Another good year for Maine tourism

State reports $8.4 billion in spending

BY TOM GROENING

Maine’s tourism economy rarely seems to enjoy a normal year. Factors such as fluctuating gas prices and airline fares, terrorist attacks, and pandemics play their part in either inflating or deflating visitation.

But despite these variables, the numbers make the case that tourism remains a major economic sector in the state. Beyond spending by visitors, tourism officials are now drawing links between those visiting and other economic challenges, such as an aging population and shrinking work force, with the tourism draw holding potential to ease those demographic burdens.

At the annual Governor’s Tourism Conference in Bangor on March 28, officials reported that visitation in 2022 was down slightly from the previous year— from 15.6 million to 15.3 million. But spending was up, from $7.8 billion to $8.4 billion, no doubt tied to broad inflation.

That spending supports 151,000 jobs, officials said, contributing $5.6 billion in earnings to Maine

Kim

Hamilton

households. Restaurant and lodging taxes paid by tourists reduced the tax burden to Maine households by $2,172.

Given the variables in a very competitive environment, the Maine Office of Tourism works on adjusting its marketing strategies to match ever-changing

trends. One constant buoying Maine’s tourism is the rate at which visitors return.

“Their interest in coming back is significantly higher than in other regions,” said Heather Johnson, commissioner of the state’s Department of Economic

continued on page 4

named Institute president

Island, nonprofit background cited as strength

BY TOM GROENING

The Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront, named Kim Hamilton as its president, effective April 1. Hamilton has served as the organization’s

interim chief programs officer since September, overseeing the Institute’s climate, economic resilience, and leadership programs and serving on its senior leadership team.

The Rockland-based nonprofit’s board of trustees cited Hamilton’s

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

“strong leadership, mission-driven focus, proven fundraising success, and commitments to Maine’s coastal and island communities” in selecting her for the position.

Hamilton earned a Ph.D in demography from Brown University and a master’s from John Hopkins University. Her professional experience includes a tenure as president of FocusMaine where she led efforts to accelerate job creation in the agriculture, aquaculture, and biopharmaceutical sectors. She has also served as chief impact officer at Feeding America and director of strategy planning and management at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Hamilton is originally from North Yarmouth and now lives on Chebeague Island.

She steps into the role as the organization marks 40 years of working to build sustainability in island and coastal communities and sharing solutions for addressing the coast’s most critical concerns.

“During her time as interim chief programs officer Kim has done a fantastic job advancing our work to create a sustainable coastal economy, create climate solutions, and advancing our history of creating leaders for Maine’s coastal communities,” said Kristin Howard, chairwoman of the board of trustees. “We

continued on page 5

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities published by the island institute n workingwaterfront.com volume 37, no. 3 n may 2023 n free circulation: 50,000

Gov. Janet Mill, left, poses with Paul Coulombe in front of TV cameras at the Governor’s Tourism Conference in Bangor on March 28. Coulombe was honored with the Governor’s Award for Excellence in Tourism for his philanthropy and commercial development work in Boothbay Harbor.

PHOTO: TOM GROENING

“I want us to be known as the organization that fights hard for Maine’s islands and coastal communities.”

—Kim Hamilton

On the record with…

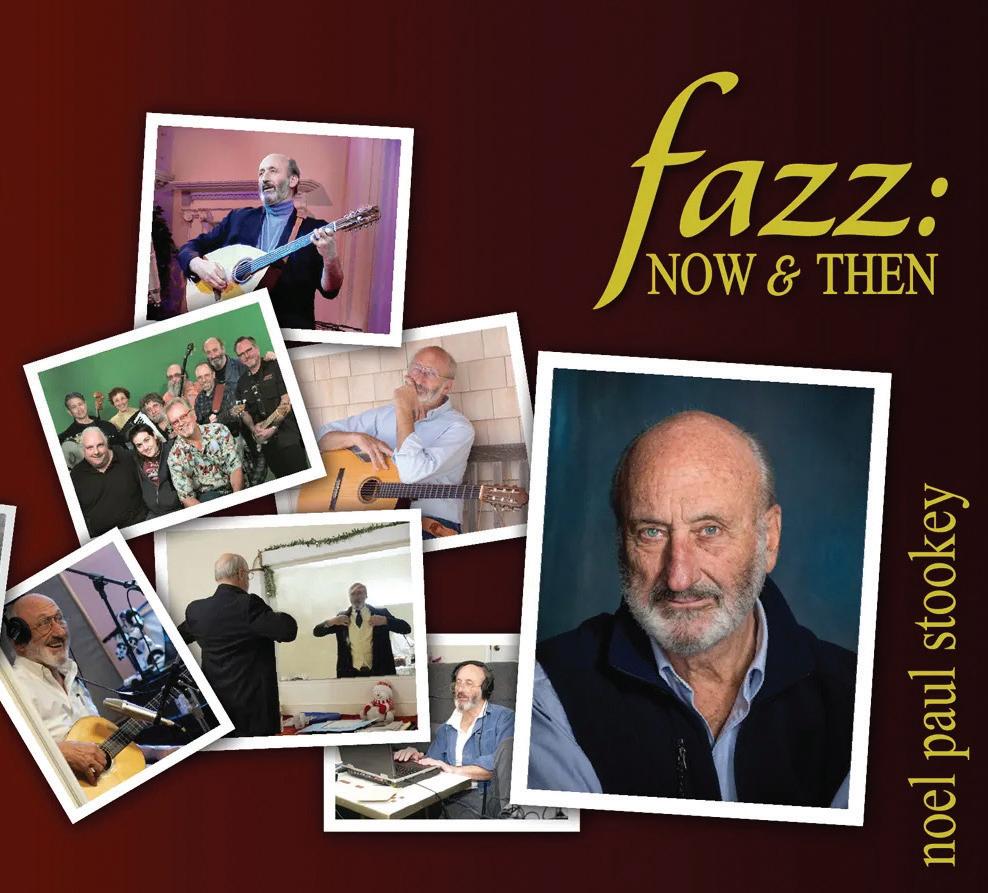

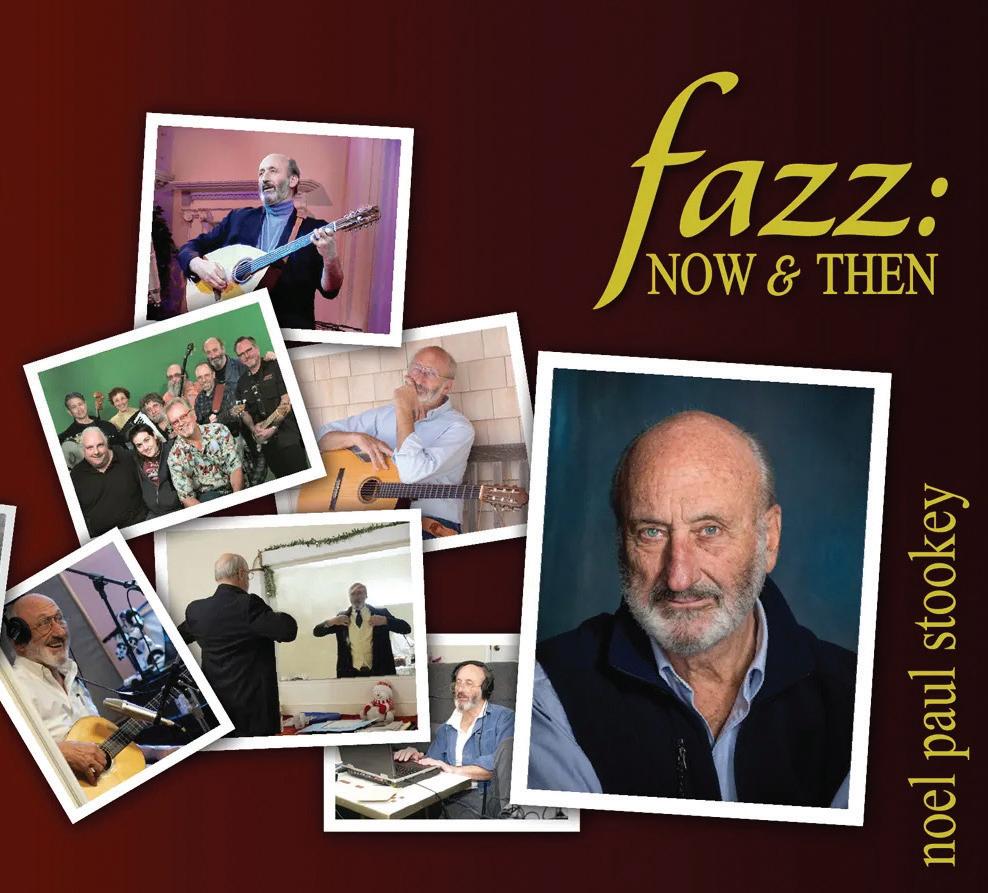

Musician Noel Stookey of Blue Hill

Coming to Maine spurred by Nearings, Gordon Bok

BY TOM GROENING

His given name is Noel, but most over the age of 60 know him as Paul Stookey, a member of the folk music trio Peter, Paul, and Mary, stalwarts of the 1960s, known for covering such songs as “Blowin’ in the Wind” by a then-unknown Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger and Lee Hays’ “If I Had a Hammer,” and of course, “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

Stookey continued to make music with and without his former bandmates, and even at age 84, has released a new album, Fazz: Now & Then, a collection that infuses jazz chords and a beat sensibility to his folk roots. Or maybe the other way around.

Stookey hails from rural Maryland, but in the early 1970s, he chose to settle in coastal Maine, where he and his wife raised three daughters in Blue Hill Falls, a few miles from where E.B. White lived and wrote. He cites the landmark how-to, Living The Good Life, by Scott and Helen Nearing, who later lived in Brooksville, as influencing his search for a rural life. He also espouses Christian beliefs, which has threaded through his music.

Our conversation over Zoom, with Stookey in his Blue Hill home, was edited for length and clarity.

The Working Waterfront: How did you come to live in Maine?

Noel Stookey: We bought a house in New Hampshire, and actually spent about three months there, and just decided that it was too insular. We were fortunate enough to be able to afford to experiment with actual purchases. I think we were still living in Westchester County (N.Y.) at that point. This would have been the early ‘70s. I had just—what we referred to in Peter, Paul, and Mary as “taking time off for good behavior”—I had just gone through such a spiritual change that the only way I could see discovering and defining the clarity of that experience was moving to someplace like the country.

Both my wife and I had been brought up in rural areas. So my experience and reverence for the woods, for the pond that was at the top of the big hill that I would go explore, and my dad’s encouragement, because he was a young man growing up on a ranch in Utah, transmitted that kind of awareness for the personal responsibility for living one’s life, based in natural circumstance. Ultimately, I was in my 30s when I moved to Blue Hill.

WW: When was the first time you visited Maine? Had you toured here?

Stookey: I had gone with my dad fishing here. We had a trailer that we took around a lot. Mom would stay in the trailer and Dad and I would go fishing. Betty, my wife, actually, made annual visits to Ogunquit or Kennebunkport, so she was familiar with Maine from a vacation point of view.

WW: So what were your impressions of Maine then and in the ‘70s?

Stookey: I have to tell you that the background of moving to Maine also included Gordon Bok [the Camden-Rockport-based folk singer], who, coincidentally, we saw just recently in Rockland at the Sail, Power, and Steam Museum.

When Betty and I determined that we wanted to find a place in the country we had an RV at the time, which we used for every conceivable kind of errand, from birthday party pickups to McDonald lunches, to even driving into New York City.

The RV took us up to Nova Scotia, all up the East Coast. One of those trips, when Betty and I wanted to move to the country, was to Camden to talk to Gordon. And he said, “Well, if you’re looking for something on the ocean, you’re not going to find it here or south. It’s all gone. But head on up north and I’m sure you’ll find something.” We drove a circuitous route, just touching the shoreline all the way up to Eastport, and didn’t really see anything that spoke to us until we hit the town of Blue Hill, which was like a scene out of It’s A Wonderful Life with Jimmy Stewart. There was the town hall, there was the hospital, there was the post office. A perfect little town. And has retained, to a certain extent, in spite of the infusion of people trying to escape cosmopolitan consequences of the pandemic, it has maintained a lot of its character, I think to a large extent because of the artists who live here. Rob Shetterly, Richard Kane, the filmmaker, Becky McCall, Gail Page. There are a lot of talented folks here who contribute to the society.

WW: Did your three daughters go to George Stevens Academy in Blue Hill?

Stookey: Initially. In their sophomore years, we thought they should try a prep school. So Kate went to Milton, Anna tried St. Paul’s for one year, but came back to GSA, and commented, publicly and privately, that the instruction was better as George Stevens. And Liz went to Middlesex.

WW: And of course, Kate is now the executive director of Maine Coast Heritage Trust. And looking at that job and that nonprofit, through her eyes and your eyes, what are your views of the challenges that the coast of Maine faces, given what you’ve seen in your time here?

2 The Working Waterfront may 2023

JB Paint Company INDUSTRIAL MARINE COATINGS & SUPPLY Blast Media & Blast Supplies, Sprayers, Sprayer Repair/Supplies... Plus much more... 2225 Odlin Road, Hermon ME 04401 207-942-2003

Noel “Paul” Stookey performing in the studios of WERU-FM (89.9), the community radio station he helped launch in 1988. PHOTO: COURTESY WERU-FM.

Stookey: There is the challenge of maintaining a balance between making a living from the ocean and the shoreline, and conserving the ocean and the shoreline. Kate’s advanced thinking on this is realizing the need for inclusion of all of the aspects of the nonprofits who are concerned with the conservation of resources here in Maine. And some of them are not mainstream. But they should all have access to the information, that it could be shared, and by those means, a stronger case can be made, because it will include more people.

Our first purchase in the town of Blue Hill was a henhouse. Though we made the unfortunate mistake of renting a house from a family called the Coops, which immediately led everyone to believe we were living in the henhouse that we bought, which was abandoned for two or three years.

It came with 47 acres of forest bordering on the Salt Pond which runs behind the South Blue Hill peninsula. Kate had many opportunities during the years and summers that she was here to be at one, in sense, with the surrounds. She was delighted to come back and celebrates the fact that her meetings with the board of directors generally take place in forests or on trails or on the ocean of some donor.

WW: And back to the henhouse: I think it’s fair to say that there would be no WERU-FM without you and David Snyder…

Stookey: And Reg Bennett. Reg Bennett was an ex-cop in Ellsworth, who had a real heart for kids and for some reason or other, was really into recording. I didn’t really have room for him in the studio as an engineer, but he came around the henhouse often enough that when something went wrong with the equipment, you could give it to him and he’d take it upstairs to a little shop, and he’d bring it back fixed.

WW: The radio station, from my perspective, has been a real cultural resource… Stookey: Absolutely.

WW: And I think some of the newer volunteers have no idea about your role in it. Stookey: My role was really more of a funding agent. Reg and I would have some battles. Reg wanted it to be a Christian radio station. And I was holding out for the community radio station.

The manner I’ve approached music since that period of my life when I discovered the divine, and that love, in fact, was the key component of anybody’s happy life. There’s a song on the new album called “Love With a Capital ‘L’” in an attempt to bridge that gap between people’s perception of love between our brothers and our sisters and that larger love which is the image from which we draw our inspiration.

Reg and I went head-to-head on it for a while but he finally acquiesced.

When they brought out the list of call letters that were available there was one that was circled, and the mind just plays intuitive tricks on you, and to see We Are You (WERU). There it was! How could you not?!

WW: Is Maine a friendly place for music, or folk music?

Stookey: I think it’s a little bit of a throw-back. It does hold onto the traditional forms. Which prospers the singer-songwriter more than the rock band. I like the fact that WERU is able to bridge much of that gap [between music styles] by having such a diverse presentation. I particularly enjoy “On The Wing” [an eclectic format]. But they do everything. These are hard times for musicians, no matter what your bent.

I’m in the last phases of a biography that’s being co-written by a woman named Jean Finley. Coming up for a name for the book, we finally settled on Don’t Use My Name because that was the word from the Lord that was given to me at a concert. I was packing up my guitar case and a couple came up to me—this was in England—and I said “Hi,” and they said “Hi,” and they said, “We think we have a word of the Lord for you.” Your heart starts racing a little when people from the outside begin to interfere with your faith. They said, “Don’t use my name. We don’t know what it means, but...”

So, the immediate association is, “Stop preaching. Don’t talk about Me,” with a capital “M,” at all. Or, use parables, dummy. You’re a songwriter. Use metaphor. And that changed my whole writing perspective.

The “Building Block” song, which was the radio station’s theme song for a while, was written sitting on the front steps of the henhouse, looking at the fact that the ice had broken, and was drifting.

“When I am down and unsuspected With a burden that does not show I think what time has resurrected And how the sun can make the water flow.”

WW: Nice.

Stookey: It’s been a good life. And given the enormous blessing of the space that Maine has bestowed on my family, I can’t imagine revising any part of that.

Linkel Construction,

3 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023 G.F. Johnston & Associates Concept Through Construction 12 Apple Lane, Unit #3, PO Box 197, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679 Phone 207-244-1200— ww w. gfjcivilconsult.com — Consulting Civil Engineers • Regulatory permitting • Land evaluation • Project management • Site Planning • Sewer and water supply systems • Pier and wharf permitting and design

John Martin, Bud Staples, and Elsie Gillespie chat around the woodstove at the annual town meeting.

Gerald “Punkin” Lemoine

Levi Moulden

Sea Farm Loan FINANCING FOR MAINE’S MARINE AQUACULTURISTS For more information contact: Nick Branchina | nick.branchina@ceimaine.org |(207) 295-4912 Hugh Cowperthwaite | hugh.cowperthwaite@ceimaine.org | (207) 295-4914 Funds can be utilized for boats, gear, equipment, infrastructure, land and/or operational capital. Lower Interest Rates Available Now!

Bud Staples

Locally owned and operated; in business for over twenty-five years. • Specializing in slope stabilization and seawalls. • Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) certified. • Experienced, insured and bondable. Free site evaluation and estimate. • One of the most important investments you will make to your shorefront property. • We have the skills and equipment to handle your largest, most challenging project. For more information: www.linkelconstruction.com 207.725.1438

Inc.

TOURISM continued from page 1

and Community Development, which includes the Maine Office of Tourism. Research showed that last year, 32% of visitors had been to Maine more than ten times, and 91% surveyed in 2022 said they would return.

Johnson suggested tourism might be linked to the state’s recent in-migration rate, which was higher last year than any of the other New England states and seventh-highest in the U.S.

With a statewide unemployment rate of just 2.8%, Johnson said, attracting visitors who might become residents is critical to keeping the economy humming.

A couple of themes emerging in the data presented about the industry were the need to appeal to a more diverse population, and that key draws are Maine’s status as a safe, low-crime state with charming downtowns.

“People feel safe to come here and find their futures here,” Johnson said.

How people travel is evolving, she added, and the state’s 2023 tourism marketing plan reflected those changes by adding technical assistance for businesses.

Steve Lyons, director of the Maine Office of Tourism, described 2022 as “a good year,” but a year of transition as the state moved past the COVID pandemic.

In her remarks, Gov. Janet Mills praised the industry—about 350 attended the conference at the Cross Insurance Center—for working to maintain the state’s status as a destination.

“You all worked hard to protect Maine’s reputation as a state to visit,” she said. “You are the face of Maine, making people fall in love with Vacationland.”

Some 47% of visitors surveyed said they noticed the office’s paid advertising with 28% of those reporting they were influenced to visit by those ads, a 9% uptick from the previous year.

Lyons said research showed tourists visit multiple regions in Maine, but 35% said they visited the Midcoast region and

islands, 27% visited Greater Portland and Casco Bay, 27% named Maine beaches, and 25% listed Downeast and Acadia. Other survey data showed that the top reasons given for visiting Maine were to relax and unwind (34%), sightseeing and touring (31%), and visiting family and friends (26%).

Data presented by Downs & St. Germain, a research firm contracted by the Maine Office of Tourism, showed that travel to Maine by those from outside the U.S. grew by 5% over 2021.

Maine residents traveling 50 or more miles for pleasure are considered tourists in the research, and so 19% of tourists started their journeys in the state. Residents of the other New England states accounted for 32% of visitors (14% from Massachusetts), 20% came from the Mid-Atlantic region, 10% from the Southeast U.S., and 4% from Canada.

Emerging markets include Florida, and the Chicago and Atlanta metropolitan areas, which likely would mean those visitors would come by air. Currently, 85% drive to Maine, with just 5% traveling through Portland International Jetport.

Demographic profiling showed that the typical Maine visitor is 49 years old, female (55%), and white (89%).

‘Sea Side Park’ and church

READERS GLEN MAYBERRY of Portland, David Verrill of Scarborough, and Michaeel Percy had information to share about the photo we featured on the op-ed page in the April issue of The Working Waterfront. The photo, which appeared to be from the early 20th century, showed a banner over a street reading, in reverse, “Sea Side Park.” A building at the right of the image was recognized.

“The building in Old Orchard Beach is still there on the corner of Old Orchard Street and Portland Avenue,” wrote Mayberry. “It is now part of St. Margaret’s Catholic Church.”

Verrill wrote that the church is still “serving Mass and performing baptisms, weddings, and funerals. The next building beside it, going down the hill, is St. Margaret’s Parish Hall which has hosted a variety of activities over the years including beano, parish suppers, Christian Doctrine and Catechism classes, meetings of the Ladies Sodality and the Knights of Columbus, and ballroom dance lessons,” he added.

“This photo should evoke many memories for the parishioners and summer visitors to Old Orchard Beach over several generations,” Verrill wrote.

Thanks for your sharp eyes!

Tourism industry honored

Among those honored by the Maine Office of Tourism at the conference were Paul Coulombe, a Lewiston native who sold his White Rock Distilleries in 2012 for $600 million. Coulombe honored with the Governor’s Award for Tourism Excellence for his development and philanthropy work in Boothbay Harbor and Southport.

Also honored were:

• the Schoodic National Scenic Byway committee with the innovative and creative award for developing children-centered signage along the route

• Husson University’s School of Hospitality, Sport, and Tourism Management with the leadership and growth award

• Maine Craft Weekend with the collaboration award.

That typical visitor is a college graduate (77%), married or in a domestic partnership (76%), and has an annual household income of $89,100.

Food and drink were cited by 74% as a top activity, followed by touring and sightseeing (53%), and shopping (50%).

Other key numbers from 2022 reported by Downs & St. Germain include:

• Room occupancy rate—56.1% (up 13.6% from 2021)

• Average daily room rate—$197.84 (up 35.2% from 2021)

• 69% of visitors started planning their trip 51 days in advance

• 66% of visitors considered visiting only Maine (down 6% from 2021)

• Of the 47% who noticed advertising, the top sources were social media (39%), internet (35%), and magazine (21%)

• Typical Maine visitor traveled with 2.9 people in party

• 18% traveled with at least one person under the age of 18

• Typical visitors stayed 4.6 nights

—Tom Groening

4 The Working Waterfront may 2023

Gov. Janet Mills, center, poses with students and faculty from Husson University’s Hospitality & Tourism master’s program.

PHOTO: TOM GROENING

HAMILTON

continued from page 1

look forward to seeing Kim build from this early success in the years to come.”

Hamilton cites her ties to the region in informing her approach.

“As a Mainer and islander, I deeply understand the dynamics of year-round island living and the challenges and opportunities faced by Maine’s islands and coastal communities,” she said. “As Island Institute president, I am honored to step into this role as we celebrate our first 40 years and lay a strong foundation for our future.”

Hamilton agreed to answer questions from the newspaper:

The Working Waterfront: What drew you to the Island Institute?

Hamilton: If you live along the coast in Maine, you’re more than likely to have heard of the Island Institute. That was true for me. It wasn’t until I had the opportunity to step in as chief programs officer, however, that I understood the span of its reach and its extraordinary history.

I’ve also come to know and deeply appreciate the people in the organization and their commitment to Maine’s coastal and island communities. I don’t know of a more dedicated team so singularly focused on the future of Maine’s coast.

Now that I live on Chebeague Island where my family has deep roots, I especially appreciate the community connections the Island Institute has cultivated. I know some of the young people who have benefitted from scholarships and aquaculture farmers who have received support. The impact is tangible and real, and with a 40 year history, it spans generations. The opportunity to build on that legacy is exciting.

WW: What has your island experience taught you about how community works, and where and how an outside organization like the Institute can help and support it?

Hamilton: It’s not just an island thing. Every community is different, and has different assets,

opportunities, and challenges. This is as true in Mali as it is on Monhegan. That’s why taking time to build relationships, listen to community members, ask questions, and commit to a long-term partnership is important.

That’s only the beginning. Showing up, delivering on what you promise, and offering practical solutions gets you invited back. It’s a privilege to be invited into a community, and we need to honor that.

WW: Tell me about your professional background.

Hamilton: If you’re looking for a through-line in my career, you won’t find it, except that I’ve always been drawn to organizations that are tackling big challenges—from immigration to food insecurity to job creation in Maine.

I spent many years working in global philanthropy at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other foundations helping visionary leaders build strong organizations. I’ve learned so much from those experiences about perseverance and vision.

I’m trained as a demographer, which has given me an appreciation of the long-term population trends in Maine and the impact on the state’s economic vitality.

I was drawn back to Maine, however, by the opportunity to launch FocusMaine, a terrific organization working on growing high-growth sectors in the state, like aquaculture. That experience deepened my understanding of the extreme changes facing Maine’s coastal communities and islands as well as the opportunities that are ours to seize.

WW: What are those big issues facing Maine coastal and island communities in the next five to ten years?

Hamilton: It’s a long list. Sea level rise, the warming of the Gulf of Maine, challenges to Maine’s iconic lobster industry, rising housing prices, economic volatility, energy security, and a working waterfront under duress. That’s why we talk a lot about hope and community resilience at the Island Institute.

Communities all along the coast have evolved and responded over hundreds of years. Ingenuity is in our shared DNA, and I don’t believe that will ever change.

WW: How would you like the Institute to respond to these concerns? And how would you like the organization to be understood by the communities it serves?

Hamilton: We’ve worked hard to develop strategies that play to our strengths and respond to community needs, with a special focus on climate solutions, economic resilience, and community leadership. These provide a framework for community solutions, not a prescription.

I want us to be judged by the value we bring, the ideas we share, and the respect we have for the communities that invite us in. I want us to be known as the organization that fights hard for Maine’s islands and coastal communities.

Friends of Acadia purchases inn for housing

IN MARCH, Friends of Acadia became the official owner of the Kingsleigh Inn in Southwest Harbor. Formerly a bed and breakfast inn that housed visitors to Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park, Friends of Acadia plans to convert the inn to workforce housing for the park’s seasonal employees.

Though Friends of Acadia owns the property, it will be managed and operated by Acadia National Park in similar fashion to existing park housing. The building has eight bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms and a twobedroom apartment, so the plan is to provide seasonal housing for ten employees. The property will remain on the town’s tax roll.

Friends of Acadia has partnered with the National Park Service (NPS) to address the housing crisis on MDI and its surrounding communities. The housing shortage has a direct impact on Acadia’s ability to hire a seasonal workforce to provide a quality visitor experience, care for cultural and natural resources, make progress on diversity and inclusion initiatives, and advance other strategic priorities.

“Seasonal employees are essential to operating and providing visitor services in the park from May to November,”

said Kevin Schneider, Acadia National Park’s superintendent.

“Last year, we were not able to fill all of our available seasonal positions largely because of the lack of housing options in and around Acadia. By expanding housing options, the Kingsleigh property will increase our capacity to recruit and retain seasonal staff members,” Schneider said. “We are incredibly grateful to Friends of Acadia for helping to support this need.”

Purchase of the Kingsleigh Inn falls within one of several strategies Friends of Acadia is taking in partnership with the NPS to expand seasonal workforce housing and address MDI’s housing crisis.

“Our goal is to add 130 new beds over the next decade for the park and its partners,” said Friends of Acadia President and CEO Eric Stiles. “We’ve developed a three-pronged approach that includes adding bedrooms to existing park units, repurposing commercial properties, like the Kingsleigh Inn, and constructing new housing units on sites within Acadia.

The housing crisis is not unique to Acadia National Park. Rather, it’s an issue faced by many parks throughout the National Park Service.

“Supporting our talented and dedicated staff is a key component of fulfilling the National Park Service mission to preserve and protect amazing places like Acadia National Park for the enjoyment of current and future visitors,” said Schneider.

“It will take all hands on deck to provide housing for our workforce

on MDI and surrounding communities. In doing this work, we are not just addressing the housing problem, but also the equity issue. We’re removing a huge barrier to employment and helping to ensure that employment here remains available and affordable to all,” Stiles said.

5 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023

Kim Hamilton is the Island Institute’s new president.

From left, Dave Edson of Friends of Acadia’s board of directors; Kevin Schneider, park superintendent; Jack Kelley, Friends of Acadia board chairman, and Eric Stiles, Friends of Acadia president and CEO, in front of the Kingsleigh Inn in Southwest Harbor.

PHOTO: GINNY MAJKA/FRIENDS OF ACADIA

book reviews

Fictional drama added to shameful reality

Novel drawing on Malaga Island horrors perpetuates myths

Harding’s stark fictional backdrop of Apple Island is salted by the demands of Maine’s unforgiving coastline and the ever-swirling, multi-generational eddies of mainland malevolence grounded in fear, suspicion, racism, and eventually eugenics. Harding also spices his Apple Island storytelling with allusions to incest and suspicions of murder.

This Other Eden

By Paul Harding

W.W. Norton & Co., 2023

REVIEW BY TOM WALSH

KATE MCBRIEN needs not even ten words to describe her reaction to This Other Eden.

One will do: “Offensive.”

Maine’s state archivist has found getting through Paul Harding’s newest coastal novel something of a challenge.

“It perpetuates all the myths about early Maine history. And none of them are true. That’s problematic.”

The novel’s characters include mixed-race generations of castaways, “queer squatters” living on a very small island amid nearly 100 years of undiluted genetics, with extended families existing hand-to-mouth within a haunting, other-world reality.

That bothers McBrien, who lectures on the history of Malaga Island. The 42-acre Casco Bay Island near Phippsburg was inhabited for more than 100 years by a small, racially diverse fishing community that extended over six generations. Those who lived there were evicted by decree of Maine’s governor in 1912, a process that demolished the homes of 47 residents, including eight inhabitants deemed “feeble-minded” who were then committed to a state institution.

Corpses buried there were exhumed and removed to an on-shore cemetery. To preclude resettlement, the state bought the island for $471. It was acquired by Maine Coast Heritage Trust in 2001 and is now an offshore preserve popular with tourists in kayaks.

“It’s sensationalistic,” McBrien says of The Other Eden. “There was no incest. There were no murders. But I hope at least it sparks interest in the real story because it is an important story of the role abolition, racism, and eugenics played in Maine’s early history.

“Malaga Island was the only Maine community broken up by eugenics, although it happened in other states and to other individuals. I hope at least this book sparks an interest in the real story. Paul Harding has won a Pulitzer Prize, so I suspect that readers might think this is the real story. There is one book now in progress that better reflects Malaga Island history.”

Harding’s debut novel Tinkers is also multi-generational and Maine-based. First published in 2009, it won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

History aside, Harding’s methods of melding words and his way with characters of his own invention is often stunning, both in concept and execution: “The islanders were so used to diets of wind and fog, to meals of

Class clashes and conspiracy logic

into the community. Their son, Stephen, is born and attends the local elementary school. Enough trust builds up around Walter to get him elected a selectman.

Everyone, however, remains aware of the socioeconomic divide between town and Raths, as evidenced in Stephen’s hilarious, uncomfortable interactions with his little friends from the town’s trailer park.

Land of Cockaigne

By Jeffrey Lewis, Haus Publishing Ltd. (2022)

REVIEW BY DANA WILDE

THE CENTRAL thing you need to know about the protagonist family in Jeffrey Lewis’s novel Land of Cockaigne is that they are from away.

Walter and Catherine “Charley” Rath arrived in Sneeds Harbor, located somewhere along the rim of Mount Desert Island, after Walter had made a ton of money early in the Silicon Valley heyday. They bought a yawl, sailed around, found Sneeds, and decided it was a quaint, remote place to make a home.

A pretty nice home, of course. In their own patient time, the Raths come to fit

Walter hires Donnie Cormer, the father of one of Stephen’s friends, to caretake their home. Donnie is one of those rock-solid, stand-up guys whose integrity quietly keeps small Maine towns running. As time goes by, he remains loyal to the Raths and the Raths to him, even amid the inevitable town chatter about them, some of it warm, some chronically skeptical, some kind of nasty.

Eventually Stephen goes off to college and gets involved in social work. In New York City, a random disaster shakes everything up, launching the main story.

Charley and Stephen’s black girlfriend, Sharon, concoct a plan to build in Sneeds Harbor a sort of glorified summer camp for underprivileged young men from the city. Walter skeptically calls it a “land of cockaigne,” invoking the 16th-century painting

by Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicting peasants lolling in gluttony and satiety. Charley is chafed by Walter’s skeptical irony. And likewise, the possibility of actual cocaine and other defilements infiltrating Sneeds Harbor chafes some of the townspeople, especially those with a disposition to suspect people of color—which the campers are expected to be—of being rife with criminality. A former governor’s actual embarrassing words are put to biting, ironic use in illustration of this.

As the camp takes shape, so do long-underlying frictions between the well-off Raths and the less-welloff locals, as well as between Charley and Walter. The camp’s pros and cons, so to speak, are debated in town gatherings, unofficial and official. Rumor and fear bubble together.

In one chillingly realistic conversation, stolid Donnie is harangued by his buddy Rine, who has been surfing conspiracy-theory websites.

“Where would you guess,” Rine says, “Walter Rath comes from?”

“Michigan.”

“Yeah, but ethnicity. Nationality. What I’m saying, we got a socialistic plot right here in River City. It could be a small part of the enchilada, but it’s definitely a part, one more part, and

slow-roasted sunshine and poached storm clouds, so used to devouring sauteed shadows and broiled echoes.”

Fictional travels through The Other Eden island’s stony woods include a delicate and insightful portrait of a young man as an artist, a boy whose pale-skin and brilliant talent doom him to wander from a cloistered life of island isolation onto the mainland and well beyond, perhaps even as far as the killing fields of the trench warfare French battlefields of World War I. Equally brilliant is Harding’s crafting of intriguingly eccentric Apple Island characters, including a recluse known to the community as Zachary Hand to God Proverbs, age unknown, a master woodworker who lived alone as freezing temperatures would allow in a hollowed out oak tree of his own design. Working by candlelight, Zachary carved scenes from the Bible on the inside of his oak – Samuel beheading Saul, Judas kissing Christ. Before eviction, he cuts his totem down.

Historical fiction? Or Fictional history? Therein find the rub.

Tom Walsh is a retired journalist, academic, and author of Erin’s Hope, a historical novel about Irish rebellion in 1867.

they get enough parts together and that’ll be the ball game. You know who Karl Marx was, Donnie? … Karl Marx was the whole inventor of communism, and he was … a Jew. … And Walter Rath? … Jew.’”

Charley, Rine observes, could be Jew “by proximity.”

Donnie has bitter choices to make between the Raths and his town.

The young men at the camp are mostly black and Latino, and in the latter part of the story we learn as much about several of them as we do about some of the townspeople, amid funny, ironic, and eventually violent events surrounding the camp.

Jeffrey Lewis’s skills as an Emmy Award-winning TV screenwriter translate artfully into a skillful, skating literary voice whose wry tone and quirky diction dance, throughout, on the edge of glibness. But the story nonetheless conveys an accurate feel for the ways values sprung from sharply different means both mesh and clash in small towns like those around MDI and Castine, where Lewis is a part-time resident.

There is plenty for everybody to laugh uncomfortably at in this book.

Dana Wilde is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.

6 The Working Waterfront may 2023

set in Maine airs dirty laundry

Novel

Harding’s methods of melding words and his way with characters of his own invention is often stunning…

Have you seen the Scuttlebutt?

Guide captures nuances of waterfront town

BY TOM GROENING

The phrase “buyer beware” seems inappropriate for someone settling in a pretty Maine waterfront community. But maybe “buyer aware” makes some sense.

After all, if that town has a working waterfront, a newcomer’s expectations may not match reality. Fishermen’s pickups driving by at 4 a.m. in summer. Diesel boat engines firing up a little later. Stinky, dried bait on the dock. Equally stinky lobster gear stacked nearby.

Those pretty fishing boats bobbing at their moorings in golden sunlight at cocktail hour come with all of the above.

Several years ago, Maine Sea Grant produced brochures distributed by real estate agents making those new homeowners aware of what it meant to live in Harpswell and Jonesport-Beals. Now, Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, Harpswell Heritage Land Trust, the Holbrook Community Foundation, the Harpswell Anchor newspaper and website, and Cundy’s Harbor Library have taken the concept up a notch or two with Scuttlebutt: A Guide to Living & Working in a Waterfront Community.

The 5-1/2- by 8-1/2-inch glossy publication, illustrated with engaging photos and graphics, welcomes visitors and new settlers to Harpswell, which, with 216 miles of shore, has the longest coastline of any Maine town. Other numbers included in the publication are that this town of 5,031 residents is surrounded by 200 small islands (only 94 are named), and that it has 79 commercially zoned wharves. One of the ideas behind Scuttlebutt is that it can be replicated in other waterfront

communities, says Monique Coombs, director of community programs at Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association.

“There’s a lot of changes happening in Maine’s coastal communities because of things like COVID migration, the ability to work remotely, and gentrification,” she said.

“We have to balance these with the culture and industry that has made up working waterfront communities for generations,” she said. “We think helping educate new and summer residents about living and working in a waterfront community allows us to celebrate commercial fishing and mitigate potential future conflict.”

The Harpswell version is fact-filled and makes its points about the salty realities of the town, including defining the terms access, commercial fishing, working waterfront, rights of way agreements, and working waterfront convenants.

“Wharves are beautiful and full of activity, but they can be slippery, rickety, and potentially hazardous,” one page notes. “Forklifts beep when backing up, bait trucks are noisy and smelly, boats have bright lights so they can see and be seen, and things are often moving quickly.

“If you live near a wharf or are just visiting to buy some lobsters, pay attention to what’s going on, watch your step, and recognize that fishermen are working hard to provide the best seafood in the world.”

Scuttlebutt also offers advice on how to “be a good neighbor and steward of the Gulf of Maine ecosystem” by minimizing or eliminating the use of lawn fertilizers and insecticides, cleaning up after dogs, and using rain barrels to conserve well water.

Acadia announces new entrance fees

THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE (NPS) has approved an increase in the weekly and annual entrance pass fee for Acadia National Park. The fee increase will go into effect on April 1 and is required year-round. The new seven-day entrance fees are as follows:

• private vehicle— $35

• pedestrian/cyclist—$20

• motorcycle—$30

• The annual fee for Acadia is $70

The majority of Acadia’s entrance fee revenue is retained locally to fund the Island Explorer bus system and other projects that directly benefit visitors and protect park resources. The increased fee revenue will allow Acadia to expand Island Explorer service over the coming years to help alleviate traffic and parking congestion and parking in the park, which is a key part of implementing the park’s transportation plan.

The entrance fee increase does not affect commercial entrance fees for businesses operating in the park under a commercial use authorization or the National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Passes that can be used at Acadia, including the annual, senior, access, 4th grade, military annual, and military lifetime passes.

Visitors under 16 years of age are exempt from paying an entrance fee.

Visitors can also enjoy entrance fee-free days that provide free admittance to all national parks for everyone. The remaining free entrance dates for 2023 are:

• April 22—the first day of National Park Week

• Aug. 4—Great American Outdoors Day

• Sept. 23—National Public Lands Day

• Nov. 11—Veterans Day

Prior to the approval, the NPS solicited public feedback on the proposed fee increase during a 30-day comment period, which closed Dec. 30. The public comments were predominantly supportive of the entrance fee increase. The NPS also consulted with the congressional delegation and other key partners and stakeholders before approving the fee increase.

But it’s not preachy.

The guide also includes recipes for making lobster stock and crab dip, tips for dealing with the salt air, and descriptions of other fisheries. It even directs readers to other nonprofits working to sustain the way of life towns like Harpswell enjoy.

Interestingly, the publication notes that the term “scuttlebutt” referred to the cask of drinking water aboard a ship, the maritime version of “water cooler.”

The guide was created following a series of panel presentations in the fall

of 2021 and spring of 2022, “Living and Working in a Waterfront Community: A Conversation Series.” Coombs says 1,500 copies were printed, though more will be published this summer to distribute to visitors.

Those interested in developing such a guide in their community should contact Coombs at monique@mainecoastfishermen.org. The organization offers to help communities fundraise and produce a similar guide specific to the community. The approximate budget is based on printing; the cost of producing 1,500 was about $2,000, Coombs said.

Trenton wetlands conserved

THE MAINE DEPARTMENT of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife in partnership with the Frenchman Bay Conservancy have won a $1 million grant to conserve 216 acres of intertidal and freshwater wetlands and adjacent uplands in Trenton.

Sen. Susan Collins, the vice-chairwoman of the Appropriations Committee, and Sen. Angus King, the chairman of the Senate National Parks Subcommittee, announced the award.

“Trenton is a beautiful gateway to Mount Desert Island, and protecting its ecological health is critical to the surrounding region, including Acadia National Park,” said Sens. Collins and King in a joint statement. “By preserving more than 200 acres of land, this conservation project will promote coastal resilience, safeguard native ecosystems and wildlife habitat, and provide economic benefits.”

Coastal wetlands are vitally important in protecting from floods, filtering water, supporting recreation and local economies, and providing habitat for fish and wildlife. Despite their importance, there has been a steady loss of coastal wetlands.

The funding was awarded through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of $19 million in competitively awarded grants supporting 21 projects in eight coastal states to protect, restore, or enhance nearly 14,000 acres of coastal wetlands and adjacent upland habitats under the National Coastal Wetlands Conservation Grant Program.

The 2023 grants will help recover coastal-dependent species, enhance flood protection and water quality, provide economic benefits to tribes and underserved communities, increase outdoor recreational opportunities, and benefit habitat and wildlife at several national wildlife refuges.

7 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023

On-demand gear tested off Massachusetts

Lobstermen’s association remains skeptical

BY CRAIG IDLEBROOK

This spring, researchers were given an expanded opportunity to test lobster trap gear that eliminates the need for vertical buoy lines in waters traversed by critically endangered North Atlantic right whales.

Under the direction of NOAA and with permission from the Massachusetts Department of Marine Fisheries, a fleet of ten vessels has been allowed since Feb. 1 to use special on-demand lobster traps in either state or federal waters along the eastern coast of Massachusetts and south of Martha’s Vineyard. The fleet has until the end of April to test the traps in areas that are otherwise closed to traditional lobstering to protect the endangered whales from entanglement.

As of late March, lobstermen have retrieved the traps from the ocean floor 186 times, according to NOAA data. The lobstermen and the researchers are continuing to test the effectiveness of both the on-demand gear and the mapping technology used to find the traps.

In this round of permitted fishing, one focus is ensuring the tracking technology is accurate even when traps are in proximity to one another. Semiretired lobsterman Marc Palombo said this tracking technology recently passed a critical test in federal waters.

“We got another vessel with a satellite with internet on its boat and had it go right next to my boat, and I could see his gear and he could see my gear,” he said. This effort represents the largest chance yet to experiment with the on-demand traps in real world

conditions in New England. For years, researchers have been working to design traps that could eliminate the need for standing vertical lines. Those efforts have met with some resistance, however.

For example, the Massachusetts Department of Marine Fisheries (DMF) denied an application by a group of lobstermen to test experimental gear in 2022. That group did gain an 11th-hour permission from federal regulators to try the gear in lobster harvesting, but only for a few days.

Since then, NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center received an exempted fishing permit from federal regulators to allow up to 100 fishing vessels to test and improve on-demand gear in a variety of fisheries. Scientists from the center then devised a plan to test the lobster gear in federal waters and approached Massachusetts DMF for permission to fish in state waters just off the coastline. DMF agreed, and both efforts are being directly supervised by NOAA.

In his letter allowing NOAA to set the experimental traps, DMF Director Daniel J. McKiernan did express some skepticism about the practicality of the on-demand traps for coastal lobstering.

“DMF’s view is that on-demand technology works best for those that fish long trawls on the larger vessels in the fleet,” he wrote. “Its applicability and affordability is far less for smaller vessels that fish single traps or short strings of gear in dense gear fields.”

Erica Fuller, a senior attorney for the Conservation Law Foundation, said that even with those doubts, it still made sense for state regulators to greenlight testing near shore, where lobstering activities are at their densest.

“There were some questions about how close can you actually fish this gear to another guy, and those questions weren’t so much being answered in the far offshore,” Fuller said. “While they were trying to get close, those [offshore] trawls are so much longer they’re generally not right on top of one another.”

DMF Director McKiernan is not alone in his skepticism. When asked about the latest round of testing of on demand gear, Beth Casoni, executive director of the The Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association sent the following statement:

“The Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association does not support the use of on-demand gear as the economics are not feasible and it will destroy the American lobster fishery.”

For now, Palombo is one of a minority of lobstermen who doesn’t share his colleagues’ pessimism on the evolving technology, and he has been recruiting other Massachusetts fishermen to the effort to test the new traps out. He knows the technology may still be unaffordable at this point for most fishermen, but he says the funding is there to help develop the trap gear, and he’s seen the improvements each year in the experimental gear. People need to remember that it’s a long process to create a new technology, he said.

“I like to use the analogy that we’re the Wright brothers right now,” Palombo said. “They didn’t start out with the F-15 fighter. They were at Kittyhawk, and that’s where we’re at right now. We’re at Kittyhawk.”

8 The Working Waterfront may 2023 A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too. We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings. Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs. We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what. That’s the Allen Advantage. Call today. (800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com Owning a home or business on the coast of Maine has many rewards. We are an independent, employee-owned company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville. Monhegan Skiffs for Sale 9 1/2ʹ and 11ʹ plywood and lapstrake Starting at $2,300 Call 677-2614 or email director@carpentersboatshop.com 100 N. Main Street Stonington, ME 04681 207-348-3084 Market & Smokehouse Fresh seafood, fish, crab & lobster meat, smoked mussels, live crabs & lobster. Available year-round! Farm-fresh beef & chicken, Maine-made cheese, dips, eggs, and many other items! Open Mon. 10-4, Tue. – Thurs. 10-3, Fri. 10-4, Sat. 10-5 We ship! coldwaterseafoodmaine.com coldwaterseafoodllc@gmail.com

“DMF’s view is that on-demand technology works best for those that fish long trawls on the larger vessels…”

Immigration lawyer offers Maine perspective

Terminology, facts shed light on realities of issue

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

Immigration law is surrounded by politics, controversy, and debate and is constantly in flux, Jennifer Atkinson told a small audience at Skidompha Public Library in Damariscotta in March.

“It’s very political,” she said. “Depending on the administration, you can see huge changes in what you’re doing and what you have to pay attention to.”

As a state that historically has not seen large influxes of immigrants, the immigration debate has not had the same urgency here as it has in places such as along the southern border, but with asylum seekers coming into the Portland area in numbers the metropolitan area is struggling to manage, immigration issues are on the minds of Mainers.

In order to provide some insight into the complexities of immigration in the U.S., Atkinson, an immigration lawyer at Gallagher, Villeneuve and DeGeer in Damariscotta, presented an immigration law primer as part of the Chats with Champions lecture series.

She did not delve into the current asylum seeker influx to Maine or the ways in which immigration law intersects with international human rights law. But she did highlight a number of things that often are not discussed around the kitchen table or in media reports, such as:

Who exactly is an immigrant?

An immigrant is a person born abroad who is living permanently in the U.S. Someone who is born abroad but is living temporarily in the U.S. is not an immigrant. Undocumented immigrants are people born abroad who are living in the U.S. but who entered the U.S. without proper documentation, such as a visa. Only people from abroad who are lawfully living in the U.S. as permanent residents can naturalize and become citizens.

The U.S. applies different standards for those entering the country.

Unlike other countries, Atkinson said, the U.S. operates on the basic assumption that if you are coming here, you’re doing so to stay.

a matter of going online and applying under the Visa Waiver program.

But for people from places such as Guatemala, there is no easy online process. These people must make an appointment with the U.S. Embassy to persuade an official there that they don’t want to live here permanently. That official has full discretion as to whether to approve the person applying for entry or not.

“If you’re from a less-developed country, it becomes much more difficult to come to the United States as a non-immigrant,” Atkinson said. The hoops to go through to become a permanent resident are even more strenuous and are partly restricted by quotas. Other restrictions can include national security, morality (criminal activity, for example), public health, and flatout racism and xenophobia (the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the more recent Muslim ban, for example).

As the so-called land of opportunity, the U.S. is a popular choice for migrants.

The U.S. accepts more immigrants than any other country, and businesses are “clamoring” for more workers from abroad, but with so many people wanting to move here, a “broken” immigration system, the lasting impact of the pandemic, and staffing shortages, the backlog of people waiting to get here is enormous, said Atkinson.

“If you are a U.S. citizen and you have a brother or sister in another country and you would like to help them come to the United States, you’re allowed to do that and they can get approved on that basis,” Atkinson said. “However, they’re going to have to wait 16 years for a visa.”

The wait can be even longer if the person is from a country such as India or China. And the immigration process is not cheap, she pointed out.

As of 2018, 4% of Maine residents are immigrants, Atkinson said, with the bulk of those people coming from Canada.

“If you are someone who wants to come here to visit or to study or work temporarily, you have to prove that you are not coming to stay here permanently,” she said.

Proving your intention is easier for people from certain places in the world, she said, for example, places such as Sweden, France, Australia, and New Zealand. For people from these places, it is often just

“U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is a fee-based organization, so the fees that they raise pay for them,” she said.

If someone is a foreign national already residing in the U.S., married to a U.S. citizen, the cost of filing fees alone will be around $2,000, she said. For certain types of cases, people can pay an additional $1,500 to $2,500 to expedite the process, she noted.

Maine has never had a large immigration population.

As of 2018, 4% of Maine residents are immigrants, Atkinson said, with the bulk of those people coming from Canada. Nine percent of that 4% are undocumented.

“The undocumented people I have met here in Maine,” she said, “have all been European.”

9 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www pro C k M arine C o M pany C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro

Advertise in The Working Waterfront, which circulates 45,000 copies from Kittery to Eastport ten times a year. Contact Dave Jackson: djackson@islandinstitute.org

Full Service Boat Yard, Repairs, Storage & Painting P.O. Box 443, Rockland, ME • knightmarineservice.com 207-594-4068

Jennifer Atkinson

rock bound

Remembering conflict on the home front

War’s misery ripples out far and wide

BY TOM GROENING

MEMORIES OF long-ago events are cemented into our hearts and minds when they are baptized in emotion. Where were you when…? Without a visceral response at the “what,” the exact “where” gets fuzzy.

With other big news events in recent weeks—another school shooting, the legal woes of an ex-president—an important anniversary may have been overlooked, but it’s been 20 years since the U.S. under President Bush invaded Iraq.

I have a powerful memory of the day Congress voted to authorize that invasion, and it’s marked by an odd trio of images—bicycle locks, an elevator, and the Marx Brothers.

The Bangor Daily News sent me to cover a protest at then-Sen. Olympia Snowe’s office in Bangor as the drum beats built toward the invasion. I think a half-dozen folks had entered Snowe’s office, without being unduly disruptive, and demanded to speak to the senator before she voted. The long-time office manager—a woman I knew slightly—said she would pass on the message to Snowe’s Washington D.C. office, but suggested a phone conversation was unlikely.

The protestors sat on the floor in the small office, and after a couple of hours, three of them—all in their 20s, as I remember it—took those long U-shaped bicycle locks, put them around their necks, connected them to each other, and locked them. The protest had suddenly ratcheted up a notch.

I sometimes wish I could be a more dispassionate observer, but that’s not my make-up. At one point, as the group lay about on the floor of the small office, the manager didn’t lift her leg quite high enough to step over someone, and inadvertently kicked a protestor, though ever so slightly.

The protestors, well, protested, somewhat angrily.

I knew that the office manager had a degenerative nerve disease that no doubt made stepping over them difficult. I quietly told one of the protestors that fact about 15 minutes after the incident.

I could feel the emotions rising in me. I dreaded what the invasion would bring. Nothing happens in a vacuum; the Bush war had philosophical ties to the 9/11 attacks. Those attacks had their genesis in U.S. dealings with the fighters driving the Soviets out of Afghanistan, effectively abandoning them after the Soviet withdrawal.

reflections

Back in Bangor, the office was preparing to close at 5 p.m. The protestors refused to leave. Police were summoned. Officers were gracious and professional, giving the protestors time to consider leaving before arrests would be made. Most accepted that offer.

The three young adults linked by the locks quietly conferred with each other and agreed to not produce the keys. A locksmith was called. As he gestured and touched the upper chest of one of the women, showing where he would cut the lock, a woman officer scolded him, warning him to keep his hands clear.

Finally, the locks were cut, the three were handcuffed—if memory serves, zip ties were used—and refusing to walk, they were dragged to the elevator door. It was time for me to leave to write my story. As I walked out, the youngest of the three—a woman— was lying on her back, alone, by the elevator, handcuffed.

Her eyes met mine, and I saw fear and the beginning of tears. My tears were on their way, but I held them until I was in my car.

At home that night, I asked the family to join me in watching Duck Soup (1933), the brilliant Marx Brothers

Hearing stories of love and loss

The past has an enduring power

Reflections is written by Island Fellows, recent college grads who do community service work on Maine islands and in coastal communities through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

BY OLIVIA JOLLEY

BEING A “person from away” is not a new experience for me. I was born in the Southeast where my parents’ family roots lie but I moved to Southern California before I could develop my own Southern twang.

I listened to my parents’ stories, visited my grandparents every summer, and learned how to make my Great Granny’s chicken and dumplings. But living across the country I didn’t know much about my family or their history.

As an Island Fellow, I moved to Swan’s Island for two years to work with the Swan’s Island Historical Society on various projects—saving a church building from the 1800s, digitizing archives and curating exhibits, and being an extra set of hands for whatever tasks arose at the volunteerled organization.

Swan’s Island astounds me because everyone I’ve encountered seems to agree that knowing who and what came before you is important. There is a reverence here for preserving the past and savoring the present that I haven’t experienced anywhere else.

People live and die here. Generations of their family have cultivated the culture and community of this island. The soil is steeped in a history that lives on through the people who stay. It’s not just an island, it’s their island.

I thought I knew the value in preserving and sharing history, but my first few months on this island showed me that my appreciation and understanding of the past were just budding.

It has always been hard for me to connect to stories focused on people. I gravitated towards periods of time, events with impacts spanning the globe, and traditions that endured centuries while people came and went. People were always a part of the story but never the focus, the part that kept my attention.

Through my work with the Swan’s Island Historical Society, I’m starting to see that those individual experiences are not just a piece of the larger picture, a means to an end.

Working with the collections of old family photos has taught me the most—portraits of stern-faced men and women from the 1800s, candid shots of fishermen of all ages buzzing around wharves, and glimpses of the little things that make life different out here.

One photo has been stuck in my head for months.

Two boys sitting in front of a Christmas tree dripping with tinsel and surrounded by their new toys. Their father stands in the doorway, leaning against the frame and looking at his sons with the softest smile. I can’t help but wonder if the person behind the camera saw his smile, too.

I’ve never met the man or the boys, but I’ve cried for them, looked at their

satiric comedy about war (“To war! To war! Freedonia’s going to war!”).

I wanted my teenaged kids to have a good film education, and of course the Marx Brothers were an essential part.

But it is a satiric film. Groucho and his brothers were in their 30s and 40s when the film was made, and they would have known men who had died or were maimed in the Great War that ended 15 years earlier. The cause of that war still is barely understood, which would not have been lost on those seeing the film and Groucho’s insincere outrage over the perceived slight that triggers the movie war.

My anguish, and the plight of the protestors, pale in comparison to the young men and women in Iraq who were killed, or who walk around today missing a limb or an eye, as well as the young Americans asked to serve in the conflict. We need to count the cost. War is no laughing matter.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be reached at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

faces fondly as if they were my own flesh and blood. I’ve seen their relatives who haven’t walked the earth for decades grow like weeds with their brothers and sisters, go to war and not always come back, and spend their last years at home on Swan’s Island.

These human stories might feel mundane to those living them but they have the power to captivate others, to pique curiosities and shift perspectives.

Stories of love and loss, community and kindness, empower folks to reflect on their own lives, introduce them to different ways of living, and help find common ground and connect with others.

Olivia Jolley works with the Swan’s Island Historical Society digitizing its artifacts and archives. Born in North Carolina, Jolley grew up on the coast of southern California and moved to Maine to attend College of the Atlantic.

10 The Working Waterfront may 2023

There is a reverence here for preserving the past and savoring the present…

BEACH TOWN—

The town of Lincolnville, just north of Camden, has two villages: the Center and the Beach. This image of the Beach, circa 1948, looks remarkably similar to a contemporary view. Most, if not all of the buildings visible here remain, though the business names have changed. The second building from the left has a sign reading Nichols Garage. To its right is the Village Store, which has remained a store to this day. To the right of the store is the post office. In the last 20 years, a new post office has been built a hundred yards or so to the south.

The following was released by Maine’s congressional delegation and Gov. Janet Mills:

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, when NOAA began working on regulations that drastically affect Maine’s lobster fishery without meaningfully advancing the stated goal of protecting endangered right whales, the five of us pledged that we would pursue all policy solutions to protect our hardworking lobstermen and women.

The inclusion of provisions in the federal omnibus funding bill that postpones the implementation of any new whale rules by NOAA for six years is a down payment on that pledge. Working together in a nonpartisan spirit and across levels of government, we achieved a victory for our state, for our iconic and vital lobster industry, and for common sense.

While we are proud of this accomplishment, the resilience shown by the men and women of the industry was our inspiration. In the face of misguided threats to their livelihoods and their way of life, they responded with determination and facts. The expertise provided by the Maine Department of

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kr istin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGi nnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis

Michael Sant

Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

Marine Resources, Maine Lobstermen’s Association, and Maine Lobstering Union was essential to this process.

Our provisions mean that for the next six years, the current right whale regulations will be frozen in place, allowing more time to gather data to pinpoint what is causing the demise of the right whale.

It is a measure to protect the family businesses of the thousands of Mainers who make their living from one of the best managed and sustainable fisheries on earth. It also gives the industry and regulators time to develop effective and practicable policies regarding fixedgear fisheries and marine mammals. Without this provision, an industry that contributes more than $1 billion annually to Maine’s economy and supports small businesses all along our coast could have been faced with a complete shutdown, and the ripple effects across our state would have been widespread.

Maine lobstermen and women have long demonstrated their commitment to maintaining and protecting their sustainable fishery. They have invested in countless precautionary measures to protect right whales, including removing more than 30,000 miles of line from the

water and switching to weaker rope to prevent whales from being entangled. And the fact is, there has never been a right whale death attributed to Maine lobster gear. We know the right whale population can be protected along with a thriving fishery because Maine lobstermen and women are already doing it. This industry has a longstanding ethic of practicing sustainability by protecting the health of the lobster stock, and also by treating the entire marine environment with respect and care. The industry recognizes the precarious situation of the North Atlantic right whale, and for decades has been proactive in ensuring that the fishery and the whales can co-exist.

In addition to postponing the implementation of additional regulations for six years, the provision in the funding bill provides $20 million for a grant program that could fund innovative gear technologies and the monitoring necessary to support the dynamic management of fisheries. Fishermen and other participants within the maritime industry would be among those eligible for this funding. Another $22 million was provided for additional research and monitoring efforts for

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published

All members of the Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery:

right whales, so any future regulations would be informed on real data, not hypotheticals. We also secured an additional $10 million for states to provide direct payments to lobstermen and women to offset the costs associated with the gear modifications that they have made over the past several years.

The lobster industry is Maine’s economic engine, sustaining not only the men and women who fish but entire communities. Fishermen are willing to make changes to proactively protect whales and have been active participants in the ongoing discussions, but Maine’s lobster industry is not to blame for the decline in the right whale population.

Before any additional regulations are implemented, lobstermen deserve to know that these measures are backed by sound science. As this process moves forward, we will continue working together to push for reasonable solutions that protect Maine’s vital lobster industry and safeguard right whales and other marine mammals.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of the Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

11 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023 op-ed

by the Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

Join the Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

Submitted by Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King, Reps. Chellie Pingree and Jared Golden, and Gov. Janet Mills.

Delegation, governor inspired by lobster fishery Regulatory ‘pause’ product of cooperative work

Like no other

provisions

Garden & Market

Over 100 Maine Craft Beers, Kombuchas, and Ciders

• Freshly made sandwiches & salads

• Hot entrees: soups, chili, and chowders

• Large selection of wine, craft mixers, and Naut-E botanical spirits

We also have wonderful unique gifts, from finely crafted Japanese teacups, award-winning Folkmanis puppets, and our iconic coffee mugs and sweatshirts—this year’s line being in Pantone’s 2022 color of the year, Peri.

Open Daily 10-5

5 Castine Road • Castine, ME windmillhillprovisions@gmail.com

12 The Working Waterfront may 2023

PHOTOGRAPHS AND ESSAYS by David Owen will be on display at the Fifth Maine Museum on Peaks Island from May 26 to Oct. 9 in a show called “Peaks—Like No Other Island.”

CASTINE MAINE

On Rt. 1 in the Village of Hancock, ME, on just under an acre, this commercial building houses a wine shop, a seafood shop, a dog grooming shop, each of which have been updated, and an empty space ready for a tenant’s business. The wine shop is charming with incredible wine selections and a one-bedroom apartment above with beautiful views to a farm behind the building. Lovely village, close to beaches, docks and hiking trails, halfway between Acadia National Park and the Schoodic branch of Acadia. Live above your business, with lots of possibilities for your ideas and a beautiful space in one of the most traveled corridors of Maine highways. $499,000

TACY RIDLON

(207) 266-7551

TACYRIDLON@MASIELLO.COM

13 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023 www.landvest.com Camden: 23 Main Street | 207-236-3543 Northeast Harbor: 125 Main Street | 207-276-3840 Portland: 36 Danforth Street | 207-774-8518 HQ: Ten Post Office Square Suite 1125 South | Boston, MA 02109 If you are Buying We offer spectacular properties for sale throughout New England and beyond If you are Selling We understand Maine’s waterfront and can help you achieve your property’s best value whether it’s a marina, boatyard, land or luxury estate If you need Consulting We provide land planning, appraisal, and project management for significant real estate assets If you invest in Timberland We lead the nation in the marketing and sale of investment timberland properties

traveled the back roads, we’ve navigated the waters, and we know Maine.

We’ve

That ‘other’ Portland

Photographer visits Portland, Oregon’s waterfront

PHOTO ESSSAY BY KELLI PARK

PHOTO ESSSAY BY KELLI PARK

Photographer Kelli Park visited Portland, Oregon recently and documented that city’s waterfront. The city of 641,000 (almost ten times the size of our Portland) has its share of high-rise office buildings, but Park says she was struck by the number of food trucks, live music venues, and restaurants.

“The waterfront was interesting,” she writes “because it was very industrial in some areas, but then it had a really nice park/ green space that ran the length of downtown. The marina downtown was home to a lot of boats that had seen better days,” and little evidence of commercial fishing.

Nine bridges cross the Willamette River in Portland, making that area busy with traffic, she reports.

The cherry trees began to blossom the day she departed.

14 The Working Waterfront may 2023

15 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2023

Our Island Communities

Islesboro student flying solo at 16

Jack Moore will soon have pilot license

BY TOM GROENING

Living on an island and relying on a ferry to get to the mainland and the wider world might inspire a young person to seek other modes of transportation. But for Jack Moore, 16, pursuing an airplane pilot license seems to spring from something more profound.

“It was kind of a fascination with all things flying,” he explained in a recent phone interview. “Even birds.” Of course, flying in a small Penobscot Island Air plane with the late Kevin Waters at age 11 also fueled the passion.

“I was hooked from then on out,” Moore says. Moore lives with his father, Terry Moore, on the island where he is a junior at Islesboro Central School, and also with mother, Avery Larned, at her home in Belfast.

He began taking flying lessons at age 15 from Dave Aldrich, a certified instructor, using Belfast’s airport as a base.

“I didn’t really have a goal, a plan,” Moore recalls, and when Aldrich traveled to Florida for the winter,

“I was looking for something more permanent.” He found that at Penobscot Island Air’s flight school in Owls Head, which includes five weeks of classroom time.

“I started to realize I wanted to do this as a career, and get a license as quick as possible,” he explained. Now, he’s about ten hours of flight time from earning a private pilot license.

Even though he doesn’t have that license yet, Moore has “soloed” many times. Those flights bring home the full nature of the experience.

“You can definitely appreciate the technical skill needed to fly the airplane,” he says, especially when the weather is rough. “Taking off is optional,” he says, invoking the pilot’s creed. “Landing is required.”

Yes, there is inherent danger, but “It’s really never the airplane that fails,” he asserts. Almost all crashes come from human error. Moore admits to having “messed up radio calls, using the wrong frequency,” and once flew a little too close to a jet.

“The most important thing you can have is leeway” for those moments, he says.

The joy comes in the “complete and utter freedom”

of traversing the open sky, flying at 3,000 feet and passing beneath a flock of birds, he says.