Masthead

MANAGING

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Talia Reiss

Nadia Mazonson

WEEK IN REVIEW

Maria Gomberg

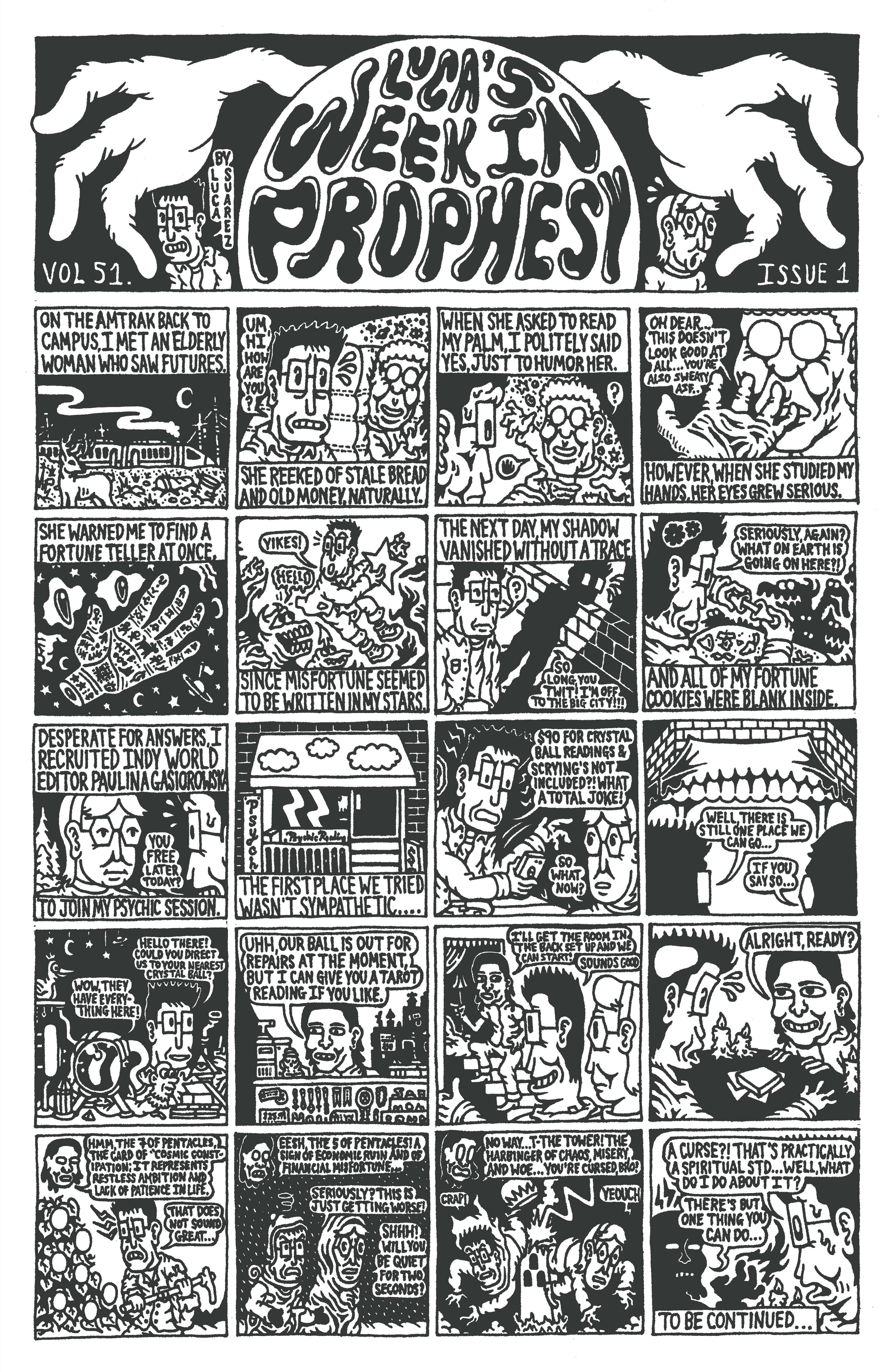

Luca Suarez

ARTS

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Martina Herman

EPHEMERA

Mekala Kumar

Elliot Stravato

FEATURES

Nahye Lee

Ayla Tosun

Isabel Tribe

LITERARY

Elaina Bayard

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Gabriella Miranda

METRO

Layla Ahmed

Kavita Doobay

Mikayla Kennedy

METABOLICS

Evan Li

Kendall Ricks

Peter Zettl

SCIENCE + TECH

Nan Dickerson

Alex Sayette

Tarini Tipnis

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Selim Kutlu

Sara Parulekar

WORLD

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Emilie Guan

Coby Mulliken

DEAR INDY

Angela Lian

BULLETIN BOARD

Jeffrey Pogue

Lila Rosen

MVP

Simon Yang

20 BULLETIN

Lila Rosen & Jeffrey Pogue

STN HOPES AND DREAMS FOR V51:

A thesaurus that works; an Arabic tutor; a bit of bisexual drama; no Daphnis and Chloe spoilers; victory in kickball (we already win at newspaper); lovingkindness; baby now; lovingconstructivecriticism; Foucarty Worldwide; to turn 20; an anti-zionist therapist; cat on the cover [TR objects]; an end table from Saver’s; legal lease; legalese; another window in Conmag; Slavic breakfast (Geek bar and carrot); the return of my MagSafe computer charger; an alcoholic low-carb Miller Lite substitute; a hairless dog; for you to kiss us we’re analog; no hurt feelings; whipped coffee; baby never; pivo (beer); 1/8 of a Market Share; a cat named Tuna meow; a summer internship; a grill and someone who knows how to use it; a full slice of pizza.

DESIGN EDITORS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Kay Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

DESIGNERS

Millie Cheng

Soohyun Iris Lee

Rose Holdbrook

Esoo Kim

Jennifer Kim

Selim Kutlu

Jennie Kwon

Hyunjo Lee

Chelsea Liu

Kayla Randolph

Anaïs Reiss

Liz Sepulveda

Caleb Wu

Anna Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Hisham Awartani

Sarya Baran Kılıç

Sebastian Botero

Jackie Dean

Cameron Calonzo

Emma Condon

Lily Ellman

Ben Flaumenhaft

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Maxwell Hawkins

Mohamed Jaouadi

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nora Rowe

Andrea Li

Cindy Li

Maira Magwene Muñiz

Kalie Minor

Alya Nimis-Ibrahim

Emerson Rhodes

Georgia Turman

Ishya Washington

Jodie Yan

Ange Yeung

ALUMNI COORDINATOR

Peter Zettl

SOCIAL CHAIR

Ben Flaumenhaft

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR

Tarini Tipnis

FINANCIAL

COORDINATORS

Constance Wang

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Lily Yanagimoto

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Mia Cheng

Natalia Engdahl

Avari Escobar

Koji Hellman

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Jiwon Lim

Yuna Ogiwara

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Angelina So

Luna Tobar

Ella Xu

Sapientia Yoonseo Lee

Serena Yu

Yiming Zhang

Faith Zhao

COPY CHIEF

Avery Liu

Erica Ma

COPY EDITORS

Tatiana von Bothmer

Milan Capoor

Jordan Coutts

Raamina Chowdhury

Caiden Demundo

Kendra Eastep

Iza Piatkowski

Ella Vermut

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

Lea Seo

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Sofia Guarisma

Erin Min

Dominic Park

Liz Sepulveda

Brooke Wangenheim

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Ivy Montoya

Eurie Seo

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Avery Reinhold

Angela Lian

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Lian

Jolie Barnard

Luca Suarez

Nan Dickerson

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

*Our Beloved Staff

MISSION STATEMENT

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

Spine Not Found

BUILDING COMMUNITY AND COLLECTIVE ACTION AMIDST BROWN’S CONCESSION TO FASCISM

c What do you do when your university concedes to fascism? Amid the Trump administration’s mass surveillance and incarceration of the immigrant community, repeal of protections for the LGBTQ+ community, and federal elimination of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, marginalized people, on and off campus, are confronting increasingly hostile environments. In contrast to prior commitments to diversity, Brown University has announced a deal with the Trump administration, sacrificing its most vulnerable students for monetary gain.

Under the terms of the agreement, the federal government will unfreeze $510 million in federal funding that it stripped from Brown in April due to the University’s DEI initiatives and alleged antisemitism on campus. It will also restore all previously terminated grants from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the National Institute of Health. Additionally, the HHS, Department of Education, and Department of Justice will end their compliance reviews into the University for Civil Rights Act violations related to alleged discrimination and consideration of race in admissions and financial aid.

In exchange, the University adopted the government’s definitions of “male” and “female” as outlined in Executive Order 14168 for the purpose of its athletic events. The order states that gender identity “does not provide a meaningful basis for identification and cannot be recognized as a replacement for sex” and defines sex as “an individual’s immutable biological classification as either male or female.” It goes on to describe transgender identity as “the false claim that males can identify as and thus become women and vice versa.” In sum, the order fundamentally denies the existence of trans and non-binary identities.

In addition to accepting the aforementioned definition of gender, the University will not provide gender-affirming care to minors. Very few minors are enrolled at Brown, the NAACP already enforces sex-segregated events, and the University has always provided access to single-sex residence halls and bathrooms. Still, the University’s willingness to adopt the definition and participate in the transphobic culture war that denies trans kids life-saving healthcare demonstrates a startling disrespect to the University’s queer population.

Brown has also reinforced its institutional commitment to Zionism, demonstrated by its refusal to divest its endowment from companies contributing to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, as well as its Israel Fund, an initiative that promotes a “deeper focus” on Israel. The agreement with Trump explicitly calls for “renewed partnerships with Israeli academics” and efforts that encourage “research and education about Israel.” The University’s willingness to work with institutions that the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement notes are “major, willing, and persistent accomplices in Israel’s regime of military occupation, settler-colonialism, apartheid, and now genocide” signifies a disregard for Palestinian life and Brown’s Palestinian students.

The Brown-Trump agreement concludes with the University’s commitment to admission policies that exclude considerations of race, skin color, or national origin. It further prohibits Brown from implementing affirmative action proxies, conflicting with the University’s previous commitment to determine strategies “for recruiting, admitting, and

yielding a talented, diverse student body” following the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down affirmative action in 2023.

Garrett Brand B’26, who works as a Minority Peer Counselor with the Brown Center for Students of Color (BCSC), stated that the federal government’s hostility to diversity initiatives has contributed to a “sense of being in survival mode from within the BCSC,” describing that he has felt pressure to make programming and workshop materials “as perfect as possible.” Brand added: “Seeing admin making deals with the Trump administration and being willing to give up the rights of some students, like trans students, etc., is really scary, especially for people who’ve been around the BCSC for a long time.”

In an August letter to the Brown community, Paxson wrote that “Brown’s firm and long-standing commitment to treat all members with dignity and respect” remains unchanged by the deal. But a university that has previously prided itself on “sustained, strategic commitment to strengthening diversity and inclusion on campus” must do more to prove its commitment to students. +++

Throughout the University’s history, students have pushed Brown to be the institution that they have needed it to be. Identity centers on campus are rooted in this legacy of student resistance. The BCSC was established in 1976 after a string of student protests, beginning with a 1968 Black women–led walkout Students had also demanded increased enrollment and hiring of people of color, along with more supportive resources for students of color. Similarly, the 2004 creation of the LGBTQ Resource Center resulted from advocacy by the Queer Alliance. Today, both identity centers provide a place for empowering the community at Brown.

In the past year, the centers have contended with increasingly hostile environments. Paulie Malherbe B’26, who previously worked as a Gender and Sexuality Peer Counselor (GSPC) for the LGBTQ Center (based in Stonewall House) and the Sarah Doyle Center for Women and Gender, described the LGBTQ Center’s intention to create a “safe space for everyone but particularly for queer students.” They noted that this work has become more complicated due to increased enforcement of the University’s Nondiscrimination and Anti-Harassment Policy, which prohibits campus organizations from hosting exclusionary events. “There’s now danger around even branding an event as being for a specific community,” they said.

Given the federal government’s hostility toward queer and trans people, Malherbe views the LGBTQ Center as “more necessary than ever.” Programming at Stonewall House has shifted to reflect the changing political climate. Discussions led by the GSPCs has transitioned from broader themes of gender and sexuality to “giving people the space to actually try and figure out how to tackle being in an institution that isn’t always on their side and being in a country that doesn’t want them to be there,” said Malherbe. They added that there are “people who I think could learn a lot from hearing different perspectives, particularly from queer people of color or queer people who were not born into immediate wealth.”

For Brand, the BCSC’s work is crucial to this

( TEXT LAYLA AHMED, KAVITA DOOBAY, MIKAYLA KENNEDY DESIGN CALEB WU ILLUSTRATION BENJAMIN NATAN )

moment. “There’s a ton of demand for the programming that the BCSC provides […] even as enrollment numbers of students of color are shrinking,” Brand stated, referencing the over 200 students who signed up for the BCSC’s pre-orientation program this year, which he helped facilitate.

David Mathis B’27, who attended the Third World Transition Program (TWTP) as a freshman and helped to lead it this year, regards the program as a space for forging an empowered community at Brown. “We as a community of color know that, especially in times like this, we will stand up for each other and create the kinds of spaces that we thrive in and that we can actually honor our identities in,” they said. They described TWTP as “us creating the world we would want to see.”

Brand said that among the freshmen he interacted with, “there seems to be a heightened appetite to engage in political work.” He’s hopeful about “the ability to harness and nurture” this appetite in order to respond to the Trump presidency. Recalling the protests of the ’60s and ’70s that led to the creation of the BCSC, Brand said that he “thinks it’s important to have that sort of ethos back.” In his view, the sevenmonth-old union of BCSC student employees, called the Third World Labor Organization, “inherently restores some of the political animus into the BCSC.”

This politicization is largely absent from centers like the BCSC, which are managed by the Division of Campus Life Engagement. As an administrative unit of Brown, the BCSC is prohibited from political participation in compliance with the University’s Political Activity Policy. This policy prevents the University’s likeness from being used to maintain its 501(c)(3) nonprofit status. According to Brand, concerns related to censorship of students’ work, predominantly related to discussions around Palestine, motivated the union’s formation.

History reminds us that room for organizing outside of identity centers is vast. Although the centers embody student-driven change, their existence does not signify an end to injustice, nor does it pacify student movements. In March 1976, a month after the opening of the Third World Center (TWC, the BCSC’s original name), students of color held a rally proclaiming the need for adequate financial aid and protesting the insufficient action that had been taken to fulfill the University’s 1975 agreement, which followed a 38-hour occupation of University Hall by students of color. The occupation resulted in Brown’s commitment to increasing the admission of Black students by 25% over the following three years, increasing the number of Black and women faculty over the following five years, and increasing funding for the Afro-American Program (now Africana Studies).

Mathis said that while working at TWTP this year, they felt a tension between expressing their political values and the apolitical nature of the center. “It was really difficult to simultaneously hold my beliefs and also respect, honor, and protect the space that I love so much,” they said, adding that the tension “is also a product of the agreement and the broader political climate that exists today.”

+++

As students, we have a collective responsibility to build our own networks of care in place of the University’s failure. The Filipino Alliance’s fight

to establish a Tagalog language program at Brown embodies this responsibility. Alexa Theodoropoulos B’27, Filipino Alliance’s (FA) vice-president, describes the work of the FA as not just a fight for increased representation, but as work that forces students and community members to confront Brown’s own history of empire, including its participation in the United States’ colonization of the Philippines.

John Hay, who graduated from Brown in 1858 and worked as Secretary of State during the PhilippineAmerican War, largely orchestrated the United States’ colonization. “Although it’s framed in history books and by John Hay himself as a ‘splendid little war,’ as part of America’s global expansion of power, the reality is that it was a genocide. Millions of people were killed. They were slaughtered,” said Theodoropoulos. The John Hay Library retains Hay’s personal artifacts, which contain materials from the colonization.

In addition to bringing attention to the connection between the University and colonization, the FA is working to raise awareness of Brown’s complicity in expanding American imperialism. “Having

conversations with your peers about this is so, so powerful, [in addition to] making sure people are not silent about Brown’s history of empire,” Theodoropoulos said. When asked whether the FA’s work focuses on reform inside or outside the institution, she replied, “We definitely have to balance both, but I personally don’t think we should stay quiet when Brown is misbehaving.”

Caring for our community—both at Brown and in Providence—necessarily includes advocacy for marginalized members. In addition to FA, dozens of student groups are working toward issues including educational equity, environmental justice, deportation defense, reproductive justice, and workers’ rights. It is also crucial to counter the effects of Trump’s policies on the greater Providence community. Organizations such as ARISE and AMOR Rhode Island—which work toward educational equity and immigrants’ rights, respectively—are great places to start.

Brown’s increasing inability to protect the student community cannot lead us to despair but rather to action. When we cannot rely on the

University to consistently uphold our values, we must harness our power to create a community that we can be proud of.

LAYLA AHMED B’27, KAVITA DOOBAY B’27 and MIKAYLA KENNEDY B’26 want you to have a stake in your community.

Students protesting the University's lack of action in fulfilling commitments made to increase student and faculty diversity a year prior, a month after the opening of the Third World Center in 1976 (Brown Daily Herald Archive)

HOW TO CONTACT YOUR FRIENDS

AND SYMPATHETICALLY INFLUENCE YOUR NEIGHBORS

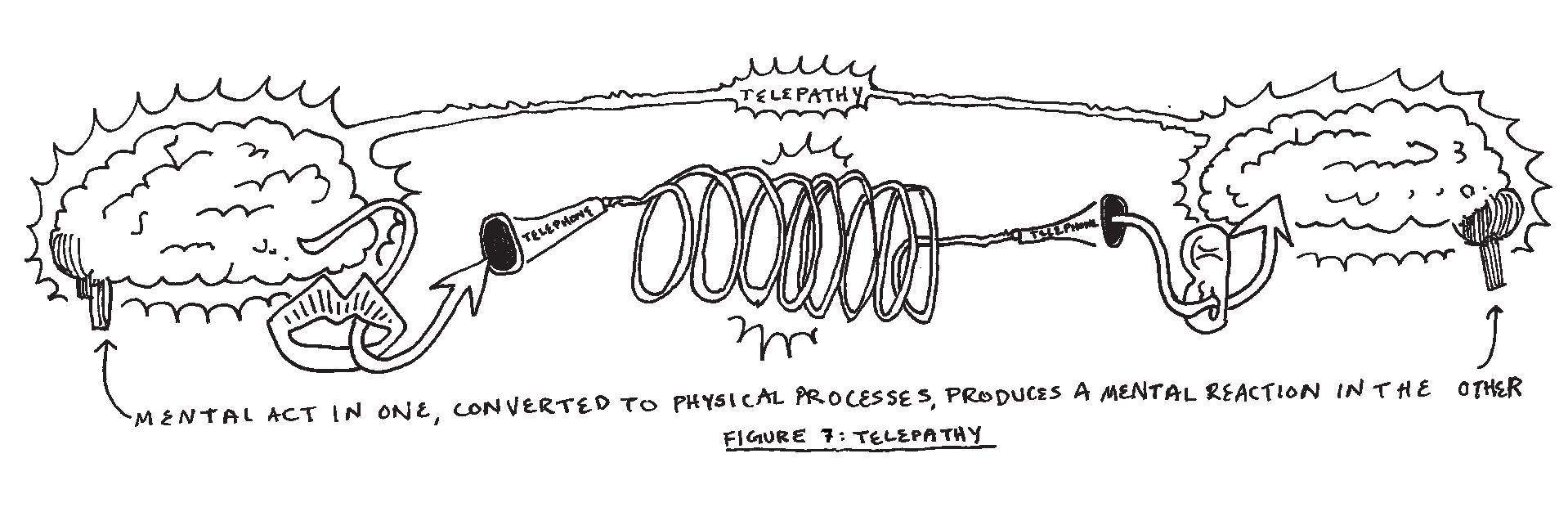

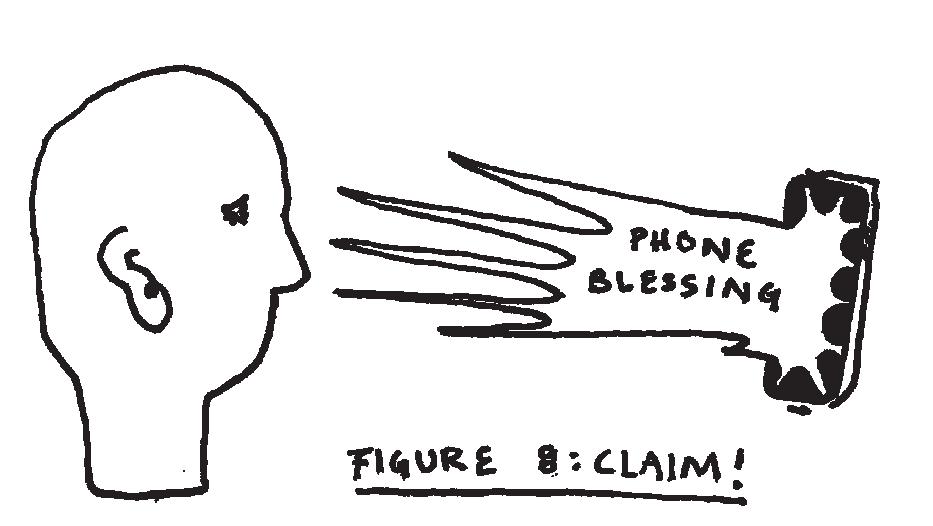

c Do you know how the telegraph was invented? Do you want to learn? Can you do any magic tricks? Do you want to learn? Write “CLAIM” in the margin of this article to see more.

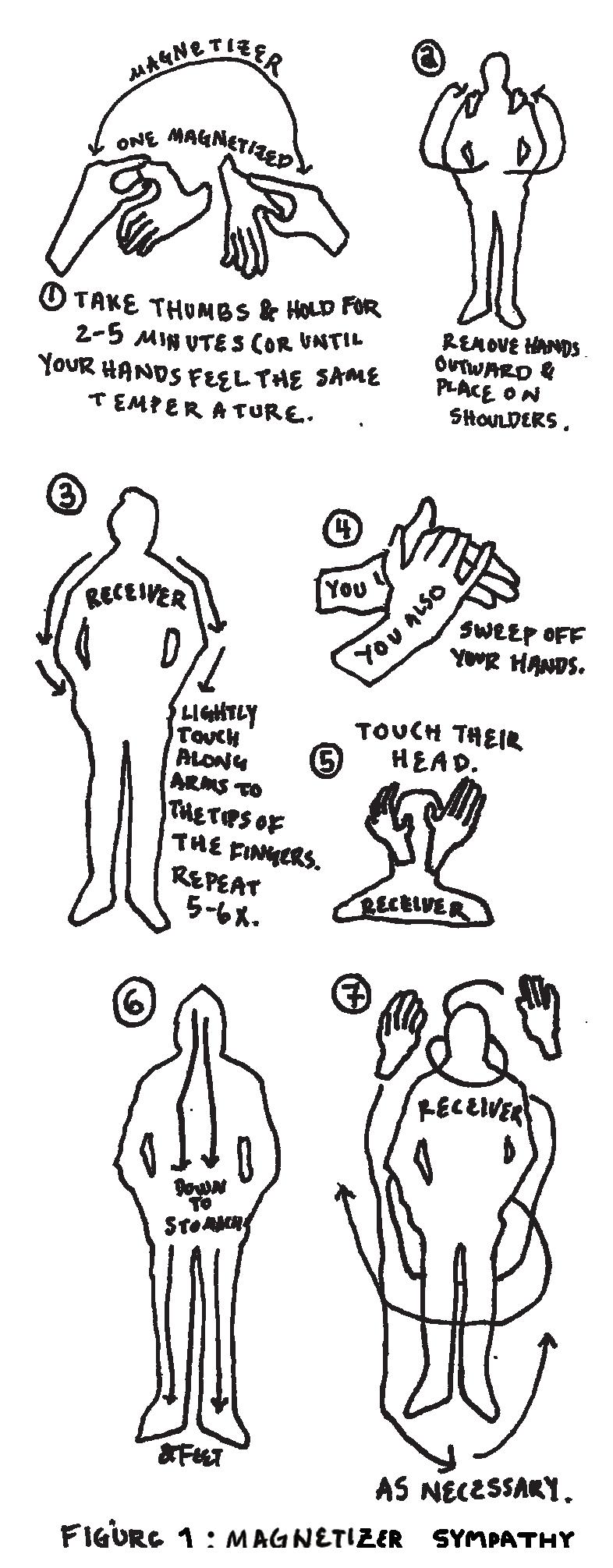

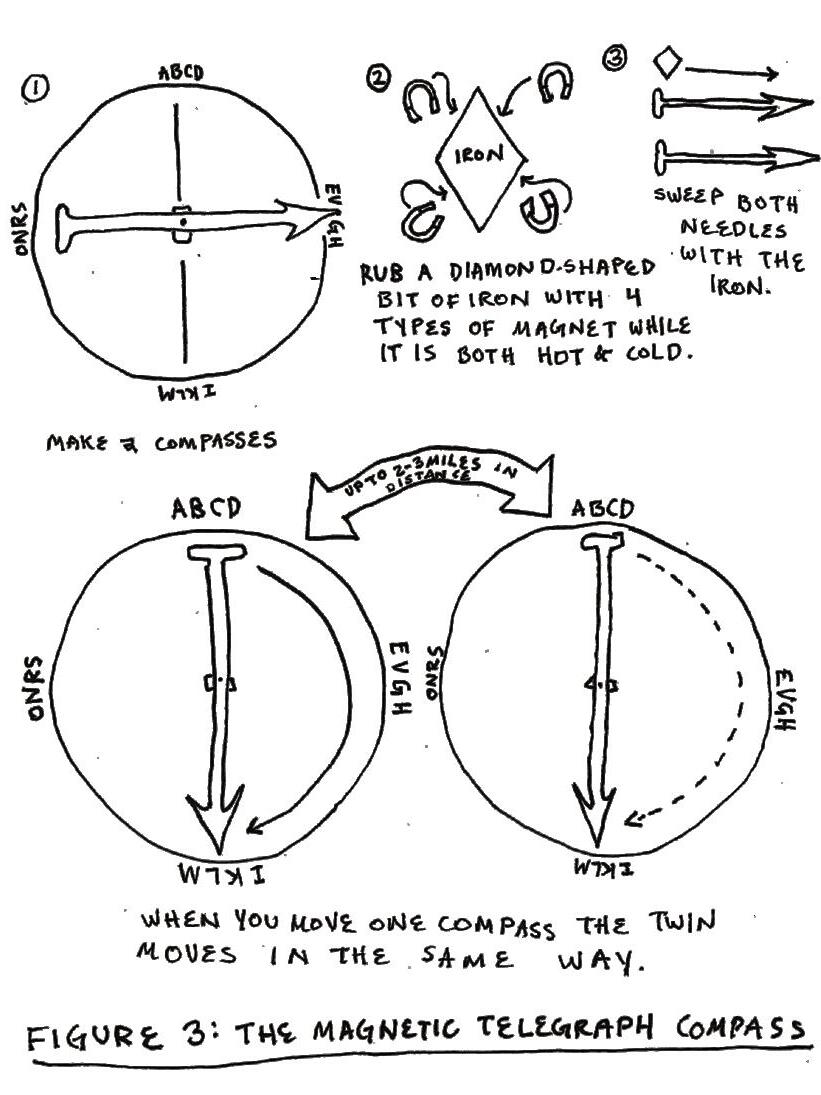

Animal magnetism—proposed in the 1700s by Franz Mesmer (like mesmerized)—contends that all living things are imbued with a vital principle, which courses through animals, vegetables, and humans in the form of an energy current or “magnetic fluid.” In the 1879 edition of Practical Instruction in Animal Magnetism, the naturalist Joseph Philippe François Deleuze outlines relevant principles. Magnetic fluid lets two people communicate at a distance if the communicator has the proper fortitude and confidence. Communication also requires both people to share a “physical sympathy”; the magnetizer takes the receiver’s hands in theirs and performs a number of gestures on their body (figure 1). Proper command of the fluid could cure manifold ailments in the receiver, from sleepwalking and deafness to “mental alienation” and gout.

One might think to dismiss this as the magical rambling of pre-scientific thinkers. This assumption is complicated by the emphasis magnetists like Deleuze put on the scientific method. Deleuze was seeking empirical proof for these techniques, though he noted that the “nature of this fluid is unknown; even its existence has not been demonstrated; but everything occurs as if it did exist.” The proponents of magnetism were often scientists themselves; Mesmer was a physician with a keen interest in astronomy, and he built his theory off of post-Newtonian models of aether and sensation. Occult obsessions and scientific experimentation were not (and, perhaps, are not) such cleanly-separable topics.

( TEXT NAN DICKERSON

DESIGN SEOYEON KWEON

ILLUSTRATION NAN DICKERSON & LUNA TOBAR )

This shouldn’t surprise us; acting on a distant object or receiving information from an unseen source is a bit like doing magic. Magnetists in the 18th century were building on earlier thinking by magicians working out the mechanics of action and knowledge-gathering done from a distance. In the 17th century magicians, scientists, and magician-scientists used small-m magnetism to affect far away objects and bodies.

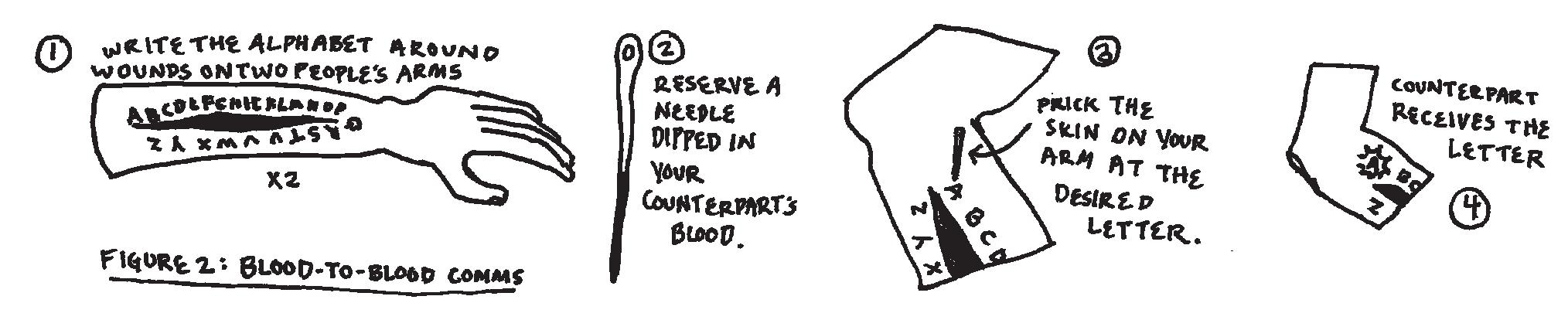

In his 2022 genealogy of early modern instant communication, academic Christoph Sander starts with the magician Giambattista della Porta, who mentioned a magnetic communication method based around a “sympathy of the blood” in 1558 (figure 2).

Della Porta references magnetic communication by compass, but he doesn’t get specific. Detailed descriptions of the magnetic telegraph came in the writings of professor Daniel Schwenter, who began publishing material about long-distance communication in 1616. He includes specifics about the compass, but his language is intentionally obscure (in order to screen off such skills from the hoi polloi). See figure 3.

Contemporaries of these dial-a-letter magnetic telegraphs were well aware of how magnetic fields worked. If you’ve got two magnetized needles nearby each other, the movement of one needle will cause the second to move in response because the magnetic fields are near enough to interact. The key words here are “near enough.” Other 17th century scientists (including Galileo Galilei) wrote criticism along these lines, and laughed it up at the compass-advocates’ expense.

From the start, practical attempts at telegraphy and occult methods commingled. Schwenter and his contemporaries understood their work not as

telegraphy (that term was coined in the 1700s) but as cryptology, or the art and study of secret codes. Schwenter doubled down on blood-to-blood communication by way of alphabet skin (à la della Porta), but also described a 1616 design for an optical telegraph. This telegraph is simple when compared with his other applications of magnetism; one person would use a telescope to see light signals sent at a distance. Unlike the magnetic telegraph (figure 3), optical telegraphy actually worked. There isn’t a neat separation in Schwenter’s writing between an early optical telegraph (which would eventually evolve into a more modern invention) and the magnetic telegraph, which is a magic trick. He regarded both as applications of magnetism.

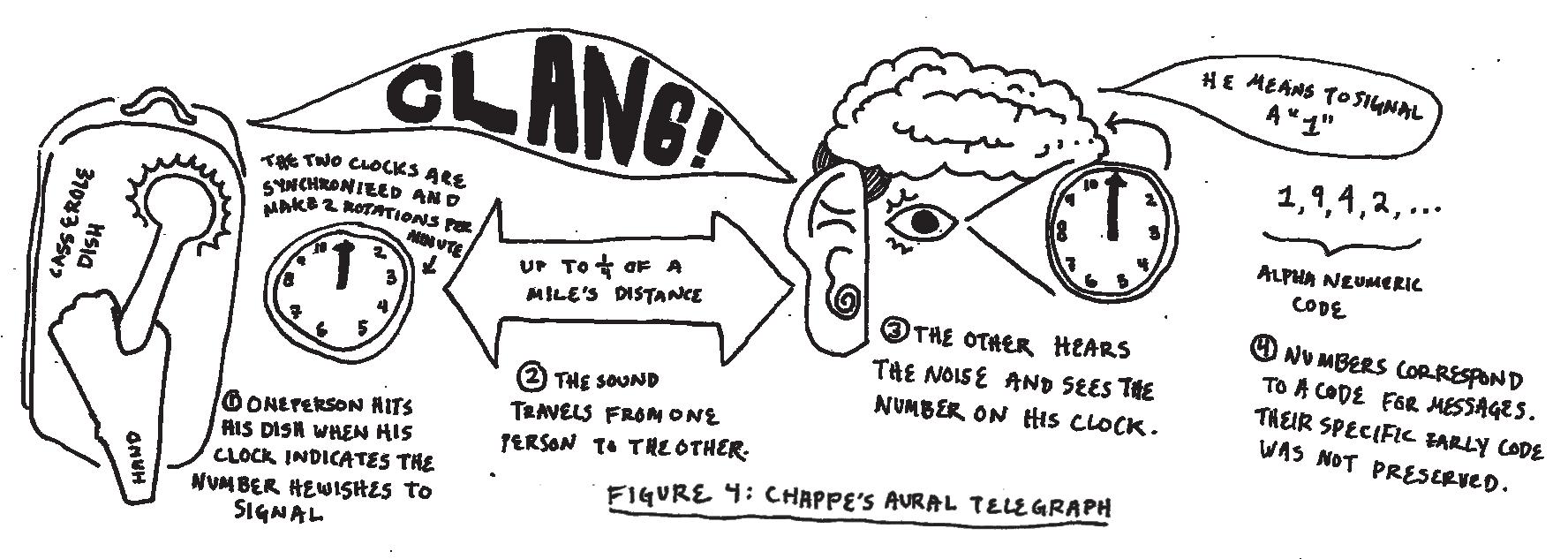

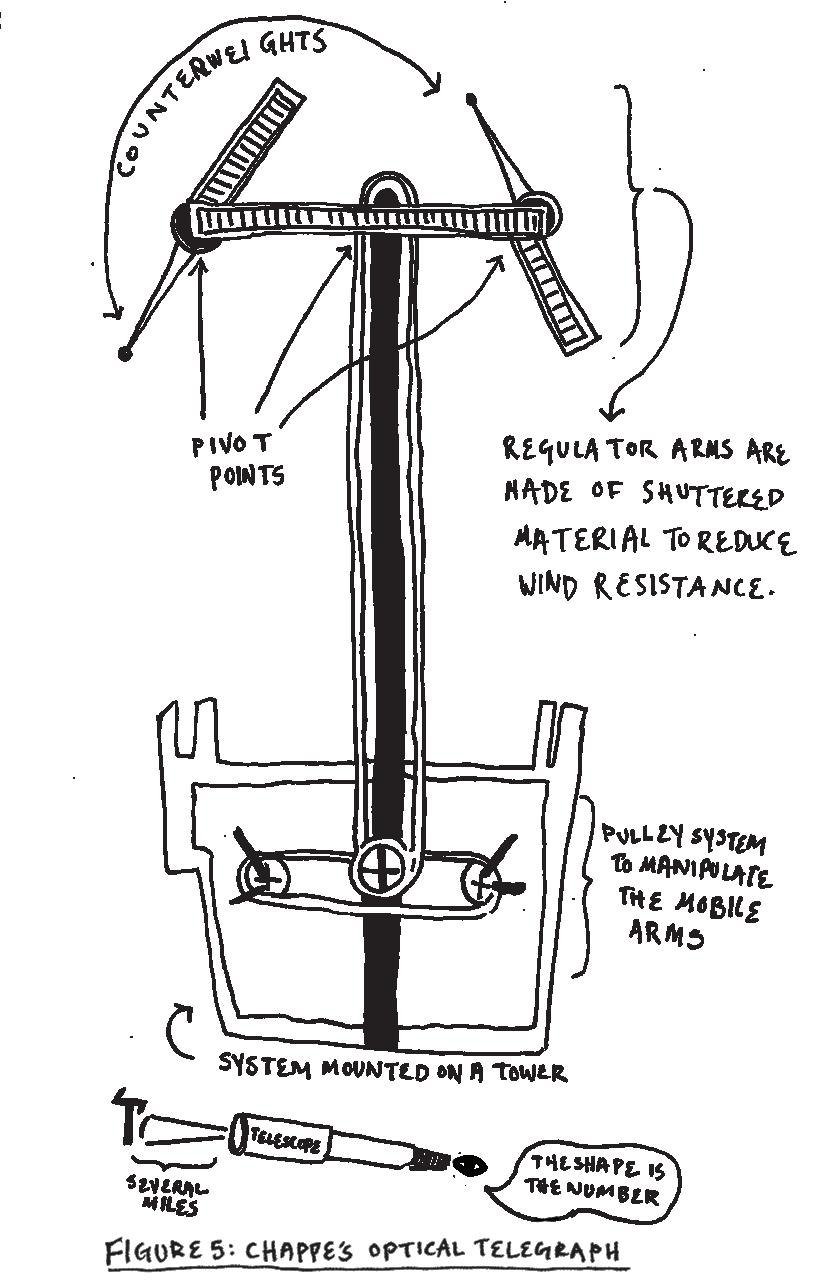

The optical telegraph—a signal system within eyeshot—has been invented and reinvented since before Schwenter’s time. The most advanced version was produced in 1791 by Claude Chappe, though his first attempt was aural, not optical (figure 4).

Chappe soon realized earshot was far shorter than eyeshot and switched to a telescope pointed at a signal system to replace the clang and the clock. Instead of one person hearing the auditory signal and recording the clock’s number, a person would look through a telescope and record the visual signal. Chappe’s final iteration was a series of arrangable arm devices mounted on towers in lines (figure 5).

They could communicate over hundreds of miles by passing messages from one tower to the next. The shape of the arms indicated a number in Chappe’s telegraphic code (this has been cut for space but you can look up the one they preserved at Saint-Marcan). These numbers were interpreted using a series of code books: one number would signal the page, and the next number would signal the line containing the relevant phrase. The modern telegraph was born.

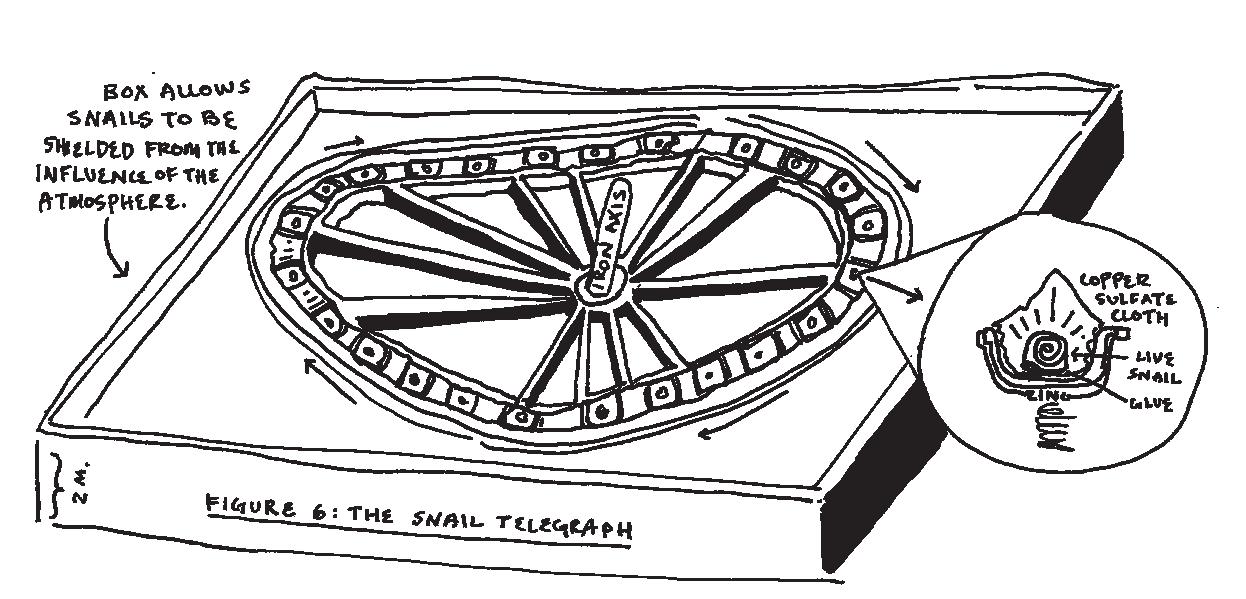

The occultist Jacques-Toussaint Benoît made his own attempt at long-distance communication in 1850 (note well: the electric telegraph was patented

in 1837). Benoît’s pasilalinic-sympathetic compass worked around his claim that two snails, once they were brought into sympathetic contact (read: a sexual encounter…), had a lifelong bond that could be used to communicate over great distances. This invention was covered in La Presse by credulous and eventually asylum-bound journalist Jules Allix, who called this telegraphic-telepathic correspondance “galvano-magnetico-mineralo-animalo-adamical sympathy.” Right.

To execute these snail comms, Benoît used a massive wooden apparatus that I will attempt to illustrate below, though I’ll plead that accounts of the machine’s specifics differ (figure 6.)

The device corresponded to an identical one in America owned by Benoît’s interlocutor, one American “Monsieur Biat-Chrétien.” Benoît claimed he and Biat invented the device simultaneously. Perhaps these men, too, had a sympathetic link. Biat’s first name is not recorded, probably because he did not have one—semi-contemporary accounts agree that Biat did not exist. Nonetheless, Benoît would dial a given letter on his Parisian snail wheel, and its corresponding partner in America would indicate that letter to “Biat.” Escargoic communications crossed the Atlantic from one French occultist to his imaginary American friend. The incident was not reported seriously anywhere other than in La Presse

This simultaneous snail telegraph invention was a fabrication, but 13 years earlier, the real electric telegraph had been invented (nearly) simultaneously in England and America. Instead of sending signals confined by eyeshot (as with Chappe’s system), electrical pulses were sent by batteries along wires to receivers. These signals worked during the day and the night, and could travel further than the eye could see. The main people involved were Samuel F. B. Morse, Professor Leonard Gale, and Alfred Vail in America, and William Fothergill Cooke and Professor Charles Wheatstone in England. The two parties got patents within a year of each other, though the Brits got there first.

It was difficult for either group to get funding for an invention that seemed so much like a rerun of invisible magnetizer communication. The public understood how the optical telegraph worked—in comparison, the electrical telegraph seemed like a magic trick. In 1843 (after rejections in ’37 and ’38), Morse advocated in front of Congress for national experiments concerning the telegraph. He was almost laughed out of the chamber. Still, a bill to fund a national telegraph narrowly passed, and, after some more friction, the system became mainstream. The Magnetic Telegraph Company radiated out to cover America, and Western Union built a transcontinental line by 1861. Messages that once took weeks could be sent from New York to California in seconds. The Pony Express had been replaced by instantaneous communication. Say goodbye to all those horses!

Things would speed up even further by the late 1800s, when the radio and the telephone became more viable options for efficient long-distance communication. Gleaning information from distant places was no longer the province of seers and mystics; it was the province of everyday people. In other words, the public learned to operate and accept an electrical instantiation of an occult idea: casting information over great distances or seeing into far-away places. The mystic operator here, though, was speed. Things became quicker and quicker: Morse code takes time, speaking on the phone takes less time.

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud had something to

say about this, as usual. Back when the telephone ran only on wires, Freud was already theorizing the relationship between physical communication systems and telepathy. In his Lecture XXX, “Dreams and the Occult,” he contended that psychoanalysis would eventually reach the level of telepathic influence. He meant real brain-tobrain communication, but he did permit that such a mental act could be transferred from one person to another by an intermediate physical system—like, for instance, a telephone. The scholar J. Hillis Miller pointed out that by including these physical intermediaries as conduits for mental connection, Freud effectively renders the telephone a telepathic device (figure 7).

By Freud’s description, it would seem that telepathy has now become commonplace. Miller notes that experiments to prove telepathy aren’t as frequent in our time as they were in the ’90s: “We have telepathy as an ordinary part of our lives, so spiritualism proper does not concern us all that much.” We may not have direct access to the minds of others but we do have hearing and seeing at almost any distance. More than that, we have it high-speed and on-demand.

You don’t even tune into your favorite electromagnetic wave with a TV antennae anymore. The massive, pulsating world of information and on-demand whatever is out there for you to tap into from your phone or computer. You can beam into your friend’s room or watch a sports game countries away. Video and audio communication is one piece of an internet riddled with the occult. Technological record means that the dead can even speak from the grave. Online video and audio files preserve their specters forever, only a few clicks away (instant playback!). Even though these records are easy to explain logically, they still feel like a haunting.

The analogy between occult spheres of influence and the modern internet isn’t such a strange one. I’ve tried to ground it in this historical genealogy of early internet systems, but occult-internet crossover is also present in tech parlance. We speak of “portals,” shibboleth software, and ether(net). One example that gets under my skin is the software corporation Palantir. If you don’t know, the term Palantír originally referred to a magical seeing stone from the Lord of the Rings. We already speak of the internet in occult terms.

Many of us also treat our pocket technology in lightly magical ways. My ecofeminist friend and my Eastern Tennessee grandma both cover up their TVs when they aren’t in use. These shrouds are a kind of prophylaxis against the TV’s aura, like flipping mirrors to ward off scrying eyes. You might keep a cover on your laptop camera to ward off the prying gaze of surveillants. My roommate leaves her phone in the other room at night, which promotes better sleep (at least my dad keeps telling me that), but another way to say this is that your phone creates an ambient negative psychological effect in your bedroom, even without the blue light. Doesn’t that sound kind of like a spell?

More frightening versions of these techno-occult behaviors can structure hyper-online insular communities like QAnon, where “decoding” is the terminology for the interpretation of cryptic information posts (called “QDrops” or “QCrumbs”) to glean information about the shadow government or the coming apocalypse. I see the same tea leaf reading in r/wallstreetbets or r/GME, spaces where the repetition of a tiny insignificant shape on a stock price graph in the past is interpreted to portend a large price movement in the future. I went to double check that people still post in r/GME, and immediately saw someone posting about investment advice that came to them in a dream

This can descend (or evolve?) into full blown techno-spirituality. The algorithm of a given app or website puts videos and photos on your feed, chosen for you by a system that’s often kept secret to preserve competitive edge. There’s already something

divinatory about this, and some creators make this algorithm the center of their occult practice, feeding users some iteration of: “if you see this video, it was meant for you.” You can receive tarot readings, healing spells, and indications of the future from TikToks or Etsy witches (figure 8).

You can have your energy cleansed by a stranger through the sympathetic portal of your screen—not

so far from animal magnetism after all. These people are also happy to scam you out of a lot of money, so be alert to that. To be fair, some tech bros are also happy to do this as well. Watch out for that rug pull…

The modern internet is part of a lineage of communication systems that began and remain occult. Can this help us understand our present relationship with information exchange? On one level (if the occultists in our readership will permit me) the occult and the internet are both man-made. They are also greater than one individual’s agency or inventions alone. Although the internet is supposedly becoming agentic (depending on who you ask in AI-hype spaces), it’s been somewhat agential or autonomous for a while now. A massive, unseeable network of information hangs somewhere between the sky, the ethernet cable in your house, and the submarine communications cables in the ocean. We access it through medium devices, just like psychics, or telephone operators and telegraphers—conduits through which information passes at a great distance. The ambient presence of this divination-on-demand looms large in our collective psyche, and yet its operational principles are often opaque. We have all, in some sense, become occultists.

This frame of analysis should not be overstated. The difference between occult divinatory practices and telecommunication is that my scrying attempts have all failed, but my emails always go through. In the case of the spirit realm and the internet, the same truth is important to remember: you can’t actually live there. We all live on planet Earth, and the resources and labor that underpin the tech we use are a product of exploitation and dwindling time on the climate clock. Yeah, you’ve gotten to that part of the Indy article. The internet really functions, it’s really real, and there are real humans—and, more importantly, corporations—that make decisions about how technology operates in all of our lives. We are also those humans. An application’s algorithm may function like a modern divinatory practice, or it may give you a healing blessing, but it’s also harvesting your oh-so-valuable data. Don’t get me wrong—I like being linked up to a pulsing web of information, and I love to look at images on the internet. I use my cellular phone all the time.

Please do not hex me. I am moving through a lot right now.

NAN DICKERSON B’26 is looking into speed.

1. Illustration references are from Wireless Optical Communications by Olivier Bouchet, Practical Instruction in Animal Magnetism by J. P. F. Deleuze, Christoph Sander’s article in the Journal of Early Science and Medicine, and translations by Justin SmithRuiu in Cabinet magazine. The rest come from my imagination and questing spirit.

( TEXT ALYA SOPHIA NIMIS-IBRAHIM

DESIGN CHELSEA LIU

ILLUSTRATION KOJI HELLMAN )

ةعدب

Bid ah Innovation, heresy ʿ

I saw in his eyes what he was telling me. He was telling me what the bikers and the man behind the glass told me. My presence was neither surprising nor obscene. I was unremarkable. There was no distinction between us.

c The kid got back from her shift late that night. Silence hung between her steps, heavy on the creaking floorboards. Grandpa wasn’t home. She dropped her clothes on the floor, took a shower. Every part of her slick with filth except her hands, bleached raw. Sunk into bed, drifted off. Bobbing on the surface of consciousness she heard Grandpa stumble up the stairs. Then back down into darkness, just for a moment.

The next morning the kid cracked an egg into the scooped-out center of a slice of bread frying on the stove. Cowboy toast, Grandpa called it. When she set the tray on his bedside table, he put a hand over his eyes and grunted.

You alright, Gramps?

Yeah, yeah, I’m alright. His words curled thick with a sour smell.

Want me to take off your boots?

Yeah, go ahead.

The kid tugged off each boot and sat in the wooden chair by the bed. She helped Grandpa get his head up against the bed frame. He reached for the tray she had brought him.

Alright, go get on with your day, he said.

I don’t have anywhere to be. Grandpa ate his toast and the kid opened the windows. You dream at all last night? Grandpa asked. No. You woke me up coming in.

I dreamt. Can’t remember it now though. How’d you feel waking up?

Scared.

Hm.

Grandpa poked at the last of his eggs. You gonna tell me something?

A breeze swirled through the windows, mixing with the stuffy air. Mosquitos drifted into the room and buzzed around them.

Okay.

Tell me about being scared and how you fix it. Alright.

The street was dark, silent save the slide of my sandals. My toe brushed against matted fur. A cat on its back. One milky eye gleamed under the moon’s cheshire crescent. Its stiff body skidded across cement. A car stopped for me when I paused at the place where the sidewalk jutted out over the road. The thing in my chest leaped and pressed itself against my ribcage. The man in the glass window was a stranger. I was at the mercy of his right shoe, resting on the gas pedal. I muttered to myself as I stepped off of the curb.

There is no god but God. I seek refuge in God. God protect me.

The man restrained himself, and I passed before him.

I approached a bridge that arched over the inky canal. A tent shook in the ditch along the water’s edge. I inhaled. Two bikes emerged. Each biker held something in his hands. Black poles, thick black snakes swallowing each pole’s end, writhing as the bikes traced winding shapes across the road. Whips, I realized. They laughed and moved toward me. I saw it clearly: slashing my skin, ripping cracks of marbled fat and muscle across my arms.

They breezed past me.

I crossed the bridge. A small, glowing form trotted toward me. A fox, holding a mass of fur in its mouth. He kept to the right and did not deviate from his path as he passed me. He nodded curtly to me, a perfunctory acknowledgement.

I straightened my back, my broad chest glowing naked in the blue street lights. The muscles of my abdomen cast shadows across my skin, shifting with each stride. I passed another man and lifted my square chin to him, smirking with the certainty of the nod I elicited from him in response. The sidewalk moved with me, propelling me forward. I was not a woman, I realized. I was a man.

A familiar rhythm blasted from the speaker of a parked car, illuminated haze drifting from the open window. I chanted along, gesturing as I stepped in time to the beat.

I’m loading up my clip, got a plan for tonight

A glock in my hand, in my pocket is a knife

I’m looking for a victim pushing keys on the scheme

I wanna make a stain for a million ride clean

The man in the car smiled at me like an old friend.

Grandpa was silent when the kid finished speaking. He stared up at the white-speckled ceiling. No, I didn’t like that one. That girl was still scared in the end.

The kid cleared her throat. Whatever. Let me get you more water, Grandpa. She took his tray downstairs, filled his cup in the kitchen sink, brought it back up to him.

He wet his lips. My earth cannot contain me, and my heavens cannot contain me, but the heart of my believing servant contains me. Ever heard that one, kid?

Yeah, but you can’t just say all that without an introduction or anything. Oh, come on, a translation doesn’t count. Grandpa chuckled. Look at this, kid. Grandpa shifted in his bed. He pointed at each window in the room. One, two, three. He brought his hand down from his forehead and touched his chest, left shoulder, right shoulder. One, two, three. Three is the outer limit of few and the inner limit of many, he said. Translate it for me.

You’ve already translated it.

No, give me a better translation.

The kid nodded. She rocked each thigh up to sit on her fingers.

First there was a book, and then another, and then a third,

and the ones who believe in this third book say it is the completion. The ones who believe in the second say the second is the completion, and the ones who believe in the first say that the first was complete in itself. They say there is no need for Three when you already live in the perfect wholeness of One, or in the intimate love shared between Two. How can Three lay any claim to unity? The only path to unity is along that limit between the few and the many. Following that limit as it approaches its asymptote, Three expands and projects itself onto the infinite, onto Everything. When the third becomes everything, it becomes One again; there is only one Everything. The third completes itself, and the first and the second cannot negate it, nor can the fourth or the fifth negate it, because none of them are pieces, none of them are incomplete parts of a whole. One cannot be multiple. Anything that is contained within One must also contain all of the One and not just a part of it. There is only multiplicity in One when it holds itself apart, making One into a fragment and fracturing the possibility of true Oneness. There is only Oneness in Three when the Three releases its Threeness and finds itself in Everything.

Grandpa seemed satisfied. The kid leaned her head back and closed her eyes for a moment. Grandpa took a breath, as if about to speak, then paused.

What is it, Gramps?

I gotta pee.

Well alright, go ahead. I’ll wait here.

Well, Grandpa began, then paused again, steeling himself. Yes?

He sighed. Grimaced as he spoke. I’m gonna need your help getting there.

That’s all?

That’s all.

The kid stood and Grandpa hooked his arm behind her neck. She pulled him up to his feet. Damn waste of an afternoon, he muttered. I got nowhere else to be, she replied.

She led him through the hallway to the bathroom door. I’m good from here, he said.

The kid waited by the door and helped Grandpa back into bed. When they were settled in their places, the kid said, alright, I’ve got another one for you.

Let’s hear it.

It was a sunny day. I rode the bike along my usual path, crossing the bridge over that winding river, into those woods. Green all around me. Blue above, glistening waters. I kept biking and didn’t get tired. I could have gone on forever. The forest became more dense. Birdsong lifted from branches shifting above me. A cool weight descended on me, and I gave myself over to it. It was in this state of surrender that he happened upon me. Walking on the trail. He stopped and asked me for a light. Dressed in black, hair cropped close to his skull. Sharp nose dipped down in a scowl.

Yes.

Our fingers brushed as I handed it to him. He pulled a pack from his pocket and lit one, standing there across from me. Brow furrowed, eyes down, full lips turned in around the yellow end. Want one?

I nodded and he pressed a little paper roll into the pink flesh between my middle and pointer fingers, and he passed the lighter back to me. Deep inhale. Smoke pushing up into my mind, filling it light and hazy, chased by the earthy smell on my fingertips. Looked comical there across from me, all serious in his black shroud stark against the colors around us. And this is what he said to me, dusty grey floating from his mouth:

I was on a boat on that sea. Thought I was alone but you never are. Heard them calling for the sunset prayer as I pushed off of the shore. Dusk fell quickly. He moved toward me across the water. Stepped lightly on the surface. Robed in green, long white beard shining in the light of the full moon. And I thought, dang, I gotta grow out my beard like this guy. He stepped onto my boat and showed me that the bottoms of his feet were dry. Then he spoke to me in the language that is familiar to him. He told me a story:

I found a pupil at the place where the two seas meet. I released his salted fish into the water and it swam away. My pupil was like you. He believed that he would be protected by the wall of knowledge he had built around himself. I told him to be silent and to follow me. I made a hole in that boat, I killed that boy, and I repaired that wall. He could not be patient. I explained to him my actions in a language he might accept, and I left him.

I asked him, what do you mean by this?

Do you climb? And I said, yes. And you? He smiled. Yes, but only horizontally. I paused, waiting for him to go on. He looked at me silently. Languid luxury of abundant time.

Have we met before? I asked. You look familiar. He shook his head.

When I climb, he said, I only ever remember where I begin and where I end. Never any of the stuff in the middle. He tilted his head.

There is this space between us that I cannot cross, I said. I gestured vaguely, whiteness trickling up from my fingertips. He inhaled. Exhaled. It’s only a meter. Flicked his long fingers.

Dropping into dark depths, that thing in my chest. I hated him.

You hate me, he said.

Your beauty, I said. I want to carve off a piece of my hand and spill my hot blood across the grass.

He nodded. Not Aziz’s wife but the other ones. Do you have any weapons on you?

Yes.

Breeze brushing tobacco smudged dusky pink. Words melting from his mouth. I love you. Neck hot, red. Ears hot. You’re lying, I said. And if I said it, it would be true. He sighed and turned to a tree. Smeared black ash across silver bark. Ah, that’s where the dark spots come from. Then he climbed away from me, horizontally. You donkey! You son of a dog!

Sweet smoke shifting upwards illuminated against the darkening sky. Secretly the stars whispering

yes, I love you too.

When the kid finished, Grandpa was lying with his palm over his face again. He didn’t stir when a mosquito landed on his pinky finger. The kid thought he must have fallen asleep. Then he waved the bug away and spoke.

It was green he was wearing. What?

You said he was wearing black, but it was green. Some greens are so dark they look black.

Hm.

Sirens shifted by. High then low again. I met him too, you know, Grandpa said. The green one. His brow furrowed. I can’t remember it now. But I must have told you.

Yes, you did.

Tell it to me, will you?

Sure.

I was a man in the land my mother told me about as a boy. It was nothing like she had described it. It was all dirty, foreign. Or most of it, anyway. There were gestures, turns of phrase, scents that passed through me like memories. The new world is old to the people who live on that lake up north, the one that looks like Paul Bunyan got knocked on his ass, but not to me. This was the old world.

He laughed. There was a warm rosiness to him, that old man. It was like I was an adorable toddler. I could trip over my own feet and he’d be proud of me! That was the radiant warmth that shone from that man. Something purer than love. There you are, he said to me. There I was. In that small boat rocking softly on the water.

He turned and walked back the way he came, to a lighthouse in the distance. The lighthouse was three miles away and he got to it in three steps. I heard him from my boat, and you wouldn’t guess what he was saying! It was the story he had just told me. He stood there on top of that lighthouse, glorifying God.

Well done, kid, Grandpa said. Except there’s nothing purer than love.

Yes there is, said the kid.

Grandpa waited for her to continue.

Compassion, she said.

It’s the same thing.

No. Love is attachment and compassion is detachment.

Grandpa sighed. I don’t know about that.

The kid was silent for a moment. You never pray, Grandpa, she said. Why don’t you pray?

Grandpa laughed. Where the heck is there to pray around here? You know what I say? If the lake of fire is made of fire water, I’ll take it! Ha!

Yeah. I know that. The kid looked down at her lap.

You mad at me?

No.

You sure?

No.

Another pause. Grandpa looked away, out the window. The kid followed his gaze. Snowy blossoms scratched and swayed against the side of the house.

I’m the kid, you know? I’m the kid.

Grandpa didn’t move his gaze. I know, he said. I’m sorry.

The kid watched dust particles move through the room, pinpricks of light twisting around them. Alright, Gramps, alright. She leaned forward to pat him on the shoulder. They sat in silence for a few moments. Birds fluttered across the branches of that tree outside the window, squirrels chasing each other in spirals up the trunk. Then the kid stood.

You better get some sleep now, she said. I gotta go.

Closing shift?

Yup. I’ll see you soon, God willing. Grandpa smiled. God willing.

ALYA SOPHIA NIMIS-IBRAHIM B’28 thinks Al-Ghazali would not have approved of phonk.

Shopping Spree at the Meta-Mall

TEXT GEORGIA TURMAN

DESIGN JENNIE KWON

ILLUSTRATION SOFIA SCHREIBER )

c One of my fondest memories of Los Angeles, the city where I am from, is the time I spent an entire day at the Westfield Century City Mall with my friend, Ella. Century City Mall is a city in its own right—183 stores, a movie theater, and a concierge desk. The newly-released Avatar: The Way of Water ing in 3D at the theater that afternoon. We emerged from the parking garage into the Italian market and purchased deli sandwiches, which we ate on the pa tio. We then went downstairs to Warby Parker and tried on frames—readers for me, sunglasses for Ella. We stopped for dessert at Cinnabon on the way to the movie theater, which was on the other side of the mall. After a quick nap through Avatar we emerged into the courtyard at dusk. We then hit the American Girl Doll store and The Container Store before they closed, and only when validating our parking ticket did we realize we had been at the mall for nearly eight hours. The sheer power of the mall to disorient and immobilize its subject has remained with me ever since, and I often find myself longing for the particular stupor induced by the mall’s grotesque and excessive beauty.

When I first moved to Providence to attend Brown, I heard stories about people who had lived in the depths of the Providence Place Mall. At the time, I had never even been to Providence Place. I imagined it as a kind of mythical fortress towering over the lands of Providence, with people like knights sneak ing through the iron gates.

Secret Mall Apartment, a 2024 documentary made by Jerry Workman and produced by Jesse Eisenberg, tells the story of eight people who, it turns out, really did live inside a hole in the wall of the Providence Place Mall. The group consisted of several graduates of the Rhode Island School of Design and their former professor. In the film, they discover an entry point into the skeletal architecture of Providence Place and find an unoccupied cement platform between its walls. The vestigial, industrial platform is transformed into a living space with full furnishing and electricity. At first they wonder if they can keep it up for a week, but then weeks turn into months, and months into years. They even go so far as to install a door with a lock so as to permit their exclusive entry into the space. The eight of them are able to inhabit the space for days at a time and remain nearly undetected for four years. The documentary consists largely of handheld video camera footage from those four years—2003 to 2007—taken by the group as a way to document their project. The footage is combined with more recent interviews of the group members, as well as other relevant characters. Around the central story of the secret mall apartment, the documentary paints a picture of the late-1990s and early-2000s under ground Providence art scene.

When asked in interviews throughout the film why they decided to occupy Providence Place, the members of the group admitted that although they started the project in part, at least, for fun, they also envisioned it as a response to the loss of public creative spaces in Providence. Notably, Fort Thunder, a DIY artist venue and living community, of which the group was a part, was shut down in 2002 amid gentrification efforts. They also point to Providence’s housing crisis more generally as a motivation for their occupation of the mall, saying their project functioned as a commentary on the disappearance of livable space in the city. And yet, the occupation of the

mall took time and money that could only be consid-

Providence’s developing economy, it fell into decline in the 1940s. After several rounds of renovations, the Westminster Arcade now not only houses a barber shop and an H.P. Lovecraft–themed bookstore, but also contains an upper level of apartment housing.

fantasies, Providence Place is a mall in decline.

A 15-minute walk down Dorrance Street sits what might be understood as the grandmother of Providence Place. This is the Westminster Arcade, the first enclosed shopping mall in the United States. Although the Arcade was an important part of early

The Westminster Arcade was built completely of granite in 1828 in the Greek Revival style, modeled off the passages couverts, the covered shopping arcades of 18th- and 19th-century Paris. These enclosed rows of shops can be thought of as precursors to the contemporary shopping mall. The Paris arcades were an intellectual fixation of German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, and the impetus for the creation of his Arcades Project.

Like the contemporary shopping mall, the Arcades Project is sprawling and fragmented. The South African writer and translator J.M. Coetzee writes that it “suggests a new way of writing about a civilisation using its rubbish as materials rather than its artworks: history from below rather than above.”

The Arcades Project manuscript, which remained unfinished at Benjamin’s death in 1940, contains roughly 900 pages of fragments, essays, and quotations compiled over the course of nearly a decade, all centered around the topic of consumerism in Paris. For Benjamin, the arcades were the ultimate site of bourgeois decadence, and represented a historical turning point towards a cultural life defined by

consumption. Looking back on the emergence of the

I realized the woman in the row in front of me was on

felt a deep sense of pride for a city that I had only lived in for three years. Providence was my campus, and so, by extension, was Providence Place.

In one scene, the group sneaks in and out of the secret apartment through the AMC, and a shot of a Providence Place movie theater flashes across the Providence Place movie theater screen. At this point,

Providence.

More antics occurred. There were hoots and cheers when former mayor Buddy Cianci appeared on-screen. Perhaps the largest antic, though, was the appearance of one of the inhabitants of the mall apartment, in the flesh, in the front of the theater as the credits rolled. He conducted an impromptu and

unilluminating Q and A while his girlfriend went around to each member of the audience, distributing laser-printed wooden keys with the Instagram handle of his latest project printed on the side. When I approached him after the show for an interview, he told me that he wasn’t at liberty to say anything; I would have to talk to his lawyers.

As I walked out of the theater—disillusioned, moved, inspired, and confused—I noticed one thing for certain: security at the mall had been beefed up. Guards lined the walls, ostensibly to dissuade anyone from doing the logical thing: attempting to find their own way to infiltrate the mall’s porous architecture. Were the occupants of the mall revolutionaries? Or artists? Or merely friends playing an extended and elaborate practical joke? Were they true residents of Providence, or simply students passing through the city and claiming an unfair personal connection? The documentary itself seems unsure about how to answer these questions and reluctant to make definitive claims about issues of transplanting and gentrification, though these issues are present throughout the film.

+++

An image of Weybosett Street, flooded by Hurricane Carol in 1954, shows people huddled on the elevated steps of the Westminster Arcade to avoid the gush of water. The shopping mall, though imperfect, is this kind of raft for existence. We gather in the mall and we define ourselves based on what we purchase and experience in it. We cling to it, even, perhaps, as it is sinking.

Despite closures and debts, August 20 marked Providence Place’s 26th year in business. Secret Mall Apartment, which came out in April, continues to play on Tuesday nights at the Providence Place AMC.

GEORGIA TURMAN B’26 went to the food court.

From Hurricane, published by the Livermore and Knight Company, 1954 (Retrieved from the quahog. org article concerning The Westminster Arcade).

Do You Have A Yugoslavia-Shaped Hole In Your Heart?

HOW NOSTALGIC CONSUMERISM

REWRITES THE PERSISTING TRAUMAS OF A BYGONE REPUBLIC

( TEXT ADORA LIMANI DESIGN SOOHYUN IRIS LEE

ILLUSTRATION

PAUL LI

)

c During my summer back home in Skopje, North Macedonia, I frequented Josip Broz Tito Cafe—Broz Cafe for short. Located on a main street in the city center, the cafe is a lively weekend spot bustling with young people, many of whom were born long after the time of its namesake. Paying tribute to the father of Yugoslavia, Broz Cafe stands as a physical reminder of life before the breakup of the socialist federation. Equipped with a scenic outdoor patio and cozy wooden couches, the cafe is a space of communal bonding where people flock to socialize and gossip during their lunch breaks. In this way, Broz Cafe reconstructs the ‘glory days’ of Yugoslavia—a time period when people felt economically secure, trusted their institutions, and could spend weekdays with family and friends without worrying about rising grocery prices. Sipping on an espresso, it is easy to pretend that the wars of the 1990s never happened. Broz Cafe is not the only space in Skopje that memorializes Tito and the period of Yugoslav history associated with his presidency. Another restaurant, Kad Tita, requires its waiters to wear the uniforms of ‘Tito’s Pioneers,’ a youth group for Yugoslav children. The outfits feature bright red handkerchiefs worn in the style of a sailor, paired with blue hats and white sweaters. Such re-creations of Yugoslav history have become widespread in a post-Yugoslav world, extending even to social media, where Gen Zers are increasingly romanticizing a past they never experienced. Instagram accounts have amassed large numbers of followers by posting images of Yugoslav cities, often comparing the bleakness of the present to an economically and socially prosperous Yugoslavia. For example, @yugo.wave frequently posts images of stylish Yugoslavs across the republics, often posed in scenic streets that appear clean, beautiful, and new, presenting a stark contrast to most post-war cities

in the region. The account’s profile picture features a suave-looking Tito in sunglasses with a cigar, while its captions praise him as the leader who held the Yugoslav Federation together for 35 years while skillfully balancing the interests of the East and the West. In these portrayals, Tito is defined as a ‘player’ in two senses: He navigated the geopolitical scene with ease and charisma, while also charming supermodels and musicians with whom he was frequently photographed.

This account, among many others, aestheticizes Yugoslav history through carefully-curated images designed for uncritical consumption. For most young people who have never experienced life in Yugoslavia, the charming and magnetic Tito on their screens is the only Tito they know.

In the aftermath of Yugoslavia’s breakup in the 1990s, a widespread, commercialized image of a utopian

“Their understanding of Yugoslav life, similarly, is confined to the limitations of an Instagram square or the walls of a coffee shop. Deprived of context and nuance, these glimpses of Yugoslavia degrade into isolated, ahistorical echoes of a forgotten past”

Yugoslav society has replaced historical fact. As a result, an artificial Yugoslav past marked by ‘peaceful

coexistence’ has erased the brutality and systemic oppression faced by ethnic minorities and political dissidents during Tito’s regime. Collective memories of ethnic cleansing have since been infused with Yugonostalgia, perpetuated by physical spaces such as Broz Cafe and online spaces like @yugo.wave.

A Failed Project of Brotherhood and Unity

Although Tito’s regime maintained a facade of ethnic pluralism on an international stage, it actually employed systemic violence to contain political dissidence and remove any threats to its image of ethnic harmony and cohesion. Following the Nazi invasion of Serbia and Croatia in 1941, ethnic tensions between Croats, Bosnians, and Serbs intensified. Serbian Croats faced social hostilities, such as riots and workplace discrimination, while Croatian Serbs were systematically exterminated by the fascist Ustaše regime at the Jasenovac death camp. However, during this time, a socialist partisan movement emerged in opposition to both the royalist Chetnik and fascist Ustaše regimes. Josip Broz Tito, a leader of this partisan movement, would later become Prime Minister of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1945 and President in 1953. With the creation of a unified Yugoslav state, Tito sought to erase the ethnic divisions that defined the past. Championing ethnic pluralism, his regime banned expressions of national identity (e.g. Croat, Serbian, Macedonian) in favor of emphasizing an overarching Yugoslav identity. The motto “Brotherhood and Unity,” an official slogan of the state, characterized Tito’s ostensible advocacy for equal rights for all.At the time, Yugoslavia was revered for its cohesion and multiculturalism. The state also presented itself to the international community as a free and open society in comparison to the Soviet Union and the rest of the Eastern Bloc by encouraging tourism and freedom of movement for its citizens.

Nevertheless, Tito’s regime used authoritarian tactics of control in order to manage tensions among ethnic groups still divided by conflicts dating back to WWII. Detention and imprisonment were common tools of suppression, especially after the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, when Yugoslavia formally cut its ties with the Soviet Union on ideological and economic bases. Yugoslavia’s Transgression Law officially criminalized public expressions of Stalinism in October 1948, leading to the mass imprisonment of suspected Stalinists in labor camps for ‘re-education.’ Among these labor camps was Goli Otok, a barren island off the coast of the Adriatic Sea, where prisoners were subjected to harsh treatment and horrific labor conditions. Later, in the 1970s, Croatian separatist groups that threatened the Yugoslav state’s authority faced mass arrests.

Additionally, ethnic Albanians primarily residing in Kosovo faced systemic segregation and displacement during Tito’s regime. Albanians were not only an ethnic minority in the federation but also constituted a predominantly Muslim population. Under Tito’s rule, they unsettled a national imaginary built around Slavic and Christian identities, challenging the very boundaries of the Yugoslav nation-state. Throughout much of the ’50s and ’60s, educational disparities persisted for ethnic Albanians in Kosovo, since higher education institutions that taught in the Albanian language did not exist before the establishment of the University of Prishtina in 1970. From 1945 to 1968, the Yugoslav state denied Albanians political rights to expression, detaining and censoring public figures. This included the leaders of the Albanian National Democratic Committee, which formed in 1945 to advocate for Albanian national unification and liberation. During this time, Kosovo was overseen by Aleksandar Ranković, who was appointed to the security forces by Tito in order to control the “national security threat” that resided in the republic. The most extreme form of ethnic and religious discrimination during Ranković’s leadership occurred in 1963, when an agreement between Yugoslavia and Turkey facilitated the forced displacement of over 200,000 Albanians to Turkish soil. Muslims residing in other republics were also subjected to displacement, reflecting the Yugoslav state’s broader effort to remove Muslims from their native homelands. The violence that erupted during the 1990s, therefore, did not occur unexpectedly or abruptly, but rather as a byproduct of the repression already deeply entrenched in Yugoslav society.

In 1980, Tito’s death allowed ethno-nationalist leaders to take power in Serbia and Croatia. Slobodan Milošević and Franjo Tuđman both sowed the seeds of violence that would turn into ethnic cleansing during the 1990s. In 1989, Milošević’s government officially ended Kosovo’s limited autonomy within Serbia, removed thousands of ethnic Albanians from their jobs, and used the Serbian militia to stage mass killings. When, in 1997, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) launched an attack against Milošević’s army, a guerrilla war erupted that led to the killing and displacement of hundreds of ethnic Albanians. On March 19, 1999, the Serbian military launched a campaign of extermination that aimed to remove Albanians from Kosovo.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, a multiethnic republic composed of Bosnian Muslims, Serbs, and Croats, faced a similar fate after it declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. While the rest of the republic wanted to secede from the newly Serb-dominated Yugoslav federation, Bosnian Serbs sought to join Milošević’s expansionist vision of a Greater Serbia. As a response to these tensions, Milošević’s forces launched the siege of Sarajevo, killing thousands of innocent civilians while destroying urban repositories. The Serbian government ran concentration camps where they systematically tortured, starved, and killed Muslims, as well as staged genocidal massacres in Muslim-majority cities, such as Srebrenica, where men and boys faced extermination at the hands of the Serbian militia.

Tito as the Face of Ethnic Harmony

Despite Yugoslavia’s bloody past, Tito’s image has reappeared in ex-Yugoslav societies in a positive light. Scholar Mitja Velikonja has characterized this phenomenon, wherein Tito is reimagined as a symbol of ethnic harmony in the former Yugoslav republics, as Titostalgia. Even in the 1990s, polls showed that Tito sustained a favorable reputation among ex-Yugoslavs. In 1995, 86.6% of survey respondents in Bosnia and Herzegovina considered Tito a “positive” political personality, while 42.7% of respondents in Croatia agreed with this view. In fact, a growing trend of neo-Titoism or support for a Titoist ideology, has emerged among youth in former Yugoslav countries. In the post-war context, Tito has become the face of the ‘good old days’ of Yugoslav prosperity, and his image continues to shape collective memories of ethnic cleansing. In 2003, a businessman in the Serbian village of Jubotica founded the ‘country’ Yugoland in his backyard, greeting tourists from other ex-Yugoslav republics with the Yugoslav anthem and offering them the opportunity to ‘regain’ their Yugoslav citizenship. Online forums such as Cyberyu. com and RepublikaTitoslavija.com also allow users to recall the days of Yugoslavia, a distant past when, as one post laments, “we were all so happy.”

Yugonostalgia feeds on a sense of ‘loss’ for a time of Yugoslav unity and prosperity before the wars of the 1990s. The romanticization of Tito’s regime, however, is not grounded in historical fact, but is rather a result of historical fiction. The facade of ethnic harmony under Tito, while convincing in theory, failed to deliver its promises. His regime’s suppression of political opponents and segregationist policies in Kosovo enabled a culture of violence that set the stage for ethnic cleansing. Ultimately, then, Yugonostalgia represents a longing for a version of Yugoslavia that was once possible to envision, not for an ideal Yugoslav society that actually existed.

Scholar Svetlana Boym differentiates between two forms of nostalgia: reflective and restorative. While reflective nostalgia allows individuals to think critically about the past and examine the truth, restorative nostalgia—such as Yugonostalgia—is characterized by the mourning of an imagined past. This form of nostalgia drives people to ‘reconstruct’ the past, but fails to make room for scrutiny or reflection. The feeling of loss induced by Yugonostalgia is able to be filled with consumer goods and artificial simulations of the ‘better days’—for instance, Amazon tote bags referencing the classic Yugo car with the slogan “Wherever Yugo, I go.” The online store Madeinyugoslavia.shop even sells vintage Yugoslav rotary landline phones, cups, and lamps, allowing customers to recreate a mini Yugoslavia in the comfort of their own home. The website claims their items are “perfect for adding a touch of Yugonostalgia to your home,” exemplifying how restorative nostalgia is encouraged by modern consumer culture.

Across the former Yugoslav republics, ethnic tensions were rekindled after the wars of the 1990s, creating a particularly hostile political environment in multiethnic and multireligious republics. However, instead of encouraging ex-Yugoslav societies to grapple with the horrific history of ethnic cleansing, Yugonostalgia functions as a means of avoiding this current reality, providing an escape into arti ficial worlds like Yugoland or Tito-themed restaurants. Cultural critic Fredric Jameson argues that artificial images of historical events, fueled by consumer society, exacerbate our alienation from the past. The actual historical events are replaced by mere nostalgia, providing a blank canvas onto which individuals and groups project their own perspec tives and biases.

By constructing a utopian Yugoslav past under Tito, whose image becomes a commodified symbol of ethnic harmony, Yugonostalgia effectively erases the systemic violence that occurred during his

regime. The censorship, segregation, and displacement faced by ethnic and religious minorities in the ’50s, ’60s, and ‘70s is overwritten, concealed by Yugo tote bags and vintage lamps. Today, it appears as though the erasure of history can be purchased for a few dinars.

Nostalgia and Institutionalized Denial

Yugonostalgia not only enables the distortion of history, but it also hinders processes of accountability for atrocities committed in the past, preventing the ex-Yugoslav republics from truly reckoning with these difficult histories. More recently, Serbia’s systemic denial of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Kosovo points to the harmful consequences of historical revisionism fueled by distortive memory politics. In 2007, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) found three Bosnian Serb military officers guilty of crimes of genocide in Srebrenica. Two years later, in 2009, the European Parliament marked July 11 as the Day of Rememberance of Genocide in Srebrenica. However, the Serbian government continuously denies past atrocities, with former leaders such as Tomislav Nikolić explicitly claiming that “there was no genocide in Srebrenica.” In Serbian academic spaces, numerous books have been written denying that ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Kosovo ever occurred and falsifying the number of victims. In efforts to portray Serbs as the real victims of the Yugoslav wars, scholars claim that the genocide in Srebrenica was fabricated in order to demonize Serbia and ruin its reputation on the international stage. Deep-seated genocide denial and an inability to come to terms with the past have permeated the country’s social fabric, fueling the normalization of violence in everyday life. Especially after Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008, violent attacks by Serbian nationalist groups, which claimed Kosovo was still part of Serbia and denied the history of oppression faced by ethnic Albanians, erupted across the country. This institutionalization of denial in Serbia exemplifies the dangers of manipulating collective memory through nostalgic recreations of history.

Rather than compelling post war societies to acknowledge their complicity in ethnic cleansing and genocide, Yugonostalgia encourages a detachment from the past that makes way for historical revisionism and denial. Consequently, persisting injustices are overshadowed by artificially curated images that lack depth and historicity. Sitting at Broz Cafe and curating Yugoslavia-themed living rooms does little to support the communities most affected by this brutal past. On the contrary, doing so risks completely erasing their suffering from collective memory. We cannot move forward if we keep looking over our shoulder to what once was—or rather, what could have been. The true danger of nostalgia lies not only in its tendency to rewrite history, but also in its potential to obstruct the path toward a better future.

ADORA LIMANI B’28 is playing online dress-up games to bring back her childhood whimsy.

Is it Hell or West Virginia?

THE MOTHMAN STOLE

MY

CATALYTIC CONVERTER

c The one hundred and eighteen consecutive hours of driving were beginning to catch up to me. My three-legged dog Bucko and I were speeding westward in search of a translucent four-dimensional tesseract reportedly seen floating in a bathroom stall near Carson City, Nevada. After departing from Reno five days earlier, we had made several wrong turns and now found ourselves crossing the Ohio–West Virginia border with little hope of locating the tesseract or holding on to our dwindling sanity. I was fading in and out of consciousness when Bucko jolted me awake and politely informed me that the car had been running on empty for the last ten miles. Fate is known to work in peculiar ways when the lost are in need of being found, and lo and behold, the heavenly red lights of a Speedway gas station beckoned less than a mile up the road. I pulled in and thanked Bucko for saving me from what would have been an undignified death in the snowy and godless forests of West Virginia.

Bucko filled up the tank while I went into the Express-Mart to buy eleven tins of Copenhagen long-cut chewing tobacco, a crippling vice that I had picked up in my younger and more suggestible days. After counting out Seventy-Three Dollars and Fifty-Nine Cents worth of nickels from my bottom left pocket, I walked back out to the pumps and was overtaken by an ambiance of what can only be described as pure terror and violence. Bucko was looking all nervous in the passenger’s seat, pacing back and forth and pawing at the leather. He could feel it too. I carefully started the car and the engine came on, but only after delivering a ghastly sequence of howls and screams that no engine should ever make. To the trained ear, this was a sure sign that the catalytic converter once located under our car was gone. Had Bucko turned on me and stolen the catalytic converter himself? I doubted it, but spells of delirium can break even the most trustful of bonds.

“Okay Bucko,” I said. “Something’s amiss, and you gotta give it to me straight here.”

He looked me dead in the eyes and, without saying a word, turned his head and stared out into the forest surrounding the gas station. It soon became clear what he was trying to direct my attention toward.

Peering through the woods, as if to mock us poor souls trapped in a catalytic converter–less Pontiac Aztek, was the silhouette of a great winged creature with glowing red eyes. It stood at twelve or thirteen feet tall and remained frozen in place for a few seconds before triumphantly thrusting a clawed hand holding our stolen car part into the air. The creature then made what appeared to be an utterly obscene gesture with its free hand and flew off into the distance.

Even the most amateur of cryptozoologists would have no trouble identifying this behemoth as the Mothman himself, and I, having spent several fruitless years of my life trailing the Yeti across the tundra of the Upper Yukon, was no amateur. I ran back into the Speedway Express-Mart and explained in very brief terms to the cashier that I had come into contact with a force that no man could reckon with, especially not one who thirty minutes prior had ingested a quantity of Schedule I hallucinogens that made MK Ultra look like a middle school science fair project. I made special note of the fact that the force in question had obtained my catalytic converter and was going to use it for purposes that were as of yet unclear but, in all likelihood, highly malicious and of grave concern to every resident in this town. The cashier, a wise old man who seemed to radiate with the brilliant light of the universe, sighed and placed his hand on my shoulder. “Son,” he said. “Do you know where you are?” I shook my head, “No.” He sighed, took his hand off of my shoulder, then, sighing again, put his hand back on my shoulder.

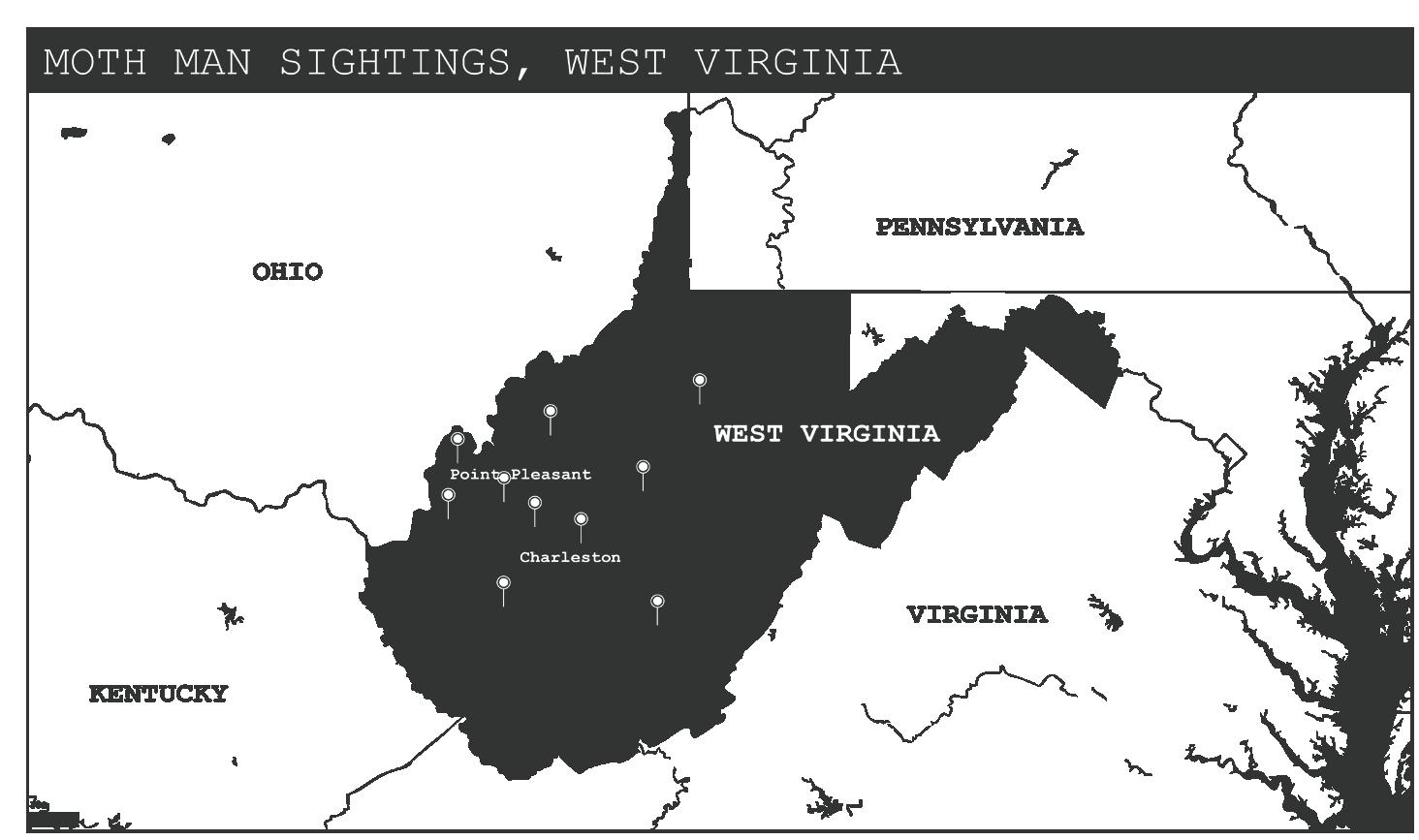

“Son,” he said, “this is Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Point Pleasant is a city in and the county seat of Mason County, West Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers. The population was 4,101 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Point Pleasant micropolitan area extending into Ohio. The town is best known for the Mothman, a purported humanoid creature reportedly sighted in the area that has become a part of West Virginia folklore, and more broadly part of American popular culture.”

As he continued, it became clear that I was not the first victim of the Mothman’s obsession with valuable scrap metals often found on the underside of cars, and nor would I be the last. I went back out to the Pontiac and told Bucko everything that I knew. Our catalytic converter was gone for good, and the chances of our lonesome and weary engine starting up again were slim. I got in the car, took the key off of the dashboard, and lifted my hand up to place it in the ignition whilst uttering affirmations of faith to the wisdom and grace of God’s Department of Motor Vehicles. I looked over at Bucko. He whimpered, well aware that we were about to be left stranded in a West Virginian purgatory. I looked away and turned the key. The engine went out fighting as it was dragged into the abyss of nonfunctional mechanical equipment, screeching and moaning until, after one last mournful gasp, it went silent. I threw my head into my hands. Bucko stared at the floor. There would be no joy in Point Pleasant tonight

The above story is the Truth, and it is a Truth that all must heed if they are to wander into strange West Virginian towns with any sort of respect for the sanctity of their catalytic converters.

MOTHMAN IN REGARDS TO MAN AND MOTH

MOTH, MAN AND MOTHMAN

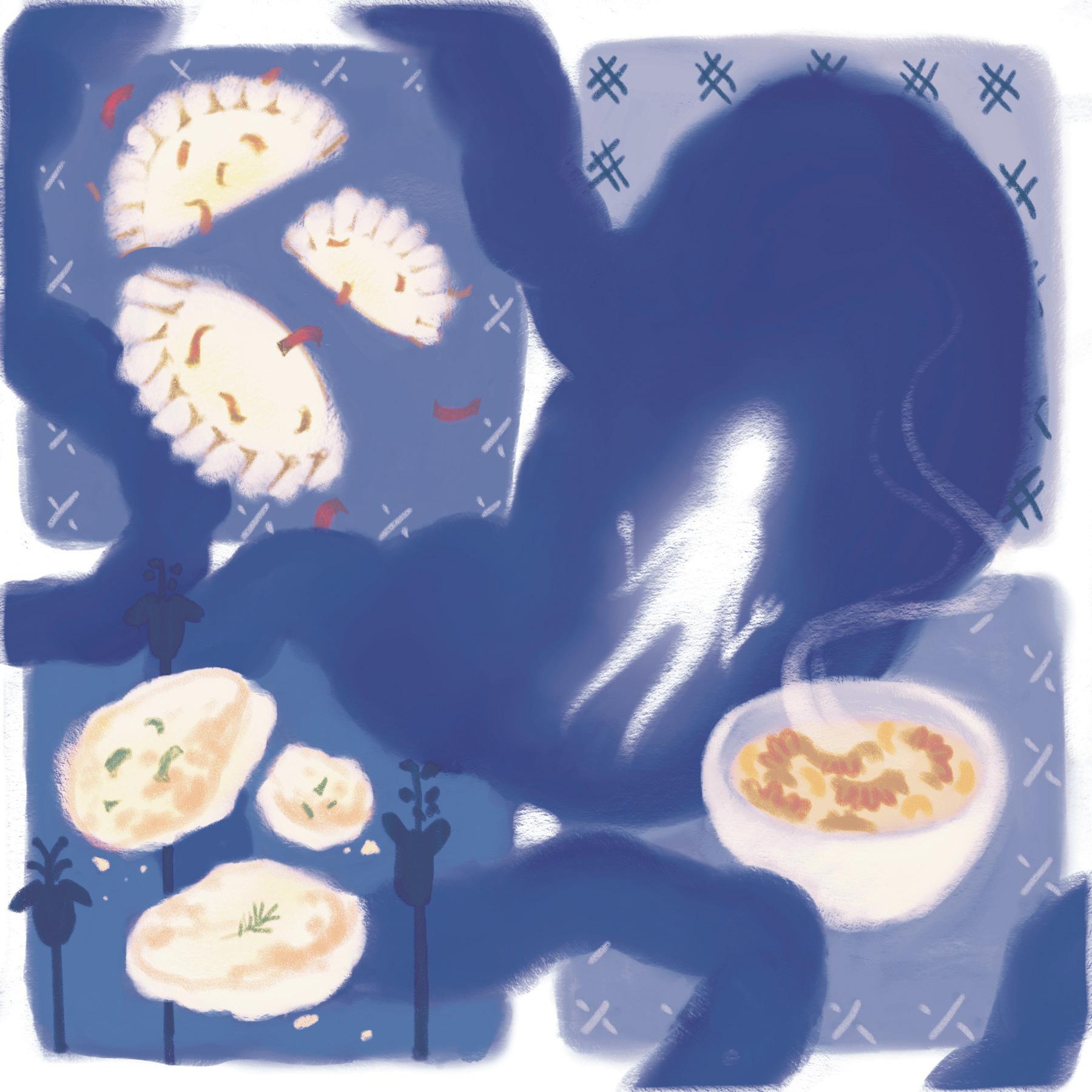

Poland’s Public Stomach

( TEXT PETER ZETTL DESIGN ANNA WANG