The Superyacht Report

A Special Tribute to Paolo Vitelli

I know this all sounds boring and takes time, and there are plenty of parties pushing to get the deal done and the build slot secured, including the client sometimes, but I just get so frustrated when we hear of owners suing shipyards for failing to deliver something that was perhaps overambitious and improbable at the time of signing an LOI and committing to that precious space in the

Then you also have to deal with the army of owner-approved and endorsed experts again, who all have an opinion on ‘how to build it’, many of whom may have been involved with one or two builds in semi-custom yards near the Med and are now faced with a Northern European project, but the owner was introduced to them and he got a good vibe.

I often ask myself if a new build left to the full control of the shipyard would be a novel idea and if the client would end up with a better project, on time and on budget, where the owner trusted the shipyard completely and the relationship is such that they are all confident that they actually know what they’re

Anyway, we all know that a good new build takes time and plenty of investment, so by adding another six months to the pre-build phase and perhaps another 15 per cent to the budget, I wonder if the end result would be a better boat, costing less and without

Yes, time is money, but so are protracted legal fees following bitter legal battles caused by a badly written

Galley design: Why yacht chefs are the missing ingredient

Brennan Dates, a head chef with 22 years of charteryacht experience, explains that the involvement of a marine catering professional is vital when designing galleys for new builds.

Raising the industry standard

Terry Allen, surveyor and build manager, discusses the importance of a clear distinction between Flag and Class, and why it’s vital to raise standards to ensure a successful yacht build.

New-build paint jobs: Five key steps to aesthetic heaven

Rory Marshall, owner and director at Newmar Overseas Ltd, sets out the key fundamentals for yacht owners and captains to consider to ensure they achieve a visually stunning finish.

Guest columns Features

A peek into the pockets

We take an informed look at the significance and quality of entry-level yachts from 24 to 40 metres –and ask what more can be done to operate these smaller vessels more efficiently and safely.

The inside take on yacht sustainability

TSG talks to renowned design houses RWD and Winch Design to assess the positive impact that interior design choices can make towards guiding the superyacht industry to a more environmentally friendly future.

Dr Paolo Vitelli

A tribute to the founder and president of the Azimut-Benetti Group.

Cracking the glass ceiling

As glazing projects in superyacht design become increasingly ambitious, and demand for more advanced glass grows, will the industry will meet it, or is the situation approaching a breaking point?

‘Only busy people make the time’ 58 Having worked on more than 50 new builds across five decades, project consultant Charlie Baker breaks down the evolution of construction, the art of project management and the lessons today’s generation can learn from the old school of yachting.

All hands on tech!

A new generation of digital billionaires has entered the superyacht market from global brands such as Amazon, META and Alphabet … and they’re spending big on standout legacy projects.

Litigation isn’t sport … it’s the last resort

70

Syncing the link

67 Meeli Lepik, founder and chief consultant of Holistic Yacht Interiors, highlights the importance of bridging the gap between yacht construction and the realities of day-to-day on-board operation.

82 Industry veterans Jay Tooker and William MacLachlan, partners at international law firm HFW, explain the intricacies of litigation in yachting, how the industry has learned from past mistakes and why it should never be a weapon of choice.

Are sailing-yacht owners the smartest owners?

Martin H. Redmayne takes a deep dive into some of the most iconic sailing-yacht projects … and says it’s easy to see what stimulates billionaires and UHNWIs to invest in them.

92

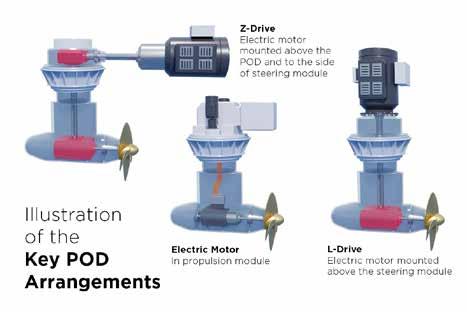

The power of the POD

87 Senior naval architects at Lateral investigate whether traditional shaft lines are becoming obsolete, with developing electronic propulsion systems offering a compelling alternative that aligns with the industry’s trajectory towards more optimised, comfortable and manoeuvrable yachts.

Demystifying HVO … and its role in reducing the environmental impact of the yachting industry

100 Water Revolution Foundation’s environmental expert Awwal Idris explores HVO as an opportunity for transition and its potential role in reducing emissions within the superyacht industry, including specific examples for superyachts.

Engineering a sea change

The propulsion sector has been dominated by Caterpillar and MTU Rolls-Royce for decades, but now the MAN engine portfolio is also making big moves into superyachts, it’s finally time for the industry to make a clean break from conventional fossil-fuel-burning engines.

104

A unique way of being, of living, of doing.

The Superyacht Report

QUARTER 1/2025

For more than 30 years The Superyacht Report has prided itself on being the superyacht market’s most reliable source of data, information, analysis and expert commentary. Our team of analysts, journalists and external contributors remains unrivalled and we firmly believe that we are the only legitimate source of objective and honest reportage. As the industry continues to grow and evolve, we are forthright in our determination to continue being the market’s most profound business-critical source of information.

Front cover: The Godfather of Superyachts and founder of the Azimut-Benetti Group. Image credit: Benetti, Assouline.

Editor-In-Chief

Martin H. Redmayne martin@thesuperyachtgroup.com

News Editor

Conor Feasey conor@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Sustainability Editor

Megan Hickling megan@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Guest Authors

Terry Allen

Ollie Cooper

Brennan Dates

Awwal Idris

Meeli Lepik

Rory Marshall

Matt Venner

COMMERCIAL

Head of Commercial

Eliott Simcock

eliott@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Group Account Director

Luciano Aglioni

luciano@thesuperyachtgroup.com

INTELLIGENCE

Head of Intelligence

Charlotte Gipson charlotteg@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Research Analyst

Isla Painter isla@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Senior Research Analyst

Amanda Rogers amanda@thesuperyachtgroup.com

Data Analyst

Miles Warden

miles@thesuperyachtgroup.com

DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Content Manager & Production Editor

Felicity Salmon felicity@thesuperyachtgroup.com

ISSN 2046-4983

The Superyacht Report is published by TRP Magazines Ltd (trading as The Superyacht Group) Copyright © TRP Magazines Ltd 2025 All Rights Reserved. The entire contents are protected by copyright Great Britain and by the Universal Copyright convention. Material may be reproduced with prior arrangement and with due acknowledgement to TRP Magazines Ltd. Great care has been taken throughout the magazine to be accurate, but the publisher cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions which may occur.

The Superyacht Report is printed sustainably in the UK on a FSC® certified paper from responsible sources using vegetable-based inks. The printers of The Superyacht Report are a zero to landfill company with FSC® chain of custody and an ISO 14001 certified environmental management system.

SuperyachtNews

Spanning every sector of the superyacht sphere, our news portal is the industry’s only source of independent, thoroughly researched journalism. Our team of globally respected editors and analysts engage with key decision-makers in every sector to ensure our readers get the most reliable and accurate business-critical news and market analysis.

Superyachtnews.com

The Superyacht Report

The Superyacht Report is published four times a year, providing decision-makers and influencers with the most relevant, insightful and respected journalism and market analysis available in our industry today.

Superyachtnews.com/reports/thesuperyachtreport

The Superyacht Agency

Drawing on the unparalleled depth of knowledge and experience within The Superyacht Group, The Superyacht Agency’s team of brilliant creatives, analysts, event planners, digital experts and marketing consultants combine four cornerstones – Intelligence, Strategy, Creative and Events – to deliver the most effective insights, campaigns and strategies for our clients. www.thesuperyachtagency.com

YOUR COATING CONSULTANTS

Follow The Superyacht Group channels on LinkedIn

@thesuperyachtgroup

@thesuperyachtgroup @superyachtobserver @superyachtagency

Join The Superyacht Group Community

By investing in and joining our inclusive community, we can work together to transform and improve our industry. Included in our Essential Membership is a subscription to The Superyacht Report, access to SuperyachtIntel and access to high-impact journalism on SuperyachtNews.

Explore our membership options here: www.superyachtnews.com/shop/p/MH

With over 25 years of experience, we have overseen more than 150 successful new-build and refit projects in all major international yacht locations. Trust us for state-of-theart materials, cutting-edge technology and unparalleled expertise. Guarantee a flawless finish with WREDE Consulting.

Why size matters

A peek into the pockets

We take an informed look at the significance and quality of entry-level yachts from 24 to 40 metres – and ask what more can be done to operate these smaller vessels more efficiently and safely.

BY MARTIN H. REDMAYNE

Every time I see on social media the top 100 lists and the ten biggest launches of the year, I breathe a huge sigh of frustration and wonder if the market really understands the dynamics and the matrix of superyachts.

There are two categories that need some focus and attention, for obvious reasons. Not only do these sectors represent the vast majority of superyachts when you take the official regulatory definition – 24 metres LOA and above –but also there are thousands of owners of pocket yachts with the potential to migrate to larger vessels.

Let’s put it in perspective. As a fleet number, there are just under 4,000 yachts in the 24 to 30-metre category globally and there are an additional 4,000-plus yachts in the 30 to 40-metre category. Yes, they are primarily semi-custom or production yachts, built predominantly in glass reinforced plastic, or aluminium and steel occasionally, but they represent, in hull units, more than 80 per cent of the market, and in terms of deliveries

and existing fleet, they are also the most active sales pipeline for buyers entering the superyacht category.

These sectors are dominated by the big brands – Azimut-Benetti, Ferretti, Sanlorenzo, Sunseeker, Princess and myriad other brands – and the brand graphic on page 12 gives you a picture of the spectrum of competitors. These companies have wide-reaching sales networks and global marketing budgets and are, in very simple terms, the builders that bring the majority of new clients into the industry with these entry-level projects, both new and second hand.

As you’ll see from the chart on pages 10 and 11, the annual delivery activity in these two size categories is so significant that its success or failure can have an impact on the wider market. If the big brands are suffering, there may be storm clouds brewing; if the big brands are booming, it’s a good sign that superyacht buyers are currently in a positive mood.

Obviously, as we’ve highlighted in previous reports, one significant project

from Feadship, Oceanco or Lürssen is, in volumetric and financial terms, a significant proportion of the market performance, where a 100-metre project can be measured in multiples of one 30-metre production superyacht perhaps by as many as 20 times. But when you look at the market performance and future growth, a consistent production of these pocket superyachts is critical to all economic elements of the market. However, there are one or two caveats and cautions that are worth highlighting, specifically related to the entry-level fleet (24 to 40 metres): firstly, quality of design and build, and secondly, the safety and quality of operations and manning.

Quality of design and build

Following a few interesting conversations with captains, surveyors, managers, brokers and even Class societies, it’s apparent that concern is developing about the topic of design and working space on the sub-500gt fleet, where

sacrifices are made to give the owner maximum living space and comfort but to the detriment of the space required by those who may live and work on board for several months at a time – the crew.

It’s easy to see how designers and sales teams will push for the best sales presentation, with beautiful renders and videos of amazing interiors, far more spacious than on the previous model, but it’s even easier to see how the long-term problems will emerge.

A recent conversation with Antoine Larricq, of Fraser Yachts, in my opinion one of the most intelligent brokers out there, showed serious concern about the lack of space and consideration in the sub-500gt models for crew and service. These yachts won’t work for the owner and their guests when the crew have such poor space or limited storage on board; it will damage the guest experience and not deliver what they expect.

Perhaps the time has come for the 24 to 40-metre fleet to spend some time

reconsidering the operational profile and build of these entry-level superyachts with the crew in mind, so they can operate them efficiently and safely.

In addition, when talking to a wellknown Class surveyor and project manager, there’s a clear concern about build quality and engineering, where the piping systems, ventilation and electrical systems are potentially below the requirements, and where technical people are building yachts that meet the minimum safety standards and not looking to go beyond. In fact, there was a very bold statement from this conversation that some builders are looking to build a yacht that will last only a couple of years, just beyond the warranty period, and then need significant upgrades.

This needs further investigation but I feel that the market should think carefully about the concept of doing everything for the owner and then cutting costs technically, only to find that the

yacht’s resale value, operational profile and crew turnover create a significant headache for the buyer.

Safety and operations

In addition to the design and build quality, there’s a clear issue of on-board safety, not only in terms of crew and their living and working conditions, but also technical safety. Yes, if the crew are unable to do their job properly or have cramped sleeping quarters, the quality of service and support for the owner is affected, but mental health, fatigue and high-turnover all have an impact on safety. As we have all witnessed over the past few years, there has been a proliferation of incidents within the smaller superyacht fleet, with groundings, collisions, sinkings and, more importantly, fires of all sizes.

One well-known surveyor shared some candid opinions on the topic because it’s clear that the majority of the fires that make their way to the social-

media channels, or happen in highprofile marinas or shipyards, are in the 24 to 40-metre sector, often with captains and crew who have yacht master tickets and in many cases with no permanent engineer on board, or on yachts left at night with no crew on watch. This is something that the regulators, marina management and Flag states should review and explore.

There’s been an incredible surge in the use of lithium batteries across this fleet too, with silent-mode operations, charging systems and next-generation electric water toys all sitting on the specification. Yes, there are marine guidance notes (MGNs) for the use of these batteries but, as my surveyor friend highlighted, these aren’t comprehensive or strictly followed by the manufacturers or operators.

The issue is not with quality suppliers or reputable companies but perhaps more with the cheaper copy-cat models where the source of the battery is often un-

known. As he recommended, there needs to be a study of all recent cases involving lithium fires on board the smaller superyacht fleet, perhaps financed by the insurance market or Flag and Class, because there’s an urgent need for the market, the manufacturers, the owners and the shipyards to better understand how and why these incidents are happening relatively frequently.

Every time some social-media influencer gets excited by another yacht fire and posts lots of images of a yacht becoming gutted by insane flames and ending up as a blackened carcass, I wonder how many owners, guests and crew consider their own risk.

Moving up the market

What is key in this whole topic is the process of being able to trade these yachts on the second-hand market and help these clients move up the ownership ladder. One quick review of the brokerage market’s performance shows

What is key is the process of being able to trade these yachts on the second-hand market and help these clients move up the ownership ladder.

Pocket superyacht builders worldwide

that a vast majority of the transactions and tonnage for sale are in the 24 to 40-metre size category, for obvious reasons. However, owners are migrating with their sales contact up the branded ladder because they’ve seen a cooler, newer, slightly bigger model from these major brands.

Perhaps the fact that the owners and their guests only use their pocket superyachts for short-range hops along the coast or from island to island keeps them isolated from the potential problems because they are on board for relatively short periods of time. But the bigger issue is the potential for a reasonable percentage of these owners in the sub-40-metre category to migrate

up the market into 50 or 60 metresplus and beyond, and this is something that needs further debate. Not only is the financial leap significant, from a production pocket superyacht to a custom project, new or secondhand, but the demands, decisions and dollars multiply exponentially.

I refer back to the fact that buying and building of the best quality often pays huge dividends for the owner, where the crew have been considered at the design phase, the engineering meets the highest safety standards and the maintenance costs are considerably less, not to mention a more palatable depreciation curve. However, in a super competitive market with a vast array of

brands and models on offer, with a price point spectrum from Holland to Italy to Turkey to Asia and beyond all adding to the decision process, it’s wise at this stage to break the market in two parts in the way that SYBAss has advocated.

Smaller pocket superyachts (24 to 40 metres) making up 80 per cent of the fleet (8,000+ yachts) is one market and the remaining 20 per cent of the fleet above 40 metres (2,200+ yachts) is the exclusive, more complex and, perhaps, real superyacht market.

So when you read about the data and size and scale of superyachts, it’s vital that we stop putting them all in the same boat. MHR

All analysis was undertaken by our data and research consultants. We provide bespoke consultancy projects that help clients make informed, data-driven decisions. Scan the QR Code to see examples of our work.

Leading provider of luxury outfitting for yachts, hotels, private aircrafts and homes.

Streamlined Service

We offer a complete customer experience with historical purchase information, billing and quotations. Enabling a simple reorder process and removing the need for multiple suppliers. We offer storage service and inventory control assistance.

In-House Design

Our interior designers will help you with all aspects of a project. From reviewing the finer details to implementing a major refit. Our graphic designers will assist with branding, logos and supporting artwork.

Industry Experts

Backed by 20 years of experience in the yachting industry, we work with the best brands and artisans to ensure that only excellent results are delivered to our clients. We offer free advice and consultancy to make sure our clients take the right decisions.

Column

by Brennan Dates

Galley design: Why yacht chefs are the missing ingredient

Brennan Dates, a head chef with 22 years of charter yacht experience, explains that the involvement of a marine catering professional is vital when designing galleys for new builds.

When a yacht owner dreams about life at sea on their new build, they will think of designer staterooms, sprawling teak decks … and world-class food that matches their global dining habits. However, they rarely think about the galley and the service areas that need to be in place to deliver on this achievable goal. This is a call to raise attention to how important these rooms are to the owner’s overall vision.

Why galleys matter

One of the most critical and often overlooked aspects of the superyacht experience are the galley and service areas. This space is the heartbeat of the yacht on a guest trip as well as the busiest on board. Food is one of the most crucial and intimate aspects of a guest trip and can singlehandedly make or break it. The industry understands that the food served on board is a critical aspect to a topperforming programme – whether private or charter.

It’s a cornerstone of guest satisfaction. It keeps the busy crew up and running with meals they can look forward to as they work three weeks or more without a day off. Yet despite its importance, 80 per cent of galleys are designed without input from professional yacht chefs.

From a 10-metre Azimut to a 150-metre Lürssen, most of the galleys for owners have no chef feedback at the critical early stages of planning the general arrangement. All yacht sizes can benefit immensely from involving a yacht chef to fit the essential equipment in a space that, nine times out of ten, is too small.

Let’s talk money

On a new build, galleys cost, on average, one per cent of the entire price of the vessel. I’m not saying we need to expand the budget, I’m just trying to illustrate that with a tiny bit more advice on that one per cent, the guest experience improves significantly.

When yacht chefs are ignored in the design phase and shipyard subcontractors take over the galley and service area build-out with no real expertise, it results in workspaces that are a nightmare to operate in. No one wants to work in them, crew turnover is likely to skyrocket and the owner struggles to keep a solid team on board.

A galley designed without chef input can often require an extensive refit sooner rather than later. These retrofits can be very costly, disruptive to the owner’s schedule and very avoidable. The galley of one 80-metre new build was installed by

a shipyard that subcontracted the job to a third party, with no input from a yacht chef. The result was a poorly designed workspace with inefficient workflow, inadequate food storage and domesticgrade equipment that was never meant to support 25 crew and 12 guests.

Within five years of launch, a number of chefs had resigned due to the impractical layout and home equipment, while engineers were frustrated with constant equipment failures on guest trips. Eventually, the owner was forced to spend more than $750,000 on a refit just to install the right equipment and reconfigure the layout of the space.

Had a yacht chef been involved from the outset, this huge cost could have been avoided. Not only would the galley have been designed for efficiency from day one, it also would have directly improved food quality, crew performance and the guest experience – the guest experience being the overall point of the yachting industry. We need to find ways to improve this experience, not just keep the same sub-par status quo.

Even the best shipyards in the world don’t build their own galleys. Instead, they outsource the work to subcontractors –entities that, more often than not, lack the professional oversight required to

create a high-functioning galley. Unless the owner’s build team includes a yacht chef, or the owner has their own yacht chef actively involved in the early planning stages, galleys are typically laid out by non-chefs who select equipment based on profit margin rather than performance. This approach leads to galleys that simply don’t work for the owner.

Professional yacht chefs bring invaluable insights into equipment type, placement, storage needs and operational flow, reducing the likelihood of an expensive post-launch refit. Involving chefs from the outset ensures the galley is built to meet the practical demands of a busy private or charter season.

Enhancing efficiency and performance

Superyacht galleys are unique environments that demand seamless functionality. From serving children’s meals along with the nannies 30 minutes before an intimate family dinner for 12 to executing large-scale catering events, to being woken up throughout the night to make food for drunk guests, yacht chefs face diverse culinary challenges.

On a charter boat you have no idea what food requests guests will throw at you and it’s your job to deliver. There’s no place for home-equipment manufacturers such as Miele or Gaggenau. It might be labelled ‘professional grade’ on the front panel but every chef knows you won’t find this equipment in top restaurants or luxury hotels.

Even on a 30-metre yacht with six crew and 12 guests – 18 people to cook for three times a day – an enormous load is placed on sub-par, domestic-grade equipment more suited to a casual home kitchen than the demands of a superyacht galley. Chefs have to try to deliver on all these high-end expectations with basic equipment, sometimes alone in the galley with no sous chef and lots of mouths to feed, constantly. Why is this the norm? A galley designed with chefs’ input directly enhances efficiency, minimises wasted space and streamlines service to deliver a better guest and crew experience.

Marine-grade equipment

The marine environment presents specific challenges that land-based kitchens don’t face – from corrosionproof materials, safety hinges on heavy oven doors to dishwasher float switches that don’t like sloshing around underway. Selecting the right equipment is crucial. Every piece of equipment needs to not only meet marine standards, but also align with chefs’ culinary needs. This dual perspective helps bridge the gap between ideas that will work in restaurants versus what will work at sea.

Let’s not forget maintenance either, such as easy access to filters, water and power connections etc., which makes it easier to properly maintain, service and fix equipment. This reduces the downtime of a galley drastically.

Designing a superyacht galley without involving a chef is akin to building an F1 race car without consulting an F1 driver. It’s a misstep that undermines the very essence of performance, efficiency and luxury food service.

A

logical collaboration

Designing a superyacht galley without involving a chef is akin to building an F1 race car without consulting an F1 driver. It’s a misstep that undermines the very essence of performance, efficiency and luxury food service. Professional chefs understand the nuances of their craft and bring unmatched value to the design process, and building a galley without involving a chef creates expensive problems sooner rather than later. A galley designed by an outside company that has never worked in a galley can’t compare with a foundational galley layout and equipment list specified by an ex-yacht chef.

While individual preferences may vary, professional yacht chefs consistently prioritise functionality, efficiency, and durability in a galley, with core principles such as proper workflow, adequate refrigeration and high-quality cooking equipment remaining universal. Just as all yacht captains may have slightly different preferences for bridge layouts, yet their input is never ignored, chefs should be involved in galley design through a chef consultant who ensures the space is built to work for any professional, not just for themselves.

Resolution

The galley is more than just a place where food is prepared, it’s the foundation of a trip for both guests and for the crew delivering the guest services. By involving professional yacht chefs in the design process, owners and builders can create a galley that elevates the guest experience, avoids costly refits, benefits galley crew retention and enables top-tier performance. Having a consultant involved in the build process can create a standardised design that will work for any chef, where the investment is minimal but the rewards of getting it right vastly outweigh the costs.

For those aiming to deliver the ultimate luxury experience, this collaboration is not just beneficial to the chef, it’s also essential for the smooth operation of the owner’s greatest asset. BD

The inside take on yacht sustainability

TSG talks to renowned design houses RWD and Winch Design to assess the positive impact that interior design choices can make towards guiding the superyacht industry to a more environmentally friendly future.

BY MEGAN HICKLING

While interior design may not have the biggest influence on the environmental impact of a yacht throughout its life span, it’s still a significant factor in improving its footprint across environmental and social aspects, particularly because an estimated 80 per cent of that impact is determined at the design phase. Interior design is much more visible and notable to those on board so it can present the opportunity to bring these issues to the forefront.

The storytelling nature often found in interiors can also hook people into doing more to reduce harm to the planet. Aino Grapin, CEO at Winch Design, and Laura Nagy, senior interior designer at RWD, are at the forefront of what is being done in this sector of the industry to improve impact and have their own experiences of sustainability in superyacht interiors.

It’s clear from both that interior designers work to improve a yacht’s footprint through a wide array of actions. However, Nagy says this can feel quite overwhelming at times. “It’s a big topic,” she admits. “There is a lot of information out there and it’s difficult to know where to begin, but it’s a worthwhile challenge.”

As part of this effort, Water Revolution Foundation’s Sustainable Yacht Designers Taskforce –chaired by Grapin – which includes multiple leading design firms including Winch Design and RWD, is bringing designers together to talk about their issues and solutions. The Taskforce has created what Nagy calls a “great little Bible” – the Designers’ Protocol, an advisory document detailing different considerations, actions and approaches that should be made by designers to reduce environmental impact throughout the yacht’s life.

For RWD, this structured approach aligns with a broader commitment to responsible business practices, reflected in its B Corp certification. As one of the only design studios in the yachting industry to achieve this status, RWD is dedicated to integrating social and environmental accountability into its work – principles that are also embedded in the Protocol’s guidance.

The Protocol introduces the ‘R’ ladder concept to introduce different considerations to be made to increase circularity, which reduces consumption and waste and, therefore, environmental impact. Particularly for interiors, ‘refuse’ and ‘reduce’ are key because they relate to the material choices made, whether that’s more renewable/recycled

materials, or those that are more durable and longer lasting. At the other end, interior designers can assist with later-life aspects such as refurbishment and recycling by choosing products and materials that can be maintained to extend their life span, and which can also be repurposed or recycled once they have reached the end of their life on board. One such example given in the protocol is the life span of a chair that can be extended to 20 years through repair and reupholstering, thereby reducing CO2 emissions by 40 to 50 per cent.

The protocol also examines alternative materials that can be used and, as highlighted by both Nagy and Grapin, this is an area where interior designers have a lot of control and influence. “We can actively guide our clients in planning meetings,” says Nagy. “It’s down to us what we take in to present. I think you can always find finishes that are less impactful that fit the style, even if the clients want something a little bit more lavish.”

Recognising the importance of this, Winch Design has employed a specialist who is 100 per cent dedicated to researching new materials to be added to its library. Improved materials can range from basic materials such as timber and stone to special finishes using more innovative techniques and materials.

Grapin splits these alternative improved materials into a few different categories, such as finishes and materials made from food waste. Egg-

“It’s really important to understand the lifestyle and the intended use for the yacht. As a designer, you can bear that in mind when you select the finishes.”

Sustainable materials from Winch Design include faux coral eggshell composite, a hand-painted wall covering sample made with water-soluble pigments/products, and a salvaged upcycled teak panel made from prime teak reclaimed from abandoned houses.

shells, for example, are made to mimic brain coral and peppercorns suspended in bio-resin are used to mimic the pattern found on shagreen leather. This is where innovative ideas in the interiors world can be translated into really interesting and inventive products that tell a story as well as being highly sustainable.

Renewable sources such as cork or birch bark can be taken and grown back. Nagy says that cork is exciting because of its versatility, and lauds its other benefits as an alternative, less ecologically harmful, decking material. “I like the whole story behind it,” she says. “It’s interesting – it’s got a warmth and feels like an honest material.”

Alternatives such as these will become ever more important as the European Union cracks down on unethically sourced timber. Grapin explains, “Our current projects are still mostly teak decking. My understanding is that this will probably change over time, so we’re following with interest alternatives like cork and Tesumo.”

Innovative techniques such as 3D printing, which can utilise recycled plastics or even ceramics, minimise waste due to the nature of its production as well as creating some interesting and durable products. Innovation can also involve natural and biobased products as demonstrated by businesses such

as Nature Squared, a Swiss-based design company using organic materials and by-products. F-List’s F/LAB is creating materials such as a type of faux shagreen made from marble waste that’s more durable. Grapin cites another alternative ‘leather’ that is made from elephant ear, a type of palm plant which is also extremely durable. Nagy says there’s a big push towards bio-resins to achieve high-gloss surfaces – as well as its other purposes, emphasising its versatility. Grapin also highlights the fantastic storytelling arising from utilising these products: “The amazing stories you can tell your friends … ‘this unique coffee table is made with eco resin and the beautiful flowers were taken from leftover flowers found on the floor of a flower market’.”

The use of recycled products and substances is clearly a vital part of the process when choosing materials for the interior. For example, the Winch material library includes carpets made from recycled fishing nets, which also consumes less water and energy in its production, reduces CO2 emissions by 30 per cent and is much more resistant to stains, fire, water and mildew . “This is something that the industry can really get behind because the whole yachting industry is really committed to ocean conservation,” says Grapin. “I think we’ve also realised that without beautiful oceans, without

Laura Nagy, senior interior designer, RWD.

fish to snorkel with and clean interesting oceans to enjoy, the yachting industry can’t exist.”

Interestingly, not all materials in these libraries are new innovations. Nagy points to terrazzo as a great example of improved circularity – once popular in the 1970s, it’s making a comeback in high-end projects due to its use of stone offcuts. By repurposing waste from other projects, terrazzo exemplifies how traditional materials can be reimagined for a more sustainable future.

Grapin says there’s a misconception that these sustainable materials are by definition kind of earthy, natural and have a given look. “Actually, a lot of these sustainable materials you can have in any colour. It could be vibrant colours, it could suit any design choice, so it doesn’t have to be your expected beige.”

Misconceptions persist in the industry, one being that sustainable solutions are always more expensive. However, Nagy points out that this isn’t necessarily the case. In fact, using more durable materials can lower maintenance and repair costs over time. For her, the idea that these materials require a compromise stems largely from a lack of exposure.

Another is the feeling that these alternatives to mainstream options aren’t going to be as good, but Grapin says they would never compromise as designers on the best interiors. She explains it’s exactly this drive that results in these alternative materials being included in their portfolio. “It’s not just about pushing sustainable materials for sustainability’s sake only.”

An informed team that can confidently discuss sustainability is key to dispelling these misconceptions. Nagy explains that at RWD, sustainability is embedded in their daily practice, with regular team discussions ensuring it remains a central focus in both project planning and design. Additionally, maintaining a diverse library of materials allows designers to show clients that they can achieve their desired aesthetic while making lowerimpact choices – without significant compromise.

Nagy says the younger generation seems to be much more aware of sustainability issues and keen to act. “I think a greater number of clients, especially the younger generation, are quite aware of it,” she argues. “And they do actively take an interest.”

While these special finishes may be eye-catching for clients with their origin stories, Nagy emphasises the importance of recognising that the use of more ‘standard’ materials such as timber and stone is much more prevalent across projects compared with individualistic special finishes, and these can have the biggest footprints.

Although there are many promising alternatives out there, research is needed to ensure they continue to make a greater impact – whether that is verifying certification or investigating suppliers on a deeper level to gain an understanding of the whole process. Specifically, both RWD and Winch send questionnaires to their suppliers to gain a better understanding of their supply chain and the origins of their products.

However, as always, it’s all about how the material is used. One of Grapin’s bugbears is the replacement of carpets every year. Winch has specified carpets on yachts that are still in use 20 years later. Grapin stresses, “Let’s use durable materials that are authentic and let’s not be wasteful.

As with other aspects of sustainability, there’s no

Aino Grapin, CEO, Winch Design.

one solution; a range of options to suit individual needs will lead to better impacts. “It’s really important to understand the lifestyle and the intended use for the yacht,” says Nagy. “As a designer, you can bear that in mind when you select the finishes.” She emphasises the importance of having this understanding as early as possible in the process.

Beyond the materials themselves, the specifications of a finish can determine how impactful they are. “Some clients seek perfection in the aesthetic presentation of materials, whereas for natural materials it is those imperfections that give the character and beauty to the surfaces,” Nagy says, adding that in some cases, due to the design and material, this can mean up to 200 per cent wastage. She has seen efforts to combat this in recent years due to “a deeper consideration towards the construction of surfaces and how clever design solutions can help to use more of the material and reduce the wastage”. Changing the split lines on a wall or the entire panelling design itself, for example, can make optimal use of the material.

Grapin also details the efforts Winch Design is making to reduce such wastage, such as veneers and faux-wood wrapping – which covers existing surfaces rather than disposing of them to be replaced – focusing more on the mindset of how these finishes are presented. “Introduce that it’s not a defect as much as a natural character of timber that can be celebrated,” she suggests. Winch’s work with contractors to make these changes to the finish can save half or two-thirds on the waste. However, she asserts this is an issue the industry has to continually work to improve. “The perception of the industry needs to shift and maybe the trends in interiors will help us with this as there is a shift towards ‘perfect imperfections’.”

Nagy has observed a significant shift in awareness over the past few years, with sustainability becoming an enduring priority rather than a passing trend. “I think it’s here to stay, and it has to stay,” she emphasises. As understanding deepens, clients are becoming more receptive to sustainable materials, not just for their environmental benefits but also for their aesthetic appeal. She notes that many now seek designs that align with global architectural trends, favouring pared-back luxury and a more natural, authentic feel.

“If we all went on this quest for information and there was more transparency among industry and partners in the supply chain, I think that would really help us. And I do think it’s happening.”

“All of our clients are interested in the stories, the uniqueness. These materials are popular with clients and designers as the story makes it a unique selling point. Clients are hooked into either the sustainability story or just the fact that it’s original and hasn’t been seen before.”

Grapin has noticed another beneficial trend. “Some of our clients are very focused on the emissions that materials have,” she says and explains they are concerned about what they will be breathing in on board and the impact on their family’s health. Often, less impactful material will be VOC-free, demonstrating that while these options are better for sustainability there are other benefits too. Winch has been researching low VOC materials, testing them for the Flexplorer 146 project they are currently working on.

“There are definitely solutions out there that are innovative and more durable,” she says. In some cases there can even be cost savings. They can often also be more intriguing pieces that have

new and interesting back stories. “All of our clients are interested in the stories, the uniqueness. These materials are popular with clients and designers as the story makes it a unique selling point. Clients are hooked into either the sustainability story or just the fact that it’s original and hasn’t been seen before.”

Sustainability isn’t just about choosing options that result in better environmental impacts; there can also be choices that improve social impact. Interior designs can be champions of small independent craftspeople. Grapin says that without the craftspeople, they can’t turn dreams into reality, and Winch is really passionate about preserving craft. She points out this is industry-wide. “Yachting in general has really supported craft – and that is

Robert Walker, QEST scholar specialising in hand-crafted signmaking known as verre églomisé, a process of applying both a design and gold on to the rear face of glass, as well as hand-painted sign-writing and large-scale typographic murals.

a story that needs to be told more. Our clients are passionate also about craft.”

Winch is a proud participant in the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST). The fund supports craftspeople of all ages and backgrounds by funding their courses, apprenticeships or oneon-one training with masters. Winch works closely with the artisans of the trust and always looks for new individual talent to nurture.

While designers work with clients to imagine and realise their dream interiors, others are involved in making these ideas and plans a reality on board. Making interiors more sustainable is also reliant on the rest of the supply chain. The focus at every stage should be on improving what can be controlled and for suppliers this means sourcing materials from more environmentally and ethically responsible origins, involving less impactful production methods. One obvious and straightforward choice is the consistent maintenance of these materials during the use of a yacht to extend their life as long as possible.

Working closely with suppliers or interior contractors demonstrates that even more everyday materials can be improved through collaboration and honest conversation, says Nagy. “The result of this collaboration with the supplier is a better product, a unique product and a more sustainable product,” says Grapin.

The benefits of this cooperation can go beyond materials and relate to other elements of the design and build process, with Nagy looking for suppliers in the vicinity of the shipyard to reduce travel emissions. Grapin also calls for the industry to focus more on the impact of a yacht in its later life. “Work with the interior contractors to make the interiors more modular so that they can be changed in the future without impacting necessarily the whole interior.”

Alongside the Task Force mentioned earlier, Water Revolution Foundation and F/Yachting, specialists in bespoke design and outfitting of superyachts, hosted a workshop in their innovation hub in Austria, bringing together superyacht designers, project managers and shipyard representatives. [Editor’s note: see Martin H. Redmayne’s article in issue 222]. The theme was ‘The Future of Yachting Industry Interiors & Exteriors’, fostering discussions and more effective collaboration to generate better impacts in yacht design. Particular focus was also on how to futureproof design by using life-cycle assessment (LCA) thinking to choose better materials and working to better measure the industry’s environmental impact.

Also at this workshop, Water Revolution Foundation launched a new chapter of the Designers’ Protocol, looking further into alternative decking solutions. More of these workshops are going to be hosted in the future, and Nagy lauds such efforts. “Water Revolution Foundation is great, just bringing different people from industries, different aspects of the industry together to have more conversations. That is how we all learn,” she says.

Alongside the education aspect, interior designers themselves are desiring more understanding and knowledge of the quantifiable aspects of these products. One mechanism would be the Environmental Product Declaration. This is a Type III environmental declaration according to the ISO 14025 standard based on the results and information from an LCA and is third-party verified. The declaration report includes objective and comparable data about the product or service’s environmental performance from an LCA.

The in-depth nature of LCAs, which include a significant level of detailed information, makes it an extensive piece of work to complete, and as such it can be difficult for smaller producers, such as the craftspeople working with the superyacht industry, to have the time and capacity to create these declarations.

Quantification is crucial as LCA looks to dispel options that may seem more environmentally friendly but, due to their production methods, may not be in practice. More yacht-specific, if a product is ‘greener’ but has a much shorter lifespan than the typical option, then it isn’t as ‘green’. Hopefully, this can be improved through Water Revolution Foundation’s efforts to verify solutions using LCA methodology.

Winch is working to estimate its own footprint across all its projects to generate a baseline impact, so it can set objectives to quantify the reductions made through a choice of alternatives. Recognising that this will take a significant amount of work to complete, Grapin says, “If we all went on this quest for information and there was more transparency among industry and partners in the supply chain, I think that would really help us. And I do think it’s happening.”

Nagy believes there will be a big push to have a readily available LCA tool that can be easily accessed. This, while requiring significant information-gathering across the industry, would greatly help with understanding how to improve impact in designs.

It’s clear that interiors are an important sector of the industry working towards guiding it to a more responsible future, con-tinuing to provide clients with designs that are not only the best, but also have a better impact on the world, along with the confidence, understanding and desire to choose these options.

It is to be hoped that more quantified data, along with these choices and processes, will become more standard and expected across the industry. Continued innovations and collaborations, being more transparent and wanting to learn from each other and work together towards better outcomes, will be the key to successful change.

Grapin issues one last call to the industry. “The other new normal I think we should all aim for is more cross-industry commitments to certain standards. It would be great to see that across the industry, not just for designers or shipyards. A common goal for the industry would invigorate everyone.” MH

Continued innovations and collaborations, being more transparent and wanting to learn from each other and work together towards better outcomes, will be the key to successful change.

FEADSHIP

ONE WITH THE SEA

In the world of superyachts, there is one that stands above the rest: the 75.75-metre Feadship ONE With a seamless blend of elegant design and superior functionality, this yacht offers an unparalleled experience for those seeking the pinnacle of luxury. ONE is the embodiment of singularity, where luxury, design, and craftsmanship come together into a unique, harmonious whole. Step onboard and discover a world where every detail is meticulously crafted, every space invites relaxation, and every moment becomes extraordinary.

There are yachts and there are Feadships.

Dr Paolo Vitelli Founder and president, Azimut-Benetti Group

A special tribute by industry friends and colleagues.

BY MARTIN H. REDMAYNE

Over the past 36 years, I’ve met, dined, chatted, brainstormed and walked slowly around shipyards and yacht projects with perhaps the most important man in the superyacht industry. We lost Dr Paolo Vitelli, the Dottore, prematurely during the 2024 Christmas holiday season and I’m still coming to terms with the fact that he has gone.

His legacy is far-reaching, his impact huge, his wisdom vast and his passion unwavering, and he touched so many people in our industry with his charming style of engagement and his ability to listen to anyone who had something interesting to say. He’s built brands, fleets and products that have delivered success, innovation and enjoyment to so many, and it’s hard to think about our industry without him, and our thoughts are with his family, friends and vast network of colleagues and employees over the decades of his tenure at the helm of the Azimut-Benetti Group.

We’ve dedicated this issue to the Dottore, with some personal comments from his colleagues, friends and those people he influenced and inspired over the years. In very simple terms, this man has, over the past 40 years, since he acquired Benetti, transformed our industry into what it is today, with myriad designers, suppliers, subcontractors and shipyards all benefiting and growing thanks to his vision and entrepreneurial spirit.

The performance chart on pages 34-35 shows the evolution of Benetti since his acquisition, demonstrating the impact and success he achieved over the past four decades.

Rest in peace Dottore … fair winds and following seas.

DR PAOLO VITELLI

BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

Paolo Vitelli, born on 4 October, 1947, in Turin, Italy, was a visionary entrepreneur whose passion for boating and keen business acumen led to the creation of the Azimut-Benetti Group, a global leader in luxury yacht manufacturing. His journey from a university student to a titan of the yachting industry is a testament to his innovative spirit and relentless pursuit of excellence.

In 1969, while still studying economics and commerce, Vitelli founded Azimut Yachts, initially focusing on boat rentals. The company’s early success attracted international builders seeking to enter the Italian market, prompting Vitelli to transition into boat manufacturing. By 1975, Azimut had launched its own project, marking the beginning of its evolution into a prominent yacht builder.

A significant milestone occurred in 1985 when Vitelli acquired the Benetti shipyard, a renowned name in Italian yacht craftsmanship. This acquisition led to the formation of the Azimut-Benetti Group which expanded to include five shipyards across Italy. Under Vitelli's leadership, the group became the world’s most prolific yacht builder, topping the global order book for the production of yachts over 24 metres for 25 consecutive years.

His contributions to the industry were recognised with numerous honours, including the title of Cavaliere del Lavoro (Order of Merit for Labour) in 1996 and an honorary degree in mechanical engineering from the Politecnico di Torino in 2004.

Paolo Vitelli passed away on 31 December, 2024, at the age of 77, following an accident at his residence in Valle d’Aosta. His legacy endures through the AzimutBenetti Group, which continues to set benchmarks in luxury yacht manufacturing, and through his daughter, Giovanna Vitelli, pictured above with Paolo, who assumed leadership of the company in 2023.

Under her guidance, the company remains committed to innovation and sustainability, reflecting the visionary principles established by her father. Vitelli’s life and career exemplify the impact of his visionary leadership and dedication to excellence. His contributions have left an indelible mark on the yachting industry and continue to inspire future generations of entrepreneurs.

DR PAOLO VITELLI

Credit: Benetti , Assouline.

Credit:

a launch ceremony in

THE EVOLUTION OF BENETTI YACHTS (1985-2025)

Benetti Yachts, one of the most iconic names in luxury yacht building, has consistently redefined the art of craftsmanship and innovation in maritime design. From its early focus on traditional wooden yachts to its dominance in the fibreglass and steel superyacht market, Benetti has transformed the yachting landscape over four decades, blending Italian heritage with cuttingedge technology and sustainability.

The 1980s: A foundation of excellence

In 1985, Benetti was already a prestigious brand with a rich legacy dating back to 1873. However, the company faced challenges stemming from rising competition and shifting client demands. This period marked a turning point as Benetti was acquired by the Azimut Group, led by entrepreneur Paolo Vitelli. The acquisition provided Benetti with critical financial resources, enabling modernisation of its production processes. The

Azimut-Benetti Group became a financial powerhouse in the yachting industry, leveraging synergies to dominate the luxury-yacht sector.

The 1990s: Pioneering customisation

During the 1990s, Benetti’s business strategy shifted towards semi-custom and fully bespoke yachts. This allowed the company to diversify its offerings, attract new clientele and boost its financial performance. By the mid-1990s, the AzimutBenetti Group achieved annual revenues exceeding €195 million, with Benetti contributing significantly. Investments in composite materials and more efficient production lines enabled the company to increase profit margins while maintaining its artisanal craftsmanship.

Benetti’s reputation for delivering highly customised yachts allowed it to weather economic turbulence, such as the early 1990s recession, while expanding into new markets, particularly in North America.

The 2000s: The era of megayachts

The 2000s marked Benetti’s strategic pivot towards larger, more opulent vessels. This shift was driven by rising demand for superyachts among ultra-highnet-worth individuals (UHNWIs). The company’s ability to produce yachts exceeding 50 metres in length cemented its dominance in the market. Notable launches such as the Benetti Ambrosia III (2002) showcased the brand’s capacity for technological and aesthetic excellence.

By the end of the decade, Benetti’s parent company, the Azimut-Benetti Group, had annual revenues exceeding €700 million, positioning it as the world’s largest producer of luxury yachts. Benetti’s strong financial performance was bolstered by robust demand in emerging markets, including the Middle East and Asia, where oil wealth and economic growth spurred interest in luxury assets.

*2025 figures are an estimation based on our current data.

2010–2025: Innovation, sustainability and financial growth

The 2010s were marked by significant investment in sustainability and innovation, a move driven by both market trends and regulatory changes. Benetti introduced hybrid propulsion systems and fully electric yachts, such as Luminosity (2020), a 107-metre gigayacht featuring cutting-edge energy storage systems and low-emission engines. These innovations required substantial investment, with Azimut-Benetti allocating more than €50 million annually to research and development during this period.

Despite these investments, the company remained profitable, supported by growing demand for eco-friendly yachts. By 2020, the global luxury yacht market was valued at more than €5.8 billion, with Benetti capturing a significant share. The pandemic-induced surge in wealth accumulation among UHNWIs

further drove sales, as more clients sought private leisure options.

From 2020 to 2025, Benetti's annual revenues consistently exceeded €800 million, with operating margins bolstered by a shift towards high-value superyachts. The average price of a Benetti yacht during this period exceeded €40 million, reflecting the company’s focus on ultraluxury craftsmanship.

Looking forward: financial leadership and market position

As of 2025, Benetti remains a global leader in the luxury yacht industry, with a commanding market share in both custom and semi-custom sectors. The Azimut-Benetti Group, now valued at more than €1.2 billion, continues to invest heavily in sustainability and technological innovation. Benetti’s shipyards in Viareggio and Livorno operate at nearfull capacity, producing over 35 yachts annually.

The company’s ability to balance tradition with modernity has allowed it to cater to a diverse clientele, from European aristocrats to tech billionaires in Silicon Valley. With increasing demand for sustainable yachts, Benetti is poised for further growth, targeting annual revenues of €1 billion by the end of the decade.

Conclusion

From its humble origins as a traditional yacht builder to its current status as a financial and technological leader in the global luxury-yacht market, Benetti’s journey reflects its ability to innovate and adapt.

With strong financial backing, a commitment to sustainability and a focus on client-centred design, Benetti is not only shaping the future of yachting but also redefining what it means to balance luxury with responsibility. MHR

DR PAOLO VITELLI

The other Vitelli

“He filled any room he entered. He listened to everybody, with a poker face that was more respectful than dubious. Listening was for him a mighty tool, and he was a master at it, while letting you feel it was him that was in command. There was no job too small if he thought he could do it for the benefit of others. That tranquillity he always exuded made him big and extremely easy to be respected. He was the universal gentleman many of us would love to be. He had [the] King Midas touch and knew to use it for everybody’s advantage (his daughter being the best proof). Mr Paolo Vitelli was, for me, a Leader. Thank you Mr Vitelli for having shown the way to so many people. Including me.

OSCAR SICHES _ MARINA, REPAIR SHIPYARD AND YACHT HARBOUR CONSULTANT

Paolo, Giovanna and I are sitting on the floor of the pantry in Benetti’s office eating pizza. It sounds like a start of an anecdote but, in reality, it’s [an] eagerly awaited happy end to one of the most challenging projects for all of us. The construction of these giga [yachts] was not an easy thing: countless changes at the construction phase, suppliers’ replacements, the delivery in the middle of a pandemic and a very demanding client on a top of it all! Stress at its peak, 12-hour meetings, all the parties are exhausted. The situation was really tough, and I wondered how we managed to endure it all. I was amazed at Paolo’s patience, respect to the team and loyalty to the client, no matter what. Later, I realised that this is just an exceptional professionalism, backed by dedication to [the] company with the family behind and their reputation as a lifelong endeavour. There are many things I’m grateful for in life and one of them is undoubtedly that pizza, shared late at night after the final inspection.

ALISA DOBROSERDOVA OWNER'S REPRESENTATIVE

We would like to pay tribute to Paolo Vitelli. Especially to his remarkable companies, Azimut and Benetti. As Resintex, we have had the privilege of working with them for many years. We deeply respect the consistency of their work. The organisation and discipline within their team. Their exceptional ability to industrialise yacht production through a rationalisation process that few have achieved in a market with a growing and genuine appeal for sustainability. As a family business ourselves, we hold great admiration for the Vitelli family’s dedication. We share common values with Azimut-Benetti. Our thoughts are with the family during this difficult time.

LAURA FABI RESINTEX TECHNOLOGY

Many years ago, Giorgia Gessner, editor of the magazine Barche, introduced me to him. The impression was immediately of an extremely active and attentive person, firm and polite, eyes lively beyond words, an empathetic and extraordinarily warm approach. When we met up over the last years, even though extremely busy, Dr Vitelli never failed to have a kind word, a rare attention in a world always in a hurry. Over the time we have admired his exceptional industriousness, his continuous look to the future, the courage and intuition of the great entrepreneur, founder of the Azimut-Benetti group, the pride of the Italian naval industry all over the world. The evil fate has snatched him from us, but we have not lost him. His shining example of a greatest entrepreneur and his kind smile of a real gentleman will remain alive in all of us for a long time. Goodbye Dr Vitelli, your imprint will always remain on the most beautiful boats of the world!

PAOLA TRIFIRÒ SINIRAMED SAILOR AND PREVIOUS OWNER OF S/Y KOKOMO OF LONDON, ZEFIRA AND RIBELLE, CURRENTLY OWNER OF EXPLORER MABELLE

DR PAOLO VITELLI

The news of the loss of Paolo Vitelli struck me deeply, both because of the enormous human and entrepreneurial calibre he represented and because our paths, after 30 long years of collaboration, had recently parted, not without deep sorrow on my part. Fate has robbed us of the hoped-for chance to meet again. Paolo Vitelli believed in me by giving me teachings, trust and responsibilities to manage. He passed on to me the concept of leadership as well as the ability to read the company and its functioning through numbers. Countless projects we tackled together, many not pursued but just as many brought to success. An immense mentor, one of the most fundamental people in my entire life. I would not be who I am if I had not encountered such an amazing person on my journey. To his daughter Giovanna and the entire Vitelli family, I would like to extend my and my family’s heartfelt condolences, who have learned much from this enlightened entrepreneur.

GIORGIO CASARETO _ PORTOSOLE SANREMO

Thank you, Dottore Vitelli

ALBERTO MARIA BETTINI _ VABER INDUSTRIALE SPA

Comandante

Tom

– It’s not the watch you wear, but the way in which you wear it!’ Paolo Vitelli was so humble and gracious when he told me

this

one

evening at dinner with Terry Disdale

in Genova. I never forgot what a great man he was and so inspiring. A legend in his own lifetime, a gentleman of honour and old school. Paolo, you will be sadly missed indeed by all.

CAPTAIN

TOM BURLAND MNI BENETTI & AZIMUT

“

Not just a public industry leader of the yacht industry, but also a silent driving force without whom we would not have been where we are today. R.I.P.

ENGEL JAN DE BOER LLOYD'S REGISTER

“ ”

Admiration for a master

ALDO MANNA MCYACHT

“ ”

I will never forget the day Mr Vitelli, by then already an icon in our industry, made a 1,000km touristic drive up north to do a bit of Gran-Turismo steering but also to visit me in Holland to discuss some sketched layouts we made for the smaller models of the Azimut Magellano series. Even during his off-time he would never stop working … The very friendly but also very efficient meeting, held at my private country-kitchen table, brought our studio a lot of follow-up business. But what I remember most was the fact that, after finishing our smokedeel lunch, Mr Vitelli started cleaning the table and it took me a lot of convincing to not have him do the dishes as well! We, as an industry, owe him a lot and we will dearly miss him for sure!

COR D. ROVER COR D. ROVER DESIGN

”

DR PAOLO VITELLI

“I made my first work steps in some of his iconic and visionary projects: the Alps Hotellerie in Mascognaz, the Fiera di Genova waved cover, and of course the magnificent yacht shipyard in Viareggio, for 12 years being always pulled by his magnetic force of avanguardia, improvement and determination. You are right: incredibly charming in listening and stimulating to the next level of conversation whatever core, whatever worker or manager or owner .... same – educated, polite and respectful man the Dottore was.

PAOLO SITIA HEAD OF ARCHITECTURE, EXPLORA JOURNEYS, MSC CRUISES

Paolo Vitelli was always the ‘Dottore’ for me too, until he called me in the summer of 1999: “Engineer, we need you in UCINA!”. From that day, since I joined the Italian Industry Association as his secretary general, he became, and remains, my ‘Presidente’.

I spent more than seven overwhelming and passionate years with him, covering most of his time as chairman of the Association. So many memories of this time which defined unforgettably my entire professional and personal life. Working with him meant never stopping, never giving up, simply because he never rested, never gave up. Being always committed with your work because this work was “the only thing I’m able to do”. He was demanding and inflexible with his managers, but less so than he was with himself. It was impossible not to follow him.

But having had the privilege to share such a long and intense time with him, my memories go to the human being. I discovered in him the fatherly pride and love on receiving, with tears in his eyes, a call from Giovanna, at that time still a professional attorney. I shared with him the enthusiasm for the results when being informed of the famous ‘Italian leasing’, which signalled an authentic booming of the market: on the phone he was like a sports supporter celebrating a victory, a ‘kid’ who had received his long-awaited gift. As a Catholic, now I should say “Presidente, rest in peace”. But, no way. I’m sure he’s not at peace, still not at rest – I’m sure he’s now negotiating with Saint Peter to secure fair winds for our beloved industry!

Grazie Presidente, it has been an honour to serve you.

LORENZO POLLICARDO TECHNICAL & ENVIRONMENTAL DIRECTOR, SYBASS

I write these words with a heart full of emotion and gratitude, trying to pay tribute to a person who has been a beacon in the world of yachting and in the lives of all those who had the privilege of knowing him, both as a man and as an entrepreneur. Working alongside him for 25 years has been a source of security for me and for all of us. Hearing him talk about boats made us eager to build them with passion, exactly as he liked – with great ‘pride’!

His example of dedication, expertise, his vision always ‘beyond’ and his ability to face every challenge with intelligence and courage have been a source of inspiration and foresight for all of us and, without any presumption, for the entire yachting world. The Doctor always knew how to give his best, not only through his boats (and there are many, believe me!) but also with his way of leading and supporting others, precisely in that world, the yachting world, where he knew how to see further than any other man of the sea, never as a limit, nor as a destination ... but as only a visionary could. With his personal values, sacrifice and immense attitude, he was able to aim for excellence, not as a destination, but as a continuous journey towards the best, towards the finest product: his.

His passing leaves a profound void in his Group, not easy to fill, but at the same time, the traces he has left are indelible and will continue to illuminate the path of those who had the privilege of knowing the Doctor.

It has been an honour for me to hear many times, referring to my work, “Grazie Architetto!!” with that unmistakable French ‘r’, which made me feel important. With much affection.

MARIA ROSA REMEDI INTERIOR DESIGN MANAGER, BENETTI YACHTS

DR PAOLO VITELLI

I knew this day would come. Not today. Not so soon. We had many more projects to imagine, ideas to discuss, to tear apart and start over again. More home-cooked carbonaras to share. Your retirement you worked so hard to enjoy … alas was not meant to be. I thank you for the fond memories. For the special place and time you reserved for me. For the opportunities you bestowed on me. For the lessons you allowed me to learn. For the wisdom you so eagerly shared. For your unwavering guidance and loyalty which over time led to the success we were about to celebrate on our 20th anniversary. Thank you for your immense generosity. Thank you for being unreservedly you. You will always be the most humble GIANT anyone will ever know. I shall be forever privileged to have grown under your wing, Paolo Vitelli. A formidable visionary and mentor. Yachting will never be the same without you, Paolo. Caro. Un abbraccio. Fin quando ci rivederemmo. Renderemo orgogliosa la tua memoria ...

NIKI TRAVERS TAUSS _ AZIMUT YACHTS MALTA

Column

by Terry Allen

Raising the industry standard

Terry Allen, surveyor and build manager, discusses the importance of a clear distinction between Flag and Class, and why it’s vital to raise standards to ensure a successful yacht build.

The best way to raise the standard is first to create one. Five major items create the basis of a good build: the specification, the contract, the Classification society, the Flag state and a good build management team that includes individual specialists in:

• Noise and vibration

• HVAC

• Structural engineers

• Paint surveyors

• The Classification society

• The Flag state

With all this expertise at hand, the build process still needs to be well managed and have support from all team members. So how can it still go wrong? Let’s consider the new-build scenario, which has similar steps to a conversion or refit. The client is excited about their new adventure and investment and should be guided in a manner where the investor gets what they want, not what the broker or whoever wants to sell. It should be very easy for the client to say this is what I want, this is where I want to go and this is what I want on my boat. Easy and simple – the client gets what they want, not what someone wants to sell them.

1. The Specification

The concept specification should be a document of around 150 pages that reflects the client’s requirements. During the build, the specification becomes a compilation of thousands of pages made up with installation guidelines by the manufacturer/supplier of the components to ensure the client gets what they want.

Just to add a bit of humour and context to this, the funniest specification I have ever seen on a job was a six-page specification, with the front page being a picture of the boat and job descriptions such as, and I quote, “It is understood that the crew area should be upgraded”. There were some other things in the other four pages and the shipyard had quoted 2.8 million to do the job. The upgrade of the crew area was ‘gutted’ back to the bare hull. The project finished at 11 million.

That’s how important a good specification is!

Once the specification is all clear and the chosen shipyard has reviewed with comments and the lawyers are happy, then it is safe then to go to the contract phase.

2. The contract

The contract should be written to reference the specification with all the legal bits added and the milestone points. The shipyard signs and the investor signs and it’s on with the show.

3. Class

The Classification society is contacted for a ‘kick-off’ meeting with the owner’s team, bearing in mind that during the build phase the Class surveyor is wearing the hat of the shipyard.

4. Flag

The Flag state is called in for a ‘kickoff’ meeting just like the Classification society. Here’s where it gets sticky if the Class surveyor walks through the door and says, “Hi everyone, I am also appointed by the Flag state”. As an owner’s rep/build manager, I have a problem.

A lot of Flag states delegate certain responsibilities of the build to Classification societies, which I understand should be beneficial to the project providing due diligence is maintained in respect of all the rules.

But now the Class surveyor has four hats to wear:

• With new build, Class is engaged by the shipyard: Shipyard hat

• The Classification society: Class hat

• Flag state: Flag hat

• Then, at the end of it all: Boat hat

It’s a very fine line that is easily determined as a conflict of interest because of the shipyard/Class/Flag and vessel relationship. But, at the end of the build, the Classification society wants to wear the boat hat. It’s a difficult balancing act.

I’ve experienced this scenario, and maintaining build quality is made more difficult because as an owner’s representative/build manager, a very important avenue of appeal over nonconformity, build standards or noncompliance is compromised by one person’s interpretation. The only person who loses out is the client/investor.

Flag state surveyors must be actively involved in on-site inspections to at

least ensure the appointed Class surveyor is doing the job expected and that the ‘due diligence’ is covered, which is a part of the package of the Flag state registry.

To ensure build standard during the build process, as an owner’s representative/project manager, the only things on my side are Class, Flag, the specification and the contract. Whatever I think outside of those four things is just my opinion and can be accepted or rejected accordingly, and I have no avenue of recourse unless I am disputing ‘an interpretation of the rule’ which, in most cases, will be dismissed by someone else’s interpretation of the rule that keeps the shipyard happy.

Once, when I told a Class surveyor that he was an insult to his profession, the gent in question obviously wasn’t happy but he must have thought about it a lot and three days later he came to me, shook my hand and then he was my best friend, and the build standard was maintained from a Class perspective.

Litigation is expensive, long and there’s always uncertainty of the outcome where the only ones certain to win in the story are the lawyers.

When things start to go south, what avenues of appeal does the investor/ client have?

Litigation

Litigation is expensive, long and there’s always uncertainty of the outcome where the only ones certain to win in the story are the lawyers. Suing the shipyard for poor build standards is a very grey area.

The first question is always, whose standards are we talking about? Honestly, hand on heart, when a shipyard director tells me that the client bought the Fiat not the Mercedes, what chances do you stand with that reply? Non-compliance of the specification, providing it is all clear cut, maybe. And all very costly, long and creating a lot of heartache for everyone.

Organisations such as Lloyd’s Register, ABS, DNV, BV, GL, etc and the Flag states provide safety and technical standards for ships and offshore structures. If they fail to meet their responsibilities, such as by incorrectly certifying a vessel or being negligent in their inspections, it can lead to lawsuits, particularly if such failures result in accidents, environmental damage or loss of life.

This a very long and expensive route that has a very limited chance of success unless things are crystal clear. If the client wants to proceed, they should be well informed of the elements and the hurdles involved in making this choice.

Classification societies

Contractual limitations, burden of proof, international conventions and treaties, industry protections and expert testimony: