10450 - 174 Street

Edmonton, Alberta T5S 2G9

Ph: 780.413.0331 Fax 780.413.0388

Email: info@sportscene.ca www.sportscene.ca

Fall 2025 Issue

Editor in Chief Kyle Stelter (CEO)

Editors

Peter Gutsche

Nolan Osborne Bill Pastorek

Contributors

Larisa Murdoch

Helen Schwantje, DVM

Design & Layout

Sportscene Publications Inc.

Printing Elite Lithographers Co. Ltd.

Editorial Submissions

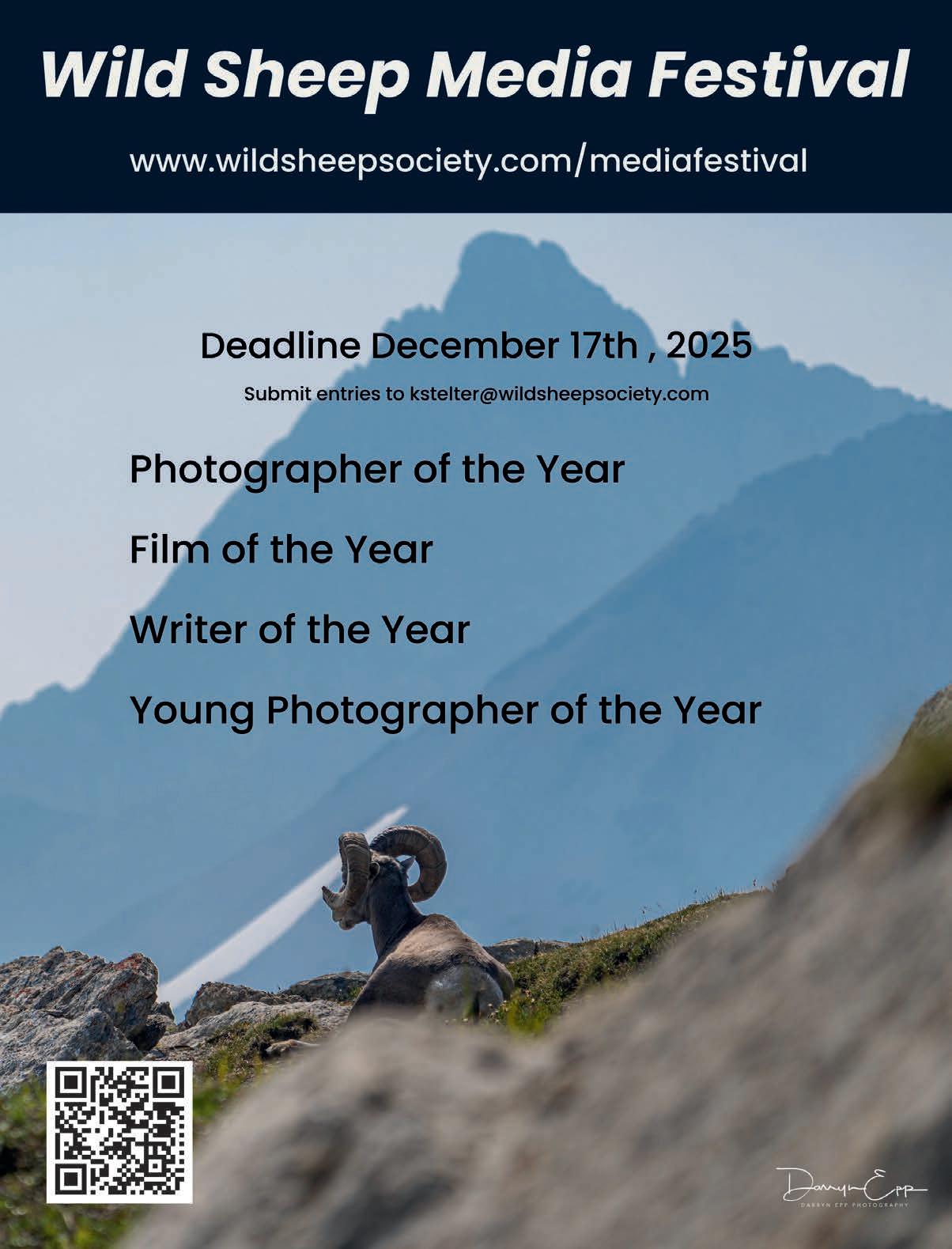

Please submit articles and photos to kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

No portion of Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine may be copied or reproduced without the prior written consent of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia. The views and opinions expressed by the authors of the articles in Wild Sheep Society of BC Magazine are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia. PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 43363024

Sheep Society of British Columbia #101 - 30799 Simpson Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 6X4 www.wildsheepsociety.com

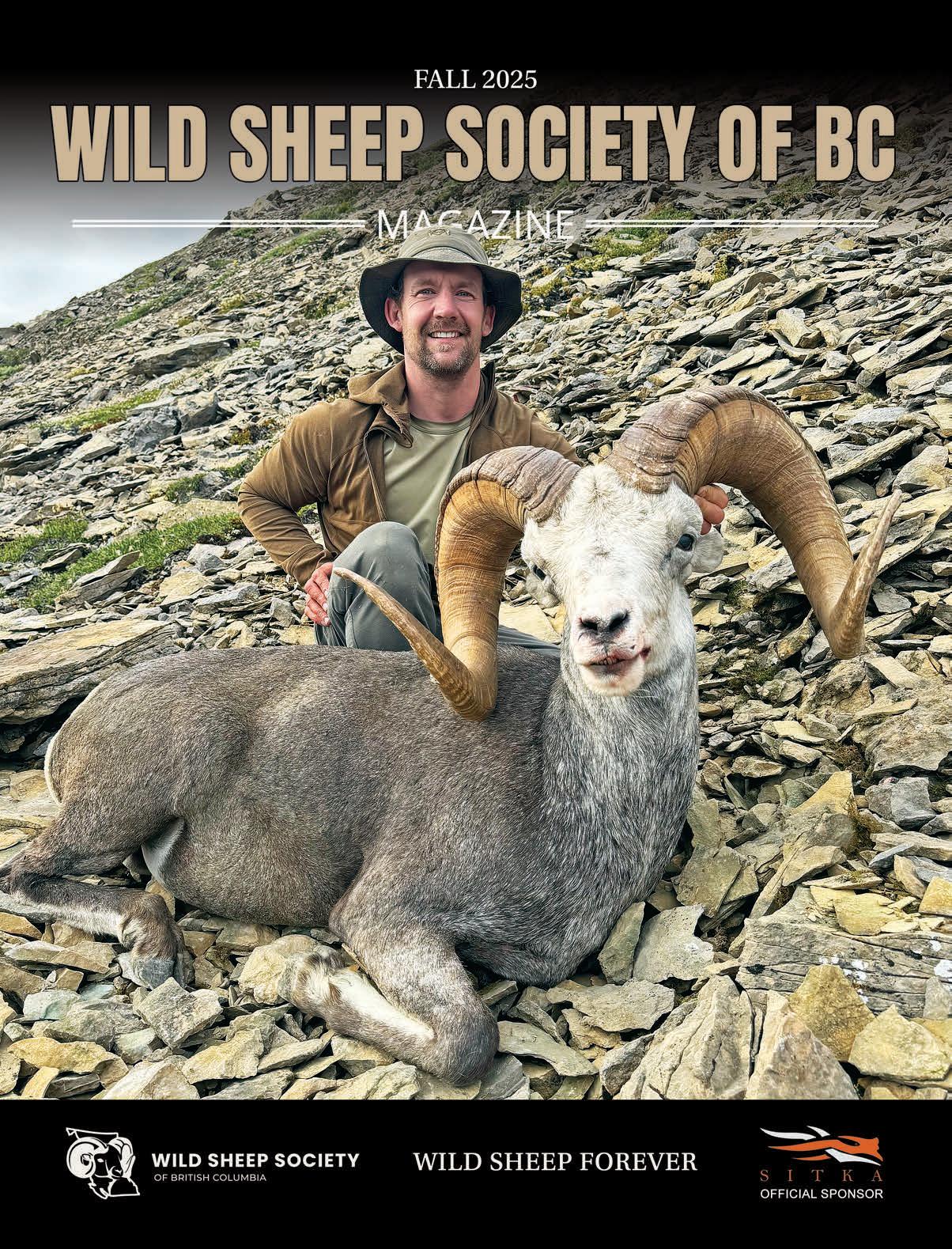

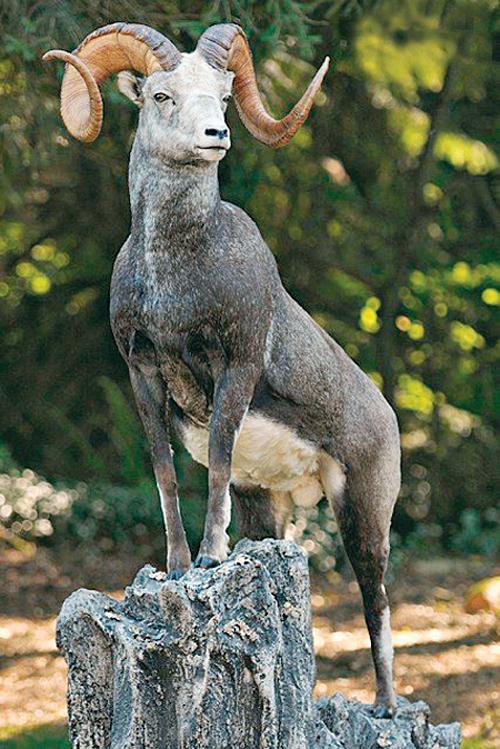

Cover photo by Waylon Vipond

Chief Executive Officer – Kyle Stelter 250-619-8415 ● kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

President – Greg Rensmaag 604-209-4543 ● rensmaag_Greg@hotmail.com

Vice-President – Chris Barker 250-883-3112 ● barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

Joe Eppele

647-986-3859

joe.eppele@gmail.com

Peter Gutsche 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Ken Jyrkkanen

250-319-7759

Email: kjyrkkanen@gmail.com

Vice-President – Mike Southin 604-240-7337 ● msouthin@telus.net

Secretary – Colin Peters 604-833-5802 ● colin.peters12@gmail.com

Treasurer – Joe Humphries 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Justin Kallusky 236-331-6765 kallusky@hotmail.com

Benjamin Matthew MD 778-558-0996 ben.matthew@ubc.ca

Matt McCabe 250-320-6048 mattmccabe.wssbc@gmail.com

James Mitton 778-808-9001 jamesmitton15@gmail.com

Greg Nalleweg 778-220-3194 greg@nextgenelectrical.ca

Colin Peters 604-833-5802 colin.peters12@gmail.com

Communications Committee

Chair: Kyle Stelter ● 250-619-8415 kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

Fundraising Committee

Chair: Korey Green ● 250-793-2037 kgreen@wildsheepsociety.com

Government Engagement Committee

Chair: Greg Rensmaag ● 604-209-4543 rensmaag_greg@hotmail.com

Hunter Heritage Committee

Chair: Jann Demaske ● 970-539-8742 demaskes@msn.com

Indigenous Relations Committee

Chair: Peter Gutsche ● 250-328-5224 petergutsche@gmail.com

Membership Committee

Chair: Matt McCabe ● 250-320-6048 mattmccabe.wssbc@gmail.com

Projects Committee

Chair: Chris Barker ● 250-883-3112 barkerwildsheep@gmail.com

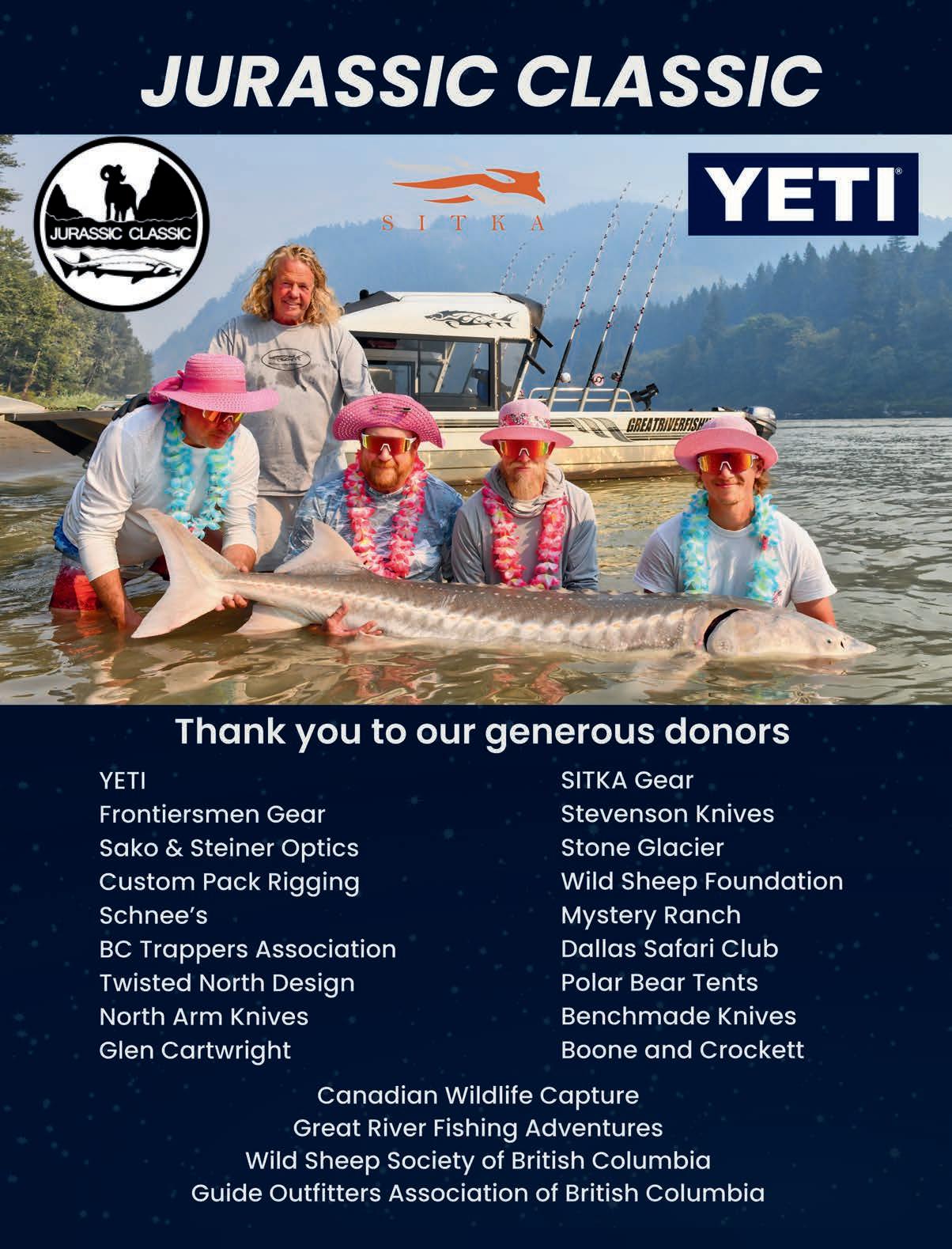

Jurassic Classic

Kyle Stelter ● 250 619-8415 ● kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com

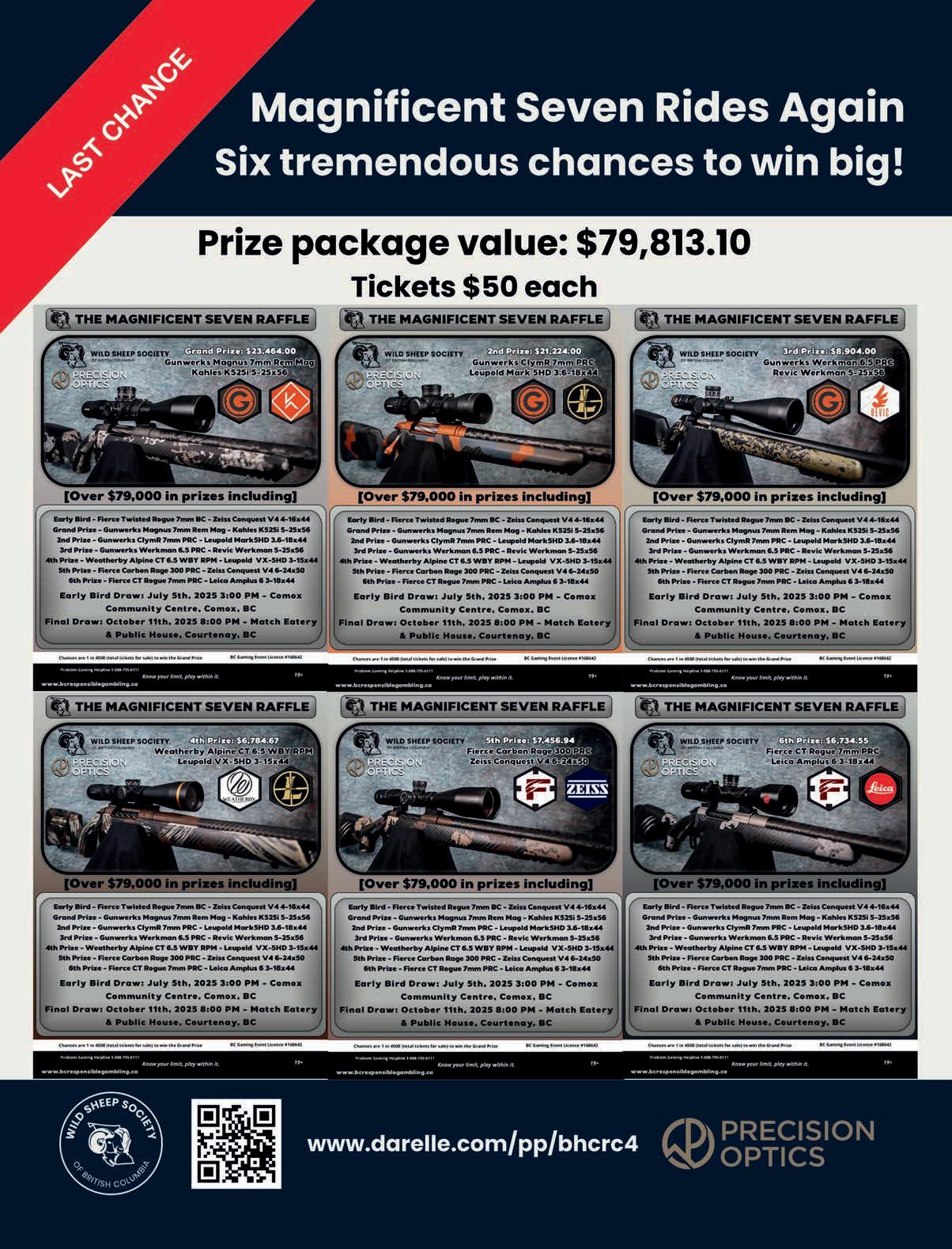

Raffles

Joe Humphries ● 250-230-5313 ● joseph_humphries@hotmail.com

Women Shaping Conservation

Rebecca Peters ● 778-886-3097 ● rebeccaanne75@gmail.com

Bookkeeper

Kelly Cioffi ● 778-908-3634 kelly@dkccompany.com

Executive Assistant

Hana Erikson ● 604-690-9555 exec@wildsheepsociety.com

Hunting Expo Coordinator

Kris Wrathall ● 604-340-4903 ovisslam@outlook.com

Projects Administrator

Nicole Barker ● 250-361-5734 projects@wildsheepsociety.com

Danny Coyne Darryn Epp Trevor Carruthers

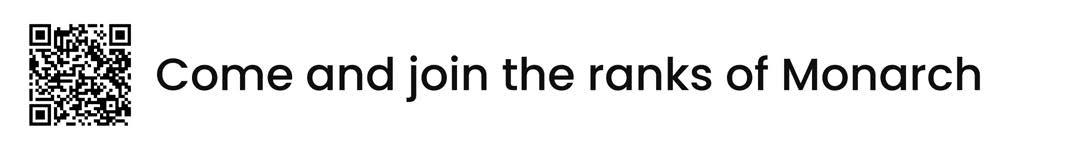

very time I sit down to write this message, I’m reminded of just how powerful this community is. The last few months have been filled with milestones and wins for wild sheep, and none of them would have happened without the passion and commitment of our members, volunteers, sponsors, and donors.

This summer took us to Florida for the Chapter & Affiliates Summit XVII, hosted by the new South East Chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation. It was a privilege to join conservation leaders from across the continent and to be part of raising more than $200,000 USD for the Coming Home Project. This initiative will help restore California Bighorns from Oregon back to BC, and it was incredible to see WSSBC at the table driving such meaningful conservation and contributing $50,000 towards the project. Back at home, our own events kept the momentum rolling. The 3rd Annual Mountain Monarch Golf Tournament in Kamloops brought members together for a day of fun, fundraising, and friendship. Across the province, our Horn Aging and Field Judging Rams seminars were delivered in every region, and the response from members was inspiring. Watching hunters of all ages lean in, ask questions, and commit themselves to responsible practices gave me hope for the future of sheep hunting in BC.

Our Women Shaping Conservation program continues to break new ground. This year’s Elevate hiking trip brought together women from all walks of life, many of them members, who left with not just stronger connections to each other, but to conservation as a whole.

On the conservation front, our projects are showing real progress. The Fraser River Project continued and the follow up sheep counts, sponsored by APE Equipment, revealed strong lamb recruitment this year, giving us optimism for the future of these herds. The Psoroptes Drug Trial Project also continues to move forward, and thanks to the support of MP Blaine Calkins and the hard work of so many dedicated people, treatments should already be underway by the time this magazine reaches you.

And then, of course, there was the 9th Annual Jurassic Classic in Chilliwack. With 162 sturgeon landed and memories made for a lifetime, it was another event to remember. The team from Alaska took home the grand prize, but the real winners were wild sheep across the province. This event exists because of you, our volunteers, our donors, our participants, and our signature sponsor YETI. I want to give a special thank you to Denis Cabana and Nolan Wannop for their hard work, along with numerous volunteers, to deliver an incredible feast on the banks of the Fraser River.

We also had the honour of being a Platinum Sponsor for the Wildlife Disease Association Conference in Victoria, where important conversations on wildlife health took place. It was a proud moment to see WSSBC represented so strongly on an international stage.

A Word About Our Members

If there’s one thing that makes me most proud, it’s you, our membership. You are the backbone of this organization. More than half of our members are life members, a staggering number that speaks to the long-term passion and dedication within this community.

At our Horn Aging seminars, I spoke with young hunters eager to get it right from day one, and seasoned sheep veterans who still wanted to sharpen their skills. At Elevate, we saw women stepping into leadership in conservation and bringing new energy into the fold. At Jurassic Classic, I watched volunteers work tirelessly behind the scenes, some of them giving up their entire weekend just to make sure others had an unforgettable experience, all because they care about wild sheep.

These moments show what makes WSSBC truly special. Our members don’t just pay dues; they show up. They bring their families. They invest their time, their energy, and their hearts. And because of that, we are moving the needle for wild sheep in BC in ways that simply wouldn’t be possible otherwise.

So, to every one of you, whether you’ve just joined, renewed your annual membership, or committed for life, thank you. You are conservation in action, and I am deeply grateful for your trust and support.

The past few months have been wildly successful, but I believe the best is still ahead of us. With your continued involvement, we’ll keep writing the story of wild sheep conservation in British Columbia, together.

See you on the mountain, Greg Rensmaag President, Wild Sheep Society of BC

have always had a deep appreciation for the outdoors and enjoy spending as much time in nature as I can. I grew up in Saskatchewan in a family that always prioritized outdoor activities and spending time out on the land. I developed a deep connection to the land and wildlife through various outdoor activities, including hunting, fishing, farming, snowmobiling, and quadding. From a young age, I loved animals and dreamed of working with them one day. At the time, I thought the only way to do that was by becoming a veterinarian or working in agriculture with livestock, even though I was always most interested in wild animals. It is not widely advertised how you can get a career working with wildlife. When a friend told me about how you can take Wildlife Biology courses at the University, it was like I finally had some direction in a career that interested me. I ended up with a Bachelor of Science, majoring in Environmental Biology.

My first wildlife job was with tree swallows, where I helped gather longterm monitoring data on the impacts of neonicotinoid seed coatings on aerial insectivores. Over this time, I expanded my research experience by working on projects with snakes, skinks, mallard ducks and sanderlings. While I found this work valuable and engaging, my passion has always been with large mammals. When I learned about efforts in the prairies to address invasive feral pigs, I joined the project as a feral pig research technician. The feral pig work has focused on documenting the spread of feral pigs and wild boar in Canada since the 1990s, mapping their current range and distribution, and supporting eradication efforts. While working on the feral pig project, I realized I wasn’t finished with school and wanted to pursue a master’s degree. I reached out to a biologist in Nelson, BC, to inquire about potential opportunities, and he offered me an auxiliary biologist position supporting

grizzly bear research, along with a master’s project at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna, where I would continue studying grizzly bears. After completing my master’s, I joined the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA) Natural Resource team in Kelowna, BC, as a tmixʷ (Wildlife) Biologist. Over time, I grew into my current role as the tmixʷ (Wildlife) Program Lead, where I help facilitate and support wildlife stewardship across Syilx Territory. I was drawn to working with ONA because I wanted to be in a role where my passion for applied landscape and wildlife ecology could directly inform conservation on the ground. For me, it has always been important that my work not only advances science but also creates meaningful management outcomes for wildlife and communities, while building lasting relationships. In this role, I have been able to focus on building stronger, collaborative approaches to wildlife management. I believe deeply in the importance of working closely with Indigenous Nations, internal partners, and external stakeholders to ensure that conservation efforts are both respectful and effective. My time at ONA also introduced me to wild sheep conservation, an area that has since become a significant focus of my work. The wild sheep community is one of the most passionate and dedicated groups I have ever encountered, with a strong collective commitment to conservation and restoration initiatives. Being part of this community has reinforced for me how much more we can accomplish when we bring people together around a shared goal. I look forward to working alongside the Nation and partners to achieve meaningful outcomes for wildlife conservation, especially in advancing the recovery of wild sheep.

2025 Wild Sheep

August 22-25, 2025 – Chilliwack, British Columbia

he 9th Annual Wild Sheep Jurassic Classic once again brought conservationists, anglers, and supporters together for a weekend of fishing, friendship, and fundraising on the Fraser River. This unique event pairs the pursuit of an iconic fish—the white sturgeon—with support for an equally iconic mountain species: the wild sheep of British Columbia.

This year’s event welcomed 56 participants from across Canada and the United States, all gathering in the spirit of camaraderie, conservation, and connection. Thanks to the world-class outfitting service of Great River Fishing Adventures, anglers landed more than 160 sturgeon throughout the weekend.

While the Classic is about more than competition, the tournament always brings excitement.

A 9-foot-2-inch giant earned Team Wild Sheep Foundation of Alaska (Molly McCarthy-Cunfer, Scott Cunfer, Frank & Nancy McCarthy) top honours. An incredible five fish measured over nine feet.

Prize sponsors: YETI & Stone Glacier (YETI gear + Stone Glacier Terminus 8700 packs).

Wild Sheep Jurassic Classic participants, guides and volunteers

Team Guide Outfitters Association of BC (Kevin Church, Roger Gysel, Tyler Camille, James Lulua Jr.) tallied an impressive 89 feet, 11 inches of sturgeon.

Prize sponsor: SITKA Gear (full SITKA Dewpoint rain systems).

A tie between Liberty Buus (SCI Manitoba Chapter) and Dan Agte, each landing a feisty 1-foot-7-inch sturgeon.

Team Canadian Wildlife Capture (Ben Berukoff, Jordan Smaldon, Chris Procter, Brad Siemens) won the Mystery Length prize.

Prize sponsor: Schnee (Granite 200g boots).

This year’s Signature Sponsor was YETI, joined by major partners SITKA Gear, Stone Glacier, Sako Rifles, and Steiner Scopes. Their generosity helped deliver a $15,000 prize package and a memorable experience for all participants.

A special highlight was Sako Canada’s donation of a Sako 90 Adventurer in 6.5 Creedmoor topped with a Steiner scope to support the Fraser River Test and Remove Legacy Project.

As always, our volunteers were the backbone of the event, ensuring seamless organization and hosting the legendary Fraser River barbeque—complete with smoked sturgeon, sockeye salmon, and even sturgeon ceviche.

The 2026 Jurassic Classic (August 21–23) is already sold out to the public. The only way to attend is by purchasing team entries through wild sheep chapters, affiliates, and conservation partners who auction off spots to raise funds for their own initiatives. With its perfect mix of fishing, fundraising, and community, the Jurassic Classic continues to live up to its title: “BC’s Full Curl Fishing Experience.”

by Logan Calvert

n February 20th, my 2025 hunting season started with some exciting news. I was drawn for a Dall sheep LEH tag in Northwest British Columbia. This would be our fourth trip north to chase sheep. I knew getting educated on the sheep in the area would be beneficial, so I reached out to the biologists in the Skeena region and they were happy to help out with recent info on sheep in the area. The WSSBC count at Spences Bridge was the first chance of the year we got to glass sheep. This would be one of the most educational weekends in the time I have had, in regard to sheep hunting. My wife Illiana and I met and got to spend time glassing with a long-time sheep hunter. The knowledge he shared about the mountains was an inspiration for the hunt ahead. We kept in contact texting different plans for our hunt and different areas that might be worth looking at.

July 19th, I left my home on Vancouver Island and after a quick 2500 km drive, I was in Whitehorse. I spent the next few days exploring the area. I picked Illiana up at Whitehorse airport on July 25th. We wanted to get our eyes on some Dall sheep before the hunt, so we headed to Sheep Mountain in Kluane National Park. What an amazing hike and area to glass sheep.

July 29th had us sitting at the Alpine Aviation float plane base. After getting everything loaded, we were off to our destination some 40 minutes away. After a quiet ride in and a smooth landing we had a quick chat with the pilot. He suggested that we take a look at the draws on the backside of the mountain before moving to some of the bigger drainages to the north. “Don’t spook the rams” was the last he said before taking off down the lake. After a few hours of hiking, we found a good spot to drop

our bags and glass for the afternoon. Before I could get my binoculars up, I was staring at three white dots on the skyline. As my binoculars came into focus, I could tell immediately that I was looking at three rams. We slowly got our packs back on and moved back a few hundred yards out of site of the rams. I kept an eye on the rams as we moved, and they were unaware of our presence. As we set up our camp near the end of the small lake, a group of five ewes and two lambs fed down, close to our camp. The lambs and ewes fed off and I was able to get my spotter on the rams. The band of three turned into six with three rams that looked to be mature.

July 30th, we started our day in the mountains as we have many days before; coffee and a freeze-dried breakfast. I loaded my pack for the day as we set out to find the rams from the day before. We were about five minutes from camp when I spotted the rams a bit lower down on the mountain feeding. As I set

up my spotter, the group of lambs and ewes from the day before fed down close to us. As I focused my spotter on the rams, Illiana said, “that’s a bear.” I turned to look at what she was looking at and all I could see on the hillside was a large rock that I thought she was referring to. When she said again “that’s a fkn bear,” I looked to see a large grizzly charge down the hill towards the lambs and ewes. They ran directly towards our camp with the grizzly in pursuit. One ewe bravely ran at the bear and diverted his attention towards her as the others climbed up and out of sight. The ewe and bear cleared a rise and were out of sight as they had run directly into our camp. I explained quickly to Illiana that we needed to move in and verify the bear wasn’t destroying our camp. The next time I saw the bear he was running full speed away from us up and over the skyline a few kilometres away. Illiana turned and said, “we need to move our camp,” so we packed up and moved around to the north side of the mountain that we saw the rams on.

After finding a large snowpack with water, we set up camp. I decided I wanted to set up our small tarp with our trekking poles before unpacking bags to keep as much of our gear out of sight. After getting our tent set up and boiling some water for dinner, I looked up above camp and the six rams from the other side were bedded 850 yards from camp. we both got under our tarp and out of sight of the rams. Over the next few hours, I was able to get a really good look. three of the rams were full curl with two of them looking like they had more annuli stacked in. I filled my phone with photos and video. As the sun faded, the rams got up and fed around the corner not spooked but just going for a feed.

July 31st, I woke up and decided it didn’t make sense to do a bunch of moving around the day before the opener. We spent the day glassing from camp and reviewing video of the rams. After working through the videos, I was feeling pretty good about what I was seeing. Number 3

ram appeared to be full curl and seven years old, number 2 ram was full curl and I was getting a count of eight, and number 1 lead ram was a beautiful full curl ram that I was getting a count of nine annuli. The information we learned at the WSSBC horn aging event in Comox and online seminar was crucial in feeling like we were making the right decision based on what we were seeing.

We hadn’t seen the rams all day, so I decided to go for a short walk and check a large drainage we hadn’t seen yet. After turning up a mountain goat I decided to head back to camp. At this time, I saw someone I didn’t recognize walking toward me—turned out to be a local guide who had a bow hunting client. After a few minutes, we discussed each other’s hunting plans and exchanged numbers to keep each other updated. They were going to get

after some rams they had seen on the far end of the range. I went to bed nervous and excited for what was to come.

August 1st, The alarm clock woke us at 4 am and I got up and scanned the hills. The wind was blowing clouds in and out of the peaks we were hoping to hunt. After a quick coffee and making a few last-minute adjustments to our packs, we set off up a long finger ridge that was above camp.

Over the next few hours, we climbed slowly staying off the skyline constantly scanning for sheep. We followed a small trail that took us up into the loose steep rock. As we got to the peak, the wind, fog and rain really kicked in. We found a small flat spot on the peak in between two rock pinnacles, pulled out our light-weight tarp, and made a dome over ourselves. After about an hour, I lifted the tarp to see we were in the middle of a cloud. We moved back down the sheep trail

through the fog to where we could see. I was able to make out the bodies of the six rams bedded on a plateau about 800 yards away. I watched as the rams got up and started to move in the direction we had seen them the first day. We decided if we moved up into the fog and along the ridge, we could be in a position when they fed out below. So back up the steep loose rock we went, along the ridge, down and around an outcropping and back to the ridge just off the skyline.

As the fog cleared, I saw movement in the bottom of the drainage. The rams had gone the opposite direction, not spooked just moving slowly down. I told Illiana we needed to go all the way down, back off the mountain we just climbed to get down to the rams. So back up the ridge and down the sheep trail, back down and off the mountain keeping tabs on the rams as we went.

As we rounded the corner I was scanning with my binoculars where we had last seen the rams—nothing. I took another few steps and looked a little to the right—rams! We dropped our packs and I got my rifle set upon a nice grass flat. I ranged the rams at 500 yards they were all headed down feeding. I got my spotter set up and took a look at who was who. With a slight turn of his head I was able to tell I was looking at the lead full curl ram. As he stepped clear of the other rams I got settled into my rifle and went through my process. When the echo’s left the valley the ram was

laying where he last fed. The craziest feeling of adrenaline and anxiety came over me and I needed to confirm what I had been seeing through the spotter. As we approached the ram, his horns kept growing and as I put my hands on him, what I was seeing was confirmed—nine true annuli—a beautiful full curl Dall. He was perfect in every way; my dream first ram. We sat and enjoyed the moment with the ram, each other and the mountains. After gathering our thoughts and getting some photos we got to work processing. A few hours later, I had removed every piece of meat and Illiana had deboned the 4 quarters. We loaded all our gear into Illiana’s backpack and loaded all the meat and horns into my pack. As I got to my feet with the weight of the ram on my back, I felt the most overwhelming sense of accomplishment for Illiana and I.

Once back at camp I kicked a trench

into the snowpack and lined it with a garbage bag that we put the game bags in, and our meat was cool. At this point the gravity of the day we had was setting in. We climbed into are sleeping bags with a bagel and an electrolyte drink and called it a day.

August 2nd, I woke up in the morning and looked to see his golden set of horns lit up by the morning sun. We got up and enjoyed the bluebird morning with the ram. We organized our gear from the day before and checked on our meat, which was doing great on ice. After a few inreach messages, we had a float plane coming to pick us up later that afternoon.

A few hours later we had packed our camp and the ram down to the small lake. The unforgettable sound of the float plane filled the valley. As we flew out of the mountains I couldn’t help but think of all the steps to this adventure and all the people who helped along the way—thank you.

by Waylon Vipond

e first saw Houdini the day before opener; a stone ram so massive his horns looked like they were the size of car tires. In nearly two decades of sheep hunting together, Chase and I had never seen anything like him.

July 27th, the day after my oldest daughter’s birthday, we headed north with the truck bed loaded and our minds set on the 2025 stone sheep season. The drive was a familiar ritual—coffee too hot to drink, talk of old hunts, and the silent hope that this year would bring something special.

By August 30th we’d reached our camp spot; a high knob tucked into the timber with a commanding view of the hills. From here, we could watch miles of country without giving away our position. That first night, we

glassed hard, turning up only one young three- or fouryear-old ram. Still, we went to bed with high hopes for our own version of Christmas Eve—sheep opener.

Morning broke, and we glassed every inch of our range—nothing. Early afternoon, a lone figure appeared on the skyline, walking openly for an incredible distance. Chase and I stared at each other, “What the flip is he doing?”

Minutes after the stranger dropped off the ridge, three rams appeared, moving out but not in full panic. Among them was the biggest ram we’d ever laid eyes on—thick horns sweeping low and deep. Our target—Houdini.

The stranger had unknowingly pushed him, but we marked the direction and prayed he wouldn’t leave the country. That night, I lay awake replaying every second, picturing those massive horns over and over.

We were up at 4 am on opening day. The sheep weren’t in their previous spot, so we decided to keep glassing until 10 am, then move during the quiet part of the day.

By early afternoon, the land paid us back. At two miles out, I spotted two ewes, a lamb, two young rams, and Houdini himself. We set up to watch. When he finally bedded, it looked like he was there for the long haul. Time to move.

The stalk would be brutal—down the mountain, through a tangle of buckbrush and prickly undergrowth, then clawing up the far side into position. Four hours of sweat, bruises, and constant wind-checking. Every step could undo everything.

The last ridge was the worst; steep, loose, and silent as a church. I crept around the mountain’s shoulder, knowing

one wrong move would send him vanishing for good. At 110 yards, I glassed him again. Eight years old— legal and then some. My heart pounded in my ears. Breath steady. Crosshairs settled.

The shot broke clean.

When I walked up, Houdini somehow looked bigger than through the glass. No ground shrinkage here, he had grown in my mind and grown again in my hands. The weight of the hunt hit me all at once, and I let the emotion go.

Chase and I hugged like brothers. Two decades of sheep hunting together, and we both knew this was the hardest, most satisfying one yet.

Houdini had lived up to his name right until the end, but this time, the escape artist didn’t get away.

A Women’s Backcountry Hiking Experience

by Hana Erikson

his summer, 11 women from all corners of the province, of all ages and abilities, and with varying degrees of experience came together in the South Chilcotin Mountains for an epic weekend of camaraderie and conservation. What brought them together? A brand-new event hosted by Women Shaping Conservation; Elevate. Elevate came to fruition out of a deep desire to offer a positive and educational experience for women, in the backcountry. To immerse them in the majesty of the mountainous terrain our treasured Bighorn Sheep call home,

to educate those who do not know, on the importance of protecting and preserving these places and the wildlife that call it home, and to ignite a fire and passion within them for everything it means to be a conservationist. What took place was even more profound than event leaders, Hana Erikson and Rebecca Peters, could ever imagine. Elevate was a transformation of lives!

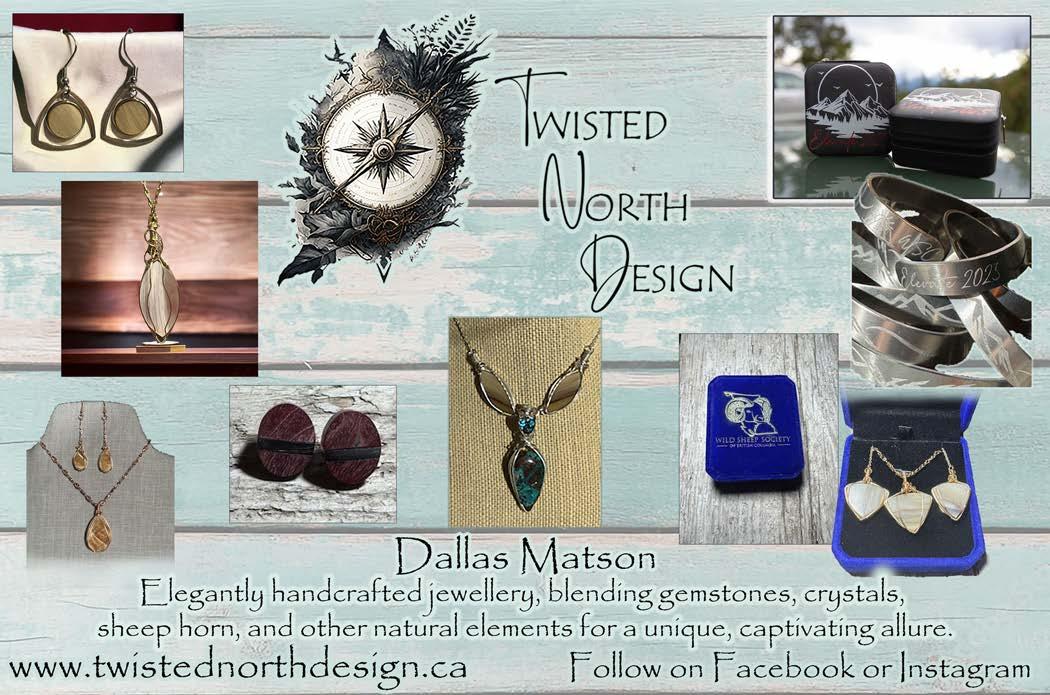

The eager hikers came together, the first evening, at a base camp that could be reached by vehicle where they received unexpected welcome gifts provided by YETI, 1 Campfire, WSSBC, WSC, and the most unexpected gift of

all; a custom jewelry and keychain set for each woman provided by Dallas and Jennifer Matson of Twisted North Design. Lainey Daudelin of Brunoso Photography announced that she was donating her time and skills to the weekend, capturing golden moments. There were few dry eyes at the campsite that evening, be it from tears of gratitude at the incredible generosity of our donors, or tears from laughing so hard that faces were sore as stories were shared around the campfire.

The following morning, Rebecca provided a hearty breakfast for everyone, and the group headed to the trail head, eagerly anticipating the climb to come. The next several hours tested the women’s physical and mental stamina, but not without breaks for snacks and more laughs! Upon emerging from the treed valley, the group was met with the beauty and splendor of the alpine that sheep hunters know all too well, but that many of these women had only seen just now for the first time! A happy babbling stream fed by glacial melt trickled past camp and wildflowers dotted the surrounding landscape. For many, this would be their first time camping in such country. What a thing to be able to share with each other! That evening and the following morning were spent sharing stories, enjoying meals, discussing life and all things conservation minded, and exploring the area. A mountain goat was spotted by one of the ladies and everyone spent time discerning whether it was a billy or a lone nanny. Pictures were taken in abundance of the overwhelming beauty of the landscape and of each other. Each woman seemed in her element, soaking in her surroundings and there was a general sense of peace and wonder amongst the group.

The climb back down to the vehicles was another test of endurance, but there was an obvious change in the women; a sense of strength and self- assurance. They had just climbed up the day before and, with new-found confidence, the descent seemed like child’s play. And it was! The women laughed and talked the whole way, their paces quickened and upon reaching the trailhead, each one felt a sense of pride and accomplishment... and a little remorse that the trip was only one night instead of two.

Each woman came away from this experience with an added level of understanding about the conservation work WSSBC does and were very excited to know that all proceeds from the event were designated to the Adopt a Sheep program to support the treatment and, hopefully, the elimination of Psoroptic Mange in Okanagan Bighorn Sheep herds. Some women even made further donations to the cause, showing that Women Shaping Conservation is on track to become an important female-based contributor to wild sheep conservation!

Hana and Rebecca received the most incredible testimonials from the ladies that attended this event—life altering testimonials! Keia Holm’s testimonial summarizes perfectly what these women felt and shared after the experience. It is our pleasure to share it with you:

Elevating Strength: My Journey on the Women Shaping Conservation Hike

This summer, I had the incredible opportunity to participate in the Women Shaping Conservation Elevate Hike, a backcountry journey along the Taylor Creek Trail in British Columbia’s awe-inspiring South Chilcotin Mountain Range. What I thought would be a challenging

but straightforward outdoor experience turned out to be something much deeper—a transformative, soul-shaping journey that has changed me in more ways than I can count.

The terrain was rugged, raw, and beautiful—just like the women I hiked alongside. Each of us brought our own story, our own reason for being there, and our own quiet (or not-so-quiet) strength. From the moment our boots hit the trail, I felt a sense of connection—not only to the land, but to this community of women who were all walking toward something more. We weren’t just navigating mountain switchbacks and alpine passes; we were each pushing through personal boundaries, doubts, and limitations.

The hike was physically demanding, but it was also emotionally grounding. There’s something about being so immersed in nature, disconnected from everything but your surroundings and your own body, that brings a kind of clarity. As I climbed, I found myself growing more confident, more grounded, and more capable with every step. I discovered that I am far stronger than I often give myself credit for.

One of the most profound realizations I had on that trail is just how much this experience has prepared me for what lies ahead—specifically, my upcoming sheep hunt with my husband. It’ll be my first time taking on a hunt of this scale, and I won’t lie—I’ve been both excited and intimidated. But after the Elevate Hike, I no longer feel unprepared. This journey gave me more than physical stamina; it built my mental resilience, sharpened my focus, and taught me that discomfort is a place where real growth happens. I now feel

ready to meet that next challenge head-on—with strength, confidence, and the belief that I belong out there. And while the landscape was unforgettable, the women I shared it with were the most inspiring part of all. Every single one of them had a fire within her. Whether it was wisdom, courage, humor, quiet leadership, or raw determination, each woman brought something invaluable to the group. We cheered each other on, we shared stories, and we leaned on one another when the trail got steep. We didn’t just hike together—we elevated each other.

This experience reminded me that the outdoors is not just a place of escape or recreation—it’s a space for transformation. It’s where we go to remember who we are, and to become who we’re meant to be. The Women Shaping Conservation Elevate Hike wasn’t just a trail—it was a launching point. I left the mountains with a deeper understanding of myself and an unwavering belief that I can do hard things.

I will carry the lessons from this hike with me into every step of my sheep hunt and beyond. I know now that whatever I set my mind to, I can achieve. And I will forever be grateful for the trail, the mountains, and the extraordinary women who helped me see that.

– Keia Holm

Ladies of Elevate, we were honoured to have you. Here’s to this year’s incredible hike! Here’s to Elevate 2026! And here’s to you!

Keia and Brandy

by Jennifer Matson

saw the request for stories from youth members that explained what the outdoors meant to us. That’s such a tough question but I was able to put some of it in writing. I sent it in, then found out that my essay had been selected as the winner and I was fortunate enough to get to go to the Wild Sheep Foundation of Alberta’s youth camp in Hinton Alberta! I was really excited!

On the first day, we met at the gun range in Hinton, checked in and then were introduced to Beth Mcallum, the biologist that works with Cadomin Mine on the reclamation of the mine. She went over a number of things before we got on the bus. Her passion for the animals and the project was infectious. After that we loaded up and started on our way to the mine. I feel so lucky to go to the mine, and on a tour there, as this is a place that not many people get to experience like this—my Papa has always wanted to go.

After checking in with the mine staff and getting our escort for the day we headed into some of the reclamation sites. The first one we visited was new Leskar Lake—that portion of the mine was named after the lake. At our first stop we listened to Beth explain the degrees of incline the pit walls needed to be to be accurate for the animals that lived there. We also got to watch some young marmots playing.

We went up the hill to a different portion of the mine that is fully reclaimed to see what the end of the process looks like—it was beautiful. We stopped for a break here, glassed

to see bighorn sheep on the mountains in the background, and watched the marmots try to figure out what we were bouncing from rock to rock. We learned about what types of grass and vegetation they use to replant these areas. We went across to a different area, and there we saw a number of elk and bighorn sheep. We also saw a few wolves. There were at least 2 bands of sheep, some ewes and lambs,

and some rams. We got to look closely at the rams to look at age and size. There was also a lot of cow and calf elk that we got to watch move around on the mountains. I was lucky to take some amazing pictures.

On the second day, we got to spend a day at the range engaging in a variety of activities: archery, trap shooting, shooting with 22’s and long guns, search and rescue, as well as a video on transmission of MOVI to wild sheep, produced by WSSBC. There was close to 60 youth participating in the second day. It was cool to be around that many like minded youth. We also got an introduction to conservation, with information on aging sheep. We learned about antelope as well. The Fish and Wildlife officers did a lot of explaining about what they do and how. They need more recruits and were encouraging us to take a look into that career.

I had a great time! It was an amazing experience. I would go again in a heartbeat. Thank you to WSSBC for your sponsorship to go, and WSFAB for having me!

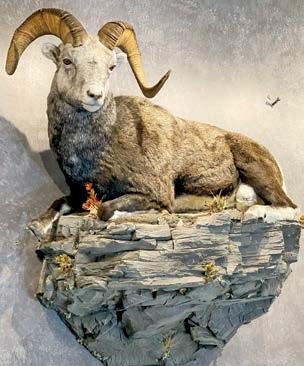

by Ray Wiens

Reprinted with permission from Journal of Mountain Hunting.

or those of us fortunate enough to live and hunt in the Western portions of Canada and the United States we are afforded many amazing hunting opportunities. My home province of British Columbia, especially, allows us to take to the wilderness in search of an amazing variety of game. Mule deer, moose, elk, caribou, four sub species of mountain sheep, mountain goat, and black and grizzly bear are all available to hunt in this great Province I call home. The remoteness of the country combined with the opportunity to chase this variety of game is second to none. However, to access many of the areas these animals inhabit means travelling deep into the mountains where very few people have ever set foot. And although this represents a large part of the appeal of mountain or wilderness hunting it comes with numerous “logistical” challenges. Many non-hunters have a simplified view of what’s involved with a true backcountry hunting trip and can’t fully grasp the extent of the planning and work required to come home with an animal. From field dressing to meat care, caping and skinning, as many will say “the real work” starts after the kill.

One of the biggest challenges for many hunters is dealing with the skinning and preservation of capes, especially on an extended backcountry hunt. Mountain hunts are not easy. We are more often than not required to go the extra mile to access our planned hunting area by means of backpacking, packtrain, float plane or jet boat, and we often find ourselves at least a day or more away from civilization. Far away from freezers or friends who know how to look after the hard earned animal you were after. If you are planning on preserving the cape and hide for some form of mount it is imperative to inform yourself on what you’ll need and how to properly care for your animal in these types of situations. Over the next few paragraphs, I’m going to go over what I feel are the essential skinning and caping tools and techniques.

To me, taxidermy is not about preserving a “trophy”. It is a memory, an accomplishment, a symbol and reminder of the hunt, the difficulties overcome, the people I was with and the country we were fortunate enough to experience. It is also a way to respect and preserve the beauty of the animals we chase.

To ensure you end up with the most representative mount, proper “in the field” care of the animal’s hide is absolutely essential. As a taxidermist, caping is the first thing I do in the field. The meat is always important, however, I like to take the shoulder or life-size cape off of the animal before gutting or boning out the meat. This way the incisions

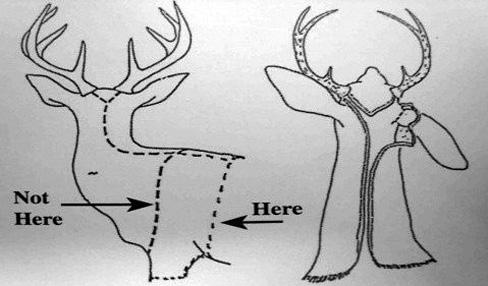

you make to field dress the animal won’t compromise the quality of the cape and the meat can still be promptly taken care of with no risk of spoilage. There are only a few items needed for field care and when on a backpack hunt especially keeping gear and tools to a minimum is important. Generally speaking, my caping kit only includes a scalpel handle and a few spare blades. I keep my salt at base camp unless I know I’m going to be more than a couple days away from base camp or I’m anticipating warm weather. In this case I pack a 1L plastic bottle of fine salt. Once the animal is down, the pictures are taken and your heart rate finally starts to normalize, the real work begins. The key here is to know exactly what you want! There are several options for mounts and knowing which specific one you want will dictate where you cut.

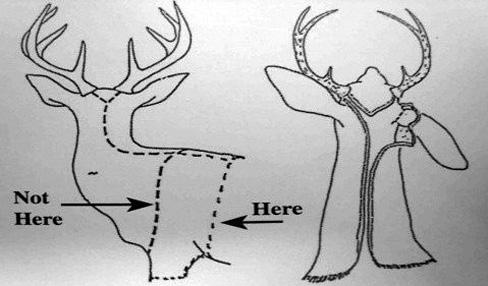

There’s the standard shoulder mount, for this mount cuts can be made down the back to fully behind the shoulder, around the shoulder and part of the front legs (photo A). Pedestal mounts are similar to a shoulder mount but more cape is needed to cut the cape back to mid-belly or even further.

Then there are rugs or life-size mounts which should be skinned with either a ventral incision (photo B) or a dorsal incision (photo C - next page). For dorsal skinning, make your cut from the back of the animals head, down the spine to the base of the tail. Note the incision lines in the photo labeled “B”. I recommend for a rug to start your incisions from the heel of each paw to ensure the correct line. Cutting to the top of the foot is probably the most common error I see on bear rugs. Ventral incisions are fairly common and when in doubt, use this method

Photo A Photo B

For dorsal skinning, make your cut from the back of the animals head, down the spine to the base of the tail. Begin skinning the hide off of the animal and work your way down to the legs. Once you are part way down “tubing” the legs out, a relief cut can be made on the back of each leg to help finish skinning the hide off. There are benefits to both the ventral and dorsal skinning methods and the one you utilize is dependent on the species involved, desired position of the final mount, and your taxidermist’s preference. It’s always a good idea to call your taxidermist ahead and discuss your hopeful caping priorities. If you don’t know specifically the type of mount you want the best option is to skin the whole animal out with a ventral incision. During the initial skinning process, I remove the hide up to the head and feet and then detach these from the carcass so I can finish skinning and caping out afterward at camp.

Caping out the head intimidates a lot of hunters. I always recommend people attempt to cape out an animal that they have no intention of turning into a mount prior to shooting their ram or another trophy of a lifetime but sometimes that isn’t an option. It obviously isn’t ideal to learn to cape in these memorable situations but when it’s the early season and weather is warm or you’re going to be stuck in the mountains for days it’s better to try than to let the cape spoil. It’s much easier to fix a small hole or two than to replace an entire cape or repair a spoiled section of hide. Caping out the head refers to removing the skull from the hide and includes, “turning” the ears and splitting the nose and ears. I get many capes through my shop every year that have been skinned out nicely but without the ears properly turned. The ears are just as susceptible to spoilage and need to be turned inside out in order for the salt to take effect. A properly preserved cape with bald slipped ears doesn’t make for the best mount. (Slippage = losing hair in patches due to bacteria, often not visible until the cape is in the tanning process) When skinning out a head just remember to take your time, use a sharp blade and cut the connective tissue towards the skull not towards the skin. The first challenge you will encounter will be to free the ears from the skull. Feel for the base of the ear where the

ear canal is below the skin and cut through the ear butt muscle and ear canal cartilage (photos D and E).

Next, you will come upon the horns or antlers — unless it’s a predator species — for sheep, goats and other horned animals the hairline and horn blend into each other. Make a cut around the horn just above the hairline then proceed to skin from underneath the skin towards that cut freeing the skin from the horn. With antlered animals, I skin from underneath the hide, up the pedicle and pry the skin off of the base of the antler (photos F and G).

Once you’re past the animal’s headgear skin carefully towards the eyes and lips. When you get close to the eyelids, keep checking the hair side of the specimen. I like to pinch the eyelid with my other hand and pull it away from the skull, this way you can clearly see where the eyelid is and cut through the membrane connecting the eyelid to the skull (photos H and I). Carefully free the entire lid from the eye orbital. Also, take care when skinning off the lachrymal gland (tear duct).

Photo C - Head is on the left

Photo D

Photo E

Photo F

Photo G

At the corner of the mouth at least a half-inch from the corner lip line, you will need to cut through the muscle and lip tissue towards the jaw bone. Follow the lip line and cut where it connects to the upper and lower jaw bone. As you skin the muzzle forward, peel the skin down towards the nose to within one inch or so of the nose pad. Here you will cut through the nasal cartilage towards the lips. After this point, the hide should be free from the skull (photos J and K).

Once the hide is free I begin “splitting the lips”. This simply refers to filleting the lip open all the way around the mouth. When salting a hide fine salt can penetrate up to a quarter-inch so keep this in mind when doing all

the finer detail skinning. The purpose of splitting the lips is to simply get salt to penetrate right to the lip line so remember the quarter-inch rule, you don’t need to be any more precise than this (photos L and M).

Next, split the nose cartilage open. After I’ve skinned around the nose as far as I feel comfortable, I take my knife and carefully cut through the septum splitting it open right up to the inner nose pad (photos N and O).

As mentioned above, turning the ears is the most overlooked step I see in the shop. Do not forget or avoid this essential part of the caping process! Start by cutting around the ear butt muscle towards the ear cartilage and then start to turn the ear inside out (photo P - next page). I use a dull wooden edge that I place against the hair side inner ear and use as a pivot point to aid in the turning. Carefully cut the connective tissue that attaches the ear cartilage to the back of the ear. Cut towards the cartilage as you’re less likely to cut through the cartilage than the skin. Continue to work around the ear until you get close to the

Photo H

Photo I

Photo J

Photo K

Photo L Photo M

Photo N

Photo O

edges (photo Q). Continuously check how close you are to the edges of the ear. Remember, a quarter-inch to the edge will allow the salt to do its job and keep you from busting through the ear.

At this point, you have basically finished the skinning portion for a shoulder mount or pedestal mount. Go over your cape and scrape or cut off any remaining meat or fat. Carefully look over the entire hide and check that nothing has been missed. Once you are satisfied that you’ve done a thorough job, take your fine salt and heavily apply it to the cape on the flesh side (photo R). Rub it into the hide making sure to not miss any nooks or folds. Take the salt and rub it towards the edges of the cape, capes tend to want to roll in at the edges. I’ve had several capes come in over the years where the edges were missed and spoiled as a result. You want to cover the entire flesh side of the cape. If you’re on a backpack hunt make

sure you have enough salt to at least cover the flesh side for one application and do the second application when you get back to base camp. If you are near base camp and have lots of salt with you, apply it heavily. Fold the cape up flesh side to flesh side. The following morning, shake or scrape off the sloppy wet salt and apply another coat. Keep your cape out of the rain. Do your best to keep it as dry as possible. Once the cape has been salted and resalted, on the third day (if possible) hang it up out of rain or direct sun and let the flesh side “crisp up” and the hair side dry. At this point your hide is good to go. You do not need to worry about getting to a freezer or any other steps to preserve it. Just keep it dry.

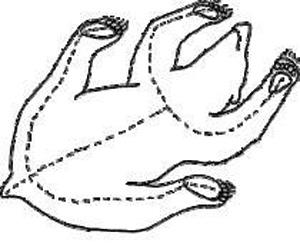

For rugs or life-size mounts, things get more involved as you will still need to skin out the feet, tail, and genitals. Ungulates can be a little tricky. You’ll want to cut down towards the hoof and can actually cut through the hoof on the inside of the foot (photo S). You’ll need to free the bone from the connective tissue within the hoof. Once it is free, cut through the tissue at the joint and pop the bone

Photo P

Photo Q

Photo R

Photo S

With predators, if the mount is going to be a rug you can cut around the pads and completely remove them from the hide. If a full mount or half-mount is desired, leave the pads attached on one side (of the pad). Make your initial cut where the pad and the hairline meet, cut around the pad leaving a section uncut if you want to keep the pad on or cut it right off for a rug (photo U).

Skin around the foot as you would any other part. When you reach the toes I recommend cutting a trough into the bottom of the foot towards the toe pads until you get to the edge of the webbing (photo V - next page), then flip the

Photo T

Photo U

foot over and, while pulling the hide away from the bone cut the tissue on that side. At some point, locate the joint closest to the toe pads and cut through the joint, popping the bones apart one at a time (photo W). This can be a slow process when you’re not used to doing this.

Cut the tail open at the bottom and skin out the tailbone and look for the genitals, and skin them off as well. This is a good habit to get into when skinning the hide of any animal, as many Provinces and States require evidence of sex to be left attached to the carcass.

Certain species will have very thick portions of hide to work through. Large black and grizzly bears can have very thick skin on the back of their necks and mountain goats at times can have very thick hide on their rear ends. If you think the hide is exceptionally thick, it’s a good idea to score or cross hatch cut the hide in these areas to help the salt penetrate. But, do this carefully as you don’t want to cut too deep and sever the hair follicles. After all these steps are complete, follow the same salting steps mentioned above.

Pictures, videos, and articles can be a great reference

Ray Wiens owns and operates Ray Wiens Taxidermy, a full-time studio located in Merritt, BC. Together with his wife, Maureen, they have served customers from all over BC as well as all over the world. He specializes in big game taxidermy and is familiar in mounting all local (BC) species as well as African and other exotic animals.

when skinning for a mount but there is no replacement for good old practice on the real thing. I strongly recommend practicing on another animal you have no intention of mounting and learn from the mistakes we’ve all made. Calling a local taxidermist or the taxidermist you plan on using can be incredibly helpful as well. Find out if they have any preferences so you know ahead of time how to best prepare your cape when in the field. Some taxidermists want the necks to be tubed out, others do not and some refer a dorsally skinned animal for a life-size job, while others prefer it done ventrally. For the record, with shorter haired species I recommend avoiding dorsal skinning. Also, see if the taxidermist will allow you to stop by and watch something being caped. As with any aspect of hunting, preparation and planning are integral to a successful outcome. Learn everything you can before the trip so that when the time comes and you get the opportunity you’ve been dreaming of and training for, you’ll have the skills required to properly care for the animal and preserve the memory for a lifetime.

To Ray, the mounts are so much more than just a trophy of an animal. They are a sign of reverence for the species taken and a means to display the beauty of the animals as well as show the importance of conserving and saving our wild places. To learn more about Ray and see examples of his fine work go to www.rwtaxidermy.com.

Photo V

Photo W

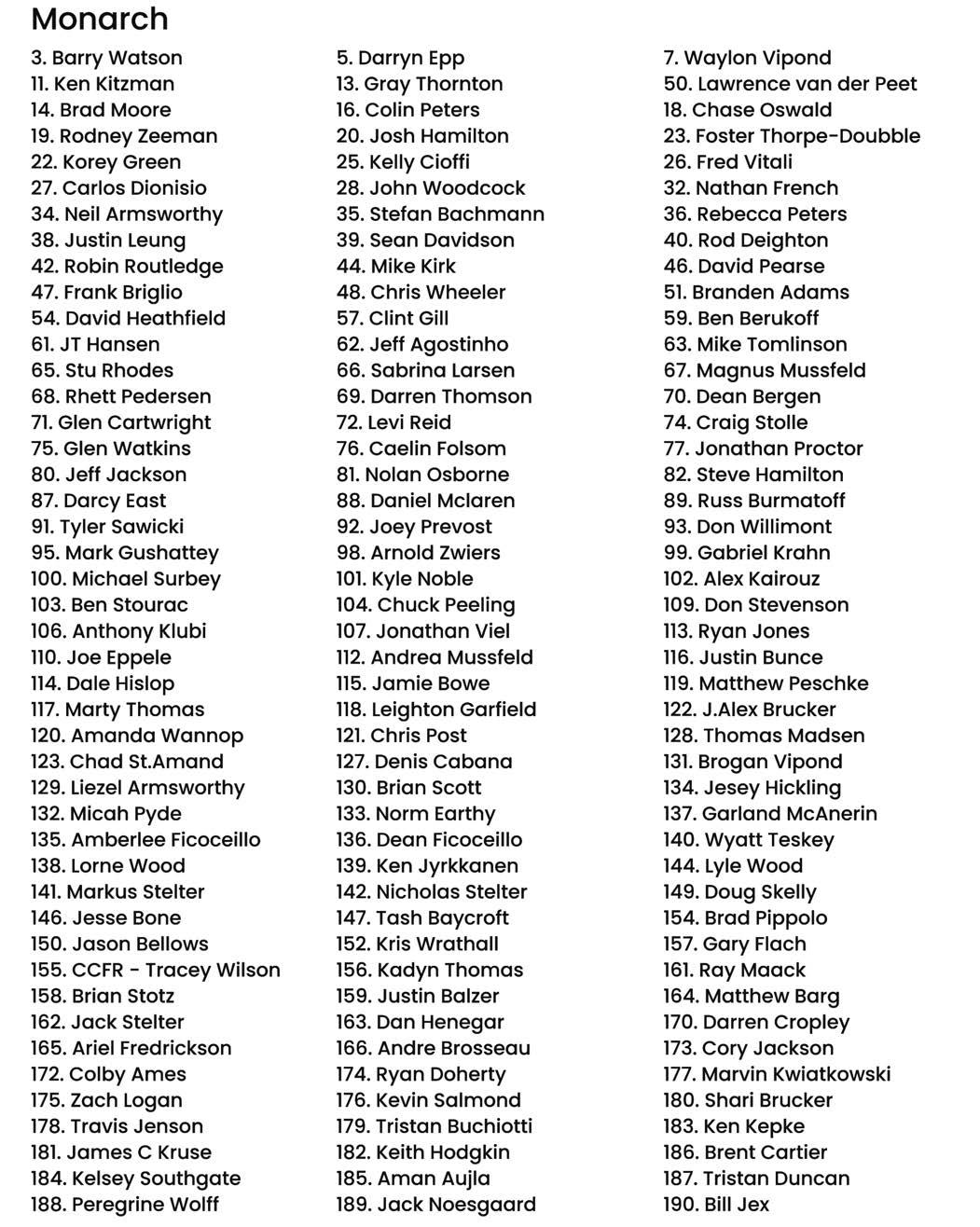

ait, I think I saw one!” Driving some forest service roads, we had turned a corner and I looked out the back window to check the road behind us just in case. Something big and black. A bear! We stopped the truck and jumped out, rifle at the ready. This spooked him, he looked at us and then quickly disappeared into the bushes. In hindsight we should have continued driving, parked and then crept back but I think we were all excited to see the first bear of the trip.

I was out with my Women Hunt mentor Greg S and his friend, Greg A, looking for my first spring black bear. I had been out the spring prior by myself and while I had managed to find quite a few bears they were never close enough to shoot. At the time I didn’t feel comfortable shooting any distance and trying to get closer always spooked them. This was likely a good thing as I had little experience in field dressing or meat care. My participation in the WSF’s Women Hunt class of ’24 changed all of this. I gained the shooting skills, experience and confidence to take these shots, got hands on experience of processing multiple animals and thanks to Women Hunt working with WSSBC, I was paired with Greg S as my mentor. Greg S is the best mentor you could hope for, an accomplished hunter and dedicated conservationist. He has helped many learn to hunt and harvest their first animals.

We continued on, seeing two young bears in different spots and lamenting spooking what was likely a big boar early on. We came round another corner and spotted a good sized bear feeding along the road side. The bear was standing up on its hind legs feeding on the small trees by the side of the road. It was alone. The wind was perfectly in our favour. Learning our lesson from earlier, we backed up the truck out of sight. On foot we tucked in to the side of the road and stalked down from maybe 600 to just over 100 yds. I got set up, felt calm and focused. I had to wait a bit until it turned broadside and then I took my shot. It felt good and I saw the impact in my scope. It jumped up and then ran off across the road. I looked back at Greg. “How did it feel?” he asked. “Good” I said, “Okay yeah it looked good” he said.

We walked to the hit site and found blood and scuff marks and followed it a short way into the bushes. For a moment the Greg’s looked worried. “Hmmm no more blood” said Greg A. “Oh wait there it is!” We had gone right past it, it went down only a few metres from the road.

We thought it was a male but it turned out to be female, we’d had some time to observe her during the stalk so I felt good about her being alone. I was excited but also relieved. More than anything I wanted to make a good shot and for my animal not to suffer. I also wanted to do a good job out of respect for my mentors. It is a lot to ask to have someone take you out hunting, from a safety and responsibility point of view. I did not want to let them down.

I got to check out her beautiful thick long fur, big nails and teeth. I cut my tag and we took a couple of quick photos before getting to work. Greg A showed me how, starting at the wrists and working up the inside legs, I mirrored what he was doing. It felt strangely familiar and very natural. Perhaps it was the Women

Hunt training, perhaps my childhood exposure to hunting, or perhaps it’s just in us, since we were all hunters once. Maybe a mix of all of those. With three of us, it didn’t take long until she was all packed up in game bags and in the truck. I would have been there a long time if I had of been alone and I was especially grateful for the instruction and help at the ankle and neck joints.

I thought I might feel sad or feel some regret with taking my first big game animal but I didn’t. Just respect for her, pride in myself and gratitude for my mentors. Knowing that she didn’t suffer and that all parts of her would be used gives me peace in my decision and actions.

I still have her skull, the blood and hide I have used and am still using for blood tracking training for my dog. The meat is long gone and the last batch of bones are in the slow cooker making broth for my dogs. I can wait to get more adventurous with the next bear harvested. I want to give my dog the opportunity to track it, I want to clean and prepare the hide myself and then to try making my first sausages with some of the meat.

With one bear in the freezer, I still had a second tag that I was hoping to fill. I was lucky to be invited to join some other WSSBC members on a spring bear hunt in June of this year. Our group of five was a mix of experienced and new hunters. We got a comfortable camp set up, checked our rifles and then spent four great days chasing bears around. We saw grizzlies, mule

deer and some skittish black bears. We put a run on a few but despite our best efforts did not manage to harvest. That didn’t seem to matter and we had a blast getting to know each other and have made some tentative plans for a repeat, next spring.

I decided to learn to hunt because I wanted to be more self sufficient and be able to harvest my own healthy

source of protein. I also wanted to gain the physical and mental skills that being a hunter would require of me. I expected it to be a solo journey and to be lonely at times, but it has been anything but that. I have met and been helped by many people. I will be forever grateful to the Women Hunt community for giving me the skills and confidence that I needed as well as some life long friends. Women Hunt through WSSBC matched me with the very best mentor that a new hunter could hope for and through it I have met some wonderful friends within WSSBC and am excited to see what the future holds. If you are ever in the position to offer mentorship to a new hunter, please do it. You have the chance to give them a positive first hunting experience and really shape their ethics and behaviour as a hunter, conservationist and community member going forwards.

Thank you to Women Hunt, WSF, WSSBC, Women Shaping Conservation, Greg S and Greg A.

Members, send us your hunt story (~50 words plus a picture or two) to kstelter@wildsheepsociety.com.

A dream, a goal and an accomplishment. Soren Salinas clipped his tag on the ram of his dreams in 2025 with the help of Life Member and WSSBC supporter, Brogan Didier. “Time for some new boots.”

Last fall was one for the books. My first LEH moose tag had us hunting eight days in new country before finding a hidden bog. We called, and in he came—grunting, drooling, the rut alive. It was also my first true pack-out, a challenge I’ll never forget.

Weeks later, after a season of solo hunts, passing bucks, and even getting the side-by-side stuck, November finally delivered. In another new area with my husband, a legal 4-point mule deer stepped from the trees. Two hard-earned hunts, two incredible memories, and a season that proved patience and persistence always pay off.

– Keia Holm (Life Member)

The bull had been fighting with an even larger bull over a harem of cows and the four hunters snuck in just after the fight had ended. Unable to call the victor away from his harem, the group worked in on this bull for hours, with Hana grunting and raking a couple hundred yards behind while Kelly snuck in towards the bull, cow calling as he went; leading the bull to believe he was going to be able to steal the cow from this other unknown bull. Kelly and Aj closed the distance, and Kelly was able to get one quick shot as the bull made a fatal mistake and finally stepped out in the open to claim his cow.

Members AJ Anderson, David Winger, Kelly Cook and Hana Erikson with a beautiful bull moose in Northern B.C.

I have been bear hunting since I was 10 years old when my father introduced me to it. Some of my earliest memories include cruising old logging roads, pipelines, hiking grassy slopes and most importantly spending quality time together. Now being 23, it has become my favourite time of year to be with family, friends and my two dogs Remie and Finley. We started early this spring with an early melt. We had been on bears early in April which is not common in our area of the peace. Although we had not found a mature boar to harvest, at the end of May, we found a very large set of tracks that were 6” wide. On a bear, the width of the paw + 1” is generally the overall length of the bear in feet. I hunted this bear everyday for 3 weeks, and during that

Out here in the mountains, hunting is far more than the kill—it’s about connection and tradition. With my baby on my chest and my older child by my side, I’m reminded that this way of life isn’t only about putting food on the table, but about passing down lessons of strength, respect, and gratitude for the wild places we call home.

– Kristin

Eppele

time I had been bluff charged three times—once by a black bear and twice by a grizzly. I had 3 encounters with the bear I’d been pursuing. The first, he was in hot pursuit of a sow. The second. I was not able to get a clean shot.

The following evening my girlfriend Madison and I found him nearby with a rather large sow. After stalking close to 30 yards on June 19th, and trying to judge which bear was which, he fed into 25 yards for a perfect shot. This had been a bear I had dreamed of since I was 10 years old. My father always talked about these old mature bears; I had often thought they were “myths”. Having Madison and our two dogs Remie and Finley there made it even more special.

– Davis Schmidt

Congratulations to WSSBC member Shad Hulse on his 2025 Gana River Dall Sheep.

by Bill Pastorek

by Bill Pastorek

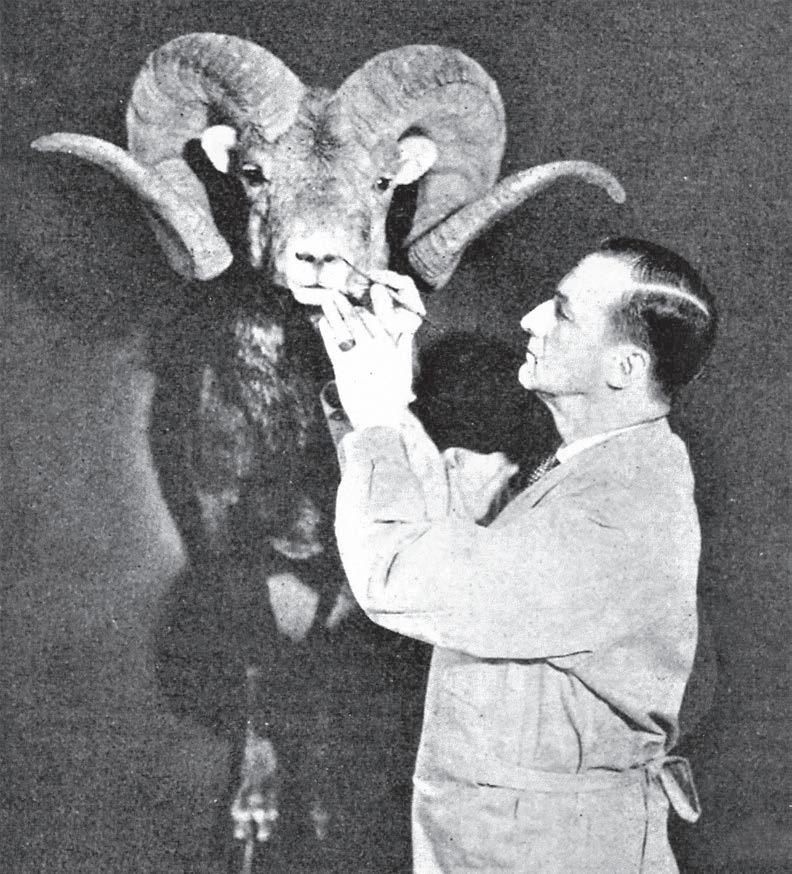

t’s hard to imagine what Chadwick must have been thinking when he and his three guides finished taping the incredible horns of his world record breaking Stone sheep. When Chadwick, Hargeaves and Golata rode into camp just before dusk on that fateful day in late August of 1936, they brought out of the Muskwa River country a trophy that has yet to be matched. With a right horn measuring 50 1/8 inches in length, and the left horn even longer at 51 5/8, this very special ram ultimately scored an astonishing 196 6/8. In the more than 80 years since that extraordinary late summer day, no other ram has come close to Chadwick’s. Most, if not all, sheep hunters believe that Chadwick’s ram will never be beaten.

The Chadwick ram, though, has sadly had a precarious history. It’s hard to believe that the magnificent head was grossly neglected. Beautifully mounted by James L. Clark at the American Museum of

Natural History in New York, the Chadwick head was placed into the National Collection of Heads and Horns. In later years, Clarke authored one of the most important sheep books of all time, The Great Arc of the Wild Sheep.

The National Collection was established around 1910 by three men: Theodore Roosevelt, shortly after his presidency; explorer naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews; and author and conservationist Dr. William T. Hornaday. The National Collection served as a permanent repository for outstanding big-game trophies and was housed at the New York Zoological Society’s Bronx Zoo in New York City.

Almost without exception, hunters took it for granted that the trophies entrusted to the National Collection would be well cared for and publically displayed. Sadly, that was not the case.

Early in 1977, Lowell Baier, a lawyer and sheep-hunting enthusiast, made a trip to New York to view what he

called, “The Holy Grail of Hunting.” Shortly after his disappointing visit, Baier penned a bitter open letter to his sheep hunting fraternity.

In the letter, he explained that he almost cried when he learned that “the heads cannot be seen by the general public and are no longer maintained. They are dusty, dirty, not humidified, and many of the hides are badly in need of repair.” Moreover, Baier lamented that “Security is terrible, with a number of record heads have recently been stolen.”

Two top twelve Rocky Mountain Bighorns, one hanging on each side of the Chadwick ram, had disappeared. Luckily, the Chadwick trophy had been mounted with the full shoulders and front legs attached. It was not taken, most likely because it was too heavy and bulky for the thief. Can you imagine the loss? In the sheep hunting world, if the Chadwick ram was stolen the ensuing search would be like the search for the Holy Grail.

Mr. Baier worked on trying to find a suitable home for the Collection, his

letter asking hunters to band together to raise funds to preserve and house this national treasure. The Safari Club International, the Boone and Crockett Club, the Hunting Hall of Fame and the National Rifle Association were all appealed to in the letter. Sadly, nothing happened at this time, but the seed was planted. Frank Bays, a Grand Slam holder from Michigan who was later elected vice president of the newly organized Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, flew to New York and brought the trophy to Dearborn, guarding it as if it were crown jewels. There was good reason. One of the conditions of its loan was that it be covered with a $25,000 insurance policy while it was away from its home. Possibly, now that someone was interested, the Chadwick ram had gained value.

Bays told 200 fellow sheep hunters at the meeting that he was as shocked as Baier had been at the conditions under which this and other trophies were kept in the National Collection.

He also reported angrily that officials of the New York Zoological Society made no secret of the fact that a strong anti-hunting bias among the society’s membership was behind the deliberate neglect of the collection. Not surprisingly, though, the Chadwick ram stole the show.

The Midwest Chapter of the North American Sheep Hunters Association had called the Dearborn meeting.

The hunters who attended, along with some of the top sheep guides from North America, swapped hunting tales and got to know each other. Most importantly, they talked about the problems of wild-sheep management and how they needed to band together to protect them. Thankfully, the outcome of the meeting reached far beyond the saving of the Chadwick ram.

Following the Dearborn meeting, plans were completed to organize the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep (FNAWS). Lloyd Zeman, a Grand Slam holder, wildlife biologist

and journalist, was one of the prime movers behind the Foundation and was named President. Unfortunately, a few years later Zeman was killed in a horse-back accident near Yellowstone Park. Frank Bays became the first Vice-President. Sadly, Frank Bays passed away in the summer of 2017.

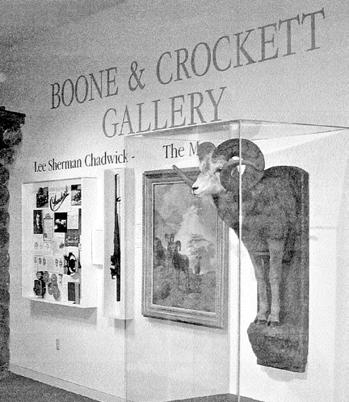

The newly formed Foundation was the first sportsmen-conservation organization in the country dedicated to the protection and preservation of North America’s four kinds of wild sheep. The desire to preserve Chadwick’s ram brought together the sheep hunting community in a way that continues to benefit hunters and the wild sheep of North America. Thankfully, after some serious negotiations, the Chadwick ram and other record heads were safely housed and displayed in the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody, Wyoming. This happened with the assistance of the Boone and Crockett Club, which currently owns the collection. For

many years the Chadwick ram was safely on display at this wonderful museum. Many a sheep hunter made the trek to see the finest trophy of all time

In 2016 the Chadwick ram was moved from the museum in Cody, Wyoming to its new home at the state of the art, 350000 square foot Johnny Morris’ Wonders of Wildlife National Museum in Springfield, Missouri. Located next to Bass Pro-Shops’ National Headquarters, it’s truly the largest, most impressive Wildlife Conservation attraction in the world. With over 1.5 miles of trails winding through wildlife displays and dioramas, along with 1.5 million gallons of both fresh and salt water aquariums, this monument is a sight to behold. Springfield is a long way from my home in British Columbia, but I’m thinking two words: road trip. The new home is a fitting resting place for the Chadwick Ram. It’s a trophy that speaks of the challenge of mountain wilderness and the

excitement and suspense of sheep hunting. A great many sportsmen and women, and most sheep hunters, rate it the most magnificent North American big game trophy.

During his account of taking the ram, Chadwick said, “There is a chance that some lucky hunter will sometime find this old boy’s daddy, with a still larger head.” It hasn’t

happened yet, and really, there’s very little chance that it ever will.

Regardless of where it’s housed, we’ll always remain in awe of the Chadwick ram because it signifies humankind’s long fascination with the biggest and the best.

I would personally like to thank Lowell Baier and Frank Bays for their efforts in rescuing the Chadwick ram.