Keeping the dogfish away

Bycatch repellent would help fishermen

BY CLARKE CANFIELD

“Dog!” whoops Ben Gowell as he reels in his line 12 miles offshore, pulling up a spiny dogfish from nearly 300 feet down. The dogfish, well-known among recreational and commercial fishermen, is one of many that have been landed this mid-July day aboard a University of New England research boat.

Gowell is among the students taking part in a research project to collect data and determine if a device attached to the lines is effective in repelling dogfish—thereby reducing the shark bycatch for fishermen from Maine to Florida.

The contraption, called a bycatch reduction device or BRD, emits weak electrical stimuli that keep sharks away. They operate under the same concept as electrical dog controls, commonly called “invisible fences” and give off electrical fields to keep dogs in their yards.

If the data show that the BRDs are effective—and preliminary findings suggest they are—the goal is to commercialize them for widespread use, said John Mohan, an assistant professor of marine science at UNE who is overseeing the student-led project.

BREEZING UP—

“Industry adoption is the ultimate goal,” Mohan said as he manned the wheel of the Sharkology, a 34-foot boat with twin 250-horsepower engines. Spiny dogfish are abundant throughout New England waters and along the Eastern Seaboard. They have little commercial value and are generally viewed

as a nuisance, reducing fishermen’s harvestable catches and sometimes damaging gear.

The UNE project is testing the devices at sea and in some large tanks in UNE’s Marine Science Center. The research focuses on recreational fishing,

continued on page 5

Downeast farms happily singing the blues

Wild blueberry growers diversifying, tout healthy product

BY SARAH CRAIGHEAD DEDMON

When Lisa Hanscom leads tours of Welch Farm, she showcases a working wild blueberry farm, and a slice of her family history, too. Hanscom’s

grandparents purchased the Roque Bluffs farm in 1912, moved in after their wedding on Christmas Day, and over time, her grandfather converted the fields to wild blueberries.

Today, four generations of the family still bring in the harvest

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

from seaside barrens overlooking Englishman’s Bay.

Hanscom’s lengthy family relationship with the blueberry is overshadowed only by the incredible 10,000-year story of the wild blueberry itself, and that, she says, is what captures visitors’ imaginations. After their tour, Welch Farm visitors filter in and out of a red barn, leaving with jams, jellies, and a better idea of what those iconic little berries mean to Maine.

They also add about $250 million to Maine’s economy each year.

“Part of our mission here at Welch Farm is to educate people about the wild blueberry,” Hanscom says. “If I have to do it one person at a time, I will.”

“ Wild blueberries are native to North America, and in any given field, there are going to be 1,000 different varieties.”

“Wild blueberries are native to North America, and in any given field, there are going to be 1,000 different varieties. They all look different, and they all taste different, and they’re all planted by Mother Nature, not us,” says Hanscom.

Hanscom isn’t alone in her mission to educate people about the wild blueberry. In fact, it’s a songbook the entire industry is singing from, spreading the word that wild blueberries are different from their farmed counterparts— containing twice the antioxidants, 70% more fiber, and higher concentrations of anthocyanins that can support eye, heart, and brain health.

Then there’s the undeniably romantic appeal of a plant that followed receding

continued on page 4

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com volume 37, no. 7 n september 2023 n free circulation: 50,000

Crew aboard the schooner Ladona, under the direction of Capt. J.R. Braugh, modify sail and set the course during the Great Schooner Race on July 6. The schooner J&E Riggin is off the Ladona’s stern, and Mark Island is visible in the fog. PHOTO: JIM DUGAN

Special Edition: ISLAND INSTITUTE TURNS 40

Electric outboards show their stuff

Island Institute, Pendleton Yacht Yard partner on project

IN AN EFFORT to “electrify the working waterfront” in Maine, staff from Island Institute (publisher of The Working Waterfront) along with Gabe Pendleton, owner of Pendleton Yacht Yard on Islesboro, put new electric outboards through their paces on Rockland Harbor on July 27.

Pendleton Yacht Yard’s new fully electric boat, named Take Charge, will be used to demonstrate electric marine propulsion in a partnership with Island Institute.

“We’re thrilled to be using an electric boat for our business,” Pendleton said. “We’re just beginning to appreciate the benefits of electric propulsion and look forward to sharing what we learn from

this demonstration project with other businesses in the Midcoast.”

The business will use the boat— powered by a 40-horsepower Flux Marine electric outboard, charged with solar power—for service calls, moving marine equipment and materials, and other working waterfront needs. While the boat is in use, data will be gathered using a “baseline usage device” to help inform improvements in future electric boat hull design. As part of the partnership, Pendleton will host a number of sea trials for other businesses and individuals interested in electric propulsion, offering firsthand experience with this emerging technology.

“We have a vision for a fully electric working waterfront in Maine,” said Kim Hamilton, Island Institute president. “It’s right for the environment and right for business resilience. This partnership with Pendleton Yacht Yard, and others in the works, are important steps in moving our state towards its climate goals—seeing is believing.”

Electric outboard motors offer many benefits including significantly reduced Co2 emissions (even when charged with non-renewable energy sources), less water pollution, more predictable operating costs, and quiet operation.

In addition to funding the partnership with Pendleton, Island

Institute’s Center for the Marine Economy is working in a number of areas to advance the electrification of Maine’s working coast including creation of an introductory course on electric boats (with Maine Community College System and Mid-Coast School of Technology— and a follow-on course planned for electric outboard maintenance), solar energy installations at wharfs and docks, and seeking to improve the charging infrastructure on Maine’s coast.

The boat’s name—Take Charge—was the winning entry in a contest that drew almost 300 entries. The winner was Judy Long of Orrington.

Charming 3-bedroom cape on a beautifully landscaped acre with fruit trees, perennials, and veggie gardens and includes a ROW to the shore. With a 3-car garage, there is plenty of space for cars and a boat. The interior is lovely with wood floors, two full baths, wood stove in the living room to supplement HWBB heat, and a southwest face composite deck with retractable awning from which to enjoy the gardens. Twenty minutes to MDI for restaurants, galleries, and museums, and Acadia National Park for hiking and biking or just walking. Six miles from Ellsworth. $510,000.

We’ve

2 The Working Waterfront september 2023 G.F. Johnston & Associates Concept Through Construction 12 Apple Lane, Unit #3, PO Box 197, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679 Phone 207-244-1200— ww w. gfjcivilconsult.com — Consulting Civil Engineers • Regulatory permitting • Land evaluation • Project management • Site Planning • Sewer and water supply systems • Pier and wharf permitting and design

John Martin, Bud Staples, and Elsie Gillespie chat around the woodstove at the annual town meeting.

Gerald “Punkin” Lemoine

Levi Moulden

13 www.workingwaterfront.com April 2020

Bud Staples

Headquarters: 888 Boylston Street Suite 520 | Boston, MA 02199 Maine Offices: Camden: 23 Main Street | 207-236-3543 Northeast Harbor: 125 Main Street | 207-276-3840 Portland: 36 Danforth Street | 207-774-8518 If you are Buying We offer spectacular properties for sale throughout New England and beyond If you are Selling We understand Maine’s waterfront and can help you achieve your property’s best value whether it’s a marina, boatyard, land or luxury estate If you need Consulting We provide land planning, appraisal, and project management for significant real estate assets If you invest in Timberland We lead the nation in the marketing and sale of investment timberland properties

traveled the back roads, we’ve navigated the waters,

SCAN TO EXPLORE TACY RIDLON (207) 266-7551 TACYRIDLON@MASIELLO.COM

and we know Maine. www.landvest.com

3 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023 You can join the talented men and women in Rockland ME who build boats such as this 39o Outboard Motor Yacht. Elegance of the design and superb workmanship have made Back Cove a leader in luxury yachts, built in Maine and sold all over the world. No previous boat building experience required. Apply today at backcoveyachts.com/careers COMPANY BENEFITS • 100% Paid Associate Health Insurance • 4 Day/40 hour work week • 80 Hours of Paid Time Off – Starting • Paid Short Term Disability • Paid Life Insurance • 401K with Match • Tuition Scholarship for Children of Associates • 2 Week Paid Parental Leave • Tuition Reimbursement for Associates • $ 500 Contribution to a NextGen College Savings Account for the birth of a child • Additional Parental Benefits • Additional Paid Time Off • Attendance Bonus And More... 355 Flye Point Road Brooklin, Maine 207-359-4658 www atlanticboat com A Full Service Boatyard A Full Service Boatyard Storage ~ Service ~ Moorings Storage ~ Service ~ Moorings A T L A N T I C A T L A N T I C B O A T C O M P A N Y B O A T C O M P A N Y

BLUEBERRIES

continued from page 1

glaciers onto the sandy soils of eastern Maine, creating millennia-old barrens that glimmer purple in August, then flaming red in autumn.

These are just a few of many things, say Maine blueberry farmers, that make the wild blueberry far from ordinary.

“From an industry perspective we need to continue to decouple the wild blueberry from the cultivated blueberry. Consumers often don’t understand the differences between them,” says Colleen Craig of Wyman’s, another Downeast business with deep roots in blueberries— the Milbridge-based grower and processor is preparing to celebrate its 150th anniversary next year.

Wyman’s is the largest branded supplier of wild blueberries in America, selling its distinctive blue bags into grocery store freezers across all 50 states. Recently, Wyman’s added a line of frozen fruit cups, and shelf-stable products like wild blueberry juice and dried blueberry powder.

“Our mission is to help people eat more fruit. According to the USDA Dietary Guidelines from 2020-2025, eight out of ten Americans are not getting the recommended daily amount,” says Craig. “We’re committed to innovation within the industry and developing fruit-forward products.”

VALUE ADDED

In business speak, converting a basic product like a wild blueberry into something like blueberry juice is known as “adding value.” Some farms are taking other paths to increase their profitability. One of Maine’s largest growers, Passamaquoddy Berries, which manages 2,000 acres of wild blueberry barrens, cushions volatile field prices by selling some berries under its own brand. Hanscom has diversified her farm’s business with the addition of two rental cabins, and plans to begin hosting weddings next year.

Eric Venturini, executive director of the Maine Wild Blueberry Commission, says there is growing excitement for value-added wild blueberries, both in the industry and among consumers.

“There are a lot of opportunities for producers to diversify their offerings, increase the cash flow to their business, and have a more consistent income and stability,” Venturini says.

Consistent income and stability can be hard to come by in agriculture, and wild blueberries are no exception. Significant price drops over the last decade hit a low in 2017, when the average price to growers was 26 cents per pound. Since then that number has rebounded and last year hit 72 cents per pound, and there are other positive indicators.

Over the last five years, frozen wild blueberry sales at retail have increased 88%. But as in the rest of the U.S. economy, wild blueberry farmers are facing rising costs and labor shortages.

The industry is keeping its eye on other challenges too, like the potential impacts of climate change, including droughts like the ones that impacted Maine growers for several years before this year’s plentiful rainfall turned that tide.

“We are working very hard to free up financial and technical support to help people become more resilient to climate change through sustainable water resource development and irrigation,” says Venturini.

Blueberry research is one of three major focus areas for the Wild Blueberry Commission, alongside promotion and policy work, and they are not alone. In her work as wild blueberry specialist with the University of Maine Cooperative Extension and School of Food and Agriculture, Dr. Lily Calderwood connects farmers with research conducted by UMaine and vice versa. Recently, Calderwood’s group completed a two-year study on the use of mulch to help retain moisture on the fast-draining, sandy soils where wild blueberries grow. The good news is it helps.

“These drought years have been so severe that mulch alone will not solve the problem most likely, but it can buffer the problem. Some fields will still need irrigation,” says Calderwood.

Abbie Sennett and husband Jacob Lennon relied on their irrigation system during the drought in 2022. Now in their 20s, the pair met as young teenagers working on Abbie’s family farm in Albion, perhaps even more well-known for bees than for blueberries. Abbie’s father, Lincoln Sennet, is the founder of Swan’s honey, a famous Maine brand.

After harvesting their berries from barrens in Machias, each day Abbie and Jacob transport them back to Albion, where they have easy access to labor for processing.

“The biggest challenge we face is labor shortages,” says Abbie. “A monthlong job isn’t enticing to most people.”

At their young age, and with their willingness to assume leadership roles in the industry, Venturini says Abbie and Jacob represent a positive direction for Maine’s wild blueberry industry.

As of two years ago, the average age of a Maine wild blueberry farmer was 64.5 years old.

“I’m very hopeful that will continue,” says Venturini of the younger folks, “and we can help prepare a new cohort of wild blueberry farmers to step into the industry and continue this tremendous tradition that’s really part of the cultural underpinning and part of Maine’s heritage.”

Like many Mainers, Abbie has fond childhood memories of blueberry

season, and says she misses the days of hand raking. But she’s also fond of wild blueberry farming, today.

“There’s something about the Downeast area when everyone goes for the harvest, the tourists want to see the fields and buy blueberries, I think it’s special,” she says. “What’s more Maine than wild blueberries? There’s not much.”

4 The Working Waterfront september 2023

Raking blueberries is a traditional way to harvest.

Sunset over a wild blueberry field in Washington County.

DOGFISH

continued from page 1

but is being done in collaboration with a separate project to determine if the BRDs are effective on commercial longline fishing vessels that are targeting swordfish and tuna off the coast of North Carolina. Both projects are receiving funding from a NOAA Saltonstall-Kennedy grant.

The North Carolina study previously captured 141 sharks (covering nine species) in 15 days of commercial longline fishing, but only 34 of those were on hooks with BRDs that emitted an electrical field. That represents a shark catch reduction of more than 50% with BRD-equipped hooks.

For the Maine project, students this day are fishing four fishing rods with 60-pound test line. Two are equipped with active BRDs emitting electrical fields, and two have BRDs that are not activated and serve as a control group. The cylindrical devices are 8.5-inches-long, made of PVC, and equipped with microprocessors and lithium batteries.

Sharks are repelled by the BRDs because they have the uncanny ability to sense tiny electrical fields, which allows them to home in on their prey. Fish, however, are not repelled because they don’t have the same sense.

Out at sea off Biddeford, students are pulling in pollock, red hake, and white hake in addition to dogfish. Of the 21 dogfish hooked during the day, only a handful of them go after the chum on lines with active BRDs. The results suggest the devices are effective, but not 100%.

Clayton Nyiri, a marine science major at UNE, is leading the field testing portion of the project. When the dogfish are brought aboard, he measures them and takes blood samples to determine their stress levels. Some of them are put into a water-filled cooler to be brought back to land to be used for laboratory tests.

Collecting the data is vital to determine the viability of the devices, said Nyiri, who plans to make a career studying sharks. He hopes to write an academic paper on the project this fall and have it published in a scientific journal next year.

Bycatch reduction devices would help fishermen financially, while also helping shark populations remain healthy, he said.

“It’s a win-win,” he said. “Reducing bycatch is good for the fishery, and it’s good for the environment.”

UNE graduate student Michael Nguyen is leading the laboratory testing trials, with Mohan—who has a doctorate in marine science—serving as the adviser to both Nguyen and Nyiri.

Nyguen said the battery life and the device housing need to be revamped to make them durable, so it could take time before they are in widespread use.

“As of now, [the testing] serves as a proof of concept and it's exciting to see that in the lab and field it works well deterring the most common shark in the western North Atlantic,” he said.

Whether the BRDs become must-have equipment for fishermen remains to be seen. But the interest was high among recreational fishermen at an informational table that UNE set up at a recent fishing seminar hosted by Saco Bay Tackle at Dunegrass Country Club in Old Orchard Beach.

“They were like ‘Can we buy this from you now, because we need something like this,’” Mohan said.

Atlantic Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias)

APPEARANCE:

Dogfish are slim with a narrow pointed snouts, two dorsal fins and ungrooved large spines. They are gray above and white below with characteristic white spots. Males grow up to 3.3 feet, and females grow up to 4 feet.

RANGE:

Along the Eastern Seaboard, dogfish live from Labrador to Florida, and are most abundant from Nova Scotia to North Carolina.

MARKET:

There is little consumer demand for dogfish in the U.S., but it is commonly used in Europe as the fish in “fish and chips.”

5 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023

John Mohan, an assistant professor of marine science who is overseeing the research, says the ultimate goal of the study is to have the bycatch reduction devices in widespread use among recreational and commercial fishermen. PHOTO: Clarke Canfield

Source: NOAA Fisheries

University of New England student Clayton Nyiri unhooks a dogfish caught by fellow marine science student Jamison Saunders.

PHOTO: Clarke Canfield

University of New England student Ben Gowell holds a dogfish in one hand and a bycatch reduction device in the other.

PHOTO: Clarke Canfield

A delicate dance between sea and land

BY CATHERINE SCHMITT

Behind the forested dunes of Popham Beach, where the Kennebec River finally meets the sea, is an extensive salt marsh. Great blue herons hunt for eels amid blooms of sea lavender and milkwort; saltmarsh sparrows search for spiders in the grass.

As in all marshes, the grasses and rushes each have their own unique tolerance for salt and flood, and their growth reflects tidal patterns, with fine smooth salt hay and black rush in the upper zones that only flood occasionally, and wider cordgrass along edges, creek banks, and low areas.

With each high tide, plant stems slow the rush of water, allowing sand and silt to settle to the marsh surface before the ebb. With each season, organic matter accumulates as plants grow and die, and their roots and stems build peat in the saturated soil.

In this way, above and below the surface, salt marshes flourished with the gradually rising sea for thousands of years.

It’s a delicate relationship, however. Any changes, like more frequent flooding, less sediment being delivered, or plants growing faster, can disrupt the equilibrium. Marshes are also

a

running out of room, as waves erode their edges, storms tear them apart, and people convert their grass and mud into lawn, concrete, and pavement. Such conversion has already consumed one-third of the region’s salt marshes.

The acceleration of sea level rise over the last century prompted many

coastal ecologists to worry, and this worry only intensified as they started focusing on “blue carbon.” Would the remaining salt marshes be able to keep up, or would they drown? Would salt marshes continue to play an outsized role in sequestering carbon?

In answer, scientists have been measuring rates of marsh growth, deploying filters to capture settling sediment, installing frames of suspended pins that move up and down with the marsh surface, coring into the peat to date the layers and correlate them with historical pollution.

Recently, in Long Island Sound and around Cape Cod, researchers found that marshes were indeed growing at increased rates.

A new coastwide study, led by Nathaniel Weston of Villanova University and funded by the National Science Foundation, confirms these findings. Analysis of 31 soil cores at nine sites from Georgia to Maine showed that marsh growth has actually accelerated.

In many places, including the Kennebec River, marshes are growing vertically two or three times faster than they were 100 years ago. The change in the growth of the marsh appears to closely mirror the change in rates of global sea level rise.

Weston was surprised. His previous research documented declines in the amount of sediment washing down rivers to marshes as a result of reforestation, erosion control, and dam construction.

“We wondered if we could see this signal of changing sediment supply in the marshes, if accretion rates had slowed,” he said. “We didn’t find that. Instead, we found acceleration everywhere.”

Sediment is necessary, but more important for building marsh is the below-ground accumulation of organic matter. In order for the marsh to sequester carbon, it has to escape

decomposition by bacteria and fungi which produce carbon dioxide or methane as they break down plants. Microbial activity is higher in warmer temperatures, and Weston thinks this helps explain slower rates of marsh growth in some of the more southern marshes (the York River in Virginia, Cape Fear River in North Carolina, and Edisto River in South Carolina).

These new findings suggest that rather than being passively “resilient” to rising sea levels, salt marsh ecosystems have the capacity to respond to accelerating rates of change. The response is dynamic, but patchy. And however well salt marshes have kept up in the past—however well-documented by well-meaning researchers— that response is less and less relevant for predicting the future.

Whether or not salt marshes continue to keep up depends on how fast the sea continues to rise, how much temperatures continue to warm, and whether or not there is a continued source of sediment.

“We are losing marsh in some places, gaining in others,” said Weston. “Overall, we’re going to continue to lose in most systems, some more quickly than others.” A separate study in southern New England found that salt marsh vegetation loss is both widespread and accelerating.

“Marshes are keeping up, until they don’t,” said Weston, who plans on continuing to monitor marshes to identify signals of tipping points. He acknowledged that our information is biased because it is based on data from salt marshes that are surviving, rather than ones that have already disappeared.

“We can’t core a marsh that isn’t there.”

At Popham, the rising sea and shifting sands reshape the beach with each high tide and every storm. The river delivers fine sediment, the marsh grass grows toward the sky, and roots hold everything in its place. For now.

6 The Working Waterfront september 2023 A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too. We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings. Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs. We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what. That’s the Allen Advantage. Call today. (800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com

We are an independent, employee-owned company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville.

Owning

home or business on the coast of Maine has many rewards.

Salt marshes absorb sea level rise—until they don’t

Scarborough Marsh in May 2021. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Legislature, governor pass offshore wind bill

Proponents say ‘guardrails in place’ to protect Gulf of Maine

In what proponents describe as a way to jumpstart a new offshore wind industry for Maine, the legislature passed and Gov. Janet Mills signed into law LD 1895, “An Act Regarding the Procurement of Energy from Offshore Wind” on July 27.

The coalition of groups that support the bill say it will generate not only a historic investment in affordable and reliable clean energy to power Maine’s homes, businesses, and transportation, but also an investment in the working Mainers needed to make it a reality.

Bill sponsor Sen. Mark Lawrence said offshore wind energy must be part of the state’s future.

“To combat climate change and invest in Maine’s energy independence, our state has set ambitious goals for renewable energy. It’s clear that this effort will involve offshore wind energy projects. We need to have guardrails in place to make sure this is done right and truly benefits Mainers,” he said.

“This bill will mean jobs, lower and more stable energy prices while combating climate change at the same time,” Lawrence continued. “LD 1895 represents a detailed path to smart offshore wind development.”

The legislation combines two critical initiatives to advance a new clean energy industry for Maine by setting a procurement schedule and constructing a port. It will:

• Set a procurement schedule for a goal of 3 GW of installed offshore wind power in the Gulf of Maine by 2040, supplying affordable, reliable offshore wind to power homes, businesses, and transportation.

• Incentivize responsibly developed wind projects that protect wildlife and avoid Lobster Management Area 1, one of Maine’s key fishing grounds.

• Set strong and comprehensive labor and workforce development standards for good-paying jobs

and ensure inclusive benefits for Maine’s most vulnerable communities.

• Support the creation of a world-class, Maine-built offshore wind port that will bring in billions of dollars in economic development.

• Help meet Maine’s bipartisan emissions reduction targets and put the state on a path to meeting Gov. Janet Mills’ proposed goal of 100% renewable energy by 2040.

“Maine is well positioned to be a leader in renewable energy and offshore wind,” said Sen. Chip Curry. “This bill will make sure that Maine’s workers, ratepayers, and economy get the best benefit possible.”

Three prominent environmental groups support the law.

Kelt Wilska, energy justice manager at Maine Conservation Voters, said the law “sets a national example for how to responsibly develop a new, affordable energy source, grow good-paying jobs for our workers, and do so without compromising Maine values.”

Jack Shapiro, climate and clean energy director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, said the governor and legislature “are moving us decisively towards a clean energy future that will bring thousands of family-supporting jobs, protect the rich array of wildlife in the Gulf of Maine, avoid conflicts with important fishing grounds, and put us on a path to meet a goal of 100% renewable energy by 2040.”

And Eliza Donoghue, Maine Audubon’s director of advocacy, said the law represents “a serious and measurable step toward accelerating our clean energy transition and reducing our dependence on fossil fuels. This legislation is necessary to help ensure that appropriately sited and operated offshore wind development safely co-exists with Gulf of Maine wildlife and the marine habitats they rely on.”

7 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www pro C k M arine C o M pany C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST Advertise in The Working Waterfront, which circulates 45,000 copies from Kittery to Eastport ten times a year. Contact Dave Jackson: djackson@islandinstitute.org Full Service Boat Yard, Repairs, Storage & Painting P.O. Box 443, Rockland, ME • knightmarineservice.com 207-594-4068 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro

A GREAT (SPRUCE HEAD) READ—

Howard Seaver sent us this photo of Great Spruce Head islanders reading the The Working Waterfront. Shown are Charles Porter, Scott Fuller, and Christina Fuller. PHOTO: ANINA P. FULLER

from the sea up

A history worth celebrating

Island Institute’s 40th prompts look ahead

BY KIM F. HAMILTON

WHEN I JOINED Island Institute as president a little over three months ago, we were preparing for our 40th birthday as an organization serving Maine’s islands and coastal communities.

We were founded in 1983—the year the English rock band, The Police, topped Billboard’s year-end “hot singles” with “Every Breath You Take” and the year that 10-year-old Samantha Smith from Manchester began a Cold War peace mission through her correspondence with Soviet leader Yuri Andropov.

Richard Attenborough’s Ghandi took best picture at the Academy Awards, Michael Jackson’s international sensation Thriller was released, and the grip of a global recession was finally loosening around the U.S.

It was a curious time for an organization focused on Maine’s islands to come into this world. The challenges and cultural references of the early 1980s seem so very global.

From today’s perspective, the founding of Island Institute was prescient. Had we known then that the Gulf of Maine would become one of the fastest warming bodies of water in the world, that access to affordable housing

stood to become one of the defining challenges facing coastal communities and islands across the country, and that a simple demographic truism (more deaths than births over time can lead to severe labor shortages) would threaten our economic growth, we would have wondered what took us so long.

As a relative newcomer to Island Institute, my read of its history suggests that we have always been ahead of major trends.

Already in 1985, the Institute had launched our island schools program to ensure that even the smallest schools remained at the heart of community. We partnered with the state in 1988 to turn uninhabited islands into destinations for recreational use, eventually incubating the Maine Island Trail Association as its own organization.

Our advocacy in the mid-1990s led the U.S. postal service to reverse its decision to close post offices on several islands, thus guaranteeing access to this service that is even more critical today.

This foreshadowed our pioneering work to bring world class broadband to rural communities, including those at the end of the most distant peninsulas or on islands. We’re proud to have worked alongside more than 85 municipalities

rock

bound

My happy Maine anniversary

Forty years after arriving, the love remains

BY TOM GROENING

AS I WRITE this in early August, it’s a couple of days away from the 40th anniversary of our moving to Maine. I’m not expecting the governor to make the day a state holiday or that friends and neighbors fete us with food and drink, but I believe this 40-year love affair is worth reflection.

I grew up in New York, and my prior experience in Maine was confined to three visits. As an eight-year-old, I traveled with my parents through the state to Quebec. My father shot home movies of a log drive on the Kennebec, a practice that would end in ten years. The other two visits were to my now-wife’s family camp on a lake east of Lincoln while I was 21 and 22.

When I was hired as a teacher at a boarding school near Augusta, we figured on staying for five years then trying to buy land in rural Massachusetts. But having to stay on campus every other weekend meant on the off weekends we’d hit the road—Popham Beach, Portland, Rockport, MDI, Deer Isle, Rangeley, Moosehead Lake.

It was a courtship that led us, just a year later, to want to buy land on the coast, which we did, in Belfast, in 1984.

I later learned we were part of a second wave of migrants, coming a decade after the back-to-the-landers. We had no illusions of living selfsufficiently as many of them did, but the opportunity to build own house, cut firewood to heat it, and live closer to the land than we did in surburbia was appealing.

The back-to-the-landers had changed the landscape, making previously insular communities less so. And when they left the woods for towns, they added food coops, boutiques, fine dining, and more art galleries, which we also found appealing.

What did we and our cohorts in this second wave bring? Well, some brought significant capital (we sure didn’t). Most of us brought education and skills. The rap on we newcomers has been that we try to usher in amenities we miss from our homes, but I think we also brought lessons about failing to protect from poorly planned commercial and residential development.

What has Maine done for and to me? Our former columnist Colin

and helped them access yet another crucial economic development tool.

Our early island energy efficiency work in the 2000s ushered in clean energy, climate mitigation and adaptation, and marine economy programs. This work puts those who make their living on the ocean and the businesses that make coastal communities strong at the center of our work. It means that our commitment to protecting Maine’s working waterfront, first detailed in 2005, has not waned.

At a recent dinner, I shared that while I was deeply honored to be at Island Institute to celebrate this important 40-year milestone, the more interesting question to me is what will we celebrate at our 50th? A very smart guest challenged me to answer my own question: what, in fact, will we celebrate?

While I cannot fully anticipate the next decade, I do know that our history must guide us. First, as a community development organization, we will only be as strong as the number of communities we listen to. The way we work is as important as what we do because it grows the most important currency: trust.

Second, the Gulf of Maine is our Rosetta Stone. Understanding

changes in the Gulf of Maine will help us decipher the future of our coast, our economy, and our living environment—whether from the potential for shellfish and seaweed aquaculture, the changes in the lobstering industry, or infrastructure and innovations we can’t yet envision. Finally, we will inspire communities to build a smarter, climate-friendly, inclusive future without sacrificing their heritage. For us, heritage and community resilience have always gone hand-in-hand.

Ten years is not that far away, yet the Maine coast is changing in ways once unimaginable. Community development is not understood as a nimble, adaptive field. Our historically unique position, however, bridging decades of change among diverse, coastal communities, will strengthen our ability to anticipate rather than to react to change.

That is a history worth celebrating.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

Woodard’s American Nations comes to mind. In it, he argues—persuasively— that the U.S. is made up of 11 distinct regions, each with deeply embedded social and political values that hold sway. As Woodward defines them, Maine is “Yankeedom.”

I have embraced far more libertarian, “live and let live” values in these 40 years, developed a healthy cynicism about policy that is removed from practical application, and have come to respect the validity of that catch-all phrase “common sense.”

Back in the late 1980s while covering a Belfast City Council meeting on a summer night and hearing a consultant describe what seemed to me a lovely addition to the downtown streets, I was brought up short when a councilor observed that this amenity wouldn’t stand up well to the business end of a snowplow. That’s common sense.

Maine—existing at “human scale,” as someone I recently met put it—has allowed me to see impact in my work. Yes, some transplants might be said to come for the chance to be big fish in

a small pond. But that is a cynicism I have not embraced. That impact may be short-lived, but it’s real.

And Maine has given our children— now adults with their own families in Maine—a stellar environment in which to grow and spread their wings.

In our early years, I was awed at Maine’s beauty—Camden’s High Street in autumn, a wind-whipped early spring day climbing Blue Hill, a hot summer morning at Roque Bluffs, the glowing dusk of a December day in Stonington.

Soon, I realized that what I loved most was the power of community it provides. I walk down Main Street in Belfast and say hello to someone, and if I stop to think how we first met and come up empty, well… that’s community.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. He may be reached at tgroening@ islandinstitute.org.

8 The Working Waterfront september 2023

I have embraced far more libertarian values in these 40 years.

A BAILEY SUMMER DAY—

This photo, believed to have been shot around 1900, shows the steamboat landing at Bailey Island in Harpswell. The sign on the building reads “Mackerel Cove,” and the advertising sign at right reads “Stanley Marine Motors, Low in Price, High in Quality.” Despite the ankle-to-head attire the women are wearing, it appears that the image was shot in summer. Aren’t we all lucky to live in a less formal age?

Let’s return to a native view of resources

Wabanaki

BY SARA FRESHLEY

THE WABANAKI NATIONS have an excellent history of sustainable resource management. Before colonizers dominated the resources of this area in the 1600s, the Wabanakis had lived here for 12,000 years, self-regulating their consumption and relationships to the land and one another.

In a fraction of that time, the society that colonizers brought to these shores manifested a tragedy of the commons in mere generations. It’s a tragedy we live in today.

We live in an economy that relies on people consuming goods for survival instead of relying on one another. Society has drastically changed from one of community living to one of individualism. This has caused resource depletion, poverty, and climate change.

Instead of embracing and sharing the Wabanaki people’s way of life, we dismissed it as wrong and shunned them. Despite this, the Wabanaki people are rooted firmly on this land and it is time that living descendants of colonizers listen to them.

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGinnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis

Michael Sant

Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

Government regulation and oversight have been our answer to preventing resource depletion. In this individualistic society which we have built, we cannot trust one another to take only what we need, therefore regulation is necessary.

The Wabanaki people have resided on this land for so long in part due to a community mindset—community that extends to the surrounding ecosystem.

Instead of seeing nature as a commodity, the Wabanaki recognize that we are a part of nature. Instead of learning from the original stewards of this land, colonizers have continuously silenced the Wabanaki people, believing that our way of life is the only way; as if it has to be one or the other.

Despite this, there are examples outside of the Wabanaki where people have embraced successful resource regulation without government oversight. The Maine lobster industry

began marking egg-bearing females with a V-notch in their tails in the early 1900s. This mark lasts several molts, allowing the female to hatch and raise potentially thousands of lobsters.

Conservationists applaud this method and many credit it as a reason the lobster industry remains a critical economic driver for Maine. This system puts the power in the hands of the people.

While I cannot speak for the Wabanaki people and do not know the depth and details of their way of life, I do know that they have survived with the land for so long, in part because they prioritize the community over the individual, they consider future generations in their decisions, and they understand that to survive, the ecosystem needs to thrive.

Imagine the wealth of success stories if we respected the Wabanaki nations as partners instead of subjects. Suppose

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery:

Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209

E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org

• Visit us online:

we embraced instead of dismissed their way of life.

The Wabanaki nations have lived on the banks of what we now call Moosehead Lake, the shores of what we now call Casco Bay, and in the forests of what we now call Baxter State Park for 12,000 years.

They have survived off the lobster, the trout, and the deer long before scientists created quotas and the government’s required permits. The Wabanaki Nation takes care of the land, and the land takes care of them.

It is well past time that the descendants of colonizers, who live here as a result of Wabanaki genocide, recognize the Wabanaki people for what they are, a sovereign nation that knows how to not only survive but thrive. The first step is to listen.

Sara Freshley grew up in Maine, has a bachelor’s degree in marine science, and a law degree in environmental law and policy. She works as community organizer for Friends of Casco Bay and serves on the Maine Conservation Alliance and Voters Boards.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org

542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

9 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023

op-ed

non-profit

by Island Institute, a

organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

giving.islandinstitute.org 386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

model worked for 12,000 years

In this individualistic society which we have built, we cannot trust one another to take only what we need.

Rockland gallery featuring Ralston images

Limited-edition print show opens Aug. 18

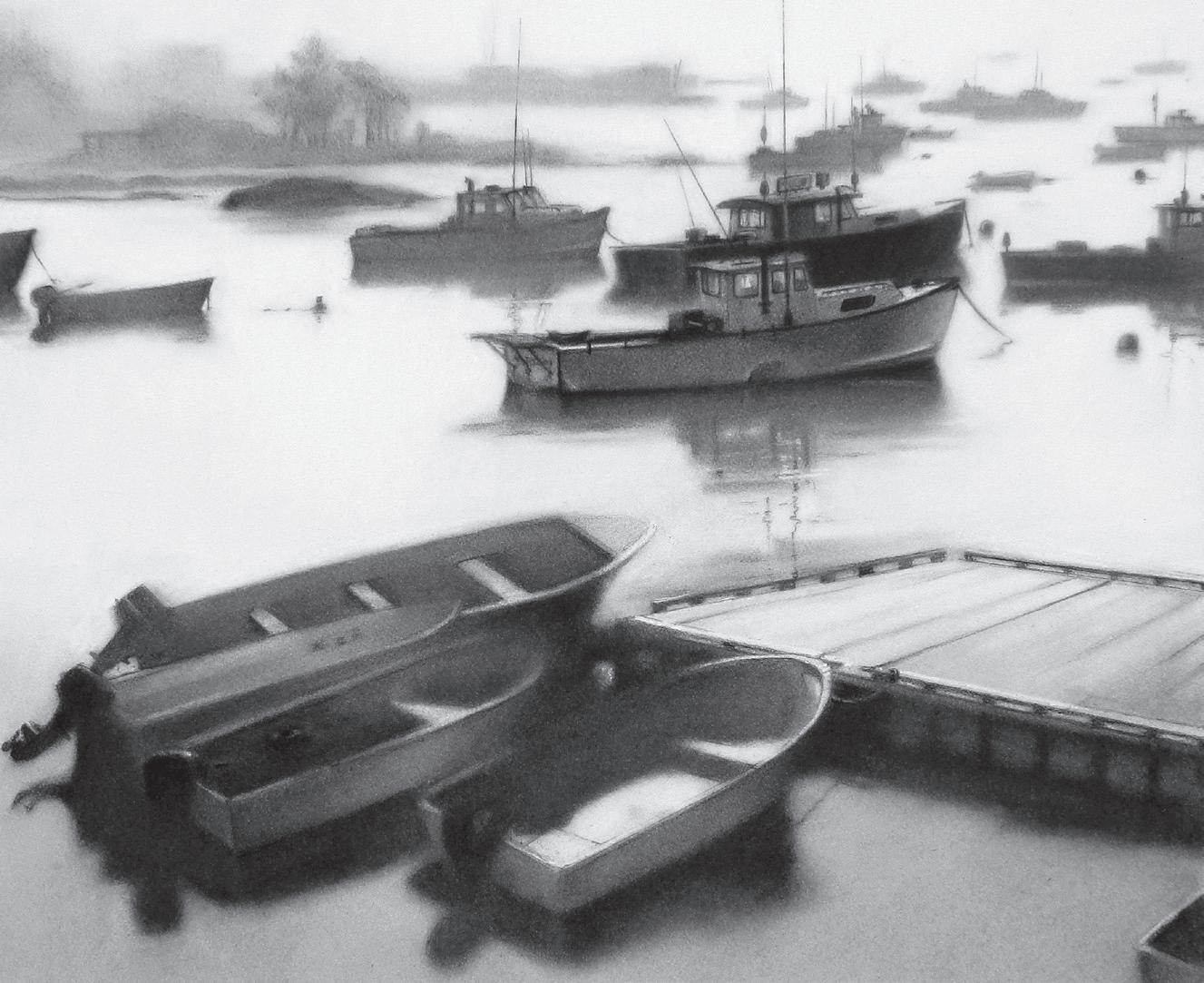

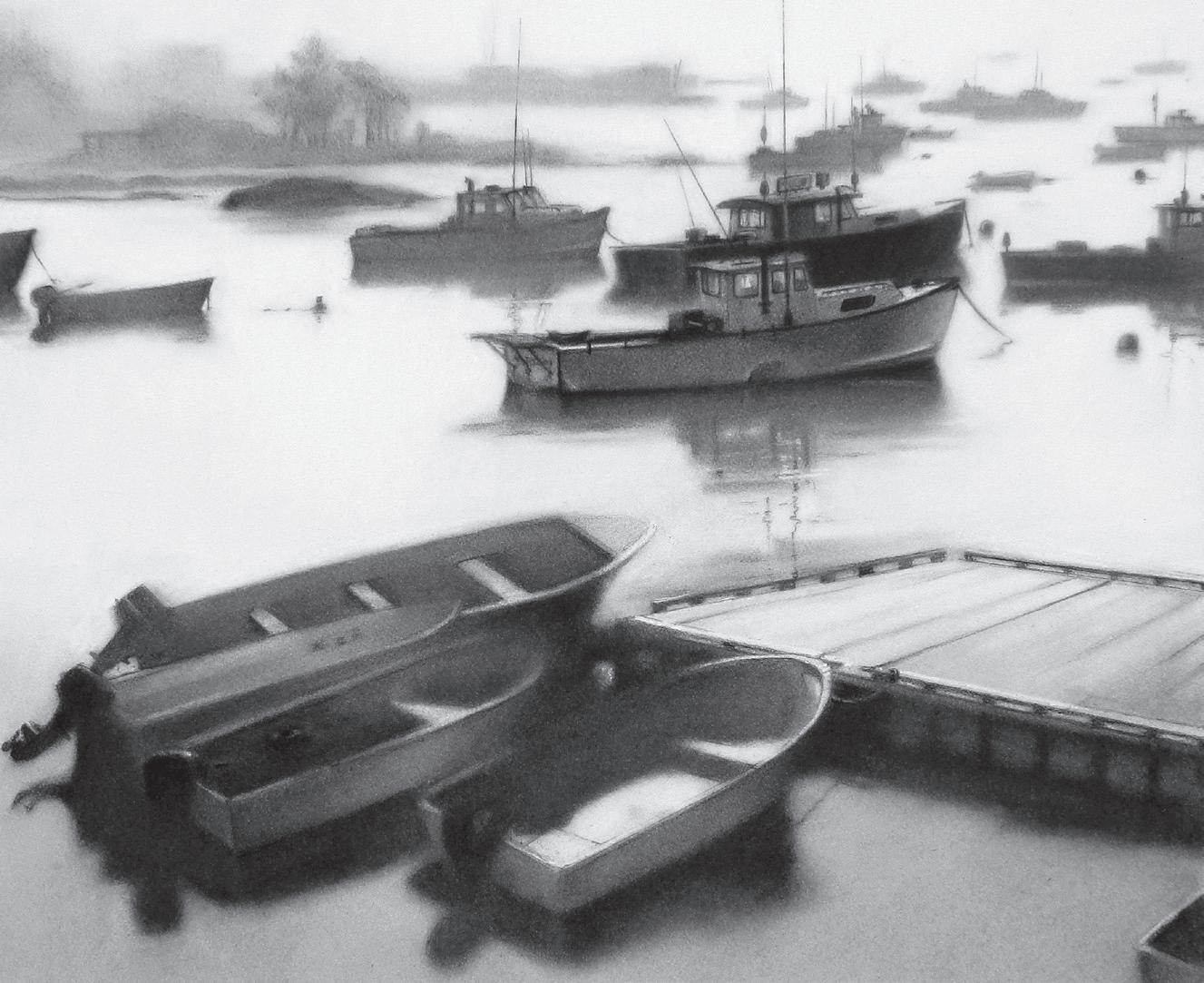

Blue Raven Gallery at 374 Main Street in Rockland announces its first collaborative exhibition on Aug. 18 with an opening reception 5-7 p.m. featuring the pre-eminent Maine photographer Peter Ralston and his release of a new, limited-edition suite of large prints, The Raven Edition. The exhibition will include over 50 images, many never before exhibited, as well as his “Pentecost,” voted by Down East magazine the “most iconic Maine photograph of all time.” This one-man show celebrates Ralston’s 45 years of photographically documenting the coast and islands of Maine, his experiences as co-founder of Island Institute, as well as his lifelong connection with the Wyeth family.

Ralston grew up in Chadd’s Ford, Penn., worked for a decade as a freelance photojournalist and then photographing the coast of Maine beginning in 1978, drawn especially to the working communities that define the coast’s enduring character. His work has been seen in many books and magazines, featured repeatedly on network television, and has been exhibited in galleries, collections, and museums throughout the U.S. and abroad.

“My photographs are my statement,” Ralston says. “I don’t pretend or aspire to be cleverly intellectual about what I do. I just poke around the nooks and crannies

“The Harbor, Sea Smoke,” by Peter Ralston.

of this coast, always with my camera. As far as I’m concerned, I’m just storytelling, albeit straight from the heart. These are the places I’ve been and the people I’ve met, and sometimes there’s metaphor not far beneath the surface.”

Jodie Willard, founder of Blue Raven Gallery, is the new owner of the historic

bank building located between the Farnsworth Art Museum and Island Institute. As a graduate of Brooks Institute of Photography, Willard has a special interest in photography and collectable fine art photography.

The gallery will also exhibit contemporary art in a variety of

fields, including paintings, bronze sculptures in the roof top garden, mixed media, and one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces.

To learn more visit www. BlueRavenGallery.com and subscribe by email, or on Instagram @ BlueRavenGallery.

10 The Working Waterfront september 2023 IT'S HERE! Get your copy today www.islandjournal.com Discover Maine Art, Discover Maine Craft 386 Main Street, Rockland ME | 207-596-0701 | Tues - Fri, Sun 10 - 5, Sat 10 - 6 Shop and support Maine artists at our website TheArchipelago.net Owners have decided to sell their complete line of molds for the Calvin Beals and Young Brothers boat lines and CAD drawings for the ever popular Calvin Sports Fishing Design. Trademarks, web addresses and e mail accounts for each line are also included. Please call or e mail for a list of the mold’s beings sold.

Douglas Erickson, CCIM SVN The Maseillo Group erickson@soundvest.com

Community Authenticity Remains Our Focus

The details have changed, but supporting community is the common thread

BY TOM GROENING

Reprinted from the 2023 edition of the Island Journal, Volume 39

You’ve probably heard the term “elevator pitch,” right? It’s mostly used in business circles, capturing the idea that an entrepreneur needs to be able to explain a business concept in a timeframe equal to the average elevator ride. That journey provides the ultimate captive audience, and so a clever pitch in that short time might land an investor.

Well, here at Island Institute, we sometimes crave an elevator trip up Burj Khalifa in Dubai, with its 163 floors, to give us time to explain where the organization has been and where it is going.

This year marks the Institute’s 40th year. Maine’s islands and coast were very different places in 1983, yet as we reflect on those four decades, it’s satisfying to see consistent themes threading through the years.

These days, we often describe ourselves as a community development organization. What

does that mean? It means we recognize how essential those units of human congregation are; community coalesces around shared economic and cultural activity, and over time, it grows its own values and learns to identify threats. Yet at the same time, community cannot thrive without change, without innovation, and the courage to pursue new opportunity, new ways of doing things.

And at the heart of it all is an idea that’s best captured in the phrase “a sense of place.” It’s a vague phrase, yes, but I think it embodies something of the shared identity people have with a community, a sentiment that joins people in loyalty and affection and even love for that place. And that love must be fierce in the face of winds from storms that sweep across the globe.

When Philip Conkling and Peter Ralston launched Island Institute 40 years ago, they recognized that island communities, especially those not connected

1983

by bridges to the mainland, risked becoming ghost towns. This wasn’t a hypothetical risk. Conkling notes that in the year 1900, there were some 300 year-round island communities off the Maine coast. Their geographical setting made practical sense, of course. Until the 20th century, goods and people in our corner of the world were most efficiently moved by ship. New York and Boston were more accessible from Vinalhaven and Bass Harbor than from Augusta and Lewiston.

Conkling, who had trained as a forester, tells the story of being hired to do a timber survey on an uninhabited island Downeast. When fog prevented the lobsterman from picking him up, he was left island-bound for another day. He wandered around and discovered foundations from a settlement, which piqued his curiosity: Who were the people who had lived here, and what had happened to them?

Philip Conkling, a forester and writer, founded the Institute in 1983 and led the organization through 2013, along with cofounder Peter Ralston, a photojournalist.

1984

Conkling and Ralston, supported by funding from Betsy Wyeth, published Island Journal in 1984, featuring the nowiconic cover image of sheep being towed to an island.

1985

1987

The Institute, in part reflecting the strength of Conkling’s writing and Ralston’s photography, added more publications, launching The Island News (1987), Inter-Island News, and The Working Waterfront (1994), the latter now circulating 45,000 copies ten times a year from Kittery to Eastport.

11 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023

Early on, the Institute recognized the crucial role island schools— often, one-room schools—played in these offshore communities. Education conferences, linking island schools through video and inperson meetings, and scholarships helped sustain these schools.

ISLAND INSTITUTE AT 40

1988

The Institute teamed with the state to study uninhabited state-owned islands and concluded recreational use was possible, leading to the formation of the nowindependently operated Maine Island Trail Association, or MITA, in 1988.

Back on the mainland, Conkling asked questions at the town office, looked into records, and soon discovered that the island community had been abandoned. So, with fewer than 20 year-round island towns remaining in Maine at that time, a mission was born—helping sustain these communities.

Conkling met Ralston on Allen Island off Port Clyde. The island had been purchased by renowned artist Andrew Wyeth and his wife, Betsy. Betsy had hired Conkling to do a timber survey and Ralston, who had grown up next door to the Wyeths in Pennsylvania, was visiting the family. Ralston had been working as a photojournalist, often traveling the world for magazine assignments.

1994

In the early 1990s, the federal government began automating and abandoning lighthouses and even demolished one in Maine. In response, the Institute intervened and by an act of Congress helped transfer remaining lighthouses to municipalities and nonprofits.

The nonprofit was formed on Hurricane Island, itself a vivid reminder of what was at stake. In the 19th century, the island essentially had been a labor camp, with families living there to work the granite quarry, and paying the company for housing and food and other staples. As the market for granite began to disappear, the owners demanded the resident workers and their families make a quick choice—be transported to nearby Vinalhaven or to the railroad station in Rockland. It was a sad end to an unsuccessful island community.

Conkling was a writer, and given Ralston’s photography experience, the two thought they’d launch their organization with a publication. Betsy Wyeth agreed to support the effort, but with a caveat—do it well, she said, rather than produce one of those mimeographed newsletters so many nonprofits published.

One of the Institute’s universally praised programs is the work its Island Institute Fellows do in island and coastal communities. The program, launched in 2000, places recent college graduates in communities, where their focus ranges from community gardens and afterschool activities for children, to digitizing historical collections and helping draft municipal ordinances. To date, some 350,000 hours of assistance have been provided.

2000

And so, with Wyeth’s generous support, the first Island Journal was published in 1984 with Ralston’s now-iconic cover image of sheep being towed in a boat. Island Journal, like the organization that produced it, has evolved, but at its heart the publication still aims to reflect the richness of island culture—and that’s “culture” in the anthropological sense, not the arts (though that, too, is featured).

Several years ago, some of us decided to empty and organize file cabinets at the office, and perusing the materials within was like a trip back in time. We found several forestry plans Conkling had completed for small, privately owned islands—a way to bring revenue into the fledgling nonprofit. Early newsletters outlined the Institute’s work over the previous year; one memorable stand the organization took was to oppose a large-scale residential development on an island off Portland. “Responsible development” of the islands was what was needed, the Institute asserted.

Other publications were launched: the Island News, Inter-Island News, and finally, The Working Waterfront. The latter, Conkling has explained, was established in 1994 because the 4,500 year-round islanders needed more political clout. They needed friends on the mainland, he said, and so the newspaper covered concerns shared by island and coastal communities.

2000

In 2000, the Institute opened Archipelago in its new Main Street office in Rockland, which serves as a retail store and art gallery featuring work of island and other Maine artists and artisans.

Another moment in the organization’s evolution can be seen in the archives of these publications. At one point, the Institute’s leadership wondered if accepting advertising for island real estate was undermining that “responsible development” principle. Of course not, they concluded. After all, it was islanders who began and ran those real estate agencies.

Back to the idea of community: What are its essential elements, especially in the finite world of an island? One concept is the “three-legged stool,” whereby an island town needs a school, a store, and a post office to remain vital. Other components might be substituted, and certainly economic opportunity is critical.

2005

In 2005, recognizing the growing threat to working waterfronts, the Institute published The Last 20 Miles report, identifying the shrinking access for those working on the water. The Institute helped support passage of a constitutional amendment that reduced tax assessments on these properties.

So Island Institute created education programs to assist the several one-room island schools. It established the Teaching and Learning Collaborative—TLC—to foster communication between those schools. Before Zoom became a way of life for many, children in those schools developed friendships through screens, often facilitated by an Institute staffer.

Island leadership and governance also have been challenges. So the Institute formed the Maine Islands Coalition, made up of representatives of each island who meet quarterly to discuss issues they confront.

The marine economy has always been a focus for the Institute, and remains so today. Staff work to see over the horizon to help fisheries-dependent communities

12 The Working Waterfront september 2023

ISLAND INSTITUTE AT 40

prepare for downturns in certain harvests. In recent years, the Institute helped many start small-scale aquaculture businesses as a hedge against declining fishing revenue.

More than a decade ago, the Institute broadened its mission scope to include serving “remote coastal communities.” That soon evolved to include the entire Maine coast, and beyond.

One of the organization’s best strategies has been to bring groups facing similar challenges together, even if those groups don’t share a geography. Fishermen from the United Kingdom once gathered with their Maine counterparts in Rockland to share their experience with wind turbines in the North Sea. Residents of Block Island did the same as wind turbines were becoming a reality off Rhode Island. Islanders from the Great Lakes traveled to Maine to see how our islands addressed challenges.

These convenings, as we like to call them, share the lessons our communities have learned with the wider world.

And in fact, despite the broadening scope of the mission, islands remain—as former Institute President Rob Snyder used to say—our North Star, informing and guiding our work. Islands can be understood as living laboratories, or even crucibles where solutions for difficult problems are tested. How does Matinicus get rid of its old washing machines, refrigerators, and hot water heaters? How does Monhegan move away from a diesel generator for its electricity? And how do Frenchboro and Isle au Haut find enough housing for lobster crews during the summer?

In 1983, could Conkling and Ralston have imagined today’s threats of a shrinking workforce and a rising sea? In a sense, yes. Stemming the falling tide of islanders moving to the mainland was a concern back then, and fragile island environments were always on the Institute’s radar.

Could they have foreseen the Institute’s need to help island and rural coastal communities secure reliable internet? Again, in a sense, yes. Connecting communities to the wider world has always been the mission.

Another part of the Institute’s story is its board of trustees. Today, the organization is guided and grounded by a board that includes a range of thoughtful people, including a veteran lobsterman, a boat yard owner, a seafood marketer, an environmental scientist, a school administrator, and more. Their roles, often behind the scenes, are essential as we plot a course forward in this century.

And so is the leadership emerging from Kim Hamilton, the Institute’s fourth president, named in April, and the first woman to hold the post. With an impressive nonprofit background that includes work with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and FocusMaine, she agreed to take on oversight of our programs work on a temporary basis and, she says, fell in love with the organization.

Hamilton, a native Mainer, has generational ties to Chebeague Island, where she now resides.

If you boarded that elevator for the long ride with me and asked about the Institute’s mission, I would tell you an imagined story about a summer resident of, say, North Haven, driving a visitor from California into the island village. He might point out the caretaker who checks his house during the cold Maine winter months and he might wave to the postmistress who activates the family’s box for the summer. He also might nod to the lobsterman who provides his catch for family feasts, the town administrator who keeps the streets paved, and the school principal who ensures island children are well educated. And as he takes his visitor to his boat, he might introduce him to the crew that rebuilt its engine.

My imagined North Haven resident wants his island community to remain authentic, I would say, and avoid becoming a sort of gated community. And that’s what Island Institute works at, year after year. Oh, and by the way—our imagined summer resident probably has a few copies of Island Journal on the family’s coffee table.

Islands face some of the highest energy costs in the country, and so the Institute began helping communities find efficiency, from organizing weatherization of homes, to replacing lightbulbs with LEDs, and assisting in analyzing the costs and benefits of wind power, photovoltaics, and microgrids.

Doing business in island and coastal communities brings challenges tied to geography, transportation, and technology, and the Institute, with the Tom Glenn Community Impact Fund, has provided grants and loans for entrepreneurs to help with energy efficiency, infrastructure, and other business support.

High-speed internet—known as broadband—has become as essential as ferries and roads to island and remote coastal communities, and so in 2015 the Institute began helping them establish this service.

With the lobster fishery facing uncertainty, the Institute in 2016 began offering training for starting small-scale aquaculture businesses to raise kelp, oysters, and mussels.

The greatest threat to our way of life on the coast and islands in the 21st century is climate change, disrupting the lobster fishery, bringing higher sea levels, and making the ocean more acidic. The Institute has worked with Luke’s Lobster to create new markets for fishermen, helped lobsterdependent communities prepare for changes, and worked to help the working waterfront embrace electric power instead of fossil fuels.

To view a more comprehensive timeline of Island Institute’s work, visit: islandinstitute.org/40-years

13 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023

Tom Groening is editor of Island Journal and The Working Waterfront.

Photos by Peter Ralston, Jack Sullivan, and Island Institute staff.

2009

2012

2015

2016

2017-PRESENT

ISLAND

INSTITUTE AT 40

14 The Working Waterfront september 2023 TACY RIDLON (207) 266-7551 TACYRIDLON@MASIELLO.COM Congratulations to Island Institute on your 40th Anniversary and thank you for all you do for the Coast of Maine! You are my favorite publication in which to advertise and the only one where I get fabulous responses to my ads. Keep going for another 40!

Congratulations to the Island Institute on 40 years of helping to sustain Maine’s island and coastal communities.

ISLAND INSTITUTE AT 40

A trusted friend along the Maine coast since 1905. (207) 288-5097 seacoastmission.org

Portland to sell building to island group

Affordable Peaks Island apartment plan moves forward

BY CLARKE CANFIELD

An affordable housing advocacy group has unveiled renderings of a building with three apartments that it plans to have constructed and occupied by next June on Peaks Island.

Home Start, a nonprofit dedicated to expanding the pool of affordable housing on Peaks, has entered into a purchase-and-sales agreement with the city of Portland for a former parish hall once owned by St. Christopher’s Church on Central Avenue, said Betsey Remage-Healey, president of Home Start. The organization still has to take steps to secure funding, but has received detailed plans on what the building will look like.

Remage-Healey said it’s vital for Peaks to have affordable housing

to ensure it remains a year-round community where people who grew up or work on the island can afford to stay, raise families, and keep the school alive and well.

“If we don’t have affordable housing, it just becomes an enclave of wealthy folks who can afford the ever-rising costs of housing on the island,” she said.

Home Start was founded in 2008 with the goal of expanding the affordable housing stock on Peaks, where home prices have soared in recent years. It purchased a house on Luther Street more than a decade ago and worked with another nonprofit organization, Volunteers of America, to build and manage two homes on an adjacent lot. Home Start sold the Luther Street home last year and is using the proceeds from that sale toward the purchase of the

former parish hall and construction of the new apartments.

Home Start has been working with Backyard ADUs, a modular housing company in Brunswick, on a design for a one-story structure with solar panels on the roof and apartments that will rent for below-market prices.

After looking at different options, the Home Start board voted in May to demolish the existing building, rather than renovate it, and have Backyard ADUs construct the new building with three apartments, each with a separate entrance. Two of the apartments will have two bedrooms that will rent for $2,012 a month, and one will have three bedrooms that rents for $2,324. The rental rates are no more than 80% of the average rent in the Greater Portland area based on a formula from the U.S.

Vinalhaven takes action on housing

Nonprofit forms to investigate solutions

The Vinalhaven Housing Initiative (VHI) has been established to create year-round, sustainable housing options for decent and safe housing that is affordable to lowerand middle-income individuals and families, senior citizens, and physically challenged people who would otherwise be unable to afford rental or homes due to rapidly escalating prices.

The housing organization is an IRS approved, 501c (3) non-profit organization which is eligible to receive tax deductible contributions. It is working in partnership with Vinalhaven’s town government and community organizations to obtain funding, building sites, and the rehabilitation of selected housing.

In late 2020, the town’s board of selectmen established a housing

committee in response to the need for an increased supply of year-round and updated existing housing. VHI was created as a direct result of the housing committee’s work.

Housing committee members communicated directly with the staff and board members of several other Maine island housing non-profit organizations and became convinced that a not-for-profit housing initiative was the most expedient way to address the housing crisis on Vinalhaven.

Like similar non-profits, VHI will be funded predominantly through private donations from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government grants.

There are many typical situations that illustrate the challenges faced by those who need decent, affordable year-round housing on Vinalhaven.

Linkel Construction, Inc.

For example:

• People wish to come to Vinalhaven for jobs critical to the island—police, medical, teachers. With no housing available the community cannot benefit from their much needed skills and talents.

• Rentals with no hot water or heating.

• Several generations of islanders living in the same home because there are no other housing options.

• Elders on limited incomes in older housing that is hard to heat, maintain, and is not adapted to their physical needs.

• Young islanders are moving away because of the lack of housing. VHI is assessing a variety of housing types that could meet the need: single family and duplex modular homes, tiny houses, multi-units in new apartment

Department of Housing and Urban Development, Remage-Healey said.

Home Start planned to apply for a zero-interest forgivable loan by the end of June through the Affordable Housing Initiative for Maine Islands, a program administered by Maine Housing. It also plans to seek smaller amounts of funding for the project from the city of Portland’s Jill Duson Housing Trust Fund and the Peaks Island Fund, which is administered by the Maine Community Foundation.

Remage-Healey said Home Start has agreed to pay the city what’s due in back taxes—probably around $35,000 or so—on the building when the purchase is finalized after it secures funding. A family bought the parish hall from the church years ago, she said, but it was taken over by the city for back taxes.

structures or renovated buildings with both rental and ownership options.

It is reviewing possible building sites that could be acquired through donation or purchase. Sites with town water and sewer are the most desirable for accessibility and to keep construction costs down.

Affordable housing is critically needed to sustain Vinalhaven as a functioning year-round island community. Island economies are like a delicate fabric. If one thread is pulled out the fabric begins to unravel.

Currently, the VHI board of directors is in formation and seeking additional members and advisors. For inquiries or more information, please contact Elin Elisofon at eelisofon@gmail.com (207) 450-1937 or (207) 867-4866.

15 www.workingwaterfront.com september 2023 Our Island Communities

Sea Farm Loan FINANCING FOR MAINE’S MARINE AQUACULTURISTS For more information contact: Nick Branchina | nick.branchina@ceimaine.org |(207) 295-4912 Hugh Cowperthwaite | hugh.cowperthwaite@ceimaine.org | (207) 295-4914 Funds can be utilized for boats, gear, equipment, infrastructure, land and/or operational capital. Lower Interest Rates Available Now!

Locally owned and operated; in business for over twenty-five years. • Specializing in slope stabilization and seawalls. • Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) certified. • Experienced, insured and bondable. Free site evaluation and estimate. • One of the most important investments you will make to your shorefront property. • We have the skills and equipment to handle your largest, most challenging project. For more information: www.linkelconstruction.com 207.725.1438

book reviews

Weeding needed in gardening book

Compilation of columns provides ‘cheerleading’

and children’s stories and is a retired nurse. She emphasizes growing healthy food, organic and pesticide-free. She also provides lots of encouragement to novice gardeners in a cheerleader role she seems to relish.

A Maine Garden Almanac: Seasonal Wisdom for Making the Most of Your Garden Space

By Martha Fenn King, Down East Books (2023)

REVIEW BY TINA COHEN

By Martha Fenn King, Down East Books (2023)

REVIEW BY TINA COHEN

THERE ARE A LOT of books I end up reading because they have “Maine” in the title. Even if not for review purposes, I’d probably grab them anyway, be they fiction or nonfiction, familiar author or new name.

Martha Fenn King is someone I hadn’t heard of, although she has written a gardening column for her local newspaper, The York Weekly. A Maine Garden Almanac compiles those columns.

Besides having a vegetable and flower CSA, she has written poetry

This book might appeal to those looking for that enthusiastic support, some advice on growing techniques and varieties of veggies, and a better understanding of the bugs and weather which can wreak havoc in a home garden.

This is a kind of folksy “down home” book that isn’t intended to be great literature. And it isn’t an authoritative book on growing food like those of another Mainer, Eliot Coleman.

King thanks her editor but the book has some flaws an editor should have caught—her punctuation is frustrating, for example. I noticed a Bangor Daily News article excerpting a chapter of hers that included an editorial note: “This has been lightly edited for clarity.” The whole book would have benefited from that kind of help.

An island’s hold on family

Memoir finds Vinalhaven was home base

families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Because it is a compilation, topics end up being covered multiple times. Garlic is an example, with repetitious advice. No time frame is provided with dates of articles, so references to “this summer” or “that season” are somewhat meaningless.

I think when these were columns, one or two platitudes per column could have been bearable. But to read the collection in its entirety, the book starts to feel saccharine, sappy, and cliche-ridden.

The pictures are great, and there are many. And I do feel inspired to start growing ginger and sweet potatoes, for which she provides ample directions. This book could be a step towards what I suspect King would do brilliantly— combine her gardening advice and health concerns with her hearty can-do attitude and generous enthusiasm in a book aimed at a younger audience. I think she’d make a great “coach” who could get more kids growing food.

Another Mainer, Roger Doiron of Scarborough, founder of Kitchen

Gardens International, was successful in convincing First Lady Michelle Obama, in her early months in the White House, to start a vegetable garden on the grounds. Not only did she do that, but she brought children from Washington D.C. elementary schools in to help and learn.

There is evidence to support that when children work in gardens, it has a positive impact on many areas of their lives, including school performance. They practice skills like planning and patience.

And as King writes, “We have so much to learn about life, just from the humus under our feet.” She continues, “If we can care for our organic matter, perhaps we will have more nutritious foods to eat, microbes for health, and a sponge to soak up the rain. Let us care for our humus... our ecosystem and microbiome—the Earth depends on our help.”

Who more importantly needs to hear this concern than children growing up today?

REVIEW BY TOM GROENING

As the state ferry approaches North Haven in the Fox Island Thorofare, my eye goes to the large, sprawling cottagestyle mansions that line neighboring Vinalhaven’s cliffs to the south.

The buildings, which in the offseason are shuttered, or at least without signs of life, date to the late 19th or early 20th century. I often muse to myself about the people who built these grand escapes, and what role they served in their lives and the lives of their families, even now, generations later.

Is their appreciation of Maine island life less or more than the rest of us who live here year-round, and maybe get to visit an island once in a while? The grandeur of the homes suggests wealth, which reminds me of the line from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “All happy

Well, no need for me to muse any further. Abigail Trafford’s memoir High Time opens the shutters on at least one of those mansions, and though Trafford has found peace and yes, even happiness in her 80s, there is also some of Tolstoy’s unique unhappiness in what appeared to be an otherwise charmed family life.

Reading and speaking about the book at the Vinalhaven Public Library in late July, she said it represented an accounting, a making sense of a family and a personal life marked not by privilege and good times under sunny skies on a Maine island, but by broken lives and broken relationships.

in Europe during World War II, and it marked him—as it did most—so that she understands him in Before The War and After The War terms.

She worked as a reporter and editor for The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, covering such envied beats as the U.S. space program…

“It was high time to come clean,” she said at the event, invoking the title of the book. “Time” is a refrain in her writing, with earlier books titled My Time, As Time Goes By, and Crazy Time.

Yes, Trafford’s mother and father were well educated and hailed from old money, but that tells only part of the story. Her father saw prolonged action

Correspondence she quotes between her father fighting in Europe and her grandfather back home reveal a quiet fatalism in the soldier. Though he was a sensitive soul who lived to play music—photos in the memoir bear witness to the family’s habit of gathering around a piano at the Big House in Maine— he stuffed his feelings away. Her mother suffered several miscarriages before bearing Abigail and a sister and brother. Her brother was diagnosed with autism. The trauma of the miscarriages seems to have triggered mental illness, Trafford writes, and her mother tried to treat it with drugs and alcohol.

Trafford’s adult life was far from charmed, though it brought opportunity. She worked as a reporter and editor for The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, covering such envied beats as the U.S. space program in the 1960s, but after her first divorce, trying to raise two daughters alone, she had to take in boarders to pay the bills.