MAN JAANO

A Critique on Ghana’s land tenure system through public space

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requiriments of Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design - Projective Cities by Beryl Amartey

Architectural Association

School of Architecture

2024/2025 MAN JAANO

A critique on Ghana’s land tenure system through public space

Cover art: Seek III by Wiz Kudowor

Programme:

Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

Name(s): Beryl Naa Amarteley Amartey

Submission title: MAN JAANO: A Critique on Ghana’s land tenure system through public space

Course title: Dissertation

Course tutor(s): Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi, Anna Font

Declaration:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student:

Date: 21st of March 2025

A place that is accessible to the public. Communal area.

To God. To family. To friends. To me.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE: LAND AND PROPERTY

Customary land tenure system

Statutory land tenure system

The urban plannning conundrum

CHAPTER TWO: THE ERA OF ASHANTI SOVEREIGNTY

Gyaase

Dwe Berem

CHAPTER THREE : THE BRITISH GOLD COAST COLONY

The Open Compound

The Community Centre

CHAPTER FOUR: THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA

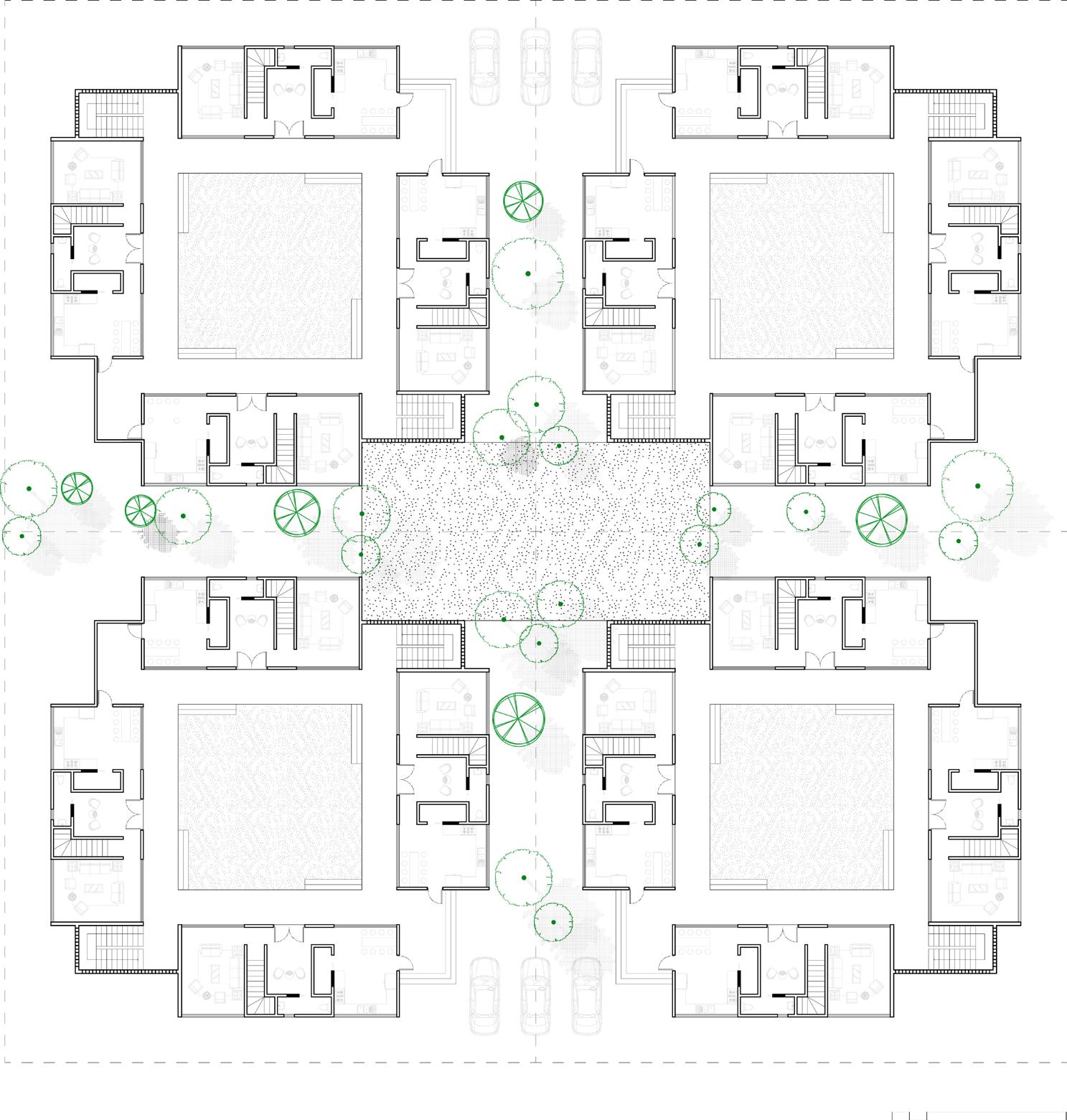

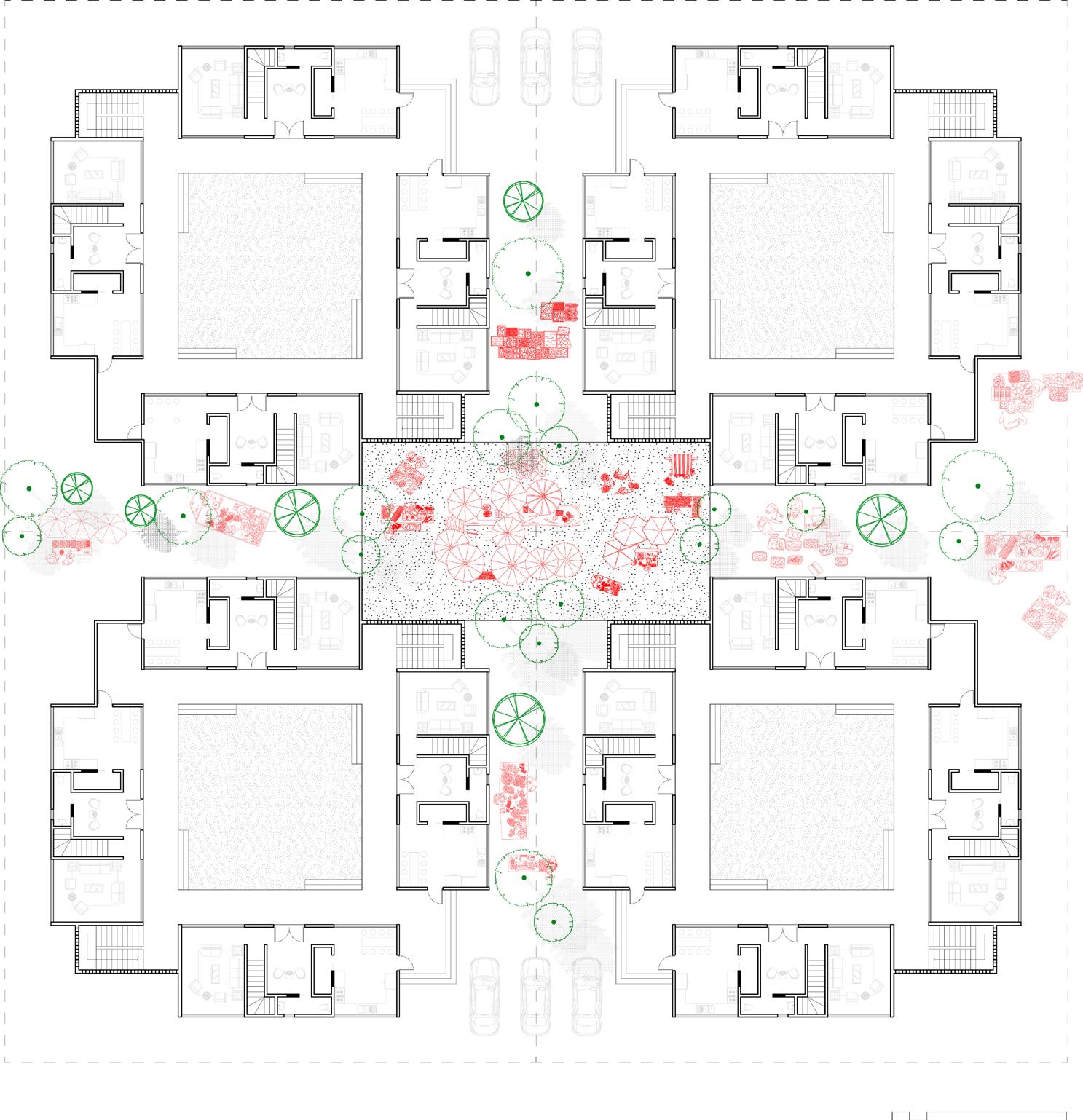

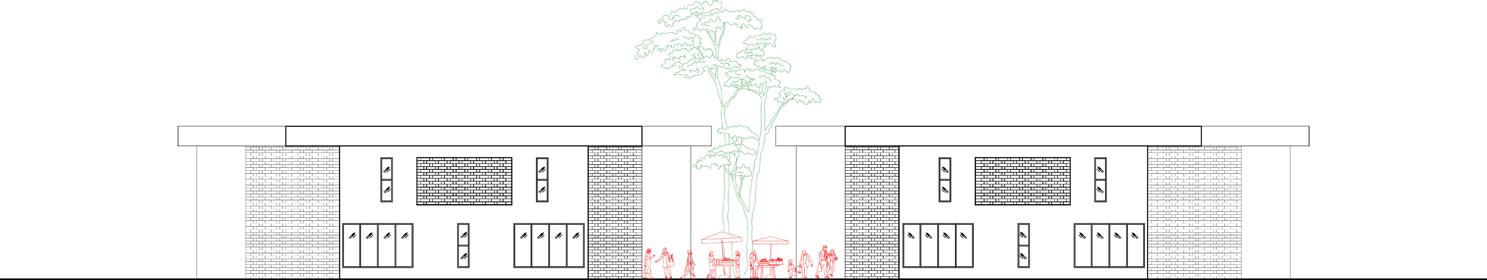

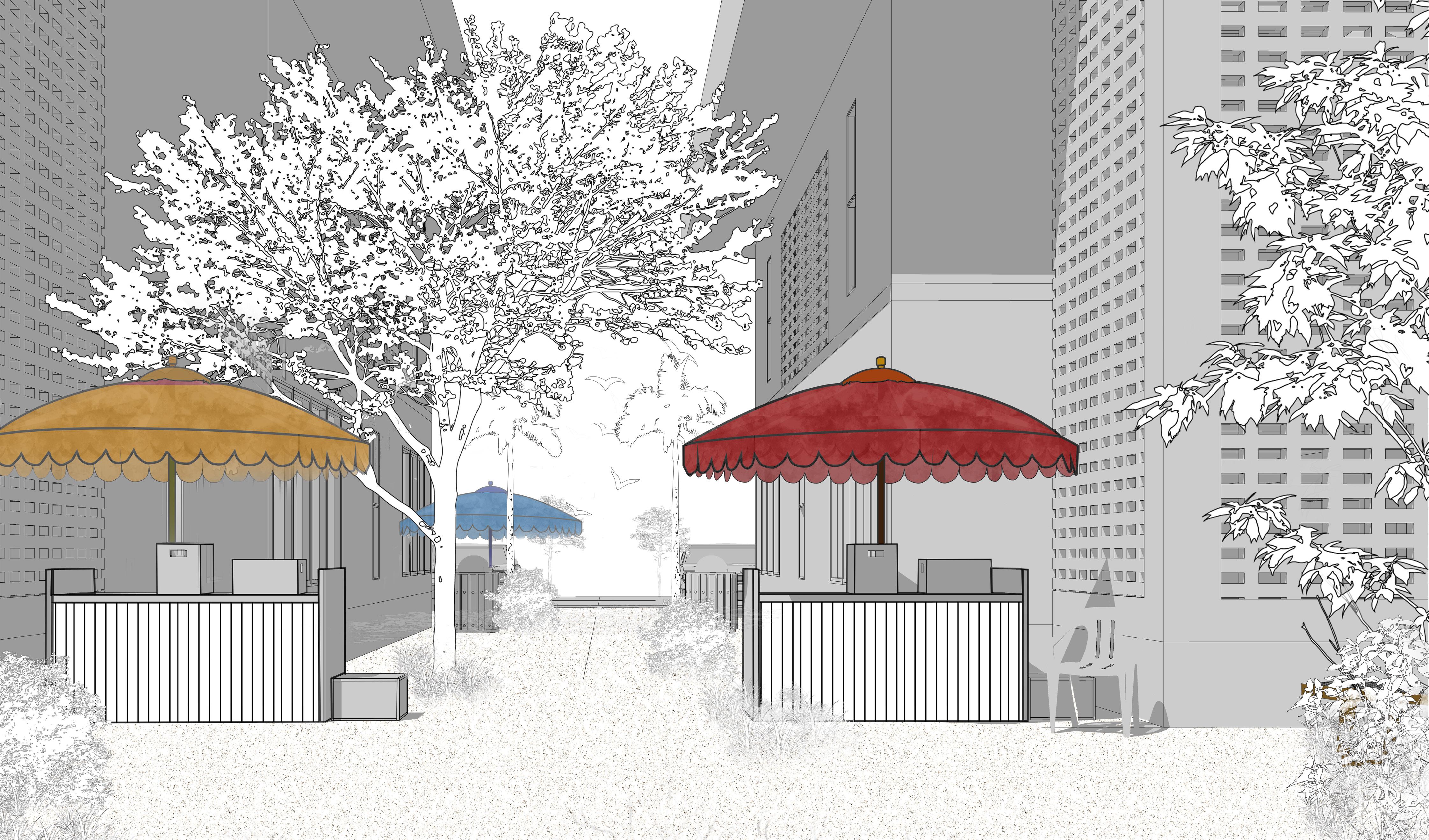

The New Gyaase

The Reimagined Dwe Berem

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABSTRACT

Ghana, a multicultural nation, is characterized by the shared history and traditions of its people. The culture is deeply rooted in the principles of community, encouraging “coming together,” “living together,” and “growing together.” At the heart of this communal way of life are what this research terms the “man jaano”—spaces created by architectural elements that function as shared environments. These man jaano are informal and fluid, serving as essential social spaces where children play games like “ampe” and elders’ broker important social agreements, such as marriages. They are crucial to the social fabric, providing places of common good where orphans are nurtured, and widows are protected.

The importance of this research lies in its challenge to traditional conceptions of public space and its exploration of the evolving public sphere in Ghana. By delving into historical contexts and societal changes, this study offers valuable insights into how social interations have shaped public spaces and vice versa in the Ghanaian context. Understanding the concept of the “man jaano” in Ghana involves a multidimensional approach that bridges literary exploration, spatial analysis, legal scrutiny, and direct observation. This research embarks on a journey through time and space, from 18th century Ashanti Kingdom to 21st century Republic of Ghana, to unravel the significance and evolution of gathering spaces.

This research investigates Ghana’s man jaano by analysing literary and narrative pieces on western african civilisation understand precolonial concepts. Two key books are pivotal to this categorisation - Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe and Mission from Cape Coast to Kumasi by Edward Bowdich. Spatial analysis of the identified gathering sspaces will document insights into layout, usage patterns, and cultural significance providing a background for comparisons with the modern-day man jaano.

A review of Ghana’s pluralistic land laws and urban planning will assess conflicts and opportunities for identified communal spaces. This interdisciplinary approach aims to uncover historical roots, contemporary challenges, and potential enhancements for communal spaces in Ghanaian neighbourhoods, contributing to broader discussions on community cohesion and urban development.

INTRODUCTION

The evolution of land tenure in Ghana can be traced through three key periods: pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial. These periods marked significant legislative interventions as the region transitioned from customary law to dual legality. In the pre-colonial period, land was primarily managed through customary practices, which were embedded in the social and cultural structures of various ethnic groups. Land was communally owned, with rights to use land often tied to social status and community membership 1. The arrival of the British introduced significant changes. The Crowns Land Bill of 1894 sought to transfer all land and mineral rights in the Gold Coast to the British Crown but was resisted by the Aborigines Right Protection Society 2 The compromise reached during the colonial period resulted in a dual legal system. Customary authorities retained control over land, while statutory laws began to govern land use and planning 3. This arrangement allowed for the continuation of traditional land tenure practices while introducing new regulatory mechanisms. The implications of this dual system have continued to influence land governance in Ghana, shaping both urban and rural landscapes.

RESEARCH PROBLEM

In Ghana, property rights are shaped by the tension between customary land ownership and statutory planning frameworks. Customary authorities hold ownership over land, while statutory regulations dictate its subdivision and use. This dual system results in fragmented urban planning, where conventional communal spaces are affected. Except that in the Ghanaian context, public space is not conventional but is embedded in everyday social and economic interaction. This nuanced understanding challenges traditional urban approaches and necessitates a reconsideration of how communal spaces are designed.

RESEARCH AIM

This research aims to examine the concept of public space in the Ghanaian society by investigating how planning frameworks, land tenure systems and socio-cultural practices shape the definition and evolution of communal spaces. Through an analysis of historical and contemporary spatial practices, the study seeks to redefine these communal spaces beyond conventional public parks and greenery, instead situating them within the lived realities of Ghanaian urban life.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Typological

To document gathering spaces in Ghana.

To determine how social interactions influence the identified typologies.

Urban

To examine how the dual land tenure system has impacted the development and use of the “man jaano” .

Disciplinary

To uncover the potential of non-traditional models of public spaces within Accra.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Typological

What are the typologies oaf the “man jaano” in Ghana?

How do social interactions influence these typologies.

Urban

How does the conflict between the customary and statutory planning regulations influence the development and use of the “man jaano” ?

Disciplinary

What is the potential of non-traditional models of public spaces within Accra?

SCOPE OF THE STUDY

The research spans three historical periods:

Eighteenth-Century Ashanti Kingdom – The study explores the Ashanti Kingdom as the dominant empire in the region, where its architectural forms and spatial practices influenced public space throughout West Africa. This historical account provides insight into indigenous spatial configurations as gathering spaces that shaped communal life.

1950s British Gold Coast Colony – The research then shifts to the mid-20th century to analyse the intersection of traditional and modern planning during British colonial rule. It specifically examines the housing and urban interventions of Fry and Drew in Ghana, illustrating how colonial planning sought to integrate indigenous spatial concepts with modernist ideals.

Twenty-First Century Republic of Ghana – Finally, the study tackles contemporary Ghanaian urbanism, critiquing the legacy of statutory planning, which fragments land into residential plots. It concludes with a reimagination of how communal spaces could persist and adapt in the absence of formally designated public spaces.

By tracing these transformations, the research situates public space within Ghana’s unique socio-political and spatial context, offering a different take on communal spaces that reflects both historical precedents and contemporary realities.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To achieve the research objectives, an extensive literature review was conducted to examine the existing land tenure system and its impact on public spaces in Ghana. This included an analysis of Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe and Mission from Cape Coast to Ashantee by Edward Bowdich, which provided insights into the archetypes of communal gathering spaces in 18th-century West African societies. A spatial analysis

of these identified spaces was carried out to understand their physical configurations and social functions. To trace their transformation from the Ashanti Kingdom through the colonial and post-colonial periods, archival research was undertaken. Field surveys documented the contemporary functions of public spaces in Accra, highlighting both formal and informal interactions. As a research-by-design thesis, these findings were tested through a design intervention at South La Estates, using spatial principles to explore new ways of creating the public.

ORGANISATION OF THE RESEARCH

The research is structured into four main chapters, along with an introduction and a conclusion.

Chapter One establishes the foundation by investigating Ghana’s dual land tenure system. This chapter explores the legal framework that is in operation and examines the impact on public space.

Chapter Two looks into the Ashanti soverieign era of the 18th century. It identifies and analyses two key communal gathering — the gyaase and the dwe berem.

Chapter Three examines the British Gold Coast Colony and presents a comparative study of indigenous public space models and the colonial reinterpretations of these spaces in the 20th century. By analysing these adaptations, the chapter highlights the shifting spatial paradigms introduced under British rule.

Chapter Four focuses on contemporary Accra, critiquing the legacy of colonial grid planning and its influence on the public realm. This chapter serves as both an analysis of modern urban space and a testing ground for the research’s findings, culminating in a speculative reimagining of public space within the city.

NOTES

1. Janine Ubink, “Legalising Customary Land Tenure in Ghana: The Case of Peri-Urban Kumasi,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009),

2. Amanor, Kojo. “The changing face of customary land tenure.” Contesting land and custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen (2008): 55-80.

3. Agbosu, Lennox Kwame. “Land Law in Ghana: Contradiction between AngloAmerican and Customary Conceptions of Tenure and Practices,” 2000; Amanor, Kojo.

“The changing face of customary land tenure.” Contesting land and custom in Ghana: State, Chief and the Citizen (2008): 55-80.

CHAPTER ONE

LAND AND PROPERTY

In Ghana, the land tenure system is an interplay between customary law and statutory law which has created a unique legal landscape that significantly impacts urban planning. Unlike some nations where land is nationalized, Ghana’s constitution recognizes the rights of customary authorities in land administration. However, the scope and power of these authorities have evolved over time. The concept of customary authority held different meanings before British colonization and has been redefined multiple times throughout Ghana’s post-independence history. What remains today is a negotiated arrangement between the state and customary authorities, reflecting an ongoing interplay between tradition and modern governance. The state has leveraged its position within this arrangement to expropriate land, often redistributing it to politically connected elites, with each successive government perpetuating this practice to benefit its allies. Customary authorities have similarly capitalized on their control over land, frequently engaging in practices such as selling the same parcel to multiple parties1. This chapter examines the historical account of this dual system and assesses their implications, highlighting the complexities and challenges that arise from this intersection of legal systems.

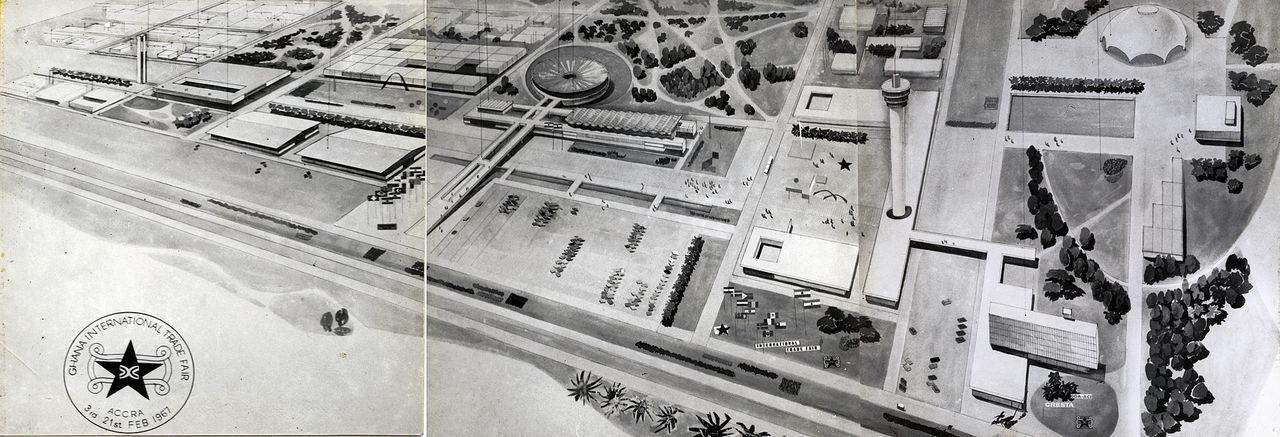

In Ghana’s current land system, the public sphere is one of the most significant casualties. This thesis challenges the Western notion of public space, which often emphasizes parks, plazas, and greenways as markers of communal life. Such a framework is rooted in Western ideological traditions and remains impractical for African societies, where the concept of “public” carries distinct cultural meanings. To better capture the Ghanaian context, this thesis adopts the term man jaano from the Ga language of the Ga-Adangbe people, which roughly translates as “a place where the people gather.” However, as land ownership structures evolved over centuries, what happened to the man jaano? The answer is evident in the absence of formalized public spaces in many Ghanaian neighbourhoods. If one looks for parks and green spaces as indicators of public life, they will often find none. The duality of land governance— customary and statutory—fosters contested ownership, stalled developments, and unpredictable land-use patterns, complicating urban planning efforts. Rising land values, fueled by market-driven demand and the competing interests of both state and customary leadership, make it nearly impossible to set aside land for communal purposes. Within this framework, land is too economically valuable to be reserved for mere greenery. Moreover, when land belongs to families, disputes often arise over how it should be used, with individual family members asserting conflicting rights. This results in uncoordinated urban landscapes, creating lifestyles that deprioritize parks and pedestrian-friendly environments. The urban fabric becomes defined by private interests rather than collective well-being. This tension is particularly evident in the case of Tse Addo, where land expropriated by the state for the Ghana Trade Fair was partly reclaimed by the original customary owners and subsequently sold to private investors and real estate developers. Such instances reveal how Ghana’s land tenure system undermines the possibility of public space as understood through a Western lens. Ultimately, Ghana’s urban spaces are not neutral grounds for communal benefit but battlegrounds for competing interests. To move forward, it is essential to re-examine the role of public space in Ghanaian life—not as an imported concept but as man jaano, a culturally resonant space for gathering, exchange, and community life. This thesis argues that only by reclaiming man jaano as a central tenet of urban design can Ghanaian cities truly reflect the social and cultural needs of their people.

CUSTOMARY LAND TENURE

Ghanaian ethnic groups hold a sacred connection to land, rooted in religious and ancestral beliefs. In northern Ghana, land is seen as the property of an earth spirit that bestows it for the cultivation and livelihood of the people2. The Ga-Adangbe people attribute land ownership to sacred lagoons3, and the Asantes venerate “Asaase Yaa,” which means “ Earth born on Thursday” – a female deity responsible for the land’s fertility and sustenance4. She is worshipped as the source of harvest, the one who governs the earth’s fertility. In folklore Asaase Yaa is also characterised as the goddess of birth and death. She as the womb of the earth opens up to collect the spirits of the dead. It is at this point that land moves beyond a practical value to a more spiritual significance. Land, the earth, is the resting place of the ancestors. In Ghanaian society, ancestors are deeply revered, and land is viewed as their enduring legacy. This belief system shapes the mythology surrounding land stewardship: if neglected, the land—and by extension, its deity—could bring misfortune; but if properly revered and placated, it promised prosperity and well-being5

Customary law in Ghana is grounded on these cultural and religious values of its diverse ethnic groups. As a republic composed of numerous ethnic communities, each models its customary laws differently, resulting in the absence of a unified system that comprehensively ties all these laws together. However, there are general similarities that can be explored across these varied practices6. The customary land tenure system in Ghana is built on the social and cultural structures of tribes, clans, and families characterized by its social legitimacy and community-based governance7. The majority of land in the country is held and managed under this system, which, is diverse and varied across regions and ethnic groups8. Under this law, property is generally classified into four categories: land itself, encompassing the soil or earth; things associated with land, such as houses, huts, and farms; movable property; and intangible property, including medical or magical formulae. Another common classification is based on ownership, distinguishing property held by the stool, the family, or the individual.

The term “stool or skin” refers to the royal or chiefly families of the precolonial states of the Gold Coast colony9. Land rights are distributed among individuals,

families and stools. These traditional rulers function as public corporations on behalf of the community. Chiefs hold the highest title in this political structure, acting as trustees10 and managing land for the benefit of the living, the unborn and the dead11 This stewardship concept emphasizes the long-term, intergenerational responsibility associated with land management. Chief Justice Rayner who was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1946 to 1958 wrote on West African land tenure, the heart of which read :

“The next fact which it is important to bear in mind in order to understand the native land law is that the notion of individual ownership is quite foreign to native ideas. Land belongs to the community, the village or the family, never to the individual. All the members of the community, village or family have equal right to the land, but in every case the Chief or Headman of the community or village, or head of the family, has charge of the land and in loose mode of speech is sometimes called the owner. He is to some extent in the position of a trustee, and as such holds the land for the use of the community or family. He has control of it and any member who wants a piece of it to cultivate or build a house upon goes to him for it. But the land so given still remains the property of the community or family. He cannot make any important disposition of the land without consulting the elders of the community or family and their consent must in all cases be given before a grant can be made to a stranger 12.

The rules for owning a land under customary leadership date back to a time when communities were involved in subsistence farming and the land did not hold as much value as the people and the community13. This has changed and customary land tenure has not remained the same. The interference of government agencies in land affairs has shifted primary responsibility from traditional authorities instead, land is now the subject of a revenue sharing arrangement where any revenue collected from the sale or rent of any piece of land is declared and shared between the central government agencies, local government and customary authorities14.

The 1992 constitution of Ghana reinforces the legitimacy of customary land tenure, stating in Article 36(8).

“The state shall recognize that ownership and possession of land carry a social obligation to serve the larger community and, in particular, the state shall recognize that the managers of public, stool, skin and family lands are fiduciaries charged with the obligation to discharge their functions for the benefit respectively of the people of Ghana of the stool, skin or family concerned and are accountable as fiduciaries in this regard”15 .

Despite its social legitimacy, the customary land tenure system faces challenges. The diverse and often oral nature of customary law makes it susceptible to exploitation by stakeholders, including traditional rulers, the state, and individuals16. The lack of written records and formal documentation can lead to disputes over land ownership and boundaries, complicating land transactions and development projects. There is minimal accountability and transparency in land transactions under customary tenure, enabling customary authorities to exploit the system. It is not uncommon for the same parcel of land to be sold multiple times to different buyers. Within customary law, land is often held by family heads, which can lead to disputes among family members, each asserting their claim and independently engaging in transactions with unsuspecting buyers. This fragmented ownership structure fuels conflicts and complicates land administration.Additionally, some chiefs, motivated by financial gain, may attempt to renegotiate the price of land previously sold if they recognize an increase in its market value. Traditional authority itself is contested in many parts of Ghana, and the absence of a robust legal framework further encourages the misuse of customary law, perpetuating insecurity and distrust in land dealings 17 .

STATUTORY LAND TENURE

Land transactions in the nineteenth century were fraught with challenges arising from conflicting concepts of land ownership and rights, leading to frequent disputes in business dealings. The core issue lay in the fundamental difference between the customary understanding of land ownership and the European perspective18. Within the customary framework, land governance was characterized by diverse rules and categories, further complicated by the ambiguous distinctions between “chiefs” and “stool lands,” as well as “family heads” and “family property” 19. These terms were context-dependent, applied differently based on local customs and practices. Unsurprisingly, colonial authorities struggled to regulate land ownership, especially given the widely held belief that land was communally owned rather than individually20 The regulation of land became increasingly significant during the gold rush of the 1880s, when the British sought to vest all land in the region of modern-day Ghana in the Crown21. This intention materialized through three key legislative instruments: the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1894, the Lands Bill of 1897, and the Forest Bill of 191022 These were the first statutory interventions in Ghana’s land governance. However, they faced strong opposition from the Aborigines Rights Protection Society (ARPS), a coalition of chiefs and educated locals, who contested the legality of these laws as a violation of customary landownership. Their successful resistance compelled the colonial state to revise its approach23. Instead of imposing direct control, the British adopted a strategy of indirect rule, aligning their land interests with those of local political and economic authorities24. This approach, of “selective involvement,” – the colonial authorities choosing when to intervene - allowed the colonial government to maintain legal oversight while presenting chiefs as the primary land administrators. Chiefs retained authority on paper but operated within the mandates prescribed by the colonial state 25. This period marked the formalization of customary law. A notable example is the Akyem Abuakwa Stool Lands Declaration, enacted by Chief Ofori Atta and his council, which defined stool lands as “land attached to the stool over which the stool exercises some measure of control [such as approval before sale]” 26. This moment signified the birth of the modern customary legal system—a compromise

between colonial and local interests. Previously unwritten and ethnically diverse, customary law was now codified, regulated, and subject to uniform standards. This dual system, combining customary and statutory frameworks, became the foundation of Ghana’s land tenure system27. Rather than imposing European norms directly, colonial authorities restructured indigenous practices into a simplified form that could coexist with statutory regulations. In this process, customary law was not merely preserved but actively redefined. For instance, in Akyem Abuakwa, Chief Ofori Atta utilized statutory law to determine what constituted “customary” law within his jurisdiction28. The traditional rulers became the lynchpin from which the British Crown launched their indirect rulership29. This arrangement had a lasting impact and paved the way for the future of government-chieftaincy partnerships30. The 1992 Constitution, along with other legal instruments such as the Land Title Registration Law of 1986 and the 1994 Act, provides the statutory framework for today’s land administration. Key institutions established under this system include the Lands Commission and the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands, which manage land registration, titling, and urban planning regulations as stipulated in Article 267(3) of the constitution.

There shall be no disposition or development of any stool land unless the Regional Lands Commission of the Region in which the land is situated has certified that the disposition or development is consistent with the development plan drawn up or approved by the planning authority for the area concerned31.

This implementation strategy has been plagued with challenges including conflicts with customary authorities, who may resist state regulations perceived as encroaching on traditional rights. Moreover, issues such as unclear mandates, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and corruption undermine the effectiveness of statutory land governance.

THE URBAN PLANNING CONUNDRUM

And so we have a country that has its land regulations subject to customary and statutory systems which entail exclusive procedures with the expectation that they co-exist within the same framework32. The constitution vests the state with power to seize any land if it can prove it is needed for national interest. The term “public interest” is not scrutinised enough and has been known to be used to expropriate land by the state for wealthy and political allies in the regimes33. The authority of chiefs is conter-productive; especially when they disagree on the intended use of the land by the government or take offence if they have not been consulted . The chief of Sempe in the Greater Accra region echoed a this sentiment in saying that

if the land was “really [being] acquires for public purposes” he would “consider what steps to take “ but if it was being acquired “for the occupation of aliens, my elders have advised me nit part with the said land., I shall be willing however, to propose that the land remain the property of the Stool after the government has collected all expenses incurred on the building thereon34.

The mandate given by legal instruments to traditional authorities has also been abused to accumulate wealth and promote selfish interests. Chiefs have been known to swindle a man or two out of their already purchased land if they thought they would gain a better advantage by selling it to another buyer. Some have gone to the extent of making multiple transactions on the same piece of land, failing to comply with already agreed contracts35. In the midst of this land system, urban planning suffers. The framework leads to a disconnect between stakeholders, and the corruption it breeds undermines the overall urban planning system36. Planning authorities often face resistance from traditional leaders who assert their custodial rights, while private developers navigate unclear procedures, further complicating land-use coordination. Consequently, urban expansion occurs in an ad hoc manner, prioritizing private interests over cohesive community planning, leaving little room for public spaces and infrastructure.

A stakeholder interview by Cobbinah and Darkwah (2017) saw a traditional leader assert that

“. . . the land is ours [traditional leaders]. We are the traditional custodians . . . Nobody can develop our land without our consent, not even the government. If the planning people [TCPD] want to plan our community or land, they should contact us first and seek our approval . . .” 37

On the flip side, local governments are allowed to,

“prohibit, abate, remove, pull down or alter so as to bring into conformity with the approved plan, a physical development which does not conform to the approved plan…” 38 .

The law is vague in defining the criteria for structures or buildings that conform to these yet-to-be developed zoning and planning schemes39. An instance was reported in the national newspaper, the Daily Graphic of the plans of the Accra metropolitan assembly (AMA) to demolish 1800 structures within Agbogbloshie. A protest led by residents was covered with the spokesperson declaring:

“. . .we will not allow anyone to come and demolish our homes because we are not illegal settlers. . .If the officials of the AMA fail to listen to our plight and want to go ahead with the exercise, they must as well kill all of us because we will not leave”40.

NOTES

1.Kojo Sebastian Amanor, “Securing Land Rights in Ghana,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009), 118.

2. A. W. Cardinall, The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast: Their Customs, Religion and Folklore, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 1920), 17, https://doi. org/10.4324/9781003387367.

3. Madeline Manoukian, Akan and Ga-Adangme Peoples: Western Africa Part I, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 1950), 86, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315297859.

4. K. A. Busia, The Position of the Chief in the Modern Political System of Ashanti (London: Oxford University Press, 1951), 40.

5. Samuel K. B. Asante, “Interests in Land in the Customary Law of Ghana: A New Appraisal,” The Yale Law Journal 74, no. 5 (April 1965): 848–885, https://www.jstor. org/stable/794709.

6. Ibid

7. Joseph Blocher. “Building on custom: land tenure policy and economic development in Ghana.”

Yale Hum. Rts. & Dev. LJ 9 (2006): 166.

8. Ibid

9. Kasim, Kasanga, . “Land Administration Reforms and Social Differentiation: a Case Study of Ghana’s Lands Commission.” IDS Bulletin 32, no. 1 (January 2001): 57–64. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32001007.x.

10. Sarpong, G. A. “The legal framework for participatory planning: final report on the legal aspects of land tenure, planning and management in Ghana.” FAO, November (1999).

11. Joseph, Blocher. “Building on custom: land tenure policy and economic development in Ghana.” Yale Hum. Rts. & Dev. LJ 9 (2006): 166.

12. Samuel K. B. Asante, “Interests in Land in the Customary Law of Ghana: A New Appraisal,” The Yale Law Journal 74, no. 5 (April 1965): 848–885, https://www.jstor. org/stable/794709.

13. Janine Ubink, “Legalising Customary Land Tenure in Ghana: The Case of Peri-Urban Kumasi,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009), 165.

14. Kojo Sebastian Amanor, “Securing Land Rights in Ghana,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009), 98

15. Constitution of Ghana, 1992, Article 36(8).

16. Janine Ubink, “Land, Chiefs and Custom in Peri-Urban Ghana: Traditional Governance in an Environment of Legal and Institutional Pluralism,” in The Governance of Legal Pluralism, ed. W. Zips and M. Weilenmann (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2011),

17. Kojo Sebastian Amanor, “Securing Land Rights in Ghana,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009), 118

18. William Malcolm Hailey, Native Administration in the British African Territories (London: Oxford University Press, 1950), 221.

19. Charles K. Meek, Land Law and Custom in the Colonies (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), 192.

20. Naaborko Sackeyfio, “The Politics of Land and Urban Space in Colonial Accra,” History in Africa 39 (2012): 310, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23471007.

21. Kojo. Amanor, The New Frontier: Farmer Responses to Land Degradation: A West African Study (Geneva, London: UNRISD, Zed Books, 1994),

22. D. Kimble, A Political History of Ghana: The Rise of Gold Coast Nationalism, 1850-1928 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963);

23. Kojo Amanor, “The Changing Face of Customary Land Tenure,” in Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chiefs and the Citizen, ed. Janine M. Ubink and Kojo S. Amanor (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2008), 58.

24. Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah and Margath Walker, “Legal Pluralism, Land Tenure and the Production of ‘Nomotropic Urban Spaces’ in Post-colonial Accra, Ghana,” Geography Research Forum (2016):88

25. Kojo Amanor, “The Changing Face of Customary Land Tenure,” in Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana: State, Chiefs and the Citizen, ed. Janine M. Ubink and Kojo S. Amanor (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2008), 58.

26. Kimberly Firmin-Sellers, The Transformation of Property Rights in The Gold Coast: An Empirical Analysis Applying Rational Choice Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 64.

27. Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah and Margath Walker, “Legal Pluralism, Land Tenure and the Production of ‘Nomotropic Urban Spaces’ in Post-colonial Accra, Ghana,” Geography Research Forum (2016):89

28. Rathbone, Richard. Murder and Politics in Colonial Ghana (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 62.

29. R.B. Benning, “Land Ownership, Divestiture and Beneficiary Rights in Northern Ghana,” in Decentralisation, Land Tenure and Land Administration in Northern Ghana: Report on a Seminar Held at Bolgatanga, Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 1996, 28-30.

30. Antony Allott, New Essays in African Law (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), quoted in Joseph Blocher, “Building on Custom: Land Tenure Policy and Economic Development in Ghana,” 184

31. Constitution of Ghana, 1992, Article 267(3).

32. Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah and Margath Walker, “Legal Pluralism, Land Tenure and the Production of ‘Nomotropic Urban Spaces’ in Post-colonial Accra, Ghana,” Geography Research Forum (2016):90

33. Kojo Sebastian Amanor, “Securing Land Rights in Ghana,” in Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. Janine M. Ubink, André J. Hoekema, and Willem J. Assies (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2009), 120

34. Naaborko Sackeyfio, “The Politics of Land and Urban Space in Colonial Accra,” History in Africa 39 (2012): 319 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23471007.

35. Janine, Ubink, 2006

36. Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah and Clifford Amoako, “Planning by (Mis)rule of Laws: The Idiom and Dilemma of Planning within Ghana’s Dual Legal Land Systems,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 38, no. 1 (2019): 98.

37. Cobbinah and Darkwah, “Stakeholder Interview,” in Urban Planning and Politics in Ghana, 1239.

38. Constitution of Ghana, 1992, Article 462(53).

39. Emmanuel Frimpong Boamah and Clifford Amoako, “Planning by (Mis)rule of Laws: The Idiom and Dilemma of Planning within Ghana’s Dual Legal Land Systems,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 38, no. 1 (2019): 98.

40. T. Ngnenbe, “Tension Mounts at Agbogbloshie Over Intended Demolition Exercise,” Daily Graphic, Graphic Online, December 20, 2018, https://www. graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/tension-mounts-atagbogbloshie-over-intendeddemolition-exercise.html.

CHAPTER TWO

THE ERA OF ASHANTI SOVEREIGNTY

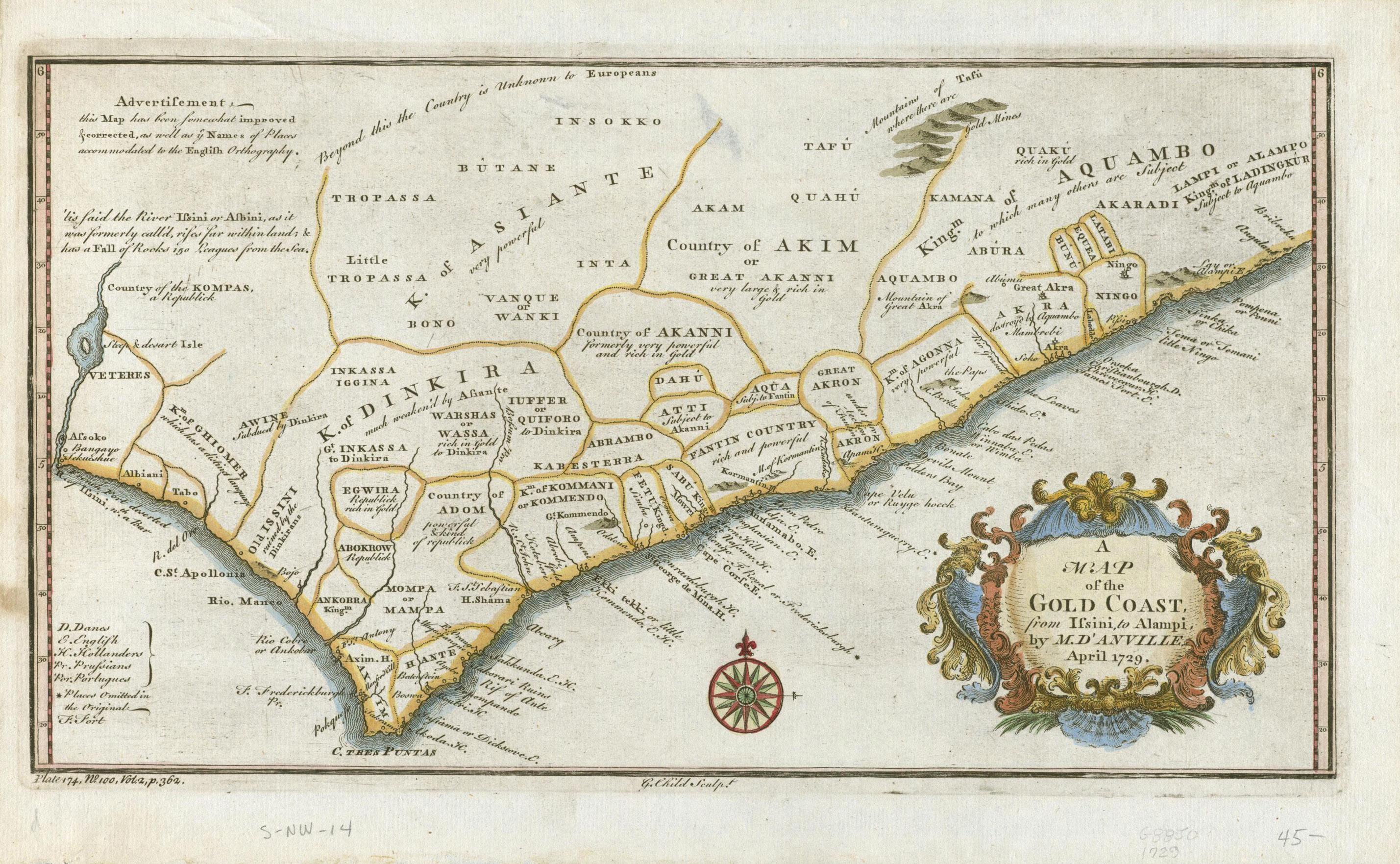

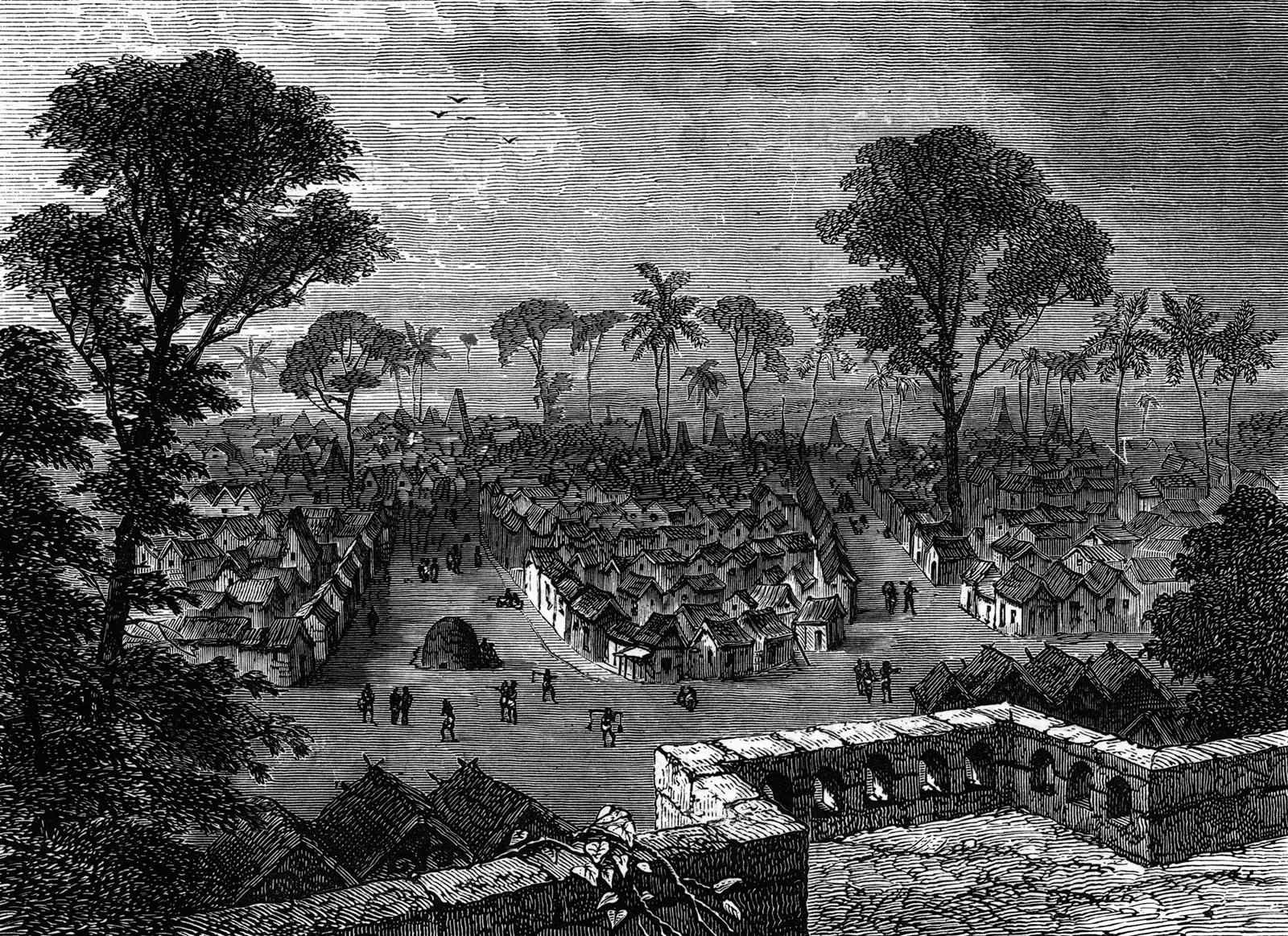

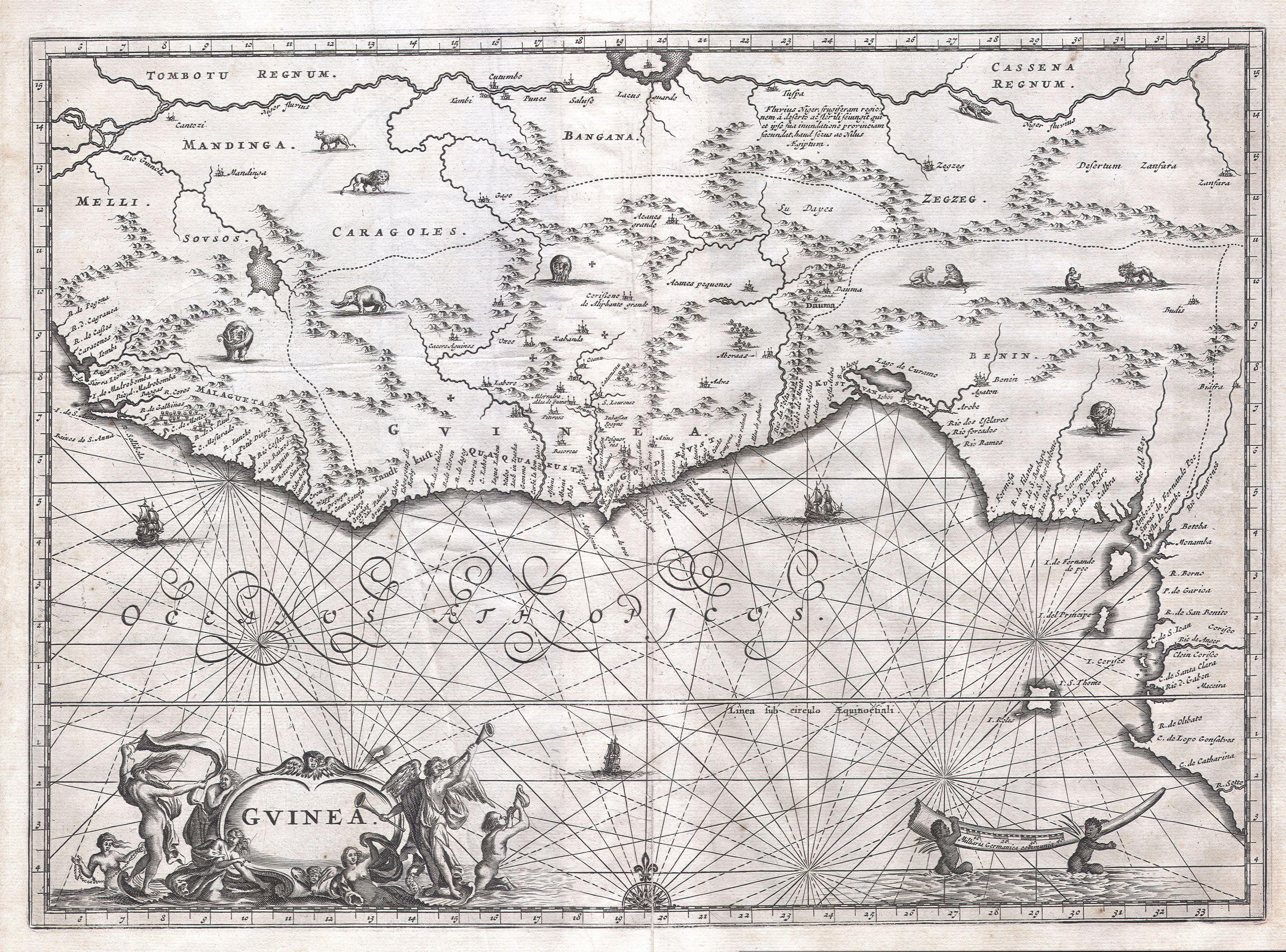

This chapter investigates 18th-century West Africa, a time before colonial boundaries fractured the region into modern nation-states. It delves into the architecture of the Ashantis, a polity built on structures of Denkyira and Bono-Mansu that expanded to the size of present-day Ghana1. The Ashanti Empire occupied a strategic position between the Atlantic and Saharan trade networks, leveraging its wealth in gold and its centralized governance to sustain political dominance well into the 19th century. It was known as the “kingdom of gold,” a title that underscored its economic significance and far-reaching influence2.The built environment of the Ashanti reflected both its political power and cultural traditions. As an empire, its architectural forms spread across the region, shaping the landscapes of its controlled territories. These spaces were more than physical locations; they were arenas for governance, commerce, ritual, and social life, playing a central role in structuring the interactions of individuals and communities. Through this exploration, the chapter seeks to identify the architectural and spatial elements that constituted gathering spaces in Ashanti society—what might be understood as the historical foundations of man jaano.

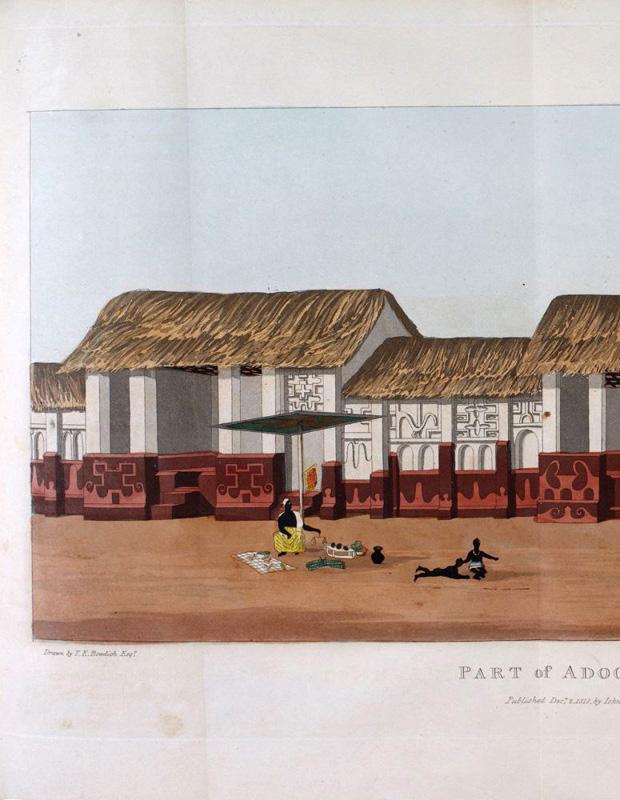

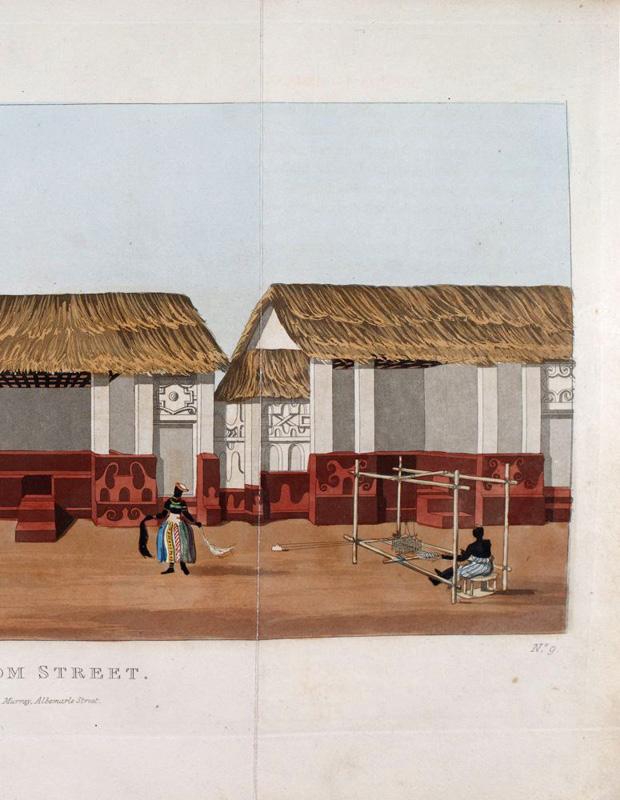

Africa’s landscape is scattered with the past’s artefacts, about which there is “little to say by way of written evidence” 3. Unlike European or Asian civilizations, where written records and architectural treatises have documented urban development, much of Africa’s history is preserved through oral traditions, material culture, and lived experiences rather than extensive textual archives. Yet, this absence of written records does not imply an absence of urban and social structures. Africa’s cities— Accra, Cairo, Kinshasa, Nairobi—continue to embody histories shaped by centuries of trade, migration, conquest, and governance. As a region, West Africa has long been home to diverse ethnic groups that, despite their distinctions, share cultural values, social structures, and spatial practices. The interconnected nature of the region led to the diffusion of architectural and urban planning principles across ethnic and geopolitical boundaries. Given these commonalities, it stands to reason that notions of public space were not confined to a single ethnic group but were instead shaped by broader regional practices and interactions. These spaces were often multifunctional, fluid, and adaptable, in contrast to the rigid zoning principles characteristic of Western urban models. For the purposes of this research, gathering spaces are defined as spaces of socialization, entertainment, and information exchange. To analyze these spaces, this research draws upon historical accounts, particularly Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee by Thomas Edward Bowdich. Written in 1819, Bowdich’s book provides a firsthand account of his diplomatic mission from Cape Coast Castle, a British fort, to Kumasi, the capital of the Ashanti Empire. His narrative offers a rare glimpse into the urban and spatial organization of the empire, detailing its landscape, people, customs, and political structures. The text also provides descriptions of key public rituals, including the reception of the British delegation by Asantehene Osei Bonsu and the elaborate court ceremonies that underscored the power and prestige of the Ashanti leadership. By systematically mapping instances of gatherings described in Bowdich’s text, this research identifies two primary classifications of gathering spaces: the gyaase and the dwe berem. These spaces, though serving distinct functions, were deeply interwoven into the socio-political and cultural fabric of Ashanti society. Each of these gathering spaces is examined in the subsequent paragraphs, unpacking their historical functions, architectural elements, and broader societal implications.

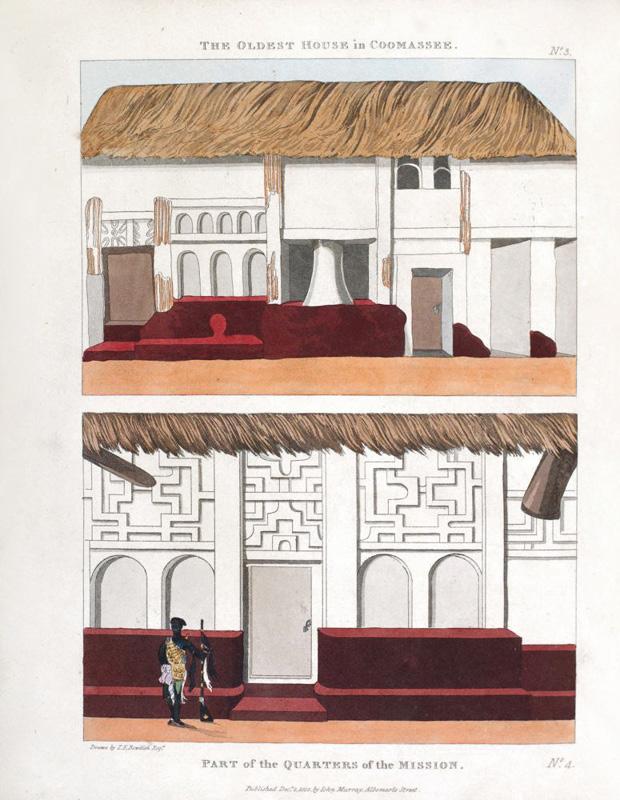

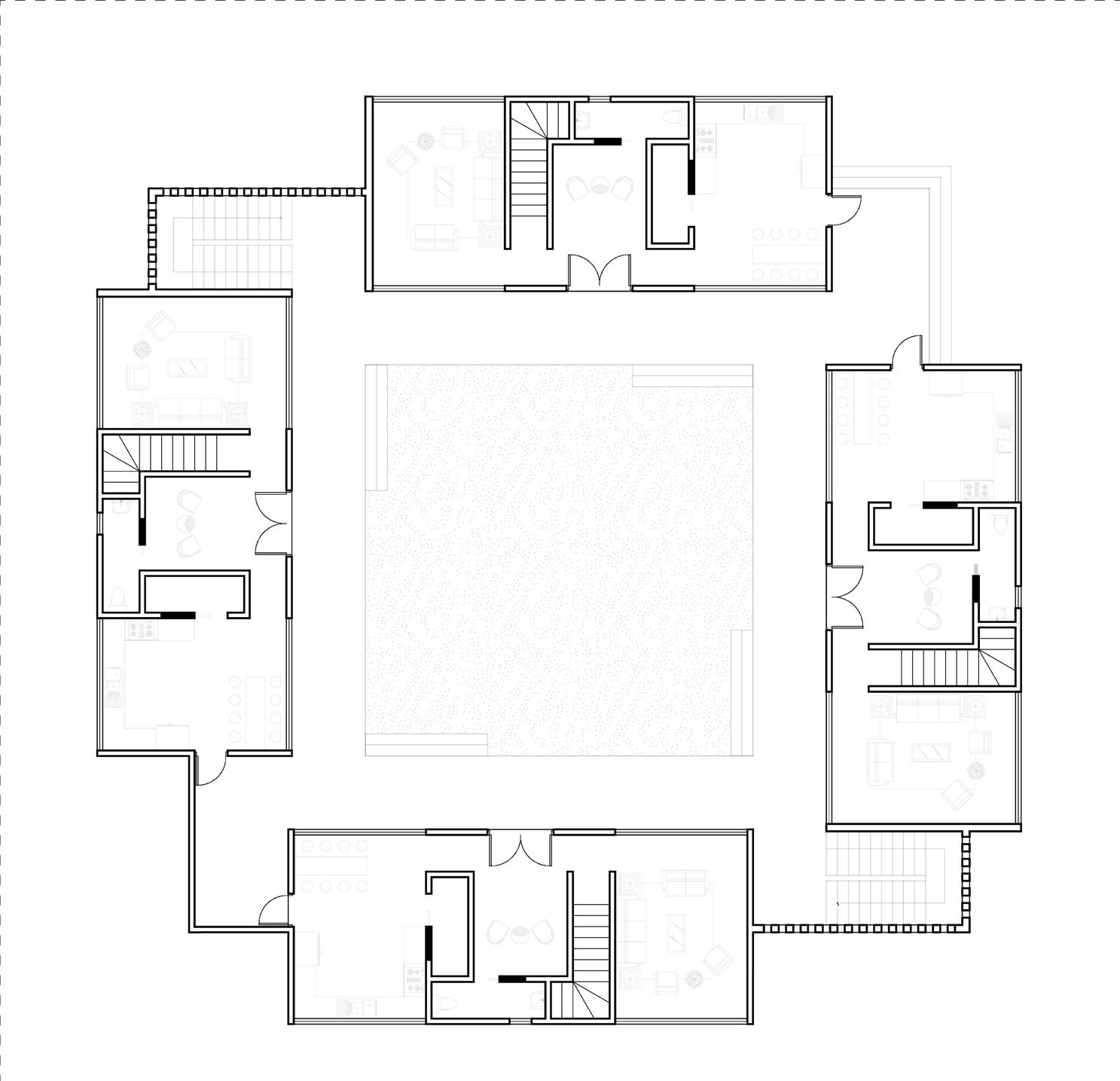

GYAASE

The Akan word “gyaase” is directly translated as “below or beneath the hearth4. The house with the courtyard, the compound house is a housing type for multigenerational with a central open space and enclosing spaces that are public, semipublic5. The open spare, which is enclosed on both sides, functions as the gyaase, the critical component of the space. This is evidenced by the elaborate adornment of the interior façade, while the exterior bounding walls remain plain. This contrast in decoration highlights the significance of the gyaase as the central, most revered part of the shrine, with the plain exterior serving to delineate the sacred from the surrounding environment6. Bowdich described some houses that European visitors stayed in during their visits to Kumasi. His descriptions paint a picture of a basic model all the dwellings conform to albeit small differences.

‘[…] a square of four apartments that were entered from an outer one, where several drums were kept; the angles were occupied by the slaves, and his own room which had a small inner chamber, was decked with muskets, blunderbusses, cartouch belts fantastically ornamented, and various insignia’ 7 .

These accounts point to a set of individual buildings that enclose at its core open-air court, a gyaase8. The gyaase constructs a network of settings that permeates the habitual rituals of daily life. It inculcates the collective social values of the society, passing down intergenerational knowledge and secrets. As a central space, it is the access to other spaces. A “microcosm of a public square set within the private domain”9. The gyaase was not merely a physical space but a dynamic system of relationships, where political authority, communal responsibilities, and ritual practices intersected. Within the palace structure, the gyaase comprised attendants, advisors, and service providers who maintained the king’s court, but in a broader urban and architectural context, the gyaase also referred to spaces where these interactions took place. On Reverend T. B. Freeman’s visit to the Asantehene, he met him in a courtyard; where the monarch

received the gifts that had been brought to him. He recounts that

“the houses are all erected on the same plan from that of the King, down to the lowest rank of the captains” 10 .

Ten shrine houses remain a prototype of the Ashanti traditional style of the 18th century. Built to house deities believed to protect the community, these shrines share architectural similarities with Ashanti residential homes of that era. Today, they are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage monuments. This research focuses on the Ejisu Besease Shrine House to explore the function and use of the gyaase.

Ejisu, a district in the Ashanti Region, is famously known as the hometown of Yaa Asantewaa, the queen mother who led the Ashanti resistance against the British in 1900. The name Besease translates to “under the kola nut tree,” derived from bese (kola nut) and ase (under, beneath, below). The Besease Ejisu Shrine House as one of the ten reaming Ashanti shrine houses embodies the spiritual and cultural essence of Ashanti architecture while reflecting the spatial and architectural principles of its time. Analyzing its spatial composition—ground, plinth and stairs, and boundary—reveals a mediated relationship between the shrine and the broader social fabric of Ashanti life.

The ground upon which the shrine stands is not merely a physical foundation but a ritualized space, signifying its connection to the earth and ancestral spirits. The plinth and stairs function as transitional elements, regulating movement and access within the space. Lastly, the boundary establishes a spatial hierarchy that reinforces both inclusion and exclusion, shaping the way individuals engage with the shrine and its surroundings. Through this spatial analysis, the shrine emerges as a spatialized expression of Ashanti governance, where the gyaase acted as a bridge between sacred, political and social life.

GROUND: A Living Archive of Collective Memory

The ground is the foundation and reference point for architectural interventions, it is the level of the street, a constant datum for pedestrians11. In his seminar essay “Platforms and plateaus”, Utzon puts forward an architecture that defines space without enclosing it. This space gives way to the subtleness of the platform and yet it’s the ground that is manipulated to make the defined but unenclosed architectural space, ambivalent12. In the context of the gyaase, the ground is composed of red earth The red earth is a practical choice, as it is a material inherently tied to the geography and ecology of the region. Beyond its functional use, the red earth holds deep spiritual significance, being associated with the deity Asaase Yaa, the guardian of the land and the provider of livelihood. This material also serves as the physical base where both ordinary and extraordinary events unfold. The soil tells stories of the quiet rhythms of life. Gatherings and rituals turn the space into a living archive of activities and emotions. Every soil layer, every buried artifact and every trace of habitation reveals a vibrant culture determined to endure13. The ground is a battlefield that silently testifies to the cycles of destruction and reconstruction, bearing witness to the resilience of those who inhabit it. The ground is a sanctuary and becomes a site of renewal and regrowth14. In this dual role the ground is a an architectural stage where the conflicts of the past and present converge and the seeds of future liberation are sown. The ground, in its physical and symbolic roles, transcends mere functionality to become an essential medium for architecture, culture, and memory. It supports and frames human activity, embodying the tension between permanence and transformation. In the gyaase, the red laterite ground becomes a the stage where histories unfold, layering meaning over time. It is both witness and participant, silently bearing the scars of conflict, the rhythms of resilience, and the promise of renewal. The ground is a foundation for architectural interventions and a profound narrative space—one that reflects the continuity of human life while anchoring the aspirations for a better future.

Asante Traditional Buildings: Survey and Condition Assessment, 2014

PLINTH AND STAIRS: A Transitional and Performative Element

The plinth, a common architectural feature, has long been associated with monumental and religious structures. It raised buildings above the commonplace and distinguished between the holy and the everyday. Throughout history, the platform has been used in many cultures, demonstrating its role as a functional and symbolic construction. The architectural plinth works by its restricted verticality, in contrast to the gallery plinth, which separates art items for viewing. It grounds the structure in its surroundings while highlighting elevation and isolation. In these patterns, steps are essential because they turn movement into a rhythmic, dramatic performance15 . According to historian Mary B. Hollishead,

“[T]he foot’s repeated contact with a sequence of horizontal surfaces at regular, predictable intervals translates to a sense of organization and system. Close intervals and compression of steps express intensity of effort, or conversely, broader spacing brings a slower rhythm”16

In the context of the gyaase, the platform’s steps similarly dictate the rhythm of movement, shaping how inhabitants engage with the space and each other. These elements form transitional zones, marking the boundaries of activity. The act of ascending or descending—stepping into the vibrant communal life of the courtyard or retreating into the quiet interiors—becomes a spatial metaphor for social hierarchies. Vertical movement subtly reinforces the order of the gyaase, shaping interactions through spatial context. Inhabitants and visitors alike are offered an unobstructed view and a decision – to observe or to participate in the rhythms of daily life. For children, this form becomes a site of discovery and play. Its edges, steps, and corners form a natural playground, encouraging exploration and imaginative interactions. For adults, it offers a place to pause, rest, or engage in spontaneous conversation The plinth and stairs serve as tangible manifestations of the hierarchies of daily life, bridging the sacred and the mundane, the private and the public, the functional and the symbolic.

Traditional Buildings: Survey and Condition Assessment, 2014 0m 1m 2m

Asante Traditional Buildings: Survey and Condition Assessment, 2014

BOUNDARY: Enclosure, Threshold, and Custodian

From the towering defensive walls of early settlements to the porous thresholds of modern cities, boundaries have continuously evolved to reflect shifting social, cultural, and spatial dynamics. Boundaries in architecture not only delineate space but also facilitate movement and connection through elements like streets, bridges, and squares. On a smaller scale, architectural thresholds mediate internal and external conditions, embodying both separation and unity17. The Architectural Review in the thirty third issue of the readding list; borders and boundaries notes, “Lines are drawn to make sense of things. Boundaries articulating here from there, inside from outside… define belonging and exclusion”18. In the gyaase, the boundary is the rammed walls that enclose and the steep thatch roof that extends over the wall. It reinforces the distinction between the sacred interior and the communal exterior19. The boundary is a barrier and a point of initiation, defining the compound’s territory while facilitating controlled interactions with the outside world. It is an active participant in the spatial, social, and cultural life of the compound marking the transition between the private, familial space and the broader communal world. Beyond its physical presence, the boundary symbolizes the custodial responsibility of the family inhabiting the gyaase. Its upkeep, repair, and adaptation over time reflect care and ownership, reinforcing the family’s presence and agency within the space. Yet, this custodianship transcends individual roles; the boundary embodies collective values and shared heritage, situating the family within a broader social and cultural network. Physically, it offers security, shielding inhabitants from external disruptions. Symbolically, it safeguards traditions, memories, and rituals, preserving the essence of the compound’s identity. Boundaries have evolved alongside humanity’s relationship with space, culture, and power. In the gyaase, the boundary protects and connects, serving as both a marker of familial identity and a mediator of communal relations. It is not merely a line of separation but a living, dynamic entity. It bridges tradition and modernity, family and community. Between inclusion and exclusion, belonging and separation, the boundary stands as a testament to the enduring interplay of space, culture, and identity.

Asante Traditional Buildings: Survey and Condition Assessment, 2014

Boundary

Ejisu-Besease Shrine House

by author

Asante Traditional Buildings: Survey and Condition Assessment, 2014

0m 1m 2m 10m

INTEGRATION: A Unified Spatial and Cultural Ecosystem

The interplay of ground, plinth and stairs, and boundary creates a cohesive spatial system that defines the gyaase. These elements do not function in isolation but instead operate in tandem to shape the rhythms of daily life, reinforcing the social, cultural, and ecological structures of the compound

The ground anchors the inhabitants to their environment and acts as a medium through which cultural memory is inscribed. Its association with Asaase Yaa, reinforces the Ashanti people’s spiritual and material dependence on the earth. The connection to red earth fosters a cyclical relationship between land, dwelling, and livelihood, where human activity is inextricably linked to the rhythms of nature.

The plinth and stairs act as transitional elements, facilitating movement and delineating hierarchy within the compound. The elevation of the plinth provides structural stability and protection against erosion and flooding and creates a layered threshold between public and private domains. Stairs further emphasize this transition, becoming sites where conversations unfold, rituals are performed, and authority is subtly expressed through spatial positioning

The boundary plays a crucial role in ensuring both protection and continuity. It marks the limits of the compound, safeguarding its inhabitants from external disruptions while simultaneously preserving the integrity of inherited customs and practices.

Together, these elements form a spatial and cultural ecosystem that embodies the Ashanti’s deep-rooted connection to land, history, and community. The gyaase, as both a physical and symbolic hearth, serves as a dynamic space where values, practices, and identities are not only preserved but actively performed and transmitted across generations. It is within this space that the past and present merge, where customs are reaffirmed, and where the architectural and spatial logics of the Ashanti way of life continue to evolve in response to shifting social and environmental conditions.

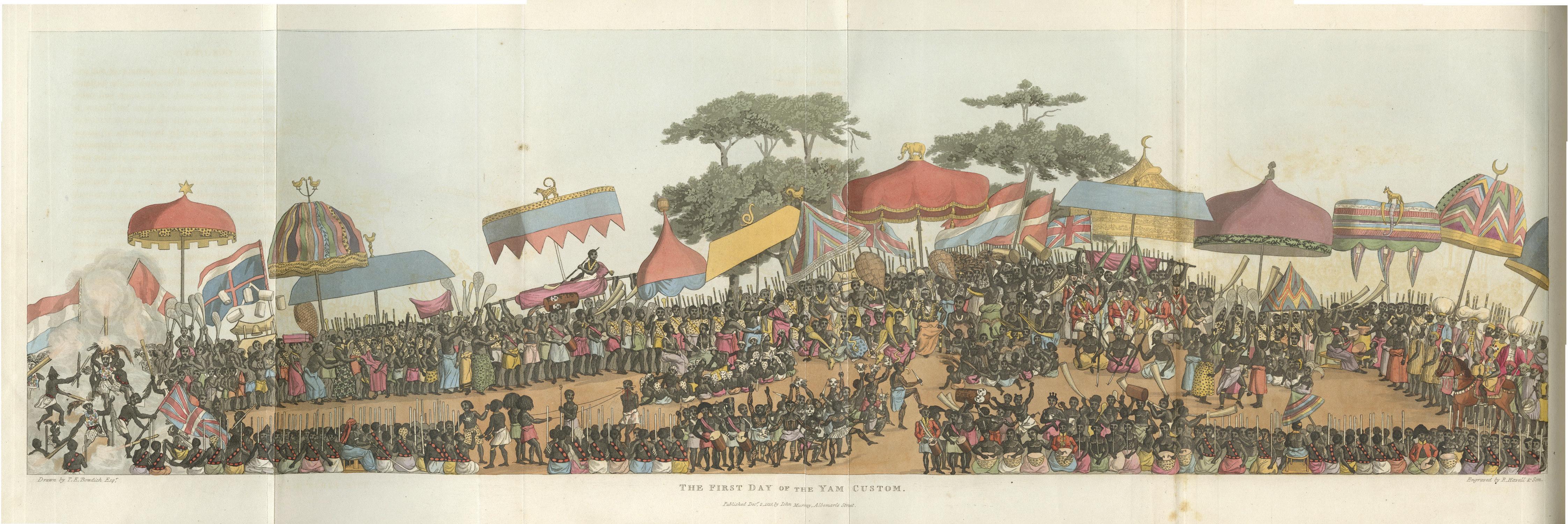

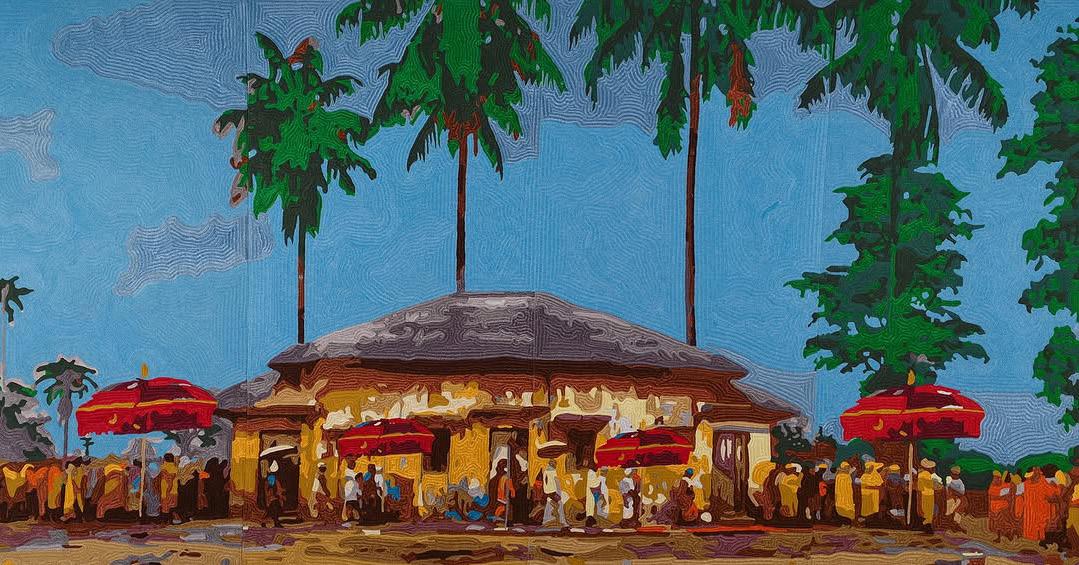

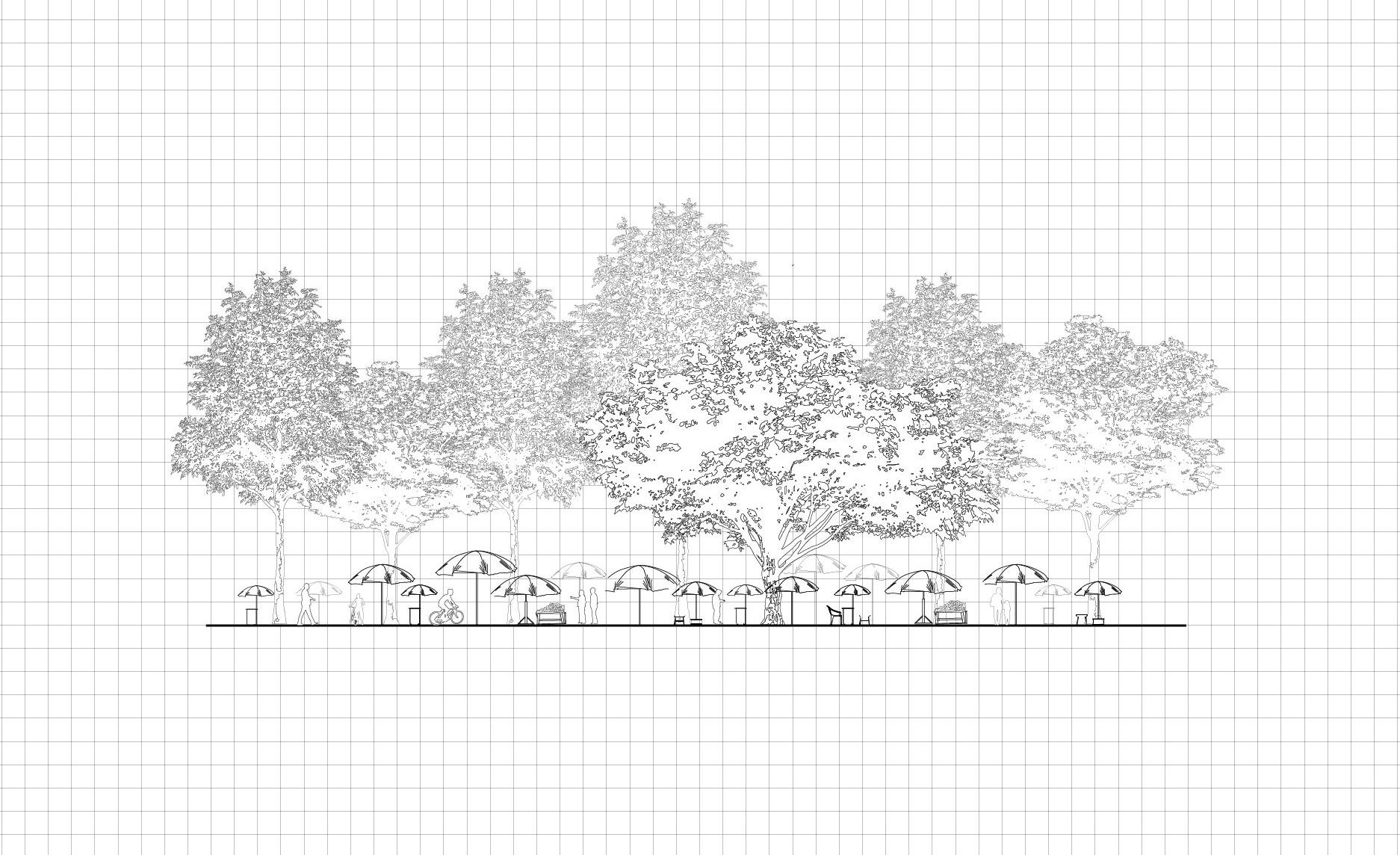

DWE BEREM

Bowdich’s account describes another gathering ground, dwe berem translated to mean the great marketplace. In his narration,

the delegation […] passed through a very broad street, about a quarter of a mile long, to the marketplace’20.

A ground plan of Kumasi he sketched has a large circular feature marked as the great marketplace. More than just a site of commerce, the marketplace functioned as a gathering space that facilitated social interactions, large meetings, entertainment, and festivals. It was a hub of information exchange, economic activity, and public ceremonies, making it a dynamic and multifunctional space within the city. The significance of this gathering space was not only in its function but also in its location as argued by Sheales21. The marketplace is delineated by the spirit grove indicated by three trees. This grove is where

“the trunks of all the human victims were thrown,” and the ‘[…] the extent of the daily sacrifice was indicated by the number of vultures that settled in these trees’ 22

The description paints a picture of the spritual weight this gathering ground carried. The Ashanti placed great importance on honouring the dead, and the positioning of these trees at the edge of the dwe berem created the impression that the ancestors were watching over and guarding the living. The spirit world was in the background witnessing important events, lending importance to this gathering space23. This deep spiritual connection shaped the marketplace’s broader functions. The great marketplace was an extension of the king’s courtyard, much like how the king’s courtyard reflected the gyaase within each household. In the courtyard, the king held private audiences and managed state affairs. However, when an event required public validation and ancestral presence, it was moved to the dwe berem. Here, the gathering

took on a performative and ritualistic dimension—both the people and the ancestors became witnesses, reinforcing the legitimacy and communal significance of the event. This is in line with why the delegation of the British missions were summoned to the marketplace to state their reason for visiting as opposed to the royal residence24.

Beyond its ceremonial and political roles, the marketplace was fundamentally a centre for commerce. It facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas, positioning it as both an economic and intellectual hub. Merchants, travellers, and traders brought diverse influences to the space, making it a site of continuous negotiation and interaction. This space was fluid and versatile taking on different characteristics according to what the city demanded. It was the stage for large and public festivities25. It was where the visitors to the city were received. This marketplace was a court, a public meeting forum, a playground.

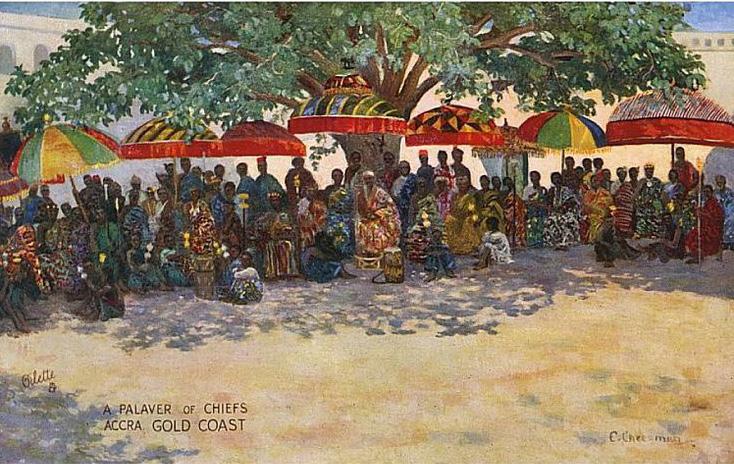

The marketplace was not just defined by its function but by its atmosphere. The play of light and shade, the canopy of trees, and the cool retreat of shadows created an ambience of safety, relief, and comfort structuring this gathering ground’s use over time. These spatial and cultural markers coordinated when and how the marketplace functioned, shaping its role as a sacred, social, and economic space. This is marked by three elements – the tree; the canopy and the shade. The tree as a landmark and the representation of the ancestral spirits; the canopy, formed both by the natural crown of the trees and the artificial structures of royal umbrellas (kyini). These two elements coming together to create shade; shade as a civic necessity and social equaliser. In a climate where the sun dictated the rhythms of movement, shade was more than just relief—it was an essential feature that structured the use of space, creating areas for rest, gathering, and negotiation. These elements together define the landscape of the marketplace and dictate the rhythms of social interaction.

TREE

The tree was a symbol of spiritual significance and sacred presence within dwe berem. More than just a natural element, the tree served as a threshold between the physical and spiritual realms, anchoring the marketplace to an ancestral connection. The spirit grove, marked by three towering trees, delineated the sacred perimeter of the space, forming a bridge between worlds. These trees did not stand as passive markers; they witnessed, and legitimized important events.

As a placemaker, the tree defines the dwe berem, serving as both a landmark and a spatial anchor. It holds ecological and spiritual significance, shaping the atmosphere of the space as much as its function. In Bowdich’s account, blood sacrifices were offered beneath the tree trees, reinforcing its role as sites of covenant and obligation. They were the visual representation of the ancestors, ever-present and watchful. In Ashanti culture, the ancestors are guardians of tradition and enforcers of justice. The idea that they could exact vengeance for broken oaths underscored their authority, reinforcing a system of social and spiritual accountability.

If tradition holds that these were kapok trees, their physical dominance over the space must have been striking. Reaching heights of up to 70 meters, with crown diameters stretching 40 meters and massive trunks of 3 meters in diameter, they would have been an imposing presence, their scale alone commanding reverence. The three trees together would have created a monumental grove, visible from afar, signaling the importance of dwe berem before one even entered the city. Beyond their spiritual role, the vast canopy of the trees also provided a crucial function—offering shade, a reprieve from the sun, and a natural meeting place.

Photographs and historical accounts frequently depict chiefs gathered with their backs to the trees, seated in the cool shadows cast by their broad crowns. This physical relationship validates the trees as protector, as shade-giver and as a symbol of ancestral oversight. The marketplace unfolds around it, shaped by its presence, structured by its shade, and legitimized by its spiritual authority.

UMBRELLA

The umbrella in dwe berem offers protection from the elements while acting as an emblem of power and authority. In this context, the umbrella, locally known as kyinie, is more than a simple shade-giving device. While its primary function is to shield individuals from the sun, it also visually asserts status, hierarchy, and control over space.

The interplay between the tree and the umbrella is significant. The tree, representing the ancestors, provides a vast natural canopy under which people gather. Beneath this ancestral presence, additional umbrellas are erected, layering shade upon shade. These umbrellas, ranging in size from one to three meters in diameter, create distinct zones of coolness and refuge—a stark contrast to the heat and movement of the bustling marketplace beyond.

But the kyini is more than a practical shelter; it is a visual and political statement. The size, colour, and ornamentation of the umbrella reflect the authority of the person beneath it. Larger, more vibrantly decorated umbrellas signify greater power and prestige, marking the presence of chiefs, royals, and dignitaries.The smaller umbrellas going to the lower ranking traditional authorities. The umbrella’s intricate designs and bold colours communicate lineage, rank, and the legitimacy of the leader it shades.

Under the umbrella, hierarchy is made visible. It defines who is protected and who remains exposed, subtly regulating social order within Dwe Berem. The canopy of umbrellas mirrors the broader structure of Asante governance, where layers of authority exist beneath the overarching presence of ancestral oversight. Just as the tree provides a sacred shelter for the people, the umbrella creates a space of sovereignty within the public realm—a domain of order, stability, and distinction.

SHADE

The Shade is more than a byproduct of the tree or the umbrella—it is a fundamental resource that regulates the body and dictates the rhythms of life within dwe berem. Shade serves as a civic necessity, particularly in a marketplace where large gatherings take place under the intense sun. Whether cast by the towering tree or the wide-spanning canopy of an umbrella, shade is a public good, offering relief from heat and exhaustion. It is a social equalizer, providing comfort and protection for all—merchants, travelers, elders, and workers alike.

The presence of shade creates an ambience, shaping how people experience the space and interact with one another. The tree stands as a landmark, its broad canopy forming a sanctuary of coolness. The umbrella, while temporary, is no less significant, erected when needed and packed away once its function is fulfilled. Together, these elements dictate not just temperature but also the social rhythms of the space. The marketplace is not structured by built form but by the play of light and shadow, the movement of air, and the sensory qualities that govern behaviour.

The shade transforms Dwe Berem into more than a mere gathering space— it becomes a stage, an arena for collective experiences. At festivals, umbrellas are hoisted high, their colors vibrant against the sky, as tree branches sway, animating the space with movement. In these moments, Dwe Berem is alive, charged with an energy that is both structured and spontaneous.

Ultimately, the elements of Dwe Berem—the tree, the canopy, and the shade— are deeply interconnected. How does one separate shade from ambience? The tree provides a lasting, rooted shade, while the umbrella offers a temporary shelter, yet both contribute to a carefully orchestrated environment that responds to nature and human presence alike. This space is shaped by a deep understanding of natural markers— light, shade, temperature—that guide behavior and regulate the rhythms of social life.

INTEGRATION: A Unified Spatial and Cultural Ecosystem

The dwe berem was a dynamic space where commerce, social interaction, and authority converged, shaped by three defining elements: the tree, the umbrella, and the shade. These elements not only structured the marketplace but also influenced movement, gathering, and the spatial organization of the space.

At the heart of the dwe berem was the tree, symbolizing ancestry and continuity. It served as both a spiritual and physical anchor, offering a focal point around which activities were centred. The tree grounded the space in tradition, reinforcing the marketplace’s role as an extension of the king’s courtyard. This connection to ancestry and hierarchy imbued the space with a sense of order, with the tree becoming a marker of cultural and social significance.

The umbrella, an emblem of authority, played a critical role in defining the power dynamics within the marketplace. Royal umbrellas, typically used by those of higher rank, not only provided shelter from the elements but also signified control over the space. These umbrellas established a visual hierarchy, orchestrating the arrangement of people in the dwe berem. The presence of an umbrella indicated the importance of the individual and influenced where others could gather, thus maintaining social order and reinforcing the idea that the space was not merely for commerce but also a site of governance and power.

The shade, cast by the tree and the umbrella, became a key spatial mechanism that shaped daily life in the dwe berem. As the day progressed, the shifting shadows dictated the rhythms of activity, from commerce to conversation, rest to ritual. This fluidity in the space, governed by the movement of shade, allowed the marketplace to adapt to the needs of its users. It created a dynamic environment where interactions could be intimate or public, structured or spontaneous, depending on where one stood in relation to the shade.

In these ways, the tree, the umbrella, and the shade transformed the dwe berem into more than just a marketplace. Together, they made it a ceremonial and civic space where authority, tradition, and daily life coexisted, shaping the community’s social fabric and reinforcing cultural practices.

NOTES

1. Kwasi Konadu and Clifford C. Campbell, eds., The Ghana Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 125,

2. Toby Green, “A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution,” in A Fistful of Shells (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 148.

3. Táíwò Olúfemi, “It Never Existed,” Aeon, January 13, 2023, https://aeon.co/essays/ the-idea-of-precolonial-africa-is-vacuous-and-wrong.

4. Labelle Prussin, “Traditional Asante Architecture,” African Arts 13, no. 2 (1980): 65.

5. Bushra Mohamed, “FIHANKRA,” AA Files 78 (2021): 100.

6. Labelle Prussin, “Traditional Asante Architecture,” African Arts 13, no. 2 (1980): 65.

7. Thomas Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee: With a Descriptive Account of That Kingdom (London: Griffith & Farran, 1819), 18; Fiona Sheales, “Sights/ sites of spectacle: Anglo/Asante appropriations, diplomacy and displays of power 1816-1820” (PhD diss., University of East Anglia, 2011), 81.

8. Fiona Sheales, “Sights/sites of spectacle: Anglo/Asante appropriations, diplomacy and displays of power 1816-1820” (PhD diss., University of East Anglia, 2011), 81.

9. Bushra Mohamed, “FIHANKRA,” AA Files 78 (2021): 103

10. Reverend Thomas Birch Freeman, Journal of Various Visits to the Kingdoms of Ashanti, Aku and Dahomi, 1844 (as seen in Labelle Prussin, “Traditional Asante Architecture,” African Arts 13, no. 2 [1980]: 64), 55.

11. Manon Mollard, “Future Archaeology: Excavating Concealed Histories,” The Architectural Review, April 8, 2021, https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/ future-archaeology-excavating-concealed-histories

12. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, “Platforms: Architecture and the Use of the Ground,” October, 2019.

13. Dima Srouji, “Depth Unknown: Archaeology of Resistance,” The Architectural Review, September 3, 2024, https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/depth-unknownarchaeology-of-resistance.

14. Mollard, Manon, Eleanor Beaumont, and Kristina Rapacki. “Ground - The Architectural Review Issue 1514, September 2024.” The Architectural Review, October 21, 2024. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/letters-from-the-editor/arseptember-2024-ground.

15. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, “Platforms: Architecture and the Use of the Ground,” October, 2019.

16. Hollinshead, Mary B. “Monumental Steps and the Shaping of Ceremony.” In Architecture of the Sacred: Space, Ritual, and Experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium, edited by Bonna D. Wescoat and Robert G. Ousterhout, 27–65. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

17 Arthur Barker and Michael Louw, “Evolution of the Boundary: Theories of Threshold, Poché and Stereotomic Design, and Their Manifestation in the Work of Henri Comrie,” South African Journal of Art History (2022): 1–26,

18. “AR Reading List 033: Borders and Boundaries - The Architectural Review.” The Architectural Review, September 15, 2022. https://www.architectural-review.com/ archive/reading-lists/ar-reading-list-033-borders-and-boundaries.

19. Arthur Barker and Michael Louw, “Evolution of the Boundary: Theories of Threshold, Poché and Stereotomic Design, and Their Manifestation in the Work of Henri Comrie,” South African Journal of Art History (2022): 1–26,

20. Thomas Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee: With a Descriptive Account of That Kingdom (London: Griffith & Farran, 1819), 33-34

21. Fiona Sheales, “Sights/sites of spectacle: Anglo/Asante appropriations, diplomacy and displays of power 1816-1820” (PhD diss., University of East Anglia, 2011),104

22. Ibid

23. Thomas Edward Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee: With a Descriptive Account of That Kingdom (London: Griffith & Farran, 1819), 323

24. Fiona Sheales, “Sights/sites of spectacle: Anglo/Asante appropriations, diplomacy and displays of power 1816-1820” (PhD diss., University of East Anglia, 2011),105

25. Ibid

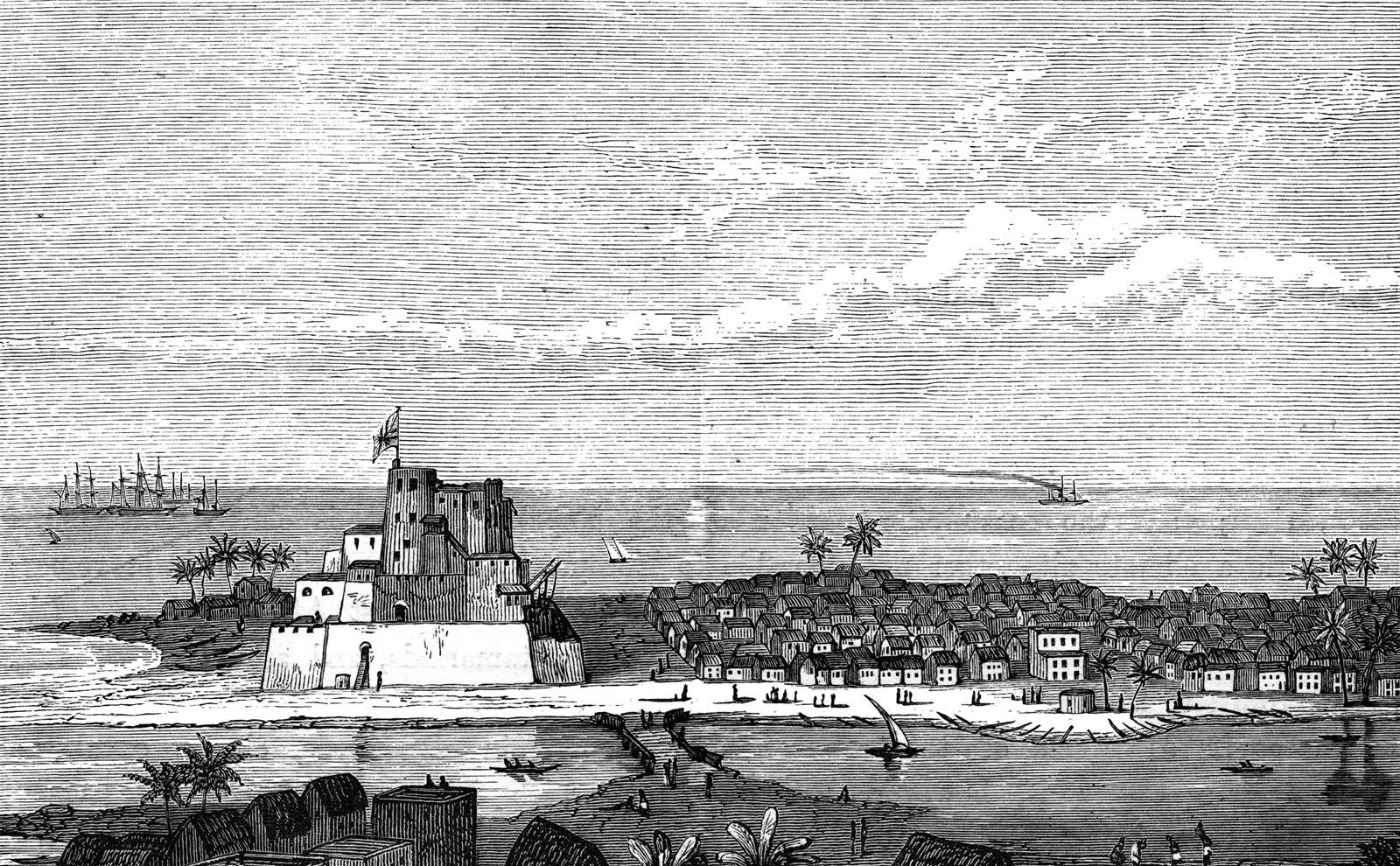

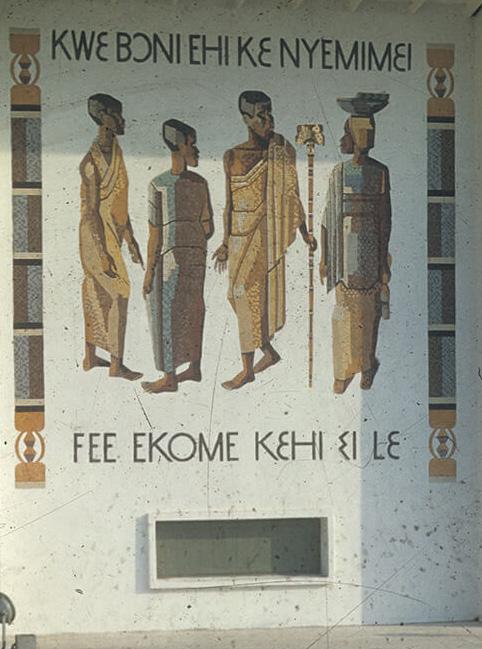

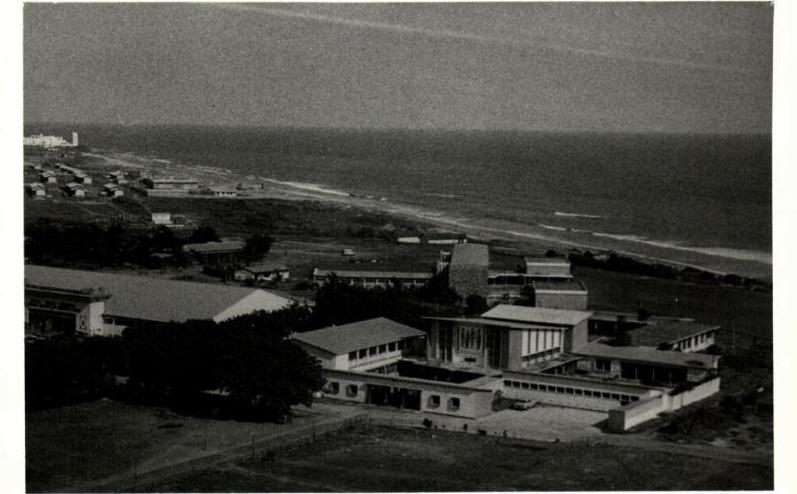

CHAPTER THREE

THE BRITISH GOLD COAST COLONY

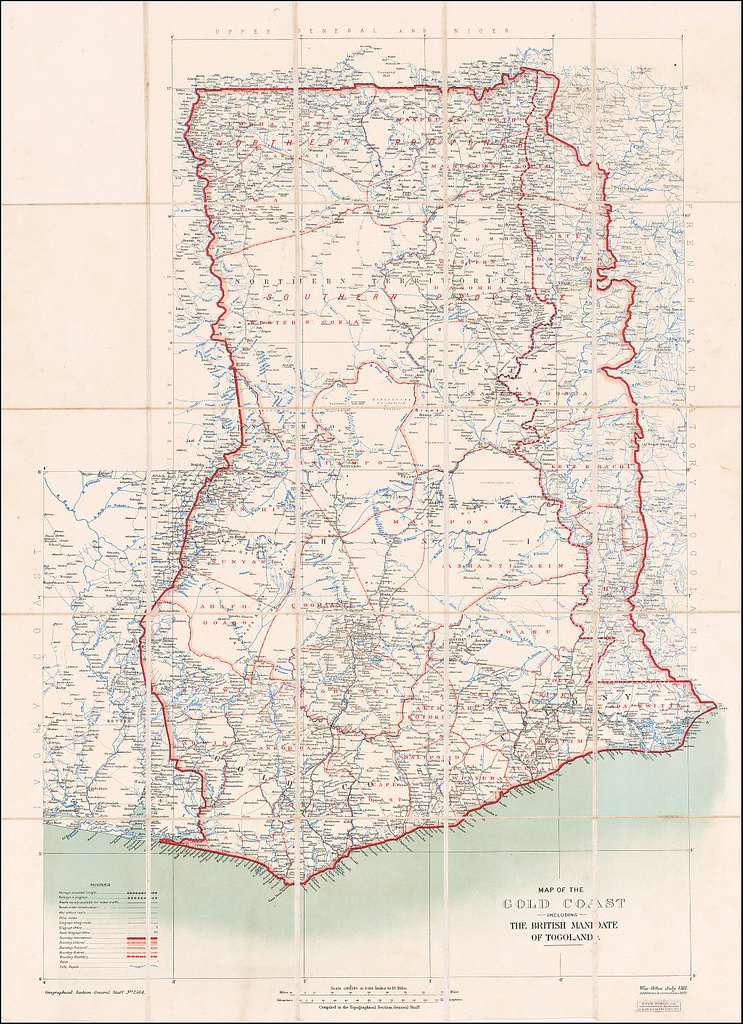

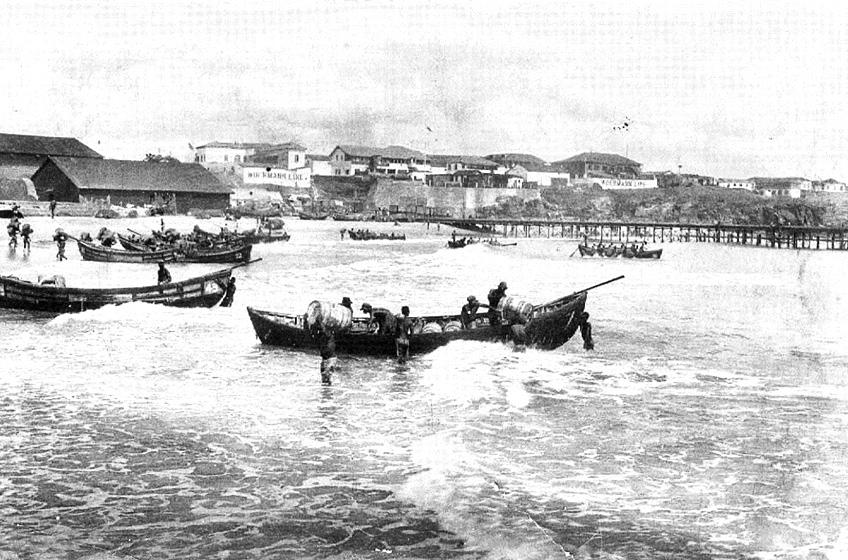

The first documented instance of contact between the people of Gold Coast and the Europeans was in 1471 when the Portuguese docked on the shores of Elmina. It was a commercial relationship where both parties traded in gold, spices and slave. By the 18th century, British interest in the region had intensified, leading to the establishment of the African Company of Merchants. Supported by subsidies from the British government, the company was tasked with protecting British interests in the region, primarily by maintaining diplomacy with the local population1. Four centuries later, British influence had grown significantlyHowever, escalating attacks by the Ashanti Empire on coastal towns forced local leaders to seek British protection, leading to the signing of the Bond of 1844. While initially framed as a mutual protection agreement, the Bond became the lynchpin for Britain’s colonial ambitions, enabling the gradual imposition of British authority. By January 1902, the Gold Coast Colony had been officially established, comprising the coastal towns, the annexed Ashanti Kingdom, and the northern territories. The addition of German Togoland in 1921 further defined the geographical boundaries of present-day Ghana2.

Colonial rule profoundly disrupted traditional society. Urbanization was prioritized over traditional ways of life, and individualism began to supplant communal values. Traditional education, religion, and governance were systematically replaced by colonial institutions. The authority of the chieftaincy was eroded, as rulers were reduced to ceremonial figures and governance was transferred to bureaucratic offices. Ultimately, the cultural fabric of society began to crumble under the allure of financial and social opportunities promised by the colonial agenda3. The colonial administration’s progressive encroachment on local governance and land rights culminated in projects like Tema Manhean, where modernist ideals were imposed on traditional communities, reflecting the broader tensions of colonial planning.

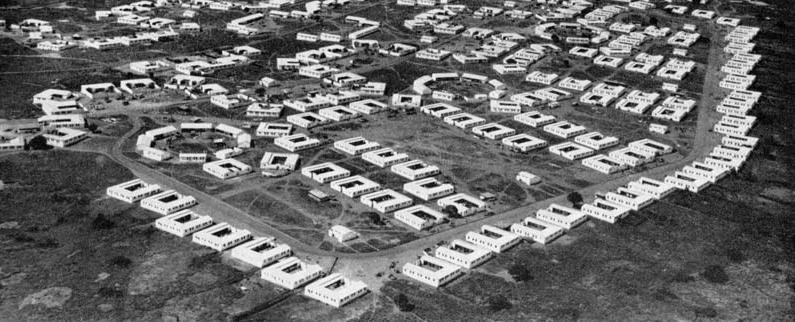

The term “Tema” specifically refers to the Tema Acquisition Area, a 63-square-mile tract within the Accra district that was officially designated for development under the 1952 ordinance4. This legislation granted the Governor of the Gold Coast the authority to appropriate land for the construction of a new town and port at Tema, along with related infrastructure projects. To prevent land speculation within the Acquisition Area, the ordinance declared that all land would be “vested absolutely and indefeasibly” in the Governor, eliminating the need for formal conveyance. This legal measure ensured that the land was free from adverse claims, competing rights, or private interests, effectively granting the government unrestricted control over its use and distribution5. The Ga people at the coast were then tasked with moving out of their ancestral lands to make way for the new port. Alcock defended this provision, arguing that it was designed to capture land value increases for the city, ensuring that any financial gains from development would be reinvested in public infrastructure rather than benefiting private speculators. However, for local communities, this policy meant the erasure of ancestral land rights, leading to social displacement and economic hardship. The ordinance thus laid the groundwork for future tensions between traditional landowners and state authorities, as dispossession and urban expansion reshaped the socio-political landscape6. While the legal framework set the stage for Tema’s transformation, its urban planning principles reflected broader ambitions.

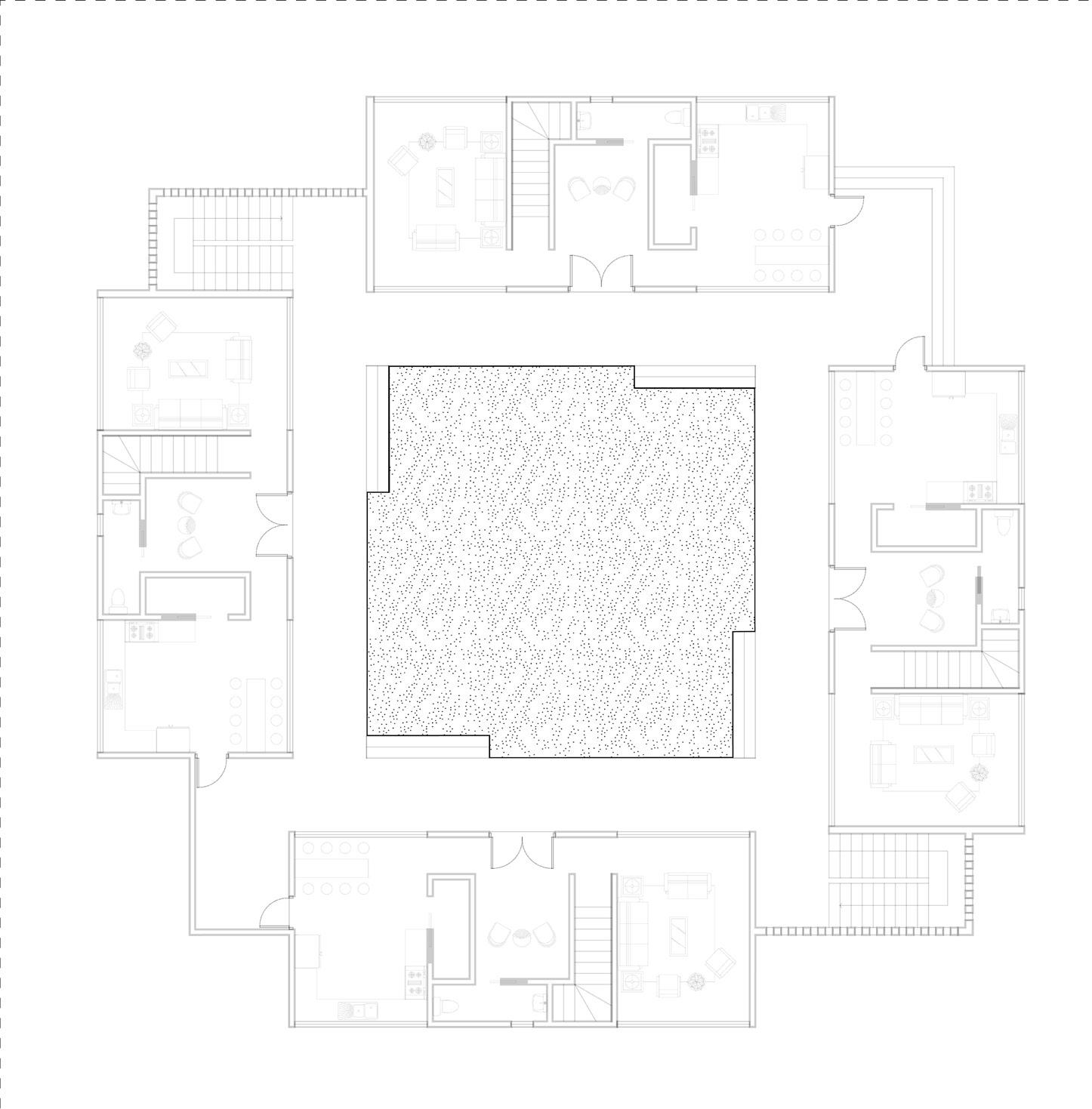

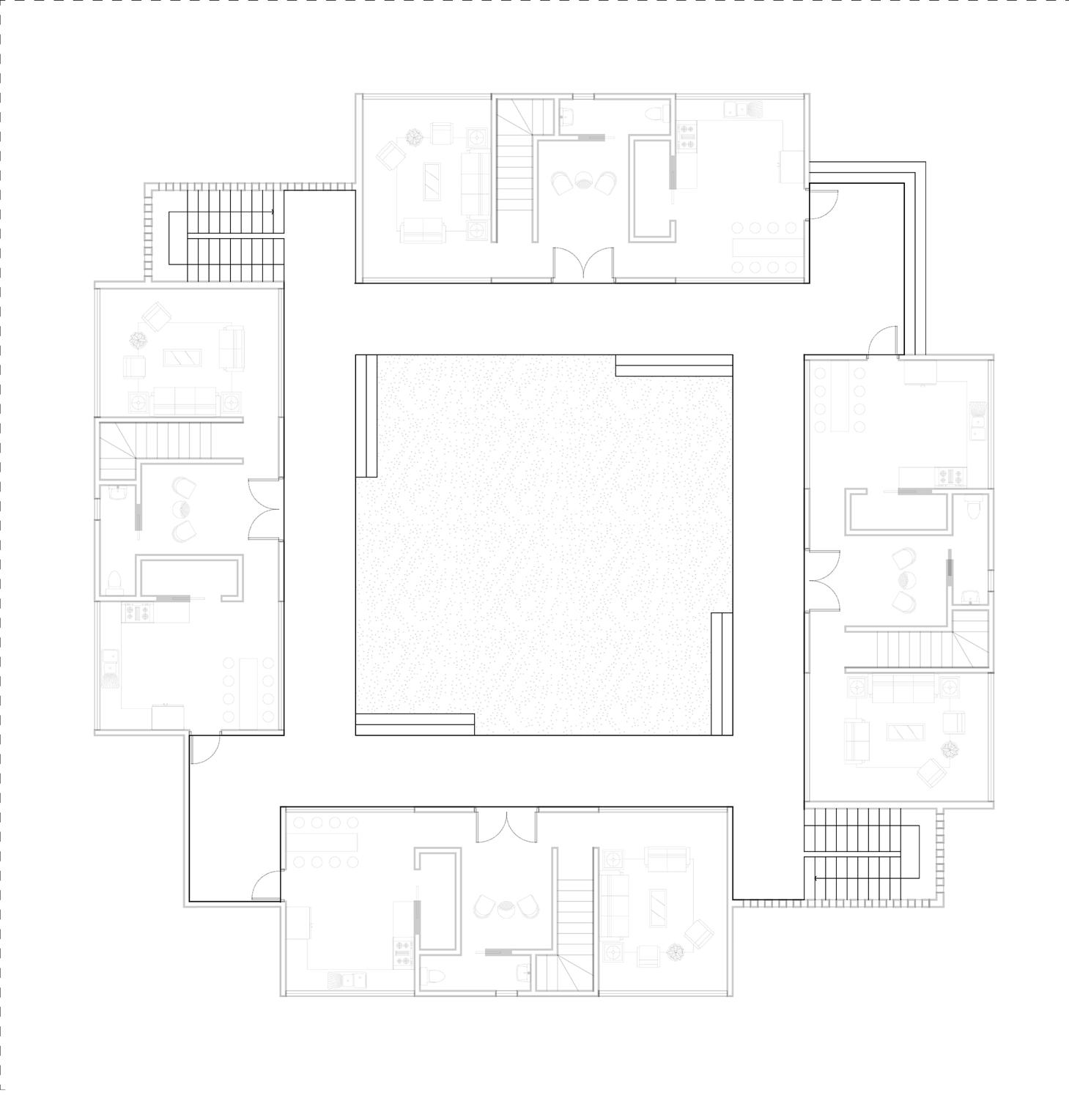

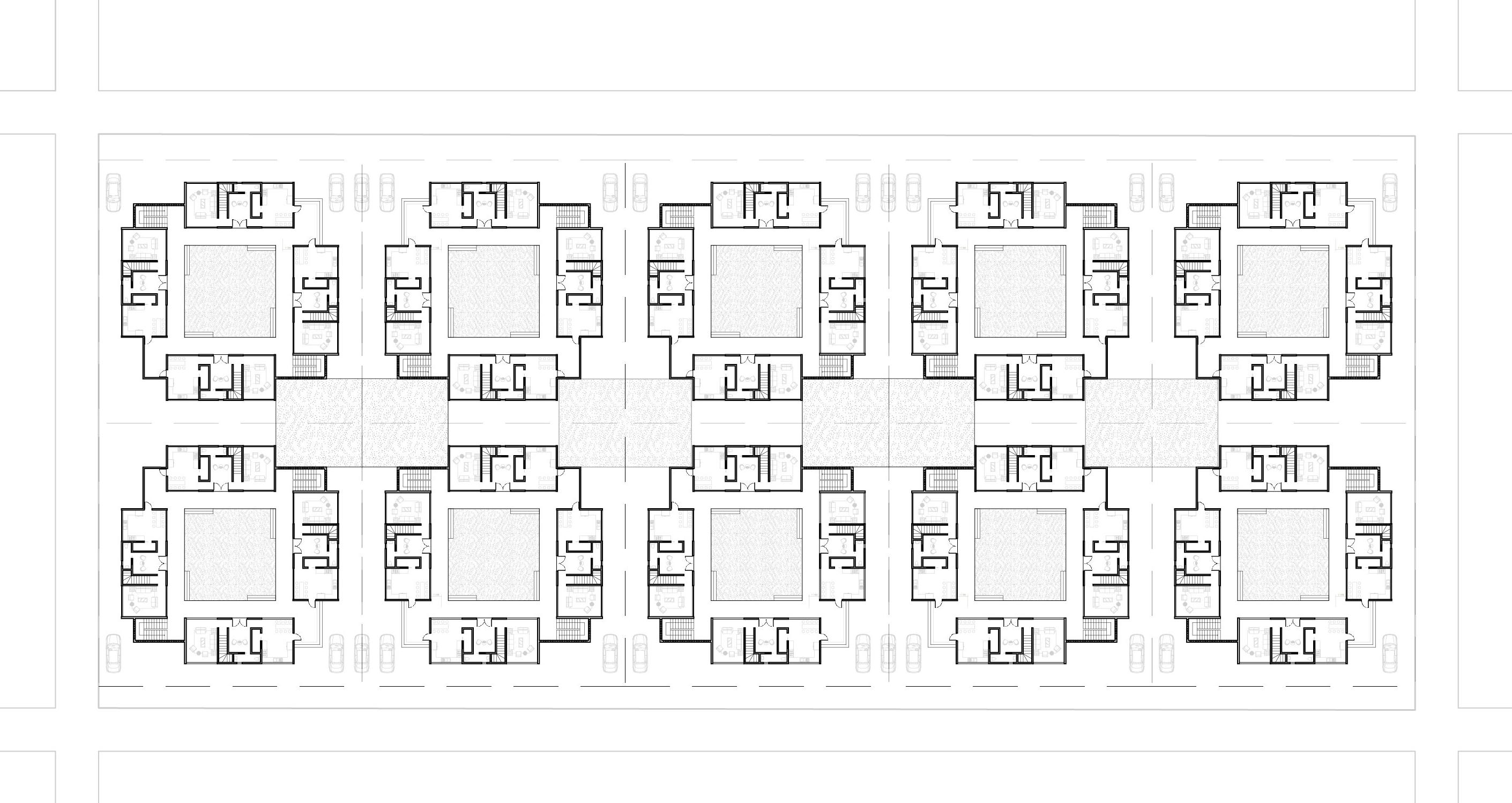

OPEN COMPOUND

The open compound was a housing model proposed by British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, whose mid-20th-century work in West Africa sought to adapt European architectural principles to local climates and social structures. Their design of the open compound emerged as a response to colonial critiques of the traditional compound house, which authorities deemed climatically unsuitable and unsanitary. The proposed open compound was conceived as a modernist reinterpretation of the traditional compound, aligning with what Fry described as an “intermediate type” of housing that could bridge African and European lifestyles7. This model was intended for construction in Tema Manhean, where colonial policies mandated the replacement of traditional compounds with private family dwellings. However, Fry and Drew recognized the symbolic and functional importance of the traditional compound house. They acknowledged that the clustering of homes around a shared courtyard was not merely a spatial arrangement but a fundamental aspect of social organization and cultural continuity8. Their proposal, therefore, sought to integrate elements of communal living within the framework of modernist design, balancing local traditions with colonial-era urban planning ambitions.

The open compound included modifications to improve hygiene and ventilation, such as larger windows, elevated floors, and the use of more durable materials. While these changes were intended to address health concerns, the design also reflected Fry’s vision of a “differently organized life of the future,” one that prioritized individualism over the communal living arrangements traditionally seen in compound houses9. This design captured certain aspects of West African social life but oversimplified local customs into fixed pattern that did not account for the evolving needs of the people that were to relocate to these communities. The Ga communities in relocating lost a connection to their ancestors, history and identity as a branch of the Ga ethnic community. The breakdown of the traditional governing structures and authority soon followed10. As an appropriated type the open compound comprised the same three elements as the gyaase of the Ashanti Kingdom. The ground, the plinth and stairs and the boundary.

GROUND

The courtyard of the open compound remained a multipurpose space, much like in traditional compounds. It was used for drying clothes, children playing, social interactions, and hosting both monumental and ordinary activities. However, while the functions persisted, the deeper cultural rationale behind them became less pronounced. The open compound functioned as a social hub, yet its ability to sustain the spiritual and ancestral connections embedded in traditional compounds was diminished. The materiality of the ground in the open compound was notably different. While traditional compounds had an earth-based floor, reinforcing a direct connection to Asaase Yaa (the earth deity), the open compound was paved, most likely screeded. This shift altered the sensory and ritual experience of the space. The ground in the gyaase was composed of native red laterite earth, shaping and framing the human activity that unfolded upon it. It was more than a surface; it was a living archive, a stage for daily life—a silent witness and an active participant in the rhythms of existence. In the traditional compound, bare feet on the earth maintained an intimate connection to the land and its ancestral spirits. In contrast, the paved ground of the open compound severed this connection, subtly shifting the relationship between the people and their environment. The architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Frye overlooked the importance of materiality in facilitating these interactions. The red earth, offered a tactile and emotional connection to the land. When children ran across it, or parents prepared the evening meal, the red earth grounded them in their environment, embodying a sense of belonging. This connection differentiated the experience of living and engaging in the gyaase from performing the same activities in a courtyard-type house. The ground mirrored tradition, yet its materiality and philosophy bore the marks of modernist abstraction. The ancestral spirits, once ever-present in the traditional compound, become distant figures in this new architectural form. The social activities remain, but their rootedness in ritual and ancestry is lost. The ground was not the ground of the gyaase—the sacred earth, once an intimate part of daily life, was now paved. The courtyard remained, but its soul—the ancestral presence, the spiritual resonance—had been diluted. 0m 1m 2m

The planning of late colonial village housing in the tropics: Tema Manhean, Ghana

Iain Jackosn and Rexford Assasie Oppong, 2014

The planning of late colonial village housing in the tropics: Tema Manhean, Ghana

PLINTHS AND STAIRS