Portland Fish Exchange faces financial pressure

By Clarke Canfield // Photos by Michele Stapleton

By Clarke Canfield // Photos by Michele Stapleton

Scores

of hard-plastic crates filled with icecovered fresh fish sit on the floor of the Portland Fish Exchange, ready for inspection before the bounty is auctioned in lots to the highest bidders. The fish comes from eight boats that brought their catches of cod, haddock, monkfish, grey sole, and other groundfish here on this late September day.

Days like this, with more than 16,000 pounds of fish, have been too few and far between as of late at the Fish Exchange, a landmark on the Portland Fish Pier for 36 years. Hurt by a declining number of boats bringing their harvests to Portland and recurring financial losses, the exchange is bracing for operational changes to come, possibly by the end of the year.

At the request of the Portland Fish Pier Authority, the exchange board of directors solicited requests of interest from private firms interested in providing management services. The two interested compa nies, Vessel Services Inc. and Bristol Seafood, both located on the Fish Pier and well-known in the fishing industry, will soon submit proposals on how they would manage the exchange and what changes they might recommend. The board has also hired

a temporary business manager—Mike Foster, the general manager of Vessel Services—to oversee the exchange in the interim.

Bill Needelman, Portland’s waterfront coordinator, said changes are needed because the exchange has been going through a long period of uncertainty with a revolving door of managers and dissatisfaction

Deer Isle causeway worries officials

Storm damage could bring economy to standstill

By Tom GroeningOneway in, one way out. That’s how community offi cials often describe Deer Isle and Stonington, and it’s a worry when that one way includes a sometime

deteriorating Route 15, a circa-1939 bridge spanning Eggemoggin Reach, and a causeway linking Little Deer Isle and Deer Isle.

The causeway was the subject of a Sept. 20 meeting with concerns focused on a warming climate’s impact on the

among many seafood sellers and buyers with certain facets of how it is run.

The biggest issue, however, is the exchange’s ongoing financial troubles. In the past year alone, the Fish Pier Authority has provided the exchange $300,000 to cover revenue shortfalls and capital

roadway. Splash-overs and seaweed on the road coinciding with high tides are becoming more common, officials said, prompting concerns over a storm that might tear a breach in the causeway.

“It’s a huge vulner ability,” said Jim Fisher, Deer Isle’s town manager, and the rising seas could become a monthly, or even daily problem.

Andy Sankey, director of Hancock County’s Emergency Management Agency, explained to those attending the meeting in person and online that some 30 regional public safety officials—including those representing public works, fire departments, ambulance services, and law enforcement—had undertaken

a “tabletop” exercise simulating the response to a breach of the causeway which carries Route 15 and is the only road link from Deer Isle and Stonington to the mainland.

Sankey said the premise of the exercise had “a 30-foot by 30-foot by 3-foot deep hole” cut into the two-lane causeway, presumably by a storm, which “absolutely, very much so” could happen.

Currently, seaweed and rocks must be cleared from the road a couple times a month, he added.

The planning exer cise considered a breach that might cut off traffic for 48 to 72 hours. Such an event would disrupt mainland medical

“The fact that we’re the biggest risk factor in Hancock County will also mean we’re at the top of the list for some of those infrastructure funds…”

—LINDA NELSON

FISH EXCHANGE

continued from page 1

repairs while also deferring rent payments through February. The continuing financial woes have served as a wake-up call that the time has come for a new strategic direction, said Needelman, who is vice president on the Fish Exchange board and also staffs the Fish Pier Authority.

“The Fish Exchange has had some rough financial times for a number of years, and the last two years has had unstable management through a succession of general managers,” he said. “This is a process to discover greater stability for the facility financially and from a staffing standpoint so services can continue and hopefully expand.”

Many members of the Fish Exchange board oppose changing the management regime, said Rob Odlin, a fish erman who serves as president of the Fish Exchange board. Instead, he said, the focus should be on providing incentives and looking at other ways to attract boats that might otherwise take their catches to Gloucester or New Bedford in Massachusetts.

Odlin, who owns two boats that currently fish for scallops, lobster, and squid, said most board members support having a “neutral party,” not an outside firm, run the exchange. The final decision comes down to the exchange board, but the board is backed into a corner because it receives funding from the Fish Pier Authority.

“We think it’s being managed correctly,” Odlin said. “The reason there have been no landings is because the boats have left Maine.”

When the exchange opened in 1986, it was said to be the first wholesale fresh fish display auction in the U.S. In its heyday in the early 1990s, the auction handled more than 30 million pounds of product a year. But as the fishing industry struggled under the weight of fewer fish and more regulations, the numbers went down—to 10 million pounds, 5 million, and finally under 1 million.

The situation became particularly dire this year when volumes dropped to unprecedented levels well below projections, bottoming out in May when only 5,000 pounds of fish were landed at the auction for the entire month.

Although landings picked up in July, August, and September, the uptick is attributed to rebates that fishermen receive for exchange fees, fuel, and ice, as well as Fishermen Feeding Families, a Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association program that buys fish at the exchange and ensures that fishermen have a market for their catch. The rebates and the Fishermen Feeding Families program are made possible from funds from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act economic stimulus bill, also known as the CARES Act.

But that money is scheduled to come to an end next spring, leaving the question: “What then?”

Furthermore, the exchange is at a disadvantage because Maine law doesn’t let fishermen sell lobsters that are inadvertently caught in their nets; they have to toss the lobsters overboard or go to Massachusetts

where they can be sold—which could amount to thousands of dollars per fishing trip.

Some board members suggest the city and/or the state should continue providing incentives to fish ermen in the form of fuel, ice, and exchange fee rebates, giving them added reason to come to Portland. They also favor changing state law that prohibits lobsters caught in nets from being landed in Maine.

Meredith Mendelson, deputy commissioner of the Department of Marine Resources who serves as president of the Fish Pier Authority, said it’s impor tant to explore all options, something she hopes a new management administration will bring to the table. Money is limited, she said, so it’s crucial that a sustainable business model be developed.

She agrees that bringing in an outside management team would be a big change.

“But I would also say it’d be very unfortunate— and a big change—if there were no place to land groundfish in Portland because of inadequate funding,” she said.

It’s not clear exactly what changes an outside entity might bring to the exchange; that will be part of the process of reviewing the proposals from Vessel Services and Bristol Seafood. But what is clear to Nick Alfiero, co-owner of Harbor Fish Markets in Portland and Scarborough, is that the auction is crit ical for fishermen, fish buyers, consumers, and the city’s reputation for quality seafood.

Alfiero, who also serves on the Portland Fish Exchange board, has been buying seafood here since day one of the auction.

“It allows me open access to fish that are landed,” he said inside the exchange. “It also allows me to inspect fish for quality. It’s also local, I don’t have to truck it. I can buy fish here in the morning and have it on display at our stores that same day.”

“It’d be very unfortunate—and a big change—if there were no place to land groundfish in Portland…”

DEER ISLE

continued from page 1

appointments for residents, as well as school and business affairs, including the delivery of fuel.

“It was a lot of ‘what ifs’ to find out what the public safety response was,” Sankey explained. “It would get fixed in a couple of days,” he said, and emergency plans have been drafted for such a scenario.

“Those plans exist. Will they work? I guess we’re not really sure,” he said. “We want to make sure we have a very realistic view. The causeway is at the top of our list here in Hancock County.”

Sankey referred to road washouts in Prospect Harbor and Roque Bluffs in June 2021 from a heavy rain storm.

“It took weeks and weeks to get it repaired.”

Linda Nelson, economic and community develop ment director for Stonington, presented information on what is at stake if road access is lost.

“We know we have two single points of failure—the

Stonington by boat across the water. Without a bridge, the island was becoming more and more isolated.”

It took two years to build the bridge, Nelson noted, but about ten years to secure construction funding.

Nelson urged the communities to act while federal funding is available through the recently passed infrastructure bill.

“The fact that we’re the biggest risk factor in Hancock County will also mean we’re at the top of the list for some of those infrastructure funds so we can do the mitigation that climate change in requiring,” she said.

“We’ve had problems with the causeway for years, and now it’s much more vulnerable. What’s also more vulnerable is our economy.”

Communication and power lines are strung across the causeway, she said, and an average of $55 million in lobster is landed each year in Stonington, Nelson said.

“These are live creatures that are dying the minute they come out of the water,” she said, “so the timely transportation of lobster from Stonington is hugely, hugely important.”

In addition to the lobster industry, construction and tradespeople use the causeway, as well as tourists. Lumber and fuel trucks also regularly travel the road.

“That point of failure is a two-way street,” she said.

The Isle au Haut boat service also relies on the

causeway, with the company reporting it carried 10,000 non-resident passengers in 2021, Nelson said.

Dale Doughty, head of planning for the state Department of Transportation, told the gathering that a causeway failure “would garner a lot of state wide attention.”

DOT has begun evaluating the causeway, he said, with any work coming with funding in the summer of 2024. Drill crews will soon be on the causeway to gather data.

“We’re doing the engineering studies right now,” he said.

On the matter of medical transport, Julie Eaton, a local lobsterwoman, promised that she and others in the business would use their boats to carry patients to Brooklin Boatyard, if the need arose.

In a related matter, residents of Islesboro at a special town meeting on Sept. 22 approved borrowing $1.75 million to build and renovate town buildings, including a new “up-island” fire station. That northerly part of the island is linked by a single road that passes over a section called the Narrows. Town officials have said if the road were to wash out in a storm at the Narrows, fire trucks could not reach the homes in that part of the island.

with…

Alexa Dayton of the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries New director brings experience in fisheries policy

By Laurie SchreiberAlexaDayton took the reins as executive director for the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries in Stonington on Oct. 3.

She has over 25 years of leadership experience with L.L. Bean, Maine Huts & Trails, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and, most recently, the University of Maine System. That includes 15 years of direct experience in fisheries science and policy, working with fishermen around the U.S. as a leader of the Marine Resource Education Program.

“The vision of vibrant fisheries and sustainable coastal Maine communities forever really resonates with me, empowering the next generation with hope for a bright future and sustainable economic outlook is everything,” Dayton said. “It takes a mix of science, education, and getting out into the community for a lot of listening, to bring this vision to reality.”

MCCF’s 10-person staff works with commu nity and fishery partners to develop collaborative programs addressing topics including climate change, gentrification, and ecosystem management.

We asked Dayton to expand on her ideas for MCCF. Here’s an edited transcript.

Working Waterfront: Where were you born and raised?

Alexa Dayton: I was born in Ann Arbor, Mich., and raised largely in Europe.

WW: What brought you to Maine?

Dayton: I finished my engineering degree at the University of Michigan, went west to explore, became homesick, and returned east. Portland, Maine, spoke to me.

WW: How did you career unfold?

Dayton: I was at L.L.Bean almost 10 years, moving through the ranks and doing direct marketing and catalogue circulation planning in the outdoor business space product areas.

I was with Maine Huts & Trails three years as director of communication and development. At GMRI, I did

MALLOY FOR MACHIAS—

Abrahm Malloy of Bar Harbor was recently sworn in as a marine patrol officer. He will serve in the Machias patrol. Malloy lives in Bar Harbor and is studying for a degree in Criminal Justice from Husson University. He has worked as a sternman on commercial and recreational fishing vessels in Seal Harbor and Northeast Harbor. From left are Capt. Colin MacDonald, Deputy Marine Resources Commissioner Meredith Mendelson, Malloy, Col. Matthew Talbot, Major Rob Beal, and pilot Steve Ingram.

marine resource education programming for the federal fisheries around the country. That was the source of my interest in fisheries and the marine space. With the University of Maine System, I was COO for a unit called Maine Center Ventures.

WW: What attracted you to MCCF?

Dayton: During my time at GMRI, I had the pleasure of working with the founders and staff of MCCF in the fisheries convening and education space. MCCF was a collegial, collaborative, neutral arbiter of science, education, outreach, and convening. That was similar to the mission and vision I pursued at GMRI.

WW: How do you view MCCF’s mission unfolding?

Dayton: I want to be sure that what I do is grounded in what the organization believes about itself. Sustainable fisheries and sustainable communities in the Gulf of Maine forever—that vision still holds true and still resonates for everyone. What may have changed is the portfolio of programs.

WW: In what way?

Dayton: The three pillars of collaborative science, collaborative education, and collaborative outreach still hold true. And there are long-term projects and partnerships that carry forward and will remain core to the portfolio. But I think we need to look at how fisheries need to adapt and what we need to provide for education support, adaptation support, business planning support, data and science support. There are a variety of pressures on the use of the ocean environment. We need to do a lot of listening and convening of our industry. I think we can play a role in enabling dialogues.

WW: What are a few specific projects MCCF will pursue?

Dayton: We have a couple of vessels we’ve been working with that have been testing ropeless gear. We’ll continue to do that and to look at how the economics and management might change. It’s complicated and costly and it takes time to adapt.

There’s a wind energy consortium just beginning in the Gulf of Maine and a roadmap proposal that a number of institutions signed onto. MCCF and insti tutions like ours can potentially generate data to help understand the ecosystem and provide a baseline before wind companies start to implement programs.

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than many other places on the globe. The connection between the watershed and ocean have been underestimated. We’ve had an exciting project underway, working with partners to look at watershed issues across the Downeast fisheries. That kind of approach is important for maintaining our ecosystem on a holistic level.

WW: Other projects?

Dayton: MCCF will work toward diversification of marine businesses and helping the industry understand how they can be more efficient.

Yesterday, we had a wonderful kick-off of our Eastern Maine Skippers program, with 45 high school students participating. They have a lot of future ahead of them. We need to help them see that future so they will stay in the community and continue to keep those fishing traditions alive. It’s about that next generation.

B ook R eviews

A radio reporter’s bad static Journalist, islander lives revealed

Soft Features

By Gillian Burnes; Littoral Books (2022)

Review by Dana Wilde

By Gillian Burnes; Littoral Books (2022)

Review by Dana Wilde

WHERE GILLIAN Burnes got the name “Coralie Threlfell” for the narrator of her novel, Soft Features, I don’t know. But it rings exactly true for a public radio reporter.

Coralie works for the local NPR affil iate based in fictional Winston, Maine, in the mid-1990s. She lives on a farm with her two young daughters and her husband, Lonny. Burly, lionhearted Lonny runs the farm, works the local barter-and-trade network, and writes bad young-adult science fiction stories in his spare time.

Coralie’s newsroom is exactly like newsrooms I’ve known, except they’re

making stories for radio, not print. Her colleagues are fairly typical reporters and editors, dedicated to their craft and, not surprisingly, lacking in everyday life the snottiness that often characterizes the on-air voices of public radio personalities. Coralie herself is recognizable to any news room journalist. She’s the experienced, highly skilled reporter who never stops making phone calls and follow-ups; who’s in a perpetual state of fret over whether she’s covered all the bases; who’s constantly chasing weird leads that some times go down rabbit holes but sometimes turn into home runs; and who quietly, sardonically sees through the bean counters who think they know more about news than newspeople.

to report or requires her to withhold. The whole episode provides a startlingly authentic look at islanders’ lives and an outside journalist’s inner struggles.

Coralie ushers us around her hectic day-to-day with clever, highly literate, tongue-in-cheek good humor, and pretty much every page of the book is buoyed by her more or less light hearted banter with herself, her family and her colleagues. But something is not quite right, and she knows it.

One of her stories— a “soft feature”— is about a medical boat that serves the more remote islands…

The story takes us inside Coralie’s farm and on her reporting trips. One of her stories—a “soft feature”— is about a medical boat that serves the more remote islands on the coast. She ends up making several outings, and when her reporting leads her into the middle of a feud between families that results in sunken boats, Coralie has to decide what her journalistic integrity allows her

At one point she leaves an animal rescue clinic emotionally shat tered by the suffering of the animals, not to mention a jaded veterinarian. Later in the story when she can’t bring herself to make phone calls to families grieving the deaths of chil dren—probably the most depressing task in any newsroom—we understand that Coralie is stricken with journal ism’s version of compassion fatigue.

In one of many fascinating asides, she argues with herself about the meaning of the word “tragic.” It’s complicated. Relentless bad news grinds down many reporters and editors similar to

the ways teaching grinds down many teachers—both professions are moral callings, and both grapple endlessly with seriously affecting human prob lems. Coralie, in “Soft Features,” reports her own extreme case of it.

Things fall apart when, following a hysterical meltdown at an Augusta news conference, Coralie sets off without authorization to investigate weird rumors she’s been hearing about a house-burgling ghost, the “Ptarmigan Pond Goblin.” (The goblin, we gather from Burnes’s acknowledg ments note, is modeled on the North Pond Hermit, a national news story broken by Kennebec Journal reporters.)

The whole story and all the charac ters in Soft Features ring exactly true. It tells a wholly accurate story about the complications and obstacles most jour nalists face as they struggle to live up to their own and their professional ethics. And it provides an authentic evoca tion of the good humor most reporters are blessed—or cursed—with, even at the worst of times. People who are cynical about journalists whose lives and work they know nothing about, should read this book.

Dana Wilde is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. He lives in Troy.

Meanwhile, down on the gentleman’s farm…

a bad strategy, few have reached that lofty success.

I don’t believe Roy Barrette was trying to fill White’s large shoes, but as I learned from reading A Countryman’s Journal, a collection of Barrette’s columns for the Ellsworth American and Berkshire Eagle, he actually lived just down the road from White in Brooklin. In fact, the two men were friends.

A Countryman’s Journal: Views of Life and Nature from a Maine Coastal Farm

By Roy Barrette (Islandport Press 1981, 2022)

Review by Tom Groening

By Roy Barrette (Islandport Press 1981, 2022)

Review by Tom Groening

FOR MY MONEY, no one can top E.B. White in the short essay genre. White’s work, especially that written from his farm in Brooklin and collected under the title One Man’s Meat, hits the mark on being reflective, insightful, colorful, and as easy and companionable as a chat with an old friend.

I think a couple of generations of newspaper columnists have tried to emulate White, and though that’s not

The Countryman’s Journal seems to pull from columns published in the period from 1958 to 1981, when the collection was first published. The content in One’s Man Meat came from the late 1930s and into the 1940s, so A Countryman’s Journal can be seen as the next generation of the genre and an artifact of a Maine era in which outside forces wrought changes still visible today.

Islandport Press reissued the collec tion this year, and I’m glad they have.

While newspaper columns often, necessarily, address issues of the day, the selections of Barrette’s work are timeless, or at least they lead one to contemplate the timeless and universal qualities of life on the Maine coast.

The columns lean heavily on the natural world, and particularly on his and his wife’s gardening and animal husbandry at their farm on the road

that leads from Brooklin center to Naskeag Point. The property is wellknown to locals and people like me, who have driven by on their way to the point and harbor. Several years ago, the farm was purchased by two-time inde pendent gubernatorial candidate Eliot Cutler. Cutler was in the news earlier this year for an arrest on child pornog raphy charges, an association that shouldn’t mar enjoyment of reading this collection.

Barrette’s knowledge of garden vege tables, fruits, and flowers is not that of recently retired hobbyist. Though born in the U.S. in 1897, he was raised in England, and much of his under standing of farm life seems to have come from that upbringing.

In fact, he makes a point of reminding readers that while he and his wife are financially comfortable, their refrig erator, freezer, and pantry are wellstocked with critters and produce raised there.

The one criticism I have of A Countryman’s Journal is that there are no dates associated with the selections. When Barrette expresses regret about the way the world is “today,” I wonder if he responding to the social and polit ical upheaval of 1968 or 1979.

Still, I suppose the universality of his ponderings supersedes dates, like this:

“I believe, too, as I believe nothing else, that man’s greatest need today is for occasional solitude, time for contemplation… Fog has hung over Naskeag Point every day now for more than two weeks. I could bemoan it and complain that it is mildewing my roses and spoiling my view…

“But I have noticed that the robins are swooping low over the pasture gathering insects (blackflies, I hope), and that the wet leaves of my lilacs look varnished in the light from the kitchen windows. Who am I to quarrel with the shape of life?”

Barrette died in 1995 at the age of 98.

Though different in style and subject, A Countryman’s Journal reminds me of another pleasurable read that evokes a recent Maine past. Salt Water Town— Tales from Castine, Maine, by Donald A. Small (Penobscot Press, 2016) is a collection of vignettes, some literal, some fictionalized, of that lovely Hancock County harbor town in the 1950s.

As autumn creeps toward winter, I think you could do worse than settle in with these two books.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront.

The full Nelson

B ook R eviews

Cold Spell: The View from the End of a Peninsula

By Todd Nelson (Down East Books 2022) Review by Carl LittleWHEN ASKED what they love about New England—or miss, if they’ve moved away—more often than not folks will say the seasons. Todd Nelson underscores this notion in his new collection of 50 or so short essays, Cold Spell: The View from the End of a Peninsula.

From his home in Penobscot, the writer studies his surround ings through the lens of Carole King: “Winter, spring, summer or fall / All you got to do is call….”

Another cliché is the recurring question seasonal visitors ask of yearrounders: “What’s it like in Maine in winter?” As if in response to this annoying query, Nelson begins his collection in the off season, acknowl edging that “everything in Maine life is sequelae of cold.”

While winter is “a source of pride and complaint, pleasure and pain, hibernation and exuberant embrace,” it also has a Stephen King quality, “always out there, watching and waiting for its chance to return.”

To such time-honored New England subjects as picking out the Christmas tree, monitoring the wood pile, surveying rock walls, picking blue berries, and maple syruping, Nelson brings fresh perspective and prose, personal and universal.

He also adds out-of-the-ordinary items to the list. His tribute to a winter clothesline, for example, is just plain gorgeous, an accumulation of ways in which this humble cord enhances our lives, including aesthetically:

“The clothesline has a graphic allure. Our favorite paintings in any medium are clotheslines. Perhaps even in their static, two-dimensional state, they inevitably suggest motion, wind power, and the alchemy of evaporation.”

Nelson’s riff on the Cape Racer sled is equally memorable. The sound of it sliding prompts him to consider “a hidden extinction,” namely, “the lost sounds familiar in former times.”

The piece sent me to Daniel Hoffman’s poem, “The Cape Racer,” in which he immortalizes the sled, “so sleek it seems prepared for flight / over the clouds as well as the frozen hills.”

In “My Next Bear,” Nelson describes a “persistence of vision” that compels him to look at the same spot in the landscape where he last saw a bear. Again, his becoming prose led me to a poem: Philip Booth’s “How to See Deer” with its advice, “Expect nothing always; / find your luck slowly.”

Booth, Thoreau, Dylan Thomas, Robert Frost, E. B. White, John McPhee, e. e. cummings, E. O. Wilson—these writers and others are Nelson’s gods. Like them—and Rob McCall, Cherie Mason, Susan Hand Shetterly, Don Small, and other area writers—he is a great appreciator, of life, nature, family.

“On some mornings,” he writes of his son Spencer, “his fishing stance was more reminiscent of playing air guitar than fishing, as he strode the dock with the rod perched over his shoulder and twirled around as he reeled and plucked the line.”

Lucy at sea in pandemic times

Latest Barton novel comes back to Maine

the father of their two grown daughters. It is March of 2020. People are getting sick with “that virus,” as she refers to it.

William, a scientist, grimly and quickly recognizes the threat and forms a plan before Lucy even realizes the pandemic’s scope and impact. He tells her they’ll drive to Maine, live on the coast for a while.

And she wants to know what’s going on elsewhere.

With humor and fine word-smithing, Nelson brings insight to our shared wonder and, sometimes, despair. Describing his sadness when an exca vator begins to dig the hole for the basement of his future home—“This land will never be the same again,” he thinks—brought back my own memo ries of feeling guilty at the clearing we made for our house.

“I must be satisfied that our dwelling will eventually harmonize with the landscape,” Nelson writes. “After all, the house is a stationary object. The forest is dynamic.”

All but one essay—“Time, Tide, and Tuscany”—take place in and around Castine. Nelson loves his adopted town, be it the elms that live on despite disease and age or his students at the Adams School where he was principal for six years (2004-2010).

Cold Spell opens with a beloved observation from E. B. White: “I would really rather feel bad in Maine than feel good anywhere else.” Nelson adds his own bon mot to the canon: “Maine doesn’t leave you as it found you.” No, it doesn’t.

Carl Little’s latest book is Mary Alice Treworgy: A Maine Painter.

Lucy By the Sea By Elizabeth Strout (Random House, 2022) Review by Tina CohenIN REVIEWS of Elizabeth Strout’s earlier Lucy Barton novels, I have not only pointed out but complained about the main character’s hesitant, unsure, anxious attitude. In her latest work, Lucy by the Sea, it now makes complete sense. Since the novel is set at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, it’s a reason able response to the times.

Not only is this the second book in a row to primarily focus on Lucy Barton, but it picks up where Oh William! left off. Lucy is back in New York City after several trips with William, her ex- and

Whereas previously Lucy might have seemed paranoid, her fears are now valid. People in Maine are treating the couple not just as outsiders, but as a danger. There is no mistaking the overt hostility.

Bob Burgess, an old friend of William and someone Lucy also knows (as do readers from his previous appearances in Strout books, including one about his family, The Burgess Boys), has arranged for them to stay in a recently vacated home in “Crosby,” the fictional coastal town we also know from other Strout books. (Would anyone be surprised Olive Kitteridge is also mentioned? And Isabelle?)

Despite the conditions and measures in response—wearing masks, main taining social distancing, many busi nesses closed—Lucy is not reclusive, but instead curious to see more of Maine with day trips, and to get to know some of the locals.

She is aware of the politicization of the virus, with questions about how real it was or how much protection could be mandated. She watches on TV the demonstrations and protests in support of Black Lives Matter and defunding the police. Her daughters, living tempo rarily in the Connecticut home of the married one’s in-laws, are themselves out marching in the streets in New Haven.

William and Lucy take the dangers of the virus seriously, and see their children only briefly and infrequently.

But William, once relocated to Maine, rebuilds his family to include members he’d been cut off from.

Lucy, after having initiated his possible reconciliation in Oh William!, is now uninvolved with that process; supportive but not included. Her focus on family is on their two girls, missing their regular contact. She worries there are things she is not being told and suffers the limits to her involvement. It is hard for her to accept. On the other hand, there is an improved, easier inti macy with William, and a growing friendship with Bob Burgess.

This book holds many pleasures. For Strout’s regular readers, Lucy is now

an old friend. We know about her childhood, its abuse and neglect; her divorce, her widowhood after another marriage. We can under stand her insecurity.

But even with loss, all kinds of loss—a constant reality of the pandemic—Lucy rises to the chal lenges. Many of us will recognize ourselves in the pandemic experi ence Lucy has, especially those of us who wanted to be in Maine in 2020.

When Lucy tells Bob they will not return to New York yet, he ques tions her tone of uncertainty. Lucy responds, “I mean I don’t know what will happen when all this is over.”

Leave the coast? Maine? Some dramatic and positive changes to their lives occurred that otherwise might not have. She and William are a reconciled couple, they have a home there now, he is interacting with family and heading into a new professional role, and she is finally writing again.

What has helped Lucy through the pandemic? Was it Maine? By the sea?

Tina Cohen is a therapist who is a seasonal resident of Vinalhaven.

Voters to consider passenger limits

Bar Harbor is state’s top cruise ship port

By Laurie SchreiberMasses of cruise ship passengers coming into Bar Harbor from April through November bring a pretty good chunk of change for owners of local shops.

Although no one really knows how many folks come off the ships in any given day, it could theoretically be 5,500, since that’s been the town’s passenger cap.

“The ships account for 25%-30% of my revenue in the average year,” Robin Wright, owner of three downtown shops, wrote in comments reviewed by the town council this summer.

Ron Wrobel, owner of a small coffee shop called Acadia Perk, wrote that this year, with the return of cruise ships, the business was up nearly 40 percent year-to-date.

So why is Bar Harbor getting set to restrict ship arrivals with lower daily caps along with monthly caps and a shorter season? It’s an effort to relieve what many residents say is simply too many people coming all at once.

Like ports the world over in 2020, Bar Harbor experienced its first season in decades without the presence of cruise ships.

In subsequent months, as residents contemplated the industry’s inevitable resumption, a groundswell of comment rolled out from residents interested in cutting back ship traffic, at least to some degree.

Now the town has two initiatives underway to address those interests.

At a special town meeting on Nov. 8, voters will decide whether to adopt an amendment to the land use ordinance, brought to the town via a citizen petition, that would limit the number of people disembarking from cruise ships to an aggregate of 1,000 per day. A public hearing is scheduled for Oct. 18, after this issue of Waterfront is printed.

In July, petition organizer Charles Sidman told the council the proposal was driven by the sense among signatories that the town has been “overrun” by cruise ship traffic.

Separately, the town council recently passed a plan to remove April and November from the season, cut the daily cap to 3,800 in four of the remaining months and to 3,500 in the other two months, and impose monthly caps of 30,000 in May and June, 40,000 in July and August, and 65,000 in September and October.

The plan was worked out through negotiations with the cruise ship industry after consulting with a maritime attorney, said Town Manager Kevin Sutherland.

The plan will become effective in 2023 but will honor bookings made under the 5,500-passenger cap. Ships under 200 passengers are exempted. The proposal calls for developing memoranda of agreement with each shipping line that visits Bar Harbor, reviewing the caps each season, and working with state and federal governments to increase the number of ports of entry in Maine to spread demand.

Bar Harbor has been booking over 150 ships in recent years, many carrying several thousand passengers.

At one time, the community was looking to promote Bar Harbor as a port of call. Today, it’s Maine’s largest cruise ship port, tying in with Acadia National Park as a marquee destination. It’s also a logical customs check and port of entry for ships coming from Canada, according to a report by the group that developed the town plan.

Although cruise ships have grown larger in recent years, their absolute size isn’t the only factor in determining the industry’s impact, the report noted. For example, packages for a 500-passenger ship included a bus tour of Acadia, requiring 10 buses. But a recent visit by a 2,300-passenger ship made the park tour an add-on—ultimately calling for only two buses.

Residents come at the topic from various angles. Some say the industry causes congestion on the waterfront, impedes the waterfront viewshed, and pollutes the water and air with sewage and smoke.

Others say passengers are a small segment of overall tourism, yet provide significant revenue.

If the citizen amendment passes in November, it would supersede the town plan.

But questions have been raised about the amendment’s legality.

The citizen initiative “is a guaranteed lawsuit tying us up in litigation for years” Gary Friedmann, a town councilor, said in August.

If that happens, he continued, the town’s plan would at least go ahead with a level of reduction.

“The best thing is it has us in real communication and constructive dialogue with the cruise lines themselves,” Friedmann said. “And if we can continue to have a downward trajectory, that’s Bar Harbor’s goal.”

Report: Lobster remains a responsibly harvested species

By Tom Groening

Theharvesting of lobster in Maine and beyond “continue[s] to meet the criteria of our Gulf of Maine Responsibly Harvested program,” the Portland-based nonprofit Gulf of Maine Research Institute asserts in a report issued in September.

The report aims for a science-based approach in analyzing the clash between federal protection of North Atlantic right whales and the lobster fishery, whose harvesters maintain they pose little threat to the marine mammals.

The whales, which are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act and whose popu lation numbers fewer than 350, “face extinction unless human-caused mortalities, including ship strikes and entanglements in fishing gear, are considerably reduced,” the report states.

The context, though, is that a warming climate is “changing the habitat where whales normally feed, causing the whales to migrate through different areas seeking food,” which increases the likelihood of ship strikes and entanglement. Food also is less readily available due to a changing climate.

Fixed-gear fisheries, like lobster traps left on the bottom with vertical surface lines, “pose the greatest entanglement risk to right whales.” In the Northeast, the lobster and Jonah crab fisheries account for 93% of fixed-gear buoy lines in right whale habitats, the report notes.

On the other side of the conflict is the substantial economic sector that is lobstering, estimated at $1 billion in Maine, if ancillary businesses are included.

The fishery, “stretching from the Canadian border to Cape Cod, supports thousands of families and communities,” the report states, and in the past five years, whale deaths mostly have been confined to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and south of Cape Cod.

But it is difficult to determine where a whale first was entangled by rope and gear.

Right whales have been seen within three miles of the Maine coast, the report states, though those incidents are rare. Still, “with so

many traps in inshore waters, it leads to elevated entanglement risk…”

Given this confluence of factors threatening the whales, NOAA, which regulates fishing, published an updated biological opinion in May 2021. That resulted in rules for lobster and Jonah crab harvesting which were put in place early this year and were expected to reduce the risk to right whales by 60%. Those rules include closing a portion of the Gulf of Maine to lobstering, adding additional traps for each vertical line, and adding weaker rope or links designed to break if a whale become entangled. Gear also must be marked to indicate its origin.

Lawsuits from both lobstering advocates and whale protection advocates followed, with no changes coming from the courts—yet. In response to a suit brought by the Center for Biological Diversity, a judge ruled NOAA’s regulations “do not go far enough or fast enough,” the report notes, but a prescription for NOAA to address that failure has not yet come.

“Regardless, it is likely that more regulations are coming and will have to be implemented on a faster timeline,” the report concludes, and it “will present an existential challenge for the fishing industry.”

Switching to “ropeless” fishing gear is a possible solution, but GMRI’s report asserts that this tech nology is not yet commercially viable.

“Fishermen have abided by regulations for many years to ensure they are responsibly harvesting lobster and other species in the Gulf of Maine,” the report concludes, “but their livelihoods are being impacted by regulators doing everything possible to prevent [right whales] from going extinct.”

Lobster, along with monkfish, pollock, white hake, and winter skate harvested in the Gulf of Maine meet GMRI’s responsibly harvested criteria “because they are abundant and the existing rules are sufficient to maintain healthy populations of these species,” the report states. The health of another, mammalian species, though, may eclipse that good news.

Rock B ound

Will innovation save lobstering?

Bleak outlook on right whale rules are a driver

By Tom GroeningTHE CONCEPT OF innovation tends to inspire images of bio-geneticists tinkering with DNA to create cancerresistant cells. But sometimes, innovation comes in decidedly low-tech form.

I attended the every-other-year Beaches Conference in June, and one of the presenters showed slides of how the town of York dealt with peren nial ocean splash-over on a beach front road. The road—which probably shouldn’t have been built along the shore to begin with—was protected by large boulders configured at about a 30-degree angle.

In big storms, the waves sloshed up the ramp-like structure, flooding the road, and then slid back down to wash out parts of the beach.

Recently, the town built what amounted to large granite steps, about 2-feet high and maybe 3-feet deep.

The waves now hit the first vertical block, splash up onto the flat area, and, having lost most of their energy, fall back down, doing little damage.

A photo showed how well this worked—after a snowfall, the road that still featured the rocks was clear from the saltwater melting the snow, while

the snow was still visible along the section with the granite steps. Innovation.

Another low-tech innovation that comes to mind was conceived and adopted by the lobster fishery. Vents in traps, configured to allow under-sized lobster to escape, have kept the popu lation healthy.

I was reminded of this history recently after two conversations, one with someone very close to the industry, and the other with a scientist somewhat removed from the fishery.

The first conversation left me with a sense of dread. The fishery might very well face regulations to protect North Atlantic right whales that could effectively shut down lobstering, my source said. Scary stuff.

the Endangered Species Act or embrace new ways of fishing.

You can make the case that federal law is too reactive for threatened species. While standing by to watch a species die out is not good for the long-term health of our world, you have to wonder if the law could be eased to correspond with severe economic impacts.

If lobstering is choked out of existence, the Maine coast will be unrecognizable.

If lobstering is choked out of existence, the Maine coast will be unrecogniz able. Not a good outcome.

But my new scientist friend suggested that tech nology is available to elim inate vertical lines, the gear regulators say puts whales at risk. He conceded that yes, it will be expensive to outfit boats with one of several ways buoys and ropes might be deployed from the bottom.

possible, he said. And certainly scien tific measuring devices could be affixed to traps, and that, too, would come with funding.

But his most compelling argument was that with Sen. Susan Collins the ranking member of the powerful appropriations committee, and with Sen. Angus King holding a vote essen tial to Democrats, Maine might land federal funding for the fishery to make the transition to ropeless fishing. Just as federal money supports corn growers in Iowa, helping the iconic Maine lobsterman might be an easy sell.

And here is where we return to the idea of innovation. It must be embraced.

The second conversation was more of a listening session, during lunch at an Island Institute conference in Portland. A scientist with a back ground at a Massachusetts nonprofit made the case that if lobstering does indeed face crippling regulations, there are only two ways out—amend

R eflections

He also asserted that federal defense funding might be directed toward Gulf of Maine lobster trap upgrades. Why?

Because along with the wireless commu nication between boat and trap, there might be opportunities to include elec tronic surveillance equipment, he said.

Lobster traps monitoring the Russian submarine fleet? Hmmm. Well, it’s

Imagine the meeting at which an engineer first suggested that kinetic energy from slowing a car might be harnessed to charge a battery, another low-tech concept. Crazy talk! Or is it what made Prius a household name?

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be reached at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

Island balances character with change

Comprehensive plan crucial step in moving forward

Reflections is written by Island Fellows, recent college grads who do community service work on Maine islands and in coastal communities through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

By Melanie NashI

BEGAN MY fellowship on Long Island a little over a year ago, at the beginning of September 2021. I have spent the past year watching the community here prepare for its future, largely due to my involvement in the Long Island Comprehensive Plan.

When I arrived on the island, my first task was to decipher the responses of the community survey and lead hot-topic forums for residents. Out of the feedback from the forums and the community survey, I worked on devel oping a data report that would shed light on islander priorities and help shape the content of the next plan.

The overall feeling from the survey data and community engagement was that people have a resounding desire to keep the island the unique and special

place that attracted them here and keeps them coming back. Interestingly, this did not translate to “no change.” The overwhelming sentiment was that sustaining the character of the island that everyone knows and loves will require it to grow responsibly.

There was acknowledgement that town government and residents have work to do. Sustaining the island way of life will take a tremendous amount of work and will require some carefully managed and thoughtful change.

After being on Long Island for the past year, the spirit of volunteerism stands out to me. People step up to work for the changes that they want to see in their community. Long Island relies on volunteers, some of whom receive small stipends from the town government, to do everything from governing the town to running committees like finance, planning, and the school board.

The town’s emergency services and wellness council and all community organizations that we depend upon for social engagement like the library, historical society, and civic associa tion are all volunteer-run. This spirit

of engagement and responsibility to the community you live in strikes me every time I set out on another fellow ship work goal, and every time I attend a community event or am able to take advantage of town resources.

Over the past year, my work has shifted. The comprehensive plan passed unanimously at town meeting in May, and was officially submitted to the state at the end of the summer. The next step is to figure out the best ways to imple ment its recommendations and goals, many of which are already begun. A groundwater quality committee was started last fall as the concerns about our water supply rose to the top of discussions in public forums. Long Island participated in the first steps of the resilience training program with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and the Island Institute, starting to plan for climate impacts such as sea level rise. Broadband internet, the top strategic concern according to the 2021 community survey results, was installed on the island in spring and summer 2022.

There is so much good work happening and so much good work

to come. One question in the commu nity survey was “What is your greatest hope for the future of Long Island?” But responses also included “work,” “change,” and “build.”

The community is determined to have the island keep its character and its way of life while still allowing for planned growth, and I am grateful to be involved at such a transformative time. Last year, I got to work with the community to plan for its future. This year, I will be able to support and work with those who are already making change and planning for the future.

Melanie Nash works with the town of Long Island on a new 10-year comprehensive plan. She grew up splitting her time between Connecticut and the Pemaquid Peninsula. After graduating from Clark University with a degree in human environmental geography, she earned a master’s degree in marine affairs at the University of Rhode Island.

WALKING THE WATERFRONT—

This iconic image is well-known around Belfast. It shows the Belfast & Moosehead Lake Railroad just northwest of the station and freight yard, as well as the many waterfrontrelated businesses housed along the waterfront. It probably dates from the late 19th or early 20th century. Note that the man on the right is carrying a lunch pail, and is probably on his way to work. Today, workers at the Front Street Shipyard might be seen on that stretch of waterfront.

oped

Offshore wind blows across Searsport

State considering four staging options

By Rolf OlsenHAVE YOU heard there’s another plan to develop Sears Island in Searsport?

The state is considering using 100 acres or so on the western shore as a site where enormous floating wind turbines will be built and then deployed to the Gulf of Maine as part of Maine’s renewable energy plan.

I agree with the urgent need to develop new sources of renewable energy, but not with the sacrifice of an ecological and recreational treasure on the Maine coast, whose forests and marine systems already store carbon.

Over more than 50 years, several plans to industrialize Sears Island have been proposed and ultimately rejected, for environmental and other reasons, but only after first stirring up consider able discord.

The entire 941-acre island is owned by the people of Maine. The state acquired it in pieces, over time, from Bangor Investment Company, part of Bangor and Aroostook Railroad, which had hoped to develop a resort there in the early 20th century.

The state took the first 50 acres in 1985 by eminent domain for a possible

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kr istin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGi nnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis Michael Sant Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

cargo port, built the causeway, and started a jetty, but the project fizzled by 1996. In 1997, the state purchased the rest of the island (except for the fiveacre parcel with the cell tower at the south end of the island).

In 1995, permitting for a proposed cargo port met resistance because it would degrade or destroy important terrestrial and marine habitats. In 2003, opposition to an LNG terminal led Gov. John Baldacci, in January 2006, to convene stakeholders in the Sears Island Planning Initiative. About 45 stakeholders discussed their ideas for the future of Sears Island, and 38 signed a consensus agreement dated April 12, 2007.

The agreement states several uses and activities that are not appropriate for Sears Island, including nuclear or coal power, for example. It also states that “Mack Point shall be given pref erence as an alternative to port devel opment on Sears Island.” Today, 601 acres on the east side are protected by a conservation easement, with 330 acres reserved for possible future use as a “cargo/container port.”

To advance discussion of the current development plan, the state

Department of Transportation has convened the Offshore Wind Port Advisory Group, a 19-member stake holder group charged with “advising” the state on siting the proposed marshalling port. A marshalling port is where all components for the floating wind turbines would be gath ered—blades, nacelles, turbines, tower sections, and more—and the floating foundations would be constructed of concrete and steel.

From there the floating turbines, with bases about 750-feet across, would be constructed and launched into Penobscot Bay, then towed to the deployment area in the Gulf of Maine.

At the Sept. 29 advisory group meeting we learned there are three possible marshalling port loca tions under consideration. Two are in Searsport—Sears Island, and the existing Sprague Terminal at Mack Point. The third is the Port of Eastport.

We also learned about four configu ration options. Three are to place the entire marshalling port on about 100 acres at Mack Point, or Sears Island, or Eastport. The fourth configuration would use both Mack Point and Sears Island, with each location fulfilling

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by the Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

All members of the Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery: Join the Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

different functions and materials being barged across Long Cove, as needed.

There are many factors to consider in each location. Is suitable land currently available? Is dredging required? What might be the impact on water, fisheries, wildlife, plants, and other habitat? How about impact on adjacent recreational land, residential areas, businesses? Are there archaeological, historic, or cultural considerations? What will be the impact on the host community, in terms of noise, lighting, visual, or aesthetic factors? Where will the work force come from, be trained, live?

Based on what I know now, the better site for the proposed development is Mack Point, an industrial site for more than a century, so a considerably “greener” option. It is also the site that I believe would draw the fewest challenges, thus the option that would move forward most expeditiously toward helping Maine achieve its climate goals.

Rolf Olsen lives in Searsport and is vice president of Friends of Sears Island and is a member of DOT’s Offshore Wind Port Advisory Group. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the position of Friends of Sears Island.

Editor: Tom GroeningOur advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of the Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

David and Judy’s excellent electric adventure

By Tom GroeningYou

can trace the evolution of cleaner energy solutions over the last 45 years through the lives of Belfast-area couple David Foley and Judy Berk.

Deep-seated values and interests in their profes sional and personal lives have led to cautious, thoughtful steps toward efficiency and environmental responsibility over those decades. And as Foley says a few times during our conversation on their deck on a late summer day, each step didn’t bring hardship or a sacrifice in quality of life.

That journey began in the late 1980s with what was considered the best way to insulate a new house through today, with the couple now proud owners of two electric vehicles.

Foley is an architect designer, working with his professional partner, Sarah Holland, out of a small office at the homestead in Northport that Berk dubs “Ocean Glimpse Farm.” Berk retired in 2019 after 28 years as communications director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

Their move toward energy independence—which has included adding photovoltaic panels to their buildings and, most recently, those electric vehi cles—is, as Berk explains it, a matter of their values influencing their work, and their work influencing their values.

“It’s going to percolate up and it’s going to percolate down,” Foley says of the steps they and others have taken to power their lives with electricity.

It’s a move that would have been costly and foolish a few decades ago, but the couple is banking on elec tricity being the power of choice in a carbon emis sions-free world in the coming years.

Berk moved to Maine in 1975, moved into an old cannery building in Brooks, west of Belfast, with no insulation, running water, electricity, or phone.

The following year, she landed a job at a small busi ness in Belfast called Alternative Resources, which

offered such products as woodstoves, solar power components, and composting toilets. With many young “back-to-the-landers” arriving in Belfast just as the Arab oil embargo drove up energy costs, the time was right.

“I got indoctrinated there,” she says. “All those big old houses in Belfast didn’t have insulation and were

heated with oil,” she remembers.

She ended up managing the store and began writing a related column for the Bar Harbor Times, (Belfast) Republican Journal, and Waldoboro Weekly newspapers, called “Power Play.”

That work was followed by a stint with the state, working on energy issues for Waldo and Knox

LAUNCH

STORAGE

counties. In 1979, Berk managed a $300,000 energy grant through the cooperative extension service using five offices, and Foley was hired the following year to work in the Bangor location, which is how they met.

Foley was raised in Bangor and later Dixmont, and remembers his father, drawing on his Yankee frugality, putting him to work caulking, weather stripping, and insulating the house in Dixmont. The resources in plain sight just need to be tapped, as Mainers have been doing for centuries, he believes.

“We have sun, we have wind, we have falling water, we have biomass,” Foley says. “There’s no reason we can’t do this.”

While attending Dartmouth College, he worked with Vermont’s energy office, and one project included helping dairy farmers find more effi cient ways to cool their milk. Foley later earned a master’s degree at the University of California at Berkley.

The couple put down roots in Northport, building their modest but cozy house in 1989, later expanding it so it now includes about 1,650 square feet of living space.

They used rigid polyiso cyanurate foam, stuffed into the stud and rafter bays, for insulation in the first construction phase.

For the addition—after learning about new, better practices—they chose dense-packed cellulose.

It heats with a cord and a half of firewood in the woodstove.

Foley echoes what energy experts often say, that the best investment a homeowner can make is fixes that stop energy waste.

“You start with the efficiency stuff. You don’t unplug one inefficient tech nology and install another one,” Foley says. “If your refrigerator is harvest gold or avocado, it’s time to get rid of it,” he says with a laugh.

In 2009, they built the architecture office, which is about half the size of the house.

In 2012, they installed 12 photo voltaic panels (PVs) on the roof of the office—which runs computers, printers, copiers, and plotters—then

added another 16 in 2015-2016 on an outbuilding.

“There’s zero risk,” Foley says of solar energy.

In 2016 they installed air-source heat pumps.

“The one part of our energy systems we can ‘green up’ is electric,” Foley explains, meaning that relying on elec tricity to power much of the house and office is to move away from fossil fuels.

In 1996, Foley won a grant to visit Europe for two months to see how Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany addressed energy needs.

Some 40% to 60% of energy used in Sweden, Denmark, Spain, and Italy comes from renewable sources, he says.

“And life’s good there!” he says with a laugh.

On Facebook, Berk usually posts the couple’s electricity story at the end of the calendar year. Every year since 2012 except one, they essentially had no electric bill, thanks to the PVs on the roof. Net metering allows residents to sell the electricity they produce to the utility company for credit.

That virtually free electricity prompted the couple to consider switching to electric vehicles, and earlier this year, they took the plunge, purchasing a Kia Niro and a Hyundai IONIQ 5. The Kia is a hybrid, so it includes a gasoline engine and a plug-in chargeable battery. The Hyundai is a straight electric, charged by plugging it in.

The Kia gets 50 miles to the gallon of gas, and has a 512-mile range. The Hyundai is rated at 265 miles on a full charge, but they are finding that it can go 330 miles on a charge. The Hyundai also features all-wheel drive.

Berk is proud to report that the all-electric car has passed a Humvee going up a hill, while Foley points out “We can drive 100 miles for $6.40.” But for Berk, the real test is that she can fit three trash cans and her small kayak in one of the cars, testifying to the lack of sacrifice that comes with this new technology.

“We can’t shoot ourselves in the foot for our values,” Foley says.

SEEING RED, WEARING RED—

the back roads,

If

“We have sun, we have wind, we have falling water, we have biomass,” Foley says. “There’s no reason we can’t do this.”

A different kind of Downeast launch University of Maine at Machias students prepare for next steps

PHOTO ESSAY BY LESLIE BOWMAN

PHOTO ESSAY BY LESLIE BOWMAN

finishing a degree in psychology and is focusing on coaching and sports. She is considering pursuing an advanced degree in physical education and Kinesiology. At UMM, she works in the student records office and as a RA.

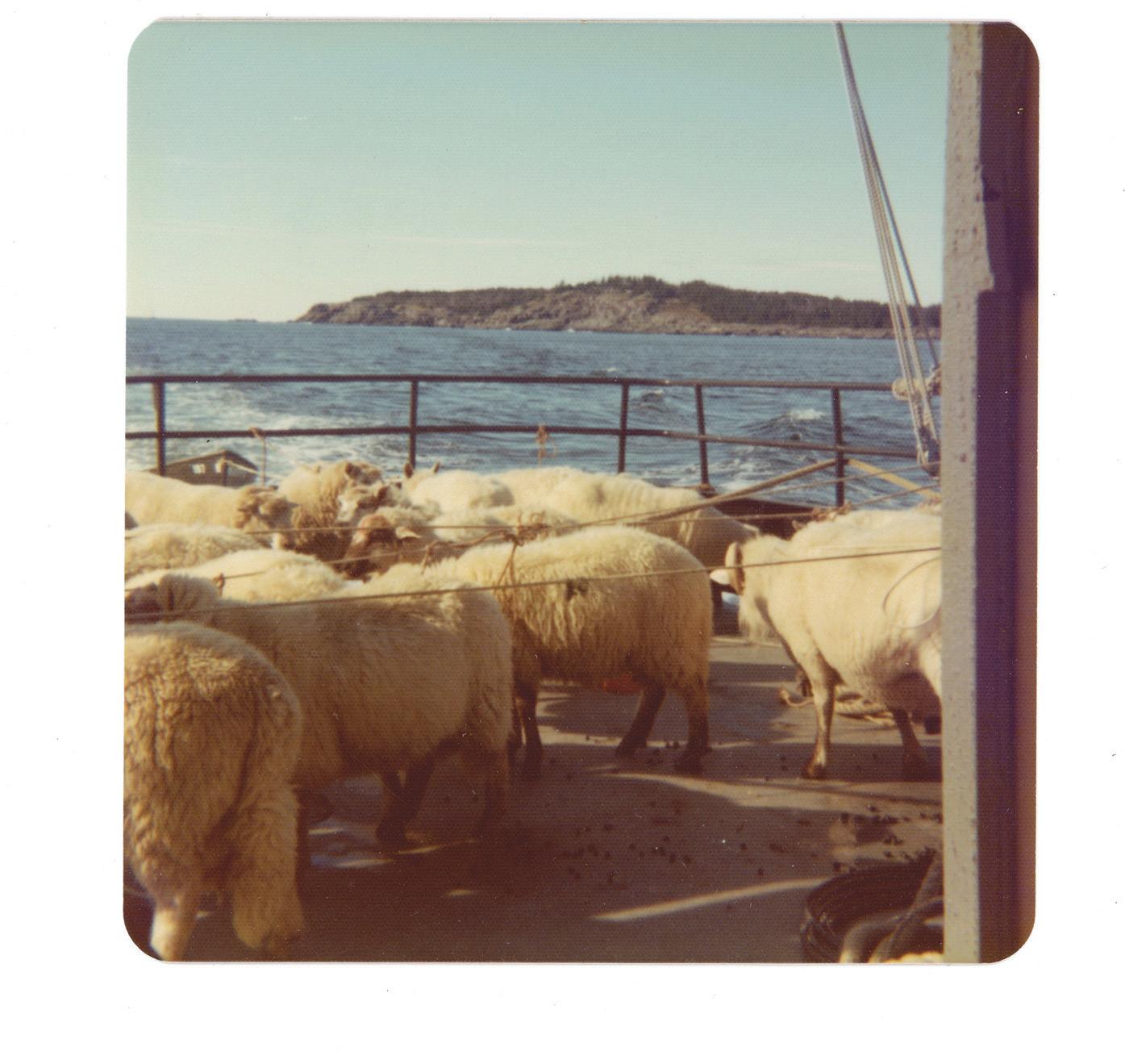

SHEEP AT SEA—

Maine Seacoast Mission’s vessel Sunbeam has served a lot of purposes in its many years on the water—floating community center, health care clinic, and, yes, sheep ferry! In 1976, these fuzzy friends hitched a ride on the Sunbeam IV from Manana Island, the small island next to Monhegan Island. The 22 sheep were owned by Ray Phillips, the “hermit shepherd” of Manana Island. He had died and the sheep needed new homes.

If you’re turning into a fair-weather sailor with enough years behind you of down pours and battling a weather helm, this cottage is the place for you. With a view of the harbor where you can see your boat on the mooring, this 1907 cottage, on half an acre, is charming with a wood-burning fireplace with two ingle nooks either side, dining room, cottage kitchen with original beaded spruce cabinets, 4 bedrooms which include a bunk room, one full bath and a half bath and a large porch facing Frenchman Bay. You can be reading by the fire until the weather breaks and calm seas beckon. When it clears and the breeze blows just right for an easy run, you could enter a weekend regatta with no pressure except a little jostling around the start but a great time for an afternoon. Incredible views from the house with Schoodic Mt. to the north, islands and mts. around MDI to the east and south with bay frontage across the road. Steps to the dock and moorings, tennis courts, summer library, and a long-standing inn with great food. Time to enjoy the summer and have it all right here on Hancock Point. $850,000

LePage: ‘Look to the free market and work’ Pledges to fight lobster regulations

The Working Waterfront submitted identical questions to the two major party candidates for governor via email and each responded with written answers.

PaulLePage, a Republican, served as Maine governor from 2011 to 2019. Before that, he served as mayor of Waterville and general manager of Marden’s stores. Earlier in his business career, he worked in the paper and wood products industries.

LePage was born in Lewiston, the eldest of 18 children, who ran away from home at age 11 to “escape severe domestic violence,” according to his campaign website.

LePage holds business degrees from Husson and the University of Maine.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT: Both you and your opponent have spent most of your personal and professional lives away from the eight coastal counties we cover in our newspaper. Explain what qualities, in your view, characterize life on the coast.

LEPAGE: Following my tenure as governor, Ann and I spent significant time on the coast working in the service industry. We have the most beautiful working coast in the nation. Through my time serving our state, I have been fortunate to meet, learn from, and help Mainers who call our coast home. These are hard-working people who care about maintaining our state’s abundant resources, value their communities, and hope to pass their quality of life and traditions on to their children and grandchildren.

Unfortunately, whether you are in Lewiston or Islesboro, the increased cost of food, oil, and housing jeop ardizes every Mainer’s future. I have heard from lobstermen and women who, between increasingly restrictive federal regulations on fishing and the high costs of diesel, don’t know how much longer they can continue to turn a profit. I’ve spoken to single mothers, and seniors living on fixed incomes, who are worried about making it through the winter.

For too many, it’s a choice between heating or eating. There is also an increasingly dire shortage of housing. As costs of lodging, building supplies, and raw materials go up, many coastal Mainers struggle to find affordable housing. I can’t begin to tell you how often I am approached by Mainers who desperately need affordable housing. These issues put a pit in my stomach. As a homeless child, I knew what it was like to be cold, hungry, and without a place to call home, and as governor, I’m going to work to make sure no other Mainer ever has to experience what I did growing up.

WW: The lobster fishery continues to face challenges from right whale regulation, offshore wind turbines, and

warming waters. Realistically, what can state government do to support this important coastal economic sector?

LEPAGE: It’s no secret that Maine’s lobster industry is one of the most sustainable fisheries on Earth. Our commercial lobstermen and women care for marine life and are outstanding stewards of our environment.

As governor, I exempted the sales tax on fuel used in agriculture to help provide some relief to our hard-working lobstermen and women.

As your governor again, I will push back on organizations falsely attacking our lobster industry, as well as the Biden administration’s destructive regula tory policies aimed at destroying the liveli hoods of our fishermen over the false notion they are harming whales.

Our lobster-fishing industry leaders have worked diligently for years to protect these whales and the environment.

Janet Mills says she will fight for our lobster industry, but time and time again, she panders to radical extrem ists. Now more than ever, our lobster industry needs a steady, proven ally, not someone who says one thing but then does another.

If Mills were serious, she would examine the financial harm being done to the state of Maine and seek any legal remedy to halt this false attack. As your next governor, on day one, I will fight to protect our vital Maine fishing industry. You can expect to see a lawsuit: LePage v. Biden and the federal government.

WW: Climate change consequences like rising sea levels and storm surge will impact coastal areas in the coming

years. What will state government do under your leadership to mitigate or reverse these threats?

LEPAGE: It’s no secret—Mainers treasure our outdoors. Whether you are a hunter, hiker, or just enjoying a picnic in the park, we care about preserving our God-given natural resources for future generations.

As governor, I made simple, common-sense changes to promote energy efficiency. I installed heat pumps in the People’s House, cutting our energy bill of $40,000 by 70%.

China and India are the world’s largest polluters. We need to push the federal govern ment to hold those countries accountable.

Maine people are doing their fair share to combat climate change. China and India should be held to the same standard.

It is clear that our nation needs to look toward the future, but we can’t do that through regula tion and restriction. We have to look to the free market and work to provide incentives for energy innovation so that there is competition in the market and consumers can pick what works for them.

As a state, we can’t combat a changing climate alone, but we can embrace Dirigo’s spirit and lead by example to sustain our natural resources.

WW: Tourism is a major economic driver in the eight coastal counties. What is our tourism strategy doing well and what might be improved?

LEPAGE: Who doesn’t want to come to Maine? Our state is a worldrenowned natural beauty and, as such, we have an excellent tourism-based

industry, but that’s not to say there isn’t room for improvement.

Small businesses are the bread and butter of our economy, and right now, they are hurting. As governor, I’m ready to get to work and cut taxes like the income tax, reduce wasteful government spending, and slash unnecessary regulations.

Janet Mills’ policies created severe work force shortages. Removing work require ments from public assistance has been a disaster for Maine’s small businesses. There is no reason why able-bodied people should not go back to work.

As governor, I would implement policies that would bring our work force participation levels back to where it was before I left office. Tourism depends on a strong, vibrant work force. My administration would priori tize getting Mainers back to work.

WW: The lack of affordable housing along the coast is worsening worker shortages, hampering businesses from growing. What will you do to ease the pressure on workforce housing?

LEPAGE: Maine has a housing shortage but an abundance of old school buildings and mills. We should look to our existing empty structures for quick, simple, affordable housing.

Another critical aspect of affordable housing is an affordable cost of living. How are Mainers supposed to afford housing when they can barely afford to put gas in their tank, heat their home, and buy food?

We have to take action to provide relief. Instead of paying people to stay home, while driving up inflation, we need to focus on strengthening Maine’s economy. We must phase out the state income tax, starting with retiree and pension income. We must also address Maine’s skyrocketing heating and electricity costs. A strong economy produces higher paychecks, and better options for housing.

“For too many, it’s a choice between heating or eating.”

Mills: ‘Clean, renewable sources of energy’ Programs addressed workforce, housing, tourism

The Working Waterfront submitted identical questions to the two major party candidates for governor via email and each responded with written answers.

lobstermen this year, putting money back in their pockets.

Janet

Mills, a Democrat, was elected governor in 2018 and is seeking a second term. Mills hails from Farmington. Her siblings include former Republican state senator Peter Mills and former Maine CDC director Dora Ann Mills.

She previously served as a legis lator, district attorney, and the state’s attorney general.

She holds degrees from the University of Massachusetts at Boston and the University of Maine School of Law.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT: Both you and your opponent have spent most of your personal and professional lives away from the eight coastal counties we cover in our newspaper. Explain what qualities, in your view, characterize life on the coast.

MILLS: Our coast is more than pretty scenery and stately lighthouses. It is home to hardworking people, and it sustains the lives and livelihoods of Maine families. That’s why I have worked hard to preserve our working waterfronts.

In the legislature I fought for the amendment to the constitu tion that now provides a lower tax rate to working waterfronts, and I have always supported the Land For Maine’s Future program that protects traditional working waterfronts from development.

I have lived in Farmington, Gorham, and Portland. On my father’s side, the Mills were from Stonington going back several generations. The coast of Maine is in my blood and in my heart. As governor, I’ve spent a lot of time in coastal and island communities, and I know that the good people who call the coast home are tough, kind-hearted, and independent-minded, with a strong moral compass that leads them to fiercely defend what is right.

Our coast is also fragile, with communities under increased devel opment pressures, which makes it hard for young people and workers to find affordable housing.

WW: The lobster fishery continues to face challenges from right whale regulation, offshore wind turbines, and warming waters. Realistically, what can state government do to support this important coastal economic sector?

MILLS: I will always fight to protect the lobster industry, a cornerstone of our economy. Fishermen are going through tough times, especially with high costs; that’s why I’ve directed federal COVID relief funds to the lobster industry and reimbursed all license fees for commercial

On right whales, the federal govern ment and the federal court are dead wrong. I joined the lawsuit against the federal government and I have fought the Trump and Biden administra tions on this issue. They have refused to consider sound science and are not acknowledging the many conserva tion measures lobstermen have taken, at great expense to themselves. There’s never been a right whale death attrib uted to Maine lobster gear and there’s been no entanglement in Maine lobster gear in nearly two decades.

On offshore wind, I proposed and signed a law prohibiting offshore wind turbines in state waters because it’s such an important fishing ground for lobstermen. In federal waters, I am pushing the federal govern ment to allow Maine to test a small floating research array pioneered by the University of Maine to understand how offshore wind interacts with the marine environment and with existing maritime industries.

I believe that offshore wind can be a source of clean energy to lower elec tricity costs and create jobs, but what’s most important is that it’s done right, and I want the federal government to follow Maine’s lead and listen to those who rely on the ocean for their lives and livelihoods.

WW: Climate change consequences like rising sea levels and storm surge will impact coastal areas in the coming years. What will state government do under your leadership to mitigate or reverse these threats?

MILLS: My administration recognizes the serious threat climate change presents to Maine, our people, our economy, and our environment—and we are taking action. One of the first actions I took as governor was to remove Maine from the Outer Continental Shelf Governors Coalition, which Paul LePage joined, that had Maine participating in the exploration of offshore oil and gas drilling in the Gulf of Maine.

Since then, we have adopted bipar tisan climate goals and are on a path to achieve them; we have embraced clean, renewable sources of energy; we are incen tivizing home weather ization and high efficiency heat pumps; and, importantly, we have launched the Community Resilience Partnership. This program supports communi ties, both along the coast and inland, to prepare for the impacts of climate change.

We have also provided signifi cant funding to upgrade stormwater

infrastructure, to help coastal commu nities deal with rising waters, and we have significantly increased funding for efficiency and energy programs for homeowners, towns, schools, and small businesses to reduce energy bills.

Municipalities are on the front lines of climate change, and we will continue to work with them.

WW: Tourism is a major economic driver in the eight coastal counties. What is our tourism strategy doing well and what might be improved?