Masthead

DESIGN EDITORS

WEEK

Ilan Brusso

Kat Lopez

ARTS

Beto Beveridge

Ben Flaumenhaft

Elliot Stravato

EPHEMERA

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

M. Selim Kutlu

FEATURES

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Nadia Mazonson

LITERARY

Sarkis Antonyan

Elaina Bayard

Nina Lidar

METRO

Arman Deendar

Talia Reiss

METABOLICS

Brice Dickerson

Nat Mitchell

Tarini Tipnis

SCIENCE + TECH

Emilie Guan

Everest Maya-Tudor

Alex Sayette

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Lucas Galarza

Ash Ma

Izzy Roth-Dishy

DEAR INDY

Kalie Minor

BULLETIN BOARD

Anji Friedbauer

Natalie Svob

MVP

Vibes

20 BULLETIN

Anji Friedbauer, Natalie Svob

ND: We’re curating a vibe in here. For the folks watching from home: “here” is conmag, where we put on all the finishing touches. There are no “real” candles in this room because that would be a fire-code violation, but we have a bunch of conceptual candles. Do you know anyone with a lamp? We have a speaker and some cheese (thanks, April!). Can I smoke a cigarette in conmag? Can I light it on that candle?

EV: Don’t ask. Just do it. You have three weeks of power left. Do not reference. Be referenced.

ND: EV like electronic vehicle. Cool. Nifty.

EV: ND like NDA.

ND: Whatever. We’re going to be out of copy soon, hopefully, which is one of our earlier iterations. I’m sending prayers out to my friends writing theses right now. We’re thinking of you!

EV: I can’t believe I’m graduating. Feels like death.

ND: It’s hard out here. Smoking out the window watching frat boys piss on the Lit Arts building. They’re using everything.

EV: Walk to the store. Carry it up in a paper bag. Get your shit together. And also say it. Go together. Multiply. Stick your head out the window! I’m going to miss you, and all of you, and very much.

ND: We will miss you. We miss you already.

DESIGNERS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Jolin Chen

Esoo Kim

Minah Kim

M. Selim Kutlu

Seoyeon Kweon

Iris Lee

Hyunjo Lee

Anahis Luna

Liz Sepulveda

Justin Xiao

Isabella Xu

Shiyan Zhu

STAFF WRITERS

Layla Ahmed

Aboud Ashhab

Hisham Awartani

Grace Belgrader

Emmanuel Chery

Nura Dhar

Kavita Doobay

Lily Ellman

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Elena Jiang

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nahye Lee

Cameron Leo

Cindy Li

Evan Li

Angela Lian

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Gabriella Miranda

Coby Mulliken

Naomi Nesmith

Kendall Ricks

Lily Seltz

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

Luca Suarez

Daniel Zheng

COVER

COORDINATORS

Johan Beltre

Brandon Magloire

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Lucas Galarza

FINANCIAL

COORDINATOR

Noah Collander

Simon Yang

MISSION STATEMENT

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Mingjia Li

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Julia Cheng

Mia Cheng

Anna Fischler

Zoe Gilmore

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Ellie Lin

Ruby Nemerof

Jessica Ruan

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Luna Tobar

Catie Witherwax

Lily Yanagimoto

Nicole Zhu

COPY CHIEF

Jackie Dean

Lila Rosen

COPY EDITORS

Kimaya Balendra

Justin Bolsen

Cameron Calonzo

Jordan Coutts

Kendra Eastep

Leah Freedman

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Christelyn Larkin

Eric Ma

Becca Martin-Welp

Isabela Perez-Sanchez

WEB EDITOR

Lea Seo

WEB DESIGNERS

Sofia Guarisma

Clemence Jeon

Janice Lee

Liz Sepulveda

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGERS

Eurie Seo

Ivy Montoya

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Martina Herman

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Emily Mansfield

Kalie Minor

SENIOR EDITORS

Jolie Barnard

Arman Deendar

Angela Lian

Lily Seltz

Luca Suarez

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

*Our Beloved Staff

WEEK IN PLANNING OUR PARENTHOOD

“THAT

WILL BE $1200, DOLLFACES!”

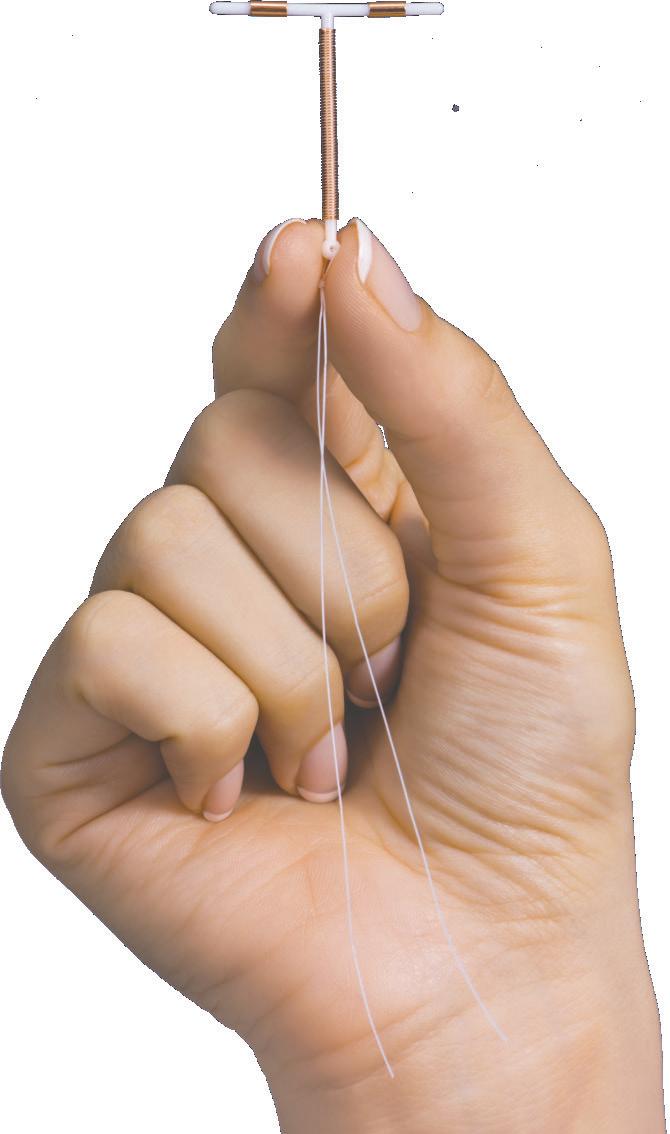

c The Brown University Wellness pharmacist reached out her soft, meaty paw for our shared credit card, which we won in a raffle. Her hand was soft, like meat. Soft meat :} It was beautiful. Her other hand held two brown paper lunch bags which held two golden little Intrauterine Devices. You guessed it! IUDs. I Understand Dis! She shook the bag like a maraca. It jingled.

Upon hearing the exorbitant price, we were like, “Hmmm, nuh uh uh!” So we shoved our shared raffle credit card into the thingy and booked it to Planned Parenthood way down southwest. There, there is Love, and most forms of insurance are Accepted, and thus we booked our appointments for Theirs and Hers IUDs. For purposes of Clarity and Whimsy, Kat (a notable they/she) will be using they/them pronouns exclusively, and Emily will be the token she/her. Don’t get confused. Or else.

+++ EMILY’S PART

SHE (Emily) sauntered in first at 11:50 on the dot, doped up on 1000mg of Tylenol. The waiting room was souplike. The chairs were split pea soup green and regular carrot soup orange. They were soft under Emily’s legs. After waiting just long enough to get antsy, she got antsy. She texted THEM (Kat): “i’m scared i’m gonna fart when they’re looking at my v*gina.” They said back, “u should.” She typed angrily, “not a joke.” Our first pre-IUD fight. Emily (me/her) waited in the soupy room for what felt like infinity (13 minutes) until the suspense was too much. “WHAT’S TAKING SO LONG?!!!” me texted Kat. They responded, knowledgeably, as usual, “they’re in there welding it” which got Emily all nervous about whether or not it would be hot when they put it in there. Kat reassured her that the doctors would blow on it first. As Emily sighed a breath of relief, a gay man in an Ariana Grande Eternal Sunshine Deluxe hoodie (he/ him) crinkled his nose and beckoned her with his finger, leading her to a little bitty room. He took her vitals and said, “Wow, you’re perfect.” She asked, “I’m perfect?” “Your vitals.” “Oh, ok.” So yeah. She was perfect, pretty much. Then she peed in a cup and placed it carefully in a metal cabinet with two doors. A hand on the other side of the wall opened the second cabinet door and grabbed the cup. It was like a portal. Like Narnia, kind of. Nice.

With an empty bladder and an open heart, Emily marched into the room. She pulled down her skort, slipped off her crocs, put her feet in the stirrups, and cuddled up under the paper blanket. Cozy. The doctor (she/her) was a White woman with a fierce jawline. She was dazzled by Emily’s sparkling Sonic the Hedgehog croc jibbitz. Everything was going according to plan.

Emily texted Kat a flick of the situation, captioned: “IUD with socks on?” and they probably laughed. Me hopes so at least. Kat texted back, “that means it’s not gay.” The speculum went in. Ow. Undeterred, Emily typed, “joke homophobia is not funny, Kat.” Our first mid-IUD fight.

Then the doctor started measuring stuff and sticking things up there. Even with the lidocaine injections to numb the area, and the gram of Tylenol, it was painful as bruh. “What the bruh,” Emily cried as her uterine muscles cramped. That was a lie. She didn’t actually say that. But still she tensed up real bad, prompting a, “You’ll be just fine, girl” from the doctor with the jawline. Then Emily realized that she would be just fine, girl. And just like that, it was over. She hobbled home to hand the IUD baton to Kat, becramped but excited for the future of her uterus. Her futerus.

+++ KAT’S PART

THEY (Kat) had a secret weapon. Something secret that Emily did not have. Some secret agent (a doctor) who was secret and mysterious (doing their job) had slid ONE PILL of VALIUM under the table (prescribed it diligently and legally to manage anxiety during the appointment).

Kat sat in Emily’s common room. “They gave me Valium,” they muttered.

“You should probably take it,” Emily responded, becramped.

“Yeeeeeah! I guess I will!” Kat squealed, turning into a 1920s rubber-hose style cartoon of themself (Betty Boop style) and devouring the entire bottle WHOLE, which held one pill. They spit out the bottle, which no longer contained a pill, and returned to their live-action form before asking a becramped Emily, “What does Valium do to you again?”

Oh god. Oh fuck. What DOES Valium do to you again? Kat’s mind raced as fast as a racecar. They googled “what does valium do to u again please” as fast as a racecar. They received an answer racecar-fast: relaxation, drowsiness, euphoria, confusion, and reduced coordination. Hmmm. Cooooooool, sorta. When Emily asked “Do you think you need a chaperone?” Kat realized they thinked they needed a chaperone.

Through a portal in the ceiling, an angel appeared. Cecilia “Cece” Bartin B‘27, angel of the waking world and roommate to Emily Mansfield B’27, announced in a booming angel voice, “I HAVE NOTHING TO DO TODAY AND I WILL GO WITH YOU TO PLANNED PARENTHOOD TO GET YOUR IUD, KAT.” She had just now bought Chipwiches from CVS.

“canwehave thechipwich es whenwe getback,cece” Kat said, coherently, the Valium dancing its way through their veinz and into their brainz. With a sage nod from Cece, Kat jumped for joy and set off towards IUDhood.

Down at the clinic, Kat breezed through the check in process and floated into the Vitals Checking Room, which was pure white, like a vial of milk. “I’m sitting in this milky vial,” mused Kat, “and I feel this burning, radiating sense of calm, like a white-hot brand to the vagus nerve. I am one pure smile in a bowl full of soft human heads. Is that normal? Or is it God I’m feeling?”

“Pee in this cup, diva,” said the Nurse Practitioner. So Kat peed in the cup.

“I’m worried I didn’t pee enough, Nurse Practitioner,” they confessed. “I’m worried it’s too small, and the world is immense. Is the world too immense?”

“Is there pee in the cup?” The Nurse Practitioner asked.

“Ya!” smiled Kat.

“Oh, then you’re good.” Kat knew what this meant. It meant the pee in their cup was always enough. The world is never so immense that the pee in one’s cup means nothing. If there is pee, it is enough.

Newly affirmed in the volume of their urine and also their spirit, they traipsed into the procedure room and waited patiently on the Big Chair. The throne if you will. The room was pale green, like their eyes. They marveled at the fact that their eyes were both in and outside of their head. The beautiful doctor waltzed into the room, eyes on the prize, and got right to work.

“You’re beautiful,” said Kat.

“So is your cervix,” said the doctor. Kat smiled.

“What do I do after this?” Kat asked. “What are my next steps? Will I see the world differently? Does an IUD clear out your soul as well as your uterus?”

“It’s up to you, babygorgeous. Some people get right to fucking on the back of a jetski. Some people experience deep spiritual renewal. Others… Others head back to their friend’s suite and enjoy a delicious Chipwich.”

Kat sat up straight. “How did you know about the Chipwiches?”

“I know a lot of things.”

“I’m on Valium.”

“I know that too. Sit back down.”

Kat sat back down and the thingy went in their thingy and it hurt but not a lot. Kat emerged from the operating room, and threw themself into Cece’s strong, toned arms. Cece then chucked them over her shoulder and brought them back to the suite to nibble on a Chipwich. It was the best Chipwich anyone has ever nibbled.

+++

After a long, becramped day, as the smiling sun set and the cheeky moon rose, we snuggled up in our shared bed which we won in a raffle. Warmed by the power of friendship and progestin, we dreamt sweetly of Chipwiches, jetski fucking, and a country in which a woman’s ability to choose is not a privilege but a right.

KAT LOPEZ B’27 and EMILY MANSFIELD B’27 put the “bod” in “bodily autonomy.”

Bureaucracy Over Urgency

RHODE ISLAND’S FAILURE TO ADDRESS EMERGENCY SHELTER INFRASTRUCTURE

c “It sounds kind of wussy—but I’m afraid of the cold.”

When Donald King was living in a tent for almost a year, he was forced to endure brutal Rhode Island winters. Access to warming shelters was sporadic at best. On Wednesday, April 2, he testified for a House Resolution in the Rhode Island General Assembly that would outline specific standards for when extreme weather shelters must be open. King said, “when I was in my tent, I froze. I was sick and getting sick all over myself and I slept right through it just because of the cold. Somebody checked up on me and I was there in two inches of water, feces, and vomit. I had to get up in [nine-degree-weather] and change. That wasn’t pleasant. At all.”

During his testimony, King described his experience navigating the unpredictable emergency warming shelters in Rhode Island, saying, “There’s just been no rhyme or reason as to the [hours for the] warming or cooling shelters. There was just no structure to it. So if you don’t know it’s gonna be open, or you don’t know it’s open, you just don’t go.”

King’s frustrating experience with the state’s emergency shelter infrastructure is one echoed by people experiencing homelessness, community advocates, physicians, and politicians and many others year after year. However, city and state officials’ lack of urgency and willful neglect is fatal for

many unhoused Rhode Islanders. This reality became increasingly apparent to the hundreds of individuals known to be sleeping outside this winter.

Last December, at the first meeting of the Rhode Island Interagency Council on Homelessness in eight years, attendees expressed their anxieties about the upcoming winter. They stressed the need for a coordinated effort to increase the availability of emergency warming shelters and efficient communication with community leaders, outreach workers, and unhoused community members.

The Indy reached out to Governor McKee’s office for comment on his administration’s leadership this past winter. The response we received from the Department of Housing describes McKee’s approach as “dynamic, adapting to seasonal needs and leveraging both state and federal resources to create sustainable solutions for Rhode Islanders.”

There do exist some emergency warming shelters—temporary safe havens for unsheltered individuals during extreme weather, used especially in times of extreme cold and heat. Some warming centers also offer food, blankets, and social support services such as access to outreach workers, basic medical assistance, or—at a select few— behavioral health support. However, despite McKee’s “dynamic approach,” most warming shelters in Rhode Island don’t even have enough space for people to lay down. “It’s not dignified—it’s humiliating,” said Dr. Rebecca Karb, an emergency medicine physician and the director of the Street Medicine Program at the Council meeting. Dr. Karb was one of many community members to sound the alarm on the state’s lack of preparedness for the upcoming winter, noting that the North Main Street warming shelter in Providence “has been full

pretty much all year,” with limited room to increase their capacity as it got colder. She asked, “what is the backup plan here for right now?” In addition to Dr. Karb’s testimony, other outreach workers and unhoused community members offered their own perspectives on the situation going into this winter. Michelle Taylor, the Vice President of Social Health Services at Community Care Alliance, said, “our system is deeply, deeply, deeply broken.” +++

The Department of Housing told the Indy that “the McKee administration has implemented strategies to increase indoor, overnight capacity during winter, including the availability of emergency winter hubs, funded through the state’s Municipal Homelessness Support Initiative.” However, in 2024 the City of Providence received no funding from the Initiative to prepare for this past winter. At a rally organized by the Rhode Island Homelessness Advocacy Project (RIHAP) in December, Kevin Simon, a pastor at Mathewson Street Church, said that the City was asked to apply for warming center funding during the first round of the program, but decided to only apply “if someone told them how many times they would have to open [the shelters].” As nobody could provide that information, the City never applied during the first round, significantly decreasing the capacity of warming centers at the start of this winter.

In early January, the winter housing crisis came to a head. A polar vortex hit Rhode Island, bringing the temperatures into the teens and the wind chill into single digits.

To address the lack of shelter during the vortex, Providence council members Justin Roias and Miguel Sanchez led a call to open the Providence City Council Chambers as an emergency warming center. In an

Instagram post, Councilman Roias reflected on the significance of the move, writing: “City Hall became what it should always strive to be: the people’s house. In this unconventional but absolutely necessary moment, we are sending a message to our most vulnerable neighbors—the ones who are often forgotten—that they matter, that their lives have value, and that their humanity is seen.”

This effort faced political pushback, especially from Providence Mayor Brett Smiley, who argued that “opening City Hall as a shelter disrespects the hard work of our community partners who have the expertise to adequately provide support for our community and this action distracts from the serious solutions the City and our partners have been leading to support our unhoused populations.”

In an interview with the Indy, Councilman Sanchez responded to Smiley’s criticism, drawing on his experience working at Better Lives RI, a non-profit social service organization that the city has collaborated with on housing efforts. Sanchez noted, “it’s important to acknowledge and elevate the people doing this work…But there’s still specific gaps that need to be covered.”

Beyond the failure to ensure enough space for everyone at warming centers, the state was unable to maintain a set schedule for warming centers during this past winter. On January 12, the last day of the polar vortex, an extreme weather shelter in East Providence closed despite forecasted temperatures reaching 24 °F; current evidence shows that hypothermia can occur at temperatures above 40 °F given the right conditions.

In response, Representative Teresa Tanzi introduced H5953, a bill that defines the conditions for when emergency weather centers will open. At the bill’s hearing, a volunteer outreach worker with Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE) shared that it was “outrageous” that “once these shelters open, they seem to close in an arbitrary fashion, and no one is able to figure out why.” Many outreach workers echoed the importance of maintaining reliable schedules in their own testimonies.

Representative Tanzi also noted that the resolution had previously failed to pass, as the Emergency Management Agency “raised their red flags at the last minute,” opposing the bill as an interference in emergency management. This intervention is indicative of a larger trend across every branch of government in Rhode Island, one of bureaucracy overriding urgency. As Councilman Sanchez said, there is a consistent “lack of urgency and resources when it comes to helping our most vulnerable.”

The Department of Housing also noted that, as a part of their efforts to “identify areas for system-wide improvements,” the state had recently launched a “public dashboard that provides a high-level overview of shelter capacity, showing shelter bed utilization for the prior night and the total number of available beds.”

On the right-wing radio show The News with Gene Valicenti, McKee referenced the dashboard’s data to posit that there were beds available. The segment garnered considerable public backlash, with many organizations noting that the data does not reflect open beds saved for specific identity groups or beds held for people expected to return from the hospital. Councilmember Roias denounced the Governor’s claims as a dismissal of “the urgent reality that people in our state are literally freezing to death.”

The Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness (RICEH) operates the Coordinated Entry System (CES) Hotline, where outreach workers or indi viduals experiencing homelessness can call to get connected with open shelter beds. Three days after the Governor’s appearance on WPRO, the Coalition released a statement detailing the overload and long wait times that the CES hotline was facing: “despite the rising demand, CES has not received adequate funding to expand staffing, leaving the existing team to manage a heavy workload with limited resources. With fewer personnel available to answer calls, wait times have stretched, making it more difficult for individuals needing assistance to access help.” The Coalition emphasized that “this issue is not just a temporary inconvenience but a reflection of the urgent need to address an insufficient homeless response system.”

Journalist Steve Ahlquist also responded to the Governor’s claim, arguing that “the Coordinated Entry System (CES) is a dynamic system that is constantly shifting, but no shift is possible in the system that will allow it to accommodate the 674 people now waiting for shelter in Rhode Island.”

In response to the Coalition’s statement, a reporter from The Boston Globe shared on X that Governor McKee has plans to “reevaluate” the Coalition’s contract to operate the CES Hotline.

As state Senator Tiara Mack noted in a recent newsletter, “addressing our state’s homelessness crisis without addressing the key root causes of homelessness—our eviction crisis and housing instability— will never solve homelessness.”

The McKee administration shared their RI 2030 housing goals with the Indy, outlining plans focused on “investing in the long-term solution of increasing the availability of affordable housing, keeping in mind the ultimate goal of transitioning individuals from shelters into stable, long-term housing solutions.” Overall, RI 2030 prioritizes “increasing homeownership and housing production for long-term stability.”

However, housing justice advocates have noted that the Governor’s support of these initiatives is insufficient to meet his stated goals. An advocate from HOPE—who was granted anonymity for fear of retaliation for political speech—spoke with the Indy, outlining a three-pronged approach to support the Governor’s current plan. In addition to increasing the availability of affordable housing units, the HOPE advocate noted that rent stabilization, just cause eviction, and public housing are crucial for addressing the ongoing crisis.

Rent stabilization, largely unpopular among Rhode Island landlords, focuses on capping annual rent increases. Current proposals at the state level limit caps at four percent, though the legislation seems unlikely to pass. Just cause eviction aims to increase renter protections by limiting the reasons that landlords can evict a tenant or refuse a new lease. The HOPE advocate noted that the current “fear of retaliation when tenants speak up against their landlords…is a huge barrier for housing security.”

Across all levels of government, there has been a clear failure to protect the well-being of unhoused community members in Rhode Island. The crisis this winter serves as just one example of a nationwide trend of lawmakers refusing to address the systems that perpetuate harsh inequities in housing, choosing to criminalize homelessness instead.

ON CGI’S UNEXPECTED ORIGINS

AND THE MILITARYENTERTAINMENT COMPLEX

c A purple spiral blooms out of an iris. It brushes a cluster of eyelashes and eventually consumes the screen. The backdrop of a woman’s features slips into oblivion. Then it’s spiral after spiral—spinning, swiveling, distending the remainder of Vertigo’s title sequence. Most of their centers yawn open to a dark cavern of a pupil, or black hole, mimicking the optics of an eye. All of this very apt for Hitchcock’s film on obsession. A spiral curls unto itself into perpetuity. Consumed by its own contours, always and still expanding closer and closer.

This title sequence from the iconic 1958 thriller is the first use of computer-generated imagery, or CGI, in a live-action motion picture. Hitchcock recruited graphic designer Saul Bass to draw the spirals. For inspiration, Bass turned to 19th-century mathematician Jules Antoine Lissajous. Lissajous’ research into systems of parametric equations resulted in the Lissajous curve, which graphs the intersection of two sinusoidal curves (waves with smooth and periodic oscillation) with differing frequencies. But Bass’ sketches of these twisting spirals couldn’t be animated by any animation stand of the time without its wiring becoming tangled, which was where John Whitney came in.

Whitney breathed motion into the designs. He did so by repurposing an obsolete, analog computer from World War II: the M5 director. With its interior mechanisms for endless rotation, the director could now track the movement of a pendulum in perfect (mathematically controlled) tandem. With multiple pendulums swinging at differing rates, they could emulate the motion of a system of moving parametric functions—surging sine waves, overlapping curves, and of course, spinning spirals. In a contributing article in a 1972 issue of People’s Computer Company, Whitney wrote that the “very acceptance [of the mathematical basis of computer graphics] has opened the door to a new world of visual design in motion whose true essence is digital periodicity.” Whitney viewed the rhythm of joining still images as an unexplored concept in animation. This rhythm of periodicity mirrored harmonic periodic phenomena, which then could be mathematically graphed (like our sinusoidal functions), which then could be animated by a computer. But before any of this theory developed, Whitney first rigged a pen to the machinic set-up and watched Bass’ envisioned spirals seep onto the animation celluloid. The first instance of computer animation emerged from those swirling depths.

Gun directors are anti-aircraft technology used to calculate and then transmit data to guide a firing crew to shoot down moving targets. The M5 director specifically required multiple soldiers to operate its system of over 11,000 components, which together determined the altitude or slant range of moving aircraft and continuously calculated a corresponding firing solution. These computers aim to predict an aerial target’s future positioning, capturing the perfect frame in its crosshairs. Here the director (military)

( TEXT EMILIE GUAN

DESIGN JOLIN CHEN

ILLUSTRATION ELLIE LIN

seems to operate much like the director (cinema).

Technological advancements in photography and by extension, cinema, share a long, perhaps underexposed, relationship with military demands.

A 1963 technical report by Robert G. Livingstone, a field office chief at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, details the history of military mapping camera development. He explains how the Air Force pushed for the development of two lines of aerial cameras: reconnaissance and mapping. For the reconnaissance cameras, their primary focus was enhancing photographic resolution, which resulted in developments such as high-resolving-power lenses, film magazines with image-motion compensation, and gyroscopically stabilized camera mounts that reduced vibrations and acceleration effects. As with many other scientific and technological breakthroughs, the military’s wartime demands and extensive funds propelled advancements in photographing technology—advancements that aided in the maiming and killing of enemy forces and civilians before being shuttled off to production companies decades down the line.

That many technical advancements have now-obsolete military origins may seem inconsequential. After all, does it matter who was paying if it means someone else developed a better camera stabilizer that produced an Oscar winner? Why should we care if US military satellites like the 1960s CORONA photoreconnaissance system were some of the first “digital cameras,” or that engineers developed early semiconductor image sensors like the charge-coupled device primarily for military use? The Department of Defense (DoD) has a Science and Technology sector that funds research for three budget activity levels: basic research, applied research, and advanced technology development. The last level receives the most funding from Congress (around 9 billion dollars for FY2025) and is stated to “have a direct relevance to identified military needs.” The DoD also emphasizes that successful projects with military utility should be quickly available for “transition” to field use. It’s clear that the DoD pursues research with martial and material purposes. If Defense S&T and adjacent government and military actors actively dictate which projects and areas of research to pursue through discriminant funding, they necessarily influence the types of technological and information systems that science research produces and reinforces. Perhaps therein lies the danger—a militarized system inextricably links the martial to the supposedly “objective” science and even “civilian” entertainment spheres.

French philosopher Bernard Stiegler writes that “the question of war is inevitably contained within the question of technics,” in which technics refers not just to technical tools but technicity as a system. This follows Heidegger’s take on technicity in The Concept of Time, where he conceptualizes technology not as a tool but a process that is constitutive of the human and a new way of understanding the world. The tools of war are ballistic missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles and hunter-killer drones, all guided by imaging systems. The technicities of war, then, are pervasive systems of surveillance and targeting and control,

where vision can mean annihilation. In The Eye of War, scholar Antoine Bousquet posits a framework of the “martial gaze,” which refers to a “general disposition and various sociotechnical means accreted toward the rational organization of perception for the ends of military domination and control.” The martial gaze’s main functional constituents include sensing, imaging, and mapping—all of which rely on and perpetuate logics of relentless tracking and capturing. Think rifle scopes, infrared and night-vision goggles, and laser-guided bullets for sensing. Camera guns, reconnaissance planes, and Gorgon Stare drones for imaging. Barrage maps, satellite geopositioning, and subterranean sonic charting for mapping. The martial gaze’s purview is everything it sets its sights on, which Bousquet warns can be every corner and domain of the world.

+++

My earlier explanation of the M5 director wasn’t entirely forthright. As an analog computer, the director gathered input data from soldiers sighting with telescopes, each tracking a different variable such as elevation, range, and angle, which they then transmitted through levers. To sight an aircraft renders it a burning meteor of metal and flesh in the blink of an eye. Under the extreme martial gaze, Bousquet argues that the act of pulling the trigger is enveloped in the act of seeing itself—vision equals annihilation. The site of the machine is remade and redirected by human vision, yet using it also augments and enframes our vision in a way that perhaps, in line with Heidegger, encloses our relationship to technology. Heidegger envisions our relationship to technology as unfree, especially when blind to what he deems “the essence of technology.” He claims this essence lies in enframing: a use of technology that turns nature into a resource, which, when taken to an extreme, also turns humans into a resource. This relationship is not uncommon in modern society, where companies treat human labor and workers as resources, complete with human resources departments. Meanwhile, the military’s mechanization of their soldiers similarly enacts enframing. Bousquet argues that the soldier is inevitably made into the machine, especially when human vision is mediated through mechanical or autonomous tech, such as a telescope-dictated computer. Already we see a new bodily relationship between the human and the (imaging) machine, and a new paradigm of visuality and perception that orients toward

Already we see a new bodily relationship between the human and the (imaging) machine, and a new paradigm of visuality and perception that orients toward control and being controlled.

control and being controlled. We can see this process performed in operating the M5 director. Scholar Zabet Patterson argues that the gun controller is a uniquely important site to explore the relationship between body (especially vision) and machine, just like the original camera obscura and the later film camera. She traces Alfred Crimi’s ball turret gun controller designs, which had a spherical enclosure hanging underneath the fighter aircraft to hold a soldier. The gunman both operated and acted as the eyepiece for the gunsight. They were “constrained and enclosed— locked into a circuit of machines.”

This concept of the soldier-machine follows French theorist Paul Virilio’s take on apparatus theory to address our modern technological condition. Apparatus theory in cinema broadly considers how the production, presentation, and consumption of a film imparts its underlying ideology and constructs the viewer through the viewing. A film’s power is in its potential to shape consciousness and align the audience eye with the camera eye. Similarly, for Virilio, certain uses of technology align our senses with that very technology or apparatus, such as the optical logics of ballistic weapons. To see through the apparatus changes the way we perceive the world. The eye becomes one with a missile, and everywhere looks to be—perhaps truly becomes—a target. This is an example of a spectator becoming an apparatus-subject; the eye becoming the kino-eye (eye of the camera, or speeding train, or WMD). We may think we are in control of the machines we are looking through and operating, but like the act of watching a movie, there is constant messaging and mediating that changes the viewer, whether we are aware of it or not. Virilio, Bousquet, and Patterson would all argue we are more enframed and controlled—less free— by using these machines than we’d think. If seeing enacts material consequences, what happens when we see through a purposely obscured war machine? What about the silver screen?

+++

In 1939, John Whitney moved from Paris back to California to flee WWII. He worked at Lockheed Aircraft Factory, dealing with high-speed missile photography, bombsights, and of course, anti-aircraft gun directors. As Whitney adapted the army surplus machinery to create his own cam machines—like the one used to create Vertigo’s spirals—he transformed the field of computer animation. He pioneered the concept of “motion control,” a technique that enables precise control of camera movements,

which now allows for the composition of multiple elements into the same image and CGI integration with live-action footage. But we can also read it as an aptly-named gesture toward systems of movement control (soldier deployment, raids, invasions, etc.) reminiscent of war logics. Whitney’s prediction of these early, revolutionary systems of precise tracking and mapping aligns with Bousquet’s martial gaze. Like the camera that needs precise data and relentless imaging to create a final visual composite, the martial gaze seeks to capture data on civilian and military rhythms alike to target and build up a surveillance state. This “targeting” encompasses everything from cookies for targeted advertising, to Baltimore Police Department’s 2020 aerial surveillance “spy” plane (supposedly able to track every person in public for crime-reduction purposes), to US drone strikes in Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Somalia in the last two decades. It’s another reminder of where the civilian and the military incestuously intersect under the martial gaze’s logics.

It’s another reminder of where the civilian and the military incestuously intersect under the martial gaze’s logics.

In Pure War, Virilio argues that modern warfare no longer manifests as Total War, such as WWII, but instead as Pure War, in which all aspects of society are mobilized by its techno-militaristic logics. There are “acts of war without war,” and there is no longer a distinction between “wartime” and “peacetime.” War is no longer just conducted on the battlefield, between soldiers, but across sectors and with actors historically under civil domain. The US may serve as a concrete example. In Virtuous War, James Der Derian traces the evolution of the Military-Industrial Complex, first coined in Eisenhower’s 1961 farewell address, into our current Military-Industrial-MediaEntertainment Network, or MIME-Net. This transition saw the informal alliance between military, politics, and defense contractors broaden to entangle media, Hollywood, and the gaming industry.

Since the 1910s, the Pentagon and Hollywood have established a mutually exploitative relationship. One of the first cases may be then-President Woodrow Wilson enlisting filmmakers to garner support for US participation in WWI. Army engineers went on to provide their expertise for American Civil War battle

scenes for D.W. Griffith’s pro-KKK film The Birth of Nation (1915). During the Cold War, the Pentagon founded their own Motion Picture Production Office to assist the development of numerous war movies, including The Longest Day (1962). Now, the DoD operates an Entertainment Media Office (EMO) to coordinate “militainment” collaborations. They commonly use tactics such as blocking and rewriting scripts under the guise of “accurate cinema depictions” in order to control its public image through a revisionist lens. For instance, the Godzilla (2014) script initially took a critical stance toward US use of nuclear weapons. One scene, now-deleted, featured a Japanese character referencing his grandfather surviving Hiroshima, which evidently was too much for the DoD. Under their influence, the final film flipped to celebrate nuclear usage (since that’s what creates Godzilla himself, enabling him to fight alongside US military) and evade all mention of the devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. So why do many prominent filmmakers and franchises willingly have their scripts vetted by the DoD, and even tailor scripts, characters, and narratives to appeal to their Pentagon friends?

The DoD essentially offers a hefty subsidization for movie-making costs: They lend expensive equipment (the flyaway cost for a F-35A fighter jet is around 80 million dollars), grant access to military locations for shooting, provide personnel as extras (whose salaries are paid by taxpayer dollars and not the studio), and supply military advisors for technical jargon and ensuring “realism.”

Beginning in the mid-2010s, researchers Tom Secker and Matthew Alford made multiple Freedom of Information Act requests into the DoD’s influence on Hollywood. Secker then collected the documents into an online archive, spyculture.com. Through accessing office diary reports, script notes, and production folders, he was able to compile an initial 2014 list of roughly 330 DoD assisted or funded films, which grew to around 420 in 2016. These films include classics and blockbusters such as Top Gun, Transformers, Iron Man, Jurassic Park III, Pearl Harbor, and Black Hawk Down. In a 2016 interview with Phil Strub, the head of Pentagon’s Film Liaison Office, scholar Sebastian Kaempf asked him what the DoD stands to gain out of the relationship. He responded: “All I can say is that the dawning of or the maturation of CGI did nothing to stop their [Hollywood’s] interests in gaining access to our installations, our equipment, and our people… What we get out of it is an opportunity to influence the military portrayal.” As scholar Tanner Mirrlees outlines in “The Militarization of Movies and Television,” this partnership manufactures media and ideology that “construct and uphold racist stereotypes of US enemies,” glorify American exceptionalism, and construe the US empire and its violence as necessary for global security and stability. From the content to the CGI, cinema and war spiral together in inextricable and dangerous ways. With every film, the martial gaze extends its scope.

+++

Back to Vertigo: Perhaps it is fitting that a movie on obsession and the male (we may consider adding “martial”) gaze features the computer-animated spiral. It’s not just a visually-apt motif but a material instantiation of a design only decipherable and trackable through military weaponry. This first case of CGI is but one in the extensive, enshrouded history of art sharing a bedrock with the engine of war. Directors and directors both scoping and shooting. Undergirding the spectacle of entertainment is a dark curve of militarism. It bends us towards systems of visual control and skewed images. It begs for a blind eye. It spirals closer and closer.

EMILIE GUAN B’26 is spiraling.

META-REPLACEMENTS

META-REPLACEMENTS

WHERE IS THE JEW IN FORTRESS EUROPE?

( TEXT COBY MULLIKEN DESIGN ANAÏS REISS ILLUSTRATION MINGJIA LI )

c Had Jörg Haider—the erstwhile leader of Austria’s Freedom Party (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, FPÖ)— not driven himself off a cliff in 2008, he might have taken issue with his party’s recent maneuvers. Haider, the son of middle-class Nazi activists, spent his twenties transforming the FPÖ from a marginal liberal party of the moribund pan-Germanist tradition into Austria’s most prominent hard-right organization, while preserving the Nazi politics of its founder, the Nazi Reichstag member Anton Reinthaller.

Starting as a youth leader of the party’s Carinthian branch, Haider would become state chancellor in 1989 and ultimately lead the FPÖ into a national coalition government in 2000. His rise, however, was dogged by controversy. Like many politicians of his ilk, Haider’s commentary pushed the boundaries of the discursive terrain set out by Austria’s postwar hate speech laws. These laws, imposed by the Allied occupation forces in 1947, prohibit expressing approval of the Nazi regime.

Haider referred to concentration camps as “punishment camps,” described Waffen-SS veterans as “decent people of good character,” and fought to remove non-German place names from road signs. Most egregious to the Israeli government—which would later assign him a Mossad dossier—was his distaste for the Zionist project. Haider lambasted Ariel Muzicant, the head of the Jewish Community of Vienna, as a “Zionist provocateur,” and, amid the 2006 Lebanon War, demanded the expulsion of Israel’s ambassador from Austria. One former aide claimed he maintained an extensive network of connections with “Arab dictators.”

Nearly two decades after Haider’s death, the FPÖ has reinvented itself again. Gone is the explicit Holocaust denial and anti-Zionism; in its stead is a tacit alliance with the government of Benjamin Netanyahu alongside a new vision of Israel not as a maligned hub of global Jewry but rather a Western outpost against Muslim hordes, a forward base for the ‘Fortress Europe’ they hope to construct. Israel, the new FPÖ line goes, shares with Austria a common enemy of ‘Islamist terror.’

Implicit in this pivot is the possibility of escape from the allegations of antisemitism that had once confined the party to the political sidelines. Now, when critics highlight the FPÖ’s habit of running candidates who celebrate April 20 (Hitler’s birthday) with Eiernockerl (egg dumplings, reputedly Hitler’s favorite dish), party officials can exclaim, denying their antisemitism, “Of course we are not antisemites! We were the first in Austria to condemn October

7!” (Note that even in their condemnation, the FPÖ’s base point was that sympathy for the Palestinian cause in Austria was the result of the “significant Muslim population that [Austria had] brought in.”) Antisemitism has, in other words, been othered. Not in a structural sense—indeed, the narrative patterns that brought the FPÖ and similar parties to power over the past decade bear a striking resemblance to those which fueled the ‘Conservative’ Revolutions of the 1930s—but in a rhetorical one. In assimilating antisemitism into ‘Islam’ (I say ‘Islam’ because I really mean the spectre of Islam), the FPÖ and its counterparts deterritorialize what is in reality an indigenous phenomenon. So indigenous, in fact, that the medievalist David Nirenberg once described it as the West’s “means of thinking the world.” +++

The Great Replacement theory has permeated European political discourse in the past two decades. Broached by the novelist Renaud Camus in a series of texts in the mid-2000s—since cited by several perpetrators of white supremacist violence, including the Christchurch and El Paso shooters—the theory describes a small group of “replacist elites” endeavoring to replace Europe’s native-born (white) population with Muslims in what Camus calls “genocide by substitution.” European governments, the argument goes, have opted to solve their demographic woes— plummeting birth rates, aging populations, emptying countrysides—by importing rapidly reproducing masses of Middle Eastern and African migrants.

But there is another replacement latent in Camus’ oeuvre: unlike earlier narratives of this type (think The Protocols of the Elders of Zion), Camus’ perpetrator is not explicitly Jewish. This is not to say his followers have rejected this trope; at Charlottesville, American white supremacists gleefully rendered Camus’ “you will not replace us” as “Jews will not replace us.” And yet, Camus denies any antisemitic undertones. He has gained a following among certain right-wing French Jews, Alain Finklekraut and Éric Zemmour among them, and has disavowed his supporters’ use of the swastika.

Europe, Camus says, is “a sort of great Israel.” Eternally threatened by the existential threat of ‘invasion,’ the two share an interest in erecting barriers to the flow of Muslim migrants. Alas, according to Camus, the Europeans lack the “attachment to their land, the…fidelity to their membership” that characterize the Israelis, and thus face a bleaker fate. This

is a startling reversal. Whereas Ashkenazi Jews were once—in early 20th century antisemitic discourse— characterized by their rootlessness, landlessness, and disloyalty, they now—remade by the cataclysmic violence of the Holocaust—embody exactly the opposite of that for which they were persecuted. Indeed, they exceed in these qualities those who persecuted them by virtue of the latter’s despiritualization and materialism.

It appears Camus sees in Zionism exactly what French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre saw when he visited Israel in 1967. Though Sartre had once doubted the possibilities inherent in what he called “Jewish authenticity” (read: political Zionism), in visiting he saw at last the opportunity for the authentic (read: Israeli) Jew to become “one of the most superior men to be found in history.” Sartre, of course, was commenting from the political left, but his insight was the same as that of Camus: Zionism promised to transform the Jew into an ur-European character, an ultranationalistic yeoman bound by blood and history to his land.

Lost on both commentators is that Zionism itself constitutes a sort of replacement. Whether or not one takes Zionism’s historical claims seriously, its central project is undeniable: the establishment of a demographic majority and political hegemony in a region currently inhabited by another people. This is not a controversial claim—this is what political Zionism is. On some level, this is all that it is. In any case, it is also almost exactly the definition Camus gives of his ‘Great Replacement.’

So what gives? I think we can only grasp the real structure of Camus’ argument if we abandon his preferred discourse of indigeneity and occupation for the older terrain delimited in Samuel Huntington’s 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations. To Huntington, a political scientist and advisor to Jimmy Carter, the wars of the 21st century would be fought not between nation-states but between vast civilizational groups, among them “the West” and “the Islamic world.” Since both Christianity and Islam are “missionary religions,” Huntington says, they are destined to clash at their borders. For the contemporary European right, this clash necessitates physical delimitations— the erection of a “Fortress Europe”—and a continent-wide mobilization against Europe’s enemies.

It is from Huntington that Camus draws the phrase “global superclass,” a group he names as the culprits of his grand replacement plot. This class, he says, consists of the “Davoscrats,” the “stateless financiers,” and the “multinationals.” Their motive?

The dismantling of Europe “for the benefit of major investors.” Though the ‘Davoscrat’ is not necessarily Jewish, he fulfills an arguably identical role to the ‘international Jew’ of Nazi propaganda, intent on the destruction of Aryan peoples. Needless to say, even if ‘the Jew’ is not present in Camus’ theory, the figure’s narrative shadow is present as ever.

I woke Monday morning intending to write a section of this article attending to French politician Marine Le Pen’s remarkably successful campaign to convert her father’s quasi-Nazi platform National Rally (Rassemblement national, RN) into a mainstream political force. This was complicated by the fact that, overnight, Le Pen had been sentenced to four years in prison for embezzlement and barred from running in France’s 2027 presidential election. Most interesting about this development—sure to spark conspiracies of its own—is, in a testament to the efficacy of Le Pen’s overhaul, how little of an effect it is bound to have on France’s political future.

When Le Pen inherited the RN—then called the National Front (Front national, FN)—from JeanMarie Le Pen, her father, the party had been shut out from French political discourse. Plagued since its founding by its close association with Nazis (including its founder Pierre Bousquet, a former Waffen-SS officer), the party had never cleared 15 percent of the popular vote. When Jean-Marie made a surprise advance to the second round of the 2002 presidential election, he was defeated in a 64–percentage point landslide by the widely unpopular incumbent Jacques Chirac.

Marine’s approach was different. When, in 2015, her father suggested that Nazi-operated gas chambers had been merely a “detail” of World War II, she expelled him from the party. Since then, she has sought to erase the blackshirt aesthetics of her father’s era from the party’s public image, while preserving the party’s fundamental political orientation. It seems to have worked. Even if her conviction is upheld, opinion polls show the party’s current parliamentary leader Jordan Bardella trouncing his opposition on the center and left.

Bardella, a 29-year-old, is emblematic of the party’s rapprochement with Israel. In 2023, he spearheaded the FN’s participation in the March for the Republic and Against Antisemitism where the party’s security detail was provided by the far-right Jewish Defense League (JDL). (The JDL was previously

implicated in an assassination campaign that targeted prominent Arab-Americans, including the Palestinian activist Alex Odeh and the Republican congressman Darrell Issa). The FN’s participation provoked criticism from some Jewish organizations, and prompted the formation of Golem, an anti-Zionist Jewish group that confronted the marchers along their route.

Netanyahu has clearly appreciated these overtures. Two weeks ago, Bardella—alongside Marion Maréchal, Marine Le Pen’s renegade niece—appeared at The International Conference on Combating Antisemitism in Jerusalem, where he attended events such as Antisemitism in Education in North America – From K[indergarten] to Academia and The JudeoChristian Bond Aligning Values Across the Atlantic. A number of invitees, including the UK’s chief rabbi Ephraim Mirvis and the Zionist French commentator Bernard-Henri Lévy, boycotted the conference due to Bardella’s—and others’—attendance.

In a keynote address on the conference’s first day, Bardella acknowledged the international dimension of Israel’s “respiteless war,” which, he said, was “also ours.” Drawing on the popular notion of islamo-gauchisme (Islamo-leftism), he attributed French antisemitism to “Islamist fundamentalism and its best ally today, the French radical Left.” Indeed, the islamo-gauchiste spectre—remarkably similar to that of the ‘Judeo-Bolshevist’ during and after the Russian Revolution—is arguably the dominant one of our time.

It is under the mantle of ‘fighting antisemitism,’ after all, that President Trump and his allies have canceled research funding for universities—Brown among them—and taken increasingly restrictive stances toward speech, protest, and boycott. These are demonstrations of power more than anything else; I would be shocked if Trump or his allies could name a single way in which Brown has supported antisemitism as an institution, even according to their own politicized definition of the term. This is to say that they are not so much fighting antisemitism as weaponizing it against their political enemies.

Still, antisemitism is far from eradicated among the global right. (Search through the old Facebook posts of FPÖ candidates, and this becomes immediately clear.) Indeed, it cannot be. Terms such as global superclass, ‘Davoscrat’, and islamo-gauchiste may be accurate, but they are not precise. The average person cannot conjure up a face behind the ‘Davoscrat,’ nor can they bring themselves to hate or blame everywbillionaire—the enduring popularity of Musk and Trump evinces this. Rather, those angry with immigration and multiculturalism will seek more

clearly-articulated targets, targets they can visualize and from which they can distinguish themselves. ‘The Jew’ is a more familiar figure—arguably the West’s oldest—and for this reason, I think, will remain the real specter behind rationalized images of ‘globalist elites.’

I am, of course, not the first person to make this point. But I think this is worth highlighting because it underlines the oft-missed fact that the figure of the Jew has not simply been swapped out for that of the Muslim. To claim otherwise would be to elide the essential difference in the pair’s narrative roles. Whereas the Jew threatens the West by virtue of his fewness—his secrecy, his esotericism, his cabal— the Muslim threatens by virtue of his manyness, his membership in a horde. These are distinct prejudices, with distinct functions in the topoi of Identitarian thought.

What is at work, rather, is a bifurcation—‘The Jew’ of old has been split in two. On one hand, we now have the rooted Israeli Jew: muscular, olive-skinned, and eager to defend his land from the Muslim hordes; on the other, we have the rootless global Jew (who needn’t necessarily be Jewish), who, by virtue of his resentment, greed, or base evil, endeavors to destroy the West from within. Though the dynamic is not new—the Italian fascist Julius Evola famously declared that an Aryan could have a Jewish soul, and vice versa—only recently does it seem to have seeped into the mainstream.

Or at least seeped thoroughly enough for Austria’s Profil magazine to run a profile of Jewish FPÖ voters under the title “Anti-Semitism from the Left is More Dangerous.” This is a precarious place to be. The FPÖ is, at base, still Haider’s party; its sudden support for Israel signals not a turn toward moderation, but a rearticulation of the same exclusionary logic that has characterized the party since its founding. Some will say this is a reasonable bargain. But, as Masha Gessen observed in a recent article, “A country that has pushed one group out of its political community will eventually push out others.” Jewish people should take little comfort in our temporary—and illusory—respite from the crosshairs.

COBY MULLIKEN B’27 wants to be a Davoscrat when he grows up.

(

Difference in Repetition

Abstract

This experiment aims to investigate the permeability of closed systems when met by human interference. Using a 3D-printed spirograph, 24 participants were given an identical set of materials (pen, paper, gear set) and instructions (starting position, rotation direction, number of rotations) to produce geometric drawings. The spirograph, a mechanical apparatus modelled on the parametric equation for a hypotrochoid (see Fig.1), is treated as a closed system designed to yield predictable curves. To quantify the deviation introduced by human participation—symptomatic of a destabilized, open system—the results were compared to a digitally rendered baseline. While some drawings closely adhered to the expected form, many revealed distortions and asymmetries introduced by gesture: erratic lines, shifting patterns, bleeding ink. These variations suggest that even in a tightly controlled environment, human nuance undermines deterministic systems, offering insight into the limits of automation, and the illusion of perfect repetition in supposedly “closed” systems. (Also observed were the difficulties many participants faced in counting to 15).

Context

The spirograph, popularised as a children’s drawing tool in the 1960s, was born out of a cultural marriage between maths and art ushered in by the science of cybernetics. Defined by mathematician Norbert Wiener as the “control and communication in the animal and the machine,” cybernetics looks at the circulation of information underlying the behaviour of both mechanical and biological systems. These paths of information were modelled as feedback loops wherein the output of a system is continually fed back into itself as input, allowing for self-regulation over time.

Artists, notably Roy Ascott, saw cybernetics as the pinnacle of the avant-garde, merging its emphasis on process, interaction, and behaviour with characteristics of Dada, Surrealism, Happenings and Fluxus. The role of the cybernetic artist was to create systems, not forms, centering the live and participatory art to liberate art from the modernist ideal of the “perfect object.” As feedback loops and the audience’s involvement in these systems became central to the artwork, cybernetic art emerged as a field in which the boundaries between objective systems and subjective experiences were materialised.

The spirograph embodies a cybernetic system: each movement of the gear informs the next, and through this closed mechanical feedback loop, a drawing emerges. When a participant engages with the tool, they interfere with a system whose output is shaped both by fixed parameters, and, as evidenced by the experiment, by the specificities of their input. What begins as a closed, predictable system is blasted into unpredictability and openness by small variations in movement that, compounded by repetition, result in a field of diverse outputs.

The vulnerability of the closed system to human interference exposes the limitations of automation: namely, that it cannot fully abstract the human element or error, from its processes. Even under conditions designed to ensure mechanical precision and objective predictability, the human gesture re-inserts itself into the system, molding it into an open, chaotic system of variability. Thus, the machine does not eliminate difference, it merely conceals it, until the slippages—in scattered lines and broken patterns—make it visible again.

As automated systems produce consistent and predictable results, they forge an illusion of impenetrability. The inner workings of the “machine,” and its limitations, are concealed behind their perfect outputs. Instances of deviation become significant sites of exposure, puncturing the system’s precarious claims of precision, control, and objectivity. These visual glitches emphasise the ways in which automation is never immune to the subjectivities of those that operate within it.

Methodology

We instructed participants to:

1. Place a blue pen in the inner gear hole A.

2. Rotate the inner gear 15 times around the circumference of the larger fixed gear.

3. Place a red pen in the inner gear hole B.

4. Repeat step 2.

Results Discussion

Each the product of identical materials and instructions, the 15 loop hypotrochoid curves that make up this 4 by 6 grid imply a degree of mechanical consistency. Yet, as one moves left to right down the page, the near perfect curves steadily deteriorate into a full collapse of the spiral form (see Sample D6).

Approximately one third of the samples closely adhere to the expected baseline form (Samples A1-B4), upholding the illusion of a closed automated system—save a gentle tremor of the line. However, across rows 3-5, incomplete loops, overly rotated paths, and structural breakdowns begin to take over. In several cases (Samples A3, A4, A5, D5, A6, D6), the system fails to return to its origin, and gear slippages create new complex patterns(Samples D3, D4). The final row, composed almost entirely of overdrawn and structureless drawings, reveals the breakdown of the system and the victory of the gesture. The variations in participants’ wrist motions, speed, pressure, or even patience thresholds, are inscribed into these “malfunctioning” drawings, demonstrating the system’s failure to resist human nuance. This grid indexes the gradient from a closed predictable system to one of destabilised open subjectivity; a visualised entropy.

Fig. 1 A diagram modelling the construction of a spirograph using the parametric equations of a hypotrochoid curve.

Fig. 3 3D rendering of the spirograph tool.

Fig. 4 3D printed spirograph set up.

Fig. 2 This grid represents

Fig. 5 Instruction sheet handed to participants alongside the gear set.

( DESIGN ILLUSTRATION

Love in the Time of Cannibalism

c If you’re 12 and watching The Joy Luck Club for the first time, there’s one scene that you won’t forget: An-mei walks into the room to see her mom bearing a knife at the edge of her grandmother’s bed, arm stretched out, carving her flesh into a boiling pot of soup. A pot of unassuming soup probably isn’t the image you’d first conjure up when thinking about cannibalism. In the West, cannibalism is most often discussed in fantastical scenes: nightmarish sequences from horror movies, or sensationalized news stories about ‘exotic’ groups. The Joy Luck Club rejects the notion that cannibalism comes only from psychotic or barbaric sources. Instead, it is an act of love.

Filial slicing, also known as filial cannibalism, is an act of medicinal cannibalism that originated in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) and was primarily performed by daughters and daughter-in-laws for their ailing parents. There were two main types of filial slicing: 割股 (gegu), cutting tissue from one’s arm or leg, and 割肝 (gegan), cutting parts of one’s liver. Filial slicing was most commonly practiced in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) and occurred within the confines of the home, so it is difficult to place an exact number on how often this was practiced. While it was occasionally outlawed by different emperors in Imperial China, anthropologists have broadly concluded that these practices were uncommon but not rare: according to Lane J. Harris in the Peking Gazette, they were largely culturally accepted. Children willing to sacrifice their bodies for medicinal purposes were heralded for their dedication and moral excellence. Beyond serving a purely medicinal purpose, during times of instability, governments glorified stories of these acts to reinforce filial piety, the basis of Confucian values. In the aftermath of rebellions during the Qing Dynasty, the emperor built memorial arches for children who had partaken in demonstrations of immense filial emotion to stabilize social and family structures.

While in literature and mythology both men and women engage in filial slicing, the sacrifices of women dominate news accounts and media depictions of this practice. Both in real life and literature, acts of self-mutilation and filial cannibalism position the female body as a site of violence. Why is it that daughters are always the first to be sacrificed? Donald Sutton, in Consuming Counterrevolution, argues that due to gender discrimination, women were never ‘true’ members of either side of the family, and thus, this was the ultimate act of desperation and love to solidify one’s familial bond. By giving the flesh of her arm away into soup, the daughter’s body is physically

Consuming Contradictions

DIGESTING CANNIBALIST HISTORIES, LIMB BY LIMB

incorporated into the digestive systems of her parents or in-laws, with traces of her flesh scattered throughout. This is not only an act of sacrifice but a surrendering of one’s body to someone else’s control—possibly even to another family.

Accounts of filial sacrifice in the Peking Gazette largely feature the stories of daughters sacrificing themselves for their fathers. In The Joy Luck Club, while An-mei’s mother slices her flesh, An-mei reflects, “This is the most important sacrifice a daughter can make for her mother.” She reiterates this notion, saying “the pain of the flesh is nothing,” and that her “mother did this with her whole heart even though her [own] mother had disowned her.” In An-mei’s eyes, her mother’s act was exceptional not because of its violence but because it showed her immense love. Despite her estrangement, she still surrenders herself to her mother to save her. While this is a moment of reconciliation for her and her mother, the expectation that she sacrifices her body for her family forces her to surrender her agency.

The question of gender is especially interesting in the case of concubines. In Chinese literature, concubines have been frequently cannibalized in service of masculine superiority. The portrayals of concubines and cannibalism change significantly throughout Late Imperial China, particularly in dramatic works about Zhang Xun, a Tang Dynasty general, and his concubine, whose name we have no record of. In Tang Dynasty texts, Zhang Xun is praised for sacrificing his concubine—it is presumed that he did not want to inflict any violence upon her—and stands as a figure of 文武 (wen wu) masculinity. In later recountings of this story from the Ming and Qing dynasties, the concubine becomes a female martyr, while Zhang Xun is criticized and portrayed as cruel. Some theatrical works allow the concubine to reclaim her agency after death, reappearing as a ghost rather than fading into the background to allow Zhang Xun’s storyline to take center stage. In others, the concubine is regarded as a deity, surpassing Zhang Xun’s status and transforming into a goddess of protection. This adds another complication to the cannibalization of women. These stories of filial slicing and the cannibalization of concubines frame them as heroic characters while later texts contribute to the critique of not only cannibalism but also the societal oppression of women. These works of theater not only gave women the attention of the narrative but the moral high ground as well.

Revolution and Regurgitation

Between 1967 and 1968, at least 421 people were eaten in the Guangxi province. Not driven by famine

or necessity, these acts of cannibalism were the culmination of the gratuitous political violence catalyzed by the Cultural Revolution. However, cannibalistic acts were not isolated, sporadic occurrences of intense brutality perpetrated by crazed idealists. Rather, they were ceremonies, systemized banquets, through which the political struggle of the revolution splayed out in sinew and flesh.

In Confucian China, death by mutilation was most dishonorable—a violation of one’s ancestral duty to maintain the wholeness of the body. Dismembering the corpses of enemies served as a powerful political ritual, one that degraded social Others from man to meat. Throughout the conflict between two competing factions of the Communist Party that seized the Guangxi region, revolutionaries regularly left bodies hanging from trees or paraded dismembered body parts around in victory celebrations. For instance, after military leader Zhou Weian was defeated in battle, he was executed, and his head and legs were given as sacrificial offerings. Cannibalism was a natural extension of this violence. Through cooking and consumption, the body was not only dismembered but atomized, obliterated by the metabolics of their enemy, their stomach acid, their digestion.

However, eating the Other served as more than just a vector for violence, to disrespect and dishonor political enemies. Echoing traditional beliefs about the medicinal qualities of cannibalism, participants believed that eating the powerful (rich peasants, landowners, etc.) conferred not only longevity and potency to the somatic body but to the revolution as a whole. Since Chinese medicine and political theory understood the heart and liver to be at the core of life and sovereign power, revolutionaries targeted these specific organs: in more than 80 percent of cases, the heart and liver were cut from the victim. Women were rarely eaten, as their exclusion from political life and power rendered their flesh ‘inedible.’

Thus, cannibalism during the Cultural Revolution was not simple destruction, but rather a complex metabolic process in which bodies were consumed in service of the political fervor and might of the revolution. Sutton argues that cannibalism offered a satisfying conclusion to the three-part ritual employed by the revolutionaries: separation, marginalization, and aggregation. First, enemies of the movement were identified. Their social separation was physically enacted when they were brought onto stages or in the middle of crowds. Then, they were marginalized— forced to confess their wrongdoings, endure beatings, and face the accusations of the people. Finally, they were aggregated. Often this would look like a reintegration into social life, albeit with heavy shame and

satisfy that which execution or expulsion left unsatisfied.

By creating a communal ceremony of cooking and preparing human meat in the flesh banquets, consumption of the Other served to strengthen the social bonds between revolutionaries, creating a sense of community through commensality. Through consumption, political enemies were physically reintegrated into society, fundamentally changed, the act of digestion symbolically “softening and civilizing…the previous acts of wildness and disorder.” Thus, through the metabolic processes of the body, cannibalism worked to bring the social body back into equilibrium after the violent upheavals of the revolution.

Of course, eating is never that simple. While the cannibals comforted themselves with Sutton’s idea that none of “the evil intent of the enemy is retained in the flesh,” as sinologist Carlos Rojas notes, “the figure of cannibalism itself involves a paradoxical combination of identification and alterity, of violence and desire.” Even though revolutionaries imagined a smooth digestion process in which the political Other would be slowly emulsified into lifeless meat, the Other instead lodges in the intestinal tract of the social body. Because you only consume what you desire. Because you are what you eat. Despite practicing cannibalism to enforce the utter Otherness of the bourgeoisie, revolutionaries recreated the same hierarchy in their violence that they meant to overthrow. Instead of conviviality in the human flesh banquets, consumption was stratified: governmental officials were given first servings of the flesh; soldiers would take the liver or the heart; youths were left to eat the unwanted intestines.

This paradoxical nature of cannibalism, this simultaneous desire, and distaste for the consumed, revealed itself before the Cultural Revolution. During the 1919 May Fourth Movement, a student-led nationalist movement that rejected traditional Confucian values, organizers decried the Chinese feudal system as a ‘cannibalistic society,’ a discourse popularized by leading reformist Lu Xun’s short story Diary of a Madman. Simultaneously, however, they characterized their own movement as a cannibalist one. In a 1915 article titled Call to Youth, revolutionary Chen Duxiu argued:

Youth have the same relationship to society that the new and lively cells have with respect to the human body. In the metabolic process, the old and rotten cells are constantly being weeded out, and openings are thus created which are promptly filled with fresh and lively cells. If this metabolic process functions correctly, the organism will be healthy; but if the old and rotten cells are allowed to accumulate, however, the organism will die. If this metabolic process functions properly at a social level, society will flourish; but if the old and corrupt elements are allowed to accumulate, society will be destroyed.

Situated within a metaphor about the immune system, the call to a symbolic, political form of

cannibalism is unmistakable: old cells must be consumed, eaten away and destroyed, so that space may be made for the new. Thus, paradoxically, activists mobilized cannibalism in their political messaging both to critique their political opposition and articulate their own praxis. For participants in the May Fourth Movement and later, during the Cultural Revolution, cannibalism carried no innate moralistic baggage, and could be both good and bad, backwards and modern. It produced what was the Other and in doing so, allowed the Other to be simultaneously rejected and

Cannibalism as an Othering Force

In English, the concept of cannibalism has deep ties to colonial encounters between settlers and Indigenous peoples. After Christopher Columbus’ return to Europe, the Spanish word for canni, replaced the word , which the Indigenous people he encountered in the Caribbean used to describe themselves. In The Mouth That Begs, Gang Yue, a Chinese studies scholar, argues that the use of the term cannibalism evokes images that are “all about [creating] the ‘other’ [that is] unrelated to ‘us,’” suggesting that the word has more to do with othering groups than the act of cannibalization itself. Most synonyms for ‘cannibalism’ or ‘cannibal’ denote inferior or ‘primitive’ groups rather than describing the action of eating other humans. In comparison, Chinese phrases for cannibalism are more concerned with the practice itself than its politics, with phrases like 吃人肉 (chi ren rou), eating human meat, and 人相食 (ren xiang shi), people eating people. In both phrases, the characters directly translate to people, 人, to eat, 吃, and food, 食. Peter Hulme, a postcolonial studies scholar, argues that cannibalism is “a term that has gained its meaning from within the discourse of European colonialism.” He asserts, “it is never available as a ‘neutral’ word.” While there is a neutral word for cannibalism in English, anthropophagy, it is seldom used. Anthropophagy is, without fail, almost always conflated with cannibalism, which anthropologist Devin Bittner argues should be reserved to describe the fantasy of the flesh-eating ‘Other.’

Western publications on China published many accounts of cannibalism in the late 19th and early 20th century, some written with such extreme attempts to construct China as an Other that even the readers did not believe them. These accounts exemplify what Edward Said has termed “Orientalism,” the fabrication of irreconcilable differences that separate the Orient from the Occident. These differences were not based on material realities but were instead born from sensationalized representations of Chinese culture. The height of these published accounts coincided with a mass mobilization of sinophobia globally, which led to anti-Chinese riots and killings stretching from Australia to Mexico. Records of cannibalism in China positioned it to be the West’s polar opposite, delineating the ‘civilized’ from the ‘barbaric other.’