The Superyacht Report

FROM MONACO TO AMSTERDAM

The Editor-in Chief on the two most important hubs in the superyacht landscape.

As I sit at my desk with a few days to go before leaving for the Monaco Yacht Show, having just returned from Amsterdam and met with the team at METSTRADE and The Superyacht Forum, it made me think about these two superyacht hubs and how important they have become. One is the home of the largest and most valuable in-water yacht show and the other is the home of the largest and most important trade show and conference. Both are juxtaposed with some of the most important stakeholders in the industry: the premier builders, brokers, design studios and management companies. One has the world’s most important and influential Yacht Club and the other has some of the most important associations and research institutes on their doorstep.

Barcelona, Mallorca, Istanbul, Athens, Bremen, Hamburg etc., the idea of spending a third of the working year in the various yacht shows around the world will end up being very exhausting and repetitive.

BY MARTIN H. REDMAYNE

So, as I compare and contrast Monaco and Amsterdam, and having bumped into one or two transient superyacht characters at Schiphol airport last evening, it is fair to say that Monaco has become the Capital of Superyachts from an owner and customer perspective and Amsterdam has become the Capital of Superyachts from a product, technology and business perspective, and they both play a symbiotic role with the industry. Which is why as a company we have made the decision to attend only the Monaco Yacht Show and the Superyacht Pavilion of METSTRADE, as they both deliver everything we need from a yacht show/exhibition perspective.

However, throughout the year, as perhaps for all of us, there are weekly, monthly or quarterly visits to Monaco and Amsterdam for meetings and other connections with specific companies. This has become our preferred strategy and works well. If we visit Livorno,

What is also worth noting is that as shows grow and become more valuable, the sheer number of side events that appear alongside – hospitality experiences, press conferences and social gatherings or pop-up conferences are starting to dominate the overall calendar and it becomes almost impossible for the most important customers and VIPs to decide what to attend. This overload maybe needs some level of control, otherwise we are diluting our audiences. Another important message to share on the eve of the Monaco Yacht Show is that we will not have groups of young day workers trawling the show with trolleys, laden with bulky magazines and newspapers to hand-deliver to the stands and yachts, just for them to sit on coffee tables for a few days. If someone wants to read this issue or any of our issues, they can do this after the show on their iPad when they have the time, or perhaps on their flight home, as many choose to leave bulky media behind as they travel with hand luggage.

So, to close this column, we will always focus on Monaco and Amsterdam as our two most important superyacht hubs and shows. We can’t attend everything we are invited to, so I apologise in advance. We are instead focused on finding the real stories and not just the press release and we will always try to be a little bit different in our approach, as this is how I feel we can make an impact.

I look forward to seeing many of you in Monaco. MHR

All change for the yachting industry

Daniel Küpfer, founder and managing director of Yanova, observes how the yachting landscape has evolved to create a much more complex but highly competent and professional environment for today’s mariners.

Charter – it’s more than just about looks …

Neil Hornsby, co-founder of Yomira charter brokers, presents the golden rules to optimise charter income from a superyacht while still protecting the owner’s valuable asset.

When charm outshines competence

An anonymous contributor raises the issue of how the role of manager and consultant is often overlooked in comparison to the profile of the more visible broker.

Crew spend their whole careers trying to come ashore … why I went the other way

Emily Beck, Director at The Build Purser, explains the vital role of purser and her decision to move from an onshore position to one at sea.

Putting the WELL into well-being 62

Kelda Lay introduces WELL certification – a programme for building superyachts, whether existing or new build, that could increase charter appeal and resale while creating a holistic environment on board.

Yacht crew safety culture and well-being

Lloyd’s Register on why the industry needs to go beyond compliance and focus on human-centred safety.

MYBA – a clarification

Raphael Sauleau, MYBA President, responds on behalf of the MYBA Board to a recent article on SuperyachtNews about the newly launched MYBA Charter Agreement.

Revision, revival, revolution: the REV Ocean story 6 REV Ocean is a story of vision, persistence and reinvention. We trace its journey, dissect the vision and hear from the heroes behind the scenes who helped steer it from challenge to success …

Martin H. Redmayne looks at the impact of Lürssen Yachts over the past century and a half, with a personal take on COSMOS, the builder’s 150th-anniversary statement.

The professional yachting world –some inconvenient truths

Rod Hatch spells out the steps the PYA has taken to improve conditions for crew and why the engagement of professional bodies is essential when it comes to achieving meaningful change.

Yachting deliberately

Aino Grapin sets out how she believes the industry is on the cusp of change in embracing sustainability, where shipyards and visionary owners can work together to leave a positive impact on yachting.

The final frontier: a neo-Homeric odyssey 55 He’s been to space and summited Everest, but Victor Vescovo’s magnum opus might be unfolding in the uncharted darkness of the deep.

brokerage league table

A look at what a good broker can bring to the table and who’s been doing the deals this year.

Deck to the future! Part II

The second part of The Superyacht Report’s review of the teak industry reveals how eco-conscious thinking about alternative decking materials can result in creating sustainable innovation.

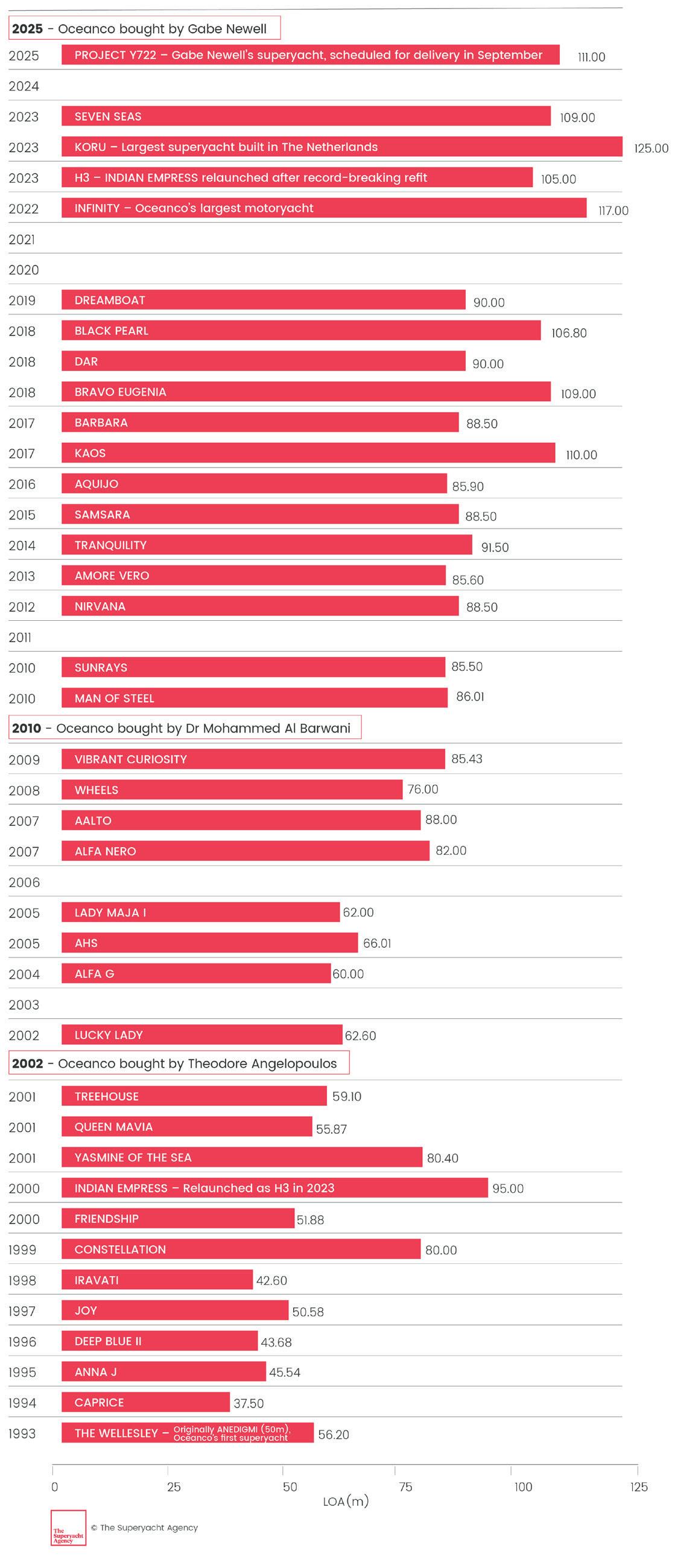

Transfer of ownership – the future of Oceanco

A brief history of the shipyard and what the future may hold under its new owner…

The Superyacht Report

QUARTER 3/2025

For more than 30 years The Superyacht Report has prided itself on being the superyacht market’s most reliable source of data, information, analysis and expert commentary. Our team of analysts, journalists and external contributors remains unrivalled and we firmly believe that we are the only legitimate source of objective and honest reportage. As the industry continues to grow and evolve, we are forthright in our determination to continue being the market’s most profound business-critical source of information.

Front cover: 114-metre COSMOS, Lürssen’s 150th-anniversary statement. Image: © Tom van Oossanen

Editor-In-Chief

Martin H. Redmayne martin@thesuperyachtgroup.com

News Editor

Conor Feasey conor@thesuperyachtgroup.com

INTELLIGENCE

Senior Research Analyst Amanda Rogers amanda@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Data Analyst

Miles Warden miles@thesuperyachtgroup.com

DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Content Manager & Production Editor Felicity Salmon felicity@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Guest Authors

Emily Beck Director, The Build Purser

Aino Grapin

CEO, Winch Design, and Chairwoman, Water Revolution Foundation

Captain Rod Hatch

PYA board member and Director for Training (Deck)

Neil Hornsby Co-founder, Yomira

Daniel Küpfer

Founder and managing director, Yanova

Kelda Lay Founder, Well Yachts

Lloyd’s Register

Raphael Sauleau

MYBA President

ISSN 2046-4983

The Superyacht Report is published by TRP Magazines Ltd (trading as The Superyacht Group) Copyright © TRP Magazines Ltd 2025 All Rights Reserved.

The entire contents are protected by copyright Great Britain and by the Universal Copyright convention. Material may be reproduced with prior arrangement and with due acknowledgement to TRP Magazines Ltd. Great care has been taken throughout the magazine to be accurate, but the publisher cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions which may occur.

The Superyacht Report is printed sustainably in the UK on a FSC® certified paper from responsible sources using vegetable-based inks. The printers of The Superyacht Report are a zero to landfill company with FSC® chain of custody and an ISO 14001 certified environmental management system.

SuperyachtNews

Spanning every sector of the superyacht sphere, our news portal is the industry’s only source of independent, thoroughly researched journalism. Our team of globally respected editors and analysts engage with key decision-makers in every sector to ensure our readers get the most reliable and accurate business-critical news and market analysis.

Superyachtnews.com

The Superyacht Report

The Superyacht Report is published four times a year, providing decision-makers and influencers with the most relevant, insightful and respected journalism and market analysis available in our industry today.

Superyachtnews.com/reports/thesuperyachtreport

The Superyacht Agency

Drawing on the unparalleled depth of knowledge and experience within The Superyacht Group, The Superyacht Agency’s team of brilliant creatives, analysts, event planners, digital experts and marketing consultants combine four cornerstones – Intelligence, Strategy, Creative and Events – to deliver the most effective insights, campaigns and strategies for our clients. www.thesuperyachtagency.com

YOUR COATING CONSULTANTS

Follow The Superyacht Group channels on LinkedIn

@thesuperyachtgroup Instagram

@thesuperyachtgroup @superyachtobserver @superyachtagency

Join The Superyacht Group Community

By investing in and joining our inclusive community, we can work together to transform and improve our industry. Included in our Essential Membership is a subscription to The Superyacht Report, access to SuperyachtIntel and access to high-impact journalism on SuperyachtNews.

Explore our membership options here: www.superyachtnews.com/shop/p/MH

With over 25 years of experience, we have overseen more than 150 successful new-build and refit projects in all major international yacht locations. Trust us for state-of-theart materials, cutting-edge technology and unparalleled expertise. Guarantee a flawless finish with WREDE Consulting.

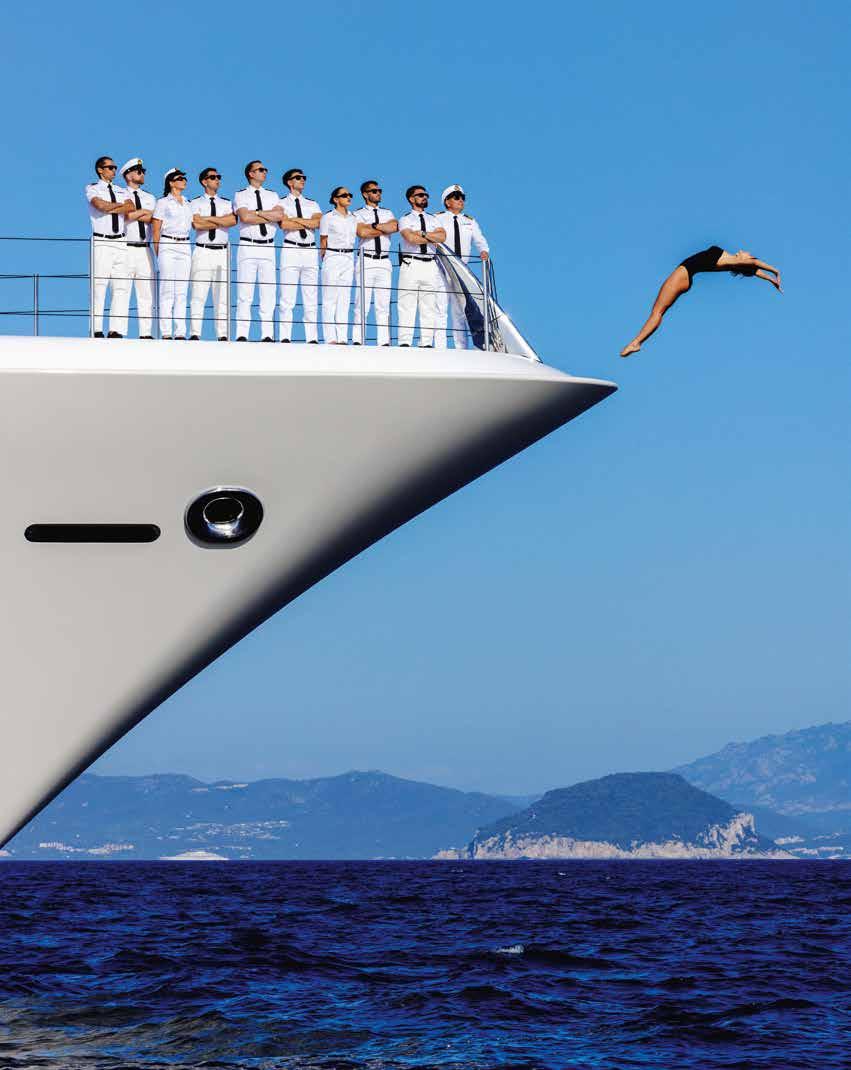

REVISION, REVIVAL, REVOLUTION: THE REV OCEAN STORY

One of the most ambitious feats of naval engineering achieved by finding bold solutions to complex obstacles, REV Ocean is a story of vision, persistence and reinvention. We trace its journey, dissect the vision and hear from the heroes behind the scenes who helped steer it from challenge to success …

BY CONOR FEASEY

Revolution by name, ocean by nature. Just as the sea remains predictably unpredictable, so too is every ambitious project that moves from the drawing board to steely realisation. And when it comes to its sheer scale and ambition, few projects in the history of ocean science or yachting come close. Originally conceived as the world’s largest research and exploration vessel, it’s arguably the most purposeful.

The story of REV Ocean could be told as a formal, neat line of specs. At 195 metres long, 19,000gt, it is powered by hybrid diesel electric propulsion, featuring a jacuzzi, cinema, nine laboratories and a submarine capable of diving to 2,300 metres. But it would wildly undersell the shipbuilding saga that has unfolded in a tale of ambition, revision, nearcollapse and a stoic revival piloted by unsung heroes who fought for its survival and the perpetuation of the mission’s vision beyond the shipyard.

REV Ocean splits itself into two. Below deck, it runs as a research vessel, with the labs, hangars and operations to match. Above deck, it looks every bit the superyacht. The split extends to her schedule. Two-thirds of the year, it sails in research mode, with the ship and all its equipment handed over for free to scientists around the world. The other third is allocated to the ultra-wealthy, using the revenue to fund research missions in a self-sustaining funding model.

But it’s about more than funding: guests bring both resources and the influence to spark change. The hope is to show them the ocean’s wonders and fragility first hand, to inspire them to fund, to use their influence, to become part of the solution. Most people only ever encounter the ocean at its surface. A day at the beach, a few metres down on a dive, a brief glimpse and no more. But the deep blue remains the planet’s largest ecosystem and REV Ocean exists to explore that world.

The project’s conception belongs to its owner, Kjell Inge Røkke, the Norwegian industrialist and Chair of Aker ASA, who joined the Giving Pledge alongside Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. Having built industries in the seas, he vowed to give back to them and to the people striving to understand and protect them. As REV Ocean undergoes final outfitting at Damen in the Netherlands, the finish line is at last in sight with delivery expected in 2027, and a highly skilled team plugging away behind the scenes to see the dream through to reality.

The build

Having grown up trawling up and down the River Thames fixing boats, British native George Gill started his engineering apprenticeship at 16 and worked his way through the ranks to some of the most iconic vessels in the fleet on board the likes of Maltese Falcon and Adix in the years that followed. A self-proclaimed boat nut, the seasoned mariner worked for six years across Mr Røkke’s sailing fleet, rising to the rank of chief engineer, striking up a friendship with the Norwegian businessman bound by a shared passion for sailing. His initial involvement with the project started on 16 May 2016, with a blank piece of paper and a 20-minute phone call.

“Mr Røkke basically phoned and said, ‘Do you fancy doing a a hybrid science research vessel/ motoryacht?’ Up until that stage, I’d been working on a replacement for the sailboat, so it was a complete tangent to start talking about motorboats suddenly. But he did. He said, ‘Put something together for me. I’ve got a meeting with some shipyards in five days’,” Gill recalls.

“He told me, ‘You know me well enough. Put together a design brief for a hybrid research yacht, with everything you know about me and what I’d like in a boat.’ At that stage, he had a little sketch, I’m not quite sure where it came from, of a 140-metre silhouette. So I worked on that. I literally left the boat, went home and spent 72 hours pulling together the design brief. I didn’t really sleep. I was absolutely wired, super excited. But at that point, I was helping him out. I didn’t expect to be the project director and owner’s representative. He’d just asked me a favour. And it sounded exciting.”

That summer played out as a blur of split responsibilities, keeping Røkke’s sailing yacht running smoothly while simultaneously steering a dual competition between the VARD and Kleven shipyards. Immersing himself in the process, he took in information from both yards, refined the drawings and learned on the fly as the project began to take shape. By August that year, Røkke suggested bringing in a dedicated project manager. Gill polled his peers for advice and recommendations, but he kept circling back to the same idea.

“So, I thought, well, it’s an opportunity you only get once. I approached him on the side deck of the sailboat and said, ‘Would you consider letting me be the project manager?’ And he replied, ‘Oh, I thought

you already were.’ That was it. That’s the interview. Job done. But if only it were that simple,” he laughs. “If anything, that was just the beginning of what would probably become the biggest project of my career.”

As the project began to snowball, the renowned designer Espen Øino entered the project just after the Monaco Yacht Show, bringing with him some early sketches. At that stage, the team was still running a dual process with VARD and Kleven house. When the decision was made to place full focus on VARD as the chosen builder, the Norwegian veteran was asked to come across and join the project. Around the same time, Jonny Horsfield, founder of H2 Yacht Design, was brought in, his work on the 107-metre explorer Ulysses proving invaluable as inspiration. With the build strategy centred on constructing a ship based on sustainable design principles before transferring it elsewhere for outfitting, Horsfield’s expertise offered a way to design the interior so it could be made to the highest standards, while also minimising the environmental footprint.

Opting for passenger ship notation set a higher threshold than the yacht code, which ultimately changed the complexion of the project. It allowed far more people to be carried on board than conventional regulations would permit, an essential requirement for bringing in scientists in significant numbers. At the time, there was accommodation for 22 guests, but the notation meant scientists could also be housed in crew cabins, pushing capacity to more than 100 berths. Once the core crew was in place, as many as 24 scientists could join a mission. It’s far from the easiest framework to work within, but the flexibility it offered outweighed the complications.

“In some respects, it’s been positive. It’s a very safe vessel. The rules are written for cruise ships with 5,000 passengers, so sometimes you might look at REV Ocean and think, well, we’ve only got 22 or 30 guests, so it doesn’t make much sense. But in the general scheme of things, you’re getting an incredibly safe boat. And of course, there were exemptions we had to achieve, but we managed them with good dialogue with DNV,” Gill explains.

“For example, we have lifeboats above the main hangar hatches. On most yachts, that wouldn’t be an issue, because hatches are kept closed until you’re in a bay or alongside, when you launch a tender and off someone goes. But for us, those hatches have

to be operational at sea for long periods to launch equipment. Sometimes it’s a coring device that pulls up long cylinders of seabed, other times it’s a CTD, the instrument package used to measure salinity, temperature and depth through the water column. They need to be opened, semi-closed and closed again, which created a unique challenge. We had to make the case for opening the hangar hatches at sea, which required adding extra lifesaving apparatus. DNV was open to it and understood what we were trying to achieve.”

These trials and tribulations come with building something genuinely new. Gill set out to combine a 140-metre research vessel onto a 140-metre yacht with as little compromise as possible, but a limit did come in ice class. REV Ocean is not a full-blown icebreaker, but in a way, it was never meant to be. The brief demanded a ship that could work as comfortably at the equator as in the Polar seas. So while the vessel can’t chew through two metres of ice, it can handle enough to support serious research in the Arctic and Antarctic.

REV Ocean was built to work, to stay busy, to be useful wherever it goes. Because it was never meant to be a yacht with a lab tacked on, nor a research ship with a helipad.

REV Ocean is a platform for science, handed over to researchers who are always challenged with access to ship time.

This adaptability courses through the veins of the entire programme, and the ship carries enough range to cover almost any discipline. One day trawling for live specimens, the next holding position on dynamic positioning (DP) to sample the seabed, then moving off to run sonar surveys, still gathering data as it makes passage. It was built to work, to stay busy, to be useful wherever it goes. Because it was never meant to be a yacht with a lab tacked on, nor a research ship with a helipad. REV Ocean is a platform for science, handed over to researchers who are always challenged with access to ship time.

The Science

REV Ocean’s director of science, Eva Ramirez Llodra, grew up in Spain and forged a career as a deepsea ecologist, finishing her PhD in Southampton before moving to Norway to work at the Institute for Water Research. By the time REV Ocean hit the headlines in 2017, she, like many scientists, could hardly believe it. A billionaire was building the world’s largest research vessel and putting it at the disposal of the scientific community for free, on her doorstep. It sounded too good to be true.

“I applied and I was lucky enough to get the job. I joined REV Ocean in 2019 as science coordinator, while Alex Rogers from the UK was the science director at the time,” says Ramirez. “The magnitude of the project hit me pretty early, though. I was sitting at a large table when the CFO began talking, showing a picture of a helicopter and saying, ‘OK, I’m about to sign the contract for this Airbus’. I’m a researcher, and suddenly I thought, OK, this is big. That was the first time I felt taken out of my comfort zone as a scientist. Even though I had worked with submersibles and ROVs, this was something else.”

When Eva joined, the vessel was still scheduled for delivery in 2021. Alongside the then science director, Prof. Rogers, she began shaping the programme that would define REV Ocean’s mission. Rogers had already completed an exhaustive review and narrowed the focus to three priorities: plastic pollution, unsustainable fishing and climate change. There are countless other challenges in the ocean, but the team chose to focus their efforts rather than spread themselves too thin.

“There will be red lines we don’t cross, and we’re not allowing things that we don’t think are ethical. We cannot be saving the world while at the same time allowing things on board that we disagree with.”

The REV Ocean science team does not conduct the research themselves. Their job is to build the programme, set the priorities, prepare proposals and hand the platform over to scientists who need it. REV Ocean supplies the ship, the kit and the access. The team supplies the framework to make it work. During research periods, there will be no guests. The vessel is vast but not vast enough to support a whole charter operation and a complete research mission at once. Every bunk, every technician and every crew member is needed to run the science.

The big adjustment for Ramirez came with the superyacht side. That world was new and still is, forcing her and the team to climb a steep learning curve as they bridged two cultures on board. Yet it also opens a door to the very problem REV Ocean is built to confront. Very wealthy people can step on board and be inspired. They hold the power to fund research after seeing, for example, an octopus breeding ground. They have the connections to influence policy. Some even run companies that can build the technology to tackle problems like plastics. It is a form of leverage Ramirez admits she has never considered before.

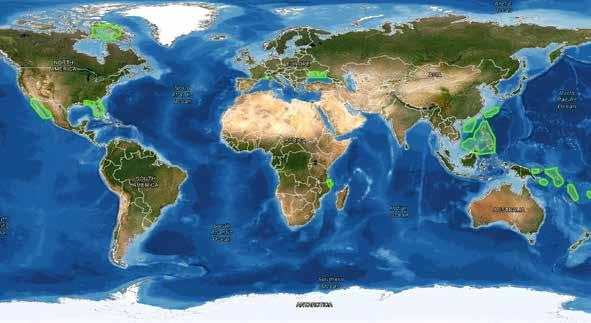

Palau is a case in point. The Micronesian island nation now boasts the largest marine protected area in the world relative to its size. In the years leading up to its establishment, then-president Tommy Remengesau Jr joined scientists on a submersible dive to get a glimpse of Palau’s deep reefs first hand, giving him the evidence and language to argue for protection on the international stage. By 2020, 80 per cent of Palau’s waters were closed to commercial fishing – a decision the president repeatedly linked to what he had seen with his own eyes beneath the surface.

Too often, the people writing laws about the ocean do so from behind a desk, never having seen the places they are protecting or destroying. REV Ocean has the means to change that. With nine science labs and all the instruments to sample from

the surface to the deep seafloor, it is more than a research vessel. It has a classroom, a 30-seat lecture theatre, a boardroom, a media lab and a 3D printing lab. Add to that its VIP cabins and you can bring in heads of state and ministers, to let them see it for themselves. To see the plastic on the seabed, the scars of bottom trawling or the beauty that can still be saved if action is taken now.

“At the same time, we will be very clear. There will be red lines we don’t cross, and we’re not allowing things that we don’t think are ethical. We cannot be saving the world while at the same time allowing things on board that we disagree with,” Ramirez clarifies. “Maybe some guests insist on having water in plastic bottles and there is obviously no need. Now maybe that’s what they want, and maybe that’s what they have to get, but at the same time, we can say: here is your bottle of water and here is an analysis of the microplastics within it. Always constructive, never negative, I try to educate in a way that lets them make their own decisions. But there are certain things we won’t do. We’re not going to go hug dolphins just because a guest wants it. There will be red lines and that applies to science as well.”

Ramirez concedes there may be moments when the lines blur. In research mode, the owner can always step aboard, and others might too, provided they accept the ground rules on the basis that science, and science alone, sets the course. If the schedule means holding station in rough seas, then that is what happens. Charter periods are different. Here, the plan is to give guests the chance to take part in a variety of science, depending on their interest. Not the kind of missions that demand every vehicle and technician, but projects that still add value. There is plenty that can be done with guests on board and the idea is to make them part of it rather than spectators.

“For example, we can collect data while mapping the seafloor. Or if guests are interested in sharks,

we could bring a couple of scientists to tag sharks, recover tags or observe whales. They can be part of that. Or we can take them down in the submersible to see a seamount full of corals and collect a few samples. We will never collect samples just as souvenirs. But if we’re already collecting them for scientists, then we can include guests in the process. They get an amazing experience while contributing to research.”

The delay

You can’t tell the REV Ocean story without talking about what might have been. The original vision was set for a 2021 final delivery, but the project hit a wall when, in June that year, REV Ocean confirmed a three to five-year delay. The issue pointed to technical and weight issues during outfitting, as the ship was not in accordance with the performance expectations. In plain terms, the boat sat too deep and could not meet its mission profile as built; the root of the issue had to go back to the sequence of the build, where the hull was fabricated and launched in Tulcea, Romania, in 2019 and towed to Norway for outfitting. Gill acknowledges that they knew the build was never going to be simple, going from 145 metres to 164 to 168 with design changes. And adding another half metre of beam, suddenly the balance tipped. Everything came to a halt.

By all accounts, this was a difficult period with a real sinking feeling that REV Ocean might never see the water. But Ramirez and the science team didn’t sit idle. With the ROV Aurora and the sub Aurelia already complete, the latter finished in 2021-22, they pushed ahead by deploying them from other vessels. That meant REV Ocean’s science was happening even without REV Ocean being completed. Ramirez herself returned to finish a project close to her heart in the Arctic, exploring hydrothermal vents from her days at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research. The team also took Aurelia to the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, sampling in the mesophotic zone between 60 and 500 metres. Chagos is one of the world’s largest marine protected areas, but the designation was based only on the shallow regions accessible by scuba. REV Ocean’s submersible was the first to reveal the deeper layers, expanding knowledge of the ecosystem and strengthening the case for protection. Several more cruises followed with Aurora, proof that even without its flagship the REV Ocean mission was alive and delivering discoveries. And as the scientific mission endured, so too did the building process. For Gill, those years were

defined by frustration and graft in equal measure. The vessel grew in fits and starts, before finally settling at 195 metres. What looked like endless redesigns and stoppages at the time would, in hindsight, make the ship stronger. “There were things I wanted in round one that just weren’t possible. When the decision came to lengthen her, it gave us space to bring those elements in,” he reflects. “The irony is that the delays that threatened to derail the project also opened the door to refine it, to make it the vessel it was always meant to be.”

It was a radical but necessary fix, a somewhat inelegant surgery on a yacht of this size to cut the hull and lengthen it by twelve metres. It takes time, but it gives the design more margin and unlocks space for science. A hangar for the submersible, a dedicated CTD hangar, a container storage, a media studio, a robotics and 3D printing lab. What began as a stability problem became a chance to double down on capability. It was a worthy process to suffer through the lens of science, says Ramirez. “The delay was frustrating, of course, but we ended up with a better platform. All twelve of those metres went into the science areas. More labs, more space for technicians, better workflow. In the end, we get a better ship than the one we thought we would have.”

In March 2025, Vard declared the initial construction complete and sent the ship to Damen Shiprepair Vlissingen for the final push. Roughly 15 to 18 months of outfitting remain before sea trials and delivery in 2027. Covid disruption, subcontractor struggles and the scale of the redesign made the path longer and harder. The team used the pause to create a better platform. The longer hull restores performance and range, the aluminium rebuild trims the high weight, the new hangars and labs facilitate smooth science operations and maintain a clean deck environment. It is the kind of rethink that hurts in the moment and pays back over decades of service.

“The owner and I are very solution-oriented,” adds Gill. “There had to be a way we could do this. We just had to figure out the best way of doing it. And I had a great, quite a small team, actually, around me from different disciplines, helping me to figure out the solutions. They were really great. I remember the day I took delivery. It was quite a surreal moment. I felt very emotionally detached from it, having come so far. It was probably only when she arrived at Damen that I suddenly thought, okay, tick. Delivered the ship to the outfitting yard. Done – two years late but done.”

In March 2025, Vard declared the initial construction complete and the ship went on to Damen Shiprepair Vlissingen for the final push.

The future

It’s been a long journey, particularly for the likes of Gill, who spent sleepless nights and dawning days problem-solving. By the time the project is realised, it will be over a decade of steering the project for Mr Røkke. His two daughters, aged four and five when he started, have had their whole childhood marked by their dad’s stress over this project, only coming on board earlier this year for the first time. “My wife and kids have been incredibly supportive, because it hasn’t always been easy,” he says.

“I’d be lying if I said the responsibility didn’t weigh heavily at times. It has been tough. But the support takes a lighter burden. The owner and I share a passion for boats; we can spend three hours talking about a tender as easily as we discuss REV Ocean. That shared passion alleviates the responsibility, because I usually understand what he’s aiming for and I can help define or support it. It’s easier when you’re working for someone who is as passionate about it. Their boat is similar to the one you are about to build. I think my own stubbornness also keeps me going, as I try to prove to myself that I can finish it. Some people might have scaled back or said it was too ambitious, but instead, we doubled down. The vessel is bigger and better as a result. That sums it up: we doubled down.”

Forever a steely owner’s rep, yet a nautical romantic, Gill insists that everyone is committed to the project and its goals. People have hung in there thick and thin, driven by a genuine desire to be involved due to what this project represents. Most people don’t experience the ocean. It feels alien, otherworldly, with its deepest, darkest depths five thousand metres down often dismissed as an abyss devoid of life. But in fact, it’s one of the highest biodiversity areas in the ocean. Fifty per cent of our oxygen is produced in the sea. It regulates the climate, provides food and ultimately provides livelihoods.

Now, as REV Ocean sits in the Netherlands, the vision of bringing accessible knowledge and resources to the world is tantalisingly tangible. “When the vessel was being moved to Damen, the instruments on board hadn’t been taken care of during the long build process, so we went on board

to check everything was working and to familiarise ourselves with the labs,” recalls Ramirez. “We even slept on the vessel for two nights, because the crew was there and the galley was working. Eating on board, sleeping in a cabin – it suddenly made everything much more real. The first night, I thought: I’m in a bed on REV Ocean. This is real.”

For such an ambitious project, success will wear many faces. It might mean gathering data that feeds straight into policy and helps draw the lines of a new marine protected area. It might contribute to a country’s 30 by 30 target* or even the first high-seas protected areas. It could prevent benthic trawling from damaging the seafloor or provide the kind of evidence that drives real decisions. Perhaps through technology, REV Ocean could develop a way to lock away carbon without damaging other ecosystems. Or it could mean building capacity where none exists, not just flying in to collect data, but leaving behind skills and infrastructure so communities can keep monitoring their own waters long after REV Ocean has sailed on.

“I’ve been asked before what success looks like, and I always say: at the end of the day, a happy owner. That’s why I do it, and that’s why most owners’ reps do it. This whole journey has been a professional evolution. I’ve been lucky to learn from good people, be surrounded by them and hold my own with them. I feel like I’ve weathered the storm. Not invincible, but stronger.” says Gill.

“But beyond that, I think of the youngsters, students who struggle to get time on research vessels or who face all the hurdles of government-

* A global and EU-level goal to protect at least 30 per cent of land and sea by 2030.

led programmes. REV Ocean can provide them with the time and space, along with the necessary equipment, to conduct their research. If one of them, a 21-year-old genius, came up with something on board that advanced ocean solutions or sustainable energy or anything groundbreaking, that would be my proudest moment.”

REV Ocean is the meeting point of oceanography and yachting culture. It’s the amalgamation of two worlds shared by a passion for the sea and bound by a will to learn, save and preserve the most important ecosystem. It carries the weight of a decade of setbacks and breakthroughs, sleepless nights and stubborn persistence, but also the promise of something scarce. On this democratised platform, science and wealth, technology and storytelling, can align in service of the deep blue.

“The dream is when guests come on board, fall in love with the experience, become interested in the science and then contribute to other projects, whether locally, regionally, or back home. If their involvement leads to more data and more solutions in their own region, that’s success as well,” says Ramirez.

“And our vision for the future, training and inspiring the next generation, is vital. It’s not just about researchers in the natural sciences. Communication is just as important – raising awareness, bringing the ocean into people’s homes. Ultimately, we vote for our governments and they are the ones making the decisions. So it is on us, all of us, to genuinely make a positive change for our world.” CF

REV Ocean is the meeting point of oceanography and yachting culture. It’s the amalgamation of two worlds shared by a passion for the sea and bound by a will to learn, save and preserve the most important ecosystem. It carries the weight of a decade of setbacks and breakthroughs, sleepless nights and stubborn persistence, but also the promise of something scarce.

Leading provider of luxury outfitting for yachts, hotels, private aircrafts and homes.

Streamlined Service

We offer a complete customer experience with historical purchase information, billing and quotations. Enabling a simple reorder process and removing the need for multiple suppliers. We offer storage service and inventory control assistance.

In-House Design

Our interior designers will help you with all aspects of a project. From reviewing the finer details to implementing a major refit. Our graphic designers will assist with branding, logos and supporting artwork.

Industry Experts

Backed by 20 years of experience in the yachting industry, we work with the best brands and artisans to ensure that only excellent results are delivered to our clients. We offer free advice and consultancy to make sure our clients take the right decisions.

by Daniel Küpfer

All change for the yachting industry

Daniel Küpfer, founder and managing director of management service provider Yanova, observes how the evolution of the yachting landscape has created a much more complex but highly competent and professional environment for today’s mariners.

Over the past 25 years, the yachting sector has changed significantly. Yachts frequenting the most beautiful cruising grounds in the world have gained remarkably in size, range, seagoing capacity and comfort. With this evolution, awareness around yachting has shifted and regulation has increased across nearly all areas of the industry.

In yacht management and owner representation, whether it concerns a new build, a substantial refit or ongoing operational support, the core disciplines remain the same. Yet the depth, complexity and regulatory environment surrounding every aspect of yachting have grown considerably.

When asked how the industry has evolved since I joined, I often reflect on my early days as a mate aboard a 40-metre motoryacht in the early

1990s. At the time, this was considered a very large yacht. Thanks to MYBA, we operated under a solid charter agreement, while the yacht was registered privately, no safe manning regulations applied, the captain was accredited by the insurer, and no one asked about VAT on charter fees – a scenario completely unthinkable today.

What has emerged over the decades is a far more competent and professional landscape. Shipyards, brokers, charter managers, corporate service providers, yacht managers, suppliers and, last but not least, on-board personnel have all had to raise their standards.

Yet alongside this professionalisation, the industry has also become a labyrinth for owners to navigate. Multiple stakeholders engage with the owner, each from their own perspective. The owner’s perception

of the industry is often shaped by the position of their advisors.

With increased complexity, a fragmentation of services has taken place, with individual providers and services selected on a case-by-case basis, more often to fill immediate gaps and often under very strict budget considerations, rather than to pursue a coherent and long-term strategy that serves the owner’s best interests.

At the same time, there is often overlap in services. As an example, yacht management should never be in competition with the captain. Both are distinct roles. In commercial shipping, the boundaries are thankfully clear. This should serve as a reference, whereby in yachting, captains require a high level of autonomy to manage the vessel and crew to the standards expected today.

What is clear is that today’s complexity requires a more integrated and thoughtful approach to yacht management and owners’ representation. Fragmentation of services and concerns over potential conflicts of interest lead owners, especially those of very large yachts, to rely more on trusted individuals.

Guest demands have increased dramatically over the decades, while owners often take a much more tolerant stance. With many guests, especially under charter, everything is expected to be available instantly, like fresh AI-generated content on social media. Crew expectations have also changed. This is often criticised but running a vessel as if it were still 2000 is not a realistic option. Understanding the perspectives of younger generations and adapting to new realities is essential for the leadership team on board and ashore to deliver the service of the entire team successfully.

Environmental and governance factors have entered the yachting landscape. Ownership is increasingly scrutinised. The wealth that has made these yachts possible is now more visible than ever, and with that visibility comes pressure. While protection of private data is taken more seriously, the accumulation of private wealth seems to become, all too often, a justification in our society to exclude individuals from the same privacy rights afforded to others.

The above is only a snapshot. There is, of course, much more to be said about the evolution of the yachting industry.

What is clear is that today’s complexity requires a more integrated and thoughtful approach to yacht management and owners’ representation. Fragmentation of services and concerns over potential conflicts of interest lead owners, especially those of very large yachts, to rely more on trusted individuals working closely with their offices than on full-circle management structures provided by established organisations. However, neither captains nor individual owner representatives can be experts in every field.

The role of trusted individuals remains essential in the yachting sector. Owners should choose their representatives in an informed manner and provide the necessary support to protect their loyalty. Competency and reliability should be chosen over sales talk. At the same time, the trusted individuals must be

well supported by the service sector of the industry in order to ensure success in their role, which is both highly specialised and deeply personal.

On-board decision-makers deserve greater recognition and autonomy. At the same time, those ashore must remain alert to what lies ahead. Constantly developing environmental standards, competent media response and efficient crisis management will become increasingly relevant in the future.

Owners and their offices must be in a position to place trust where it is truly deserved. The maritime industry is too complex for expert guidance to be left aside. At the same time, those ashore must remain alert to what lies ahead, including environmental expectations, media awareness and crisis response.

The ultimate goal for the yachting sector must be to ensure that yachting remains a source of joy for owners, charterers and guests, supported by a well-functioning service sector that is prepared for both the challenges and opportunities of the future. DK

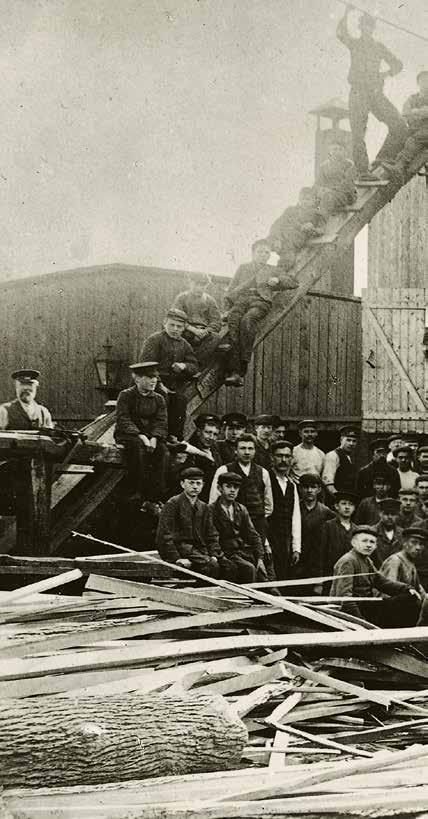

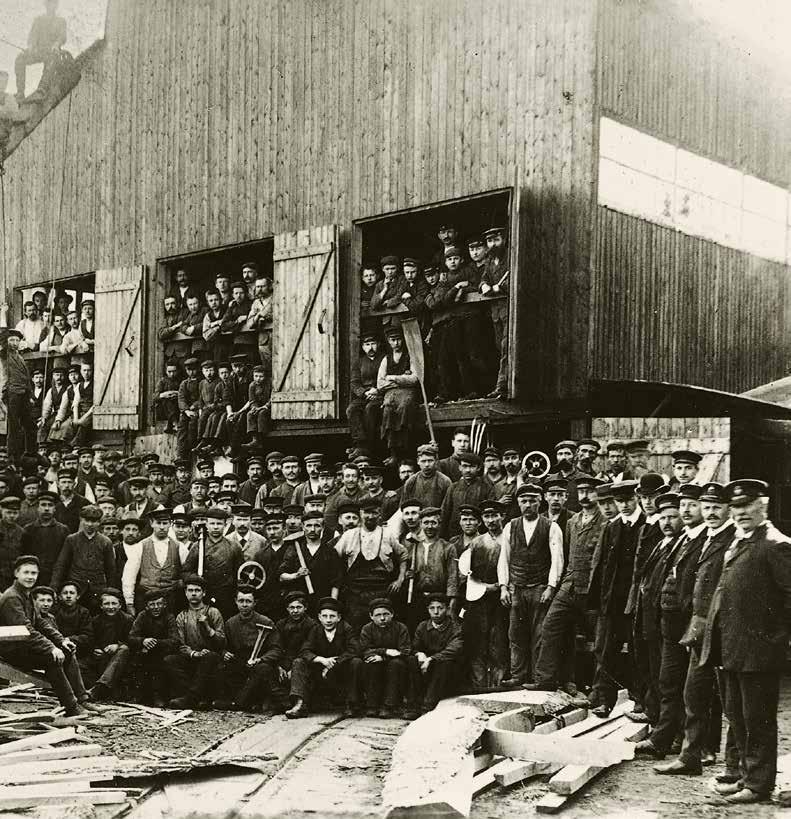

150+ YEARS TO 150+ METRES

Martin H. Redmayne looks at the impact of Lürssen Yachts over the past century and a half, with a personal take on COSMOS, the builder’s 150th-anniversary statement.

It’s wonderful to be able to celebrate 150 years and to show the history and cultural changes over time, with generations of workers, all of whom have left their fingerprints on the steel and wood of the Lürssen fleet.

We have typically measured and analysed this industry in decades, specifically looking at the past few decades as a growth phases, when wealth and luxury exploded in our superyacht world. However, in the past few years we have witnessed several celebrations of legacies and historical landmarks across our primary brands in the industry, and most recently I have been privy to some incredible imagery and chronicles of the whole Lürssen family, including one where Peter Lürssen looks elegant, youthful and charming alongside his father.

Yes, it’s wonderful to be able to celebrate 150 years and to show the history and cultural changes over time, with generations of workers, all of whom have left their fingerprints on the steel and wood of the Lürssen fleet. It’s hard to imagine the thousands of hands that have crafted myriad vessels, the millions of man hours that have toiled to create wooden row boats all the way through two World Wars to now building some of the most impressive superyachts cruising the oceans.

Rather than tell the story of 150 years and repeat much of the legacy that has been shared across the media, we decided to look more closely at the impact Lürssen has had on the superyacht market. There was a moment in time, in the early ’90s, when The Superyacht Report was invited to Lürssen to witness and capture the build of the ground-breaking 96-metre M/Y Limitless. It was hard to comprehend that the market would ever go beyond this mark in terms of complexity, scale and elegance, but fast

forward to the 2000s and the past 25 years and it’s impressive to witness the evolution and expansion of this company, combined with the sheer volume of complex projects delivered to some of the most powerful and wealthy individuals on the planet.

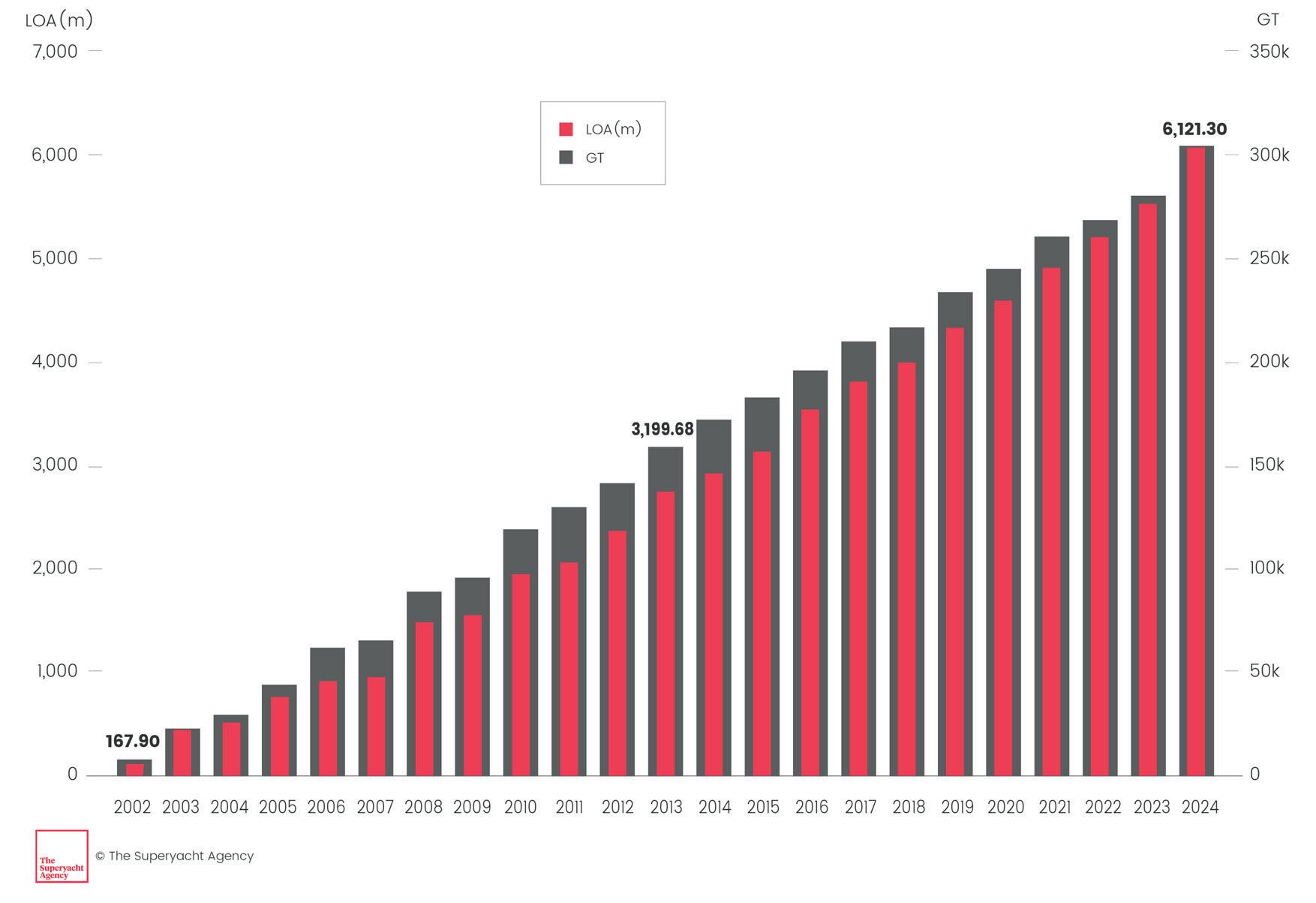

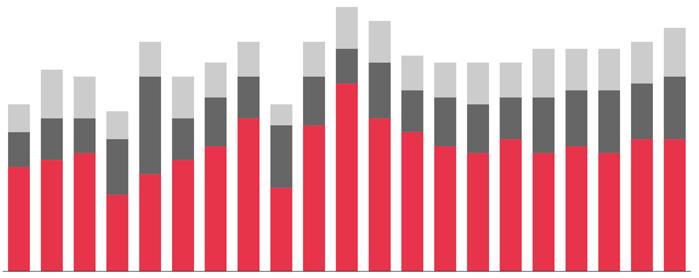

We sat down with Miles Warden, Head of Data at The Superyacht Agency, and started to dissect the numbers, and the impact that Lürssen has had on the industry suddenly became very clear. More than 300,000gt delivered in the past 25 years, from a complex fleet of 62 significant superyachts, cannot be ignored and is such a dramatic transformation from those pre-war days when small wooden craft were being showcased in Monaco.

The following charts are a clear and intelligent demonstration of how Lürssen has shaped the market, since a project like Limitless entered the wider fleet. Just sit back and consider the numbers: over 6,000 metres and 300,000gt in 25 years; that’s the equivalent of 200 x 30-metre Ferretti semicustom yachts end to end or nearly 1,600 of the same 30-metre Ferretti’s in terms of GT volume. For those who have never had the pleasure of exploring a 100-metre-plus Lürssen, especially the 150-metreplus members of their fleet, it’s hard to comprehend the scale and dimensions of these projects.

Standing alongside a giga-project at the dock is overwhelming but stepping on board and walking the thousands of metres of interior passageways and stairwells is mind blowing. All one can do is contemplate the millions of man-hours of welders,

For those who have never had the pleasure of exploring a 100-metreplus Lürssen, especially the 150-metre-plus members of their fleet, it’s hard to comprehend the scale and dimensions of these projects.

pipe benders, engineers, electricians, carpenters, painters and myriad other craftsmen and women spending their lifetimes creating some of the most impressive projects on the planet, projects that will be cruising the planet’s oceans for many more decades to come.

The gargantuan yachts that have now become synonymous with the Lürssen brand and family are the modern-day legacy, if only those workers in the 1910 shipyard image could see what their future generations have created. What’s next will be very interesting to watch and we hope to catch up with the senior management in the coming weeks to explore exactly that question.

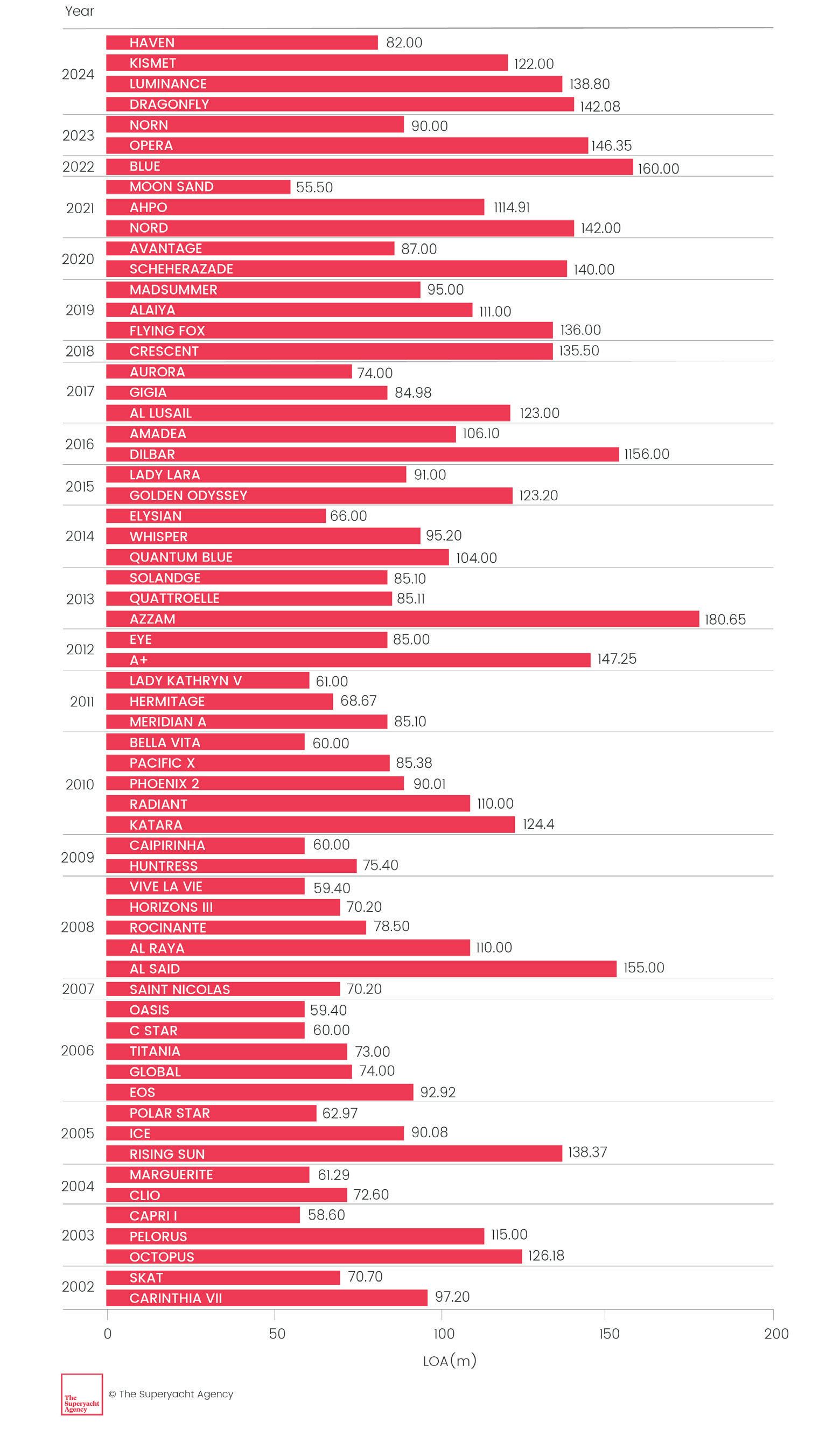

Lürssen yachts built 2002-2024

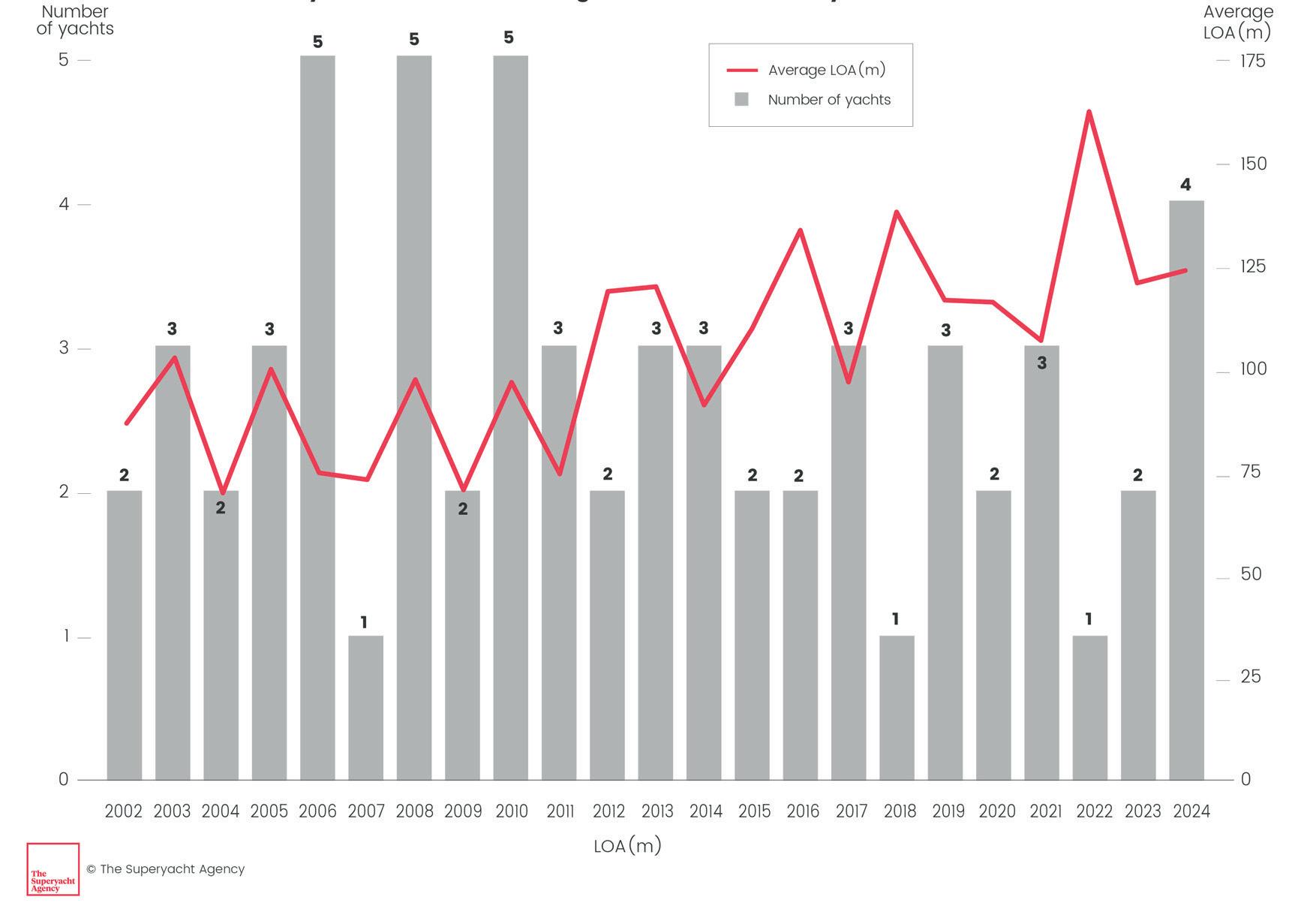

Annual yacht count and average LOA(m) of Lürssen yachts, 2002-2024

Cumulative gross tonnage and LOA(m) of Lürssen yachts built since 2002

The birth of COSMOS: A superyacht that looks to the stars

Earlier this year, somewhere along the Weser River, a unique leviathan slid into the water with quiet confidence. At 114 metres, it’s not just another superyacht – it’s COSMOS, Lürssen’s audacious 150th-anniversary statement, a floating manifesto on how luxury at sea might look for the next generation.

Even in a world where “bigger, bolder, better” is the unofficial yachting creed, COSMOS feels different – a kind of celestial apparition. Designed by Marc Newson, the acclaimed industrial designer whose work graces everything from Apple products to Qantas’ first-class lounges, it is all sweeping lines, sculptural glass and a futuristic presence that stops short of science fiction.

“This is a rather special project,” Peter Lürssen, the shipyard’s CEO, tells me, his voice betraying both pride and a hint of awe. “While no two yachts we build are ever the same, there are some that leave an indelible mark on our history. COSMOS is undoubtedly one of them.”

A visionary owner, a blank canvas

The yacht was commissioned by a client with both the budget and the imagination to ask for something never attempted before. “Everything from the smallest detail to the silhouette – outside, inside and everything in between – is our design,” Newson says, almost reverently. “The owner gave us permission to explore every creative possibility. That kind of freedom is rare and exhilarating.”

The result is a vessel that feels like a singular object rather than a collection of parts. The design flows organically from bow to stern, inside and out, with no detail left to chance.

The glass palace

Perhaps COSMOS’ most spellbinding feature is the glass-domed owner’s study – a crystalline bubble perched high above the deck, with a private sky terrace suspended over the ocean. The engineering challenge was formidable: bending

COSMOS is more than a yacht. It is a provocation, a love letter to adventure, a reminder that luxury doesn’t just mean excess – it can mean ambition.

thick glass into perfect curves, eliminating all imperfections and achieving an almost spiritual clarity.

Throughout the yacht, glass is not just a material but a motif. A continuous ribbon of glazing wraps the cabin deck, blurring the line between inside and sea. Beneath the helipad, a glass-encased observation lounge offers cinematic views of the horizon. Aft, a glass-balustraded balcony invites guests to linger and watch the wake stretch away into infinity.

The spirit of exploration

But COSMOS is not a mere trophy yacht destined to sit at anchor in Monaco. It is Ice Class 1D certified, built to slip through light Polar ice, and carries the range to circumnavigate the globe – a floating passport to all five oceans and all seven continents.

The open aft deck is designed for both play and practicality. At its centre is a swimming pool and

Jacuzzi, flanked by lounge seating. Aft is a dry dock with a sledge system for launching COSMOS’ largest tender – because true explorers bring their own means of discovery.

A laboratory for the future

Even the powertrain hints at what is to come. As part of the owner’s commitment to innovation, COSMOS will host a methanol fuel cell research installation – turning methanol into hydrogen, then into electricity – an ambitious test case for a cleaner, quieter future of yachting.

In the end, COSMOS is more than a yacht. It is a provocation, a love letter to adventure, a reminder that luxury doesn’t just mean excess – it can mean ambition. Standing on the pier as COSMOS slid into the water, it was hard not to feel that we were watching not just a launch but the beginning of a new era. MHR

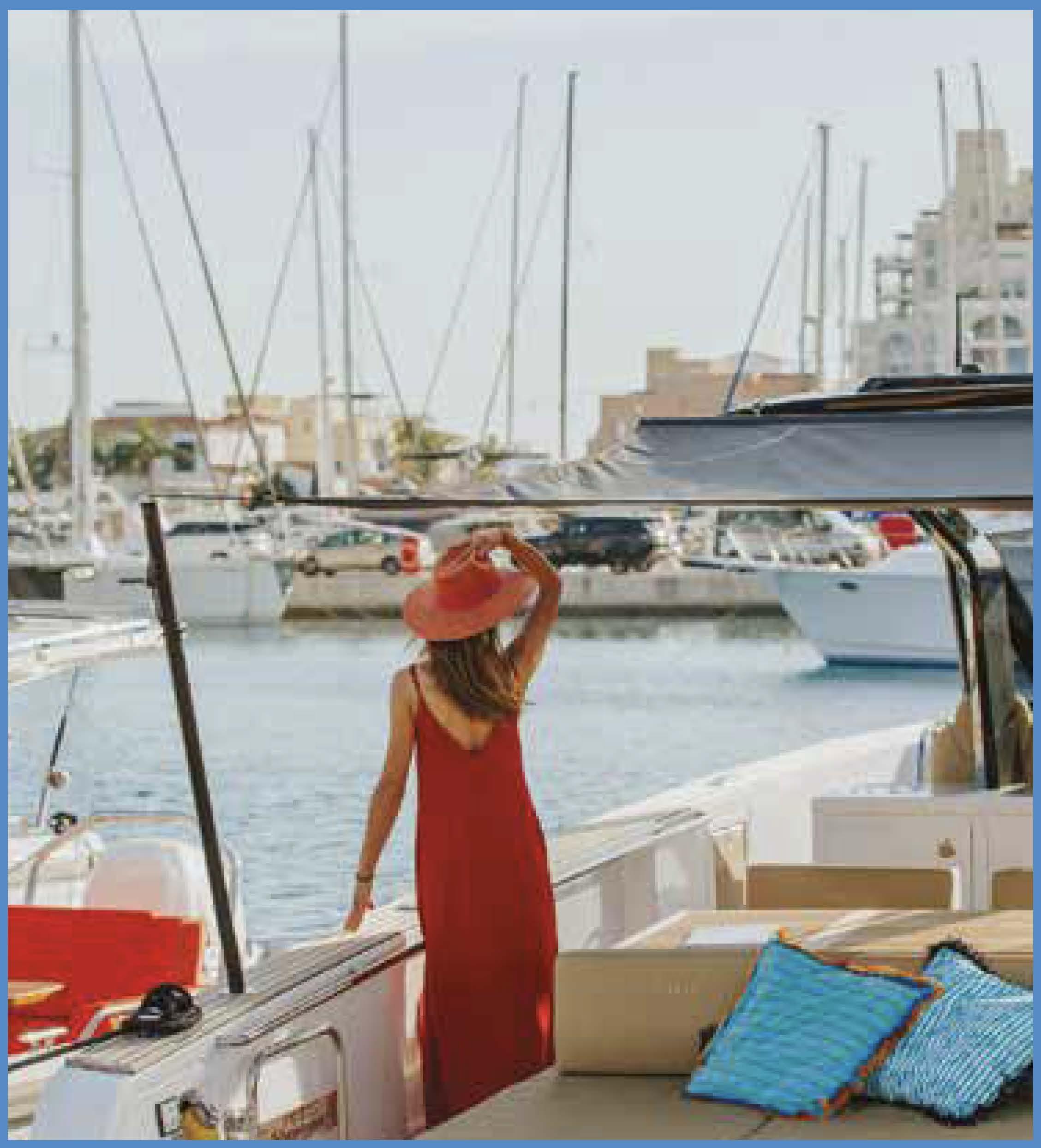

Charter – it’s more than just about looks …

Neil Hornsby, co-founder of Yomira charter brokers, presents the golden rules to optimise charter income from a superyacht while still protecting the owner’s valuable asset.

Not everyone wants strangers on board their pride and joy, particularly as it represents a significant investment, but there can be substantial benefits to making a yacht available for charter, particularly if an owner is only using the yacht for short periods during the year.

Key considerations, such as operating costs, tax and Flag state benefits and crew requirements are varied yet easily navigable with the right advice, but the largest decision is which company to choose to represent your asset?

From the current fleet of approximately 6,000 superyachts worldwide, roughly one third are available for charter. Charter demand has increased exponentially over the past five years, reflecting the huge popularity and demand for superyacht holidays.

Successful charter yachts can build reputation in the market: they generate positive publicity and can attract potential buyers if and when you decide

to sell. A strong charter record can often help the resale value by demonstrating the yacht’s desirability and income potential.

When you are ready to take the plunge the next step is to appoint the right ‘central agent’ (CA) with a charter manager to look after your vessel; there is a myriad of choices out there, some better than others. Like any business, time taken at the start to get the right agency on board is time best spent to achieve the right results for your objectives and reduce any lag time before the bookings start.

Speak to a handful of agencies, get a good handle on what their approach is within the very competitive market that is yacht charter. Ask for a detailed charter proposal with realistic income forecasts – the highest charter fee doesn’t always attract the most charters, priced too low and it could create a negative perception. Drill them to ensure they will meet your objectives. The most

successful charter yachts don’t rely on their looks alone and it’s a competitive market, particularly for the more popular cruising grounds of the Mediterranean.

Some agency models are better suited to an owner just wanting the occasional charter, others are better geared to brand building and promotion to maximise income potential. Will the company ensure your yacht is given the same, if not more, exposure as another, similar size vessel from the same yard? How will they achieve this? Would you be better suited being part of a larger fleet or a smaller bespoke agency?

The appointed charter manager should be multi-faceted with experience in the charter field, the right business sense and sales mentality by default, not only to protect the reputation of your prized asset but secure the best deals with the minimum of fuss. You don’t want a ‘yes man’ who is unable to broker a deal, you need them to have your best interests at heart.

Having a solid reputation with the fraternity of charter brokers that generate many of the bookings is also a key consideration and having the rubber stamp of a reputable industry body behind them such as MYBA or the IYBA is essential to demonstrate credibility.

The CA will be able to advise you on the key components of running a yacht commercially for charter:

Offset operating costs

Superyachts are expensive to run: annual maintenance, crew salaries, insurance, fuel and berthing costs are often around 10 to 15 per cent of the yacht’s value. Chartering can generate meaningful income to help offset these ongoing expenses and a successful yacht can achieve around 15 to 20 weeks of charter a year, particularly if it does dual Med/ Caribbean seasons.

Tax and regulatory benefits

In certain cruising areas, particularly in the EU, placing a yacht into commercial charter may offer tax advantages such as VAT deferral or exemption on the purchase, fuel or refit work. You would need to effectively charter your own yacht when you want to cruise, but the benefits can often outweigh any difficulties. Seek proper advice from a professional yacht management company before you go any further.

Crew retention and motivation

You have worked hard to hand-pick the best crew and want to keep them, but long idle periods can lead to boredom and higher crew turnover. Having a professional crew year-round is also costly. Chartering helps ensure the crew stays active and motivated so your prize team is there to there to greet you when you return. They can also get pretty

Chartering can generate meaningful income to help offset ongoing expenses and a successful yacht can achieve around 15 to 20 weeks of charter a year, particularly if it does dual Med/Caribbean seasons.

good tips from happy clients, which is another incentive to stay. Your crew needs to be flexible enough to adapt to the varied demands of charter clients, a crew that’s ‘fixed in the owner’s ways’ and drilled to an owner’s precise service requirements don’t always make the best charter crew.

Key input you need during the initial stages of chartering include advice on the best set-up, particularly when it comes to entertainment and watersports as well as the production of professional marketing materials: high-end photography, videos, brochures and virtual tours. A cookiecutter approach with marketing collateral doesn’t always build brand recognition, so depending on your objectives it’s worth challenging this from the outset.

The charter manager should also list your yacht across the top charter platforms and promote it regularly to the global network of charter brokers. Having the yacht attend some of the industry’s leading boat shows such as Monaco, San Remo and Antigua is also vital not only to showcase the yacht’s best assets but also for brokers to see the crew working as a team to gain trust, build reputation and attract publicity.

The charter manager should screen the charter inquiries and secure high-quality clients that will hopefully turn into regular repeat customers. They will negotiate charter rates and terms according to your remit, optimise the booking calendar to avoid long idle periods, manage the charter funds throughout the process and provide frequent reports on earnings, projections and recommendations on the best cruising areas to optimise income.

With the right CA on board and a clear strategy, your yacht can not only help offset its running costs, but also build a reputation that enhances its value, ensures a happy crew and keeps it in demand season after season. NH

The professional yachting world – some inconvenient truths

Captain Rod Hatch, PYA board member and Director for Training (Deck), spells out the steps the organisation has taken to improve conditions for crew and why the engagement of professional bodies is essential when it comes to achieving meaningful change.

The recent tragedy on board motoryacht Far From It drew strong reactions from within the yachting community. Paige Bell’s parents issued a statement regarding their appreciation of all the expressions of fond memories of, and heartfelt tributes to, Paige, which they found genuinely supportive in their grieving. That support reflects well on the type of people we have in this industry. It may be some consolation for her parents to feel sure that Paige worked in an environment of caring and sensitive friends, shipmates and colleagues. On the other hand, one has to hope that those parents never become aware of the crass behaviour by some totally insensitive individuals who attempted to capitalise on their daughter’s death by promoting their own commercial interests.

Companies in the business of background checks bombarded social media, crew agencies and management companies in the days immediately after the news broke, raising a hysterical cry for mandatory criminal checks on all yacht crew. The proposal is a nonsensical distraction from taking a responsible look at lessons to be learned, which will actually be in the area of better understanding and application of current regulations, not crying for new ones.

The truths

• Expectations that crew agents should carry out criminal background checks are totally daft, as such agencies may have up to 30,000 prospects on file.

• There is, so far, no evidence that the accused person in the incident had a criminal background.

• There is no empirical evidence that any single criminal conviction of an individual automatically predicts future violent behaviour.

• There are no standard norms which define criminality – for instance in Mombai the law makes it a criminal offence to drink alcohol in any public place without applying for a licence to do so, which is why a large proportion of the city’s populace and countless tourists are de facto criminals in India.

• As seafarers, yacht crew are by definition peripatetic and over time may be nationals of, reside in or pass through many national jurisdictions, making it an impossible task to make a thorough search unless an employer, state or private individual has strict security requirements and enough funds to throw at worldwide criminal background checks.

• Some national jurisdictions have onerous conditions concerning the release of criminal records, and others allow the erasing of such records after a set time period, thereby curtailing the comprehensiveness of international checking.

• Owners have always had the option to carry out whatever background checks they wish and would resist any attempt at regulatory coercion to dig deeper than they choose.

• Such mandate would only be effective if applied across all Flag states with no exceptions; and finally

• The maritime regulatory bodies (IMO, ILO) will anyway not take any action in response to an isolated incident involving a single person (see notation at the end of this article).

The following examples illustrate why this is true

• The loss of RMS Titanic (over 1,500 fatalities) in 1912 instigated worldwide revulsion at the prevailing casual provision of lifesaving equipment at sea, leading to the first version of SOLAS two years later.

• A series of maritime disasters, culminating in the capsize of The Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987 (193 fatalities) then the Scandinavian Star fire in 1990 (159 dead), led to the drafting of the ISM code and its implementation in two phases, in 1998 and 2002, a time lag of 11 to 13 years.

• In response to the 9/11 terrorist attack on the US mainland in 2001 (2,977 killed), the ISPS code was implemented in 2004, three years later.

• In 2000 the ILO realised that a hodgepodge of almost 70 maritime labour instruments needed to be consolidated

The yachting industry is by no means free of faults when it comes to crew safety and welfare. Any improvements will come from a measured co-operation between existing organisations that are already working in this field and the maritime regulatory bodies.

and updated. Even at the beginning of the 21st century many seafarers, especially those from developing countries, still worked under appalling conditions for low pay. From agreement among ILO members of the need to address this situation, to the drafting phase beginning in 200 to adoption in 2006 to ratification in 2012 to implementation in 2013, covered a timeline of 13 years. Subsequent amendments to MLC typically take four to five years.

These examples illustrate the truth about the magnitude of tragic episodes which will attract the attention of the IMO or ILO, and the timelines needed to draft and implement responsive mandates.

Regarding the workings of existing legislation, seafarers have legal protection against NDA litigation if they report infringements of their rights or criminal acts against them.

The yachting industry is by no means free of faults when it comes to crew safety and welfare. Any improvements will come from a measured co-operation between existing organisations that are already working in this field and the maritime regulatory bodies. Effective interaction with these authorities needs to be carried out by crew representative bodies which already have established credentials there.

A lot of online noise by individuals who sometimes have very limited onboard experience and who now aspire to be the sole valid voice of yacht crew is a

A lot of online noise by individuals who sometimes have very limited onboard experience and who now aspire to be the sole valid voice of yacht crew is a hindrance to working towards achievable goals.

hindrance to working towards achievable goals. Everybody has a right to express an opinion and anybody can come up with a novel proposal to improve any aspect of yachting. However, social media are currently awash with demands for a ‘new’ approach to yacht crew working conditions, such as owner accommodation to be offset against expanded crew living spaces; expanding safe manning levels; standardised pay levels; safe working conditions; universal legal coverage for yacht crew against unfair dismissal; enforcement of hours of work and rest; and even a nebulous entity to monitor remotely all on-board crew interactions and send back recommendations to the on-board chain of command.

These are all either impracticable or are already covered under SOLAS, STCW, ISM and ILO mandates or are entirely at owners’ discretion (such as wages). A lone voice pleading at the doors of the IMO or ILO will never be heard. The truth is that at that level everything is done in a tripartite format and is always concerned with the interests of all seafarers.

Yachting is a tiny fraction of the international shipping industry – 00.8 per cent by value and negligible in terms of tonnage. Advancing beyond online discussion and ‘likes’ to establish a new organisation aimed at realising a wishlist of changes would soon hit the wall of reality. If money is involved via subscriptions or donations, there must be transparency in whatever jurisdiction such organisation is formed. There would be requirements for accountability, meaning registration according to the local legal format. The articles of association would need to specify all aspects of its raison d’être and remit, plus internal audits to ensure compliance therewith.

The next two hurdles would be (1) Recognition and (2) Credibility. The Professional Yachting Association(PYA) does not blabber in the cyber world. We have the recognition and credibility to act in the real world and we get results. Here are some examples of what it takes to establish these two touchstones.

(i) If you are reading this and you hold an MCA COC (Yachts), then it is thanks to the PYA. In 1990 a small number of yacht captains contacted the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) and the Department of Transportation (DOT,

now called the MCA) with an urgent message. Pending changes in STCW regulations would mean that many current captains and officers in yachting would lose their positions, which could then only be filled by persons with full commercial certificates. The RYA and DOT listened, and they were invited to visit a selection of yachts in Antibes and to interview their crews. Impressed by the level of professionalism on board, which included some who held an RYA Yachtmaster certificate, the DOT agreed that yacht-specific professional qualifications were needed.

The PYA was then established in 1991 and was consulted by the DOT as the first training modules were rolled out, leading to the issuance of the first ever yacht-limited COCs (Deck) in 2002. That is how we established recognition and why we were subsequently invited to work with the MCA on the development of a COC Engineer (Yachts). In the immediate aftermath of the COC (Yachts) rollout, the MCA established the Yacht Qualifications Panel (YQP). The PYA then worked with the MCA on the YQP to establish the Yacht Rating Certificate.

The MCA COC (Yachts) scheme has since been mimicked by other Flag states or accepted by them for issuance of CECs. The PYA continues to work closely with the MCA, both directly and through representation on various work groups with which the MCA consults on training and certification matters.

(ii) The PYA cemented its credibility right across the industry at the time of the introduction of the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (MLC), which was written by the International Labour Organization (ILO). If you are working on a yacht right now, and you wish that your cabin could be somewhat larger, there is a mathematical rationale which limits its size. It is thanks to the PYA that all sectors of the industry came together to design the best living arrangements possible on various types of yacht.

If you are working on a yacht right now, and you wish that your cabin could be somewhat larger, there is a mathematical rationale which limits its size. It is thanks to the PYA that all sectors of the industry came together to design the best living arrangements possible on various types of yacht.

Immediately after publication of the Convention, with its looming entry into international law, the PYA, on its own initiative and at its own expense, flew a team to Geneva and London to meet with the ILO and Nautilus respectively, and also contacted the MCA in Southampton. We alerted those three bodies to the overlooked fact that the MLC crew accommodation requirements were physically impossible to build into yachts. Implementation of MLC would mean that the construction of any commercial yacht would be stalled, all around the globe, for an indeterminate number of years while an amendment could grind its way through the ILO legislative mechanism. The potential economic consequences were incalculable.

A critical finding at the meeting with the ILO was that the ILO had no idea of what yacht crew living and working conditions were actually like. At the ILO’s request, the PYA agreed to carry out a Qualitative Study to answer the ILO questions. The PYA then commissioned the Seafarers International Research Council (SIRC) at Cardiff University to conduct the survey, which was drafted by the PYA and promulgated to all crew across the yachting sector, not just PYA members. The resulting 42-page SIRC report is a historic document, the significance of which will be explained later.

During the same year, and again at its own expense, the PYA hosted representatives from the MCA, the ILO and Nautilus in Antibes, to inspect various sizes of power and sailing yachts to see for themselves the on-board realities of accommodations and to seek crew opinions. In response, the MCA established the Large Yacht Sub Group, to explore solutions to the MLC impasse.

All parties accepted that it would have been geometrically impossible to build an MLC-compliant yacht under 3,000gt after MLC implementation date.

About 30 delegates sat around the table at the opening meeting in the MCA building in Spring Place, Southampton. Delegates included: the PYA and Nautilus to represent crew; MYBA to represent owners; SYBAss to represent large-yacht builders; ICOMIA and Sunseeker to represent smaller yacht builders; surveyors from all the Red Ensign Group (REG) Flag states, plus Malta and the Marshall Islands; Classification Society surveyors; and representatives from the maritime authorities of Italy, Germany and Holland, whose yacht-construction sectors faced a potential crippling shutdown.

An MLC Amendment being mission impossible in the near term, we had to find a solution from within the MLC itself, which fortunately allowed for “substantial equivalence”. A deadline by which to submit a reasoned substantial equivalence proposal to the ILO made the situation urgent. A month or so later, due to a clash of schedules over room allocations in Spring Place, the MCA was faced with cancelling the next meeting. The PYA, concerned over the urgency of the situation, provided the money to rent a conference room elsewhere in the city. At that salvaged meeting a naval architect from SYBAss was tasked with designing a quantitative survey studying the degree to which the typical crew quarters on yachts of various sizes could or could not meet MLC specifications.

Discussions and idea exchanges over the next several months led to the development of a ‘sliding scale’, whereby at different cut-off tonnages, each crew cabin would approach the MLC specifications as tonnage increased. When the final proposal was sent to the ILO, it had the backing of other Flag states which had been kept informed of our work and which intended to apply the same parameters in their own jurisdictions.

The quantitative survey was the second of the two historic documents which persuaded the ILO Committee

Crew recruitment and retention are perennial topics at yachting conventions and seminars. Paradoxically, bullying and sexual harassment are often equally regular topics on the same day’s agenda. The balancing act is addressing the reality of the latter without impeding the former.

Let’s ask if it’s true that sexual harassment is “rife” within our industry. There have always been accounts of its occurrence. There is no measurable way of tracking its non-occurrence on secure yachts, so there is no percentage data about its level of frequency. Is it really a dark secret which pertains especially to yachting?

template is being watched by the MCA, for whom it can provide a copy-and-paste solution for drafting their own syllabus.

of Experts to accept the final proposal submitted by the MCA as providing ‘good faith’ substantial equivalency in the yachting sector. That equivalency was embodied in the REG Large Yacht Code and subsequent amendments, to which the PYA continues to contribute.

(iii) At the PYA we are often questioned as to whether we have ever asked the MCA to develop a mandatory certification regime for interior yacht crew, to raise their status alongside deck and engineering crew. We did ask, a long time ago. The MCA’s response was (and remains) that unless and until the IMO decides to expand STCW certification to include service crew across the maritime industry, there is no future in expending MCA political capital on the issue at the IMO.

Notwithstanding the MCA’s position, a PYA council member, with years of experience in deck and interior roles, decided anyway to launch a PYA nonmandatory training programme for interior crew. Any training centre that wished to participate had to abide by a defined syllabus and auditing of course delivery, including practical sessions. This GUEST (Guidelines for Uniform

Excellence in Service Training) scheme was soon recognised as an objective standard for assessing the level of training of interior crew. Although not mandatory, GUEST has always been fully supported by the MCA.

The GUEST programme was ultimately presented by the PYA to the board of International Association of Maritime Institutes (IAMI). IAMI members are MCA-recognised to teach the mandatory training modules which lead to deck and engineering COCs. The credibility attained by GUEST as the industry benchmark in non-mandatory training persuaded the IAMI board to bring GUEST under its aegis. Since then, the GUEST acronym has been altered to read Guidelines for Uniform Excellence in Superyacht Training, to accommodate the expansion into other departments (for example purser) and even on-shore positions.

An upcoming important IAMI/ GUEST addition will be our industry’s first courses in AV/IT training (with the PYA as a member of the founding work group). Notably, in anticipation of a future IMO STCW mandate regarding AV/IT training, the IAMI/GUEST AV/IT

We don’t rest on our laurels. The PYA digital Service Record Book (D-SRB) was launched four years ago, the first of its kind in the industry, and a fully digital Sea Service Testimonial was launched earlier this year, both with the approval of the MCA. Currently the PYA also has the MCA mandate for development of an upgraded fit-for-purpose digital training book (TRB) for deck crew, to be followed by the engineering TRB version. In 2024 the PYA was invited to join the Superyacht Alliance as a board member and can now represent its members at this important industry meeting of minds from all sectors of the industry. Returning to the opening paragraph in this article, in the past few days Elle Angeline Fisher has posted her own plea for mandatory criminal background checks on yacht crew. She has released an account of her experiences of severe sexual harassment during her yachting career. Her courageous account is certain to arouse a chorus of anger about the events and outrage over the weak responses.

Nothing excuses the perpetrators and her story cannot be trivialised. But how to respond? Not by going down the criminal background checks deadend. Let’s ask if it’s true that sexual harassment is “rife” within our industry. There have always been accounts of its occurrence. There is no measurable way of tracking its non-occurrence on secure yachts, so there is no percentage data about its level of frequency. Is it really a dark secret which pertains especially to yachting? Well, the Me Too movement did not spring from our industry. It spread across the entertainment, fashion, music, advertising and other worlds. It has been exposed in the UK’s Royal Air Force, in the United States Marine Corps and even in Antarctic research stations. It is globally endemic. The first step towards curtailment is exposure, which is harsh on victims who need support and justice.

The industry is not sustained by down-trodden wretchedly compensated crew. There is no yachting proletariat that needs to have its woes raised abroad by a workers’ council that sounds like something out of the Soviet Revolution.

Are there mechanisms already in place in yachting to address the problem? There is maritime legislation, there is criminal law and there is civil prosecution for compensation. The PYA and Nautilus listen and act within their own respective remits. There are voluntary support bodies such as ISWAN. There are mental health support groups which can be found within the Raising The Bar group. There are teachable methods to deter or defend against physical assaults. What is missing is education rather than more legislation.