Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine is published four times per year for the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia by

Sportscene Publications Inc.

10450 - 174 Street

Edmonton, Alberta T5S 2G9

Ph: 780.413.0331 Fax 780.413.0388

Email: info@sportscene.ca www.sportscene.ca

Spring 2025 Issue

Editor in Chief

Kyle Stelter (CEO)

Editors

Peter Gutsche

Nolan Osborne

Bill Pastorek

Contributors

Larisa Murdoch

Helen Schwantje, DVM

Design & Layout

Sportscene Publications Inc.

Printing Elite Lithographers Co. Ltd.

Editorial Submissions

Please submit articles and photos to kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

No portion of Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine may be copied or reproduced without the prior written consent of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia. The views and opinions expressed by the authors of the articles in Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 43363024

Return Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia #101 - 30799 Simpson Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 6X4 www.wildsheepsociety.com

Chief Executive Officer – Kyle Stelter 250-619-8415 ● kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

President – Greg Rensmaag 604-209-4543 ● rensmaag_Greg@hotmail.com

Vice-President – Chris Barker 250-883-3112 ● barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

Joe Eppele

647-986-3859

joe.eppele@gmail.com

Peter Gutsche 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Ken Jyrkkanen

250-319-7759

Email: kjyrkkanen@gmail.com

Vice-President – Mike Southin 604-240-7337 ● msouthin@telus.net

Secretary – Colin Peters 604-833-5802 ● colin.peters12@gmail.com

Treasurer – Joe Humphries 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Justin Kallusky 236-331-6765 kallusky@hotmail.com

Benjamin Matthew MD 778-558-0996 ben.matthew@ubc.ca

Matt McCabe 250-320-6048 mattmccabe.wssbc@gmail.com

James Mitton 778-808-9001 jamesmitton15@gmail.com

Greg Nalleweg 778-220-3194 greg@nextgenelectrical.ca

Colin Peters 604-833-5802 colin.peters12@gmail.com

Communications Committee

Chair: Kyle Stelter ● 250-619-8415 kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

Fundraising Committee

Chair: Korey Green ● 250-793-2037 kgreen@wildsheepsociety.com

Government Engagement Committee

Chair: Greg Rensmaag ● 604-209-4543 rensmaag_greg@hotmail.com

Hunter Heritage Committee

Chair: Jann Demaske ● 970-539-8742 demaskes@msn.com

Indigenous Relations Committee

Chair: Peter Gutsche ● 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Membership Committee

Chair: Matt McCabe ● 250-320-6048 mattmccabe.wssbc@gmail.com

Projects Committee

Chair: Chris Barker ● 250-883-3112 barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

Jurassic Classic

Kyle Stelter ● 250 619-8415 ● kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

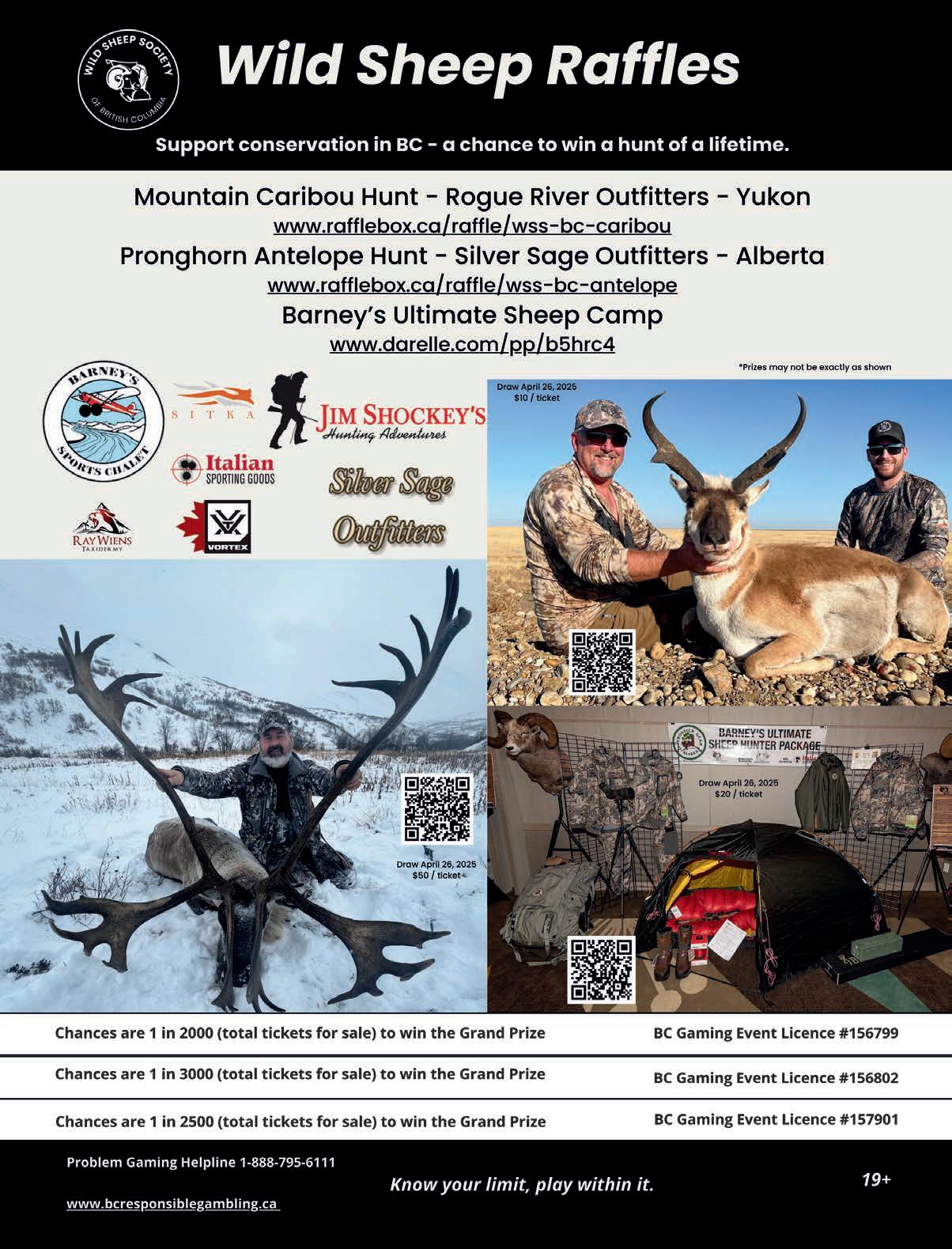

Raffles

Joe Humphries ● 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Women Shaping Conservation

Rebecca Peters ● 778-886-3097 ● rebeccaanne75@gmail.com

Bookkeeper

Kelly Cioffi ● 778-908-3634 kelly@dkccompany.com

Executive Assistant

Hana Erikson ● 604-690-9555 exec@wildsheepsociety.com

Hunting Expo Coordinator

Kris Wrathall ● 604-340-4903 ovisslam@outlook.com

Administrative Coordinator

Rebecca Peters ● 778-886-3097 wildsheepsocietyofbc@gmail.com

Danny Coyne

Darryn Epp

Jeff Jackson

Trevor Carruthers

As I write this today, I am reminded of one simple truth: Success in conservation is never achieved alone. It takes a community—united by purpose, passion, and unwavering dedication.

This season has been a powerful reminder of the commitment from our volunteers, donors, members, staff, and board of directors. You are the backbone of this organization. Every hour you give, every dollar you contribute, every event you attend—it all matters. You are the reason we continue to push forward, year after year.

We began the year with our annual pilgrimage to the Wild Sheep Foundation’s Sheep Show in Reno, Nevada. This year, we took a new approach by becoming one of the six sponsors of the Legacy Night Banquet, which took place on Friday night. As part of our sponsorship, we also supported the Less Than One Club. The evening brought together over 2,200 like-minded individuals, all united in the fight to secure a future for wild sheep. After presenting a short video highlighting our successes from the past year, I had the honor of sharing the stage with industry leaders to emphasize the importance of collaboration and partnerships within the wild sheep family. The partnerships we continue to cultivate in Reno are a testament to the fact that when we work together, we make meaningful progress for conservation. One such collaboration is the recent $35,000 USD donation from the Washington Wild Sheep Foundation to support the Psoroptes Drug Trials in Penticton, which recently kicked off.

Following Reno, we traveled to Dawson Creek for our Northern Fundraiser. As always, the crowd in the North came out to show their support for wild sheep in northern British Columbia. We saw firsthand how deeply conservation means to the people in the North. They not only showed up but also shattered fundraising records for the event. Every dollar raised directly impacts conservation efforts in the North, and none of this would be possible without the ongoing generosity of those who support us year after year. To everyone who contributed—thank you for making a real difference. I would also like to extend special recognition to our Past President, Korey Green, who continues to exceed expectations for this event.

Next, we moved to Penticton. We put together this event, and you all delivered in remarkable fashion!

The energy during the Salute to Conservation and Mountain Hunting Expo was nothing short of electric. The passion in the room throughout the weekend was truly special. Every conversation, every handshake, and every commitment made was a step forward in ensuring that wild sheep will remain a part of our landscape for generations to come.

During the event, we held our Annual General Meeting. As we all know, life often gets busy outside the world of wild sheep, and I would like to take a moment to express my heartfelt gratitude to my friend Tristan Duncan for his years of dedicated service. Although Tristan did not run for a board position this year, he will continue to contribute at the committee level.

It is with great pleasure that I welcome Ken Jykannen to the

Board of Directors. Ken, a long-time volunteer and committee member, is a valuable addition to our team, and we are fortunate to have him on this journey with us.

As I conclude, I would like to end this message in the same way I ended my speech in Penticton: You cannot wait for everything to be ok, nature will run out of time. Let’s be the reason future generations will continue to see wild sheep on the landscape.

I raise a glass to all of you—our dedicated members, supporters, donors, and volunteers.

To each and every one of you who believes in this cause, who fights for wild sheep conservation, and to the future we are building together. Here’s to wild sheep, to conservation, and to making a lasting impact.

I look forward to serving this membership for another year as your President.

Sincerely, Greg Rensmaag President, Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia

y journey as a sheep hunter probably started oddly enough with my first LEH goat tag about 20 years ago. But to go back even further, life in the mountains began when I first moved to British Columbia as a young teen. The mountains called to me then and one of the first things I did was join the local hiking club. We went for a couple day hikes to Revelstoke and Glacier National Park. I was instantly addicted. I remained active in mountaineering for a few years but, as life goes, I drifted away from the mountains because of university, work, marriage, and family.

A sad tragedy in the family brought me back to the mountains. While attending the memorial in Canmore, we were thrust into the mountains and, when my wife Stacey saw the beauty of those places up close, she wanted to strap on a pair of hiking boots and see those same vistas! We started an annual camping pilgrimage to Lake Louise with our daughter and son in tow, doing all the hikes we could. Eventually, with those brilliant hikes in the Rockies, I started dreaming of combining mountain hunting with my passion for the mountains. Hunting, fishing and harvesting was a longstanding tradition in my family from my early years in Manitoba. Then came the goat tag! Those first mountain hunts were grueling as I learned hard lessons about essential gear, the environment and, most importantly, fitness! Day hiking the Rocky Mountains and other destinations in BC were not enough for the sort of backcountry mountain fitness one needed to be successful. Those early hunts were challenging. That first goat hunt experience proved riveting, and it would be the start for many more mountain hunts.

shorter trips in the Fraser for sheep. I saw a few rams that ‘looked’ legal but not enough to convince me to pull the trigger. I also met good friends and hunt partners, even resorting to social media to connect with potential hunt partners when plans fell through with others. All are good friends to this day! My family thought I was crazy going into the backcountry with someone I didn’t know! Just last year, my neighbour Richard and I hit a double header, kicking both of us out the ‘<1 Club’, when we harvested two beautiful Stone Rams! You can read that story in the WSS magazine.

One fortuitous conversation around 14 years ago about sheep hunting with my friend, and good army pal, Brad, led to a plan to accompany him on my first sheep hunt in the northern mountains. It was an awesome experience! We saw rams and were convinced we saw a legal ram on a distant ridge. But we weren’t able to make that opportunity pay off, mainly because there were other hunters on that same mountain! And with that came a lesson about hunting sheep at opener. But I was hooked!

Since then, I’ve been on eight mountain hunts and many

My introduction to the Wild Sheep Society of BC came many years ago, when a fellow hunter and friend convinced me to attend a convention in Kamloops. I volunteered to help with the Big Boar Shoots, went on to attend the Spences Bridge and the Kamloops sheep counts, and volunteered for the Kamloops Golf Tournament fundraiser. I’ve participated with the Society Government Relations Committee raising awareness of conservation, science-based decision-making and hunter heritage issues with our local MLA’s. Along the way, I became a Life Member and eventually a Monarch Member.

Upon retiring from my career a few years ago, I felt now was the time to give back. I am currently a Director on the Board of my local Royal Canadian Legion Branch and am active with my military regimental association and former regiment. I have 24 years service as a Canadian Forces

Reservist in the Rocky Mountain Rangers, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel in command of my regiment. I worked with the provincial government for 30 years as a social worker, retiring five years ago, and am currently casually employed with Interior Health. I am also a keen hunter of other species in BC.

In the Wild Sheep Society, I see an incredible community of dedicated hunters and conservationists. We are all ultimately focused on the health of wild sheep on the mountain, as well as hunter heritage and hunter rights. But the Society is more than just a social club reminiscing about old times and great, and not so great, hunts! This group takes the mission seriously and ‘walks the talk’ with its fundraising and work in the field.

I am honoured to be elected to the Board of Directors for the Wild Sheep Society. I believe that successful conservation, as with any volunteering, is built on three pillars: time, sweat and money. Some refer to it as Time, Talent, and Treasure. When you care about a cause, you look to give as much of the three as you are able, and if you are less able to give to one, give more to the others. I hope to apply my time and skills as best I can in the time ahead and live up to the examples of others who lead in the Society. There are big shoes to fill, and I am humbled and excited to get on with the role as your newest Director! And this all started with the love of the mountains and a goat tag. I’m still looking for my first goat!

by Peter Gutsche

soroptic mange, caused by the parasitic mite Psoroptes cuniculi (the rabbit version of the mite), is a significant disease affecting bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), in the Okanagan region of British Columbia and Washington State. The disease was first identified in a bighorn sheep population in Olalla, BC, in 2011, when a very sick ram was seen along the highway. Since then, research has confirmed a widespread presence of the mite throughout the South Okanagan herds from Penticton through to the Similkameen and Ashnola and southwards through Chopaka and into the Palmer Lake area of Washington State. We have since learned that the disease originated from the Okanagan Game Farm, which closed in 1999.

The Psoroptes mite primarily affects the ears, causing crusting, irritation, and sometimes whole-body hair loss and skin disease (mange). This leads to discomfort, increased vulnerability to other diseases, and decreased overall fitness, which can lead to higher mortality from predation. Infested populations have experienced a significant decline of over 50% since the first detection but are potentially even higher than this in certain groups of sheep.

Managing Psoroptes infestations is complicated due to the transboundary nature of the affected bighorn sheep populations between Canada and the U.S. Additionally, there are limited effective drug treatment options. However, recent developments, such as injectable treatments, offer new hope for disease management.

In light of these developments, the fight against Psoroptes cuniculi has taken a major step forward with the launch of the Okanagan Bighorn Psoroptes Treatment Program in Penticton. This collaborative effort brings together the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia (WSSBC) and the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA), with crucial funding support from the Wild Sheep Foundation, Washington State WSF, and other partners. Work has been going on behind-the-scenes for over a year, led by ONA Biologist Mackenzie Clarke, with support from BC Gov Biologists Craig McLean(BC Parks) and Andrew Walker(WLRS), BC Gov Wildlife Veterinarian Caeley Thacker, PIB Biologist Matt McPherson, WSSBC Director Peter Gutsche, and of course the retired provincial wildlife veterinarian Helen Schwantje, as well as a host of additional staff and volunteers coming together for the benefit of wild sheep.

Over the course of four days in late February and early March, a dedicated team of wildlife experts and conservationists successfully captured 28 bighorn sheep through helicopter net-gunning and ground darting from the Okanagan and Similkameen regions. These animals were carefully transported to specialized sheep pens on PIB land in Penticton, where they will undergo much-needed treatment and monitoring for Psoroptes infestations.

In the air, recent Lex Ross Award recipient Ben Berukoff of Canadian Wildlife Capture did an incredible job of flying in some challenging terrain. Andrew Walker acted as net gunner with Mackenzie Clarke providing the much-needed additional support as the mugger. On the ground, Matt McPherson, Cailyn Glasser(ONA) and Peter Gutsche led a team of handlers from WSSBC, ONA, Penticton Indian Band, and Lower Similkameen Indian Band in receiving the sheep, where they collected health samples such as temperature, weight, hair, fecal, blood, nasal swabs, ear tissue, body condition, measurements, and age, before tagging and releasing the animals into the pens.

The collaborative efforts to conduct these captures is something we can all be proud of and is further proof that by putting our respective differences aside, we can achieve so much for the things we collectively care about.

As we move into the next stages of the program at the Penticton facility, the captured bighorn sheep will receive targeted treatment over the next 15-18 months, being handled on a monthly bases, including trials of injectable medications aimed at eliminating the Psoroptes mites.

In addition to direct treatment, the program will monitor disease progression by tracking infection rates and recovery

to improve treatment protocols, assess drug efficacy by testing new treatment methods to determine the most effective approach, and expanding conservation strategies through using findings from this program to develop future management plans for wild sheep populations in British Columbia and beyond.

This program represents a significant milestone in wild sheep conservation efforts. By bringing together Indigenous knowledge, scientific research, and conservation funding, the initiative aims to restore the health of local bighorn sheep populations and create a model for managing Psoroptes at the landscape level, be it in BC or beyond. It is our collective goal to see these populations restored to their historic levels.

The success of this initiative is only possible through collaboration. To this end, the WSSBC, ONA, Wild Sheep Foundation, and Washington State WSF have provided essential resources, expertise, and financial support. Moving forward, the program will continue to evolve, with ongoing monitoring and adaptive management strategies to ensure long-term benefits for bighorn sheep in the Okanagan and Similkameen, as well as in Washington State.

Throughout the year, we will continually provide updates on the treatment progress and the impact of this groundbreaking conservation effort through the WSSBC magazine, as well as on our WSSBC social media platforms, and on the @ Okanaganbighorns Instagram account and the soon to be launched Okanaganbighorns.com website.

If you are interested in learning more, or volunteering your time for the monthly handling of our captured bighorns, please reach out to WSSBC Director Peter Gutsche at petergutsche@gmail.com.

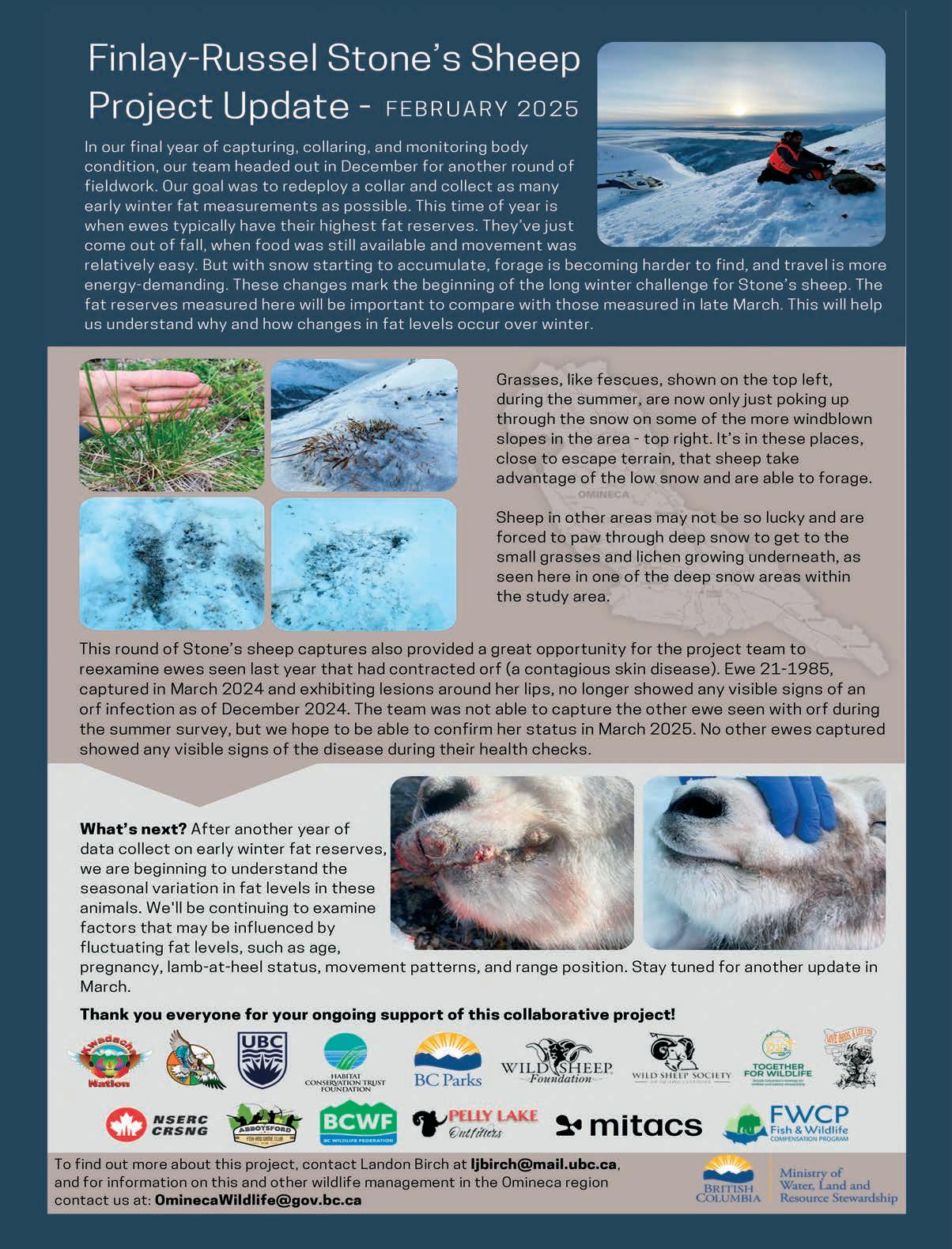

by Wild Sheep Society of BC

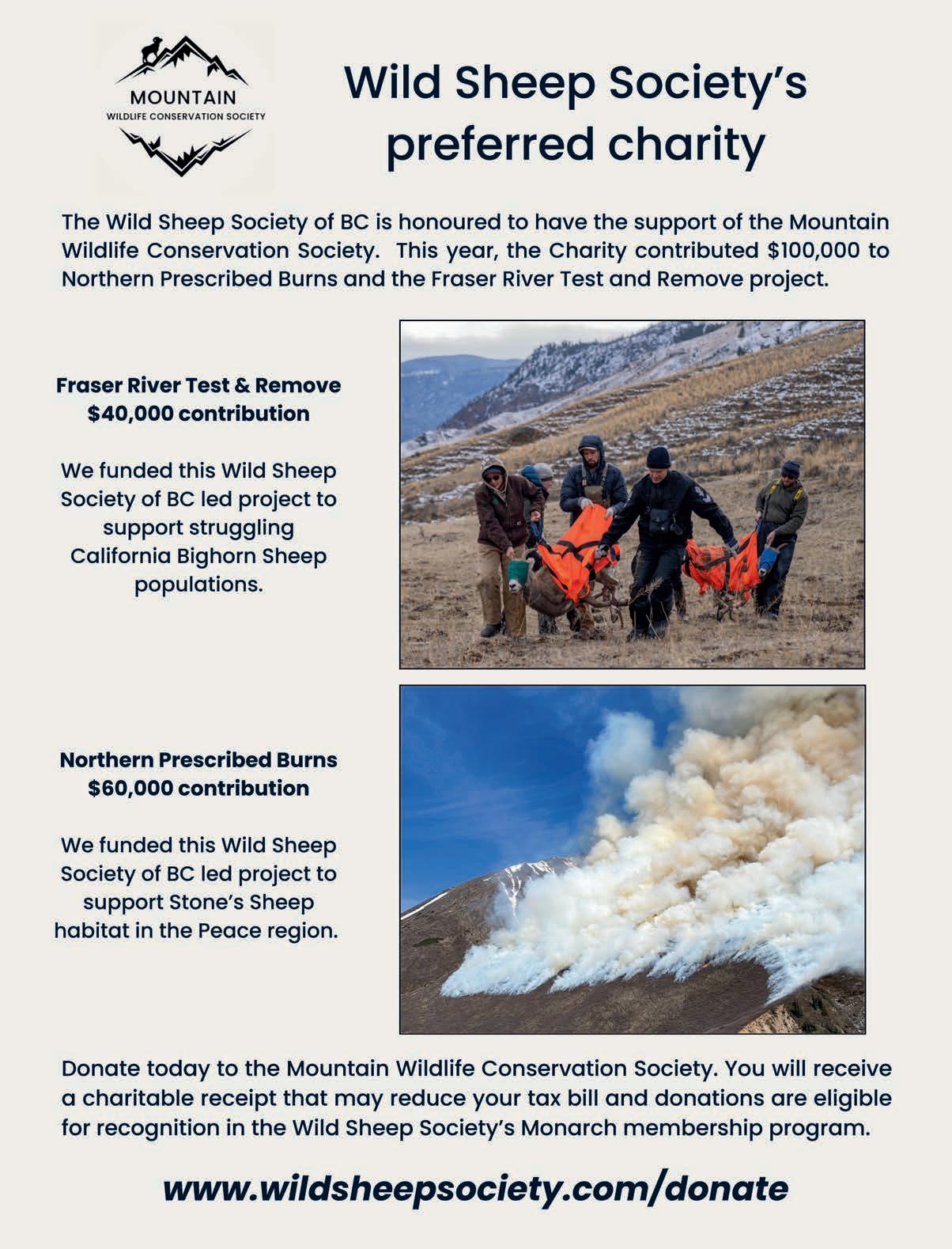

Wild Sheep Society Financial Commitments in 2024:

January Approvals

$50,300 – Ungulate enhancement – BC Trappers Association

$10,000 – Sportsmen and Sportswomen advocacy – CCFR

$5,000 – Honorarium for Disease Symposium – Dr. Schwantje

February Approvals

$1,200 – MITACS Student – Larissa Murdoch (Region 3)

$25,200 – MITACS Student – Jon Weissman (Region 7)

$29,665 – Northern Burn Recruitment Surveys (Region 7)

$1,500 – 2024 BC Chapter of the Wildlife Society & The Canadian Section of the Wildlife Society AGM

$25,000 – Test & Remove – Fraser River (Region 3)

$10,000 – Ungulate Enhancement – Kootenay (Region 4)

$5,000 – Lower Similkameen – Ashnola Bighorn Sheep Enhancement (Region 8)

$11,000 – Tsihlqot’in sheep survey’s (Region 5)

March Approvals

$10,000 – Sportsmen and Sportswomen advocacy – CCFR

$7,500 – North America Wildlife Enforcement Officer Association

May Approvals

$65,000 – Cheatgrass Mapping Assessment (Region 3/5)

$30,000 – Shulaps Collaring Project (Region 3)

$8,000 – Removal of (2) MOVI positive Ewe’s (Region 3)

July Approvals

$10,000 – Sportsmen and Sportswomen Advocacy – Manitoba Wildlife Federation

$10,000 – Chapter and Affiliate Alberta Bighorns: Grotto Mountain Sheep Habitat Enhancement Project

August Approvals

$3,400 – Annual Advancing Women In Conservation 2025 Vancouver Summit

$70,000 – Fraser River Test & Remove (Region 3/5)

$15,000 – Ungulate Enhancement (Region 4)

$30,000 – 80 Wild Sheep Health Sample Kits

$33,000 – Finlay–Russel Stone’s Sheep Continued Project Support (Region 7)

$258,000 – Prescribed Burns (Region 7)

September Approvals

$21,000 – “On the Landscape” film project with Golden Rod & Gun film conservation work.

$68,700 – South Okanagan Bighorn Disease Recovery (Region 8)

October Approvals

$25,000 – Skook’s Landing boat launch, construction & improvement (region 7)

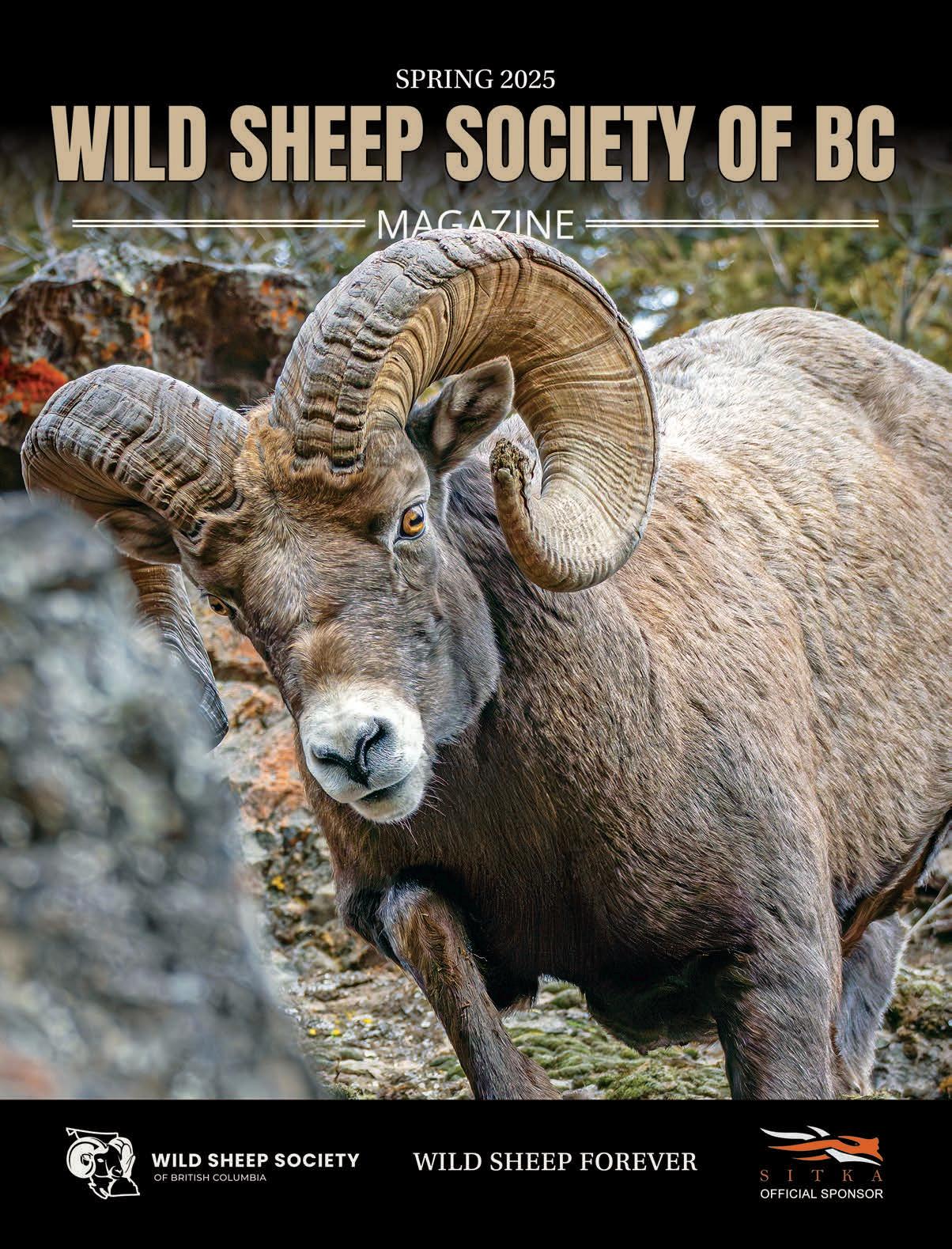

Comparing Thinhorn and Bighorn Sheep

by Larisa Murdoch

igh atop North America’s rugged peaks and sprawling deserts, two species of wild sheep reign supreme: the bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) and the thinhorn sheep (Ovis dalli). Though they share a common ancestor, these majestic animals have evolved into distinct species, each with its own adaptations, behaviors, and survival strategies. From the bone-rattling headbutts of bighorn rams to the stealthy resilience of thinhorn sheep in the Arctic wilderness, these two species are icons of the continent’s wild landscapes. But how do they compare? Let’s take a closer look.

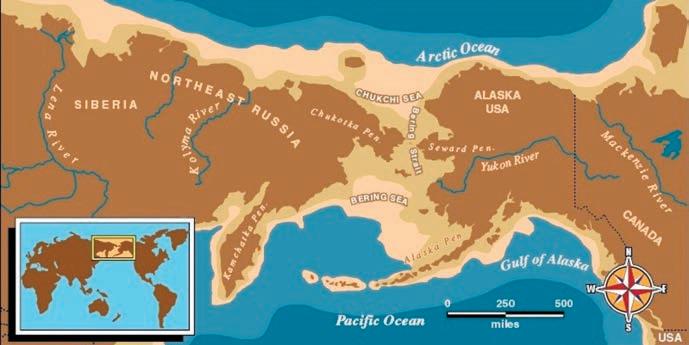

Bighorn and thinhorn sheep trace their lineage back to ancestral wild sheep that migrated from Eurasia across the Bering Land Bridge roughly 750,000 years ago. Over time, these early sheep populations adapted to different environments, leading to the split between bighorn and thinhorn sheep approximately 300,000 to 500,000 years ago. Bighorn sheep adapted to the deserts and mountainous regions of the western U.S., Canada, and northern Mexico, while thinhorn sheep thrived in the remote, high-altitude landscapes of Alaska, the Yukon, and northern British Columbia.

Bighorn sheep inhabit the Rocky Mountains, Sierra Nevada, and the deserts of the southwestern U.S., with their range extending from southern Canada to Mexico. Subspecies include Rocky Mountain bighorns, California bighorns, and desert bighorns. In contrast, thinhorn sheep prefer colder, more remote environments and are found in Alaska, the Yukon, and northern British Columbia. They are further divided into two subspecies: Dall’s sheep, which are pure white, and Stone’s sheep, which have darker coats blending brown and gray.

Few wildlife spectacles are as dramatic as the bighorn sheep rut. During mating season, rams engage in brutal headbutting battles, smashing their thick skulls together at speeds up to 32 km/h (20 mph). These duels can last for hours, with the loud cracks of impact echoing through the mountains. The winner earns the right to mate, while the defeated ram retreats, often nursing a sore head. Thinhorn sheep rams also fight for dominance, but their battles are less violent and shorter in duration. Instead of repeated headbutting contests, they rely more on posturing, chasing, and strategic horn clashes. Some younger rams even adopt a sneaky strategy, mating with ewes while dominant males are distracted.

Both species face threats from predators like mountain lions, wolves, and bears, but their survival strategies differ. Bighorns rely on speed and agility, sprinting up to 48 km/h (30 mph) and zigzagging up steep slopes to evade predators. Thinhorn sheep, on the other hand, often freeze in place, blending seamlessly into their rocky surroundings. Their remote, high-altitude habitat also provides them with natural protection. When it comes to physical adaptations, their horns play a crucial role in both defense and dominance. Unlike antlers, which are shed yearly, both species keep their horns for life. Bighorn rams have massive, curling horns that can weigh up to 14 kg (30 lbs), while thinhorn sheep have longer, more slender horns that curve gracefully backward. Their specialized hooves have a rough, textured surface that provides excellent grip on steep and rocky terrain, allowing them to scale near-vertical cliffs with ease.

Meanwhile, their coat colors aid in camouflage—thinhorn sheep’s lighter coats blend into Arctic landscapes, whereas bighorns’ brown coats match their mountainous and desert habitats.

Bighorn sheep live in sex-segregated herds for most of the year, while thinhorn sheep often form smaller, more fluid groups. Both species use body language, vocalizations, and scent marking to communicate, but bighorns are more vocal, especially during the rut. Rams will rub their

scent on rocks or vegetation to mark territory. In terms of migration, bighorns are more migratory, following seasonal routes to find food and shelter, moving between summer alpine meadows and lowerelevation winter ranges. Thinhorn sheep, however, tend to stay at high elevations year-round, only moving when heavy snow forces them to seek more accessible forage.

Both species are herbivores, but their diets vary based on habitat. Bighorn sheep are more likely to graze on

Figure 1. Current home range of bighorn sheep and thinhorn sheep.

grasses and shrubs in meadows and foothills, whereas thinhorn sheep often browse on lichen and alpine plants, relying on whatever they can find in their harsher environment. As grazers, both play a crucial role in shaping vegetation by influencing plant growth and biodiversity, and their droppings help fertilize alpine ecosystems, maintaining a healthy nutrient cycle.

Figure 2. Bering Land Bridge where the common ancestor of bighorn and thinhorn sheep crossed over from Eurasia to North America.

Both species face threats from habitat loss, human encroachment, and climate change. Bighorn sheep are highly vulnerable to pneumonia outbreaks, which have decimated populations in some regions. Thinhorn sheep may face more significant habitat changes as Arctic climates warm, potentially increasing disease risks. Hybridization between bighorn and thinhorn sheep has also been recorded in overlapping ranges, particularly in northern British Columbia, and its genetic implications are still being studied.

Despite their differences, bighorn and thinhorn sheep are both incredible examples of survival, adaptation, and resilience. Whether navigating the scorching deserts of the southwest or

the frigid peaks of the Yukon, these wild sheep continue to captivate scientists, conservationists, and outdoor enthusiasts alike. As we work to protect their habitats, one thing remains certain: North America wouldn’t be the same without these mountain monarchs.

Both species are incredibly agile, with bighorns known for their impressive jumping abilities, clearing obstacles up to 6 meters (20 feet) in a single bound. Thinhorn sheep, on the other hand, are expert climbers, often scaling near-vertical cliffs to escape predators. These athletic adaptations ensure their survival in extreme environments where few other animals can thrive.

Larisa Murdoch grew up in Ottawa, Ontario before moving west to complete her Bachelor of Science at the University of Victoria. She completed an undergraduate project studying the denning behaviour of African Wild Dogs in Zululand, South Africa, which sparked her interest in research. She is currently a student at Thompsons River University in Kamloops working on her Master of Environmental Science, where she is partnered with WSSBC, the Ministry of Water Land and Resource Stewardship, Tk’emlups, and Skeetchestn’ Indian Band investigating bighorn habitat selection with lambs. When Larisa is not focused on her thesis, she enjoys outside exploring new places, snowboarding, reading, and volunteering with the WSSBC!

Sources

● Geist, V. (1971). “Mountain Sheep: A Study in Behavior and Evolution.” University of Chicago Press.

● Valdez, R., & Krausman, P. R. (1999). “Mountain Sheep of North America.” University of Arizona Press.

● Festa-Bianchet, M., & Apollonio, M. (2013). “Mountain Ungulates of North America.” Cambridge University Press.

● BC Ministry of Environment. (2021). “Thinhorn Sheep Status Report.”

● U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2022). “Bighorn Sheep Conservation Strategies.”

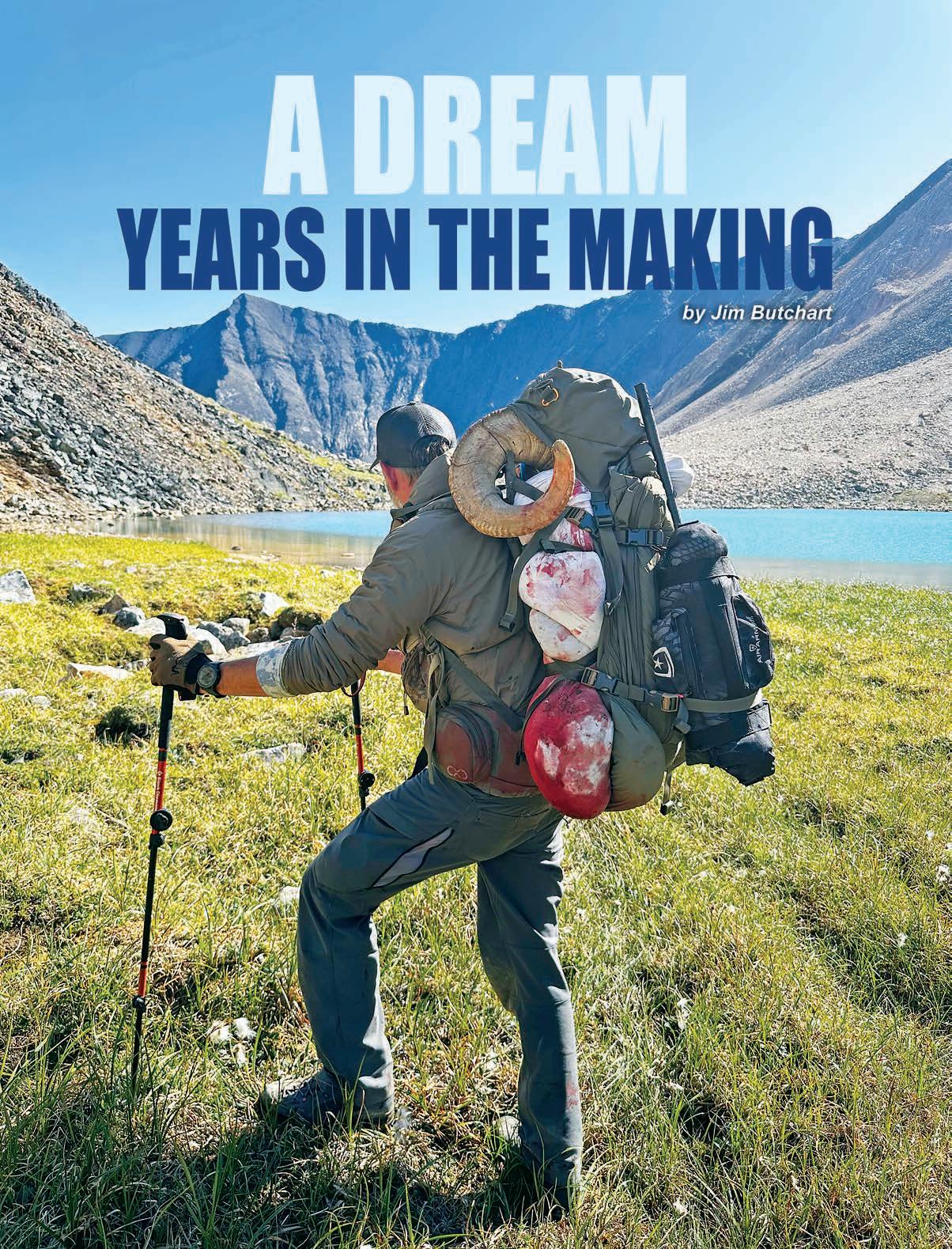

The early morning of July 31, 2024, marked the beginning of an adventure I’d been eagerly anticipating for years. My alarm jolted me awake at 3:15 am, but there was no need for the backup I’d set for 10 minutes later—I was already wide awake, adrenaline coursing through my veins. The journey that lay ahead was not just a physical one but also a culmination of years of dreaming, planning, and preparing. I was finally going sheep hunting.

As I set off on the four-hour drive to Denver International Airport, the reality of what I was about to undertake began to sink in. For the first hour, my mind raced with thoughts of what lay ahead, but eventually, a calm washed over me. This was it. I was actually doing it. The dream that had taken root in my mind back in 2017 was about to come true.

Back then, in my mid-40s, I’d started yearning for a true adventure hunt—something that would take me far from the comforts of home and push me to my limits. At that time, the closest I’d been to the north country was through the internet, where I spent countless hours researching, dreaming, and planning.

In 2019, I got my first taste of what I was seeking when I hunted woodland caribou and Canadian moose in Newfoundland. While it was a thrilling experience, it didn’t quite satisfy my hunger for adventure. The cabinbased hunt, complete with creature comforts, was far from the rugged, remote challenge I craved, and I knew I wanted more.

THE DECISION TO PURSUE SHEEP HUNTING

In June of 2020, I got serious about making my dream a reality. After listening to a Kifaru podcast, I reached out to Clay Lancaster, whose hunting chops had been endorsed by Aron Snyder, someone I admired. Initially, I inquired about a mountain caribou hunt, thinking a sheep hunt was financially out of reach. Clay explained that the mountain caribou hunt was challenging and took place in terrain similar to a Dall sheep hunt, and I should consider it. But he also said and without a hint of pressure, if I’m even considering a Dall hunt there’s no reason to wait.

For months, Clay and I exchanged texts, discussing the possibilities and logistics. Eventually, I made up my mind—I wasn’t getting any younger, and if I was going to hunt sheep, it had to be now. To make it happen, I’d need to save every bit of disposable income, but it was a commitment I was willing to make. The fear of living with regret as I got older was a powerful motivator. The timing couldn’t have been worse, with the world in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, I put down a sizable deposit on a hunt scheduled for August 2024, nearly four years in the future. It was a hard decision to wrap my head around, but I knew that if I was going to do it, I needed to act quickly. And so began the long wait. I had to file away my excitement and focus on other things, knowing that one day, the time would come.

PREPARATION AND ANTICIPATION

The years passed slowly, but they were filled with experiences that helped prepare me for the adventure ahead. In September 2021, my good friend and hunting partner and I headed north to the Brooks Range of Alaska for a barren ground caribou hunt. This DIY drop camp hunt was just the adventure I needed to test myself and my gear in the tundra. The hunt was incredible, and I took a beautiful bull caribou early in the trip. Looking back, I realize how important that hunt was in building my confidence and proving to myself that I could indeed hunt in that type of terrain.

January 2024 finally arrived, and with it, the realization that this was the year of my Dall sheep hunt. The anticipation had been building for years, but now it was real. I had spent countless hours consuming sheep hunting content, listening to every podcast, and watching nearly every YouTube video I could find on Dall sheep and the Northwest Territories. While I did my best to stay in shape year-round, I ramped up my training eight months out, eager to be in peak condition for the hunt. As soon as the snow melted in the spring, I started hiking the mountains surrounding my home in Colorado, pushing myself harder with each outing.

By July, I started documenting the lead-up to the hunt on Instagram. I was even a guest on The Hunt Backcountry

podcast, where we discussed the preparation and anticipation as part of their “Before and After Series.” At this point, there was no turning back—everyone I knew was aware of the hunt and how much it meant to me. Not that turning back was ever an option.

THE JOURNEY NORTH

The morning of July 31 was the start of my journey north. I had a direct flight from Denver to Edmonton, and upon arrival, I was beyond relieved to find all my gear in baggage claim—a huge logistical hurdle successfully cleared. I wheeled my gear into my room at the airport hotel, did a quick inspection, and then met up with a new hunt buddy I’d met on the flight for a burger and beers.

The next day, after a solid night of sleep, I continued my journey north, expecting to spend the night in the backcountry. My flight plan with Canadian North was a series of hops: from Edmonton to Yellowknife, then to Inuvik, and finally to Norman Wells. From there, I would take a floatplane to June Lake, the main hunt camp for NWT Outfitters, before being flown via helicopter to the backcountry.

As I boarded my first flight, I noticed I was surrounded by hunters, many of whom had already taken several sheep. It quickly became apparent that sheep hunting was largely a rich man’s game, a realization that made me feel even more determined to make the most of this opportunity.

Our final stop with Canadian North was Norman Wells, where I held my breath again as I watched the checked

luggage make its way down the belt. My rifle and gear bag safely in hand, I joined the rest of the crew hunting with the Lancasters and boarded our final flight to the June Lake Base Camp. After a short shuttle to the floatplane, we streamlined our gear, leaving big bags and rifle cases in a secure shed for the hour-long ride into base camp.

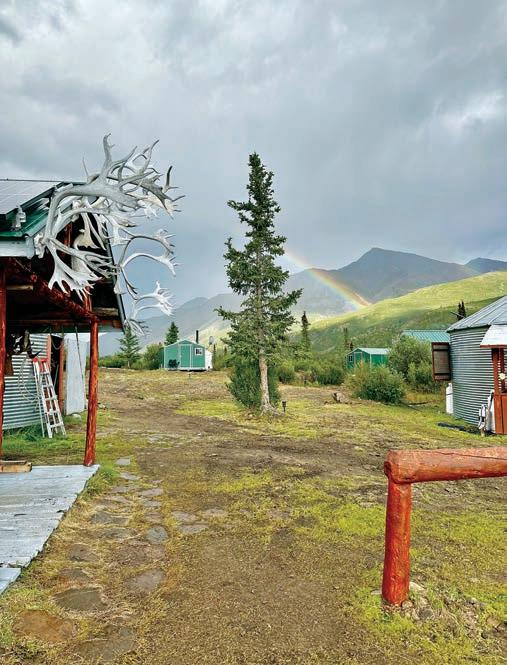

BASE CAMP ARRIVAL AND LAST PREPARATIONS

Upon arrival at base camp, all eight hunters were assigned to share bunkhouses, with two to three hunters per cabin. We settled in quickly and gathered for a hunt meeting led by Clay. He covered important details like helicopter safety, rifle etiquette, and tag distribution, then paired us up with our guides. My guide, Don, and I were slated to hunt a block furthest from base camp, so we didn’t make it into the field that day. Time simply ran out, but I was okay with that. It gave me a chance to organize my gear and chat with Clay, his partner/uncle Jim, and the man who started it all, Clay’s dad, Stan Lancaster. Meeting these legends of the NWT was a true highlight of the trip. The next morning, August 2, I enjoyed a leisurely start to the day, sipping coffee and indulging in a big breakfast. As I waited for our departure, I spent the morning glassing the countryside for caribou, grizzlies, and wolves. The anticipation built as I readied my gear for what felt like the tenth time. Around lunchtime, we got word that two sheep had already been shot—a rifle hunter had his down, and a traditional bow hunter had a hit but no recovery yet.

Finally, I heard the words I’d been waiting for: “Gear up, you’re heading out in 20 minutes!”

With a mix of excitement, nerves, and the culmination of nearly four years of planning swirling in my head, I loaded into the helicopter with Don, and we were off the ground. We were dropped at the head of a beautiful basin, with an incredible turquoise alpine lake as our backdrop. We quickly set up our tents as rain was about to hit, and since we needed to wait 12 hours before we could hunt, there was no rush. It was 4 pm, and we had a shooter ram on the other side of the mountain.

THE HUNT BEGINS

On the morning of August 3, we were out of camp by 7 am after a quick breakfast and coffee. We ascended just shy of 1,000 feet and slowly crept over the saddle where we expected to find the rams in the valley below. But there was nothing. We glassed for a bit and then contoured about 600 yards to get a better angle up the valley. The loose boulders and shale, combined with numerous no-fall zones, had my heart rate sky-high. One false step could have resulted in a dangerous slide.

Despite our efforts, the sheep were nowhere to be found, as they had countless options to evade us. We suspected they were at the head of the valley, so with the wind in our favour, we pushed on, stopping to glass and taking our time. As we reached the head of the valley, Don dropped to a knee, giving the telltale sign that he had spotted sheep. The hunt was on.

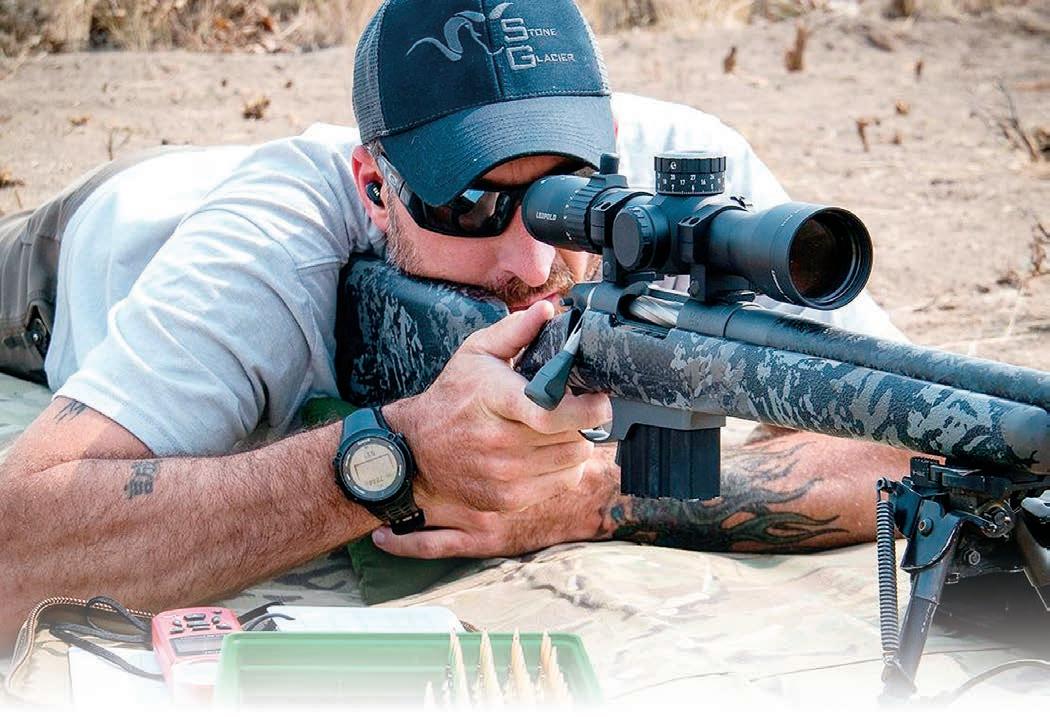

Unfortunately, a young ram had us pegged at 480 yards. While he didn’t spook, he kept his attention on us. All we could do was hold our position and hope to spot the 10-year-old ram we were looking for. Eventually, the old ram stood up out of his bed, and I slowly positioned my rifle in hopes of getting a shot. I had mentally set a max yardage of 400 yards before the hunt, and the shot presented was 480 yards, corrected to 435 for the angle. I was steady with the old ram in my crosshairs, but the sheep were far from calm at this point. After one more confirmation of range from Don, I checked my turret and level and took a deep breath. Safety off. My mind raced, thinking about my self-imposed yardage limit—not the thought pattern one wants before taking the most important shot of their hunting career. Safety back on. I looked at Don and said, “I’m not comfortable at this range.” It was one of the hardest hunting decisions I’ve ever made. We tried to gain 75 yards, but in the process, we spooked the sheep. I quickly got on the ram again, but now, as the sheep moved away and across the mountain, the distance increased from 450 to 475 to 500 yards. Eventually, we called it off. The sheep continued to climb and ended up bedding down about a mile away on the highest peak overlooking the valley. We watched them for a couple of hours, mostly in silence, each of us replaying the events and calming ourselves. As I replayed the decision in my head over and over, I hoped I wouldn’t regret not taking that shot.

We hiked and glassed our way back into the valley where we had camped, hoping the sheep would roll over the top of the mountain into our valley. We glassed the ridges separating the two valleys, and sure enough, after an hour or so, we spotted one of them on top where we had left them. Rain came in hard, and we retreated to our tents to wait it out. After a couple of hours, the weather broke, and we ate our dinners, discussing the game plan for the next day.

THE CHALLENGES OF THE HUNT

The next morning, August 4, started with a short hike across our valley to ensure the rams hadn’t moved to our side while we slept. Once cleared, we worked our way to where we had left them the night before. We took it slow, glassing along the way, as the sheep could have bed down anywhere. The terrain was deceiving—from the main valley floor, you’d have no idea the side valley we’d been hunting even existed. It was about a 500-foot climb, picking through boulders until we reached a plateau that opened into an entirely new valley. We gained some more elevation and set up to pick apart the entire bowl. It didn’t take long to spot our rams at the far end of the valley, about a third of the way down a 3,000-foot face and a mile away. With no way to make a stalk and the wind unfavourable, we decided to hunker down and keep an eye on them, hoping for a chance to make a move. The rams fed around, bedded down, fed some more, and moved only a couple of hundred yards the entire day. These sheep were

spooked and not budging. After 12 hours of waiting, we backed out and returned to camp. Doubt started creeping in. The morning of August 5 played out similarly to the previous day—hike, glass, hike some more. We climbed into the valley, and to our dismay, the sheep were nowhere to be found. We glassed intently for a couple of hours and then took the opportunity to regroup and refresh our spirits at a beautiful spring, soaking our legs and feet. We rested in the sun, ate some lunch, and came up with a new plan to relocate camp a couple of drainages over. I fought off the demons of doubt as best I could, reminding myself that I was still very much in the game. But in the back of my mind, I couldn’t help but think that it just might not happen. If you’ve been hunting long enough, you’ve had your fair share of unpunched tags. Would I forever regret not taking the shot on my first day? I tried to convince myself that no matter what, I would stay positive and hunt until the end with all I had... With tent stakes pulled, air mattresses deflated, and packs loaded, we made the move to a new camp. We set up and finished our dehydrated meals by 11 pm. Darkness didn’t come until around 1 am. With tired legs, we devised a plan for the next day and retired to our tents. Sleep was tough to come by as nerves and excitement swirled in my head.

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH

The morning of August 6, I stumbled out of my tent and found Don already kitted up and finalizing his pack for the day’s adventure. By the look on his face, I knew I needed to get myself together quickly. After drinking half a cup of coffee, I caught up with him, and he laid out the day’s plan. We had a short but steep climb out of camp to the adjoining basin, where we would slowly and methodically work our way out to another basin. Don made it clear that we would be following the 2/20 rule: walk two yards, look 20 yards, walk two, look 20—slow and methodical. The rams could be anywhere. He also emphasized the importance of being ready and being quick to set up if a shot presented itself. In short, this could be our last crack at this ram, so I needed to make it count.

Our route led us to a crossroads. To our left was a big alpine lake, and to our right, the valley continued, offering more country to explore. We chose to go right,

even though the wind would be unfavourable, in hopes of catching some rams on either side of the steep mountain before they winded us. This was a low-percentage stalk but our only play.

I felt Don’s pace pick up a bit, and I thought to myself, “So much for the 2/20 rule!” After about half a mile, we came to a small mossy patch offering a five-yard reprieve from the ankle-twisting boulders. It seemed like a perfect spot to stop, catch our breath, and regroup, but instead, Don kept pushing forward.

After another 10 minutes of hiking, something caught my eye up on the steep hill we were contouring. I brought up my binoculars as I’d done a hundred times before, but this time I made out the rounded top of a ram’s horns. It took me a second to register what I was seeing—it was surreal. With Don about 30 yards in front of me, I got his attention and mouthed the words, “Rams above.” As Don brought up his binoculars to look, the young ram I had spotted was now peering down to see what had interrupted his nap.

I was already unslinging my pack and positioning myself prone on the steep mountainside. I had enough wits to put in my right ear plug, leaving out my left so I could quietly communicate with Don. He confirmed that our old ram was the furthest left, at 166 yards. I chambered a round and steadied the rifle on my pack. After one more confirmation, I took a deep breath in, slowly exhaled, and began taking up the slack of the trigger.

The shot broke, and immediately my left ear was ringing. I racked another round and reacquired the ram in my scope, just in time to see him teeter and fall backward. I had killed the old ram we were after. I was in disbelief. From the time I spotted them to the time I shot; no more than 90 seconds had passed. Just like that, my tag was punched.

It’s not uncommon for hunters to experience an adrenaline dump post-shot, and it comes in all forms. Some hunters begin to shake uncontrollably, while others scream with excitement. My dump was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. I gave Don a huge bear hug, and as I looked up the mountain, I began sobbing. I couldn’t and didn’t want to control the tears. I was brought to my knees—I was a mess!

After regaining my composure, I began the short but steep hike up the mountain to lay my hands on my trophy.

Yes, TROPHY. That term gets such a bad rap in the hunting space, primarily from non-hunters, but I can tell you this: all animals I kill are trophies to me, and nothing is wasted.

After what seemed like more than enough climb to where I felt my ram should be, I saw nothing. I climbed a little further, thinking, “Just keep climbing...” At one point, I looked back at Don, asking if he saw him yet. “No, not yet. Just keep climbing,” he replied. Maybe the shot wasn’t as good as I thought. Maybe he got up and ran off. Then I caught a glimpse of white, and my heart started racing. A few more steps up over a small rise, and there he was. Had he gone another couple of feet, he would have tumbled down another 800 feet to the valley floor. The tears came again as I knelt to thank this old warrior and pay my respects. I was in complete awe of the animal and the moment.

Perhaps it was the four-year lead-up or all the preparation, physically, mentally and logistically. This was far from a cheap hunt—outside of a house, college payments, and vehicles, this hunt was the largest single payment I’ve ever made. The brief history I had with this old ram—letting him walk on day one, then glassing him out of reach for 12 hours, only to lose him for another day and a half—certainly added to the drama of this hunt.

We sat for a long while admiring him, taking in the moment and reflecting on the hunt. It was a bluebird day, and we had a good spot on the side of the mountain with a postcard backdrop. We relived the hunt, each recounting our own perspective of how the morning played out. We shared our personal emotions about what hunting means to us. Don spoke about family members lost in tragic hunting accidents, and I described how I hadn’t felt emotions like this since the birth of my children and my mother’s passing. I wouldn’t trade the time we afforded ourselves for anything in the world.

We took full advantage of the weather and scenic backdrop to capture photos that I will forever cherish. Then we got to the task of skinning and caring for the meat.

We enjoyed a small snack, and then with heavy packs, we began our descent. The first few steps off the mountain were the most challenging, given the steepness, loose shale, and heavy load testing my balance. After a couple of failed attempts to drop in, I finally mustered the courage and began my controlled slide down.

Clay later measured and scored my ram at 10.5 years old, with a respectable score of 156 inches; exactly the type of ram the team likes to take. While the old bruiser might have lived another winter or two, it was time to let the younger, stronger rams take over the breeding and lead the next generation forward.

REFLECTION ON THE JOURNEY

In the end, I felt an incredible sense of accomplishment and relief to have completed what I set out to do. I got my ram, but in the end, I got so much more than I ever knew was possible. I tested my mental stamina, overcame fears, and kept my head in the game. The experience was not just about hunting; it was about the journey, the challenges, and the emotions that came with it. It was about pushing myself beyond my limits and emerging on the other side, not just as a successful hunter but as someone who had truly lived out a dream. The adventure of hunting Dall sheep in the remote wilderness of the Northwest Territories was everything I had hoped for and more. It tested me in ways I hadn’t anticipated and rewarded me with memories and experiences that will stay with me for a lifetime. As I reflect on the journey, I am filled with gratitude—for the opportunity, for the people who helped me along the way, and for the incredible animals that make these adventures possible.The dream that started in 2017 had finally been realized, and it was worth every moment of the journey.

This hunt and all the others would never be possible without the support of my loving wife, Angèle. I am forever grateful for her understanding of my passion to hunt.

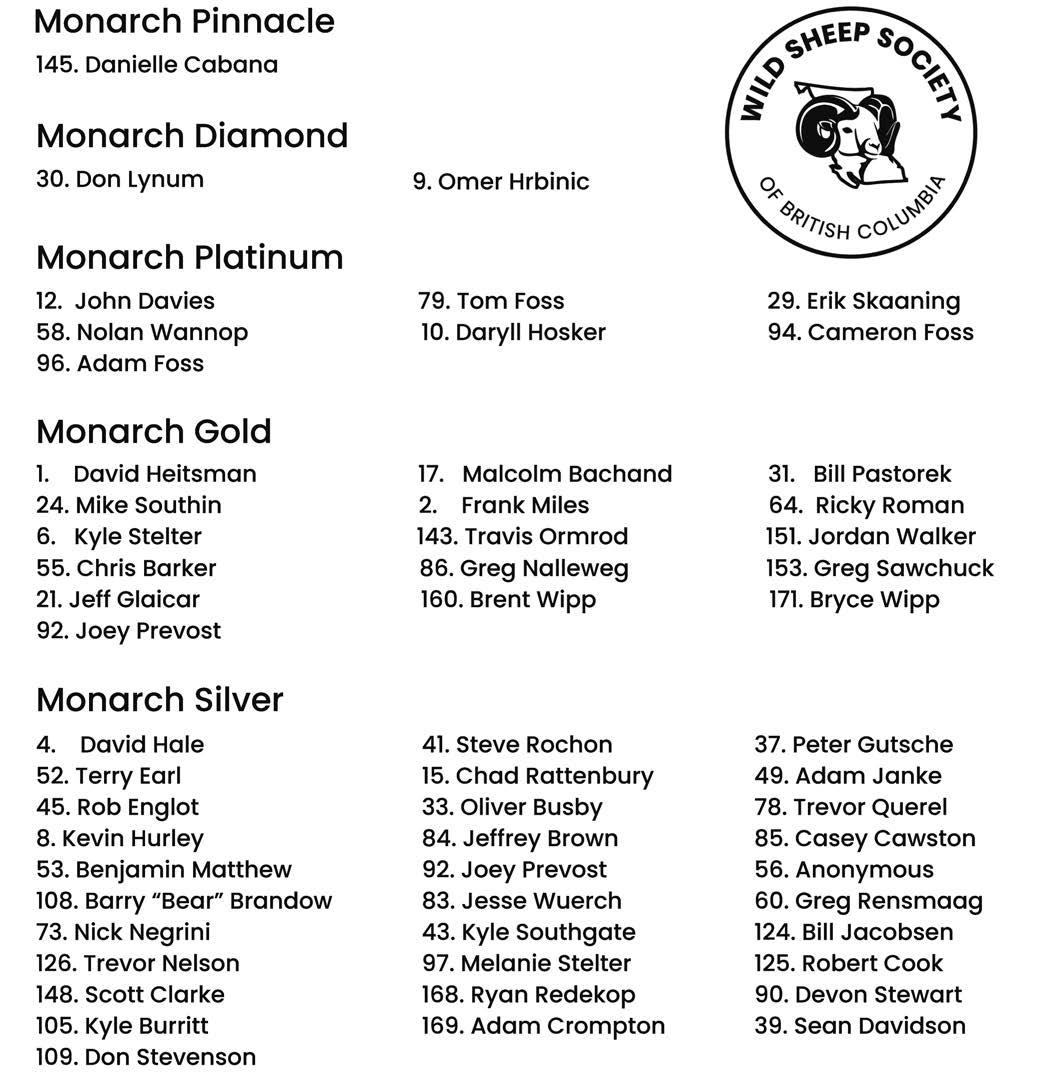

t’s been a busy couple of months for the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia when it comes to membership, and we couldn’t be happier about it. Between the WSF Sheep Show in Reno, the Northern Fundraiser in Dawson, and the Salute To Conservation and Mountain Hunting Expo in Penticton, we have added to our ranks of dedicated conservationists at every level of membership.

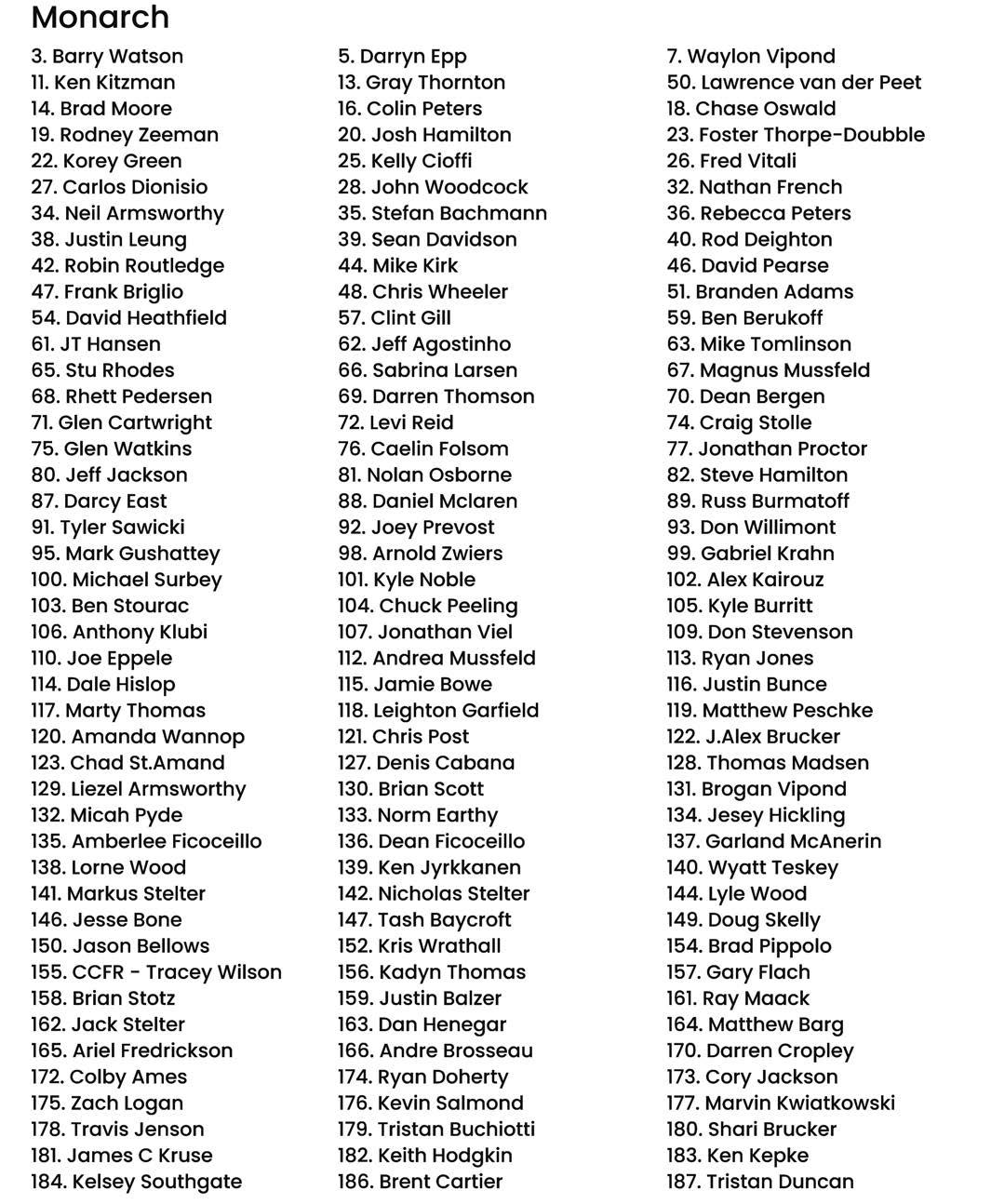

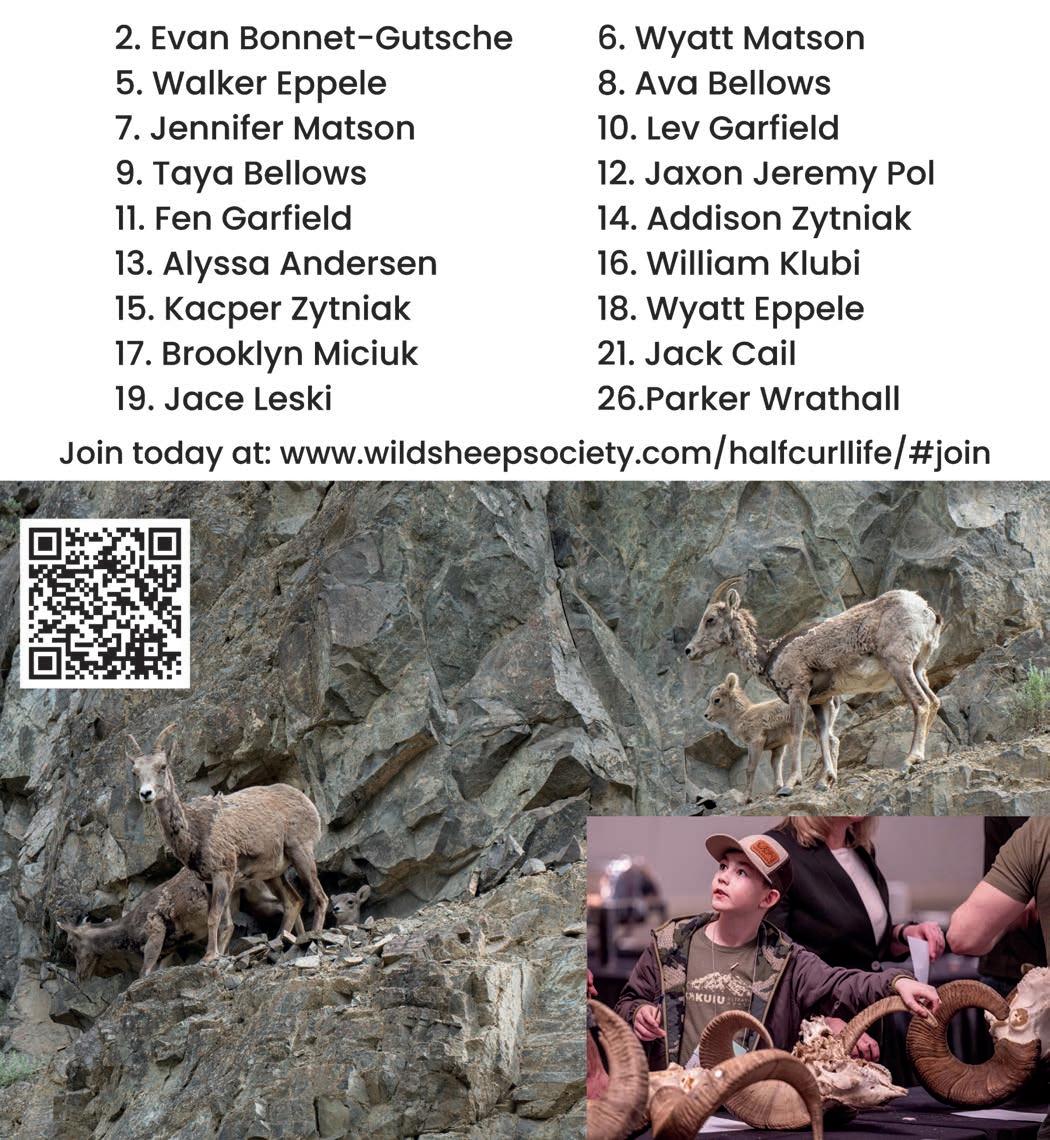

Between these three shows, we were able to add 70 new members to our ranks bringing our current total membership to 1637 as of early March 2025. In addition to this, we had many folks upgrade their memberships, welcoming 27 new life members and 17 new Monarch’s to the fold. With these new additions we currently stand at 869 Life Members and 186 Monarchs. The continued dedication of you all truly inspires us, and we are forever grateful to you for your support.

For those of you considering an upgrade, we do have a couple of promotions that will be running through to our 2026 Salute To Conservation. On February 23rd, 2026, we will be giving away a Gunwerks ClymR package in 300 PRC to one lucky Monarch, with every $100 contribution giving you an entry. For anyone who purchases a life membership until then, we will be entering you to win a Fierce CT Rage 7PRC. In Penticton, we had a goal of increasing our Half Curl Youth Life Memberships and we are pleased to welcome seven new members to this group, bringing our total to 25 now. It is our hope that we will continue to see a rise in this over the coming year, as these folks are the future of our organization.

To that end, we are pleased to have been able to hand out our Half Curl plaques and Don Stevenson knives to a number of these youth at our Life Member Breakfast. We cannot state how thankful we are to Don for his contributions to this, as well as to Dallas Matson for her incredible work. As we look to the future, we are working on the creation of a Youth Camp and hope to have more on this soon.

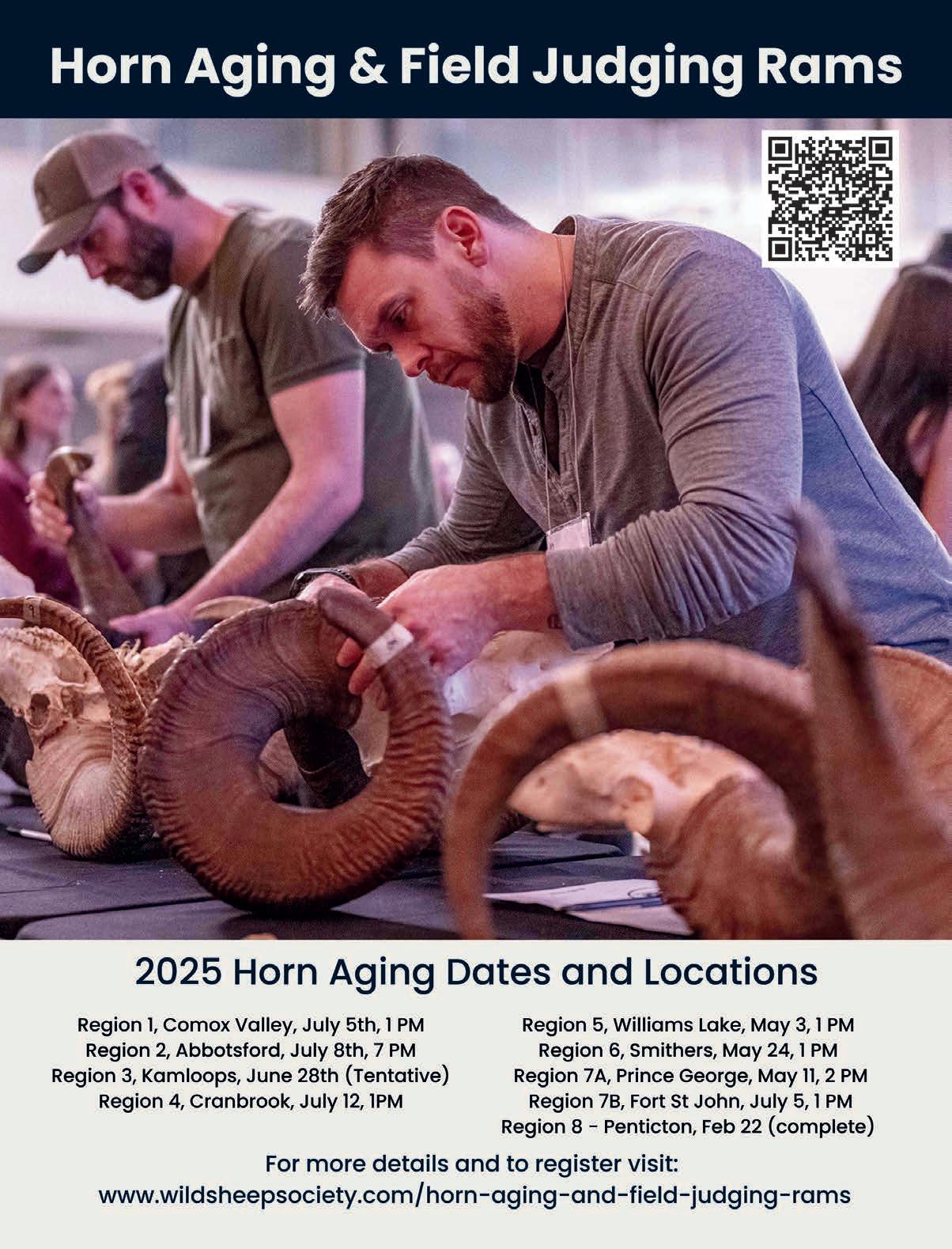

From an education perspective, we are continuing to promote seminars on horn aging and field judging throughout the province in 2025. We have a seminar scheduled for every region of the province:

Region 1, Comox Valley, July 5th, 1 PM

Region 2, Abbotsford, July 8th, 7 PM

Region 3, Kamloops, June 28th, TBC

Region 4, Cranbrook, July 12, 1 PM

Region 5, Williams Lake, May 3rd, 1 PM

Region 6, Smithers, May 24, 1 PM

Region 7A, Prince George, May 11, 2 PM

Region 7B, Fort St John, July 5, 1 PM

Region 8 was held in Penticton at the Salute To Conservation

In addition to these events, we will continue to look for ways to get our members together, be that at a sheep count, golf tournament, pub night, shooting event, or on a project. To that end, we will be hosting the Spences Bridge Sheep Count on April 5th, our 3rd annual Mountain Monarch Golf Tournament June 6th and 7th in Kamloops, and our Aim for Impact Women Shaping Conservation shooting event in Abbotsford on April 26th, and Ruck for the Shulaps in July.

This upcoming year will also offer greater opportunities than ever before for our members to get their hands on a wild sheep as the Psoroptes Bighorn Drug Treatment Program in Penticton has now commenced, with 28 local sheep have been captured and placed in the sheep pens where they will be held for the next 15-18 months. We will be handling sheep on a monthly basis.

Wild Sheep Forever

by Dr Mike Slatnik MD, MPH, CCFP

could hear him eating huckleberries below me as I knelt in the grass with my rifle resting on a stump. He was close. I was elk hunting in mid-September 2020 in the Kootenays when I spotted this bear about 500 yards away in a patch of berries; with a favorable wind, I crept in as close as possible. When he emerged from behind the bushes 25 yards below me, my rifle sang loudly, and death was quick for that bear. I was in the subalpine forest about 3km from the closest road, and that thought weighed heavily on me as I set to work on this big black bear boar. He was too heavy for me to roll,

and with legs tied out to saplings, I could skin and break down the big carcass into parts enough so I could pack out the 3km to the road in two trips, with a very heavy pack. I don’t recall that pack out fondly, after dark and in the rain.

The meat from that bear was the best game meat I could recall; it was neutral in taste and odor and very fatty. Many stews, ground meals, and pulled meals were enjoyed from that bear. I wasn’t too strict about meat cooking as I had thought that 30 days in the freezer would kill Trichinella larvae, and I never really researched that. Unfortunately, in mid-winter, I

undercooked some pan-fried meatballs that I didn’t temperature check before serving, and several others, and I contracted trichinosis. Everyone recovered, but it was a very unpleasant illness that I would not wish on anyone: my personal experience included nine days of fever, severe muscle aches, and night sweats. Trichinella infection in humans consists of an enteral phase (guts), a parenteral phase (parasites leave the guts), and a cystic phase (cysts form in muscles). Following ingestion of infected undercooked meat, stomach acid breaks down the cysts and releases the live larvae, which invade

the lining of the intestine. There, they mature and travel through the lymphatic system within one week to reach muscle tissue (skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle). The initial enteral phase results in (often mild) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. The secondary parenteral and cystic phases result in muscle pain and inflammation as the larvae form cysts and take residence in your muscle; symptoms can include fever, malaise, decreased appetite, abdominal pain, muscle aches, rash, facial swelling, red eyes. The life cycle of the parasite is completed within two weeks. Treatment is available, although often not indicated for mild cases as the disease is selflimited (it usually just runs its course). Treatment with certain antiparasitic medications can halt the disease’s spread and lessen symptoms, although treatment is expensive and difficult to access. Proper diagnosis by a medical professional is important when the

disease is suspected, to consider treatment, to monitor for worsening symptoms, and to identify the source. Specific antibody lab testing is available to detect Trichinella infection. However, it takes weeks to obtain a result and is often negative in early infections. There are several subtypes of Trichinella. Trichinella spiralis is the most common and infects domestic animals (mainly pigs) worldwide, although cases in domestic pork in North America are unheard of in current times. T spiralis is the reason we all know to cook pork to 160F. Freezing is an effective method of killing larvae of T spiralis (-15C for 20 days), however, importantly for us as hunters, this is not effective for other subtypes of Trichinella that can be found in wild meat, such as T britovi, T murrelli, T nativa, and the unclassified Genotypes T6, T8, T9.

After my positive Trichinella antibody test, public health and the BC Centre for Disease Control were quite

interested in this rarely diagnosed illness in BC. I provided public health with a meat sample which was tested at the BCCDC and found to contain Trichinella Genotype T6.

I wrote this article to ask all hunters to keep in mind two things when eating bears (as well as wild boar, wild cat, wild dogs, seals, and walrus):

● Freezing does not kill Trichinella larvae

● Cook the meat to 160F

For most bear consumers, this might include not cooking steaks and having a meat thermometer. Slow cooker/ crock pot cooking and frying ground meat usually reach a very high meat temperature and are excellent ways to enjoy bear.

I still hunt and enjoy bear but my hunter’s toolbox now includes an excellent meat thermometer. Bears in BC are a wonderful animal to chase and eat, and following a few guidelines can be safely consumed and enjoyed.

References

1) Trichinellosis, BMJ Best Practice Guidelines, Feb 8 2019

2) Diaz J, Warren RJ, Oster MJ, The disease, ecology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management of trichinellosis linked to consumption of wild animal meat, Wildnerness and Environmental Medicine 2020; 31(2): 235-44

3) Cheung M et al, The brief case: an infectious hazard of hunting, Journal of clinical microbiology 2023; 61(4): 1-6

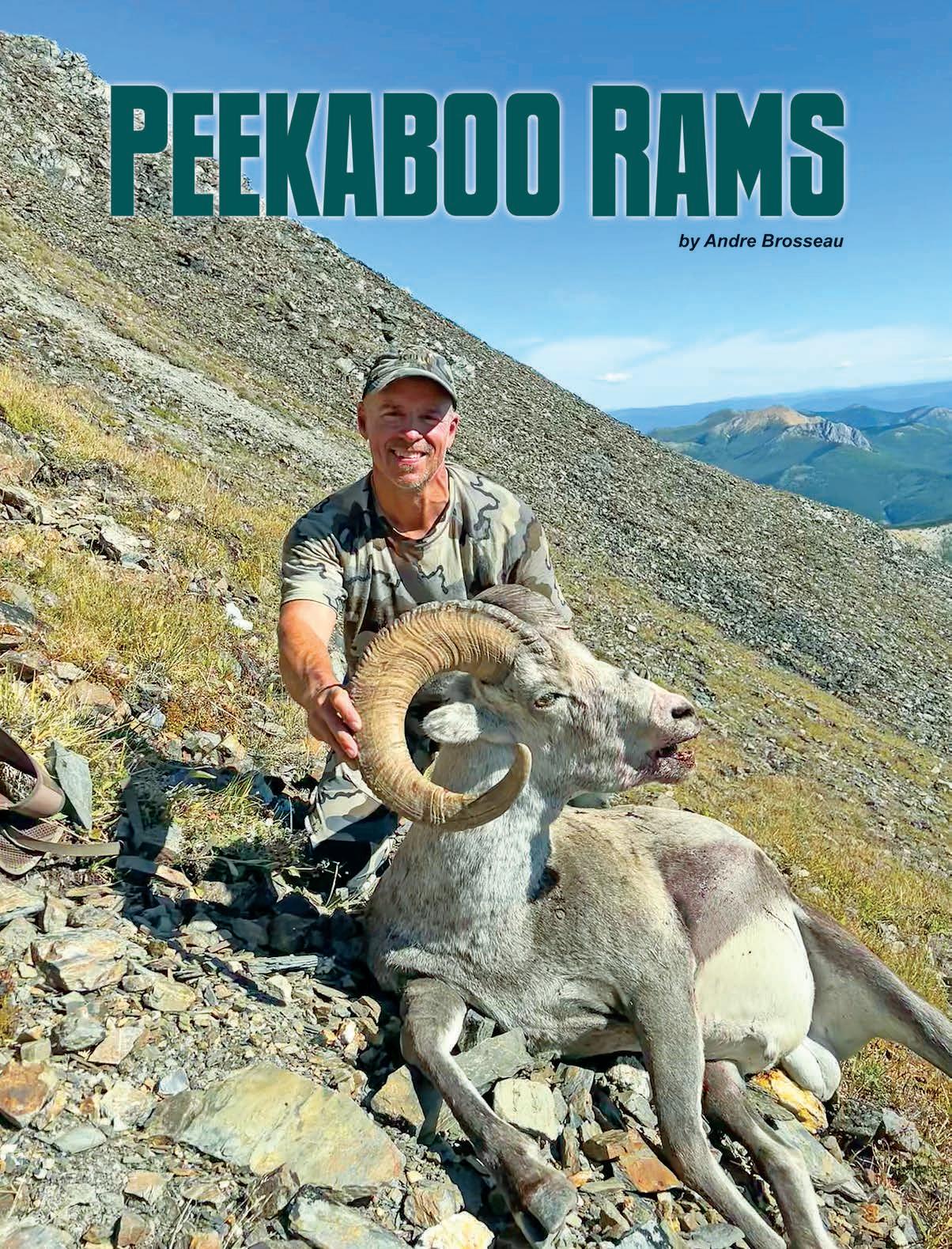

on’t... move... a muscle... we’re going to get busted,” I whispered to my hunting partner, Scott.

We are stuck behind a boulder the size of a Volkswagen Beattle with a band of eight Stone rams mulling around as close as ten yards. I always try to get close and personal when stalking in on sheep, but this was an unnerving proximity.

My first sheep hunt was way back in 1985 at the age of 16. A green kid from Alberta whose parents trusted enough to allow him and a friend to make the five-hour trek West. With minimal knowledge of what they were doing and no sheep hunting experience whatsoever, but the mystical allure of a true mountain hunt fueled by stories read in Outdoor Life. We figured out quickly that it would not be easy, and though we were fortunate to see sheep, we had no clue what we were doing. The next couple of years, I went on a few 2-3 day solo hunts with nothing to show, so I decided to hit the pause button;

deer were easy, plentiful, and had comparatively little time commitment. The bucket of water thrown on the sheep hunting fire never fully extinguished it – just enough to keep it smoldering. Though it took almost 20 years for the flame to be rekindled, and after killing my first Bighorn in 2006, the fire raged.

Moving to British Columbia in 2013 presented a new opportunity... Stones. Although he had not hunted the area for years, a friend had “the spot” and wanted to return. I geared up, including lightweight gear and a skinny water-running jetboat to propel us back on the unnamed rivers and channels held in secret. My friend ultimately couldn’t commit to going due to life circumstances and put an “X” on the treasure map.

I made my first trip to “Anywhere Range” in 2021. I had no success, but I learned the territory and saw sheep. 2022 was a new year with some new gear and renewed optimism. At 53 years old, I didn’t truly know how many more of these hunts I had in me. For my hunting partner Scott, this was his first sheep hunt. He had dreamed of

going, and it took no convincing when I called—he immediately said yes. There is no way to romanticize it, the 3500 ft climb from the river bottom into the alpine sucked. No nicely groomed, well-marked hiking trails with doggy poop bag dispensers. It was eight hours of deadfall, washouts, and the evil of all evils, bog birch. A splendid good time with 30-degree Celsius heat sucking the life out of you. We arrived at camp early evening, settled in, and rested well for the next day’s hunt. On day one, we ambled up the 1200 ft mountain ridge, checking each bowl and trudging on in the heat to a predetermined glassing spot 1 ½ hours from camp that provided the best view of the opposing slopes. Within minutes, rams were spotted on the far mountain, but the 1 ½ mile distance across presented its issues. After several hours of glassing, we could tell there were interesting-looking sheep, but 4 to 5 hours to get to them lacked appeal without being certain. As we watched, the rams suddenly scattered; a big grizzly came over the ridge in hot pursuit, without success, but made for high-stakes entertainment.

We called it an evening and made the trek back to our base to think about our options for the following day. After a hearty breakfast of granola, we made the decision to repeat the previous day’s steps and see if the Rams made a move because of the grizzly show. Up we went, following the identical route, and as we crested a ridge, there they were, seven rams 350 yards away. The Swarovski was quickly sent up, and a speedy inspection with a few phone scope shots revealed a couple of rams that had the potential to be at least eight years old, just what we were looking for. It can’t be stressed enough the importance of spending the time behind the glass and being 100% sure they are legal, preferably taking the older rams even if a younger ram breaks full curl. The commitment was made that eight years minimum was our goal even if they were legal by curl.

We dropped out of sight so we could move in closer for a better inspection,

but when we popped back up, they had done the “Harry Houdini” and disappeared. They couldn’t be far, so we trudged on doing the “sneak and peek” on every little ridge. An hour later, our tactic paid off, and we found ourselves 50 yards above the band. The two nicest rams gave us ample opportunity to inspect, but we couldn’t see a distinguishable 8th annuli, so we retreated to our predetermined glassing spot.

We split up on separate vantage points to see what we could pick up. Within a few moments, Scott signaled that he found rams. I scurried over and set the spotter up to get a good view; it was clear that two out of the eight held potential. As I watched the largest ram perched atop a big rock, we planned to circle and belly crawl in using the boulder he was standing on as our point of reference. An hour later, we poked our heads out of a draw 30 yards from the bolder but could see no rams. We snaked bellied to the rock and surmised that we

should be able to view the rest of the hillside from there. As I peeked over with binos in hand, they were there... 15-30 yards right in front of us, looking in the other direction. It was obvious who the lead ram was. He had all the characteristics of an older ram: sway back, Roman nose, and definitely in charge… if I could only get him to turn his head so I could count rings and see if he was full curl, he was only 20 yards for goodness’ sake. As Scott held tight, the ram got up and walked straight towards us and at 10 yards, turned fully around to expose the back of his horns, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8... He quickly angled away, and my heart pumped, “Did I count 8? Was that actually 8?”. I could not convince myself 100% that he was eight years old. He was just a hair short of full curl, so I could not risk it. The sun was behind him, and the annuli were not well-defined, so I could leave nothing to chance.

I slipped down from the rock to

move around and get a different view when the Rams decided to head straight for us. “Don’t move a muscle... we’re going to get busted.” We were pinned down, but they had not seen us yet. As they came closer, we moved around the rock in a game of cat and mouse. Fortunately, they turned and headed down. As hard as I tried, I could not get a confident look that would tell me to pull the trigger. “That was quite the game of peekaboo,” Scott said. Good name for the rock...

That was a sleepless night. I was almost sure he was legal but just couldn’t tell; maybe I would catch up with them tomorrow.

Morning came, and within a couple of hours, we found the band again moving into a deep bowl. We watched them bed and snuck within 200 yards and set up to scope them out. This old ram just would not cooperate. He bedded just out of sight, with the only thing visible is the top of his horns on occasion. We sat for hours, then

he got up and headed in the opposite direction, leading the band away.

At our wit’s ends, we hiked back to camp, contemplating everything unfolding. I told Scott, “All I need is a real good look, and I am so certain he is legal. Even that other ram looks good. Maybe we can get a doubleheader?” The debate raged on.

The next day, we awoke to another beautiful morning. Maybe today would be the day; the third day is a charm. It was getting hot as we slogged up the 1200 ft climb to start looking into the bowls. I poked my head over into a steep shale slide, and to my amazement, there were both bands of rams and a group of ewes all bedding down 80-150 yards below us.

This was the setup I had been waiting for, and finally, it was a perfect viewing spot with ample time to make some clear decisions. As luck would have it, the two Rams that had been haunting us were the closest.

It took a bit of time, but the 2nd option, Ram turned his head in a

perfect position, and unequivocally, he was eight, no doubt, 100%. But he was not my target. I was after the larger-bodied, older-looking ram. I was locked on him, and finally, he presented; he was definitely over eight years old. Two shooters.

Tired of lugging the extra weight, we left Scotts 10-pound 7mm Mag back at camp. This created a bit of a conundrum, but I was rather confident that when the opportunity presented itself, assuming I made a good shot, we would have opportunity to take the second ram. From previous experiences, the sheep will get a good startle from the crack of the rifle but mill around for a bit until they figure out what is going on.

I grabbed a granola bar and water, never knowing how long it would be until they stood up. The gun was set up and ready with a bipod in front and a pack in the back to make a rocksolid rest. I knew once that ram stood up, the adrenaline would kick in, and I wanted to leave nothing to chance.

The plan was I would take the olderlooking ram, and if fortune was with us, I would quickly rechamber and pass the rifle to Scott and he would drop the other ram.

I was perfectly calm until the smaller of the two rams stood up. Within a blink of an eye, I was set up and locked on like a cat, ready to pounce, as if there was no way this mouse was going to get away. The grey ghost stood up perfectly broadside, and there was not a second of hesitation. With a quick squeeze, the rifle barked, the ram toppled over and went for a 50-yard slide, dead on impact. My first stone lay motionless.

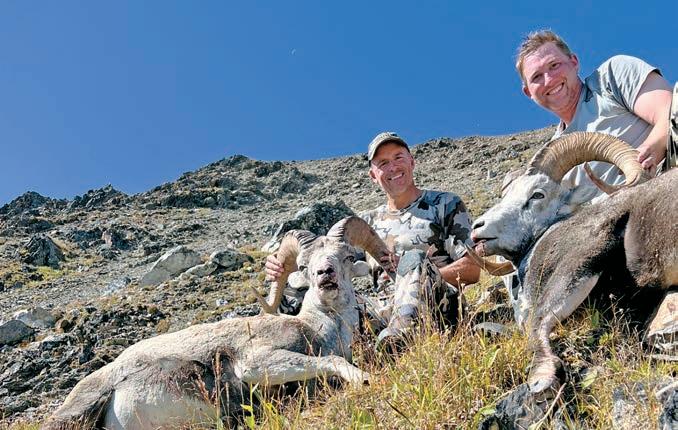

As predicted, the sheep scattered momentarily, trying to make sense of what had just transpired and why the monarch lay motionless below in the shale. I quickly passed my Tikka for Scott to find the 2nd ram, which bolted out of sight. He didn’t go far. In less than a minute we found him on an outcropping, trying to make sense of what just happened. At less than 75 yards, it was a chip shot. A boom, a short run, and he, too, was motionless, less than 100 yards from his elder. Inside, we were screaming with elation, but we kept out of view and

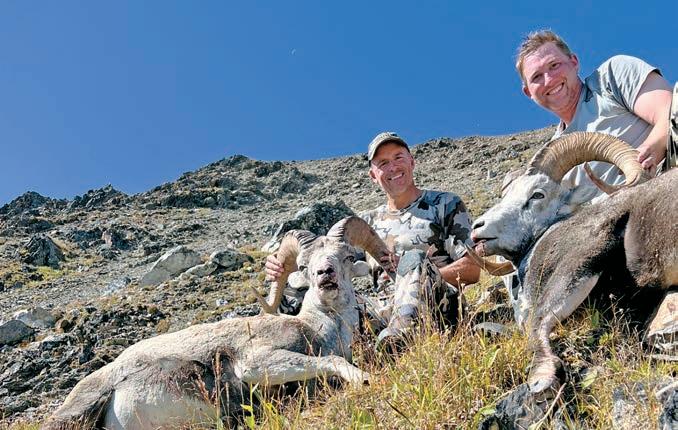

remained silent. These sheep had no idea what had happened, and it was so important to keep it that way. For an hour, they just milled around until another older ram had enough, and the bands moved out; then, we celebrated... an incredible doubleheader. My first Stone and Scott’s first sheep; no sweeter taste. Sliding down to Scott’s ram, we decided to move his the short distance to get pictures of the two rams together as the likelihood of a repeat was highly improbable. Scotts was a gorgeous eight-year-old with a spectacular coat, and mine was a big grey ten-year-old. A few hillside pictures in the searing heat, and we quickly got to work deboning and caping.

The whole trip, Scott kept saying we would shoot two rams. I was not so confident and secretly prayed we would not have such luck. As he slipped on his pack loaded with meat and horns, he looked at me; “what have we done”. With a smirk and a chuckle, I responded, “Welcome to sheep hunting, son.”

We took the next day to flesh out capes and rest up for what we knew would be an arduous journey. The strain from 130-pound packs for the 10-hour haul out was undeniably exhausting, but we made it, and no one got hurt. Was it a good decision to take two rams so far out? Probably not. But as I always say, “bad decisions make for good stories”; I certainly have my share.

by Ronnie Rennich

efore we were a guiding family, we were just a hunting family. My name is Ronnie Rennich, I was born and raised in the central Kootenays of BC, and I was also born and raised to a man who eats, sleeps and breathes elk hunting, Shane Palmer. I’m the oldest of six children, four girls and two boys, and we all shot our first bull elk between the ages of eleven and thirteen. However, our passion for hunting, conservation and the outdoors started long before our first successful hunt and looking back, I realize just how important that was.

Ronnie 2010

Growing up, we always had horses and would spend all of our time outdoors. With horses and a love for the backcountry, it only made sense to combine the two. We started doing backcountry pack trips when I was seven years old. My Dad and my uncles would load the kids, pack the horses and we’d be off. Us on our little ponies practically swimming in the river crossings, playing tag, or bolting off the trails to try to get ahead of the next rider. Our childish antics made the three-and-a-half-hour horse ride to camp an exciting adventure that always went by too fast. At first, it was mostly me and the boys and wasn’t until my sisters got a little older that it turned into an entire family affair. This was the camping my family did, there was no campsite, no camper trailer, it was all packed on horseback and far from civilization. We were gone most weekends and were practically raised on those trails. Before any of us could legally hold a hunting license of our own, we were fortunate our dad still let us tag along for the excitement. Elk hunting is no easy task, elk hunting with a six or an eight-year-old trying to keep up... impossible. Even with the odds stacked against us I still remember countless five points and encounters close enough to instil a passion for hunting that will never dissipate. Fast forward to 2010, Levi (eleven) and I (thirteen) had our very own elk tags in hand. Go big or go home, as the thought of a whitetail or mule deer buck never even crossed our minds. While we were still in school and my dad had committed to guiding two hunts for a family friend, we became limited to hunting weekends. My dad was able to get his bull before work one morning when he went back to logging, and even though the freezer was full, Levi and I still had that itch that needed scratching.

It wasn’t until Thanksgiving weekend that Levi and Dad hiked straight up the face of a mountain after a bull they’d seen the night before. It was a long quiet morning as they didn’t hear a single bugle until they stopped for lunch. When the bull finally piped up, he was about 400 yards away, a mixture of hiking and calling happened before Levi made a perfect 25-yard shot on a wicked bull elk. Now being only one man with an eleven-year-old kid, Dad made an executive decision that they would call in “sick” to work and school the next day to bring the horses up and pack the elk out. It took the majority of the following day to retrieve his bull with some sketchy mountain goat maneuvering the horses had no choice but to accomplish.

It was finally the last weekend of elk season and what I knew was going to be my last chance at cutting my first elk tag. My dad called in two buddies for backup and we took off up the same lucky mountain face where Levi got his bull. After hiking for what seemed an eternity we were faced with a dilemma when two bulls in opposite directions started answering. Splitting up was the only logical solution. Dad and I to the right while the other two

went left. We ended up getting winded before I could get a shot on a bull at thirty yards while the others had complete success. A bull was down!

We prepped the elk and packed a load off the mountain but again decided to return the following day with the horses to get what remained. This terrain was steeper than a cows face, and unfortunately, we couldn’t ride the horses straight up so instead would have to ride close to 20 kilometres up and around. We started riding with a few hours until daylight as this was going to be my last hurrah and I was determined. Our group of four eventually came to a junction point where we were to split up as they were going to get the rest of Justin’s bull and we were going to hopefully find one for me.

We didn’t have to ride far into the frozen forest before Dad’s bugles were answered with a bull coming in hot. It was a mad dash tying the horses up and getting myself as ready as I could for what might happen. The sounds of his hooves on the hollow ground echoed as he tried to find the elk, we were immaculately imitating. He came running up to just under thirty yards before turning his head just enough to get a count, as my dad whispered “he’s a six” under his breath I was already bringing the old .270 win up to the shoulder and the scope to my sight. One shot and a few feet later my first bull elk crashed into the earth. It’s a hard feeling to describe as you watch an animal as majestic as an elk take their last breaths, but it also brings a sense of responsibility and respect. We packed every usable portion of the elk onto our two riding horses and started our long hike back to the truck where we would meet up with the others.

Levi 2010

By 2013 Levi and I had a few bulls under our belts and this year it was our younger siblings Trulie (twelve) and Rocky’s (ten) turn. Rocky hunted hard, but the stars just never aligned for him to connect on a bull his first year out. On October 12, Tru alongside our dad, Rocky, and cousin Parley set off on her very first elk hunt. Before sunrise, they were saddling the horses and making sure everything was ready to hit the trail. It didn’t take long before they had their first elk encounter when a young rag horn bull trotted into 10 yards of them and the horses. He turned out to be more of a nuisance as he wouldn’t leave them alone. Later in the morning after shaking their tag along, a different bull started answering to the bugles. Everything fell into place when the six came in just under 100 yards and Tru dropped him. All her practice and patience were rewarded at that exact moment with the thrill and adrenaline of her first bull. The next year, 2014 was definitely going to be Rocky’s year. He was another year older, wiser and slightly bigger than a now eleven-year-old. Rocky and our cousin Texas are the same age and joined at the hip. Dad, his brother Chrome, Rocky and Tex were hunting an area we call the ‘hell hole’, they’d been up there all day with no bugles. It wasn’t until right before dark they finally got something talking way down the ridge. Dad, Rock and Tex ran down and sat above the bull waiting for him to come out, but the only thing they laid eyes on were cows. They kept chasing but eventually, the darkness hit and they were forced to ride away leaving the bull screaming.

Morning couldn’t come fast enough. First light saw them back up the mountain and right away he answered. Still on the horses they rode towards the bull closing the gap. They popped over a ridge and there he was. In the chaotic scramble to get off the horses, Dad let out a cow call stopping the bull just long enough for Rock to get his shot. He ran up, shot one more time to finish him off and lay his first bull to rest. Rocky assures us that moment of triumph was nothing short of amazing especially after the tough season he had the previous year.

2014 was also the year our family started guiding and getting to share these kinds of adventures. Dad and Chrome were able to take over and start guiding the area we were already hunting and spending all of our summers. The territory hadn’t been run in quite some time and took a lot of work to get it “client-ready”. We spent the next few years developing and establishing a name for ourselves as Saddle Axe Outfitters and as the guiding picked up, the family hunting slowed down. We made it our mission to maintain our remarkable elk population and chose to keep the number of clients we took each year low.

My younger sister Mel was 12 years old and had been hunting for two years with no luck. September 1, 2017 Mel, Rocky, Levi and Dad headed for a day trip to start off the season. Riding into the new found honey hole on the first day of the season and the excitement was unbeatable. When the sun rose so did the elk, Dad let out the first bugle of the day and it was met with two different bulls answering. As soon as we heard the bugles, we tied up the horses as fast as they could, Levi and Dad took off after the first bull. Levi lined up on a nice 6x6 bull, but unfortunately missed. Right after Dad grabbed the crossbow, handed it to Mel and they ran down the trail a few yards to get her all set up where he thought the other bull would come out. It wasn’t long before he came into sight and Dad was able to get a count. Once she got the go-ahead Mel placed the bull in the crosshairs and made the shot. The bull took off running but crashed about 100 yards away. Mel says the excitement was like nothing she’s ever experienced. In archery season you can shoot any bull but she just so happened to harvest a beautiful 6x7. Hunting has always been a way of life for our family and she was so happy to a part of it.

Thanksgiving weekend of 2018 and it was elevenyear-old Libby’s turn. As the youngest of the crew, she had been itching to finally join the club. The anticipation was almost unbearable as she knew this weekend hunting trip could be the one. Libby, Mel, Chrome, Tex and Dad all made their way into camp and were planning to spend the entire weekend. Once

Trulie 2013