Celebrating Achievements and Preparing for the Fall Season

irstly, I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to all our members for their continued support. Your unwavering dedication has been instrumental in helping the Wild Sheep Society of BC (WSSBC) achieve remarkable milestones in our conservation efforts this year. Together, we have taken significant strides toward preserving the health and sustainability of wild sheep populations across the province.

Celebrating Achievements

This year has been marked by several notable accomplishments, and I am proud to highlight a few key successes.

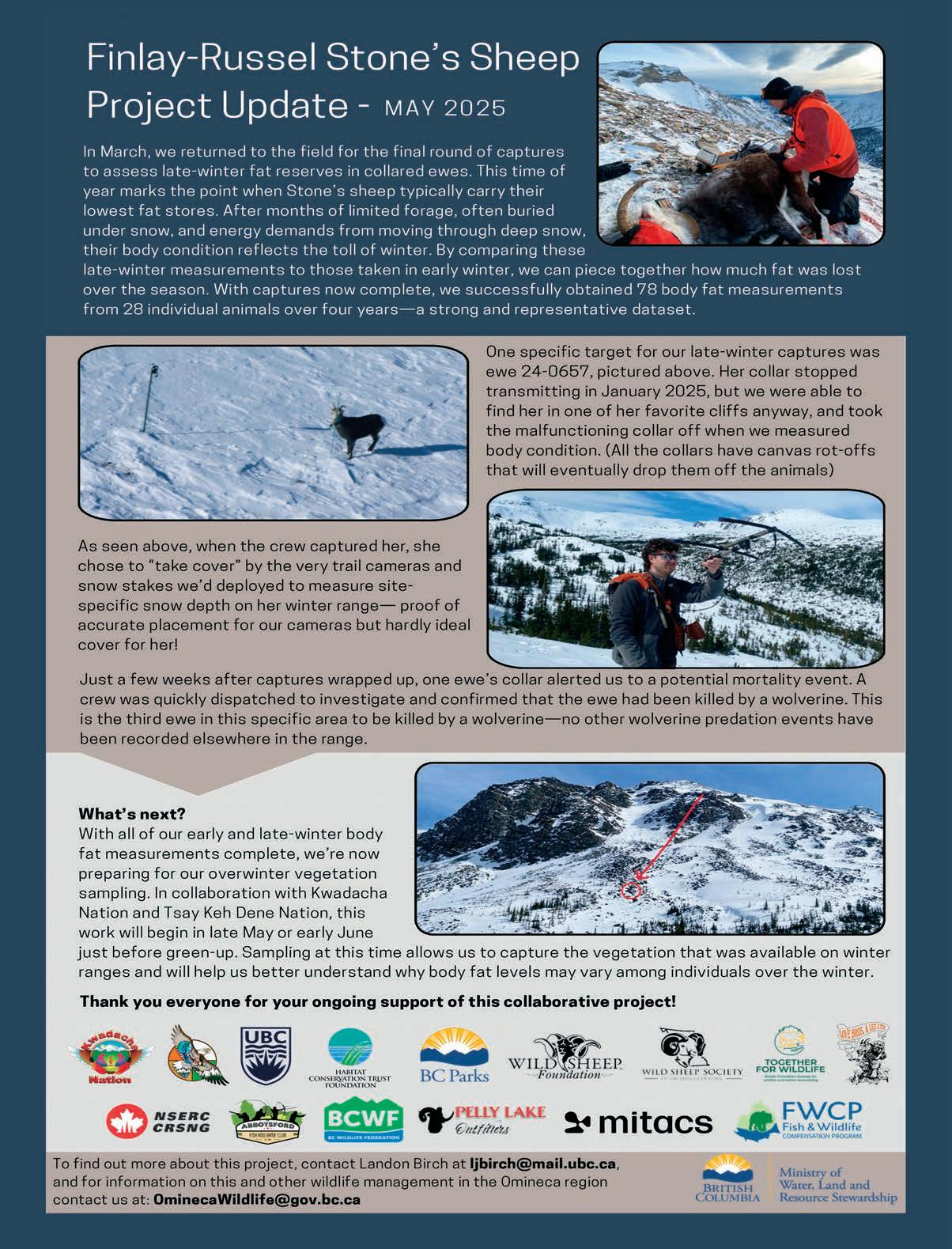

● Controlled Burns: We successfully completed 1,200 hectares of controlled burns, a critical measure to restore essential habitats for wild sheep.

● Fraser River Test and Remove: Our efforts in disease mitigation have seen positive outcomes with the Fraser River Test and Remove initiative.

● Bighorn Sheep Psoroptes Drug Treatment Trial: In collaboration with the Okanagan Nation Alliance, we undertook an innovative Psoroptes Drug Treatment Trial. This research is pivotal in combating the infections that can severely impact wild sheep’s health and well-being.

These achievements, made possible through your support, partnerships, and collaborative efforts, are testaments to what we can accomplish together. Thank you once again for helping to make these initiatives a reality. I also wish to recognize our many partners in these efforts which include the Wild Sheep Foundation, Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, Washington Wild Sheep Foundation, Hudbay – Copper Mountain Mine, Dallas Safari Club Foundation, Grand Slam Club Ovis and Abbotsford Fish and Game.

Message to Sheep Hunters

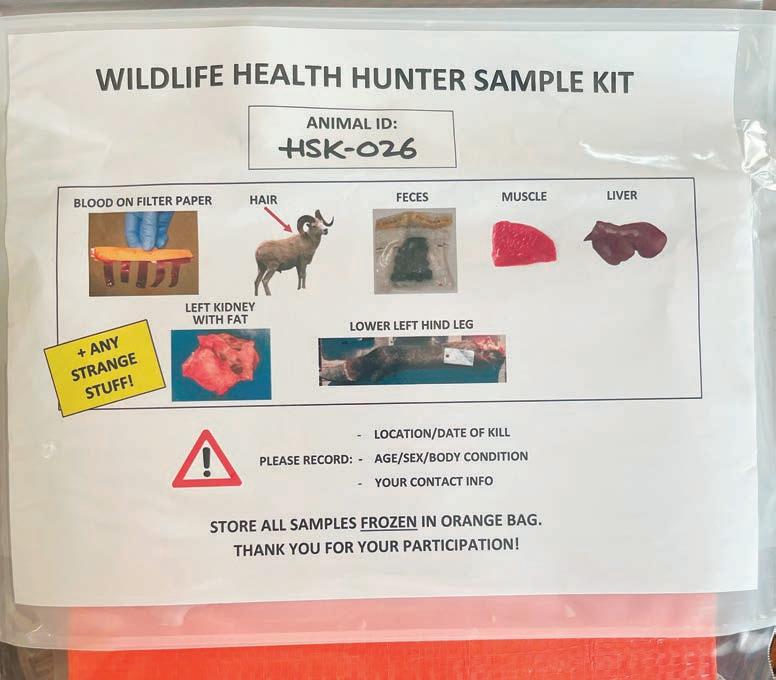

As the fall sheep hunting season approaches, I want to take a moment to address our dedicated sheep hunters. Your role in the conservation of wild sheep is critical, and we are counting on your commitment to ethical hunting practices to help ensure the sustainability of these magnificent animals for generations to come.

One of the most important aspects of ethical sheep hunting is the selection of mature rams. Choosing mature rams not only supports the population dynamics of wild sheep but also aligns with our collective goals of conservation and stewardship. I encourage every hunter to take the time to educate or refresh themselves on the importance of horn aging and the selection of mature animals.

Horn Aging Education

Over the past several months, the WSSBC has made significant efforts to educate hunters across British Columbia on horn aging and ethical hunting practices. We have offered horn aging courses in every region of the province, successfully educating several hundred sheep hunters. These courses provide invaluable insights into identifying mature rams and understanding their role within the herd.

For those who may not have had the opportunity to attend these in-person courses, we are pleased to offer additional resources. On our website, you will find a 30-minute educational video, which serves as an excellent guide for honing your horn aging skills. This video is designed to be accessible and informative, making it a great tool for both novice and experienced hunters. Furthermore, we are excited to announce the upcoming release of an online educational course in partnership with Silvercore Outdoors. This course will provide hunters with an in-depth understanding of horn aging and ethical hunting practices, all from the convenience of your own home. We believe this initiative will further assist and empower sheep hunters to make informed decisions in the field.

Looking Ahead

As we prepare for the challenges and opportunities of the fall hunting season, I urge all hunters to remember the importance of conservation in every step of their journey. By selecting mature rams, educating yourselves, and sharing knowledge with your peers, you play an essential role in safeguarding wild sheep populations.

Let us continue to work together as stewards of the land, upholding the principles of ethical hunting and conservation. Your dedication and actions make a tangible difference, and I am confident that this season will bring not only success in the field but also progress in our collective mission to protect and preserve wild sheep across British Columbia.

Conclusion

Thank you once again for your support and commitment to the Wild Sheep Society of BC. Our achievements this year would not have been possible without your contributions, and I look forward to continuing this journey with all of you. Let us celebrate our successes, embrace the upcoming challenges, and remain united in our mission to protect and sustain wild sheep populations for future generations.

Happy hunting and thank you for being an integral part of our wild sheep family.

Sincerely,

Kyle Stelter CEO, Wild Sheep Society of BC

nless you’ve read the masthead, you might not know everyone involved in this fine publication.

My name is Nolan Osborne, and I am one of the editors of the Wild Sheep Society of BC magazine, although Kyle Stelter and Peter Gutsche do most of the heavy lifting. My story with wild sheep and sheep hunting started a bit later in life. In fact, in the infancy of my hunting journey, I didn’t even know you could hunt wild sheep, or that four subspecies of them lived in Canada. Growing up in Southern Ontario, I spent a large portion of my youth outdoors, mountain biking and skiing, occasionally fishing, and didn’t start hunting until later in my teens. I quickly fell in love with hunting, and every free weekend from then on was

spent hunting ducks, geese, turkeys, and whitetail deer whenever possible. Hunting opportunities are limited in southern Ontario, with nearly onethird of Canada’s population residing in the southern one-tenth of the province. Public land for hunting was scarce and often shared with mountain bikers, snowshoers, dirt bikers, dog walkers, and others. Studying commercial photography in college near Toronto further restricted my ability to get outdoors, though I made the most of what I had.

A year after college, a good friend’s older brother and duck-hunting partner offered me a job as a fisheries research technician under his supervision. He would be pursuing a PhD in the evolution of Chinook Salmon across multiple watersheds of the Great Lakes and needed a

competent field hand for long hours on the river. I was building steam as a commercial photography assistant living in Toronto, but I figured it was worth a shot. Hell, I left the city to play in the swamps and rivers every opportunity I had, on my dime... why not get paid to do it? Little did I know how that job would alter the trajectory of my life.

I felt a calling and needed a change. I have always loved all aspects of nature, and spending time in it, as well as hunting, consumed my thoughts. After a strong October/November in Ontario hunting ducks and deer, grouse and snowshoe hare, I crammed my life’s possessions into my old Ford Ranger. I struck off towards British Columbia, in search of adventure and a new life in the guiding industry. With virtually no experience with

horses or in the mountains, it took some time, but I finally found a gig wrangling for a sheep outfit in the Yukon, and my obsession with sheep had begun. Thousands of hours on horseback, a couple of dozen wrecks, and a shattered humeral head later, and I’ve found my home guiding in BC’s Northern Rockies—the true home of the beautiful stone sheep. For over a decade, I’ve had the great fortune of spending my summers and autumns in the mountains, hunting sheep, moose, goats, and caribou, and helping clients turn their dreams into memories. A fortune that’s owed in many ways to the guides who helped mentor me, the outfitter who allowed me to turn a passion into a career, and, of course, my beautiful wife, who has supported my dreams and put up with me being in the mountains so many months a year.

In many ways, guiding is one of the last vestiges of a bygone era, before technology, immediacy, and efficiency consumed our lives—A

trade that hasn’t yet been completely optimized and modernized through technology. As anyone who has hunted on horseback knows, there is a slowness to it that is often hard to find elsewhere, and for the lessons I’ve learned on the trail, I am forever grateful. I’ve had the opportunity to experience some incredible hunts with incredible hunters, friends, and landscapes, and cut the odd tag myself along the way.

Beyond guiding, hunting, and sheep in particular have always stirred my thoughts, and for several years those offseason flames were fanned through my work with the Journal of Mountain Hunting—primarily as a writer and managing editor, and later as co-host of the Beyond The Kill podcast. It was through Adam Janke and JOMH that I was first introduced to the Wild Sheep Foundation and the Wild Sheep Society of BC, as well as the conservation aspects of the sheep and mountain hunting world. I’ve since moved on to working as

the Communications Manager for Frontiersmen Gear—a conservation partner of the WSSBC—in my offseason, and the passion for sheep and conservation continues.

It’s been a pleasure helping to breathe new life into this publication over the last couple of years, alongside Peter Gutsche, Bill Pastorek, who carried the torch alone for eternity, and our Editor in Chief, Kyle Stelter. It never ceases to amaze me the work that the Society does and the contributions to conservation that our members make. Oddly enough, this is about as close to writing a resume as I’ve come in the last decade, and to that, I find some small victory. Sheep hunting, much like guiding, is a celebration of tradition, storytelling, and the wilderness, as well as the conservation of sheep and the wild haunts they call home. That’s something worth holding onto and passing on to future generations of sheep and sheep hunters.

by Peter Gutsche

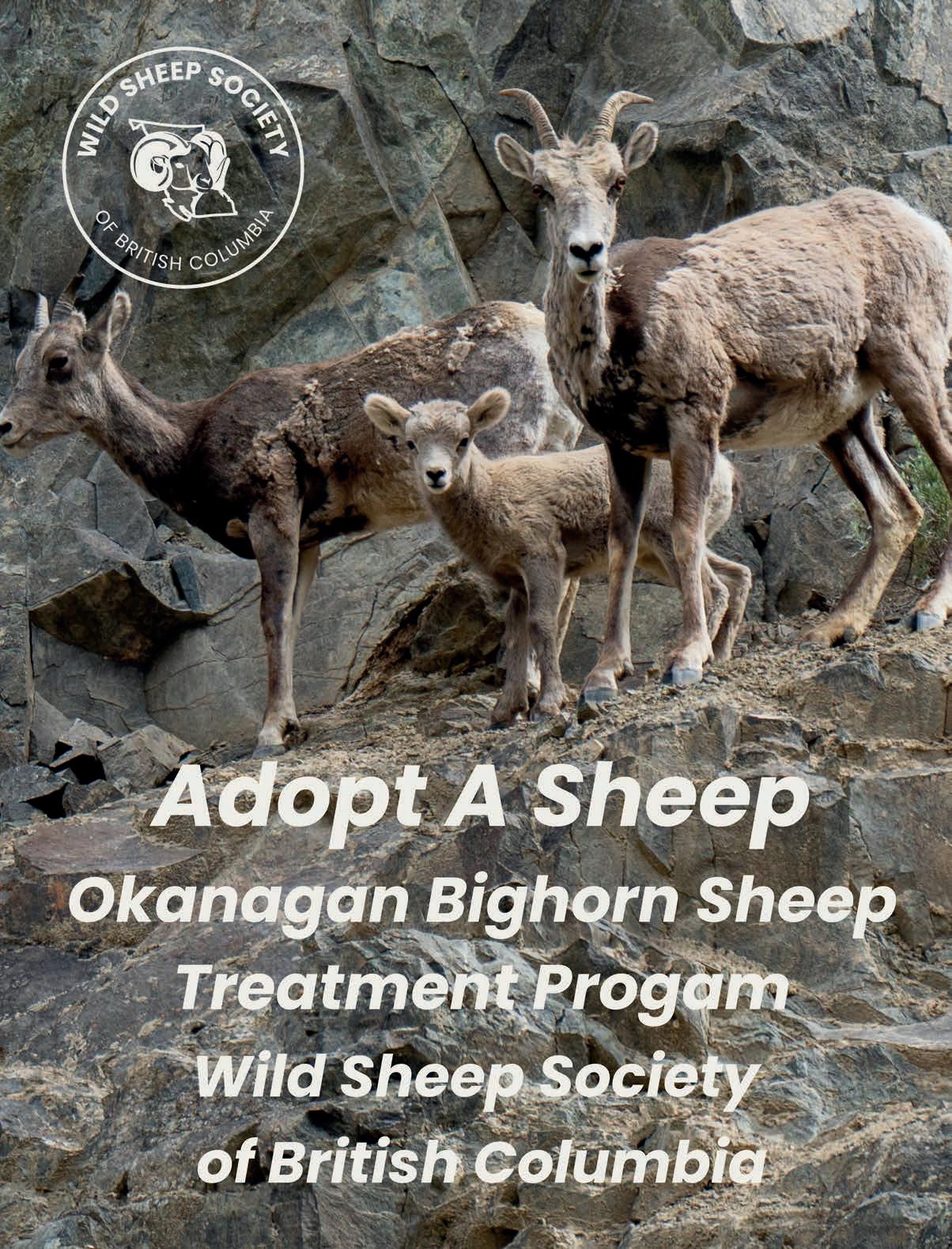

soroptic mange—caused by the Psoroptes cuniculi mite—has severely impacted bighorn sheep in the South Okanagan and Washington State, contributing to population declines of over 50%. The condition causes intense irritation and scabbing in the ears, hair loss, and weakened immune function, making infected animals more vulnerable to predation and other illnesses.

While the disease’s origins trace back to the nowdefunct Okanagan Game Farm, efforts are no longer just about understanding how we got here. They’re about what we do next.

Thanks to a collaborative partnership between the Wild Sheep Society of BC (WSSBC), the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA), and key support from the Wild Sheep Foundation and Washington State WSF among many others, a comprehensive treatment program is now underway. This initiative has brought together Indigenous knowledge, wildlife biologists and veterinarians, conservation leaders, and dedicated volunteers with a

singular goal: to eliminate Psoroptes mites from wild sheep and restore healthy herds across the region.

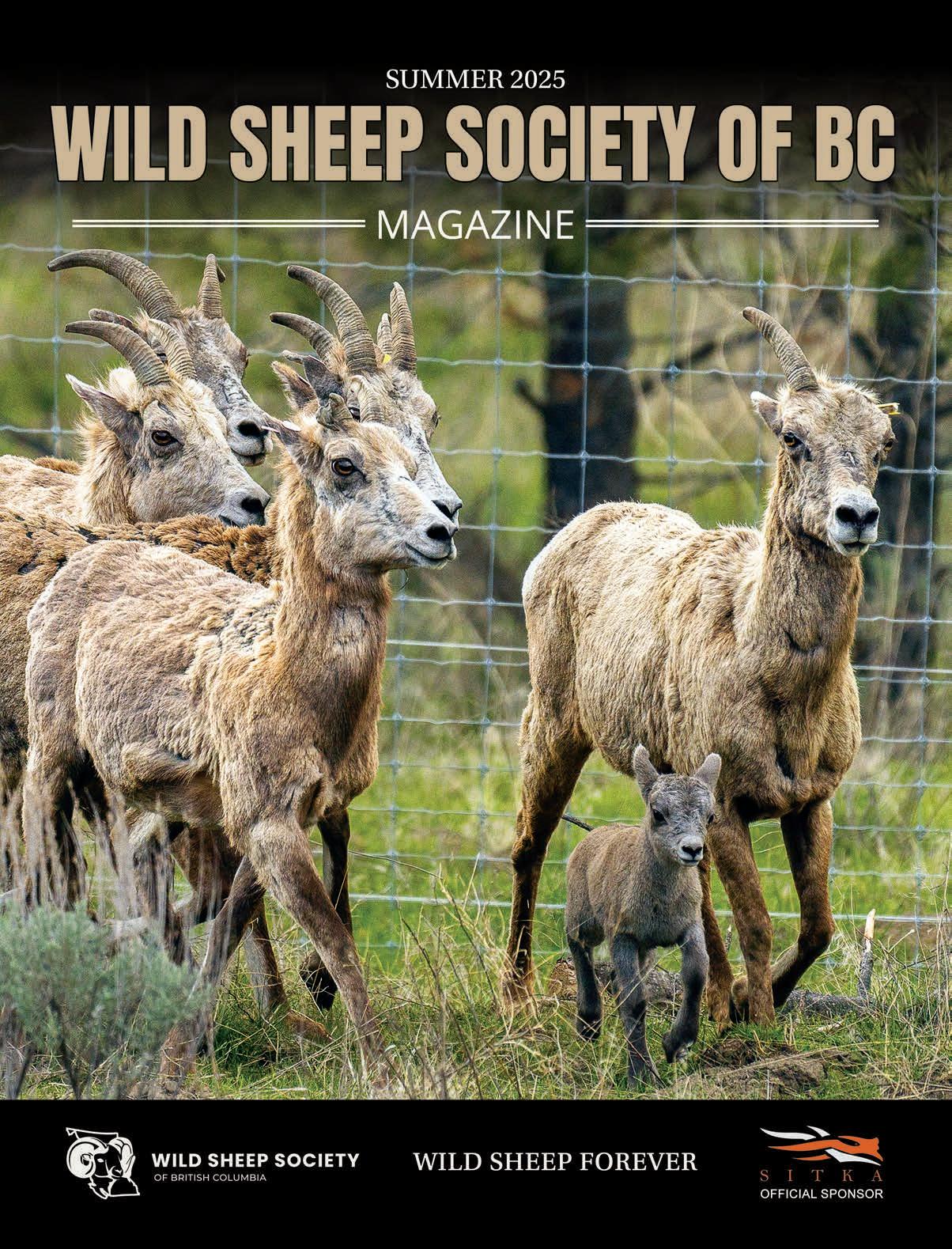

In early 2025, 28 bighorn sheep were captured from the Okanagan and Similkameen through helicopter and ground methods and relocated to specialized pens on Penticton Indian Band land. This marked the start of an intensive 15–18 month treatment and monitoring program.

Since then, we have successfully completed baseline health assessments and welcomed the birth of 11 lambs in the pens—a sign of resilience and hope. Volunteers now play a key role in daily animal care, and outreach efforts, such as field visits to the pens, have helped engage the community in this shared conservation mission.

The months ahead are critical. The team will conduct regular monthly handling of each sheep to administer treatments, monitor health, and evaluate progress. These sessions are also vital for testing and refining

new injectable drugs aimed at eradicating the mite more effectively and efficiently.

Beyond treatment, the project is laying the groundwork for broader conservation strategies:

● Tracking health outcomes to assess treatment success and adjust protocols.

● Evaluating drug efficacy to identify the most promising approaches.

● Building long-term plans that use this pilot program as a blueprint for managing Psoroptes outbreaks in other regions.

More importantly, this effort is shaping a future where Indigenous knowledge, modern science, and public engagement come together to protect iconic species. As the program matures, its insights and techniques will inform regional and even international wild sheep management.

We are optimistic that with our strong partnerships, the framework we are building today has the potential to reverse decades of decline in bighorn sheep populations.

The success of this ambitious initiative depends on continued collaboration. We invite you to stay informed and get involved—whether by volunteering for monthly sheep handling or by spreading the word about this innovative conservation effort.

Follow our progress through the WSSBC magazine, our social media accounts, the @Okanaganbighorns Instagram page, and Okanaganbighorns.com. To volunteer or learn more, please contact WSSBC Director Peter Gutsche at petergutsche@gmail.com

Together, we can ensure that we have Wild Sheep Forever in the Okanagan, and beyond.

by Wild Sheep Society of BC

Okanagan Psoroptes Disease Treatment Trial (Penticton)

This targeted disease management initiative is focused on controlling Psoroptes cuniculi (ear mite) infestations in yilíkʷlxkn (bighorn sheep) herds in the South Okanagan. The trial evaluates injectable treatment options, improves diagnostic tools (e.g., ELISA), and tracks disease transmission in a previously unexposed population. Up to 20 sheep will be captured, GPS-collared, and monitored for movement, health, and herd interaction. The project also assesses co-infection with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae (M.ovi) and builds a predictive contact risk model.

Project Expenditures: $200,000

Project Partners:

● Okanagan Nation Alliance

● Wild Sheep Foundation

● Washington Wild Sheep Foundation

● Hudbay Minerals

● Wild Sheep Foundation Chapter and Affiliate

Fraser River Bighorns Test and Remove (Fraser River)

This program uses a Test and Remove (T&R) strategy to manage Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae (M.ovi) in Fraser River bighorn sheep herds. In response to population declines of up to 70% since the 1990s, infected adult females—identified through PCR testing—are selectively removed to reduce lamb infections and improve recruitment. The program combines collaring, aerial surveys, and genetic work to inform herd recovery and manage reinfection risks.

Project Expenditures: $2.5 million

Project Partners:

● Government of BC (Ministry of Water, Land & Resource Stewardship)

● Wild Sheep Foundation

● Midwest Chapter Wild Sheep Foudnation

● Abbotsford Fish and Game

● St’at’imc Nation

● Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation

Prescribed Burn for Stone’s SheepNorthern BC

This is a large-scale, prescribed burn program to restore and enhance habitat for Stone’s sheep in northeastern British Columbia.

Project expenditures: $2 million

Project Partners:

● Wild Sheep Foundation

● Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation

● Canadian Wildlife Capture

● Grand Slam Club Ovis and Grand Slam Club Ovis Canada

● Dallas Safari Club Foundation

● Washington Chapter Wild Sheep Foundation

by Alicia Woods

n May 2025, the Wild Sheep Society of BC, in partnership with Ridgeline Wildlife Enhancement, conducted prescribed burns in the Besa-Prophet and Toad River areas of northeastern BC. A total of 450 hectares (1,100 acres) was burned across four sites in these two study areas. The burns are located in late winter, lambing and summer habitat, which will provide immediate benefits to ewes and lambs as they graze on the new forage growth resulting from the burn. Not only will the sheep have access to the new green grass earlier than they would without burning, but the post-burn vegetation also has higher nutritional value than last

year’s vegetation growth. Burns were conducted in areas adjacent to the escape terrain that are important for predator avoidance during all seasons. Throughout this multi-year project, we have also been monitoring use of the burn sites by Stone’s sheep and other wildlife before and after the burn is completed. Freshly deposited pellet samples have also been collected across Stone’s sheep range in northeast BC to determine if sheep that have access to burned habitat are less stressed (based on hormones measured in the pellets) than sheep that do not have access to burns. This data continues to be collected and will be assess by a PhD student at the University of Northern British Columbia.

This project continues to provide real, on-the-ground benefits to Stone’s sheep and is exciting to see after years without prescribed fire and appropriate habitat management. We strive to continue this work each year, targeting critical habitats and sites that have not been burned for over 40 years. This work would not be possible with our partners and generous supporters including the Wild Sheep Foundation (our largest contributor), Dallas Safari Club Foundation, Grand Slam Club Ovis – Canada, Mountain Wildlife Conservation Society, and of course the members of the Wild Sheep Society of BC.

Stayed tuned for future updates on our post-burn monitoring results.

Essay Contest Content Winner

t is hard to put into words exactly what the outdoors means to me. Nature, outside it is all part of daily life. Wyatt and I walk to the bus stop almost every day; we see wild rabbits, squirrels and chickens. We see them so often its almost expected. I am also very fortunate to live in a rural area. This is where I have learnt to spot the animals, watch for patterns and behaviours. Across the road from our house is a gravel pit, this is where we witnessed 2 bears fighting—it was an amazing and unexpected sight. On our trail cams we see elk, deer and many other critters. We love to see the fawns and calves and watch as they grow throughout the summer.

by Jennifer Matson

Our family uses the land for many resources. We pick wild blue berries, saskatoons and huckleberries every year to stock our freezer. We also participate in hunting and fishing to support both our own family as well as our extended family and friends. I was very fortunate to have harvested a bear and a elk my first season to help fill our family freezer and provide food for us. My twin brother also harvests animals to contribute; we don’t harvest more then we need but are thankful for the animals we do. We so spend time on the water as we do on the land, from lake fishing to ocean fishing with our Uncle Mark (our own mad gaffer fishing adventures)— which is a highlight to our summer.

While we are in Prince Rupert, we spend time hiking and watching the tides, looking at the things we don’t see often inland.

My family spends a lot of time talking about conservation both of animals on the mountains and closer to home. We spend a lot of time watching the local elk population, see how the numbers are, how the calves are, and how many predators are around. We like to see them thrive and the habitat support them. We spend a lot of time observing the ungulates and watching the deer play and feed. There is something very calming about watching everything.

There are so many lessons to learn through being outdoors, even if you

just go on a drive. As much as we learn from them, I think they learn about us as well.

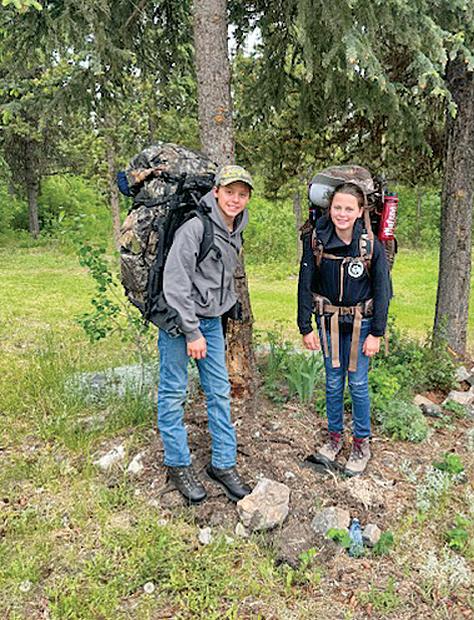

I try to live by the examples my parents and other family have set. For example, if you pack it in you pack it out. I am fortunate to be able to help teach and challenge my friends. My brother Wyatt and I have also been fortunate to participate in some amazing opportunities thanks to this community. I am currently on the count down to the elevate hike with the WSSBC. I travelled to Haida, Gwaii with our Army Cadet Corp.

The amazing people we have met, I feel like some are more family than friends. The hunting and conservation community is so open and welcoming, I love being able to contribute. The passion for the outdoors is amazing. I try to emphasise the importance of getting more people involved even in small ways, but I love to see other women and youth involved. I would be very excited to have the opportunity to go to the WSFA Sheep Camp. To see the sheep in Cadomin Mine would be an unreal experience. This is a place my Papa and Uncle Ty

have told me about, but I have never seen with my own eyes. It would mean a lot personally to me to be able to see the area near where my Papa guided years ago, near where my mom grew up. It would also be a neat experience to meet a group of youth close to my age to connect with about hunting and about nature and the overall outdoor experience. Kids with similar interests for hunting and conservation. I am hoping to be able to contribute more to WSSBC and other groups as I get older. Thank you for the opportunity.

’m perched high on the mountainside in the dark. Some might even call it moronically dark, considering the treacherous hike it took to get there. It’s so early the light isn’t even a promise hanging in the sky. But hey, that’s sheep hunting. The stars are luminous and bring a sense of wonder, the heavens tracking in their perpetual cycle. I feel diminished. Small. Just a mere speck in the infinite. But I’m happy. So I sit. I wait. And I think.

The self-guided California Bighorn hunt I’m on north of Lillooet, British Columbia is considered untraditional these days with civilization crowding in, but it wasn’t always this way. This region was the first in the province to open to sheep hunting back in the 1800s. The lure of gold brought prospectors, and they had to eat. Salmon, deer, and mountain sheep were standard table fare...basically whatever was available became their next meal. Word eventually spread through the hunting community, and over time the first primitive outfitters were guiding deep-pocketed businessmen from the eastern United States and even Europe. Pulling myself back into the moment, I hear the mighty Fraser River rushing below. From my pre-season scouting, I know there’s agricultural land across the river, bordered by a highway, railway tracks, and power lines. Then come the mountains, towering maybe two miles off to the east. “Hope there’s a ram for me in that mess of peaks and valleys,” I mutter to myself. I put my mind at ease by recalling the herds of sheep I’d spotted the evening before while on a short scouting trip after setting up camp. One herd was 11 ewes, lambs, and young rams. The other counted exactly 20. No big rams yet, but with the rut approaching it shouldn’t be long.

The odd car weaves along the distant highway, its headlights carving swaths through the darkness. As the sky slowly brightens, the river’s tumultuous surface begins to sparkle

and dance like a thousand tiny diamonds. Bird song flutes through the receding shadows, and I start to glass. Of course, gazing east through binoculars isn’t exactly a clever way to start the morning, but this is the best vantage point around. The mountains are high, which means I’ll get 60 to 90 minutes of light before the sun crests the peaks making everything virtually invisible through optics. Each minute it gets brighter, and each minute the mountain reveals more detail.

Just as the sun breaks over the ridge and my hopes plummet, I swing the binoculars one last time across the mountains. My heart skips a beat when I count three chunky rams. They’re moving swiftly across a scree slope, almost to the timber, while I fumble with my spotting scope. By the time I’m ready, they’re gone. I inhale the tangy, pine-scented forest air and sit back in amazement. I already know where I’ll be late this afternoon— repositioned directly across the river from where the rams disappeared.

That’ll cut the distance. I’ll even set up my 45-power spotting scope on its heavy, solid tripod. My summer scouting trip had convinced me I’d need to bring out the big guns. It’s nice to be proven right once in a while. By midafternoon, I’m in position up high, gazing across the vista. Earlier, I’d spotted a ewe and lamb down by the river, along with two young rams going walkabout from the river to the distant mountains. They managed to safely navigate the highway, but even from way up here, I heard a car horn echo. Now nothing. The shadow from the high mountains behind me creeps across the flats, a quiet reminder the day is slipping away. “Where did the two bigger herds go? Are they tucked away somewhere I can’t see, or did they move on?” I wonder. I’m curious if anything exciting has joined them. The shadow marches off the flats and begins climbing the far mountains, and before long it passes the spot where I’d seen the three rams earlier. Despite the impending darkness, I keep glassing. Suddenly, there they

are. The trio has moved about a quarter mile and is now in the timber. I quickly get the spotting scope on them. There’s not enough light for precise detail, but I can easily dismiss the first ram—his small body size gives him away. “Oh geez,” I whisper, “Now there’s four rams.” The side views don’t tell me much thanks to the low light. But wait...eventually, they all turn, and I catch glimpses of the other three from behind. Their mass is exciting, one slightly heavier than the others. Then, just like that, it’s dark. Dusk doesn’t linger long when you’re glassing up rams.

“The first day’s in the books...and what a hell of a start,” I murmur. It’s been a good day. I’ve seen rams, even

if it’s still not clear if any are legal. It’s late now, time to head to camp. Perhaps tomorrow will yield the truth. I’d set up base camp a bit out of town at the BC Hydro Seton Lake Campground. In summer, I imagine it’s a zoo, but now, in mid-October, it’s nearly deserted. With staff living onsite, I feel comfortable leaving my gear out. Perfect. Earlier, while driving between spotting areas, I’d loaded the truck with dry firewood. Before the engine has a chance to cool, I’ve unloaded the wood and built a fire. Above all else, I need my campfire time.

Dinner is one of the meals I prepped back home to warm over the fire; comfort food that puts a smile on

your face and a little fat on your gut. I enjoy cooking, but that joy fades fast after a 14-hour day. As I savor the last bite, I lean back and take in the acrid scent of the pine fire. Closing my eyes, I’m enveloped by the fire’s popping and crackling and the soothing sound of the nearby creek burbling along. I’m transported back to my twenties. Every year I’d load up my gear, and Boomer, my Golder Retriever, into the truck, and we’d head out on our own for a long weekend. Hunting, fly-fishing, it didn’t really matter. The point was simply spending time alone. I’ve always believed you need to learn to be comfortable in your own skin before you have room for anyone else. In other words, how can you truly love someone if you don’t even love yourself? I know, I know, such deep thoughts, but that’s what campfire time is for.

My decision to make this a retro hunt is possibly rooted in those past years—those long weekends spent alone. Let’s face it, I’m now on the far side of 60, with two hip replacements and a wonky knee. The warranty’s well past its expiration date. I work hard to stay in great shape, but I’m keenly aware this might be my last sheep hunt. Like most sheep hunters, I’ve got copious amounts of updated gear. But the tent I’ve pitched is one I’ve had for nearly 40 years. It’s survived countless hard miles, like me. I’m not expecting rain in this desert area, so the nostalgia feels a safe bet. Waiting for my weary body inside the tent is the behemoth of a sleeping bag I got as a gift on my

16th birthday. My pack of choice is a heavy old thing from the ’80s. Not quite ‘Trapper Nelson’ old, but getting there. Like most of the gear I’ve brought, except for the optics, it all screams outdated technology. But I want it with me on this final sheep hunt. I’m not exactly sure why... maybe it’s the growing awareness of my own mortality.

Along with reminiscing, campfire time is for planning. The next move would be an easy decision if I wasn’t by myself. The proper way to hunt this area is to have someone glassing from across the Fraser River, while I’m positioned on the east side. But that plan won’t work, at least not yet. I’m alone for the first part of the hunt. My friend Jason Helzel is joining me around Day 6, but that doesn’t help me now. So I’ve got two options: keep glassing from across the river like I’ve been doing or try to find a spot near where the rams were and hope they magically reappear. “I guess I’ll sleep on it,” I murmur to the dying flames. In what only sheep hunters would dare call morning I’m back at it, climbing to the area overlooking where the rams had been feeding. If I can find the right spot in the dark, I’ll hopefully be close. But navigating unfamiliar terrain in the pitch black rarely goes well. I struggle up the steep slope to the railroad tracks, slipping, sliding, and silently cursing. After a couple miles picking my way along the rails—each step stiff-legged and awkward, the tracks forcing that unnatural gait—it’s time to head up. The cut bank looks about right in shape and length. After a steady 30-minute climb, I find a little nest in the dim light. Sitting on a boulder surrounded by pungent sagebrush, I know my scent and movements will be masked.

It’s clear I’ve made the right call as I watch the rams feed their way into view less than 200 yards out. Staying low while sneaking behind the backpack spotting scope, I count only three rams now. They’re in no rush, so I settle in for a good, long look. The first ram is four years old,

lamb-tipped, and legal by a bit. A ¾ curl. The second is the same age but already broomed on both sides and isn’t legal. The third, and largest, is a five-year-old, broomed back evenly on both sides and clearly legal. “Well, how about that?” I ask the sagebrush. The truth is, only a large, old ram will truly tempt me. And who am I kidding? There’s no way I want what might be my last sheep hunt to end so soon. Still, doubts creep in. I was fortunate enough to draw a California Bighorn tag way back when I was in my late twenties—my first sheep hunt, some 40 years ago. Getting two California Bighorn draws in one lifetime is astoundingly lucky, so odds are I’ll never draw another. That thought lingers in the back of my mind, niggling away at me...a bird in the hand, a bird in the hand. Back then, I knew nothing about sheep hunting. Somehow, I still found rams but managed to screw up royally and went home empty handed. I’ll save that story for next time we’re around a campfire, soothed by a dram or two

of whisky. Still stings. Funny how those memories stay etched in your mind the longest. The bird in my hand keeps calling, but I stay strong. I slip out of sight. The rams never knew I was there.

As usual, I wake up ridiculously early the next morning. But something’s different. My body is yelling, “What the hell’s the matter with you? Don’t do that again!” Coming off the mountain after leaving the rams, one moment of inattention had me sliding and rolling a short distance instead of carefully picking my way down. At the time I figured it was no big deal. Funny man. After that inauspicious start, this day, and the next few, devolve into what I call DSS days: didn’t see s**t. Nothing. Absolutely nothing in the areas that traditionally held sheep. “Maybe it’s time for something stronger around the campfire to clear my mind,” I muse. “Sacrificing a few brain cells to the sheep gods might just change my luck.”

The next morning Jason shows up,

and we quickly hatch a plan. I’ve got to say I sure appreciate the company. We decide to take two trucks and split up. I’ll head to the east side, and Jason will work his way to the west. It’s not even properly light out yet when Jason calls. He’s spotted a ram on a knob out in one of the alfalfa fields, chasing a big bunch of ewes. I figure the group of 20 has magically reappeared. Within minutes I’m there, but they’ve already moved on. “Is this just another case of sheep doing what sheep do, disappearing into the earth?” I ask Jason. Turns out they’d dropped back down along the river... and the ram wasn’t a keeper anyways.

Never saw them again.

A couple DSS days later, we catch sight of three rams feeding in the open field, knee-deep in alfalfa under the mid-morning sun. Did I mention this isn’t your traditional sheep hunt? Unfortunately, the rams are in a nohunting area. Today I’m glassing from the west side, while Jason is on the east, so once again I’ve got to careen through town to get to the other side. In the meantime, Jason finds a great vantage point. After joining him, we weigh our options. “It’s 50/50 whether the rams bed down along the river or climb the mountain to the east where I saw rams earlier in the

trip,” I surmise. Jason nods. “The big question is are any of these rams the one?” I take a long look and think it over. Two seem to be legal fiveyear-olds. But the third...he’s at least six or seven, full-curl on one side and broomed back a bit on the other. “There’s a ram I’d be content with. Easily the biggest-bodied one I’ve seen. Makes me think his horns will be proportionally larger too. I bet he’s spent most of his life in the fields, living the easy life. Let’s go for it.”

I can’t get permission to hunt below the highway, so my only option is to climb above the rams and hope for an ambush opportunity to develop. I find a spot about a mile down the highway where I can tuck my truck out of sight, scramble up to the tracks, and attempt that stilted, body jarring run where you hit every second tie. With a mile and a half to go, I can already tell my body won’t be happy in the morning. Forty-five minutes later, I’m in position above the rails at the head of a cut that holds the most sheep tracks. Sitting mostly hidden, I soak in the beauty that only total silence brings. A couple hours pass before one of the younger rams trots across the alfalfa field towards the highway. The other two follow, with Chubby bringing up the rear.

“Well, how about that...this may actually work,” I whisper to myself. Before crossing the highway, the rams disappear from view, and I know I won’t see them again unless they come close. Too many minutes creep by. I hope they’re just held up feeding, but down deep I know the truth: they’re not coming. I wait until dusk before trudging back. Jason’s waiting, and together we deduce the rams likely passed not far to my right. By first light the next morning, the rams are back in the field, having maneuvered down the mountain in the dark. “Okay, no worries. We know the route they’ll take.” Jason smiles and adds, “I think we’ve got them, Bill.” All morning, the rams laze and eat in the warm sunshine, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a little jealous. When they finally move

mid-afternoon, I’m in position at the head of the new draw. But nothing. Later, we figure they passed me again to the right, up a different draw. They clearly didn’t know I was there. Jason even snapped a solid photo of Chubby bedded down maybe 500 yards above me before rejoining his buddies. I wonder, “Am I being paranoid, or is Chubby mocking me?”

We repeat the same routine the next morning. The rams have travelled down the mountain in the dark and are once again relaxing in the same field. The terrain suggests they probably won’t head to my right, so I hide where they came up the day before. But of course, they come up where I’d hidden the day before that. “I’m starting to think we’re stuck in a ‘Three Stooges’ episode,” I tell Jason. He laughs, but I notice he doesn’t disagree. I’ve always believed you make your own luck—that the harder you work, the luckier you get. But after this trip, I’ve amended that line of thinking. For the most part, you make your own luck. Earlier this year, I was blessed to take my best bull elk in decades. It had come way too easily, except for the ‘getting it back to camp’ part. Had I used up my luck for the year? Are we each allotted

only so much? Now those are the kinds of questions best mulled over by the campfire. Anyway, we had a good plan, but in the end no ram.

Never saw them again.

A few days later, my friend Malcolm Bachand drives a couple hours to help us glass, bringing his buddy Nick along to assist. Malcolm has hunted this area for years, back when it used to offer a full-curl open season. “I know of a place that sometimes holds rams near the end of the season,” Malcom says. He explains where, and I reply, “Well, that’s too bad. It’s just outside of my zone, down at the south end.” But Malcom adds, “The rams usually only hang out there briefly before heading down to the big group of ewes that live on the Reserve. They

often cross the creek that marks the boundary to your hunting area, follow the powerline, and drop down to the females.” We’d been seeing those ewes almost daily on the Reserve, so I was more than a little excited about the possibilities. Malcolm and Nick head out to check the area. Within the hour, I get a text: “Rams. Get your butt over here.”

By the time I arrive, Malcolm and Nick already have their scopes out. Jason’s joined them, and now three spotting scopes are pointed high into the distance. Four rams are up feeding and all are very legal. Two of them are massive. I quickly set up, but even though it’s still fairly early, heat waves are already dancing with the image. Just when I think it’s not

going to happen, the largest ram steps into profile and, for a split second, my sightline clears. “Well, Bill,” I think. “You’re done. No other ram will do.”

He’s everything a bighorn in his prime should be—sleek, blocky, and heavily muscled. You can tell he’s the ‘King of Many Mountains’. He stands on a steep hillside in an old burn, facing left, maybe 2000 feet above us and well over a mile away. His far horn, broomed back to the thickness of my wrist, comes awfully close to the bridge of his nose, maybe even up to that line. His left horn, the closer one, is broomed heavily too, but not rounded. The tip comes to a sharp point, looking like a miniature pyramid at the end of the horn. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen that before. The curl drops very low. “Man, now that’s a ram,” I whisper.

All four of us crane our necks and contort our bodies, trying unsuccessfully to get a clear photo through our spotting scopes of this elusive beast high on the mountain. The excitement is palpable, and language colorful, as the rams slowly bed out of sight. The grin on my face couldn’t be knocked off with a stick. We’ve found my ram.

A few hours later, Malcolm and his buddy say their goodbyes and head home. Later that afternoon, much to my surprise, the weather begins to turn. Until now, it hasn’t been a factor, but the sky quickly thickens. I can already tell there won’t be a sunset. The gloom rolls in fast, the sky shifting from gray to black. What had been a refreshing breeze now

cuts straight through to my bones. Leaden clouds scuttle past, creeping lower and lower. The first horizontal raindrops smack Jason and me in the face. Was it just my imagination? Maybe. But I swear the wind howled, forming words: “Stop being a friggin’ moron. Go to town.” Not wanting to get rag-dolled by Mother Nature, I suggest, “How about a pizza back in civilization, Jason? Maybe even a couple motel rooms if things don’t calm down.” The relief on Jason’s face matches the relief I feel climbing into the truck. Twenty-yearold me would’ve greatly appreciated the greasy meat lover’s pizza I wolfed down. Still, I’d say I did the meal justice.

After a comfortable sleep and with full bellies, the next morning on the mountain feels especially grey and wet. Jason and I start by checking the Reserve for the rams. No luck, though a bunch of the ewes are missing. As we continue searching, we notice the wind has died down, leaving slate grey clouds hanging low, in no hurry to move along. The only way we’ll spot the rams—if they’re still there— is if the clouds either blow away or rise at least 1000 feet. We wait all day in vain. The weather is raw and disagreeable. I reluctantly call it, knowing time is running out.

Dawn breaks clear and crisp on the final day of the season. Fall hangs in the air, and the deciduous trees have taken note, their leaves mottled with shades of red, yellow, and bronze.

The evergreens, as always, are too stoic to care. When it’s finally spotting scope light, we find the rams. But now there are ten in total. A couple more are clearly legal, and most importantly, the big guys are still with them. It doesn’t take long before they start milling around, looking for a place to bed. One of the rams curls his upper lip and sniffs the air, as rams do. The others follow suit, facing west instead of north, the direction I need them to go. Then they’re off, racing downhill toward the timberline, not the powerline. Within minutes, they vanish from sight, likely drawn by the scent

of the missing ewes hidden somewhere near the creek winding through the finger of timber. For what feels like centuries, I just stand and stare.

Never saw them again.

You never know where the trapdoors are in life. For me, one was applying for a sheep tag early on...and getting it. Sheep hunting and sheep conservation became a big part of my life. Though I didn’t take a ram on this hunt, I’d still call it a great success. After all, how often do you get to lay eyes on a ram you know would rank high in the record books? And how often do you get to go on a final sheep hunt? Even though my face is wrinkled and rutted by laughter, time, and the sun, I’m content. I’ve travelled a long road, and I know now: you can’t recapture youth with retro gear. Truth be told, I wouldn’t want to. Those years are gone, and that’s okay. What remains are the memories made on the mountains, and the lifetime of friendships forged along the way—things no amount of time can take away.

There are tears in my eyes. I may never see rams again.

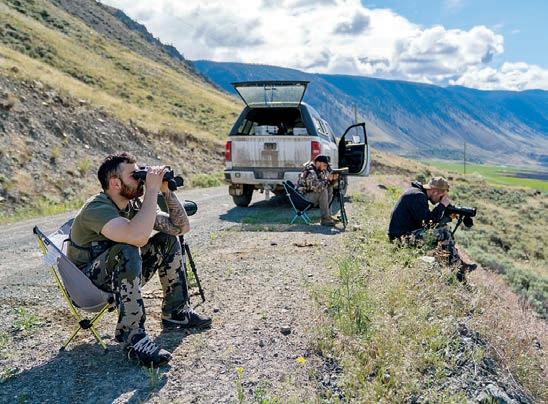

s we roll into the summer months, our WSSBC family continues to grow in numbers while providing increased opportunities for those interested in helping with on-the-ground work for the wild sheep in our province. We recently conducted the first of three sheep counts out on the majestic Fraser River and while it was a wet day, over 20 volunteers had a great time outside, sharing tales around the campfire after a day of searching for California Bighorns. The next two counts will be taking place in July and August so if you have any interest, please reach out to WSSBC Director Greg Nalleweg at greg@ nextgenelectrical.ca to get involved!

In the Okanagan, we are continuing our work on the fight against Psoroptic Mange at the sheep pens in Penticton. There is ample opportunity for volunteer involvement with this project, or simply for a visit. Please reach out to WSSBC Director Peter Gutsche at petergutsche@gmail.com or on Instagram at the @okanaganbighorns account.

With our increased focus on promoting youth initiatives, WSSBC Vice-President Chris Barker recently attended the “Hell Hole” archery shoot in Duncan, BC put on by the Cowichan Bowmen. WSSBC helped to sponsor this event, which held youth specific challenges. It was great to meet new people and grow our collective conservation family.

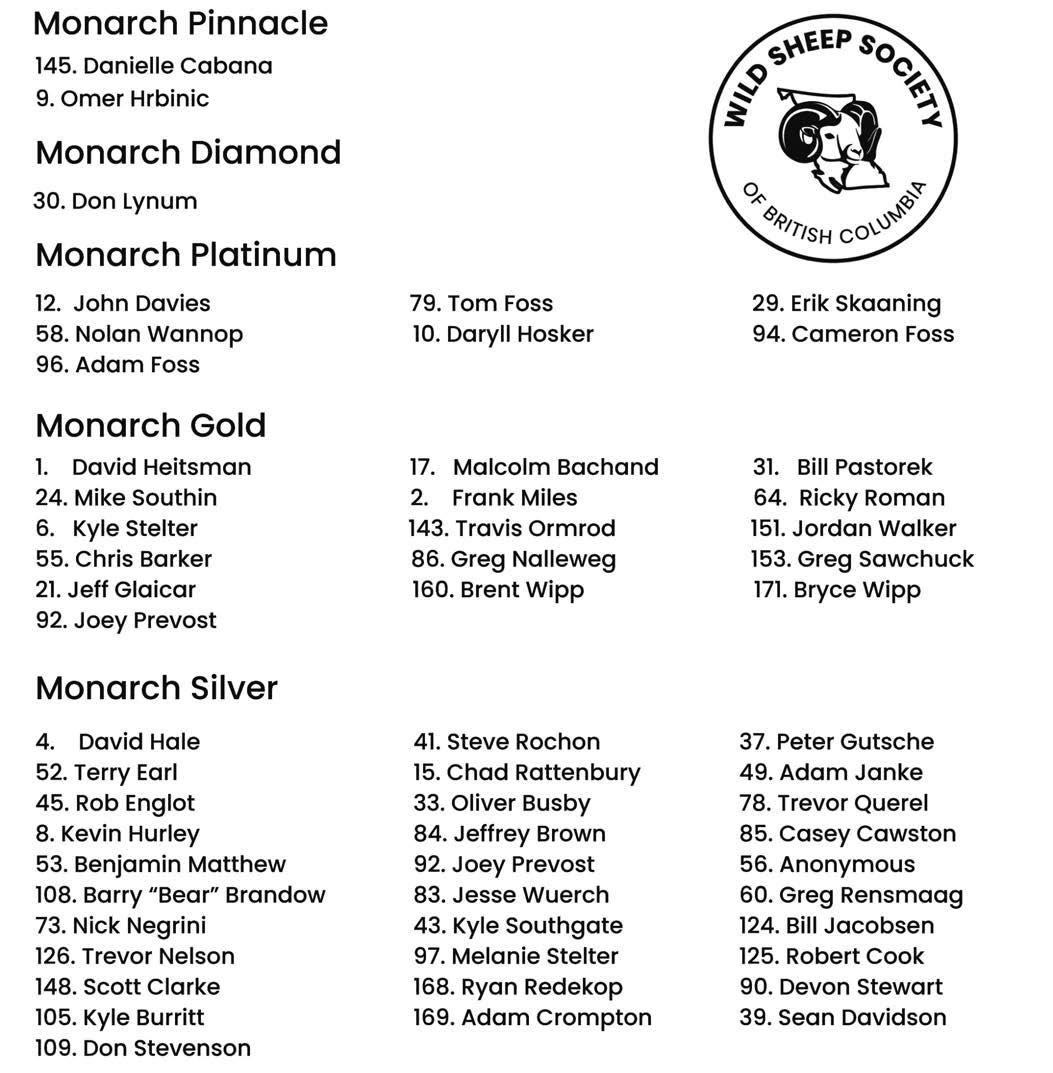

We are currently sitting at 1641 active members, with 881 Life, 187 Monarch, and 26 Half Curl’s respectively. As we continue to march towards our goal of hitting 2000 we are offering a referral program with a full day sturgeon fishing trip for four people with Streamline Guiding as our grand prize. All you need to do as an active member is have your friend or family member enter your name as a referee when they join and you will both be entered for this amazing prize. There is no limit to how many entries a person may receive. We will be running this promotion until December 31, 2025 or until we hit 2000 members.

For our Life and Monarch members, we have a couple of amazing prizes up for grabs. For those of you upgrading to a Life Membership, you will be entered to win a Fierce CT Rage in 7PRC. For those upgrading in the Monarch tiers, you will receive one entry for every $100 contribution towards a Gunwerks ClymR package in 300PRC. We will be drawing both of these prizes at our Life Member Breakfast at next year’s Salute to Conservation taking place in Penticton.

We can’t thank you enough for your continued support.

WSSBC Volunteer Opportunities & Events: https://www.wildsheepsociety.com/volunteer/

July 4-6, 2025 – Ruck for the Shulaps, with Matt Ward

July 5, 2025 – Horn Aging Seminar, Comox

July 5, 2025 – Horn Aging Seminar, Ft. St. John

July 8, 2025 – Horn Aging Seminar, Abbotsford

July 12, 2025 - Horn Aging Seminar, Cranbrook

July 12, 2025 – Fraser River Sheep Counts

July 20, 2024 – Horn Aging Seminar, Prince George

August 9, 2025 – Fraser River Sheep Counts

August 22-25, 2025 – Wild Sheep Jurassic Classic, Chilliwack

January 30-31, 2026 – Northern Fundraiser, Dawson Creek

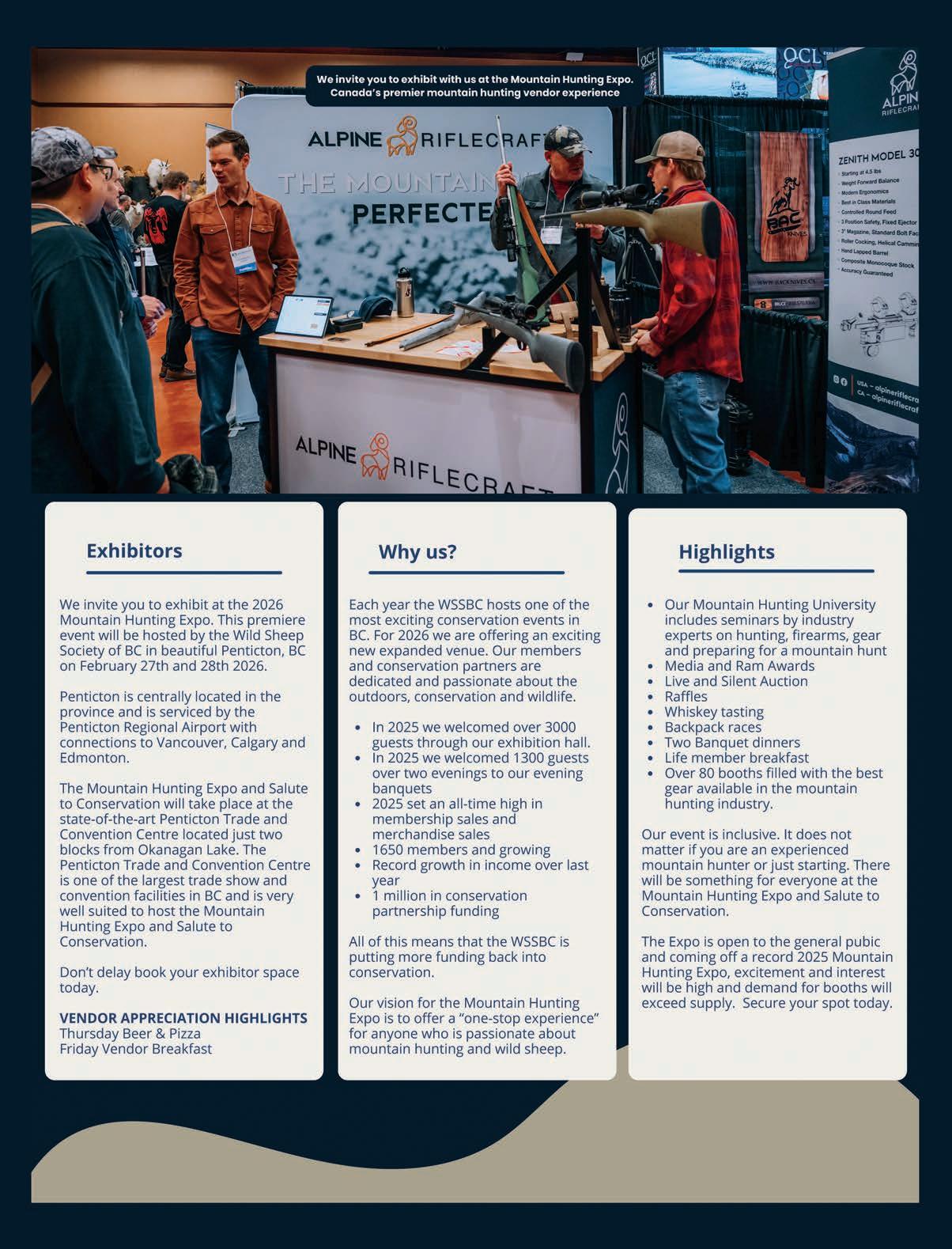

February 26-28, 2026 – Salute To Conservation and Mountain Hunting Expo, Penticton

ummer 2023 and British Columbia is on fire. From April until August 16th, over 1800 wildfires had burned over 1.61 million hectares (4 million acres) and there was no reprieve in sight. My hunting partner Scott Landale and I had checked our spot, and it didn’t appear to be burning so we still planned to leave on the 19th from the Southern Interior city of Kelowna for the 2 day trek North. August 17th changed our plans. A small fired that was spotted above West Kelowna, a city of 40,000 across the Okanagan Lake, had turned into a raging category 5-6 forest fire fanned by high winds and extreme heat. Hundreds of firefighters with air support fought but as night fell there was little that could be done. Thousands were evacuated as the fire ripped down the mountain taking everything in its wake. Living on the other side of the lake we felt relatively safe as the 3 kilometres of water should be a large enough break; we were wrong. At 8 pm that night, the fire jumped the lake into a wooded area and was now exploding in the suburbs. As I sat in my office the next morning processing what was going on, I could see the fire crest the hill less than 2 kilometres in the distance right adjacent to subdivisions—it was not looking good. We made the decision to call off the next morning’s

departure and play it day by day. By daybreak it was estimated that over 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) had been burnt and over 70 homes and structures lost.

Fortunately for us, by the 19th the winds were calm, the weather cooled, and over 500 firefighters from across BC were on site. After a good discussion with our families, we felt confident enough that we would be able to head out the morning of the 21st, which we did, and nothing eventful happened as we exited cell service 2 days later.

After 2 days of driving, and a lengthy jetboat ride, we made it to our trailhead just before sunset which allowed us to have a bite to eat and get rested up for the next day’s pack in. The weather was warm and clear, we departed early to get a good start while the temperature was relatively cool. The previous year we spent hours clearing deadfall and overgrowth on an old trail which made the going definitely easier in spots but the darn bog birch and willow relentlessly pulled at us as we pushed our way up. After 7 hours and 3000 feet we finally broke timber, filled up extra water and made the final 500 ft at 45-degree incline push. The heat and the strain took its toll on my 54-year-old body. I was beyond exhausted but we made base camp and were able to get some muchneeded rest.

Having hunted this range for the past 2 years we had a solid idea of where the rams could be and ultimately what we had to do if they did not turn up. The next 2 days we scoured every nook and cranny but nothing but a few ewes. Our inclination was the sheep were holed up in the next ridge as that is where we previously spotted rams first. The decision was made to pack up the next morning and make the trek.

As we packed up camp the next morning, leaving one tent behind with some excess supplies in it, Scott came to me, “do you hear that?”

“Here what?” I replied.

“In the brush about 40 yards over there you can see the shrub moving and hear some grunting, I think it’s a bear.”

I listen intensely and sure enough I could hear some grunting and see the brush moving, “It’s probably just a caribou, sound like one.”

I really hadn’t convinced myself of what it really was but didn’t want to sound the alarm bells just yet; that was probably not the best decision as we would later come back to a pile of bear scat in the camp. Thankfully upon return everything was left untouched.

Having never explored the other range, we had no idea if there would be water, so we made the 5 hour journey to the top peak with 4 days of food and 14 extra litres of water, adding over 15 pounds to each of our packs. We wanted the ability to stay on top for at least 3 days so if we were

not too active a couple of litres per day each should keep us going. The hike was worth it; the terrain looked fantastic, but fantastic terrain does not always turn into rams. That first evening and for 3 hours in the morning was spent glassing from camp but turned up nothing but ewes. We looked at the closest peak, which was only about 1 kilometre away, and decided to grab some basics, about ½ litre of water each, and have a quick look. I hate losing elevation, but we had to drop down 500 feet to a saddle then up another 700 on a shaly slope which took us over an hour of scaling our way. As the wind howled, which it always seems to, we glassed for a few minutes but nothing popped out, so I slid down to a small ridge to get a better vantage of the slopes below. Glassing below I picked up movement on the timber line 1800 feet below; 3 rams. I quickly scrambled up to grab my spotter to get a better look, but the unrelenting wind prevented any stability. We picked up 5 more rams in the drainage, we needed to get in closer and get out of the wind to determine if there was a shooter. Dropping elevation and peering over ridges after ridge we could not locate the rams. At the halfway mark I looked back and shook my head, we were a long way down from camp and I was not convinced there was a good ram. Scott could tell I was uncertain. “One looked like it had good mass,” he said.

I thought for a moment, “well this maybe our one opportunity and we have come so far so we better be certain.”

Down we went, further and further

until we got to the point where I thought we would be on their laps. We side-hilled along a ridge covered in bog birch, my favourite, and we glassed carefully. I saw a single horn, that was it, 100 yard below and I froze. He was bedded in thick shrub and all that was sticking out was this left horn. My thought was that the other rams were hidden as well, one wrong move and we would bust them out. This ram was young—only 5—so no sense looking at him anymore. We held tight to survey the situation to see if we could pick up the others, but all was still. Packs slid off our backs and I sneaked ahead about 20 yards when motion below caught my attention. I whispered to Scott to grab the spotter and the rifle to be prepared just in case.

I sat partially hidden with Scott behind and slightly up. The young ram got up and looked up at us as he knew something was out of place. With binoculars in hand and using a tripod as rest I remained motionless as he inspected us, moving his head side to side in a curious manner. He finally put his head down and I was able to pick up the ram where I saw the motion previously. He was bedded under a small pine and seemed promising, but I couldn’t get a clear look. He stood up, adjusted his position and by the look this one had potential.

The 5-year-old locked on us again and I realized that my perch was on top of an ant hill, they were crawling all over me. I was pinned down again looking though my binoculars as my skin crawled with these annoying insects. It was almost unbearable as I

was getting bitten; Scott laughed later as he could see them going up my neck and under my hat—I didn’t find it very amusing at the time.

For an hour and a half I endured the little creatures, then the target ram stood up for a stretch. At less than 100 yards I was able to get a great look— decent length; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 annuli. This was a nice ram and like the one I took the previous year, exactly what Scott was looking for. There was motion beside him, I picked up another horn under the tree... this one had mass! He lifted his head out of the brush for a brief second and my heart picked up a beat. He was heavy, broomed, undoubtably 8, and a fantastic full curl—reminded me of a bighorn. I had told Scott that I wouldn’t shoot one unless he made my eyes pop—they popped.

I whispered back, “Hand me the gun, I’m going to take that ram!”

The ram swiftly bedded back down. I removed my binoculars from my tripod and set it up the height to have a steady rest for my rifle. Within minutes the ram rose and there was no hesitation; the crack of the 300 WSM filled the air, there was the unmistakable smack as the bullet found its mark. He took a few steps and tilted over out of sight.

We remained silent and slowly I handed the gun to Scott. I knew taking a second ram in this location would not be a wise decision but there was no way I could deny him should the opportunity present. The rams did not go far, we moved ever so slowly trying to pick them up. As experience has taught me, when you take a lead ram out the others will rarely go far

and as long as you remain silent and out of sight you will have ample opportunity to pick them up again. Working along the brush covered ridge we could see a younger ram approaching where the ram had fallen. He stopped for a moment and looked down at the now still ram, trying to make sense as to what had transpired and why he was not leading the band—it was a very surreal experience. This is a glaring testimony as to why it is a hunter’s responsibility to take older rams. The younger ram needs the experience of the older rams to teach them how to get to be an old sheep. In BC, a Stone Sheep is legal by either being full curl with the horn breaking the bridge of the nose or 8 years old as defined by 8 visible annuli. Younger 6- and 7-year-old rams may be legal by curl, but I believe whenever possible these sheep should be left. 8 years old plus and the greater the age the superior the trophy, no matter the horn size.

We pressed forward through the bog birch, and we picked up the other 9-year-old ram, but he was in tight with 3 other rams and there was no shot opportunity. They went over into the ravine never to be seen again. I felt remorseful but also very thankful at the same time. I know how badly

wanted to shoot a ram and if it wasn’t for my jaw dropping, he absolutely would have.

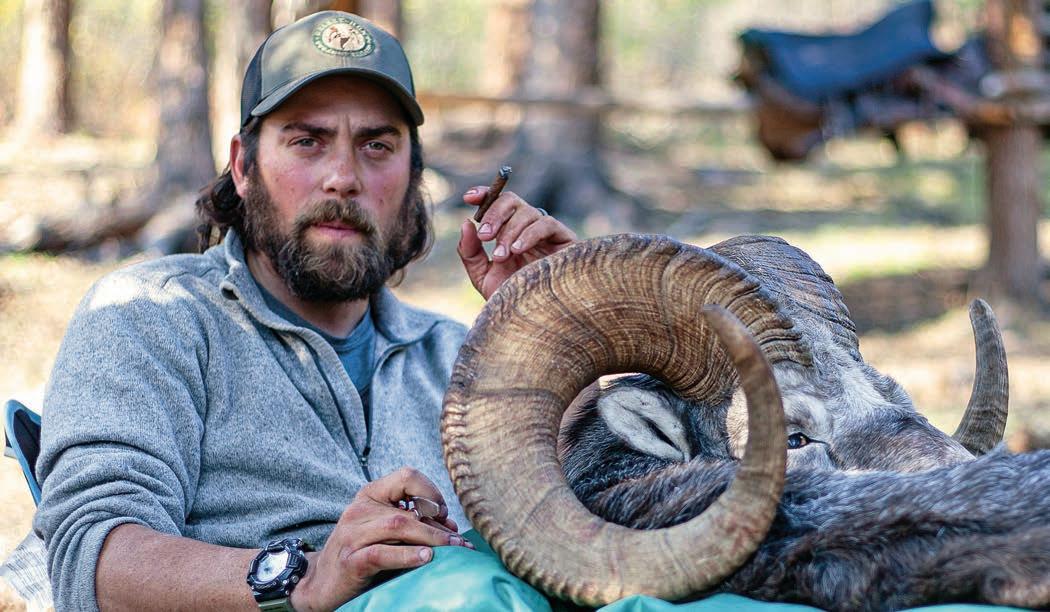

A short search of the brush and we found the ram—there was no ground shrinkage—an absolute beauty in the eye of beholder. He was a tight curled 8-year-old and would later measure out at 34 inch in length and 14 ½ inch bases. I cut the tag, took some photos, and found the shade of a tree to have a rest before all the work began.

“What time do you think it is?” I was asked... “3?”... “try 6 pm.”

In all the excitement I guess we lost track of time. Both dehydrated from the heat and lack of water we knew the next few hours were not going to be much fun. We both reflected back, and it was a blessing we didn’t find that other ram in a shootable position. I made swift work with the knife, deboning and caping out. By 7 pm we were loaded down and looking up at the ominous 1800 ft climb we were about to embark. Still feeling the effects from the previous days trek and dehydrated, we trudged praying the waterhole we saw earlier would be relatively clean. Some 2 hours later with the sun now just set, we found the waterhole and it looked spectacular. A quick fill up, added the emergency tablets and set my alarm

for 35 minutes. I got Giardia 2 years prior so was not taking any chances. For the next 35 minutes we side hilled on a barely visible sheep trail until the alarm went off; that chemical smelling water never tasted so good! In short order we made it to the saddle where we had a steep 600 ft vertical climb to make to camp. I looked at Scott and he had hit the wall and I was not far behind.

“Lets drop the meat and the horns, we can get it in the morning.”

There was no argument, we were cooked. A short rest, put the headlamps on and we crawled our way up the final stretch, arriving at 10:30 pm— some 3 ½ hours after we started. It was a quick bite of bagged food and an exhausted slither into the tent.

Fortunately nothing touched the sheep during the night, a welcome relief as we had seen fresh Grizzly sign. A couple of hours round trip and we were back at spike camp fleshing the cape and gathering our gear for the pack back to base camp. We hit the trail at 2 pm in the heat of the day and it was hot. We made the 1400 ft drop to the saddle below and looked ahead at the 1200 ft climb we had ahead. With 80-90 pound packs, this was not going to be much fun considering our deteriorating condition.

Scott

The heat was taking its toll and Scott determined it would be a great idea to strip off his hunting pants and go in underwear... best suggestion of the day! It must have been quite the scene with two men loaded down with hunting packs and wearing no pants. On the range we had noticed several trail cameras set up on poles and assumed there was a research project being conducted on Stone sheep. We had been careful to avoid them as we really didn’t want to give our location up. I had been laughing with Scott about me stripping down to nothing, covering my face and walking by butt naked; I am sure that would have raised some eyebrows! We didn’t go that far but instead walked by with loaded packs in our underwear, but

still covered our faces for safe measure.

We made it to base before sunset, put the meat in a small spring to keep cool (and yes put pants back on), and surveyed the skies—That was a bit of a “oh crap” moment.

BC was not just on fire in the South, it seemed every corner of the province was. As we looked across the drainage there was a massive mushroom cloud, and we could see smoke rising in the general direction of where we had to boat though. The original plan was to take a day off and rest up for the final push—this quickly changed. The thought of jetting though a fire was not very appealing if even possible. Day 7 was the final push. We packed up early to make the 3500 ft drop

coming out heavy. By late afternoon we made the river and wasted no time getting the jetboat on step and hammering down the river. We could see smoke billowing in the distance and anxiously cruised along anticipating the worst and hoping for the best. A stroke of good fortune as the normally prevailing winds had changed direction and as we approached the smoke we could, it was blowing away from the bank; and thank goodness as when we passed the fire it was less than ½ mile from the bank. If the winds had not changed I firmly believe we would have been trapped.

It was an eventful trip and without question the most physically demanding hunt to date.

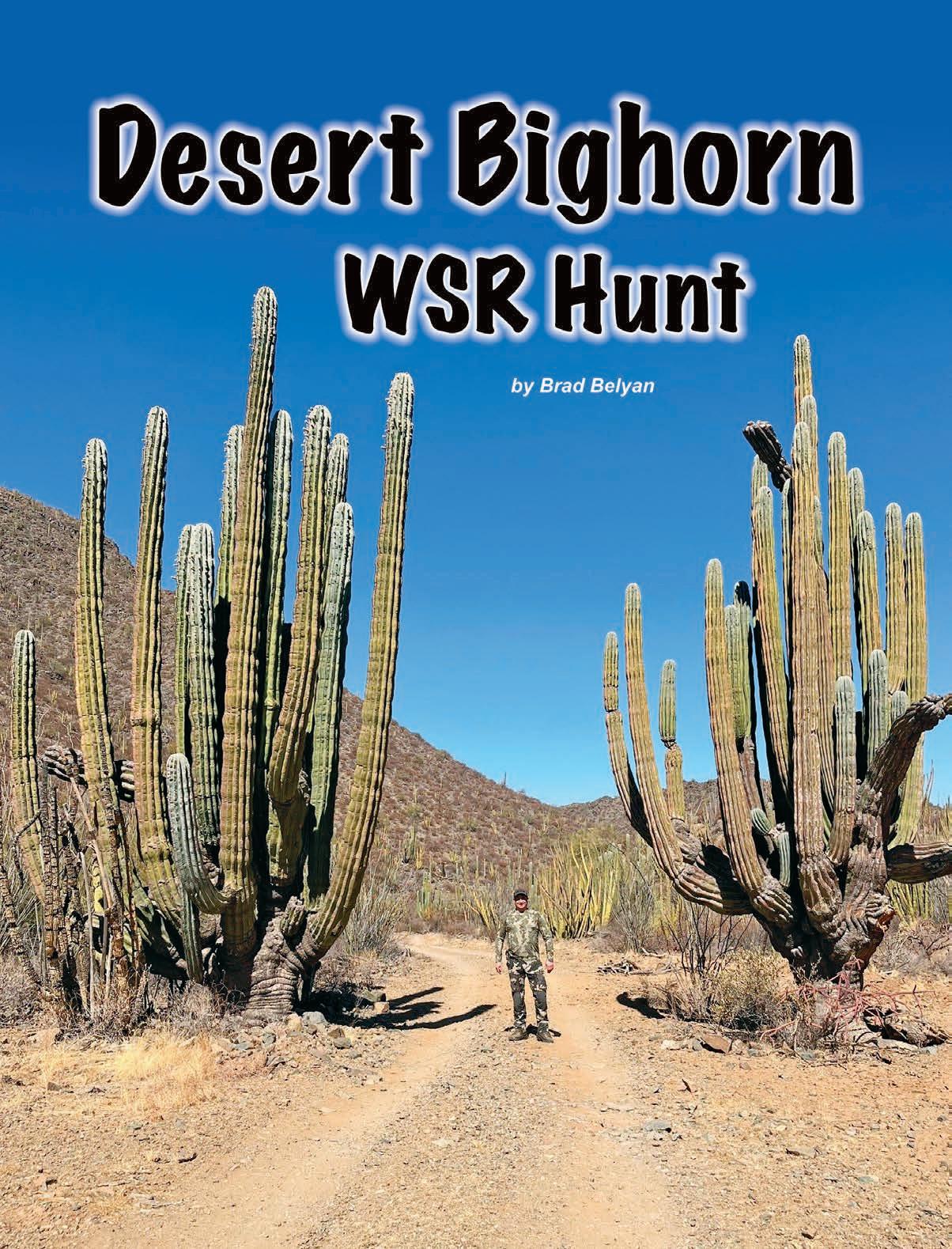

n March 23, 2024, I received an unforgettable phone call from the Wild Sheep Society of British Columbia. They informed me that I had won the hunt of a lifetime, a Desert Sheep hunt with Alcampo in Sierra El Alamo, located in the stunning Sonoran Desert of Mexico. Excitement filled the months leading up to the trip, and on February 28, 2025, I finally set off on this incredible 7 day adventure. Even more special, I had the opportunity to share the experience with Ken, the 2023 winner from Houston, BC.

From the moment we arrived, it was clear that this would be an extraordinary hunt. The guides were not only highly skilled and knowledgeable but had also dedicated immense effort to transforming Sierra El Alamo into a thriving ecosystem. Their work in managing this vast 94,000-acre expanse ensured that all forms of wildlife flourished, a testament to their deep passion for conservation and sustainable hunting. Seeing firsthand how they singlehandedly created an environment where wildlife thrives was truly inspiring.

The experience was further enriched by the incredible accommodations. We stayed in a

200-year-old lodge that once served as a mining camp, adding a historical charm to the adventure. The food was nothing short of phenomenal— ceviche, pork, sheep, beef—each meal was a feast that added to the richness of the trip.

Each day brought new challenges and excitement, from scouting the rugged terrain to tracking these majestic rams. Both Ken and I were fortunate to harvest magnificent rams, each a symbol of the dedication and perseverance required in such an endeavor. In a fitting and memorable moment, I took my ram while a cholla cactus was painfully embedded in my calf—an experience that only added to the adventure’s authenticity and will forever be etched in my memory.

Beyond the hunt itself, this journey was about more than just the pursuit of a trophy. It was a testament to the importance of conservation, the dedication of those who work tirelessly to preserve wildlife, and the camaraderie that forms between hunters who share a deep respect for nature. The memories, the challenges, and the breathtaking landscapes will stay with me forever.

This was truly an experience of a lifetime, one I will cherish forever. Thank you, WSSBC, for making this dream a reality!

by Rebecca Peters, Chair – Women Shaping Conservation

im for Impact, a women’s shooting event co-hosted with the Abbotsford Fish and Game Club (AFGC) and Women Shaping Conservation (WSC) under the Wild Sheep Society of BC (WSSBC), brought together over two dozen women of varying backgrounds, ages, and experience levels for a full day of hands-on firearms training, mentorship, and connection.

With generous sponsorship from AFGC, WSSBC, Silvercore, Reliable Gun, and donations from Kuiu and Mystery Ranch, this unique event offered women a chance to break through comfort zones, develop new skills, and a deeper sense of personal agency in the outdoors. The response was overwhelmingly positive, with many women calling it one of the most

impactful days they’ve experienced, both literally and figuratively.

The roots of ‘Aim for Impact’ grew from a common realization: while more women are showing interest in conservation, outdoors and hunting, and shooting sports, there are still barriers, both real and perceived that keep many from taking the first step. Some feel intimidated walking into a gun range for the first time. Others don’t know where to begin. Many simply need a space that feels safe, supportive, and judgment-free. This event was designed to be exactly that.

Participants were invited to rotate through three core shooting disciplines: shotgun, handgun, and rifle. Each station was led by experienced instructors and range officers from Silvercore, Reliable Gun and AFGC, who volunteered their time and expertise to

ensure that safety, education, and encouragement were at the forefront.

For many women, this was their first time holding or firing a firearm. One participant summed it up beautifully: “I walked in feeling nervous and unsure. I walked out with confidence, a sense of control, and a deep respect for the skills involved.”

Before the first shot was fired, safety briefings and demonstrations were conducted at each range. Women learned about firearm handling, safe loading and unloading practices, body positioning, stance, recoil management, and what to do in case of a firearm malfunction. The instructors were patient, approachable, and knowledgeable qualities that made a significant impact on those who were new to the shooting world.

Lindsay Lynum, a first-time attendee, shared this reflection: “I attended Aim for Impact not really knowing what to expect, as it was my first time ever going to any sort of women and shooting event. I was nervous. But after meeting the women from WSC and WSSBC, and the instructors from Silvercore, Reliable Gun and AFGC, my nerves started to calm down. Everyone was so knowledgeable and kind it made for a great experience. I learned about body mechanics, firearm safety, loading and unloading, and how to deal with a jam. I felt so empowered. It was such a positive experience, and I highly recommend it to any woman who wants to gain confidence and have fun while shooting.”

Lindsay’s story wasn’t unique. Many women echoed her sentiments,

noting that being in a group of all women made a significant difference. It allowed them to feel more comfortable asking questions, more willing to try something new, and less intimidated to make mistakes, something we often forget is part of the learning process. Midday, participants gathered for a hot lunch provided by WSC and AFGC, where the real magic of the event began to take shape: the conversations. Women shared stories of how they got into hunting and the outdoors, what drew them to firearms training, or how they were interested in conservation work but didn’t know where to start. These peer-to-peer exchanges often become the seeds of mentorship and long-lasting connection, especially in spaces where women are still forging their place.

After lunch, a series of door prizes were drawn, generously donated by Silvercore, Reliable Gun, AFGC, WSSBC, WSC, Kuiu and Mystery Ranch. Every woman walked away with something but more importantly, they left with a renewed sense of purpose, possibility, and confidence.

Following the event, WSC gathered feedback to help improve future programming. A resounding message emerged: do more of this.

Women wanted more access to firearm training. More space to build friendships in the conservation community. More opportunities to learn, connect, and challenge themselves. And more events that prioritize education and confidencebuilding over competition or performance.

One attendee noted: “I’ve always

wanted to learn how to handle a gun properly, but I didn’t know where to go that wouldn’t feel intimidating. This was the perfect introduction. Please host more!”

Another shared: “Being surrounded by supportive women who are passionate about conservation and learning was incredibly refreshing. I would attend this event again in a heartbeat.”

It’s easy to think of shooting sports and conservation as separate interests, but in truth, they’re closely linked. Understanding how to safely and ethically handle a firearm is an essential step for women who want to get involved in hunting, wildlife management, or stewardship work. When women build confidence around these skills, they’re more likely to step into leadership roles, volunteer for conservation projects, mentor others, or even harvest their

own wild game. Events like Aim for Impact are more than just a day on the range they are catalysts for long-term engagement, learning, and advocacy.

None of this would have been possible without the vision and support of our partners and sponsors. Thank you to: Abbotsford Fish and Game Club, Silvercore, Reliable Gun and Wild Sheep Society of BC.

Your collective efforts are helping build a more inclusive, skilled, and confident generation of women in the outdoors.

Aim for Impact is just one of many events we’re hosting in 2025. Women Shaping Conservation continues to grow thanks to the energy, curiosity, and courage of the women who show up and the organizations who stand beside them.

If this was your first WSC event, welcome. If you’ve been part of our movement from the beginning, thank you for continuing to lead the way.

Let’s keep shaping conservation together!

by Nolan Osborne

“If

I’ve learned one thing in 40 years of seeking the majestic wild ram, it is that hunting him is not a privilege to be taken lightly.” – Jack O’Connor.

firmly believe that there’s never been a time in the history of hunting wild sheep that learning to age rams and select for maturity correctly has been more critical than now. That’s not to say that all is doomed and we are in dire straits regarding sheep herds, but anyone who has been around long enough will tell you that our numbers aren’t what they once were, and sheep hunting has never been more popular. Aging rams can be contentious in practice. Age disputes between friends, guides, compulsory inspectors, and biologists happen regularly. Knowledge is sometimes guarded, and incorrect information or false confidence can lead to seasons like 2021, when the BC Conservation Officer Service seized an alarming

number of illegal rams. Despite my sentiments regarding BC’s thinhorn full curl regulations and cautions against age-based harvest, there is a good reason they advise against harvesting based solely on age. Many sheep hunters don’t have the experience to make a sound judgment call.

Accurately aging sheep is a skill developed through repetition - there is no short way around it, or special cheat. The more rams you see in the field, the more you put your hands on and confirm true annuli, the easier it will become. Pictures on Instagram are a helpful way to spark conversation, but they do not substitute real-world experience. Heat waves, spotter shake in the wind, a feeding ram’s movement, and changing light conditions cannot be replicated from the comfort of your home.

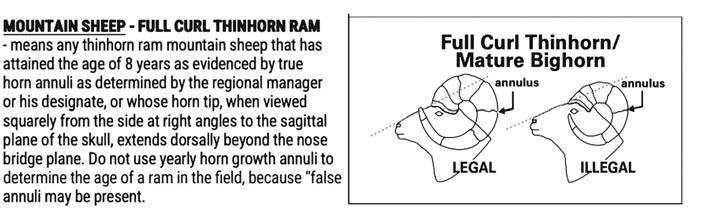

The Regulations

It is essential to understand and acknowledge that in British Columbia, the regulations are the final determination of the legality of harvested thinhorn sheep. Regardless of what you, your hunting partner, or some guide on the internet says about a ram, the province will determine legality based on the guidelines in the regulations. A key line in the regulations states, “8 years of age as evidenced by true horn annuli as determined by the regional manager or his designate.” Human variability can always be a factor at play, and while many of our provincial biologists are experienced professionals and sheep hunters, not every Compulsory Inspector is.

Harvesting “short” rams on age alone is not a practice I am advocating for unless

Photo: Lorne Trousdell

you are a very experienced sheep hunter willing to err on the side of caution and walk away from rams you aren’t 100% certain about. The only way to be absolutely sure that you are harvesting a legal ram is to be selective and take full curl rams. As much as I feel that full curl regulations can reduce genetic potential and are a contributing factor to many “immature” rams being taken annually, we must adhere to the rules. This article aims to help you find the oldest ram on the mountain that meets legal requirements, and not embolden you to roll the dice on a broomed ram.

Every full-curl thinhorn is a legal ram—and therefore “fair game”— though I cannot stress enough the importance of being selective and passing on young rams. I firmly believe that our province’s regulations are designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator, and as avid sheep hunters and conservationists, we need to lead by example. There has never been more external pressure for the young mountain hunter to come home successful, and yet there’s never been a time that it mattered more to leave our up-and-coming sheep on the mountain. Those six- and seven-yearold full-curl rams are the future of our wild sheep, the most likely to survive the winter and pass on their genetics. Left to thrive, they carry the seed of our conservation efforts forward into the next generation of wild sheep. One that our children and grandchildren can grow to see wild, as they always have been, and as our forebearers once experienced them.

Taking a mature ram is a far greater achievement than just taking a ram—an achievement we should strive towards and celebrate. There is a small but present percentage of sheep hunters who are all about numbers, with the

mindset that they must come home every trip successful, regardless of the age of the ram they punch their tag on. I find this behaviour abhorrent and antithetical to the conservation values of organizations like the Wild Sheep Society of BC and the greater family of sheep hunters. While many successful and seasoned sheep hunters take to the hills annually, searching for that ram that is older, or something special, it is the ones who continue to harvest young rams well into their sheep hunting career that will ruin it for the rest of us. While legal is legal, if we want to maintain our herds and their genetic quality, we must cull and admonish this behaviour for our future as sheep hunters, and the future of wild sheep.

Common Mistakes

When I worked for the Journal of Mountain Hunting, we ran several podcasts that covered aging sheep and the importance of targeting mature rams—It’s a topic that I’ve been quite outspoken about. At the same time, we would receive messages and images from listeners and young sheep hunters, asking for my opinion on a ram’s age they believed was eight when they pulled the trigger. Yet, the compulsory inspection gave them seven, or even sometimes six.

One of the mistakes new sheep hunters make when aging rams is trying to make a ram eight years old. I get it... Sheep hunting is hard work. You’ve likely trained all year, prepped your gear, booked your time off work, and maybe even paid for a costly charter flight. Sheep hunting can be an emotional roller coaster. When you are finally lying a couple hundred yards from a band of rams, every bit of your being wants to find eight or more rings etched into the lead ram’s horns. But this is where the problem lies.

Anyone who has sat in a whitetail stand hours before daybreak understands how well our brains can trick us into seeing what we want to be there. The movement on the treeline 100 yards away that you swore in the pre-dawn haze was a buck’s ear flickering, which turns out to be a leaf twitching sporadically in the wind. The same happens with sheep—you stare through the shimmering heat waves in your spotter for long enough to believe that false rings are real rings, and there just MUST be one more at the hairline. While it may seem self-explanatory, counting what’s clearly there and not trying to “make” a ram eight is a mental shift that will save you a ton of headaches initially. With more time and experience, you’ll likely pick up on more subtle cues that give away a young ram; however, until you reach that point, focus on gathering data, rather than trying to create it.

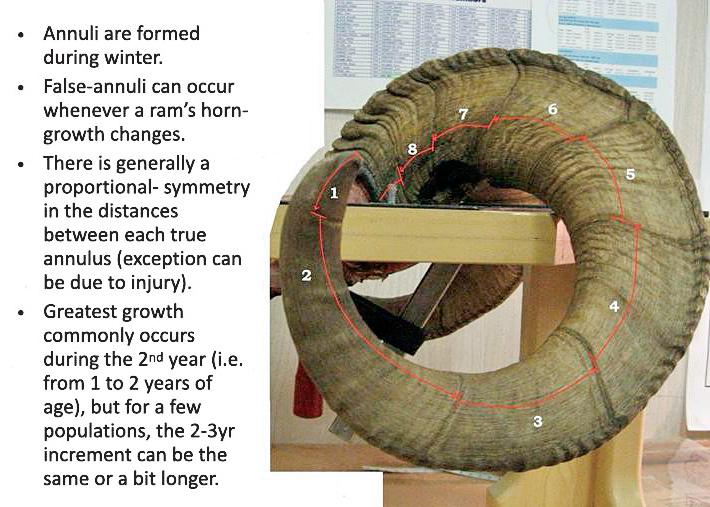

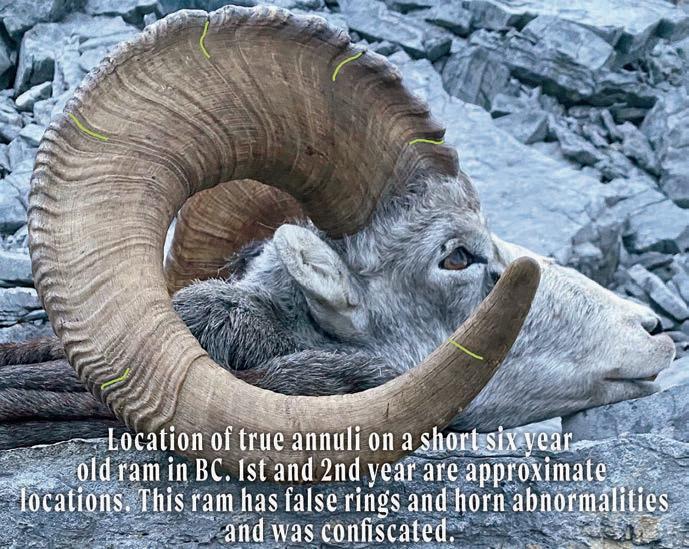

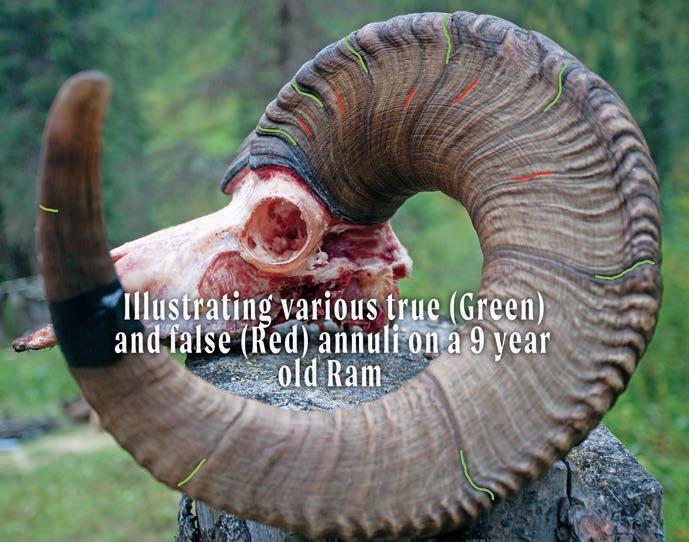

False Annuli

Annuli, like the rings of a tree, are formed during winter, when the nutrition in the feed available to sheep is low and stress on the body is high. “Annual horn growth often results in consistent patterns of growth, and because they are a secondary sexual characteristic, growth can be affected by nutritional intake, individual fitness, genetics, and seasonality.” (A Guide to Understanding Thinhorn Sheep Aging, Ministry) True annuli are well-defined lines that break the longitudinal growth strands or lines in the horn, and are generally formed with proportional symmetry to each other. What this means in terms of growth is that typically, the first-to-second-year or second-to-third-year growth, dependent on region, will be the largest, and each year after will be incrementally and proportionally smaller. Rams that have suffered an injury may be an exception to this rule; however, if you adhere to this—only counting annuli that follow the proportional symmetry—it’s tough to over-estimate the age of a ram in the field. I have underestimated the age of rams before, and if you’re going to be wrong on age, that’s how you want do to it.

Counting false annuli as true rings is likely the number one culprit of mis-aged rams, coupled with a hunter’s desire for that ram to be eight years old. False annuli are those sneaky little lines that, to the untrained eye, appear to be true annuli. They appear as ridges

on the horn, often darker in colour. These typically do not extend across the front and rear surface of the horn, and they do not create a true separation in the longitudinal horn growth. From a distance, in a spotter, some may even appear as dark and convincing as true annuli. Still, the key here is remembering the notion of proportional symmetry—horn growth that gradually and consistently decreases in length

with every year. If you see a “ring” that breaks this pattern of incrementally smaller growth, it’s almost always going to be a false annuli, so treat it as such. Some rams have few, if any, false annuli; others may have many. As with horn coloration and growth, there is a wide array of possibilities—if you focus on finding that proportionally symmetrical pattern of horn growth and discounting anything that strays from that pattern, you are going to set yourself up for success in the field. Sheep hunting is a marathon, not a race, and so are the skills that are built with it. Over time, you will begin to see these patterns and quickly recognize what true and false annuli are, even from a distance.

One in the Hairline

Second to incorrectly counting false rings, believing that there will be an extra ring in the hairline is one of the top reasons people mis-age rams in the