TAKING BIRTH INTO OUR OWN HANDS

TAKING BIRTH INTO OUR OWN HANDS

MANAGING

Sabine

Talia

Nadia Mazonson

WEEK IN REVIEW

Maria Gomberg

Luca Suarez

ARTS

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Martina Herman

EPHEMERA

Mekala Kumar

Elliot Stravato

FEATURES

Nahye Lee

Ayla Tosun

Isabel Tribe

LITERARY

Elaina Bayard

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Gabriella Miranda

METRO

Layla Ahmed

Mikayla Kennedy

METABOLICS

Evan Li

Kendall Ricks

Peter Zettl

SCIENCE + TECH

Nan Dickerson

Alex Sayette

Tarini Tipnis

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Selim Kutlu

Sara Parulekar

WORLD

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Emilie Guan

Coby Mulliken

DEAR INDY

Angela Lian

BULLETIN BOARD

Jeffrey Pogue

Lila Rosen

MVP

Santino Suarez

Lila Rosen & Jeffrey Pogue

Beautiful names for a baby girlhorse:

Polenta, Moses, Melatonin, Myspelf, Oedipa, Uvula, c-drizzle, Zillow, Hypothalamus, Rappell Choan, Mae (short for Mayonnaise), Franzia, Grekepten, Sabbatical, Fallopia, Babby, Autonomy, Chalant, Moduelle, Bucephalus, Blessica, Raskolnikov, Syterious Johnson, Fleance, Allegra, Palantir, Dubloon, Gringo, Slim Jim, Lateral T, Kugel, Azamiah, COCAINE, Church (short for Winston Churchill), Étienne, Panopticon, High Life, Jan Švankmajer, Maureen, Casserole, Perpeter, Slim Easy, BOLT, Chechnya, Moon Unit, Memorable Factor, Shucker, Sedro-Woolley, Chestnut.

DESIGN EDITORS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Kay Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

DESIGNERS

Millie Cheng

Soohyun Iris Lee

Rose Holdbrook

Esoo Kim

Jennifer Kim

Selim Kutlu

Jennie Kwon

Hyunjo Lee

Chelsea Liu

Kayla Randolph

Anaïs Reiss

Caleb Wu

Anna Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Hisham Awartani

Sarya Baran Kılıç

Sebastian Botero

Jackie Dean

Cameron Calonzo

Emma Condon

Lily Ellman

Ben Flaumenhaft

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Maxwell Hawkins

Mohamed Jaouadi

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nora Rowe

Andrea Li

Cindy Li

Maira Magwene Muñiz

Kalie Minor

Alya Nimis-Ibrahim

Emerson Rhodes

Georgia Turman

Ishya Washington

Jodie Yan

Ange Yeung

ALUMNI COORDINATOR

Peter Zettl

SOCIAL CHAIR

Ben Flaumenhaft

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Tarini Tipnis

FINANCIAL

COORDINATORS

Constance Wang

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Lily Yanagimoto

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Mia Cheng

Natalia Engdahl

Avari Escobar

Koji Hellman

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Jiwon Lim

Yuna Ogiwara

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Angelina So

Luna Tobar

Ella Xu

Sapientia Yoonseo Lee

Serena Yu

Yiming Zhang

Faith Zhao

COPY CHIEF

Avery Liu

Eric Ma

COPY EDITORS

Tatiana von Bothmer

Milan Capoor

Jordan Coutts

Raamina Chowdhury

Caiden Demundo

Kendra Eastep

Iza Piatkowski

Ella Vermut

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Sofia Guarisma

Erin Min

Dominic Park

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Ivy Montoya

Eurie Seo

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Avery Reinhold

Angela Lian

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Lian

Jolie Barnard

Luca Suarez

Nan Dickerson

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

*Our Beloved Staff

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

c Welcome to r/Providence, the largest community of Providence, RI aficionados on Reddit! We remind you to only contribute posts pertaining to PVD and the surrounding areas—no, Boston does not count as a Rhode Island suburb. We also kindly ask that you refrain from ad hominem attacks, libel, and other misbehavior. PLEASE STOP POSTING ABOUT THE PROVIDENCE SHITTER, WE DON’T GIVE TWO GAFS. Soliciting is fine with us! Keep it civil, keep it brief, and enjoy scrolling through the thousands of pictures of the Providence skyline from slightly different angles of the pedestrian bridge.

OutrageousForm8509 5h

Restaurant Recommendation?

Hello everyone, I am new to this sub, so please let me know if I should be posting somewhere else.

Hubby (M24) and I (F23), are celebrating our 2 month anniversary this weekend, and we have decided to take a little getaway trip to Providence! We are taking the Amtrak from Boston and we are wondering where we should eat for our one meal in the city. Please tailor your recommendation to the fact that my husband does not like seafood or skim milk, and we would prefer an establishment that doesn’t do iPad tipping because I have a nailbed sensitivity. Oh, did I mention that we will be bringing our basset hound-rottweiler mix? His name is Tripp, DM for pictures.

I am aware that Providence has a vibrant and exciting food scene due to the JWU influence so I am really looking forward to your recommendation. Yum! Yum! Yum! “Up-and-coming” has never tasted so good.

SpiritedSock4829 19h

SMITH MOGGER APPREHENDED

The woman who has been spontaneously Mogging innocent passersby in the Smith Hill area has finally been apprehended and issued a warning for causing a public disturbance. Her jawline has been safely bridled, and the citizens of Smith Hill are breathing easy once again.

JoyousIngot0234 2d

Chance me for BrownU?

Hello everybody! My name is Ethan Pantsboy and I am a sophomore at a small private research high school on the East Coast. I am currently trying to narrow down my college list, and Brown seems to be my top choice atm. Go Bruno!! I have taken the SAT twice with a superscore of 1550, but will be retaking in the fall to make sure. My school doesn’t do GPA, just emoticons, but at the moment my report card is mostly and . My extracurriculars are not super strong but I am a youth equestrian (I have worked two horses to death in the last year), I run my own fundraising non-profit fundraising non-profit (for teaching non-profits how to fundraise), and I am in the national honor society. Do I have a chance this application cycle? Let me know what you think!

I look forward to Vartan Gregorian Quadrangle!

Penalty_Brave1349 2d

Providence Place Mall is featured in a Hulu show nobody has ever seen!

She looks resplendent!

Penalty_Brave1349 3d

RENT IS TOO DAMN HIGH.

And I just got charged a delivery fee on my utilities bill that is triple our actual usage. The prices in this city are not livable and the landlords are just oppressive. Helloooo? Can anyone hear me? Is anyone listening? John? Rachel? Sue? Anybody? I’m still here… hellooooooo.

Penalty_Brave1349 3d

Can someone recommend a restaurant?

Hello, I don’t know if this question has been asked on here before, so mods, this is at your discretion. Are there any restaurants in Providence??? I live in Brooklyn and am trying to understand the lived experiences of the less fortunate. I have to come visit next week because my little cousin is at RISD and he is depressed… will there be food? Should I bring my own? Where can one find a decent granita?

What about Brunch?

How can I romanticize working in PVD when I commute?

I have a big girl job at a small lawfirm with an office at 1 Financial Plaza (where are all the elle woods girlies at??). I currently live in Seekonk, and commute over an hour into the city 3 days a week.

Any recommendations for little things I can do during the work day or immediately before or after? I am finding some fun workout classes and my iced caramel Cashew milk latte from Plant City is a must on my way into work, but maybe there are cute or cool places to visit that aren’t too off my path back and forth between downtown and the Henderson Bridge? I’ll walk around Kennedy Plaza occasionally on lunch break and to the Malted Barley for drinks after work, but I feel like I’ve seen pretty much everything at this point

How can I add some ~fun big city vibes~ to my life? Thannnnnks girls.

3d

What happened to the Providence punk scene?

When I was growing up in RI it seemed like PVD was the mecca of punk shit. Every saturday, my buddy’s mom would drive us to a different show, and we would mosh all night long. I remember going to shows at video palace hopes street, The RIDGE PVD, Spaghetti Armpit, Fort Thunder, Dirt Palace, and. S3XDNGN. What happened to those spots? Now everything is AS220 Emo-night this and community space that! Fuck that! Make Providence crusty again.

pull up to our show at pvd fringe. Catch our matinee at the steal yard on tuesday, and follow us @thepunkmusicalsss.

DoctorNearpod 3d ...

RE: Missed connection at the Bajas on Thayer (skinny).

For whoever posted the missed connection last week. I think it’s me. I have a Hatsune Miku backpack and hair to my knees just like OPs post! DM me, would love to

Accepted_Snow3841 4d

queer haircuts pvd?

SpiritedSock4829 4d ... hey frieeeeeeeendz! i am a recent graduate and queer friendly tattoo artist (high femme sliding scale stick and pokes <3) based in the pawtuckett area. haha. looking for someone who can give me a ratgirl-core/goblin-core razor cut. I am not rlly active on here these days, so dm me on ig @/peepeesticks. thanksssss. p.s. trade and barter onlyyyyyyy btw.

title

BRETT SMILEY IS A RAGGEDY BITCH.

U/MARIAGOMBERG B’26 is most of these guys

c On July 1, 2022, the Rhode Island Doula Reimbursement Act took effect, codifying the ability of certified doulas to be reimbursed by Rhode Islandbased insurance companies and Medicaid for their work during the prenatal process.

The bill was championed by community doulas in Rhode Island in response to Black maternal health disparities in the state. Quatia Osorio, a retired doula and founder of two reproductive health organizations in Rhode Island, said “The first thing you read is about Black maternal health.” Osorio described the bill as an ode to upholding community birth values, addressing injustice for Black maternal health, and honoring Black women.

The bill’s passage reflects an increased use of holistic and community care practices that have been seen across the U.S. in recent years. People are turning to community health workers like doulas and midwives at higher rates as a response to high maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the U.S., particularly among Black birthing people. Doulas have proven to mitigate maternal harm and improve infant health, as they “provide culturally sensitive pregnancy and childbirth education,” in addition to services including “labor coaching, breastfeeding support, and parenting education,” according to the community-based reproductive health organization Health Connect One.

Unfortunately, access to doula care has long been limited. Before 2022, Rhode Island residents had to pay out of pocket for prenatal and postpartum services from a doula, creating an accessibility barrier to the care that doulas provide. A 2022 report by the National Partnership for Women & Families highlighted that only 6% of birthing people in 2011 and 2012 worked with a doula during birth, despite the proven benefits. The report highlights the need to expand doula training and support—especially focusing on birth justice education and community-centered work.

In Rhode Island, efforts to pass the bill were intentionally community-led. Osorio recalled, “We held the focus groups. We extracted the data. We designed and ruled the certification policy [...] [and] we designed those policies collectively together as a community.” She added that this community involvement was done with the intention of ensuring that doulas would utilize this bill, noting concerns about the underutilization of similar legislation in Oregon and Minnesota, where efforts were not community-led.

Historically, community care practices have been the primary source of birth care for Black and Brown people in the United States. Black women who were enslaved and denied medical treatment established the practice of midwifery out of the necessity to care for one another. Even after emancipation, hospitals remained inaccessible to both formerly enslaved people and white residents of the rural South, leading Black midwives to continue caring for these populations. This community-centered knowledge was passed down through the generations. As people increasingly turned to hospitals to give birth after the 1940s, community midwives became less common. Though this birth work was considered sacred, it was usurped by the medicalized, unnatural, feet-in-stirrups methods of the modern medicalized age. This prompted a home birth movement in which people turned to doulas—a practice derived from early birth workers—for physical, emotional, and mental support during birth.

Deidre Cooper Owens and other Black studies scholars pinpoint the origins of medicalized gynecology to the makeshift “lab” of James Marion Sims, who violently experimented on enslaved Black women. This dehumanization of Black bodies and dismissal

of Black pain did not die with Sims. It pervades the privatized birthing care system that continues to cause high disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity: Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, and Asian/ Pacific American birthing people all experience higher rates of severe maternal morbidity compared to white people. Indigenous and Black birthing populations, who respectively experience pregnancy-related deaths at rates more than two and three times higher than white people, face the highest disparity. These origins created a necessity for alternative practices rooted in care for the whole person, rather than treating the pregnant body as a condition.

Doula care remains a model that improves maternal health and produces better outcomes for Black, Indigenous, and other birthing people of color. This week, the Indy spoke to three Providence doulas about the role of community-based versus institutional training in ensuring holistic reproductive care.

Osorio, who has worked in the Providence community for seven years and is now training to be a midwife, founded and continues to run Our Journ3i, a prominent site for training community doulas in Rhode Island. She also founded the Urban Perinatal Education Center, a community-based doula birth, perinatal, and postpartum service for Black and Brown people. Her community-based care centers the health of Black and Brown birthing people.

Before becoming a doula herself, Osorio hired one to assist with the pregnancy for her fourth child. “I was a Black stay-at-home mom, which not everyone is or has the capacity to be. It allowed me to move in spaces that most people weren’t in, and that’s where I learned about doula work,” she said. To select a doula, Osorio attended a meet-up organized by Doulas of Rhode Island, an organization focused on increasing

“That’s not the way we’re approaching it. We’re approaching it like every life I touch as a doula can make an impact and a difference in this person’s life. That is who I fundamentally want to be.”

public awareness of doulas and fostering patientdoula relationships, and looked for “someone who I really felt a connection with immediately, physically, and also in conversation.” There, she met her doula, Jennifer Gruslin, whose mentor, Lisa Gendron, is now one of Osorio’s midwifery instructors, which she highlights as a full-circle moment.

Osorio credits her community “decid[ing] that they wanted a community doula” as the impetus for beginning her doula journey. After being trained in New York, Osorio returned to Rhode Island and began working as a doula. Then, there were very few doulas—and even fewer Black doulas—with community-based training. “I honestly can’t even count because the Doulas of Rhode Island was very small. At the time, it was only me and one other Black doula in the actual organization,” said Osorio.

In 2018, when Osorio held her first community-based doula training in Rhode Island alongside another doula, she followed the methods from the Shafia Monroe training program, which was specifically designed to increase the number of positive birth outcomes within the Black community and other communities of color and pays tribute to the African American midwives of the 20th century. This experience grounded in the legacy and culture of midwifery motivated Osorio to root the training she provides in lived experience, cultural competency, and social drivers of health. This type of training equips doulas with a more holistic view of their patients’ circumstances. “People [are] not making it to their appointments because they’re about to lose their damn housing,” Osorio said, adding that “at 10 weeks, the priority is having a stable home to bring [the client’s] child to, so [they] don’t have insecure housing” and face the threat of having their child taken from them.

According to Osorio, experienced birth workers are uniquely suited to teach doulas-in-training about the real-life challenges of doula work, which can include dealing with hostility from nurses and hospitals lying about who has the right to a doula. Learning how to navigate such situations is taught “within the community framework,” she said. “But if you weren’t in this framework, if you don’t know how we operate, how could you possibly be hosting your training?”

Rosa Sierra, a doula who was trained by Osorio and the founder of Connexion Intimacy Resource Center, an organization that provides multicultural and multilingual sex and reproductive education, said that the compensation- friendly framework introduced by the bill allows doula work to be a “viable career.” This

can encourage people to become doulas, who are an appreciated alternative to traditional obstetric care. For Sierra, “Working alongside providers, surgical providers specifically, grounded me in the reality that clinicians don’t actually have a lot of time for their patients. And patients often don’t have the sense of safety and space to be able to confide in their providers about the kind of support that they actually need.”

With greater accessibility to compensation and payment, doula care is gaining popularity. “Right now doula [work] is a hot commodity, and people only look at [it] as a commodity. However, the people who are community-led look at it because it’s people. We’re not looking at data. We’re not being like, ‘Oh my gosh, you can bill insurance! You could make so much money,’ expressed Osorio.“That’s not the way we’re approaching it. We’re approaching it like every life I touch as a doula can make an impact and a difference in this person’s life. That is who I fundamentally want to be.”

While Osorio recognizes how the Doula Bill may be used to commodify the practice, she emphasized its importance in ensuring doulas are properly compensated. Since only certified doulas can accept insurance reimbursements under the bill’s terms, there is a concerted effort in the community to ensure access to certification. Organizations like Osorio’s Our Journ3i offer a comprehensive Certified Perinatal Doula training program that stretches 40 hours over the course of a week, includes childbirth education and lactation training, and is explicitly designed to be community-centered, trauma-informed, and culturally sensitive.

To be considered a “certified doula,” as defined by the Doula Bill, one must be CPR certified and have attended an approved doula training course. According to the Rhode Island Certification Board, a Certified Perinatal Doula must have at least 20 hours of training: “12 hours must be in birth doula training, antepartum doula training, postpartum doula training and/or childbirth education. At least one training must be a doula training, 2 hours must be in breastfeeding or document a valid lactation certification, 2 hours must be attendance at a childbirth class or document a valid childbirth education certification, 3 hours must be in cultural competency and 1 hour must be in HIPAA/client confidentiality.”

Last spring, Roger Williams University’s Extension School added a doula training program to its course offerings. This program meets the 20-hour doula certification requirement and is taught by Jennifer Parent, a doula of 15 years. The training walks doulas through the basics of pregnancy, perinatal care, postpartum care, comforting techniques, and how to start a solo doula business. However, according to Parent, the training does not emphasize the specifics of health disparities in Rhode Island. Although the course discusses birth justice in its early units, it does not appear in later material, and it does “not [use] official statistics” related to the community. Parent adds that, “We talk about how to find clients, how to find your demographic, how to chart your worth, how to start your own business, how to find other doulas, [and] how to market yourselves.”

For Sierra, the issue of how to provide doula training is complicated: “I think it’s a tough space

because education is education. I don’t think that people should be barred from accessing this kind of education, should they want it,” she said. “What becomes challenging is when people come out calling themselves doulas but are not actually being available to the community they are a part of, which is the inherent difference between doulas trained for and by their community and one that is a representative of that space.”

To Osorio, institutionalized doula work is antithetical to the practice. She recalled doulas trained outside of community networks who wanted “to know about the idea, the ideology, the philosophy [and] the overview” of doula care but “didn’t want to be at the birth [on their] hands and knees…or doing hip squeezes with someone’s naked butt in [their] face.” Although the Doula Bill aided in providing compensation to doulas, Osorio notes that it also led to an “infiltration” in the community.

Osorio highlighted the ways in which institutional doula work conflicts with community-centered practice. “Academia has no business doing community doula work,” she said. “What they should be doing is funneling funding into community doula organizations so that they continue to do the work.” These entities risk “co-opt[ing] the work that was done” by community-based doulas, she said.

The type of community-based training doulas receive can impact the ways in which they interact with their patients. In recent years, Osorio has seen many out-of-state doulas get trained in Rhode Island to offer strictly virtual appointments to Rhode Island residents. “When you have people who aren’t from the state, who aren’t investing in our state, [and are] taking money away from our state, it’s very much extortionist. It’s very much predatory,” Osorio said. “This model was not meant to be copy-pasted into institutions that really don’t understand the framework of community doula work.”

For anyone who wants to engage in maternal health work from this community-engaged perspective, Sierra urges them to “talk to us,” adding that “we really do want to foster that relationship with young and older folks [and] anybody in our community who has interest in this space.” She highlights that social and political engagement by “keeping a pulse” on related legislation is the path into uplifting this community practice.

This past legislative session, the Urban Perinatal Education Center and other community health organizations introduced more bills to improve access to community-based care, including H5861 to require health insurance to cover certified lactation counselor services, S0479 to require insurance plans to cover certified professional midwife services, and S0478 to establish a certified professional midwife’s scope for prescribing medication to patients. They plan to reintroduce these bills in the spring.

RITA BEYENE B’27 wants you to care about Black maternal health and keep an eye on the state legislature in the next session!

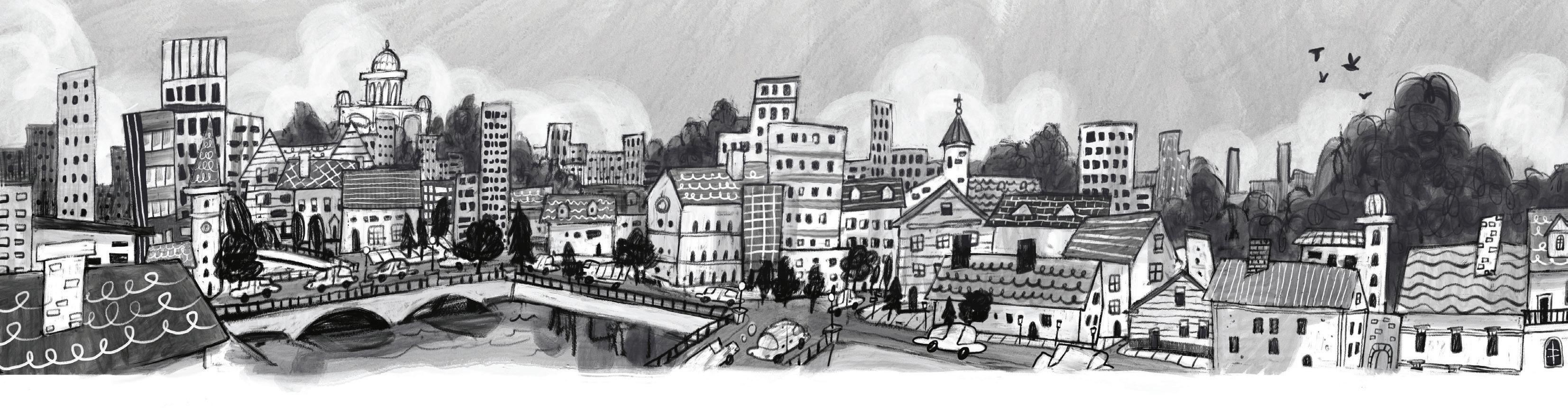

c When we arrived at the estuary, the oysters were ready to harvest. It had been 12 months since oyster seeds the size of a fingernail had been placed in mesh cages and dropped into the western Narragansett Bay. Sun filtered through the brine-colored clouds but not enough to warm the early dawn. I said I liked the way it smelled. “It smells like a lobster bay,” Max Namba, a current Brown sophomore and part-time oyster farmer, responded sensibly. He pulled up industrial-yellow waders and stepped into rubber boots. The gravel parking lot gave way to rows of commercial fishing docks where vessels sat briefly dormant, a tangle of steel pipes and blue fishnet. The boats’ surfaces had a dulled shine, washed clean by gruff powerwashing.

We walked past the pier entrance and about halfway down stopped at an offshore fishing boat. Passing a cabin door mural of a blonde 20-something poorly dressed for the open ocean and an unintelligible whiteboard of numbers and letters displaying previous days’ catches, Namba disappeared into a storage compartment. He returned with a fistful of zip ties in his right hand. These would be cinched next to dated tags on the small buoys anchoring the oysters to ensure emptied cages would not be pulleyed up again. Today, he sought only tags bearing a 09-XX-2025. Clenched in Namba’s other hand were 15 mesh oyster bags, each of which “have to be filled with 102 oysters. Not 100. The shucker could break one.”

On the brisk walk to a small flat-bottom skiff— the boat best suited for oyster farming—we passed another dock. The first dock was imbued with a New England pragmatism and worn by long days of tactile labor. The second dock anchored multi-bedroom yachts and tourist fishing catamarans, each one futuristic white or gray fiberglass and minimally adorned. Parked in front was a holographic green Cybertruck. While the commercial fishing dock had been crowded with various tools and apparatuses, the leisure vessels were spaciously bare.

“Pretty soon it’s gonna be like Newport,” said Ian Campbell, the owner of Afternoon Delights oysters, in one of the first Rhode Island accents I had heard since moving to the state. As the skiff made her way out of mooring, towered over by recreational yachts and industrial fishing vessels alike, I dipped my hand into the pleasantly warm water under which millions of oysters were ripening. ��������

Campbell was raised in Rhode Island’s aquaculture industry. On the early September morning I met him, he was wearing a distressed baseball cap, dark sunglasses, and shorts. Campbell spent most of his life on the southwest stretch of Point Judith Pond between Beef Island and High Point in the Narragansett Bay. If, like me and many other Brown students, you are unfamiliar with Rhode Island’s geography, that is about 37 miles south of College Hill. Arriving at the estuary, the structure of oyster farming was made apparent by its minimal visibility; there were few workers and no above-water equipment. Oystering is conducted on a small

scale—up to 10 acres can be leased for an oyster farm in Rhode Island—and structured as owner-operated. Afternoon Delights is one of these, an oyster farm run by Campbell and his sister Stesha. Namba has known the siblings since he was 12, when he paddled his kayak out and met his now boss, who was working the farm in front of his grandparents’ house. Although Namba does not come from an aquaculture family, he became fascinated by oystering and officially started farming for Afternoon Delights at 15. By 18, he was managing the farm over the summers and weekends. This is characteristic of the industry, which is “not a closed community but an incestuous one: people pass it to family and to friends they know,” said Namba. “It’s not like I can go on Indeed and find an oyster job.” He paused before amending—“there are obviously going to be exceptions as more corporations come in.” When I asked about the existence of the oyster-industrial complex, he responded: “Oyster farming is the least industrial way of farming.”

Most of Campbell’s career has been in the commercial fishing industry, an unforgiving business subject to the whims of the sea. “If you don’t catch anything, you don’t make anything,” Namba told me. Oystering is a different game. Farmers can expect to harvest an East Coast oyster around 18 months after planting its seed in cages or bags. With a far more reliable catch and lighter paper trail, the proverbial waters are calmer in the estuary. Campbell turned to oyster farming 10 years ago “to supplement the fishing. The oyster farm is always there.” Beginning as a three-acre farm, Afternoon Delights has since doubled in acreage and sells to a major Galilee Port distributor.

Aquaculture is a multimillion dollar industry in Rhode Island, generating a farm-gate value of $8.8 million and providing over 3,000 jobs, according to the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council’s (CRMC) 2024 report. Oystering accounts for 99% of this production. Aquaculture is now the the third-largest agricultural industry in the state, superseded by the plant nursery and dairy industries, and it has a distinct sentimentality tied to Rhode Island’s romantic maritime (romaritime?) past.

While the Narragansett and Wampanoag have harvested wild oysters and fished in the Narragansett Bay for thousands of years, cultivated aquaculture was introduced in the United States when Rhode Island granted the first oyster farm lease in 1798. The state’s identity has, practically since its conception, been intertwined with the fate of the oyster.

Rhode Island oyster farming is, at first glance, a rapidly expanding industry, one that should attract major players. The eastern oyster is Rhode Island’s most valuable aquaculture product, and 2024 saw a record sale of 11.6 million individual oysters. Despite these lucrative prospects, the state only allots 5% of estuary water for oyster farming, and the establishment of new farms is anything but politically insulated. Only after a public notice which raises no objections within 30 days may an oyster farming lease be approved. When I looked out over Afternoon Delights’ murky waters, the only indication of the high-production farm beneath were a couple dozen white buoys the

( TEXT JACKIE DEAN

DESIGN CALEB WU

PHOTOGRAPHER ELI DIKER )

size of baseballs. Only a few ambiguous cage-like shapes could be made out beneath the calm ripples. Several hundred feet ahead, the shoreline elevated into a small ridge on top of which New England–style vacation homes lounged. “Some of them used to hate me,” Campell said, gesturing toward the summer homes. “They didn’t understand what I was doing in the water.”

Out-of-Staters, Weekend Warriors, Second-Homers, Non-Rhode-Islanders, Outsiders. These were part of the lexicon frequently used at the 11th Ocean State Oyster Festival where oyster farms, Afternoon Delights historically among them, sold directly to local oyster lovers. Held in 195 District Park, College Hill loomed in the distance across the Providence River, seemingly unaware of the city beneath. The average attendee was 35 years old, dressed like they could be on either extreme of the political spectrum, and carrying an egg carton of oysters and poker chips, which operated as oyster tokens ($16 for five, $35 for 10…). The afternoon sun beat down on buckets of discarded oyster shells, reflecting off their metallic ridges. A mime, a band, strawberry margaritas, and vendors with names like Walrus & Carpenter, Rocky Rhode Oyster Co., and Wild Goose Oysters gave the impression that you had wandered into a children’s book.

I walked up to a man with gray hair wearing a T-shirt that read “2015 Intern.” Carl Farmer has been a part of the annual Oyster Festival since its inception when he struck up a conversation with the event’s organizer in Campus Fine Wines. After lamenting that the festival no longer had a shucking competition, he scrutinized my ballet flats, Brown student ID, and messenger bag and warily asked: “Are you from New York?” Relieved at my insistence that I was not, he described the New Yorkers who “buy waterfront fuck-you homes and don’t like the oyster farmers already there.” Although all Rhode Island residents are authorized to recreationally harvest quahogs on shorelines without a license, they told Farmer to “get off [their] land” while he was digging for the clams. Farmer’s response: “I am in the water.”

These tensions underlie the ambiguities of water jurisdiction, raising questions about who has the right to be in a common-use space. The power dynamics between Rhode Island’s two historical giants—the blue-collar seafood industry and out-of-state vacation wealth—are contentiously fluid when posited in waterways.

The water-rich eastern states follow the legal doctrine of riparian rights, which grants landowners adjacent to a water source “reasonable use” of the water. This common-law principle, which does not allot ownership of the water but authorizes use of the water’s surface, is not universally applicable, but rather meted out on a case by case basis. Coastal landowners have recently begun to activate riparian rights across Rhode Island, directly threatening small owner–operated oyster farms. The resulting conflicts are not just anecdotal but legal and legislative, as

demonstrated by the numerous oyster-centered lawsuits in the past half-decade.

In April 2020, Patrick and John Bowen applied to the CRMC for an acre lease in the Sakonnet River, about 500 feet from the Seapowet marsh preserve. Recreational water users mobilized and lobbied for a proposed 1,000 feet buffer zone from the median high tide line, which Representative John Edwards (D-Tiverton) introduced in the Rhode Island house. The bill would reclassify selected waters for “passive recreational use” only.

Rep. Edwards described Bill H8224 as a means to protect the “very, very unique” shoreline habitat along with its recreational users. Although the buffer bill did not make it out of committee, supporters of the proposal including Save Seapowet For All (a citizen group of recreational water users) filed hundreds of letters of protest with the CRMC. Last June, Edwards and Save Seapowet For All passed a law that “prohibits commercial activities in Seapowet Cove waters.” The four-year legal battle was over.

While a statewide buffer law was not enacted,

there is still public pressure to push aquaculture into deeper waters. As coastal conflicts increase, oyster farms are exploring waters that are less likely to raise landowner objections. The question of aquaculture relocation out of the estuaries and into more open ocean has entered the oyster discourse, leaving the industry at risk of significant changes. The flavor profile of an oyster, called the merroir, is threatened by the prospect of relocation as it depends on the depth and salinity of farms. As farther-offshore projects come with increased capital costs, the migration

into deeper waters would favor larger industrial farms, also potentially shifting the class profile of farm owners.

This conflict arises not from blanket opposition to aquaculture, but where it should be located. One criterion is clear: not in the backyard of out-ofstate second home owners. In 2016, out-of-state buyers accounted for 15% of single-family home and condominium purchases in Rhode Island. During the pandemic this number increased, and as of this summer 23.5% of home purchases are made by non-Rhode Islanders. In this same decade, years-long lawsuits have engulfed the Narragansett Bay, fueled by coastal residents’ objections to oyster farm establishment and expansion. Although not all of these complaints can be attributed to out-of-state home owners, there is a clear correlation. Namba noted that out-of-staters “aren’t aware of the industries that built the towns they live in.”

It is surprising that NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard) is so fervent in coastal Rhode Island. Objections to floating gear oyster farming, in which buoyant gear is partially submerged to allow for constant exposure to oxygen and thus remains visible, are reminiscent of classical wind turbine NIMBYism—but this farming method is rare in the state. Instead, most Rhode Island farmers use off-bottom culture methods where cages are anchored several feet beneath the tideline and practically invisible from shore. There is also an irony to wealthy New Englanders objecting to oyster farming when they are the primary consumers of the luxury food. The consumption of oysters became a signal of class in the early 20th century, when runoff pollution and overfishing depleted the previously bountiful wild beds that had made the oyster the mollusk of the people. Rhode Island fishermen “don’t like to say it because they don’t like tourists, but the wealth are the clients,” Namba confided. It seems preferred that oysters be farmed over there, in a place we cannot see and do not think about, where the rest of America’s food is produced.

When Matunuck Oysters was met with a ‘float-in’ kayak and boat protest to their expansion of operations, owner Perry Raso asked “how anyone can own a part of the ocean.” Matunuck is a name synonymous with Rhode Island oysters. An aquaculture graduate of the University of Rhode Island, Raso started Matunuck Oysters in 2002 as a seven-acre

farm in Potter Pond before opening an internationally renowned oyster bar to sell directly to consumers. In other words, Raso put Rhode Island oysters on the bathymetric map.

Matunuck’s three-acre expansion into Segar Cove was approved in the winter of 2017, but opposition came in the spring. This was because, as Segar Cove resident David Lantham told the Rhode Island Monthly, “most people don’t winter in Matunuck.” Lantham and his neighbours sent hundreds of letters of complaint to the CRMC under the Save Potter Pond organization.

Denouncements of oyster farming are often made under the banner of environmentalism. The monster of industry violating the sanctity of water is of grave

concern, especially when it happens near federally protected land and resident housing. Opponents have raised the issue of physical ecosystem disturbance by oyster infrastructure and pollution from boat runoff. However, the argument of conservationism is also used by aquaculture acolytes. Oyster cages create new ecosystems, serving as artificial reefs that increase biodiversity—patricularly valuable in soft-sediment seafloor like that found in Rhode Island’s estuaries. Oysters “literally clean the bay,” Farmer repeatedly told me. The World Wildlife Fund describes oysters as “unsung heroes in a changing climate”, they filter out excess nutrients and particles, control harmful algae blooms and promote seagrass growth—another vital habitat for marine life. All of the oyster farmers I spoke to brought up the sustainability of their practice in the first five minutes.

Lantham gave credit to Raso for his sustainability

and his business, but noted to the Rhode Island Monthly that the Matunuck residents “just don’t want him to do it on the back of those using the pond” in other words, those who summer in Matunuck. It is a misnomer to refer to ‘summerers’ as locals or even residents (which they are not, according to the state of Rhode Island). They are, however, recognized in the courts of Rhode Island, where Save Potter Pond is waiting for the CRMC to file the legal rationale for the approval of Matunuck Oysters’ Segar Cove lease then they can file an appeal to the Superior Court, which would ideally place a hold on construction during the appeal process.

The near decade-long legal dispute over Matunuck Oysters is a testament to the extensive resources that wealthy waterfront owners have to mount legal and regulatory challenges. The presence of this out-ofstate influence continues Rhode Island’s long tradition of vacation wealth, beginning in the Gilded Age when Newport was a summer resort for America’s industrial elite—unaffectionately titled ‘robber barons.’ As Joan Didion writes in her 1967 essay “The Seacoast of Despair”: “I went to Newport not long ago, to see the great stone fin-de-siècle ‘cottages’ [...] monuments to something beyond themselves; houses built, clearly, to some transcendental point. No one had made clear to me exactly what that point was.” I would argue that The Breakers and Rosecliff House, Newport’s most famous Gilded Age mansions, were monuments to the lack of federal income tax. The 1913 advent of a national income tax is cited as the beginning of the end for Vanderbilt’s playground.

This past month, the Non-Owner-Occupied Property Tax Act was passed in Rhode Island’s 2025

budget bill. Otherwise known as the “Taylor Swift Tax”, a reference to the artist’s $18 million estate in Westerly, Rhode Island (fittingly called Holiday House), the act recognizes that luxury houses utilize local services while their residents only seasonally contribute to the local economy. The act will impose an additional surcharge tax of $2.50 on every $500 above the $1 million threshold for houses that are not occupied for at least 183 days of the year. The city of Providence is also considering a student impact fee which would charge landlords renting to college students $300 per student annually. That these measures will make Rhode Island less appealing to wealthy out of state-ers—today Brown/RISD students and pop stars, not standard-oil heiresses—is unlikely. However, it marks a transition in the state’s approach to the wealth disparity between out-of-state summerers and Rhode Islanders. The tax is designed to fund affordable housing programs, addressing how out-of-state wealth has helped create and exacerbate the affordable housing crisis in coastal and college neighborhoods.

“Oyster farmers have worked on the water their whole life but they can’t afford a property that looks over it,” Namba said, gesturing first to the water and then to an unassuming gray bungalow above. “Ten years ago that house would’ve gone for maybe $300,000; it just sold for over $1 million.”

The crisis has also made its way to the docks. Escalating fees for marina slips are putting strain on small-scale operators, mainly oyster farmers and quahoggers like Raso, who expressed concern over Matunuck dock prices. As vacation home–ownership has increased, so have recreational boaters willing to pay considerably more for slips, resulting in a luxury transition in the dock market. This is visible in the corporate acquisitions of independent marinas. Safe Harbor Marinas is one such corporation, which, after purchasing Warwick’s Wharf Marina in 2020, raised the price from $85 per foot to $118–122 per foot the following summer. The scarcity of slips exacerbates the docking crisis; in some areas, the waitlist for town-managed moorings can extend up to 40 years.

Rhode Island’s temporary residents are fundamentally changing communities to serve their seasonal needs. The ambiguities of water property rights demonstrate the extent to which out-of-state wealth influences local politics, leaving small-scale oyster farmers vulnerable. But arguments around prioritizing out-of-state wealth in Rhode Island’s public spaces reach beyond the water to the streets. Wealthy landowners’ claims over public water echo

calls by the Brown community and the Brown Daily Herald’s editorial board to enforce a noise ordinance on Thayer St. It also parallels the housing crisis in Providence, largely triggered by the ability of Brown and RISD students to pay higher prices than locals. I want to remind students that most of us will not be here after our four-year season. Rhode Islanders will.

The pulley brought the wire cage into view, out from beneath the dark Narragansett water. Hands reached in and drew out a mesh bag. Oysters clattered to the bottom of the bag as it was set down in the half-inch of water that coated the floor of the skiff. The first set of hands briskly took out each oyster and determined its fate: to be sold, to be put back in the cage for further maturation, or to be thrown into the ocean, as it would never grow into the ideal shape. The second pair of hands counted each developed and oval oyster before scrubbing off any growth and throwing it into an industrial ice box. The discarded oyster will float to the bottom of the estuary, one wild oyster in a bed of thousands, reproducing long after vacationers leave for the winter and farmers return to their inland homes.

JACKIE DEAN B’28 wants to keep the oyster in the discourse.

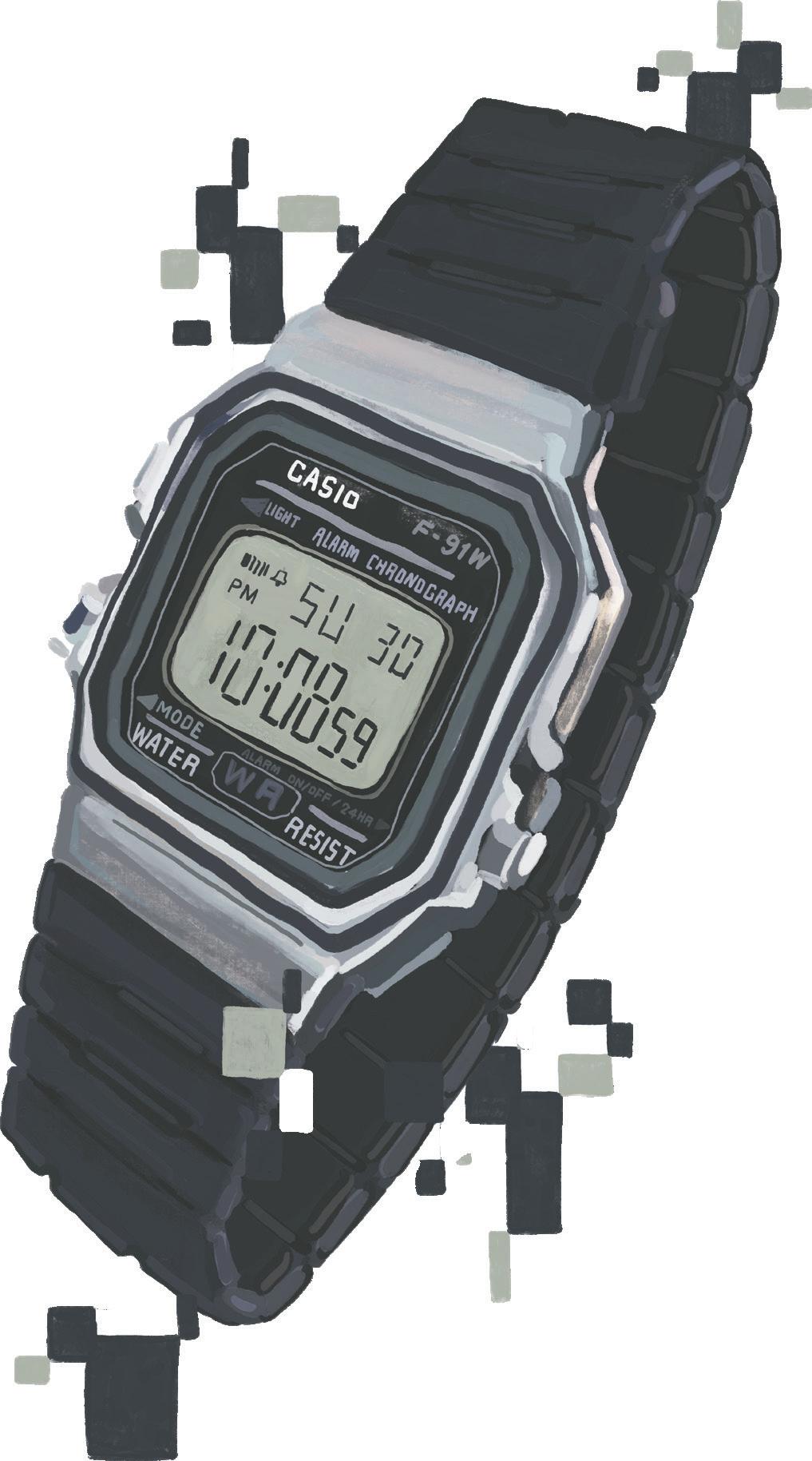

c The video begins with a throng of clamorous young men escorting an imposing figure through a hallway to a cacophony of unsynchronized beeping noises. They exit the school building and congregate around him. As he is handed a small parcel containing the symbol that will signify his membership in this organization, one of the youths calls “takbīr!” He is met with a response of “Allāhu ʿakbar!” which is followed by a roar of applause. Several individuals appear with forefingers raised, a symbol of tawħīd (the Islamic concept of the oneness of God). This is not a video produced by Al-Qaeda or somesuch organization. This recording is the work of Katā’ib Ansār Al-Casio (the Militia of the Partisans of Casio), a group founded by several of my high school classmates (including myself) with the sole purpose of spreading the gospel of the Casio F-91W.*

There was not much more to it than that; we liked the classic digital watch, and sought to get as many people as possible to wear it. The towering figure from the video was our economics teacher, a veritable mountain of a man, upon whom we bestowed his very own F-91W. But all was not cookies and cream (or indeed sunshine and rainbows) in Casio-land. The founding members soon splintered over the permissibility of wearing the metallic A158W model (the standard F-91W has resin straps). Some considered it a proper F-91Wform (I have made this term up), and thus ħalāl to wear, while others considered it a completely impermissible bid ʿah (innovation). The splinter became a schism, and before long, the two factions were keeping clear of each other. Hostilities persisted until the end of the year. Why the hell did we care so much about this watch?

First, it behooves us to elucidate what we are talking about. The Casio F-91W is a quartz digital watch with resin case and strap. The case measures 37.5 by 34.5 by 8.5 millimeters, and comes equipped with three buttons: the top left illuminates a feeble green LED backlight, the bottom left cycles between functions (time notation, alarm, and chronograph), and the bottom right triggers the associated action for each function (switching between the 12- and 24-hour clock, editing the alarm settings, and starting and stopping the chronograph). Various combinations of these controls produce a range of functions, which can be facilely ascertained after a few minutes of involved fiddling with an F-91Wform in hand: for instance, holding down the bottom-right button in the alarm settings produces a continual beeping noise, as in the opening scene of the article.

The F-91W was the culmination of 15 years of digital watch innovation by the Casio corporation. The technology company of calculator fame released their first digital watch, the metallic Casiotron in 1974, soon followed by the Casiotron X-1 and Casiotron for women. The first watch of the resin-based F-series was the F-100, released in 1978. Throughout the 1980s, Casio threw all sorts of horological spaghetti at the wall to see what would stick: watches with calculators, electronic English-Japanese dictionaries, thermometers, touch screens, data banks, FM audio transmitters, sensors for predicting weather patterns, planetary orbit displays and Muslim prayer compasses. Alongside these Inspector Gadget–esque fixtures, the F-series continued as a mainstay of bare-bones yet versatile timekeeping. The F-91W was released in 1989, and instantly became a roaring success. Why the F-91W became the best-selling watch in the world—and not, for instance, the (highly similar) F-20R, F-84, F-87W, or various other

F-91Wforms—is not something I have found an explanation for. Perhaps Casio had mastered lightning-bottling technology at last. Regardless, the F-91W would go on to break every chronometric record on the books (and some that hadn’t even been considered for the ledgers). Although Casio is quite cagey with their sales figures, it’s been said that three million F-91Ws are produced annually, amounting to 100 million units since its release.

The astounding proliferation of these resinated watches meant that they were ubiquitous across the globe. As a result, when Al-Qaeda were looking to implement a timing mechanism in their bomb-making activities, the utilitarian F-91Wforms seemed the logical choice. The watch became a staple in the realm of explosive fabrication, and soon American security services decided it was a mark of suspicion. In fact, leaked documents from the Guantanamo Bay detention camp revealed concerns that F-91Wforms were symbols of Al-Qaeda; officials began to use the watches as evidence that detainees were enemy combatants. The irony of using the most commonly worn watch in the world in racial profiling was apparent to Abdullah Al-Kandari, a Kuwaiti national held four years without charge, who remarked: “We have four chaplains [at Guantanamo]; all of them wear this watch.” While it is true that there are plenty of images of Osama Bin Laden sporting the F-91W, there are also similar images of individuals such as Eric André, Nathan Fielder, Ryan Gosling, and Barack Obama with wrists proudly Casioed. The F-91W is simply too universal of an accessory for such generalizations to be made.

In fact, it is this tension between the ubiquity of the F-91W and its receptiveness for semiotic plasticity which was at the core of the Ansār al-Casio’s factionalization. It is a tension of this sort that media theorist Marshall McLuhan captures in his phrase “the medium is the message”; media themselves, in their characteristics and circulation, carry meaning. In illuminating its environs, the seemingly scantily semantic lightbulb creates light where there otherwise would have been dark. The incandescent apparatus thus emits rays of meaning-creation through how it changes its surroundings. In the same vein, the Casio F-91W was the first truly universal chronograph, and it brought the hands of time previously guarded by costly and complicated mechanical movements onto the wrists of the masses. Time became democratized.

In a world moving toward globalized systems of trade and communication running on a strict schedule, timekeeping was a necessity, and the F-91Wforms captured this niche. They could orchestrate transcontinental conference calls, coordinate international cargo shipments, or simply ensure a rendezvous took place punctually. At the same time, its prevalence and pan-ubiety made it a powerful sign-receptacle. The medium could manifest myriad messages. The F-91Wform could be a terrorist timepiece, the first rose-tinted watch of nostalgia, a retro fashion statement, a rejection of smart watches, or simply a symbol of pertinence to a high school in-group.

Our group’s struggle over the permissibility of the A158W was more than a matter of resin versus metal straps; we were vying to delineate the boundaries of the F-91W’s semiotic potential. To the conservative faction, the A158W diluted this potential. Why not include the G-Shock (another popular digital Casio watch), or any of the other various digital horologia that had come to see widespread use? To me, this argument seemed fallacious. It was the fact that

( TEXT HISHAM AWARTANI DESIGN MARY-ELIZABETH BOATEY ILLUSTRATION SUZIE ZHANG )

the Casio F-91W was the first truly universal chronograph, and it brought the hands of time previously guarded by costly and complicated mechanical movements onto the wrists of the masses. Time became democratized.

we were able to speak of a category of F-91Wforms in the first place that I found significant. The A158W was released concurrently with the F-91W, and ever since the F-91Wforms have acted somewhat isomorphically in popular imagination and function. Resin or metal, pink or black or silver, corner LED or full backlight, F-91Wforms as a category will always represent the people’s watch, the first of its kind.

HISHAM AWARTANI B’25+1 has been proudly beCasioed since age five.

‘A’ ‘Universal’ ‘History’

The book is a finite and enclosed set of pages. It is also a commitment. When you pick up the book, it commits to having a beginning, to having an ending, and to having something happen in between.

Sometimes, this commitment is too much for the book to handle.

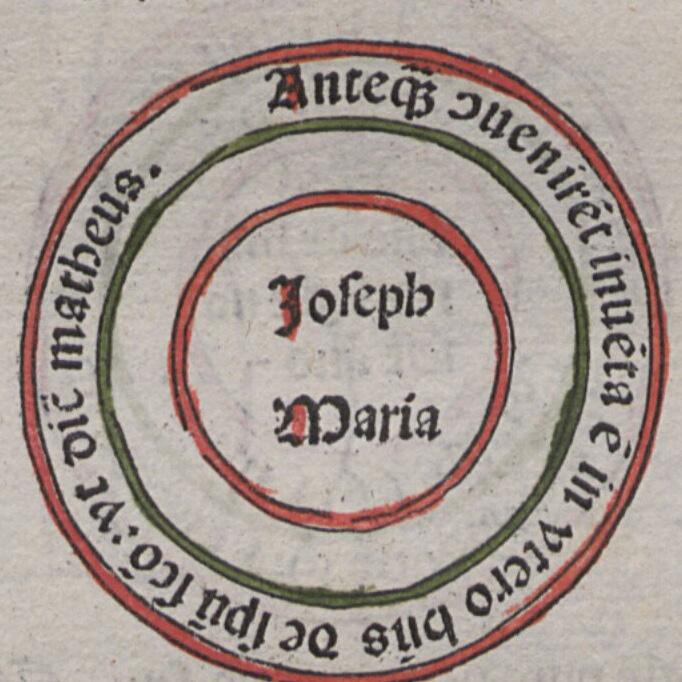

Fasciculus temporum omnes antiquiorum cronicas complectens (FT) is the title of one of the most popular universal histories of late 15th century Europe. It translates to “A little bundle of time comprising all the chronicles of the ancients.” The book purports to encompass the entirety of recorded history, and to do so within just 150 pages.

DESIGN SCHEMA HQ

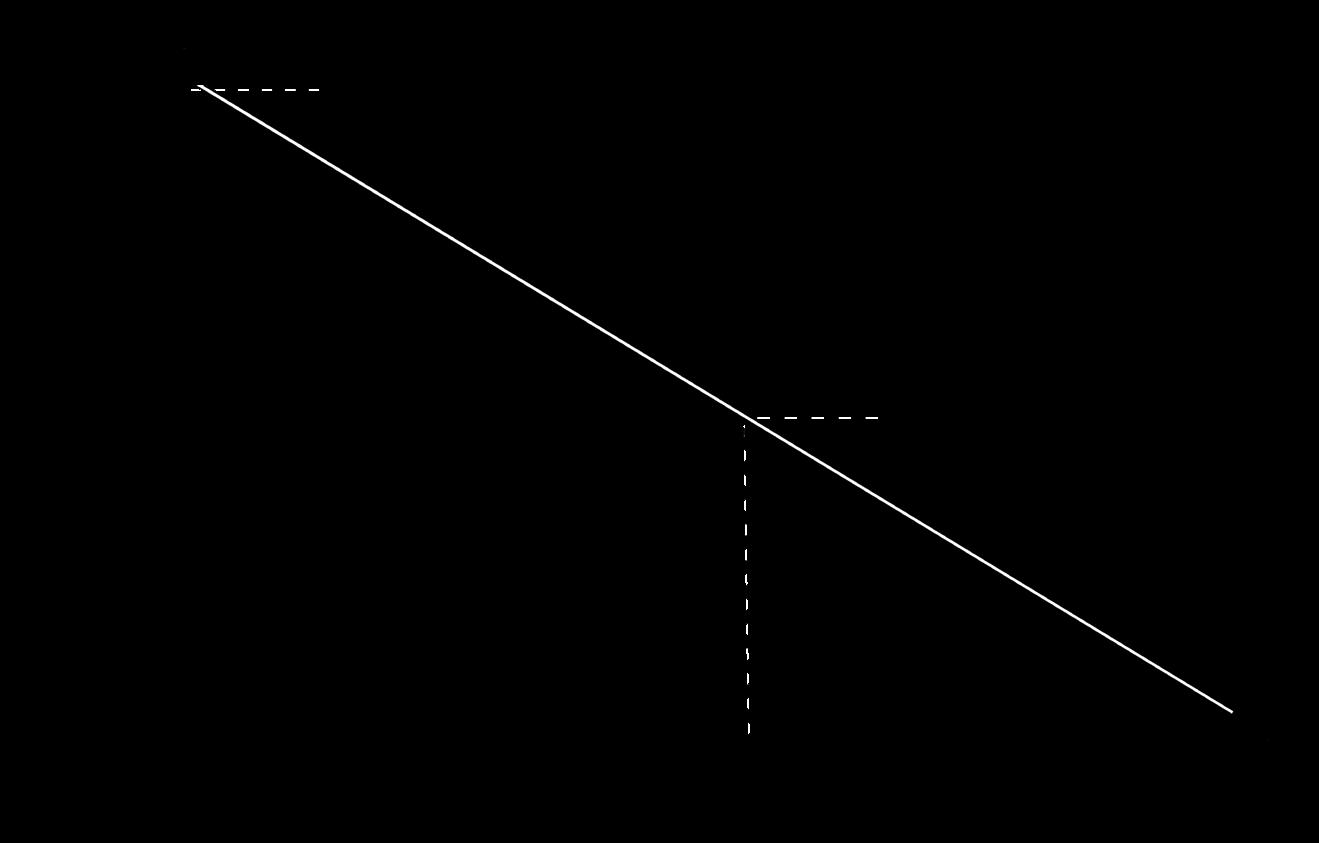

In the prologue to FT, its author states that whenever the timeline is counting up, it is descending, and when it is counting down, it is ascending. As in, although this new way of time-keeping runs along the horizontal axis, its author still thinks of it in the old way, as a genealogy running along the vertical axis. Time in FT can thus be graphed in slope form, with the beginning of the world (universal year 0) and the birth of Christianity (0 AD) as the narrative and geometric pinnacles of the chronicle.

Two things to qualify here.

One FT’s timeline reads like a tree. Length signifies diachronic succession via rightward thrust. Width signifies simultaneous lineages of hegemony among Judeo-Christian leaders. In FT, power progresses, but it does not disperse. It is not like a tree of life, whose limbs grow into branches and these branches grow into twigs; it is like a tree of culture, whose elements fuse at least as much as they diverge.

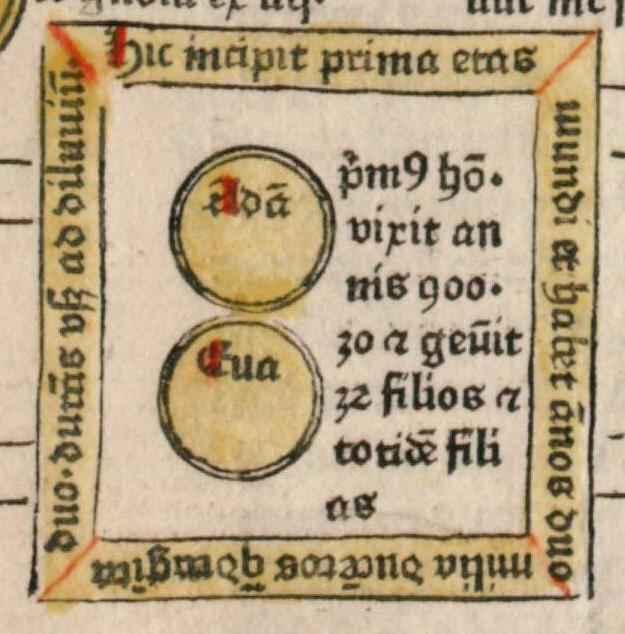

Two. The first element on FT’s timeline is not the first day of creation, but the name of the first son of God, Adam. Historical time starts when Adam dooms humanity by eating from the tree of knowledge. Afterward, only one element ever interrupts FT’s universal time-keeping: an icon of the resurrected Christ, which overtakes an entire page. Historical time starts again when Christ—the Son of God, the second Adam—redeems humanity by dying on a wooden cross.

Moving forward as it is moving down, all the while originating from the Fall of Man, FT’s timeline reads like a fallen tree.

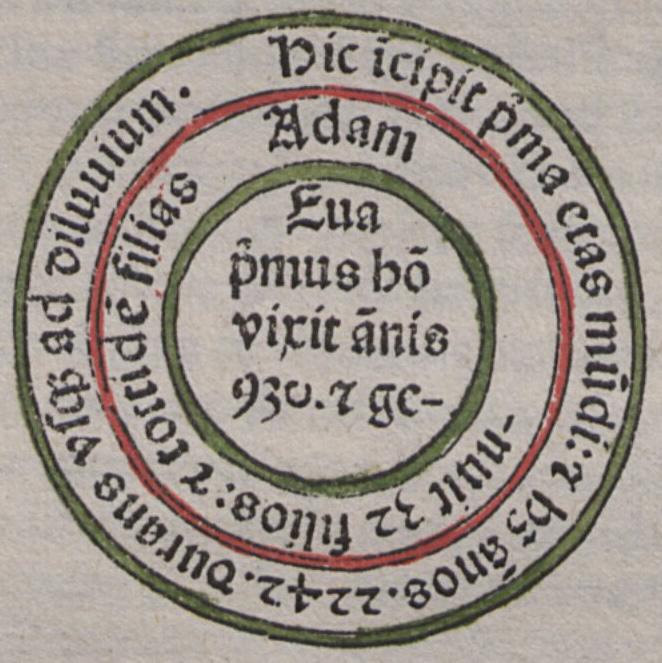

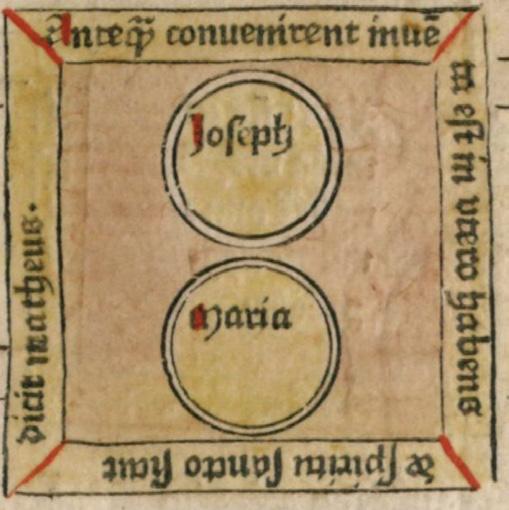

As impressive as that may sound, FT is not at all famous for its text, but rather for its design. The book operates across the three scales of History: the historical event, the historical cycle, and the longue durée. Names of significant historical figures are inscribed into eye-catching circles: these are our individual historical units. Their names are then ordered into lineages (of biblical ancestors, ancient philosophers, medieval kings, etc.) across six ages—Adamic, Noachian, Abrahamic, Davidian, Babylonian, and Christian—each of which begins with a larger circle or square: these are our cyclical historical structures. Finally, a horizontal timeline runs across the center of each spread, coordinating all these historical patterns into one, unified, linear movement: this is our enduring longue durée

FT, this ‘little bundle of time comprising all the chronicles of the ancients,’ cares much less about “chronicles” and much more about “comprising.” The balances of its historio-graphic value do not fall on the side of its reputable ancient histories, but that of its novel graphic design. FT is so successful with its schema that its text is relegated to the status of annotation. Do we even have to read the book to grasp the Christian vision of universal history as ordained, sustained, and enclosed by God? Can’t we just look at it? Isn’t the form all the content we need?

A.h Ma

Because of this timeline, FT is the first European book in which time moves from left to right (like reading a sentence), rather than from top to bottom (like a genealogical tree). The timeline runs in two directions: the upper line counts from the beginning of the world in the Book of Genesis (universal year 0) to the present day (universal year 6673), and the lower line counts in reverse, toward the birth of Christ (universal year 5199 as 0 AD), and then continues counting to the present day in tandem with the upper line (universal year 6673 as 1474 AD).

Indeed, FT passed through the presses of many urban centers across Western Europe—Cologne, Leuven, Basel, Venice, Seville, Lyon, to name a few—resulting in over thirty printed editions up to the year 1500. FT’s author was aware of the potentials, but also the dangers, that mass reproduction of his book would entail. Though the prologue welcomes reproductions of his universal history, it asks that any attempt commits to the “exemplar” structure and aesthetic of his first official edition.

This request rubs against the fact that each of FT’s twenty printers— not to mention almost as many of its scribes— interpreted this commitment differently, even if only a little. But, if FT’s typographic form changes, even a little, doesn’t its chronological content change, at least a little? Isn’t each new edition of FT a new book? And doesn’t the author’s prologue frame each of these reproductions as “exemplars”?

A universal history published in late 15th century Europe could, for the first time, strive to reach a universal audience. The rise of print exploded access to textual knowledge from the elites onto the masses, producing more books and reproducing all of them across more copies than ever before.

Figurative. Handdrawn. God stands. Eve emerges out of Adam’s side. A serpent coils around a tree. Contains author’s prologue.

Schematic. Printed Adam’s circle is above, superior to Eve’s. Square frame reflects the rectilinear timeline.

Schematic. Printed.

Adam’s name is above Eve’s, his circle encloses hers. Curvilinear design, distinct from the timeline.

Schematic. Printed. Adam’s name is still above Eve’s, but her circle encloses his. Curvilinear design, distinct from the timeline.

Figurative. Printed. Eve faces a serpent. Adam stands by the tree. Commercial focus on the image over the schema.

As this tree exemplifies, sometimes, the many scribes and printers of FT did not commit to the schematic minimalism and symmetrical hierarchies of the first printed edition—sometimes, because they produced their books before the publication of that first official edition. In fact, sometimes they did not even commit to the unified, divinely sustained design of the timeline. From 33 (out of 33 known) printed editions and 7 (out of 14 known) manuscript copies:

The different reproductions of FT visualize, spatialize, and conceptualize time differently. The form changes, and so does the content. This pushes Michel Foucault’s notion of the repeatable materiality of the statement to its limit.

Schematic. Figurative. Handwritten. Handdrawn. In the first, Joseph’s circle is above, superior to Mary’s. In the second, Christ is present, Joseph is missing.

Schematic. Printed. Joseph’s circle is above, superior to Mary’s. The aesthetic analogy between the first Adam and the last Adam (Christ), is successful.

Schematic. Printed.

Joseph’s name is above, superior to Mary’s. They are in one circle, together. The aesthetic analogy is semi-successful.

Schematic. Printed. No concentric circles. Joseph’s name is below, subordinate to Mary’s. The aesthetic analogy is unsuccessful.

Let’s not even go there

A statement is not just a linguistic unit or an instance of its reproduction. As Foucault describes it, it must have “a substance, a support, a place, and a date. And when these requisites change, it too changes identity.” For example, the graph is a statement because “any sentences that may accompany [the graph] are merely interpretation or commentary; they are in no way an equivalent:…in a great many cases, only an infinite number of sentences could equal all the elements that are explicitly formulated in this sort of statement.” The timeline in FT’s first official edition is a (graphic) statement: a statement about Christian universal time, printed on paper, in Cologne, in 1474. In the face of its powerful, unified design, the text around it becomes auxiliary. However, if the timeline is a little offset by a budding Venetian printer in the 1480s, or if it is fractured while getting translated into German, or if it is completely gone, historical time in FT “changes identity.” It does not repeat. It becomes something new.

Because, as a universal history, FT professes to contain total, ideal knowledge, the repeatable materiality of the statement is pushed to the limit purely by virtue of the reproduction of the text in the form of the book. Foucault argues that “successive editions of a book…do not give rise to the same number of distinct statements,” because changes in “texture”

(typeface, ink type, text base, layout, etc.) are “small differences” that are not “important enough to alter the identity of the statement and to bring about another; they are all neutralized into the “general element” of the text, “an authority that permits repetition without any change of identity.” For FT, this authority of repetition is located in the author’s prologue—he welcomes it, but only with a commitment to preserving the “exemplar” form of his text. However, because the prologue appears in every edition, it authorizes every edition as the one whose form must be preserved. Regardless of how small, unimportant, or neutralizable the change in the texture of a specific reproduction may be, it always produces a new statement, a new universal history, and a new “exemplar” to commit to.

FT professes to be a unified, infinitely reproducible tree of knowledge. Instead, it is a mass of different and finite reproductions; in this sense, FT can be read as a forest of felled, disfigured trees.

Because FT is a book, it must have an ending. But because it is meant to contain all historical knowledge, it can never have a definite, universal ending. That is, its ending must always be updated based on the particular time the reproduction is being made and the particular prior edition it derives from (which does not need to be the most recent edition). Every reproduction of FT ends with a colophon—a closing statement that records the name of the maker and the date of the publication of a book. What is consistent across the colophons of all FT reproductions is that they are different. Ultimately, what matters is that

PAULINA GASIOROWSKA B’27 would like to thank Jacques Derrida, Hayden White, and Franco Moretti for not making it into this piece.

c In the opening shot of “The Most Beautiful Exit,” a hospital room is set out to sea, its antiseptic interior disappearing into the light of the sun as it is pulled further and further oceanward by foaming waves. It’s a surreal shot, but for a video about a woman choosing to die by voluntary euthanasia produced by Simons, a Canadian fashion company, perhaps surrealism is fitting.

The rest of the video’s three-minute play time matches the beginning’s dreamy aesthetic. Through a series of interspliced shots—of the woman sitting in a forest, getting a fern tattoo, smiling as she feels the vibrato of a cello—“The Most Beautiful Exit” constructs a gorgeous tableau of her final days. As it winds down, the uplifting background music quiets to the solemn rushing of the waves. A text overlay tells us that the woman’s name is Jennyfer, that she lived from June 1985 to October 2022. The video ends with the Simons logo.

It’s hard to decide what to call “The Most Beautiful Exit,” the first (and only) entry of Simons’ ill-fated 2022 “All is Beauty” campaign. If it’s a commercial: Why not a shred of Simons-branded clothing within its three-minute runtime? If it’s a documentary: why the Simons logo at the end? And why in the world would I have encountered it as an ad before a Minecraft speedrunning video? Interviews with people behind the project do little to clear the confusion. When asked what the project was, Jay Chaney, the chief strategy officer of Broken Heart Love Affair (the advertising agency Simons worked with), launched into a philosophical meditation on the fundamental purpose of advertising. “We’re helping somebody facilitate societal change in some way.

And ultimately, isn’t that the same thing as advertising?” he concludes. I roll my eyes.

The one position Chaney is willing to stake is that “The Most Beautiful Exit” is about beauty. Immediately after its release, the video became caught up in a torrent of vitriolic backlash. Conservative news outlets lambasted it for promoting voluntary euthanasia as an aspirational life goal, for violating the sanctity of life. Chaney insists that it’s not about politics. It’s not about Canada’s voluntary euthanasia program, MAiD (Medical Assistance in Dying). It’s about dappled treetops, jellyfish sculptures. It’s about cheesecake.

Despite Chaney’s abstraction, the intractable fact is that “The Most Beautiful Exit” is a video about a woman who chooses to end her life. And although the purported objective behind the “All is Beauty” campaign was to highlight the ability to find beauty in the most unexpected places (even in death), “The Most Beautiful Exit” takes this message a step further. It’s right there in the title: There doesn’t just exist beauty in death, but such a thing as a ‘beautiful death.’ Moreover, the fact that one death can be the most beautiful implies there’s a hierarchy, a pageantry of passing. So, how do you die beautifully?

For the philosopher Michel Foucault, death is no longer central to the exercise of power. Moving away from the sovereigns of old, kings and queens who maintained their divine right by killing their dissenters and enemies, Foucault instead argues that we live in an age of governmentality, in which control

is exercised primarily over life, through a politics of cultivation, improvement, and elaboration. To him, the medical system is a quintessential example of this new operation of power. In the name of health, we subject ourselves to fitness regimes, turn away carbohydrates, and allow the collection of intimate bodily data by healthcare providers. Of course this isn’t an act of benevolence. Rather, the government helps maintain our bodies, so that we don’t call in sick for work.

In her essay “The Biopower of Beauty,” the feminist scholar Mimi Thi Nguyen, interrogating the strategic deployment of beauty by the United States during the War on Terror, shows how beauty is also an operation of biopower. She argues that within this discourse of aesthetics, the Western imagination takes superficial beautification of the body through adornments such as makeup or clothing as a makeover of one’s inner life: a restoration of dignity, liberation. Analyzing Vogue’s profile of the burqa, Nguyen identifies how the clothing, to Americans, becomes a perfect synecdoche for the gendered violence of the Taliban. Too hard to maneuver in, too hot to wear, the burqa becomes not just a symbol of oppression but a form of Taliban violence on its very own. In Western campaigns against the burqa, its removal cloaks a violent imposition of Western culture under the guise of a liberatory project. As Nguyen argues, conformity to Western beauty standards becomes both the “means and the ends of a civilizing process.” What she means is that beauty is a right, which unlike others, can be made visible on the body’s exterior. Lipstick and eyeshadow become badges pronouncing one’s inclusion in a free society. But they are markers that

one must constantly be adorned with. How else could someone know you are liberated? Beauty then becomes both an ideal for Afghani women to aspire towards and a demand for them to perform. It is a demand which requires “waging war,” in which death simply becomes an unfortunate byproduct. Eyeliner becomes emancipation. Lululemon liberation. The War on Terror: an invasion of makeup pencils and mascara, tanks and unmanned drones.

“The Most Beautiful Exit” relies on similar logic. As Jennyfer intones, “Dying in a hospital. It’s not what’s natural. That’s not what’s soft.” To let the hospital room wash away into the ocean in the opening shot is to symbolically separate the ‘beautiful death’ from the disciplining forces and technologies of medicine. For “The Most Beautiful Exit” then, a ‘beautiful death’ is that which putatively escapes the horrors of the medical system. Sure, it seems to say, the hospital keeps patients alive, but it does through the most molecular exercise of violence and control. IV tubes, blood tests, bed pans extend biological life only by sacrificing life’s very meaning.

But don’t be fooled by a pretty face. It’s precisely “The Most Beautiful Exit” conflates” of the aesthetics of a beautiful death with that death’s rightness which occludes the necropolitics of medical care. Return once again to the opening scene. In the corner of the hospital room is a wheelchair, which represents the video’s main critique of the medical system. Confined to a wheelchair, a patient loses their freedom to move, their right to choose; confined to the healthcare system, people have no choice. By then juxtaposing the wheelchair with Hatch sitting in a chair set out on the beach to watch the sunset, the video affirms that she, unlike her hospitalized counterparts, retains the right to agency. Unhindered by the bureaucratic chains of the hospital, she is free to be surrounded by her friends, to get a tattoo, to draw in the sand. Under the shining ray of choice, even her tears, distillations of all the pain that comes with ending her life, can refract gorgeous spectrums of light.

+++

Yet if we simply widen the frame, this fantasy of choice disappears. Shortly after the ad aired, CTV News reported that Jennyfer Hatch had anonymously testified about her lack of access to proper treatment for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. She did not want to choose euthanasia but recognized that “it [was] far easier to let go than to keep on fighting.” Though initially only those with terminal illnesses could participate in Canada’s MAiD’s program, it has since expanded to include people living with disabilities. The United Nations condemned the expansion as a violation of the fundamental tenets of the UN Convention

on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Facing grotesque, institutionalized inequities in the system, many people with disabilities are often coerced into choosing euthanasia. Hatch’s life was, as Foucault put it, “[disallowed][…]to the point of death.” However, by portraying her death as beautiful because she had somehow escaped the power of the healthcare system, “The Most Beautiful Exit” obscures the vectors of violence and control that structured her life and death.

For many Canadians who have actually interacted with their healthcare system, this is the ugly truth. Although Canada’s healthcare system is public, major staff shortages, patchy coverage in rural areas, and long wait times persist, challenging Foucault’s characterization of the medical system as a cultivator of health. This is the theoretical intervention that Achille Mbembe makes in his book Necropolitics. As Hatch’s death demonstrates, death is still vital in the exercise of power. Looking to colonies, slave plantations, and occupations, he identifies how the ability to expose certain populations to chronic violence —whether through warfare or a slow death by institutionalized degradation—forms the foundation of government rule today. In Canada, necropolitical control is exercised through a denial of care to the disabled and chronically ill, through encouragement for them to take their own life rather than ‘burden’ society and themselves.

A ‘beautiful death’ indexes the moments when biopolitics and necropolitics collide, or, perhaps more precisely, when they become indistinguishable from each other. As the queer theorist Jasbir Puar argues, biopolitics and necropolitics, far from opposites, are mutually reinforcing dynamics. Necropolitics makes its presence known “at the limits and excess” of biopolitics, while biopolitics “enable[s] the proliferation” of necropolitics. It is the Western demand for Afghani women to beautify themselves that justifies American invasion, their murder. It is their death which allows for the expansion of Western governmentality, the cultivation of a new populace to control.

Although governmentality may control and cultivate its citizenry, for the marginalized, the disabled, and the racial Other, bodily violence is still very much the state of affairs. For his theory’s elegance, Foucault missed this simple ugliness, this truth.

It’s also simple to call “The Most Beautiful Exit” an ad. Peter Simons (yes, the company is five-generations nepotic) told Le Journal de Québec, “the world doesn’t revolve around commerce […] It revolves around relationships and our ability to stand together in community.” These are not mutually exclusive truths.

Through biopower we are made to desire our subjection, and we want others to desire it too. We form a community around it. That’s why it’s so insidious. We meet gym buddies, so together we can train for capitalism. As Nguyen argues, Afghani women are made not only to desire their own beautification but also to “extend an enlivening beauty to others.” Jennyfer Hatch participated in the very video which erased her oppression. Isn’t that the precise purpose of an ad: to sell you something that’s probably not good for you? To kill you beautifully?

Of course Mbembe reminds us that these communities are simply discardable populations for governance. Beauty and ads are nothing more than thin veneers.

A month after releasing “The Most Beautiful Exit,” Simons pulled the ad and ended the “All is Beauty” campaign. When asked for an interview, a senior consultant simply emailed back: “Simons is now entering their annual holiday sprint […] The holiday season is an extremely busy time.” +++

Jennyfer Hatch was a music therapist. She was 37. She would be 40 today.

EVAN LI B’28 thinks death is bad actually

c There’s a point in your life when America becomes, for you, what it will be for the rest of your life. You think: America is a series of parks and temples. America is overvalued advertising. America is Del’s Diner and Hair by Natasha and Ricky’s Autoparts and Casa de Carlitos. America is all glass underfoot: dig into the ground outside any urban center and you’ll hit shards, green and amber and window-clear. America is Fox News’ wet-lipped pastors praising the Lort. America is an intersection with complicated signals and statistically significant rates of auto-injury. America is a best-selling novel taken from third-hand experiences. +++

For nine months in my early twenties, I lived with a man who impersonated presidential assassins. He was a professional; he was the best in the biz. One night, he was John Wilkes Booth, the next, Lee Harvey Oswald. Charles J. Guiteau and Leon Czolgosz were demanded less frequently, because nobody cared about the presidents they murdered and nobody could pronounce their names. There was no great demand for any given assassin in Tandem, or even in Shreveport, but with an arsenal of all four he stayed afloat. He had a cookie tin that he kept on a credenza by the front door, full of mustaches and sideburns and beards—high quality stuff, reusable. On occasion, hopeful and usually high, I would peek into the tin hoping to find the Royal Dansk Danish Butter Cookies promised by its lid rather than his tasteful collection of human hair, but I never did.

When I say ‘lived with,’ I don’t mean to imply ‘slept with.’ The man was twice my age and straight: a brother of a friend of my aunt from the years in California she referred to, with rue and satisfaction, as her ‘wild days.’ Less than a year out of my English BA and lacking any wild days of my own, I was extremely susceptible to those of others. I was also increasingly poor, increasingly desperate to move out from my parents’ house, and increasingly frustrated with increasingly late-stage American capitalism. I needed to get to the root of it; I needed something to write about. My aunt’s description of Louisiana and my soon-to-be-roommate indicated depth and intrigue at an astonishingly low cost. I thought: indulgent monasticism. Rs swallowed in new and exciting ways. Tennessee Williamsesque ruins of people and places. All of my references, besides Boston—just outside of Boston—were literary: Delillo’s New York. Ballard’s London. Pynchon’s San Narciso. I read half of A Streetcar Named Desire and a few sentences from a local tourist agency’s online article entitled, “Tandem, Louisiana, Is the Friendliest Town in the South,” populated with links to other hard-hitting