Spring/Summer 2025

The Revolution Takes Shape: Summer 1775

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865

Washington Takes Command & The Birth of An American Army

In This Issue

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865 page 16

Spring/Summer 2025

The Revolution Takes Shape: Summer 1775

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865

Washington Takes Command & The Birth of An American Army

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865 page 16

Spotlight: The Landscapes of Beyer page 22

The Revolution Takes Shape: Summer 1775 page 8

Washington Takes Command & The Birth of An American Army page 24

Virginia History & Culture No. 23

Questions/Comments newsletter@VirginiaHistory.org

428 N Arthur Ashe Boulevard Richmond, Virginia 23220 VirginiaHistory.org 804.340.1800

Galleries and Museum Store

Open 10 am – 5 pm daily

Research Library

Open 10 am − 5pm, Monday – Friday 2nd & 4th Saturdays

NEWSLETTER TEAM

Editor

Graham Dozier

Designer/Production

Cierra Brown

Contributors

Jamie Bosket, Danni Flakes, James Herrera-Brookes, Sam Florer, Elizabeth Klaczynski, Tracy Schneider, Andrew Talkov

EXECUTIVE TEAM

President & CEO

Jamie O. Bosket

VP for People & Culture

Paula C. Davis

VP for Operations & CFO

David R. Kunnen

VP for Education & Engagement

Michael B. Plumb

VP for Advancement

Anna E. Powers

VP for Collections, Exhibitions & Research

Adam E. Scher

VP for Marketing & Communications

Tracy D. Schneider

THE VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF HISTORY & CULTURE

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Chair

Carlos M. Brown*

Vice Chair

J. Tracy Walker IV*

Immediate Past Chair

Richard Cullen*

Honorary Vice Chairs

Austin Brockenbrough III

Harry F. Byrd III*

Nancy H. Gottwald

Conrad M. Hall*

Thomas G. Slater, Jr.*

Regional Vice Chairs

William H. Fralin, Jr.

Susan S. Goode*

Gen. John P. Jumper*

Lisa R. Moore

Gerald F. Smith*

*Executive Committee

B. Marc Allen

Neil Amin

Charles L. Cabell

Victor O. Cardwell

Herbert A. Claiborne III

William C. Davis

Melanie Trent De Schutter

Molly G. Hardie

Victoria D. Harker

Russell B. Harper

Rudene M. Haynes

Paul C. Harris

C. N. Jenkins, Jr.

Edward A. Mullen

Gen. Richard B. Myers

John R. Nelson, Jr.*

William S. Peebles IV

J. Sargeant Reynolds, Jr.

Xavier R. Richardson

Pamela Kiecker Royall*

Elizabeth A. Seegar

Robert D. Taylor

Alexander Y. Thomas

Founded in 1831 as the Virginia Historical Society, the VMHC, a private, non-profit organization, is the oldest museum and cultural organization in Virginia, and one of the oldest and most distinguished history organizations in the United States. The museum cares for a renowned collection of more than nine million items representing the far-reaching story of Virginia.

years ago, following our American “shot heard ’round the world,” armed conflict of the American Revolution began—George Washington took command, our army was born, and the American colonies further united.

As the 250th of America on July 4, 2026, draws ever closer, we are poised to highlight these inflection points—milestones, both famous and less so, on our road to revolution and independence—for the benefit of people of this Commonwealth and beyond.

The VMHC’s 250th Initiative is one of the most robust programmatic portfolios of its kind in the nation. As you have no doubt seen over the past few months (and years), we have been purposeful in our planning, always with the promise that we will be ready when these important moments arrive. Well, now they are here, and we are ready!

Give Me Liberty, the first major 250th exhibition in the nation, is on display through the end of the year before moving to our partners at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown. Presented by VA250, this is Virginia’s official

semiquincentennial exhibition. It explores the continental and global forces that brought about a model of democratic government that changed the world. It is a great achievement that brings together the stories you might expect of the Founding with some you may never have heard. Indeed, a recent New York Times feature positioned the VMHC at the top of the national list of organizations doing this work.

With its collection of more than nine million objects, the Virginia museum — itself nearly 200 years old — seems well positioned to tackle the American Revolution, with all its repercussions, achievements and contradictions.

“

New York Times

I encourage you to see this special show (or see it again!) and reflect with us on Virginia’s key role in the making of America. I also encourage you to keep up with what will be an increased cadence for our commemorative activities. In the year ahead, we will publish two new scholarly works, travel a version of Give Me Liberty to some 50 communities, open two additional exhibitions at the VMHC, and host major celebrations and events. Through these and the rest of our 250th Initiative activities, we will ensure that the lead-up to the big day of July 4, 2026—and all the meaningful moments in between—are made memorable and engaging, as their historically significant stories deserve.

Thank you, again, for your wonderful support.

Jamie O. Bosket, President & CEO

One of the major legacy projects of our 250th Initiative is creating a hub for civics education in Virginia, helping to ensure generations of students are educated and equipped for informed citizenship. We are honored to welcome Virginia Civics—their team and partners—as we work as one and with passion and purpose to grow our positive impact throughout the state and beyond.

VMHC President & CEO, Jamie Bosket

The Virginia Museum of History & Culture’s bold vision and goal of creating the premier hub for civics education in Virginia achieves a major milestone with peer organization, Virginia Civics, joining its effort. Charlottesville-based Virginia Civics, home of Virginia’s We the People competition and other leading programs, has formally joined the VMHC through an impactful, forwarded-looking merger. The John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics similarly joined the museum in 2023. Each of these organizations brings missional alignment, programmatic excellence, and innovative instructional approaches to

the VMHC’s historic investment in civics education, part of its multi-year celebration of America’s 250th anniversary, one of the most robust efforts of its kind in the nation.

Virginia Civics is dedicated to strengthening civic education across Virginia. As the Virginia affiliate of the Center for Civic Education, Virginia Civics promotes constitutional literacy and civic engagement through its flagship programs. We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution is a nationally recognized and beloved civic education program that engages students from upper elementary through high school in the study of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. It allows students to participate in regional, state, and national competitions, demonstrating their understanding of constitutional principles through simulated legislative hearings in which they respond to judges’ questions. The program culminates in the We the People National Finals annually in Washington, D.C. Two Virginia teams placed in the top 10 at this year’s National Finals held on April 12–13. Douglas S. Freeman High School placed sixth, and Maggie Walker Governor’s School placed seventh.

Project Citizen teaches students public policy processes by guiding them through the development of policy proposals that address real-world issues in their communities. Students present their research and policy recommendations at state and national showcases, where they receive feedback from public officials, educators, and community leaders. The program encourages active participation in democratic governance.

Virginia Civics also provides professional development for educators and collaborates with institutions and organizations to enhance civic education statewide by managing the Virginia Civics Coalition.

Through this unique coming together of respected nonprofits, VMHC further expands its reach across the Commonwealth and unlocks limitless potential to serve Virginians as the leading source for K-12 civics education.

Adding to the excitement of Virginia Civics joining the VMHC, The Rule of Law Project (ROL), a longstanding educational initiative developed with support from the Virginia Bar Association (VBA) and the Virginia Law Foundation, agrees to join VMHC’s civics effort through its own strategic merger. The ROL, which educates middle and high school students about the underpinnings of democratic ideals, was founded in 2009 under the umbrella of the VBA. It was led by G. Michael “Mike” Pace, Jr. and Timothy Isaacs and later became a stand-alone entity, the Center for Teaching the Rule of Law, which was housed at Roanoke College until 2024. ROL’s innovative educational resources are now enriching Civics Connects, the VMHC’s newly launched educational resource that deeply covers the standards of learning for civics and economics in the middle grades and has the endorsement of Virginia’s state educational leadership. Dedicated rule-of-law lessons will be supported by lesson plan outlines, interactive slides for direct instruction or individual learning, activities and games, vocabulary, collections highlights linking rule-of-law principles to objects in the VMHC’s collection, as well as assessments and additional resources. Rule-of-law principles will also be integrated and tagged throughout Civics Connects’ 10 units and 50 lessons, making them searchable by topic.

“The rule of law is the foundation of fairness and justice in our country,” said John Marshall Center Director, Joni Albrecht. “We are proud to carry on the excellent work of ROL, promoting an early understanding of vital rule-of-law principles through innovative resources and classroom instruction that help students in Virginia and beyond make deep and lasting connections to essential knowledge.”

2025 will see the return of the VMHC’s Conrad M. Hall Symposium for Virginia History, a one-day event where historians, practitioners, and enthusiasts gather to explore our shared past. Featuring panels and presentations that highlight groundbreaking research into Virginia history, tailored gallery tours that celebrate revolutionary Virginians and their ideas, and a special keynote lecture, the symposium links past with present to inspire future generations. Learn more and register at VirginiaHistory.org/Symposium THE 2025 CONRAD M. HALL

Saturday, Oct. 4, 2025 | 9:00 am–5:30 pm

The VMHC is proud to present Revolution Revisited—a dynamic podcast series exploring Virginia’s pivotal role in America’s path to independence.

Season 1 is now complete and available for listening, offering a lively, story-driven crash course on the American Revolution. From the French and Indian War to the eve of independence, discover the rebels, rule-breakers, and rabble-rousers who shaped the nation—both the famous names and the overlooked figures who deserve the spotlight.

And the revolution isn’t over yet—minisodes are dropping throughout the summer, featuring fresh insights, behind-the-scenes stories, and bonus content you won’t want to miss.

Stream Season 1 and subscribe for new episodes at VirginiaHistory.org or wherever you get your podcasts.

Revolution Revisited is made possible by William and Karen Fralin and is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube Podcasts, and more.

On June 1, 1775, prominent men from across Virginia answered their governor’s call and gathered in Williamsburg’s Capitol to attend to the business of the colony. By the late 1700s, this ritual was already more than 150 years old, the House of Burgesses being the oldest legislature in the western hemisphere. But this would be the final time that body met to conduct regular proceedings. In less than a year, colonial Virginia’s House of Burgesses would be no more, replaced by the independent state of Virginia’s House of Delegates.

The summer of 1775 witnessed the blossoming of an official revolutionary movement, as Virginia’s Patriot and British authorities prepared for what increasingly seemed like an inevitable clash of arms. The previous six weeks had seen Britain’s North American colonies slip from relatively peaceful protests to the brink of a full-scale armed rebellion. In Massachusetts, war was already underway as an army of New Englanders besieged the British garrison in Boston following the Battles of Lexington and Concord. In Philadelphia, delegates from all thirteen colonies gathered for the Second Continental Congress and debated how to respond to the crisis. In Virginia, Royal Governor Lord Dunmore threatened to burn Williamsburg to the ground in response to the intimidating actions of Patriot militias after his removal of gunpowder from the city’s magazine. Cooler heads prevented bloodshed, but tensions in Williamsburg remained high.

It was in this context that Dunmore reconvened the House of Burgesses, which had not met since he dissolved the body in May 1774 following its declaration of a day of “Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer” in support of the people of Boston. Now a year later, Dunmore needed the burgesses to reconvene so they could consider British Prime Minister Lord North’s recently arrived “Conciliatory Resolution.” North’s proposal promised to remove parliamentary taxes if the colonies contributed to their own defense and administration, but left those contribution amounts up to Parliament to decide and did not address the wider issues of colonial self-government. Importantly, North wanted each colonial assembly to take up the resolution in the hopes some would agree to it, thus undermining the unity of the Continental Congress.

Two days before the opening of the session in Williamsburg, the sounds of bells, drums, and cheers announced the arrival of someone described as “the father of [his] country, and friend to freedom and humanity!” This most respected of Virginia’s leaders was Peyton Randolph, recently returned from Philadelphia where he served as president of the Continental Congress. Randolph returned to his hometown to resume his role as speaker of the House of Burgesses, a position he held since 1766 largely because of his moderate political beliefs. Highlighting the divided political opinion of the burgesses, several men joining Randolph in the

Flight of Lord Dunmore, postcard, c. 1907 (Courtesy of Library of Congress).

Capitol wore fringed hunting shirts and carried tomahawks and rifles—the uniform of the recently formed Patriot militias.

Considering the ongoing crisis, Dunmore opened the session with a remarkably temperate address to the assembled burgesses, urging them to agree to North’s resolution. The next few days continued to be uneventful, as a committee crafted a response to the proposal and the burgesses addressed the backlog of mundane petitions from Virginians across the colony. But this calm was shattered by a gunshot the night of June 3. As three young men attempted to break into Williamsburg’s magazine, they triggered a hidden spring gun, an 18th-century booby trap used to deter robbers. Although two of the men suffered severe injuries, they all survived.

Though Dunmore denied knowledge of the contraption, Patriot leaders used the incident to whip up renewed hysteria against the governor. Ignoring the fact that the young men were clearly acting criminally, the Virginia Gazette branded Dunmore an attempted murderer. Even the normally moderate Edmund

Pendleton agreed that if Dunmore was responsible for installing the guns, “he might well fear what he must have been conscious he deserved, Assassination.” Days later, a mob stormed the magazine and removed the remaining military supplies. Rumors swirled that marines from nearby British warships were on their way into town. Armed Patriot militiamen patrolled the streets day and night as Dunmore reported his “house was kept in continual Alarm and threatened every Night with assault.”

In the early morning hours of June 8, just one week since Dunmore reconvened the House of Burgesses with the express purpose of finding a compromise to the growing crisis, the governor, his family, and his closest aides quietly slipped out of the Governor’s Palace and made their way to H.M.S. Magdalen, the same British warship who’s crew seized the gunpowder from the magazine in April. By the afternoon, Dunmore transferred to the larger H.M.S. Fowey, anchored off Yorktown. Civilian British authority in Virginia’s capital city had officially ended, never to return.

When the burgesses learned of Dunmore’s flight, they proclaimed their shock and disbelief. The night before, the governor had leisurely walked across town to dine with Attorney General John Randolph, hardly the actions of a man fearing for his life. Many grew suspicious that his departure coincided with the arrival of two British warships from Boston. But Dunmore was likely right to worry. Both Patriot and Loyalist Virginians later reported that a plot had existed to kidnap Dunmore, either to put him on trial or use him as collateral in the event the British captured Patriot leaders. Regardless, Dunmore refused the burgesses’ pleas to return to Williamsburg so that the colony’s government could resume normal operations. Three weeks later, after declining to approve North’s resolution without first consulting the Congress in Philadelphia, the House adjourned. This would be the last time in its storied history that the House of Burgesses conducted any meaningful business.

With Dunmore gone and the House of Burgesses adjourned, there was no longer any official government authority in charge in Williamsburg. At the same time, hundreds of men from throughout Virginia poured into town to protect the capital from

a feared invasion by Dunmore and his recently reinforced British naval force lurking offshore. Hundreds of virtually unsupervised armed men, with nothing consequential to do, soon plunged the wider Tidewater region into anarchy. George Gilmer, one of these enthusiastic volunteers, described the gathering as more “invited to feast rather than fight.” Random gunshots rang out at all times of day, the city’s taverns were constantly full, and residents suspected of Loyalist sympathies were forced before ad hoc tribunals and threatened with assault . . . or worse.

More seriously, a group of men broke into the now abandoned Governor’s Palace and stole the hundreds of pistols, muskets, and swords that adorned the walls of the front hallway, distributing them to volunteers who lacked arms of their own. Meant to awe visitors to the palace as a symbol of Britain’s military power, those same weapons were now being used to directly challenge Dunmore’s authority. Meanwhile, volunteers seized funds from the colony’s treasurer and custom officials, and others threatened to march on Norfolk to suppress suspected Loyalists. Many moderates worried what would happen next.

Swords and pistols, displayed in the entryway to the Governors’ Palace at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia (Courtesy of Library of Congress).

Although radicals praised the volunteers’ actions, most of Virginia’s traditional leadership class was aghast at the chaos. Fearing they could lose the economic and social power they had spent decades carefully acquiring, they quickly realized they needed to reassert control. To fill this power vacuum, Peyton Randolph called for a Third Virginia Convention to meet once again at St. John’s Church in Richmond. Convening in July 1775, the next six weeks saw Virginia’s revolutionary movement take a more definite shape.

Realizing the independent volunteers represented an increasing threat to their own authority, the convention created an official three-tiered military structure. For immediate local defense, including the suppression of enslaved people, they reauthorized county level militias who would answer to their local committees of safety. In the event of a larger military threat, the convention created a minuteman system of 8,000 men spread across 16 military districts. Training more often than the militia, but not permanently under arms, the minutemen were designed as a semi-professional reserve force. Finally, they called for a regular army of 1,000 men, led by officers appointed by the convention, who would serve for one-year enlistments. Attempting to put the chaos that had lately engulfed Williamsburg behind them, the convention dissolved the independent volunteers and passed more than 70 rules and regulations governing the conduct and operation of all these new units. Underscoring the rapidly evolving situation, these formations were created just four months after and in the same room where Patrick Henry’s famous call for “Liberty or Death” set Virginia on a path toward war.

eleven-man Committee of Safety that would make decisions in between sessions of the convention. This body took on an extraordinary amount of both executive and legislative powers, with the sole ability to purchase military supplies, establish military manufacturing, and command the movement of troops.

Reflecting the convention’s desire to ensure civilian control of the coming war, military officers were not allowed membership on the committee. Finally, the convention reformed the local committees of safety, which had proved instrumental to the on-the-ground implementation of the revolutionary movement, mandating annual elections and limiting their size and authority. Adjourning at the end of August, a little more than a year after the First Virginia Convention kick-started the process, the Third Virginia Convention had essentially created a parallel Patriot government and army to rival Dunmore.

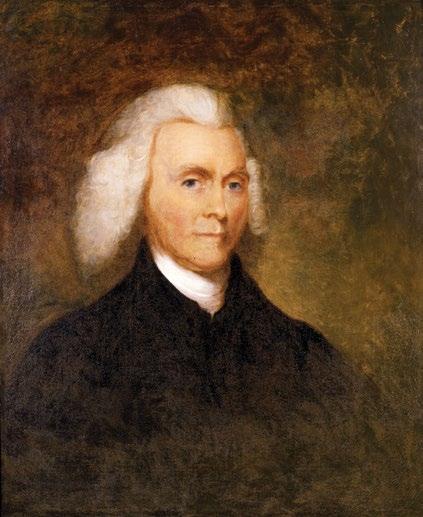

To oversee this new Patriot army, the convention turned to the creation of a civilian government. They settled on an

Though these were inherently radical measures, for the most part, they were being enacted by deeply moderate men. This can be evidenced by the selection of Edmund Pendleton as the Committee of Safety’s first president, essentially replacing Dunmore as the head of Virginia’s executive branch. Today, Pendleton is often left off the short-list of founding fathers, but his contemporaries considered the longtime lawyer and politician from Caroline County as one of the most highly respected voices of moderation in the Patriot movement. In contrast to his rival Patrick Henry, Pendleton argued for a cautious, methodical response to the imperial crisis. During April’s gunpowder incident, Pendleton privately denounced Henry’s march on Williamsburg as “very injurious to the common cause.” To further emphasize the influence of the moderate majority, the Third Convention adjourned with a declaration proclaiming their “faith and true allegiance to his majesty George the third” and promising, “it is our fixed and unalterable resolution to disband such forces as may be raised

in this colony whenever our dangers are removed.” Even after Dunmore’s abandonment of Williamsburg, the creation of a civilian government to replace him, and the raising of an army to fight him, many of Virginia’s Patriot leaders held out hope for a compromise that would keep them loyal subjects of the crown.

Meanwhile, Dunmore prepared to reassert crown authority in Virginia by force. By August, the governor had moved his small flotilla to the waters off Portsmouth, where he hoped to receive reinforcements from the British garrison in Boston and build support among the Loyalist population of nearby Norfolk. Unfortunately for Dunmore, his colleagues in Boston had their hands full with the recently created Continental Army (see the “Washington Takes Command” article in this issue). The June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill resulted in more than 1,000 British casualties and meant few men could be spared for other colonies. Instead, Dunmore received reinforcements from the south. On July 31, a detachment of 70 soldiers from the 14th Regiment of Foot arrived from

St. Augustine, East Florida. Apart from one additional small detachment from the 14th that arrived in October, these would be the only British reinforcements Dunmore received.

To increase his chances of success with such a small force, Dunmore mobilized the traditional enemies of Virginia’s elite. At the end of August, the governor sent experienced frontiersman John Connolly north to obtain permission, arms, and money from the British commander in Boston to raise an army of frontier Loyalists and Native Americans. Connolly would invade Virginia from the west as Dunmore moved up Virginia’s rivers in the east, catching the Patriots in a pincer movement. Back in the Tidewater, Dunmore encouraged enslaved people to join his forces by declining to return them to Patriot enslavers. As the convention’s army took shape in Williamsburg, Dunmore recognized the important manpower potential of Black Virginians. But much like Abraham Lincoln in a later war, because of the far-reaching impact he knew it would have, Dunmore decided to wait to enact an official policy on the recruitment of enslaved people until he could do so from a position of strength.

Unlike in New England where full-blown war raged, up to this point, relatively little blood had been shed in Virginia. But as summer turned to fall and temperatures cooled, the Revolution in Virginia was about to heat up.

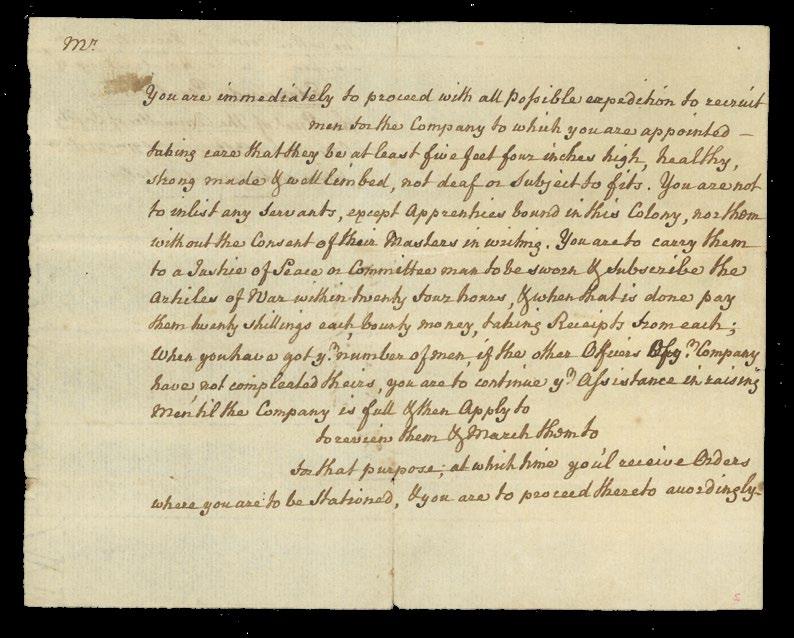

Written by Edmund Pendleton, this blank recruitment form would have been filled out when new officers were appointed to Virginia’s Patriot army and tasked with recruiting soldiers (VMHC Collection).

Free for members!

Cold War Virginia by Francis Gary Powers, Jr.

June 26 12:00 pm

Proximity to Power: Rethinking Race and Place in Alexandria, Virginia by Krystyn Moon

Aug. 7 12:00 pm

Member Mondays

Enjoy a relaxing evening in the Virginia House gardens with live jazz music. Aug. 11, Aug. 25 & Sept 8 5:30 pm

Virtual State of Museum

Join VMHC President & CEO for an in-depth presentation on the museum’s recent progress & future plans.

Sept. 25 5:30 pm

Visit the Vault Tours

First Fridays at VMHC

The museum remains open late for this free, family-friendly event.

*First Fridays will not take place on July 4th.

First Fridays made possible with support from Virginia R. Edmunds. First Friday each month 5:00 pm–8:00 pm

Front Lawn Fun

This free, familyfriendly program will feature outdoor games and toys from yesteryear.

Tuesdays June 10–Aug. 12 10:00 am

Themed Thursdays

Step back in time this summer with VMHC Educators every Thursday from 10:30–11:30 for a hands-on journey through 18th-century history! Each month features a unique theme:

June: Colonial Crafts

July: Revolutionary Replicas

August: 18th-Century Archaeology

Thursdays June 12–Aug. 14 10:30 am–11:30 am

Get special access to the VMHC’s rare book and manuscript vault for a short tour highlighting some of the museum’s most unique treasures. Select Saturdays See website for details

SAVE THE DATE

Join the VMHC for these annual events featuring beer, distilled spirits, and wine from across the Commonwealth, live music, food trucks, and after-hours access to the galleries.

Virginia Brews Aug. 2

Virginia Distilled Sept. 13

Virginia Vines Oct. 11

Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation Highlight Tours

Join members of the VMHC education team for thirty-minute tours and learn about Virginia’s role in the Revolution. Saturdays June 7–Aug. 30

Gather at the VMHC for Independence Day to watch America’s newest citizens take their oath, enjoy live music, explore the galleries, and see rare artifacts on display for one day only. July 4 11:00 am

HAZEL & FULTON

CHAUNCEY LECTURE

The Fate of the Day:The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777–1780 by Rick Atkinson

July 16 5:30 pm

Movie Mythbusting LIVE!— The Patriot

Join the VMHC for an in-person screening of the Revolutionary War epic The Patriot (2000), with live commentary from VMHC staff on what’s true, what’s not, and unique connections to the VMHC collection. July 25 6:00 pm

Virginians Will Dance or Die!— 18th Century Music and Dancing Demonstration

Join the VMHC for a hands-on exploration of colonial-era music and dancing. Aug. 21 5:30 pm

To register and view all of our upcoming events, visit VirginiaHistory.org/Calendar

Reserve tickets at VirginiaHistory.org/ July4

Many will not recognize those names or know the stories of the people who once bore them. The Virginia Museum of History & Culture’s newest exhibition, Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865 seeks to change that.

Un/Bound explores the lives of those who strove to secure legal, economic, and personal liberty in the shadow of slavery and in the face of immense hardship from the arrival of the first captive Africans in 1619 to the end of the American Civil War in 1865. The exhibition also examines the roles free Black people played during Reconstruction and features descendants to help visitors understand that the legacies of free Black Virginians persist beyond the nineteenth century.

Through powerful objects, first-person accounts, and a wide variety of documents, guests will discover how Virginia’s free people of color achieved their freedom, influenced politics, impacted public opinion, and persevered within a legal system that recognized them as free but not equal. Guests will also learn how family, faith, and community relationships fostered kinship, hope, and inspiration.

Un/Bound will tell a complex, nuanced, and deeply human story of the ways in which real people navigated—successfully and unsuccessfully—within a society that limited their liberties and prospects. The exhibition will also challenge visitors to understand how the experiences of people like Jane Driggus, Matthew Ashby, Nancy, Ann Copeland, and Andrew Weaver are relevant to their own lives today.

Jim Dyke, Virginia’s first Black secretary of education, and Tim Sullivan, former president of the College of William & Mary, published an article in the February 28, 2021, edition of the Richmond Times-Dispatch recognizing “that Black history is Virginia history.” They also argued that the stories of free Black Virginians are under-represented in most conventional narratives of our Commonwealth’s history, an omission that does not allow us a full appreciation of our state and nation’s struggles for genuine freedom and equality. The duo paired up with Alvin Schexnider, former interim president of

Norfolk State University, and approached the Virginia Museum of History & Culture with an opportunity to make the history of Virginia’s free people of color more visible to the public.

Un/Bound is the result of that collaboration. Although other institutions have mounted exhibitions on free Black Virginians within a specific region or span of time, Un/Bound is the first exhibition that focuses on the history of free Black people on a statewide level, and with such an extensive chronological reach.

Guests will travel through six sections that trace how Black Virginians gained, protected, and valued their freedom through time.

The “twenty and odd Negroes” who disembarked the White Lion and stepped onto the shores of Point Comfort, Virginia in 1619 shaped American history. They arrived in a tumultuous colony marked by demographic, economic, and political instability. The seventeenth-century English jurisprudence colonists followed was ambiguous regarding the institution of slavery: it certainly

did not contain any mention of the race-based system of chattel slavery Virginians developed as the century unfolded. Black Virginians won and cherished their freedom, even as laws regulating their behavior and existence grew more restrictive. The Driggus family exemplifies how the earliest generations of Black Virginians navigated the murky spaces between slavery and freedom. Emanuel Driggus secured his own freedom and that of his foster daughter, Jane Driggus. He could not, however, win the freedom of three of his own children.

In 1705, the General Assembly passed “An act concerning Servants and Slaves.” The law, comprised of 41 sections, significantly strengthened the institution of slavery and imposed harsher restrictions on free Black people. The stabilization of Virginia’s economy and the development of a transatlantic consumer culture depended on the legal, economic, and social hardening of the institution of slavery. Opportunities for legal manumission narrowed—self-emancipation, or “running away,” was the only viable option for many seeking liberation.

Group of Free Blacks in Richmond, 1865 (Courtesy of Library of Congress).

Virginia’s free Black population remained small in the eighteenth century. Many people were free because they were born to free white women, many of whom were servants. In 1662, the General Assembly had shifted dramatically from English common law and declared that one’s status—if you were free or enslaved—followed the status of your mother. Matthew Ashby’s mother was a free white woman; therefore, Matthew was also free. He worked hard and saved enough money to purchase his wife and children. His daughter’s birth is recorded in the Bruton and Middleton Parish Register in Williamsburg. All of Matthew’s children attended the Bray School, one of the earliest schools dedicated to the education of Black children in the thirteen colonies. Matthew Ashby, although limited by discriminatory laws and cultural practices, nevertheless did all that he could to secure a better future for his family.

The American Revolution was a seismic moment that touched the lives of everyone in Virginia. Free Black men served in the armies on both sides of the conflict, spurred on by personal convictions or practical considerations. Thousands of enslaved Virginians ran behind British lines, galvanized by Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation that promised freedom to anyone enslaved by the “rebels.”

The ideas that fueled the Revolution did not disappear with the war’s end. The intellectual atmosphere of the Revolution was saturated with notions about natural rights, the meaning of liberty, and the nature of Christianity. Some, like Robert Carter III, who was a member of one of Virginia’s most prominent families, felt compelled to release the people they held in bondage.

People like Carter could more easily free those they enslaved because of a law the General Assembly passed in 1782. Previously, in 1723, the Assembly mandated that an enslaved person could only be freed if they obtained the permission of the governor and the Governor’s Council. This was a difficult process, and, consequently, manumission rates were quite low in the eighteenth century.

In 1782, the Assembly overturned that law and stated that private manumissions—or emancipation through legal instruments, such as wills or deeds—were allowed. People

no longer needed the consent of the upper echelons of government to free enslaved men, women, and children. Nancy gained her freedom in Surry County. She was 21 years old. She left the courthouse with a certificate, or her “free papers,” on October 22, 1800. The certificate detailed her appearance and named her former enslaver. Nancy used that document to prove that she was free: no one owned her body, she could not be sold, and her labor belonged to her alone.

(1806–1861)

The liberalized manumission law of 1782 generated an explosion in Virginia’s free Black population. For example, the 1790 census registered 575 free Black people as inhabitants

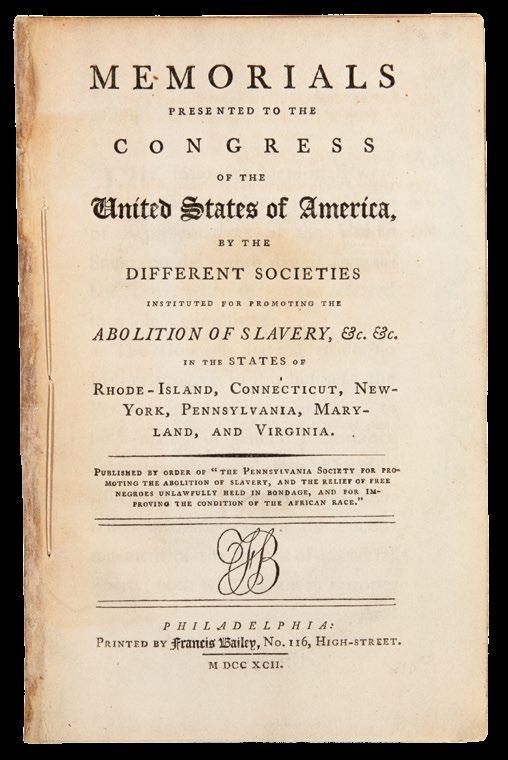

‘Virginia Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, or Others, Unlawfully held in Bondage, and Other Humane Purposes,’ 1792 (VMHC Collection).

of Richmond and Petersburg, combined. The 1810 census noted that 4,837 free Black people lived in those two cities.

Such a dramatic increase in the number of free Black Virginians provoked the ire of some white people. The 1782 law had faced immediate backlash; the population growth just deepened the resentment and fear of those who characterized free Black Virginians as lazy, dangerous, and financially burdensome.

In 1806, the General Assembly addressed the conflict unleashed by the liberalized manumission law by issuing a “compromise.” Private manumissions remained legal; however, anyone emancipated was required to leave Virginia within one year of obtaining his or her freedom. Those who wished to stay had to successfully petition their local government for the right to remain.

The 1806 expulsion law represents many of the challenges free Black Virginians faced in the nineteenth century. Opportunities existed alongside restrictions that impacted free Black peoples’ relationships, movement, economic prospects, and other components of civil society. Free Black Virginians created distinct communities, established churches, founded mutual aid societies, purchased property, and generated income through jobs and trade. They married, passed inheritances to their children, and built relationships with their neighbors. At the same time, free Black people could not vote, could not

testify against white people in court, and could not assemble to learn literacy skills, among other restrictions. Mixedstatus families in which some family members were free and others enslaved exposed those families to the violence of slavery and the threat of separation through sale.

Some free Black Virginians left the state voluntarily, hoping for a better life in the free states or abroad. Some traveled as far as the west coast of Africa, where the newly established colony of Liberia offered the prospect of improved economic opportunities and less oppression.

Others, like Ann Copeland, remained in Virginia. In 1861, Ann wrote to her husband while he was away, confessing that, “My wishes are to see you darling one.”

This poignant sentence reminds us that free Black people built meaningful lives despite the limitations they faced.

Sectional tensions that had been mounting for decades erupted into civil war in 1861. Free Black Virginians were pulled into the conflict as civilians and in military roles. The Confederate Army impressed scores of Black men to work in camps and build defenses, even as those men resisted the coercion of their labor. Free Black Virginians largely supported the U. S. Army and understood the war as one of freedom and emancipation. Free men labored for the U.S. Army, and free women supported the military as cooks, laundresses, and spies. At least 5,700 free Black men enlisted in the United States Colored Troops, including Andrew Weaver, a young man from Fredericksburg. Andrew saw action and was wounded at the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg.

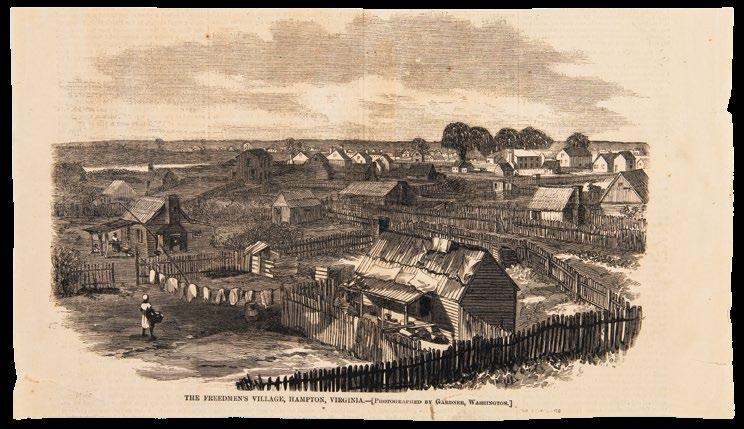

Thousands of enslaved Virginians fled to the lines of the U.S. Army as “contrabands of war.” Although not legally free, their escape to freedman’s villages established around U.S. encampments were often the first step toward the promise of liberty.

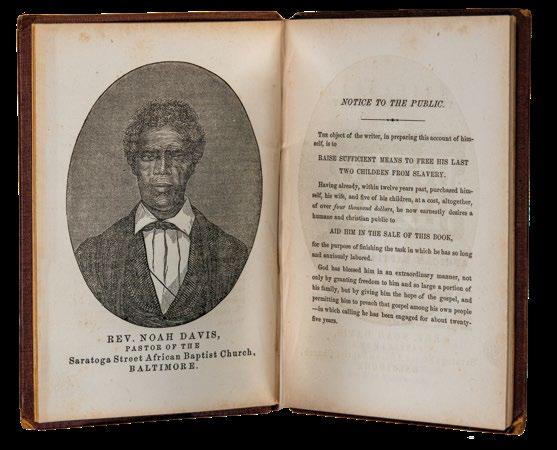

A Narrative of the Life of Rev. Noah Davis: A Colored Man , written by himself, at the age of fifty-four, 1859 (VMHC Collection).

UN/BOUND

Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865

On Display Until July 4, 2027

EXHIBITION ADVISORS

Dr. Melvin Ely, College of William & Mary

Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Norfolk State University

Dr. Evanda Watts-Martinez, Richard Bland College

Dr. Stephen Rockenbach, Virginia State University

Sabrina Watson, Virginia State University

EXHIBITION SPONSORS

Commonwealth of Virginia

Google Data Centers

Melanie Trent De Schutter

Dominion Energy

Conrad Mercer Hall

Dr. Tamara CharityBrown & Carlos M.

Brown Exhibition Fund

Balfour Beatty

Huntington Ingalls Industries

McGuireWoods

PNC

Riverside Sentara

Carilion Clinics

Mr. & Mrs. W. Heywood Fralin

National Counseling Group

Thompson Hospitality

Washington Gas

The end of the Civil War brought legal freedom to all Black Virginians. Many of those who had been free before the war became leaders in politics, education, and civic life during Reconstruction. They used the advantages and resources they had accrued before General Emancipation to help those who were, for the first time, permitted to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by freedom.

The legacies of free Black Virginians extend far beyond the nineteenth century. Descendants of free Black people live among us today and carry their families’ histories with pride and reverence. The VMHC has commissioned Ruddy Roye, an award-winning, Jamaican-born photographer, to create large format portraits of four groups of descendants. Their likenesses are a reminder that this history and these people are not distant, lost, or remote. Rather, they persist to this very day.

Jane Driggus. Matthew Ashby. Nancy. Ann Copeland. Andrew Weaver.

Although their names may be largely unknown, their experiences and their stories, and those of many thousands of other free Black Virginians, ask us to contemplate the meaning and value of freedom. Un/Bound is a testament to the courage, perseverance, and ingenuity of those who asked our nation to live up to its founding ideals.

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865 will be on view at the VMHC from June 14, 2025, to July 4, 2027. The exhibition is accompanied by a publication available in August 2025. A traveling panel version of Un/Bound will be available to museums, libraries, and community organizations throughout the Commonwealth.

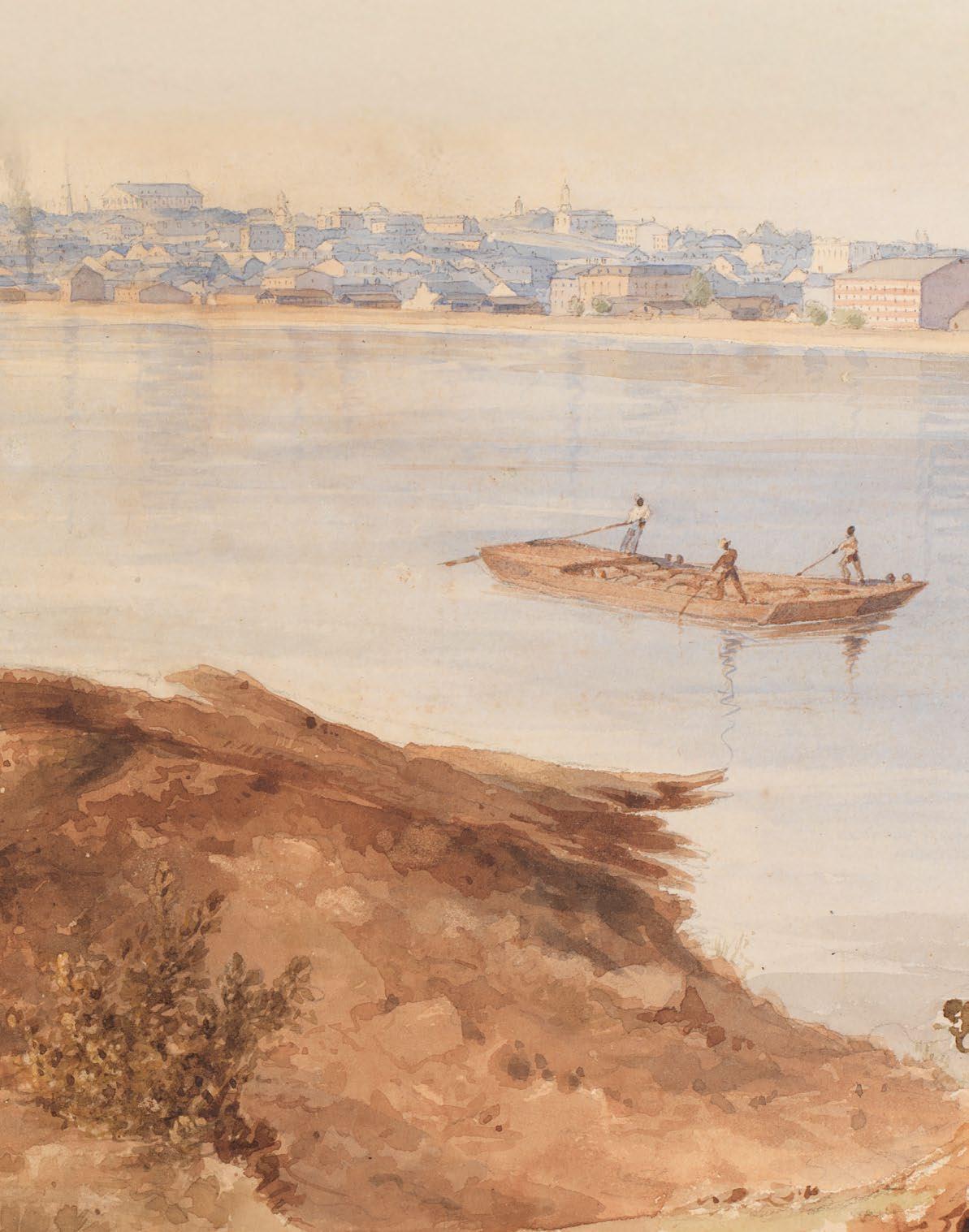

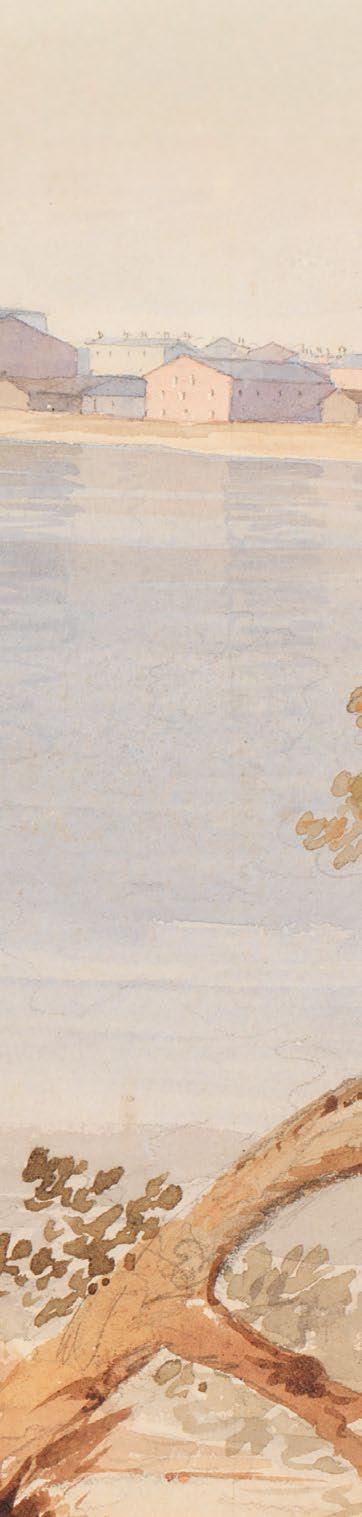

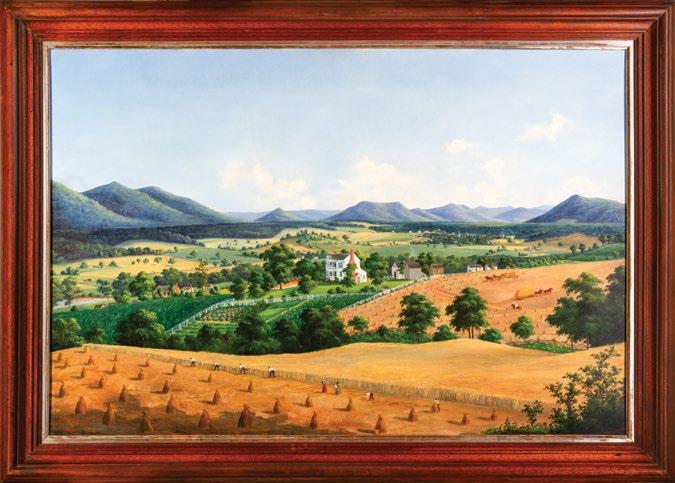

For three years during the 1850s, itinerant German artist Edward Beyer (1820–1865) traveled across Virginia drawing and painting a beautiful and vibrant landscape. In more than twenty-five oil paintings, he carefully rendered the Commonwealth’s prosperous towns, industrial cities, and natural wonders. Beyer is best known for his 1858 Album of Virginia, which includes 41 lithographs capturing views from the Ohio River to the Atlantic Coast. Particularly attracted to Southwest Virginia, he received several commissions in that region, including one recently acquired by the VMHC, Bellevue: The Lewis Homestead, Salem, Virginia

Born in the German Rhineland, Beyer trained at the Düsseldorf Academy, a school of painting and drawing renowned for the finely detailed landscape art style that bears its name. Likely escaping the chaos created by a wave of European revolutions, he and his wife traveled to the United States in 1848. Arriving in New Jersey, Beyer worked in Philadelphia and Cincinnati before traveling to Virginia in 1854. The couple frequented the resorts surrounding the healing waters of Virginia’s mineral springs, offering paintings for $50 plus room and board. Spending much of 1855 in Southwest Virginia, he supported his travels by selling landscape paintings of several growing towns, including Wytheville, Christiansburg, and Salem—all of which are currently in the VMHC collection. It was during his time in Salem that Beyer came to the attention of Dr. Andrew Lewis.

In Bellevue, Beyer captures the beauty of the landscape and intentionally demonstrates the prosperity of the painting’s sponsor. Dwarfed by the lush Blue Ridge Mountains, the Lewis house, kitchen, smokehouse, and garden stand near the center, while the golden fields of wheat, the source of much of the Lewis’s wealth, dominates the foreground. Beyer also depicts some of the 29 people the Lewis’s enslaved—both in the fields and around the house. Rendered in such detail, viewers can almost hear the scythes as they cut through the

wheat before being piled high onto the wagons to be brought to the barn. In the far distance, at the base of the mountains, the church steeples of Salem rise from the landscape. In addition to pastoral landscapes, Beyer documented the technological potential of Virginia—perhaps most notably in his view of Richmond’s James River factories—but even here, near Bellevue, the steam from a distant train engine can be seen.

The rich detail of Beyer’s paintings and lithographs offer nearly photographic documentation of the landscapes, towns, homes, and cities across Virginia on the eve of the American Civil War, and they are a valuable source for researchers and the interpretation of daily life. For many years, the VMHC has featured Beyer’s work in publications, on souvenirs, and in exhibitions. This painting of Bellevue adorned the cover of a 2003 VMHC publication, Old Virginia: The Pursuit of a Pastoral Ideal, but the painting remained in private hands. Today, thanks to the generosity of Josephine and Grant Griswould, Beyer’s Bellevue has been gifted to the collection and joins Beyer’s other remarkable landscape paintings.

On June 14, 1775, nearly two months after fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress established an “American continental army” to fight Great Britain during the Revolutionary War. The next day, a forty-three-year-old Virginian, George Washington, was appointed the Continental Army’s Commander in Chief. Intending to provide common defense to the Patriot cause, the army was to centralize and organize armed opposition to the British. The army drew together New England Patriot forces and extended military participation by allocating infantry companies to Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

It was important to have continental flavor. Having an experienced general from farther south, from Virginia—the largest, most populous, and richest colony in British North America—would bring greater benefits than just good leadership. Led by American officers rooted in British martial tradition, the Continental Army would eventually be influenced by French and Prussian ways of warring, too. The army’s goals were ambitious, embracing the tactics and organization of some of the world’s most effective European fighting forces. But starting by having a Virginian lead a force of largely New England troops signaled a political unity and a common cause across the colonies. It helped that Washington was voted in unanimously, solidifying the image of a national army.

George Washington made sense, mostly. He had even indirectly started a war as a 23 year old. Washington got his start in the military in 1752 when he joined the militia, putting colonists through their army paces.

Within a couple of years, the French and Indian War (1754–1763) broke out, pitting the North American colonies of Britain and France against one another in a conflict that pulled in various Indigenous nations and would ultimately leave the British as the dominant power on the continent.

Early in 1754, Washington was dispatched with the First Virginia Regiment and Indigenous allies to the Forks of the Ohio, out in the “Ohio country,” to confront the French. There, he led an ambush that massacred a small French force, including the commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, who was carrying a diplomatic message intended for the British. Washington and his men fled to Fort Necessity, where they were quickly outnumbered by vengeful French troops. When the French overwhelmed the fort, Washington surrendered. As he signed the surrender document, and because he didn’t read, write, or speak French, he, perhaps unwittingly, took responsibility for killing Jumonville. This Washington would later contest, and even some French doubted the veracious claims of their government as the event ignited into the French and Indian War.

A year later, Washington had a chance to rebuild his reputation. He accompanied General Edward Braddock on his infamous 1755 expedition, known unfortunately as Braddock’s Defeat. Washington was just in time, recovering from a nasty bout of dysentery, to serve with gallantry at the Battle of Monongahela, but the battle itself was a disaster for the British. Nearly 1,500 British regulars and American provincial troops were routed by less than 900 French, Canadians, and their Indigenous allies. Braddock went down with a mortal wound after three hours’ fighting, shot in the lung. He might have been killed by his own men. He was certainly pulled to safety by them.

Confusion followed, but Washington shone. He and the Virginia soldiers fought from the trees to match the informal tactics of their enemy—a skill they learned from years of fighting Indigenous people on the frontier. Washington and the Virginians formed a rear guard that allowed the British to disengage more effectively, and he left the field with a bullet-pierced coat and hat as proof of his heroics.

For the rest of the war, Washington commanded the Virginia Regiment as it defended hundreds of miles of frontier. The regiment trained and more than tripled in size, and

Washington learned of British tactics and strategy as his confidence grew and his skills as a leader strengthened.

Washington and the Virginians joined the lackluster Forbes Expedition in 1758, when the French burned and abandoned the target, Fort Duquesne, before the British arrived. Washington advised on the campaign and was assigned command of a brigade to assault the fort, but the French force’s early departure led only to a British friendly fire incident that caused forty casualties. Despite good leadership, he failed to attain a royal commission. Frustrated with a lack of recognition and decisive action on the frontier, Washington resigned and returned to Mount Vernon that same year.

In 1759, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, which only added to his prominence in Virginia. He grew tobacco and wheat and had many side ventures. Washington more than doubled the enslaved population at Mount Vernon, became wealthier and gained more land, and was eventually elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses.

After a steady start, Washington grew politically active in the 1760s. He opposed taxation by Parliament, was angered by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 banning settlement west of the Alleghenies, celebrated the repeal of the 1765 Stamp Act, and urged a boycott of British goods in response to the Townshend Acts. Though moderate, he was still a staunch defender of colonial rights.

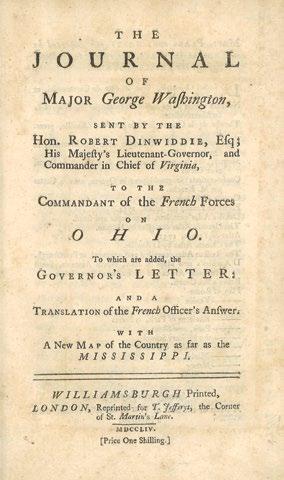

first British edition, of Washington’s journal, following the virtually unobtainable Williamsburg edition.” The book was available for a shilling and introduced Washington and his exploits to readers on the Atlantic coast and in Britain.

Washington’s military experience, skills and organization in land management, loyalty to the Patriot cause, even his stature and appearance—he was 6’2 and broadly built—singled him out as the ideal candidate to lead the forces besieging the British at Boston. John Adams said it well, noting, “By his great experience and abilities in military matters is of much service to use.” Benjamin Rush was blunt: a European king would be likened to a servant if seen stood by Washington’s side. In a June 19 letter in the VMHC collection, Washington wrote his stepson, John Parke Custis, communicating his concerns about taking on the role. “It is an honour I neither sought after, or was by any means fond of accepting, from a consciousness of my own inexperience, and inability to discharge the duties of so important a trust.”

It did help that, despite apparently not wanting the job, Washington dressed for it. He appeared at the Second Continental Congress wearing his military uniform, as he productively engaged in committees related to the war. It probably helped Washington’s perceived status that almost everyone around him was a military amateur.

Despite some notable blunders, Washington earned a great military reputation across the colonies, helped in part by the publication of the 1754 book, the aptly titled The Journal of Major George Washington, which provided his account of an adventurous 900-mile round trip a year earlier into the Ohio country and back. The earliest copy in the Virginia Museum of History & Culture’s collection is, as the publication information states, “the third edition overall, and The Journal of Major George Washington, 1754 (VMHC Collection).

As Washington prepared to leave Philadelphia for the forces amassed at Boston, he bought books on military strategy, several horses, and ordered a new uniform. Ironically, as he headed north to Massachusetts, his was the only name on the books of the new American army. As he and the Continental Congress picked out aides-de-camp and generals, geographic representation remained key. Soldiers typically wanted to be led by officers from their own colony, but Washington worked to create an army unhindered by divisiveness caused by colonial differences.

Washington pushed on to Boston through New York, slowed by cheering crowds and irritating

politicians. Receiving news of the costly British victory at Breed’s Hill (Bunker Hill), Washington was anxious about the situation in Boston. He arrived quietly on a dreary Sunday, but the weather soon cleared and there was pomp in camp as Washington reviewed the troops. Washington’s presence inspired the men, but the soldiers were a ragtag, undisciplined bunch from across the New England states. A professional force was needed. The appointment of former British officers like Horatio Gates and Charles Lee were intended to foster the professionalism necessary to go toe-to-toe with the opposing regulars.

There were ups and downs. As Washington took command, the British barged smallpox-riddled Bostonians toward American lines. The general saved lives with isolation and inoculation. Sanitation was a significant concern throughout the war: disease would claim considerably more lives than battle. It wasn’t just physical health that was important to the general, but moral behavior, too. Washington wanted his soldiers to be upstanding, and repeatedly bossed them on drinking, gambling, and foraging. But for all of Washington’s martial and moral instruction, an early issue was that soldiers were disciplined only to disappear. They signed up for year-long enlistments. Moreover, constant logistical shortages and delayed pay hindered the performance of the army.

It didn’t help that Washington and his command initially barred Black men from service in the army. But in November 1775, Virginia Royal Governor Lord Dunmore put out a proclamation offering freedom to enslaved people who would fight for the British, and Washington backtracked. At times, the number of Black soldiers in the Continental Army numbered as high as 12 percent.

and changed perceptions of an army that appeared in the throes of defeat. But it wouldn’t be until the Prussian military mastermind Baron von Steuben beat the army into shape during the grueling winter of 1777 at Valley Forge that the army markedly improved its abilities. Von Steuben organized the Continental Army with a tough training program, instituting European techniques and raising standards and morale. The Prussian’s manual, Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States (1779), remained in use until 1814, and still influences army practice to this day.

Because the Continental Army relied on volunteers provided by the states, Congress provided each state a quota of men to provide based on their populations, and it was up to state and local governments to fill those quotas through drafts, bonuses, and bounties. Those who served in Washington’s

Patriot soldiers battled British troops, gaining experience through victory and defeat. Washington’s daring and demanding attack on Britain’s Hessian allies at Trenton in December of 1777 was a masterstroke that, despite seeing little strategic gain for Washington, inspired American Patriots

Arnold Friberg, 2002 (Courtesy of First Freedom Art Company)

This beloved painting is on special display at the VMHC through August 31, 2025

army were young, mostly between the ages of fifteen and thirty, and were farmers, tradesmen, mechanics, and merchants. Often joining the armies were the wives and children and those who served, known as camp followers. They dispensed crucial emotional and physical support to soldiers.

Washington fought an uphill battle for the entirety of the American Revolution. Facing off against a superior though tactically restrained enemy, he also regularly navigated mutinous troops, insubordinate generals, and meddlesome politicians. Despite achieving victory over the British foe, the Continental Army only won a third of the major battles it engaged in and spent much of the war in retreat. But those engagements were strategically significant, and Washington didn’t need a grand, decisive victory. He only had to avoid handing one to Britain.

As the war continued, the Continental Army proved its fighting abilities at significant engagements, despite the situation looking increasingly desperate. This included the Battle of Camden (1780), where the militia fled but the continentals held their own against a superior British force until being surrounded. The next year, fortunes seemed at an all-time low. The three-year enlistment terms that replaced one-year service expectations began to expire, Congress was bankrupt and unable to outfit the army, and support for the war was at its lowest. Critical aid from the French, in both land and naval forces, ultimately allowed a Franco-American force to combine in the summer of 1781 to move south and entrap the British at the Siege of Yorktown. The capture of a significant British land force pressured Parliament to effectively end offensive operations in North America, paving the way for ultimate victory with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

George Washington’s determination to strengthen the Continental Army wasn’t just a wartime measure necessary for achieving victory, but an experiment in nation building.

As the first truly national organization to emerge from the Revolution, the army solidified unity among thirteen disparate colonies and created a new body of American citizens that understood the power of a strong central government.

As Washington bade farewell to his army in 1783, he commended them as a “one patriotic band of Brothers.” It was a unity that had won the war and would keep the peace.

Virginia & The Forging of A Nation Special Exhibition

On Display Until January 4, 2026

Virginians—through their ideas, influence, and efforts—helped forge a new American nation.

Commemorating the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence,

Give Me Liberty highlights Virginia’s leading role in the American Revolution. It explores the continental and global forces as well as the actions of both iconic and ordinary people that brought about a model of democratic government that changed the world.

Give Me Liberty was produced in partnership by the Virginia Museum of History & Culture and Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. It is presented by Virginia’s American Revolution 250 Commission.

The VMHC is proud to announce a new partnership with Stella’s Grocery that brings the popular flavors of the area restaurant and markets to the museum with the opening of the Commonwealth Café.

Inspired by the legacy of namesake Stella Dikos and the deep connection between her family and the Richmond community, this new endeavor blends culinary tradition with cultural heritage. Commonwealth Café begins offering a selection of Stella’s grab-and-go, dine-in, and retail products starting June 24.

The museum’s governing body welcomed two new members in April 2025.

Rudene M. Haynes

Rudene Mercer Haynes lives in Midlothian, Virginia. She is managing partner of Hunton Andrews Kurth’s Richmond office, co-leader of the firm’s servicer advance financing practice, and has historically represented Ginnie Mae in its Multiclass and Mortgage-Backed Securities programs. Rudene has contributed greatly to the success of this practice that enjoys top rankings in representing issuers and underwriters in US asset-backed securities and mortgage-backed securities. Ms. Haynes received degrees from the University of Virginia and the University of Texas School of Law.

Gen. Richard B. Myers

General Myers lives in Spotsylvania, Virginia. He is a retired General in the United States Air Force who served as the 15th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (2001–2005). As the nation’s highest ranking military officer, he served as the principal military adviser to the President of the United States, the Secretary of Defense and the National Security Council. Prior to becoming Chairman, the general served as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. After his military career, from 2016 to 2022, General Myers served as the president of Kansas State University. General Myers received degrees from Kansas State University and Auburn University.

VIRGINIA & THE FORGING OF A NATION

Give Me Liberty: Virginia & The Forging of a Nation , VMHC’s newest exhibition companion publication, explores Virginia’s central role in the American Revolution. Iconic individuals like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, are revisited with new perspectives, and many others—caught up in extraordinary, Revolutionary events— are introduced for the first time.

This new work brings together essays by leading scholars of the period to offer a wideranging narrative of a colony-turned-state at the very heart of the American Revolution.

Order online at VirginiaHistory.org/ GMLBook

BOOK LAUNCH

UN/BOUND: FREE BLACK VIRGINIANS, 1619–1865

August 20 6:00pm

Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619-1865, a new companion book to VMHC's forthcoming exhibition, explores the lives of free people of color in Virginia, revealing under-told and often inspirational stories of Virginia’s past. Join the leading and pioneering contributors to the book for a discussion about free Black people's rich and varied experiences.