Shoring up Cushing’s working waterfront

A fishing town aims to add a public boat launch

BY CHARLES EICHACKER

Longtime fisherman Danny Staples has his own wharf on Pleasant Point Gut in Cushing, where he and several others can access the water, land lobster, and do some maintenance of their vessels.

But that piece of waterfront didn’t help Staples this past fall, when his boat’s rudder broke as he was several miles out to sea hauling traps, near Old Horse Ledge. He first got towed back to Cushing, where he beached the boat to assess its damage. Fixing it there wasn’t possible, so he had to get it towed another nine miles up the St. George River to Thomaston so it could be removed from the water for a repair.

The ordeal highlighted a difficult aspect of fishing in Cushing: while the Knox County town has plentiful deep harbors where fishermen can bring their catch ashore, it has no public boat launches. If it did, Staples could have gotten his broken-down vessel out of the water much closer to home.

“I needed to be hauled out ASAP,” he said. “It would have been awful nice, and awful secure, to be

able to do it right here, and know that it’s on land. Then I could assess what was wrong, and how to go about fixing it.”

Soon, that could change: Cushing is in the early stages of an ambitious plan to buy two waterfront

parcels that would eventually become a public launch for commercial and recreational boaters. If the project goes ahead, it would provide a reliable new option for reaching the water in the town, where

Rising seas require long-term planning, experts warn Maine conference explores accelerating

BY CLARKE CANFIELD

Sea level rise will accelerate in the decades ahead, and coastal communities should act now to assess risks and identify solutions for

sea level rise

the long term—generations or even a century or more into the future.

That was the message delivered by the keynote speaker at the fourth annual SOS Saco Bay Coastal Conference on October 7.

Cameron Wake, director of the University of New England’s Center for North Atlantic Studies, told attendees that the ocean level has risen about 8 inches in Portland Harbor since 1912. By 2100, the level is projected to rise even more, from 1.6 feet on the low end to close to 9 feet on the high end, Wake said.

When looking ahead, people along Maine’s coast should imagine what their communities might look like with 10 feet of sea level rise, he said. Under that scenario, people should ask themselves: What does a resilient coastal community look like? What does a working waterfront look like? What does access to the ocean look like?

“At any given dock there’s likely to be more water in terms of depth in the future.”

residents can be in their homes for as long as possible, we need to prepare for the inevitable, which is many feet of sea level rise in the future that’s going to require an entirely different response,” Wake said after his presentation.

“I understand there are the near-term challenges that are going to occupy people’s attention, but we need to start inserting in those discussions the longer-term challenges, which I think are going to require a transformation of the way we think of the coast and build on the coast and live on the coast.”

Save Our Shores (SOS) Saco Bay is a nonprofit advocacy group that works to preserve and restore the shoreline along Saco Bay. Close to 200 people attended this continued on page 5

“Even given the enormous challenges of protecting our coastal areas so our continued on page 5

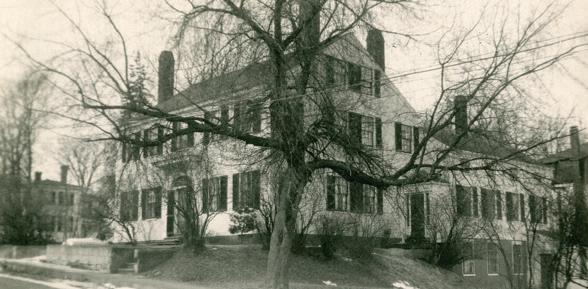

Historic Eastport mansion restored to new life Underground railroad, Land Claims Act tied to house

BY LURA JACKSON

One of Eastport’s behemothic houses—a remnant of the port’s mercantile legacy— has been saved from demolition. Beyond its historic value, the Isaac Hobbs mansion carries a vital connection to stories much larger than its own. One of the last stops on the Underground Railroad and the former home of Don Gellers, an attorney who worked on the Indian Land Claims case, the house has long been associated with society’s underserved.

“It was more a passion decision than a prudent one,” said James Pollowitz, who with his husband Bruce Ellis bought the house three years ago after moving from Connecticut to Cutler. “I was especially looking for a project that could preserve history, and a house that was most at risk.”

Having endured seven decades of neglect, the Hobbs house had a standing order for its attached carriage house to be demolished. It fit the bill perfectly for Pollowitz, who saw value in the property beyond its 10,000 square feet.

The house dates to 1816 when Isaac Hobbs, a carpenter who ran a mercantile business with his brother George, built the first story of the west wing. As Hobbs found success, he worked on expanding the dwelling, adding its Federalist body in 1823. Merchant Samuel Witherell bought the house in 1846

and added the east wing and a second story to the west wing in 1849.

Once purchased, the house required rapid triage.

“The east wing was really in the most critical shape,” said Pollowitz, noting it was near “imminent collapse” with three sides of its brick foundation exposed. After some searching, they were able to find a carpenter able to dig out the foundation and build a cement retaining wall.

In the meantime, the west wing—which was in equally bad condition but had a stable foundation— was converted into livable quarters with running water, electricity, and heat. In total, the house has 25 rooms, all with 10-foot ceilings, along with eight staircases and nine fireplaces.

Walking into the house today creates an impression of timeless opulence lent by the high ceilings and immaculate restoration work in the finished kitchen, dining areas, and parlor rooms, each of which are fully furnished with museum-quality antiques—a sensation put into quick juxtaposition by the as-yet unfinished portions that remain wrought by time.

While the house was made to showcase wealth, not every room was designed to that effect. Deep in the basement behind a chimney rests a small cubby about six foot long and four feet wide. Hidden by a sliding cloth, the cubby could hold two or three people—former slaves on their way to find freedom in Canada.

“They knew exactly where his bedroom was, went there and ‘found’ six marijuana cigarettes,” Pollowitz said.

At the time, it was enough for Gellers to be disbarred and charged with a felony. He contested it, but to no avail, and eventually emigrated to Israel. After his death in 2014, Gov. Janet Mills reopened his case, and Gellers subsequently was awarded the state’s first posthumous pardon. Recognizing the importance of Gellers’ work, Pollowitz and Ellis donated the desk to the Passamaquoddy’s Sipayik Museum.

While some items have left the house, many more have since come in. Most are from Pollowitz’s collection, assembled over the years from museums and historic homes. Some incoming pieces were gifts donated by the house’s fanbase, represented in part by a 4,500-member Facebook group.

In total, the house has 25 rooms, all with 10-foot ceilings, along with eight staircases and nine fireplaces.

One such gift was a quilt that would have been hung from a window to signify the house was a safe place during the days of the Underground Railroad. Another gift came from a terminally-ill woman from the Midwest who came to Eastport to bring a toy chest built by Hobbs’ great-great-great nephew. It now sits in the restored tack room near a display case of horsemanship medals from another donor. Other gifts include two stunning chandeliers, one Venetian and one Napoleonic.

The restoration has uncovered occasional treasures, including Don Gellers’ rolltop oak desk. Gellers, who worked as a representative for the Passamaquoddy tribe, reportedly endured harassment culminating in a raid by the Maine State Police directly after filing the land claims suit.

“The members of the Hobbs page have been my greatest wellspring of support and encouragement,” Pollowitz said. Many see the restoration of the mansion as inspirational for their own projects.

The restoration process, now about 60% complete, hasn’t been without its challenges.

“This is the epitome of a money pit,” Pollowitz said, though he refrained from estimating its cost. One problem is insurance, with several factors weighing against the house, including its coastal location and its condition. For the time being, it’s under contractor insurance, though Pollowitz hopes to expand the policy down the road.

He has been able to save money by learning to do some restoration himself—notably the original windows. “It’s very laborious, but it also saves a tremendous amount of money for other parts of the restoration.”

The largest remaining block to be restored is the east wing, which will house an upstairs library and

additional bedrooms. Electrifying the bedrooms and restoring the fireplaces to working order will come in the future, further increasing the building’s livability.

The goal is to open the house for tours and events, with Pollowitz noting that around 100 guests recently came for a tour during the Salmon & Seafood Festival.

Based on the favorable response, a traditional Christmas event is planned for Dec. 13, complete with carolers in period dress.

The restoration has been acclaimed by local residents, including Hugh French, director of the Tides Institute & Museum of Art.

“The Hobbs house is an extremely important building to Eastport’s unique historic architectural heritage,”

French said, describing it as the “finest example” of a Federalist home and noting that it possesses the last Federalist period carriage house on the island.

“It could easily have been lost. What Jim Pollowitz and Bruce Ellis have done to save the house at a critical moment and make enormous strides in restoring it is extraordinary.”

Pollowitz feels good about his contribution to Eastport.

“It’s just a wonderful thing to be able to present this to the community, a house that was shuttered and abandoned for so long, to bring it into its former glory, and to have people so excited to see it and how it’s all been redone.”

The state of local journalism

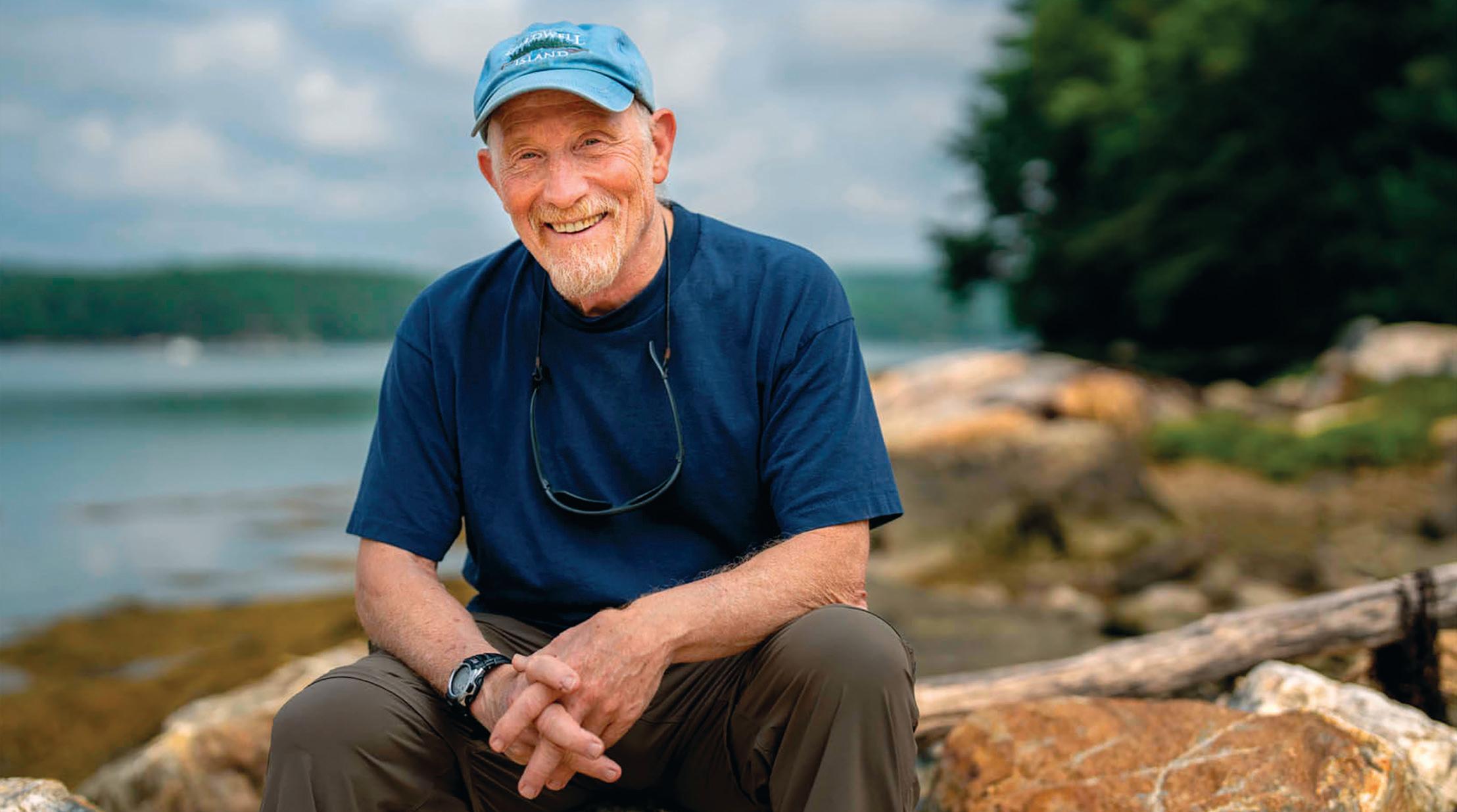

A send-off for retiring Island Institute editor Tom Groening

BY CHARLES EICHACKER

An Oct. 30 event honoring Tom Groening, the retiring editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal, was as much a toast to his own career as it was an uneasy reflection on the important but precarious role journalism plays in the world.

The event opened with remarks by Colin Woodard, an author and journalist who began his career as a foreign correspondent in Eastern Europe and the Balkans around the collapse of the Soviet Union before returning to the U.S. and writing for publications including The Working Waterfront and Portland Press Herald.

The program then featured a conversation between Robin Alden, the founder of Commercial Fisheries News and a former commissioner of Maine’s Department of Marine Resources, and Groening, who spent years at local Maine newspapers before coming to Island Institute slightly over a decade ago.

While the journalism industry faces real threats, all three speakers argued that it remains a force for good that can do everything from informing citizens in struggling democracies, to presenting the science behind different industries, to simply marking community milestones such as births, deaths, and which kids made the dean’s list.

show up in the paper, and then you do an interview with them, and you profile them, and you know, you listen and you really hear their story and what they’re about. That feels good.”

Groening got laughs when he recalled a reaction he once received to an editorial piece he’d written for the Republican Journal in Belfast, now part of the Midcoast Villager, endorsing a slate of candidates for City Council.

“Someone came up to me, I won’t mention his name, and said ‘Thank you for writing that. I take that into the ballot booth and I go opposite every one of them,’” Groening said.

Alden recalled starting Commercial Fisheries News while living in the Stonington area 53 years ago, based on her belief that commercial fishing, when done properly, can support the environment and help communities to thrive. The idea came after she overheard an argument between an oceanographer and a shrimp fisherman.

“ You can rebuild journalism from the ground up and people are doing it, you know, nimble online newsrooms.”

Some 150 people attended the event, which took place at Bayview Point Event Center in Belfast and was titled “Trust in Community Journalism.”

At one point, the presenters were asked what they’re most passionate about in journalism.

Groening named several things, including analysis pieces that go deeper to explain the stakes behind different stories, as opposed to “stack[ing] up facts” and leaving readers to “figure it out.”

On a simpler level, Groening said he likes getting to write about ordinary people who “never would

“They both knew what they were talking about, and they could not hear each other,” she said. “… I saw that what was missing was connecting everybody’s different types of knowledge and building understanding.”

On a more wistful note, Alden told the crowd that Commercial Fisheries News would be publishing its final issue in December.

Woodard, who now runs the Nationhood Lab at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center in Rhode Island, painted a dire picture of the news industry.

“I guess you would call my talk ‘the fall of journalism and what we might do to rebuild it,’” he said at the start of his remarks.

After growing up in Maine, Woodard started his journalism career as a foreign correspondent before moving back to the U.S. and shifting

to national and state reporting. He noted that changes in the journalism industry have forced many newspapers to eliminate all those types of positions. Among the challenges have been the growing availability of classifieds and other information online, and new owners and investors who have slashed what they see as the least profitable parts of news organizations.

The result has been once-robust regional papers that now put out a fraction of the original reporting they once did and instead rely more on contributed material from wire services such as AP.

“And as these papers disappear, and then other entities, broadcast media, radio, 60 Minutes, you know, all vanishing very rapidly,” Woodard said. “So that’s a terrible thing for democracy.”

But Woodard and the other speakers also pointed to new business models—many of them nonprofit organizations such as The Maine Monitor, Harpswell Anchor and Peaks Island News—that could help fill the growing gaps in traditional reporting. The Monitor, for example, has just launched a local reporting initiative that’s covering rural western and Downeast Maine.

“You can rebuild journalism from the ground up and people are doing it, you know, nimble online newsrooms,” Woodard said.

During a question-and-answer session, Jo Easton, director of development at the Bangor Daily News, offered a hopeful assessment for the local news landscape in Maine and said colleges and universities here could follow those in other parts of the country that have enlisted student journalists to plug reporting gaps.

In Groening’s last column as the editor of The Working Waterfront, Groening expressed his admiration for two of the nation’s best-known journalists: Bob Woodward and Superman.

To that end, Island Institute President Kim Hamilton concluded the Belfast event by presenting Groening with a gift: his own version of the Man of Steel’s red-and-yellow cape.

WORKING WATERFRONT

continued from page 1

roughly 70 local fishermen together catch more than 2 million pounds of seafood each year. It would also give community members a local spot for putting in their watercraft and help the town better handle emergencies on nearby islands.

While Cushing is unique among Midcoast fishing towns in lacking a public boat ramp, its efforts to create one can offer lessons for many other communities along Maine’s coast that have struggled to protect their working waterfronts from worsening storms, competition from land developers, and other challenges that have accelerated in recent years.

Two decades ago, the Island Institute put out a landmark report that found just 20 miles of Maine’s 5,500 miles of shore were still being used for fishing, aquaculture, or other marine businesses.

It was around the time of that report that Cushing made its own decision that, years later, could allow it to take the unusual step of reinforcing Maine’s working waterfronts.

At the time, Staples was serving as the local harbormaster, and he found it unusual that a peninsular town with miles of shore didn’t have its own public landing. He also was paying boat excise taxes and proposed that the town save up a portion of that combined revenue for the purpose of improving public access to the water.

Good Neighbors Park, but that area is too shallow for anything but clamming, kayaking, or similar uses.

Five or six years ago, Staples—who has also been on the Select Board and other local committees—learned that a family might be willing to sell a waterfront property in South Cushing that had once been used by a local lobsterman, but that opportunity vanished as the property was sold on the private market.

Fearing a similar outcome, officials are now pouncing on the chance to obtain a separate property that also once belonged to a fisherman, but who has passed away and whose family is now negotiating a sale to the town.

“I needed to be hauled out ASAP.

The Select Board has approved a preliminary agreement to buy the property, which takes up two adjacent parcels on Barnacle Lane and includes an aging pier that sticks out into Pleasant Point Gut—just a stone’s throw from Staples’ own wharf—as well as an old home and some sheds.

It would have been awful nice, and awful secure, to be able to do it right here.”

Local officials sent the idea to voters, who approved it, and since then the town has annually transferred between $10,000 and $15,000 into the water access account, which now has about $340,000.

Even with that money, it hasn’t been easy for the town to go ahead with its original vision for improving access to the water. In 2017, the community did accept a gift of 15 acres along the water which is now

RISING SEAS

continued from page 1

year’s conference, including municipal and state planners, representatives from nonprofit organizations, college students, and members of the public.

The all-day event at the Ferry Beach Retreat & Conference Center featured classroom sessions, a trade show, and outdoor field stations on the beach. One track focused on coastal resilience, particularly in the face of rising oceans.

Sea levels are on the rise primarily due to increased global carbon dioxide emissions that have warmed the planet, and the melting of massive ice sheets and glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica, Wake said.

The combination of rising seas and a warming climate has made Maine susceptible to more frequent coastal flooding. That vulnerability was fully exposed in January 2024 when two vicious storms in four days caused widespread destruction and damage from Kittery to Eastport. They destroyed fishing wharves, damaged and flooded oceanside homes, swamped neighborhoods, demolished roadways, eroded beaches, and swept old fishing shacks and other structures out to sea.

In the wake of those storms, one of the pressing concerns has been the impact to the state’s working waterfronts, which fishermen and other commercial interests rely on for their livelihoods.

The town would buy the site for an estimated $730,000, with half coming from its savings and the rest from the Land for Maine’s Future Program. The board of that state program tentatively approved the funding at its September meeting, but the town must meet several conditions to receive it, including getting a new survey and appraisal and holding a local vote that’s likely to take place in early 2026, according to current Harbormaster Austin Donaghy.

Eventually, officials hope to remove the pier and home and rebuild the site with a boat ramp and floating dock. That work would require additional funding and at least two or three more years of work.

In addition to providing access to fishermen, Donaghy noted that the project would also help

local property owners put recreational vessels into the water. And it would give the town somewhere to store its own boat and better coordinate the response to medical emergencies or fires. Staples noted that one blaze burned for several days on Gay Island, which is just across the harbor from his wharf and includes several homes.

If the town can complete the project, it’ll represent a small but significant victory for Maine’s working waterfronts, which are critical access points for the fishing and aquaculture businesses that land hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of seafood each year.

Those properties have been threatened by worsening storms, like the ones that battered Maine’s coast two winters ago. It has also been hard for private wharf owners to hold onto their property given the growing demand for housing on Maine’s coast.

Several things came together to help Cushing with its own project. It took foresight for the town to start saving up money years ago, as well as the additional pledge of money from the Land for Maine’s Future Program, which provides grants for water access and working waterfront protection.

Olivia Richards, a community development officer at Island Institute’s Center for Marine Economy, helped the town seek the LMF funding.

“Working waterfronts are critical for Maine because if these access points didn’t exist, people couldn’t get onto the water,” Richards said. “It’s as simple as that. We need wharves. We need these access points in order for the marine economy to flourish and thrive.”

Both Staples and Donaghy also praised the owners of the property on Barnacle Lane for entertaining the town’s offer, when they could likely get more for the prime shorefront land on the private market.

“There’s very little working waterfront left,” Staples said. “If you pass up opportunities like this, they don’t come around weekly, monthly, or yearly.”

Coastal towns have a variety of strategic approaches at their disposal to help them transition or transform in response to the threat of sea level rise and increasingly violent storms. Those strategies, outlined during a panel discussion on coastal resilience, are:

• Protecting (keeping water away from homes)

• Accommodating (elevating buildings and infrastructure to allow higher water to pass through)

• Avoiding (preventing new development in hazardous areas)

• And retreating (removing or relocating critical infrastructure away from danger)

The panel discussed whether some sort of property buyout program would be appropriate for Maine to purchase homes that have been damaged by or are at risk from coastal storms. Similar programs have been implemented elsewhere in the country, but there are many questions about whether buyouts should be considered in Maine.

It’s important that any decisions on buyout programs—and the cultural, economic, and social implications of such programs—should come from community members themselves, panelists said.

“This is not a strategy that should be done top down,” said panel moderator Jessica Brunacini, a coastal resilience expert at the Wells National Estuarine Reserve.

During a presentation on communicating the impact of Maine’s changing climate, News Center Maine meteorologist Ryan Breton said plenty of people were climate change skeptics a decade ago. But nowadays, he said, people he talks to are more interested in learning how the changing climate is affecting the weather rather than expressing doubts about climate change.

It’s uncertain exactly how fast sea levels will rise in the future, and it’s hard to say how towns will transform in response to higher oceans, Wake said. Some places will have to explore bold measures around housing, flexible infrastructure, and ocean access.

At the same time, rising sea levels might open up new opportunities for Maine’s working waterfronts, he added.

“The opportunity I see is there’s going to be more water,” Wake said. “How we address that opportunity I think is a discussion we want to open up. I don’t have the answers, but at any given dock there’s likely to be more water in terms of depth in the future. The challenge is going to be do we build higher docks? Do we build higher wharves? How do we get people to and from the waterfront? Where do people live and work along the waterfront?

“There are a lot of challenges, but I also think along the way there might be some new opportunities.”

Maine’s new jobs need a waterfront

Understanding its role makes case for protection

BY KIM HAMILTON

I’M FASCINATED by working waterfronts—those extraordinary places along the Maine coast that link coastal communities to global trade, connect people to the ocean and good food to our tables, and provide a window onto our heritage and our future.

These places also happen to be endangered.

Here’s the problem: capturing public attention, investments, appreciation, and awe for the working waterfront is surprisingly challenging. It’s not cuddly. On its best days, it’s busy, fishy, and filled with the noise of livelihoods in the making. In a howling storm, it’s undeniably dangerous.

A friend recently suggested we need our own approachable, well-known animal as a symbol of our hopes and dreams for the working waterfront. Think of the dolphin, monarch butterfly, or bald eagle—creatures that encourage people to open their minds and wallets.

Many would say we already have that powerful messenger: the lobster. It is iconic—our own charismatic, aquatic arthropod with its lovely carapace,

sensitive antennae, and powerful crusher and pincer claws. It says that the working waterfront matters.

But, despite the persuasive power of the lobster, Maine’s working waterfronts continue to disappear.

For personal reasons, my thoughts go toward the people whose lives center on the working waterfront and those whose careers expand from there. The fishermen and sternmen, yes, but also the oyster and scallop farmers, chefs, food processors, pilot boat captains, gear manufacturers, boat builders, and more. These are the faces of today’s maritime economy.

I’m biased, though. Not because I don’t love lobster—I do. But because my now 96-yearold father spent his career working on a pier, and I had a close-up view. It was the place where he once docked a ship in a nor’easter when the wind chill factor was 60 below. As he told me matter-of-factly, “You can’t change shipping because the weather is bad.”

Earning a community’s trust Introducing the new editor sweetest in the gale from the helm

BY CHARLES EICHACKER

I’M NOT FROM Maine, but I’ve talked to many people since I got here.

There are other ways I could open this piece, to introduce myself as the new editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal.

But as I try to fill the big boots left by outgoing editor Tom Groening, I think it best to start with the obvious: I’m not from here.

Although I grew up in Maryland— another state known for its clawed seafood—I’ve never lived on an island or worked on a boat. Hand me a fishing rod, and I’d likely cast it twice before needing you to untangle the line.

What I have done is spent 11 years working as a journalist in Maine, getting other people to talk to me. They’re the ones who have given me credibility to take this role.

So I’d like to start with them.

I’d like to start with Bruce Campbell. In the fall of 2014, I was less than a year into covering the town of Bucksport for The Ellsworth American when Verso Paper announced that it was closing the local mill and laying off more than 500.

With several days to go until our print deadline, my editor tasked me with interviewing as many workers as I could,

That pier was a global crossroads, with ships carrying crews from Venezuela, Norway, India, Aruba, and beyond. The team docked ships 24 hours a day, seven days a week, depending on the tides.

It was demanding, carefully practiced work. Three men forward and three men aft would take the heavy, manila rope from the ship and hook it to the bollards. And they were just getting started.

Capturing public attention, investments, appreciation, and awe for the working waterfront is surprisingly challenging.

More personally, the working waterfront put me through college. Without my father’s job, combined with my mother’s, the likelihood of higher education would have been greatly diminished for me and my brother. I am grateful for working waterfront jobs and what they make possible.

I asked my father recently what would happen if the working waterfront disappeared. He paused for a moment and said, “You’d lose a lot

of jobs and income. Activities would shift to another port. If you lose all of those, you’ve lost a way of life.” Then he thought a little more and added: “You need the waterfront to sustain life.”

There it is. An essential kernel of truth: our working waterfronts sustain life and sustain livelihoods.

This is why Island Institute has launched a new Working Waterfront Fund to support our work with communities to protect shoreside access, strengthen the infrastructure that underpins the last 20 miles of working waterfront shoreline, invest in renewable energy solutions, and build new and necessary skills.

It’s a big bet, and it’s also deeply personal to me. In my father’s words, “It’s the waterfront. It’s where it all happens.” But we need to fight to keep it that way. Please join us.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

so that we could show how this would affect them and what was being lost. At that stage in my career, I didn’t immediately know how to go about finding the workers or convincing them to talk to me, especially at the very moment their lives were getting upended.

Finally it occurred to me to try the local bar. That’s where I found 64-yearold Campbell.

A flannel-shirted union electrician with more than 40 years at the mill, Campbell quickly noted that he was lucky to already be near retirement.

He described the highlights of his own career—enough money to put his daughter through Colby College, a better payout at the end—and lamented that his younger colleagues wouldn’t get to enjoy the same.

I had been to Maine previously, but the first time was on a childhood vacation to the Midcoast, and the second was when my own parents put me through Colby College.

Now, as I take over a newspaper that aims to reflect how people live along Maine’s more than 5,000 miles of coast, what I can say is that I’ve spent years getting hundreds of other people to trust me with their stories.

What I can say is that I’ve spent years getting hundreds of other people to trust me with their stories.

He argued that the U.S. pulp and paper industry couldn’t compete with the low wages or government support of mills in other countries. His take: “We’re right between a rock and a hard place.”

By that point in my life, I didn’t have much firsthand experience with the hard places of the world.

After the Ellsworth American, I moved on to daily reporting at the Kennebec Journal and Bangor Daily News, then digital and radio reporting at Maine Public.

Most recently, I was the coastal and state editor at the BDN

Many of the stories that my colleagues and I have written have been about hardships on and off the water, from health threats to housing insecurity to storms that have sunk ships and destroyed property.

But as readers of this publication know, there is more to journalism than just describing the problems. It can also identify solutions. It can highlight

the history, science, and culture of a region. It can entertain and distract. Its photos can capture more than words. I’m eager to continue in that tradition. The task feels daunting, in part because The Working Waterfront and Island Journal have offered all these things and more under Tom’s leadership. On top of putting out a paper and magazine, we’ll also need to find new ways to reach readers who get most of their information on smartphones and social media.

As I figure those things out, I won’t forget to keep earning the trust of this community.

Charles Eichacker is the new editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. He may be contacted at ceichacker@islandinstitute.org. He has named his column “Sweetest in the Gale” after a line in the Emily Dickinson poem “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” which uses a bird in a storm to represent hope in dark times.

ROOFTOP VIEW —

This unusual perspective on downtown Boothbay Harbor with the harbor itself in view at the top of the image was shot in August of 1939 by Herbert Mayer. Do readers know anything about Mayer and his connection to Maine? An internet search suggests he photographed for the U.S. government, but we can’t confirm that. If you can share any information, contact editor Charlie Eichacker at ceichacker@islandinstitute.org.

the public’s policy

Advancing Maine’s blue economy

A task force charts a path for growth

BY NICK BATTISTA

MANY MAINE communities have a strong tradition of fishing, boatbuilding, or people otherwise using the Gulf of Maine to support their families. Building on that strong heritage, the state has attracted scientists and researchers who study the ocean as well as inventors pioneering equipment to support this work. From using lobster or kelp as an ingredient in skin care, to developing software to support aquaculture farms or collect data for research, entrepreneurs are developing businesses in and adjacent to these sectors.

In 2024, lawmakers saw the need for Maine to take a more proactive approach to supporting this growth and innovation. They established a task force to study how to “support Maine’s emergence as a center for blue economy innovation and opportunity in the 21st century.” The charge included developing a definition of Maine’s “blue economy,” reviewing how other states and countries approach this investment, and identifying parts of Maine’s blue economy that could benefit from more economic development attention.

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Doug Henderson, Chair

John Conley, Vice-Chair

Bryan Lewis, Secretary, Chair of Philanthropy and Communications Committee

Katherine Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Michael Boyd, Clerk

Shey Conover, Chair of Programs Committee

Michael Sant, Chair of Governance Committee

Robert Baines

Pamela Baker-Masson

Sebastian Belle

Des Fitzgerald

Christie Hallowell

Kristin Howard

Nadia Rosenthal

Michael Steinharter

Carol White

John Bird (honorary)

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

The task force focused on sectors that had received lower amounts of statewide attention and didn’t have something like a strategy, plan, or roadmap. For example, the fishing and seafood economy has already been deeply analyzed through an industry-led initiative called the Seafood Economic Accelerator for Maine, or SEAMaine.

The blue economy task force identified five areas that are primed for innovation and growth: marine research and ocean data; marine biotechnology; marine vegetation; resilient coastal infrastructure; and maritime propulsion systems and sustainable boatbuilding.

Other states like Rhode Island and Washington have created focused economic development plans in specific areas of the blue economy, which has helped them attract significant public and private funds. Canada, Norway, Belgium, Korea, and other countries also have some version of a center focused on the blue economy, or an “ocean cluster,” that supports economic development and serves as a hub for businesses, investors, and others.

One of the Maine task force’s recommendations was for the Legislature to establish a similar Center for the

Blue Economy to serve as a central, coordinating hub of information and resources. Another was to better understand the education and workforce training programs to support Maine’s evolving ocean economy as well as the needs and challenges for these sectors.

Last spring, the Legislature formed a second Blue Economy Task Force to make recommendations for tackling these two areas. This work started in earnest late this summer with more than 35 participants. The process moved quickly—with a report due back to the Department of Economic and Community Development and the Legislature in early December.

As the co-chair of this task force, I have had the pleasure of hearing from numerous businesses in the five sectors about their needs for better support and coordination. I have also heard from many of Maine’s research and higher education institutions who work in these areas about how important strong state leadership is to pulling together different interests. A modest state investment in creating a Center for the Blue Economy can help ensure Maine has the leadership to compete with other states and the coordination

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that boldly navigates climate and economic change with island and coastal communities to expand opportunities and deliver solutions.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

and knowledge to better tap the growth potential of these sectors.

It is also clear that while there are numerous programs available to develop and support the workforce in some of these sectors, the state would benefit from better understanding the needs of two which are growing and need additional focus: resilient coastal infrastructure, and maritime propulsion systems and sustainable boatbuilding.

As the task force wraps up its work, I am grateful for the deep thinking from its members—many of whom could have spent that time working on businesses—as well as to the consultants who collected and analyzed a significant volume of information and thoughts that became the report. As with all good ideas, creating the center and delivering on the workforce recommendations will take money—I look forward to those conversations in the coming months.

Nick Battista is chief policy and external affairs officer for Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at nbattista@islandinstitute.org

EDITOR: Charles Eichacker ceichacker@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

guest column

Remembering Susan Jones: A guiding light

Her editorial leadership helped sustain a voice

BY ROBIN ALDEN

THE MAINE FISHING industry lost a guiding light when Susan Jones passed away in early September in Stonington at the age of 78. Her leadership shaped the fishermen’s newspaper, Commercial Fisheries News (CFN), for 40 years, from the early 1980s until her retirement in 2014, during which it was the paper of record for the New England fishing industry.

When Susan was named editor of CFN in 1988, I wrote an editorial noting that she had already improved the paper’s look and readability, tightened its content, and added features such as market reports and profiles of fishermen.

“Throughout, her accuracy and fairness have been evident. Commercial Fisheries News can only get better under her direction.”

Indeed, accuracy and fairness were the hallmark of her work. CFN is a trade publication with a very targeted audience. But Susan’s work ethic, her incisive questions, and her attention to detail would have been valued at any major publication.

Susan and I first met in 1972 when I interviewed her about clamming for the local Stonington paper. That interview was the start of our friendship. That story was also the start of CFN.

Listening to what clam diggers knew about the flats and their frustration with state management was one of the sparks for CFN: a place to share fishermen’s knowledge, and that of scientists and agency people, so that Maine fishermen could fish forever.

From then on, Susan and I were friends and shared our belief in CFN. Indeed, her talents and our shared purpose made it possible for me to leave the paper and pursue other ways to bring that vision for Maine’s fisheries to reality.

Susan built a team of writers, particularly Lorelei Stevens and Janice Plante. They were young when they started and remember how Susan’s patience, kindness, and high standards nurtured and inspired their development.

Plante, who went on to be the public information officer for the New England Fishery Management Council, remembers working with Susan after the U.S./Canada Hague Line decision

in 1984. Susan was wrestling with CFN’s coverage of the monumental decision’s impacts, as they related to Gulf of Maine groundfish fishermen and those who fished on Georges Bank.

Plante said that late-night session epitomized who Susan was, how much she cared about fishermen and their families, and how much she wanted fishing communities to thrive.

It takes more than writers and graphics to make a newspaper, and Susan understood the need for advertising. She knew many of the advertisers and saw them as part of the community that made CFN. She nurtured the creativity and hard work of a young Brian Robbins—something readers have felt directly since he took on the editorial role at CFN (as well as everything else) in the last 12 years.

Before CFN, Susan was secretary of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association (MLA) and worked with then-MLA President Ed Blackmore on the Sternman Project, helping pass a 1976 federal law that exempts fishermen from paying employment taxes for their sternmen. She also worked with him to secure the Stonington Fish Pier.

All the while, Susan was a fisherman’s wife, a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. She and her husband, Donald, were a team throughout.

Susan was my dear friend. For 50 years we shared a vision for Maine’s fisheries as a place where regular people can make a good living, using their smarts, using the ocean so that generations to come can still fish from their harbors. She carried CFN for years and brought its mission to life.

Those who knew and worked with Susan are filled with gratitude for this kind, smart, principled, and strong woman who has made such a difference for fishing on the Maine coast and in our lives.

Robin Alden is founder and former editor and publisher of Commercial Fisheries News. She was commissioner of Marine Resources in the Gov. Angus King administration. She is collecting memories of Susan to share with her family. Please send them to: robin.alden3@gmail.com

Tourism office reports longer stays

Canadians visited in greater numbers than expected

THE MAINE OFFICE of Tourism released its summer visitor tracking report which includes data collected May 1 through August 31.

The report shows the number of overall visitors to Maine this summer decreased by 6% compared to 2024, but the total number of days spent in Maine by these visitors was nearly unchanged compared to 2024. The length of stay increased with 34% of visitors staying five nights or more, underscoring Maine’s enduring appeal as a destination where travelers spend time exploring beyond a single stop.

Another positive indicator is a stronger-than-projected number of tourist visitors to Maine from Canada this summer, following extensive outreach from Gov. Janet Mills to welcome Canadian visitors amid heightened political tensions. Following early season concerns, the share of total Maine visitors originating from Canada this summer was 4%, down from 7% in 2024.

For the summer season, Mills created signs for Maine businesses and border crossings to welcome Canadian visitors and traveled on a goodwill mission to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

The report also showed 97% of visitors would recommend Maine, and 94% saying they will return for another visit.

In 2024, tourism generated $9.2 billion in direct spending and supported 116,000 jobs in Maine. In 2025, the report found that direct spending from overall visitors declined by 3.5% while spending per visitor increased by 2.5%.

The Office of Tourism’s Destination Management Plan promotes sustainable visitation by attracting values-aligned travelers who appreciate destination stewardship, outdoor recreation, and cultural and culinary experiences, while encouraging longer stays, higher spending, year-round travel, and broader distribution of tourism’s benefits in all eight tourism regions of Maine.

State’s new economy anchored in the sea

UMaine president extols ‘blue

On Maine’s rugged coast, where shipbuilding, fishing, and working waterfronts have defined generations, leaders say the future is once again tied to the sea— this time through aquaculture, marine technology, and research.

University of Maine President Joan Ferrini-Mundy told attendees at the 2025 Maine Blue Economy Innovation Summit on Oct. 3 that the state’s success depends not only on innovation, but also on the people prepared to drive it.

“You don’t get to focus on an economy without thinking about the people who make and drive that economy—and that will be our trained, skilled workforce,” FerriniMundy said in her plenary address in Portland.

She recalled UMaine’s history as a land grant university rooted in agriculture and forestry. That mission broadened more than 50 years ago when the university began federally funded research into cold-water marine environments— work that helped launch decades of leadership in the blue economy.

economy’ future

Ferrini-Mundy highlighted the role of UMaine MARINE, the university’s hub for aquaculture and marine technology research, which connects faculty, students, and industry partners across the state.

She noted UMaine’s network of coastal research facilities—including the Aquaculture Research Institute in Orono, the Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin, the Darling Marine Center in Walpole, and the Down East Institute in Beals, which serves as the Marine Science Field station for the University of Maine at Machias.

“Our researchers are working on sustainable aquaculture methods, new feed alternatives, and innovations that strengthen Maine’s seafood sector,” she said.

“Researchers are working on sustainable aquaculture methods, new feed alternatives, and innovations that strengthen Maine’s seafood sector…”

“Over the last five decades, of course, we’ve been a global leader in this state, in the blue economy,” she said. “It’s all about partnerships. It’s about communities coming together to bring this economy to a forefront that is critical for our state.”

She added that UMaine scientists also collaborate with boatbuilders and coastal communities on projects ranging from vessel design to extreme weather.

“We see ourselves as Maine’s research and development department, advancing basic science, applied research, and innovation that keep our communities strong and our economy competitive,” Ferrini-Mundy said.

The Oct. 3 summit drew business leaders, researchers, policymakers, and students from across the state.

The agenda included plenary remarks, panel discussions, breakout sessions and an innovation showcase. Program tracks focused on aquaculture and fisheries, coastal engineering and boatbuilding, and community resilience.

Michael Duguay, commissioner of the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development, delivered the keynote address.

The sea has always shaped Maine’s economy, he said, from shipyards to lobster boats. What’s changing is how the state is harnessing that connection through aquaculture, advanced marine technology, and ocean-based research.

“Our blue economy touches every coastal town in Maine,” Duguay said. “It supports tens of thousands of jobs, strengthens our working waterfronts and positions us to lead in industries of the future.”

Maine’s maritime industries have always been about adapting to change.

“Shipbuilding, fishing, and maritime trade weren’t just industries. They were ways of life,” Duguay said. “But what defines us is the ability to evolve.”

That evolution is accelerating, with aquaculture leading the way.

“Maine is the largest producer of farmed seaweed in the United States, and the value of our aquaculture industry has doubled in the last decade,” Duguay said. “This isn’t just about oysters and mussels. It’s about kelp as a food source and as an input for everything from animal feed to cosmetics. It’s about salmon and trout farming to meet rising demand for protein.”

at barbara.boyce@arrowsic.org or

appointment to fill out

For further details, see: https://arrowsic.org/shellfish/shellfish_lottery_notice_2026.pdf

He also pointed to growth areas such as seafood processing, biotechnology, and advanced materials.

“Our tradition of boatbuilding, combined with new composite technologies, positions Maine at the forefront of sustainable marine transportation,” he said. “And marine biotech—from pharmaceuticals to new materials—is another frontier where our researchers are already laying the groundwork.”

State support has been crucial in preparing the industry for its next phase, Duguay said. More than $10 million in grants were directed to businesses and nonprofits after last winter’s storms.

“Those grants prevented closures, retained local employment and helped rebuild stronger infrastructure,” he said. That momentum extends to workforce development.

“By partnering with universities, community colleges, and trade programs, we’re training Mainers for careers in aquaculture, boatbuilding, and marine technology.”

Why is there a grain silo

on Rockland Harbor?

Answer reveals a maritime transportation footnote

BY PAUL KAROFF

Drive through the smallest no-stoplight town in the Midwest and you’ll encounter a hulking grain elevator. The ubiquitous structures define the landscape in the country’s grain-producing midsection. But what is one doing on the harbor in Rockland?

The answer, it turns out, involves mid-20th century competition between rail freight and maritime shipping, an ill-fated entrepreneurial venture—and chickens.

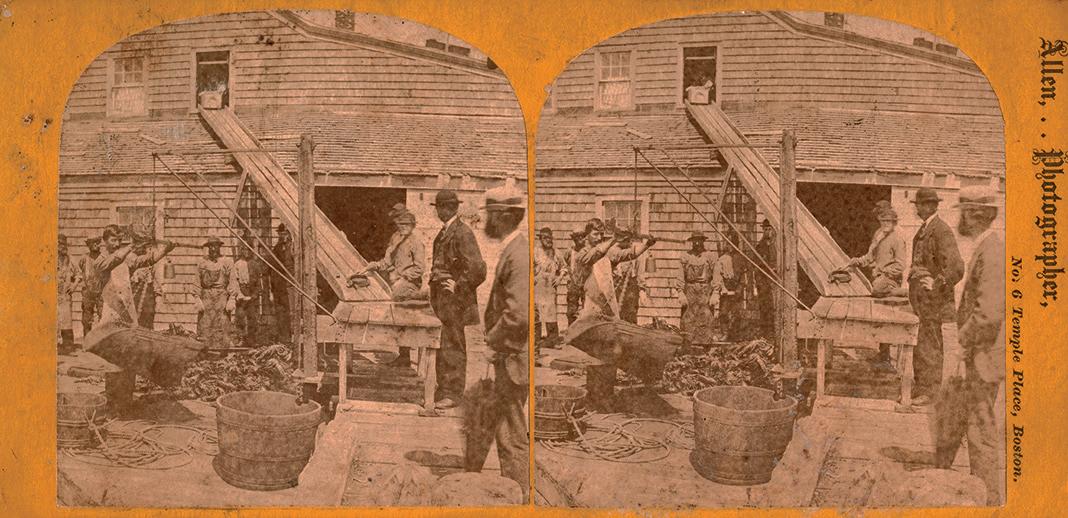

It was the early 1960s and an enterprising group of local business leaders hatched a plan to transform an unused parcel of harbor frontage at the foot of Mechanic Street in Rockland’s South End into working waterfront in support of the region’s burgeoning poultry industry.

Chicken production had seen meteoric growth across the state, especially in Waldo and Knox counties. By 1952, gross farm income from broilers, at nearly $24 million, was the state’s top agricultural product, with an

economic impact rivaling that of the storied sardine canneries that dotted the Maine coast. Large processing plants employed hundreds in places such as Belfast, which proclaimed itself the “Broiler Capitol of the World” and hosted an annual festival that featured what was billed as the world’s largest chicken dinner.

All those birds —mostly broilers raised for meat but also layer chickens for egg production—required feed.

Railroads had a monopoly on the transport of feed grain and producers complained that high freight costs were putting them at a competitive disadvantage to southern rivals. The Rockland plan called for the construction of a terminal for receiving grain shipments by barge, along with a mill to process it into feed, and four massive concrete silos.

The project attracted an influential champion, Sen. Edmund Muskie, who helped secure federal financing and in 1966, a modern grain mill and the first 100-foot-tall silo rose. Prock Marine, a mainstay on Rockland Harbor today, constructed a sturdy granite pier.

If there was celebration after a newly purchased 2,500-ton ocean-going barge brought the first grain delivery to Rockland in 1967, it was short lived. The railroads immediately responded to the ocean-faring competition, reducing their fees and eliminating the newcomers’ price advantage. Meanwhile, the venture proved to be tragically ill-timed; Maine’s poultry industry had passed its peak and entered a steep decline.

Only one barge shipment of grain was delivered to Rockland. Although the mill continued to process into the 1970s—with grain delivered by rail—the whole operation was a spectacular failure. The owners declared bankruptcy. Citizens who purchased bonds to help finance the enterprise never saw a penny in return. Within a few years of opening, Rockland’s grain terminal sat unused and mothballed.

After being foreclosed by the banks and passing into city ownership, the property was purchased by the Passamaquoddy Tribe in 1985 as part of a larger transaction that included other properties, notably the Dragon Cement operations in nearby Thomaston. The

tribe sold off the Dragon plant within two years of acquiring it but has held the Rockland harbor front property ever since.

Over the years, various ideas were floated for the dormant site, including a municipal fish pier, reviving poultry operations, condominiums, and a Wabanaki heritage center, but none panned out. Some envisioned using the deepwater pier to serve an expanded commercial fishing fleet and early backers even made a play to be Maine’s landing point for ferry service to Nova Scotia, in the end losing out to Bar Harbor.

The current vision is to raze the structures and return the site to a working waterfront, potentially as part of a future aquaculture project the Passamaquoddy Tribe is pursuing at its Pleasant Point reservation outside of Eastport. But a spokesman cautioned that there is, so far, “no definitive plans… it’s a vision.”

Today, the fenced-off site is overgrown and a flock of pigeons roosts on the decaying silo and mill building, which sit as forlorn monuments to a vision from another time.

Saving Marshall Point

Locals preserved iconic lighthouse 35 years ago

BY TOM GROENING

One of the Maine coast’s most recognizable, beloved—and accessible—scenes might have had another fate. In 1988, a rumor circulated through St. George—which includes the villages of Port Clyde, Tenants Harbor, and Martinsville— that the Marshall Point Lighthouse would be converted into a hotel and resort property.

This is the iconic site that appeared in the 1994 film Forrest Gump, in which Tom Hanks as Gump ran down the walkway to the light tower (in fact, visitors often mimick Gump’s run up and down the walkway). It’s the place where untold numbers of engagement and wedding photos are shot. Where school children study the contents of tidal pools. Where tourists feel the bracing breeze off Penobscot Bay and locals point out for them the cliffs of Monhegan Island on the horizon.

All those years ago, locals and summer folk alike mobilized to save the Marshall Point Lighthouse from going into private hands, and that’s worth noting.

But it’s also worth noting, says Nat Lyon, chairman of the Marshall Point Lighthouse Committee, that as of June, the walkway has been stabilized after being damaged from the January 2024 storms.

“The water came right up to the base of the porch steps,” he says, and the road was strewn with rocks. The $150,000 project was completed with funds raised by the committee, not the town.

And if anniversaries are important, well, the museum now housed in the first floor of the keeper’s house opened 35 years ago.

Lyon moved to the area in 1999 from Massachusetts and so wasn’t around when the hotel plan was thwarted. But he’s familiar with the story, and his recounting of the town’s response is blunt: “They said ‘No way!’”

Other key dates in the lighthouse’s history include it being established on the site in 1832, though the current light was built in 1858. The keeper’s house burned in 1895 and was rebuilt.

In 1971, the last lightkeeper left the post, and when Loran signal technology was installed, the Coast Guard abandoned the property in 1981 and boarded up the windows on the keeper’s house. A summer kitchen, which had been added to the land side of the building, was torn down when the operation was automated, as were a barn and a lifeboat station near the shore.

Back in 1988 when the hotel rumors were circulating, locals, including Irene Rizkalla, organized the committee and launched a campaign to rehabilitate the keeper’s house and open a museum there.

“I was heart-broken,” Rizkalla remembers feeling when she heard the rumor, which included the possibility of tearing down the keeper’s house. “It made me totally heartsick. The people from Port Clyde,” which is where Marshall Point is located, “were very upset. And when I heard, I got very upset!”

She lives in a circa-1790 house in St. George village and in conversation, it’s clear her roots and love for this community run deep. She points to seats at her dining room table where people gathered to plan their effort to block the hotel.

“We made a plan, got the key, and started cleaning the building,” she remembers. “The Coast Guard thought we’d lose interest. Well, that never happened. Three years later, we opened the museum.”

In fact, the Coast Guard entered into a 30-year lease, initially with the St. George Historical Society.

The committee has succeeded raising enough money to sustain maintenance of the lighthouse.

“We’ve put more than $500,000 back into the property,” Lyon says. Some of the revenue comes from renovating and then renting a second-floor apartment in the keeper’s house.

“It has to be someone who can live in four small rooms,” Lyon said. “Great views, but small space.”

The museum, with free admission, has been a success, he says, with about 23,000 visiting during the warm months. In 1995 the committee added back the summer kitchen structure which houses the collections.

There are displays of old lobster buoys and sardine cans, tools from the granite industry, vintage photos of the site, explanations of Loran, light lenses, and historical documents and genealogies, along with a gift shop. This year, 64 volunteers were on-hand to keep the museum open for visitors.

Though Lyon moved to the area 26 years ago, he has been active in the community, working as a sternman for 11 years and on the Monhegan Boat Line for five. And he’s proud to be part of the effort to sustain the property.

“That’s the whole thing, to preserve this as long as we can,” he says.

Rizkalla, too, expresses pride in “the fact that we have done it, and now own it. No one can take it away from us.”

Good idea, but…

To the editor:

Stephen Rappaport’s entertaining article (“Landings reports: Good science, but unpopular,” August/ September issue) shows how any important idea can transform itself into punishment. Sustaining a resource and a luscious economic delicacy is a no-brainer; turning the working stiffs of lobster industry (and their uncompensated spouses) into sea-level (somehow “on the ground” doesn’t work!) data collectors for the needed science is, in plain terms, nuts!

My professional life involved the practice of “policy science,” the study of how knowledge can be brought to bear on the formation and evaluation of public policy. If, during the years thereafter as a university dean, I had been asked to improve administrative performance by daily tracking memos I wrote, the program and student evaluations I’d sought, the support I provided faculty and staff, and whether I placed my own calls or had a secretary do it, I’d have left the role for one in which I could do the work I was hired for, not study it.

Pertinent data can inform good policy. But asking the working stiffs to daily collect and monthly report is understandably crazy-making for them, will alter the appeal of the

letters to the editor

sometimes-dicey livelihood to those with gumption to take it on and bears re-thinking from top to bottom. There have to be more sensible approaches.

Hendrik D. Gideonse Brooklin

‘Good noise’

To the editor: I just finished reading every word (as usual) in the October/November issue of The Working Waterfront. Editor Tom Groening has led this impactful, practical, human, and fascinating publication that continues to make “good noise” about the island and coastal universe. I know from experience that Tom will look back with satisfaction at his career.

Roger Demler Ashland, Mass.

‘Gentle power’

To the editor:

I was stunned to read Tom Groening’s latest column in The Working Waterfront to discover that it would be his last as editor. I can’t tell you how much pleasure he has given me (all of us) over the years

through the gentle power of his writing, insights, humor, and ability to bring home the complicated beauty of the Maine coast to those of us who don’t live there full time.

After 40-plus years on Monhegan, I’m closer to wrapping up my own time there. I’ll be 80 next month and bad knees are not a good fit for those trails. I hate the idea of a golf cart but that may be my extender.

Bob Mrazek Ithaca, N.Y.

Meeting the mission

To the editor:

I’d like to offer a simple thank you for the enormous contributions Tom Groening made in helping the Island Institute meet its mission over the last many years. If it seeks to connect islanders to information about themselves and from the wider world, and to connect Mainers (and others) to the treasure and differences of the inhabited Maine islands, then the work has been a huge part of that success. I have to comment on the excellence of what was written by the four island columnists in the October/November issue. Each is poignant in completely different ways. Their issue-by-issue

contributions have cumulatively added insight and humanity to the rest of the reporting on issues, challenges, and trends affecting Maine islands. In retirement, I’m filling volunteer roles on three different boards. It’s just like work, except more satisfying. I hope Tom finds similar ways in retirement to add value to the things you care about.

Richard Mersereau Brunswick

‘Heart’

To the editor:

I’ve always appreciated the heart Tom Groening put into every chapter of his work in Maine newspapers. He’s left a meaningful impact on readers, the community, and colleagues like me.

Jill Lang Hope

‘Facts are key’

To the editor:

Thank you for the column “Reflections on a ‘great business’ and job” in the recent issue. I appreciated Tom Groening’s reflections on journalism,

his career, the great Bob Woodward, and the changes to them over the years.

When Tom said to his wife about The Working Waterfront, “I think I can make some noise with this paper,” he was correct!

I know that my life has been enhanced as a reader of The Working Waterfront during his tenure and for that I am thankful. The dedication to craft and adherence to the notion that “facts and context are key, and they are best presented plainly and clearly” is what I have admired about his writing.

Also, one of the bonuses of your leadership has been that we can send you emails and know that they will always be read and considered. Tom’s ability to “listen” is one of your superpowers and is a skill that so few of us remember to practice.

Thom Heyer

New York City/Islesford

‘Making waves’

To the editor:

Many thanks to Tom Groening for his work at the Island Institute and The Working Waterfront. I live in Alabama but have had a long love for the Maine coast and working harbors particularly the islands. Despite my run-on

letters to the editor

sentences and poor grammar, I love the written word and have particularly enjoyed The Working Waterfront for some time now. It is chock full of useful information that I would find very hard to come by were I not reading the entire issue each month.

I do think Tom and the paper have and are making waves and making a difference. Sorry to see him go, but congratulations on a job very well done!

Robert Willis Israel Mobile, Alabama

A quick thank you

To the editor:

I’m writing a quick note to thank Tom Groening for his perspective and insight with The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. I especially appreciate the longer view and putting issues, large and small, into perspective and context—a skill that is greatly missing in today’s media. I have also enjoyed the photo essays, which are a different view in storytelling. I hope he enjoys retirement but keeps writing!

Doug Tuttle York Harbor

FULL INVENTORY READY FOR YOUR WATERFRONT PROJECTS!

• Marine grade UC4B and 2.5CCA SYP PT lumber & timbers up to 32’

• ACE Roto-Mold float drums. 75+ sizes, Cap. to 4,631 lbs.

• Heavy duty HDG and SS pier and float hardware/fasteners

• WearDeck composite decking

• Fendering, pilings, pile caps, ladders and custom accessories

• Welded marine aluminum gangways to 80’

• Float construction, DIY plans and kits

Delivery or Pick Up Available!

(207) 772-3796

www.customfloat.com

Fair seas’

To the editor:

I read the most recent edition of The Working Waterfront and was surprised to see Tom Groening will be completing his fine work there and exploring the fun avenues of retirement in the winter! I am a fan of retirement, but losing this voice and vision for the publications of the Island Institute after all these years will take some coping! I have enjoyed all that he brought to us month after month—and the stunning Island Journal each summer. I wish him well, and fair seas!

Thom Buescher Cushing

‘Other people’s stories’

To the editor:

I’d heard of Tom Groening’s impending retirement from Island Institute President Kim Hamilton, and now I see in The Working Waterfront that it’s official. I especially like his line in his farewell that we journalists let other people tell their stories. How true that should be. He’s had a great run and has made both Island Journal and The Working Waterfront important publications in

this part of the world and deserves a smooth and happy retirement.

David K. Shipler Swan’s Island

Good journalism

To the editor:

Congratulations to Tom Groening for his retirement. It’s certainly well-deserved. I’ve always respected his adherence to the ethical practices of good journalism, with fair, balanced, and accurate articles that tell the stories of the communities along the Maine coast.

Too much journalism these days seeks conflict or sensationalizes. Tom’s efforts to listen to people, with a dose of humility, and provide gentle guidance exemplify the best journalistic standards.

Edward French Publisher/Editor, The Quoddy Tides Eastport

The Working Waterfront accepts letters to the editor of 250 words. Send them to editor Charlie Eichacker at ceichacker@ islandinstitute.org. Longer opinion pieces should be approved by the editor before being sent.

Seasons change in former mill town

Fall foliage around Bucksport

PHOTOS BY LINDA COAN O’KRESIK ESSAY BY CHARLES EICHACKER

Drivers heading east along Route 1 get to a stoplight just after they cross the Penobscot River.

Turning right, as many do in the summer and fall, eventually brings them to Acadia National Park and beyond. Going left leads to the downtown of Bucksport, a small waterfront community that lost its paper mill just over a decade ago. Bucksport has mostly weathered the loss of its largest employer, although a land-based salmon farm proposed for the mill site still hasn’t materialized. A healthy number of new restaurants and shops have opened downtown in recent years, in some cases replacing older ones. It’s a good spot to take in Maine’s fall foliage, especially with other scenery including historic Fort Knox and the towering Penobscot Narrows Bridge & Observatory, and the more offbeat smokestack still standing at the former mill. The community offers other frights in October, including a Halloween festival called Ghostport and the rumor of a curse on a stone monument commemorating the town’s founding father, Jonathan Buck.

Our Island Communities

Saving a Little Diamond shore Casco

Bay island fought erosion with nature, community

BY KAI HOLLOWAY

In September, I visited the small community of Little Diamond Island in Casco Bay to witness something remarkable: a shoreline restoration project marked by new science and sheer community determination.

Hosted by Island Institute, the event brought together island residents, representatives from neighboring Casco Bay islands, and others eager to learn how coastal communities can protect themselves against the relentless force of the sea.

The story begins in January 2024. Two severe storms battered the island, eroding 60 feet of shoreline along Casino Beach. The waves washed away the community’s golf cart parking area and washed out the road connecting the island to its public dock.

For the small Little Diamond community the damage was devastating. The destruction left the community wondering, “What do we do now?”

Several island leaders responded, and through trial and error, crafted a solution that was as natural as it was strategic: a coastal sand dune system.

Sand dunes are more than beach features. They are living barriers against erosion and storm surges. Acting as sponges for wave energy, dunes protect inland areas from flooding while supporting native vegetation and wildlife.

By planting beach grass, communities can stabilize and prevent sand from washing away, and enable the coastline to rebuild itself naturally. For Little Diamond, this approach was both environmentally responsible and permitted.

At the town hall, known locally as the “Casino,” residents presented their project. Then we walked the short distance to the dune system. The work was impressive. Every contour, log placement, and patch of grass reflected careful planning and countless volunteer hours.

Even with the dunes in place, the project required additional reinforcement. The storms had left a gaping hole along the shoreline, threatening to funnel water directly at the newly constructed dunes. To address this, the gap was filled with crushed rock, creating a natural drainage system to protect the dunes and the rock wall they had constructed behind the dune.

The wall, made of large stones, serves as a backup barrier. While dunes absorb most wave energy, the rock wall ensures that even in extreme conditions, waves won’t breach the island’s infrastructure. It’s a layered approach: dunes first, rocks second, vegetation throughout the dune—a system designed to withstand the sea’s unpredictability.

Next came the work that truly showcased the island’s spirit: volunteers dedicated countless hours to lay “coir” logs along the base and contours of the dunes. Made from tightly bound coconut fibers, coir logs hold sand in place, slow water runoff, and encourage native vegetation to grow. Over time, they biodegrade naturally, leaving behind reinforced dunes ready to withstand wind and waves.

Once the logs were in place, dune grass was planted by hand, then carefully fertilized and watered to ensure it would take root and thrive. By the end of the project, the dunes were not just functional—they were a living testament to the dedication and hard work of the island’s residents.

Now, almost two years after the storms, the dunes blend seamlessly into the shoreline and haven’t

sustained any damage. For Little Diamond residents, the project represents more than protection—it embodies pride, resilience, and the power of their community.

The total cost of the project was approximately $140,000, including a $110,000 contract with Lionel Plante Associates and $25,000 for materials supporting volunteer labor.

Little Diamond Island’s approach demonstrates that protecting a shoreline doesn’t always require massive concrete seawalls or expensive engineering projects. A well-designed sand dune system, reinforced with rock walls and supported by native vegetation, can

provide a sustainable, cost-effective, and visually appealing solution.

Visiting Little Diamond Island left me with a renewed appreciation for what’s possible when science, planning, and community spirit come together. For coastal towns facing the growing threat of erosion, the lessons here are both practical and inspiring: sometimes, the best defense against the sea is sand, sweat, and shared purpose.

Kai Holloway is an 18-year-old journalist who lives on Cliff Island. He is a feature writer for Islands.com and his blog is at Kaioutside.com.

Daphne Pulsifer’s threedimensional life on Monhegan

Sculptor found love and life 12 miles out to sea

BY MOLLY RAINS

This story first appeared in the Lincoln County News and is reprinted with permission and gratitude.

Twelve miles out at sea on Monhegan Island, sculptor Daphne Pulsifer often works in near solitude. In her peaceful, airy studio on Light House Hill Road, she shapes her pieces accompanied by her dog, Emma, and the visitors who occasionally stop in during open hours to peruse her work.

Yet in these quiet moments of creation, Pulsifer reflects on the connection with others she says inspire each sculpture and have populated her life on and off the island.

Pulsifer was born in Newport to a family with deep roots in Maine. When she was very young, her family left Maine and she grew up in New Jersey and Philadelphia. Much of her extended family remained in Maine and she remained connected to the state and visited often.

“We grew up coming home to Maine every summer,” she said. “There was always this sense that Maine was home.”

As a child, Pulsifer was incessantly creative.

“My mother used to complain and say that I didn’t have any clothing that didn’t have paint or ink stains or something on it,” she said.

However, it wasn’t yet clear to Pulsifer that she would become an artist. After

high school, she enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, where she intended to study architecture. In retrospect, the move was not one she had thoroughly thought through.

“I don’t think I had a clear idea of what that could mean in terms of a career, and once I was involved in the academics of it, it didn’t hold me,” she said.

What did captivate Pulsifer was the idea of living out at sea. For one of her classes, she and her peers researched coastal islands, and she became captivated by the island and artist colony of Monhegan.

“I thought, I want to go check that place out,” she remembers.

Pulsifer traveled to the island one May while still a student

She settled on the island in 1983. She began her tenure working at the Trailing Yew Inn and at the Monhegan House, but also found a place within the art scene.

She also met and fell in love with her husband, Daniel Bates, on Monhegan.

“He was just on the road, digging a ditch,” she recalled. He had two children and together they had two more. The island encouraged the family to be selfsufficient, Pulsifer said.

“ That was the big, big moment, to come here and think, OK, this is kind of cool. I think I’m going to stick around.”

“That was the big, big moment, to come here and think, OK, this is kind of cool. I think I’m going to stick around,” she says. “I loved the beauty of the environment, and being able to just be present and walk around and read and draw.”

After that first visit, Pulsifer dropped out of college. She would return to Monhegan just months later, in the fall, to spend winter on the island.

“It just felt so natural to me to be here,” she says.

“When we were raising our children here, we didn’t have many alternatives,” she said. “We didn’t go ashore for long periods of time or even short periods of time during the winter.”

The family would move to the mainland in 1989 so Bates could go back to school, but after the kids graduated from high school, the couple would continue to return to Monhegan during the summers.

Over the years, Pulsifer’s art style continued to evolve, moving from printmaking to sculpture, working in wood, plaster, bronze, and even blocks of blue Styrofoam, used to keep floating docks aloft, and that wash up on Monhegan’s shores.

She loves the physicality of sculpture and the extra layer of difficulty involved in creating three-dimensional artwork.

“It’s an engineering problem almost every time where I have to consider, OK, how is this going to be molded,” she said, “How is this going to, literally, support itself, and what are the different considerations that might come into play?”

Humans, wild and domestic animals, and flowers feature often in Pulsifer’s sculptures.

As a sculptor, she does not engage with the art community in a typical way.

“A lot of the work I do is solitary work. I don’t work with other artists. I’m not like a plein air painter. I kind of envy them sometimes, because they can take their work anywhere and go with their friends and be a group,” she said.

She does host gatherings with other artists, though.

“It’s important to me to have connections even though I actually kind of work in isolation most of the time,” she said.