The making of a coastal state park

When the Civilian Conservation Corps came to Camden

BY PAUL KAROFF

On an overcast morning in June 1936, 23 young men scrambled into two brown trucks in Southwest Harbor and headed south. By midday, they arrived at a soggy field beside a fir grove on the outskirts of Camden. There, six Army trucks from Fort Williams in Portland were waiting, loaded with supplies and equipment. The men set to work unloading the trucks and “erecting sufficient canvas” to provide temporary shelter.

The cook dug a fire pit for his field range. A truck was sent to the Camden Fire Department to bring back water. The leader of the group, Army Reserve Capt. Herbert C. Pendergast, went to town and returned with a ham, one slice of which comprised each man’s first meal at camp.

The men were issued candles and mosquito netting. When they laid down on folding cots, propped on shims because of the slope of the hill, a cold fog rolled in from Penobscot Bay. It would rain for eight of the next nine days.

So began the 1130th Company of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Over the next six years, hundreds of CCC boys spent thousands of man-hours reworking the landscape—clearing undergrowth, building roads,

trails, and structures, creating water and sewer systems— to create Camden Hills State Park. They did this work largely by hand; no power chain saws, only axes, hand saws, two-man crosscut saws, shovels, and pick axes.

More than 80 years after the CCC camp closed, many of the projects those men completed have been lost—there is nothing left of an ingenious timber bridge that used no nails, and a mile and a half of downhill ski trails have been reclaimed by nature. But

key elements have endured, from the stone stairways on countless hiking trails to the elegant entry gate and gatehouse to the current park director’s quarters to Tanglewood Camp along the Ducktrap River. The federal government had acquired 4,331 acres in Camden and Lincolnville for the “Camden Hills Mountain Park Project.” According to a report in the Rockland Courier-Gazette, the 58 parcels purchased

continued on page 4

‘Glamping’ is growing, but not always welcomed Ordinances need updating, impact to resources considered

BY WILL ROBINSON

Ferncrest Acadia is one of the newest glamorous camping or “glamping” businesses to come to the coast of Maine. Its futuristic geodesic

domes sprang up on a former blueberry barren that once housed a local take-out shack and mini golf course in Sedgwick, a small town on the Blue Hill Peninsula.

Ferncrest Acadia’s owner, Caleb Scott, also operates a small traditional

campground in nearby Deer Isle. After a few years of operation, Scott’s 4-acre camp reached maximum capacity. He decided to expand into Maine’s rapidly growing glamping industry.

“Glamping is still new, but in the years to come, I see it as essentially a blue ocean. [The market] is wide open,” he said.

Ferncrest Acadia is expected to open in early August. Like a lot of glampgrounds in the region, Scott’s new venture was set against a vocal group of neighbors and residents who had a host of objections to the project.

features 400-square-foot plastic-covered domes with windows, offering panoramic views of the landscape.

“ They have beds, they have premium amenities but they have the ability to disconnect in the woods.”

As its name suggests, glamping is a marriage between the natural setting of a campground and the glamorous amenities of a luxury hotel.

Other glampgrounds have large “safari style” canvas tents, yurts, cabins, and even tree houses. Most glamping accommodations come complete with king beds, private bathrooms, and electricity. The properties themselves usually feature restaurants, stores, wellness centers, and common spaces for guests.

“Glamping is a hybrid,” Scott said. “It allows people to have the comforts of home. They have beds, they have premium amenities but they have the ability to disconnect in the woods.”

Some of glamping’s allure comes from its unusual dwellings. Scott’s glampground continued on page 9

Landings reports: good science, but unpopular

Lobstermen must report a host of data points to state

BY STEPHEN RAPPAPORT

From the shore, the life of Maine’s lobstermen may look idyllic. They work their own hours and set their gear wherever they want. They enjoy spectacular sunrises and vistas of the open sea and the magnificent coast. And, at least from that shoreside perspective, they are unfettered by the constraints that limit most who work ashore.

Of course, that’s bunkum.

Lobstermen do set their own hours, but most hit the water long before dawn and work well into the afternoon. And where they can set the hundreds of traps they fish is limited both by law—generally lobstermen may set their gear within three miles of shore and only in the defined lobster management zone in which they’re registered—and by local convention.

No fisherman has legal claim to any particular piece of the ocean floor, but generations of Maine lobstermen have informally marked out sections of fishing bottom where strangers who set gear may find buoy lines tied in knots when they come back to haul. And those sunrises and vistas? Maine lobstermen spend a lot of their time poking around in dungeon fog and near zero visibility or struggling to work their gear in seas that would keep any reasonable recreational boater snug at the dock.

But those travails aren’t the worst of it.

Rough seas, cold rain, blinding fog, they’re all parts of the life that lobstermen freely choose. What they haven’t chosen, and what many lobstermen hate, is the sense that they are under government surveillance whenever they are fishing and, for some, even when they aren’t.

Since the beginning of 2023, Maine lobster harvesters have been required to report detailed information about their fishing activity to the state Department of Marine Resources on a daily, or trip level, basis. The reports may be filed either by using an app, “VESL,” via smartphone or tablet, or by using DMR’s computer-based “LEEDS” program. Reports must be filed at least monthly, and the penalty for not filing is the inability to renew the required annual lobster harvester’s license.

Kristin Garabedian, a community development officer at Island Institute, has been talking with lobstermen and helping them learn the intricacies of the reporting system which, she said, calls for “a lot of information at a granular level” using systems that can be “confusing and difficult.”

That’s an understatement.

The LEEDS report for each trip calls for specific information:

• the number of traps, and the number of multi-trap trawls, hauled

• the total number of traps and buoys in the water

• the depth at which the traps are set

• the number of crew

• how long the traps “soak” (stay in the water between hauls)

According to Garabedian, lobstermen have expressed “a lot of frustration,” both about the complexity of the reporting systems and the fact that the fishermen are not able to access their own data once it has been submitted. And some fishermen just don’t have access to the technology that reporting requires.

Hilton Turner, president of the Downeast Lobstermen’s Association and a longtime Stonington lobsterman, raised the same issue recently while talking about the many problems inherent in the reporting system. Many lobstermen, especially the older ones, don’t have computers, and some don’t even have smartphones. A friend of Turner’s, like many lobstermen who aren’t technologically savvy, pays someone to file his reports, but he still has to manually compile the data for every trip.

The rationale behind installation of the trackers is, according to DMR, “to collect high resolution spatial and temporal data…”

• the length of the trip in hours, the location where traps were hauled, based on nautical charts showing each of the state’s lobster management zones divided into numbered, roughly 10-squaremile sections.

The reports also call for the quantity of lobster landed and information about where that occurred, whether at a dealer or elsewhere.

Turner’s wife, a teacher, does his filing, presumably on an unpaid basis.

“If it weren’t for my wife, I’d have it all messed up,” he said. Most lobstermen who fish only in state waters, and not in federal waters outside the three-mile limit, rely on LEEDS rather than the smartphone VESL app that fulfills both state and federal reporting requirements.

Lobstermen with permits to fish in federal waters have even more to deal with. In addition to the required reporting, each boat must be equipped with an electronic vessel tracker that operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and transmits the vessel’s position via cellular service once per minute while the boat is moving and every six hours when it isn’t underway.

The only time the tracker may be turned off is if the boat is powered down for at least a month. That’s usually during the winter when many boats are ashore.

The rationale behind installation of the trackers is, according to DMR, “to collect high resolution spatial and temporal data to characterize effort in the federal American lobster and Jonah crab fisheries for management and enforcement needs.” That will “improve stock assessment, inform discussions and management decisions related to protected species and marine spatial planning, and enhance offshore enforcement.”

Turner’s son fishes in federal waters, reports via VESL, and has a tracker on his boat. He regards the reporting system as “a POS” that frequently malfunctions, or spits back data or even changes what has been entered.

Despite complaints about required universal reporting, recently appointed DMR Commissioner Carl Wilson said the collection of detailed landings and fishing data is critical for Maine’s lobster industry.

“The requirements for 100% of Maine lobster fishermen to report landings and for federally permitted lobster vessels to install trackers are now providing a complete picture of effort in Maine’s lobster fishery as well as greatly improved spatial information on where the fishery is occurring,” Wilson said in late June. “This is critical for targeted, effective regulations that maximize resource protection and minimize adverse impacts to commercial fishing, whether in management of the lobster fishery itself, or the pending federal whale regulations.”

Turner understands the need for good data but, unlike Wilson, he has to deal with the reporting requirements on a daily basis and has a different perspective about them.

Filing those reports “every day, year after year” can be frustrating, Turner said. “We don’t want to be bookkeepers,” he said. “We just want to be working men.”

Greens gone wild Former Hancock County golf course returned to nature

BY CATHERINE SCHMITT

On a hot morning in late June, the western shore of Jordan River in Hancock County teemed with wildlife. Osprey and cliff swallows soared over a sea of tall grasses, where bobolinks and savannah sparrows perched atop clumps of alders. Fritillary and crescent butterflies wandered among blooming clover and daisies; deer had worn tracks through the grass. The air smelled of wild strawberries and the salt water that bordered the rolling fields.

Except for the occasional sand pit and numbered granite pillar and lowslung wooden clubhouse at the top of the hill, it would be easy to forget that not too long ago, this land hosted an 18-hole golf course, and before that a dairy farm.

In 1967, local residents, funded by individual donations and a federal government loan, constructed the Jordan River Country Club on 150 acres between Route 204 and the Jordan River, an estuary of Frenchman Bay. It never became the community recreation center they had envisioned. Over the ensuing decades, various owners continued to manage the site as a golf course. On what was billed as “Maine’s most scenic and challenging 18-hole golf course,” closely clipped greens, separated by trees planted in lines like strands of beads, surrounded

a large pond created to provide irrigation for thirsty grasses, to keep the greens, well, green.

Undamming that pond is now the core element in Frenchman Bay Conservancy’s plans to restore ecological function of the property, according to the group’s director, Aaron Dority. Funded with $2 million from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Coastal Wetlands Conservation Grant Program, as well as support from The Nature Conservancy, Maine Coast Heritage Trust, Anahata Foundation, Maine Natural Resource Conservation Program, Broadreach Fund, and private donors, the land trust will reconnect streams to the sea and allow the fringe of salt marsh to expand inland.

The marsh was the primary motivation for purchasing the property in 2023, said Dority. Though relatively rare in Maine, salt marshes play an outsized role in providing habitat for fish, birds, and other wildlife while keeping water clean, protecting uplands from storms, and storing carbon. Marshes are also at risk of disappearing beneath rising seas.

explaining the project to staff members Chrissy MacKinnon and Mike Whittemore as they walked along the earthen berm that separates fresh water from salt water.

A defunct culvert stuck out from the side of the berm, the pond’s exit channel eroded by recent storms. In August, work will begin to remove bridges and culverts from beneath old fairways, uncovering long-buried streams.

“We’ll let forest regrow over most of the greens, but we’ll also maintain some area as open meadow to sustain birds as well as bees and other pollinators,” said Whittemore.

For those who consider golf courses symbols of everything wrong with the state of humannature relations, the idea of “rewilding” is a dream come true.

“This is a place where we could support marsh migration,” he said,

The land trust is working with Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Service to assess wildlife habitat.

Back in 1967 when the Jordan River Country Club was created by Charles Katsiaficas and Kenneth Blaisdell and other locals, it was open to tourists but was meant primarily to serve Hancock County residents.

Frenchman Bay Conservancy has similar intentions. It has retained access

for marine worm harvesters to more than one mile of coastline and plans to create accessible trails so that more people can experience the place. The gentle slopes and grass foundation are well-suited to trail construction, said MacKinnon.

For those who consider golf courses—with their sterile, sculptured terrain of imported plants constantly mowed and sprayed with chemicals— to be symbols of everything wrong with the state of human-nature relations, the idea of “rewilding” is a kind of dream come true. But a golf course is still green, open, unpaved space.

Because the land was a golf course, said Dority, it remained intact and retained the possibility of once again becoming forest, stream, and salt marsh.

“Rather than demonizing the property, we want to help people see something different in the land,” said Dority.

The groundcover may be imported but it is nevertheless alive and growing. The soil may have chemical residue from years of fertilizer and pesticide treatments, but it is still soil, layered and deep. Native plants and trees, kept as screens and scenic backdrops, flourish around the edges.

Standing amid the waist-high wildflowers, looking out at fish jumping from the sparkling turquoise waters of the Jordan River, the team did not have to work too hard to, once again, imagine the property as a community resource.

STATE PARK continued from page 1

included “many poor farms which are unable to support their present owners.”

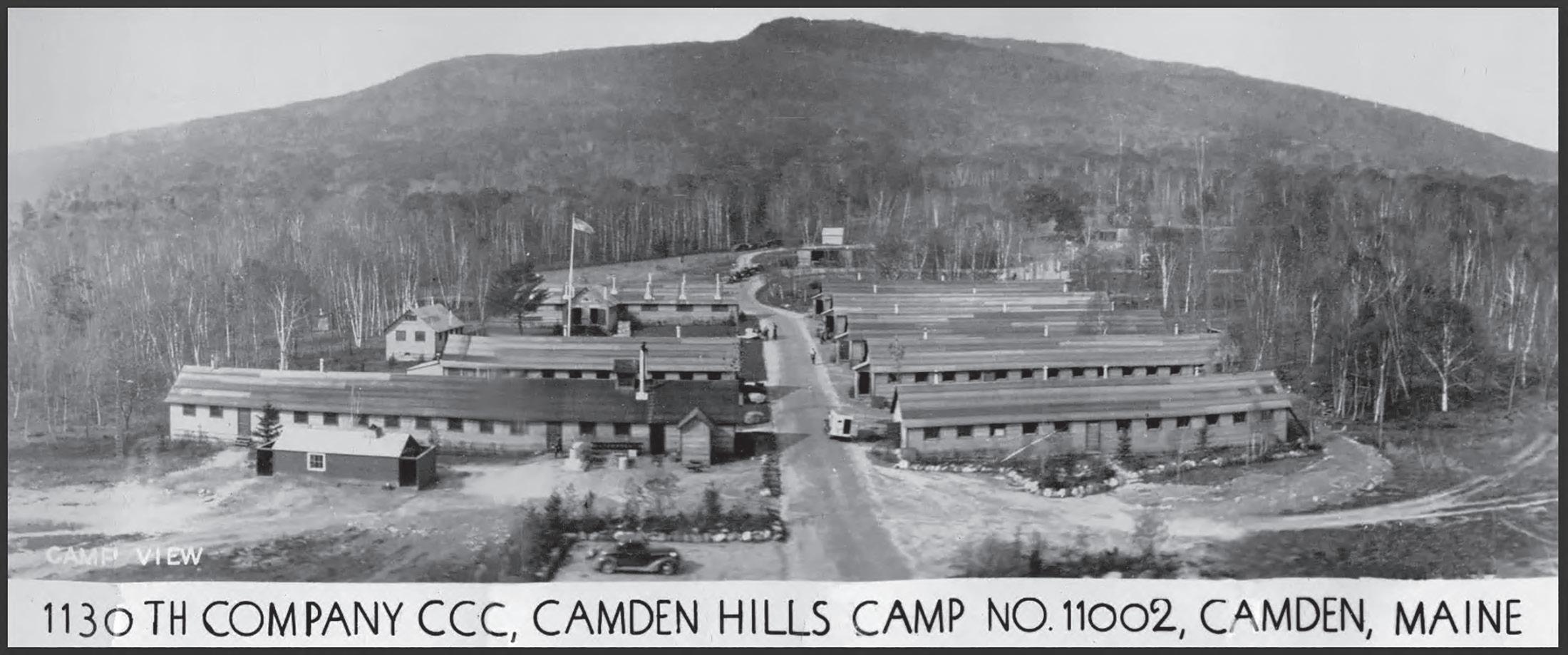

The CCC camp was located a mile north of Camden village off Route 1, on the site of the former Sagamore Dairy Farm, whose buildings had burned down years earlier. Within weeks, the initial CCC cadre was augmented with reinforcements to help construct permanent camp buildings—four barracks, each housing 50 men, a laundry/bathroom, kitchen and mess hall, recreation building, infirmary, administrative building, officer housing, garages for trucks and equipment, repair shop, blacksmith shop, and tool building.

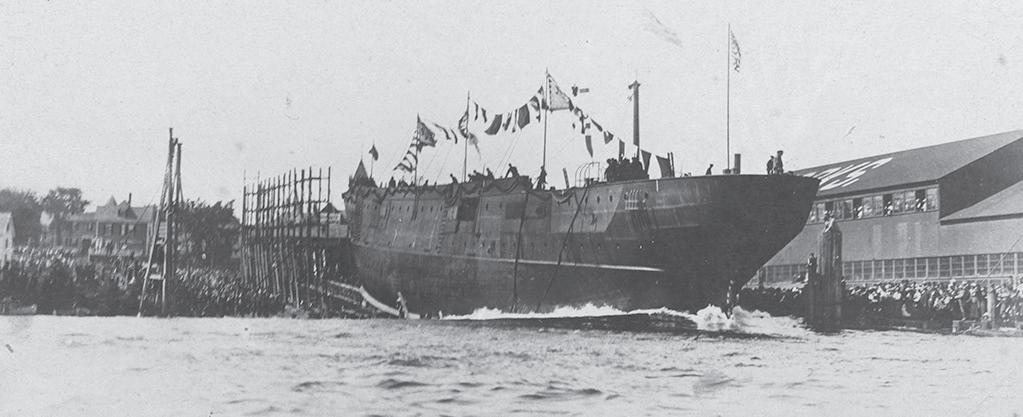

At 10:40 a.m. on Aug. 10, 167 new CCC enrollees stepped off a train at the Rockland railroad station. An hour later the group arrived in Camden and were soon having their first meal in the camp mess hall. For the next six years, a steady complement of 200 men rotated through, toiling to carve a park out of the Camden Hills.

Arguably one of the most successful Great Depression-era jobs programs, the Civilian Conservation Corp—sometimes called Roosevelt’s Tree Army—employed three million men in conservation-related work from 1933 to 1942.

One in four American workers was out of work at a time when most households relied on a single income. Bank closures, and home and farm foreclosures were sapping the economic vitality and morale of communities from coast to coast. People skipped meals,

Aquaculture for People and Planet

OUR

7

TH CLIMATE OF CHANGE FILM

Join us for a free screening of Aquaculture for People and Planet! Learn how Maine’s shellfish and seaweed farmers are leading in lowcarbon, climate-friendly food production. This short film from our Climate of Change series highlights how Island Institute is supporting a resilient, sustainable seafood economy. A panel of local aquaculturists and Island Institute staff will explore the promise of low-emission, locally grown seafood—and how Maine can lead the way.

turned off their heat, and sometimes electricity as well, inserted cardboard scraps in holey shoes, and used paper from free shopping catalogs for toilet paper.

The prospect of three square meals and steady work was attractive to boys who were going hungry

JULY 21 FILM PREMIERE!

7:00 pm-8:30 pm | Lincoln Theater, Damariscotta

AUGUST 26

7:00 pm-8:30 pm | Neighborhood House, Northeast Harbor

AUGUST 27

7:00 pm-8:30 pm | Opera House Arts, Stonington

SEPTEMBER 24

7:00 pm-8:30 pm | Maine Beer Company, Freeport

at home or, in some cases, had no place to call home. In fact, even among those who cleared the physical fitness bar, 75 percent of CCC enrollees entered underweight, many weak from malnutrition.

Snaring a spot as a CCC member was competitive. By 1939, only one in five applicants was selected. Enrollees had to be 18 to 25 years old, physically fit, unmarried, and unemployed. They were paid $30 a month, of which $25 was sent to their family. The CCC also provided spots for smaller numbers of out-of-work World War I veterans (no age or marriage restrictions), as well as so-called Local Experienced Men from the immediate community who could train the regular recruits in the skills needed to accomplish their work, such as handling an axe or forestry management.

In the April 1936 issue of The Sagamore, the Camden camp newsletter, the CCC was described as having “two fundamental objectives: the completion of worthwhile projects and the building of manhood … In the Civilian Conservation Corps camps many opportunities are given you that are not to be had on the outside: honest work, the chance to learn different jobs, religious, social, athletic and educational advantages—these are all here.”

In addition to stable employment, educational opportunities were a core component of the CCC. Most enrollees had no more than a high school education and thousands of boys learned to read and write thanks to the camp education programs. The Camden camp provided courses four evenings a week in practical subjects such as business, arithmetic, automatic grease gun operation, blacksmithing, English grammar, first aid, typewriting, diesel engines, etiquette, navigation, and auto mechanics. There were also less academic offerings: radio club, boxing club, bow and arrow making, fly fishing, orchestra.

Camden was one of 28 CCC camps in Maine, each with a complement of roughly 200 men, in addition to 50 “side camps” with 50 to 75 men. More than 16,000 Mainers found employment in the CCC. They worked on what became Acadia National Park, Baxter State Park, hundreds of miles of fire roads, dozens of fire towers, telephone lines, erosion control, water and sewer lines, tree planting, rip rap projects, and forest insect and disease control.

The 1130th Company in Camden worked under the direction of Hans Heistad, a gifted landscape architect who was the visionary behind the most iconic elements of the fledgling park. The stone park gate and gatehouse were Heistad’s design, as was a cascade and rock picnic area on the lower Sagamore section and the warming hut at the base of the ski trails on the east slope of Mt. Megunticook.

“We don’t disturb nature. We just improve on it,” Heistad told a Rockland Courier-Gazette interviewer. “We make a picture out of the material God has let us have.”

Company leaders submitted a comprehensive park master plan for approval by CCC authorities in Washington. Work progressed on a project-by-project

basis, with detailed accounting of man-hours and materials expended on each aspect of the park’s construction.

Not everything in Heistad’s master plan was realized. The CCC never dammed several streams near Spring Brook Valley to create a fishpond. Nor did his most ambitious vision come to fruition: a 1,500-seat amphitheater carved into the hillside of the lower Sagamore section, appointed with stone terraces and overlooking Penobscot Bay to Islesboro, Vinalhaven, and North Haven.

The CCC crews built Tanglewood Camp on a 50-acre tract along the Ducktrap River in Lincolnville, including 40 rustic buildings with capacity for 72 campers plus staff, and an 80-by-120-foot swimming pool supplied by an artesian well.

In 1939, when the YWCA of Bangor and Brewer occupied it, the Bangor Daily News described Tanglewood Camp as “a modern recreational project built by the government as a demonstration of the best in architectural planning for a character-building camp.” Today, the University of Maine Cooperative Extension operates a 4H camp there.

When they weren’t building picnic areas, scenic drives, hiking trails, camp sites, Adirondack-style shelters for use by overnight hikers, a fire lane around the 5,000-acre park property, or planting more than 7,000 trees and shrubs throughout the park, the men of the 1130th Company were put to work away from Camden. Fifty members worked for weeks-long stretches at a “side camp” near Katahdin, building the truck trail into Roaring Brook Campground in the recently created Baxter State Park. Camden CCC boys were called on to fight forest fires in nearby Lincolnville and as far away as Boothbay Harbor and assisted in search and rescue missions. On at least one occasion, they helped search for an escaped prisoner from the Thomaston prison.

While Americans generally supported the CCC, many residents were apprehensive about a camp being sited in their community. Locals fretted about how 200 young men fresh off the breadlines and unaccustomed to discipline would behave when they ventured into the local community on a Saturday evening. But the record suggests a symbiotic relationship between Camden’s CCC boys and the host communities.

Camp leaders regularly emphasized the need for the boys to comport themselves in ways that would reflect well on the reputation of the camp. In March 1937, Commanding Officer Capt. M.D. McLaughlin wrote: “The boys of this camp have been well received by the inhabitants of Camden and have many friends there. They have entered social life, assisting social groups in putting on shows and so forth. Some of the enrollees have taught in church schools and have done other church work as well.”

At Christmas, CCC boys repaired toys for needy children. During the winter of 1940-41, CCC enrollees volunteered weekends to help with the construction of a ski jump and other elements of what is today the Camden Snow Bowl at Hosmer Pond.

In turn, Camden and Rockland schools loaned 3,000 textbooks for the camp library and education programs and enrollees had borrowing privileges at the Camden library.

Not only did men serving in the camp’s close quarters form lifelong friendships, more than a few men struck up romantic relationships with local girls that led to marriage.

Most of the senior leaders of the 1130th were commissioned officers or had military backgrounds. Some were veterans of “the World War” (in those years, few contemplated a second great global conflagration).

The Roosevelt administration explicitly fashioned the effort as a civilian undertaking, resisting voices advocating a more military flavor. As the years passed, some questioned that approach. By 1936, some members of Congress proposed giving CCC boys limited military training and weapons familiarization. Three years later, 75 percent of respondents to a Gallop survey thought that “military training should be part of the duties of the boys in the CCC camps.”

While no such change was ever implemented, CCC enrollees nevertheless benefitted from military discipline.

“All aspects of our lives as CCC boys were Armyoriented,” wrote Norman Wetherington of the 1124th Company in Bridgton. “We lived by Army regulations and ate Army chow. Our clothing, equipment, and inspections were Army, much of which was World War I vintage. The one exception to regulations was that we did not have to salute our officers. We were a civilian organization.”

The U.S. officially entered the war on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. CCC camps across the country were closing because the men were needed in uniform. Ultimately, the training and physical fitness of CCC men qualified them for quick acceptance into the armed forces and 90 percent went on to serve.

On August 8, 1941, the Camden Herald carried a three-paragraph item at the bottom of page 2 reporting that the 1130th Company had left town. By then, only 78 men were still at the camp; 48 transferred to Bar Harbor and 30 to the camp in Alfred. As CCC members went to war, the Camden camp became home to an army detachment.

The 1130th Company “successfully carved a ‘park’ out of land that had been lumbered, burned over, and neglected,” recalled Earlyn W. “Stubbie” Wheeler of Rockport, a foreman at the camp. “It left its mark on the community and on the hundreds of enrollees that came and went during its existence.”

Nationwide, the CCC instilled in thousands of men a deep appreciation for conservation goals and principles, values they shared with their families and communities.

The state of Maine took over management of the Camden Hills State Park in 1947.

The power of big dreams

High-speed internet casts a net to the world

BY KIM HAMILTON

MY HOME on Chebeague Island entered a new age last year—we finally connected to high-speed internet. Honestly, it’s so simple now that it’s difficult to remember being on the wrong side of the digital divide, where telehealth, telecommuting, and teleanything was out of reach.

The opportunities on the other side of that digital divide have long been apparent to Island Institute. With rural, coastal, and island communities already struggling for resources and attention, we knew that broadband offered a pathway for a different future. This is why we tackled the challenge head-on beginning in 2013 when the consequences of exclusion were already in play.

Small businesses could not compete with others that had better, faster connections. Islanders with health issues easily managed through a remote visit faced long commutes and delays. Seniors longing for more frequent community and family connections were especially feeling the brunt. And of especially high concern, young

people and young families dependent on reliable, high-speed access could not aspire to work in the community in which they lived.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all pattern for high-speed internet in small communities. That’s why we developed an approach as unique as the communities we serve.

Our community-driven broadband process provided a model that engaged communities in designing the future they wanted from broadband. This included assessing the true costs over time, structuring a partnership with a provider, and considering universal access for all community members.

Over the past ten years, we have provided nearly half a million dollars in broadband planning grants to help communities better understand how to move forward. We helped secure more than $50 million in public and private funding to support community initiatives.

Working with partners, we also helped lead a successful $15 million bond campaign—resulting in the largest investment to that date ever made by the state in high-speed internet expansion.

rock bound from the helm

This sort of community-driven work is a true long game. In June, Island Institute joined a community ribbon-cutting ceremony on Isle au Haut to celebrate the completion of a project that has been almost a decade in the making.

This was no small feat. It required laying 6-and-a-half miles of cable from the island itself to Stonington and from there to a central network. It also called on community volunteers who had the staying power and passion for a long game. For this community of 50 year-round residents, broadband became a foundational investment in their future and worth the wait.

Access to broadband isn’t enough, of course. Knowing how to use the new technology is just as important. For example, all commercial lobster license holders are now required to report electronically the location and the amount of their catch every month.

Working in Stonington with the Connectivity Hub and the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, we’re helping to train lobstermen on new electronic reporting requirements. In this way, we’re building critical digital

literacy skills that turn broadband into the Swiss army knife of community solutions.

Nick Battista, our chief policy and external affairs officer, likes to say, “Never bet against an island community when they want to go big.” Isle au Haut — like Bremen, towns along the Blue Hill Peninsula, Chebeague, and many others —is an extraordinary example of a small community doing big things.

The audacious tenacity that brings these big dreams to life in small communities is the secret sauce we like to invest in. It’s even sweeter when these big dreams become reality and ensure the places we love most can remain a home for generations to come.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

Camping adventures and misadventures

The call of the wild has grown much quieter

BY TOM GROENING

THIS ISSUE of The Working Waterfront features a story about the emerging trend of “glamping,” a term coined to describe a version of camping that’s a bit more glamorous.

I’ve had some camping experiences, most of which weren’t glamorous.

My father, being a schoolteacher, had summers off, and after several summers of working odd jobs during the break, he purchased a small travel trailer and lugged my mother and my three brothers and I off to various national and state parks.

A memorable trip came in 1965 when we and another family traveled from home in New York across the country, visiting many of the iconic national parks—Grand Canyon, Zion, Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Teton, Glacier, and Crater Lake among them. Even at the tender age of six, the images of those dramatic landscapes— reinforced by home movies—left their mark on my understanding of the beauty and scale of our country.

Later summers included trips to Florida (way too hot and buggy), Maine and Quebec (my father’s home movies captured the last of the log

drives on the Kennebec), and then we settled into a series of two-week stays at state parks on lakes in New York’s Adirondacks, working our way north through the summer.

By the time my older brother and I were teens, we rankled at the confines of the small trailer we all shared, and Dad bought us an 8-foot by 10-foot cabin tent, and we would be able to stay up as late as we wanted, reading by the light of a Coleman lantern and listening to New York City AM radio stations beaming the Top 40 hits off the ionosphere.

Being away from our friends for eight weeks during that long school break had my older brother and I longing for home.

rooms, watching re-runs of Gilligan’s Island and Bewitched.

Later, I understood our parents were wise in giving us a more active and wholesome summer.

We would be able to stay up as late as we wanted, reading by the light of a Coleman lantern and listening to New York City AM radio stations…

Once, when the boat’s outboard needed work at the dealership back home, we returned for a few days in late July, and I gleefully biked to my friends’ houses to join in whatever fun and mischief they’d gotten up to. I was surprised to find them lounging in their living

When I was about 12, I won a floorless pup tent for selling chocolate bars as a fundraiser for my Boy Scout troop. The scouts provided a different version of camping, more akin to Lord of the Flies.

My father tells the story of me returning home after a weekend scout camping trip, ranting about the terrible state of the food we ate—undercooked burgers, chicken that had fallen into the fire, dirt on everything. Who did the cooking, my parents asked. “I did.”

Our scoutmaster left us way too under-supervised.

After sleeping with another six or seven boys in ancient canvas tents that leaked, I was pleased to use my new pup tent on one scouting trip. It didn’t leak, as I learned when an older

boy decided to empty his bladder on it as I readied my bedding for the night. For one summer—a full eight weeks—I slept in that little tent by myself, before we had the cabin tent. With the family inside the trailer every night, I would head out to my little tent, the only thing between me and ground a piece of hard Styrofoam. To this day, I wonder what I was trying to prove to myself. I relented in sleeping inside the trailer on the very last night as the temperatures dropped in late August. I relish being outside in glorious summer, in Maine and elsewhere in New England. But at night, I’ll take a nice Airbnb over the fresh air.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. He may be contacted at tgroening@ islandinstitute.org.

ALL IS WELLS AT THE SHORE—

This beach scene from Wells in the 1930s features a grocery store and ice cream shop offering Deering Ice Cream.

the public’s policy

Good policy comes from informed policy makers

Working waterfront protection is now better understood

With this issue we’re introducing a new, regular column dedicated to exploring and explaining the nuances of public policy at the federal, state, and local levels as it impacts Maine’s marine economy, climate resilience, and community vitality.

BY NICK BATTISTA

FOR THE LAST 20 years, Island Institute has worked on public policy dedicated to protecting Maine’s working waterfronts. In that time, attention by policy makers has ebbed and flowed—and the last year represents the highest watermark yet in terms of substantively advancing this policy area.

Since the fall of 2023, we have made a concerted effort to drive public policy towards addressing the needs of Maine’s working waterfront businesses by expanding the understanding amongst policy makers, working to include these issues in guiding documents for the state, and supporting funding for this sector.

A couple of years back, I remember talking to a colleague who is deeply involved in efforts to retain jobs and grow the economy, about how

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Secretary, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Michael Sant, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

John Conley

Shey Conover

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Des Fitzgerald

Christie Hallowell

Nadia Rosenthal

Mike Steinharter

John Bird (honorary)

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

important working waterfront infrastructure is to the economy of coastal communities. There was an incredulous look when I started talking about how these facilities have ten to 15 jobs and were absolutely integral to the success of 30, 40, or even 100 small businesses.

Those of us who work in coastal communities understand the vital role working waterfronts play in supporting jobs in our communities, yet this role has not been as clear in statewide discussions.

In the fall of 2023, while working on updating the Maine Won’t Wait climate action plan, we noted a key opportunity to influence the development of a policy document. As this process started, Island Institute convened the Working Waterfront Coalition, and together, we worked through the major issues facing working waterfronts and the potential policy interventions.

Going from the initial framework to the language that appears in specific strategies of Maine Won’t Wait took about nine months and more than 20 public meetings, which included those interested in working waterfront protection and state agency staff. As a co-lead of the group focused

specifically on working waterfronts, I’m proud of the work this group did to come together around key issues.

Some of these ideas eventually became activities included in the state’s successful $69 million resilience grant. Many other policy interventions became part of the 2024 update to Maine Won’t Wait, and these focused on increasing the resilience of Maine’s heritage industries, including protecting critical infrastructure like working waterfronts.

They also informed the development of the working waterfront recommendation in the Infrastructure Rebuilding and Resilience Commission (IRRC) report released in May.

The damage the January 2024 storms did to coastal communities launched working waterfront-related policy from a relatively small, niche issue to a significant issue for policy makers. The storms also revealed that privately owned infrastructure requires new policy solutions. In response, the Legislature provided $25 million in the spring of 2024 to help rebuild those private working waterfronts. These funds start to close a critical gap in public support for this sector.

The clearest articulation to date of the needs of working waterfronts

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that boldly navigates climate and economic change with island and coastal communities to expand opportunities and deliver solutions.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

comes from the IRRC report where one of the 11 strategies is focused on the need to protect and promote working waterfront resilience. In this strategy, the commission recommends:

• Identifying and mapping the most vulnerable working waterfront infrastructure

• Investing in resilience upgrades for public working waterfronts

• Strengthening the resilience of privately owned working waterfronts

• Creating new policy options, funding, and technical assistance to protect working waterfronts from conversion to non-working waterfront related uses.

• State government is poised to support these goals.

Island Institute looks forward to continuing to partner with the state and members of the Working Waterfront Coalition to advance this important work.

Nick Battista is chief policy and external affairs officer for Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at nbattista@ islandinstitute.org.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

The making of a captain, by intention Alliance trains next generation of

BY CRAIG IDLEBROOK

The making-of-a-fisherman myth we often subscribe to has him growing up on a boat, eventually making captain, and then inherently knowing how to succeed as he takes the helm. In this scenario, the fishing fleet is continuously reinvigorated by the children of fishermen.

In reality, the New England fishing fleet is rapidly graying. For example, the average age of groundfishermen is 55 years old, according to a recent National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report.

Regional fishery advocates formed The New England Young Fishermen’s Alliance in 2022 to help the next generation of fishermen and fisherwomen to obtain their own boats and succeed in the industry. Each year, the Alliance offers its “Deckhand to Captain” program, a nine-month-long, free training program that provides aspiring New England captains with the business skills and mentorship to succeed in the region’s fishing industry.

The classes are held Monday nights each week in Portsmouth, N.H. The program has recruited trainees mainly

New England fisherfolk

from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. This year, the organization also received a special grant for outreach in Southern Maine from The Builders Alliance, a foundation seeking sustainable solutions for energy and food production.

Such a training program is needed because young people in the fishing industry are facing headwinds when it comes to taking the next step in their careers to becoming captains, says Andrea Tomlinson, the Alliance’s executive director.

These fishermen have witnessed the collapse of New England’s groundfish industry and have seen the cost of doing business rise. They also have seen rapidly changing ocean conditions which affect the health of fish stock, along with the imposition of new regulations. Some of these fishermen are being discouraged by older fishermen from investing in their own boats, she said.

enter the lobster business, and they were quite upset that he entered the training program,” Tomlinson said.

“But we still got his dad, a lobsterman, to be his mentor.”

Since the trainees must have at least three years of commercial fishing experience to be accepted into the program, they already know the work. The program focuses on the other skills needed to be successful in the industry.

Some of these fishermen are being discouraged by older fishermen from investing in their own boats…

“We even had a trainee last year whose family did not want him to

For example, facilitators discuss how to create a business plan and keep accurate business records, and trainees then talk with lenders who provide loans for boat purchases.

Trainees are paired with mentors in the industry who can share their wisdom as small business owners. They also receive training in public speaking, which Tomlinson

said has become a necessity, as fishermen often need to advocate for their industry.

“We are constantly getting media questions,” she said, such as: Are there young fishermen that we can talk to? Are there young fishermen you can bring to this meeting? Can you get them to the council meeting? Can you get them down to the port authority meeting?

The answer to those questions must lie with the young fisherfolk, she said. “We have to teach young people to advocate for themselves.”

Public speaking skills are also important when trying to reach consumers, Tomlinson said. The program helps fishermen think about how they can brand and market their product to get a higher price for their catch.

“We give the fishermen and women a concept that you don’t have to dump your stuff at a low-ball wholesale price to a broker to make a living. You can do that 80% percent of the time, and 20% of the time you can sell direct to consumer in a community-supporting fishery model or in a farm store model,” she said. “Diversification is so key right now.”

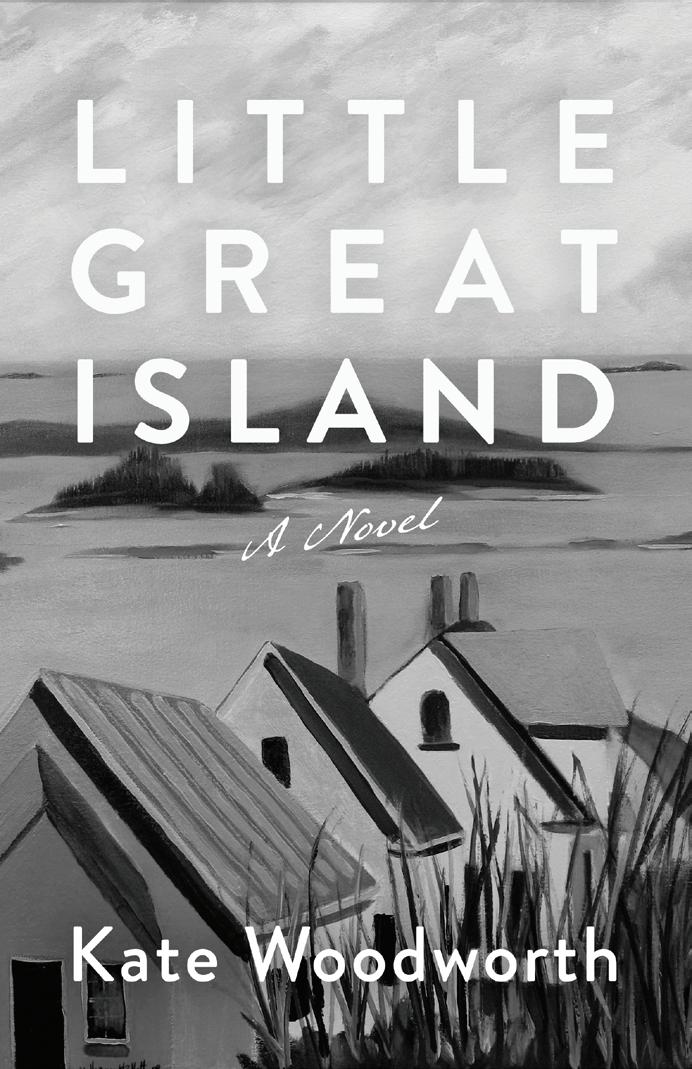

LITTLE GREAT ISLAND

“An extraordinary achievement and a pure pleasure to read.” —National Book Award Winner Ha Jin

“A delightful read for anyone in need of a strong dose of Coastal Maine.”

—Linda Greenlaw Wessel, author of The Hungry Ocean and The Lobster Chronicles

AUTHOR APPEARANCES

Vinalhaven Library

August 6, 7pm

North Haven

August 7, 5pm

Anodyne Book Shop

Searsport

August 10, 2pm in conversation with novelists Shannon Bowring and Linda Greenlaw Wessel

Print: A Bookstore

Portland September 3, 7pm in conversation with novelist Nick Fuller Googins and climate sociologist and author Kate Olson, PhD

The glamping industry has generally seen tremendous growth in the past decade. A 2022 report from Kampgrounds of America (KOA) found that the number of U.S. glamping brands grew from 59 in 2012 to 230 in 2022. The report estimates that over 17 million households went on at least one glamping trip in 2021.

A 2025 KOA report shows the number of new glamping guests dropped significantly after peaking in 2021 but has been steadily increasing each year since. It estimates that glampers made up a third of all camping guests in 2024. KOA’s report also found that over 60 percent of glamping guests have children, and almost half are millennials.

In Maine, the area around Acadia National Park, which attracts four million visitors annually, has seen several glampgrounds emerge in recent years.

In 2020, KOA—one of the largest camping corporations in the country—converted its traditional Bar Harbor campground into Terramor, a luxury glamping resort. The Montana-based glamping company Under Canvas opened Under Canvas Acadia in Surry in 2021. In 2022, the glamping site Acadia Wilderness Lodge opened in Tremont, just a few minutes away from Acadia National Park.

“People want to be able to be close enough to attractions that bring them to Maine, but—in our case—they want to have a nice, quiet, relaxing place to come to at the end of the day,” said Dan Cashman, spokesperson for Acadia Wilderness Lodge.

As business continues to grow, glampground development in Maine has run into resistance from towns, neighboring landowners, and groups of residents.

Because the industry is relatively new, glamping developments often aren’t written into local land use laws, unlike motels, hotels, and traditional campgrounds.

In Tremont, the permitting process for Acadia Wilderness Lodge took more than a year while the town grappled with changing definitions in its zoning. The project also faced resistance from a group called Concerned Tremont Residents. The glampground was eventually approved but, in 2023, Lamoine voters passed an addition to its land use ordinance that limited the size and density of all “recreational lodging facilities.”

“A lot of ordinances, especially in small towns, aren’t written to recognize these types of structures,” said Tremont’s code enforcement officer, Angela Chamberlain.

That same year, the Arizona-based company Clear Sky Resorts proposed 90 geodesic domes on a property in Lamoine. The project was halted and ultimately abandoned after residents passed a 180-day moratorium on campground development. Lamoine later added glamping to the list of definitions in its building and land use ordinance.

In 2024, a two-year-long permitting process for a proposed glampground in Deer Isle ended in a lawsuit between the out-of-state developer, the town, and a small group of citizens. The lawsuit was dropped after the developer walked away from the project, eventually selling the 40-acre property to a local nonprofit land trust. Along the way, Deer Isle voters approved a wholly new commercial building ordinance that, among other things, limited the size of campgrounds and glampgrounds.

Scott submitted his permit application for Ferncrest Acadia in May of this year. Within days, a Facebook group opposing the project amassed several hundred members under the banner “Grow the Peninsula Responsibly.”

The group raised concerns about water usage, stormwater management, traffic, and increased use of boat landings and swimming spots. They attempted to block the development with a 180-day moratorium but were unable to complete the process before Sedgwick’s planning board approved Scott’s permit, allowing him to move forward.

The business models of Maine’s glampgrounds are almost as diverse as their lodging options. Some, like Under Canvas in Surry and KOA’s Terramor resort in Bar Harbor, are owned by large companies that operate nationwide. Some small local campgrounds have added a few glamping tents to their existing

sites. Others, like Acadia Wilderness Lodge, are owner operated.

Scott lives year-round near his new glampground. He and his family manage the business, but it is a franchise of Ferncrest, a glamping company based in Pennsylvania. Ferncrest supplies the dome tents, the blueprints for buildings, handles booking, and uses its large social media following to drive marketing. Scott pays an initial franchise fee and a percentage of his annual revenue to Ferncrest.

“[Ferncrest] provides a lot of assistance and support to their franchisees to handle a lot of the back-end stuff,” Scott said. “A lot of the things that, when you start your own business, are a little overwhelming.”

Scott’s 30-acre property is the third glampground in the Ferncrest franchise, with the other two locations in Pennsylvania and Oklahoma. As the glamping industry continues to grow nationally, Scott said the company is looking to expand around the country, with the goal of roughly a dozen new glamping franchisees within a year.

Existing glampgrounds in Maine have also announced upcoming expansions. Under Canvas and Acadia Wilderness Lodge both intend to add more lodging capacity over the next several years.

Cashman, speaking for Acadia Wilderness Lodge, said the glamping resort sees about 1,500 guests per season with its eight yurts. The company hopes to add more yurts and glamping tents to meet a growing demand.

“We know that we are not alone in this business, so it is gaining traction through our efforts as well as other operators who are acting in good faith,” Cashman said.

Contact Dave Jackson:

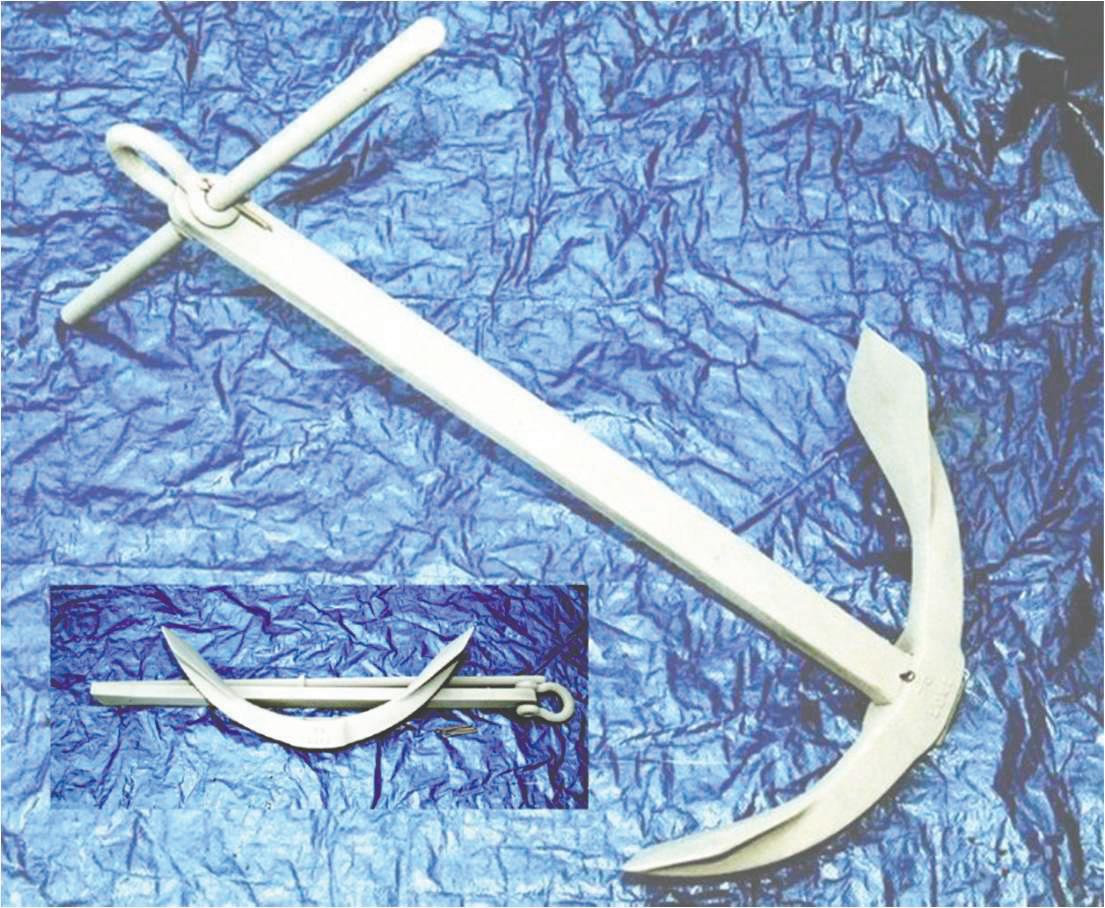

Downeast boat school sees revival

New life as ‘Maine Marine Technology Center’ expected

BY LURA JACKSON

The Boat School is riding a wave of momentum as the Eastportbased institution nears the completion of the first of six steps in its revival. The famed school, which opened in Calais in 1969 before moving to Lubec in 1971 and settling in Eastport in 1978, could reopen as the Maine Marine Technology Center within the next few years if supporters have their way.

Since its earliest years, the Boat School has been a lifeline for students involved in boatbuilding and its various associated industries.

For Dean Pike, who was born in Lubec, it was a way to stay in the area when aquaculture was still in a fledgling phase.

“I had marine biology at heart, and had to figure out how to make a living in Washington County,” he recalled. Then he realized “every aquaculturist, every fisherman—they need a boat. The Boat School seemed like an obvious choice.”

Pike enrolled at the Boat School in 1978 and graduated in 1980. The same year, he finished building his first house—and opened Moose Island Marine, a supply store that started business just in time for the unloading of freight to kick off at the nearby breakwater.

The Boat School gave him a foundation for everything he needed to know, including significant portions of building his house.

“There’s so much to learn. Boat building involves being a carpenter, a composition technician, a plumber, an electrician, a mechanic, a rigger, a painter,” Pike said. “There are so many trades involved in building a boat and maintaining a boat.”

Soon after graduating, Pike was approached by Boat School Director Junior Miller to teach when former instructor Clint Tuttle developed a wood allergy. He continued teaching there until the school closed in 2012 while under Husson University’s authority in what remains a controversial decision in the community. During Pike’s time with the school he taught hundreds of students from all over the world in courses ranging from marine surveying to joinery.

Among those Pike taught is Matt LaCasse, who enrolled at the Boat School in 2002 after graduating from Calais High School. He took courses in wooden and composite boatbuilding, marine systems, boat design, and electrical and mechanical systems, and built a 15-foot Whitehall rowboat in his first year and a 19-foot cold molded skiff in his second year.

“My instructors were extremely knowledgeable and took their jobs very seriously,” LaCasse said. “We worked and studied hard from sunup to sundown every day. My classmates and I were excited and proud to be diving into the world of Maine boats, the communities and social circles therein.” It was a fitting combination, and LaCasse “enjoyed it so much that I never left.”

When Pike sold Moose Island Marine, LaCasse bought it and renamed it Moose Island Marine Supply. He now operates it alongside its parent company, Eastport-based Deep Cove Marine Services.

For Bret Blanchard, who was involved in the behind-the-scenes work of the school’s chaotic early years and then through to its closure under Husson, restoring the Boat School would be restoring a historic Maine institution. In part through his guidance, the Boat School’s advisory committee developed an associate of applied science in marine technology degree, being among the first of the AAS degrees awarded under its then-parent school, Washington County Technical College.

“For my work on the project I won a few awards,” Blanchard says, “but what we really won was proving hands-on, dirty trades could award AAS degrees.”

Crediting the school with helping him find his “life’s passion” as a teacher in the marine trades, Blanchard is one of over a thousand alumni of the school, many of whom are keenly interested in seeing the school’s return. A handful, known as the Friends of the Boat School, are steering the course toward a $4.2 million restoration project, with the first phase— remediating the water-damaged buildings—to be completed by August.

To fund the first phase, the Friends won a $675,000 grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

and a $120,000 grant from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, both of which enabled the replacement of the main building’s roof and asbestos removal, work that began in late spring.

Next will come infrastructure updates, followed by the acquisition of equipment, fixtures, and furnishings. It’s admittedly a long road ahead, but it’s difficult to doubt the sincerity of the school’s supporters.

While the school’s original draw was wooden boatbuilding, “We have to expand it,” Pike says. Along with incorporating traditional components, the new curriculum would focus on developing its composite education and composite design and construction offerings, tying into everything from aircraft to automobiles.

“It’s all about transportation,” Pike says of the field. “It’s all about moving people and products.” Other new components could be marine upholstery and welding, both of which have wide application.

Provided the Boat School meets its funding goal, enrollment expectations are straightforward enough. It could sustain itself with 50 students paying between $20,000 and $30,000 a year, Pike said. During its peak, the school hosted 100 students. If it were to reopen, it would be the third postsecondary school currently operating in Washington County.

“The Boat School is Eastport,” Pike said, looking out at Passamaquoddy Bay from a table at Horn Run Brewing. “Anybody that sits here and thinks we shouldn’t have it—I scratch my head.”

Maine seafood is a ‘green’ choice

Innovative energy applications cut emissions

BY SAM FELDMAN

Your favorite seafood dinner may be better for the planet than you think. Sitting down to a bowl of Maine-farmed mussels likely means consuming only one-fourth of the carbon footprint you’d get from the same amount of protein in tofu.

We know this from a suite of greenhouse gas (GHG) assessments that Island Institute commissioned between 2022 and 2024, which focused on seafood businesses that produce lobster, kelp, mussels, and oysters. This is a first for seafood in Maine.

By looking at multiple businesses across Maine’s seafood sector, we can compare learning from business to business, highlighting opportunities for improvement at both the business and systems scale.

For example, vessel fuel use dominates emissions across many seafood operations, accounting for a staggering 60 percent of emissions in Luke’s Lobster’s supply chain. The pattern holds across shellfish aquaculture, ranging from 19% to 59% across the four oyster farms that were assessed and representing 27% of total emissions at Bangs Island Mussels.

These opportunities for improvement come at a time when Maine’s seafood sector has been beset by climate change impacts, ranging from rises in ocean temperature and acidification, which kills off oyster spat, to increased storm surges washing critical infrastructure into the sea.

Make no mistake—our access to healthy seafood from fishermen and aquaculturists is under threat, along with the thousands of jobs and iconic heritage that bring it to your table. But there are available solutions that can both reduce the seafood sector’s GHG emissions and assist businesses on the financial side.

One elegant solution has already been piloted by Luke’s Lobster. After receiving the results of their GHG assessment, Luke’s installed gel packs in its industrial freezer; they function like the cooler ice packs you bring with you on your trip to the beach.

Using them allows Luke’s to avoid using electricity during peak hours, which reduces its electricity bill, leads to fewer GHG emissions, and lowers the overall strain on the electrical grid. Innovations like these utilize technologies that have been commonplace in

REGISTER TODAY! bigelow.org/cafesci

Wednesdays at 5 p.m. | July 16 – August 6

other industries for some time. More direct innovation has often been considered something that will come in the future.

Maine’s marine businesses aren’t waiting for the future; they’re building it now. Hylan and Brown Boatbuilders in Brooklin recently swapped its gaspowered engine for an electric outboard, using Island Institute grant funds to also install an off-grid solar array. As a result, its work skiff charges directly at the dock, using nothing by solar power.

On the New Meadows River, Bombazine Oyster Company has also leveraged Island Institute’s financial support to upgrade its floating solar array on the farm. With increased solar capacity and energy storage, the business now powers all its on-thewater processing equipment with solar energy and has enough left over to help charge the electric outboard it’s planning to add. These innovations build on earlier pioneers like Mere Point Oyster Copany, which has been running a solar powered oyster tumbler on their farm for years.

These innovations represent more than isolated success stories—they’re proof that Maine’s seafood industry can

LIFE SEA

© Brian Skerry

Bigelow Laboratory’s Café Sci is a fun, free way for you to engage with ocean researchers on critical issues and groundbreaking science.

This year’s Café Sci will be held in our brand-new center for ocean education and innovation. Come see this beautiful new space!

lead the nation in sustainable marine business practices. From Brooklin to the New Meadows River and beyond, these forward-thinking companies are showing us how marine businesses can thrive while protecting the environment they depend on. Their pioneering efforts demonstrate that the transition to clean energy isn’t just possible for marine businesses; it’s practical and already happening.

To bring stories like these to Maine’s coast, Island Institute will host public screenings of our new film, Climate of Change 7: Aquaculture for People and Planet, with panel discussions featuring our staff and Maine seafood industry members. These events showcase both the sustainability of Maine’s farmed seafood and our ongoing work to catalog emissions and drive innovative decarbonization efforts across the state’s seafood sector.

Sam Feldman is a community development officer with Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront, focusing on helping sea farms transition away from fossil fuels. He may be contacted at sfeldman@ islandinstitute.org.

A new bank built for New England’s farms & fisheries.

“It’s a breath of fresh air to find a financial institution that’s aligned with our values.”

DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS NORTHEAST NON-PROFIT

Maine’s fractal coast

Measuring the coast involves some abstractions

BY DANA WILDE

Day in and day out, summer after summer when I was a kid, I flew back and forth over Casco Bay with my father in his Piper Cub seaplane. From the air I saw thousands of spooked seagulls, smooth, steel-colored sea rollers in identical ranks, wind-beaten chop, whales, porpoises, schools of mackerel churning the surface, a shark so big it looked like a driveway with fins, the salt-scoured lighthouse at Halfway Rock, dark schools of herring snugged up into island coves in the evening.

There also was the mysterious fact that most of the islands and rocks were elongated in the same direction, roughly northeasterly. You could see it as we approached Bailey Island to land in Mackerel Cove, a tube of water between two spits of land about the same size and shape as the cove. Out of the plane and scrambling around on low-tide ledges, you could see grooves and ridges in the rock running in the same direction. On a map of Casco Bay, the whole coast looked like grooves and oblongs all running the same parallel direction.

That grooving, at the small scale and the big scale, happened when around 14,000 years ago the glacier was inching back toward the Arctic, scratching ruts and gouging inlets and coves with something like icy claws.

How long is this coved and inletted ancient coast? To measure it, would you run your imaginary tape straight from Kittery to Lubec and let it go at that? Or would you measure into the bays, too? The detours into Casco, Penobscot, Blue Hill, Frenchman, Machias, and Cobscook bays would add uncountable miles—should you measure all the coves? And all their nooks and corners?

It turns out there is literally no end to Maine’s jagged contour. Better mathematical minds than mine were considering this problem of measuring crooked distances before I noticed it at the age of about 12, and one of them, Benoit Mandelbrot, noticed that natural objects such as coastlines do not conform to geometry based on straight lines.

In other words, the lines, planes, and cubes you learn about in high school geometry are ideal forms that do not actually exist in nature. So how do you measure the irregular thing itself?

Turning out to be a person who notices similarities rather than a person who notices numbers, I don’t understand how Mandelbrot’s methods help figure coastal lengths. But I can explain the general idea.

Since a line in nature is not exactly a line, and a plane not a plane,

Mandelbrot figured out how to assign a number to the way a line (of a jagged coast, for example) leaks out of its straightness to some extent into a plane. It’s not exactly a plane, but not exactly a line either.

If a line is one-dimensional, represented by 1, and a plane is two-dimensional,

represented by 2, then the line of Maine’s coast is in between 1- and 2-dimensional. In other words, it is “fractal.”

A study published in the Journal of Coastal Research in 2006 calculated the fractal dimensions of four areas of Maine’s coast. The southwest coast which has a lot of beaches that are more or less straight has a mean fractal dimension of 1.11—a slight bend off a straight line. The south coast which includes Casco Bay is 1.35. (Another analysis showed the fractal dimension of Boothbay, where my mother’s family arrived in the 18th century, is 1.27.)

The north coast around Mount Desert Island is 1.23. The northeast coast from Machias into Cobscook Bay is 1.26; Cobscook Bay itself has a uniquely irregular coast-scape and comes in at 1.37. The overall fractal dimension of Maine’s coast looks to be a bit upwards of 1.2.

Now another thing Mandelbrot noticed about fractal dimensions is that as you look more closely at a line in nature, its shape at large scales tends to be similar to its shape at smaller scales.

In other words, along the coast around Casco Bay, the coves are similar to the grooves in the ledges, as I noticed when I was a kid. They are “self-similar,” which is to say they are fractals of each other. These similar shapes go on indefinitely downward, with the bays shaped like their coves, the coves shaped like their ledges, the ledges shaped like their grooves, the

grooves shaped like their ruts, the ruts shaped like their scratches.

This apparently is true not only of coastlines, but also of the outline of a snowflake, a mountain range, a mathematically generated pattern. The shape of the small part of an object is basically the same as the overall shape of the object.

This goes on infinitely downward as far as there are corners to be turned. And presumably, infinitely upward. A planet-moons system is similar to a star-planets system, and star-planets systems similar to galaxies.

Nature appears to be fractal through and through, mirroring itself at every turn and nook.

A child is a fractal of an adult. My son has the same contours I did at his age. And apparently he thinks thoughts like me. When he was 6, he shone a flashlight on a sheet of shiny metal, and the light splayed into a strangely deeplooking conical shape. “Look, Dad,” he said. “It’s a small future.”

The child is father to the man in thought as well as body, it seems, and no doubt in whatever other form we eventually take. Infinitely upward, it is to be hoped.

Dana Wilde is a former college professor and newspaper editor who lives in Troy. He writes the Off-Radar and Backyard Naturalist columns for the Central Maine newspapers. He may be contacted at DWildebdn@gmail.com.

FULL INVENTORY READY FOR YOUR WATERFRONT PROJECTS!

• Marine grade UC4B and 2.5CCA SYP PT lumber & timbers up to 32’

• ACE Roto-Mold float drums. 75+ sizes, Cap. to 4,631 lbs.

• Heavy duty HDG and SS pier and float hardware/fasteners

• WearDeck composite decking

• Fendering, pilings, pile caps, ladders and custom accessories

• Welded marine aluminum gangways to 80’

• Float construction, DIY plans and kits

Delivery or Pick Up Available!

Rising ‘Tides’ in Eastport

Nonprofit gathers, preserves region’s culture

Since its founding in 2002, the Tides Institute & Museum of Art has worked to establish itself as a significant cultural institution for the eastern coast of Maine with connections to neighboring Canada and inclusive of the Passamaquoddy. Acting as part cultural anchor, part cultural catalyst, TIMA’s efforts include rebuilding the region’s cultural legacy, fostering new cultural works and initiatives, and preserving and repurposing historic buildings.

Artsipelego is an initiative TIMA began with others in 2012 that includes an annual cultural guide and map of the U.S/Canada Passamaquoddy Bay region and regular postings on the region’s cultural events and activities.

TIMA’s StudioWorks Artist-in-Residence program is in its 12th year of operation. For nine months, artists come from across the U.S. and abroad to work out of TIMA’s downtown studio building in Eastport. Some 119 artists from 28 different states and nine foreign countries have participated in the program.

TIMA now has nine historic buildings, including three in downtown Eastport, which it is restoring and repurposing. Its current largest building project involves the 1887 Masonic Hall which will become its primary museum.

Our Island Communities

Matinicus: A Lighthouse Play performed on islands

Great Cranberry, Isle au Haut, Matinicus treated to free showings

After a successful three-week run at the Bangor Opera House, the Penobscot Theatre Company has partnered with Maine Seacoast Mission to stage Matinicus: A Lighthouse Play on three of Maine’s remote, unbridged islands in July.

The theatre company will travel aboard the Misson’s 74-foot Sunbeam to the islands during a trip from July 21 to July 24. Performances will occur on Great Cranberry Isle on July 21, Isle au Haut on July 22, and Matinicus on July 23. This tour is supported by a grant from the Margaret E. Burnham Foundation and individual donors.

Written by Jenny Connell Davis, Matinicus tells the true story of the distinctive, Maine historic figure Abbie Burgess who as a young woman single-handedly manned a lighthouse on Matinicus Rock in 1856.

Abigail moved with her family to the isolated island on the outskirts of the Penobscot Bay to tend the light. Told from Abigail’s perspective, this onewoman play navigates us through that first harrowing year when ultimately her father needs to head out for supplies, leaving her to care for her family and tend the lighthouse just as a fierce Nor’easter barrels ashore.

Using intelligence, bravery, and sheer force of will, Abigail manages to save her family while keeping the lights burning and the passing ships safe.

Her story and impact on the small, 2- by 6-mile island is especially significant to residents of all Maine’s remote, unbridged islands, and is a testament to the grit and resilience of those who choose to live there.

Mission staff provide health, educational, and community building services to residents of all 15 of Maine’s unbridged islands with a year-round population. As a part of that work, Sunbeam makes routine visits to some of these islands throughout the year.

“The significance of Abbie Burgess in the history of Maine island life is poignant and inspiring,” said John Zavodny, Mission president. “The Mission is honored to bring our community partner Penobscot Theatre Company’s stage production of the play to its namesake island.”

During the original showing of the play, the Mission was the theater company’s community nonprofit partner and shared information on both

Katie Peabody plays Abbie Burgess in Matinicus: A Lighthouse Play.

the Mission’s work on outer islands, as well as the history of Matinicus Island.

Also, after a matinee performance, the Mission’s Director of Island Services Douglas Cornman and Matinicus’ First Assessor Laurie Webber did a question and answer, “talk-back” session about what life is like on Maine’s most remote island.

Matinicus is directed by Julie Arnold Lisnet and stars Katie Peabody. Lisnet is an actor, director, producer, educator, and teacher at the University of Maine where she received a BA in theater and MA in acting. Peabody was born and raised in Seattle and

graduated from the University of Southern California School of Dramatic Arts.

Scenic design was done by Gwen Elise Higgins, costume design by Kevin Jacob Koski, lighting design by JP Sedlock, props design by Thomas Demers, and sound design was done by Neil E. Graham.

On writing the play Davis said:

“I will say that this is about living in a place that is fiercely beautiful, but where the weather isn’t always our friend. And about those moments in life when forces much larger than us rise up to remind us both how small we are, and how strong we are.”

Aquaculture apprenticeships grow workforce

Aquaculture association celebrates program with documentary

BY JACK SULLIVAN

Kelly Morgan moved from California to Maine to work on an oyster farm. By way of the Maine Aquaculture Apprenticeship Program, she landed a job on the New Meadows River in Brunswick farming oysters with Bombazine Oyster Company.

Nearing the end of her apprenticeship, she’s already asking her mentors, “How do I grow in this industry?”

The program pairs applicants with aquaculture farms—primarily oyster and mussel farms—along the Maine coast for a hands-on learning experience that helps participants, farms, and Maine’s coastal economy. A collaboration of the Maine Aquaculture Association, Gulf of Maine Research Institute, and Southern Maine Community College, with investment from various Maine nonprofits, the program fills a critical shortfall in skilled, qualified, and dependable workers.

“That gap that we see on farms is in middle management,” says Christian Brayden, project manager at Maine Aquaculture Association. “On small Maine farms, you have the owner, and you have farm hands, but often they lack crew chiefs and farm managers, people with experience and knowledge to run a farm. Our apprentices are moving quickly from farm hands to middle management.”

Brayden has been a driving force for the program since its inception in 2018. The program operates on a $130,000 annual budget, funded by the USDA National Institute for Food and Agriculture, FocusMaine, Jobs for the Future Foundation, and others.

The apprenticeship includes 2,000 hours of paid work on the farm and 144 hours of classroom time, which takes one to two years to complete. Farms must provide nine months of employment per year, which can be a hurdle for some of the more seasonal businesses.

The classroom portion is primarily designed and conducted by GMRI’s aquaculture program manager, Carissa Maurin. Maurin notes that even though there is a fair amount of coursework—including basic biology—the program does not require a college education. Applicants with marine science backgrounds are valued, but the program also seeks applicants with skills including electrical and mechanical experience, carpentry, and plumbing.

Experience working on the water is an added advantage, but the program teaches basic skiff-operating skills and knot tying. One of the most popular parts of the hands-on coursework is the Yamaha motor maintenance and repair course.

The program even provides boots, bibs, and a life vest to apprentices, an expense that can top $500 and be a barrier to entry for some.

Michael Scannel, formerly a sternman on a lobster boat, spoke about his transition to aquaculture during a panel discussion at an MAA event on May 1 at O’Maine Studios in Portland.

“When I started off lobstering, I watched a lot of the changes going on in the industry,” he said. “I was looking for a way to diversify, and it seemed like aquaculture was a no-brainer, a way to provide another opportunity to be on the water and stay in Maine.”

Young lobstermen like Scannel are part of the target audience of MAA’s new educational documentary about the apprenticeship program. A teaser for the film was screened at the Maine Fishermen’s Forum earlier this year and the film premiered at the May 1 event.

Trixie Betz, outreach and development specialist at MAA, says interest and enthusiasm for the program has been growing substantially, and more farms and apprentices are applying. MAA produced the documentary film because it needed a way to explain the program, highlight the gritty nature of working on a year-round aquaculture farm, and demonstrate that a career in aquaculture is achievable and yields results.

Betz also hopes the film educates those outside the sector and helps demystify aquaculture in Maine.

“Farms are currently growing. They are applying for more acreage,” she says. “A lot of these farms that

started five to ten years ago are starting to turn a real profit. So along with this growth comes a need for a growth of workforce.”

Housing has been one obstacle to that growth. “A couple farms this year, had to drop out of the program,” Brayden says. “There are parts of the state that apprentices weren’t willing to move to. But the most common reason was that they weren’t able to find housing,” especially in the Mount Desert Island region.

Scannel, the former sternman, is completing his apprenticeship but is already a farm manager at Madeleine Point Oyster Farms in Yarmouth. Kelly Morgan, who is wrapping up her apprenticeship at Bombazine Oyster Company, is working directly with GMRI’s Carissa Maurin to chart her future in the industry. With a background in education and research, and now with hands-on experience working on the water, Morgan wants to apply what she’s learned to support the aquaculture industry. She may even want to start her own business. “A year ago,” she said with a laugh, “I’m not even sure I knew what an LLC was.”

Maine Aquaculture Association’s film Tending the Tides has upcoming showings including a July 24 screening in Portland as a part of the Maine Outdoor Film Festival. Learn more at maineaqua.org/tendingthe-tides.

Trans-Atlantic art

Tradition continues in the Azores

HORTA, THE TOWN at the eastern end of Faial, one of the islands that make up the Azores in the North Atlantic, has long been a major destination or stopping point for trans-Atlantic sailors, including many from Maine.

It’s customary for visiting sailors to commemorate their voyages with paintings on the town’s big breakwaters. Today there are thousands of these paintings, stretching along what may be a mile of concrete and granite wall.