Our process sensors give you high performance at prices that are easy on your budget.

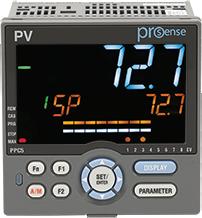

NEW! MP Sensor P.Touch Series Pressure Transmitters

All priced at $197.00 (5-11-3132-030200)

NEW! ProSense SC6 Series High-Density Signal Conditioners

MP Sensor P.Touch series pressure transmitters feature an intuitive touchscreen interface and a rugged stainless steel housing suitable for harsh industrial environments.

• Pressure ranges from vacuum to 2000 psig

• TFT touch screen display

Starting at $149.00 (SC6-2001)

• IO-Link v1.1 compatible

• IP65/67/68 IP65 protection ratings

ProSense SC6 series high-density signal conditioners feature an ultra-narrow design for high-density mounting. New pulse isolators and frequency input models handle a variety of discrete, pulse, and frequency signals.

• Pulse isolators support NAMUR/ NPN/contact inputs, up to 5 kHz, dual outputs, splitter function, and line fault detection

• Models also available for voltage, current, and temperature conversion

• Frequency models handle frequencies up to 100 kHz and provide configurable analog or relay outputs

NEW! SBLT Series Small Bore Submersible Level Sensors

Starting at $777.00 (SBLT-010-L50)

• Sensing ranges up to 461.3 ft WC

• 4 to 20 mA output

• 316L stainless steel construction

• Built-in lightning protection

ProSense SBLT series small bore submersible level sensors feature an ultra-slim housing, extended sensing ranges, and cable lengths up to 500 feet. They provide accurate, reliable level measurement in deep wells, narrow boreholes, and standpipe installations.

• UL Water Quality Classified to NSF/ANSI 61 and 372 for use in drinking water applications

• IP68 protection rating

NEW! ProSense XTD2/XTH2 Series Fixed-Range Temperature Transmitters

Starting at $99.00 (XTH2-0100F-J)

ProSense XTD2 and XTH2 fixed-range transmitters convert temperature sensor inputs into accurate signals for PLCs, meters, and controllers. XTD2 units mount on DIN rails, while XTH2 models install directly in DIN Form B sensor heads.

• PT100 RTD and Type J, K, and T thermocouple input options

• NAMUR NE 43 compliant fault indication

• 4 to 20 mA output

• Screw or push-in terminal options

EDITORIAL

VP, Editorial Director Paul J. Heney pheney@wtwhmedia.com

Editor-in-Chief, FPW Mary Gannon mgannon@wtwhmedia.com

Technology Editor Ken Korane kkorane@wtwhmedia.com

Editor-in-Chief, Design World Rachael Pasini rpasini@wtwhmedia.com

Contributing Editor Josh Cosford

Contributing Editor Carl Dyke

Contributing Writer Robert Sheaf rjsheaf@cfc-solar.com

www.nfpa.com

PRODUCTION

VP, Creative Services Matthew Claney mclaney@wtwhmedia.com

Art Director, FPW Erica Naftolowitz enaftolowitz@wtwhmedia.com

Art Director, FPW Digital Eric Summers esummers@wtwhmedia.com

Director, Audience Growth Rick Ellis rellis@wtwhmedia.com

Audience Growth Manager Angela Tanner atanner@wtwhmedia.com

PRODUCTION SERVICES

Customer Service Manager Stephanie Hulett shulett@wtwhmedia.com

Customer Service Representative Tracy Powers tpowers@wtwhmedia.com

Customer Service Representative JoAnn Martin jmartin@wtwhmedia.com

Customer Service Representative Renee Massey-Linston renee@wtwhmedia.com

Customer Service Representative Trinidy Longgood tlonggood@wtwhmedia.com

FLUID POWER WORLD does not pass judgment on subjects of controversy nor enter into dispute with or between any individuals or organizations. FLUID POWER WORLD is also an independent forum for the expression of opinions relevant to industry issues. Letters to the editor and by-lined articles express the views of the author and not necessarily of the publisher or the publication. Every effort is made to provide accurate information; however, publisher assumes no responsibility for accuracy of submitted advertising and editorial information. Non-commissioned articles and news releases cannot be acknowledged. Unsolicited materials cannot be returned nor will this organization assume responsibility for their care.

FLUID POWER WORLD does not endorse any products, programs or services of advertisers or editorial contributors. Copyright© 2025 by WTWH Media, LLC. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

MARKETING

VP, Operations Virginia Goulding vgoulding@wtwhmedia.com

Digital Marketing Manager Taylor Meade tmeade@wtwhmedia.com

SALES

Ryan Ashdown 216-316-6691 rashdown@wtwhmedia.com

Jami Brownlee 224.760.1055 jbrownlee@wtwhmedia.com

Mary Ann Cooke 781.710.4659 mcooke@wtwhmedia.com Jim Powers 312.925.7793 jpowers@wtwhmedia.com Judy Pinsel 630.538.2638 jpinsel@wtwhmedia.com

LEADERSHIP

CEO Matt Logan mlogan@wtwhmedia.com

Co-Founders Scott McCafferty Mike Emich

SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Free and controlled circulation to qualified subscribers. Nonqualified persons may subscribe at the following rates: U.S. and possessions: 1 year: $125; 2 years: $200; 3 years: $275; Canadian and foreign, 1 year: $195; only US funds are accepted. Single copies $15 each. Subscriptions are prepaid, and check or money orders only.

SUBSCRIBER SERVICES: To order a subscription please visit our web site at www.fluidpowerworld.com

FLUID POWER WORLD (ISSN 2375-3641) is published six times a year: in February, April, June, August, October, and December by WTWH Media, LLC; 1111 Superior Ave., Suite 2600, Cleveland, Ohio 44114. Periodicals postage paid at Cleveland, OH & additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Fluid Power World, 1111 Superior Ave., Suite 2600, Cleveland, OH 44114

WELCOME TO your last issue of Fluid Power World for 2025! We’ve had a great year and hope that, despite ongoing market challenges, you have, too. We added a brandnew digital-only issue this year, which we trust you’ve found valuable, as an avenue to share more of our technical content each month. We also offered more webinars this year that met your needs with educational training on fluid power technologies.

As we wrap up 2025, I’d like to invite you to continue subscribing as we expand how we provide the most in-depth hydraulics and pneumatics content out there. In this issue, you will find five deeply technical articles on selecting and specifying key technologies in fluid power systems. There are also a couple engineering basics articles, as in years past, that provide you with the foundations for selecting the right components for your systems, to ensure they run reliably and efficiently throughout their lifecycles.

We plan to write more articles like these in the coming months, so if you find them useful, stay tuned for more. Additionally, we will be relaunching our e-newsletters under the new name Fluid Power Forward, and they will now hit your inbox twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Our

Tuesday e-newsletters will include technology focuses, where you will learn about new products in the market, but, most importantly, how to specify them and use these components in your machines. If you don’t currently receive them, subscribe at fluidpowerworld.com/sign-fluid-power-worldenewsletters.

Other new features to look out for in 2026 include two online event series: the Hydraulic Systems Unlocked: Building Efficiency from the Inside Out and Smart Air: Driving Efficiency in Pneumatics and Compressed Air Systems. Our hydraulic series will launch in April, with one technical, educational webinar each week for six weeks. The pneumatics sessions will be a two-part series in September.

We have other new programming slated

for 2026, and we’re excited to introduce those to you in the future. So stay tuned, especially for our February and March issues and e-newsletters, where we’ll be taking a razor-sharp focus on the construction market as we cover CONEXPO-CON/AGG. Hope to see you there!

Thanks always for reading and being a part of our fluid power community. May you have a joyous holiday season and a happy new year!

Mary C. Gannon •

Editor-in-Chief

mgannon@wtwhmedia.com linkedin.com/in/marygannonramsak

ALTHOUGH OFTEN AN AFTERTHOUGHT, FITTINGS SHOULD BE PART OF THE INITIAL MACHINE BUILD TO ENSURE EFFICIENCY, SIMPLICITY AND RELIABILITY.

THE HYDRAULIC DESIGNER most frequently creates a hydraulic schematic to represent the entirety of the hydraulic pumps, valves, actuators, accessories, and plumbing of a machine. After the first sketch is pencilled, the circuit is migrated to CAD software for refinement, while the bill of materials is systematically populated to reflect all the chosen major components. A few revisions later, due to unexpectedly expensive items or those with unacceptable lead times, many designers will move on to the next project. What's not on the schematic, and per-

haps of little care to the designer, is the plumbing and connections used on the reallife machine. Often, these decisions are left to the technician building the machine or power unit, which, depending on the size of your company, might be subject to "whatever's in stock" and can be made to work with the inventory available on that particular day. Furthermore, technicians have their preferences, so without thoughtful planning of the plumbing aspect of machine design, you may have two entirely differently plumbed machines should another make its

way down the pipeline.

In reality, hydraulic fittings and adapters should be part of the design process, which not only provides the most efficient build but also a consistent appearance using the fewest SKUs possible. A hydraulic design should be comprehensive and consider the best combination of effective fittings that balance cost and performance, while also being sensitive to the region to which the machine is shipped, if not local.

The designer must ensure that the chosen fittings and adapters are suitable for the

working environment, which includes ambient conditions, fluid compatibility and pressure rating. Many fittings come standard as nickel or zinc-plated steel, but corrosive or oxidative ambient conditions may call for stainless steel. The designer should bear the responsibility of adhering to risk-based regulations, such as EU REACH or American TSCA, to avoid selecting fittings and adapters that contain banned substances in their manufacture or plating.

There are many thread standards to choose from, and the designer knows they are not created equally. Sure, NPT is inexpensive and readily available, but it is designed for a one-and-done installation and is not intended for regular servicing and disconnection. Soft seal technology rules the day, so look for ORB port fittings with ORFS (O-ring Face) fittings that are reliably leak-free for the life of the machine. Is the machine going to Europe or Taiwan? Be aware that fitting preference aligns geographically, so BSPP

should be installed for machines heading to Europe, while BSPT (British Taper) might be more suitable for Taiwan.

Once the construction type and standard are defined, the designer must understand the nature of the plumbing layout on the machine. Preselecting the appropriate elbows, tees, and adapters that best suit the porting of the pumps, manifolds, and actuator orientations should be part of the design stage and not relegated to the technician. For example, a vertically mounted cylinder with horizontally oriented ports should include a 90° adapter so that the hose hangs with no radial stress. Selecting these fittings ahead of time limits the guesswork during installation, and also avoids any surprise rat's nests that appear when multiple fittings and adapters are joined together to create the result of an intelligently planned single fitting.

Probably the most underestimated criterion the designer is responsible for is the siz-

ing of fittings and adapters. The designer has the opportunity to select a size appropriate to the circuit's flow rate, which ensures fittings are large enough for the related flow but not oversized, thereby not detracting from the budget. And with appropriately sized fittings comes appropriately sized plumbing, so you must view all of the fittings, hoses and tubes holistically.

Once the bill of materials is complete with the list of fittings and adapters, the designer or buyer may send out the RFQs to their preferred suppliers to bid against. This helps to ensure you can not only select the best price and lead time, but also reduces the stress that comes with last minute surprises of low stock or poor selection, both of which can lead to poorly plumbed machines. If you're a designer not already selecting fittings and adapters, consider taking on this responsibility. It will enhance your capabilities and you will be helping to reduce costs and lead time for your employer. FPW

PERHAPS MORE THAN ANYTHING ELSE, cylinders define fluid power and its advantage over other technologies. Whether discussing rapid air cylinders or powerful hydraulic versions, these linear force devices offer unmatched performance in countless configurations. With so many forms, it can be daunting to select the right medium, size, mount and variant right for your application. This designer’s guide will drill down every aspect of air and hydraulic cylinders to help you select the best option for your machine, application and budget.

between hydraulic or pneumatic options

Perhaps the easiest part of cylinder selection is deciding between air and hydraulic motivation. It’s likely you already know if you’re in need of air or hydraulic cylinders, but there’s an area of crossover that is important to consider. If your shop, factory or machine is currently equipped with a compressed air system, and your force requirements are minimal, it’s likely a pneumatic cylinder is a solid choice. However, if you require a force capable of lifting houses or crushing cars, your only real choice is hydraulics.

You're correct in assuming the choice isn't as simple as selecting either the red pill or the blue pill. Energy isn't free, so even if you're excited to build your first automated beer bottling production line, your fivehorsepower Walmart air compressor won’t fit the bill (nor does it likely make five horsepower, but that’s another story). Unless your application is light-duty, such as some small pneumatic clamps for your welding jig, you'll likely need a compressor and airline upgrade for continuous-duty pneumatic cylinders. Conversely, hydraulic cylinders require a dedicated pump and control system specific to the requirements of your cylinder and of your machine. These vary vastly based on the pressure, flow and the control circuit unique to your application. You’ll either have to design and build a custom hydraulic power unit that includes the appropri-

ate valves (or have someone do it for you), or accept the limitations of a second-hand power unit or one piggybacking the duty.

I don’t want to spend too much time on the two energy sources since this is a guide about actuators, so know that either a compressor or power unit will probably put you back five digits minimum, unless your requirements are light. Compressed air systems are manufactured to suit the needs of all your shop air equipment, while power units are machine-specific.

I can sum the selection process as such. Suppose you require rapid actuation of loads about 1,000 pounds-force or less while executing repeated movements to and from the same location, operating in a clean environment for a reasonable cost. In that case, air cylinders are your most likely choice. However, for massive force in even a small envelope, where precise and safe control of cylinder load and position is idealized, your only option might be a hydraulic cylinder and the expense concomitant with it.

It should be said that powerful pneumatic cylinders are available, just as are highvelocity hydraulic cylinders. It's not unrealistic to manufacture pneumatic presses with 10- or 20-ton capacity, especially when you combine two or more large-bore cylinders (think 12 in. bore and up). The downside is their thirst for air if you expect much more than a few inches per minute of velocity. And of course, the larger the air cylinder,

the larger the potential improvised explosive device, so be sure only to trust quality manufacturers with a reputation for safety.

Hydraulic cylinders, on the other hand, make at least a ton of extension force even for the smallest bore designation, and there is no limit to the ceiling of force potential, especially as you increase the pressure above 5,000 psi. Just as with pneumatics, expect to maintain high favor with your local electrical utilities provider if you want both high force and stratospheric speed.

For either air or hydraulic cylinders, the calculation for static force is piston area multiplied by hydraulic pressure. You must first calculate the area of the piston, which is A=πr2, where r is the piston radius in inches. The solution to the area equation is factored with your available or ideal hydraulic pressure, F=P x A. As mentioned, this is for static force rather than dynamic force, since we quickly jump through the looking glass into the realm of calculus when you want more precise force and position calculations. So, if dynamic force is part of your machine requirement, a 20-30% bore size increase is a decent rule of thumb.

Once you’ve arrived at the desired bore size, you’ll need to assess your stroke requirement. There is no right or wrong here; if you need a quarter of an inch, then there are cylinders out there to suit your

needs (just don’t expect cushions). This part, in some cases, could be harder than it seems at first glance and could lead to a recalculation of your force needs. Any pivoting or rotating arms or booms must use trigonometry to calculate the required stroke length and determine where the cylinder mounts the arm or boom, as well as the subsequent angle changes that affect the effective force output of the cylinder. Be sure to do your homework here, since you risk either the incorrect stroke length or the incorrect force output.

For most applications, such as presses or material handling, the required stroke is simple to calculate based on the needs of the machine. I recommend allowing your cylinder to bottom out on your machine, preventing the piston from slapping against the inside face of the head or cap. If this is not feasible, ensure you specify cushions. If space is not a limitation and the machine will accept a very-long cylinder, be mindful of the limitations regarding long and thin piston rods, especially with hydraulic cylinders. If the attachment points of the cylinder mount and rod end are subject to radial misalignment, such as a pivoting boom or lever arm, the odds for column misalignment are high. So long as you can sacrifice pulling force, increasing the rod diameter will be necessary to improve strength, since a thicker rod bends less readily.

Even with a beefy rod, your hydraulic cylinder may be subject to a stop tube requirement. A rule of thumb is to specify a stop tube when the distance between the rod end and the mounting point is longer than about 40 in. and when the rod isn't rigidly guided. For head-mounted cylinders, (head trunnions, ME5 flanges, MF1 flanges, etc.)

you can get away with longer stroke, especially when the rod end is rigidly guided. For rear-mounted cylinders, like rear clevis, cap trunnion, cross tube mount, or cap flanges, you’ll definitely require a stop tube for longer stroke. The stop tube is essentially a pipe that slides over a turndown on the rod and is held in place when the piston is installed, which prevents the cylinder from extending its full stroke. This effectively extends the support length between the rod bushing and the piston guide strips, equivalent to holding a second hand on your fishing rod ahead of the reel rather than just the bottom. In case you are wondering, air cylinders are offered with smaller rod options, so we rarely employ stop tubes because they simply produce a fraction of the force that hydraulics can.

Often, the choice of bore and stroke consider the mounting styles, since the type of mount plays a role in column strength, as mentioned above. Some cylinders are “plain,” in that they have no real mount and perhaps some tapped holes in the back of the cap, such as with pancake or ISO air cylinders. However, and just as with many lightduty, aluminum-bodied air cylinders, the strength of the mount is rarely a limiting factor. The compact (and often stainless steel body) air cylinder often comes standard with a combination mount including nose, cap and cap eye, allowing myriad methods of connection, including optional foot brackets. These light-duty mounting methods make no sacrifices due to the limited force capacity of the smaller bore sizes, unlike hydraulic cylinders.

Some mounts are rarely or never used in

pneumatics, such as cross tubes, ME5/ME6 flanges (the mounting flange is also the cap or head), spherical bearing (MP5), and largebore cast iron bodies. It’s not that these are not capable; quite the contrary, these mounts are overkill and would price themselves out of your machine budget. There’s no reason to install a $30,000, 5,000 psi cast-iron press cylinder on a pneumatic machine that could make do with aluminum construction.

With so many options, how does the designer choose which mount to use? When in doubt, look for the “acceptable” mount and then jump up one notch in the strength ladder. Do you have your eye on the endbracket mount? Select the foot mount instead, which uses welded or bolt-on feet with superior strength. Do you feel like the rear clevis might only just get by? Switch your design for the cap trunnion mount for added strength.

Once you’ve selected the bore, stroke and mount of your air or hydraulic cylinder, you need to ask if standard construction mate rial is suitable or an upgrade is required. Although many heavy-duty air and hydrau lic cylinders are manufactured from painted mild steel, most light-duty air cylinders make do with primarily aluminum construction, while others consist of a combination of alu minum and stainless steel.

Stainless steel is popular where wash down occurs, such as the food and bever age industry, but alloys like 316 SS may be required for offshore, boating or even caus tic environments such as black liquor used in the paper industry. Many cylinder man ufacturers will offer stainless steel versions of their cylinders, but you can expect your investment cost to at least quadruple. There may be a middle ground, however, so a highquality epoxy paint might provide a good balance between reliable surface protection

Meet Automation Studio™, the industry standard for mobile machine innovation. From hydraulics and manifolds to electrical harnesses, unify how your teams design, simulate, document and deliver every stage of your machine’s lifecycle.

Highly efficient trade-oriented design process

Encompass the entire machine knowledge

Simulate and troubleshoot digital twins

Over 1 billion manufacturer part numbers

Fluid Power – Electrical Harness – Manifold

and a reasonable budget.

In reality, any metal treatment suitable for steel parts in general will also be suitable for your cylinder choice; black-oxide, carbonitriding or electroless nickel plating all have their benefits and a wide range of costs. Black-oxide is a superficial treatment applied to the surface of steel parts, creating an attractive black finish that offers mild protection for cylinders stored on the shelf for an extended period. However, it will quickly rust in the presence of heat and humidity. Carbo-nitriding is a chemical reaction that hardens the surface of metal, while also offering excellent corrosion resistance. The cylinder rod may only be "nitrided,” but some manufacturers offer the process for the entire cylinder. Nitriding turns the steel a gunmetal grey color that you can leave

vides an excellent foundation for hydraulic cylinders, but a hybrid of both polymers is fairly common.

It's the designer’s responsibility to select the seals for conditions not suitable for standard nitrile or urethane choices. Hot ambient applications in steel mills, for example, will require high-temperature seals rated for high water-based fluids, so a combination of EPDM, PTFE (Teflon) and hydrolysis-resistant polyurethane makes an excellent combination depending on factors such as velocity and load-holding requirements.

For high-velocity air cylinders, standard O-ring piston and rod seals are unsuitable, so Teflon with a nitrile energizer makes a good choice, although even just a nitrile U-cup offers excellent breakaway while sacrificing only a moderate load-holding capac-

unpainted. The electroless nickel plating process is perfect for high-temperature, wet environments with the potential for rapid rust. Such a surface treatment can provide similar benefits to stainless steel construction but at a fraction of the cost, while also offering customers what is perhaps the most attractive finish.

When it finally comes to selecting the sealing technology for your air or hydraulic cylinders, nine times out of ten, the standard package offered by the manufacturer should be good enough for most applications. You can expect primarily Buna Nitrile for most air cylinders, although polyurethane won't be terribly rare for heavy-duty air cylinders. For its more robust nature, polyurethane pro-

ity. High-velocity hydraulic cylinders may do away with traditional seals altogether and move towards a series of rod buffer seals and cast-iron piston rings. Such a combination enjoys extremely low breakaway, although the trade-off is high internal leakage, so don’t use these seals on anything other than dynamic machines such as motion control or destructive test rigs.

Finally, know that you don't have to take an off-the-shelf cylinder if your application requires a unique option, and you may not be aware that these options are included in many manufacturers' catalogs. Cushions are used for both air and hydraulic cylinders to dampen the velocity at end-of-stroke to prevent noise and damage from the pis-

ton slapping against the head or cap, especially due to the inertia of the load. They can be fixed or adjustable, and include options like breakaway check valves or configurable adjustment needle location.

Other options include the stop tubes discussed earlier, but the custom option could be as simple as the port location. If you require the head port on one plane while the cap port on the opposite surface, it's usually just a different part number callout. The same goes for port options; you are welcome to order your air cylinder with ORB ports just as you're welcome to select Code 61 flange ports in your light-duty air cylinder. Every designer has their preference, and so long as you don’t mind the extra cost, you can configure any combination of port style and location.

Electronic additions are also relatively common in both air and hydraulic cylinders. Electric reed switches are ideal for end-of-stroke sensing on aluminum-bodied air cylinders with magnetic pistons. However, adding solid-state proximity switches to hydraulic cylinders also offers the same benefits, albeit with a vastly more expensive investment cost. For the most sophisticated electronic upgrade, linear transducers offer PLCs with infinite position feedback, perfect for accurate pick-and-place applications or advanced motion control simulators.

Despite catalogs with specific options and part numbers clearly spelled out, most manufacturers will be happy to oblige any reasonable request. Other possible choices include valve packages mounted into the head and cap, such as built-in counterbalance valves, or possibly high-impact pistons where cushions are unsuitable. The tandem cylinder takes two (often pneumatic) cylinders stacked end-to-end to provide double the force using the same bore size, albeit with half the stroke for a given size.

Just as with fluid power systems at large, there’s more than meets the eye when it comes to designing the best hydraulic cylinder for your application. Understanding your machine, its operating conditions and a cylinder’s available options will ensure the highest possible performance at the most reasonable investment cost. FPW

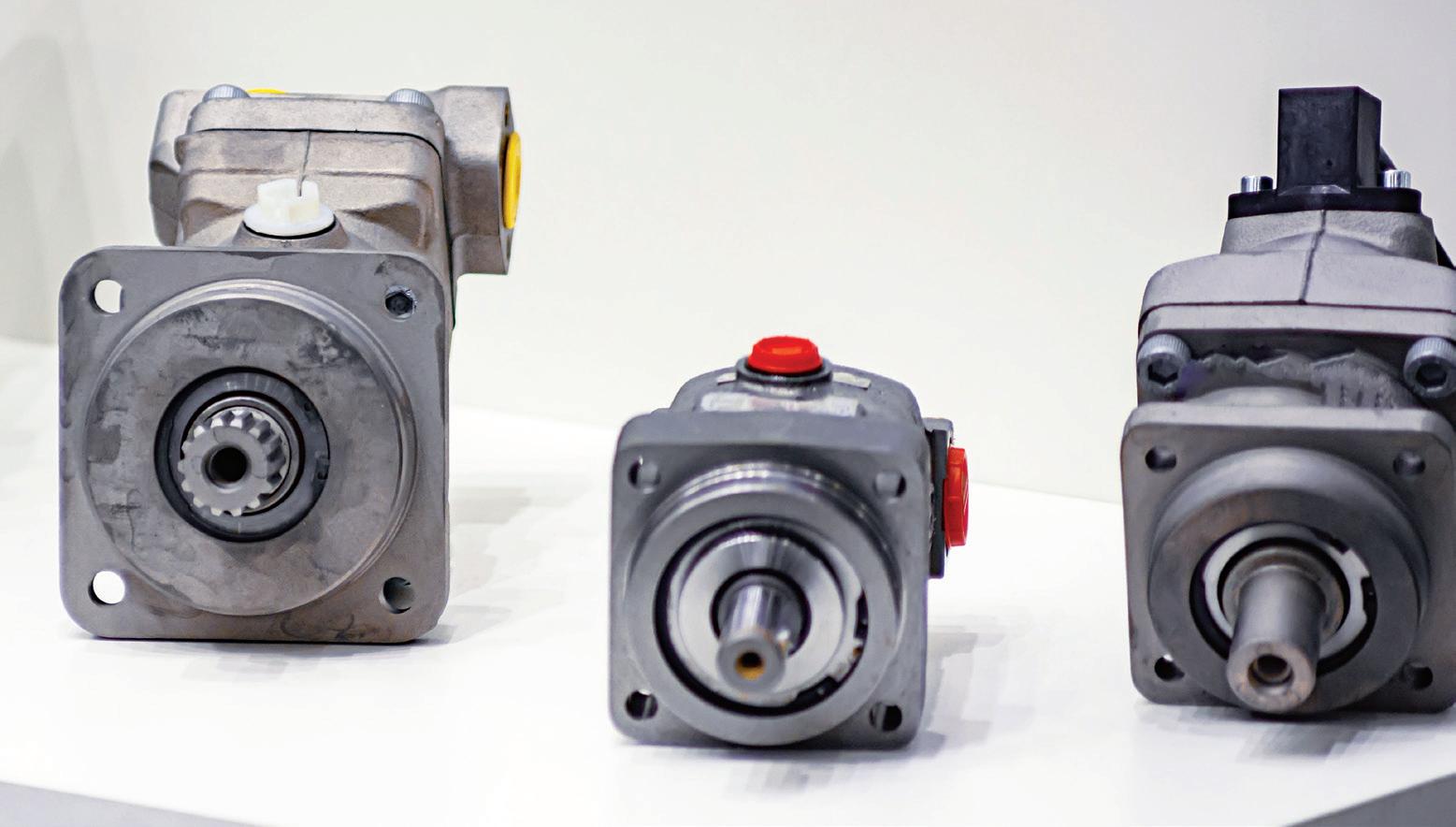

AS AN ENGINEER, hydraulic specialist or budding designer, knowledge of the various hydraulic pump options is imperative to provide your company or customers with the best possible option for any given machine. Despite personal preference for each pump type, dismissing any given design can potentially reduce system effectiveness or result in excessive costs. A gear pump, for example, may be a poor choice for a high-performance system, while a load-sensing piston pump is overkill for a bin tipper.

In many cases, the hydraulic circuit will dictate the pump choice, and it's during the initial planning stage that the type of valves specified will jibe with the pump requirement. And it's perfectly fine to use inexpensive parts to build inexpensive equipment, so simply selecting the most economical options makes sense when the customer understands they're not buying a Rolls-Royce. Meanwhile, some complex valve circuits simply won't function with a fixed-flow gear pump, such as those required when using mobile valves with load-sense technology. This designer's guide to pumps will help you select the hydraulic pumps that are best suited to your application, factoring in flow, cost, controls, and efficiency. Before select-

ing your pump, you must first calculate the required flow rate based on the ideal veloc ity of your actuators. There are two ways to calculate the raw flow.

Cylinders:

a good start for constant cycling, although with infrequent yet rapid traverse, look into an accumulator to handle the extra buffer.

Q = Flow in gpm

A = Area in.3

v = Velocity in./min

231 = in.³ in a gallon

Motors:

Q = Flow in gpm

D = Displacement in.3

N = rpm

231 = in.³ in a gallon

After you arrive at your raw flow numbers, you'll have to factor in things like acceleration/transients and efficiency. While being sure that working pressure was first calculated with sufficient extra pressure to help with acceleration, adding a bit of flow margin will also help with cycle times, especially

Although hydraulic cylinders are nearly 100% efficient, motors experience a wide range of fluid lost through leakage and lubrication. Expect only 60-90% efficiency for motors ranging in order of efficiency from low-speed high-torque gerotor style, gear motors, vane motors and then piston motors. The percentage of fluid lost to inefficiency must be added to the pump flow rate to compensate. So, if the theoretical flow of 10 gpm meets the rpm requirement, divide by the efficiency. For example, 10 gpm ÷ 0.60 = 16.7 gpm for gerotor motors, or 10 gpm ÷ 0.90 = 11.1 gpm for piston motors. These two examples demonstrate the importance of selecting an efficient design.

Once you’ve calculated your flow requirement, you can now calculate your pump displacement. Remember that pumps also experience both mechanical and volumetric inefficiencies, the scope of which depends on the pump type. Given that, you must factor efficiency when deciding your pump's displacement, but otherwise, it's calculated essentially the opposite of motors.

We expect your worst every day. It’s why we engineer and test for it in every one of our high-performance hydraulic hoses. With abrasion resistance second to none you can treat our hose like dirt. As for our team, they’ll treat you like gold. See why we’re the name to know. Make A Continental Shift.

Pumps:

D = Displacement in in.³

gpm = Gallons per minute

231 = Cubic inches in a gallon rpm = Revolutions per minute of the prime mover

Going back to our previous example of the 10 gpm gerotor motor, let's say we're looking for 1,000 rpm (take your time and crossreference the formulas). Our 60% efficiency crutch means we need to throw 16.7 gpm at a 2.31 in.³ motor (ignore pressure for now). To make up for the energy lost to the gerotor, let's spec an axial piston pump operating at 90% efficiency run via a 1,750 rpm industrial electric motor. Keep in mind that speed from engines will vary, but it's always safe to base your math on the rpm where your engine produces the lowest brake-specific fuel consumption.

Running the calculations, once again, our theoretical flow rate to determine displacement is 18.6 gpm after we factor in the efficiency rating. And then again putting the 231 in.³ into the mix (because we don't rate pumps by gallons/revolution) and then the speed of the motor, we arrive at just under 2.5 in.³ of pump displacement. Many piston pumps are described in metric, so multiply by the constant of 16.4 to arrive at around 40 cubic centimeters per revolution.

Let's start fresh now that you know how to calculate your required pump displacement, because you have a few pump options to choose from. Gear pumps are the most economical choice, and operate using two spur gears installed in a pump body. With one driven and one idle gear, the prior motivates the latter as fluid is pushed around the circumference of the pumping chamber to create pressure and flow. While we’re on the topic, always remember that pumps create pressure, which allows flow to occur and not the other way around.

Gear pumps offer the widest range of displacement, from tiny fractions of a cubic cen-

timeter all the way into the hundreds. They are the most resistant to contamination and enjoy the most lax contamination control protocol. However, they are very inefficient, even when new, and will only go downhill as they wear. They may include valve trickery, such as unloaders, but for the most part, they are simple and have fixed displacement. I should mention that the inside gear pump is highly efficient, but it comes with the penalty of an exponential investment cost compared to the outside spur gear style.

Vane pumps are a popular industrial pump choice because they are quiet while still reasonably priced in their fixed-displacement variant. They offer higher efficiency than gear pumps, but be prepared to pay two or three times the cost for fixed-displacement versions. Variable displacement vane pumps are popular in the machine tool industry, where they provide inexpensive pressurecompensated function in small to medium flow applications. You can find higher-flow, higher-pressure variable displacement vane pumps, but considering how expensive they are, it might be better to look at piston pumps unless you absolutely require a quiet option.

Piston pumps are the most efficient of the Big Three, but they come with a considerable price handicap, especially as you step up to the more advanced control systems. They're also the most varied, not just in construction, but also in methods of compensation and control. Outside of specialty pumps, they generally range from around 5 to 1,000 cc

per revolution or higher. You know the math for displacement, but let’s explore what other features are important to the designer. There are three popular types of piston pumps: the axial, bent-axis and radial designs. The bent-axis piston pump has a (normally) fixed angle between the input shaft and the rotating group of pistons. The design includes a strong shaft bearing assembly that makes the motor highly resistant to side-load and suitable for very high speed, such as engine-powered applications. A few manufacturers make a variabledisplacement version, although they are uncommon; most pumps are fixed-displacement. If you want highly reliable, reasonably priced access to high-speed, high-pressure pumps, consider the bent-axis version.

The radial piston pump sits atop the throne of high efficiency, with many designs returning 95% efficiency. Their WWI airplane engine appearance inherently converts linear force into rotational force with minimal waste product, and is also available in variable displacement versions. Their limitations are two-fold: the triple-thick manhole cover size and weight for larger displacements, and the expected financial capital to purchase a hydraulic pump the size of a triplethick manhole cover.

By a wide margin, the most popular piston pump is the axial piston variety, which comes in the (rare) fixed-displacement and (common) variable-displacement siblings. The latter uses an adjustable swashplate tilted by a control piston to vary the stroke

1

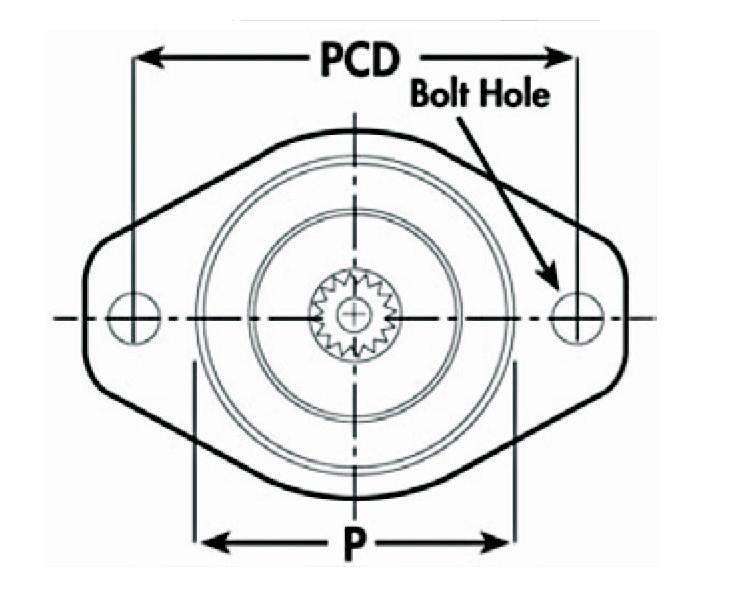

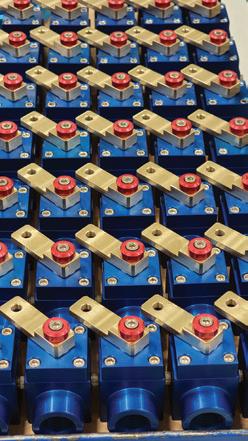

PUMP MOUNTING IN NORTH AMERICA IS PRIMARILY A VARIATION OF THE SAE J744, WHICH DEFINES THE FLANGE BOLT PATTERN, SHAFT TYPE AND PAD INTERFACE.

length of the rotating pistons. Their pistons reciprocate in parallel with their rotating shaft, offering the most compact package possible, considering their extensive list of features.

I could write a book on the various control technologies available for variable displacement piston pumps, but I'll do my best to explain the basics. One thing in common with most of these is their requirement for closed-circuit valves, which block flow in their neutral state. The basic pressure-compensated version uses what is essentially a relief valve to direct pilot pressure to the control piston, which pushes hard against the swashplate to counter the bias spring/ piston, which is attempting full displacement. Should the flow rate encounter enough resistance, say, 3,000 psi worth, the compensator will direct more pressure to the control piston to reduce swashplate angle to reduce displacement until there is equilibrium.

The second most common control method adds load sensing to the pressure compensator function, which uses a series of pilot lines that measure pressure downstream of any metering elements (flow controls or proportional valves) to maintain a particular pressure drop. Whereas pressure compensation alone stuffs its entire spring value worth of energy in the system to create flow (e.g., 3,000 psi), load sense provides only enough flow to maintain the 300400 psi of pressure drop equal to its setting.

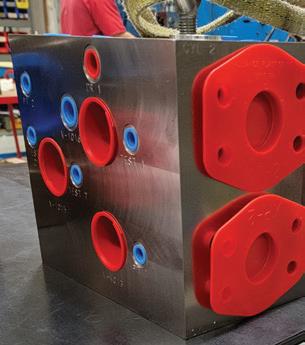

Such a system is astronomically more efficient, although it comes with the cost and complexity required to acquire a pressure signal from every workport line in the system. As such, these are often limited to systems using specialized valves (like sectional mobile valves) or custom manifolds using check or shuttle valves neatly ported inside.

Pressure compensation and load sensing are, by far, the two most common types of control. Still, there are many useful options that you should be aware of. If your machine

is limited in horsepower due to emissions standards, yet you want the best of both worlds in terms of pressure and flow, select the horsepower-limiting pump. This option is capable of high flow or high pressure, but will restrict total power output to prevent them from occurring simultaneously, and will do so seamlessly. Nearly all excavators, for example, use a horsepower control pump to enable rapid work functions when loads are low, but can ramp up pressure while slowing down speed to overcome heavy loads.

Less common, although widely available, are electric or electroproportional control of pumps. From simply using a directional valve to switch between two different pressure settings on two different compensators, to servovalves that operate alongside closedloop electronic control to vary pressure and flow precisely. Remote compensation uses a separately plumbed relief valve directing its pilot line to the pump so that pressure is easily adjusted away from the pump. The relief valve could be either knob-operated or electroproportional. Before we conclude on controls, remember that some vane pump designs come with several of these options.

Now that you've selected your pump type, along with its displacement and control option (if applicable), the designer must know how these are installed and plumbed. Fundamentally, the principles are the same, despite geographical variations – you need to mount the pump, drive the pump and then connect the plumbing.

Pump mounting in North America is primarily a variation of the SAE J744, which defines the flange bolt pattern, shaft type and pad interface. The flange comes in 2- or 4-bolt configurations, with bolt centers ranging from 3.25 to 12.5 in. (on large pumps). For heavier pumps, the 4-bolt design is recommended to manage the overhung mass better. The pilot of a pump is a critical design element preventing shaft misalignment. The pilot is a cast or machined counterbore that inserts into the mount or bell housing, avoiding the time-consuming radial and axial alignment techniques of yesteryear. For metric options, it's less

for pump mounting flanges and shafts, as the standards for mounting flanges may differ from the pump standard. Nevertheless, the ISO 3019-2 standard is a cousin to the SAE J744 and describes the flanges and shafts on most pumps on the overseas market. For ISO mounts, many pumps use a rectangular flange, although the bolt centers and pilots will be entirely different from those of SAE Mounts.

What’s common is the need for a bellhousing (pump/motor mount) that conjoins the pump and prime mover while offering a central space for the shaft connection. Many manufacturers of power unit components offer various standard mounts for a variety of NEMA and Metric motors, which themselves employ a bolt circle and pilot to oppose the pump’s. The distance between each flange face accommodates the shafts, which themselves are connected to one another with couplings. Ensure that you calculate the combined lengths of the pump

and motor shafts with sufficient room to accommodate the polymer insert.

Bellhousings are offered in horizontal and vertical styles, which are selected based on the type of reservoir used on its power unit. The horizontal type must be strong enough to hold the (sometimes heavy) pump in free air. The vertical type often coincides with the in-tank pump mounting method on ver-

tical reservoirs, where it actually sits within the oil. Be sure to select the correct pilot and bolt centers that match your reservoir. Your final criterion for selection is the port and plumbing standard. This requires less lengthy discussion since you'll likely just choose what's appropriate for your locale: SAE ORB or Flanges for North America, BSPP or Flanges for Europe, and the rest of the world will vary. As a designer, avoid tapered ports and, if possible, use flanged ports to make installation easier, as fitting and hose orientation are less critical during installation. Otherwise, just select what is popular in your area.

Selecting the perfect pump for your hydraulic system ensures you can balance the best combination of performance, price and maintainability. With so many options, it's easy to be paralyzed by choice. However, if you follow this designer's guide and work through each criterion, your biggest challenge will be how quickly you can get it. FPW

Check Valves

Flow Control Valves

Needle Valves

Flanges & Adapters

Bar & Custom Manifolds

Pressure Gauges & Snubbers

SSW Power Unit Systems

Transfer Pumps

Industries Served:

• Oil & Gas

• Industrial Hydraulics

• Mining

• Forestry

• Chemical & General Processing Plants

• Medical

• Aerospace

• Factories

• Mobile Equipment

• Defense

• Machine Tool

• Testing Equipment

• Ocean Depth Technology

• Automotive

• Food Processing

• Agriculture

• Industrial

• Aviation

• Petrochemical

• Marine

• Subsea

HYDRAULIC MOTORS ARE POWERFUL and energetically dense rotary actuators with designs as versatile as their applications. As a hydraulic designer, you should know how to select a hydraulic motor that best suits your machine, balancing performance, price, and reliability. The range of options is vast, but this guide will steer you through the selection process to find the model best suited for you.

Calculating the torque required from a hydraulic motor is quite a bit more involved than with a cylinder, but we'll work through a couple of examples together. For simplicity, we will start by running the calculations for a winch application before moving on to a drive wheel application. We'll limit the number of variables, where possible, while still explaining the concept and math effectively.

A winch is a simple hydraulic machine that uses a hydraulic motor to rotate a drum to reel in a cable or rope. Some employ a gearbox, but we’ll stick to direct drive winch

motors for now. You must first select the force required from the pull of the cable, described conveniently enough as line pull. If you wish to pull or lift 10,000 pounds, for example, your line pull is 10,000 lb if we ignore any complexities added by pulley blocks. We then must calculate the torque on the drum where the cable lies:

T = F x rT = Torque at drum (foot pounds)

F = Line pull (pounds force)

r = Drum radius (feet)

The drum radius varies based on its cylinder diameter and the combined thickness of the cable wrapped around it. The larger the radius, the more torque is required to rotate the drum for any given line pull, so your calculations must factor in the layer build of the stacked cable. A full drum requires more torque, so make your calculations accurately and avoid assuming the torque is the same

as with an empty drum. One more thing –if your winch needs to pull a thing, be sure that thing is part of your equation. Whether an anchor or a load of concrete, it must be contained within your line pull figure.

Using this math and a drum radius of 1.5 ft, our required torque is 15,000 ft-lb. However, as you'd guess, that's just a raw number subject to detrimental factors, such as inefficiencies and a safety factor. If you plan to pull exactly 10,000 lb, offering a hydraulic motor rated for a theoretical 15,000 ft-lb would be a dangerous proposition.

Imagine an overhead crane running on the hairy edge of performance with a construction crew working 100 ft below. Depending on the industry you operate in, you need to apply a safety factor of 1.2 to 2.0, ranging from off-road winches to overhead cranes. Say our winch is designed for marine use, and we use 1.5 as our multiplier, which results in 22,500 lb-ft of torque. This extra fudge factor should include inefficiencies of the drum itself, such as the bearings, couplings and possible sealing elements.

22,500 lb-ft is a respectable amount of torque, especially considering there's no gearbox involved, but now we know what we need from our hydraulic motor. The most important consideration is ensuring that the motor's actual output matches your requirement. It sounds easy, but because the efficiency of a hydraulic motor varies widely with pressure and speed, you must select the displacement for the worst-case scenario. Unlike hydraulic pumps, which often follow a rule of thumb for efficiency, hydraulic motor data sheets are sometimes published with performance curves that show the sweet spot for efficiency at a particular speed and pressure. (Yes, these curves are also available for pumps, but they're often closely guarded secrets.)

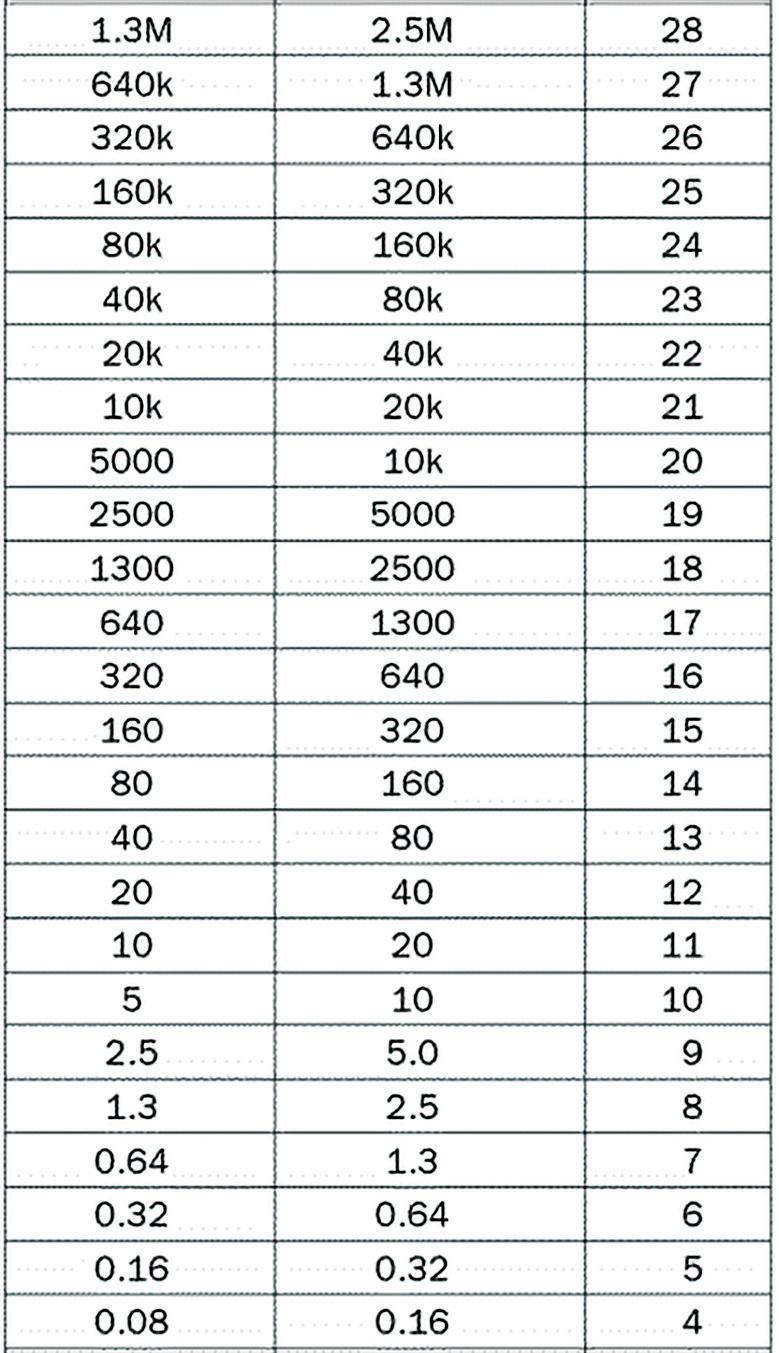

The example in Figure 1 is a performance curve that compares torque (pressure) with speed (rpm), and shows where the motor is happiest running. You can see that between 10,000 and 25,000 lb-ft and 5-12 rpm, this

motor is 96% efficient, which is extraordinary. Without knowing more, we can see that this motor would be pretty good for our winch application, where it will be highly efficient during normal operation but also packs plenty of room to spare in the safety factor department.

Many of you already know you’re looking at the curve for a radial piston motor, which can produce monstrous torque with remarkable efficiency. However, not every motor manufacturer publishes these curves, especially for some of the lower-cost options.

Gerotor and disc valve motor manufacturers proudly publish the performance data for the world to see, despite less-than-stellar efficiency. Their data is arranged in grids, so you'll have to calculate efficiency manually, but if you can find the exact sweet spot, you can achieve 85% efficiency or higher. Also called orbital motors, these units can easily drop to below 50% efficiency when operating outside their ideal range.

Besides these two examples, and because pump curves are unavailable, you must make assumptions surrounding efficiency. Other motor options are the gear (80% efficiency), vane (85% efficiency), and axial and bent-axis piston (90% efficiency) designs. These can vary, so check with your preferred manufacturer. Regardless, we need to use efficiency numbers in the selection of motor displacement, which is calculated as such:

D = Displacement (in.³)

T = Torque (in.-lbs)

∆P = Pressure drop (psi) n = efficiency (%)

You'll notice that we switched to in.-lb for torque, which is done to keep the units consistent in the formula, as we don't specify motor displacement in cubic feet per revolution. Multiply by 12 to get inch-pounds. Additionally, instead of just discussing the pressure available at the motor's inlet port, we must subtract any pressure at the outlet port, which is why the "delta" is described above in terms of pressure drop. Running through the above winch motor example, which requires 22,500 ft-lb of torque and assuming we have 3,000 psi of pressure drop while using that sensational 96% efficient motor, we arrive at around 589 cubic inches of displacement (or about 9,600 cm³). I told you it was big.

Although not part of the motor selection process, consider that this motor will require over 260 gpm of flow to reach a reasonablefor-a-winch speed of 100 rpm. The calculation for motor flow requirement is opposite

to that of pumps, as follows:

Q = Flow (gpm)

D = Displacement (in.³)

rpm = Revolutions Per Minute

231 = Cubic inches in a gallon

n = Efficiency (%)

Increasing complexity

We’ve come this far, and we've learned to calculate the torque, displacement and flow requirements of a hydraulic motor for a winch application. But what if you're building something like a hydraulic ROV, then we’ll have to kick the complexity up a notch:

= Ftotal · r (1 - s) · nm =

(µr W + W sin θ + W + Fd) · r (1 - s) · nm a g

T = Torque required

Ftotal = Total Force

r = Wheel radius

s = Wheel slip

nm = Motor efficiency

µr = Rolling resistance coefficient

W = Weight of vehicle

a = Acceleration required (ft/sec²)

g = Gravity (32.174 ft/sec²)

Fd = Drawbar force

You can see that total force is equal to which is, in order, rolling resistance, grade resistance, acceleration force and drawbar pull. It's a lot of math, but it's not hard math unless you've forgotten how to do trigonometry (which is required for the hydraulic specialist certification, anyway).

(µr W + W sin(θ) + W + Fd) a b

We can’t work through every single step

and variable here, and we don’t want you to glaze over this article trying to follow along with grade 8 math. We can make some assumptions as far as variables go, however. If we build up an example, let’s go on the generous end of the variable range to ensure we have appropriate torque to overcome modest obstacles.

Rolling resistance: Let's assume soft ground and apply 7% of the vehicle's weight to soft tires (a coefficient of 0.07).

Grade resistance: We'll say a 10% grade should be overcome, such as you'd see driving a golf course.

Acceleration: Our hydraulic ROV is not a drag car, so let's cap acceleration at around 3 ft/sec².

Wheel slip: Since we have soft tires on soft ground, let's say 10%.

Motor efficiency: A fixed displacement axial piston motor sounds good, so let's say 90% here.

Weight: We're just building a generic prototype for fun, so let’s say 1,500 lb.

Wheel radius: I think a 30 in. tire would be perfect, so let's say 1.5 ft radius here.

Drawbar force: Let's just keep the trailer out of the picture for now – vehicle and operator only.

Plugging it all in, we arrive at around 732 lb-ft of torque from our axial piston wheel motor, which is a respectable amount. Running the displacement numbers discussed earlier, and ignoring the efficiency because it has already been factored into our calculation, we will need an 18.4 in.³/rev motor (or approximately 300 cc/rev). I should mention that there are many ways to calculate vehicle drive force, many of which require multiple steps; however, this version is the most compact. Regardless, if you come across another method, it's okay to use that one as well.

Once you've calculated your required hydraulic motor displacement, you can review the available types to determine which one suits your application and budget. As mentioned earlier, our options are gear, orbital, vane and piston. Not every option is available in the sizes you may need, so be sure to check manufacturer literature to

confirm what is available.

Gear motors are the most basic design and are essentially gear pumps that include an upgraded shaft seal for unidirectional versions, allowing them to handle the pressure in both ports. Bi-rotational gear motors may use check or shuttle valves to bleed pressure to the opposing port, as internal leakage may otherwise build to a dangerous level.

Believe it or not, gear motors also offer respectable high-rpm operation, with many capable of 3,500 rpm or more. Their economical cost of entry is also a benefit, although the downsides reflect the price point. They offer generally poor efficiency, even when brand new, although they're very reliable and resistant to contamination. They stake a claim to the smallest size, easily down to a fraction of a cubic inch displacement, and some manufacturers offer upwards of twelve cubic inches per revolution or more.

Vane motors are an interesting group, offering all the same benefits as their pump siblings: quiet operation, decent efficiency, and a wide range of sizes. Many are based upon their pump counterparts, so expect the same appearance as the venerable units that have proliferated in steel mills for the past five decades. They are easily repairable, and specific designs are easily modified to change the orientation of their ports. Expect a price point midway between gear pumps and piston pumps, but possibly lower if you opt for the knockoff versions.

Piston motors offer the broadest range of displacements, the most varied control systems, and the most specialized applications. Axial piston, bent-axis, and radial piston motors offer the highest power density due to their high-pressure capacity, which ranges from 5,000 to 10,000 psi. They range from tiny fixed-displacement designs to monstrous 13-liter units capable of twisting the Empire State Building.

The axial piston motor features a rotating group that spins around the shaft, while the pistons reciprocate parallel to the shaft. A fixed-angle swashplate controls the depth of stroke, and displacement is a factor of the number, diameter and stroke distance of its pistons. Variable displacement axial piston pumps are less common, perhaps because

of their “medium duty” pressure rating (if you consider 5,000 psi medium-duty), but look for these as an excellent option for hydrostatic wheel drives with integrated hubs. Because axial piston motors are less popular, they're not available in a wide displacement range, such as other designs.

The bent-axis piston motor is a high-pressure, high-speed design with a fixed- or variable-yoke angle, and a side-load-resistant design suitable for pulleys or gears. They're offered in many variations for general-purpose or wheel-motor applications ranging from 5 cc (0.3 in.³) to over 1,000 cc (61 in.³), and capable of over 7,000 psi and 11,000 rpm in extreme examples. One particular manufacturer offers a 5 cc version that offers over 35 horsepower in a package that will fit into your coffee cup.

Radial piston motors wear the crown if charged with ruling the land of power and expense. For (mostly) slow, high-torque applications, such as winches, wheel drives, and crushers, nothing else comes close. They're inherently capable of high pressure, and like all high-pressure pumps, they are sensitive to particle contamination. Radial piston motors, with a few exceptions, aren't available as variable-displacement and are relatively devoid of advanced control features outside of braking systems or multi-speed control. Don't even look at these if your application calls for small displacement, but for everything else above a thousand cc's, this is pretty much your only option.

No discussion on motor types is complete without the orbital motor. Also called gerotor motors, these are a unique design and are essentially a type of inside-gear motor, where the inner rotor and outer ring gear rotating as directed through one of various internal valve functions. Available from a tiny 0.3 in.³ to a massive 75 in.³, they cover the torque and speed range requirements for most motor applications. They use various valve technologies to port fluid sequentially to create power; spool valves, disc valves or various other designs, they're actually quite clever.

They're highly economical, readily available and easy to install, but come with the downside of poor efficiency, especially when run outside their ideal pressure and speed range. They’re commonly found in mobile machinery and are also available in specialty applications such as wheel drives with integrated braking functions.

With so many hydraulic motor options, it may seem overwhelming to choose any given design. However, when you work through the math, consider your unique requirements and then factor in your budget, the ideal design will ultimately come down to a couple of realistic options.

FIGURE 1

MOST PNEUMATIC CYLINDERS ARE AVAILABLE WITH STAINLESS STEEL OR ANODIZED ALUMINUM CONSTRUCTION.

may be simple if your load is lifted vertically by the cylinder, so use this version of the

understand your requirements. I won't pretend that application isn't the most important deciding factor, but the same can be said of any fluid power actuator. This guide provides all the information you need to select the pneumatic cylinder design best suited to your machine.

First and foremost, I recommend you first read A Designer’s Guide to Cylinders (see page 8) which covers a lot of technical but general information related to cylinder selection. This article is to elucidate the specific nature of pneumatic cylinders to help you refine your selection amongst the myriad standardized and custom solutions offered by manufacturers.

First and foremost, calculate the static force required by your cylinder, which gives us a starting point for deciding upon a bore size. By “static,” I mean essentially the mass of the load you’re moving. The calculation

Pressure differential and more You’ll notice that I used the term pressure , which is important to understand, but we’ll get to that in just a second. In the meantime, let’s say we have 500 pounds to lift, and our shop pressure is 100 psi. Running the math, we arrive at an inconvenient bore size of 2.52 in., which is slightly larger than the 2.5 in. standard typical in North America. We'll have to jump up to the 3.25 in. to accommodate the 500 lb of our load, which likely, we’d do anyway to avoid a marginally capable cylinder.

You must not assume that compressor supply pressure is available in its entirety at the actuator. Even with an FRL located just ahead of the directional valve showing adequate pressure, you must subtract the pressure drop through the valve system and the airlines, and then finally subtract the pressure measured at the cylinder's opposing work port. This last part is essential because pneumatics is sensitive to pressure drop — in other words, the differential pressure across the piston. (See sidebar on page 27 for more on FRLs).

Many designers prefer to meter out, which means installing the flow control valve oriented to restrict flow exiting the cylinder, which in turn creates back pressure. That back pressure must be subtracted from the work pressure. There is no hard-andfast number here because the generation of

that back pressure depends on the actuator speed, the flow control setting, and the load-induced pressure.

Also, remember that this pressure differential only describes the dynamic properties of the cylinder, where motion itself creates back pressure. A slow-moving or static load is not affected by back pressure from metering out, but since we're still working through our bore size calculations, let's use an estimate of 20-40% pressure loss. Although you can install pressure gauges in the work ports of your cylinder, we still need to select our bore size to lift 500 lb, so let's use the mean figure of 30% reduction from our 100 psi shop air, so we arrive at 70 psi for dynamic loads.

As it turns out, a 3.25 in. bore cylinder can still lift 580 lb with only 70 psi available, and although marginal, should be fine for this application. Acceleration won't be rapid, but will suit our application. And before you ask, we like to meter out in pneumatics to create some level of "hydrostatic tension," which offers more stable control.

Once we've settled on the bore, we can move on to selecting our construction type. The stroke is less critical for this process, so long as the construction type is long enough for your application. Some cylinders are limited in stroke, so if our lift requires more than thirty inches or so, we’ve automatically disqualified many designs.

As mentioned in A Designer's Guide to Cylinders, the construction type is usually a preference, but you need to be aware of each. Although not by any means comprehensive, the following chart provides a list of the most common construction types or standards, the range of sizes and their typical application. Please note that I didn’t survey every single worldwide cylinder manufacturer, so if you’re a manufacturer making products outside these sizes, good for you.

PNEUMATIC CYLINDER CONSTRUCTION TYPES

Pancake 1/2"-4" 4"

There is some crossover to many of these cylinder types. For example, ISO 21287 with compact, square bodies may be available with non-rotating pistons, although normally such cylinders are unique designs not interchangeable between manufacturers.

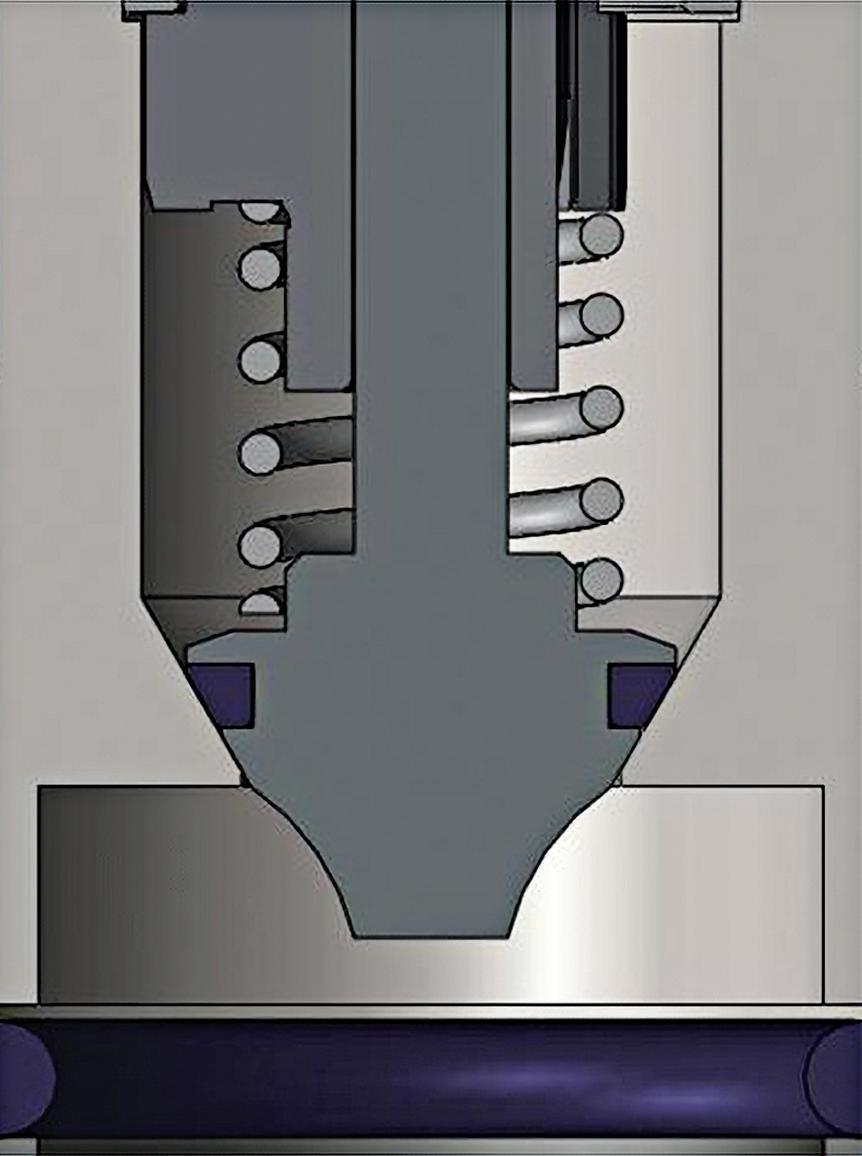

When you see "clean" under the Typical Use column, it means a cylinder devoid of construction materials that would emit or outgas during operation, such as grease, assembly lube, or wear particles. They're typically stainless steel or anodized aluminum, Figure 1, and have more streamlined designs that are easy to clean and resistant to the accumulation of biofilm in crevices or joints. They're typically used in semiconductor, pharmaceutical, medical, and food & beverage industries.

NFPA and mill type cylinders are, as far as pneumatics is concerned, extreme duty options with inherent strength many times what’s required. You’re unlikely to ever break one of these cylinders, so aside from seal kit replacement, these cylinders should last a lifetime. NFPA tie-rod cylinders are industry-standard mounts, and many manufacturers now offer a light-duty "interchange" version with aluminum construction. NFPA cylinders from Company ABC will directly cross to Company XYZ, so don’t be afraid to use your favorite local supplier.

Aluminum body, steel or SS rod Very light duty, custom applications Compact, inexpensive

Many of the ISO designations offer standard or common options, such as extruded aluminum profiles that encourage the use of reed switches, which easily slide into a protection position at the side of the cylinder where they can sense the magnetic piston, Figure 2. These profiles make manufacturing simple as the extrusions are cut to either standard or custom lengths and then heads and caps are bolted to either end using threaded studs to seal the cylinder tightly.

The sleeve-nut style studs provide what

is essentially a standard cylinder with the option for various common accessories and mounts. The base cylinder could be mounted directly to the four sleeve nuts on the head or cap, or be used to mount one of various clevises, eyes, spherical bearings, head/cap flanges or foot mounts, Figure 3 When selecting your mount of choice, just remember that side load (forces from any direction other than the same axis as the piston) are not your cylinder's friend and will subject the cylinder to early failure. Ensure

your load is guided rather than simply hanging from the rod end.

Once your mount is finalized, you may need to consider the maximum cycle time or velocity. Cycle time factors acceleration and cushioning (deceleration), while maximum velocity is a design limitation of the cylinder, its construction and its seal package. U-Cup seals typically offer quicker breakaway than O-rings or their variants (like quad rings), which are "interference fit," and subject to higher static friction. Such seals are great for some applications, such as those holding position for longer, but expect a lower velocity rating.

That being said, air cylinders are fast. A U-cup (lip seal) equipped cylinder can expect to perform at over 20 in./sec velocity, while O-ring equipped cylinders might cap at half that speed, although sometimes slower, depending on the construction. In reality, the cylinder will move as fast as it's being asked to when you throw enough pressure and flow at it, but you risk damaging the cylinder or the machine if you don't curtail velocity.

When you exceed the recommended velocity of a particular design, the seals are the first to go. More speed means more friction, and the seals will generate heat, leading to rapid wear. You could also see cata-

WHEN SELECTING AN FRL , one must not overlook the significance of understanding FRL air flow characteristics, which is more complex by nature than more simple components.

Airflow is critical in determining the efficiency of pneumatic systems, as any pressure created to overcome restrictions is forever lost as heat. An FRL matching the system’s required flow rate ensures that the equipment and actuators receive an adequate supply of clean, pressure-regulated air. Insufficient airflow can lead to decreased system performance, slower actuation times, and compromised productivity. On the other hand, oversized FRLs may result in unnecessary energy consumption, increasing both capital and operational costs. Understanding air flow helps strike the right balance, optimizing efficiency and maximizing output.

Regulating air pressure is crucial to ensure safe and reliable operation of pneumatic systems. By understanding airflow requirements, one can select an FRL that can effectively regulate pressure within the desired range. Insufficient pressure control can result in erratic actuation, unstable operation, and potential damage to components. Conversely, excessive pressure can cause leaks, premature wear, and even equipment failure. FRLs’ flow characteristics are described in two ways — flow rate and pressure drop.

The flow rate through an FRL is dictated partially by the size of the filter, regulator and lubricator, as well as the construction style of each component and the pressure setting of the regulator. The filter media construction and micron rating affect the backpressure across the filter, with deep pleated designs down to 0.01 micron tending to resist flow more than inexpensive 5-micron filters. Still, it’s easy to oversize your assembly rather than sacrifice filtration quality.

The lubricator reduces flow the least in the FRL and instead is just an oil reservoir using the Bernoulli principle to atomize the lubricating fluid into the air stream. The flow reduces slightly as it passes through the venturi, where the increase in flow rate reduces localized pressure, thereby pulling oil up the

capillary tube where it’s introduced into the air stream.

The regulator influences airflow the most through an FRL and, by its very nature, may restrict flow to subsequently reduce pressure. The essential function of a regulator inherently restricts airflow to reduce downstream pressure. Using poppets, pistons or diaphragms, the regulator’s spring and its preload control the force required to open the valve and allow flow to occur. Users may adjust the spring tension to adjust the preload to increase the pressure that prevents the restrictive element from closing as easily. The regulator seamlessly balances the restriction with the outlet pressure to smoothly control pressure at the desired setting, opening the valve to increase pressure or closing it to reduce pressure.

Regulators have an operating range best suited to their design, and any pressure and flow used outside that range results in either weak pressure control with unstable flow or a locked regulator with no flow. Downstream pressure must remain well enough below the regulator set pressure, or the unit may lock up and allow no flow at all. Conversely, when the flow is high while pressure is low, much energy is wasted to pressure drop. It’s also important to know that the higher you set your regulator, the less it will flow. As previously mentioned, the regulator restricts flow to reduce pressure, so trying to regulate pressure in the upper reaches of the design range may restrict flow to an unacceptable degree. Be sure to select a regulator that flows well in the upper-pressure range, should you need it.

The above descriptions are simplified because regulator design is surprisingly varied. Singe stage regulators work well with stable, low-pressure regulated machines and tools. However, if your plant’s air usage varies widely or machine demand is not stable and constant, a two-stage regulator provides a superior choice. In some cases, regulators are also available with the pressure-compensated option that helps maintain stable flow despite fluctuations from inlet or downstream pressure.

strophic slipping, tearing or extruding of the seal when left unchecked. Then comes physical damage, as the piston slams into the head and the cap, or perhaps damages the cushion system or bumpers.

It’s rare that cylinder airflow needs outstrips air supply, especially in industrial manufacturing and automation, where large compressors supply massive airflow on demand. In pneumatics, we first choose our cycle time and then work backwards to calculate the required cfm to do the job. Once you are set on your cycle time (the number of times the cylinder extends and retracts per minute), you can use the following to determine the required cfm. The (0.7) assumes you can only achieve 70% of your cycle time due to acceleration, which is a safe number:

CFM = Cubic feet per minute

A = Area of the piston

S = Stroke length in inches (0.7 acceleration factor)

N = Cycles per minute

1728 = Cubic inches per cubic foot (because we're using two different units)

If you’re more concerned with velocity, you can use the following formula. Remember that this is only full speed velocity and doesn’t factor acceleration:

The mount plays a role in pneumatic cylinder performance and reliability, so please reread A Designer's Guide to Cylinders for specific information on column strength, head versus cap mounts and other important information. The reality is that pneumatic applications are slightly less critical in terms of strength limitations, since they're responsible for only a fraction of the force required by hydraulics. Still, pneumatics carries far more risk as it pertains to velocity. A small mass accelerated rapidly still has the potential to cause self-induced damage, so be wary of using weaker mounts with highvelocity cylinders.

CFM = Cubic feet per minute

A = Area of the piston in square inches

V = Velocity in inches per second

N = 60 seconds in a minute

1728 = Cubic inches within a cubic foot (see note above)

To recap, the weaker mounts are those with pivot cap mounts, such as rear clevis, rear eye, or perhaps less so, cap trunnion. They extend the column length to more than twice the stroke length and, without a stop tube or oversized rod, can be very weak in long-stroke applications. Even with shorter cylinders, remember that inertia can mimic

PNEUMATIC CYLINDER SPECIAL OPTIONS

Option Details

Cushions Decelerates at the end of stroke to prevent slamming and subsequent damage — may be adjustable or fixed

Switches and Sensors Reed or proximity switches can read sense the magnetic piston through the aluminum tube for position sensing

Double Rod End For dual-purpose actuation or to equalize force and speed in both extension and retraction

Special Materials and Finishes Anodized aluminum or stainless steel are common for harsh environments

High- or LowTemp Seals For use in high heat environments or for extreme cold in harsh environments

Non-rotating Piston

Adjustable Stroke

Using either guide rods or multiple pistons attached to a single rod end, these prevent unintentional rotation

Manufacturers offer various methods to adjust the stroke length of a pneumatic cylinder

Rod Locks Installed at the cylinder's head, these use pneumatic collets to lock a rod in place for extra safety

Rod Boots

Rod End Accessories

Tandem Cylinders

Spring Extend/ Retract

Bumpers

Textile or rubber bellows attached to the head and rod end to protect the rod from various elements

Every conceivable option is available; clevises, rod eyes, spherical bearings, and alignment couplers, etc.

More than one piston mounted inline to achieve more force from the same diameter actuator

A spring installed around the rod side offers spring retract, and at the cap end offers spring extend

Rubber bumpers installed on either size of the piston as end-of-stroke protection, but non-adjustable

Low Speed Seals Seals that do not chatter or skip when velocities are low

End Effectors Rod attachments that are also pneumatic actuators for gripping or rotating

a heavier load, increasing the risk of detrimental effects such as rod buckling. Don't let this warning scare you away from these mounts – just be wary. As previously mentioned, pneumatic cylinders are generally strong enough for their force output, so these problems are indeed rare.

The head trunnion is the strongest pivot mount, so consider that or intermediate trunnion for extreme duty applications. Otherwise, most of the fixed mounts should be of sufficient strength for most applications and often come down to your machine’s particular requirements, serviceability and economics. In many cases, such as with pancake, compact, and rodless cylinders, there are only a few mounting options. But when strength does matter, flange mounts are the best, when available.

Despite the many standardized cylinder types for pneumatics, their special options list is extensive. They feature modular and simple construction with extruded bodies, sleeve nuts and cast aluminum heads and caps, which does very little to limit their functionality. As you can see from the list of special options in the chart above, you have a plethora of helpful accessories and modifications to suit your machine’s unique requirements.

Most are self-explanatory, but I’ll discuss a few of the more unique choices available to you. Adjustable stroke, for example, seems self-explanatory but could mean several things. There are cylinders with adjustments to modify the stroke partially. For example, a double rod 10 in. stroke cylinder

could employ a device on the cap end rod that acts as a stopper. That stopper can be adjusted to a given length of, say, two inches, allowing stroke adjustment anywhere between 8 and 10 in.

Another form of adjustable stroke offers multiple stages of discrete positioning. Imagine two piston-rod assemblies installed into a single cylinder and separated by an intermediate head. There are four ports, one each for the rod and cap port of each assembly. The rear assembly will typically have a shorter stroke, but its piston rod pushes against the piston of the front assembly. Imagine that the front cylinder strokes 10 in. and the rear cylinder strokes 3 in. The single cylinder can position itself from fully retracted, 3 in. extended (rear cylinder) and 10 in. extended (front cylinder) rapidly and precisely.

Rod locks are a great tool to add safety to air cylinders that would typically be inherent to hydraulics using pilot-operated check valves. Because air compresses easily, you can't simply hold a load safely with PO check valves; but instead, it must be physically blocked by other means. The rod lock is a component mounted to the cylinder head (rod end) that uses a collet to clamp the rod. It is typically used as a safety device to prevent loads from endangering workers, but it can also lock a load in place anywhere along the stroke length when operated at low speed.

Low-speed seals are an important addition to pneumatic cylinders that stroke at low velocity. The effect of "stick slip" causes the piston to chatter as it is stroked at slow speed as the seals grab onto the rod and/or barrel, and then subsequently release with extra energy. Low-speed seals provide more consistent breakaway and allow smooth operation at slow speeds. Sometimes these seals may be used in conjunction with a polished barrel internal diameter.

Pneumatic cylinders are diverse and offer many options for the designer to choose from, and we didn't even discuss custom designs. With so many choices of construction type and available options, it's easy to refine your application with the perfect pneumatic cylinder. FPW

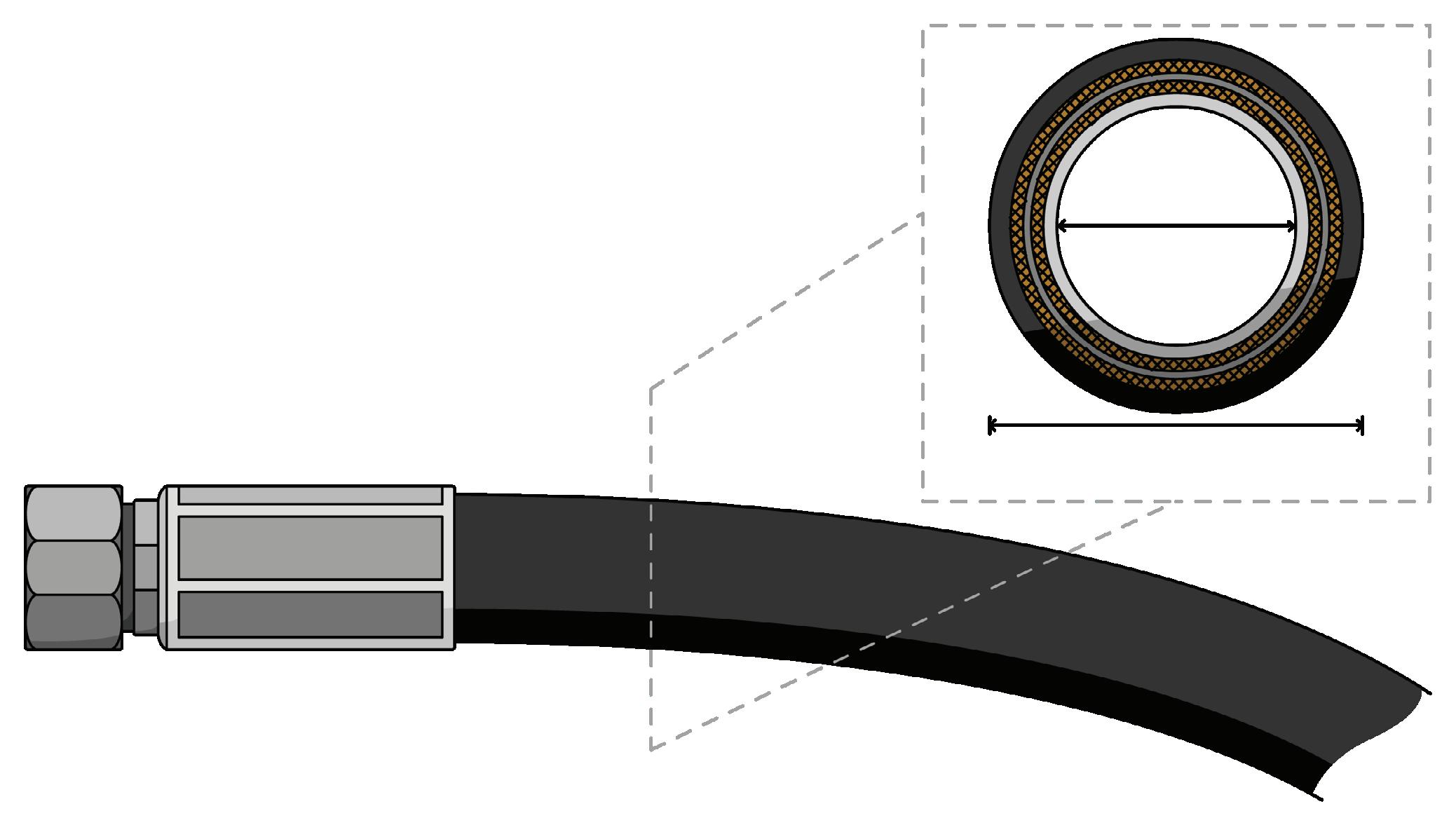

LIKE THEIR FITTING AND ADAPTER

brethren, hydraulic hose assemblies are often an afterthought to the hydraulic designer. I'd rather be working on crafting a unique hydraulic circuit as well, but we shouldn't forget the importance of a holistic approach to machine design. Your fluid power technicians are an essential piece of the puzzle to ensure hoses are expertly crafted and installed, but your forethought goes a long way toward saving costs, easing installation, and improving reliability.