I FROM TRANSIT CITY TO URBAN ISOLATION

Sacha Trouiller

Course

Architecture as an Apparatus of Government

Tutor

Eleni Axioti

2024-2025

Architectural Association School of Architecture

MARSEILLE:

From Transit City to Urban Isolation

Separated from Europe by a mountainous belt, Marseille turns its back on its inland territory and naturally looks towards the Mediterranean. Founded by Greek sailors over 2,600 years ago, the former Massalia developed around trade, serving as a crossroad between land and sea. Although less flamboyant today due to the relocation of its port activities to Fos, the ‘Phocaean City’ has resisted complete absorption by the French nation state. Marseille has remained, at least in part, more Mediterranean than national, escaping the idea of a common identity with a unique history and language. However, this resistance to French absolutism was not without its contradictions. The development of the port city since the 16th century has been intimately linked to that of France’s colonial imperialism. As the gateway to North Africa, Marseille faces Algiers beyond its blue horizon. Their basilicas, both built at the same time and in the same Romanesque-Byzantine style, stand as mirrors to each other. In 1937, Julien Duvivier used the port of La Joliette in Marseille to shoot the end of his film Pépé le Moko, which was in reality set in Algiers. This fictional relocation reflects the real gemellity between these two sisters of the Mediterranean, a long shared tradition that goes beyond the bond forced by colonisation. The climate, the warm white and grey tones of the buildings and the bare limestone terrain - these were all elements that gave those leaving Algeria after its independence in 1962 the impression of returning to a familiar place. The port city, initially conceived as a simple transit point, quickly became the main destination for French nationals repatriated from Algeria and North African immigrants. What was the impact of this post-colonial migratory shockwave in Marseille? a city that had not yet recovered from the bombings of the war, a city that had seen the apogee and fall of a colonial empire in just a few decades, a city of departure that became a city of arrival.

Against the backdrop of Algerian decolonisation, this work investigates the dynamics between migratory flows and the built environment in Marseille. It traces a history of social and spatial violence and examines the multiplicity of the notion of foreigner through two residential trajectories: that of Algerian pieds-noirs housed in the La Rouvière estate, and that of Mediterranean immigrants displaced from shantytowns to the Petit Séminaire transit estate.

The aim is to better understand how the urban, economic and social policies of the last sixty years, at the crossroads of the colonial heritage, segregation through housing and Algerian war, have shaped the current fragmentation of this territory. This work does not pretend to resolve or even to grasp in its entirety such a vast subject, but rather to recount from an architectural angle the urban and human reality of a lasting stigmatisation in a city of transit and immigration, of strangers and foreigners.

Fig. 0 (left page) Windenberger, Jacques. Arrival of the Liberte at the Joliette port. Est-ce ainsi que les gens vivent?: Chronique documentaire, 1969-2002. Parenthèses. 2005.

1. The term ‘Algerian War’ was officially used for the first time by the Government 1999.

2. Although a colony, Algeria was legally defined as a department and was under the responsibility of the Ministry of the Interior.

3. (Organisation de l’Armée Secrete) Secret Army Organisation.

4. (Front de Libération Nationale) National Liberation Front.

This part examines the exodus, arrival and permanent settlement of the pieds-noirs in Marseille. The term, literally ‘black feet’, refers to the French from Algeria, and by extension to French people of European descent living in the colonies of North Africa. Popularised during the Algerian War, the term was often used pejoratively by the metropolitan population. However, it was quickly appropriated by those concerned, reflecting a new awareness of their own identity in French society. The Algerian war, refferred for a long time by the French authorities as the Algerian ‘events’1 occurred after more than 120 years of colonial rule on a territory considered to be an integral part of metropolitan France2. Opposing the French army and clandestine paramilitary groups against Algerian national movements, the conflict started in 1954 and led to the signing of the Evian Accords on 18 March 1962, giving Algeria its right to self-determination. But in the final months of French Algeria, the violence of the OAS3, a French terrorist organisation close to the extreme right, made it impossible for Europeans and Muslim Algerians to live together. At the same time, the new governance of the FLN4, the Algerian nationalist party that advocated a society based on the rules of Islam, could no longer guarantee the safety of Europeans, stripped of any political power.

Often regarded as repatriates, the pieds-noirs had little connection with metropolitan France. The majority were people of modest origins who had left Europe in the hope of a better life, far from the image of the rich, exploitative colonist. Sometimes unable to withdraw their savings from the bank before fleeing, some arrived in Marseille with no money and no family to welcome them, and despite their citizenship, they landed as foreigners, they were national migrants.

5. These numbers are based on a research conducted by historian Jean-Jacques Jordi.

5. These numbers are based on a research conducted by historian Jean-Jacques Jordi.

In total, it is estimated that almost two and a half million French people left Algeria for mainland France. While some fled in the months or even years preceding the signing of Algerian independence, the ‘return’ of pieds-noirs examined here corresponds to the migratory peak of 1962, with almost half a million people crossing the Mediterranean that summer alone. Between May and August, the positive difference between arrivals and departures at the port of Marseille was more than 500,000 people, i.e. around 100,000 in May, 355,000 in June, 120,000 in July and 95,000 in August5.

To put this in perspective, Marseille, France’s second-largest city, had a population of just 700,000 before 1962. In just a few months, the ‘Phocennean City’ was overwhelmed by the constant influx of arrivals, and saw its permanent population rise by 30% to almost 900,000.

This migratory shockwave that put Marseille on the verge of collapse was initially denied or at best minimised by the authorities. Robert Boulin, then Secretary of State for Algerian repatriates, would explain that these people were just ‘‘vacationers’’6, and that there was no exodus, contrary to what the press was already suggesting. At the same time, the port of La Joliette was being swamped on a daily basis by overloaded boats from Algeria, such as the Bordeaux, a supposedly 420-seater ship that in reality had more than 1,400 pieds-noirs on board.

The single reception office for repatriates and the few rooms initially planned near the port were no longer sufficient to absorb the wave of arrivals. In a state of improvisation and urgency, the authorities requisitioned the Rougière social housing estate in the eastern part of the city, even though its construction had not yet been finished. Military tents were set up in front of the buildings to register new incomers. They were crammed into flats without doors, furnished only with cots provided by the army. Although vast, this spontaneous transit camp could only hold 3,000 people at a time, and only 90,0007 of the 450,000 repatriates who landed in Marseille in 1962 were able to be assisted by the authorities. The rest had to manage with the generosity of a few independent associations and the limited supply of hotels, whose prices had at least tripled for the occasion.

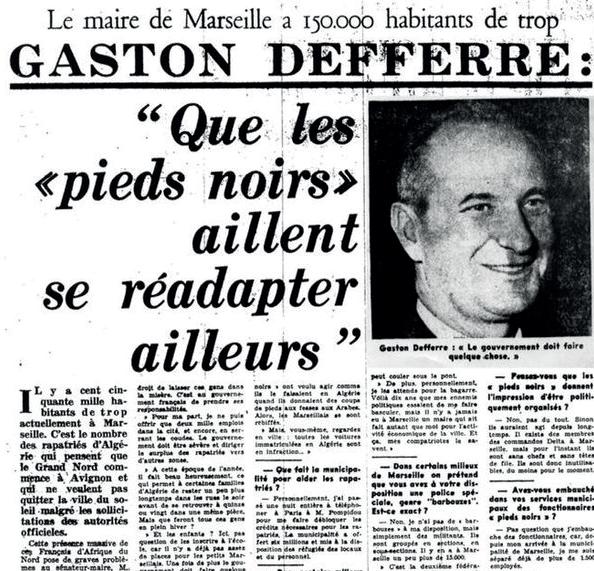

These national migrants faced hostility from the local authorities, supported by public opinion and echoed in the media. The infamous statement from Mayor Gaston Defferre written in a local newspaper ‘‘Marseille has 150,000 excess inhabitants. The pieds-noirs should go and readapt elsewhere!’’ was coupled with slogans painted on the walls of the port and city centre by such as “The pieds-noirs back to the sea!”9. This general apprehension took place in a damaged Marseille, as the city had not yet fully recovered from the roundups and bombings of the war and had already been suffering from demographic saturation for several decades10. In this precarious context, the pieds-noirs, although citizens in the same way as the metropolitan French, seemed to belong to a past that France was trying to turn its back on. Considered by some to be responsible for the Algerian conflict, and by others to be colonisers who did not deserve national support, these repatriates embodied a disastrous decolonisation process and a political failure. Their presence, almost anachronistic with the metropolitan reality, was an unpleasant reminder of the loss of Algeria and, by extension, of the past colonial grandeur.

Once the initial hostility and chaos had faded, the authorities changed their attitude when they realised the development opportunity that this demographic change represented for the city. The government released funds to build tens of thousands of homes as a matter of urgency, and guaranteed 40% of them to households repatriated from Algeria12. Marseille began to expand, leaving behind the stone of the bastides and their domains to make way for the concrete of the large housing estates that grew up on the limestone relief despite the geographical constraints.

Some repatriated households were even able to buy flats off-plan before they emigrated in residences that were under construction at the time. La Rouvière imagined by the architect Raoul Guyot is a notable example. Commissioned in 1962 and fully delivered in 1974, this enormous co-property of 2,200 homes for 8,800 inhabitants overlooks Marseille with its seven buildings, including four immense 20-storey blocks and a 30-storey tower. Conceived as an autonomous city within the city, La Rouvière epitomises the modernist attempt to create an environment on the boundary between the urban and the landscape. The flats have generous glazed surfaces and south-facing balconies. The very narrow blocks, barely 10 metres wide, provide comfortable through-planning. The dozens of piedsnoirs families who have moved in have in some way recreated their community of Algiers or Oran, away from the rest of Marseille’s population.

Its architectural morphology resembles those of other Grands Ensembles14 in the region, with endless facades of now worn paint, blinds whose orange colour has been bleached away by the sun, and rusty ironwork. And yet, despite showing their age, the communal areas, roads and gardens are meticulously maintained, and the immense residence seems to have escaped the almost programmed deterioration seen in the surrounding housing estates. But what will strike the visitor most is the strange sense of detachment conveyed by this neighbourhood, completely disconnected from the rest of the city.

Over the years, La Rouvière has become increasingly protected, and is now secured with a guard at every gate. Although the pied-noir population has naturally declined over time, many have stayed and established themselves over several generations. The residents’ committee filters all new arrivals to the co-owned property and only accepts certain profiles and social classes, with a clear rejection of foreigners. This unwritten rule of ‘entre-soi’15 embodies the social fragmentation of the city, with a trend towards gentrification in the southern neighbourhoods and impoverishment in the north.

So, while the case of La Rouvière demonstrates that a modernist building can be architecturally viable in Marseille16, it also raises a number of questions about the future of the city’s other major developments. Is the slight deterioration of the site due to the residents owning the property, the very high maintenance costs, the employment of around 50 guards ensuring intense surveillance, or the explicit rejection of black or Arab foreigners? In other words, the challenge would be to succeed in imagining a more resilient future for these large housing estates, without falling into the gated communities model that is increasingly affecting Marseille today.

17. The post colonial racist context marked the first retention camp in France: The Hangar D’Arenc in the Marseille port. llegal, it was kept secret for more than a decade.

18. HLM (Habitation à Loyer Modéré) is the French low-income housing solution.

Most of the Grands Ensembles were HLM.

The pieds-noirs, although the largest in number, were not the only ones to leave North Africa in the early 1960s in the context of decolonisation. The harkis, Algerians who volunteered or were recruited to fight alongside the French army, were also forced to flee Algeria to avoid the massacres perpetrated by the FLN following its rise to power. Although several thousand made their way to France, very few settled directly in Marseille. This second part focuses on the migratory trajectory of Algerian and, by extension, Maghrebians families who immigrated to Marseille, sometimes even brought by the French Government, in a context of urgent reconstruction and labour shortages.

This migration, intended to be temporary, for as long as it took to build the Grands Ensembles, perfectly reflected a Western vision of the foreigner, whose presence was only tolerated and justified by his status as a worker. This did not prevent numerous expulsions for those who did not present sufficient papers and justifications when they debarked in the city. The port of Marseille, once thought of as a gateway to the sea, became the solid frontier where a clear line was drawn between those who were allowed to stay and those who were not. The way asylum seekers were treated during this period was more one of control and expulsion than of reception17.

19. Official extract from the Circulaire Relative aux Cités de Transit. April 19, 1972.

The North African populations, who were allowed to stay but were unable to access the HLM18 reserved for French citizens, settled in unsanitary buildings or in the shanty towns that were growing up on the outskirts of the city. But with the Algerian conflict and the consequent terrorist attacks on metropolitan territory, these hard-to-control areas were perceived as dangerous by the authorities, and various urban policies were put in place to try and resolve them. One of these ‘treatments’ was the cité de transit, literraly transit estate. Referred to by the authorities as ‘social re-education housing’, ‘re-housing sites’ or ‘promotional housing’, and by the public as ‘drawer housing’, ‘prison housing’ or ‘dumping sites’, these transitional estates were eventually legally defined as ‘‘housing complexes used for the temporary accommodation of families whose access to permanent housing cannot be envisaged without socio-educational measures designed to promote their social integration and promotion’’19.

Put simply, this is one of the first examples in metro-

politan France of positive segregation through housing. In its apparent benevolence, the vocabulary used in the official documents, which speak of the ‘aptitude’ of these people to ‘evolve’ and ‘integrate’ into society, is reminiscent of colonial management. By its very definition, the cité de transit embodies a discriminatory practice assumed by housing, and can be seen more as a tool of control than of integration.

The reality confirmed this: almost all the shantytown households were transferred to the transit estates, and the ‘socio-educational’ action promised by the authorities only very rarely took place. Isolated from the rest of the urban fabric, these supposedly temporary settlements became more and more permanent settlements. The residents who were forced to move there were then condemned to stay in overpopulated accommodation that rapidly deteriorated. Based on very high levels of solvability and more subjective criteria21, access to the upper echelons of social housing was almost impossible for these immigrants, who did not pay rent as such, but rather a sort of occupancy allowance. As a result, they couldn’t benefit from tenant status and the associated rights, including the right to re-housing, which obliges the landlord to provide new accommodation when the current one becomes uninhabitable. Unable to achieve any sort of residential mobility, they were trapped in the most degraded buildings and were gradually moving away from common housing rights. More than an apparatus for marginalisation, transit estates became a tool for the immobilisation of these populations, perceived as ‘at risk’, always last on the list and condemned to the status of foreigners.

14

22. Of Greek origin and born in Baku in the USSR, Candilis apprenticed with Le Corbusier on the Marseille Unité d’Habitation before working on residential projects to rehabilitate shanty towns in Algeria and Morocco when they were still colonies.

23. Opération Million, a government scheme launched in 1955 to tackle the housing crisis.

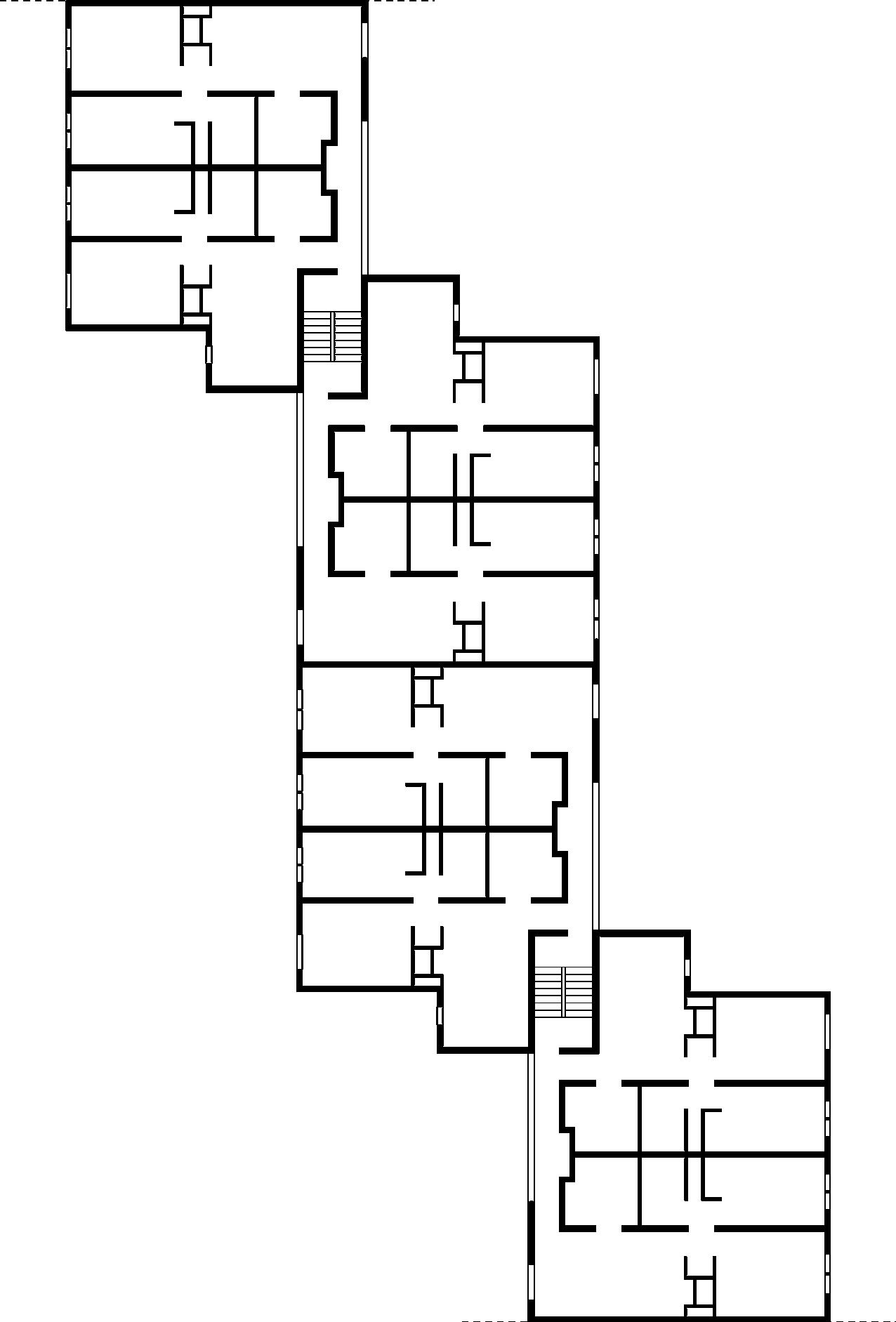

Built between 1958 and 1960 on a rugged hill in the Marseille countryside, Le Petit Séminaire is a transit estate with 240 units arranged in 4 blocks of 5 storeys. Its architect Georges Candilis22 had to work with a very limited budget: one million francs23, or around 22,000 euros today, for each flat. Residents were not provided with heating, hot water or lifts, and the green spaces, paths and play grounds featured on the plans were never built.

Initially, the first occupants stayed only temporarily in the accommodation, as planned, but the large influx of households from the cleared shanty towns soon put the estate in a precarious situation. These new arrivals - gypsies, immigrants from the Maghreb, Turkey and Greece, as well as piedsnoirs whose solvency was insufficient to secure HLM housing - were temporarily allocated empty flats in Le Petit Seminaire. Forced out of the shantytowns at first, this population was soon condemned to stay in their under-equipped homes for the same reasons mentioned previously.

24

Lisa. Image for MarsActu. January 25, 2019.

25. This analysis of the estate is based on an extract from the CERFISE report. 1981.

Overcrowding and a lack of maintenance led to the rapid degradation of the estate, with its facades, blackened by leaks and fires, gradually losing their shutters. Marginalisation was accentuated here by urban isolation. The infrastructure, almost non-existent, was obsolete: the roads were still made of dirt and the planned bus line was almost 20 years delayed25.

As early as the 1980s, the question of demolishing Le Petit Seminaire was raised. The temptation to tear everything down to clear the site of its embarrassing image and to rebuild more profitable housing almost succeeded, but ultimately the decision was made to carry out a rehabilitation project26. For the first, and last time, the residents were listened to during participatory sessions, a number of changes were made to the buildings and a bus route was finally opened. However, these operations, closer to a bricolage due to the limited resources available, were mainly cosmetic and did not resolve the real causes behind the degradation. Many residents of the surrounding neighbourhoods couldn’t even understand why money was being spent on these foreigners with ‘no future’. In the same year as the rehabilitation project, a bomb exploded in a nearby estate, claimed by a nationalist group calling for the expulsion of immigrants in Marseille.

Despite the precarious living conditions28, Le Petit Seminaire conveyed a strong sense of mutual support and resistance. Residents liked to describe their community as a village, and a number of initiatives such as a local newspaper and neighbourhood festivals showed a desire to settle down29. These initiatives were the only possible means of fighting against the total abandonment of the authorities and developers, who were waiting for the estate to fall into ruin. Yet they were not enough to prevent its destruction in 2020 and the definitive eviction of its last occupants

Fig. 30 (right) Zachmann, Patrick. Chérif, Yahia and Hocine at the Bassens transit estate.

Series ‘North Marseille’, 1984/2007.

Although one of the first to be razed, Le Petit Seminaire is not an isolated case in Marseille. Other transit estates that became permanent homes by default are now facing demolition to make way for more profitable private developments, with no guarantee of rehousing for their rightless residents.

La Rouvière and Le Petit Seminaire embody two distinct residential trajectories but share a common origin. They are the remnants of a post-colonial migratory crisis, which it would be more accurate to call a reception crisis. While one has fenced itself off from the marginalised other, both estates have been the apparatus of fragmenting urban policies, some of whose practices of spatial and social violence have been perpetuated to the present day.

Marseille, a city of immigrants and foreigners, was as much coloniser as it was colonised. Its peripheries were built according to the ideas of a few decision makers as to what was appropriate for these new comers, judged incapable of determining their own future. Like the cities of Algeria, these modernist projects did not see Marseille as an actual, specific site, but rather as an abstract desert on which to build new housing solutions for these foreigners, French or not. During decolonisation, colonial practices were simply transferred to metropolitan France, and in particular to Marseille.

31. Although recent amendments allow for exemptions, French law still considers assisting undocumented migrants to be a criminal offence. As stated in the article L. 622-1 from the CESEDA).

The current desire for a tabula rasa to get rid of the problematic image of the transit estates will not be enough until there is a thorough rethink of our approach between immigration and integration. In the current context of intensifying repression, new urban policies and architecture should support freedom through movement rather than control through immobilisation. But more than that, it is the whole public’s perception of what it means to be a foreigner that needs to shift, and this will be a complex task for a country where solidarity can still be a crime30.

Abdallah, Mogniss H. Cités de transit : en finir avec un provisoire qui dure!. Article for Plein Droit, (Dé)loger les étrangers, No. 68. April, 2006.

Angélil, Marc. Malterre-Barthes, Charlotte. SOMETHING FANTASTIC. Immigration et ségrégation spatiale - L’exemple de Marseille. Parenthèses Editions. November 24, 2022.

Baudier, Jeremy. S’ancrer à Marseille, 3 quartiers facoonnés par l’immigration. Research for EHESS Social Science School of Marseille. 2023.

Bonilio, Jean-Lucien. Borruey, René. Chancel, Jean-Marc. Hayot, Alain. Graff, Philippe. Perloff, Michel. Peyre, Catherine. Atlas des formes urbaines de Marseille. Volume 1 : Les types. INAMA Laboratory Publications. 1998.

Brettell, Caroline B. Repatriates or Immigrants?: A Commentary. Chapter 4 of Europe’s Invisible Migrants. Amsterdam University Press. 2003

Castelly, Lisa. Au Petit séminaire, les locataires ne sont pas prêts à renoncer à leur “village”. Article for Marsactu. January 25, 2019.

Cohen, William B. Pied-Noir Memory, History, and the Algerian War. Chapter 6 of Europe’s Invisible Migrants. Amsterdam University Press. 2003.

Cooper, Frederik. Postcolonial Peoples: A Commentary. Chapter 8 of Europe’s Invisible Migrants. Amsterdam University Press. 2003

Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine. Colonisation, racisme et roman national en France. Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol. 45, No. 1. 2011.

De Barros, Francoise. Les bidonvilles: entre politiques coloniales et guerre d’Algérie. Métropolitiques Editions. March 5, 2012.

Dewhurst Lewis, Mary. The Strangeness of Foreigners: Policing Migration and Nation in Interwar Marseille. Article from French Politics, Culture & Society, Vol. 20, No. 3. Berghahn Books Publishers. 2002

Firebrace, William. Marseille Mix. AA Publication Bedford Press. May 16, 2011.

Gilbert, Pierre. Vorms, Charlotte. L’empreinte de la guerre d’Algérie sur les villes françaises. Métropolitiques Editions. February 15, 2012.

Jaillette, Jean-Claude. Soins de beauté pour une cité de transit. Article for Le Monde. December 19, 1983.

Jordi, Jean-Jacques. The Creation of the Pieds-Noirs: Arrival and Settlement in Marseilles, 1962. Chapter 2 of Europe’s Invisible Migrants. Amsterdam University Press. 2003

Lévy-Vroelant, Claire. Migrants et logement : une histoire mouvementée. Article for Plein Droit, (Dé)loger les étrangers, No. 68. April, 2006.

Petit, Fanny. Les règles de l’inhospitalité. Article for Plein Droit, (Dé)loger les étrangers, No. 68. April, 2006.

Schaller, Angélique. Cités à raser : ils en font toute une histoire. Article for La Marseillaise. Jully 29, 2022.

Simoner, Valérie. Marseille transit. Miloud Amara. Résister dans la cité. Article for Libération. April 29, 1998.

Zappi, Sylvia. A Marseille, l’entre-soi d’une cité sans immigrés. Article for Le Monde. January 31, 2016.