Care Devolution and Inter-Household Cooperation Towards a Cluster Model of Common Institution of Land, Dwelling and Care

Clinton Thedyardi Prawirodiharjo

Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities), 2019/2021

Architectural Association School of Architecture London

Care Devolution and Inter-Household Cooperation: Towards a Cluster Model of Common Institution of Land, Dwelling and Care

Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities), 2019/2021

Architectural Association School of Architecture London

Author: Clinton Thedyardi Prawirodiharjo

Tutors: Platon Issaias and Hamed Khosravi

Submission: 28 May 2021

Acknowledgements

This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of the many people who have been involved in this 20-month process. First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my family for their unconditional and constant support throughout the programme. Additionally, I would like to thank those who have been by my side during my studies, particularly Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi and Doreen Bernath, for their kindness, care and commitment in helping me develop my dissertation during the difficult circumstances thrown up by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, I would like to thank my fellow students who have always been very supportive and helpful both inside and outside the studio. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the help of Hannah Emery-Wright from London CLT and representatives from HEBA Women’s Project who gave me key insights and inspiration for the proposed project. Thank you for your valuable contributions during my studies at the AA.

Abstract

Care Devolution and Inter-Household Cooperation: Towards a Cluster Model of Common Institution of Land, Dwelling and Care investigates alternative forms of community care in the context of London. In recent times, London municipalities have been responsible for delivering social care services for local communities, the majority in collaboration with private or volunteer agencies. Although the NHS delivers a high standard of service, health and care provision in London is still facing challenges regarding limited services, neglect and managerial barriers. Primarily, these issues are the legacy of the UK’s centralised system of care and the emergence of contemporary issues such as increasingly diverse communities, a growing elderly population and a rise in demand for mental health services. In response, communityled care initiatives organised in collaboration with local municipalities and care agencies are springing up in London in the form of daycare centres, senior clubs, various associations and volunteer carers to provide collective modes of care. At the same time, the provision of land by the Community Land Trust raises another possibility for establishing community-led care as a public-private project by shifting personal care in the dwelling unit to a neighbourhood care model.

Reflecting on the ambitions of the 2017 London Health and Care Devolution Programme, the project proposes the creation of a cooperative mutual care organisation to enhance integration between the local council and vulnerable communities. Through a cooperative strategy, the dissertation aims to respond to the spatial and managerial challenges of social care and community services provision at the neighbourhood scale. The research traces the history of the architecture of collective care in London and revisits alternative approaches in terms of social structure, forms of sharing and daily rituals through a collective way of living. The dissertation rethinks care through cluster forms as a typological and urban question to generate new possibilities for community care activities and protocols.

The proposed neighbourhood care model addresses the problematic provision of space for social and care services, services that are sidelined by dominant commercial and residential developments and transport infrastructure and constrained by land value and limited access to ownership and usership and the lack of coordination and collaborative management. The design aims to propose a London neighbourhood care model by rethinking the aforementioned social care issues across three conditions: co-housing, the care cluster and the high street in Tower Hamlets. The neighbourhood care model suggests a new mechanism for the provision of land, dwellings and care by the Mayor of London. The proposal is underpinned by the concept of the cluster to coordinate vulnerable groups through the collectivisation of domestic services, informal care and co-living as a common framework. The research and design investigations respond to the question: how does a system of clusters provide the spatial organisation for collective care across the dwelling unit, social infrastructure and neighbourhood plan as a series of interconnected projects?

Key words: devolution, social care, community-led, cluster form, neighbourhood care model

Research Question

Disciplinary Question

How can the current regulatory framework for land, dwellings and care be reassessed to provide an affordable, community-led care framework?

How do the alternative forms of housing provision could promote local autonomy?

How can this relationship be organised?

Urban Question

How can a series of mutual care activities and spaces be organised within a neighbourhood care model?

How could forms of collective living enhance the connection between existing social care services and emerging community-led care initiatives?

What kind of social diagram produced by these different care agencies? What are the protocols?

Typological Question

What are typological organisation of mutual care co-living in ?

How are mutual care activities organised to form the basis for alternative modes of care?

How does cluster type provides spatial organisation of community-led care across housing cooperatives, clusters and neighourhood layers?

Research Aims and objectives

The dissertation rethinks alternative modes of social care through mutual care initiatives as a care neighbourhood model. The aim is to think beyond centralised care provision by investigating the practices of vulnerable groups to create a network of health care, social and economic projects that increase the resilience of underprivileged communities. In doing so, a neighbourhood care model is proposed as a spatial framework for organising care activities and social support and to create a cooperative mechanism to support the Health and Social Care Devolution Programme. By investigating care provision and historical models of collective care and community-led care projects in London, the research aims to rethink multiple forms of inter-household cooperation as alternative modes of care. Therefore, the proposed project aims to provide a spatial framework for new models of care through the arrangement of multi-scalar care activities in cluster-type architecture and under different collective living conditions.

1. London Health and Care Devolution Programme Team. Health and Care Devolution: What it means for London. (London: November 2017 Report.)

2. Cottam, H. Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationship Between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare System. (London: Vigaro, 2018).

Introduction

Rethinking a New Model of Care: On the London Health and Care Devolution

Recently, the provision of social care has undergone a major shift towards a decentralised model. The exponential growth of the elderly population and the diverse background of vulnerable groups in London are amongst recent trends that have challenged the existing national health care model. Rapid, large-scale urbanisation and gentrification of working-class neighbourhoods in London have affected the local support networks and forms of mutual care that vulnerable communities rely on. Moreover, the current social care crisis has been exacerbated by a downturn in the growth of services for vulnerable groups. The criticism of the nationalised health care model focuses on its centralised nature, which produces managerial barriers, resource dependency and uneven distribution that mean the National Health Service (NHS) is sometimes no longer able to address emerging issues.1 Moreover, centralised decision-making can lead to limited resources and mismanagement by the NHS and its partners and thus delayed services.2 In 2017, the Health and Care Devolution Programme was introduced by the Mayor of London and the NHS. This programme makes local councils responsible for the provision of health care, social care and community services. The transfer of managerial control from the national level to local boroughs opens up numerous possibilities regarding the provision of social care through public-private collaborations and community support networks. Furthermore, care devolution raises challenges concerning the spatial organisation of community-based social care beyond existing health care spaces such as hospitals, clinics, GP surgeries and care homes.

3. Healthcare UK. Healthcare UK: Public Private Partnership. (London: UK Trade & Investment, 2013).

4. Jubilee Debt Campaign. The UK’s PPPs Disaster: Lessons on private finance for the rest of the world. (London: February 2017 Report).

5. Cottam, H. Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationship Between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare System. (London: Vigaro, 2018).

Health and social care provision in London have always been challenging in terms of its ownership, management and the scope of services provided. The UK is well-known for the NHS, founded in 1948, and its public-private partnership (PPP) model adopted in 1991.3 The collaboration between the public and private sectors in health care has resulted in the establishment of NHS Trusts and Foundation Trusts, which aims to decentralise care provision to the local level in the forms of primary care and community services. Health and social care PPPs in the UK have transformed public infrastructure from a public good into an investment asset, enabling banks and private equity investors to extract wealth from the public sector via contracts enforced by the government.4 However, the complexity of sharing investments, responsibilities and accountability in PPPs creates major issues, such as the privatisation of public health assets and managerial burdens, as well as creating care discrepancies across communities. Consequently, the dissertation argues that the decentralisation of care in publicprivate collaborations should be rethought as a project that enables a secured model of ownership, the participation of the care subject and facilitates the shift from personal care at home to a care environment in the neighbourhood. The proposed care activities are organised across multiple scales through the collectivisation of care activities through a cooperative strategy and are spatially arranged as a cluster system. As increasing inadequacies of care do not only have an impact on physical health but can also have social and psychological ramifications for vulnerable groups, multiple scales of intervention that enable informal care exchanges between the care subjects should be considered.5 Therefore, the shift from the cell unit to the cluster as the smallest unit reconceptualises care as a process involving extended households and informal care between multiple subjects as part of a collective way of living.

In rethinking the current model of health and social care, mutual care initiatives are investigated as a potential support network that is initiated by vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups in London, who come from a wide variety of cultural, ethnic and social

6. Mayor of London. The London Plan: The Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London. (London: Greater London Authority, 2017). < https:// www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/ planning/london-plan/new-londonplan> [accessed 04 September 2020]

7. Baiges, C. Ferreri, M. Vidal, L. International Policies to Promote Cooperative Housing. (Barcelona: Lacol SCCL, 2017).

8. Ibid.

1.1 Community-led Housing in London

London municipalities have encouraged community-led housing as a framework for affordable housing through self-governed management, local community enhancement and sustainable development.6 However, the key challenge for new housing cooperatives is not the lack of enthusiasm; it is the high price of land in London, which has caused property prices to rise exponentially. Since the 2000s, there has been a resurgent interest in communityled housing and experimenting with new models, including Mutual Home Ownership Societies (MHOSs) and CLTs encouraged by national legislation such as the Housing and Regeneration Act (2008) and the Localism Act (2011).7 In 2019, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan enhanced the conditions for community-led housing when he formed the London Community-led Housing Hub with the support of the London Community Housing Fund (20192023). This collective housing platform was allocated funding to act as capital for the implementation of community-led affordable housing developments.8 Khan also established ‘small sites’ on land owned by TfL or public land reserved for small-scale communitybased developments. Information on small sites is available as open access data through the official website. Subsequently, the municipalities’ responsibilities have been devolved and now fall on communities, which must submit their project development proposal to the local CLT. The Community-led Housing Hub also assists with feasibility studies, small developers support construction efforts and the central government prepares grants and subsidies for land procurement or long-term rents.

In the context of providing affordable housing in London, housing cooperatives as community-led housing offers a model to secure land ownership and tenancy by adopting common property, a highly relevant feature in the face of rising land values and privatisation. The focus on actively involved community members as both clients, project teams and occupants signifies a paradigm shift in housing as a process achieved through an act of appropriation, dissemination, empowerment, networking and subversion. The shift towards collective living has resulted in cooperation as the new subjectivity and has produced multi-scalar design questions. The autonomy of the subject is reclaimed in daily life by providing the possibility for them to appropriate and change the spatial and social configuration of their surroundings as agreed collectively. Spatial configuration, in this context, refers to a social space which is a product of the broader socio-economic and political context.9 Therefore, the housing cooperative as a model could be envisioned as an alternative way to provide housing in London. Although the number of communityled housing initiatives in London, especially housing cooperatives, is still low compared with other types of housing provision, there are several international examples of successful housing cooperatives.

In London, as previously noted, the key challenge for new housing cooperatives is the high price of land and resultant exponential rise in property prices, not a lack of interest in these initiatives. Furthermore, millions of low-income Londoners are now faced with the risk of losing their homes as government legislation now stipulates that new ‘affordable’ rents cannot be controlled because they must be fixed to market rates.10 Community-led housing thus has an important part to play in securing the ownership of land and dwellings as common property based on cooperative protocols.

Although the majority of these small sites are located in urban peripheries, the small sites in the city centre (in Zone 1-2) become a new opportunity in the housing cooperatives development, which can be explored. Multiple small sites can be organised under the umbrella of Community-led Housing Hub for mediation between the smaller community groups or coops in the earlier phase, while each small site can be constructed, developed and managed in later stages with Community Land Trust (CLT). At the same time, Community-led Housing Hub provides funding (for feasibility studies) and advice to set up housing cooperatives, working with boroughs, developers, housing associations, and funders. For financing, aside from low-interest rates from the bank, the model of rootstock (loan stock) enables coops that have surplus to invest in new coops. The combination of these regulatory frameworks, from the land stock, financial model and legislation might be the first step in unlocking London housing crisis based on cooperation.

As a framework for the proposed care neighbourhood scheme, the dissertation rethinks care as a communal activity. Care as an interpersonal action provides possibilities for the exchange of collective resources between vulnerable communities. The shift from centralisation to devolution means care as an act should be related to generating collective activities among vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups should be understood not as customers, but as locals with the ability to organise care activities based on their needs. For locals or collectives to establish autonomy vis-à-vis capital and the organisation of production processes is a form of resistance to social, economic and political forces and a means of establishing new forms of governance and non-state ‘rules’.11 Therefore, the dissertation puts forward cooperatives as a shared institution that acts as a mediator between local government support and vulnerable communities. More importantly, the cooperative strategy is adopted to provide a collective platform for mutual care activities to accommodate and enhance resource and knowledge exchange between vulnerable communities and public and private health care organisations as a step towards locals achieving autonomy over their care. Subsequently, the care neighbourhood scheme produced within the devolution framework can be reproduced as a ‘common ground’12, constructed to underline exception and made in line with local protocols obligations and forms of behaviour. In terms of scale, the common ground can accumulate multi-scalar interventions based on common ownership and usership of vulnerable groups. These series of spaces are organised based on collective resource management, related social agencies and how common boundaries are generated. Essentially, care neighbourhood as a common ground distributes care to address specific asymmetries of power, dismantling dominant hierarchies.

1.2. Collectivised Domesticity:

The Case of Cooperative Housekeeping and Older Women Co-housing

The Cooperative Housekeeping Movement

Cooperative housekeeping was a movement pioneered by Melunisa Fay Pierce. It championed the professionalisation of housekeeping as paid labour to realise a ‘domestic revolution’. In the following case studies, forms of care were envisioned as a space where women could be liberated from their daily responsibilities through the employment of paid or volunteer housekeepers and domestic carers. These housekeepers and carers provide assistance and social support within the kitchen, laundry, dining room, bedroom and other amenities. Housekeeping is organised as a cooperative process where the pooling of domestic activities leads to the more efficient distribution of resources and subsequently saves time, money and domestic labour.13 The systematisation of domestic activities in a cluster-type arrangement can exemplify the benefits of labour carried out as the result of an exchange between the private unit and shared services. Collectivised domestic work was intended for the middle-class under the influence of nineteenthcentury radical theories, from utopian socialism to cooperativism and even feminism. Cooperative housekeeping, from the feminist point of view, asserts that modes of reproduction can become the foundation of the ‘social factory’ and change the conditions under which we can reproduce ourselves through modes of sharing is essential to creating ‘self-reproducing movements’.14

17. Borden, I. ‘Social Space and Cooperative Housekeeping in the English Garden City’, Journal of Architectural and Planning, Vol.16, No.3 (1999).<https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030503?seq=1> [accessed 30 April 2021]

Quadrangle:

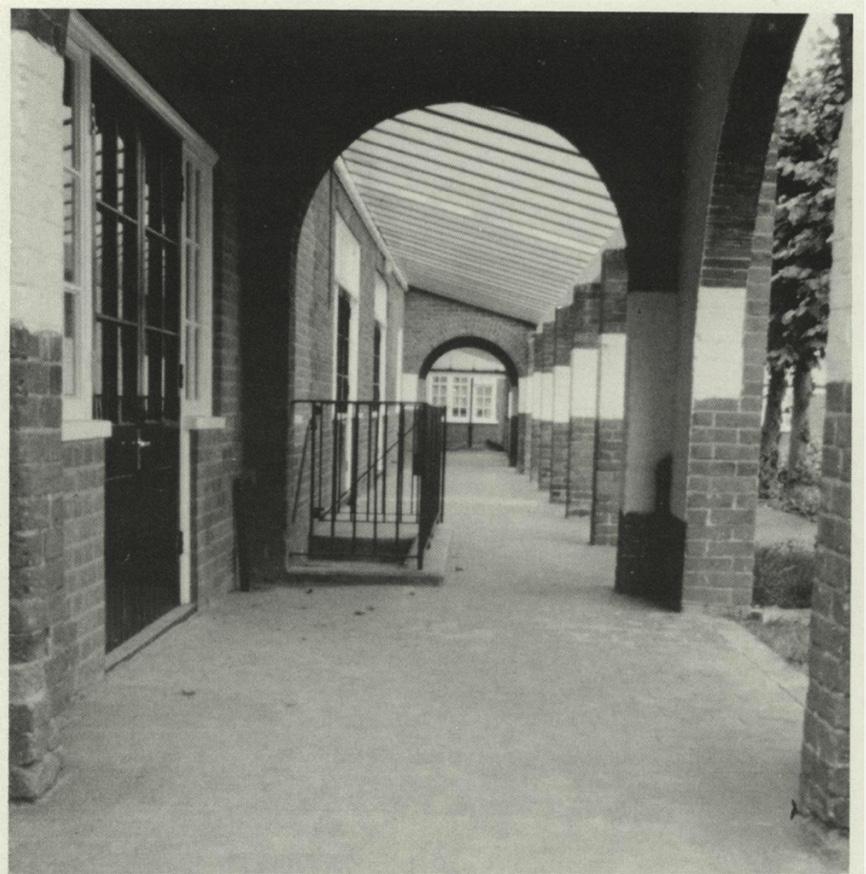

Homesgarth Cooperative Quadrangle (1909), Letchworth by H. Clapham Lander

The organisation of dwellings in a cluster type is based on the centralisation of domestic services, as in the case of the cooperative housekeeping quadrangle model. As described above, cooperative housekeeping was a movement pioneered by Melunisa Fay Pierce to achieve ‘domestic revolution’ through the professionalisation of housekeeping and caregiving work. In Homesgarth, the quadrangle liberated women from their daily responsibilities through the employment of two to four paid housekeepers.17 These professional workers worked in the centre of the quadrangle where the kitchen, laundry, dining room and other amenities are located. Domestic services were shared within the cluster containing six to eight households. Each unit was limited to a sitting room, living room and bedroom and catering, heating and maintenance of the properties and gardens were the responsibility of trained staff. The housekeeping system was organised as a cooperative where the pooling of domestic activities led to the more efficient distribution of resources and resulted in savings in terms of time, money and domestic labour. The systematisation of domestic activities in cluster type projects can thus create a productive exchange between the private unit and shared services.

Neighbourhood:

Cooperative Neighbourhood Tobolobampo (1885), unrealised, by Marie Howland, Albert Kimsey Owen and John Deery

The collectivisation of dwelling infrastructure in a platform system does not necessarily mean creating a form of ‘housing’ as we may know it but establishing housework as a system of common networks. These platforms assemble different spatial relations, from the kitchen to the unit, cluster, pedestrian access, daycare, clinic, garden, etc., as a continuous process. Although they operate through the creation of limits and boundaries, their primary objective is to penetrate multiple spaces, scales and subjects through collectivisation.

An early example is the cooperative neighbourhood conceptualised for Topolobampo, Mexico, where the systematisation of the kitchen and dining room creates particular urban planning. Backed by the feminist movement, the project imagined paid housework as a domestic service system through which women could contribute at the neighbourhood-district level. However, this project was not realised. A project that was realised was that of a community kitchen in Lima, Peru, which was built as a small-scale, autonomous initiative to provide food security for low-income households.

Image 1.16. Cooperative Neighbourhood Tobolobampo Collectivised Domestic Infrastructure Axonometric

18. Older Women Co-housing (OWCH). OWCH History. (London: Calverts Cooperative, 2016). <https://www.owch.org.uk/history> [accessed 07 March 2021]

19. Brenton, M. ‘New Ground’ Cohousing Community, High Barnet: resilience and adaptability. (London: Housing LIN, 2020). <https://www.housinglin. org.uk/blogs/New-Ground-Cohousing-Community-High-Barnet-resilience-and-adaptability/> [accessed 07 March 2021]

Older Women Co-housing (OWCH), High Barnet, London, 2016

Older Women Co-housing (OWCH) is the first model of care-based co-housing seen in the UK. The movement has been active since 1999 when it began with just six members. They believed in the possibility of mutually organising collectivised modes of living through regular meetings and campaigns focused on their rights to live as they pleased. Seven years after establishing themselves as a company limited by guarantee and opening a bank account, in 2006, they received funding from the Tudor Trust for running expenses and a Housing for Women grant for social rents.18 From 2009 to 2016, OWCH cooperated with the Hannover Housing Association and Housing & Communities Agencies to set up the co-housing model in which older women supervised and established co-living protocols, as well as overseeing project development and building construction.

OWCH’s mission is to create neighbourhood clusters that reduce health and social care demand and dependency.19 The older women aim to reduce primary care dependency, thus shifting their care demand to mutual interdependency as part of their daily routine. The shift towards mutual interdependency is also reflected in OWCH’s attempt to adopt alternative modes of co-housing, moving away from the current care-based dwelling such as the retirement village and care homes. Furthermore, the stigmatisation of the elderly as a burden on the family and the state, as well as generalisations about how they should live and be cared for, tends to overlook their demands and ability to contribute.

In contrast, co-housing offers an alternative way of living that gives the older women agency over their dwelling and care and thus open up the opportunity for them to determine forms of organisation and living protocols based on cooperation. Although facing financial difficulties and regulatory barriers, the older women have found another way to live established through common ownership, extended households, collectivised services and informal care within the grouping system of the cluster type.

Image 1.17. Founding Members of Older Women’s Co-Housing (OWCH), 2016

Source https://www.dezeen. com/2016/12/09/pollard-thomasedwards-architecture-first-older-cohousing-scheme-owch-uk/

The cluster type is adopted to spatialise the grouping system of twoto-three older women as an extended household. Co-housing as an architecture of care is built with the purpose of establishing a domestic environment where community life becomes a new ‘family’ life, which can be achieved through solidarity and support. Although facing financial difficulties and regulatory barriers, the older women found an alternative modes of living, in this context, is established through common ownership, extended household, collectivised services, and informal care – within the grouping system of cluster type. Cluster type is adopted to spatialise the grouping system of two-to-three older women as an extended household. Co-housing as an architecture of care is built with the purpose of establishing a domestic environment where community become a new ‘family’ live can be found through solidarity support.

Currently, OWCH has 26 members who organise the management and operation of their living arrangements based on mutual support, with additional care provided by social workers in the Barnet neighbourhood. The co-housing project features a cluster unit of one-bedroom to threebedroom units facing a communal garden. The unit adopts a deep plan type with a living room and kitchenette, while communal facilities such as the communal kitchen, dining area, laundry, garden and community farm on the ground floor. Every morning, the older women wake up, make breakfast with their household members and garden on the balcony or in the shared gardens. Next, they do laundry or go for a cycle around the neighbourhood. Workshops, dancing classes and community farming are weekly events that take place in the shared garden, while monthly meetings are held in the hall. In the evening, the women cook and eat together in the communal cooking and dining areas as their daily communal activities. From their first act of getting up in the morning, the women move between rooms, clusters, buildings and neighbourhoods through collectivised domestic activities and personal desires that blur the barriers between inside and outside. The example of OWCH shows that the nature of the household as a singular and private entity can be expanded by the collectivisation of domestic services to achieve the common ownership of property and nurture the concept of cohousehold family life.

Image 1.18. Activities in Older Women’s Co-Housing

Source https://www.dezeen. com/2016/12/09/pollard-thomasedwards-architecture-first-older-cohousing-scheme-owch-uk/

Image 1.19. Older Women Co-housing (OWCH) Organisational Structure

The design proposes the hybrid of enfilade and linear type in light of users’ mobility concerns, to optimise the distribution of domestic services and to generate spatial connectivity that enables the collectivisation of domestic services, social support and supervision between vulnerable individuals through inter-household forms of care. In doing so, the cluster type minimises circulation, provides the possibility for care acts appropriation and sets up spatial gradation as a series of interconnected spaces. Therefore, the cluster as a group form of architecture requires typological rethinking to ensure it can accommodate different care activities and establish new relationships between residents. In the context of co-housing, the cluster type adopts a mixed typology by combining separating the dwelling unit and common areas, which are organised according to accessibility, common activities, personal care and private units. The cluster type is formed by the combination of a double-loaded system for dwelling units, open-plan common areas in the centre and a linear strip of connected terraces adjacent to the dwelling unit for outdoor activities.

Drawing on the study of shared elderly accommodation, in the proposal presented here, each co-housing cluster accommodates 8 to 12 households in a duplex system that enables visual connection and care supervision by carers while simultaneously providing larger spatial volume for diverse care activities in the common area. The first floor is dedicated to the elderly and vulnerable people and is directly connected to the common area, including the terrace and shared domestic services spaces. Each unit is equipped with a bathroom and kitchenette, while domestic services such as cooking, washing and laundry are organised in separate areas. The common area is organised as a multi-purpose space that enables shared informal care between households. Meanwhile, gardening, clothes drying, sunbathing and other outdoor activities can be practiced on the terrace as a cluster or inter-cluster space. Personal care demands can be satisfied in the private unit, while consultation, conversation and light exercise can be done in the common area or terrace. The second floor is intended for use by care workers or volunteers there to provide care assistance either person-to-person or through visual supervision.

The Condition 1 project proposes an elderly co-housing model to be achieved through a cooperative mechanism under the CLT model. The project is designed for implementation on two sites. First, on the St Katharine’s and Wapping site, which is a small site on TfL land suitable for small builders and, second, on the NHS Royal Hospital site on Whitechapel High Street within the proposed neighbourhood care model. The elderly co-housing project aims to accommodate modes of collective living for elder minority groups to give them common ownership of their dwelling space and, at the same time, to increase their independence by reducing their dependency on primary care and public institutions in favour of community care activities. The co-housing organisational scheme is divided into three levels: (1) the cluster, where informal forms of care are practiced with the elderly subject, (2) the building, used by housing cooperatives to organise daily activities, pool resources and manage the co-housing, and (3) the neighbourhood, where the care manager helps to organise requests and schedules with the cooperatives and provide additional social care support. The proposed co-housing care activities are further organised into the unit (bedroom, closet, study), cluster (kitchenette, bathroom, storage, dining room) and inter-cluster (shared kitchen, dining area, laundry, drying area, living room, semi-outdoor garden, vertical circulation, etc.) according to the collectivisation of domestic work, circulation and inter-household relations involving the exchange of caregiving and care-receiving in the dwelling.

4th FL. AXONOMETRIC

21. Donzelot, J. The Policing of Families (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

22. Graham, H. ‘Caring: A Labour of Love’, in J. Finch and D. Groves, (eds.). A Labour of Love: Women, Work and Caring. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983).

23. Ibid.

24. Tronto, Joan C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethnic of Care. (New York: Routledge, 1994).

25. Ibid.

26. Trogal, K. ‘Caring for Space: Ethnical Agencies in Contemporary Spatial Practice’ (PhD thesis, University of Sheffield, 2012)

2.1. Rethinking Care:

Between Domestic Unit and the Public Institution

Care as an inter-personal relation is practiced in the domestic realm of the family in the form of domestic labour. As Donzelot argues, family has become the smallest unit of the state through marriage and the social roles imposed on each member, with the wife as the intermediary between the state and the family.21 From this perspective, care is conceptualised and performed as: (1) practical work or caring as labour towards the reproduction of the family through housework and childcare and (2) psychological care as an emotional phenomenon involving feelings of love and affection expressed through emotional support.22 Graham is similarly concerned with the reproduction of the family in the domestic domain as the essential inter-personal care relation.23 Within the domestic realm, care organises the household or oikos as an economic means of reproduction, where economic relations are reproduced and practiced through familial relations. Care, in this sense, is an economic model of interrelation produced within the realm of the oikos (house, property, private space) through the affective labour of women. Care takes place in terms of the concern manifested when people live together day-to-day where it can be characterised as both a single activity and a process.24 As an act, care forms subject interrelation through four phases; caring about, taking care of, caregiving and care-receiving.25 The four phases of care create multiple agencies, social roles and forms of labour as inter-scalar practices that go beyond the walls of private homes and hospitals. As Trogal argues, care can also be understood as a civic activity that builds connections between people and thus communities.26 Therefore, care as forms of inter-personal relation has always been political in the sense that it creates the subject and organises behaviour and our existence as interdependent creatures. In rethinking this issue, the spatial organisation of the household provides another possibility for social interdependencies and interpersonal modes of care.

27. Federici, S. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. (New York: PM Press, 2012).

28. Pitts, Frederick H. ‘Beyond the Fragment: Postoperaismo, Postcapitalism and Marx’s ‘Notes on Machines’, 45 years on’, Economy and Society, 46:3-4, 324-345 (2017) < https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ full/10.1080/03085147.2017.13973 60> [accessed 10 May 2021]

29. Kropotkin, P. Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution (United States: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014).

30. Thomas, C. De-Constructing Concepts of Care. (Sociology Vol. 27, No.4, 1993) <https://www.jstor. org/stable/42855270>

31. Tronto, Joan C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethnic of Care. (New York: Routledge, 1994).

The concept of reproductive work, care as an act, reflects the larger issue of capitalism in terms of affective and immaterial labour. The notion of care work emerged in the 1980s with the division of labour within reproductive work and the separation of the physical aspects of this work from the emotional.27 Forms of care from the capitalist perspective were first discussed by Marx under the title ‘Fragment of the Machines’ in the Grundrisse (1857-58), Marx’s unpublished notes. Marx draws on technological advancement, capitalist modes of production and the class struggle as the issues underpinning his main arguments while ignoring the discussion of security in old age and elder care of the working class themselves.28 It is argued that cooperation is exclusively a qualitative form of inter-personal relations and the capitalist organisation of work to achieve maximum production and labour efficiency. However, this understanding of cooperation neglects solidarity and the many ‘institutions for mutual support’ such as associations, societies, brotherhoods and alliances that were present in the industrial population at that time.29 Capitalism dictates that the supposed solution offered by the technological innovation of eldercare is the only way forward. A change in social relations based on a collective process would undermine capitalisms command over social activity and reproduction. Care, in these terms, becomes both modes of reproduction and forms of cooperation that reproduce different engagement between people.

On the other side of the coin, the state manages care through public institutions within a welfare state framework. Social care, mainly eldercare, in capitalist society has been in a constant state of crisis for which the reasons are twofold: the devaluation of reproductive work in capitalism and the stigmatised of the elderly as no longer productive.30 Moreover, relentless campaigns by political economists and governments have portrayed eldercare provision as the goal for old age through the ‘rewards’ of a pension and social security despite the reality that is often poverty and a huge tax burden on younger generations.31

In London, the NHS provides health and social services on a national scale within the British welfare state framework. Despite the fact that the domestic realm and public institution operate at different scales and are organised differently, both are still performed by women as day-to-day reproductive work. At the same time, caregiving and care-receiving are found in more than one relationship. For example, a frail elderly person living alone may receive support from a daughter-in-law, a friend, a district nurse and social service workers32. Nonetheless, care still tends to be provided in the form of a service industry that often generalises the labour and affective subjectivities involved. Although the current provision of health and social care adopts a decentralised model through collaboration with private and volunteer organisations, care providers continue to share the same gender, race and class characteristics. In the West, the history of care labour is the history of the work of slaves, servants and women. In modern industrial societies, caring responsibilities continue to be disproportionately carried out by women, the working class and people of colour.33 The pattern of employment in the care sector reveals that care activities are undervalued and care work is underpaid and disproportionately conducted by women and minorities. This is without considering that women take on the majority of caring tasks in the home, such as caring for the infirm, children and elderly. The proposed scheme argues that care as a project should reduce dependency on a single and a centralised institution and create interdependencies between the practice of caregiving and care-receiving.

32. Thomas, C. ‘De-Constructing Concepts of Care.’ (Sociology Vol. 27, No.4, 1993) <https://www.jstor. org/stable/42855270>

33. Tronto, Joan C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethnic of Care. (New York: Routledge, 1994).

In recent times, a new notion of care has emerged in the form of mutual care practices. One example is the HEBA Women’s Project in Tower Hamlets. This group of women from minority backgrounds has gradually redrawn the notion of care as belonging neither to familial kinship relations nor public institutions. Although the gendered nature of care from the domestic realm continues, mutual care practices manifest care as mutually organised interhousehold activities undertaken with private and public parties and that exist between the domestic and the public. However, some vulnerable communities cannot access the care support they need due to centralised managerial issues and economic limitations. This interrelated form of care proposed by the HEBA Women’s Project supports social care at different scales. The intermediate nature of mutual care practices shows how care as a project can be realised outside of both the domestic realm and the central public institution through mutual collaboration and common goals. Care thus becomes a spatial and organisational question based on a decentralisation model.

In line with the Health and Care Devolution Programme, care must be rethought as an alternative model of cooperatives that can mediate the managerial and spatial gap between public and private care agencies. In so doing, this dissertation proposes a cooperative strategy to create a common institution within the neighbourhood to organise collective care. Moreover, the dissertation adopts a cluster type as the spatial configuration of inter-scalar care conditions: co-housing, the community care cluster and the high street within the care neighbourhood. Furthermore, care as a form of interdependency should not be understood as a contract but as a condition that is constantly changing through common protocols and inter-household support. The project aims to reduce the dependency on public institutions for economic purposes and at the same time, allow care-receivers greater autonomy and choice about their care.

Workhouse

2.03. Building Plan of Kennington Workhouse, London, 1724.

36. Foster, L. ‘The Representation of the Workhouse in the Nineteenth-Century Culture’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Cardiff University, 2014), p. 18

37. Crowther, M. A., The Workhouse System 1834-1929: The History of an English Social Institution. (London: Routledge, 2017).

38. Crowther, M. A., ‘The Workhouse’, Proceedings of the British Academy, 78, 183-194 (p.188).

The implementation of the British Poor Law led to the emergence of the workhouse as the first welfare institution built in London with the initial mission of dealing with beggars, vagrants and parish children. The house was divided into two sections, a Keeper’s Side for the house of correction and a Steward’s Side, which functioned as a residential workhouse and industrial workshop for poor children. The organisation of vulnerable groups under the church not only aimed to provide welfare support but also to recruit the vulnerable, mainly the poor, as a workforce. Although perceived as a normalising institution, workhouses were developed ‘outside’ of the social system by adopting the impermeable courtyard type that organised the poor based on gender, age and types of work. Paupers were assigned penitentiary-type tasks such as stone-breaking and oakum-picking.36 It thus can be argued that the workhouse as a social institution was the combination of prison, hospital and church. The recurring issues of inadequate diet and poor hygiene resulting in death prompted a movement against the workhouse. An investigation by MPs and the House of Commons lists appalling workhouse practices. These included the elderly and infirm being removed from their homes and friends when they became destitute, husbands and wives separated in the workhouses, children forced from their mothers and indecent behaviour by workhouse officers. It was not until 1948 that the Poor Law was officially abolished, though, by this point, many workhouses had been renamed and transformed into specialised institutions.37 Many of the buildings used as workhouses went on to become hospitals but the fear evoked by the workhouse did not dissipate after the function of the buildings changed. The negative associations of the physical site of the workhouse were such that, years after the last institutions closed, tales still circulated of a generation of working-class people reluctant to receive medical treatment in that institution. Subsequently, the new model of lodging house and almshouse emerged as the preferred approach to the vulnerable by the state.38

40.

org.uk/APPGInquiry_HAPPI>

Almshouse

The almshouse as a structure and social care provider has experienced multiple transformations. Originally, the almshouse was part of the church and how it provided for vulnerable communities and it adopted a monastic way of living. The current almshouses have been transformed into elderly housing to provide assisted living. These almshouses are under the control of trustee organisations and a warden or scheme manager. The almshouse adopts a semicourtyard or quadrangle type consisting of buildings up to three storeys high and single-loaded circulation facing the central court. Within the framework of the welfare state, the almshouse reflects a shift from an institutionalised form of care such as the workhouse to a more communal model where interaction between the vulnerable is enhanced. The communal facilities such as dining areas and kitchens are placed in the middle section of the quadrangle, while the central court is used for gardening and parties. The residents organise workshops, sketch clubs, dance classes and bingo in the hall as their routine common activities.

As an archetype of care accommodation, the almshouse plays a crucial part in coordinating personal care support using the cluster type.39 This form of care accommodation creates inter-personal relations between vulnerable persons through extended household structures that share property, activities and domestic services as a group of two to four household units. The typological challenge of the cluster is to minimise internal mobility while enhancing room connections by centralising the corridor or adopting enfilade organisation. Furthermore, spatial comfort is considered an essential part of informal care and therapy achieved by creating a connection between the indoors and the outdoors as in the case of the balcony, terrace and garden.40 In the context of London, this cluster type has been tested previously in the almshouse and care homes as collective care dwellings for the elderly. Although the almshouse still represents a heavily dependent form of care, the typological notion of the cluster in the almshouse shows signs of moving towards collective living.

42. Ibid.

Research &

As the twentieth century’s contribution to care accommodation, the nursing home or care home was first introduced as a result of the reformation of former workhouses. In 1927, the Nursing Homes Registration Act made care homes official institutions responsible for providing nursing care for those suffering from any sickness, injury, or infirmity.41 Consequently, the post-war UK formed the welfare state in response to the urgent need to provide mass health care services, which evolved into the NHS in 1948. Furthermore, the old Poor Law was abolished by the 1948 National Assistance Act, which made local authorities responsible for assisting ill, disabled and older people with care, primarily through care homes. The growth of care homes came in the 1980s under the 1980 Right to Buy law under Thatcher, which enabled the privatisation of care homes as private businesses. Currently, there are approximately three times as many beds in care homes as there are in NHS hospitals.42 Although it can be argued that privatisation can improve the quality of services and space in care homes, it creates socio-economic and managerial barriers impacting the accessibility of care homes. Furthermore, the relationship between private care homes and public health care is uncertain; care home residents have inequitable access to NHS services, particularly in terms of specialist expertise such as dementia, rehabilitation and end of life care.43 Therefore, an integrated model of care accommodation should be considered not only to better mediate the relationship between vulnerable groups and public health care but also to accommodate the independence of the care subjects. Typologically, care homes adopt a cluster form by grouping vulnerable subjects in two- to three-person clusters. Care homes, however, do not provide collectivised domestic services, which can allow the elderly or frail to conduct their daily activities independently, as these services are assigned to care workers. The ability to reproduce daily and care activities through collective responsibility and cooperation must be introduced in care accommodation models. The act of caregiving and care-receiving should not become a one-way process to prevent the re-emergence of the past workhouse experience.

2.3. Cluster as Forms of Social Care Infrastructure

The cluster type has the potential to organise life across multiple social and spatial conditions. In the above examples of collective care models, the cluster type acts as a tool to choreograph daily activities and establish the framework for daily rituals. As an architectural device, a cluster organises the arrangement of rooms, the distribution of collectivised services and creates privacy. Influenced by the specific socio-political context of the early Poor Law provisions, the cluster type was initially exploited as a politicised spatial strategy to control vulnerable groups through spatial separation and disconnection based on gender, age and labour in the workhouse. In the almshouse and care homes, the cluster type acts as a socially embedded spatial configuration through the use of the courtyard, circulation design and centralised communal facilities. Reflections on the agency of the cluster type are inseparable from the social understanding of vulnerable groups that prevailed at that time. Currently, the existing model of institutionalised care provision is experiencing a shift to a greater focus on the resilience and autonomy of the subject, as seen in community-led care initiatives. In this emerging context, care, as a political interrelation, is exercised through adaptation, collectivisation and cooperation, in which case the cluster type should be able to organise unexpected activities, social interrelation and multi-scalar activities from one’s room to the neighbourhood.

The dissertation proposes the cluster type as a key design proposition for organising vulnerable groups within an extended household structure. The cluster, as a system of groupings, raises the possibility of practising informal care among the elderly by collectivising domestic activities and setting up boundaries from the outside. These boundaries are constructed through common protocols where the state of exception as trespassing, exceeding or crossing spaces is exercised.44

From Agamben’s point of view, states of exception revolve between the private life and the public sphere, not only as a citizen of state but even to the point of acting upon their own way of living.45 To spatialise this state of exception, the cluster operates both as an enclave (space of containment) and armature (space of distribution) to maintain its porosity. Although the cluster proposes forms of collective care, it could result in a closed enclave that excludes and distinguishes itself from the outside. On the urban scale, the cluster that loses its threshold character can become a fatal trap (if this enclave takes the form of camp) or a zone of protection (if this enclave takes the form of a secluded area of privilege), as in the case of exclusive gated communities.46

44.

45. Agamben, G. State of Exception. (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

46. Sennett, R. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012).

The second condition, the community care cluster, aims to propose a spatial framework for social care decentralisation to enhance community-led initiatives and promote collaboration between local communities and the central health care body through a cooperative strategy. The community care cluster is designed for implementation on the NHS Royal London Hospital site, Whitechapel, in response to the 2017 London Health and Care Devolution Programme. The cluster is composed of an individual pavilion and pilotis system with open space in-between that promotes interchangeable activities and sets out spatial relations between different groups. Care as a set of collective activities is exercised through the design principles guiding the articulation of movement, inside-outside relation and framework of appropriation. In the community care cluster condition, community-led care activities are defined as adaptable and periodically changing according to a common protocol. Thus, the pavilions are open plan structures with adjustable dividers, each equipped with a storage room for furniture and objects of use in multiple activities.

Condition 2 proposes a community care cluster for implementation on the NHS land on which sits the Royal London Hospital within the neighbourhood care model for Whitechapel High Street. The project aims to convert the surplus public land into community care infrastructure that accommodates social care services through the cooperation of multiple community-led organisations in the neighbourhood. Within the community care cluster, the proposed activities are arranged based on modes of assistance, collective participation and exchanges with community-led care initiatives to create an integrated system of neighbourhood social support. The proposed care activities relate to health (neighbourhood clinic, apothecary, outdoor gym), finances (workshops, training, ESL English courses, co-op store and café), social life (bingo hall, discussion area, seating area) and recreation (playground, community farm, greenhouse).

The community care cluster is developed as a series of interconnected pavilions using the pilotis system to create hybrid indoor-outdoor spaces. The difference in spatial qualities provides diversity in accommodating and appropriating spaces as part of a process of independent cooperation. The proposed programmes are envisioned as collective care acts in the form of a spatial framework that can be changed as per the scheduled protocol. The architecture of the care cluster is developed as a group form, accommodating collectivised mutual care activities with the aim of producing common ground. Common ground is both an organisational and spatial framework that provides collective autonomy for vulnerable communities in terms of ownership, decision-making and care activities. The cooperation between care collectives and vulnerable communities regarding care provision and daily management establishes a system of solidarity networks to reduce socio-economic dependency on institutionalised care. In the community care cluster, care as a political interrelation is exercised through adaptation, collectivisation and cooperation. The cluster type should organise unexpected activities, social interrelation and multi-scalar activities from a single room to the neighbourhood.

Neighbourhood Model: Community-led Care Framework

47. Cottam, H. Welfare 5.0: Why we need a social revolution and How to make it happen. (London: UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, 2020).

48. Ibid.

49. Pipe, J. Two years on, what has the Localism Act achieved? (The Guardian, 2 November 2013). < https://www.theguardian.com/ local-government-network/2013/ nov/02/localism-act-devolution-uk-local-authorities>

50. Ibid.

3.1. Towards a Devolved Model of Social Care

In rethinking the shift towards a decentralised and devolved proThe inheritance of the post-war period, the modern welfare state is facing multiple issues that go beyond the standardisation of health care services, such as mental health, emerging social care demands, community care movements and social inequalities.47 In Welfare 5.0, Cottam argues that these modern issues of care are rooted in the inability of the traditional welfare state to move away from its centralised character.48 The Localism Act (2011), which was enacted by the government to implement the wide-ranging decentralisation of public services and housing, may appear a promising first step in addressing this challenge. Decentralisation transfers the authority for administrative management from the central government to local councils. However, the decentralisation proposed by the Localism Act does not challenge the deep-rooted centralisation of service provision in London and the UK.49 An example is access to housing, which is governed by the housing authorities which decide who to support and the conditions of support and express a preference for the homeless and people living in unsanitary conditions.50 Assessment and decision-making are still based on the centralised organisation system creating managerial issues that can lead to the neglect of certain vulnerable groups. These recurring managerial barriers have prompted further devolution initiatives in the 2016 Cities & Local Government Devolution and the 2017 Health and Care Devolution Programmes. The devolution of social care responsibilities proposed by these programmes is designed to allow vulnerable groups and communities to participate in and contribute to social care provision at the borough level. With the emerging mutual care organisations at the borough and neighbourhood level, devolution opens up the possibility of integrating local council and community-led care practices using an intermediate organisational structure, alternative spatial conditions of care and other forms of social care infrastructure.

51. Awan, N. Schneider, T. Till, J. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture (New York: Routledge, 2011).

Social care devolution in London aims to integrate existing public assets and infrastructure at the local level. In this case, social care devolution for vulnerable groups can not only improve health care accessibility but also these groups’ quality of life in terms of housing and socio-economic necessities. The integration of different social care conditions should establish a two-way system where vulnerable groups are able to contribute based on their ability and choosing in return for an affordable and secure model of provision model and the possibility of change.

Drawing on the CLTs’ secured model of land and housing ownership, the dissertation proposes cooperatives to act as intermediaries between the local council and vulnerable groups. Under the supervision of the CLT, cooperatives can obtain secured co-ownership of their dwelling, organise their own mutual care and cooperate with local care agencies. As agency is described as the ability of the individual to act independently of the constraining structures of society51, care agencies should enable the vulnerable subjects to organise towards an independent care-based living. Moreover, the establishment of a cooperative system aims to reduce dependency on health care services such as hospitals, clinics and care homes. The proposed mechanism of different social care conditions conceptualises care as a multi-scalar intervention that enables care supervision whilst simultaneously providing care subjects with the spatial framework they need to independently organise their care activities as collectives. From making tea at breakfast in the living room to planting at the community farm, the proposed design rethinks each daily activity as a basic form of care from the scale of the room to the neighbourhood.

52. Vaughan, L. ‘Clustering, Segregation and the ‘Ghetto’: the spatialisation of Jewish settlement in Manchester and Leeds in the 19th century’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Bartlett School of Graduate Studies, University College London, 1999).

53. Peach, C. ‘South Asians and Caribbean Ethnic Minority Housing Choice in Britain’, Journal of Urban Studies, 1981, Vol. 35, No. 10.

3.2. Case Study: Community-led Care Network in Whitechapel

In Whitechapel, community-led care initiatives are organised as mutual care activities for vulnerable groups. Established as mutual care initiatives and recently acquiring the support of the local council, these care projects provide an organisational and spatial understanding of community care that opens up the possibility of working within the social care devolution framework.

As a borough, Whitechapel has an historically diverse community that dates back to the early twentieth century and is the result of colonialisation and migration. The majority of minority communities in Whitechapel are Indian, Middle Eastern and Bangladeshi, who utilise spaces in multiple ways, on the one hand, to ensure their economic survival and on the other hand, to maintain their ethnicsocial ties within an alien culture and environment.52 As the dominant migrant population, the Bangladeshi community in Tower Hamlets share similar kinship ties and grouping patterns.53

The dissertation investigates Bangladeshi communities’ care networks as a case study of mutual care initiatives and considers its historical roots and more progressive activities within the context of Whitechapel. These community-led practices are attempts to frame care as a resilience project. The community-led care initiatives administer both the distribution and collectivisation of care as a system of solidarity networks. These solidarity networks focus on providing vulnerable groups with social care beyond their health demands, that is, with care that also addresses their socio-economic needs, among other issues

58. Ibid.

The mutual care initiative HEBA Women’s Project is a volunteer organisation that focuses on the empowerment of vulnerable groups by women. Launched by a group of Bangladeshi women, HEBA Women’s Project organises mutual care support for black, Asian, minority ethnic and refugee (BAMER) women’s groups in the multicultural East End of London. Language difficulties, childcare and lack of confidence were ascertained as the most difficult barriers for some BAMER women to overcome not only in terms of care but also life in general. The needs of individuals are frequently diverse, such as welfare information, access to housing, legal status, employment and education/training.57 Local council support exists but is patchy and support for immigrant women particularly suffers from a lack of capacity and funding.

Confronted with these barriers, these vulnerable women have organised and collectivised their care in the form of activities and networks that aim to fill gaps in service provision. Consequently, HEBA Women’s Project consists of multiple initiatives based on intergenerational care support. These activities include sewing workshops, nurseries, ESL courses, school gardening clubs, charity lunches and community farming within the neighbourhood.58 HEBA Women’s Project shows how mutual care initiatives can challenge the conventions around care through de-institutionalised organisation and by emphasising its domestic nature through care labour distribution to different subjects of multiple households. Therefore, an integrated system of care support should be proposed as a local approach within the devolved framework to enable collaboration between local welfare support and mutual care initiatives.

Community-led Care Network in Whitechapel

In Tower Hamlets, Whitechapel, a community-led care network has been organised as a mutual care initiative by a voluntary organisation peopled by vulnerable groups themselves. Started as a collective movement, community-led care in Whitechapel has since gained administrative support from the local council. The shift to local governance by the Mayor of London and community organisations has forced London boroughs to establish social and infrastructure frameworks.

The community care network established in Whitechapel forms inter-scalar spaces that organise multiple activities such as welfare support, elderly clubs, an informal economy, language classes, sewing workshops, food banks and community farming and redistribute care labour within the neighbourhood. For example, the Spitalfields City Farm enlists volunteers from the elderly club with the help of voluntary carers from HEBA Women’s Project. These communityled care spaces involve cooperation between different social agents to conduct acts of care.

In providing the act and process of care, vulnerable communities are transformed into locals who decide for themselves what, when and how to produce and how to distribute the products of labour and tasks of social reproduction according to need, desire and ability rather than money, managerial hierarchy and power.59 In this way, locals construct alternative infrastructure and modes of living, resulting in the emergence of new subjectivities and the movement outside of the state and the capitalist system.

Although local people practice care with limited intervention, their efforts aim to move towards collective autonomy. From this perspective, autonomy is generated by the interaction between actors across a social network in such a way that the network produces these interactions and the social boundary is defined.60 New care agencies are constructed as a result of this bottom-up movement, which always tries to push the boundaries of centralised power and control. In this case, architecture has experienced a significant shift from seeing itself as a space-making discipline to understanding that it is within its capacity to design relationships, giving rise to the possibilities of supportive co-existence.

61. Mawson, A. ‘The art of doing good’, Guardian 9 January 2008, digital source: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2008/jan/09/socialenterprises.regeneration [accessed 20 May 2021]

62. Ibid.

Bromley-by-Bow Centre

I arrived in Bromley-by-Bow one cold November evening in 1984, to be greeted by 12 people, all over 70 years of age, in a 200-seat United Reformed church. I felt strongly that all of my theological training to date had been equipping me for working in the inner cities, but as I stood at the pulpit in the freezing church hall in the East End of London, I couldn’t help but wonder what I’d got myself into.

- ‘The art of doing good’, Andrew Mawson61

The Bromley-by-Bow Centre was founded in 1984 by Andrew Mawson alongside the local community to provide a centre for the community and entrepreneurship. This involved buying three acres of derelict land to create the first integrated health centre in Britain through a development trust built and owned by the community. The Bromley-by-Bow Centre aimed to re-conceptualise the prevailing social care model and move away from the traditional welfare state model offered by the NHS. At first, the proposal faced opposition from the NHS. The turning point came when the project won the support of the Tory Health Minister and the New Labour project in 1997, which was focused on ‘community’. The project proposed the integration of health, education, housing, environment, enterprise and the arts. The Bromley-by-Bow Centre brings together GPs, employment, housing advice, church, art organisations and cafés to provide a one-stop-shop for care in one of the poorest areas of the UK. Here, the doctor can prescribe more than tests and medications but also activities, including art courses, access to community care and an allotment.62 Bangladeshi women learn English, art skills and try to find a job.

64. National Health

Designing Integrated Care System (ICSs) in England: an overview on the arrangements needed to build strong health and care systems across the country. (London: June 2019 Report)

The dissertation proposes neighbourhood care as a framework for community-led care networks and current social care devolution efforts. In particular, the 2017 London and Care Devolution Programme proposes the transformation of how decision-making, ownership and agency of care provision is conducted with the intention of moving power from a centralised government system to a more collaborative one.63 Furthermore, the dissertation argues that devolution requires a shift in the spatial framework, modes of service and the scale of the social care services. Throughout the three care conditions proposed, elderly co-housing, community care clusters and the high street, the proposed social care framework is conceptualised on the scale of the neighbourhood. Moreover, the dissertation proposes a shift in our understanding of the scale of services from the listing system (based on postcodes, building numbers, and Trust numbers) to a network system of cooperatives that arrange multiple vulnerable groups and local communities based on mutual interdependency. The project understands that this shift is essential to providing forms of care for vulnerable communities that cannot be listed or are difficult to access due to managerial boundaries in the formal health care system.

While the NHS defines a ‘neighbourhood’ under their integrated care system as 30,000 to 50,000 people,64 the proposed care neighbourhood will be based on the district level, as in the case of Whitechapel. This model aims to provide a spatial framework for affordable and secure social care, as well as additional socio-economic support across the three care conditions to preserve the local community. The neighbourhood care model thus proposes a gradation of management through cooperatives as the intermediate organisations standing between vulnerable groups, community-led organisations and the local council. The cooperative strategy provides a common platform for vulnerable communities and organisations to collectively design and manage their ownership, protocols and activities and to actively participate in the development of spatial conditions in the neighbourhood. Therefore, the neighbourhood care model should be developed to establish a scale of service provision and a common space for community-led care.

Condition 3 proposes the appropriation of Whitechapel High Street to accommodate an inter-disciplinary network of community-led care practice in the neighbourhood. The high street distributes care for the vulnerable through various activities and subjects, such as informal economic activities and social support network. The proposed Whitechapel High Street aims to explore the spatial intervention of informal care activities by vulnerable communities in socio-economic relations. Furthermore, the project rethinks how public infrastructure can create the space to accommodate such care activities. Condition 3 redefines the high street as a care infrastructure where multiple care agencies and activities intersect and are practiced to achieve different forms of resilience.

The proposed model uses pilotis as elements to create both spatial and boundary frameworks that enhance the interplay between indoor and outdoor activities while giving users the freedom to appropriate space and engage in a variety of activities. The design adopts two levels of intervention: (1) the freestanding pilotis structure for shelter, the extended activities of shophouses and space for street vendors, and (2) the open street for more flexible activities and screening for street activities. The proposed activities aim to accommodate existing modes of resiliency into the high street (street vendors, bus stations, bicycle parking, food carts) while also establishing a spatial framework for other possible activities (community farm, street gallery, seating areas, outdoor cafés, artwork, information centres and even temporary accommodation for the homeless). The transformation of high street typology into a pilotis system of care infrastructure allows the street to become a space for the temporary shelter of the vulnerable subject and a space that can enhance the variety of movement and acts between the shop, the pilotis and the open street. Through condition 3, the project aims to rethink the street and conceptualise it as not only a channel of care distribution but also as a place of care where vulnerable communities can find protection and opportunities for participation to improve their living standards.

From an Act of Care to a Right to the City

On a larger scheme, the project aims to unveil the emerging phenomenon of community-led care in contemporary London. The importance of community participation shows the possibilities in redefining the right to the city to go against capitalist modes of production in social care. The case of community-led care initiatives in Whitechapel proves the argument of David Harvey on the ‘right to the city’, in which he describes not as a pre-existing right nor right to citizenship, but as a collective struggle in producing the city and creating the life in it.65 Although the scale of their action seems minute, working together as an oppressed community, they fought against the process of displacement and dispossession that creates urban restructuring.

67.

Fighting against the long-accumulated urban commodification, these networks of interdependency try to overcome ever-increasing land value, housing price and social care inaccessibility. In doing so, care become commons that are practised with the collective and non-commodified principles. The vulnerable groups overcome the process of capitalist urbanisation in London by depending upon their collective power, as Harvey argued, as one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.66

As Lefebvre argued in his theory of urban revolutionary movements67, the dissertation believes that these vulnerable subjects did not wait for ‘the grand revolution’ by the private initiatives or local authorities. They started a small urban revolution as a result of collective spontaneity by realising that their co-protocol can produce a change. The project aims to rethink the spatialisation of these forms of social relation, where care neighbourhood as a scale can help vulnerable communities through commoning. Commoning, in this context, is created by transcending the public-private relation and providing the spatial framework for the reproduction of collective modes of living. In order to take back the right to the city not through violence, but through caring.

These socio-economic and political barriers have always been the main struggles not only for housing collectives but for community organisations in general. Therefore, social care devolution has to provide security and integration opportunities for cooperatives or community-led care organisations by providing institutional positions for care collectives to enable them to manage their own and subsidised resources. By doing so, cooperatives can become a common platform through which vulnerable communities can gain collective ownership and craft protocols of mutual care in a manner that prevents marketisation, exploitation and exclusion on the local level.

Care, as the dissertation argues, has shifted from the practice of caregiving by the service industry to a form of interdependency where each vulnerable subject practices their care acts in daily life. The rise of community-led care practices has blurred the boundaries of care and its relations and moved care away from the domestic unit and the public institution. Although care has always been a political act that includes interrelation between subjects, any new care model requires an understanding of the current issues of care (diverse communities, social exclusion and mental health issues) and must embrace a democratic way of delivering care (community participation, adaptation and cooperation). The cooperation of multiple care agencies (household members, private and public parties) creates a paradigm shift of care as shared and formed through the establishment of co-protocols as a state of exception. Therefore, the act of care can be redefined as part of a collective struggle to achieve affordable and democratic care for vulnerable subjects.

The project shows how the act of care started to dismantle the notion of domesticity, disconnecting the distribution of affective labour from the domestic realm and opening up the notion of post-domesticity. A paradigm shift in what constitutes a care agency, which now includes women’s group, elderly co-housing, care collectives and technological tools, has redefined care through inter-household relations that transcends the predefined structure of the nuclear family and ‘home’. The dissertation argues that post-domesticity, from a care point of view, was realised by the cooperative housekeeping movement, which itself was inspired by community care groups. Care, as a form of interdependency, is used in the project as an intersectional theme to push the limits of domesticity through the subject (elderly, migrant women, intergenerational subjects), cluster type (indoor-outdoor connect, common spaces, thresholds) and modes of co-living (collectivised services, co-protocols, groupings).

The research proposes the cluster type as a formal tool to develop a new socio-political context for social care. The cluster type is used as a biopolitical apparatus of the welfare state, as was and is the workhouse, almshouse and hospital, and establishes a system of control over the movement and hygiene of the body within a massproduced service system. Additionally, the cluster type is a group approach to accommodating collective care activities (community centre, women’s groups, elderly clubs), which is achieved by creating boundaries and a state of exception for vulnerable people. States of exception, in this term, does not means creating impenetrable boundaries from the outside, but to produce common protocols that binds spatial, organisational and managerial system of the project. From these two opposing uses (between delineation and bringing the community together) of the cluster, the project understands the potential of the cluster type to give structural organisation to vulnerable bodies and, at the same time, open up possibilities of interrelation.