Racing against the tide

Deer Isle Causeway work still a year out

BY JACK BEAUDOIN

The Maine Department of Transportation expects to issue initial engineering plans to replace the 90-year-old Deer Isle Causeway in late February or March, moving replacement of the 4,100-foot stretch of roadway across Eggemoggin Reach another short step closer to reality. But construction—currently planned to commence in 2026—can’t start soon enough for year-round and seasonal residents of Deer Isle.

While islanders had grown used to an occasional overtopping from king tides coinciding with Nor’easters over the past 20 years, concerns about the thin strip of pavement escalated dramatically after 2024’s January storms, when a foot-and-a-half of water covered the causeway. The state was forced to temporarily close Route 15, the only connection between the island towns of Stonington and Deer Isle, and the Blue Hill Peninsula. For a short period of time that felt intolerably long to residents, ambulances weren’t able to transport patients to Blue Hill Hospital, fire trucks couldn’t reach Little Deer Isle in case of a fire and Versant Power crews couldn’t cross onto the island to remove and repair downed lines.

“It was not just a few inches,” recalled Deer Isle Town Manager Jim Fisher. “It was 18 inches underwater,

SUMMER HARVEST—

and rocks were thrown up on it. So even people who tried to venture across it were hitting rocks, and it just was a terrible situation.”

Adding insult to injury, when the tidal surges from each of the storms receded, they pulled away tons of stones and soil, undermining the integrity of the exposed

Fish farm futures unclear

Projects in Belfast, Bucksport, and Jonesport in limbo

BY JACQUELINE WEAVER

Two land-based fish farming proposals—one in Jonesport and one in Belfast—are in legal limbo

at the moment, while a third proposed recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) in Bucksport has let its permits expire.

The only active land-based project currently is Great Northern Salmon in

road surface. In the days and weeks that followed, contractors hired by DOT feverishly rebuilt portions of the causeway abutments that had washed out.

“It had been identified as a top priority for years,” said Fisher. “And after last year’s January storms, the

continued on page 2

Millinocket, which is aiming to build a salmon farm that will produce more than 7,500 metric tons, or 16.5 million pounds, of freshwater raised salmon per year.

The co-founders of the Millinocket company, Marianne Naess and Eric Heim, were at one time involved in the proposed Belfast project under the corporate banner of Nordic Aquafarms. Naess, the CEO of the Millinocket project, says she holds little hope for the success of any salmon farm on the coast.

opinion, is in freshwater and away from the coast. I don’t think you’ll see any RAS facilities on the coast in the near future.”

Opponents say wastewater from the operation would pollute Chandler Bay with nitrogen, among other things, and could lead to toxic algae blooms.

Great Northern Salmon is located on a 45-acre former paper mill site. Working in partnership with Our Katahdin, a local nonprofit, the company has begun cleaning up two lagoons located on the property—one five acres and the other 22 acres. The papermill filtered the sludge and deposited it in the lagoons before discharging the residue into the river.

“Basically, this is a clean-up project funded by the EPA,” Naess said. “‘Our Katahdin got a $5 million grant to do this.”

“This is my fourth,” Naess said. “I was involved in one of the contentious ones on the coast [Belfast.] The future of salmon farming in the U.S., in our continued on page 3

continued from page 1

Maine Emergency Management Agency ranked it among its top two or three priorities. But it has always been vital for the 3,000 year-round people who live down here, and it’s also important for commerce— the biggest lobster landings in the state are in Stonington—and it’s important for tourism, because our population probably doubles in the summer.”

Linda Nelson, Stonington’s Economic and Community Development Director and co-chair of the state’s Infrastructure Rebuilding and Resilience Commission, said the causeway’s viability impacts people off-island as well.

“Ours is the largest port in the state,” she said, “so it’s a vital part of Maine’s economy. It’s the southern terminus of State Route 15, a vital transportation corridor that starts at our port and goes all the way up to Canada, connecting to all parts of the state. And we’re the second largest island in the state. I think we have to remember these things and keep them out in front of everybody.”

HISTORY

Prior to the construction of the causeway and adjoining Deer Isle Sedgwick Bridge, goods and people reached the island via steamboats from Rockland or a 130-year-old family-run ferry service between Sargentville and Little Deer Isle.

But the growing affordability and popularity of automobiles put pressure on state and federal officials to connect the island to the mainland with a real roadway. In 1927, state representative George E. Snowman of Little Deer Isle introduced a bill to fund causeway construction between Deer Isle and Little Deer Isle, and won a $15,000 appropriation to begin work. It was a vital factor in attracting federal and state assistance to build the bridge that crosses the Reach from Little Deer to the mainland town of Sedgwick.

The original causeway opened in 1938. It followed a natural sand bar that was submerged at high tide and was known locally as Scott’s Bar. The narrow roadway follows the serpentine path of Scott’s Bar from one end to the other, an unfortunate route that has resulted in regular accidents over the years. Its construction also ended the exchange of water in the local basin between Penobscot Bay and the Reach, which local shellfish harvesters argue has harmed its ecological diversity.

FIVE ALTERNATIVES

While the causeway had been a local concern for at least two decades, state transportation officials launched the replacement project with scoping meetings in 2023. In addition to input from both towns and the Hancock County Emergency Management Agency, the state solicited input on environmental impacts from both the University of

Maine and the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries. The MCCF also helped with the long and arduous process of gathering public input over the next year.

“Designing a new piece of public infrastructure is a drawn-out process because you need a lot of community input,” Nelson observed, listing a series of presentations at select board meetings, town halls, and “virtual watch parties” that took place on Zoom. “But now we are in serious, let’s-build-this-puppy, engineering mode.”

In August of 2024, preliminary designs from StanTec Engineering produced five alternatives. All of the designs would raise the causeway from nine feet to about 13 feet—about 2 feet above the direst predictions for sea level in 2100—and widen the road to 32 feet, adding five-foot shoulders on either side. The designs would also include slope stabilization to prevent further erosion.

“It was sort of three alignment options, and then two possible culvert or bridge options,” Fisher said, summing up the alternatives. One alignment followed the current path of the causeway, while the other two involved realignments that would push the roadway further out into the water between Deer Isle and Little Deer.

“Each further alignment added $5 million or more to the ticket,” Fisher said. “So, they went with keeping the current alignment.”

“The [UMaine] study focused on potential shortterm impact on commercial fisheries but did not address the current impact of that separation and any long-term impact on the adjacent sea beds, habitats and their biology,” another resident wrote. “We will likely have only one opportunity in our lifetimes to open flows between the two bodies, and it should not be missed at this time.”

Acknowledging such objections, Van Note cautioned that deviating from the preferred design would not only raise the price tag but possibly endanger the project’s completion timeline.

For a short time, ambulances weren’t able to transport patients to Blue Hill Hospital, fire trucks couldn’t reach Little Deer Isle, and Versant Power crews couldn’t repair downed lines.

Already eyeing a $20 million price tag for the most basic design, the state decided against including culverts or a bridge to the plan.

“Our option will result in more resilient and dependable causeways using conditions observed during recent storms and 2100 sea level projections from Maine’s Climate Plan,” DOT Commissioner Bruce Van Note wrote in a letter to town officials explaining the process. “Indications from the UMaine study team are that there will be a finding of minimal ecologic benefit of a bridge or minor span openings through the causeway systems. Accordingly, we are proceeding with a design that does not include such openings.”

MIXED RECEPTION

Reception from islanders was decidedly mixed. In written comments on the project collected in 2024 after the five alternatives had been presented, many residents worried that the state was under-engineering the replacement. “It appears that your ‘experts’ in Augusta have used ‘tidal data’ as the determining factor in setting the new height of the causeway,” one objected. “It is NOT TIDES that are causing and will continue to cause flooding. It is WEATHER.”

Others were disappointed about the lack of an opening between the Reach and Penobscot Bay.

“Continued efforts by advocates to seek additional study and more complicated design concepts could slow environmental processes and delay the project delivery schedule,” he warned in his letter to town leaders.

“It is difficult, of course, to know how fast sea level rise will be,” Fisher conceded. “There are some concerns that we’ve underestimated the speed at which sea level will go up... But if the tide was 18 inches deep during that storm and they’re going up 51 inches, that’s pretty good. And I’ve learned that if you ask enough times, the answer becomes no.”

NEXT UP: THE BRIDGE

The causeway, of course, is just half of the island’s transportation equation.

Nelson and Fisher are already lobbying Van Note to consider replacing the Deer Isle-Sedgwick bridge, which requires expensive annual maintenance and inspections. When the Hancock County Emergency Management Agency simulated a truck accident on the bridge—it carries an average of 4,130 vehicles per day, including 18-wheelers and small trucks—it projected a catastrophic structural failure that would, in real life, mark the end of the span’s useful life.

“We’re trying to find a process or path forward for replacing the bridge, and that’s a bigger, much bigger undertaking,” Fisher said. “I don’t want to give the impression it’s dangerous, but it’s obsolete and it needs to be replaced. The DOT considers that a billion-dollar job. So, it’s an enormous expense.”

And one that the state and federal government are unlikely to take on in the near-term.

“This bridge has been and remains a major focus and priority of MaineDOT … because of the very significant costs and challenges associated with replacing the structure,” Van Note wrote. But based on recent evaluations, the department “concluded that the critical components of the bridge (the towers, main cables, piers, abutments, and anchorages) can remain in service at least another 20-25 years.”

FISH FARM

continued from page 1

She said the remediation work is expected to be finished by late summer 2025. The company projects the salmon farm will create 70 full time jobs with benefits. Unlike virtually every other salmon farm proposed in Maine, the Millinocket plant has encountered no opposition during the permitting process.

“We have great support in the community,” Naess said. She said Great Northern’s operation will be small in comparison to projects proposed along the coast. The product, she said, will be trucked to Boston and distributed regionally.

“It can’t be too small,” she added, “but with all of the technology you have to implement and the treatment discharged, you need a certain scale. There is a sweet spot. A lot of these proposals, I think, initially, were too big.”

Kingfish, Maine, Inc., a subsidiary of The Kingfish Co. in the Netherlands, is awaiting a

decision by the Law Court of the Maine Supreme Court on a permit related to its proposal to grow yellowtail kingfish on land.

Kingfish is proposing a $110 million RAS facility, which the company says will eventually produce 8,000 metric tons of yellowtail kingfish a year and create between 70 and 100 jobs.

The Maine Business and Consumer Court is considering a challenge to the permit the Jonesport Planning Board granted to Kingfish. The permit is being contested by the conservation group Protect Downeast and four individuals.

Opponents say wastewater from the operation would pollute Chandler Bay with nitrogen, among other things, and could lead to toxic algae blooms. But Kingfish representatives claim there are multiple safeguards to monitor the effluent going into the bay.

Farther down the coast, Nordic Aquafarms, which has faced strong opposition in Belfast to their

York County kelp firm wins grant

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF Agriculture has awarded a value-added producer grant to Cold Current Kelp in York County. The company grows, harvests, processes, and produces value-added products from kelp raised offshore in Kittery.

The business will match the $24,700 planning grant with another $25,000 and invest the total to develop business and marketing plans and to explore ways to efficiently increase production.

“Maine’s long history of innovation on the sea is not a thing of the past,” said USDA’s Maine director, Rhiannon Hampson, in announcing the grant. “Companies like Cold Current Kelp demonstrate the potential for the Gulf of Maine to provide us with new, sustainable economic opportunities.

USDA Rural Development is proud to support entrepreneurs who are raising awareness of the value and abundance of our oceans and stepping up to elevate Maine’s reputation with the creation of high-quality products.”

Kelp is a nutrient-dense and environmentally friendly aquaculture product that has grown increasingly popular in recent years. Though it is well known as a specialty food and dietary supplement, Cold Current Kelp instead uses its farmed kelp to create luxury skincare products.

Krista Rosen and Dr. Inga Potter founded the company in 2021 and manage most aspects of growing and processing the seaweed themselves.

Staff from Island Institute and the Maine Technology Institute encouraged the entrepreneurs to pursue ambitious grant proposals. That encouragement paid off, first with a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration SaltonstallKennedy grant for farming red seaweeds. They then secured a USDA Small Business Innovation Research grant

to develop improvements to their extraction process. Now the valueadded grant funding will help them develop solid business and marketing plans, work with Maine Manufacturing Extension Partnership on a manufacturing planning and feasibility study.

“It’s exciting to be involved in all steps of the process, but very time-consuming, which is why the value-added grant program is important,” said Rosen. “It will be a huge benefit for us to be able to rely on other Maine-based professionals to help develop our marketing and business plans. It sets us up for bringing our company to the next level.”

Sebastian Belle, executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association, has been following Potter’s and Rosen’s work.

“Cold Current Kelp is a great example of how Maine aquaculture entrepreneurs are adding value to the wonderful products we grow in Maine’s pristine environment,” he said. “The development of innovative value-added products is critical to the continued growth of the aquaculture sector, and USDA Rural Development programs are vital to those efforts.”

Rural Development anticipates announcing more awards in Maine for this round of funding.

USDA’s Value-Added Producer Grant program helps agricultural producers expand their businesses and increase their incomes by developing new products and reaching wider markets. Farmers, producer groups, farmer-cooperatives, and others are eligible to apply for this program.

For more information contact Ivana Hernandez Clukey, Loan Specialist, Business & Cooperative Services (ivana.hernandezclukey@usda.gov or 207-990-9127).

proposed $500 million salmon farm on the Little River, has a suit pending in Maine Superior Court against the Belfast City Council. The suit was triggered by the council’s vote May 7 to reverse approval of the seizure of intertidal land Nordic required to lay pipes between the farm and the sea.

The city reversed its approval of the eminent domain action following a court ruling that Nordic Aquafarms did not have the right to lay pipes across the mudflats, which had disputed ownership.

In Bucksport, Whole Oceans in 2018 proposed building a land-based salmon farm on the site of the former Verso paper mill. Local residents embraced the project as a means of replacing the jobs and taxes once provided by Verso. But since that time, Whole Oceans’ local permits have expired.

The Maine Monitor recently reported the development, operation, and management of the project are likely the issue with the end cost much higher than what was originally projected.

Study suggests gulls get a bad deal Gulf of Maine seabirds losing in ‘interspecies conflict’

BY TOM GROENING

You’re sitting outside at a waterfront restaurant and a few gulls swoop over and land nearby. Chances are, you and your companions will not marvel at their beauty and grace. In fact, you probably will shoo them away, worrying about them grabbing your food or pooping on your head.

The several species of gulls seen on the shores of the Gulf of Maine may not face extinction, but according to researcher Liam Taylor, the disdain the birds face—from regulators and the public alike—is unfair and unwise.

Taylor, an evolutionary biologist and ornithologist completing a doctorate at Yale, along with colleagues Wriley Hodge and Katherine Shlepr, published a report that argues gulls have been victims of management policies which, though well-intentioned, are not sound.

And as exacting as science may be, Taylor says, subjective biases have played a part in favoring one species over another.

Their study suggests that gulls may be unfairly losing out in an “interspecies conflict,” perhaps because of mistaken assumptions about their populations.

Gulls, he said, are seen as “nonseabird creatures. There’s sort of ‘seabirds,’ and then there’s gulls.”

The report’s title bluntly signals where the researchers landed: “Interspecies conflict, precarious reasoning, and the gull problem in the Gulf of Maine.”

Gulls have been understood as pests or worse, Taylor says, for many decades.

In the 1950s and 1960s, A.O. Gross, an ornithologist at Bowdoin, led “indiscriminate nest destruction” efforts in the Gulf of Maine. Gross used a mixture of motor oil and formaldehyde and, with a pesticide sprayer, applied it to eggs in gull nests.

The concoction would kill the unhatched birds, Taylor explains, “but the gulls wouldn’t re-nest because the eggs would look viable.”

While working on his doctorate, Taylor completed an independent study on Great Duck Island off Frenchboro; the island is owned by College of the Atlantic. And study also was conducted on Kent Island off Grand Manan Island in New Brunswick; that island is owned by Bowdoin College.

“Contemporary conservation science requires mediating conflicts among nonhuman species,” the report notes, “but the grounds for favoring one species over another can be unclear.”

The students “examined the premises through which wildlife managers picked sides in an interspecies conflict,” it continues.

“Managers in the Gulf of Maine follow a simple narrative dubbed the ‘gull problem,’” the report asserts. “This narrative assumes Larus gulls are overpopulated and unnatural in the region. In turn, these assumptions make gulls an easy target for culling and lethal control when the birds

come into conflict with other seabirds, particularly Sterna terns.”

Taylor said reviewing historical and ecological data resulted in no scientific support for the view that gulls are overpopulated in the Gulf of Maine region. And in fact, claims to the contrary originated “from a historical context in which rising gull populations became a nuisance to humans,” the report argues.

Seabirds breeding in the Gulf of Maine include several species of gulls: (Laridae: Larinae), terns (Laridae: Sterninae), and auks (Alcidae), as well as double-crested cormorants (Nannopterum auritum) and a small population of Leach’s storm-petrels (Hydrobates leucorhous), the report notes.

“Two of these groups, gulls and terns, have come into direct conflict.

Large Larus gulls can disturb tern nesting behaviors, depredate nests, and even eat adult birds,” and so conservation managers have chosen a side in this conflict.

Another argument for acting to reduce gull populations, Taylor explains, is that their numbers are higher than they ought to be because of human interaction, such as the food they find in trash landfills. The research found only limited support for this conclusion, he says.

And historical data may not be of great value, the report suggests:

“It is possible that contemporary Gulf of Maine seabird diversity and breeding habitats are less than two centuries old. The historical record offers no guidance for a proper, stable, or long-term population size for gulls, terns, or any other seabird...”

The decision-making process on managing bird populations that are threatened or in decline became a focus of the work Taylor, Hodge, and Shlepr did.

“We’ve been treating certain birds as disposable,” Taylor argues. “We care about nature, and some birds

are under pressure while others are disposable,” a position that didn’t sit well with the researchers.

“We need better reasoning. It may still be worth it to kill them, but not on the basis of foolish reasoning. No matter how much data you have you’re blind to your own biases,” he says.

Regulators must separate gull numbers from the consideration of what they are worth in the ecosystem, Taylor says. He and his colleagues became immersed in “tricky” ethical questions and began examining the intuitions that regulators perhaps allow to influence them.

Eagles, for example, are considered noble, majestic birds, yet their habits are “much more scavenging that was imagined.”

The study report is available at: conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1111/cobi.14299

Rising seas—how high?

Accurate predictions needed to prepare

BY SAIMA SIDIK

Last month, a group gathered in a conference room beneath the Marriott Marquis hotel in Washington D.C. They were there to discuss a question that’s relevant to all coastal residents: We know climate change is causing sea level to rise, but just how much will the water go up?

The discussion was one small part of a massive Earth sciences conference organized by the American Geophysical Union. For five days, roughly 25,000 scientists descended on Washington, many of them to discuss why and how the climate is changing.

But the group gathered beneath the Marriott was different. They were among the few attendees whose job was not to study climate change, but to figure out what to do about it. This was a session for practitioners—city planners and engineers, for instance—and the scientists they work with. In other words, the people tasked with making sure cities remain intact as the world changes around them.

knocking at the door when scientists change their minds every few years?

Take the Army Corps of Engineers’ plan to protect the New York/New Jersey area from another Superstorm Sandy-like event, for example. The Corps is tentatively planning to spend $52 billion on seawalls, levees, breakwaters, and the like to protect New York City and surrounding areas from another event like the 2012 storm, which caused widespread flooding and $19 billion in damages.

At Rockaway Beach in Queens, New York, for instance, they’re building a seawall buried inside a sand dune…

Sea level rise is one of the issues that keeps these folks awake at night. In recent years, estimates of the worst-case scenario have varied wildly—from under one meter to over three meters of sea level rise by 2100—and changed frequently.

“And this is really challenging,” said Philadelphia Chief Resilience Officer Abby Sullivan. How’s a practitioner to know how much water will come

Coast Guard lands repair funding

SEN. SUSAN COLLINS, vice chairwoman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, announced that she has secured a total of $42 million in funding the U.S. Coast Guard requested for repairs to Coast Guard facilities in Rockland, Southwest Harbor, and Portland damaged by recent storms.

This funding was included in disaster relief legislation that has passed Congress and been signed into law. It includes more than $210 million for construction projects, of which a portion will be allocated for repairs to Coast Guard facilities in Maine.

“Through search and rescue missions, ice breaking operations, and navigation assistance, the U.S. Coast Guard plays an important role in ensuring safe maritime traffic,” said Collins. “I worked hard to secure this funding, which will allow for the essential repair of Coast Guard facilities that have been damaged by recent storms.”

The funding requested by the Coast Guard and provided in the disaster relief legislation includes:

ROCKLAND: $40,700,000 to repair the pier and boathouse, which have been in need of renovations, but have significantly worsened as a result of recent storms.

SOUTHWEST HARBOR: $880,000 to replace dolphin piles, short ties, lighting and fender systems, and piles on the pier. This funding will also support remediation and repairs to water damage to the command and boat maintenance building.

PORTLAND: $502,000 to repair the pier and survey for future dredging.

“People are spending just scads of money based on this problem,” said climate scientist Timothy Bartholomaus from the University of Idaho. If working with a more accurate prediction of sea level rise can save even a fraction of a percentage of the cost, “I think that sounds like a really worthwhile investment,” he added. At the same time, revamping design plans every time climate scientists come up with a new estimate of sea level rise would be an overreaction, some participants said. At some point, practitioners have to stop planning and actually do something.

To strike a balance between caution and pragmatism, one has to be willing to bend a bit and consider risk tolerance on a project-by-project basis, said William Veatch from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

At the same time, “We are in the army, so of course we have regulations,” Veatch said. He proceeded to

describe the regulations the Corps uses to incorporate flexibility into regulations, but things got far too convoluted for this reporter to follow.

His examples were more straightforward. At Rockaway Beach, in Queens, New York, for instance, they’re building a seawall buried inside a sand dune to protect against storm surges. It’s easy to add height to the wall and the dune later if need be, so they’re planning for relatively minor sea level rise to keep the cost low.

An elevated roadway, on the other hand, is hugely difficult to raise once it’s been built, so here they’d plan for the worst-case scenario.

Figuring out how to turn scientific publications into this type of risk-benefit analysis is a lot of work for overburdened practitioners. Sullivan said she sometimes does this work “at 11pm, you know?”

She asked the group whether there should be a central U.S. government agency that reviews new scientific evidence on sea level rise, decides whether it’s mature enough to warrant consideration, and issues advice to practitioners. In the United Kingdom, the country’s national meteorological service plays this role.

The response was mixed, with some session participants thinking such a thing is sorely needed and others fearing that a central authority might try to impose a one-size-fits-all solution on a country that values individualism in all aspects of life.

As the session wound down, the tone was a funny contrast to the climate scientist’s habitual refrain of “When will people take us seriously?” Here, the message seemed to be, “How can we take this just seriously enough?”

Storm-related counseling available

STRENGTHENME, a program of Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services, is offering free, confidential, and anonymous mental health and spiritual care services funded through by FEMA in partnership with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. These services are available to individuals, families, and groups in need of support.

One of the providers, Spiritual Care Services of Maine (SCS Maine), has trained chaplains available to speak remotely with anyone seeking to build resilience and hope as they prepare for the challenges ahead. SCS Maine also offers outreach services for groups, especially in industries concerned about

how the upcoming winter might affect their livelihoods, morale, and overall well-being.

The chaplains at SCS Maine offer a compassionate, non-anxious presence for people of all faiths or no faith tradition. To request a call back from one of their chaplains, leave a message at (207) 261-5200 or complete the request form at www.scsmaine.org/ requestachaplain.

If you’re interested in having a chaplain provide resilience training for your community group or workplace, please reach out to Jackie Thornton at jackie@scsmaine.org.

More resources are available at www.strengthenme. com/storm-response-resources/

Reaching the next coastal champions

Our newspaper must evolve with changing times

BY KIM HAMILTON

AS WE PLAN for a new year at Island Institute, I am reminded of the important role that this newspaper plays in our mission. Through our columnists, contributors, and expert staff, we provide accurate and inspiring information about the issues you care about, connecting readers from all over the globe to a shared understanding of the coast of Maine.

The Working Waterfront links our readers to the communities they love, provides a platform for the exchange of ideas, and puts a human face on the issues shaping our coastline, from the quotidian and humorous to the profound.

In 2025, we are renewing our commitment and our responsibility to explore complex issues and share the stories that define the Maine coast. To more fully capture the breadth, speed, and complexity of the challenges facing coastal communities, we are expanding our coverage this year through in-depth videography, social media posts that capture fast moving news, and stories shared from this paper to our blog, website, and Island Institute social media channels. Together, these additions will ensure we provide timely, relevant, and

rock bound from the sea up

accessible information and, importantly, reach younger generations of people who share our commitment to the Maine coast but access their news in different ways.

It is no surprise to anyone who follows journalism that a 32-year-old newspaper wouldn’t survive without adapting to a new reality. So, early in 2024, we enlisted a group of esteemed journalists, communications experts, and publishers to help us understand the new landscape for community journalism.

We also surveyed our readers and our members about what they value most about our publications. We shared more about this in our September issue. Two data points really jumped out to us:

• You trust us for news and information on Maine’s coast by a 5:1 margin over other news sources, such as broadcast media, daily newspapers, and more local sources.

• 80% of our readers are over 65 and more than half of you already access The Working Waterfront content online.

As a highly-trusted source of news and analysis, we found ourselves poised between two very different ways

of communicating and connecting: through the traditional printed newspaper that so many of us appreciate (me included), and in the digital world that moves so much more quickly and visually and is essential for cultivating new interest in and solutions to coastal and community challenges.

What to do? The Working Waterfront launched well before high-speed internet was even a concept—has been distributed for free to thousands along the coast of Maine and delivered directly to mailboxes on dozens of island and coastal communities. More than 2,600 members also opt for direct mail of their papers, including many who reside outside Maine. This direct connection, literally to your doorstep, is a special quality of our newspaper.

Knowing how the landscape for news is changing, however, our question inevitably became, “Who are we missing?” and “Who needs to be in these critical conversations who isn’t?”

With this in mind, we’re excited about the steps we are taking to expand the tent of champions for Maine’s coastal communities. In the coming months, we will provide more of the news, stories, and videos you want via our E-Weekly news and our Instagram, LinkedIn, and other social media channels.

Judging a good man, a life well-lived

Remembering a former legislator and justice

BY TOM GROENING

IN 1999 I was sitting in the Superior Court in Rockland, covering some routine motion hearing for the Bangor Daily News. The business concluded and all were asked to rise as the judge exited. A minute later, the door to the right of the bench opened, and there stood the judge, his robe unbuttoned, gesturing toward someone in the small group milling about. The clerk gestured back, as if to ask, “Me?”

No, the judge indicated, and pointed again, more emphatically. I suddenly realized he was pointing at me and summoning me to the front. Everyone watched as I nervously made my way from the back of the courtroom. What had I done?

Fear and panic must have been on my face. The judge looked at me and said, “Do you want me to hire someone to take a decent picture of you?”

I burst out laughing.

That morning, the BDN had run a promotional photo of me and the other new reporter in the Rockland bureau. The photographer had made a joke, and I laughed as he clicked, resulting in my having a pretty goofy look on my face in the photo.

The judge was Francis Marsano, someone I had known in Belfast for years, meeting him when he was attorney for The Republican Journal, the weekly paper I joined in the late 1980s. He died in late December.

I cringe a bit when I think of my early interactions with him. I seemed to pick fights with him over his (moderate) Republican politics which, looking back, I think sort of amused him. After I became editor of the weekly, he told me he had edited the law review in college. Francis was a proud Bowdoin grad, then attended law school in Michigan.

He was a prominent and well-liked attorney in the county, a status enhanced by his looks—tall, thin, with boyishly curly hair. He moderated town meetings throughout the county and represented the school district and other public institutions, keeping him in the public eye.

But more importantly, he seemed to embrace public service, working on countless nonprofit boards.

Francis was elected to the Legislature and served as his party’s assistant leader in the House. The one night of the week we burned the midnight oil at the newspaper, I could look across Main Street to see the light on in Francis’s office; he would be in Augusta

New video stories and series will offer more immersive and engaging coverage of the issues you care most about: climate and sea level rise, our extraordinary environment, the marine economy, and Maine’s iconic fishing industry.

While we expand our digital coverage, we will continue to print The Working Waterfront six times a year instead of ten, with a standing commitment to unique coverage of the issues you’ve told us are most important. We’ll continue to do all of this with the signature local flavor and sense of place that our newspaper readers and members hold dear. The challenges facing the coast of Maine are big and complex. By opening the digital door of The Working Waterfront, we are issuing an invitation. Come, join us, in whatever format is most comfortable to you. You are welcome here, your commitment to the Maine coast is needed, and we are happy to have you.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

during the day, then attend to his legal work at night. I suspect he worked those hours every night.

His appointment as judge made Belfast residents proud. While covering other motion hearings in Rockland, where reporters sat in a box to the right of the judge’s bench, Francis would be listening to a lawyer droning on and give me a wink.

I used to joke that he would also “hold court” in the produce section of the Belfast Hannaford. We’d see him there, standing in one place as various local folks recognized and then began chatting with him.

He was always kind and interested in my kids. I told them to address Francis as “your honor,” and my then-young son forgot the exact term and called him “your majesty.” Hey, close enough.

My wife Gail and Francis became friends, and in recent years, she spoke with him more than I did, as they saw each other on Belfast’s Harbor Walk. In fact, he was key in persuading older Belfast residents to support the restoration of the former Route 1 bridge as a footbridge, which is now a well-used part of that Harbor Walk.

Francis was always in great shape and climbed Katahdin every year well

into his 70s. He also had an eye for pretty women; not leering, but you could tell he enjoyed noticing and chatting them up.

In the early 1990s, Francis was the judge in a high-profile case Downeast in which a father was accused of methodically beating his son with a baseball bat for various infractions. The boy died of internal bleeding.

I asked Francis how he could sit through the gruesome testimony, day after day. He said he would go see high school basketball games in the evening, just to be around normal folk to restore his perspective.

My connection to the man is but a sliver of his full life, but I treasure it, and I wonder if my generation is as committed to public service as his was.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org

LONG ISLAND LANDING—

This image comes from an undated glass negative photograph showing Ponce’s Landing and the Granite Springs Hotel & Casino on Long Island in Casco Bay. A sign identifying a billiard hall can be seen under the porch of the building on the right. The steamship Machigonne is docked at the landing.

State needs to prioritize working waterfronts

Long-term planning too often derailed in Legislature

BY MORGAN RIELLY

OVER THE PAST YEAR, there has been a growing movement to address the issues facing Maine’s working waterfronts— from Gov. Mills’ Infrastructure Rebuilding and Resilience Commission and Maine’s updated climate action plan, to the Working Waterfront Coalition and community conversations like those hosted by Maine Sea Grant on storm response and preparedness in working waterfront communities.

Despite the great work these task forces, coalitions, and conversations are accomplishing, they still don’t address a key structural barrier: the ability of the Legislature to engage in long-term planning. The January storms of a year ago didn’t just reveal the vulnerabilities of our infrastructure; they exposed a clear breakdown in communication between advocates, coastal communities, and the Legislature.

The Legislature contains many institutional flaws that make it hard to set strategic long-term goals. We have term limits, which results in high turnover, which then leads to poor institutional memory. Our current system incentivizes short-term priority setting and is

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Secretary, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Michael Sant, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

John Conley

Shey Conover

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Des Fitzgerald

Christie Hallowell

Nadia Rosenthal

Mike Steinharter

John Bird (honorary)

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

reactive in policymaking. Additionally, we are faced with constant competing priorities and crises. One thing I have heard time and again in my conversations with nonprofits, communities, fishermen, and aquaculturists is the need for the state to center working waterfronts as a long-term priority.

With this in mind, it is evident the Legislature needs an ongoing, permanent commission on working waterfronts. This permanent commission can serve as a “brain trust” for the Legislature, allowing for consistency in advancing and crafting policy as representatives and senators come and go.

Further, the commission will allow for better coordination between policymakers in Augusta and outside partners, continuing to hold the Legislature accountable when it fails to meet its goals. This will help center working waterfronts as a strategic priority for the Legislature, instead of acting only when crisis strikes.

The Legislature needs an ongoing, permanent commission on working waterfronts…

communities, including members of the Wabanaki Nations, towns, nonprofits, trade organizations, educational institutions, and industries. This group of community members will be tasked with developing a statewide plan for the Legislature to use as a roadmap and will consolidate, incorporate, and build off the work that has already been done by state agencies, nonprofits, and task forces.

That work will ensure that, despite turnover and shifting priorities in the Legislature, supporting our working waterfronts will still be of high importance. Further, this commission will have the ability to aid committees and legislators in drafting effective legislation.

This necessary structural change will lead to thriving working waterfronts years into the future, a fix we must make soon. Without our working waterfronts, our state not only risks losing out on a major source of revenue, but we also risk losing a key piece of our identity.

Failure to protect our working waterfronts also jeopardizes our state’s long-term food and energy security. It’s time the Legislature recognizes that the health of our working waterfronts impacts all Mainers.

I welcome feedback on how this permanent commission should be structured and how it can best represent and advocate for the needs of stakeholders and communities. Together, we can center the protection of our working waterfronts as a long-term priority for my colleagues in the State House, not just for those who represent coastal and island communities, but for all of Maine.

This commission will be led by key members of Maine’s working waterfront

I believe that with annual updates and recommendations from this commission, legislators will receive the information necessary to better support our working waterfronts and make them a strategic priority, not just for our coast, but for our entire state.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that boldly navigates climate and economic change with island and coastal communities to expand opportunities and deliver solutions.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

Morgan Rielly, a Democrat from Westbrook, is serving his third term in the Maine House of Representatives and is a member of the Environment and Natural Resources Committee and the Marine Resources Committee.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

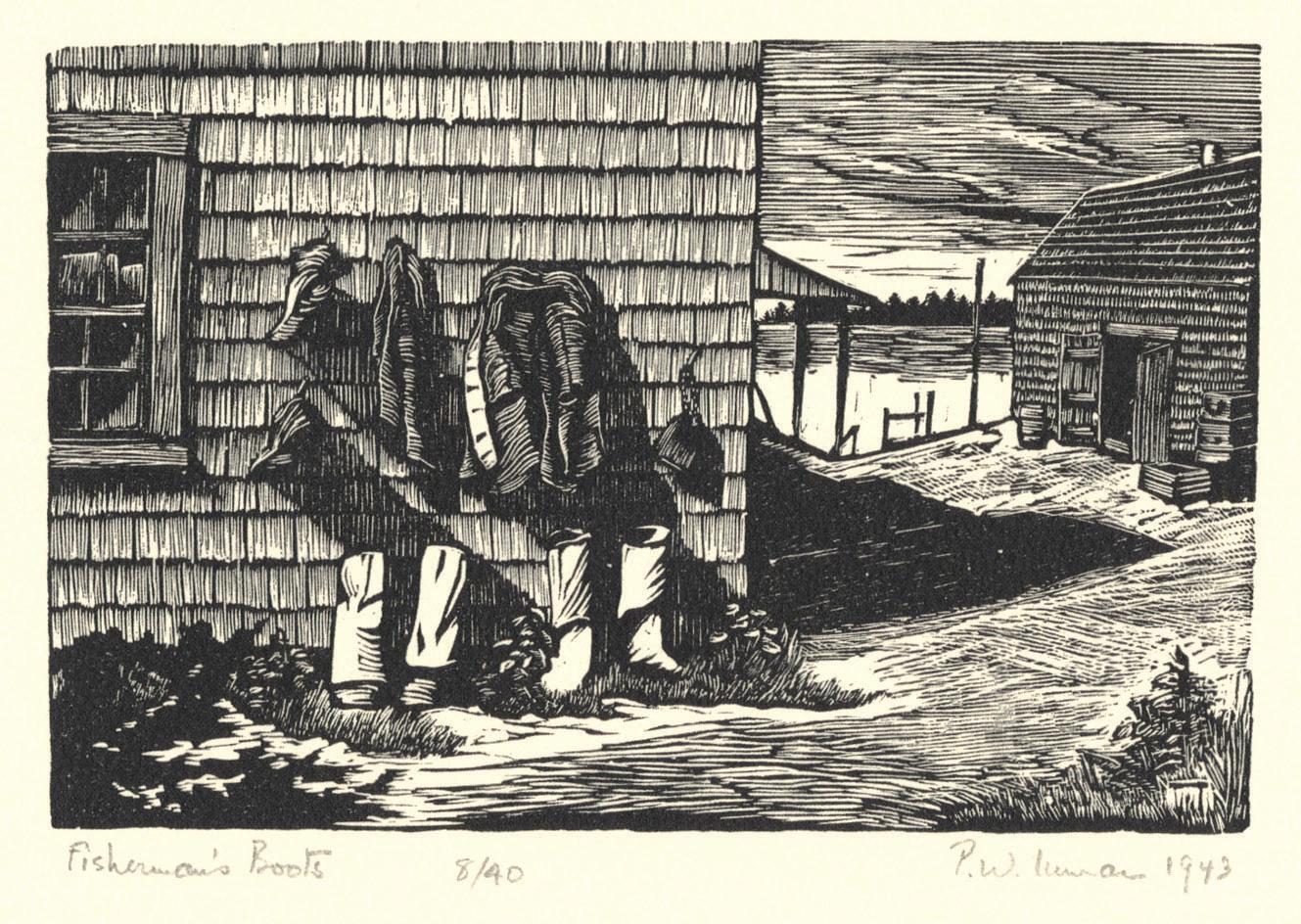

How Newfoundland fishermen protected their own

Fishermen’s Protective Union changed lives in outports

BY LINDA BUCKMASTER

“It could cut the heart out of a man to think too much about what he was working for.”

—Michael

Crummey, Hard Light

To call the life of Newfoundland outport fishing families tough would be a gross understatement. Never mind the incessant wind, the seas, the weather, the sleet, and the bony land that was difficult to farm; they were also caught in an economic system that allowed almost no escape.

The coin of the realm from the 16th century onward was salt cod, which was the only product the families had to trade. But the people themselves had little to say about the value of their fish or the cost of necessities.

Newfoundlanders were employed in the merchant “truck” system. Fishermen were required to fish for and buy their kits and household needs for the year from the merchant companies. Families were so poor in some cases they couldn’t purchase their own hooks to fish for themselves. Women and children were the beach laborers in the grueling work of “makin’ the fish” well into the 20th century.

One fisherman said about the inshore salt cod operation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, “We’s catches

‘em and the womens makes’em.” The skill of turning whole fish into salt cod in the barrel was key to the quality of the finished product’s grade and the price paid to the fishermen.

An industry broadside from the 1850s, “Grades & Classifications of Salt Fish,” describe the characteristics of 24 different grades.

There were variations along the coasts on the exact way to make the best grades, but the basics always were gutted and headed cod, salt, time, and wooden barrels that held a quintal—112 pounds. After the filets soaked in brine for five to seven days, each was laid out in the morning, flat on cobble beaches or raised platforms built of cut saplings, then stacked into a pile at evening.

As one woman in the oral history, Strong as the Ocean: Women’s Work in the Newfoundland and Labrador Fisheries described it: “When [the pile] got so high, we used to make it up almost like a sharp roof, like a peak on a house. This was a real art and had to be done just right, or it didn’t suit.”

When the weather threatened, they were piled up again and laid out afterward. Drying could take weeks. The hardened fish was stacked, filet by filet, into the barrel. Once sealed into the barrel, the salted fish stayed good, even in the tropics.

A finished lot of processed fish was then graded by the merchant’s fish buyer, usually at the end of the season. It

was then the family debt from that year was paid off and what was left could be used to buy flour, lard, clothing maybe, candle wax, and all they needed until the spring when the cycle started again.

As another woman commented: “In the morning sometimes I sat on the bed and me legs be that still and tired, I could hardly get me stockings on.”

The fishermen didn’t fare any better. “Water pups” were the bane of hauling lines in and pulling fish up yearround—a painful string of blisters around the wrist chafing from constant salt water. Newfoundland poet Mary Dalton describes it as “[t]o burn with the fire of water pups.”

It was into this environment that the Fishermen’s Protective Union was initiated by Newfoundland businessman William Ford Coaker. He recognized that the system meant fishermen had no direct access to markets or control over prices.

This state of affairs was a major barrier to improving not only the standard of living for fishing families and their communities, but also to the economic well-being of all of Newfoundland and Labrador. At this time, cod exports were still the backbone of the island’s economy and much of this product was being produced in the outports, small coastal villages accessible only by sea.

On Nov. 3, 1908, Coaker delivered an hour-long speech at Orange Hall in Herring Neck arguing for the formation of a fishermen’s union. He was promoting a more equitable system to spread the great wealth of the fisheries to the common fisherman. He asked those who were interested to stay behind to talk about it and 19 did.

By 1909, 50 local councils had joined with 1,200 members. Five years later, the Union boasted 21,000 members in 296 councils—over half of the island’s fishermen.

It became the British colony’s most dynamic social, economic, and political force. The Union’s rallying cry, “To Each His Own,” was based on the conviction that Newfoundland’s outport “toilers” needed to have more of the profit on the fish they produced.

To that goal, they set up the Fishermen’s Union Trading Co. (UTC) and established stores throughout the province which would not only purchase fish from fishermen for cash but would also bring in goods to sell to fishermen directly.

The FPU also recognized the need to inform and educate the fishermen on what was happening in the various villages and the wider world. To this end, they established the newspaper The Fishermen’s Advocate, published in Port Union, which was called the “only union-built town in the province,” meaning the new fishing port was purpose-built by union labor. The paper was published in both daily and weekly editions from 1914 to 1924.

They soon recognized there was political arm needed to be heard in government and The Union Political party was formed. The so-called Bonavista Platform included items such as schools for every settlement with over 20 children, and subsidies for steamers bringing coal to outports. At the top of the list was standardization and transparency in fish standards and pricing.

On Nov. 3, 1908, Coaker delivered an hour-long speech at Orange Hall in Herring Neck arguing for the formation of a fishermen’s union.

The union operated on three fronts: Foremost was acting as a cooperative for selling the catch to have some say on the grading and pricing. But that wasn’t the whole problem; they also needed to circumvent the inflated pricing by the St. John’s merchants on their gear and household items they needed.

Coaker stepped down as union president in 1926 to focus on FPU’s commercial activities. Many FPU companies had long-term success. According to the Canadian Atlantic Business magazine, the Union Electric Light and Power Company operated until 1967 when it merged with other utilities to form Newfoundland Light and Power.

“The union slowly faded away after its final annual convention in 1939,” the magazine notes. “However, as the first organization of its kind, its impact

on Newfoundland’s fishery cannot be denied. Today, Port Union and many FPU buildings are designated historical sites. [Over a hundred] years later, ripples of influence remain.”

Linda Buckmaster has lived in Waldo County for 50 years. Her most recent

book, Elemental: A Miscellany of Salt Cod and Islands, was a finalist in the Maine Literary Awards. Her traveling literary exhibit, “Of Cod and Communities,” toured Maine coastal libraries. She is currently working on a novel set in late 19th century Newfoundland.

Insurance for

Belfast school launches Marine Institute

Students engage in practice and theory

BY KELLY WALLACE

The ideas were flying, fast and furious, despite the trying circumstances.

As social distancing and remote learning redefined 2020’s educational landscape, Belfast Area High School history teacher Charles Lagerbom was meeting with a handful of likeminded colleagues to discuss a transformation of a very different sort.

Their goal was to grow the school’s existing marine curricular component from a loosely defined set of electives into a full-fledged, multidisciplinary program that would foster deeper connections between students and the Gulf of Maine ecosystem surrounding them.

The Belfast Marine Institute, as the initiative was later named, has come a long way in a short time, bolstered by significant funding and a clear educational framework that features multidisciplinary, STEAM-based coursework; student-led research; internship opportunities; and community engagement.

“In some of those very early meetings, we were kind of sitting there going, all right, what do we want? What do we want to do?” Lagerbom recalled. He and his colleagues settled on several essential objectives. They wanted their students to develop an appreciation

of Maine’s marine resources; an understanding of the issues affecting the marine environment, and an awareness of the many marine-related scientific, technological, and commercial careers available to them. And there was one other goal, which reflected the educators’ hopes for the health and longevity of the state’s working waterfront.

“It was almost kind of selfish on our part,” Lagerbom said, “but it was to keep [students] in the area. To show them that you don’t have to go to Boston or New York or California if you want a marine-related career.”

In 2022, Belfast Area High School was awarded $250,000 in funding from the Maine Department of Education as part of the DOE’s Rethinking Responsive Education Ventures (RREV) program, which allowed the school to implement a pilot for the Marine Institute and Internship Program.

In the school’s grant application process, BAHS’s then-vice principal Jessica Woods emphasized the students’ desire for a clearer line between classroom curriculum and career options down the line.

“When the Marine Institute program was described to students as a flexible pathway to gain skills for jobs of the future through immersive field experiences

and community-based internships in marine and maritime studies, over 90% of students responded that they would seriously consider enrolling.”

Woods also wrote of the school’s wish to better accommodate students with diverse interests, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Our students demonstrate a wide variety of needs and have an even larger range of career aspirations. These demographics necessitate the need for a flexibly designed program that could

support combined [initiatives] such as marine biology research and marine diesel technology exploration in the same classroom.”

As the 2022-2023 school year unfolded, the Marine Institute became a hive of activity, buoyed by the RREV grant that would need to be spent within the next two years.

“We were awash in money and ideas,” Lagerbom recalled. “It was a whirlwind.”

As problems go, it was a good one to have. The institute’s earliest orders of

business included significant, strategic equipment purchases that would carry the program’s initiatives forward, even after the RREV funding ended.

That academic year saw the acquisition of an on-campus wet lab with a 500-gallon water tanker and kelpgrowing materials, as well as a limitedpurpose aquaculture license that permitted students to seed, and later harvest, the institute’s first kelp farm.

In the Marine Studies class, students also experienced diving through a SCUBA discovery course, and engaged with the community through field trips and involvement in Maine’s Fishermen’s Forum and World Oceans Day. They were also certified in cold water safety training, first aid, CPR, and AED—to the entire school’s immediate benefit.

“Each time we do that,” Lagerbom said, “there are 15, 20 new kids walking around the building who can save a life.”

By the time RREV funding concluded at the close of the 2023-2024 school year, the program’s resources included a new fleet of kayaks, a Sonde data recorder, a Garmin Chartplotter, a new ROV, and additional first aid and emergency equipment. An additional $100,000 award from a RREV sustainability initiative allowed the institute to purchase a work boat: a 21-foot Carolina Skiff named Sea Lion, which has contributed to a growing sense of ownership and responsibility among students who are given every possible opportunity to learn the equipment—and then maintain it.

With two years of intense, grantpowered development behind it, the Marine Institute is now increasing its

FULL INVENTORY READY FOR YOUR WATERFRONT PROJECTS!

• Marine grade UC4B and 2.5CCA SYP PT lumber & timbers up to 32’

• ACE Roto-Mold float drums. 75+ sizes, Cap. to 4,631 lbs.

• Heavy duty HDG and SS pier and float hardware/fasteners

• WearDeck composite decking

• Fendering, pilings, pile caps, ladders and custom accessories

• Welded marine aluminum gangways to 80’

• Float construction, DIY plans and kits

Delivery or Pick Up Available!

(207) 772-3796

www.customfloat.com

concentration on the practical applications of a broadening curriculum. As elective offerings expand to include topics like sea stories, navigation, ocean chemistry, small business development, computer science, and technical drawing, the teaching team is also eager to give students an early leg up on the job market with marine-related internship experience and access to formal accreditation in areas like small boat handling, aquaculture, and ROV/drone piloting.

On the administrative side, the institute’s costs are now a part of the RSU 71 annual budget, and the team will be seeking continued local support on its quest for long-term sustainability.

“It’s been interesting for us to be finding our place in the whole system,” Lagerbom said, who noted that, despite some inevitable bureaucratic hiccups,

collective enthusiasm for the program from the school’s administration and broader regional community has been healthy. “A lot of great people and organizations have stepped up, and I think speaks very well for the program’s future.”

Lagerbom also puts great faith in the institute’s students, whose personal interests and goals continue to drive the program’s mission, and Lagerbom, personally.

“The enthusiasm in these kids has totally rejuvenated me as an educator,” he said. “I’m not worried about the future if it’s [led by] teenagers like these. Yes, there are distractions, there are challenges. But to see them come alive like they do over a set of whale bones or putting in a kelp farm… the future’s going to be fine. You get that switch flicked earlier than later, and there’s nothing these kids can’t do.”

The view from Casco Bay’s ‘Friends’

The advocacy group Friends of Casco Bay recently hosted its “Frame the Bay” photo contest, with more than 150 photographs submitted from 50 photographers. The contest’s categories were: Scenic, Wildlife and Animals, Student Photography, and Diversity of the Bay. We’re pleased to show some of the winning work.

Our Island Communities

Went scalloping, caught a porter

Fisherman hauls up 19th century bottle

Henry MacVane of Long Island fishes for lobster, elvers, and scallops, but as any fisherman who drags the bottom knows, sometimes the catch isn’t what was sought. Still, this surprise was interesting.

On the Facebook page devoted to Long Island, MacVane shared the tale:

“Found a really neat bottle near Soldier’s Ledge between Long and Peaks the other day scalloping. Figured I’d share it. I went on to join a few English antique pages to find more info and someone came through!

“For those struggling to decipher the imprinted text, I believe it reads as ‘Jones’s — Ale & Porter Merchant – 20 & 22 Wilton Street – Liverpool –Established 1831.’”

The helpful source from England provided this:

“Wilton Street no longer exists. I think it was bombed during the war [but] it ran between St. Anne Street and Soho Street, near the city center and not far from Lime Street Station. Although proudly claiming to have been founded in 1831, Jones’s obviously didn’t last long.

“I have gone through the Census returns for 1841, and the only Jones still living in Wilton Street was Thomas Jones, then aged 70. By the next Census, in 1851, 20 Wilton Street was occupied by Mary White, aged 53, a widow, but trading as a Publican, suggesting that the building was still involved in brewing.

CHEBEAGUE CONSERVATION—

The Chebeague and Cumberland Land Trust has secured two properties for conservation. The two forested properties, known locally as Sheep Pasture and Hayden Hill, total 17 acres on Chebeague Island. In the fall, the land trust was able to purchase properties which are located in the island center. Funds are still being raised to cover the costs of the land and long-term stewardship.

These woodlands will expand the existing 27-acre Littlefield-Hamilton-Durgin conservation area. Conserved parcels in this largest intact block of forest on Chebeague offer significant island-wide benefits, including recharging the island’s only drinking water source, protecting habitat for keystone bird species, and providing erosion control. In the coming years, both properties will be connected to the historic cart-path network.

“Next door, number 22, was home to Anne Turner, aged 62, also a widow, and cited as ‘Relict of a Merchant.’ Both employed live-in servants, so were quite well-to-do. There was still a Jones living in Wilton Street, at #3, but Joseph was aged only 25.

“I suppose this helps to date the bottle to around 1840, or before. The bottle would originally have contained porter, which is a type of dark stout, like Guinness, but stronger than today, so around 6% or 7% alcohol by volume. It was typically aged in casks for about a year before being prepared for sale by being decanted into stoneware bottles.

“Proprietors and licensees ordered batches of bottles like this one, with their names impressed, because the bottles were re-used and remained their property. Customers were expected to return them for refilling, and most carried a deposit of one farthing.

“The brewing was often small-scale, a bit like today’s craft brewers, and one supposes Jones’s was a fairly domestic undertaking.

“As a rare survivor from a little-known early 19th century brewer, I imagine this would be quite collectable. One similar from a Norfolk brewer recently sold for £250. More typically, they fetch £30-£50 each, if rare, but just a tenner otherwise.”

Thanks to Henry MacVane for sharing this with our readers!

Former island hospital back on market

Historic Great Diamond Island property caught in new law

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

Last March, the city of Portland put out a request for proposal to sell what was once Fort McKinley’s hospital on Great Diamond Island in Casco Bay. The city received one bid for the tax-acquired building. By October, a purchase and sale agreement with the bidder was awaiting the expected approval from the city council when the proverbial wrench jammed up the works.

The city’s attorney was attending a training during which new changes to the state law mandating how municipalities handle the sale of tax-acquired property was discussed. Among the new amendments are changes to how municipalities sell their tax-acquired properties.

Municipalities are now required to hire a real estate agent to list tax-acquired properties instead of soliciting bids through a request for proposal. The new change, effective Aug. 9, 2024, meant that Portland had to restart its effort to sell the hospital.

to Portland-based developer David Bateman in the mid-1980s. Bateman spent 30 years redeveloping the property.

Today, the property is a mix of restored historic fort buildings and new construction, with single-family residences, condos, an inn, and a restaurant that are part of the nonprofit Diamond Cove Homeowners Association. While the city of Portland owns the hospital building and the land directly under it, the land beyond the foundation is owned by the association.

Bateman had an option on the hospital to redevelop it, too, which he ultimately didn’t take. When the option period passed, the city was left with the responsibility of a deteriorating building.

Built in 1903, the two-and-ahalf story, brick hospital has been empty for nearly 80 years.

Built in 1903, the two-and-a-half story, brick hospital has been empty for nearly 80 years. According to the Fort McKinley Museum website, the fort’s construction began in 1890 as part of a federal effort to strengthen coastal defenses.

Fort McKinley was active from the late 1800s through the Second World War. The fort had a staff of around 800, ballooning to 1,400 during World War II. The U.S. Army left the fort in 1947 and the U.S. Navy took over the property in 1954. The property was sold by the navy to private owners in 1961.

In a state of neglect, the fort, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, was sold

“At the end of the day, we just want that building to be redeveloped,” said Greg Watson, Portland’s director of housing and economic development. “We’ve done just some very bare things to make it safe and to keep people out of it, but it is rapidly deteriorating, and we would like to see it brought back to what it was. It’s really a beautiful building.”

When it was built in 1903, Fort McKinley’s hospital’s slate roof was pristine. Its large windows were flanked by shutters. Wood wraparound decks on the first and second floors were made for stretching the legs or sitting to catch an ocean breeze. No tree or shrub obscured views of Casco Bay.

After nearly 80 years of abandonment, the Colonial Revival-style building is posted with no trespassing signs, its remaining wood structures collapsing or collapsed, its windows either missing glass or boarded up. Overgrown trees and shrubs nearly envelop it.

While it’s frustrating that the city had to restart the process of selling the building, Watson is hopeful that a deal will happen. The city is working with real estate agent Sara Reynolds, who listed the hospital for sale in December for $250,000. The listing has resulted in some questions about the property, Watson said, but no offers were made as of the end of December.

The bidder from last spring, Jon Miller of Hemlock House Development of North Yarmouth, has a right of first refusal to any offer that comes in. Portland’s city council approved the right of first refusal agreement in October in lieu of approving the purchase and sale agreement that was made moot due to the changes in state law.

Miller says he’s still interested and plans on making an offer for the property. “The original purchase and sale that we intended to complete will just be the same,” he said at the beginning of January. The Portland Press Herald reported in August that Miller’s bid was $201,500.

“The intent is still to do condos that align with the existing association out there,” he said. In his bid to the city last spring, he proposed nine market-rate condos ranging from 1,500 to 2,600 square feet. If he is able to purchase the hospital, he’d like to begin construction in the spring of 2026, he said, but he is well aware of the significant challenges the project faces.

Among them are financial capacity, obtaining historic tax credits, the costs and complications of construction on an island, adhering to historic property rules, and working closely with the Diamond Cove Homeowners Association.

“Whoever tries to develop it is going to have to really negotiate with the association long and hard, to be honest, because everybody’s very concerned about this,” said MaryEllen FitzGerald, the association’s liaison to the city for the hospital redevelopment project, who lives seasonally in one of the renovated

historic buildings of the fort and in Cape Elizabeth the rest of the year.

While FitzGerald believes most homeowners in the association would support a residential or hospitalityoriented project, such as an inn, everyone is worried that a developer will start the project but not be able to complete it, leaving it in worse shape than it currently is in, she said.

There’s also the huge issue of the septic system. The hospital does not have one, FitzGerald said, and it won’t be able to connect to the association’s overboard discharge system because it is at capacity, so the developer will need to get an easement from the association to put a septic system on association-owned land.

“That will have to be negotiated— and not just negotiated; it has to be approved by 67% of the homeowners,” she said.

If the property can’t be appropriately developed by a highly-qualified developer who has the ability to work with the association, the homeowners would rather nothing be done to the property, said FitzGerald.

For now, everyone is waiting to see if any offers come in. According to the amended state law, the city has to keep the listing active for a year if a sale doesn’t take place.

book reviews

Digging deep into Maine’s recipe pantry

Sandy Oliver’s latest gathers cooking wisdom and stories

Down East Delicious: 175 Recipes from Down East Kitchens

By Sandra Oliver

REVIEW BY TINA COHEN

Sandy Oliver, of course, should be a familiar name to readers of The Working Waterfront. For many years, she has written the “Journal of An Island Kitchen” column for the newspaper. Oliver studied as a food historian and who, as her column tagline notes, “gardens, cooks, and writes on Islesboro.” She also wrote the column “Taste Buds” for the Bangor Daily News for many years.

Her new book, Down East Delicious: 175 Recipes from Down East Kitchens, is joined by a reissue of her earlier Maine Home Cooking.

The recipes from readers of her columns have become content for the two cookbooks. She loves getting recipes, she notes, especially those specific to Maine, which have been passed along generations and still hold up, and often include some family

history. And she gets lots of questions asking for time-tested recipes, and for her own personal favorites.

Oliver enjoys providing suggestions for using seasonal produce, as home gardening is a favorite activity. In her August column for The Working Waterfront she provided great suggestions for beets (use raw beets baked with butter and blue cheese, or grated raw beets and sweet potatoes mixed together and fried like latkes.) In Maine Home Cooking, Oliver features a beet relish recipe. Using cooked and cubed beets with horseradish and cider vinegar, and sugar and salt to taste, she thinks of it more as a salad than a garnish.

On the topic of relishes, her introduction begins, “Basically, making relish seems to be about taking some firm bland vegetable that you have a lot of, chopping it all up, adding spices, sugar, and vinegar, and putting it away to brighten up the flavor of dinner later on.” One example is a zucchini relish. There are also recipes for chutneys, one of the things I most like to make

every summer (and enjoy the rest of the year, with a fruity schmear topping goat cheese or cheddar on a cracker). Last year I used some of my apples and quince for chutney, this year blueberries. But next year I’ll try a recipe from this book and use rhubarb.

There’s “swaggon,” for example. Cooked on the stove top, the dry beans include some salt pork and onion…

In Down East Delicious, Oliver shares what she’s received as recipes, questions, and suggestions from 2012 on. Delving even more deeply into Maine’s classic cooking, she provides recipes for dishes that might be unfamiliar.

There’s “swaggon,” for example. Cooked on the stove top, the dry beans include some salt pork and onion, with milk and butter added towards the end, making it more of a chowder or stew.

With a French-Canadian influence, we get poutine, and from Ireland, a Dublin coddle.

Other less-familiar foods you may not have heard of, eaten, or made at home include old-fashioned milk toast, mincemeat (which can utilize venison), vinegar

pie, lumberjack cookies, double-scrub chocolate cake, and smoked haddock with mashed potatoes and cheese.

Marlborough Pudding Pie is an apple-type pie, made with applesauce instead of sliced raw fruit. I’m looking forward to baking that, as I usually freeze homemade applesauce every fall and enjoy new recipes using it.

Both books feature Oliver’s homespun stories about recipes, contributors, and history, and offer real insight into authentic Downeast cooking, from both the past and the present. And you don’t need to feel you’ve embarked on scholarly research while perusing recipes here—the books read as if a friendly neighbor is sharing her passion with you and making it accessible.

Oliver, from experience in her own Islesboro kitchen, appreciates flexibility in recipes and points out when minor changes are possible, given availability of ingredients. And most importantly, these books help make old styles of cooking things, like using a wood-fueled stove, now work in our 21st century kitchens and with modern-day groceries.

Tina Cohen is a Massachusetts-based therapists who spends part of the year on Vinalhaven.

Susan Webster and Stuart Kestenbaum harmonize

Deer Isle artist, poet create a book to

A Quiet Book: Collaborations in Writing and Visual Art

By Susan Webster & Stuart Kestenbaum (Brynmorgen Press)

REVIEW BY CARL LITTLE

OVER THE YEARS, artist-activist

Susan Webster and her husband, poet Stuart Kestenbaum, have teamed up to create a variety of text/image artwork.

A Quiet Book began during the couple’s residency on Fogo Island off the northeast coast of Newfoundland.

Webster had brought along a cache of scraps from previous artwork to create collages, an approach inspired by the late David Driskell (1931-2020). Kestenbaum responded to her images, each poem hand-written using a Micron pen to make the dots to form the letters.

As the poet explained during a talk at Cove Street Arts in Portland, the pair works this way “because [Susan’s] work has more ambiguity and is open to textual response.”

‘calm our shaken spirits’

slow them down. Describing himself as “a kind of demented Torah scribe,” he embraced the format’s limitations, using ampersands and stretching words to make everything fit.

The 54 pieces in the book are arranged in alphabetical order, from “Air” to “Yield.” The connection between text and image is often subtle.

In “Breathe,” for example, the opening lines, “Sometimes we are/ better off not see/ing clearly and em/ brace whatever t/he horizon brings/ us,” appear to reflect Webster’s accompanying abstract landscape.

Describing himself as “a kind of demented Torah scribe,” he embraced the format’s limitations…

Composed in one go—“no safety net,” Kestenbaum noted—the words (all caps) and lines are arranged—and broken—to fit a defined space, with no punctuation to

In “Drift,” the link is more oblique. What is it in Webster’s enigmatic collage that inspires Kestenbaum to begin the poem, “We like to say th/at teenagers ar/e like ice bergs/how so much of th/eir emotional li/ves are hidden b/eneath the sur/face”? Each element, the visual and the textual, works on its own, but also sets up a nice tension of meaning. Kestenbaum has noted a sense of mortality in some of these poems. Two pieces titled “Eternity” address the end of life, “some pa/rt of me adrift/gone floating o/ver

this sweet/and sad world” in one and, in the other, an evocation of “the tran/ sfer of energy” from roadkill snake to hungry crow.

That said, a lot of celebration also takes place in these poems: flowing, yearning, rejoicing, praying, planting. “Harmony” starts with seeds—a recurring motif—and ends with singing, where “we’re all afloat & dancing.”

Printed in Hong Kong, the book was designed and produced by metalsmith Tim McCreight at Brynmorgen Press in Portland. McCreight and Webster developed the greenish-gray tones that serve as backdrop for each piece.

Susan Webster and Stuart Kestenbaum, “Breathe,” 2023, mixed-media collage and handwritten and letter-stamped text and title, 8 x 8 in.

COURTESY: COVE STREET ARTS, PORTLAND

In her foreword, poet Naomi Shihab Nye calls the book “a profoundly warm meditation to hold us in a better space of thought, to calm our shaken spirits”—amen to that. With its unusual and sometimes challengingto-read presentation, A Quiet Book compels the reader to take the time to consider, as Kestenbaum writes at the end of “Mercy,” “this wo/rld this breath this life oh life.”

Carl Little writes about art, poetry, and islands from Mount Desert.

Beware of explaining islands to islanders

Readable novel veers a bit toward preachiness

By Kate Woodworth (Sibylline, May 2025)

REVIEW BY COURTNEY NALIBOFF

Islands are tempting microcosms for storytelling. The fragile ecosystems, the upstairs/downstairs narrative potential of a summer and year-round population relying on each other for survival, the weathered brow of the lobsterman—these are the lowhanging fruit of island-based novels.

Kate Woodworth has harvested some of that fruit for her upcoming novel, Little Great Island (Sibylline, May 2025). The titular island provides a backdrop for cult escapee and former year-round islander Mari and recently widowed summer resident Harry to collide, with pleasant but not unpredictable results.