Marissa

Dri de Faria, Benjamin Flaumenhaft, Isabel Tribe, Gabriella Miranda, Evan Gray-Williams, Lillian

Marissa

Dri de Faria, Benjamin Flaumenhaft, Isabel Tribe, Gabriella Miranda, Evan Gray-Williams, Lillian

DESIGN EDITORS

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Anji Friedbauer, Natalie Svob

��: It is when you’re smiling though you’re crying though you’re shaking though you’re feeling more alive than ever though you’re laughing yourself to death that you know it’s been good. I’ll miss counting my Conmag time in days, I’ll miss the (delirious) power and the (nonexistent) prestige, I’ll miss missing deadlines and caring so, so much about it. After this issue goes to print, so many will be leaving the Indy* (how f*cking dare they), and we’ll be leaving the fate of the Indy* in the hands of the new MEs. What have we left behind? What will we have left?

��: This is the worst/best/living/leaving/mourning/dead/hungry/terrible/good/ distracted/abandoning/bug-bitten/walkaround/cyclical/heartbroken/dried-out/ crazy-eyed/bigger-thing/messed-up/petty/predictable/anticipated/ruin-it/accept-it/ dusty/allergenic/fated/saved/sensible/list, like-always/like-only/well-of-course-this/ it-had-to-be copy. It will end all of a sudden. I’m walking home for the last time. Terribly, I’m predicting. Nan says there’s always leaving. It’s a middle goodbye.

��: We are in Conmag with everyone bringing this final issue of Volume 50 in for its landing. We’re encountering the limits of legibility and pulling quotes and opening windows. We have snacks and chargers and copious back issues and almost no space left on the table. The rest is “light work.” Help! Someone I love works for the College Hill Independent. All the things I can think of to put here are poorly written and (worse!) sentimental. I am so lucky.

MANAGING

Emily Vesper

Nan Dickerson

WEEK

Ilan Brusso

Kat Lopez

ARTS

Beto Beveridge

Ben Flaumenhaft

Elliot Stravato

EPHEMERA

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

M. Selim Kutlu

FEATURES

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Nadia Mazonson

LITERARY

Sarkis Antonyan

Elaina Bayard

Nina Lidar

METRO

Arman Deendar

Talia Reiss

METABOLICS

Brice Dickerson

Nat Mitchell

Tarini Tipnis

SCIENCE + TECH

Emilie Guan

Everest Maya-Tudor

Alex Sayette

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Lucas Galarza

Ash Ma

Izzy Roth-Dishy

DEAR INDY

Kalie Minor

BULLETIN BOARD

Anji Friedbauer

Natalie Svob

MVP

April, Anaïs, Andrew, Ash, Audrey, Daniel, Emilie, Emily,Izzy, Kay, Layla, Lucas, Nadia, Nan, Sabine, Talia, and PG.

*Our Beloved Staff

Kay Kim

April Sujeong Lim

Anaïs Reiss

Andrew Liu

DESIGNERS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Jolin Chen

Esoo Kim

Minah Kim

M. Selim Kutlu

Seoyeon Kweon

Iris Lee

Hyunjo Lee

Anahis Luna

Liz Sepulveda

Justin Xiao

Isabella Xu

Shiyan Zhu

STAFF WRITERS

Layla Ahmed

Aboud Ashhab

Hisham Awartani

Grace Belgrader

Emmanuel Chery

Nura Dhar

Kavita Doobay

Lily Ellman

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Elena Jiang

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nahye Lee

Cameron Leo

Cindy Li

Evan Li

Angela Lian

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Gabriella Miranda

Coby Mulliken

Naomi Nesmith

Kendall Ricks

Lily Seltz

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

Luca Suarez

Daniel Zheng

COVER COORDINATORS

Johan Beltre

Brandon Magloire

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Lucas Galarza

FINANCIAL

COORDINATOR

Noah Collander

Simon Yang

Mingjia Li

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Julia Cheng

Mia Cheng

Anna Fischler

Zoe Gilmore

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Ellie Lin

Ruby Nemerof

Jessica Ruan

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Luna Tobar

Catie Witherwax

Lily Yanagimoto

Nicole Zhu

COPY CHIEF

Jackie Dean

Lila Rosen

COPY EDITORS

Kimaya Balendra

Justin Bolsen

Cameron Calonzo

Jordan Coutts

Kendra Eastep

Leah Freedman

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Christelyn Larkin

Eric Ma

Becca Martin-Welp

Isabela Perez-Sanchez

WEB EDITOR

Lea Seo

WEB DESIGNERS

Sofia Guarisma

Clemence Jeon

Janice Lee

Liz Sepulveda

SOCIAL MEDIA

MANAGER

Eurie Seo

Ivy Montoya

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Martina Herman

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Emily Mansfield

Kalie Minor

SENIOR EDITORS

Jolie Barnard

Arman Deendar

Angela Lian

Lily Seltz

Luca Suarez

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

(clock towers blowing up, people late for first dates,

’s woundedness, and in this state -

ness and without peace, it moves through walls and The and return to the snow, smog, and buildings, I am overcome with a sense of deep and indissuadable regret. I believe that a world has ended, even though I cannot specify the people that inhabit it, its rules for belonging, or the social fabric that holds it together.

Jack Nicholson waiting in his office for the clock to strike 5:00 p.m.; Black Moon (1975), a young woman throws an alarm clock out of the window; The Wrong Man (1956), “What time will Dad be home?” “5:30!”; against my better judgement, I extend my stay by five minutes. And then five more. Then I lose count. The Clock hits 5:51 p.m., and I resignedly text an apology to my friends because it is now clear that I will be late for dinner. I gather my belongings and rush out of the museum. The sun has set into a dark acidic fog; the streets are narrow; and the sheer density of buildings obscures the horizon. I get lost finding the subway, largely because the buildings are indistinguishable, anonymous filing cabinets, the windows like rebar-inlay handles. The afterimage of The Clock inscribes itself on all the clocks I pass by: the subway announcement, the top-right hand corner of my phone, an atomic clock refracted in the window of a pharmacy; they form a vein structure that maps The Clock across the whole city of New York. A new kind of time is spreading.

December 21, 2024, 11:20 a.m.: From a Google search, I learn that in 2020, artists Gan Golan and Andrew Boyd installed the Climate Clock on 14th Street Building, One Union Square South. As stated on the Climate Clock website, “the project is centered on a simple tool: a clock that counts down the critical time window to reach zero emissions (our ‘Deadline’).” I walk to Union Square expecting to see a handful of tourists photographing the clock. Maybe a memorial site with recent IPCC models, photographs, and statistics. I find none. The Climate Clock is simply a red digital clock, silently counting down to an unreadable, inscrutable, and anonymous end. It is, at once, a deep threat and an ambient non-issue. No one is watching it, and everyone is being watched by it. No one knows what geologic changes the rupture—that imposing “0”—will bring. But everyone can quantify exactly how long the waiting time will last.

December 25, 2025, 3:00 a.m.: A thick sheet of snow has muffled the sounds of cars and birds. I am back at MoMA; this time I’m carrying a notebook. The Clock is a porous film. It is a film that lives by remainders, pushing and infringing on all that exists outside of the film theater. There is, conventionally, an unquestionable disjunction between “reel” time (cinematic time) and “real” time (duration). In film, time is subject to the laws of narrative; it may be sped up, slowed down, suspended, etc. Further, cinematic time is never bound to the time of its screening; a film in which a heist takes place at 10 a.m. in a diner may be screened at night. Neither of these two principles hold for The Clock, in which on- and off-screen time

contract watching Marclay’s film: by living with The Clock, I am indexed into its history. It is, reciprocally, indexed into my own.

January 5, 2025, 5:40 p.m.: New Year’s has come and gone, along with my 21st birthday, which has set off a countdown towards an unreadable and unplaceable deadline. In slow episodes of dread, I have been glimpsing that which may or may not arrive: a six-month OPT work authorization running out, a legislative order that will eventually force me to leave the country. It is a self-effacing threat, terminating my world out of sight while insisting on possible visa changes in the indefinite future. I walk to Union Square, and this worry doesn’t register louder than a radio hum. I sit in the park, where my attention is being increasingly occupied by the Climate Clock. A large set of red LED numbers glow against the side of a building. The numbers decrease by the second. I wait, and the seconds turn to a minute, then two. What exactly is being counted down? I look around me: a wave of headphoned commuters leave the station; a woman is falling asleep while selling plastic sunglasses and iPhone cases; six pigeons dive towards a man as he sends breadcrumbs up in the air in parabolic lines. The Climate Clock tells me nothing about the world, only that it is ending. From the interface of the Climate Clock, we would not know the qualitative attributes of an ending world. Without a verifiable metric for ending in sight, we must acknowledge the possibility that we’re already living in the terminal span. Pigeons, trains, phone cases: is this what it means to live at the end of the world? The countdown extends the duration of a rupture, the “0,” and I come to believe that I am not anticipating it, as counting down would suggest, but inhabiting it.

January 7, 2025, 12:00 a.m.: I have spent too long watching The Clock. I have trains to catch, errands to run, work to do. I should leave. But leaving The Clock feels too significant, almost dangerous. Because The Clock has no “strict” end (as in, when a film’s credits roll or its tape runs out), leaving seems fatal for the film. Yes, The Clock will keep running when I leave, but in doing so, I end the singular and irreducible story it has told me. To stop The Clock, I must decide on the precise point where my obligations to the “outside” world outweigh attending to the film. This choice, to forsake watching The Clock and return home, makes me responsible for its cinematic end. Not only does this imply a kind of woundedness within The Clock which can never be experienced “in full,” and is always eventually left behind—but it also suggests that the porosity of The Clock is, in part, the result of my culpability in ending our shared time. My exit

: From MoMA, I take two trains in the wrong direction. Projected a couple of vectors away from my aunt’s apartment, I am nowating public transport. This is how I end up back at . But I have no time to attend to it; I have to get home. No trains, no buses, so I order a Lyft. On the app’s interface, my driver circles a nearby park, then teleports four streets away. I try to chase my ride to the new location, and I mistake a man smoking marijuana inside a black car for my driver. I repeat the process—I open Lyft, Lyft requests a driver and sends the message to some satellite in the stratosphere, a frequency of light or sound bounces back to New York, drivers teleport, I chase them on foot—and only then do I notice how outstandingly silent Union Square is. The Climate Clock surveils and illuminates the empty street—now, with an additional banner of scrolling text: “THE EARTH HAS A DEADLINE.” And again: “THE EARTH HAS A DEADLINE.”

This is a command. And yet, the apocalyptic quality of its language does little to provoke me. The threat of climate collapse is always ambient—diffuse and evasive. The ecotheorist Rob Nixon once called it a “slow violence.” This is a particularly fitting phrase, as the attritional violence produced by climate collapse possesses no spectacularity—it comes slowly, with the worst, most visible violences displaced to conflict zones, heatwaves in a desertified Sahel: far, far away from New York. This is why it is important to watch The Clock. Its porous ability to recode attention into time and make us wonder at all the interfaces of timekeeping we live with brings the slowness of climate collapse, and therefore the Climate Clock, back into vision. The double-walled glass of corporate skyscrapers is funded by gold reserves. On this street and in the mines of Sierra Leone, diamonds are the primary instruments of sense-making. These places and things—like The Clock’s montage—are connected. Reinscribed with meaning, the Climate Clock seems to follow us—and as the operative inverse of a shadow, haunts not as darkness, but pure light. In the morning, this light will break down relations between family members. It may be the reason a hospital turns away a patient—because it lacks not beds but saline, which is manufactured and exported from Puerto Rico, a graveyard of U.S. extractivism and destruction. How much quotidian terror does it take to make us look the Climate Clock in the eye? Maybe The Clock will remind us of the still-insistent, still-earnest cliché: time is of the essence. People begin and end with clocks, die with them, search for them, kill with them. To make sense of the end, and to begin to reckon with its coming, we need to watch the clock.

TARINI TIPNIS B’26 is is clocking out.

( TEXT NATHANIEL MARKO

DESIGN SOOHYUN IRIS LEE

PHOTOGRAPHER NATHAN GOLD )

c Baseball is free from the clutches of time. In football, basketball, and soccer, the clock operates like the hand of God. The game begins and ends at its command. Baseball gives no such power to the fourth dimension. It is a game that chooses its own pace. It is, in principle, an infinite game. But the forces of reality dictate otherwise. There has been no Infinite Game. There never will be. Without fail, the game ends, the curtain falls and the stadium empties, waiting for the next act to begin.

For Pawtucket and its surrounding communities, there will be no next act. After 50 years in Rhode Island, the Pawtucket Red Sox packed their bags in 2020, relocating to Worcester, Massachusetts and the shiny new stadium the city promised to build. Now Pawtucket’s last remaining connection to the team has fallen under the hammer. The concrete giant of McCoy Stadium, standing proud since 1942, is in the midst of a demolition process that will erase the last vestiges of professional baseball from Rhode Island.

The day is April 18, 1981. The Rochester Red Wings are scheduled to play the Pawtucket Red Sox at McCoy Stadium. Trouble with the floodlights delays the start of the game by 30 minutes. Just after 8 p.m., Pawtucket’s Danny Parks throws the first pitch in front of 1,740 fans. The longest game in baseball history has begun.

Minor League Baseball occupies a unique space in the American sports scene. It cannot compete financially against the higher-level and more popular leagues that have teams in the nation’s major metropolises. Instead, it finds its life within the margins. Cities and regions not populous enough to attract teams from the MLB, NBA, and NFL are prime candidates for a Minor League Baseball franchise.

The Rochester-Pawtucket game goes six innings locked in a scoreless stalemate. Starting pitchers Danny Parks and Larry Jones have not allowed a run. In the top of

the seventh, the breakthrough finally comes. Chris Bourjos drives in Mark Corey with a single, giving the Red Wings a 1-0 lead.

Some of these teams have been met with less enthusiasm than others. Dwindling attendance has begun to plague Major League Baseball. The Minor Leagues are even more vulnerable to such struggles. Many teams thrown into less populated areas find it difficult to create a strong fanbase. But Rhode Island and the Greater Providence metropolitan area are blueprints for the foundation of a minor league team’s success.

The score is 1-0 Red Wings going into the bottom of the ninth. Larry Jones is still pitching for Rochester. One more scoreless inning will mean victory. Pawtucket’s Chico Walker hits a double off of the outfield wall. He takes third base after Jones throws a wild pitch. Russ Laribee hits a deep fly ball. It is caught, but Laribee has given Chico Walker enough time to cross home plate. The score is 1-1. The game is tied after nine innings.

Despite containing a concentrated population base within New England, Rhode Island has by and large been left out of the highest level of American sports. The prestigious Boston franchises always attracted a good amount of attention and support from their southerly neighbours, but could not be considered ‘local’ in the same sense that a Rhode Island-based team could. The Pawtucket Red Sox, who began their love story with the Ocean State in 1970, had a gap to fill.

The 1970s marked an inauspicious beginning to the PawSox’s time in Rhode Island. The team found themselves changing owners three times in their first seven years, falling into bankruptcy in 1976, and enduring several threats to be relocated out of the state. It appeared as though the PawSox were bound to be another failed Minor League experiment. In 1977, however, local industrialist Ben Mondor took ownership

of the team and supplied the cash flow needed to take the PawSox on an upward trajectory. After stabilizing the team’s finances, Mondor invested in renovating McCoy Stadium and building a foundation for the team’s long-lasting ties with the community. Mondor was the head of the PawSox from 1977 until 2010 and saw the team’s annual attendance increase from 70,000 spectators to over 600,000 under his ownership. By the 1980s, the PawSox were beginning to attract a fair amount of attention and respect from local fans. By the 2000s, they were one of the most well-supported teams in Minor League Baseball.

Six innings go by after the end of the 9th. Nobody can score. Both teams remain tied at one run. The game goes into the top of the 16th. We are now entering unfamiliar territory.

I found Rick Patterson sitting at the bar of a Chinese restaurant just a block away from McCoy Stadium. He is a grizzled veteran of the baseball world who has supported the PawSox since the very beginning. He grows visibly emotional at the mention of his team.

“Find me someone here who didn’t love the PawSox!” He sweeps his hand across the table. “There was no better community for baseball. There was no better community to come and watch a game with on a Sunday afternoon. This was the heart and soul of the city.”

The PawSox led their league in seasonal attendance three times between 2004 and 2008. They were the golden standard for organizational success and community support. But in 2015, the team changed ownership and with it, the course of its history. Its new figureheads Larry Lucchino and James Skeffington had their sights set on a more lucrative future for the organization, no matter the consequences for the fans that had given it so much love. “Nothing is forever,” said Rick as he stood up and walked out into the midday Pawtucket sun.

“Remember that.”

The game has entered its fifth hour. Pawtucket right fielder Sam Bowen hits a long fly ball that looks destined to land on the other side of the fence. Rochester center fielder Dallas Williams thinks that it is going over his head for a home run. It does not. “It was gone…but it came back in, and I caught it,” Williams tells a reporter after the game. A strong gust of wind has robbed the PawSox of a walk-off victory. The game goes on.

On February 23, 2015, Larry Lucchino and James Skeffington took charge of the Pawtucket Red Sox. On the very same day, they announced their intention to build a new venue for the PawSox. McCoy Stadium is old. Built in 1942 as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, it hosted a Noah’s Ark of transient and unsuccessful minor league teams before finding a more permanent resident in the PawSox. McCoy has stood the test of time remarkably well. But that is not what mattered to Lucchino and Skeffington. A new stadium means higher ticket prices and more luxury accommodations, creating a better bottom line for those on the receiving end of the cash flow. A new stadium lets owners leave their mark on something concrete and tangible. Lucchino and Skeffington’s demand was non-negotiable.

It is the top of the 21st inning. Rochester scores off a double. It is now 2-1. Pawtucket goes up to bat. They have not scored a single run in the past 10 innings. With a runner on second, future MLB Hall of Famer Wade Boggs comes up to bat and hits a double into the gap. Both dugouts are dejected. “I didn’t know if the guys on the team wanted to hug me or slug me,” says Boggs after the game. The score is now tied at 2-2. The 22nd inning begins.

Lucchino and Skeffington’s initial proposals targeted potential stadium sites within the Greater Providence metropolitan area. The pair’s first vision was to build a new ballpark six miles south on the banks of the Providence River. After Skeffington died unexpectedly in 2015, negotiations with state officials began to stall. Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo eventually declared the riverfront property unsuitable for new development and nixed the proposal. In 2017, Lucchino set forth a proposal to build a $83 million ballpark in downtown Pawtucket. While $45 million would be funded by the team, the state would be left to pay $23 million, with the City of Pawtucket responsible for the remaining $15 million. The City found the proposal financially unfeasible and turned it down. With his options in Rhode Island seemingly exhausted, Lucchino set his sights beyond the borders of the Ocean State.

In 2018, Lucchino announced that he had finally found his opportunity: the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, was willing to build a new stadium. The PawSox would no longer be the PawSox. They were to be stripped from their home, moved 40 miles away, and rebranded as the “WooSox.” In 2019, the Pawtucket Red Sox played their final season in Rhode Island. In 2020, the city of Pawtucket had its first baseball-less season in fifty years.

It is now 12:50 a.m.. According to the league’s rulebook, this is the time at which a game should be suspended by the umpire and resumed at a later date. Head umpire Dennis Cregg’s rulebook is missing this clause. There will be no curfew.

At 2:00 a.m., Pawtucket pitcher Luis Aponte, who has already been relieved after throwing from the 7th inning to the 10th, approaches his manager and requests to go home. His wife, he says, will not believe him if he tells her that the game has been going on for almost six hours. The manager lets him leave. When Aponte opens the front door, his wife Xiomara confronts him and demands to know where he has been.

“At the ballpark,” he replies.

“Like hell you were.”

After the team announced its intention to build a new stadium in 2015, Pawtucket residents quickly mobilized to prevent a move away from McCoy. The final decision in 2018 to leave for Worcester led to even more fervent backlash against the PawSox’s ownership. Fans

and local businesses participated in public demonstrations and sent out petitions demanding that the team stay in Pawtucket. The pressure generated through community organizing was immense but ultimately failed to prevent the PawSox from leaving. The promise of a greater paycheck across state lines proved a stronger pull to Lucchino than the forces of local resistance. Several former PawSox fans whom I spoke to also expressed a deep frustration toward the City of Pawtucket for the team’s move. For these residents, the City’s efforts to keep the Sox were too half-hearted to reflect the deep ties that ran between the team and the community.

“I can’t believe they would let the team go like that. I can’t believe they would do that to us,” said Jill, who works at a restaurant across the street from McCoy. “That Mayor Grebien has grease on his palms. Talk to Grebien, don’t talk to me.”

When I spoke to Mayor Don Grebien, he was adamant that the City did everything in its power to keep the PawSox around. “We pursued multiple avenues, including proposals for a new stadium and infrastructure improvements. However, some options—such as fully financing a new ballpark—were not feasible. We remain proud of the work we did to keep the PawSox, and I am confident we did everything we could to keep them,” he said.

The temperatures are freezing and the winds are severe. The players are cold and exhausted. They resort to burning wooden benches and broken bats to keep warm. Several report experiencing symptoms of delirium. The game stretches into its sixth hour.

Around 2:30 a.m., Pawtucket general manager Mike Tamburro decides to call league president Harold Cooper. Cooper does not pick up the phone. Tamburro keeps calling. At 3 a.m., Cooper finally answers. He awakes to the news that the Rochester Red Wings and the Pawtucket Red Sox are still playing. Cooper immediately orders that the game be suspended upon completion of the current inning and resumed at a later date.

Pawtucket, like many population centers across New England, has experienced a period of significant economic decline. The Great Depression saw much of the textile industry move to the South in search of cheaper labor, leaving their Northeastern hubs struggling to find their footing. Pawtucket, once a successful mill town, has long been one of these cities. The 2020 US Census reported that 20.1 percent of residents under the age of 18 lived below the poverty line. Several of Pawtucket’s educational institutions have been among the lowest-performing in the state, with five schools placing within the bottom five percent of Rhode Island and requiring targeted state interventions. It is a city unable to provide enough support for its youngest generation, leaving significant parts of the population trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty.

Looming over the city are monuments of a more prosperous past. Apex Pyramid, one of the most recognizable landmarks in Rhode Island, is an abandoned department store that cannot find a new tenant. After the PawSox’s move to Worcestor, McCoy Stadium became another empty monolith that, having lost its main tenant for good, had little hope of finding a second life.

Grebien, now in his seventh term, has led the charge to transform Pawtucket’s landscape in the hopes of boosting the city’s economic prospects. His most noteworthy decision thus far has been to finance the building of a new soccer stadium, Tidewater Landing, with help from the state’s Tax Increment Finance (TIF) plan. Rhode Island FC’s opening game at the venue, scheduled for May 3, has already sold out. Now, with the momentum of this victory on his side, he has announced that McCoy Stadium will be demolished.

Taking McCoy’s place will be a new high school, which Grebien hopes will bolster Pawtucket’s underfunded educational institutions. Grebian envisions a new dawn, unhindered by the concrete ghosts of the past. His administration has shown no desire to cling to a bygone era. “The stadium’s demolition is emotional for

many, but the transformation of the site into a new high school promises a bright future,” he said.

It is 4:09 a.m.. The 32nd inning has just ended. Head umpire Dennis Cregg receives news of Cooper’s order. He steps forward and waves his arms to call off the game. It has been eight hours since Danny Parks threw out the first pitch.

In the first inning, there were an estimated 1,740 fans in attendance. By the time the game is called off, only 20 of them remain.

For the last several months, the sword has been hanging over McCoy’s head. The wait is now over. This March, the demolition began, starting with the outfield bleachers and restrooms. The procession of wrecking balls has now made its way to the main grandstands, where the majority of PawSox fans sat to watch their team play. It will be a long, painful few months as the last vestiges of the PawSox’s physical memory are stripped away piece by piece.

The game is scheduled to resume nearly two months later on the evening of June 23. Tickets are quickly sold out. 140 members of the media are in attendance. All of baseball’s eyes are on Pawtucket. The game resumes in the 33rd inning. It ends in the 33rd inning. 5,745 fans are in attendance to watch Dave Koza drive in a run to give the PawSox a walk-off win. The game has ended less than 30 minutes after it resumed.

For Julia, owner of the nearby Right Spot Restaurant, a popular meeting spot for fans and players, nothing will be able to replace the PawSox. It was part of her life in a way that is hard to put into words. Her eyes water as she speaks. “It was a beautiful thing. But what can I say? It is over.”

The Rochester Red Wings and the Pawtucket Red Sox have played the longest game in baseball history. A total of 14 records have been set. This is the closest that a game of baseball has come to manifesting its potential for the infinite. There may never be a game that comes closer.

I had the opportunity to visit McCoy Stadium the day before the demolition process began. It is a strange thing, knowing that you are seeing something for the last time. McCoy is dying. The glass has been smashed out from the top of the press box. Torn banners hang limp from the outfield walls. Seats have been ripped out of their foundations. It is one big quiet funeral, and I am one of its last witnesses. The wind blows softly and the overgrown infield grass quivers under its weight. McCoy is taking its last breath.

NATHANIEL MARKO B’27 would have stayed for all 33 innings.

c On April 15, the nation’s first state-regulated overdose prevention center celebrated its 1000th visit. The milestone has come just three months after the center opened on Providence’s South Side, in a red-brick building now owned by the harm reduction nonprofit Project Weber/RENEW. Once inside, clients sign consent forms allowing trained staff members to deliver life-saving medical intervention at the first signs of overdose. They are then led towards rooms designated for injection or smoking— where, under close supervision, they may consume pre-obtained drugs without fear of being arrested, violated, or overdosing.

In a state that saw roughly 327 lives claimed by overdose last year, staff members at the center have already intervened in a total of 44 potential overdoses. Each has been resolved with simple first-response treatment; not once have they had to call 911.

Two overdose prevention centers (OPCs) already exist in New York, but are run independently by the city government. Rhode Island was the first state in the country to pass legislation allowing the state itself to regulate OPCs, granting the controversial harm reduction spaces a new level of legitimacy and backing. The center in Providence will not be funded by tax dollars; instead, the state has allocated funds from a lawsuit settlement with pharmaceutical corporations—reparations for the companies’ role in provoking and perpetuating America’s decades-long opioid epidemic, which has now claimed over one million lives.

The day after their 1000-visit milestone, I visited Project Weber/RENEW’s drop-in center, downstairs of the OPC. I wanted to get a sense of how things were going in the months since it had opened, beyond the encouraging statistics. Inside, things were busy; folks from the neighborhood had come to do laundry, or to take a shower, or pick up fentanyl strips, or grab food. Some of the people I greeted might have just come from the consumption booths—80% of those who use the OPC are discharged to the drop-in center afterwards.

Dennis Bailer, the overdose prevention program director at Project Weber/RENEW, met me by the reception desk and beckoned me in. Before we ducked into his office, we lingered for a moment in a lounge area. There were a dozen or so people there, chatting and playing video games on the couch. Eighty percent of the center’s client-base is unhoused, Bailer told me once we sat down. One of the most valuable services the center can provide is simply a clean, comfortable, safe space to breathe.

“I think when people think of an overdose prevention center, if they’re not familiar with it, the visual image that they get—it’s just people using drugs, it’s a madhouse, it’s wild, sex and drugs and whatever…” Bailer said. “And it’s not. It’s just very controlled, very detailed, very safe.”

Eight years ago, when the Indy last reported on

Rhode Island’s opioid crisis, the center 45 Willard Avenue seemed like an impossibility. “I don’t think [OPCs] would pass in Rhode Island, because of the conservative impulse that if you invite people to a place for safe use, more people will start using,” said Diego Arene-Morley—a Brown alum who was working for another harm reduction nonprofit—in an interview with the Indy at the time.

To be sure, those conservative impulses still exist in the state, and they crop up on both sides of the aisle. But they have been overpowered by a critical mass of politicians, organizers, and residents who find hope in what OPCs promise to their community.

At the beginning of this month, the state House re-approved Rhode Island’s OPC pilot program in a 52-17 vote. Shortly after, a research team at Brown evaluating the OPC in Providence published a study showing that 74% of the residents and employees nearby were in favor of its opening in their neighborhood.

Among other things, these displays of support are a testament to an ever-growing sense of urgency surrounding the opioid epidemic, a crisis that has left no part of the country unscathed.

+++

When experts talk about America’s opioid epidemic, they draw attention to four distinct waves.

It had begun with prescription opioids, doled out by doctors at staggering rates at the behest of drug companies in the ’90s. Aggressive marketing campaigns by corporations such as Purdue Pharma insisted that products such as OxyContin rarely fostered addiction—a rate below 1%, they said. We know now that as many as one in four people prescribed opioids for long-term use become addicted. Faced with acute withdrawal symptoms, sustaining that addiction begins to feel like a matter of life and death for the user. Dr. Josiah Rich, a professor and physician at Brown with decades of experience researching addiction, told me that the brain sends signals “saying that you are gonna die if you don’t get some opioids into your system.” This physiological response is what turns prescribed or recreational use into a life-altering affliction.

In 2010, a second wave of the epidemic saw many turn to heroin—a cheaper and more potent drug than its prescription predecessors. And when that supply strained to accommodate demand, the illicit drug market offered fentanyl as a solution—a third wave. The cheap synthetic substance is often cut into street drugs without users’ knowledge and is lethal in amounts larger than a few grains of salt. Six out of 10 fake prescription pills today contain such doses. Since 2012, fentanyl has become the number one killer of Americans aged 18 to 45.

All three initial waves hit Rhode Island with remarkable force. For years, the state ranked consistently among the highest in overdose rates. Over the phone, Dr. Rich speculated why: It could have been the still-intact mafia distribution networks, or the smuggling done through Rhode Island’s fishing fleets, or simply the state’s position in the corridor between New York and Boston. Whatever the cause, it is hard

to find someone in the state who does not know someone struggling with or lost to addiction.

For the past two years, Rhode Island has seen its overdose rates dip. But that progress is threatened by a new, fourth wave in the epidemic, marked by the increased use of stimulants like meth and cocaine. These drugs are often laced with fentanyl, too—but users tend to assume they’re safer than opioids, and so fail to take the necessary precautions to prevent an overdose. In 2022, Rhode Island had the nation’s fourth-highest cocaine-related overdose deaths. In one of the least populated states in the country, a person dies from an overdose every day.

For decades, America’s response to the millions of people afflicted with opioid addiction has hinged around mass incarceration. As of 2020, one in five people in prisons were there on drug charges. Once released, they are at an increased risk of a deadly overdose—their tolerances have plummeted during their time in prison, but few are given the resources required to seek long-term treatment. Detox rehabilitation programs, which aim to treat substance-use disorders by stopping consumption cold turkey, often lead to similar outcomes. “You can lock ’em up or you can lock ’em in the hospital,” Dr. Rich told me. “Most of the time they survive. Sometimes you can give ’em medications to make ’em feel better, but then what proportion of people that go through that detox are gonna start up again?”

The answer, he says, is 90%. Eleven years ago, Dr. Rich’s nephew was one of many who went through detox treatment in an effort to get clean. He was my age, 23 years old. The day he was released, he met his craving with opioids and passed away.

In recent years, advancements have been made in medication-assisted treatments (MAT), which employ drugs like methadone to directly alleviate a patient’s opioid cravings. These are incredibly effective medications, Dr. Rich tells me. In many other countries, people with substance use disorders can easily pick up a prescription for them at the pharmacy. But in America, taking methadone and similar drugs requires visiting a treatment facility every day. “Somehow this population is deemed unable to understand how to use the medication properly,” Dr. Rich said.

The Indy has written in the past about the success of MAT in Rhode Island’s prison system. But many formerly incarcerated people—and working-class people in general—find themselves too busy to carry on with treatment after being released. They, like many, are left behind by healthcare and legal systems that refuse to treat their illness as anything other than a judgment on their character.

+++

Harm reduction policies—which aim to reduce the clinical, social, and legal impacts of drug addiction— have come to America in fits and starts. Fentanyl test strips, which have been widely distributed to detect traces of the substance in street drugs, may already be slowing the rates of overdose deaths. Massive naloxone distribution and education campaigns have been effective in doing the same. Even still, since naloxone

requires another person to be present and alert in order for it to be administered, and since its distribution alone fails to address any of the root causes of addiction, it’s a far cry from a complete response. Overdose prevention centers, which ensure immediate medical intervention and connect clients with wellness and recovery services, fill a critical gap in the treatment landscape.

OPCs have already been operating legally in other countries since the 1980s. Time and time again, research shows that they are effective in combating local opioid epidemics. In Toronto, the areas surrounding OPCs saw a 69% reduction in overdose mortality rates. In France, OPC users shared needles 90% less than their counterparts. In New York, 42% of OPC users decided to enroll in treatment within two years. OPCs have saved money for these communities, alleviated stress on emergency medical services, and reduced the amount of public, drug-related disruption. In Bailer’s words: “They simply work.”

But they face a tremendous amount of resistance in America. On both sides of the aisle, they are derided as glorified ‘opium dens’ where drug use may run rampant. In 2023, efforts to establish OPCs in Colorado and Pennsylvania faced no-votes and outright bans. Community boards in Philadelphia warned that the centers would bring more drug users and dealers into their neighborhoods. (Research and anecdotal evidence disprove this claim.) “You can have your addiction, but you don’t have the right to impede on my quality of life,” said one neighborhood organizer rallying against OPCs.

Bailer is no stranger to these arguments. When I brought them up with him at the center, he told me it was ridiculous to think that OPCs would incite more drug use; almost everyone who uses the center was already doing so on the neighborhood streets.

“‘Substance use being normalized’…Damn right,” he said. “They’ve been using drugs since the founding of our nation...Drug use needs to be normalized.”

Residents have seen the alternative play out intimately in the small state of Rhode Island: decades of efforts to de-normalize drug use through criminalization and social stigma have not only failed to reduce rates of addiction, but have caused more lives to be lost to unattended overdoses.

“Perhaps, if our punitive measures haven’t worked over the last 50 years, we should try something different,” said one initially skeptical Rhode Island state representative.

The state’s size—which seems to have magnified the failures of the war on drugs—might be the exact reason why Rhode Island became the first state in the country to authorize OPCs in 2021.

“If you’ve been here in Providence for a while, you know someone who knows someone who’s experienced this,” Bailer said to me. “Maybe it’s a cousin, maybe it’s an uncle, maybe it’s a family member. Maybe it’s a child of a friend of yours—[it’s] that small state connection.” In fact, Rep. John G. Edwards (D-Tiverton), who co-sponsored the initial OPC legislation, lost two cousins to overdoses. Rep. Gregory J. Constantino (D-Lincoln), one of 51 yes votes on the bill that renewed the pilot program this

month, testified that, when he was 27 years old, he had to bury his brother for the same reason.

“If this harm-reduction center saves one person— what’s the value of that life?” Rep. Constantino asked the House floor before the bill passed. “I’d give everything that I have—everything I own—to see my brother one more time.”

In three months, the harm reduction center has done much more than save just one person’s life. Beyond intervening in several overdoses each week, staff have connected 800 of their clients with the impressive range of wellness resources offered at the drop-in center downstairs, from free clothes to HIV testing. And when clients are ready to pursue recovery, the center is equipped to help them do so. Of the 236 individuals who have used the OPC in the past three months, 31 have already been referred to treatment programs. Staff members have connected their clients to over a thousand nights of recovery housing, a critical service for their mostly-unhoused client base.

Bailer emphasized that these wrap-around services are as crucial a component of their work as the OPC itself. In fact, one of the OPC’s great successes is that it has brought new faces in to access care and recovery services that have already been offered by the organization for years.

“It’s not just about the overdose prevention center,” he said. “It’s about everything else that supports people who use drugs, that supports people who want to stop using drugs, that supports people who are unhoused, that supports people who are trying to find their gender identity. You know—it’s life. It’s life, and the challenges that people face during that process.”

Bailer understands these challenges as intimately as any of his clients. Like many of the staffers at Project Weber/RENEW, which is a peer-led organization, Bailer is in long-term recovery. When we met, he shared with me his experience selling off his possessions, separating from his loved ones, and navigating the criminal justice system as he struggled through addiction. Now, all of these past experiences allow him to connect with the people who turn to the center for care.

“It’s much different than if I were someone who had read all about it and worked around the field or whatever. […] You don’t know what the person has gone through—those quiet nights, those hard nights. [...] As peers, we just connect at a different level, because we understand how that life is,” Bailer said. “It’s a hard life. It’s a hard, hard life.”

Bailer and his colleagues know better than most that many people who enter the OPC are choosing to consume drugs in a safe, controlled environment when they would otherwise be using on the street. That relocation is particularly important for women, who are at higher risk of sexual assault when consuming drugs. OPCs provide a place where all community members can exist without fear of arrest, judgment, or public shame. That, Bailer says, is no small thing.

“We’d rather not be outside doing it. We’d rather

not be in your backyard, looking up through windows, looking around with the neighbors, you know? The nervousness, the discomfort, the concern, makes us behave in ways that are way different than if we could behave if we were in a comfortable spot.” This anxiety, he says, is what so often provokes the erratic fight-orflight moments that lead to public nuisance calls and arrest.

The recent study by Brown researchers suggests that residents of South Providence have faith that OPCs are an asset to their community, not a stain upon it. Canvassing campaigns led by Project Weber/ RENEW have emphasized to residents that the center has already been operating in the neighborhood for years. Far from attracting more drug activity, the OPC would only serve to move some pre-existing activity indoors. Bailer and his colleagues told their neighbors what the evidence shows: that OPCs reduced drug-related litter, that they might even be associated with decreases in crime. The organization’s sustained efforts to educate their community are likely a significant factor behind the high levels of support today. They speak to the importance of orienting new harm reduction policies around those who have already been doing the work.

When Dr. Alexandria Macmadu and her colleagues surveyed residents for the study, they did not gather information on why residents might support the center. But when I asked if she had any guesses, she gestured beyond the practical allure of cleaner, safer neighborhoods.

“I think that community members care about each other. Or at least I hope so,” she told me. “And I think that our findings may be a reflection of that— just valuing other human life and wanting to keep other people safe.”

This move towards safety and care—which lies at the core of harm reduction philosophy—can have a transformative effect on the most vulnerable and marginalized members of our communities.

“Whenever I speak about people who are actively using, I always want to remind people that those were not the dreams we had when we were younger,” Bailer told me. “Normally, at some point in our lives, we want to get back to those wants, those dreams, those desires. The thought of stopping is always there.” But, he says, entertaining that thought becomes impossible when an individual is uncared for—whether they are ill, or hungry, or ashamed, or distrustful of doctors and treatment facilities.

Beyond the life-saving work done at OPCs, it is the basic respect they offer towards their clients that makes them so promising as solutions. Safety, care, trust, recognition—these are all prerequisites to recovery. Two decades into this epidemic, more and more people seem to find it hard to imagine another way forward.

The research team at Brown—working jointly with a cohort in New York—will be the first to assess OPCs in an American context, filling a critical gap in the existing body of research. If what they find reflects what studies in other countries have shown, then their work could have a profound effect on the effort to destigmatize OPCs in America.

The research team at Brown—working jointly with a cohort in New York—will be the first to assess OPCs in an American context, filling a critical gap in the existing body of research. If what they find reflects what studies in other countries have shown, then their work could have a profound effect on the effort to destigmatize OPCs in America.

Dr. Macmadu told me that she and her colleagues are focused primarily on how the center impacts the wellbeing of the individuals who use it—an evaluation that will be measured through changes in overdose risk, treatment uptake, and engagement with health and social services. Beyond that, she and her team will continue to examine the ways in which the OPCs impact their surrounding communities. That means the neighborhoods themselves, but also local healthcare and legal systems—OPCs aim to take burdens off of them, too.

For his part, Bailer is confident that the research will confirm what he already has seen on the ground: that things are “simply going well.” His neighbors are not reporting higher rates of crime or disturbance, nor do the police need to “hang around” to monitor the center. For the past three months, he and his colleagues have been able to serve their community exactly as they hoped they would.

Still, Bailer said that he is grateful to be partnered with a research team that is as respectful of their work as they are diligent and impartial.

“Having Brown doing the research, collecting the data, is just gonna be another way to prove that this is a benefit to our community,” he said. “And hopefully other states who may not believe what comes out of Dennis’s mouth will believe what comes out of the Brown University study.”

The partnership between Project Weber/ RENEW and the Brown research team shows that, in spite of the fraught relationships that often

emerge between universities and their surrounding communities, meaningful collaboration is possible and necessary. Researchers like Dr. Macmadu and Dr. Brandon Marshall, who leads the team at Brown, have been working with Bailer and his colleagues for years. Both sides of the partnership affirmed to me that their collaboration is based in mutual respect. Though the OPC investigation is pointedly independent, members of the nonprofit sit on the project’s advisory board to offer guidance and feedback on the research process.

“We trust Brown, [and] I think Brown trusts us,” Bailer said. The product of that trust will serve, for the rest of the country, as a litmus test for what OPCs can make possible.

A few hours after I spoke with Professor Macmadu, The Washington Post and Inside Medicine leaked a memo indicating that the Trump administration planned to slash nearly half of the budget of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)—the largest funder of biomedical research in the world and the sole source of funding for Brown’s OPC research study.

As of writing, it is unclear how or whether this cut will affect their work. Although the team recently received a notice of award to continue year three of their research, that’s a weak promise in the current landscape. Just a few days after the leak, the NIH itself announced that it would ban grants to universities who refuse to comply with Trump’s orders to ban diversity, equity, and inclusion programs—demands to which Brown University has yet to respond.

Professor Macmadu tells me now that she’s very troubled by the news and “deeply concerned about the programs of research—including ours—that these policies may imperil.” But even when we spoke earlier, she had been under no illusion about the security of her work. For the most part, all she and her

colleagues can do is wait and see.

“We will adapt to changes and the challenges as they make themselves known,” she said. “We’re keeping fingers crossed and holding up just like I think most other researchers and investigators in this climate right now.”

Beyond cuts to research, the new administration has shaken the already unsteady future of OPCs—and of harm reduction writ large. In his first months in office, Trump has cut $12 billion in COVID-era funding for certain health programs, many of them focused on addiction. In the wake, countless programs—like one in Colorado which offered peer counselors for individuals in recovery—have been left to scramble or collapse.

“In so many cases, these are lifesaving programs and services, and we worry for the well-being of those who have come to count on this support,” said Dannette R. Smith, the commissioner of Colorado’s Behavioral Health Administration, in an interview with the New York Times.

At the drop-in center, I asked Bailer whether he was concerned about…all of it…which I couldn’t formulate in words but gestured through urgent hand motions. He nodded.

“Obviously we gotta be concerned,” he said. “But I heard somebody say something along the lines of— harm reduction has always had pushback…The only way people succeed is they just keep going forward.” The actions of the new administration are alarming, to say the least—but work like Project Weber-RENEW’s has always operated at the margins. It will continue to do so in the face of federal repression.

For our part, Bailer says, it is up to community members to “get off their asses and get involved.”

CAMERON LEO B’25 hopes you will start by donating to Project Weber/RENEW.

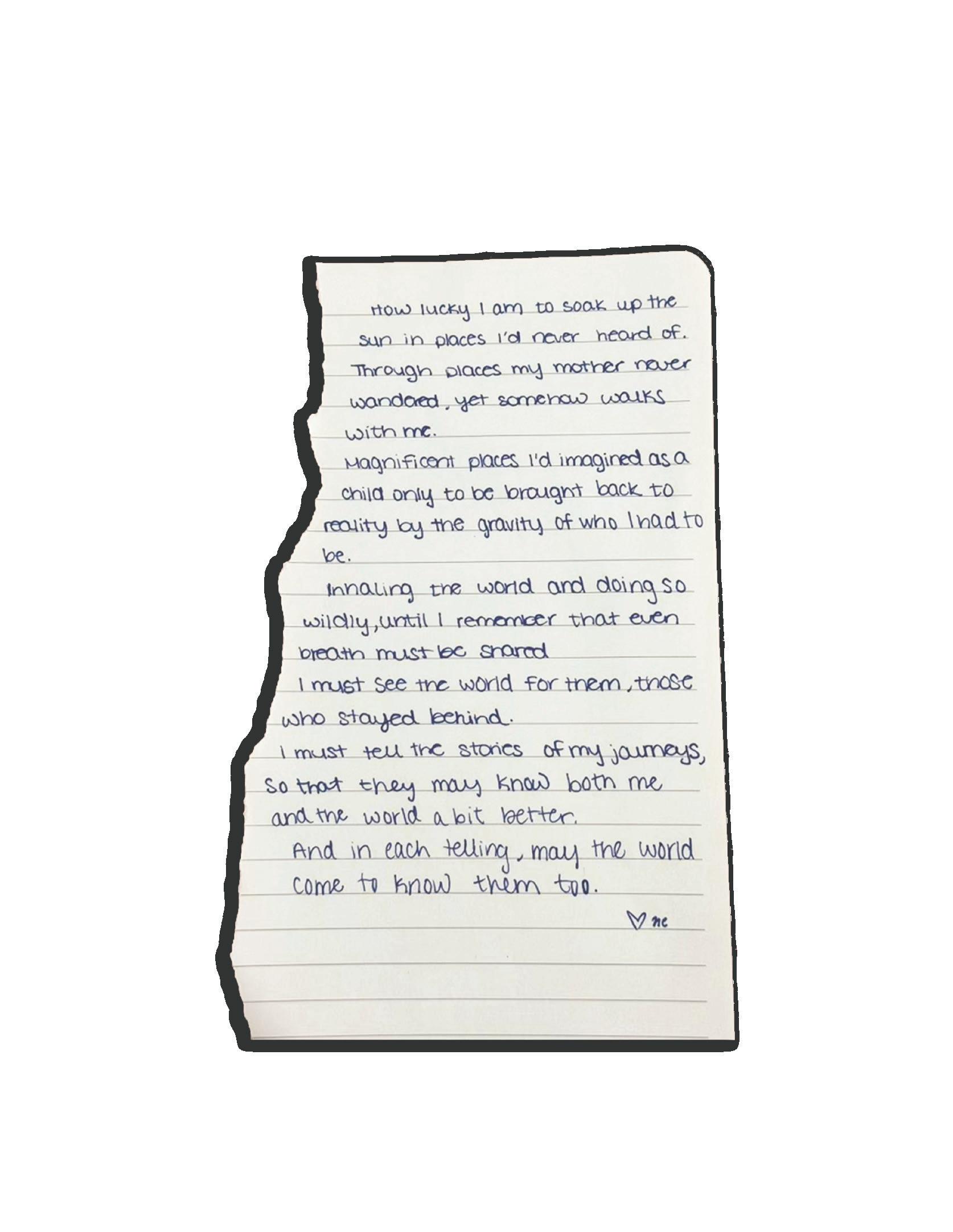

¿Te cuento un secreto?

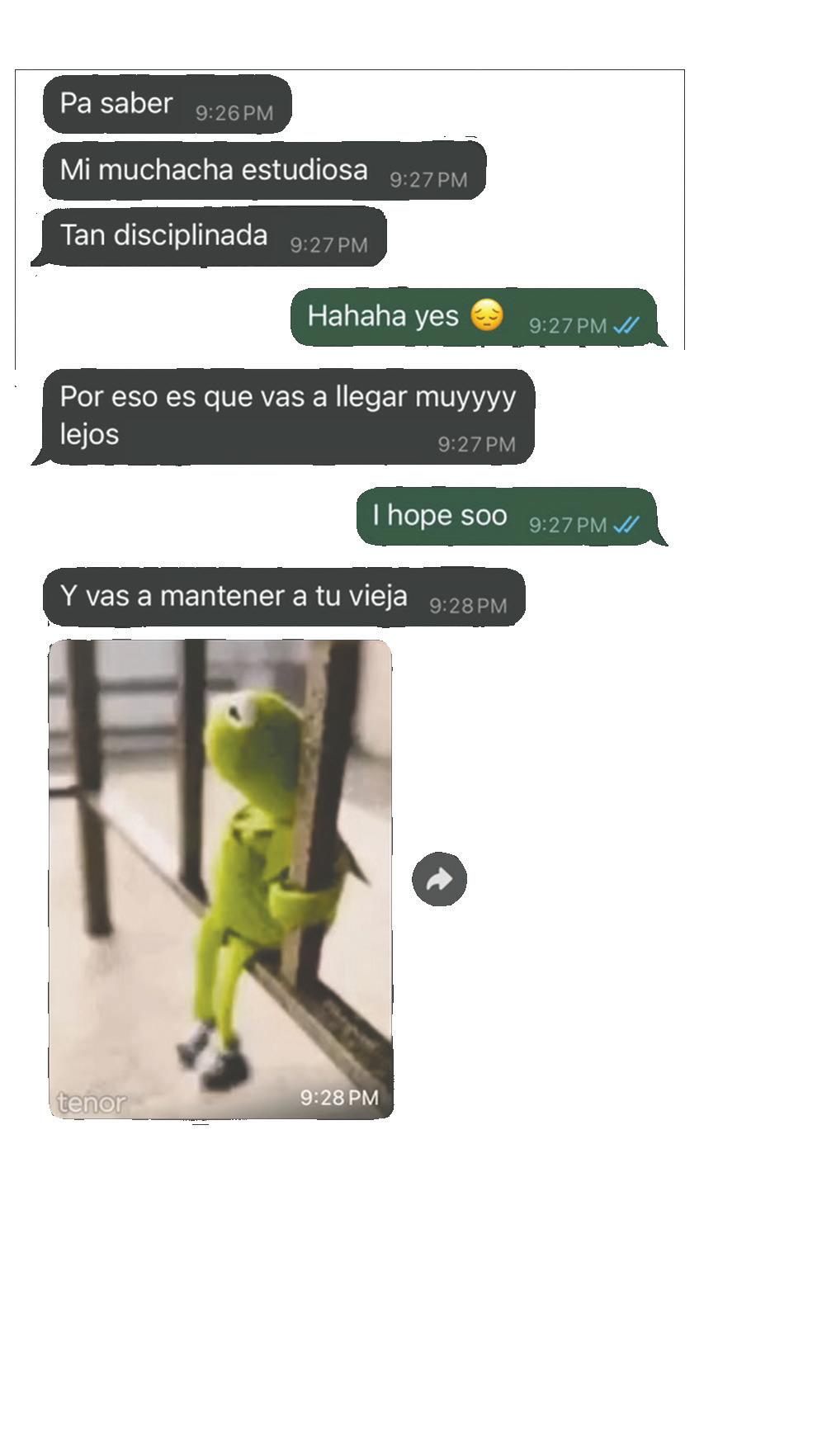

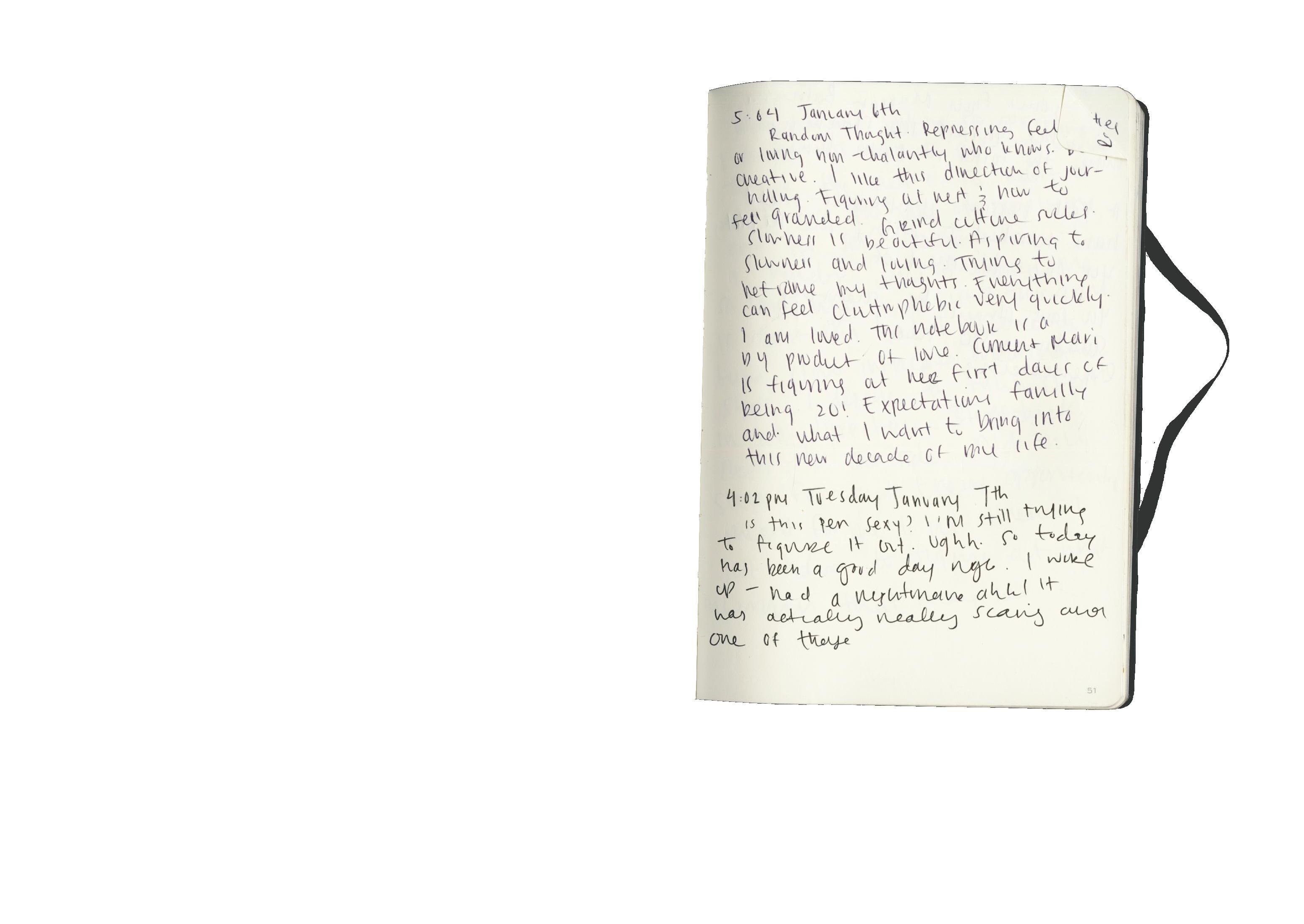

c Davíd and I have collected diary entries, receipts, texts, and Notes app thoughts from our peers who also experience a love-hate relationship with Brown, the places it has led us, and all we had to sacrifice to get here. Many are pieces of wisdom I’ve collected and carry with me every day. Each of them is a testament to a love that transcends borders, generations, and space. We hope that this piece is a reminder of our collective capacities for care and that we are more than how we are defined. That we are not the enemy, just byproducts of the systems in place.

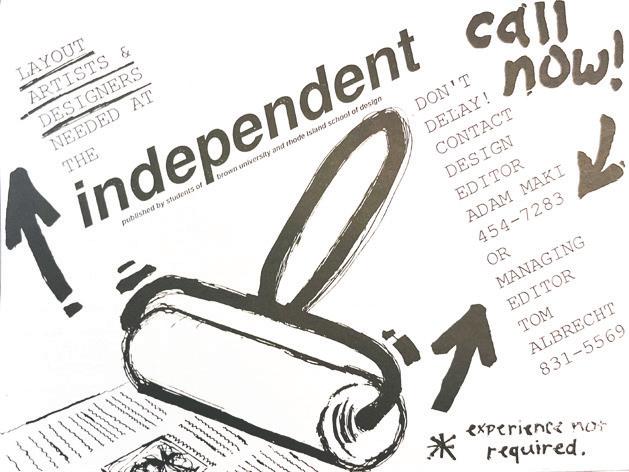

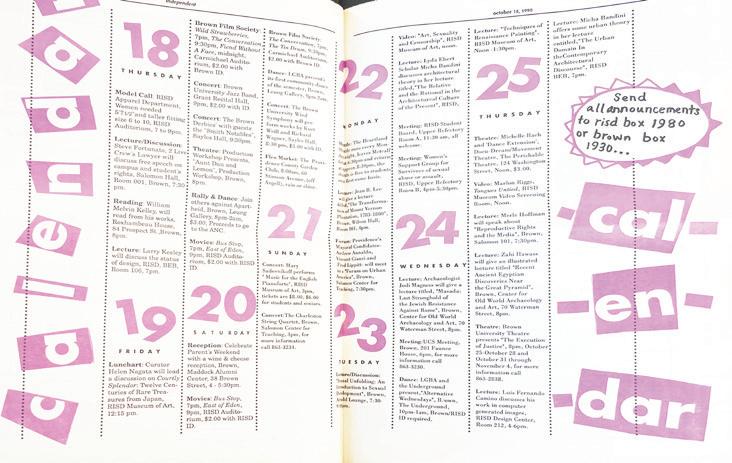

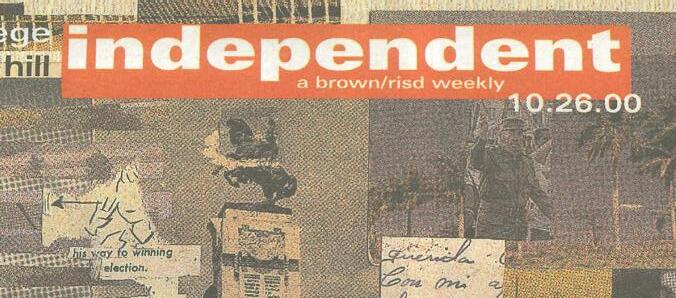

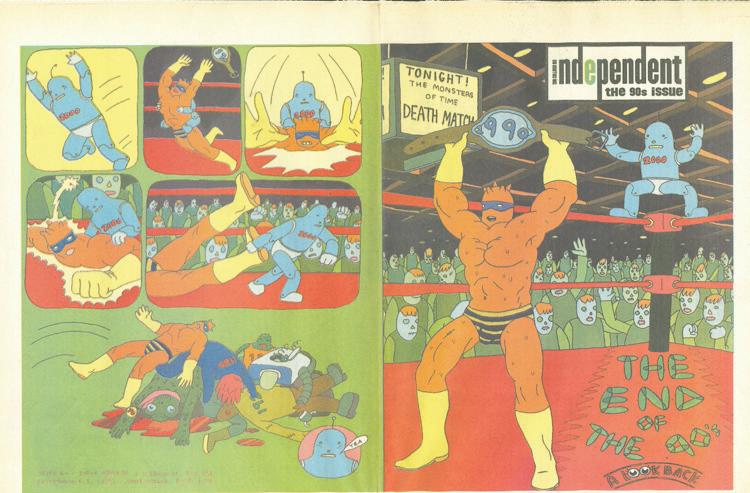

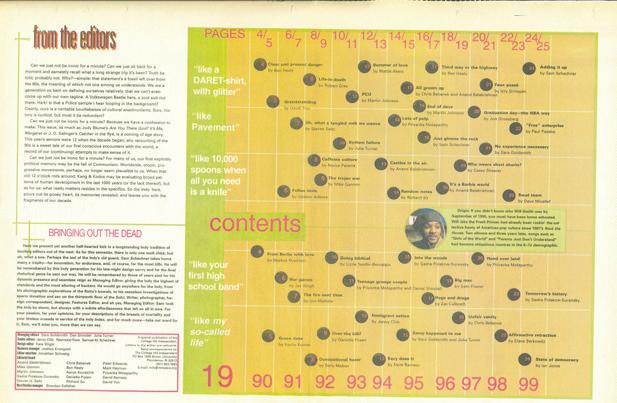

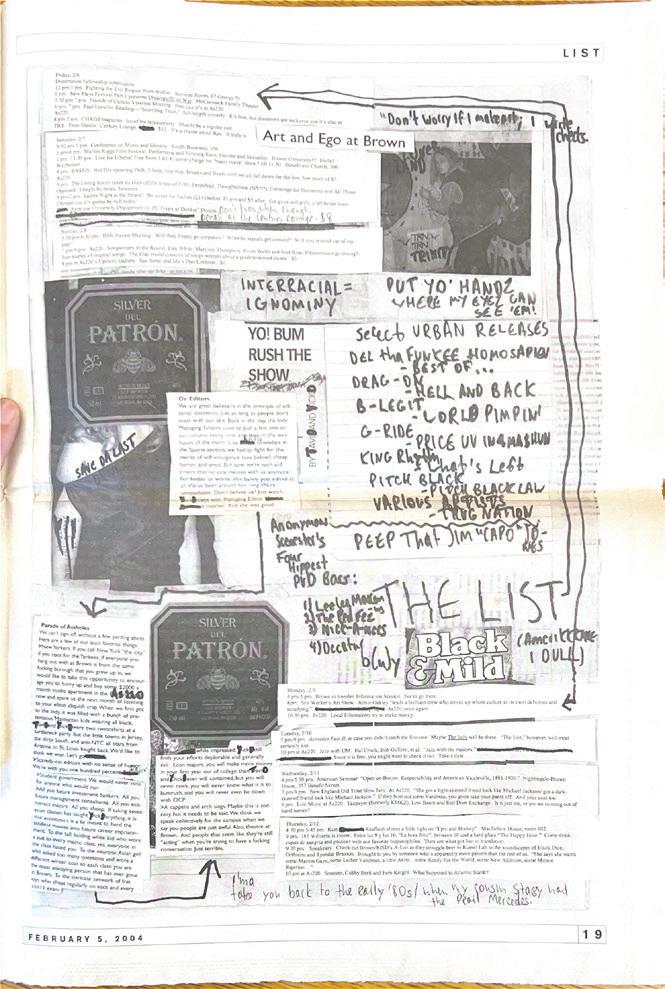

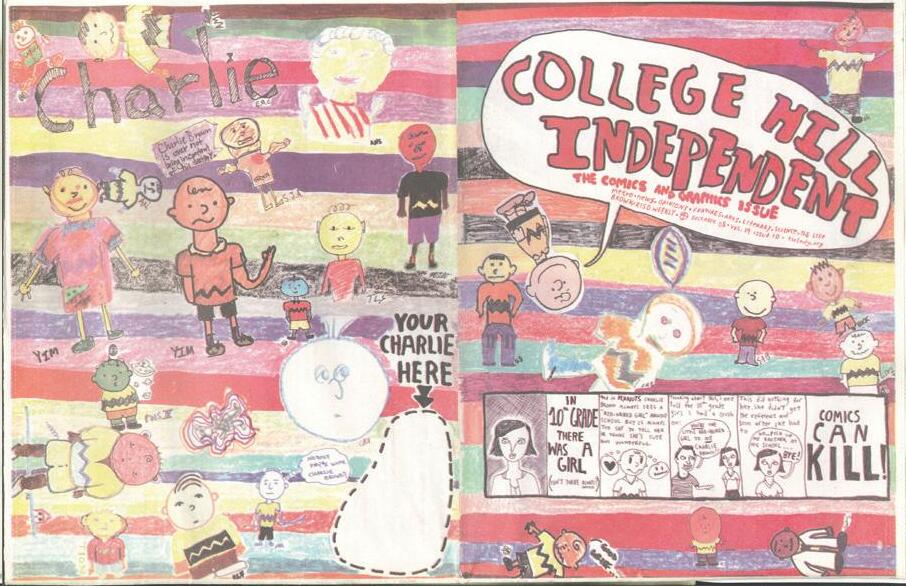

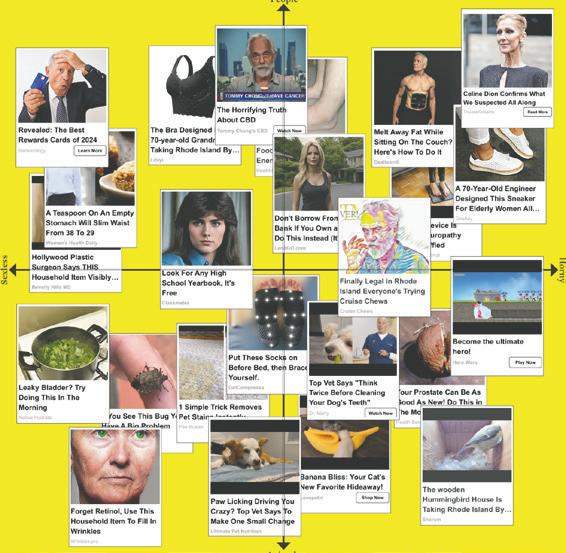

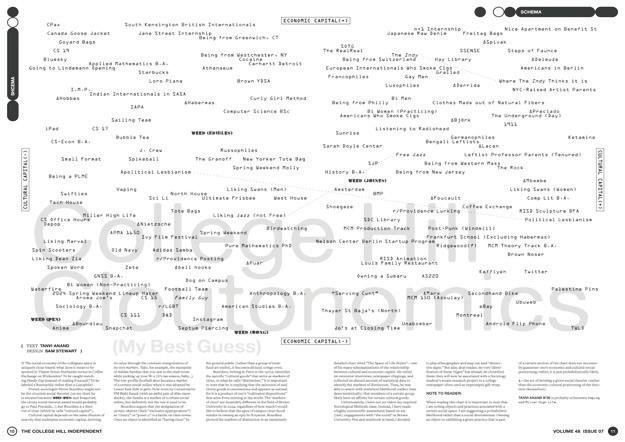

This semester marks the 50th volume of The College Hill Independent, first published 35 years ago in 1990. We promise the math makes sense (it doesn’t).* In celebration, we (a team of devoted Indy writers and editors) got our hands dusty and dug through three and a half decades of Canadianmade newsprint (recently tariffed).

On August 30, 1990, the 13th issue,* Indy co-founder John Roberti wrote an article titled: “The College Hill Independent: Who We Are And Why You Should Join.” In lieu of an official mission statement, Roberti offers the closest thing. The Independent, he writes, was “[the] idea of a group of Brown students who felt there was a need for a weekly newspaper dedicated to analysis in addition to news gathering.” The initial volume, averaging 28–32 pages per issue, was distributed 12 times a semester on Thursday evenings at “approximately dinner-time.”

The Indy was founded in a transitional moment. “These were the Gregorian years, the years where the first campus email addresses were set up, the years where they demolished downtown in order to rebuild it,” wrote former managing editor David Levithan in an email to

deep-dives into current events were intercut with sports coverage and the occasional black-and-white illustration, comic strip, or humor piece. People also looked to the Indy for things to do: the back pages were filled top to bottom with listings for recitals, parties, gallery nights, puppet shows, film screenings, dance workshops, and basketball games.

In his 1990 piece, Roberti outlines some “general principles” upon which the paper was founded: “fairness and accuracy…reaching out to the Providence community…intellectualism ruling over sensationalism…high-quality writing and reporting…serving as a teaching tool.” The vagueness of these statements seems a sharp contrast to the explicit leftism of the Indy’s mission today.

the Independent. “We were lucky that we were at a technological point where we could design the paper on the computer,” said Levithan. “We were unlucky because we would then have to print out our design, cut out the columns, and hot-wax the printouts onto flats that the printer had given us; if the first few years of the Independent seem a little slanted (physically, not ideologically), that’s probably on me.”

In the earliest Indy volumes, we found work both reminiscent of and unfamiliar to the Indy we know today. There were debates, critiques of critiques, and passionate (sometimes scathing) letters to the editor.

In one case, Eric Broudy, an associate vice president at Brown, sent in a response to an article on unionization claiming that the piece had “distorted facts.”

The Indy published Broudy’s complaint alongside a thorough refutation from one of the original authors. It’s difficult to imagine a Brown administrator putting so much stock into the Indy today. In its early days, the Indy carried more weight among students, too. “It’s hard to explain the power a newspaper could have, before we were all digitally connected,” said Levithan.

Early issues of the Indy resembled more a traditional newspaper. Straightforward reporting and

“I don’t know that I was conscious of one particular mission for the Indy [in the late 2000s],” said former managing editor Nick Greene. “I would say our mode defaulted to questioning the authorities at the school, in regional politics, and in the arts.” In 2016, Indy staff raised the question of creating a formal mission statement. In a “From the Editors” note, the volume’s managing editors asked: “What are the Indy’s politics, and who gets to decide? What’s the point of trying to present relevant and critical reporting on the university’s dime and timetable?”

By 2017, the Indy had made up its mind. On February 10, as part of the launch of the Indy’s website, the managing editors published a mission statement online. It resolved to “address…systems of oppression by centering the voices, opinions, and efforts of marginalized people in Providence and beyond.” This mission statement also outlined “evolving” efforts towards inclusivity and accountability.

Our current mission statement, revised in 2021, describes the Indy as an “open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists.” Cultivating a mission for the Indy has been an iterative and non-linear process. In this piece, we have traced this history through 35 years of headlines, quotes, covers, illustrations, and ephemera.

DANIEL ZHENG B’25, LAYLA AHMED B’27, JORDAN COUTTS B’28, NAN DICKERSON B’26, AUDREY HE B‘27, NADIA MAZONSON B’27, TALIA REISS ‘B’27, EMILY VESPER B’25 and SCHEMA HQ look forward to V100 (do the math!).

“I sincerely hope our readers will not be driven from our pages after ready Eric Broudy's [VP of University Relations] letter, especially since, after careful examination, it is clear that Broudy is merely picking nits.”

–One of the Authors Responds

*It’s the question everyone’s asking: 50 volumes in 35 years? For a long time, we thought it was simple: the first few volumes of the Indy lasted a whole year, and then we switched to a new volume every semester. This is true—but it’s not the whole story. Through agonizing archival work, we’ve solved The Independent’s most enduring mystery. It happened like this: We began with the elegant, professional volume-per-calendar-year. By the late ‘90s, we ended up with the pragmatic volume-semester. In between—a bit of a mess. There were some school-year volumes, a whole year unlabelled, and three consecutive Volume Xs (Fall 1998, Spring 1999, Fall 1999). Emerging clean on the other side, the volumes continued at one per semester into the aughts. And it was easy and simple until Fall 2009—Volume XXIX—we used Roman numerals back then. Then, disaster struck. Spring 2010’s MEs—they shall remain nameless in their shame—labelled the new volume “XX.” We skipped ten volumes back. Since then, we’ve remembered how to count. We’ll stick with Volume 50, though.

1998

“Ninety-five theses nailed to a chapel door. The world changes. One ‘From the Editors.’ It is the year 1998. Let the chips fall where they may.”

–V10, September 17th

“We're responsible for educating the student body because I don't think the administration's going to do that very well.”

–Volume Unlabeled, February 5th

"Gwahahahahahaha. Hello Ghouls and Boys, welcome to the College HELL Independent. Hwahahahahaha. Or perhaps, the Cthulu Hill Independent. Bwahahahahaha!!! There is no escape, you cannot flip the page, you cannot close your eyes. Stare, little one, stare at the pictures of eeeevil, the scaaary, spooky pictures. These are the images you fear. Feeeeeeeeeee-r. You can't go home now! Your incestuous family has turned into moles, burrowing blindly under the ground. You have no home. Your new home is in front of you, two dimensional, flat and spooky. Your world is Spooky World." –V11, October 26, 2000. section called Spooky World??

“Turn on the news and you will find statement. This is the attack on America, the next Pearl Harbor; there has been an Act of War, and the Face of History has been changed. Everything seems to be done even before it has finished, in light of the profusion of analysis, the chapter instantly drawn up in future history books. Here, instead, we offer you response, our varying responses, in hope that this will form a fitting use of our voice on campus.”

–V13, September 14, 2001

“Jury selection for Mayor Buddy Cianci’s corruption trials got underway this week, with 16 people passing the first round of questioning on Wednesday. A total of 18 jurors will be selected, not a small feat for this high profile scandal in a state where everybody knows everybody. In a speech here at Brown University Tuesday night, Cianci maintained his innocence of the 97-page federal indictment charging him and his colleagues with running a criminal

–V14, April 18, 2002

“As the drag queen piece points out, it is not easy to be a woman. Even on the Indy editorial staff it is not always easy to be a woman, as the gender ratio is about two boys for every girl. If it feels like a boy’s club in print, that may because it partially is.”

–V16, April 17, 2003

“To the Editor: I most strenuously object to the contention made by the FTE in the previous edition of this paper that “forgetting is part of the ritual of consumption.” It is precisely this kind of pre-fab, pre-digested, pseudo-gramscian, hallucino-paranoic cockamamieism that foments and retroactively justifies the newspaper’s consignment to oblivion. So much “chatter.” To seesaw Mr. Zevin’s tidy as it is smug assessment of Baudelaire, he is ‘right for being wrong.’ This post-Benjamin hystericism (what would Adorno say?) bears a striking resemblance to the science fictions spoken by power and and is equally deserving of our incredulity. A press written by such a mob of self-inflating hacks was precisely the stock and ply of nineteenth century journalism that for all its romanticized vitality sewed the seeds of catastrophe. The newspaper may be “the talking cure” for the geopolitical, but The Indy would do well not to forget the wisdom of the good book: heal thyself, herr doctor.”

–Kilroy Penzance B’53 V19 November 4, 2004

2010

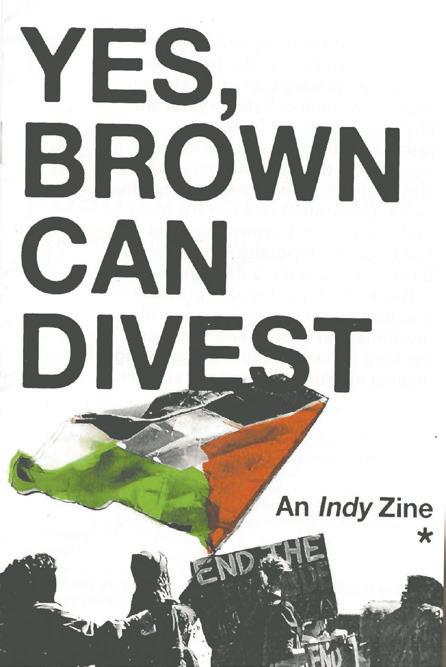

"As students at an institution with endowment and tuition investing power, we at Brown have a responsibility to say, "In this I won't participate." Brown once took a stand to divest from Apartheid in South Africa. Now, we must demand Brown's divestment from the Apartheid project of Israel."

–V28, February 12, 2009

"Sophomore year, in front of a DPS office (how far we've come from Stonewall!), and very proudly, I sucked a strawberry-flavored pasty off of someone's nipple—I wouldn't say friend, really, because I haven't seen her at any parties I've been to since—but mine and Delaney's point is that she and I have been intimate, and I'm happier for it."

–V29, November 11, 2010

The Paper Cut Stings: How Long Till the ProJo’s No More?

"On October 10, the paper laid off 31 members of its news staff...While cuts like the ProJo's have occurred at many papers across the country, in a small state of Rhode Island, they will have an immediate effect on local readers as well as other local news outlets."

–V19, October 30, 2008

The Gates Foundation and its plans to make American children less stupid: Or, how throwing money at a problem solves everything

2011 Occupy Keeps Occupying: City deadline passes in peace

“The Indy was founded in 1990. The first commercial internet also. Our new site theindy.org is quick and principally easy. From astrology to gardening to punk rock, just select by pushbutton. Don’t forget the three Ws. You know, I think your son would really enjoy this NASA website. Wow, she’s really clicking. Refresh. Refresh. Refresh. By the end of today you’ll be taking your wife and kids surfing on the net like a pro!”

–V26, May 3, 2013

Why 2015 Might Actually Shake the Status Quo: The Changing Politics of Development and Climate Change

“This page is left blank because its editors are too tired to make something this week. Instead, we’re cleaning, worrying, crying, sleeping. Trying to love our families, friends, communities, and cats from afar. We’re resisting the urge to be productive or formal. We’re refusing to push forward while our peers fall behind. We’re demanding universal pass, compensation for student workers, raises for essential staff. And we’re choosing S/NC no matter what!”

–V40, March 27, 2020

“This week, and for the forseeable future, the Indy will publish community aid funds and other ways you can contribute to coronavirus relief in lieu of our traditional event listings.”

–V40, March 27, 2020

Presence, Play, and Postmodernism: Rethinking Zoom

Save the BCSC

War of Performance: Spectatorship and combat in Fortnite: Battle Royale

“For Khaled Almilaji, a doctor from Aleppo, Syria, Trump’s travel ban meant that he couldn’t come back to Providence to finish his Masters in Public Health at Brown University. It also means that he is unable to reunite with his pregnant wife who lives in the United States. Khaled traveled to Turkey to assist with humanitarian work for his home country. He was about to take a plane back to Rhode Island when he found out that the US Consulate had revoked his student visa. This happened on January 17, 2017. He remains in Turkey.”

–V34 i4, March 3, 2017

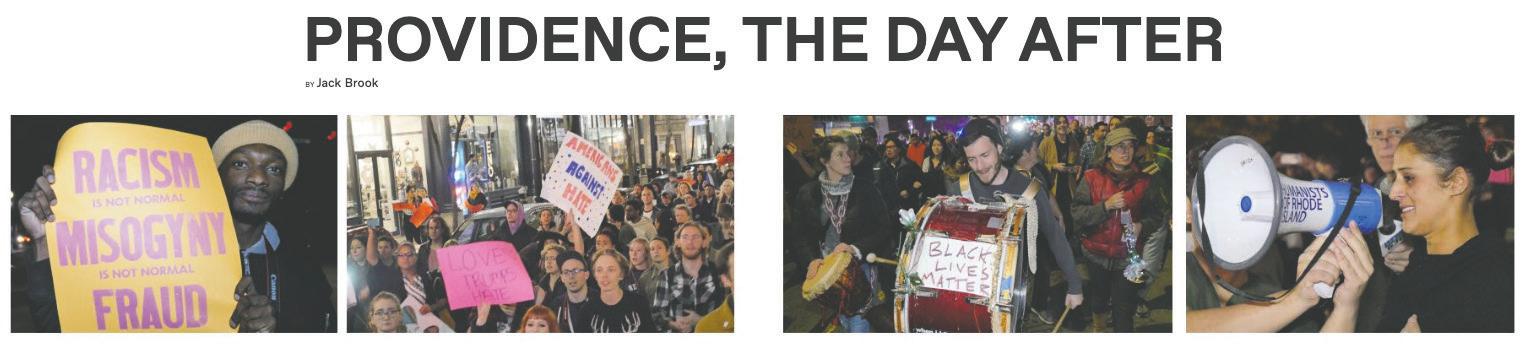

“For months, we looked around and saw that our friends were voting for Hillary and we felt that that was good enough. Now, with dread, we confront a future that feels increasingly destructive, and we face our complicity in enabling that future.”

–V33 i8, November 11, 2016

“Filling in the ___: How AI is changing the way we see writing”

“[...] This is not about Hisham Awartani though. It was never about me. On November 15 I joined my fellow Brown students to write the names of thousands of Palestinians killed in the war on Gaza. They gave us a document issued by the Gaza Health Ministry, and out of curiosity the first thing I did was look up my name. There were 30 results. 13 people named Hisham and 17 with Hisham as a middle name [...] I am the Hisham you know. I lived. My story is being told. The 13 other Hishams were killed, their stories forever erased. They were human and they did not have to prove that to anyone. They knew no respite, no justice, no peace.”

–V47, December 1, 2023

c On the night of October 22, 2023, when Javier Milei took to the stage following his presidential victory, he did not temper his tone with the typical language of reconciliation and national unity. Instead, he brandished a chainsaw—physically during his campaign and rhetorically in his speech—as a symbol of what he had promised to do to Argentina’s “casta política” (political caste). Although the country doesn’t have a caste system, the same surnames have historically permeated the political sphere, as well as the higher socio-economic classes.

Milei describes his fiscal policy as “shock therapy”: dramatic and immediate budget cuts to address Argentina’s spiraling inflation and debt crisis. His plans included the elimination of several government ministries, threats to dollarize the economy, and the privatization of state-owned enterprises. Following decades of economic stagnation in Argentina, Milei was able to secure 56% of votes thanks to his promise of actualizing these measures. Although his policies present themselves as prototypical ambitions of orthodox neoliberalism, what distinguishes Milei’s program is its theatrical presentation—its dramaturgic framing as a biblical war between good and evil, freedom and tyranny, la casta and the Argentine nation. +++

This election constitutes a clear break from Argentina’s historically progressive politics. The country was one of the earliest in Latin America to grant women the right to vote in 1947, elect a female president in 2007 (although president Juan Domingo Perón’s wife and vice president Isabel Perón inherited the office 1974 after he died), and legalize abortions in 2020. In the early 20th century, Argentina had one of the world’s highest GDPs per capita, making its citizens some of the wealthiest in the world, and some of the first to live in a parliamentary democracy, beginning with the first democratic legislative elections in 1912.

Milei’s war against diversity, social justice, and climate change—what he calls the ‘woke’ agenda—is particularly striking. Historically, these battles have been carried out by the Left, particularly by the many divisions within Peronism. Juan Domingo Perón was president from 1946 to 1955 and from 1973 to his death in 1974. His big hiatus was due to a proscription from Argentinian politics after a coup d’etat, as a result of which he sought refuge in Franco’s Spain and Mussolini’s Italy. Although his party began as right-wing, with strong ties to the army Perón himself had served for previously, its focus shifted to social justice issues very quickly. Coining the term “los descamisados” (the shirtless ones), Perón and his wife Evita appealed to the people and the working class, with measures including creating the Ministry of Work and promoting workers’ rights and wealth redistribution at a time when landowners and agricultural producers were the richest people in the country. This led to the creation of workers’ unions, which have since become a fundamental political power in today’s Argentina. To further appeal to minorities, Evita championed women’s suffrage until it was approved in 1947. Both their ghosts are still haunting national politics, and are kept alive as banners and fundamental examples of leadership and morality for left-wing political parties, social organizations, and social justice promotion.

However, after decades of political turmoil, economic instability, and recurrent social crises, the country has changed dramatically. The memory of its past glory, as it continues to fade, remains the standard against which every president is measured. Milei debuted on the political stage as an eccentric, albeit well-read, economist who appeared on TV to criticize the government. He attacked the general State structure, expressing his “infinite contempt for the State” and blaming it for enabling and sustaining the biggest, most irresponsible public-spending of the country’s money, a.k.a. the taxpayer’s money. He had never

worked for the State before, which painted him as “innocent” with regards to corruption: he had not yet had the chance to make mistakes, which was perhaps his most potent alibi.

Embedded in Milei’s promise of austerity is a deeply populist mode of rhetoric, cloaking the violence of fiscal contraction in the language of moral purification, heroic struggle, and prophetic anti-elite vengeance. In what has become his defining lexicon, society is divided into “los buenos y los malos” (the good and the bad). This binary moral framing posits “the good” as hardworking Argentines and “the bad” as the scrounger elites—politicians, union leaders, la casta—to whom Milei not only attributes the origin of corruption, but blames for the very existence of poverty, inflation, and economic decline altogether. Their presence in bureaucratic environments is framed as a disease, “the cancer that must be eliminated,” “an epidemic that must be cured,” and claiming that because of them, “society is infected by socialism.” Beyond reducing Milei’s political opposition to a mute facticity whose contagious nature is almost pitifully fixed, this rhetoric also suggests the availability of a simple metaphysical cure to the cancerous spread—manifested literally through the chainsaw he wields at political rallies. Milei cuts Argentina along sharp lines, separating los buenos, who

are threatened by imminent decay, and los malos, who Milei wants to amputate in a supposed effort to save los buenos from pollution, agglutination and political armageddon.

Milei’s habit of comparing himself to the figure of Moses reveals his self-aggrandizement as a God-ordained savior of Argentinian politics. In his mission to purify the State (and therefore the political class), however, Milei appropriates la casta by taking the presidential office, seemingly rejecting it and its values, but ultimately reconfiguring it to his own desires. In other words, he is the messianic outsider saving Argentina from the “parasites” depleting its financial resources from within.

Since becoming president, Milei has stated his desire to “let it all blow up, let the economy blow up, and take this entire garbage political caste down with it,” along with Argentina’s legacy of progressive political pioneership. Through his ideologized fiscal and bureaucratic revolution, he conceals Argentina’s historical heritage, turning this history of democratic trailblazing into a site of erasure. But Milei is not the first to approach national legacy in this way. Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro frequently discredited historical narratives criticizing Brazil’s military dictatorship. Similarly, Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán continues to restructure his country’s education system and media outlets to rewrite Hungary’s role as an ally of Nazi Germany. In the United States, Donald Trump calls for a regression to a past “great” America, attacking the legitimacy of experts, scientific data, and journalistic institutions to justify the violence of his policies, suppression of dissidents, and gutting of educational institutions like ours. In portraying the United States as a swamp

ILLUSTRATION LUNA TOBAR )

in need of being drained, he mirrors Milei’s narrative of “the parasite,” the internal threat requiring heroic purification delivered by one man. Not only does the ideological and rhetorical alignment of these modes of erasure facilitate their normalization on a global scale, it also tests the limits and expands what is thought of as acceptable in public discourse. This numbs voters to the extremity and severity of these false narratives about national legacy and history’s residue in administrative institutions, ultimately detaching the present from the past. If continuously successful, these methods of erasure erode the significance of political commemorations and undermine statements like “never again,” opening a door for history to repeat itself.

Milei’s ‘chainsaw plan’ operates under the logic of erasure, imagining the public sector as a site of rot, where accumulated bureaucratic excess must be violently and abruptly excised. The national ministries Milei is hell-bent on dismantling are not just administrative bodies; they constitute an archive, a historical record of ideological struggle, economic experimentation, and collective memory. Education, labor, health, and culture are no simple budget lines, they are institutional expressions of what the country has chosen to fight for, remember, and preserve. The choice of which ministries to eliminate—the Ministry of Culture, Women, Gender and Diversity, or the Ministry of Science—reflects a desire to break from the historical narrative that had won Argentina international praise in the past. By dismantling the institutions through which the State has embodied a role of protection and redistribution, Milei casts them as illegitimate entries in the national ledger, as mere distortions imposed by la casta. What Milei offers in its place is not just austerity, it’s amnesia.