INTERFAMILY LIVING:

Building A Community of Public Housing in China

by Huajing Wen

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my very great appreciation to my tutors, Dr. Sam Jacoby, Dr. Platon Issaias, Dr. Hamed Khosravi amd Dr. Mark Campbell for their patient guidance and help throughout the whole process of my dissertation as well as two-year study in Projective Cities.

I would also like to thank my parents who supported me throughout the way with their immense love.

I am also grateful for the supports and encouragement from my friends, Minglu Ma, Han Chen and Wenwen Wang, as well as from my colleagues at Projective Cities, especially Gianna Bottema, who offered enomorous help in the past two years.

To Yunhong Wen, who offered her help when I needed most without hesitation, and encouraged me to overcome the most difficult times.

At last, I would like to offer my special thanks to my cats, Haitai and Xiatiao, for their faithful companions in those long nights.

ABSTRACT

Public housing has become one of the major focus of the Chinese government since 2007. It becomes the solution to the housing shortage and city renewal throughout the country. While driven by housing market as well as efficient planning and construction, public housing is becoming a small version of commercial housing in terms of producing generic units and layouts, which not only fails to coordinate the on-going demographic change but also fails to improve the existing inefficient service provision system.

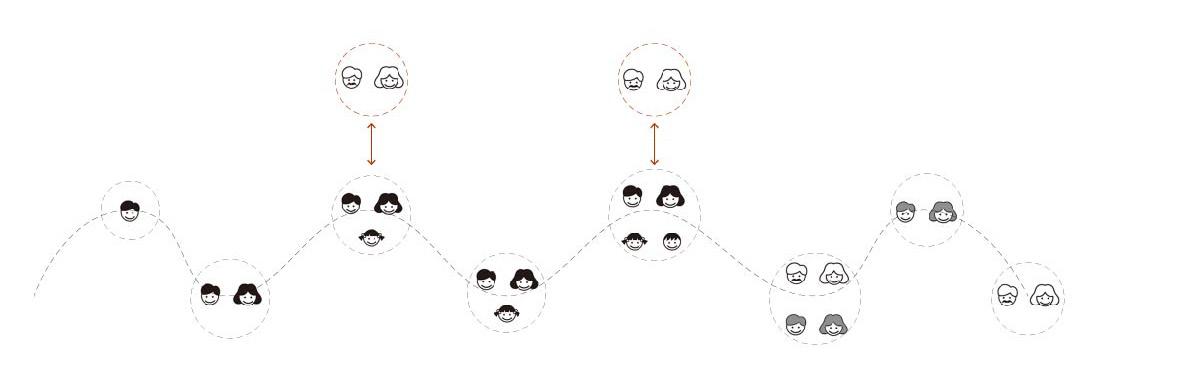

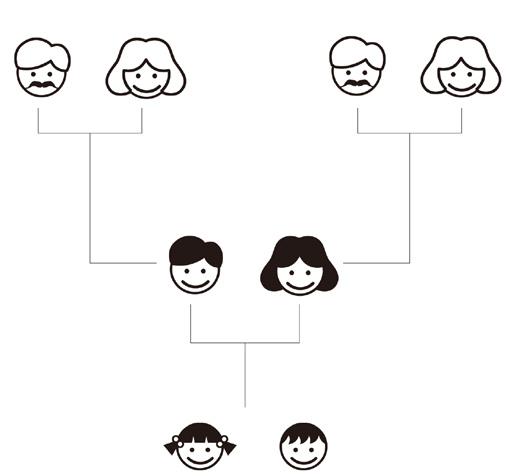

On the other hand, the ageing society brought by one-child policy raises problems around elderly care and upbringing of children. With the inefficient public service system at present, the changing demography points to the possibility of interfamily living, which is based on but goes beyond the extended family. By sharing particular living space where some public facilities are inserted with different groups of people, the daily activities of the residents are associated with a more hierarchical service provision system of a new housing typology.

This dissertation aims at providing a new typology of public housing that is based on interfamily living, to challenge the current way of single-family living and its relation to public service provision. It will also analyse the relationship between public housing and urban governance, to rethink how spatial elements can help to redefine residential relationship for better social cooperation. In this process, the role of public housing will also be challenged to become an instrument to build up a more efficient public service system.

INTRODUCTION

In October 2015, the Communiqué of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee announced that the state now recommended a couple to have two children. This announcement put an end to the one-child policy since 1980. In the past 35 years, the constitution decreed that a couple in the city should only have one child. This policy was put forward as the solution for an unexpected high growth rate of the population, which led to huge pressure on the limited social resource. Three decades later, the policy also accelerated the growth of an ageing society.

According to the population forecast by the State Council in 2017, the population of people over 60 years old will reach up to 25% in 2030, whereas in 2013 the proportion was 13%. The ageing society will not only influence economic growth but also put pressure on the national welfare system in terms of elderly care, especially when the single-child generation is becoming the central workforce. Despite the abolishment of the one-child policy, the birth rate dropped by 3.5% in 2017. The low birth rate implies the worry of young couples having no financial capability as well as time to raise children, due to various reasons such as short maternity leave, job market competition, gender inequality, etc.

While the current welfare system in China is unable to deal with the massive pressure of elderly care, traditional ethics require children to take care of their parents. Meanwhile, the parents are the only reliable carers for newly born babies of young couples that both work full-time. This demographic change has resulted in changing household structures. As the proportion of emptynest and single family grows, there is also a tendency and particular needs of the return of an extended family.1 Studies show that the relationship between

the housing projects in China are market-driven and not part of the system.

Even public housing tends to copy the same development models and typologies of market housing without considering the difficult situation of existing service provision system. In the past 27 years, housing was treated more as a commodity by government, developers, contractors, planners and even ordinary residents, rather than a daily living space that supports, encourages and regulates people’s everyday life, influencing social relationship, cooperation and governance. As a result, when public housing was put forward as a solution to urban renewal and housing shortage, more attention was paid to quantity than quality. With massive public housing projects in construction all over the country, most of them are a small version of market housing with generic individual units isolated from each other. Few projects consider the actual on-going demographic change and the rise of diverse household types. Even fewer view the need to integrate housing with a public service provision.

The privatisation of housing makes it possible for the division of land use right and ownership so that the state can lease the land use right to private developers and get enormous profits in return. However, in this process, the state also gives up part of their control at the neighbourhood level in terms of design, management and planning of service provision. Even though there are regulations and building codes to make sure all housing constructed by developers meet specific standards, the market drives the developers to produce similar housing typologies to make the highest possible profit. As a result, we see thousands of newly built neighbourhoods with tower blocks of 2 and 3-bedroom units for nuclear families without any practical daily services except pure landscape in between the towers. ‘It is part of the game the occupants get to bear’, as Niklas Maak described, to tout the single-family house as an anthropological necessity and thereby raise it to the status of an indisputable natural form of existence to which there is no alternative.’ 3

The rise of public housing should be an opportunity for both the state and residents to rethink the nature of housing and what it can contribute to the improvement of existing service provision system, which is based on communities as the providers of general public facilities. With a different ownership pattern, public housing allows the state to enter the neighbourhood scale again, which offers the opportunity to address the gap between the domestic scale and urban scale in the existing service system. On the other hand,

an ageing society encourages a new housing typology to deal with changing household structures and the complicated residential relationship between different generations and individual families, which leads to the possibility of interfamily living. Interfamily living is common space at multiple scales between individual dwelling and community that is currently missing. This research tries to discuss the possibility of integration of housing and service provision through a new public housing typology based on interfamily living.

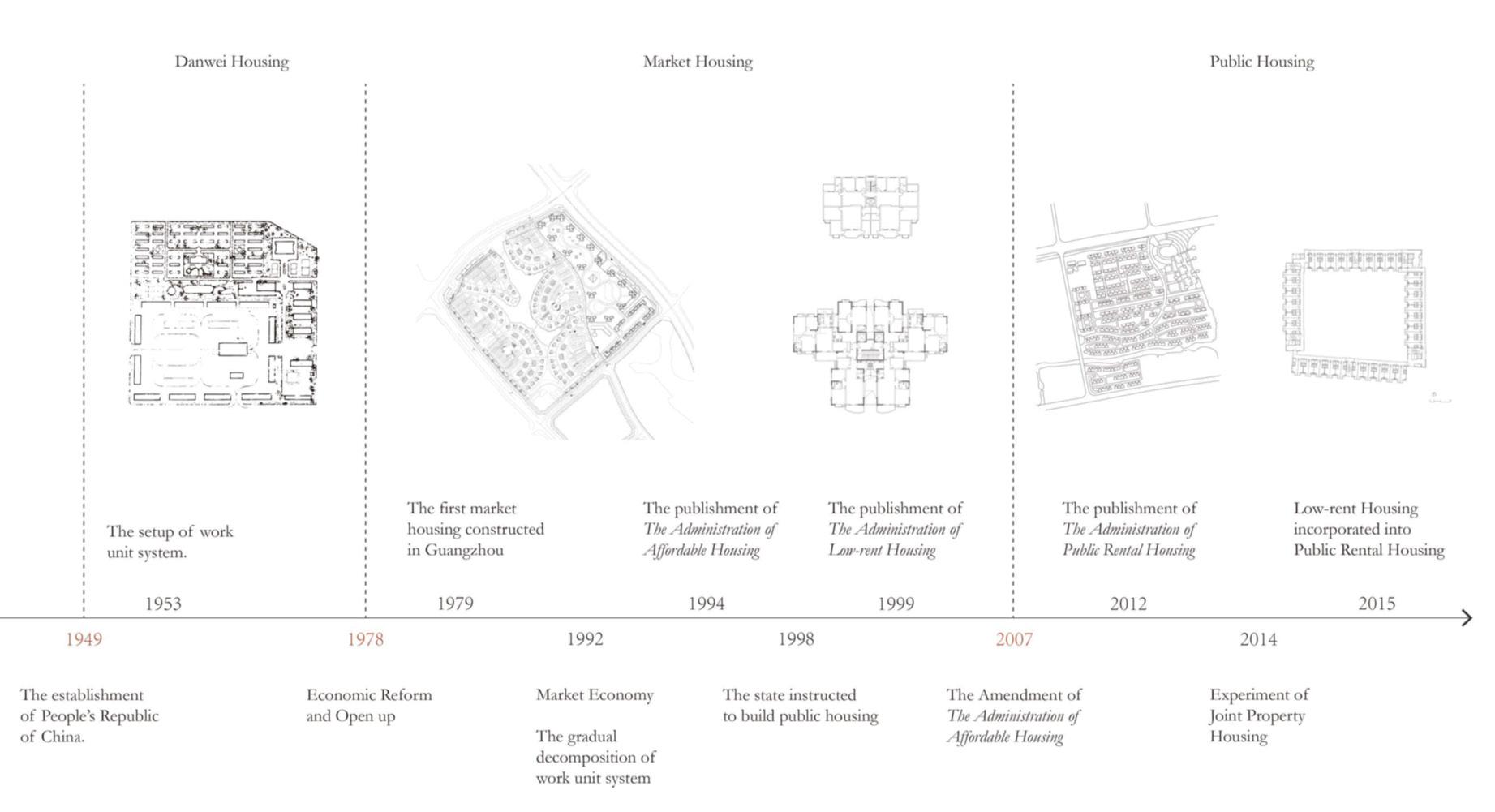

The methodology of this research is based on a typological study of architecture and urban planning, by looking into the transformation of housing typology from work unit, to market housing as well as existing public housing, and their relation to the transformation of service provision system, ownership pattern, development mode, etc. The first chapter is based on the study of historical housing transformation in China, exploring and analysing the social, political and economic context and revealing the current situation and problems. The second chapter is based on several case studies in both the UK and China, which helped me develop the design elements and design proposal for interfamily living. The third chapter is based on the analysis of relations among housing, urban form and urban governance, which led to the coordination of housing and service provision for a newly proposed urban community.

Research Questions:

Disciplinary question: What is the role of public housing in building up an efficient public service provision system?

Typological question: What are the spatial elements of in the scales of interfamily living? How can interfamily housing deal with the problem of changing household structures? How can it help to integrate the function of public services in public housing?

Urban question: What is an urban community in terms of both its residential and administrative functions? How will the urban form be changed when housing becomes an instrument of urban governance?

his tour of inspectation in Southern China, during which the 'Free-market Economy' was proposed. On the right is the first new paper reported the new economic policy.

Poster celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Reformation and Open Up policy, from 1978 to 2018

4. ‘Ghost town’ referring to newly developing town with newly constructed housing but with no resident actually lives there. These towns are usually far away from cities and have ineffective provision of infrastructure and service.

However, this was followed by an inflation of the housing market. In 2016, the average housing price in China was three times higher than in 1999. This rise was even more dramatic in large cities like Shanghai and Beijing. The high housing cost became a tremendous economic pressure for Chinese citizens, including the middle class. While the middle class struggles to buy a small apartment, the working class has no choice but to live in poor conditions in urban slums. On the one hand, housing is in shortage. On the other, housing becomes an investment for the upper middle class, who may own several flats in different districts or even in different cities. However, most of these flats remain empty, since they are often in the periphery of the cities where it is difficult to attract tenants. The demand of the investment market at the same time encourages developers to build more market housing, which results in an absurd situation: there are newly built fancy ‘ghost towns’4 and there are still millions of people struggling to own a flat.

Land Ownership Pattern

In order to enable the land development and make use of the value of the land, the land use right is seperated from the landownership. While the land is still owned by the collectives (namely all the villagers or members of an agricultural collaboration), the use right will be distributed to every farmer family. The land use right can be transferred among individuals or private sectors. However, the law restricts the function of the land, meaning that the farmlands cannot be used in other proposes, such as real estate development.

Therefore, when a piece of farmland are going to be transformed into a residential or commercial block, it has to be firstly retrieved back by the state from the collective and become state-owened land. Compensation will be given to the collectives and land use right owners in return. Then, the land use right will be lent to private developers who will pay the rental to the state.

Fragmented City

The privatisation of housing contributes to the formation of a fragmented city in terms of management and service provision. In fact, Chinese cities were already fragmented back during the work unit period, when all the neighbourhoods were gated and managed by the different state-owned enterprise as a ‘danwei’. Each danwei was responsible for its service provision, and the quality would be based on the financial capability and size of the danwei. This led to the uneven distribution of public facilities. When entering the era of market housing, the revision of landownership coordinates with a new kind of development model working under the modern urban planning method based on functional zoning. Urban Planning conducted by the government never enters the neighbourhood scale as before. Instead, they produce regulatory detail plans to organise the zoning of a large area. Designing the neighbourhood scale becomes the responsibility of private developers. Although their designs will be restricted by a set of building codes and regulations, developers are always driven by the market to make a maximum profit by producing specific housing typologies.

This furthermore leads to the problems of management and public service provision. The privatisation of housing makes the land use right inside a neighbourhood the private property owned by the occupants, meaning that it is impossible for them to become a public space for public facilities. As private

property, market housing neighbourhoods remain gated to prevent outsiders from entering and using the space. Property management companies are hired to manage these spaces in terms of security and the maintenance of facilities. However, the facilities in most of the market housing estate are poorly designed. On the one hand, in order to maximise their profit, investment into these facilities by the developers are limited. On the other, the demands and expectations of occupants are low for these services, as they are unwilling to pay for them. In other words, the profit-driven market itself at this moment cannot take responsibility for a positive environment and foundation for an efficient service provision system. That is when the state should take responsibility and step in.

However, because of the privatisation of housing, public facilities provided by the government can only arrive at the level of community, yet are excluded from the neighbourhoods. Nowadays, most of these services, such as gymnasium, sports field, community centre, community library, public square, etc., are situated on specific pieces of land planned by regulatory detail plan. The user groups that they target at are lacking in definition, meaning that they could be shared by hundreds or even thousands of people living in different neighbourhoods of the community. Consequently, these facilities are difficult to reach for many residents, not only because they are outside the neighbourhood, but also because the enclosure of these neighbourhoods discourages daily activities from happening on the street. As a result, the city becomes fragmented with thousands of isolated urban blocks that fail to share public service provisions. The discontinuity of the existing service provision system at the neighbourhood scale leads to inefficiency and, furthermore, influences urban governance.

Housing for Individual

Before the debate of whether housing should be defined as a commodity in the late 1970s and early 1980s, housing was provided as part of the social welfare. Although citizens did not need to pay for their houses, the political impetus to put production at highest priority led to scarcity in social resources. Housing as unproductive expenses received less investment from the state, which resulted in the housing crisis in the late 1970s. According to the survey in 1978, the national average living area was 3.6 m2 per person, while in 1952, this was 4.5 m2, and 35.8% of the urban citizens needed housing.5

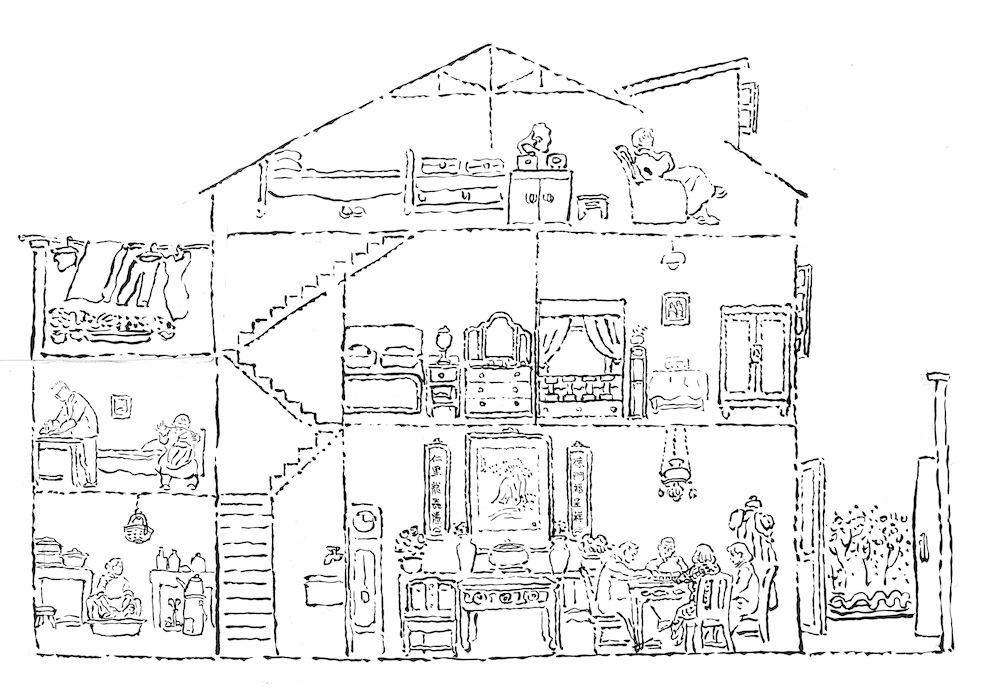

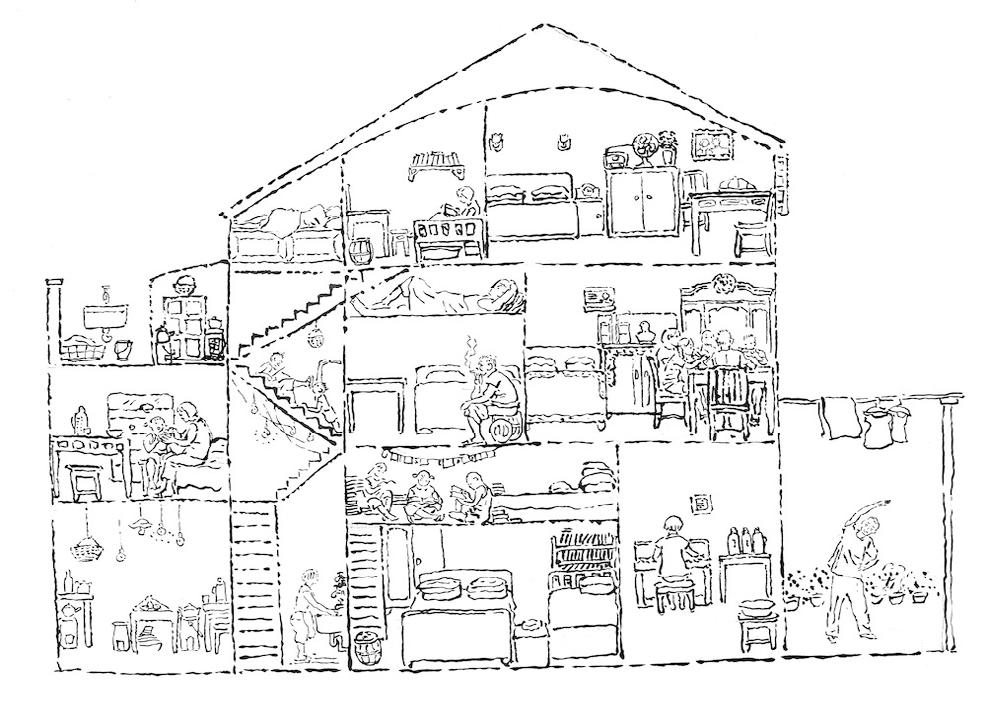

The extreme shortage in housing meant that occupants had to share many living spaces with others in collectively-owned housing. In the work unit, it was typical for a 3-room unit to be shared by two or three families. Kitchen and bathroom were also shared. At the neighbourhood scale, other facilities were collectively owned, including communal bath, canteen, gymnasium, etc., to compensate for lacking functional spaces in individual units. This situation continued until the mid-1980s when a survey showed that only 62.56% of the citizens had a private kitchen, and 24.23% of them had a private bathroom.

75% of citizens lived in flats without all standard functions.

The housing crisis encouraged the commercialisation of housing, for the state could not afford the expenditure all by itself. As the reformation of state-owned enterprises changed the distribution of national income, citizens had higher savings and were eager to own a flat with well-equipped bathroom, kitchen and living room, after having to live in small, shared dormitories for decades. To own a flat with all functions was considered representative of modern life.6

While there is nothing wrong with the desire of home ownership, the emphasis on privacy and private property became mainstream. The situation shifted from one extreme of almost sharing everything to another extreme of wanting to share nothing. In a typical market housing block, only the circulation space is shared, and architects will use every means possible to reduce the shared area in order to lower the development cost. No one wants to pay for the space that does not exclusively belong to him or her. Therefore, the area of individual unit grew from 50m2 per unit at most in 1978 to an average 80100m2 per unit nowadays. This also explains the inadequate facilities provided in the neighbourhood. Residents are willing to give up part of the quality of shared spaces for a better private space but not the other way around. The loss might be more problematic than they think; however, when children have no place to play with their friends after school and retired old people have no place to go but stay at home. However, even young adults suffer from loneliness. A survey shows that 45% of young adults in China feel lonely.7

Today’s housing is housing for individual living, is about providing a private space in which residents can isolate themselves physically from the rest of the world safely. However, it is necessary to question what problems will be brought by maximising the quality of individual living, while compromising the common space.

1.2 The Chinese Context: Public Housing for Whom?

Public housing could be an entry point to change the situation of inefficient services and generic unit types caused by housing privatisation because of its different ownership pattern. Although designed and constructed by developers, all rental housing is ultimately invested into, owned and managed by the government or relevant national institutes. As for affordable housing, most of it is housing for sale at 70% of the market price and invested into by state-owned companies. It is owned by the state before the transaction and owned privately by the resident after. In recent years, there has been a tendency for affordable housing to transfer into joint-property housing, owned both by the occupants and the state, meaning that the state is taking more control in the ownership of public housing.

The national ownership of public housing makes it possible for the state to enter the neighbourhood scale again, meaning that it is once again possible for the processes of planning, designing, constructing and managing to be more systematic and integrated at the neighbourhood level. It thus offers an opportunity to rethink the site layout and housing typologies in terms of whether they still make sense concerning the street, the urban fabric and service provision system. For example, as a state-owned property, is it still necessary to have these neighbourhoods gated?

Evergrande Future Town is a typical market housing real estate developed by one of the most popular developers, the Evergrande Group. With commercial facilities open to the street at the periphery of the neighbourhood, the central area is enclosed as private garden for the residents.

4-unit

is

of the most vastly

However, these questions are ignored in the current public housing projects, which are just a small version of market housing. It is crucial for the state, the planners and the architects to be aware of the problems of existing housing typologies, of its generic units that fail to meet the demands of changing household structure as well as its bad coordination with public service provision. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the subjects, the typologies and the problems of current public housing.

Migrant worker flows are the result of urbanisation. From 1993 to 2012, around 96 million migrants from rural areas moved into the city of Shanghai, making up 40.3% of the whole population.11 This phenomenon happens all around the country. However, most migrants are working class. Among the low-income groups, migrant workers became a new group in the past two decades.12 They became the major productive force in cities, but are underpaid and unable to afford a decent living space. The previous Hukou policy prevented them from having equal rights to townspeople to access urban service provisions, including applying for public housing, education and pension. In recent years, the state amended the Hukou policy to reduce the restrictions. Now migrant workers with a Temporary Residential Permit for two years and above can apply for public housing.

Relocated families are families who used to live in certain areas, either in the inner city or periphery, but are moved to other areas due to urban renewal and expansion. This phenomenon is quite common in Chinese cities due to land ownership. Since the state owns the land and has the right to transfer the use right, residents will have to give up their houses and receive compensation in return. In most cases, relocation programmes offer significant benefits to relocated families, improving their living conditions with modern accommodation and financial support. However, it is also problematic since most of the relocation housing estates are far away from the inner city where these people lived before. As public service provisions are much denser in the inner city, those who move out will lose their access to these facilities.

Young professionals refer to people who just graduated from university and started their careers. Unlike the other two groups, these young professionals are mostly well-educated white-collar workers. Typically, these people will not be considered as the subject of public housing in many other countries. In China, however, this group is thought highly of by the state because of the competition of human resources. On the one hand, the state tries to attract overseas graduates to come back and serve the country through a series of policies and benefits. On the other, different provinces and cities also want to attract young people and big companies. Consequently, housing is one of the most important problems, since the housing and rental price is even unaffordable for these young professionals. This encourages the development of public rental housing in many cities, many of which later transform into ‘talent apartment’. 13

The Typologies of Public Housing

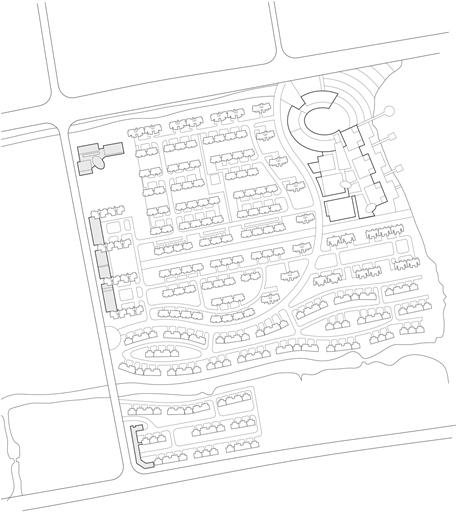

Nowadays, most of the newly built public housing follows the same development model and typologies of the existing market housing. In this mode, housing projects are assigned to different developers, with pieces of land zoned for residential blocks by regulatory detail planning. The size of a neighbourhood varies from case to case. The ones in the inner city are usually smaller with only one or two residential blocks, while others in the periphery are several times larger.

After calculating the FAR, height limitation and density, the number of residential blocks and their number of floors will be decided. Building orientation and minimum distances will determine the site layout. The space between buildings will be designed as green space with some outdoor fitness equipment, a playground or a small square. In the periphery, fences will be constructed along the edge with only one or two entrances guarded by security. Exceptionally, some neighbourhoods may contain a small store, but usually, there is no other service. Some shops may be located on the ground floor of residential blocks on the periphery, but they usually open to the streets and will not be managed by the neighbourhood.

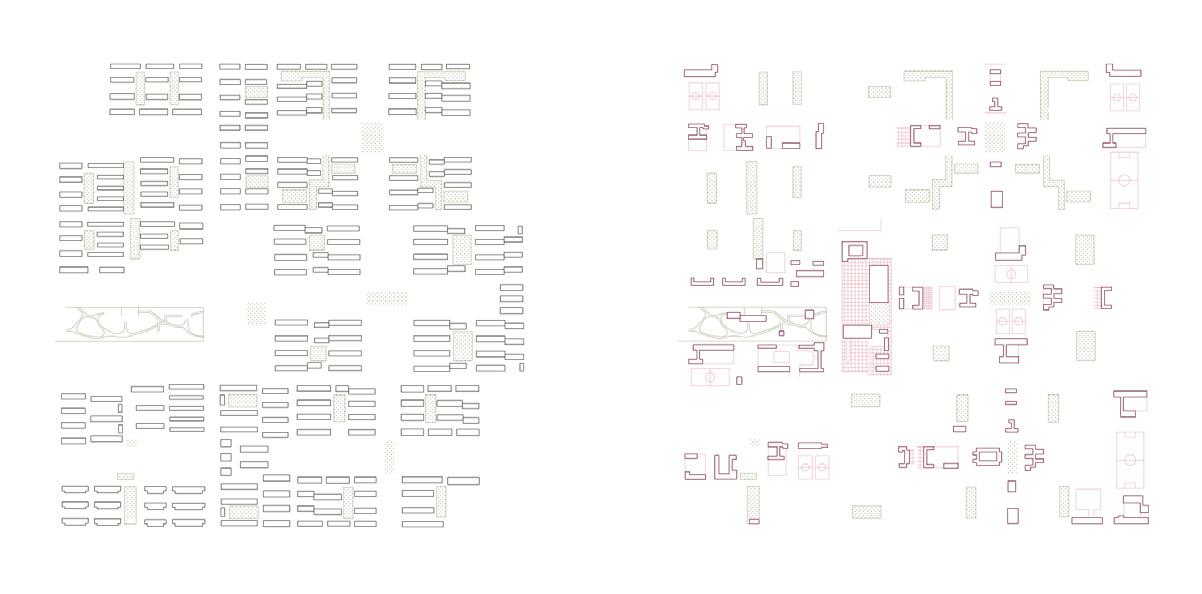

High-rise tower blocks are the most popular housing type for both market and public housing, as it is more cost effective. Exceptions can be found in a commercial neighbourhood, where houses and medium-rise blocks are constructed. The high-rise tower usually contains 4 to 6 units each floor. Some might contain up to 8 units. The most popular model is four units per floor, with two smaller units (usually 1- or 2-bedroom units) facing south and two larger units (usually 2- or 3-bedroom unit) facing both south and north, allowing every unit to have access to direct sunlight. In public housing, the area of a unit is smaller than in market housing. Between these units, there is no redundant space other than circulation space.

This housing typology works very efficiently in terms of the individual living within a nuclear family. Most of the essential daily activities can take place in one’s unit: cooking, sleeping, resting, entertaining, etc. However, since the units of public housing are smaller, they become inconvenient for sharing among family members, such as dining together, using the living room for indoor exercise, working without disturbance, etc. Even most of the market housing unit cannot provide generous space for activities like hosting a party or big family dinner. Since there is no such space for these activities, people have to go somewhere else outside the neighbourhood, such as a cafe, gym, restaurant, or library, most of which are commercial spaces. With public facilities in the inner city still being insufficient, there is a more significant shortage of facilities in the public housing neighbourhood, since most of them are in the newly developed area in the periphery.

Besides the problem of lacking facilities, the units themselves are problematic as well in terms of accommodating other household types than the nuclear family. Most of the existing units are designed for the nuclear family only, while there is a significant proportion of extended family and single-person households. With problems of an ageing society, elderly care, raising of children and the 4-2-1 family, the current unit types will not be able to fulfil the demands of various household types. On the other hand, the intergenerational relationship should also be rethought and carefully dealt with instead of simply providing more rooms. More and more young couples and old parents express demand for privacy and independence between two families, whereas great necessity also exists for mutual help both emotionally and physically.14 Moreover, this multi-generational household is less stable over time than a nuclear family, meaning that a specific unit type is inappropriate for it. In other words, the problem of intergenerational living is not a problem of size and area of units, but a problem of the organisation of the residential relationships.

Both the problems of service provision and intergenerational living are critical for the subjects of public housing. As vulnerable groups, these subjects should have equal rights to access public services like other citizens. In regards to intergenerational living, it is vital for migrants (including migrant workers and young professionals) to permit their families moving to the cities they live in.

As for relocated families, which are highly likely to be extended families, it is also essential to consider how to accommodate them without separating them. All in all, new housing typologies are needed for public housing.

18.

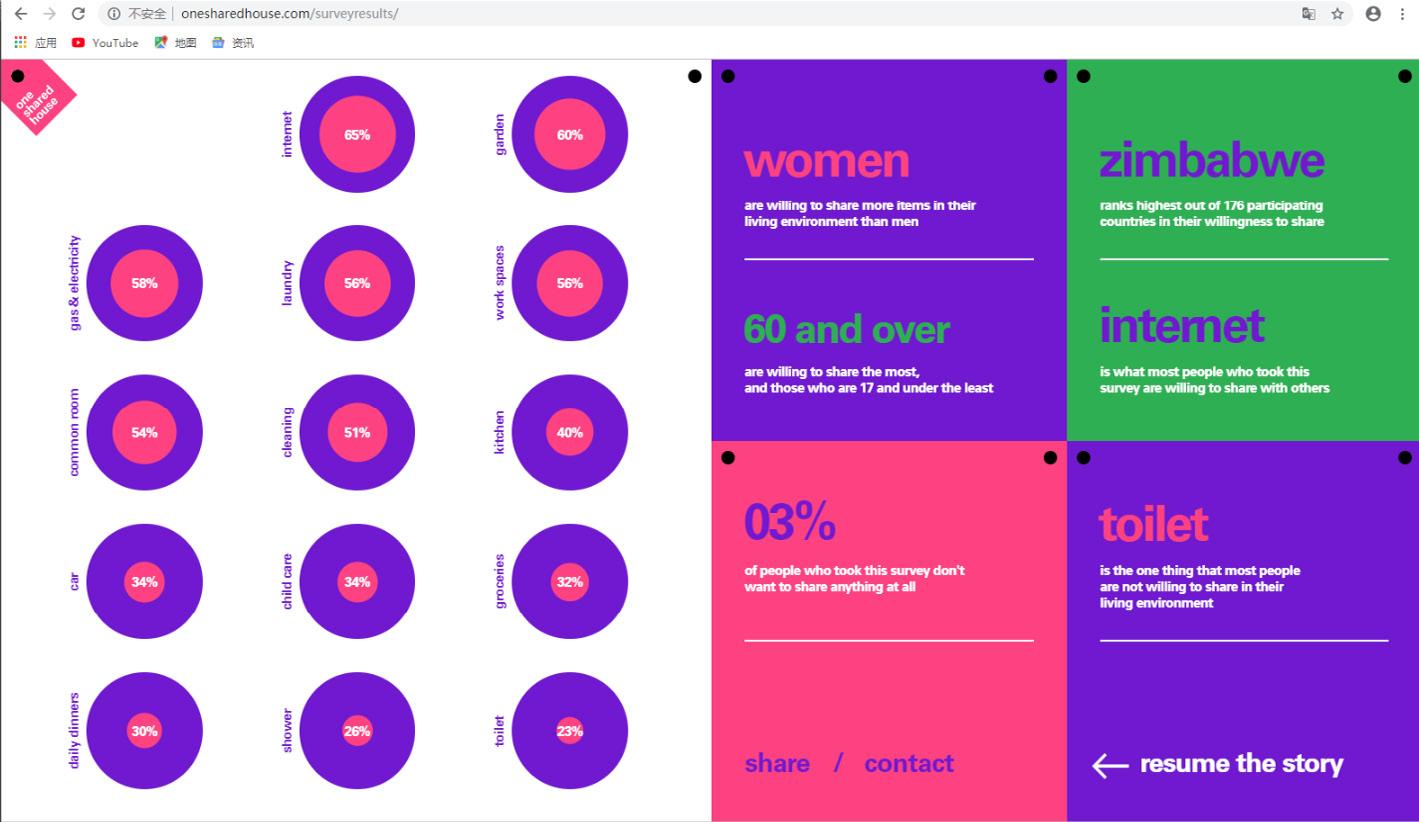

Afterwards, co-housing as a new living model spread to other European countries and then to the United States and Canada. Various housing typologies have been tried out for this new living model, from detached housing and terrace housing to multi-floor apartment. For example, a 9-story point block called Staken was constructed in Sweden in 1980, with five units per floor and 33 units in total. Later it also transformed into private rental housing projects such as the Crystal City by WeLive, a company specialises in the co-housing apartment. In 2017 an online survey launched by Space10 named ‘One Shard House’ collected data from over 7,000 participants in over 150 countries to investigate what and how people would like to share.18 The outcomes show that people in China prefer single women, couples and single men in their community; they are happier with access to multiple homes they could easily move between; they would be willing to pay extra for a service layer to manage all house related items, etc. The survey gives many insights into the following design proposal.

In general, the idea of co-housing as an alternative way of living has become more acceptable all over the world.

What is Interfamily Living?

Although the idea of co-housing is well accepted globally, it has seldom been applied in a public housing project. There are three main reasons for this. First of all, the original co-housing idea came along with the autonomy and negotiation among the residents, which would be challenging to realise in government-led public housing projects. Secondly, as it is housing for lowincome people on welfare, the budget is too limited for the extra expense of shared facilities. Financial factors are considered more than well-being. Thirdly, the great demands of housing call for typologies that can be constructed quickly and accommodate as many people as possible, which are high-rises for hundreds of residents, whereas a co-housing community should remain of a certain size for residents to know each other.

These three reasons can also be applied to the Chinese context. The national land ownership, as well as the huge population, make it neither possible for democratic negotiation in housing delivery, nor for the development of lowdensity terraced housing. Therefore, the Danish model of co-housing can never be applied in China. However, with inefficient service provision in private housing and the problem of intergenerational relationship, there are particular needs for families to live together as a small family group for better social cooperation. This co-living is not the succession of Danish co-housing since it is not based on self-organised private property, but state-managed public housing. It is also different from intergenerational housing, which focuses more on mutual help between young people and the old. It targets a broader problem of co-living between families without kinship, and how interfamily relationships can coordinate with a new service provision system. To underline the difference, I define it as interfamily living.

Interfamily living refers to several scales between the scales of individual unit and the community. These scales are now missing in modern neighbourhood because of housing privatisation. The idea of interfamily living originates from the changing household structure in terms of the consolidation of extended family due to demographic change, but goes beyond it into the problems of

service provision and urban governance. There are two main reasons for the consolidation of extended family: home-based elderly care and upbringing of children, both of which result from the inefficient service provision. As the state hopes extended family to work as compensation of inadequate service, supporting facilities should be provided by the state at the scale of interfamily living. Besides, the in-between scales also provide space for introducing other facilities, that not only deal with problems within a family, but also between families without kinship. By rebuilding the in-between scales, the gap of public service between community and individual dwelling is filled by densified facilities, serving smaller groups of people within the reach of their daily life, in the neighbourhood just outside their doors

On the other hand, extended family is less stable than the nuclear family since it changes according to different need of different generations at different stages of life. Therefore, the unit should be adaptable to future changes. There are usually two leading solutions to achieve flexibility in architecture. One is to design a flexible building system, in which functions, walls, structure, etc., can

be changed according to need. This solution is hard to realise and implement at scale, because of the high cost and necessary sophisticated building technology. The other is to design a flexible building management system, which allows certain functions to be converted and provides limited scope for extensions in pre-designed spaces. The latter is more suitable for interfamily living in public housing.

By dividing an extended family into two or three nuclear families or singleperson households, and accommodating them in separated but adjacent units, a certain degree of privacy and independence is secured, while mutual help and daily interactions between young families and the old are still possible. Every unit will have full functions from the bedroom to cooking space, but more generous sharing space will be designed between these units to enhance the relationship. As independent units, they can be sold back to the state after the older generation passes away or the young couples move out. This is when interfamily living comes in, since the units will be sold to other applicants of public housing. As a result, interfamily living is co-living beyond kinship, becoming a small family group that allows public services to be inserted in the in-between scales.

Compared to individual living, interfamily living has many advantages. First of all, it provides a flexible living space that can accommodate the extended family while avoiding some conflicts between generations. This helps to moderate the problems of elderly care and raising of children. Secondly, it allows those who can only afford public housing to enjoy a more generous

ROOM, UNIT AND MODULE

Public housing has been constructed all around the world since the middle of last century. There is a great deal of experience in public housing design that can be referred to when dealing with the new demand in China. This chapter will present several case studies of public housing in London as well as an experimental rental housing design in Shanghai, China. The case study will help to define the spatial elements of interfamily living in public housing, in terms of function, dimension, orientation and circulation, which will guide the design. The design proposal will serve as a prototype for interfamily living and should be improved and tested later in architectural practice by architects, planners and the government.

2.1 Case Study

Public Housing in Post-war London

The public housing of the UK originated as private property supplied by the private sector before it was transferred as the responsibility of the council to provide social housing for the low-income group after the 1890s. After the Second World War, social housing went into large-scale construction from 1945 to 1975 in order to rebuild the city of London destroyed in the war, as well as to fulfil the great demand of modern housing. These projects were invested in and planned by the LCC (and GLC after 1965)19 and their housing design was assigned to architects either from the private sector or working for the local councils. More than 4.6 million of dwellings were built during this period.

Public housing in post-war London represented contemporary ideas of highdensity living in modernist architecture, especially in terms of its housing

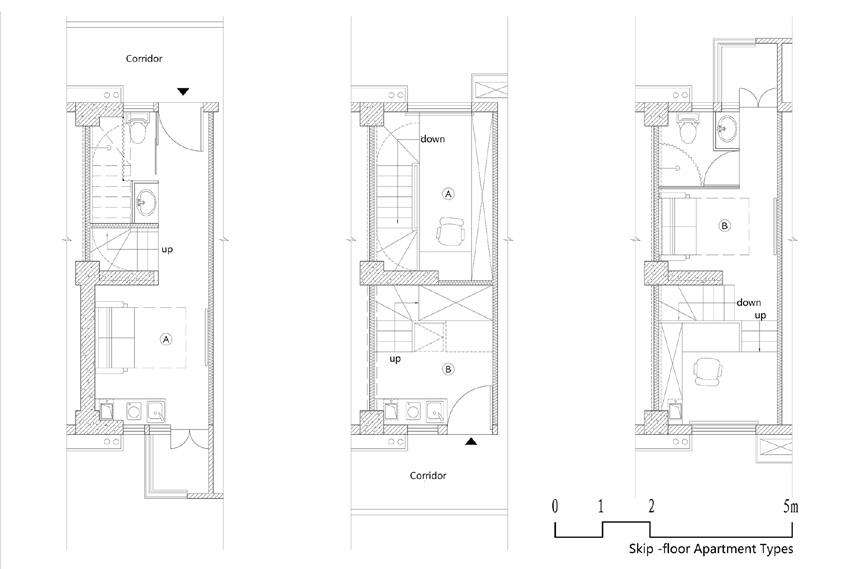

typologies. High density, efficient construction and cost-effectiveness were the essential considerations. Medium-rise and high-rise were the most popular types of this housing, and prefabricated concrete was predominantly used in their construction. Three typical kinds of circulation that defined floor layout were applied in order to accommodate more residents: deck access, central corridor and central core.

The circulation determined the arrangement, orientation and dimension of units. Housing with deck access would usually have the units on one side of the corridor, and the units would always have greater depth compared to central corridor type and tower type. Each unit would have dual aspects and access to daylight, where kitchen, living room and bedrooms would be situated. Different from the deck-access type, housing with central corridor would have units on both sides. These units would be less deep and would only have one side that access to daylight. As a result, many of them would occupy two floors, so that more rooms in one unit could access to daylight. Housing with

20. The Great British Housing Disaster. A documentary film by Adam Curtis, to investigate how the council housing of 1960s came to be built so poorly that thousands later needed to be demolished. The film gave following 6 main reasons: 1. Construction became ‘the number game’ of political competition. 2. Deals between contractors and local councils. 3. The innovative system building was untested before going in massive construction. 4. Bad construction on site. 5. Lack of subsidy. 6. Later untested repairing

a central core was usually a high-rise tower block, with more floors but fewer units (usually four units) on each floor. These units would have a smaller ratio of depth to width and would have access to daylight from two adjacent sides.

Among all, a specific favourite unit type called ‘maisonette’ was widely used. This unit type has two floors connected by an internal staircase. It was popular not only because it allowed more rooms in one deep unit, but also divided different functional space in a clearer and more efficient way. Typically, entrance, living room, and kitchen would be situated downstairs, while upstairs spaces would be used for bedrooms and bathroom, spaces with more privacy. The staircase also made the dwelling look more generous, giving occupants the feeling of living in a house.

Apart from the social-political factors that caused a low construction quality, and later led to the conclusion of ‘a failure’ in architectural history,20 public housing in post-war London still contributed much to the public housing practice later in both the UK and other countries. The housing typologies with three different circulations and maisonette unit types are useful references when having to accommodate more residents in cities with large populations and high density. It did not work well in terms of service provision, however, for it lacked in public space and proper maintenance due to the limited budget, which led to a failure of the original idea of shared corridors to encourage interactions among residents. However, if being designed with better spatial elements, these can become advantages, by widening the corridor or inserting public facilities between units, for example.

Regarding the context of China, it is also essential to test the possibility of adopting other housing typologies in public housing, not just the centralcore tower block, which is the dominant type in the current housing market. The deep unit type can also be modified by rearranging the functional spaces due to different standards in the building code, to make it more efficient in accessing daylight and cross-ventilation. For example, the main entrance can directly lead to a living room, while the living room serves as the entrance hall leading to other rooms. This allows a deeper unit type with less width but better daylighting than a deck-access apartment. Moreover, the maisonette unit type provides a prototype for dealing with interfamily living and intergenerational relationships with its efficient division of functional space.

Different from the UK where public housing generated new housing typologies at the beginning because of the influence of new building technologies and modernist architecture at that time, public housing in China was mainly constructed two decades after the prosperity of market housing began. Thus, it followed the typologies of market housing. As argued earlier, market housing mainly is high-rise or medium-rise point blocks with central cores, whereas deck access and central corridors are more common in old work unit dormitories, which would be considered as ‘incomplete functions, no privacy and uncomfortable’ and be defined as ‘housing for the poor’.21 As a result, most of the newly constructed public housing also avoids adopting these typologies, even though they are more efficient in housing small household of one or two people.

Recently, some public housing projects aimed to try out some experimental designs in order to encourage interactions among tenants. Most of them are rental housing projects. Different from affordable housing, which is also invested into by developers and for sale, rental housing is publicly owned and invested into directly by the state. With support from the state, these projects have a better chance of being given to famous architects to test their design concepts and innovations, as they have sufficient financial support, whereas in standard cases developers or design institutes will be assigned the job. The Longnan Garden in Shanghai is a typical example of these experimental projects.

Unlike other public housing, Longnan Garden combines deck access and courtyard in its building layout. Six out of seven blocks have a central yard surrounded by residential blocks that are connected by an outdoor corridor as a whole. These blocks are high-rise, varying from 7 to 18 floors. Although having four blocks of only seven floors and two blocks of 12 floors, which have comparably lower floor areas than typical high-rise residential blocks, the FAR of Longnan Garden still reaches 3.0, containing 2,021 units, which is even higher than typical market housing estates with high-rise tower blocks. The density comes partly from the larger shared circulation space, the corridors, but the lower ceiling and mezzanine also contribute to that. This gives supporting

evidence for the argument that high-rise is not the only solution for housing large populations in high-density cities.

The outdoor corridors are not only used as circulation space, but also potential space for interactions between tenants. Many residents unconsciously occupied part of the corridor as their own semi-private space to place a floor mat, umbrella, or potted plants. Moreover, some tenants would even sit on their benches together with their neighbours eating snacks and chatting in the corridors, which will never happen in a central-core tower block. The design itself also tried to encourage these interactions by providing space for bicycle parking and small sitting and reading areas on the ground floor next to the main entrance.

The unit types of Longnan Garden are also different from typical unit types. They are similar to the unit types of post-war UK public housing with more significant depth and smaller width. The area of these unit ranges from 35 to 60m2, which is very small compared to typical unit types. There are six unit types in total, two of which are lofts, three are studios and only one is a 1-bedroom flat. Most of the units are designed for singles or young couples without children. However, some couples with young children also live in the neighbourhood. In lofts, where functional space is more divided over different

floors, two tenants may share them.

Most residents are young white-collar workers around 25 to 30 years old. For most of them, living with neighbours at their age is encouraging and comfortable, helping them to expand their social networks. Consequently, the management of the neighbourhood is more democratic, with a stronger awareness of responsibility by the residents. These young tenants express their views and suggestions through the group chat on WeChat (an online chatting app) and thus connect to the property management company easily. They also have many private group chats for communications about activity organisation to information sharing. ‘The tenants of this estate are hard to deal with,’ said the security guard of Longnan Garden during the field study22, ‘they are all well-educated young people with a strong sense of their rights. They know each other and express their voice through social media quickly. As an exemplary public rental housing estate, the government thinks highly of the views of its residents.’

Although there are some innovations in the design of Longnan Garden, other problems reveal themselves in the actual usage of the facilities and living conditions. The courtyards that are intended to provide hierarchical public squares for residents of different blocks fail because of the inappropriate design. Instead of providing various facilities for actual activities, these courtyards were designed as a pure landscape with low fences to prevent entry. As a result, residents cannot use them. At the building scale, the public sitting area is too small to be shared by over 200 residents living in one block. Thus it remains a redundant space covered with dust, yet it is the only shared functional space. The width of the corridors is only useful for circulation, even though there

is a need for tenants to use them as extra space. The demands of extra space also reveal the fact that the units are too small. With widths ranging from 3 to 4.5 meters, the indoor space is too limited for all functions to be contained. Residents find no place for a washing machine, dining table, television or an additional cabinet or desk. It is impossible for hosting a small party or family dinner without occupying the public corridors.

The case of Longnan Garden shows that a neighbourhood with a better residential relationship can be achieved by using appropriate building typologies and design. The closer relationship among tenants also inspires taking responsibility in the management process. On the other hand, it is clear that providing space without providing actual facilities is meaningless. Providing sharing spaces should not become formalistic without really considering actual demands. Also, reducing individual living areas for cost saving purposes should be compensated with more generous shared space. Both the advantages and disadvantages need to be considered in the design of interfamily living.

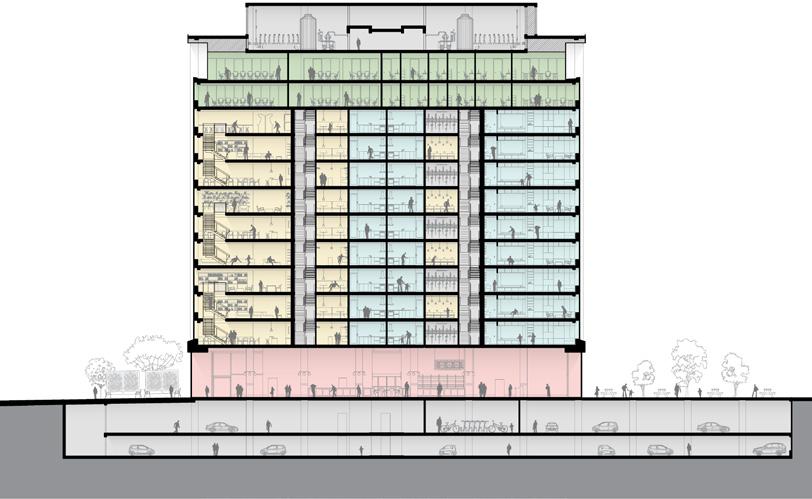

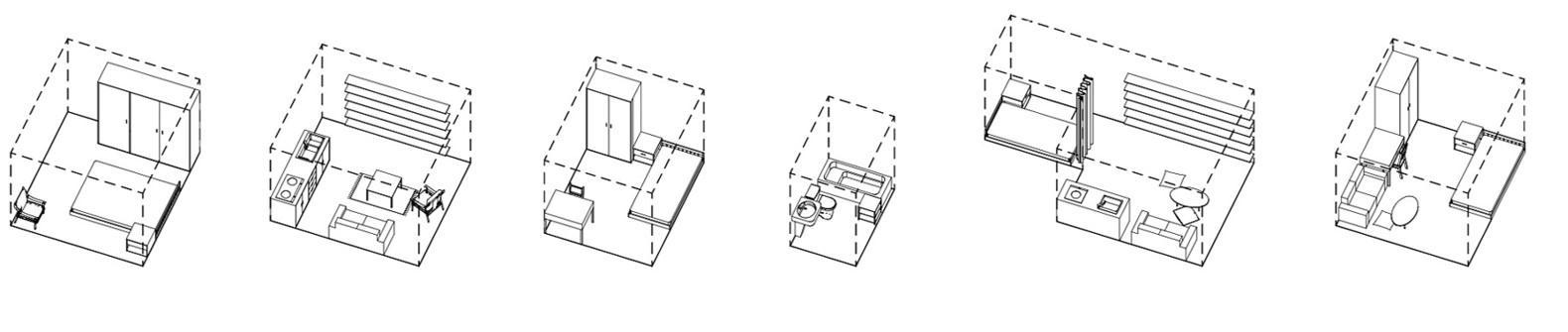

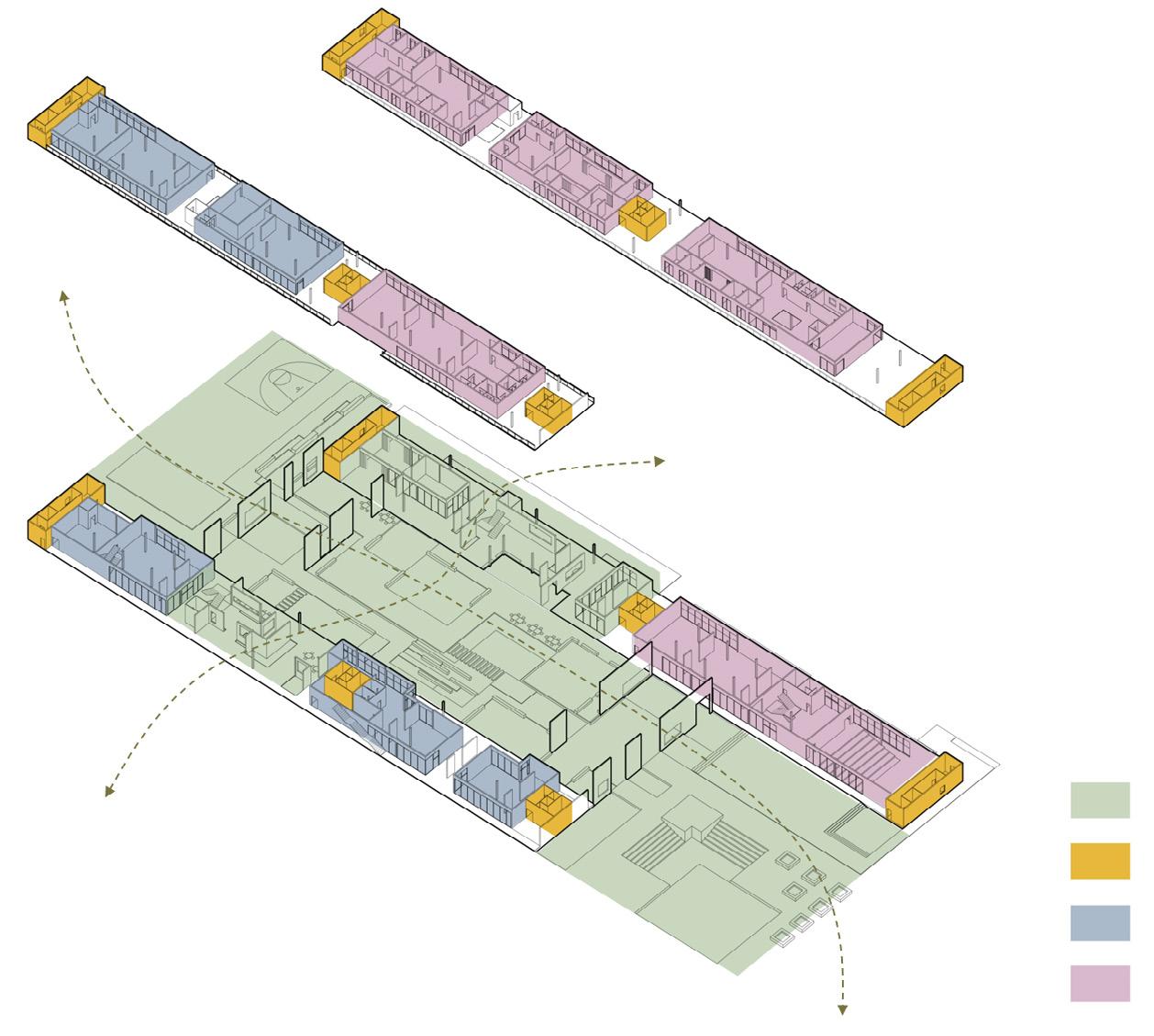

2.2 Design Proposal: The Prototype

There are two main goals that interfamily living aims to achieve. Firstly, it should have the ability to accommodate changing households to enable mutual help. Secondly, it should be able to coordinate with inserted common facilities as solid supports for a more hierarchical service provision system. As a result, the proposed prototype is one possibility that includes the following design considerations: independent units that accommodate the full functions of a modern apartment, flexibility of the unit arrangement, in-between spaces for common facilities to share, and convenient access to facilities for limited users. It is based on rental housing, which is owned by the state, and joint-property housing, in which individual units owned by the residents (but can only be sold back to the state when no longer needed), and in-between space owned by the state for shared rental.

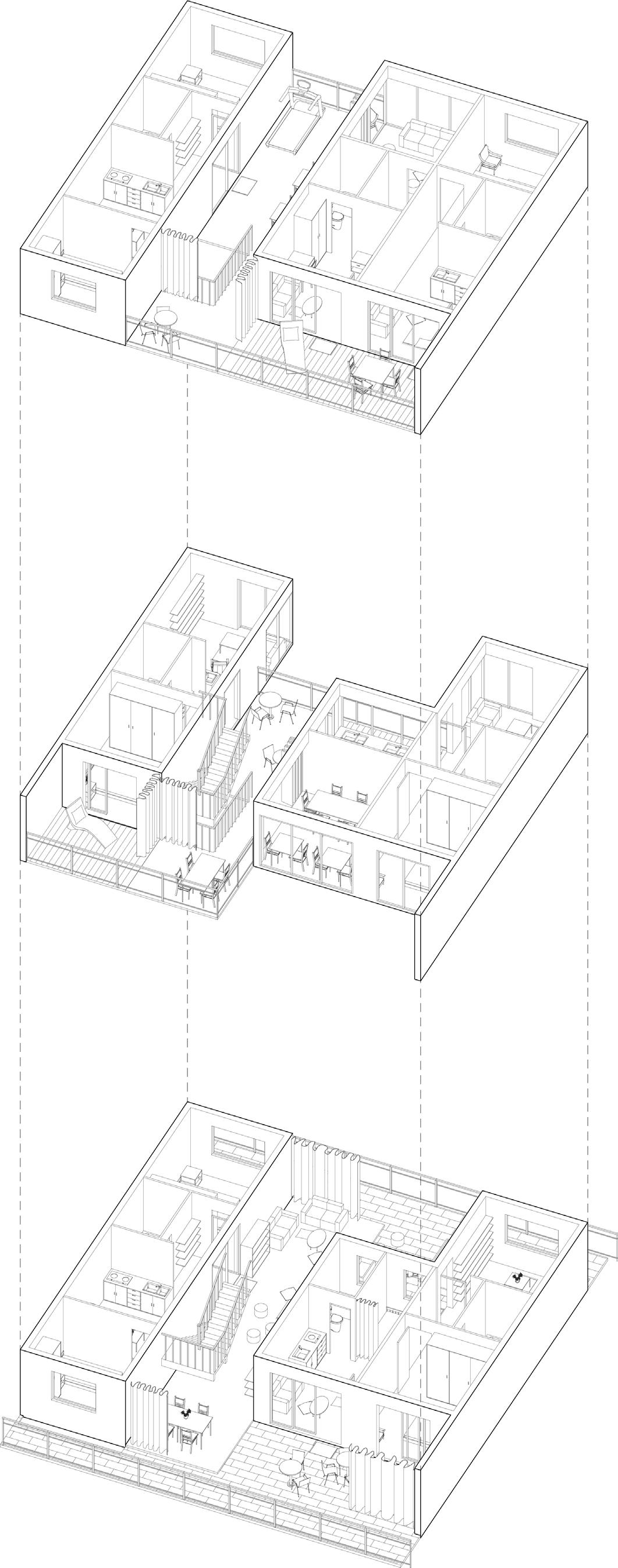

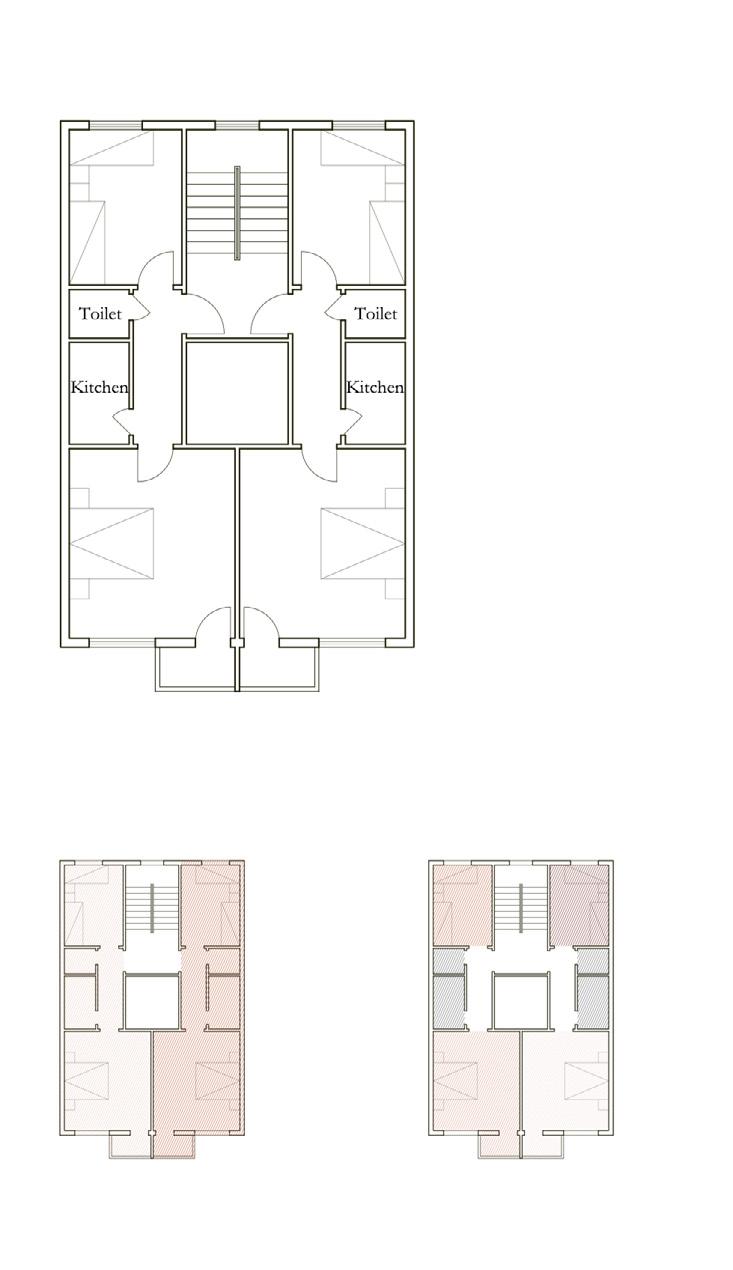

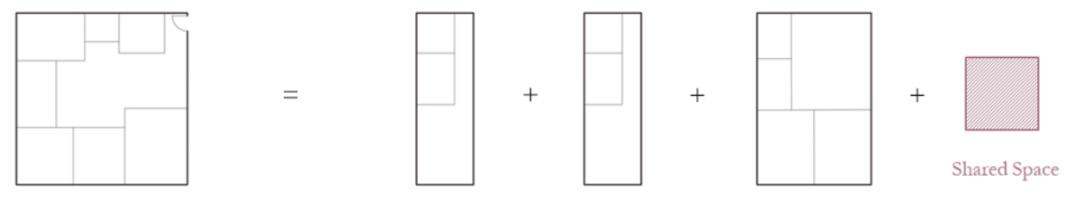

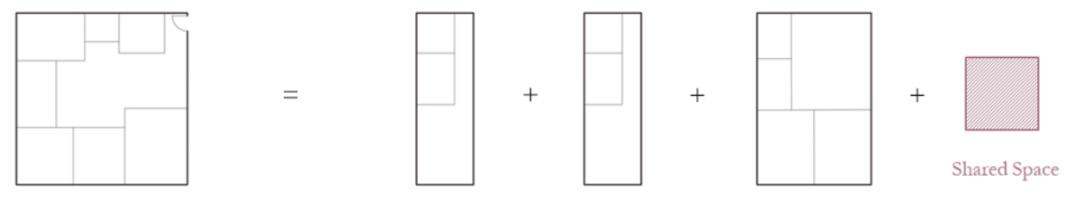

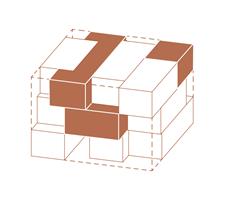

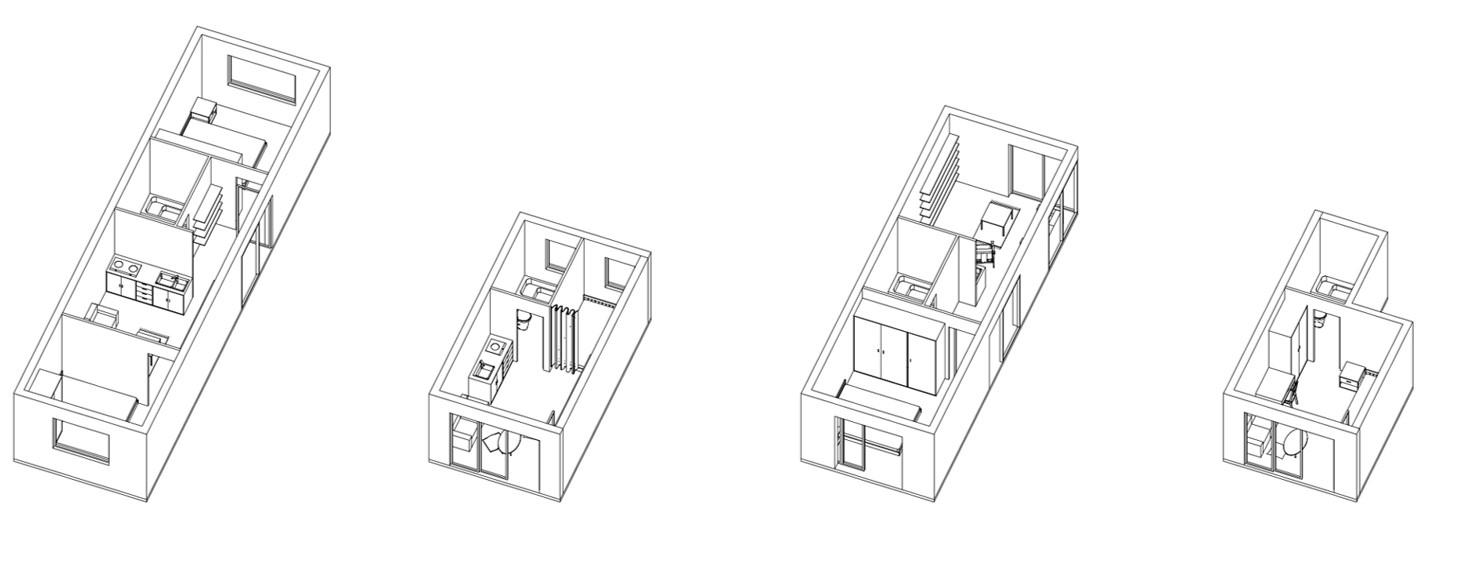

Module for The Family Group: Basic Components of Interfamily Living

In order to ensure limited access to facilities for better management and maintenance purposes, the number of families for the interfamily living should remain small, also to ensure better cooperation and communication. There is a natural limit to the number of people who can know each other by name and share common facilities as an extension to their own home. In their book, McCamant and Durrett discuss the features of a co-housing community of three sizes: small (6 to 12 households), medium (13 to 34 households), and large (35 or more households). They conclude that in small developments, residents know each other so well that it required more compatibility and commitment, while in large developments, the group identity was diluted and personal accountability diminished. 23

However, when being applied to neighbourhoods of high density, more problems need to be considered than co-housing projects in suburban Denmark: housing typologies of the medium and high rise, building system and structure, orientation, ventilation and daylight. These factors limit the size of a co-housing unit in a horizontal development, while a vertical expansion may not work well due to limited accessibility.

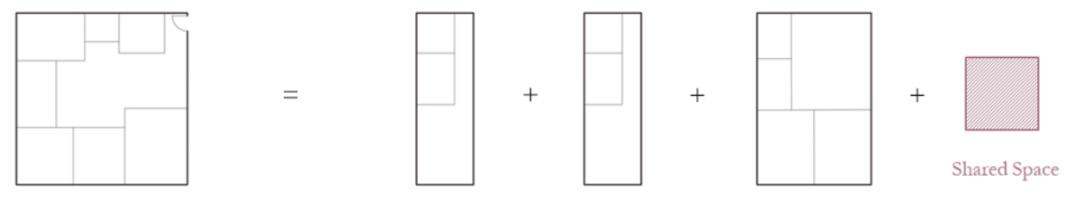

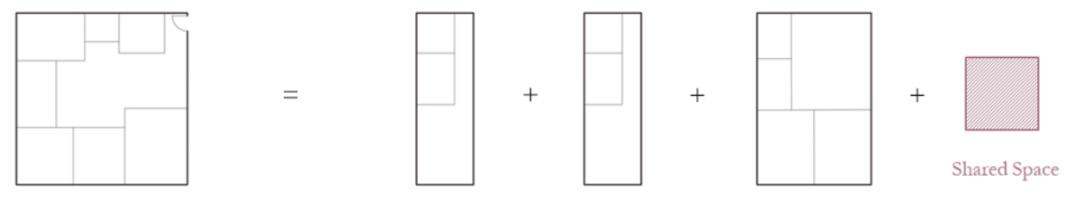

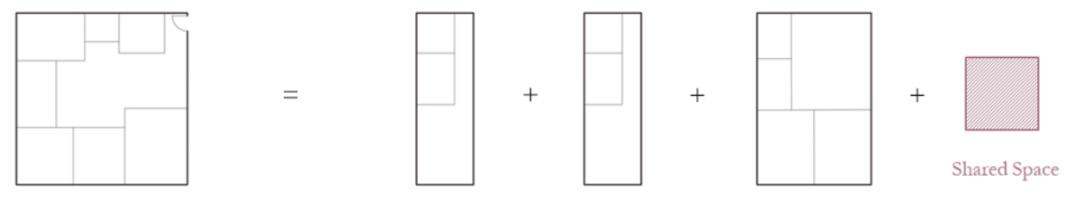

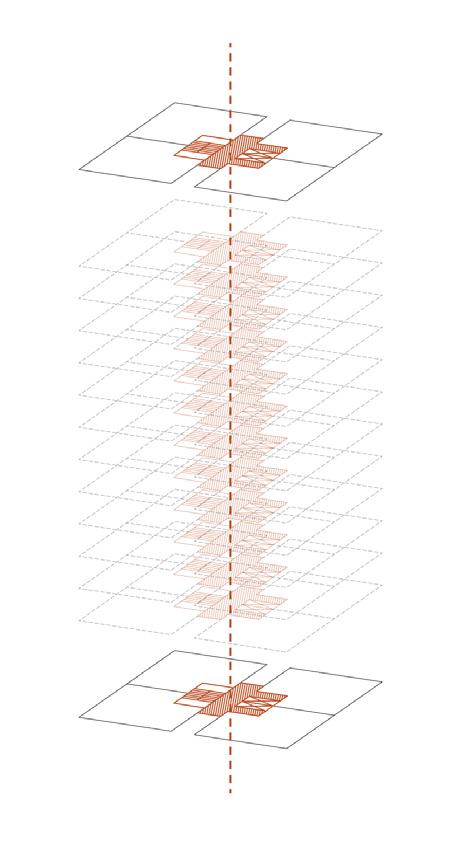

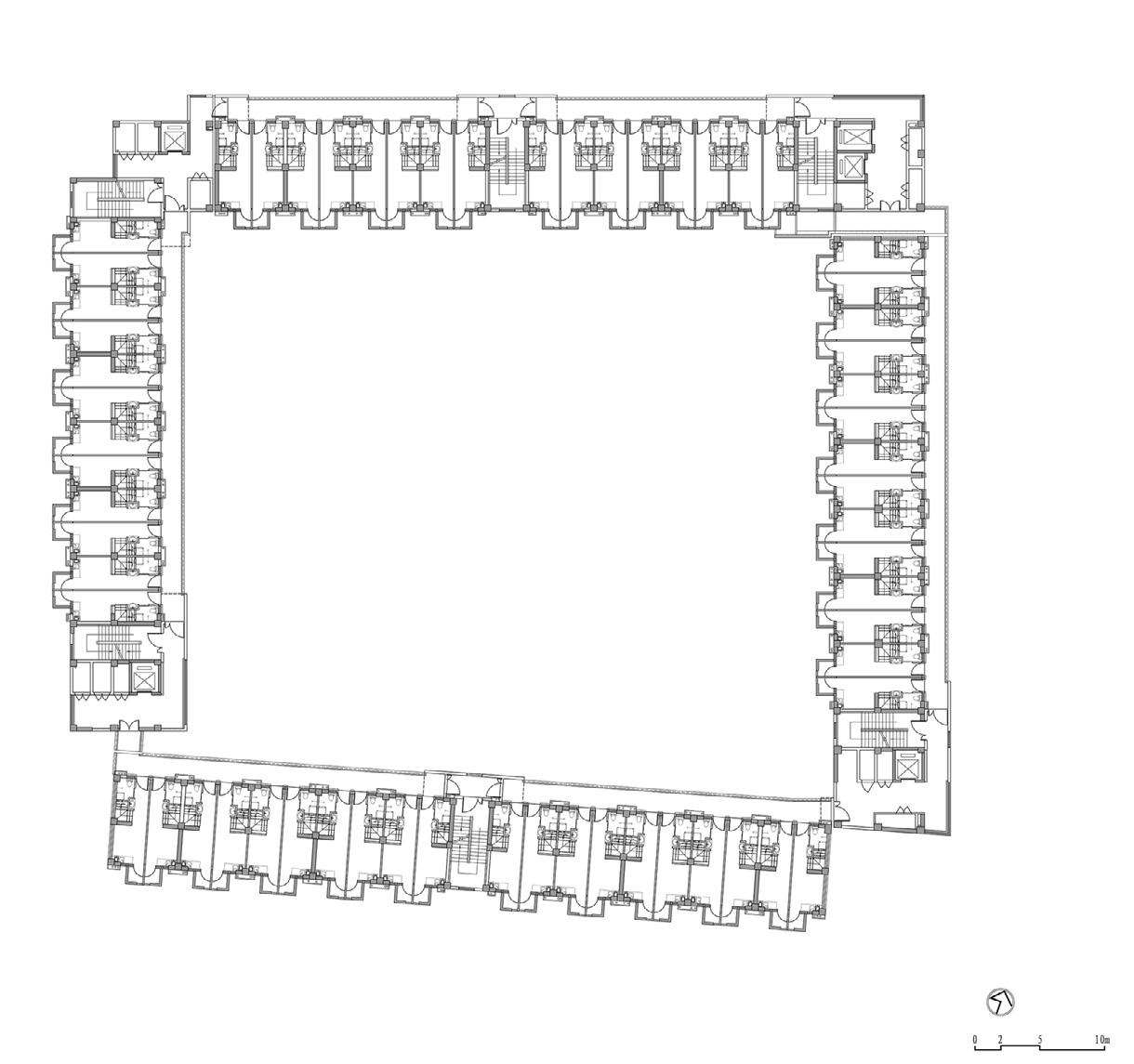

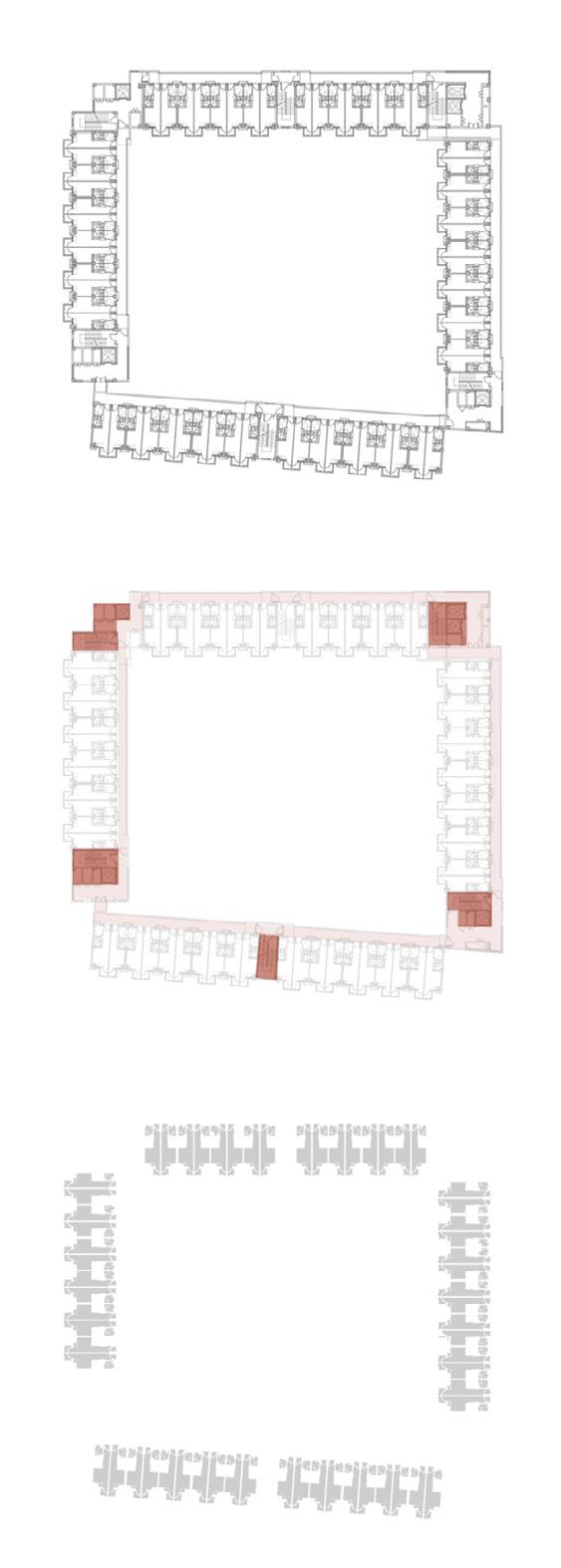

As a result, the prototype proposes a more hierarchical composition of a community, with family groups consisting of 7 to 15 households (depending on the size of these households) of 14 to 20 people as the basic units, to form ‘extended family groups without kinship’. These family groups will also share facilities such as a gym or a mini-garden at the scale of the floor. To distinguish from a unit that refers to a full-functional dwelling, the physical space of a family group is defined as a ‘module’. A module will consist of several individual units and in-between space for common facilities.

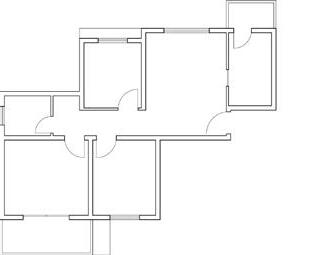

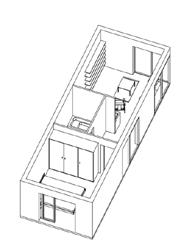

A module consists of 3 floors with a shared staircase shared by all family group members. The vertical division helps to create shared spaces for different functions and privacy. The first floor is the only floor that has access to public circulation space. It serves as the entry hall of the family group with sitting

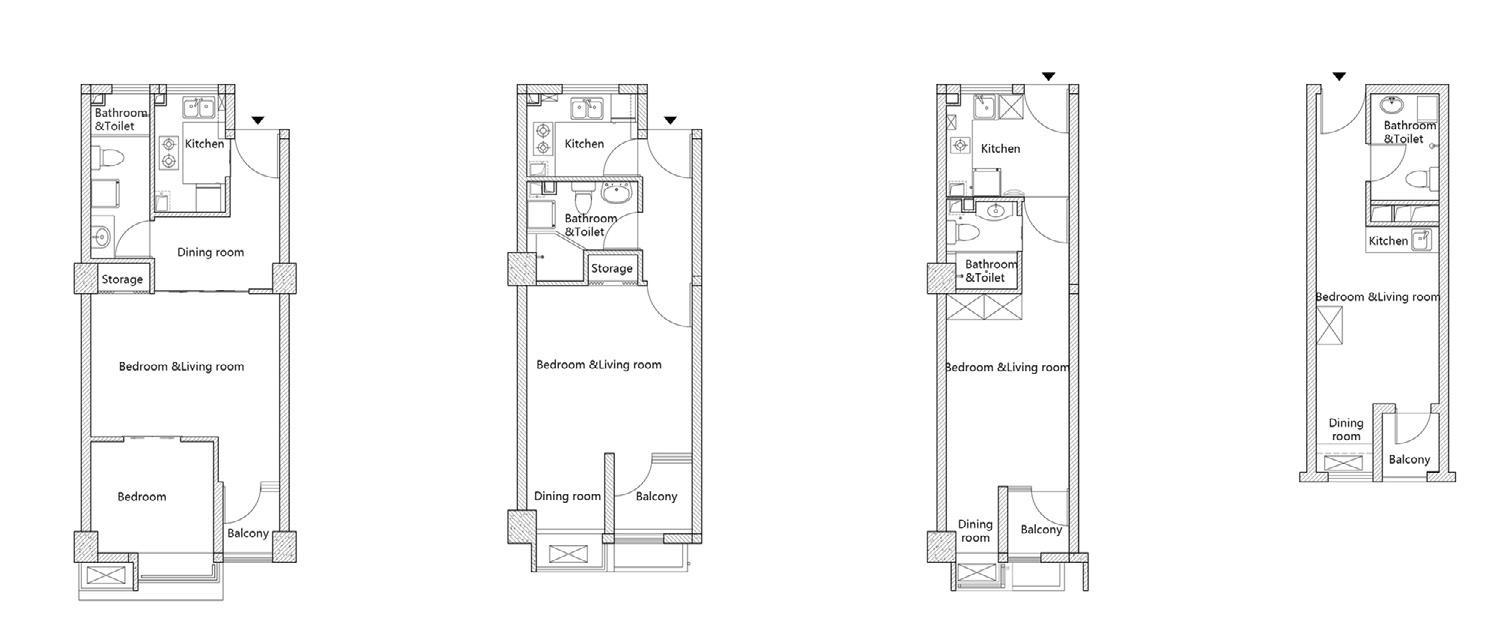

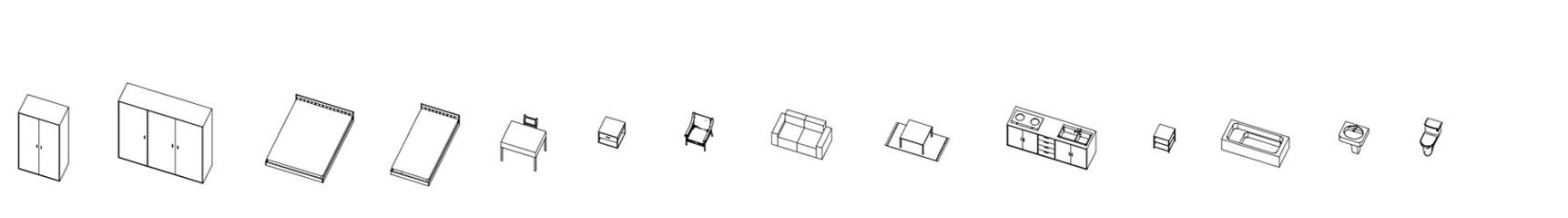

Individual Unit: An Economical Space for Individual Living

Different from collective living in the work unit or people’s commune, where people were forced to share almost everything and have limited privacy, the proposed interfamily living model encourages sharing of specific spaces and interaction among residents while protecting the privacy of every individual. As a result, the individual units within a module should be seen as a shelter where residents can hide from sociality whenever they choose to. Thus, an individual unit should have the following essential functions to fulfil the needs of residents’ everyday life: bedrooms or a sleeping area, a small living room or a sitting area, and a bathroom. Kitchenettes are optional for small studios of single occupants, but necessary for units of a nuclear family or a couple. The individual units can be both sold as affordable housing and rented out as rental housing.

The module of interfamily living changes the relationship between neighbours as well as the relationship between family members of an extended family. Instead of providing a larger unit of more rooms for the extended family, the module provides only small units from studio to 2-bedroom flats by dividing an extended family into several nuclear families. For example, an extended family with grandparents and a young couple with their children can be seen as two nuclear families and be accommodated in two individual units within the same module. These two units can either be on the same floor of the module, or different floors connected by a shared staircase. To say it differently, the

module can be seen as a 3-floor cottage, while the units can be seen as different rooms in it. The only difference is that the ‘rooms’ have more functions and can be used as an independent dwelling.

This arrangement system adds excellent flexibility when dealing with interfamily relationships. First of all, it allows the rearrangements of these units over time. As mentioned, the Chinese extended family is less stable than a nuclear family. Grandparents may only live with their children and grandchildren for a short time. When they move out or pass away, their unit’s use can be agreed on with other occupants.

Also, when the family decides to have more children, the older children can be accommodated in another unit within the same module. Secondly, it helps to avoid conflicts between family members of different generations. Since every unit is equipped with the facilities needed by daily functional needs, relatives do not have to meet each other every day. This reduces the chance for tension between family members when both the old and young generation wants to take control.

Finally, it coordinates with the retrieval of public housing by the government. When an extended family becomes smaller and no longer needs additional

units, these units can be retrieved by the government and be rented or sold to other applicants while the original family can still stay in the same module. The flexible arrangement is not only designed for an extended family, but also interfamily living beyond kinship relations. The variety of units can accommodate different household types: single, a young couple, and a young couple with one or two children.

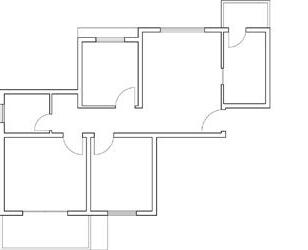

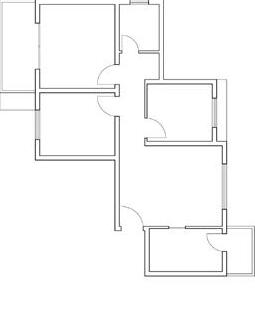

The dimension of individual units is carefully determined based on both the building code and the flexibility of room conversions anticipated. For costsaving purposes, the individual units are designed with the smallest possible dimension, just meeting the existing standard. This also encourages the use of shared spaces that are more generous. The distance between the grid is 3.3 metres, which can exactly be the span of a double bedroom, a living room, a bed and sitting room, a single-bedroom (on the longer side), as well as double the span of a bathroom. The double-bedroom, living room and bed and sitting

room have the same dimension, which allows their conversion into each other easily. The bathroom and the entrance hall also have the same dimension and share the same span between two axes. This allows the division of a unit into two smaller studios (or one-bedroom flat, depending on the original unit type), both of which have a bathroom and sleeping area. More flexibility can be achieved by the construction of an extra room in certain pre-designed areas within the in-between space. These flexibilities are designed to adapt to the variety of subjects in public housing, who have different household compositions and demands, at the same time allow the possible retrieval by the state to help as many people as possible.

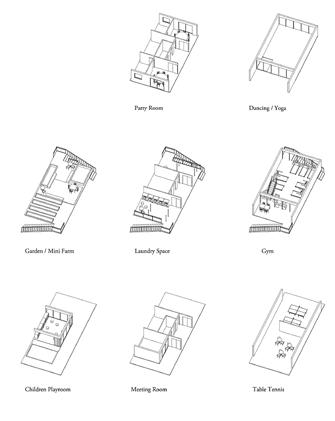

In-between Space: The Additional Space for Interfamily Living

Considering the financial capability of the residents in public housing, the individual units are designed to be ‘just enough’ for private daily life and should be affordable by residents, whereas the in-between space with shared facilities offers more generous living areas to the family group members as ‘extra space’ in compensation of their small units. Different from individual units, the inbetween space will be invested into and owned by the state as part of the service provisions at the grassroots level while being used and managed by the family groups themselves. This allows every individual to have equal access to the facilities with a more efficient way to provide service.

The Tower type works better in small plots since it occupies fewer area on the ground floor and left more land for open space. it aslo has more flexible orientation, though some units might not be able to orient north and south.

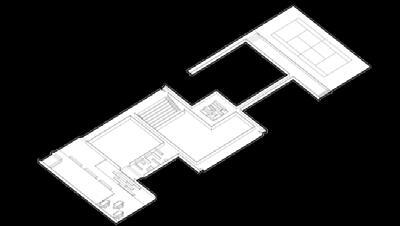

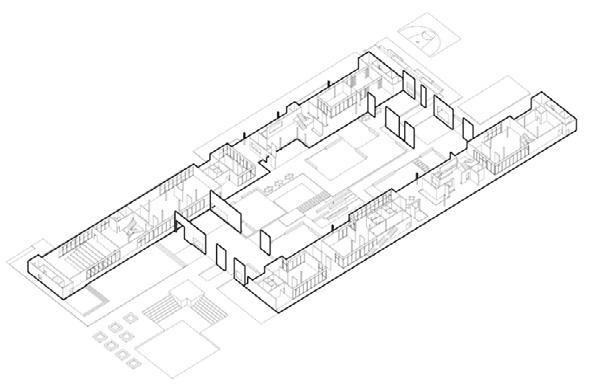

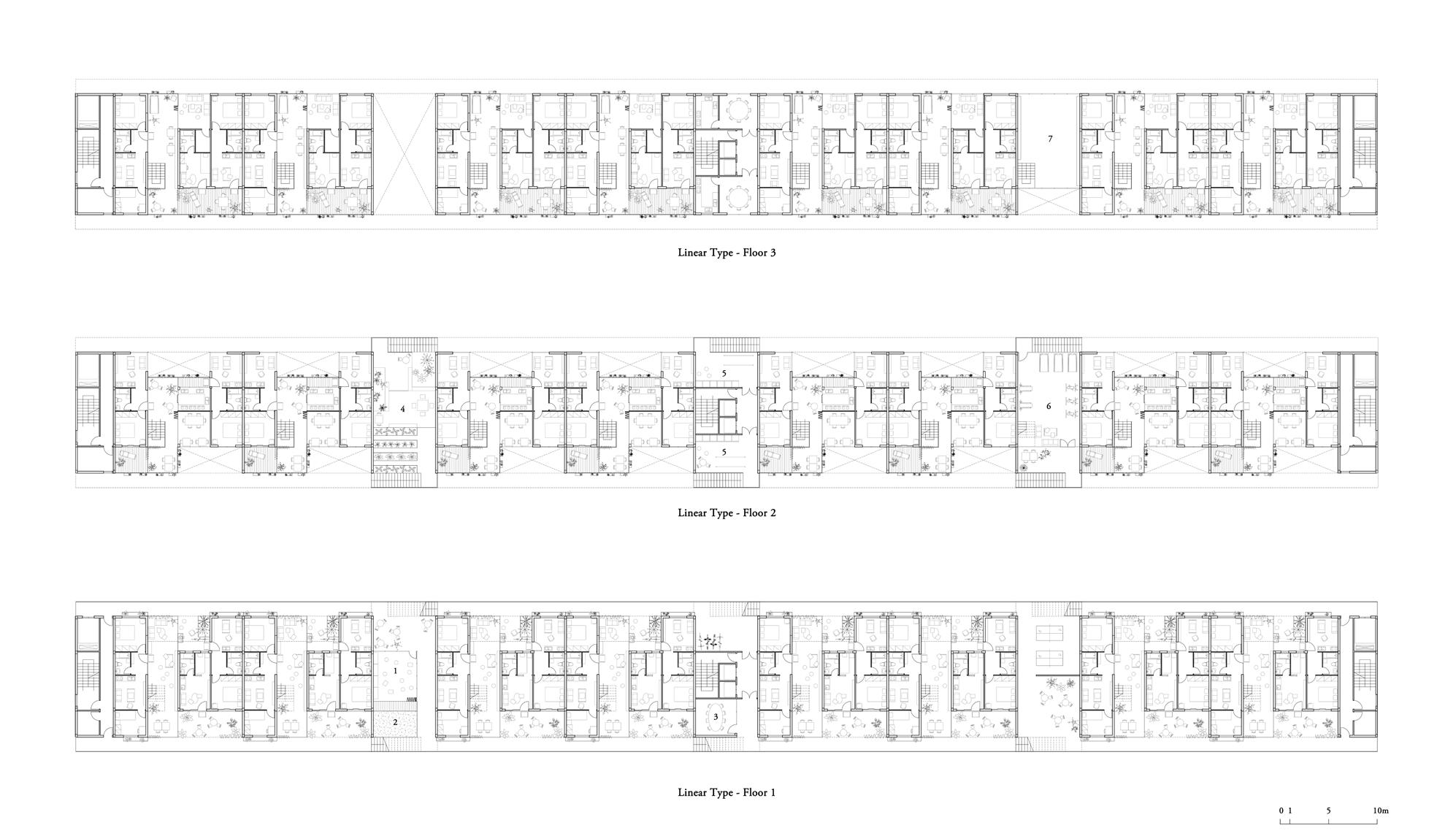

The Scale of The Floor: Two Housing Types

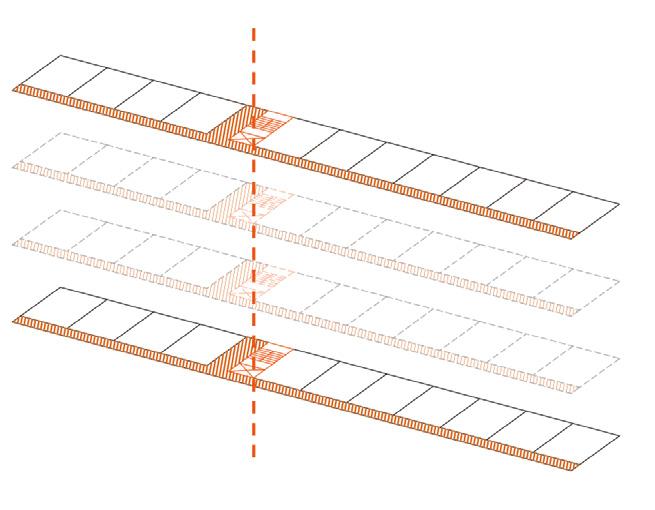

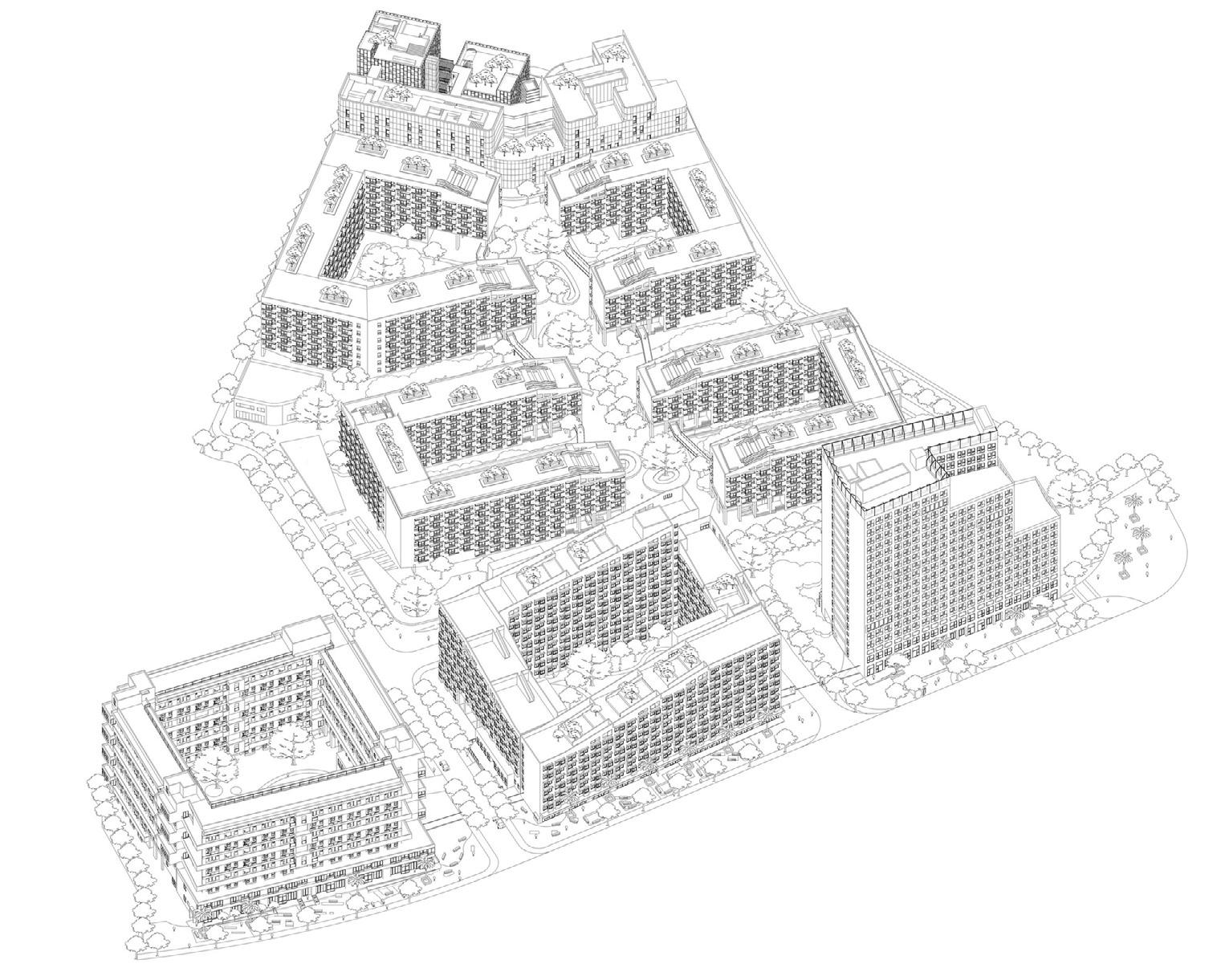

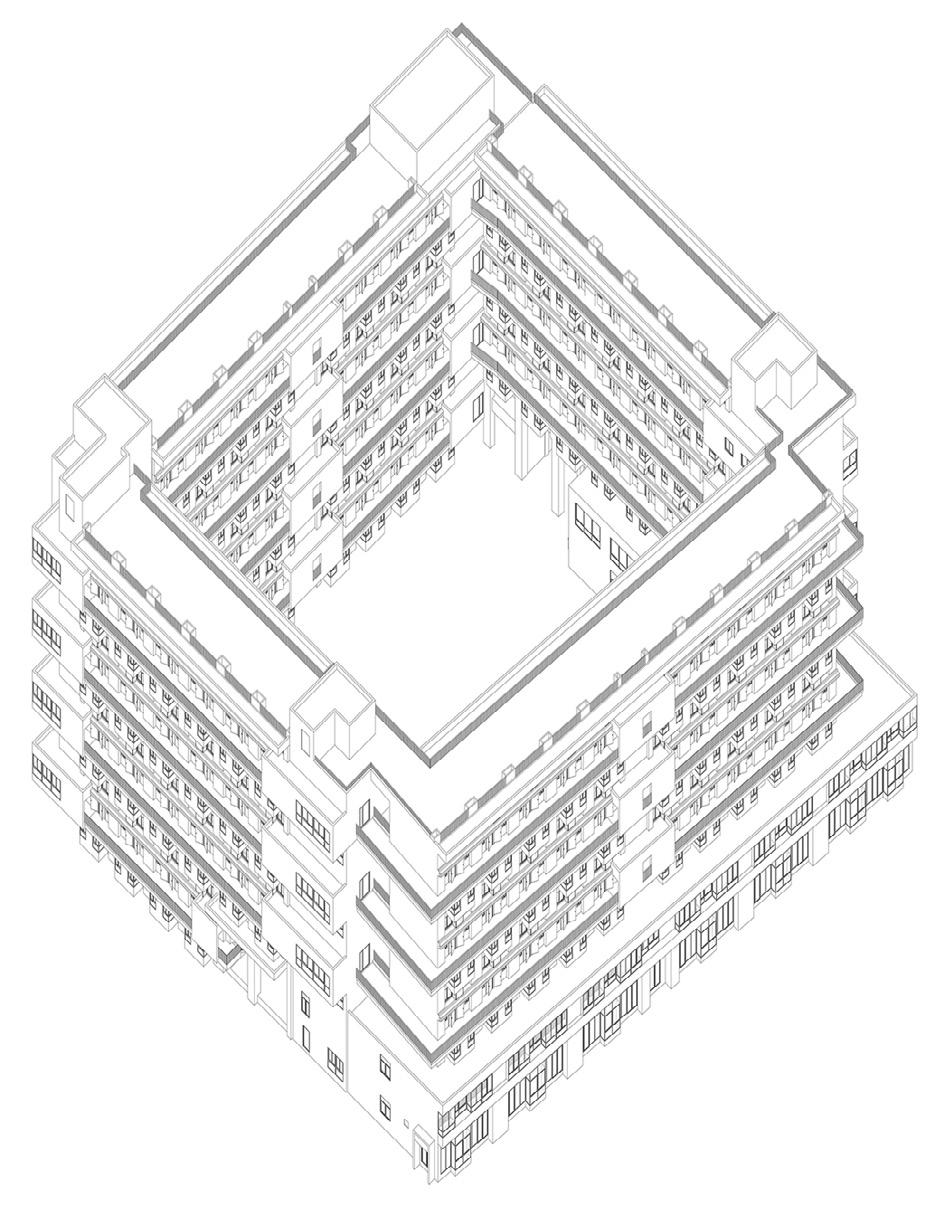

In order to adapt to different density, urban fabric and environment, two different types of floor layout are designed with different spatial organisation of the unit, the module, the shared facilities and the circulation: the linear type and the tower type.

The linear type is framed by external corridors, or deck access, on both sides of the module. As a result, the layout of the module has all the bedrooms or sleeping area in the units facing the corridors for daylight and ventilation, and other functions in the middle part, having doors opened to the in-between shared space. The in-between space is mainly a widened linear circulation space with shared facilities, having access to both sides of corridors, letting air to flow across the module. Between every two units, there is a larger shared space for facilities of more specific functions, such as children playroom, meeting room, laundry, small gym, mini-garden, etc. These are shared space at the floor scale, used by residents of this floor and encourage the interactions between different modules. They provide additional functions that cannot be fitted into the smaller scale of the module.

The tower type adopts the central core circulation, with four modules every three floors, surrounding the central core with vertical circulation in the centre. Due to different orientation to daylight, the organisation of units in the module is different from the linear type. The in-between shared space is also like a core in the centre of the module surrounded by units. Spiral Staircase is used to save space. Compared to the linear type, the tower type is more centralised, both within the module and on the floor plan. The connection between units and modules will be closer.

These two types serve as the example of how modules, as well as facilities and space shared between them, are arranged at the scale of the floor. Changes will be made when they are adapted to different existing context of actual sites.

Floor 1 consists of three units of different size (2-bedroom, 1-bedroom, studio). The in-between space serves as the entrance hall of the module, which also allows cross circulation between decks as both sides. Floor 2 has two units on two sides. The central space is for common kitchen and dining room. Floor 3 again includes three units and a small common living room. Space for exercising is also designed.

Layout of the Unit in The Linear Type after Division Some designed shared areas will be occupied as extension to some units when needed, by renting them from the State

There are a few considerations in design that can discourage these from happening. First of all, the spatial design should emphasise the identity of individual members in order to build a closer relationship among them. When getting more familiar, people start to feel embarrassed for doing something unpleasant that might undermine their relationship. Other considerations, including their reputation, others’ comments also help to restrict people’s behaviour in a small face-to-face society. These can be achieved, on the one hand, by limiting the number of members in a family group to make sure it remains in a small size. On the other, every individual unit should have some minimum spatial features, a small terrace for a rolling chair or a front door facing the flowerbeds, for example, to make them more distinguishing with their own identity.

Shared space and the facilities in it can also encourage interactions when frequently used by members, as long as they are appropriately designed. However, clearer boundaries should also be defined for divisions of responsibility. If only one or two families use a circulation space, then it is more likely for them to enclose that space. If the circulation space is more open and others pass by frequently, it is less likely to be occupied. Therefore, the location of the entrances of individual units and the dimension of the in-between space should follow the theory of environmental behaviour. For example, different materials can be used as the implications of different space and degrees of privacy. The same can be applied to the pre-designed space for extensions. In order to avoid disagreement among group members, only a few units can be extended into a pre-planned space. The potential extensive space will be decided at the beginning, and the following extensions in the future will not influence the integrity of the in-between space.

Establishing visual connections between in-between space and the individual unit can also help to maintain order. Surveillance by other members and eyes contacts between residents remind people to behave well. In order to achieve that, the in-between space should be visually open to both the outside and the individual unit. French windows and glass doors facing to the sitting & reading area or small flowerbeds can help to realise the visual connection. These can also be used as the division of the common kitchen and dining room. Moreover, the open plan of in-between spaces itself also allows the visual connection to be established.

Establishing a credit system in public housing could also be a possible way to deal with conflicts among group members. For instance, every applicant should have their records in the public housing application system, where group members can rate their neighbours or leave reviews. The records should be private but accessed by relevant professional officers and would be able to influence their application for public housing in the future. Online surveys should also be included in the process of application for applicants to join proper family groups. Websites for an online community should also be built up for early communication of applicants to make friends and look for suitable neighbours.

The discussion around negotiation within a community is a complicated interdisciplinary topic that is not only related to architecture, but also sociology, economics, psychology, and so on. Due to the limitation of time and knowledge, this thesis only discusses several potential problems and provides a few solutions which need to be developed further. This further development can be another focus of study in other research or practice in the future. What is certain at this moment is that negotiation is key to the success of any projects that challenge individual living. The process of negotiation itself also helps to establish a collaborative relationship, which furthermore inspires residents’ awareness of responsibility and self-governance. These are the fundamental support structures for a brand-new service provision system that I will talk about in the next chapter.

3.1 The Transition of Urban Governance in China

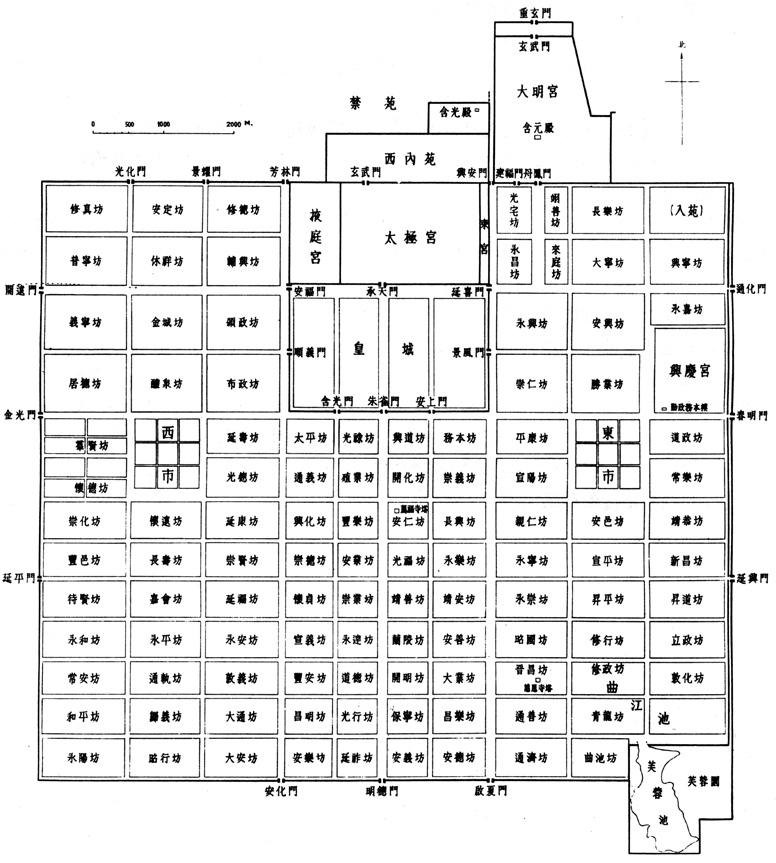

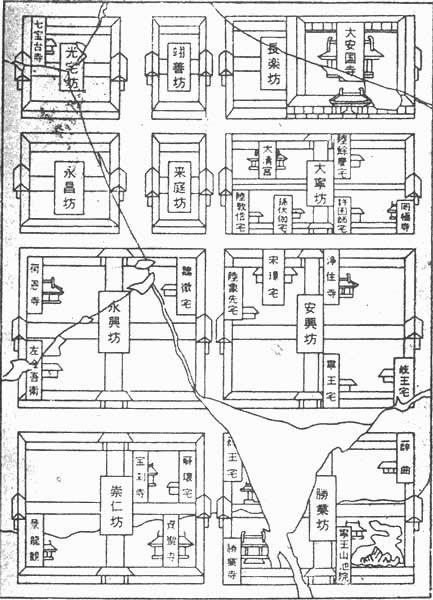

Urban Governance in Ancient China

For thousands of years in ancient China, urban planning of the city was an instrument of governance. It had its own feature and systems which developed through time.

There were two significant periods of urban planning. From the Zhou Dynasty to early the Tang Dynasty, a city was divided into several ‘Li for residential and Fang for commercial activities, which had walls surrounding the areas with gates that opened only at certain times. The ‘Lifang’ system was introduced to increase political control and military purposes. After the late Tang Dynasty, the prosperity of commercial activities led to an easing of the restriction of Lifang, making the city more open. In the Song Dynasty, Jiexiang’ replaced Lifang to became the main ordering typology of cities, where residential and commercial areas were no longer separated. This model continued until the late Qing Dynasty, when western urban planning ideas were brought to China.

The urban governance model of ancient China still influenced the later development of urban form in modern China, especially on the neighbourhood unit, work unit and the contemporary neighbourhood. The Baojia registration system related to Lifang system also illustrated the relationship between space and organisation of community as well as the administration of social order in traditional Chinese cities. This profoundly influenced the application and practice of a western theory of the neighbourhood unit and community in post-war China.

Communist Living in the City: The Work Unit

In the first five years of the new China, urban planning was guided by western theories, and the neighbourhood unit was introduced in many large cities. Later the Soviet Union as the political ally sent professional planners to help China with the construction, thus brought the idea of the superblock to China. Then the political movement of the Culture Revolution24 promoted the construction of people communes in rural areas and the work units in the cities. The work unit system lasted for more than 30 years until the end of the 20th century.

In the city, work units not only served as the areas of residential, commercial and industrial, but also as the basic unit in urban governance. It was an effective measurement to motivate and involve all citizens into the well-organised massive national production, especially in an unstable society of scarcity at that time. Due to the shortage in all kinds of resources, the work unit system enabled the state to monopolise the distribution of social resources and control industrial production, while work unit was the subject that resources were distributed through. As a result, work units held the responsibility of public service provision, including housing, health care, education, elder care, amenity,

27. According to the Organic Law of the Urban Residents Committee of the People's Republic of China, the Residents Committee should have the following duties: 1. publicising the Constitution, the laws, the regulations and the state policies, safeguarding the lawful rights and interests of the residents, educating the residents for the fulfilment of their statutory obligations and for the protection of public property, and conducting various forms of activities for the development of an advanced socialist culture and ideology; 2. Handling the public affairs and public welfare services of the residents in the local residential area; 3. Mediating disputes among the residents; 4. Assisting in the maintenance of public security; 5. Assisting the local people's government or its agency in its work related to the interests of the residents, such as public health, family planning, specialized care for disabled servicemen and family members of revolutionary martyrs and servicemen, social relief, and juvenile education; 6. Conveying the residents' opinions and demands and making suggestions to the local people's government or its agency.

As an administrative unit, there is no clear definition of the size of a community in China. It varies from one to another, sometimes contains only one large neighbourhood, or contains several smaller neighbourhoods. Residents Committee is set up to be in charge of the community every 100 to 700 families typically. It is a self-governing organisation composed by volunteering residents, following the guidance of the Street Office, the lowest level of government. The Residents Committee is financially supported by the government and coordinates with the Street Office. This makes the self-governing organisation, in fact, a subsidiary of the Street Office and accomplishes political assignments delivered from the upper government, while its duty should have been providing public service and organising democratic meeting of the residents.27

3.2 Public Service: Who is Responsible?

In a work unit, it was the duty of the enterprise to provide public service for its residents, the employees and their families. When work unit system is gone, the responsibility falls back to local governments, which provides the central planning and financial support, while the actual practice of measurement of providing public facilities is through local authorities, the Street Office and the Residents Committee.

28. The survey was conducted in August 2018, in three different public housing estates: Longnan Garden Rental Housing Estate, Xinkai Public Housing Estate and Huinan Minle Residential District. In total, 66 residents were involved.

One crucial dilemma of the Residents Committee is that they seldom receive public recognition. The committees are supposed to be representatives of residents and are chosen through voting. However, in reality, most of the residents in the community do not know either these committees or their duties. In a survey28 conducted by the author, 47 out of 66 residents in three different communities knew nothing about the daily work of local Residents Committee, another 13 only contacted them several times. 80% of the residents never participated in any organised activities, and 59% never knew about any of them. These data show the low efficiency of Residents Committee.

There are several reasons for low efficiency. Firstly, the scale of a community is so big that it is impossible for every individual to be involved. Secondly, the social ties among residents are weak, due to both the modern housing typology for individual living model and the scale of a community. Residents feel no responsibility for participation. Thirdly, the awareness of democracy among the public is still weak, and the authority (both the Residents Committee and the government) lacks support. People do not believe their decisions would make a difference. Finally, everyone is so busy in life in modern cities. Though sounds too general, the final reason also points to the inadequate service provision, including public facilities and activities, which fails to encourage interactions and build up congregation among residents. In general, community governance needs improvement.

The Current Service Provision System

The enactment of general laws of service provision system had not been put forward until recent years. Before that, unilateral laws29 were used for the management of public service, which was only valid for specific cases. The first local policy of public service was published in Guangdong province in 2012, which put forward the enactment of laws for public service in other cities and provinces. In 2017, the Central Council published the Public Cultural Service Guarantee Law of the People's Republic of China. 30

These policies and laws define the responsibility of local authority for planning, providing and maintaining the facilities of public service. Take Shanghai as an example. The Policy of Public Cultural Service Provision in Community of Shanghai 31 published in April 2013, defines that the Street Office is responsible for the management of public service facilities of its area, including the setup and construction, daily operation, future maintenance, effectiveness evaluation of them. Residents Committee also has the responsibility for the facilities in their jurisdiction.

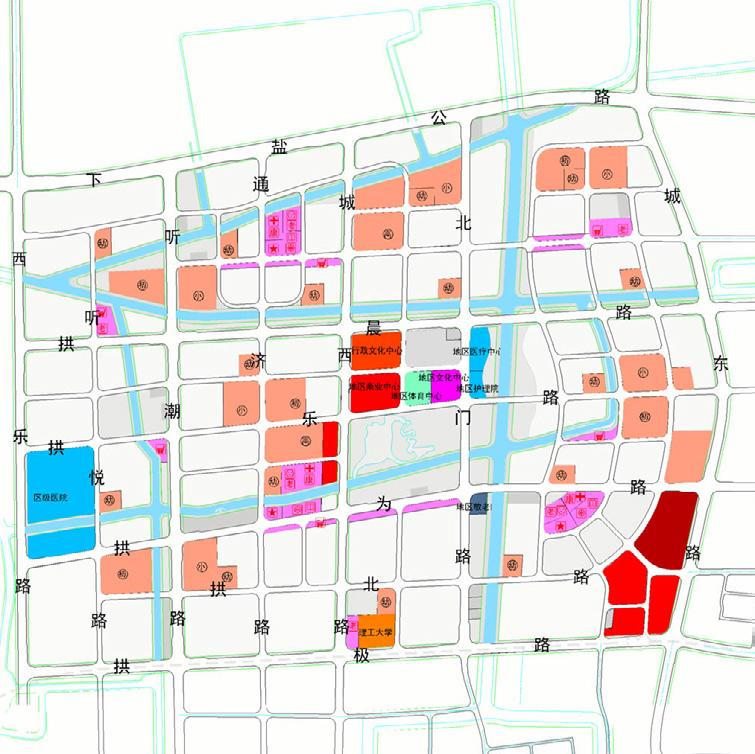

The functions, location and density of these facilities are also stipulated in the policy as well as the Standard for Public Facilities of Urban Residential Area and District . The public service of a residential district includes facilities of administration, culture, sport, education, health care, commerce, welfare, green space, municipal administration, etc. Community Cultural Centre should be

29. For example, the Administration of Public Library in Shanghai published in 1996, only validated for management of libraries in Shanghai. There were more than 300 laws and policies of library, cultural centre, etc.

30. Wei Jianxin, Duan Ran, 2017. ‘Analysis of Legislation Norm of Local Public Cultural Service’ (The South China Sea Law Journal, 2017)

31. DGJ08-55-2018, revised in 2018

in the centre with a service radius of less than 1,000 metres. Every community should have one or more community activity rooms. A high school should be set up every 50,000 residents. A junior school and elementary school every 25,000 residents, and a kindergarten every 10,000 residents. Health care centre and clinics should have a service radius of less than 500 metres. A community elderly care centre should be set up every 25,000 residents, a daily care centre every 15,000 residents, and an elderly activity room every 5,000 residents.

Recent years witnessed the increasingly attention from both the state and the public on public service provision, also with the propagation of Community Building Policy started in 2000. Therefore, for years, there was a trend for building community centres, even in the design course in the school of architecture. A community centre usually would include a meeting room, a reading room or small library, activity rooms, classrooms, gym, etc. Some of these rooms would be used for the public class of dancing, singing or other social activities. A community centre would contain most of the facilities associated with amenity in a community. It would be managed by staff worked for Residents Committee and Street Office, or volunteers from the community. To coordinate with that, there are also Community Health Care Centre, Helping Centre, Elderly Activity Centre, etc.

However, this model of public service provision has also been doubted by both the public and the professionals. Many of them have been accused of lousy quality, lacking diversity as well as professional management, low participation and low utilisation rate, facing only to one single subjects, the old, etc. In most case, these are true. Due to budget, the scale and construction area of the community centre is limited, especially in some old neighbourhoods where there is not much land left for the new building. Same to the equipment and facilities inside, from air conditioners to flooring. Most of the stuff is ordinary government officers who seldom likely to have professional skills in library science or elderly care, for instance.

The other thing that has been widely criticised is that the facilities lacking diversity, and quality fails to attract various groups of users, namely young adult, teenagers or children, which take up 90% of the population in the urban community.32 These groups seek for diverse entertainment with better quality that current public service system cannot provide, even though they need to pay extra money for that, despite they already paid their tax for free public service. This furthermore influences the function of democracy and autonomy of community, which based on the high participation rate, high public recognition, collaborative neighbourhood relationship, as well as awareness of right and responsibility, of the residents. While the current public service provision system still being taken full responsibility by the government, it is hard to change the situation.

Question: Should the State Take All the Responsibility?

For a long time, back to the work unit, people are used to the thinking that the state has to provide, manage and maintain public service facilities. True it is, but not an excuse for ignoring people's responsibility when using them. There is a vicious cycle in the state-responsible-only system: On one hand, the vast expense on investing public service and later maintenance makes it difficult for improvement of its quality, density and diversity. On the other hand, citizens take it for granted without feeling responsible for giving reviews or suggestions, helping to improve the system or maintain the facilities in good shapes. The lower the quality and harder to access, the less general residents would use the facilities, the less attention would be paid to manage them, the fast they would malfunction, and the more unwillingly people want to be responsible.

Instead of putting all the responsibility and power of control on the shoulders of the government, the proposal of a new system adopts a more hierarchical system of responsibility division. When public service is provided in the scale of the neighbourhood, not only the facilities but also the responsibility of maintaining them are refined, divided and distributed to different groups of subjects, in this case, every family group and the members of interfamily living. Public housing offers good opportunities for the new system due to its state ownership. This system should be combined with the development of new housing typologies for interfamily living, in which the shared space in and between modules offer perfect locations for the insertion of small-scale public facilities, such as small gardens, gym, meeting room, reading area, working space, laundry, children playroom, etc. With the users of these facilities being so specific, the responsibility of maintenance is also clearly divided, by which at least people know who is accountable if any of these facilities worn out more quickly than others. Residents will also cherish more the free resources they can get. The state, who are only responsible for the initial investment of public service and periodical refurbishment now, are relieved from the burden of daily manage and maintenance of them.

The improvement is not only on the efficiency of the service provision but also on the neighbourhood relationship and governance of the urban community. Unlike the old system in which public service is inconvenient to reach, these facilities are free to reach only a few steps from home for general residents, and the quality of them will be assured since they are shared by the people they know. By sharing and maintaining these facilities together, collaborative relationship among neighbours are developed, as well as a friendly neighbourhood environment and sense of responsibility. The healthy neighbourhood environment and intimate relationship among residents encourage them to improve their living environment, express their views and give suggestions, help to build up a sense of autonomy and democracy on the grassroots, which is another principal aim of urban community building in China.

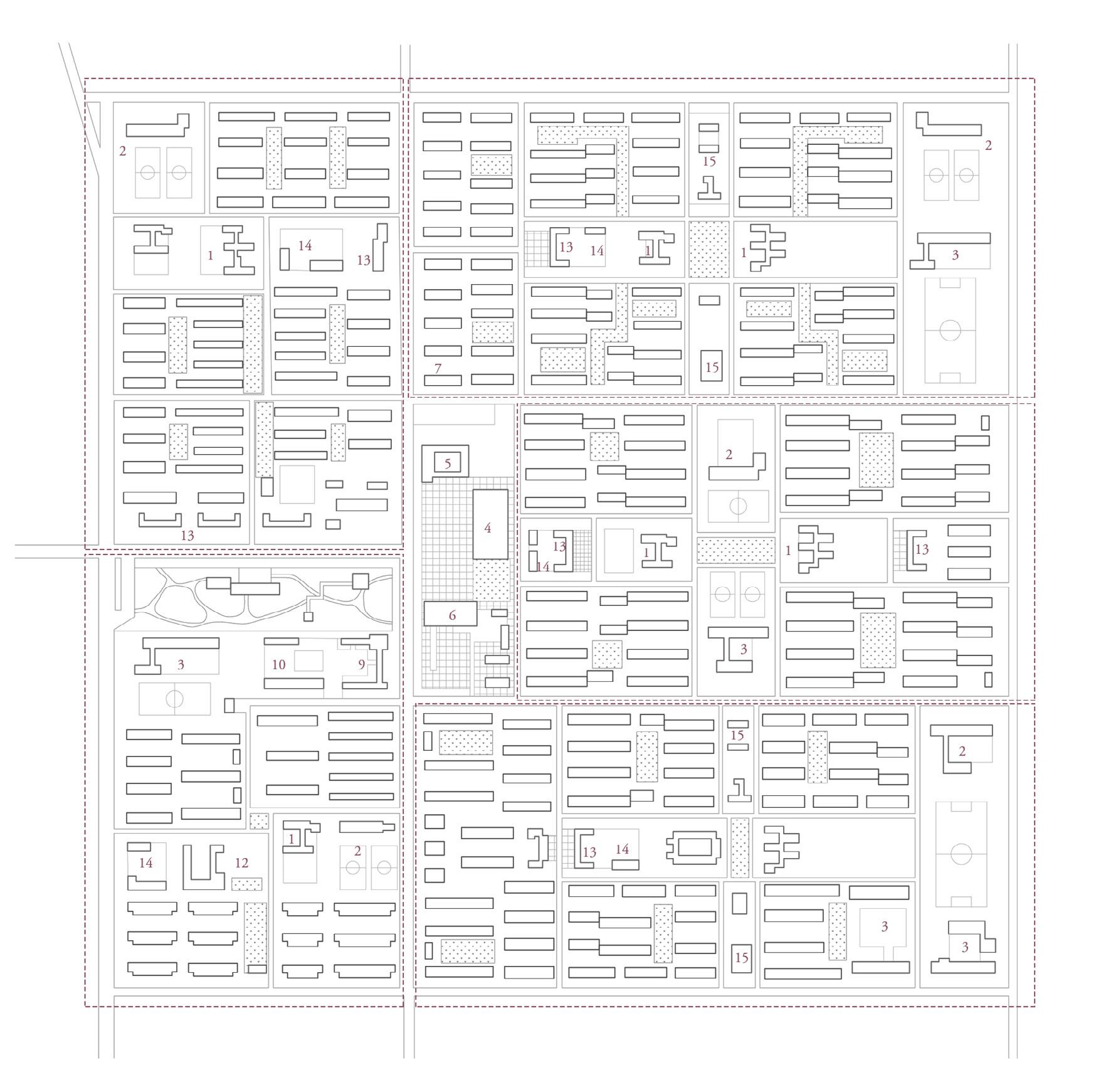

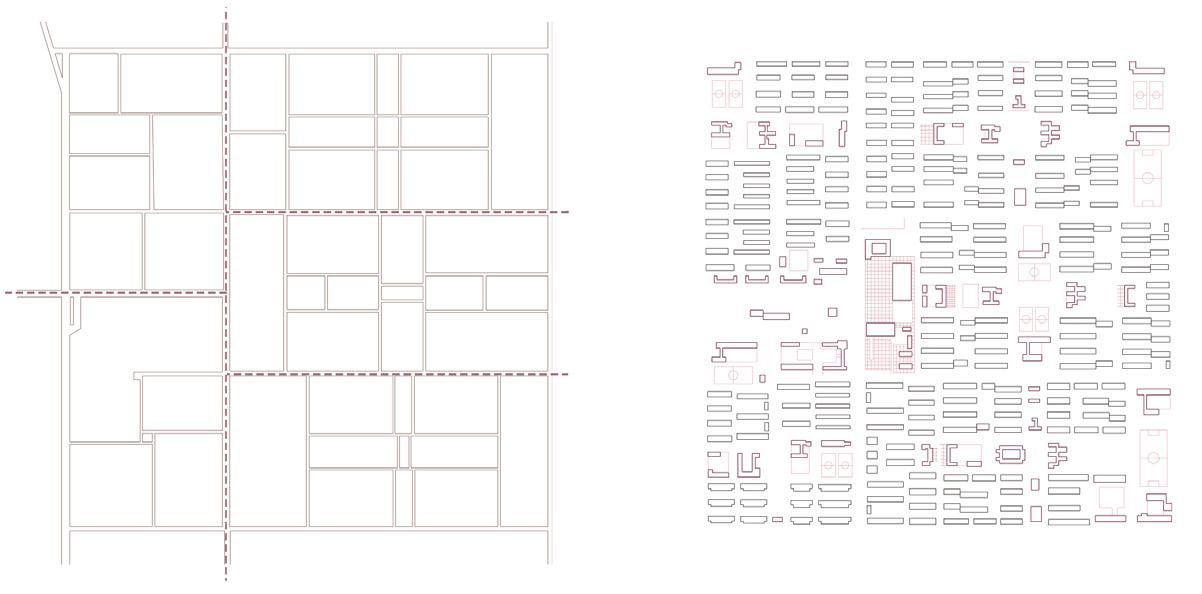

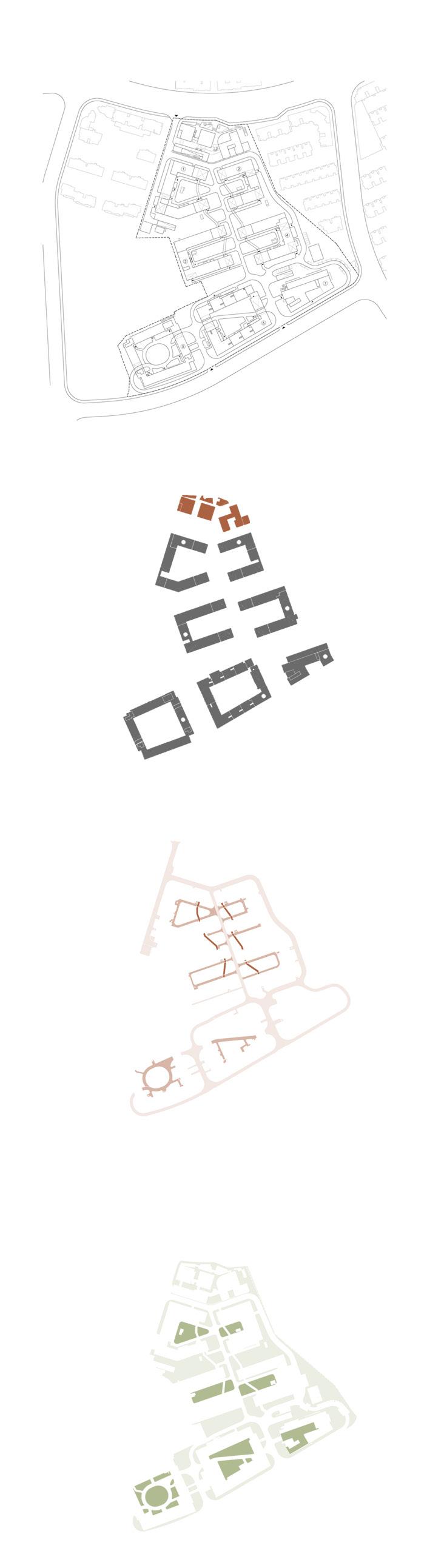

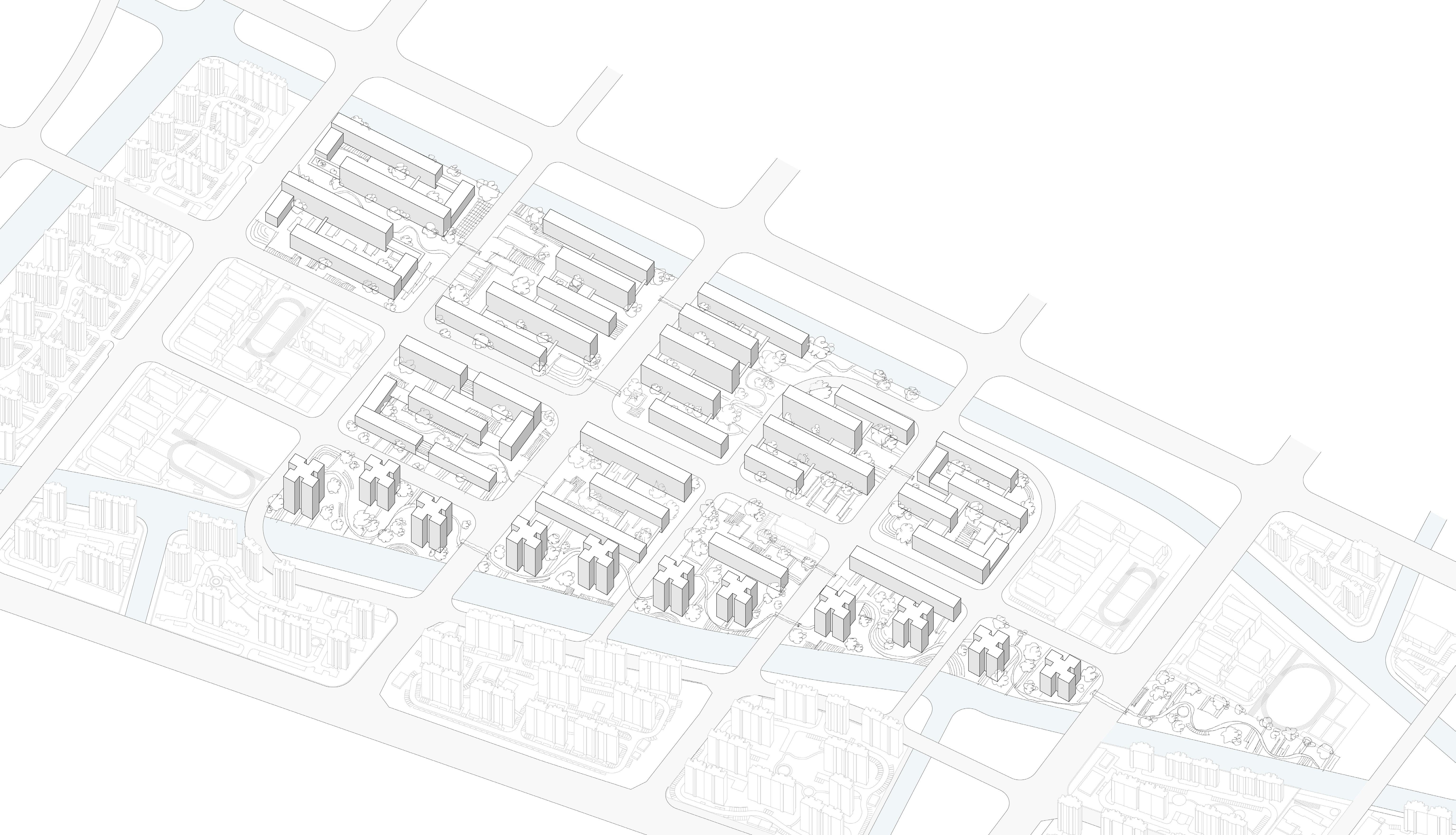

3.3 Design Proposal: The Urban Community

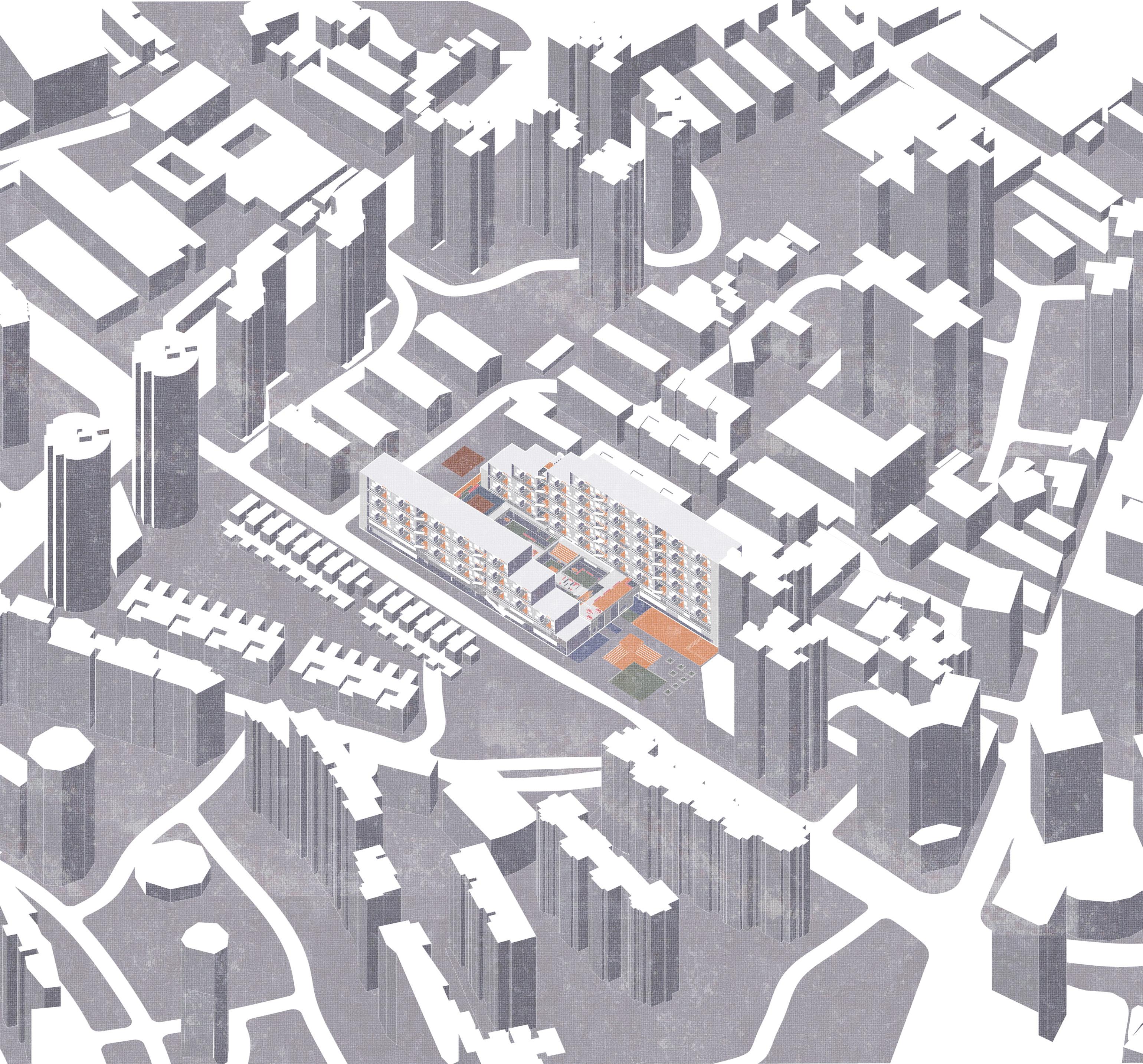

In this chapter, designs at several scales between the module of the family group and community of neighbourhoods will be introduced. The proposal will show how the prototype of interfamily living will be practised through different scales, coordinating with each other and finally related to the urban environment, based on two existing sites in Shanghai, China.

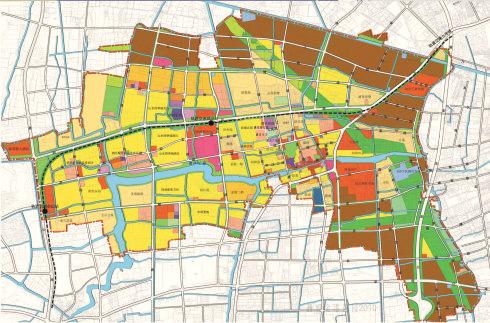

(1) Site 1: Block No. 115

The block No. 115 is a site of 10,350 m2, situated in Jin'an District in Shanghai. Jin'an District is one the oldest district of Shanghai City, which can be dated back to more than 100 years ago. It is a central area in the inner city of Shanghai, where the housing price is the most expensive of the city, at an average pricing of over 90,000 yuan per m2

As the oldest part of the city, it contains a lot of old traditional Lilong housing33 firstly built in the 19th century, as well as danwei housing of the 1960s to 1980s. Most of these buildings are low or medium rise housing of out-of-date drainage, electricity, gas or water system, for which the residents live in poor condition.

From the Tenth Five-year Plan34 in 2001, the Shanghai government have started the demolishment and rebuilding of old housing in the inner city, by classifying them in two kinds. The Level-2 Old Lilong (二级旧里 in Chinese) with the worse living condition and less value for reservation will be torn down and replaced by modern housing or other functions according to planning.

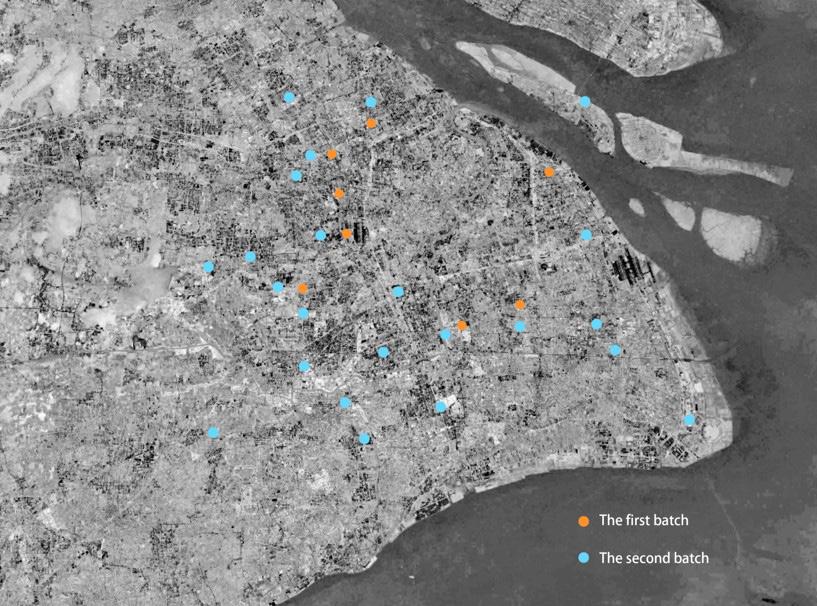

After 18 years, most of the old Lilong in Jin'an District have been replaced by new urban blocks, and the rest will be demolished in a few years.