Fort Gorges— Time for new ownership?

Advocacy group suggests state or national park

BY CLARKE CANFIELD//PHOTOS BY JOEL PAGE

Fort Gorges has stood prominently in the middle of Portland Harbor for more than 150 years. A group that advocates on behalf of the granite Civil War-era fortress wants to make sure it stays that way into the future.

The Friends of Fort Gorges nonprofit organization is taking steps to raise additional funds toward improving the Portland-owned fort and making it more accessible to the public. Organization leaders are also asking out loud whether the fort would be better served under new ownership.

Paul Drinan, executive director of Friends of Fort Gorges, said it’s vital to stabilize and improve the historically significant fortress, which was modeled after Fort Sumter, the South Carolina fort where the Civil War began on April 12, 1861. While the Friends group has not made any formal proposal, Drinan said the time may have come for Fort Gorges to join the ranks of similar forts nationwide that are run as state or national parks.

“At the end of the day, there will never, ever be another Fort Gorges,” he said on a recent day while giving a tour of the fort. “Nobody will ever build anything like this ever again.”

The city of Portland now manages Fort Gorges as a city park and works in partnership with the Friends group to maintain and promote it. The city mows

the fort’s parade grounds each year and contributed $16,000 toward an Army Corps of Engineers stabilization project six years ago.

But with the city’s Parks, Recreation and Facilities Department overseeing 67 parks, 30 playgrounds, 40 athletic fields, and 11 community gardens, it’s hard to

continued on page 2

Commission approves lobster size rules

Changes would be triggered by species decline

An interstate regulatory commission has approved a rule that could change the minimum and maximum sizes for lobster harvesting as a means of protecting the species. The change was adopted May 5 by the Atlantic

States Marine Fisheries Commission’s lobster management board.

The new rule establishes a trigger mechanism to implement management measures—specifically gauge and escape vent sizes—to provide additional protection of the Gulf of Maine

SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

and Georges Bank spawning stock biomass. It also implements changes to management measures for two lobster conservation management areas and outer Cape Cod to improve the consistency of regulatory measures.

The commission board said it adopted the new rule as “a proactive measure to improve the resiliency of the Gulf of Maine-Georges Bank stock.”

Since the early 2000s, lobster landings have rapidly increased, with the Maine harvest increased from 57 million pounds in 2000 to a record high of 132.6 million pounds in 2016. Landings here have declined slightly but were still high at 97.9 million in 2020 and 108.9 million in 2021.

Since 2012, lobster settlement surveys throughout the gulf have generally been below average in all areas.

Since 2012, lobster settlement surveys throughout the gulf have generally been below average in all areas. These surveys, which measure trends in the abundance of juvenile lobsters, can be used to track populations and potentially forecast future landings. Persistent low settlement could foreshadow declines in recruitment and landings.

The new rule establishes a mechanism where changes to the current gauge and escape vent sizes will be implemented automatically based on observed changes in the abundance of juvenile lobster. If the abundance index declines by 35% from the three-year average from 2016-2018, a series of gradual

continued on page 7

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities published by the island institute n workingwaterfront.com volume 37, no. 4 n june 2023 n free circulation: 50,000

CAR-RT

Paul Drinan, executive director of the Friends of Fort Gorges, poses inside the fort in Portland Harbor during a tour.

FORT GORGES

continued from page 1

put Fort Gorges high on the priority list, said Ethan Hipple, director of the department. If a new ownership opportunity presented itself, perhaps with the state or federal government, Hipple said he would be “all ears.”

“Ultimately we want what’s best for the fort,” he said. “If there’s another entity that has the resources to do more than the city of Portland can, I think it’s worth looking into.”

Named for Ferdinando Gorges, the proprietor of the Province of Maine from 1629-1647, Fort Gorges was one of 42 military forts built between 1816 and 1867 as part of a broad national defense strategy that included a new generation of waterfront defenses called the Third System of Coastal Fortifications. The stone and brick forts were built on the eastern seaboard, the Gulf of Mexico, and California and featured bombproof rooms, called casemates, and cannon openings, or embrasures.

Built between 1858 and 1865 on a barren rock called Hog Island, Fort Gorges was never in battle and troops were never stationed there. The navy used it to store mines

and munitions during World War I, and mines, munitions, and anti-submarine equipment during World War II. The federal government gave it to Portland in 1960.

A 2016 study estimated that 8,000 people visit the fort each year, but Drinan thinks the number has since grown to 10,000 or more. Most visitors arrive by kayak, and those who go by power boat have to arrive and depart within two hours of high tide. In recent years, the Friends has organized musical and theater performances and other events to small groups of fewer than 50 people, transporting them on a private charter boat. The Friends, along with a number of boat owners and tour companies, also offer historical tours.

Fort Gorges has undergone periodic improvements, such as the Army Corps project for stabilization and safety improvements that included steel railings and an observation outlook offering a spectacular view of the city and the surrounding islands. But overall, a lack of maintenance and the forces of nature have their toll on the structure.

Take a walk through the fort and you’ll see brick-masonry arches that are separating, bricks that have fallen free, and a walkway that is slowly sinking. The fort’s granite block wharf is in need of repair, and viewing areas on top of the fort are overgrown and unsafe. A sign at the entrance warns visitors to “Enter at Your Own Risk.”

2 The Working Waterfront june 2023

The brick ceiling can be seen separating.

Steve Russell, a Friends of Fort Gorges board member, walks through the yard.

The landing area for boats and kayaks.

Russell, left, and Drinan on top of the fort.

The Friends group is now taking steps to tap into additional funding that, in time, could be used to stabilize the fort and increase access for visitors. It plans to petition the National Register of Historic Places to have its “level of significance” elevated on the register from local to national—thereby opening up new opportunities for grant funding. It has also submitted applications with the offices of Sen. Susan Collins and Rep. Chellie Pingree for $1.1 million in earmarks, to be voted on by Congress this fall, to rebuild the massive granite wharf. If that happens, Drinan said, the group could install a dock with a gangway that would allow more boats to visit.

The Friends group also thinks it’s worth considering what the best ownership structure might be. Drinan likes the idea of turning it into a state park, but is also open to it becoming part of the National Park System or perhaps taken over by a land trust that has more resources than the city.

Of the 42 Third System forts built after the War of 1812, one is gone and a couple are in ruins, said John Weaver, a fort historian and author of A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867.

Of those still standing, about half are owned by the federal government and about a third by state governments, he said. A handful are privately owned, and three—including Fort Gorges—are owned by the cities in which they’re located. Weaver has spent more than 40 years studying these forts, and has visited all of them multiple times. While each fort is different, Weaver thinks the federal

government is probably the best owner for them. “The National Park System does an incredibly good job and has adequate funding to take care of these forts,” he said.

Steve Russell, a Friends of Fort Gorges board member, said one model worth looking at is Fort Knox, a Third System fort on the banks of the Penobscot River in Prospect. Fort Knox is owned by the state and leased to and managed by the Friends of Fort Knox organization.

“It’s a matter of figuring out the pieces of the puzzle and making them fit,” Russell said while joining Drinan on the visit to the fort.

Bureau of Parks and Lands spokesman Jim Britt said both he and Bureau Director Andy Cutko have visited Fort Gorges and agree that it’s special and unique. But they also recognize that it would be “massive project” to make it a state park and transform it into what the Friends of Fort Gorges imagine it could be.

Maine’s state parks, which attract more than 3 million visitors annually, are now undergoing numerus maintenance and improvement projects using $50 million in federal relief funds allocated to Maine under the American Rescue Plan Act, Britt said.

“The appeal of the fort is great, and it absolutely is a great idea,” Britt said. “But now is not the time for the Bureau of Parks and Lands to consider a project of that magnitude for a number of reasons, including limited funding, limited staffing, and the monumental task facing the bureau right now of the state park restorations that are getting underway. So now would not be the time.”

3 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023 G.F. Johnston & Associates Concept Through Construction 12 Apple Lane, Unit #3, PO Box 197, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679 Phone 207-244-1200— ww w. gfjcivilconsult.com — Consulting Civil Engineers • Regulatory permitting • Land evaluation • Project management • Site Planning • Sewer and water supply systems • Pier and wharf permitting and design

annual

John Martin, Bud Staples, and Elsie Gillespie chat

around the woodstove at the

town meeting.

Gerald “Punkin” Lemoine

Sea Farm Loan FINANCING FOR MAINE’S MARINE AQUACULTURISTS For more information contact: Nick Branchina | nick.branchina@ceimaine.org |(207) 295-4912 Hugh Cowperthwaite | hugh.cowperthwaite@ceimaine.org | (207) 295-4914 Funds can be utilized for boats, gear, equipment, infrastructure, land and/or operational capital. Lower Interest Rates Available Now!

Bud Staples

Linkel

Locally owned and operated; in business for over twenty-five years. • Specializing in slope stabilization and seawalls. • Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) certified. • Experienced, insured and bondable. Free site evaluation and estimate. • One of the most important investments you will make to your shorefront property. • We have the skills and equipment to handle your largest, most challenging project. For more information: www.linkelconstruction.com 207.725.1438

Construction, Inc.

A view through one of the fort’s arches. Signs warn visitors to proceed at their own risk.

How’s the weather? Arlene Cole will tell you Newcastle woman recorded data for weather service for 58 years

BY CLARKE CANFIELD//PHOTOS BY JESSE GROENING

Ask Arlene Cole what the weather was on May 13, 1965, and she’ll tell you the high was 62, the low was 43, and 0.19 inches of intermittent rain fell at her home in Newcastle. In fact, Cole can tell you the weather conditions—the highs and lows, rainfall, snowfall and snow depth in her yard—for each and every day since then.

That date in May more than 58 years ago was the first day that Cole served as an official weather observer for the National Weather Service. She’s been at it every day since and is believed to be the longestserving and oldest volunteer in the Weather Service’s Cooperative Observer program in Maine.

Like clockwork, Cole takes daily temperature readings from a digital thermometer in her home at 5 p.m. She then trudges outside—at 92, she uses a walking stick and moves a lot slower than she once did—to measure the water or snow in a standard rain gauge, the snow that has fallen since the day before, and the snowpack in her front yard. She mails her information to the weather service each month, while also keeping records of her daily observations in her home.

Cole has also reported her weather observations to the Lincoln County News weekly newspaper for even longer. Her observations have been appearing in the paper every week since 1960.

Cole is humble about her work for the weather service and knows the day will come when her duties will come to an end.

“I’m on borrowed time,” she said with a big smile on a recent day at her home. “But I’m enjoying each day.”

Weather has always been an important part of Cole’s life. Growing up on a farm in Jefferson in the 1930s, she recalls her father looking to the east each morning to assess what the day’s weather would bring. Back then, you couldn’t go online or turn on a TV to get the day’s forecast.

After high school, she attended Colby College for three years before marrying her high school sweetheart, George, in 1950. He passed away in 2012.

While raising a family, she began taking weather observations for her own pleasure in 1957 and reporting them to the Lincoln County News beginning in 1960.

She became a National Weather Service observer in 1965, taking over for friend who had passed away. Today, she is one of about 10,000 volunteers nationwide, 63 of them in Maine, in the National Weather Service’s Cooperative Observer Program, which was established in 1890. The observers record temperature and precipitation data in cities and suburbs, at farms, on the seashore, and from mountaintops.

The data are used in real time for the weather service’s forecast models, while also serving as a historical record of the nation’s climate. Nikki Becker, the manager of the observer program for southern Maine and New Hampshire, says observers are “basically the backbone” of the climate network, helping professional meteorologists make their forecasts.

“The cooperative program is really important and what they do matters a lot, not only to our local forecast office but to our whole agency,” she said. “We can’t be everywhere, to collect the weather everywhere. We need help.”

In this high-tech world, Cole uses low-tech equipment to record her observations. The NWS installed a digital thermometer inside her kitchen in 1984 that measures the current and daily high and low temperatures for the day, but there’s still an old whiteshuttered wooden shelter in her yard with mercury thermometers that she uses when the power goes out.

For precipitation, she measures the water or snow in an open-mouth can on legs that serves as rain gauge. The snowpack is measured by a 60-inch wooden stake with measurements on the side stuck in the ground. And for the daily snowfall, she has to locate one of two simple 2-by-4-foot boards that lay on the ground

and use a rule to measure the snow. Finding the board under all that snow can sometimes be tricky.

When she lumbers outdoors after a snowfall, she wears her late husband’s rubber boots, which are a size or two too big.

“And mittens are very important,” she adds, “because I have to clean off the snow boards.”

Through the decades, Cole’s neighbors and friends have stepped up to take the measurements when she and her family went on vacation. She’s also involved with the Newcastle Historical Society, which she founded in 1998, and wrote a book about the history of the town.

Becker says the weather service is always looking for more volunteers, especially on Maine’s islands.

Cole has been honored with numerous awards for her service and her longevity, many of which are framed and hang on walls in her home. Among them

is the program’s highest and most-prestigious honor, the Thomas Jefferson Award, named for the third U.S. president, who kept a nearly unbroken string of weather records from 1776 to 1816.

And while 58 years is a long time to keep weather records, it’s not even close to the record held by Edward Stoll of Nebraska, who served as a weather observer for 76 years, from 1905-1981.

With so much focus on climate change these days, weather data is perhaps more important than ever. But Cole doesn’t inject herself in the climate change debate.

“I keep out of that,” she said. “One of the coldest days I’ve ever recorded was this past winter. Sometimes I think we get less snow, then we get 11 inches and I change my mind. So I don’t get involved in that.”

For more information about the weather observer program, visit: weather.gov/coop/overview.

4 The Working Waterfront june 2023

Arlene Cole

Cole stands near the snowfall measuring stick.

Arlene Cole points to the platforms she uses to measure snowfall.

book reviews

Island crime, battled with humor

Two appetizing novels by Camden resident

Jane Roberts has arrived to live there after deciding to divorce a cheating spouse and give herself a fresh start. She’d been an attorney at a major law firm but then enrolled at the Maine police academy.

The first island crime she’s called out on is a dog running loose with a string of clothesline holding underwear, snatched from the inn. She is the dog control officer but the timing is bad, interrupting her thoughts of dinner—maybe a pear parmesan pecan salad with roasted chicken?

Lobsters Without Borders (2022) Don’t Touch My Cocktail! (2023)

By Carol Chen

By Carol Chen

REVIEW BY TINA COHEN

CAROL CHEN, a Camden resident, is debuting as a mystery writer with two books out now, Lobsters Without Borders and Don’t Touch My Cocktail!. Both feature “Jane Roberts,” a novice public safety officer working in a small island community off the Maine coast.

It’s hard to know if “St. Frewin’s” is mostly modeled on a real Midcoast island reachable only by ferry (Islesboro? North Haven?). It is surprisingly devoid of cellphone service and the internet, a town decision made after a terrible car crash when a distracted driver hit another car, killing an entire family.

These fictional residents then eliminated access to that technology. Can you imagine that happening in real life? As a result, it’s become a “retreat” destination, a place where you can really get away.

But it is mostly home to year-round families with island roots. There’s also an enclave of wealthy summer residents, a classic old inn, and a yacht club.

Her island career launch is marred not only by chasing after undies but the subsequent discovery of a dead body holding a grisly souvenir—a raw lobster shoved down the victim’s throat, giving “stuffed lobster” a new and perturbing twist.

Chen calls her books comedy and crime. The comedy is largely due to Jane’s “thought bubbles,” as they were. We’re privy to her unspoken comments and reactions, which can be droll, self-deprecating, and sarcastic. Jane is funnier and quirkier than she lets on to others. She gets into some situations providing a laugh-out-loud moment, but sometimes an intended zaniness instead feels overwrought, contrived.

quiet office days and good home-cooked meals. (Her details about food brought to mind Robert Parker’s mysteries starring a male detective, Spenser. Readers paid as much attention to his almost-recipes woven into the story as to clues about murders.)

We can tell Jane is, shall we say, evaluating the dating scene, but we’re left wondering if, on that small island, the right person at the right time could be there.

Her island career launch is marred not only by chasing after undies but the subsequent discovery of a dead body…

Don’t Touch My Cocktail! addresses that last lingering question, returning us to St. Frewin Island only months later. I liked the inclusion of a “cast of characters” at the beginning of that book, something I had hoped for as a guide in her first one.

Chen does a remarkable job individualizing her long list of characters with dialect, personality, idiosyncrasies, backstories, and family trees. Her writing of dialogue is well executed and believable. Of course, there’s also what every crime novel has in a formulaic way, besides crime—some bad guys and some you hope are good guys but can’t be 100% sure, plus plot twists and a few red herrings that effectively keep you guessing who done it until the end.

When Jane’s sister shows up on the island for a surprise visit, we see Jane’s facade of professionalism put to the test. As much as Jane wants to stay in the background and be respected for her propriety, her sister’s arrival stirs unexpected excitement. There’s instant recognition; she’s familiar to those appreciative of the adult film genre in which she works. Jane prefers

The‘solastalgia’ of pandemic life

Debut novel describes family’s painful pivot

“The Her,” their children to a certain extent steal the show. Shetterly captures youthful traits—squabbling, sulking, sighing—with pitch perfection. Sophie and Iris serve as brokers and liaisons—voices of reason and unreason.

The chapter titled “Solastalgia” delves into its namesake condition, “the distress… produced by environmental change” (had to look it up), brought on by height of summer.

Pete and Alice in Maine

By Caitlin Shetterly, HarperCollins (2023)

THE PANDEMIC interrupted the lives of many families, including the foursome that take center stage in Caitlin Shetterly’s first novel, Pete and Alice in Maine. The title’s couple and their daughters, Sophie, 11, and Iris, 5, flee New York City at the beginning of COVID, finding refuge in a summer home on the Blue Hill Peninsula overlooking Eggemoggin Reach.

From the outset, a certain dysfunction reigns as the household experiences various ups and downs—the abrupt move, shifting personal dynamics, isolation, homeschooling, lack of internet service, etc. At the same time, as Alice thinks early on, the family’s “privilege” is “clear, almost criminal.” Theirs is a first world challenge.

While the parents try to work out their issues, including Pete’s affair with a woman Alice refers to as

“It’s too much to bear in this heat,” thinks Alice, “in this strange hovering place we’re in.” She goes on: “We are forever suspended in the unrelenting quotidian of life on pause”—an inspired reflection on the pandemic condition.

Shetterly’s narrative is peppered with diverse cultural references, from Virginia Lee Burton’s picture book The Little House and Talking Heads to Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility and Slack, the messaging program. Some were lost on me, sending me to Google to discover that Ryan Bingham is a singer-songwriter and Tomten is a character in an Astrid Lindgren children’s book.

Happily, most characters from Without Borders return in Cocktail, with international and political intrigue added. It’s more ambitious than Without Borders and maybe not quite as much fun. I was glad that both books dabbled in food porn—Chen’s references to succulent homemade dishes. Me, I’m ready for thirds.

One nit to pick: the occasional insertion of native Mainer language written phonetically (“keep ta yoah-selves”). It seems patronizing and somehow inauthentic.

Some of us may not want to be reminded of the pandemic years—the quarantines, the masks, the Zoom family gatherings—especially as the virus hasn’t entirely receded from our lives. That said, Shetterly hits at the heart of the plague in her lively narrative. At one point she has Alice repeat a line from Philip Booth’s poem “First Lesson” about teaching his daughter how to swim: “lie up, survive, lie up, survive, lie up, survive.”

“ We are forever suspended in the unrelenting quotidian of life on pause.”

In an episode that was, as it were, ripped from the headlines, someone cuts down two trees across the family’s driveway so they can’t get out—an unsubtle signal from locals that infected New Yorkers should stay put. Such an incident garnered national attention in March 2020 (plug in “tree blocks driveway in Maine” in your search engine).

Shetterly comes to fiction wellprepared. Editor of the anthology Fault Lines: Stories of Divorce and author of two memoirs with messages, Made for You and Me: Going West, Going Broke, Finding Home and Modified: GMOs and the Threat to Our Food, Our Land, Our Future, she’s a natural to take on a tale of COVID distress. Pete and Alice in Maine is a splendid debut.

Carl Little is curating two shows this summer: “Generations” at the Maine Art Gallery in Wiscasset and “Avian Artistry: Treasures from Maine Collections” at the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor.

5 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023

Tina Cohen is a therapist who spends part of the year on Vinalhaven.

REVIEW BY CARL LITTLE

‘Working the Sea’ is Marine Museum’s summer show

Industry photography captures evolving fisheries

The Penobscot Marine Museum’s 2023 exhibit “Working the Sea” will feature photographs from the museum’s National Fisherman and Atlantic Fishermen collections inspired by an upcoming photo book by long-time National Fisherman contributor Michael Crowley. The exhibit will run May 25-Oct. 15 with a reception scheduled on Thursday, May 25, from 4-7 p.m.

Fishing is a fundamental and dynamic industry with large-scale drama and everchanging technologies. It involves grueling work and exposure to the elements, the gaming of natural systems, fierce competition, navigating the tension between prosperity and limitation, and the race to get the product to consumers.

The photographs of National Fisherman and its predecessor Atlantic Fisherman have captured these elements of the industry for decades. In his upcoming book, Crowley will share these photographs and their stories.

Working the Sea: America’s Fisheries as Seen Through the Photographs of National Fisherman and Atlantic Fisherman has been generously sponsored by Diversified Communications.

Penobscot Marine Museum brings Maine’s maritime history to life on a campus of beautiful historic buildings in the charming seacoast village of Searsport. Exhibits throughout the campus tell unique stories of ship captains and their families, the industries of Penobscot Bay, global maritime trade, and today’s fisheries.

In addition to exhibits, Penobscot Marine Museum has over 300,000 historic photographs, an extensive collection of maritime artifacts and archives, and a maritime history research library. Visit penobscotmarinemuseum.org to learn more.

Market & Smokehouse

Fresh seafood, fish, crab & lobster meat, smoked mussels, live crabs & lobster. Available year-round!

Farm-fresh beef & chicken, Maine-made cheese, dips, eggs, and many other items!

Open Mon. 10-4, Tue. – Thurs. 10-3, Fri. 10-4, Sat. 10-5

We ship!

coldwaterseafoodmaine.com coldwaterseafoodllc@gmail.com

A love letter to Vinalhaven

“The book is beautiful, emotionally evocative, and it does a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of Vinalhaven.”

“A treasure for all time.”

6 The Working Waterfront june 2023 A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too. We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings. Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs. We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what. That’s the Allen Advantage. Call today. (800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com Owning a home or business on the coast of Maine has many rewards. We are an independent, employee-owned company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville.

Savor the beauty and charm of Vinalhaven with this new coffee table book featuring images by professional photographer Joel Greenberg and narratives by well-known Maine author Phil Crossman.

Vinalhaven: Portrait of a Maine Island is available in local shops. Order online and find out more at vinalhavenbook.com 100 N. Main Street Stonington, ME 04681 207-348-3084

A dipnet full of scup, or porgies, rests on the trap boat gunwale as Tony Coccoro repeats the endless task of repairing tears in the weir net.

PHOTO: MILSON MOORE, NATIONAL FISHERMAN COLLECTION

LOBSTER SIZE

continued from page 1

changes to gauge and vent size will be initiated in the following fishing year.

These include two increases to the minimum gauge size in the Gulf of Maine and a single decrease to the maximum gauge size in offshore federal waters and outer Cape Cod.

The gauge and escape vent size changes are intended to increase the proportion of the population that

is able to reproduce before being harvested, and to enhance stock resiliency by protecting larger lobsters of both sexes.

Additionally, the rule implements measures that resolve discrepancies between the regulations for state and federal permit-holders, provide a more consistent conservation strategy, and simplify interstate commerce and enforcement across management areas.

Specifically, the rule implements a standard V-notch definition of 1/8 inch with or without setal

Air quality—a tale of two Maines

Portland, Bangor see divergent results

MAINE’S AIR QUALITY is experiencing mixed results since last year’s report, according to the American Lung Association’s 2023 “State of the Air” report.

Bangor remains one of only seven cities in the nation that ranks on the cleanest cities lists for all three measures of pollution and is celebrating its sixth consecutive year as one of the cleanest cities for ozone pollution. Alternatively, the Portland metro area recorded slightly more unhealthy days for ozone, and went from a ranking of 100th most polluted, down to 65th most polluted for ozone in this year’s report. Nationally, the report found that nearly 120 million people, or more than one in three in the U.S., live in counties that had unhealthy levels of ozone or particle pollution.

The Lung Association’s 24th annual “State of the Air” report grades Americans’ exposure to unhealthy levels of ground-level ozone air pollution, annual particle pollution, and short-term spikes in particle pollution over a three-year period. This year’s report covers 2019-2021.

“As we can see from this year’s report data, there is much work to be done to improve our air quality,” said Lance Boucher, of the Lung Association.

“Even one poor air quality day is one too many for our residents at highest risk, such as children, older adults, pregnant people, and those living with chronic disease. That’s why we are calling on Gov. Mills and the legislature to continue moving forward on policies to ensure that everyone has clean air to breathe,” Boucher said.

The Lung Association wants the state to finalize the Advanced Clean Cars II standard, continue to

strengthen electric vehicle infrastructure, and push forward on efforts to increase clean energy.

Nationally, the report found that ozone pollution has generally improved across the nation, thanks in large part to the success of the Clean Air Act. However, more work remains to fully clean up harmful pollution, and short-term particle pollution continues to get worse.

In addition, some communities bear a greater burden of air pollution. Out of the nearly 120 million people who live in areas with unhealthy air quality, a disproportionate number—more than 64 million (54%)—are people of color.

In fact, people of color were 64% more likely than white people to live in a county with a failing grade for at least one measure, and 3.7 times as likely to live in a county with a failing grade for all three measures.

Compared to the 2022 report, Bangor continued to experience zero unhealthy days of high ozone in this year’s report. “State of the Air” ranked Bangor as one of the cleanest cities for ozone pollution for the sixth year in a row. Penobscot County received a “A” grade for ozone pollution.

Compared to the 2022 report, Portland experienced slightly more unhealthy days of high ozone in this year’s report. “State of the Air” ranked Portland 65th most polluted for ozone in this year’s report, as opposed to its ranking of 100th in last year’s report. Both Cumberland and York Counties received “C” grades for ozone pollution.

The report also tracked short-term spikes in particle pollution, which can be extremely dangerous

hairs in lobster conservation management area 3 and outer Cape Cod, and a standard maximum gauge size of 6-¾ inches for management area 3 and state and federal permit holders in outer Cape Cod. It also modifies the management program so that for conservation management areas 1 and 3 permit holders, states must limit the issuance of trap tags to equal the harvester trap tag allocations unless trap losses are documented.

The implementation date for these changes is Jan. 1.

and even deadly. Bangor’s short-term particle pollution remained at zero unhealthy days in this year’s report, which means the city earned its title as one of the cleanest cities for particle pollution for the 14th consecutive year.

The 2023 “State of the Air” found that year-round particle pollution levels in Bangor were slightly lower than in last year’s report. The area was ranked 5th best for year-round particle pollution.

Portland continued to rank as one of the cleanest cities for short-term particle pollution, with zero unhealthy days. For the sixth consecutive time, and for the ninth time in total, both Androscoggin and Cumberland Counties, posted zero unhealthy days (A grades) for this pollutant measure.

Year-round particle pollution levels in Portland were slightly lower than in last year’s report. The area was ranked 164 most polluted for year-round particle pollution, better than the ranking of 133 last year. The American Lung Association is calling on President Biden to urgently move forward on several measures to clean up air pollution nationwide, including new pollution limits on ozone and particle pollution and new measures to clean up power plants and vehicles. See the full report results and sign the petition at Lung.org/SOTA.

7 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www pro C k M arine C o M pany C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST Full Service Boat Yard, Repairs, Storage & Painting P.O. Box 443, Rockland, ME • knightmarineservice.com 207-594-4068

The Portland metro area recorded slightly more unhealthy days for ozone…

Pondering the poverty question

What is the true price we pay for the poor?

BY TOM GROENING

I GREW UP in a middle-class neighborhood in a small ranch house on a quarter-acre of land in suburban New York. When I was ten, my parents doubled the size of the house with a firstfloor addition. “Poor people” were those who lived on the other side of a twolane highway, in similar houses but with broken shingles, scruffier looking yards, and a banged up car in the driveway.

Moving to Maine in 1983 for a teaching job at a private boarding school, we were exposed to wealth like never before. One student’s parents would drive their Rolls Royce onto campus when they visited.

But in those early days in Maine, exploring the state’s backroads, I saw tarpaper shacks backed up to woods and trailers with plastic over broken windows and decrepit cars in the yard. Maine, I was told by colleagues, was a poor state.

After leaving teaching, I worked for a time in the social service realm, and had a personal encounter with those who lived in poverty. I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, but many of those with whom I worked on job seeking and training lived in a world characterized by short horizons.

We helped one young man land a job for which he had no transportation for the 25 miles between job and home. “Well,” he told me, “I’ll just stay with my brother’s family,” who lived near the job. “I can sleep on the couch.” The brother, he had told me earlier, was going to be moving from the area in a couple of months. What he would do then never crossed his mind.

Hope, as trite as it might sound, for a better future and the skills to build a ladder to it were not part of the thought process.

In the early months of the Great Recession, I began working in Bangor, commuting the 76 miles round-trip from home. Spiking gas prices gobbled up the raise I’d gotten, so I found a carpool partner, a woman who lived in subsidized housing in Searsport who worked at a social service office in Bangor.

When she drove, we listened to conservative talk radio. One morning, she shared her anger over the 20-something young men who would sometimes march in to her office with their 18-yearold girlfriends, both carrying fancy coffee drinks that my friend couldn’t afford, asking that the agency “sign her up” for every benefit for which she was eligible.

My carpool friend told me, through tears, of raising her teen grandson and

reflections

how his big appetite would empty the pantry days before her next food check would arrive.

Today, Maine’s poverty rate—for a family of four, income of $25,100 or less—is about 11%, which means there are more than 140,000 of our fellow Mainers in this bracket.

Is there a moral quality to poverty?

That explanation began creeping into discourse during the Reagan years and never really left. But what if something more sinister were at work? Like a system that relies on poverty as a means to sustain affluence?

Matthew Desmond, the author of Poverty, By America, argues that poverty is maintained, not fought. Recently, on the WBUR show “On Point,” he said: “If you really look at the full nature of the welfare state, you learn just how utterly lopsided it is and how we’ve chosen this subsidization of affluence over the alleviation of poverty.”

He explained that wages, taxes, and housing policy contribute to poverty for those of us “who enjoy a level of economic security in America… We like cheap goods and services that the working poor produce,” advantages that “require a kind of human sacrifice—the price of poor, poorly paid workers.”

Clam ‘garden’ sows sustainable future

Downeast communities must tell their stories

Reflections is written by Island Fellows, recent college grads who do community service work on Maine islands and in coastal communities through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

BY KAWAI MARIN

MY ALARM CLOCK rings, I turn over and look at the time—it’s 4:48 a.m., still dark, very breezy, and by the looks of the frost lingering on the window, it’s undoubtedly cold. Normally, in moments like this I would sink back into my covers and call it quits until the first warm rays of early morning sun peered through my windows.

But this was not a normal day. Most days you can find me behind a screen at home in Cutler, or at the Sunrise County Economic Council office in downtown Machias. But on this day, I would be knee deep in muck trudging through the mudflats of Sipayik, the Passamaquoddy Tribe’s community at Pleasant Point near Eastport.

And what does trekking through the mud on a cold spring morning

have to do with my fellowship work? Well, everything!

Throughout the Downeast region there is so much work happening, and I’ve been lucky enough to participate in it first hand—fisheries management, conservation, tourism, and education. But there is often a lack of external communications between local organizations and the communities they are trying to impact.

So again, why trudge through the muck on a cold spring morning? For communication’s sake, of course!

The Downeast Fisheries Partnership is one program working with communities across Washington and Hancock counties. It’s worked along the Bagaduce, St. Croix, and other rivers restoring habitats, researching, educating the community, and advocating for policy.

of the main barriers to soft-shell clam revival along the cove’s intertidal zone has been the abundance of invasive European Green Crabs (carcinus maenas) in the region.

Tax breaks for mortgage interest, wealth transfers, and college savings do not benefit the working poor, Desmond says.

A couple of months ago, I visited the Maine Seacoast Mission’s center in Cherryfield. A woman who worked with the impoverished families in the area explained how she would chase down funding to fill a home’s oil tank, or get a box of food there, or help them navigate the paperwork to secure repairs to their house.

Important work, of course. But Desmond says our approach to poverty is like discussing the plight of someone who jumps out the window of a burning building, rather than learning how to stop the blaze and prevent other fires.

A hand-out, certainly. But the “hand up” part must be bolder, more sophisticated, and yes, it will cost more. Now, more than ever, with labor shortages and the scarcity of affordable housing, Maine can’t afford so much poverty.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be reached at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

Just one green crab can consume 40 half-inch clams a day.

These pesky crustaceans are known to dig down more than 6 inches to find clams to eat, and just one green crab can consume 40 half-inch clams a day. In areas where European green crabs have established large populations they are known to consume as much as 99.9% of the juvenile clams. For tribal clammers and other members of the working waterfront this could mean a reduced level of food security and income.

When planting that day, I couldn’t help but wonder how many other communities were being impacted by similar issues.

knowledge with modern science and management techniques, paving the way for more sustainable solutions to complex problems such as this one.

As the project progresses, the lessons learned and successes achieved will continue to fuel further collaboration, empowering communities to safeguard their invaluable marine resources while fostering a more sustainable, resilient future.

I was asked to work with a “clam garden planting” event in Sipayik, part of DFP’s initiative to replenish the once abundant clam flats surrounding Half Moon Cove. Experts believe one

The Sipayik Clam Garden project will certainly serve as an inspiring example for other coastal communities. It demonstrates the power of combining traditional ecological

Kawai Marin works with the Sunrise County Economic Council focusing on marketing, outreach, and communications. Originally from Brazil, he spent most of his life in Massachusetts and earned a bachelor’s degree at Bates College where he studied environmental studies and anthropology.

8 The Working Waterfront june 2023

rock bound

CHURCH BLOCK—

Why we must modernize the bottle bill

BY SARAH NICHOLS

STEP INTO YOUR local redemption center and what you will see is the beating heart of Maine’s most effective recycling and litter prevention program. These hard-working businesses hand sort thousands and thousands of bottles and cans—perhaps redeemed by your child’s classroom or sports team— ensuring a strong, successful market for recycling glass, metal, and plastic.

Unfortunately, Maine’s local redemption centers are struggling to survive. Inflation and labor shortages have forced some to close and many others to operate at a loss. Some of you may have witnessed these stresses firsthand if you’ve had trouble redeeming bottles and cans, or seen bags of returnables piled up at CLYNK depots in Hannaford parking lots.

It’s why Maine’s lawmakers need to act quickly to modernize the Bottle Bill this year.

Maine’s Bottle Bill is a big part of our culture and environmental ethic.

Hundreds of Mainers have built their lives and small businesses around bottle redemption. It helps cities and towns reduce waste and save money,

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kr istin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGi nnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis

Michael Sant

Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

and results in more than $2 million a year in donations to local charities.

The Bottle Bill began in 1978 and today is responsible for recycling more than 40,000 tons of material each year, including all glass containers and more than 60% of all plastics. Maine is one of ten states with a bottle bill, and it’s the most comprehensive and successful.

But during the 45 years since the Bottle Bill began there have been many new types of beverages brought to market, advancements in technology, and a growing consumer demand to return to refillable containers.

Local redemption center owners, environmental groups like the Natural Resources Council of Maine, and others who care about the future of the Bottle Bill are encouraging Maine lawmakers to take swift action this legislative session to help redemption centers stay in business and ensure that Mainers have places to redeem their bottles and cans.

The first bill (LD 134) is an emergency bill to provide immediate relief by increasing the handling fee that is paid to redemption centers by big beverage companies for each container that is redeemed.

This handling fee, set by the legislature, does not keep pace with inflation

and hasn’t been increased since 2019. Unlike other business owners, who can raise their prices to cover new costs, Maine’s redemption centers have to ask the Legislature to raise the fee.

Thankfully, this bill passed with unanimous bipartisan support from the Environment and Natural Resources Committee, and the Legislature recently approved this bill with the two-thirds majority vote that was required for the legislation to be implemented right away.

The second bill, sponsored by Rep. Allison Hepler of Woolwich, would modernize the Bottle Bill to make it more efficient, effective, and resilient for the future. It would streamline the program for hard-working redemption centers by eliminating the tedious brandlevel sorting and instead requires all containers be sorted by material type— plastic, glass, steel, and aluminum. A proposal for a new “commingling cooperative” would guarantee timely pick-up of and payment for redeemed beverage containers by beverage manufacturers.

The bill also redirects the deposits paid by consumers who never redeemed their containers to support sorely needed improvements that will

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published

All members of the Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery:

Join the Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209

E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

increase consumer convenience and reduce trucks on the road. It also invests in new programs that could help us shift away from some disposable containers toward more reusable options.

These two bills work together to support the redemption centers while we work to make the Bottle Bill stronger for the future.

As individuals, one of the best ways we can get involved is by encouraging lawmakers to support these bills. We also need to redeem our containers. Twenty-five percent of beverage containers sold in Maine aren’t being returned, and that money stays with big corporate brands like Coke and Pepsi. Redeeming your containers ensures the money goes back to you or to whatever local charity you’re supporting.

No other program can deliver the environmental, economic, and social benefits of the Bottle Bill. Local redemption centers mean so much to the communities they serve. The time is now to bring our Bottle Bill into this century and support the local businesses that will ensure its long-term success.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of the Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org

542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

9 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023

op-ed

by the Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

This circa-1875 photo shows the “church block” to the left of the old custom house in Bath, evidence of the high standards Maine towns and cities maintained for their public buildings and institutions.

Sarah Nichols in Sustainable Maine’s director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

Improvements would divert more bottles and cans

NAVAL VISIT—

Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King visited Bath Iron Works on April 24, to join Admiral Mike Gilday, chief of naval operations, to tour the shipyard, which is owned and operated by General Dynamics. Collins, who is vice chairwoman of the Appropriations Committe, is the ranking member of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. King is a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee. In one photo, King can be seen pretending to listen closely as Gilday discusses the Navy’s future shipbuilding needs. The USS Carl M. Levin, a DDG 120 destroyer under construction, was the backdrop for the event.

PHOTOS BY JESSE GROENING

PHOTOS BY JESSE GROENING

CASTINE MAINE

Garden & Market

Over 100 Maine Craft Beers, Kombuchas, and Ciders

• Freshly made sandwiches & salads

• Hot entrees: soups, chili, and chowders

• Large selection of wine, craft mixers, and Naut-E botanical spirits

We also have wonderful unique gifts, from finely crafted Japanese teacups, award-winning Folkmanis puppets, and our iconic coffee mugs and sweatshirts—this year’s line being in Pantone’s 2022 color of the year, Peri.

Open Daily 10-5

5 Castine Road • Castine, ME windmillhillprovisions@gmail.com

10 The Working Waterfront june 2023

provisions

Money for art and where to find it Conference presenters help connect artists with funding

BY TOM GROENING

If you were an artist looking for funding during the Renaissance, you might have hit up the Medici family. Today, the best sources are government commissions and private foundations, according to a presenter at the Island Institute’s Artists & Makers Conference on April 28.

“I’m assuming you’re here because, like me, you don’t have a trust fund,” said Kim Bernard, a sculptor who also teaches at Maine College of Art and Colby College.

Karen D’Silva, another presenter at the conference, led a session on “Marketing for Non-Marketers,” a strategy for selling work.

Bernard said there is a surprising amount of funding available for artists whose work might benefit the public in some way.

“There’s a lot of money out there for creative projects,” she said, often using her own kinetic sculptures and temporary installations as examples.

Bernard recommended that artists who have not yet pursued grant funding start small. A good first step, she said, is to look into local and regional sources of funding.

“Apply for something local first,” she said, because the odds of success are greater. She also urged participants to get specific.

She suggested creating a grants calendar that lists application deadlines, and scanning other artist websites to see who is funding them.

“What are you applying for money to do?”

Self-reflection is a first step, Bernard said, with two approaches possible—looking for funding for a creative

goal, or tailoring work to an available funding source. And applying for any grant helps an artist focus on goals.

“Even if you don’t get funded, you’ll probably move in that direction,” she said.

If funding is available, discipline is required. Keep the writing simple, direct, and authentic, she recommends. Follow grant guidelines; if a PDF is required, don’t send jpegs. And show that this project is part of a life’s work trajectory.

And how will the audience benefit?

“If a foundation invests in you, they want to know that you’ll give something back to the public,” she said.

Some of the funding sources Bernard listed are:

• Maine Arts Commission

• New England Foundation for the Arts

• Creative Ground (which is New England based)

• Artwork Archive

• Maine Community Foundation

• National Endowment for the Arts

Of course, another way to fund an artist’s work is to sell it. Karen D’Silva, a potter, said creative people tend to avoid marketing their work because “You feel like you’re forcing yourself on someone.”

Instead, she said, “You’re doing them a favor. You’re sharing your passion.”

Describing herself as a self-taught marketer, D’Silva said people fail because they see marketing as the goal, rather than a habit.

“Focus on the system, not just the goal,” she said, and “create little steps, little wins along the way.”

The heavy lifting is developing a strategy for reaching people and learning which tools to use, but this is done just once, she said.

Having your work—the product—where people will see it requires ongoing research, she said, and “keeping in touch” with an interested audience through email and other means also requires maintenance.

D’Silva addressed website design, and recommends having a visible logo up high, and social media icons at top right, and a mailing list button.

She highlighted the use of Pinterest, which she said is essentially a search engine for shopping; YouTube; and Instagram, which feeds into Facebook.

Search engine optimization is also key, and without it, she said, it's like building a hotel with no roads leading to it.

Built in 1828 for Capt. John Berry as his home port, Berry Hill Farm sits on a lovely, elevated site of 10 acres of fenced pastureland. With 4-bedroom suites with private baths, the house was completely restored between 2000 and 2002, meticulously and tastefully. First floor, a custom kitchen with separate pantry, breakfast nook overlooking the pasture facing west for beautiful sunsets across the fields, lovely living room, dining room, 1 bedroom suite on the first floor and 3 on the second floor. The updated systems include a heating system with 7 zones with radiators in each room, completely rewired for cable and wi-fi on the first floor and second floors in each of the suites. Large barn with a hayloft with new joists and floor, large workshop area open to the peak, and lots of storage rooms. Septic system consists of a leach field sized for 6 bedrooms. There is a conservation view easement on this property to protect the fields and these 10 acres abut 20 acres in conservation to access a salt-water cove. A treasured property inside and out with beautiful surroundings. $650,000.

11 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023 www.landvest.com Camden: 23 Main Street | 207-236-3543 Northeast Harbor: 125 Main Street | 207-276-3840 Portland: 36 Danforth Street | 207-774-8518 HQ: Ten Post Office Square Suite 1125 South | Boston, MA 02109 If you are Buying We offer spectacular properties for sale throughout New England and beyond If you are Selling We understand Maine’s waterfront and can help you achieve your property’s best value whether it’s a marina, boatyard, land or luxury estate If you need Consulting We provide land planning, appraisal, and project management for significant real estate assets If you invest in Timberland We lead the nation in the marketing and sale of investment timberland properties We’ve traveled the back roads, we’ve navigated the waters, and we know Maine. TACY RIDLON (207) 266-7551

TACYRIDLON@MASIELLO.COM

Karen D’Silva

Kim Bernard

Along Rockland’s hard-working waterfront

ROCKLAND, home base to the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront, has one of the longest working waterfronts on the Maine coast. From Snow Marine Park in the South End, through Journey’s End Marina, the Maine State Ferry Terminal, and then to marine-related businesses in the North End, it’s a hard-working waterfront, too.

12 The Working Waterfront june 2023

PHOTO ESSAY BY JESSE GROENING

13 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023

Our Island Communities

Grindle Point Lighthouse:

A beacon still shining Islesboro’s history illuminated through light

BY OLIVIA LENFESTEY

From the top deck of the Margaret Chase Smith ferry, the first thing that can be seen approaching Islesboro is the Grindle Point Lighthouse. Standing at the northern edge of Gilkey Harbor and next to the ferry pen, the lighthouse greets residents and visitors alike to the island.

At first glance, the tower is unassuming. It is square and short in stature, connected by a pitched roof ell to a keeper’s house that appears untouched by time. But in fact, it presents a passageway to the past, out of the now and into the thickets of the culture and history of the island.

What the story of the Grindle Point Light station reveals is a space that has been fought for and preserved by the residents of Islesboro. Time and time again, it is a symbol of community and a vision of the island’s identity.

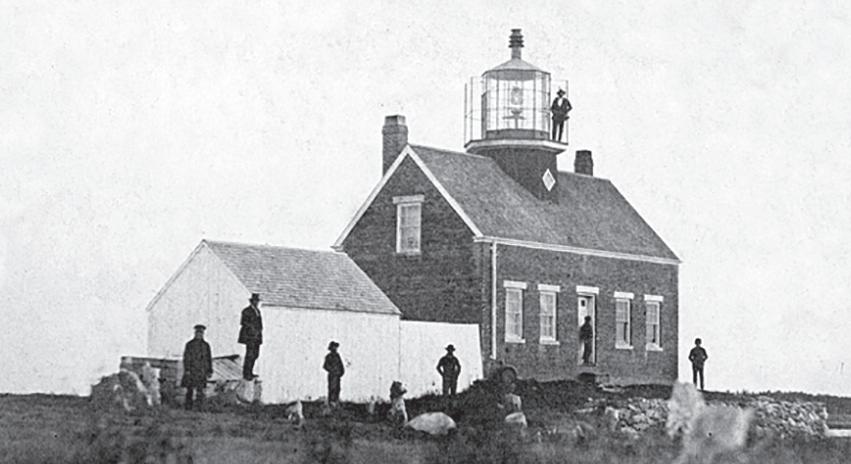

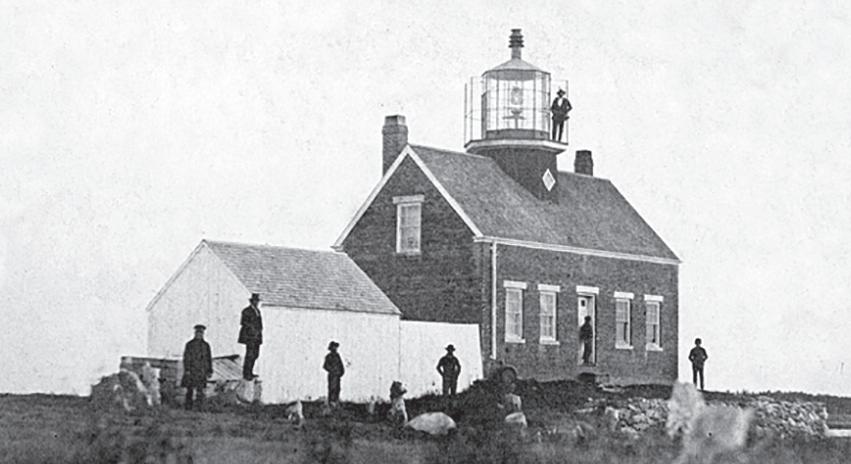

The Grindle Point Lighthouse was originally built in 1850 after the first significant steamboat route to Islesboro was established and marine traffic in the surrounding waters increased. The original lighthouse included a single-story keeper’s house with a lantern room cupola perched on its roof. The station was built on land purchased from Francis Grindle, who later served as keeper, for $105. It was the 37th lighthouse to be built in Maine.

In 1875, after several keepers had passed in and out of service on the point and kept the oil burning brightly, it became clear the structure was in such bad condition it was advised to rebuild it rather than repair. A year later, the brick tower that stands today was erected on the limestone ledge and a new two-story keeper’s house was built beside it. The roof of the original structure was lowered to form the ell connecting the house to the tower, making it the only lighthouse to include part of its original structure in its current design.

Even as the tides of island residents shifted in and out with changing seasons, a beam of light circled the harbor each night, guiding mariners through rocky and uncertain seas. In 1938, as the Great Depression tightened its grip on the American economy and diminished marine traffic, the Coast Guard decommissioned the station.

The last keeper, William C. Dodge, and his collie named Tray, who had learned to sound the station’s fog bell, packed their belongings and abandoned the light. The Fresnel lens was removed and dumped into the ocean. In its place, an 18-foot metal framed skeleton tower was positioned on the ledge and flashed its unattended acetylene light into the darkness. The light station was sold to the town for $1,200 and turned into what is now The Sailors’ Memorial Museum.

What is the value of lighthouses? With GPS, electric running lights, and well-tested charts mapping precise coastlines and ledges, lighthouses are no longer necessary navigational aids.

Since the first lighthouse was built at the entrance to the Greek city of Alexandria along the Nile Delta in 297 B.C., they have been markers of human presence on shorelines around the world. They are loved for their liminality and the space they inhabit between land and sea, light and darkness.

Lighthouses provide a place in which coastal residents can claim their inhabitance of the waterfront.

Fifty years after the Grindle Point Lighthouse went out of service, the Islesboro Select Board and members of the community lobbied the Coast Guard to bring the light back. On Nov. 4, 1987, a crowd of 300 gathered at Grindle Point under stormy gray skies to see Capt. John Williams, commanding officer of Coast Guard Group Southwest Harbor, remove the skeleton and install a solar powered beacon back into the tower. The light has been active ever since.

Now the future of the Grindle Point Lighthouse is threatened by a much a larger and less predictable kind of change: Our current climate crisis. As sea levels rise due to thermal expansion and melting land ice, including the Antarctica and Greenland icesheets, lighthouses around the world are vulnerable.

With the Dec. 23 storm this past winter, the Grindle Point Lighthouse, which sits barely a foot above current sea level, experienced significant flooding at the base of the tower and in the original foundation. Once again, the lighthouse is caught in liminality. With many questions arising about the future of human inhabitance of the waterfront, its serves as a new kind of beacon: a warning sign of our changing coastline. Will it survive another 50 years or be washed away with the higher tides?

On July 1, the Grindle Point Lighthouse Sailors Memorial Museum will reopen to the public with new exhibits on the history of mariners on Islesboro and in Penobscot Bay. The museum will host an art installation created by Islesboro Central School Students and visiting artist, Pamela Moulton, drawing attention to sea level rise.

Olivia Lenfestey is an Island Fellow through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront, working with the Grindle Point Lighthouse Museum and Islesboro’s Sea Level Rise Committee. She grew up in Santa Fe, N.M. and graduated from Pitzer College in Claremont, Calif., where she studied English, creative writing, and environmental analysis.

14 The Working Waterfront june 2023

The original Grindle Point Lighthouse, with the light tower inside the keeper’s house.

Monhegan Skiffs for Sale

9 1/2ʹ and 11ʹ plywood and lapstrake Starting at $2,300

JB Paint Company

Exploration has brought humans to our planet’s greatest heights and deepest depths, pushing upon the boundaries between the known and unknown. It has taught us elusive lessons about our world and ourselves that we would never have learned otherwise. At the same time, exploration brings us face to face with dynamic and hard to resolve ethical questions about the impact of exploration on human and non-human communities.

From July 31–August 4, join College of the Atlantic and the National Geographic Society for the 2023 Summer Institute: Reimagining Exploration, as we gather some of the greatest living explorers, writers, artists, and thinkers to help reimagine exploration.

In conversations with those who have ventured into extreme landscapes, the deep sea, the human mind, the world of art and other disciplines, we will examine exploration in the broadest sense. Ultimately, we hope to recast an approach to exploration that is rooted in inclusivity and reciprocity, while also preserving the magnificence and health of our planet and its people.

15 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023 355 Flye Point Road Brooklin, Maine 207-359-4658 www.atlanticboat.com A Full Service Boatyard A Full Service Boatyard Storage ~ Service ~ Moorings Storage ~ Service ~ Moorings A T L A N T I C A T L A N T I C B O A T C O M P A N Y B O A T C O M P A N Y

INDUSTRIAL MARINE COATINGS & SUPPLY Blast Media & Blast Supplies, Sprayers, Sprayer Repair/Supplies... Plus much more... 2225 Odlin Road, Hermon

ME 04401 207-942-2003

coa.edu/si

677-2614 or email director@carpentersboatshop.com

Call

The tragic end of MDI’s Capt. Rumill Race, working conditions, and justice in 1905

BY TOM GROENING

BY TOM GROENING

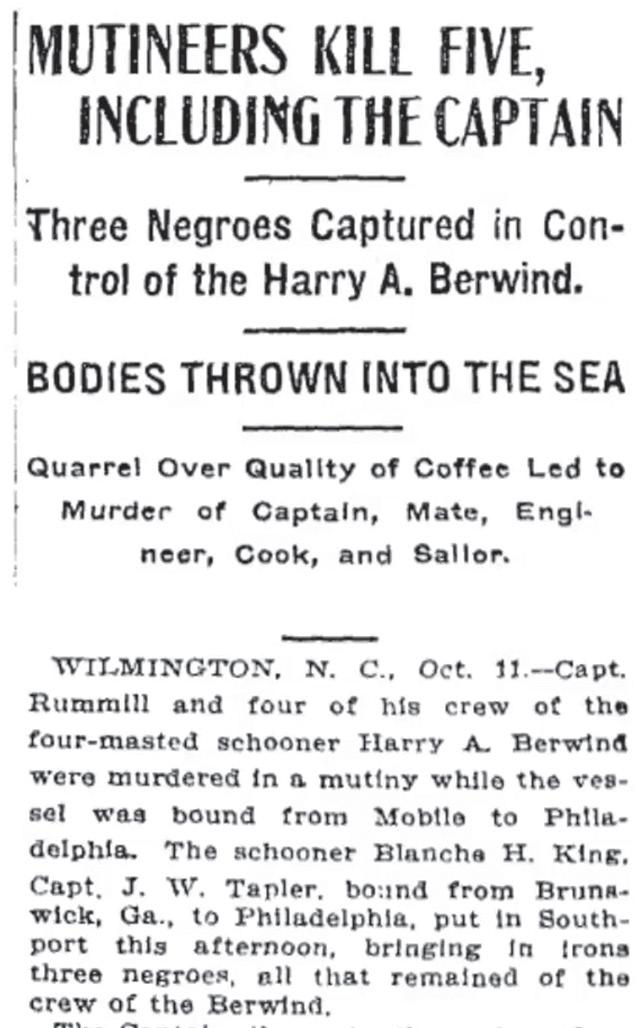

On the night of Oct. 10, 1905, John Taylor, captain of the Blanche King sailing off North Carolina’s Cape Fear, observed something that raised his concern.

Taylor saw “a four-master schooner, sailing erratically outside the usual shipping channel, with her red light hanging from its rigging.” What Taylor soon discovered aboard that wayward schooner was the grisly scene of one of the worst maritime mutinies and murders ever recorded.

The tale of the four-masted schooner Harry A. Berwind, and its captain, Edwin Rumill of Pretty Marsh on Mount Desert Island, was recounted by Tim Garrity for an April 13 installment of Chebacco Chats, a lecture series hosted by the Mount Desert Island Historical Society. Garrity was executive director of the organization 20102020, and wrote about Rumill and the Berwind for the maritime edition of the organization’s publication Chebacco

The Berwind’s taffrail, a device that records a sailing vessel’s distance traveled, is among the historical society’s artifacts, and it triggered Garrity’s interest in what turned out to be a shocking and illustrative bit of history

“It’s sort of like an odometer for a sailing vessel,” Garrity said of the item. “It hangs off the back of the boat and drags through the water.”

A note attached to the taffrail indicated it was owned by Capt. Edwin Rumill “and that he died in a mutiny in 1905.” Garrity was intrigued and began to investigate, but was suspicious of the substance of the note.

“I had my antennae up for this, that maybe this was not quite true,” he said. But upon digging he found documentation, including a biography of Rumill by Jaylene Roth, and the story was every bit as dramatic as the note suggested.

The mutiny, which resulted in the murder of the ship’s four officers, including Capt. Rumill, and one of its black sailors, is best understood in the context of the era and the maritime world, Garrity explained.

Rumill had been a mariner for some 30 years, sailing the globe and returning infrequently to Pretty Marsh. His granddaughters, who live on MDI, estimated

that he spent a total of about 75 days on the island during his maritime career.

“He was very ‘salty,’” Garrity said, and was aboard several ships that wrecked. He served on one-, two-, three-masted ships and a steamer before captaining the four-masted Berwind.

“We often have a romanticized view of the days of sail,” Garrity said, “the great ships that traveled around the world. There is a reality that is revealed in this story that life at sea was really hard and violent. The conditions that sailors worked under were absolutely brutal.”

A government study published in 1874 concluded that “life at sea is worse than any prison,” Garrity found.

“It was also a place where AfricanAmerican sailors could find an alternative that was marginally better than a life of enslavement or working in the Jim Crow South,” he added.

Black sailors were common, and for mariners from New England and Maine, encountering them for the first time was often surprising.

MDI native Augustus Savage in 1854 wrote to his wife that while taking a merchant ship to Jacksonville, Fla., “I have not seen anything but Negroes since I have been here.” While serving aboard a ship during the Civil War, Savage wrote that half the crew were black.

But despite their prevalence, black crew were segregated aboard ship. And officers had well-established power over their crews. Rumill wrote about a conflict with a ship’s cook in which he choked the man, leading to him suspecting the cook was poisoning his food in retaliation.

“It was routine that harsh discipline was meted out,” Garrity said.

On that fateful journey, the Berwind sailed from Philadelphia in July with a load of coal to Cuba, and returned to Alabama where lumber was loaded aboard. Though it was a 200-foot long vessel, the ship had just four white officers and four black crew members.

“There was a great deal of racial strife aboard the ship,” Garrity said, including an exchange between a crew member and an officer in which the phrases “black son of a bitch” and “white son of a bitch” were used.

The heat of the southern regions exacerbated tensions, along with the challenging work “and abysmal food,” he said.

“Serving bad coffee was said to be the match that lit the bomb of the uprising on board the Berwind,” according to reports at the time.

Off Cape Fear, Capt. Taylor recognized the Berwind because its captain Rumill was a friend. As Taylor’s ship approached, men aboard shouted, “For God’s sake, come to our assistance, we’ve got a man here who has killed the captain, the mate, the engineer, and a steward, and just now a sailor!”

16 The Working Waterfront june 2023

Capt. Edwin Rumill of Pretty Marsh on Mount Desert Island was master of the Harry A. Berwind.

Arthur Adams, left, and Robert Sawyer were charged with mutiny and murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

Taylor, upon boarding, found two black sailors had bound another. Puddles of blood revealed where the others had been murdered, and he learned that two of the officers may have been alive but wounded when they were thrown overboard. The ship was leaking and a part of a mast was broken.

The three black men—Robert Sawyer, Arthur Adams, and the bound Henry Scott—were suspected of working together.

Town meeting, painting lines, eating doughnuts, and throwing rocks

As winter winds down, islanders mix prep work and gatherings

By Barbara Fernald

“This was immediately interpreted as a race mutiny,” Garrity said, “an uprising of the blacks against the whites,” even though Sawyer and Adams reported apprehending Scott and that a fellow black sailor had been killed in the struggle to stop the violence.

bright red with a black stripe) and, like every other lobster fisherman in Maine this winter, he read about, talked about,

ACTIVITY on the islands, at the end of February and into March, is like a mirror image of the action at the end of August into September. Just as the summer residents of the Cranberry Isles end their vacations right before fall, many year-round residents end their winter breaks just before the spring equinox.

The Ellsworth American headline read: “Murdered on the High Seas by Mutinous Negroes!”

The latest whale regulations require all Maine lobster fishermen to use new markings on the ropes they attach to lobster traps. Depending on how close to shore they fish, they will have to add 2-4 purple marks on each buoy line. On warps that are 100-feet or less there

The three were brought ashore in Wilmington, N.C.—where a lynching had occurred just weeks earlier—and tried for mutiny and murder. Sawyer and Adams, though they had apprehended Scott, were convicted and sentenced to hang. Scott faced the same fate, but when a minister visited with him shortly before his execution, Scott exonerated the others. He also reported that Rumill had withheld food and water from the crew.

It’s time to get back to work and reconnect.

Our annual town meeting takes place on the second Saturday in March. For selectmen and town employees, winter has been anything but a vacation. They have been working steadily, gathering information to write the warrant for town meeting. It’s the time of year we come together as a town to decide on projects and spending and how much money is to be raised by property taxes.

President Theodore Roosevelt commuted Sawyer and Adams’ sentences to life in prison. But the story didn’t end there. Their plight came to the attention of stage and silent film actor H.B. Warner, “the Tom Hanks

Discussion of the school budget alone can take well over an hour. The islands take turns hosting the meeting and the luncheon. This year, town

ing while someone else has the floor!) In January and February, Bruce and I got to spend a lot of time with our grandchildren in Southern Maine. Visiting them was the main goal of most of our winter travel. We considered trying to paint our kitchen, but we kept catching odd coughing viruses and experienced more down time than we wanted, so we never got to it. Maybe I’ll paint it in May, when I can have the windows open.

inch purple mark within 2 fathoms of the buoy. If the warp is longer that 100 feet, the requirement is for a 12-inch purple mark near the trap, a second 12inch purple mark halfway to the buoy, and a 36-inch mark near the buoy.

piece of purple rope to the end of the buoy line or toggle, but all attachments must be made with a splice or a tuck. lowing Maine whale rope require ments with a workshop, but a person could return home from ei ther and say that they’d been paint ing in their spare time. If Bruce were writing an essay on how he spent his winter vacation, painting would be a part of it. Another part would be the description I heard him tell his brother Mark about walking to get doughnuts, in February, with our son Robin, and our grandchildren Henry and Cora. I was away with friends in Portland, and Stephanie was away with friends in Florida. Father and son were in charge.

of his time,” as Garrity described him. Warner and attorney Joseph Buhler worked to free the men, and President William Howard Taft finally commuted the sentences to time served.

After being freed, Sawyer was hired by Warner as his personal assistant and Adams was hired by Buhler for similar work. Garrity played a clip from the

Bruce saw more than enough paint, anyway, this winter. During his “time off” he painted 600 buoys (white and

1946 film It’s A Wonderful Life featuring Warner late in his career playing Mr. Gower, the pharmacist for whom the James Stewart character worked.

Capt. Rumill’s son George was an early aviation hero of World War I and also flew in World War II and his daughter Edna became a drama teacher. Edna’s daughters still live on MDI.

Bruce figures he will be putting 1,500 to 1,800 markings on his rope in all; two to three weeks of extra work if he does it without hiring help. A number of fishermen are applying paint to their ropes by resting them in 3-foot long gutters made from lengthwise-halved PVC pipe. Bruce’s first attempt was with spray paint but he soon moved on to the more efficient brush and latex paint.

Some fishermen will add a 3-foot

“Yeah, we got doughnuts at The Cookie Jar and then walked to the beach for a picnic and to throw rocks.”

Garrity left the audience with a question: Why has the mutiny and murder been relegated to a footnote in Maine maritime history?

Eating homemade donuts and throwing rocks at the beach—if that isn’t a mirror image of many childhood summers on Islesford, I don’t know what is. q

To view Garrity’s presentation and learn about other Chebacco Chats, see: mdihistory.org.

Barbara Fernald lives on Islesford (Little Cranberry Island) with her husband Bruce.

17 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2023 Independent. Local. Focused on you. Boothbay New Harbor Vinalhaven Rockland Bath Wiscasset Auto Home Business Marine (800) 898-4423 jedwardknight.com c R epo

•Building supplies •Asphalt/concrete trucks •Utilities/well drilling •Gravel, stone •USCG licensed •Hazmat endorsed Central Office: (207) 594-7860 • Cell (207) 266-3547 transporter@rocklandmarinecorp.com • www.islandtransporter.com M/V Reliance and Tug Josh With service along the entire coast of Maine ISLAND TRANSPORTER, LLC MARINE TRANSPORTATION OF EQUIPMENT AND MATERIAL Acadia Fuel & Marine, LLC Barge service available for hire. Fully licensed and insured. *Specs: Deck space 47’x14’, 50 ton cap, hydra crane with 30’ reach, 10 knot cruising speed. Call to reserve 207-244-9664 or visit www.acadiafuel.com WE CAN LAND ON UNDEVELOPED SHORE WILL BARGE ANY WHERE ON THE EAST COAST OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Landing Craft for Charter Acadia Fuel Fuel & Propane drivers needed. Must have Hazmat. Must apply in person.

Marine Full service marine—commercial and industrial work.

barges available for charter! Our first barge, BEACON, transports our heating products and company trucks.

barge, SALVAGE III,

construction. The

We

floats and repairs. State wide service. Boom truck rental also available. Call to reserve 207-244-9664 23 www.workingwaterfront.com April 2020

Acadia

Two

The second

does marine

barge is 86 x 24 ft. with 100 ft. crane reach.

build docks, piers, floats, complete mooring work, salvage work, and haul for winter storage of

The actor and activist H.B. Warner. The taffrail that belonged to Capt. Edwin Rumill, now in the MDI Historical Society’s collection.

saltwater cure

Uphill and downhill—walking off feelings

A loss prompts unplanned jaunt and reflection

BY COURTNEY NALIBOFF

ONE DAY in April, I became very sad and took a long walk.

I was sad because one of our cats died suddenly, about which I will only say that he was old, had a wonderful life, and was spared any long illness or infirmity. I took my long walk in the afternoon on the day we lost him because I’ve found it’s the best way to process any sort of change and find some semblance of emotional resolution.