherit the world but reimagines it. Let us lead not for recognition, but for purpose.

And no matter where life takes us, may we always remember the home and the family we built right here at SOS-HGIC.

This is an abridged version of Alexander Gamel-Kwame’s speech during the 2025 SOS-HIGC Graduation Speech and Prize Giving Day on June 7.

WHEN I joined SOS-HGIC in July 2021, I was a quiet, curious student from SOS Children’s Village Meru, Kenya. I had just earned the opportunity of a lifetime through the Global Scholarship Programme – a chance not just to study, but to grow, lead and discover who I truly am.

At first, Ghana felt far from home. But HGIC quickly became that home I didn’t know I needed – a place where I was welcomed, challenged and supported.

In these past four years, HGIC has shaped me into a better version of myself. I found my voice here – the first as Kenyan Country Head, then as Student Representative Council Vice President. These roles pushed me to step up for

others, to listen to my peers and to be a bridge between the student body and school leadership.

Whether it was helping resolve concerns within the Kenyan student community, advocating for improvements in the hostels, or organising community events, I have learned that leadership is about being present, accountable and empathetic.

Beyond student leadership, I have also grown through service and clubs. As the Growth Specialist for Mogul Club, I helped expand our community, bring in diverse voices and launch initiatives like Mogul Monday – a weekly newsletter that keeps the school informed about global gender issues.

It gave me a chance to lead conversations that matter and connect my passion for equity and finance in a meaningful way.

Another highlight of my journey was in the Chess Club, where I served as Training Officer. When the club risked fading out, I took the initiative to rally the team and relaunch our meetings and tournaments. Watching the club come back to life reminded me that leadership is not about titles – it is about taking action when it is needed most.

Sports have also played a big role in my story. I tried many – football, basketball, athletics – but it was in volleyball that I finally found my rhythm. Though it took time, commitment and resilience (especially when I did not get selected for competitions), I kept showing up.

Over time, I improved and found confidence not just in my skills, but in my determination. Volleyball taught me that growth is a process, not a moment.

Now, as I prepare to graduate and pursue a degree in Accounting and Finance at Middlesex University in Mauritius, I look back on my time at HGIC with nothing but gratitude. This school did not just prepare me academically – it taught me how to lead, how to collaborate and how to turn challenges into opportunities.

To the Global Scholarship Programme and all the supporters who made this journey possible: thank you. Your support has opened doors that once seemed out of reach.

Because of you, I have lived an experience that has forever changed my future. You have not only invested in my education – you have invested in my purpose in life. And for that, I will always be grateful.

I CAME to SOS-HGIC with the intention of furthering my education and earning the prestigious IB Diploma. It had been a long time since a student from Liberia had joined the school, so when I received the opportunity, I was both excited and determined to make the most of it. I had heard a lot of good things about the school, its culture, principles and academic excellence, so I saw it as the ideal place to challenge myself and improve. Most importantly, I understood that achieving the IB Diploma from HGIC would open doors for me both academically and personally and lay a solid basis for my future.

My time at SOS-HGIC has been transformational. In terms of leadership, I have learned what it means not just to hold a position, but to truly lead with purpose and integrity.

I served as the International Head for a while before transitioning into the role of Compound Prefect, and both positions taught me how to listen, collaborate and make decisions that benefit others. These experiences helped me understand leadership as service and taught me to balance responsibility with compassion. Personally, I have grown in many ways possible. I have acquired valuable life skills, become more self-aware and developed a deeper understanding of myself and others.

Academically, the school has provided me with every possible resource, from teachers, materials, support systems and learning platforms to ensure that I reach my full potential. The school does not just focus on academic achievements, but also pushes everyone to become a wellrounded, holistic individual.

Whether it is through sports, clubs, or everyday interactions, the environment and resources around us are built to shape us into a resilient, thoughtful and capable people. |I have also been stretched beyond my comfort zone in ways that have made me more knowledgeable and confident.

The school has made me realise that challenges are part of growth. I remember sometimes when I felt like giving up, thinking the IB was too difficult. But through mentorship, peer support and the school’s nurturing environment, I learned to view those moments as opportunities for growth. HGIC has taught me to persevere, to ask for help when needed and to always keep sight of my dreams.

I love rendering help to others, and I plan to pursue a career in medicine/ nursing. I want to spend my life making people feel better, both physically and emotionally.

HGIC has played a crucial role in helping me discover and commit to my dream. The school encouraged me during times of doubt, reminding me of my purpose and giving me the strength to push forward. The support I received, academically, emotionally and socially, has been essential in keeping me focused and motivated.

Thanks to HGIC, I now feel fully prepared for university and life beyond. I have learned how to manage my time, communicate effectively and take the initiative. More importantly, I have learned the importance of resilience, empathy and self-discipline.

The values and skills I have developed here, from integrity, open-mindedness, to courage, will guide me wherever I go. I leave HGIC not only with an academic qualification but also with a strong sense of identity and purpose, ready to take on any challenge that comes my way.

HGIC more than just a place of learning –Niyat Hagos Hailu (Ethiopia), aged 18

I JOINED SOS-HGIC in July 2021 after completing secondary school in my home country, Ethiopia. I came to HGIC because I was looking for something more – a better education, broader opportunities and a new perspective.

I have dreams and life goals I always look up to and eager to achieve in the future. I have always had a dream of travelling abroad and attending an excellent school with an internationalminded community. Moreover, I also want to make my family proud and make life much better for them.

Being awarded a scholarship was a life-changing moment and a big step toward my future dreams. It gave me the opportunity to study in an international environment that challenged me academically and personally. Leaving my home country was not easy, but I knew that growth often comes from discomfort.

Over the past four years, I have worked hard to adapt – not just to the academic demands, but also to the culture, the people and the pace of life here. I had to learn how to navigate unfamiliar systems, form connections in a new community and stay

grounded in who I am while embracing change.

HGIC has become more than just a place of learning – it is where I discovered my potential, resilience and began to see the world through a much wider lens. I came here for an education, but I’m leaving with so much more: perspective, confidence and a deep appreciation for everything this experience has taught me.

My experience here has been incredibly formative on multiple levels. Academically, I had access to challenging coursework and excellent teaching that pushed me to think critically and work independently through the rigorous International Baccalaureate (IB) programme. But beyond the classroom, I gained a lot more than just knowledge.

Being in an international environment forced me to step out of my comfort zone constantly, whether that was adjusting to a new culture, communicating across language and cultural barriers, or learning how to advocate for myself in unfamiliar settings.

I also had the chance to grow as a leader. From collaborating on group

projects to taking the initiative in extracurricular activities, I learned how to listen, organise and bring people together toward a common goal.

My amazing leadership experiences included working as an international student head, working with the student body and the school management team. These experiences helped build my confidence. connection and taught me how to lead through empathy and example.

Overall, I have grown into someone who is more adaptable, independent and aware of the world around me. I am leaving this experience not only with academic achievements but also with a stronger sense of who I am and how I want to contribute moving forward in the next part of my life.

My first goal is to pursue a career in the economics, finance, or management fields where I can combine analytical thinking with real-world impact. I am particularly interested in how economic systems influence development, business decisions and people's lives on a broader scale. University will be a space for me to dive deeper into these areas, strengthen my problem-solving skills and hopefully explore entrepreneurship or policy work in the future.

HGIC has been foundational in preparing me for this next step. The academic rigour helped me develop the discipline and time/self-management skills I will need at university, especially in demanding fields like economics and finance. The IB curriculum challenged me to think critically, make connections across various concepts and approach problems with a global perspective – all essential in finance and economics.

But beyond academics, HGIC taught me how to adapt. Living in a diverse community pushed me to understand people from different cultures and work effectively in teams; something that is vital in any leadership or business environment. I also had opportunities to take the initiative, whether in group projects or extracurricular activities, and that helped me grow into someone who does not just follow but also leads with clarity and empathy.

In short, HGIC did not just prepare me for university – it prepared me for the bigger world I am stepping into.

INITIALLY, the only reason any student would have wanted to come to SOS-HGIC was because of the laptops we get and that we get to travel abroad after completing school. But there is more to it. Coming to SOS-HGIC has been a lifechanging opportunity. One that I will never take for granted.

Transitioning from my Ghanaian traditional learning system to this modern, rigorous programme was not easy. Starting the Middle Year Programme (MYP) felt like entering a completely different world. I could barely use a laptop effectively like the other students, and research being one of the core skills here was something I had little experience of.

I spent most of my time using Mavis Beacon, a typing website to improve my typing skills. I am now well equipped with

the technological skills that this modern world requires.

Looking back now, HGIC has given me far more than just academics. I have grown into a resilient, independent and confident person. I have learned how to adapt, how to manage pressure and how to thrive in a diverse environment. I have built lifelong skills; critical thinking, collaboration emotional intelligence that I would not have gained in a regular school setting.

I have also learned how to lead myself before leading others. I have occupied different roles in school clubs ranging from Public Relations Officer to vice president. I have founded an initiative called Bertha's Nurturing Seedlings (BNS), which aims to provide early literacy to young children. This will help them require the necessary

skills to survive wherever they find themselves.

As I exit the gates of SOS-HGIC, I leave not just as a student, but as someone fully equipped to face the real world and well prepared to step into university. I have seen the highs and lows, and I have learned how to manage them with strength and maturity.

HGIC has given me an upper hand; emotionally, socially and academically over many students in the traditional systems, and I know that while others may still be figuring it out, I have already been trained and shaped to take on life. My plan is to pursue higher education in the healthcare field where I can give back to the community and save lives with the skills and knowledge acquired from this notable institution.

A sense of pan-African identity – Martin Boraya

EVER since primary school, I heard my siblings speak highly of SOS-HGIC – not just as a place for academic excellence, but as an environment that nurtures personal growth and development. I was inspired by the idea of being part of a diverse community where I could grow intellectually, socially and emotionally. The school’s emphasis on holistic education and networking opportunities is what truly sparked my interest in joining SOS-HGIC.

My journey has been both rigorous and rewarding. I have developed essential skills such as leadership, effective communication, research and critical thinking. I have had the opportunity to serve in leadership roles that challenged me and helped me grow.

Beyond academics, I have formed lasting connections with peers from Rwanda, Burundi, Zimbabwe, the US, the UK, Uganda and many other countries. Most importantly, HGIC has nurtured in me a strong sense of integrity and pan-African identity, values I will carry with me throughout my life. I plan to pursue a degree with the goal of making a meaningful impact in my community and across the continent.

SOS-HGIC has prepared me for this next step by teaching me how to think critically, communicate effectively and lead with purpose. The school’s multicultural environment has broadened my worldview, and its rigorous academic programme has equipped me to thrive in any university setting.

More than anything, HGIC has shaped me into a self-aware, adaptable and socially responsible individual – ready to take on the challenges of the future with confidence and determination.

Africa’s mineral fortunes are being reimagined in the age of climate action. Jon OffeiAnsah explores how clean energy demand, ESG reform and digital transformation are turning the continent into a critical mineral powerhouse.

AFRICA’S rich geology has long been both a blessing and a burden. For generations, its vast mineral wealth—from gold to copper to rare earths—was funnelled outward with little domestic benefit. But now, the forces of geopolitics, climate policy and supply chain shifts are converging to rewrite that story.

According to the 2025 Special Mining Report by African Mining Week and Moore Global, Africa stands at the threshold of a new industrial era—one powered by critical minerals and framed by global demand for clean energy infrastructure. In an age where batteries are as valuable as barrels of oil once were, Africa is no longer just exporting ore. It is exporting opportunity.

As the world races to meet net-zero targets, the technologies that power the transition—electric vehicles, solar panels, grid-scale batteries—depend heavily on a suite of minerals concentrated in Africa. The continent holds over 30 percent of the world’s known mineral reserves and produces a majority of the global supply for several key elements.

Cobalt from the DRC, lithium from Zimbabwe, manganese from Gabon and graphite from Tanzania are no longer fringe exports—they are cornerstones of the future economy. Global players have noticed. The report highlights how companies like Glencore, Marula Mining and Black Rock Mining are signing offtake agreements with African firms to lock in long-term access.

These deals are increasingly contingent on local value addition—processing the minerals on the continent, creating skilled jobs and retaining industrial profits that have historically flowed outward. This marks a major shift from Africa’s legacy of extractive dependency to a new era of resource sovereignty.

One of the most telling developments is the growth of Africa-based gigafactories. Morocco, South Africa and Zambia are now sites for battery precursor manufacturing, lithium-ion assembly and regional supply hubs.

Morocco’s $6.3bn gigafactory project, Zambia’s copper-smelting expansion and the DRC’s cobalt refining initiatives show how the continent is positioning itself for more than just mining. These industrial ambitions are backed by supportive policy moves, international partnerships and growing interest from both Western and Asian investors.

Even the Faraday Institution projects that by 2030, Africa could be producing battery materials 40 percent more costeffectively than global averages—if the necessary infrastructure and policy conditions are in place.

But minerals alone do not create prosperity. They must move—from mine to market—efficiently, securely and sustainably. This is where Africa faces its most immediate challenge: logistics.

The Special Mining Report outlines how fragmented and ageing transport

systems raise costs and create uncertainty. Without reliable corridors, investment in production loses viability.

The Lobito Corridor is a promising outlier. Backed by the US, EU and African Development Bank, the corridor links the DRC and Zambia to Angola’s Atlantic ports, slashing export times from weeks to days. Its successful first copper shipment in 2024 is a signal that infrastructure-led industrial policy can pay off.

Other corridors—like Tanzania’s Central Corridor and Mozambique’s Beira and Nacala routes—are being modernised, but remain constrained by congestion, inefficiencies and inconsistent governance. Until these arteries are fully functional, Africa’s mineral ambitions remain shackled.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) performance is now non-negotiable. Investors, particularly in Europe and North America, will not back mining projects without robust sustainability metrics.

The Special Mining Report reveals how this is transforming project financing. Private equity firms like Equitane are

pouring funds into ESG-aligned mining plays—from low-emission iron ore to solar-powered gold mines. Development finance institutions, too, are tying disbursements to ESG compliance.

South African mining companies are deploying blockchain to trace minerals and satisfy EU Battery Passport rules. Egypt’s Sukari mine and Mali’s Fekola operation are running on hybrid solar-battery systems, cutting diesel use and emissions.

In short, ESG is now the passport to capital—and the foundation of long-term profitability.

As carbon markets boom, Africa’s mines are poised to become not just mineral producers but climate asset managers.

Methane capture, ecosystem restoration and renewable energy use are creating carbon credits that can be traded internationally. According to the report, these could generate $6bn annually if managed properly.

Examples abound. The Beatrix Mine in South Africa uses methane flaring to create saleable credits. Morocco’s solarpowered Bou Azzer mine sells renewable energy certificates (RECs) to global automakers. Even biodiversity efforts— like COMILOG’s protected habitats in Gabon—are contributing to carbon offsets.

But the market is volatile and trust is fragile. Just 12 percent of Africa’s carbon credit projects meet top-tier standards. Uganda’s ECOTRUST was criticised for underpaying farmers. To secure longterm gains, Africa must ensure equity, transparency and third-party validation across the board.

No country illustrates the highstakes nature of transition better than South Africa. Long dependent on coal, the country faces social, economic and environmental headwinds as it attempts to go green.

The report shows how over 91,000 jobs in coal mining are at risk, and municipalities reliant on coal royalties face budget shortfalls. The decommissioned Komati Power Station is both a symbol of ambition and a warning—transformation without reskilling and investment creates dislocation.

Yet there is hope. The Just Energy Transition Implementation Plan envisions ZAR1.5 trillion ($83.3 billion) in investments. Projects like Seriti’s wind farms and Exxaro’s blockchain-certified

worker retraining programmes could offer replicable models. Repurposing coal infrastructure for solar and battery use is underway.

But the clock is ticking. Unless international pledges are fulfilled and policy bottlenecks resolved, the transition may falter under its own weight.

Investor appetite for African mining is strong—but it depends on regulatory clarity and consistency.

The Special Mining Report outlines how countries like Zambia, Rwanda and South Africa are digitalising licensing, improving transparency and streamlining approval processes.

Zambia’s new Integrated Mining Information System led to a 79 percent year-on-year jump in new licences. Rwanda’s Inkomane Digital platform has won praise for reducing bureaucracy. South Africa’s June 2025 digital rollout is expected to catalyse investment in platinum group metals.

But regulatory assertiveness also has a flip side. Zimbabwe’s ban on raw lithium exports, Namibia’s permit pause for rare earths and Mali’s increase in state equity stakes reflect a trend toward resource nationalism.

Still, these are not expropriations. They are recalibrations—attempts to capture more local value. For investors, the message is: adapt or miss out.

Early-stage exploration companies— once the lifeblood of African mineral discovery—are struggling. Capital is scarce, risk appetites are shrinking, and political volatility looms large.

To survive, juniors are forging joint ventures with majors. The Cobre-BHP deal in Botswana is a case in point. Others are experimenting with royalty financing, streaming agreements and even crowdfunding.

DFI-backed funds like African Lion Mining Fund III continue to support earlystage gold and base metal exploration, but their numbers are dwindling. Without fresh financing, the future pipeline of mineral production may dry up.

The junior crunch is a warning: without discovery, there can be no delivery.

Two final forces will shape African mining’s future—technology and geopolitics.

Digital transformation is accelerating. Mines are using drones, AI and real-time analytics to boost yields and cut costs. Blockchain tools trace cobalt from mine to battery. Automation is improving worker safety in remote zones.

At the same time, geopolitical realignment is tilting supply chains.

The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act and Trump’s 2025 tariffs have created urgency around non-Chinese sources. The US-backed Lobito Corridor is as much a diplomatic move as an economic one.

Africa finds itself in a rare position of leverage. The question is: can it turn that leverage into leadership?

Africa has all the pieces: resources, relevance and a growing regulatory toolbox. The world wants its minerals—not just for industry, but for the survival of the planet.

But ambition alone won’t be enough. Governments must invest in infrastructure, skills and policy clarity. Investors must look beyond short-term returns. Communities must be part of the value chain, not casualties of it.

As the 2025 Special Mining Report makes clear, the next five years will define Africa’s role in the clean energy future. It can be a supplier—or a shaper. The difference lies in vision, execution and the courage to lead.

Ghana’s first lithium mining project is touted as a win for local development. But concerns about compensation, participation and environmental impact persist.

Jon Offei-Ansah has been reading a recent study on the issue by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

AS the global push for green energy intensifies, Ghana is stepping into the spotlight with a rare and highly sought-after resource: lithium. The soft, silvery metal is critical for electric vehicle batteries and clean energy technologies, and global demand is skyrocketing. In 2023, Ghana signed a 15-year lease with Barari DV Ghana Ltd, a subsidiary of Australian-based Atlantic Lithium, to develop the Ewoyaa deposit in the Central Region. The deal is historic: it is Ghana’s first lithium mining agreement, and it comes with high expectations.

For Ghana’s government, the project offers a chance to shift from raw material exporter to value-added processor. For the people of Ewoyaa, a village of 580 mainly farming residents, it represents both opportunity and risk. Will this critical mineral deliver jobs, infrastructure, and long-term growth, or will it follow the path of previous extractive projects that brought more harm than good?

The government has pitched the Ewoyaa deal as a fairer, forward-looking model. Royalties stand at 10 percent— double the historical rate for other minerals. The Minerals Income Investment Fund (MIIF) will hold an additional 6 percent stake in the project, alongside a 3.06 percent equity in the parent company listed abroad. Local listing on the Ghana Stock Exchange is also planned, aiming to open investment opportunities to Ghanaian citizens.

A key provision is that one percent of company revenue will feed into a Community Development Fund to support local education, health, and farming. There are also plans for Barari to conduct a feasibility study for a chemical processing plant within four months of the lease's activation. If this does not materialise,

the company must sell by-products like feldspar to local industries such as ceramics. The fund is intended as a direct channel to ensure the community benefits tangibly from mining activities.

This agreement, structured under Ghana’s Green Minerals Policy, seeks to break the cycle of raw mineral export. The policy mandates a minimum of 30 percent state participation in green mineral operations, prioritises domestic value addition, and aligns with the African Union’s Africa Mining Vision. With global firm Piedmont Lithium—a Tesla supplier—acquiring a 50 percent stake in the Ewoyaa project, the stakes are high.

Despite the optimism, Parliament has yet to ratify the deal. Critics question the royalty terms and the depth of community engagement. Civil society organisations like IMANI Africa and the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) have expressed concern that the arrangement resembles a traditional concession model tilted in favour of foreign interests. They argue for a joint venture structure with

a government-owned company leading mining operations. As the IEA noted in 2023, the deal reflects a ‘colonial-type’ contract and must be restructured for Ghana to truly benefit from its resources.

Meanwhile, questions around transfer pricing and windfall taxes remain. IMANI has warned about potential underreporting of profits through relatedparty transactions, proposing benchmarks based on international lithium market prices. The IEA has pushed for clearer value addition commitments, demanding that mining commence only after a refinery is in place. Other experts have pointed to Latin America—particularly Argentina and Bolivia—as examples of more beneficial lithium models that combine government control with private investment.

What do local residents think? Two focus group discussions conducted in Ewoyaa in 2024 revealed a mix of hope and apprehension. Most villagers are aware of the project and some expect employment. But understanding of lithium’s value, or the environmental

consequences of its extraction, is limited. Initial engagements by Barari reportedly bypassed community consultations, with exploratory drilling damaging crops and prompting compensation disputes. Some farmers received as little as 200 Ghanaian cedis ($19.15 at current rates) for significant losses, while others were left empty-handed.

There is strong support for employment opportunities, particularly among the youth. However, scepticism persists. Many young people lack the formal education required for skilled roles. While training programmes have been promised, few details have been shared. The gap between aspirations and qualifications remains a critical barrier. As one participant in the youth focus group said, “The company just went straight to employ some of the youth in the community without the entire community knowing what they are here to do.”

The environmental impact also looms large. Community members cited concerns about water and air pollution, drawing parallels with nearby regions affected by illegal gold mining. The Ghana Water Company has blamed illegal mining for severe turbidity in the Pra River, which has disrupted water supplies in towns like Cape Coast and Elmina. Ewoyaa residents fear a similar fate. “There will be air pollution,” said one focus group participant. “The cars that will be moving around the community will cause a lot of dust in the atmosphere. Again, it will result in water pollution.”

Resettlement adds another layer of uncertainty. While some villagers welcome new housing and infrastructure, others are anxious about losing farmland and traditional livelihoods. One elder recalled, “We made it clear to them that it will be welcoming news to us. Our main request

will be for them to employ our youth to work with the company.”

Without proper planning, resettlement could lead to long-term poverty. Previous mining-induced relocations in Ghana have shown that unless new sources of income are secured, compensation funds are quickly exhausted. A female farmer lamented, “I was given 200 GHS for the destruction of a lot of crops. I had to even give them 60 pesewas as change.” Another respondent added, “They were not paying for the damages. However, when the locals started complaining, then they started paying something.”

To ensure community gains, the Ewoyaa project must be underpinned by transparency and accountability. Traditional leaders need access to technical expertise to negotiate fair terms. Compensation must be properly structured and disbursed in a timely manner. Communities must be informed participants, not passive observers. As one respondent said bluntly, “They don’t know that the trap is property to us, which we use to catch meat for sale.”

Effective regulation is also key. Institutions such as the Minerals Commission and the Environmental Protection Agency must be well-resourced to monitor environmental standards, enforce local content requirements, and uphold best practices in community engagement. The current legal framework, while strong on paper, often suffers from weak implementation.

Investment in education and vocational training is vital. If Ghanaian youth are to benefit from this project, they must be equipped with the skills the sector demands. Partnerships with universities and technical institutions, such as the University of Mines and Technology, can

bridge this gap. Scholarship schemes, apprenticeships, and internships should be built into Barari’s corporate responsibility commitments. As a local leader explained, “The chief said it has entered into some agreement with a company to train us, so that we can be employed when the work starts.”

Atlantic Lithium and its subsidiary Barari must do more than meet regulatory minimums. They must actively invest in the social infrastructure of Ewoyaa. That includes building schools, clinics, water systems, and roads. They should also consider creating business development grants and mentorships to support local entrepreneurship. Transparent reporting of royalty payments and community fund disbursements would further enhance accountability.

A useful model may be drawn from Indonesia’s ban on raw nickel and bauxite exports, which forced companies to invest in local smelters and led to higher foreign exchange earnings. Ghana could consider similar strategies to keep more of the lithium value chain in-country. Creating partnerships between Barari and local firms, universities, or vocational schools could also help deepen local participation.

In addition, Ghana’s mining regulatory regime could require all mining companies to dedicate a percentage of their profits to reinvestment in host communities. These funds could be earmarked not just for infrastructure, but also for health and environmental monitoring, agriculture extension services, and women’s cooperatives. These measures would ensure that benefits extend beyond the life of the mine.

Ghana’s lithium project represents a rare opportunity to get mining right. If managed well, it could mark a shift towards inclusive, sustainable resource governance. But this will require a commitment to more than just economic metrics. The true measure of success will lie in whether Ewoyaa's farmers, families, and youth see tangible improvements in their daily lives.

This moment is pivotal. Ghana must decide whether it wants to set a new benchmark for green mineral extraction or repeat the mistakes of the past. With global attention focused on lithium, the stakes could not be higher. The Ewoyaa deal may well shape the future of mining across Africa. The question is whether it will be remembered as a model—or a missed opportunity.

As demand for critical minerals intensifies, Jon Offei-Ansah analyses how West African nations are reclaiming sovereignty, redrawing mining rules, and confronting foreign giants in a global resource tug-of-war

THE global mineral rush has entered a new phase—one not marked by discovery, but by defiance. From Bamako to Accra, a growing bloc of West African states is rewriting the rules of engagement in the extractive sector. Foreign firms, long accustomed to preferential treatment and pliant regimes, now find themselves facing abrupt licence cancellations, heavier tax demands, and rising political resistance.

At the heart of this movement lies a resurgent belief: that natural wealth must serve national development—not just global supply chains. With gold, lithium, bauxite, uranium and other critical minerals in high demand, West African governments are demanding a bigger cut— and in some cases, full control.

This is not merely economic policy. It is a geopolitical recalibration, reshaping the region’s relationship with foreign powers and realigning its future industrial base.

Africa is home to roughly 30 percent of the world’s critical mineral reserves, but its wealth has long served others. Much of the continent still exports raw materials while importing processed goods—a trade imbalance that limits industrial development and locks in dependency.

Nowhere is this more evident than in West Africa. In 2023, Burkina Faso and Mali saw gold contribute 87.5 percent and 94.5 percent of total exports, respectively. Ghana exported $15.6bn worth of gold, more than half of its total export value, while Guinea-Conakry exported $9.6bn in gold and an additional $7.6bn in bauxite— making it the world’s second-largest bauxite exporter after Australia.

Despite this mineral bounty, economic dividends have remained limited. Most

refining and high-value processing occurs abroad, leaving countries with little more than royalties and job creation. That is changing.

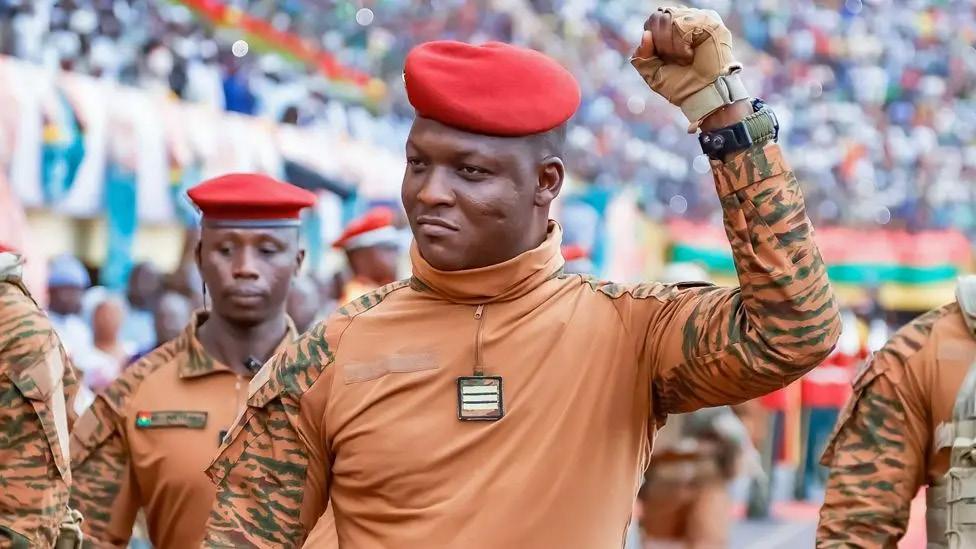

In recent years, a wave of military takeovers in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has ushered in populist, anti-Western regimes. These juntas, now part of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), are making assertive moves to reclaim control of their mineral sectors.

In Burkina Faso, Captain Ibrahim Traoré has become the figurehead of this new nationalism. Declaring that his country’s gold must no longer be “looted”, his government expropriated two mines from British firm Endeavour Mining in August 2024. Two months later, he warned that Western companies could lose

their licences. Canadian mining stocks nosedived—Iamgold dropped 15 percent, Fortuna Silver and Orezone Gold each fell 10 percent.

The message was clear: old deals are off the table.

Niger’s post-coup regime has been similarly aggressive. The country contributes nearly five percent of global uranium output and was once a major supplier to Europe. But since the 2023 coup, Niger has halted uranium exports, revoked the Imouraren mine licence held by French state-owned Orano, and shut down the Somaïr mine in December 2024.

Somaïr’s uranium stockpiles, estimated at €200 million, remain locked in limbo. Orano, once dominant in Niger’s uranium sector, is now considering a full exit—

likely opening the door to new players from Russia or China.

Mali has gone even further, rewriting its mining code in 2023 to sharply increase state stakes, tighten permit rules, and demand retroactive tax payments. In September 2024, it hit Barrick Gold with a $512 millon tax bill, prompting a legal standoff.

The government escalated matters: four Barrick employees were detained, exports were blocked, and in January 2025, 3 tonnes of gold were seized. Barrick shuttered operations at the LouloGounkoto mine—80 percent owned by the Canadian firm—only for the government to request its reopening under state control.

The case is now before the World Bank’s arbitration tribunal, but Mali may ignore any ruling, citing sovereign tax authority.

Guinea, too, is flexing its muscles. In May 2025, the junta revoked 129 mining permits on grounds of underuse, effectively clearing the slate for a new round of high-stakes negotiations. Major players in bauxite and gold mining are now walking a diplomatic tightrope, hoping to keep assets while appeasing an increasingly assertive regime.

Emirates Global Aluminium, a key player in Guinea’s bauxite sector, is in talks to retain its licence after failing to build a promised refinery.

Ghana, though politically stable, is also asserting greater control—this time through regulatory overhaul rather than confrontation. A new law has banned foreign firms from the local gold trade. Instead, all gold must be sold through the newly formed Ghana Gold Board (GoldBod), which acts as sole buyer, vendor, and exporter.

Large-scale miners are still allowed to operate, but must sell 20 percent of their output to GoldBod at a slight discount. It’s a move designed to give the state a stronger grip on pricing and reserves without alienating investors.

Western firms are not the only ones under pressure. Despite their political alignment with Sahelian juntas, Chinese and Russian companies are also being scrutinised. In Mali and Niger, Chinese firms have faced fines and threats of expulsion for alleged environmental violations and labour abuses.

Still, both Beijing and Moscow continue to expand their presence. Russia’s Norgold has secured a gold project in Burkina Faso. Rosatom is reportedly eyeing uranium opportunities in Niger. Meanwhile, China is advancing lithium projects in Mali and iron ore extraction at Guinea’s Simandou mine.

The competition is fierce, but the rules have changed.

Across West Africa, the message to international firms is blunt: mineral wealth is no longer up for grabs. Companies must align with national development plans, honour local regulations, and accept reduced profit margins—or risk losing access altogether.

Some have adapted. Nine major gold miners in Ghana, including Chinese, Swiss, and Australian entities, recently agreed to GoldBod’s terms. Others are fighting court battles, scaling back operations, or exiting the region entirely.

Yet the overall direction is unmistakable: sovereignty now trumps convenience. The days of resource concessions as routine paperwork are over.

This moment is not just a legal shift— it’s a historic realignment. For decades, West Africa’s mineral policies were shaped by colonial legacies, donor expectations, and foreign investor pressures. That model is crumbling.