10450 - 174 Street

Edmonton, Alberta T5S 2G9

Ph: 780.413.0331 Fax 780.413.0388

Email: info@sportscene.ca www.sportscene.ca

Summer 2024 Issue

Editor in Chief Kyle Stelter (CEO)

Editors

Peter Gutsche

Nolan Osborne

Bill Pastorek

Contributors

Helen Schwantje, DVM

Design & Layout Sportscene Publications Inc.

Printing Elite Lithographers Co. Ltd.

Editorial Submissions

Please submit articles and photos to communications@wildsheepsociety.com

No portion of Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine may be copied or reproduced without the prior written consent of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia. The views and opinions expressed by the authors of the articles in Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 43363024

Return Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia #101 - 30799 Simpson Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 6X4 www.wildsheepsociety.com

Chief Executive Officer – Kyle Stelter 250-619-8415 ● kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

President – Greg Rensmaag 604-209-4543 ● rensmaag_Greg@hotmail.com

Vice-President – Chris Barker 250-883-3112 ● barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

Tristan Duncan 778-921-0087 tristan@wildsheepbc.ca

Joe Eppele 647-986-3859 joe.eppele@gmail.com

Peter Gutsche 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Vice-President – Mike Southin 604-240-7337 ● msouthin@telus.net

Secretary – Colin Peters 604-833-5802 ● colin.peters12@gmail.com

Treasurer – Joe Humphries 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Justin Kallusky 236-331-6765 kallusky@hotmail.com

Benjamin Matthew MD 778-558-0996 ben.matthew@ubc.ca

Matt McCabe 250-320-6048 mattmccabe.wssbc@gmail.com

James Mitton 778-808-9001 jamesmitton15@gmail.com

Greg Nalleweg 778-220-3194 greg@nextgenelectrical.ca

Colin Peters 604-833-5802 colin.peters12@gmail.com

Communications Committee

Chair: Kyle Stelter ● 250-619-8415 kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

Fundraising Committee

Chair: Korey Green ● 250-793-2037 kgreen@wildsheepsociety.com

Government Engagement Committee

Chair: Greg Rensmaag ● 604-209-4543 rensmaag_greg@hotmail.com

Hunter Heritage Committee

Chair: Jann Demaske ● 970-539-8742 demaskes@msn.com

Indigenous Relations Committee

Chair: Josh Hamilton ● 250-263-2197 josh.wssbc@gmail.com

Membership Committee

Chair: Peter Gutsche ● 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Projects Committee

Chair: Chris Barker ● 250-883-3112 barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

Jurassic Classic

Trevor Carruthers ● 250-919-5386 ● trevor.carruthers@shaw.ca

Raffles

Joe Humphries ● 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Women Shaping Conservation

Rebecca Peters ● 778-886-3097 ● rebeccaanne75@gmail.com

Bookkeeper

Kelly Cioffi ● 778-908-3634 kelly@dkccompany.com

Executive Assistant

Hana Erikson ● 604-690-9555 exec@wildsheepsociety.com

Hunting Expo Coordinator

Kris Wrathall ● 604-340-4903 ovisslam@outlook.com

Administrative Coordinator

Rebecca Peters ● 778-886-3097 wildsheepsocietyofbc@gmail.com

Danny Coyne

Darryn Epp

Jeff Jackson

Trevor Carruthers

want to start off by thanking all of our members for their unending support for our conservation efforts. This has been another incredible year for the Society, with our members, donors and supporters elevating our conservation work and the support we have given wild sheep to the next level.

This past winter we had several successful projects move forward. We were excited to execute on three prescribed burns in the Peace Region totalling 600 hectares (approximately 1500 acres) that will enhance habitat for Stone’s Sheep. This was a challenge given the dry spring; however our contractor was able to safely execute these burns early in the season before the risk became too high.

On the Fraser River we continued our Test and Remove project for California Bighorns. This winter we treated 64 sheep for a total of roughly 615 sheep to date. We are seeing significant lamb recruitment increases in treated herds with 47 lambs per 100 ewes versus 13 lambs per 100 ewes in untreated herds.

As we are now firmly into the summer season, sheep hunting season is right around the corner and I know many of our members have fall hunts planned. One of the things we continue to hear from the government is that we must be more vigilant in the rams we harvest. 2023 proved to be another challenging year with too many underage and illegal rams being taken.

We educated roughly 200 sheep hunters at our Mountain Hunting Expo in February in Penticton and have numerous courses plan for this July. Be sure to visit our website and

check the dates. We have free horn aging and field judging seminars planned for Comox Valley, the Lower Mainland, Cranbrook and Prince George this summer. Even if you are an experienced sheep hunter come out and visit with your fellow sheep hunters and sharpen your skills. For new sheep hunters, please take advantage of one of these courses and be sure you are ready when that ram is in your scope.

Additionally, we offer an online video that has about a thirtyminute run time that provides more background and insight into horn aging. We are working hard behind the scenes to provide an online Wild Sheep Hunting, Horn Aging and Field Judging Rams course in conjunction with Silvercore Outdoors. We are hopeful with these tools you will be better equipped for taking the right ram. I do ask that if you are not sure about the legality of a ram or whether you should pull that trigger, DON’T.

Sheep hunting is about the experience, it is not about taking an animal. Just going on a sheep hunt is a reward in itself, and if you happen to come home with the right ram, it is icing on the cake. The true reward of sheep hunting is the time on the mountain, so don’t fall into the trap that you must take a ram for your trip to be a success.

In early June, Vice-President Chris Barker and I travelled to Ottawa to attend the Conservative Caucus Hunting, Angling and Conservation Outdoor Symposium. I was asked to present on Disease in Wild Sheep and this was an incredible opportunity for the Society to raise awareness specifically relating to Mycoplasma Ovipnuemoniae. The presentation was

followed by a round of questioning and fulsome dialogue on the disease. There was a lot of support in the room for seeking policies and strategies that will help wild sheep.

I won’t have the privilege to do another CEO update prior to the hunting season opening, so I wish you all a safe, rewarding and enjoyable time in the field this fall. Like I mentioned earlier, let’s all do our very best to ensure that when we are sheep hunting we give pause to reflect to ensure we take the right ram. There has never been a more critical time to ensure we are doing everything we can to support the wild sheep resource and harvesting illegal rams exacerbates the issue. Remember, age matters, when it comes to wild sheep. I look forward to your stories and pictures this fall. Please be sure to share your successes with us as we love to see the great time you are having afield. I hope to see a number of you at one of our horn aging workshops this summer.

Yours in Conservation, Kyle Stelter

I was born and raised in Manitoba, where my childhood was filled with adventures in the great outdoors. Some of my earliest and fondest memories involve camping trips, fishing excursions, canoeing adventures, and stomping through the bush. These experiences fostered a deep appreciation for nature from a young age.

At 18, I moved to British Columbia and instantly fell in love with the province’s stunning landscapes—the majestic mountains, the vast forests, the ocean, and the incredible wildlife. BC’s natural beauty sparked my commitment to conservation efforts, especially as I think about the world I want to leave for my children.

I’ve been in the construction industry for over 20 years, working with my hands to provide for my family. I have a deep love of hiking; it’s a passion that has brought me countless moments of joy and solace. One recent summer, I spent every weekend finding two or three peaks that I could stand on top of, soaking in the views and the fresh air. I finished that summer by hiking the West Coast Trail. When life gets tough, you’ll usually find me out in the mountains, finding peace and clarity among the trees, the jagged peaks or the cold mountain lakes. It’s in those moments that I’m reminded why conservation matters so much to me; nature’s my sanctuary, and I want to make sure it stays that way for everyone to enjoy.

While I didn’t grow up in a hunting family and didn’t have many opportunities in my youth, I always admired those who had deer mounts or bear rugs adorning their walls. Deep down, I knew that one day, I would be among them. My first hunt

was with a buddy, clad in borrowed camouflage. Sitting in a friend’s field, armed with an old Tikka rifle that had been gifted to me by an old-timer, his adventures with it had become cherished memories of days gone by. It was on this trip that I shot my first whitetail, sparking a newfound passion.

My introduction to the Wild Sheep Society of BC came through my wife Cory. Volunteering at the Jurassic Classic was my first experience with the society, and it opened my eyes to the incredible conservation work being done. Inspired by their efforts, I decided it was time to contribute more actively.

This year, I am honoured to join the board of directors. I am proud to be part of an organization that is dedicated to the preservation and

protection of wild sheep and their habitats. I look forward to working alongside fellow members to support and advance our conservation goals.

by Landon Birch

eing a Stone’s sheep researcher is, by design, not a great way to have warm hands. It was -30 degrees midday, we had an animal on the ground, and were fumbling with an 8mm locknut trying to get the collar put on our 24th sheep of the study. The urgency to get the collar fitted and the animal released as quickly as possible was in the back of our minds. But we also had to remember to take all of the samples we needed, and most of all, to take the magnet off the GPS collar. The magnet keeps the collar from activating, thus preserving precious battery life—and there is no worse feeling in wildlife tracking than watching an animal run free after capture only to realize that the magnet is still on the collar. Fortunately, I held the magnet in my hand as we watched Ewe S045F bound through the two-foot-deep snow back to her winter range.

It’s year three of our research project in the Finlay-Russel range, within the traditional territories of Kwadacha and Tsay Keh Dene Nations, and this time we’re trying to collect samples from 21 previously collared ewes. It’s a tall order, as anyone who knows sheep knows that they aren’t always in the easiest places to get to—and I think that’s why we love them. Avoiding the deep snow, Stone’s sheep are usually found in rugged rocky outcrops and cliff faces in the winter where you’d often see mountain goats. It’s the perfect escape terrain for them, where they can run and climb to quickly get away from predators like wolverines and wolves that might be roaming nearby. Daylight this time of year is in short supply, making our working hours short and essential to start as early as possible in the morning. Days in the field like this, start by waking up each morning from a frosty, remote camp room by the airstrip and checking the forecast and hoping it holds for the day. With the promise of good weather, we then see how much has changed overnight, firing up the chilled laptop to check in on each collared sheep’s last locations. Updating our navigational maps with this information, we make a game plan for the day, planning an efficient

route to get to each animal. The study area is huge—just over 12,000 km2 making this last part of planning our routes and ensuring everyone knows all the safety protocols all the more critical, especially when fuel caches are few and far between.

The Finlay-Russel Range, located roughly 350 kilometres north of Prince George, constitutes the southern extent of Stone’s sheep range in the central interior of the province. Beautiful and rugged, it also lies in a snowbelt where snow can reach incredible depths, and temperatures can fall below -40°C.

Layering up and stepping outside, we all tend to our various jobs. Our pilot, Russ, wakes up the helicopter for the day, pulling the heaters out and covers off the dark blue Jet Ranger. Meanwhile project team member Morgan Anderson, Omineca Region Senior Wildlife Biologist, and I pack the dried-out nets into their respective canisters. After grabbing “a splash of fuel” and double-checking all of our equipment, we’re off.

The reason we’re out here to begin with, collaring sheep and collecting samples, is all the more important— the population here appears to have declined by 50% since 1993. Being so remote, and the only population of Stone’s sheep in the Omineca region, very little monitoring has occurred in

the area, making it unclear whether the survey from 1993 was a high estimate, and if the most recent survey from 2020 represents a decline or a change in distribution. To begin tackling these questions, stakeholders (Wild Sheep Society of BC [WSSBC], Wild Sheep Foundation [WSF], and local guide outfitters to name a few), government agencies, Kwadacha Nation, and Tsay Keh Dene Nation together discussed the various knowledge gaps for sheep in the area, like movements, habitat use, seasonal ranges, survival, recruitment, and health. With so little known about this population, it was difficult to determine what may have caused the apparent decline, and so this collaborative project was initiated in 2022.

As on many wildlife projects like this, maximizing the usefulness of the data collected, like collar data, was at the forefront when this project was conceptualized. Early discussions to have a graduate student jump onboard and explore analyses beyond what the team had capacity for, were quickly agreed on and, a short time later, that’s where I came in.

I had been waiting for the right time to jump into graduate school, hoping that the right opportunity would come along. Partnering with the University of British Columbia and the renowned

Wildlife Restoration Ecology (WiRE)

Lab—led by Dr. Adam Ford, I knew I would have the support and resources needed to tackle the complexities of this research and contribute valuable insights into the ecology and conservation of Stone’s sheep. Back in the cold, after a short 15-minute ferry to get to our first collared sheep of the day, Morgan dials in the VHF telemetry to zero in on where the ewe is located. With the constant “beep” of the collar chiming in, Russ positions the helicopter to find her. Equipped with antennas on the right and left side, Morgan and Russ work together, isolating each antenna, to determine which side the collared ewe is on. After a few calls of “left” and “right”, we spot the ewe. She’s just below the mountain peak with three other sheep—not a good spot, but just behind her is a flat snow-filled bench that would work. Harnessed up with a canister ready, we close in on her as she approaches the flat bench. Hovering within 15 feet of her, she’s quickly netted and we’re on her straight away. With a great net placement, she’s tangled up nicely in a

patch of snow. Working quickly, Morgan and I step out of the helicopter and work together to untangle her, place a blindfold over her eyes, hobble her, and collect the samples as efficiently as possible so the ewe can be back on her feet and with the rest of the band in no time.

You are most likely wondering, what are the most important samples being collected from this ewe? Health samples! Nasal swabs, tonsil swabs and blood samples collected here will tell biologists a great deal about how healthy this ewe is. Though not as close in proximity to domestic farms as Bighorn sheep are in southern BC, Stone’s sheep can still travel huge distances, particularly during the rut, and may run into domestic livestock where diseases can be rampant. One Stone’s sheep ram from the nearby Schooler Range was documented travelling over 100 kilometres in under two weeks during the rut, highlighting the risk Stone’s sheep have of being exposed to domestic pathogens like Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. Although no major outbreaks of domestic pathogens have been documented in Stone’s sheep yet, diligent surveillance such as this will be critical for early detection and prevent further spread in the event of an outbreak.

Among the other indicators of health, and the one I am most interested in for

this research, is fat. Fat is a powerhouse for energy storage in many species, and for a sheep trying to survive the winter on a wind-swept rocky ridge, fat stores are a matter of life and death. Like everything living beyond the equator, sheep live through seasons. In those seasons there are periods of high energy availability—like the summer when lush forage covers the mountains— and periods of low energy availability—like the winter when most forage is buried under deep snow or ice, and poorer in quality. Because of this cycle of energy availability, sheep need to be able to store energy when it is readily available to prepare their bodies for leaner times in the future. Winters can be long, cold, and very physically demanding, so the more fat a sheep can store, the more likely they are to survive and give birth to a healthy lamb. To date, no one has looked at how Stone’s sheep body condition is related to habitat conditions.

Back on the mountain, pulling the portable ultrasound machine out of her pack, Morgan moves toward the rump of the sheep to check just how fat this ewe is while I keep an eye on the monitor. Squinting in the bright morning sun to see the tiny screen, we can see a thin white line indicating a change in tissue from 3mm to 16mm. We then measure the thickness of this

tissue on the monitor. In this case, the ewe’s rump fat is about 13mm thick—which is fairly good for this time of year. Overall, this winter has been relatively mild compared to past winters. In 2022, most of these sheep had almost no fat at all, averaging just 2mm! With all of the samples collected, and a quick check of the collar fit, the blindfold and hobbles are removed, and the ewe is up and away, rejoining her band—just 12 minutes after being netted. One down and twenty more to go.

This will be the first of two sessions this year where we will be measuring fat reserves, the later session occurring in March. Doing two sessions in early winter and late winter will allow us to compare fat measurements when sheep enter winter and at the tail end to see if certain sheep lose more fat reserves than others. Using this information and pairing it with vegetation samples that will be collected from each sheep’s summer and winter ranges, we can determine which seasonal range, summer or winter, has the greatest influence on fat reserves—the second primary goal of this research. Though summer is when most animals tend to accumulate the most fat, high quality winter range can reduce the amount of fat loss, improving survival and reproduction as well. Investigating the influence of seasonal ranges on fat reserves can have significant influences on how we

conduct habitat management for Stone’s sheep. Traditionally, late winter peaks in sheep mortality have often led to habitat enhancement activities specifically on winter ranges. Elsewhere in North America, recent research found that late winter body condition is primarily a consequence of fat stores built up on summer ranges—a term ecologists refer to as nutritional carryover. This seasonal relationship with fat will be

used to maximize the benefits of investments in habitat enhancements for sheep.

So, despite the cold, the long hours, and the demanding conditions, the goal of enhancing the habitat for Stone’s sheep makes it all worthwhile. The information we gather during these frigid winter months is crucial for developing strategies that will help conserve and protect this remarkable species for future generations.

Landon Birch is master’s student at the University Of British Columbia. Originally from New Brunswick, Landon moved to British Columbia in 2013 to work as a hunting guide in North Central BC. From there, his interest in wildlife biology led him to a BSc degree in Natural Resource Management - Fish and Wildlife from the University of Northern British Columbia. After graduating, Landon worked for several years at Wildlife Infometrics in Mackenzie, BC, where he primarily focused on projects involving Stone’s sheep and caribou before beginning his graduate studies at UBC in the fall of 2023.

by Wild Sheep Society of BC

he Wild Sheep Society of BC along with our project partners continue to support the Fraser River test and Remove Project. Mycoplasma Ovipneumoniae, a respiratory disease is currently affecting the California bighorn sheep along the Fraser River. Current science suggests the bacteria Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae (M.ovi) is the single most important pathogen implicated in pneumonia related die-offs of wild sheep and is considered the largest threat to wild sheep in North America. Given the history of domestic sheep on the Fraser extends at least to the early 1900s, Fraser River bighorns have likely been exposed to M.ovi in the past. Some northern herds were used as source stock for translocations to the USA in the 1950s and 60s and the numbers of sheep recorded by the early to mid-1990s were the highest ever recorded. At that time, there were more than 2,400 sheep along the Fraser River north of Lillooet. In the mid to late 1990s, Fraser River bighorn sheep appeared to have experienced a pneumonia-related die-off with persistent pneumonia observed in

juveniles for years afterward. Sheep declines occurred in all areas and that pattern has continued.

In 2020 there were approximately 800 sheep in the same area, approximately a 70% decline. Since 2000, the provincial animal health laboratory has had the ability to test live and dead animal tissues for Mollicutes, and more specifically for M.ovi, and research has confirmed that M.ovi is a primary causal agent of pneumonia in bighorn sheep.

The implementation of the Fraser River Disease Mitigation Program supported by the Wild Sheep Society of BC alongside our partner Wild Sheep Foundation, consists of two key phases. Phase 1, health sampling to document the distribution of M.ovi along the Fraser River and Phase 2, test and remove treatments and treatment effectiveness monitoring.

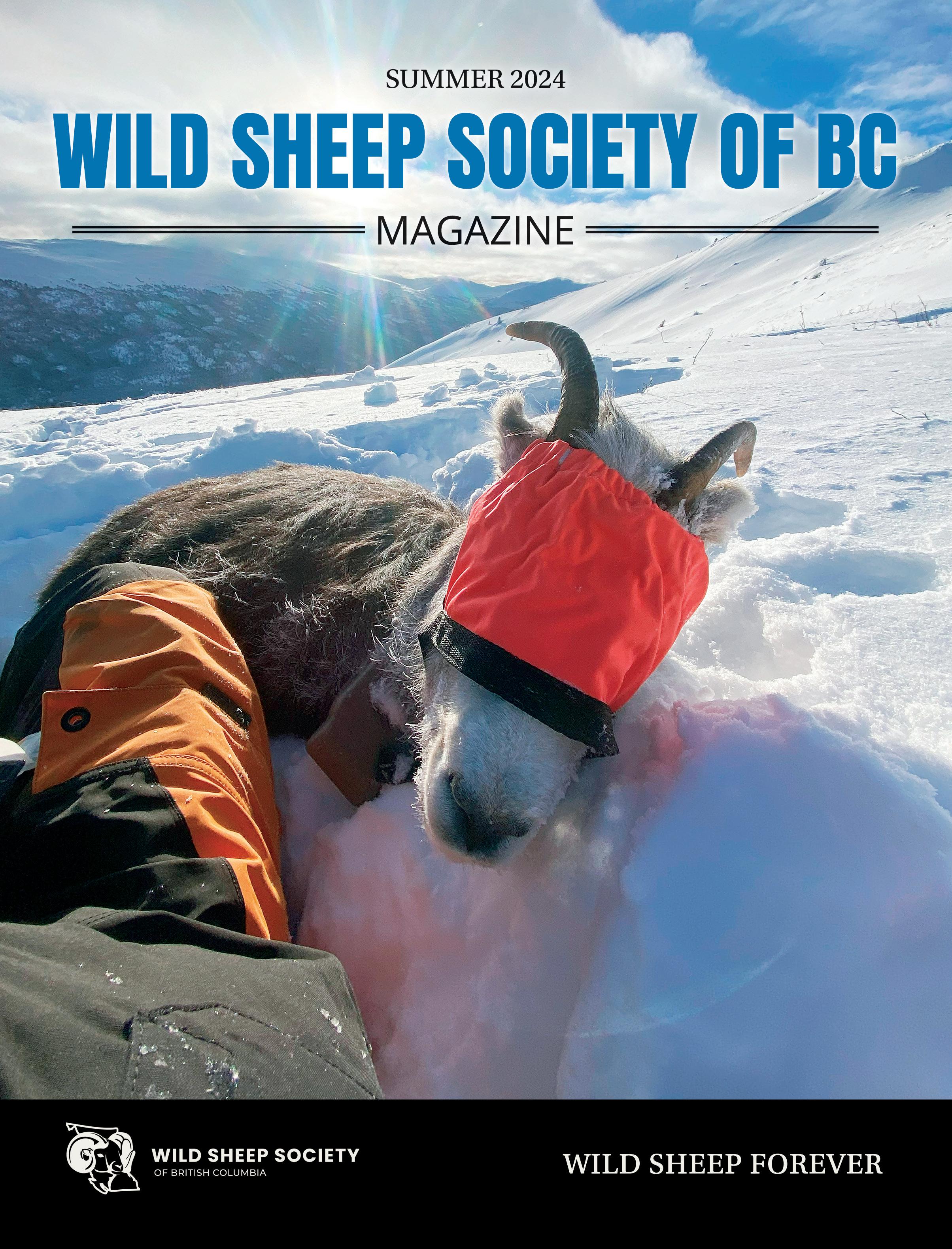

This project is scheduled over a ten-year period and we just concluded our sixth year of treatment. Over the winter of 2023/24 sixty-four bighorn sheep were captured at Big Bar and the Chasm area.

Since the inception of the project, we have tested over 600 Bighorn Sheep. We are seeing significantly increased

lamb recruitment in the treated areas which indicates that wild sheep populations have likely been cleared of M.ovi and we anticipate significant growth in these herds moving forward. Out latest data shows a post treatment lamb recruitment of 47 lambs per 100 ewes compared to a pre-treatment lamb recruitment of 13 lambs per 100 ewes. However, there is significant work to complete on this project in the remaining four years with a budget of 2.43 million dollars over the life span of the project. Our vision is to restore the struggling California Bighorns on the Fraser River to their historic carrying capacity of over 2400 wild sheep. It is through the collaborative supportive of the following organizations who have provided funding, that makes this project possible: The Wild Sheep Society of BC, Wild Sheep Foundation, Canadian Wildlife Capture, Wild Sheep Foundation Mid-West Chapter, Abbottsford Fish and Game Club, Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, Guide-Outfitters Association of BC, and the province’s Together for Wildlife program.

by Wild Sheep Society of BC

n early Spring, we were able to conduct a second prescribed burn of ~300 ha (741 acres), resulting in a total of 600 ha (~1,500 acres) of habitat and range enhanced for Stone’s sheep in northeastern BC. This site had not been burned for over 30 years and had become overgrown with shrubs, reducing the amount of forage and also the availability of the forage to sheep.

Conditions were ideal to achieve a burn to reduce shrub and aspen encroachment, which will increase forage and allow for sheep to move

through the area more easily. Given the dry conditions and fewer natural fire breaks this year, areas burned were carefully selected to maximize benefits to sheep and avoid areas that could result in hot spots and holdovers that could cause problems through the summer.

The fire lasted a few hours and was deemed out less than 2 days post-burn. Target burn areas were focussed on sites adjacent to the steep cliffs that sheep use as escape terrain. In addition to meeting habitat objectives, the two burns conducted this spring will reduce

fuel loading and therefore minimizing the risk of destructive wildfires. Thank you to our consultant Alicia Woods of Ridgeline Wildlife Enhancement for leading this project, Northern Burn project coordinator Josh Hamilton and Project Chair Chris Barker. Funding for this burn was provided by the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia, Wild Sheep Foundation, Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation (HCTF), North Peace Rod and Gun Club, Grand Slam Club Ovis and Grand Slam Club Ovis Canada.

1. Job/Volunteer Title Wildlife Biologist, Ridgeline Wildlife Enhancement Inc.

2. Job/Volunteer Description

Four years ago, I started my own consulting company with the primary goal to make a positive, on-the ground impact to wildlife habitat and populations in Northeast BC. Currently, I am working on a few habitat restoration projects for species Stone’s sheep, other ungulates, and sharp-tailed grouse using prescribed burning. I also conduct wildlife inventories to support population management and occasionally provide scienceand regional-based expertise to support stakeholders and First Nations achieve wildlife and habitat objectives.

3. Related Experience/Duration in Industry

I grew up in Fort St. John as the kid of a regional wildlife biologist and knew at an early age that my passion was for wildlife. I completed a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in wildlife biology from the University of Northern BC and since then have spent my entire 20-year career as a wildlife biologist working in Northeast BC. I worked for the provincial government as a wildlife and ecosystems biologist for 9 years, during which time I gained valuable experience in

harvest management, population inventories, and developed a unique skillset in using prescribed fire to enhance and restore wildlife habitat. As a consulting biologist, I have initiated and managed a number of habitat restoration projects, and, more recently, have focussed my work on developing and implementing prescribed burn programs to restore and enhance wildlife habitat in Northeast BC.

4. Why are you passionate about wild sheep?

Growing up in Northeast BC and spending time both on the ground and in the air throughout the region, I have an appreciation for the diversity of ungulate and predator species that the northeast is renowned for. I think my passion for Stone’s sheep comes from my love of the mountains and the backcountry and is fostered by the fact that half the world’s population of Stone’s sheep is within my home region. This drives me to use my skills and knowledge to ensure we have healthy and sustainable populations of sheep in Northeast BC for my kids to enjoy and have

appreciation for.

5. Favourite parts of your role that affect wild sheep.

Simply, I love to burn. I have seen firsthand the benefits of burning to Stone’s sheep and their habitats. When I am in the helicopter, dropping those magical little pingpong balls, and can see the flames and smoke, all I can think of is the happy sheep (any everything else that relies on fire-disturbed landscapes) that will be using this rejuvenated habitat. As part of all the prescribed burning projects I am part of, monitoring the response of wildlife to the burns is also rewarding. Nothing warms my heart more than seeing lush post-burn vegetation growth and the sheep taking advantage of the nutritious vegetation. At the end of the day, I can say that I genuinely helped sheep populations by making an on-the-ground impact. That is the most rewarding part of my job.

6. External influences/ challenges you face in your

job to help average people understand it’s more difficult than it my appear.

By far the most significant challenge in conducting all habitat restoration work is working through the permitting process to receive all the approvals and permits required to conduct habitat restoration activities. By far, the office-based work that goes into running a prescribed burn and other habitat restoration projects easily accounts for 90% of the time before a burn can even be completed. The second challenge I face in implementing prescribed burns is the weather. When doing spring burns, the weather window needed is short and conditions need to be just right. The target areas need to be snow-free (but we still need snow in the trees) and dry (but not too dry), at minimum 3-4 days without rain, a slight breeze (but not too windy), low humidity (but not too low), and preferably sunshine because those clouds just don’t allow for a good burn. Needless to say, there are a lot of moving parts, and factors that are out of our control, which need to line up so we can achieve our burn objectives.

7. Any comments relating to your appreciation for, or involvement in WSSBC.

I am always so impressed by the passion and commitment of the Wild Sheep Society of BC and their members. If you’ve ever attended the annual WSSBC’s Northern Fundraiser in Dawson Creek, this passion and commitment can be seen firsthand by the money that is raised during this event. The Prescribed Burns to Enhance Wild Sheep Habitat in Northeast BC program that I am a part of is a result of the initiative and funding provided by WSSBC and their partners. It is truly inspiring what WSSBC contributes to Stone’s sheep in Northeast BC.

by Justin Kallusky

When the sun sits high late in July

A mass migration begins

Hunters clad in camo and plaid

Start heading north again

Unable to sleep and dreaming of sheep

The mountains call them home

For deep in the peaks past the timber and creeks

Lives a sheep they call the stone

They’ll hop in their trucks giving zero fucks

About the cost of diesel or gas

After all you can’t be cheap if you want to hunt sheep

Said the man selling Swarovski glass

With the truck safely parked the hunters embark

Into the harsh and lonesome land

Toting water jugs and swatting bugs

They’re off to find a ram

After a few hours in the hunters begin

To feel the weight of their heavy packs

But onward they climb for deep in their minds

They know there’s no turning back

With the light beginning to fade they’re happy they’ve made Their way to camp just in time

And if all goes well in the morn they’ll be giving er hell

Chasing sheep in the sweet alpine

But wouldn’t you know in the night they get snow

Undeterred they tend to the task at hand

“We didn’t come all this way to sit in the tent all day”

“Come on let’s go find a ram!”

Despite the weather boy did they ever

A full curl like none other they’d seen

At the top all alone like a king on his throne

He was indeed the ram of their dreams

It’s hard to describe what goes on inside

Two men as desperate as this

As emotion ran high one looks to the sky

And whispers “Dear God don’t let me miss”

After 4 years in the making while trembling and shaking

The bullet is sent on its way

And it goes down in the books as the day they took

Their first ram on that fateful day

It just goes to show as we learn and we grow

Don’t give up and keep chasing your dreams

Because despite the past hard times can’t last

It’s where you’re going and not where you’ve been

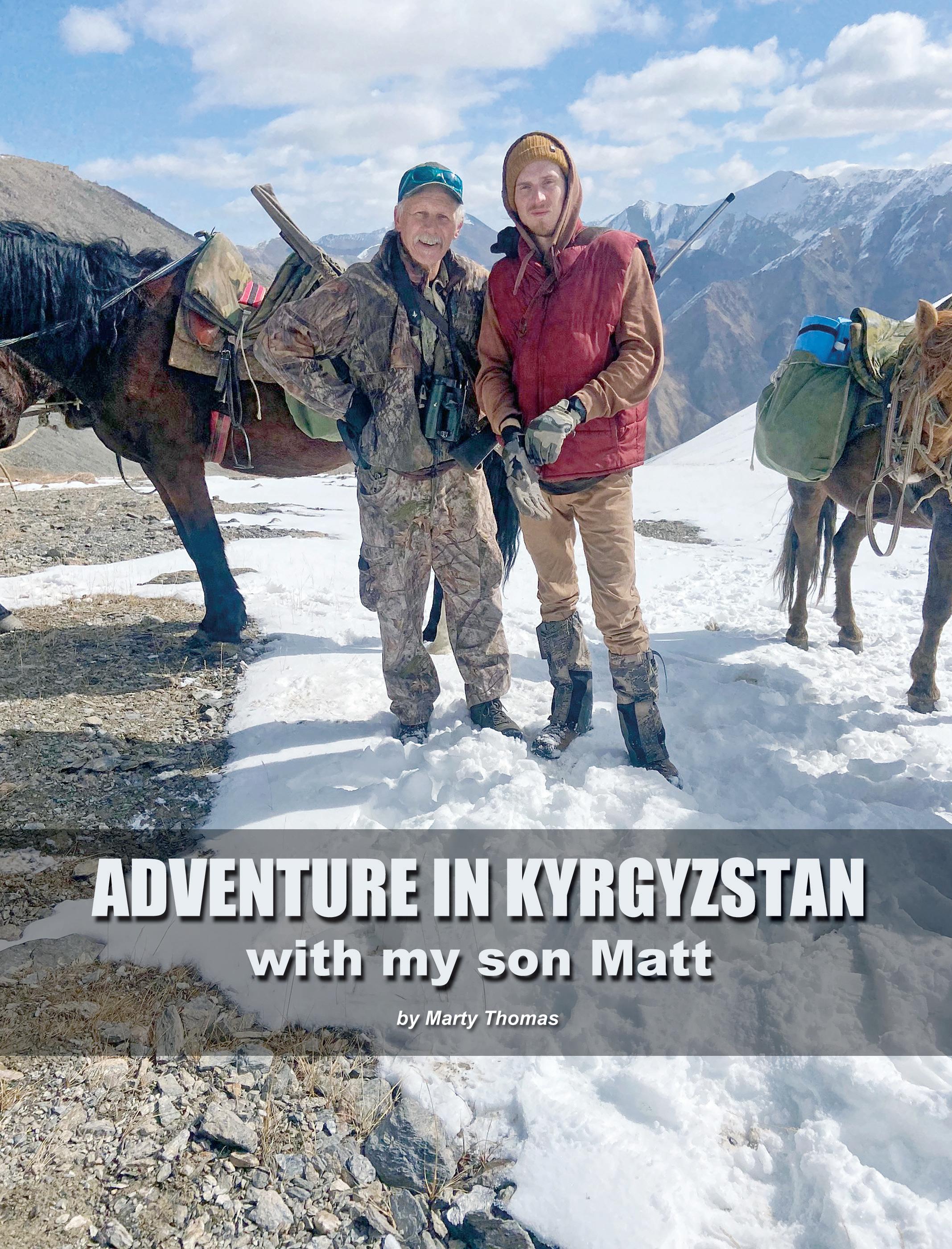

ix of us on Kyrgyz horses are looking for two dandy Marco Polo rams that I had spotted two days before from a different valley. Cresting a rise, one of my Kyrgyz guides spots two rams about 800 yards across a basin, we all stop, get off the horses and I must get a look with my binocs to see if they are the same ones. Slowly I peek over the crest and immediately know these are the same rams.

We get the horses closer and are now going on foot, myself, my translator and Cubaa, one of my guides. I say “I want my son to come on the final stalk”... “No” the translator Dan replies, “three is enough” ... so I agree, giving Matt my spotting scope so he can see a bit better. Now Cubaa, Dan and I are sneaking towards the feeding rams. They have luckily dropped out of our sight into a depression, so I think great, 100 yards to go and we’ll be only 150 yards above them.

Halfway there, a ram lifts his head and is fixed on us, we freeze and drop down out of his sight. Why rams get old is because they’re so wary and now they’re both trotting across the basin away from us, so we quickly sneak to the edge of a bank, and I throw my pack down. About 400 yards I believe, so just as they stop for a final look back, I try to get my .270 short Mag focused on the big ram on the right when I hear Dan say, “Take the ram on the left.”

This hunt started years ago. After guiding rams for the majority of a 40year career, I decided years ago that to get a nice Marco Polo would be on my bucket list for sure. In 2022, we had an avid sheep hunter from Spain in my Beaver Creek camp. I told him about my quest, and he gave me a contact, Natalia in Kyrgyzstan as her dad and family had hunted there for over 20 years. In late December I had a hunt confirmed with her for October of 2023. As my son Matt said yes to accompanying me, I arranged for us both to take an Ibex as well. I’m sure glad he came with me!

Now booking the right airfare is a story in itself as I booked our flights in early August. Then in early September, I phoned Hub Air to see if we had time at a couple international airports to collect our firearms and recheck everything? No was the answer, so I had to book more flights and then deal with Manulife insurance for the first flights. That was a 3-month ordeal and I only got 50% back because it wasn’t cancelled for a medical reason.

Now we’ve paid $200 extra to Air Canada for an extra duffle bag and our firearms case and going through security, I realize I have my Leatherman Supertool on my belt. “Holy s...” I tell Matt, so the guy measures the blades and says, “sorry sir, you can’t take this with you.” I said I’ve had it for 20 years, he asks how far is your vehicle? Ok, great, so I run through the crowd, through the parking lot to my truck, throw it inside and run back to the airport where the guy waves me through... “just preparing for my sheep hunt” I say... “You’ll do well” he replies!

The flights were long but a few games of crib along the way with

some beer and we made it to Bishkek where we got a room at 3:30 in the morning... 2 nights there and we get picked up for the 8 ½ hr drive to camp. I must say this was part of the adventure—lots of small villages, cows, donkeys and kids on the road are quite normal over there. Then driving over a huge pass was interesting with many switchbacks, snow near the top with wolf tracks alongside.

We got into camp, unloaded our gear and had time to sight the rifles in. My custom Accurate Arms .270 Short mag is shooting better than Matts 7mm-08 Tika. As they want us to shoot long range, “do you want to try 600 yds?” they ask me. “No, I usually try to get a bit closer to my target” I reply not realizing how they really hunt over there. We meet the staff, have dinner and head into our quarters to downsize our gear. The next morning, we realize that no duffle bags can come along with us. The horses have these green pack bags that are tied behind our saddles, so our gear and backpacks also go in these bags and our guns are slung over our neck and shoulder, which worked surprisingly well.

We’re soon on our way when we turn out of our valley and up and over a steep snow-covered pass and arrive at our 1st camp mid afternoon. We unpack and the guides go back where we came from to scout up a couple draws. We were left in camp, so I think I’m here to hunt so I tell the others I’m walking down the valley aways to glass. Half an hour later I find some Ibex and then a band of 12 female Marco polo sheep. Glassing around, I see movement right on the skyline, so put my spotting scope up there and I see rams. “Holy s..., there’s two big rams, both look good, walking west along the very ridgetop.” I get some pics through my Swarovski scope to show the others. Back in camp the guides come in and I show them the pics. They look ok and they agree, and I tell them that I want to hunt them tomorrow. Fast forward to the next cold morning, we are riding up the mountain with only one guide, the other, Cubaa, has gone scouting back up the valley again. We’re halfway up almost when Midland, our guide sees Cubaa way down below waving at us, so we turn around and head down and meet him. He says he has found three rams, one big one and two small ones,

so we start sidehilling with the horses to the East.

I’m starting to realize how they hunt; they try and hunt only if they can get the horses close to the quarry. We ride across some very steep sketchy ravines where I would never take my horses back home. I must say now that these Kyrgyz horses are incredible and I believe they’re the same horses used by Genghis Kahn years ago. They are shod on all 4 feet and never tire out! Now after four ravines we finally locate the three rams. I’m carrying my rifle and spotting scope, and there they are about 500 yards across and above us and have already seen us. I get the spotter on them right away and I see none are even full curl, so I relate this to the group.

Midland and Dulot, our government ride-along looks and later asks why we waisted four hours going after these rams? Here’s the answer; its a third-world country, the guides are poor and don’t have good optics at all. One guide had cheap binocs and the other guide had a cheap small scope with no tripod, just tied it on his horse. They also don’t carry backpacks like we do in North America, which cuts down the animals you can go after.

Now four hours later, we are back going up the original draw to where the big rams were. Right up through the rocks, poor horses, but we finally stopped where Dulot stayed and the rest of us climbed to the top.

This was our first high altitude climb, and my son 27 years young and myself 65 years old, realized that 11,000 to 12,000 ft elevation does make a difference in one’s ability to hurry up the mountain. At this stage we were glad we brough altitude sickness pills, which is a must on a hunt like this. Now we’re walking along the very top, following in the snow Ibex and the big ram tracks from the evening before. Soon we find the rams away down low on the other side of the valley but have a good look through the spotting scope. Both are legal rams and over the nose, one has darker horns, but the lighter horns are on the bigger ram. This is immediately locked away in my sheep hunting memory. Without time today we make plans to climb over a pass and go after them tomorrow. This I am happy with but surprised as we can’t get the horses to the rams.

Back in camp that evening, Nurbek shows up on another horse—he is the

Chief Guide of the Outfit. He looks at the pics, says 45-46 inches, not a bad ram, but the plan is changed. Next morning we pack up camp and move our gear to our 2nd camp just over two hours down the valley where we unpack and sort things out. Now we’re all riding down another valley to come around on the rams. Almost four hours later, we are near them when Midland spots them.

We make a stalk on foot and I’m about to shoot when Dan says “take the one on the left.” Lucky I had been warned that they will do that sort of thing to save the bigger one for someone else, so I ignore the comment and settle the crosshairs on the bigger ram on the right. I squeeze one off and they run about 30 yards into a tiny draw. The other ram runs out and I know I got mine with one shot, the moment of truth, and that makes one feel good!

The others are bringing the horses, I hurry across the basin, and I get up

to the ram first. Wow, I am humbled. This is the ram I came half-way across the planet to hunt, and at great expense! Matt and I admire the 10-year-old ram but have a long way to get back to camp, so lots of pics and I cape him out for a pedestal shoulder mount as I don’t have room

for a life-size ram in my Wildlife Museum back home. We all slept well that night!

So now its my sons turn to shoot. We all ride nearly five hours up this long valley, glassing many groups of Ibex along the way, a few good ones that see us and go over the mountain.

We watched a big grizzly up one draw who smelled or heard us and took off right up into Ibex terrain. Unfortunately, way up this valley I lost my favourite shooting glasses. Lucky I had a backup pair, but my favourites are still lying up there and I believe I know where.

We hunted our way back but made no stalks. Bugger, as it’s supposed to snow tomorrow, but we have no control over that. Back in camp we eat, not fresh sheep backstrap but boiled meat, as they boil everything, then off to bed. I didn’t know my sons stomach was bugging him but at 12:30 that night I sure knew it as he ‘ralphed’ all over our gear beside his bed. I awoke immediately and went for a bucket for his 2nd and 3rd time—poor kid was all I could think. The next morning, he informed me it was out of both ends so it was good we had extra long johns. It had snowed overnight, only two inches or so and Matt almost stayed in camp. Luckily, he came with us and soon Cubaa spotted a big group of Ibex billy’s and nannies. We started zigzagging up this steep mountain. After awhile, we got off the horses and were going on foot, steep and

difficult at the elevation. Now we come up to a ridge top and the ibex are up the hill. Matt takes my rifle, I range the distance at 402 yds and Matt shoots. They break into a run and are soon out of our sight into a big draw.

We are hiking towards the draw and looking for his Ibex. Dulot is just beside me looking down into the draw trying to find it first, so I scan up the draw and there he is piled up in the snow about 200 yds up. “There he is, good shot Matt” I exclaim, and it was, considering the night he had. So now pics and we take a lifesize cape. They get the horses into this steep rocky drainage and after finding out Matt hit him right in the heart, and all the skinning, they load the whole Ibex on two horses and we start down. Matt and I walked down, and they led the horse.

We are back in the camp mid afternoon and they decide that we’ll head back to base camp today and go to another camp for another Ibex. We had a couple beers to celebrate the hunt to this point. Unfortunately, Matt got sick again in the night, so he decided to stay in camp the next day and not come with me for my Ibex. We had three days left and rode up

another long valley to a camp where I got a nice Ibex, but I’ll save that for another story. It was a great adventure with my son, a once in a lifetime trip for both of us. My ram was 52 ½ inches, Matts Ibex 42 inches and mine just over that. Unfortunately, we got out to Bishkek where I had arranged to pay $500 US to get a CITIES permit to bring them all home with us as extra luggage, only to get a text from Natalia that night saying “We have a problem, there are only two officials in Bishkek that can sign the Export permit and they are both away at a Convention.”

Wow, what to do, I am at their mercy, so I had to end up leaving them there to be shipped later. As I write this up Dec 20th, they have just arrived at the Vancouver airport—going through inspections and Customs, and about $3,000 extra.

So, we had some ups and downs but a great Adventure for a father and son. I’m sure my second trip might have less bumps in dealing with certain things, like paying almost $600 to bring my firearms and one extra bag back. The language barrier is a bugger! Looking forward to doing some great mounts on them.

he rain wouldn’t stop. Should I go home? Should I wait it out. With daylight slowly creeping up on me I decided to wait it out as the rain had seemed to subside. I grabbed my pack and rifle and ambled up the road closure with my headlamp guiding the way. As the rain picked up again, I found a giant fir tree and hunkered down. With daylight dancing over the distance ridges, I had to keep going up to my desired location for the day.

Upon arrival I found myself staring at a decent 4x3 buck chasing a hot doe through a wide open flat. After a quick look he got the pass and I kept on going up the road closure. My target spot was a wide open ridge that I had previously hunted and had success before. As I made my way up the ridge I carefully picked my route through the open timber and small amounts of dirty blow down. The farther I made it up the ridge the more deer sign I encountered. I turned and looked back down the valley I noticed the clouds were disappearing. The sun was finally coming out. I had hoped today was going to be a nice day as I only had two days to hunt mule deer.

Picking my way up the ridge I was starting to bump into more deer. The first group was a bunch of does and fawns. With no buck in sight I decided to move up and around the deer and keep going up the ridge. As nice as the weather had turned it quick decided to turn nasty again. I was greeted with sideways winds and snow, on goes my Kuiu kutana rain jacket. I sat in the heart of this storm with not much cover just hoping it would end soon. As fast as it came in, it left not long after. The past times I’ve hiked this ridge I’ve always worked a migration trail up the mountain until the mornings winds switch to uphill drafts. With lots of time on my hands I patiently worked the ridge

back and forth trying to go slow and use my Swarovski binoculars to pick apart the sparse timber face. Bush cruising for mule deer was my favourite thing to do, you never know what you’re in for. Most times you’re left with broken pieces of frame, forks and mass to try and judge a buck before he makes you and takes off—a game I’ve been successful at before with having taken a couple nice bucks this way. As I was finishing off sneaking through a timber patch I noticed an odd white spot above me about 80 yards up the trail. I paused, put up my El ranges and confirmed it was the white rump patch of a mule deer. Not being able to see its head I was forced to hang tight. A few moments later it lifted its head—a doe. Then another deer came into view, a doe, and another and another. Does and fawns had this ridge covered, there had to be a buck with them. I let the ladies feed right to left then carefully picked my way up and over to where they were headed. Creeping slowly along a frozen deer trail while trying to stay quiet, I was surprised by two more deer standing in a fairly open area. Not being able to see their heads I carefully took my rifle off my pack and got ready just in case things got interesting. The long blonde grass was blowing downhill showing me that I had the wind in my favour. The does I had originally seen were now across from me and up above the two deer I had just spotted. I just needed them to move as they were covered by some sparse timber.

The farthest deer had taken a couple steps up the face and revealed himself. A tall and heavy 4x4, his forks weren’t the best but it was a nice buck. Definitely one of the better bucks I’ve seen over the years. As I watched this buck, the closest deer had finally turned and presented himself. The sunshine had revealed a dark heavy chocolate frame with great forks and a sticker point in between his g2 and his g3. I

couldn’t see his other antler and he was staring at this other buck hard, almost like it was a stare down of the century. My eyes focused back on the big 4x4 above me. He was a nice buck. Something told me to look back at the other heavy antlered buck below him. I turned and put glass on him again. Just as I found him, he stepped out and turned His head and looked uphill. Holy s...! This buck had it all. There was trash everywhere, it looked like two stumps on his head. As he stepped up the open face it was clear he had the swagger and was the boss. A true ghost of the timber. Off came my pack. Off came my gloves. I switched the safety off on my kimber 280 Ai. Time stood still.

I’ve dreamt of this situation for 25 years, the length of my short hunting career. This buck had it all. Mass, forks, width and copious amounts of trash. The swagger in this buck was inviting, to sit there and be able to watch this buck unnoticed was a opportunity of a lifetime. My quick little day dream was ruined when the other buck had noticed my yard sale of gear merely 80 yards away. Thankfully he was so in love with the doe above him, his attention had quickly changed to her. He chased that doe up the open face. I was only hoping the big non typical would follow them and I would be presented with a shot. Swagger had enough, these were his does. He took two steps into the opening and started to quarter away from me. I had 20 feet of opening to stop him before he disappeared into the dark timber patch above them. I let out a quick whistle and he stopped. He was inside 100 yards, quartered away. As my crosshairs from my Z5 rifle scope settled on his massive ribcage, I slowly squeezed the trigger. The mountain side erupted with the roar of my 280Ai as it sent a 140gr accubond down range towards Swagger. I watched in awe as he didn’t even flinch, not even a

jump. Did I miss him? Swagger ran uphill about 20 yards, stopped, did a 360 and started to tumble down the ridge. As excitement came over me, I gathered my gear and ran as fast as I could towards where I had last seen Swagger at. From the distance, I could see one side sticking up from a pile of blow down, there was junk everywhere. As I pulled him out of the pile of gnarled wood I was in awe as his other side was even bigger then the side that was in the air. I stood there in disbelief. In all the years of chasing mule deer I had finally harvested the buck of a lifetime. I quickly cut my tag, phoned my wife and just let out all the emotions. We sat there and talked about how the hunt unfolded and how proud she was of me, and for all the time and dedication it takes to do this stuff. The time away from home and family. After I hung up the phone I snapped a few pictures and sent them to a couple of my hunting partners. The distant sun was starting to shine and cut through the fog filled air that surrounded Swagger and myself. I just sat there and watched the beautiful morning unfold in front of me. Rain clouds turned to bright blue skies and sunshine. It felt like an hour had passed and I hadn’t even started the job of getting this monarch off the mountainside. Since I was solo I had the chore of doing photos by myself. A quick call to my buddy Dallas Cota and he hammered out some pointers for quality solo pictures, not till after I told him the story and sent him some shots first.

After a very lengthy photo shoot, a phone call to my dad and my wife again, I started the breakdown process of Swagger. Within the hour I was loaded and ready to head down to my parked truck. Both my wife and father offered to come help but I insisted that I need to do this for myself and Swagger. To harvest a deer of this magnitude is not only a fortune but a gift from god, the man who put these animals on the landscape so we could enjoy them for eternity. With a whole deer and a three quarter cape, I was

ready to amble down the ridge.

The walk down the mountain was surreal, and heavy. I had stopped many times just so I could turn around and admire him through the shadows the sun cast on the mountain side. Two and a half hours later. I was at the bottom and ready for a scotch and hot tub.

I’m super grateful for the

opportunity to hunt these animals every year over the counter. I’d like to thank my two dads for involving me in their hunting adventures and passing along the dedication and heart it takes to be successful. I hope to be able to pass this same attributes off to my young kids as they get older and start the same adventures as I did a mere 30 years ago. To my wife, thank you.

by Dana Dykema

t is interesting how the seasons of life can unfold. You can be busily going about your business, aware of certain things and suddenly one of those things comes alive to you. Hunting and conservation are those things for me most recently. I did not grow up in a particularly outdoorsy family. I was born and raised mostly in the city. On occasion my dad would take us camping around Southern BC and in Alberta. I remember one time we went to a noncampsite campsite in Jasper, basically a field off the beaten path. I can recall waking up in our tent and unzipping the zipper to greet the day. As I opened the flap I found myself face to face with an inquisitive bull elk. I figure I was about 7 or 8 years old and I had no fear. Dad told me to close the zipper pretty quick!

The summer after high school I got a job at my friends’ parents fishing lodge, about 300 kilometres up the coast—the middle of nowhere. I lived on a barge attached to land with long, strong ropes and spent the summer watching orcas, humpbacks, seals, eagles and all manner of salmon and halibut. I even landed my first fish, which was exhilarating. Little did I know then, that I wouldn’t fish again for 20 years.

I met my husband and married just after high school. Four babies soon following in close succession. My 20’s are a blur of diapers, strollers, tee-ball games at the park and daily trips to the grocery store just to feed my crew through another day—survival. By the time my 30’s came around, the fog of early motherhood was

starting to clear and I had some space to think and process, to figure out who I was an adult. What did I like? What lit me up? I dabbled in furniture restoration, Beach Body workouts and became a beauty consultant for a clean beauty brand. While I was dabbling with hobbies, my husband hit middle-age. He didn’t grow up in a hunting family either; his father was a chicken farmer and his mom worked for a car dealership. Some primal charge went off within him at 40. He had the desire to get his PAL (Possession and Acquisition License) and then his CORE (Conservation and Outdoor Recreation Education). He squeezed through the last narrow sliver of in-person courses and the exams before things shut down in 2020. Thankfully he passed.

At the time I had no interest to join him in his quest to hunt and gather. This was his thing and he was able to get out a couple times a year to develop his newfound interest and skill. I was content to have him be the Daniel Boone of the family.

During Covid I also had my own awakening; all about food. I learned that almost everything at my local grocer was imported, sprayed with chemicals and grown with suspect farming practices. I became educated on the basics of gardening and became obsessed with wanting to buy from local, regenerative farms. I started to rid my fridge and pantry of all the chemical junk that laced our produce from every corner of the world. I wanted to disconnect from the grocery store and had such a desire to know where my food came from.

In the fall of 2021, I started a business bringing farm fresh produce from the Fraser Valley to the North Shore. It was through that business that connections started being made. In so many areas of life, it’s who you know, as much as what you know. I met folks who not only valued farm fresh food, but straight up cooked fish over open flames right on the riverbank after a successful “bobber down”. I was rivetted by this. One couldn’t get much closer to their food than catching it themselves.

These connections also led to getting to know the manager of Reliable Gun and before I knew it I was driving my kids to various gun ranges in the Lower Mainland to attend “My First Day at the Range” events he organized. These were a valuable opportunity for kids to shoot under guided instruction. My kids had a blast, pun intended.

I also met the Region 2 chair of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. He invited me to their monthly Pint Nights and I began to make friends in this community. Like a boulder tumbling down a mountainside, my interest in hunting and fishing and getting out to the backcountry gathered steam. Stories of adventure, harvesting meat and hiking into the bush with no other human around for miles whet my appetite. I devoured podcasts from Silvercore and Hunter Conservationist, learning all I could

about the ethics of hunting and the current plight of gun owners and hunters in Canada.

Before I knew it, I was the one speaking at a BHA Pint Night about the importance of knowing where our food comes from. I also had the opportunity to be interviewed on the Hunter Conservationist podcast regarding my business and budding interest to learn the skills as old as time—hunting and fishing.

Although I was warmly welcomed into the conservation community, I didn’t have a mentor—someone to glean from in real time, preferably a female. But life’s like that sometimes. Sometimes you’ve just got to forge ahead as best you can and fumble your way forward. If you don’t, you could be sitting on your hands a mighty long time. So I started. I began planning fishing trips, took my kids crabbing and earlier this year got my own PAL and CORE licenses.

Conservation organizations not only build community, they also keep their finger on the political pulse of what’s going on in regards to conservation, hunting, angling and access to public land. Politics affect people. It can be a messy business. Listening to the podcasts and keeping up with the provincial wildlife foundation (BCWF), I learned that one of the best ways a person can affect change is to simply get involved. As an “adult onset hunter”, I do not want to be too

late to enjoy the wonderful diversity my province has to offer. I want my kids and their kids to have access to land to hunt and fish. I am concerned about some of the forestry practices. What can I do about it? We’ve all signed petitions to support causes we believe in but there has to come a time where that isn’t enough. Face to face meetings are an effective way to show up so I thought I’d give that strategy a go. I booked an appointment with my local MLA. I wanted to discuss the provincial budget which has been diminishing over the past 30 years. I looked up some facts that I wanted to touch on, formulated some questions and printed off the introduction and conclusion of the most recent response from the BCWF. While the meeting went as I expected, I think my greatest takeaway personally was

the fact that I did it. Getting a little uncomfortable for the cause.

The more we, who love the outdoors, are aware, educated and willing to go to task on the political level in whatever way we can, the more we won’t be left out of the conversation. One person having a 30 minute discussion might not achieve much, but if hundreds or thousands of us began having these meetings with our local representatives, it will move the needle and ensure we influence the decision-making when it comes to where our money and resources go into the future.

Volunteering is also a fantastic way to build community, make connections and give back. This winter the BHA crew head out for a beach cleanup at a popular waterfowl hunting spot. I brought my three younger kids.

Dana Dykema lives in North Vancouver, BC with her husband and four children. She is an entrepreneur and a homeschooling mom. She enjoys trail running, gardening, fishing and camping with her family.

They were real champs that day. The local newspaper even wrote about our time at the beach. It’s also important for members of the public to see hunters taking care of the places they hunt in.

Most recently I brought my younger boys to pitch in with Pitt Water Fowlers and their nesting box maintenance day. They thoroughly enjoyed getting out on the water, cleaning and repairing the boxes and collecting data. Time out with my kids like this is pretty special. It broadens their horizons and helps them see their place in conserving and protecting our wild places.

As I write this I am preparing to go out on my first hunt next week. My husband and I are hoping to fill one of his spring bear tags. I’m looking forward to pushing past my nerves and joining the ranks of all the hunters who have gone before me.

In the words of Anne of Green Gables, “I like adventure and I’m going to find some.”

This article has been lightly edited for the magazine.

The full article can be found here: https://mtntough.com/blogs/mtntough-blog/mental-stamina-strategies

he backcountry is unforgiving. Here, mental stamina is as crucial as a good rifle or a sturdy pair of boots. It can define your outdoor experience, keeping you focused and resilient when the trail gets tough.

Your mind is your first line of defense in the backcountry. Preparation is a combination of gear prep and strengthening your mind for what’s ahead - and you’re never entirely certain what the future entails.

This underscores the importance of picturing all possible outcomes as you prep and tackle the terrain ahead. Acknowledge the hard parts and plan your tactics each day you break camp. It’s like plotting a battle strategy. You’re the leader, and every hike’s a mission. Understand your environment, know your abilities, and be prepared to adapt.

Facing challenges head-on is what separates the tough from the quitters. When the path gets steep or the weather turns nasty, your mental game plan is what keeps you from breaking. Mental toughness in the wilderness means expecting the unexpected and tackling it with grit.

Long hunts and hikes test your heart and mind just as much as your body. They can bring a storm of emotions that need to be understood and managed in order to keep pushing forward.

The key is to recognize and manage your emotions. When exhaustion sets in and the hill seems endless, that’s when your heart needs to be strongest. Understanding that these moments of doubt are temporary is crucial. You push through them with sheer will, just like you push through a tough climb.

Fear is a tool, not a hindrance. Remember that. Distinguishing between rational caution and unnecessary panic is one of the most valuable things you can do to remain safe out there. Fear based on respect for nature is healthy; it keeps you alert and cautious - and doesn’t run counter to toughness.

But when fear starts clouding your judgment, that’s when logic needs to take over. Dissect your fear, challenge it with facts, and turn it into a driving force, not a roadblock.

When you feel like turning back in a moment of weakness, goals should be in place to remind you why you’re on the journey in the first place. They’re not about lofty ideals; they’re about real reasons to hit the trail - the thrill of hunting, getting fit, finding yourself, staying safe in the backcountry, or simply connecting with the wild.

Building your goals around an enduring experience rather than a temporary reward (a trophy bull, a PR trail, etc.) keeps you grounded and focused, especially when things go sideways.

Once you’ve defined your realistic goal, it’s time to break it into smaller pieces.

Creating Milestones to Track Progress

Think of milestones as checkpoints or trail markers to your goal. They’re chances to regroup and evaluate your gear and grit. They’re wins, showing you’ve got what it takes to keep pushing. They’re also your moments to rest and rethink your strategy.

● Is your goal still the right one?

● Are you pushing too hard or not enough?

● What’s working? What’s not working?

These checkpoints keep your journey realistic, matching your progress with what the trail throws at you.

Are you jumping from challenge to challenge? Feeling doubt or overwhelmed by the experience? If so, this is your reminder to stop coping and start dominating.

As soon as you recognize that challenges are guiding you through the backcountry instead of your goals, call a timeout. This is your moment to reset.

To do this, bust out your mental toughness toolset and regain control of your experience. Utilize any of the mental strength exercises listed below:

Mindfulness for Focus

Despite its hippie-like reputation, mindfulness has nothing to do with zoning out and everything to do with intense focus on the present.

Mindfulness is keeping your mind where your boots are and when you’re mindful, you’re tuned into every aspect of your backcountry experience – the terrain, the weather, and your own thoughts. This sharp focus keeps you grounded and alert, ready for anything in the bush.

It’s an incredible tool for staying connected to the present, making you more effective in handling the mental game of being out in the wild.

Meditation Isn’t Mindfulness

More than just mindfulness, meditation is taking time to shut off the noise and sharpen your mental edge. Simply put, giving your brain a break. In the process you can refocus and recharge.

Regular meditation builds your mental stamina, preparing you for long, demanding treks. It’s like a pit stop for your mind, getting you back on track with renewed clarity and determination.

Breathing for Clarity

Breathing techniques are your quick fix for mental clarity. Simple but powerful, controlled breathing keeps your mind steady and your nerves calm.

Deep, focused breaths help you regain control in challenging situations, keeping panic at bay. It’s a straightforward tool, but in the tough conditions of the backcountry, mastering your breath is mastering your mind.

If these three techniques aren’t already in your training regimen, now’s the perfect time to add them. Don’t wait until you’re in a jam on the side of the mountain to start practicing these techniques. Master them before you need them so you can refocus and push forward unshaken when you need it most.

Where the techniques above will bring you back to center, your mindset defines the center. While both concepts are closely related, your mindset is the North Star of your mental strength. It’s critical to set course for an outlook that cultivates positivity through challenges. Celebrate every win, no matter how small.

Topping a ridge or pushing through fatigue? That’s a victory. See hurdles as chances to toughen up. Keep your spirits high with simple but powerful affirmations. They’re like mental kerosene. And remember, your hunting and hiking crews are more than just company; they’re your support system, turning solo struggles into team victories.

Visualization to Overcome

Visualization is like scouting the terrain with your mind. Imagine mastering tough situations – packing out elk or

navigating rugged paths. These mental rehearsals build confidence, slash stress, and get you ready for the real thing. It’s not all about the grind, though.

Use visualization to create calm scenes in your head, helping you relax when you need a breather.

Regular practice keeps your focus razor-sharp, crucial for staying on top of your game in the wild. Visualization isn’t daydreaming; it’s mentally preparing for success, making sure you’re as ready in your head as you are on the ground.

A multi-day hunt or hike will deplete every strand of fiber in your body. So, your diet needs to counter this as much as possible with a mix of carbs, proteins, and fats to keep your mind sharp and body moving.

● Complex carbs like grains and legumes are your energy reserves.

● Protein from lean meats and nuts keeps your muscles going strong.

● Fats, especially omega-3s from fish and nuts, are brain boosters for clear thinking.

Don’t forget the small stuff – vitamins and minerals. They’re key players in keeping your brain focused and avoiding fatigue. In the wild, your food choices directly affect your ability to stay sharp and make crucial decisions. Hydration is a key player in your mental strength in the backcountry as well. A drop in hydration means a drop in concentration and memory. Dehydration can be as dangerous as a wrong turn. Stay hydrated, but not just with water – add electrolytes to replace what you sweat out. This balance is essential for your brain to function at its peak.

Timing is also an important consideration. For peak mental

stamina, align your meals and water breaks with the toughest parts of your hike. This strategy will keep your mind alert and ready for the challenges ahead.

Routine can be an anchor for mental stamina. It breaks the chaos of nature into a structured day. This order saves energy and sets a rhythm you can count on. With a daily routine, even massive situations become more manageable and less intimidating. Your day should have a clear pattern.

● Start with packing up camp, a process that gets smoother with practice.

● Break for your hunting spot early to avoid the heat.

● Make time for planned breaks and meals and have them plotted ahead of time.

● When the sun dips, setting up camp signals the end of your day.

This discipline creates a comforting rhythm for both body and mind, creating a shield of sorts to unpredictability. It provides familiarity amid change, conserving your mental strength. Decisions are constant in your mission. A set routine cuts down these daily choices, saving mental energy for the critical decisions.

It also keeps spirits high. Hitting daily goals, like reaching a specific point by noon, brings a sense of achievement, fighting off doubt and frustration. Your routine is a stabilizing force in an environment where anything can happen.

Pushing through deadfall or tackling sidehills, your body and mind need to work together. A strong body builds a tough mind, and a resilient mind drives the body. It’s a cycle where improving one strengthens the other. Physical readiness breeds mental confidence, preparing you to tackle

the wilderness head-on.

Rest, for muscle and mind, is a non-negotiable factor of a successful time in the backcountry. Pushing hard matters but knowing when to slow down is key. Rest rebuilds mental strength. Without it, your mind gets foggy, your decisions slip, and your drive wanes. Balance is critical – hit the terrain hard, but rest when your brain signals for it.

Resting is simply part of the journey, paying respect to your mental limits as much as the physical ones. Regular rest helps you handle stress and avoid burnout. They let you reset emotionally and plan your next moves with a clear head.

Spotting Mental Fatigue

Keep an eye out for mental fatigue. Signs like getting irritated easily, losing focus, struggling with decisions, or just not feeling the hike signal a need for a break. These are warnings – your mind’s way of saying it’s time to recharge. Mental sharpness is a must. If you see these signs, it’s time to rest up.

Whatever calls you to the middle of nature, your mind must be as ready as your body and gear the entire journey. It will drive you when everything else fails. Your mental grit sets the tone for conquering or quitting.

Fear, excitement, frustration – you’ll run the gamut of emotions out there. How you work through them can make or break your experience.

Max your mental toughness long before you start your excursion. Master the techniques to bring your mind back to center in training too. With a higher ceiling and the tools to reach it on demand, your mental stamina will continue to be the force that pushes you up every hill, over every falling tree, and across every ravine.

Dear Wild Sheep Society members,

This Summer we are undertaking our largest Membership Drive to date, and we need your help.

The WSSBC currently sits at just over 1500 members, a truly incredible tally when we consider where we were just a few short years ago. We could not be more grateful for your incredible support, as we call over half of you lifetime members alongside our 165 Monarchs. Still, we have bigger goals to attain and our next marker along the way is 2000. We are hoping to achieve this result by our 2025 Salute To Conservation in late February, but it will not be possible without leaning on all of you.

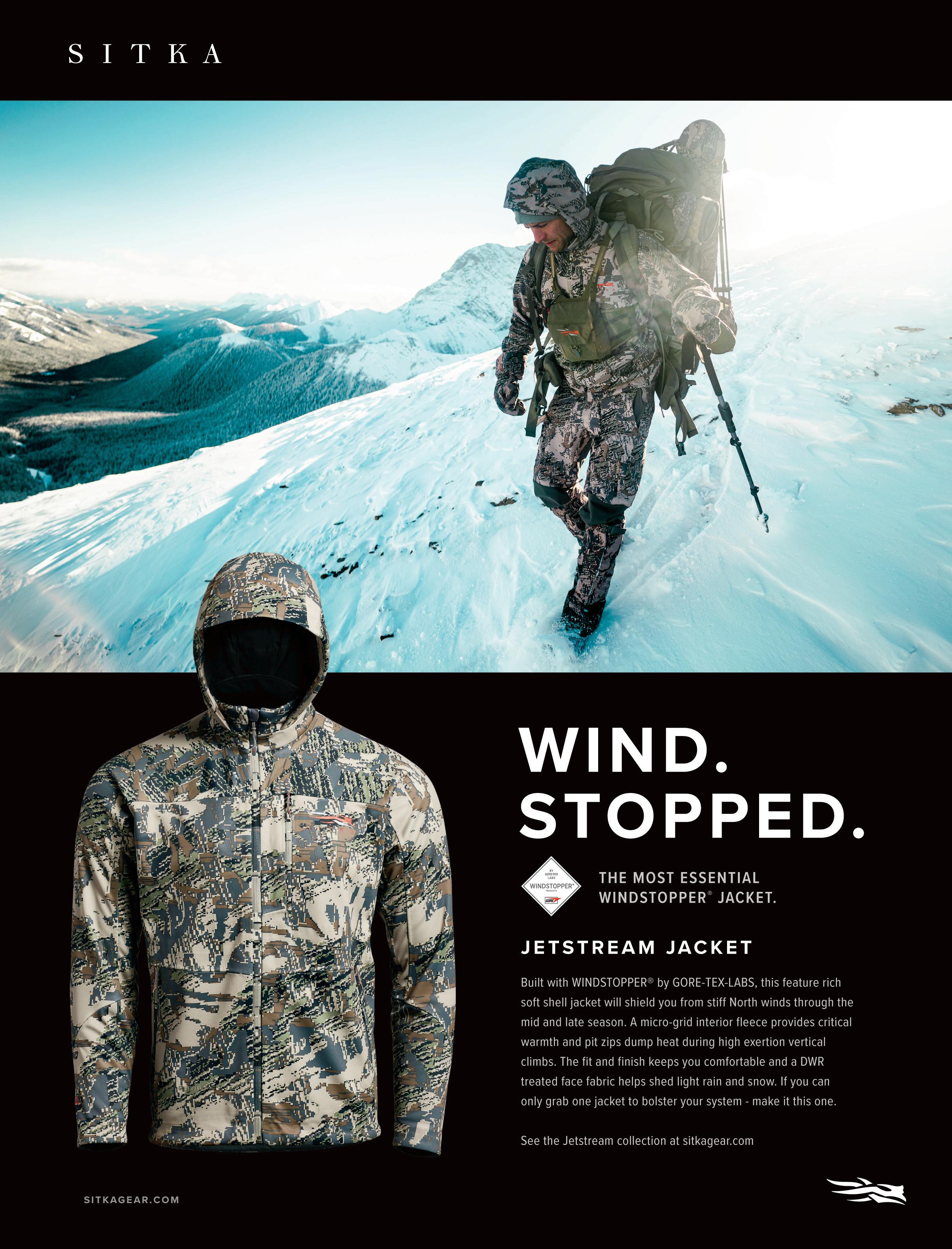

For this Membership Drive, we have put together our largest prize package ever, supported by many of our Partners in Conservation, this package has a $10,000 value. This package includes a Frontiersmen Gear Mountain Series Backcountry Blade Kit, Zeiss Conquest HD 10x42 Binoculars, two WSSBC branded Yeti coolers, Sitka Gear Mountain pants and Drifter Duffle, Stone Glacier Terminus 7000 pack, Schnee 0g Granite Boots , and a lifetime Elite OnX membership. We’re also tossing in 20 WSSBC branded Fresh Trek meals for your upcoming adventures. Differing from past Drives, this time around we are doing a points-based system with referrals. This means that you can earn points by having a friend, family member, or anyone else you meet along the way join our ranks. You can even sign them up yourself by purchasing a membership on their behalf!

Points are earned as follows:

New Membership: One year, Threeyear, Youth, Family – 1 entry, Life, Youth Half Curl Life Membership – 2 entries, Monarch (any level) – 3 entries

Upgrade your membership: to a Three year – 1 entry, to a Life Membership – 2 entries, to a Monarch Membership (any level) – 3 entries, Levelling up your Monarch Membership – 3 entries

A couple of sales pitches for your consideration:

● WSSBC has invested over $1.2 million to project work for the benefit of Wild Sheep throughout the province in the last two years alone.

● WSSBC has built relationships with Federal and Provincial governments,

First Nations, and many provincial, national, and international NGO’s.

● WSSBC is committed to fighting for your ability to hunt and own firearms, contributing $50,000 to the CCFR in the past year.

● WSSBC Director’s sit on numerous committees, boards, and working groups behind the scenes, working tirelessly to support our cause.

We want to continue to do more for Wild Sheep here in BC, so that we can ensure that future generations are able to experience what we have been fortunate to. We thank you, our members, for your continued support, it means the world to us.

Sincerely,

Peter Gutsche Membership Chair

WSSBC Volunteer Opportunities & Events: https://www.wildsheepsociety.com/volunteer/

July 5-7, 2024 – Ruck for the Shulaps, with Matt Ward and Matt McCabe

July 6, 2024 – Horn Aging Seminar, Comox

July 9, 2024 – Horn Aging Seminar, Abbotsford

July 13, 2024 – Fraser River Sheep Counts

July 20, 2024 – Horn Aging Seminar, Prince George

August 18, 2024 – Fraser River Sheep Counts

August 23-25, 2024 – Jurassic Classic

January 31-February 1, 2025 – Northern Fundraiser, Dawson Creek

February 20-23, 2025 – Salute To Conservation and Mountain Hunting Expo, Penticton

by Andrew Spear

ine Years ago I was fortunate enough to enter the fraternity of sheep hunters.On a backpack hunt into the Tuchodi river basin, I harvested a nine year old Stone ram with a light pepper cape. In the years since, I have spent multiple trips into that high country, earning my stripes helping good friends take rams in 2014 and 2016. I began to invest some time in the Thompson sheep herd but 2020 saw us back again in upper Muskwa, only to return with more mountain wisdom and sore feet. 2021, we came close on a few mature heavy horned Rocky’s, but the north country was always calling.

Plans were laid, packs weighed and re-packed, meals planned, and shells loaded. An unexpected health issue left our trip cancelled in 2022. I was destroyed, hopeful to return and claim a stone for myself after years of helping friends. I couldn’t believe the low I was experiencing. “I really thought this was the year” I told my wife. She had and idea, my 7-year-old son has a best friend, and her dad Devon, I knew was an avid hunter. “So, you wanna go on a sheep hunt?” I asked. “I’ve been waiting for someone to invite me” he replied. Just like that, redemption was in sight.

We booked our flight and in Sept, we drove the 18 hours to Muncho lake ready for whatever the mountain

had to teach us. Devon took the flight hard, he lost all his breakfast and then some, a rocky start we figured was good luck.

A few minutes to drop coolers, and a few hours later down the trail. We learned the hard lesson I have learned before, “don’t get off the horse trail.” It took us two days of bushwhacking to find our way into the high country. 3 days of goats, grizzlies and a few ewes made us decide to move camp. We side hilled for 5 kilometres, hit a valley bottom with water, and dropped camp. It was later in the day but we figured we should hike into a saddle and start glassing. 30 minutes after we sat down, I heard the sweetest words “I got rams.” 2 kilometres away at the

height of land, in the crag Devon had spotted two rams—one looked pretty good. 5 min later, another ram crested the ridge and bedded down.

“Legal ram, 100%” I said, “whatever happens in the next 6 days, we are going to get that ram.”

We decided we would sit on the rams until well after dark, hike the 4 kilometres back to camp and be back well before first light. Then with 45 min of light left, the big ram got up and started moving towards us. There were three rams on the skyline, and in a few minutes all of them were on their feet and moving quickly. Two more rams materialized out of thin air in the rocks. “If those rams go into that caldera, this is going to happen tonight” I said.