The Superyacht Report

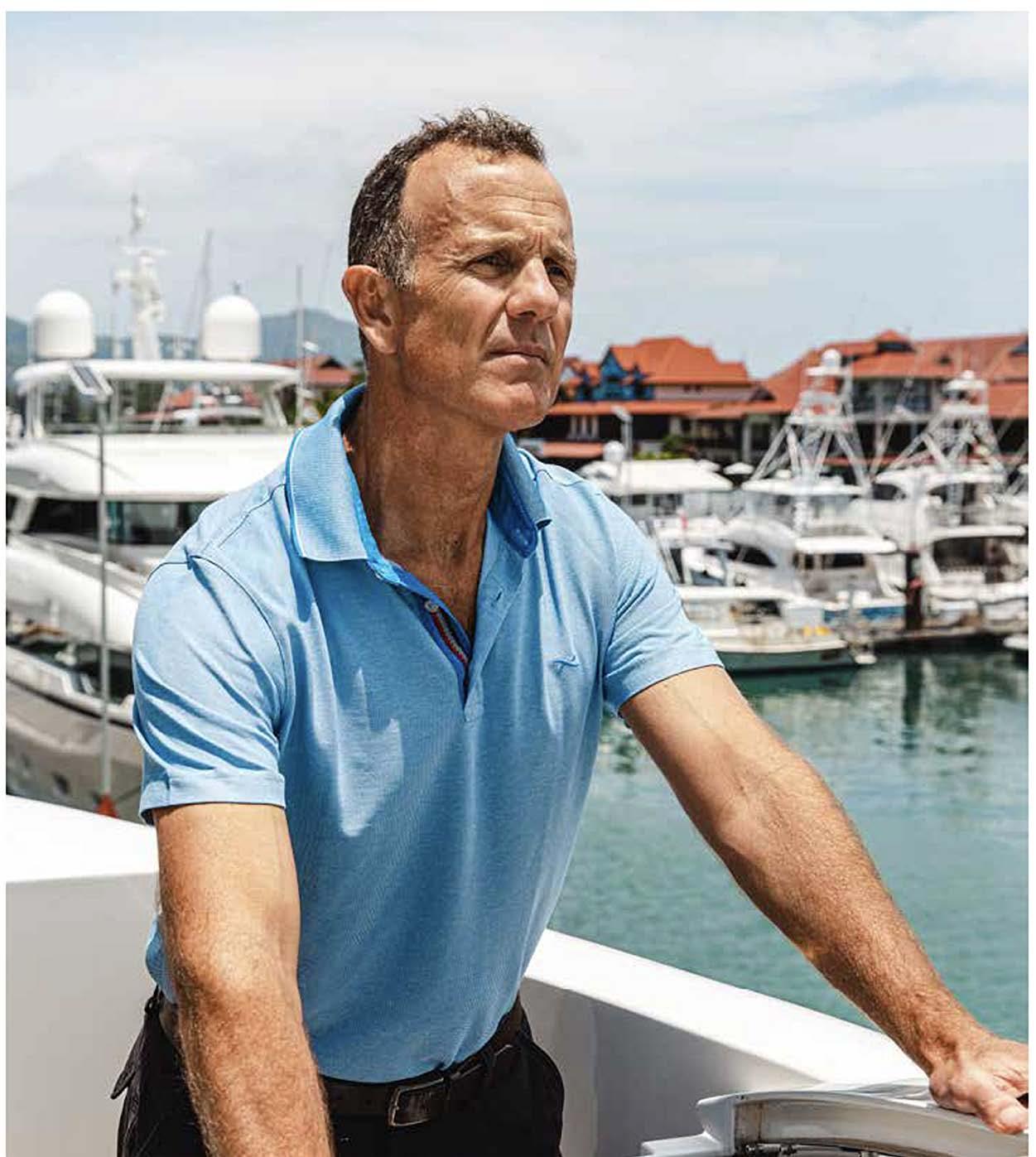

CALLING ALL CAPTAINS

Captains are the most vital on superyachts; their insights must shape yacht design through an anonymous, open communication platform.

Who is the most important person on board a superyacht? Now that’s an interesting question and no doubt plenty of people will say the owner but here’s a challenge to that obvious response. Yes, the owner has invested millions in buying their floating toy/asset and is the one that keeps the cashflow flowing every day and supports the industry with their demands and expectations, but they are only on board for several weeks a year.

Over the past 35 years I’ve met hundreds, if not thousands, of captains operating yachts of all shapes and sizes. Some I would describe as friends, others as confidantes and sounding boards for topics and questions. If you look at the sheer volume of captains events, captains associations and how captains have become valuable members of yacht clubs and other gatherings, it’s become more and more apparent that they are one of the most, if not the most, important people on board and carry a huge responsibility with their command.

So my title is ‘Calling all Captains’ for a simple reason, as I want to call on captains to share, communicate and challenge the industry to listen and learn from their experience and expertise.

BY MARTIN H. REDMAYNE

I was having lunch with a captain from Brazil with a South American first-time owner and he shared some horror stories in strict confidence, which I have to respect, but the basic premise of the conversation related to poor build quality and lack of storage and operational setup to allow him and the crew to deliver what the owner was buying into.

The message was clear: in the size category between 24 and 40 metres, there were some significant shortcomings that would potentially drive buyers and owners away from yachting and never progress up the size categories. I’m looking forward to Cannes Yachting Festival this year to walk around a wide spectrum of the production superyachts to explore what he was saying.

Back to my calling out to captains: for

the past two decades we have asked captains to take part in confidential research as part of our Intelligence Consultancy, but now I want to give you an unfettered and anonymous voice/ channel to share your experiences and frustrations with the market – basically, looking at what works, what doesn’t and what needs to change. You are without doubt the key stakeholders in the firing line, literally, when the owner cannot get a hot espresso on the aft deck in the morning.

The objective is really simple … by inviting hundreds of captains to share their ideas, opinions and experiences related to how systems work, how yachts perform and what impact design or build has on their primary job of making the owner and their guests happy, we create a platform that other captains will appreciate, owners may enjoy and learn from, and the industry relishes as a learning platform. Too many yachts are designed and built based on a platform and with very little operational feedback on what really makes sense or without the knowledge of what was refitted or upgraded and why.

Over the next three months, we will be reaching out to our wide-reaching captains network and creating a communication channel/platform that is both private and exclusive, where captains can share their experiences, expertise, frustrations and examples of system failure or lack of intelligence when it comes to a design or build feature. We know you’re busy and juggling all the on-board balls, so the proposition is to share when it’s on your mind via WhatsApp, e.mail or an sms and we’ll follow up when the time is right. If you find you have time on the bridge or in your cabin to jot down your thoughts or what’s on your mind, even better, it only takes 10 minutes to record a voice note on your phone and send it.

‘Calling All Captains’ – you are, in our opinion, the most important people on board and we want to give you an open platform to say what you really think, with full anonymity. MHR

Keeping up appearances

A captain’s guide to exterior surface maintenance, by Rory Marshall, owner and director at Newmar Overseas.

Rethinking superyacht operations: a call for culture change

Christophe Bourillon, chief executive officer of the Professional Yachting Association, says that addressing the cultural gap between the standards owners apply in their corporate lives and those they bring to their yachts is essential for improving conditions at sea.

Bridging the gap: The human side of superyacht operations

Marianne Danissen, group head of yacht management, Camper & Nicholsons, explains how knowledge sharing can help alleviate the demands of crew life while raising industry standards.

Regulations and compliance –meeting standards that matter

The yacht industry is plagued with systemic issues that remain largely unaddressed. Emma Gillett, founder and CEO of SeaFeedback, raises a call for compliance to be held to a standard that must be met.

Brendan O’Shannassy has seen every side of the yachting ecosystem from Fremantle to the Austrian Alps. Now, he’s calling for a values-based revolution to future-proof the industry and reclaim its potential.

Baptism by fire and ice

Our intrepid News Editor learns the difference between Master and Captain – and the value of stabilisers in eight-metre waves.

A

insight from experienced expedition

Christoph Schaefer of M/Y V6’s exploits while cruising around Japan.

A deep dive into the drive to replace the endangered-teak supply chain with upcoming deck materials that are fast becoming the sustainable replacement options.

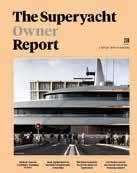

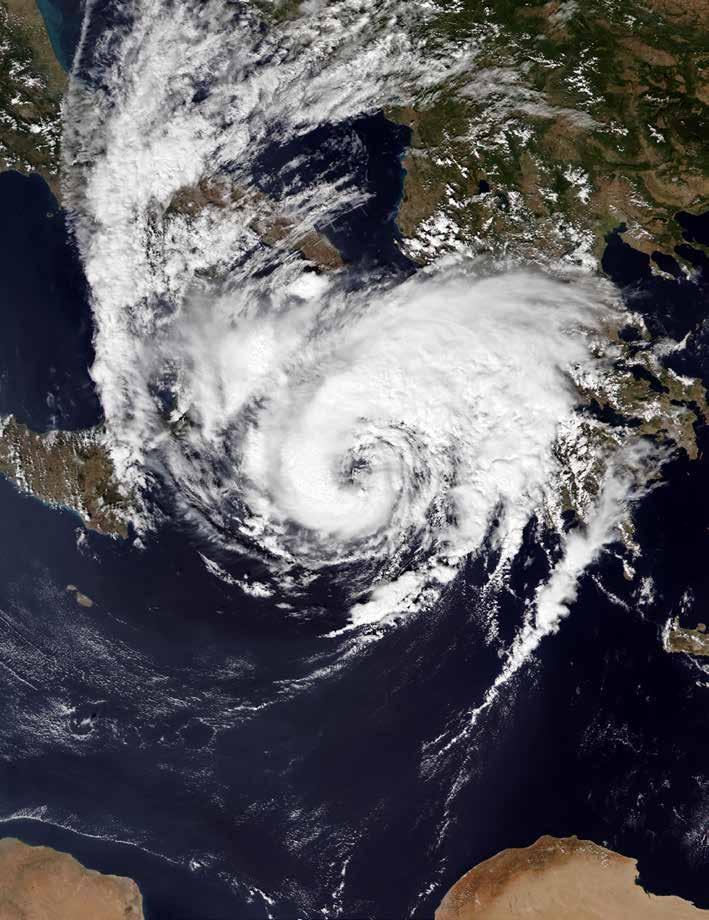

Martin H. Redmayne on the effect extreme meteorological patterns could be placing on super-sized sailing yachts like Bayesian.

We ask the question: who is shouldering the burden of training costs and career progression in 2025?

The Superyacht Report

QUARTER 2/2025

For more than 30 years The Superyacht Report has prided itself on being the superyacht market’s most reliable source of data, information, analysis and expert commentary. Our team of analysts, journalists and external contributors remains unrivalled and we firmly believe that we are the only legitimate source of objective and honest reportage. As the industry continues to grow and evolve, we are forthright in our determination to continue being the market’s most profound business-critical source of information.

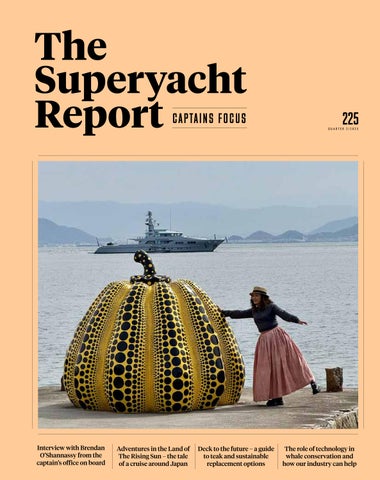

Front cover: Motoryacht V6 exploring Japanese shores. Full story by Captain Christoph Schaefer on pages 40-47.

Editor-In-Chief

Martin H. Redmayne martin@thesuperyachtgroup.com

News Editor

Conor Feasey conor@thesuperyachtgroup.com

INTELLIGENCE

Senior Research Analyst Amanda Rogers amanda@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Data Analyst

Miles Warden miles@thesuperyachtgroup.com

DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Content Manager & Production Editor Felicity Salmon felicity@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Guest Authors

Rory Marshall Owner and director, Newmar Overseas

Christophe Bourillon Chief executive officer, Professional Yachting Association

Marianne Danissen Group head of yacht management, Camper & Nicholsons

Emma Gillett Founder and CEO, SeaFeedback

Christoph Schaefer Captain, M/Y V6

Matthew Zimmerman CEO, FarSounder

ISSN 2046-4983

The Superyacht Report is published by TRP Magazines Ltd (trading as The Superyacht Group) Copyright © TRP Magazines Ltd 2025 All Rights Reserved.

The entire contents are protected by copyright Great Britain and by the Universal Copyright convention. Material may be reproduced with prior arrangement and with due acknowledgement to TRP Magazines Ltd. Great care has been taken throughout the magazine to be accurate, but the publisher cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions which may occur.

The Superyacht Report is printed sustainably in the UK on a FSC® certified paper from responsible sources using vegetable-based inks. The printers of The Superyacht Report are a zero to landfill company with FSC® chain of custody and an ISO 14001 certified environmental management system.

SuperyachtNews

Spanning every sector of the superyacht sphere, our news portal is the industry’s only source of independent, thoroughly researched journalism. Our team of globally respected editors and analysts engage with key decision-makers in every sector to ensure our readers get the most reliable and accurate business-critical news and market analysis.

Superyachtnews.com

The Superyacht Report

The Superyacht Report is published four times a year, providing decision-makers and influencers with the most relevant, insightful and respected journalism and market analysis available in our industry today.

Superyachtnews.com/reports/thesuperyachtreport

The Superyacht Agency

Drawing on the unparalleled depth of knowledge and experience within The Superyacht Group, The Superyacht Agency’s team of brilliant creatives, analysts, event planners, digital experts and marketing consultants combine four cornerstones – Intelligence, Strategy, Creative and Events – to deliver the most effective insights, campaigns and strategies for our clients. www.thesuperyachtagency.com

YOUR COATING CONSULTANTS

Follow The Superyacht Group channels on LinkedIn

@thesuperyachtgroup

@thesuperyachtgroup @superyachtobserver @superyachtagency

Join The Superyacht Group Community

By investing in and joining our inclusive community, we can work together to transform and improve our industry. Included in our Essential Membership is a subscription to The Superyacht Report, access to SuperyachtIntel and access to high-impact journalism on SuperyachtNews.

Explore our membership options here: www.superyachtnews.com/shop/p/MH

With over 25 years of experience, we have overseen more than 150 successful new-build and refit projects in all major international yacht locations. Trust us for state-of-theart materials, cutting-edge technology and unparalleled expertise. Guarantee a flawless finish with WREDE Consulting.

Can we afford not to?

Let’s preserve what inspired our passion

Discover our solutions to drive sustainability and improve value REFIT FOR THE FUTURE!

A BAPTISM OF FIRE AND ICE

Our intrepid News Editor learns the difference between Master and Captain – and the value of stabilisers in eight-metre waves.

We all have sliding-door moments, the kind that changes everything, often before we even realise it. Mine came in the form of a last-minute call and a berth on Hanse Explorer, an iceclass explorer superyacht bound for Antarctica with EYOS Expeditions. Less than 24 hours later, I flew to Argentina, preparing to cross the Drake Passage and travel further south than I’d ever imagined.

As a journalist, I’ve written thousands of words about expedition vessels, remote cruising and the evolving definition of adventure yachting, but nothing compares to experiencing it first-hand. What I found in Antarctica was a full-spectrum education in operational discipline, environmental humility and human resilience, all delivered in utter luxury in one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

For captains, officers, engineers and interior crew alike, there is no better classroom. But for a young journalist trying to find his sea legs for the very first time, it was a baptism of fire and ice.

When we first embarked aboard Hanse Explorer, we were met by Captain Andriy Bratash, Master Mariner and Ice Pilot – titles I would come to hold in the highest esteem by the end of the voyage. We exchanged pleasantries and I was also introduced to Chief Stewardess Iryna Roodt, both of whom I pestered for ten days straight with all the curiosity of a kid on a ship for the first time.

This was my first real experience of life aboard a yacht. The warmth, comfort and standard of service are far from what I was used to, but seeing under the hood, so to speak, changed everything. I arrived with a journalist’s curiosity and left with a deeper appreciation for the unspoken systems, soft skills and seamless communication that make expedition yachting work at this level.

The thing is, you do not just arrive in Antarctica. It has to be earned (if you opt to sail rather than fly, that is). The Drake is infamously precarious, and when Captain Bratash addressed us all for the first time in the salon, presenting the weather forecast for our two-day crossing, he was surprisingly chipper for someone who had just informed a boating novice and seasoned superyacht charterers that we would be experiencing two- to four-metre waves.

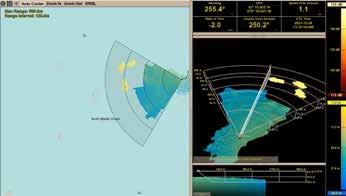

The charts showed an armada of green and yellow-backed arrows pushing against our position. Green is universally known as the ‘good’ colour.

By nightfall, the motion had arrived. It was gradual at first, a slow, creeping roll, then more assertive. Drawers creaked. Footsteps changed. People started reaching for handrails they hadn’t noticed earlier.

Yellow, of course, still suggests some degree of cautious comfort and warmth – but on the Drake, not so much. “At least it’s not purple”, we were assured.

That night, we slipped lines and set off through the Beagle Channel in blissfully still water. But by nightfall the following day, the motion had arrived. It was gradual at first, a slow, creeping roll, then more assertive. Drawers creaked. Footsteps changed. People started reaching for handrails they hadn’t noticed earlier.

However, operations on board felt fundamentally unchanged; the crew moved through it all, albeit perhaps waiting between dips and peaks for the opportune moment to cross the floor. With the stabilisers

Captain is a title you are given, Master is one you earn. Bratash was both. But it was telling that, even among the crew, the word Master came naturally. It was never performative, just unanimously understood.

adjusted for beam swell, the interior team moved like they had extra limbs. One hand for the tray, one for the rail, one for the guest. The cabinetry was secure, glassware double-wrapped. The motion was accounted for. Nothing wobbled, nothing spilled. If there was any stress behind the scenes, it never surfaced. Stabilisers quickly became my new favourite component.

I, on the other hand, found my feet surprisingly stable and made myself at home on the bridge, befriending Amnay Choukri, the 2nd officer on watch, as the roll of the waves began to intensify. It was Amnay’s first season with Hanse, having moved from commercial shipping to the vessel specifically to traverse the Drake – the dream for a seafarer who aimed to have sailed every ocean.

In fact, several of the engineers held Chief Engineer Unlimited tickets during their time in commercials. That level of experience is essential in Antarctica. Seawater cooling systems can freeze, insulation delaminates and fuel waxing becomes a genuine risk. Nothing is taken for granted. Amnay, who’d spent two decades at sea, complimented my calm, looked surprised, turned a little pale and politely excused himself. I pretended not to notice. That seemed like the right thing to do.

I was confused at first by how everyone referred to Andriy as Master, not Captain, as I’d expected. I assumed it was a quirk of formality or translation, But throughout the trip, I learned the distinction. Captain is a title you are given, Master is one you earn. Bratash was both. But it was telling that, even among the crew, the word Master came naturally. It was never performative, just unanimously understood. Every person I spoke to on board – deckhand, steward, officer – praised his technical ability and his courage, calm and deeply rooted sense of

empathy. He led in a way that didn’t need announcing; you just felt it.

That clarity of leadership became most evident when we reached the Weddell Sea. We entered through a tight belt of brash ice, with radar and visual lookouts working in tandem. The pack was dense and Andriy took us through at reduced speed, using slight rudder adjustments to keep the hull gliding cleanly between floes. Just constant low-voiced updates between bridge officers and deck crew, ice charts checked every few minutes.

This was the same region where Shackleton and his crew were trapped for months, their ship crushed and abandoned. Nearly every yachting journalist has quoted Endurance at some point. I never planned to join them. But standing on the bridge, watching Andriy navigate the same waters over a century later, it was impossible not to draw the line.

We moved through it with precision, nothing rushed, no guesswork. The ice sheets shifted ahead of us like pawns in a chess match he was already five moves into. And that kind of confidence doesn’t come from instinct alone, it comes from preparation, patience and absolute fluency in your environment.

Below deck, the same capability held. Every day had its theme, from Thai Jungle to German Oktoberfest or the final American barbeque. There was a rhythm to it all and a level of creativity that everyone

truly appreciated. The interior team used it to keep things fresh for guests, yes, but also for themselves. No two days felt the same as the landscape shifted around us all.

One of our final landings was Port Lockroy, signalling the crew’s last Antarctic stop of the season –a former British research station, now a museum, post office and gift shop, shared with several hundred Gentoo penguins. This time, guests, guides and crew all disembarked together. There were laughs, photos and postcards written. It felt like a small exhale on an intense few months for those on board. Not a closing ceremony as such, but a moment of shared arrival. Everyone was involved, everyone was present. It was the level of camaraderie I felt slightly honoured to see in person, having written about positive work cultures on board for some time.

On our last full day on the peninsula, we were treated to what our guides described as probably the best humpback whale sighting they’d ever had – their words, not mine. Communication across the boat was instant. The crew spotted movement from the bridge

and radioed it to the zodiacs already on the water. Some crews were with us in the tenders, sharing in the whole ridiculous experience, while others stood on deck with binoculars, watching us drift to within touching distance of a fully grown humpback.

Later, back on board – in the sauna, obviously –Andriy and I sat and debriefed on what had just happened. Then, because Antarctica is theatrical like that, another humpback breached right past the porthole. We just looked at each other and laughed. What else are you supposed to do? There was a real buzz on board. That kind of moment doesn’t happen every trip. And it didn’t feel like a ‘guest’ experience because everyone shared it. This felt like one of the rewards for all the hard work that had gone into getting there. That evening ended, as most good ones do, with penguin onesies and a jump into the icy water off the stern.

But the next day, it was time to head back to land. I’m told Shackleton used to serve drinks before breaking bad news. So it felt appropriate that Andriy handed out cocktails before presenting the forecast

Here’s what I really took away. In Antarctica, everything is tested: steel, systems and people. And what stood out most was how leadership filtered through the whole operation. It’s easy to think of leadership as a command, but down there, it looked more like consistency, empathy and trust.

for our return. Now, while red is generally a bad colour, purple is worse. And considering some guests had struggled when the charts were still green and yellow, there was understandable concern about how they’d fare this time.

One guest, who had become increasingly grumpy after being told he wasn’t allowed to pick up a penguin, insisted we were leaving a day early. Andriy calmly moved the forecast forward 12 hours and pointed at a screen that looked more like something from Prince’s wardrobe than a weather map. “We’re not leaving early,” he said, “we’re leaving on time.” And he was right, completely.

That’s what good captains do. They make calls that might not please everyone but keep everyone safe. And it’s not just about skill, but time, judgement and surrounding yourself with people who know their jobs and aren’t afraid to speak up. Leadership on Hanse Explorer was methodical, as it was collaborative and earned.

The return crossing was, bluntly, horrible. In sixto eight-metre waves, my sea legs gave up entirely. When I wasn’t curled in a foetal position in my cabin, I was back on the bridge for one last watch. Andriy and I talked about the stabilisers working constantly, rotating between six and eight degrees. I suggested that it felt like a lot. He laughed. “Before stabilisers,” he said, “we’d see forty-five. You’d be standing at the window, looking straight down at the sea floor.” I returned to my cabin shortly after.

Arriving back in Puerto Williams was bittersweet, of course. But I was very glad to see land again. For the crew, it marked the end of the Antarctic season. There was a real last-day-of-school feeling. The rain had passed, but the wind hadn’t. It was blowing hard enough that we couldn’t dock. The vessel sat at anchor in the bay, pinned at an angle by the gusts, swinging gently but constantly.

Most people at this point would call it. But most people aren’t sailing the roughest ocean on Earth as a day job. The American barbecue – originally planned for calm conditions and the aft deck – went ahead anyway. It was barbecue extreme. And, in many ways, a tasty testament to the crew’s refusal to let the weather dictate spirit, a fitting end to what had been a whirlwind of a trip and a deeply educational journey.

It also said a lot about the culture on board. Because here’s what I really took away. In Antarctica, everything is tested: steel, systems and people. And what stood out most was how leadership filtered through the whole operation. It’s easy to think of leadership as a command, but down there, it looked more like consistency, empathy and trust. Not just being in charge but just being someone others are willing to follow, especially when it’s cold, late and difficult. For captains, there are few better places to sharpen that than this.

And thank goodness for stabilisers. CF

SERVICING SUPERYACHTS ACROSS

With shipyards and service centres in Malta, Greece, Cyprus and France - Melita Marine Group is perfectly positioned to support superyachts wherever they cruise. This prime positioning gives us unmatched access, speed and flexibility for superyacht refit and service. Wherever you are in the Med, world-class support is always within reach.

Melita Marine Group, Malta info@melitamarinegroup.net melitamarinegroup.net

MPD info@melitapower.com melitapower.com

SERVICING SUPERYACHTS ACROSS THE MEDITERRANEAN

WORLD-CLASS SUPERYACHT SERVICES IN MALTA AND GREECE – WHERE ENGINEERING PRECISION MEETS A PASSION FOR THE SEA.

Melita Marine Group began with a simple ambition in 1989: to provide a reliable Agency and Repairs for yachts in Malta. In 1998, the company started to expand with various acquisitions over the years, today operating in multiple locations in the Med employing hundreds of technical people in various trades directly.

From those early days, the group has evolved into a Mediterranean powerhouse, offering full-scale refit, repair and engineering solutions across Malta and Greece, Cyprus and now France. With the Malta facilities capable of servicing yachts up to 110 metres out of our in-water facilities and with a network of skilled professionals, Melita Marine Group (MMG) continues to grow while staying true to its roots.

Our commitment to quality has earned us industry accolades including the MTU Distributor of the Year across a number of years and Captain’s Recommended Service Awards. MMG proudly represents leading brands such as MTU, SCANIA, ALFA LAVAL and AWLGRIP – delivering precision, performance and passion across every project.

Melita Marine Group has grown into a Mediterranean leader in superyacht refit and repair. With our facilities in Malta our team provides a full-service offering for yachts up to 100m – from engineering and painting to bunkering and agency.

Backed by premium brand partnerships and award-winning service, we deliver quality, reliability and results.

MELITA MARINE SHIPYARD

At the heart of Melita Marine Group’s operations, our Malta shipyard offers full-scale refit, repair and maintenance for yachts up to 110m and 5,000 tons.

Backed by in-house divisions MPD Engineering in Malta, Greece and Cyprus, Melita Yacht Painters, and over 130 skilled professionals, the facility delivers every service from A to Z – including engine overhauls, teak replacement, painting, interior refits and complex conversions.

With one of the largest yachting docks in the Mediterranean, the yard is equipped with mechanical, electrical, steel, wood and upholstery workshops, as well as tender storage and ISPS/ ISO-certified infrastructure. Our project managers ensure seamless delivery on time and within budget – supported by trusted subcontractors and technical specialists available around the clock.

Agency Services

From berthing and bunkering to customs, concierge and technical support, Melita Marine Group offers 360° shore-based agency services to superyachts visiting Malta and beyond. With 24/7 availability and deep local knowledge, we anticipate needs before they’re asked.

Whether it’s securing berths in high-demand marinas, arranging customs clearance or coordinating provisioning, transport and crew support - we deliver with speed, precision and discretion. Our in–house teams and preferred partners cover every detail: itinerary planning, hotel and restaurant bookings, private travel, repairs, chandlery and freight logistics. No request is too small and no demand too complex. With over three decades of trusted service, we’re Malta’s leading partner for captains, owners and crew.

MPD

With over 5,000 sqm facilities in Malta, Greece and Cyprus, MPD Engineering is the exclusive distributor of RollsRoyce Power Systems, MTU and Detroit Diesel Engines. From sales and spares to overhauls and reconditioning, our expert teams deliver certified service and full support across the region. Whether it’s mechanical engineering, electronics or diagnostics, we specialise in complex engine projects on land, at sea and across defence, commercial, industrial and superyacht sectors.

Backed by decades of experience, global OEM certifications and industryleading technicians, we combine highperformance systems with preventative maintenance, genuine parts and cuttingedge digital solutions. Whatever the power challenge, MPD is ready.

GREECE

CYPRUS

ACROSS THE MEDITERRANEAN

Guest Column

by Rory Marshall

Keeping up appearances

A captain’s guide to exterior surface maintenance, by Rory Marshall, owner and director

at Newmar Overseas.

Maintaining a superyacht’s exterior is more than a matter of appearance, it’s about stewardship, operational foresight and delivering the standard of care expected by owners, guests and charter clients. Whether the vessel is heading into a high-profile season or laying up after extensive cruising, taking a methodical approach to coatings maintenance can preserve both value and visual impact – without unnecessary spend.

Here’s a practical guide to staying ahead of the curve.

1.Begin with a clear-eyed assessment Before any cosmetic work begins, take the time to assess the yacht’s current condition honestly and objectively. Regular exposure to UV, salt, washdowns and exhaust residues takes its toll, even on newer finishes.

An independent coatings survey can identify subtle signs of wear that may escape routine checks – like early dulling, mechanical abrasion or contamination build-up.

Objective readings for gloss levels, delamination risks and surface integrity provide a solid base for prioritising maintenance actions and setting

realistic expectations with owners and shipyards.

2.Gloss and colour uniformity: tracking what the eye sees Gloss and colour retention are key indicators of coatings health, but they can decline faster than expected in sun – in heavy cruising regions like the Med and Caribbean. Issues such as streaking, micro-oxidation or uneven polishing often develop gradually.

Captains should aim to benchmark gloss levels across exposed zones annually. If readings drop significantly from known baselines, it may indicate early system fatigue, especially on newly painted vessels still under warranty.

3.Routine washdowns: protect, don’t diminish

Regular washdowns are essential but done improperly, they can cause long-term damage. The right technique protects coatings; the wrong one creates dull patches, swirl marks or even micro-cracks.

Best practice reminders:

• Use soft, approved materials: microfibre mops and pH-neutral detergents.

• Avoid aggressive brushes, pressure washing or solvent-based cleaners.

• Rinse and dry thoroughly to prevent mineral spotting.

• Work top-down, using clean equipment for each section.

Crew training and standardised washdown protocols go a long way towards extending the life of the coating system.

4.Spot repairs: know the limits

Quick touch-ups can be tempting midseason, but poorly matched spot repairs stand out just as much as the original damage. Without controlled conditions and experienced hands, feathered edges or gloss mismatches can draw the eye in the worst way.

Maintain a detailed paint log with product codes, batch numbers and application methods. For anything outside minor scuffs, bring in a specialist. It’s a more cost-effective decision in the long run than redoing an entire panel later.

5.Managing soot and exhaust residue

Exhaust soot is a slow, corrosive threat, particularly on white or light-coloured surfaces. It not only stains but can etch into the topcoat if left unchecked.

Many marine coatings warranties now come with strict stipulations around cleaning agents, inspection intervals and restricted maintenance techniques. Falling outside these terms, even unintentionally, can void protection.

Strategies to consider

• Regularly monitor exhaust behaviour and optimise burn conditions.

• Consider water injection or filtration systems where feasible.

• Apply sacrificial coatings in vulnerable zones.

• Schedule soft, post-transit cleanings to prevent build-up.

Staying on top of this reduces longterm cleaning costs and preserves topcoat integrity.

6.Polishing: where less is often more Polishing restores gloss but also removes clearcoat with every pass. Over-polishing accelerates system breakdown and leads to expensive repaint cycles well ahead of schedule.

Recommendations:

• Polish only when needed – ideally post-season or pre-show.

• Use only approved materials and document each session.

• Avoid machine polishing unless done by experienced professionals.

• Focus on isolated dull areas rather than uniform polishing.

For vessels repainted within the last two years, always consult the applicator or

coatings supplier before any polishing programme is introduced.

7.Don’t neglect the details

The visual effect of a well-maintained yacht is holistic. Small areas – locker interiors, fairleads, davit arms, garage bays and deck fittings – can quickly fall behind. These spaces are often the first to show wear and can undermine the impression of overall condition.

Including these in your regular visual walkthroughs and crew checklists ensures consistency and highlights care across the vessel.

8.Documentation matters, especially under warranty

Many marine coatings warranties now come with strict stipulations around cleaning agents, inspection intervals and restricted maintenance techniques. Falling outside these terms, even unintentionally, can void protection.

Keep structured records of all surfacerelated work, including:

•Inspection reports

• Cleaning schedules and materials used

•Polishing activities

•Any repairs or modifications

If there’s ever a dispute, a clear paper trail goes a long way toward defending your position – and your owner’s investment.

Conclusion: Excellence in the detail

For captains, maintaining a yacht’s exterior isn’t about polish for polish’s sake, it’s about smart asset management, protecting the owner’s investment and presenting a vessel that reflects professionalism at every level. With the right practices, timing, and support, you can deliver both visual impact and long-term coatings performance – without overspending. RM

Leading provider of luxury outfitting for yachts, hotels, private aircrafts and homes.

Streamlined Service

We offer a complete customer experience with historical purchase information, billing and quotations. Enabling a simple reorder process and removing the need for multiple suppliers. We offer storage service and inventory control assistance.

In-House Design

Our interior designers will help you with all aspects of a project. From reviewing the finer details to implementing a major refit. Our graphic designers will assist with branding, logos and supporting artwork.

Industry Experts

Backed by 20 years of experience in the yachting industry, we work with the best brands and artisans to ensure that only excellent results are delivered to our clients. We offer free advice and consultancy to make sure our clients take the right decisions.

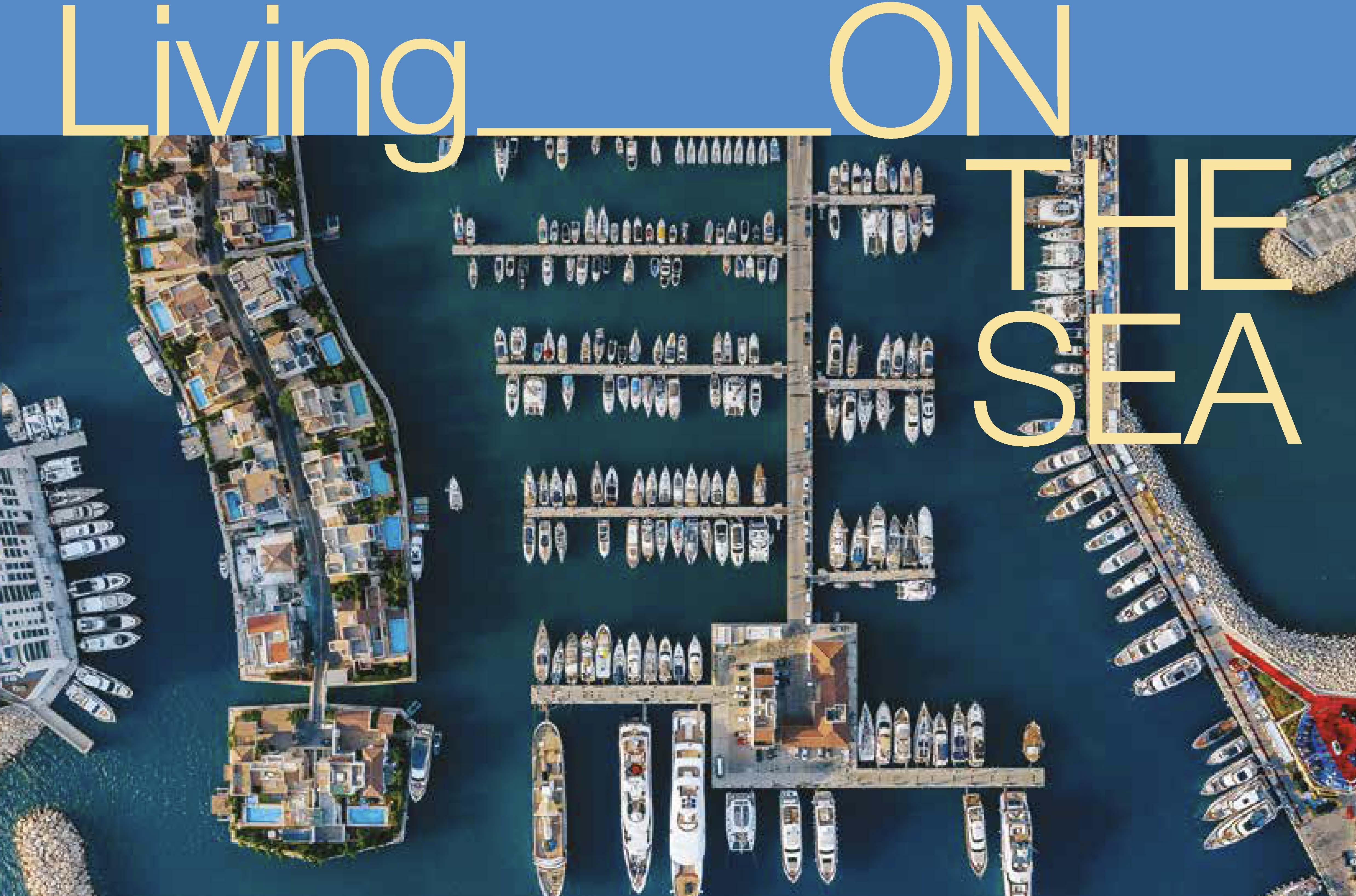

Future-proofing marinas

Marinas of the future

BY MARTIN H. REDMAYNE

What captains and marina managers expect.

Prior to the recent Balearic Superyacht Forum, we conducted a brief survey of the market to find out what captains, managers and senior crew wanted from the Mediterranean marina landscape, from a future-proofing perspective. This drove much of the discussion and debate in the Keynote Session in late April, with technology, energy, waste, training and education being at the forefront of their expectations. Some of the key survey comments included:

• A significant reduction in administrative response times in the authorisation processes for investment in the redevelopment of existing concessional facilities

• Communication. A basic requirement in doing business that is rarely achieved by many European marinas. Clear, accurate and timely communication around bookings, services available during a stay, H&S requirements, events happening in and around the marina, and onshore support is essential.

• Digitisation & AI-powered marina management. Develop a Mediterraneanwide digital platform that integrates real-time berth availability, automated docking systems and predictive maintenance using AI. This platform could also include a dynamic pricing model, like the airline industry, adjusting berth costs based on demand and seasonality. Impact: Increases efficiency, improves customer experience and maximises marina profitability.

• Develop multi-use marinas that offer offseason experiences, such as waterfront co-working spaces, maritime innovation hubs, winter boat storage and maintenance packages, and wellness tourism. Impact: Reduces reliance on peak summer months, increases marina profitability, and creates a more resilient business model.

• Improve waste-disposal systems with better recycling facilities, hazardous waste handling, and wastewater-treatment plants tailored to yachting needs.

• Sustainability and green initiatives. Eco-friendly marinas: implementation of solar, wind and water energy solutions for marina operations.

Waste management: Better systems for handling wastewater, oil spills,and plastic pollution.

Electric and hybrid boat support: Expanding infrastructure for electric charging stations and incentivising green boating.

• The provision and placement of cleats and power boxes on a dock should always be adequate for a number of different scenarios. All yachts have different layouts for their decks so there is no one solution fits all but more bollards on the dock are always useful.

This is a sample list of fundamental topics (there are many more from the research) that need addressing and exploring as marinas are often not fit for purpose and investors are not willing to upgrade quickly enough, due to concession limitations. Having been involved in various marina developments around the

Craftmen’s village, Port Vauban, constructed in 2023, includes workshops for nautical professionals, a shipchandler, showers and a restaurant.

world, as a strategic consultant, advising on financial models, operations and infrastructure, it’s become a key part of our consultancy focus, as the market is changing dramatically, yet marinas often can’t keep up with the pace. Having sat on stage at both the YARE and Balearic Forums, with a variety of marina management, specialists and investors, the future of marinas is a major debating topic, especially in the Mediterranean, where capacity and demand are heading in a critical direction.

INVESTING, BUILDING AND OPTIMISING

MARINA INFRASTRUCTURE FOR THE FUTURE

The main hurdle for the traditional approach to BIG marina investment in infrastructure comes from the investors needing a longer (infra-style) view on returns, the kind they can have on freehold but are difficult in short-term concessions.

While this is very logical, what we are actually seeing is that concession issuers haven’t identified a clear way to calculate and value new longer-term concessions to attract the investment. It’s not impossible to achieve, because if we wind the clock back 30 to 40 years there was a clear calculation of term based on the infra capex required, giving the investor the chance to make their investment work for them. Currently with the confusion around how concessions are calculated by region, let alone nationally the desire to reinvest in ageing or no longer ‘to spec’

infrastructure is blocked by the fact that the sums won’t add up.

More work needs to be done to help, advise and raise awareness of the sector to national policy makers so that they can create infra-investment agreements that benefit all stakeholders.

REVIEWING THE LAYERS OF CUSTOMER

This is indeed our day job and we should know intimately what is required for each customer type. Do we though? If we believe that our personal experience alone is the answer, then we’re on the back foot. Any specialised industry that has fewer than 50 to 100 experts globally can’t afford to not write things down and start to educate others … collaborate, collaborate and collaborate some more. If we believe that our personal knowledge is our competitive advantage, then we might have a problem. Are we afraid to feed our knowledge, customer feedback into some AI engine that will educate everyone to progresses the sector? Maybe some are, but what will they do if someone does create this customer knowledge bank?

OPTIMISING AND IMPROVING THE BOOKING AND OCCUPANCY MODEL WITH A DISCUSSION ON TRANSPARENCY AND PRICING

I’ll comment on this in reverse… Pricing – how do you set a price for a 100-metre megayacht to stay overnight, plug into some huge power, have traceable waste collection, ISPS security,

vehicle access, the ability to bunker fuel, maintenance and provide the crew with an attractive environment, in the most desirable and valuable real estate locations in the world? The same applies for anything above 30 metres, by the way. Transparency – If we believe everything that everyone tells us then all agencies and captains know the prices of every marina because they all talk to each other, that’s quite transparent ... Or everybody is looking for some sort of special requirement, is trying to negotiate ‘any rate’ because they have to manage their own yacht ops budget? Or marinas will negotiate each deal based on how much they need the boat? It will be one of these three that will make it difficult to achieve sector transparency. Booking and berth availability – If you’re a single operator then it's difficult to justify the investment to digitise. With a single marina there is either a diary or an Excel, maybe even a berthing board that will be checked to know if a berth is free. If the team don’t know what’s going to be available, they won’t be able to tell the customer. It takes investment in process, team training and then digital investment to have a solution that a customer would recognise as a real booking system.

EXPLORING WASTE MANAGEMENT

This is an interesting one because like anything that really works, you need to measure and manage the solution and for commercially minded people

it’s quite difficult to get their heads around investing in something that the yacht throws away. But we must. Just like resorts, hotels and yachts, waste is inevitable and having a solution is a must. The best way to prove that we do this well is to measure our performance by subscribing to a performance standard.

BUILDING AND DEVELOPING THE SKILLS AND CAPACITY FOR THE FUTURE

A little bit like point 2, some of us might believe that our expert knowledge is our competitive advantage. Well, let’s see how long that can be strung out. The reality is that unless a sector can attract high quality people they will eventually run out of good guys and girls and the sector will shrivel. I like the US NMMA ‘discover boating scheme’ as it promotes boating in general but also raises awareness of the sector so that people understand that there is a career opportunity in the sector. Maybe it’s time to promote careers in marinas, collectively?

SAFETY, SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT, AND CAN SMART HELP?

Safety comes from an acute understanding and awareness of the risk; if you don’t have this then no amount of SMART tech is going to help. If you do know your biggest risks and you’ve built a process and a working solution to mitigate the risk then SMART tech is a real turbo boost for your safety performance. D-Marin have an aspiration to lower the risk of fire and sinking to the lowest possible level

and sensors help them to do that, silently monitoring the situation 24/7 and alerting the team prior to the issue escalating.

FUELS, ENERGY, SIZE, SCOPE AND TECHNOLOGY. ARE WE DEVELOPING AND EXPANDING MARINAS FIT FOR THE FUTURE FLEET?

A HUGE question and a Think Tank Session all by itself. Refer to point one for the beginning of this answer. There are isolated examples of this happening, D-Marin's collaboration with Azimut| Benetti, for instance, gives them insight into what the yards are building based on their customers’ requests. With this knowledge they can create appropriate facilities with the correct fuel solutions. Marinas are not just centres of luxury and recreation, they are also highly concentrated sources of pollution. Despite growing environmental awareness and regulatory pressure, wastewater disposal, plastic pollution and hazardous waste management remain some of the biggest environmental failures in the yachting sector.

THE HIDDEN PROBLEM: UNSUSTAINABLE WATER CONSUMPTION

One of the most overlooked environmental issues in marinas is their excessive use of municipal potable water for boat cleaning and maintenance. Every day, thousands of litres of fresh drinking water are wasted on hull rinsing and deck washing, often in regions already

facing water scarcity. This practice is not only environmentally irresponsible but also economically inefficient, increasing operational costs and placing additional strain on local water resources.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: A WASTE CRISIS BELOW THE SURFACE

In addition to unsustainable water consumption, marinas face broader waste and pollution challenges that directly impact marine ecosystems and the industry’s reputation:

• Lack of proper grey-water and blackwater treatment facilities, leading to silent pollution in key yachting destinations like the Mediterranean.

• Insufficient waste segregation systems, resulting in plastics, oil and other hazardous materials contaminating local waters.

• Inefficient bilge-water management, llowing fuel and oil residues to seep into the environment, harming marine biodiversity.

• Poorly managed recycling programmes, failing to divert waste away from landfills and incineration.

A CALL FOR SMARTER WASTE AND WATER MANAGEMENT

If the yachting sector is to maintain its environmental credibility and avoid harsh government-imposed restrictions, marinas must adopt bold, scalable solutions that:

• Reduce reliance on potable water for yacht maintenance, implementing seawater filtration, rainwater collection and water-recycling systems for vessel cleaning.

• Upgrade wastewater treatment infrastructure, ensuring all marinas have modern grey-water and black-water

processing facilities to prevent pollution.

• Improve waste segregation and hazardous material disposal, establishing efficient collection, treatment and recycling pathways for plastics, oil and toxic waste.

• Implement smart water and wastemonitoring systems, providing real-time tracking of environmental compliance, reducing regulatory risks.

THE INDUSTRY MUST ACT – NOW

The time for symbolic sustainability efforts is over. Marinas must transition from reactive to proactive environmental management, treating waste and water efficiency as core operational priorities rather than afterthoughts. If the industry fails to self-regulate, stricter governmental policies will inevitably force compliance – at a far greater cost.

The question is not whether marinas need to change, but who will take the lead in making sustainability the new standard.

Marinas are among the largest energy consumers in the maritime sector, relying heavily on fossil-fuel-based power grids while serving an industry that increasingly markets itself as sustainable. This contradiction is both glaring and unsustainable.

Despite the rapid advancement of solar, wind and hydroelectric energy technologies, most marinas have failed to integrate renewable solutions at scale. The infrastructure to support hybrid and electric vessels remains inadequate or entirely absent in many prime yachting destinations. Key challenges include:

• Lack of charging stations for hybrid and electric yachts, limiting the transition to greener propulsion.

• Outdated or insufficient shore power infrastructure, forcing yachts to rely on

Marinas are among the largest energy consumers in the maritime sector, relying heavily on fossil-fuel-based power grids while serving an industry that increasingly markets itself as sustainable. This contradiction is both glaring and unsustainable.

on-board generators, increasing emissions in ports.

• Minimal investment in renewable energy projects, despite growing pressure from regulators, yacht owners and environmental groups.

TRANSFORMING MARINAS INTO SELFSUFFICIENT ENERGY HUBS

To bridge the gap between sustainability goals and real-world implementation, the industry must rethink how marinas generate, distribute and store energy. Future-ready marinas could:

• Integrate floating solar farms, harnessing solar power from marina basins and coastal waters to generate clean energy.

• Expand shore power infrastructure, ensuring all berths, especially for superyachts, offer high-capacity connections to reduce emissions in port.

• Develop hydrogen and biofuel bunkering stations, preparing for next-generation propulsion systems that will replace diesel.

• Implement smart energy grids, optimising energy consumption by balancing renewable inputs, yacht energy demands and marina operations.

A NEW BUSINESS MODEL FOR SUSTAINABLE MARINAS

The transition to zero-emission marinas is not just an environmental necessity, it’s an economic opportunity. Sustainable energy integration can:

• Reduce long-term operational costs by cutting reliance on traditional power grids.

• Attract eco-conscious yacht owners looking for greener destinations.

• Align with global environmental regulations, securing government incentives and avoiding future restrictions.

• Enhance marina competitiveness, positioning them as leaders in sustainability-driven innovation.

A CALL TO ACTION FOR THE INDUSTRY

The time for small-scale pilot projects is over – marinas must embrace largescale renewable energy integration to stay ahead of regulatory and market demands. The question is no longer if this transition should happen, but who will take the lead in redefining marinas as self-sufficient, energy-efficient hubs for the future of yachting. Who is ready to drive this transformation? MHR

Guest Column

by Christophe Bourillon

Rethinking superyacht operations: a call for culture change

Superyacht operations are at a crossroads. As vessels grow in size and complexity, the demands on captains and crew have never been greater. Yet a persistent cultural gap exists between the standards owners apply in their corporate lives and those they bring to their yachts. Christophe Bourillon, chief executive officer of the Professional Yachting Association, says that addressing this disconnect is essential for improving operations, safety and working conditions at sea.

The double standard: yacht vs aircraft

Many superyacht owners are CEOs of global corporations, accustomed to rigorous standards in human resources, sustainability and corporate responsibility. However, when it comes to their yachts, these same individuals often treat the vessel as a private bubble, exempt from the rules and respect they uphold elsewhere. This is starkly evident in the way captains are treated compared to aircraft pilots.

It is all about ’professional respect’. Owners rarely question a pilot’s authority on safety, weather or technical issues, yet may pressure yacht captains to take risks or overlook fatigue and unresolved problems. This double standard undermines safety and morale, especially as yachts become more complex and the consequences of poor decisions more severe. This leads to ‘operational pressure’ and a number of

captains do report being asked to depart in unsafe conditions or with tired crew –requests that would be unthinkable in aviation. This not only endangers lives but also erodes the professional standing of the captain.

Bridge design: aesthetic vs functional Unlike aircraft, where cockpit design is standardised and certified by test pilots for safety and ergonomics, yacht bridge design is often dictated by aesthetics. This can lead to non-standardised layouts whereby controls and displays may be placed for visual appeal rather than operational efficiency, increasing the risk of error.

The same goes with the drive for a paperless bridge : the push for digitalonly navigation, without adequate backup or training, can create vulnerabilities. Regulatory bodies like the Red Ensign Group are beginning to address these

issues, but more industry-wide focus is needed.

The evolving role of the captain Today’s superyacht captain is far more than a seafarer. As yachts grow larger, captains must act as CEOs, managing multi-million-dollar assets and large teams; HR managers, handling recruitment, training and conflict resolution; mental health counsellors, supporting crew welfare in a high-pressure, isolated environment; and crisis managers, prepared for emergencies ranging from technical failures to medical incidents.

However, most captains receive little formal training in these areas. Leadership, crisis management and mental health support should be core components of captaincy training, not afterthoughts.

By respecting the professionalism of captains and crew, prioritising safety and welfare, and embracing innovation, the industry can ensure that superyachts remain not only symbols of luxury but also models of operational excellence and responsible leadership.

Crew welfare: beyond minimum standards

While regulations like the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) set minimum standards for accommodation and working conditions, compliance alone is not enough. The reality for many crew members includes long hours and job insecurity. Despite the glamorous image, crew often work extended shifts with little downtime, leading to fatigue and burn-out, along with mental health challenges, where isolation, high expectations and lack of support can take a toll.

Proactive measures – such as access to counselling, better connectivity and structured time off – are essential, as are professional development – crew need clear career pathways, ongoing training (onshore and especially on board) and recognition for their contributions. This not only improves retention but also enhances operational excellence.

The need for a culture shift

To truly improve superyacht operations, a fundamental culture change is required.

Respect for professionalism: Owners must treat captains and crew with the same respect and trust they give to other professionals, like pilots or senior executives. This means deferring to their expertise on safety and operational matters.

Adoption of corporate standards: The best practices owners use in their businesses – transparent HR policies, sustainability initiatives and social responsibility – should be applied on board. This includes fair contracts, diversity and inclusion, and environmental stewardship.

Collaborative design: Involve captains and senior crew in bridge and systems design to ensure functionality and safety are prioritised over aesthetics.

Embracing technology and data: Technological advancements offer opportunities to enhance operations and working conditions:

•Smart yachts: IoT [Internet of things] devices and data analytics can optimise maintenance, improve safety and reduce crew workload by automating routine tasks.

•Predictive maintenance: Data-driven approaches anticipate equipment failures, minimising downtime and stress for crew.

•Sustainable operations: Innovations in energy efficiency and waste management not only benefit the environment but also align with the values many owners espouse in their corporate lives.

Recommendations for change

Mandatory leadership and crisis management training: Make these skills a requirement for captains and senior crew.

Standardise bridge and crew cabin design: Develop industry-wide guidelines, with input from operational professionals, to ensure safety and usability and appropriate crew rest.

Enhance crew welfare: Go beyond regulatory compliance by providing mental health support, fair working hours, and career development opportunities.

Transparent communication: Foster open dialogue between owners, captains and crew to build mutual respect and understanding.

The superyacht industry stands to benefit enormously from a culture shift that aligns on-board operations with the high standards owners uphold elsewhere. By respecting the professionalism of captains and crew, prioritising safety and welfare, and embracing innovation, the industry can ensure that superyachts remain not only symbols of luxury but also models of operational excellence and responsible leadership.

Owners should see their yacht as an extension of their corporate values, not an exception to them. CB

Interview with Captain Brendan O’Shannassy

The value in crisis

Brendan O’Shannassy has seen every side of the yachting ecosystem from the America’s Cup in Fremantle to the Austrian Alps. Now, he’s calling for a long-overdue reckoning to topple false idols; a values-based revolution to future-proof the industry and reclaim its potential. His interview isn’t from an office in yacht management or brokerage, it’s from the captain’s office on board – he speaks with passion of still loving (almost) every day in command at sea.

BY CONOR FEASEY

Captain Brendan O’Shannassy doesn’t deal in vague ideas. After decades at sea running some of the fleet’s most iconic yachts, he’s had time (and reasons) to question how the industry actually works and how much of it still doesn’t. Now based in the Austrian Alps, O’Shannassy has gone off piste, trading Fremantle’s Indian Ocean breeze for alpine air, operating ski apartments when he’s not sailing as captain on a leading charter yacht.

At first glance, it’s an unusual turn. From dive shops and naval service to the helm of superyachts up to 10,000gt, his career has always revolved around structure, service and the people who deliver both. That full-circle journey gives him a rare vantage point, one that sees through the Potemkin village and speaks plainly to the gaps. With calm, precise conviction, he’s calling time on the blind spots and inefficiencies that no one else seems willing to touch.

“Over the past two decades, we’ve massively increased what yachts can deliver,” he explains: “spa treatments, fitness installations, multiple and larger tenders, watersports centres and of course now the padel court. The experience has gone up tenfold and really it’s a great compliment to the designers and builders. However, we’re still operating under the same manning model as we did twenty years ago. It’s just not sustainable. We’re asking more from the platform, more from the crew, more from the design, but we haven’t changed the way we operate. And that gap is getting harder and harder to square.”

And it’s this seemingly widening crevasse between capability, culture, service and structure that O’Shannassy has spent a career navigating. But his journey into yachting and the insight that came with it began long before he ever stepped foot on board.

The foundations

Born in the coastal town of Fremantle, Australia, the son of hoteliers, a young O’Shannassy spent his youth diving, sailing and racing boats, spending any pocket money he had in the local dive shop. By the time the America’s Cup came to town in 1987 (the result of Australia II winning the Cup in 1983, breaking the New York Yacht Club’s 132-

year winning streak), the dream of a life at sea had already taken hold.

Just like the most recent return, the America’s Cup arrived in the middle of a recession and bleak job prospects for young people. So, although he was studious, bright and ambitious, instead of following the conventional route through university, he joined the Royal Australian Navy through a programme that combined officer training with a formal degree. It was a disciplined environment that provided realworld experience and responsibility from the outset.

“I really enjoyed my time there. I travelled, learned a lot and completed my sea service, but after a decade, I realised that the good times were over in a way. Until that point, it was fun, but the ten years right ahead of me looked like serious administration,” he recalls. “So I left and went to commercial shipping and had to go back to scratch because the recognition of naval qualifications wasn’t in place.”

It was a grind, but a formative one. Over the next several years, he worked his way up through tugs, barges and offshore vessels across the Pacific and northern Australia, eventually gaining his Master Unlimited ticket. It was here that he also received training as an operator, rather than just a navigator. Yachting entered the picture unexpectedly in 2001, but at just the right time.

“I’ve had countless awkward conversations with disappointed owners who don’t understand why we’ve got five tenders and you can only run two at the same time. They rightly want to understand why their boat doesn’t function as they’ve imagined.”

The journey to private yachting

An old friend from the Fremantle dive shop had become a chief engineer and offered him a deckhand position. That was it. No promises, no fast track. “That’s all I’ve got. It’d be great to spend some time together again,” the friend had said. O’Shannassy took it. “It was what was on offer, and I was ready for something different,” he says. “Commercial maritime had taught me a lot about operating vessels. Yachting was about people, meeting owner expectations, logistics and learning it all on the fly.”

He moved quickly from deckhand to bosun to second officer, but the inevitable discovery of his Master Unlimited ticket changed everything. In 2006, a crew agent put him forward for a role that marked a turning point. At the time, the 126-metre Lürssen Octopus was one of the largest and most technologically complex vessels in the world and was still very much finding its sea legs, but taking the helm as co-captain was a welcome challenge for the ambitious Aussie.

The early impression was that it leaned too far towards a cruise ship, all scale, not enough soul. “It was big and new and no one was sure how to work,” he says. “So I skippered Octopus with the mandate of making it more like a yacht.” Bringing it in line meant adjusting service expectations and finding a yacht rhythm inside a 126-metre hull. It worked and it shifted his entire trajectory. “I allowed myself to be funnelled into that bigger yacht space. So that has driven my career, that I’ve been in the plus 3,000-ton area. Bigger isn’t better, it’s just where I landed.”

From then on, he was part of a rare subset of captains trusted to run some of the biggest platforms afloat, not just from the bridge but from the moment the first lines were drawn. Projects like Vava II, Amadea and Andromeda followed,

with ambition and complexity becoming the common thread among shipyards, owners, and crews. And with them came the same pressure to bridge capability and consistency, experience and execution. O’Shannassy’s prowess in these has become bread and butter.

The infrastructural issues

Now, most of us would agree that a lot has changed since the mid-naughties. Flip phones aren’t as cool as they used to be, AIS wasn’t a given and neither was a helipad, but yachts are now infinitely more capable, more complex and more luxurious than ever before. O’Shannassy has seen expectations in the industry skyrocket in tandem. Owners demand more, guests want more. But underneath all the shiny surfaces and cutting-edge tech, the same basic structures that the industry had 20 years ago remain. And, according to the industry vet, this is the fundamental root cause of most operational issues across the fleet and needs to be addressed.

The result is a kind of operational dissonance. Yachts that have evolved in virtually every facet and by every metric but are still run as if they haven’t. “A 45-metre from the mid-90s had 15 crew,” O’Shannassy says. “Now a 50-metre has eight or nine and is far more capable. It’ll have a spa, some specialised feature, and the same crew is expected to run all of it. That can’t be right, can it?”

It’s a pattern he’s seen time and again. Yachts built to impress at the dock in Port Hercule but not equipped to function at sea. “I’ve had countless awkward conversations with disappointed owners who don’t understand why we’ve got five tenders and you can only run two at the same time. They rightly want to understand why their boat doesn’t function as they’ve imagined,” he says.

“Across all the anchorages – from St Tropez to St Barts, from Portofino to Palau – the refrain on board is, ‘We need more crew’. There is a commercial and real-estate barrier to this and it’s not the silver bullet crew think it is. When they sing ‘more crew’ what they are really saying is ‘more efficiency’. We need the yachts to have built-in efficiencies to help us deliver what we should.

“In some cases, the inefficiencies are so embedded they’re just accepted. During stores, I’ve joined the line of 30 crew members, carrying provisions down into the boat, for a total of two hours of manual lifting. That’s 60 labour-hours just to put the food away, oh and about half again to carry the waste packaging/product off. Why couldn’t it be prepackaged, sized for storage and delivered through a purpose-built loading bay? It still doesn’t. It’s these kinds of tweaks that seem superficial at first glance but are imperative to operational efficiencies that satisfy our patrons.

“Part of this efficiency drive is to remove as many functions that can be done by a shore office. We should not be managing the plane, while flying it. The guest-use days could/should increase and the ‘downtime’ requests decrease.”

“Real operational feedback rarely reaches the owner because what actually happens is often filtered out. They’re not told how their yacht works, they’re told what they want to hear.”

So while service expectations have risen along with technology, the infrastructure, human resource, and other aspects haven’t kept pace. We’re trying to meet this higher level of expectation on this more capable platform by doing the same things over and over, while the gap is getting harder to square. Basic logistics, such as the food delivery example, show how far off course things have drifted.

What makes this different from other industries is that inefficiency doesn’t carry consequences. There’s no pressure to streamline when the system doesn’t track its performance. “We don’t have the trading feedback loop. We don’t have monthly books,” he adds. “If you’re running a corner shop and you can’t make payroll, you’ll know your business isn’t up to snuff. But a yacht rolls along inefficiently.”

The weaknesses in the recruitment process

Where this strain shows up most visibly is in crewing, where the manning model hasn’t kept pace either. Rotation, often held up as a solution, is misunderstood. “There’s quite a lot of prayer at the altar of rotation. It’s a false idol,” he says. Rather than being designed around crew welfare, it’s often reactive, a patch for more profound systemic fatigue. It may be suitable for some operations, but it’s frequently applied for the wrong reasons. “We risk developing the wrong culture and recruiting the wrong people,” continues O’Shannassy. “Young people entering the industry should be looking to

work hard while they can, see the world and save money. If you’re joining to go home as soon as possible, you’re the wrong person.”

And fatigue is just one piece of a much broader challenge. Yachting’s offer to new entrants doesn’t stack up the way it once did. “My daughter earns more working at a ski hut than a new-entrant yacht crew does,” he says. “The EU staff in our coffee shop earn more gross per month than a deckhand.” Factor in patchy tax exemptions, inconsistent pay, limited training and high turnover and the cracks in the pipeline shatteringly resonate.

This is why we are at a crisis point. How can we attract the right talent to our industry when we can’t or don’t offer them competitive benefits? The value proposition is so skewed, and for young people looking to form a career in hospitality or engineering, yachting doesn’t provide adequate opportunities compared to other sectors vying for their signature. It sells them an idea that they will be enjoying champagne on the aft deck or in a jacuzzi, rather than making beds, cleaning rooms and daily washing the same area of an already clean yacht.

For all the ambition, investment and complexity etched into the modern fleet, O’Shannassy believes the industry still fails on one essential point: it doesn’t behave like a system. The problem, as he sees it, is structural as much as it is about recruitment.

The need for structure

“We should be looking up at the Four Seasons Hotels. For how much our owners invest, we

should be training their crew, their service team, but, in practice, the opposite is true. So when my close friend and VP of Four Seasons talks about service excellence, get your pen out. They train it constantly. They drill it into culture. They build careers,” he explains. “In yachting, service is often spoken about aspirationally with big language and bigger assumptions, but the systems behind it are rarely in place. We don’t offer real training. When you look at the delivery of hotel services on board comparatively, sorry, it’s embarrassingly lacking.”

And the situations are not due to a lack of solutions, rather a sheer lack of willingness to adopt them. “It’s not like we need to invent anything. Hotels, private aviation, they all operate in this manner. The systems are already there. We just have to copy it.”

The contrast matters because it exposes what is missing. In most businesses, poor performance is evident quickly in balance sheets, customer reviews and staff turnover. In yachting, there’s no such feedback loop. In most companies, you know when you’re underperforming. You miss payroll, your numbers dip, the alarm bells ring. Yachts roll along inefficiently. There’s no P&L logic, no guest night metrics, no standardised KPIs. Instead, managers discuss building pedigree, crew placement or charter bookings. However, how a yacht actually runs and performs as an asset does not receive the same scrutiny.

“Beauty in design is directly correlated to efficiency, not in conflict: the master stateroom,

“Leadership is about giving your crew clarity so they can make good decisions without you. It’s not about knowing the answer to everything 100 per cent of the time.”

So what’s the answer? Simply put, We Standardise what should be standard. Give people the tools, measure what matters, set expectations, share knowledge ...

the best deck entertainment area cannot reach its full potential if the areas ‘behind the curtain’ are not optimised. In new constructions yacht owners correctly obsess about ceiling heights and the flow from the spa to the cabins. This is the correct focus for the end-user, so long as they have someone in their team with the same obsession looking to the laundry, the fridges and the service paths.

“Real operational feedback rarely reaches the owner because what actually happens is often filtered out. They’re not told how their yacht works, they’re told what they want to hear. Instead of metrics, there is marketing, accolades for the build pedigree, interior styling and LOA. What does that tell an owner about the day-to-day, and in a broader scope, the annual runnings of their yacht?” questions O’Shannassy. “Tell me how many days you’re at anchor, how many days you’re underway, how many days you’ve got guests and how many per day. That’s the business model. Everything else is downstream from that.”

The mismatch between owner expectations and reality

Scale is where the cracks protrude deeper. For all the talk of large fleet operations, most management companies operate more like intermediaries than operators. “One hundred yachts under management? No. You’ve got one hundred times one. That’s not a fleet,” he adds. “You’re not capturing any of the operational value. There’s no appetite to fix the model. We romanticise what yachts are, but we don’t want to run them that way. We want to believe we’re a fleet, but we act like a collection of exceptions.”

Procurement is one of the clearer examples, being fragmented, unleveraged and inconsistent. Uniforms, fuel, insurance and catering are all

sourced independently, often with no data or oversight. O’Shannassy stresses the fact that we could save owners (conservatively) tens of thousands just by acting like a commercial fleet, with one management company handling the logistics and saving time. “The uniforms are still yours, but the supplier is shared. The fuel specification remains, but the rate has been negotiated. The contracts are consistent. But right now, that structure doesn’t exist. It’s not a supply chain, it’s a supply spider web.”

This is why so many yachts end up, undertrained and poorly aligned with their owners’ original expectations. “If I were a yacht owner, I’d be appalled,” he says. “You’re sold the dream and then left with a nightmare, trying to figure it out one tender launch at a time. And this, O’Shannassy argues, is the problem in miniature, as the yacht may be extraordinary, but the system running it is not.

The need for leadership

With all this visible, O’Shannassy is more motivated than disillusioned. What frustrates him is the gap between what the industry could be and what it’s still settling for. And it shouldn’t take much. A bit of structure, accountability and transparency would go a long way to change the whole operating rhythm of the boat. That rhythm starts with clarity, however, not technology. Just knowing what the job is and how to do it.

Yachts don’t need another app to be efficient. They need return to the fundamentals of business practice and seek efficiency at every turn. From there, it’s understanding and preparing for the fundamentals of asking the owner their vision, backed by the data. “That’s your business,” he adds. “If you don’t know those numbers, you don’t know your yacht.”

Structure, for O’Shannassy, is about enabling people to do their jobs properly and that begins with leadership. “Paraphrasing the ISM code, my job description says: communicate, clarify, motivate. And that’s beautiful. Leadership is about giving your crew clarity so they can make good decisions without you. It’s not about knowing the answer to everything 100 per cent of the time.”

The veteran is just as clear on culture. We will continue to hear the old guard talk about work ethic and loyalty. But younger crews aren’t broken, he argues, they’re better. “These guys are fabulous. They’re better educated than we were. They have better boundaries,” he says. “They’re not fragile. They won’t tolerate the same things and will fire poor leaders faster than the reverse. And that’s not a problem, that’s an upgrade. I don’t buy into the idea that psychological safety is a soft issue; it’s the largest performance driver.”

“We’ve treated mental health like a crisis,” he adds. “It’s not. It’s an opportunity. It should be a lever to elevate our standards across the board. Because when you create that safety, you get accountability. You get better decisions, better service, better everything. And the truth is, most people want to lead well, but they don’t have the structure to do it. “No one gets up saying, ‘I want to be toxic today’. But without clarity, you lead from frustration. And that’s where it all starts to fall apart.”

The solutions

So what’s the answer? Simply put, We Standardise what should be standard. Give people the tools, measure what matters, set expectations, share knowledge. These problems are blatant and staring us in the face in every guest complaint, every burnt-out crew member and every confused owner wondering why they haven’t received the boat they were promised when they signed on the dotted line.

Yachting continues to talk about excellence without defining it. It celebrates scale without achieving it, recruits talent without retaining it. It discusses training, leadership and guest experience as if they’re aspirational ideas, rather than the foundations of any serious operation. And the fact is, the playbook exists. The standards are already proven in other sectors, and O’Shannassy’s hotel business is a testament to that. What’s missing is the will to connect the dots that align capability with culture, design with delivery, and cost with consistency.

“This industry isn’t broken,” O’Shannassy says, “but we just can’t keep pretending it works as it is. If we don’t address this value gap and if we don’t professionalise properly, we’ll lose the very people, performance and reputation we rely on. If we want it to last and keep talent, keep value, keep the experience worth paying for, then we’ve got to stop pretending it’s already perfect. And start building something that actually works. There’s huge value in this crisis. But only if we choose to respond to it.” CF

©CIBAR

SINGULAR MARINAS

+ Tarragona

PORT TARRACO

Valencia

MARINA Mallorca

Salerno

MARINA D'ARECHI

PORT VALENCIA PORT ADRIANO CAPR

Ibiza Este

IV1AI'\JLAI\J .J SPAII\J

MARINA SANTA EULALIA

Ibiza Sur

BOTAFOC IBIZA

Singularmarinas intfieheartof theMediterranean

The Mediterraneanisfullof uniquespots. OCIBAR transformsthemintoleadingnauticaldestinations.

Formorethan25years, OCIBARhas beenmanagingmarinas withtheirownpersonality, whetherduetotheirlocationor theexperiencetheyoffer. Eachportsharesthesamevision: quality,designandinnovationasitshallmark.

Ocibar Marinas

by Marianne Danissen

Bridging the gap: The human side of superyacht operations

Marianne Danissen, group head of yacht management, Camper & Nicholsons, explains

how knowledge sharing can help alleviate the demands of crew life while

raising industry standards.

In the world of superyachts, where precision, performance and polish are expected at every level, the human element is often the most fragile and the most overlooked. From my position in yacht management, I see daily how high expectations from owners and guests meet the complex, demanding reality faced by crew on board. That gap between what’s expected and what’s operationally possible continues to grow. And unless we start talking honestly about it, we risk missing the opportunity to make this industry stronger, more sustainable and more human.

The weight carried in silence Crew life is demanding in ways few outside the industry fully understand: long hours, minimal separation between work and rest, and the constant pressure to deliver a five-star experience in an environment that allows for very little personal space or downtime. Every yacht is different and so are the expectations placed on crew. Cultural differences add another layer of complexity. If a crew member is not confident in who they are or lacks self-awareness, the pressures can erode well-being quickly.

What concerns me most is how unprepared many new crew members are when they first step on board. They often don’t know what they’re entitled to, what behaviour is acceptable or how to speak up if something feels wrong. This lack of foundational understanding creates an environment where bad practices can go unchecked and wellbeing takes a back seat.

More than lip service: championing crew welfare