Island wind power succeeded on cost

But challenges remain as turbines age

BY SUSAN MUSTAPICH

Fifteen years after its spinning blades began generating electricity, the Fox Island Wind project succeeded in saving islanders money. In fact, customers on the islands it serves—Vinalhaven and North Haven—have paid less for electricity than their mainland counterparts in the first decade of operation.

But challenges loom, including the aging of the turbines, which will force a vote in the near future on either repowering or decommissioning wind energy generation.

The 1.5-megawatt-producing turbines have achieved laudable climate goals, the staff of the nonprofit Fox Islands Electric Cooperative report, offsetting the release of 36,600 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The turbines are owned by the cooperative, its subsidiary Fox Islands Wind, and the resident customers of Vinalhaven and North Haven. Fox Island Electric now owns the property where the wind turbines stand and leases the land to Fox Islands Wind.

The power company hired Amy Turner, an attorney and previous general counsel for a large electric cooperative in Colorado, as CEO in 2020. In the face

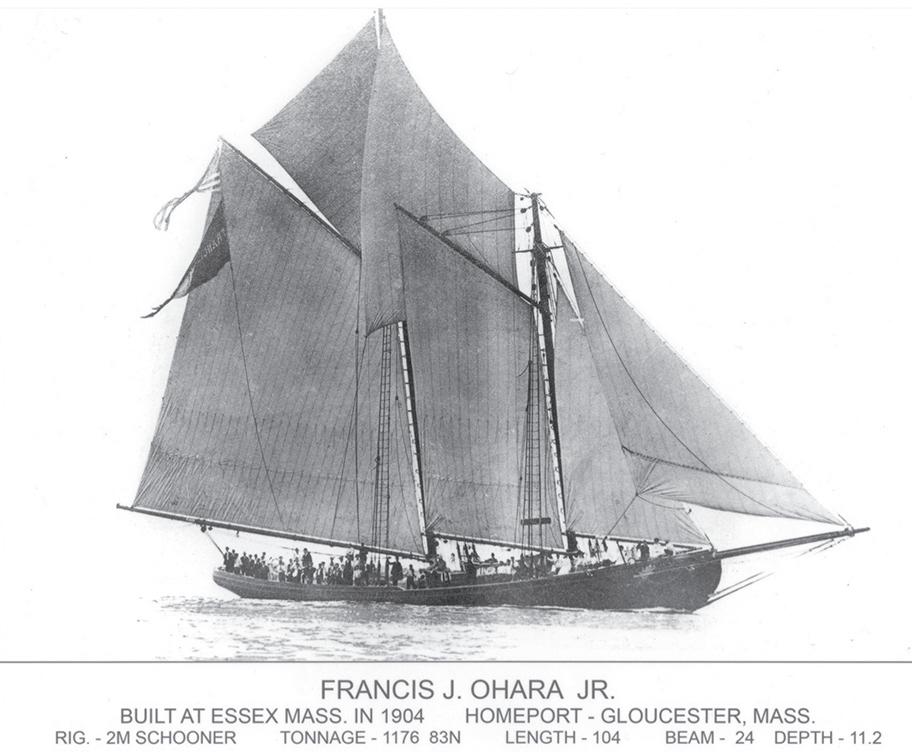

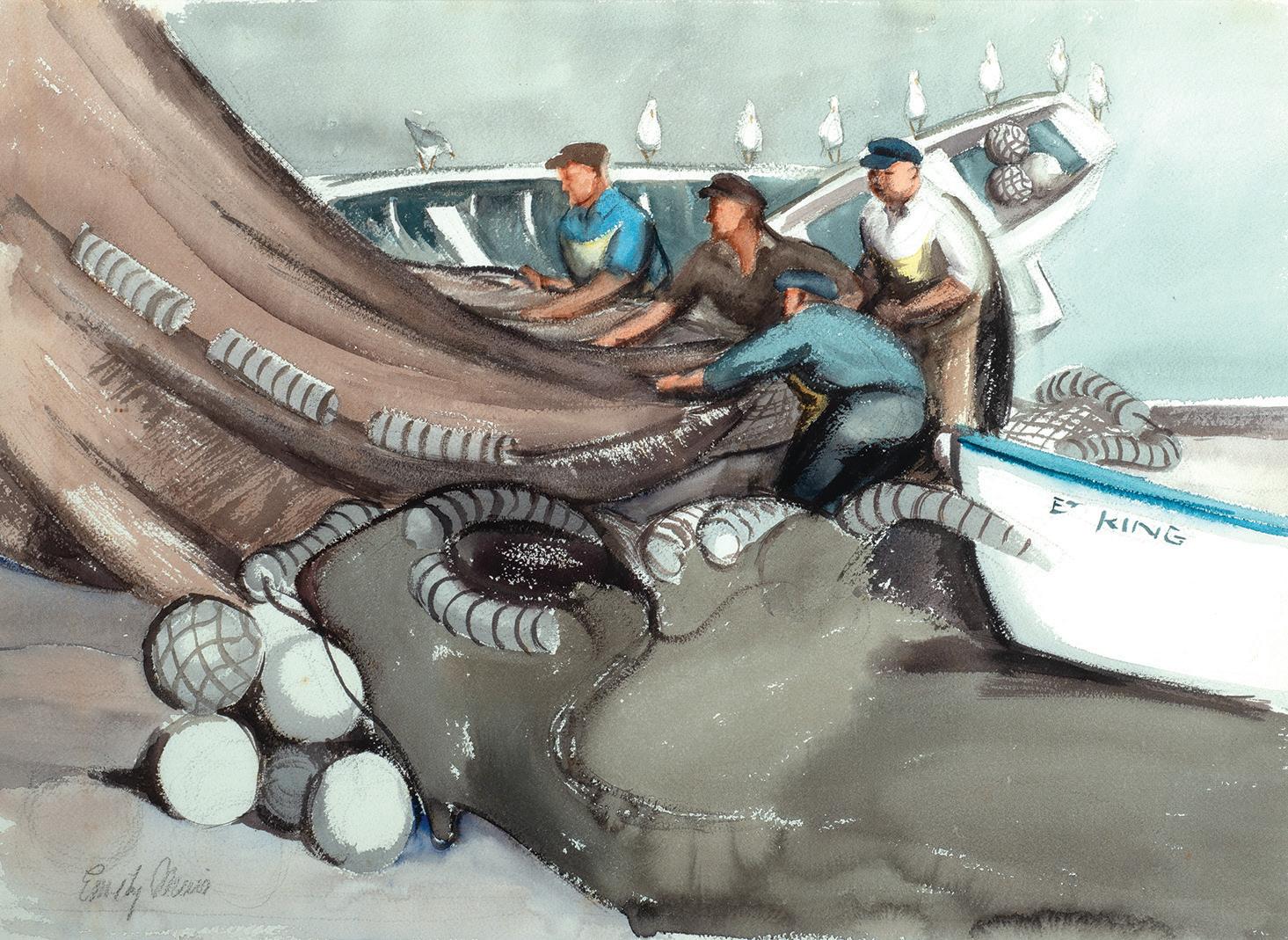

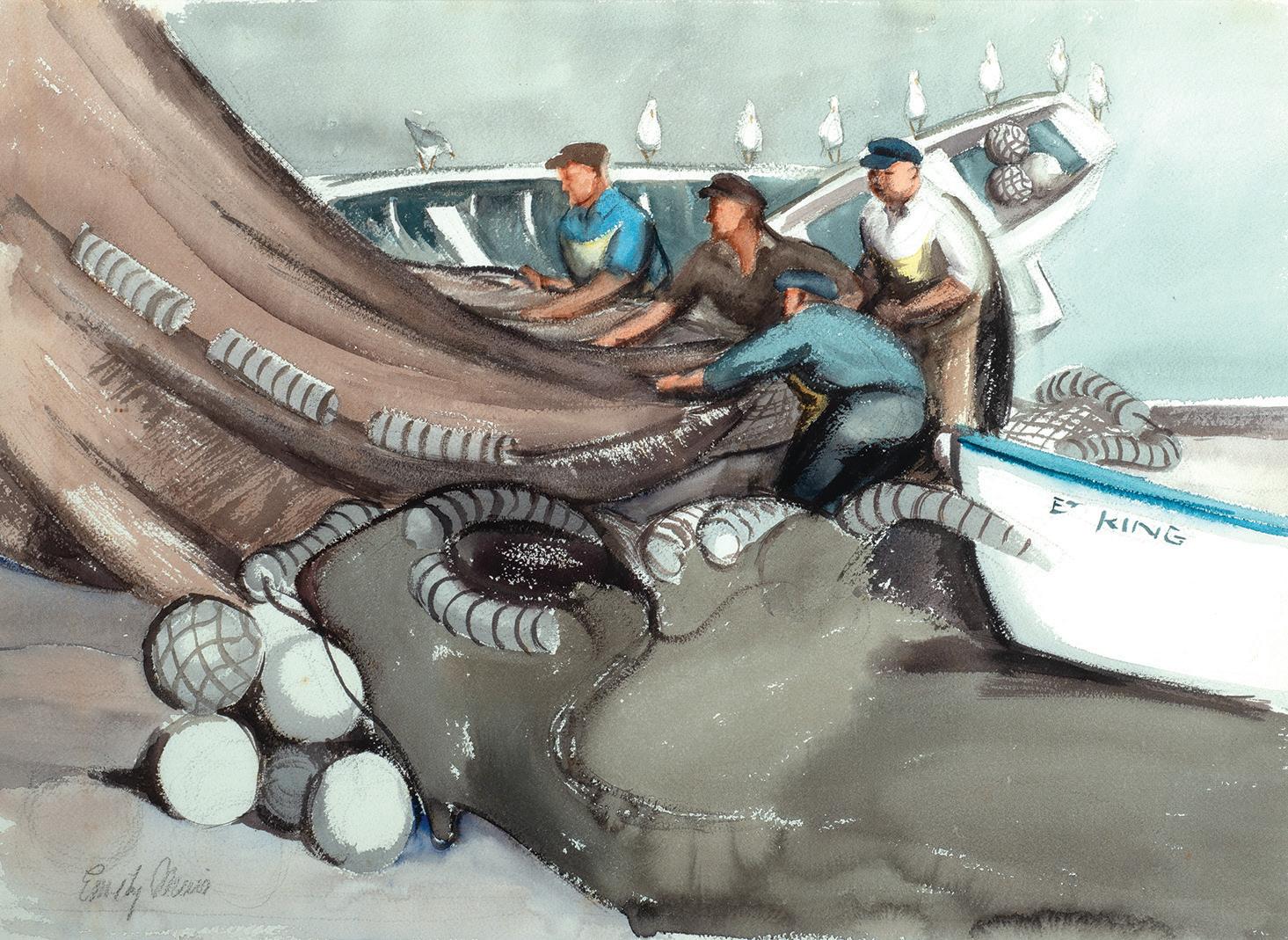

READY TO HAUL—

of change, the cooperative is seeking input and maintaining transparency, she said.

“The directors of Fox Islands Electric and Fox Islands Wind have been hosting community meetings to discuss the challenges and options of creating, operating, and maintaining a modern electric grid that meets our community’s vision,” Turner said. Past

Ferry service proposes higher fares

Inflation cited for revisiting 2019 fare hike

BY TOM GROENING

The Maine State Ferry Service is proposing a 18.3% hike in ferry passenger and vehicle fares, citing inflation’s impact on wages, fuel, and vessel repairs.

A fare hike was adopted in 2019, finalized only after significant opposition from residents of some the islands that faced especially high fare adjustments. The final rates were amended and won acceptance from most island communities.

meetings can be viewed on the FoxIslandsWind.com website, where future meetings are also announced.

The meetings are also preparation for a decision on the future of the wind turbines. At close to 15-years-old, they are nearing their 20-year life span. Turner is focusing on providing residents with

continued on page 4

The state ferry service, part of the Department of Transportation, serves Frenchboro, Swan’s Island, Islesboro, North Haven, Vinalhaven, and Matinicus.

The new rate proposal, or tariff, continues a tradition of higher rates during the summer months. It also shifts some of the burden of the hike onto trucks.

By law, the ferry service is supposed to be funded in a 50/50 split between the state highway fund and fares and fees. In some recent years, the highway fund has borne more than that 50%, which has prompted changes, including eliminating the discount for tickets purchased on islands.

tariff was held at the Samoset resort in Rockport on March 12. Ferry service director Bill Geary, a Vinalhaven native who now lives in Rockland and who studied at Maine Maritime Academy and served in the Navy, opened the hearing by outlining his emphasis.

Geary cited higher costs for diesel fuel, parts, supplies, contractors, and staff.

DOT pays all of the cost of new boats and port improvements.

“My top priority since coming on has been to build a strong collaborative relationship with all the communities we serve,” he said.

“Since 2019, Maine DOT has spent over $79 million in state and federal funds on the Maine State Ferry system,” including operational and capital costs like new vessels. “No increase is easy, but as I’m sure you’re all aware, the cost of just about everything has gone up.”

Geary cited higher costs for diesel fuel, parts, supplies, contractors, and staff.

A public hearing at which public comment was sought on the proposed continued on page 4

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com volume 38, no. 3 n may 2024 n free circulation: 50,000 CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

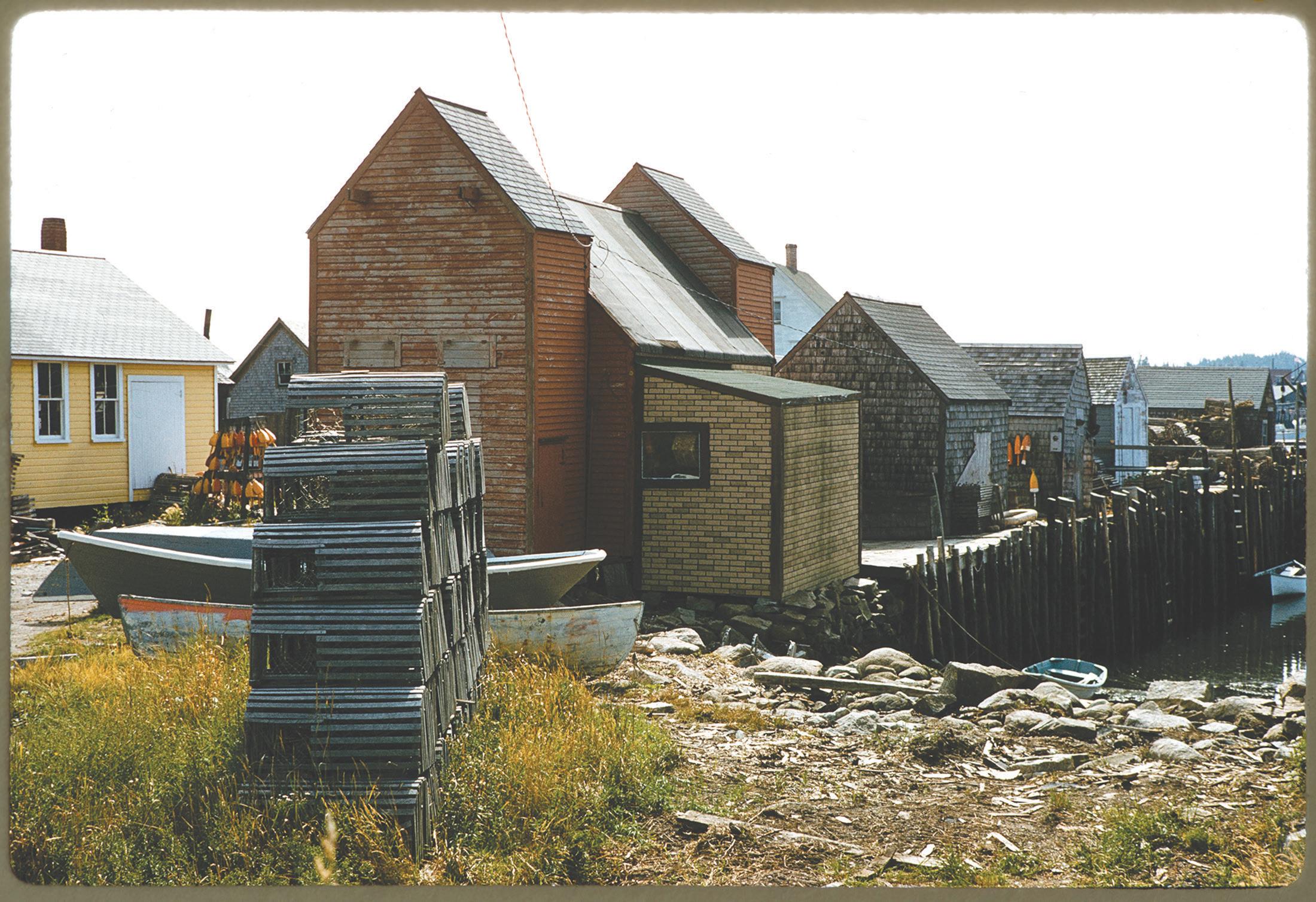

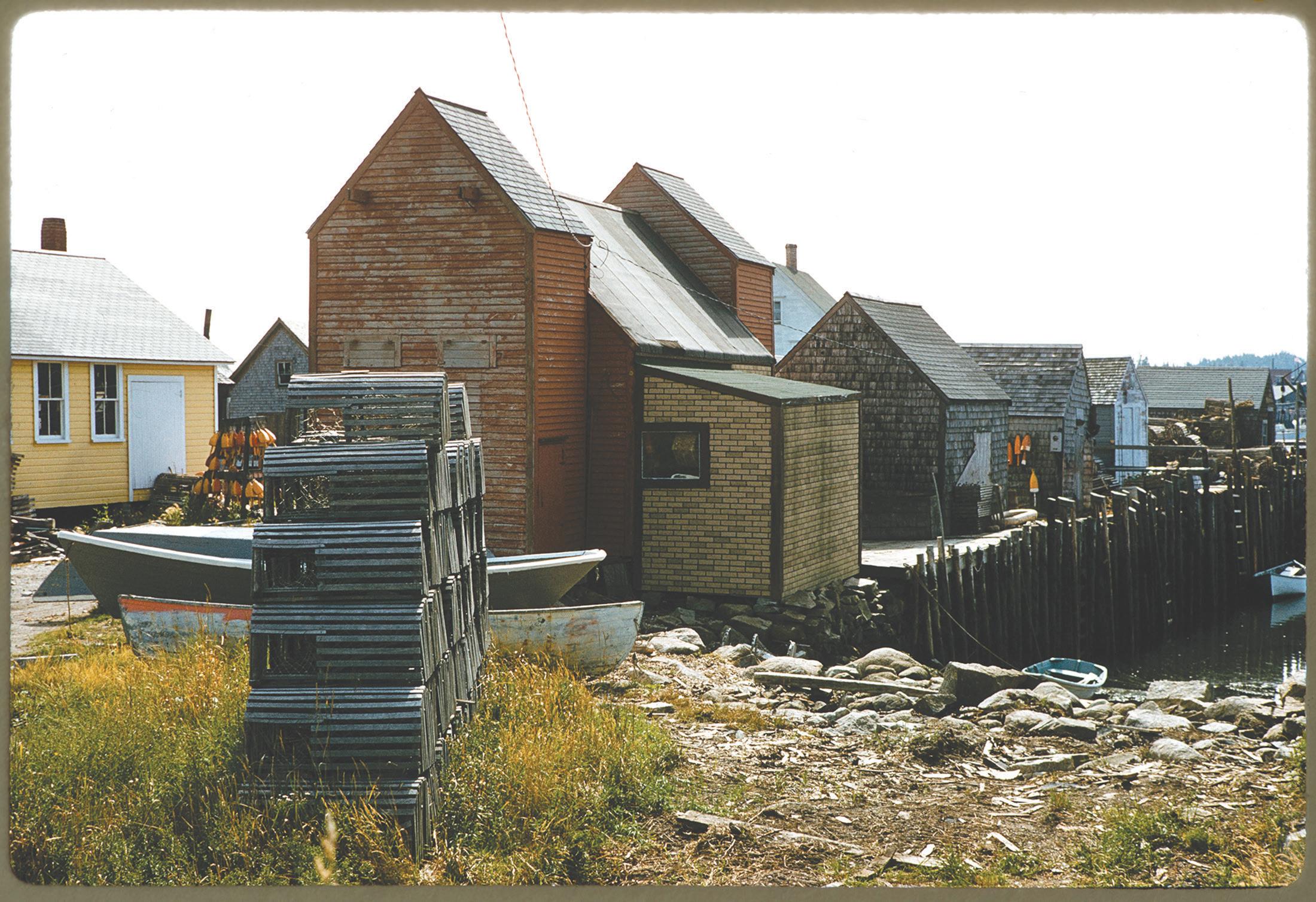

Despite the wild swings in Maine coastal weather in recent weeks, the lobster fishery will be on the water setting traps before too long. In Jonesport, Dirk Sawyer, who has been fishing since he was ten, was readying his boat and fishing gear at the public landing. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Despite legal restrictions, rockweed business thrives

Ocean Organics in Waldoboro sells to golf courses, farms

BY TOM GROENING

Seaweed has been used as a soil amendment for as long as crops have been grown, with documented use dating to the Roman Empire. In Maine, it was used by indigenous people, and then during the colonial period, hauled in wagons from the shore.

It remains in use today, and the enriching elements of Maine rockweed are nourishing golf courses and potato fields as far away as California, thanks to Ocean Organics, a company based in Waldoboro’s business park.

The company’s vice-president George Seaver is a passionate advocate for the industry, and he worries the supply of rockweed—harvested from the intertidal zone—may be threatened by recent court rulings, which he calls “troubling.”

That concern is well-founded, given the landmark ruling by the state’s supreme court in Ross vs. Acadian Seaplants, which found that rockweed growing between the low tide and high tide lines was owned by the “upland” landowner. That landowner could deny harvesters access to the plant, even if the cutting was done from a boat.

For now, Seaver’s business is getting the rockweed it needs. And the 4-foot-cubes sitting in the parking lot, bound for customers across the country and Canada, attest to the demand for the product.

Seaver moved to Maine from Connecticut in 1977, inspired by a story in Down East magazine about early seaweed entrepreneur Bob Morse.

“That’s what kind of got me up here,” he said during a conversation in the office adjacent to the company’s plant. Seaver worked for Morse from 1977 to 1991. The business, Atlantic Laboratories, dries seaweed and makes liquid extracts, among other uses. Though rockweed has been sustainably harvested in Maine for a long time— Seaver says it was cut in Boothbay Harbor in the 1860s, used to fertilize tobacco fields in Connecticut—there is opposition to the practice today.

“We are viewed by conservation groups as evil industrialists who are going to ruin the shore,” he says. “We’re kind of the good guys, but we’re

perceived as not,” he says, arguing that over-harvesting or cutting the rockweed—which, as its name implies, attaches itself to rock—too severely would be bad business.

“It’s completely counter-productive to have a short view of the resource,” he says.

Most rockweed in Maine is harvested in the Downeast part of the state where tidal ranges are greatest, though the plant can be found as far south as Rhode Island.

Ocean Organics was born from Atlantic Laboratories, also located at the Waldoboro site. “We compete a little bit, but not as much as you would think,” Seaver says. Between the two businesses, more rockweed is processed here than anywhere else in the state.

A customer in Michigan purchasing from Atlantic Laboratories wanted a dedicated source to provide its product, and so Ocean Organics was established. Since then, the business has developed other customers.

“It’s sort of a niche,” he says. “We’re shipping products all over the world.”

Seaver is careful about sharing competitive specifics but explains the product is a sort of tea made from the rockweed with other substances added. The business purchases “several hundred tons a year” of rockweed, harvested by independent contractors from a couple locations on the coast.

The product is delivered to customers in 4-foot square totes, hauled on tractor-trailer trucks, and sold in 2.5-gallon containers, often as a “private label,” meaning the individual customer then mixes in additives tailored to the use. One common use of the product is to fertilize golf courses, though Seaver reports that potato fields have seen 5% to 15% increases in yield when the product is applied.

“A lot of it gets on potatoes,” he said. When the economy crashed in 2009, the company pivoted from golf courses to agricultural customers. Export markets in South Korea, Japan, and China are being developed.

“We spend well over $100,000 a year on research,” he says, working with Cornell, Rutgers, Virginia Tech, and others.

A dried product made from the residue of the liquid-making process is also sold. “We make some really good,

granulated fertilizers used on some of the best golf courses in the country.”

But will this business, which employs about two dozen at the Waldoboro plant, remain as constant as the resource it extracts? Seaver worries courts may be out of their depth when it comes to ruling on matters intertidal.

At the root of the legal wrangling is a nearly 400-year-old piece of legislation that still holds sway. The Colonial Ordinance of 1647 stipulates that access to the intertidal zone is permitted for three general purposes: fishing, fowling, and navigation. The state defines harvesting seaweed as fishing, Seaver says, and he believes the court’s ruling is in conflict with current Maine law.

But Seaver argues that the ordinance’s language was about proprietors, who were allowed to build docks, and suggests that it gave control of the intertidal zone to shorefront business owners, not ownership of the property in the intertidal zone.

If shorefront landowners do indeed control the intertidal zone, he argues they should confirm ownership through title searches, be taxed on that property, and be responsible for marking it.

Environmentalists argue that harvesting is harmful to the habitat rockweed creates. Seaver counters that harvesters must leave 16 inches of plant, and that mechanical devices are designed to avoid overharvesting. One analogy is that it’s like cutting fir

boughs to make wreaths—the plant survives and thrives from the pruning.

Despite what seems to be a trend toward restricting harvesting, Ocean Organics is thriving. Seaver gives a tour of an unused industrial building across the street in which the operation will expand.

2 The Working Waterfront may 2024

Seaweed harvesting.

The fertilizer product made from rockweed.

The fertilizer product in totes, ready to be shipped.

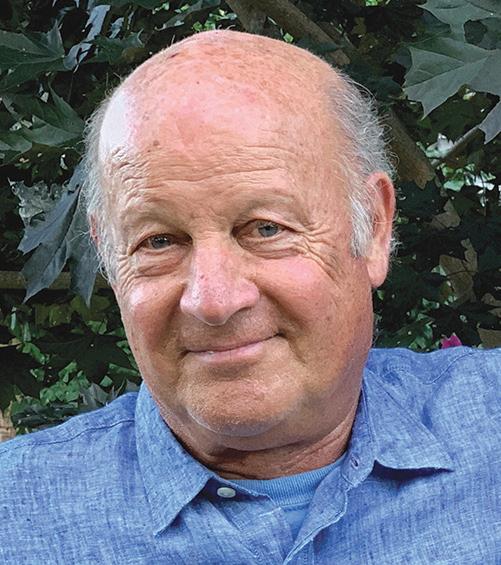

George Seaver.

An aerial view of the business park.

Women of the waterfront

Three harbormasters describe juggling competing interests

BY DORATHY MARTEL

Facilities manager. Juggler. Mediator. First responder. Diplomat. Code enforcer. These are some of the roles harbormasters fill, as revealed during a panel discussion hosted by Midcoast Women on March 13 at Rockport Public Library.

Kathy Given has been Belfast’s harbormaster for 30 years. She’s not sure whether she was Maine’s first female harbormaster, but she remembers that she was the only woman with that job title in the state when she started in 1994.

When she first moved to Maine in 1982, Given said, “Belfast was not really a place where most people wanted to go.” Now the city is a destination for mariners, who can “walk off the boat and provision, get dinner, go to a movie.”

Like Givens, Rockport Harbormaster Abbie Leonard prioritizes harbor access for a wide range of people. She described her office as a fishbowl from which she juggles the needs and wants of many “strange bedfellows”— fishermen, taxpayers, transient boat owners, children.

Rockport finds ways to bring people together at the harbor, she said, through activities such as concerts and New Year’s Eve fireworks displays. The result, she said, is like a Norman Rockwell painting and “so much of what Maine should be.”

“Just because there’s no boats in the water [in winter] doesn’t mean the job is done.”

—ABBIE LEONARD

Givens said she has “always been a big proponent of diversity,” naming fishermen, rowers, kayakers, and school science programs as some of the various users of the harbor and its facilities.

However, balancing the competing needs of constituencies is key. For instance, she explained, “You can put a T-shirt shop anywhere, but you can’t put a fisherman anywhere.”

Leonard didn’t always aspire to be a harbormaster: She wanted to play for the Red Sox. That didn’t happen, and she managed marinas instead. Then, 16 years ago, her father told her that if she didn’t turn in her resume for the position of Rockport harbormaster, he’d bring it to the town office for her. She was hired and has held the job ever since.

Harbormaster is a year-round job, Leonard said.

“Just because there’s no boats in the water [in winter] doesn’t mean the job is done.” Maintenance—and finding ways to fund it—is a concern regardless of the season.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funds some of the repairs needed due to storm damage, but working with them “is a nightmare,”

she said. “They want to spend a dollar to save a dime.”

FEMA funds projects that return damaged infrastructure to pre-storm condition, which doesn’t solve the problem, since pre-storm fixes don’t take climate change into account. For example, water has “come over” six times in her career, Leonard said—and half of those events occurred since Jan. 1 of this year.

Molly Eddy, a year and a half into her time as Rockland’s harbormaster, described herself as the “baby” of the three panelists. She applied to be assistant harbormaster “as a joke.” She got the position, her boss resigned six weeks later, and she has been in charge ever since.

Eddy, too, mentioned access, conflict resolution, and responding to storm damage as important parts of the job. Rockland, she said, has received funding to raise the middle pier, where the food trucks are, and also plans to raise Harbor Park at some point.

Making these changes requires an openness to diverse points of view. People will talk about sea level rise, she said, “if you take the buzzwords out. People working on the waterfront know about it in the way people sitting in their living rooms don’t.”

Given noted that Belfast, too, is working on a hazard mitigation plan.

“To have five substantial storms in a year and a half really wakes you up,” she said.

Climate is impacting property insurance Eastern Washington County seeing higher premiums

BY LORA WHELAN

Coastal property owners may be in for a surprise when their home insurance is up for renewal. Damages to homes from this winter’s high winds, storm surges, and driving rain has meant higher premiums and canceled policies in some zip codes.

Roger Quirk of Lubec learned that one company no longer insures any real estate in his zip code.

“I didn’t realize insurance companies could say ‘no,’” he said. Quirk eventually found property insurance with a regional agency with knowledge of where his property is located and the risks, or lack of, from increasingly challenging weather.

Climate change is having an impact on properties in zones now considered risky but also on properties that aren’t at risk, explains Paul McKee, president of the Maine Association of Realtors. Flood zone maps are being updated for Washington County later this year, he notes.

“That will certainly have an impact,” he says. “A lot of [coastal] properties

will now be in flood zones. We’re seeing more flooding, dangerous winds, and houses having been built close to the ocean seeing increased damage and increased claims.”

Even properties not near flood zones are being affected by the change in insurance policies. McKee describes a real estate transaction he is working on in southern Maine. The property is on a high hill and in no danger of any flooding but like many older Maine houses, its basement is damp. The mortgage underwriter then wanted to research whether the dampness was a threat to the building. What once was common for old homes in New England is now a possible obstacle to securing a mortgage and insurance.

Eastport’s historic Hobbs house, located in the middle of the city’s residential area and well above the flood zone, has not been without its own insurance hiccups. Owner James Pollowitz has been renovating and restoring the Federal era house and used Lloyd’s of London during the construction phase. Once the construction phase was complete it was difficult to find an insurer.

“I tried eight or nine insurance companies, all leads from neighbors,” he says. Agents “were sticklers for lead and peeling paint. I’m finding that most companies have no interest in historic homes,” particularly when they are secondary homes, as is the case with the Hobbs house.

“The whole market is completely changing because of climate change. Winds are a huge factor,” says Pollowitz. “They’re getting huge numbers of claims on houses that probably shouldn’t have been built where they are.”

Compounded by the larger national insurance issues of fire, hurricanes, and tornadoes that are influencing insurance company decisions, Washington County’s demographics don’t help, he adds. The insurance company’s replacement cost for the Hobbs house would be in the millions, a price tag that isn’t realistic for the area. “That tipped the scale to be excluded” from being insured. He finally found a local agent “who was wonderful and very supportive.” The trend is for insurance companies to divest of coastal properties, Pollowitz was told.

Property buyers and sellers need to be aware of the changing insurance market, says McKee.

“We are seeing more and more challenges,” he notes, “even in properties that aren’t close to flood zones.” Those changes are happening almost weekly, he adds.

Prospective real estate buyers “need to research insurance at the beginning of the due diligence phase, not at closing. You better get it then, because you need to be able to get out of the contract if you can’t get insurance or the premiums are too high.”

McKee recommends property owners and buyers regularly check the Federal Emergency Management Agency flood zone maps to see if current or potential property is located within flood zones. FEMA has web-based interactive maps that can be searched by address, zip code, or region at msc.fema.gov/portal/search or on the website of the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry’s mapping resources on the floodplain management page.

A longer version of this story first appeared in The Quoddy Tides and can be viewed at QuoddyTides.com. It is reprinted here with permission and gratitude.

3 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2024

Kathy Given, Belfast’s harbormaster.

Molly Eddy, Rockland’s harbormaster.

Abbie Leonard, Rockport’s harbormaster.

TURBINES

continued from page 1

the full picture of what electrity has cost in the past 15 years.

She is also working on realistic projections of what future electricity will cost if the turbines are repowered and coupled with battery storage and other renewable energy such as community solar.

Hannah Pingree, director of the Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future, co-chair of the Maine Climate Council, and a North Haven resident, took part in the dedication ceremony for the turbines in 2009.

“Fox Islands Wind came about as our island communities faced an urgent crisis of how to replace a failing, expensive power cable and realize the benefits of locally generated clean power,” she said. “Its existence speaks to the ability of small communities to accomplish big, clean energy projects for the benefit of local citizens.”

Pingree supports the proposed “upgrades and additive clean energy investments,” she said, “such as battery storage, to benefit island ratepayers and strengthen the resilience of our energy grid against intense storms and other climate effects.”

Board member Charles Gadzik said that before Turner’s arrival as CEO, the local power company had not provided enough information about its wind power over the years, leaving residents questioning whether the cost of the turbines was worth it.

Both Turner and Gadzik agree the cost of electricity is the main concern for many.

Turner, who explained the history of Fox Islands electricity costs at a December community meeting, has dug into all the data.

The success that comes out of the historical data shows that the more power the island produces and then uses to meet the islands’ needs, “the better off we’re going to be from the standpoints of reliability, affordability, and environmental responsibility,” Turner said.

The numbers show that for ten of the first 11 years of wind turbine operation, Fox Island electricity cost less than the ISO New England market rate.

Initially some of the increase over 6 cents per KWh was due to actions initiated by five residents living near the turbines who objected to sound levels. The actions resulted in environmental regulations to curtail noise by powering down the turbines overnight between the hours of 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. and replacing the original blades with a quieter version.

In 2020, a failed gear box put one of the turbines out of operation and the islands lost 30 percent of their power generation. Insurance covered much of the cost of the repair, but over the next few years the premium increased from around $50,000 to $270,00 annually, adding to overall electricity costs, according to Turner.

The cost of electricity has also increased due to buying peak rate power from the ISO New England power market to meet peak electricity needs on the islands. Though the turbines produce more electricity over the course of the year than the two islands use, production does not track with demand, and so a submarine cable drawing from the New England grid remains in use.

Turner explains that initially residents were given cost projections for the 20-year life of the turbines that overestimated how much electricity the turbines would produce.

Due to the intermittent nature of wind, turbines produce more power during high winds, and less during low winds.

When the turbines make more electricity than needed by customers, the excess electricity is sold to the New England market. When less electricity is produced than needed, power is purchased at market rate. The market rate fluctuates day and night, depending on demand.

On the islands, winds quiet down somewhere between the hours of 5 p.m. and 9 p.m., every day, year-round. This lull in the wind coincides with the time

electricity demand is highest on the island and throughout New England.

During the lull, Fox Islands purchases electricity at peak demand rate. Excess electricity is often sold for lower rates at times of lower demand.

Transmission to and from the islands also adds costs. Turner points out that what residents may see as 10 cents per KWh for electricity supply on a CMP bill, would cost 14 cents per KWh to purchase on the island due to a transmission cost.

Another cause of revenue loss is transmission across the cable under Penobscot Bay to the mainland. While the cable is in good condition, a percentage of power is lost during transmission. This increases the cost when Fox Islands buys power and decreases revenue for power sold, Turner explained.

Electricity cost data does not include the on-island distribution costs, which Turner said are part of the bill, regardless of where the energy comes from. She praises Fox Islands’ four-member crew and others who work together to get the power back on during outages caused by storms and fallen trees. The

local crew also does preventative maintenance and will always resolve outages faster than a mainland company, which prioritizes population centers, she said.

In keeping with lessons learned, future plans to repower the turbines aim to maximize economic benefits and reduce revenue losses by storing excess electricity produced by the wind turbines and using it on the islands.

Repowering would require replacing the turbine gear box and blades, and possibly reusing the towers, she explained. The cost is currently estimated at about half of the original investment, as the site for the turbines and other important infrastructure is in place.

New turbines would be insulated, and run quieter, and at 1.9 MW can produce more power.

Turner is investigating the costs and benefits of battery storage to keep the energy produced for use on island, in place of selling power to and buying from the New England grid.

Community solar paired with battery storage is also being explored in order to meet peak demand during the summers.

FERRY continued from page 1

The service has begun offering recruitment and retention bonuses and creating stipend positions to address what he said was a global shortage in mariners.

The goal, he said, is to establish prices so another adjustment isn’t needed in at least four years. The 18.3% increase will help the service “keep up with the 50% split,” he said.

An early draft of the new tariff raised more revenue by hiking rates during the warm-weather months. Then, at DOT Commissioner Bruce Van Note’s suggestion, the rates paid by trucks was raised, with Van Note arguing that trucks took up space on the boats.

Finally, after input from islanders through the ferry advisory board, a blending of the two approaches was drafted.

At the hearing, ferry advisory board member Duncan Bond of Frenchboro

said his island residents “find this reasonable and not a burden for us.”

Eva Murray, the board’s representative from Matinicus, echoed that view and thanked the service for taking into consideration her island’s special needs.

Advisory board chairman Jon Emerson of North Haven said his community wanted a return to reduced rates for islanders.

In 2019, ferry officials said regular travelers, such as commercial truck drivers, would buy a one-way ticket on the mainland, then buy the reduced round-trip tickets at the island terminal for the rest of the summer.

Emerson suggested than an island residency card might fix that problem. He also suggested senior rates, and expressed worry that higher rates for trucks would mean higher costs for consumers on the island.

Alan Barker, the Vinalhaven representative to the advisory board, argued

that trucks would disproportionately bear the rate hike. Currently, during off-peak months, a 62-foot truck took up about three car spaces on the boat but would pay the amount that eight to nine cars paid. Under the proposal, that truck would cost the amount that 9.3 cars would pay.

“That’s a huge increase,” he said.

Karen Mundo of Islesboro said her husband recently had surgery and would have to travel to the mainland, often at $52.50 under the new tariff, a financial burden. She suggested a senior rate be established.

Islesboro’s Maggy Willcox, publisher of the Islesboro Island News, read a letter from resident John King, which suggested island resident, senior, and commuter rates be added. With just 600 year-round residents, King argued, a reduced rate wouldn’t impact revenue.

Roxanne Tolman, representing the Vinalhaven Fishermen’s Coop, said

that their island had a much higher percentage of truck traffic on the ferry, and so would be impacted.

“That’s how we get our lobster off the island. That’s how we get our bait on the island,” she said.

The proposed rate hikes for a roundtrip vehicle for Frenchboro, Swan’s Island, North Haven, and Vinalhaven go from $38.50 to $48.50 in the June 1-Sept. 30 peak season, and $31 to $36.50 during the Oct. 1 to May 31 period.

For a round-trip vehicle trip for Islesboro, the rates increase from $29.50 to $37.50 during peak season, and from $22 to $26 during the colder months.

For Matinicus, the rate for a roundtrip vehicle, with a reservation, would go from $90 to $108, regardless of the time of year.

Truck rates for Frenchboro, Swan’s Island, North Haven, and Vinalhaven would increase during peak season from $4.75 per foot length to $6.25.

4 The Working Waterfront may 2024

The Fox Island Wind turbines, located on Vinalhaven, appear closer to the shore than they actually are in this image, shot with a telephoto lens. FILE PHOTO: TOM GROENING

Fox Island Wind’s CEO Amy Turner.

Funding is ending for affordable internet program

Access to internet is critical to rural, low-income Mainers

BY AMBER BLUM

Brenda Hunt lives in a shipping container on her five acres of land in Blue Hill. But her rugged dwelling is equipped with fiber optic cables, which are expected to be able to deliver highest-speed internet for many years.

The internet has reached more people in the U.S. now than ever before, largely due to programs like the federal Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP).

Hunt’s life has been dramatically enhanced through broadband—the term for high-speed internet—made accessible through the ACP. After a year of assisting low-income folks get internet in their homes, the ACP has lost its funding and will cease operating by May.

Tough decisions about home internet service loom for many.

As the internet became ubiquitous in our personal and work lives, many federal and state programs were developed to get every American connected. Total connectivity occurs through two channels: infrastructure and digital equity.

“Broadband infrastructure” refers to the actual cables and hardware. “Digital equity” is making sure everyone has access to and the understanding of how to use broadband.

Some of the largest barriers to digital equity are lack of affordable internet service plans, lack of devices, and lack of interest. The ACP, the largest affordability program in U.S. history, was created after the COVID pandemic revealed the extent of the digital divide.

In Maine, more than 95,800 households have benefited from the ACP.

“ACP enrollees include young learners, grandparents, and everyone in between,” says Geoffrey Starks, commissioner of the Federal Communication Commission. “To put it plainly, ACP is the most effective program we’ve ever had in helping lowincome Americans get online and stay online.”

Congress’s Digital Equity Act, part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, identifies several populations that need more support in achieving digital equity. These include low-income households, older adults, the incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, veterans, individuals with disabilities, individuals with language barriers, members of racial and ethnic minority groups, and those who reside in rural areas.

Hunt falls into a few of these identified populations and was able to get the ACP discount of $30 off her monthly internet bill. It took a friendly neighbor who leads the Peninsula Utility for Broadband (PUB) group to convince her to get fiber optic connections to her home and sign up for the ACP.

Butler Smythe leads the PUB, an advocacy group aspiring to connect the Blue Hill Peninsula, including Deer Isle and Stonington, with fast, flexible, affordable, and reliable broadband internet. Smythe also happens to live near Hunt, and one day decided to drive down her dirt road to tell her how broadband could improve her life.

Hunt said many people she knew were hesitant; registering for government services can be very intimidating.

“People didn’t know about the program. They were skeptical,” she explained. “You have to be careful when you are low income because you do not have the confidence or the right to this or that.”

With high-speed internet Hunt saw improvements in her quality of life. She was able to swap her satellite dish for a smart TV. Instead of paying for cable, she now watches on subscription services such as Netflix or Hulu. She also uses her smart TV to watch free YouTube videos on everything from gardening to mental health.

She has learned more about herself and her community by using the internet to engage online. She also canceled her landline and uses Wi-Fi to make phone calls. Her relationship with her grandchildren has improved because she can call them any time without worrying about dropping the call. She can also research what her grandchildren are interested in these days.

Hunt now sees having good connectivity as a high priority. She says she will “have to shuffle around a couple of things” to stay connected.

According to the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society:

• Nationwide, 49 percent of ACP households are subscription vulnerable, meaning they find the internet difficult to fit into their monthly budgets and are on the edge of disconnection

• 68 percent of ACP households reported they had inconsistent or zero connectivity prior to ACP, and 80 percent cited affordability as the reason for this lack of connectivity

The closure of the ACP will not only affect those with low income but will also affect the reach of infrastructure funding such as the $270 million coming to Maine through the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment program. ACP makes it less risky for internet service providers to build out to rural areas, because more of the serviceable population can afford to subscribe.

According to the Benton Institute, ACP creates $16.2 billion in annual benefits to users of the service subsidy, nearly twice the $8.4 billion it costs for the $30 monthly subsidy.

President Biden has asked Congress to fund ACP as part of his budget, and recently called again on Congress to extend its funding. There is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to fund ACP through the proposed Affordable Connectivity Program Extension Act. Advocates argue that connectivity promotes civic engagement, education, and healthy communities.

“We encourage folks to get involved however they can to support our neighbors who will be most harmed if this program ends,” said Christa Thorpe, a community development officer at Island Institute, which has been supporting coastal communities with broadband and digital equity planning since 2016. Among the help that may be offered is “lobbying our federal delegation, approaching your town about digital equity planning, or volunteering at places like libraries that are on the front lines of helping close the digital divide,” Thorpe said.

In Blue Hill, Hunt will continue with her current internet plan.

“Having internet is more important than having a car these days,” she said.

Amber Blum is an associate community development officer with Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at ablum@islandinstitute.org.

5 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2024 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www. pro C k M arine C o M pany. C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro Reliable transportation for all of your island needs 207-466-2636 www.midcoastbargeworks.com

Full Service Boat Yard, Repairs, Storage & Painting P.O. Box 443, Rockland, ME • knightmarineservice.com

207-594-4068

A vision for Maine’s marine economy

Opportunities abound, but we must invest

BY KIM HAMILTON

FIVE YEARS AGO, a group of people committed to the future of Maine’s marine economy embarked on an ambitious journey to develop an economic development roadmap for Maine’s marine living resources, or MLR. I was part of this group, and MLR was our shorthand for an extensive set of activities, including lobstering, fishing, aquaculture, valueadded processing, shipping, logistics, and other related components of the sector.

We also included life sciences, the small but growing part of the marine economy that looks to the ocean to develop important health and related solutions.

Called SEA Maine, and funded by the U.S. Economic Development Administration, the Maine Technology Institute, and FocusMaine, the initiative centered on five goals:

• To grow the overall value of the MLR economy by 10% by 2030

• To increase employment in the sector by 1,000 employees by 2030

rock bound from the sea up

• To increase investments, capital, market development, and R&D to support the sector

• To maintain and expand working waterfront access and working waterfront business activity

• To build the sector’s ability to respond to the changes and opportunities from climate change and demographic shifts

Five years later, with a pandemic that began and ended in the interim, the results are in, and the opportunities outlined in this report are worthy of attention.

This sector contributed over $3.2 billion in total economic input to the Maine economy in 2019 and employed more than 34,000 people. Downeast Maine is identified as an especially big contributor to this sector, accounting for nearly 20% of the employment, but the impact of the sector is state-wide.

This effort reveals that our dependence on the marine economy is more expansive than many of us appreciate. Commercial fishing and increasingly aquaculture, such as mussels, kelp, oysters, and scallops, are often our

mental models for this industry. But when you add boat building and repair, seafood preparation and packaging, wholesaling, specialty food preparation along with shipping, restaurants, and supermarkets, it is quickly apparent how the tentacles of this industry reach from bait to plate and beyond.

Because of this investment, and the engagement of industry, nonprofits, higher education, and our federal delegation, there is now a trove of research and practical tools to inform everyone’s efforts to support our marine economy.

I am especially drawn to the materials produced by the Workforce & Talent Development subcommittee. Any young person wondering whether there is a future in a marine economyrelated job will find inspiration and information about education pathways and other credentials. Any employer who is concerned about retaining and training employees will find practical tools to support employees while also growing the business.

Ultimately, this effort will be powered over the long-term by the Maine brand—something we all have a stake

When communes sprouted in Maine

Those living arrangements may have been doomed to fail

BY TOM GROENING

POLITICALLY MOTIVATED violence. Defiance of the legal order. Rejection of long-held moral values. A widespread move toward a new social order.

I’m not talking about the state of our nation today, but about the late 1960s and early 1970s, an era that impacted coastal Maine and in many ways still does.

Last summer, I ran into an acquaintance who insisted on sharing with me a memoir he had put together about those years and his arrival in Maine. David is a gentle sort of guy who spent his working years in education. I know his wife, and happened to write stories about their son when he was in elementary school and then later when he was an adult.

I wasn’t sure what to expect, flipping through the slim, spiral-bound collection, but once I began reading, I couldn’t put it down. Titled “Twitchell Hill Commune Reminiscences,” its entries are inspired by and include passages from David’s journal during those days, when he and several friends left Boston and landed in Montville, intending on creating a commune.

It’s worth considering the meaning of the term; I suppose the key elements of a commune are living together with a group of people, sharing property and responsibility. A commune doesn’t

have to be rural, but the folks in those years wanted to move to the country and build their houses and grow much of their food.

It’s hard to believe this about David, but as he writes about his activism with the Students for a Democratic Society—the SDS—he discloses his move toward a more radical group, a response to being attacked for his opposition to the war in Vietnam and the lack of change in U.S. policy.

“I lost my patience with nonviolence and joined up with the violent Weathermen,” he writes. “Being part of the Weathermen was a frightening, terrible, traumatic experience. In the fall of 1969 I was shot twice in the right side and shoulder by the Chicago police while participating in a demonstration.”

David left the group after a year, and he writes about how he grew to understand that his intractable, harsh political stances were hurting his relationships.

David and his friends, who knew each other from Northeastern University, decided to come to Maine and buy 70 acres in Montville, a farm community west of Belfast.

From his journal, an entry on Sept. 3, 1971:

“We all just finished a long meeting of sorts discussing what style house we

in protecting. While it is commonplace to talk about Maine’s cold, clean waters and our fresh-from-the-ocean catch, it is worth remembering that these are resources that we need to fight hard to protect. With 34,000 jobs in the balance and billions of dollars at stake for the Maine economy, investments in community planning, clean energy, fisheries management, and working waterfront access become not just important but truly urgent.

The next time you enjoy a plate full of Maine seafood goodness or support your working waterfront, know that you are a part of something much bigger—you’re helping build the longterm sustainability of an extraordinary asset that is uniquely Maine’s.

For more information about SEA Maine, go to www.seamaine.org

want—saltbox type or barn-roof type. I wanted a smaller place. Most everyone else wanted a large house. It wasn’t what we talked about tonight that was so far out. It was the quality of discussion. The ‘meeting’ was really lots of fun.”

David’s descriptions of his and the group’s interactions with the locals are especially colorful and sweet. The farmers and their families seem to accept these outsiders and help them. The group runs afoul of the law in “scrounging” for their house what they think are cast-off railroad ties, but matters resolve peacefully.

Dairy farmer Henry Peavey “treated me with kindness and respect and went out of his way to help us out,” David writes. When it came time to build the chimney on the house, which David volunteered to do, he realized he had no idea how to proceed.

“David, I’ll show you how to build a chimney,” Peavey tells him with a big smile, and mixed the mortar and started the work to get David going. Late that fall, Peavey shows up at the commune, hauling a shed on a trailer that was going to be torn down.

“Thought you might be needing this,” he says. And they did. It was impossible to heat the large house they’d built that first winter, and so they spent a lot of time in the shed.

Not surprisingly, the commune didn’t last, and David and the others settled down with spouses in their own places.

About 25 years ago, a different version of “intentional community” was created in Belfast, dubbed a “co-housing ecovillage.”

Imagine living “in a small neighborhood where everyone knows each other—a caring and stimulating environment where you all share some important core values…” was the pitch. The houses sell well-above median prices, and there is a common building for shared dinners. It’s a far cry from David’s experience scrounging lumber and trying to get a house up to livable temperatures in winter.

Can people live together in a group or is the family unit a more natural and fruitful arrangement? I’ll leave it to the sociologists to discuss. But David and his family have contributed to making Belfast a better place, and I’m glad they’re here.

Tom Groening—who lives with his wife in the woods away from other people— is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@ islandinstitute.org.

6 The Working Waterfront may 2024

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

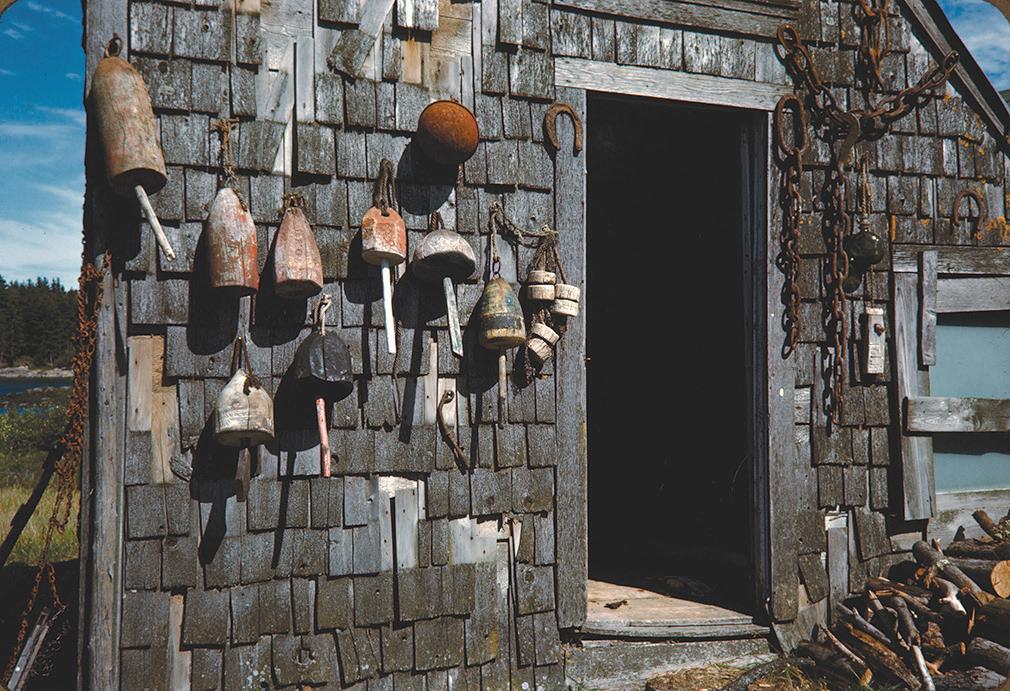

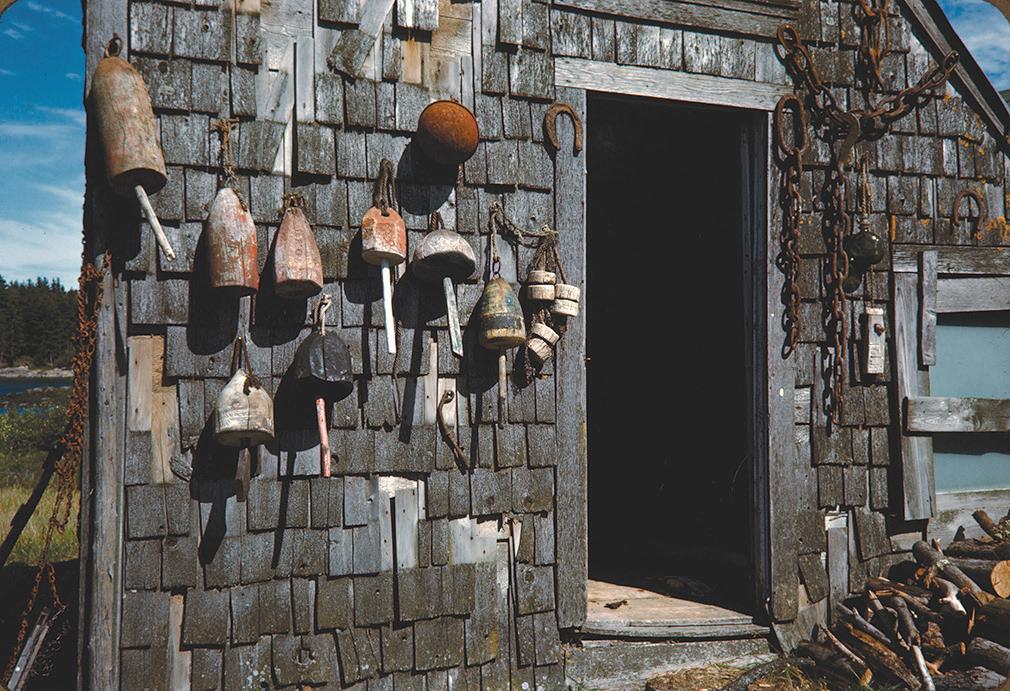

HANGIN’ OUT IN PORT CLYDE—

This image from Port Clyde is dated to the early 1940s. The names written on the back of the print are: Lionel Heal, Alton Chadwick, Allison Wilson, Joan Wilson, Sandra Simmons, Maurice Powell, Ida Wilson, and Douglas Powell.

Listening led to harbor dredging funds

Frenchboro’s connection to mainland was shoaling

BY ALEX ZIPPARO

LAST MONTH, Sen. Susan Collins secured $500,000 in federal funding to dredge Frenchboro’s Lunt Harbor. The small island eight miles off Mount Desert Island relies on marine transportation and fishing for survival, so a safely navigable harbor is critical for the island’s everyday function.

The harbor, the main point for commercial fishing activity, is also the only access point for all mainland needs, including mail, groceries, medical services, and other supplies. The harbor had not been dredged in more than 50 years and because of that gap in maintenance, shoaling has severely limited harbor navigation, with access only possible during certain phases of the tidal cycle.

This new funding provides the financial capability to get the job done, enhancing access to the central hub for Frenchboro’s economic activity and basic community needs.

Serving islands takes a good listening ear and a keen eye for opportunity, and it also helps to be in the right place at the right time. The Frenchboro dredging project is a good example of that.

I took my first work trip out to Frenchboro nearly two years ago to meet with municipal officials and other community leaders about their needs, goals, and vision for the island. After spending the day touring the island with community members, I got back on the boat to return to the mainland, where I met Frenchboro resident Eric Best. As we made our way back to Bass Harbor, Eric asked me about my role at Island Institute. When I told him about how I engage with municipalities, he said “Maybe you’re the exact person I need to talk to! I am a new select board member and I want to get our harbor dredged.” I said I would see what I could do to help. Once I was back in the office, my colleague Nick Battista, Island Institute’s chief policy officer, and I reached out to the Army Corps of Engineers to get the ball rolling. From there, I worked with Best and the Army Corps of Engineers to analyze findings from a previously conducted harbor study for the island to confirm the need for dredging, which started the process to finally dredge Lunt Harbor.

While it was a relief to finally have all the pieces in motion, the timeline for project completion was years away. In my work supporting island needs, I regularly interface with Maine’s congressional delegation staff to help them understand the issues that impact our islands most so they can intervene when appropriate.

The harbor had not been dredged in more than 50 years…

In this case, Sen. Collins was able to help expedite the dredging project timeline though Congressional Directed Spending funds she secured.

The project will be completed by the Army Corps of Engineers in the next couple of years which has brought a sense of relief to the community.

The story of how Frenchboro got to this point illustrates how Island Institute serves communities along Maine’s coast. A lot of what my colleagues and I do is leverage internal and external resources to help islands and coastal communities meet their needs.

In this case, residents of Frenchboro communicated the need for dredging to Island Institute staff and entrusted

us to work with our federal partners to navigate a path to meet their goals. In a letter to Sen. Collins about the funding request, Frenchboro residents and members of the fishing community, Rachel Bishop and David Lunt said: “Island Institute has worked with the Frenchboro community for decades and have added their support for this project and the efforts to help us address the decreasing navigability of our harbor. They recognize the critical role that our harbor plays in the economic and community resilience of our island. The need for safe, reliable access to the inner harbor is critical for all aspects of island life and work.”

We couldn’t be more thrilled about this success story of how a collaboration between a community development organization and dedicated public servants can make a big impact on a small and mighty Maine fishing community.

Alex Zipparo is a community development officer with Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. They may be contacted at azipparo@islandinstitute.org.

7 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2024

column Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers. To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801 www.WorkingWaterfront.com Island Institute Board of Trustees Kristin Howard, Chair Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair Shey Conover, Secretary, Chair of Governance Committee Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee Bryan Lewis, Chair of Philanthropy Committee Megan Dayton, Ad Hoc Marketing & Comms Committee Mike Boyd, Clerk Sebastian Belle David Cousens Mike Felton Nathan Johnson Emily Lane Michael Sant Mike Steinharter Donna Wiegle Tom Glenn (honorary) Joe Higdon (honorary) Bobbie Sweet (honorary) John Bird (honorary) Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio) THE WORKING WATERFRONT Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere. All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org 386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

guest

New life for the last sardine cannery

Former Stinson’s plant gets assist from town

ANALYSIS BY JACQUELINE WEAVER

Editor’s note: Jacqueline Weaver serves on Gouldsboro’s select board.

When the auctioneer announced the new owners of the former Stinson sardine cannery in the Gouldsboro village of Prospect Harbor, the business partners had a deerin-the-headlights look. They had just spent more than $1 million (price, plus outstanding liens) for the 100,000-square-foot complex and more than 90 acres, but were not quite sure what they would do with it.

For 135 years, what is known locally as “Stinson’s,” after the name of the founder, was home to a sardine cannery. The last owner was Bumble Bee Seafood, which abruptly closed its doors in June 2010. It was the last remaining sardine cannery in the country. Two more businesses took over, one after the other. The 40-foot “Big Jim” billboard looming over the property for decades had held a giant can of sardines. It was repainted with Jim hoisting a wooden trap with lobsters—a reflection of those owners’ lobster processing operations.

Maine Fair Trade, the second lobster processor, moved its equipment out several years after purchasing the property in 2012, and focused its attention on a much larger seafood processing operation in New Bedford, Mass. What was looking more and more like a white elephant was purchased in 2022 by American Aquafarms, a company made up largely of Norwegian investors who proposed locating an industrial-scale salmon farm in Frenchman Bay and hatch eggs, process, and transport salmon out of the former Stinson plant site. But the state of Maine had other thoughts. The Department of Marine Resources terminated American Aquafarms’ permit application, citing

issues with the source of the eggs and the eggs’ genetic makeup.

On June 15, the property, consisting of a large office space and multiple, cavernous buildings, was auctioned and purchased by three local business people. Tim Ring had owned a paving company. Kevin Barbee and Josh Trundy are in construction. They had collaborated on projects over the years.

A single tenant was unlikely. No seafood operation had bid on the complex.

The price was $975,000 plus more than $300,000 in liens. They knew going into the auction that the property was zoned Commercial Fisheries/ Maritime Activities, which meant only “functionally water dependent” business could take place within the 11 acres or so on the water. This meant that the new owners could not, for example, store blueberry boxes—which one potential renter had inquired about. But they also knew how important the property was to the town of Gouldsboro. People overall wanted to see ongoing business operations on this centrally located, waterfront property in town. They also wanted commerce that was in keeping with the scale of the town. The partners also hoped the town could help them create a zoning environment that would help pave the way to profitability. A single tenant was unlikely. No seafood operation had bid on the complex. Planning board members scratched their heads about what could be done with what they feared could remain a ghostly, hulking presence in Prospect Harbor, albeit with multi-million-dollar views.

But Bill Zoellick, a resident who is very active on climate resiliency preparations, and Becky O’Keefe, who had opposed the industrial salmon farm and was hoping an array of small, marine related businesses could fill the buildings, hunkered down and did some investigating. Under shoreland zoning, Zoellick said, a town has six options: Resource Protection; Limited Residential; Limited Commercial; General

Island Institute awards storm recovery grants

Over 50 waterfront businesses get funding

ISLAND INSTITUTE, a community development nonprofit serving Maine’s island and coastal communities, has delivered a total of $250,000 in business resilience storm response grants to 52 waterfront businesses in the wake of the back-toback January storms.

The grants were awarded to fishing cooperatives, lobster wharves, and processing centers that are relied upon by the fishermen, distributors, and retailers that are the backbone of Maine’s marine economy. These grants are supporting 540 working waterfront jobs and helping rebuild infrastructure relied on by 1,195 commercial vessels.

“Building back along Maine’s coast will require a sustained programmatic and policy effort,” said Kim Hamilton, Island Institute president. “These grants are just one part of our response and helped jumpstart recovery and ignite a sense of hope. When you’ve just watched an extraordinary storm wash away your business and decades of hard work, it’s good to know that your community has your back.”

Within a week of the first storm, Island Institute had launched its storm response grant program, received applications, and began sending funds to critical working waterfront businesses along Maine’s coast.

On Mount Desert Island, Thurston’s Lobster Pound was particularly hard hit, suffering damage to its wharf.

“Island Institute was the first organization that was right there within days after the storm, offering a grant to help rebuild,” said Derek LaPointe, general manager. “And we immediately put that towards lumber cost because we needed to get stuff built so we can serve the 22 lobstermen we support.”

From bait to plate, the seafood sector contributes more than $3.2 billion in total economic output annually to Maine, supports more than 33,300 jobs statewide, and relies almost entirely on the 20 remaining miles of working waterfront infrastructure in our state. Without safe and reliable wharves, docks, and access ramps, Maine’s fishing communities are at risk of grinding to a halt.

To address the importance of working waterfront infrastructure for our coastal economy, Island Institute aimed these grants along with programmatic and policy efforts toward rebuilding with future resiliency in mind. Each applicant was asked if they had identified ways to rebuild to be more resilient and was offered help from Island Institute staff on how to plan for future storms.

Island Institute targeted these grants toward communities that are major contributors to the marine economy, were highly impacted by the storms, and are at particularly high risk of future damage due to climate change.

The institute also hosted two public webinars, the first—held three days after the second storm—provided

Development I; General Development II, and Commercial Fisheries/Maritime Activities.

After weeks of conversation between Zoellick and the Department of Environmental Protection, the town at a special town meeting in December voted unanimously to change the designated zoning to General Development District I with added restrictions to keep the site as working waterfront. The planning board also included language that prohibits residential use within the designated area and requires that 25 percent of the site be used for marine activities.

General District Development I applies to areas of two or more contiguous acres devoted to commercial, industrial, or intensive recreational activities, or a mix of such activities. Those activities can include, but are not limited to, areas devoted to manufacturing, fabricating or other industrial activities; wholesaling, warehousing, retail trade and service activities, or other commercial activities.

It also includes intensive recreational development and activities, such as, but not limited to, amusement parks, racetracks, and fairgrounds. Areas having patterns of intensive commercial, industrial, or recreational uses are recognized as well. The matter then went to the DEP for approval. If no word was received in 45 days, the town could consider the new zoning in place.

The deadline for comment passed in March. Suddenly, the white elephant had a future. The DEP explains in its Maine Shoreland Zoning document that the development of a waterfront management strategy can be a complex process. “There are many different techniques that can be used to tailor an ordinance to reflect local goals and resources,” it is stated in the shoreland ordinance. “But other zoning variations are also possible which may be much more specific about what types of functionally water-dependent uses should be permitted, make use of more than one type of waterfront district, may include standards for assessing the impact of proposed development on water dependent uses, and may include specific provisions to encourage certain types of public benefits.”

attendees with timely information from leaders of the Maine Department of Marine Resources, Maine Emergency Management Association, and Department of Economic and Community Development about reporting storm damages and applying for assistance. The second focused on storm science, explaining how climate trends are likely to impact our coast in the coming decades.

Island Institute’s storm response efforts are part of its ongoing work in helping Maine’s island and coastal communities navigate changes in our climate and economy, with recent efforts that include:

Supporting LD 2225, legislation proposed by Gov. Mills which, if approved by the legislature, will result in the investment of $50 million to help rebuild storm damaged infrastructure, including working waterfronts.

Supporting Gouldsboro, Swan’s Island, Frenchboro, Matinicus, and Isle au Haut in applying for $50,000 grants through the state’s Community Resilience Partnership for infrastructure resilience projects.

Leading the development of a working waterfront strategy for the Coastal and Marine Working Group of the Maine Climate Council that focused on both the needs of privately owned working waterfronts and the importance of resilience upgrades to both public and private working waterfronts.

For more information, see IslandInstitute.org.

8 The Working Waterfront may 2024

‘Attainable’ housing: lessons learned

Stonington panel discussion offers successful approaches

BY TOM GROENING

Deer Isle and Stonington and Mount Desert Island are separated by a short hop across Blue Hill Bay. But if housing shortages are to be addressed, those two regions should tailor their work differently, and consider solutions within the context of a micro-region.

That was one of the takeaways from a March 20 panel discussion at the Stonington Opera House, part of a community Talk of the Towns series, this one devoted to affordable housing. The series concludes April 24 with a discussion of small-scale aquaculture.

Other recommendations from panelists on housing included the importance of:

• working to educate banks on financing unusual housing projects

• seeking private funding

• paying attention to the “visual cues” of public housing to avoid opposition from neighbors

• focusing on what moderator Linda Nelson called the “missing middle,” those whose incomes were not low enough to qualify for assistance, yet not wealthy enough to purchase in the area

Robert O’Brien of Camoin Associates, an economic development consulting firm, said part of the acute shortage of affordable housing is the result of “a decade of under-production” after the Great Recession that began in late 2008. Along with the steep drop in demand for houses, regulations for lending for housing tightened, further limiting construction.

One of the housing successes in the region is the recently completed tenunit complex on Deer Isle, developed by the nonprofit Island Workforce Housing group.

Founder Linda Campbell said the Oliver’s Ridge project got off to a bumpy launch.

“We started it during COVID,” she said, with construction material costs skyrocketing and contractors busy elsewhere. Still, “We came in relatively close to what our budget was,” in large part because of “thousands of hours of volunteer work.” Remarkably, no public funds were used.

Marla O’Byrne, executive director of Island Housing Trust, described how the effort to preserve Jones Marsh on MDI led to her group working with Maine Coast Heritage Trust to put the land into conservation easement while also building ten housing units. The houses may be purchased, but the land is leased.

“Nobody can afford to build housing now without subsidy,” said Mark Primeau of the Genesis Fund, a Maine nonprofit that loans money for housing, referring to private housing development companies.

Subsidies may be available for projects that serve households with less than 80% of the area median income, or AMI, which in Stonington, is about $68,000 for a family of four. Instead, Primeau said, communities want projects that serve families making 120% of AMI.

“Nobody can afford to build housing now without subsidy.”

—MARK PRIMEAU

“We raised $1.8 million in a year and a half,” Campbell said.

Jim Fisher, Deer Isle’s town manager, credited the “diverse skills on the committee” overseeing the project, which included an architect, someone working in finance, and a builder.

On MDI, an unusual collaboration succeeded in building workforce housing. Noel Musson of The Musson Group, a planning and permitting consulting firm, said the Island Housing Trust volunteer group wisely began by thinking island wide.

“Think about housing as a microregion,” he advised, seeking solutions that may only work in one area.

“We’re pretty dark in the winter now,” Nelson said of Stonington, where she serves as the town’s economic and community development director, meaning that yearround residents are few. Plumbers, electricians, and carpenters must commute to the island, she said, along with many of those working on lobster boats.

Fisher echoed Nelson’s description of Stonington lacking much year-round population.

“This is a very desirable place to be,” he said. “A lot of people want to be here, if only a few weeks a year.” Nelson said that Stonington’s population has declined over the last decade, though the pandemic brought an influx, at least temporarily.

“We really would want them to stay,” she said.

The stigma associated with public housing projects was also discussed.

“One of the things we have to talk about out loud is how a neighborhood looks,” O’Brien said. The recent straw poll in Cumberland in which a 102-unit building project was rejected

was cited as evidence of what is often an uphill climb in establishing subsidized housing.

Musson, who grew up on MDI, said people don’t like change, and so developers should carefully consider the “visual cues” so the buildings fit into the community.

“Litigation as planning is a terrible approach,” said Jim Fisher, town manager for Deer Isle. “It’s expensive.”

“You have to be above the fray,” Musson said of the offensive comments

that often follow a proposal to build housing for people with lower incomes.

Even the jargon on the issue is charged. Panelists, responding to a question from the audience, said “affordable housing” is defined by federal income standards.

O’Byrne defined it as “housing for people who are under the median income.”

O’Brien’s definition was more concise and perhaps more clarifying: “attainable housing.”

9 www.workingwaterfront.com may 2024

Independent. Local. Focused on you. Boothbay New Harbor Vinalhaven Rockland Bath Wiscasset Auto Home Business Marine (800) 898-4423 jedwardknight.com

The Oliver’s Ridge workforce housing project on Deer Isle, shortly after construction concluded.

Despite regeneration ability, sea stars are dying

Sea stars—and their five heads—face climate threat

BY LYNDA DEWITT/THE MAINE MONITOR

Turns out we’ve been looking at starfish all wrong.

First, they’re not fish. They belong to a group of marine invertebrates called echinoderms, which also includes sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers. Starfish now go by the classy common name of sea stars.

Then there’s the matter of those arms. It’s true, sea stars can regrow, or regenerate, if an arm should be torn off by, say, the sharp bill of a hungry sea gull. But recent studies show those arms are actually heads. So instead of a body with five arms, sea stars have only heads.

Something else about sea stars has confounded scientists: What is killing them?

“All marine life is struggling to adapt at the speed of climate change,” said Andrew McCracken, a Topsham native and Ph.D. student at the University of Vermont. “The Gulf of Maine, which is warming faster than other ocean waters, is an area of particular risk.”

Besides waters that are warming and becoming more acidic, possible stressors include low oxygen levels (due to increases in bacteria in the water using up the oxygen), and perhaps a virus.

Whatever the cause, what happens to sick sea stars is fodder for a horror flick. A white, gooey lesion on its spiny skin soon spreads, causing the tissue to soften and twist. Within days the sea star can completely disintegrate—a sickness called sea star wasting disease.

The disease traces back to at least the 1970s, when similar symptoms were first observed and documented in Maine and elsewhere on the East Coast,

said McCracken, who is studying how marine animals adapt to stress.

Then in 2013, large-scale die-offs began on the Pacific Coast from Mexico to Alaska. On the East Coast, with fewer sea star species and smaller populations, the die-offs haven’t been as dramatic.

But it’s happening regularly, from Acadia National Park to at least Massachusetts, said Dr. Melina Giakoumis, the associate director of the Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History. And, she adds, it seems to be happening more frequently and more severely.

Maine’s two common sea star species, the Forbes sea star (Asterias forbesi) and the northern sea star (Asterias rubens), have both been listed as “species of greatest conservation need” by the state. The 2016 listing claims sea stars are “undergoing steep population declines,” which, if unchecked, likely will lead to “local extinction and/or range contraction.”

Since sea stars aren’t a commercial species, the Department of Marine Resources is monitoring the population rather than working on mitigation.

Yet Maine’s sea stars are considered keystone species, meaning “they have a disproportionately large effect on their community,” said Giakoumis. “It’s important to protect them because they help keep other species in check, which increases stability and resilience in the entire ecosystem.”

The sea stars may already be helping themselves survive the wasting disease. Giakoumis has documented that the hybridization of Maine’s two

Feds provide funds for Lincolnville terminal

SEN. SUSAN COLLINS announced that the Maine Department of Transportation will receive a grant award of $7.1 million through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Ferry Service for Rural Communities Grant Program.

The funding will go toward upgrading and modernizing the ferry terminal in Lincolnville to better meet current and anticipated future demand. Earlier this year, Collins wrote DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg in support of the funding request, which originated with the Maine DOT.

“The Lincolnville ferry terminal plays a crucial role in the daily lives of local residents and businesses alike, providing freight and postal services while transporting students to school and people to their jobs,” Collins noted. “This investment will help to ensure safe and reliable transportation service for the estimated 180,000 passengers that travel to and from Islesboro every year.”

Earlier this year, Collins and Rep. Chellie Pingree announced $33

major sea star species is occurring from the southern Canadian Maritimes to New England.

“This adaptation perhaps provides genetic variation the species need to survive,” she said.

McCracken also wants to know if and how sea stars might adapt and survive. Last spring he was awarded a three-year National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to study how thermal extremes impact physiological changes in echinoderms, work that has specific relevance for the Gulf of Maine.

“By the time it takes to unravel the possible multiple causes of the disease, it may be too late,” said McCracken. “Working to protect the surviving populations is something I’m excited about. Are there actual traits that make them immune? Do they have the genetic capacity to adapt? These are the questions I hope to help answer.”

Getting the answers will take help from the community. Giakoumis is

working on an app that will allow citizen scientists and trained scientists to plug in data on when and where they see sea stars, and if they observe evidence of the disease.

“Sea stars tend to be more visible in the summer when they come into shallower waters,” said Giakoumis. “In winter months they tend to stay in deeper water.”

We can help sea stars and all marine life now by “protecting what we can control,” said McCracken. “By not overfishing and not raking the sea floor, we will protect marine habitat, and give sea stars and other marine life the best chance of survival.”

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from the Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter at TheMaineMonitor.org.

million in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to support, improve, and modernize passenger ferry service in Maine. The funding was awarded to Maine’s DOT through new ferry grant programs to support passenger ferry systems as they transition to climatefriendly technologies.

The current ferry terminal, constructed in 1959, is reaching the end of its service life. In addition to necessary modernization, improvements are also needed to accommodate a new plug-in hybrid ferry, which is expected to be delivered in 2027. This vessel will primarily operate on battery power, supported by a diesel backup system, and will have the capacity to transport ten additional vehicles.

As one of the six island communities that the Maine State Ferry Service serves, the Islesboro route is the most traveled, serving roughly 600 year-round residents. The route carries roughly 180,000 walk-on passengers and more than 80,000 vehicles every year.

Michaud wins ‘officer of the year’

Maine Marine Patrol Officer Alex Michaud received the 2024 Maine Lobstermen’s Association Officer of the Year Award during the Maine Fishermen’s Forum in Rockport in early March.

The award is presented to a Marine Patrol Officer who has demonstrated outstanding service in support of the lobster industry. Michaud, who joined the service in 2017, serves in the St. George-Warren area.

In addition to strong patrol work, search and rescue support, and community relations, Michaud was recognized for investigating many lobster fishery violations including cases related to V-notching, untagged traps, fishing under suspension, and trap limits. A bureau of the Maine Department of Marine Resources, the Maine Marine Patrol provides law enforcement, search and rescue, maritime security, public safety services on Maine’s coastal tidal waters.

10 The Working Waterfront may 2024

Young, healthy sea stars were found in Acadia National Park.

Maine Marine Patrol Officer Alex Michaud, center, receives the 2024 Maine Lobstermen’s Association Officer of the Year Award during the Fishermen’s Forum. From left are and MLA board president Kristan Porter Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher, Sgt. Matthew Wyman, and Major Rob Beal.

James Croll and sea level rise

A genius janitor was a real-life ‘Good Will Hunting’

BY STEVE ZOLOTH

“THAT’S THE WAY it looks from here” was the jaunty sign-off of Lou McNally, Maine Public Radio’s longtime weather forecaster, and we knew a storm was coming. But king tides and climate change played another game.

On Jan. 13 the Maine coast was inundated. Water flowed into hundreds of towns, along the working waterfront. Businesses and roads were awash with water.

On Vinalhaven, the town’s parking lot had whitecaps as the storm moved through and the main street was impassible. On North Haven, Brown’s Boatyard, a century-old business, saw its pier and workshop damaged. Portland’s tide gauge read 14.57 feet, a new record.

There is no question that the sea level is rising. From Miami to Maine, stories of flooded streets, homes, and businesses come with each new tide. On the West Coast, multimillion-dollar houses teeter on cliff edge as storms erode the land beneath them.

Yet we look at these events in isolation. A flooded home, a shopkeeper throwing away damaged goods, and police directing traffic away from a flooded street. But seeing these events across the breadth of the East Coast suggests more—sinking coastlines, disrupted habitats, and rising seas.

Who first called attention to this problem? When did science begin to understand the concept that land could sink, glaciers melt, warming seas could rise, and contemplate the flooding that could occur?

Surprisingly, there is no single person who could be seen as the originator of the modern idea of sea level rise. It goes as far back as Archimedes who demonstrated water displacement, but it was in the 1800s that climate became part of the scientific discussion. And it was in the 1880s that the self-taught son of a Scottish farmer sat down and wrote his text on geography. While he did not specifically discuss rising sea levels he was an early contributor to the possibility of changing coastlines.

He was James Croll, whose amazing history produced an amazing man. He was born in poverty on a croft, a Scottish term for a small parcel of land on a large estate. When he was three, the lord told his family to leave, and they relocated to poor bottomland. Croll left school to work on the farm at 13.

At 16 he became a carpenter, a trade he pursued until an injury made it too painful to continue. He then held an astonishing number of jobs from insurance salesman to newspaper clerk, from temperance hotelier to tea salesman and tea merchant.

Through it all, as he wrote in his memoir, was “a strong and almost irresistible urge to study.” Without much formal schooling, he taught himself by reading Penny Magazines, founded by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge to provide education to the working poor.

Eventually, Croll found work as a janitor at a Glasgow museum. The museum was open a few hours each day so he had ample time to study, mastering physics, astronomy, and

geology. He later recalled, “I have never been in any place so congenial to me as that institution.”

In 1864, this self-taught scientist began to publish in the most respected scientific journals of the times, contributing his thoughts on geology, tides, and the earth’s rotation. His notable paper: “On the physical cause of the change of climate during geological epochs” brought scientific recognition.

By 1875, his reputation had grown, and this son of a poor Scottish farmer without much formal schooling was inducted into the Royal Society of London and granted an honorary doctorate from St. Andrews. James Croll, a janitor, a genius, was very much like the Matt Damon character in Good Will Hunting.

But the story doesn’t end there. Sir Charles Lyell, head of the Geological Survey of Scotland, read his works and offered him a position as office secretary, since Croll couldn’t be given the appropriate title of geologist without formal education.