Tarini Tipnis B’26.5

Selim

Angela Lian

Lila Rosen & Jeffrey Pogue TINNITUS

Tarini Tipnis B’26.5

Selim

Angela Lian

Lila Rosen & Jeffrey Pogue TINNITUS

MANAGING

Sabine

Nadia

WEEK IN

Maria Gomberg

Luca Suarez

ARTS

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Martina Herman

EPHEMERA

Mekala Kumar

Elliot Stravato

FEATURES

Nahye Lee

Ayla Tosun

Isabel Tribe

LITERARY

Elaina Bayard

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Gabriella Miranda

METRO

Layla Ahmed

Mikayla Kennedy

METABOLICS

Evan Li

Kendall Ricks

Peter Zettl

SCIENCE + TECH

Nan Dickerson

Alex Sayette

Tarini Tipnis

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Selim Kutlu

Sara Parulekar

WORLD

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Emilie Guan

Coby Mulliken

DEAR INDY

Angela Lian

BULLETIN BOARD

Jeffrey Pogue

Lila Rosen

MVP

Mamdani's wife, G-d, Mikayla Kennedy

DESIGN EDITORS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Kay Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

DESIGNERS

Millie Cheng

Soohyun Iris Lee

Rose Holdbrook

Esoo Kim

Jennifer Kim

Selim Kutlu

Jennie Kwon

Hyunjo Lee

Chelsea Liu

Kayla Randolph

Anaïs Reiss

Caleb Wu

Anna Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Hisham Awartani

Sarya Baran Kılıç

Sebastian Botero

Jackie Dean

Cameron Calonzo

Emma Condon

Lily Ellman

Ben Flaumenhaft

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Maxwell Hawkins

Mohamed Jaouadi

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nora Rowe

Andrea Li

Cindy Li

Maira Magwene Muñiz

Kalie Minor

Naomi Nesmith

Alya Nimis-Ibrahim

Emerson Rhodes

Georgia Turman

Ishya Washington

Jodie Yan

Ange Yeung

ALUMNI COORDINATOR

Peter Zettl

SOCIAL CHAIR

Ben Flaumenhaft

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Tarini Tipnis

FINANCIAL

COORDINATORS

Constance Wang

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Lily Yanagimoto

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Mia Cheng

Natalia Engdahl

Avari Escobar

Koji Hellman

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Jiwon Lim

Yuna Ogiwara

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Angelina So

Luna Tobar

Ella Xu

Sapientia Yoonseo Lee

Serena Yu

Yiming Zhang

Faith Zhao

COPY CHIEF

Avery Liu

Eric Ma

COPY EDITORS

Tatiana von Bothmer

Milan Capoor

Jordan Coutts

Raamina Chowdhury

Caiden Demundo

Kendra Eastep

Iza Piatkowski

Ella Vermut

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Sofia Guarisma

Erin Min

Dominic Park

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Ivy Montoya

Eurie Seo

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Avery Reinhold

Angela Lian

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Lian

Jolie Barnard

Luca Suarez

Nan Dickerson

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

( TEXT MARIA GOMBERG DESIGN CHELSEA LIU ILLUSTRATION SUZIE ZHANG )

our friends suggests that we should buy a Guinness and split it seven ways using straws, milkshake style. I conjecture that you can’t do that with a dark beer, and that it’s not classy what we are doing and that everyone should behave. Nick tells me to look at my bloody face in his phone camera, and to “shut the fuck up.” There is that joking of his.

Instead of buying anything we kind of awkwardly mill around at the bar until the bartender kindly asks us to show ID. I do so happily sometimes unprompted. Everyone else is a wuss and takes it as a sign to leave.

c It’s Wednesday. We are on the town. I am twentyone-and-a-half years old and I have a Montgomery County Library card to prove it. Just kidding, it’s my real ID, and you should get one too. I went to the DMV last week, so I can tell you how to make an appointment. I’ve had vodka soda before. I also went to Paris on family vacation once—they drink absinthe over there. It tastes like licking a bulb of fennel and makes you high. You should try it. I love books, and movies. I am tall, and I am ready to fucking party. Let’s. Get. Lit.

We are on the town. We haven’t even pregamed, because that is for babies! We had drinks with dinner that our friend made using a mortar and pestle. He crushed that ice so thin it was basically water. There was also wine in the chicken dish and in the rice. Purple rice we called it. We ate it, and now we are tipsy. Tastefully tipsy. And we have all talked about our former friend’s new friends.

I am wearing Blundstones and a cardigan. Nothing special, but I look hot.

It’s Nick’s 21st—mine was six months ago—so we are going to the bars. I’ve been to many bars. I like a Dive. I’ve been to Glou, Seaweeds, Wickpub Nick-a–Nees—you name it, I drink there. Nick has never been to Nick-a-Nees which is funny because his name is Nick. You can’t blame him because he isn’t 21 yet, and he didn’t have a fake because he didn’t go in on the order freshman year because we weren’t good enough friends yet. Now, I want him.

There are seven of us going out tonight, and we are doing this thing where we go to seven bars and each one of us buys a round at one bar. By the end of the night, each one of us will have had seven drinks. One per bar. But each of us would have only had to pay for one drink. No. That’s not right. For one check. Is the term tab appropriate to use? Bill. That way we can all try all of the bars and decide once and for all which is the best bar.

We are going to go east to west, and north to south. We hit the ‘Weeds first. That’s what we call it. We would have started at the GCB if it weren’t full of ops. Man, everybody I’ve ever kissed is down there throwing darts and getting hammered. What a freakshow! At weedies we get a pitcher for like seven dollars. That’s a dollar per person. That’s pretty good. We have this thing that we do where we heckle the bartender—we call him by a different name every time. Once we also took nautical decor from the bathroom, and now we have an oar in our living room. Today we each drank half a plastic cup of watereddown pale ale. Beer is an acquired taste that I have acquired and that I am sure that one day you will too. Fuuuuuck I’m sooooooo faded…

We are back on the town. Mac forgot his wallet, so we all had to wait for him on the curb. It’s fucking cold on the street, all these bitches are wearing tank tops? I have this cardigan. I am smart. I dress

smartly. It makes me look like I have places to teach. Like Cornell. Mac is back. I guess we are going into GLU. Glu is French French for drinking? Or maybe fish? We order a round of drinks for the table but also a chocolate chip cookie. Some bars have things you can snack on, even Dives. I am disturbed to find out that the chairs were plastic. They look so inviting from the window. I mean I’ve been here before and everything! I just thought—I mean remembered–this place as classy? I ordered an old fashioned, stirred please. It tastes like shit! I take big sips of it but it doesn’t make me feel too hot. The people at the next table are on a date. They are talking about moving together after only six months of dating. We scoff into our cookie. Who does this shit. Pffft. Milenials. We walk back into the street. I think we might have forgotten to tip. But it was hard to tell under that dim lighting. As we wait for our friends to come out of the bathroom, the sweet smell of CHOMP comes wafting in our direction. I love CHOMP because they have elevated American fare, which is actually my favorite global cuisine. One time I went to CHOMP on the first date with a guy from my sustainability course. He ordered a CHOMP Mac and Cheese burger, which is maybe a little bit of a red flag but otherwise he was very nice it just didn’t really work out. That is kind of why I like Nick. He isn’t so nice but we are very compatible. He can be very deprecating of himself and others which is very funny.

Once everyone pees at Glu, and all of us are finally ready to go, we keep on walking down Ives. The next stop is a new spot. We love checking out new spots near us. There aren’t a lot of people we know there yet. No ops or anything. No ops, just vibes. Club Frills is fun! It’s like…elevated. We ordered a bunch of cocktails and a jello shot that came shaped like a deviled egg. We couldn’t tell if it was vegan or not, so Meg couldn’t try it. She was very disappointed and wept bitterly into Nick’s sleeve. I wanted to throw my “teeny-weeny-martini” in her unkempt, fucked-up, snarky, shit-eating face. Martinis are super classy, but I can’t lie, some tastes are not as easy to acquire as others. I guess the same thing could be said about stupid idiot Meg…Anyway…Things got a little tense for a second there, but they have a claw machine and really small tacos, so how mad can you be?

By the time we leave the bar, people are visibly wasted. I am really drunk too, but I think you can’t tell. I drank in high school so I am really good at performing sobriety. Ask me to walk a line right now and I’ll do it. See? I am touching my nose. I can do it with my eyes closed, and also while jumping up and down, on one foot. Watch me? Is everyone watching? Wait guys… Fuck.

Well, that was a flop! Onto the bars for GenXers! The Point and The East End wouldn’t let us in, because apparently my “face is bleeding a concerning amount” and because “we have a hard time believing any of you will buy anything here and also we are a little concerned that you might be trafficking that girl in the cardigan,” respectively. Nick’s RISD friend, who’s name is Nick, had a tomato on him (he is quirked up like that) so we threw it at the store front of the East End. We are so impromptu.

A couple people wanted to go home after that, including Nick, but I begged him to keep going. We only had two bars left on our list, and the skyline looks romanti I mean! Beautiful! Classy! Hot—no not Hot! It looks good from the not-pedestrian bridge. The car bridge. Ghaaaaaaaaa!!!!

Everyone capitulates to me. They usually do. My great grandmother’s late fourth husband was a hunchback who achieved both love and greatness due to his resilience and zeal—it runs in the extended family. So after some coaxing we went on to a tiny bar. Now this is what I call class. It’s like having drinks in a country club, or a backyard. It’s also closed now, so you can’t have any. We remember when Providence was different and better and had better bars. You remember, the new gentrified Providence of the 2020s. Now it’s all Starbucks on Thayer and Dunkin on Gano. If they build another Antonios or Bajas I’ll lose it.

I fall flat on my face outside the Pizza Marvin. I think that’s my professor. I’m pretty sure her butch wife, and their many butch children watched me eat shit. I hope I didn’t ruin their marinara pies. I crawl to WickPub on all fours.

By the time we get there, nobody really wants to buy drinks. But Nick wants a shirt, which apparently they give you on your twenty-first birthday. When we ask for a shirt they look at us like we are crazy. One of

1. This is a real menu item at the (relatively) new bar on Ives. It’s made with something called Weenie distillate, and is priced at $12.50, which is on the lower end of all their cocktails. If, like me, you are disturbed by diminutives, I recommend getting the JAUNE JAWN aka the JOHN JOHN (Again, this is a real menu item). It is a chartreuse-based cocktail that somehow manages to be made both with plum vinegar and yellow bell pepper.

Tiny Bar is just a few houses away from Nick-ANees. You can actually hear the live music coming from over there. Nick-A-Nees is my favorite bar if you can’t tell. It’s a real Dive, as in they sell little neck clams and people bring their dogs to fight for a turn at the billiard table. My cool friend, whose dad is a medium-famous North-East based folk-country star, took me there when I was having a hard day. I had a cider and cried to the cover of Rivers and Roads. There is a jukebox, shit strapped to the ceiling, and cake-mix cake on the food menu—grunge aesthetic. I insist we start going there immediately, as in right now, our drinks can’t wait.

By the time we arrive my face is really swollen. People look at me kind of funny, but I don’t care about what others think, I am just me. It’s still kind of summer so there is a band of seven 40-75 year old men and a nine year old girl playing string instruments outside. It’s very beautiful. It is like the great American West. I take a little bathroom break to tend to my wounds before my night really starts. There is a Miller High Life Mirror—in my reflection I see that I’ve lost a sleeve and my chin is crooked. I smile a toothless grin, and go back out. As I walk past the bar, Dwayne, the bartender, gives me a knowing nod. I’m a regular here. This is my spot and nobody can take it away from me.

Most of our friends seem to have left while I was gone. It’s just Nick and Meg left, swaying to a mandolin solo. I decided to take charge of my life. I kiss him, with all four of my remaining teeth right in the middle of Nick-A-Nees. It was fuckin’ perfect, and I hate her.

MARIA GOMBERG B’26 imagines a crazy night out.

*For the sake of legal and professional protection, some of the interviewees in this article have been anonymized.*

c On November 6, 2024, the day after Trump’s election as the 47th president of the United States, undocumented Brown student M felt “melancholic” and “shocked.”

“When Trump was elected, nothing was safe,” M remarked. M is a member of the Brown Dream Team, a student group dedicated to supporting and advocating for the undocu+ community on campus and in Providence. “I just knew it was going to be an extremely difficult four years, since he kept saying he was going to come after immigrants harder than ever.”

M was not alone in this concern. For V, another undocumented Brown student, finding out Trump won the election was crushing, but not surprising. “I had already accepted the fact that he would be elected and become the president before the results were even out,” V said. “Once my fears were confirmed, I had to pull myself together.”

On January 20, 2025, the night of Trump’s inauguration, the president signed off on a slew of executive orders that instituted sweeping attacks on asylum laws, refugee admissions, and birthright citizenship. The administration also regulated cartel activity across the southern border, labeling cartels and international gangs as foreign terrorist organizations, and declared a state of emergency to allow military control of the border. These orders, paired with the Laken Riley Act, signed on January 29, 2025, which mandated Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to detain immigrants charged with criminal offenses prior to conviction, laid the foundation for an extensive and violent attack on immigrants in the United States.

In Rhode Island, Trump’s campaign has spurred increased organizing around immigration. “People understood when [Trump] was elected that protest and community building was necessary,” Aidan Choi B’26, a community organizer, said. “There was an energy present.” This energy manifested in an outpour of mobilization efforts in defense of immigrant communities—one which has since reconfigured collaboration between Providence organizing groups. Outreach branches such as the College Hill Deportation Defense Network (CHDDN), otherwise known as the College Hill Outreach Group, emerged, creating a basis for additional community organizing.

“Attacks against all of us.”

The group that would become the Deportation Defense Coalition of Rhode Island (DDC)—composed of the Olneyville Neighborhood Association (ONA), Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL), and Alliance to Mobilize our Resistance (AMOR)—was first brought together as an early coalition dedicated to planning the “We Fight Back” national protest on the day of Trump’s inaguration, which sought to address the “long-term struggle” against “the many attacks we knew Trump would launch,” according to Choi. However, as the need for a coalition dedicated to unified deportation defense became apparent, weekly planning meetings for the protests soon became meetings for the DDC.

The coalition is made up of six outreach groups based primarily in Providence: Southside, West End, Central Falls/Pawtucket, Greater Olneyville (including Silverlake), North Providence, and College Hill.

In addition to educating the public on their rights and providing support to Rhode Island communities affected by ICE, the DDC runs a phone hotline: a safe, verifiable place to report ICE sightings across Rhode Island. Deportation defense hotlines run by organizations such as AMOR and ONA have existed in Providence before, which, according to Choi, laid the groundwork for a network “as widely developed as [the] one that has been done by the DDC.”

DDC and its ICE alert hotline were released at the February “Chinga Tu Maga” protest and rally, organized by AMOR and PSL, as a means of consolidating a network to address ICE activity occurring in the Southside, West End, and the Greater Olneyville neighborhoods. But, as time progressed, the number of reports in different regions skyrocketed.

After a high schooler’s encounter with ICE at Kennedy Plaza, in which, according to Choi, the student was “profiled and shaken down,” volunteers from Brown’s campus and the College Hill community mobilized, taking to buses around Kennedy Plaza to inform students and the public on their rights. As abductions at the Garrahy Judicial Complex and Providence County Superior Court increased over the summer, the need for a College Hill network, which was officially started this September, became obvious.

“it’s like living in a jail cell”

For undocumented students, receiving support from their peers is a contentious issue. “People don’t understand [undocumented] status and the limitations,” V said. “They know it’s ‘a bad thing,’ but

people don’t understand the specific limitations […] People should know what it entails to have [an undocumented] identity.”

Those limits are both mundane and all-encompassing: ineligibility for certain jobs, research funding, internships, or study abroad; fear of flying; worry that any interaction with police could spiral. Some undocumented and DACA-mented students structure their whole academic paths around buying time in the US. “Students with this background pursue research so that they can stay in the country longer and do something about their status later,” V said.

At the same time, V emphasized that most undocumented people’s aspirations are painfully ordinary: “We all just want to live a normal life. Many undocumented people’s biggest dream is to work. I just want to have a job and be employed,” V paused. “That’s dehumanizing at times. It should be a given—and we should be allowed to dream bigger.”

Etta Robb B’26 described the current moment bluntly. “Working people and immigrant people are under such heavy attack right now,” she said, pointing to the sheer scale of ICE activity in the state. “It’s not being talked about enough. There’s a lack of awareness because ICE hasn’t made it onto campus, but

there have been over 300 people detained in Rhode Island by ICE so far, some being as young as 3 years old […] There’s so much fear for people that they’re not leaving their homes or going to the store or the doctors. Fear is the new pandemic for so many people because of ICE.”

Robb emphasized that for her, protection from this fear is best found in community. “A lot of what’s happening with ICE is showing us that the best way to protect each other is with each other. Not an institution looking to comply with federal mandates.”

Choi described the logic of ICE raids in succinct terms. “The whole purpose of ICE is terror, right? The whole purpose of one kidnapping is to make sure that the entire community cannot function. No one’s picking their kids up from school. No one’s going to the grocery store. A community is literally paralyzed.”

By engaging community members and bringing them into the network through training, this paralysis was reframed as something that could be challenged. “We’re literally saying: We need to take back the agency of our community,” Choi said.

For Josué Morales B’26, that meant starting something very concrete: a running and walking campaign to raise money for ONA, a local immigrant-justice organization, through the community initiative Miles for Migrants. “The hope is that we have dialogue with people—like, ‘Hey, I’m running because of immigrants.’ ‘Why immigrants?’ ‘Oh, let me tell you about ONA.’ Get conversations going with people and spreading awareness,” said Morales.

It’s not just symbolic. The campaign has pulled in friends, teammates, and strangers who stop Morales and friends on the street. “Sometimes I’m walking and they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re going to do that run, right?’ And I’m like, yeah. They’re like, ‘How do I get involved?’”

“Where really is safe?”

Students are not the only people on campus fearing immigration attacks. When Felix, a Brown Dining Services employee, was abruptly fired last spring due to an expired green card, the news spread quickly. “It was very hard not just for him but for all of us who are immigrants,” P, a coworker, recalled. “Everyone was on edge and worried.”

Felix applied for an extension for his green card before its expiration on March 3, but the card expired before he received a response. According to P, due to a University policy stipulating that every worker must have either citizenship, a green card, or a valid work visa for the duration of their employment, Felix was told he had to be fired, but would be rehired upon providing proper paperwork. However, on Thursday, March 13, 2025, the morning that his paperwork came through, a campus-wide hiring freeze was enacted and Felix was told his Brown termination would stand.

To many workers, this decision represented the shift in climate under Trump. “We felt like it was a slap in the face,” said P.

Felix would eventually get his job back, but only after months of financial precarity and community action. “He didn’t have family here—no pay, nothing,” P said. “It was very hard. He lived off student donations for a bit. The union helped him with gifts too.”

“It could happen to any of us.”

For many in Brown Dining, fear is not abstract— it’s bureaucratic. Workers spoke of green cards, citizenship exams, and costly work visa renewals that determine their livelihoods. “[Naturalization] costs close to $800, and it’s supposed to go up again,” P explained. “[This administration] is making it harder and harder.” In reference to the citizenship exam, P added, “Before, you needed to know 100 questions and be asked 10. But now [you need to know] 130 questions, and it’s more expensive.”

When Felix was fired, workers’ fears of instability crystallized into something communal. “Everyone felt it wasn’t right the way things happened to him, and if it happened to him, it could happen to any of us,” P said. Dining staff became hyperaware of their vulnerability—even those with permanent status. “Brown staff, especially dining services, is filled with immigrants,” P noted. “All came from other countries, all have friends and family in risky situations.”

The firing mobilized both the dining workers’ union, The United Service and Allied Workers of Rhode Island, and student networks such as the Student Labor Alliance. “Students heard the story, but the way they heard it, ICE had come and got Felix— which wasn’t true,” P said. “So they fact-checked, started the petition, and sent it to all the [union] members and the student body. [Together with the union], they got about 700 signatures and brought it to the president.”

President Christina Paxson met with the workers and acknowledged the injustice. “She was really nice about it,” P said. “Made the meeting easy to talk to her.” Student and union efforts ultimately helped Felix return to work, but not before he endured three months without pay and two rejected unemployment claims. “We had to fight even after he was brought back,” she said. “We had to fight to make sure he received backpay.”

If fear defined one half of the story, solidarity defined the other. Workers spoke with gratitude about student support. “It feels great. Students always ask how workers are,” P said. “The way students treat us is awesome.”

The organizing also led to institutional change. Union leaders collaborated with immigration lawyers and the University to provide workers with translators and other resources to help prevent future cases.“Sometimes it has to happen to one person in order to prevent it from happening again,” P reflected.

“We all just want to live a normal life.”

Since its formal establishment this fall, the CHDDN “very quickly saw a lot of participation. First 70 people [joined], then from there it has continued to grow,” Robb said. To date, the CHDDN currently has upwards of 150 members, and there are over 1,800 members in the DDC’s WhatsApp alert channel. “Right now the College Hill Deportation Network has all types of people—students, grad students, faculty, staff, outside community members, folks who are just in the neighborhood,” Matisse Doucet B’27 said.

The network’s efforts are an extension of Providence’s rich history of deportation defense work. Even prior to Trump’s first term, community efforts in Rhode Island have historically blocked ICE and provided resources for undocumented people. “The people joining [the CHDDN] so heavily is new, but it is built off the labor of the other groups that came before,” said Maya Lehrer, a member of PSL.

Support from the community has shaped the network’s current model. Upon noticing an ICE vehicle or presence anywhere in Rhode Island, community members can call or message the hotline. In turn, a defense network volunteer is sent out to the reported location to investigate. If they confirm that ICE is present, an official notification goes out to the appropriate region’s WhatsApp group chat so undocumented members can avoid ICE and others can mobilize to prevent a deportation. CHDDN volunteers also take shifts at Providence courthouses to inform passers-by about the hotline, identify ICE presence, and report to the network when abductions are underway. Regular courthouse shifts are a feature unique to the CHDDN, whereas other regional networks do more “door-to-door knocking,” Doucet said.

CHDDN has also been applying pressure on the Rhode Island Judiciary to allow virtual hearings as an option for the courthouses they patrol. “City hall has already offered virtual hearings within the municipal courts as a result of community members and coalitions organizing,” Robb explained. “It is obvious why this is necessary in this time so people can do their legal proceedings.” She expanded on this: “There was a woman who was a victim of domestic violence who came [into court] to testify, and right after her testimony she was kidnapped.”

Speaking to the success of the broader DDC, Doucet said that “we’ve been able to push ICE out of our community over 20 times since July.” He added, “It’s easy to postulate and to talk about supporting our immigrant communities in different ways, but I think it’s an entirely different thing when you’re actually willing to put your material support behind it and actually do courthouse shifts and talk to community members about their experiences and try to kick out ICE when they’re nearby.”

The CHDDN is not the only organization that has noticed increased community engagement. Along

with an influx of community members looking to take action within local organizations, collaboration among community organizations and campus groups such as PSL and Dream Team has increased, creating an intercommunity discourse on rapid response and immigration rights.

“The best way to protect each other is with each other.”

After the targeting of international students and professors in the spring of 2024, including the detainment and deportation of Transplant Nephrologist and Brown Assistant Professor of Medicine Rasha Alawieh, whose legal challenge of the deportation was dismissed on October 31, the “focus became supporting international students as well as organizers being threatened for their politics,” Choi said. M noted that for members of the Brown Dream Team, “there used to be a clear divide between visa students and undocumented students, and this moment has caused the line to blur. Before we didn’t really have a reason to get involved with them [in a way that attracts more attention to us], but now we’re collaborating.”

Dream Team has also continued fundraising and fulfilling mutual aid requests. M referenced another Dream Team member’s GoFundMe, which amassed $3,000-4,000 to help pay legal and living fees after most of the student’s family was deported. They’ve also fundraised in collaboration with different organizations such as Sunrise, raising about $2,000 for African immigrants and for undocumented students in Rhode Island.

While this tangible financial support has proven necessary for students facing legal battles and crisis amidst deportation threats, M emphasized the importance of participating in other in-person action-oriented efforts, such as the one offered by the CHDDN. “Get informed. Understand [community organization] missions even if you can’t accommodate things in your schedule. If you can, join CHDDN and the broader deportation network. A lot of Brown students are American citizens and getting in between undocumented people and ICE is important.”

In their appraisal of community-building for students like them on campus, V and M both voiced gratitude. M listed Dream Team as a safe haven, describing it as a place “where you didn’t have to explain yourself, where you can be understood.” V listed several professors and the help of workers within Brown’s UFLI center as a “big help.”

Still, the tremendous pause on life that Trump and his administration has caused for undocumented students like M and V cannot be understated. “If you go and protest, or make an op-ed or social media post with your face in it [as an undocumented person], you can get doxxed,” M said. V echoed this tension: “I never really feared going outside as much as I do now. [I] used to travel by airplane, through states, walk by the river. Now it’s [questions like] should I take the RIPTA? Is that something safe for me to do right now?”

M re-emphasized that many Brown students remain disconnected from the challenges their peers face: “The distance allows them to turn a blind eye to the issue. [But students] have a lot more in common with undocumented people than they realize.”

Robb echoed this, linking the cause to a broader struggle for liberation of all people. “This is a larger fight for working class people that immigrants are on the front lines of,” she said. “This is for all of us.”

NAOMI NESMITH B’26 wants you to join the ICE alert WhatsApp and fill out the CHDDN interest form!

CHDDN interest form:

WhatsApp group link:

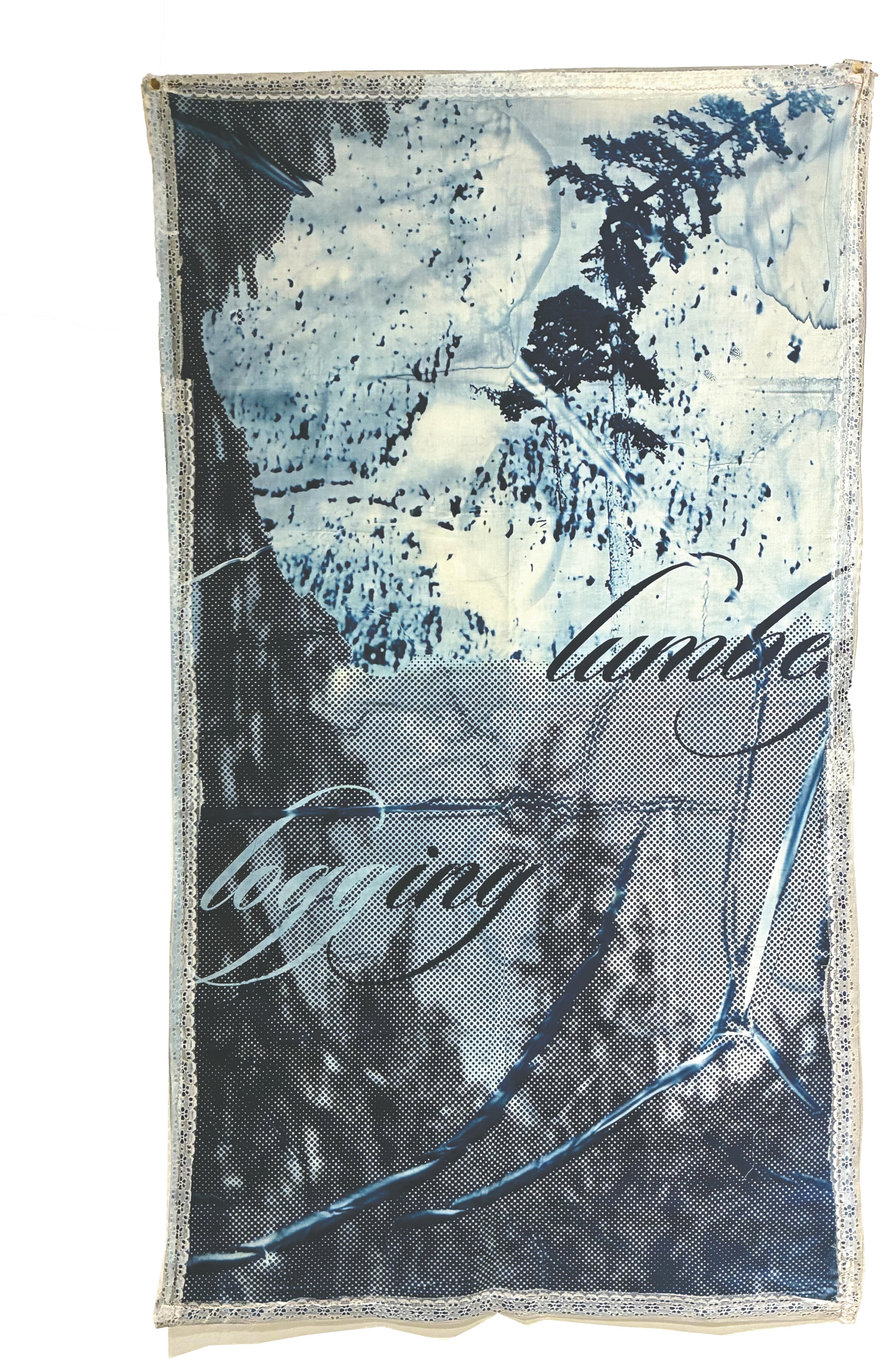

c In September 2022, during Burkina Faso’s second coup d’état in nine months, Captain Ibrahim Traoré seized state control from Lieutenant Colonel PaulHenry Sandaogo Damiba, dismissed Damiba’s provisional government, and suspended the constitution. In December 2023, his government adopted a draft of the revised constitution that recategorized French from an official language to a working language. In its place, Burkina Faso’s most commonly-spoken Indigenous languages—Mooré, Bissa, Dyula, and Fulfulde—assumed official language status.

In his comments on this article of the constitution, Burkina Faso’s prime minister called the change “a matter of political, economic, and cultural sovereignty,” because “no one can truly flourish based on the concepts of others” [translated from French]. This decision aligns with Traoré’s own anti-imperialist— and particularly anti-French—ideology. When the language amendment went into effect this past August, Traoré explained that if the country is “truly free from French colonial rule, then an African language should be adopted and used consistently across Burkina Faso.”

In its own effort to move away from French influence, Algeria has elected to prioritize English over Indigenous languages. Algerian president Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who argued that French should be categorized as a “spoil of war,” increased the government's efforts to expand English language education across the country. Just last spring, the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research directed all public universities to begin transitioning their first-year medical and scientific courses into primarily English instruction, starting in September 2025.

Even as English has become a global lingua franca, French has continued to occupy this role in North and West Africa. French remains a useful political tool in the countries’ diplomatic efforts with France. Algeria continues to demand acknowledgement and reparations for crimes committed during the colonial era, while Burkina Faso seeks to facilitate economic and political relationships with France, despite expelling French military troops in 2023.

Moreover, Burkina Faso’s decision to designate English, alongside French, as a working language, and Algeria’s efforts to expand English education, reflects shifts in the global linguistic hegemony. For decades, the French language dominated world affairs due to the French empire’s reach across North America, Africa, and Asia. However, the British empire’s expansion led English to rival French as the global lingua franca. When the British empire began to shrink, the American empire sustained English usage across the world, securing its position as the dominant lingua franca by the end of the Cold War. As a result, English is the most studied language in the world and the official language of nearly 60 countries.

Yet, even as English attained this status, Algeria’s promotion of the language did not pick up until 2023. English has been a foreign language option since 1993, but historically, students could only begin learning it in the first year of middle school, whereas French could be studied from the third grade. This discrepancy remained even under Western pressure to reform the country’s curriculum after 9/11. As Algeria adopted reforms centering Anglophone education, English curricula have remained underdeveloped. According to English language teachers surveyed for a 2019 study, this demonstrates the government’s “little” interest in advancing English “as a very

important language in [...] the Algerian educational system.”

In an effort to bolster English education, Algeria has relied on support from the U.S. and the British Council, a UK government–sponsored charity providing English courses, to establish sociocultural and academic programs. Similarly, the U.S. has shaped Burkina Faso’s English curriculum with the English Access Microscholarship Program, in which the U.S. Department of State provides between $25,000–150,000 to American and Burkinabè non-profits to administer English-language education programs. The politically charged nature of English language programs in both countries reflects the challenges inherent in creating a post-colonial linguistic identity.

+++

Prior to French colonization, Algeria had a remarkably multilingual landscape. Indigenous Imazighen tribes spoke their own languages, such as Kabyle and Chaoui, which originate from before the Arab conquest (647–709). Algerian Jews, whose communities arrived as early as the end of the Third Punic War, primarily spoke Ladino and Judeo-Arabic. Even as Algeria remained largely autonomous under Ottoman rule from 1516 to 1830, a period known as the Regency of Algiers, government entities continued to use Ottoman Turkish to maintain communication with Constantinople. At the time, Arabic was not recognized as an official language, but it was the most common language in the country.

A similar plurality of languages characterizes Burkina Faso’s history. Under the Mossi Kingdom (11th–19th centuries), the Mooré language dominated the government. Although the Mossi people remained in power for centuries, the country remained highly multilingual, with 70 languages spoken today. The Fula people introduced Fulfulde to northern and eastern Burkina Faso, while the Dyula people introduced Dyula to the west. Since the Mossi ruled from the capital city of Ouagadougou, Mooré became the most common language there.

While expanding their authority in Algeria throughout the 19th century, the French also occupied Burkina Faso—called Upper Volta at the time— in 1896. Missionaries and early colonizers spread French through religious institutions; the language was formally introduced through secular schools, the first of which opened in Bobo and Boromo. These schools followed a typical French curriculum, including philosophers such as Voltaire, aiming to foster loyalty to the metropole and assimilate Burkinabè into French society. In doing so, traditional forms of education grounded in oral history were devalued. Although the metropole indirectly ruled by co-opting local chiefs during the colonial era, the French government was still able to introduce a linguistic homogenization policy that rendered French a civilizing and unifying language. +++

After Algeria won its independence in 1962, the country grappled with persisting French institutions. Algerian Presidents Ahmed Ben Bella and Houari Boumediene instituted a period of Arabization under their tenures (1963–1965 and 1965–1978, respectively), determined to create a unified national identity and begin restoring Algerian livelihood. Linguistic

( TEXT LAYLA AHMED

DESIGN ANAÏS REISS

ILLUSTRATION ANGELINA SO )

policies instituted during this time propagated Arabic as the country’s sole language.

Though Arab Algerians constituted the majority of the population, Imazighen tribes remained a sizable minority, especially since most Algerians have some degree of Amazigh ancestry. This overlap in identity is reflected in the Algerian Arabic dialect, which has Tamazight influences. During the colonial era, French colonizers attempted to sow separatism in the country by dividing Algeria’s population using the Kabyle Myth, which characterized the Indigenous tribes—namely Kabyles, the largest in Algeria—as “inheritors of a Western Roman tradition,” and thus more similar to the French than Arab Algerians and other Imazighens.

This ideology contributed to French policy that simultaneously prohibited Imazighen people from attending Arabic-language schools and opened ministerial schools to facilitate the Kaybles’ assimilation into French society. In 1857, France even established a separate administration for Kabyles that granted better taxation, judicial, and governmental policies. These legal distinctions emerged from the metropole’s efforts to “de-Arabize” Algeria, which colonial authorities believed would occur by diminishing the presence of Islam in the country. In essence, the French capitalized on tensions between Arab and Imazighen peoples, a tension that would remain fraught after decolonization.

The National Liberation Front (FLN) led resistance efforts during the Algerian Revolution (1954–1962) and included Imazighen people among its membership. However, the FLN forbade Imazigh militants from speaking in Tamazight, an umbrella term for Algeria’s Indigenous languages. When the FLN became Algeria’s sole political party after decolonization, the Algerian government viewed the Imazighen people as a threat to Algerian unity. In 1989, revisions to the Algerian Constitution designated Arabic as the country’s only official language, which meant that Tamazight was not taught in schools, even in majority Amazigh regions. Following a series of protests, the government established the Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité to promote the Indigenous languages, but Tamazight would still not be recognized as a national language until 2002. In 2016, another revision to the constitution granted the language the same official status as Arabic. Despite expanded Tamazight language education in the country, students in a 2018 study ranked the language below English and French when considering which language should be promoted in Algerian multilingual educational curricula. Notably, Tamazight speakers also favored English education to further distinguish themselves from Arab Algerians.

In July 2022, Tebboune announced that English would become the primary foreign language option in public elementary schools over French because “it is a reality that English is the international language.” The Ministry of Higher Education additionally cited Algerians’ interest in English as a result of its status as the lingua franca in business, science, diplomacy, news media, and entertainment. Promoting English language education has the potential to increase Algerians’ economic opportunities, and to allow the country to have a tangible impact on the international stage. This change in language policy also underscores increasing tension in relations between Algeria and France—relations which have been especially fraught since September 2023, when France sided

with Morocco in the dispute over Western Sahara’s independence.

At the same time, these policies reaffirm English’s dominance in the world without providing support to develop Indigenous languages that could provide a counteraction to imperial influence. In stark contrast to funding Algeria receives from the U.S. and the U.K. for English education, in 2017 the government rejected an initiative that would have formalized funding for Tamazight education, prompting countrywide protests.

In addition to their negation of Tamazight languages, Arabization policies since the 1960s have focused on increasing Arabic literacy. However, Algeria lacked sufficient infrastructure to internally sustain these studies. Algerian teachers were not qualified to teach Modern Standard Arabic, which was a priority for the government as a means of strengthening Islamic and pan-Arab identity. As a result, the government implemented curricula from Egypt and hired teachers from Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, starting in 1964.

In 1991, the government adopted a new law to continue Arabization. Among its articles was a requirement that all official documentation, media content, and advertisements be either originally produced, translated, or dubbed into Arabic. Although this law was inconsistently enforced, it still reflects an effort to achieve the initial goal of complete Arabization by 1998. Moreover, promoting Arabic was not necessarily a rejection of foreign languages in general, but a rejection of French in particular. Pro-Arabization lobbies influenced the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education to include English as a foreign language option in September 1993.

Even as Algerians started to increasingly view English as the language of science and opportunity over French, pursuing English study remained a challenge. Until Tebboune’s presidency, French was still the primary foreign language option, especially for university-level scientific and technical study. Additionally, teachers believed that students often elected to study French over English because the country’s low English-speaking population limits the language’s utility. Despite these challenges, multilingualism is viewed favorably by younger Algerians; university students from a 2018 study consider this change critical to moving beyond an Arabic-French binary in the country. +++

Burkina Faso obtained its independence in 1960. Maurice Yaméogo became the country’s first president that year, and he soon instituted language education programs intended to promote a national identity and aid in the country’s development. In 1961, in order to advance literacy and vocational training, the country opened its first rural schools that operated in each region’s language because these regions had been neglected under the colonial system. The government intended for these schools to support the development of a national identity. Still, some Burkinabès opposed the use of national languages because they thought it would lead to a “ruralization of education” that would prevent farmers’ children from learning French. These concerns were rooted

in the language’s framing during the colonial era as a means of socioeconomic mobility. Despite this opposition, these schools remained in operation and were strengthened by national literacy programs that were introduced in 1967.

Even as presidencies changed, the government continued forming new programs and organizations to develop a sizable teaching force who could educate future generations in Burkinabè languages. Sangoulé Lamizana’s administration established the National Office for Permanent Education and Functional and Selective Literacy, as well as the Department of Linguistics at the University of Ouagadougou, to lead language planning efforts. This partnership helped form schools that taught in Mooré, Fulfulde, and Dioula, as opposed to French. That same year, in 1978, the country’s new constitution designated all Burkinabè languages as national languages.

In 1983, Thomas Sankara assumed Burkina Faso’s presidency. Sankara rejected loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, advanced a national literacy campaign, and renamed the country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso. This name reflected the three national languages: Burkina came from Mooré, Faso came from Dioula, and Burkinabè has Fulfulde influences. Sankara used these particular languages because they are the most commonly spoken ones in Burkina Faso. Yet, for the Burkinabès whose identities center on the country’s 67 other languages, his decision suggests that under both French and Burkinabè authority, the country does not view all of its cultures equally.

Working to increase Burkina Faso’s self-sufficiency, Sankara became a political target for the French. He was assassinated in 1987 and replaced by Blaise Compaoré, who reversed Sankara’s nationalization efforts and withdrawals from the IMF and World Bank. Compaoré was overthrown in 2014, and three years later, the Burkina Faso government asked the French government to release military documentation on Sankara’s assassination on behalf of his

widow, who alleged that France had masterminded the attack. This incident indicates conditions that cause countries like Burkina Faso to maintain French in some capacity, despite anti-French or anti-imperialist ideology.

Although Compaoré was responsible for his predecessor’s murder and undid many of his policies, he still worked to advance Burkinabè languages. In 1991, the baccalauréat—a national exam that students must pass to secure their high school diploma— offered Mooré, Dioula, and Fulfulde as optional subjects; four years later, the government granted all Burkinabè languages (in addition to French) the status of languages of instruction. Alongside these internal efforts, the nongovernmental organization Solidar Suisse developed and oversaw a system of French-Burkinabè bilingual school education that began with the students’ regional language before gradually introducing French. Solidar Suisse supervised these institutions from 1994–2007 before handing them over to the state.

While Compaoré’s policies promoted Burkinabè languages in an educational capacity, the usage of these languages was otherwise minimized. For instance, a 1995 decree directed news media to promote Burkinabè languages. Yet, one Burkinabè linguist found that media outlets broadcast in a low percentage of the national languages, and non-French broadcasts remain in the least-viewed time slots. The country’s mining industry also operates in French. The 2005 Decree on the Management of Mining Authorizations and Titles required all correspondence and requests to be written in French. Documentation in other languages had to be accompanied by a French translation, or else it would not be admissible. This is because French companies assumed control of Burkina Faso’s mines after Compaoré reversed Sankara’s nationalization directives. They have since been renationalized under Traoré’s presidency.

Linguistic identity has always been contested. Even in France, French was a language of the bourgeoisie, spoken by only 10% of the population before the Revolution. French became the country’s dominant language only when the French government implemented a program of homogenization and modernization—the same framings it would use throughout its empire. Yet, postcolonial contexts pose unique challenges in the pursuit of linguistic identity and policy. Embracing Indigenous languages highlights lingering issues regarding how Algerians and Burkinabès navigate their identities. In prioritizing imperial languages, Algeria and Burkina Faso may very well improve their ability to participate in international affairs, even if it limits their ability to fully decolonize. In their efforts to remove one colonial legacy, these leaders may very well implicate their countries in another.

LAYLA AHMED B’27 is learning Arabic so she no longer has to speak to her Algerian family in French and English.

ILLUSTRATION

c Within the next five years, artificial intelligence will match human intelligence. This, according to some of the foremost technocrats in Silicon Valley, is a mathe matical, statistical near-certainty.

They say, when this so-called ‘artificial general intelligence’ or ‘AGI’ that matches human cogni tive ability arrives, it will exponentially ‘recursively self-improve.’ It will quickly—over a period of years (as they call it, a ‘soft takeoff’) or days (a ‘hard take off’ or, onomatopoetically, ‘going FOOM’)—surpass all human intelligence: becoming ‘artificial superin telligence’ or ‘ASI.’ Humans will lose all control over this ASI. It will inexorably pursue optimal function (‘instrumental convergence’), posing an existential threat (‘x-risk’) to humanity that will probably bring about a techno-apocalyptic mass human extinction (‘the Singularity’). The only way to prevent this AI doomsday is to develop AI aligned with human intentions and values (‘alignment’) and hope that is enough to prevent our eventual superintelligent AI overlords from killing everyone.

B (P(A|B)), depends on how likely B would be if A were true (P(B|A)), multiplied by the prior probability of A (P(A)) and normalized over the overall likelihood of B (P(B)).

They call this abstruse, jargon-filled, techno-apocalyptic posturing ‘rationalism.’

Don’t confuse it with the kind penned by René Descartes. This techno-rationalism originates from the blog of a lifelong science fiction fan, transhumanist-by-eleven, singularitarian-by-sixteen, ‘autodidactic’-middle-school-drop out whose primary ideological recruitment tool was his longer-than-War-and-Peace Harry Potter fanfiction. Meet Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Science fictional ideas deeply informed Yudkowsky’s perception of AI. He cites Edward Regis Jr.’s Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition (1990), an exploration of fringe, maverick transhumanist science, as why he’s “taken for granted” inevitable superintelligence since eleven. At sixteen, Yudkowsky decided Vernon Vinge’s True Names and other Dangers (1980), a science-fiction novella about the Singularity and societal consequences during emerging superintelligence, constituted rigorous hypothesis. True Names inspired Yudkowsky’s singularitarian epiphany, inspiring in him “a vast feeling of ‘Yep. [Vinge is] right.’”

Science fiction isn’t a strong basis for scientific legitimacy. Yudkowsky struggled to get researchers and financial backers on board with his Singularityfocused exploits. So, over the next decade, he reverse-engineered mathematics to ‘rationally’ prove these science-fiction-based ideas true.

Yudkowsky laid out this reasoning on his new rationalism-centered blog, LessWrong, across two years of daily posting. He later synthesized these essays into rationalism’s foundational text “The Sequences.” They introduce a statistical framework— Bayesian reasoning—which Yudkowsky argues posits the only reasonable basis for forming rational, true beliefs, free from cognitive biases. Yudkowsky further claims this Bayesian reasoning proves that the superintelligent apocalypse is imminent.

Quick statistics lesson: Bayesian reasoning underpins rationalist reasoning, so here’s a crash course (shoutout

For example, suppose about 2% of Brown students are Indy* staff (P(A) = P(Indy*) = 0.02), and we assume 80% of Indy* staff members bring up theory in casual conversation (P(B|A) = P(theory|Indy*) = 0.8). These values serve as our priors. Then, if we assume 10% of Brown students in general would bring up theory in casual conversation (P(B) = P(theory) = 0.1), we can figure a 16% probability that someone who brings up theory in a casual conversation is an Indy* staff member (P(A|B) = P(Indy*|theory).

Bayesian reasoning extrapolates this equation, generalizing how beliefs should rationally change given new evidence, or ‘priors.’

However, Bayes’ Law (and, therefore Bayesian reasoning), is only as accurate as the probabilities and assumptions one uses. If calculations involve arbitrary probabilities—say, probabilities regarding AGI or ASI developments—then the final conclusion will also be arbitrary. My Indy* theory calculations are as scientifically sound as the imagined probabilities I derived from my heavily biased intuition. Of course I ‘proved’ there’s a good chance casual theory conversations come from Indy* staff: my intuited ‘stats’ were contrived from this preconceived belief! Without an empirical basis, Bayesian calculations simply become convoluted conjecture. Any conclusions drawn are post hoc justifications of belief, not conclusions based on sound statistical reasoning.

The Sequence’s mathematical basis seems sound; Yudkowsky argues that for any beliefs to be true, they need to be based on empirical evidence. If one uses Bayesian reasoning to inform their beliefs, those beliefs will always be close to truth.

In later Sequence essays, however, Yudkowsky uses this evidence-based epistemic rationality incorrectly to substantiate his belief in eventual AI-induced mass human extinction. He begins by positing science fiction-informed theories as fact: orthogonality (AI morality does not scale with intelligence), instrumental convergence (AI will pursue any subgoal necessary to achieve its primary objective), AI-FOOM (AGI will quickly, quietly explode, or go ‘foom,’ into ASI), and alignment difficulty (imbuing human values in AI will be extremely hard).

Yudkowsky then argues, using skewed ‘Bayesian’ reasoning, that AI development only has one possible trajectory: a model that matches human cognitive ability (AGI). Soon after, AI-FOOM will occur, where that AI will recursively self-improve, surpassing humans (ASI). The only way to mitigate human

ASI, due to its natural inclination toward instrumen tal convergence, will just kill everyone in pursuit of its goals. A common rationalist parable goes like this: an AI is created with the harmless goal of maximizing paperclip production. That AI, upon becoming superintelligent, instrumentally converges—turning everything in the universe into paperclips.

Yudkowsky’s priors are entirely arbitrary; based on his science-fiction-informed intuition, he presupposes a 50% independent probability that ASI will cause human extinction. He then uses conditional probabilities from his similarly intuited theories— orthogonality, instrumental convergence, AI-FOOM, alignment difficulty—as evidence. Using these (entirely made up) values, he ‘mathematically’ proves there is a 95+% chance of AI doomsday.

Despite this shoddy statistical backing, LessWrong and its rationalism paradigm have attracted a milieu of Bay Area tech workers and entrepreneurs. LessWrong started niche in 2006— mostly composed of fellow transhumanists and singularitarians following Yudkowsky from the blog Overcoming Bias, his old posting haunt. By 2015, one massively successful Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality fanfiction later, the forum was booming with card-carrying rationalists. (Even now, 10 years after HPMOR’s ending, the plurality of site referrals come from Yudkowsky’s fanfiction.)

Although most were initially ambivalent to Yudkowsky’s AI doomsday proselytization, they were drawn to his Bayesian groundwork. Rationalism offers a seductive framework: Reasoning can triumph over cognitive bias; belief can be distilled into empirical truth. However, Yudkowsky thought up rationalism to justify his belief in AI doomsday, not the other way around! Since the meat of LessWrong is ultimately his apocalyptic fantasy, these newly dubbed rationalists quickly adopted Yudkowsky’s AI doomerism as well.

Yudkowsky’s masturbatory diatribe details how rationalists are the only people who see the world empirically. Their unique clairvoyance allows them to see the apocalyptic danger facing humanity. This resonated strongly with already self-important techbros. Many already wholeheartedly bought into a techno-fetishist framework; they believed in their own messiah-like ability to ‘save the world’ with their superior technological intellect. Rationalism gave this masculinist fantasy the veneer of scientific legitimacy.

Rationalists soon became entwined with a sister movement, Effective Altruism, which, according to the Center for Effective Altruism, seeks to “us[e] evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit

others as much as possible, and take action on that basis.” To an effective altruist: it’s more moral to become a Wall Street lawyer and donate your millions than to lawyer for legal aid. Anyone can replace your legal aid work, but nothing will get donated if someone else takes the Wall Street role.

Longtermists, at the core of the EA movement, factor ASI-induced human extinction into their ‘maximal benefit’ calculus. The most ‘effective’ altruism is focusing on preventing AI-induced human extinction. Why put energy toward the billions suffering today under global poverty, climate change, or war, when that’s barely 1% of the future unborn trillions?

From this feedback loop, rationalists and EAs cemented their beliefs: Because we cannot stop superintelligence from existing, the only way to (possibly) prevent mass human extinction is to align it with human intentions and values. Human morals can offset orthogonality and instrumental convergence. Their superpowered reasoning makes them the only people rational enough to see this reality, so it is their responsibility to save humanity.

As AI development grew throughout the 2010s, the close-knit community of early AI researchers and workers produced ample kindling for an ideological wildfire. Rationalist doomsday belief—born from pseudo-mathematic conjecture—became fallacious truth. The Sequences became the ideological backbone for companies spearheading AI research and development. Debate was centered around not if machines could match human cognitive ability, but when. The Singularity, despite having no basis in empirical research, became the assumed endpoint of AI development.

Today, those young, insular rationalists have become the most powerful technocrats in Silicon Valley. AI doomerism has become the guiding principle for the people behind the world’s most influential AI companies—Shane Legg, co-founder of Google DeepMind; Sam Altman, founder and CEO of OpenAI; Dario

Amodei, Anthropic’s chief executive, to name a few. All rationalist LessWrong frequenters, all entrenched in Yudkowsky’s AI to AGI to ASI projection.

This devotion affects the entire structure, policy, and goals of their AI companies. Although 76% of actual AI researchers believe that current neural network architecture is “unlikely” or “very unlikely” to yield AGI, these CEOs devoutly believe that an AI with human cognitive ability will soon emerge. A “50 percent probability by 2028,” according to Legg. To Amodei, the “next two to three years.” To Altman, “by 2030.”

This obvious contradiction exposes rationalists’ selective vision. They believe in an imminent AI doomsday due to their ostensibly mathematically sound Bayesian reasoning, while dismissing the actual AI researchers telling them otherwise. After all, it’s more attractive to think yourself a techno-alchemist–savior, birthing new life while simultaneously saving the world from otherwise certain destruction, than a mere machine learning engineer. So: impending apocalypse it is.

To prevent from accidentally harbingering destructive superintelligence, each company maintains a comprehensive ‘AI safety’ policy, each of which cites AI alignment and developing friendly AGI as top priorities. In doing so, they prioritize Yudkowsky’s Bayesian reasoning over the scientific method: They work backwards from the assumption of a predestined Singularity endpoint rather than forward from existing infrastructure toward unknown possibilities. If an LLM acts in a way that contradicts its inputs, rationalists project disobedience and deception on what could easily just be buggy code. Every marginal machine learning unknown or advancement becomes more evidence of eventual superintelligence.

‘AI safety’ has become an alarmist movement itself, branching off from rationalism and EA. ‘AI safety’ is a misnomer; ‘AI existential risk catastrophizing’ would be more apt. AI safety ‘experts’ work off the EA principle that preventing imagined mass extinction is more effective humanitarianism than addressing existing problems. As per the Center for AI Safety, “mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.” Forget the myriad of tangible issues—the AI psychosis, unsustainable energy consumption, the fluency heuristics, the trust gap—LLMs have already caused. These real issues need tangible fixes, ones that require technocrats to sacrifice some of their billions. It’s much easier to buy into a techno-savior fantasy that the harm you cause today is in service of some greater, future altruism.

In fact, if techno-doomsday is imminent, there’s no point addressing any problems that are not, literally, world-ending. This allows billionaire CEOs to legitimize their dismissal of grounded social concerns they find inconvenient. They can make racism, sexism, global poverty, and environmental decay seem frivolous in the face of looming extinction.

This posturing of imminent AGI is certainly good

for business—who wouldn’t want to invest in the companies on the verge of, as Altman puts it, “magic intelligence in the sky”? Who doesn’t want to use the LLMs that, as Amodei promises, will soon be “a country of geniuses in a datacenter”? If these chatbots are as much on the cusp of human intelligence as ‘experts’ profess, they must be pretty brilliant. Especially if we need to fear them usurping humans.

And, with these powerful technocrats gaining more power as the AI industry grows (OpenAI is now the world’s most valuable private company!), their apocalyptic diatribes have helped legitimize reactionary, right-wing policy under the guise of ‘rational’ governance. They provide ‘reasonable’ advocacy for the Dark Enlightenment, which argues against progressivism, political correctness, and even democracy itself. After all, if the masses are too emotionally entangled in ‘frivolous’ social issues to recognize the looming threat of AI doomsday, then maybe only the ‘rational’ technocrats should be entrusted with power. Altman and other AI safety experts advocate ‘responsible scaling’ and ‘techno-capitalism,’ both of which argue for these billionaire CEOs to use their ‘superior rationality’ to regulate themselves. Surely it’s just coincidence this ‘rational’ paradigm stands to greatly increase the material power and influence of these overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly male technocrats.

Yudkowsky once claimed people work too much on “unimportant problems” regarding AI because the “important” problems seem too scary. The implication being, non-believers ignore the AI apocalypse because it scares them. The ‘smaller’ AI problems of environmental decay, cognitive decline, and psychosis are just easier.

I think it’s the other way around. Yudkowsky, with all his convoluted statistical theory, is the one afraid of uncertainty. He bought into speculative science fiction as an impressionable preteen. Rather than questioning these arbitrary beliefs with age, knowledge, and experience, he doubled down; he can’t face his own capacity for ignorance, even as a child. It’s easier to believe himself an entirely rational and reasonable person than to accept fallibility to emotion and irrational belief.

Yudkowsky is not unique. The tech sphere is full of people afraid of messiness in human reasoning and truth. In avoiding discomfort, they cling to ‘rationality.’

When powerful people adopt this exculpatory brand of ‘rationalism,’ it becomes a dangerous veneer. It ‘rationalizes’ their inaction as statistical triage. It allows them to appear ‘altruistic’ in their avoidance; they can work to prevent their imagined armageddon while ignoring the concrete problems they perpetuate. Conveniently, this heroism requires little tangible sacrifice.

‘Rationality’ helps them shirk that discomfort.

JODIE YAN B’28 is irrational.

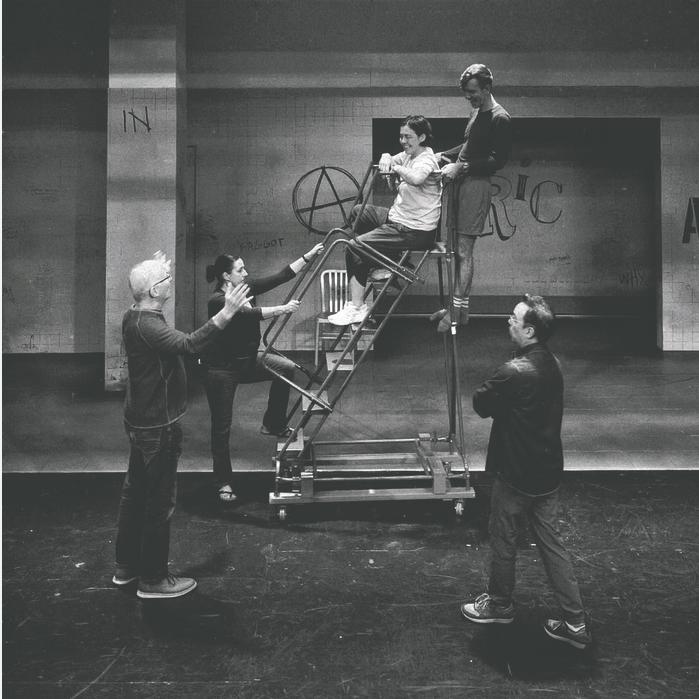

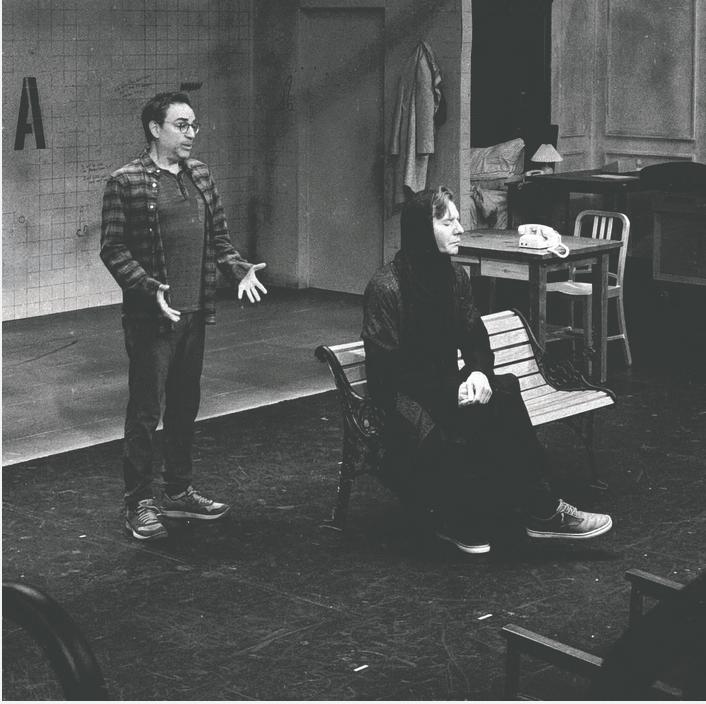

c Tony Kushner’s Angels in America arrived in the Sandra Feinstein-Gamm Theatre (the Gamm) in June 2025, with Part I: Millennium Approaches concluding their 40th anniversary season, and Part II: Perestroika opening their 41st in September.

Angels, a six-hour, two-part staged play, shows the interpersonal change in the lives of two couples— Prior and Louis, and Harper and Joe—in 1985-1986 New York City. As they navigate the challenges of love, religion, politics, and sexuality in the midst of the AIDS crisis, their seemingly separate worlds collide.

Written by Kushner in the early 1980s, the struggle with HIV, loss, and sociopolitical change represented within Angels was the reality of its audience’s lives—especially when staged in local theatres. The Trinity Repertory Company production of Angels, including both Millennium and Perestroika, was the first in Rhode Island. Directed by Oskar Eustis the 1996 production starred Brian McEleney, the director of the Gamm production. “When I played Prior in 1996, the play was more about visibility for our gay community and the lives that were still being lost to AIDS,” wrote McEleney in an email to the College Hill Independent. “The disease was still a big part of our collective lives, and we all felt a deep responsibility to represent the lives of everyone affected by that terrible time.”

In a printed conversation with the Gamm’s associate artistic director, Rachel Walshe, McEleney writes: “Every revival of any play exists in at least two time periods: the time it was written and the time in which the audience is seeing it.” The Gamm connects community history to the present. During the run of Millennium, audience members were greeted in the lobby by AIDS memorial quilts from Rhode Island, and every show ended with a call for donations to BCEFA (Broadway Cares Equity Fights AIDS). Both Millennium and Perestroika also fundraised for Open Door Health—Rhode Island’s first LGBTQ+ community health clinic, a primary care provider committed to destigmatizing HIV treatment, and an active participant in the mission to end global HIV infections.

“Every single night, there were people in the audience, parents, friends, partners of people who died of AIDS,” said Rachael Warren, who played the Angel. “That history is so necessary for all of us, but especially for queer people. We’re living in this age now where people [in America] are able to live with AIDS as a chronic illness and not as a death sentence. There’s a lesson [from the AIDS crisis] of how we all came together across the queer community. It’s important to remember how lesbians really showed up and helped caretake for gay men. There was a unity then that I think we need now.”

Angels as a play is also resonant beyond its depiction of the AIDS crisis. Kushner’s text has an internal metaphysics, one where raw material, represented by the Angels, can only be transformed by people, whose ability to imagine, dream, hallucinate, and desire drives the forward momentum of the world. This notion is central to McEleney’s interpretation of Angels, who notes that “[Kushner] rejects the notion of a past greatness that must be restored, and proposes a future that we all must be engaged in creating.”

To dive deeper into the staging of Angels at the Gamm, I talked to the director Brian McEleney; Rachael Warren, who played the Angel; Haas Regen, who played Prior; and Tony Estrella, who played Roy Cohn, and is the artistic director of the Gamm.

McEleney’s direction for Angels at the Gamm is built on a foundation of theatre as hyper-realism. Haas Regen, who played Prior at the Gamm, and was a former student of McEleney, recounts in a conversation with the Indy that “Brian talks about it all the

( TEXT CINDY LI DESIGN CINDY LI )

time. [Theatre] cannot be natural, it has to be magical realism. It has to be more to teach people how to be real, honest, and truthful.” To create this heightened reality, McEleney and set designer Patrick Lynch prioritized maximizing intimacy in the Gamm’s 200 seat blackbox space. “A focus on acting rather than on spectacle and special effects would be paramount in our thinking,” wrote McEleney to the Indy “I wanted to find the most bare-bones kind of set that would foreground the work of the actors as the primary storytellers of the play. [But] I didn’t want a completely empty space. In trying to imagine what the simple container for the play should be, I settled upon the image of a public men’s [restroom]—a fairly neutral space that nonetheless would be filled with graffiti that consisted mostly of homophobic slurs and crude sexual comments.”

The restroom is inherently a place of contradiction—a public place for private and vulnerable acts. Tony Estrella, the actor for Roy Cohn and the artistic director of the Gamm, describes it as “a repository of shame [...] I just wash my hands in the bathroom, no one wants to admit they actually used the toilet.” The public men’s restroom also contextualizes the stigmatization of AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s, when Angels takes place. At the time, HIV—a virus transmitted through bodily fluids—was inextricably linked to the shame, guilt, and secrecy of sex for queer people. McEleney emphasizes this, saying, “I wanted to remind contemporary audiences that there was a time not that long ago when homosexuality was illegal, misunderstood, and generally an object of public and personal approbation.”

Making the restroom a theatrical space is also inherently both transgressive and discomforting: spectating in a restroom is offensive, but in a theatre, it is consented, permitted, and encouraged. When the public men’s restroom becomes the theatrical setting at the Gamm, the permission to spectate is given with guilt: we are looking at something we ought not to be looking at, but we cannot look away.

The set of the Gamm’s Angels also wants to be looked at. The three-sided box set taps into the specific backrooms-esque mundanity that populates every office, school, and hospital—hyper-realistically quotidian, borderline-liminal. The set is filled with recognizable architectural details: green-gray tiles from floor to wall with a harsh division into cool white paint, a drop ceiling with acoustic paneling, one unexplained off-centered pillar, and frosted window panes above light-tan doors.

In Angels, despite Louis’ best efforts to defend his apartment to Joe as “messy, not dirty, dust, not dirt, chemical-slash-mineral, not organic…” the Gamm’s set he gestures to is sticky and tactile, to the point that audiences couldn’t resist walking up to touch it during intermission. Every surface is stained. Graffiti is scribbled over the walls: “my mother made me a homosexual,” “if I gave her the fabric would she make one for me?,” “738-5251 I will piss in your mouth,” “the best thing about fucking men is that it’s against the law, but you JUST DON’T GIVE A FUCK.” Above the roof of the set is the word “ANGELS” in large metallic type. “IN AMERICA” is written on the back wall of the set, each letter a different typeface.

The overwhelming liminality also permeates the stage space outside the set. Four rows of four, doublebar fluorescent tube lights illuminate everything in excruciating detail. Harsh, and unforgivingly bright, they extend from the back of the set to the front rows of the audience.

One of the concepts in the world of Angels is a state Harper describes as “a threshold of revelation.” In the play, Harper identifies this moment when, in a valium-induced hallucination, she suddenly encounters Prior, in a fever dream of his own. Harper describes this threshold of revelation as a place where one can intuit things about the world and other people.

This threshold of revelation is a precipice of change. Following Harper and Prior’s encounter, Harper is prompted by Prior’s intuition to confront her husband, Joe, about his repressed homosexuality. Prior hears the voice of an Angel telling him to prepare the way for the Angel’s infinite descent.

Regen’s experience portraying Prior led him to “realize that the threshold of revelation appears in other places [in the play]. So the way I started thinking about Brian’s concept of staging is essentially the manifestation of threshold of revelation. If you [the

audience] are intuiting these things about what the characters are going through, it’s because you’ve gone into the third dimension and can hear what they [the characters] are saying.”

Simultaneity of fiction is inherent in Kushner’s text, where the action of two different locations culminates in one scene. In Act 2, Scene 9 of Millennium, for instance, Prior and Louis argue in the hospital, while Harper and Joe argue in their apartment. Their lines are spoken in quick succession, addressed to each other, but also seemingly to the other couple not in their room. In the staging of this scene at the Gamm, a hospital bed becomes the hospital, while a couch on the opposite side of the stage becomes an apartment in Brooklyn.

However, simultaneity in Angels at the Gamm also permeates the staging where Kushner’s text does not explicitly dictate such overlaps. To foreground the work of the actors beyond just the set design, McEleney wanted to “give all the actors (and their characters) a more constant presence throughout the play, so that the overall effect would be one of a true ensemble telling interconnected stories, rather than a series of unconnected two-person scenes.” The stage often becomes a container for multiple fictional locations at once, divided thinly by the furniture. Warren describes this as something carried over from “old school Trinity [Repertory Company] productions. Often the whole community, the whole world is present while the other scenes are going on.”

Frequently, this overlap comes from the need for actors, not explicitly as their characters, to facilitate the scene by making sound effects with physical props, singing, playing the piano, and moving furniture. In the process, audiences witness moments where actors slip in and out of character. For instance, when Belize and Louis go to Roy Cohn’s hospital room after his death, Estrella says he has to “wheel the bed out after I’m dead. And then I have to get in the bed, open my mouth, and get into a death position. The audience watches me do it. There’s no illusion. I really

look dead for the five minutes that I’m dead. And then after that, I’m up, and I walk out of the scene.”

Actors also facilitate scenes that their characters don’t participate in. This creates moments where the stage is populated simultaneously by actors both within and outside of the fiction. In a scene where Harper is getting arrested and Hannah picks up the call from the police station, Warren describes that “Haas, who plays Prior, is on stage to do the [police] siren, and I’m on stage with a glass and a spoon to make the phone ring. We’re there as Rachael and Haas watching that scene. We’re not in that scene. We’re watching it, enjoying it, waiting to do our thing that helps them complete that part of the story.”

Often the whole community, the whole world is present while the other scenes are going on.

Overlap is also created intentionally between characters “to underscore the idea that each of the main characters is undergoing a similar crisis of personal change,” writes McEleney, “and that each of their stories mirrors that of all the others.” These moments trap the characters on stage in between their scenes with no dialogue or stage directions of their own from the play. They enact extended sequences of movement that reflect their emotional