WHEN President Cyril Ramaphosa declared South Africa ‘broken’, he did more than show candour. He exposed the depth of his own political fragility. His proposed National Dialogue— nine months of consultations across provinces to address unemployment, racial inequality, crime and land reform— sounds grand. But for a country crippled by blackouts and staggering joblessness, the idea feels like a costly diversion rather than a credible solution.

A spectacle with shaky foundations

Publisher Jon Offei-Ansah

Editor Desmond Davies

Contributing Editors

Prof. Toyin Falola

Tikum Mbah Azonga

Prof. Ojo Emmanuel Ademola (Technology)

Valerie Msoka (Special Projects)

Contributors

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chief Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo

Corinne Soar

The ‘Eminent Persons Group’ of public figures such as rugby captain Siya Kolisi, actor John Kani and former Constitutional Court judge Edwin Cameron gives the project star power. Yet key voices have already walked away. The Democratic Alliance, Ramaphosa’s uneasy coalition partner, dismissed the effort as hollow. The uMkhonto weSizwe Party is boycotting. Even the Thabo Mbeki and Desmond Tutu foundations—pillars of democratic moral authority—have withdrawn, citing rushed planning and a price tag of R700 million ($38.5 million). In a nation where millions live in poverty, the symbolism is hard to justify.

Reputation management, not reform

IJon Offei-Ansah Publisher

Kennedy Olilo

Gorata Chepete

Desmond Davies Editor

ANC decay and structural failure

n 2018, six of the 10 fastest-growing economies in the world were in Africa, according to the World Bank, with Ghana leading the pack. With GDP growth for the continent projected to accelerate to four per cent in 2019 and 4.1 per cent in 2020, Africa’s economic growth story continues apace. Meanwhile, the World Bank’s 2019 Doing Business Index reveals that five of the 10 most-improved countries are in Africa, and one-third of all reforms recorded globally were in sub-Saharan Africa. What makes the story more impressive and heartening is that the growth – projected to be broad-based – is being achieved in a challenging global environment, bucking the trend.

Deputy Editor

Angela Cobbinah

The timing betrays another motive. With Donald Trump back in the White House and reviving inflammatory claims about land seizures and farmer killings, South Africa again faces a hostile international narrative. Ramaphosa’s dialogue doubles as soft-power theatre, meant to reassure the world that democratic consensus still thrives. Yet no amount of town-hall debate will restore investor confidence while power cuts, crime and policy drift persist.

Stephen Williams Contributing Editor

Director, Special Projects

Designer

Simon Blemadzie

Country Representatives

South Africa

Edward Walter Byerley

Michael Orji

In the Cover Story of this edition, Dr. Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist at the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), analyses the factors underpinning this performance. Two factors, in my opinion, stand out in Dr. Hippolyte’s analysis: trade between Africa and China and the intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development.

Much has been said and written about China’s ever-deepening economic foray into Africa, especially by Western analysts and commentators who have been sounding alarm bells about re-colonisation of Africa, this time by the Chinese. But empirical evidence paints a different picture.

Despite the decelerating global growth environment, trade between Africa and China increased by 14.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018, surpassing the growth rate of world trade (11.6 per cent), reflecting the deepening economic dependency between the two major trading partners.

South Africa’s crisis predates Ramaphosa, but his party bears heavy blame. The African National Congress rode its liberation legacy into complacency, then corruption. The Zuma era entrenched ‘state capture’, draining state coffers and weakening institutions. Ramaphosa inherited a hollowed-out government, but his own hesitation has deepened cynicism. High-level prosecutions remain rare. Eskom’s blackouts worsen. Youth unemployment exceeds 50 percent.

Justice Lee Adoboe

Chuks Iloegbunam

Joseph Kayira

Zachary Ochieng

Olu Ojewale

Oladipo Okubanjo Corinne Soar Contributors

Gloria Ansah Designer

These failures collide with historic inequities. Apartheid’s economic design privileged a minority, leaving the post-1994 state to spread opportunity without spooking investors. Three decades on, land reform is stalled, schools remain unequal and South Africa ranks as the world’s most unequal nation. Growth hovers below one percent—far from enough to reduce poverty or absorb millions of job seekers.

Country Representatives

South Africa

Dialogue is no substitute for action

Empirical evidence shows that China’s domestic investment has become highly linked with economic expansion in Africa. A one percentage point increase in China’s domestic investment growth is associated with an average of 0.6 percentage point increase in overall African exports. And, the expected economic development and trade impact of expanding Chinese investment on resource-rich African countries, especially oil-exporting countries, is even more important.

Supporters hope the National Dialogue might rebuild trust and generate a shared vision. But without binding outcomes and real policy commitments, it risks becoming another glossy report gathering dust. Citizens need functioning power grids, reliable policing and job creation, not speeches in church halls.

The resilience of African economies can also be attributed to growing intra-African cross-border investment and infrastructure development. A combination of the two factors is accelerating the process of structural transformation in a continent where industrial output and services account for a growing share of GDP. African corporations and industrialists which are expanding their industrial footprint across Africa and globally are leading the diversification from agriculture into higher value goods in manufacturing and service sectors. These industrial champions are carrying out transcontinental operations, with investment holdings around the globe, with a strong presence in Europe and Pacific Asia, together account for more than 75 per cent of their combined activities outside Africa.

Edward Walter Byerley Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096 Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887 Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Ramaphosa presents himself as the reformer who will heal a fractured nation. Yet this dialogue suggests a leader buying time, projecting activity while avoiding hard decisions. True renewal requires decisive action: prosecuting corruption at the highest levels, fast-tracking land and education reforms, and crafting an industrial strategy to tackle unemployment and energy insecurity.

A survey of 30 leading emerging African corporations with global footprints and combined revenue of more than $118 billion shows that they are active in several industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Dangote Industries), basic materials, telecommunications (e.g., Econet, Safaricom), finance (e.g., Ecobank) and oil and gas. In addition to mitigating risks highly correlated with African economies, these emerging African global corporations are accelerating the diversification of sources of growth and reducing the exposure of countries to adverse commodity terms of trade.

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria Taiwo Adedoyin MV Noble, Press House, 3rd Floor 27 Acme Road, Ogba, Ikeja, Lagos Tel: +234 806 291 7100 taiadedoyin52@gmail.com

Kenya

Top Dog Media, 5 Ascot Knights 47 Grand National Boulevard Royal Ascot, Milnerton 7441, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0) 21 555 0096

Cell: +27 (0) 81 331 4887

Email: ed@topdog-media.net

Ghana

Nana Asiama Bekoe

Kingdom Concept Co. Tel: +233 243 393 943 / +233 303 967 470 kingsconceptsltd@gmail.com

Nigeria

Nnenna Ogbu #4 Babatunde Oduse crescent Isheri Olowora - Isheri Berger, Lagos Tel: +234 803 670 4879 getnnenna.ogbu@gmail.com

Kenya

Patrick Mwangi Aquarius Media Ltd, PO Box 10668-11000

Nairobi, Kenya

Tel: 0720 391 546/0773 35 41

Email: mwangi@aquariusmedia.co.ke

This makes me very bullish about Africa!

Until such measures are taken, South Africa’s democracy will endure more strain than any dialogue can mend. Ramaphosa’s legacy now hinges not on the number of meetings held, but on whether he proves that leadership is about delivery, not performance.

Naima Farah Room 22, 2nd Floor West Wing Royal Square, Ngong Road, Nairobi Tel: +254 729 381 561 naimafarah_m@yahoo.com

Africa Briefing Ltd 2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

©Africa Briefing Ltd 2 Redruth Close, London N22 8RN

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 208 888 6693 publisher@africabriefing.org

Multinationals must pay their fair share in Africa

Africa must look after its own health

Reality finally dawns on South Africa

When the South African leader launched a National Dialogue this September to try to put things right in the country, it was the wake-up call millions of citizens have long been expecting as they watched things going downhill while their leaders buried their heads in the sand, writes Desmond Davies

Is xenophobia’s shadow a threat to South Africa’s future?

Violence, unequal access to opportunities, health care and education, as well as migrant and refugee policies targeted at foreigners are having a negative impact on South Africa’s post-apartheid vision of an inclusive, non-racial democracy, while also tarnishing its international image, writes Stephen Ndoma

Africa must do better on the rule of law

Evidence suggests that foreign direct investments move more to countries that have political stability, stable democracies, transparency and low levels of corruption, says Akinwumi Adesina

UN at 80 needs mutual collaboration to move forward

As the world body turns 80 in September, Ibrahim A. Gambari offers strategies for taking the Pact of the Future from paper to practice, using Nigeria as an example

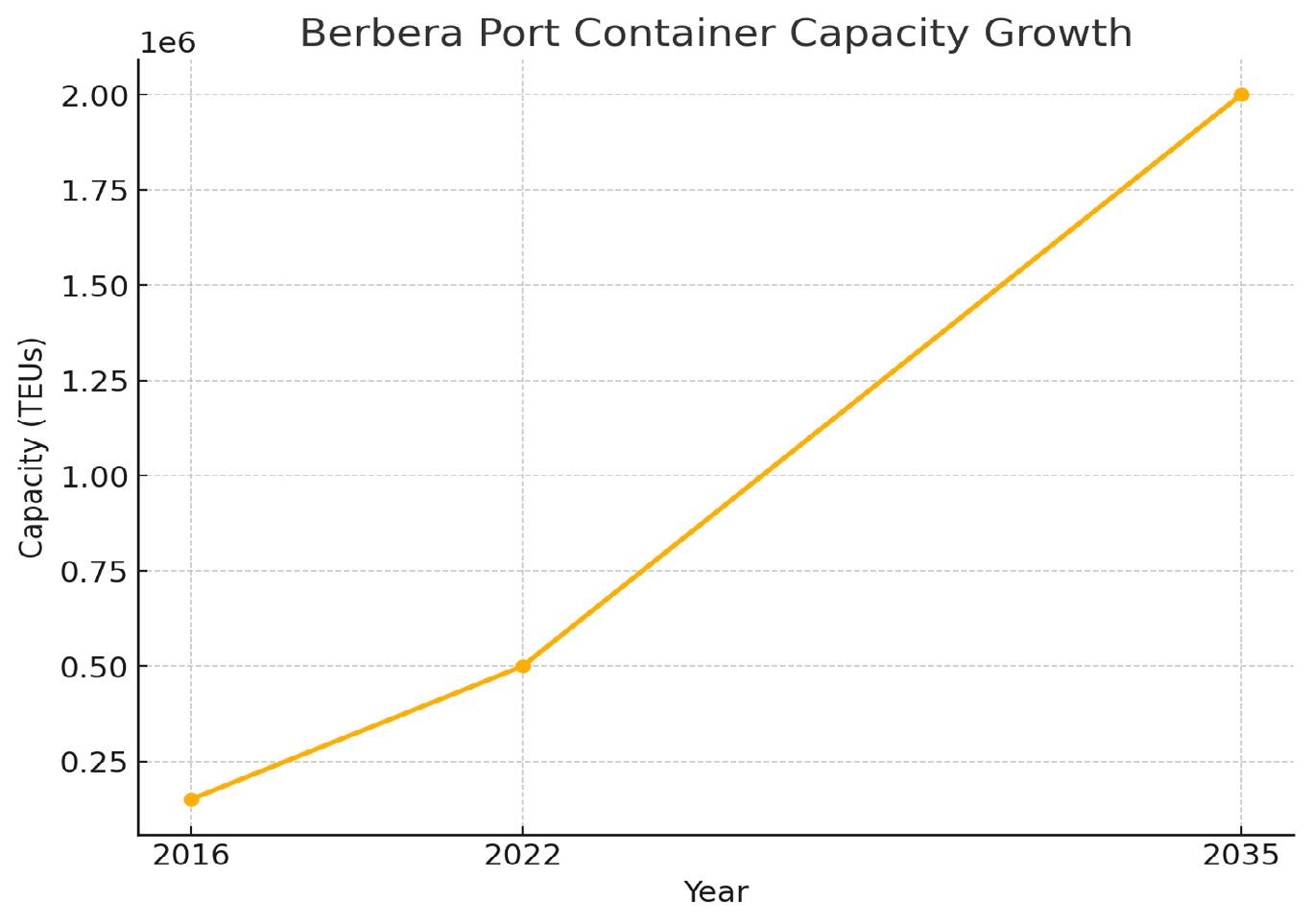

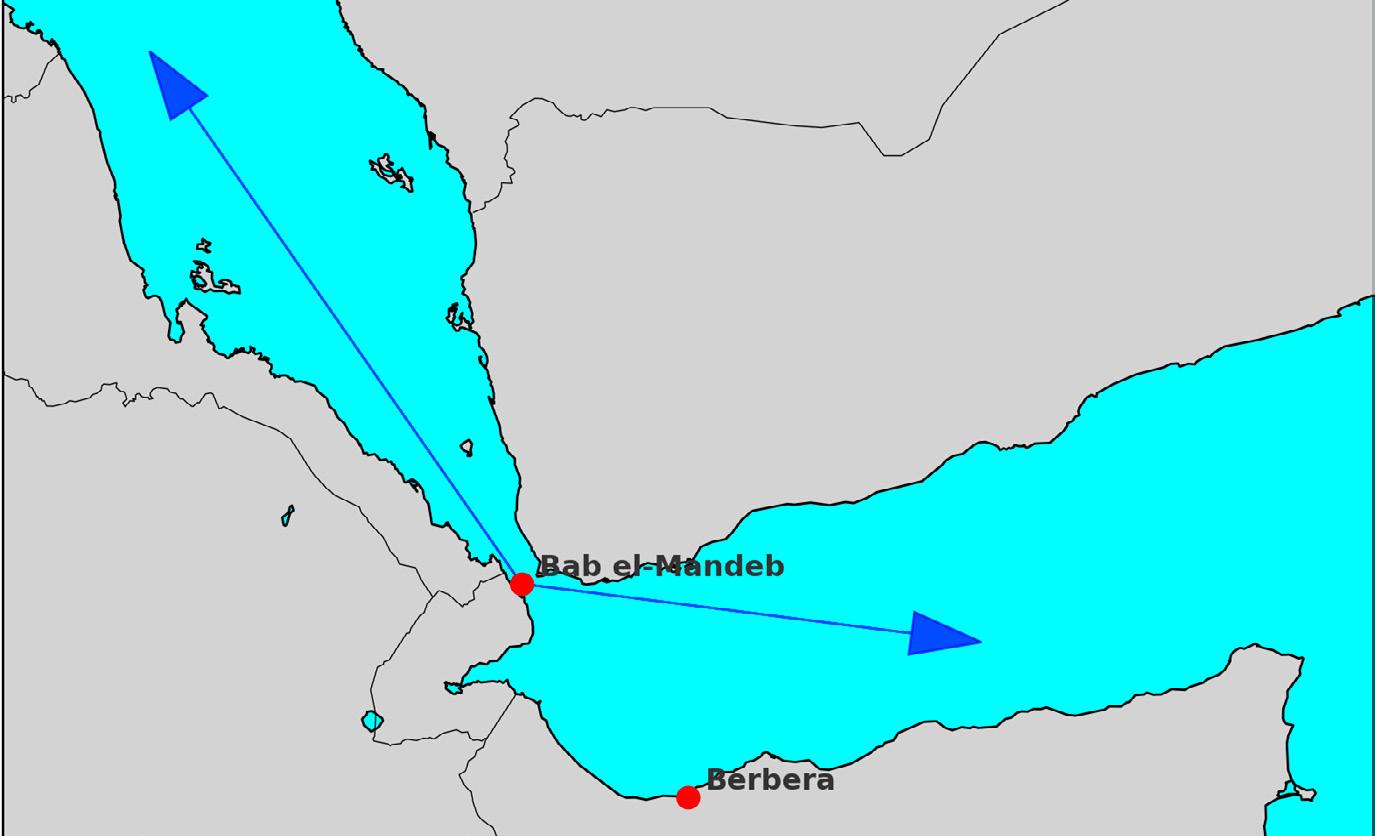

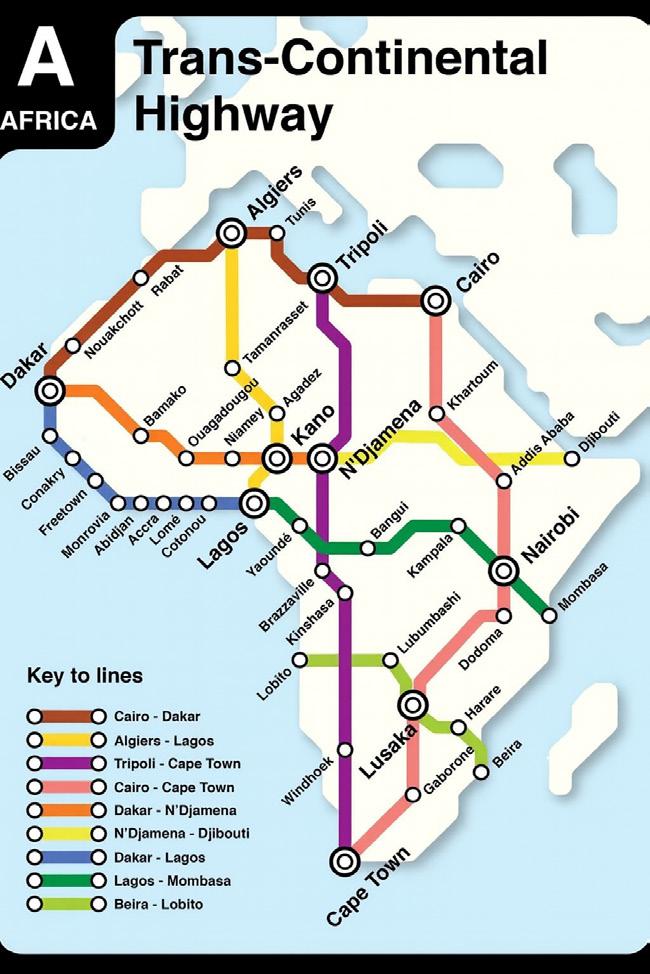

Roads to unite Africa’s trade future

In this in-depth analysis, Jon Offei-Ansah examines how a fully connected network of continental highways could unlock the African Continental Free Trade Area’s vast potential—lifting millions from poverty and reshaping regional trade

28 30 18 22

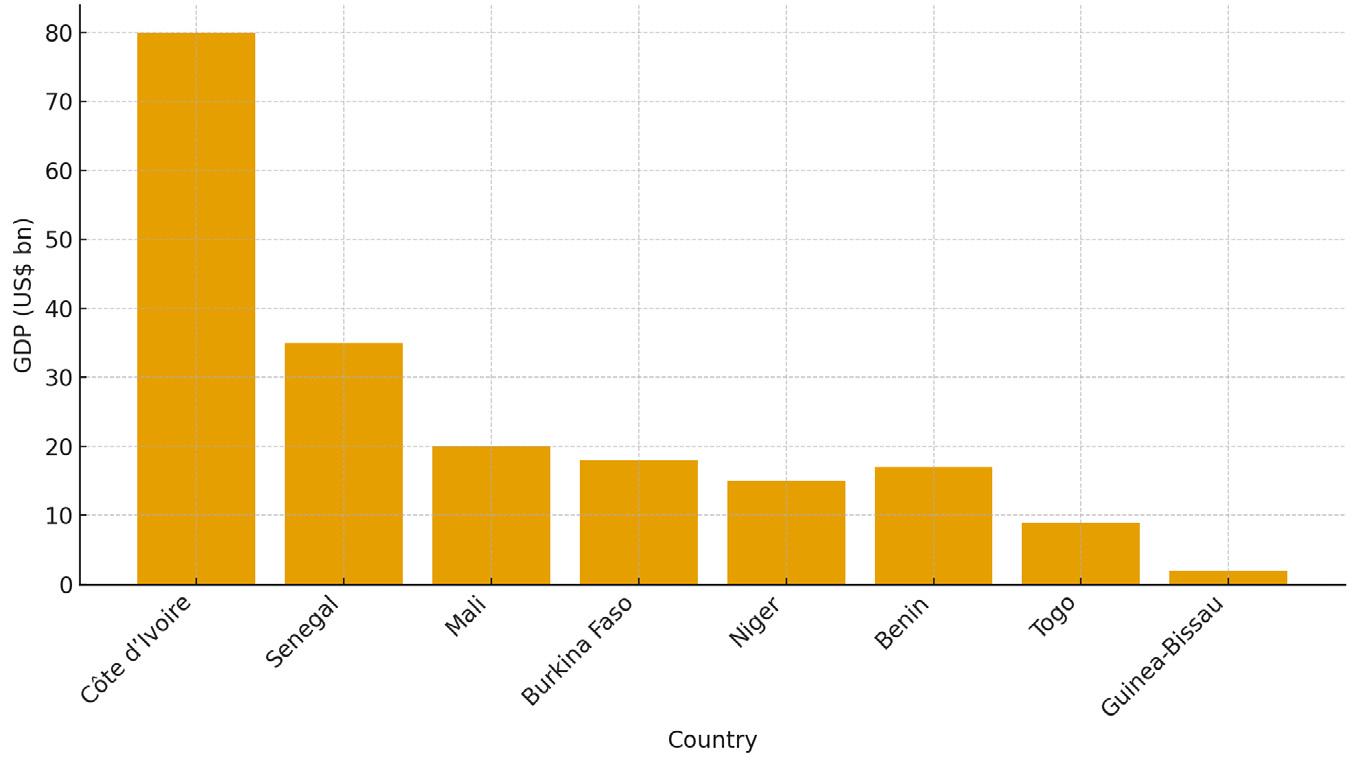

Sahel states test West Africa’s economic order

Jon Offei-Ansah examines how Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have upended West Africa’s economic order, leaving ECOWAS and forming the Alliance of Sahel States in a bold bid for sovereignty that could redefine the region— or deepen its fractures

Africa’s AI crossroads of risk and reward

Christopher Burke analyses how artificial intelligence could reshape Africa’s economy, jobs and sustainability, weighing the continent’s vast opportunities against rising risks

Established in 2002, Shanghai Grand International Co., Ltd. offers a variety of shipping and transportation options via air, sea and ground. Our company is based in Shanghai, China, with branches across the nation. Ranging from customs declaration, warehouse storage, containers and consolidated cargo shipping we have a large array of options to meet your needs.

In addition to being approved and designated by the Ministry of Transportation of China as a First Class cargo service provider, we have also established excellent business relations with major shipping companies including Maersk, CMA, ONE, SM line, and

C.E.O President.

Mr, Felix Ji

EMC over the past 15 years. In addition we have also built long term business relations with major airline cargo departments. In order to expand our global operation, we are looking for international partnerships to work together in this industry. Should you ever import any goods from Peoples Republic of China please ask your exporter and shipper to contact us. We will provide our best service to you.

Room 814, 578 Tian Bao Lu, Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China

E-Mail: felix@grand-log.net phone: 86-13501786280

FOREIGN aid to Africa is shrinking, with many donor countries citing domestic pressures, austerity measures and changing geopolitical priorities. Yet, even as aid contracts, multinational corporations continue to reap vast profits from Africa’s natural resources, consumer markets and labour force, often while contributing next to nothing to the public purse.

Africa now needs, more than ever before, sustainable revenue streams to fund development. But those most capable of paying are actively avoiding their obligations.

At the heart of the problem lies the weakness of Africa’s taxation systems. For decades, many countries have struggled to build robust tax administrations.

Corruption is another major issue. But corruption and weak tax systems do not explain the scale of the challenge. Structural imbalances, archaic legal frameworks and the dominance of transfer pricing abuse – where companies shift profits across borders to low-tax jurisdictions – all sap governments of their rightful dues.

The situation is compounded by the fact that commercial disputes involving African assets or contracts often play out in European or American courts. Oil concessions in Nigeria, mining deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo, or telecom licences in Kenya are routinely litigated in London, Paris, or New York.

This reflects both the lack of trust in African judicial systems and the legal muscle that Western firms bring to bear. But it has a pernicious consequence: decisions that affect African revenues are made far from the continent, under laws and norms designed for foreign investors, not African citizens.

If Africa is ever to retain a fair share of its wealth, it must strengthen both its tax courts and its contract enforcement mechanisms so that disputes are settled on African soil.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials was meant to address some of these distortions by criminalising the bribery of officials abroad. It is one of the rare instruments

that recognises the corrosive impact of corruption not only on governance but also on development financing.

Yet, enforcement has been patchy. Some countries take the obligations seriously, prosecuting firms that bribe their way into contracts. Others treat it as a boxticking exercise.

The Trump administration’s calls to weaken or bypass this convention were particularly troubling. If the US – which has the capacity to enforce corporate accountability through its own Foreign Corrupt Practices Act – signals that bribery abroad is acceptable, it sets back global efforts by decades. American companies may be prevented from bribing officials at home, but if they are free to corrupt systems in Africa, the damage to fragile democracies and treasuries will be catastrophic.

Western tax institutions themselves provide a cautionary lesson. Corporations like Amazon, Starbucks and Google have all at various times exploited loopholes such as profit-shifting techniques and complex corporate structures, to avoid paying tax even in economies with sophisticated enforcement systems. The difference, however, is that public outrage and investigative journalism in Europe and the US have forced governments to act.

Starbucks was shamed into voluntary tax payments in the UK; the European Union has levied billions in back-tax

countries must act collectively, through the African Union and regional blocs, to legislate against such practices and push for stronger international rules that prevent profiteering from poverty.

So, what can be done? First, African governments must modernise their tax administrations, adopting digital tools to monitor profit-shifting and collaborating with each other to close the loopholes multinationals exploit. A united front, especially in extractive industries, can prevent countries from being played off against each other in a race to the bottom on tax incentives.

Second, civil society and investigative journalists must be empowered to expose tax avoidance and corruption. Just as outrage in Europe forced Starbucks and Amazon to back down, public opinion can pressure African governments and corporations into fairer practices.

Third, Africa’s courts need strengthening. If foreign investors know they cannot simply bypass local justice and appeal to London, they will think twice before structuring deals that exploit weak oversight.

Finally, global cooperation is essential. Rich countries cannot cut foreign aid while simultaneously allowing their corporations to drain Africa of revenue. If the West truly wants to see African self-reliance, it must enforce anti-bribery laws, close tax havens and support African efforts to

aid while allowing their corporations to drain Africa of revenue

claims against Apple. The lesson for Africa is clear: transparency, strong institutions and political will can make even the most elusive corporations contribute.

But Africa also faces uniquely rapacious actors: vulture capitalists. These are firms that buy distressed African debt cheaply, then sue governments for full repayment plus interest in foreign courts. Zambia, Congo and Liberia have all fallen prey to such predators. These firms siphon away scarce public funds meant for health, education and infrastructure. African

recover stolen assets.

’

The drying up of aid need not spell disaster for Africa; but only if the continent captures the wealth that it already generates. Taxation, fairly enforced, is the cornerstone of sovereignty.

It is time that multinational corporations paid actual taxes to the nations whose resources and markets enrich them, and not just lip service to “corporate social responsibility”.

Anything less is exploitation dressed up as partnership. AB

THE other day, the US government announced its new plans to address global health issues after the Trump administration slashed billions of dollars earlier this year from America’s aid budget. NGO-types, who were already up in arms after the cuts, are now even more irate by what they see as another major blow to development assistance.

The “America First Global Health Strategy” released by the State Department marks a dramatic shift in US engagement with international health. It calls for US health assistance to flow directly to countries through multi-year bilateral agreements tied to clear performance benchmarks and co-investment requirements.

For me, the most crucial point is the pledge to ensure that funding goes directly to “frontline health workers and medical commodities”, while technical assistance and overhead costs are sharply reduced.

According to the State Department, “less than 40 per cent of health foreign assistance goes to frontline supplies and health care workers” under current programmes. Therein lies the rub. Whatever happened to the more than 60 per cent of funding?

Is it any wonder that health projects in Africa take so long to deliver? At the same time African governments place their faith in NGOs to sort out health problems that the people elected them in the first place to resolve.

This dependency syndrome has led to Africa’s political leaders sitting on their hands while foreign members of the Third Sector rule the roost on the continent. This does not mean that the NGO-types are better financial managers either.

Take, for example, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2013-2016). Financial mismanagement of health funding was on both sides: governments and donors.

When MPs of the British parliament’s International Development Committee visited two of the three West African countries that were in the throes of the

deadly Ebola virus, Liberia and Sierra Leone, in 2014, they were in for a shock

The politicians said they were surprised to discover that only $3.9 million out of $60 million given by the European Union to support Liberia’s health sector was passed on by the country’s Ministry of Finance over a two-year period. Apparently, the $56 million or so had gone walkies.

In Sierra Leone, financial mismanagement was down to the UK’s Department for International Development, the MPs discovered. They just could not make head or tail of DFID’s accounting procedures, prompting the delegation to note: “The Committee was appalled that the Department could not provide an overall figure for its total spend in Sierra Leone.”

Given this and countless similar circumstances, one can understand where the Trump administration is coming from. For the American leader, it is just money down the drain.

Excellence stands as proof that Africa is ready to compete with the best in global healthcare.

“Our vision for the African Medical Centre of Excellence is not just to provide top-notch healthcare but to serve as a catalyst for the transformation of the African health sector, making a bold statement to the world that Africa is finally taking its destiny into its own hands in healthcare sovereignty and global standards.”

Oramah is spot on. The AMCE is the largest specialised private hospital in Nigeria and West Africa focusing on cardiovascular services, haematology, comprehensive oncology and general medical services. It currently boasts of 170 beds with a plan to expand this to 500 beds upon completion. Positively, the plan is to replicate ACME Abuja across the continent.

This initiative should help to stem the flow of health professionals from Africa to Europe and North America. According to

‘ ’

Africans spend a whopping $10 billion annually on health

It is not that there is no money in Africa to easily fund health facilities. According to the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), Africans spend a whopping $10 billion a year on health tourism, with Nigeria accounting for $1 billion.

But the indefatigable President of Afreximbank, Professor Benedict Oramah, will have nothing to do with this flagrant waste of money. Under his influence, his institution has opened a world-class $300 million African Medical Centre of Excellence (AMCE), in partnership with King’s College London, to cut down on the continent’s dependency on foreign health systems.

At the opening of AMCE Abuja in June this year, Oramah said: “We are making a bold, collective statement: we will no longer accept medical vulnerability as destiny. The African Medical Centre of

the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 16,000 Nigerian doctors got jobs abroad in the past seven years.

In the case of nurses, according to the UK’s Nursing and Midwifery Council, between 2022 and 2024 more than 42,000 nurses emigrated from Nigeria to the UK. In 2024 alone, the Council registered 13,656 Nigerian nurses, up 28 per cent from 2023.

This is the same Nigeria that had a sterling healthcare sector in the 1960s and 1970s. Institutions such as University College Hospital in Ibadan and Lagos University Teaching Hospital held their own globally. Indeed, Nigeria was a destination for medical tourism.

Now, with Trump’s massive aid cuts, things might change for the better so that Africans look after their own health. AB

When the South African leader launched a National Dialogue this September to try to put things right in the country, it was the wake-up call millions of citizens have long been expecting as they watched things going downhill while their leaders buried their heads in the sand, writes

Desmond Davies

ELECTRICITY blackouts, crumbling infrastructure, staggering unemployment and an uncertain political climate have become part of daily life for millions of South Africans. These are the realities that have forced President Cyril Ramaphosa to declare that South Africa is “broken”. Yet for a sitting president to use such blunt language by admitting this signalled more than candour: it suggested desperation.

The question is why now. Is this initiative an honest attempt to revive South Africa’s flagging reputation in the face of global criticism, particularly Donald Trump’s renewed assaults on the country’s stability? Or is it primarily a survival tactic for a president cornered by coalition partners and an increasingly sceptical electorate?

The issue is not only Ramaphosa’s political predicament but also the structural conditions that have brought South Africa to this moment – weighed against the promises and pitfalls of national dialogue.

The National Dialogue, according to Ramaphosa, will run for six to nine months, spanning all nine provinces. Citizens will meet in town halls, churches, schools and online forums to debate

South Africa’s most urgent challenges: unemployment above 33 per cent, persistent racial inequality, rampant crime and the unresolved land question.

To lend credibility, an “Eminent Persons Group” has been assembled, featuring figures like captain of the national rugby team Siya Kolisi, actor John Kani and former Constitutional Court judge Edwin Cameron. Their diversity mirrors the Rainbow Nation ideal: a reminder of a time when dialogue was not just symbolic but transformative.

But scepticism abounds. The Democratic Alliance, now Ramaphosa’s coalition partner, has dismissed the initiative as meaningless. The uMkhonto

weSizwe (MK) Party has boycotted it outright. The Thabo Mbeki and Desmond Tutu foundations – institutions that embody the moral gravitas of South Africa’s democratic journey – have withdrawn, citing rushed planning and spiralling costs, estimated at R700 million ($38.5 million). The scepticism is understandable: can a cash-strapped state, struggling to provide basic services, justify such an expensive talking shop?

South Africa has long prided itself on punching above its weight internationally. It has hosted peace negotiations, driven African Union initiatives and cultivated a reputation as a champion of multilateralism.

Yet in recent years, that standing has eroded. Zuma-era corruption (“state capture”) was the final straw. The Indian Gupta brothers ensconced themselves within the government, wielding immense influence.

They were later accused of salting away hundreds of millions of dollars from the country. While the rapacious brothers are now settled in Dubai, South Africa must contend with recurring blackouts and declining investment ratings.

Enter Donald Trump. During his first term, he infamously accused South Africa of “land seizures” and “largescale killings” of white farmers, echoing narratives popular among the global far-right. The South African government dismissed those claims, but the damage lingered. With Trump back at the White House and his rhetoric returning, South Africa is once again portrayed internationally as a nation on the brink.

When Ramaphosa turned up at the White House in May this year, the US leader waylaid the South African president. Trump performed a three-card trick: with a sleight of hand, he contrived the impression that, under the ANC, the 3rd Boer War had begun in South Africa –confounding Ramaphosa.

In this light, the National Dialogue looks partly like a reputational strategy. By showcasing a consultative, inclusive process, the government hopes to reclaim the moral high ground: a reminder that South Africa still believes in democratic consensus-building. In essence, it is soft power politics for a domestic crisis.

The dialogue is also a move by Ramaphosa for political survival. Once hailed as the pragmatic reformer who would clean up Zuma’s mess, his presidency has been defined instead by hesitation and half-measures. Efforts to root out corruption have been slow;

Eskom’s rolling blackouts remain unresolved; and unemployment, especially youth unemployment, has reached catastrophic levels.

Worse, the ANC itself is in decline. In the 2024 general election, for the first time since 1994, the party lost its outright majority, winning just over 40 per cent. Ramaphosa was forced into a fragile coalition with the Democratic Alliance and smaller parties. This arrangement constrains his manoeuvrability: every major decision must now balance competing interests, limiting bold action.

Launching a national dialogue allows Ramaphosa to project leadership at a moment when his power is contested. It creates the illusion of momentum, even if concrete policy shifts remain elusive. Critics argue it is a distraction tactic, a way to shift public attention from daily crises to a grand narrative of healing.

Why has South Africa reached this stage? For a start, it goes beyond the current administration. The roots lie in both the failures of the ANC and the structural burdens of South Africa’s socio-economic system.

For decades, the ANC enjoyed neartotal dominance, built on its liberation credentials. But over time, power bred complacency and corruption. The Zuma years (2009–2018) institutionalised “state capture,” with billions siphoned off through corrupt contracts. Infrastructure decayed, public trust evaporated, and the party lost its moral authority.

Ramaphosa inherited a hollowed-out state. His inability – or unwillingness – to prosecute high-level offenders has

reinforced public cynicism. For many, the ANC is no longer the vehicle of liberation but of misrule.

At the same time, South Africa’s economic system is uniquely burdened by history. Under apartheid, the economy was designed to serve a privileged minority white population. By 1994, South Africa had a modern industrial sector, but one overwhelmingly skewed towards the needs of a small elite.

Post-apartheid governments faced the near-impossible task of redistributing opportunity to a majority long excluded from land ownership, education and capital access – without scaring away investors or destabilising growth. Two decades later, land reform has stalled, the education system remains unequal, and unemployment is entrenched.

The failure is dual: an ANC weakened by internal rot and an economic system whose structural inequalities are too deep for incremental reform alone.

The apartheid South African economy, by the late 1980s, was under sanctions, facing capital flight and suffering from sluggish growth. The economy was unsustainable precisely because it excluded the majority.

Yet there are contrasts worth noting. In terms of growth rate, in the early 1990s South Africa averaged modest growth despite sanctions. Post-1994, the country experienced a “boom” in the 2000s, peaking around five per cent growth under Thabo Mbeki. Today, growth hovers below one per cent, barely keeping pace with population increases.

Employment has always been a problem. Under apartheid, official unemployment rates were artificially low, but only because black South Africans were systematically excluded from formal statistics and forced into subsistence or informal labour. Today, with universal measurement, unemployment sits at over 33 per cent, with youth unemployment above 50 per cent.

South Africa remains the most unequal country in the world. While a black middle class has emerged, wealth distribution is still overwhelmingly skewed. Land ownership remains concentrated in white hands, and many townships look much as they did in 1994.

Members of the black middle class have diverted attention from themselves

by pointing their fingers at the millions of African refuges and migrants in South Africa. It is not surprising that the country is witnessing high incidences of xenophobic violence (see following article).

In this toxic mix, the post-apartheid government must manage an economy for all, not just a minority. That is an ethical imperative, but it comes with immense structural pressures.

Some argue that the task was always impossible: no government could take a deeply unequal society, integrate millions into the formal economy and achieve prosperity in one generation. Others counter that the ANC squandered its best opportunities.

In the early 2000s, when growth was

is less about whether South Africa’s burdens are “too much” and more about whether its leadership has been equal to the task.

So, what can the National Dialogue achieve? South Africans remain remarkably committed to democracy, even as institutions falter. A genuine process of listening could rebuild trust, provide consensus on difficult issues like land and generate a new social contract.

’

At worst, it risks becoming a costly diversion. Without binding outcomes, the dialogue could end in a glossy report gathering dust while the state continues to fail at basic delivery. The very act of spending nearly R700 million on a symbolic process could deepen resentment in a country where millions live in poverty.

The National Dialogue is both an attempt to rescue Ramaphosa’s presidency and to revive South Africa’s tarnished reputation. Yet the deeper truth is that South Africa’s predicament cannot be solved by dialogue alone.

The ANC’s failures, combined with the structural inequities inherited from apartheid, have brought the country to the brink. South Africa is not ungovernable, but it is trapped in a cycle where bold reforms are endlessly deferred. Dialogue can provide cover, but not solutions.

strong and state coffers healthy, bold reforms could have accelerated land redistribution, improved education and reduced reliance on extractive industries. Instead, resources were mismanaged or stolen. Shades of many African countries after independence,

Thus, while the challenge is undeniably vast, it is not insurmountable. The issue

For Ramaphosa, the stakes are personal. His legacy will depend on whether this initiative produces more than symbolism. For South Africa, the stakes are existential: whether a nation once celebrated for its miracle transition can find renewal before despair hardens into permanent decline.

Violence, unequal access to opportunities, health care and education, as well as migrant and refugee policies targeted at foreigners are having a negative impact on South Africa’s post-apartheid vision of an inclusive, non-racial democracy, while also tarnishing its international image, writes Stephen Ndoma

SOUTH Africa is an economic giant of Southern Africa and stands out as a preferred top destination for migrants from within and beyond the region. In 2023, South Africa had an estimated total of 2 ,60,495 officially recognised immigrants.

Due to its socio-economic and political status, South Africa attracts foreign migrants for economic, safety and security reasons. It is also home to many refugees and asylum seekers from various African countries.

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNCHR) reports that there were over 250,000 refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa, although the figures may be inaccurate due to the presence of many undocumented refugees. These refugees and asylum seekers are driven away from their countries of origin due to poverty, political violence and war. These countries include Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Somalia and Zimbabwe.

Some of the benefits that accrue to destination countries due to migration include the filling of labour gaps, while countries of origin can also benefit from remittances. However, destination countries normally face unbearable pressure due to the influx of foreign migrants, and South Africa has not been spared from this. The country faces several challenges due to a burgeoning number of immigrants, including those seeking political refuge.

A parliamentary monitoring group highlighted some of these challenges, including xenophobic violence, unequal access to opportunities, health care, and education, as well as migrant and refugee policies. To buttress this, three foreign nationals were killed in the Eastern Cape province in May of this year following violent revenge attacks, while hundreds of women and children were driven from their homes.

With a long and bloody history, xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa often leaves a trail of destruction. Xenophobic attacks in May 2008 saw about 62 people killed and thousands displaced. Similar clashes between South Africans and foreigners in 2015, mainly in Durban and Johannesburg, forced several foreign immigrants to close their business operations and request voluntary repatriation to their home countries.

Reports of foreign migrants being denied healthcare services also abound. These attacks partly stem from local perceptions that foreign immigrants place pressure on already strained resources. Groups like Operation Dudula have made calls for prioritising South Africans and

have blamed migrant workers for rampant crime and for contributing to the country’s high unemployment rate by taking jobs away from locals.

These episodes have a negative impact on South Africa’s post-apartheid vision of an inclusive, non-racial democracy, while also tarnishing its international image. To compound matters, discrimination, particularly against African immigrants, casts a dark shadow on the country, strains diplomatic relations, and threatens regional cooperation and economic integration initiatives.

Speaking at a recent summit of liberation movements in Southern Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa called for a rejection of xenophobia, and emphasised

that migration is “a consequence of underdevelopment, war and global inequality, and not a moral failing of those who migrate in search of hope”. He also urged liberation movements to advocate for “people-centred regional migration policies that affirm dignity, rights, and solidarity as well”.

While citizens who engage in xenophobia may have their reasons, how tolerant is South African society towards immigrants and foreign workers? Public opinion data can help unpack this puzzle. To better understand the scope and implications of this issue, Afrobarometer survey data is used to gain valuable insights into public perceptions on tolerance and their potential impact on xenophobic tendencies.

This was gauged through questions measuring citizens’ attitudes towards immigrants or foreign workers and their acceptance of refugees and asylum seekers.

Survey data shows that the South African society is generally tolerant to immigrants or foreign workers, a view shared by 58 per cent who said they do not care or at least like having them as neighbours, while 39 per cent disliked it. On the downside, above half (53 per cent)

expressed opposition to a scenario where asylum seekers are accepted and protected in South Africa, while 24 per cent endorsed such a scenario.

and

are scarce and feel that the government is underperforming in that respect. The South African government is therefore urged to handle the matter in a delicately, with the aim for a win-win outcome that benefits both locals and foreign immigrants in order to ensure stability and social cohesion.

The following measures could be key in the fight against xenophobic tendencies:

• Promoting cultural exchange and education through organising cultural events, workshops and programmes that showcase diverse cultures and traditions.

• Supporting inclusive language and media representation – this can be achieved through advocating for

About seven out of 10 adult citizens (71 per cent) agreed that employers should prioritise locals when job opportunities are scarce, while 62 per cent had negative assessments about government’s performance in terms of ensuring that this is respected.

These findings provide evidence that South African society can be susceptible to xenophobia given what the data shows about citizens attitude towards immigrants and foreign workers, and the reluctance to accept asylum seekers. Calls for locals to be considered first when job opportunities are scarce and perceptions that government is not doing enough in terms of giving preference to those born and bred in South Africa are also likely to fuel xenophobic attitudes.

South Africa is undoubtedly an economic hub that will continue to attract migrants from beyond its borders, as people flock to the country in search of opportunities to improve their socioeconomic well-being. This will continue to place pressure on the resources that are already under strain. Citizens have made their voice heard: while there is general tolerance towards immigrants or foreigners, there is low acceptance of the protection of asylum seekers.

Many believe that employers should prioritise locals first when job opportunities

inclusive language and representation in the media, highlighting the contributions and experiences of diverse communities.

• Fostering community engagement by encouraging community-led initiatives that bring people together, with the ultimate goal of promoting social cohesion and building trust between diverse groups.

• Provision of social support services for migrants and refugees to help them integrate into their new communities.

• Supporting research and data collection on xenophobia in order to inform evidence-based policies and interventions.

• Review of immigration and refugee policies to ensure they are fair, humane and aligned with international human rights standards.

• Prosecuting politicians and influencers who incite xenophobia and alleviation of root causes of xenophobia, e.g. inequality.

• Stepping up diplomatic roles within the region through helping to resolve problems in neighbouring countries, which often compel foreign nationals to flock to South Africa and exert pressure on resources.

Throughout Southern Africa, from South Africa to Mozambique and beyond, the press faces a barrage of threats that make statutory protections seem little more than paper promises, write Tambudzai Gonese and Melusi Simelane

AS outlined in international human rights treaties and most African constitutions, freedom of expression is a fundamental right. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Universal Declaration on Human Rights affirm that every individual has the right to hold opinions and to impart and receive ideas.

This Article has served as the basis for recognising this right in the constitutions of most African states. This freedom is essential in a democratic society because it allows people to participate civically and promotes accountability.

The foundation of this is what is known as a ‘free press’. Freedom of expression provides the necessary basis for the media to deliver important information that helps citizens stay informed about and engage in governance, which is vital for accountability.

The Zimbabwean Constitution, for example, explicitly recognises the freedom of expression for the media, even stating that everyone has the right to media freedom, including protections for journalist sources.

The Zimbabwe Constitutional Court, in Chimakure v Attorney General, affirmed that freedom of expression is sacrosanct, regardless of whether the information conveyed is false or offensive, provided it does not incite violence or spread hate speech.

Although the right is not absolute, any restrictions must be proportionate and reasonably justified within a democratic society. When criminal law is employed to silence the media, it is concerning, especially when charges are based purely on exercising freedom of expression rather than on accusations of inciting violence or hate speech.

Sedition offences and insult laws are such statutes that have no place in a democratic society, particularly when they seek to suppress political speech or critical views about the state. Zimbabwe has a troubled history of using criminal law to silence dissenting voices. With the adoption of a new Constitution in 2013, it was hoped that this practice would cease.

However, recent events such as the arrests of journalists for broadcasting interviews with critical voices or publishing satirical articles that critique the state have cast doubt on that. This is possible because laws that undermine freedom of expression, like criminal insult laws, still exist.

Yet, Zimbabwe is not alone in this struggle. Throughout Southern Africa, from South Africa to Mozambique and beyond, the press faces a barrage of threats that make constitutional protections seem little more than paper promises.

Despite these enshrined values, freedom of expression remains an illusion for the media, undermined by restrictive laws, physical attacks and systemic intimidation that hinder accountability and democratic debate.

In South Africa, once seen as a beacon of media freedom on the continent, concerns are mounting about the decline of press independence due to state actors. Concerns have been voiced about the role of the State Security Agency in undermining journalistic integrity, including harassment and threats against reporters covering corruption or political unrest.

The 2025 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders identifies economic instability as the primary threat.

Nonetheless, in South Africa, this is worsened by verbal attacks from political leaders and activists, which weaken the media's capacity to scrutinise those in power.

Recent incidents, such as the targeting of SABC's head of news following leaks critical of the ANC, exemplify how state mechanisms are being utilised against dissenting voices.

In Mozambique, press freedom violations nearly tripled during the 2023 municipal elections, increasing from 11 cases in 2022 to 28 the following year, according to the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA). Journalists such as Bongani Siziba and Sbonelo Mkhasibe

Centre (SALC), led in challenging these injustices.

In a historic victory on July 16, 2025, the Malawi High Court declared criminal defamation unconstitutional, a ruling SALC supported and celebrated for its potential to dismantle laws that create a chilling effect on public debate and media freedom. This decision not only strengthens protections for journalists in Malawi but also serves as a model for the region, demonstrating how strategic litigation can reclaim rights eroded by authoritarian tendencies.

As member states of the Southern African Development Community (SDAC) like Zimbabwe, South Africa and Mozambique continue to violate

were detained while reporting on events, highlighting a pattern of arbitrary arrests that suppresses coverage of electoral irregularities and corruption.

Similarly, in Botswana, reporters faced assaults while covering ruling party primaries, raising safety concerns in a tense political climate. Generally, we have seen a bleak picture across East and Southern Africa, documenting widespread intimidation, harassment and detention of journalists, with authorities escalating attacks to stifle the flow of information.

These violations are not isolated; they form a regional crisis where governments exploit outdated laws and extra-legal measures to suppress criticism. The 2025 State of Press Freedom in Southern Africa report by MISA states that physical attacks on journalists have decreased slightly.

However, the environment remains “problematic” due to restrictive legislation, harsh working conditions and increased risks during elections or corruption investigations. Online threats, including AI-enhanced harassment of women journalists, further deepen the chill on free expression.

Amid this gloom, there are glimpses of hope through civil society initiatives. Our organisation, the Southern Africa Litigation

democratic norms through attacks on freedom of expression, the SADC must focus on stronger accountability mechanisms.

SALC and other civil society actors have highlighted the urgency of defending democratic values, especially the fourth estate’s role in ensuring transparency and justice. Without regional enforcement, such as binding protocols on media protections and sanctions for violators, the false impression of press freedom will endure, enabling corruption and abuse to flourish unchecked.

Southern African countries’ constitutions may declare lofty ideals, but the reality for journalists is danger and censorship. The SADC must rise above rhetoric, demanding tangible reforms to decriminalise defamation, protect reporters from state harassment and foster an environment where the press can genuinely hold power to account.

Civil society, led by organisations like SALC, shows the way forward. Still, it requires collective political will to turn freedom of expression into a realisable goal rather than a distant hope. The moment for stronger regional accountability is now before the voices of truth are silenced forever. AB

A landmark report warns that punitive laws across the Commonwealth are suffocating press freedom and free expression. With over 200 journalists killed in member states in the past two decades, reform is urgent – but will governments act on their own promises?

THE Commonwealth likes to style itself as a community of nations bound by a shared commitment to democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Yet a damning new report released this September suggests that, when it comes to free expression, the organisation’s rhetoric has long outstripped reality.

The report, Who Controls the Narrative? Legal Restrictions on Freedom of Expression in the Commonwealth, published by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), the Commonwealth Journalists Association (CJA) and the Commonwealth Lawyers Association (CLA), paints a sobering picture: restrictive national laws in dozens of member countries are being used to muzzle dissent, intimidate journalists and criminalise legitimate public debate.

Of the Commonwealth’s 56 members, 41 retain criminal defamation statutes, 48 enforce sedition provisions and 37 still apply blasphemy-like legislation. Most of these laws are relics of colonial legal systems.

Yet instead of being consigned to history, they have been repurposed by modern governments to stifle scrutiny. “Too many Commonwealth countries continue to enforce colonial-era laws that criminalise speech and silence dissent, in clear violation of their international obligations,” said Sneh Aurora, Director of the CHRI.

This is not merely a matter of restrictive texts on the statute books. These laws are actively wielded against journalists, human rights defenders and political critics. Their very existence fuels a climate of fear and self-censorship,

particularly in states where judicial independence is fragile.

Legal restrictions are compounded by violence. According to UNESCO figures cited in the report, 213 journalists were killed in 19 Commonwealth countries between 2006 and 2023. In a staggering 96 per cent of cases, the killers have never been brought to justice.

For William Horsley of the CJA, this impunity is both scandalous and corrosive. “The almost complete failure of Commonwealth countries to prosecute and punish those responsible for the killings of over 200 journalists in 20 years is shameful. This culture of impunity must be swept away,” he said.

The danger is clear: when journalists are murdered with impunity, entire societies are deprived of the information they need to hold power to account.

There is, however, a glimmer of hope. At their 2024 summit in Samoa, Commonwealth leaders adopted the Commonwealth Principles on Freedom of Expression and the Role of the Media in Good Governance – an 11-point framework that recognises the centrality of free media to democracy.

This was the product of an eight-year campaign by grassroots organisations and advocacy groups. But while its adoption was hailed as a breakthrough, the real test lies in implementation.

The new report makes clear that unless governments move swiftly to repeal or amend punitive laws, the Samoa Principles risk becoming yet another unfulfilled declaration.

The CHRI, CJA, and CLA are urging the Commonwealth Secretariat and member states to:

• Develop concrete action plans to scrap criminal defamation, sedition, and other “speech crimes.”

• Strengthen protection for journalists and civil society watchdogs.

• Reform the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) and appoint a dedicated Envoy on Freedom of Expression.

• Work with civil society and UNESCO to monitor implementation of the Samoa Principles.

The stakes are high. As misinformation spreads globally and authoritarian tendencies gain ground, the ability of journalists and citizens to speak truth to power is more essential than ever.

The Commonwealth is often dismissed as a talk shop, more comfortable with symbolism than substance. But advocates argue that the Samoa Principles and the new report provide a genuine opportunity for reinvention.

If the organisation can help its members dismantle laws that criminalise dissent and protect those who risk their lives to inform the public, it might yet give meaning to its lofty ideals. Failing that, the gap between its stated values and lived realities will only grow wider.

As Horsley warned, “A genuine Commonwealth engagement to protect the truth-tellers from threats and reprisals would give the organisation a vital new sense of purpose at a time when the concept of truth is under fierce attack.”

The question now is whether Commonwealth leaders will seize the moment – or allow colonial ghosts to continue dictating the terms of free expression in the 21st century.

Press freedom in the Commonwealth: Africa highlights

• ACROSS Commonwealth Africa, constitutional guarantees of freedom of expression are frequently undermined by broad legal exceptions relating to national security, public order, and morality – routinely enforced through defamation, sedition, and cybercrime laws, as well as intrusive regulatory regimes, to suppress dissent and stifle debate.

• Journalists in Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Uganda face intimidation and violence for exposing corruption and abuse of power. Judicial failures to hold perpetrators accountable perpetuate a climate of impunity.

• Ghana, Lesotho, Seychelles, Sierra Leone and South Africa have decriminalised defamation, while courts in Malawi, The Gambia and Kenya have ruled it unconstitutional. Yet 14 of 21 Commonwealth African states still retain criminal defamation laws, enabling authorities to silence critics.

• Blasphemy laws remain in force in 14 of 21 countries, targeting dissenting religious views and restricting

freedom of belief. In some Nigerian states governed by Sharia law, blasphemy offences may carry the death penalty.

• Sedition laws remain in force in Botswana, Cameroon and Nigeria, though reforms have been undertaken in Malawi, Sierra Leone, and Uganda.

• National security laws are widely used by authorities across Commonwealth Africa to suppress dissent. In Cameroon, Rwanda and Uganda, enforcement is particularly harsh, often targeting journalists and activists. Similar patterns exist in The Gambia, Togo and the Kingdom of eSwatini, where such laws are leveraged to maintain political control, especially during elections and protests. Although less frequent, in Botswana, South Africa and Ghana these laws are still used to silence critical voices.

• Cybercrime and cybersecurity legislation are increasingly used to police online speech. High-profile cases such as Stella Nyanzi in Uganda and Agba Jalingo in Nigeria show how vague provisions are weaponised to penalise dissent in digital spaces.

• Media independence remains under pressure. In Cameroon, Gabon, Rwanda, Seychelles and Uganda, state control of media outlets fuels self-censorship. Journalists in Botswana, Malawi and Mauritius enjoy greater press freedom, but they still face harassment covering sensitive issues. Ghana and South Africa have relatively more open media spaces, yet both struggle with political interference and concentrated media ownership. SLAPPs [Strategic Lawsuit Against |Public Participation] have risen in South Africa, while violence against journalists has increased in Ghana.

• Access to Information (ATI) laws are in place in 15 of 21 countries, but weak implementation – particularly in Botswana, Cameroon and the Kingdom of eSwatini – undermines transparency and limits public engagement. Even where laws exist, enforcement is hindered by bureaucracy and broad national security exemptions.

• Botswana, Ghana and Sierra Leone are members of the Global Media Freedom Coalition, committing to promote media freedoms and support initiatives such as the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists.

Source: Who Controls the Narrative? Legal Restrictions on Freedom of Expression in the Commonwealth

Evidence suggests that foreign direct investments move more to countries that have political stability, stable democracies, transparency and low levels of corruption, says Akinwumi

Adesina

THE Global Rule of Law Index from 1996-2023 shows that the topmost six countries are Finland, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, Austria and Luxembourg.

African countries ranked very low on the global rule of law index, starting in the 60th position with Seychelles, Botswana (70th), Rwanda (80th), South Africa (85th), Ghana (97th) and Morocco (111th), while Nigeria ranked in the 151st position.

Africa must do better on the rule of law index.

That is because the rule of law, which also includes the sanctity of contracts, is an important factor in attracting investments to countries.

So important is the rule of law in attracting foreign direct investment that the American Bar Association has in place a rule of law initiative to “promote justice, human dignity and economic opportunity through the rule of law”, which it considers a “necessary condition for robust economic development”.

To fill financing gaps, nations turn to foreign direct investment. Africa faces an annual foreign direct investment financing gap of over $100 billion.

Evidence suggests that foreign direct investments move more to countries that have political stability, stable democracies, transparency and low levels of corruption.

Other important drivers include independent and transparent judiciary, strong regulatory frameworks, public accountability, efficient public service, competition policy, as well as respect for intellectual property rights.

These factors are especially important for Africa, where many countries rely on revenues from natural resources to finance their economies. However, this richness in natural resources has not always translated into economic prosperity.

At the heart of the dissonance is the issue of governance and rule of law over natural resources. Africa’s natural resource-rich countries should learn from successful experiences of countries that have turned their natural resource wealth into prosperity for their populations.

Norway, which relies largely on oil and gas, has in place strong and transparent natural resource laws that guide concessions, acquisition and exploration of natural resources, while protecting biodiversity and securing the prosperity of future generations.

Through such laws and regulations, Norway has been able to establish the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, worth about $1.9 trillion from revenues from its oil and gas for the benefit of generations. Norway is a AAA-credit rated country.

Saudi Arabia, which relies on oil and gas for its economy today, has its national oil company, Aramco, with a market capitalisation of over $1.6 trillion.

What lessons can African countries learn from this? First, there is nothing really called ‘natural resource curse’; how could what makes some nations rich end up making some poor? The difference lies on governance, transparency and public accountability over natural resources.

Second, natural resources of countries should be targeted for the benefit of the people; avoiding rent-seeking, rentgrabbing, and elite-driven state capture or corruption.

Third, communities should be involved in the management of natural resources; and strong efforts should be made to ensure that multinational corporations are held accountable for environmental externalities based on the polluter pays principle.

Fourth, the judiciary should play a greater role in development of natural resource laws that ensure good governance over the nation’s natural resources. The judiciary should also play a greater role in ensuring compliance with these laws.

Fifth, nations should have a longerterm perspective on their natural resources.

I would also like to propose that the judiciary should get involved on the issue of rising public debt for developing countries, especially in Africa. Today, Africa’s public debt has exceeded $1.3 trillion. The structure of debt has changed over time, as traditional concessional debt from multilateral and bilateral creditors are declining and being overtaken by reliance on Eurobond debt to commercial creditors.

The change in the structure of Africa’s debt which has led to a greater reliance on commercial creditors has raised a lot of challenging legal issues for many African countries.

While restructuring of debt of nations, official and commercial creditors are required to agree on comparative debt treatment to bring debt to manageable levels. However, the framework has always been undermined by uncooperative private creditors. By refusing to sign on to the debt restructuring frameworks, the holdouts devise legal plots to rip countries off.

‘Vulture funds’, backed by hedge funds, buy off the debt of countries on secondary markets at a discount. Then taking advantage of the lack of a legally binding framework or global institution for dealing with bankruptcy of nations, they turn around to sue debtor nations for full payment of the discounted debt, including backdated interest payments and legal fees.

Africa has not been spared. The vulture funds take advantage of legal jurisdictions in creditor countries where they always secure favourable judgements.

‘ ’

Earnings from natural resources should be invested in building human capital, social development and infrastructure, which will ensure the sustainable development of their economies.

Nations should guard against wasting windfall revenues from natural resources by simply ramping up public expenditure. Rather, they should establish and grow their sovereign wealth funds and pension funds. These funds are important to secure the prosperity of future generations.

What lessons can African learn and what roles can the African legal profession play? First, the practice where debt agreements are signed and subject to law in jurisdictions that have been known to always favour the creditors not the debtor nations should be reviewed to ensure fair hearings, equity and justice before the law.

Investors choice of foreign jurisdictions suggests preferences for legal systems they know and trust, and their belief that there is rule of law, judicial

independence and transparency in their nations.

By implication it suggests that they do not trust the judicial systems in African countries. They should rise to this challenge. They must assure judicial independence that engenders trust and confidence of foreign investors in dealing transparently, justly and fairly with disputes – essentially, assure the rule of law.

This will be further enhanced through greater ethical standards and reduction of perceived corruption in the judiciary. There is no substitute for a very transparent, capable, fair, just and independent judiciary to curtail currently existing moral hazards in the global debt arbitration systems.

Second, African countries should also prioritise legal arbitrations in their jurisdictions. Equally important is building and strengthening of the capacity of African arbitral institutions.

The establishment of the African Arbitration Academy, to train young arbitrators, is a good development. Such efforts should also deepen and strengthen partnerships at the national and regional level arbitral institutions, while aligning with international arbitral institutions and treaty agreements.

Third, investors should use Africabased arbitration systems for loans and agreements signed with African

governments and corporate entities. This will avoid the inherent biases, cultural differences and loopholes often existent in legal systems of the creditor countries, as well as lack of sensitivities to local contexts of nations.

Fourth, the judiciary should get more involved in the development of their countries and move beyond the text-based interpretations of law and the constitution, as important as those are.

When, for example, vulture funds take advantage of legal loopholes in

debt, where they can be easily bought at discounts on the secondary debt market and used for subterraneous financial motives.

Many African countries lack the capacity to properly negotiate public contracts. Yet, these contracts will shape the future of economies.

That is why the African Development Bank established the Africa Legal Support Facility, to support African governments to protect their sovereignty, negotiate fairer deals and defend their constitutional and

international debt resolution frameworks, threaten the asset of countries through enforcement of liens on national assets; the judiciary should get involved in safeguarding their countries’ national interest and assets.

Fifth, to prevent the pernicious effects of vulture funds on debtor countries, global debt resolution systems should have enforcement systems that prevent free transferability or assignment of sovereign

economic rights.

Since its inception, the African Legal Support Facility has supported over 50 African countries in negotiating and renegotiating commercial, extractive, infrastructure and sovereign debt contracts.

Through its work, the Africa Legal Support Facility has helped to avert more than $ 4 billion in potential public losses; resources that have been redirected toward national development.

As a public institution, the African Development Bank holds itself to the highest standards of transparency, public probity and accountability.

At the core of this is ensuring that Bank-financed projects do not cause irreparable damages to communities, are inclusive, while providing voice and ensuring compensation for those affected by the projects.

For the African Development Bank Group, strengthening public finance is inseparable from enforcing constitutional safeguards and legal accountability. The Bank has helped countries to improve their systems on governance and the rule of law.

Collectively, these interventions underscore a simple but profound truth: public finance cannot thrive in a vacuum. It must be protected by transparent governance, reinforced by judicial efficiency and anchored in constitutional safeguards.

In essence, public finance, when aligned with constitutional principles and the rule of law, becomes not just a means of managing national budgets. It becomes the foundation for economic sovereignty and sustainable development across Africa.

Parliamentary oversight is the democratic backbone of Public Finance.

At the African Development Bank, public finance is not simply about disbursing funds, it is about anchoring every financial decision in democratic legitimacy and national ownership. This is why, for the

effectiveness of any public sector loan, grant, or guarantee, the Bank requires clear evidence of parliamentary oversight and authorisation.

Public finance without parliamentary oversight is undemocratic and nonsustainable. Democratic scrutiny does not delay development; it protects it. Parliamentary approval is not an obstacle. It is a safeguard that ensures every dollar borrowed serves the public good, not private interest.

With constitutionalism and the rule of law firmly established, it is critical that legal systems and the judiciary be strengthened across the continent. A nation’s legal system serves as its

institutional backbone, safeguarding public resources, protecting the rights of citizens and creating the certainty and predictability upon which all economic activity depends.

An independent judiciary, underpinned by constitutional safeguards and protected by the clear separation of powers, ensures that the management of public finances is not left to unchecked discretion, but is bound by clear legal frameworks and subjected to impartial oversight.

Where judicial independence is compromised, courts become vulnerable to political influence, fiscal rules are bypassed, public borrowing escapes scrutiny and public confidence collapses.

One cannot speak meaningfully about constitutionalism, the rule of law and investment in Africa without addressing the foundational issue of access to justice and fair compensation. These are the very conditions that foster public trust and build the confidence investors need to commit capital.

When justice is accessible, and compensation is fair, development becomes inclusive, governance earns legitimacy and economic growth becomes truly sustainable.

And more importantly, laws should be changed to ensure that women have secure property rights. No nation can develop without its women. No bird flies with one wing. It is not just about right. |It is about equity, fairness and justice.

Because we know this truth: justice is not a byproduct of development. It is the foundation of development.

As the world body turns 80 in September, Ibrahim A. Gambari offers strategies for taking the Pact of the Future from paper to practice, using Nigeria as an example

WE gather at a consequential moment: the United Nations has turned 80, and member states have adopted the Pact for the Future with 56 actions and two annexes on the Global Digital Compact and the Declaration on Future Generations. This Pact is ambitious by design; it calls for us to translate multilateral consensus into national progress, especially in the international peace and security sector.

This is taking place at a time when the UN is facing a severe financial crisis, with year-end cash deficits; severe cuts in funding for peacekeeping operations and indeed in resources across the UN system which may shrink by up to 30 per cent compared to 2023. In this regard, UN Secretary General António Guterres had announced on March 12, 2025, UN 80 Initiative aimed at moving “from less with less” to “more with less”.

I want to offer four strategic lenses for taking the Pact from paper to practice in Nigeria – each paired with actionable roles for the UN Country Team (UNCT) and practical examples already moving the needle.

The New Agenda for Peace and the Pact for the Future recentres prevention, politics and people. It calls for anticipatory action, realistic mandates, data-informed decisions and integrated approaches that protect civic space and advance women’s and youth participation. This is not abstract: it’s an operational doctrine for country teams.

The Kaduna State Peace Commission (KSPC) – created by state law in 2017 – offers a homegrown model for institutionalised mediation, early warning and grievance resolution across ethnoreligious and resource tensions. It shows what durable subnational prevention architecture can look like.

The Community Conflict and Dispute Resolution Centre (CCDRC) is an Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) relaunched in 2022 by Savannah Centre for Diplomacy, Democracy and Development (SCDDD) in collaboration with Katsina State Government under Governor Aminu Bello Masari. Within just two months of its relaunch and following capacity enhancement training for officials, the CCDRC successfully resolved over 3,000 community disputes out of court.

What can the UNCT do? It can scale state-level peace infrastructures; provide technical support and catalytic funding for state peace commissions, with national standards and peer learning between states.

It can protect and expand civic space; align governance programming with the Pact’s emphasis on rights-respecting prevention; integrate women, peace and security/youth, peace and security

systematically in dialogue platforms and local peace committees.

The UNCT should invest in political diagnostics; use shared political economy analyses to steer UN portfolios toward drivers of conflict: land governance, justice chain bottlenecks, extractives/community relations and climate security hotspots.

The Pact and the New Agenda for Peace emphasise regional prevention and stabilisation. In Nigeria’s northeast, the Lake Chad Basin Regional Stabilisation Facility (RSF) – now in a new 2024–2028 phase – has demonstrated how rapid investments in security, services and livelihoods can create breathing space for governance and social cohesion.

Borno State’s response to mass defections – often referred to as the “Borno Model” – has evolved communitybased reconciliation, reintegration and transitional justice pathways for adults and children associated with non-state

armed groups. These approaches are challenging, but necessary, and they are being documented and refined.

The UNCT can create an Accelerated Stabilisation Stack. This should bundle security-sensitive infrastructure, basic services and livelihoods with community reconciliation and survivor-centred justice, and apply it not only in the northeast, but also in high-risk corridors in the northwest and northcentral zones.

The UNCT should standardise reintegration safeguards; support federal and state partners to adopt codified community-based reintegration standards with independent monitoring.

Stabilisation should be linked to local government performance. For example, SCDDD partnered with the Borno State government to host a fourday capacity-building workshop aimed at raising awareness and improving the implementation skills of the State’s elected 27 Local Government officials and other key stakeholders.

By the end of the workshop, all 27 LGAs led by their Chairmen or Deputies, were able to create a sample strategic development and implementation work plan for a priority project of their choice, using the project development templates that were taught during the training.

Data should be made a frontline asset: from early warning to early action. The Pact’s peace and security track underscores evidence-driven prevention

and smarter use of technology. Nigeria already generates substantial data – from humanitarian assessments to security trendlines to social protection registries. The question is how to fuse and act on it faster.

In Nigeria, the Humanitarian Needs Overview integrates conflict and

‘

mediators or service packages when thresholds are crossed.

The Pact calls for fit-for-purpose financing and a stronger bridge between development, humanitarian and peace efforts. In Nigeria, the returns on prevention financing are visible where small, fast funds unlocked localised stability – then leveraged larger development flows. Financing should be tied to measurable peace dividends.

A practical action agenda for the UNCT in Nigeria is to launch a Nigeria Pact for the Future – Peace Compact. A compact with federal and three pilot states to deliver five measurable peace dividends each; and report quarterly to the UN Resident Coordinator and Governors’ Forums.

In my view, UNSG Guterres’ UN@80 Initiative is not a replacement for the ambitions of the Pact of the Future. It is aimed at the need for and ability of the UN to do more with less financial and other resources, and thereby serve “we the people of the United Nations” better in the three main pillars of the Organisation’s mandate: Peace and Security, Social and Economic Development, and Human Rights and Humanitarian Services.

displacement data for the northeast. The Peace Building Fund (PBF) projects in Borno are building policy frameworks for reconciliation metrics; and the Regional Stabilisation Fund has piloted results tracking across locations. These are building blocks for a national prevention dashboard.

What can the UNCT do now? It should create a joint Risk & Resilience Lab. This is light, interagency cell that blends conflict/event data, climate risk, market signals and social listening into district-level heatmaps; set triggers that automatically move funds and deploy

At 80, the UN’s relevance will be judged not by how eloquently we describe the future, but by how concretely we build it – town by town, budget line by budget line, partnership by partnership. The Pact for the Future has given us a direction of travel and the political authorisation to act. Nigeria has the institutions, talent and lived experience to show that prevention pays, that stabilisation can be people-centred, and that inclusive politics is the surest pathway to peace.

Let us move from commitments to consequences – for the better.

Prof. Ibrahim A. Gambari is a former UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs. He served as Nigeria’s Permanent Representative to the UN from 1990 to 1999. The above is an edited version of his address to the UN Country Team in Abuja in August this year

African leaders used the UN General Assembly’s 80th session to demand sweeping reforms, warning that without a permanent African voice on the Security Council the world body risks irrelevance amid climate shocks, debt crises and persistent conflicts

ON the third day of the United Nations General Assembly’s 80th high-level debate, African leaders delivered a strikingly unified message: the UN must undergo meaningful reform or risk sliding into irrelevance. Their appeal was grounded in a shared frustration with a global order that continues to marginalise developing nations even as it grapples with overlapping crises – from persistent conflicts and climate disasters to crushing debt burdens.