Mills highlights housing wins

Costs, federal uncertainty impact affordability

BY TOM GROENING

The lack of affordable housing impacts much of the state’s economy, and much of the economy impacts housing.

That was one of the conundrums emerging from the Maine Affordable Housing Conference on Sept. 9 in Bangor.

When housing options are few or too expensive, the workforce—which is already facing generational decline—tightens. And as building materials grow more costly and federal funding support for projects shrinks, the rental market becomes tighter.

“There just isn’t the money that was available in 2023,” said Dan Brennan, MaineHousing director. Still, the state’s goal is to see 80,000 new homes by 2030.

“It’s costing a lot more to build homes,” Gov. Janet Mills noted in her remarks at the conference, blaming, in part, the Trump administration’s tariffs on certain imports. Building materials were 6% higher in August than the previous August, she said.

Housing shortages threaten prosperity, she said.

“We don’t want to think about it as a siloed issue,” Mills said. “It’s part of economic development.”

Despite the challenges, the governor highlighted what she sees as wins.

About $315 million has been spent during her administration to build housing, five times what was spent in the period from 2000 to 2018. Some 2,100 new apartments and houses have been built, 1,800 are under construction, and 1,500 are in the pipeline, she said.

Monthly mortgage payments in Maine are the lowest in New England, she said, and the rent-toincome ratio also is lowest in the region.

About two dozen housing-related laws were enacted in the last session, she said, including those to support historic preservation efforts.

“We’ve got to revitalize the downtowns,” Mills said, acknowledging the trend that began with the pandemic in which office space has become underused. Such spaces should be converted to multi-use, she said.

continued on page 4

Scientists now predicting whale movement

Food, temperature inform science on right whales

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

In early June, conservation patrol officers with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans were on a patrol flight in an area known as the

Sackville Spur, about 310 miles east of Newfoundland’s coast, when they spotted a North Atlantic right whale, identified as Eternity, swimming with a group of pilot whales in a location where right whales normally aren’t.

The officers were surprised to see the endangered whale there, but the scientists working in the Tandy Center for Ocean Forecasting at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay were not—because they’d predicted it.

“Where exactly did that whale occur?” asked postdoctoral scientist Jonathan Syme. “It was right there on that little bit of blue in this area that we predicted would become right whale habitat,” he said as he pointed to a slide projected above his head in the forum space of the newly opened Harold Alfond Center for Ocean Education and Innovation at Bigelow.

“ When we know where the food is, we’ll be able to predict where the right whales are likely to be.”

annual summer lecture series, Café Sci. Held July 16, their presentation shared some of the science-based modeling and forecasting tools scientists at Bigelow are using to predict where and when North Atlantic right whales may show up in the short-term and the long-term. With the current disagreement about regulations to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale—of which there are an estimated 350—“there’s a really important role for science to play,” said Record, director of ecosystem modeling at Bigelow’s Tandy Center, “when these different approaches to management start to crack and fall apart.”

Syme, along with postdoctoral scientist Rebekah Shunmugapandi and senior research scientist Nick Record, presented the first lecture of Bigelow’s continued on page 3

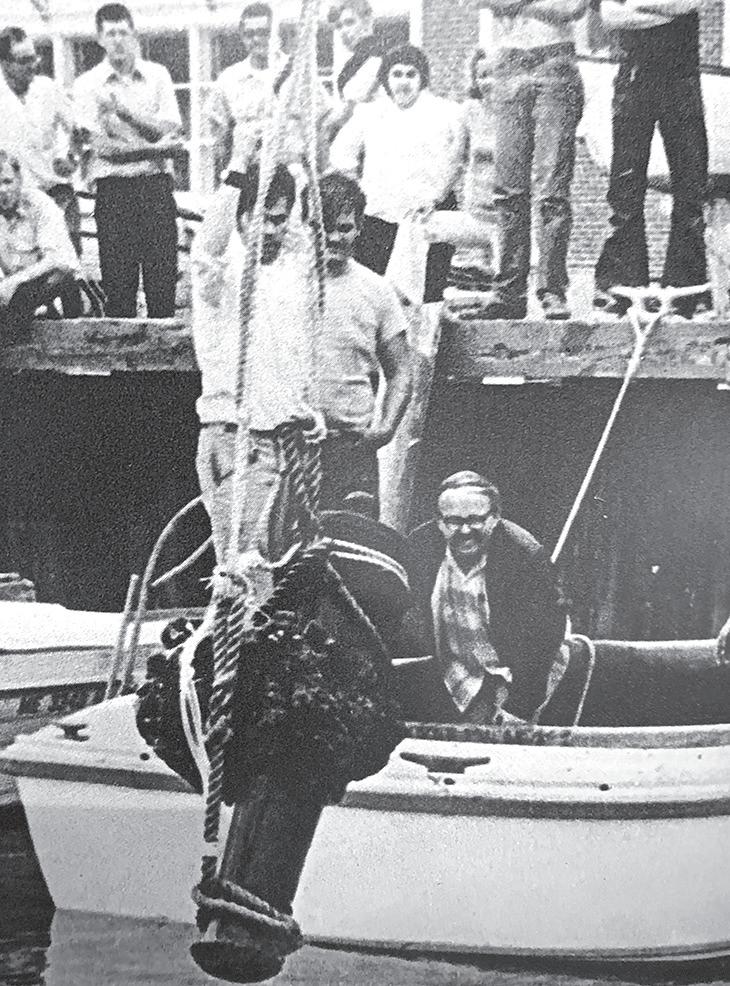

Remembering the ill-fated Defence Victim of Penobscot Expedition in harbor mud

BY TOM GROENING

When a group researching the final resting place of the Defence got their hands on one of the ship’s cannons, buried in the mud of a Maine harbor for 200 years, their archaeologist partners at Texas A&M asked an important question: Is it loaded?

It was, as it turns out, explain David Wyman and Donald Small, two retirees who, over the past two winters, built a 1/16 replica of the 85-foot Defence. Both men taught at Maine Maritime Academy. Wyman and others took dives on the wreck in the 1970s.

The ship was part of the colonial effort to dislodge the British from Castine during the war for American independence.

Building the replica took a couple of winters, the men say. Raising key parts of the Defence back in the 1970s took several summers. And the work was potentially dangerous, as they learned.

“You need to show that the cannon is unloaded,” Small remembers the Texas A&M researchers advising when it was raised.

“The ball, wadding, and powder were all there,” Wyman adds.

That long-loaded, now disarmed cannon today resides in the Naval History Museum in Washington D.C., while most of the Defence still lies on the bottom of Stockton Harbor, a good-sized cove between Cape Jellison to the east and Sears Island to the west.

Researchers have been guarded about the wreck’s exact location, and with good reason—at low tide, she’s in only about 11 feet of water. Souvenir seekers might be tempted to retrieve some part of the ship.

The Defence replica was an appropriate project for Wyman, Small, and the others to tackle. The ship played a role in an important part of the town’s history.

The Penobscot Expedition in 1779 was the American attempt to drive the British from Castine, a headland strategically situated at the top of Penobscot Bay near the mouth of the river. But the colonial forces were routed, due to “poor coordination, bickering commanders, inadequate training, and inexplicable delay,” according to the Castine Historical Society’s website.

Paul Revere, one of the leaders of the Penobscot Expedition, was court-martialed for his part, but later exonerated.

The Americans fled in their ships, and the Defence—a two-masted brigantine, or brig, which Small says probably was square rigged—ducked into Stockton Harbor as the British vessels pursued.

“The crew took her into Stockton Harbor thinking the British wouldn’t see her,” Small explains, perhaps hoping she would be hidden behind Sears Island. But when the British forces closed in on her, the captain and crew jumped overboard and swam to shore, setting the vessel on fire as they left.

on a shipwright’s personal approach. The names of the owners are known, he added, and one was of the prominent Cabot family of Boston.

The Defence served as a privateer, a vessel sanctioned by the fledgling U.S. government to attack British shipping.

“They were sailing, hoping to make money on what they could capture,” Small said.

It was Dean Mayhew, who joined the Maine Maritime Academy faculty in 1963, who came to believe the sunken ship was in Stockton Harbor. According to Underwater Dig: The Excavation of a Revolutionary War Privateer, by Barbara Ford and David C. Switzer (William Morrow and Company, 1982), Mayhew had become interested in the Penobscot Expedition while he was a student, and when he arrived in Castine, he began investigating.

A letter from the period by a British admiral noted an enemy vessel had been caught in Stockton Harbor. Almost 200 years later, Mayhew learned that a local fisherman, Cappy Hall, reported snagging his nets on something unusual in the area, according to Underwater Dig.

The vessel’s “breast hook,” a timber near the bow to which framing members were attached, was found, still with bark on it.

The fire was probably set near stern where the magazine was stored, which Small believes contained a sizable amount of gunpowder.

The ship landed on her side as she sank and over the years, settled into the bottom, “with about the deck line” above the mud, Small says.

Other American vessels, including the Samuel, Warren, Vengeance, General Putnam, Charming Sally, Hector, Black Prince, Monmouth, Hazzard and Tyrannicide were scuttled as they fled up the Penobscot River. Those wrecks lie north of Sandy Point through to Bangor.

It’s believed the Defence was built somewhere north of Boston, probably in Beverly.

“American ships at that time were not constructed from any plans,” Small explained, but rather relied

In 1972, the Academy organized a summer ocean engineering project for the school’s students, as well as for some attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. One of the tasks for students was building and operating a sonar device. Needing a target to test their work, someone remembered Mayhew’s theory that a shipwreck lay at the bottom of Stockton Harbor.

Wyman remembers the students working at making the sonar able to identify objects to the side rather than just downward. Passing over the location where the fisherman snagged his net, an unusual shape was identified. Students with scuba gear dove and immediately found items that appeared to be cannons. Soon after, a “shot rack,” a carved wooden shelf holding cannon balls, was found and raised.

In all, 16 cannons that would have fired six-pound balls were found. The divers also found a brick cook stove, dishes, spoons, belt buckles, and leather shoes. The vessel’s “breast hook,” a timber near the bow to which framing members were attached, was found, still with bark on it. The Maine State Museum in Augusta has in its collection a tin with blueberries, a ration for one of the 100 who served on the Defence. The crew was probably small, the men say, with the others aboard serving with the Massachusetts militia.

The excavation work continued each summer, Wyman remembers, from 1972 through 1980, by carefully working in 5-foot by 5-foot grids. “We dove every day for six weeks,” he said. “There was some discussion about raising it,” he said of the ship, but it seemed too difficult.

“I took a lot of the measurements,” Wyman remembers, carrying a tape measure down to the bottom with him into the Stockton Harbor mud. “Getting the measurements took multiple years.”

In recent years, when Small and Wyman would walk around town together, they began discussing the idea of building a scale model of the Defence Others agreed to help, including Dick Anderson, Steve Brookman, and Walt Murphy.

“We worked one morning a week once the snow fell,” Small said. “There was probably as much conversation as work,” he joked.

Unlike most ship models, the viewer is able to see into the structure, so replicas of the breast

the

and the

are

The

is

WHALES

continued from page 1

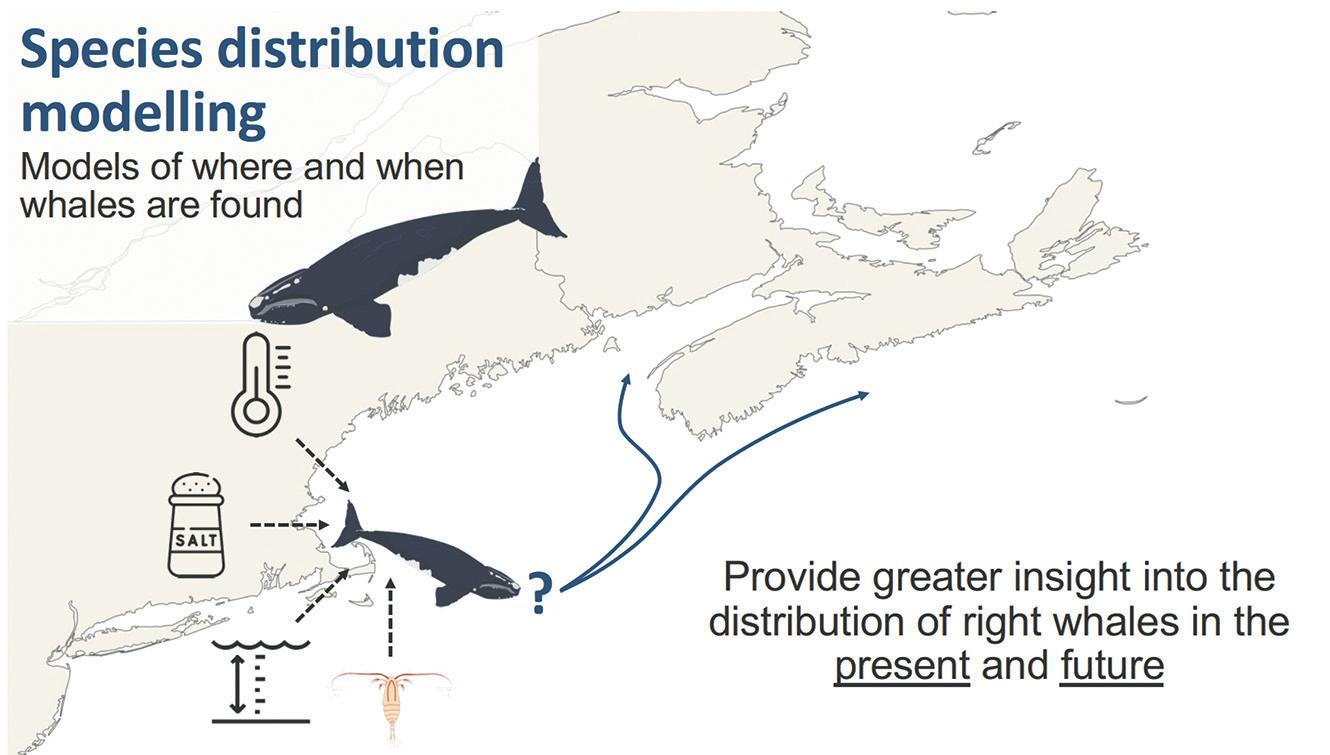

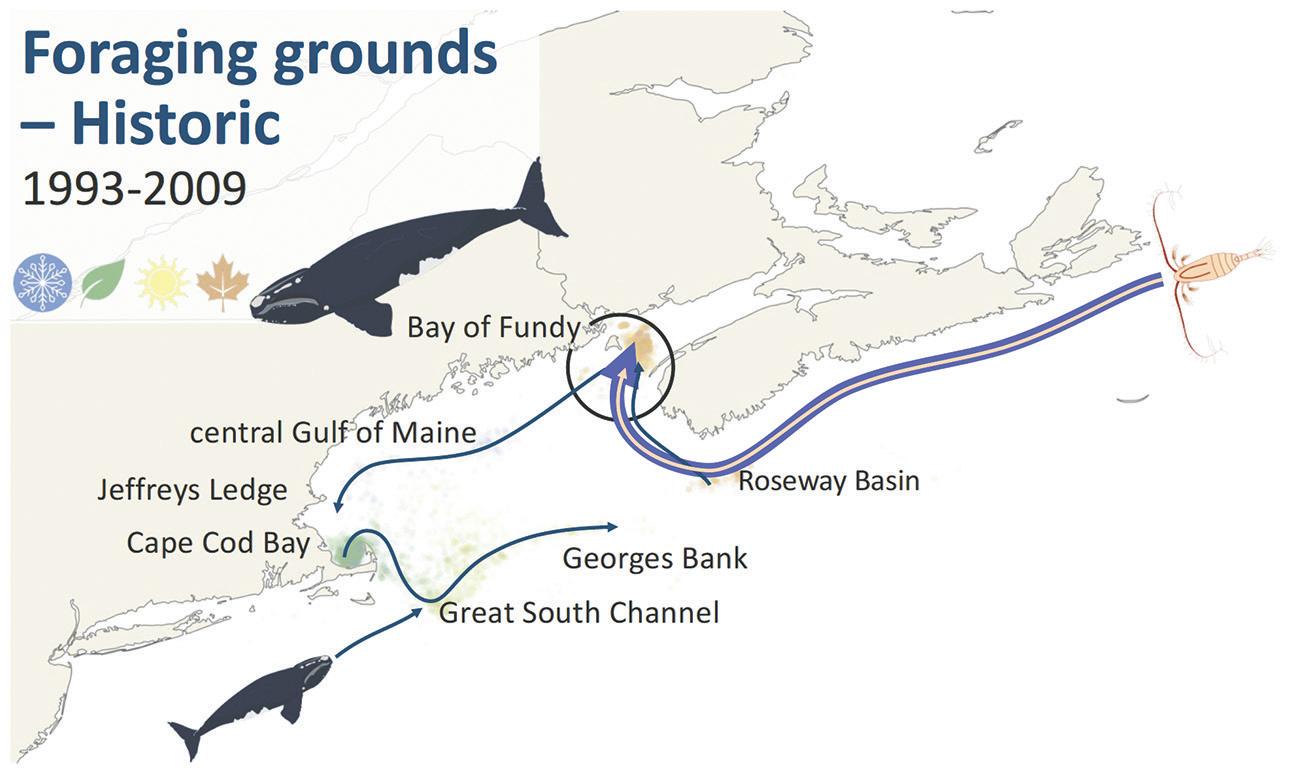

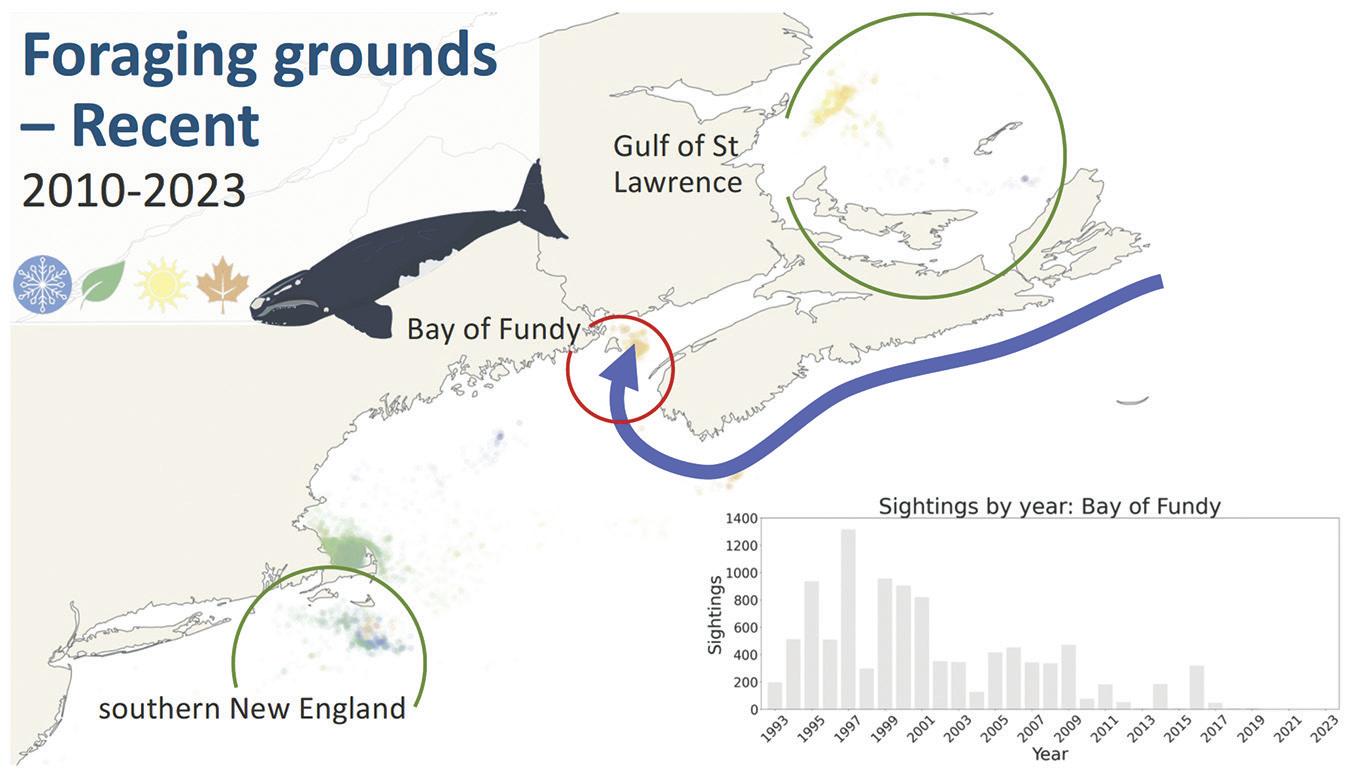

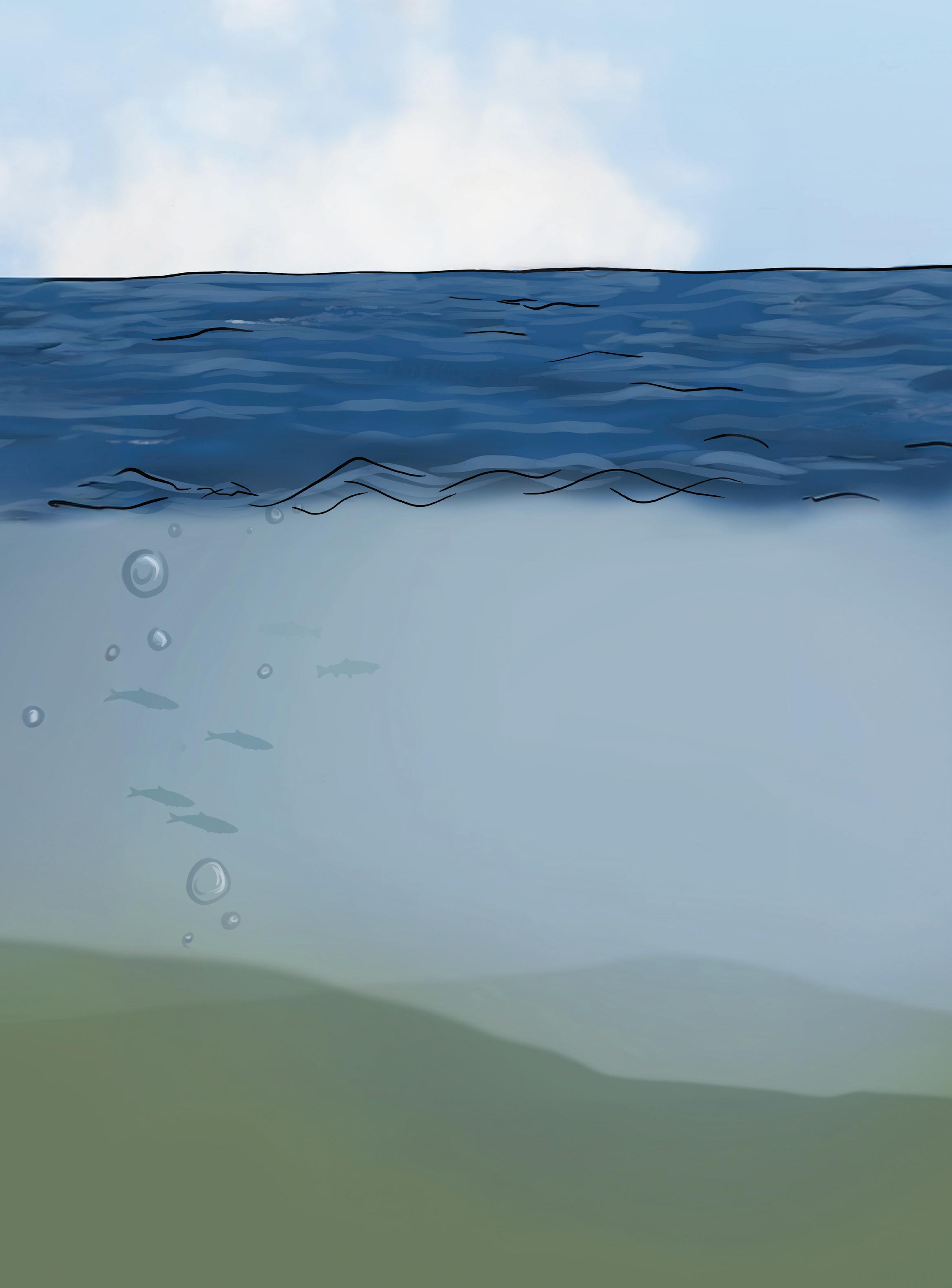

To make the long-range forecast that pinpointed the Sackville Spur as a place right whales would eventually go to in the next five to 20 years, Bigelow scientists used prey data and regional and seasonal right whale movement data along with parameters such as water depth, temperature and salinity from 1990 to 2015.

The modeling using this data predicted which historical foraging areas would be maintained, and which would not, and which areas right whales would go to in the future, including the Sackville Spur area.

“Just like you have a weather forecast that says what the probability of rain or clouds or sun is in the next few days, we can make maps that tell what is the probability of whale occurrence in the coming days, and these maps could be used by researchers and management and fisheries to inform their decisions,” Syme said.

Bigelow scientists are also working on incorporating realtime data from satellites into their models, Shunmugapandi said.

“We want to use the remote sensing methods to detect whale food,” she said. “When we know where the food is, we’ll be able to predict where the right whales are likely to be.”

The places North Atlantic right whales are foraging are shifting because the changing climate alters ocean currents, the scientists said, which in turn affects where whale food will show up. Being able to more easily determine where North Atlantic right whales are going to go ahead of time is crucial for both the whales’ survival and for the industries that are most affected by regulations to protect the whales.

“One of the things that we’re hoping these forecasts can do,” said Record, “is help get a heads up before whales show up in large numbers in an area so that we can have some planning in terms of what we do.”

To watch the lectures of the Café Sci series, go to Bigelow’s YouTube channel.

HOUSING

continued from page 1

“We can’t quit building now,” Mills said. “We’ve proven we can build housing without creating sprawl,” while retaining “that sense of place.”

A panel discussion including Stockton Williams of the National Council of State Housing Agencies and Rep. Traci Gere of Kennebunkport, moderated by Erik Jorgensen of MaineHousing, focused on the challenges.

“The market is broken for most Maine people right now,” Jorgensen said, with Portland real estate assessments up by 43% from a year ago.

Williams said he sees Congress as being more pro-housing than at any time in the last 25 years, yet Trump’s budget proposal cut 50% on low-income rent vouchers. Those cuts were reversed in the final budget bill.

Gere cited an evolution in regulations, as seen in a housing development in Newcastle which, under old rules, would have required 32 parking spaces. Calculations for such projects no longer use a 1.5 multiplier for each resident.

A bit of good economic news is the state’s modest, but noteworthy population growth. From

2021 to 2024, Maine saw a net gain of 40,000 residents. Observers attribute the growth to people escaping more urban areas during the pandemic and working remotely.

“People are moving here and staying here,” Mills said.

State Economist Amanda Rector dove deeper into the numbers in her presentation. From 2010 to 2020, Maine grew by 2.6%, then grew by 3.1% from 2020 to 2024. All the growth is attributed to in-migration, most from other states, she said.

But with the oldest median age in the nation at 44.8, and the largest percentage of population over 65, Maine faces challenges.

“We have more people exiting the workforce than entering the workforce,” Rector said.

And on housing, Maine was first in the nation in price increases, a statistic “you don’t want to be first” in, she said.

Innovation, ill-fitting regulations, and the need for financial literacy also were themes at the conference.

Affordable housing must be understood more broadly than building two-bedroom, one-bath starter homes, speakers said. In response to mobile home parks being bought up by large corporations, state law now facilitates residents buying the land

Herring Gut honors Mook, Soctomah

The Herring Gut Coastal Science Center has named Bill Mook, owner of Mook Sea Farm, and Chris Soctomah, fisheries biologist for the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik Environmental Department, as recipients of the 2025 Phyllis Wyeth Visionary Award for Excellence in Marine Science, Education, and Trades.

The award honors individuals who embody the innovative spirit and dedication of Herring Gut’s founder, Phyllis Wyeth, who established the Center in 1999 with a mission to inspire future generations in marine conservation and support Maine’s traditional fishing communities.

Bill Mook founded Mook Sea Farm, in Walpole, in 1985 and has spent nearly four decades pioneering advancements in shellfish aquaculture. From his early work at the Darling Marine Center to his leadership in developing resilient technologies for oyster farming, Mook has been a driving force in strengthening Maine’s aquaculture industry.

Chris Soctomah serves as fisheries biologist for the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik, where he oversees and implements fish passage studies and projects at the Skutik (St. Croix), Boyden, Pennamaquan, and Denny’s watersheds. His efforts facilitate and

Aquaculture for People and Planet

OUR 7 TH CLIMATE OF CHANGE FILM

Join us for a free screening of Aquaculture for People and Planet! Learn how Maine’s shellfish and seaweed farmers are leading in lowcarbon, climate-friendly food production. This short film from our Climate of Change series highlights how Island Institute is supporting a resilient, sustainable seafood economy. A panel of local aquaculturists and Island Institute staff will explore the promise of low-emission, locally grown seafood—and how Maine can lead the way.

OCTOBER 16

10:00 am - 11:00 am | FREE WEBINAR SCREENING

Featured Speakers: Matt Moretti (Bangs Island Mussels), Susie Arnold (Island Institute), Sam Feldman (Island Institute). Moderated by Sam Belknap (Island Institute).

collectively and owning their residence. Thirteen parks are now resident-owned, three purchased in the last year. In all, 8% of housing in the state is in mobile home parks.

The governor said modular homes are another innovation and have made building faster and cheaper, citing their use by advocacy groups on North Haven and Peaks Island.

Regulation changes to allow accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, in a homeowner’s yard are having an impact, Mills said. The Brunswick business Backyard ADU recently delivered its 100th unit, she added.

At a break-out session, real estate agents and bankers discussed how loan preapprovals are now the norm, and that first-time buyers often aren’t aware of the money they need to have saved to purchase.

Housing expansion has been supported around the state, Brennan said, though he gave emphasis to the phrase “in most areas.”

Mills sounded a similar criticism, noting that Scarborough’s town council killed a 90-unit housing proposal on Route 1 that would have served lowerincome seniors and workforce renters, citing traffic.

“We can’t be parochial about this,” she said. “They’ve got to be in somebody’s backyard.”

implement western science approaches while also incorporating traditional ecological knowledge.

Honorary mention went to nominees Krisanne Baker, ecological artist and art educator; Chris Davis, innovator in residence at Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center; Alison England, middle school science educator at St. George Municipal School Unit; Sarah Gladu, community science director at Coastal River Conservation Trust; Alison McKellar, select board Member, Camden; Marci Train, educator Long Island School; Krista Tripp, owner of Aphrodite Oyster; and Charlie Walsh, CTO/ Co-founder of Seascal.

Next ocean farming crop—scallops

UMaine studies methods to learn effectiveness

Much of the scallop farming techniques used in the U.S. derive from practices in Japan, where scallops have long been a part of the country’s seafood industry. Researchers from the University of Maine are working to test and adapt those practices to help grow the industry in the Gulf of Maine, where oyster farming is currently the most wellknown form of aquaculture in Maine’s blue economy.

Building off a four-year study published in the spring, which compared the effectiveness of two different Atlantic sea-scallop farming techniques, UMaine researchers further analyzed the economic advantages and disadvantages of the same two methods of scallop aquaculture.

Lead researcher Damian Brady, professor of marine sciences at UMaine, and co-author Chris Noren, a postdoctoral researcher, used their results to develop a user-friendly application that helps interested parties compare the different costs and possibilities associated with building their own scallop farms.

“Now new farmers can make educated decisions on what option is going to be most viable for them, taking into account their location, timeframe, budget, and all the other pieces that go into scallop farming,” Brady said. “Ultimately, our goal is to help Maine grow this industry to its fullest potential and preserve Maine’s working waterfronts—an integral part of the state’s culture and history.”

Published in the journal Aquaculture, the study looked at two of the most common options for scallop farming: lantern net and ear-hanging. Previously, lantern net methods were thought to be more cost-effective, but this study shows the ways in which the ear-hanging method can be more cost-efficient over a longer period of time.

Researchers concluded that ear-hanging production was more advantageous if the scallops’ life cycles exceeded three years, and lantern-hanging is slightly more profitable when scallops are harvested under three years. They also found that the most optimal time for harvesting, regardless of farming method, was when scallops reached an age of 3.75-4 years.

Lantern net aquaculture uses tiered, circular nets that attach to a long line and hang vertically in the water column—an easier and less expensive system to set up compared to the ear-hanging method. Scallops sit in each tier of the lantern net, which can cause

overcrowding and issues with food resource accessibility. However, research showed that over time, the overcrowding can make lantern net farming productive over a four-year cycle.

Developed from Japanese methods, ear-hanging involves drilling holes into the “ear,” or the hinge, of the scallop shells, which are then pinned and hung on vertical lines in the water column. This method allows for individual scallops to have more space and access to resources. While it is more expensive to set up, labor costs significantly drop and overall expenses level out over a four-year period.

To combat start-up price, Japanese scallop farmers have used a number of different technologies and techniques that could be applicable in Maine. This includes specialized equipment, such as automated drilling and pinning machines, or a multi-partner ownership, in which one partner does the drilling and preparation, while the other does the farming and de-pinning. Cooperative partnerships allow each group to invest and specialize in a fraction of the machinery and equipment.

The study looked at two different scallop metrics over a four-year period: the height of the entire scallop shell in millimeters and the weight of the adductor muscle in grams. Both metrics have applications for the current U.S. market and its potential to expand.

Generally in the U.S., the adductor muscle is the only part of the scallop that is sold or used. The bigger or heavier it is, the higher the price.

The U.S. market for whole scallops, which include other parts of the bivalve along with the adductor muscle, is limited, but methods that increase the size of either part of the scallop have the potential to improve market value. Although ear-hanging requires more front-end labor and the equipment is more expensive than the lantern net method, the rate of production is significantly faster over a longer time period. It is also more space efficient, which requires a smaller lease and is less expensive.

Additionally, the researchers stressed the importance of a working waterfront for doing tasks that do not require being on the water. This allows for less weather-dependent work days and for small farms to grow with less limitations.

Ear-hanging is not only economically more effective in total labor costs and leases; it also results in ear-hanging scallops growing larger adductor muscles on average, according to the study.

Researchers concluded that the long-term benefits of growth size, lease cost, and total labor costs make the higher start-up costs of ear-hanging worthwhile for farmers entering the market for longer than three years.

New State of Maine training vessel launched Ship is built for ‘multi-mission’ service

On Aug. 26, the U.S. Maritime Administration celebrated the christening of the State of Maine, the third of five cutting-edge national security multi-mission vessels, at Hanwha Philly Shipyard in Philadelphia. Built for Maine Maritime Academy, the State of Maine will serve as a next generation training ship, supporting both the academic development of cadets and America’s humanitarian relief.

Spearheaded by the U.S. Department of Transportation and the Maritime Administration, this program is revitalizing America’s maritime training infrastructure—a cornerstone of President Donald Trump’s executive order on restoring maritime dominance. The program supported nearly 1,500 skilled jobs in Philadelphia and boosts American competitiveness at sea and ashore.

“The State of Maine is more than a ship. It’s a strategic investment in the people and infrastructure that keep America’s maritime economy strong,” said Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy. “Our cadets deserve cutting-edge tools and training to become the industry leaders who will keep our nation strong and ready when it matters most,” he said.

“This vessel marks a new era for American maritime power,” said Sang Yi, acting administrator

of the Maritime Administration. “Our mission to modernize sealift and empower the merchant marine hinges on relentless innovation and partnership.”

Maine Maritime Academy is internationally recognized as a leader in maritime education, noted MMA President Craig Johnson, “and this vessel represents a major step forward in our mission to train the world’s finest mariners. It’s a game-changer for our mission and a powerful reflection of what’s possible through strong partnerships and shared vision.”

The Maritime Administration is replacing aging training vessels from the National Defense Reserve Fleet with new, purpose-built ships designed to meet modern academy needs—and to provide critical capabilities for disaster response and national emergencies.

At 525 feet long, the State of Maine can accommodate 600 cadets and up to 1,000 people in times of humanitarian need. The vessel includes eight classrooms, labs, a training bridge, auditorium, helicopter pad, advanced medical facilities, and roll-on/ roll-off and container capacity, ensuring cadets get unmatched hands-on training.

State of Maine joins Empire State and Patriot State already in service, with two more under construction

at Hanwha Philly Shipyard, destined for Texas and California maritime academies.

The State of Maine is designed for a 21-foot, 4-inch draft, with a beam of 88-feet, 7-inches, a speed of 18 knots, and a deadweight of 8,487 metric tons.

A lesson in island living

Staying cool while waiting for a refrigerator

BY KIM HAMILTON

EVERYTHING IS harder when you live in a remote, rural town. Especially on an island. Especially in summer. When George Gershwin wrote about the easy livin’ of summertime, he wasn’t on a Maine island.

Your houseguest’s forgotten prescription? The missing ingredient in the recipe you are making? (It was on the store shelf last week!) The desperate search to find an electrician, or a plumber, or a carpenter—or really anyone who is handy—when things inevitably fall apart.

These frustrations are of our own making. We live here by choice, after all. It is a lifestyle that favors the patient and the problem-solvers over the rest of the world, where the livin’ is easier.

Those who do choose to stay (and increasingly, those who can afford to stay) live by three simple rules.

First, everything takes longer, or costs more than you plan. Second, Mr. Roger’s advice “to look for the helpers” must have been forged on an island. Bless the extraordinary neighbors who save everything, from small bits

Reflecting on a ‘great business’ and job A career in journalism has met expectations rock bound from the helm

BY TOM GROENING

I MET Bob Woodward in 2012. Colby College gave him the Elijah Parish Lovejoy award for his life’s work in journalism and I was covering it for the Bangor Daily News that weekend.

When I think of who inspired my career choice, George Reeve and Bob Woodward come to mind.

Reeve played Clark Kent/Superman in the 1950s TV show, which was popular as a re-run when I was growing up in the early 1960s. One episode had Superman, still donning his tights and cape, rush into an empty newsroom to bang out a story on Clark’s manual typewriter. Very cool.

But Woodward inspired a more mature career pathway. I was home sick in 9th grade for a few days when the Watergate hearings began, and I was glued to the TV, though I didn’t understand much of the discussion. I was 15 when Nixon resigned.

When the film All The President’s Men was released, I convinced my brother to drive us to the theater to see it. What a great job! Part detective, part moral crusader for Truth, Justice, and the American Way, as the Superman TV show used to put it.

of wire, twine, and wrapping paper to vegetable seeds, bobby pins, and tiny gaskets. These are our helpers and our life savers. Third, plan for the worst and hope to be delighted.

It’s very difficult for others to understand the ebb and flow of a ferry schedule, or the way the tides or weather affect barge services. On an island, anything that actually gets fixed or delivered is a small, daily miracle.

Take our new refrigerator, for example. It was lost at sea for two days. After 26 years, our reliable old Sears and Roebuck Kenmore refrigerator was giving up the ghost. We hated to see it go, not because it hadn’t done its duty over the decades and served us well, and not because it had incurred some unattractive dents across the years. We hated to say goodbye because getting a new refrigerator was surely going to be a hassle. We weren’t disappointed.

life here, planned the delivery carefully. He researched the new models, took copious measurements, removed doors from hinges, and hinges from doors. He lined up local help to take away the old and deliver the new. He conferred with the freight team at the ferry terminal and roughly knew when the fridge would arrive. He greeted each ferry expectantly. And he waited.

Despite assurances from the freight team that our fridge had been delivered, it was not to be found.

Despite assurances from the freight team that our fridge had been delivered, it was not to be found. Lose a box of groceries? Maybe. But a refrigerator? Adventure and sleuthing ensued. My husband was hot on the trail. The mystery was finally solved: Our refrigerator had indeed been delivered. To a wharf… on another island.

and is now stationed in our kitchen, a reassuring reminder of the dozens of things that go right every single day to keep island life humming along.

These days, it’s easy to lose sight of what’s important, to fret over the annoyances and inconveniences of our lives. But living on an island teaches us a valuable lesson. Resilience, patience, determination, neighborliness, and gratitude form the warp and weft of community living.

In a world that values speed, technology, and even divisiveness, these words might ring of nostalgia and sentimentality. For those of us who choose to live where the living isn’t easy, however, we know that this tightly woven fabric is the only thing that truly matters.

My husband, originally from San Diego, but rapidly learning the ways of

Islanders know that nearly everything eventually finds its way home. Our refrigerator is no exception. It continued its travels down Casco Bay

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

And the weapon of choice? Words, with which I had an early affinity.

One summer during my college years, I worked at an all-night gas station. From 1 a.m. to 5 a.m., it got mighty slow, so I had time to read, and worked my way through All The President’s Men.

I think I chickened out from the daunting task of breaking into the business. Instead, I taught high school English and then worked as an employment counselor for community action agencies. Important work, of course, but not aligned with my passion.

Back to Woodward.

That weekend was stressful. The small staff of reporters working weekends meant I had to cover and produce a fair amount of content.

On the bright side, the BDN hired my son Jesse to video and shoot photos of the event, so it was a thrill to be working with him.

I sat quietly, waiting for the talk to begin. A Colby staffer approached me and asked if I wanted to talk to Woodward privately. I flagged down Jesse and we were escorted to a small room. I told Woodward I was one of his stepchildren, telling him about reading the book.

“It’s a great business, isn’t it?” he said. I remember hesitating a second or two before agreeing. The business, as has been well documented, was facing significant challenges then. And now.

Cars, real estate, and what used to show up in the classifieds are now sold online for a fraction of what newspaper ads cost. With web access free in those days, subscription revenue was plummeting.

Yes, it’s a great job, but it was becoming precarious, with lay-offs and down-sizing.

A few months later, I learned the Island Institute was looking for an editor for The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. Landing this job was a godsend.

I’ll admit it was a welcome downshift. But within a month, I realized this newspaper, already widely circulated and much read, provided an opportunity. “I think I can make some noise with this paper,” I remember telling my wife.

At that Colby event, Woodward recounted sitting next to Al Gore at a dinner shortly after George W. Bush defeated him in the election. Why didn’t Woodward “go after” Bush, Gore asked, the way he “went after” Nixon?

Well, Woodward explained, because journalists aren’t charged with picking winners and losers.

The term “storytelling” is bandied about in journalism circles these days, but I’m not fond of it. At our best, we let other people tell their stories. Yes, we like narratives and look for conflict and resolution as we craft our work, but facts and context are key, and they are best presented plainly and clearly.

This is the last issue of The Working Waterfront for which I am editor, though I may contribute in retirement, if our new editor deems that valuable. I never did get to dash into a newsroom in tights and cape to write a story, but it’s been a wonderful career, 38 years in all. Thank you for reading.

Tom Groening will retire in midJanuary. He may still be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

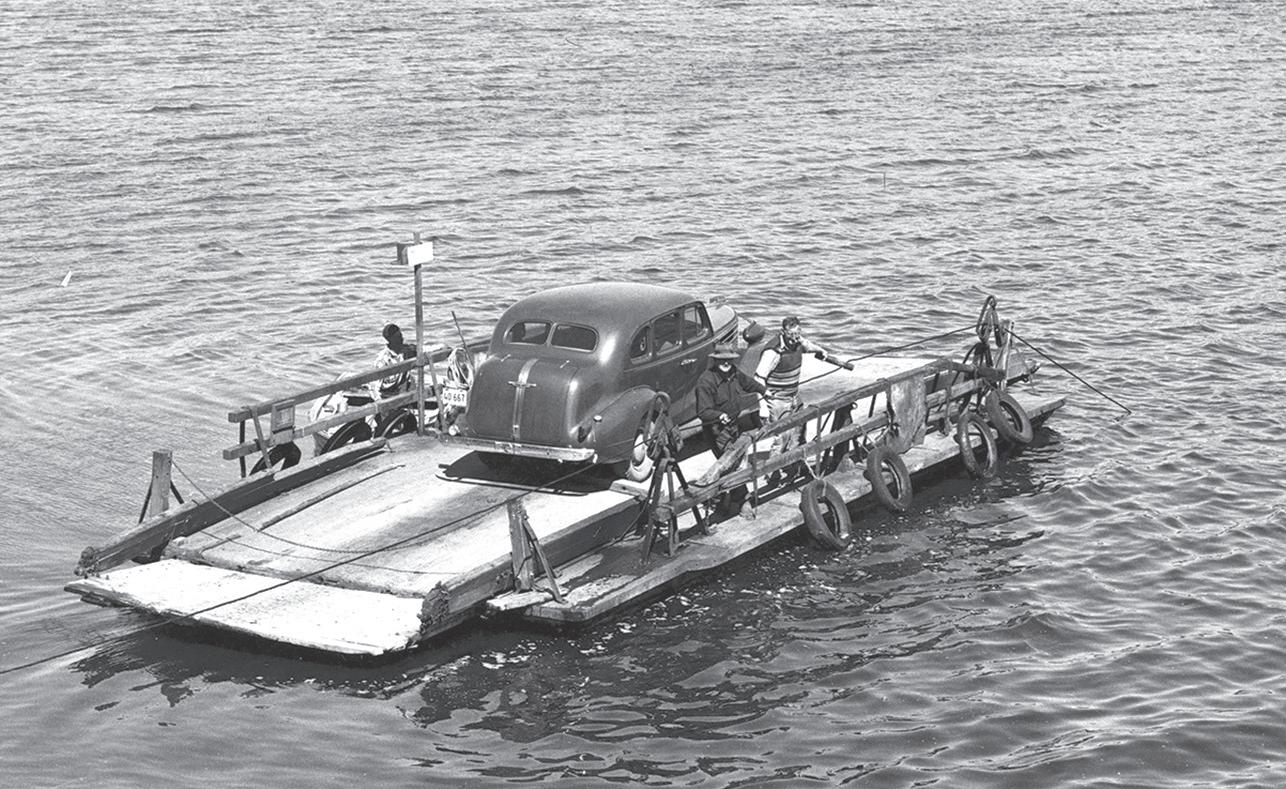

BEFORE THE BRIDGE—

This image from 1941, courtesy of the Maine Department of Transportation, shows how cars were able to reach Westport Island before the bridge was built. Or maybe how a car could reach the island; there wasn’t much room for a second vehicle on this crude ferry.

the public’s policy

Powering the pine tree state

Maine is taking bold steps toward efficiency

BY ERIN QUETELL

ONE OF THE biggest energy issues in Maine is cost. Mainers pay some of the highest electricity rates in the country, a burden that lands squarely on families, small businesses, and municipalities.

High costs are driven by factors like aging infrastructure, a growing electrical demand, and an energy mix heavily reliant on natural gas—a fuel prone to sharp price swings.

What might look like a line item on a utility bill translates into real choices: whether a family heats their home fully in the winter, whether a small shop can stay competitive, or whether a town can stretch its budget to cover other needs.

In December 2020, the state launched Maine Won’t Wait, its first climate action plan. It set ambitious targets: 80% renewable electricity by 2030 and 100% by 2050. Just three years later, state leaders doubled down, moving the 100% clean energy goal forward a full decade, to 2040. The message was clear—clean, affordable energy is essential not only for climate goals, but also for economic security and resilience.

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Secretary, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Michael Sant, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

John Conley

Shey Conover

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Des Fitzgerald

Christie Hallowell

Nadia Rosenthal

Mike Steinharter

John Bird (honorary)

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

The results are already visible. By 2024, Maine reported:

• 55% renewable electricity production

• Over 100,000 heat pumps installed in homes and businesses

• More than 15,000 jobs in the clean energy sector.

These numbers tell stories. Heat pumps mean warmer homes and lower bills in the winter. Jobs in solar, wind, and efficiency mean new career paths for Maine workers. And more renewable power means less reliance on volatile fossil fuel markets.

In January 2025, the Governor’s Energy Office released the Maine Energy Plan, a roadmap for the years ahead. Around the same time, the Legislature passed LD 1270, creating the new Department of Energy Resources, a cabinet-level agency to oversee energy policy and coordinate efforts across state government.

This move reflects a recognition that energy is no longer just a utility issue—it is an economic, environmental, and community priority that needs strong leadership.

The 2025 Maine Energy Plan lays out five core objectives:

• deliver affordable energy for Maine people and businesses

• ensure systems are reliable and resilient against storms and disruptions

• responsibly advance clean energy like solar, wind, and offshore projects

• deploy efficient technologies to lower costs

• expand clean energy careers and support innovation

Still, the transition is not without challenges. Transmission bottlenecks slow down renewable projects connecting to the grid. Communities wrestle with siting decisions, balancing the need for new projects with protecting heritage landscapes, working waterfronts, and “The way life should be.”

As more households adopt electric vehicles and heat pumps, demand on the grid grows, making investments in modernization and resilience even more urgent.

However, we all know Mainers have never shied away from hard work.

From lobstermen testing hybrid and electric boats, to homeowners insulating drafty farmhouses, to students

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that boldly navigates climate and economic change with island and coastal communities to expand opportunities and deliver solutions.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

training for jobs in clean energy, the state’s people are already adapting.

The path forward will require collaboration across all sectors, a role Island Institute continuously plays with complicated community issues. It will require state agencies, municipalities, utilities, and community leaders to invest in resilient infrastructure that is community informed, ensuring that clean energy does not just arrive, but arrives in a way that lowers costs and improves quality of life.

A stronger, cleaner, more affordable energy future for Maine is not a distant vision—it is already taking shape. And if the progress to date is any sign, Mainers are ready to lead the way.

Erin Quetell is public policy director for Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She works with communities and partner organizations and leads government relations work and public policy campaigns to advance the resilience of Maine’s island and coastal communities. She may be contacted at equetell@islandinstitute.org.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

Study examined tuna’s new food source

The decline of herring stocks prompted inquiry

BY NATHAN DEVENEY, UMAINE RESEARCH MEDIA INTERN

Maine’s coastal communities have been hooked on the Atlantic bluefin tuna since at least the late 1880s—first as bycatch, until the 1930s, when the fish became a prized target in fishing tournaments. Through the subsequent decades, bluefin tuna have and continue to support working waterfronts in Maine and beyond.

Despite a decline in prices, a single bluefin tuna can land over $10,000, and in 2024 alone, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that commercial and recreational landings exceeded 3.5 million pounds, fueling a range of economic activities from food markets to boat building and gear sales.

Sammi Nadeau, the lab manager at UMaine’s Pelagic Fisheries Lab, conducted a study recently published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series that illustrated a shift in the tuna’s diet and described the role of foraging in the tuna’s lifecycle.

“You can imagine that those migrations from across the ocean and things like reproduction are extremely energetically demanding,” said Nadeau, “So

being able to get a really good meal, fill back up, and get ready to go back across the ocean is important to fulfill their life history.”

Prior studies dating back to the 1980s found that Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Maine primarily feed on Atlantic herring. In recent years, though, the Atlantic herring stock in the Gulf of Maine experienced a population decline and hit historic lows.

Understanding the role Atlantic herring have historically played in tuna diet, researchers, resource managers, and those working in the fishery were prompted to ask how tuna were filling this new gap.

Nadeau and the Pelagic Fisheries Lab, led by associate professor Walt Golet in the UMaine School of Marine Sciences, teamed up with partners in fishing tournaments and commercial fishing operations in 2018 and 2019 to secure tuna stomachs, which were later filtered for their contents.

The goal was to identify everything in the stomach, determining exactly what species were present. This can be a lengthy process, with researchers identifying what they can visually before sending what cannot be identified off for genetic testing, which can take months.

Researchers observed a large shift in tuna diet away from herring towards menhaden, another fatty pelagic fish, sometimes called pogies or bunker. Additionally, they found that Northern shortfin squid were among the primary prey species tuna consumed in 2018 and 2019. While Nadeau and the other researchers expected to find a declined role for herring, they were surprised by how large a role menhaden played, taking over as a primary prey species.

Menhaden already has a commercial role in fish oils. Now as a food source for an important predator, populations will have a larger burden placed on them. Diet and foraging ecology research ensures marine resource managers have the information necessary to create commercial limits and reduce burdens on fish populations when needed. Additionally, this information helps researchers understand Atlantic bluefin tuna as a species that migrates thousands of miles each year, visiting a diverse range of environments.

The study also quantified how “energetics”—the energy that food sources

NEW GM, CEO—

provide to the tuna—were affected by these dietary shifts. Once the stomach contents were identified, it was possible to find fish from those species and find out just how energetically rich each prey item was.

To conduct this work, researchers use a tool called a bomb calorimeter, which tests a sample by burning it in a sealed container surrounded by water and measuring the change in temperature to see the energy released by the reaction. By and large, researchers believe that menhaden and Atlantic herring share a similar energetic profile, which in addition to the other prey, enables the tuna to migrate and reproduce.

Along with Nadeau and Golet, the study was co-authored by Maine Sea Grant Director Gayle Zydlewski and John Carlucci, a quantitative fisheries scientist and member of the Pelagic Fisheries Lab. This work was made possible with help from the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Association, the Scanlan Family Foundation, and the fishermen who have collaborated with the project.

Casco Bay Island Transit District, also known as Casco Bay Lines, announced the appointment of Ben Dinsmore as its general manager and chief executive officer. A seasoned maritime professional with over 25 years of global experience, Dinsmore brings deep operational expertise, strategic leadership, and a personal understanding of Maine’s island communities. Raised on Maine’s coast and the son of a Maine State Ferry Service captain, Dinsmore has captained large commercial vessels, overseen new vessel construction, and held senior roles overseeing marine operations in both offshore oil & gas and renewable energy sectors. He also previously owned R.E. Thomas Marine Hardware, a Downeast Maine-based engineering company that manufactures marine driveline components for a variety of vessels.

Reflections on divides, as island summer wanes

A community is healthy, but conflict rules country

BY CANDICE DALE

THE BIRDS IN our front yard take turns at the two feeders—a yellow finch, a chick-a-dee, a cardinal, sometimes a bluebird. I watch the elegant dance of two whirling hummingbirds who return each day to suck the sugar water hanging off a feeder on the front porch column.

We humans also share on the island: our fresh grown tomatoes, our zucchini, books we’ve just finished, a power tool, clipped blossoms from a deep blue hydrangea bush. We make potluck meals with friends, share music at the VFW on the hill, bring in guest speakers to expand our horizons.

And each night we fall asleep peacefully to the ringing of the bell buoys in Hussey Sound and the slapping of the waves on the sandy beaches.

Several hundred people live together year-round. This number grows to close to 1,200 when unheated cottages fill up during the warmer months from May to October. We all come to Long Island in Casco Bay with different histories, different politics, different skill sets; and yet, we find a way to work together, year-rounders and summer people, to support a rich island life.

We share photos of stunning sunsets and sunrises on Facebook. We participate in town meetings to find ways to promote workforce housing, to preserve a working waterfront, to support a vibrant small library, to keep the small elementary school open with the dwindling student population (only four students this fall).

Road races, sandcastle contests, Fourth of July parades, Bake House Trivia evenings, and morning coffee at the Boat House Store bring us together to share our stories.

Each day the angst and noise of our troubled country worry me, and I grow afraid of tomorrow for my children and grandchildren, for our communities, for our democracy. I feel as tense and uncertain as I did during the pandemic just five years ago.

I wonder how we will climb out of this chaos and stop the bitter, ugly fighting of our political leaders. I have already lost one old friend over differences of opinion during this past year, and it makes us both feel sad.

Daily I walk around the island to calm my mind, to try to understand the divide in our nation. Why does community seem possible to build on a small island but not nationally?

Each time I walk, I find peace in the sight of a blue heron, a small turtle on a lily pad, an osprey couple caring for their young in a nest built high on an abandoned wharf piling.

Today on my walk the island schoolchildren and their teacher invited my friend and me to join their morning meeting as they gathered on the lawn of the playground. Each child gave a thumbs up or down about the morning mood and shared one weekend adventure.

I found it easy to share my own positive thoughts. I joined them in saying aloud the pledge of allegiance to the American flag hanging on a pole outside the small schoolhouse, not remembering the last time I pledged “liberty and justice for all.”

Machias photo ID

To the editor:

I am writing about the historical photo of Machias in the June/July issue. Although I no longer live in Machias, I did grow up on Water Street, but much farther up. The photo shows the lower part off Water Street approaching an intersection which leads to the bridge and the entrance to downtown.

At the top center of the photo is the Burnham Tavern, peeking out between a tree and the larger dark building (now gone). Directly in front of the Burnham Tavern is a building (Crane’s Garage then) which, when I was growing up, was a beauty parlor, then a dwelling place, and later a gift shop called The Sow’s Ear.

I think the buildings on either side may be gone now. The white building on the right rear is either

Like our stories, columns, and photos? Check us out and “like” The Working Waterfront on Facebook!

One young boy suggested that we sing “Yankee Doodle Dandy” before returning to the classroom, and I joined in. The children’s laughter and bright Monday morning smiles assured me that we will survive.

On this small, independent island, it is possible to listen to one another and to work together to find solutions to community challenges. Of course, it’s not always easy (an offensive political sign, a thoughtless word at a public hearing, a misunderstanding with a neighbor), but for the most part people know and care for one another and want to work together to improve our island way of living.

It is easier to dismiss someone who disagrees with us if he or she lives thousands of miles away or talks to us through a television screen. It’s harder to grow angry with a neighbor whom you’ll see again on the morning ferry or at the island store when you need more milk.

I haven’t found complete relief from my fears about our world falling apart, but during the months I live on Long Island from late spring through summer to early fall, my faith grows that we Americans can find a better way to talk about our differences and to live together in harmony. We can listen carefully to our neighbors, step up to become involved in community problem solving, and walk often so we can to learn from our natural surroundings about how to grow and how to let go and how to find faith in tomorrow.

Candice Dale taught humanities at St. Paul’s School in Concord, N.H. for 29 years. In 1988, her family bought a cottage on Long Island where they enjoy summers. She now lives in South Portland.

Contact Dave Jackson:

the Armstrong House or a dwelling over a garage. The water side of Water Street at that location has been built out and is a small parking lot. It’s fun to see these old photos and figure them out!

Hope for a safer fishery

Nonprofit formed in wake of tragedy

BY TESS WROBLESKI

Liz Michaud has one hope for the fishermen of Maine—that they all return home to their families.

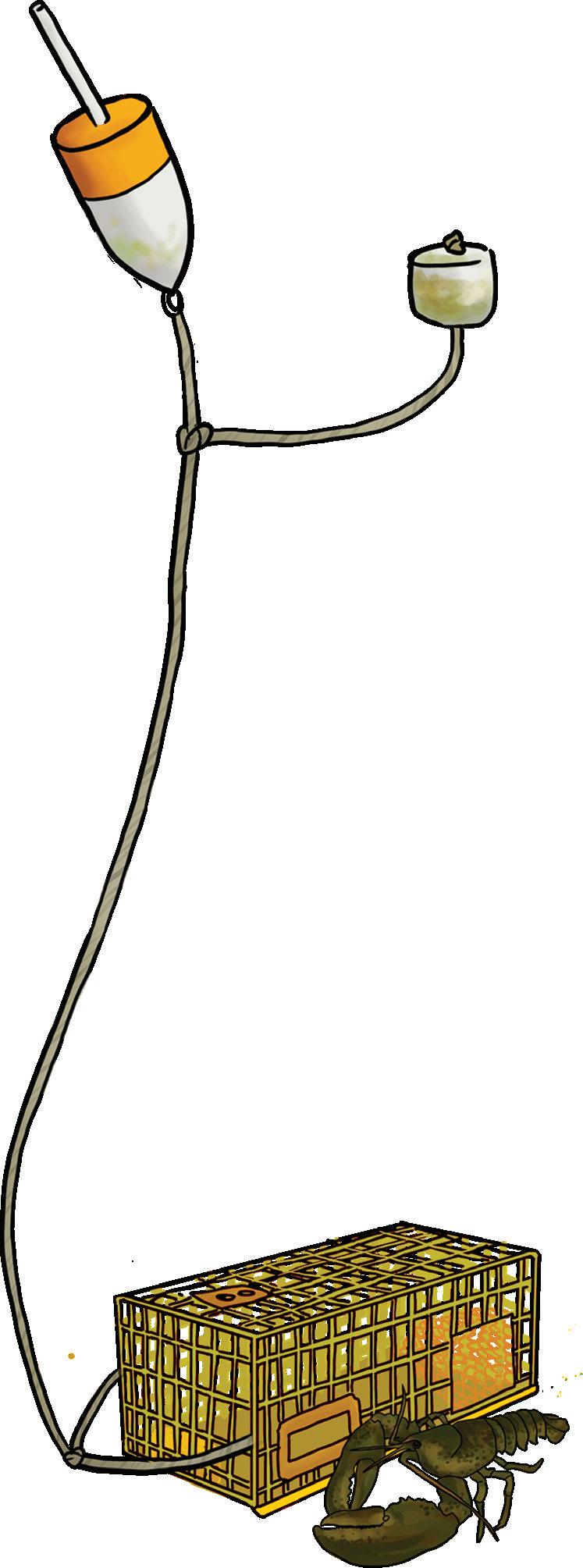

Michaud is the founder of Green and White Hope, a nonprofit organization improving safety for commercial fishermen. She started the organization following the death of her nephew, Tylar Michaud, in July 2023. Tylar had been lobstering alone off of Petit Manan when he was lost at sea. The family had celebrated his 18th birthday just one month earlier.

“He was missing at first, and I tried to keep the hope,” Liz Michaud says. “I thought, maybe he’s on an island with some of his friends. But it didn’t turn out that way.”

Fishing Partnership Support Services, McMillian Offshore Survival Training, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, and the Maine Department of Marine Resources.

“Green and White Hope is really about amplifying the work other people are doing and establishing a coalition for commercial fishing safety in support of that community,” Michaud says.

The fatality rate for fishermen was more than 40 times the national average in 2019.

Michaud launched Green and White Hope, named for the colors of Tylar’s buoys, in April 2025. The organization aims to “honor those lost by learning lessons from their passing, identifying gaps in knowledge, process, or technology that may have helped, and then partnering with subject matter experts to deliver solutions back to the industry,” Michaud says.

They work in several key areas— education and training, technology and equipment, and rescue and recovery.

Partners are critical to the organization’s approach. They work alongside many organizations involved in fishermen’s safety and well-being, including

Monique Coombs, director of community programs for the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, partners with Michaud on safety and wellbeing programs for fishermen. Coombs is a fisherman’s wife and the mother of fishermen. She says promoting holistic well-being for fishermen helps keep them safe at sea.

“If you’re fatigued, or pissed off, or have an overuse injury—even if you’re doing everything you can, there can still be slip-ups,” she says.

Commercial fishing is a notoriously dangerous occupation. The fatality rate for fishermen was more than 40 times the national average in 2019, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

While commercial fishing is dangerous on the whole, certain activities can raise or lower the risk. A 2010 report from the Center for Disease Control showed more than half of the fishermen who died after falling overboard were fishing alone, and none of them were wearing

a personal flotation device (commonly known as a life jacket).

Green and White Hope and their partners address this issue by expanding training related to fishing alone and by promoting the use of life jackets, providing free or discounted life jackets to fishermen, and improving life jacket design.

Life jackets have not always been well-suited for commercial fishing. Thirty years ago, life jackets were cumbersome to wear. Their long straps could get caught in gear, and their bulky fit could restrict movement. In some cases, Michaud says, fishermen felt they caused more harm than good.

In 2025, however, life jacket technology has advanced considerably— from life jackets with very slim profiles, to jackets embedded into the bibs fishermen already wear, to jackets that auto inflate when submerged in water.

Coombs’ son wears a waterproof oilskin coat with flotation woven into the material.

Regardless of the type, “the best personal flotation device is the one you’ll wear,” Coombs says. “That little bit of

support if there is a fall overboard can really make a difference in your safety.”

Green and White Hope has also worked to honor commercial fishermen by helping establish Maine Commercial Fishing Remembrance Day. Michaud and Coombs joined Gov. Janet Mills, Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Carl Wilson, and several other leaders on July 21 for a ceremony in Lubec to honor the first annual Day of Remembrance.

Though the day also marks the two-year anniversary of Tylar’s disappearance, Michaud says it should not be centered on Tylar. “It’s bigger than that,” she says.

Instead, it’s about honoring “the fishermen who have risked everything to put food on our table,” and centering hope for avoiding future tragedies.

The word “hope” is critical, Michaud says. Across the many organizations she has partnered with, “hope is a word that is used quite a lot, because there’s been so much sadness,” she says. “We have to transition towards working on things that bring people home. That’s what gives us hope.”

App tracks coastal change, flooding

crowdsources storm damage, tides

BY CRAIG IDLEBROOK

Anyone living near the ocean knows the coastline changes often with the tides and the seasons, and that it can be difficult to keep track of the coast’s “normal” appearance. With climate change, it becomes even more difficult to distinguish between the normal historical flux of the coast and a fundamental reshaping.

Institute’svalues align with a changing world

HopefulPersistence:

IMPORTANT every now and organization to test its process reinvigorates how an organization important as what it does. team members in fundamentals of the mission. It values are more than wall; they are meant to are muscles we need to build.toshareIslandInstitute’s with readers of TheWorking They are the result of deep about Island Institute’s we engage with communiwe navigate a complex and changingworld,andwhywe work in Maine. organizations may share fundamental values, like respect, integrity, and accountability, we have worked to identify those characteristhat make us unique among our (or,infact,ourpiers).

MyCoast is a digital platform that helps people document coastline changes. Coastal residents and visitors who download the app can upload photos that provide crowdsourced evidence of storm damage, coastal debris, extreme high tides, and beach erosion along the U.S. coast. Some 17,000 users have submitted 58,000 photos and generated 39,000 reports of coastal change, flooding, or debris.

MyCoast also has partnered with seven states, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and a Connecticut community on specific coastline documentation projects. In New England, the platform is currently working with the states of Massachusetts and Rhode Island to document storm damage, coastline adaptation, and flood hazards.

We are reliable, nimble, and relentless with a bold vision for Maine’s future. We move forward enthusiastically in the face of changes. Connection to Place: We appreciate the value and the beauty of the natural resourcesuniquetowhereweworkand live.Weapproachchallengescreatively whilerespectinghistoryandculture.

“hopefulpersistence.”

of exceptionally high tides in Bar Harbor and Portland.

The platform was co-created by Wes Shaw, a coastal hazard policy expert, and Chris Rae, a programmer. They say that enlisting citizens to document damage after a storm or flood multiplies the abilities of officials to document damage.

Authentic Collaboration: We are present, engaged, and build long-term connections to foster trust and deeper understanding. We respect different perspectivesandadaptbasedoninput.

Currently, MyCoast doesn’t have a formal partnership with Maine, but individual users have uploaded reports

culture is secure rock bound from the sea up

In Bristol, R. I., for example, a search of photos shows how high tide can creep dangerously close to a shoreline road, and then how that same road can be strewn with rocks from flood damage.

I am old enough to remember when the acronym VUCA became a common term in the policy and organizationalleadershipworlds.Volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. VUCA described a world that seemed at the time unpredictable and opaque with entangled and complicated parts. This was the world of the famous “unknown unknowns.” It is not unlike today, where the unknown certainly seems to overshadow the known. Will the intensity of last January’s storms revisit us, and ifso,when?Whatdynamicswillshape

Clarity of Purpose: We work where community needs align with our mission. We focus our efforts where we add the most value.

On MyCoast’s Massachusetts page, there are photos of the streets of Salisbury awash with flooding, as well as efforts to prop up a Salisbury beach house. Such photos can help communities and state agencies provide

grounded. We know that hope, when linkedtogoalsandwillpower,isnotapiein-the-sky feeling. It is a framework that allowsustoplanforabettertomorrow.

evidence of the effects of flooding and erosion which can prove useful when competing for funding for coastal adaptation projects, they said.

Another value of the platform, Rae said, is that it gives people a tangible way to interact with the effects of climate change along the coastline.

FromthefirstdayIsteppedintothis role, I have never wavered in my hope that Maine’s coastal communities will chart their own future. I alluded to this two years ago in this column where I wrote, “even in the most challengingtimes,we’veseeningenuityprevail.”

“Quite a few of the projects that people are running on MyCoast are as much about getting people interested in being involved in this, keeping track of this, and caring about it as they are about collecting data for science,” Rae said.

Maine’s critically important fishing industry and the jobs that rely on it?

Can small rural, coastal towns hold fast against eroding infrastructure and the soaring cost of housing? What is lurkingoutsideofourlineofsight?

Such crowdsourcing may also offer an early-warning system for invasive species.

Our newest value, “hopeful persistence,” captures that ingenuity and compels us to be reliable, nimble, relentless, and, yes, enthusiastic in the face of change. Hope tethered to pragmatic solutions has never failed us, and persistence in the face of so many hurdlesisouronlypathforward.

specialized training to monitor for European green crab in Puget Sound; the crabs already are being seen on Washington’s outer coast. These crabs outcompete native crabs while also destroying seagrass and shellfish beds.

To look for the crab, trained MyCoast users look for and measure empty molting crab shells. Shaw was pleasantly surprised by the enthusiasm of area residents to hunt for the invasive species and said that the reports provide valuable insight for the state.

For those of you who know Island Institute well, I hope you can see the heart of our work in the values below.

Resourcefulness: We solve real world problems with practical solutions and an innovation mindset. We allocate and manage the financial and human resources entrusted to us with thoughtfulnessandintegrity.

There is no one right way to approach such overwhelming uncertainty. For us, hope and perseverance provide much needed purchase on this shifting ground.

Trust in COMMUNITY JOURNALISM

Preserving

our

IslandJournal’s place in

BY TOM GROENING

island and coastal

documenting

Celebrating Tom Groening’s contributions to The Working Waterfront newspaper and Island Journal

THEY SAY DAILY journalism is history’s first draft. The idea is that impact and context often take time to emerge,andsotrulyunderstandingwhat happenedisn’tpossibleinthemoment.

of every Island Journal, from the first editionin1984throughtheearly2000s when the content began to appear online, and scan them at our office.

HEAR FROM: Robin Alden—founder of Commercial Fisheries News, co-founder of the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, and Commissioner of Marine Resources in the Angus King administration

So what draft of our coastal and island history is contained in Island Island Institute’s annual publication, whose first edition was publishedin1984?

A few years ago, I received an email from Robin Alden, co-founder of what is now the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries in Stonington and a former commissioner of the Department of MarineResources.Shewaslookingfor a story she remembered from a longagoeditionofIsland Journal.

Colin Woodard—author of The Lobster Coast, American Nations, American Character, The Republic of Pirates, Union, and Nations Apart

I think we then spoke by phone and when I told her we didn’t have most of the Journals indigitalform,shegently scolded me, noting that the publication contained important history about our communities and should be more accessible. She was right. And that prodded me toaction,howeverslowly.

In Washington, for example, some MyCoast users opted in to receive

KimHamiltonispresidentofIsland Institute,publisherofTheWorking Waterfront. Shemaybecontactedat khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

“We have a large number of reports, a surprising number of reports for something so technical,” Shaw said. “There’s no remote sensing way to do this very easily. You need people out looking.”

history

spy it. Many a Saturday morning, I’d sit with a cup of coffee and immerse myselfintheseoffshoreworlds.

And those stories did transport me to what was, especially then, a different world.PeterRalston’sphotosrendereda spare, sometimes mono chromatic scene that matched the struggles of an endangered way of life explainedinthetext.

storiesOurJackSullivan,whosephotosand began appearing in the Journal in recent years, took over integrating those scanned pages with our website. It was a slow, arduous process, but all those stories and photos are now saved as PDFs and available to view on our website: islandinstitute.org/stories/ island-journal/. When I arrived at the Institute 12 years ago, I was excited about having my writing appear in of the Journal. What a privilege, to have my work presented in such an esteemed publication, accompanied by such beautiful photography. Going back farther, I remember, as editor of the weekly newspaper in Belfast in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Island Journal would appear in themaileachyearandIratherselfishly took it home before anyone else could

Ideally, you should be able to pick up an Island Journal from 15 years ago and still find something interesting to read.

Join us for a conversation with TOM GROENING about the important role of trusted community journalism, considered through the lens of Island Institute’s 32-year-old newspaper, The Working Waterfront.

cation,Onthe20thanniversaryofthepubli the editors noted that Journal had shaped the organization. It was a daring venture, they admitted, with half the Institute’s annual budget devoted to the first edition.

Rob Snyder, a former Institutepresident,would say Island Journal aimed to capture island life and culture. Culture, he would explain, was not what artists and writers were up to (though it’s included in the publication), but, having an anthropological background, he meant the Journal was immersed in what made island life different from that on the mainland. Ideally, you should be able to pick up an Island Journal from 15 years ago andfindsomethinginterestingtoread.

WHEN: Thursday, October 30 | 4:30–6:30 p.m.

WHERE: Bayview Point Event Center, Belfast RECEPTION: Drinks and appetizers served

This is your chance to celebrate trusted reporting, ask questions, and connect with readers of The Working Waterfront newspaper.

Hosted by

“IslandJournal…wouldbeameeting place for ideas, a forum for discussions, a venue for poetry and literature, a showcase for photography and the visual arts,” they wrote. It would represent “a new way of thinking about the isolated communities that stretch along theMainecoast”bytellingtheirstories. Click the “View and Download” option for an individual issue. But a warning:it’sveryeasytobeginreading and then look up to realize an hour or morehasdisappeared.

Early in my tenure editing the magazine, I leaned too heavily on stories that were newsier, and I heard from some readers that this was not their

TomGroeningiseditorofTheWorking Waterfront and Island Journal. He maybecontactedattgroening@ islandinstitute.org.

We hired a young woman I know, Danielle Weaver—a part-time fisherafishingfamilyontheSt.

page

North Haven celebrates

PHOTOS BY JACK SULLIVAN

On Aug. 13, North Haven hosted its annual Community Days celebration, and the weather, visitors, and residents all cooperated to provide a

gathering. The 2025 Island Journal is available at Archipelago at 386 Main Street in Rockland (open Tuesday-Thursday 10-4, Friday and Saturday, 10-5) and online at thearchipelago.net/ collections/just-in/products/ 2025-island-journal

FULL INVENTORY READY FOR YOUR WATERFRONT PROJECTS!

• Marine grade UC4B and 2.5CCA SYP PT lumber & timbers up to 32’

• ACE Roto-Mold float drums. 75+ sizes, Cap. to 4,631 lbs.

• Heavy duty HDG and SS pier and float hardware/fasteners

• WearDeck composite decking

• Fendering, pilings, pile caps, ladders and custom accessories

• Welded marine aluminum gangways to 80’

• Float construction, DIY plans and kits

Delivery or Pick Up Available!

Out of their shells

Downeast Institute in Beals celebrates clams

PHOTO ESSAY BY LESLIE BOWMAN

Downeast Institute, a nonprofit in Beals dedicated to marine research and education and focused on commercially important shellfish for stock enhancement and aquaculture development, hosted its annual Shellfish Field Day on Aug. 9. Visitors toured the hatchery and labs, sampled seafood, took rides on R/V Susan, and participated in a clamshell “flying” competition. Downeast Institute is now the field station for marine programs at the University of Maine at Machias.

Our Island Communities

An island patriarch is laid to rest

David

Lunt’s legacy remembered on Frenchboro

BY PHILIP CONKLING

On July 16, a beautiful sunny island day, over 100 family members and guests assembled at the edge of Lunt Harbor, Frenchboro, to celebrate the life of an island patriarch, David Lunt (1938-2025).

The state ferry brought many of the guests from the mainland, the Maine Seacoast Mission’s Sunbeam brought additional guests, while Lunt family lobster boats transported those members of the family now living ashore.

I arrived by outboard from Burnt Coat Harbor on Swan’s Island where Peter Ralston and I had been detained the previous evening by a diesel engine failure.

Over 100 guests assembled on the steep-sided western shore of the harbor overlooking the Frenchboro Church, schoolhouse, and library, the community institutions that anchor this small island in the sea. David Lunt’s sons and grandchildren seated around the gravesite brought to mind Peter Ralson’s stirring photograph of David’s father, Dick Lunt with his hand on Dick’s great grandson, Nate, who had his hands solidly around a large codfish.

Dean Lunt, David’s youngest son, presided over the solemn event, with spiritual comfort provided by the Maine Seacoast Mission pastor who arrived on the Sunbeam. Following the committal in the small cemetery that the Lunt family had donated to the town, guests boarded a solemn procession of lobster boats out of the harbor into a lifting fog to assemble off the western shores of Frenchboro to scatter the remainder of David’s ashes, fittingly in the sea.

I served on the Board of the Frenchboro Future Development Committee chaired by David, which successfully applied for and received funding from the Maine State Housing Commission for a large grant to construct the first seven new houses, including one for the island school teacher, and also repair deteriorated and decrepit docks along the waterfront and patch the roofs of community buildings including the church and school.

The 50-acre parcel for the new houses on the east side of the harbor had been donated by the Rockefeller family as an area where the year-round fishing community could expand.

David Lunt, never one to mince words, explained that the community wanted to attract young families “We need young breeders,” was how he put it.

The Frenchboro community building plan was such a compelling story it got picked up in the press and soon became national news, including a front-page story in the National Enquirer, “Come Live With Us on Fantasy Island!” Within the three-month application period, there were over 3,000 applications that flooded in from all over the country.

MIDDLE: The Frenchboro School, students, and teachers. PHOTO:

TOP: An on-the-water gathering to honor the memory of David Lunt.

David was really the engineer driving the selection process to identify the new islanders and new neighbors. He had a keen eye for those families who could make it in the fishing industry, which was and is the economic backbone of the year-round community.

Rather suddenly, Frenchboro’s one-room schoolhouse would go from one student to about a dozen and with David’s exceptional leadership, a new chapter in Frenchboro’s long and tenacious history had begun.

This moment, in 1998, was captured by Peter Ralston’s memorable photograph of a dozen young school children on the Frenchboro schoolhouse porch.

Next school year, Frenchboro’s schoolhouse will be closed, as most of the island’s children will be going to school on Mount Desert Island, where they

benefit from a larger number of school friends and activities—including sports. Nevertheless, there are a number of younger children on the way, including from one of David Lunt’s grandsons, Joe, who is now Frenchboro’s head selectman.

The tides on Maine islands do not just go out, they also return. Looking out over Lunt Harbor on this momentous occasion, I am struck by the sight of over a dozen lobster boats with Frenchboro as a hailing port, bigger, better-rigged and more prosperous than I can remember seeing their fleet in years. As long as the Gulf of Maine continues to produce marine life, island communities such as Frenchboro will have a future.

Philip Conkling is the founder of Island Institute, along with Peter Ralston.

An island lifeline at 50

Chebeague Transportation Co. provides 11 daily trips

BY LAURA HAMILTON

On April 15, 1975, The Chebeague Transportation Company (CTC) carried its first passengers on the 1.7-mile ride between Chebeague and Cousins islands.

Over the next half-century, the company has fulfilled its original mission of providing safe and reliable year-round service to residents and visitors to the unabridged island in Casco Bay.

To celebrate this milestone, Chebeaguers gathered on July 19 for a birthday party and to watch the new documentary, Lifeline of an Island, chronicling the role CTC has played in the community.

Today, CTC transports more than 140,000 passengers annually, owns two ferries, operates a barging service, manages two parking lots, and maintains a fleet of shuttle buses. The company handles 90% of all travel to and from the island. (Casco Bay Lines also serves Chebeague.)

“I just can’t imagine the island without a CTC,” says Carol Sabasteanski, who was named the first general manager of the company, retiring in 2020. “It is its lifeline.”

CTC operates 4,000 regularly scheduled trips a year. In addition to transporting islanders, off-island workers, summer residents, visitors and school students, CTC also provides 24-hour emergency service, working closely with Chebeague’s volunteer rescue squad.

“The most critical part of CTC is the rescue,” says George “Cap” Leonard, one of the founders of the CTC and a former board member. “It is the principal lifeline of Chebeague Island.”

CTC crews are on duty 24/7 to respond to emergencies, transporting the sick and injured to Cousins Island. Additionally, CTC transports law enforcement personnel to the island as needed.

The importance of ferry access goes beyond emergencies. It is a vital connection that sustains the yearround community, which numbers about 400 people. With 11 regularly scheduled trips daily, the CTC ferry is the “bridge” to the mainland, enabling islanders to commute to work, shop, and manage other necessities.

“Boat access is essential,” says Donna Damon, a Chebeague native and island historian. “If we didn’t have safe, reliable service, this island would become a summer place.”

This is particularly important for island families with children, she continues. “It is very important for kids to have access to the mainland,” to be able to participate in after-school activities, sports, “to be part of the bigger world.”

Leonard and Damon both credit CTC for being responsive to community input. “CTC is part of the fabric of the members of this community,” according

to Leonard. As an independent transit company, it is able to respond to needs as they change.

Established in 1971 as a for-profit company, CTC’s shareholders (eventually numbering 2,500 people) always insisted that any profits be plowed back into the operation to sustain it financially. CTC converted to nonprofit status in 2014.

The company currently employs 27 people, eight of them full-time, including boat captains, deckhands, bus drivers, and parking lot attendants. CTCs primary ferry is the 52-foot-long, steel-hulled Independence, built by Washburn & Doughty of East Boothbay and launched in 2019. The $1.2-million vessel replaced CTC’s 35-year-old ferry, the Islander, which now serves as the company’s backup vessel.

At the time, the Islander, also built by Washburn & Doughty, had logged 408,000 miles, almost all on the 15-minute trip between Chebeague and Cousins islands. Beyond its practical role and daily transportation duties, the ferry also doubles as a popular gathering place for passengers. While the ferry ride is a fact of life for long-time islanders, it provides the opportunity to catch up with friends, finish a grocery list, or to just relax.

It is also a source of some good stories. Long-time CTC deckhand Kim Munroe has a wealth of them. Including one about the forgotten child.

“Someone forgot their daughter at Cousins Island, sleeping in the freight shed [on the wharf],” recounts

Munroe. “It was the last boat of the evening. We got halfway across, and all of the sudden the mother is like, ‘Oh my God, my daughter’s sleeping in the shed!’ So, we turned around and got her. She was very mad at her mother.”

And there was the first-time traveler who arrived on Chebeague at high tide, returning the next morning, demanding to know what Munroe had “done with all the water.”

In 2013, shortly after moving with his family to Chebeague, Matt Ridgway was hired as a CTC ferry captain.