DESIGN IN SYSTEMS

An Emergent Paradigm Shift in Research and Practice

Emergent Paradigm Shift In Design

Method

How To Read This Report

Designing within

Case Study I: The World Hakka Expo Case Study II: 1640 Riverside Road

05

MAKING AS KNOWING

Material Engagement as Epistemic Practice

Tools for Making Sense of Systems

Reclaiming Creativity and Depth in

Design Ideation

Examining Assumptions

Case Study I: Design Movement on Campus

Case Study II: Rebuild by Design

References

06

ALIGNED INTELLIGENCE

Human-Machine Synergy

Immersive Interfaces

Decentralized Digital Communities

Case Study I: Human–AI Collaboration through Tools and Experiences

Case Study II: MIT Tangible Media Group

References & Cases

07

LEARNING TO NAVIGATE

Competency in Complex Systems

From Silos to Synergies

Design Leadership

Case Study I: Young Designers’ Exhibition (YODEX)

Case Study II: Carnegie Mellon’s “Environments” track

References & Cases 08 CONCLUSION

PREFACE I

Design today stands at a crucial juncture. The complexity of our world, driven by technological acceleration, ecological disruption, and shifting social values, demands that design evolve beyond creating objects to shaping systems, beyond solving isolated problems to reimagining entire possibilities. This transformation calls for new methods and a fundamental rethinking of the paradigms that guide design itself.

Design in Systems: An Emergent Paradigm Shift in Research and Practice emerges from this recognition. Over the past decades, design has steadily outgrown its traditional boundaries, shifting its attention from the production of objects to the orchestration of systems, and broadening its perspective to embrace the interconnected relationships and actors that sustain our planet. These shifts have not occurred in isolation; they are part of a broader movement toward relational, ethical, and ecological forms of thinking that connect creativity with responsibility. In this light, design becomes a vital social and cultural force that shapes how we live together on this planet.

At TDRI, our mission is deeply aligned with this vision. As a national institute, we leverage design as a strategic force for systemic change in policy, industry, and public innovation,

driving competitiveness while advancing sustainability, inclusion, and well-being. This publication reflects the Taiwan Design Research Institute’s ongoing commitment to advancing design as a field of knowledge, inquiry, and public value. It discusses key directions reshaping the field, including emerging areas such as systemic and regenerative design, decolonial practices, the ethics of AI, and the infrastructures of care that support collective well-being. Together, these insights invite us to see design as a living inquiry, a continuous process of learning and transformation.

In this context, Design in Systems is both a reflection and a projection: it reflects how far the field has come, and it projects the possibilities that lie ahead. As we look toward the future, I hope this book encourages designers, scholars, and policymakers alike to embrace the uncertainty of transition with openness and imagination. The paradigms we construct today will shape how we design and how we think about design itself, its purpose, its ethics, and its power to create meaningful change.

I invite you to engage with these ideas, to question and expand them, and to join us in exploring what design can become in this time of profound transformation.

Chi-Yi Chang President of Taiwan Design Research Institute

PREFACE II

At the 2023 IASDR Congress in Milan, I had the honor of representing the Taiwan Design Research Institute (TDRI) in accepting the role of host for the next congress. From that moment, I began reflecting deeply on the theme that would shape our upcoming gathering.

Hosting IASDR 2025 in Taipei holds dual significance. Geographically, it marks the congress’s return to Taiwan—its inaugural venue—after twenty years. Temporally, these two decades have witnessed a profound evolution in design research, a trajectory highlighted in Milan, where the call for “life-changing design” resonated widely. In response, our organizing team reviewed the thematic developments of the past twenty years and proposed “Design Next” as the congress theme. This title not only reflects the transformations in design research and practice but also points to the emerging directions and actionable challenges these changes present.

Later that year, during TDRI’s International Design Week, we invited three successive presidents of the World Design Organization (WDO). After their keynote lectures, I posed a question: “Have you noticed that all your talks touch on design’s new mission? Could this risk expanding design’s scope to the point of becoming limitless?” A TSMC executive once joked that he, too, was a designer—of microchips. These exchanges capture both the promise and the tension within design’s ever-expanding domain.

In preparing for the congress, we consulted senior colleagues in the United States and Japan. Despite differing contexts, they shared a common concern: while design fields are rapidly evolving, what’s missing is a coherent, systematic framework to guide this transformation.

This raises two central questions: What major changes have emerged in the research issues and methods of design as a discipline? And how can this congress catalyze discussions that shape its future trajectory? This book was conceived to address precisely these questions. It serves both as an intellectual prologue to the IASDR 2025 theme, Design Next, and as a foundation for further collective exploration.

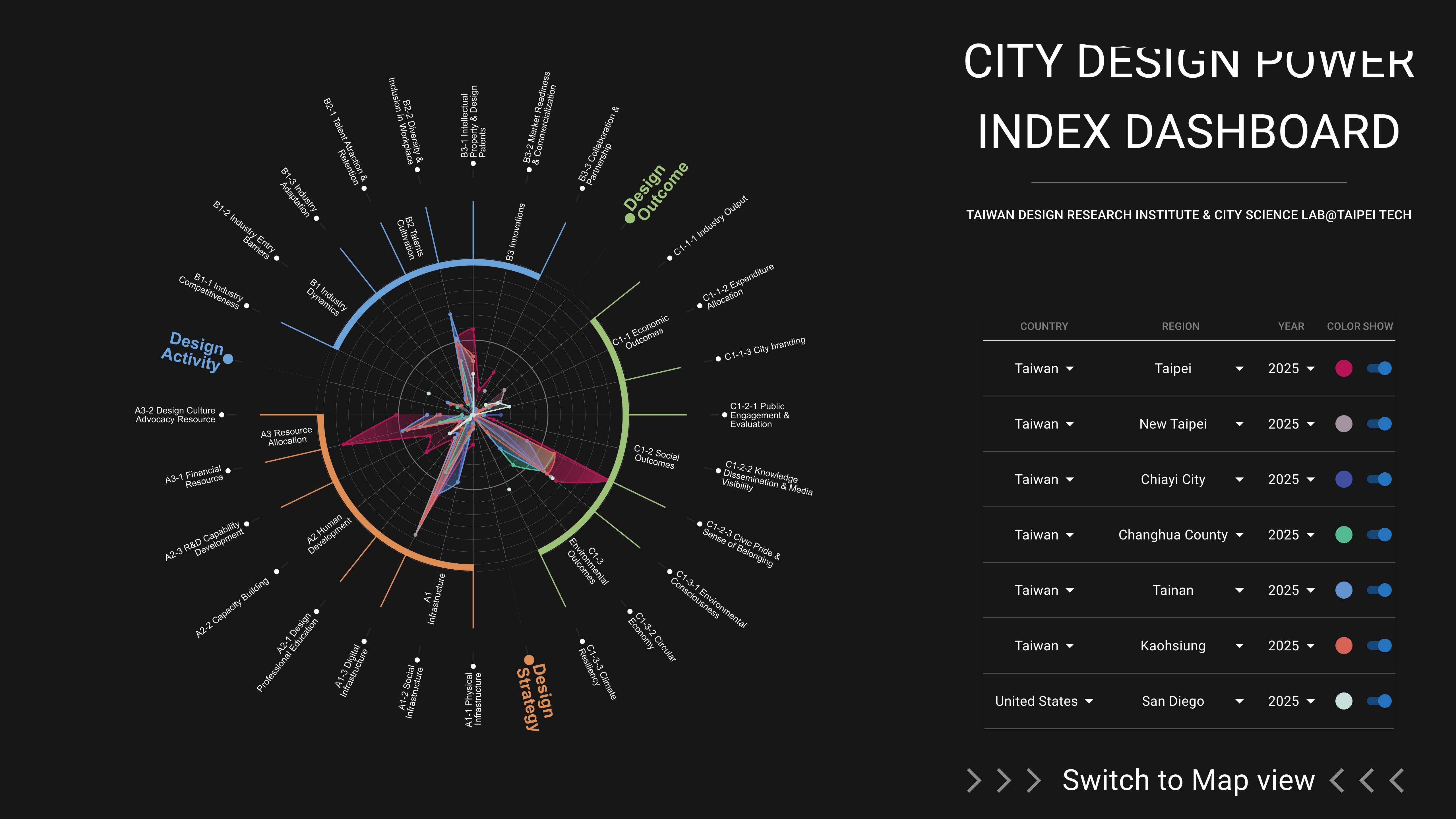

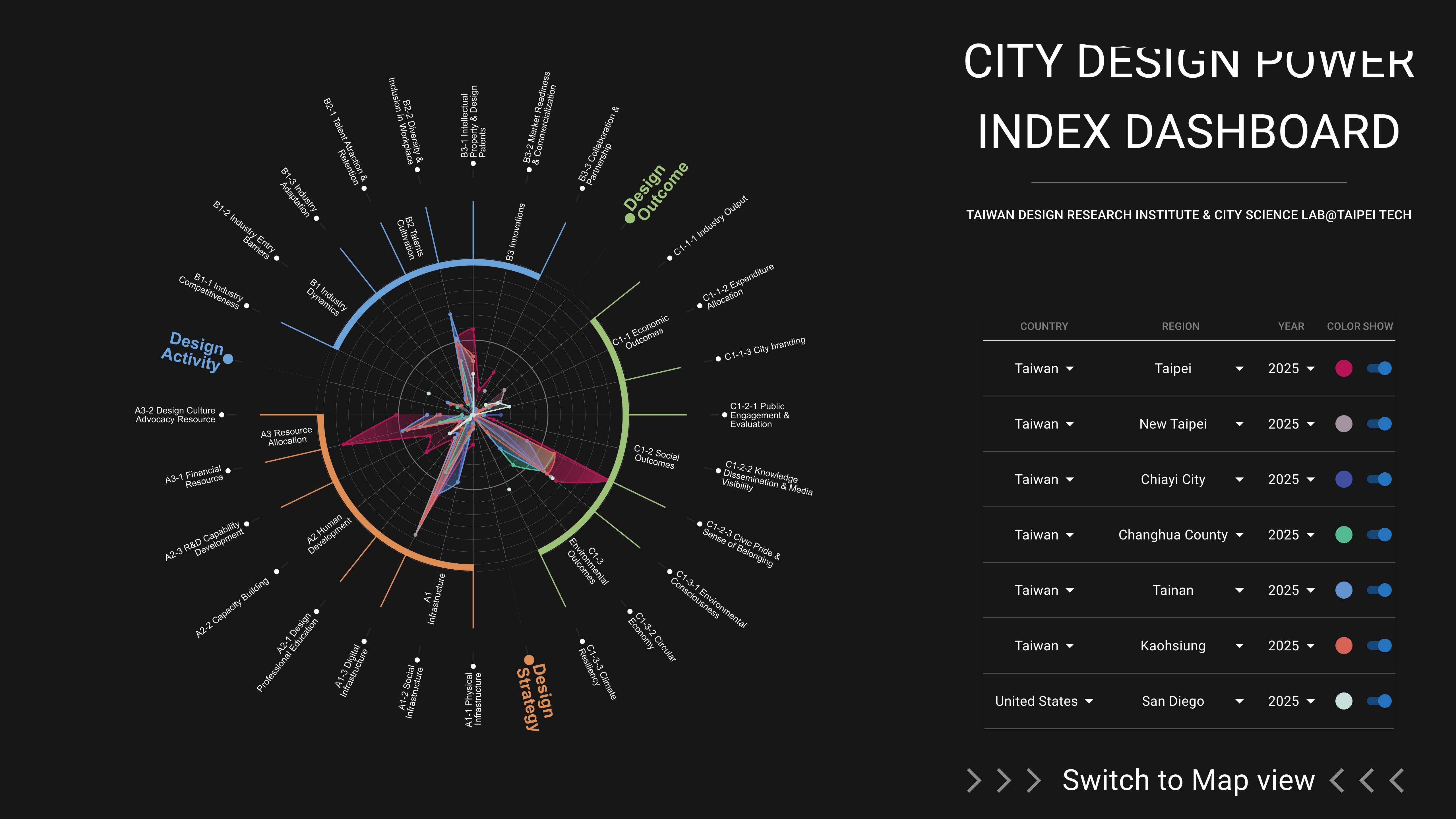

As the proverb says, “Virtue is never solitary; it always has companions.” On this journey, my own companions include the WDO, with whom we collaborated on the City Design Power Index. During a visit to San Diego—the 2024 World Design Capital—I had the pleasure of meeting Don Norman. In his recent book, Design for a Better World, he presents a pivotal argument: the need to shift from human-centered to humanity-centered design.

At the time of writing this preface, I had just returned from WDO 2025 in London and was en route to Detroit for the 60th anniversary of the IDC. The theme in London was “Design for the Planet,” while

Detroit focused on “Honor the Past, Design in the Present, and Shape the Future.” Together, these events signal an emerging paradigm shift, converging toward a shared vision for the future.

History also offers valuable perspective. In 1956, Herbert Simon—widely regarded as both the father of design science and artificial intelligence—joined leading scholars in challenging behaviorism and opening the “black box” of the human mind. Through the development of information-processing theory, they laid the foundation for cognitive science. Following in that spirit, this book adopts Thomas Kuhn’s framework of paradigm shifts to examine the future trajectory of design. We aim to explore design’s evolving teleology (its purposes) and ontology (its essence), and to consider how such shifts may redefine its epistemology (forms of knowledge) and methodology (practices). Beyond this analytical lens, the book surveys and synthesizes the work of leading contemporary scholars to identify several critical themes shaping the future of design.

This publication draws on insights from numerous TDRI projects and is the product of a deep and dynamic collaboration—shaped by the dedicated efforts of Ingrid P. Hernández Sibo at TDRI, Eric Charles Singleton at Stanford d.school, and me. Above all, it is offered with humility. It is an invitation to collective reflection and debate about design’s future—about how we might recognize and navigate paradigm shifts in values and methods. It is not a final statement, but a scaffold for dialogue: an extension of IASDR 2025’s mission to surface controversies, inspire deeper inquiry, and provoke new directions.

I am confident the congress itself will generate many more inspiring and thought-provoking contributions. Already, the 1,120 submissions across its twelve subthemes reflect a remarkable diversity of perspectives and interpretations. Beyond the proceedings and this volume, we are curating the Design Next Exhibition, which will further foster exchange and imagination—offering diverse modes of presentation to expand our collective vision for the future of design.

Shyhnan Liou Vice President of R&D at Taiwan Design Research Institute

“As it reckons with past choices and considers future implications, the field of design is in the midst of a paradigm shift.”

INTRODUCTION

Across diverse fields of design, both the issues addressed and the methods employed are undergoing profound transformation. For instance, the World Design Organization’s (WDO) 2025 Congress adopts the theme “Design for the Planet,” signaling a paradigm shift from human-centered products and services toward systemic and planetary-scale transitions. Similarly, the IDC 2025 60th Anniversary Conference embraces the triadic vision “Honor the Past, Design in the Present, and Shape the Future,” inviting the design community to reimagine future trajectories of the discipline.

The IASDR 2023 Conference in Milan advanced this momentum under the theme “life-changing design,” where each subfield called for transformation within its own domain. Yet amidst this proliferation of reformist discourse, a critical question arises: Can these fragmented movements be understood through a coherent, systemic framework that explains the logic of design’s ongoing transformation? Why—and in what ways—is design evolving as a professional and academic field?

This book seeks to address these questions by tracing the intellectual and methodological trajectories that underpin the current paradigm shift in design research and practice. In doing so, it aligns with the central inquiry of the upcoming IASDR 2025 Conference: What is “Design Next”?

EMERGENT PARADIGM SHIFT IN DESIGN

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962)1. Thomas Kuhn introduced the concept of paradigm shift to explain how scientific progress occurs through periodic transformations in foundational theories and methodologies. According to Kuhn, paradigms serve as established frameworks that guide research, problem solving, and knowledge production within a field. He posits that progress occurs through cycles of transformation. These cycles comprise three key phases:

1) The ‘pre-paradigm’ phase, marked by competition and a lack of unified theory

2) The ‘normal science’ phase, defined by a dominant paradigm structure; and

3) A ‘revolutionary’ phase, marked by anomalies (problems) in the current paradigm, which culminate into crises that trigger a brand new paradigm.

Problems like warming oceans. Like rapidly developing digital landscapes. Like the growing reckoning that many of the systems we designed over the past five centuries do not work for the modern day. Kuhn’s paradigm shift framework offers a structure for understanding the turbulence and transformations currently occurring in the design field, pointing toward a new direction:

PRE-PARADIGM: THE 20TH-CENTURY ERA OF ARTIFACT-CENTERED DESIGN

This era was predicated on industrialization and maintained by capitalism. With the Industrial Revolution came inventions like the steam engine and the power loom. Consumption skyrocketed, and mass production was possible at a scale never seen before. Given the rise of the consumer economy, many products were designed to solve problems of productivity and efficiency. As time progressed, industrial production intensified, devaluing traditional craftsmanship and artistic intuition, as they could not meet global demand. There was also no singular ‘design method’a in the 20th century. Many designers attempted to merge fields and disciplines through gatherings such as the Conference on Design Methods in London in 19622. A systematic design practice firmly rooted in efficient product development was beginning to coalesce. This is why many people associate industrial manufacturing with design.

NORMAL SCIENCE: THE DOMINANCE OF HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN

In the second half of the 20th century, breakthroughs in microelectronics, software, and networked communication ushered in a digital experience economy. Design was no longer just

about building beautiful artifacts–it was about personalization. Digital and physical worlds were shaped according to individual user needs. Design thinking became a widespread practice3. Insights were “unlocked” through design ethnography and abductive analysis, further establishing design as a structured discipline rather than an art form. Companies such as Apple and Microsoft (now two of the biggest companies in the world) incorporated brand perception and storytelling into their digital interfaces. Human-centered design became the dominant paradigm in both practice and scholarship, and has defined the field for decades4 This is why many people associate design with UI/UX and the tech industry.

REVOLUTIONARY: CRISES LEAD TO ASSEMBLAGE-CENTERED DESIGN

From the beginnings of industrialization to the current day, Western hegemony and consumerism have heavily influenced the field of design. Behind these systems are core values of control, power, and wealth accumulation. They have incentivized short-term gains, neglecting time-honored knowledge and the delicate balance of the Earth and its resources5 The dominant strategy has been to exercise power and control across systems without fully acknowledging or understanding them. Systems scholar Donella Meadows described this as the “omniscient conqueror” mentality in her book Thinking in Systems6. In 2025, systems forged through this mentality are failing. The illusion of control is eroding, and persistent problems–wealth inequality, war, climate change–are escalating into global crises. What’s more, the pace of technological systems development over the past several centuries has been astounding, and the curve continues to steepen. No example is more salient in today’s society than the rise of artificial intelligence, which has led to questions of how to be a designer in an increasingly posthuman world7. Design is no longer just about the products we develop or the experiences we create. It is about how these actions map onto complex, inseparable systems .

We are out of balance in a globalized world. A decision made in one corner of the planet could spark instability in another. Commercial products have far-reaching environmental and ethical consequences. Our systems perpetuate the choices of our past. Yet as designers, we exist within an opportunity space. By deconstructing the impacts of earlier phases of design and contextualizing them within dominant global paradigms, we deepen our understanding of what got us here. This opens up opportunities for radical creativity and for coordinating skill sets across disciplines to dismantle these systems and move forward. Designers around the world are forming the conditions for a paradigm shift in the field, one that centers the systems we exist within.

Artifact-Centered

Design as a fragmented practice primarily focused on creating tangible products.

Human-Centered

Positioned the user at the core of design processes and became the dominant paradigm.

Assemblage-Centered

A fundamental restructuring of design’s role in shaping long-term planetary and societal well-being.

Crisis

An emphasis on individual ‘userism’ proves inadequate for addressing systemic, large-scale challenges.

EMERGENT

PARADIGM SHIFT IN DESIGN

Anomalies

Climate change, social inequality, and the systemic risks posed by unregulated AI development.

METHODS

This publication explores the revolutionary period in design we are currently in as we move toward assemblage-centered design. Given the depth and diversity of the field, we conducted a multi-source analysis of changes occurring within design research and practice between 2023 and 2025. This report is grounded in two main approaches: top-down and bottom-up approach. The top-down approach draws on the theoretical framework of paradigm shifts and scientific revolutions. This helps us understand the progression of human knowledge and the influence of the spirit of the times. The bottom-up approach is rooted in a multi-source analysis of changes occurring within design research and practice between 2023 and 2025. This provides field-specific insights into what is being discussed across the design field. Given the depth and diversity of the field, the analysis included a wide range of sources,

Entangled in Emergence Connectivity and Creativity in Times of Conflict Life-Changing Design

This Space Intentionally Left [Blank] Narratives of Love Research and Education Forum Rivers of Conversations Preferences of Design Design Across Borders: United in Creativity Resistance, Recovery, Reflection, Reimagination Beyond Boundaries: Design Policy Conference Ethical Leadership – A New Frontier for Design Relational Design Arcs of Impact Designing for Planet

● Organizations: Systemic Design Association (RSDX), Cumulus, IASDR, Nordes, WDO, Design Research Society (DRS)

● Data Extracted: 15 Conference Proceedings 59 Conference Tracks 1651 Conference Papers

Delft The Royal College of Art (RCA) Department of Design – Politecnico di Milano PolyU Design SNU – Department of Design

Design

Schools Curriculums

● Universities: Stanford, TU Delft, RCA, Aalto, Politecnico di Milano, PolyU, SNU (Seoul National University), MIT, Linnaeus, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland.

● Data Extracted: 10 Curriculums 894 Courses

● Organizations: Gensler, Frog Design, iF ● Data Extracted: 6 Reports 46 Key Design Trends

We made sense of these data using a step-by-step guide for thematic analysis. After collecting all these data, we developed an initial coding framework covering ideas, methods, theories, and critiques. Through iterative coding, we identified patterns and synthesized related codes into 19 emerging topics grouped under six major themes. These themes are broad–the truth is, each one could be its own publication. Nevertheless, they provide insight into what designers are thinking. Industrialization, health, colonial legacies, virtual reality, and futurism are some of the many themes being discussed, and designers are contemplating how they may use the tools of design to reimagine systems.

INPUTS

Data sources: journals, conferences, debates, curricula, and reports

PROCESSES

- Get familiar with the data

- Generate initial codes

- Search for emergent topics themes

- Iterative coding

- Define + name major themes

OUTCOME

A report outlining major themes for paradigm shift in design

Academic Design Journals

● Journals: CoDesign, Design and Culture, Design Studies, She Ji, The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation

● Data Extracted:

12 Journal Issues

242 Journal Articles

56 Special Journal Issues

31 Articles Selected for Special Issues

Special Issues

Expanding the Frontiers of Design

The Future of Design Education

Designing Against Infrastructures of Harm

Future Making

Towards Pluriversality: Decolonising Design and Capital

Reports Core Themes

Design Strategies for the Human Experience: Collide, Connect, Care.

Transformations in Our Society, Exploring Impact. Future Scope

Creating Design Impact with Optimism and Innovation

Scholars Debates

● JISCMail: PhD-Design mailing list led by thought leaders in the design field, including distinguished scholars, PhD students, and practitioners.

●

Data Extracted:

20 Debate Topics

159 Email Threads

Debated Topics

Reframing Artifacts: Systems Thinking in Design Practice and Theory

Design and Social Science

Rethinking Design Education, Research, and Industry Readiness

Rethinking Design in ID Education

Educating Design Students for Professional Life

Reflections on Design, Technology, and Globalization

Human, AI, and Design

Rethinking Measurement, Innovation, and Meaningful Change in Design

Measuring the Impact of Design for Sustainability

Pausing AI Experiments

Is the Era of Design Thinking Over? Reflecting on IDEO and the Future of Design

User-Centered Design and the Limits of Transferability

Designing for Activism

Designing with History: Practice-Based Uses of the Past in Design

Designing Ways of Knowing in the Age of AI

Ethnomethodological Approaches to XR Design

Affordance Revisited

The Role of AI in Design

Decolonizing Design: Theories, Strands, and Practices Toward Pluriversal Futures

Predicting User Behavior with Multiple Affordances

HOW TO READ THIS REPORT

Everything in this report–from text, to graphics, to images–has meaning. We invite you to read, ponder, and allow the information to sink in. Remember, this is a broad publication that includes some (but not all) examples of how designers are approaching this work. Explore new ideas beyond these pages.

This report contains six chapters, each corresponding to a central discussion about paradigm shift within the design community. There is no need to read sequentially–feel free to find a title that piques your interest and dive right in.

Jump around and build connections. You will see several “related work” boxes throughout the text, linking a concept in one chapter to another.

There are many concepts, definitions, and frameworks covered in this report. To keep this report concise, we included 1) a glossary for key definitions, with links to advanced readings, and 2) a list of key references and case studies that illustrate real-world applications, placed at the end of each chapter. All of these give you a chance to explore concepts further.

MAKING AS KNOWING

Across its phases, design has emphasized intuition, creativity, and disciplinary depth. A focus on systems emerged in the 20th century, when several design scholars and practitioners began integrated cybernetics and wicked problems (two systems-oriented frameworks) into design thinking. Now the time has come to integrate these practices more widely across the field. As designers shift toward becoming systems practitioners, these skills can address complex issues through assemblage-centered design. To release ourselves from the grip of the past, we must evolve as a field to create with kindness, broaden our perspectives, and return to long-term thinking.

“Living successfully in a world of systems requires more of us than our ability to calculate. It requires our full humanity–our rationality, our ability to sort out truth from falsehood, our intuition, our compassion, our vision, and our morality.”

— Donella Meadows

REFERENCES

Kuhn, T. S. (1997). The structure of scientific revolutions (Third ed., Vol. 962). University of Chicago press Chicago.

Jones, J. C. (1977). How my thoughts about design methods have changed during the years. Design methods and Theories, 11(1), 48-62.

Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard business review, 86(6), 84.

Norman, D. (2009). The design of future things. Basic books.

Norman, D. A. (2023). Design for a better world: Meaningful, sustainable, humanity centered. MIT Press. Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in systems: International bestseller. chelsea green publishing.

Niewöhner, N., Asmar, L., Röltgen, D., Kühn, A., & Dumitrescu, R. (2020). The impact of the 4th industrial revolution on the design fields of innovation management. Procedia CIRP, 91, 43-48. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2020.02.149)

At the heart of any paradigm shift is a fundamental change in mindset. Increasingly, designers are moving away from strictly human-centered approaches, recognizing people as just one of many actors within broader systems. Design operates within and influences both natural ecological systems and human-made cultural systems. The natural system encompasses the organic conditions necessary for our survival, while the cultural system reflects the accumulated knowledge and intelligence through which humanity has evolved. A system is both spatially holistic and temporally dynamic; it is shaped by categories and history. In this context, the purpose of design is to support the sustainable and resilient co-evolution of ecological and cultural systems, promoting environmental continuity alongside cultural vitality through a systems-oriented approach. As our understanding of these systems deepens, design holds the potential to imagine and shape new frameworks that are inclusive, adaptive, and transformative.

FORCES OF TRANSITION

DECENTERING THE HUMAN

Regarding the natural system, who—or what—should we consider vital actors in the design process? Artifact-centered design has traditionally focused almost exclusively on the creation of products and services for humans. This phase led to increased productivity but also resulted in the exploitation of both people and natural resources. Human-centered design brought empathy and broader participation into the design process. However, it remains just that: centered on humans. Both artifact- and human-centered approaches operate within the same anthropocentric paradigm, one that places humans at the center of all considerations. This paradigm obscures the Earth’s vast and ancient history, a history shaped by countless nonhuman entities that have, over billions of years, designed artifacts, formed relationships, and shaped global systems. In design, our practices have largely prioritized human problems and solutions. We rarely consider plants, animals, rivers, molecules, and other nonhuman forces as vital agents in the design process. To fully engage with the complexity of today’s systems, our frameworks must evolve to grant rights and agency to nonhuman actors1. They are a crucial part of the puzzle for understanding complex systems.

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) reinforces this by asserting that it is the relationships among human and nonhuman actors that make systems function. Agency arises through connections, and shifts in these relationships can ripple across entire networks. Take, for instance, an urban public transit system. The actors include both human elements (passengers, conductors, engineers) and nonhuman ones (buses, trains, payment systems, weather patterns, even music, viruses, and the AI managing autopilot systems). The system’s functionality relies on the coordination of these diverse actors. If a turnstile breaks, commuters

RELATED WORK:

‘Decentering the Human’ ties directly into incorporating pluriversal and decolonial perspectives in design. Flip to page 26 in the next chapter to learn more.

may be blocked from entering. Rain may reduce ridership and delay buses. This is one example of how a post-anthropocentric lens can be applied to design.

This mindset underpins the emerging paradigm of assemblage-centered design. In this model, a "user" might be a pollinator or an algorithm. A “stakeholder” could be future generations not yet born. The "environment" refers not only to nature but to an interwoven ecosystem of digital, cultural, and ecological systems. This approach reveals the many often invisible systems that sustain our world.

In the cultural and social sphere, designers must now account for the well-being of multiple worlds in their ideation processes. This represents a significant departure from Western-centric paradigms. Fortunately, numerous theories and knowledge traditions can guide this shift. Feminist new materialism proposes that matter is not passive but an active agent that shapes bodies and behaviors. Assemblage thinking emphasizes that wholes are more than the sum of their parts, and that new behaviors emerge from interactions within systems2 Multispecies ethnography provides a rigorous foundation for design research that explores the cultures and experiences of nonhuman beings. These frameworks echo the teachings of many Indigenous cultures, which have long understood how to live in reciprocity with nonhuman life. Despite being marginalized by capitalist and colonial systems, these traditions endure as some of humanity’s most ancient sources of wisdom. They offer vital insight, developed over centuries, and across millennia, into how we might design more harmoniously with the entire web of life3.

SPECULATIVE REFLECTION

The temporal dimension of system design highlights that systems are inherently ecological and organic. The central task of design, therefore, involves navigating the dynamic mechanisms of temporal flow: integrating forces over time, discerning patterns from the past, and envisioning the continuous evolution of the future. Design draws on both insight from experience and foresight, an ongoing process of making sense of the present while shaping meaning for what lies ahead. It is a continuous act of creation, rooted in both sense-making and sense-giving. The world around us is constantly in motion, yet we often remain unaware, not because we’re incapable of noticing change, but because our attention is directed elsewhere. Just as we seldom notice the Wi-Fi until it stops working, we tend to overlook nonhuman systems until they break down. Speculative design serves as a powerful disruptive tool, allowing us to interrogate what is often invisible. It sheds light on the structures that shape everyday life and invites reflection on possible futures. Unburdened by the constraints of efficiency or monetization, speculative design exists to provoke questions and explore alternatives.

Design fiction and discursive design are two prominent speculative practices. These approaches involve creating artifacts that bring abstract or distant issues, such as climate change, into the realm of present-day experience. By offering tangible forms of complex systems through visualization and interaction, they make the intangible more graspable. A simple radio with unusual broadcasts,4 for example, can raise questions about the sustainability of current systems. Hauntology offers another powerful lens for speculative work, revealing how unresolved historical traumas—such as colonial legacies—continue to shape our present. Futures once imagined but never realized linger as ghostly traces, subtly influencing today’s perceptions, choices, and systems.5

Speculative methods use design tools to pull participants out of the status quo and create space for imagining new systems. By embracing ambiguity, discomfort, and debate, these approaches encourage users to confront difficult questions, challenge assumptions, and consider the long-term implications of technologies and policies. This space fosters greater representation and creativity than traditional strategic tools like scenario planning or forecasting. Rather than simply preparing for the future, speculative design offers a medium for exploring how the future could be different—an intervention that invites audiences to see the world with fresh eyes.

TRANSITIONING SYSTEMS

Many speculative design projects reveal systemic failures already evident in today’s world. The so-called “dystopian” futures imagined in the Global North, such as water scarcity, energy shortages, or climate-driven displacement, are the lived realities of many communities in the Global South. These conditions are not inevitable; they are the direct outcomes of industrialism, capitalism, and anthropocentrism. Together, these systems have created what some describe as “structured unsustainability,” where the pursuit of infinite growth clashes with the planet’s finite limits. Addressing these challenges requires design practices that can reimagine how societies live, work, consume, and relate to nature, particularly in the face of complex problems with no clear solutions and deeply contested values.

To do so, we must learn to recognize and transform the systems that shape our relationship with the environment. This situates design as a catalyst for long-term systemic transitions toward sustainability and resilience6. Responsible design today demands a nuanced understanding of the interactions between natural, social, and technical systems. It must guide interventions that are both ethically grounded and ecologically sound. This shift calls for moving beyond isolated problemsolving to addressing the root causes embedded in dominant socioeconomic and ecological structures: how we power cities, grow food, and manage waste—all while emphasizing a vision of coexistence between human and ecological systems7. At the heart of this perspective is the recognition that today’s systems; human, planetary, technological, and otherwise, are deeply interconnected. Meaningful design must consider how individual components impact the broader whole. It requires extensive coordination across disciplines, institutions, and stakeholders, along with a commitment to long-term thinking that ensures these systems continue to function together sustainably.

Transition design is central to assemblage-centered approaches. It maps the societal shifts in values, behaviors, and infrastructures needed to address the failures of existing systems. True to foundational design principles, transition design treats ambiguous problems not as puzzles to be solved once, but as ongoing challenges that require continuous engagement. It does not simplify complexity but instead embraces it, acknowledging that large-scale systemic change cannot rely on one-size-fits-all solutions8 Regenerative design goes a step further by aiming to restore ecosystems and uphold the dignity of both human and nonhuman life. This includes models like circular economies, which create closed-loop systems that foster more reciprocal relationships between people and the environment, moving away from the linear models of industrial extraction. Regenerative practices are often led by local communities. For example, the rice terraces of the Ifugao people9 embody a resilient, socially embedded system of circular agriculture. Sustained for nearly 2,000 years, this system is now under threat from urbanization and climate change. To move beyond the increasingly precarious task of merely sustaining life, and toward actively regenerating it, we must embrace these kinds of integrated, place-based practices.

CASE STUDY I:

WeWe Futures

In collaboration with the Ministry of Digital Affairs, TDRI posed a forward-looking question: Can emerging 6G communication technologies enhance citizen participation in public affairs? This inquiry forms the basis of a quintessential digital democracy project.

Through the “WeWe Futures” initiative, citizens of all generations were encouraged and empowered to envision the future. The project gathered over 3,000 proposals, each reflecting diverse visions of what lies ahead. These ideas were synthesized through an alignment assembly, a participatory process designed to transform individual insights into collective intelligence, ultimately informing policy recommendations for national development.

Both the WeWe Futures: Tap to Your Future ideathon and its subsequent exhibition at the Taiwan Design Museum demonstrated how speculative design can create space for imagination, dissect the present, and explore potential futures. The project addressed themes such as decentralized collaboration, regenerative urbanism, and hybrid governance. During the workshops, participants examined current realities and shared forward-thinking ideas, which were later transformed into immersive installations that made abstract concepts tangible and participatory.

WeWe Futures exemplifies how speculative design can reveal hidden assumptions and foster collaborative reflection on the systems that shape our world. It invited visitors to engage with uncertainty, explore ethical futures, and examine the complex interplay between technology, ecology, and society. In doing so, the project modeled a design practice rooted in care, imagination, and interdependence.

View an overview of the exhibition at (https://reurl.cc/898XKM).

CASE STUDY II: Indigenous Fire Management in Australia

Aboriginal Australians have used cultural burning to regenerate ecosystems and prevent catastrophic wildfires for millennia but were suppressed under colonial rule. These practices are now being revitalized through Firesticks, an Indigenous-led nonprofit. Firesticks facilitates Indigenous knowledge-sharing

across communities, scientists, and policymakers by combining traditional fire knowledge with design tools such as visual mapping and participatory workshops.

Firesticks positions fire, soil, plants, animals, and the climate as active agents. This practice decenters human actors and advances more expansive ideas of regenerative systems of land care. Its co-designed maps, training frameworks, and storytelling practices transform cultural burning into a collaborative platform, showing how design can align human and nonhuman actors to build more reciprocal futures. Visit (https://reurl.cc/ekAyeM) to learn more.

The field of design is undergoing a radical shift in perspective; from a human-centered approach to a systems-centered one that considers a diverse range of actors. By decentering the human perspective and using speculative design to uncover hidden dynamics and possibilities, we can create conditions that support the emergence of transitional systems.

REFERENCES & CASES

Case: Charman, K. (2008). Ecuador first to grant nature constitutional rights. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 19(4), 131-133. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2020.02.149)

Youn, H., & Baek, J. S. (2024). Assemblage-based stakeholder analysis in design: a conceptual framework through the lenses of post–anthropocentrism. CoDesign, 20(4), 585-606. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2358966)

Nicenboim, I., Oogjes, D., Biggs, H., & Nam, S. (2025). Decentering through design: Bridging posthuman theory with more-than-human design practices. Human–Computer Interaction, 40(1-4), 195-220. (https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2023.2283535)

Case: Energy Babble Project.(http://doi.org/10.28938/9780995527720)

Patil, M., Cila, N., Redström, J., & Giaccardi, E. (2024). In conversation with ghosts: towards a hauntological approach to decolonial design for/with AI practices. CoDesign, 20(1), 55-76. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2320269)

Attaianese, E., & Rigillo, M. (2021). Ecological-thinking and collaborative design as agents of our evolving future. TECHNE-Journal of Technology for Architecture and Environment, 97-101. (https://doi.org/10.13128/techne-10690)

Case: Design capability when visioning for transitions: A case study of a new food system. Design Studies, 91, 101246. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2024.101246)

Saha, T., & Nusem, E. (2024). Ecologies Otherwise: Mapping Ontological, Speculative, and Transition Design Discourses. Design and Culture, 16(2), 191-210. (https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2024.2335429)

Case: Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras. (https://reurl.cc/3M940L)

Ethics, justice, and community participation are foundational principles that should be present at every stage of the design process. Designers are increasingly called upon to reckon with the ripple effects of their work, reflecting the interconnected nature of global systems. Integrating the ongoing work of decolonization transforms the field of design from narrow definitions to diverse possibilities.

DESIGN UNLIMITED

TOWARD HUMANITY: ETHICS AND JUSTICE

Beyond advanced functionality and efficiency, the core insight of humanity-centered innovation concerns ethics and justice. New perspectives refer to the products of design as ‘materialized morality.’ They are physical, tangible reflections of the values of a design team, and have the power to shape the worlds we live in. An electric car is a product loaded with ethical considerations. What role does the car play in offsetting carbon emissions? Where and how are cobalt, lithium, and other minerals sourced for the car’s battery? Is the car marketed as a complement or a competitor to other modes of sustainable transportation, such as trains or buses? What sense of agency does the driver have? These questions highlight important ethical considerations at every stage of the design process. In response, there is a growing critique of the use of ethical language without real accountability or substance. Many conventional design practices claim to uphold values such as sustainability and inclusion. The pervasiveness of this trend is clear from its many names: greenwashing, virtue signaling, performative allyship. Superficial ethics not only obscures the consequences of design choices but also perpetuates global systems of inequality rooted in extractivism. To counter this, robust accountability mechanisms for community oversight1 are needed to ensure that outcomes are truly meaningful.

Design justice directly asks who gets to design, which perspectives are present in the design process, and how people will benefit (or suffer) from design decisions. These questions aim to redistribute decision-making power to those voices who have been marginalized by today’s systems2. Relational ethics focuses on accountability and care within specific contexts, rather than as abstract principles. It emphasizes the capacity to respond ethically within complex networks of human and nonhuman interactions. Together, design justice frames the intention: It centers structural inequalities and those who have been marginalized by these structures. Relational ethics establishes the process: It frames the design process as a network of relationships rooted in balance and respect for multiple knowledge sources. Strengthening design ethics empowers practitioners to ask better questions, navigate ethical ambiguity, and imagine how design decisions could shape multiple futures3. It effaces the idea of neutrality within design, reminding us that “materialized morality” is a political and value-laden practice.

PLURIVERSALISM AND DECOLONIALISM

The central task of design within systems lies in recognizing and ensuring diversity and resilience. Biological and cultural diversity represent not only the ethical and democratic defense of justice but also the very conditions that enable human civilization to evolve through variation and adaptive selection. Creativity in design often arises from such pluralistic variation, the capacity to flexibly respond to changing environmental demands and to generate alternative possibilities. For instance, Bhutan’s cultural tradition embodies a mature belief system and wisdom that guides harmonious coexistence between people and their ecological environment. This cultural intelligence exemplifies the kind of civilizational wisdom essential

for sustaining resilient and enduring systems.

Western colonialism, capitalism, and anthropocentrism have restricted the field of design. They have upheld the myth that there is a singular model for progress, aesthetics, and problem solving. How can this be true, considering that these systems obfuscate the diverse array of human and nonhuman actors in our world?

Pluriversal and decolonial design realign the field toward a more sustainable and just future. They call for respecting multiple worldviews, particularly those rooted in Indigenous, Afro-diasporic, and local traditions.

Pluriversal design reframes design as an inherently relational practice. It foregrounds interconnectedness, reciprocity, and context-specific meaning-making. The sacredness of land, ancestral wisdom, and the rights of more-than-human entities (e.g., rivers, forests, and animals) are all considered throughout the design process4 Decolonial design critiques and dismantles colonial structures of knowledge, power, and aesthetics. It addresses coloniality directly: the global harm that it has caused and its persistence today through neocolonial systems of corporatization, environmental injustice, and data extraction5. Both pluriversal and decolonial design reject extractive logics that strip value from communities without reciprocity. They also reassess central design concepts such as ‘user,’ ‘efficiency,’ and ‘innovation,’ especially when these neglect spiritual, ecological, and relational dimensions of life.

Crucially, pluriversal and decolonial design do not aim to reform existing systems from within. They seek to fundamentally reimagine design itself as a space of reclamation, resistance, and possibility. Designers and community members alike begin this process through learning (and often relearning) the histories that have shaped their communities. Oral histories and counter-archives are ways to reclaim and uplift silenced perspectives in design. Oral histories expand knowledge by broadening how we learn about the past. History doesn’t have to be written to be valid–it can be sung, spoken, and even performed. They have the power to articulate values and perspectives within groups with a rich tradition of storytelling, conveying insights that could not be understood otherwise6. Counter-archives directly oppose colonial histories, offering new recollections through artifacts such as zines or community-based archives. Collaborative storytelling is yet another practice that centers co-creation. It fosters shared understanding between designers and community members through story-building that incorporates a range of perspectives. It is a powerful speculative practice, enabling collective participation in building a shared vision for a just future.

Disenfranchised communities have long endured conditions that neglect their spiritual, ecological, and relational dimensions of life. Today, design is deeply entangled with these histories, making it imperative for designers to commit to the ongoing work of decolonization. Through this commitment, the field moves toward an era of assemblage-centered design.

“The truth is one, the wise call it by many names.”

— Rig Veda

RELATED WORK:

Depending on how they are structured, creative brainstorming sessions could reinforce colonial, capitalist frameworks. Jump to page 47 to learn more about reclaiming pluriversal perspectives in design ideation.

Interpret and re-interpret

DESIGNING WITHIN REAL-WORLD CONTEXTS

In contemporary design research, understanding and addressing problems situated in real-world contexts increasingly draw on theoretical and methodological frameworks from the social sciences. Field research, for example, emphasizes the contextual and contingent dynamics that shape human and institutional behavior. Meanwhile, action research promotes a form of knowledge generation rooted in participatory experimentation and reflexive understanding within lived environments. Together, these traditions form the epistemological foundation for a systemic design research methodology that views views both the researcher and the researched as co-participants in the construction of knowledge.

Community-based participatory design exemplifies this paradigm. It challenges the designer’s traditional role as an external problem-solver and reframes design as a collaborative, diagnostic process that unfolds within complex social systems. In these “clinical” modes of inquiry, knowledge emerges through iterative cycles of observation, reflection, and intervention conducted in close partnership with stakeholders. This approach aligns with Peter Senge’s (1990) concept of community-based action learning, as well as the European Union’s Living Lab model, both of which promote co-design and co-evolution as key mechanisms for social and systemic innovation.

Under such conditions, design research and design practice become interdependent and mutually generative. Designers, together with collaborators from industry, academia, and the public sector, engage in collective sensemaking and knowledge development through the act of design itself. This collaborative epistemology repositions design as a systemic and reflective practice, one that not only produces solutions but also fosters the conditions for shared learning, adaptation, and transformation within evolving sociotechnical environments.

Community participation in design is not new; however, it has too often been treated as a box-checking

exercise in consultative practice. True participatory design, by contrast, is grounded in authentic dialogue, flattened power structures, and sustained relationships. Designers must involve community members as equal partners from the outset, shaping not only the initial idea but also the project’s structure and trajectory as it evolves7. Microethics brings attention to the everyday ethical choices that influence participatory work, highlighting how seemingly small actions; like building trust, managing conflict, and making decisions, directly affect the quality of participation and relationships. When done well, design becomes an ‘infrastructuring’ practice: the design process itself becomes a vehicle for fostering authentic, enduring relationships. These relationships are crucial in a world where complex challenges demand ongoing collaboration.

From testing small prototypes to envisioning the future of a city8, participatory design is scalable and adaptable. It values collective intelligence, a core principle of pluriversal design, where diverse knowledge systems and expertise converge toward shared goals. Organizations such as Nesta, in collaboration with UNDP, have developed toolkits (https://reurl.cc/4NKqpR) that apply collective intelligence design to address complex global challenges. In the public sphere, civic hackathons and policy labs encourage collaborative problem solving and rapid prototyping of new public service models. Ultimately, participatory design offers a flexible set of tools and methods applicable across a wide range of domains.

TOOLS FOR PARTICIPATORY DESIGN

Designers and communities move away from conventional, extractive models by using participatory practices. In this transformative approach, participation becomes a shared journey characterized by humility, mutual care, and openness to meaningful change.

Relational Facilitation

Intentionally shapes the social and emotional conditions necessary for effective collaboration.

Looks like: Deep listening practices · Attentive responsiveness · Careful facilitation of spaces to allow equitable participation and genuine dialogue.

Affective Mapping

Acknowledges and incorporates emotions, tacit experiences, and subtle relationship dynamics into participatory processes.

Looks like: Color-coding and mapping emotional reactions to a place · Cognitive Affect Maps (CAMs) to link emotions and values.

Slow Design

Rejects rapid, superficial fixes and favors prolonged, adaptive, and reflective community engagements.

Looks like: Community-led product development with designers act as facilitators · Observing users through contextual interviews with users · interactive models.

CASE STUDY I: The World Hakka Expo

As cultural evolution progresses and diversifies, design plays a pivotal role in connecting cultural research with policy, facilitating both transdisciplinary understanding and practical application. The 2023 World Hakka Expo: Travel to Tomorrow spanned 66 days and reached audiences in 20 countries, embodying decolonial design methodologies by centering the voices of the Hakka, an ethnic subgroup of the Han people. In each pavilion, Hakka leaders and designers shared their visions for a prosperous and harmonious future alongside diverse ethnic communities. The Taiwan Pavilion, titled “Roots and Prosperity Better with Hakka,” brought together 14 key Hakka counties and cities from across Taiwan. Each group shared stories that celebrated Hakka culture and illustrated how they have thrived and coexisted harmoniously with other ethnic groups in Taiwan.

The physical elements of the Expo seamlessly blended contemporary creative practices with deep-rooted Hakka traditions. Through immersive design and layered spatial storytelling, the Expo honored ancestral wisdom while engaging modern audiences. By employing participatory design and compelling narrative techniques, the Hakka Expo demonstrated the power of pluriversalism and the value of elevating non-Western approaches in the field of design—ultimately inspiring all visitors to imagine a better future.

Visit (https://reurl.cc/axAdOX) for more information.

CASE STUDY II: 1640

Riverside Road

In Abbotsford, British Columbia, architects cultural coordinators worked in partnership with BC Housing and members of the Matsqui and Sumas First Nations. Their ultimate aim was to explore how to decolonize the design process for supportive housing by embedding Indigenous knowledge, relationships, and cultural inclusion into both the project’s process and outcome. Some of the key approaches included:

From a process perspective, the team built relationships and trust within the design team by fostering open sharing allowing designers the freedom to be creative and nonconforming. They co-created long-term management plans, aligning with Indigenous placekeeping frameworks. The building itself incorporated Host Nation values and ethnobotanical elements like plant-processing shelters and the integration of culturally significant plant species. It also created intentional placeholders on façades within the building for future design by individual Host Nation artists, integrating their perspectives of a 100-year future. This case study provides powerful, concrete examples of decolonial and participatory practices within architectural design. Read more about the project at (https://reurl.cc/4NndKR).

Design is far from neutral. Products, systems, and digital interfaces can reinforce existing power dynamics just as can create new ones. A strong ethical lens and a commitment to participatory practices will aid designers in achieving true, radical systems change rooted in decoloniality and diverse lived experiences. It frees us from constraints and unlocks the unlimited potential of design.

REFERENCES & CASES

Reeb, R. N. (2006). Community action research: Benefits to community members and service providers (p. 97). Binghamton: Haworth Press. (https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203051443)

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. The MIT Press.

Case: The McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society. (https://reurl.cc/7Vmdal)

Smith, R. C., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., De Paula, R. A., Zaman, T., & Loi, D. (2024). Towards pluriversality: decolonising design research and practices. 20(1), 1-13. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2379704)

Torretta, N. B., Clark, B., & Redström, J. (2024). Reorienting design towards a decolonial ethos: exploring directions for decolonial design. Design and Culture, 16(3), 309-332. (https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2024.2356764)

Carlton-Parada, A., & Prendeville, S. (2024). Radical design praxis and the problematics of intent. CoDesign, 20(3), 387-404. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2023.2269913)

Case: Design Movement in Commercial Districts. (https://reurl.cc/WO7Nnk)

Case: (https://reurl.cc/EQe69A)

A system grounded in design ethics and justice is essential to the healthy functioning of society. Its ultimate goal is to foster collective well-being and human flourishing. Care is not limited to medical facilities; it can be embedded in the very structures and systems that promote connection and belonging. Thoughtful urban planning and an expanded understanding of care can enhance well-being in the everyday spaces where people live and interact.

FORMS OF CARE

CARE BEYOND CLINICS

Health and well-being are highly contingent on systems and relationships. They emerge from social, emotional, and environmental conditions, supported by networks of care, trust, participation, and belonging that enable individuals and communities to heal, connect, and thrive. Designers who acknowledge these interdependencies broaden the definition of public health beyond clinics and hospitals, embedding care into the spaces and structures that shape daily life.

More designers are now working across sectors to build integrated, community-based systems of care. These approaches often lead to improved health outcomes and greater engagement. For instance, Project RISE in Bihar, India, illustrates the impact of incorporating local rituals into perinatal health care1. By honoring traditions like Chhathi, designers create culturally attuned services that nourish both body and spirit. At the systemic level, care infrastructures function as relational networks, requiring sustained participation and trust. Designers contribute to these systems by cultivating long-term, holistic practices and enabling change from within institutions. This shift redefines the designer’s role: from producer to caregiver, expert to facilitator, and problem solver to coalition builder2

Healing-centered design offers a framework that integrates participatory design principles into care practices. In clinical contexts, it goes beyond managing symptoms3 and includes approaches like narrative medicine, which invites patients to share personal stories about their conditions. This practice allows the body to express its needs—a tradition found in many Indigenous cultures but often overlooked in Western medicine. Trauma-informed care empowers individuals to feel heard, respected, and involved in their own healing. This is especially valuable in designing for mental health, disability, and aging populations, where care must be central to the design of environments. This perspective aligns with the mission of Orange Technology, which champions a compassionate, human-centered approach to innovation. While Green Technology emphasizes ecological sustainability, Orange Technology symbolizes warmth and the advancement of health, care, and well-being. It underscores the responsibility of designers to embed empathy and humanistic values into the systems that shape everyday life—ensuring that technological progress fosters not just efficiency but also meaningful and humane living environments

Medical care is just the tip of the iceberg.

sharing lived experiences

sense of belonging

access to nature

freedom of mobility

visits to the doctor

RESONANT DESIGN

Broadening the aperture of care shifts design toward cultivating emotional depth and connection across domains. It requires shifting mentalities about the components of care and designing emotionally resonant digital and physical environments for daily life. Departing from the artifact-centered era, designers now treat well-being and belonging as central objectives. This expands design’s mandate beyond use and efficiency to incorporate meaning.

Resonant design in the digital world means creating emotionally attuned experiences that provide sensory feedback to promote calm, empathy, or reflection. Wearable technologies such as watches and medical devices, can monitor fluctuations in our emotional and physiological states. If they sense that we are stressed, they can support regulation through haptic feedback or audio cues. Advances in virtual and extended realities extend this idea even further, as they can provide immersive experiences, such as forest bathing in dense urban areas. These products assist with developing awareness and emotional resilience, but they also demonstrate possibilities for systems of care in an increasingly urban and digital world.

In physical and civic environments, emotional design shapes how spaces evoke belonging, memory, and emotional repair. This reimagines design’s purpose as a form of meaning-making, where products and environments embody cultural values and invite reflection. Known as emotion-driven design, this practice prioritizes narrative-building within aesthetics, aiming to resonate with users in deeply emotional ways. A well-designed product in this field is not judged based solely on its efficiency or optimization5. It’s judged by its beauty, sensitivity, and ability to tell a story. Those who engage with this type of design walk away feeling moved. Therefore, emotion-driven design is a powerful way to support healing, identity formation, and mutual recognition. Designers are developing more nuanced tools that incorporate storytelling and art-making to guide empathetic engagement and connect with users whose needs are complex. These practices feed into the expansion of design’s purpose: from solving functional problems to sustaining emotional well-being and affirming diverse human experiences6.

In 2023, the Judicial Yuan partnered with TDRI to redesign courtrooms in 22 district courts across Taiwan, aiming to transform the intimidating atmosphere often associated with courtrooms. Redesigned courtrooms now include a modular, warm, and light-filled design that brightens the space and promotes a sense of calm. The new spaces also feature soft wood tones, curved ceiling panels guiding sightlines to the judicial bench, ADA-compliant facilities, and curved double-tiered benches to improve visibility and interaction between prosecutors and the defense. This redesign promotes dignity, relaxation, and connection—hallmarks of emotionally resonant design.

INFRASTRUCTURES OF CARE

Care doesn’t stop at the interpersonal or environmental level. It is also embedded in the systems and policies that shape public life. Designers working at the intersection of governance and policy cultivate civic infrastructures of care by redefining how institutions prioritize well-being and inclusion. This work demands strategic agenda-setting, institutional transformation, and participatory policymaking.

Through collaboration with policymakers, advocacy groups, and civic organizations, designers can help make public systems more attuned to the lived realities of communities. Building infrastructures of care requires continuous feedback and iteration through participatory practices7. These practices not only integrate diverse perspectives but also strengthen civic legitimacy, and foster collective responsibility as communities co-create caring systems. This could look like citizens’ assemblies which engage community members in structured debates about key issues affecting their community. The outcomes of the assembly can feed into participatory budgeting, fostering a sense of ownership and collective responsibility. Design can shape these processes, and in turn, contribute to the structures that govern daily life and create conditions for care.

Extending care to issues like housing and mobility requires participatory practices that center those most affected by design decisions. In community-led housing, co-design projects involve both architectural design (the physical result) and social design (the way residents shape their social practices as a group living together). Product and process are equally important and inseparable. How can we reimagine cities to be more adaptive and inclusive amid the growing pressures of housing shortages, climate disruption, and shifting patterns of work and care? Initiatives like Urban Living Labs provide platforms for this kind of place-based experimentation. They are unique in that they are not prescriptive; rather, they encourage open-ended participatory innovation based on specific community needs.

DESIGN POLICY LADDER

Design plays multiple roles across the public sector. According to the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) (https://reurl.cc/7Vmd1k) the following three levels illustrate how design maturity evolves within government, from operational problem solving to strategic policymaking and institutional change.

Design For Policy

‧Design is used in policymaking, often with prototyping Encourages cross-sector collaboration and experimentation

Design

As Capability

‧Public servants apply design tools in daily operations

‧Promotes citizen-centric thinking and team autonomy

Design For Discrete Problems

‧One-off projects to address specific service or tech issues

Examples: elderly malnutrition, violence in hospitals

RELATED WORK:

How do we design caring digital infrastructure in the 21st-century? Jump to page 57 to learn more about how decentralized digital communities can be built and maintained to foster more creative and diverse digital landscapes.

1. Hybrid work and living environments8

a. Housing accommodates work life and household life, responding to the rhythms of work, rest, and care.

b. Growing in response to affordability pressures and the rise of remote work.

2. Mixed-use urbanism

9, 10

a. Blends residential, commercial, and civic functions within walkable neighborhoods (e.g., the “15-minute city”). Enhances environmental sustainability and social connections.

b. Enhances environmental sustainability and social connections.

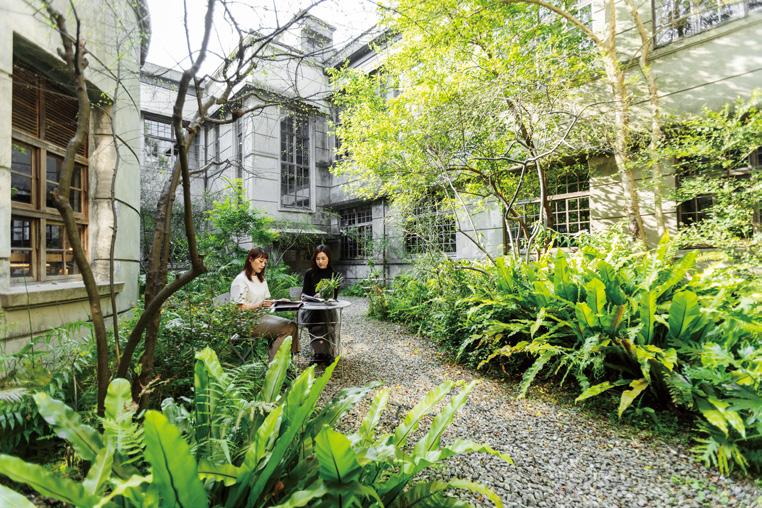

3. Adaptive reuse (creative conversions)

11

a. Transforms underutilized structures (e.g., malls) into housing, cultural venues, or community hubs.

b. Increasingly recognized for promoting sustainability while preserving architectural and cultural heritage.

4. Equity-centered urban infrastructure

a. Focuses on democratizing access to public spaces and services, allowing communities to shape their environments.

b. Includes modular housing and inclusive transit systems.

As shown above, TDRI has successfully implemented many urban adaptability projects through its Service Innovation Division12. Urban design is a powerful tool for cultivating resilience, affirming that adaptability and equity are inseparable in creating city ecosystems that everyone can enjoy.

CASE STUDY I: Citizen Participation Court

In 2023, Taiwan’s judicial system launched the Citizen Participation Court initiative. To embody the spirit of this reform movement, the Judicial Yuan collaborated with TDRI to redesign and renovate 22 courtrooms nationwide. The resulting spatial transformations fostered transparency, equality, and interaction—making this project a quintessential example of design for care.

Similarly, TDRI’s partnership with the Ministry of Education on the School Rebuilding Movement originated from a commitment to community care. The initiative reimagined not only physical learning environments but also the provision of psychological counseling services for students. These redesigned spaces promote dignity, relaxation, and connection—core attributes of emotionally resonant design.

Visit TDRI’s (https://reurl.cc/EQxDr1) for more information.

CASE STUDY II:

The National Museum of African American History and Culture

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) provides a powerful model of emotionally resonant architecture. The exterior of the museum is emblematic of three-tiered crowns used in Yoruba art from West Africa, with a bronze-colored lattice façade that pays homage to the ironwork crafted by enslaved African Americans. Visitors enter the museum by descending into underground galleries that recount painful histories of Africans being transported in abysmal conditions across the Atlantic and their subsequent enslavement in the Americas. As visitors ascend, the upper floors tell stories about emancipation, civil rights, and the many contributions that African Americans have made to the culture of the United States, including the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first Black president in 2008. The journey through this space reflects remembrance, pain, contribution, and the continued struggle for racial justice, providing a sensitive and caring space for visitors to experience it.

NMAAHC points to the crucial role of physical spaces in cultivating collective memory and healing. The building itself functions as a form of care, offering an environment for Black Americans that affirms and foregrounds generational trauma and injustice, while opening space to reflect on the contributions of

Black culture and the ongoing fight for equality. Learn more about the architecture of NMAAHC at (https://reurl.cc/898Xmo).

Designing for care signals a shift in how we build resonant, meaningful spaces. From healing-centered tools to equity-focused urban strategies, designers are reshaping cities and systems to support care, connection, and dignity across diverse communities and everyday spaces.

REFERENCES & CASES

Case: Hashmi, F. A., Burger, O., Goldwater, M. B., Johnson, T., Mondal, S., Singh, P., & Legare, C. H. (2023). Integrating human-centered design and social science research to improve service-delivery and empower community health workers: lessons from project rise. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 9(4), 489-517. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2024.02.001)

Senge, P. M., & Scharmer, C. O. (2008). Community action research: Learning as a community of practitioners, consultants and researchers. Handbook of action research: The concise paperback edition, 195-206.

Case: TDRI public Health center. (https://reurl.cc/Rkmeor)

Liou, Shyhnan. (2012) Orange Technology: From Green Technology to Orange Technology. (https://reurl.cc/MzVj6K)

Hakim, L. (2023). Moving Objects: A Cultural History of Emotive Design. In: Oxford University Press UK.

Xue, H., Desmet, P. M., & Yoon, J. (2024). On the Cultivation of Designers’ Emotional Connoisseurship (Part 2): A Pedagogical Initiative. She Ji: THe Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 10(2), 143-168. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2024.06.002)

Gaete Cruz, M., Ersoy, A., Czischke, D., & Van Bueren, E. (2023). Towards a framework for urban landscape co-design: Linking the participation ladder and the design cycle. CoDesign, 19(3), 233-252. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2022.2123928)

Case: Hadjri, K., Durosaiye, I., Samra, S., Niennattrakul, Y., Sinuraibhan, S., Sattayakorn, S., Wungpatcharapon, S., & Ramasoot, S. (2024). Co-designing a housing and livelihood toolkit with low-income older people for future housing in Klong Toey, Bangkok, Thailand. CoDesign, 20(2), 266-282. (https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2023.2268596)

Yuan, P. F., & Yan, C. (2023). Community Meta-Box: A Deployable Micro Space for New Publicness in High-Density City. She Ji: THe Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 9(1), 58-75. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2023.06.002)

Case: TDRI micro-transportation project. (https://reurl.cc/2QVj3r)

Case: TDRI Design Movement for Public (https://reurl.cc/vLYyDa)

Case: TDRI implementation of innovation in public services. (https://reurl.cc/oYAy3j )

Making has always been a cornerstone of design. Experimenting with materials, creating maps, and exploring making processes across cultures open up new ways of understanding the complexities of our world. These practices also encourage us to examine our assumptions and creative methods as we design within larger systems. They advocate a more active and reciprocal relationship between design research and design practice, positioning this integration as essential to developing systemic design knowledge.

MAKING AS KNOWING

MATERIAL ENGAGEMENT AS EPISTEMIC PRACTICE

Design has long played a central role in shaping the products and services that define our physical world. These creations guide behavior, generate knowledge, and build connections—consider libraries, eyeglasses, or high-speed rail systems. While we often recognize the importance of designed products, we must also ask: What about the designer behind them? What happens during their engagement with materials and processes? How do perspectives shift throughout the act of making? What is made—and how it is made—can reveal what matters in a given context. Making also offers a lens into the design thinking that shapes how we define both problems and solutions.

Thinking through doing is fundamental to design. It supports the development of key skills through practices like sketching and prototyping, which in turn lead to embodied cognition. The act of making reveals insights that theory alone cannot provide. Design is not merely the application of knowledge; it is also a discipline that produces knowledge through action1,2. What’s critical about material engagement, especially in assemblage-centered design, is the interaction between human and nonhuman actors. Designers work with materials that have their own agency: sometimes they behave predictably; other times, they resist, surprise, or shape the designer in return. Designers learn from the affordances and feedback of the material world. In Donald Schön’s influential concept of reflection-in-action, this is described as a dynamic dialogue between designer and material3. Through iterative engagement, designers arrive at new understandings of how parts of the material world operate.

Of course, the significance of making extends beyond form and function. Ontological design highlights that artifacts are not only functional; they are world-shaping. What we design, in turn, designs us, influencing our perceptions, behaviors, and values. This perspective situates humans within a broader, more-than-human system, filled with artifacts that function as rules, feedback loops, and flow mechanisms affecting human behavior4. A clock, for example, doesn’t just tell time; it teaches us to think of time as linear—divided into past, present, and future. It also reflects cultural norms; the

Western clock, for instance, reinforces ideals of productivity and punctuality. There are clear ethical and existential implications in what we choose to design. Merging an ontological design perspective with a rigorous making practice opens new epistemic pathways. It solidifies design as a deeply material, inherently reflective, and knowledge-generating discipline. This can be understood as an innovation of meaning5, where making and meaning co-evolve. Together, they shape what we produce, how we interpret it, and how we live with it, ultimately transforming our understanding of both artifacts and systems.

Ontological design

Embodied cognition

System sense making

ACTIONS

Reflection in action

CONTEXT

Nonhuman, knowledge ecology system

OUTPUTS

TOOLS FOR MAKING SENSE OF SYSTEMS

Wicked problems are defined by competing priorities, unclear goals, and often invisible characteristics that lead to unintended consequences. These are the defining challenges of our time: climate change, homelessness, income inequality. Designers like Richard Buchanan have emphasized the value of applying a design lens to such problems partly because you have to make in order to understand6. Design provides a range of visual and conceptual tools for sensemaking that are particularly well suited to wicked problems. These tools help make complex issues visible, highlight interdependencies, and reveal how problems layer upon one another. They also influence how problems are perceived, interpreted, and ultimately acted upon.7

Visual artifacts are central to knowledge creation in design, especially within Research-through-Design (RtD) contexts, where practice informs theory. RtD bridges the gap between design research and design practice, and it is in the interplay between these two domains that true design knowledge emerges8 Visualization becomes a form of inquiry, an active engagement with complexity that surfaces patterns, contradictions, and latent structures often missed when relying solely on academic literature. The process of making, rooted in iteration, produces emergent, abductive insights, and design research captures and communicates these insights effectively. Given the limitations of human cognitive capacity, the multimodal nature and operational dynamics of systems must be represented in ways that illuminate their emergent, holistic properties. This approach enables designers and decision makers to develop a more intuitive understanding of complex systems. Such representations also support interdisciplinary communication, collective learning, and collaborative decision making—ultimately strengthening a system’s capacity for both sensemaking and sensegiving.

In the context of paradigm shifts, such as assemblage-centered design, the field must explore ways to capture knowledge beyond anecdotal reflection. This is where visualization tools are especially powerful for tackling ill-defined, wicked problems. Multiple perspectives can generate different visual representations of the same system, revealing deeper insights into how various actors interact within it. This pluriversal approach to sensemaking allows for more nuanced and context-sensitive solutions to complex challenges.

“Visualization is not just seeing; it is imagining, and it is drawing, and it is gesturing, and it is modeling.”

— Robert McKim, Experiences in Visual Thinking

RELATED WORK:

Strengthening skills as a systems practitioner is essential for the 21st-century designer. Jump to page 62 to see how design education is making this shift, or page 21 to connect these tools to regenerative systems design.

Beyond their function as information visualizers, these tools also perform crucial relational roles. They act as “boundary objects” that facilitate negotiation and compromise across knowledge domains. They also help surface values and perspectives that might otherwise remain implicit. For example, participatory diagramming invites all participants to collaboratively build visual representations. This levels the playing field, and produces visuals that are not just representational but deeply meaningful. In the context of wicked problems, where no single “truth” prevails, a map is not merely a visualization of an issue—it becomes a tool for imagining new possibilities and actions.

Causal loop diagrams

Invite Multiple Interpretations

Visual

Artifacts