FRACTURES

Istanbul’s Informal Spaces Between Formal Houses

Ayse Elif Coskun

Projective Cities 2025 Architectural Association

Ayse Elif Coskun

Projective Cities 2025 Architectural Association

Istanbul’s Informal Spaces Between Formal Houses

Projective Cities 2025

Architectural Association

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Terms

Abstract

Research Questions

Aims and Objectives

Methodology

Introduction

CHAPTER 1: LAND LAW AND PRODUCTION OF SPACE

Land, Land, Land

Mapping Istanbul

Planning Istanbul

CHAPTER 2: HOUSING, STATE AND IDENTITY

Housing and State

Housing and Social Identity

Traditional Modern

CHAPTER 3: FORMAL, INFORMAL, and the EROSION of BINARIES

Beykoz; from Arazi to Arsa

Beykoz; Socio-Spatial Interactions

Informal Formal Continuum

CHAPTER 4: the interstitial and projections

Taxonomy of the Interstitial

This thesis is dedicated to my auntie, and second mother, Saniye Cafer, her family and neighbours, who have been an immense source of inspiration and information for the themes explored in this work.

I express my deepest gratitude to my father, and informal editor, Bulent Coskun, for his unwavering support and encouragement in pursuing new challenges; you are the light to my life. I am also thankful to Alp and Şiva Dagli, Aslıhan Öztürkoğlu, and Monty Rush for uplifting me during moments of need, even through the other side of a video call. A special thank you to my Projective Cities classmates, affectionately known as the “Projective Ladies,” whose camaraderie and debates have been invaluable. I look forward to continuing our discussions in the future. Finally, I owe a special thanks to Zachary Regen Farr for his love and boundless patience throughout this journey. Your constant support and the meaningful conversations we’ve shared have been incredibly motivating, bringing so much joy and inspiration into this dissertation.

This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and guidance of many individuals throughout this 18-month journey. First and foremost, I am deeply grateful to the Projective Cities staff for their invaluable support during my studies. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Platon Issaias and Hamed Khosravi for their insightful guidance and rigorous questioning that have shaped this body of work. Special thanks go to Anna Font for her mentorship, for sharing her methodological approach, and for serving as an inspiring role model as a woman architect and educator. I am also thankful to Christina Gamboa, Roozbeh Elias-Azar, and Daryan Knoblauch for their expertise and for offering sharp insights into the urban contexts of Barcelona, London, and Berlin from professional, academic, and personal perspectives. My gratitude extends to the Architectural Association for awarding me the bursary that made this work possible.

In remembrance of my late mother, Yildiz Yurtman Coskun, my grandparents, Sitki and Hatice Coskun, Sermet and Nurseren Yurtman, and our recent loss, my dearest Cindy Regen.

Bu tez, evimizin yardımcısı ve ikinci annem Saniye Cafer’e, ailesine ve komşularına adanmıştır. Onlar, bu çalışmada ele alınan temalara ilham ve bilgi kaynağı olmuşlardır.

Babam ve gayrıresmi editörüm Bülent Coşkun’a, yeni zorluklara göğüs germem için verdiği sarsılmaz destek ve cesaretlendirme için en derin şükranlarımı sunuyorum; sen hayatımın ışığısın. Ayrıca, Alp ve Şiva Dağlı’ya, Aslıhan Öztürkoğlu’na ve Monty Rush’a, ihtiyaç anlarında bana destek oldukları ve bir video görüşmesinin diğer ucundan bile yanımda olduklarini hissettirdikleri için minnettarım. “Projective Ladies” olarak andığımı Projective Cities sınıf arkadaşlarıma da özel bir teşekkür borçluyum; dostlukları ve tartışmalarımız bu süreçte paha biçilemezdi. Gelecekte bu sohbetleri sürdür meyi sabırsızlıkla bekliyorum. Son olarak, Zachary Regen Farr’a, bu yolculuk boyunca gösterdiği sevgi ve sınırsız sabır için özel bir teşekkür borçluyum. Sürekli desteğin ve paylaştığımız anlamlı sohbetler, bu tezi yazarken bana büyük bir motivasyon kaynağı oldu ve sürece neşe ve ilham kattı.

Bu tez, 18 aylık süreç boyunca pek çok kişinin desteği ve rehberliği olmadan mümkün olmazdı. Her şeyden önce, Projective Cities akademik kadrosuna, çalışmalarım boyunca verdikleri paha biçilmez destekleri için en derin minnettarlığımı sunuyorum. Platon Issaias ve Hamed Khosravi’ye, verdikleri yönlendir me ve titiz sorgulamalarla bu çalışmayı şekillendirdikleri için içten teşekkürlerimi sunuyorum. Anna Font’a, mentörlüğü, metodolojik yaklaşımını paylaşması ve bir kadın mimar ve eğitimci olarak ilham verici bir rol model olması nedeniyle özel bir teşekkür borçluyum. Ayrıca, Christina Gamboa, Roozbeh Elias-Azar ve Daryan Knoblauch’a, Barselona, Londra ve Berlin’in kentsel bağlamlarını profesyonel, akademik ve kişisel perspektiflerinden keskin analizleriyle ele aldıkları için minnettarım. Bu çalışmayı mümkün kılan burs desteği için Architectural Association’a da teşekkür ederim.

Merhum annem Yıldız Yurtman Coşkun’un, büyüklerim Sıtkı ve Hatice Coşkun’un, Sermet ve Nurseren Yurtman’ın ve yakın zamanda kaybettiğimiz çok sevgili Cindy Regen’in anısına...*

*Translated by AI from English to Turkish

Gecekondu [geh-jeh-KON-doo]

Informal housing settlements built quickly on unregistered or public land, often by rural migrants.

Site [see-TAY]

Planned residential developments, typically gated and constructed by institutions or private developers.

Formal Housing

Housing constructed within regulated frameworks.

inFormal Housing

Housing built outside of regulatory or planning systems.

Legal Housing

Housing that complies with zoning and construction laws.

ilLegal Housing

Housing that violates laws or regulations at the time of construction.

Spaces between buildings or urban structures that serve transitional, secluded, or collective functions.

Sofa

A multi-functional central space in traditional Turkish houses, used for connecting rooms and communal activities.

A state-led initiative aimed at redeveloping urban areas to address housing shortages, earthquake resilience, and unregulated development. Often criticized for prioritizing profit-driven redevelopment over community needs, it has reshaped land use and housing dynamics in cities like Istanbul.

A housing prototype by Le Corbusier, featuring reinforced concrete slabs and columns, allowing open plans and flexible façades. It laid the foundation for modernist architecture and mass housing. Here, “Dom” refers to house, while “Ino” stands for innovation in Latin, and it should not be mistaken for the word “domino.”

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was the Republic of Turkey’s founder and first President (1881–1938). He served between 1923–1938. He oversaw significant modernising, secularism, and urban development measures Emphasising Wester n-style urbanisation, infrastructural development, and industry, his city planning prog rams prioritised grid-based city layouts, public squares, and green areas, Atatürk helped to shape Ankara as the new capital with a modernist, planned urban form. His concept promoted public structures, transportation systems, and a methodical approach to city development, laying the groundwork for Turkey’s architectural and urban revolution.

Turgut Ozal lived between 1927 and 1993, is a Turkish politician, economist, and engineer. He was the Prime Minister of Turkey from 1983 to 1989 and then the eighth President from 1989 until he died in 1993. He was instrumental in liberalising Turkey’s economy, implementing free-market changes, privatisation, and foreign investment, opening of the nation. Özal’s ideas greatly changed Turkey’s economic environment and promoted fast modernisation and expansion. Efforts to include Turkey into the world economy while negotiating political and societal obstacles defined his term.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a Turkish politician having been President since 2014. Previously Mayor of Istanbul (1994–1998) and Prime Minister (2003–2014), he led enormous infrastructure projects like highways, bridges, and the construction of public housing through TOKİ, he was a major player in Turkey’s urban change Along with criticism for gentrification, environmental harm, and urban sprawl, his policies encouraged fast urbanisation and extensive building. Strongly supporting Urban Amnesty (İmar Affı), Erdogan approved illegal construction to merge infor mal communities, therefore benefiting the area temporarily but generating questions about long-term sustainability in urban planning, safety, and zoning violations.

Turkey’s state-run Housing Development Administration, oversees mass housing, urban regeneration, and disaster recovery initiatives. Built under Erdoğan, it creates reasonably priced homes but draws criticism on environmental effect, construction quality, and gentrification.TOKI is Turkey’s state-run Housing Development Administration: Mass housing, urban redevelopment, and catastrophe recovery prog rams are handled by TOKI. Under Erdogan, it develops reasonably priced homes but comes under fire over environmental effect, construction quality, and gentrification.

Henri Prost was a French builder and urban planner who lived from 1874 to 1959. His designs had a major impact on city planning, especially in North Africa and Turkey. He is best known for his master plans for cities like Casablanca, Istanbul, and Rabat, in which he combined modern urban design ideas with an understanding of the cities’ culture and historical backgrounds. Prost’s work focused on wellorganized street layouts, green areas, and infrastructure that worked well to support cities that were growing.

Luigi Piccinato was an Italian architect and urban planner who worked from 1899 to 1983. He is recognised for his efforts to modernise city planning in Italy and around the world. He was an expert at making city master plans that preserved history while also being useful in modern times. Piccinato was very important in rebuilding and planning cities after the war. He made plans for places like Rome and Naples, as well as for many areas in the Mediterranean and Latin America. His plan focused on human-scale planning, integrating the environment, and building good transportation networks.

Sedad Hakkı Eldem was a renowned Turkish architect. He was noted for fusing modern design ideas with classic Ottoman and Turkish architectural features. Emphasising cultural continuity and regional identity, he plays a major part in the development of Turkish architecture of the 20th century. Eldem also taught at Istanbul Technical University, where he shaped the next generation of architects. Among his noteworthy creations are several public buildings and homes reflecting his dedication to modernism anchored in history as well as the Istanbul Hilton Hotel.

Tansı Şenyapılı was a Turkish scholar and writer focused in urban planning and architecture. She was a faculty member at Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey. Among her noteworthy works is the book “Baraka’dan Gecekonduya,” which looks at Turkish urbanization and informal housing policies

This thesis explores the housing dynamics in Istanbul, focusing on the interplay between land ownership, planning policies, and socio-spatial typologies. It challenges the traditional for mal-informal housing divide, arguing that it is a product of historical urban policies and class dynamics rather than an inherent spatial logic. By examining two typical housing strategies, site and gecekondu, the thesis aims to redefine the housing landscape in Istanbul.

It looks at how Istanbul’s housing and land policies have changed over time, from the time of the Ottoman Empire to the early Republic and up to the present day. Specifically, it looks at how gecekondu communities and site developments have worked as different but connected parts in response to housing shortages, more significant societal changes, politics, and the economy. By examining these dynamics, the research underscores the pressing need for inclusive policies that recognise the value of gecekondu settlements and promote equitable urban development in Istanbul.

The dissertation aims to illustrate the changing connections between land ownership, housing rules, and spatial practices using the case study of Beykoz – an area that has seen both gecekondu and site-driven urbanisation. Here, the study of interstitial spaces not only shapes community relationships and socio-spatial organisation but also presents a canvas for projective urban interventions. This thesis looks at how these factors affect community cohesion, exclusion, and inclusion to understand how housing works in relation to land. This study’s central claim is that the conventional division between formal and infor mal housing ignores Istanbul’s urban development’s fluidity.

Building on this, the dissertation critically researches and analyses three historical and architectural issues reflected in the table of contents: land, urban planning, and building in the context of Istanbul.

Part 1 delves deeper into the understanding of land in Turkey, critically examines the terminolog y, draws a critical focal point on Istanbul’s urban planning efforts, and identifies the growth of Istanbul.

Part 2 of the thesis delves into the interdisciplinary aspects of the research, investigating the relationships between housing and state, as well as housing’s role in shaping identity. It critically examines the Republic’s evolving perspective on ‘home’ over the decades, focusing on the specific laws,

[i]

A local in Fikirtepe neighborhood, Alaaddin Demirel, refused to sign an agreement with the construction company for 4 years and his house was the only remaning house in the destruction site. the house was demolished in august 2014 and alaaddin demirel signed an agreement that made him an owner of 5 flats.

photo: Kursad Bayhan/140journos

policies, and amnesties that shaped its idiom. The thesis then shifts its focus to two distinct socio-economic moments in history where housing scarcity manifested in two types of strategies: gecekondu and site It draws on various disciplines to understand the labour-driven split in housing strategies and the state’s relationship to it while also investigating the architectural history and the borrowed models in Turkish architecture.

Part 3 critically questions the infor mal and for mal divide in the northern Istanbul district of Beykoz. It identifies land and building types and better explains the erosion of infor mal and for mal binaries in Beykoz’s housing fabric.

Finally, Part 4 will deeply analyse interstitial spaces in Beykoz, their formation, and current transfor mations. The thesis will ultimately define the wall as a segregation tool and reimagine its concrete and artificial use in Istanbul’s urban planning.

Urban:

What are the implications of urban transformation policies on socio-spatial segregation and the informal-formal binary in housing in Istanbul?

How have historical laws, policies, and perceptions of housing typologies influenced the development of Istanbul’s urban fabric, particularly in areas like Beykoz?

Typological:

How do spatial interactions within gecekondu settlements compare to the structured environments of site developments?

How have gecekondu settlements and site developments influenced urban planning policies and vice versa?

What typological shifts in housing have occurred over time, and how have these shifts transformed the spatial logic of collective spaces in Istanbul?

Disciplinary:

How can surveying interstitial spaces generate possibilities for collective urban interventions?

What are the architectural manifestations of interaction, negotiation, and segregation in gecekondu and site housing, and how can the reimagination of architectural components respond to the transformation of the urban landscape?

To critically investigate the interplay between land ownership, planning policies, and socio-spatial segregation in shaping Istanbul’s urban housing fabric, with a focus on the distinctions and overlaps between gecekondu and site housing strategies

To analyse the historical and cultural evolution of gecekondu and site housing typologies in Beykoz, Istanbul, focusing on their spatial organisation, socio-economic roles, and legal frameworks.

To assess the spatial impact of urban transformation policies on different social classes in Istanbul.

To identify and categorise the interstitial spaces in Beykoz, Istanbul, focusing on their potential for collective use and adaptation within the urban landscape

To propose alternative design methodologies that leverage interstitial spaces as a foundation for interaction and negotiation addressing housing segregation in Istanbul.

To propose design methodologies that leverage interstitial spaces to balance privacy, adaptability, and social interaction in housing.

The gecekondu topic has been extensively discussed through different lenses since its emergence. These approaches have mostly examined its housing qualities in terms of interior organisation, structural integrity, and placement within the city. This thesis aims to take a step back and look at the relationships between gecekondu houses by analysing their constant growth and connection to the land.

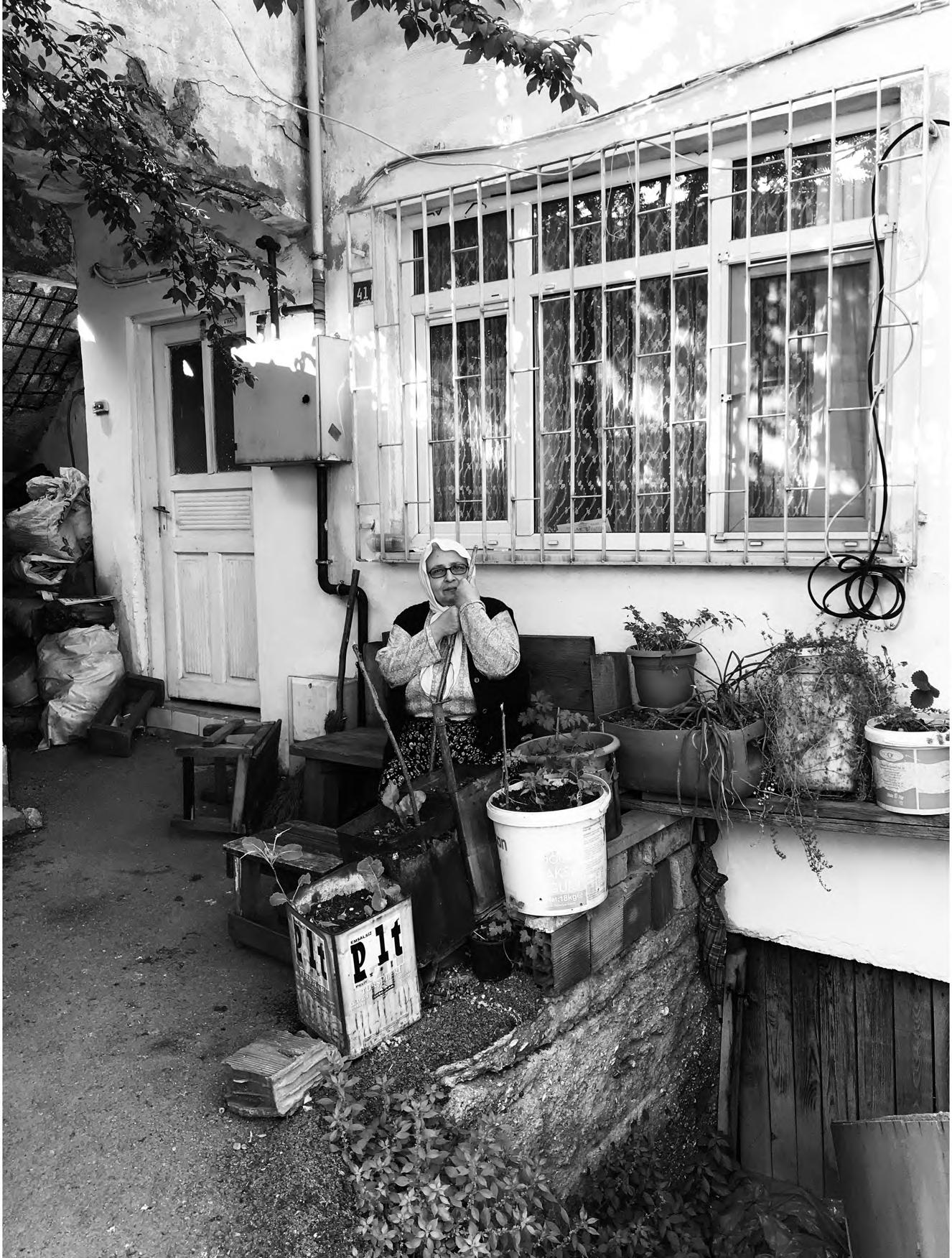

To achieve this, the thesis uses time-stamped Google Maps images to identify growth patterns between 2014 and 2024, alongside street photography in 2025 to capture social interactions. Planelevation combination drawing methods are employed to understand the spatial complexity of gecekondu interstitial spaces, where irregular houses, land divisions—or the lack thereof—and topography intersect.

A comparative analysis is also conducted with the adjacent site housing strategy, using the same methodologies. This unique approach allows for the identification, categorisation, and comparative analysis of exterior conditions that incorporate interior organisational elements.

The thesis also delves into archival material and crossreferences it with pop culture to understand socio-political shifts and their impact on Turkish architectural and construction practices. The scope spans from the late Ottoman Empire and the declaration of the Republic of Turkey to the present day This research is an architectural exploration of gecekondu and site interstitial spaces while addressing broader socio-cultural class dynamics in Turkey.

It is also important to note that Beykoz presents a unique case for both gecekondu and site developments. There are multiple typologies of both in this district, and gecekondu settlements in Beykoz are architecturally more formalised than their counterparts in other districts of the city or in other cities.

Urban planning, often considered a modern invention, is a complex endeavour that involves the organisation, regulation, and shaping of the built space. However, cities are not just collections of buildings and infrastructure but rich and diverse social, cultural, and economic organisms that evolve through time. The term urban extends beyond describing densely populated areas—it encapsulates the networks of interaction, power, and negotiation that define collective living. Similarly, planning—a concept deeply rooted in modernist ideals—seeks to impose order and rationality upon urban landscapes, often treating cities as “tabula rasa.”1 Where predefined progress models can be applied, this ideological approach assumes that urbanisation follows a linear trajectory toward modernity. Yet in many contexts, such as Istanbul, historical, socio-economic, and political conditions have shaped an entirely different urban reality—one that defies rigid classifications of formal and informal, planned and unplanned.

In Istanbul, modern urban planning, introduced during the Republican era, significantly departed from historical urban development patterns. This shift was characterised by imported models aimed at rapid modernisation, often neglecting the local context of land tenure, construction practices, and social class structures. The city’s urban, and more specifically residential, expansion was no longer dictated by organic, adaptive growth but rather by state-led interventions, zoning regulations, and legal frameworks favouring specific urbanisation forms while marginalising others. This not only separates Istanbul’s fragmented urban fabric but also exposes the extent to which planning served as a tool for control and exclusion rather than cohesion and inclusivity.

One of the most significant manifestations of this imposed planning model was the introduction of the apartment block, an architectural typology that later in history became the foundation for site

1

been used metaphorically in various disciplines, including urban planning and architecture, to describe clearing an area (physically or conceptually) to start fresh, often applied to modernist city planning.

housing developments. These mass housing projects, conceived as solutions to urban expansion and modernisation, were often linked to political and economic agendas rather than local housing needs.

In contrast, gecekondu settlements, informal, self-built housing typically on the outskirts of cities, emerged as bottom-up, adaptive housing solutions built by migrant communities in response to housing scarcity and land mismanagement. Though frequently portrayed as informal or illegal, these settlements exhibit a spatial intelligence that arises from necessity and collective experience. Their organic formation—characterised by shared courtyards, communal pathways, and flexible structures—contrasts sharply with site developments’ rigid, top-down logic. However, despite their adaptability, gecekondu neighbourhoods have been continuously subjected to urban transformation projects, legal reconfigurations, and shifting policy frameworks that seek to either formalise or eradicate them.

Housing in Istanbul cannot be fully understood without considering the broader socio-economic forces shaping the city’s urban landscape. In this study, two primary social classes that define urban segregation are borrowed from Marxist terminology: the proletariat and the petite bourgeoisie, which designate the working class with blue-collar and middle-class urban professionals. These groups represent distinct historical periods and economic conditions, each contributing to the evolution of gecekondu and site housing strategies.

The Turkish proletariat, emerging from the rural exodus caused by agricultural industrialisation, settled in Istanbul during the mid-20th century, bringing traditional communal practices, religious affiliations, and strong family ties. The modern Republican state, driven by Westernoriented modernisation, often excluded these rural migrants from the formal urban economy, reinforcing their marginalised status within the city. Over time, however, political representation and economic mobility enabled these communities to gain a foothold in Istanbul, reshaping gecekondu areas into semi-formalised neighbourhoods with improved infrastructure and legal recognition.

Conversely, the petite bourgeoisie—a new social class that emerged in the early republican and late Ottoman era—was boosted by the neoliberal policies in the 1980s, shaped mainly by the rise of the service sector, finance, marketing, and international banking industries. This class, often

composed of young professionals from Ankara and other regions, sought modern, structured living environments and became the primary occupants of newly developed site housing projects. These gated communities and apartment complexes built adjacent to gecekondu settlements, symbolised economic privilege and a deliberate social distinction from the workingclass communities next door. Thus, Istanbul’s housing landscape became a physical representation of socio-economic divisions, where urban planning reinforced class segregation rather than bridging social inequalities.

Beykoz, a district on Istanbul’s periphery, presents a compelling case study for understanding the interplay between gecekondu and site housing. Unlike other areas where one housing typology dominates, Beykoz is characterised by a juxtaposition of informal settlements and structured site developments, revealing the fluidity of housing strategies rather than a strict formal-informal binary. State-led urban transformation projects have tried to regulate, rezone, and redevelop parts of the district. Still, local housing practices have changed, making hybrid urban forms hard to put into standard categories.

This thesis focuses on interstitial spaces—the in-between spaces within and between gecekondu and site developments. While much of urban research on housing focuses on interior structures and building codes, this study argues that the spaces between houses serve as crucial sites of social interaction, community formation, and spatial negotiation.

In gecekondu areas, interstitial spaces often function as extensions of domestic life, fostering communal gatherings, informal economies, and adaptable land use patterns. In contrast, in site housing developments, interstitial spaces are often enclosed, controlled, or privatised, reinforcing spatial exclusivity and limited interaction. By analysing these spaces in Beykoz, this research seeks to uncover alternative urban strategies that leverage interstitial spaces as catalysts for more inclusive and integrated housing solutions.

This thesis distinguishes between legal and formal housing to fully grasp Istanbul’s paradoxical housing dynamics. Legal housing refers to structures that comply with zoning laws and construction codes, whereas formal housing is produced within state-sanctioned planning frameworks.

This distinction is particularly significant in Istanbul, where many gecekondu settlements—despite being labelled informal—have been retrospectively legalised through amnesty policies. So, putting housing into strict categories like “formal” or “informal” doesn’t show how Istanbul’s cities are growing; there is a wide range of legal, semi-legal, and adaptable housing options.

Ultimately, this thesis critiques the role of land management, regulatory frameworks, and state-driven planning policies in perpetuating urban inequalities. It argues that urban transformation projects must critically engage with local spatial dynamics rather than imposing top-down borrowed development models. This research proposes a rethinking of Istanbul’s housing strategies, interrogating the socio-political mechanisms that shape urban segregation and offering alternative frameworks that prioritise adaptability, inclusivity, and resilience. By using the ‘wall’ as both a physical and conceptual architectural component, this thesis reimagines interstitial spaces as sites of negotiation rather than division, challenging conventional planning paradigms and proposing new ways of structuring urban life that reflect the lived realities of Istanbul’s residents.

Land shapes not only the physical city but also its socio-economic relationships. This connection is particularly significant in Istanbul because housing conflicts result from land and dwelling relationships. To tackle Istanbul’s housing and urban sprawl, it is first essential to discuss land as a commodity.

The terminology for land can sometimes vary among professionals and lawmakers. The three most commmonly used Turkish terms are “toprak, arsa, and arazi”. Drawing from the definitions provided in the 2011 Land Terms Management Dictionary by the Chamber of Survey and Cadastre Engineers (TMMOB), we can precisely distinguish these terms. Arazi refers to a physical parcel of land, typically encompassing rural or undeveloped areas. In contrast, arsa specifically denotes urbanised land ready for development. Toprak, on the other hand, pertains to the organic and mineral soil layer. Ruşen Keleş, an important figure in Turkey’s urbanism, critiques the Turkish language reform efforts, which often merged these distinctions, resulting in the oversimplified use of toprak as a catch-all term for both arazi and arsa Though well-intentioned, he argues that such linguistic misuse obscures technical and functional differences, particularly in urban planning and land policies. For example, in taxation, arazi refers to rural land, while arsa denotes urban land, demonstrating the necessity of maintaining these distinctions for clarity and policy precision.2

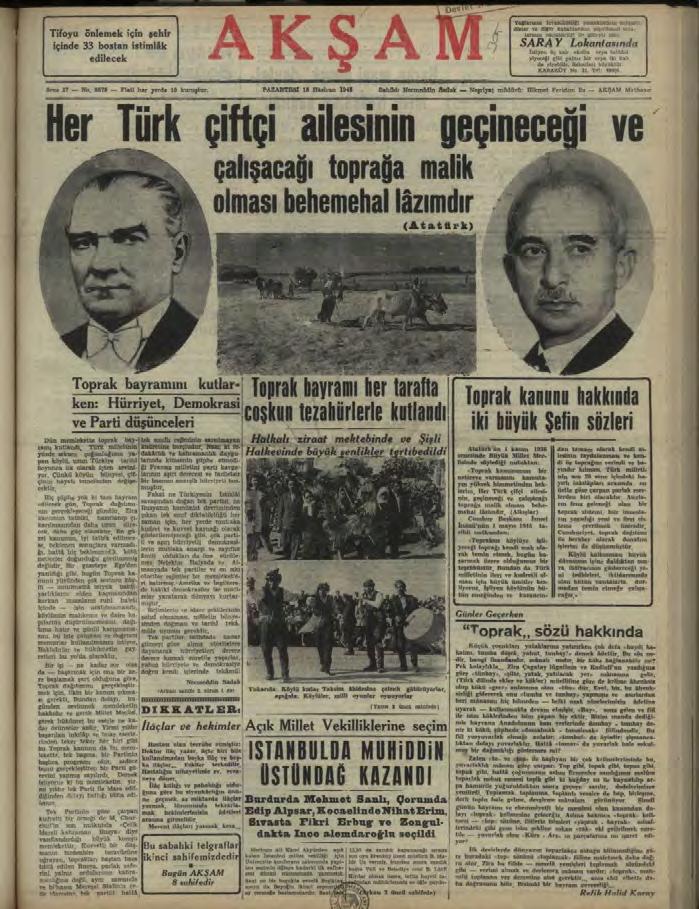

Even the first attempts by the Republic to grant land freedom to the people used a mix of three words: toprak, arsa, and arazi The first legislation for land reforms was called Toprak Kanunu, literally translated as Soil Law in English, which was celebrated with Toprak Bayramı, meaning Soil Festival. The aim was to grant ownership to villagers; therefore, the land referred to in this law was agricultural, arazi, with the goal of “letting every farmer be able to feed their family and profit from it,” as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk pointed out in his parliamentary speech on the matter. [Figure 2] However, investments in agriculture shifted, and the state’s foresight failed.

[1]

“The

Even though Turkey was not involved a part of the economic struggles during World War II, it restricted the state’s ability to move forward with Toprak Kanunu By the war’s end, the focus had shifted from agricultural land (arazi) to urban land (arsa) as industrialisation and rural exodus took precedence.

As Istanbul expands, rural and forest areas are converted for urban use. This process is often misunderstood as “arsa üretmek,” which translates to land production in Turkish. This refers to the reorganisation of existing spaces, which inflates land values through interventions such as zoning changes and increased building heights, leading to land redevelopment.

A critical example is the ‘2B Arazi’ changes. This refers to land classified under Article 2B of the Forest Law, which allows deforesting of state-owned land and their sale to individuals. Many gecekondu areas were built on forest land; these new classifications opened the way for the semi-legalisation of these settlements. However, this also led to mass privatisation and enabled developers to purchase large plots.

‘Land production’ (arsa üretmek) is a mistranslation of Henri Lefebvre’s La Production de l’Espace, which refers to the production of space rather than land, as land is not a producible commodity. Hence, land production (arsa üretmek) is only transferring arazi (agricultural land) to arsa (urban land). Keles reminds us that this artificial scarcity led to the spread of gecekondu in the first place, where a significant proportion is built on public land owned by entities like the Treasury or municipalities. Public authorities tasked with protecting these lands have often failed to act effectively, whether due to political pressures or negligence. This lack of oversight has allowed ‘informal’ gecekondu settlements to persist and, later, the state to use its gaps to create ‘formal’ housing, reflecting deeper issues in land management that continue to fuel Istanbul’s housing challenges.3

The confusion in the land at the etymological level demonstrates the linguistic and cultural base of shifting land legislation. These shifts not only fuelled uncertainty about land but also about the definitions of formal and informal housing. Just as the ‘production of space’ led to deforestation for urban land, housing developments were made fast-paced by borrowed models that were not formal nor informal in the universal sense and did not reflect Turkish living styles.

[2] Aksam Newspaper, 18.06.1946

source:Internet Archives

Headline:

“It is absolutely necessary for every Turkish farming family to own the land on which they will make a living and work”

Mid-section:

“Land Festival was celebrated everywhere with enthusiastic demonstrations”

The land legislation in Turkey owes its existence to the precedent Ottoman land laws. Private land ownership rights were not secured during the classical period of the Ottoman Empire. While far mers could cultivate the state’s land for agricultural purposes if they paid taxes, they could not claim this land as their private property. All land belonged to the state unless it was officially affiliated with a wakf or a family, and even in those cases, there were many historical instances where the state took over the property.4 Citizens were given the right to seize vacant land in 1858 with the condition that the appropriators gave it a function so that farmers farmed, soldiers fought, and the empire grew.5 By the late 1800s, the Ottoman Empire started to give outright property ownership to ensure the loyalty of their beneficiaries.

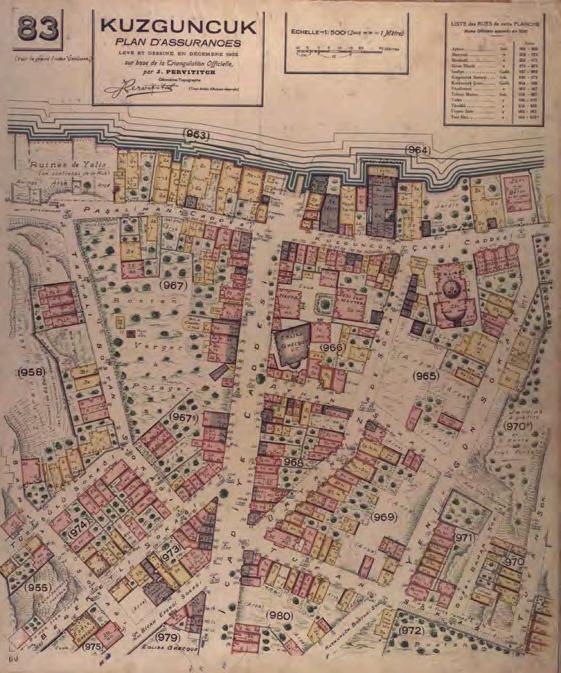

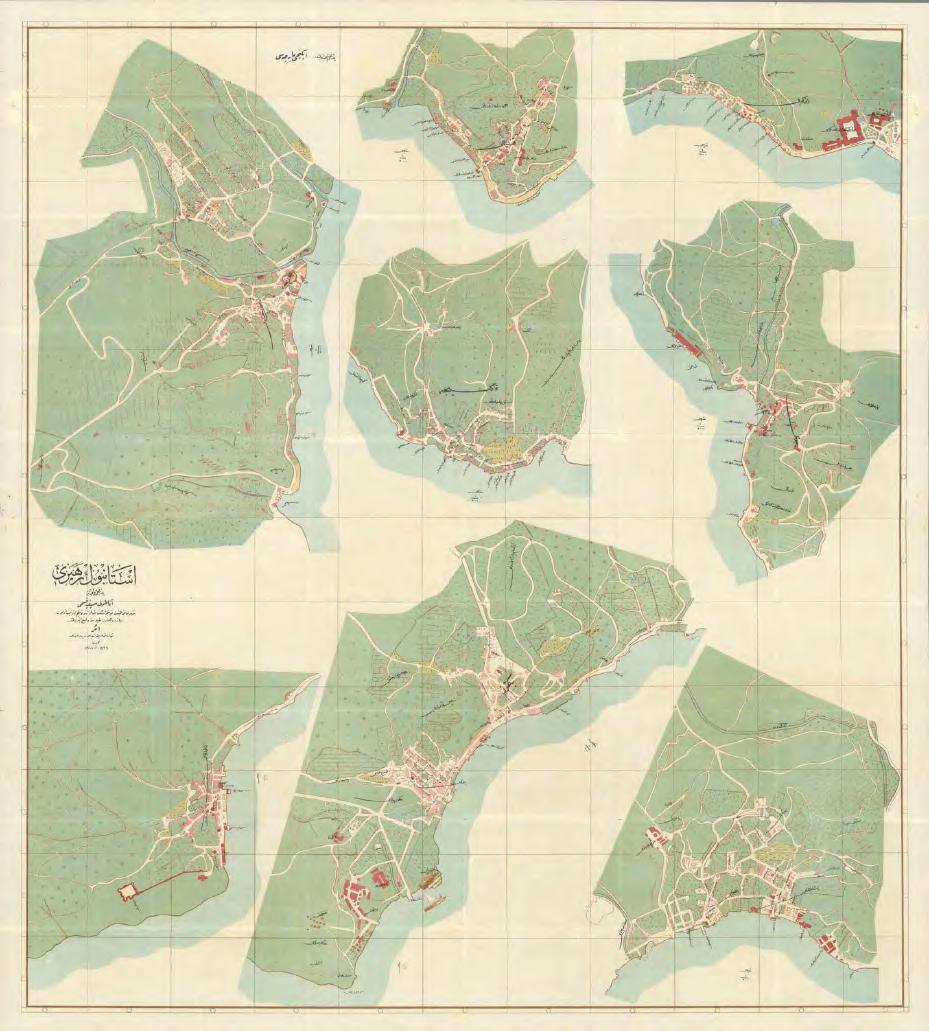

The latest Ottoman maps of Istanbul, called the Necip Bey Maps, encompassed the Istanbul Centre and its peripheries. This series of maps, one general map and smaller district and surrounding village maps, primarily focused on urban density, railways, green space, and water basins. The general map points to the Southern tip, known as the Golden Horn and its surroundings, as the densest area, shown in pink, and North as the forests. This map also points us to the border of Istanbul at the time, not reaching the Northernmost point of the Bosphorus [Figure3] Ottoman cadastral maps were redrawn in the Early Republic years. The Ottoman capital was mainly populated on the southern borders, making it economical for the new Republic to establish the cadastral maps for the most populated areas. The northernmost regions were Ortakoy on the European side and Kuzguncuk on the Asian side. So, the northern area, once on the edge and outside of Istanbul, was not registered as a part of Istanbul’s borders on these maps. This is a crucial point because the selfbuilt housing phenomena, or gecekondu, manifested more expansively on the Northern edges of Istanbul.

4 Sibel Bozdogan. 2002. “Moderism and Nation Building Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic.” (Seattle University Of Washington Press) 236

5 Neuwirth, Robert. 2006. Shadow Cities : A Billion Squatters, a New Urban World. (New York: Routledge), 163

[3] Ottoman Necip Bey Map of Istabul and its provinces, 1918. Five years before the Republic’s Declaration in 1923. The map shows urban parts in pink, which is less evident on the north parts of the city. Mode than half of Beykoz (Northeast) is not in the borders of Istanbul.

source:Internet Archives

The Republic’s reforms and the political agenda of creating a new and modern Turkish nation introduced Roman land laws, which endorsed private ownership. From 1925 to 1977, numerous land reform attempts were made to redistribute state-owned land to foundations, emigrants, and landless peasants. While some land was distributed, lack of resources and political turmoil did not allow for a comprehensive reform, which led to persistent land inequality.

[4]

Two of the first Republican Cadastral Plans, that were the edge of urban Istanbul at the time, 1927 Kuzguncuk on the Asian side and Ortakoy on the European Side.

[4]

The declaration of the Republic in 1923 initiated a Turkification and modernisation process nationwide while moving away from the late Ottoman capital, Istanbul. All resources were dedicated to planning the new republican capital, Ankara. Seven years later, in 1930, the Municipality and General Public Health Law was initiated to re-plan Istanbul by taking Western cities as examples. The first attempt at this framework began with the appointment of Henri Prost, in 1937. Prost’s approach was a circular centre around the old town, the Golden Horn, and a concentrated city. However, the following Italian urban planner, Luigi Piccinato’s approach, created a centre that points the city from Europe to Asia; his work was practical, especially in later periods.6 Both planners concentrated the city on its southern edge, recognising the northern periphery as villages. Prost’s housing approach for Istanbul was housing models and typologies per socio-economic class, although the state did not specify social class in the early Republic. Prost recognised that transferring housing models directly from France would need the institutional infrastructure that Turkey lacked. He developed a “rental housing model” specifically for Istanbul. However, the government at the time passed “social housing policies” in the Republic’s early years, even though it was never realised in practice for the average populace. 7 Prost envisioned different typologies per social class: Garden-City model for low to mid-income, Building-Block Property Model for mid to high-income, and CIAM Modern Building Blocks for high-income.8

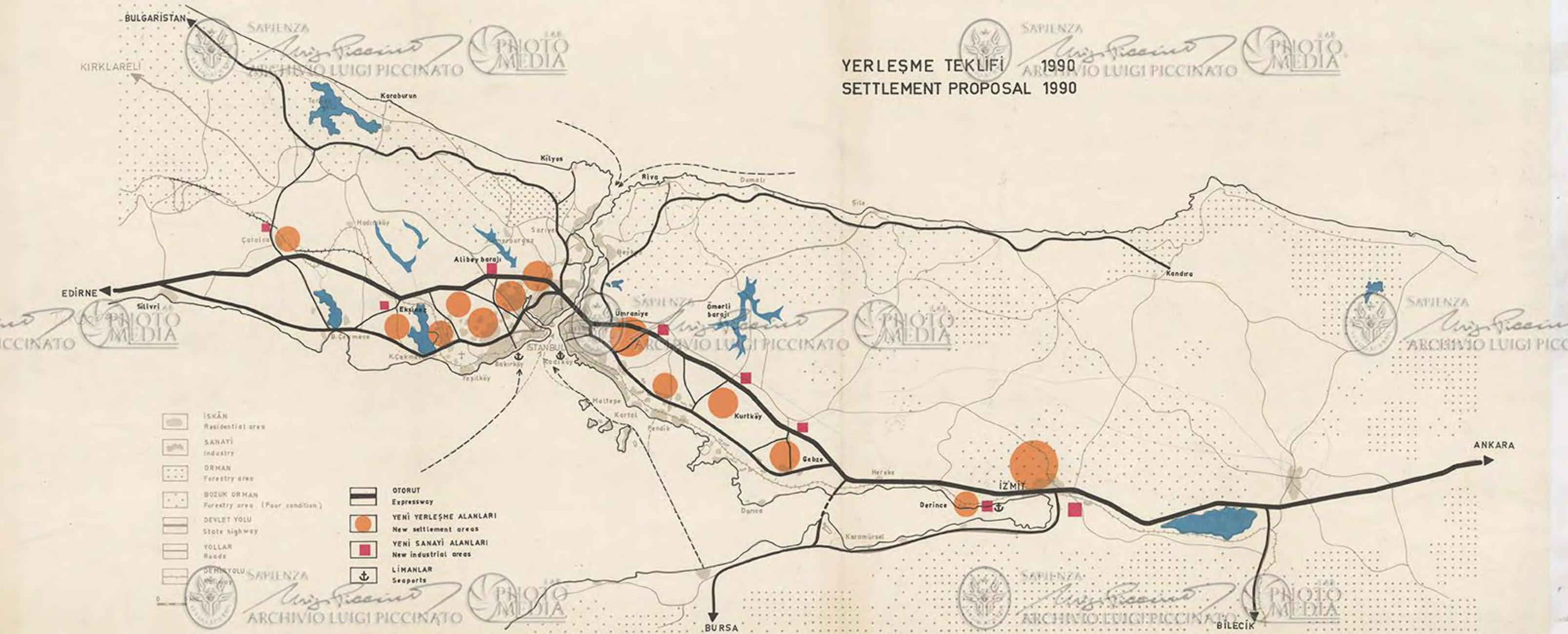

After specific critiques within Istanbul and state actors about Prost’s work, Luigi Piccinato was invited to Istanbul in 1958; however, due to political tensions, his planning was not realised then. Unlike Prost, according to Piccinato, one should look at a city from the outside, from

6 Erhan Erken. 2022. “Planning studies in the republic period in Istanbul: A comparative analysis of the effects of Henri Prost and Luigi Piccinato’s Plans on the Future Period.” (İstanbul Ticaret Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi) 1628

7 Coskun, French Planner Henri Prost’s Istanbul Master Plans, 130 8 Coskun, Ibid, 130

[5] Istanbul Urban Plan by Henri Prost, primarily focusing on the south of Golden Horn. Internet Archives

[6] Luigi Piccinato’s Urban Plan, focusing on settlements relationship to industrilisation points. This map was a settlement proposal that will be developed by 1990, next page.

its surrounding region towards the city itself. Looking at a city should not merely involve providing it with new development areas, increasing its population, organising its living conditions, and managing its traffic. Beyond this, efforts should be made to create an organism that links the city’s development to an economic function by placing the means of production in more suitable locations.9

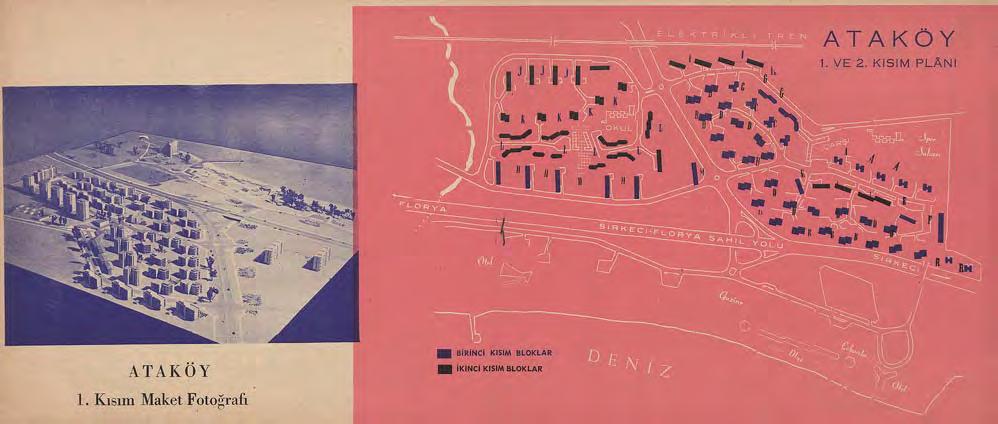

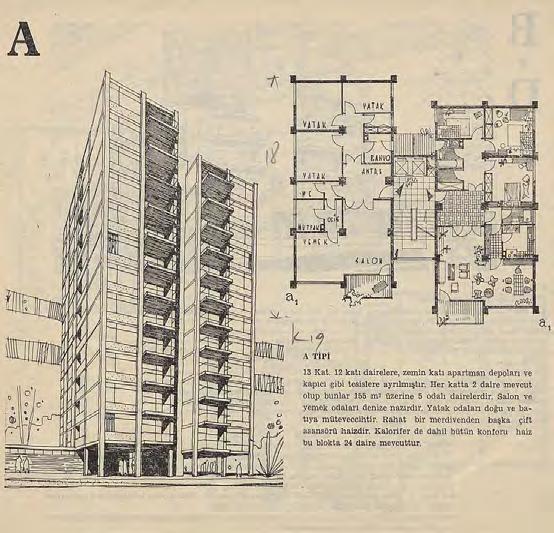

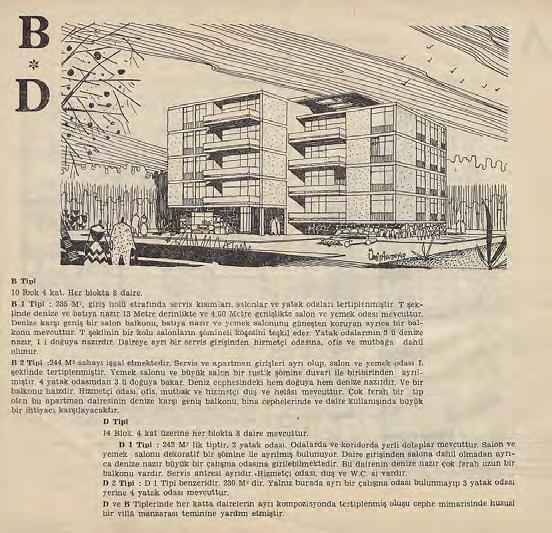

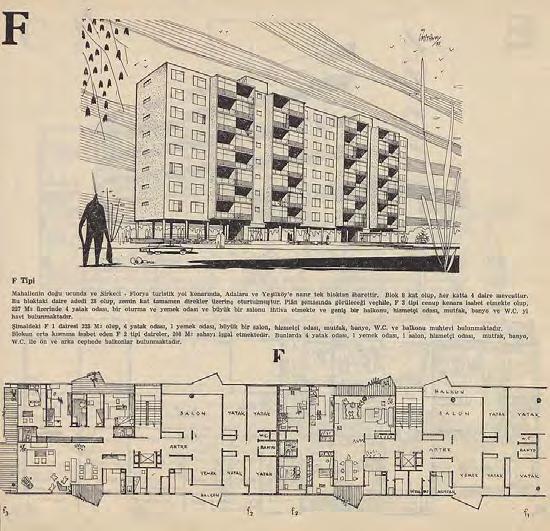

The Emlak Credit Bank Housing in Atakoy was the first initiative to build Istanbul as a modern city through mass housing. Emlak Credit Bank was established in 1946 to create housing credit for mostly middleclass citizens.10 Atakoy Housing was Credit Bank’s most significant project, which later became privately owned housing.11 It was designed by a group of architects led by architect Ertugrul Mentese The g roup took advisory and urban planning strategies from Luigi Piccinato, comprised multiple housing typologies, and created a new settlement.12 This project, which took decades, manifests different socio-economic changes in Turkey. It was planned to mimic a Turkish mahalla structure and consist of shops and even a school. Ataköy’s 1st Mahalle, covering an area of 20 hectares, is one of the examples of moder n architecture in Turkey and was completed in 1962. The project was built in two parts, consisting of 4 typologies of housing buildings with shops and parks. The 2nd Mahalle, finished in 1964, was an extension of the 1st Mahalle However, at the end of the 2nd section, the Credit Bank was less involved in the process.

The 1980s witnessed an unprecedented population influx in Istanbul, leading to significant demographic and urban changes. Household sizes decreased from 5.6 to 4.7, indicating a shift away from the larger family structure.13

9 Erken.“Planning studies in the republic period in Istanbul: A comparative analysis of the effects of Henri Prost and Luigi Piccinato’s Plans on the Future Period.” 1640

10 Usta, Ulusoy, 1980 Sonrasi Donemde Turkiye’de Konut Politikalari, 267

11 Atakoy Houses, Emlak Kredi Bankasi Booklet, Salt Research Archives, 2

12 Atakoy translates to “Leading Village”, Ata is a common name at the time for public spaces to commemorate Ataturk.

13 Erken.“Planning studies in the republic period in Istanbul: A comparative analysis of the effects of Henri Prost and Luigi Piccinato’s Plans on the Future Period.” 1641

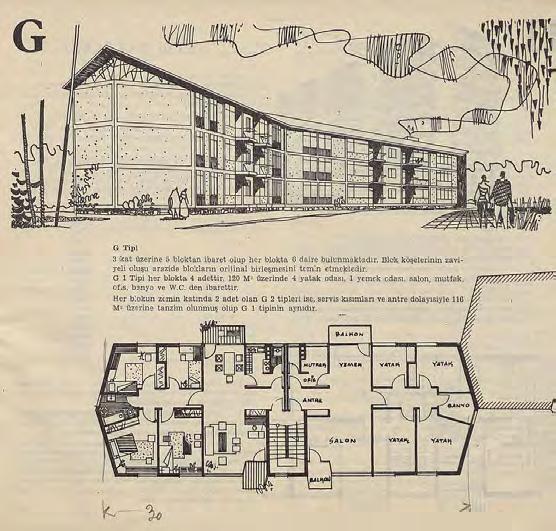

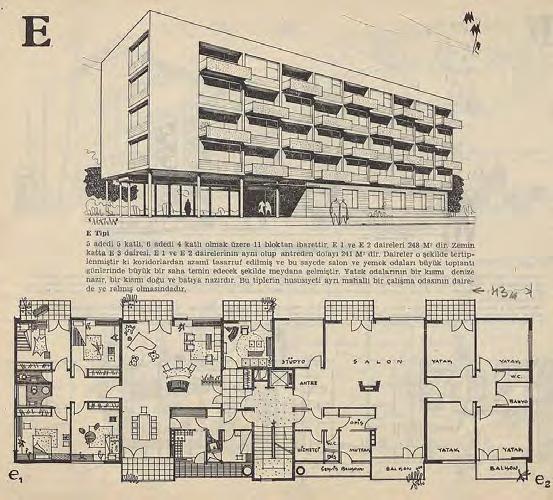

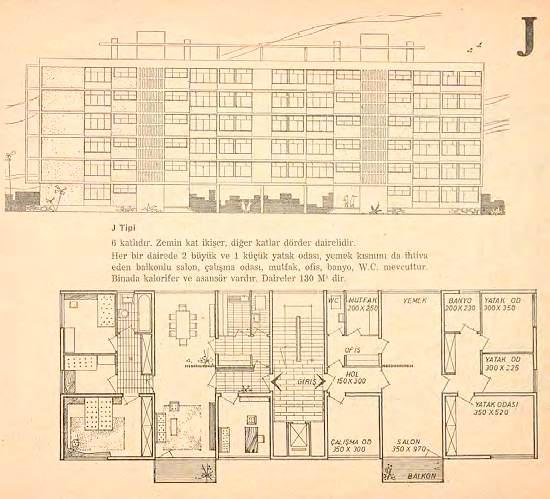

[7] Emlak and Credit Bank’s Atakoy Settlement Phase 1 and 2 Booklet and the overall urban plan

[8] Atakoy Housing Phase 2 Typologies

Architect: Ertugrul Mentese

Source: Salt Archives, next page

The period from 1961 to 1981, known as the “Planned Period,” marked a pivotal phase in Turkey’s urban development. During this time, the State Urbanization Committee developed a series of Five-Year Development Plans, which served as the framework for urban planning in major cities, including Istanbul. This led to the 3rd and 4th sections being built in Atakoy Housing. The rest of the sections were constructed during Prime Minister Turgut Ozal’s neo-liberal period when a new working middle class and housing needs emerged. However, in its totality, Atakoy Housing was the first mass housing that aimed to create a city within the city, which would end up being an extension of Istanbul. This was the first seed for a site strategy that would start in the 1980s and peak in the 1990s. Until 1990, when TOKİ (Housing Development Administration of Turkey) was established, housing issues fell under the jurisdiction of municipalities and were addressed within the broader scope of these development plans. TOKİ, or Toplu Konut İdaresi Başkanlığı in Turkish, is a governmental agency tasked with addressing the housing needs of low- and middle-income families, overseeing urban renewal projects, and managing disaster recovery housing. It has played a central role in Turkey’s approach to affordable housing and urban planning. Since the pivotal year of 2003, TOKİ’s authority has been significantly expanded, transitioning urban planning decisions to a more centralised system. As a result, the role of the State Urbanization Committee, which had been issuing the five-year plans, gradually diminished, leading to its official closure in 2003. One of TOKİ’s newly assigned roles includes strategically acquiring land, further enhancing its capacity to shape urban development across the country. Under Erdogan’s leadership, urban planning in Istanbul has been heavily shaped by “Urban Transformation”, a policy that addresses earthquake risks and modernises the city’s housing stock.14 However, these policies have disproportionately prioritised profit-driven redevelopment over equitable housing solutions, often to the detriment of the city’s lowerincome residents, creating concerns over gentrification.15 Central to this

14 Kentsel Donusum, meaning Urban Transformation, has been the ruling government’s policy since 2012. Contrary to gecekondu favoured policies that Erdogan previously adopted.

15 Fidan Yolcu. 2021. “Türkiye’de Kentsel Dönüşümün Yasalar ve Aktörler Üzerinden Dönemsel Olarak Degerlendirilmesi.” (Journal of Planning, January), 239

approach has been the expanded role of TOKİ and its sweeping powers to expropriate land, oversee large-scale redevelopment projects, and dictate urban planning with minimal local input. While the intention was to improve housing conditions and reduce seismic vulnerabilities, TOKİ’s projects have often targeted vulnerable gecekondu neighbourhoods, displacing residents in favour of luxury housing developments and commercial complexes. The 2012 enactment of Law No 6306 on the Transformation of Areas Under Disaster Risk significantly accelerated this process. In practice, this law has been used to justify demolitions in some of Istanbul’s most vulnerable neighbourhoods, uprooting decades-old communities. Many residents have been relocated to peripheral areas with inadequate infrastructure, severing social ties and livelihood access.

This centralised planning replaced local decision-making and paved the way for uniform, state-controlled developments. The state dictated who could build and where, adopting rigid and borrowed planning strategies. However, this housing hegemony could not put an end to the gecekondu crisis in Turkey, as laws and policies regarding land and housing changed with each election for political gain, causing citizens to lose confidence in the legal framework surrounding construction.

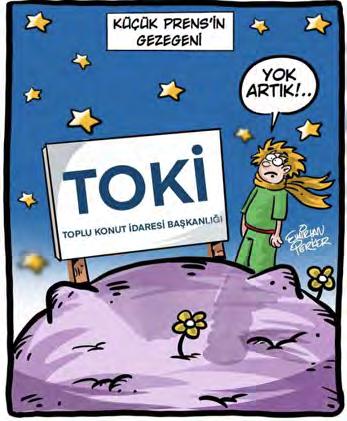

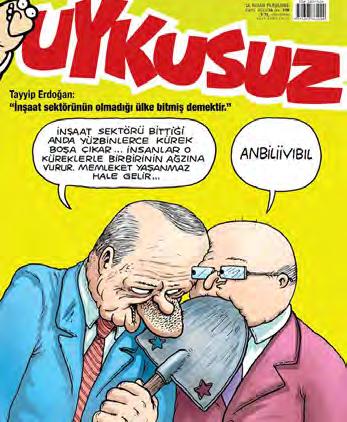

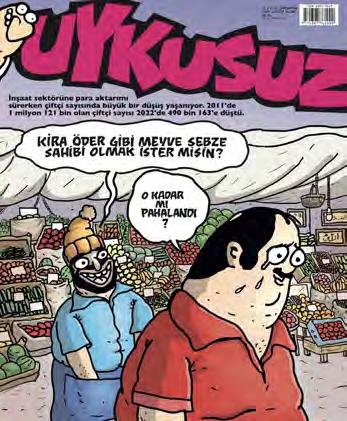

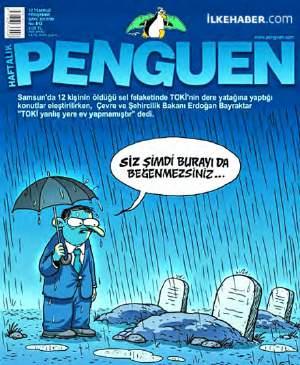

[10]

A catalog of charicatures criticising the current TOKI Laws and urban transformation policies. These charicatures are from 2002-2025.

sources: Uykusuz Magazine and Penguen Magazine,

The republican reforms and ideology significantly changed the conception of marriage and residential spaces in Istanbul. Traditional gender-based quarters, like the haremlik and selamlik, were disappearing. Under the new republican state ideology, family, home, and housing were expressed in Westernised styles, and creating a modern domestic culture became a key aspect of the state’s agenda. The utopian investment in modernity is one of the defining characteristics of the early Republic, a notdefined condition to achieve, in other words, ‘an aspiration for form rather than a recognisable style; an as-yet unrealised potential.’16 However, there was a significant gap between this imported modernism and the insufficient state of the housing infrastructure.17 The state prioritised nationalist public buildings and industrialisation over housing. Until the late 1950s, Turkish housing needs were met through private markets or initiatives, particularly for groups like government employees.

This thesis delves deeper into two significant moments in the Republic that created two socio-cultural classes in the urban setting: the early 1950s rural exodus, which led to the emergence of a blue-collar, newly urban gecekondu population, and the late 1980s rise of a working middleclass, white-collar group, born and raised in the city, residing in sites. These two distinct periods introduced these social classes into Istanbul’s urban landscape, and their housing needs have shaped the city as we know it today. The late 1940s to early 1950s, as a decade, has been seen as a bridge between the early republican party and the multi-party system with a series of radical policy changes in politics and the economy by Prime Minister Adnan Menderes. The industrialisation in the rural parts and the new factories in the urban led to a rural exodus in the late 1940s. This new proletariat class needed housing; however, neither the state nor the factories they worked for established any housing. Instead, the blue-collar workers started to build their shelters close to factories, on state-owned land, and

“Modernism and Nation Building Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic.” 196-197

away from the city centre, and the state was overlooking this occupation. The first comprehensive Building Code was established in Turkey in 1956.18 Since then, many regulations have been made to make urban planning laws more functional and to meet rising needs. It established the framework for developing, organising, and using land within urban and rural areas to ensure orderly growth, proper infrastructure, and sustainable development. However, there were many gaps in the judicial system to enforce this code.19 Three decades of periodic coup d’etat and economic and housing crises later, in 1985, the previous 1956 Building Code was disputed, and a new 1985 Building Code was established, giving mayorships and municipalities authority in urban planning 20 This law has established a framework for public spaces such as police stations, parks, religious buildings, etc. The word “housing” (konut) was used three times, and there were also three mentions of the Gecekondu Law. Even though 1948’s first amnesty regarding informal settlements, the 1966 Gecekondu Law mentioned in the 1956 Building Code contradicted it and legitimised the demolishment of gecekondu settlements.21 Moreover, twenty-two amnesties regarding informal settlements passed in the parliament over sixty years. Further laws in 1983 and 1984 were looking for a way to categorise and control gecekondu settlements; “to be preserved”, “to be preserved with improvements”, and “not eligible for the provisions of this law”. 22 These categorisations further segregated the settlers in terms of their living conditions.23

Therefore, the new and modern family was only available to a specific class of citizens. This resulted in a segregation between the state’s relationship with economically higher, middle, and lower-class citizens. However, while the state overlooked the production of gecekondu, it also created laws that would

18 Law 6785: Imar Kanunu (Construction Law, 1957

19 Cay and Kandemir, Turkiye’de Imar Ugulama Mevzuatindaki Gelisim Sureci, 27

20 Law 3194: Imar Kanunu (Construction Law, 1985

21 There were no mentions of gecekondu

22 Laws No. 2085 and No. 2981: Policy for construction of gecekondu

23 Cay, Tayfun, and Esra Sonel Kandemir. 2022. “Turkiye’de Imar Uygulama Mevzuatindaki Gelisim Sureci”(Geomatik Dergisi), 28

demolish them afterwards, and state actors blamed this separation on the gecekondu settlement for urban sprawl. The overflowing new urban-rural population affected elections, making political nuance more critical over the decades.

The 1980s neo-liberal politics by 45th Prime Minister Turgut Ozal privatised the service industry, including marketing, media and, most importantly, banking. The Istanbul Stock Exchange opened in 1985, and a population flux started from the educated and modern Ankara. A new small bourgeoisie, working middle class who were the educated and modern children of the early republican parents, worked in white-collar job titles. This new social class needed housing in Istanbul; the 1985 Housing Law initiated the new era of mass housing, which would be called the site New site housing was primarily built on non-cadastral land while having to build code-compliant designs, and the state overlooked the growth without registration, which inflated the housing market to attract foreign investments. Together with the state, these new real estate tycoons have promoted site developments as a ‘modern’ solution to Istanbul’s housing problem. The growth of Istanbul and new housing possibilities for the new working middle class expanded towards northern Istanbul with the completion of the 2nd Bridge in 1988.

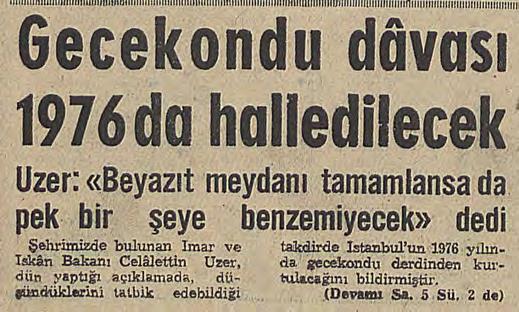

[11]

Headline:“Gecekondu issue will be resolved by 1976

Body: “Minister of Public Works and Settlements Uzer asserts that gecekondu issue will be resolved”

source: Yeni Sabah Newspaper 1964

[12]

Headline: “Committees are established in Umraniye”

Body: “With the the help of Health, Propaganda, Infrastructure sub-committees new gecekondu construction started again. During the clashes that broke out during the demolition work, five people were killed, and Ümraniye’s 1 Mayıs Mahallesi, which consists of thousands of gecekondu dwellings, began to be self-managed by its residents. With task distribution carried out by the newly formed people’s committee, efforts were made to meet the neighborhood’s needs, while 600 of the demolished gecekondus were rebuilt.

source:Hurriyet Newspaper, 1977

[13]

“Gcekondus of Sultanahmet have been Demolished”

source: Milliyet Newspaper, 1955

[14]

Headline: “Behind the Scenes of an Exclusive Neighborhood in Istanbul”

Body: “Scenes encountered in a neighborhood just two steps beyond Sisli that inspire horror and disgust”

source: Cumhuriyet, 1948

It is essential to underline that the exclusion of certain groups of citizens from the ‘right to shelter’ created an illegal status. James Holston asserts in his seminal work “Insurgent Citizenship” that all nation-states struggle to manage differences among their citizens, legitimising these social differences perpetuates discrimination against certain groups. This legitimisation of discrimination under mines the fundamental principle of equal citizenship, leading to systemic marginalisation.24

The making of illegal living conditions of gecekondu groups manifested in pop culture. A new genre of music, called arabesk, pointed to the struggles of marginalised residents. Arabesk music emerged as a response from low-income groups to the government’s Westernization policies. It reflects the experiences of rural-to-urban migrants facing economic challenges like unemployment and housing shortages and the cultural difficulties of adapting to urban life 25 The verses generally opposed the authorities and discrimination.26

In the 1989 Kemal Sunal movie, “Gulen Adam,” the struggle of gecekondu residents is represented very dramatically through the last scene where the protagonist, gecekondu resident Yusuf, builds a house with wheels as a response to the changing laws and many evictions.

Although Turkey did not inherit a colonial anthropological heritage, it was subject to hegemony in its context. The primary approach in Turkey was the distinction between ‘local and other,’ which was reflected in the divide between urbanites and peasants. Republican reforms focused on Turkification while simultaneously aiming to modernise citizens. Here, modernisation was understood as becoming contemporary or as a form

24 Holston, James. 2009. “Insurgent Citizenship” (Woodstock: Princeton University Press), 7

25 BirkalanGedik, Hande. 2011. “Anthropological Writings on Urban Turkey: A Historical Overview.” (Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development), 23

26 A perfect example is “Itirazim Var” by Muslum Gurses, a wellknown Arabesk singer. This translates to “I have an objection”. The verses include; “ I object to this cruel fate (Itirazım var bu zalim kadere) I object to this endless sorrow (Itirazım var bu sonsuz kedere) -- Injustice is the colorless thing that runs through my veins (Haksızlık damarlarımda gezenlerdir en renksiz).”

[15]

Scene from Gulen Adam, (Laughing Man)

Director: Kemal Sunal

An immigrant named Yusuf marries a urbanite police officer’s daughter despite her family’s opposition. They rent a gecekondu while worrying about having no legal rights to their home yet cannot afford anything else. Adjacent to their new home is a site development under construction.Yusuf’s father-inlaw, representing the state, demolishes their house due to city planning regulations. Eventually, many neighbourhoods, including the police’s houses and the neighbouring site development,are demolished. This demonstrates the paradoxical relationship between the state, citizens, housing, and law, highlighting the housing crisis and the inefficiencies in the system that make it difficult for citizens to secure adequate living conditions.Yusuf and her wife build a portable home.This is a critique on the legaslation on shelter.

of progress. Inherently, Western-adjacent urbanites identified themselves as the progressed Turk, local to the city, while viewing peasants moving to the city for blue-collar jobs—the proletariat—as the other. Consequently, the urbanite looked towards the West as a model for progress, while the peasant remained rooted in traditional, rural, and often Eastern cultural values. The tension between the urbanite Western bourgeoisie and peasant Eastern proletariat which within Turkey’s anthropology linked to each other has been a primary lens in many movies and TV series. While this is a universal tension—traditional poor versus modern wealthy—it is important to note that the antagonistic and elitist Westernised character typically lives in site housing in many Turkish visual arts. In contrast, the traditional poor protagonist resides in a gecekondu Therefore, the tension between the proletariat and the petite bourgeoisie is represented through housing.

The first example of the East and West dichotomy can be seen in Turkey’s first sitcom, Kaynanalar (In-Laws), where the conflict between the Westernised Hakmer family and the Eastern Kantar family is reflected in their clothing and spatial segregation. Although it is not explicitly stated, the Kantar family does not come from a gecekondu background but rather represents a traditional Turkish family, which is often associated with, or seen as sympathetic to, those living in gecekondu areas. In contrast, the Hakmer family resides in a modern apartment building [Fig 18].

In parallel, the 2003 series Çocuklar Duymasın (Don’t Let the Children Hear) portrayed the contrast between proletariat and petite bourgeoise, highlighting class divisions. The protagonists, white-collar workers Haluk and Meltem, live in a site housing complex. On the other hand, the other family—Hüseyin, an office boy at Haluk’s company, and Emine, the childcare provider for Haluk and Meltem—live in a gecekondu While this is not stated in the show explicitly, the scenes from their home and their traditional mannerisms, point to this dynamic [Fig 19]. A more recent example is the 2013 TV series Medcezir (Tide), where this tension is depicted through the love story between a wealthy young woman from a site housing development and a poor young man from a gecekondu neighbourhood.

[16]

Meydan Newspaper October 4, 1994

Headline reads “There is no compulsion in religion”, Istanbul Mayor Erdogan was captured in prayer, an unusual sight for a government official to be photographed in such a moment, at the time.

More notably, the title reads ‘From the Streets of Kasımpasa to the Mayor’s Seat,’ highlighting Erdogan’s roots in Kasımpasa, a neighborhood largely shaped by gecekondu settlements.

[17]

Prime Minister Erdogan is visiting gecekondu homes in 2009 for ifthar (fast breaking meal on Ramadan),and listening to their issues .

In the late 1990s, the propagation of the Democratic Islam Movement flipped the power between gecekondu communities and the modern Republic ideology, mobilising people around Islamic idiom. More so, the mobilisation powers lay within the importance of kinship and interpersonal relationships, creating a new sense of belongingness. The opposition to the existing government was not only opposing the modern agendas but attaching the ordinary populace’s economic needs, such as housing, to it. Justice and Development Party (AKP) used the interpersonal relationships on which gecekondu settlements were based. AKP was aware of the neglected communities and created personal relationships while conducting various ‘good deeds’, such as organising weddings, marriage counselling and participating in religious charities. This was spatially possible due to the gecekondu settlement’s inherent organisation of huddling in bunches. The governing AKP and its leader, who was from a gecekondu neighbourhood, Erdogan, fundamentally changed the state’s relationship with housing. As gecekondu areas expanded and their populations grew to constitute a majority in Istanbul, they significantly influenced local elections and integrated into urban policies. Furthermore, the aim to promote Istanbul as an ‘international arena of services and tourism’ involved setting up certain new norms and standards in dealing with land.27 The Mortgage Law, negotiated from 2004 to 2007 for three years, stimulated construction firms by leading them to the middle class, creating access to newly built housing units.28 There was no tolerance for newly built informal settlements, and the previous settlements had to be registered and legalised. Then Prime Minister and now President Erdoğan’s propaganda for gecekondu settlers was termed “İmar Barışı,” which translates to “Construction Peace,” rather than the commonly used term “İmar Affı,” meaning “Construction Amnesty.” While both terms refer to state recognition through pardoning, the choice of “peace” here is significant. The term “amnesty” implies a unilateral pardon, whereas Erdoğan’s use of “peace” suggested a mutual agreement, creating a sense of a two-part deal. This political manoeuvre secured more votes for Erdoğan and granted gecekondu settlers’ formal recognition by the state.

27 Jean-François Pérouse. 2011.Istanbul’la Yüzlesme Denemeleri(Iletisim) 292

28 Law No. 5582: Konut Finansmani Kanunu (Financing Housing, Mortgage Law)

[18]

Scene from Kaynanalar, a family scene where proletariat wife Nuriye is on the background waiting to do service.

[19]

Scene from Cocuklar Duymasin, Protelariat wife Emine is on the background while the family is seated, she works for them full time. A typical scene in comparison to Kaynanalar

[20]

Scene from Ethos, religious Meryem talking to her secular therapist Peri. The confrontation and the color contrast representing two different social classes in Turkey

The unspoken reality of this political shift is that the second generation in gecekondu areas achieved social mobility through education and the changing socio-cultural landscape in Turkey. As a result, the tension between these two social classes began to dissipate. The Netflix miniseries Ethos, written and directed by critically acclaimed filmmaker Berkun Oya, portrays contemporary Istanbul and explores social, ideological, and economic differences. The relationship between the main character, Meryem, who comes from a conservative gecekondu background, and her Westernised, secular therapist, Peri, represents the decline of secular hegemony. While Peri’s generation grew up in a secular, Western-facing Turkey where she never interacted with a gecekondu resident, this is no longer the dominant reality in Istanbul. Conversely, Meryem is no longer merely surviving but is actively part of Turkey’s new dominant class [Fig 20]. The series serves as a psychological representation of this political and social shift, reversing the 1974 Kaynanalar depiction of the struggle for legitimacy Now, it is the secular elite who find themselves on the defensive. This manifested not only in the social mobility of second-generation gecekondu youth but also in their progression within the urban fabric. A Republican idiom, to be able to move up the ladder through education, materialized through socio-economic, political, and spatial mobility. An important component of this mobility was the increasing access of gecekondu women to higher education.

The modern Republican laws restricting the use of hijabs in government institutions were further reinforced with each coup d’état in Turkey. The 28 February 1997 coup d’état intensified these restrictions as the secular and secular-nationalist army took over the government. As a result, the Head of the Higher Education Board (YÖK) banned hijabs in universities, and even students who were already enrolled were denied access to campuses. This particularly affected religious gecekondu communities, where women often wore hijabs. From that moment on, nationwide protests erupted against the law. Ultimately, the election of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as Prime Minister of Turkey’s 59th government in 2003, following crucial negotiations with religious communities, paved the way for change. After years of political debate, the ban was abolished in 2008, marking a significant shift in the social and economic mobility of young women from gecekondu backgrounds.

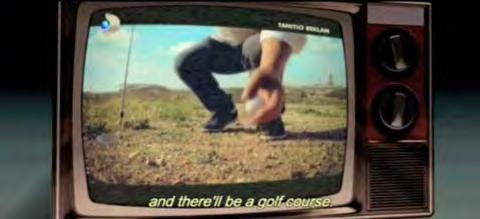

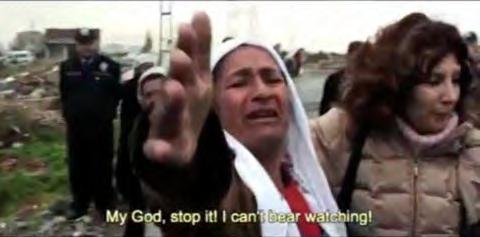

[21]

Poster:

Ekumenopolis: The Endless City “you have crossed the ecological thresholds in istanbul. you have exceeded the population thresholds. you have surpassed the economic thresholds.

so, where will this end?

director: Imre Azem

The documentary explores issues related to construction and urbanism in Istanbul, offering a critical perspective on the struggles and profits of all stakeholders. It is particularly significant as it provides a focused view of the Ayazma demolition, highlighting the real struggles of individuals affected by policy enactments.

These struggles should not be romanticized, yet should be recognized as essential in shaping Turkey’s contemporary urban and social fabric. These transformations were not just policy shifts but active negotiations of space, identity, and belonging On the other hand, Critics contend that Erdoğan’s housing policies embody a neoliberal agenda, prioritising partnerships with private developers and fostering speculative real estate markets over equitable housing solutions.29 Under the guise of Urban Transformation, redevelopment projects frequently serve middle- and upper-income groups, marginalising low-income families who face limited access to affordable housing. A stark example is the demolition of the Ayazma and Küçükçekmece gecekondu neighbourhoods, where residents—many of whom had title deeds—were forcibly relocated to TOKİ housing in Bezirganbahçe, a peripheral area far from central Istanbul [Fig 22]. In the documentary “Ecomunopolis: A City Without Limits” by Turkish filmmaker Imre Azem, Ayazma’s displaced residents recount how inadequate infrastructure and poor living conditions in Bezirganbahçe left them worse off than in their former gecekondu homes [Fig 21]. Compounding the injustice, some residents who owned their land were evicted with minimal compensation, referred to as “debris prices,” whilst their land was sold to the private developer Ağaoğlu Construction Company, which constructed luxury residential blocks on the site This case exemplifies how Urban Transformation often sacrifices the rights and well-being of vulnerable communities for profit-driven redevelopment, exacerbating social and spatial inequalities in Istanbul.

‘Modern nationality is a spatial concept, much like how the nationstate is territorial.’30 Western modernism represented an industrial and societal transformation into an urban and capitalist order; in contrast, nonWestern countries, such as Turkey, often employed modernism to reconcile their pursuit of national identity Moder nism’s influence on shaping national identity in non-Western capitals is complex. The architectural and urban planning aspects, often marked by simplification, rationalisation, and the utilisation of new materials and technologies, reflect an adaptation of Western models. However, these were not simply replicated but transformed to convey local identities and aspirations. This intersection produced what can be described as a form of “architectural nationalism,” where the built environment plays a crucial role in the nation-building narrative.31 The Republic’s early years witnessed the idea of “home” in the larger context of moder n and urban life transition into a republican concept. According to a popular magazine of 1938, “Like many other good things in life, the Turkish citizen is getting to know the idea of the house only now, in the republican period.”

In the early decades of the Republic—and even today—the terms ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary’ have often been used interchangeably, suggesting that progressiveness equates to living in modern houses and apartments [Fig 27]. Traditional typologies that accommodated extended families, such as the konak and köşk, were contrasted with contemporary designs. Architect Behçet Ünal, in an article in Arkitekt magazine, stated, ‘Our spacious sofas (entrance halls) are no longer appropriate.’32 This reflected the nation’s deliberate shift from traditional aesthetics to modern ones as part of its effort to break away from its Ottoman heritage However, in opposing European colonialism, modern Turkish architects began incorporating distinct aesthetic features to define a unique architectural identity, notably the ‘cubic architecture.’

30 Zeynep Kezer. 2016. Building Modern Turkey State, Space, and Ideology in the Early Republic. (University Of Pittsburgh Press) ,197

31 Ibid, 200

32 Ev Nedir ve Bir Ev Nasil Kurulmali? (What is a home, and how should it be organised?) Modern Turkiye Mecmuasi 1, no.1 (1938): 16-17.

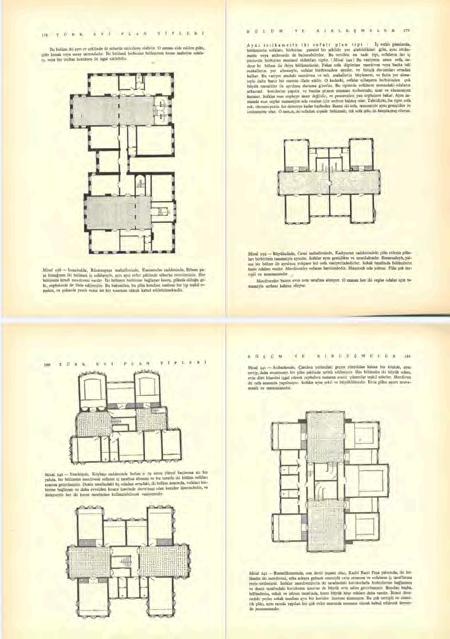

[23]

Pages from the book “Turkish House” by Sedad Eldem Istanbul Technical University 1954

This is a valuable resource and the first of its kind in the discussion of traditional Turkish vernacular architecture. It has been later republished by the Turkish Foundation For the Promotion and Presevation of National Heritage in 1984 source: Internet Archives

[24]

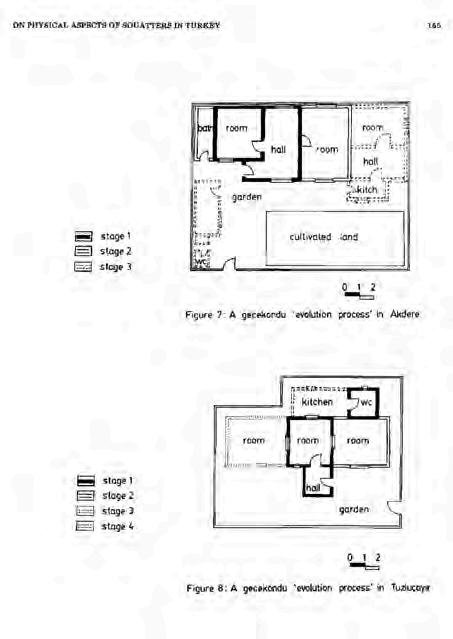

Pages from the artical “On Physical Aspects of Squatters in Turkey” in METU Series. 1986

By Tansi Senyapili

This article has been widely referenced in gecekondu research, offering an extensive survey on the architectural organization of gecekondu settlements. It draws parallels between their spatial arrangement and the room-by-room progression of the sofa layout in traditional Anatolian Turkish houses, using Sedad Eldem’s Turkish House as a key source. source: METU Archives

[23] [24]

In Anatolia, central to traditional Turkish houses is the ‘sofa’ or ‘avlu’, a patio that serves as the home’s focal point. Depending on preference, these patios, which may be roofed or open-air, evolved into well-defined, organised spaces. The traditional Turkish house is distinctly characterised by this central patio, which forms the core around which the rest of the house is built. The design promotes a sense of community and connectivity among the household members. The sofa often serves multiple purposes, including social gatherings, family activities, and dayto-day living, reflecting the cultural importance of communal spaces in Turkish architecture. Houses were built by their owners on land owned by the Sultan, though generations could inherit it. These homes’ spatial arrangements or land arrangements have not changed after the declaration of the Republic.

Sedad Hakkı Eldem, one of Turkey’s most influential architects, conducted extensive typological analyses of the “Turkish house.” Eldem advocated for a modern Turkish architecture that embraced its historical and cultural heritage. Unlike the Early Republican regime, which adopted modernism while eschewing overtly “international” symbols, Eldem sought to define the Turkish house as a continuation of Ottoman and Anatolian architectural traditions [Fig 23]. In his typological studies, he establishes the sofa as the primary building block of all Turkish typologies, from rural dwellings to konak and from yali types to large palaces like the Topkapi Palace. He dedicated his professional life to studying and adapting the archetypal “Turkish house” from the Balkans to Anatolia.33 While deeply fascinated with the Turkish house and advocating its rational spatial organisation as modern enough, he was systematic, analytical, and rational in his studies.34

By the late 1930s, the new head of the School of Architecture, Bruno Taut, shared reverence for traditional Turkish houses and their criticism of the “cubic” style with Sedad Eldem. Indeed, he assigned his student housing projects that would align with such ideas. This may be the precise reason that later site housing developments used traditional ‘konak’ typological aesthetics as their outer shell to promote the luxury and opulence of the Ottoman Empire.

33 Eldem , Sedad . 1954. “Turkish House”, (Türkiye Anıt Çevre Turizm Değerlerini Koruma Vakf)II

34 Bozdogan, “Modernism and Nation Building”, 266

[25] A comparative analysis of two distinct stages of gecekondu growth, examining different construction methods and typologies. This evolution reflects changes in legislation as well as the economic mobility gained by gecekondu residents.

However, while the later site developments used the exterior aesthetics of the konak type, the interiors were far from sofa spatial organisation. The 1950s gecekondu houses, however, were adapting the vernacular architecture of the Anatolian villages Tansı Şenyapılı’s research traces gecekondu spatial organisation back to rural behaviours, highlighting its roots in traditional building practices. Her surveys define the stages of growth for gecekondu homes, starting with a single room, often referred to as a sofa [Fig 24]. This room serves as the core of the dwelling, mirroring the multifunctional spaces common in rural Turkish houses. As gecekondu settlements grew, additional rooms and layers of functionality were added, reflecting not only spatial adaptability but also the communal and familial patterns brought by rural migrants.

The formation of laissez-faire gecekondu settlements began well before neoliberal globalisation but took a new turn in the 1980s. Introducing free-market policies and semi-legalisation through amnesties created hybrid housing forms that merged rural traditions with urban economies. This model profoundly influenced housing developments worldwide, including in Turkey. While the Domino house model was adapted through the disguise of “cubic” architecture in upper-class housing, gecekondu types adopted this strategy later in the late 1970s to the 1980s as laissez-faire. As Pierre Vittorio Aurelli notes in ‘The Dom-ino Problem’, the Dom-ino House by Le Corbusier represents a ‘marriage between advanced building technology and pre-industrial do-it-yourself construction methods.’ 35 This hybridity resonates with gecekondu settlements, where reinforced concrete construction methods blended modern materials with traditional, self-built approaches [Fig 25].

Additionally, during the late 1970s, with the introduction of real estate tax payments, living and working conditions in gecekondu areas improved, paving the way for typological developments. By the 1980s, neoliberal economic policies and semi-legalisation processes through amnesties catalysed a shift. However, this shift was not solely typological; it marked a fundamental change in how housing was perceived. No longer just informal shelters, gecekondu became commodified assets, driving a speculative real estate market. Similarly, site developments built on state-owned land

35 Aureli, Pier Vittorio. 2014. “The Dom-Ino Problem: Questioning the Architecture of Domestic Space.” (Log, no. 30) 153–68

[26]

Practical, Affordable, and Healthy Homes Magazine

Title: A Cubic House

The article speaks about the Otto Haesler designed house and defines is as a cubic house instead of modern.

source: Bozdogan, “Modernism and Nation Building”

[27]

An Home Electronics Shop Ad on Magazine

Title: Needs of the Comtemporary House

source: Bozdogan, “Modernism and Nation Building”

were on sale and rent without title deeds, which further blurred the formal and informal boundaries. This period marked the transformation of ruralinspired gecekondu structures into multi-story apartment buildings, reflecting a departure from their origins as informal shelters for rural migrants [Fig 28]. This shift was not purely architectural but economic, as the burgeoning real estate market commodified these structures. Gecekondu settlements, once emblematic of survival and solidarity, became part of a larger informal property market, creating a system of what Turkish urban planning experts called “fugitive construction” (kaçak yapılaşma) where informal ownership flourished, and became the de facto formal strategy for growth.

The unregulated construction of large apartment buildings in gecekondu neighbourhoods disrupted the spatial and social cohesion fostered by sofa spatial organisation. Once a central feature of Turkish housing typologies, and evidently to gecekondu houses, the sofa enabled collective activities and adaptability within the built environment. Its gradual disappearance from urban housing typologies marked a significant shift toward privatised and fragmented urban layouts, diminishing opportunities for interaction.

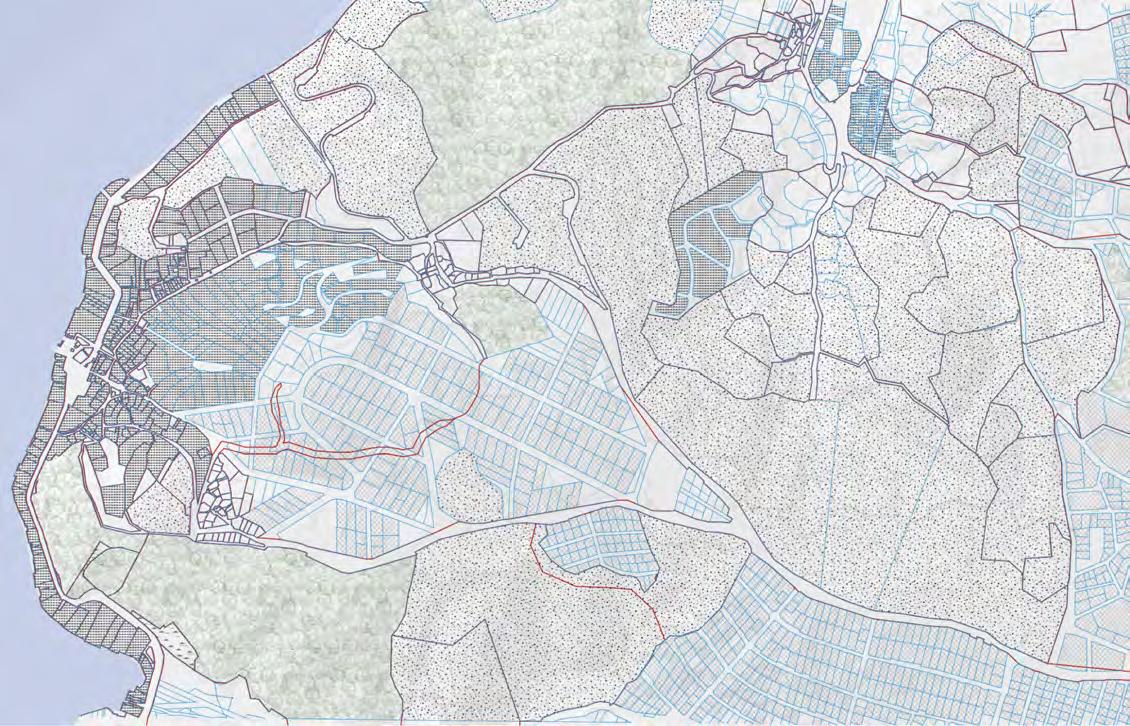

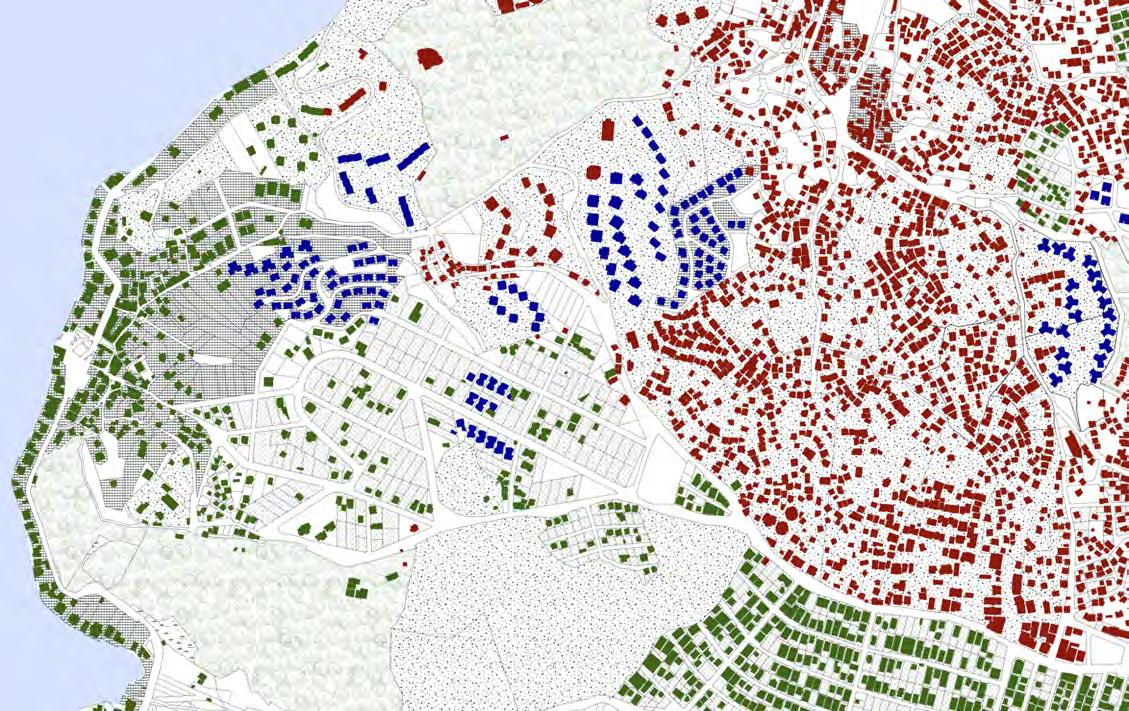

This thesis primarily focuses on Beykoz, a northern district that transitioned from rural to outskirts and finally urban later in the Republic compared to the rest of the city. This district is significant because the gecekondu and site strategies flourish and exist together more than in other districts. The closest example would be its Western side neighbour, Sariyer, across the Bosphorus.

Beykoz is one of the 32 districts constituting the province of Istanbul, the largest in Istanbul (427 km2). It is a peripheral location in the northeast of the urban area, bounded to the west by the Bosphorus and to the north by the Black Sea, covered by forest. The vast peripheral lands of Beykoz, which represent more than two-thirds of the district and are outside the management of the elected municipality, appear as the preferred zones for city builders in a state of quasi-lawlessness in urban planning 36 The 2B Arazi land type has been the primary discussion today in Beykoz’s legalisation and parcelling processes.

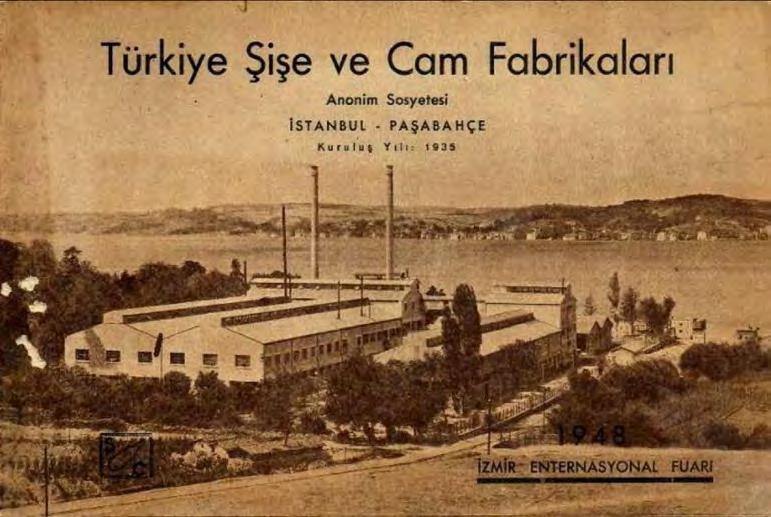

Anadolu Kavagi, Pasabahce, Cubuklu, Kanlica, and Anadolu Hisari were villages located one after the other on the north periphery of the Bosphorus, centred on a mosque. Beykoz became one of the first larger districts, encompassing all adjacent villages in 1928. First, with industrialisation, glass, leather, and raki spirits factories, and subsequently, the two Bosphorus bridges, Istanbul’s urban territory was enlarged towards the north, Sariyer on the European side and Beykoz on the Asian Side. The first wave of immig ration to Beykoz arrived in the 1950s from the northern Turkish region of Giresun. Labourers and their kins occupied public land and built the first gecekondu settlements in the late 1940s. They primarily worked at the Sisecam glass factory and the Raki Spirits factory. The second wave was in the 1980s; with the erection of the second Bosphorus bridge, Beykoz became a virgin land for white-collar housing. Factories, including the Sisecam glass factory, enlarged their factories and built housing for the white-collar working middle class.

The evolution of gecekondu in Beykoz is a physical manifestation of ever-changing policies and laws. It also encompasses the socio-economic lifestyles of their inhabitants, which are significantly shaped by their roles

36 Pérouse “Istanbul’la Yüzlesme Denemeleri”, 292

[29] View of Kanlica, Beykoz from Rumeli Hisari

Source: Old Istanbul Photography Archives

Showing the Knalica as a small Bosphorus village and the hills are empty agricultural land.

[30] View of Beykoz

Source: Alamy Images 2020 Showing the filled hills of housing, mostly gecekondu.

Research Site: Kavacik, Cubuklu