2024 Wild Sheep

by Wild Sheep Society of BC

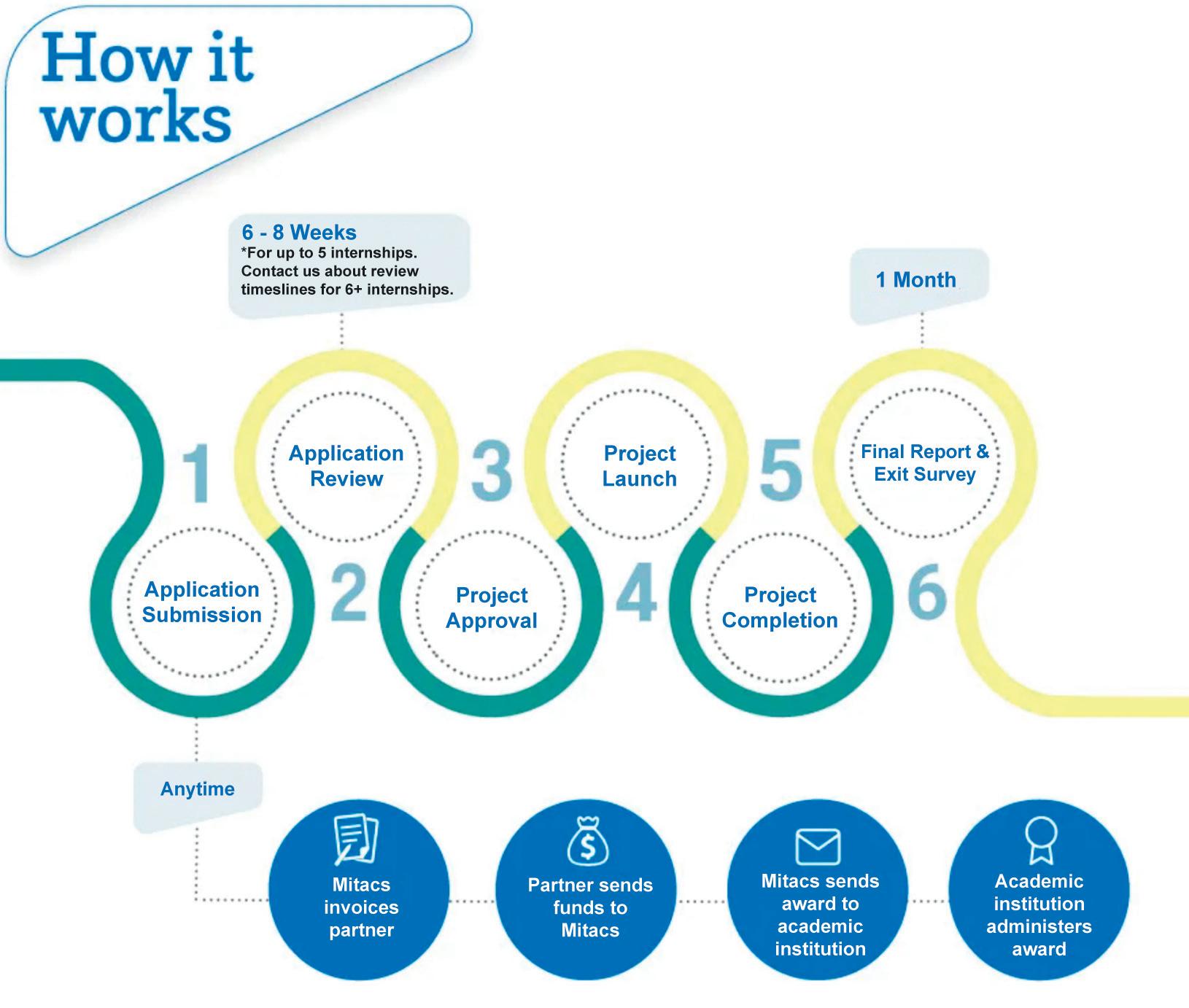

his past August 23rd to 25th wild sheep conservationists joined together in Chilliwack, British Columbia for the 8th annual Wild Sheep Jurassic Classic. This is another great event that brought people together from across North America to this province in the name of fun, fish, and fundraising. Participants come together each year and spend the weekend fishing for an iconic fish species – the Fraser River white sturgeon, all in the name of supporting an iconic mountain species, the wild sheep of BC.

This year was another sell-out event with 56 participants who came from all corners of Canada and the United States to participate in the name of comradery, connection, and conservation. The event is limited in size to a total of 56 participants each year, which keeps a wait list yearly to attend. Fourteen boats, guided by Great River Fishing Adventures, guide the 14 teams of 4 for two full days of fishing and an entire weekend full of excitement.

Despite a very wet Saturday, fishing was strong with a total of 135 sturgeon caught throughout the weekend. While the event is about a lot more than a simple fishing tournament, its hard not to look at the healthy competition that the weekend provides. Each boat tracks all fish caught and records all measurements of every fish landed. Through the support of our sponsors, this year our prize package exceeded $15,000.

Congratulations to all our 2024 winners. Topping the charts with a 9 foot 11 inch giant were Ryker Luenberger, Riley Luenberger, Erik Skaaning and Gray Thornton. A total of 135 fish were caught throughout the weekend with five sturgeon measuring over nine feet. Thank you to our prize sponsors YETI, Stone Glacier and BC Trappers Association and Glen Cartwright who outfitted the team with YETI Panga 50s, Stone Glacier Solo 3600 packs and Trail Kegs.

Mila Dilts, Jack Dilts, Mike Vidrich and John Truzzolini landed the smallest sturgeon at just one foot seven inches. Thank you to YETI for sponsoring the prize with YETI Rambler 60s.

The mystery length was won by team Canadian Wildlife Capture and Ben Berukoff, Jordan Smaldon, Paul Terhart and Landon Gill. Thank you to Schnee for sponsoring the Mystery Length with all four anglers receiving a set of Schnee Granite 200g boots.

The team of Steve Arnett, Mike Wood, Cam Foss and Dave Anderson

topped the charts with the most fish caught with 25 sturgeon to the boat over the two days of fishing.

This year we were very fortunate to have YETI represented at the event. YETI was our 2024 Signature Sponsor along with our major sponsors SITKA Gear, Stone Glacier, Sako Rifles and Steiner Scopes.

Our 2025 event which will be held August 22-25, is sold out to the public. The only way of attending is by purchasing a team entry at one of our wild sheep chapters or affiliate supporters, or other conservation

organizations who auction these coveted spots to raise funds for their own conservation initiatives. Wild Sheep Foundation Midwest Chapter, Wild Sheep Society of BC and Wild Sheep Foundation Alberta have teams available for purchase for 2024.

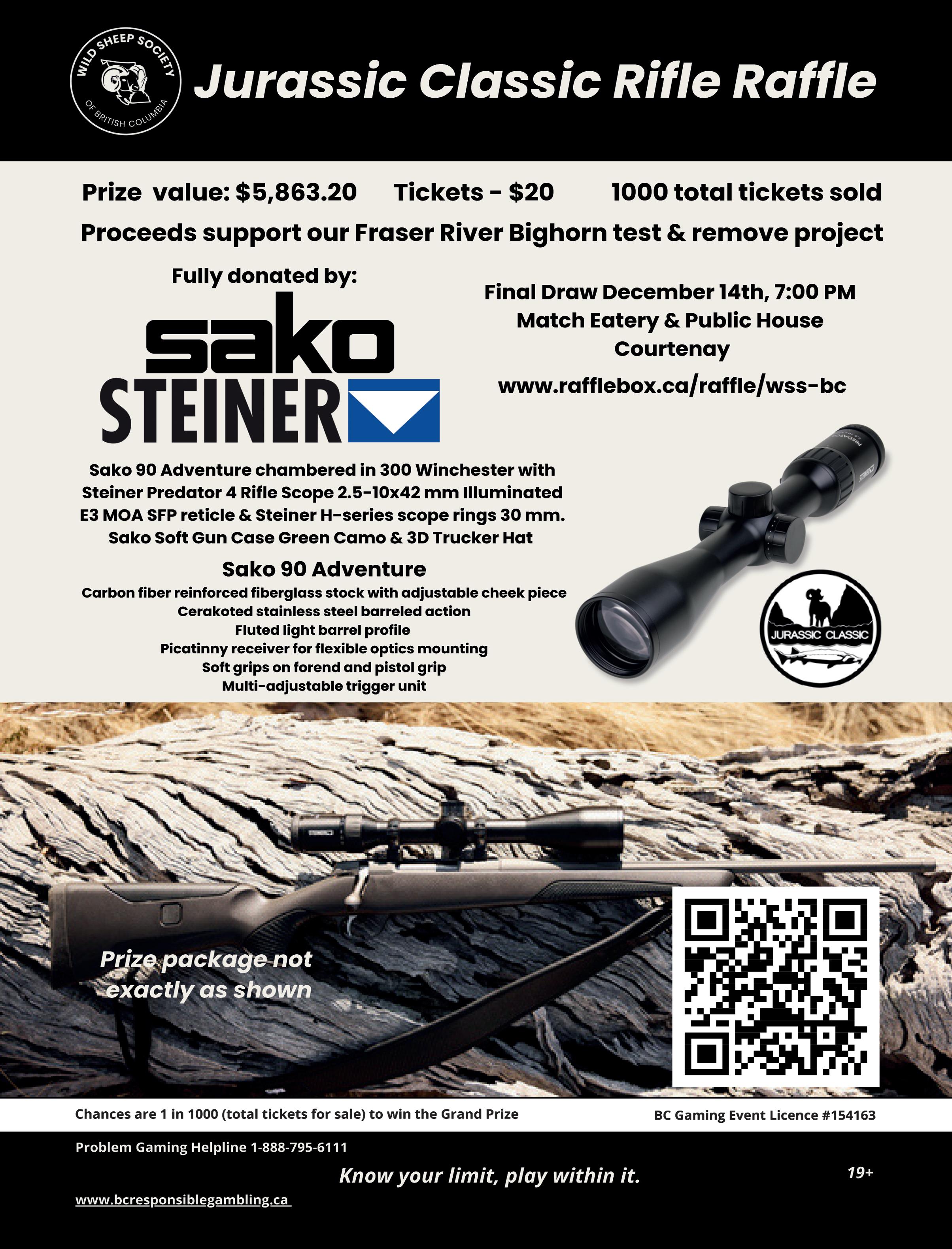

The Jurassic Classic wouldn’t be what it was without the help and support of our amazing sponsors. Our major sponsors include Yeti, SITKA Gear, Yeti, Stone Glacier Sako and Steiner. Each year funds are raised through an online and silent auction,

and in recent years a Jurassic Classic rifle raffle has been run to support the Fraser River Test and Remove Legacy project. This year Sako Canada has stepped up in a major way and donated a Sako 90 Adventurer in 300 Winchester Magnum topped with a Steiner scope.

The Wild Sheep Jurassic Classic is an event like no other in the conservation world. It is an experience that brings guests back year after year and always has a handful of new guests who come through our fundraising efforts. This all-inclusive weekend is a great way to close out summer and get ready for fall, and we look forward to future continued success in raising funds for wild sheep through the province and having a great time doing it. There is a reason we call this event BC’s Full Curl Fishing Experience!

by Jim Manley

nce we had crossed the swift-flowing icy river, the only sound was the deliberate, steady hoofbeats of our horses on the frozen dirt trail. Occasionally, the near-silence was interrupted by one of the steeds making loud nose-clearing rumbles. The sun hid behind the rugged, snow-capped mountains, and the foggy low clouds preventing us from hunting the day before were draped along the slopes nearly halfway to the valley floor. We progressed slowly, hoping the pesky layer of moisture hindering our view would be dissolved by the sun as it climbed from behind the jagged summit. The air was still and cold and filled with the smell of creekside vegetation and horses.

Steph led the three-horse parade while diligently keeping a sharp eye on the visible part of the mountainside to our left. She silently communicated with her young green mount with a light hand and slight leg pressure. I followed closely behind, looking for sheep while trying to ignore the early morning chills. Amanda, bringing up the rear, lagged back a bit like a sentinel watching for problems. As the horses methodically moved to the east along the creek, I noticed the sky was brightening. Gradually, in sync with the rising sun, the fog started lifting, revealing more hillside to scan. A little over an hour into the ride, Steph pulled up short, dropped the reins, and grabbed her binoculars. Following her gaze, I searched the mountain for whatever caught her eye. Not seeing anything, I glanced back to verify exactly which way she was looking. In one fluid motion Steph dismounted, pulled her spotting scope from the saddle bags, and plopped on the ground. By the time I climbed from my horse and figured out how to secure him, Steph was urgently whispering, “Get your scope!” I hustled, scope in hand, to where Steph sat and found a flat spot next to her. “Two rams,” she whispered as she pointed up the hill. Amanda had taken control of the horses by this time and joined us. The rams were over halfway up the mountain, a long way from us. The valley was filled with a forest of dead trees caused by a lightning fire years earlier. It was tough to get a clear look at the sheep through these snags, but we had time as the rams obviously weren’t aware of us. One was bedded, and the other was slowly feeding to the west. While studying the sheep through my spotting scope, I could feel Steph staring at me. Turning to her, I couldn’t help but notice her excitement: her jaw had dropped, her mouth was gaping open, and her eyes were the size of silver dollars. At that moment, I knew the hunt was on. The genesis of this sheep hunt was a little over a year and a half earlier. In

January 2017, while strolling the expo hall of the Wild Sheep Foundation’s Sheep Show, I passed Big 9 Outfitters’ booth. I’d heard about Big 9 for years and knew Barry Tompkins ran one of the premier Stone sheep hunting outfits. So, when I noticed the three young ladies staffing the booth weren’t busy, I stopped by to chat. I didn’t realize it then, but this was the start of a new journey in my sheephunting career.

I introduced myself and explained I wasn’t looking for a hunt but was always interested in talking sheep. Shayann Tompkins, the oldest of Barry’s daughters, extended her hand and said, “Hi Jim. I’m Shay, and this is my sister, Amanda,” pointing to the red-haired member of the trio. Then, turning her head to the right, she continued, “And this is Steph Shippy, one of our main guides.” The ladies were delightful. A bit younger than my daughters, they were personable, knowledgeable, and represented their dad’s business well. We had a great conversation, and after some good salesmanship on their part, I promised to keep a future hunt in mind. Two months later, I was booked and started my extensive mountain hiking prep.

It was an easy decision to drive up north from my Oregon home. I was retired, so I had an abundance of free time and enjoyed road trips. On September 4, 2018, with new tires and a fresh oil change, I took off. Three days and 1,400 miles later, I pulled into Fort Nelson, BC. The next morning I was heading to camp. Scattered clouds obscured the view on the flight from Fort Nelson to Big 9’s base camp, and the air was turbulent. By the time I’d settled in, the pilot was circling for his landing in the giant green meadow surrounding the lodge. As he taxied the big twin across the bumpy pasture, I saw the crew waiting to meet us. When the engines wound down and the props spun to a stop, they approached the plane. One of the guys was on a four-wheeler pulling a large cart to haul our gear. Stepping off the plane, I saw Steph coming to greet me. Even though I didn’t really know her, I got a huge smile and big hug as she said, “Glad you made it.” Amanda and Shay were there, along with three other guides and two cooks. After handshakes and hugs all around, we threw the gear onto the trailer and towed it to the lodge.

Walking to the lodge with Steph on one side and Amanda on the other, my ears were filled with the plans. “We’re riding out today, Jim,” Steph said. “We need you to get your stuff into a couple panniers as soon as you can. We have at least a six-hour ride, and it’d be nice to get there before dark,” she explained. Since it was already 11:00am, I knew I’d better hurry. I picked up my pace, and Amanda broke in, “We’ve got the horses ready, and I set out two empty panniers for you to pack your gear. Take everything you’ll need for a couple weeks.” By this time, my mind was spinning as fast as my feet. After stuffing my gear in the panniers, Steph and I headed out. Once on the trail, I remembered how much I love horses. I had my own in the past and felt like a mountain man as we cruised along the river and through the mountains. The country was fantastic. Scattered white clouds with dark bottoms slowly slid across the vibrant blue sky, occasionally hanging up on the tall peaks. Many

of the mountaintops were lost in the clouds, but the ones in view were lightly dusted with fresh snow. It was the second week in September, so nightly frosts were frequent. As a result, the fall colors were so vibrant they nearly hurt my eyes.

Four and a half hours later, the horses pulled hard up a steep hill, and the trail drifted into dark timber. Because it was shaded most of the time, the trail was muddy and slick but everything went well, and we made good time. We broke out of the trees and crossed another creek. Mountains materialized again on both sides of the trail. Tall and rugged, I could hear them calling my name. When our view opened up, Steph reined in her horse and spoke softly, “Let’s glass this hillside.” We slid out of our saddles and worked the slope with our binoculars. Within minutes Steph whispered, “There’s some sheep.” She pointed them out, and together we determined the band was comprised of five young rams. No full-curls, but a couple were only

a few years away. Back in the saddle, we headed west toward our camp, and I realized that Steph’s young and experienced eyes didn’t miss a thing. As we rode around the corner, an entire mountainside and immense side drainage came into view. We could see for miles, and it was all tremendous sheep country. And there, near the river with a panoramic view, was our camp for the next 12 days. Amanda, and Vicki our cook, rode in a couple hours later, and we made quick work of getting the supplies unloaded, horses tended to, and camp set up. After dinner, I strolled back to my tent with a full belly and stirred up the fire in my small woodstove. Anxious to kick off the hunt the next day, I crawled into bed and attempted to sleep.

Horse bells and the sound of running horses woke me at 4:30am. At dinner, I’d been told breakfast would be at 6:00am, so I pulled the sleeping bag over my head for another hour. The ladies were drinking coffee when I poked my head into the cabin. Steph

looked up and said, “We can’t see any stars this morning, and it looks like the clouds are low. There’s even a little fresh snow. Let’s hope daylight brings a better picture.” We took our time with breakfast, waiting for some decent light. Unfortunately, there were no rays of morning sunshine, just a slowly increasing dreary glow to the cloudy, damp, and cold morning. Every five minutes, one of us stepped out into the dim light to check the visibility. There wasn’t any. An hour passed, and it became apparent we wouldn’t be hunting unless things changed.

As morning slid into afternoon, the fog layer began to rise. Light winds untethered the ground-hugging clouds, and occasionally we caught glimpses of the vast mountains behind and above our camp. Visibility was still fleeting, and the day was leaning toward evening, so we didn’t consider saddling up. We set up the spotting scopes at a convenient spot and rushed out whenever there was a clear view. We saw scattered sheep and elk, but nothing we could hunt.

Once again, the ringing of horse bells pulled me from a deep sleep at 4:30am. But, now understanding the drill, I fell back to sleep until my 5:30 alarm sounded. At breakfast, Steph expressed the same pessimism as the day before. “The clouds are still low. We’ll have to wait and see.” But then Amanda announced, “We’re anxious to start hunting, so we’ve got the horses saddled just in case.” Steph added, “Let’s ride downstream and check as much of the mountain as possible. We can always come back if things don’t clear up, but we’ll keep our fingers crossed.”

A thick frost covered everything, so I put on a heavy coat, a toque, and warm gloves against the early morning chill. The horses were calm and steady as we crossed the creek and moved down the trail to the east. An hour later, Steph stopped abruptly and jumped off with her spotting scope. I guessed something good was going to happen. After scoping the sheep and seeing the excitement in

her eyes, I knew it was time to climb the mountain. Amanda did too and suggested, “Let’s take the horses over here,” pointing to a group of dead snags. Steph joined us as we all found suitable trees to secure the ponies. Then, with our backs to the mountain and voices low, we forged a plan. We decided to continue east on foot until we were two ridges past the rams, then climb to the sheep’s elevation in the cover of a deep draw.

When we reached the gorge, we took one last look at the rams through Steph’s spotting scope. They were up and feeding, a little farther to the west but still at the same elevation. Both looked mature, and one was a fair amount bigger. Trying to keep my emotions in check, I refused to consider how big he actually was. We started the climb with light packs since we had left our excess gear at the horses. Like most sheep mountains, it wasn’t too steep at the bottom, but the higher we climbed the steeper it got. There was little risk of being noticed, as two ridges were between us and the rams, plus there wasn’t any breeze to carry our scent. The three of us slogged along until we reached the rams’ approximate elevation. Then, bearing to the left, we peeked over the ridge, but all we saw was a fabulous view.

Knowing the sheep had been one more ridge to the west and feeding in that direction, we moved on, sidehilling toward where we had last seen them. Entering the next draw, we found it impassable. Sheer cliffs encased both sides of the drainage, and the area above was even more treacherous. If any water had flowed in the gorge, it would have formed an impressive waterfall. We had to move down the mountain to get below the cliffs. I wasn’t thrilled about losing elevation given how tough the climb had been, but there was no other option. After finally finding a route through the ravine, we crossed and fought our way back up, angling toward the summit of the second ridge. The footing was stable, comprised of soil and small rock with grass and bushes covered in sparkling silver frost.

The steep ridge forced me to stop frequently and catch my breath. I’d trained hard all spring and summer, and even the previous winter when the weather allowed. But my age was showing as the ladies were kicking my butt on the climb. Also, knowing the rams could be visible just over the crest of the ridge had my heart rate galloping. When we reached a set of rimrocks, we took cover and peeked into the next draw expecting

to see the rams on the opposing hillside. But nothing. Silence echoed between the three of us for a long minute. Then Steph motioned for us to take a few steps back out of sight. Hunched behind a ragged rock shelf, she whispered, “I’m going to sneak up higher through the cliffs to get a better view. It could be noisy, so you guys stay here. It’ll be quieter than all three of us going.” Twenty minutes passed before Steph eased her way back down to us. As she neared, she started shaking her head. “I could see all of this drainage and a lot of the cliffs above us. They’re not there.” Breathing a long sigh, she continued, “They must be farther out in front of us. Probably feeding faster than we’d thought.” And then, with tight lips and downcast eyes, she added, “Unless we bumped them.” We were all processing this when under my breath, I muttered, “Oh sh*t.” Simultaneously, we lifted our heads and looked at each other. Deep in

thought, Amanda scratched her lower lip with her upper teeth and whispered, “I’ll move lower and you guys continue at this elevation. I should be able to see below the rims, and you probably won’t have much of a view of that area.” Steph was quick to answer, “Good idea. Jim and I will get as far up this mountain as fast as we can. The morning is slipping away, and I’m afraid those boys will think about bedding down soon. It wouldn’t surprise me if they headed for those cliffs.” Steph pointed to the sheer rimrock that crowned the mountain above us. Before heading out, we discussed hand signals, landmarks, and the timing of our efforts. As we got ready to roll, Steph, while making a palms-down calming gesture, warned, “Remember, the rams could be anywhere now. Let’s be as quiet and careful as possible until we have a good view of what’s ahead.”

Slipping on our packs, we started the next phase of the stalk. It had been

several hours since we had seen the rams, and the thought that they might have been spooked and left the area haunted me. We climbed hard, with Steph in front setting a fast but stealthy pace. Always alert, eyes, ears, and nose dissecting her surroundings, she shot up the mountain. It was all I could do to keep up. Who am I kidding? I couldn’t. My bad knee was screaming, but I couldn’t hear it over my heavy breathing. Whenever I stopped for a quick rest, Steph took the opportunity to scour the terrain with her binoculars for any sign of the rams. She was patient with me, but I could feel her urgency to gain elevation.

We climbed the east face of a side ridge, working our way toward the summit. When we reached a narrow bench that ran east to west above a 40-foot rock cliff, we decided it was time to cross over the ridge’s crest. We needed another look below us and wanted to see more of the sidehill farther to the west. Slowly, we crept along. I was on my toes, trying to see everything possible below the sheer face. At the same time, I was nearly in Steph’s rear pocket, wanting to maintain close contact for silent communication. Suddenly, Steph stopped and motioned down the slope. There, at about 80 yards, was a ram. He was alone, feeding away from us. We couldn’t see the other ram and were afraid to speak or move. Then, one small step at a time, we snuck forward trying to find the second sheep. After moving only about ten feet, Steph suddenly froze. I was right behind her, maybe two feet. I arched my back, stretched my neck, and caught a glimpse of the very top of a ram’s horn only 40 feet below us. At this point, I didn’t know which ram was the big one, as the feeding ram hadn’t lifted his head. My immediate reaction was to take a couple steps toward the rim and prepare to shoot, but Steph’s antics warned otherwise. She must have read my mind because she slowly backed up with her hands down by her side, spread out and backward in a “V” formation, pushing me back. When

we were out of the ram’s earshot, she quietly but firmly said, “We were too close! We need to get up the mountain!” And she was on the move. Keeping up with Steph earlier was tough, but now it was a real challenge. She was practically a blur cruising up the steep grade. Partway to the rimrocks, as my tongue was dragging in the rocks, Steph stopped and threw up her binoculars. She looked down the hill and ordered, “We need to hurry!” Wondering where I’d get the much-needed oxygen, I pushed myself up the incline.

The orange-brown vertical rimrocks came into view just as we angled to our left and approached the spine of the side ridge. After a few steps, we both hit the ground as a small ram appeared from behind a spruce tree. He saw us, turned, and bounced out of sight. My heart sank, but Steph pushed on. “Hurry,” she commanded. Moving at a slow trot, we reached a bench with a decent view of the next draw and the base of the rimrocks. Steph turned to me with fire in her eyes and whispered, “Get set up!” I dropped to my knees and rolled out of my backpack. Unzipping the main compartment, I fumbled with the tripod and finally pulled it free, popping it open and extending the legs. Slipping a shell into the chamber, I laid the 6.5 across the tripod as Steph said, “Here they come.” I caught motion, and I settled into my rifle. The rams were moving in a running walk toward the rims where they would likely disappear. Unfortunately, my rest was too high. I frantically tried to lower the tripod while remaining quiet as I watched the rams come into view at under 100 yards. Meanwhile, Steph was quietly but excitedly in my ear with, “He’s the second ram! Take him!” If I had my wits about me, which I didn’t, I would have just shot from a sitting position with elbows to knees like I’d done a hundred times before. But since I’d started with the tripod, I was fixated on setting it up.

Finally, I was able to get the rams in my scope. A second or two passed as

I determined which one was the big guy. I could sense Steph starting to wonder if I was ever going to shoot. “Take him, Jim!” she urged, not bothering to whisper. The rams were going straight away and climbing fast through the giant boulders. “Shoot him wherever you can!” Steph pushed louder, as I pulled the crosshairs down on the ram’s back. Then, as if it was her usual means of communication, Steph let out a loud “Baaaa.” The old ram stopped for an instant and turned ever so slightly as I slipped a 143-grain Hornady behind his ribs, and he rolled down the near-vertical slope and out of sight.

Totally spent and with emotions overflowing, I laid down my rifle and leaned back on my elbows. Steph charged, arms outstretched, and crashed into me with a huge hug. “You got him! Great shot! He’s a dandy!” came rolling out of her mouth with boundless excitement. When she jumped up, she giggled, “Let’s go see him!”

“Give me a minute, Steph. I need to catch my breath and settle a bit,”

I answered. While collecting myself, cramming my gear back into the pack, and checking my rifle, I noticed out of the corner of my eye Steph nervously walking in circles and trying to be patient. The instant I stood up she blurted, “Come on!” and we headed down.

The ram had rolled nearly 400 yards, stopping precariously against a small, embedded rock. The terrain was equally as steep below him, so we took the time to build a rock platform to hold him steady. Amanda had heard the shot and hiked up to join us. Asking the ladies for a minute, I thanked the old ram and gave him the respect he truly deserved. He was a beauty, 42” on the long side and heavy. With his grey face, silvery neck, near-black body, white rump, and white stripes running down the back of his legs, he perfectly embodied a Stone sheep. At 10 years old, he had just slipped past his prime. His teeth were worn, a few were gone, and several were loose. The upcoming winter might have been tough for the old guy.

Eight days later, after a winter snowstorm and a successful 6-point bull elk excursion, the weather cleared, and we packed up. The ride out was every bit as beautiful as trailing in had been. The sun drenched us with warmth, and the cloudless sky looked a thousand miles deep, which I guess it probably was. Brilliant fall colors, dark green conifers, and grey granite mountains surrounded us like a colorful wrap on a package of success and good times. Thanks to the ladies!

Author’s Note: This old monarch scored 173 1/8” net B&C, won the Silver Award at the 2019 WSF Sheep Show and launched me into a new phase of my sheep-hunting career. Along with others, this hunt motivated me to write a book about my adventures. This article is an abridged version of one of the chapters. Info on the book is at: www.tracksonamountain.com.

fter a highly successful fly-in sheep hunt two years ago (double on the opener), my hunting partner and I started planning our next adventure. The plan for this trip was to use my inflatable jet boat and try to get to places that not many others can go or would go. We hit the water 5 days before opening day, knowing we had a full day of boating and at least a two day hike to get into the area we wanted to hunt. In the days before the opener we had seen 2 separate legal rams and about 7 younger ones.

Opening morning, we left camp at 4:30 am and started our hike to try and relocate the bigger of the two rams we had seen. After hiking most of the morning we relocated the ram about 2 kilometres away around 10 am in the same valley as before—still with the two younger rams. All three rams fed their way out of sight, and we made our way to get in to position to get a really good look and make sure this was the ram we wanted. Once we were closer to where we expected him to be, we started glassing but could not pick him up. I decided to hike up a big rockslide slope into some cliffs to try and get some elevation and be able to see into the ledges and rocks we thought they would be bedded in. All we could see was the head of the ram as he was bedded down, hidden amongst large boulders.

After watching the ram for some time and making 100% sure he was legal by curl and age, I got into position to take my shot once he stood up. With my hunting partner watching through the spotting scope, I pulled the trigger. The report of the rifle was followed by the anticipated “thud” and as I got back on the ram in my scope after the recoil, we both saw him go up on his hind legs and over backwards and not move again—RAM DOWN!

After some high fives and excitement, we made our way down from our vantage point and up into the cliffs to get our hands on the ram. After taking some photos and messaging my wife, we got the sheep deboned and strapped into our packs for the 8 kilometre hike back to camp. The next day was a slow start, with coffee and breakfast in camp, before we started our hike out back to the

boat. When it was all over we packed the ram 44 kilometres from where I had shot him—back to the boat with 139 kilometres total hiked and 265 kilometres in the jet boat! This trip was just as much about the adventure of going into unfamiliar places by different modes of transportation as it was about the sheep hunting. Being successful just made it that much better! The ram ended up being 10 years old.

by Heidi Stout

ake a moment to close your eyes and visualize this scenario. Imagine a world where you are unable to freely explore the mountains for hunting, trek along a dirt trail on a leisurely Saturday hike, or feel the refreshing splash of a river as you fish on its bank. The mountains have been reduced to restricted areas, allowing only a few surviving animals to wander, while other parts of the land serve different purposes as needed. The rivers are not flowing as they should, leading to a decline in fish population due to inadequate care and management. Trails are replaced with only paved slabs paths instead of dirt that guide you through a designate plot of carefully placed plants. As you closed your eyes, I imagined you saw those places the outdoors takes you. You thought of the inability to no longer being able to experience them. Without question it begins to evoke a mental and emotional connection. We are naturally drawn to the outdoors, it is vital to our health without it even being on a prescription label. We need our daily dosage and too often neglect our need.

As a child I walked streets of concrete, yards were designed with various shades of rock, and for miles I saw endless buildings of stucco. As many do in the cities each year, we would wait to plan on vacations to places that inhabited more nature and wildlife than people. Places in its natural state, places untouched by the hand of man, places that ultimately they hoped would take their stresses away and refresh them enough to go back and keep going until their next getaway. I fell into this monotony of life as a child. We didn’t have much money so we spent our time exploring places outside the city. Let me tell you when you don’t have the means to buy fancy vacations, your imagination has the means to take you wherever your heart desires. Stories like Anne of Green Gables and Laura Ingles Wilder always drew me to the places where the grass grew wild and animals roamed outside of fences. From an early age, I craved this life as if it were carved into my soul.

For many of us those places become our refuge, yet as a child you can’t grasp the concept, let alone the importance of these places. We innocently think those sacred places

will always be there for us to escape to. We assume as children the adults are taking care of their responsibilities which unknowingly means protecting the land and animals within our world. You are taught not to go on someone’s property without permission. I didn’t grow up knowing the boundaries of land when you walked into National Parks. That inevitably someone could reduce the size of what we have available and we are just told this is what you have. We would rely on voters or the government to tell us if we get to keep it.

As I grew older, I continued to live in the same state as a child—taking my kids to every place within our means that was free of buildings and where the air was so fresh that your lungs felt as if they were breathing for the very first time as intended. Then a move to Idaho and my world forever changed in so many ways. I found myself as a single Mother of four boys, looking to as they say “find myself” again. In actuality, you never

lose yourself I feel, you just have to decide to let that person exist in who you were created to be. So I turned to what always seemed to be at the core of me, my faith and the outdoors. I have an endless list of things I have always wanted to “teach” my boys as they grow into men but the truth is they are my teachers. The words of truth I speak to them and I have to remind myself to live what I speak and when I tell them take all the chances life throws at you, well, I better be the first up to the plate. They have zero fear—zero. So when they think Mom can’t do it, I prefer to take the satisfaction of proving them wrong. They are the epitome of adventurous and when things came up like wanting to learn to ski or wanting to learn to hunt, I couldn’t say no at the opportunity to spend time with them but also challenge myself to step outside my comfort zone. So all along while I have been raising them, they really have unknowingly been raising me. Not in the ways of lack of being

an adult but in the ways I need to charge at the world.

So we began fishing, skiing, camping and hunting in our free time. Even when they were little, I did as I was raised, and took them to escape to places of freedom as often as I could. Let’s be honest, taking kids outdoors is the one free thing that you can do with them and even though at times they have come along dragging their feet, their phones get put away and they live in a state of joy and peace while in those places—they begin to be kids again.

So here I was approaching the age of forty learning to hunt because my oldest son wanted to learn. So we did our Hunter’s Ed and got a rifle and compound bows. The journey

began that ultimately has evolved into one of my greatest blessings.

As I have become a hunter, I have developed a deeper love and respect for these sacred places. I have come to the realization that unless we are each fighting for it, we leave it to the hands of people that may not have the intentions of these places that have shaped who I am. I never really truly knew what it meant to be a hunter— this world foreign to many unless you begin to step into it to truly understand it. My eyes were opened to the true depth of healthy heard populations and the impact that we have.

In so many ways, the outdoors connected me with that little girl. Not the one that was surrounded by concrete waiting to escape, but the girl

imagining she was running the fields on Prince Edward Island. At some point as we become adults, our fears become a staple in our everyday life. We dream a little less and live more cautiously than we did as a child. What I wouldn’t give to go back to that moment, where I played as a child and worried a little less—I would tell her don’t leave. Don’t let go of these feelings, hold on to them as if your life depends on it because if you’re not careful, you will stop truly living.

Now don’t get me wrong, we each have a lot of life experiences that have led us to those places. Some of those fears and cautions are needed for just plain survival. But I believe there is something to be said to seeing the world in the ways we did as children. Maybe we live more cautiously all while retaining our sense of wonder, excitement, and boldness.

Now open your eyes—wait, they already are. We see these issues as our index finger habitually scrolls to what is next. We are all guilty of scrolling to see what next image will grasp our attention. Maybe instead of doing that, we put down the phones, walk outside and look around. Those mountains, those rivers and lakes, those places we all hold sacred; when will it grasp your attention to fight for it to exist for you in twenty years, and more importantly, your children’s children in fifty years? Maybe you fight for the little girl or boy you used to be. If you don’t fight for it, who will?

Heidi is first a mother to four incredible boys. She has a love for the outdoors and has recently turned that into her passion as Director of The Light Ranch—a place where those that have faced trauma can take part in outdoor programs in their healing journey. She is also Co-Host to the Soul Summit Podcast. Depending on the season will determine where outside you can find her, from hunting, to skiing, to fly fishing.

by MTN Tough Fitness

ut in the wild, when the sun dips behind the trees and you’re a good distance from any road, that’s when reality kicks in. It’s you against the elements.

No fancy prose here—just the hard truth that in these moments, your survival skills aren’t party tricks. Whether you’re a grizzled hunter, military personnel, or just out for a hike, your survival hinges on your readiness.

This isn’t about luck; it’s about knowledge and having the right gear. Make no mistake, the wilderness will test you. In the most remote locations, your gear isn’t just stuff you carry—it’s what keeps you alive. And your skills? They’re what stand between you and real danger.

You need a survival blueprint that covers the basics like navigation and first aid, to the deeper aspects of mental grit and physical stamina. Start by mastering each of the concepts below.

1. GEARING UP FOR SURVIVAL

Preparation is king when faced with survival. And the gear you bring and how you use it makes all the difference. Among an endless list of items you could bring along, here are several you’d be crazy to leave behind.

Survival Kit Contents:

When you’re miles from civilization, your survival kit is your lifeline. Carefully chosen, each item becomes a necessity if you’re thrown into a survival situation. At a bare minimum, let’s break down what should be in your survival kit:

● Multi-tool or Survival Knife: This is your go-to for almost everything. You’ll use it for cutting, fixing gear, and preparing food. It’s your indispensable pocket-sized toolbox, and a tough survival knife can handle heavier tasks like chopping wood or defending yourself. Pick one that fits your grip well—it’s as vital as your own hands out there.

● Emergency Shelter (Tent/Tarp): When the weather turns, or night falls, an emergency shelter is your safe haven. It could be a compact tent or a basic tarp. Whatever it may be,

your shelter is your first line of defense against the elements. It’s about survival, not comfort. A good shelter keeps you dry, warm, and, above all, alive. It’s your personal fortress in the wilderness, a place where you can rest and regain strength for the challenges ahead.

● Fire-Starting Tools (Matches, Lighter): Fire is a survival essential. It’s for warmth, cooking, water purification, signaling, etc. Imagine trying to light a fire in the pouring rain or strong winds—that’s when the quality of your firestarting tools really shows. Your matches or lighter should be waterproof and windproof. Quality fire-starting tools are a must—they can mean the difference between a safe night and a risky one. And be sure to pack them close by—they should always be within reach.

Water Purification Methods:

Clean water is a must. While it may be all around you in the mountains and backcountry, you know it’s not always safe to drink. Here’s what you need to make sure your water will keep you hydrated without making you ill:

● Portable Water Filter: This tool is crucial. When you’re hiking for miles and come across a stream, you can’t just drink directly. That’s where your portable water filter comes in. It turns unsafe water from streams into drinkable water. It’s lightweight and easy to use, essential for avoiding waterborne illnesses.

● Boiling Techniques: If there’s a fire, there’s a way to purify water. Boiling water is the oldest trick in the book, but it’s effective. All you need is a container and a good fire. Boiling kills pathogens and makes water safe to drink. Sure, it takes time and fuel, but in the wilderness, safe water is worth its weight in gold.

● Chemical Purification Tablets: These are your last line of defense. When there’s no filter or fire, chemical purification tablets can save the day. They’re small, easy to carry, and incredibly effective. In just a few minutes, these tablets can turn a potentially dangerous water source into a lifeline. They might leave a slight taste, but when it’s a choice between that and dehydration, the choice is clear. Be sure to include purification tablets in your survival kit.

Navigation Tools:

Aside from injury, the quickest way to enter a survival scenario in the wilderness is getting lost. All your rations and gear immediately look smaller when you’re lost. Your navigation tools are your guide back to safety. Play it safe by using the latest tech AND knowing how to navigate in the absence of battery-powered equipment.

● Compass and Map: Reliable and always ready, a compass and a map are the foundation of your navigation tools. Batteries die, but a compass and map never fail. Learn to read them correctly, and you’ll never be truly lost. They’re your silent guides, helping you understand the terrain and find your way.

● GPS (Bring An Extra Power Bank): GPS navigation isn’t what it used to be; it’s better. With powerhouse apps like onX, your phone is your navigation tool, period. Forget about weak signals and lost connections; save your maps

directly on your phone and keep exploring, no matter where you are. And here’s a pro tip: pack an extra power bank for your phone. A battery charger might be the only thing that prevents you from getting lost.

● Stars and Natural Landmarks for Navigation: When all else fails, look to the stars. Our ancestors navigated vast distances using just the night sky. Learn the basics of celestial navigation, and you’ll have a skill that won’t fail even when gadgets do. Similarly, natural landmarks like mountains, rivers, and unique rock formations can serve as points of reference. They’re the language of the land, telling you where you are and where you need to go. These essential tools are the absolute minimum for facing nature’s challenges. Choose your gear wisely and respect nature’s power. You never know when you’ll need to be flung into disaster.

2. SUSTENANCE IN THE WILD

In survival mode, your skill in finding food is key to keeping your strength up. You’re not just looking for a meal; you’re sustaining your energy to survive.

● Edible Plants – Know What to Eat: You’ve got to know which plants are safe. Edible plants are abundant in the wild, but so are poisonous ones. Before you head out, study the plants in the region you’ll be in. Use guides to learn the safe ones—look at the leaves, the colors, the textures. And if you’re not sure, don’t eat it.

● Hunting and Fishing – Skills that Feed: There’s a good chance you already know how to hunt—it’s probably what’s put you in the backcountry in the first place. That’s great, because your hunting and fishing skills can go a long way in keeping you nourished. You may need to add a few extra scrappy skills to make the most of a survival scenario though: learn to set snares, fish with makeshift gear, and hunt small game. It’s about being patient and quiet. These aren’t overnight skills—practice them every chance you get.

● Cooking Wild Food Right: Got something to eat? Make sure you prepare and cook it properly. Raw meat is risky. Clean and cook everything well. For plants, make sure they’re not just edible but clean. Cooking not only makes the food safe to eat but also easier to digest, conserving your body’s energy for survival.

Maintaining Hydration:

Water is your lifeline, not a drink. Keeping yourself hydrated will give your body what it needs to function properly.

● Finding Fresh Water: One of your top priorities is finding clean water. Flowing streams are better than stagnant pools. Stay away from water near industrial or farming areas—it’s likely contaminated—although if you’re remote enough, this won’t likely be a concern. Natural springs are gold, but rare. And always purify any water you find.

● Collecting Rainwater: In dry areas, rainwater is your best bet. Collecting rainwater is relatively simple—use any clean container or tarp to catch and store rain. Make sure the container is clean to avoid contamination. In arid environments, techniques like digging a solar still can extract moisture from the soil.

● Recognizing Dehydration: Dehydration sneaks up on you, especially if you’re at high altitude. Watch for signs like thirst, dry mouth, tiredness, and less pee. Stay ahead of it—drink regularly, not just when thirsty. When water’s scarce, lay low during the heat, stay in the shade. Eating wet food and limiting hard work helps save water too. Beyond ‘making it through’, you’ll need to wisely use what nature gives you.

3. BUILDING A SHELTER

Your shelter is your defense against the elements. There are several ways to create a solid fortification, including:

● Natural Shelters (Caves, Tree Hollows): Sometimes, nature has already done the job for you. Caves and tree hollows can be great spots to hunker down. They shield you from wind and rain, maybe even predators. But, watch out for current wildlife residents—check for fresh signs. Also, make sure it’s stable so it won’t collapse on you.

● Making a Lean-To or A-Frame: If there’s nothing natural around, it’s time to build. A lean-to, with branches against a tree or rock, can be quick to set up. An A-frame is sturdier— it’s a ridgepole with two supports, covered in branches and leaves. Keep it just big enough for you, to trap body heat.

● Insulation and Waterproofing: Don’t forget to insulate and waterproof. Lay leaves, grass, or pine needles on the ground to keep the cold out. For keeping dry, large leaves, bark, or a tarp work. Make sure your roof sheds rain and extends over the edges to stop leaks.

Where to Build:

The location of your shelter can make the difference between a safe haven and a survival risk. It means everything to your survival shelter.

● Away from Wildlife: Stay clear of animal paths, waterholes, and signs of predators (always examine trees surrounding your location.) High ground gives you a view and safety.

● Near Water, But Not Too Close: You need water, but don’t build right next to it. Find a spot a few hundred feet away to avoid flooding and animals.

● Protected from Elements: Avoid low spots where water collects or wide-open areas with strong winds. Natural barriers like rocks or thickets help. Consider where the sun hits—you want some warmth, but not too much. Building a shelter in the wild is about striking a balance between utilizing what nature offers and applying your skills to create a safe, functional space. It’s a skill that epitomizes the essence of wilderness survival: adaptability and resourcefulness.

4. WILDERNESS FIRST AID SKILLS

Your hunting first aid kit is your first line of defense in an emergency. If you view your kit as a bunch of supplies, then this section is for you. It’s your medical center in the field. For an exhaustive list of the supplies needed, be sure to check out our full list of hunting first aid kit supplies list, but here are several of the basics to include:

● Bandages, Gauze, Tape: You’ll need these for any cuts. Bandages and gauze stop bleeding and keep wounds clean. Tape holds everything in place. Out here, a small cut can turn serious fast, so these basics are crucial.

● Antiseptic Wipes, Ointments: Infections are no joke in the wilderness. Clean every wound with antiseptic wipes to kill bacteria. Antibiotic ointments help keep infections at bay and speed up healing. Don’t underestimate a small cut—treat it right away.

● Splints, Scissors: For broken bones or sprains, you need splints to keep things stable. Scissors aren’t just for cutting bandages—they’re for cutting away clothing from wounds or shaping splints. These tools are key for keeping injuries from getting worse until you can get proper medical help.

Handling Common Wilderness Injuries:

Knowing how to handle injuries is as important as having the right items. Since ankle injuries will be the most common injury you’ll face, be sure to check out our full guide on preventing and handling ankle injuries while hunting or surviving in the backcountry. as having a first aid kit.

● Treating Cuts, Burns, Fractures: Clean and cover cuts immediately. Cool burns with water and cover them. Immobilize fractures with splints or whatever you have on hand. Quick action here can prevent serious problems.

● Spotting Hypothermia, Heatstroke: Hypothermia shows up as shivering, slurred speech, and slow breathing. Warm the person slowly—no direct heat. Heatstroke comes with no sweat, confusion, and a fast heartbeat. Get them to a cooler place and cool them down. Both need medical help ASAP.

● Bites, Stings Management: Remove stingers, wash the area, and use a cold pack for swelling. Watch for allergic reactions—they can be deadly. For snake bites, keep the bitten area still and get medical help right away. Your skills and gear are what stand between a bad situation and a survival story. Be prepared and know what to do—it could save a life when you’re miles from help.There are preventative steps you can take to minimize your chances of injury before you head into the wild - so do your part and get ahead of the situation well in advance.

5. FIRE BUILDING TECHNIQUES

Knowing how to start a fire (beyond a lighter and lighter fluid) is mandatory. Here are the different techniques to master beforehand.

● Diverse Fire Starting Methods: Matches and lighters are easy, but you need more tricks up your sleeve. Learn to use flint and steel, fire plows, and bow drills. These methods rely on friction or sparks to ignite a flame. It’s about skill, not just luck.

● Choosing the Right Tinder and Kindling: Tinder kicks off your fire. Use dry leaves, grass, bark, or even lint. It’s got to be bone-dry and quick to catch fire. Kindling comes next—small sticks and branches that will carry the flame to bigger logs. The idea is to build up from small to big.

● Keeping the Fire in Check: Managing your fire is vital. Box it in with rocks or a dug-out pit. Never leave your fire

alone, and put it out completely when you’re done. Douse it with water or dirt and stir the ashes. Make sure it’s dead out.

Using Fire for Survival:

● Signaling for Help: Need rescue? Fire can be your signal. Green leaves create smoke for signaling. Three fires arranged in a triangle is an SOS signal seen worldwide.

● Cooking and Boiling Water: Fire’s key for making your food safe to eat and water safe to drink. Boiling water kills germs and parasites. When cooking, control the heat to avoid burning your meal.

● Warmth and a Mental Boost: A fire does more than cook and signal; it keeps you warm and rebuilds your confidence. It wards off hypothermia and can turn a harsh night into a bearable one. The comfort of a fire—its light and warmth— is a mental game-changer in the wild. This goes well beyond some feel-good story, it’s hardwired in mankind’s DNA to find security through fire.

6. SIGNALING AND COMMUNICATION

Being able to signal properly in the wild can mean the difference between rescue and remaining lost.

● Mirrors, Smoke, and SOS Signals: Use mirrors to catch sunlight and flash a signal that can be seen for miles. Smoke is ideal for day and night—a big, smoky fire gets noticed. Add green stuff to boost the smoke. The SOS signal—three short, three long, three short signals—is a global distress call. Use it when you’re in real trouble.

● Improvised Signaling Gear: No standard gear? Get creative. Use bright clothes to catch the eye, make noise with metal or by hitting trees, and spell out SOS big in a clearing or with rocks on a beach.

● Picking the Right Spot and Time: Signal from high ground for better odds of being seen. Open areas beat dense woods for visibility. For timing, midday is prime for mirror flashes, twilight for fires and smoke. Night’s good for sound signals—they travel further.

● Battery Life Hacks: Keep your gadgets off when not in use to save juice. Protect them from extreme cold, which kills batteries. If you can, bring a solar charger or extra batteries.

In a survival pinch, signaling and communicating smartly are key. It’s about using what you’ve got, whether old-school methods or the latest tech, to let rescuers know where you are and get you back to safety.

7. MENTAL TOUGHNESS AND RESILIENCE

Your headspace in the wild is just as crucial as your physical skills. A positive attitude is a key survival tool. There’s a ton of science behind it, specifically how your mindset impacts your physiology. An immediate order of business is to shift from ‘fight or flight’ mode and back into your full brain power steering the ship. You can get there quicker with greater mental toughness, with a key goal of remaining positive.

● Boosting Morale: It’s tough to stay upbeat in hard times, but it’s essential. Set small goals to nail that sense of achievement—be sure to study the MTNTOUGH Mindset for tactics to reach a positive state of mind. Remind yourself of your past wins. Use mental tricks like picturing yourself overcoming challenges—it can lift your spirits.

● Building Mental Resilience: This is your shield against the wild’s curveballs. Get tougher by pushing your limits safely, like during your training. The more you deal with controlled tough spots, the better you’ll handle real crises.

● Handling Loneliness and Fear: The solitude of the wild can hit hard. Keep busy to beat loneliness. Stick to a routine for a sense of normalcy. Face your fears, but don’t let them boss you around. Deep breathing and mindfulness can keep fear in check. Fear’s normal, but you decide how it affects you.

● Setting Priorities: Nail down what needs attention first. Shelter and water come before anything else. Focusing on what matters most saves your energy for the big stuff.

● Creative Problem-Solving: The wild demands thinking on your feet. No tool for the job? Figure out how to make do with what you’ve got. Improvise with what’s around you.

● Staying Calm, Staying Sharp: Panic is your worst enemy out here. Keep cool by dealing with what’s in front of you. Break big problems into smaller bits. It makes them less daunting and keeps you focused. Deep breaths help keep your head clear.

Developing mental toughness and resilience is about preparation, practice, and mindset. Equip yourself with not only the physical tools and skills but also the mental strategies to navigate the challenges of the wilderness. You can kill two birds with one stone with MTNTOUGH’s functional fitness. Remember, survival is as much about mental endurance as it is about physical endurance.

8. NAVIGATING THE TERRAIN

This goes hand-in-hand with knowing how to read a map and using your compass to prevent getting lost, but in addition to your map skills, nature can provide you with some navigational hints. Here’s what you need to know when navigating without a compass or map.

● Sun and Stars for Direction: The sun’s your daytime guide, rising in the east, setting in the west. At night, stars, especially the North Star in the Northern Hemisphere, keep you on track.

● Reading the Terrain: The land itself points the way. Rivers flow downhill, valleys might lead to settlements, and mountains can guide you longitudinally.

● Weather Patterns as Guides: Weather can steer your travel. Knowing which way the wind usually blows and how weather patterns move in the area can help you anticipate changes and make smarter travel choices.

Navigating in the wild merges skill, knowledge, and keen observation. It’s about reading the land, sky, and elements to find your way.

Becoming Always Ready

MTNTOUGH’s ‘Always Ready’ concept is a mindset that toes the line of lifestyle; a commitment to being prepared for whatever the wilderness throws your way. Being physically and mentally equipped to handle any situation is the premise. It’s also the thinking behind building your ‘Always Ready’ kit, which you can find detailed instructions at MTNTOUGH’s guide to creating an emergency preparedness kit.

The core of ‘Always Ready’ is comprehensive preparedness and understanding the unpredictability of nature while equipping yourself with the knowledge, skills, and gear to face it in the best way possible. This involves more than just having the right equipment. You need to know how to use the gear you have and cultivate a mindset of resilience, adaptability, and proactive thinking.

MTNTOUGH+ doesn’t just equip you with tools; it builds you into one. Through our programs and workouts, you’ll foster the physical strength, endurance, and mental toughness to endure and thrive in survival situations. MTNTOUGH’s functional training prepares your body and mind to be ‘Always Ready’ for a challenge.

To start building your resilience and begin your journey to becoming ‘Always Ready,’ take advantage of MTNTOUGH’s exclusive 14-day free trial. This is your opportunity to experience firsthand how MTNTOUGH prepares you for the rigors of the wilderness with no strings attached. Embrace the ‘Always Ready’ philosophy and transform yourself into someone who doesn’t just prepare for the unknown, but masters it.

$11,000 to purchase collars required for this project in the South Okanagan /Similkameen. These collars would support Disease research in a travel corridor between the Okanagan and Similkameen sub populations. When the sheep are selected and captured for collaring they also go through health sampling at this time.

Psoroptes Cuniculi has infected bighorn sheep populations in the Okanagan region in southern BC/ north central Washington for over 2 decades. Significant declines (>50%) in sub populations have been documented following the introduction of the disease. This external parasitic infection is unique to wild sheep in Canada as the only positive population with Psoroptes, and unique as the only known infection of Psoroptes cuniculi in North American wild sheep. Understanding the impacts of the disease and developing management actions is paramount to recovering local Washington state and BC bighorn sheep while proactively planning for potential introductions to healthy bighorn populations. (Cited from ONA (PIB) Bighorn Sheep Project)

am writing this article in hopes that others who work for similar large industrial businesses or any company for that matter, may find inspiration to ask the question about donating to fish habitat and wildlife projects within their local community.

In my career as a welder I have witnessed some companies that take a lot of pride in the business model and how they treat the environment and ecosystems around them. I took

an eight-year break from Mining. After moving to Keremeos, it put me within commuting distance to a local copper mine. Shortly after being hired at the mine in 2023, I approached the mine manager to find out if they would consider donating to a local bighorn sheep collaring project. The mine was very quick to express their interest and just needed some more information from me as to what aspect of this project they could donate to. Copper Mountain Mine donated

Unfortunately, the health of the Okanagan bighorn sheep has been impacted by several diseases and syndromes. A significant Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) outbreak occurred in the 1970s and re-emerged in the 2020s. In 1999, a pneumonia die-off associated with Mollicutes, likely Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae (M.ovi), occurred. A second pneumonia outbreak began in 2020, and the presence of external parasitism from Psoroptes cuniculi, along with additional outbreaks of EHD/Bluetongue disease, have collectively affected the abundance and health of the bighorn sheep in this region. Bighorn sheep in the southern Okanagan have steadily declined in recent years. This decline is theorised to be due in part to infection by pneumonia and Psoroptes mites as contributing factors to poor bighorn sheep health.

by Taylor Nairn (WSSBC Member)

photo credit: Peter Gutsche

I have been speaking further with Copper Mountain mine, now owned by Hudbay Minerals and they have expressed interest in multi-year projects and donations to support local fish, habitat and wildlife. One thing the mine needed from me was more information and budgeting items to bring forward for planning for donations in the future. I have been communicating with the WSSBC for documentation I could provide my employer to support my request for further donations to the sheep herds that are local to the community. Reclamation of industrial activities is an ongoing process that takes big commitment from companies. This spring I was invited as a guest to a reclamation workshop at the mine. Through this workshop I learned a lot about reclamation and what is required. On our site, we do not have enough topsoil to meet current standards of topsoil for reclaimed lands. We bring in biosolids to mix with native soils to meet required topsoil amounts. Reclamation work is taking place now, large grassy hillsides are growing well. Tree planting has been a challenge over the last couple years with the extreme drought and heat. During the workshop and in my discussion with our Environmental Team, I have asked questions if restoring back to a Conifer forest is practical, or could there be options to create higher elevation grasslands that are common in the region. Below the active mine site is lots of steep escape terrain and the Similkameen river. Not far from the mine is a large herd of mountain goats. The Similkameen valley has had a strong sheep population in the past and if we can get the disease issue under control, one day this mine site could become excellent habitat for sheep and goats.

Last year we saw a major donation from Teck Resources Limited of $2.5 million to help build a new wildlife overpass south of Radium in order to support a sheep population that is impacted by motor vehicle

mortalities. I hope to see industrial companies support fish, wildlife and habitat within their communities and regions. Many hunters work within resource extraction industries and for a long time it has been thought that you could not have both flourishing ecosystems and resource extraction. I would encourage anyone to speak to their management team whether you are a long term or new employee like I was—come prepared with some information about a local project that could use support. It was not easy to walk into the Mine managers office and ask for money, but I think when a manager hears that you are asking for money to support something important to the community, they will be more apt to listen and consider donating.

Editors Note: The Wild Sheep Society of BC is a member driven organization and we are incredibly fortunate to have the support we do by members such as Taylor. The Society functions primarily through member driven initiatives. While some individuals are able to support our conservation efforts by donating, there are many other ways to support the work that we do. This is a fine example of how one member can make a significant contribution to our efforts. We welcome these opportunities that members bring to us and are grateful for it. Lastly, we thank Taylor and Copper Mountain for putting this together and support our South Okanagan Disease work.

photo credit: Darryn

Epp

photo credit:

Danny Coyne

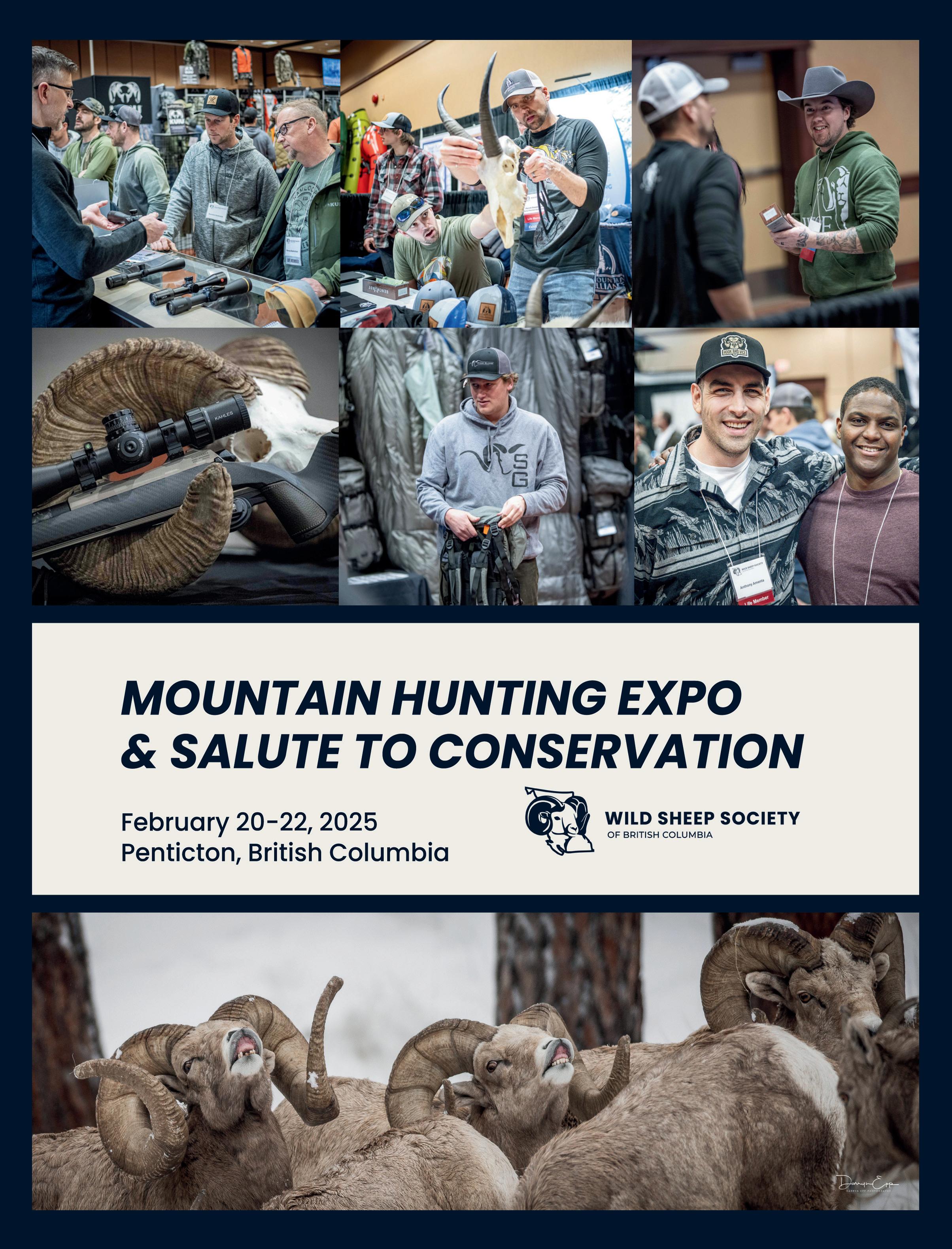

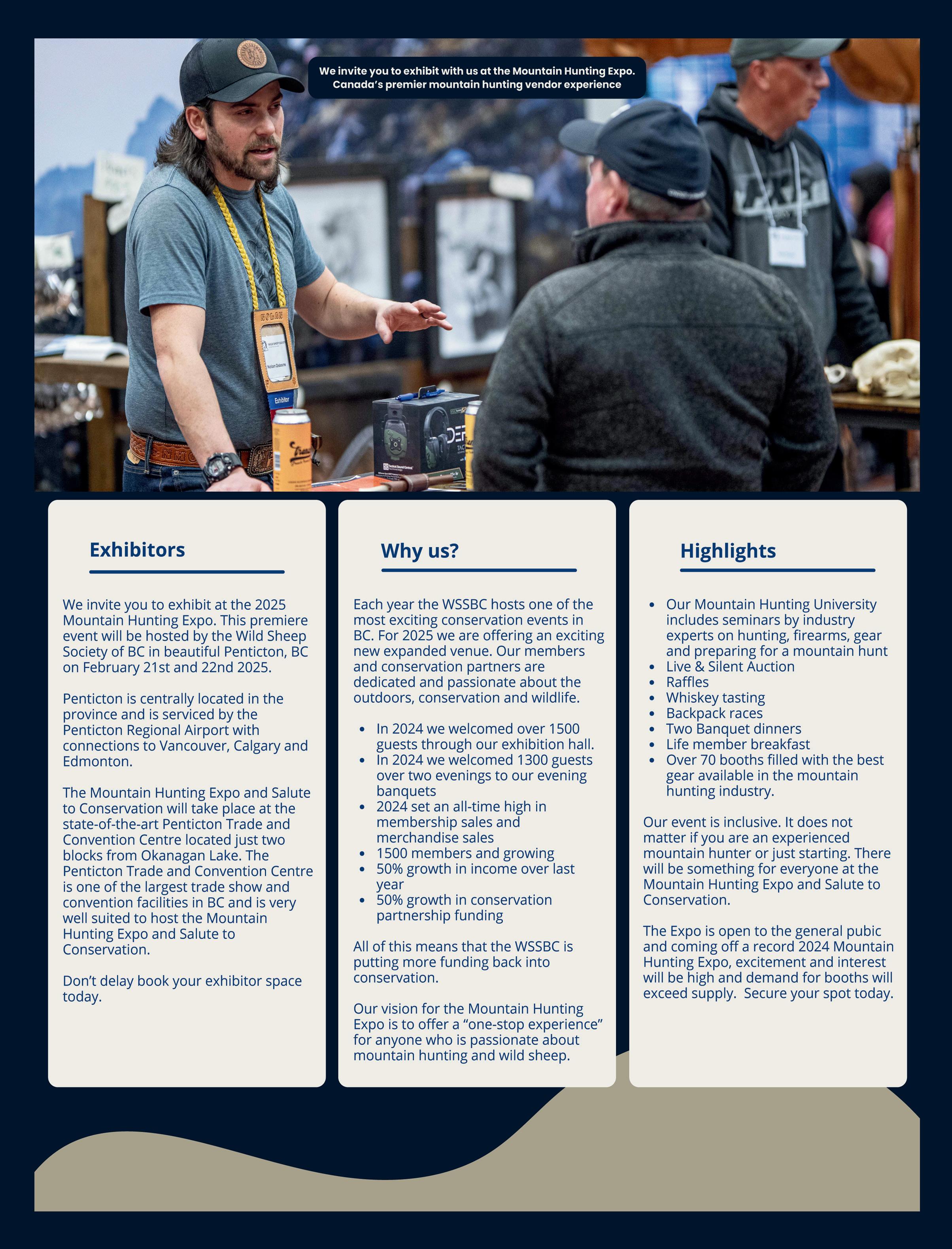

WSSBC Volunteer Opportunities & Events: https://www.wildsheepsociety.com/volunteer/ January 31-February 1, 2025

– Northern Fundraiser, Dawson Creek

February 20-23, 2025

– Salute To Conservation and Mountain Hunting Expo, Penticton

y 2024 sheep had its beginnings in December 2023 and perhaps even at the end of an unsuccessful sheep hunt in the 2023 season. I started sheep hunting about 12 years ago when I was inspired by stories of mountain hunting in the north for stone sheep. The stone sheep’s unique and beautiful markings and its rugged and remote habitat seemed to speak to a sense of journey. It harkened to the days of some of the original explorers and outfitters that first journeyed into those Northern mountains. This 2024 hunt was in the back of my mind at the end of the 2023 sheep hunt. To be honest, I was not at my best fitness level, and that for me was a personal failure. In 2023, we accepted that we needed to go the extra distance to get

into better sheep country but realized that we didn’t have it in us. This hit hard and was personally unacceptable for me at that time. I accepted I “didn’t do the work.” I thought I did, but, no, it was lacking.

So, in December 2023 I start thinking, “how do I make this coming sheep season different?” In the words of the well-known hunting personality Greg McHale, you need to “Do the Work.” I recall a visual he published that depicted how many ridges one can aspire to by how many days a week one works out. This resonated. And after a finger wag from my doctor, I made critical changes. Diet, exercise and health. At 60, with a bad knee and an occasionally troubled back, I felt like the clock was ticking and the window of opportunity was getting smaller!

I started working out regularly, took accountability for my choices and made some personal changes. The weight started to trim off and by June, I stepped up the program and designed a workout regimen to be in sheep shape for August. I eagerly posted my work to social media and many appreciated the efforts, provided encouragement and some important feedback at times! This year was really starting to feel different. Posting on social media also placed some accountability on me to walk the walk!

An important detail was lacking, however. Calendar commitments meant I needed to team up with a different sheep partner this time around. Fortunately, my neighbour Richard and I shared a passion for remote backcountry hunting, but we just never teamed up for a hunt before. We chatted one afternoon and discovered neither had firm plans for sheep in 2024, so we agreed to join up for a sheep hunt. Our initial conversations involved a possible quad-in scenario, and to canoeing to a trailhead to access stone sheep country. Then, out of the blue, Richard sends me a text of a

jetboat on a trailer hooked up to his truck with the caption, “We have options.” I immediately ran out the door to his place a couple doors down to lay eyes on his newly acquired jetboat! I simply said, “Yes, Richard, we have options.”

We started instantly discussing where we could go and, after a few phone calls with some friends who have knowledge and experience with jetboats up north, we settled on the Kechika River drainage. Evenings doing Google Earth ‘recce’s and comparing notes from conversations with others ensued in Richard’s garage, with some ale and whiskey along for good measure. We slowly developed some options for rivers we could explore should we encounter other hunters or boats where we intended to go. All the while, my personal work and preparation continued, with range time to ensure my shooting skills were honed and up to the task. When we finally left Kamloops and set off on the road on August 9th, I was 20 pounds lighter, feeling confident and as prepared as I could be for sheep season 2024.

After a first day’s drive of 16 hours, we napped on the side of the road west of Fort Nelson, and then made Skooks Landing by 10 am the next day. We encountered another boater there who said there were 48 trailers there for sheep opener. We saw a mere 8, and were thankful to have avoided the opener traffic! We were underway by 11 am and after a full day boat ride with a brief but tense breath-holder of a technical glitch, we arrived at our intended trailhead and set up day 1 camp. We were visited by a young-looking black wolf that Richard just missed getting a shot at and we glassed a goat on a close-by mountain face. We made our final pack preparations and settled in for the night.

We set off early the next day, and after a 2-day hike, made our first alpine camp. We saw sheep everyday, were visited by a wolverine and a grizzly that thankfully bolted in the opposite direction once it saw us. But an opposite ridge seemed to be holding more sheep. We shifted camp on day 4 closer to that sheep holding ridge.

This change was fortuitous! We glassed even more sheep, saw a griz chase clownishly after an ewe/lamb herd in its attempt to get the sheep that easily evaded it. And then late on day 7 we briefly saw what we thought were ‘new’ sheep but we weren’t able to get a clear ID. It was intriguing. The next day, we decided to get up on a high ridge line that would allow us to glass several other bowls and ridge lines to get a look at what we thought were the different sheep, and see into the terrain near our current camp. Our conversation drifted to what happens if we explore these spots with no success at day 8.

No sooner that we were thinking of shifting camp again or pulling out that Richard calls out “Rams!” We quickly put glass on a herd of 7 rams about 2 kilometres away. It was clear there were 2, maybe 3 legal rams but knew we needed to get closer to confirm. The rams appeared to be moving toward a bowl that we saw sheep feeding in all week, so we hurriedly headed in that direction, concealing our movement in the dead ground. We came around a shoulder that allowed us to glass into the bowl, but we saw nothing.

We circled around to see if they were in another bowl opposite the spot we just glassed. As we turned a corner, a movement caught my eye up to the right. The rams had circled around and were now above us!! We quickly got down. I ranged the rams at 200m but a clean shot was not possible. We concurred there were at least 2 legal rams by horn tip. We alternated days as ‘shooter’ and today was my day. I told Richard I think we might have a double-header. The rams moved off the skyline and looked to be headed uphill on a sheep trail towards a col we were just at about 30 minutes ago. We contemplated circling around a peak to get on top of the col but that option would take too much time. We decided to chase after them as the wind was in our favour—for now.

We ascended the shale track as quickly and quietly as possible. We eventually dropped packs and proceeded at a slow jog. Then the wind started swirling and a ‘now or never’ feeling descended upon us. As I rounded a bump, the rams were skylined at 100m. They became aware of our presence, but thankfully did not look panicked. A bino check showed 2 legal rams, horn tips well above nose bridge! I looked at Richard who was higher up on another sheep trail and we gave each other the thumbs up.

I leaned semi-prone on some shale, popped my scope covers, and was instantly hit with sun glare! Aarrggh! I shifted position to get a clear sight picture—again, legal horn tips! The band of rams was slowly moving toward the col we were just on. I calmed my breathing, squared the cross hairs on the chest of the lead ram and squeezed the trigger on my Kimber Hunter 270 with my 129LRX handload. Crack! The lead ram hunched up, I reloaded, shot again. The ram lurched. I knew I hit it well. Then Richard shot. I watched as the last of the rams stepped over the col—then silence. I looked up at Richard, yelled to him what he saw. He was already running toward the col. I had envisioned having time to shoot, lying in the prone position, spotting scope with a digi-phone attachment. This couldn’t have been farther

from that scenario! This turned out to be a real run and gun moment. I got up and, still trying to catch my breath, made my way up to the col. Richard disappeared but then came back holding his beard, looking down. I asked what do we have? He held up 2 fingers and simply said, “2 rams, legal, down.” I whooped, threw my arms in the air! With an amazing sense of relief, excitement and gratitude, I walked up to our rams, and was greeted by an amazing, maybe once in a lifetime ‘as-they-lay’ sight of two legal rams on the ground. After some hugs, high-fives and emotional moments, we took the obligatory pics and got to work breaking the rams down. We spent the next 2 days on hide and skull care, and getting off the mountain with our camp and boned out meat with horns and hide to the boat. By the end, I was exhausted and sore. The trip involved approximately 100 kilometres distance covered and 6000m elevation gain, several ridgelines and 3 separate drainages. The feeling of having finally harvested that legal stone ram is difficult to put into words. I often find myself lost in thought, daydreaming of those moments, and looking back at the pics of sheep hunt 2024. Those mountains and those sheep demand and extract a great deal. The sense of having experienced failure in 2023, done all the preparation starting in December and following the process no matter how tiring and frustrating it can be, to the moment of cancelling a tag on a stone ram is indescribable. I hope there is a message of hope here for some of my fellow hunters who are older. Commitment to health, a workout

program and ‘doing the work’ can make the difference. I am incredibly thankful for my hunt partner Richard, a much younger fellow in his 30’s who agreed to come along with someone almost twice his age! He pushed me, and at times carried me when I waned! And we have a great friendship and memories out of this. I am incredibly happy we had a double-header. I couldn’t have asked for a better partner and I am also grateful for all my previous hunt partners who have taught me great lessons and are good friends today. I am humbled by the experience, but incredibly satisfied and at times emotional about our double-header and after 12 years of sheep hunting and 8 mountain hunts finally being kicked out of the ‘<1 Club’.

Members, send us your hunt story (~50 words plus a picture or two) to kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com.

2024 Stone Sheep hunt. No tags were cut on this trip but successful none-the-less. Our optics were filled with mature rams and healthy lambs

– Brogan Didier

After thirty-five years of applying for a Roosevelt tag it finally came together for Chris connecting with this Island Roosevelt Elk at twenty-five yards with the bow. Congratulations Chris!

– Chris Barker (WSSBC Vice President)

My dad has taken my brother and I hunting with him since we learned to walk. Despite all the “shhh” and “can’t you walk any quieter?”, we kept tagging along. This has become a lifelong passion of mine that I hope to pass on to my children someday.

– Jenna Feeley

Here’s a pic of 21-year-old Cole Crook’s goat from his first backpack mountain hunt. On August 29, 2024, Cole, his Dad, Clint, and Daryll connected on this Mountain Goat. Daryll called this “Young person hunting” or “The old teaching the young” as part of Daryll’s push to get young people started in mountain hunting.

– Daryll Hosker

Richard and Jeromy Cook, two Kootenay brothers, successfully harvested two bulls, after a season spent hunting and exploring all across British Columbia. The brothers live by the phrase, “The endless desire to be everywhere, yet okay with being absolutely nowhere.” They make a good team!

year old Connor

14

Rensmaag locks in his new personal best, 7’ sturgeon on the lower Fraser River.

by Bill Pastorek

Bill Pastorek – Early 1990s – Northwest Territories Dall –Arctic Red River Outfitters. “I was hunting with my friend Rick Green and we had booked two back-to-back 10-day hunts. My goal was to find a 40-inch ram and this seemed the best way to do it. The plan was to hunt light for five days and have a food drop. After 10 days, or less if a ram was taken, we’d be picked up by Kelly Hougan at an airstrip somewhere in the far distance. We’d then be relocated.”

“The first part of the hunt went well. We alternated shooting days, and on Day Seven, my day, we spotted three rams way below us over on the next mountain. We were camped up high, very high. That’s where we’d been seeing most of the rams and felt glassing from there gave us the best chance. I grabbed my rifle, strapped down my binos so they wouldn’t bounce, and crept a few hundred yards to where a fold in the mountain hid me from the rams.”

“Then I took off at a run down the 2000 feet and up the 500 so

I could come in above them. The wind was perfect, and when I peeked over the ram was standing by himself at 24 yards. (I later ranged it.) And just like that my portion of the hunt was over. Except for the climb back up the mountain to get my tent, pack, and gear. My ram did break the magical 40-inch mark.”

“After being relocated to another drainage and dropped at the closest landing strip, we had a tough eight-mile hike upstream to get to an area that held rams. At first we removed our boots and socks for every creek crossing but it just took too much time. After about the tenth time we said screw it and pushed on, enduring sloshing boots and socks. Not sure how many crossings there were but I’d guess more than two dozen. Eventually we made it far enough upstream to see rams. It was late in the evening, so the decision was made to evaluate in the morning.”

“Up early as usual, before long Rick spotted a ram he liked. He managed to get above and to the side of the ram, but it was feeding in very rough terrain. After the shot the ram didn’t

drop where we’d hoped, as they seldom do, and the tumbling began—gave new meaning to the saying, ‘Ram Down’.”

“So far everything had gone well on the trip. Of course, that’s when Murphy came out to play. I was caping the ram back at camp and all it took was a moment of inattention to slice my finger to the bone, completely severing a tendon. ‘Well drat,’ I said. I’m sure it was something like that. There was lots of blood, but we managed to stop the flow. It was certainly an uncomfortable night.”

“Instead of hiking all the way back down to the landing strip, the decision had earlier been made that if possible, we’d create a new strip close by for Kelly. The next day, it took about six hours of moving rocks and flagging everything to bring the plan to life. After a couple of flybys Kelly settled in, happy with what we’d built. So it was back to base camp and then the next day off to the clinic in Norman Wells. That was a waste of time, and I was on the next available flight to Edmonton. The hospital and surgeon were ready as calls had been made ahead but it was to no avail. Fifty-two hours had passed since the accident and the tendon ends had pulled back too far to be reattached. Such are the things that memories are made of.”

“Kelly and Heather Hougan are wonderful people and great to be around. This was my second trip with Arctic Red. A few years prior I’d been their very first client in their opening year of business. I managed to take a 38-inch Dall on that late-July trip. It was an amazing experience and a great introduction into what the bugs can be like in the north before first frost.”

Lex Ross – 1990s – British Columbia Rocky Mountain Bighorn. “This ram was spotted while Lex was setting up for a sheep transplant in the Spences Bridge area. I believe this was the second transplant that the newly formed

Wild Sheep Society of BC did. I never did hear of this ram being taken. What amazing genetics in this herd that originally came from the Banff area back in the 1940s.”

– Bill Pastorek