INTERFACE

RAILWAY TERMINALS ON THE PERIPHERY OF CENTRAL LONDON from 1830 untill today

Cover sheet for submission: 2024-2025

Programme: Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

Name(s): Shoushu Chen

Submission title: CIVIC INTERFACE: Railway Terminals on the Periphery of Central London

Course title: Dissertation

Course tutor(s): Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi, Anna Font Vacas

Declaration:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student(s):

Date: 21st of March 2025

Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design - Projective Cities

Acknowledgments

Growth is always about breaking and rebuilding oneself. Looking back on the past year and a half, I have come close to breaking down countless times. Yet, amidst the endless overcast days and the pains of growing, everything about the Architecture Association has been a comfort. Sitting by the windows of AA library, listening to the birds in the garden, and feeling the warmth of the afternoon sun, I am reminded that I am still that young girl on her track.

A sense of belonging, I believe, is the greatest feeling AA school instils in people. Here, everyone is dedicated to turning their ideas into tangible forms to share with others. And because of this, in every exchange, in every shared glance, we find encouragement in one another. I am deeply grateful to AA school, my tutors also as my mentors, and my peers, whose dedication to their own pursuits has strengthened the belief in mine. It is because of them that I was able to submit this important work to my dream school.

Anna once said that young people inevitably face existential crises, they almost overreacted—I am no exception. I am especially grateful to Ziyi Gao, my dearest friend since our undergraduate years at XJTLU. Though he has been at Politecnico di Milano while I studied at AA School at London, miles apart, his integrity and optimism constantly remind me that this world is still worth fighting for and believing in.

To my father, Mr. Jiang, thank you for your unconditional love and support, for making me feel rooted yet free to flow. To my mother, Elina, a woman of independence, courage, love, and hope—thank you for lighting my way as always.

And finally, to myself—just as a quote from Tenet, I am the protagonist of my own story.

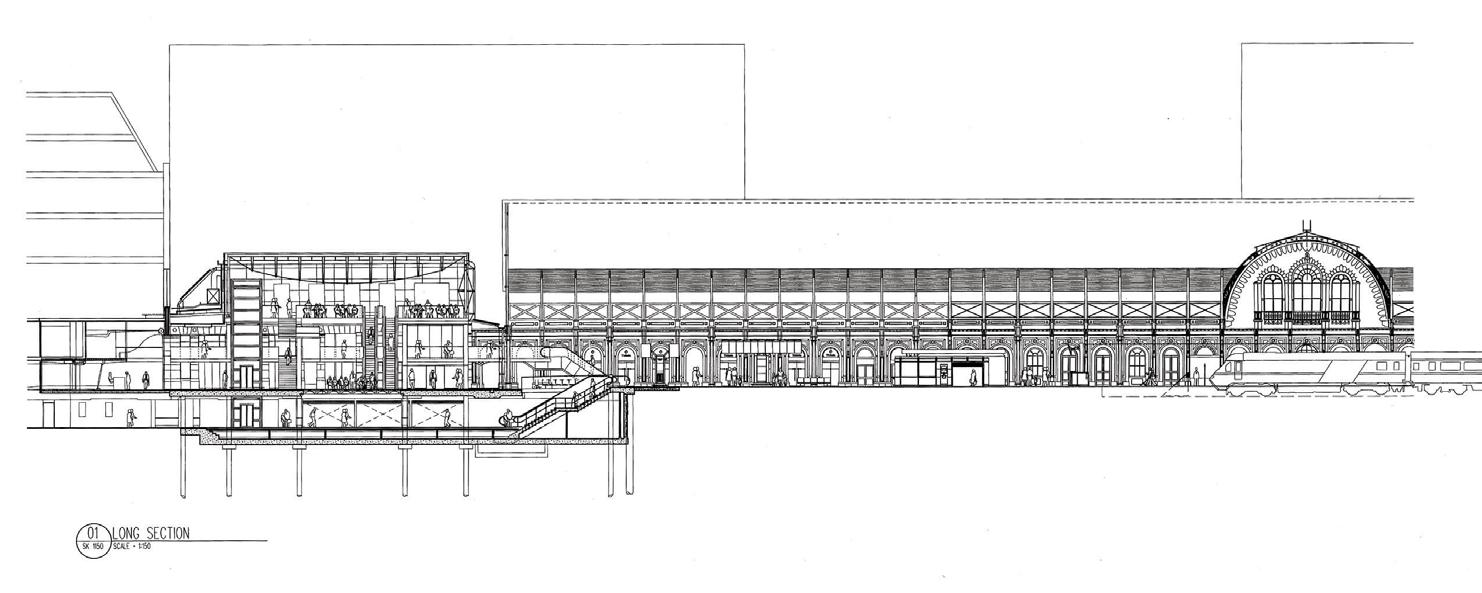

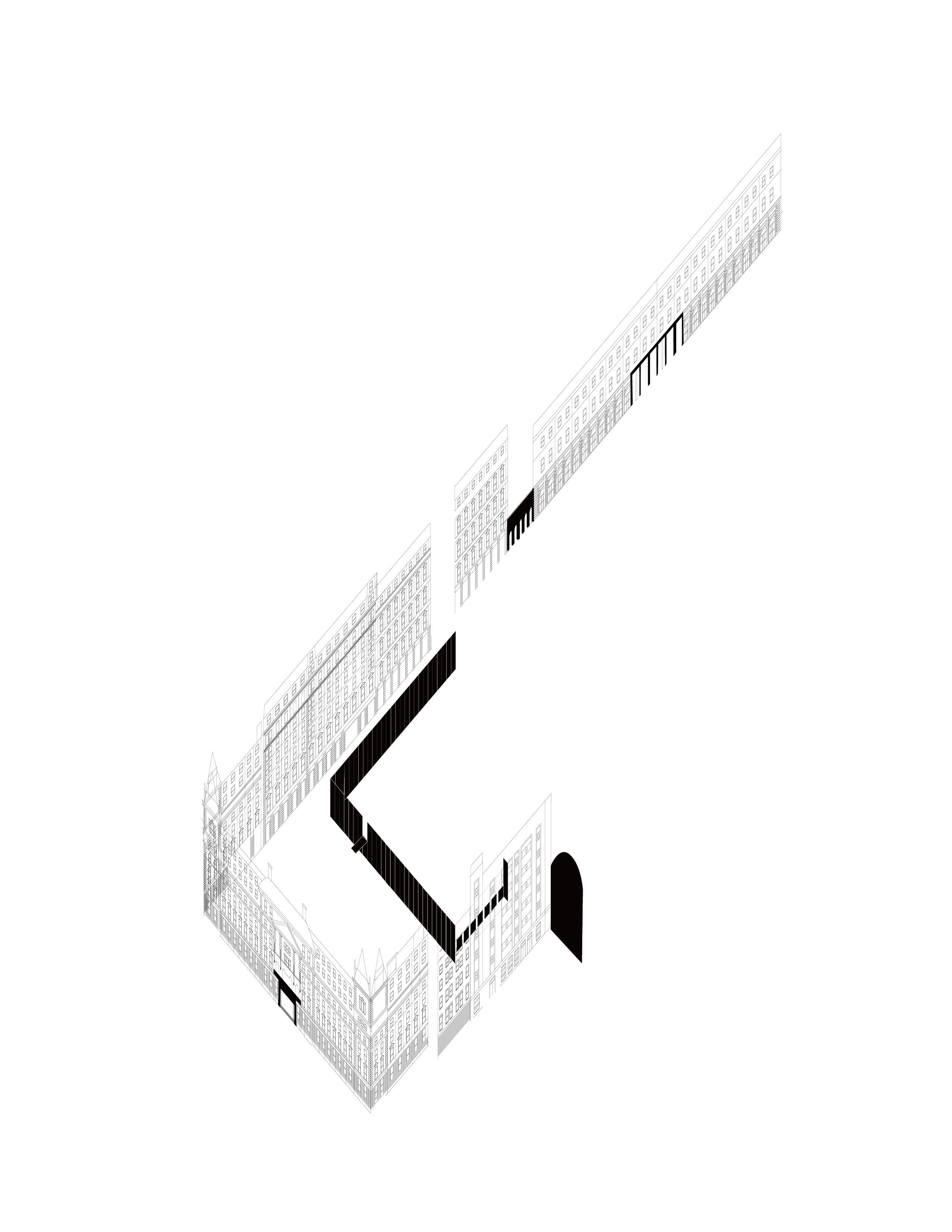

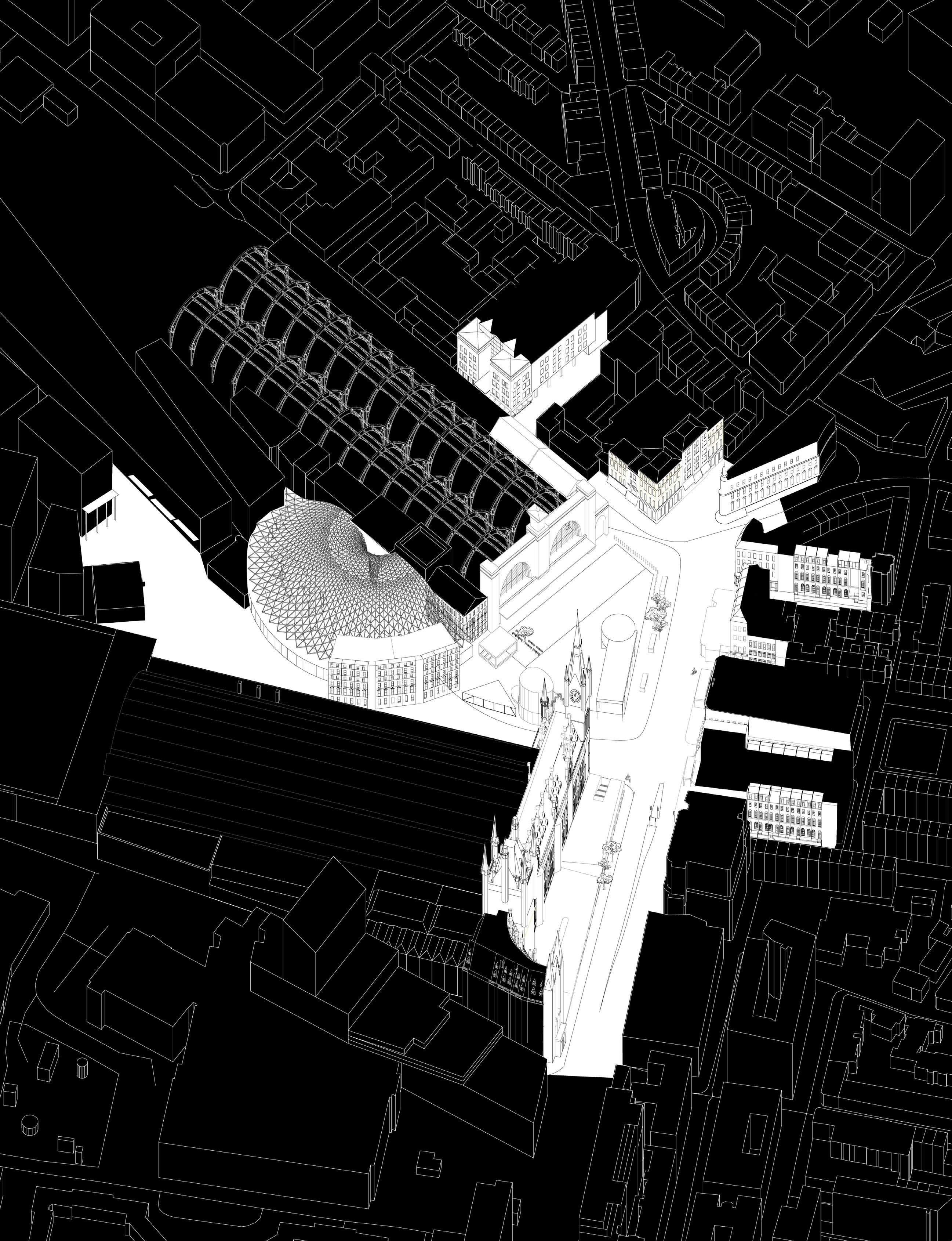

This dissertation, Inhabitable Interface: Railway Terminus on the Periphery of Central London,begins with an interest in railway construction and the observation that London’s railway terminals have become essential spaces in the city—not only for travel but also in daily urban life. It examines the historical transformation of three major railway terminals on the northern periphery of central London from the railway mania of the 1830s to the present day. These three stations—Euston, Paddington, and King’s Cross—have gained prominence and established identities that go beyond their basic function as transport hubs. Although railway terminals are traditionally seen as destinations, they have also shaped the built environment around them, fostering habitation and civic engagement. By encouraging social gathering and reinforcing civic pride, these terminals inherently embody a fundamental aspect of their typology: civicness.

Through the lens of habitation emerging from infrastructure, this study explores how railway terminal architecture has translated civicness into deeper citizen engagement. By analysing these stations both separately in chronological order and comparatively to identify commonalities, the research seeks to determine the periods when each terminal most effectively embodied civicness and how subsequent developments have either reinforced or diminished this quality.

Building on this, each terminal serves as the basis for a design proposal that challenges its current state. Rather than nostalgically recreating an idealized past, these designs aim to reinterpret civicness in a contemporary urban context, acknowledging the unique conditions of each site. Together, these interventions offer a reimagined vision of railway terminals as habitable interfaces—integrating transportation, urban life, and public engagement to create more dynamic and inclusive civic spaces.

AIMS

This study aims to deepen the understanding of civic spaces integral to railway terminals and to explore the inherent civic nature of this architectural type through a methodology of learning by drawing.

OBJECTIVES

The objectives are to deconstruct the concept of civicness in railway terminals through the analysis of typological elements, seeking to elucidate how civic qualities are manifested in these spaces.

TYPOLOGICAL QUESTIONS

How did the portico and waiting hall pioneer the concept of civicness in railway terminals during the early Victorian era?

How has the transformation of front hotel and shed impacted public accessibility and congregation over time?

URBAN QUESTION

How has the development of railway terminals influenced the growth of hospitality infrastructure in their vicinity?

How has the network of inns and pubs shaped civic life around railway terminals?

DISCIPLINARY QUESTIONS

How can the historical evolution of terminal architecture inform future civic design strategies?

How might the existing conditions of these terminals be leveraged to articulate a new form of civicness?

Contents

Acknowledgements

Abstract

Introduction

Background

Civic Infrastructure

1.1 Civilization, not yet Civicness

1.2 Arriving at the City: Portico & Its Urban Glory

1.3 Waiting in the terminal: : From Portico to the Concourse

Conclusion 1

Act 1 The New Civic Hall

Chapter 2: Enclosed plaza

2.1 The time of Grand Train Shed

2.2 Living in the Terminal: Habitable Enclosure

2.3 Interiorized Exterior

Conclusion 2

Act 2 The New Civic Plaza

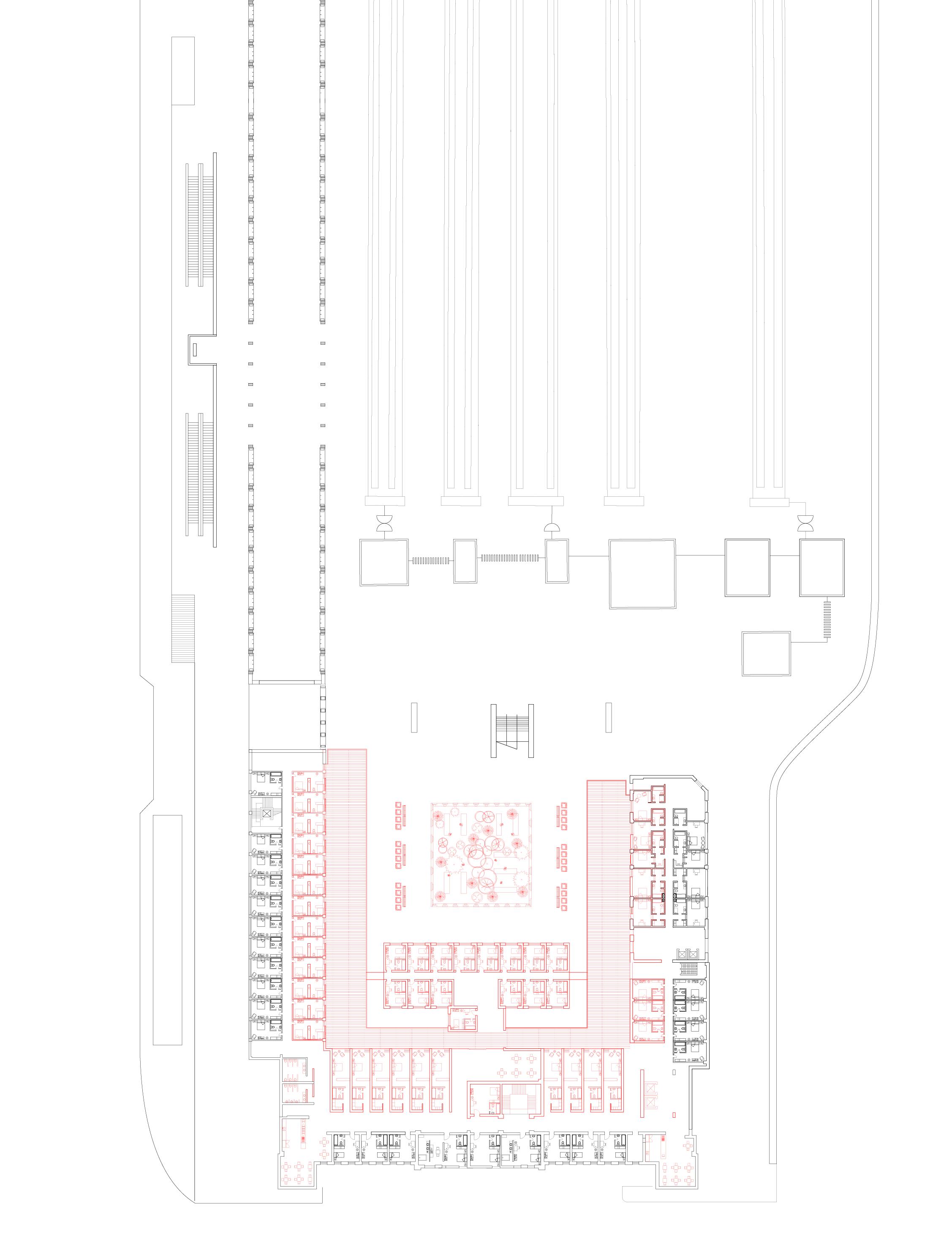

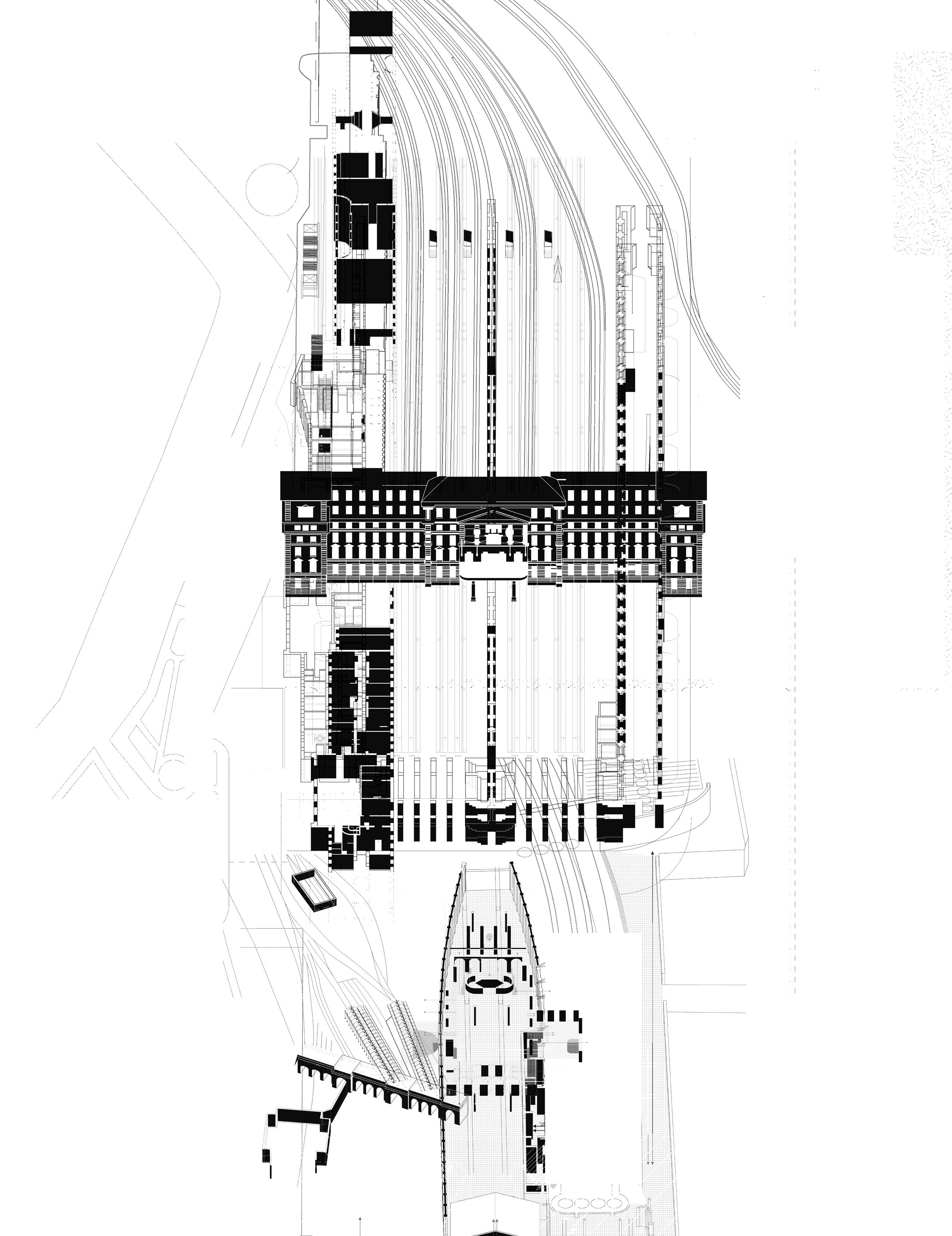

Chapter 3: Instant Urbanity

3.1 Forecourt for the City

3.2 Inhabitable Interface

Conclusion 3

Act 3 The New Civic Interface

Conclusion of the thesis

List of Images

INTRODUCTION

London’s rail mania of the 1830s brought about an explosive expansion of the network of local locomotives, transforming the urban connectivity and transportation system. The Industrial Revolution witnessed London railway terminals become iconic representations of technological advancement. Even cathedrals were overshadowed by them. These terminals were initially functional spaces dedicated to social well-being, hence the use of basic typological elements such as platforms, sheds and porches. The growing cultural importance of the railroad as the city grew led to a shift from basic functional structures to more complex architectural forms. These sites gradually revealed their civic nature, elevating the public space required for transportation to a space for public activity for citizens, while demonstrating their social and cultural relevance to Victorian Britain.

The Latin word civis has the meaning closely tied to the concept of creating and maintaining urban spaces in accordance with collective responsibilities and common cultural values. Ever since time immemorial, civis has been associated with the ideal of civilization as an embodiment of a society’s conception of civic identity and common way of life. But civic space is hard to define since it is more than fixed physical attributes. Rather, it is defined by its adaptive and evolving character. The building development of stations offers a quirky point of view from which to translate this intangible concept into material form that is possible to critique, interpret, and learn from.

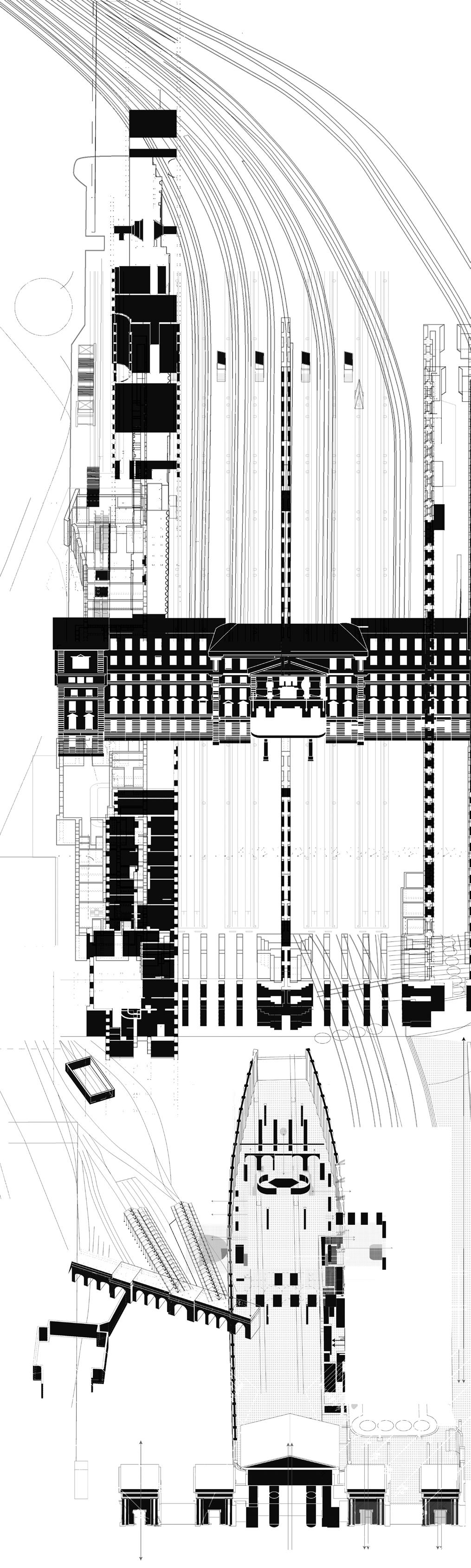

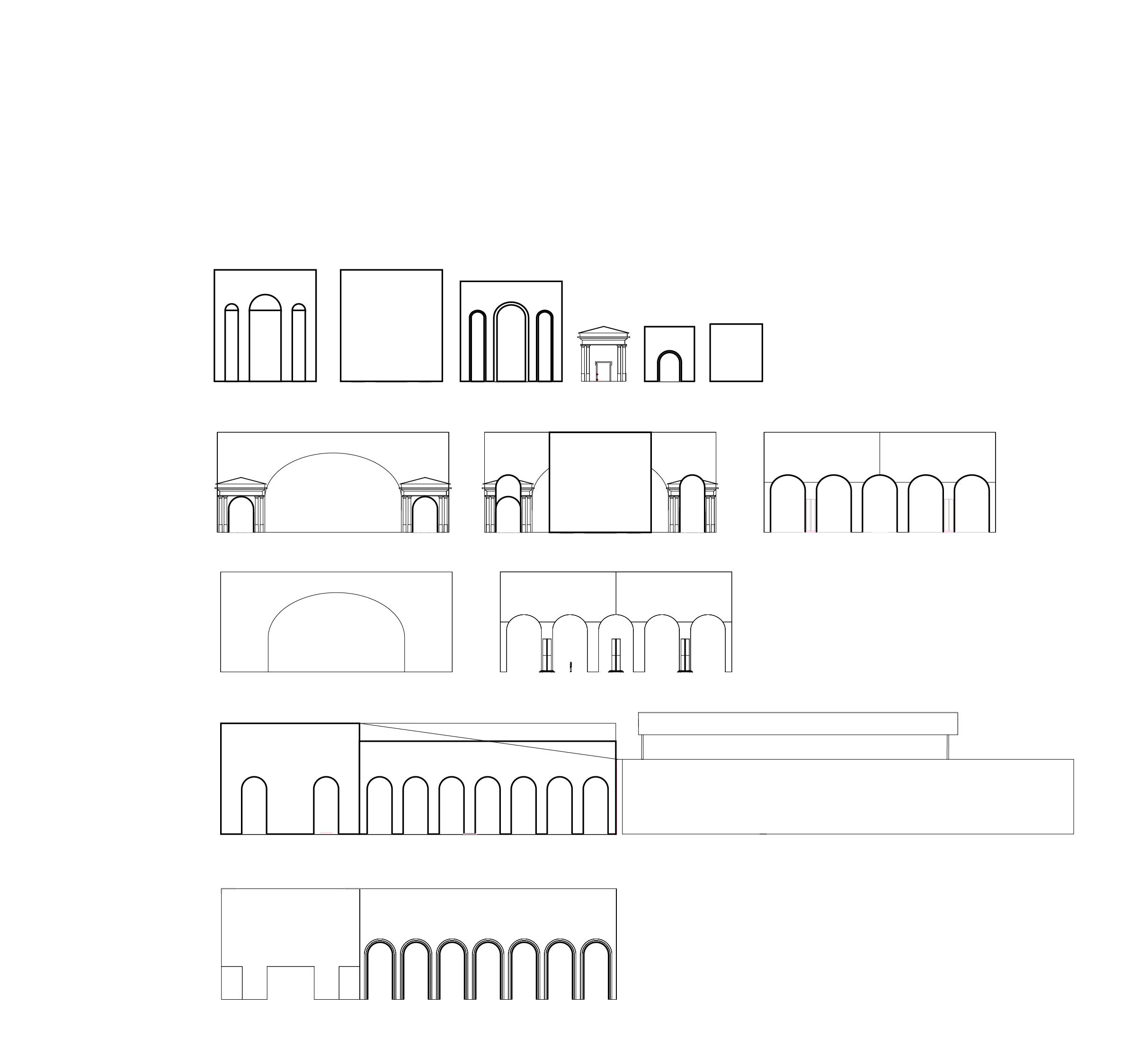

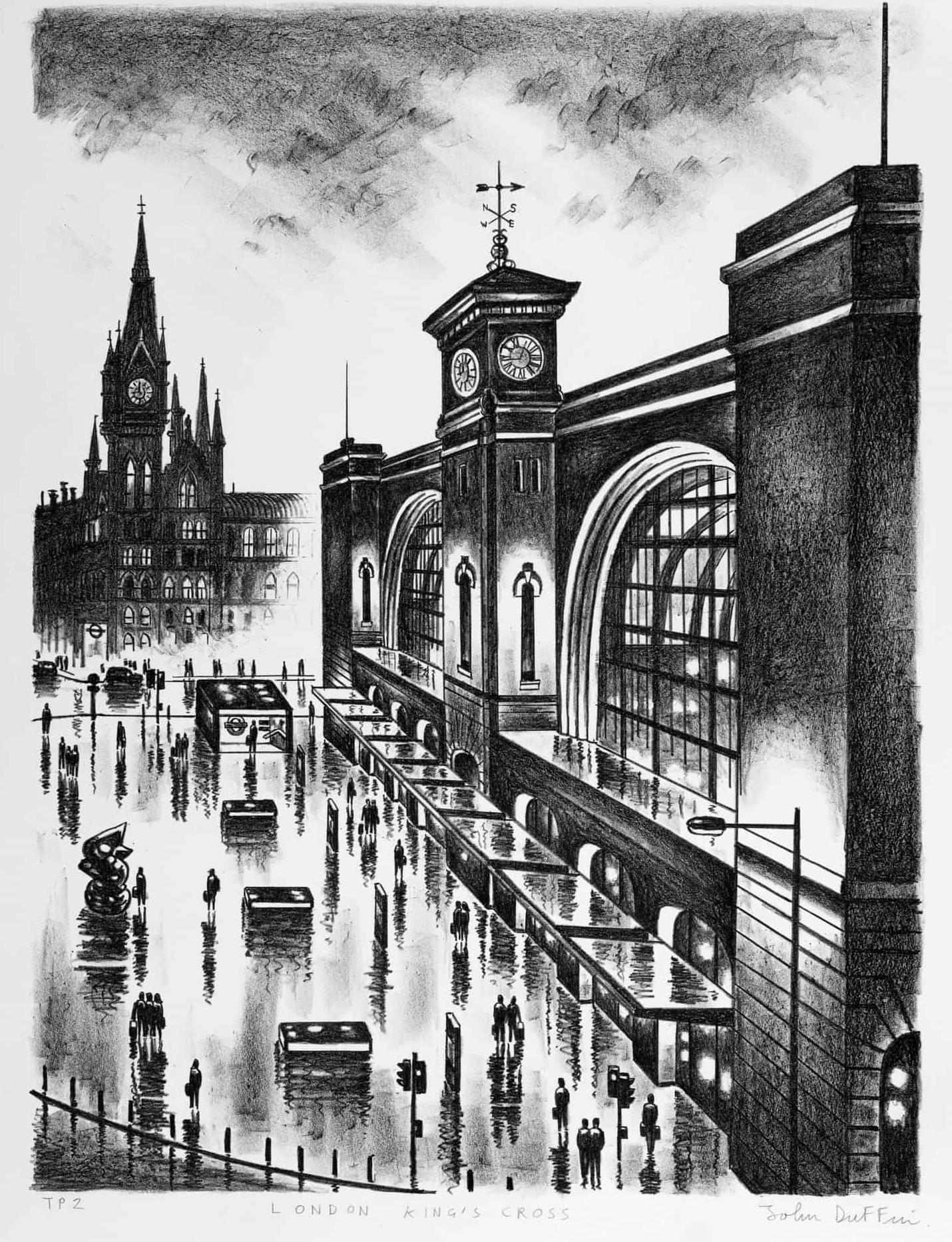

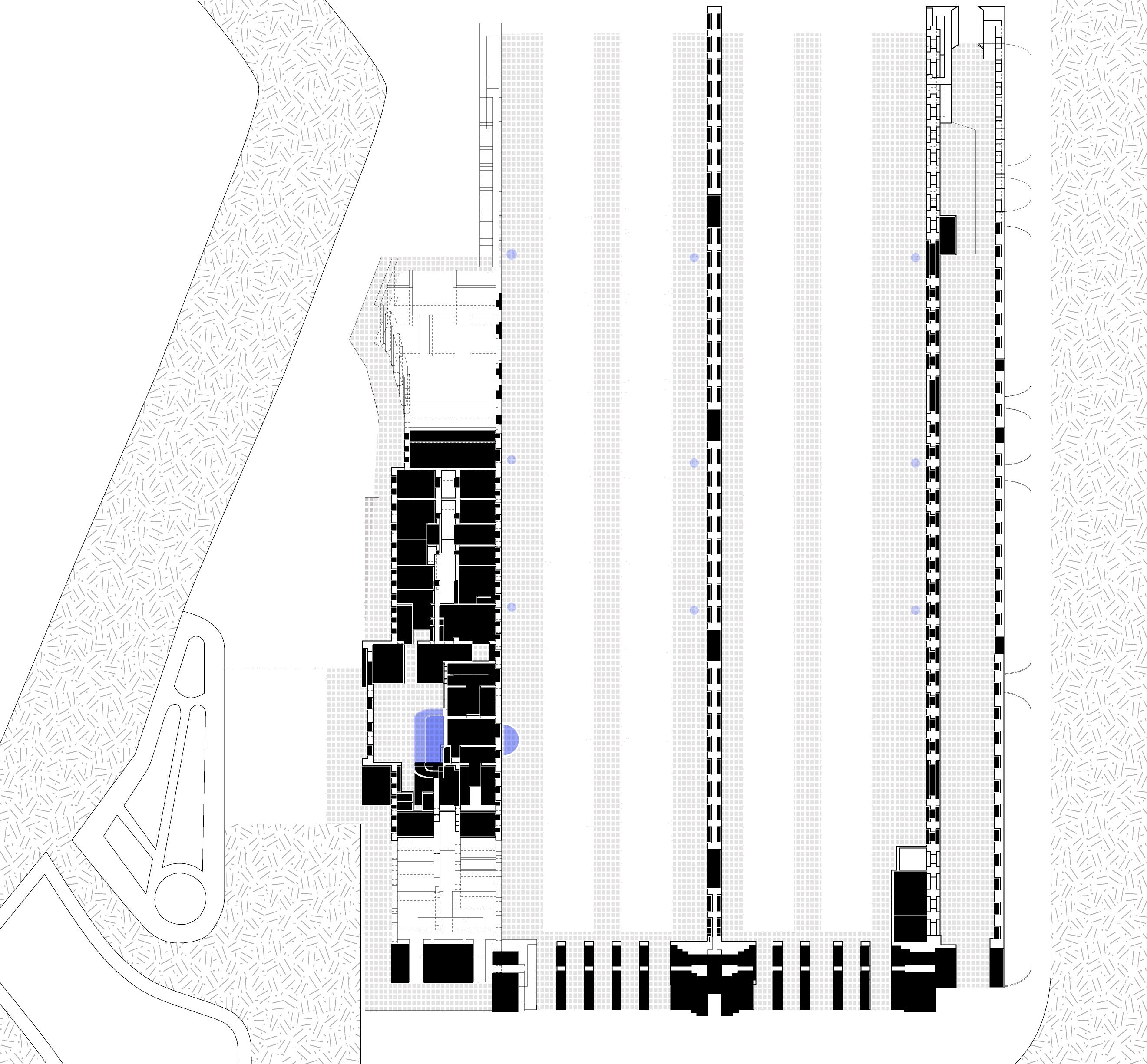

The concept of civic space, with its inherent ambiguity, is challenging and offering opportunities for this study. This dissertation aims to deconstruct the notion of civicness through a methodology of learning by drawing, highlighting the transformative potential of railway terminal as central civic space of the city. The analysis begins with Euston Station, exploring how sheds and porticos exemplified the changing emphasize from civilization to civicness, with its peak time manifested in the typological arrangement of Great Hall. Then, in Chapter 2, the focus shifts to Paddington Station, offering a detailed analysis of the architectural evolution of railway sheds and the emergence of railway-centered hospitality. This chapter critically examines the processes of gentrification and the social constraints imposed by its enclosed plaza, which emerged alongside these developments. The final chapter moves to King’s Cross Station, where the terminal and its surrounding urban fabric are integrated through a shared architectural language. This cohesion has fostered the formation of a constellation of hospitality infrastructure within the district, shaping the area’s character as a transient place of residence for the community.

By analysing the architectural and spatial components of railway terminals, this research explores how station-based civic spaces in London have emerged and transformed over time. The three chapters correspond to distinct phases: the 19th-century typological components of terminals as proto-civic elements, the 20th-century development of enclosed plazas through organized spatial enclosures, and the subsequent expansion of these civic concepts to the urban scale in the modern era. Building

on this analysis, the study proposes a series of typological reorganizations and tests across these three scales, forming the basis for an iterative design process.

These proposals reimagine railway stations as living environments that not only respond to social and cultural progress but also unlock their latent civic characteristics, interpreting them in context-dependent terms in order to optimize their function in the urban fabric and position them as agents of dynamic public life.

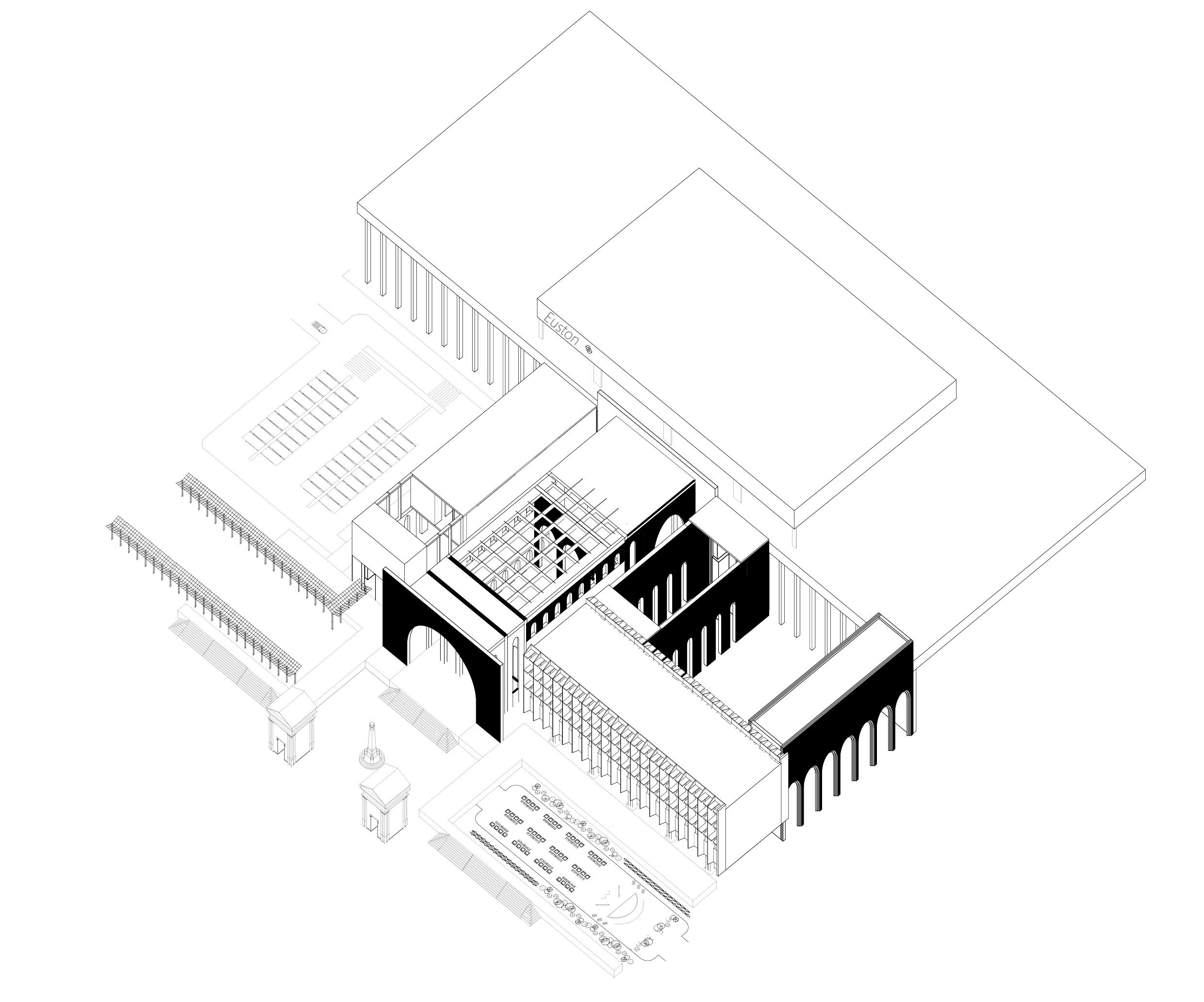

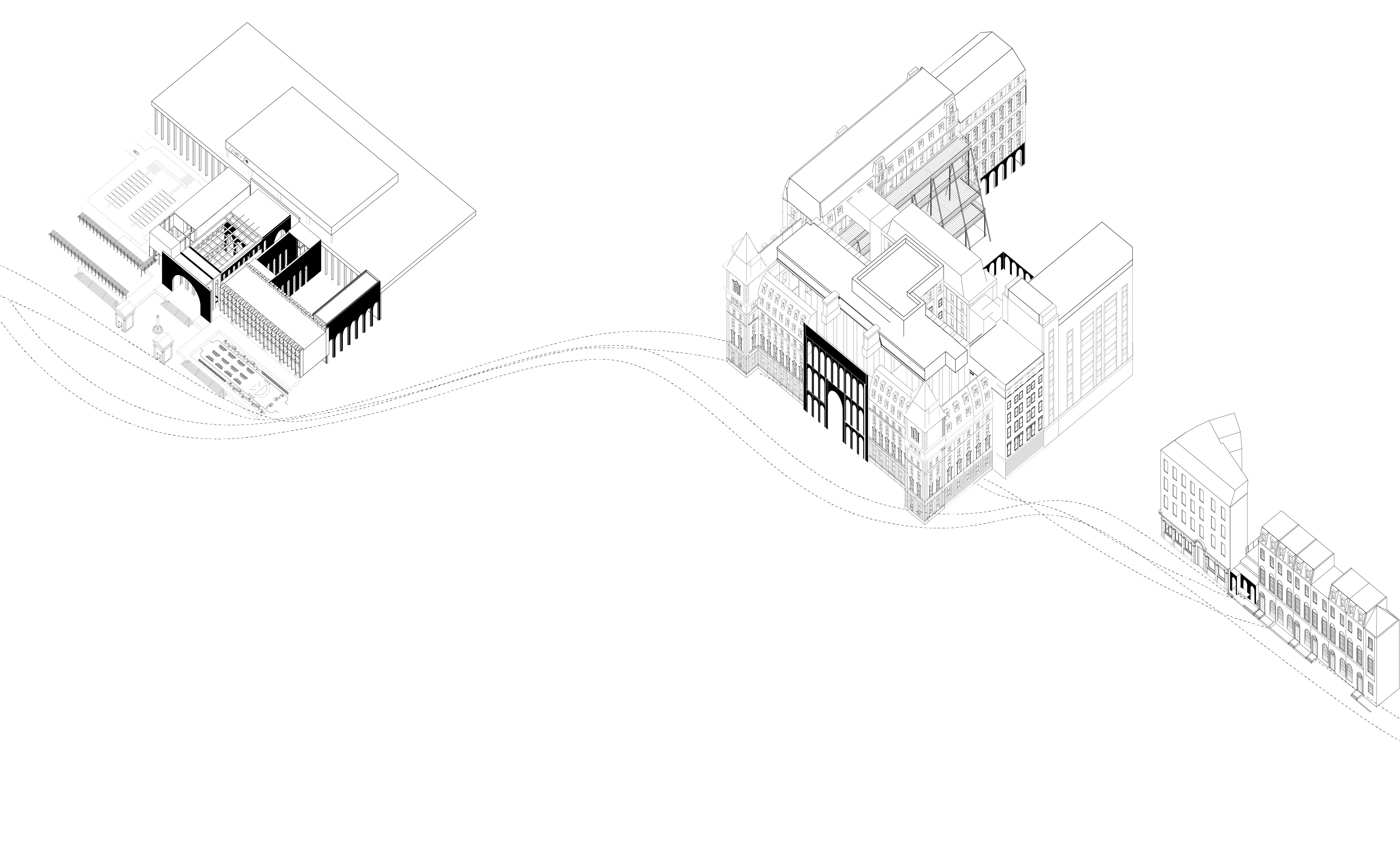

The first intervention aims at Euston Station and presents a vision of contemporary civicness as an integration of the modes of mobility. By joining various modes of transport across the rail network, this solution envisions the production of a single, uninterrupted system of transit. The second one concerns the complementarity of hospitality and transport services at Paddington Station and evaluates to what extent integrated they can make the passenger’s experience a more rewarding and smoother one. Last but not least, the third project examines King’s Cross Station and its surroundings as a laboratory for scaling up informal hospitality infrastructure to provide moments of incidental social interaction. Taken together, these proposals redefine the civic role of rail stations, offering a new vision for infrastructure as a central component of urban life. Through the recovery of their former status as centres of social and cultural exchange, the design strategies aim to build a more inclusive, dynamic, and vibrant cityscape.

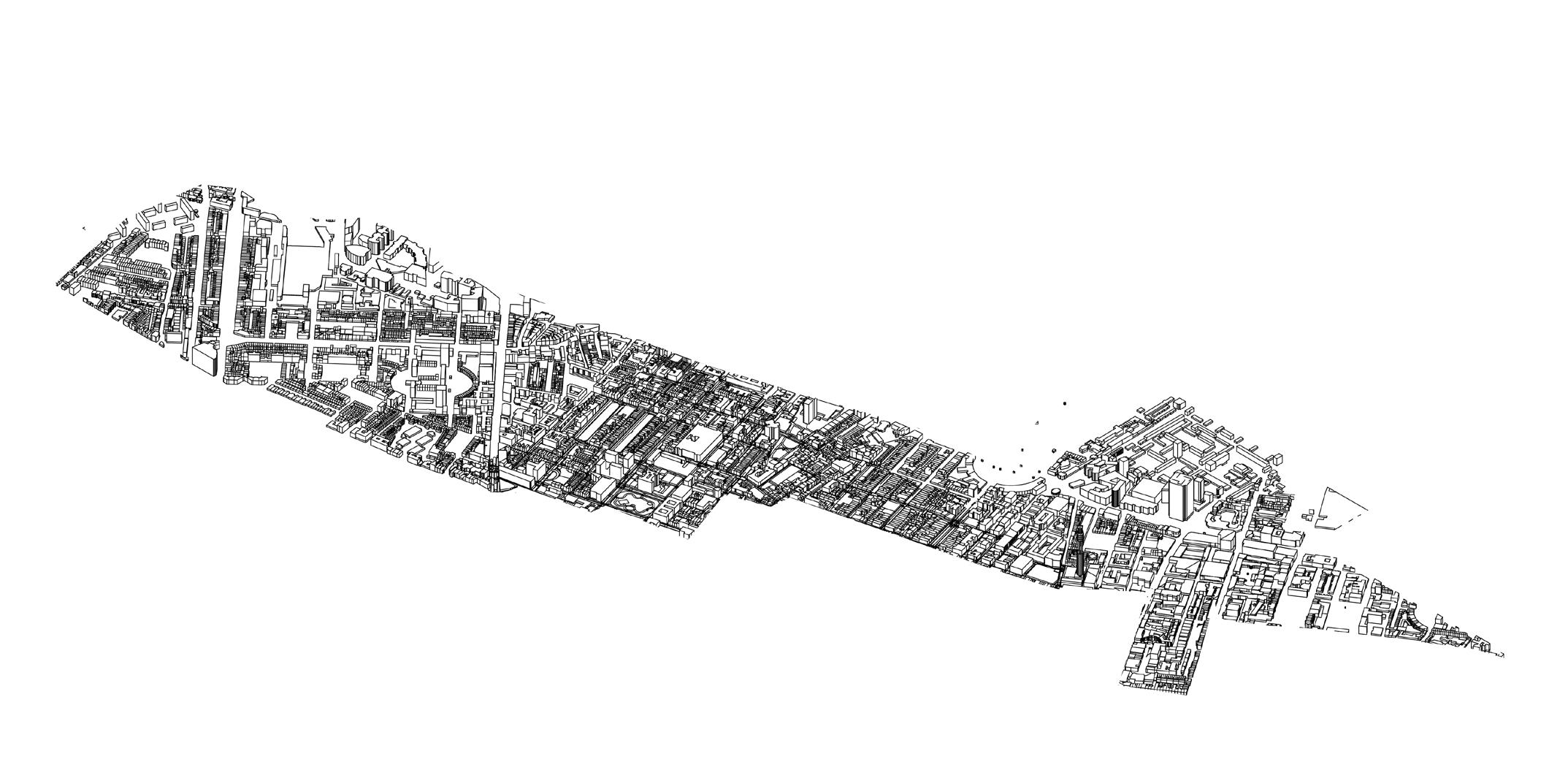

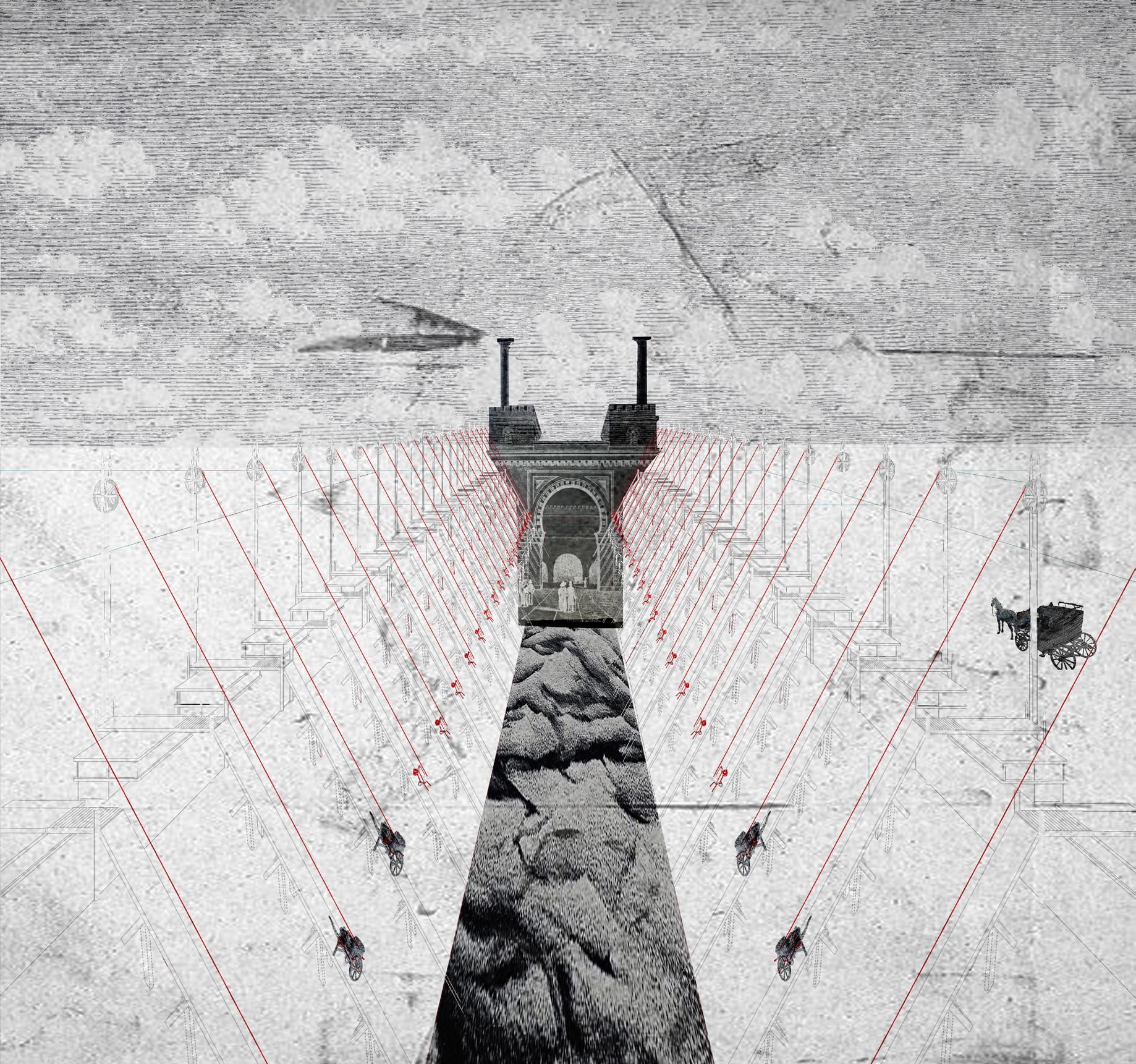

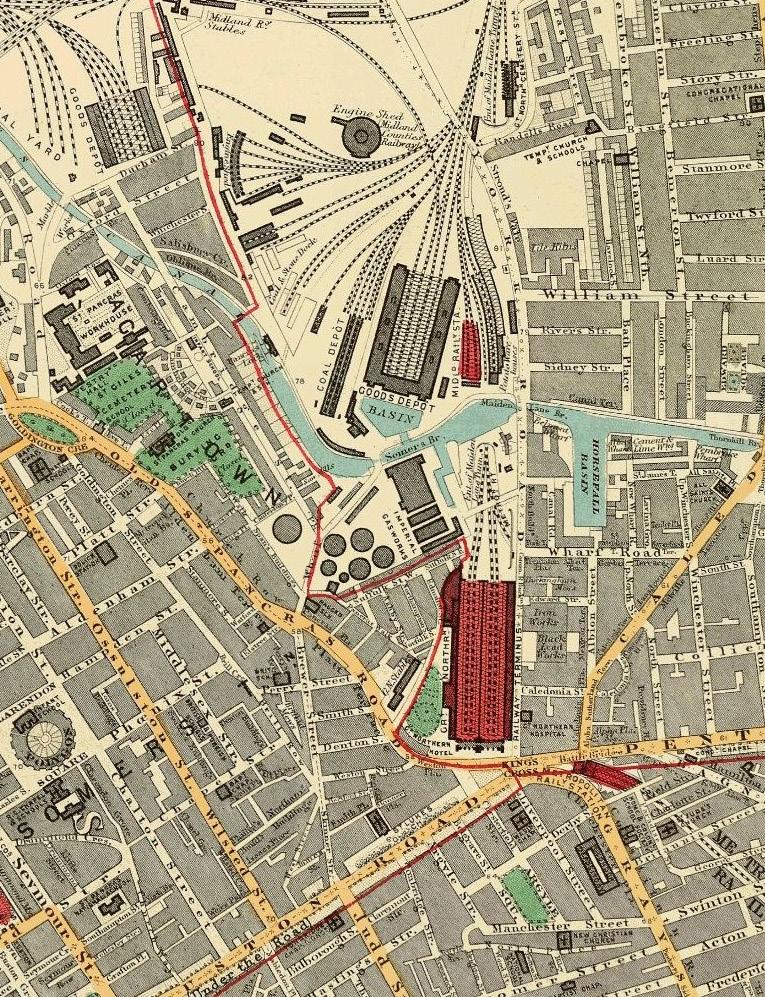

BACKGROUND BOUNDARY OF CENTRAL LONDON

This section explores how privately owned railway companies, starting in the 1830s, engaged in competitive practices that reshaped the landscape surrounding railway infrastructure. Their focus gradually shifted from merely developing railway routes to positioning London as the primary destination. The 1846 legislation later intervened to mediate these tensions, effectively providing a historical framework for defining London's central area.

BOUNDARY of CENTRAL LONDON

In Victorian London, with the Industrial Revolution quickening its own pace, construction of railway lines at breakneck speeds became the signature of the age. Railway corporations carved out their lines on the land in their efforts to extend their network and earn more revenues. Not only did this huge expansion of railway lines reshape the physical face of the landscape, but it also radically remapped Britain’s economic and social terrain.

1. S. R. Hoyle, "The First Battle for London: The Royal Commission on Metropolitan Termini, 1846," The London Journal 8, no. 2 (1982): 140–155, cited in Tom Bolton, "Wrong Side of the Tracks? The Development of London's Railway Neighbourhoods," paper presented at ACSP Conference, Philadelphia, November 2014.

As profit-making companies, they were motivated by the need for profitable routes and passengers to attract. Their initial attempts were to acquire ownership along the routes, which was also attained by standardizing architectural and design elements—such as sub-station buildings, bridges, and signs—to create a common visual identity to each company’s network. But as the rail networks expanded, the struggle shifted from fighting over territorial control along lines to a yet more lucrative objective: securing the most desirable positions for their terminals in London. The city of London was thus the prize, a strategic position in which these companies put their energies and resources, aspiring to tap its economic potential. This change from competition along routes to the battle for terminal locations in London was also reflected strongly in the intense struggle over the selection of locations for railway terminals.

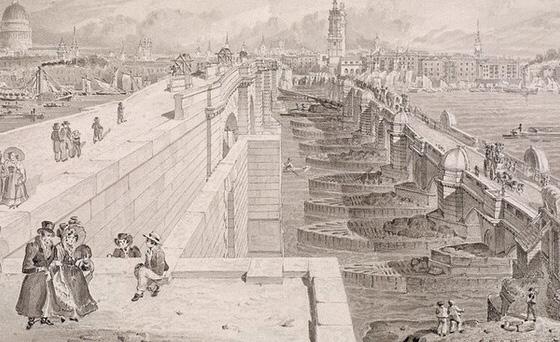

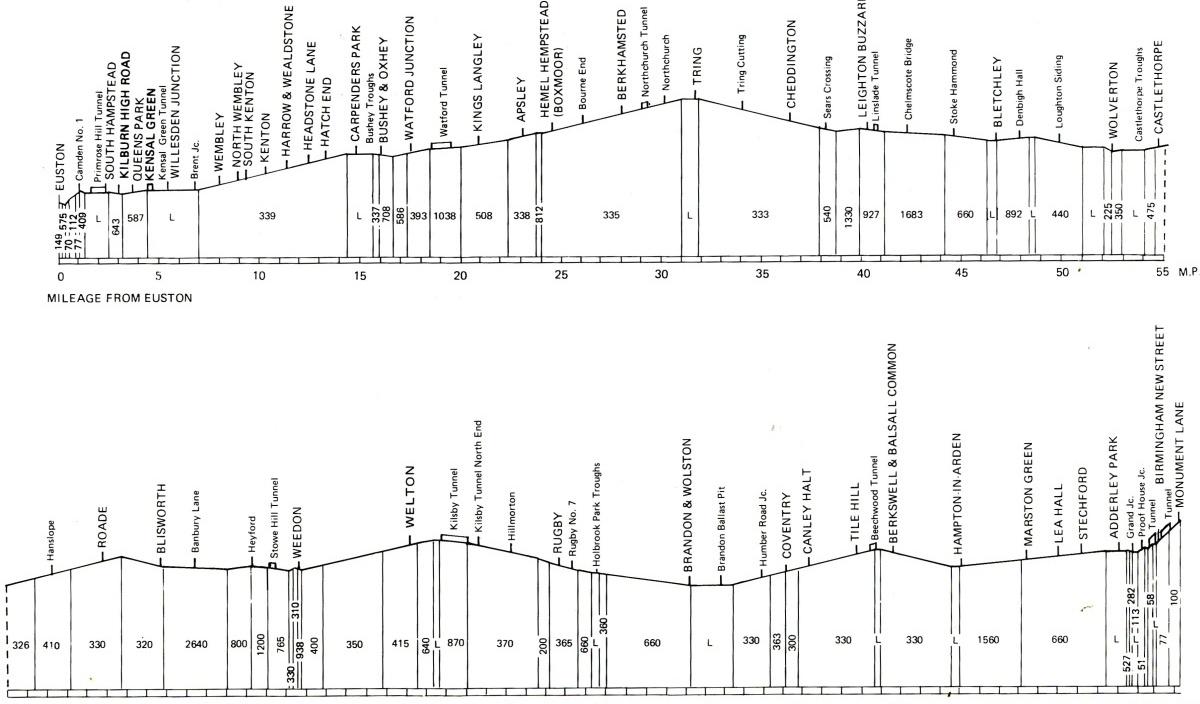

By 1846, the rapid expansion of railways had prompted the government to reconsider the impact of railway construction, with the fear that if the penetration of railways would be too aggressive on the fabric and environment of the city. This led to the Royal Commission establishing an exclusion zone, which kept railway lines from running through the centre of London. This action pushed railway terminals to the outskirts of the central city’s built-up areas, a legal principle that has had lasting impacts on London’s spatial organization.1 To this day, the contrast between inner London and its fringe remains the same: the city centre is effectively railway-line-free, whereas the fringe is heavily cut through by cuttings, embankments, viaducts, and service yards. This spatial contrast is excellently illustrated in modern railway maps, which mark the sharp edge between the central void and the vast network of tracks in the suburbs.

This division is further confirmed by the construction of the Underground’s Circle Line, whose northern part is also known as the Metropolitan Line, which parallels the historic boundary of central London. This alignment reasserts the age-old spatial ordering established in the Victorian era, as the Metropolitan Line

travels along the boundary along which railway termini were curbed.

This research places in the spotlight this, most particularly along the path of the Metropolitan Line, where Paddington, Euston, and King’s Cross stations lie. These terminals, as much or more than transport nodes, have been important nodes of civic existence for Londoners and have shaped the city’s urban dynamics in profound and fundamental ways. Their building design, with a distinct front-and-back separation, further entrenched their function as city gateways, channelling passenger traffic towards the streets opposite their fronts, which were linked to the city centre. Their legacy remains as a testament to the revolutionary impact of railways in reconfiguring the spatial and social landscape of Victorian London and beyond.

CHAPTER 1

CIVIC INFRASTRUCTURE

Chapter one analyses the role of railway terminals in addressing the potential absence of civicness during the Victorian era. The first subchapter examines the concept of civilization, which was formalized in the Victorian period through linear infrastructure, contrasts with the observable deficiencies in notion of civicness, related to political rights, labour conditions, and living standards of lower classes. It specifically underlines the construction background of the London & Birmingham Railway and its Euston Station terminal, proposing these architectural endeavours as potential mediators in societal conflicts. Upon this, the next subchapter provides introduction on the prototype of passenger railway terminal originally established in London, specifically focus on elements of porticos with its relation to the street as a conciliation to civil life. Finally, section three explores civil experience through an examination under the shed, and its influence on the notion of civicness spatially.

Nothing speaks the essence of a civilization more powerfully than its architecture. As the most outspoken one for the Industrial Revolution, it must be the room at the end of tracks, the railway terminals. CIVILIZATION, Not yet CIVICNESS 1.1

CIVILIZATION, not yet CIVICNESS

Shapes of factories, arsenals, foundries, markets, Shapes of the two-threaded tracks of railroads. Shapes of the sleepers of bridges, vast frameworks, girders, arches.

- Walt Whitman, 1860s.

2. Kenneth Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View (London: BBC and John Murray, 1969), pp.403–410.

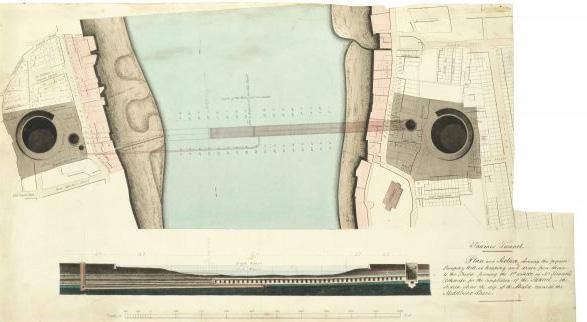

Kenneth Clark, in his seminal work Civilization, articulates that architecture serves as the most eloquent of these scripts, capturing the essence of a nation’s biography, revealing the underlying forces that shape its cultural and societal identity.2 In examining the notion of civilization in Britain, he traces it back to the Victorian era, where the extensive development of linear infrastructure— tracks, tunnels, and bridges—became a physical manifestation of Britain’s evolving self-image as a modern imperial power [8].This transformation was not merely an engineering feat but a reflection of the era’s ideological aspirations. At the core of this expansion was railway infrastructure, which not only triggered Railway Mania in the 1830s but also emerged as the most extensive and interconnected form of linear infrastructure. With its high-speed network linking cities, industries, and regions on an unprecedented scale, railways became the foundation upon which the Victorian notion of civilization was constructed.

3 Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s work, though not architectural, is key to this thesis for its analysis of railway infrastructure’s cultural impact. His interpretation of rail travel as a transformative experience helps frame London’s terminals as spaces shaping civicness through a new spatial perceptions.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), pp.16-17.

Although Clark is objective in a sense, the observation is sharp: The notion of civilization as in industrial revolution is not completely positive through the reading of civil life. Poverty and pollution are part of the subsequent outcomes. Before this, is the unswerving construction operated by different entrepreneurs. Based on the expectation of opening the London market, the railway lines are their battlefield. Schivelbusch complements this view financially by elucidating the distinctive nature of railroads compared to other linear infrastructures, focusing on the exclusive technological union of the locomotive and its tracks.3

Unlike the 18th-century roads and canals, where users could traverse using their own or hired conveyances and pay tolls for access, railroads introduced a tightly integrated system where the infrastructure and vehicles were inseparably linked.4

This marked a significant departure from earlier transportation methods, which allowed for freer, more liberal use of the infrastructure. In this new paradigm, private railway companies not only owned the tracks but also operated the trains, establishing vertically integrated control over the entire transportation process.

4 Ibid.

This monopolistic control contrasted sharply with previous systems, where the infrastructure—whether road or canal—was merely a venue used by various independent operators. Railroads thus shifted the economic landscape from a competitively open market to one dominated by a few powerful entities. Within this framework, competition existed primarily between different railway companies rather than among multiple users of a single infrastructure.

On the other hand, ordinary people have no access to political decision-making and are unable to influence the process of infrastructure development. Because, before 1832, voting rights in London and across the Great British were primarily restricted to property owners, reflecting a political system where power was

5. Acts Relating to the London and Birmingham Railway: viz. 3 Gulielmi IV. Cap. xxxvi; 5 & 6 Gulielmi IV. Cap. lvi; and 1 Victoriae, Cap. lxiv: With a General Index (London: George Eyre and Andrew Spottiswoode, Printers to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1837).

6. Lord Southampton, with significant landholdings near the proposed London and Birmingham Railway routes, played a crucial role in the railway’s planning discussions.

concentrated in the hands of wealthy industrialists and landowners. This was mirrored in the struggles between railway company boards and landowners along the proposed routes. A vivid example of this struggle among capital owners shaping the railway terminus is The Act of 3 Gulielmi IV, Cap. xxxvi5, a legislation redefining legal permissions for railway construction initiated by the council. The passage of this act directly impacted property rights along the route, particularly for those whose lands were designated for railway construction. This act smoothed the conflict between the London and Birmingham Railway and Lord Southampton concerning property disputes, enabling the board of directors and Lord Southampton6 himself to reach a consensus on the profit potential of the Euston terminal. Regardless, the decision to establish the terminal at Euston was made during a planning phase, dominated by considerations of profitability and competition among railway companies, demonstrating the decisive influence of the upper classes.

In parallel to this is the ignorance of individuals’ will, there was also a loss of political identity. Matthew Cragoe highlights the limitations of the electoral reforms of the 1830s. Despite the Great Reform Act of 1832 which has increased the recognition of citizens' rights and responsibilities, it still left ambiguities in providing a stable political identity for large number of individuals.7 Its limitation lies in the maintenance of property-based qualifications for voting, which continued to exclude many the working class and all women from voting. This meant that political power remained largely in the hands of the wealthier classes, while all women, most working-class men, and the poorest segments of society were excluded from the right to vote.

7. This act has expanded the electorate to some degree by addressing the process of annual voter registration. Besides, it has eliminated some corrupt constituencies. By Matthew Cragoe, “The Great Reform Act and the Modernization of British Politics: The Impact of Conservative Associations, 1835–1841,” Journal of British Studies 47, no. 3 (2008), pp. 602-603.

Upon the price of their competing, is the tremendous work taken by the labour.

The construction efforts documented in the Tring Vestry Minutes from 1837 epitomize this phenomenon. The records describe Upwards of a thousand men... engaged in making the Tring railroad cutting, a testament to the vast human labour invested in transforming the landscape with simple tools.[10] The illustrations portray three fundamental tools from the early railway construction era, each demonstrating the rudimentary and labour-intensive nature of the equipment used during the 1830s.

The first tool, a manual wooden crane, required a significant amount of human effort to operate, using a system of pulleys and levers to lift heavy materials. Its simple design lacked sophisticated safety mechanisms, making it a risky tool for workers. Next, a basic wheelbarrow is shown, essential for transporting smaller loads of earth or construction debris. Despite its simplicity, the physical labour involved was substantial and inefficient over longer distances. Finally, a horsedrawn cart is depicted, which, while more effective for moving larger quantities of materials, still relied heavily on animal and human exertion. The rough terrain and primitive construction of the cart often resulted in unstable and unsafe conditions, highlighting the era's reliance on basic mechanical aids and the significant risks to worker safety.

8. Here, 'personal' does not refer to a single, specific person but rather to the engineers leading railway design and the decisive role played by the board of directors, representing a form of heroism that is disconnected from the common people. By Kenneth Clark, Civilisation (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1969), pp. 335-341.

This endeavour illustrates the material heroism that Clark discusses, where human effort significantly reshapes the natural landscape in order to fulfil the operation of new technology. The alteration of the landscape prior to the railways is captured by the gradient profile of the railway cutting, indicating the transformative impact of this infrastructure.

Led by the London & Birmingham Railway Company, the railway’s construction was not just an engineering achievement but also a bold statement of humanity’s capacity to reshape its surroundings.

William

2008).

The term heroic materialism, also the title of the last chapter of Civilisation, underscores the limitations of focusing solely on the heroic personal8 achievements of the era. He candidly describes the Victorian era as synonymous with hypocrisy, where superficial decency and grandeur masked a neglect of the needs of the lower classes as well. The individual heroism embodied in the construction of railways, seen as a bold conquest over nature, contrasts sharply with the social inequities of the time. William Blake's Selected Poetry9, further reflects on the contrasts and tensions between civilization and civicness of the time:

"In every cry of every Man, In every Infant's cry of fear, In every voice, in every ban, The mind-forged manacles I hear"

This excerpt critiques the superficial splendour of society juxtaposed against the harsh realities of life for the common people. The golden shining of industrialization didn’t illuminate the lower class, mental and psychological constraints and suffering were haunting because of the widespread misery and alienation felt by its inhabitants. Although the existence of civilization is undeniable during the Victorian era, this disjunction emerged between civilization and civicness.

10. Adalbert Evers, “Civicness and Civility: Their Meanings for Social Services,” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 20, no. 3 (September 2009), pp. 242-245, https://www. jstor.org/stable/27928170.

Evers notes that the notion of civicness encompasses the concepts of the state and citizenship, hinging on the extent to which individuals recognize themselves as citizens10 and, conversely, the extent to which the state recognizes individuals as citizens. In this sense, individuals' opinions, labour, and even lives are often deemed irrelevant, and the absence of voting rights makes it difficult for them to construct their political identities through citizenship. Therefore, the grandiose imagery and implications suggested by civilization are vividly displayed in the construction of railway corridors, an occurrence that parallels the absence of the concept of civicness in early Victorian times.

PORTICO & ITS URBAN GLORY ARRIVING at the CITY 1.2

With the railway mania of 1830, Gothic pomp and circumstance had faded, and the church was to the old era while the railway terminals was to the new.

13

ARRIVING AT THE CITY

The entrance to the London passenger station, opening immediately upon what will necessarily become the grand avenue for travelling between the Metropolis and … Kingdom, ...They adopted, ... grand but simple portico, which they consider well adapted to the national character of the undertaking.

- Directors’ Report to the Proprietors, February 1837.11

11. “Directors’ Report to the Proprietors, February 1837,” The Euston Arch - Shall It Rise Again?, June 17, 2013, accessed February 15, 2025, https://the-lothians.blogspot. com/2013/06/the-Euston-arch-shallit-rise-again.html.

12.The Train Now Departing offers a detailed account of the L&BR’s development, covering its legal foundations, construction negotiations, and early operations. It serves as a key reference for analyzing Euston Station’s formation, particularly in Chapter 1.

Peter H. Elliott, The Train Now Departing: Notes and Extracts on the History of the London and Birmingham Railway (Tring: Tring & District Local History & Museum Society, 1986), accessed February 15, 2025, https://tringlocalhistory.org.uk/ Railway/c11_stations.htm

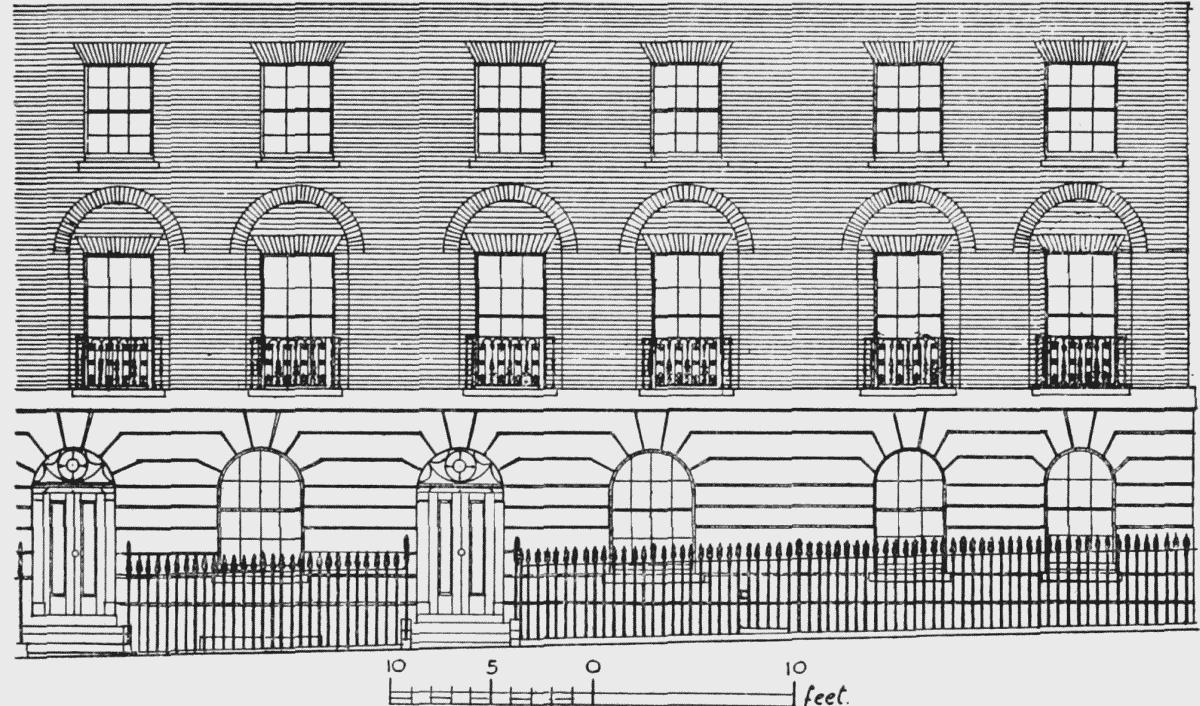

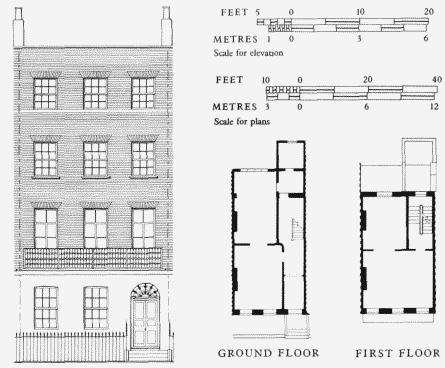

As Britain’s first trunk railway, the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) laid the foundation for subsequent railway expansion, demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale passenger transportation. Despite a contemporary perspective that often views railway infrastructure as a means of social welfare, the original impetus for constructing railway stations was predominantly driven by profit motives. This focus on financial gain is apparent in the design and operational strategies of wayside stations, which primarily served rural localities. At its inception of L&BR construction, sisxteen intermediate stations were established and classified into first- and second-class categories. First-class and mail trains stopped only at first-class stations, while mixed and second-class trains stopped at all stations. 12

First-class stations, as documented in Peter Lecount's A Practical Treatise on Railways, were designed to accommodate more complex operational requirements along the railway corridor, functioning as programmatic extensions of its infrastructure. 13 Watford Station, for instance, was constructed in 1836 as a modest single-story red brick building, serving the initial segment of the L&BR between London and Boxmoor. Positioned alongside the corridor, it housed firstand second-class waiting rooms, a departure area, a carriage shed, and an engine house, reinforcing its alignment with the operational flow of the railway rather than engaging the urban front directly.

13. Peter Lecount, A Practical Treatise On Railways: Explaining Their Construction And Management (1839; repr., 2008).

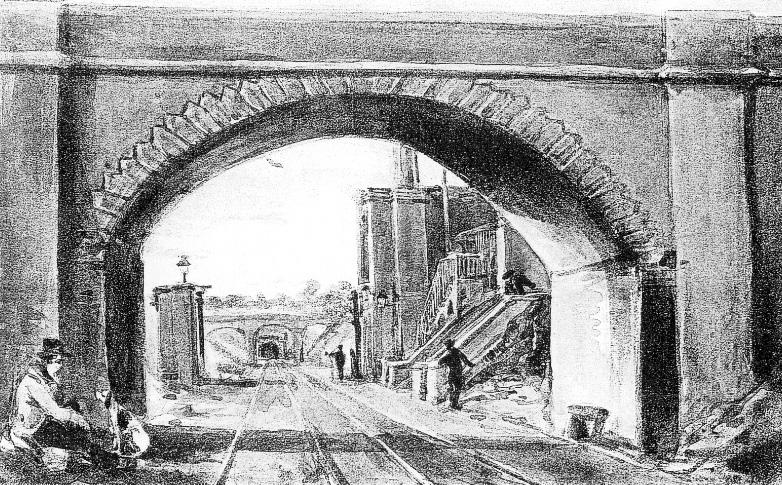

As railway corridors extended toward central London, the design of terminal stations presented a critical challenge—reconciling technological advancements with the rhythms of civic life. Unlike city streets, which become extensions of the urban environment, railway termini tended to be standalone landmarks on the periphery of the city, more portals than extensions of the urban environment. Here, they were important thresholds, creating a transition from the periphery to the city center. Having in mind the necessity to create an interface both aesthetically and functionally appealing to the city's demands, the managers at Euston Station expressed publicly the urgency of the terminal to be not only visually attractive but also an integral part of urban life, as stated previously. This was a pivotal moment in railway architecture, wherein the station is now no longer merely an endpoint of the corridor, but an intervention into buildings that responded to more universal civic issues.

14. Carlton Joseph Huntley Hayes, Essays on Nationalism (New York: Macmillan, 1926), p. 162.

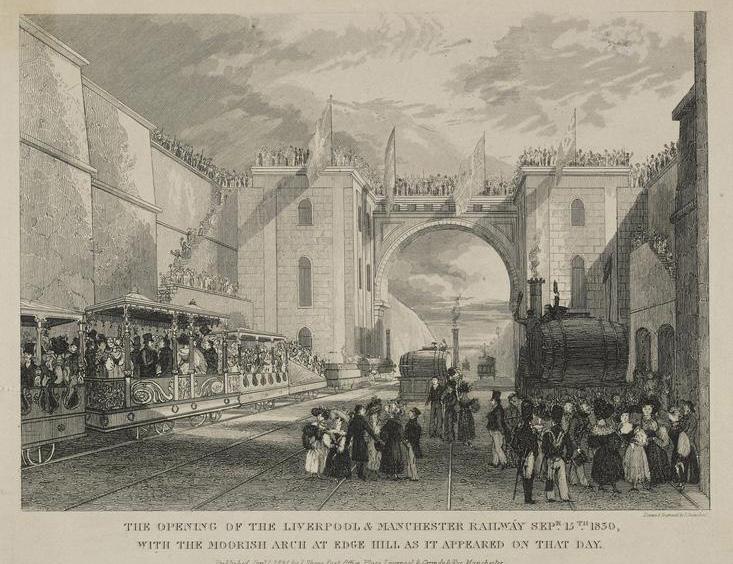

The Euston Arch was designed by architect Philip Hardwick in 1837, not merely setting a typological precedent for railroad stations, but also serving as a prototype for negotiating the transition from street to station.

15. Jack Simmons, "Railways, Hotels, and Tourism in Great Britain 18391914," Journal of Contemporary History 19, no. 2 (1984): 201-222, https://www.jstor.org/stable/260593, accessed pages 20-22.

Functionally differentiated from earlier side-station forms, the latter characteristically dividing or excluding lower classes, Euston's grand but open to all portico was an act of unification, leveling social differences between civic elites and working people. Integral to this was architectural and ideological inclusion, extending indiscriminate welcome to all travellers.

Its shape, adapted from a Doric portico, was an echo of the classical tastes of ancient Greek temples, intended to produce seriousness and permanence. Aside from its stylistic references, monumentality of the terminal also performed a psychological role in assuaging anxieties regarding new railroad technology, making the station a part of the larger civic life. As Carlton Joseph Huntley Hayes has discussed, monumental achievements were key in the construction of collective national pride:14

"The most poverty-stricken patriot in the East End of London is apt to swell out his chest when he thinks of England’s industry and wealth, for is not England’s wealth his?"

The Euston Arch not only promoted civic identity and facilitated Londoners' spatial identification with the city but also played an essential part in deciding the station's spatial order. Positioned perpendicular to the railway corridor, the portico established a pronounced axial relationship, reinforcing the directional emphasis of the corridor while structuring the terminal’s urban approach.

In terms of functionality, the portico and barriers provide security control, managing the entry and exit of personnel and logistics. Its design has set a paradigm for organizing passenger flow within railway stations, featuring a prominent main entry that directs passengers inside, complemented by smaller exits to optimize departure processes.

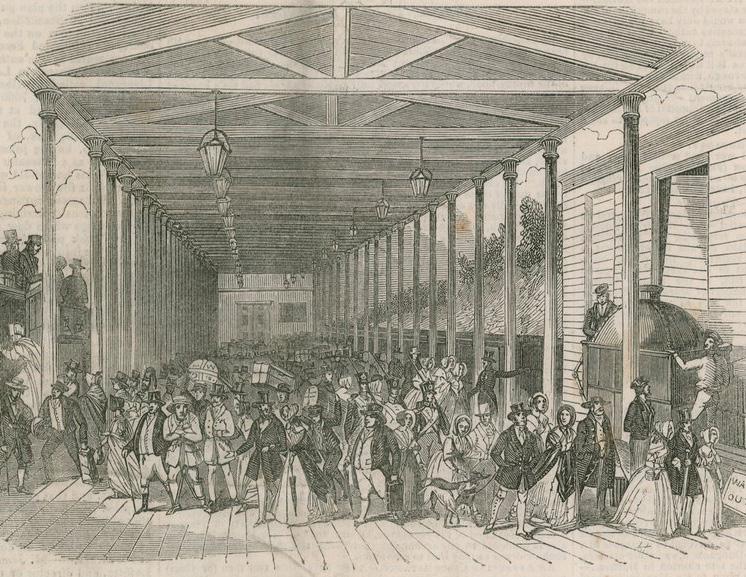

Over the next two years, the London & Birmingham Railway (L&BR) took steps to improve train travel. Initially, the early train carriages were simply modified coal transport wagons, offering very little comfort. The third-class compartments, in particular, were quite basic and did not provide any shelter, leaving passengers exposed to the weather. This made the travel experience quite harsh, especially during bad weather, as passengers had to endure the elements without any protection.[16] In response, and to attract a broader clientele, L&BR introduced the first railway-controlled hotels at Euston Station.

Opened in 1839, the Euston Hotel and Victoria Hotel were symmetrically positioned on the east and west sides of the Euston Arch, further reinforcing the station’s axial organization and enhancing the structured transition between the city and the railway.[19] Functionally, the Victoria Hotel served exclusively as sleeping quarters, prioritizing comfort and privacy while avoiding the distractions of a traditional inn, such as the sale of alcohol.

Managed by a company-appointed supervisor, it was designed to function as a respectable establishment, more akin to a private club than a public tavern.15 In contrast, the Euston Hotel was leased out, offering a higher standard of hospitality and service for overnight stays. Together, these two hotels represented an early experiment in integrating hospitality directly within railway infrastructure. Catering primarily to middle-and upper-class passengers, they provided immediate accommodation upon arrival in London.

This integration not only met the immediate needs of weary travellers but also set a precedent for railway stations as temporary urban habitats. In doing so, it redefined the railway terminus as a destination where extended service offerings transformed the experience of travel, positioning the passenger as an active participant rather than a transient occupant. This arrangement structured the transition between the city and the railway while simultaneously reinforcing the terminal’s monumental presence.

By guiding passenger movement through its directional framing, the design enriched the experience at what was initially conceived as the endpoint of the railway journey, extending the spatial and experiential scope of terminal infrastructure beyond mere transit.

Entrance Portico - Euston Grove Station, 1838.(Source: The British Museum)

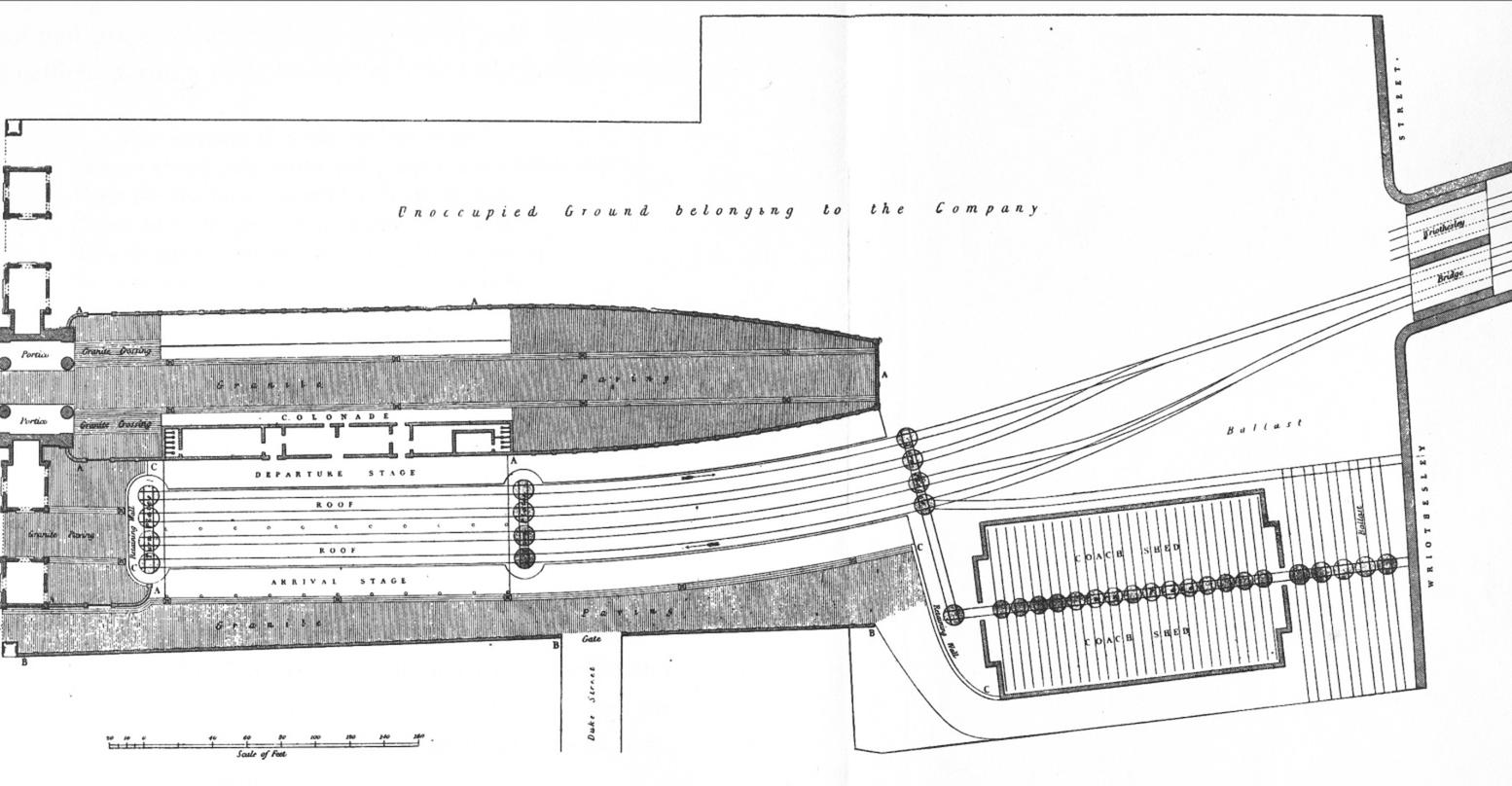

Fig.18: Ground Plan of Euston Station, 1838 - Public domain map. (Source: GetArchive)

Fig.19: London & Birmingham Railway 1839. (Source: Historic England)

WAITING HALL AS THE CIVIC SPACE WAITING in the TERMINAL 1.3

"Thus, when I am travelling, I lose the best part of my pleasure if I cannot wait a long time in the station for my train."

WAITING IN THE TERMINAL

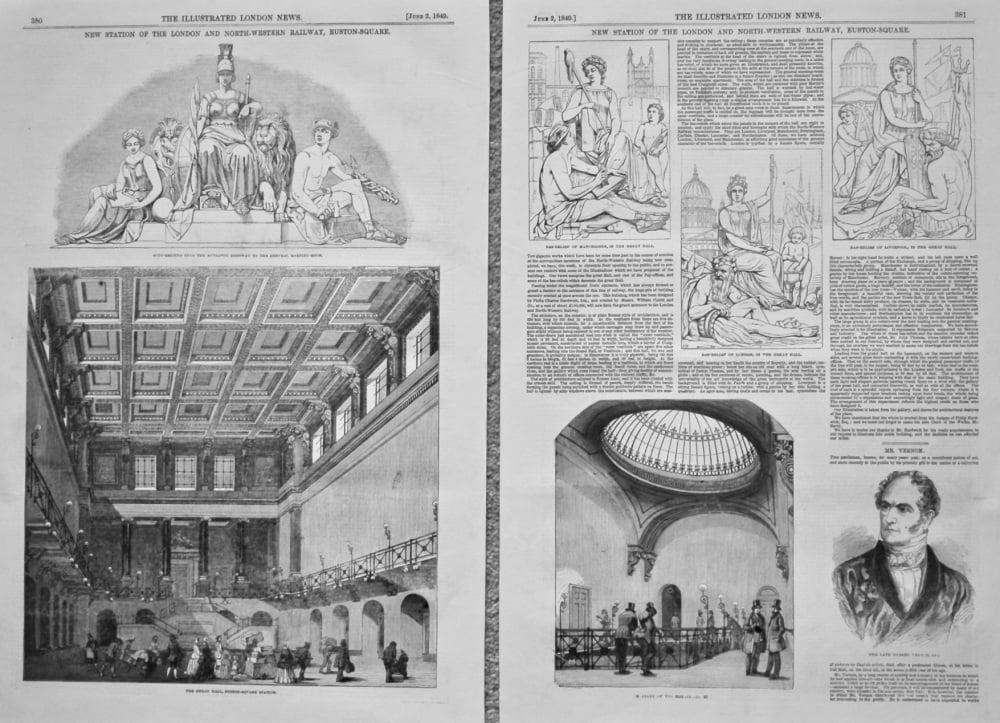

“Years ago, when hard up, I had the largest study any author ever had. It was the Great Hall at Euston Station, which was then set with tables and chairs; many of my early poems and stories were written there.”

- Agatha Christie16

16. Though it’s uncertain whether Agatha Christie or some lesser-known writer penned this, it remains a subject of speculation. Daily Mirror, 1931, cited in Will Noble, “Wish You Were (Still) Here: Euston Station’s Great Hall,” Londonist, https://londonist.com/london/ features/wish-you-were-still-hereeuston-station-great-hall.

17. Thomas Stretch Dowse, The Brain and the Nerves: Their Ailments and Their Exhaustion (Spain: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1884), pp.3-7.

18. Joseph Hayes, “The Victorian Belief That a Train Ride Could Cause Instant Insanity,” Atlas Obscura, May 12, 2017, https://www.atlasobscura. com/articles/railway-madness-victorian-trains.

The unprecedented speed of railways, far surpassing that of horse-drawn carriages, brought unparalleled convenience to Victorian society. However, it also sparked widespread skepticism and concern. This anxiety was fueled not only by the physical dangers of early train travel—such as the lack of roofs in third-class carriages until 1844 and the absence of lighting and corridors in most compartments—but also by the psychological toll of navigating an unfamiliar and unpredictable mode of transportation. Passengers were vulnerable to threats ranging from pickpockets to swindlers, and the relentless noise and motion of trains instilled a deep-seated fear.

These concerns culminated in the pervasive belief that railway travel could provoke mental illness, giving rise to the concept of the railway madman[23].

Public perception held that the stress and unpredictability of train journeys could trigger uncontrollable behaviors in passengers, behaviors that would otherwise remain uncharacteristic under normal circumstances.

19. F. M. L. Thompson, “Social Control in Victorian Britain,” The Economic History Review 34, no. 2 (May 1981), p.207. https://doi. org/10.2307/2595241.

interventions.19 The establishment of Euston Hall exemplifies this principle, demonstrating how spatial design could address the challenges of regulating passenger behaviour and fostering civic order.

In the late 19th century, psychologists such as Dowse discussed how stress, including railway travel, contributed to what he and others termed neurasthenia, a condition seen as a precursor to what is now recognized as chronic fatigue syndrome.17 He elucidated that the metal vibrations within railway carriages could have catastrophic effects on an individual’s nerves, and it was unpredictable who might go insane as a result.18 Cited by Dowse, he quoted the word of another professor, Amy Milne-Smith: “Not only could you be attacked by a madman during a railway journey, but you also stood a chance of becoming one yourself.” This insight is contextualized by the previously mentioned layout of train carriages, which were compartmentalized and smaller, unlike the open-plan carriages seen today.

Once a train departed from the station, passengers had no means to exit the carriage, intensifying their vulnerability and the fear of encountering or becoming a madman. This connection between railways and madness was thus established, with the Victorians treating what we would now describe as akin to post-traumatic stress disorder as a form of nervous disorder.

The cramped conditions of railway compartments and the moral anxieties they provoked in the early years of railway travel illustrate the limitations of legal regulations in governing public behaviour when spatial conditions are inadequate. Much of the unease and discomfort stemmed from the lack of spatial order and structured environments, highlighting the need for material interventions to shape societal norms. As Thompson argues, material environments exert a more decisive influence on shaping societal norms than direct legal or institutional

Billy Ehn and Orvar Löfgren, The Secret World of Doing Nothing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), p.32, https://www.jstor. org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppjkh.5.

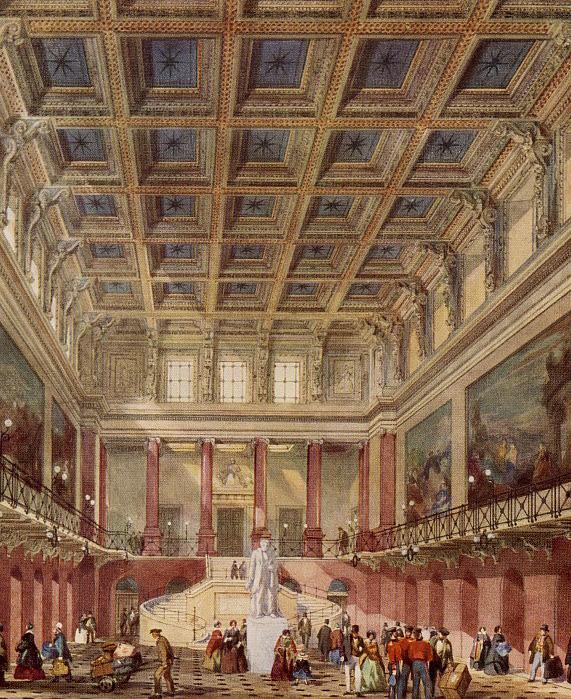

The formation of the London and Northwestern Railway in 1846—through the merger of the London and Birmingham Railway, the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, and the Grand Junction Railway—established Euston as the company’s headquarters. This consolidation not only necessitated administrative expansion but also underscored the need for a structured spatial environment to manage increasing passenger flows. In response, the Great Hall was constructed in 1849, aligned along the same entry axis as the Euston Arch, guiding passengers through an open forecourt into the main hall. The waiting areas were positioned between the servant spaces on either side, structuring movement within a controlled spatial framework. To the left, an office area was organized along a continuous corridor, consolidating administrative functions. To the right, the ticketing zone extended through a perforated structure, providing direct access to the platforms. These service spaces, derived from the earlier trackside station buildings of Euston Station, were reconfigured into a more cohesive and spatially efficient composition [Fig.24 & 26], integrating operational and passenger facilities within a unified architectural framework. This spatial arrangement reinforced circulation as a mechanism for behavioural regulation, transforming the station into a site where civic order could be actively enforced through design.

The Great Hall’s design conveys a profound sense of monumentality and solemnity, not only in its plan organization but also in its perspectival experience. Its grand proportions, soaring ceilings, and rhythmic colonnades establish a dramatic visual sequence. The juxtaposition of human scale against the vast architectural volume heightens its symbolic weight, transforming it into both a functional transit space and an enduring emblem of order and permanence. Classical references, strict symmetry, and axial alignment further enhance its ceremonial quality, evoking the dignity and discipline embedded in Victorian railway travel[25].

In 19th-century Europe, middle-class virtues such as patience, self-discipline, and foresight were embodied in the regulated practice of waiting.20 By idealizing order and punctuality, the middle class distinguished itself from both the perceived indulgence of the upper class and the immediacy of the working class.

However, railway stations, as shared public spaces, did not inherently privilege one social class over another. Instead, they transformed waiting into a universalized civic discipline, where order and decorum were not merely social expectations but essential conditions for shared use of space. In this context, the waiting hall emerged as a key architectural tool for regulating passenger conduct. Its spatial organization not only facilitated movement but also actively structured social behaviour, reinforcing expectations of patience, order, and propriety within railway stations.

Rather than being dictated by social hierarchy alone, civic order was increasingly embedded within spatial experiences and behavioral expectations that applied to all passengers, regardless of class.

The waiting hall, through its structured organization and emphasis on regulated movement, became a site where civic identity was both reinforced and enacted, shaping public conduct through material and spatial means rather than direct enforcement.

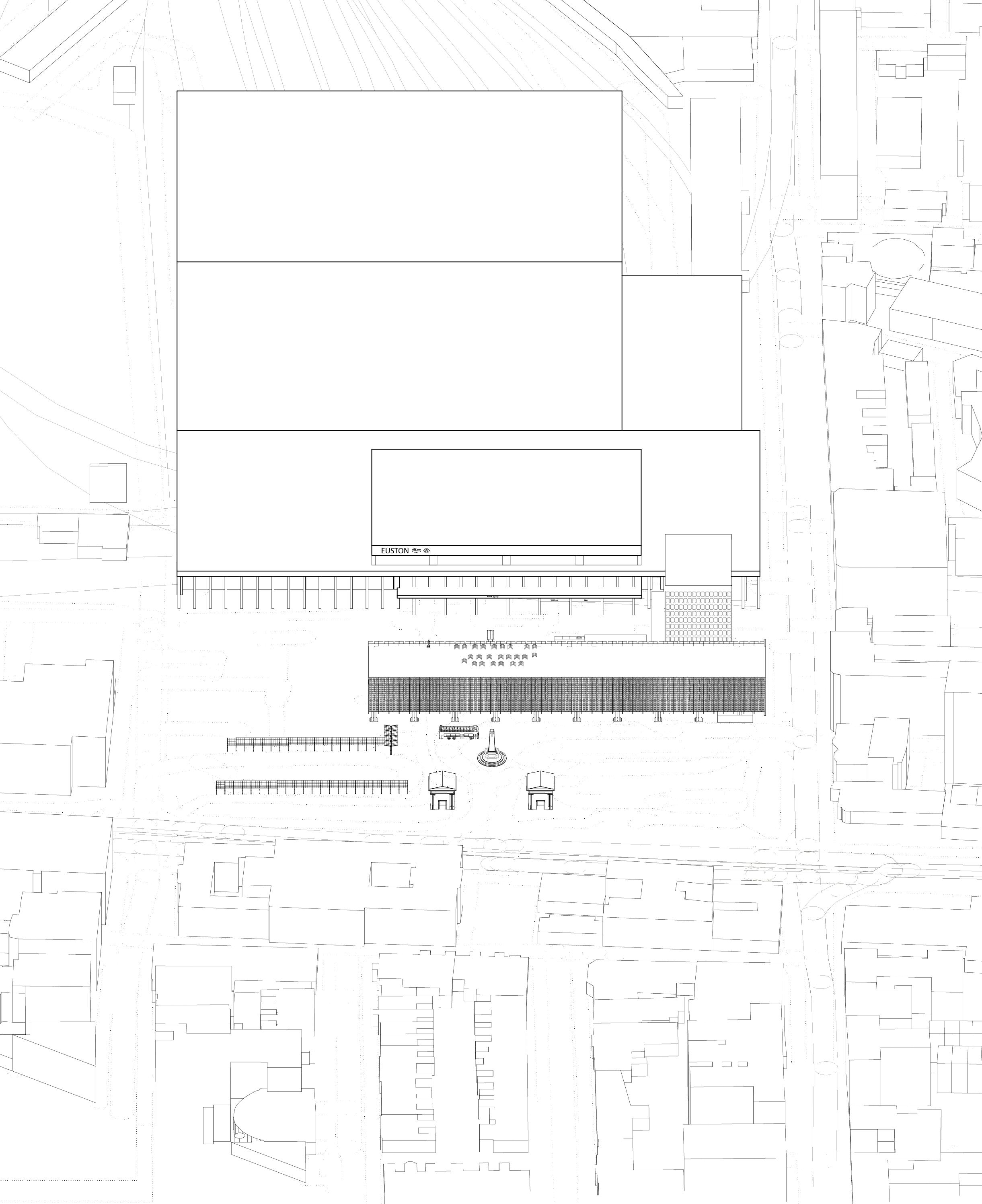

However, after the nationalization of British railways in 1948, British Railways proposed the reconstruction of Euston Station. By 1961, most of Euston Station was demolished, including the Euston Arch and Great Hall. The new station was constructed horizontally in front of the railway corridor, with the two remaining lodges of the Euston Arch standing at a distance, disconnected from the station’s new spatial composition.

The central waiting area in the new terminal was embedded within a commercial enclosure, flanked by retail stores and ticketing areas on either side. Unlike the dual-directional Great Hall, which emphasized spatial centrality and reinforced its role as a focal point for congregation, the new waiting area functioned primarily as a passage space with direct access to the platforms. Lacking the directional emphasis and guiding role, it was designed to facilitate the dispersal of passengers into surrounding commercial areas. This shift reflects a reconfiguration of the terminal’s spatial logic, where circulation was no longer orchestrated through a central monumental space but instead fragmented into a system that prioritized commercial engagement over civic cohesion.

CONCLUSION

PORTICO AS A CIVIC GESTURE

The conclusion for chapter 1 starts with the introduction of the portico, which was the very first gesture that incorporated citizenship into terminal architecture, marking the initial connection of civicness with the design of railway infrastructure.

21. Luca Molinari, cited in Ilaria Baratta, “The Ideal City of Urbino: One of the Mysteries of the Early Renaissance,” Finestre sull’Arte, accessed December 10, 2024.

The significance of the Euston Arch transcends its immediate utility. Echoing the grandeur of the Acropolis’s Propylaea, the arch was more than a functional or symbolic element; it served as a cultural beacon during a period marked by stark industrial transformation. This architectural marvel was a deliberate attempt to meld the often-grim aesthetic of industrial progress with classical beauty and prestige, thereby elevating a mere commercial enterprise to a symbol of urban elegance. Additionally, the adjacent hotels, along with postal and telegraph services, enriched this civic space, offering amenities that extended beyond mere transit, reflecting a sophisticated integration of utility and cultural enrichment.

Similar to the subtly opened central door in the painting that serves as a symbolic threshold as Luca Molinari21 described:

"(It is) a gateway that invites entry yet delineates the boundary between the city of men and the city of God..."

The Euston Arch serves a similar purpose. It acts as an elemental form of transition between place and utopia, a conduit between two worlds. Likewise, the entrance portico of Euston Station emerges as a transitional space between the external world and the new journeys brought forth by the Industrial Revolution, facilitating an entry into a utopia performance completed by industrial progress.

The portico, while aesthetic and symbolic in purpose, was also compensatory— both for the exploitation of labour involved in railway construction and for the bare, utilitarian nature of industrial infrastructure otherwise. Railway expansion was based upon strenuous physical labour, as workers endured dangerous conditions to reshape the landscape and construct monumental buildings.

Instead of acknowledging such things explicitly, the Euston Arch projected a refined, civic image onto the railway infrastructure, softening its association with the social inequalities that had enabled it. For all the superficiality of the gesture—a veil of architecture over the mechanized processes of industrial capitalism—it effectively redirected public opinion, reaffirming the image of railway stations as a site of grandeur and civic pride, rather than merely as sites of economic extraction.

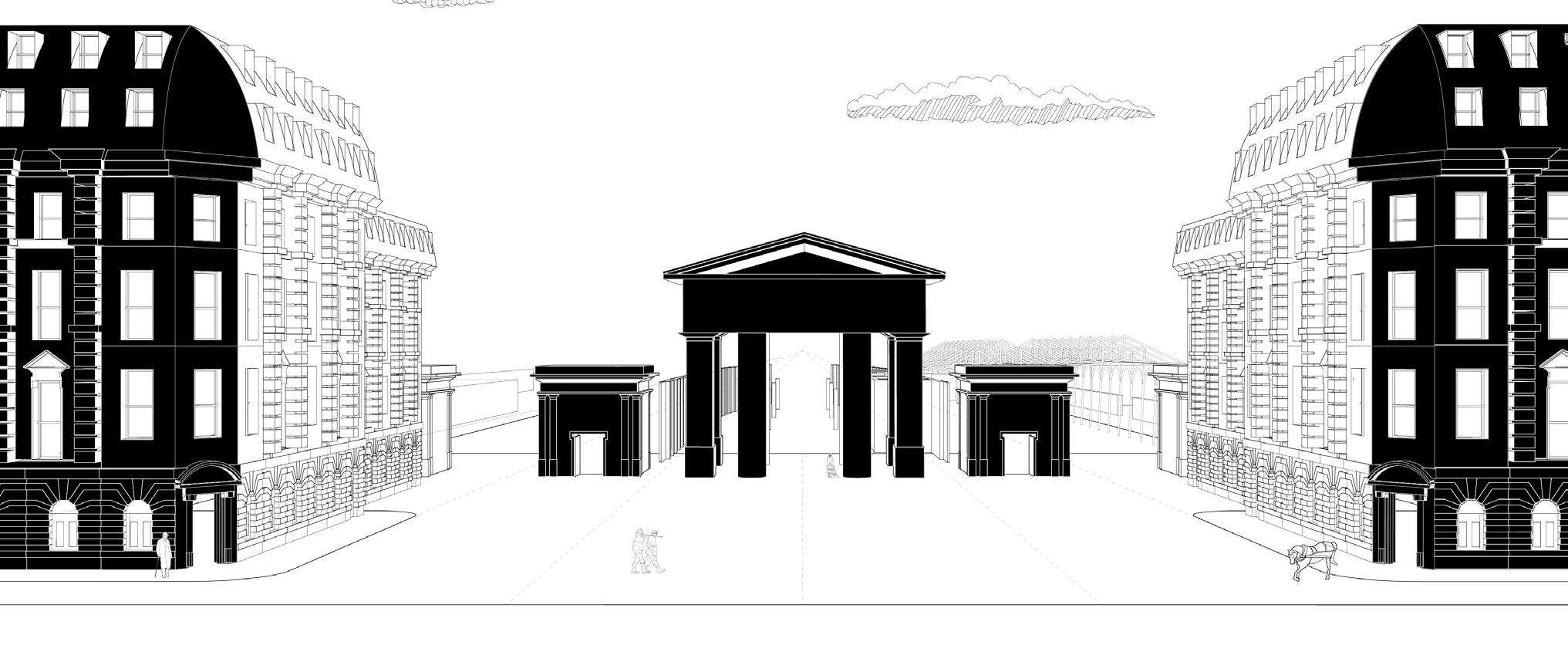

RAILWAY ENSEMBLE AS IDEAL LANDSCAPE

The ensemble of portico and railway hotels is a quintessential instance of Victorian London's ideal of a post-industrial landscape, embodying tangibly a wished-for state for an enriched life in railway travel experience, evoking the concept of the Idea City by incorporating classical architectural monumentality with the modern convenience of railway travel. Such a combination not only concentrates the urban experience but also represents an enriched lifestyle, placing the railway at the hub of city life and resonating with the ambitions of a post-industrial landscape.

These structures were Victorian London's ideal of a post-industrial urban form, integrating the advancements of the Industrial Revolution into the daily life of its inhabitants, such as the design observed in The Ideal City. With structures such as an amphitheatre and octagonal structure bilaterally positioned on either side of a central arch, these designs evoke the Roman Colosseum and medieval baptisteries or temples, as classical structures symbolizing the essential civic virtues of safety, religion, and entertainment. Similarly, the hotels and lodges close to Euston Arch, which were constructed in a neoclassical style, illustrate how a well-planned post-industrial city balances social welfare with urban planning. This equilibrium of functionalism and aesthetic ambition illustrates an interest in enhancing civic life, which is supported by the construction of railway infrastructure.

Consequently, the transformation of the terminal space from a mere point of entry to a profound statement on civicness underscored the construction of civic pride, celebrating the fusion of functional infrastructure with a refined urban aesthetic.

THRESHOLDS AS ORDER

The layered thresholds of Euston Great Hall reinforced the welcoming nature of the central axis established by the portico while simultaneously articulating a hierarchy of privacy and publicity. Sequentially progressing from the portico to the plaza, through the vestibule and hall, and ultimately to the secluded office entrance, this spatial arrangement structured access and movement with clarity and order[35].

The lateral porosity of the design hinted at auxiliary functions such as ticketing and service areas, further facilitating passenger circulation and ensuring seamless boarding[36]. This perpendicular guidance system not only defined varying degrees of publicness within the terminal but also reinforced structured movement, shaping passenger behaviour and enhancing spatial experience.

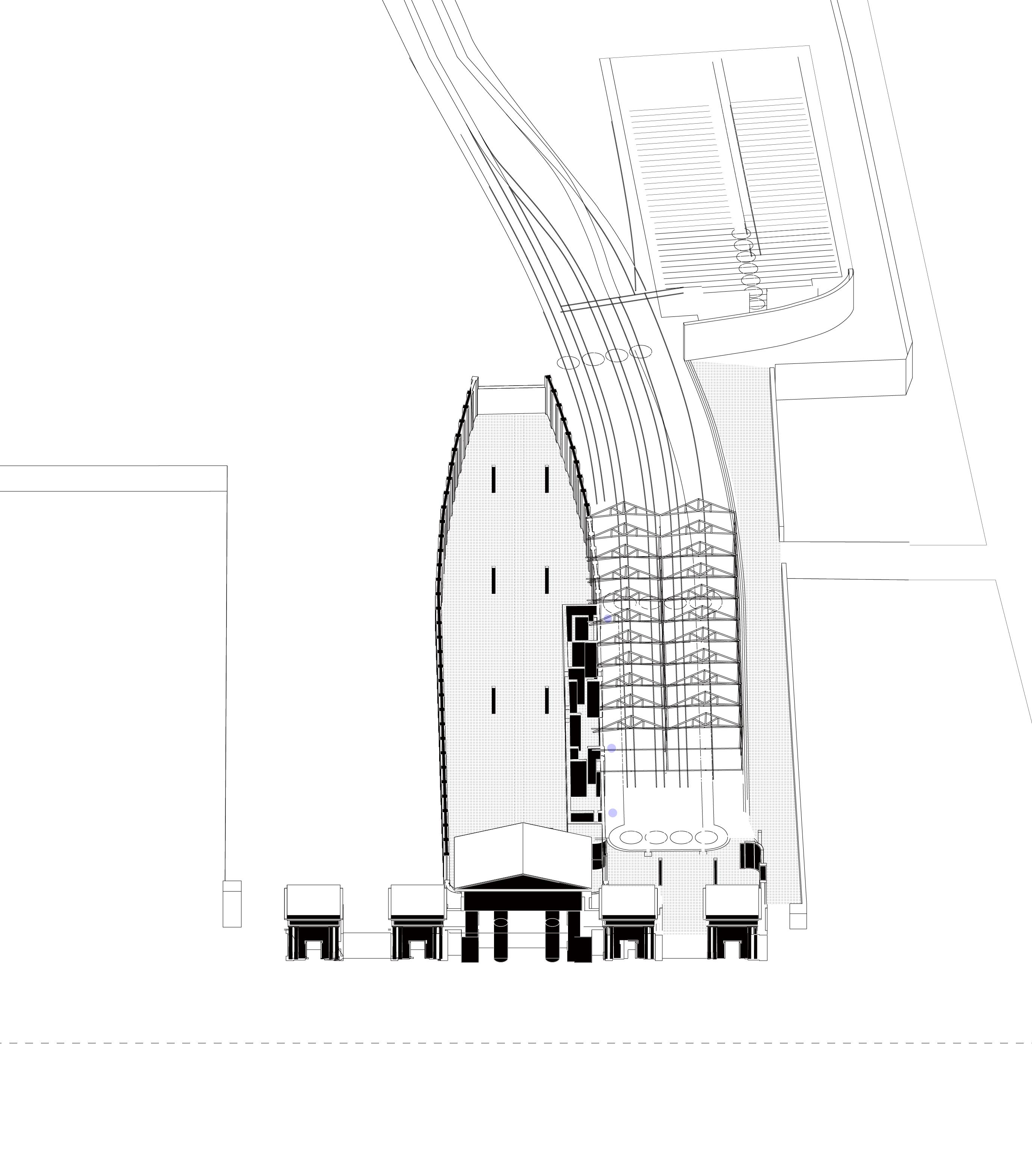

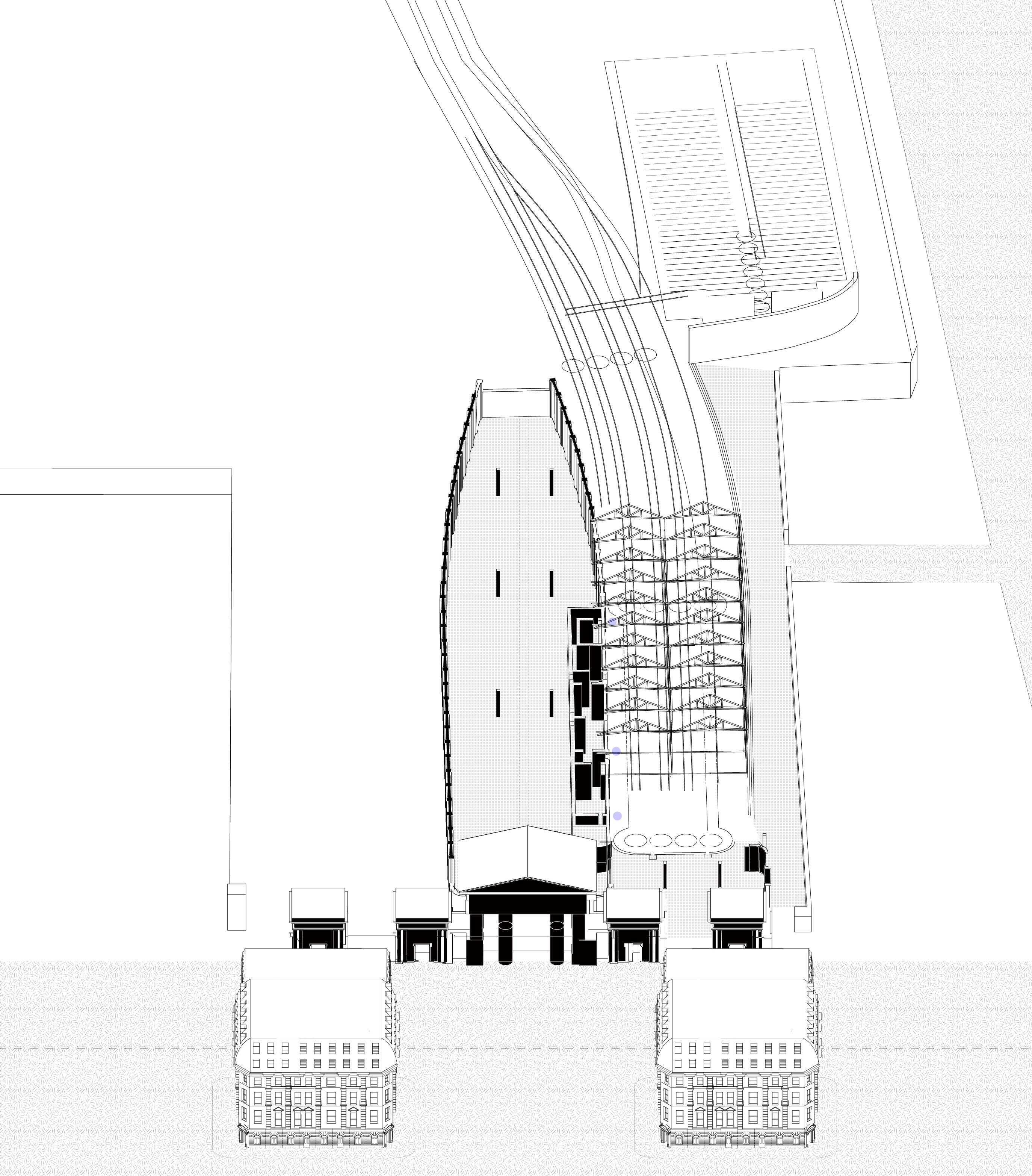

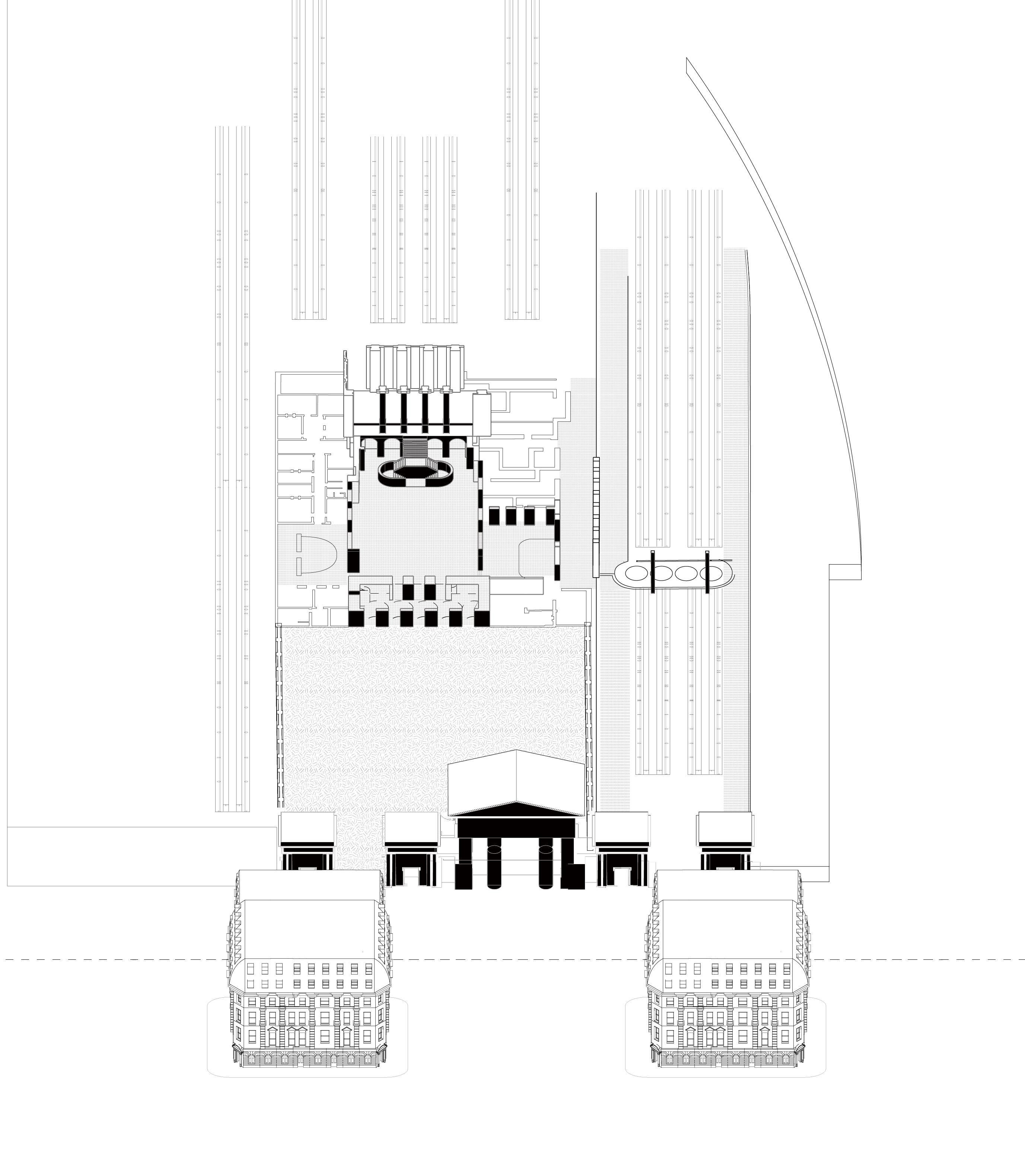

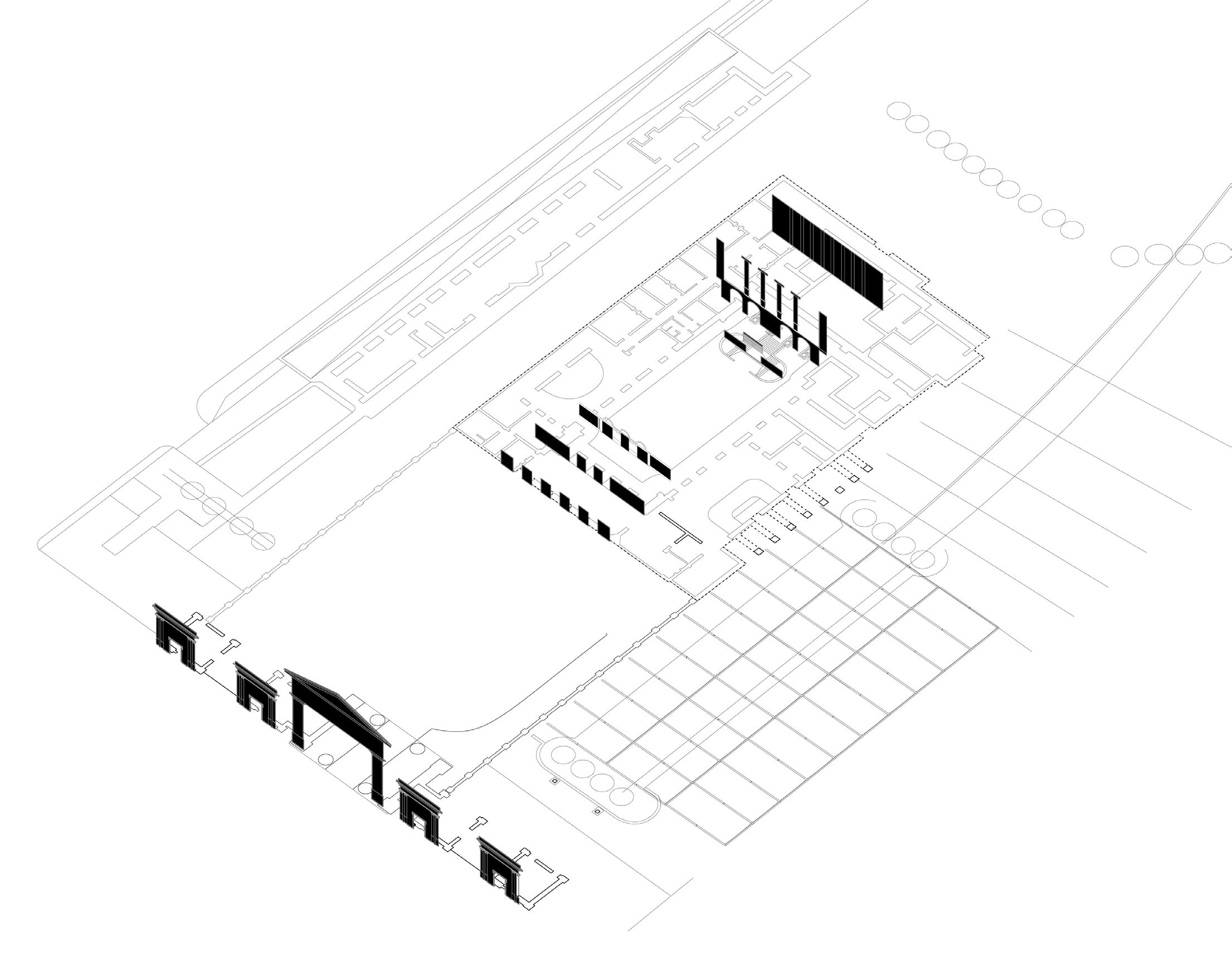

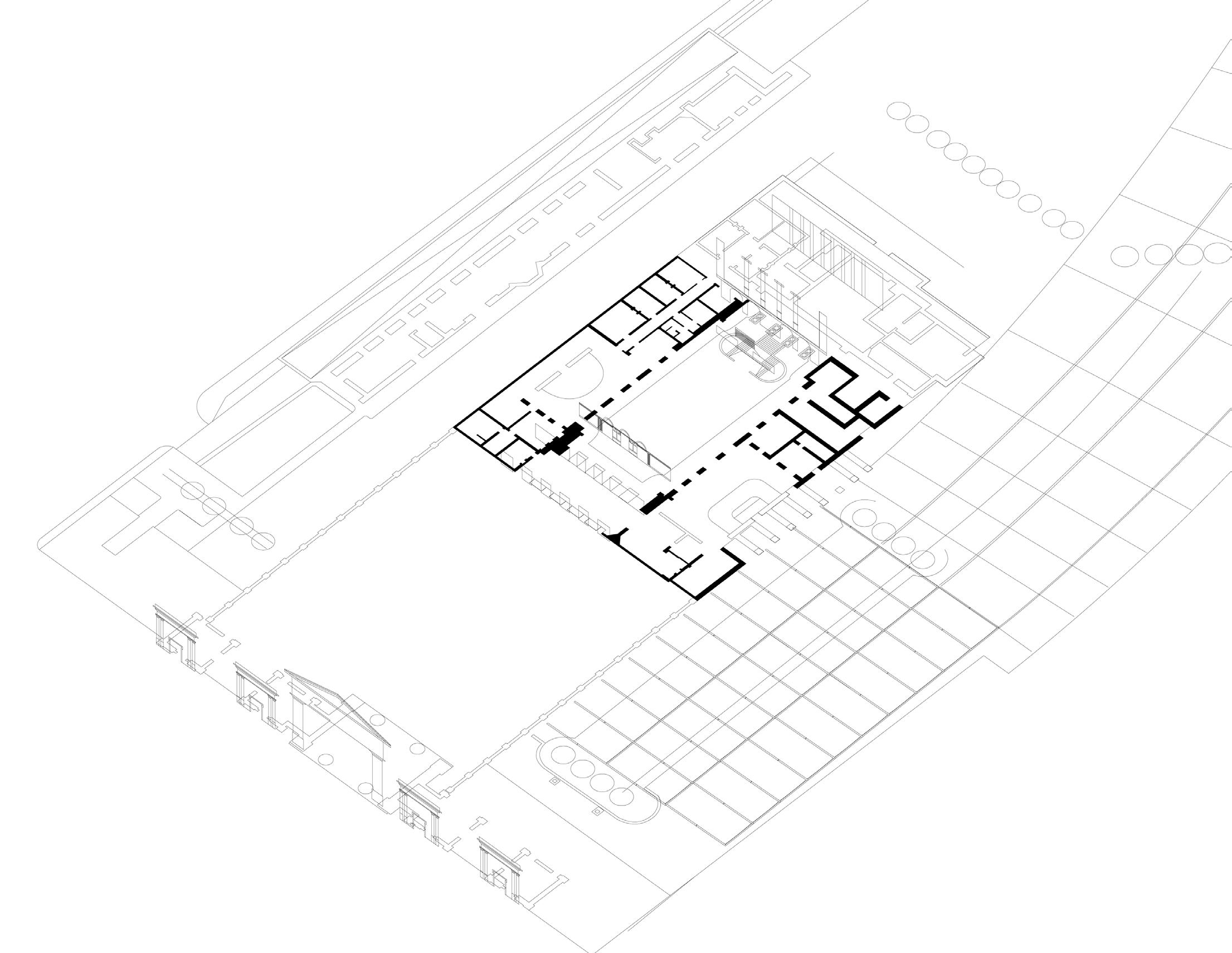

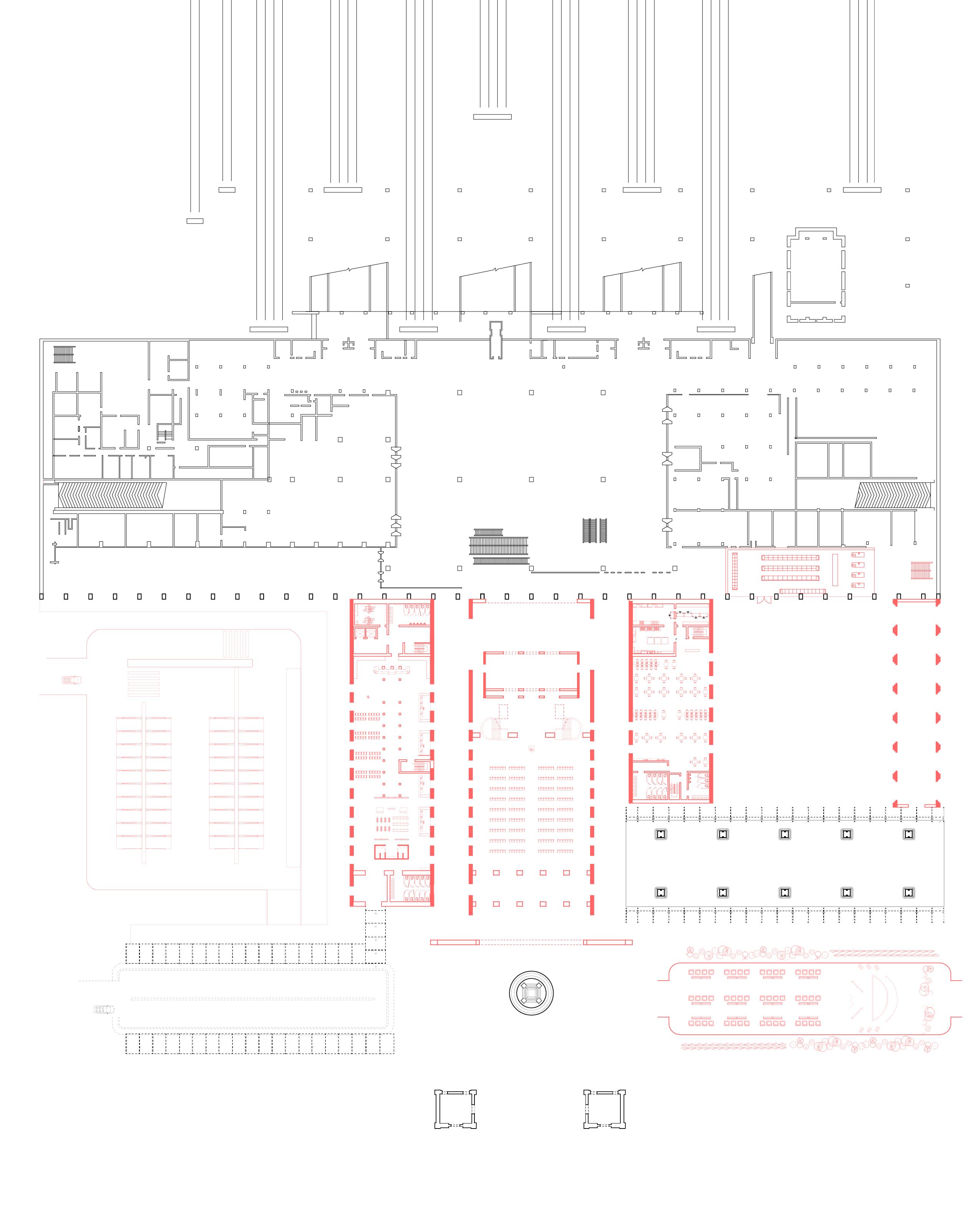

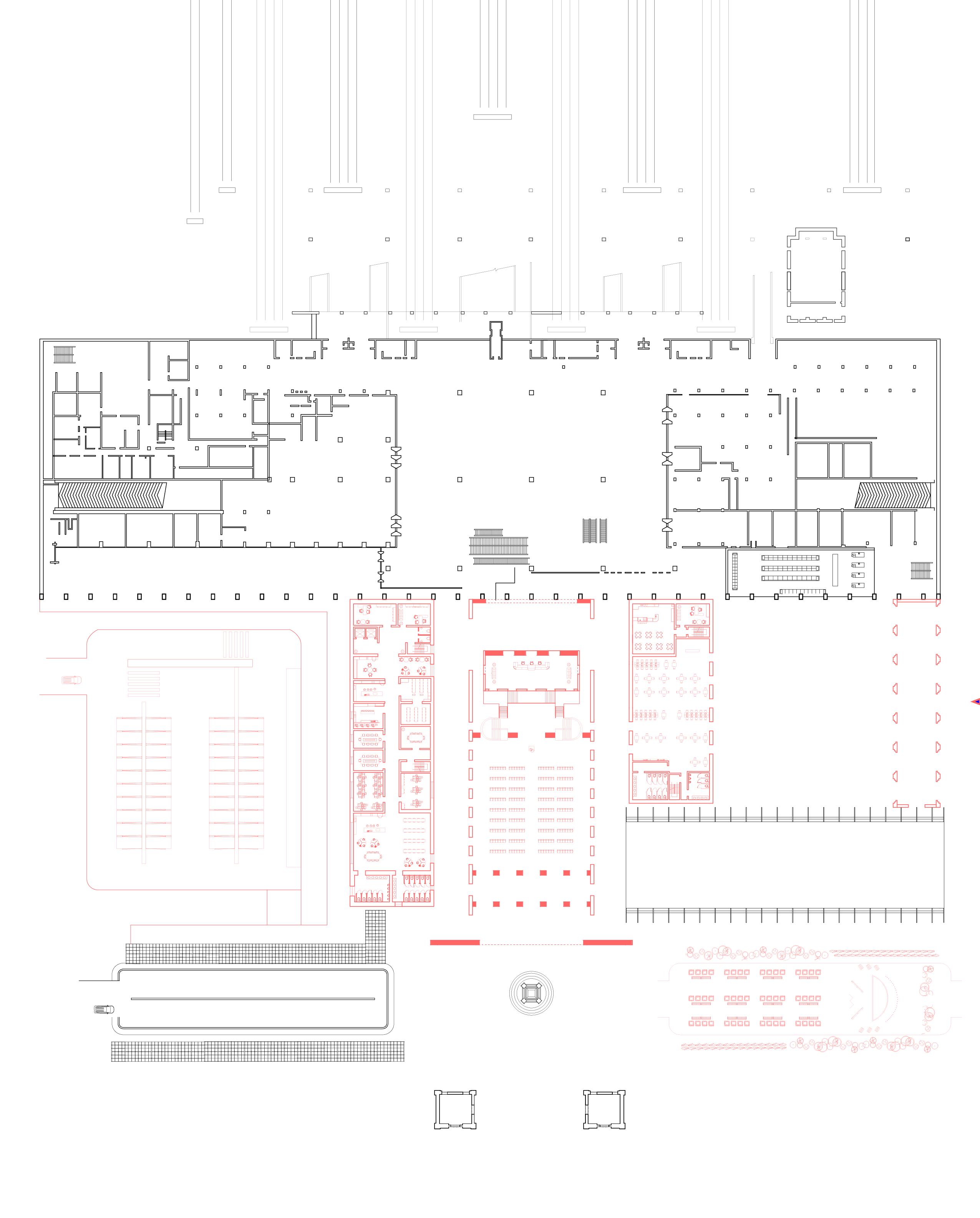

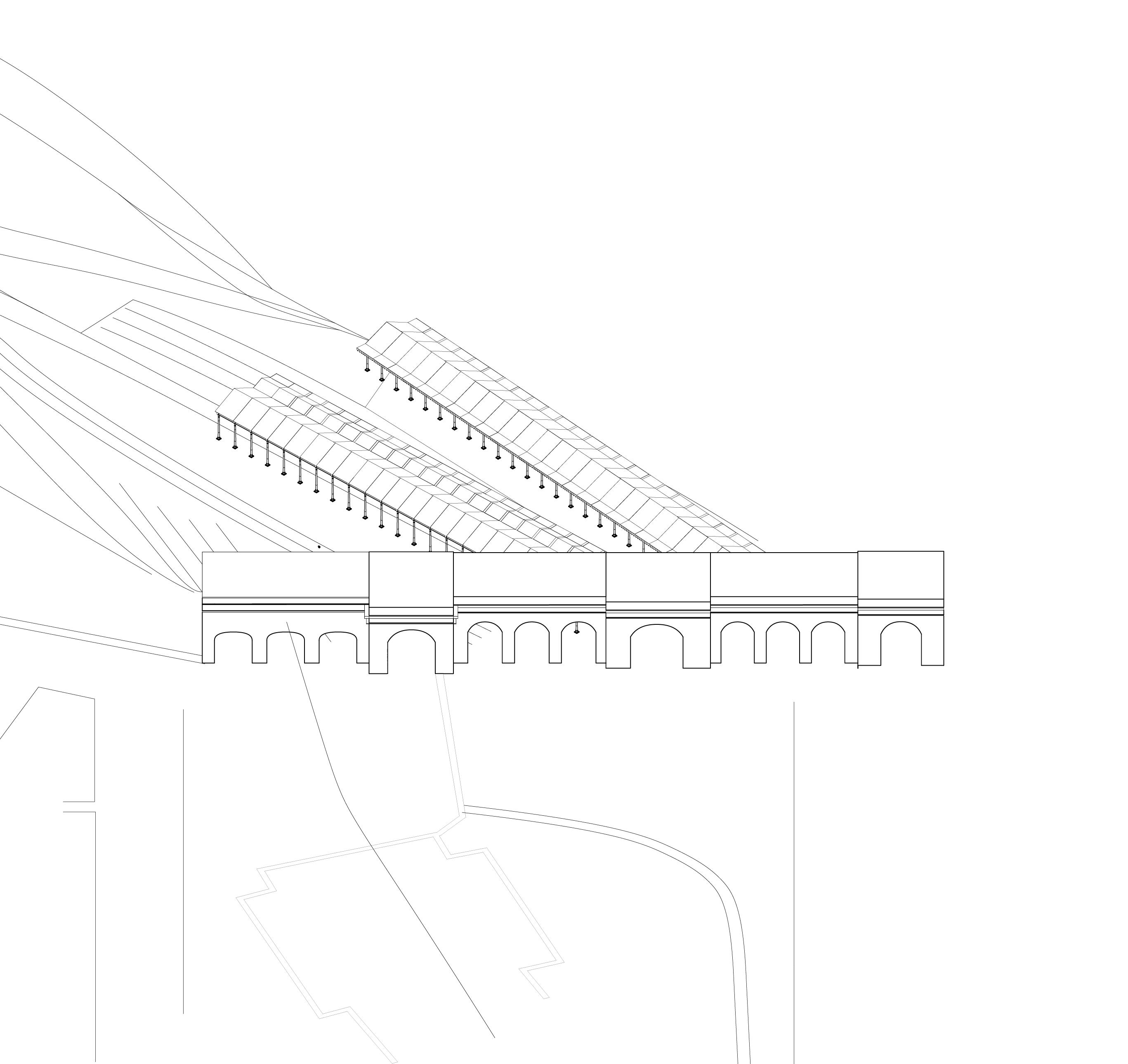

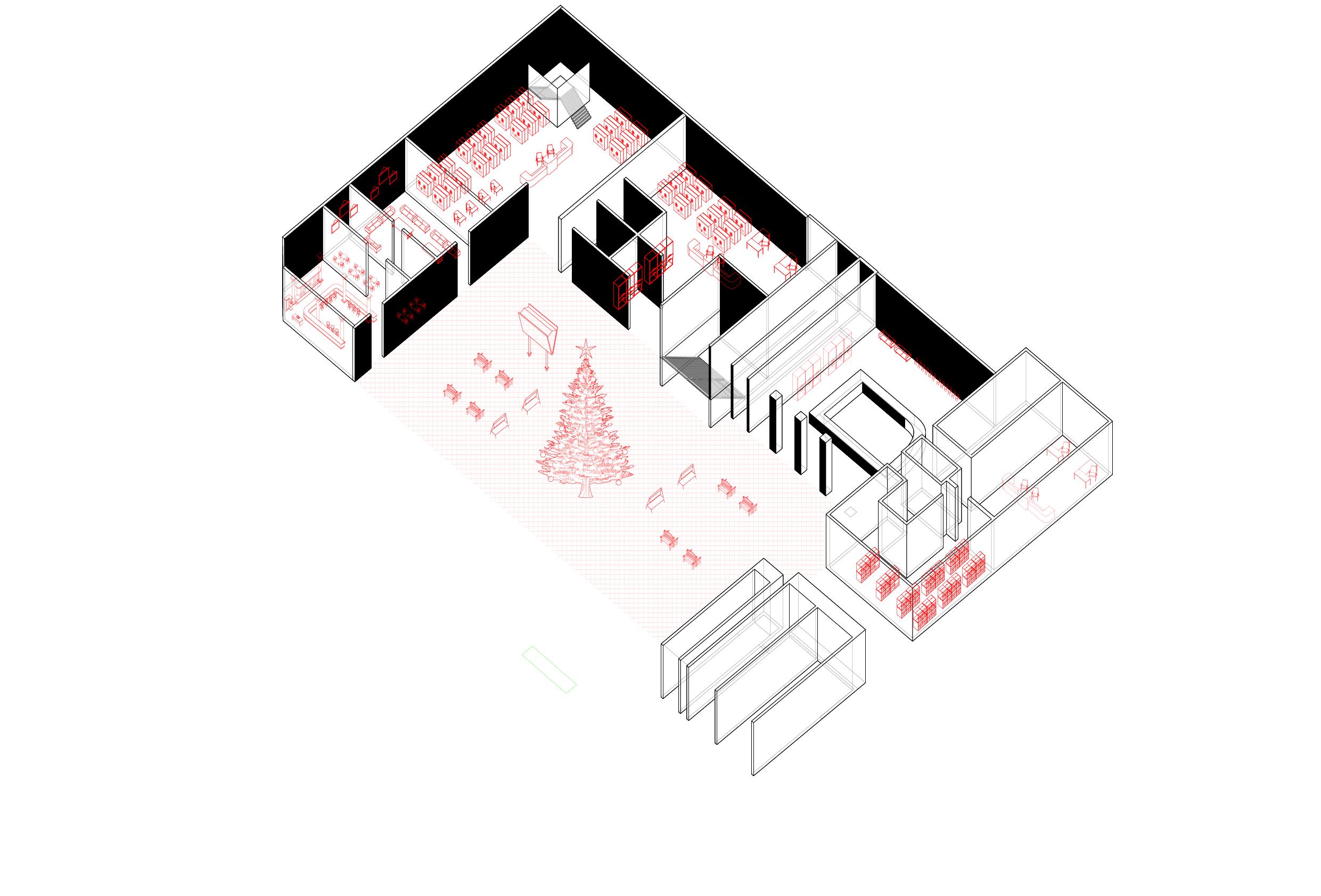

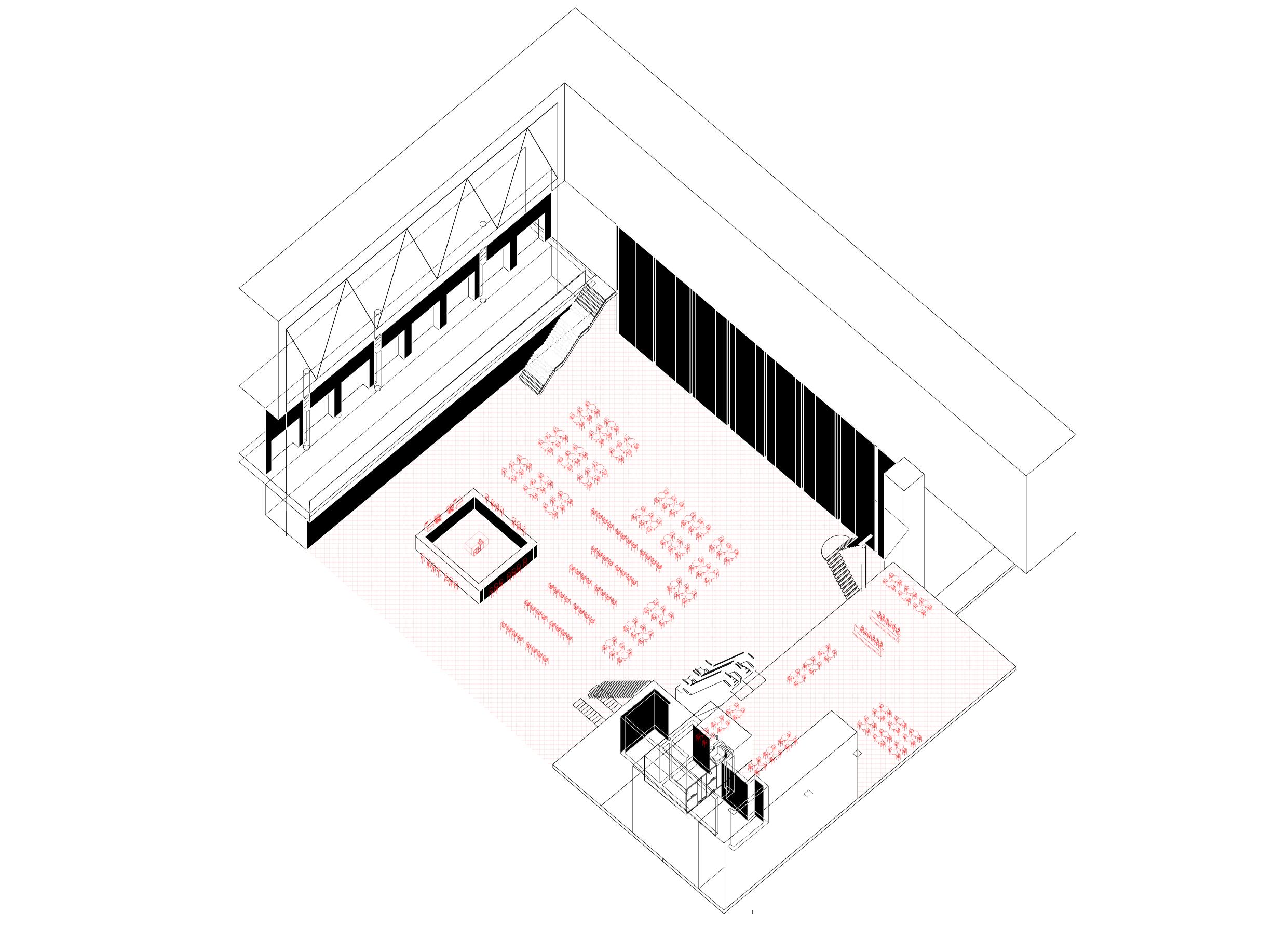

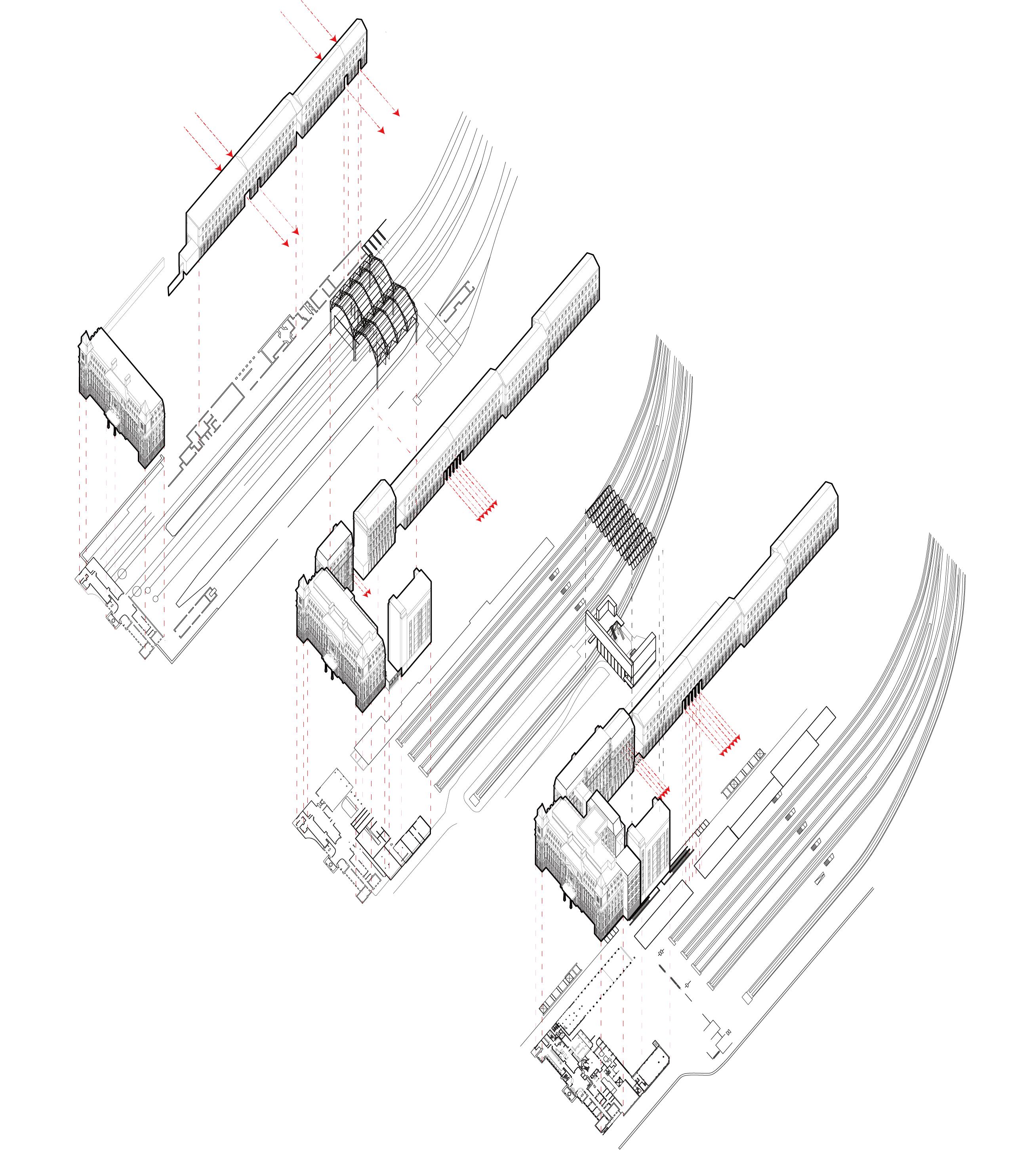

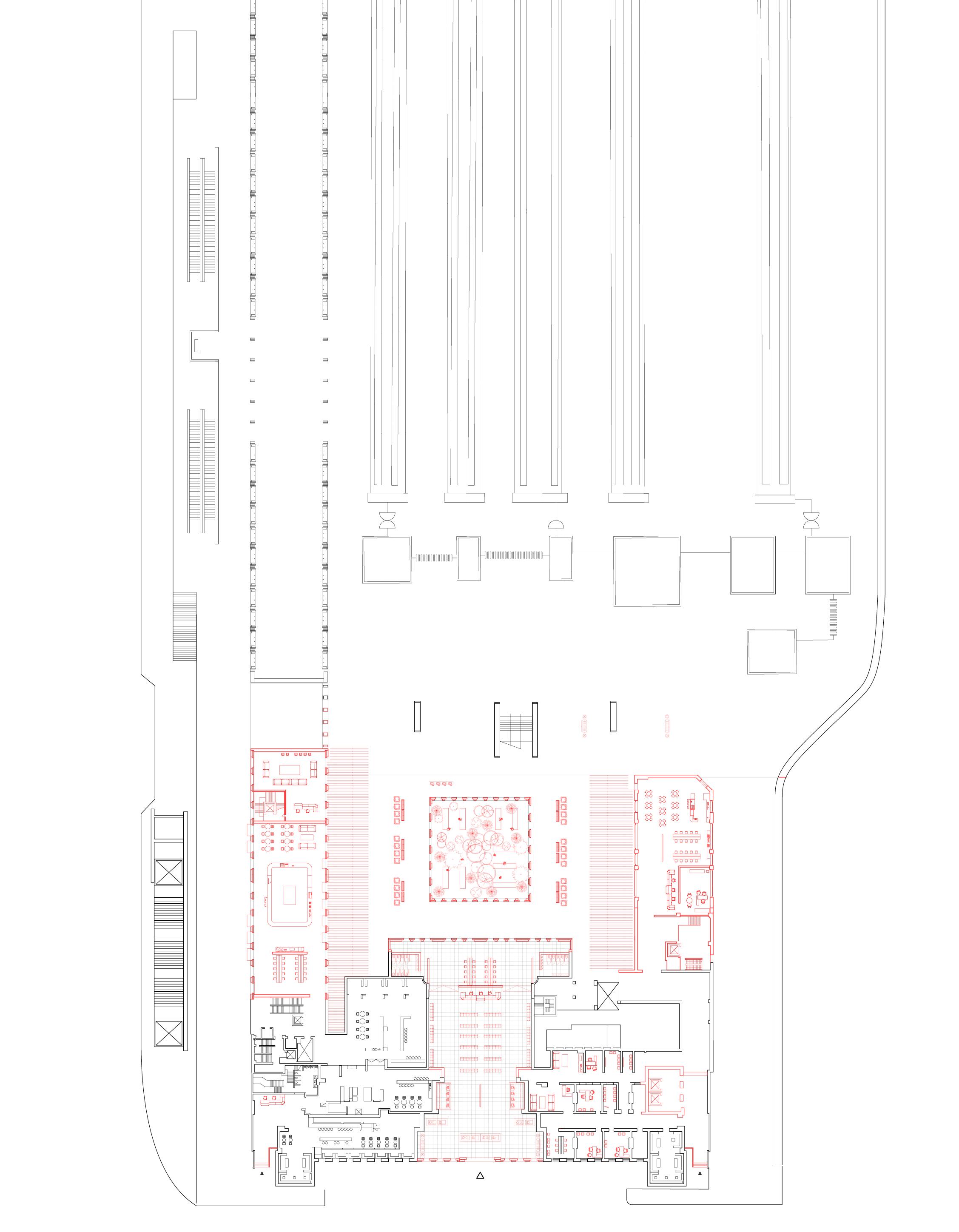

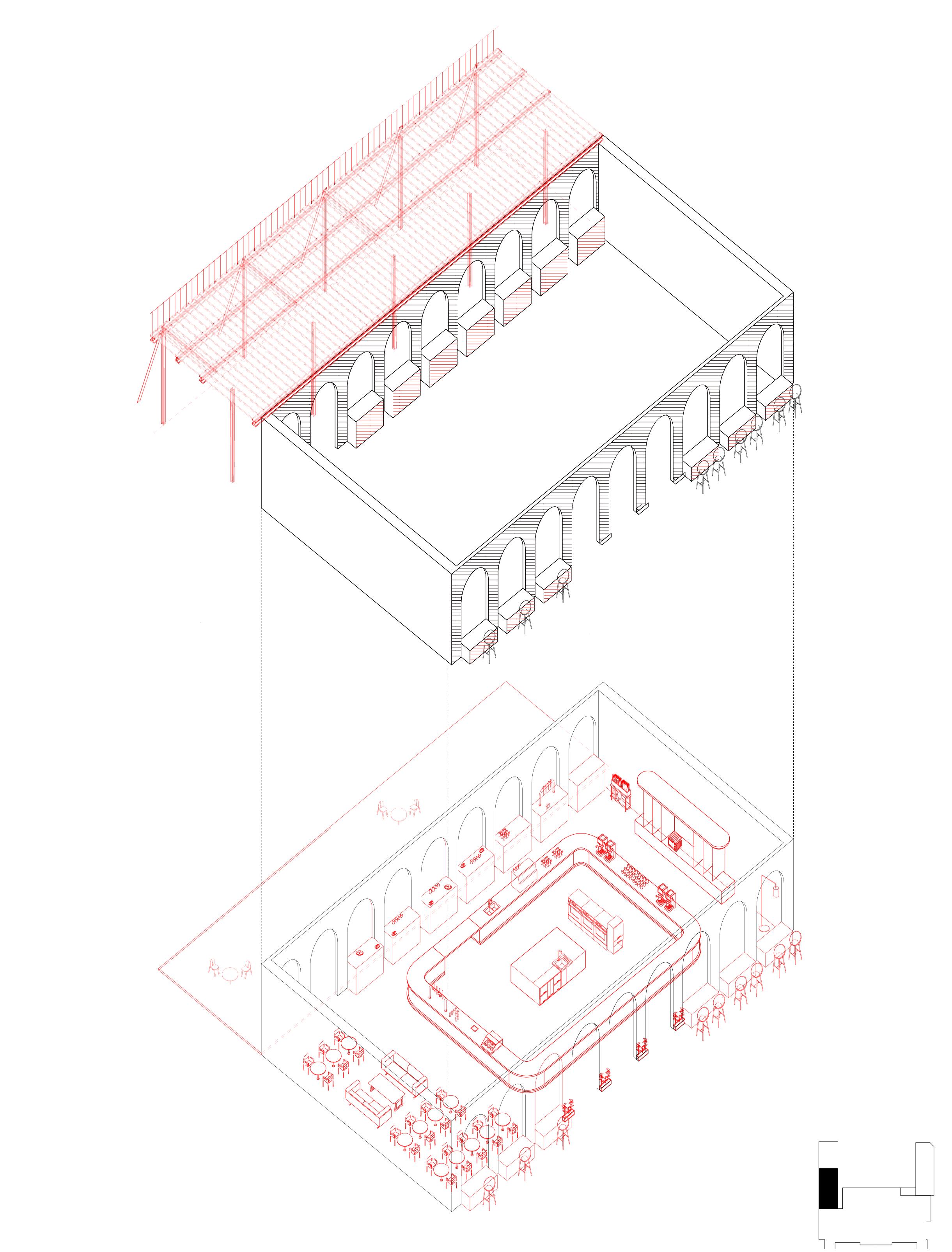

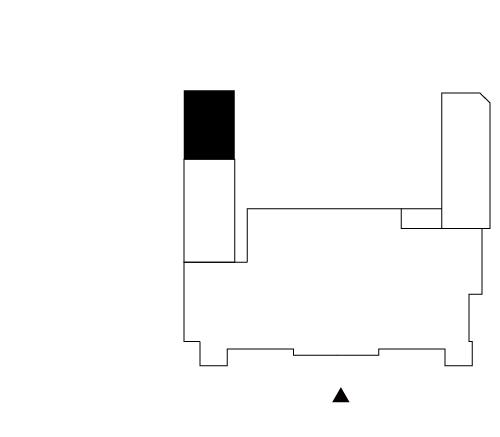

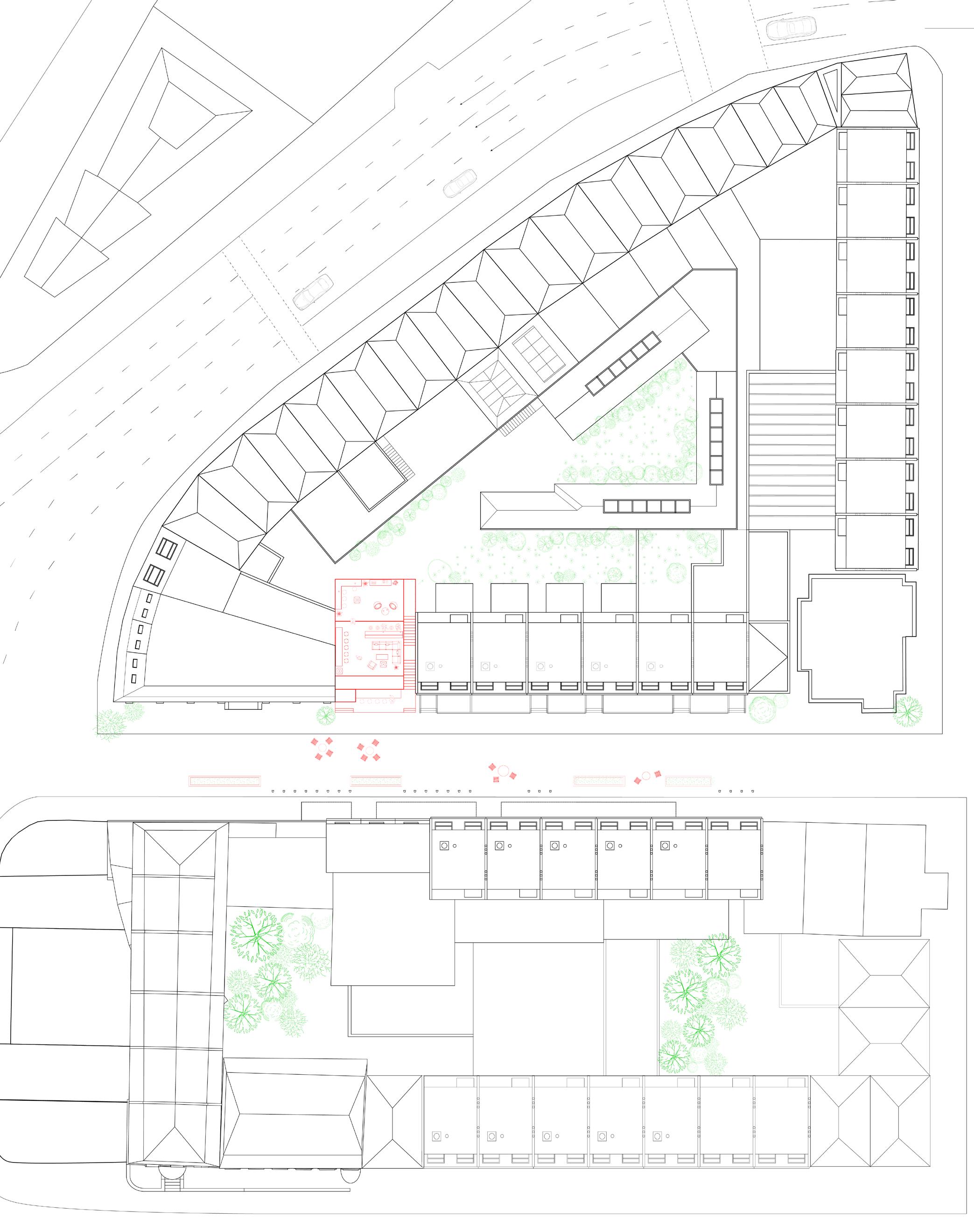

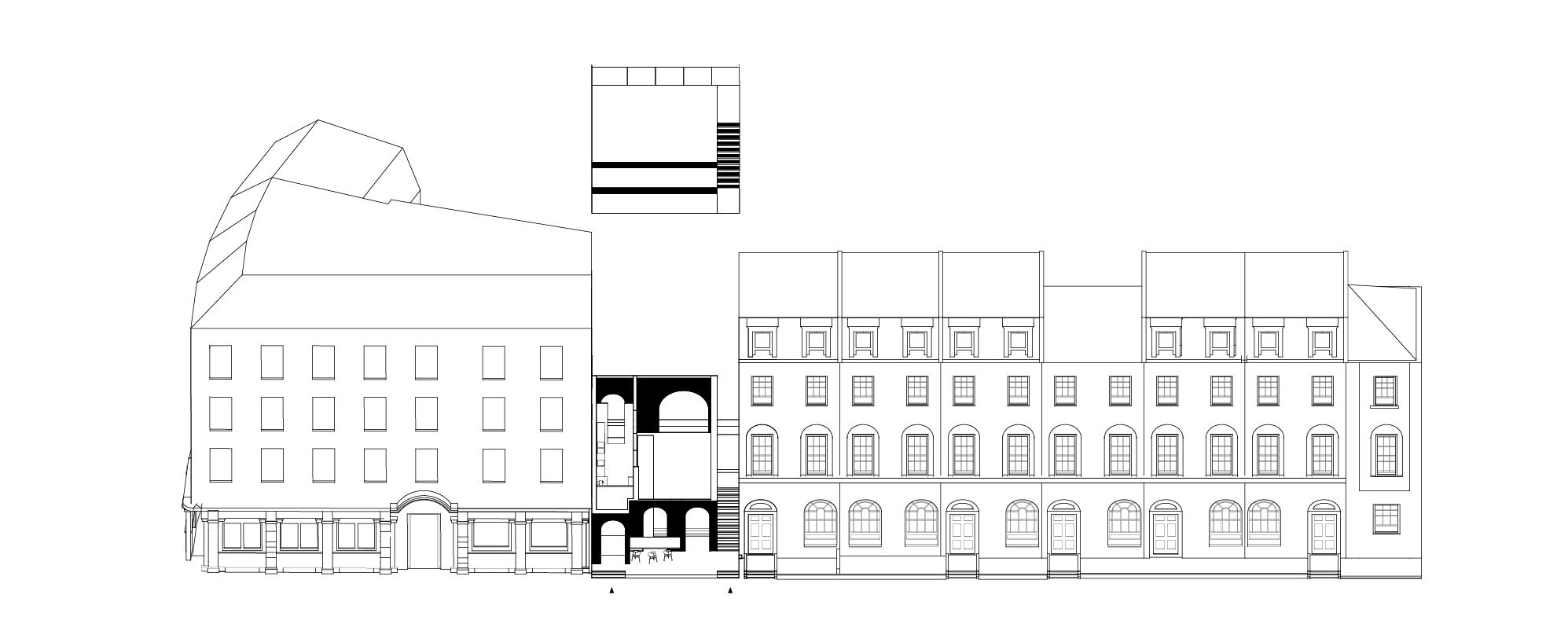

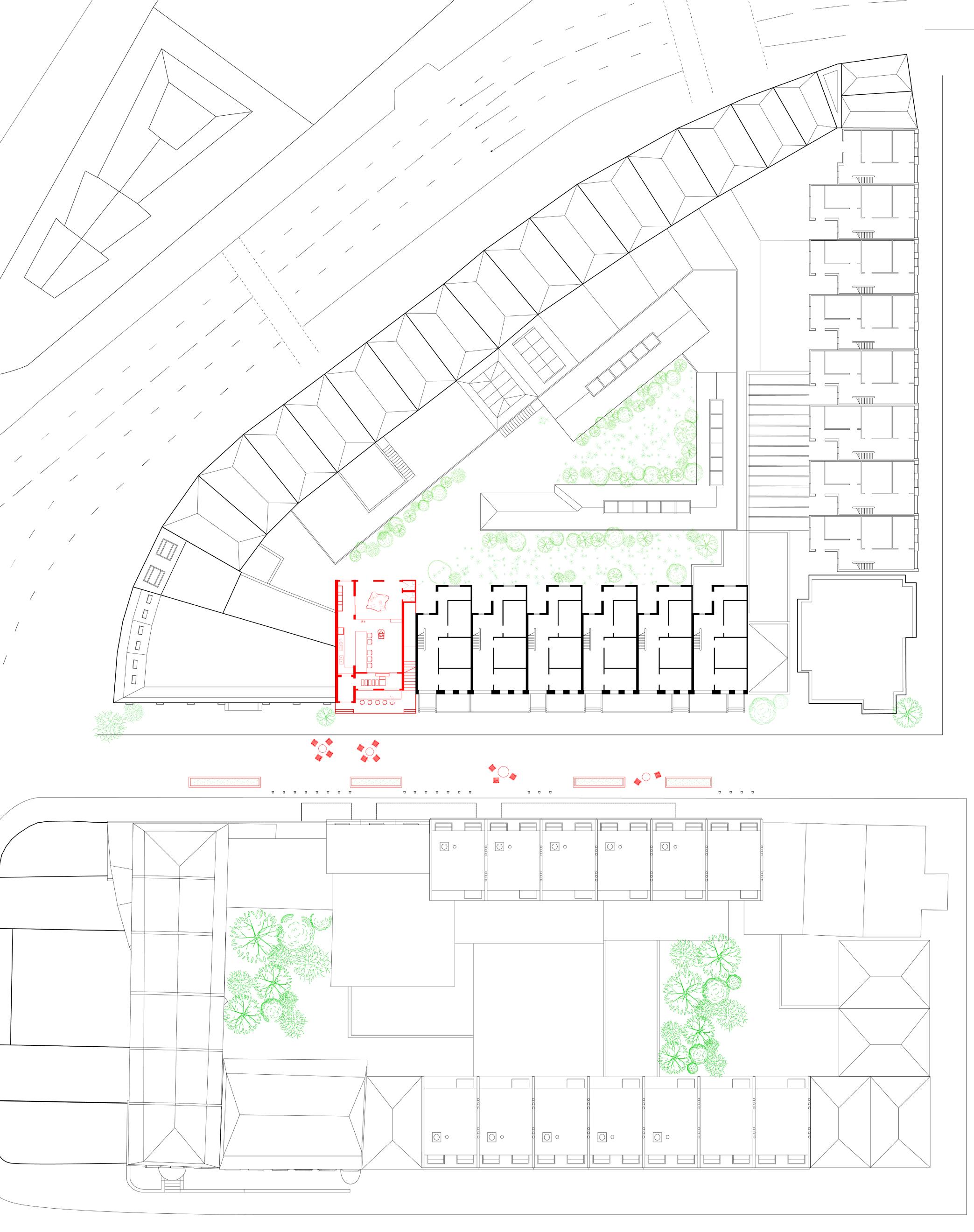

ACT 1 - DESIGN BRIEF

Reconfiguring Multimodal Connectivity

The design seeks to integrate multiple modes of transportation within the station’s frontage, incorporating the existing bus and taxi areas to optimize traffic circulation. Historically, the integration of railway infrastructure with temporary lodging and urban interfaces was a defining characteristic of Victorianera civicness. In the contemporary context, the challenge lies in redefining civic cohesion through the seamless convergence of diverse transportation systems[37]. This approach aims to establish a more coherent and efficient transportation hub, where spatial organization enhances both functionality and the station’s role as a unifying civic space.

Reorganizing the Spatial Hierarchy of the Waiting Area

In the last few years, there has been a significant increase in passenger movement at Euston Station with the expansion of regional and national rail services and a boost in commuter flows on a day-to-day basis. However, the original waiting area has not been properly developed to accommodate this growth, creating a spatial gap. As a result, many passengers have to congregate in the open space between the terminal and the adjacent bus stop, where spontaneous waiting habits have emerged. [39] In response, outdoor seating and electronic timetables have been introduced to accommodate evolving passenger habits.

The intended design seeks to reorganize the waiting area by offering additional covered spaces, addressing the shortage of indoor waiting areas. This intervention will redefine the spatial hierarchy, solidifying its role as an organized space for public gathering rather than an amorphous, transient space. Reestablishing order while preserving the proportional relationships of the surrounding building elements remains one of the most challenging tasks.

Reconstructing Horizontal Visual Continuity

The three towers and an elevated office block in front of Euston Station, designed by Richard Seifert and Partners, were built between 1974 and 1978. The ground floor of the office block was later repurposed to accommodate a bus stop. When viewed from the ground level, a sense of historical continuity emerges, as the coffered ceiling subtly references the coffered roof that once defined the original Great Hall. This architectural gesture forges a nuanced yet compelling link between the modern intervention and Euston’s historical legacy, seamlessly bridging past and present. Therefore, any future design must carefully consider and reinforce this horizontal visual continuity.

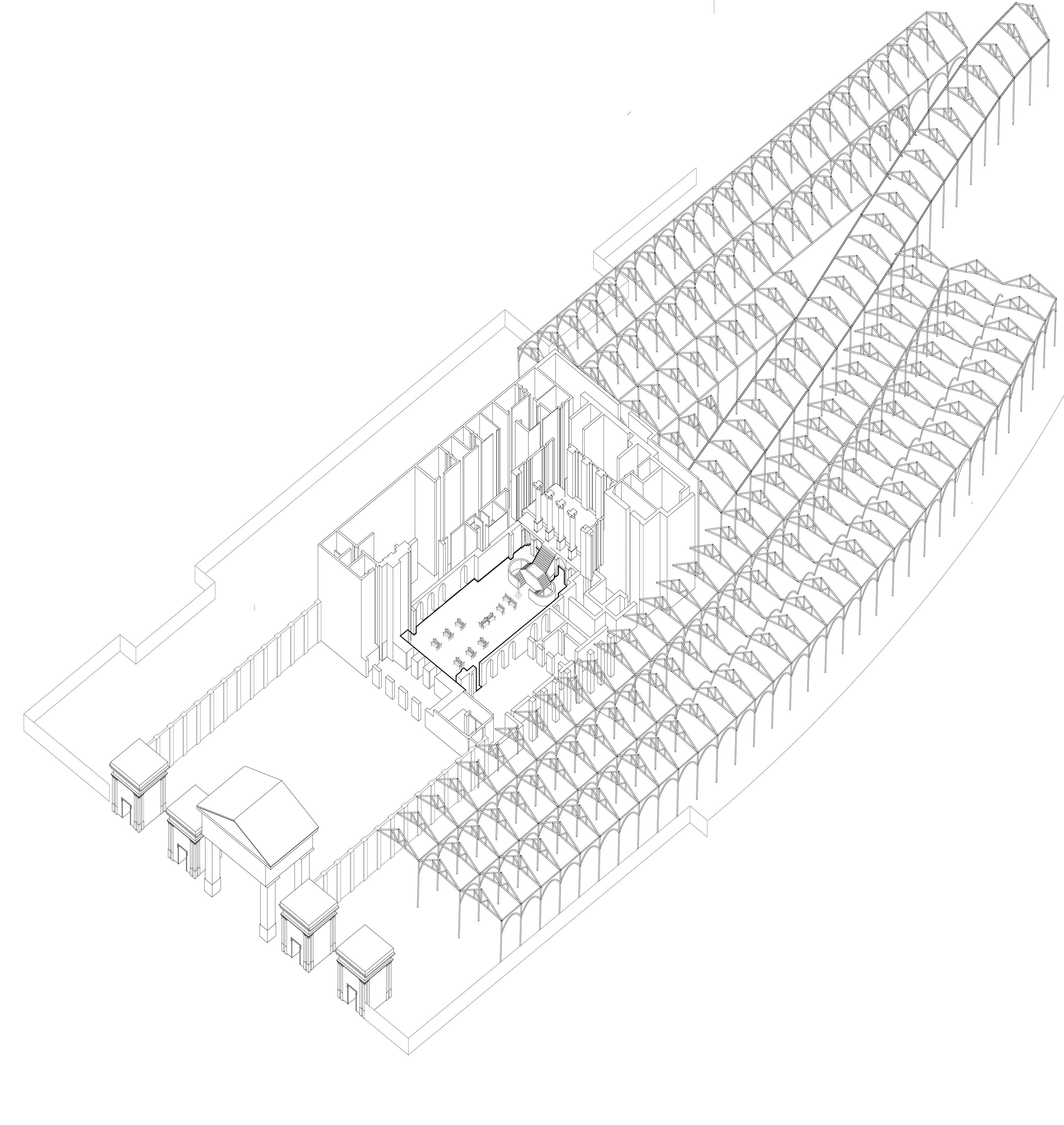

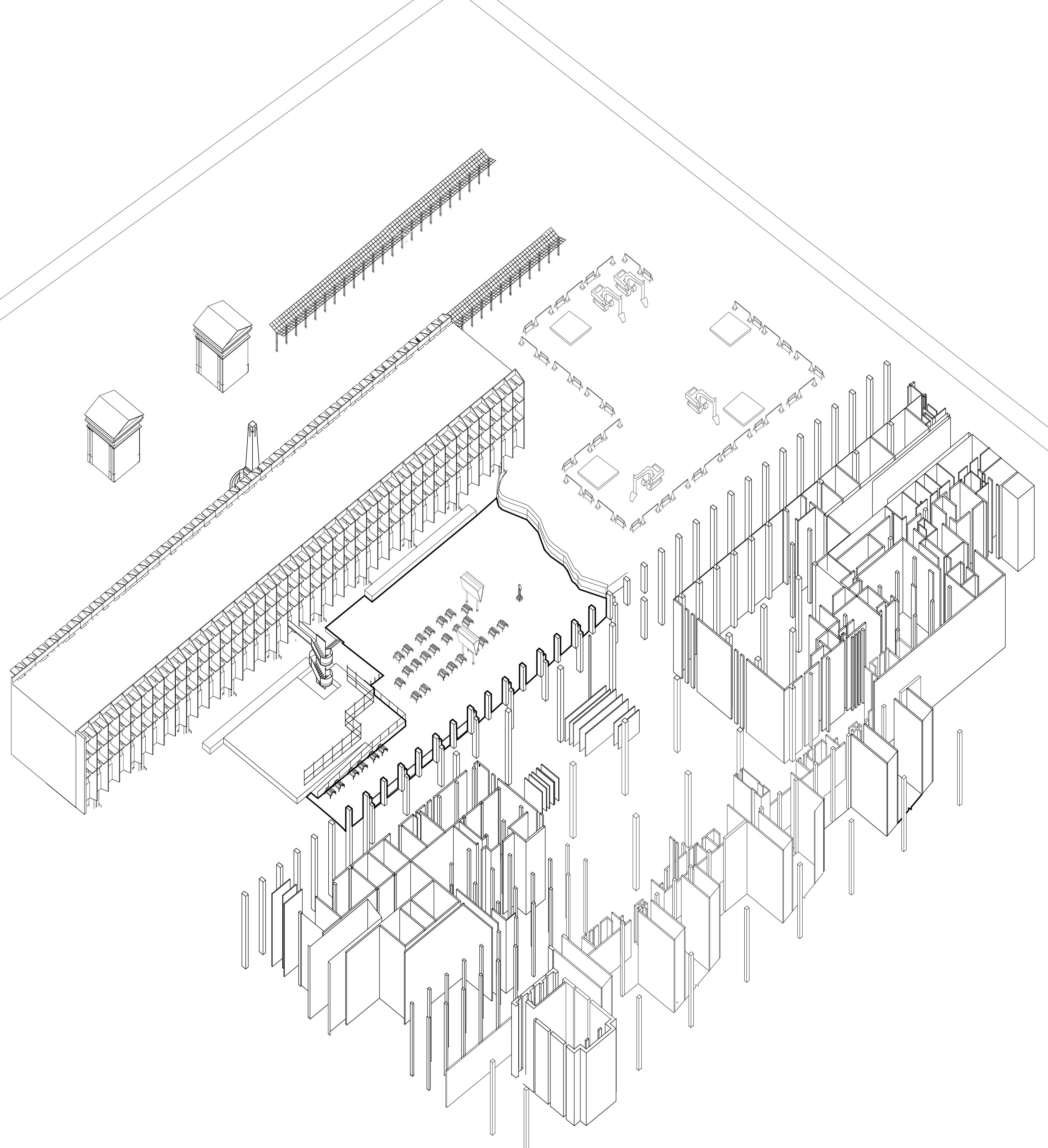

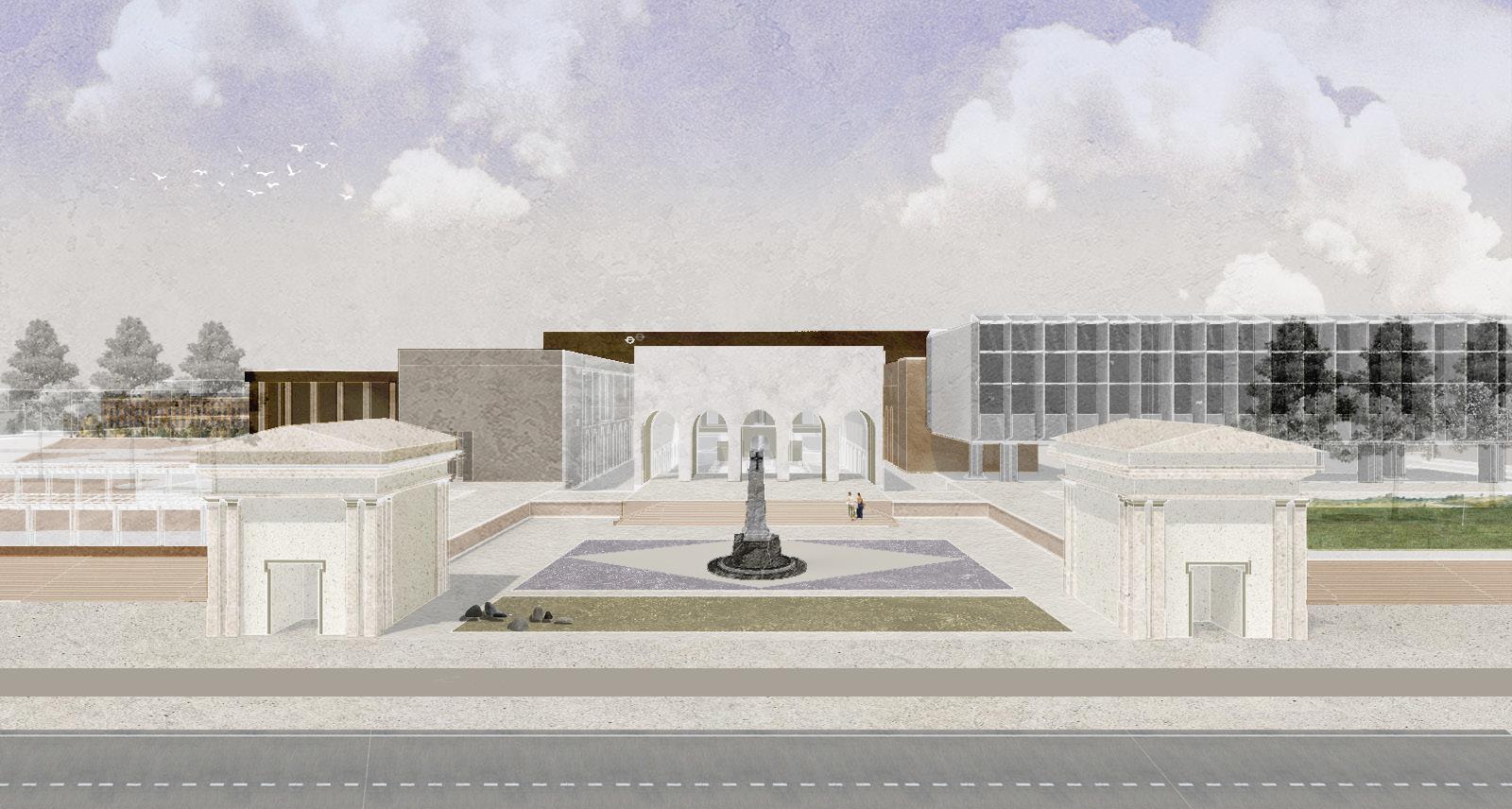

THE CIVIC HALL

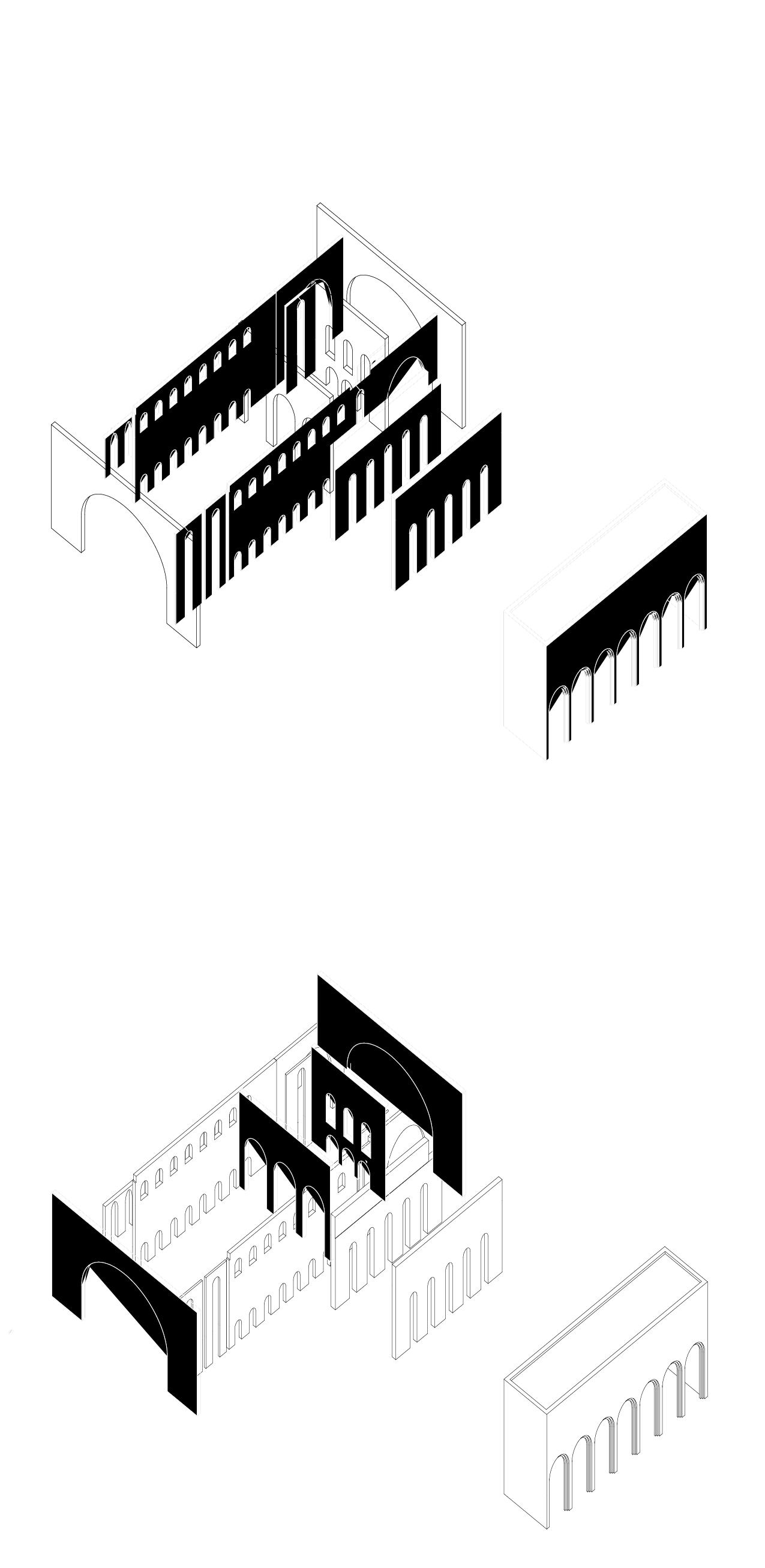

Dual directional portico reconstruction

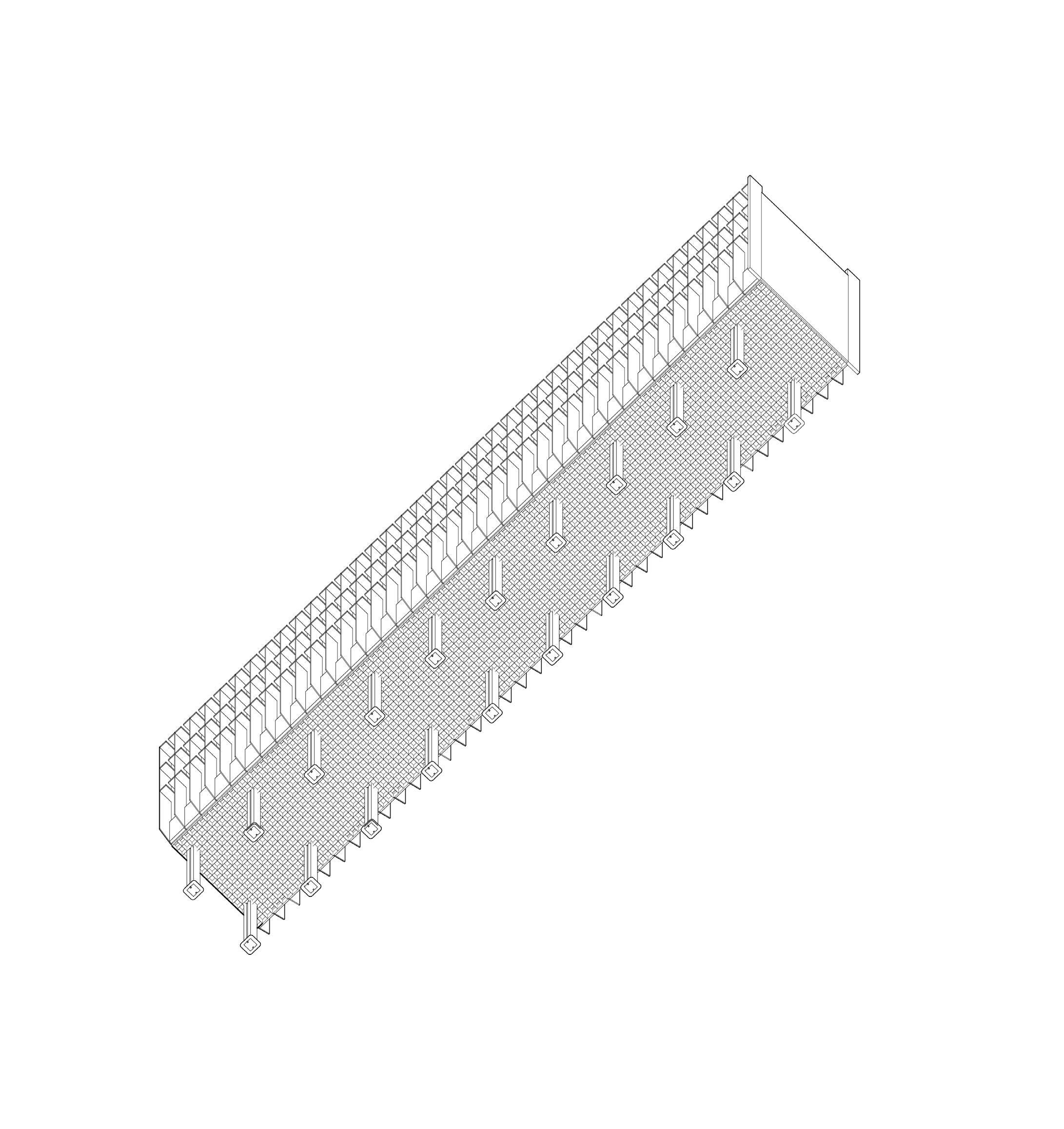

The design strategically composes directional layers of porticos to create a cohesive and functional urban space [43-44]. Along the main axis, the spacing of the front-facing portico layers reflects the dimensions of the original bus stops and parking structures, while near the Euston Terminal, it corresponds to the depth ratio of the original Great Hall. On the short axis, the porticos and thresholds are aligned with the width of the adjacent service spaces on both sides. These architectural elements converge to form the central New Hall, serving as a focal point that harmonizes the site’s historical and contemporary features.

The layers of thresholds strategically organize the transportation infrastructure: to the left, a new parking lot supports the taxi area, while to the right, shopping and dining venues coexist with bus stops and green spaces[45]. This arrangement not only facilitates efficient movement between these services but also demonstrates how portico elements can be seamlessly integrated into a diverse transportation system, enhancing the site’s civic appeal and functionality. On the second floor, offices are arranged along a main corridor that connects them, ensuring a structured and efficient layout. Similarly, on the lateral side, the threshold layers maintain this structured integration, creating a unified spatial experience.

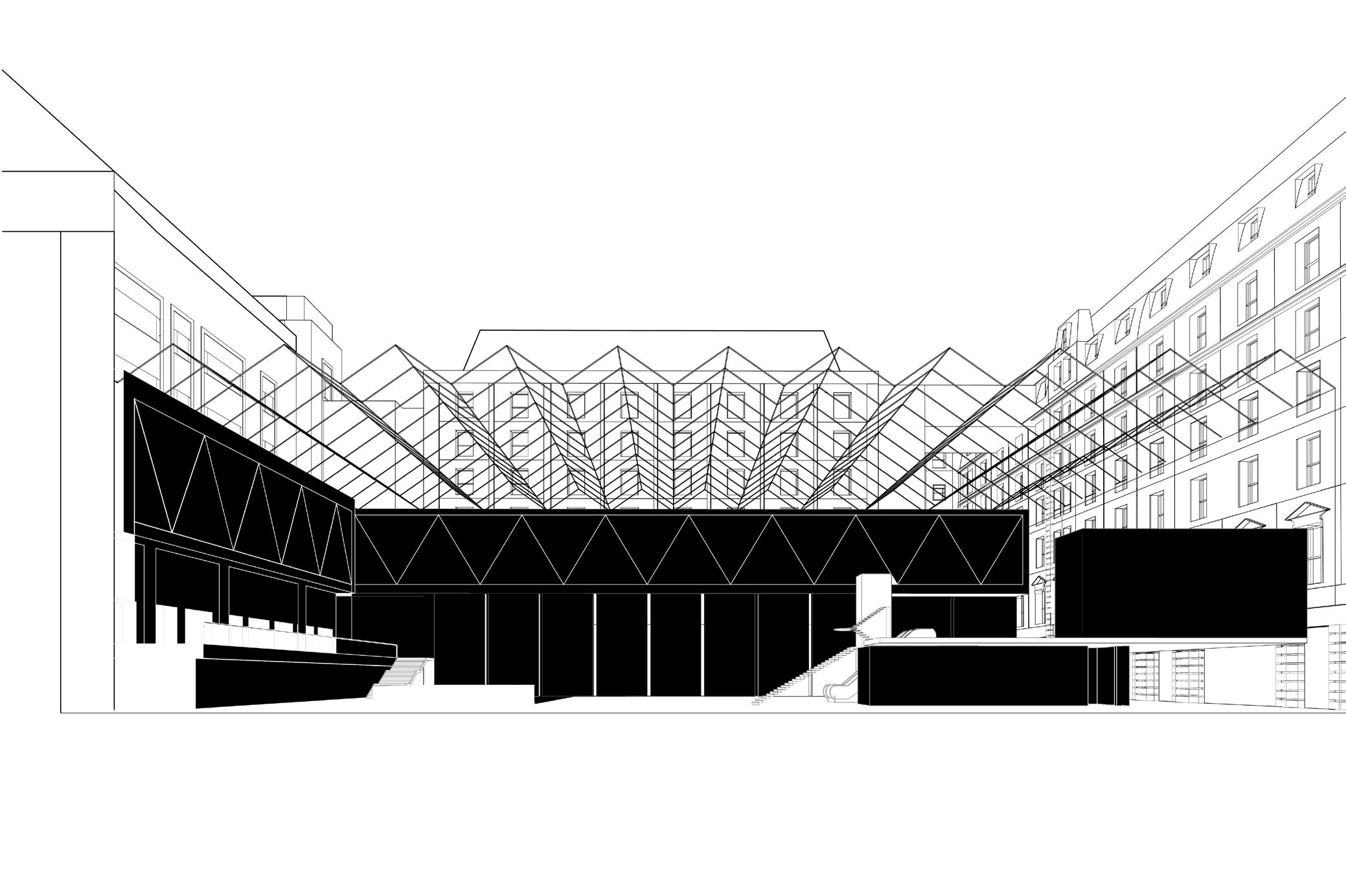

From the street view, 21st-century civicness is envisioned in a post-mobility world, where the terminal is entered by pedestrians, bus users, and taxi passengers alike [46]. This vision enhances the civic presence of the terminal along Euston Road, to make it an active urban destination that balances historical continuity and modern functionality. Through the intertwining of transport, commerce, and park spaces, the design not only solves functional requirements but also fosters a community identity and civic consciousness, placing the terminal as a necessary and community-focused public space in the city centre.

New waiting hall at the junction

The New Hall is also situated at the intersection of the two groups of threshold layers and symbolizes the original Great Hall in terms of the proportions and architectural elements for the sake of imparting grandeur and continuity of history. Designed to create an illusion of depth, the hall is bracketed by penetrable service areas that offer access and gapless continuity. Its coffered ceiling, in allusion to the original purpose, is permitted to allow natural light to pass through it, enhancing the spatial quality and creating an open and welcoming environment.

The New Hall not only replicates the proportions of the previous Great Hall but also improves upon it by inviting more natural light and optimizing circulation. Layers of openings along the thresholds further enhance its functionality as a dynamic civic gathering space, fostering interaction and movement.

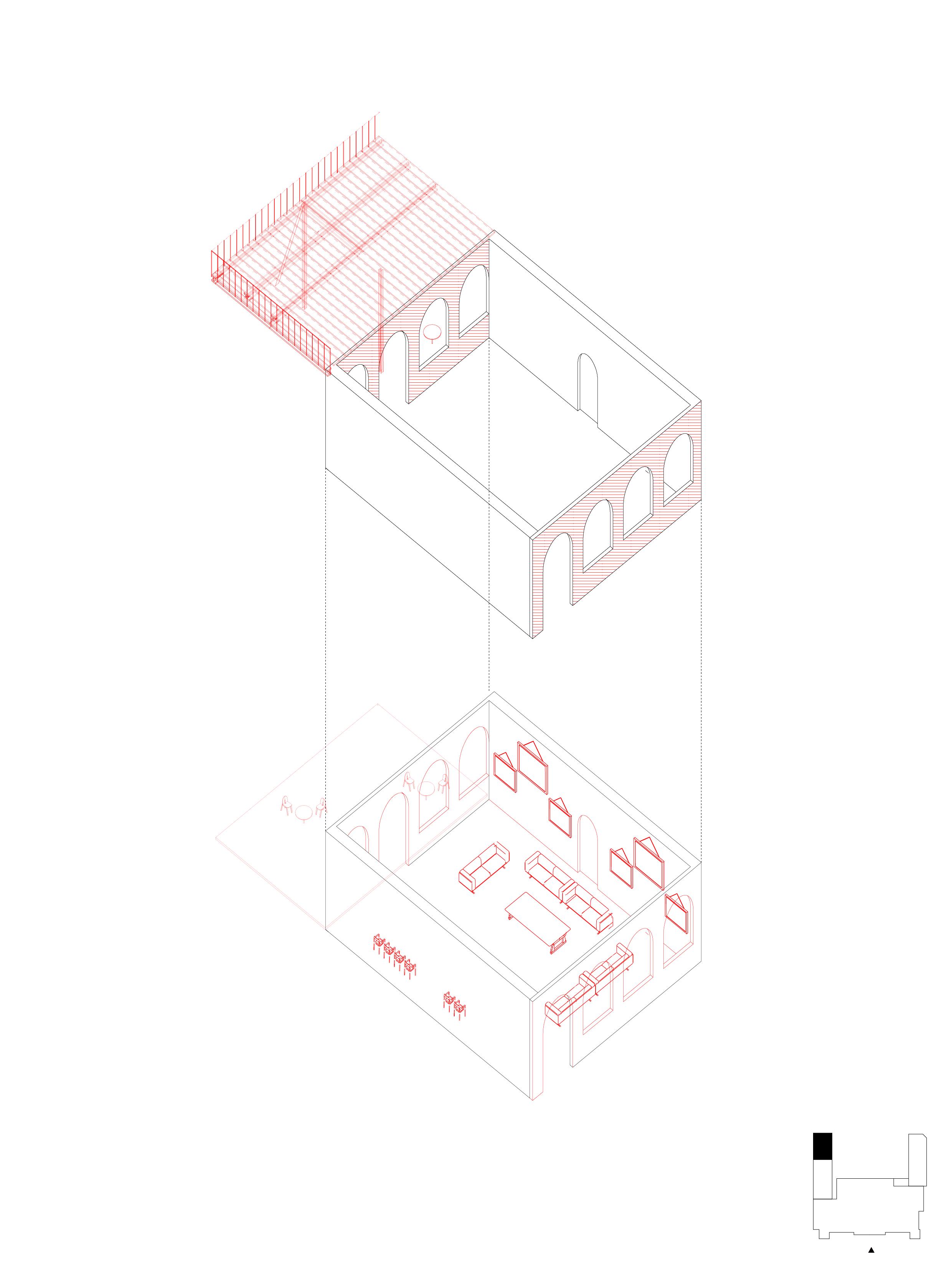

CHAPTER 2

THE ENCLOSED PLAZA

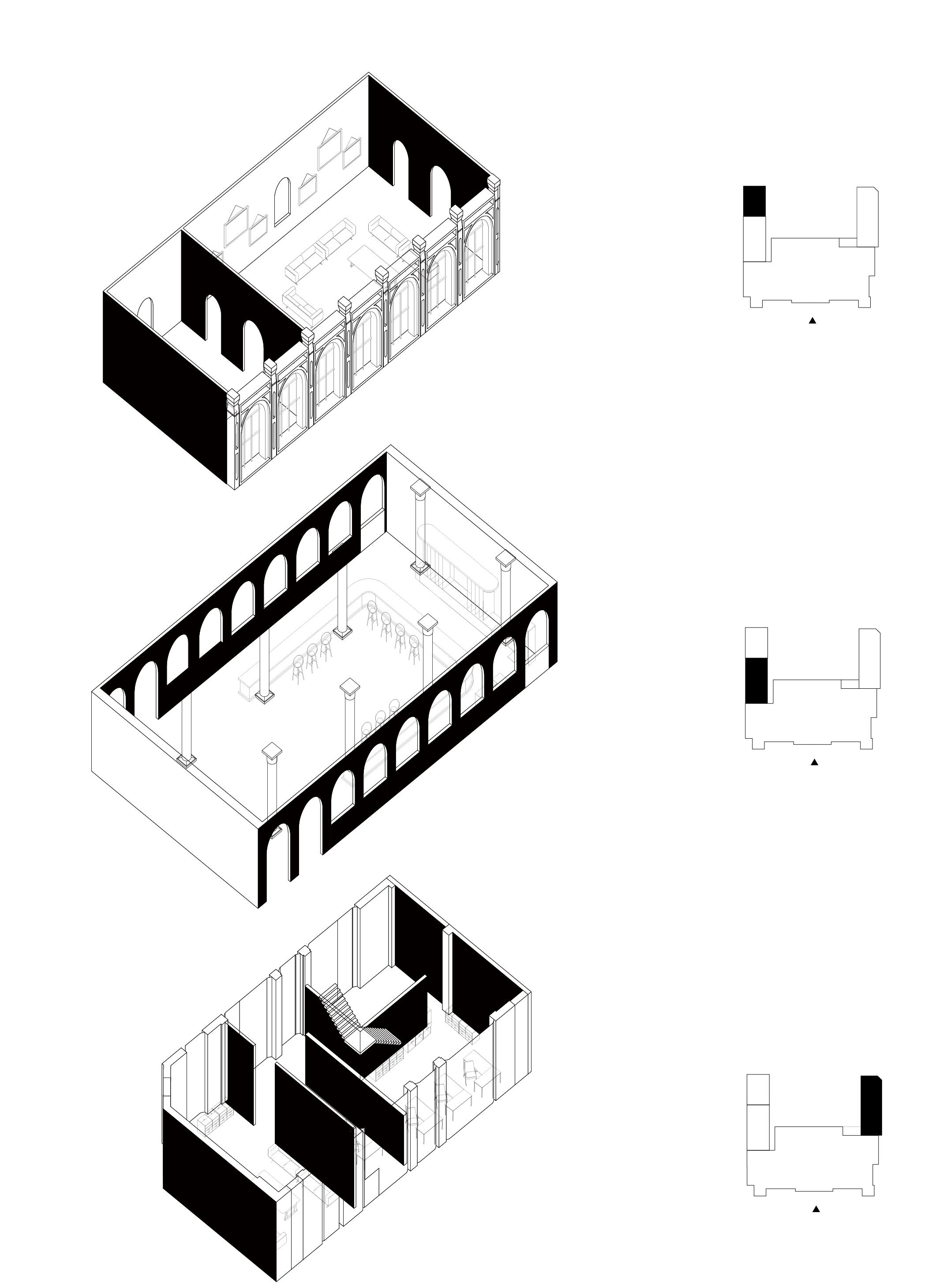

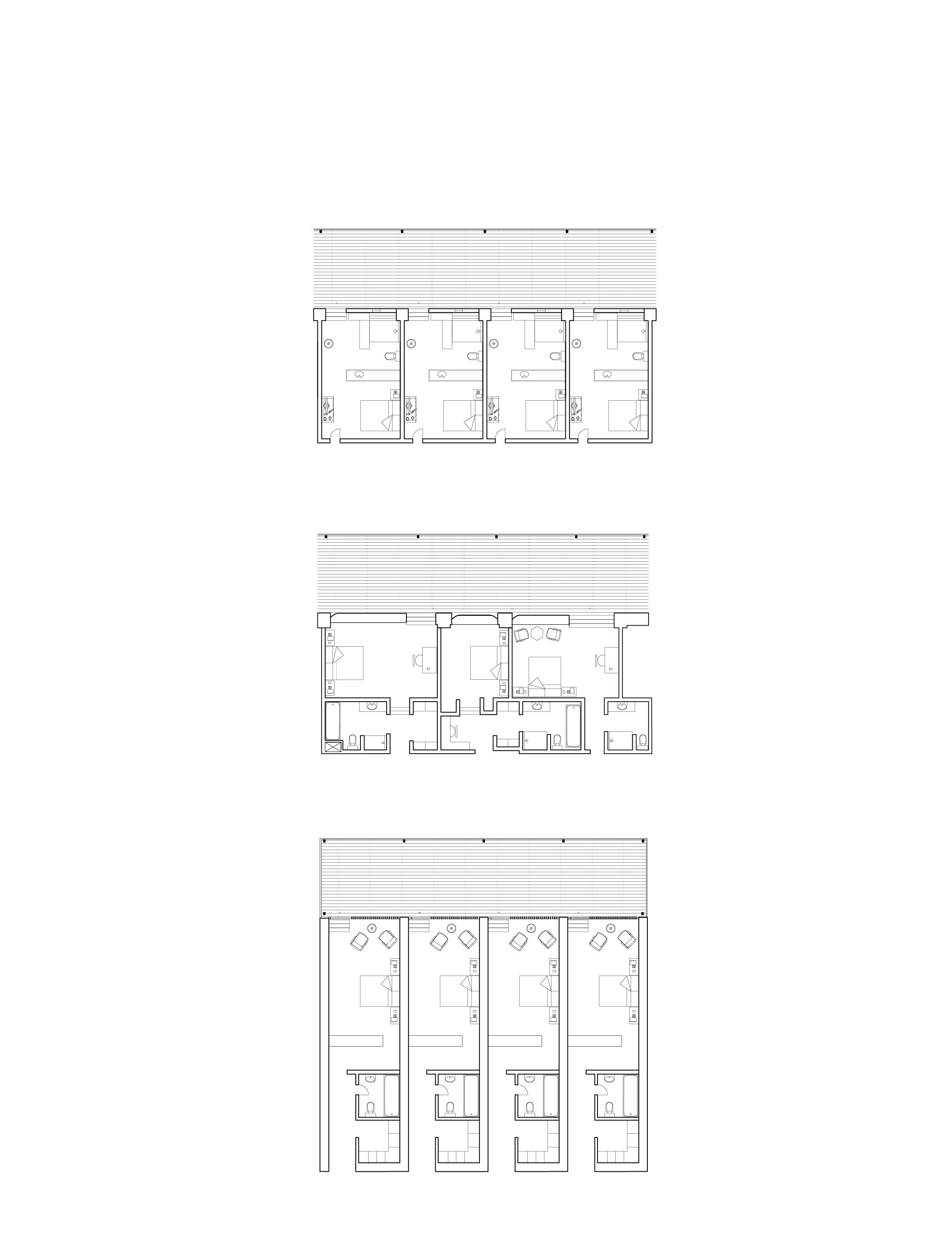

Chapter Two examines the expansion of railway terminal-based habitation at Paddington and its assimilation of surrounding buildings, which initially created a new form of civic enclosure. This civic character, however, gradually diminished under twenty-first-century commercialization. The first subchapter explores the Grand Shed era and its impact on terminal construction, emphasizing the spatial autonomy it provided. The second section discusses how Paddington’s portico, replaced by a railway hotel, reflects ongoing gentrification, while its enclosed plaza became a hub for civic activities. Finally, the last subsection explains how the terminal’s civicness has been constrained in the twenty-first century, as commercial interests overshadowed its civic role.

THE TRAIN SHED EVOLUTION ROOM the CORRIDOR 2.1

Nothing speaks the essence of a civilization more powerfully than its architecture. As the most outspoken one for the Industrial Revolution, it must be the room at the end of tracks, the railway terminals.

ROOM the CORRIDOR

( Railway terminals embody) the only truly representative architectural type we possess.

- The Building News,1875

In 1838, after negotiations with the London & Birmingham Railway for a joint terminal at Euston broke down, the Great Western Railway was compelled to establish its own terminal at Paddington. Initially, the plan was to erect a temporary terminal to meet the immediate demands of operating the railway lines. However, Paddington Station adopted a portico as its typological paradigm, aligning with the emerging architectural trend in the construction of railway terminals across London. This monumental structure ensured that train terminals presented themselves to the city in a deliberate and impactful manner, underscoring their infrastructural and urban significance, as previously illustrated in the last chapter.

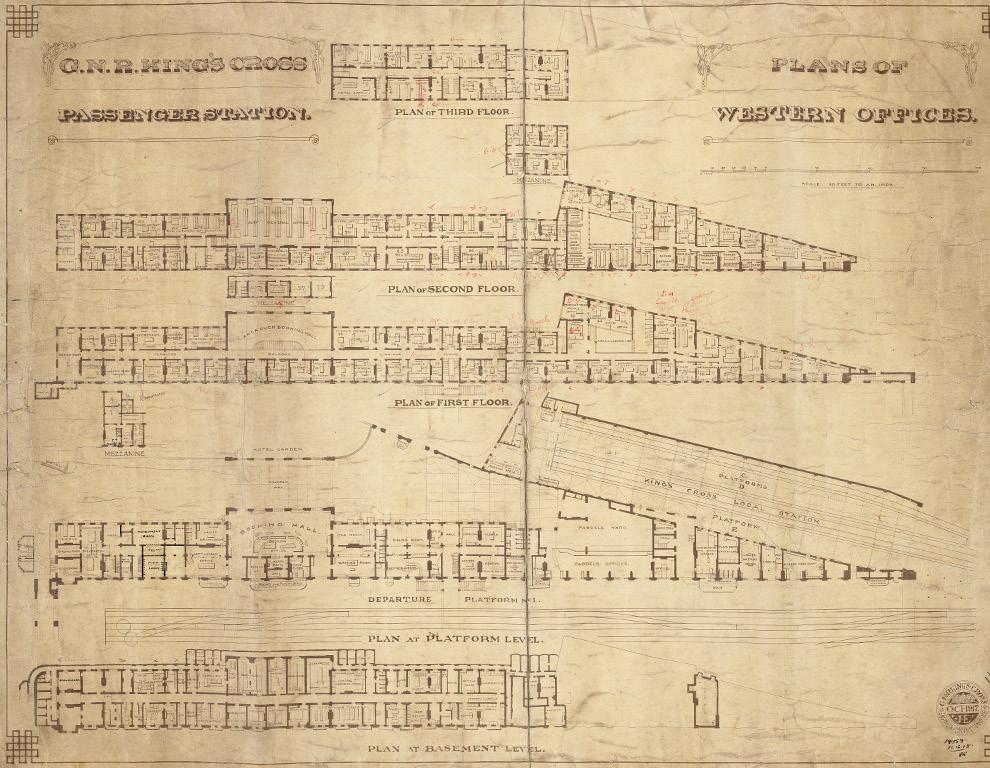

The structural composition of railway termini has historically been characterized by a combination of two key typological elements: a shed and a portico. The shed provided an undercover space for passengers to wait at the platform, while the portico, perpendicular to the city, formed the station's outward-facing image. Together, these elements constituted the earliest prototype of London's railway terminals. [51] Euston Station, the temporary Paddington terminus, and King's Cross, as some of the earliest terminals, all adhered to this dichotomy, establishing a design language that balanced functionality with civic presence.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch characterizes the architectural structure of railway terminals as inherently dualistic, which he describes as 'two-facadeness'.22 This duality is essential to bringing two distinct forms of transportation: urban streets and railway tracks. The portico faces the city, engaging directly with urban life and serving as a social and architectural threshold that frames the transition from the city to the journey. Meanwhile, the sheds, aligned parallel to the tracks, cover the platforms and facilitate the functional operation of the railways. This configuration not only supports the unimpeded movement of trains along predetermined routes, regardless of weather conditions, but also enhances the connection between city streets and railway corridors.

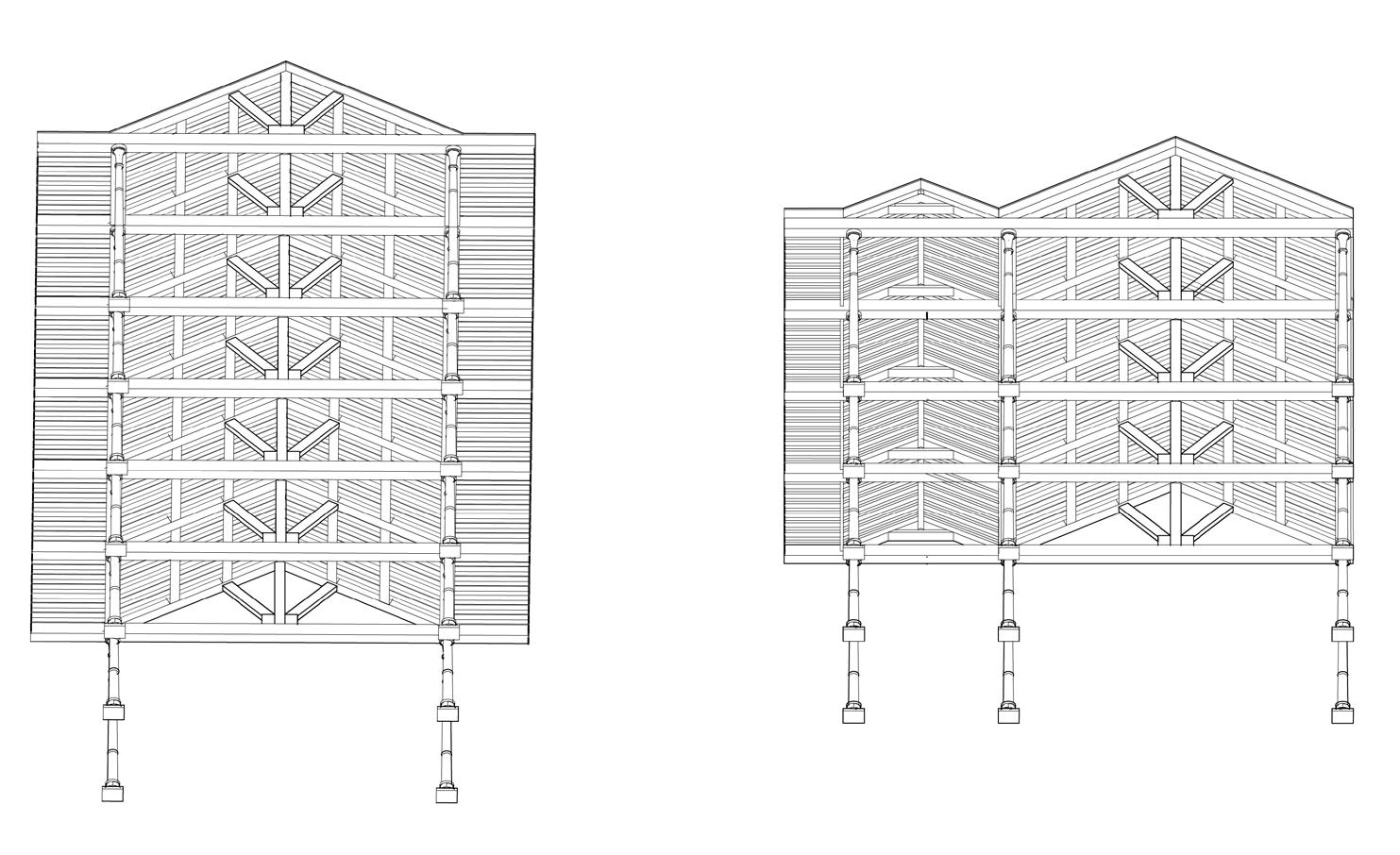

"Shed" comes from the archaic English term "scead", which means "shadow" or "shelter", Originally, the word referred to a basic structure used for storage or shelter. The evolution of train shed reflects this early usage . Originally inspired by stables and barns, train sheds were designed as simple structures to protect trains and passengers from the elements. These early train sheds were often simple wood or metal covered structures that provided the necessary protection for railway operations. The early structure was constructed from simple materials, predominantly timber, and incorporated a Howe truss system for support.

The evolution of the train shed, from its humble origins as a simple shelter to its later architectural sophistication, is exemplified by the early temporary terminal at

Paddington Station. Constructed predominantly from timber and incorporating a Howe truss system for support, the temporary train shed was a straightforward, utilitarian structure designed to shield passengers and trains from the elements. Architectural embellishments were minimal, limited to some decorative carvings on the columns [52].

Extending only over the platforms, this initial version of the station prioritized essential shelter and operational space for railway activities, lacking the grandeur and intricate design elements that would characterize its later development. The simplicity of the temporary shed reflects the pragmatic approach of early railway infrastructure, focusing on functionality over form.

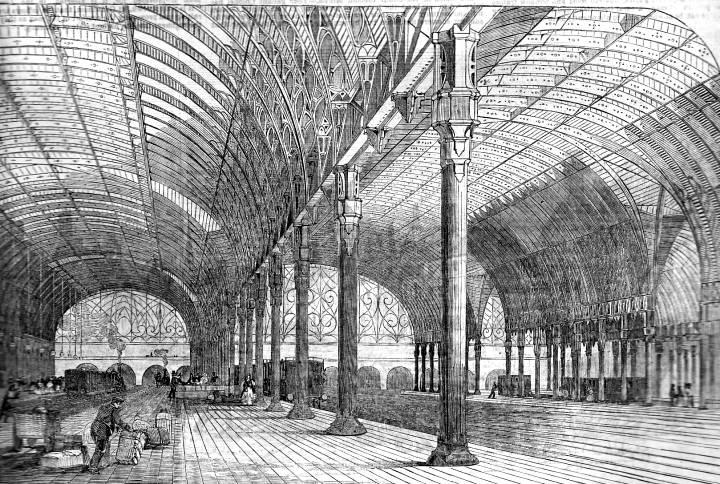

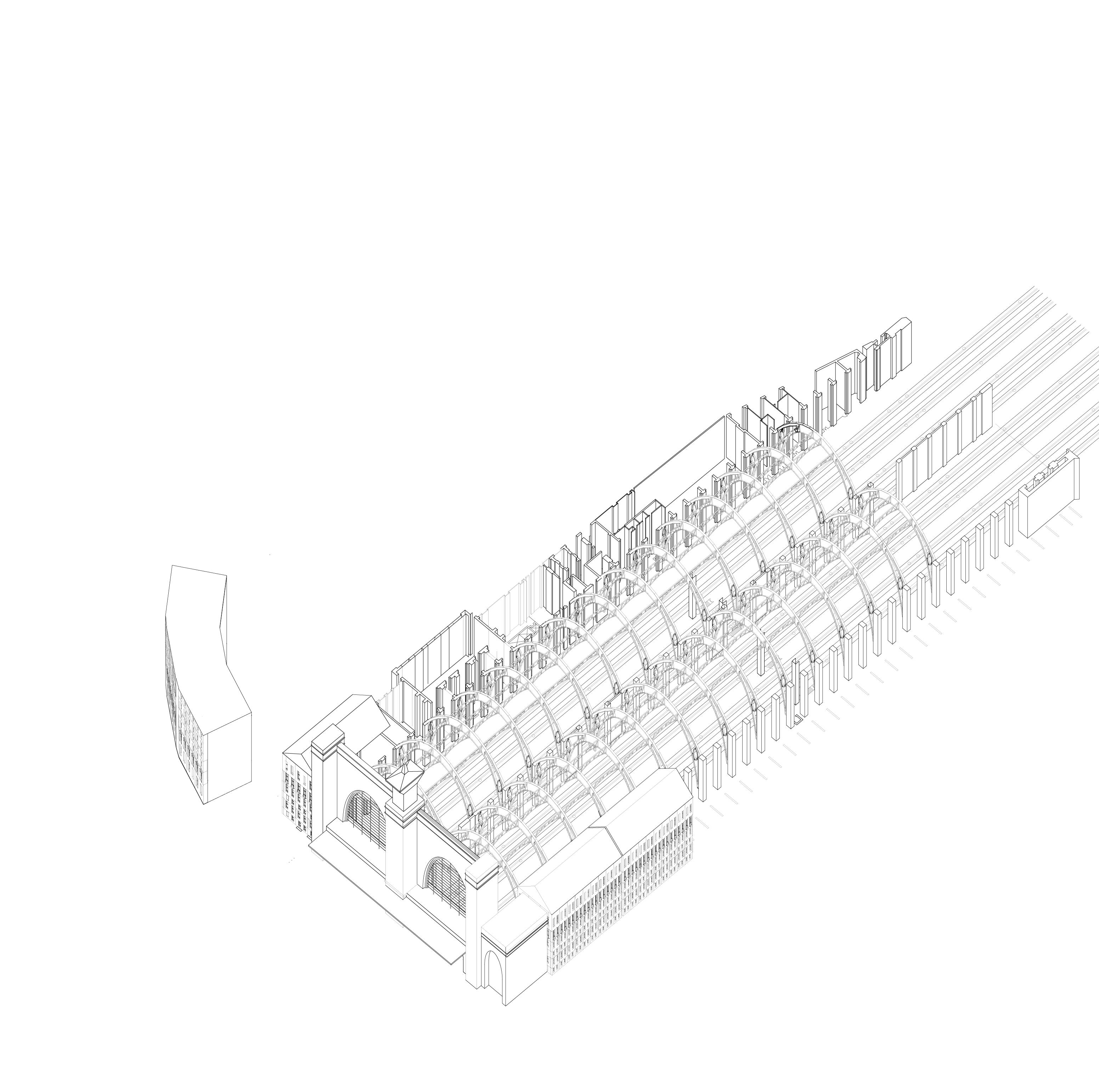

The turning point began in the mid-19th century with the advent of new industrial materials, particularly iron and glass, which revolutionized construction possibilities. Engineers and architects began to reimagine the potential forms and functions of train sheds, moving beyond their utilitarian origins. This shift coincided with the increasing passenger traffic of the 1850s, prompting the Great Western Railway to commission Isambard Kingdom Brunel to design and build a new permanent station at Paddington.

At that time, the groundbreaking "glasshouse" technology reached its zenith with the construction of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, hailed as the world's most revolutionary building. Brunel, who was closely associated with this project as a member of the building committee for the Great Exhibition[56], found in the Crystal Palace a key inspiration for his redesign of Paddington Station.23 Though his ambitious proposal sparked intense controversy, particularly regarding its permanence and aesthetic appeal after the committee invited bids from contractors, the groundbreaking design was ultimately realized. Meeks recognized the dramatic advancement in shed design as a critical turning point in the architectural design of railway terminals.

The introduction of massive semi-circular train sheds marked a departure from traditional station hall designs, giving rise to a new type of public space. He elaborated on this space as a condition of "room-streets," where the innovative design shattered the conventional boundaries of enclosed streets, fostering a more open and interconnected environment that almost completely erased the distinction between streets and buildings.24 This transformation was achieved through the structural use of iron and glass, which redefined spatial boundaries and reimagined the interplay of light and shadow.

The demand for natural light within these sheds morphed into a diffuse illumination, characterized by a lack of contrast and perspective, creating a homogeneous and almost artificial atmosphere.25 The essence of the shed lies in its structural and beam patterns, defined by repetitive, homogeneous lines rather than volumetric forms. As the thickness of these structural elements diminished into mere surfaces, the space beneath gained autonomy by shedding traditional walls and mediating directly with the outside environment. This architectural innovation not only redefined the functional and aesthetic qualities of railway terminals but also established them as dynamic public spaces that blurred the lines between interior and exterior, functionality and spectacle.

The sheltered interior of the train station, with its controlled temperature and humidity, redefined the waiting experience, freeing it from reliance on weather or natural light. This space became a new kind of semi-outdoor environment, which is neither fully interior nor exterior, but a hybrid shaped by surrounding structures rather than traditional enclosure. This indirect approach allowed ground-level functions to emerge almost organically from the horizontal plane.

By the 1850s, locomotives had ceased to be spectacles. Overshadowed by the innovative use of new materials and poetic construction techniques, they became mere components beneath the station’s vast sheds. Their presence no longer provoked anxiety or wonder, as the railway terminal itself emerged as the true architectural marvel. By this time, the terminal had become the only truly representative architectural type Britain possessed. As The Building News observed in 1875, just as monasteries and cathedrals defined the 13th century, railway termini and hotels came to epitomize the 19th century.26 This analogy highlights the terminal’s role as a symbol of industrial progress and civic pride, embodying the aspirations and achievements of the Victorian era.

Under the vast train shed, the terminal became a monument to civic pride, its form and function celebrating the technological and social achievements of the age. No longer just a place of transit, it evolved into a civic landmark testament to industrial transformation and a public gathering space where people could interact and marvel at the wonders of modern engineering. This new form of civic architecture redefined the relationship between individuals, the city, and the machine, solidifying the railway terminal as a symbol of collective identity and progress.

HABITABLE ENCLOSURE 2.2 FROM PORTICO TO RAILWAY HOTEL

Nothing speaks the essence of a civilization more powerfully than its architecture. As the most outspoken one for the Industrial Revolution, it must be the room at the end of tracks, the railway terminals.

HABITABLE ENCLOSURE

27. Lisa Hirst, “Britain’s Pioneering Railway Hotels,” TORCH: The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, accessed February 10, 2025, https:// www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/britains-pioneering-railway-hotels.

... the Great Western at Paddington, regarded as the prototype for 'the modern gigantic hotel'.

- Lisa Hirst

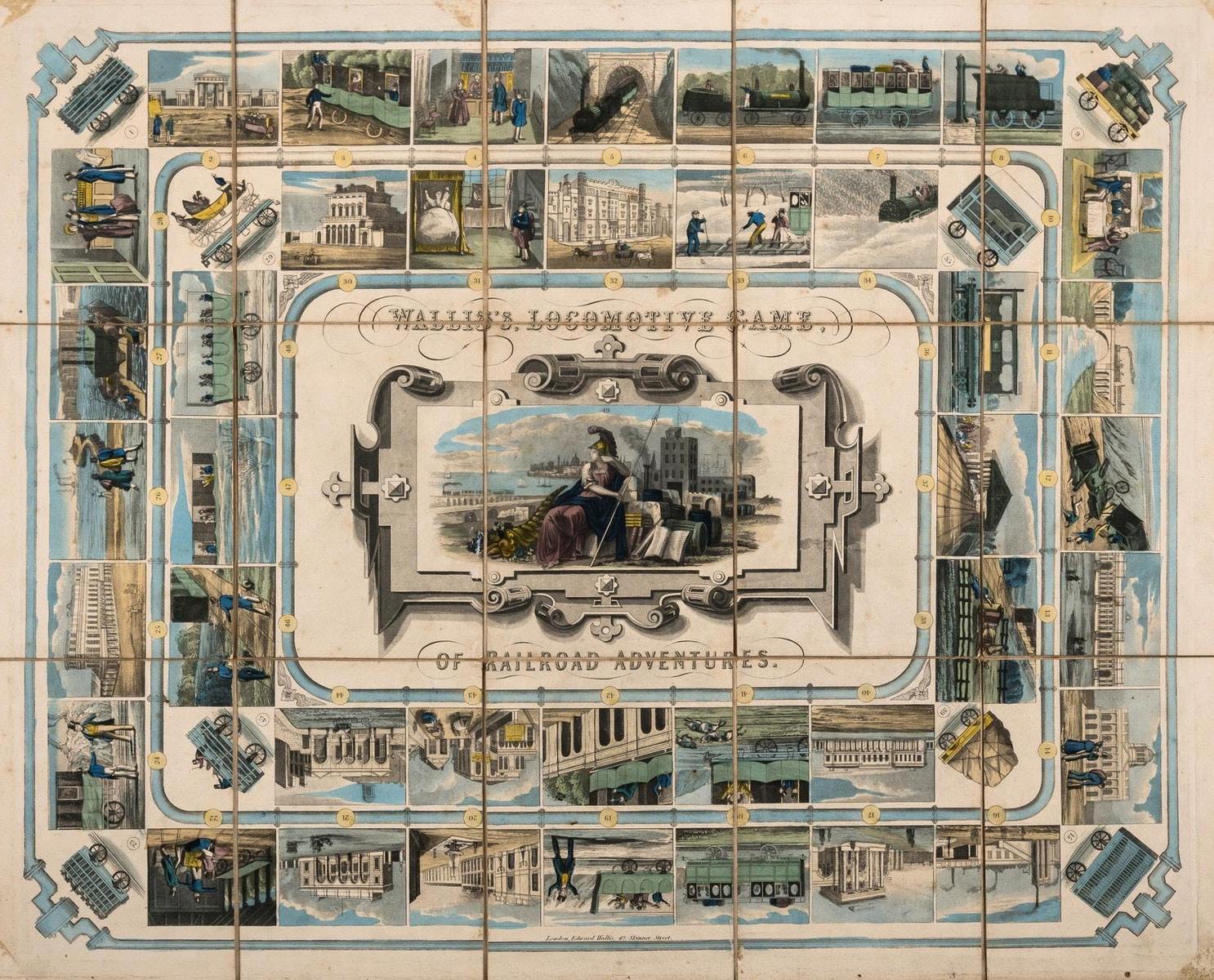

The hotels in the Euston area were widely acknowledged as valuable assets during the Victorian era, symbolizing the growing importance of railway terminals as hubs of commerce and civic life. By the 1840s, even board games[63] themed around Victorian railways prominently featured train terminals, their associated dangers, and the grand railway hotels, reflecting their cultural significance. As one of the most successful board games of the 19th century, such games were not merely entertainment but also respected educational tools, especially for children, teaching them both the conveniences and challenges of railway travel.

28.Simmons, "Railways, Hotels, and Tourism in Great Britain," 203.

This cultural phenomenon undoubtedly reflects, as Lisa Hirst’s doctoral research on Britain’s pioneering railway hotels explores, how station architecture and railway hotels were perceived as reassuring landmarks and places of refuge amid the anxieties surrounding train travel.27 These structures not only provided a sense of security and comfort but also played a crucial role in enhancing the public image of railway travel and architecture. By combining functionality with grandeur, railway hotels became symbols of stability and progress, transforming the perception of train travel from a source of unease to an experience associated with modernity and civic pride.

29.Steven Brindle, Paddingon Station: Its History and Architecture (Swindon: English Heritage, 2013), 32-33.

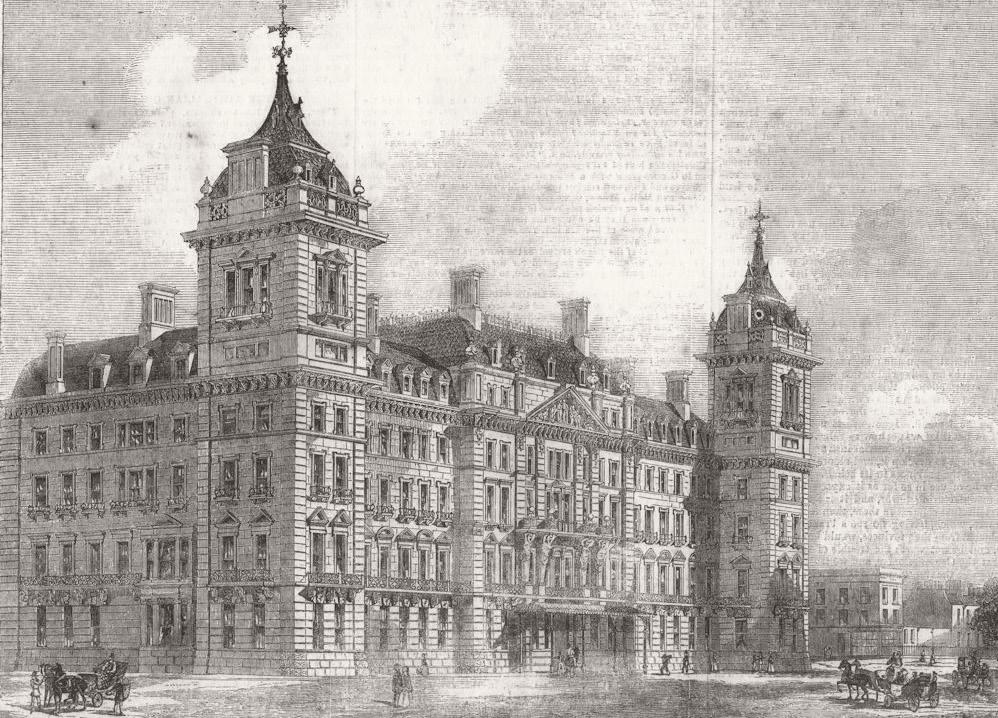

Following this precedent, James St. George Burke, one of the lawyers involved in the construction of Paddington Station, recognized the necessity of a hotel at Paddington to complement the station's expanding role. By November 1850, within just six weeks, an architect was appointed, a site selected, and the principal design concept for the hotel established.28 Isambard Kingdom Brunel was initially responsible for the master plan of Paddington Station, including its platform layout and railway facilities.

(Top of Page 84):

Great Western Hotel, Paddington 1852. Source: Antique maps and prints.)

(Bottom of Page 84):

Front Entrance of Paddington Station,

1852, by author.

His original design featured a grand central entrance from Conduit Street, with departure and arrival platforms surrounding a central main hall. However, this plan was later shelved by the board, as they preferred a front view dominated by a colossal hotel that would rival Brunel's monumental train shed. This decision reflected their ambition to create a striking architectural statement that would not only complement the station's functional design but also serve as a symbol of technological progress and luxury, epitomizing the Victorian era’s aspirations for industrial advancement and refined elegance. To achieve this, they requested a design that allocated more space for the hotel, transforming it into an independent structure rather than a mere appendage to the station façade. As a result, during Christmas 1851, the board appointed Philip Charles Hardwick as the architect for the hotel, whose father, Philip Hardwick, had previously designed Euston Station. In 1852, the Great Western Hotel was completed,

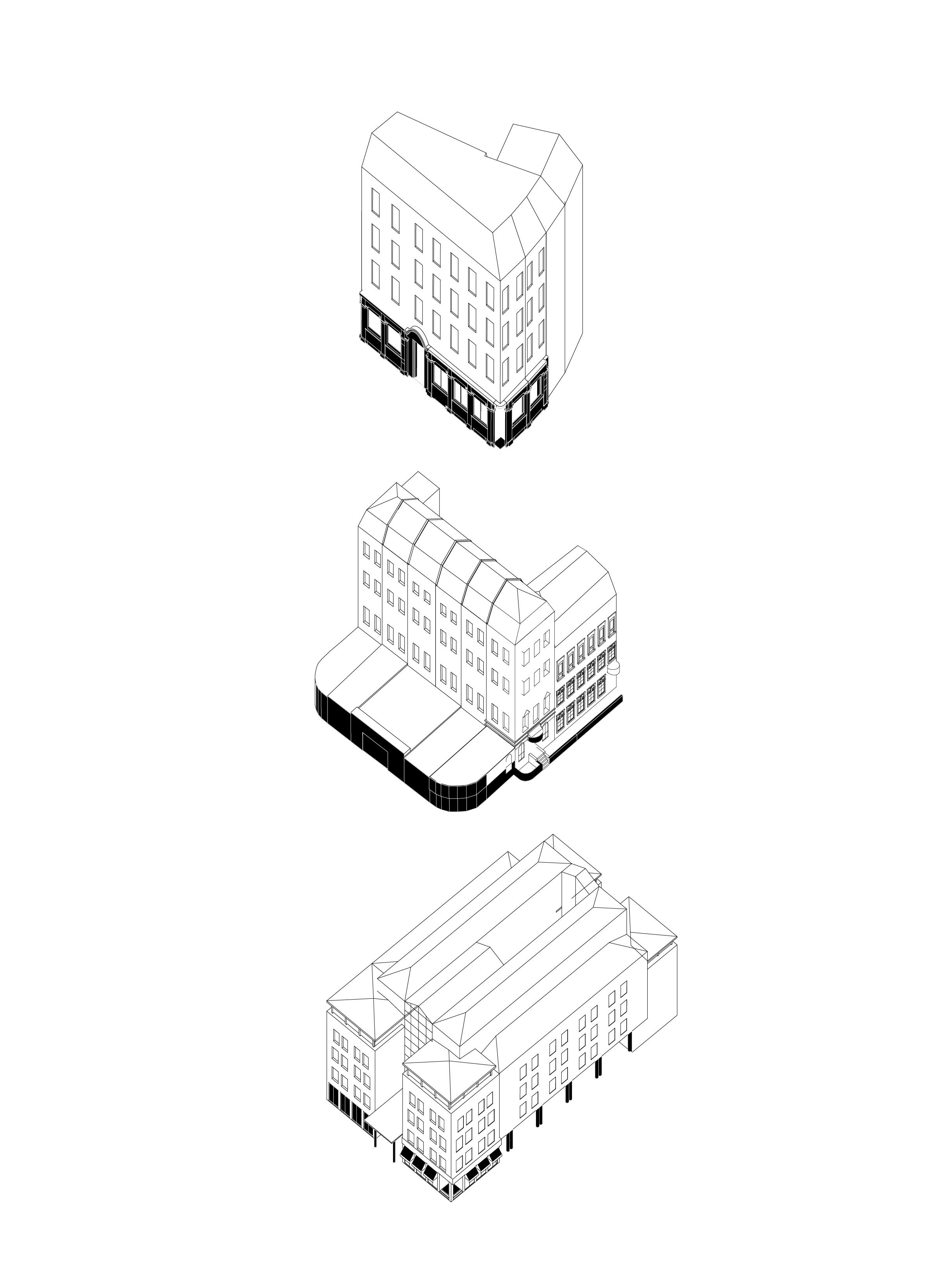

serving as the frontispiece of Paddington Station.29 His imposing structure ultimately concealed the station.[60] The hotel was strategically positioned at the station’s front, with the facade characterized by a rhythmic arrangement of classical elements, such as pilasters and cornices, which create a sense of formality and order that resonates with the surrounding Victoria style buildings. Its design employs expansive stonework and a towering exterior to project an image of prestige and permanency. Decorative details, including intricate carvings and an imposing portico, further emphasize its dual role as a luxurious retreat and a prominent public landmark within the city. While Brunel’s design emphasized engineering efficiency and practicality, Hardwick’s hotel introduced an element of luxury, reflecting the Victorian era’s ambitious standards for public architecture. Together, the train shed, and the hotel embodied a harmonious duality— functionality paired with refinement—positioning Paddington as both a symbol of industrial progress and a gateway to the city.

The success of the Great Western Hotel sparked a broader exploration into the construction of large-scale hotels, marking a significant shift in hospitality architecture. The Times underscored this transformation by contrasting traditional, long-established inns with the modern railway hotel, highlighting the latter’s superior organization, amenities, and streamlined operations. 30

For many visitors, particularly those from Europe, Great Western became the first choice of railway line for exploring Victorian Britain, with the grandeur providing by the Paddington Station. London’s railway hotels gained a strong reputation for excellence, one that has endured to this day. This success catalyzed a wave of hotel construction across the city, with notable examples including the Westminster Palace Hotel and the Langham Hotel. Between 1861 and 1899, more hotels were erected at London’s terminal stations, reflecting the growing demand for modern accommodation. This hotel mania not only transformed the urban landscape but also cemented the Paddington Hotel’s status as the prototype for the modern gigantic hotel. Its innovative design and integration with railway infrastructure set a new standard, blending functionality with luxury and establishing a model that would influence hotel architecture for decades to come.

This marked a departure from the traditional focus on civic grandeur, as reflected by the openness of the portico, to a new priority: the opulence of the hotel, which appealed to those who could afford its accommodation. At Paddington Station, the front image no longer centreed on its civic identity but instead highlighted the monumental presence of the hotel, designed to impress passersby and signal the station’s modernity and prestige.

This transformation aligned with the social and cultural shifts of the 1860s, a period marked by hedonistic liberation and the growing popularity of shortdistance leisure travel. As railways made previously inaccessible destinations reachable, the middle class embraced travel for recreation, with hotels becoming

31. Network Rail, “The History of London Paddington Station,” Network Rail, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.networkrail.co.uk/ who-we-are/our-history/iconic-infrastructure/the-history-of-london-paddington-station/.

essential touchpoints in this evolving culture of mobility. This trend hinted at the inevitability of terminal front gentrification, a shift clearly reflected in Hardwick’s plans for the Great Western Hotel’s interior spaces, which catered to this emerging demographic.

The focus on light-filled interiors, high ceilings, and upscale ambiance reflected a conscious shift toward developing spaces that attuned themselves to the aspirations of an emerging middle class.[62] With luxury and refinement embedded in their design, hotels like The Great Western Hotel not only met the needs of this new group but also revolutionized the terminal’s front as a space tailored to their tastes and expectations. This architectural and social evolution underscored the terminal's development from being a completely functional hub into an image of contemporaneity and exclusivity, reflecting broader changes in Victorian society.

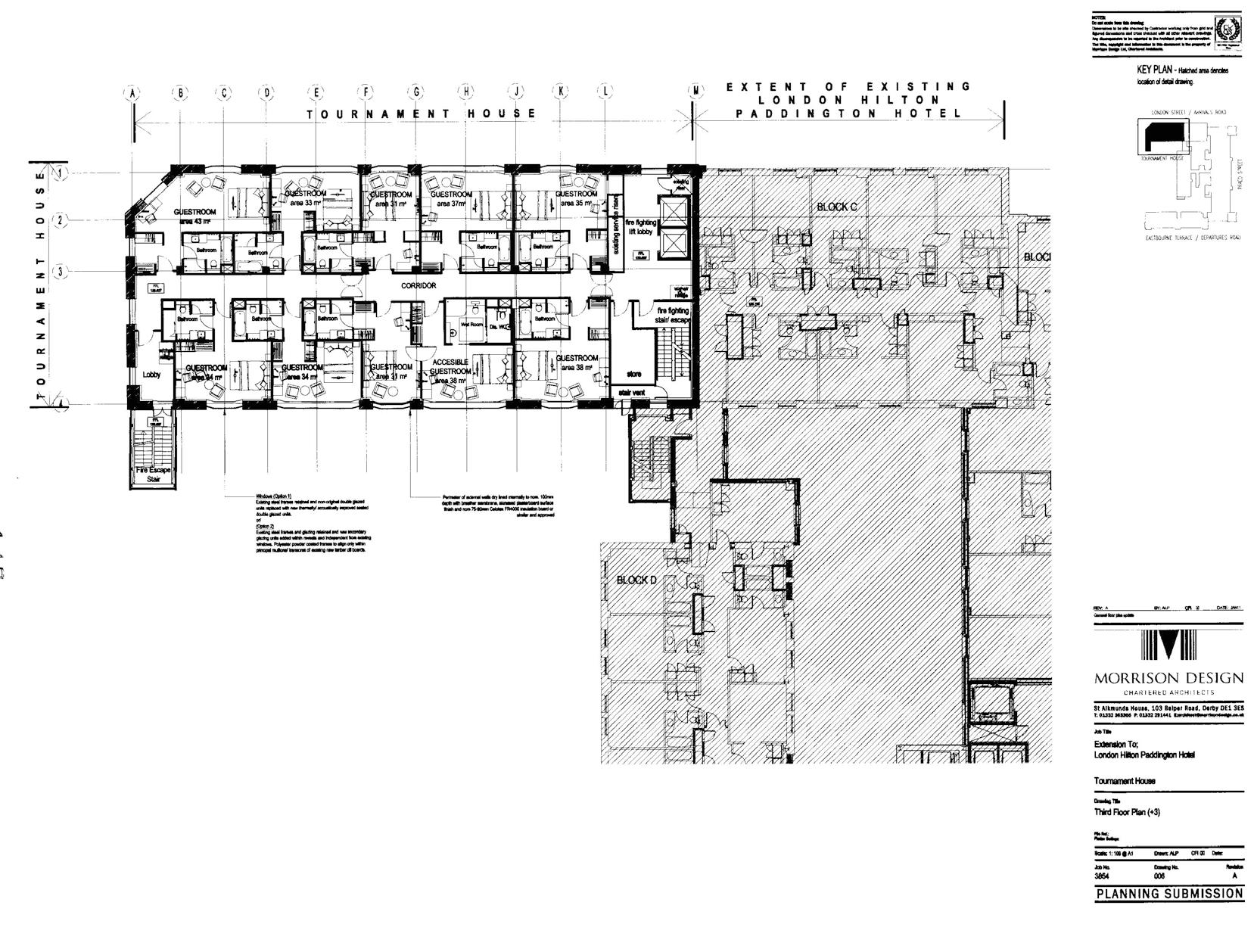

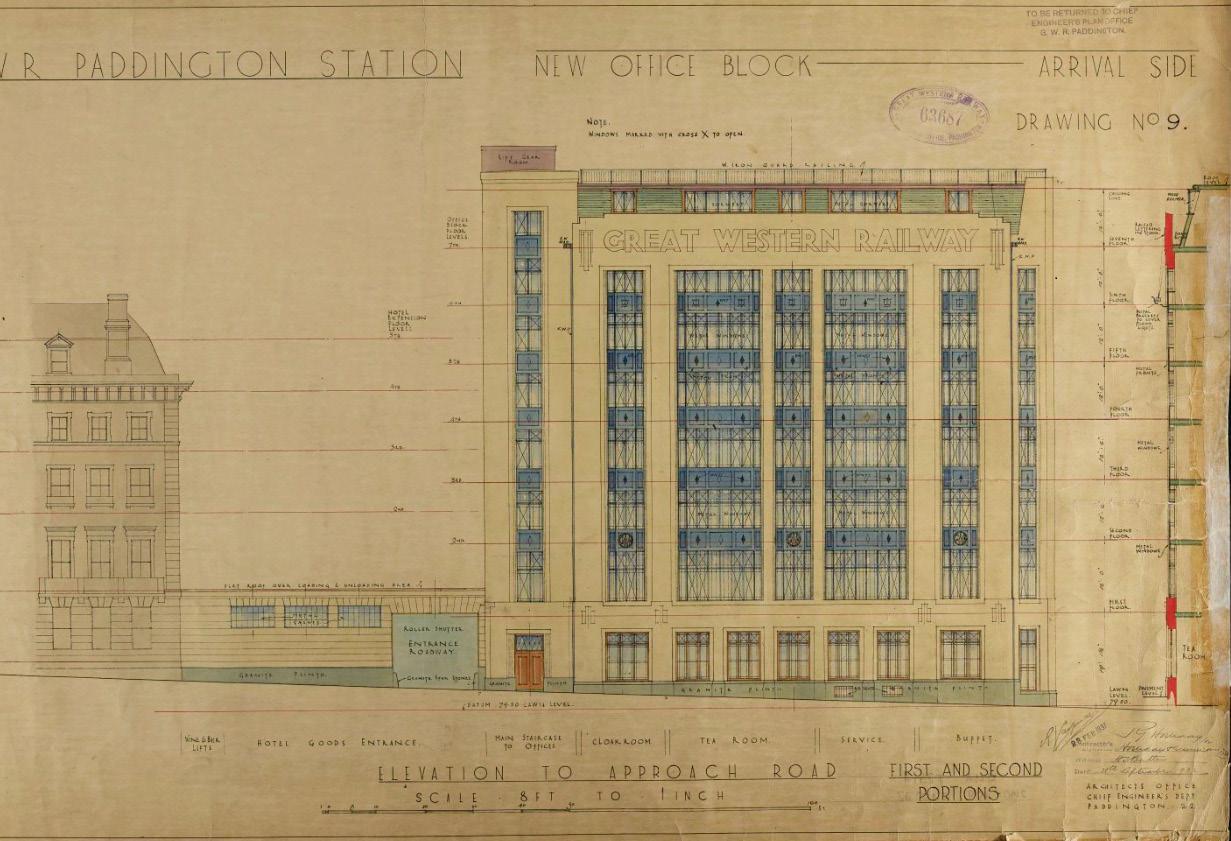

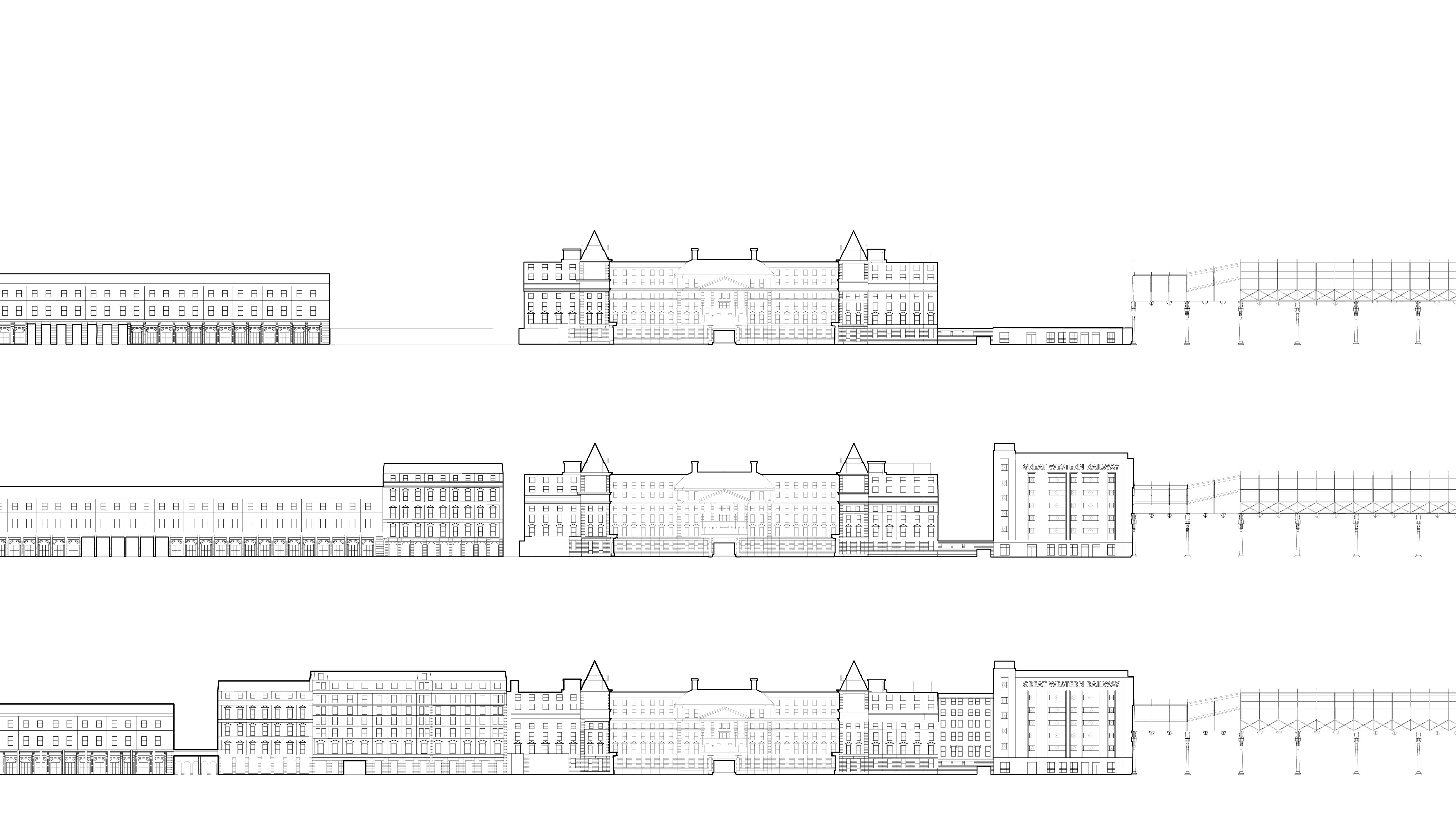

In response to increasing passenger traffic and the railway demand, Paddington Station expanded its office facility further in 1935 with the addition of a distinctive Art Deco building on its western side. Characterized by its bold architectural presence, the structure prominently featured large "GWR" lettering at the parapet, once illuminated by concealed lights within upturned shell-like fixtures. Originally named the Arrivals Side Offices, in line with Paddington’s established naming conventions, it has been known as Tournament House since 1987. 31

From the 20th to the 21st century, the railway hotel gradually expanded, although detailed architectural plans of this expansion are scarce. However, by examining old photographs and analysing the load-bearing walls, it can be pieced together the general progression of this expansion.

89):

The expansion occurred in three main phases. Initially, the hotel stood like a solid block in front of the terminal. By the mid-19th century, the hotel expanded eastward, increasing its capacity with additional guest rooms. This expansion occupied the space originally intended for the portico, forcing the main passageways to shift to the eastern side of the station, where trackside buildings parallel to the corridor accommodated the flow. In the third phase, the hotel absorbed the western office buildings, repurposing them into luxury rooms.

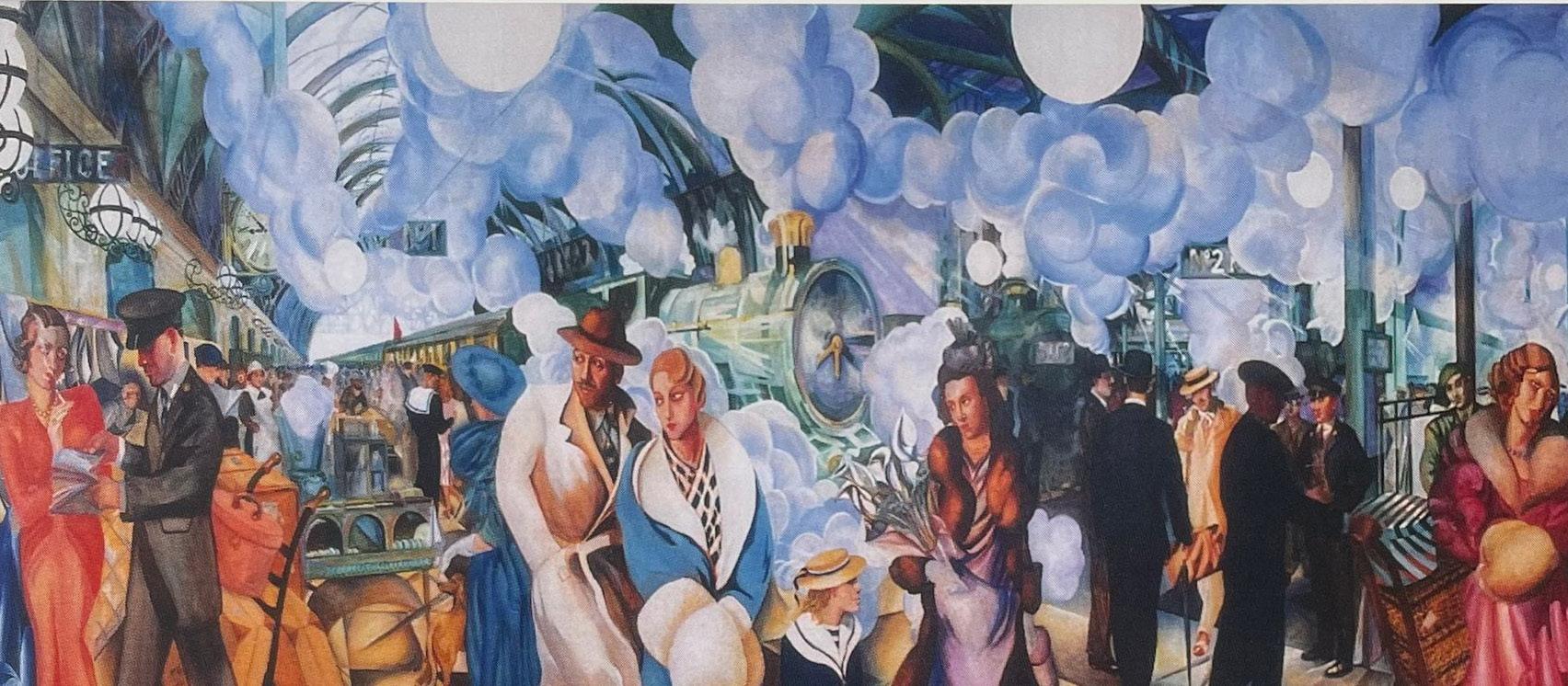

A painting by Kate Lovegrove[69], displayed in the Hilton Hotel lobby, captures this opulence, depicting the elite shuttling between the platform and the hotel. This transformation highlights the shift in focus towards middle-class travellers, prioritizing their comfort and convenience over the broader public. The painting underscores the hotel's role as a symbol of luxury and exclusivity, reflecting the changing social dynamics and the increasing importance of catering to affluent passengers. This evolution marked a significant departure from the station's original civic function, emphasizing instead its role as a gateway for the privileged.

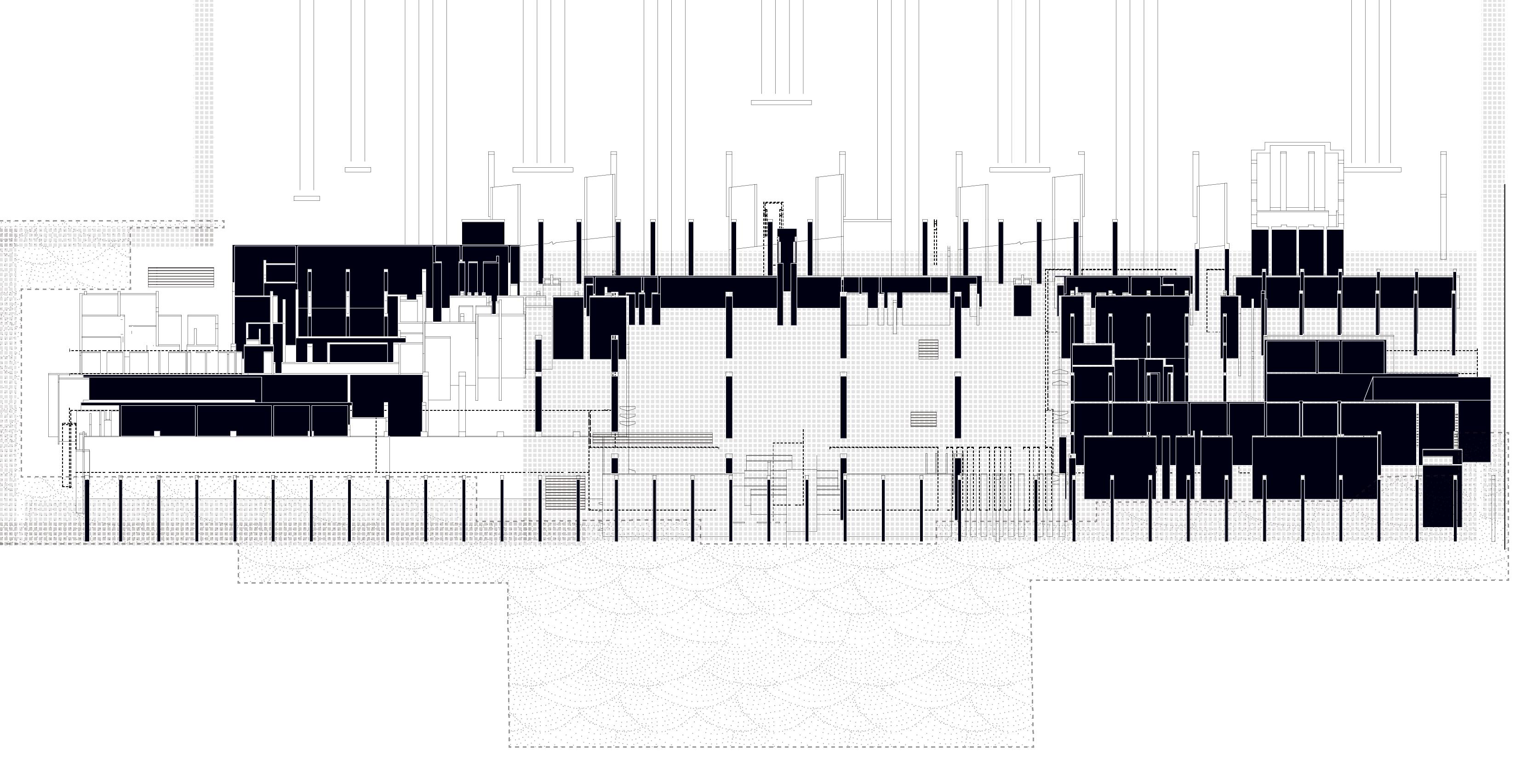

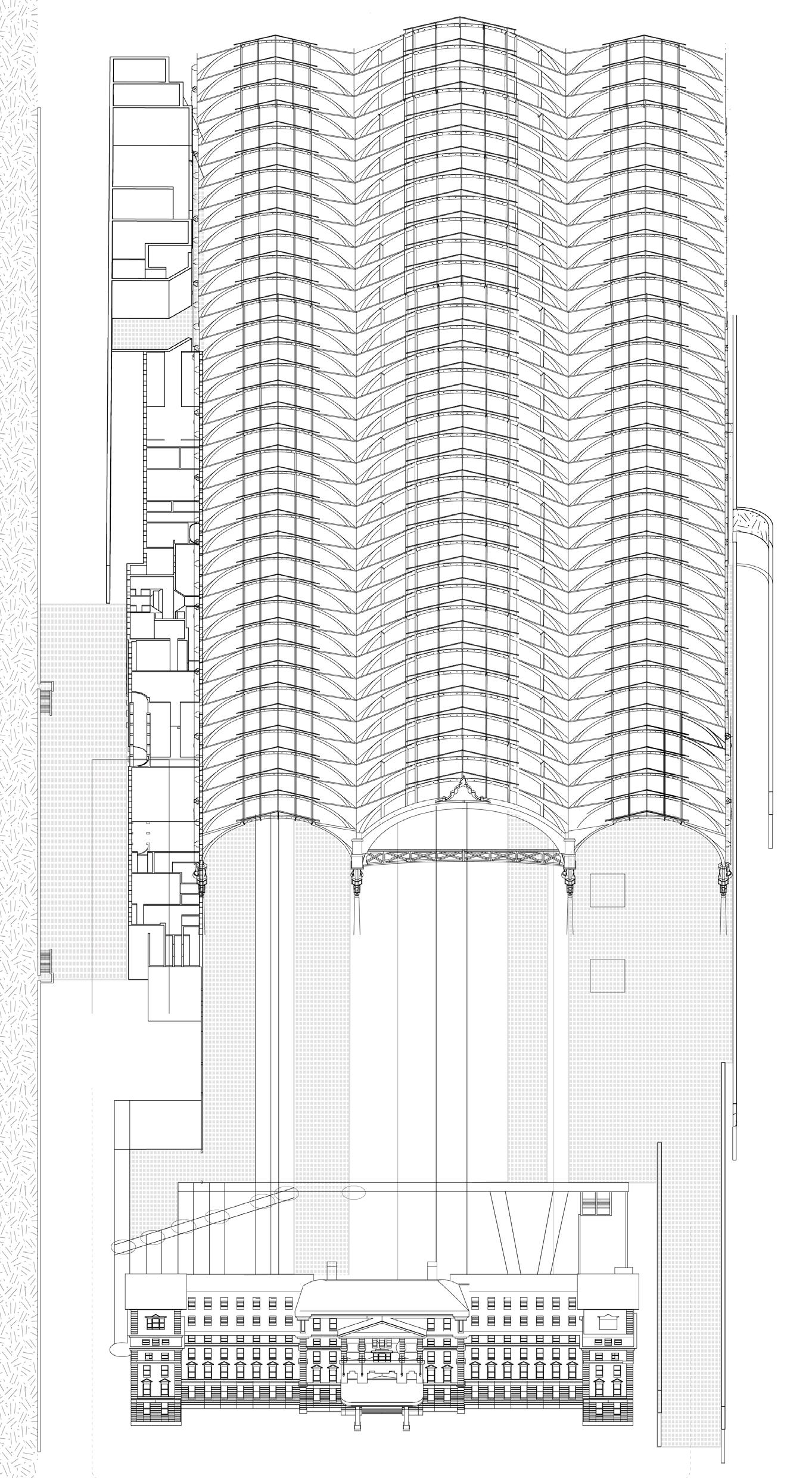

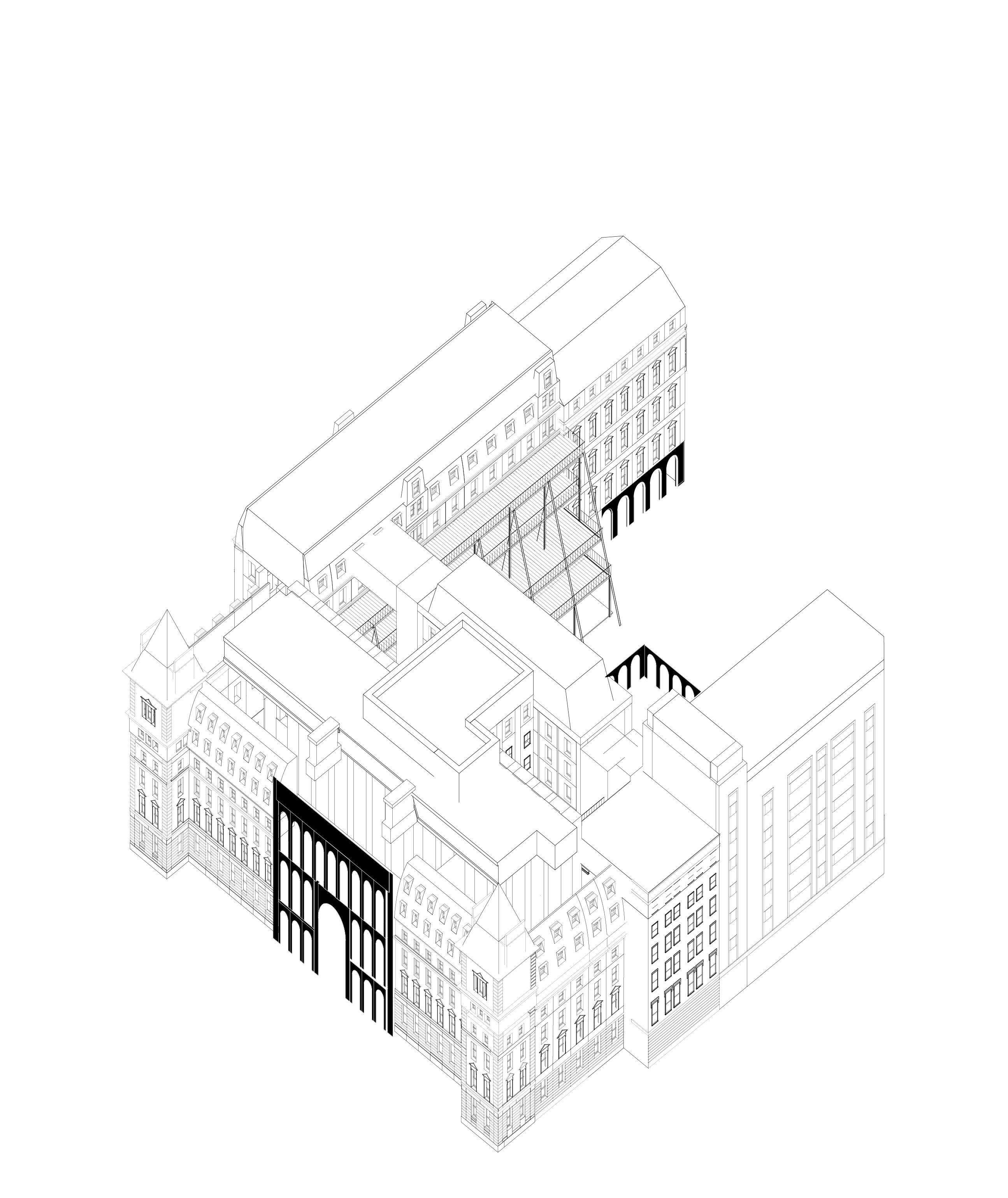

The ENCLOSED PLAZA 2.3

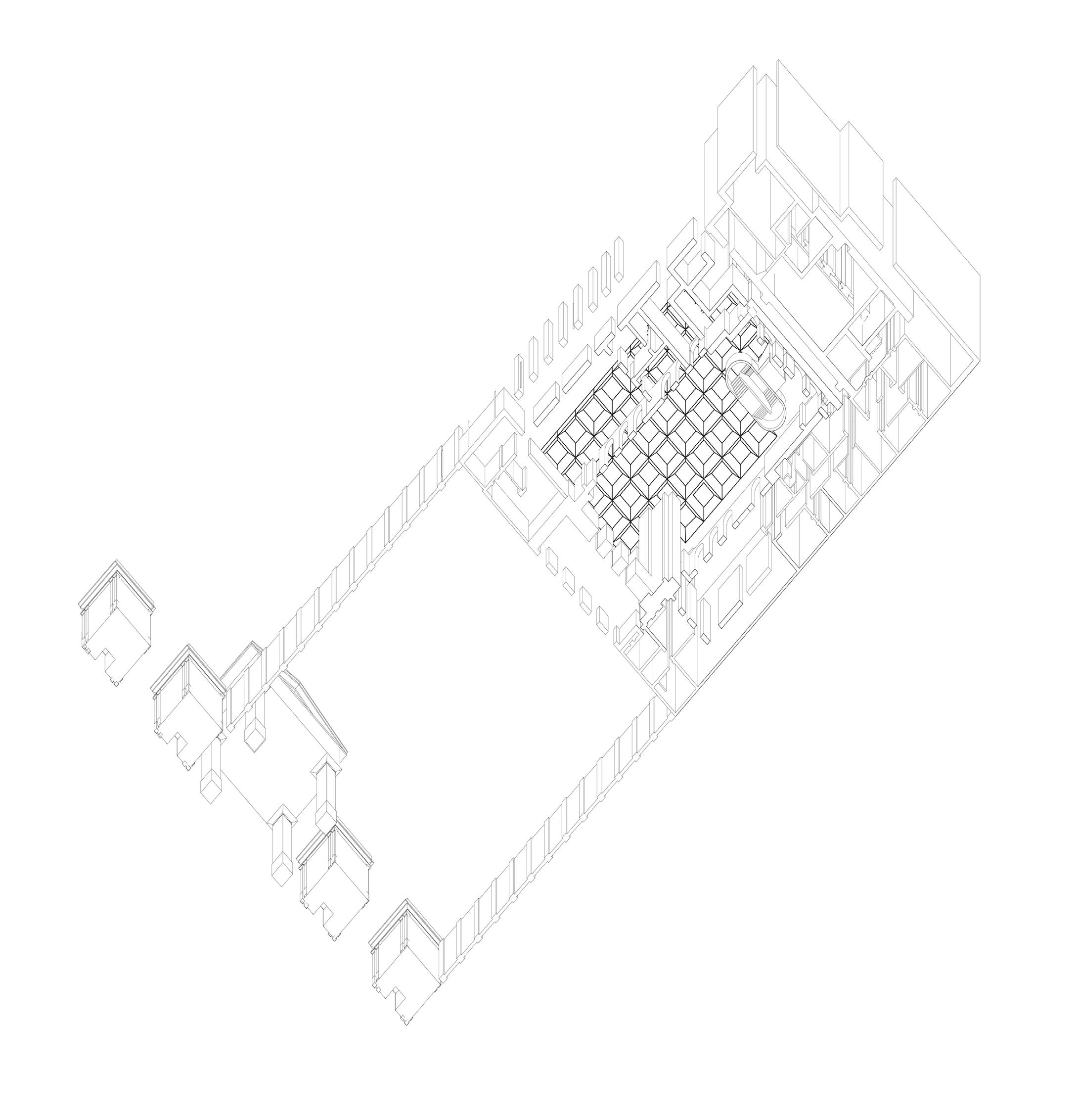

Beyond its primary function as a transit hub, the terminal’s enclosed plaza emerged as a vital urban gathering space, accommodating social interactions, cultural events, and everyday activities within the city’s railway infrastructure.

THE ENCLOSED PLAZA

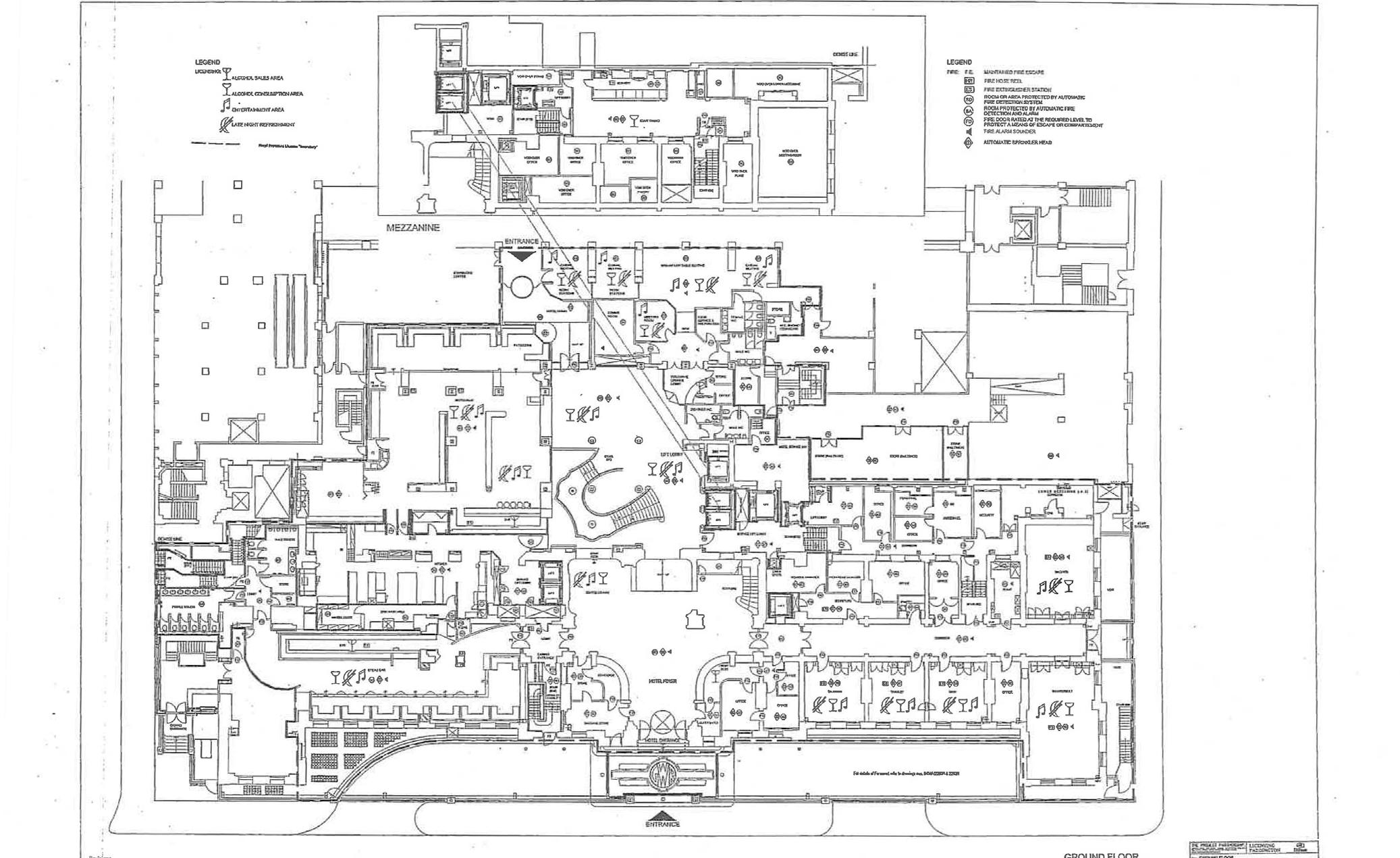

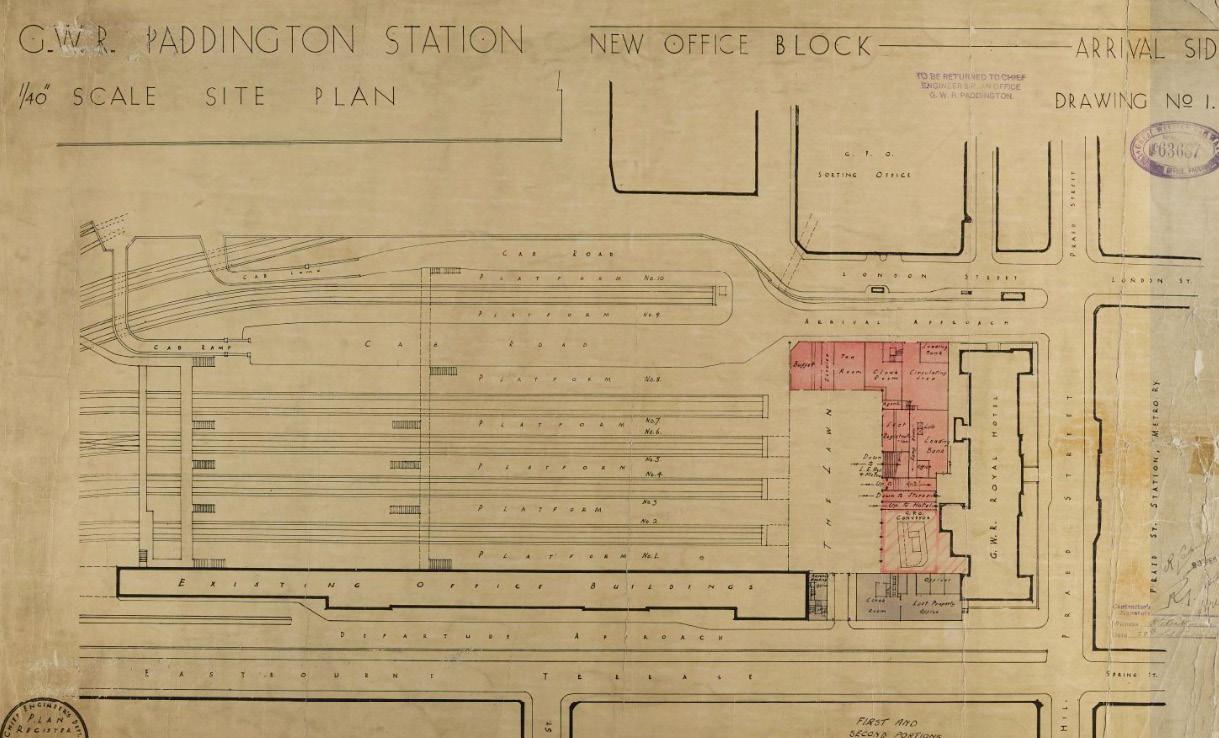

Between 1930 and 1935, a significant redevelopment project transformed Paddington Station, supported by a £1 million government loan under the Development (Loans, Guarantees and Grants) Act of 1929.32

One of the key initiatives involved demolishing 19th-century low-rise structures to construct a modern steel-framed office block (as described in 2.2, the G.W.R. PADDINGTON office building), designed by A. Culverhouse. This redevelopment aimed not only to modernize station operations but also to create a more seamless connection between different areas of the terminal. Thus, a major task of this transformation, overseen by Culverhouse and chief engineer Raymond Carpmael, was the reconfiguration of The Lawn. It used to be an area behind the hotel used for vehicle loading.33 To enhance spatial cohesion within the station, this space was repurposed into a pedestrian plaza, improving circulation and accessibility[72].

Brunel’s original master plan for Paddington had been notably forward-thinking, reserving sufficient space for this future expansion. On the eastern side of The Lawn, the hotel underwent substantial extensions, adding a postal sorting office on the ground floor, a publicity department on the mezzanine, a redesigned drawing room above, and additional guest rooms on the upper levels. At platform level, the redesigned façade facing The Lawn adopted a restrained classical style, clad in patent Victoria stone, providing a dignified architectural presence. The Lawn itself was formally established into a structured pedestrian plaza, reinforcing its role as a transitional space within the station. To complete the development, Culverhouse and Carpmael extended a steel-framed glass roof, incorporating white and amber-tinted glass panels, allowing natural light to enhance the spatial quality of this newly defined urban gathering space. 34

Encircled by dining areas, retail shops, and passenger facilities, the plaza integrated essential services into a single, cohesive environment. This spatial arrangement allowed the Lawn to accommodate both movement and temporary respite, creating a balanced space that catered to the needs of travellers while maintaining the station’s operational efficiency.