Centennial of The Indian Citizenship Act

Centennial of The Indian Citizenship Act

VMHC Launches Comprehensive Civics Program page 4

Centennial of The Indian Citizenship Act page 14

The Nation’s Guest: Lafayette’s Grand Tour page 22

Jefferson’s Summary View of the Rights of British America page 8

Going for Gold: Virginians in The Olympics page 28

Cover: Lafayette at the tomb of Washington, 1845 (Courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Virginia History & Culture No. 20

Questions/Comments newsletter@VirginiaHistory.org

428 N Arthur Ashe Boulevard Richmond, Virginia 23220 VirginiaHistory.org

804.340.1800

Galleries and Museum Shop

Open 10 am – 5 pm daily

Research Library

Open 10 am − 5pm, Monday – Saturday

NEWSLETTER TEAM

Editor

Graham Dozier

Designer/Production

Cierra Brown

Contributors

Jamie Bosket, James Brooks, Danni Flakes, Sam Florer, Elizabeth Klaczynski, Tracy Schneider, Ashley Spivey

EXECUTIVE TEAM

President & CEO

Jamie O. Bosket

Chief Financial Officer

David R. Kunnen

VP for Advancement

Anna E. Powers

VP for Collections & Exhibitions

Adam E. Scher

VP for Guest Engagement

Michael B. Plumb

Associate VP for Human Resources

Paula C. Davis

VP for Marketing & Communications

Tracy D. Schneider

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Chair

Richard Cullen*

Vice Chair

Carlos M. Brown*

Honorary Vice Chairs

Austin Brockenbrough III

Harry F. Byrd III*

Nancy H. Gottwald

Conrad M. Hall*

Thomas G. Slater, Jr.*

Regional Vice Chairs

William H. Fralin, Jr.

Susan S. Goode*

Gen. John P. Jumper

Lisa R. Moore

Gerald F. Smith*

*Executive Committee

The Virginia Museum of History & Culture is owned and operated by the Virginia Historical Society—a private, non-profit organization established in 1831.

Makola M. Abdullah

B. Marc Allen

Neil Amin

Victor K. Branch*

Charles L. Cabell

Victor O. Cardwell

Herbert A. Claiborne III

William C. Davis

Melanie Trent De Schutter

Joanie D. Eiland

Peter F. Farrell

Victoria D. Harker

Russell B. Harper

Paul C. Harris

C. N. Jenkins, Jr.

Edward A. Mullen

John R. Nelson, Jr.*

Kevin B. Osborne

J. Sargeant Reynolds, Jr.

Xavier R. Richardson

Elizabeth A. Seegar

Robert D. Taylor

J. Tracy Walker IV

The countdown begins. In just two years’ time, the United States of America will mark its 250th anniversary. As a Commonwealth and as a country, we should embrace this historic moment— extraordinary in our lifetimes—and act upon it by together renewing our commitment to the unfinished pursuit of A More Perfect Union—to reflect deeply on our past and invest with great purpose in our future.

The VMHC is well positioned—a trusted voice in a tumultuous time—to connect Virginians and Americans with their compelling and collective story. And, over the past several years, the VMHC has been preparing to meet this moment as we enthusiastically delivered on the promises of our 2018–2024 Strategic Plan. We are now fulfilling our mission in new and innovative ways, and reaching more people in Virginia and beyond than at any time in our nearly two-century history. Our museum has been reimagined, our team has been expanded, and our fiscal health is strong. Now, we look ahead from a position of strength and limitless optimism as we begin a new chapter.

As you read this, we are excitedly beginning the important work included in our new strategic plan, which was unanimously approved by our Board of Trustees this spring. This new plan was built on guidance from our guests, supporters, community, trustees, and staff. It charts a comprehensive path for our next three years that will see us through the commemoration of America’s semiquincentennial and then set the stage for our own institutional bicentennial. We will build on, and maximize, the momentum and progress we’ve made over the past several years.

With major capital improvements and transformational change successfully completed, this new plan focuses on programmatic excellence and smart growth, continued museum and library activation, investments in our intellectual core, statewide and national leadership, America’s 250th and the urgent need for civics and history education, investments in technology and digital infrastructure, and continued sustainability and fiscal strength. It is a meaningful, timely, and ambitious plan—one that will lead us thoughtfully forward.

Thank you, as always, for your support of, and great participation in, our progress.

Most sincerely,

Jamie O. Bosket, President & CEO

Even before the pandemic’s learning-loss epidemic, civics learning in the United States had been losing ground for some time. America’s resulting “civics crisis” is evidenced in low standardized test scores and in countless polls that reveal not only a lack of knowledge about democratic principles and systems but even more concerning, young America’s apathy about democratic forms of government.

Only 1 in 3 Americans (36%) would pass the U.S. Citizenship Test, which only requires correct answers to 60% of the history and civics questions asked.1

Against this challenging backdrop and in step with the vast opportunities afforded by America’s upcoming 250th anniversary, the VMHC is launching its most comprehensive civics education program ever. This July 4, the VMHC will roll out Civics Connects, a classroom-ready resource for Virginia’s middle grades, born from years of related work by the VMHC’s John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics (JMC). Civics Connects will cover all Virginia standards of learning for civics and economics in the middle grades and will align with national standards as well. Civics Connects will offer an array of educational tools, designed with significant input from Virginia educators at every level, and will include lesson plans, videos, interactive slides, onsite educators, subject matter experts, and museum field trips, components modeled on proven VMHC and JMC resources. The through-line is inquiry-based design, an educational model that helps equip students with a toolkit for exploration and discovery.

Less than half of U.S. adults (47%) could name all three branches of government. 1 in 4 respondents couldn’t identify even one.2

Only 1 in 4 U.S. adults could name a single right provided by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.2

Only about half of young adults believe democracy is the best form of government.3

1

2

3

Civics Connects videos will feature Virginia middle schoolers, who will represent Virginia’s 300,000 middle school students, serving as “civics investigators” visiting the VMHC as well as other important sites around the Commonwealth—and even the National Archives and The White House— on a quest to understand America’s founding documents, principles of democracy, and their responsibilities and rights under the Constitution.

Civics Connects resources will include games that not only convey educational content but also teach civics skills, such as civil discourse and community problem solving. Rather than individualism, as games played on phones prioritize, Civics Connects activities emphasize collaboration. For example, in learning how the U.S. Constitution was formed

from several founding documents, classroom groups solve a puzzle together. One side contains puzzle pieces of documents like the Magna Carta, the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights. When solved, the Constitution is formed.

Civics Connects will rely on a Civics Ambassador Corps comprised of educators contracted in all eight Virginia Superintendent Regions, who will pilot and promote the program beginning with the upcoming 2024–25 academic year, a year where Virginia schools will begin to transition from the 2015 standards of learning to the 2023 and will begin to make a Virginia Department of Education-recommended shift from civics and economics as an eighth-grade course to one taught in the seventh grade. Civics Connects is designed to help civics thrive rather than falter during this time of transition and disruption and help ensure that all Virginia middle school students receive a full year of civics ahead of their high school careers. Units will be

introduced throughout the year, beginning with America’s Founding Documents in July, and paced to Virginia schools’ coverage of civics and economics content.

“We are excited to offer the only resource that will cover all Virginia standards for civics and economics in the middle grades. And while we are designing it with and for Virginia teachers and students, we believe it should and will serve as a national model,” says Jamie O. Bosket, VMHC President & CEO. “We know that civics truly does connect us, to each other and to our government. To our past and to our future.”

Civics Connects, a comprehensive, classroomready resource for Virginia’s middle grades, will be available at no cost to all Virginia students. Learn more at VirginiaHistory.org/CivicsConnects

Turnkey lesson plans for 7th-and 8th-grade social studies teachers align with the 2015 and 2023 civics and economic VA SOLs. Lessons include classroom games and activities, vocabulary, collections correlations, enrichment exercises, and assessments.

Middle school students will see themselves as contributors to their communities and valued participants in democratic processes in a new series of videos hosted by Virginia middle schoolers.

Student-directed, interactive slide sets work on any device, cover all 47 lessons, and easily integrate into learning platforms used by schools.

ONSITE

Schools may request an onsite educator to lead classroom instruction remotely or in person.

Schools may request experts such as attorneys, judges, corporate leaders, elected officials, or historians to lead discussions remotely or in person.

Schools may schedule a civics and economics field trip to the VMHC for civics treasure hunts, gallery tours, and experiential learning activities.

Civics Connects is a legacy program of the VMHC’s 250th Initiative, produced by the museum’s John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics (JMC).

The JMC, founded in 1987, educates learners of all ages about constitutional history and civics and explores the life and legacy of Chief Justice John Marshall. The JMC joined the VMHC as a signature study center on July 4, 2023, and serves as a hub for civics education throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia and beyond.

Learn more at VirginiaHistory.org/CivicsConnects

Thomas Jefferson, Summary View of the Rights of British America, 1774 (VMHC Collection).

Momentum is building toward July 2026, when we mark the 250th Anniversary of American Independence with the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Note also, that the summer of 1774 saw a Virginian take a significant step taken toward that famous date. That July, Thomas Jefferson was busily drafting proposals for an upcoming convention in Williamsburg. His proposed resolutions, which the gathering of Virginians in fact rejected, were published as a pamphlet in August with the sleek title of A Summary View of the Rights of British America: Set Forth in Some Resolutions Intended for the Inspection of the Present Delegates of the People of Virginia, Now in Convention. The name belies the radical potential of Jefferson’s resolutions, which essentially stand as an early iteration of the Declaration of Independence he would author two years later.

Summary View is a landmark publication in Virginia history, and the Virginia Museum of History & Culture stewards a copy of the first edition, which was printed without Jefferson’s knowledge and of which fewer than ten copies exist today. Rather unassumingly, this important document is fourteen centimeters along its long edge, and twenty-three pages long. The VMHC also holds two copies of the second edition, reprinted on Fleet Street in London, with additions, within months of its first publication in the colonial capital. A network that included Virginia’s first female printer and an English publisher with radical tendencies contributed to the establishment of Jefferson’s reputation and helped get him the job of authoring the Declaration.

Virginia in early 1774 was quiet in comparison to American colonies to the north. The Boston Tea Party had rocked Massachusetts in December 1773, but Virginians were subdued in their initial response. They disapproved of the destruction of private property belonging to the East India Company. Nevertheless, the Tea Party’s aftershocks would reverberate in Virginia. When the British government passed the Boston Port Act, the first

of the Coercive Acts, in March 1774, Virginia leaders signaled their anger at this heavy-handed response.

In May, Jefferson contributed to a resolution by the House of Burgesses calling for a day of “Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer” to implore divine intervention to avert “the heavy Calamity which threatens destruction to our Civil Rights, and the Evils of civil War.” In response, Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, dissolved the assembly. The following month in Prince William County, Clerk for the Committee of Correspondence, Evan Williams, noted in county records, “Resolved, that the city of Boston . . . is now suffering in the common cause of American liberty.”

In July, John Randolph penned the question, “Are we to sit in Silence when a Sister Colony is environed with Ships, and has Troops quartered in her Metropolis, ready to oblige her to pay an offensive Duty, and by that Means . . . endanger the Freedom of Posterity[?]”

That same month, Jefferson was drafting a paper addressed at delegates to what would be the First Virginia Convention, due to meet on August 1, 1774, at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. The representatives considered the Virginia Conventions a natural expression

of the people’s determination to selfgovern, following Lord Dunmore’s earlier dissolution of their assembly. Jefferson posted his manuscript to Williamsburg and, while the piece attracted a positive response, the convention ultimately declined to adopt his proposals in favour of more moderate measures. Nor was Jefferson chosen to attend the First Continental Congress. But a group of delegates of the Virginia Convention soon took it upon themselves to publish his Summary View as a pamphlet.

Clementina Rind had printed the Virginia Gazette for almost a year when the convention met in Williamsburg, a venture she led within a week of her husband William’s death the previous August. Rind’s Gazette, unhelpfully to historians, was established in direct competition with another paper of the same name, also based in the colonial capital, in the 1760s. Probably born in Maryland about 1740, the thirtyfour-year-old Rind had lived in Virginia for less than a decade at the time of the First Virginia Convention. She also had five children, four of whom would reach adulthood; and a 1773 inventory listed the Rinds as owning an enslaved man, Dick, who likely performed artisanal work at the press and had some degree of literacy. John Pinkney, a relative, also assisted the family.

Deed of Clementina Rind, including matter related to her printing business, 1774 (VMHC Collection).

radical ideas by print media in Virginia during a key moment of rising tensions with British authorities in the lead up to the American Revolution. Like most political tracts of the era, it was printed without the author’s name. Instead, the credit reads, “By a Native and Member of the House of Burgesses.” But Rind’s publication of Summary View circulated widely and established Jefferson as a talented and revolutionary writer.

Summary View begins with a “preface of the editors,” the Virginia Convention delegates who took the manuscript to Rind, noting that “our present unhappy differences are traced with such faithful accuracy” and the “opinions entertained by every free American expressed with such a manly firmness, that it must be pleasing to the present, and may be useful to future ages.” They acknowledge that they had not sought Jefferson’s permission to publish a tract, but believed the public had “a right to know what the best and wisest of their members have thought on a subject in which they are so deeply interested.”

The burgesses appointed Rind as the colony’s public printer in May 1774. According to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, she is the first woman known to be elected to a position in Virginia’s colonial government. Rind again demonstrated her technical skill and political connections when Virginia Convention delegates approached her to publish Jefferson’s resolutions. Though she would die from illness by September, Rind’s August 1774 publication disseminated

So, how did Jefferson summarize the rights of British America? His goal had been to persuade the Virginia delegation to the First Continental Congress to take a forceful posture toward Great Britain. Though more moderate voices prevailed, Summary View is an integral document in Virginia and American history because most of its ideas reappeared in the Declaration. Jefferson wrote that rights derive from laws of nature and are given by God to all people; that free trade is a natural right that had been cut away by Great Britain; that a “series of oppressions” have been pursued by the king, including the suspension of colonial legislatures, that governors had been laid under “such restrictions that they can pass no law”; and that he is sending to the Americas “mercenaries to invade & deluge us in blood.”

Jefferson, himself a notable Virginia slave holder, condemned George III for the trafficking of enslaved people across to the Americas, writing “the abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infantile state.” This notion emerged again in his first draft of the Declaration but was removed by the Continental Congress for the final document. Perhaps most strikingly was Jefferson’s assertion that “the British Parliament has no right to exercise authority over us.” Previous arguments questioned Parliament’s right to levy taxes on the colonists, but Jefferson went further to question Parliament’s authority in any circumstance.

Summary View was not only issued in Williamsburg. The tract was read up and down the East Coast, even in Britain, being reprinted in Philadelphia and London.

The VMHC’s second editions, printed in London in 1774, signals the fast exchange and circulation of ideas in the mid-eighteenth-century Atlantic World. George Kearsley, the publisher who reprinted Summary View in Britain, had been arrested for libel just over a decade earlier for issuing an incendiary magazine in which John Wilkes, a popular and radical Member of Parliament, accused King George III of lying about the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). Kearsley took to a specialization in engravings after his brush with the law, but it’s not surprising he was a willing publisher for Jefferson’s pioneering pamphlet.

the program of radical opposition in England. Tribunus’s preface noted, “The present contentions with America, if not soon happily terminated, must end in such scenes of trouble, bloodshed, and devastation.” But he still held faith in King George III: “disappoint your ministers, and gratify your subjects—The Americans have not as yet revolted—They have not thrown off their allegiance. . . Do them justice, and they will esteem it an act of Grace.”

The VMHC’s Senior Conservator Stacy Rusch, an expert paper conservator who has served the VMHC for more than thirty-five years, knew on first sight that the first edition was special. Her admiration of Clementina Rind has made Summary View stand out among all the items she has worked on among the more-than-nine-million items in the VMHC’s collection. Sotheby’s, the premier auction house from which Summary View was originally purchased, included a note restricting its handling “only by members of the Books and Manuscripts Department.” A special protective box was tailor-made to securely house the first edition, and there it remains nestled.

Another preface was added in London, addressed directly “To the King” and signed “Tribunus,” a term for elected officials in classical Rome and a nod that this message derived from the people. This preface is attributed to Arthur Lee, a Virginia radical living in London and friend of Wilkes, and Lee aimed to bind the American cause to

The humble-looking pamphlet, 250-years-old this summer, underpins the most important document in American history, and one of the most significant in world history. Though Jefferson was not picked to attend the First Continental Congress, he was there for the second in the summer of 1775. Despite the previous year’s charges of radicalism, Samuel Ward, a representative from Rhode Island at the congress, observed that Thomas Jefferson was “a very sensible, spirited, fine fellow—and by the pamphlet he wrote last summer, he certainly is one.” The potent pamphlet had foreshadowed a change in discourse—driven it, even—and established a reputation that would land Jefferson the most important writing gig in U.S. history.

Asense of place has deeply shaped Virginia’s history and culture. Over time, a wide range of communities have formed that help to define the distinctive characteristics of their regions and the state. Their evolution reveals stories as varied as the landscape itself. Our Commonwealth provides an in-depth journey across the five geographical regions of Virginia—Tidewater, Central, Northern, the Shenandoah Valley, and Southwest—and showcases the experiences of its diverse people.

Mined from collections across the Commonwealth, the objects, letters, diaries, and archival photographs, from each region are arranged thematically in this beautifully illustrated narrative that provides a stirring, and often personal story about the people and the place they call home, shining a fresh light on what makes Virginia, Virginia.

Order online at VirginiaHistory.org/ CommonwealthBook

All lecture books are available in the Museum Store or online at ShopVirginiaHistory.org

Summer 2024 marks the 100-year anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted a pathway to citizenship for Indigenous peoples born in the United States. However, despite this apparent advance for Native peoples, significant rights such as the ability to vote would still be governed by state law, and Virginia Indians faced governmental barriers to voting for many more decades. Complexity also characterized the status of Indigenous peoples in the years leading up to the passage of the act. Exploring the act and its origins allows us to better understand the complicated and contradictory application of U.S. citizenship to Indigenous peoples, and the fortitude Virginia Indians exhibited when navigating a complex political and legal system.

The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship to all persons born in the country except women in 1868, was interpreted as also excluding Indigenous peoples. However, some Indigenous individuals could become eligible for citizenship if they were deemed fully “assimilated.” In Virginia, citizen status gave limited rights to Indigenous individuals. But non-citizen status was often an important “tool” used by Indigenous leaders and individuals to force the state to recognize their Indian identity.

Historically, the federal government classified tribes inconsistently, including those not formally acknowledged by the United States. Such classifications included terms like “Indians not taxed,” “Indians not a part of any state,” and “non-citizen Indians.” Though these classifications appear to refer to tax exemption, they actually identify Native people not considered assimilated or those still living as members of a tribe. The designation “Indians not taxed” originated in the Articles of Confederation and appears in the U.S. Constitution. In fact, President James Madison described the classification relating to Indigenous people as not being part of a state as meaning those “who do not live within the body of the Society.”

Indigenous peoples could become eligible for citizenship if they were deemed fully assimilated, were no longer living among their tribes, or were tribal landowners who had gained their lands based on the Dawes Act in 1887. This act privatized large swathes of reservation lands and allotted them to Indigenous families, who could in turn sell the lands and pass them out of tribal ownership. People with this status were often referred to as “citizen Indians.”

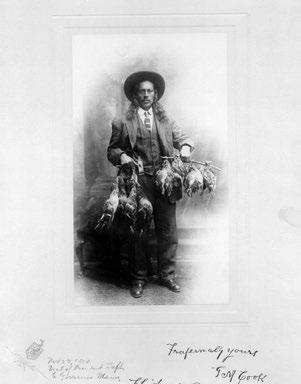

1910 U.S. Census Indian Schedule depicting the household of George Major Cook who served as Chief of the Tribe from 1902–1930 (Courtesy of U.S. Bureau of the Census).

Because of the nation’s assimilationist policies, attaining citizenship before 1924 posed a threat to tribal sovereignty. On the one hand, citizenship provided access to political status, though with the limitations and discrimination that applied to other non-white citizens during the period. On the other hand, citizenship signaled the erasure of tribal political status and the disappearance of tribal sovereignty. A tribe made up of U.S. citizens was no longer a domestic dependent of the U.S. government and thus no longer eligible for the same rights of self-determination. Thus, as Native peoples were “assimilated,” the power of Indigenous tribes was eroded.

Several of Virginia’s Indigenous communities were periodically recognized by the Commonwealth and the federal government as “Indians not taxed” or “noncitizen Indians.” The “Indians not taxed” status applied to Virginia Indigenous communities on reservation lands, leading to their exclusion from the U.S. Census. From 1800 to 1820, U.S. Marshals conducting census work omitted residents of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations. Later, members of the Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes were classified as “Indians not taxed” by the Bureau of the Census in 1870 and again in separate Indian Schedules enumerated by the bureau in 1900 and 1910. These efforts fell under the Census Bureau’s constitutional mandate to survey and record the population, excluding “Indians not taxed,” for the purposes of apportionment in representation and taxes.

The classification “Indians not taxed” applied to tribal communities in Virginia during the U.S. Civil War

and further demonstrated their continued existence outside U.S. citizenship, and when Virginia seceded, they were not considered Confederate citizens, either. Their status allowed tribes some degree of choice in their role, or lack thereof, in the war. The Pamunkey, for example, chose to serve as soldiers, gun boat pilots, guides, and spies for the United States. In response, Confederate leaders punished the tribe through forced labor and imprisonment.

Pamunkey men were forced to work for the Confederacy in places like Williamsburg and were imprisoned in the infamous Castle Thunder Prison in Richmond. The Pamunkey Tribal Council appealed to the Commonwealth to verify the status of its tribal members. The state senate considered the issue in March 1862 after Governor John Letcher protested King William County forcing of “certain free persons of mixed blood, living in what are called the Indian towns, in said county” to perform forced labor. Moreover, the governor’s sentiments likely contributed to the discharge of imprisoned Pamunkey tribal members, such as Thomas Bradby who explained he was “kept in Castle Thunder for seven weeks and finally discharged . . . because we were Indians.” Thus, Pamunkey men who were not considered citizens of the U.S. held complex status during the Civil War: those who chose to aid the U.S. did so as knowledgeable agents in Confederate-held territory. When pressed into laboring for the Confederacy as punishment for these actions, this same non-citizen status led to their eventual release.

Wars ask questions of citizenship. The classification of “non-citizen Indians” was again pivotal in 1917 at the beginning of World War I. The Selective Service Act of 1917 authorized the federal government to raise a national army through conscription. The act established local boards to administer the draft and make initial determinations regarding any exemptions as well as district boards to handle any appeals regarding exemption. The draft applied to all citizens but exempted “non-citizen Indians.” For the purposes of registration, an Indigenous person was defined as a citizen if: “(1)

Portrait of Chief George Custalow taken in 1918 on the Mattaponi Reservation (Courtesy of National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution).

he, or his father or mother, prior to his birth or before he attained the age of 21, was allotted land prior to May 8, 1906; or (2) if he was allotted land subsequent to May 8, 1906, and received a patent in fee to his land; or (3) he was residing in the old Indian Territory on March 3, 1901; or (4) if he lives separate and apart from his tribe and has adopted the habits of civilized life.”

What were the implications of these requirements? By these standards, the two reservation tribes in Virginia, the Mattaponi and Pamunkey, would be classed as non-citizens. Yet, when the local draft boards convened, they attempted to class the Pamunkey and Mattaponi as citizens liable for the draft. The tribes enlisted the help of the Commonwealth and the U.S. provost marshal general to clarify its status and ultimately ensured tribal members’ exemption from the draft. However, some government officials shared their opinions on the exemption documents of tribal members. On Opechancanough Miles’s form, the registrar allowed the non-citizen box to be checked, but then marked

“I consider him a citizen” in the Registrar’s Certification section of the card. The misidentification of Virginia Indians as citizens continued through 1918, and led to further appeals by tribes and interventions by state and federal agencies and officials to clarify the issue. Tribal appeals relating to military service were not about avoiding war participation. Once the tribal challenge to conscription was legally upheld, the same tribal members who sought exemption voluntarily enlisted to serve in World War I. Members of Virginia tribes were some of the approximately 10,000 Indigenous men across the United States who supported the country’s efforts in the war. Recognizing the service of these Indigenous men, Congress enacted legislation in 1919 offering the option of citizenship to Indigenous veterans of World War I who were not yet citizens. But the act did not automatically confer citizenship to these Indigenous veterans, and instead opened the path to citizenship.

President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act (the Snyder Act) in 1924, in part to honor Indigenous

. . . all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided that the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.

– Indian Citizenship Act (the Snyder Act), 1924

people’s significant wartime contributions. The act established U.S. citizenship for Indigenous peoples nationwide. However, not all tribal nations supported a sweeping declaration of citizenship for Indigenous peoples. Some thought it would negatively impact tribal citizenship within their communities, tribal sovereignty of their respective nations, and their unique cultural identities. Though the act granted citizenship, it did not guarantee certain citizen rights, such as the right to vote. This is because the U.S. Constitution grants states the power to determine voting rights and requirements. It

would not be until after the 1965 Voting Rights Act that Indigenous peoples’ suffrage was codified nationally.

One immediate impact the Indian Citizenship Act did have was the creation of a dual or “nested” citizenship for Indigenous peoples. This meant that Indigenous individuals were citizens of both their respective sovereign tribe and of the United States. This dual status meant varying rights and responsibilities based on whether a person was interacting with a federal or tribal governing system and whether they were within federal or tribal land jurisdiction. This citizenship status reflects the unique position of tribal nations within the United States, where such nations exist as sovereign entities nested within the larger sovereignty of the federal government.

During the same year the federal government enshrined Indigenous citizenship with the Indian Citizenship Act, Virginia was passing legislation like the 1924 Racial Integrity Act to deny recognition of the Indigenous peoples residing within the state. Though the federal government recognized Indigenous peoples as citizens of the United States, Virginia’s government legislatively denied the existence of Indigenous communities and individuals. Walter Plecker, registrar of the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics, made it illegal for Indigenous peoples to identify their race as “Indian” on their birth, marriage, and death certificates. This legislative action initiated decades of erasure of Indigenous peoples from the state’s vital and official records. These actions continued to reverberate in Indigenous communities of Virginia, and limited the ability of many tribes to provide necessary documentation when pursuing U.S. federal acknowledgment during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Before the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, paths to U.S. citizenship were not a constitutionally mandated option for Indigenous peoples in Virginia and across the country, despite the passing of the 14th Amendment in 1868. Instead, Indigenous citizenship was tied to policies that sought to strip tribal sovereignty and Indigenous identities and scatter Native communities.

Leaders of the seven federally recognized tribes who took part in a ceremony at Werowocomoco with then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke (Courtesy of U.S. Department of the Interior).

Therefore, ironically, Indigenous leaders in Virginia had to use the designations “Indians not taxed” and “non-citizen Indians” as a means to force the state’s recognition of and responsibility to its Indigenous population. When the Indian Citizenship Act was passed, it shifted how Indigenous peoples in Virginia and the United States were legally defined. Native peoples could now maintain U.S. citizenship alongside citizenship within their respective Tribal Nations. As a result of the act a century ago, sweeping changes to Indian policy shaped how Indigenous communities in Virginia understood and practiced their dual citizenship status, and more formalized relationships were established with the United States government.

– By Ashley Spivey

Dr. Ashley Atkins Spivey is an historical and economic anthropologist specializing in the archeology and culture of Powhatan Algonquian communities located in Tidewater Virginia. As a member of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe, Dr. Spivey has a close connection to the Virginia Indian community. She has worked with tribes, universities, museums, and government agencies to support historic preservation and cultural resource management programs that incorporate the needs of tribal communities.

First Fridays at the VMHC

The museum stays open late for this family-friendly event. Enjoy free admission to the galleries, specials in the Café, access to food trucks, live music, and family-centered activities.

First Fridays made possible with support from Virginia R. Edmunds. First Friday each month 5:00 pm to 8:00 pm

Front Lawn Fun

This free, family-friendly program will feature outdoor games and toys from yesteryear. Tuesdays, June 4–Aug. 6 10:30 am

Stories at the Museum

Join VMHC Education for a storytime, craft, and gallery walk related to our two temporary exhibitions Julia Child: A Recipe for Life and A Better Life for Their Children. Thursdays, June 6–Aug. 15 10:30 am

Halloween Trick or Treat

Bring your little ghouls and goblins for a historic Halloween. Oct. 25 5:00 pm to 7:00 pm

Member Mondays at Virginia House

Enjoy a relaxing evening in the Virginia House gardens with live jazz music.

Aug. 12, Sept. 9, Sept. 30 5:30 pm

Annual State of Museum (Virtual)

VMHC’s President & CEO will review the museum’s recent successes and provide a glimpse at future plans for exhibitions, programs, and America’s 250th.

Sept. 25 5:30 pm

To register and view all of our upcoming events, visit VirginiaHistory.org/Calendar

Virginia Brews

Join the VMHC for this annual event featuring beer selections and breweries from across the Commonwealth, live music, food trucks, and after-hours access to the galleries.

Aug. 3 6:00 pm

Virginia Distilled

Join the VMHC for samples of spirits produced by Virginia distillers, live music, food trucks, and after-hours access to the galleries.

Sept. 14 6:00 pm

Virginia Vines

Virginia Vines will feature wine selections from some of Virginia’s best wineries and vineyards, live music, food trucks, and after-hours access to the galleries.

Oct. 26 6:00 pm

Free for members!

An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South

By Robert D. Colby June 13 6:00 pm

Grace Sherwood: The History Behind the Legend of the Witch of Pungo

By Scott O. Moore

July 25 12:00 pm

You’ll Do: A History of Marrying for Reasons Other Than Love

By Marcia Zug

Aug. 8 12:00 pm

This Fierce People: The Untold Story of America’s Revolutionary War in the South By Alan Pell Crawford Aug. 22 12:00 pm

A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America By Andrew Feiler

Sept. 5 12:00 pm

Gallery Highlight Tours

Join us Saturday mornings this summer for 30-minute highlight tours of our marquee exhibition!

Saturdays, June–Aug. 11:30 am

Wild, Tamed, Lost, Revived:

The Surprising Story of Apples in the South

By Diane Flynt

June 27 12:00 pm

Dinner with the President

Celebrating Julia Child’s Birthday!

Join acclaimed author (and Julia Child relative) Alex Prud’homme, as he discusses his new book Dinner with the President: Food, Politics, and a History of Breaking Bread at The White House. Inspired by a series of events, including Julia Child’s televised visits to The White House in 1967 and 1976, this lecture examines the politics of food and the food of politics. Special refreshments will follow the lecture in celebration of Julia Child’s 112th Birthday!

Aug. 15 6:00 pm

Independence Day Celebration

Join the VMHC in a celebration of American independence with a moving citizenship ceremony, birthday cake for America, patriotic music, and other related activities.

July 4 11:00 am

Hazel & Fulton Chauncey Lecture

The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces and the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers by

Patrick K. O’Donnell

July 17 5:30 pm

Presenting Sponsor

Exhibition ends September 2, 2024

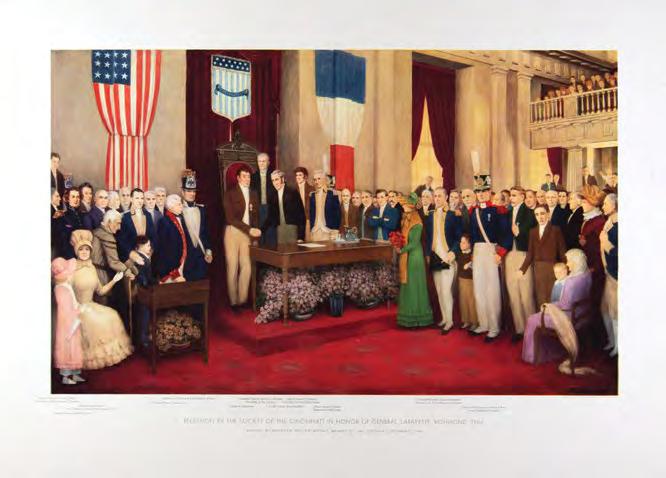

On November 4, 1824, a procession of carriages winded their way over hilly Albemarle County roads toward their mountaintop destination— Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. As the column approached the top of the hill, a bugle announced their arrival, spurring several hundred local citizens onto their feet and into a semicircle on one side of the circular drive. When the cavalry escort came into view, they took up a post opposite the crowd, forming an amphitheater of onlookers along the margins of the house’s yard. Jefferson waited on the portico as the carriage carrying the Marquis de Lafayette came to a halt. Then, as Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph recollected, Jefferson was feeble and tottering with age — Lafayette permanently lamed and broken in health. . . . As they approached each other, their uncertain gait quickened itself into a shuffling run, and exclaiming, “Ah, Jefferson!” “Ah, Lafayette!” they burst into tears as they fell into each other’s arms. Among the four hundred men witnessing the scene there was not a dry eye — no sound save an occasional suppressed sob.

Similar scenes, while maybe not quite as dramatic, repeated themselves weekly during Lafayette’s grand tour of the United States. Spanning thirteen months between 1824 and 1825, Lafayette met with tens of thousands of people from all walks of life as he visited each of the then twenty-four states, covering nearly 6,000 miles in the process. It was one of, if not the, largest, most coordinated national celebrations in the young country’s history. As we approach the 200th anniversary of Lafayette’s grand tour, communities around the country are gearing up to celebrate this momentous visit. Spearheaded by the American Friends of Lafayette, a nonprofit dedicated to celebrating the Marquis’s memory, dozens of commemorative events are planned for the next two years to coincide with his travels.

Born in 1757 to one of the oldest aristocratic families in France, a teenage MarieJoseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette inherited his late father’s title and accompanying fortune. However, the young marquis preferred the excitement of military life over the gilded rituals of King Louis XVI’s Versailles court. The brewing American War of Independence proved the perfect outlet for this restless, wealthy nineteen-year-old. When American agents in Paris sought volunteers with military experience to travel to America and lend their expertise to the Patriot cause, Lafayette jumped at the opportunity. Arriving in the newly christened United States in the summer of 1777, Lafayette’s earnest belief in the American cause and bravery in battle quickly won over admirers, including Continental Army commander George Washington. In turn, Lafayette viewed Washington as a mentor and father figure. As the war raged on, Lafayette received increasingly important commands. His biggest moment came in 1781, when Washington dispatched Lafayette

and some of his best troops to counter a British invasion of Virginia. When the British eventually moved their base of operations to Yorktown, Lafayette’s intelligence, some of which was provided by an enslaved spy named James Armistead, proved invaluable in convincing Washington that British commander Charles Cornwallis was vulnerable, leading to the decisive American victory.

Following the victory at Yorktown, Lafayette sailed back to France, but soon returned to the U.S. in 1784 to survey the new nation in peacetime. While visiting Richmond, Lafayette wrote a letter of support in favor of his old comrade James Armistead’s freedom petition then before the General Assembly. After the war, Virginia emancipated enslaved people who served as soldiers, but it did not recognize James’s contributions as a spy. While it took several more years, James finally won his hard-earned freedom in 1827, and in honor of Lafayette’s support, took the last name Lafayette as his own.

Back in France, Lafayette soon found himself embroiled in his own country’s revolution. As a nobleman who supported the causes of liberty, equality, and republicanism, Lafayette quickly became a leader of the moderate revolutionaries. However, he did not prove radical enough as the revolution progressed. When King Louis XVI was overthrown in July 1792, Lafayette’s enemies issued a warrant for his arrest. To avoid capture, and likely the guillotine, Lafayette and his family fled to Austria, where they were imprisoned for five years. After returning to France, Lafayette avoided politics as a new authoritarian took power, Napoleon Bonaparte. Upon Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, Lafayette jumped back into the political arena, hopeful that the newly restored King Louis XVIII would learn the lessons of his beheaded older brother and implement reforms. Predictably, he did not, and Lafayette found himself increasingly politically isolated as conservatives rolled back the legacies of the revolution.

In February 1824, Lafayette received a letter from President James Monroe inviting him to visit the United States. With conservatives firmly in control in France, Lafayette saw a trip to America, the world’s greatest example of successful republican government, as the best way to generate positive press for his cause back home.

On August 15, 1824, the first time he had returned to America in forty years, a sixty-seven-year-old Lafayette arrived in New York City, accompanied by his son, George Washington Lafayette, and his secretary, Auguste Levasseur. While back in France, soldiers suppressed his supporters with bayonets, his arrival in New York was met by more than 50,000 cheering people. These scenes repeated themselves in city after city. As the last surviving major general of the American Revolution, Lafayette revived Americans’ patriotic memories of the nearly fifty-year-old conflict. He also served as a needed national unifier during a fierce presidential election. Newspaper editors replaced slanderous political headlines with celebratory coverage of Lafayette’s itinerary. No matter where people lived or what political beliefs they held, all agreed on their love for Lafayette.

By October, Lafayette made his way to Virginia, where he would spend more time than any other state. His first stop was to the home of his American mentor, George Washington. Arriving at Mount Vernon, Washington’s nephews accompanied Lafayette, his son, and Levasseur to Washington’s tomb. Levasseur, who published an account of Lafayette’s trip upon returning to France, described the emotional scene, “Lafayette descended alone into the vault, and a few minutes after re-appeared, with his eyes overflowing with tears.” The party then spent some time inside the mansion, where Lafayette saw the key to the Bastille still hanging proudly on the wall. Lafayette sent the key as

a gift to Washington in 1789, after overseeing the Bastille’s destruction as commander of Paris’s National Guard.

Lafayette continued his journey to Yorktown in time for the 43rd anniversary of that momentous battle. During his two-day visit, Lafayette attended military parades, patriotic speeches, and evening balls. He also reunited with his old comrade James Armistead. As the October 29, 1824, edition of the Richmond Enquirer reported, “A black man even, who had rendered him services by way of information as a spy, for which he was liberated by the State, was recognized by him in the crowd, called to him by name, and taken into his embrace.” This moving scene inspired the creation of prints with James’s likeness and a copy of Lafayette’s 1784 letter of support for James’s freedom. Throughout his time in America, Lafayette made it a point to receive African American wellwishers, much to the chagrin of host officials who otherwise forbid Black people from joining the festivities.

Lafayette spent the next few days visiting Williamsburg, Jamestown, Portsmouth, and Norfolk. In Norfolk, Levasseur thought, “the houses are generally badly built, and the streets narrow and crooked.” The party then made their way to Richmond, where over the next three days he was addressed by Chief Justice John Marshall at the Capitol, attended a ceremony at Richmond’s Mason Hall, and enjoyed balls, plays, and horse races. After a two-day visit to Petersburg, which took six hours to travel to from Richmond, Lafayette left for his long-awaited reunion with Jefferson in Charlottesville.

among the friends of Mr. Madison the question of slavery.”

He was not afraid to tell his American friends that they should practice what they preached. Levasseur wrongly believed that “It appears to me, that slavery cannot exist a long time in Virginia, because all enlightened men condemn the principle of it.”

Lafayette was a deeply committed abolitionist, and the great irony that the land of liberty prospered due to the forced labor of millions of enslaved people was certainly not lost on him.

After leaving Montpelier, Lafayette spent the winter in the nation’s capital, attending many formal events, including addressing the House of Representatives, the first foreign dignitary to ever do so. Congress conferred more than just honors on Lafayette when they awarded him $200,000 and several thousand acres of land in Florida as thanks for his service during the Revolution.

Engraving, James Armistead Lafayette, First half 19th C. (VMHC Collection).

In January 1825, Lafayette returned to Richmond for a state dinner thrown by the Virginia General Assembly. Lafayette then left for his tour of the southern and western states, visiting New Orleans, St. Louis, and Nashville. By August 1825, Lafayette was nearing the end of his trip. However, he wanted to bid one last goodbye to Jefferson and Madison, so he returned to Monticello and Montpelier for an additional eight days. On September 9, 1825, Lafayette boarded the new American warship USS Brandywine, named in honor of Lafayette’s battlefield heroism, to begin his journey home.

Lafayette spent two weeks in the Charlottesville region, visiting with Jefferson at Monticello and former president James Madison at Montpelier. In his several days with the former presidents, Lafayette discussed politics and the issues of the day, notably slavery. At Montpelier, Levasseur recalled how Lafayette, “never missed an opportunity to defend the right which all men without exception have to liberty, broached

When Lafayette returned to France, he found himself in the even more repressive regime of the new King Charles X. When another revolution erupted in 1830, Lafayette once again jumped into action, reappointed to lead the Paris National Guard in opposition to the king’s forces. Although Lafayette had high hopes for Charles X’s successor, King Louis Philippe I, the new monarch quickly reneged on promised reforms. When Lafayette died in 1834 at the age of seventy-six, the king lined his funeral procession with armed soldiers, fearful some of the 200,000 onlookers would

Reception by the Society of the Cincinnati in honor of General Lafayette, Richmond, 1824, Frederick William Wright, 1940 (VMHC Collection).

engage in rebellious activity inspired by his memory. In a final poignant act, Lafayette requested that his grave be covered by soil from Boston’s Bunker Hill, ensuring he was buried in the soil of both countries that meant so much to him.

For his leading roles in the American and French Revolutions, Lafayette was known as the “Hero of Two Worlds.” His steadfast support for true human equality made him a central figure for future liberation movements around the world. As abolitionist senator Charles Sumner described, Lafayette was “one who early consecrated himself to Human Rights, and throughout a long life became their representative, knight-errant, champion, hero, missionary, apostle—who strove in this cause as no man in history has ever strove—who suffered for it as few have suffered.”

During his lifetime, he was far more popular in his adopted home of America than in his own country. Though most Americans today have never heard of Lafayette’s visit, the opposite would have been true in the 1820s. Across the country,

hundreds of streets, squares, towns, and cities were named in honor of the famous Frenchman. Enterprising merchants emblazoned Lafayette’s likeness on ribbons, gloves, fans, plates, spoons, and virtually anything else you could think of to sell, providing keepsakes to remember his visit by. Even regional banks cashed in, with Lafayette appearing on bank notes from twenty-seven different states between 1826 and 1860, second only to Washington’s thirty-three. His visit inspired renewed interest in commemorating the Revolution, as communities began erecting monuments to soldiers and leaders from the war.

It is fitting that the 200th anniversary of Lafayette’s visit precedes the 250th anniversary of the nation’s founding. Throughout 2024 and 2025, the VMHC plans to hold several events in partnership with the American Friends of Lafayette to commemorate Lafayette’s time in the Commonwealth, with the aim of generating the same interest around the Revolution as Lafayette’s original tour.

Our American experiment is unique in human history—a government of laws and not of individuals; a government by the people and for the people, founded on the self-evident truth that all are created equal and are endowed with the universal rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. In our first two and a half centuries, our nation, through the determination of its people, and with its unlimited capacity for reinvention and renewal, has progressed in its journey, working to fulfill by struggle and sacrifice the promise of our founding for all Americans.

In 2026, the United States of America will mark its 250th anniversary. We must embrace this historic moment—extraordinary in our lifetimes—and act upon it by together renewing our commitment to the unfinished pursuit of A More Perfect Union—to reflect deeply on our past and invest with great purpose in our future.

The VMHC is proud to play a leading role in Virginia and nationally for America’s 250th, and to produce a dynamic multi-year portfolio of activities for all Virginians. Learn more at VirginiaHistory.org/250

Let the games begin! All eyes will be on Paris, France, when the 2024 Summer Olympic Games kick off in late July. More than 700 American athletes will test their mettle in competitions ranging from swimming to surfing to equestrian showjumping. From Arlington to Abingdon, Virginians will be cheering as our fellow Americans take on the best of the best from across the globe.

Virginians have been representing the red, white, and blue in the summer and winter games since 1908. Virginians have also successfully competed in the Special Olympics, which began in 1968. Our Olympians come from a wide range of communities that represent the vast diversity of our Commonwealth. Schools such as the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech have sent dozens of student-athletes to “Team USA.” More than just talented athletes, many Virginia Olympians have achieved historical “firsts” and engaged in conversations about issues that expand far beyond the boundaries of our state. The Olympics may be about athletic excellence but, as the stories of Virginian Olympians show, the games are always about much more than sports.

The first Olympics in recorded history took place in ancient Greece in 776 B.C.E. Koroibos, a cook, won a 600-foot race, the only competition in the games. The event was dedicated to the Greek god, Zeus, and was as much a religious celebration as a showcase for athleticism. Spectators and athletes gathered every four years in Olympia (a cycle called an “Olympiad”) to honor Zeus through sports, sacrifices, and songs. Ancient Greeks believed that athletic achievement was the highest form of kalokagathia, the harmonious balance between body and mind displayed through physical beauty and virtuous behavior. Ancient Olympian victors were heralded as heroes: they were bedecked with crowns, ribbons, and palm branches before being hoisted onto the audience’s shoulders and carried back to their home cities. There, they thanked the gods, participated in lavish feasts, and enjoyed significant public acclaim.

The Roman emperor Theodosius I banned the Olympic games in 393 C.E. to promote the adoption of Christianity. The Olympics would not return to Greece until 1896.

The French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin believed “The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.” Honorable competition,

not winning, was the ultimate goal of athletic contests. de Coubertin also thought that international athletic competition could promote understanding and goodwill across cultures, thus increasing the potential for peace. de Coubertin, along with Demetrios Vikelas of Greece, C. Herbert of Great Britain, and W. M. Sloane of the United States, spearheaded efforts that would result in the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the body that governs the Games to this very day. Although the members of the first IOC established many rules that would be overturned—for example, women were prohibited from participating in the first Olympic games and professional athletes were banned from competing until 1988—the International Olympic Committee’s dedication to promoting “a better world through sport” still undergirds the spirit that makes the Olympics such an exciting and captivating global event.

The first modern Summer Olympic Games took place in Athens, Greece, in 1896. Although no Virginians ran, swam, or fenced for “Team USA” in the games of 1896, the American cohort was the most successful in terms of gold medals. They won eleven medals to host-nation Greece’s ten, despite fielding only fourteen competitors compared to an estimated 169 Greek entrants.

James Rector, a University of Virginia student, was the first person with a substantial Virginia connection to bring home an Olympic medal. One of UVA’s first sports idols, Rector was widely considered the favorite to win the 100-meter dash. Unfortunately, that is not what happened. In a major upset, an unknown 19-yearold South African file clerk named Reggie Walker beat James Rector by three feet. The “Virginia Flyer” brought home the silver medal and never ran track again.

Virginia’s time to shine in the Olympics really began in the second half of the twentieth century and continues to this day. Improved training regimes, more funding, better sports associations, and the formalization of collegiate athletic programs allowed many Virginians to reach elite status on a global stage. Technology and globalization have also increased the visibility of the Olympics and inspired more Virginians to aspire to competing on “Team USA.” The first live international television broadcast of the Games beamed out of Rome in 1960. By 1968, 17 percent of the world’s population could view the Olympics live on three continents. About half of the world’s population tuned into the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, and almost 5 billion people (or two-thirds of the earth’s population) took in the 2012 London games.

Virginia athletes have provided thrilling moments in recent Olympic history. In 1972, at just 15 years old, Springfield’s Melissa Louise Belote won three gold medals in Munich, Germany. She also set the world record in the 200-meter backstroke and the Olympic record in the 100-meter backstroke. Portsmouth native LaShawn Merritt took the gold medal in the 400-meter sprint in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, beating his teammate and rival Jeremy Wariner by .99 seconds. This remains the widest margin of victory in the 400-meter race. Merrit is a four-time Olympic medalist and was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame earlier this year.

string of owners until Fargis recognized her potential. Touch of Class and Fargis navigated a challenging showjumping course: of the 91 jumps she faced in Los Angeles, she cleared 90 of them without pulling down any rails. Kitty and Joe Fargis secured the first ever gold medals for the US showjumping team. She was also named the first non-human US Olympic Committee Female Equestrian Athlete of the Year.

Two major state universities, UVA and Virginia Tech, have also contributed their fair share of Olympic glory to our Commonwealth. Allen Wyatt, a 2001 University of Virginia alum, was a member of the U.S. rowing team that won a gold medal in 2004. The men’s eight crew had not won gold since 1964. Current UVA students Alex Walsh and Kate Douglass both medaled at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics and are top contenders for spots on the swim team the U.S. will send to Paris in 2024. Bimbo Coles was the first Virginia Tech athlete to compete in the Olympics and was a member of the bronze medal-winning basketball team in the 1988 Seoul games. Kristi Castlin was the first female Virginia Tech athlete to win an Olympic medal, bringing home the bronze in the 2016 Rio de Janeiro 100-meter hurdle. Her teammates won first and second place in the same race, making that the first time in Olympic history that American women swept any event.

Another extraordinary Olympian was the Thoroughbred mare, Touch of Class, who made history with her owner and rider, Middleburg resident Joe Fargis, in the 1984 Los Angeles games. A failed racehorse, Touch of Class—or Kitty, as she was known around the barn—was an unlikely Olympic champion. She was small, hot to handle, and had passed through a

Of course, any discussion of Virginians in the Olympics would be incomplete without mentioning Gabby Douglas. Born in Newport News, Douglas began competing in gymnastics at age six. She is the first Black American to become an Olympic individual all-around gymnastics champion and the first US gymnast to win gold in both the individual all-around and team competitions at the same Olympics (London 2012). Douglas became one of the most celebrated and influential female athletes

in modern history, appearing on a wide variety of media outlets and publishing two New York Times bestselling books. She has cultivated a career off the mat as a speaker, particularly as an advocate for mental health and the importance of perseverance.

Collectible tobacco card depicting Olympic track star, James Rector, 1910 (Courtesy of Nextrecord Archives via Getty Images).

Every two years, the world transcends the boundaries of nationality and culture to celebrate the Special Olympics World Games. The Games are the flagship event of the Special Olympics movement, which promotes inclusion, equality, and acceptance worldwide. Several Virginians have represented “Team USA” at the World Games. One of the team’s most decorated athletes is Fredericksburg resident Grace Anne Braxton. Her skills on the golf course earned her two gold medals (Shanghai 2007 and Athens 2007) and one silver (Abu Dhabi 2019), as well as a spot in the Virginia Golf Hall of Fame. She, along with her teammate, Virginia Beach’s Trasean Singletary, also medaled in the 2023 Berlin games. Braxton brought home another silver, and Singletary won gold in the 3000-meter race and bronze in the 5000-meter event. Trasean Singletary, who admitted he could barely run a quarter mile without stopping before he joined the Special Olympics program, says his experience with the Special Olympics has helped him overcome feelings about being different and that he is proud to show others how far he has come.

Olympic athletes are under tremendous pressure to perform. All the long, hard hours spent training come down to maybe a few seconds, minutes, or hours on a track, in a pool, or on a basketball court—all of which are being broadcast worldwide and witnessed by billions of people.

However, the pressure isn’t just about an athlete’s physical prowess: the athletes’ stories are about much more than the medals they win or the points they score.

The experiences of Virginia’s Olympians shows how the Games can embody political tensions and reflect challenging social issues.

Virginia’s first Olympian, James Rector, was the scion of two prominent Southern political families. Rector began running track at UVA in 1906 and garnered significant attention in the press. Southern journalists emphasized his Southern heritage and defended Rector against

perceived slights coming from snobbish Ivy League coaches and athletes.

North-South tensions weren’t the only burden on Rector’s shoulders. The 1908 London Olympics were full of intense jingoism, particularly between the British and the Americans. The United States was eager to assert its power on an international stage, and the United Kingdom was growing increasingly sensitive about its ebbing empire. Rector’s loss to a minor South African runner—a citizen of Britain’s global empire Commonwealth—added more sting to the silver medal. The Olympics can become entangled in—sometimes thorny—issues of national pride and racial strife. But, more importantly, it can also be a grand platform for progress and to make the world, as the International Olympic Committee says, “a better place through sport.”

Many people don’t know the story of Olympic boxer, Norvel Lee. Born on September 22, 1924, Lee attended segregated schools and graduated from the Academy Hill School for Negroes in Fincastle. He trained as a Tuskegee Airman and served on a ground crew in the South Pacific in World War II. Lee took up boxing at Howard University and won the gold in the lightheavyweight class during the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

On September 14, 1948, Lee boarded a train traveling from Covington to Clifton Forge and refused to sit in the “colored” section. The Allegheny County sheriff directed Lee to move or to exit the train. Lee disembarked and purchased a ticket to Washington, D.C.—he reboarded the train and sat in the exact same seat. Because Lee was on his way to D.C., his journey was considered interstate travel. Upon his return, Lee was arrested for refusing to sit in segregated seating, as per Virginia Jim Crow laws. Norvel Lee eventually won a landmark court case that ruled that state segregation laws did not apply to interstate travelers.

SAVE THE DATE | SEPT. 7, 2024

2024 will see a return of the VMHC Symposium, a one-day event where historians, practitioners, and members of the public gather to explore our shared past. Featuring panels and presentations that highlight groundbreaking research into Virginia history, behind-the-scenes tours, and a special keynote lecture, the symposium links past with present to inspire future generations.

The VMHC is pleased to award 18 research fellowships to scholars from 17 colleges and universities across the United States. Made possible, in part, by support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, these fellows will conduct research at the VMHC’s E. Claiborne Robins, Jr. Research Library in 2024 and 2025.

For information on this year’s research projects visit VirginiaHistory.org/MellonFellows

The Virginia House Loggia, one of the house’s distinctive architectural features, was among the final improvements orchestrated by Ambassador Alexander Weddell and Virginia Weddell. It was added in 1945, just three years before they were tragically killed in a train accident.

The Loggia was designed by renowned architect William Lawrence Bottomley. This project was likely of special interest because of the unique clients and the interaction between the Loggia and Virginia House’s beautiful gardens, which were designed by celebrated landscape architect Charles Gillett.

Much of the Loggia, including the balustrade, was fabricated specifically for the project. The historic columns, however, like much of the main house, were imported from Europe. The Weddells sourced the six stone columns from Spain. Wood panels with painted detail, which embellished the Loggia’s ceiling, were sourced from a 16th-century house in England.

For decades, the Loggia’s flat roof, suffering from years of exposure to the elements, has been problematic. It has long leaked and, over time, has caused significant damage. Selective repair has not done enough to stop the degradation; So, now is the time for a complete, expert restoration that brings the Loggia back to its original splendor.

As the Centennial Period of Virginia House (2025-2029) approaches—marking the 100-year anniversary of its construction—the VMHC has identified a series of investments to ensure the historic site’s future use and vitality, including an expert restoration of the Loggia

WE NEED YOUR HELP! Please consider a donation to support this timely work. VirginiaHistory.org/VirginiaHouseFund

Richmond, Virginia 23220

VirginiaHistory.org

Facebook.com/ VirginiaHistory

Instagram.com/ VirginiaHistory

Opening October 19, 2024

Celebrating the arrival of The LEGO Group in Virginia, Traveling Bricks—one of the largest exhibits of its kind—features more than 100 models of iconic land, air, sea, and space vehicles constructed from nearly 1 million LEGO® bricks.

Learn more at VirginiaHistory.org/TravelingBricks