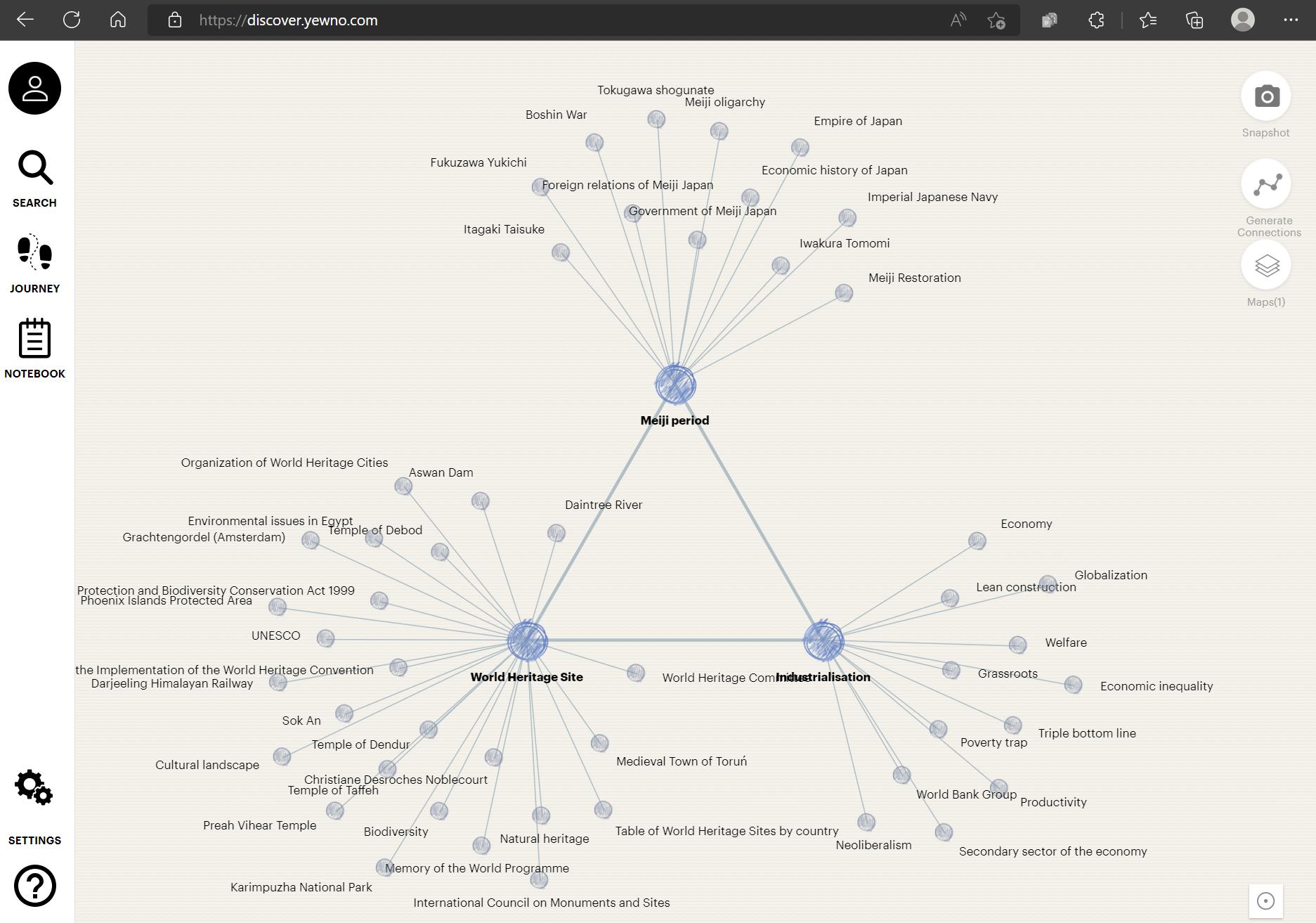

Note: The industrial revolution took place in Europe before Japan, so what was revolutionary to the Japanese, may not impress the European.

I.e.: since there is plenty authentic iron & coal heritage in Germany, why travel to Japan for it?

Well: it depends on who manages to preserve it.

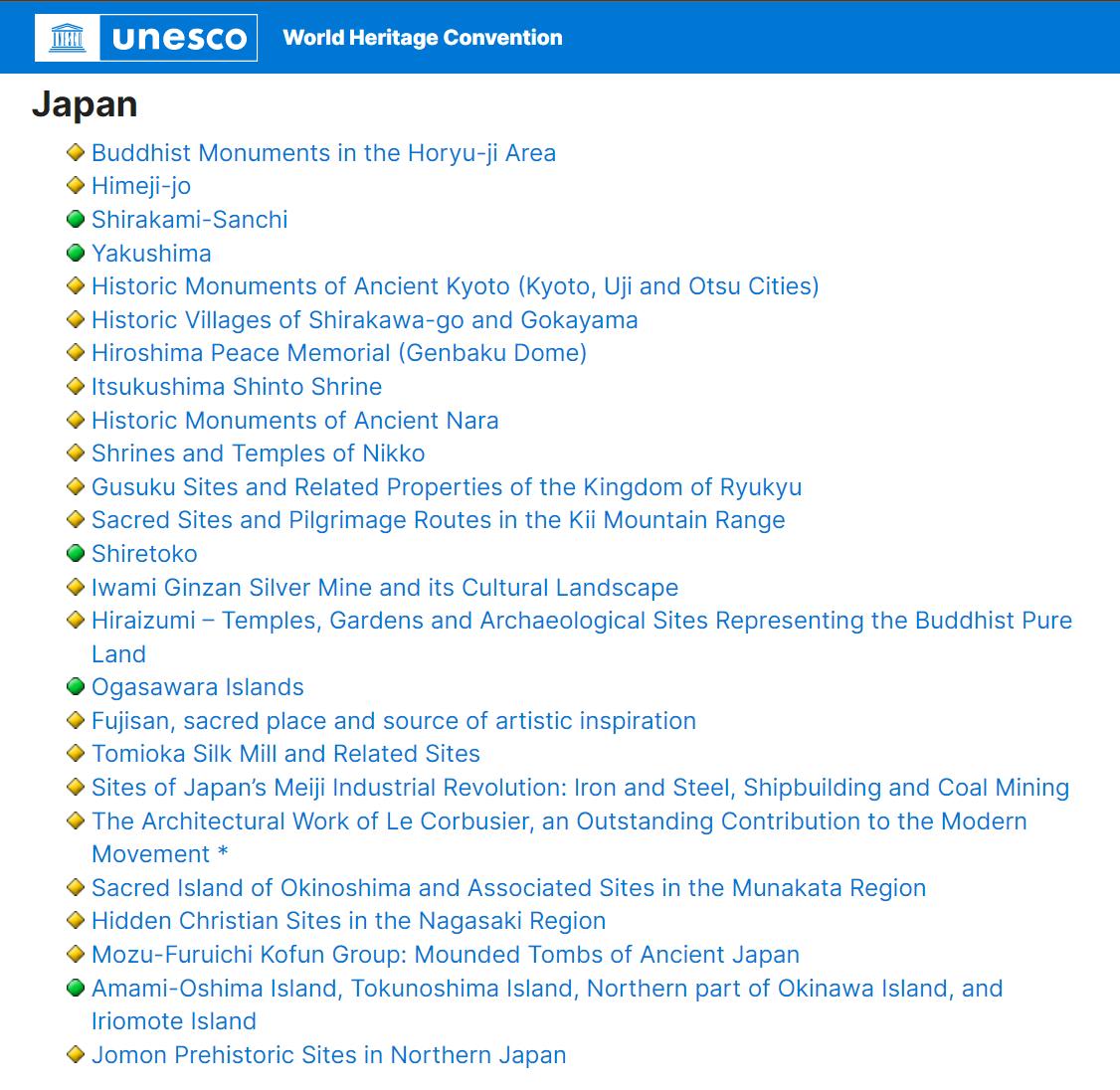

(i) to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius;

(ii) to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design;

(iii) to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared;

(iv) to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history;

(v) to be an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment especially when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change;

(vi) to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance. (this criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria);

(vii) to contain superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance;

(viii) to be outstanding examples representing major stages of earth's history, including the record of life, significant on-going geological processes in the development of landforms, or significant geomorphic or physiographic features;

(ix) to be outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals;

(x) to contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation

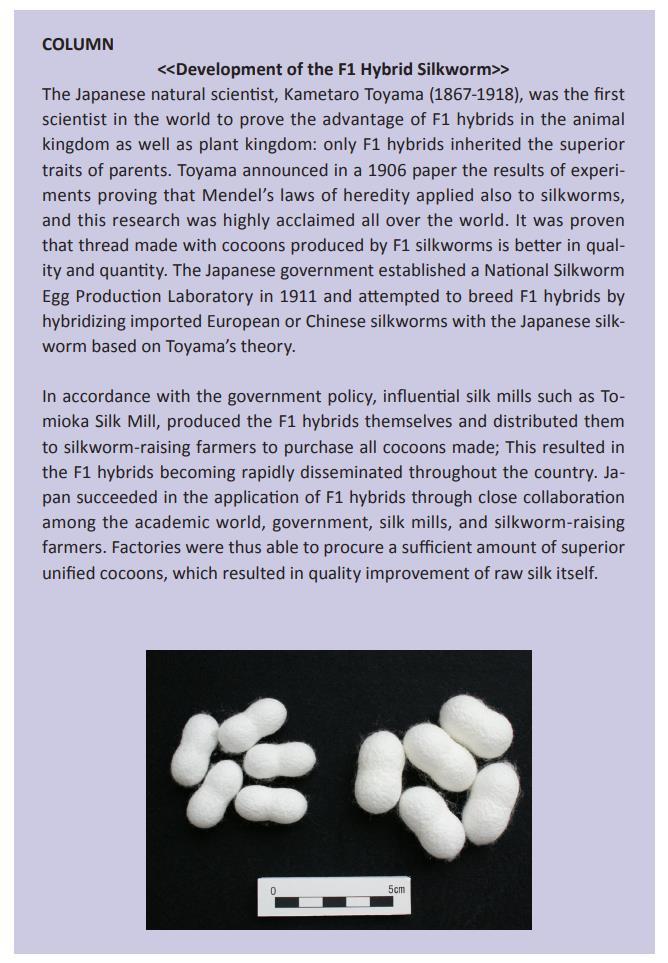

Note: In contrast to Eri (Thai or “peace”) silkwhere silkworms are allowed to leave the cocoon - Mulberry silk worms are boiled prior to emerging from the cocoon (to prevent them breaking the continuous thread)

James Harrison Wilson Thompson (Mar 21, 1906 – Mar 26, 1967 disappeared) "almost singlehanded(ly) saved Thailand's vital silk industry from extinction" (Time Magazine)

James Harrison Wilson Thompson (Mar 21, 1906 – Mar 26, 1967 disappeared) "almost singlehanded(ly) saved Thailand's vital silk industry from extinction" (Time Magazine)

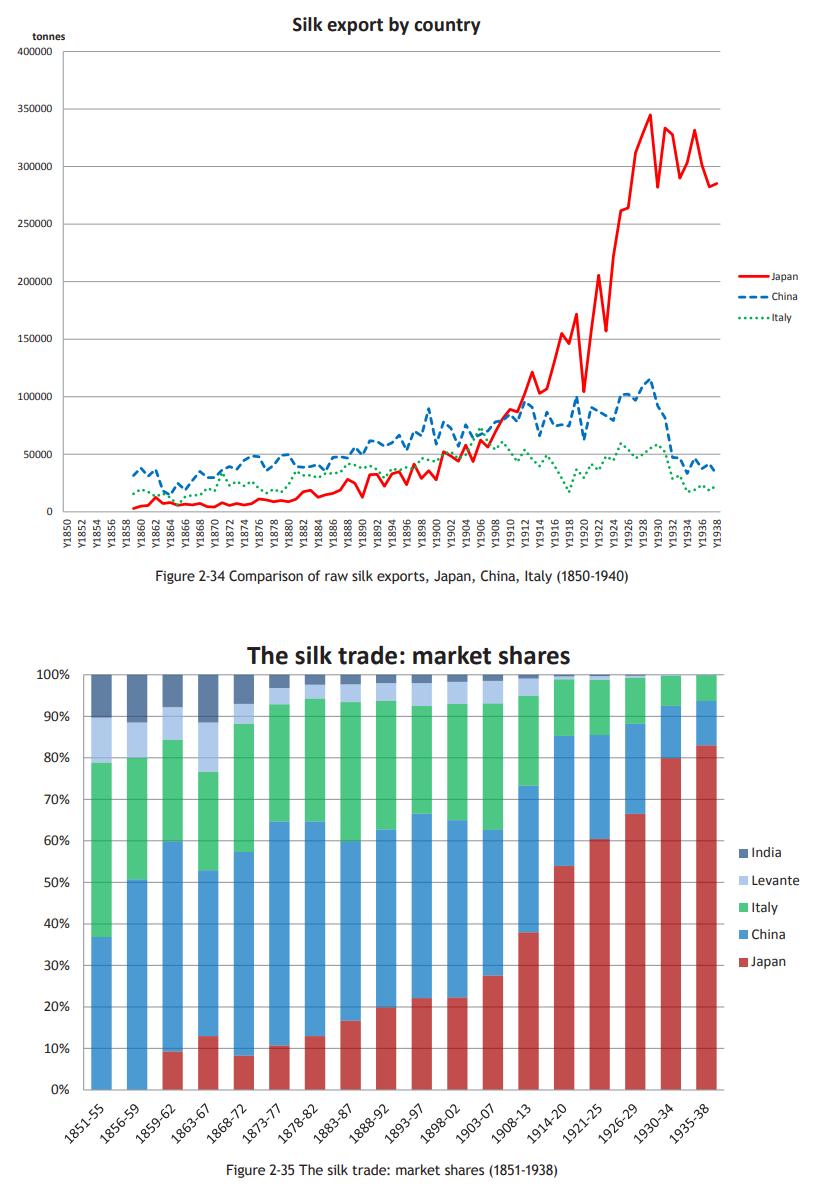

Disruptors: invention of new, synthetic fibres, e.g. Nylon-66 (DuPont, 1935), Nylon-6 (IG Farben/Toray, 1938)

Tomioka City's image character "Otomi-chan". Otomi-chan is a girl who was born in 2012 in the 140th anniversary of the founding of Tomioka Silk Mill, and has always been a 14-year-old girl.

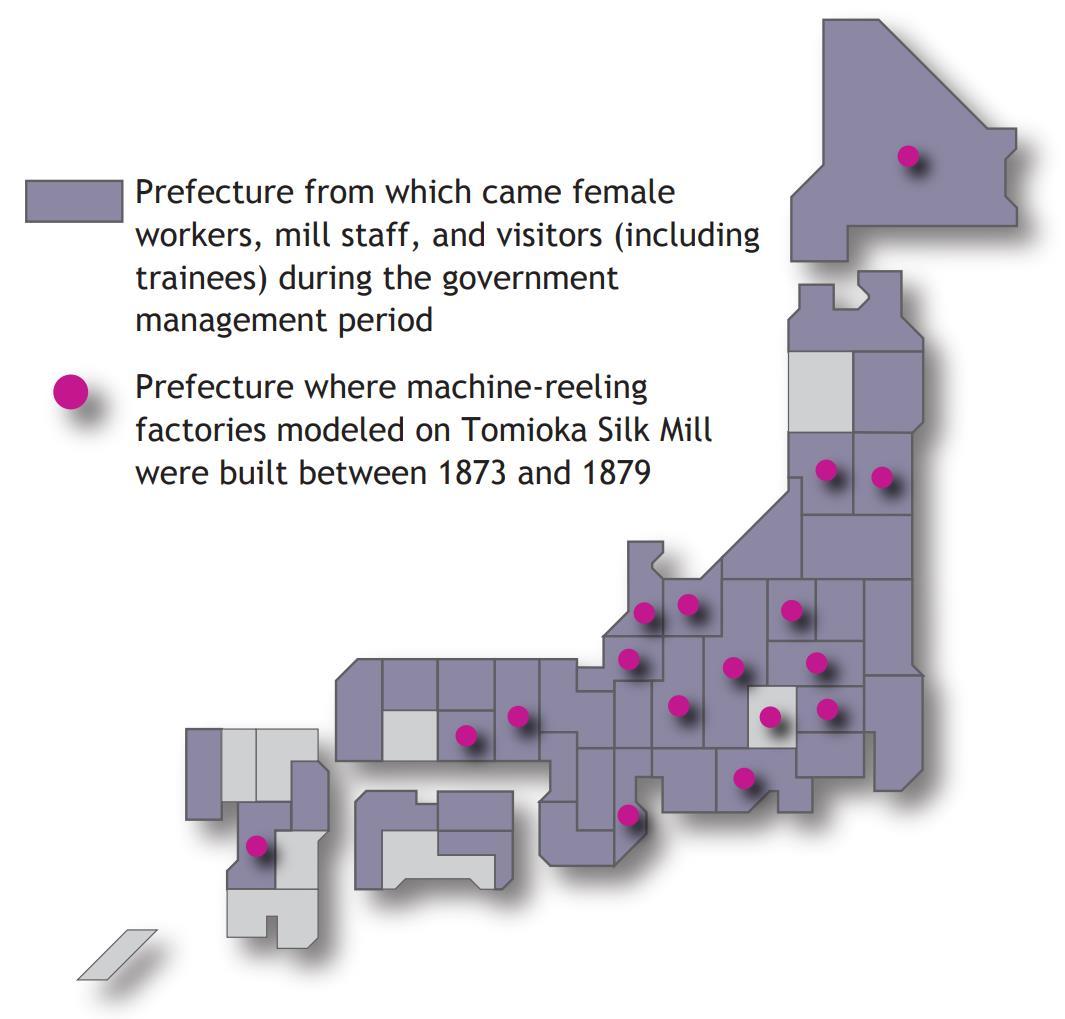

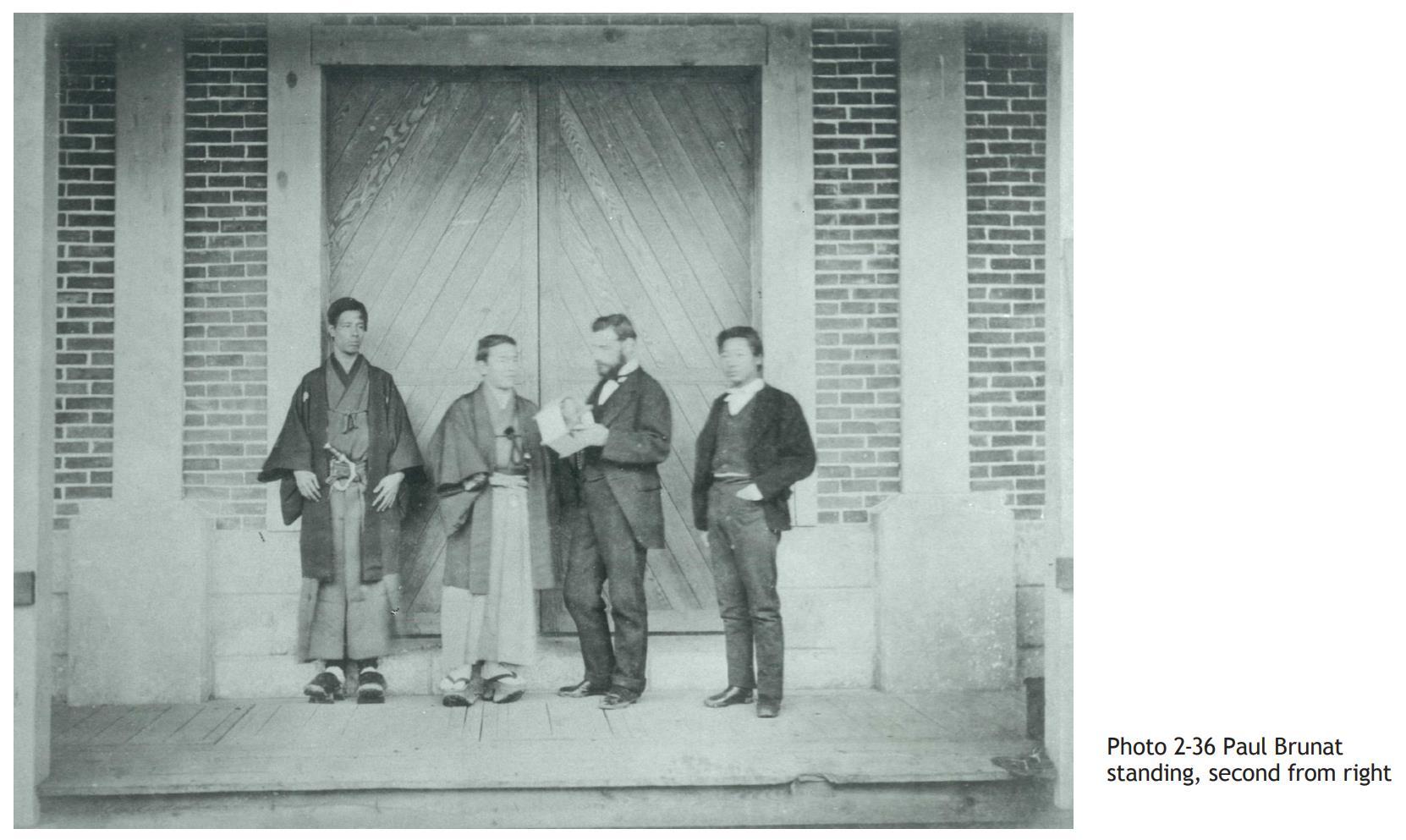

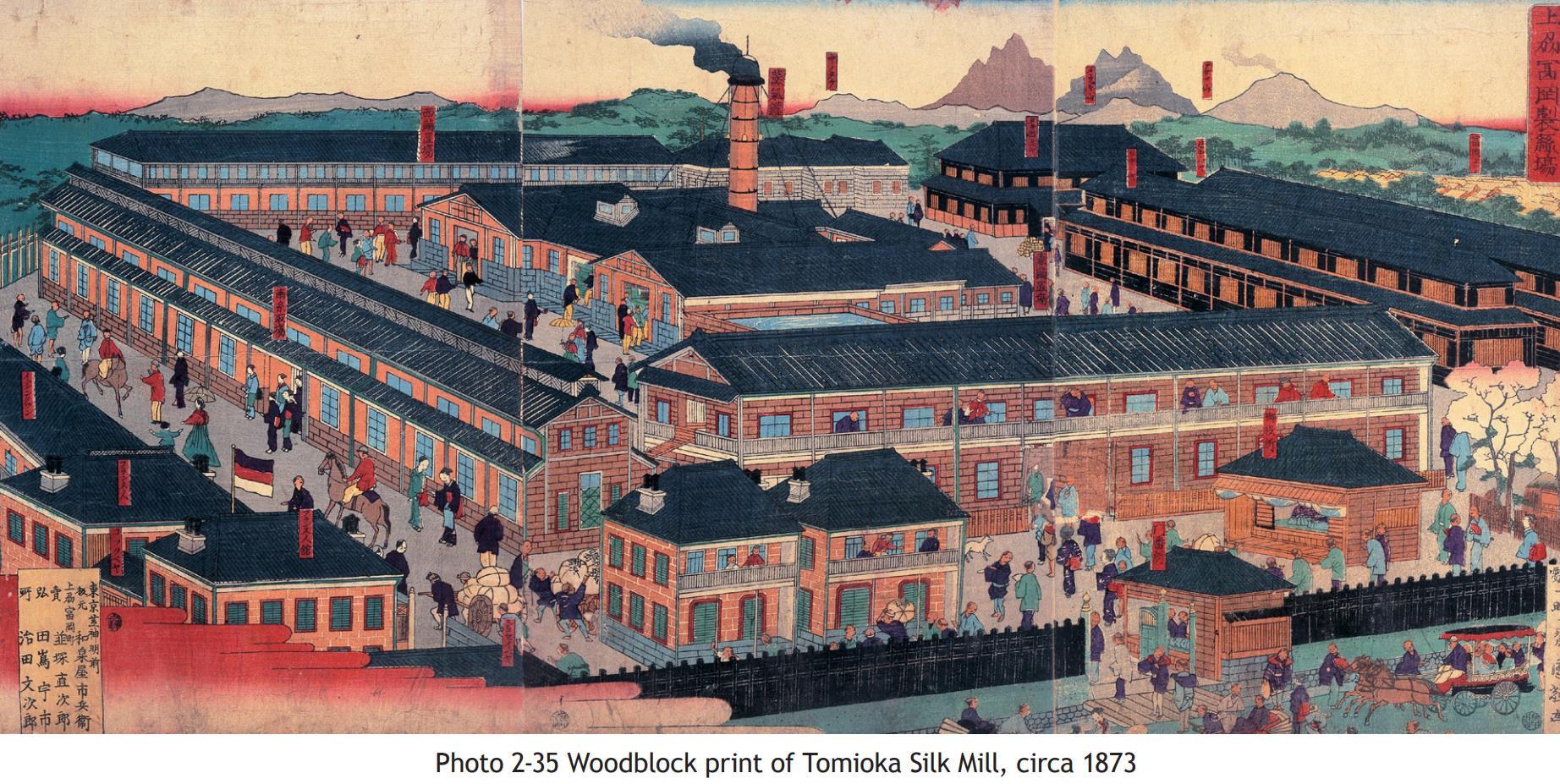

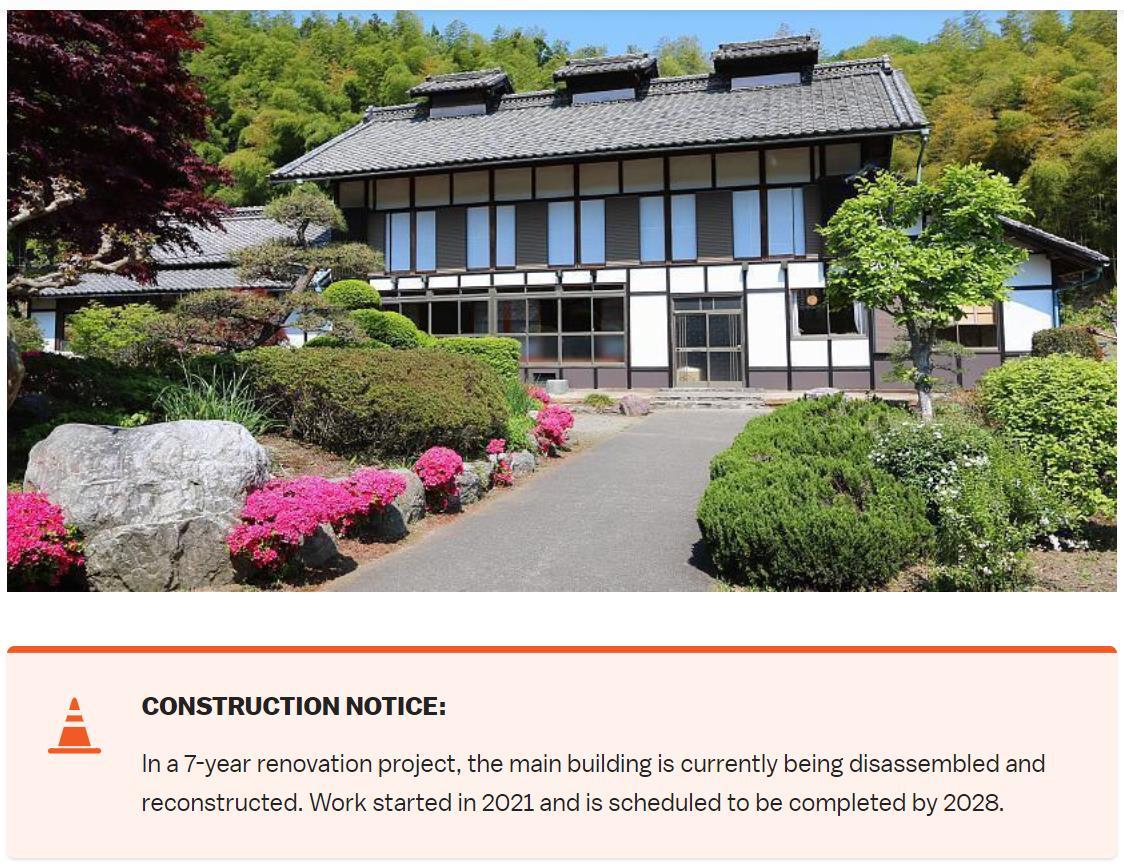

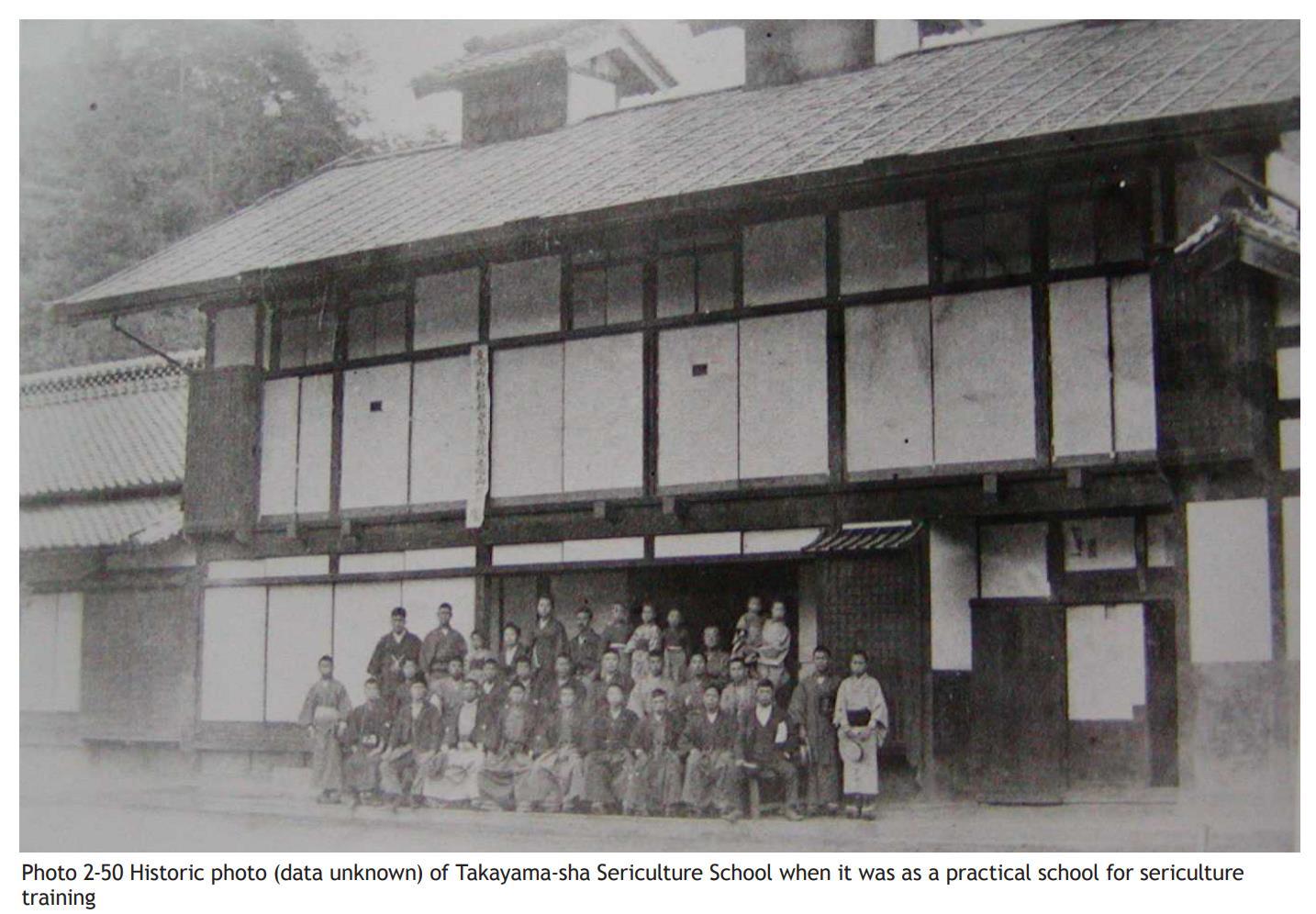

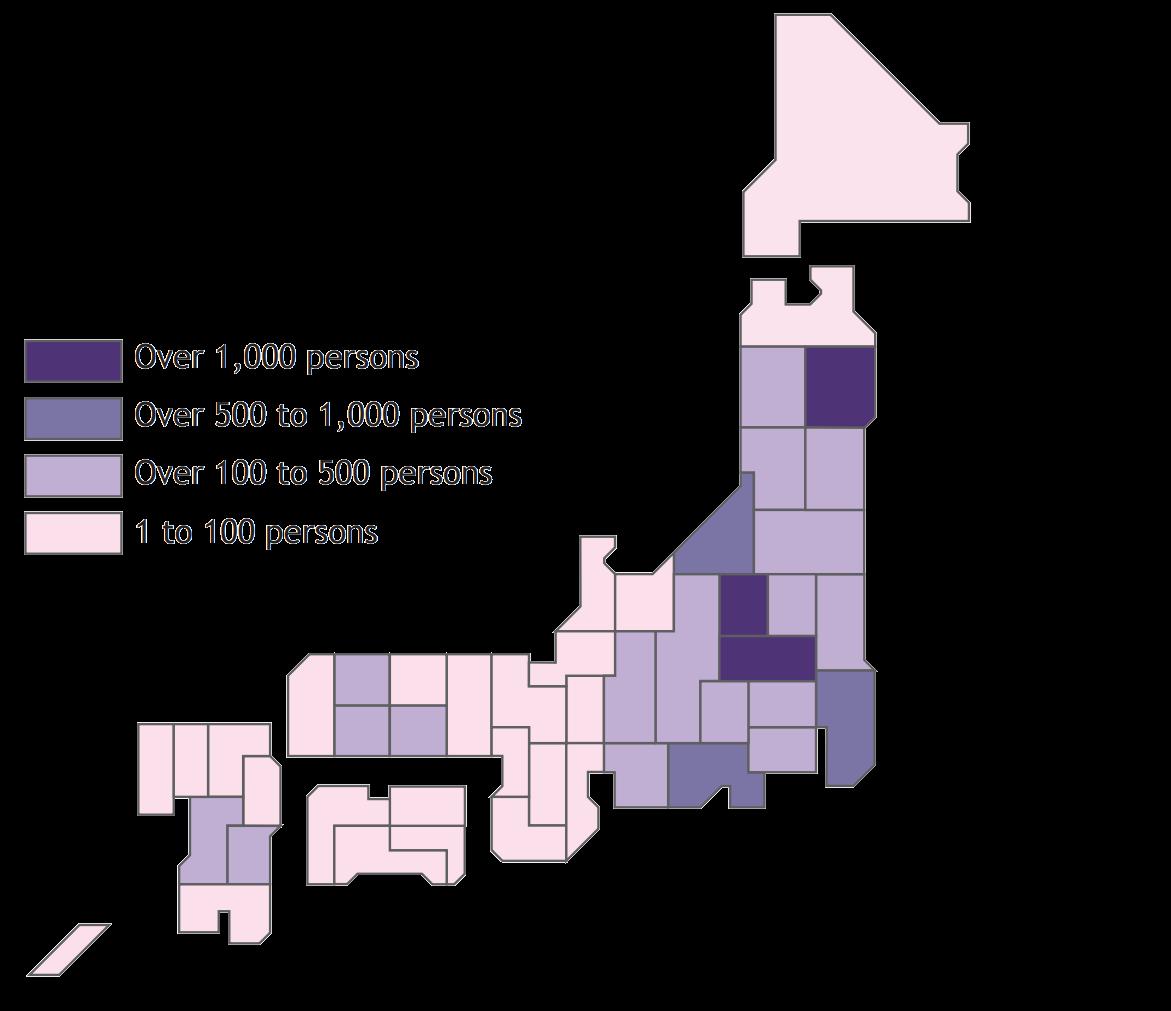

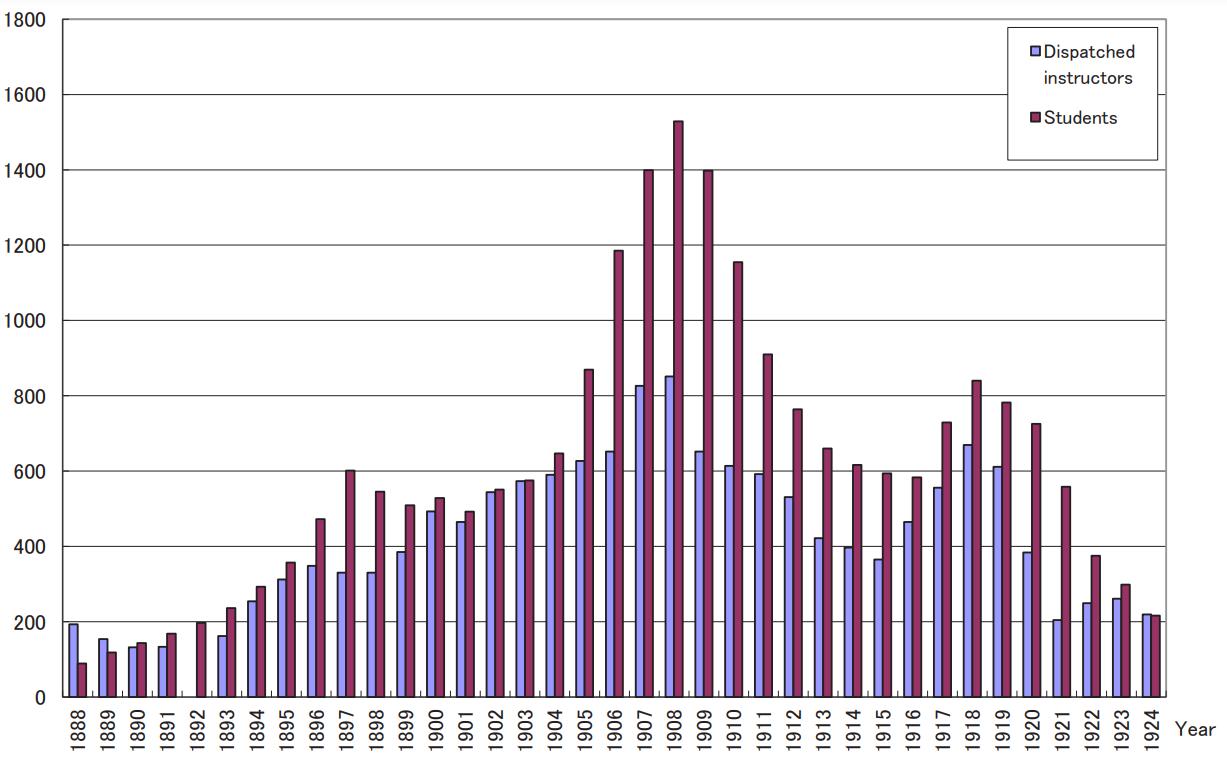

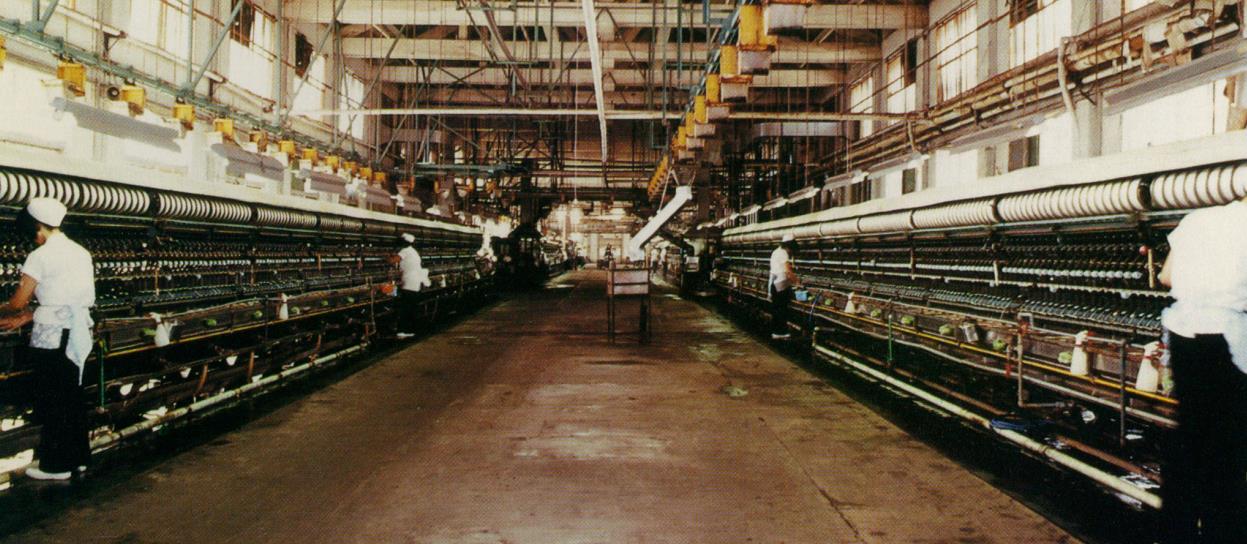

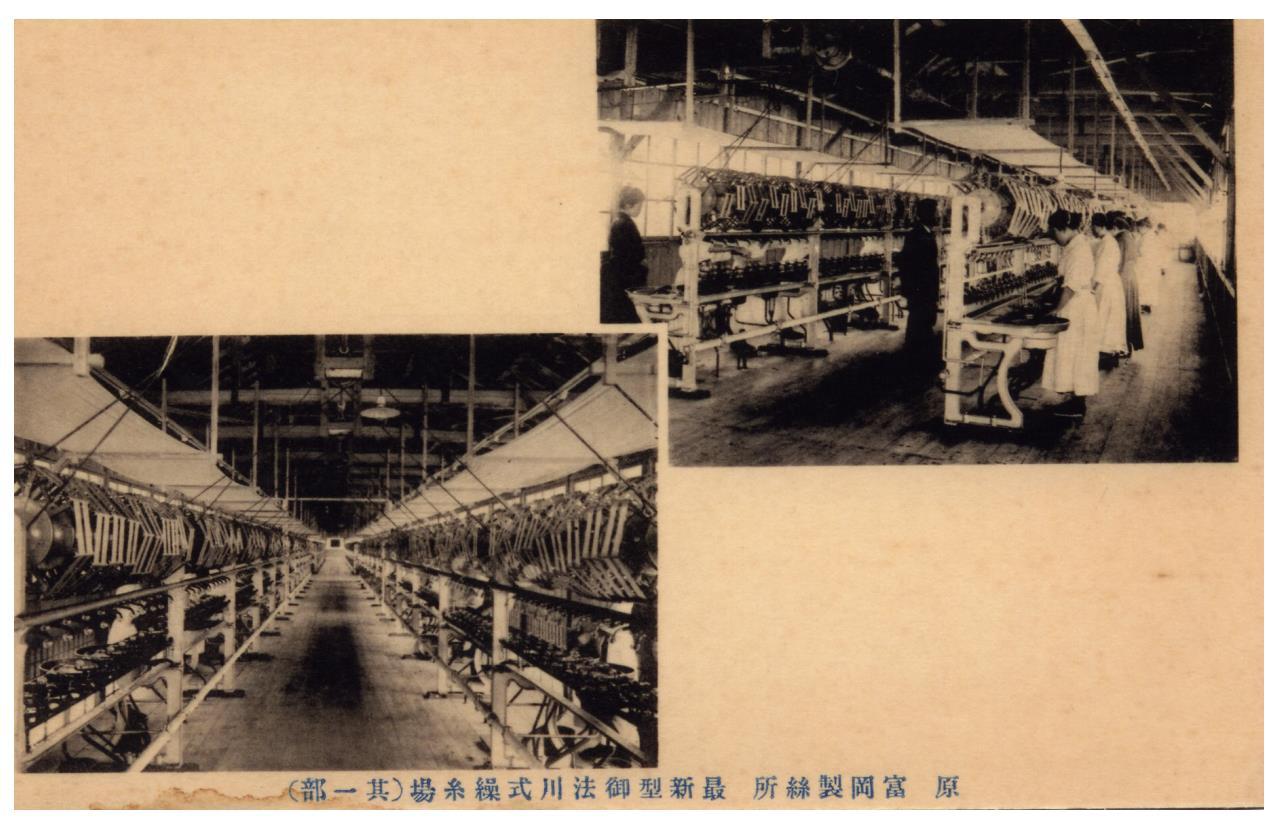

The working environment at the Tomioka Silk Mill was progressive for its time. Brunat introduced eight-hour working days, Sunday holidays and ten-day holidays mid-year and at year-end. The workers were provided with uniforms, and as the prefectural governor, Katori Motohiko was enthusiastic on education, the women workers had access to an elementary school. However, worker turnover was high, as there was considerable social pressure against women working in a factory, and friction between women from different social classes forced to work side by side. Many workers left within three years of employment, and the need to keep training new worked added to the mill's expenses. Workers were graded according to their skill level, with a system of eight ranks introduced in 1873. Silk produced at the mill received a second place award at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, and "Tomioka silk" became a brand name. Workers from Tomioka were also sent, or otherwise found employment at other privately owned silk mills which were subsequently built in Japan. (Source: Wikipedia)

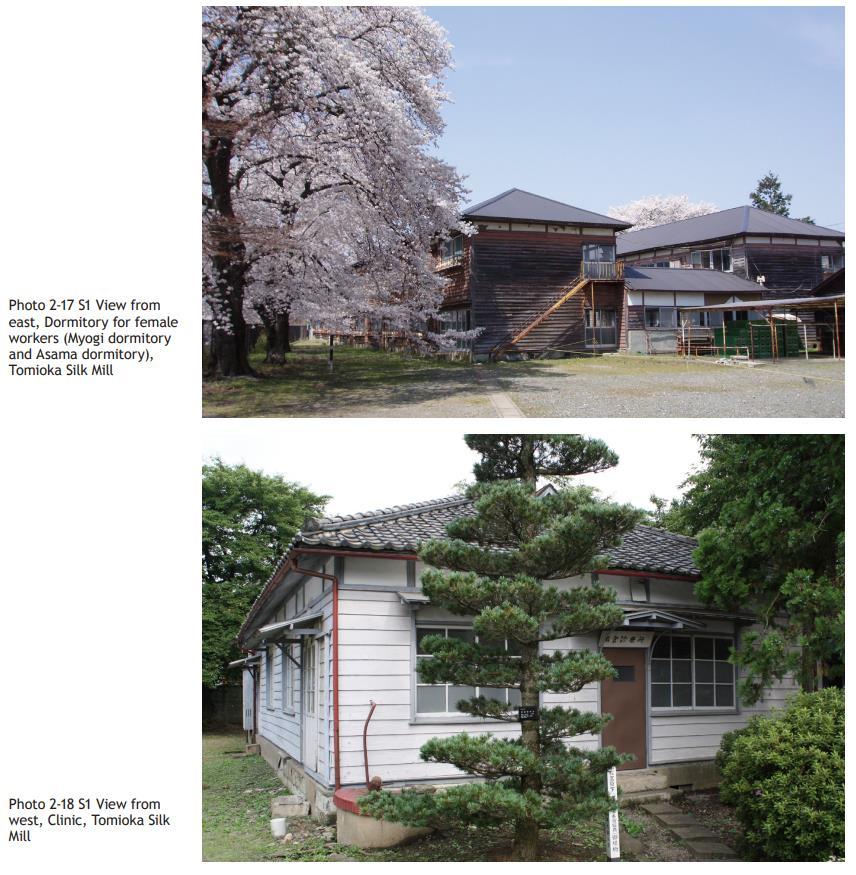

As the scale of production grew, demand for labour also increased. The number of women and male workers that came from wealthy families declined, [to be] replaced by [] young female workers from rural families. Most of the mill girls were the age of twelve to twenty, and they lived in dormitories in the nearby region. [15] [] The employers justified the low wages by providing training in silk production, which could be utilized even when they go back to their home prefectures to marry.

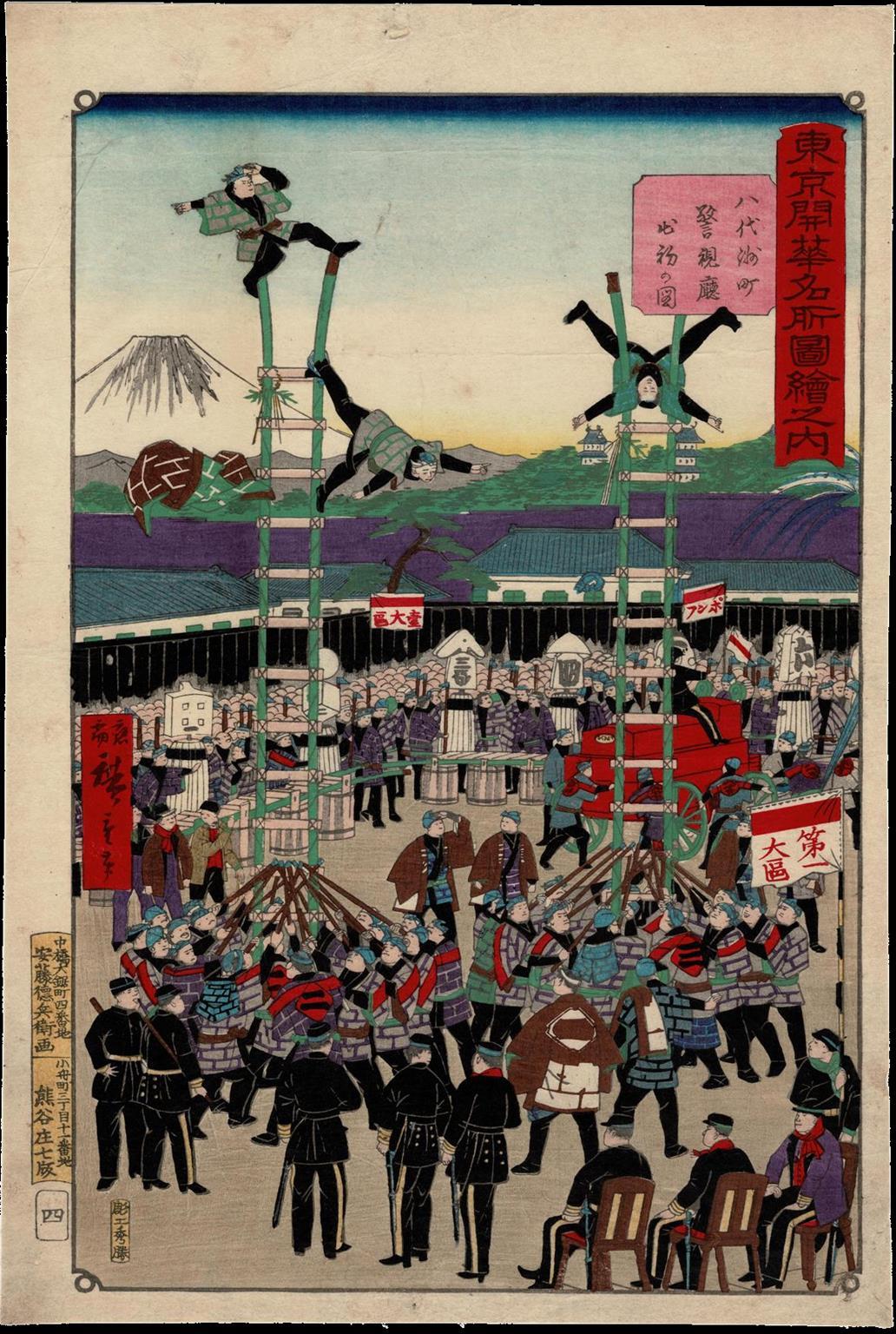

[] Working hours were repeatedly lengthened to increase production, [to] as much as eighteen hours per day during the peak period. Secondly, [the women] were not provided enough food to stay healthy, and [] not given enough meal breaks as they needed, to keep the machines working. Thirdly, the dormitory they lived in was very small and they had to sleep in a bed with many other workers []. Fourthly, they came to Tomioka mostly through recruiting agents, and only a small amount of the income went to the mill girls, employers or the agents would receive the majority of the income. Finally, the working conditions themselves were extremely unhealthy: [] the factory was always very humid and filled with dust. Hygiene facilities were inadequate []. Excessively long hours of work led to exhaustion, malnutrition, and illnesses such as tuberculosis. [17] To protest against [] sweat labour [], the first strike [in Japan] happened in Amemiya [Silk Mill, Kôfu City, Yamanashi ken] [18] in 1886 (Meiji 19) by [] female factory workers

[] In 1933, the Japanese government officially reported that the sanitary conditions of the Tomioka Silk Mill were particularly poor compared to other factories, and thus sicknesses and diseases among the workers were prevalent. In addition, Takase demonstrated that a large number of women even committed suicide due to the working conditions. [23] (Women in the Silk-reeling Industry at Tomioka Silk Mill – Digital Humanities and Japanese History (japanese-history.org)