01 SEEING AND BELIEVING

Raya Simpao R'26

Raya Simpao R'26

MANAGING

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Talia Reiss

Nadia Mazonson

WEEK IN REVIEW

Maria Gomberg

Luca Suarez

ARTS

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Martina Herman

EPHEMERA

Mekala Kumar

Elliot Stravato

FEATURES

Nahye Lee

Ayla Tosun

Isabel Tribe

LITERARY

Elaina Bayard

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Gabriella Miranda

METRO

Layla Ahmed

Mikayla Kennedy

METABOLICS

Evan Li

Kendall Ricks

Peter Zettl

SCIENCE + TECH

Nan Dickerson

Alex Sayette

Tarini Tipnis

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Selim Kutlu

Sara Parulekar

WORLD

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Emilie Guan

Coby Mulliken

DEAR INDY

Angela Lian

BULLETIN BOARD

Jeffrey Pogue

Lila Rosen

MVP

Lila Rosen & Jeffrey Pogue

It was a sticky August, and STN was in the thick of fundraising hell. Balls deep in spreadsheets and Apps Scripts produced by an exploited CS boy, TR began to Ind-rrrreeeeeaaaaaammmm…

V51 Orientation is in Texas. The entire masthead is crammed into a coach bus, and KM is driving. Frye boots on the pedals. We’re taking the scenic route, weaving on backroads around mountains and rivers (I have never been to Texas.) At a certain point, our fashionable driver is like, “Get out. We’re walking now.” So the entire masthead of the College Hill Independent struts together down an empty dirt road. RG is wearing very thin, sepia-toned sunglasses, and I try to assess whether he’s had a summer vibe shift or he’s astonishingly high. As Frye boots get dusty, the beautiful parade of the entire masthead of the College Hill Independent is intercepted by several young men in white button-down shirts. They are sexy, SO sexy, like young JFK Jr. at Brown. Incidentally, they’re also total dickheads. ND abruptly pushes me towards them. I hear a warning: “Watch out, TR. These guys are legit.” I say, “Challenge accepted.” I turn to one, and with no hesitation, I punch him in the face.

When TR awoke from the nightmare, her shoulder hurt, as if she’d been punching the air. She’s never punched a soul. But for you, Indy… for you she’d punch anyone.

DESIGN EDITORS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Kay Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

DESIGNERS

Millie Cheng

Soohyun Iris Lee

Rose Holdbrook

Esoo Kim

Jennifer Kim

Selim Kutlu

Jennie Kwon

Hyunjo Lee

Chelsea Liu

Kayla Randolph

Anaïs Reiss

Caleb Wu

Anna Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Hisham Awartani

Sarya Baran Kılıç

Sebastian Botero

Jackie Dean

Cameron Calonzo

Emma Condon

Lily Ellman

Ben Flaumenhaft

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Maxwell Hawkins

Mohamed Jaouadi

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nora Rowe

Andrea Li

Cindy Li

Maira Magwene Muñiz

Kalie Minor

Alya Nimis-Ibrahim

Emerson Rhodes

Georgia Turman

Ishya Washington

Jodie Yan

Ange Yeung

ALUMNI COORDINATOR

Peter Zettl

SOCIAL CHAIR

Ben Flaumenhaft

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Tarini Tipnis

FINANCIAL COORDINATORS

Constance Wang

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Lily Yanagimoto

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Mia Cheng

Natalia Engdahl

Avari Escobar

Koji Hellman

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Jiwon Lim

Yuna Ogiwara

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Angelina So

Luna Tobar

Ella Xu

Sapientia Yoonseo Lee

Serena Yu

Yiming Zhang

Faith Zhao

COPY CHIEF

Avery Liu

Eric Ma

COPY EDITORS

Tatiana von Bothmer

Milan Capoor

Jordan Coutts

Raamina Chowdhury

Caiden Demundo

Kendra Eastep

Iza Piatkowski

Ella Vermut

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Sofia Guarisma

Erin Min

Dominic Park

Brooke Wangenheim

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Ivy Montoya

Eurie Seo

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Avery Reinhold

Angela Lian

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Lian

Jolie Barnard

Luca Suarez

Nan Dickerson

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

*Our Beloved Staff

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

c The street thrums with noise; conversations pulse into the air as people weave across the sidewalk; cars rumble past, and someone yells a name before crossing the road. Amid the chaos, individuals throng in and out of the crowd. A man with spiky hair and a graphic tee strolls into Penguins, a coffee house situated on the north end of the street; a student clad in a knit sweater and loose-fitting slacks squints at the book covers displayed at the front of College Hill Bookstore; a gaggle of truant teenagers climb up a flight of stairs to enter In Your Ear, a record store nestled just above Café Paragon.

This is Thayer Street as it lives in frequenters’ memories, forever viewed through a haze of nostalgia. If you learned about its history from Wikipedia alone, you would only know that the street was first designated in 1799, renamed in 1823, and located in Providence’s College Hill neighborhood, among other surface-level facts. But most histories of Thayer recorded online seem unable to avoid an impulse toward subjectivity; the most extensive accounts of Thayer’s past are anecdotes compiled on ArtInRuins, a website dedicated to archiving Rhode Island’s history. Within these anecdotes, each store on Thayer Street emerges with its own universe:

“Anyone remember the clothing store Screaming Mimi’s? They had the coolest clothes ever! I bought my first Betsy Johnson outfit there in 1984. I can remember the store perfectly! They had a wide claw foot bath tub in store it was filled with broken glass. SUCH a cool store!!! Joan Pasha anyone? Blue Angel??? East Side was filled with one of a kind shops!!!” user Melissa Garcia posted.

Others remember the range of people that packed the street:

“Punks, crusties, weirdos, artists, homeless people, students and professors all mingled on the broad sidewalk. In the 70s, it was the cosmic cowboy

scene, and in the 60s, hippies and rock and roll,” a user named Camille recalled.

For others, Thayer became a place of reckoning and acceptance:

“To me, it will always remind me of 1998… the year i changed from a shy school grrl to a wyld wytche who roamed thayer at all hours and where i realized i was a lesbian,” Feather Marle reminisced.

Marc Doughty, a longtime Providence resident and an Information Security Engineer at Brown University, grew up a few blocks away from Thayer Street in the 1990s and remembers it as a “tremendous gathering place” for residents and students alike.

“It was just a place where you could say, ‘Oh, we’re all meeting up on Thayer Street’ around a general hour and then folks would gather up there,” Doughty said. “It was a place where people would meet up after school and [...] sneak off to a nearby spot where there weren’t any cameras [...] and get into a little bit of trouble.”

“I can’t count how many times I probably asked passersby if they would be willing to buy me a pack of cigarettes,” he added.

Like contributors to ArtInRuins, Doughty mentioned that the street’s shops largely consisted of local stores and restaurants, although he remembers when a Gap clothing store was still in business. Back then, “the nature of the street was very different. [...] It felt like a group of houses and small commercial buildings, you know, one or two floors, mostly populated by your friend’s parents or your friend’s friend’s parents,” Doughty said.

Lauren Berk, the executive director of the Thayer Street District Management Authority (TSDMA), grew up around Thayer Street during the late ’90s and has fond memories of the area. Similar to Doughty, Berk and her friends would gather on Thayer after school and go to Ronzio Pizza.

“I remember being there early on Sunday mornings with my dad, and we would go to Meeting Street Cafe and get cinnamon buns,” Berk recalled. “[Thayer is] kind of in my DNA. I’ve grown up there all my life. Now I have this job that is centered around Thayer.”

The forces that have shaped Thayer’s role as a nexus for these motley crowds and stores are difficult to define with precision. It may have been the fact that the street was a popular hangout spot during the grunge era of the ’90s, attracting crowds of similarly grunge teenagers; in other words, Thayer may have been a mere product of its time. “It’s where you went after school, it’s where you hung out when you didn’t want to be at home and had nothing to do,” user Ben Garber wrote on ArtInRuins. “It was exactly what an angst-ridden ’90s teen wanted.”

Likewise, Doughty attributed his experience of Thayer Street to a culture that has since disappeared. “What I experienced there was probably the tail end of a 1950s-era, American, Western social norm that has been replaced by a never-ending to-do list culture,” he said, defining this culture as “one where you limit your social interactions to your friends instead of going out into the world.” Although Doughty acknowledges that Thayer still functions as a meeting point, “it is more of a place now where you go to purchase something rather than go to just exist.”

Indeed, a sense of mourning haunts almost every post on ArtInRuins, as they often conclude with a lamentation about the decline of Thayer in recent years.

“There is not one thing left on it now to suggest that history to the transient student population, and it’s really sad,” Camille also posted. Likewise, “it ain’t what it used to be,” a user nicknamed ‘J’ wrote.

For these users, Thayer’s dynamism has brought on a kind of death for the street. Over time, stores have been replaced one by one—College Hill

Bookstore and In Your Ear shut down in 2004, while Kabob and Curry replaced Penguins. Residents are left to wonder whether Thayer Street is still the same street if its constitutive establishments have fundamentally changed.

+++

Today, the number of independent shops on the street has diminished, and the businesses largely consist of quick-service restaurants. Excluding the 87-year-old Avon Cinema and the 58-year-old Spectrum India, there are few establishments with founding years that date back to before the ’90s. Turnover rates for shops on Thayer are also accelerating. In the past year, restaurants including Yum’s Halal and Cracked PVD, in addition to retail stores such as J-Life Mart and Berk’s, have all shut their doors.

Owned by Berk and her father Stephen, Berk’s was a shoe store that closed in January 2025 after 50 years in business. Though Berk emphasized that their decision to close was due to personal reasons rather than external pressures, she noted that the Washington Bridge’s westbound closure in 2023 was detrimental to business. “We were swimming upstream all the time,” she said. “So we just decided that instead of beating our head against the wall, let’s just call it quits,” adding that “it was a good time to hang the hat up.”

Lisa Paquette, the store manager at Spectrum India, said the shop has also faced economic difficulties due to ongoing construction on the bridge. “Since the bridge went down [...] we lost a lot of our customers from East Providence, Warren, [and] Seekonk,” she said.

According to Paquette, businesses on Thayer Street are also facing a set of issues related to building ownership. “Unfortunately, the landlords on the street are focusing on restaurants because, I think, they bring in more money than retail businesses,” she said. Paquette noted that, given that Thayer Street has some of the highest rents in all of Rhode Island, “it’s really a struggle.”

“It doesn’t help that Brown University takes up every single side street and takes all the parking, and now we’re one of the only metered areas [around College Hill],” Paquette added. Berk told the Indy that there are joint efforts ongoing between Brown and the TSDMA to make parking near Thayer more accessible.

Aiya Tatari, who runs the Syrian restaurant Al-Shami alongside her father, drew attention to the disproportionate challenges that small businesses on Thayer Street face compared to chain stores. “I’ve seen firsthand how difficult it’s been for my family, how much perseverance we’ve had to have in order to keep operating as a business,” she said. “I would definitely see why it’s super easy for another family to just be like, ‘You know what? We don’t want to deal with this anymore. We’re just gonna sell the business, or we’re just gonna move to another spot.’” She added that “the high rent, the traffic, the licenses, [and] even high wages” have been difficult to overcome.

East Side Pockets owner Paul Boutros voiced concerns about the reduced interest in renting spaces for new businesses on Thayer. Over a year ago, Boutros bought an empty building just off Thayer, intending to rent one floor for apartments and one for retail. Today, the retail floor is still unoccupied. “Now, nobody’s coming in, right? People are [...] not jumping up to open a new restaurant or new retail shop,” Boutros said.

+++

Doughty, who also helps manage some commercial property in the city, understands the struggles and changes Thayer has undergone, especially as they relate to larger global trends. “The needs of capitalism to monetize space [...] have happened everywhere, but especially you feel it on Thayer Street, where the places where [fiscal] trouble could happen have been closed off and pushed away,” Doughty said. He also noted that “everyone who walks into the door” is viewed as “adding to the bottom line instead of just buying a cup of coffee and hanging out for six hours.”

Barnaby Evans, a Brown alum and the founder of WaterFire Providence, stated that he used to frequent Thayer “for the bookstore and Avon.” But today, because “Amazon has taken over the world [...] the independent bookstores, which had very passionately curated collections, are something of the past.”

On a global scale, it is nakedly apparent that e-commerce platforms have caused a paradigm shift in the ways most consumers shop for goods. Now, shoppers substitute a drive to the mall with a tap or click to purchase anything they may desire. Amazon in particular has exploded in popularity: As of April 2024, 75% of the total U.S. population had an Amazon Prime subscription. The tidal waves of e-commerce have also rocked the business world. February 2019 marked the first time that nonstore retail sales—a figure that largely consists of online order quantities, but also includes teleshopping and door-todoor sales—exceeded in-person sales from general merchandise stores.

Beyond its impact on retail businesses, e-commerce has generated a whole host of other consequences. For one, the convenience of online shopping breeds overconsumption. One Amazon U.K. warehouse reportedly destroyed over 130,000 returned products a week, with some of these items still in their original box. Online shopping also facilitates digital surveillance. E-commerce companies collect user data to personalize advertisements, enticing them to buy unneeded products, and thus exacerbating these cycles of excess and waste. Allegations of human rights abuses against e-commerce corporations such as Amazon also proliferate, raising serious questions about ethical implications of shopping for merchandise on these massive platforms.

In contrast, the physical nature of brick-andmortar shops invites consumers to more carefully peruse stores’ wares. For instance, consumers return items bought on e-commerce platforms at an average rate of 24.5%, compared to just 8.71% for items

bought in store. By encouraging consumers to gather in person, physical storefronts also foster a sense of community that is not accessible through digital platforms, and the wares that mom-and-pop shops sell in particular may encourage certain people to bond over their shared enjoyments.

Paquette echoed this view of small businesses as community-building. “We ourselves have our own friends, customers, our own little family here,” she said.

Taken altogether, recent accounts of Thayer might create a portrait of a dying street subsumed by commercialization. But Berk disagrees that Thayer’s changes are necessarily detrimental.

“There are different businesses operating on the street currently, but it’s very similar to what it was when I was growing up,” Berk said. “I think it’s just evolving. Yes, [Berk’s was] a staple on the street, but at the same time, things change. Nothing lasts forever. If you go to different communities, this is happening there as well.”

Paquette also stated that Thayer remains “a very nice walkable area. There’s a lot of places to eat and some places to shop.”

In Your Ear, the College Hill Bookstore, and Penguins are just a few of the stores that no longer exist on Thayer—but it is not as if vacant lots gape in their absence. When walking on the street itself, one could hardly call Thayer dead: The street remains host to over 40 lively businesses, and along the sidewalk, music still flows out from various shops, students still gather in clusters around storefronts, and gleaming neon lights still reflect onto worn sidewalks, marked with the treads of countless “punks, weirdos, [and] crusties.”

Likewise, Berk agreed that Thayer is “thriving.”

ANDREA LI B’28 is surprised she hasn’t been run over while jaywalking on Thayer.

ILLUSTRATION FAITH ZHAO )

c With the release of his debut The Last of Us (2016), Ala Eddine Slim quickly became Tunisia’s indie darling in the filmmaking scene. His works are distinguished by the embrace of nonlinear narratives and ambiguity in both form and content. Angsty post-rock scores, slow-motion sequences, and extended silences are the cornerstones of his craft and part of the political allegory that his films epitomize. This summer, in the sleepy coastal town of Menzel Temime, I went to a four-day film residency that showcased his body of work in the presence of Slim himself.

I’d been warned that his sophomore effort, Tlamess (2019), was unhinged. But nothing could have quite prepared me for the amount of bodily rebellion and gender-bending I was about to encounter. Tlamess, whose title is often translated from Tunisian dialect as “spells,” unfolds in two major arcs. One follows a soldier “S,” and the other follows a bourgeois wife “F,” both named cryptically with a single letter. They each flee their agonizing conditions to confront the unknown. This evasion becomes a form of resistance: a rejection of the nation-state’s militarism and the oppressive nature of the bourgeois family. The film, then, opens up alternative modes of living and queer kinships that resist the logics of power and discipline.

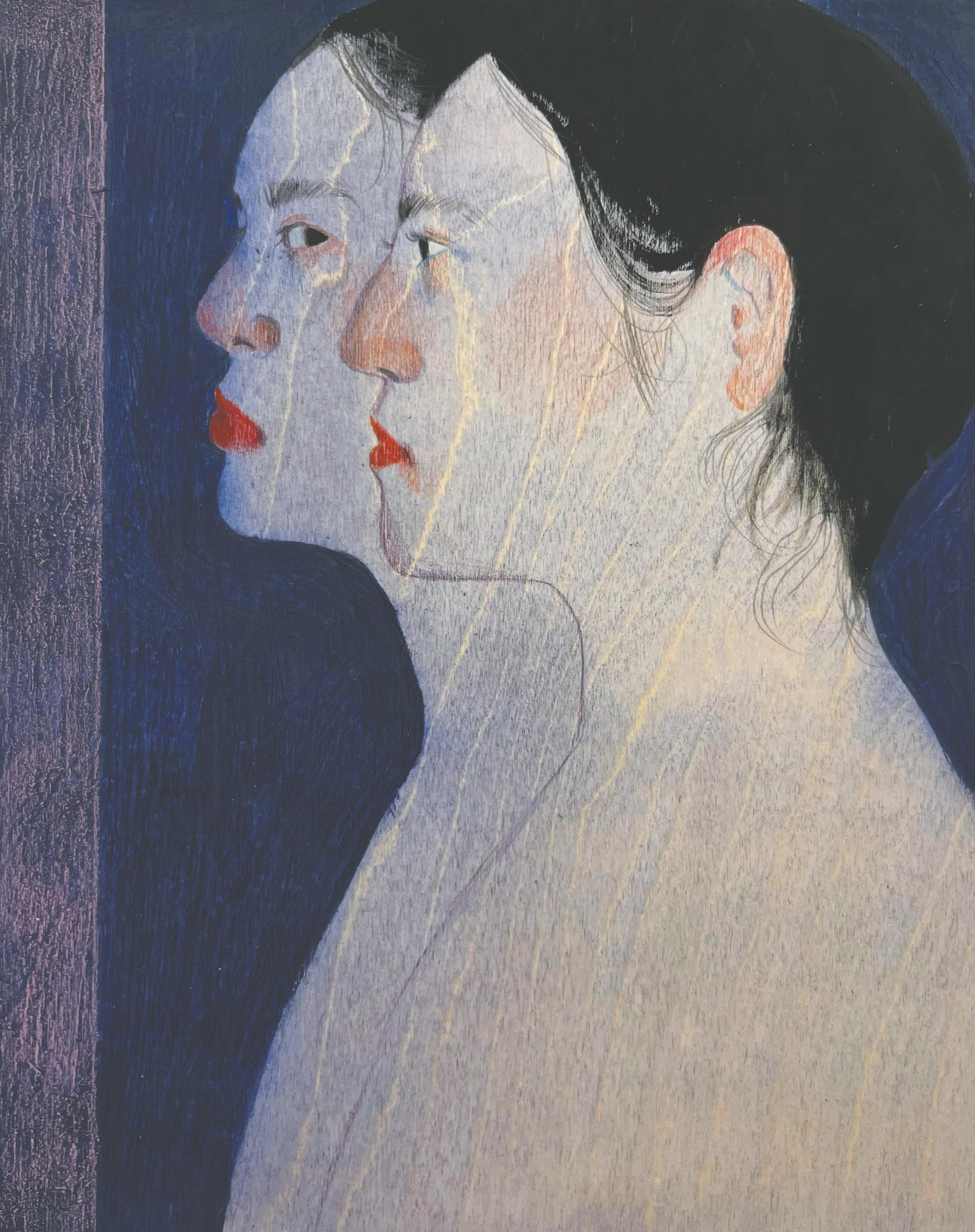

Tlamess kicks off with a historically contentious landscape in Tunisia’s collective memory and in geopolitical reality: the southern Sahara. In the post–Arab Spring era, the region has turned into a highly militarized hotspot due to its vulnerability to jihadist cells. On a dark, rainy night, viewers meet S’s military unit undertaking an overnight counterterror operation. Brief bolts of lightning are cast on a line of soldiers in a motionless and tense stasis. Later, fragmented shots capture their perfected, hypnotic choreography. We follow them in their uniforms, their steps in sync, riding small wagons in silence. But underneath this veneer of dedication and endurance, one soldier expresses to S the futility of their work, his exhaustion, and the disdain he feels toward these operations, a complaint to which S does not react.

Slim’s portrayal of the soldiers taps into an idea famously explored by the French philosopher Michel Foucault, especially in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, in which he discusses the way modern institutions shape individuals into docile bodies: bodies molded by strict control over time, space, and movement to serve the machine of power. Soldiers, he argues, are the ultimate example: their “bold steps,” “corrected postures,” and “motionless states” transform them into obedient bodies, stripped of personal freedom and turned into tools of the state, subordinated cogs of a machine. The body becomes a site constructed for the utility of state powers. Through this lens, we see how Tlamess visually enacts this concept through its representation of the military unit and mirrors Foucault’s image of the soldier as a

tool of obedience and control. This framework is also productive to understanding S’s portrayal in the film. S is only identified as “S” in the film’s plot and technical credits, never once referred to by name within the film itself. Slim’s refusal to name our protagonist beyond the letter S (which perhaps stands for soldier) might function as an analogy for how docile, disciplined bodies become devoid of subjectivity and personhood. The movements of these bodily disciplines become internalized in a manner that wipes away self-sovereignty, instead reducing the body to one capacity: its responsiveness to the state’s national security.

The protagonist in Tlamess is then only portrayed within those constraints. He does not possess any interiority because he has been constructed as a systematically reproducible machine in the hands of the nation-state. S is not granted any moments of individualization in the narrative of the film because his docility has reached a state so heightened that it abstracts any other qualities he may possess. He only bears the marker of the “S,” his marker of soldierness. This lack of complex individual identity saturates the first part of the film, rendered even more dramatic by its complete lack of speech throughout. Whereas dialogue is often seen as an exteriorization of the inner self, in the film, S does not utter a word. This absence of dialogue renders the concept of the docile body more and more tragic as the film progresses, because it empties the self of any meaning. The violence of the docilization of bodies is then aggravated.

Within this framework, the remainder of the film acts as a recovery of not only the self, but also the body and its unknown potentialities. When S unexpectedly receives the news of his mother’s death from his boss, he is granted a week’s leave, which he uses to indefinitely escape the violence imposed on his body and his missing, internal self. S breaks into a random vacant apartment to find solace and evade identification by his unit. He burns his work papers as an initial rejection of this imposed docility, which has made him a militarized voiceless subject, devoid of any inwardness. But S, under intense surveillance, is quickly identified by the state, which has framed him upon his disappearance as a dangerous, wanted individual. Although he is found by the state authorities in his temporary refuge, S eventually manages to run away into the wilderness. The wilderness, then, becomes the only possible location in which he can reside without potentially being found. Over the course of a seven-minute long scene, the camera follows S’s bleeding back as he marches forward, harsh distorted guitar riffs playing in the background. S is bleeding, bleeding out the last remnants of his docility as he steps into the evasive landscape. As the second arc of the film unfolds, Slim

temporarily moves away from S to introduce our other character, designated as F (which perhaps stands for femme, the French word for “woman”). F is immediately registered as a good-looking bourgeois woman who lives in a mansion and is married to an Algerian businessman. But she is also presented as anguished and lonely, constantly shying away from the camera. Over dinner with her husband, F unhappily announces the success of the artificial insemination procedure she has undergone. Her husband, upon noticing her anxiety, tells her that this is good news for the family.

F’s anguish reveals how the institution of the bourgeois family controls women’s reproductive choices and autonomy. In his 1884 book The Origin of the Family, Friedrich Engels, a foundational Marxist thinker, discusses how the rise of private property turned women into instruments of reproduction, who facilitate the patrilineal transfer of wealth. F, according to this logic, finds herself obliged to fulfill this duty despite her clear agony about it. Her body is coerced through the reproductive mandate of the bourgeois family. Just as nationalist military service makes S’s body docile, the ruling class makes F’s body docile in order to ensure the inheritance of wealth. Thus, S’s and F’s roles, although different in nature, are structurally analogous. The parallels continue when F runs to the wild forests and meets S’s transformed body. As their fates converge, S reappears with filthy clothes, an untamed beard, and long nails, lending him an unrecognizable, posthuman appearance.

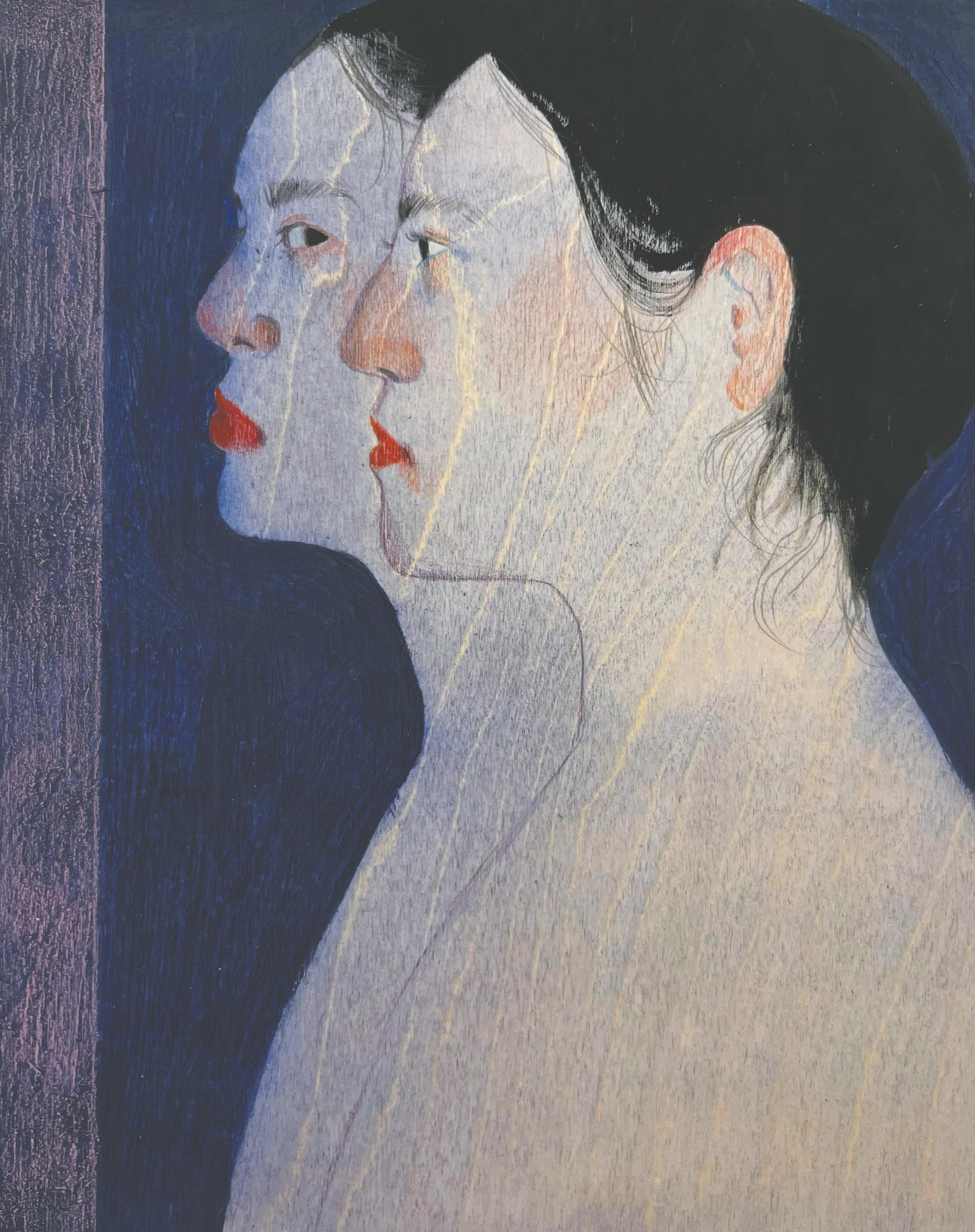

In the film’s ultimate queer-as-fuck arc, the two develop a kinship that transcends the heteronormative family-state nexus, biological ‘reality,’ and the limits of language. In doing so, they break free from their own docility. In a close-up shot, Slim places captions on both S and F’s eyes so that the two communicate through eye contact instead of dialogue. F asks, “Where is my voice?” Upon reaching this unknown wilderness, she is unable to find her voice, showing how language is foremost a social construct, not a natural one. S’s response through captions underscores that they do not have to talk to understand each other. Communicating through eye contact instead of words is a deliberate choice to avoid speech. Language becomes disposable and unnecessary in the formation of S and F’s kinship. In their 1990 book Gender Trouble, Judith Butler, a prominent queer theorist, argues that language is constitutive of the self, and its performance sustains normative identities and enables their reproduction. Language has the power to bring subjects to a confining binarism and reductionism. S’s discarding of language is, therefore, in defiance of its deterministic limiting function. Their communication is bodily-centered, allowing S and F a mode of relation that does not contain them the way dialogue does. Instead,

it enables them to emancipate themselves from the identities that language inherently ascribes to its subjects. In different scenes, S and F are seen watching the sunset, sharing food, and contemplating the river—in silence.

Their emerging relationality develops in opaque and obscure methods. For the Martiniquian philosopher Édouard Glissant, this opacity and unintelligibility grant individuals sovereignty and self-determination. In his 1990 book Poetics of Relation, Glissant claims this right to opacity, specifically for postcolonial subjects. Glissant critiques colonizers’ constant demand for transparency and total comprehension, as this demand for transparency was and is still used for the surveillance and subjugation of colonized subjects. Instead, he argues that we should allow for the incomprehension of the Other. Through their kinship and nonlinguistic communication, Slim grants S and F their right to both opacity and coexistence. This form of kinship creates multiplicity and complexities; in Glissant’s words, “opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics.”

Slim’s assertion of opacity, along with his subversion of both language and legible identities, becomes

fertile soil for the radical imagining of one’s bodily capacities and queer parenting. Time passes, and F eventually gives birth to her baby with S’s assistance. As her kin, S’s body begins to transform in order to support a physically-depleted F in the parenting of her child. At one point, S, after mysteriously growing breasts, takes turns with F breastfeeding her child. The two sit opposite each other, communicating through eye contact as they both take turns to feed the baby. Whereas the film initially presents S’s body as masculinized, docile, and disciplined, his kinship with F leads to bodily mutations that occur in opaque ways. His time in the wilderness, away from the use of language and state legibility, undocilizes his body and physically transforms it. This scene welcomes us into a portal of queer corporealities. Slim offers a vision of queerness not just as resistance, but as radical potential: one in which the body may need to reconfigure itself in response to fatigue, need, solidarity, and love.

Tlamess is thus a film about the magical potential of withdrawing from the violence of institutionalized structures, such as language, militarized nations, and the hetereonormative bourgeois family, toward opaque ways of being. The film, as seen through this

prism, is a call to question how our bodies have been disciplined to fulfill societal imperatives and to think of the infinite possibilities that such rejection of coercive docility could entail.

MOHAMED AMINE JAOUADI B’ 28 is obsessed with a film about a lactating former soldier, and you should be too.

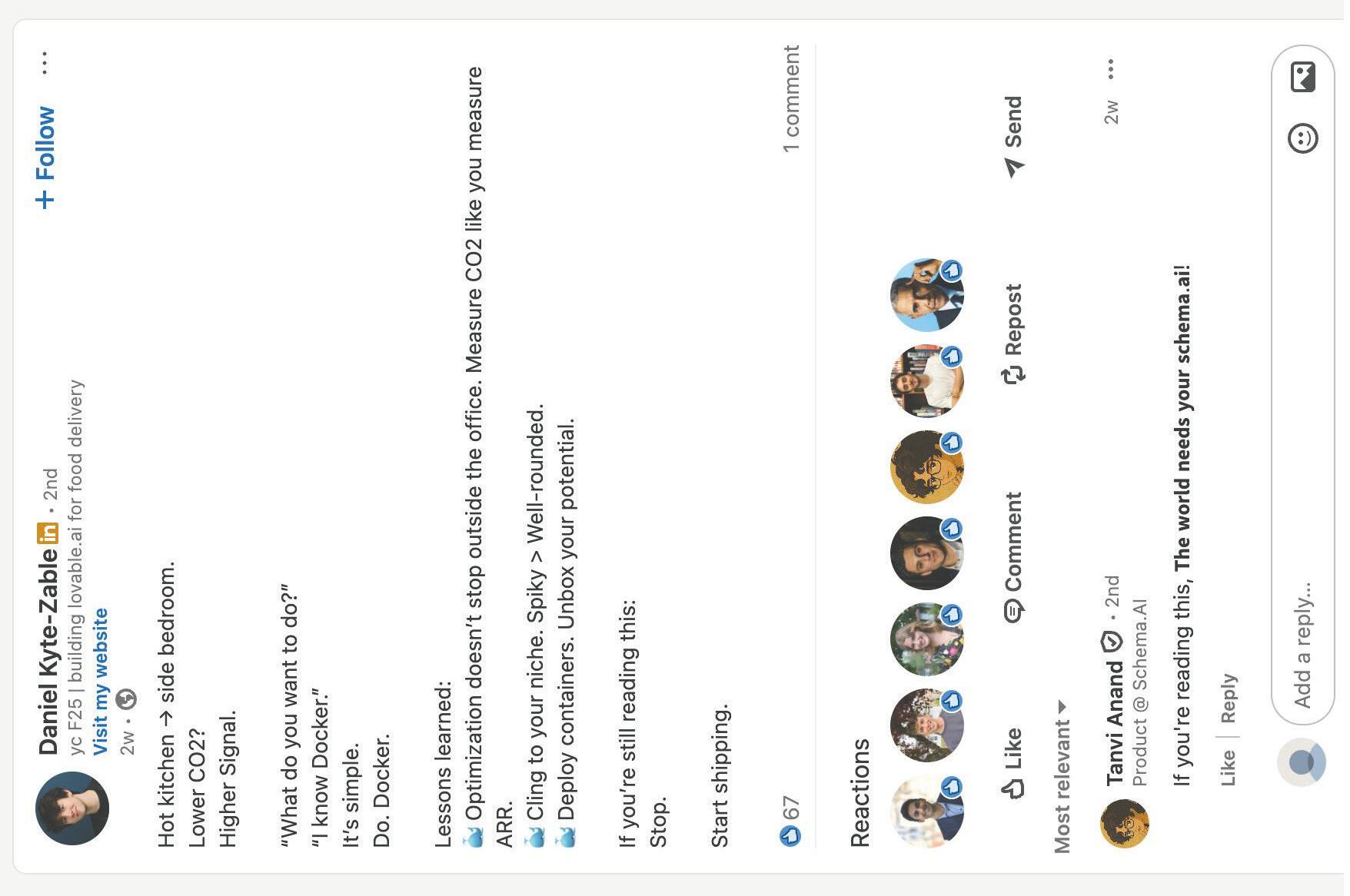

Each anecdote is repeated twice within this web: first as experience, second as LinkedIn slop—uplifted into a series of punchy, LLM-esque fragments. Here an inevitable transformation is at work: exploits are transfigured, adulterated, and expelled as slop. Perhaps, a Great Big Slop Machine…

“CAN WE HAVE A BARK OFF?!?” While livestreaming his Bay Area tour in September, YouTuber IShowSpeed was confronted outside of an In-N-Out by a man in a blue furry costume, who yipped at him. Speed, visibly unimpressed, returned a single “arf” and went inside. “I started barking,” writes Daniel Min, the man who donned the suit, in a recent LinkedIn post, “but to be honest, I did not do the best job…” He was met by an eager chorus. “Persistence is the key,” commented one user. “Need to add ‘Won a Bark off v. iShowSpeed’ to accomplishments to the resume,” commented another, whose bio proclaims that “LinkedIn is the next TikTok.” Perhaps this commenter is right. Min is the Chief Marketing Officer at Cluely, a startup founded in January by Colombia and Harvard dropout Roy Lee. The banality of Cluely’s primary product—an AI-based meeting transcriber—juxtaposed with venture backing from Andreessen Horowitz, one of the valley’s best-reputed firms, makes its C-suite’s ridiculous publicity stunts that much more absurd. On LinkedIn and X, Lee, Min and Cluely COO Neel Shanmugam boast about their Cluely-branded Labubu; spending 50k per month on DoorDash to maximize efficiency; hiring fifty interns to make TikToks; and paying employees $500 bonuses to wingman for their coworkers. This marketing strategy, although uniquely intense, is fairly common among consumerand enterprise-facing startups, who pair viral gimmicks with torrents of LLM-generated posts. We might hazard the question—why so much slop?

1.From Wikipedia:

“Docker Swarm provides native clustering functionality for Docker containers, which turns a group of Docker engines intoa single virtual Docker engine.”

…I joined his retreat from the sweltering kitchen to a side bedroom, as he, the private equity intern, was the sole person at a friend’s gathering that wasn’t (a) in the most recent YC batch, (b) an MLOps engineer, or (c) dropping out, so I found him charming, and at that moment a third person ran in, produced a metal apparatus from his coat pocket, and insisted to us that, “the CO2 concentration is leagues lower in here,” so the three of us got to talking, and I asked him what he wanted to do with his life, and he said that he, of everyone at the party, knew the most about Docker 1 , so probably that, Docker…

…she was a reporter, a friend of my roommate, and she was eager to understand my Reels consumption habits, so I spent a half hour pacing outside on the phone explaining corecore and its genealogy (cottagecore → breakcore → encore), when I ran into two women poised over a third, unconscious on the sidewalk, who each insisted that I don’t dial 9-1-1, they already had, and by the time a firetruck blared by, the reporter and I were onto those Minecraft parkour videos where Peter Griffin explains stochastic calculus or distributed computing, and, to my relief, the once-unconscious woman sprung up, ran away, and the reporter then asked if I knew any cracked students at Brown—a couple angel investors had just raised a fund, you see, and were pressing their noses to the ground…

The Slop serves as a touchstone for offline discourse. Many introductions with friends-of-friends I had this summer drifted toward this mooring, this cultural backdrop. The obverse is also true. Normal anecdotes, such as eating with colleagues or going on a date, appear inevitably on LinkedIn as parables: stripped of personal charm, contorted to evince some obscure point about the necessity of AI agent integration. In its essence, slop-production is performative knowledge acquisition. It is crucial to remember that possessing 'builder instincts,' the elusive ability to intuit what a product needs to take off, is prized far above technical mastery. Determining the quality of first-time founders is trickier than determining the quality of engineers or salespeople. Even measuring repeat-founders by their track record is problematic, since failures and successes can each be ascribed in part to luck. Prattling about the achievements of party attendees signifies that a poster is in-group; that they foretell the next great enterprise; that they can bridle the invisible forces that hoist and banish individual destinies. Shaped by these juxtaposed forces—youth, talent, luck and massive amounts of capital—slop-making emerges to govern the city and be governed by it. Buried deep within this circular dependence, SF resists all attempts to characterize its idiosyncrasies. It is incongruous. It is dense in itself.

Demographics certainly play a role—San Francisco’s startup universe is fed by a consistent stream of high school and college dropouts—but there are deeper things at work. First, there’s a difference between founding a company and being a Founder as understood within the dropout-startup-VC ecosystem. The latter has a spiritual quality. Founding excises the soul by freeing the over-competent Ivy League grad from their rank-and-file destiny at desirable firms like Bain, Google, and Jane Street. Secondly, in accelerating the pace of software development, AI becomes a creativity-enhancing tool: one which allows startups to easily confront ambitious problems without the bureaucracy characteristic of other types of workspaces. “I met a founder today who said he writes 10,000 lines of code a day now thanks to AI,” writes Paul Graham, creator of startup accelerator YC, on X. “He doesn’t have any employees, and doesn’t plan to hire any in the near future.” Every person can start a company—provided that they’re armed with a Claude Max subscription. This universe loathes stagnation above all else. Universities, tech companies, and other chokehold institutions are to be ignored or dismantled. Entropy is at play; dynamism can only be lost. Founders, encouraged to rely on AI tools and make sweeping product decisions with little information, must build zealously to effect the continuous dismantling of the old and tired, the bloated and out-of-touch. Only in the context of these themes— AI-as-deinstitutionalizing and founding-as-actualizing—does the incessant slop-production make sense.

…“well,” my roommate said, “I’d love to go to the Waymo kidnapping, but the race rank guy will be there,” and, well, it’s important that you understand that race-ranking isn’t his progeny but someone else’s left-over, half-formed joke—but we went anyway, up to the top of Coit Tower, that wonderful phantasm crowning Telegraph Hill, where fifty-some engineers, reporters, siblings-in-hijinks chattered about, gathering and entrapping within the parking lot fifty-some Waymos, dutifully dispatched from a service center at the base of the hill, each of them innocent to the abuse of the night, to their entrapment, to the race-rank guy making his case atop the Mount—“Everyone is either more homophobic, sexist or racist,” he insisted, “just as everyone has an implicit racial hierarchy,”—who then paused his sermon to throw himself before an escaping Waymo and yell “Tiananmen Square! Tiananmen Square!” to the cheers of the crowd…

…I was on Market Street the last night I was in the city. By then the fog had swept in, obscuring the SaaS company billboards that dotted the on-ramp to the highway, which took you east across the Bay to the continent’s festering summer; only San Francisco, tangled up in this fog, was spared the heat. Across four lanes of traffic, a well-dressed man, head shaved, twerked vigorously on the sidewalk. The light changed. The cars stopped and I began to cross. He leapt up, clasped his hands, and bowed.

…Curtis Yarvin’s ex-fiancé and I met at a film screening— this one consisted wholly of clips of MrBeast saying increasingly large dollar amounts—and it was only much later that I learned that she was Curtis Yarvin’s ex-fiancé, rendering me two degrees of separation from the chief architect of our democracy’s great un-making, for in the moment, I and she found MrBeast’s dinner hilarious, a golden pizza layered with truffles and caviar and foie gras, a golden pizza that cost 70,000 dollars, a price driven home by its incessant repetition—only that MrBeast and his lackeys, entranced by the thing, forgot about tax, yes, sales tax, and when they got the bill the pizza was instead 76,212.50 dollars, to which MrBeast said, “How did we end up like this?” to which one of his lackeys, glum, replied, “It was a really good pizza,” and we both cried laughing, I and she, and in that moment I could not have guessed how the character of this brief encounter we shared, she and I shared, would invert itself within the hour…

( TEXT KENDALL RICKS

DESIGN JENNIE KWON

ILLUSTRATION KOJI HELLMAN )

c I’ve been noticing a trend, and I bet you have too. It started with celebrities on red carpets and the big screen, but now I see it on the Instagrams of everyday people. In the mouths of store clerks, neighbors—my hair braider, even.

I first noticed them when I was a teenager. I remember driving home from a cookout where my parents had spent most of the time talking with a young couple. I listened in the back seat as they debriefed.

“They were very nice.”

“Extremely.”

“But did you notice his…”

“His teeth?”

“Yeah. They were just too…”

“Too…I don’t know, but it was freaking me out,” my mom said before trying to change the subject.

I leaned in as my parents worked to parse through what exactly was so unsettling about the nice man’s teeth. After all, there’s nothing abnormal about straight white teeth. At worst, we see them and curse the good genetics of the lucky owner. At best, we might even enjoy looking at them. But the teeth of this nice man’s variety were different. Grotesque, almost—more so than a bad case of gingivitis or cavity-filled molars. The shiny white surface makes you look again, drawing you into their artifice. They fit the form and definition of the thing we know to be teeth. But…they’re not?

The man most likely had veneers, composite or porcelain shells that are specially made to fit

over someone’s natural teeth. The number of people getting veneers has increased exponentially, with the market expecting to see an increase from $2.47 billion in 2024 to $3.39 billion by 2029, but they’re not new. Invented in 1928 by Hollywood dentist Charles Pincus, veneers were made to cover an actor’s teeth temporarily during a shoot, enhancing their smile for the camera. His clients included Judy Garland, James Dean, and a young Shirley Temple. In 1983, two doctors made a breakthrough, discovering the hydrofluoric acid bonding agents that enable dentists to permanently affix composite or porcelain caps to enamel. They’re not a medical necessity, and they can’t treat concerns like tooth decay, but veneers can cover a chipped, cracked, or otherwise damaged tooth, easing aesthetic concerns. When they were first introduced to general consumers in the 1980s, the goal was to match the veneer to the size, shape, and color of the natural, undamaged teeth.

In recent years, this has changed. No longer are veneers just a temporary fix or an aesthetic tweak. Now, dentists are seeing more people who are opting to have all of their teeth covered even when there are no visible signs of damage. I’ll admit, some of them look good—so good that their artifice is undetectable. But I’m not talking about those. I’m talking about the veneers that gleam brighter than the diamonds on your favorite rapper’s chain, or the pearly ones that your least favorite influencer shows off on their brand-sponsored Mykonos vacation. They’re white, they’re bright, they’re neatly lined up oh-so tight!

The wearer might feel a newfound sense of confidence, but the onlooker is plunged into the depths of the uncanny valley. In his essay “Das Unheimliche” (German for “The Uncanny”) Sigmund Freud posits several theories for that unease we feel when something or someone is not quite right. While he concedes that affective responses to various stimuli are subjective, he insists that there is a phenomenology, or an objective way of understanding the feeling. For Freud, the uncanny belongs “to all that is terrible––to all that arouses dread and creeping horror,” yet the uncanny is a unique kind of terror “which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.”

In 1970, Masahiro Mori, independently of Freud, coined the term uncanny valley: the eerie feeling one experiences when looking at an artificial entity (a robot, a prosthetic, and so on) that nearly, but not quite, mimics human features. Mori’s theory insists that our affinity for such entities increases as they more closely resemble human likeness. However, once this likeness crosses a certain threshold, its excess reads as too fake and renders the once familiar human form unreal. The positive correlation is reversed, affinity tanks, and an uncomfortable affective response is produced. Thus, the admiration one feels for nice teeth might turn to unease once the teeth are too straight and too white, beyond what is possible for a human to achieve organically.

Fake teeth aren’t always uncanny. Since antiquity, the creation of realistic dental dupes has been honed into a craft that is both an aesthetic wonder

and a scientific miracle. In his essay, Mori explains that this realism is the end goal: “to design and build robots and prosthetic hands that will not fall into the uncanny valley” because, ultimately, we don’t want artificial appendages to look perfect. We want them to look real—at least we used to.

Ours is an age of unattainable beauty. Some dental professionals noticed that the demand for veneers has increased with the rise of social media, especially during the pandemic, when people were on their phones more than ever before. Increasingly inundated with pretty faces and even prettier smiles, patients sought something more than just a better version of their real teeth. They wanted something not everyone could have: perfection. The uptick in veneers is as much a psychological and social process as it is a medical and cosmetic one. In this process, people want to look so good, it’s unreal. However, covering one’s teeth is rarely just about the optics.

To a certain extent, flashy veneers are no different from cosmetic interventions such as face fillers, breast augmentations, and the infamous Brazilian butt lift. However, veneers have a particular ability to induce uncanniness. Teeth occupy a unique space in our collective psyche—the mouth is an orificial portal between our internal constitutions and our external facades. Open half the time and closed the other, it toes the line between a public and private part. It is both an erogenous zone and a depository for some of the ickiest, and sometimes deadliest, germs in the human body.

The mouth as a dialectic is on full display in the 2024 horror film The Substance. The film follows an aging celebrity fitness instructor who, after being fired by Harvey, her chauvinistic boss, takes a myste rious substance that produces a younger version of herself named Sue. Throughout the movie, there are numerous tight close-ups on various faces, eyes, butts, and, of course, mouths. The film’s extreme focus on individual body parts is a commentary on the misogynistic way women’s bodies are surgically torn apart, scrutinized, sexualized, and punished in the public eye of a heteropatriarchal society. But the way the mouth functions in the film is of particular interest to me. Close shots of lips and teeth have the power to disgust (think Harvey going in on that burger) or to please and arouse (think of the effervescent film that covers the screen, making Sue’s lips look powdery and pink and pillow-soft). The film establishes tension between the gross microbiome of the teeth, their work of chewing and liquifying, their propensity to harbor germs, and the erotic nature of the lips. Yes, Sue’s teeth are nice, and when she parts her pillow-soft pink lips ever so slightly, the two buck teeth in the front poke out and enhance her youthful, seductive qualities. However, the more we look at them, the more ominous they become. We realize that anything this visible is in danger, and we secretly pray that she keeps her mouth closed.

pretty enough to bring to Mount Vernon. It conjures scenes of white slave owners carefully observ ing Black people’s teeth to see how pretty their incisors were, how strong and sturdy their two front teeth looked. With the mouth as a libidinal space in mind, pulling slave teeth was about more than new dentures. It reads like a practice done in lieu of or in addition to other orificial violations.

The stories we consume, especially the horrific ones, are just as potent as the sparkling smiles we see on Instagram. Teeth and the cavity that protects them are mediated as vulnerable commodities susceptible to violation, disease, and violence (which is often libidinal or racialized). In this way, undergirding the conscious desire to look better are latent fears about teeth’s intrinsic vulnerability and an unconscious impulse to armor the exposed metabolics of one’s inner, private world.

The most horrifying aspect of this recent social bend towards obvious artifice isn’t the unsettling stories we’re told about teeth or the growing preference for uncanny fakes; rather, it’s the market that has sprouted to fill the demand. On average, veneers from a licensed dentist cost upwards of $1,000 per tooth, which is probably why, for a long time, the procedure was reserved for Hollywood A-listers and the ultra-wealthy. Now, interested parties need only search their Instagram explore page for a veneer technician.

Whereas trained professionals spend years learning how to shave, shape, and mold the teeth, veneer techs (as they’re called on social media) can get a ‘certificate’ in as little as two days of a paid online course (usually offered by unaccredited websites of dubious origin). They’re untrained and not officially licensed, but they are cheap. Instead of $30k, a full set of teeth from a veneer tech can cost as little as $4,000. The American Dental Association, the largest such group in the U.S., has issued warnings about the dangers of veneer techs, but business is still booming, although the illicit nature of the industry makes it difficult to gauge just how much. The practice is illegal, and these so-called technicians tend to provide their services in rented out retail spaces or even their homes

x-rays or do proper examinations to ensure the original teeth are healthy, and many of them use dangerous unauthorized materials (such as superglue, which a veneer tech in Tampa was recently arrested for using). These houses of horror don’t just take advantage of the common desire to look better; they exploit vulnerable people who have already paid the price of systemic inequality. Garish chompers only scratch the surface in terms of the damage unlicensed technicians can leave, including chronic pain, untreated rot, and a mouthful of chipping resin.

The uncanny is more than a response to aesthetics. It is a forced reacquaintance with some truth we would prefer to not see. Underneath the shiny exterior lie complicated histories that remind us of our own capacity for and susceptibility to violence, systems of inequality that we might benefit from, and the enticing urge to forsake our individuality for the comfort of perfect conformity. More than an unfortunate trend, veneers embody an ethos unique to our time: glossy coverage guised as self improvement or reparative work. An ethos which, when consumed without question, begins to literally creep in and rot us from the inside out.

KENDALL RICKS B’27 wants to see what’s under the surface.

As the substance begins to rot Sue’s body, her teeth are the first to go. In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, Harvey asks, “Are you okay?” as the camera zooms in on his impish smile. Sue nods yes, careful to keep her lips pressed together tightly, so as to not reveal the mouthful of gaps and bloody holes behind them. “So, smile!” he demands. The music intensifies, and tears rush to her eyes before she dons a big closed-lip smirk. In this scene, the man’s demand that Sue show her teeth reads like an inappropriate request, a coercive violation of her private world, a world whose rot she is eager to keep to herself.

The film codes the impulse to see into another’s mouth, especially the teeth, as not just sexy, but libidinal—an impetus for the resurfacing of unconscious urges. This reading of the mouth rings true not just in the filmic register but also in history. While most kids might have learned that George Washington had wooden teeth, I was taught that he had slave teeth. Today, this fact conjures images in my mind of Washington at the auction block, forcing a Black person’s mouth open to examine if their teeth were

Last year, a man who called himself the “CEO of A-List Smiles” was arrested in Atlanta and charged with eight felony counts for illegally practicing dentistry on thousands of patients and offering courses to prospective ‘technicians.’ Scrolling down A-List Smiles’ now-defunct Instagram page, you’ll see mostly Black and brown faces. The same is true for similar veneer tech social media pages with usernames including “veneerexpertsvegas” or “enhancedsmilesss.” For many of their clients, or more accurately victims, the allure lies solely in achieving the perfect look at a fraction of the cost.

For others, it’s a quick fix for more pressing oral health issues such as severely rotted teeth or nerve damage. This is unsurprising given persistent disparities in dental care access for communities of color. Black and Latino adults are more likely than white adults to lack access to a dentist and have moderate to severe gum disease. Even when a dentist is accessible, past experiences of neglect and racism not only discourage patients of color from seeking treatment but also leave them with what some researchers call high dental anxiety. All of these factors make veneers seem appealing. A trip to the veneer tech presents the promise of an affordable reprieve from oral troubles without the poking, prodding, and prejudicial judgment of the dentist’s chair. The shiny white caps purport to cover the shame of

( TEXT EMILY

DESIGN ESOO KIM

ILLUSTRATION MIA CHENG )

h@nep’ajElA yUdjEhalA nedzAdEk’û’wAdAjî agat’A yUdjEhalA zAnek’û’wAdATA hEdOÔndajî ÔdE yUdjEha KAÂha ÔdE yUdjEhalA Ôk’û’wAdAnA neh@shÂKAshta yUdjEhalA nedzAdEk’û’wAd w@wahalA s’@Ta nefafâ neh@-A s@nlA nô K@thl@^falA wAshâ gOh@nTOnA wAnzAtyû sahandA yUdjEhalA’wAdA ahendA nenzAyOsh@nlA nô!

before you were born, I spoke to you in the Yuchi language someday I knew you would be able to speak back to me in Yuchi

We here are Yuchi people, so we speak Yuchi

Your entire life, I will speak to you in Yuchi

You will walk on the earth for many years and have a good life Wherever you go, the Breath-Ruler / God, will help you

Always speak Yuchi and you will be happy.

—Halay Turning Heart

c My interest in the politics of language began in a class I took my freshman year of college about bilingual education practices. There, I learned about translanguaging, a term coined by the Welsh educator Cen Williams and expanded upon by language scholars including Ofelia García, Li Wei, Kate Seltzer, and Susana Ibarra Johnson. Translanguaging theory rejects that alternating between two or more languages when communicating obstructs learning. Instead, it imagines multilingualism as an academic asset. In the U.S.—a predominantly monolingual nation— language hierarchies that situate the English language above others are common in the classroom, especially following precedents like the English-only movement in the 20th century.

Within just the past twenty years, news articles have reported that bilingual students in U.S. classrooms who use their home language rather than English have been shamed, physically assaulted, and suspended. Translanguaging pedagogy has been implemented by multilingual classroom instructors to combat this institutionalized monolingualism in linguistically diverse classroom settings. According to Li and García, translanguaging theory posits that classroom language hierarchies are informed by racialized histories of colonialism and assimilation. In the classroom, this translates to employing flexible and horizontal bilingual education practices to teach students the value of their multifaceted language identities. Over the course of the semester, I became fascinated by the concept of translanguaging, but I wasn’t quite sure how or if it worked.

revitalization movements across four Native nations with disparate languaging perspectives.

In early September, I met with my former professor Nitana Hicks Greendeer B’03 to discuss her experiences as a learner and instructor of the Wampanoag language (Wôpanâak), and ask about her multilingual and immersive language learning practices.

Wôpanâak is often referred to as a sleeping language, since, for 150 years, it had no fluent speakers. However, it was well enough documented that Wampanoag community members like jessie ‘little doe’ baird, alongside MIT linguists, were able to revive it by founding the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project (WLRP) in 1993. Although Hicks Greendeer argues that immersive language learning is the ideal model for children learning Wôpanâak, she noted to me that this goal has been largely unattainable because so few conversational speakers are alive today. The WLRP now operates on a dual language model emphasizing cultural immersion.

One of the four core purposes of translanguaging, as outlined by Li and García, is to immerse students in their family culture. In our interview, Hicks Greendeer told me that one of the WLRP’s strengths is “a curriculum […] based in environmental science and culture.” She noted that the program incorporates activities such as “berry picking […] where we try to make sure that [the students] are also bringing berries into the elders lounge at the tribe.”

One of her colleagues, Renée Lopes-Pocknett, the education director for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, placed similar emphasis on the importance of language revitalization as a tool of cultural connection, saying: “Language is culture and culture is preservation. Learning culture is prevention of social ills […] of addiction, of alcoholism, of homelessness. It’s to be whole in yourself […] Learning language alongside culture is how we know a word is sacred.” She described how using Wôpanâak forms cross-generational connections: “Our ancestors understood seasons this way, the stars this way, belonging this way.”

values align with horizontal knowledge sharing practices like these across languages and generations. However, Hicks Greendeer then drew a distinction that stuck with me—bringing English into the classroom could actually be dangerous to the integrity of the language. Teachers of Wôpanâak, she noted, are concerned that, due to the language’s recent revival and its small number of fluent conversationalists, Wôpanâak will mix with English to become a hybrid language Hicks Greendeer labeled “Wamplish.” She said that “it wouldn’t be the most terrible thing if we had Wampanoag speakers, English speakers, and then Wamplish speakers,” but due to the newness of Wôpanâak’s revitalization, introducing English might mean they are left with “only English and Wamplish.”

On the other hand, Madison noted that several parents expressed concern about decentering English proficiency in a predominantly English-speaking society. Madison said: “I got the questions, you know, ‘is my son stupid?’ ‘Is my son dumb because he can’t count in English?’ […] And I said, ‘He’s been learning to count in Wampanoag.’ I called his son over to me, and I told him in [Wôpanâak] to count, and […] he starts counting all the way up to 30 in the language, in Wôpanâak. He’ll get the English. The English is […] all around him.”

Anxieties about bilingual pedagogy continually came up in my interviews with language revitalization leaders across different nations, especially around semilingualism—the idea that bilingualism limits one’s proficiency in both languages.

Education has long functioned as a nation-building tool in the U.S., crucial to its cultivation of a homogeneous national identity. Since the nation’s founding, through routines like a mandated Pledge of Allegiance, public school lunches, and U.S.-centric curricula, schools have been imagined as a means of assimilation, narrowing the cultural divide between white Americans and immigrants.

I grew to understand how bilingualism could be fostered within U.S. classrooms—sites of cultural projection and state control—to combat those assimilatory ideals. Beyond that, I started to wonder whether translanguaging could support language revitalization movements among Native nations as well, considering the long, and continued, genocidal history of U.S. educational institutions and boarding schools. To find the answers, I reached out to seven leaders in language

Translanguaging theory views families as co-learners in children’s language learning. Because the Wôpanâak language was dormant for so long, today’s language learners are presented with unique opportunities for co-learning. When I interviewed Camille Madison, an Acquinnah Wampanoag councilwoman and Wôpanâak teacher, she described a student who picked up Wôpanâak especially quickly. One day after school, the girl told Madison:

“Ms. Camille, I want to be a teacher like you.”

“You already are,” Madison remembers responding. She asked: “I am?”

“Think about it, does Mom know the language?”

“No.”

“Who teaches her?”

“Me!” the student said, smiling.

“Does Grandma know the language?”

“No.”

“Well, who teaches her?”

“Me!”

Madison recalled, “Her little eyes just lit up. And when her grandmother came to get her, she shared that with her grandmother, and it made her grandmother feel so proud. And her grandmother later started going to elder classes to learn [Wôpanâak].” Translanguaging

I discussed some of these concerns with Warlance Chee—the director of Saad K’idilyé, a language nest program that teaches the Navajo language (Diné Bizaad) and culture to infants, children, and their families through immersion. He told me that some Navajo community members are concerned that children in his program are “lost in [the middle], emerging with fluent Navajo but without academic English.” Translanguaging pedagogy seeks to develop rigorous practices in academic contexts for multiple languages. Yet, Chee noted that anxiety about bilingual education is particularly felt by parents in a society that often equates Englishlanguage fluency with success. He noted that when Indigenous children (like his own) grow up immersed in their native language and are moved to public schooling, they are often placed in ELL programs, where they are deprived of access to an education as rigorous as their peers.

Unlike Wôpanâak, Diné Bizaad is a language with a fair number of fluent speakers. Chee, who is a Diné Bizaad first-language speaker, estimates that there are over 100,000 fluent speakers of the Navajo language. Still, this number is alarmingly low in comparison to colonial languages such as English or Spanish. Out of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S., Chee estimates that “500 or 550 probably don’t have many [fluent first-language] speakers left. They’re doing whatever they can, trying to piece language back together. Language changes, but there’s still that core piece there. Once you lose fluent speakers, it’s not there no more.”

In the face of language erasure, revitalization and cultural immersion programs like Saad K’idilyé are ever-important. Chee described how

Saad K’idilyé views cultural practices as integral to language acquisition. The program hosts “cradleboard workshops […] moccasin-making, weaving, sewing [and] storytelling of the cornfield.” These activities function as immersive spaces for language acquisition and cultural education to coincide. Chee said, “We need to get our kids out of being lost […] so knowing where they come from and their language and their culture. It provides stability, growth to make sure these kids are happy and successful.”

The translanguaging stance frames language as one of the most significant educational tools in the struggle for cultural democracy. Although Saad K’idilyé’s pedagogical practices, which incorporate Navajo cultural values and programming, align with some of the values of translanguaging, Chee still expressed his concern with the actual introduction of English to language acquisition spaces: “[to] really revitalize a language and sustain it, to keep it from going extinct, the only way to do that is to produce first-language speakers, to be unapologetic and try to really control that space as best as we can to keep English out.” Chee described that a “hierarchy” emerges when bringing the English language into Saad K’idilyé through translanguaging because the violent erasure of language through colonialism continues to place English above other languages. “That history, it’s made to dominate. Even our own people don’t always want their kids or grandkids to learn the Navajo language because they think they’re not going to do as good in the job and education world. […] Translanguaging still prioritizes other languages out there besides the original language that Indigenous people come from.” He went on to describe how, in the teaching of marginalized languages, students may not have the luxury of bilingual education. Chee said, “[Saad K’idilyé’s] mission is different […] Translanguaging might not work for us. I don’t know if it’s right to tell a child, ‘Don’t speak English, just speak Navajo.’ [...] That really gets into the ethics, yeah? But you know, I mean once they leave here it’s English, that’s all.” Chee later added, “Our need as Indigenous people [is] to be unapologetic and prioritize our culture and languages in a space dominated by American values and English.” +++

The ongoing persecution of Indigenous communities has often been perpetuated by organized colonial efforts to erase Indigenous languages. Jesse Rusche B’25, a language instructor for Nakona University, describes how “[s]omething present for all of us is that multiple generations of Nakona people, and Native people across the board, were forbidden from speaking their language. It was illegal. If little kids were speaking [Assiniboine] the punishment would be that they were taken away and put in boarding schools.” Indigenous language erasure has long been part of the U.S. education system, especially through the violent assimilatory practices of American residential schools.

Crystal Redgrave, the co-founder and chair of Nakona University, said: “The Western educational system has failed us as a people. We know that because of statistics with poverty, mortality rates, everything. There is something missing, and I say it has to do with our language, our culture, and how we're connected to each other.”

For Indigenous languages with very few native speakers, monolingual teaching practices can be nearly impossible—or as Rusche stated, not “conducive to life”—in an English-dominated society. She continued, “To say that language revitalization must only be monolingual would really cut out a lot of people […] who may be scared or without the time and energy to put towards such an immersive program. It’s important to bring language to as many people as possible who want to learn it.”

Redgrave added that when creating Nakona University, she “thought about immersion, but at that time [it] was not as successful, or as enduring, a method.” She said, “I could see […] people falling off and not coming back.” She went on to say,

“I had to think about the practical side. If generations of English speakers and our minds have been wired to think linearly, I have to somehow take that linear thought process and unravel it into the

Indigenous mind process. And so I am teaching. So I call it a bridge.”

Multilingual education can be a bridge from one language to another, but also a bridge to one’s own culture. When introducing herself, Redgrave taught me how, in Assiniboine, “when somebody recognizes you, you’re part of something that tells you how you’re connected. So it’s not a standalone ‘my name is’ […] You’re not standing alone in the universe here. When you say ‘Crystal emãgiyabi,’ you know, ‘they call me Crystal,’ I’m saying that I am part of something and they recognize me to be part of that.”

+++

Late in my interviewing process, I heard from h@lA (Halay) Turning Heart, the project administrator of the Yuchi Language Project (YLP). The YLP is an immersion school in Oklahoma, which, like Saad K’idilyé, strives to produce first-language speakers. h@lA shared a book chapter she wrote, describing the process of raising her three children entirely in Yuchi.

In her writing, h@lA articulated the importance of language revitalization: “Like all Indigenous languages, Yuchi reflects concepts and perspectives that simply do not exist elsewhere. Sometimes, it feels like we are up against the world, trying to save an entire worldview and way of life. My children are Yuchi-speaking miracles. By age two, they are reminding me and my husband n@gaKalA’wAdA (Don’t speak the English way)! Our children are decolonizing without even knowing the meaning of the word— they are a part of this process. It is powerful.”

h@lA also outlined the cultural significance of language revitalization efforts in improving children’s wellbeing. She writes: “in Hilo, Hawai'i, children who attended Hawaiian immersion schools had

a 0% dropout rate and a much higher level of college attendance than their non-speaking peers. In Window Rock, Arizona, children who began school in Diné and learned English as a second language performed almost two grade levels above their peers who started school in English.”

Still, she outlined her concerns about their continued fluency in Yuchi. She told me that she is “acutely aware of how fragile their language learning progress is, hearing stories of foreign children who grew up speaking their mother tongue fluently, only to completely forget it by adolescence.” She continued, “I pray to protect my children’s Yuchi-ness we have nurtured at home so, as they get older, it will not be whitewashed by English thinking and influences.”

In talking with these language leaders, I learned about some of the ethical and pedagogical negotiations language revitalization leaders must consider in their teaching practices—whether through a monolingual or multilingual lens.

Several of the Native language leaders I spoke with appeared to subscribe to an inverse of what translanguaging scholars call a deficit perspective; while a deficit lens has historically been used to argue that bilingual education will hamper children’s ability to speak English, these language leaders were concerned that English learning could detract from one’s native language abilities. Given past and present assimilationist language education practices in the U.S., this is not an unfounded belief. Language hierarchies and histories of repression are essential to unpacking the ethical dilemmas that underlie language education practices. As such, it is clear that language revitalization pedagogy is highly contextual. This incredible diversity in Native efforts to combat colonial education systems means that there is no single perfect practice.

Beyond pedagogical concerns, language learning negotiations are just as difficult on a pragmatic level. “People want to learn the language to become fluent, but funding sources are difficult,” Lopes-Pocknett told me. She continued: “How do you do immersion classes and live on a [$400/week] stipend? You can’t.”

In affluent places like Cape Cod, where the cost of living is extremely high, Hicks Greendeer estimated that “it costs $100,000 a year, per person, to teach. […] Nobody’s going to become a fluent speaker going to class once a week.”

As funding cuts further endanger public education, Native language leaders express concern about the future of language revitalization funding opportunities. Madison said, “The grants are out there, in some respect. For non-federally recognized tribes it can be even more difficult […] but right now, there are fewer opportunities for everyone given the climate of our administration.”

EMILY MANSFIELD B’27 wants to thank Nitana Hicks Greendeer, Camille Madison, Reneé Lopes-Pocknett, Warlance Chee, Jesse Rusche, Crystal Redgrave, and h@lA Turning Heart for their time and generosity.

LucyPierpont,age34,Waterbury,CT Feb18,1876:dressedoffthreechickens,and finished off two garments. Ned is ever so muchbetterthisafternoon June14,1876:WeironedandIpickeda quartofstrawberries,sewedsome Nov12,1876:Istayedwiththechildren,we boiledchestnutsthisevening

JanGenevieveBorgsteadt,age59,Euclid,OH 4, 1948: Went to Church then to Hazel’s. WeatwenttoseeTheFoxesofHarrow.Spentthenight her house Jan 9, 1948: Washed diapers and curtains weinstretched2prsFri.Eve.Riedapushthingsaway Maychest&straightenedbothrooms

Junie20,1948:Irene&babyspentthedaywithus. & John & Ruby were all there for dinner.Wehadadeliciousdinnerandstrawberryshort cake Yum Yum. Spent the Eve visiting and play-upingwiththebaby.Acutebabyjustlearningtosit 5 ½moold.Lotsoffun

Della Sears, age 19, Fort Worth, TX Jan 6, 1912: We went hunting this P.M. with Jas. It was cold we knew but little guessed how very cold. I killed two birds—one at a long range. The gun makes me nervous –it sounds so loud + kicks. Feb 5, 1912: Went to the Ladies Aid. Baked a French chocolate cake. Feb 18, 1912: All the denominations on this side of town met at our church. We had a good talk by a Ft. Worth preacher – a congregationalist. It was on the laymen’s movement. We planned a Kodaking trip. Feb 27, 1912: I put on my grey skirt + light blue + white waist, wearing a lace collar + my crochet tie + belt. B thought I looked awful cute. I had just pinned my belt when he knocked – just ready. He brought some forbidden chocolates again. I ate them of course – they were King’s assorted nuts. He left about ten. I was tired before my nap for we had washed and + then I swept the whole yard + read some of my book.

Lanie Zimmerman, age 17, West Coast

( TEXT TALIA REISS DESIGN SEOYEON KWEON ILLUSTRATION NATALIA ENGDAHL )

Alice Dunbar-Nelson, age 46 to 55, Madison, NJ and Wilmington, DE Aug 3, 1921: I put on boots, coat and hat and sallied forth. Meandered about the pretty town. Bought Helen a bottle of stick candy and an Atlantic Monthly and this book for a diary. Oct 22, 1921: Friday morning; make-up not completed, and ten hours necessary to run off the paper. All day Friday lagged. Boys came to sell, people came in, the dreary drag down stairs, the unfinished work, the linotyping still unfinished, Franklin up in Philadelphia still bringing home bits of galleys. Sept 26, 1930: Still hot. Still slow reservations. Still broke and worried. Finished up that bum story, “No Sacrifice.” Would have sent it in to the True Story contest, but concluded to wait for it to get into the October contest. Certainly is rotten.

June 14, 1981: Well, another day shot to hell! Woke up at 12:00. Went to Tanforan + met Kristy G. Funk there. Went shopping + bought this diary. Let’s see I’ll call you Mitchie. Sherley gave us a ride home + now were waiting to go see “Clash of the titan’s”, I hope it’s a good movie. Not much to write now. Hope life livens up. When it does, you’ll be the first to know Mitchie. June 17, 1981: Dear Mitchie, – Shirley came over here today @ 9:30 because she didn’t want to stay home all by herself. I think she regrets getting married + being pregant. But I know as soon as it’s born she’ll love him (I hope it’s a boy). We went to Taco Bell for lunch, then to Lucky’s to pick up a few things. She stayed till 4:00.

Ellen, age 15, Los Angeles, CA Aug 6, 1995: Today I did the same old thing. Went to church and bought food [...] Then went to the Glendale Galleria. I saw so many fine-guys. I just get depressed whenever I see so many fine guys. It means there are so many fine-guys and I can’t even get one. Not a single one! What are my choices Shawn and Alex! HA, I really do hope I meet some- one in high school or college like Eris. My life sucks. Then we rented movies. Aug 18, 1995: Oh well back to my boring life. I watched Jepordy and listened to the radio. I made chicken strips (Lemon flavored). I butchered a chicken. Talked to Shawn. The low-life creep who only cares about football, sex, video games, and burp- ing [...] I LOVE WEEZER!

We ironed and I picked a quart of strawberries Went to the Ladies Aid. Baked a French chocolate cake. I put on boots, coat and hat and sallied forth. Meandered about the pretty town. Bought Helen a bottle of stick candy and an Atlantic Monthly and this book for a diary. Washed diapers and curtains we stretched 2 prs Fri. Eve. Rieda push things away in chest & straightened both rooms Church. I watched Jepordy and listened to the radio. I made chicken strips (Lemon flavored). I butchered a chicken. Talked to Shawn. Went shopping + bought this diary. Hope life livens up.

dolls head 10

candy 4 thread 16 silk 18 ruffles 6 candy 17 eggs ribbon1212 yarn 25 tape dress10braid

Lucy 1876: CASH ACCOUNT- FEBRUARY

JanGenevieve 30, 1948: Joanne bracelet $2.40 Bring a game. Paper dolls. Clay. 2- Engraved glasses 2 Purses $200 3 Pr socks

Alice Aug 7, 1921: I must try to keep this diary going daily. I forget things. How silly I was not to keep one during the war; and on that wonderful trip out west. I’ve forgotten things that have happened; I’ve even forgotten places where I have spoken before and since those days. I’m a shiftless colored woman.

Ellen Aug 11, 1995: Spent $5 on food. I went to retail Slut. I bought 4 patches, $2.50 each (Dead Can Dance, Curve, Smashing Pumpkins and Greenday). Two of which I gave to Eris. I also bought bleach and dye, Turquoise. Spent $24 dollars there at Ozzie Dots I bought Eris a patent leather black bag and rubber bat. I spent about $15-$20 dollars on Eris’ present. Just what I wanted to spend. Unfortunately, I’m out $40 from my $60. I still want to see WEEZER or get a shirt. This sucks. Not unless I take out more money! Arggg!!!

Ellen Aug 5, 1995: Sometimes I hate writing in this journal. If I forget to write in it I lose track of what I did. I think I stayed home with the dogs.

Genevieve Feb 1, 1948: Went to church This must be the day Dick took me to Irene’s and we got the strooler for Dickie

Della Jan 29, 1912: Then we and Ernest played 42. We played against the boys & we won. We did not know anything about the game at all, but would not back out after saying we could beat them […] Barney told me of a nice little plan on the way home […] He wants me to go with him & we’ll go out to “The Cedars” and take a

Ellen July 23, 1995: The funniest thing was when these guys tried to pick Maisha up. One said, “Do you want to do something?” Maisha said, “Not with you, with her.” Then she pulls me close. Then as we walked by them I slipped my hand into her back pocket. Then those guys were grossed out. Then me and Maisha were busting up laughing.

Aug 27, 1995: I actually got a phone call from Shawn. He told me he went to the Street Fair and he saw gays and lesbians making out and Alex. Shawn is just one little gay basher.

Alice

Aug 30, 1921: A Bronx, some Pall Malls, and “Put and Take.” I lost 45¢ and the game was growing stale, we tried African Golf. At one time I was 97¢ to the good, but lost it all.

Alice June 26, 1930: A friend she was—and paradox of paradoxes—one of my worst enemies. Let her soul rest in peace. I loved her once. Twenty years ago, her death would have wrecked my life…