IN a world where headlines come and go with dizzying speed, every so often, a moment arrives that demands pause — not simply because it is unprecedented, but because it redefines what we thought possible. Such a moment belongs to Namibia.

For the first time in its history — and indeed, in the history of the entire African continent — the top three political offices of state in Namibia are now held by women. Not in token roles, not by appointment, and not as a public relations exercise. But by merit, by vote, and by deliberate political design. The presidency, vice-presidency and the speakership of the National Assembly are now occupied by women — a quiet revolution that has thundered across the continent.

Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, a liberation stalwart and career diplomat, has assumed the presidency. She is joined by two other formidable women in Namibia’s highest leadership offices. Together, they are not just making history — they are remaking the architecture of power itself.

This is not a side note. It is a centrepiece. It is a seismic shift in how political authority is imagined and exercised in Africa. As Africa Briefing Contributing Editor Valerie Msoka rightly and strongly puts it in her piece in this edition, this is not about representation alone. It is about redefinition.

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor

Desmond Davies

Contributing Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

Kennedy Olilo

Gorata Chepete

Namibia’s achievement sends an unambiguous message to the rest of the continent: African women do not just belong in decision-making rooms. They can lead them. They can build them. They can set the agenda for an entire nation — and perhaps, in time, for a continent.

Jon Offei-Ansah Publisher

Desmond Davies Editor

IBut as Valerie reminds us, this moment didn’t appear by magic. It is the result of decades of advocacy, constitutional reform, grassroots mobilisation and sustained political engagement. Namibian women — like many across the continent — have long understood that power is not given. It is claimed. And they have done just that, over many years, in parliaments, party structures, courtrooms, classrooms and cooperatives.

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Country Representatives

Now, the fruits of that struggle are bearing real, historic results.

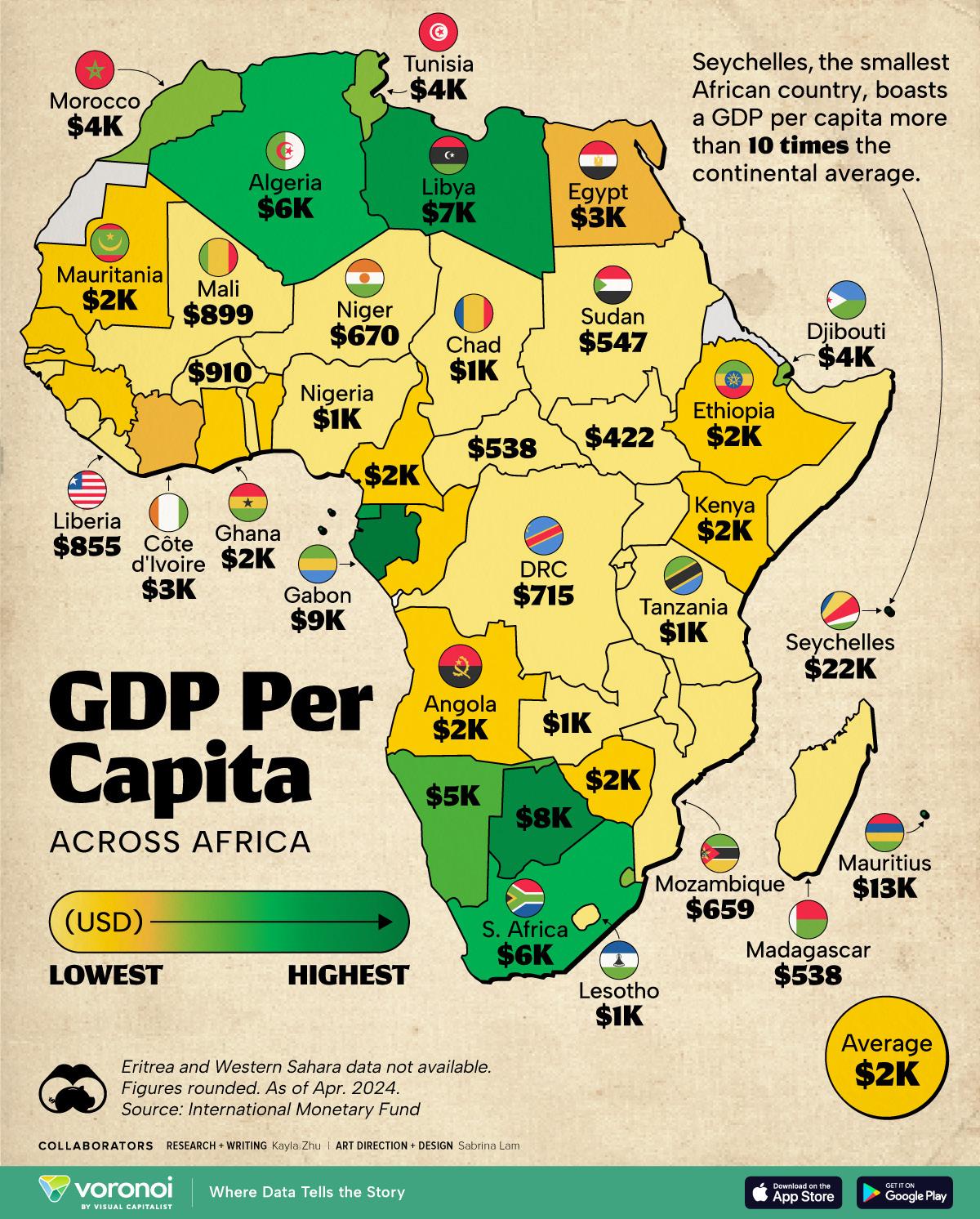

n 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa. What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

Deputy Editor

Angela Cobbinah

Stephen Williams Contributing Editor

Michael Orji Director, Special Projects

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

To understand the full weight of this development, it helps to look at the broader African context. Rwanda has long held the global record for female parliamentary representation. Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan has shown the power of calm and competent leadership in East Africa. Liberia gave Africa its first female head of state in Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Senegal and South Africa have made consistent gains in gender equity in political participation.

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar Contributors

But Namibia’s step is unique. Because this isn’t about one breakthrough. It’s about a deliberate, structural recalibration of power — from the margins to the mainstream.

Gloria Ansah Designer

The implications are vast. For every girl in Africa — from Abidjan to Addis Ababa — there is now a living, breathing example of what is possible. And for every political party, parliament and policymaker across the continent, Namibia raises the stakes. Gender equality is no longer a rhetorical aspiration. It is a governing reality. One forged in Africa, by Africans, for Africa.

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Country Representatives

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887

Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Nnenna Ogbu #4 Babatunde Oduse crescent

This moment, however, cannot be romanticised. Valerie rightly cautions that the road ahead remains steep. Patriarchal norms, institutional resistance, underfunded campaigns and gender-based violence continue to stifle progress. But Namibia has handed us a blueprint — and blueprints are meant to be built upon.

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

The challenge now is to move beyond inspiration to action. Gender parity must translate into policy reform, education budgets, leadership pipelines and economic inclusion. Regional blocs such as the AU, SADC and ECOWAS must move beyond declarations and into enforcement. They must fund leadership training, support electoral access for women, and ensure parity is not an anomaly, but an expectation.

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

Kenya

Patrick Mwangi

Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

Kenya

As Valerie powerfully puts it: ‘The question is no longer whether Africa is ready for women leaders. The evidence shows it is. The question is: how fast — and how boldly — will we move?’

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

Namibia has moved. And now, the rest of us must decide whether to follow — or fall behind.

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

©Africa Briefing Ltd

2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Double standards of international justice

It’s time to make Africa finally work Leaders must now pursue continental self-interest

Geopolitics and history have taught countries around the world that dependency on others for their survival is a risk that often fails at the worst possible moment, like now when the international order is being upended by Donald Trump. Thus, African countries must immediately begin to take control of their destiny, and to stop being overly reliant on external handouts or favours, argues Desmond Davies

12

Foreign aid and the problems of development

In the wake of swingeing cuts to US overseas development assistance by the Trump administration, Lansana Gberie looks at the state of development through the lens of a veteran in the business

28

Namibia sets pace on women’s leadership

Namibia has made history as the only African nation led by women in its top three political roles—a moment of continental significance, writes Valerie Msoka

Three AU missions, one mandate

This new transition period raises critical concerns about whether it represents a genuine step forward in addressing Somalia's evolving security needs, or simply perpetuates the status quo under a new banner with fewer troops and smaller footprints, writes Janet Sankale

40

Can the budget bring about land justice in South Africa? 6 07 08

Nkanyiso Gumede and Ruth Hall analyse the country’s ongoing land reform policy in line with the 2025 Budget, which is a response to the recent signing of the Expropriation Act

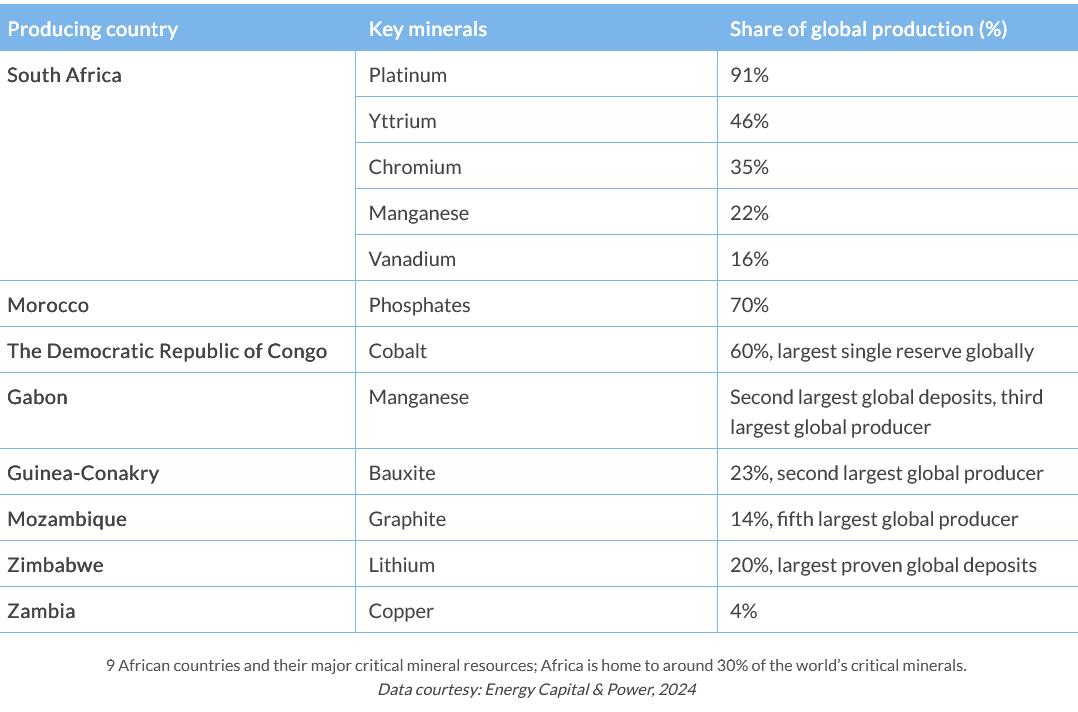

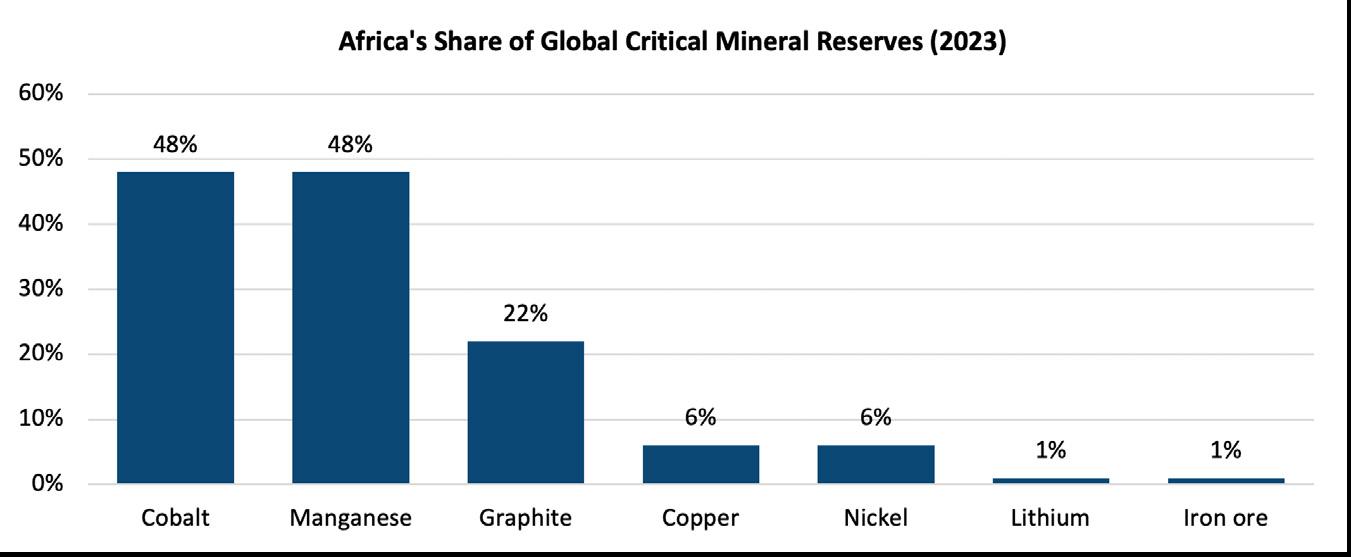

Africa's rare earth boom begins in 2025

Jon Offei-Ansah reports on how 2025 marks a pivotal moment for Africa’s rare earth minerals sector, with the continent on track to supply 10 percent of global demand by 2030

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

THE Hague-based International Criminal Court (ICC) has had a torrid time since it came into force on January 1, 2002. Its greatest critic has been the US, which, ironically, played a central role in the establishment of the Rome Statute that created the ICC.

Washington, however, has since then been playing fast and loose with the institution that deals with war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression. While various US administrations refused to cooperate with the ICC, and kept their distance, Donald Trump, in his first incarnation as leader of the US, imposed sanctions on the court and its officials. He has done so again since he began his second term in January this year.

The first time it was Fatou Bensouda. then ICC Prosecutor, who was sanctioned along with her senior members of staff. Now the current Prosecutor, Karim Khan, has come under Trump’s sanctions. Many see the action of Trump 2.0 against Khan and the ICC as the direct result of the arrest warrants that have been issued in relation to the ongoing conflict in Gaza.

The history of moral evasiveness around wartime atrocities, and now the blatant US attack on the ICC, cripples the very institution that could eventually end such impunity. The sanctions by the Trump administration, which include asset freezes and travel bans targeting ICC officials and affiliates, highlight the fact that the ICC is not shielded from a derisive global game of power and manipulation, with no regard for justice.

Enter Russia. Khan managed to indict Putin on kidnapping Ukrainian children from orphanages while Russia claimed they were evacuated from conflict zones. Needless to say, assessing the accuracy and extent of those violations is difficult while military operations continue, and access of journalists and human rights investigators is largely limited in all places including Gaza and Ukraine.

Self-defence and armed response have always been a contested terrain. Israel claims all measures are justified in response to the October 7 attacks which is always distinct from the legality of how one fights.

The actions of the ICC have often come into conflict with powerful countries such as the US when it attempts to exercise its legal mandate, making it difficult for international justice to be effective. Navanethem Pillay, a South African jurist who served as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights from 2008 to 2014, noted all those years ago that it was far from easy to hold those accused of international crimes accountable because gathering evidence was a formidable task.

She noted that most international tribunals were “mired in politics”, more so when it came to dealing with political leaders and high-ranking government officials. According to Pillay, the most powerful nations are reluctant to fight against impunity.

But these same powerful nations, when its suits them, have used the ICC to further their own geopolitical ambitions. For example, the US backed a UN Security Council referral to the ICC to issue warrants of arrest in 2009 and 2010 for then President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, even though the country was not an ICC member. The Security Council, though, has the mandate to refer cases to the ICC even if a country is not a member of the Court

African countries have also had a fraught relationship with the ICC, accusing it of focusing on the continent. But the atrocities continue.

organisation over the atrocities committed in Tigray and the ongoing violence against civilians in Sudan.

During the Tigray war the then Chairperson of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki, and the High Representative for the Horn of Africa, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, and the Ethiopian government used their agency to prevent the activation of the established mechanisms of the African Peace and Security Architecture.

The crimes committed in these conflicts are there for the whole word to see, yet there are very few voices calling for practical steps to bring about justice. No ideology or geopolitical interest justifies impunity, the dispossession of a people or the denial of their right to selfdetermination.

The role of the Western media in selectively focusing and even defending the acts of some states is unprecedented. International humanitarian law makes clear that no cause justifies war crimes –including war crimes committed by the most favoured states.

It is well known that the application of international justice is uneven. It is equally recognisable that the international criminal justice system has particularly failed the victims of atrocities in Africa.

US sanctions notwithstanding,

The African Union has been criticised for what many see as a lack of commitment to its own rhetoric when it comes to taking practical steps to oppose mass atrocities. This critique has been necessitated in no small measure by the truly outrageous silence of the continental

international law must prevail. The Commonwealth Lawyers Association said in its recent statement in relation to Trump’s action: “…sanctioning this entity [the ICC} and its principal officers is a direct attack on that rule of law institution and on the effort to end impunity for these very grave crimes.” AB

FOREIGN direct investment (FDI) and aid are drying up for Africa in the current disruptive global economic environment engendered by Donald Trump in his second term as president of the US. In this climate, it is not right for the continent to continue haemorrhaging much needed money for its development.

Every year, hundreds of billions of dollars flow out of African countries licitly and illicitly. The Indian Gupta brothers, for example, contrived to siphon out of South Africa an astronomical amount of looted funds in a financial crime now being referred to as State Capture.

The brothers are currently safely ensconced in Dubai or somewhere in that part of the world, enjoying their illgotten lucre. South Africa has no hope of recovering the money. Meanwhile, Trump and his enforcer, South African-born Elon Musk, are waging an economic war against the country.

These huge amounts of illicit financial flows from Africa are crucial to

cent. This is what AfCFTA wants to change – to make the continent’s 50odd markets one, just like India’s single market.

These African markets are too small and fragmented to support the sort of investment that is needed to industrialise the continent. African economies are dominated by one-man (or one-woman, for that matter) businesses that rarely pay tax to the government.

Apart from this, the business regulatory system is skewed. For investors (both local and foreign), they have to navigate a minefield dotted with exasperating bureaucratic delays and corruption as they try to establish productive enterprises. Governments now have to re-order their policy frameworks to attract investors to the continent’s manufacturing sector.

In all this, the issue of diaspora remittances to Africa has become paramount. Last year, Africans living abroad remitted almost $100 billion back home, surpassing FDI and aid combined.

Africans no longer need the “almighty dollar” to trade with each other

funding the private sector to make a huge difference to the continent’s manufacturing sector in line with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). It is creating a single market that is expected to boost Africa's economy to a stunning $29 trillion by 2050. By then, Africa’s population is expected to reach 2.5 billion – from its current 1.4 billion – with 66 per cent under the age of 25.

With the youngest workforce of all regions around the world these youngsters have it in their hands to power Africa’s development. This demographic advantage presents substantial economic opportunities, and with AfCFTA fully coming on stream this could boost intraAfrican trade by 50 per cent.

Right now, intra-African is in the region of 14 per cent, and the continent’s contribution to global trade is three per

’

This money now has to be put to work effectively.

Forget diaspora bonds that were floated a while back. Apart from the 2011 flotation that the Ethiopian government used to fund the country’s Renaissance Dam, others have not been so successful. They have underperformed, and lack of transparency has stunted their growth. Some Africans in the diaspora have not had any confidence in government borrowing, such as the experience under the last government in Ghana.

Nevertheless, there is no running away from the fact that remittances are now more crucial to the development of Africa than ever before. However, this funding must go to investing in large scale manufacturing businesses on the continent that will provide bigger dividends for all: flourishing industries; job creation;

more corporate and personal taxation for governments; and dividends paid to African diaspora investors and friends and relatives who normally receive money from abroad.

The African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) is on top of things. In conjunction with ARISE Integrated Platforms, it is building industrial parks and special economic zones across the continent to boost manufacturing. And they are beginning to create much needed jobs.

Textile is one sector that is providing 500,000 jobs. Years ago, Africa had a booming textile industry. Then came the Chinese, under-cutting African manufacturers and destroying their businesses.

China, funnily enough, is classed as a developing country under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, giving Peking the same preferential status as struggling African countries. So, while China can flood the world market with its products, as per the WTO (not to mention accusations of the use of slave labour), African manufacturers cannot do the same – not even for their local markets.

However, African governments can alter this by focusing on a few important things: assuring members of the African diaspora that the rule of law will protect their investments; and that there is the infrastructure (constant power and transport links) to facilitate competitively priced products that can hold their own against Chinese imports.

The best news of all is the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System that now enables Africans to trade with each other and invest across the continent without having to rely on the “almighty dollar”. Bringing together a growing network of central and commercial banks, payment service providers and other financial intermediaries, the system has simplified the payment landscape so that more Africans can trade with each other.

This is the right approach that will get Africa finally working. AB

Geopolitics and history have taught countries around the world that dependency on others for their survival is a risk that often fails at the worst possible moment, like now when the international order is being upended by Donald Trump. Thus, African countries must immediately begin to take control of their destiny, and to stop being overly reliant on external handouts or favours, argues Desmond Davies

US President Donald Trump telegraphed his intentions about how he would like to deal with African countries when, during his first term in office, he used gutter language to describe the continent. But he did not get a second term to carry out his plans.

However, as soon as he entered the White House at the beginning of this year, he took a wrecking ball to US development assistance programmes in Africa, dismantling the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and Power Africa, among others. The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), which more or less financially compensate African countries for being “good”, is under threat.

If it is any consolation for African countries, they are not the only ones that have come in for stinging criticism and economic threats from the Trump administration. Members of his Cabinet view Europeans as “free-loaders”, depending on the US to do the heavylifting when their continent is under international pressure.

Their Signal messages before the US air strikes against the Houthis in Yemen in March was “inadvertently” sent to a journalist at the Atlantic magazine. VicePresident J.D. Vance wrote that European countries might benefit from the strikes, adding: “I just hate bailing Europe out again.” Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth responded: “VP: I fully share your loathing of European free-loading. It's PATHETIC.”

The Europeans, just like Africans, had taken their eyes off the ball even though

Trump had laid down a marker in 1987 about how he sees foreign countries. Back then, he took out advertisements in three American newspapers, which read: “For decades, Japan and other nations have been taking advantage of the United States. Why are these nations not paying the United States for the human lives and billions of dollars we are losing to protect their interests? The world is laughing at America's politicians as we protect ships we don't own, carrying oil we don't need, destined for allies who won't help.”

He is finally in a position to put things right from his own perspective. However, Europe and Canada – which Trump is threatening to colonise – have the capability to counter America’s economic threats.

But Africa, it would seem, does not currently have the wherewithal to take on the US, even though the continent has the human and natural resources to help it to become less dependent on others for its survival. This, then, begs the question: might Trump’s global disorder have the salutary benefit of stimulating the growth of a collective African backbone?

It is possible. But the dependency syndrome, which was engendered by

and saying that person should stop feeding the family – and someone else would be responsible for providing food. Eventually, members of the family were being drip-fed to the extent that they all became ill and unable to do things for themselves.

Then came the World Bank and IMF prescribed Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the 1980s and 1990s that sapped the vibrant energy of Africa’s economies. It is not for nothing

foreign do-gooders who jumped on the “aid and development” bandwagon to “rescue” a continent that did not need “rescuing” in the early decades of independence, upset the apple cart.

In those years, most African countries were self-reliant when it came to food production. Their governments subsidised their farmers to feed their people – just as Europe and the US did. Enter the Bretton Woods Institutions (the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund). They told African governments to stop subsidies – and the downward spiral in food production began, which is clearly evident today. How can there be food shortages in Africa because Ukraine, which has been battling Russian invaders, cannot produce enough supplies to feed the continent? A continent that has far better weather and soil to feed all of its people.

The withdrawal of food subsidies was akin to someone entering someone’s home

that this era was dubbed the Lost Decade of Development. The 100,000 or so foreign “experts” who were unleashed on Africa wrought a monumental dislocation to the economic development of the continent.

For the legendary Malawian economist, Thandika Mkandawire who died in 2020, this was “an attack on the African state” by external forces. As one of the contributors to the 2004 book, Making the International: Economic Interdependence and Political Order, he wrote: “Africa’s economic decline in the 1980s and 1990s – the so-called ‘lost development decades’ – has been the worst of all major regions of the developing world, and as a direct consequence, Africa has been subjected to much greater external policy interventions than elsewhere.

“Indeed, the multiplicity of external and internal social actors in African governance points more sharply than anywhere else in the developing world to

the complexities of reconciling national efforts with international cooperation. International institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and powerful Western states have argued in this period that African developmental states are an impossibility and foreign advisers have assumed political and managerial roles that would be unacceptable in much of the rest of the world.”

Mkandawire continued: “The extreme nature of the international intervention in Africa provides insights into the construction and destruction of state capability which have wider application across the world. The political conditions…have encouraged irresponsible experimentation with different policies and strategies in Africa, an experimentation that has amounted, at times, to a confiscation from outside of the ability of national states to define their own role and to give expression to the political community they represent.”

Over the ensuing years, African governments have tried to reshape the future of their countries in the manner they want. It has been slow going but it is now clear that this momentum must be speeded up.

Africans must end the dependency syndrome that forces them to neglect their countries in favour of those overseas. How, for example, can wealthy Nigerians (most of whom are politically exposed persons, anyway) explain owning property worth $500 million in Dubai? How can they also explain spending $1.1 billion annually on health tourism? Or how can they explain taking $2.5 billion out of the country in 2021, according to the Central Bank of Nigeria, to support 120,000 students and dependants privately studying and living in the UK?

However, financial institutions such as the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) are changing things. It is set to launch a multi-million dollar 500-bed state-of-the-art hospital in Abuja, Nigeria,

which will be replicated across Africa to boost healthcare on the continent.

It is part of Afreximbank’s African Medical Centre of Excellence (ACME), in conjunction with King’s College London, which will serve as a pilot project for a continent-wide healthcare project, with an initial focus on East and Central Africa.

A healthy workforce in Africa makes for sanguine economic prospects for the continent. For now, Africa, with a population of 1.4 billion, is home to 17 per cent of the world’s population, with projections for this figure to double by 2050.

Yet, coverage of essential healthcare services is woefully low, with only 48 per cent of the people able to access such basic necessities for their wellbeing. This means, more than 600 million Africans are excluded from the formal healthcare system. Africa is estimated to have less than two healthcare professionals per 1,000 people, against the World Health Organisation’s recommended ratio of at

least four per 1,000.

As such, some 80 per cent of the African continent is currently experiencing medical staff shortages, due to high rates of healthcare professionals leaving to work in other countries. The WHO estimates that the shortfall in healthcare workers will reach about 6.1 million by 2030.

Prof Benedict Oramah, President and Chairman of the Board of Directors of both Afreximbank and AMCE, is upbeat about the collaboration with King’s College. Indeed, it is such collaborations that African countries and institutions must now be looking to in order to bring about the desired changes to the continent.

“The African Medical Centre of Excellence represents a defining moment in Africa’s pursuit of self-sufficiency in healthcare,” Oramah explains. “For too long, our continent has borne the heavy burden of non-communicable diseases,

capital flight from medical tourism and the exodus of skilled professionals seeking opportunities abroad. AMCE is set to change that narrative.

redirecting those resources towards strengthening our own systems.”

He added: “This initiative is more than an investment in infrastructure; it is an investment in Africa’s future. Through strategic partnerships with governments, international stakeholders and the private sector, we are demonstrating that Africa has both the ambition and the capability to provide world-class healthcare for its people. The AMCE is not just a medical facility; it is a statement of intent, a symbol of progress and a beacon of hope for a healthier, more self-reliant continent.”

This initiative should start to compensate for the cuts the Trump administration is making to support for healthcare in Africa. Where there is a will, there is a way, going by the Afreximbank’s robust financial backing for healthcare in Africa. The bank provided $2 billion for the purchase of covid vaccines during the pandemic.

Such funding must now be taken further. So, instead of South African President Cyril Ramaphosa complaining about “vaccine apartheid”, his government should strongly support his country’s excellent scientists, using South Africa’s world-class research centres, to come up with vaccines for diseases that are endemic in Africa.

This self-reliance can be replicated in almost every sector in Africa to make the continent less dependent on outside assistance. Ironically, Trump’s dislocation of the international order is a good opportunity for African countries to begin to get their act together, start to control their destiny and to no longer overly rely on external handouts or favours.

“By delivering world-class, lifesaving care to over 350,000 patients within its first five years, this facility will ensure that quality healthcare is no longer a privilege reserved for those who can afford to travel overseas. It will create 3,000 jobs, stimulate intra-African trade in medical services and strengthen critical supply chains in pharmaceuticals and healthcare delivery. “Most importantly, it will help Nigeria retain the over $1.1 billion lost annually to outbound medical tourism,

Geopolitics and history have taught countries around the world that dependency on others for their survival is a risk that often fails at the worst possible moment – like now. Indeed, as I have said over the last 30 years – and will continue to say so – the world does not owe Africa a living.

No country in the world has ever developed by expecting outsiders to do the job. This is the challenge facing the continent in the era of Trump.

In the wake of swingeing cuts to US overseas development assistance by the Trump administration, Lansana Gberie looks at the state of development through the lens of a veteran in the business

IAN Smillie, a Canadian with 50 years’ experience of development work, writes in his absorbing and insightful memoir* in 2024 that “development” is “an imprecise and much abused word whose meaning will, I hope, become clear as the clouds unfold”. But this is a retrospective judgment.

Smillie was himself quite clear about its meaning when, just out of university, he started out as a very young Canadian volunteer schoolteacher in rural Sierra Leone. This was in 1967. Sierra Leone had gained independence from Britain six years earlier. Its needs were immense.

Kono, the last of the frontiers of colonial penetration, opened up only after diamonds were discovered there in 1930, to be followed by a chaotic rush of speculators, heavy-footed colonial police, Lebanese smugglers and illicit –sometimes – violent diggers. The building of schools and other social services was scarcely considered. Smillie had offered himself, through Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO), to teach at the first secondary school in Koidu town started a few years earlier by a 30-year-old Englishman, T.C. Bartlam.

It was a heroic threadbare affair, but with the infusion of foreign volunteer teachers – there were also a few from the Peace Corps and only two Sierra Leoneans – it thrived, producing bright students who later went on to become teachers (out of admiration for the volunteers) and other professionals.

Diffident, concerned only with teaching school and making himself at home far away from home, Smillie, at this point, did not think of himself as a development worker, still less as a development specialist or professional. But development work was

exactly what he was doing.

Development then had a limited and useful meaning. It was the decade of independence in Africa, and most of the emerging countries had few university graduates or trained professionals. The newly-built schools were dependent on foreign volunteer teachers, and the government, Smillie notes, was eager to

expand such facilities as quickly as possible – relying, of course, on those outsiders.

CUSO was established in 1961, a year after President John F. Kennedy founded the Peace Corps, to respond to such needs. The great handicap to building new schools and opening new clinics and staffing agricultural extension services and even government departments, Smillie writes,

was “the simple lack of trained people”.

Development meant making available those trained personnel, funded by their overseas governments. This was foreign aid, pure and simple. The success of that programme can be measured a posteriori: none of these countries now need foreign teachers; indeed, the challenge is to provide jobs for the teachers they have trained. Those countries, however, had other pressing needs.

Smillie, only 22, had only his McGill university degree, his experience as a boy scout and a snake bite kit. Still, he had read the pioneering work of Barbara Ward, The Rich Nations and the Poor Nations, after hearing it praised by US President Lyndon Johnson. In it, Smillie learnt a lot about poverty and global inequality, and even more about the obligations of rich nations to help the poor out of their dereliction. But Ward told him nothing about Sierra Leone as a country.

When he got to Sierra Leone, he was taken by a small-gauge train from Freetown to Kenema, and then packed into an

overcrowded “comfort bus” – doubtless so named because it lacked precisely that quality – which took seven to eight hours to “traverse 130 tortuous kilometres through thick jungle on a road that alternated between broken rocks and long stretches of laterite mud so deep the passengers had to disembark twice to push the bus out of it”.

At this point, Smillie was convinced that he had embarked on a journey without maps, though, despite his adoration of Graham Greene, the English writer and journalist, his Liberian travelogue was not one of the books he had packed in his knapsack. The high-mindedness is not affected; I have known Smillie for 25 years and can testify to the purity of his commitment and dedication.

The need for development in Africa, Asia and Latin America was clear: it was the need for good roads, decent housing, food, proper hygiene and sanitation, transportation and everything that supports modern standards of living: the lack of them was underdevelopment. African, Asian and Latin American states simply did not have the wherewithal to provide those things. Assisting them to do so was foreign aid – helping those countries develop. Today, terms like “development” and “underdevelopment” are being frowned upon in some quarters: there is a preference now for “high-income” and “low-income” countries, though what these terms really mean is unclear. (There are countries in Africa with high GDP but are still underdeveloped.)

Memorable events happened while Smillie was in Sierra Leone: a coup, a countercoup and the reestablishment of constitutional rule with the elevation of Siaka Stevens, who turned out to be the disaster that would destroy that democracy and reverse much of the gains the country had made. It is part of the charm and merit of Smillie’s account that, reflecting his lack of political perspective or consciousness as a youthful provincial schoolteacher, he writes about these events as distant and irrelevant rumours. Only after Smillie’s visit to Freetown and his mistaken arrest as a “mercenary” did he begin to understand the implications of the disturbances.

This experience, it turned out, was merely for practice: after Smillie was next posted to Nigeria, he encountered a fullblown civil war, following a bloody coup and ethnic massacres seen by many as an incipient genocide. But Nigeria is a much larger country; and posted to its northern

half, with frequent visits to the west of the country – both of them unaffected by the fighting – Smillie’s understanding of the great events happen slowly, almost by accretion based upon his involvement in relief activities and his direct contact with refugees fleeing the fighting and some of the leading players.

In Ibadan, the largest city in western Nigeria, he meets with Colonel Olusegun Obasanjo, who would lead the Nigerian forces to victory over the secessionist Biafra, and with the writer Wole Soyinka, who got Smillie a cameo role in Kongi’s Harvest, his celebrated play that was made into a film by the pioneering African American filmmaker Ossie Davies.

His account of Nigeria suggests the development of some kind of political anxiety, centred on the role of emergency assistance or aid, and on larger issues involving foreign involvement in poor countries. The process is slow and understated, but discernible – again, attesting to the integrity of Smillie’s faithful record.

He describes the massive relief efforts mounted for Biafra by Western governments as “an act of profound folly” that helped prolong the doomed Biafra war effort and may have contributed to the death of at least 180,000 people in that rebel country. Worse, it was based upon a completely false, even misleading, supposition that the Nigerian forces fighting to subjugate Biafra were genocidal and meant to wipe out the Igbo people.

At the height of that war, the famous British scholar, Margery Perham, who had been an outspoken critic of the Nigerian military, voiced a similar sentiment in a broadcast to Biafra; but with the rebel state defended by such luminaries as Chinua Achebe and their eloquent, but profoundly roguish leader, Chukwuemeka Ojukwu, the obvious fact that Biafra could not be saved and that the wobbly Nigerian federation was anything but genocidal, was ignored by enthusiastic do-gooders.

Smillie’s work took him almost everywhere in the developing world, to Pakistan, Kenya, Ghana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Guyana, the Caribbean, often on short-term assignments. This was partly the result of marital life, which also gave him the time to reflect, in books, on various aspects of development he saw critical to breaking the poverty trap in those countries. The Land of Lost Content: A History of CUSO (1985) was a study of his

first employer. A year later, he published No Condition Permanent: Pump Priming Ghana’s Industrial Revolution (1986), which grew out of Smillie’s interest in intermediate technology, a sentiment that developed from the ideas of Fritz Schumacher, an economist and philosopher. It became an influential force in the 1960s following the establishment of the Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG), now called Practical Action (the publisher of this book) in Britain.

Smillie had become convinced that without a capacity for light engineering and productive enterprise, development would remain illusory. He revisited the issue five years later in Mastering the Machine; Poverty, Aid and Technology, published in 1991.

Intermediate technology was most extensively tried in India, drawing the ire of the dyspeptic VS Naipaul, who in 1976 described it as a cult centring on the bullock cart: “The bullock cart is not to be eliminated; after 3,000 or more backward

years Indian intermediate technology will now improve the bullock cart.” Naipaul believed that the idea, flowing from romantic doubts of people in the developed world about the industrialisation which they continued to cherish and rely on, was meant to perpetuate Indian backwardness: “Shouldn’t intermediate technology be concentrating on that harmless little engine capable of the short journeys bullock carts usually make?”

In Smillie’s more knowledgeable and sympathetic account, which focuses on the Suame Magazine in Kumasi, Ghana, the idea is far more attractive, though the result was none the happier. Suame Magazine, then and now, is one of the biggest open-air informal industrial areas in the world, with around 40,00 workers. (When I visited there in 2006 while living in Ghana, I was told that employees there numbered over 150,000, but this might have been exaggeration due to local vanity).

Smillie gives considerable space to Suame Magazine, clearly laying out its

foundational idea, driven by John Powell, a young British mechanical engineer. By the early 1980s, the Ghanaian economy had collapsed: it was no longer able to import spare parts and simple tools. Powell set to work with his team, to produce glue, dehydration equipment for cattle feed, bread-making equipment, a broad loom for weavers – all an aspect of intermediate technology.

The effort was rudimentary. A large part of the undertaking at Suame was vehicle repairs; there was no manufacturing. “There were two basic problems,” Smillie writes. “The first was about machines. Although there were lathe operators in Suame, there were no milling machines. This halted the project before it started.”

Powell was undaunted. He “identified four stages of technology in moving from a culture of repair to one of making things. The first and most basic stage is characterised by the use of hand tools designed without reliance on scientific principle. In the fourth, scientifically designed automatic machinery is not only in use, it can be locally developed or adapted. Although much of Africa was in stage one, governments, donors and multinational investors focused on jumping straight to four”.

Predictably, the result of Powell’s experiment was “a parody of stage four”. Nothing was developed indigenously; and at Suame, iron casting, which is the primary basis of manufacturing, was unknown until it was developed much later – perhaps the most significant outcome of Powell’s effort, though this “was almost a backyard technology in Asia”.

Towards the end of his book, Smillie, now a grizzled veteran, returns to Sierra Leone. It was not a happy moment. A brutal bush war, starting in 1991, had devastated the country; Kono, the diamond-rich district that provided Smillie’s first home in Africa, had become the epicentre of the conflict by the time he visited in 1995; the school Bartlam built had been destroyed.

The issue was no longer “development”; it was ending the war. Working with others – including this writer – Smillie embarked upon an inquiry to understand the forces driving the war. Predatory diamond hunters and gunrunners were identified as the extremely destructive forces; a foreign dictator, President Charles Taylor of Liberia, was the magnet drawing them in and reaping the spoils.

Suame

Smillie’s effort contributed massively to two important developments, which helped end the war and eased the peacebuilding process: sanctions on Taylor’s Liberia and the creation of the Kimberley Process. The United Nations intervened with a massive force, helping to disarm thousands of combatants and extending the writ of state once terrorised by the Revolutionary United Front rebels. The UN and Sierra Leone created a special war crimes court to try those bearing the greatest responsibility for the war and its atrocities, including Taylor, who was tried and convicted.

Smillie had made an effective

informal industrial areas in the world

Leone’s traumatic peace process”. A US Senator and two congressmen nominated Partnership Africa Canada, through which Smillie coordinated the campaign, and Global Witness, a British NGO which had first raised the issue of conflict diamonds, for the Nobel Peace Prize, a triumphant bookend to a gruelling campaign.

No one can argue, Smillie has written elsewhere – in response to veteran foreign aid sceptic William Easterly – that poverty “isn’t a staging ground for all manner of trouble with broad international implications: health pandemics, environmental degradation, refugees. And

Today, terms like “development” and “underdevelopment” are being frowned upon in some quarters ‘ ’

opening case in the court against Taylor, a triumphant moment – and Sierra Leone’s president, Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, wrote to him and his colleagues at the forefront of the campaign against conflict diamonds recognising their “crucial role...in Sierra

in societies where people are hungry, some – angry young men mostly – are prone to join groups fighting against perceived oppressors”. He then mentioned as an example the lesson from the fate of “the

Bourbons and the Romanovs… as they toppled into their graves”. A more accurate historical reference would have been a more recent one, the one Smillie is most familiar with: Sierra Leone.

But does aid actually work to reduce or eliminate poverty and to facilitate development? Smillie’s reflection on this issue in the chapter entitled “The Obsessive Measurement Disorder” is the best case for foreign assistance I have read; it should be circulated widely.

He had earlier referred to the work of Barbara Ward, who in the 1960s had called for a New Marshall Plan and rejecting “patchy development” assistance as insufficient for sustained growth. Ward suggested that rich countries devote one per cent of their national income to assist poor countries, noting that if they persisted in “their parochial self-interest,” the world was heading “not simply towards great disappointments, but towards disaster and tragedy as well”.

A similar case was made more forcefully by a World Bank report authored by former Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson, Partners in Development, published in 1969. The report emphasised funding for universal primary education, support for health sectors and nutrition, importance of increased global food production, and deplored the debt burden

on poor countries.

It advocated trade liberalisation, which “implies a willingness on the part of the industrialised countries to make the structural adjustments which will enable them to absorb an increasing range of manufactures and semi-manufactures from developing countries”. However, Smillie lamented, “the polar opposite” was what came to pass: “a requirement that developing countries open their economies to the manufactures” of the rich industrialised world, “while swallowing medicine that weakened their abilities to invest in the education, health, infrastructure and research required for competition in the global economy”.

The response to underdevelopment, he writes, “is not one thing”: it should include aid, foreign direct investment, trade, access to markets and good government. Smillie notes that most of the money earmarked by the rich world for development does not leave those countries: for example, money for refugee resettlement in the West, a sizable chunk, is listed as foreign aid.

None of the major economies has come close to meeting Barbara Ward’s recommendation to devote one per cent of their national income to assist poor countries. So, in response to the question “does aid work”, Smillie writes: “A partial

aid, because they often merely function as long-distance welfare payment to family members for their upkeep: they do not build clinics and schools.

In the wake of the announcement

answer has to be: how would anyone know? There has been so little of it, and so much has been confused with other things that any serious attribution is impossible.”

Nor is the headline grabbing issue of remittances of much help: of $501 billion recorded as remittances in 2019, he writes, only 4.3 per cent went to least developed countries. Remittances are no substitute for

by the Trump administration that it was axing USAID (United States Agency for International Development), a giant in the international assistance and development effort, in retirement, Smillie must view this development more in sadness than in anger – particularly as Trump has also vowed to end the sovereignty of his beloved Canada, a throwback to ideas of a different century.

Dr Lansana Gberie is Sierra Leone’s ambassador to Switzerland and Permanent Representative to the UN Office in Geneva. *Under Development: A Journey Without Maps, by Ian Smillie (London: Practical Action Publishing, 2024), 274 pages.

As the actions of the unilaterally protectionist Donald Trump begin to have a deleterious impact on global trade relations, Adekeye Adebajo looks at how South Africa fits into all this, having taken over the one-year rotating presidency of the G20 in December 2024 as the bloc’s first African host

CHINA has become the “workshop of the world”: its $18.5 trillion economy is the globe's second largest, more than that of all 27 European Union (EU) countries combined, while Beijing is the largest trading partner of over 120 countries. But the US remains the world’s largest economy at $28.7 trillion, accounting for 26 per cent of global output.

Three of the original BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries – China (second), India (fifth), and Brazil (eighth) – are now among the

world’s 10 largest economies, with all five also belonging to the Group of 20 (G20) leading economies.

South Africa – already Africa’s most industrialised country - will regain its position as its largest economy in 2025. Its participation in BRICS and the G20 has been based on pursuing its “African Agenda” of fostering economic cooperation with the continent and other developing and rich countries.

BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) governments met for the first time in New York in September 2006, before

holding their first summit in Yekaterinburg, Russia, in June 2009. After energetic diplomacy by President Jacob Zuma, South Africa was invited to join the grouping in December 2010, attending its first meeting in Hainan, China, in April 2011, thus transforming BRIC into BRICS.

The G20, for its part, accounts for 85 per cent of the global economy, 75 per cent of international trade and two-thirds of the world’s population. Founded in September 1999 to promote global financial stability through cooperation among the world’s most important economies following the

1997/1998 Asian financial crisis, the G20 consists of the original BRICS members; Western powers like the US, Germany, France and the EU; and regional powers like Japan, Indonesia, Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The African Union (AU) joined the bloc in September 2023.

As Africa’s largest economy at the time, South Africa was invited to be the only African country in the G20 in 1999. Pretoria has been vocal in promoting not only its own specific economic interests in the bloc, but also that of Africa as a whole.

The 2025 G20 summit to be hosted in South Africa will be its 20th annual summit since its first such meeting in Washington D.C. in November 2008. Both BRICS and the G20 have prioritised the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which seek to achieve specified and agreed development targets by 2030.

South Africa’s chairing of BRICS in 2023 saw the expansion of the group to nine countries. A youth council was also established. A BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) had earlier been created in Shanghai, China in July 2014 to attract investment, and has approved $32 billion of infrastructure projects, though the bloc,

like the G20, has no permanent secretariat. The grouping has convened 15 summits, with South Africa hosting in 2013, 2018, and

2023. While BRICS foreign ministers focus on expansion and partnerships of its membership, its finance ministers and Central Bank governors craft strategies on new payment schemes in local currencies, and seek convergence among the financial markets of its members. BRICS+ is also increasing people-to-people contacts through meetings

involving actors in the business, parliamentary, tourism, academic, media, youth and arts sectors.

At the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship (CAS) October 2024 dialogue, it was noted that South Africa’s foreign policy has often punched above its weight despite the fact that the country has limited technical and financial capacity, accounting for only 1.3 per cent of the BRICS+ GDP. Having been the first new member to join BRIC, Pretoria strongly championed the expansion of the group, bringing in two new African members – Egypt and Ethiopia – to bolster its African Agenda.

The non-inclusion of Nigeria –

boasting Africa’s largest population and, until recently, its largest economy – was discussed, with reports that Abuja retains an interest in joining the grouping along with other regional powers like Algeria, Turkey, Indonesia and Malaysia. A total of 34 countries have expressed an interest in BRICS+ membership.

It was, however, noted that the expansion of BRICS from five to nine members has made consensus more difficult to achieve, and there was a feeling that the group needed to integrate recent members to ensure cohesion before taking in new ones. Historical tensions between China and India, Ethiopia and Egypt, and Iran and the UAE could further disrupt the bloc’s unity.

The reported opposition of Addis Ababa and Cairo to endorsing Brazil, India and South Africa as members of an expanded UN Security Council in September 2024, was highlighted. This decision was, however, said to have been made during the 2023 Johannesburg BRICS summit at which the four new members were not yet present as full members. The statement endorsing their Council membership was part of a grand bargain that supported Beijing’s push for

the expansion of BRICS.

The grouping has also strongly promoted reform of global governance institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organisation, and championed greater South-South economic and political cooperation. Members have further increased - to 23 per cent - the use of their own currencies in conducting trade with each other, though it was noted that the idea of delinking from the US dollar could only be achieved in the long term. BRICS+ members have also been critical of the pernicious role of Western rating agencies, though they are yet to create their own alternative rating agencies.

The bloc was described by critics as a status quo rather than revisionist organisation, which was accused of pursuing a sub-imperial approach of “talk left, walk right” in which members were seeking to improve their own positions in Western-created institutions of global governance rather than overturn the world order. China and India benefitted from an increase in weighted voting at the IMF in 2015 at the expense of countries like South Africa.

The pursuit of market-oriented agricultural policies was also said to

have damaged small farmers across the bloc. BRICS+ countries – particularly China and India - were described as being among the world’s heaviest polluters not doing enough to compensate for the environmental damage to the world’s poorest countries.

Though a quarter of the bloc’s declarations relate to climate issues, BRICS+ members are fragmented into different negotiating blocs at environmental summits. Furthermore, the BRICS Bank was said to remain beholden to Western

“Fostering Solidarity, Equality, and Sustainable Development”, will be hosted by South Africa by November. The grouping has struggled to address effectively challenges of climate change, reform of global economic institutions, crippling debt burdens of developing countries, food security, global poverty and inequality, public health and digitalisation.

The conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East have also caused divisions between its members which has made consensus more difficult to reach. South Africa took over the one-year rotating presidency of the G20 in December 2024 as the bloc’s first African host.

The grouping has had some success in coordinating global economic policy, promoting debt suspension during the Covid-19 pandemic and leading debates on climate financing. South Africa’s presidency follows those of three southern powers: Indonesia (2022), India (2023) and Brazil (2024).

Indonesia touted “inclusive development” and “vaccine equity”; India pushed “the digital revolution” and “sustainable development”, while the Brazilian presidency, under former trade unionist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva sought to promote “social inclusion”, “equitable development”, and launched the Call to Action on Global Governance Reform. Brasilia and Jakarta particularly pushed support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Some key lessons from Brazil’s 2024 G20 presidency involved the need to engage grassroots movements (such as indigenous people from the Amazon rain forest) through the group’s first ever Social Summit, to ensure an agenda set by

The idea of delinking from the US dollar could only be achieved in the long term ‘ ’

rating agencies. New Delhi was fingered as a major supplier of arms to Israel, even as Pretoria continues to pursue a genocide case against Tel Aviv at the Hague-based International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The next 2025 G20 summit, themed

the priorities of ordinary citizens, and to coordinate effectively multi-national civil society networks.

An important lesson from India’s presidency was to reduce the roughly 200

meetings to about 130. The G20 summit in November 2024 focused, under Brazil’s presidency, on “Building a Just World and a Sustainable Planet”. The meeting sought to promote Brasilia’s socio-economic, environmental and global governance reform priorities, as well as initiatives such as the Global Alliance against Hunger and Poverty which seeks to reduce the 733 million people in the world suffering from hunger.

Ten substantial policy recommendations emerged from the G20 and BRICS Pretoria policy dialogues in July and October 2024:

First, South Africa must work closely with the AU during its G20 presidency to leverage the 1.4 billion strong African market, aligning its National Development Plan and the AU’s Agenda 2063 to an effective continental development strategy.

Second, Pretoria should strongly push reforms of institutions of global governance, building on the successful establishment of a 25th chair for subSaharan Africa on the IMF Executive Board in July 2024.

Third, South Africa must seek to increase Africa’s share of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights; prioritise food security; close Africa’s $130-170 billion annual infrastructure gap; and tackle the annual $88.6 billion illicit financial flows out of the continent.

Fourth, South Africa is encouraged

to commission experts to reform the IMF to be more transparent and accountable; examine how to achieve an effective division of labour between governments and international financial institutions; and leverage the resources of philanthropists like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on global health issues.

must strongly support Brazil’s call for a two per cent global tax on billionaires in order to raise $250 billion for development: an idea backed by South Africa, Germany and Spain, but opposed by Washington.

Eighth, Pretoria should champion the phasing out of fossil fuels and promoting

Fifth, South Africa’s presidency of the G20 in 2025 provides a great opportunity to push African development priorities such as suspension of the continent’s $1.1 trillion external debt, with African countries typically spending 45 per cent of their revenues on debt servicing, and Zambia, Ghana and Ethiopia having all defaulted on their debts.

Sixth, these efforts should be closely linked to the UN Pact for the Future, agreed by world leaders in New York in September 2024, which provides a comprehensive vision for strengthening the three pillars of global multilateralism: security, development, and human rights.

Seventh, the international community

green jobs, while pressuring the rich world to deliver on annual pledges of $100 billion to developing countries to combat climate change.

Ninth, it is critical that during its G20 presidency, Pretoria coordinate policy closely and effectively between South Africa’s presidency, foreign ministry and Treasury, and take advantage of its strong think tanks, as Brazil and India did during their presidencies.

Finally, South Africa must harness its “soft power” to act as a bridge between its BRICS and global South allies on the one hand, and the rich North on the other, in order to build consensus on the challenges of sustainable development and climate funding.

Adekeye Adebajo, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Pretoria’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship (CAS). The above are excerpts from a policy brief based on the outcomes of two policy dialogues held in July and October last year in South Africa.

Tiyanjana Maluwa discusses whether the Ukraine crisis has altered the focus and narrative on change at the UN organ responsible for maintaining international peace and security from the perspective of African states, and how this is likely to affect the future direction of the debate

THE Security Council met on February 25, 2022 to consider a draft resolution proposed by Albania and the US. It condemned Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and decided that the Russian Federation “shall immediately cease its use of force against Ukraine and shall refrain from any further unlawful threat or use of force against any UN member state”; and “shall immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognised borders”.

Eleven of the Council’s 15 members voted in favour of the draft text. China, India and the United Arab Emirates abstained and Russia vetoed it, even though the word “condemns” was replaced by “deplores”. All the three African non-permanent members of the Security Council, Gabon, Ghana and Kenya, voted in favour of the resolution.

All three spoke unequivocally in their condemnation of the invasion as a violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, and as a violation of the UN Charter and international law. Although they were not speaking for the African Union, their respective positions aligned with the collective view of AU members on the issues of the structural power imbalance in the Security Council and the need for its reform.

This is the Common African Position expressed in the “Ezulwini Consensus”. The relevant provisions state:

• Africa’s goal is to be fully represented in all the decision-making organs of the UN, particularly in the Security Council, which is the principal decision-making organ of the UN in matters relating to international peace and security.

• Full representation of Africa in the Security Council means: (i) not less than two permanent seats with all the prerogatives and privileges of permanent membership including the right of veto; (ii) five non-permanent seats.

• In that regard, even though Africa is opposed in principle to the veto, it is of the view that so long as it exists, and as a matter of common justice, it should be made available to all permanent

members of the Security Council.

• The African Union should be responsible for the selection of Africa’s representatives in the Security Council.

• The question of the criteria for the selection of African members of the Security Council should be a matter for the AU to determine, taking into consideration the representative nature and capacity of those chosen.

The key aspects of the interventions by the three African members may be summarised as follows. First, Gabon recalled its commitment to peace and the founding principles of the UN Charter and expressed its support for a fairer, rulesbased international order. Secondly, Gabon

called upon members of the Security Council to reaffirm their responsibility to defend these principles with determination and vigour.

Following the vote, the representative of Ghana stated that Ghana joined the 10 other members of the Council in deploring in the strongest terms the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine as a breach of its obligation to respect the provisions of Art. 2(4) UN Charter. More poignantly, Ghana stated that it was deeply disappointed by the actions of the Russian Federation as a permanent member of the Security Council, noting: “Its actions have fallen short of the standards expected of those that are considered to be the enduring guardians of international peace and security. Indeed, for those members of the Council with a special privilege, there is a special responsibility.

“[At] a time when the world looks to the Council to send a strong message that threats and use of force against other states are unacceptable, we have been unable

to do so – not because there is no broad agreement to do so but because the way and manner in which the Security Council has been structured to function constrained us.”

It is notable that both Gabon and Ghana articulated the special responsibility that members of the Security Council, in particular permanent members, have

statements is the question posed at the outset of this discussion: who will guarantee international peace and security when the guardians fail in their responsibility to do so, or breach the principle prohibiting the threat or use of force?

Ghana also invoked another point that was to be repeated in statements

as guardians of international peace and security. They both alluded to the structure of the Security Council adopted at the creation of the organisation, which has turned out to be an obstacle to its fulfilment of this special responsibility.

The subtext underlying these

by other African states in the General Assembly in the subsequent debates, namely the Russian veto as a reminder of the unfinished business of Security Council reform: “The present situation creates difficult choices that we all must consider and carefully reflect upon as we proceed

with the long-standing efforts to reform the Security Council and how it operates. “Fortunately, the ongoing process in the General Assembly provides an opportunity. All member states must genuinely commit to that process. If we fail to act proactively, our inaction will cost us permanently. “

The Permanent Representative of Kenya, Martin Kimani, also told the Security Council that Kenya voted in favour of the draft resolution “to affirm Article 2 of the Charter”. Alluding to the role of the Security Council, Kimani reminded the members of the Council and the UN that the Charter contained the tools for the pacific settlement of disputes. Furthermore, he noted: “By failing to adopt the draft resolution, [the] Security Council has failed to stop the infringement of the sovereignty of a member of the United Nations.”

A factor that played a part in the motivations behind the voting by the three African members was the perception of double standards on the part of some members of the Security Council, in

particular the three Western permanent members: France, UK and US. This can be viewed through two lenses. First, the perception that, even as one acknowledged the gravity of the situation caused by the unprovoked aggression of a nuclearpowered permanent member against a less powerful neighbour, one might recall that some past aggressions by other permanent

members in other parts of the world were never seriously challenged or condemned by the Council.

Secondly, the view that the attention given to the plight of victims of these past aggressions by Western powers was nowhere near that accorded to Ukrainians affected by the war; that these permanent members cared more about the suffering of European citizens in Ukraine than of nonWestern victims elsewhere.

This sentiment was expressed by the Kenyan Permanent Representative when he recalled the Security Council’s authorisation of intervention in Libya in 2011 and its consequences: “Even as deserved condemnations ring out today about the breach of Ukraine’s sovereignty, history’s condemnations are allowed silence in this room. We cannot help but recall that Africa’s Sahel region is in terrible turmoil due to the hasty and illconsidered intervention in Libya a decade ago.”

On that occasion, the AU sought more time for diplomacy. Its Peace and Security Council was ignored and what resulted was not peace or the safety and security of the Libyan people. Instead, terror was unleashed on African peoples in the countries to the south of Libya. There have been yet other actions of similar magnitude that have brought us to this unfortunate pass.

The allusion to the Security Council’s disregard of the efforts of the AU’s Peace and Security Council to play a role in resolving the Libya crisis was also a reminder of the occasionally fraught relationship between the AU and the UN in dealing with threats to peace and security in Africa, and their respective roles. This question, which is also somewhat linked to the Security Council reform debate, has

been discussed extensively elsewhere.

This writer partially agrees with this sentiment but does not, however, agree with the implied suggestion of a moral equivalence between the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which undoubtedly violated the UN Charter and international law (a point accepted even by those who support or sympathise with Russia’s rationalisation of its action), and the intervention in Libya. This writer has argued elsewhere that the Libya intervention was justifiably authorised by the Security Council within its Chapter VII powers, though its execution by NATO tainted its legitimacy.

The AU, as an organisation, did not formally react or issue a collective statement to respond to the Russian invasion. As it happened, the invasion started a little over two weeks after the AU Assembly had concluded its 35th Ordinary Session, held on February 5 and 6, 2022.

The AU’s position can nonetheless be deduced from a joint statement that was issued by the then Chairperson of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, and

the then Chairman of the AU, President Macky Sall of Senegal, on the day of the invasion itself. In their statement, they expressed “[their] extreme concern at the very serious and dangerous situation created in Ukraine” and called upon “[the] Russian Federation and any other regional or international actor to imperatively respect international law, the territorial integrity and national sovereignty of Ukraine”.

Furthermore, they urged “[the] two Parties to establish an immediate ceasefire and to open political negotiations without [delay]”. Even though it was not formally described as the common African position on Ukraine, the joint statement expressed what could reasonably be assumed to be the official AU position, since the Chairperson of the AU Commission personifies and represents the organisation. Still, it was left to African states to express their positions on the Ukraine war individually through their voices and votes in the Security Council and General Assembly.

It is reasonable to conclude that the paralysis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its use of the veto to block action by the Security Council have jolted states into a sense of urgency. Rather than dampen Africa’s quest for Security Council reform, the current paralysis has only served to add to the previous dissatisfaction of African states with what they perceive as an antiquated, undemocratic, unfair and unjust arrangement, and galvanised them to push for a faster resolution of the longstalled reform.

The dissatisfaction with the Security Council’s inaction and indifference to African problems goes back to the Rwanda genocide, if not earlier. Still there is no guarantee that the new-found urgency will lead to the desired outcome sooner without a radical shift of positions.

The paralysis of the Security Council resulting from Russia’s use of its veto to shield itself from condemnation and action by the Council over its invasion of Ukraine provides an opportunity for all UN member states to rethink their positions and

strategies to achieve real and long overdue reform. Alternatively, it may provide a pretext for the permanent members most vested in the current structure of the Security Council, with its anachronistic power imbalance, to maintain the status quo and continue to exploit its inaction and dysfunction to advance and protect their interests and allies.

I would only offer two concluding thoughts, as a future outlook on the reform debate. From my perspective, these are necessary steps to move the debate forward and overcome the impasse. First, as I have argued in my previous writing, for the AU, Security Council reform appears to have become a debate without end. I have also argued, however, that African states themselves cannot escape blame.

Despite the reported narrowing of differences and growing convergences between states, the maximalist positions that many member states have adopted remain intractable problems. A real change in these positions by all parties is a sine

qua non for the ultimate success of the reform process.

For African states, modification of their position on the veto and compromise with

diplomacy”.

Staeger characterises the AU’s accession to G20 membership as a good instance of the AU’s ability to