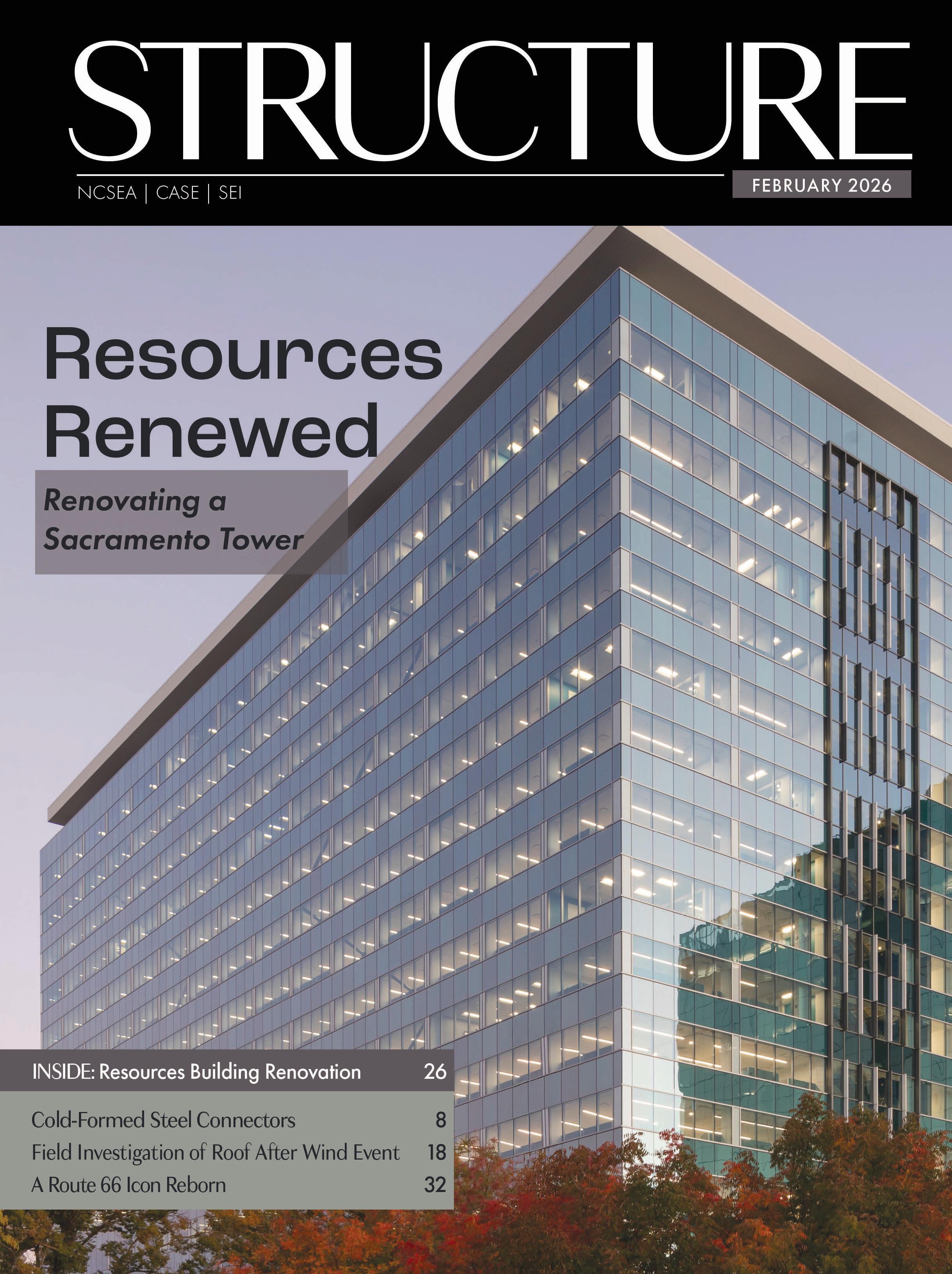

HSS CONNECTIONS HUB™ ATLAS TUBE’S

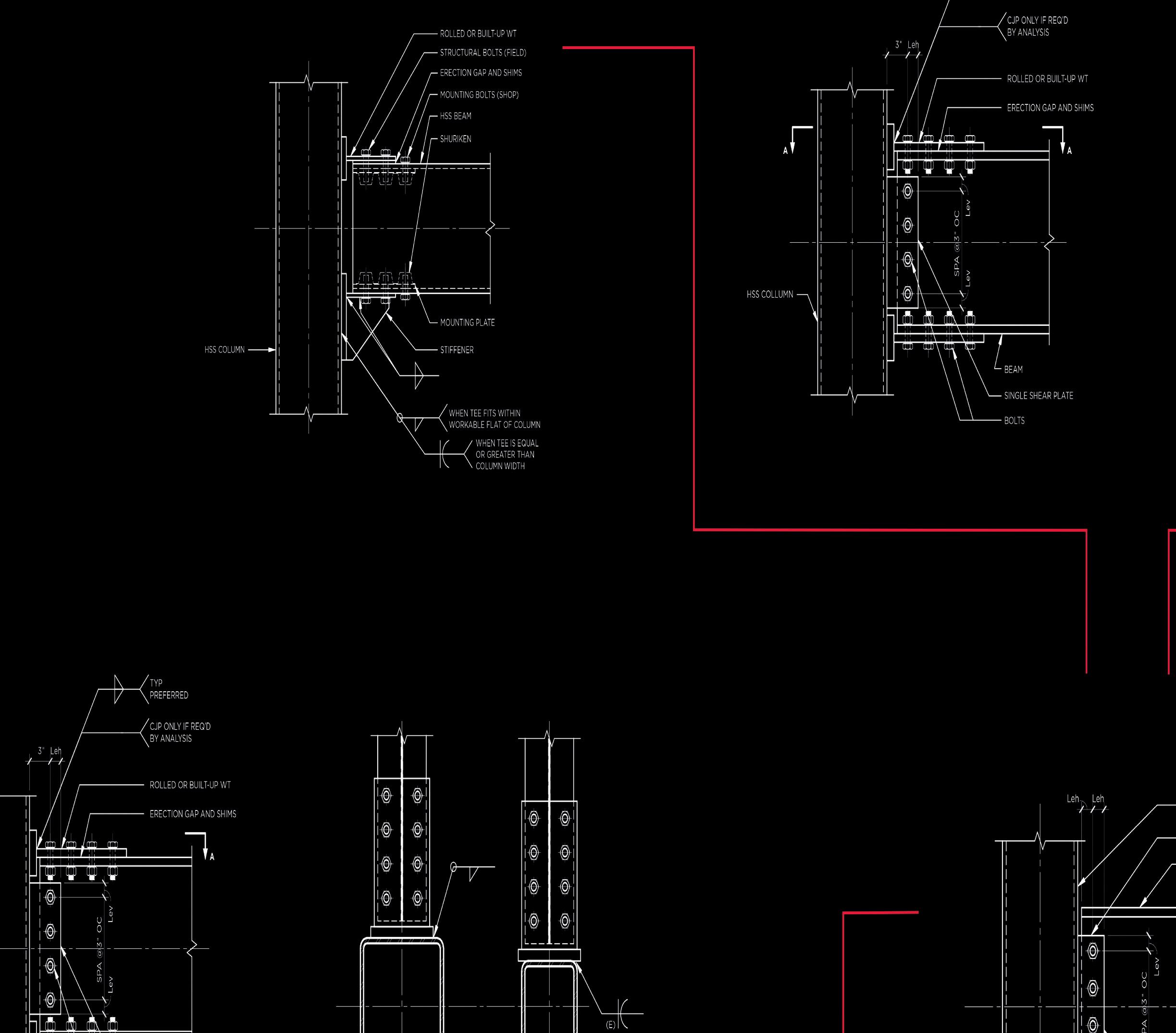

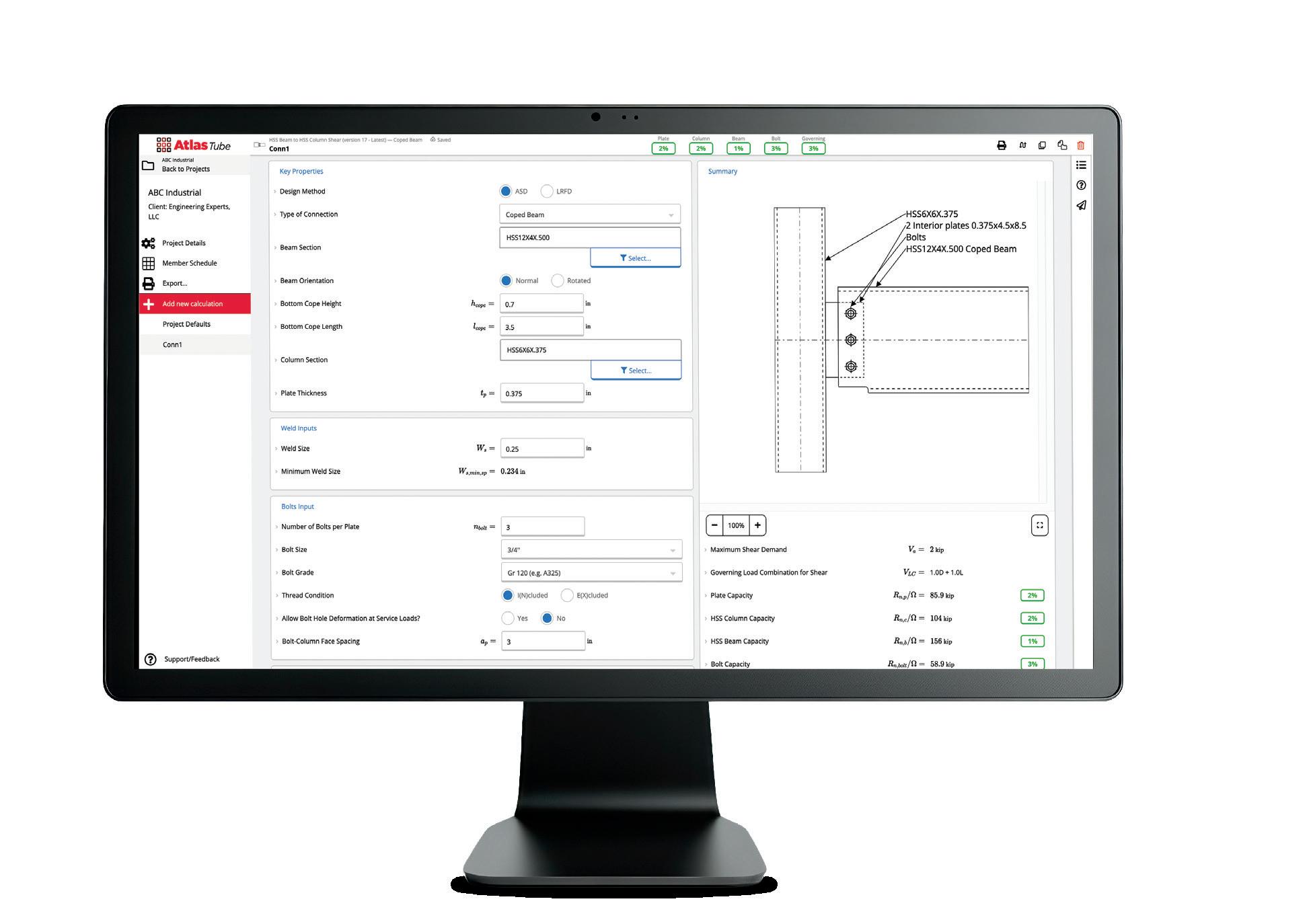

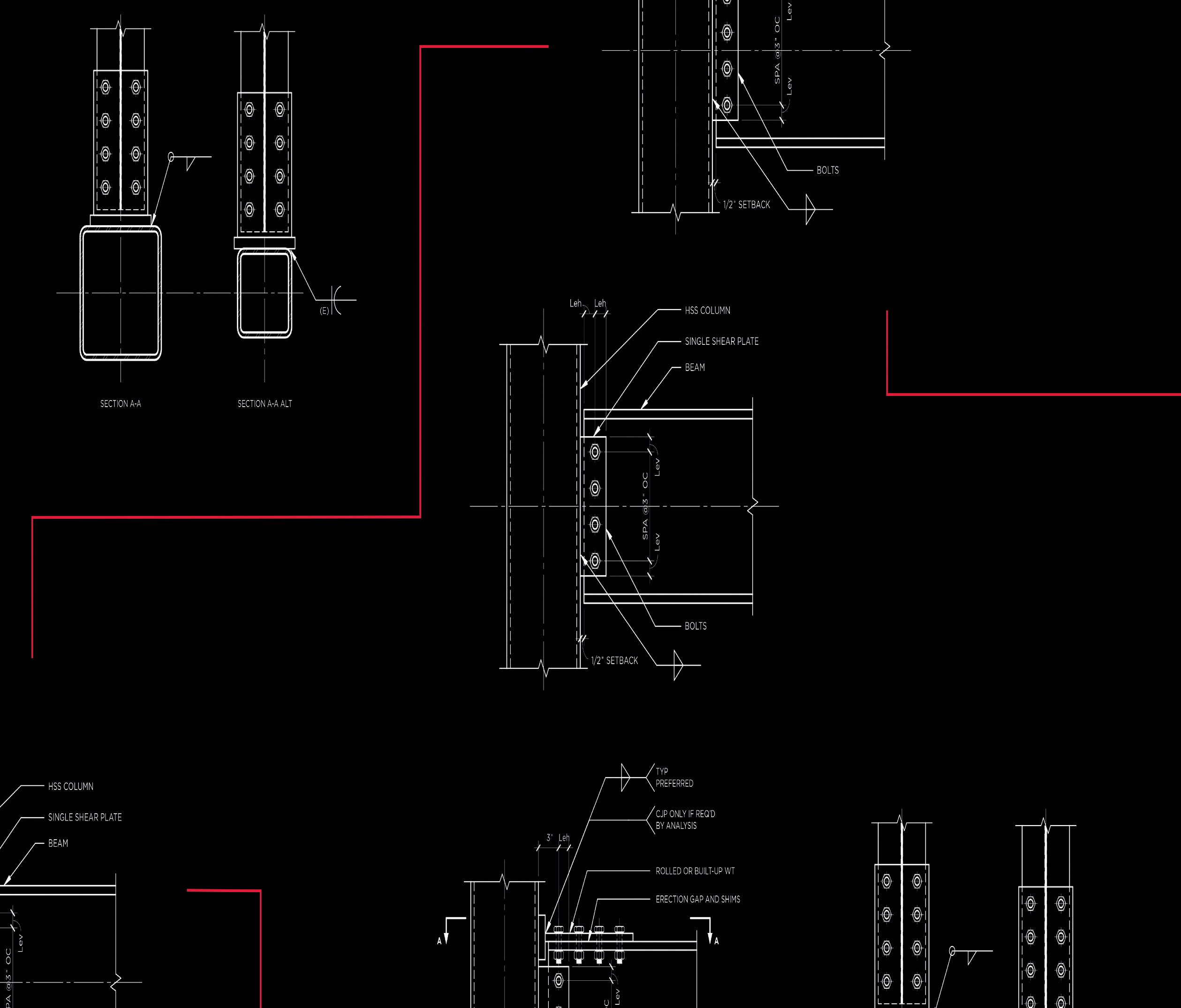

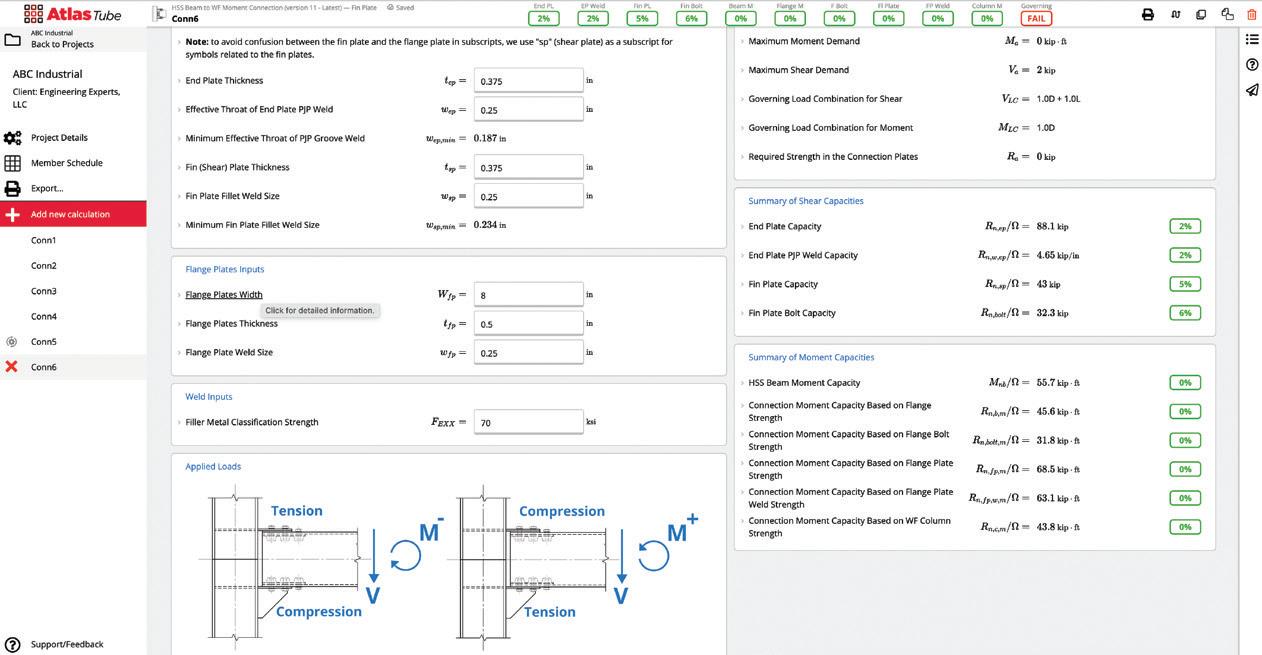

The comprehensive resource now with 70+ calculators and typical details for USA and Canadian codes.

Join 2,400+ engineers who are reclaiming their time with Atlas Tube’s complimentary HSS Connections Hub. Explore the growing tool that enables more efficient design of fabrication-friendly HSS connections.

Optimize HSS connection designs.

RELENTLESS SUPPORT.

An ever-expanding resource for engineers, detailers and fabricators now featuring over 100 new updates.

A direct path to efficient HSS connection design

This invaluable and complimentary online resource will save design time by eliminating the need for developing and maintaining custom spreadsheets.

Fabrication-friendly typical HSS details are excellent starting points for design while corresponding calculators enable design completion.

Teams can streamline the design process and enhance collaboration directly on the HSS Connections Hub. Engineers can quickly create HSS connection calculations based on the most recent design manual and specific AISC and CISC code requirements. Fabricators will receive connection designs that meet requirements and are fabrication-friendly, eliminating back-and-forth revisions.

Recently Released

• Direct-input factored loads: Import factored reactions directly from your favorite analysis software.

• Automatic truss type detection: We’ll identify the correct truss type (T, K, Y, X, etc.) for you.

• Axial loads in moment connections: Apply axial loads to moment connections—shear connections coming soon!

• Built-up tees in WT connections: Customize tee sizes for WT connections beyond handbook limits.

• Custom bolt spacing for splices: Optimize bolt spacing to maximize splice capacity.

Launching in January

• HSS columns and beams for brace calculations: Connect braces to HSS beams and columns, expanding beyond current WF options.

• New truss connections: Enjoy support for X connections with round HSS and overlapped KT configurations.

• Moment in End Plate splices: Moment loads are now supported in splice connections for greater versatility.

Available in February

• Shear in splices: Apply and check shear loads on splice connections for enhanced safety.

• Extended configuration for shear plates: Add more bolt lines and length to shear plates for increased adaptability.

• Seismic design: Seismic design category determination and Ordinary moment frame (OMF) checks.

Leverage the benefits of HSS with the HSS Connections Hub

• Access a growing library of HSS connection calculators and fabrication-friendly typical HSS details.

• Hub calculators automate and confirm connection designs in real-time.

• Clear and concise results indicate whether the designed connection is efficient and meets specified requirements.

• Full transparency: Review and verify your calculations against specific code references with a simple click.

• Download or share detailed reports and connection drawings, including dimensions, bolt sizes and other relevant information for easy communication with fabricators.

• Request support from Atlas Tube’s engineering experts on your project.

Sign up today and start using the HSS Connections Hub.

connectionshub.atlastube.com

Watch an Atlas Tube engineer demonstrate the HSS Connections Hub.

STRUCTURE ® CIRCULATION

subscriptions@structuremag.org

EDITORIAL BOARD

Chair John A. Dal Pino, S.E. Claremont Engineers Inc., Oakland, CA chair@STRUCTUREmag.org

Kevin Adamson, PE Structural Focus, Gardena, CA

Marshall Carman, PE, SE Schaefer, Cincinnati, Ohio

Erin Conaway, PE AISC, Littleton, CO

Sarah Evans, PE Walter P Moore, Houston, TX

Steven Judd Interstate Brick, West Jordan, Utah, and H.C. Muddox, Sacramento, California

Linda M. Kaplan, PE Pennoni, Pittsburgh, PA

Jessica Mandrick, PE, SE, LEED AP Gilsanz Murray Steficek, LLP, New York, NY

Brian W. Miller

Cast Connex Corporation, Davis, CA

Evans Mountzouris, PE Retired, Milford, CT

Kenneth Ogorzalek, PE, SE KPFF Consulting Engineers, San Francisco, CA (WI)

John “Buddy” Showalter, PE International Code Council, Washington, DC

Eytan Solomon, PE, LEED AP Silman, New York, NY

EDITORIAL STAFF

Publication of any article, image, or advertisement in magazine does not constitute endorsement by NCSEA, CASE, SEI, the Publisher, or the Editorial Board. Authors, contributors, and advertisers retain sole responsibility for the content of their submissions. magazine is not a peer-reviewed publication. Readers are encouraged to do their due diligence through

Executive Editor Alfred Spada aspada@ncsea.com

Managing Editor Shannon Wetzel swetzel@structuremag.org

MARKETING & ADVERTISING SALES

Senior Director for Business Development & Marketing

Monica Shripka Tel: 773-974-6561 monica.shripka@STRUCTUREmag.org

Sales Manager

Audrey Schmook Tel: 312-649-4600 Ext. 213 aschmook@ncsea.com

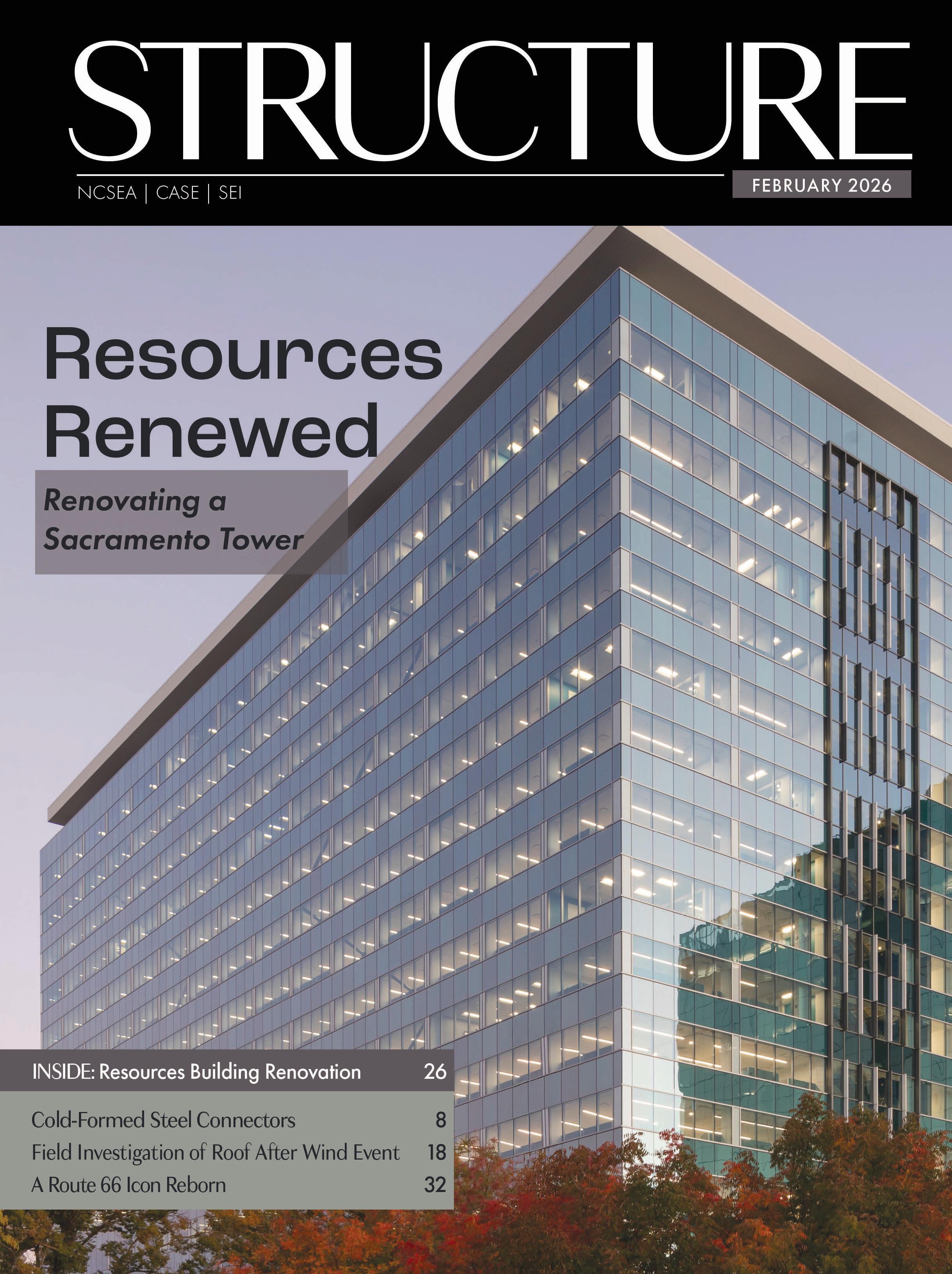

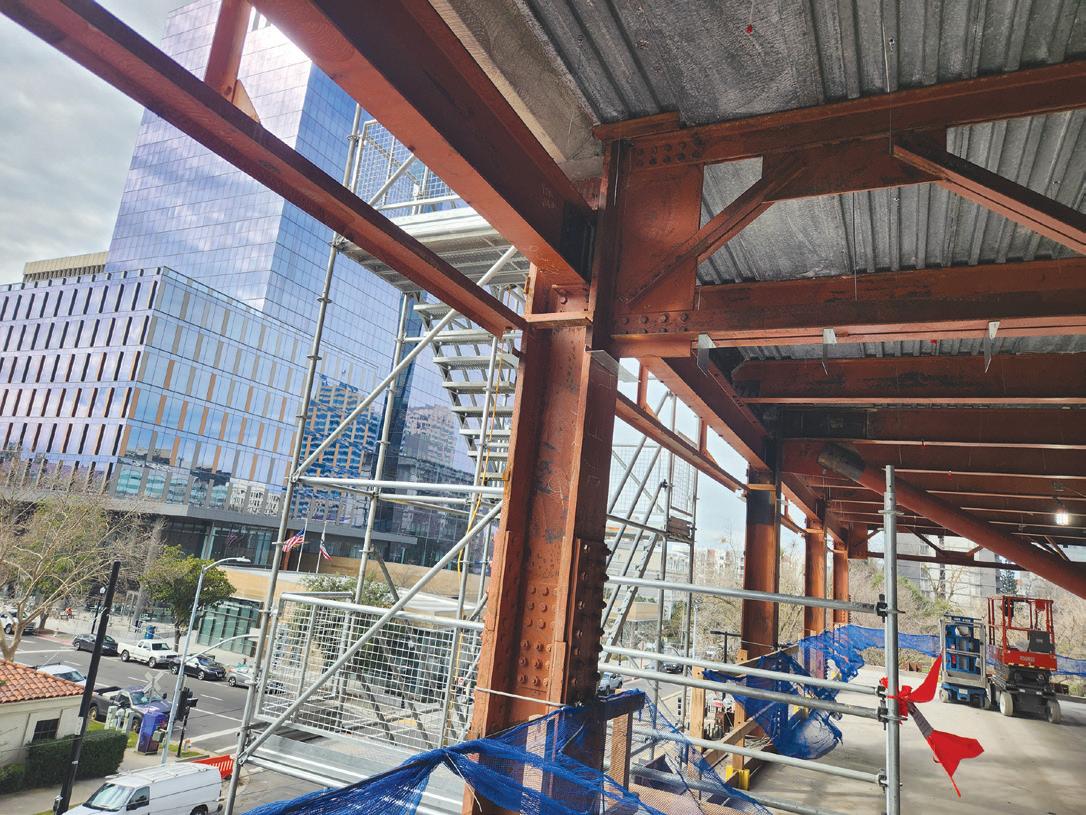

On the Cover: A 2015 assessment declared the Resources Building in California the No. 1 State-owned building most in need of repair. After a comprehensive renovation, the 62-year-old structure has turned from relic to radiant.

26 RESOURCES RENEWED

By Jason Horwedel, SE, DBIA, Matt Williams, SE, and Phil Petermann

A 2015 assessment declared the Resources Building in California the No. 1 State-owned building most in need of repair. After a comprehensive renovation, the 62-year-old structure has turned from relic to radiant.

32 A ROUTE 66 ICON REBORN

By David Neuhauser and Jose Joseph

The rehabilitation of Oklahoma’s Route 66 William H. Murray “Pony” Bridge connects the past and future.

FEATURES COLUMNS and DEPARTMENTS

Design of CMU Masonry–The Paradigm Shift Has Begun

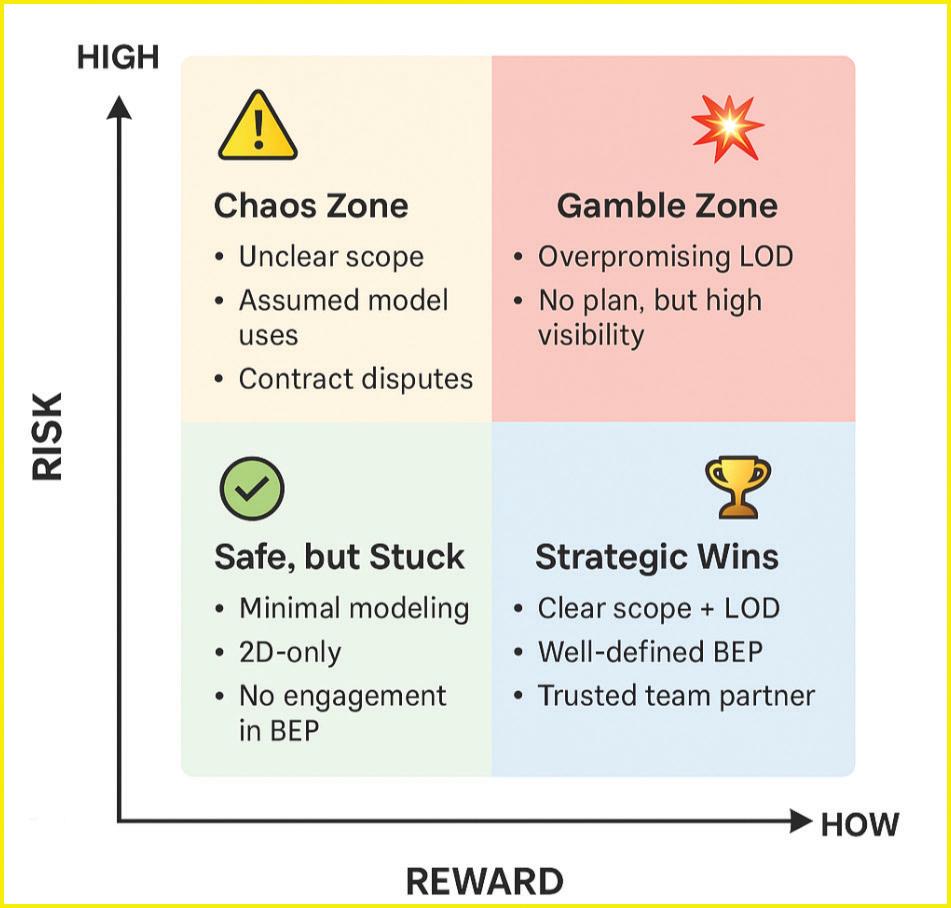

BIM Execution Plans: Towards a One -Page Communication Backbone

Matt Sweeney, Kristopher Dane, Margaret Sullivan-Miller, and the Structural Engineering Institute Committee on Digital Design 43 Structural Sustainability

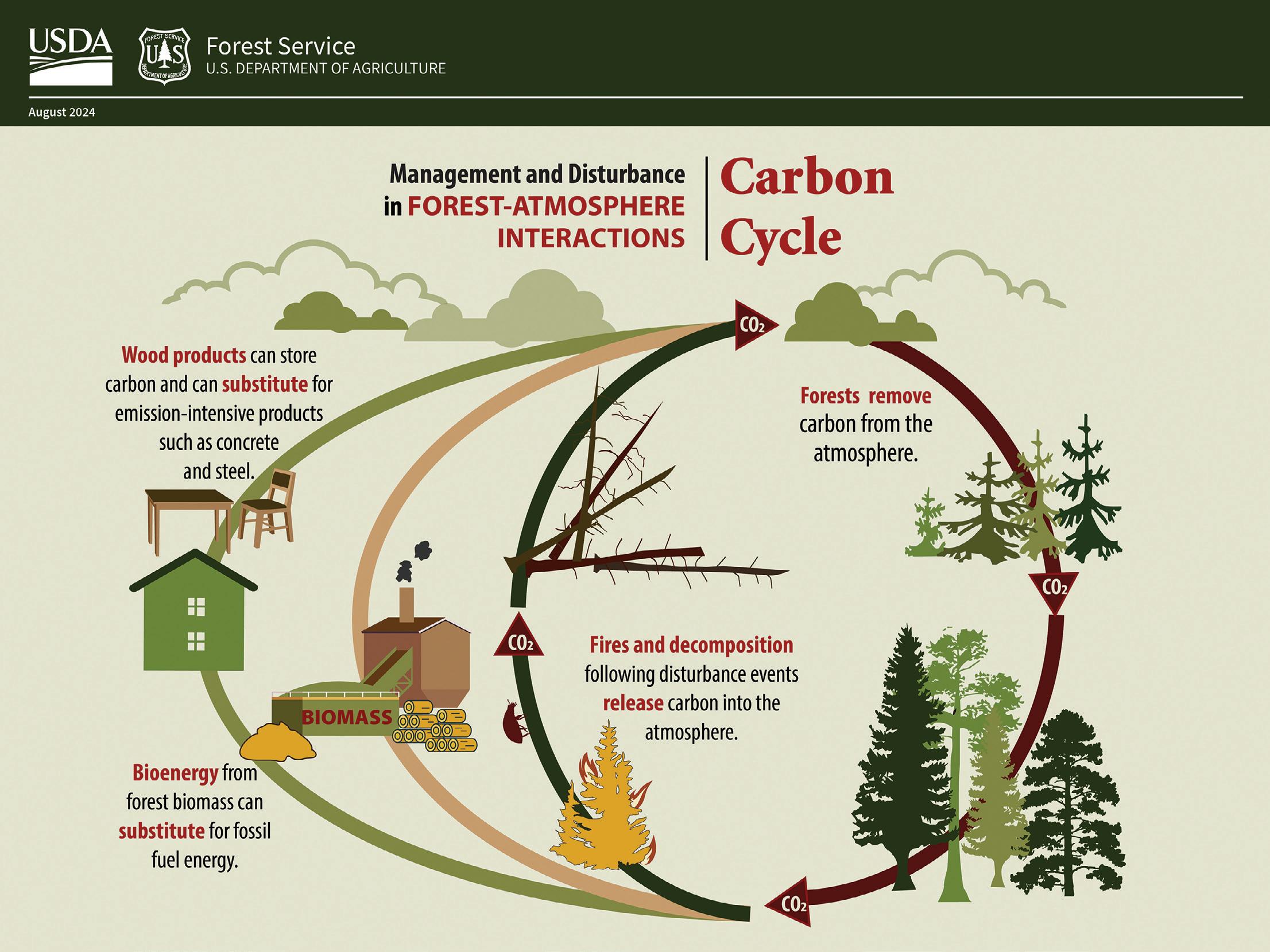

10 Things Every Structural Engineer Should Know About Embodied Carbon: Wood By SE 2050 Resources Working Group 57 Structural Forum

Sustainability Starts at the Top By Kevin Kuntz, SE, PE, Ian McFarlane, SE, PE, and Jonathan Tavarez, PE

In Every Issue

INNOVATE FREELY

CAST CONNEX ® custom steel castings realize projects previously unachievable by conventional fabrication methods.

Innovative steel castings reduce construction time and costs, and provide enhanced connection strength, ductility, and fatigue resistance.

Freeform castings allow for flexible building and bridge geometry, enabling architects and engineers to realize their design ambitions.

Custom Cast Solutions simplify complex and repetitive connections and are ideal for architecturally exposed applications.

Architects: Perkins+Will | C Design

Structural Engineers: Stewart

General Contractor: Turner Rogers JV

Steel Fabricator: CMC Structural (now SC Steel)

Photography by Mark Bealer | Studio66

CHARLOTTE DOUGLAS INTERNATIONAL

AIRPORT EXPANSION

EDITORIAL Climate Change, Codes, and the Structural Engineer’s Standard of Care

By Yvonne Castillo

Structural engineers have always designed for weather and the physical environment. What is changing is not the existence of natural hazards, but their frequency, intensity, and interaction with the built environment.

Building codes remain largely grounded in historical data, while clients, insurers, regulators, and courts are embracing forward-looking climate science. This creates a practical tension in everyday practice: how to remain anchored in code compliance while responding to evolving expectations about foreseeable conditions.

This editorial is not about rewriting codes or turning structural engineers into climate scientists. It is about understanding how the professional standard of care is evolving when past conditions are no longer a reliable proxy for future extremes.

Many jurisdictions have adopted “modern” building codes—2018, 2021, or even 2024 editions. Yet even the most current codes rely on historical datasets developed decades ago, frequently based on observations from the mid- to late-20th century.

A simple question illustrates the issue: Does the world engineers design for today look like the world of the 1970s or 1980s?

Most practitioners, regardless of their views on climate science, would answer no. This is where the concept of stationarity versus non-stationarity becomes relevant to practice. Stationarity assumes future conditions will resemble the past; nonstationarity recognizes that baseline conditions are shifting. Codes, by necessity, evolve slowly and deliberately. Climate science, by contrast, is forward looking and scenario based.

For structural engineers, this tension appears in familiar areas of practice—wind, flooding, snow, extreme heat, wildfire exposure, and long-term material durability. Engineers are not being asked to abandon codes or design for speculative futures. Increasingly, they are being asked something more modest, more challenging: Have you considered whether historical assumptions fully reflect foreseeable conditions at this site?

That question may come from a client, a client’s insurer, a public agency, or, years later, in the context of a claim following a severe event.

Standard of care: Reasonableness,

not

prediction

From a professional liability perspective, the standard of care has always been a moving target. Courts do not ask whether an engineer predicted

the future correctly. They ask whether the engineer acted reasonably given what was known or reasonably knowable at the time.

That distinction matters because a jury or judge gets the benefit of hindsight. When a loss follows an extreme event, the inquiry may extend beyond simple code compliance to questions such as:

• Was the hazard foreseeable?

• Was relevant information available in the public domain?

• Did the engineer exercise professional judgment in light of that information?

• Were assumptions and decisions discussed and documented?

No one expects structural engineers to be experts in climate modeling. But as climate science becomes widely accessible and better understood, ignoring broadly recognized trends can become harder to explain.

Climate data as a screening tool, not a design mandate

Climate models are not predictions. They are scenario-based tools that describe how hazards may change under different assumptions. Different models produce different outputs because they measure different aspects of risk.

As a result, leading firms treat climate data as a screening input. Reviewing two or three credible sources can help engineers understand hazard context without over-relying on any single dataset. Commonly referenced resources include:

• NOAA data portals.

• Argonne National Laboratory’s CLIMRR tool.

• First Street Foundation.

• FEMA flood maps, which remain essential regulatory references but are intentionally limited in scope.

• The AIA Trust Climate Factsheet. Each of these tools is valuable and has their own limitations and intended purpose. Used together, they help identify which hazards warrant closer consideration.

The risk conversation

One of the clearest trends emerging across design practice is the importance of documented conversations. Engineers advise; clients decide.

Reasonable practice increasingly includes acknowledging relevant hazards, explaining what codes do and do not address, discussing optional

resilience measures, and documenting assumptions and client decisions. This does not shift responsibility to the engineer; it clarifies roles and preserves professional judgment.

The design professional may not have control over the overall design concept and may have limited direct contact with the owner. Design decisions are often constrained by architectural intent, project delivery method, and budget. Even on projects where engineers have greater design latitude, such as bridges or other infrastructure, cost constraints remain a dominant factor.

Reasonable practice does not require structural engineers to override these constraints or guarantee an outcome. Rather, it involves exercising professional judgment on a project, identifying relevant risks, communicating options and tradeoffs, and documenting decisions when constraints limit solutions.

Signals from the courts

Recent case law offers early signals worth understanding. Courts have increasingly recognized that where credible science is publicly available, it can be reasonable for decision makers to consider future hazard conditions, particularly for long-lived assets.

Cases involving asbestos exposure, public infrastructure planning, coastal parks, and land-use decisions suggest a consistent theme: reasonableness evolves with knowledge. Engineers are not expected to guarantee outcomes, but they may be expected to demonstrate thoughtful consideration of foreseeable risks.

Looking ahead

This is not about raising the bar overnight or designing beyond the code by default. It is about recognizing that code compliance and professional judgment are not mutually exclusive. Engineers who remain thoughtful, engage clients transparently, and document their reasoning are practicing in a way that aligns with where expectations are heading. ■

Yvonne Castillo, Esq., is the Director of Risk Advisory and a professional liability risk advisor for Victor’s Risk Advisory, U.S. Group.

Overcoming Data Gaps in Proprietary Cold-Formed Steel Connectors

A testing and FEA-based approach was used to determine the resistance of a cold form steel product which did not have readily available technical data.

By Arif Shahdin and Jose Palao Jr., PE

At times, engineers may come across a situation in the design process where a cold formed steel (CFS) proprietary product is used in a project. When that happens, many non-conventional steps often are taken to understand the performance of the product/ system. Such products are becoming more common in the design practice.

The main challenge in using proprietary products in general lies in obtaining the technical data or resistance values of these products. Therefore, the inclusion of such systems/products in design projects has added new responsibilities on design engineers. Engineers cannot analytically evaluate the design resistance, nor can they access a table to pick a safety factor or a phi factor for a specific limit state. Rational Engineering approach is typically used to assess the performance of such systems. Rational Engineering is defined in AISI S-100 as an analysis based on theory that is appropriate for the situation, backed with relevant test data, if available, and sound engineering judgement.

The focus of this article is to highlight the process of determining the resistance of CFS proprietary products utilizing two techniques:

1. Physical testing

2. Finite Element Analysis (FEA).

A modular CFS structural system will be used as an example in this article for all further explanations. These bolted CFS systems are used in various industrial and commercial-type support applications.

Physical Testing:

AISI S100 2016 “Reaffirmed 2020” provides guidance in chapter K, Section 2 on how to evaluate structural performance of proprietary CFS system in accordance with Rational Engineering analysis with confirmatory testing. Before going into an example, the overall procedure can be summarized as follows:

1. Minimum of three tests shall be performed with a +/-15% deviation from average.

2. The average value of all tests shall be regarded as the nominal Strength Rn for the series of tests.

3. Only one limit state of the test specimen is permitted for evaluation at a time.

4. An LRFD (Load and Resistance Factor Design) phi factor is calculated using

various statistical coefficients such as material factor, fabrication factor, target reliability index etc.

5. A factor of 1.6 is then used to determine an ASD (Allowable Strength Design) level safety factor.

6. The nominal Strength Rn is reduced by the Safety Factor to obtain the ASD level resistance of the specimen for a particular limit state.

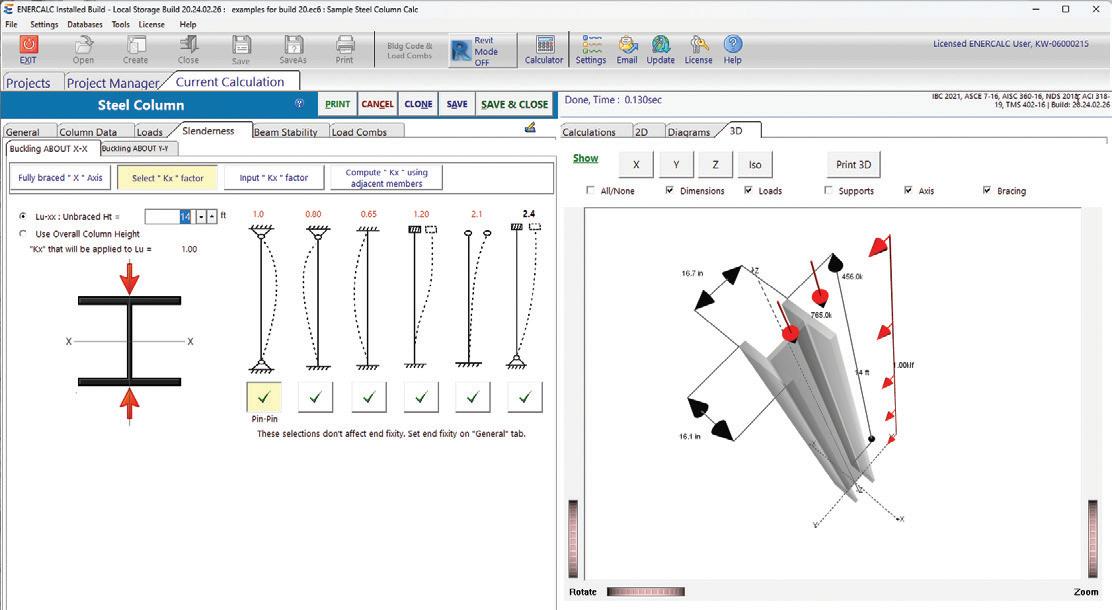

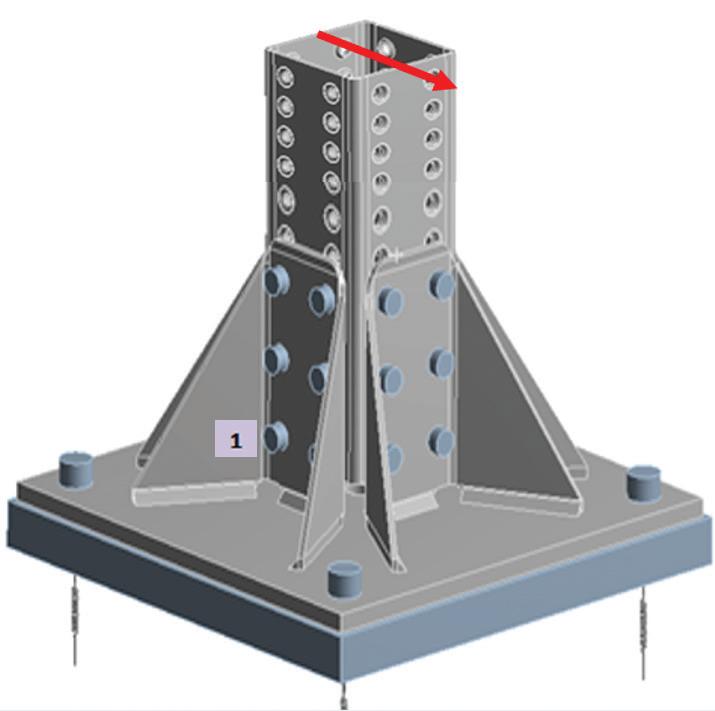

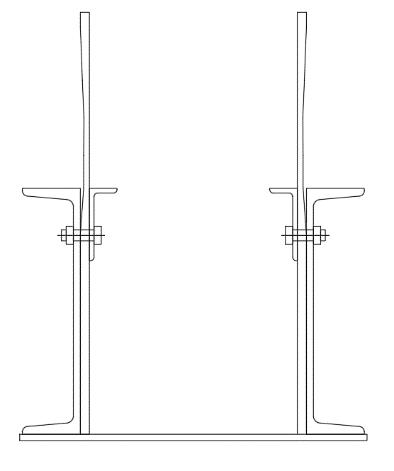

The following test elaborates on this method of evaluating the structural performance using the connector shown in Figure 1 as the test specimen. The goal is to evaluate only the +Fx direction load capacity.

a. Test setup:

Five tests were conducted using the setup shown below. The Load Displacement curves were developed and the results were tabulated for all five tests (Table 1).

b. A mean test value was calculated from Table 1.

Table 1. Load Displacement Test Results

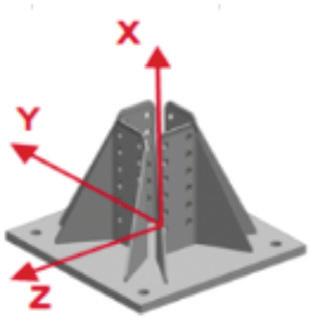

Fig. 1. The connector shown is the test specimen.

Fig. 2. Example bracket and test setup.

c. The phi factor for LRFD was calculated using Eq. K2.1.1-2 as illustrated below.

Following is a summary of all the statistical factors used in the equation above:

• Correction factor CP

where,

n=5 number of tests

m=n-1=4 degrees of freedom

• Coefficient of variation of test results V P . V R S 0 026 p

Since VP < 0.065, VP = 0.065 where,

St = 8.608 kN (1.935 kip) standard deviation of data

The following statistical data was obtained from Table K2.1.1-1(for Other Connectors or Fasteners not listed in the table)

Vm = 0.10 coefficient of variation of material factor

Mm = 1.10 mean value of material factor

Fm = 1.00 mean value of fabrication factor

Vf=0.15 coefficient of variation of fabrication factor

• Mean value of professional factor for LRFD P m = 1.0 Eq. k2.1.1-3

• LRFD target reliability index for connections

β0=3.5

• Coefficient of variation of load effect

VQ = 0.21

• Calibration coefficient for U.S./Mexico

C0=1.52

Eq. C-B3 2.2-10

d. ASD level resistance was then determined using a factor of 1.6

Ω = 1.6/0 = 1.6/0.596 = 2.683 ASD level safety factor

FxASD = Rn/Ω = 336.57kN (75.66 kip)/2.683 = 125.44 kN (28.20 kip)

Finite Element Analysis:

In addition to physical testing, FEA provides an alternative methodology for evaluating the structural performance of proprietary CFS systems when analytical equations are not applicable and physical testing alone is insufficient. AISI S100-2016 Chapter K recognizes numerical modeling as a valid component of Rational Engineering Analysis, provided that the model is appropriately calibrated and validated.

For proprietary CFS systems, particularly those with non-standard geometries, built-up assemblies, or unique connection details, FEA allows engineers to capture localized behaviors, nonlinear load paths,

and connection interactions that cannot be represented by classical solutions prescribed in standard design codes such as AISI S100. The following section summarizes the overall process of developing and validating an FEA model to determine the +Fy and +Fz load capacities for the proprietary connector (shown as the test specimen in Figure 1) introduced previously.

Due to the complex nature of the mathematical solutions involved in FEA simulations, this article only addresses a few key components of FEA to provide a high-level understanding of how it can be used to evaluate the capacity of proprietary CFS products.

Modeling Approach

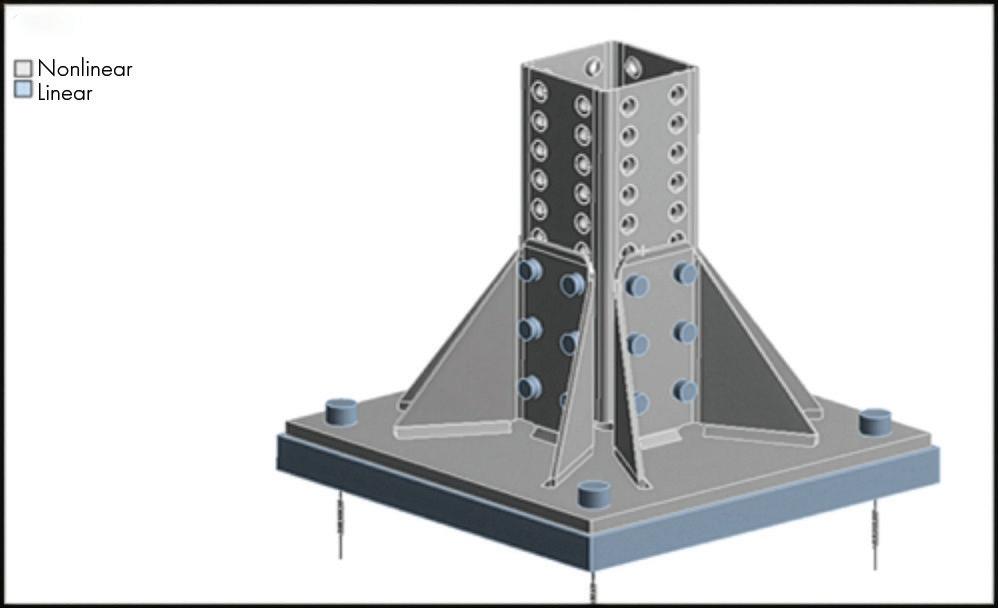

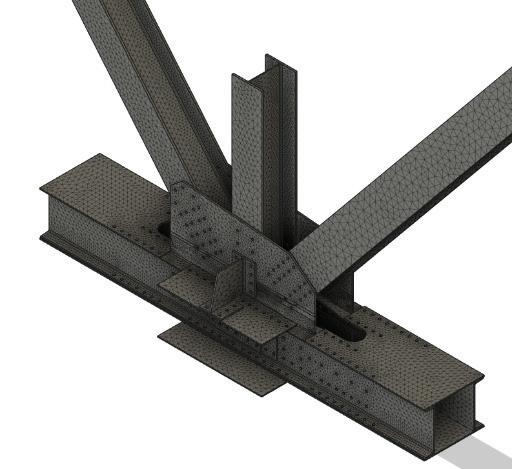

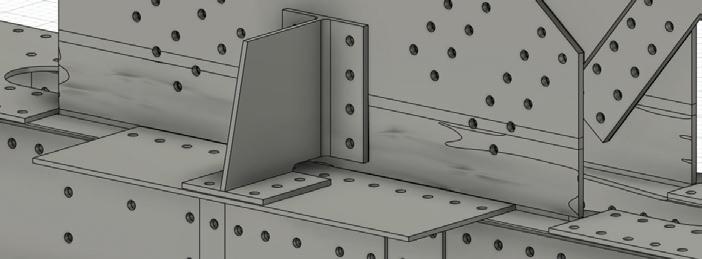

A square girder was attached to the connector and this connector and girder assembly as shown in Figure 3 was used for the FEA simulations to obtain the +Fy and +Fz load capacities of the connector. Since the connector is geometrically symmetric in both the Fy and Fz orientations, the load capacities in these directions are identical. The main modeling considerations are included below:

Geometry:

Before any modeling begins, a 3D CAD file is first provided, typically by the development/manufacturing team of the proprietary product. The 3D CAD geometry is verified against 2D drawings to ensure all overall dimensions are accurate and cross-checked. Additionally, the assembly is backchecked against the manufacturer’s installation instructions to ensure the model represents an approved configuration. The geometry is then cleaned to improve mesh quality and computational efficiency (Fig. 3).

Element Selection and Connection Modeling:

The assembly was modeled using thin-shell elements capable of capturing local buckling, crippling, and distortional deformations typical of CFS behavior. Bolt shanks and bearing surfaces were represented using solid elements for simplified geometry. Anchors embedded in concrete were modeled as tension only springs with a defined stiffness to replicate interaction with the concrete substrate.

Material Properties:

For this simulation, a bilinear elastic stress-strain curve was assumed and calibrated against empirical data that reflect the nominal steel properties.

Boundary Conditions and Loading:

Boundary conditions must accurately represent realistic support and loading scenarios. For this simulation, a free length is applied beyond the edge of the base connector, at least equal to the largest cross-sectional dimension. This free length helps simulate actual conditions and avoid unrealistic stiffness effects.

Fig. 3. Overall geometry girder and connector assembly.

External loads are applied as displacement-controlled inputs, rather than direct force application. This approach enables the generation of force–deflection and moment–rotation curves, which are critical for evaluating connection behavior. In general, load application to the 3D analytical model should closely match the physical test loading protocol conditions in order to improve the correlation between simulation and experimental results.

Evaluation Criteria

Engineers are responsible for selecting appropriate validation

and verification methods. The most common approach is comparison with physical test data. This ensures close alignment of load-displacement behavior and validates stiffness, assumptions, and load capacity. When validating the results by this method, engineers must follow AISI S100 Section K2.1.1(b), which states the correlation coefficient, Cc, between tested strength (Rt) and nominal strength (Rn) predicted from the FEA model must be greater than or equal to 0.80.

Another means of validating and verifying the numerical solution can be to reduce the connector to an idealized, simplified assembly to allow for the use of classical solutions prescribed in design codes such as AISI S100. If FEA or classical solutions using an

SPENDING GREEN... TO GO GREEN

Bull Moose Tube made a major investment in a new 350,000 ton-per-year facility in Sinton, Texas – with the goal of providing you with the “greenest” steel tube in the United States.

• SUSTAINABILITY-FOCUSED | Our state-of-the-art facility boasts the lowest carbon footprint for steel pipe & tube in the United States. Additional Bull Moose products means a greater range of possibilities for your designs…while helping you achieve your green initiatives.

• MORE HSS AND NEW PIPE PILE CAPACITY | Our new mill enables us to produce HSS up to 14” square and 18” round, up to ¾” walls, and the ability to enter the pipe pile market.

Scan for more info about our Sustainability efforts.

Fig. 5. Applied simulation load direction and Bolt #1 identification.

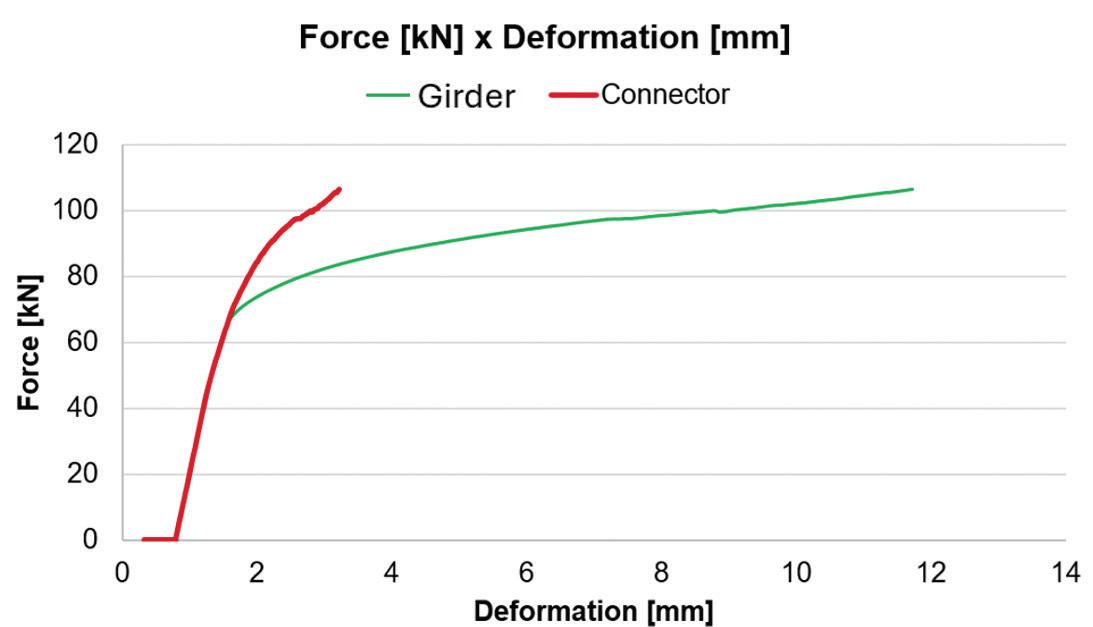

Fig. 4. Connector girder assembly force-deformation curve

idealized connector are performed, both which fall under Rational Engineering analysis, the following safety factors are applied, in accordance with AISI S100 Section A1.2(c). Per this specification, there are separate safety factors (and phi factors) for members and the connection. For members Ω ASD = 2.0 and ф LRFD = 0.80. Similarly for connections, Ω ASD = 3.0 and ф LRFD = 0.55.

Strength Determination

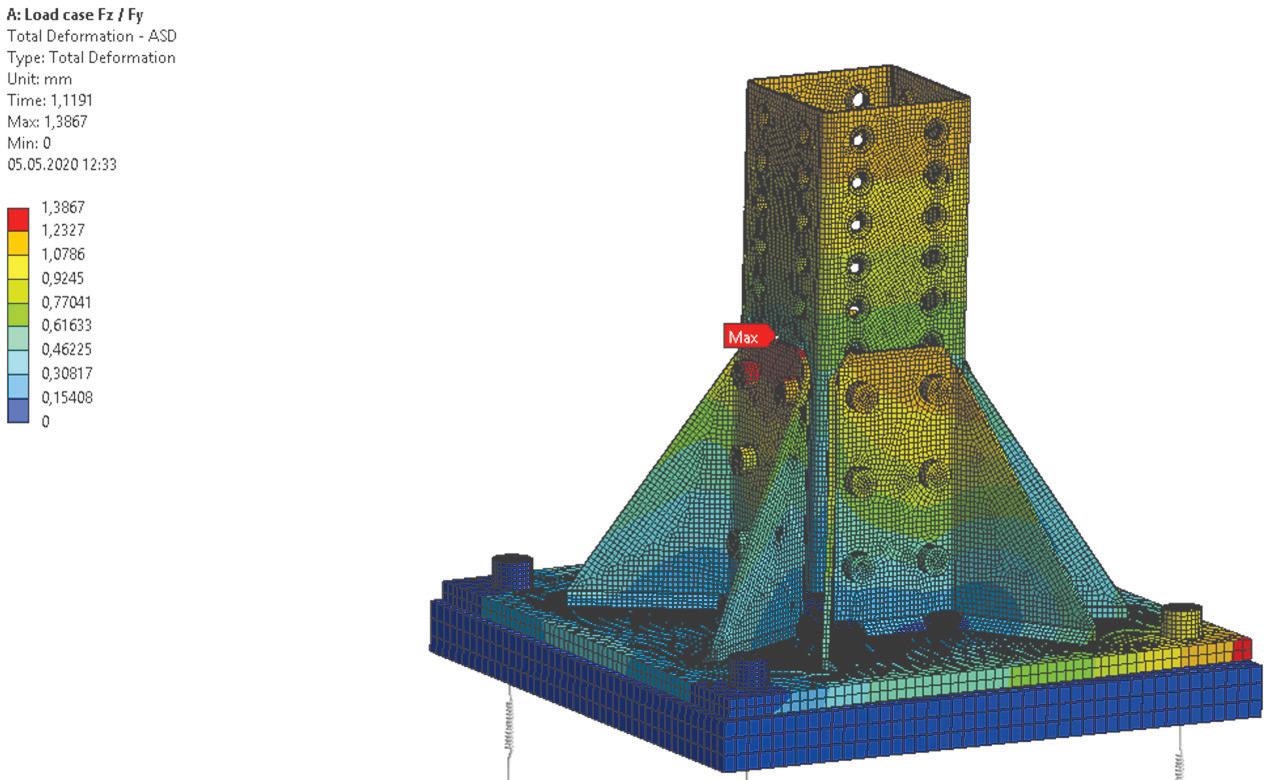

Once geometry, boundary conditions, and model assumptions are verified, the connector capacity is determined. Figure 4 shows the 3D simulation force-deformation curve, which shows a peak nominal resistance of Rn = 106 kN (23.83 kip).

Per AISI S100 Section A1.2(c), a safety factor of 3.0 is applied for ASD.

Fy-z ASD = 106 kN (23.83 kip) / 3 = 35.3 kN (7.94 kip)

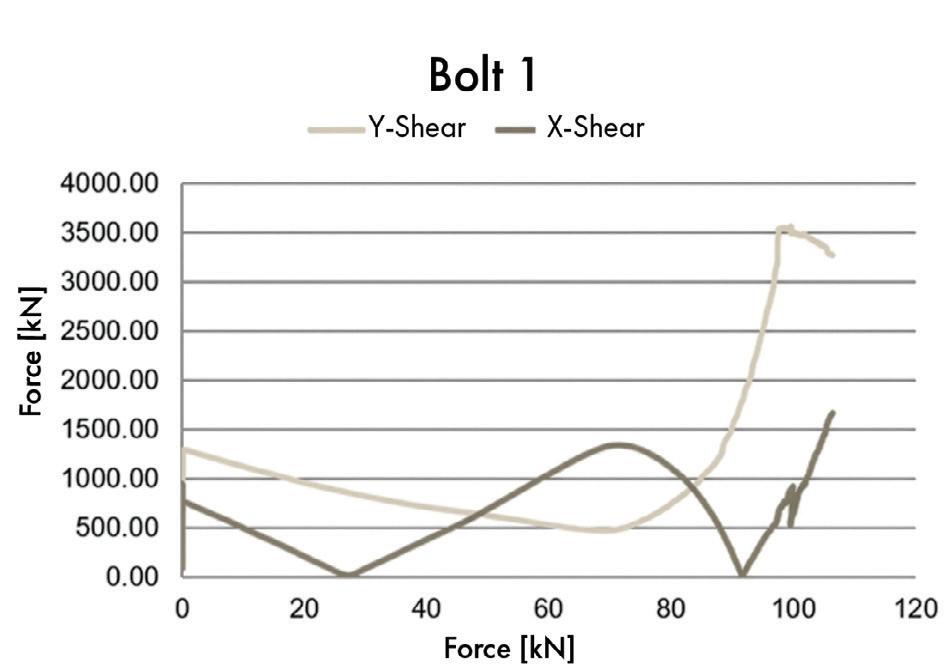

Another critical check is to evaluate the bolts that connect the connector to the girder. Figure 5 shows an example of the applied load on the simulation and the location of bolt #1. Figure 6 provides a typical example of the bolt force curve for bolt #1.

The nominal shear strength of the single bolt is 28 kN (6.29 kip)

and is based on physical testing of the individual bolt. Based on Figure 6, the maximum applied bolt shear load in the Y-direction is 3.57 kN (0.803 kip), and X-direction is 1.67 kN (0.375 kip). Therefore, the total resultant load is 3.94 kN (0.886 kip), well below the bolt’s nominal capacity.

Additional considerations would be the stress and deformation contour plots. Figure 7 provides an example of the deformation contour plot at an ASD level. The maximum deformation is 1.3867 mm (0.0546 in).

Role of FEA in Proprietary Product Evaluation

While physical testing remains the primary method for establishing product resistance, a calibrated FEA model provides several advantages:

• Ability to evaluate alternate configurations without additional full-scale testing.

• Insight into failure mechanisms and load paths not visible during testing.

• Perform parametric studies for thickness changes, bolt spacing, or geometric variations.

• Identify critical details and optimize design before prototyping. When used in conjunction with confirmatory testing as outlined in AISI S100, FEA serves as a powerful tool for developing reliable technical data for proprietary cold-formed steel systems.

Conclusion

Without appropriate technical data, usually the resistance of proprietary CFS systems is estimated by engineers using a static model and hand calculations. This might be the least cost-effective method but tends to produce very conservative results. However, at times these results could also lead to unconservative and unsafe designs. Therefore, whether using physical testing or FEA, proper guidance as provided by AISI and highlighted in this article must be used as a practice for developing technical data for designing safe structures using proprietary steel products. ■

Arif Shahdin is a Technical Product Manager in Hilti. He has over 13 years of experience as a Hilti cold form/modular steel systems experts where he has worked on the development of technical data and design practices for Hilti’s modular support system product line, including developing an analysis software for the product. Shahdin is a degreed and practicing structural engineer and an adjunct faculty of structural engineering.

Jose Palao Jr, PE, is an Approvals Engineer at Hilti with two years of experience leading code approvals and technical compliance efforts for Hilti’s cold-formed steel modular support (MT) portfolio. He has over 10 years of structural engineering experience, including the design and evaluation of low-rise reinforced concrete and steel structures, waterfront and coastal resiliency projects, shallow and deep foundation systems, pump stations, building rehabilitation, temporary support systems, and permanent earth-retaining structures.

Fig. 7. A 3D model deformation contour plot was created for the example bracket.

Fig. 6. Bolt #1 X-Y direction force comparison from simulation results.

structural DESIGN

Two-Dimensional Modular Steel to Optimize Critical Path Steel Erection

Applications and methods for modular steel have grown and evolved over the last two decades.

By James Ryan, PE

Since the early 2000s, modular design and construction have expanded from two-dimensional grating floor panels to modular composite floor and roof panels, modular girt trusses, and partially fabricated stair towers. Over the past 25 years, approximately 10,000 modular steel panels have been used in fossil and nuclear power plants, as well as oil, gas, and chemical plants. Potential applications include AI data centers, chip manufacturing plants, and large-scale global airport expansions (i.e., to mitigate operational impacts).

Truck-transported modular steel (Fig. 1) includes the most laborintensive miscellaneous steel components. The shop assemblies concurrently optimize weight and volume criteria, thus enabling truck transport without police escort or cost premium. Cost benefit includes a substantial reduction in schedule, which reduces interest costs, cranes, and other equipment costs; field supervision and engineering; home office support; and (at remote sites) per diems.

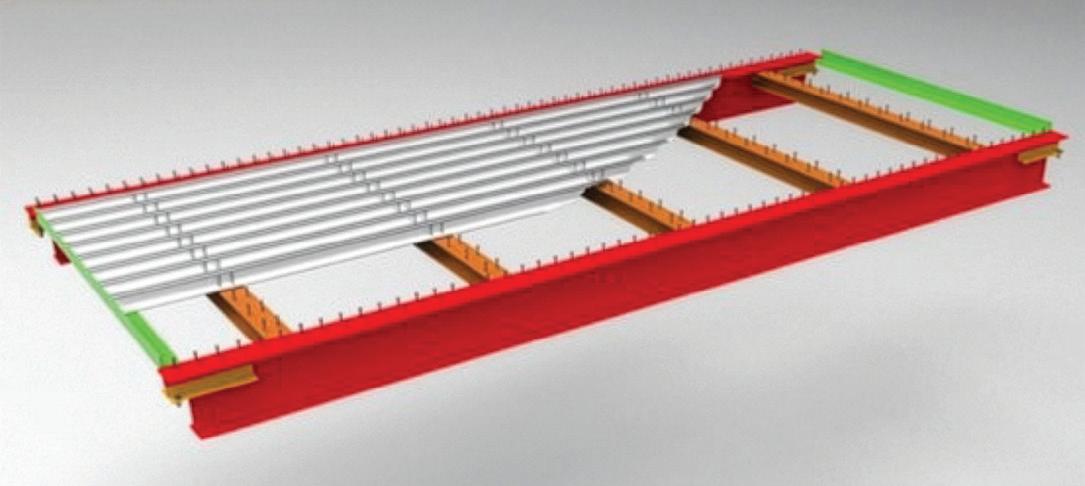

Modular Composite Floor and Roof Panels

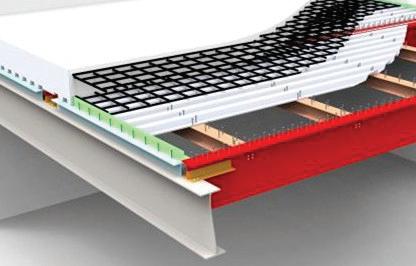

Steel composite panels (Fig. 2) are used in lieu of concrete floor and roof slabs. Panel components include two primary beams, infill beams at 12 feet maximum spacing (with dual use for commodity support), nominally 30 composite deck panels, penetrations, hundreds of steel-headed stud anchors and select HSS stubs above the floor for equipment or commodity support.

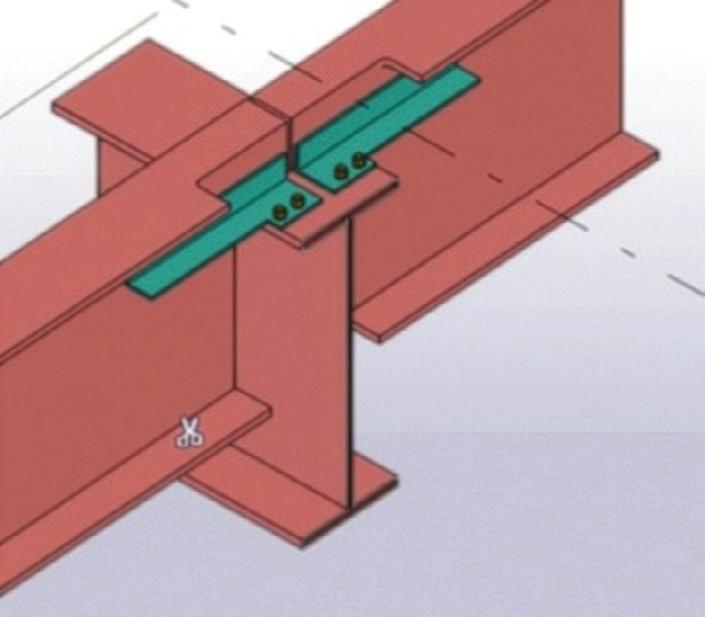

All structural and miscellaneous steel for a floor or roof bay is erected with only three modular composite panels, an incremental girder, and a greatly reduced bolt quantity relative to conventional “stick-built” construction. The web at the ends of the primary

beams is typically coped to a depth of only 8 inches to mitigate impacts to the overall floor depth. The coped web is reinforced by two 4-inch-deep angles to provide for increased shear capacity. Only two bolts are used at panel seated connections, regardless of load. Oversize (OVS) holes all plies address cumulative tolerances.

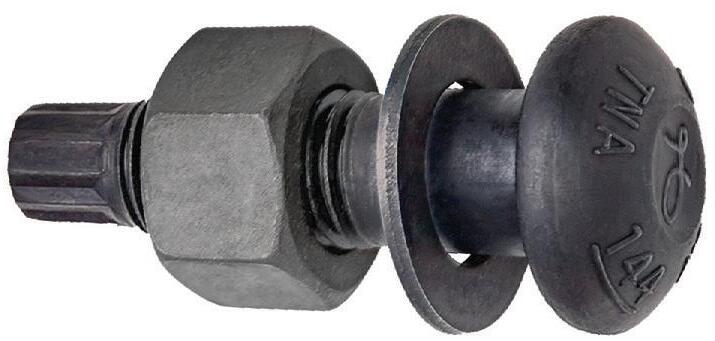

Paradoxically, the modular panels greatly improve both safety and erection speed relative to “stick-built” conventional construction. Ironworkers may walk on top of the composite deck within the floor panels and install one-sided ASTM F3148 TNA bolt assemblies from above the floor panels. In conventional construction, ironworkers straddle girders and walk on their bottom flanges. All bolt installation is made by reaching below the girder top of steel elevation. The enormous quantity of composite deck sections is not installed until much later.

The composite deck orientation within the floor panels enables 7/8-inch diameter steel headed stud anchors on the two primary panel beams. This reduces the required number of steel headed

Fig. 1. Two-dimensional modular steel panels are transported to a construction site.

Fig. 2. Steel composite panels safely expedite concrete floor and roof construction.

stud anchors by a factor of two relative to conventional construction. For conventional construction, the flutes of the composite deck above beams limit the maximum diameter to ¾. In addition, design codes impose significant deck reduction factors.

Additional benefits of the modular steel composite panels include:

• Shifting field work from elevated heights to at-grade in an enclosed fabrication shop, thus minimizing lost days due to adverse weather conditions.

• Addressing craft labor availability issues, especially at remote sites.

• Mitigating impacts of an aging craft workforce by erection friendly design.

The composite deck is typically 16 gage to mitigate wet concrete deflection and increase durability in shipment and handling. The thickness also mitigates cumulative concrete ponding from the composite deck, primary panel beams, infill beams, and girders. Longer span primary panel beams are selectively cambered to preclude contributing to cumulative concrete ponding. Reinforcing steel installation and concrete placement is consistent with conventional construction.

The horizontal legs of seated connection angles are coped away from the girder flange to improve hand access underneath (Fig. 3). Bolted connections are made only to the outer angle of each seated connection. Where up to four primary panel beams come together, the outer portion of each beam top flange is coped to allow for hand access. After bolt installation, a thin formwork plate (with shop welded bar “stops” underneath) is “dropped-in” prior to concrete placement. This plate is not shown for clarity. Closure for concrete placement between adjacent panel flanges is provided via light-gage steel strips. The plate is attached at grade to the latter panel to be installed with powder actuated fasteners (PAF).

Column line composite stub girders have lengths of WT shapes welded to the top flange to facilitate composite action (Fig. 4). Between WT segments, column line primary panel beams bear on the girder top flange. However, at braced bay column lines, panel beams are not coped but bear on erection angles, thereby facilitating conventional bracing connections.

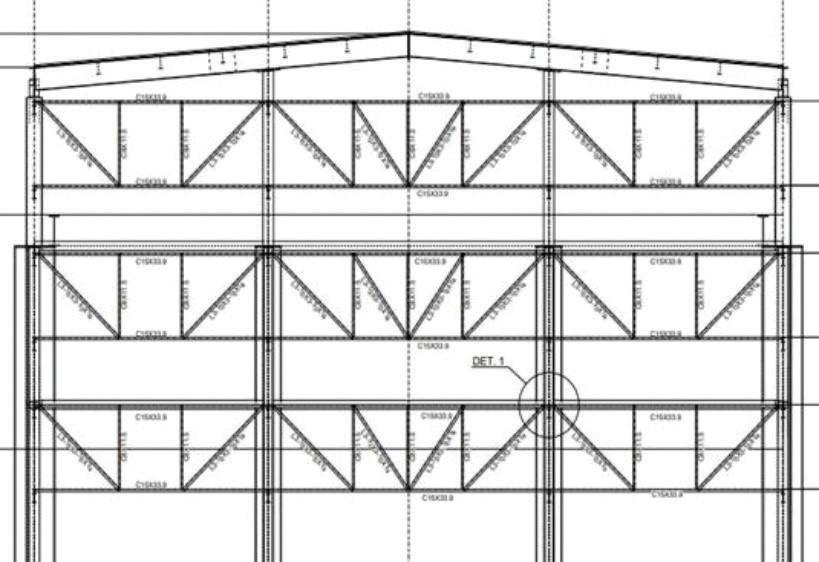

Modular Girt Trusses

Modular girt trusses are used (Fig. 5) in conjunction with thin gage, 3-inch deep, steel siding panels.

Truss configurations are typically established for two upper bound bay sizes. The shorter trusses have three truss panels and longer trusses use four panels. Truss chord members are W12s with horizontal webs. Truss verticals are channels which also serve as lateral-torsional restraint to the chord members. Truss diagonals are angles. Seated connections are used at truss ends.

The optional variation in vertical member spacing provides a common Design to Capacity ratio along the entire length. Historically, this yields a nominal ten percent tonnage reduction versus equal spacing.

Partially Shop Fabricated Stair Tower Assemblies

Partially shop fabricated stair tower assemblies (Fig. 6) are used to maximize shop labor but mitigate transport volume. Assemblies include two columns, vertical and horizontal bracing, girts on two of three sides, platform framing, grating, and pipe penetrations (e.g., fire water). The panels are mirrored and mated for shipment. Cable tray, firewater pipe, and other commodities may be attached

Fig. 3. Coped beam top flanges and horizontal angle leg allow for tool and hand access.

Fig. 4. Seated connections with composite stub girders.

Fig. 5. Modular girt trusses are used in conjunction with steel sliding panels.

at grade prior to uplifting.

Cap and base plates facilitate seated connections for module stacking (Fig. 7). Tower segments provide rapid permanent stair access for craft. Moment frames are used in lieu of braced frames in the longitudinal direction to eliminate interferences with walkway access to building interiors. However, vertical bracing may be used for the exterior column line, with moment frames for the interior column line.

Summary

TNA® is the only fastening system that delivers both a quantifiable Snug Tight condition – ensuring every bolt in a connection meets a minimum requirement for tension – and the precise required angle for the perfect final pretension. No other system or method can match the TNA® Torque + Angle Fastening System for producing the highest level of accuracy and reliability in both the snug and final tensioning processes.

Our TNA® Bolts meet the requirements of ASTM F3148 and are 100% Melt & Manufacture in the U.S.

The Combined Method (Torque + Angle) is an approved RCSC installation method.

Based on successful implementation, the cited modular steel approaches and improvements shared above are recommended for expanded industry use in all non-commercial buildings and structures. Primarily for commercial purposes, a third category of steel (Modular Steel) has been used to distinguish the design/ build approach from the Structural Steel and Miscellaneous Steel categories of AISC 303, the Code of Standard Practice. This new category captures the significant shift of field labor costs to shop fabrication costs. ■

James L. Ryan, PE, is a retired Principal Engineer specializing in Steel Design and Modular Steel. His career included 40 years at Bechtel Corporation, with an intermediate 5 years at a commercial design firm. He welcomes any questions or further discussion and may be reached at JimR21157@gmail.com

Fig. 7. Shown is a stair tower ground assembly.

Fig. 6. Partially shop-fabricated stair tower assemblies are staged in laydown.

structural ANALYSIS

Field Investigation and Evaluation of Roofing Systems Following a Major Wind Event

The findings show installation quality, material condition, and adherence to jurisdiction-specific code provisions govern real-world performance.

By Maria R. Martinez Herrera

AsTampa, Florida, marks one and a half years since the unprecedented back-to-back hurricanes of 2024, the structural engineering community continues to analyze how hurricanes expose intrinsic vulnerabilities in the region’s building envelope systems. A forensic assessment of more than 30 residential structures across Hillsborough, Pinellas, Sarasota, and Manatee counties revealed both remarkable strengths and critical weaknesses in roofing assemblies. These findings have major implications for the resiliency and sustainability of coastal communities facing increasingly intense wind events (Emanuel, K., 2005. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 436: 686–688).

Hurricane Helene made landfall as a Category 4 system along the eastern Gulf Coast near Tampa on September 26, 2024. According to the National Hurricane Center (NHC), gusts penetrated far inland due to the storm’s fast forward motion, with the strongest land-measured sustained wind of approximately 91 miles per hour (mph) recorded near Live Oak, Florida, and with maximum aircraft recorded sustained winds of 140 mph. Two weeks later, Hurricane Milton made landfall on Siesta Key (approximately 50 miles south of the Tampa region) as a Category 3 system, delivering sustained winds up to 91 mph and gusts approaching 107 mph along Venice Beach with maximum aircraft recorded sustained winds of 120 mph.

The consecutive nature of these events created a unique forensic scenario: structures were exposed to two major loading cycles within a short period of time—allowing the engineering teams to differentiate between pre-existing vulnerabilities, storm-induced damage, and cumulative deterioration across both events.

Forensic Engineering Investigation Methodology

Conducting a systematic and objective forensic investigation is crucial to ensure the integrity of the investigation, while ensuring accurate evidence is gathered in a safe and ethical manner. Post-event investigations were conducted in accordance with ASTM E2713-18 Standard Guide to Forensic Engineering, which provides guidelines on the role and qualification of engineers conducting forensic evaluations, including:

• Site observations and photographic documentation.

• Mapping of damage patterns across windward and leeward roof slopes.

• Interviews with homeowners, when available.

• Review of pre-storm aerial imagery, permit history, and maintenance records.

Takeaways: Construction Quality vs. Wind Intensity

• Approximately 70% of observed damage initiated at improperly installed or aged components, not at areas designed and installed in accordance with FBC and ASCE 7.

• Nearly 50% of shingle failures involved nails placed within adhesive strips, a direct violation of manufacturer and code requirements.

• Hurricane- related damage consistently initiated in known roof discontinuity zones, validating ASCE 7 provisionsperimeter and corner roof wind zones.

• Florida’s enhanced building code requirements as well as requirements from local jurisdictions have demonstrably improved performance compared to structures where installation did not follow the applicable code provisions. These findings reinforce that wind speed alone is not the dominant predictor of roof failure. Instead, installation quality, material condition, and adherence to jurisdiction-specific code provisions govern real-world performance.

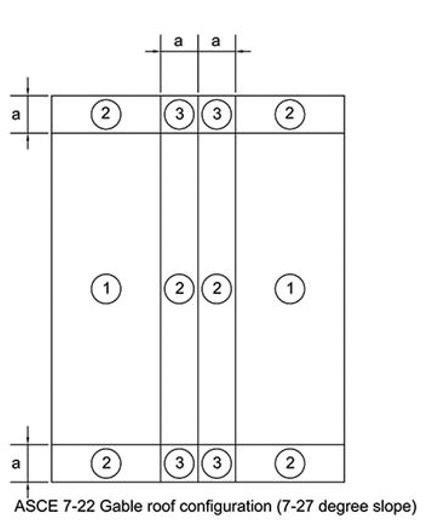

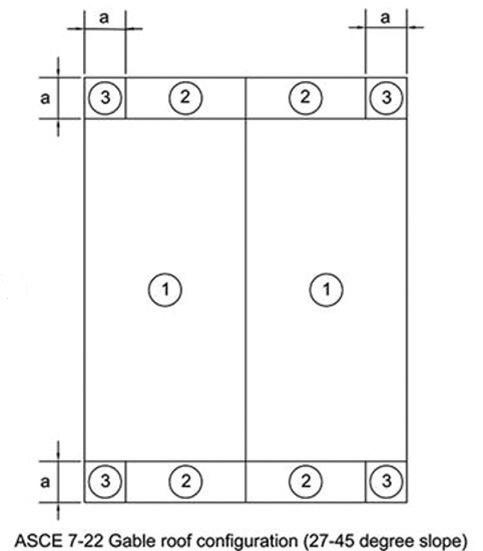

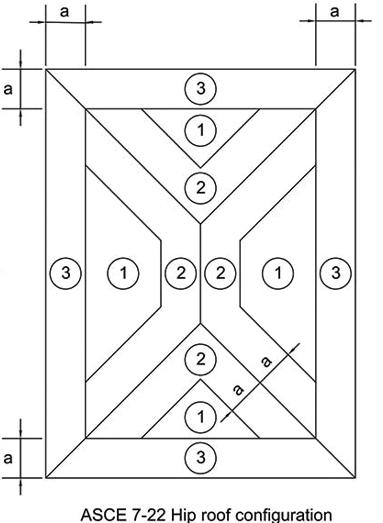

• Correlation of observed damage with ASCE 7-22 Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures wind speeds and calculated wind pressures. Wind pressures were evaluated for Components and Cladding (C&C) using ASCE 7-22 provisions, with particular attention to roof discontinuity zones where aerodynamic flow separation increases uplift demands.

Wind Design Considerations and Florida Building Code Requirements

A thorough understanding of wind effects on structures, as well as design and installation practices, enables investigators to effectively gather relevant field evidence, define minimum performance expectations, and accurately reconstruct and assess observed conditions using relevant engineering principles. The Florida Building Code (FBC) requirements and ASCE 7-22 wind design loads, were used to estimate the wind demand after each event. It’s important to mention, that current code was used for the purpose of this research to understand

how the requirements of current code would affect the performance of roof assemblies and to determine whether damage was caused by wind speeds exceeding design level forces, under-designed roofing assemblies, or installation deficiencies.

When wind interacts with a building, both positive and negative (i.e., suction) pressures occur simultaneously. However, wind pressure on a structure is not uniform pressure. Wind pressure will increase as the path of wind encounters discontinuities in a structure due to aerodynamic effects, called flow separation. Flow separation around a building occurs when wind detaches from its surface, especially at sharp edges, creating turbulent, low-pressure zones (separation bubbles) that can cause significant uplift forces. Discontinuities include hips, ridges, corners, valleys, and edges in the roof covering as well as corners on the wall surfaces.

This behavior of wind forces is recognized by applicable building codes that require these areas to be designed to resist higher forces for a given wind speed compared to the main body of the roof. ASCE 7-22 partitions roof areas into zones:

• Zone 3—Corners for gable roofs and edges for hip roofs

• Zone 2—Perimeters

• Zone 1—Field of Roof

The areas of a structure that experience an increase in wind pressure as a result of the referenced discontinuities will likely exhibit wind related damage before the remaining areas of a structure that are subjected to lower wind pressures.

The exposure of the building to wind forces also plays a significant role in the wind forces a building experiences. Buildings in Exposure D zones experienced higher pressures.

Florida’s building code differs from many other U.S. jurisdictions due to its explicit focus on high-wind events, wind-borne debris regions, and repeated hurricane exposure. In addition to the ASCE 7-22 requirements, Florida jurisdictions typically incorporate:

Higher mapped design wind speeds: Florida’s High Velocity Hurricane Zone (HVHZ) designation established by the FBC apply to Miami-Dade County and Broward County. However, most of Tampa falls into areas of Wind-Born Debris Regions (WBDR) with ultimate design wind speeds of 150 mph.

Product approval systems: All building envelope products within the HVHZ must have a Notice of Acceptance (NOA) provided by the jurisdiction. All exterior opening products used within a WBDR are required to have a Florida Product Approval (FPA) or NOA approval.

Installation Requirements by Roofing Systems

Asphalt Composition Shingles—Installation Requirements

Asphalt shingles must be tested and classified for wind resistance under ASTM D7158 Standard Test Method for Wind Resistance of Asphalt Shingles and/or ASTM D3161 Standard Test Method for Wind Resistance of Steep Slope Roofing Products and per manufacturer’s recommendation. Proper installation typically requires:

• Placement of corrosion-resistant nails (ASTM F1667 Standard Specification for Driven Fasteners: Mails, Spikes, and Staples) within manufacturer-designated nailing zones.

• Nails installed below—not through—the adhesive sealant strip.

• Adequate nail embedment and avoidance of over-driven and underdriven fasteners.

• Functional adhesive bonding between overlapping shingles. For shingle detachment to occur, wind uplift forces must exceed both the adhesive bond strength and nail withdrawal resistance.

Fuplift>Fsealantbond+Fnailwithdrawal

Concrete and Clay Tile Roofing—Installation

Requirements

The Florida Building Code permits concrete and clay tile installation using:

• Mechanical fasteners (nails or screws at pre-drilled holes), or

• Mortar or foam adhesive systems, provided products are approved and installed by NOA and manufacturer guidance. The installation of concrete and clay roof tiles and their wind resistance is governed by the Florida High Wind Concrete & Clay Tile Installation Manual (FRSA/TRI) 5th Edition Manual and Section R905.3 of the Florida Building Code. Tile uplift resistance per FRSA/ TRI 5th Edition Manual is: R=W+A∙ΔP

Where:

R = Resistance of tile-fastener assembly

W = Self-weight of tile

A = Tributary area of tile

ΔP = Differential pressure

To cause the detachment of an individual roof tile secured to the substrate

Fig. 1. ASCE 7-22 partitions roof areas into zones: 1) field of roof, 2) perimeters, and 3) corners for gable roofs and edges for hip roofs.

with mechanical fasteners (typically two nails or screws per tile) or to cause the de-bonding of an individual roof tile secured with cementitious mortar or foam adhesive, the wind uplift force must first overcome the dead weight of the tile and be of sufficient additional magnitude to break the tile, fasteners and/or the bond between the cementitious mortar or foam adhesive used to secure the tile to the substrate.

Therefore, if wind forces were to affect a tile to the degree necessary to cause detachment, the tile would be significantly displaced from its installed location and/or blown off the roof.

Metal Roof Panels—Installation Requirements

Metal roofing systems consist of large mechanically fastened metal panels or sheets that create a continuous barrier to wind. Metal roofing systems rely on:

• Continuous panel attachment to framing or decking using manufacturer’s approved fasteners, typically self-drilling or self-tapping corrosion-resistant screws.

• Secure seam connections and fastener spacing per manufacturer specifications.

• Adequate substrate support.

When installed correctly, metal panels function as integrated, mechanically secured strong, lightweight roof covering systems that efficiently resist wind uplift while providing accommodation for thermal expansion and contraction without stressing the interlocking mechanism.

Wind damage to a metal roof panel is typically characterized by displaced, partially detached, or missing panels, as well as impacted (wind debris) panels.

Single Ply Roofing—Installation Requirements

Single-ply roofing systems, such as Thermoplastic Polyolefin (TPO), Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), or Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM), are flexible membrane systems designed for low-slope roof assemblies. Proper installation is critical to ensure durability, water tightness, and wind resistance requiring the following:

• Roofing system to be installed to ensure positive drainage and to comply with minimum slope required by the FBC of no less than 1/4:12.

• Substrate to be clean, dry and smooth.

• Insulation or decking to be properly attached.

• A fully adhered membrane. Membrane is either glued to the substrate using a compatible adhesive or fastened with screws and plates at seams or edges.

• Seams to be properly welded or adhered to create a continuous waterproof barrier. Edges, corners, penetrations, and flashing details must follow manufacturer guidelines to prevent uplift and water intrusion.

The installation of single-ply roofing systems is governed by the manufacturer’s recommendation and the NRCA (National Roofing Contractors Association). ASTM Standards (ASTM D4434, ASTM D6878 and ASTM D4637) define material properties and testing requirements for such systems.

The detachment of a single-ply roofing membrane under wind forces is usually caused by a combination of improper installation (poor substrate preparation, incomplete seam welding) membrane defects, and wind loads that exceed the system’s design capacity. When installed

Aggressive environments are no match for the corrosion-resistant protection of Rhino-Dek ®. Easily installed stay-in-place bridge deck forms support new bridge construction and rehabilitation.

• Service life up to 124 years

• DOT tested and approved in many states

• Custom-color coating options

• 5 profiles for spans up to 14 feet

Table 1. Roof and Wall C&C Pressures (psf) at 150 mph

Table 2. Roof and Wall C&C Pressures (psf) at140

correctly, single-ply systems provide a continuous, wind-resistant roof system suitable for low-slope applications.

Roof Decking Requirements:

Recent updates to the 2023 FBC, Residential (Eighth Edition) have introduced more stringent requirements for roof sheathing thickness in high-wind regions. Under Section R803.2.2, the minimum thickness and required panel span rating for wood structural panel roof sheathing are established based on design wind speed and exposure category, with areas subject to higher wind loads (such as those with ultimate design wind speeds of 140 mph or greater) generally requiring a 19/32-inch (nominal 5/8 inch) panel to meet uplift resistance criteria. In less severe wind zones, thinner panels (such as 15/32-inch) may be permitted; however, each thickness must be installed with the appropriate fasteners and spacing outlined in Section R803.2.3.1 to ensure adequate attachment and resistance to wind uplift forces.

Observed Hurricane Damage by Roofing System

ASCE 7-22 C&C design pressures were used to evaluate and compare the maximum wind loads that roof and wall components of a building would be expected to resist, based on code-specified wind speeds versus the maximum observed wind speeds. For illustrative purposes, Table 1 summarizes the ASCE 7-22 C&C design pressures calculated for a basic wind speed of 150 mph with the following building parameters:

• Exposure: C.

• Risk Category: II.

• Mean roof height: 25 ft.

The values presented are representative design pressures for low-rise residential roofs and walls, providing a preliminary reference for evalu ating uplift and lateral wind loads in accordance with ASCE guidelines.

Asphalt Composition Shingles

Typical wind-related damage included missing, torn, or creased shin gles. Creasing indicated uplift forces sufficient to bend tabs without full detachment.

Fig. 2. Torn shingle (red arrow) and two missing shingles (blue arrow).

Table 3. Roof and Wall C&C Pressures (psf) at 120

In all observed instances, the observed damage was located within zone 2 of the roof, recognized by applicable building codes as an area that requires to be designed to resist higher forces for a given wind speed compared to the main body of the roof (Tables 1-3).

Concrete and Clay Tile Roofing

Observed damage primarily involved displaced or broken tiles, often due to wind-borne debris rather than direct uplift failure. Performance varied by attachment method:

• Mortar-set tiles frequently exhibited de-bonding due to aged mortar.

• Foam-set tiles failed where bead size or continuity was inadequate.

• Mechanically fastened tiles performed best when embedment met FBC requirements and placement was per product approval.

Metal Roof Panels

Metal roofing systems generally performed well under wind loading. The damage observed was primarily associated with impact from falling trees and wind-borne debris, leading to panel deformation and water intrusion through the damaged underlayment rather than uplift failure.

Single Ply Roofing

Single ply roofing systems performed well under wind loading. The damage observed was primarily associated with long-term deterioration (cracked and deteriorated sealant at intersection between roof and elevated walls), leading to water intrusion rather than uplift failure.

Observed Damage Not Caused by Elevated Wind Forces from a Single Event

Asphalt Composition Shingles:

Shingle creasing is a classic indicator of uplift force sufficient to bend the tab but not fully tear the shingle.

The most common construction deficiencies found were:

• Nails placed within adhesive strips reducing the area of adherence.

The FBC mandates corrosion-resistant nails (ASTM F1667) for shingle roofs, specifying placement within the manufacturer’s designated nailing line, typically 1 to 13 inches from the shingle’s end and below the sealant strip.

• Lack of factory-applied adhesive strip (manufacturing defect).

• Glossy finish of adhesive strip (indicating a lack of adherence).

Concrete and Clay Tile Roofing

The following damage was not attributable to elevated wind forces but to deferred maintenance, aging and/or construction deficiencies:

• Mortar-set tiles frequently exhibited de-bonding due to aged mortar.

• Foam-set tiles failed where bead size or continuity was inadequate.

• Mechanically fastened tiles slipped when fasteners were missing. Manufacturing and/or installation defects can also be exhibited as cracks at the tile corner. These defects are the result of deficiencies in the uniformity of the material mix, and the mechanics of pressing or extruding processes, which causes an isolated weakness in the tile and/or installation without provision for thermal expansion and contraction.

Fig. 3. A field tile has slipped. The tile exhibited overdriven fastener through tile.

Fig. 4. Indented metal roof panel after tree impact.

Fig. 5. Creased ridge shingle.

Material Aging Factors

It is important to mention that long–term and repeated exposure to elevated wind forces, often less than design wind speeds, will impact the roof covering that has been deficiently installed. Other conditions such as quality and age of the materials, directionality of the winds, extent of UV exposure (e.g., shaded roof surfaces vs. exposed roof surfaces), thermal cycling, and other factors (e.g., debris covered surfaces), will affect the performance and extent of wind-related damage to the roof coverings.

Table 4. Summary of Common Failure Observations by Roof Type

Roofing System Primary

Asphalt Shingles Missing and torn shingles, creased tabs

Over-driven nails, aging sealant strip, improper fastening placement. Tree impacted roofs.

Concrete/Clay Tiles Tiles cracking and slipped tiles. Tree Impact and improper fastening placement.

Metal Panels Panel deformation, seam displacement

Tree impact

Single Ply N/A N/A

ASTM D7158, ASTM D3161, FBC R905.2

Conclusions and Resiliency Implications

The forensic analysis following Hurricanes Helene and Milton confirms that proper installation, inspection, and maintenance are the most critical factors in roofing system performance. Even when exposed to near-design wind speeds and multiple wind events:

• Code-compliant systems largely remained intact.

• Failures were associated with construction deficiencies. Strengthening inspection protocols during construction, improving installer training, and enforcing Florida’s product approval and fastening requirements will continue to enhance building resilience and reduce repeat wind losses across coastal communities.

over

years

forensic investigations and the evaluation of existing structures. Her practice centers on diagnosing structural distress, identifying damage mechanisms, and developing repair and rehabilitation strategies for residential and commercial buildings.

FRSA/TRI 5th Edition Manual and Section R905.3 of the Florida Building Code.

FBC 1507.4.3, UL 580, ASTM E1592, or TAS 125.

ASTM D4637 for EPDM, D6878 for TPO, D4434 for PVC).

Maria Martinez, PE, is a licensed Professional Engineer with

10

of experience in structural engineering, specializing in

Fig. 7. Overdriven fasteners within adhesive strip.

Fig. 6. View of a matte finish and a gloss finish of the adhesion strip below a torn shingle and a fastener installed within the adhesion strip below a creased shingle.

FUTUREPROOF

New construction architecture requires special consideration for the inevitability of future upgrades. That’s why modern construction projects need hanging solutions that are built for speed, versatility, and adaptability to ensure quick and seamless renovations.

To help meet that challenge, Vulcraft-Verco has developed the PinTail™ Anchor, an innovative hanging solution that works exclusively with our Next Generation Dovetail Floor Deck, and are specifically designed to futureproof today’s construction projects for tomorrow’s renovations.

structural ANALYSIS

Inspection, Evaluation, and Rehabilitation of the Taylor Bridge Gusset Plates

During a recent inspection of the bridge, advanced corrosion was identified on numerous gusset plates along the interface with the truss bottom chords.

By Kai Marder and Dusan Radojevic

The Taylor Bridge in northeastern British Columbia represents an essential crossing of the Peace River for residents and industry. Built in 1960, the bridge carries a significant number of trucks with 30% of all traffic being heavy vehicles.

A joint venture consisting of T.Y. Lin International Canada Inc. (TYLin), Hatch Ltd. (Hatch) and Charter Project Delivery Inc. (Charter) has been contracted by the British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure (BC MoTI) to provide Owner’s Engineering (OE) Services for the Taylor Bridge Project. The project involves the development of various options for the future of the existing Taylor Bridge in northeastern British Columbia.

The Taylor Bridge is a two-lane, six-span, 712-meter-long structure that carries Highway 97 across the Peace River (Fig. 1). Five of the six spans are comprised of variable-depth steel trusses, while the remaining span is a stringer span at the north end of the bridge. Five concrete piers and two concrete abutments support the superstructure. From an articulation standpoint, the truss spans are a combination of continuous structures and suspended spans.

As part of their Owner’s Engineering Services assignment, the OE conducted a series of bridge inspections. These inspections identified the presence of relatively advanced corrosion on many gusset plate connections where the truss verticals and diagonals frame into the lower chord.

The OE determined recommended actions for the corroded gusset plates, including a scheme for strengthening.

Inspections

The OE carried out three inspections involving the gusset plate connections. The first inspection, conducted in May 2021, involved a complete inspection of the bridge, with the gusset plate connections being only one of many components included. This inspection indicated the need for more detailed measurement of the gusset plate section loss. The second and third inspections, conducted in March 2022 and April 2022, were targeted inspections, focusing on the most heavily corroded gusset plate connections.

The targeted inspections involved ultrasonic testing measurements of the remaining thickness of the gusset plates. A combination of snooper truck and rope access was used to reach the gusset plate nodes. The measurements were taken in a grid pattern over the extent of the corroded region. The ultrasonic testing measurements gave a total remaining plate thickness but did not provide information on the asymmetry of the corrosion, i.e. how much section loss occurred on each face. This was estimated in the field for each node via measuring the depth from a straight edge to the corroded face on both sides of the

Fig. 1. Taylor Bridge in northeastern British Columbia was built in 1960.

gusset at a select few points and averaging the results. An example output of the targeted inspection ultrasonic measurements for one gusset plate is given in Figure 2.

Evaluation

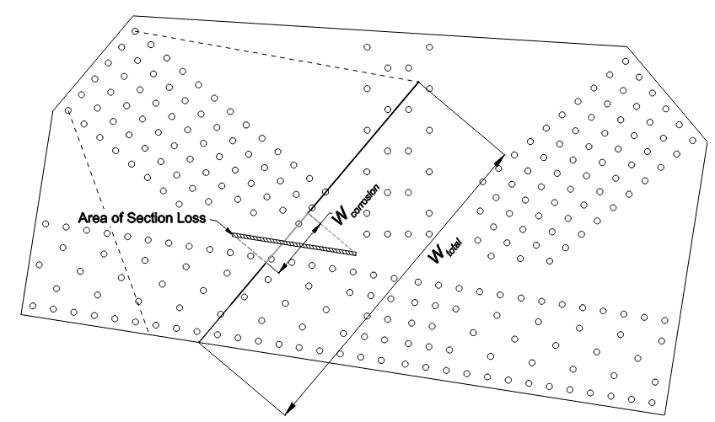

The overall load evaluation of the Taylor Bridge was conducted in accordance with Section 14 of the Canadian Highway Bridge Design Code CSA S6:19 and the BC MoTI Supplement to CSA S6:14. However, these standards contain limited information with regards to the evaluation of gusset plates and no information on the evaluation of gusset plates with localized corrosion. The methodology used for gusset plate capacity was therefore based primarily on the AASHTO Manual for Bridge Evaluation 3rd Edition . The National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report ( Guidelines for the Load and Resistance Factor Design and Rating of Riveted and Bolted Gusset-Plate Connections for Steel Bridges ), which much of the AASHTO MBE methodology is based on, was also relied upon for additional background information. The effects of localized section loss due to corrosion were accounted for in two ways: (1) considering an effective remaining gusset plate thickness, and (2) considering the out-of-plane bending stresses induced as a result of asymmetric corrosion on either side of the plate. For the effective remaining gusset plate thickness, the OE considered followed the recommendations of AASHTO MBE. Different effective thicknesses were used depending on the failure mode considered. For shear and tension checks, the effective remaining thickness was simply taken as the average remaining thickness along the shear plane or Whitmore tension plane, respectively. For compression checks, the effective remaining thickness was the average remaining thickness along the Whitmore compression plane (Fig. 3).

AASHTO MBE provisions were also followed to determine when asymmetric corrosion effects on either side of the plates need to be considered. The limit at which it was considered is given as:

(e*c)/r2 < 0.25,

Where:

‘e’ is the thickness eccentricity due to corrosion

‘c’ is the distance from centroid of gusset plate to extreme fibre

‘r’ is the radius of gyration of the effective Whitmore section of the gusset plate

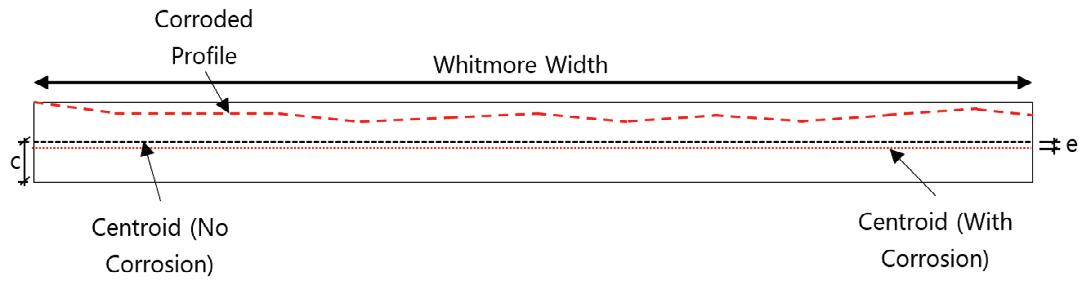

No guidance is given in AASHTO MBE on how to consider asymmetric corrosion effects when this limit is exceeded. Therefore, the OE developed a methodology that involved treating the gusset plate as a beam-column, with a bending moment equal to the axial compression in the gusset plate multiplied by the eccentricity due to asymmetric corrosion. The axial forces and bending moments were then combined using the provisions of CSA S6:19. This methodology is illustrated in Figure 4.

Finite Element Analysis

Due to the uncertainty over the remaining service life of the bridge, including the option of a full bridge replacement, it was desirable to keep gusset strengthening and recoating works to a minimum.

Furthermore, the code-based evaluation involved assumptions on the effects of asymmetric corrosion. For these reasons, the bridge owner requested a detailed finite element analysis be conducted on one truss node as a means of validation of the code-based evaluation, and to give increased confidence in the extents of strengthening and recoating

Fig. 2. In this ultrasonic thickness measurement example, gusset plate remaining thickness for each grid point (mm) is given in the table above, and measurement grid points are shown as white dots on the gusset in the picture.

Fig.3. Section Loss for Compression Checks (AASHTO MBE)

Mf=Cf /2*e

Fig. 4. The methodology for asymmetric corrosion is illustrated.

works proposed.

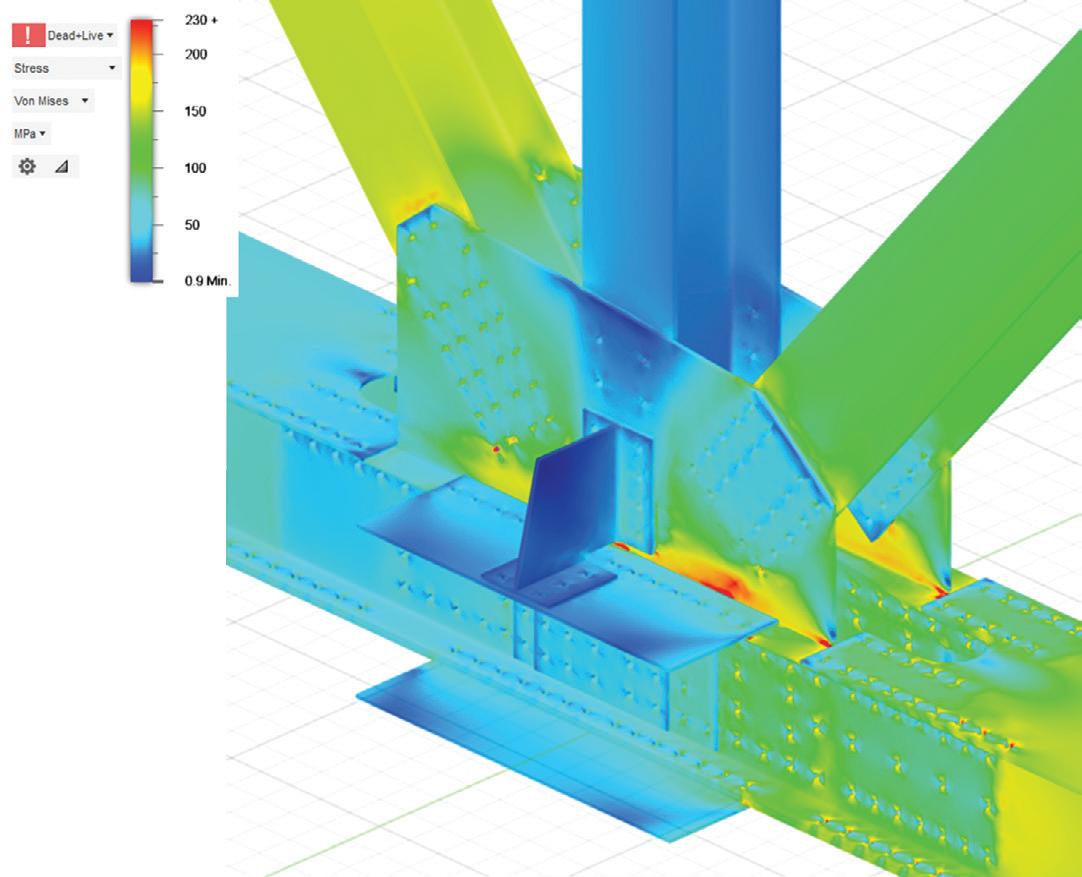

A 3D model of one selected truss node that was subjected to ultrasonic thickness testing was developed. An isometric view of the model, including the finite element mesh, is given in Figure 5. The section loss due to corrosion, based on the ultrasonic thickness measurements taken during the gusset plate inspections, was explicitly included in the 3D geometry of the gusset plate elements. The measured plate thickness at each grid point was mapped onto the gusset plate element surfaces. Figure 6 shows an example isometric view of a Von Mises stress plot of the entire node for the linear stress analysis under one selected load case. Critical stresses occur in the gusset plates under the compression diagonal (diagonal on the right side of the plot), as expected based on the code-based gusset plate load rating. The highest stresses of all the four gusset plate faces occur on the exterior face of the inner gusset. This pattern holds for all load cases considered and is consistent with what would be expected based on section loss measurements and combined bending and axial stresses due to asymmetric corrosion on either side of the gusset faces. At a level of load corresponding to a demand-to-capacity ratio of 1.0 from the code-based evaluation, the finite element analysis generally showed spreading of gusset yielding under the critical compression diagonal, but no loss of load carrying capacity. Ultimate loss of load carrying capacity in the non-linear finite element model occurred at a higher load level as a result of an inelastic sidesway buckling failure mode of the gusset plate. These results indicated that the code-based assessment methodology was reasonable albeit somewhat conservative.

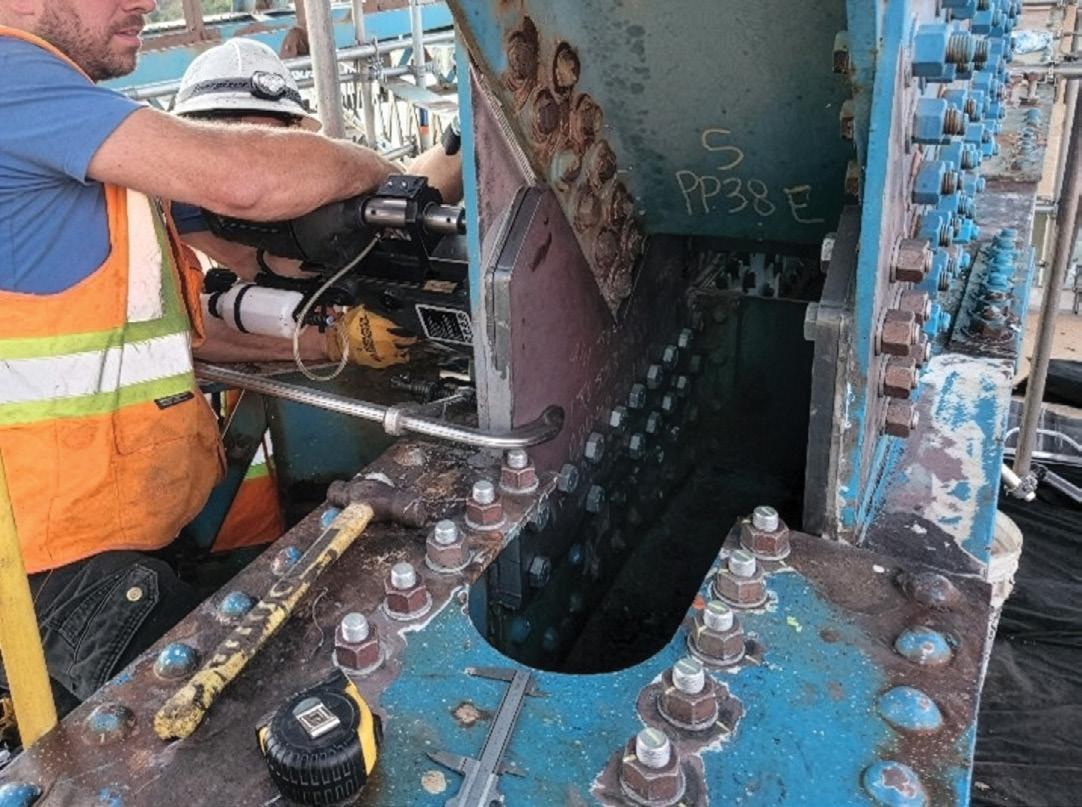

Strengthening

A critical gusset node was identified as being deficient for certain heavy vehicle loads per the previously described evaluation process. The gusset plates on this node exhibited up to 50% section loss at the interface with the bottom chord, with the averaged section loss along the shear planes and Whitmore compression plane described previously being on the order of 35%. To address the deficiency, the OE developed a design for a strengthening scheme involving the installation of doubler plates on the inside faces of the corroded gussets.

The doubler plates were shaped to fit around the vertical and diagonal members framing in. The lower half of the doubler plates were bolted to the lower (uncorroded) part of the gusset plate and bottom chord web through existing bolt holes. New bolt holes were field drilled to connect the upper half of the doubler plates to the upper (corroded) part of the gusset plate. Refer to Figure 7 for an overview of this strengthening scheme. This process was repeated for all four

quadrants of the node.

Since the bridge is an essential crossing for local residents and industry and available detour routes are long and, in some cases, not suitable for heavy truck traffic, the bridge had to remain open to single-lane alternating traffic at nights and fully open to traffic during days for the duration of the gusset strengthening work. Works were completed at night and the node was checked to ensure adequate load carrying capacity for the applicable traffic loads at all stages of construction.

To maintain load capacity during installation of the doubler plates, the existing bolts between gusset plate and bottom chord web were replaced with tight-fit drift pins one-by-one (Fig. 8). The drift pins acted to transfer shear in bearing, with each drift pin having a shear capacity that exceeded the existing rivets/bolts they replaced. The corroded region was then filled with an epoxy-based composite material for metal repair, to fill the void that would otherwise have existed between the existing gusset and doubler plate due to the section loss (Fig. 9). A high-strength epoxy material was chosen in order to provide

Fig. 5. An isometric view of the FE model showis modelling of the corroded region.

Fig. 6. As seen in the Von Mises stress distribution, critical stresses occur in the gusset plates under the compression diagonal.

Fig. 7. New bolt holes are field drilled through upper existing gusset and doubler plate. A new inner plate is also installed, and new bolts are added to the lower doubler plate through existing holes in the chord web and lower gusset.

a flush solid surface that would not crush under the application of bolt tensioning loads between the existing gusset and new doubler plate. The doubler plate was then put into position by sliding it over the drift pins (Fig. 10). The drift pins were then replaced one-by-one with new bolts, and the process was completed by the field drilling of new holes and installing bolts from the upper existing gusset to the doubler plate. Shear load transfer between the existing gusset plate and the chord web was maintained throughout the duration of the works. The tight fit of the drift pins prevented them from shifting under vibrations due to the live traffic on the bridge during the strengthening works.

Many other gusset nodes that were identified as having significant section loss but not assessed as being deficient for heavy truck loads are currently in the process of being recoated on a staged basis. Future corrosion rates were approximated based on the measured section loss and estimated number of years in which corrosion has been occurring. These rates were used to forecast which gussets may potentially become deficient over a 10-year period of ongoing corrosion. Gussets not meeting this criteria were chosen for inclusion in the recoating program.

Conclusion

Corrosion along the interface between gusset plates and truss bottom chords is a common occurrence on older steel truss bridges. The inspection, evaluation, and strengthening procedures described here may have relevance for owners and consultants working on other truss bridges exhibiting similar defects.

The analysis performed for the capacity assessment of the gusset plates demonstrated that the AASHTO MBE approach produced reasonable results in this particular case. However, verification of the AASHTO methodology using the FE analysis was deemed necessary due to the eccentricity of the corrosion profile of the gusset plates which resulted in significant eccentric out-of-plane loading on the gussets at critical locations. The dual-method approach of code-based evaluation and FE verification increased confidence in the ability to accurately identify the severity of localized corrosion that warranted gusset strengthening and/or short-term recoating. This approach proved to be valuable to accurately determine which of the Taylor Bridge gusset plates required strengthening to maintain functionality

of this vital bridge in northern British Columbia. The strengthening method used enabled the works to be carried out at night during single-lane alternating traffic, without significantly impacting the traveling public. ■

Full references are included in the online version of the article at STRUCTUREmag.org

Dusan Radojevic has 30 years of structural engineering experience working on complex infrastructure projects, including 25 years working on long-span bridge structures. Radojevic holds a PhD in structural engineering from the University of Belgrade and currently serves as the Bridge Sector Manager for Canada at TYLin.

Kai Marder has over 10 years of experience in structural engineering, with wide-ranging project experience from conventional girder bridges to longspan suspension and cable-stayed bridges. Marder holds a PhD in structural engineering from the University of Auckland and is currently a Lead Bridge Engineer with TYLin’s Vancouver, Canada office.

Fig. 8. The existing gusset plate with corrosion removed and first row of drift pins installed.

Fig. 9. All drift pins are installed and epoxy filler material applied.

Fig. 10. New doubler plate is installed and drift pins are being replaced with bolts one-by-one.

Resources Renewed

A 2015 assessment declared the Resources Building in California the No. 1 State-owned building most in need of repair. After a comprehensive renovation, the 62-year-old structure has turned from relic to radiant.

By Jason Horwedel, SE, DBIA, Matt Williams, SE, and Phil Petermann

Project Team

SEOR: Buehler

Owner: State of California, Department of General Services

Architect(s) of Record: AC

Martin + HGA

General Contractor:

Turner Construction

Specialty Contractor(s):

Taylor Devices, Farrell Design Build

Construction Manager(s):

Gilbane + Cypress CM

Structural software used:

CSI ETABS

Geotechnical Engineer:

Geocon

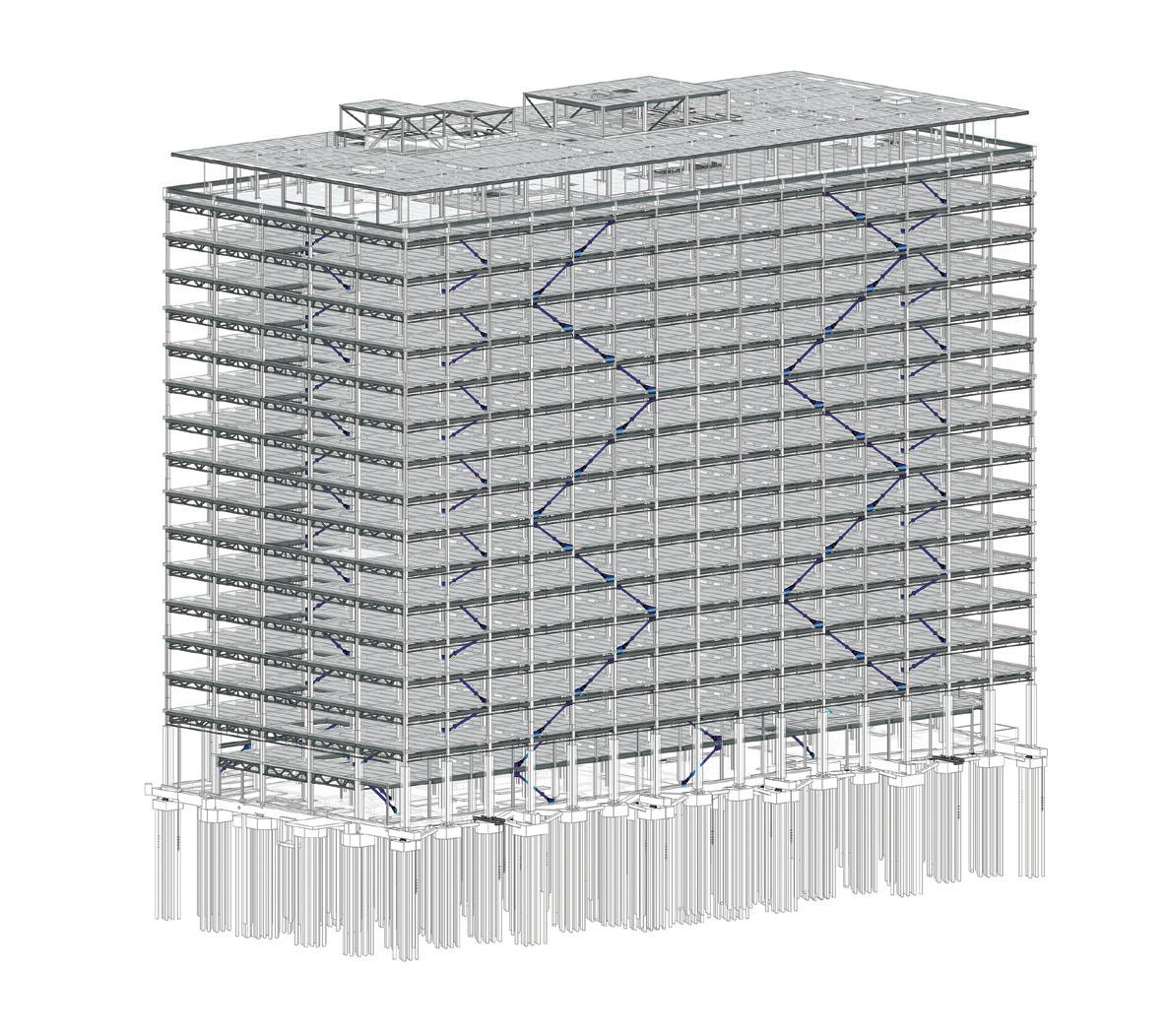

The 17-story Resources Building was a marvel when built. Located just two blocks from the California State Capitol in downtown Sacramento, the building was the fourth largest office space west of Chicago upon completion in 1964. The towering 657,000 sq. ft. workplace got its name from the State of California departments it housed: Forestry and Fire Protection, Parks and Recreation, Natural Resources, and chiefly, Water Resources. In addition to providing office space for 2,000+ employees, the building’s rooftop housed components for the California Public Safety Microwave System—cutting-edge communication technology in the 1960s. Unfortunately, time was not kind to Sacramento’s once-tallest building. A 2014 study by the California Department of General Services (DGS) identified several seismic deficiencies and the absence of modern high-rise fire and life-safety elements, putting the building’s occupants at “high risk” should an earthquake, fire, or any other emergency event occur. The following year, a statewide property assessment deemed it the State-owned building most in need of repair and identified numerous additional issues: A “spongy” roof susceptible to leaks. Asbestos in the floor, ceiling, and insulation. Electrical breakers with a history of safety problems. Lead paint. Windows that hadn’t been washed in 10 years due to a broken crane. An inadequate fire sprinkler system. In total, the 2015 assessment estimated $149M in repairs were needed within the next 12 months.

Given the litany of issues and high repair cost, questions surrounding whether it would be better to completely demolish the building and construct one anew naturally arose. However, the building was considered historic on the basis of age. Furthermore, the project Environmental Impact Report noted a significant prehistoric archeological resource was previously uncovered in the area adjacent to the Resources Building, and earthwork activities associated with replacing the structure were deemed a greater risk of destroying potentially undiscovered resources. Lastly, the location’s proximity to the State capitol meant that new construction would have to adhere to current zoning height restrictions, which would have greatly reduced a new building’s square footage. All issues considered collectively, the decision to renovate the existing building was solidified. The Resources Building is 300 feet long by 130 feet wide with an overall height of 232 feet. Typical grid dimensions are smaller than one might expect: 20 feet by 26 feet. Story heights between floors are generally 13 feet, 4 inches. The structural frame consists of 1960sera steel construction and includes concrete fill over shallow metal deck spanning to wide-flange beams, girders, and columns employing bolted double-angle shear and bearing connections and bolted column splices throughout the building. Steel truss moment frames comprise the lateral force-resisting system with double-angles forming the top and bottom chords and the diagonal web members. The truss moment frames are typically constructed with shop-welded

Photo credit: James Ewing/JBSA

connections between the webs and chords and with field-bolted connections of the last double angle to the gusset plates at the columns.

DGS has significant experience procuring projects using DesignBuild contracts for new construction, but less experience with the same procurement method for renovation projects. Despite this lack of experience, DGS leadership realized an existing building renovation of this magnitude needed a delivery method with more flexibility to account for the many unforeseen conditions that would likely occur throughout the life of the project. As a result, the State selected Progressive DesignBuild for their delivery method to allow greater design development and extensive site exploration to minimize risk and improve the certainty of the Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP).

Project Goals

The main objective of the project was to extend the useful life and viability of the building and provide a modern, efficient, and safe environment for State employees and the public they serve. This meant removing and abating hazardous materials, correcting seismic and fire/life-safety deficiencies, and upgrading all infrastructure systems,

Partial demolition of perimeter walls—building with precast concrete panels removed from upper floors and dampers installed. (Photo Credit: Nathan Canney/Taylor Devices)

Revit model with damper configuration shown in blue.

including MEP, HVAC, telecommunications, and security. All building envelope elements, including the roof, windows, and exterior precast panels, were to be removed and replaced. Additionally, three 17-story exit stair cores were to be reconstructed.

Achieving these goals meant stripping the building down to its structural frame. Due to the historic status of the building, the renovation plan and all other proposed changes were reviewed by the State’s historic preservation officer, who was also charged with ensuring the new design respected the International Style expressed in the original design as well as the equally historic Leland Stanford Mansion located nearby across the alley.

Investigation and Testing

Many means and methods of the original design and construction were known at the start of the project, but still a great many remained unknown. Drawings used to validate the project were incomplete, so the Buehler team scoured the DGS plan room for two days, uncovering additional drawings for the entire team to use.