Winter/Spring 2025

A Revolutionary Spring: 1775

Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation

Winter/Spring 2025

A Revolutionary Spring: 1775

Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation

A Revolutionary Spring: 1775 page 4

Collections Spotlight: Photo Album of the Theofanos & Athanasiou families page 12

Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation page 16

Finding Family: The Legacy of Hezekiah Gaskins page 22

Commonwealth History Fund 2025 page 28

Cover: Painting of Patrick Henry’s “If this be treason, make the most of it!” speech against the Stamp Act of 1765 (Collection of the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation).

Virginia History & Culture No. 22

Questions/Comments newsletter@VirginiaHistory.org

428 N Arthur Ashe Boulevard Richmond, Virginia 23220 VirginiaHistory.org 804.340.1800

Galleries and Museum Store

Open 10 am – 5 pm daily

Research Library

Open 10 am − 5pm, Monday – Friday

NEWSLETTER TEAM

Editor

Graham Dozier

Designer/Production

Cierra Brown

Contributors

Jamie Bosket, Danni Flakes, James Herrera-Brookes, Sam Florer, Elizabeth Klaczynski, Tracy Schneider, Andrew Talkov

EXECUTIVE TEAM

President & CEO

Jamie O. Bosket

Chief Financial Officer

David R. Kunnen

VP for Advancement

Anna E. Powers

VP for Collections, Exhibitions & Research

Adam E. Scher

VP for Guest Engagement

Michael B. Plumb

VP for Human Resources

Paula C. Davis

VP for Marketing & Communications

Tracy D. Schneider

THE VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF HISTORY & CULTURE

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Chair

Carlos M. Brown*

Vice Chair

J. Tracy Walker IV*

Immediate Past Chair

Richard Cullen*

Honorary Vice Chairs

Austin Brockenbrough III

Harry F. Byrd III*

Nancy H. Gottwald

Conrad M. Hall*

Thomas G. Slater, Jr.*

Regional Vice Chairs

William H. Fralin, Jr.

Susan S. Goode*

Gen. John P. Jumper*

Lisa R. Moore

Gerald F. Smith*

*Executive Committee

B. Marc Allen

Neil Amin

Charles L. Cabell

Victor O. Cardwell

Herbert A. Claiborne III

William C. Davis

Melanie Trent De Schutter

Molly G. Hardie

Victoria D. Harker

Russell B. Harper

Paul C. Harris

C. N. Jenkins, Jr.

Edward A. Mullen

John R. Nelson, Jr.*

William S. Peebles IV

J. Sargeant Reynolds, Jr.

Xavier R. Richardson

Pamela Kiecker Royall*

Elizabeth A. Seegar

Robert D. Taylor

Alexander Y. Thomas

Founded in 1831 as the Virginia Historical Society, the VMHC, a private, non-profit organization, is the oldest museum and cultural organization in Virginia, and one of the oldest and most distinguished history organizations in the United States. The museum cares for a renowned collection of more than nine million items representing the far-reaching story of Virginia.

In the nearly 200 years that the Virginia Museum of History & Culture has served this Commonwealth, never have we reached and engaged as many people as we did in 2024. We welcomed record numbers to the museum—tripling our historic attendance—and connected with history lovers where they are across the state and the world in meaningful new ways.

The support of many—especially our dedicated members— has propelled us to this fortunate position. With your help, we are ready to dedicate our full capacity to engaging Virginians with America’s upcoming milestone moment.

VMHC’s 250th Initiative is one of the most robust commemorative programs of its kind in the United States. Through 2026, VMHC will mount two major exhibitions onsite and send traveling versions of those exhibitions to some 50 communities across Virginia, host dozens of lectures and public programs, produce major commemorative events, deploy far-reaching digital projects, and publish new scholarship. The VMHC is also making an historic investment in statewide civics education and will launch a new program to support history museums across the Commonwealth.

In this issue, you will learn more about our first marquee 250th exhibition, Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation. This major show, opening in March on the 250th anniversary of Patrick Henry’s famous charge for independence, was produced in partnership with the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and is presented by Virginia’s American Revolution 250 Commission. You will also learn of our new podcast, Revolution Revisited, and an exciting new virtual tour of Virginia’s famous revolution-related sites.

America’s 250th provides us the timely opportunity to use history’s capacity for healing and inspiration—to bring people together in celebration, and to encourage our nation forward on its journey toward A More Perfect Union.

Thank you, as always, for your commitment to our progress and your belief in our important, timely work.

Most sincerely,

Jamie O. Bosket, President & CEO

On January 18, 1775, inside the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, an elegant ball was thrown in honor of Queen Charlotte’s birthday. The party served a dual purpose, as Royal Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, celebrated the christening of his ninth child, a daughter named Virginia. Less than four months later, Lady Dunmore, baby Virginia, and her eight siblings fled Williamsburg as the governor, his servants, and British marines fortified the palace and braced for an assault. However, this imminent threat of attack did not come from Britain’s traditional enemies, Spain or France, or from long oppressed groups, like enslaved people or Virginia Indians, but from members of Virginia’s gentry elite, many of whom would have attended Dunmore’s January ball as honored guests. By May 1775, royal authority in Williamsburg remained tenuous as Dunmore sought to retain his authority amid a rapidly growing crisis.

Similar scenes repeated themselves across Britain’s North American colonies in the spring of 1775, as revolutionary rhetoric quickly turned into revolutionary action. By examining the events and leading personalities involved in Virginia that spring, it’s possible to see just how a revolution begins.

In Virginia, the leading figures on both sides of the divide increased the odds of armed conflict. Though Dunmore inherited an earldom from his noble Scottish family, the title did not come with financial stability. This made him ambitious and eager to secure his financial future through appointment to colonial administrative posts, where he hoped to acquire large amounts of cheap American land. Briefly serving as governor of New York,

he was reassigned to Virginia in 1771. On a personal level, Dunmore enjoyed entertaining and was reportedly easy to get along with in private settings. However, when it came to governing, he was often stubborn, arrogant, and impatient. He was particularly sensitive to challenges to his authority. As these challenges increased in the spring of 1775, Dunmore grew more and more combative.

Few Virginians knew how to challenge authority better than Patrick Henry. Born into a well-connected Virginia family, as a young man, Henry suffered a string of failures as a merchant and farmer. These failures made Henry a lifelong advocate for the middle class. After finding his life’s calling as a lawyer, Henry quickly established a reputation as a charismatic speaker, stunning his audiences into silence with sweeping rhetoric and dramatic embellishments. Once elected to the House of Burgesses, he proved eager to challenge traditional institutions, including the clergy, Parliament, and even the king himself. By 1775, Henry was well known across the colonies as a leader of Virginia’s radical faction. As Thomas Jefferson described, “He was far above all in maintaining the spirit of the Revolution.”

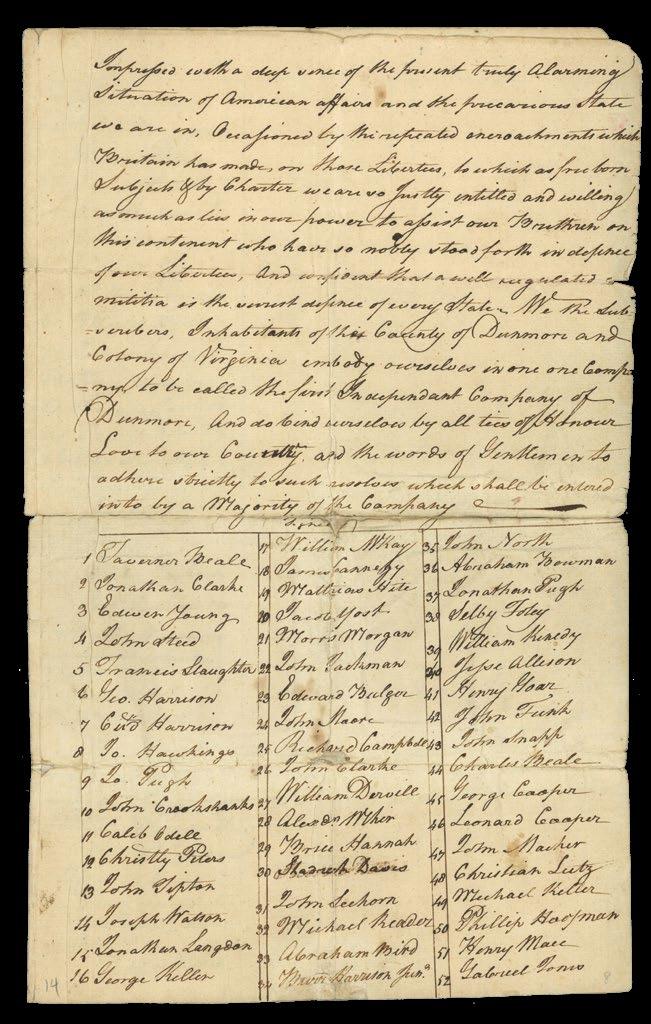

In December 1774, Dunmore returned to Williamsburg after more than five months away leading a military expedition against Indigenous people on Virginia’s frontier (see Virginia History & Culture’s Fall/Winter 2024 issue). Important revolutionary developments occurred in his absence. In August, Patriot leaders organized the First Virginia Convention, elected delegates to the First Continental Congress, and endorsed a sweeping boycott on the importation of British goods. To enforce this boycott, dozens of counties formed local committees that proceeded to investigate and punish perceived violators. A smaller number of counties went a step further and formed their own militias, called Independent Companies, answerable to their local committees instead of the governor. After reading these reports upon his return to Williamsburg, Dunmore worriedly wrote to his superior in London, Secretary of the Colonies Lord Dartmouth, “the steps which have been pursued in the different Counties of Virginia to carry into execution the Resolutions of

the General Congress are of so extraordinary a Nature, that I am at a loss of words to express the criminality of them.”

Authorities in London responded to these developments with two important orders to all North American governors. The first instructed them to “take the most effectual Measures for arresting, detaining & securing any Gunpowder, or any Sort of Arms or Ammunition, which may be attempted to be imported into the Province.” The second ordered the prevention of elections of delegates to the Second Continental Congress, which was scheduled to convene in May 1775. Virginia’s Patriot leaders recognized the need to gather again, elect their delegates to Congress, and decide how to respond to the growing crisis. To keep out of Dunmore’s easy reach, they decided to meet in Richmond.

St. John’s Church Bell (VMHC Collection).

On March 20, 1775, representatives from across the colony gathered in Henrico Parish Church, today known as St. John’s. On the fifth day of this Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry introduced three provocative resolutions. All three dealt with preparing the colony for a possible military confrontation, but the third was by far the most polarizing. Henry called for “this colony [to] be immediately put into a posture of defense” and “the embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men as may be sufficient for that purpose.” This shocked many of the moderates in attendance, who believed the adoption of this article would be perceived as the start of a military conflict instead of preparation for a future one.

In support of his resolutions, Henry rose to deliver what became one of the most famous speeches in American history. Speaking to his more moderate colleagues, he asked them to reflect

“Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

Before long, “liberty or death” became the rallying cry of Patriot militias, appearing on flags and uniforms across the colonies.

Although those in attendance agreed on the shocking impact of Henry’s speech, he did not convince everyone. As a testament to the large faction of moderates in attendance, the resolutions barely passed after a closely divided vote. Regardless of the close margin, Henry’s rhetoric raised alarm bells in the Governor’s Palace as more and more counties began arming themselves.

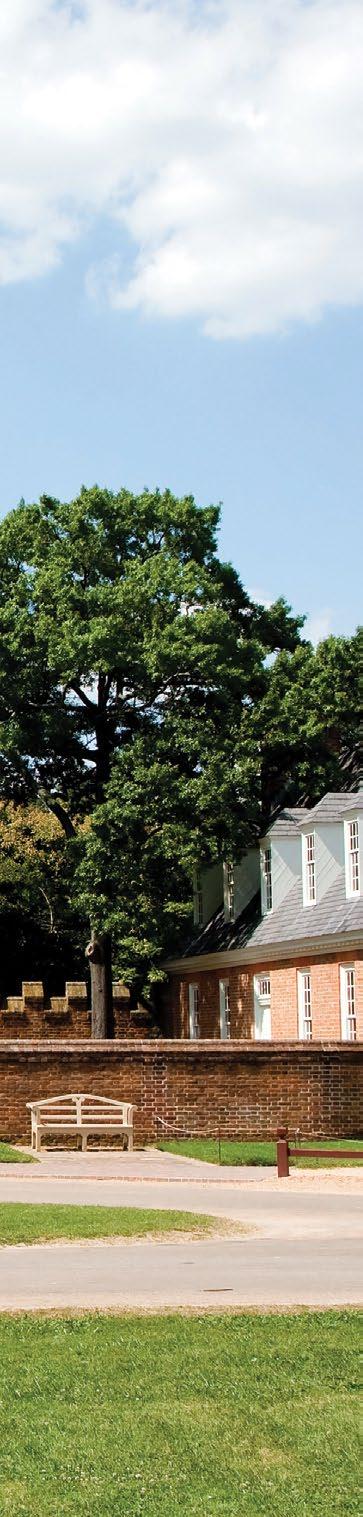

The magazine, or weapons-storehouse, at Colonial Williamsburg (Courtesy of Library of Congress).

(VMHC Collection).

upon the many years of perceived Parliamentary overreach, “in vain … may we indulge the fond hope of peace and reconciliation.” Answering the accusation he was provoking a conflict, Henry declared, “Gentlemen may cry, peace, peace, but there is no peace. The war is actually begun!” For his finale, Henry summoned all the dramatic flair he was known for, symbolically holding his wrists together and raising his voice to a crescendo as he asked his fellow delegates:

Henry’s threats of “chains and slavery” did not go unnoticed by Virginia’s population of enslaved people. As tensions mounted with British authorities, Virginia’s more than 200,000 enslaved people, roughly 40 percent of the population, took advantage of the chaos. In the spring of 1775, rumors of slave rebellions suddenly appeared across the colony, including James City County, Surry, Chesterfield, Prince Edward, Northumberland, Norfolk, and even Williamsburg itself. As Henry and his colleagues debated their political future, enslaved people’s actions heightened the anxieties of white Virginians.

It was in this context that in the early morning hours of April 21, 1775, twenty armed men from the British schooner H.M.S. Magdalen marched from their ship on the James River into the heart of Williamsburg. Shortly after they reached their destination, an alarm was raised and the men hurried to complete their work. As townspeople began to gather, the British detachment quickly returned to their ship. By the time dawn broke, Dunmore’s men had successfully removed fifteen half-barrels of gunpowder from Williamsburg’s

powder magazine. An armed crowd soon gathered outside the Governor’s Palace, demanding the powder’s return, but a delegation of city officials quickly intervened, convincing them to disperse. Nonetheless, the long fuse that would eventually lead to bloodshed in Virginia had been lit.

Why had Dunmore chosen this moment to enact such an incendiary plan? Though he publicly claimed he removed the powder to protect it from the threat of slave rebellion, in a later report to Lord Dartmouth, Dunmore directly cited the resolutions recently passed by the Second Virginia Convention as his real reason, explaining, “particularly their having come to a resolution of raising a body of armed men in all the counties, made me think it prudent to remove some gunpowder … where it lay exposed to any attempt that might be made to seize it, and I had reason to believe the people intended to take that step.”

The governor had good reason to worry. Almost simultaneously across the colonies that April, Patriot militias seized local supplies of gunpowder, including in Charleston, New

Haven, and Baltimore. Two days before Dunmore acted, Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage attempted to secure a stash of gunpowder in the small town of Concord. Unlike in Williamsburg, word of Gage’s plan spread before his troops arrived, and by the end of the day on April 19, close to 300 British soldiers and 100 Patriot militiamen lay dead or wounded. Reverberations from the “shot heard round the world” would soon engulf the colonies in all out war.

Back in Williamsburg, while city leaders succeeded in calming everyone down the morning of April 21, throughout the day and evening, young radicals convened new crowds of angry townspeople. Dunmore saw these protests as treasonous and insulting, and when speaking to a city alderman the next day, flew into a rage. He threatened that if injury or insult befell any royal official, he would, “by the living God, declare Freedom to the Slaves, and reduce the City of Williamsburg to Ashes … I have once fought for the Virginians, and by God, I will let them

see that I can fight against them.” By threatening to use enslaved people as a weapon against them, Dunmore purposefully played upon white Virginians’ greatest fears. Set in the context of the recent rumors of slave rebellions, he could not have chosen more inflammatory words.

As colonists outside Williamsburg learned about Dunmore’s threats and actions, news arrived of Lexington and Concord. Patriot leaders used this opportunity to whip up popular support for armed resistance to British authority. Up to 1,000 men gathered in Fredericksburg, intent on marching to Williamsburg and confronting the governor. Meanwhile, moderate Patriot leaders frantically tried to deescalate the situation. On their way to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress, Virginia’s delegation made sure to stop by and personally convince the Fredericksburg volunteers to disperse.

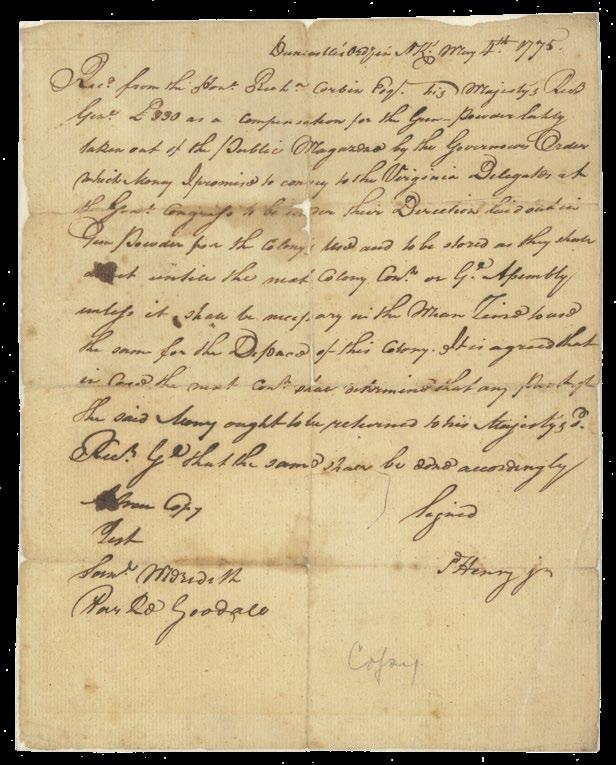

However, one member of Virginia’s delegation was not present. Patrick Henry remained in Hanover County, gathering volunteers from the surrounding area to march on Williamsburg himself. Upon hearing of these gatherings, Dunmore doubled down on his threats, fortifying the palace, calling in reinforcements from nearby British ships, and promising to execute his plans if the volunteers ventured too close to the city. Ignoring pleas to go home, Henry led several hundred men to a point just fifteen miles from Williamsburg. At the last minute, the colony’s treasurer, Richard Corbin, agreed to pay Henry the cost of the removed gunpowder. Henry subsequently committed the money to purchase supplies for Virginia’s defense. Though Dunmore labelled Henry an outlaw, he was paraded as a hero on his belated way to Philadelphia.

– John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore “ “

I have once fought for the Virginians, and by God, I will let them see that I can fight against them.

Although Virginia narrowly avoided all out violence, the damage done to Dunmore’s reputation would prove irreparable. To this point, revolutionary sentiment was concentrated in Virginia’s gentry elite, and even there, many disagreed on how far their protests should go. For this reason, Henry described the gunpowder incident as a “fortunate circumstance.” Dunmore’s actions, particularly his threats to free enslaved people, convinced more and more Virginians to support the Patriot cause. Dunmore himself admitted his “declaration that I would arm and set free such slaves as should assist me if I was attacked has stirred up fears in them which cannot easily subside.” Although he didn’t know it, by the end of May, Dunmore’s remaining time in Williamsburg was down to a matter of days. A revolution was underway.

First Fridays

The museum stays open late for this free family-friendly event.

First Fridays made possible with support from Virginia R. Edmunds.

First Friday each month 5:00 pm–8:00pm

Spring Break: Revolutionary Replicas

Join VMHC Education for revolutionary offerings themed with the newest exhibition Give Me Liberty: Virginia & the Forging of a Nation

Mar. 31–Apr. 4 All Day

Homeschool Open House

Join VMHC for a free Homeschool Open House with a variety of activities throughout the day.

May 30 All Day

Virtual Curator Conversation: Give Me Liberty Preview

Mar. 10 10:00 am

Give Me Liberty Member Preview

Celebrate the opening of our newest special exhibition, Give Me Liberty: Virginia & the Forging of a Nation, with fellow VMHC members!

Mar. 20 11:00 am, 2:00 pm, or 5:00 pm

Member Mondays

VMHC members can enjoy a relaxing evening in the spacious Virginia House gardens accompanied by live jazz music.

Apr. 14, May 12, June 2 5:30 pm

SPECIAL EDITION

Garden Party at Virginia House

May 22 6:00 pm

CONRAD M. HALL

SCHOLAR SERIES

Free for members!

Roses in December: Black Life in Hanover County from Civil War to Civil Rights by Jody Lynn Allen

Mar. 13 12:00 pm

Diplomats at War: Friendship and Betrayal on the Brink of the Vietnam Conflict by Charles Trueheart

Apr. 10 12:00 pm

A Soldier’s Life: A Black Woman’s Rise from Army Brat to Six Triple Eight Champion by Col. (Ret.) Edna W. Cummings

May 8 12:00 pm

Always Order the Pie (and Sometimes You Should Order It First) by Bill Lohmann

May 21 12:00 pm

Searching for Jimmie Strother: A Tale of Music, Murder, and Memory by Gregg D. Kimball

June 12 12:00 pm

Cold War Virginia by Francis Gary Powers, Jr.

June 26 12:00 pm

To register and view all of our upcoming events, visit VirginiaHistory.org/Calendar

Madeira Talk & Tasting

Enjoy evening access to Give Me Liberty and a tasting of various Madeira wines—a favorite of many Virginia Founding Fathers!

Apr. 10 6:00 pm

STUART G. CHRISTIAN, JR. LECTURE

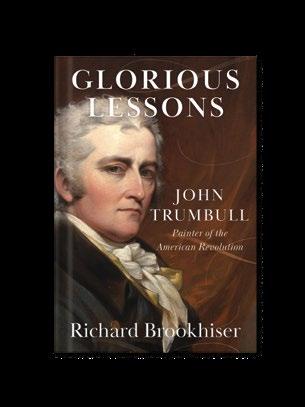

Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution by Richard Brookhiser

Apr. 16 5:30 pm

Anniversary of Lexington & Concord Military Demonstrations

Learn from living historians about military life during the Revolutionary War.

Apr. 19 10:00 am–5:00 pm

Virginia Eats: Farm to Table Bus Tour

Join the VMHC for an excursion to local Virginia farms and artisanal producers. Tastings, lunch, and Virginia wine included!

May 31 8:00 am–8:00 pm

COLLECTIONS UP CLOSE

Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: Hair Jewelry in Virginia History

Apr. 12 10:30 am & 2:00 pm

Feb. 28 to Mar. 2

FRIDAY PROGRAMS & WORKSHOPS

10:00 am HANDS-ON WORKSHOP

The Perfect Centerpiece with Mary Spotswood Underwood

10:30 am DEMONSTRATION

Seasonal Flower Fun with Meg Laughon and Foxie Morgan 10:30 am SPECIAL PROGRAM

Creating a Cutting Garden with Peggy Singlemann

12:00 pm

LUNCHEON PROGRAM

The Story of Baking in the American South: Its Roots, Recipes, and Remembrances with Anne Byrn

2:00 pm

GARDEN CLUB OF VIRGINIA FLOWER

ARRANGING SCHOOL Home in Bloom with Ariella Chezar

5:00 pm

EVENING LECTURE

All Gardens Tell a Story with Ben Page

Magnificent floral displays will be on view throughout the museum for the full threeday event from February 28 to March 2 and are included in museum admission.

Scan to get your tickets or visit VirginiaHistory.org/HistoryBlooms

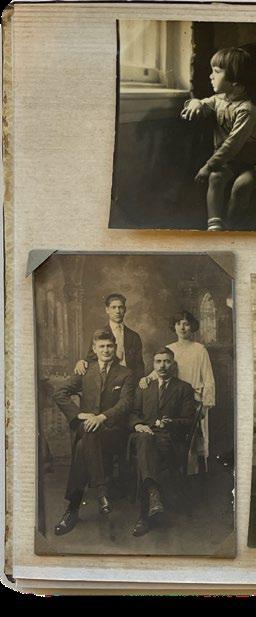

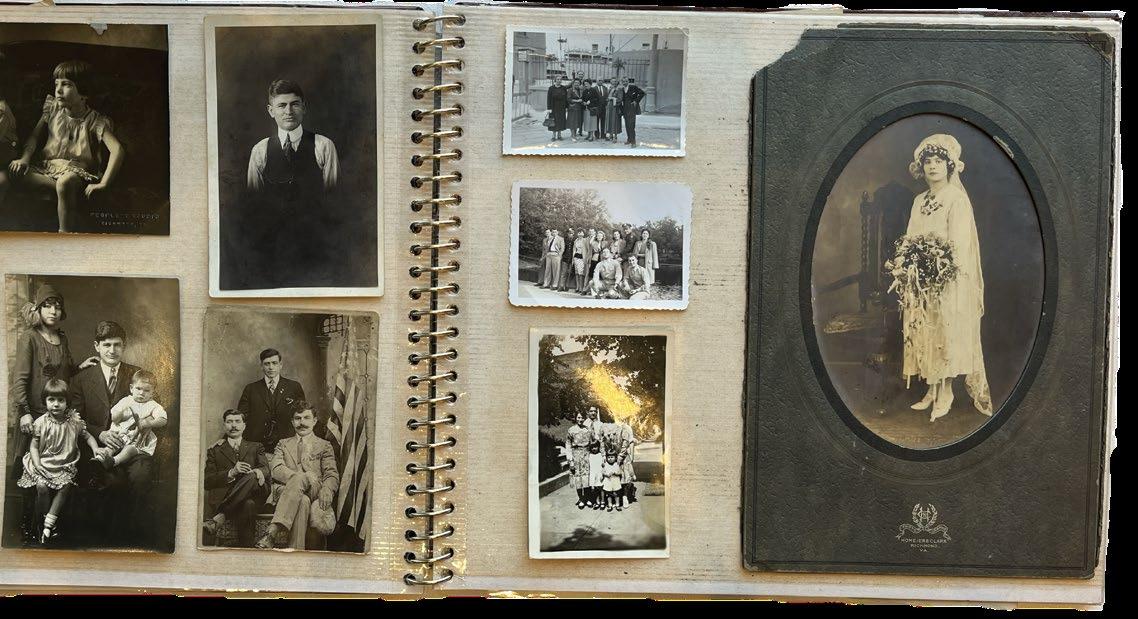

There probably aren’t many family photograph albums in Virginia that have a large image of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, stamped on the cover. But for the Theofanos and Athanasiou families, this impression kept thoughts of home front and center as they made a new life in Richmond, Virginia. The album brims with 61 photographs, as well as mementos and ephemera that celebrate Greek and American identity, entrepreneurship, religious faith, education, and patriotic service. The album is a visual record of two Greek immigrant families who married into one another as they assimilated into American life from the turn of the 20th century through to the 1980s.

This exciting acquisition came to the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in late 2024, as preparations continue on We the People, a forthcoming exhibition that will highlight the impact of the immigrant experience throughout Virginia history. Opening in 2026, this marquee exhibition promises to reveal more about those individuals and communities who, over centuries, have had a dramatic impact on Virginia as they made the Commonwealth their home.

Greek immigration to the United States generally occurred in two major waves. The first wave, where this album’s story begins, occurred as the United States transitioned through the Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914) and large numbers of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe migrated in search of employment opportunities as the U.S. economy grew. Greece, having only gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, lagged in economic development compared to its European neighbors in the later 19th century. Politics were turbulent, poverty was endemic, and education was difficult to pursue. More than 80% of the population lived in rural areas as of the 1880s, lacking opportunity in urban centers. Many left their home to pursue prospects in the United States.

Larger cities in the North, like New York and Chicago, drew in most immigrants traveling from Greece. But around one in ten settled in the South, often in cities

with burgeoning industries that were modernizing as part of the “New South” movement, like Richmond, Columbia, and Atlanta. Greek migrants faced discrimination both North and South. Though antiforeign sentiment was typically more pronounced in northern cities with larger immigrant populations, these larger communities could provide more support to new arrivals. At the same time, as a predominantly white ethnic group, Greek people were not subject to racial segregation endemic across the southern states.

Theodore Theofanas (1894–1982) was one such Greek immigrant. Theodore was actually born in Palamut, Turkey, and was identified as being of both Turkish nationality and ethnicity in a 1913 list of passengers bound for the United States, as well as in the 1930 U.S. Census. When Theodore left for the United States, he listed the village of Ganochora—then still a part of Turkey but located on the Greek Peninsula—as his mother’s residence. But Orthodox Greeks living in Turkey and Muslims living in Greece moved between the two nations following the latter’s independence, many forced and some by choice, which can make tracing an individual’s ethnicity (whether perceived or real) more difficult.

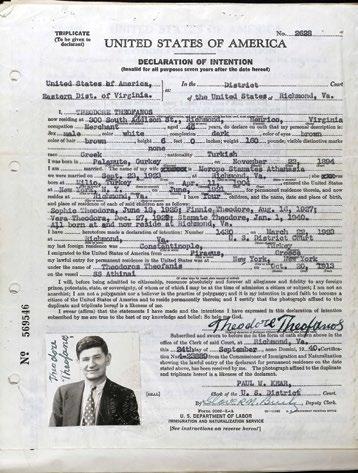

But in Theodore’s 1940 declaration of intention for citizenship he listed his ethnicity as Greek, with officials likely having made incorrect or generalizing statements on earlier official documentation. Theodore

practiced Orthodox Christianity and U.S. censuses identify both his and his wife Merope Theofanas’s (née Athanasiou) primary language as Greek. Of the twenty individuals listed on the 1913 passenger list, all Greek, Turkish, and Syrian migrants, only Theodore and one other were noted to be traveling to Virginia, in line with the general pattern of Greek migration to the northern and southern states.

Theodore and Merope married in 1924, and Merope’s wedding picture was taken at the Homier & Clark Studio at 307 E. Broad Street. They had four children together, Sophia, Finnie, Vera, and Stamate Theodore. The 1919 Richmond, Virginia city directory lists Theodore as self-employed and the proprietor of the “People’s Café” at 313 North 2nd Street, just off Broad Street in Jackson Ward. Eventually, he would open another Richmond lunchroom, the “Star Café,” around 1943. The Theofanos family maintained ties to their heritage and family through Richmond’s Greek community and visits home. The family patriarch’s entrepreneurial ventures were evidently successful, as a 1952 manifest of passengers bound to Greece noted that Theodore, then 60 years old, was able to travel first class on this visit home. Items throughout the scrapbook point to their pride both in their heritage and the lives they built in the United States. There are early photographs of the family taking trips: they pose by a car in the Virginia countryside and one picture shows four individuals, including Merope’s father Stamate, seated in front of the Yorktown Victory Monument that commemorates the 1781 victory and French support during the American Revolution. The family made efforts to learn more about formative

events in U.S. history and to visit the places where it happened.

At the same time, the family celebrated their Greek identity. Whether through ventures like Theodore’s 1952 visit home or by posing for photographs in Richmond studios in traditional Greek dress, Theodore and his family treasured their heritage even in a modernizing American city like Richmond. One interior photograph of a group gathering at a Greek Orthodox church in Richmond at Christmastime has a large U.S. flag hanging behind the group as they stood for their portrait, and another exterior photograph of the church shows two flags—one Greek and one American—flanking the entrance. Emphasizing that this effort continued over generations of the Theofanos family is the inclusion of a 1972–73 Richmond Parks & Rec annual report that features an image of the Hellenic Folk Dance Club on the lawn of the Carillon.

These bits and pieces of ephemeral print material, treasured and preserved by the album’s compilers, demonstrate the research potential of the acquisition. One newspaper clipping features Mary Frances Theofanos, a granddaughter of Theodore and Merope who attended the University of Richmond and graduated with a B.S. degree in mathematics in 1981, noting that she had been initiated into the academic honor society Phi Beta Kappa Theodore Theofanos’s federal naturalization record, 1940 (Courtesy of National Archives).

a year earlier than most other students. According to the article, Mary was a wheelchair user and had received the May L. Keller Scholarship at UR. In a feature about Mary and other scholarship recipients, she spoke of her desire to be “more independent” and “one of the crowd again.” Another later picture of a group of students shows several, including one Theofanos family member, wearing a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps uniform, signaling both the family’s pursuit of higher education and their loyalty to their country and their service to the United States.

The photograph album depicts two Greek families becoming one in 20th century Virginia. A persistent theme, one familiar to all who have come to Virginia from somewhere else, is how the family balanced their assimilation into broader American society while preserving their own identity and heritage. Over centuries, immigrants from all over the world have faced challenges and a longing for home as they sought opportunities in Virginia. Yet, these same people have

dramatically impacted our shared history, culture, and identity, bringing with them traces of their own culture and making Virginia the unique place that it is as they sought to build homes, families, and new beginnings.

To commemorate the 250th anniversary of American independence and highlight Virginia’s leadership in the American Revolution, the Virginia Museum of History & Culture and Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation joined forces to create the Commonwealth’s official commemorative exhibition, Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation. Presented by Virginia’s 250th Commission and made possible with generous support from many, this marquee exhibition opens at the VMHC on March 22, 2025. The approximately 5,000 square-foot exhibition explores the people, places, and events that created a new nation and changed the world, and examines what concepts of liberty meant for different peoples in the 1770s and 1780s. It highlights the compelling stories of individuals and families, illustrating the difficult choices that confronted all people. It also shows that the journey to fully realize American liberty is ongoing work.

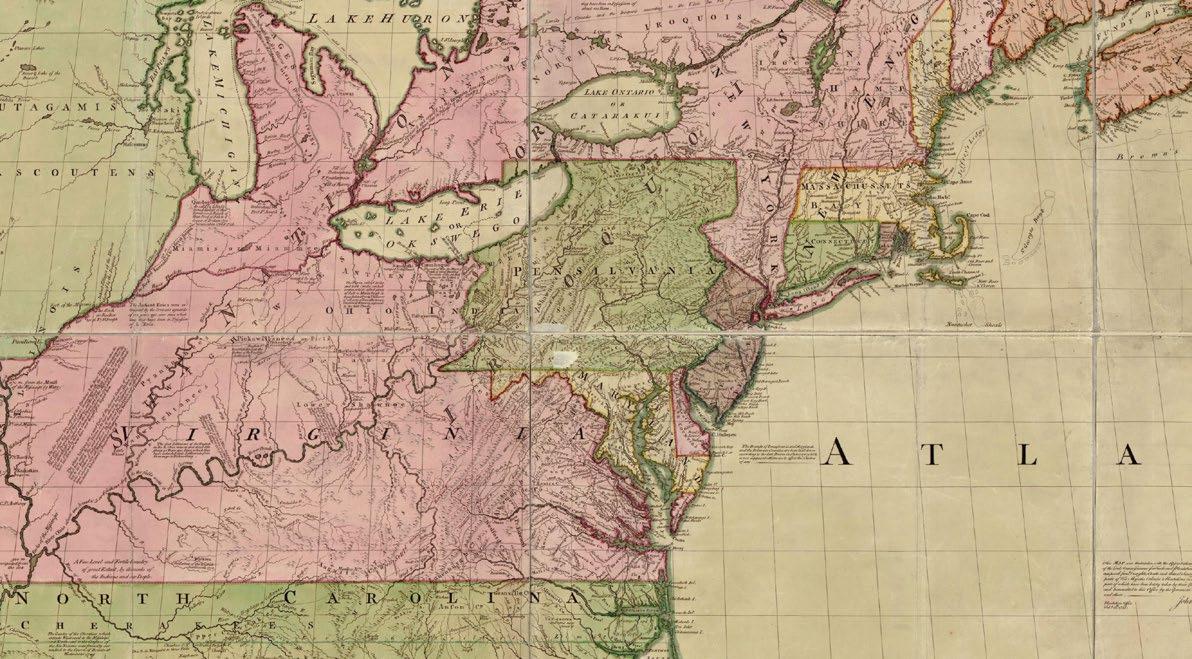

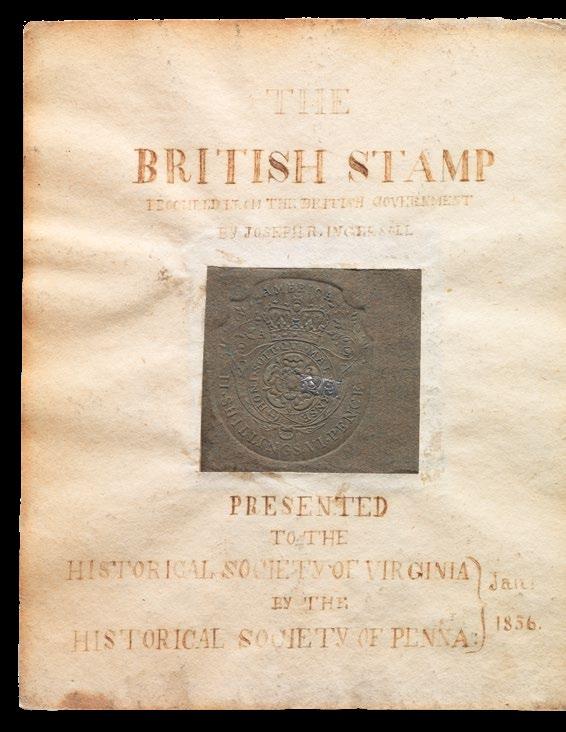

The seeds of unrest leading to the American Revolution were planted in the 1750s. Emerging victorious from the French and Indian War (1754–63), the British gained control of North American territories and created a boundary that prohibited settlers from crossing west over the Appalachian Mountains. The Crown’s threat to colonial westward expansion caused resentment and became a major factor in bringing about revolution. The Stamp Act of 1765 imposed a tax to pay for British troops to enforce the boundary. Denied access to western lands and feeling unfairly taxed, the roots of revolution began to grow across the colonies.

In 1773, Bostonians protested a parliamentary tax on tea by destroying 340 chests of tea. The British responded with the punitive Coercive Acts, which included the closing of Boston harbor. News of the events in Boston reached Williamsburg, and Virginians organized protests in support of their sister colony. Word spread quickly through newspapers and pamphlets, causing an increasing unease with British rule that grew into action. The year 1775 brought revolutionary rhetoric to gunpoint as New England patriots clashed with British troops at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. On March 23, 1775, Virginian Patrick Henry gave a rousing speech at Richmond’s Henrico Parish Church (now St. John’s Church) that spurred the passage of a resolution organizing the Virginia militia in preparation for war. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and approved

the formation of the Continental Army with Virginian George Washington as its Commander in Chief.

In May 1776, Virginia delegates passed a resolution urging the Continental Congress to propose independence for the thirteen colonies. Delegates also appointed committees to write a Declaration of Rights and state constitution for Virginia. Virginian Thomas Jefferson led the drafting of a formal statement justifying the colonies’ break from Great Britain, and on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was officially adopted. Having served the cause of liberty with the pen, Virginians then picked up the sword.

A second British invasion of Virginia began in 1780 when troops under Benedict Arnold advanced up the James River, while a larger force under Lord Cornwallis moved into Virginia from the south in 1781. British forces occupying Yorktown were surprised by allied armies in a siege that turned the tide of the war with an American victory. The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended

Early design rendering of Give Me Liberty exhibition. the American Revolution and formally recognized the United States as a sovereign, independent nation. An American journey was underway... an epic, 250-year journey toward a more perfect union.

Give Me Liberty will take visitors on a multi-sensory journey through the turbulent years of revolution using digital media, hands-on activities, and 65 rare historical artifacts, including a sword carried by George Washington and a rare printing of the Declaration of Independence. The exhibition is divided into five sections that embrace the sweeping history of America’s founding:

Protest to Action (1774): see how ordinary people, through discourse and the power of print, ignited the flames of a revolutionary movement. Visit a tavern in a 1774 Virginia town where a small printing press publishes pamphlets while townspeople gather upstairs to discuss revolutionary ideas. Meet Clementina Rind, Virginia’s first female printer who

published important documents for the colony, and Williamsburg tavern-keeper Christiana Campbell, whose establishment served as a meeting place for Patriot leaders to discuss independence.

Words to Action (1775): be transported to Henrico Parish Church in 1775 where Patrick Henry delivers his “Give Me Liberty” speech to members of the Virginia Convention. Meet William Flora, a Black patriot hailed a hero at the Battle of Great Bridge, and Dragging Canoe, a Cherokee warrior and leader of the Chickamauga who resented colonial expansion on Cherokee lands and chose to fight against the Americans.

Liberty in Action (1776): discover how Virginia became the first colony to direct its Congressional Delegation to propose independence from Great Britain. Try to match grievances found in the Declaration of Independence with the event that inspired it. Meet George Mason, author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which articulated the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, which gave birth to a new nation.

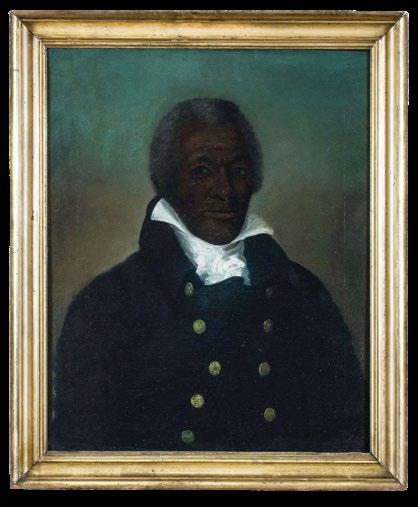

James Fayette, by John Blennerhasset Martin, 1824 (Courtesy of The Valentine).

Virginia & The Forging of a Nation Special Exhibition

On Display March 22, 2025 to January 4, 2026

Virginians—through their ideas, influence, and efforts—helped forge a new American nation. Commemorating the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Give Me Liberty highlights Virginia’s leading role in the American Revolution. It explores the continental and global forces as well as the actions of both iconic and ordinary people that brought about a model of democratic government that changed the world.

Give Me Liberty was produced in partnership by the Virginia Museum of History & Culture and Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. It is presented by Virginia’s American Revolution 250 Commission.

Virginia in Action: The Road to Yorktown (1776–1783): explore Virginia’s vital role in supporting the Continental Army, the second British invasion of Virginia in 1781, and the siege at Yorktown, which turned the tide of the war. See period military equipment, weapons, and musical instruments and a rare broadside commemorating the defeat and capture of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. Meet James Fayette, who served the patriot cause as a spy who infiltrated British high command and supported the American victory at Yorktown.

A Call to Action: The Revolution Continues (1776–today): discover how the ideas that we have inherited from the revolutionary generation continue to evolve. Explore how our definition of liberty has changed during the past 250 years. Consider the struggle and sacrifice of many that have encouraged an ongoing expansion of rights in America—spurring a fuller realization of the spirit of the Revolution. Meet James Madison, whose contributions to the Federalist Papers and Bill of Rights shaped the U.S. Constitution, and U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, who established the core principles of American constitutional law.

Give Me Liberty will be on view at the VMHC from March 22, 2025, to January 4, 2026, and

at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown from July 1, 2026, to January 31, 2027. The exhibition will be accompanied by a publication featuring essays from America’s leading colonial historians that will be in July 2025. A traveling panel version of Give Me Liberty will also be available to museums, libraries, and community organizations across the Commonwealth, visiting some 50 Virginia communities through 2027.

In October 2024, the VMHC launched a new virtual experience. Exceptional 360-degree views of exhibitions and other public spaces, as well as some behind-the-scenes views into collections’ storage and conservation areas, give viewers an exciting new way to enjoy the VMHC.

In preparation for America’s 250th, the museum has just launched an additional virtual tool, The Virginia Explorer: The American Revolution in Virginia. This new virtual experience takes visitors on a journey across the Commonwealth. From the home of George Washington at Mount Vernon to the Yorktown battlefield where British forces surrendered, Virginia

has an array of locations that played a central role in America’s founding. Online visitors can explore places like Colonial Williamsburg, where revolutionary ideals took hold; Richmond’s Historic St. John’s Church, where Patrick Henry’s call for liberty sparked fervor; and the Crossing of the Dan, where American forces outmaneuvered the British. Each featured site uncovers powerful stories of Virginia’s contributions to independence and the forging of a new nation.

Virginia Explorer: The Revolutionary War in Virginia and all of VMHC’s virtual tours are made possible by Pamela K. Royall.

The VMHC is proud to present a new podcast series, Revolution Revisited. This crash course in the American Revolution will give listeners an entertaining yet informative dive into the events leading up to and surrounding the nation’s break from Britain to form a free and independent country. This is not your ordinary history podcast. Yes, there are experts, but the storytelling is lively and colorful and meant to provide a fun and convenient way to brush up on the nation’s founding as we approach its 250th anniversary.

The podcast uncovers the stories of Virginia’s rebels, rule-breakers, and rabble rousers who shaped a nation. Beginning with the French and Indian War, each episode features both well-known characters and those who played significant roles but have been less visible in prior historical accounts.

Learn more at VirginiaHistory.org/RevolutionRevisited Revolution Revisited is made possible by William and Karen Fralin and is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube Podcasts, and more.

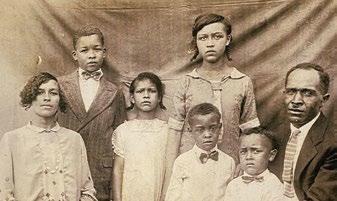

On July 31, 1854, a free Black man named Hezekiah Gaskins bought his wife and children. Hezekiah knew the man who enslaved his family well—in this small corner of Fauquier County, white and Black people’s lives were intertwined, creating a complex world defined by the spaces between slavery and freedom.

Nearly two hundred years later, on October 12, 2024, dozens of people gathered in Markham, Virginia, only miles away from where Hezekiah and his family once lived. Some had known each other for years, while others were meeting for the very first time. They were all, however, connected: they are the descendants of Hezekiah and other members of the Gaskins family. Also present was a descendant of the man who had sold Hezekiah his loved ones.

This gathering, spearheaded by Hezekiah Gaskins’s great-greatgreat-granddaughters, Karen White and Angela Davidson, was a powerful event that shows just how close the past is to the present. It was also an opportunity for the Virginia Museum of History & Culture to engage deeply and meaningfully with a descendant community as it prepares to mount a new exhibition, Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865, in June 2025.

When Karen White couldn’t find her grandmother’s birth recorded in Virginia’s 1897 birth registry, she had questions. The omission sparked her interest in history and genealogy, and she began talking with her parents about their family and researching historical laws and codes. “What one person doesn’t know, another one does. And what neither of them know, records might,” said White, who subsequently discovered that her grandmother’s birth wasn’t noted because the state wasn’t legally required to record births and deaths between 1896 and June 1912.

The silence in the archives became a call to action. White and her sister, Angela Davidson, understood that families—and in particular Black families—could empower themselves through learning about their pasts. “Our history was foreign to us,” remarked White. “It was powerful when we started learning it. It was emboldening and needed to be available to everyone.” Karen White and a friend, Karen King Lavore, co-founded the Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County (AAHA) in 1992. The AAHA’s mission: “Genealogy. Research. Collection. Preservation.” still drives the center’s commitment to providing resources for those interested in finding out more about their own families and the history of the area. AAHA’s museum

space contains 1,634 artifacts detailing the rich history of Fauquier County’s Black residents, and the AAHA offers programming for school and community groups, as well as an auditorium for special events.

White, as Director of the AAHA, has scoured churches, basements, courthouses, attics, and countless other places across the region collecting probate records, wills, deeds, family Bibles, pieces of correspondence, and other materials that can help people better understand the lives of Fauquier County’s enslaved and free Black individuals. Her efforts, and those of the many other AAHA staff and volunteers, culminated in an online portal called, “Know Their Names.” The searchable database contains the names of thousands of people enslaved in Fauquier County between 1759 and 1865, along with corroborating records, such as estate inventories, household and farm account books, diaries, census data, and much more. In 2023, the Virginia Museum of History & Culture supported “Know Their Names” with a major grant from the VMHC’s Commonwealth History Fund. That was the beginning of the relationship between

the VMHC and the AAHA that would lead to the family reunion that took place in October 2024.

Closing gaps in our history requires work, patience, understanding, and a willingness to share the story as it is told through historical documents. “ “

– Karen White

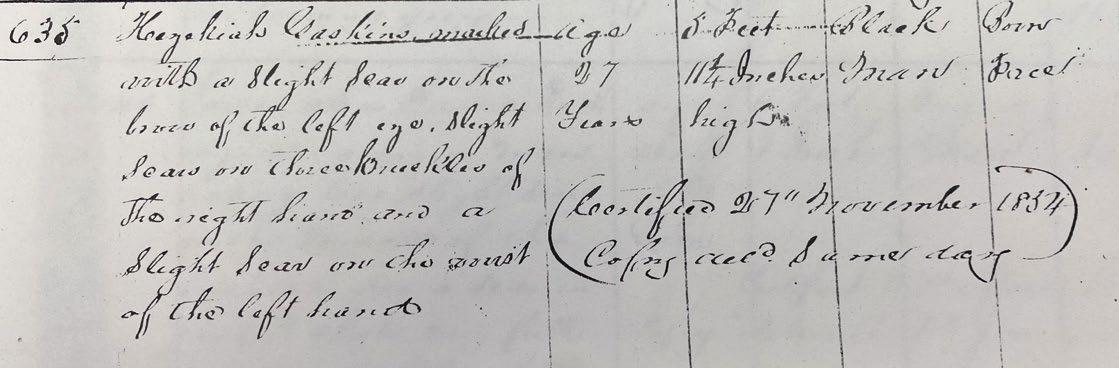

One of the factors that have kept White and Davidson motivated to continue this work over the decades relates to one of their earliest discoveries about their own ancestry. Hezekiah Gaskins, their great-great-great grandfather, was free. They were able to locate his 1854 free negro registration. In 1793, the Virginia General Assembly mandated that “free Negroes or mulattoes” were required to “be registered and numbered in a book to be kept by the town clerk, which shall specify age, name, color, status and by whom, and in what court emancipated.”

Hezekiah Gaskins, entry number 635, was described as “five foot eleven and a quarter inch high” and “marked with a slight scar on the brow of the left eye. Slight scars on three knuckles of the right hand and a slight scar on the wrist of the left. Black Man. Born Free.”

Local governments and white Virginians used documents, such as Hezekiah’s free negro registration, as powerful tools of surveillance and control. At the same time, free Black people utilized the registers as evidence of their irrefutable claims to freedom. Today, the registers

of AAHA).

often serve as the only resource descendants have to picture what their ancestors may have looked like.

White and Davidson also found the 1854 deed that sold “to the said Hezekiah Gaskins a certain negro slave named Fanny the wife of said Hezekiah and their three children Nancy, Polly, and Frances.” Hezekiah Gaskins paid Edward Carrington Marshall, the youngest son of Chief Justice John Marshall and a former member of the House of Delegates (1834–38), $300 for his family.

This was not the only financial transaction that occurred between the two men, nor the only time White and Davidson were able to use historical records to imagine what Hezekiah’s life was like in antebellum Fauquier County. In 2020, the local newspaper published an article describing the AAHA’s “Know Their Names” project. Jim Stribling, Edward Marshall’s great-greatgreat nephew, instantly recognized that his family’s papers could be helpful. He presented White and Davidson with a ledger kept by Dr. William C. Stribling, a physician who was Edward Marshall’s neighbor. Dr. Stribling meticulously recorded his transactions with Gaskins, which led to the revelation that Hezekiah was a stone mason. Hezekiah completed multiple tasks for Stribling, including the construction of a “meat house.” Jim noted, “I’ll always remember Karen and Angela’s reaction when they saw their great-greatgreat grandfather documented in the ledger.”

Studying the dollar signs on either side of the balance sheet reveals that Hezekiah earned more from Dr. Stribling than he paid Stribling for medical services. These small details—noticing that a free Black man was able to turn a profit in a business relationship with a UVA-educated doctor—reveal that free Black people were not powerless despite living in a society that denied them full freedom and equality.

Perhaps Hezekiah Gaskins’s profession accounts for some of the scars noted on his hands in his free negro registration. Perhaps he used some of the money he earned from Dr. Stribling or even from Edward

Marshall to purchase his wife and children. On August 19, 1854, just weeks after buying his family, Hezekiah emancipated them in his will. He also stipulated that his daughter Fanny and her children receive “all property debt money that I may have at the time of my death.” In 1871, Edward Marshall entered a deed that stated, “That in consideration of the sum of three hundred and sixty dollars the amount of a debt due by the said Edward C. Marshall to the estate of the late Hezikiah Gaskins, the said Edward C. Marshall hereby bargains + sells to the said Fanny Gaskins and her five children a certain lot or parcel of land in the county of Fauquier … containing 25-acres or more.”

Hezekiah Gaskins died holding Edward Marshall, the son of America’s fourth chief justice, in his debt. Born free, Gaskins worked and secured the freedom of his family. He used Marshall’s debt to create generational wealth for his descendants. And they have the records to prove it.

Asked to reflect on her family’s connection to Jim Stribling’s ancestors, Angela Davidson commented, “Meeting Jim and sharing information has brought the lives of our ancestors to a common place, where we share a complex history that includes large property owners, free and enslaved African Americans, of employer and employee, and of friends whose ancestors walked the same grounds.” On October 12, 2024, Angela Davidson, Karen White, and Jim Stribling literally walked the same grounds as their forebearers when members of the Gaskins family convened on the property Edward Marshall once owned and on which Hezekiah Gaskins worked. Bill Green now owns the land and is, like his cousin Jim Stribling, a descendant of Chief Justice John Marshall. The estate is currently Hartland Orchards: apples, blueberries, cherries, and peaches grow on the pastoral landscape. Hezekiah’s meat house still stands, a rare example of a structure associated with a free Black person still extant.

Dozens of Gaskins descendants from across the country met early in the morning at Beulah Baptist Church on October 12. “The very short ride over to Hartland Orchards to walk the grounds and see the

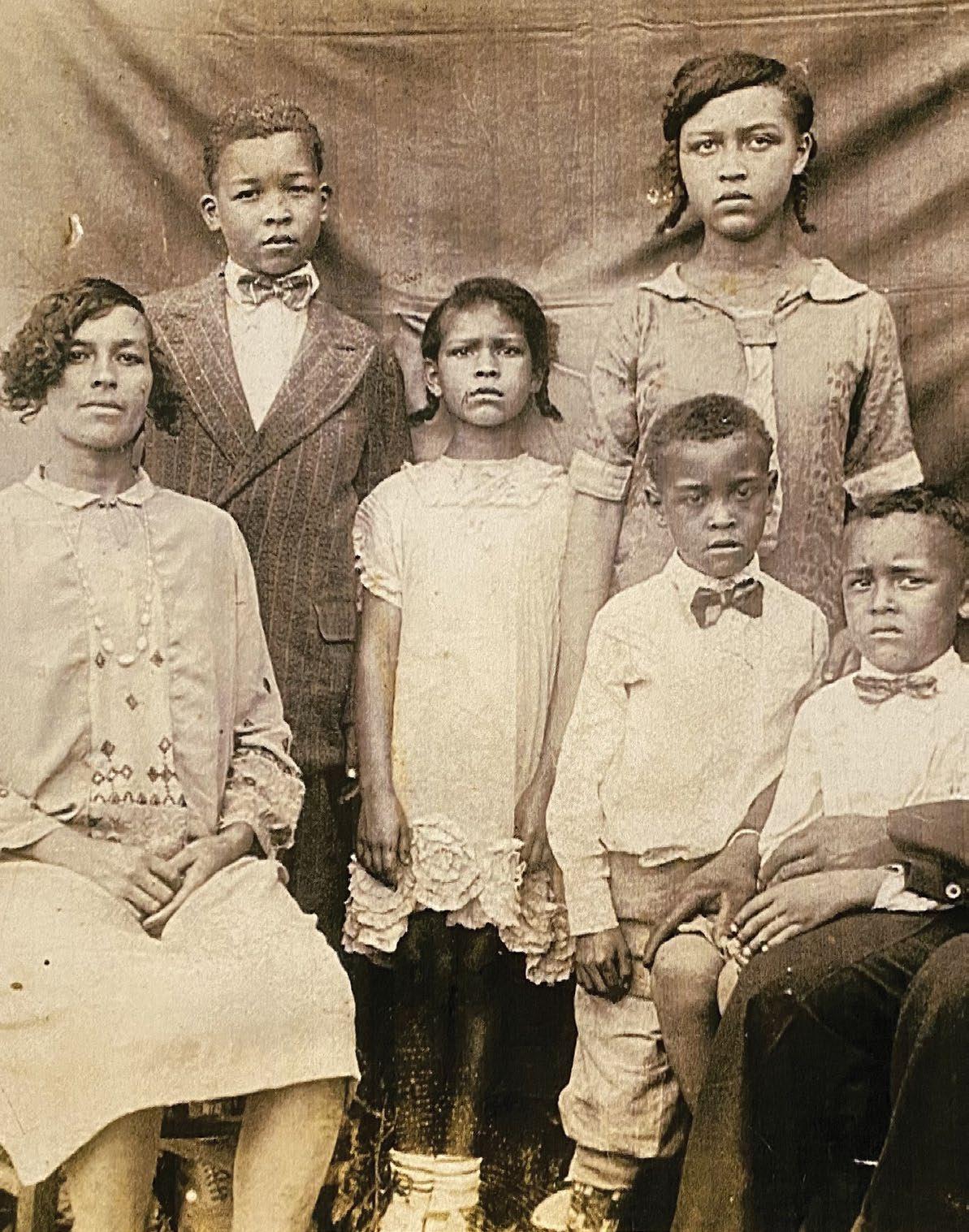

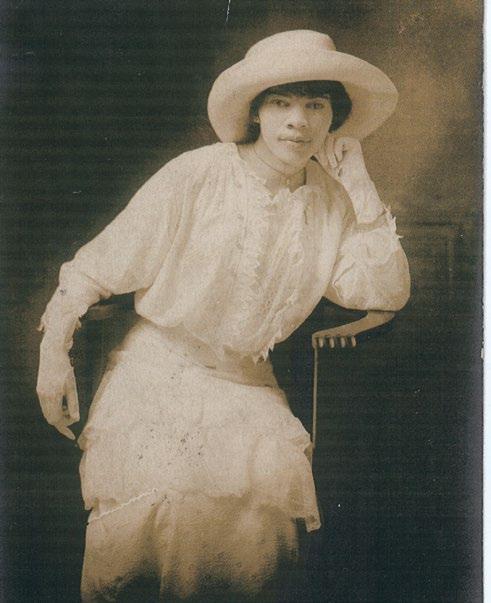

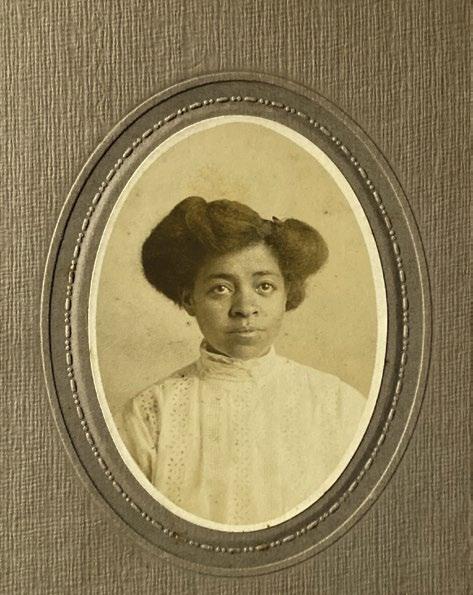

Hezekiah Gaskins’s descendant, Isabel Wanser Jackson, with Husband and Child, Early 1900s (Courtesy of AAHA).

meat house gave some of us goosebumps,” Davidson said. “Some traveled back to the orchard in the following weeks, picked apples, and showed the next generation of children the work of their ancestors.”

The group returned to Beulah Baptist Church for the remainder of the afternoon. People of all ages shared who their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great grandparents, and great-great-great grandparents were. They showed photos, told stories, and displayed family heirlooms. Dr. William Stribling’s account book was at the reunion, opened to page 25, the first time the Gaskins family appeared in the ledger.

Angela, Karen, and Jim decided to organize a gathering of Gaskins descendants after meeting with Joni Albrecht, Director of VMHC’s John Marshall Center, and Elizabeth Klaczynski, Associate Curator at the VMHC. Their aim was two-fold: they wanted to

This exhibition explores the lives of free Black Virginians from the arrival of the first captive Africans in 1619 to the abolition of slavery in 1865. Through powerful objects and first-person accounts, visitors will discover how Virginia’s people of color achieved their freedom, established communities, and persevered within a legal system that recognized them as free but not equal.

Data Centers

meet and greet old and new family members and to support Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865, a forthcoming exhibition. Un/Bound is the VMHC’s effort to tell the long, rich, complicated, and often overlooked stories of free Black people in Virginia... people like Hezekiah Gaskins and the thousands of other Virginians who, like him, occupied a liminal space somewhere between slavery and genuine freedom.

To learn more about the Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, please visit aahafauquier.org

The Virginia Museum of History & Culture is joined by more than 500 history organizations in the enduring and far-reaching mission of saving and sharing Virginia’s history.

The VMHC is proud to play a leading role in this important work, and similarly proud to be able to provide meaningful financial support to its fellow history organizations—empowering great preservation and education efforts taking place in communities all across Virginia.

Thanks to a generous investment by longtime VMHC supporter Dominion Energy, and others, the VMHC established the Commonwealth History Fund, a significant endowment and grantmaking program, in early 2022. One of the largest of its kind, the fund provides hundreds of thousands of dollars annually in grants to history projects and organizations across Virginia.

Now in its fourth year, the VMHC, through the Commonwealth History Fund, has provided grants to four dozen projects totaling more than $1,700,000.

The Commonwealth History Fund is administered in partnership with Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Funds can be used for a variety of purposes including preservation, research, publications, acquisition and conservation of artifacts, and educational programming. Eligible recipients include Virginia nonprofits, educational institutions, and Virginia Indian tribes.

The Commonwealth History Fund is one of the best tools we have as your state history museum to support history education and preservation efforts taking place in communities all across this great state.

– Jamie Bosket, VMHC President & CEO

Applications for the fifth annual grant cycle will be accepted in September 2025 with grants announced in early 2026. As part of VMHC’s 250th Initiative, grant applications related to the commemoration of America’s semiquincentennial will be given special consideration.

Awarded Total Awards To Date 48 Awardees

$1,701,206 Awarded

VMHC accepted applications from eligible organizations in fall 2024. Nearly 90 compelling applications were submitted with requested funds totaling more than $5 million. Through the hard work of professionals from VMHC and DHR, eleven projects were selected to receive a total of approximately $500,000. The impressive projects chosen spread across the Commonwealth, include organizations of all sizes, and span a great deal of historical topics and time periods (see the detailed list of awardees on the pages that follow).

Fredericksburg Area Museum & Cultural Center (Fredericksburg, Virginia)

With support from the VMHC, the Fredericksburg Area Museum & Cultural Center will mount a new exhibition on the area’s Black history called Living Legacies. With extensive community involvement, this exhibit will bring together compelling objects, images, and stories representing fundamental moments in local, state, and national history.

Historic Alexandria (Alexandria, Virginia)

With the support of the VMHC, Historic Alexandria will conduct a major research project to better understand the full history of Alexandria’s Market Square. This research will then inform future work to interpret the history of this iconic gathering place.

Historic Richmond Foundation (Richmond, Virginia)

Monumental Church is a National Historic Landmark designed by Robert Mills in the aftermath of the Richmond Theatre Fire (1811) to honor the lives lost in one of the worst urban tragedies in American history. Support from the VMHC will fund the

Fredericksburg Area Museum & Cultural Center (Courtesy of Fredericksburg Area Museum & Cultural Center).

research, design, fabrication, and installation of interpretive signage inside and outside Monumental Church, including exterior wayfinding signage, as part of a larger site activation plan.

Historic Staunton Foundation (Staunton, Virginia)

The Cabell Log House was built about 1869 by freedman Edmund Cabell and owned by his descendants for more than a century; it is the only remaining 19th-century exposed-log structure in the City of Staunton. VMHC support will allow Historic Staunton Foundation to develop a preservation and rehabilitation plan while property research and archaeological documentation are being conducted.

Historical Society of Western Virginia (Roanoke, Virginia)

With the help of VMHC, the Historical Society of Western Virginia will mount a new exhibition, Western Virginia’s Tribal Nations: Preserving Culture, Identity, and Traditions, that will interpret westward expansion, the French & Indian War, Lord Dunmore’s War, the American Revolution, and the impact each had on indigenous nations. Through archival and ethnological research, viewers will learn about the Tutelo Indians and their territory throughout western Virginia pre-contact, as well as their subsequent absorption into present-day nations.

The JXN Project (Richmond, Virginia)

Abraham Peyton Skipwith, often considered the “Founding Father of Jackson Ward,” became the area’s first known Black homeowner in 1793 and one of the first Black Richmonders with a fully executed will in 1797. VMHC funds will aid in the furnishing and interpretation of the Skipwith-Roper Cottage.

Monacan Nation Cultural Foundation (Amherst, Virginia)

Pottery has always been integral to the Monacan culture. Archaeological excavations across Virginia have unearthed thousands of pieces of Eastern Siouan pottery, the ancestral group to the present-day Monacans. With VMHC support, a new project will honor and preserve Monacan pottery traditions through an apprenticeship program and engage the broader community via a series of apprentice-led exhibition activities.

Pamunkey Indian Tribe (King William, Virginia)

The Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center (PIMCC) strives to illuminate the history and living culture of the Pamunkey people. The museum serves the Pamunkey Community as a hub for Community events with regular cultural programs aimed at educating the Tribe’s youth and other visitors. Critical support from the VMHC will help the Tribe address the roofing system at the PIMCC, ensuring the future protection of the Center and the collections it houses.

Toano Historical Society, Inc. (Toano, Virginia)

Toano, originally known as Burnt Ordinary, traces its origins to the seventeenth century when taverns and ordinaries were common markers of places throughout the region. VMHC grant funds will support the expansion of the historical district in Toano, allowing selected homes and structures to be added to and designated as part of the Toano Historical District.

Virginia Tribal Education Consortium (Ashland, Virginia)

With VMHC’s help, the Virginia Tribal Education Consortium will mark the centennial of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act by producing a new historical documentary. This new film will feature interviews with Tribal citizens across generations and other experts, and be broadly distributed for educational benefit.

Virginia)

In celebration of America’s 250th anniversary, WHRO Public Media will create public education materials featuring untold stories of Revolutionary War contributions from people in Hampton Roads. This innovative project will be designed with dynamic audio and visual elements that will engage audiences of all ages in the dramatic story of our founding.

May 17, 2025 at 11:00 am–6:00 pm

Thoughtful Productions’s inaugural HistoryFest event asks the question,

“What would it be like to be a part of history?”

The daylong festival-meets-conference at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture invites visitors to immerse themselves in history through more than 20 full-sensory presentations spanning musical revolutions, American presidents, and generation-defining events.

In Partnership with

Films That Changed America

The American Revolution: Stories You Never Learned SESSIONS INCLUDE

Jefferson: What I Think Now

Eleanor Roosevelt: Separating Fact From Fiction The Rock Experience: The Music and Stories Behind 10 Classics The History of Virginia in 10 Objects Wines of the Great World Leaders

The Virginia House Loggia, one of the house’s distinctive architectural features, was among the final improvements orchestrated by Ambassador Alexander Weddell and Virginia Weddell. It was added in 1945, just three years before the Weddells were tragically killed and stewardship of the property transferred to the VMHC.

The extensive restoration of the Loggia is among the special projects planned for the historic site as part of VMHC’s celebration of Virginia House’s Centennial Period (2025–29). Work on the Loggia began in late 2024, and will be complete in time to be dedicated as part of a special edition of VMHC’s popular Spring Garden Party.

As part of its new statewide civics education program, Civics Connects, the VMHC has proudly launched its inaugural Civics Ambassador Corps. This group of dedicated and seasoned educators from across the Commonwealth will work with VMHC’s John Marshall Center team to champion Civics Connects—a first-of-its-kind, comprehensive civics resource—in their classrooms, school districts, and regions.

Civics Ambassadors will pilot and promote the program, collect and analyze participant data, conduct professional development workshops at their school or district level, and contribute to the ongoing development and success of this exceptional new program.

Welcome, Inaugural Civics Ambassadors!

Jessica Arnold, Chesterfield

Thomas Calder, Chesterfield

Julia Day, Hanover

Kimberly Dove, Rockingham

Ann Forrest, Newport News

Megan Huftalen, Fairfax

Kyle Kimbrell, Richmond

Shelby Low, Fauquier

Maureen Ogando, Henrico

Carrie O’Hanlon, Hampton

Dana Parks, Alexandria

Charles Peterson, Amherst

Michael Sivells, Arlington

Andrea Tavenner, Chesterfield

The museum’s governing body welcomed new leadership and three new members in January 2025.

Carlos Brown, Chair

Carlos Brown lives in Richmond, Virginia. He is President – Dominion Energy Services and Executive Vice President, Chief Legal Officer, and Corporate Secretary of Dominion Energy. Vice Rector of the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia, he has previously served on the boards of the Central Virginia Transportation Authority, the Richmond Metropolitan Transportation Authority, NextUp RVA, and the Commonwealth Transportation Board in addition to other community involvement. He received his undergraduate and J.D. degrees from the University of Virginia.

Tracy Walker, Vice Chair

Tracy Walker lives in Henrico, Virginia. He is the Managing Partner at McGuireWoods and has served as national trial, class action, and appellate counsel for an extensive portfolio of clients. He served as the President of the Board of Directors of the John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics before the JMC’s merger with the VMHC in 2023. Tracy received his undergraduate degree from the University of Virginia and his J.D. from Harvard Law School.

Molly Hardie

Molly Hardie lives in Charlottesville, Virginia. A pediatrician by training, she is now co-chair of H7 Holdings, a private family investment company that owns and manages Keswick Hall and Golf Club in Keswick, Virginia, and the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville, among other properties and projects. A history lover, she is also the Chair of the Board of Trustees for The Thomas Jefferson Foundation (Monticello). She received her undergraduate degree from Dartmouth College and her medical degree from the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Billy Peebles

Billy Peebles lives in Richmond, Virginia. A retired educator with a career spanning more than 40 years, Mr. Peebles was most recently the Interim Head of School at Collegiate School. Prior to Collegiate, Mr. Peebles served as head of the Powhatan School in Boyce, Virginia, the Asheville School in North Carolina, and the Lovett School in Georgia, among other appointments. Throughout his time as an administrator, he also maintained a continuous teaching schedule that focused on courses in American history and Religious studies. Mr. Peebles received his undergraduate degree from Princeton University and graduate degree from the University of Virginia Darden School of Business.

Sandy Thomas

Sandy Thomas lives in Alexandria, Virginia. He is the Chief Legal Officer of Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), the preeminent U.S.-based nongovernmental organization devoted to the protection of unaccompanied and separated children. Previously, Mr. Thomas was a partner at the global law firm Reed Smith and served as the firm’s Chair and Global Managing Partner. Before entering private practice, he was an attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice and a Special Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Office of the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia. Mr. Thomas received his undergraduate degree from Trinity College and his law degree from Washington & Lee University.