STRUCTURE

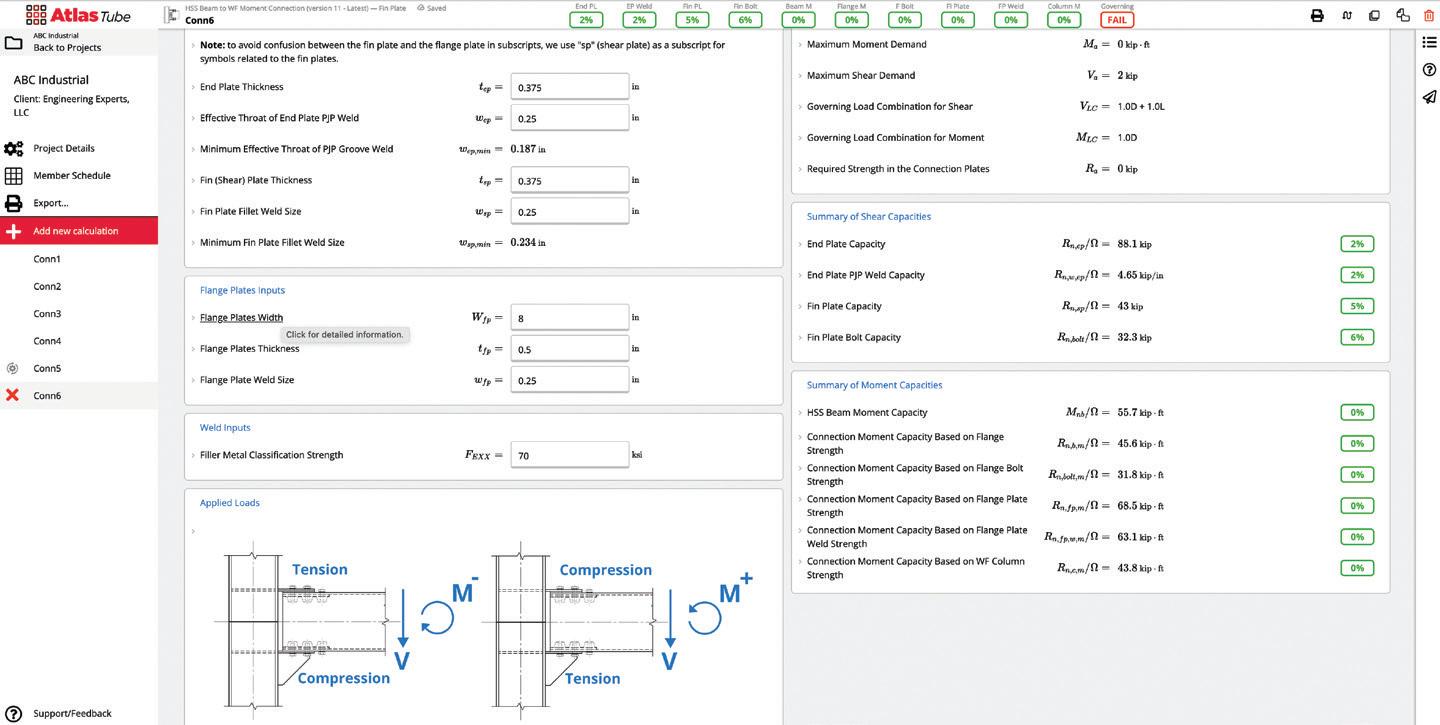

Complimentary tools and expert support for engineers, fabricators and detailers looking to better leverage the advantages of HSS.

Complimentary tools and expert support for engineers, fabricators and detailers looking to better leverage the advantages of HSS.

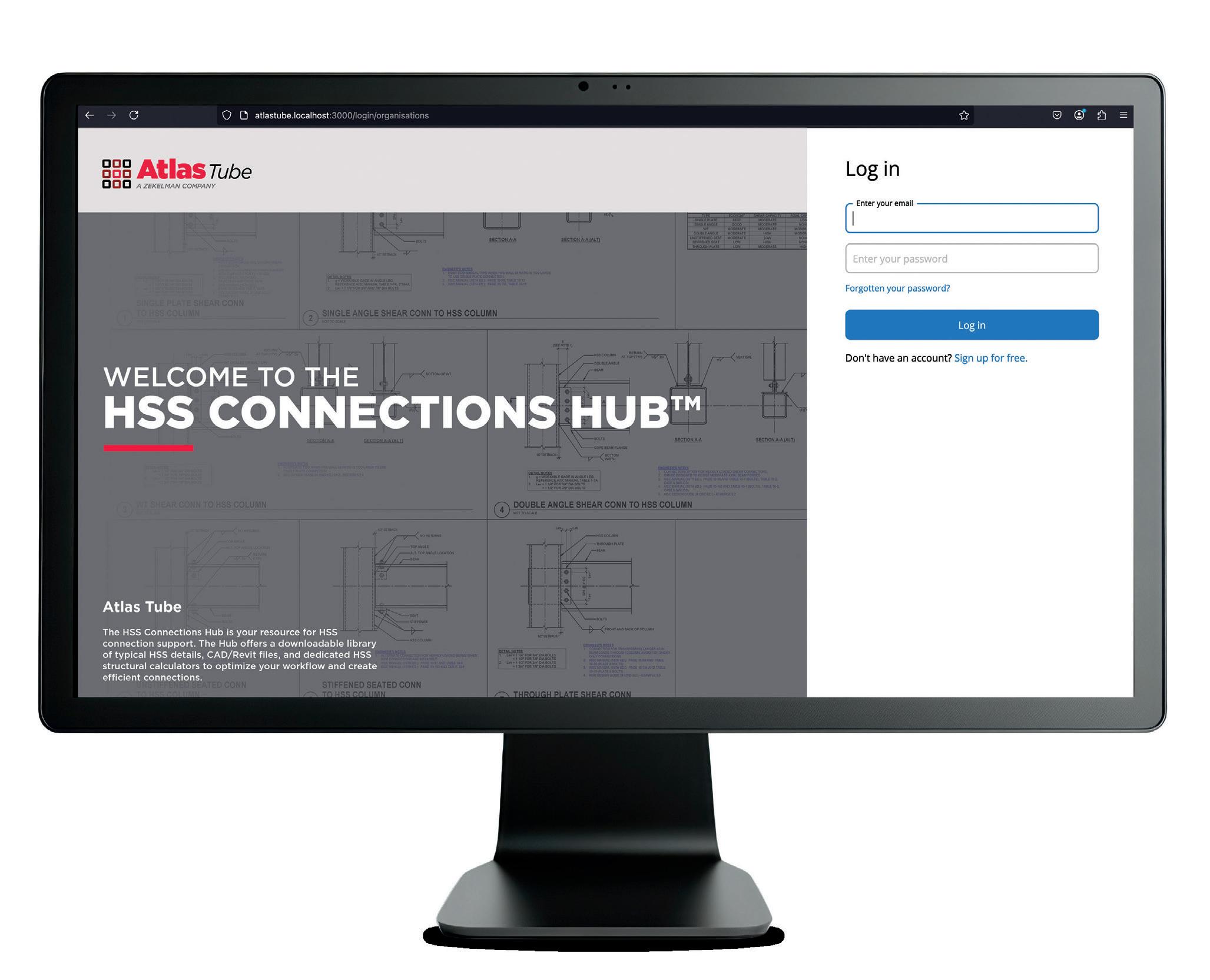

Simplify your HSS Connections today.

with the HSS Connections Hub™

This invaluable — soon-to-be indispensable — and complimentary online resource will save design time by eliminating the need for developing and maintaining custom spreadsheets. Fabrication-friendly typical HSS details are an excellent starting point for design while corresponding calculators enable design completion.

Teams can streamline the design process and enhance collaboration directly on the HSS Connections Hub. Engineers can quickly create HSS connection calculations based on the most recent design manual and specific code requirements. Fabricators will receive connection designs that meet requirements and are fabrication-friendly, eliminating back-and-forth revisions.

Since September, we’ve doubled the number of connection types and typical details available in the HSS Connections Hub to over 70. See what’s new:

• HSS Baseplate Connection

• TKYX (Shear) Y with Rectangle HSS

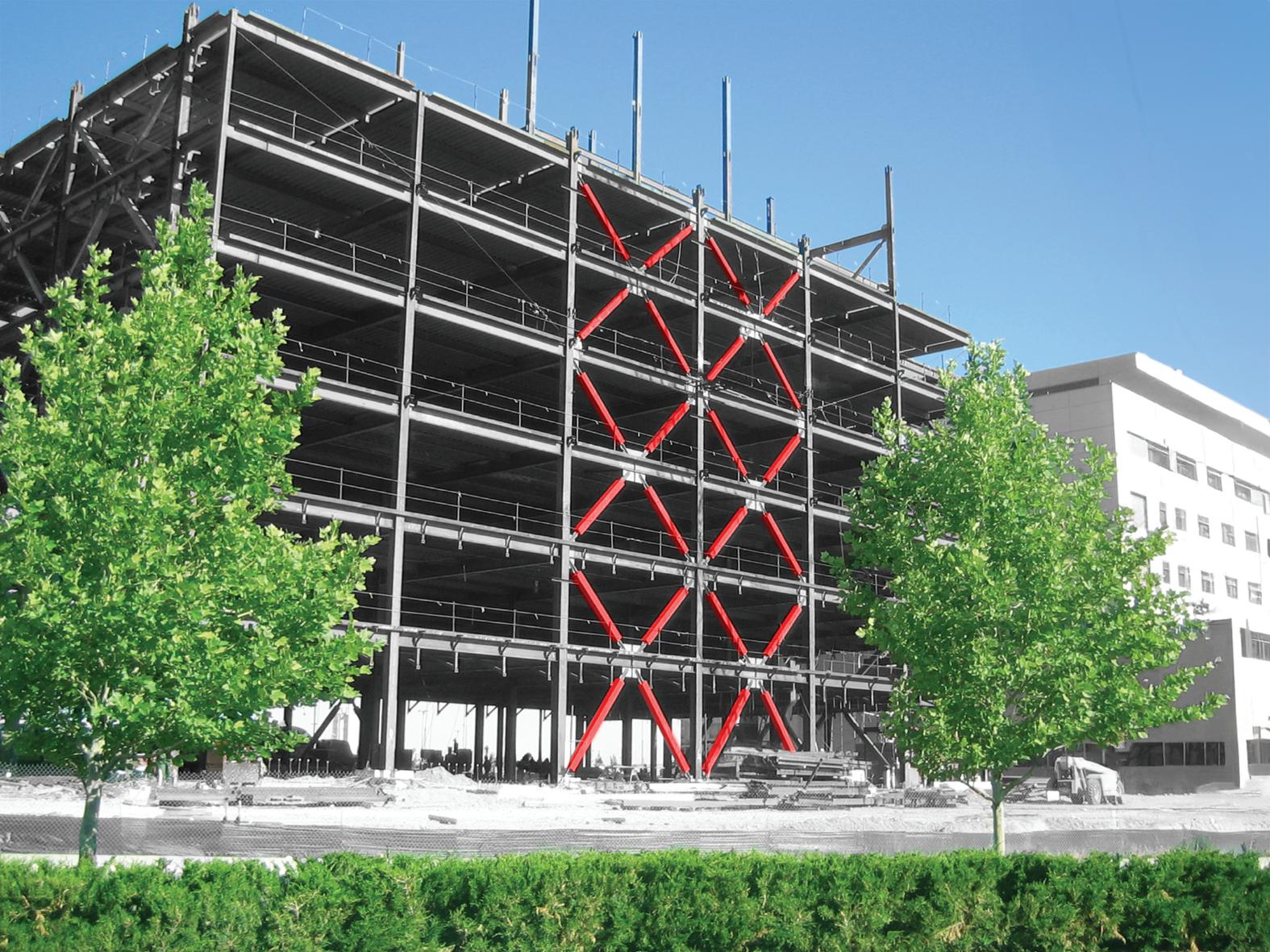

• Bracing to Column: Field-welded

• Bracing to Column: Bolted

• Bracing to Column: 2 Sides

• Bracing to Column: 4 Sides

• TKYX (Shear) Cross Connection with Rectangle HSS

• TKYX (Shear) Overlapped KT Connection with Square HSS

• TKYX (Shear) Gapped K with Square HSS

• TKYX (Moment) Vierendeel Connection with Square HSS, In-plane Bending

• TKYX (Moment) T Connection with Rectangle HSS, Out-of-plane Bending

• TKYX (Moment) Cross Connection with Rectangle HSS, Out-of-plane Bending

• HSS to WF Shear End Plate to WF Web

• WF to HSS Shear-stiffened Seat

• WF on top of HSS Post Bearing (Simple Beam)

• HSS to HSS Moment End Plate (Concrete Filled)

• WF to HSS Moment End Plate

• WF to HSS Moment End Plate (Concrete Filled)

• WF to HSS Moment Diaphragm II

• HSS to HSS Splice End Plates

• HSS to HSS Splice with Rectangular Sections

• Round HSS End Plate Splices

• Round HSS to HSS Moment Seated

• ...and more!

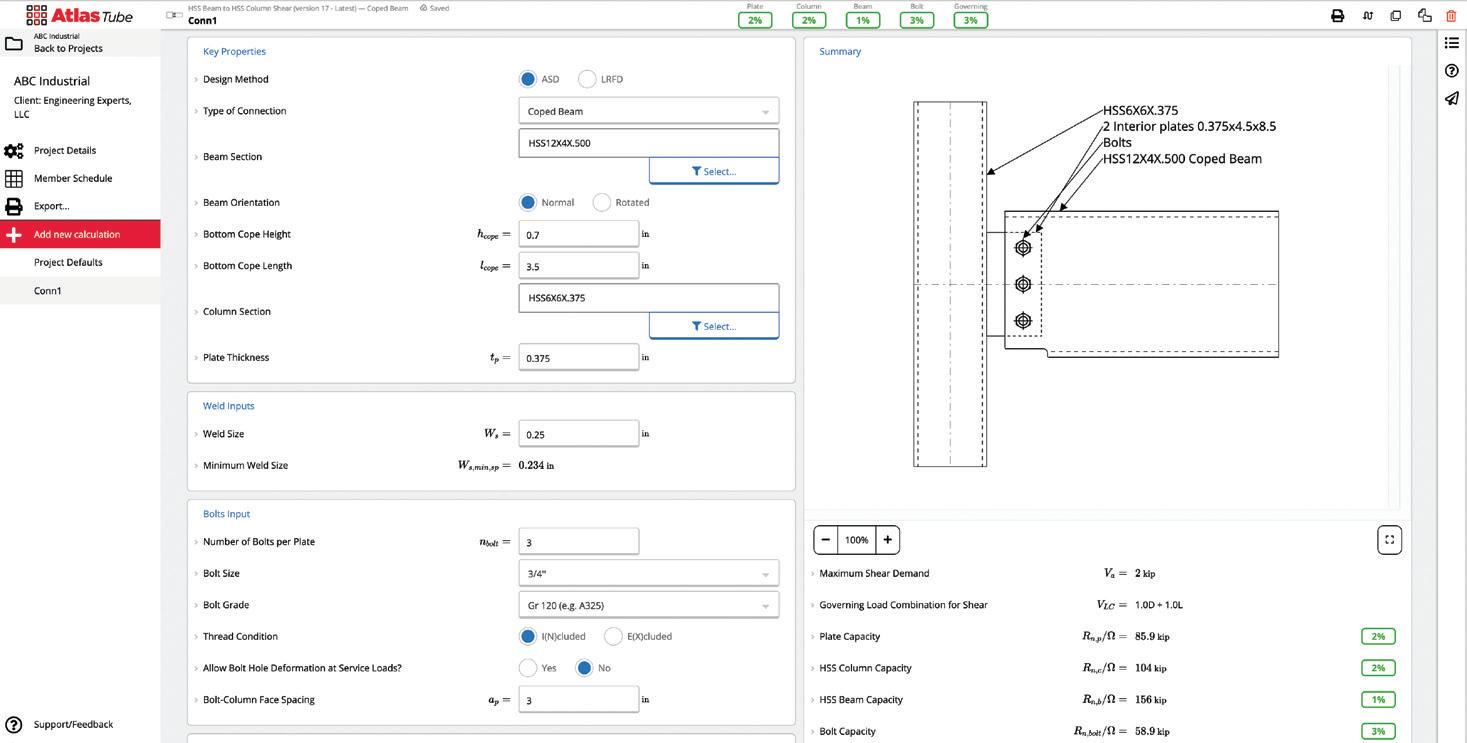

• Access a growing library of HSS connection calculators and fabrication-friendly typical HSS details, each available with a wide range of options.

• Hub calculators automate and confirm connection designs in real-time based on the AISC Steel Construction Manual, 16th edition.

• Clear and concise results indicate whether the designed connection is efficient and it meets specified requirements.

• Full transparency: Review and verify your calculations against specific code references with a simple click.

• Download or share detailed connection drawings, including dimensions, bolt sizes and other relevant information for easy communication with fabricators.

• Request support from Atlas Tube’s engineering experts on your project.

Sign up today and start using the HSS Connections Hub.

connectionshub.atlastube.com

Watch the how-to video.

Rhino-Dek® polymer-laminated bridge deck forming systems

Aggressive environments are no match for the corrosion-resistant protection of Rhino-Dek ®. Easily installed stay-in-place bridge deck forms support new bridge construction and rehabilitation.

• Service life up to 124 years

• DOT tested and approved in many states

• Custom-color coating options for enhanced aesthetics

• 5 profiles for spans up to 14 feet

Build bridges that last. Go to: newmill.com

Available Only at STRUCTUREmag.org

Publication of any article, image, or advertisement in STRUCTURE® magazine does not constitute endorsement by NCSEA, CASE, SEI, the Publisher, or the Editorial Board. Authors, contributors, and advertisers retain sole responsibility for the content of their submissions. STRUCTURE magazine is not a peer-reviewed publication. Readers are encouraged to do their due diligence through personal research on topics.

subscriptions@structuremag.org

Chair John A. Dal Pino, S.E. Claremont Engineers Inc., Oakland, CA chair@STRUCTUREmag.org

Kevin Adamson, PE Structural Focus, Gardena, CA

Marshall Carman, PE, SE Schaefer, Cincinnati, Ohio

Erin Conaway, PE AISC, Littleton, CO

Sarah Evans, PE Walter P Moore, Houston, TX

Linda M. Kaplan, PE Pennoni, Pittsburgh, PA

Nicholas Lang, PE Vice President Engineering & Advocacy, Masonry Concrete Masonry and Hardscapes Association (CMHA)

Jessica Mandrick, PE, SE, LEED AP Gilsanz Murray Steficek, LLP, New York, NY

Brian W. Miller Cast Connex Corporation, Davis, CA

Evans Mountzouris, PE Retired, Milford, CT

Kenneth Ogorzalek, PE, SE KPFF Consulting Engineers, San Francisco, CA (WI)

John “Buddy” Showalter, PE International Code Council, Washington, DC

Eytan Solomon, PE, LEED AP Silman, New York, NY

Executive Editor Alfred Spada aspada@ncsea.com

Managing Editor Shannon Wetzel swetzel@structuremag.org

Production production@structuremag.org

Director for Sales, Marketing & Business Development

Monica Shripka Tel: 773-974-6561 monica.shripka@STRUCTUREmag.org

Sales Manager

Audrey Schmook Tel: 312-649-4600 Ext. 213 aschmook@ncsea.com

By Devin Bowman

When an elevator design includes glass curtain walls or other glazing assemblies, project teams can utilize steel sub-frames to meet both fire-rated as well as dynamic and static load requirements.

By Filippo Masetti, PE, David Ribbans, PE, Lauren Feinstein, PE, and Kevin Poulin, PE

The Frick Collection recently reopened after a years-long renovation to the century-old museum. Simpson Gumpertz & Heger was tasked with engineer ing the unique solutions that addressed the archaic systems and complex structural limitations of this historic landmark.

By Michael Lynch, PE, SE, and Jimmy Liang, PE

Bethany Senior Terraces offers a compelling example of how structural engineering can drive innovation across disciplines, from modular logistics to high-performance building design.

By Sarah Outzen, PE, Clyde Ellis, and Jesse Davis

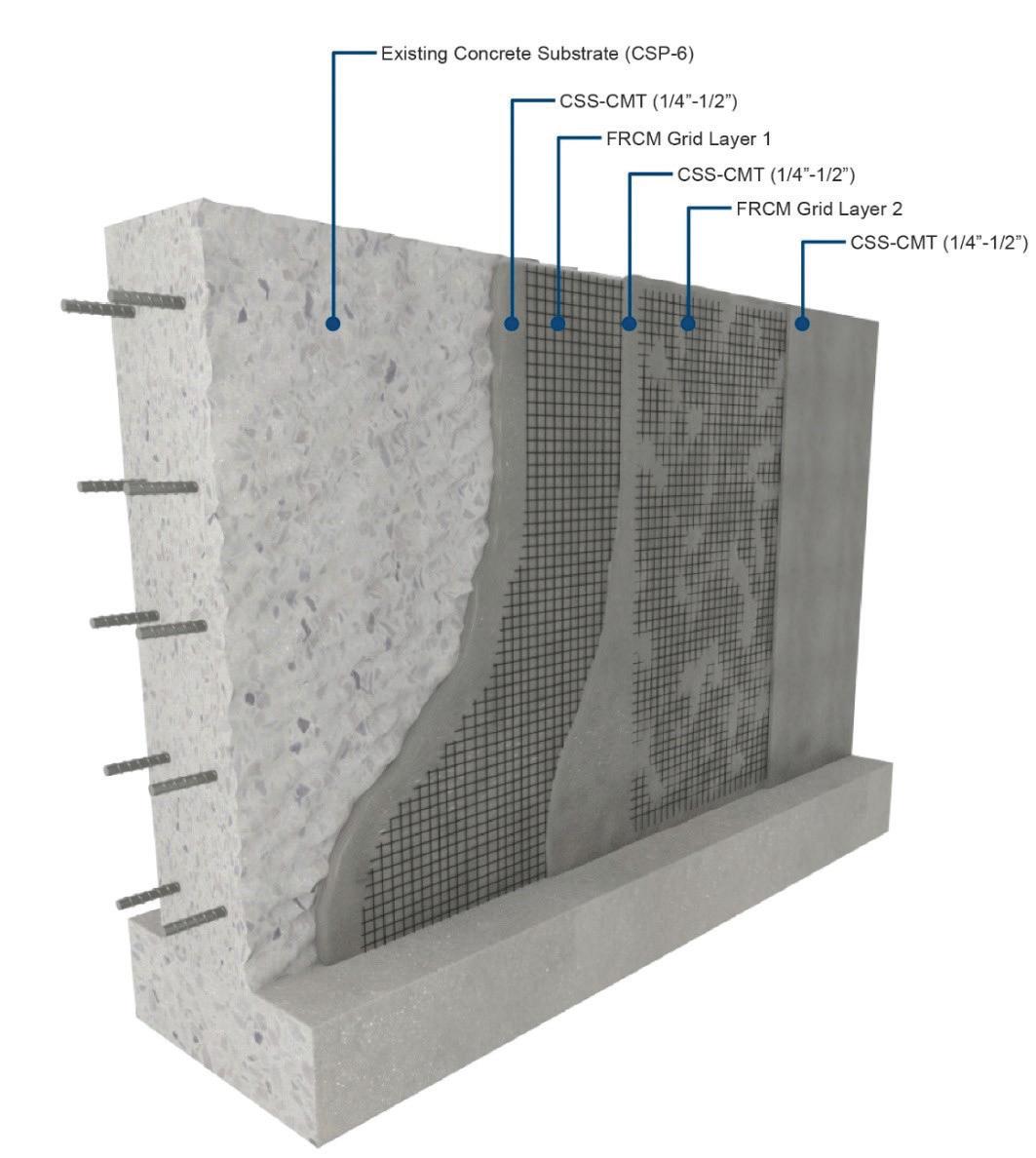

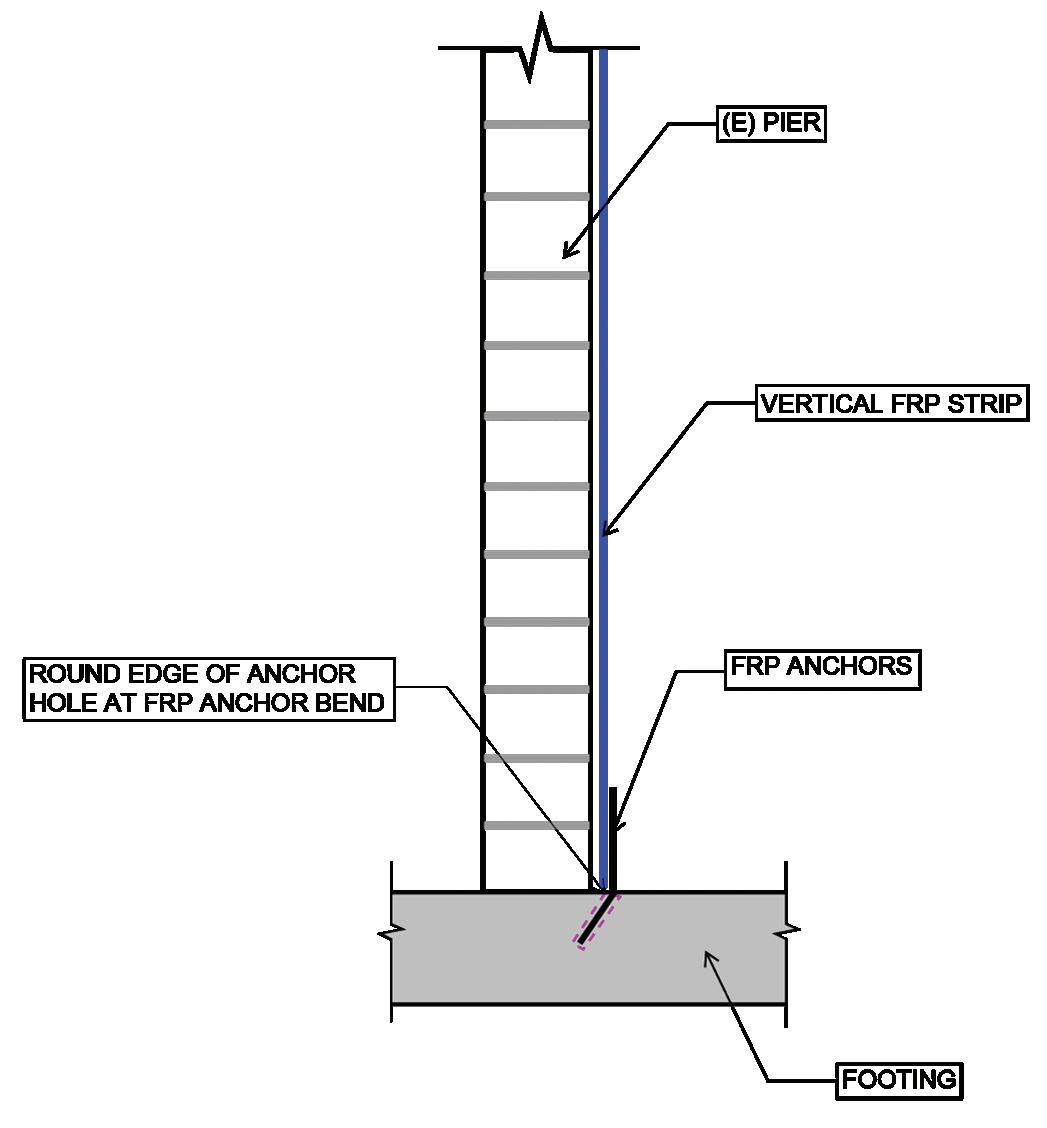

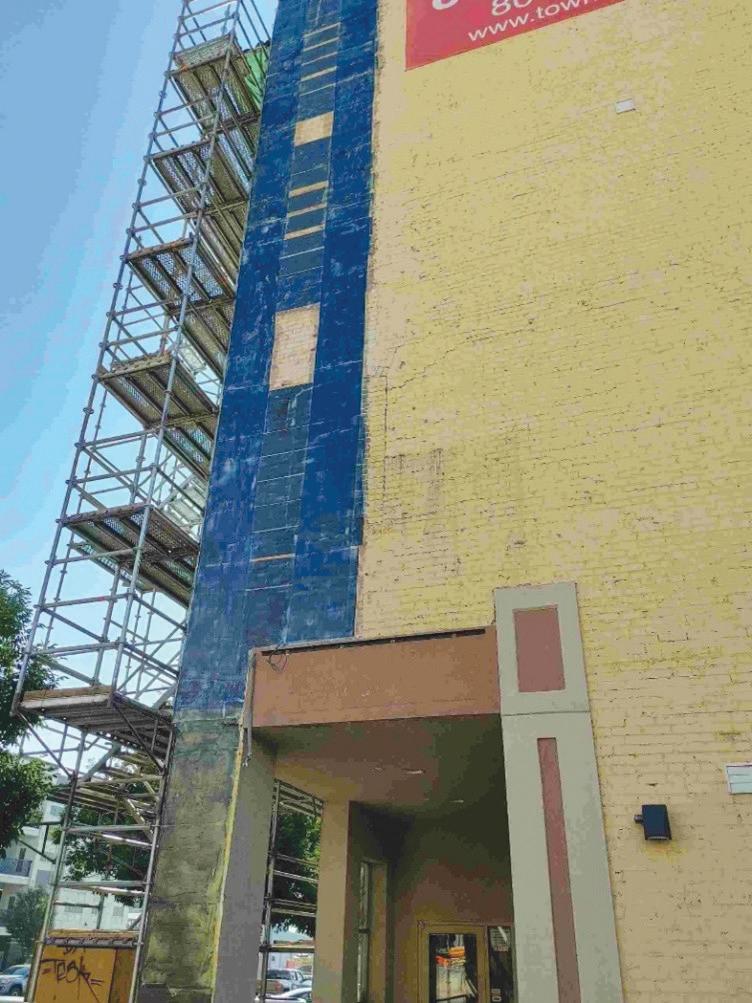

When a 2020 earthquake compromised the historic Towne Storage Gateway building in Salt Lake City, engineers faced the challenge of reinforcing its unreinforced masonry facade while maintaining its original architectural character. Through an advanced combination of retrofit techniques using FRCM and FRP, the team delivered a seismic upgrade that enhances structural integrity while preserving the building’s historic character.

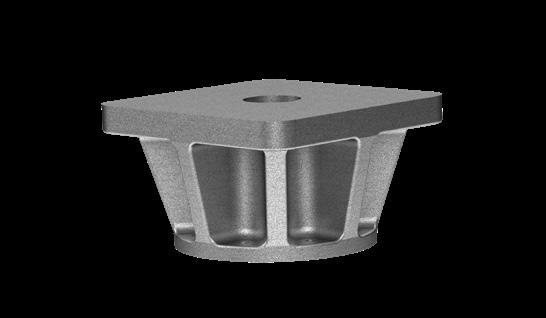

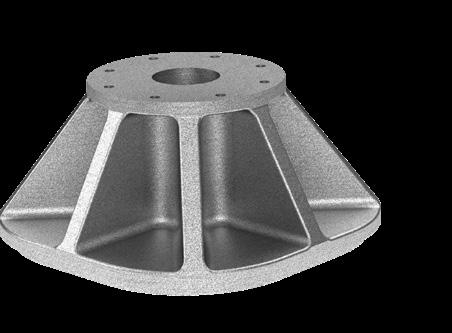

CAST CONNEX ® custom steel castings allow for projects previously unachievable by conventional fabrication methods.

Freeform castings allow for flexible building and bridge geometry, enabling architects and engineers to realize their design ambitions.

Innovative steel castings reduce construction time and costs, and provide enhanced connection strength, ductility, and fatigue resistance.

Custom Cast Solutions simplify complex and repetitive connections and are ideal for architecturally exposed applications.

ST LAWRENCE MARKET NORTH, TORONTO

Architects: RSHP | Adamson Associates

Structural Engineers: Entuitive

Steel Fabricator: Steel 2000 Inc

Steel Erector: E.S. Fox

Photography by Karl Hipolito

By Anthony LoCicero, PE

My one-year term as Chair of CASE started in May at the ACEC Spring Convention in Washington DC. Now halfway through my term, I have had a lot of time to dwell on the challenges facing our profession. While my nomination and election was not exactly contested, here is a brief version of what my campaign platform would have been had I needed one.

Issues surrounding the rollout of the new Computer Based Test (CBT) PE Structural Exam, needed for SE licensure, have been documented within these pages, such as here (https://www.structuremag.org/article/ what-in-the-world-is-going-on-with-the-newcomputer-based-structural-exam/) and here (https://www.structuremag.org/article/ big-changes-in-se-exam-are-a-big-concern/), NCEES needs to communicate more openly with the professional community and work with organizations like CASE, SEI, and NCSEA to review the data and address unintended impacts. Upholding high standards also means being accountable and transparent about how those standards are measured. While I am hopeful that the changes they plan to implement in the spring of 2026 will allow for increased pass rates, only time will tell if they are impactful enough. In the meantime, readers are encouraged to reach out to their state licensing board to voice their opinions. Share your perspective, lend your expertise, and take part in the discussions ahead. With the licensing boards engaged, we are more likely to see the impactful changes that our profession needs.

The structural engineering sector is confronting a significant workforce challenge that threatens both productivity and innovation. For example, the ASCE reports that the U.S. needs approximately 25,000 new civil engineers each year just to replace retirees—and this figure does not fully account for the surge in demand from major infrastructure initiatives. Meanwhile, the broader engineering-workforce outlook shows demand for engineering skills is projected to grow by about 13% from 2023 to 2031, with an estimated 186,000 openings per year in architecture and engineering occupations combined. Many experienced professionals are nearing retirement, creating a widening skills gap that younger engineers are not filling quickly enough; in 2023 only 298

bachelor’s degrees were awarded in structural engineering specifically. These combined factors—accelerating demand, a limited influx of new entrants, and an aging workforce—result in firms turning away work, increasing project delays, and elevating pressure on existing staff. To help combat these issues, our senior leaders must foster growth in our next generation. We can do this by actively engaging in knowledge sharing, whether through professional associations, conferences, or online platforms and serving as stewards of our profession.

While climate change is a charged topic these days, there is no doubt that it is impacting our practices and elevating our risk. As an example, the court in Conservation Law Foundation v. ExxonMobil Corp. stated “… ‘good engineering practices’ include consideration of foreseeable severe weather events, including any caused by alleged climate change.” How are practicing engineers to design to this stan-

Ultimately, the future of the profession lies in expanding beyond the technical to embrace leadership, advocacy, and creativity.

dard? Historically, we have relied on codes to prescribe the requirements of a given design. Because many codes are based on past data rather than future projections, an engineer who designs only to meet code may not be designing to what some clients, regulators, or courts might consider reasonable best practice under changed climate conditions. (I am confident that our colleagues at ASCE and other code making bodies are studying recent events, but surely they do not have a crystal ball.) In response to this growing risk, engineers should collaborate with legal counsel and insurers to update contracts, explicitly defining how climate-related risks are considered, allocated, or disclosed to clients. Professional associations can strengthen the industry’s position by developing guidance, training, and model language to help practitioners align with the evolving standard of care. At the individual level, engineers must stay current with climate science, code development, and liability trends,

treating continuing education on resilience and sustainability as essential—not optional. Our industry is also facing other legal chal lenges from courts and politicians alike. For example, in my home state of Pennsylvania, the state Supreme Court is currently hearing an appeal in Clearfield County v. TransSystems et al. which could have significant impacts on the Statue of Repose. The County (Clearfield County) filed a civil complaint in January 2023 against the architect (and structural engineering successors) and contractors involved in the construction of its county jail alleging a construction defect: specifically that a required bond-beam under the roof deck was missing, which became evident during a 2021 renovation and cost the County an additional ~$4 million. The trial court ruled that the County’s action is time-barred by the Pennsylvania statute of repose (12 years) because the original construction was completed in 1981 and the lawsuit was filed 42 years later. The county’s attorney raised a pretty obscure legal provision called nullum tempus, essentially claiming that, since the project is considered a public work, no expiration on the claim should apply. While many practitioners in Pennsylvania are watching this case closely, all practicing engineers need to be watchful for similarly challenging litigation and legislative activity in the jurisdictions where they work.

The structural engineering profession stands at a pivotal moment. Licensure difficulties, workforce development, climate change, and a shifting legal environment each represent profound challenges.

Ultimately, the future of the profession lies in expanding beyond the technical to embrace leadership, advocacy, and creativity. Structural engineers are not just builders of towers and bridges; we are custodians of public safety, sustainability, and resilience. By confronting these critical issues head-on, the profession can continue to provide the backbone of a thriving and sustainable built environment. ■

Component analysis & design

Code updates

Yes - over 50 modules for wood, steel, concrete and masonry components

We find them, we update them

Professional output with graphics, consistent module-to-module output

Low — user-friendly tabular inputs and Help Manual documentation with explanations for the underlying assumptions and code provisions

Industry-standard trusted by 65,000 engineers

No — you create manual calculations from a blank spreadsheet YOU DO IT ALL to every spreadsheet

Manual formatting needed

Higher — reliant on manual formulas, no built-in validation tools, user-dependent accuracy

Varies — generally accepted with rigorous set-up, but not a dedicated structural engineering tool

Veronica Cedillos is an engineer and the President & CEO of GeoHazards International (www.geohaz.org) based out of Pleasanton, California. Veronica earned her Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering at MIT and her Master of Science in Civil Engineering at Stanford. Her career spans roles in practice as a building engineer, and non-profit work at Engineers for a Sustainable World, GeoHazards International, and the Applied Technology Council. She was the 2025 Shah Distinguished Lecture recipient, a 2017 Housner Fellow, the 2011 Shah Family Innovation Prize recipient, and a 2010 ASCE New Faces of Engineering awardee. She can be reached at cedillos@geohaz.org.

STRUCTURE: Can you please explain the term Geohazard, what hazards it encompasses, and how it relates to your work?

Veronica Cedillos: Geohazards pertain to natural geological processes or events that can result in disasters and include earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides, and tsunamis.

I work on disaster risk, which is the intersection of natural hazards (e.g., earthquakes), exposure to such hazards (e.g., built infrastructure and people living in harm’s way), and vulnerability (e.g., buildings that are not designed to withstand earthquakes). I have dedicated most of my career to working in places with a high disaster risk, meaning they have a high likelihood of hazard events, high exposure, and high vulnerability. These are the places that are most likely to suffer severe damage and losses from future disasters.

STRUCTURE: As a leader in the non-profit sector, can you tell us a little more about GeoHazards International and your current projects?

Cedillos: GeoHazards International (GHI) is a small, global non-profit with the mission of saving lives by empowering at-risk communities worldwide to build resilience ahead of disasters and climate impacts. We work before disasters to help protect people and communities from harm. This is important as the vast majority of funding for disasters (about 96%) comes post-event, after irrecoverable harm and loss has already occurred. We focus our efforts in areas that have a high fatality risk from disasters, may not be aware of their risk, and have limited technical and financial resources to reduce their risk.

Our approach emphasizes equipping local leaders, professionals, as well as the broader community with knowledge and skills to take efforts into the future. This is fundamental, as building disaster resilience requires long-term efforts, not just a one-off project.

Current initiatives include: (1) technical assistance for national leaders in Bhutan on planning for earthquake resilience in their capital city of Thimphu where there are many vulnerable buildings; (2) a recentlylaunched project focused on improving the disaster resilience of health infrastructure in Haiti in order to support continuous delivery of medical care during and after emergencies and hazard events; (3) a program in the Philippines that integrates nature-based solutions, particularly mangroves, as a way to reduce risk from tsunamis and other coastal hazards; and (4) a multi-faceted program in Nepal focused on protecting the lives of schoolchildren in vulnerable, collapse-prone school buildings. This multi-faceted program includes training local builders and/or engineers on seismic vulnerability assessments and earthquake-resistant

techniques for new construction and retrofit, as well as training local manufacturers to produce Earthquake Desks, which are specifically designed to protect schoolchildren from falling debris during earthquake shaking. Earthquake Desks provide a valuable, interim solution until schools are made safer, which will take decades given the vast number of vulnerable school buildings in Nepal.

STRUCTURE: What or who encouraged you to seek a career in structural engineering?

Cedillos: I think structural engineering is an amazing field. We design and build bridges, buildings, and critical infrastructure that provide essential services and value to people and communities. Its roots in service to humanity attracted me to this field. My father is a civil engineer, and I was always intrigued by his work. I was first exposed to earthquake engineering and earthquake-resistant design during my master’s degree, which fascinated me as I realized this technical knowledge could save people’s lives.

STRUCTURE: You worked in practice before moving to nonprofits. What did you learn there or who did you meet then that proved useful later? How can engineering practice and non-profits better engage?

Cedillos: I worked as an Engineer at Gilsanz Murray Steficek (GMS) in New York City prior to my master’s degree and my work with nonprofits. I found that experience incredibly valuable as it grounded my knowledge in practice. It was wonderful to reconnect, years later, with my former boss at GMS, Ramon Gilsanz. He was engaged as a board member at the non-profit, the Applied Technology Council (ATC), where I also worked. Ramon now also sits on our (GHI) Board of Trustees.

Several engineering firms have provided probono support to GHI over the years, in addition to corporate sponsorship. I find our engineers value these opportunities to apply their skills to benefit at-risk communities because they inherently understand why this work is important. A challenge is ensuring that the pro-bono support includes financial backing for our team to coordinate and ensure that the technical support is impactful for the communities we are serving. This is not trivial and can require significant effort on our end. I hope we have more opportunities to engage with engineering firms in the future.

STRUCTURE: In practice, projects are typically funded by owners. How are projects funded at GeoHazards International? What are the greatest impacts to funding?

Cedillos: Our funding is typically from funding agencies, corporations, family foundations, and individual donations. Flexible funding—which typically comes from corporate sponsorships, family foundations, or individual donations—is my favorite. This is because we can have more control over how we design and implement projects. This flexibility allows us to adapt to changing contexts, and more effectively address evolving needs on the ground. A major challenge of funding our work is that we work pre-disaster. The majority of worldwide funding for disasters is focused after events (e.g., disaster response, recovery, and reconstruction). Of course these are critical, but if we ever hope to see a different outcome from natural hazard events, we need to start investing more in resilience efforts in advance. Mitigation and preparedness efforts are the most effective way to save lives and protect communities, and are cost effective (studies show that every dollar invested in advance can save up to $15, or more in some cases, in post-disaster recovery). This is where we focus our efforts.

that consider the local context, gaps, and leverage points. This can be different in varying contexts. For example, we have found that working with the national government in Bhutan is incredibly effective at leading to change in policy and planning. In other countries, we have found that working at the grassroots level is more impactful (e.g., hands-on training for local builders and community-based activities).

We also consider timing. Over the years, we have learned that disasters can encourage communities to take bold steps towards resilience. This increased interest can arise even if a disaster does not directly impact the community, as proximity, cultural relevance, or emotional connections can evoke a sense of urgency. We aim to lead initiatives in at-risk communities during these critical moments, as it can be an effective time for accelerated progress.

STRUCTURE: Much of GeoHazards International work is in developing countries. How is the approach different from engineering in the United States?

Cedillos: I actually think there are more similarities than differences and there’s a lot we can learn from each other. For example, the barriers to integrate disaster resilience in codes and building practices are similar, whether it’s lack of resources, interest, or other more pressing needs. The challenge is in bringing these issues to the forefront. Differential vulnerability and exposure to hazards is also something we see in the U.S. and abroad. Those with fewer resources tend to be most at risk. Many places, including in the U.S., have a large number of existing vulnerable buildings and infrastructure. Specific technical solutions may vary depending on construction types, typical vulnerabilities, and local resources, but effective approaches and strategies to managing disaster risks over time can be similar.

STRUCTURE: There isn’t enough funding to pursue all worthwhile initiatives. How do you select which projects you pursue?

Cedillos: We are a small organization with limited resources, so we seek initiatives that can have the most impact given our strengths and abilities. Our on-the-ground staff are native to the places where we work and are well connected to local decision makers and professionals. They are incredibly valuable in helping us identify high-impact initiatives

STRUCTURE: Of all the initiatives you have been involved in, what has been the most rewarding? Of what are you most proud?

Cedillos: I am very proud of our work in Indonesia on tsunami evacuation. This project focused on providing recommendations to a city of close to a million people that faces extreme risk from tsunamis. Our efforts provided several recommendations, many which were taken up and implemented by local leaders. This included constructing several tsunami vertical evacuation buildings, improving access to high ground, and focusing new development outside the tsunami evacuation zone. I feel incredibly proud to have contributed to those efforts, which will save thousands of lives in a future tsunami.

Overall, I’m also very proud of GHI’s approach, which centers on equipping and empowering local people to drive efforts forward. We see our work as planting seeds, and it’s deeply rewarding to learn, years later, how those seeds continue to bear fruit.

STRUCTURE: What lessons did you learn that were valuable for later?

Cedillos: A key lesson was that local ownership is absolutely key, and with local ownership, it’s important to let go of control. When I was in the middle of the tsunami project I had my own ideas of what success meant and when it had to be done. At first I felt that our efforts were a

failure, mostly because results didn’t happen right away and didn’t turn out exactly as I had envisioned. But with time, I realized that local leaders took up many of the recommendations we had co-developed with our Indonesian colleagues. They didn’t look exactly as planned, but they were even better as they were fully locally owned. This means they are much more likely to continue into the future, which is ultimately what is needed to sustain impact.

STRUCTURE: Your 13 years with GeoHazards International were split up with a 4-year stint at the Applied Technology Council in the middle. What attracted you to the work of ATC? What drew you back to GeoHazards International?

Cedillos: I learned of ATCs work while at GHI when I was working on tsunami vertical evacuation structures. I learned of technical guidelines ATC developed for FEMAon this topic and became very interested in their work. Later I got the opportunity to work for ATC, which was an incredibly valuable experience. I learned a lot about technical practice development, and the progress, as well as remaining challenges, of building disaster resilience in the U.S. My work there made me realize how disaster resilience takes time. It struck me that California, a leader in earthquake resilience, has been working on this topic for a century and we still have work to do. This insight influenced my perspective on how to effectively make a meaningful impact elsewhere – it requires a long-term approach. I was quite happy at ATC, but when I was offered the position to lead GHI, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity.

STRUCTURE: How has your background contributed to where you are today?

Cedillos: I grew up in the border town of El Paso, Texas. I spent a lot

of my childhood visiting family right across the border in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. This experience made me deeply appreciate the importance of opportunity and how it can influence one’s life trajectory. I have felt a deep desire to do meaningful work in my life since I was young. I like structural engineering from an intellectual perspective, so my work with non-profits (both GHI and ATC) has been a perfect intersection of my interests and desire to contribute to a meaningful cause.

STRUCTURE: What is the best advice you’ve been given in your career, or otherwise?

Cedillos: I’ve had so many wonderful mentors along the path of my education and career. I have been lucky, but I have also deeply valued

the people who have been willing to share their wisdom and insights with me. I find that most people are quite generous in sharing if you are authentically interested in their thoughts and advice. I forget who first highlighted the importance of mentors to me, but I continue to apply it in my career (and personal life, for that matter). In fact, one of the things I enjoy most about working at GHI is engaging with board members. GHI’s board is made up of incredibly talented and experienced people from various backgrounds, all who want to help GHI succeed. I have benefitted so much from engaging and learning from them. I feel similar about my global team across 6+ countries. They all bring different perspectives and insights that continue to shape the way I see the world.

STRUCTURE: What is the biggest challenge that GeoHazards International is facing?

Cedillos: GHI, like many others, has been deeply affected by the federal funding cuts this year. Our largest ongoing program, which was funded by USAID, was terminated along with over 80% of USAID’s projects worldwide. This program represented about 1/3 of our annual revenue, involved on-the-ground work in four countries, and consisted of teams totaling 32 people across nine countries.

We are pivoting and adapting, and although our work volume has reduced, our commitment towards our mission has not. We have other ongoing projects across multiple countries, and already had efforts underway to diversify our funding streams. Many people and organizations who believe in our work and our team have also stepped up to help. It is a challenging time, but I’m confident that our resilient, global team will be able to continue our work despite the unprecedented circumstances.

STRUCTURE: What can practicing structural engineers do to help?

Cedillos: Structural engineers play a critical role in ensuring the safety and resilience of our built environment and therefore in protecting people and communities. With increasing disasters, this is all the more important. Structural engineers can advocate for ensuring that disaster resilience is integrated into our industry. Disaster resilience is not achieved in silos, so I encourage structural engineers to learn about other relevant disciplines and learn to communicate effectively to decisionmakers and people who are influential in the industry.

More specific to GHI, structural engineers can follow our work, share it with others who may be interested, and spread the word as to why our programs are important. ■

Proficiency, efficiency, legibility, and continuous improvement are key criteria in measuring whether a quality program is yielding better work.

By Mark Walsh

As architects, designers, and engineers, we believe that Quality Assurance and Quality Control improve the work we do, but how do we really know that’s true? More specifically, how does a firm know if the QMS they have in place is effective, provides value, and improves project outcomes?

The answer to that question comes in three parts. The first is establishing a system of document review that is meaningful, repeatable, and consistent. The second is determining effective metrics to assess deliverable quality in the document review. And the final part is comparing the adoption rates of QA and QC processes with the document review results to determine whether the Quality Program and its components are yielding better work.

The first step in determining the Quality Program’s effectiveness is to establish a document review system that is consistent, repeatable on a regular cycle, and measurable. The system’s components are:

Determine which deliverables will be reviewed.

In the current AEC industry, the most predictable and consistent deliverables are made for the end of the Construction Documents phase, making the contract documents a good choice. Given the sheer volume of information contained in the specifications, reviewing only the drawings is more achievable and better suited to yield broadly actionable results. This also applies to projects that are fast tracked or have multiple bid packages; any drawing set delivered for bidding would be suitable.

Determine how many deliverables will be reviewed.

Reviewing a representative cross-section of the firm’s work helps ensure the process is meaningful and broadly applicable. Being a multi-office firm, the author’s firm decided on a sliding scale between three and six drawing sets, based on office head count. The assumption being that larger offices produce more work so more sets are needed to get a representative sample.

Set parameters for eligible projects.

Depending on the firm’s breadth of work, it may be necessary to establish parameters that help select the most representative

work. That can mean identifying eligible project types or setting upper and lower cost or size limits. To ensure that current practices are being assessed, it is also important to establish a timeframe in which the documents were issued. Because the review is conducted annually, the timeframe is limited to the 12 months prior to the document review.

Determine the project data to be collected.

It can be helpful to collect information on project type, project size, cost, delivery method, and project-specific delivery conditions to add context to review results. For instance, if very large projects consistently score poorly, the firm might be ineffectively staffing or managing these types of projects.

Determine a review frequency.

Review process results are useful in any given cycle, but they are more likely to reveal trends and patterns if they’re gathered regularly. Establish a review frequency to ensure that the process repeats on a regular and predictable basis.

Select reviewers.

Reviewers can influence an evaluation system’s success or failure as much as any other factor. Reviewers need the requisite experience to effectively and efficiently evaluate the drawings, and they should also be open to novel and innovative approaches that can surface during a review process. Another consideration is whether to maintain a consistent reviewer group across cycles, to consistently select new reviewers, or to implement a combination. A consistent reviewer group can help reinforce firm standards and bring consistency to the process but can also be resistant to innovation and potentially institutionalize suboptimal practices. Regular turnover can result in inconsistencies, but it brings a variety of perspectives and approaches and can help encourage new delivery methods. The decision is primarily a matter of firm culture and review process goals.

a scoring system.

After establishing evaluation criteria, it is equally important to create a scoring system to apply them. A system with a large range, say 1-10, allows nuance and flexibility in scoring, but it can also lead to a lack of clarity in the results. Conversely, a small

Change Order (CO): A written agreement to implement changes in a construction project after a contract for construction has been executed.

Contract Documents: A deliverable that describes the work required to complete a building project that is usually delivered at the end of the Construction Documents design phase and typically includes drawings and specifications.

Deliverable: A document, or set of documents, issued by the design team to describe a building project at one of the conventional design phases, Schematic Design, Design Development, or Construction Documents. Deliverable requirements are typically defined for each phase in an architect’s contract.

Document Review: A regularly recurring and firmwide review of Contract Documents that is separate from Quality Control and specifically designed to provide a broad assessment of the firm’s output.

Quality Assurance (QA): The planned and systematic set of procedures necessary to meet Quality Program goals. All project team members participate in this ongoing process.

Quality Control (QC): The systematic examination of documents to ensure the project team has performed appropriate Quality Assurance processes and has met the Quality Program goals. Quality control is a point-in-time review that is typically done by someone not regularly involved in the project.

Quality Program: Also called a Quality Management System (QMS), this is a set of Quality Assurance and Quality Control processes and procedures performed on every project. The goal is to ensure regulatory compliance and efficiency in the design and delivery process, as well as adherence to professional standards and contractual requirements in the deliverables.

Request for Information (RFI): A standard form for owners, designers, and contractors to request further information from each other during construction.

Because the evaluation criteria are subjective and the reviewers bring their own perspectives and experiences to the task, it is important to control for subjectivity. Have multiple reviewers evaluate each of the submitted drawing sets and average the reviewer scores to balance out individual biases.

Collect, analyze, and disseminate the results.

After reviews are complete, analyze the data to correlate reviewer scores with project parameters and attributes in a way that makes sense for the firm. Rankings can be based on individual project scores, projects by office (for multi-office firms), projects by building type, or delivery method. The analytics will be based on the firm’s structure and goals for the evaluation. Disseminating the results to firm leadership, office leadership, and project teams is critical to improving future outcomes.

Measuring the effectiveness of a Quality Program has two primary challenges. First, every building project is shaped by its unique site, program, constraints, requirements, and parameters. As a result, every building project is, essentially, a “prototype” that requires bespoke approaches, documentation, and delivery. In manufacturing, prototypes are made and then analyzed, tested, and revised to create an ideal product that production versions can be compared to. The unique nature of every building project means the design process and documentation differ from project to project and cannot be measured against predetermined “ideals.” How, then, do you measure the effectiveness of a Quality Program if you don’t have something to compare the outcome to?

Second, design and construction take a long time. Most projects take a year or more, and the largest and most complex can last for a decade. By the time the drawings can be evaluated for their effectiveness in conveying information, design processes, tools, and staff are likely to have changed, significantly limiting the feedback’s value. Before discussing a proposed evaluation system, it is worthwhile to look at the metrics frequently suggested in the Architecture/ Engineering/Construction (AEC) industry: RFIs, COs, and Legal Claims. While each of these can provide information on the quality or completeness of a set of documents, none are reliable as primary measures of deliverable quality.

range like 1-3 provides great clarity in differentiation and can help make sense of the inherent subjectivity of the evaluation criteria, but it lacks nuance. Considering all factors, a simpler and smaller range is recommended to provide clarity.

A large-scale evaluation of a firm’s deliverables is a significant undertaking, so establish a timeframe to help manage the cost and effort. In setting guidelines for the time spent on each set, remember this is an evaluation and not a detailed QC review. An hour or two per drawing set is sufficient for an experienced reviewer to make a reasonable evaluation.

RFIs: Tallying the number of RFIs on a project is easy, and we can use that number as an indication of document quality. While RFIs will be issued as a direct result of document quality, RFIs are also issued for many reasons that have nothing to do with the design documents. RFIs can be submitted due to unforeseen site conditions, market forces, confirmation of a change, or even mistakenly because the contractor missed information contained in the deliverables.

COs: Similarly, some COs may result from document deficiencies, but they are equally likely to stem from owner changes, client (architect) changes, regulatory requirements, or unforeseen site conditions. Additionally, the total number of RFIs and COs and their causes will not be known until construction is complete and, as noted previously, months or years after the completion of the QA and

QC processes. Even if RFIs and COs were effective measures of document quality, that information would not be available until too late to positively impact future design work.

Legal Claims: As with RFIs and COs, legal claims on building projects have many causes. Some are legitimate, some are spurious, and most have a multitude of contributing factors. They also typically take even longer to surface than RFIs and COs, making them even further removed from the design and documentation process and less effective as a metric.

If these are not the correct metrics, what are?

One measure of efficacy is QA/QC process uptake, which is fairly straightforward to evaluate. However, a high adoption rate of QA and QC tasks does not, by itself, prove the system is working. Understanding a Quality Program’s effectiveness in improving the design process and its outcomes is significantly trickier.

A two-tiered approach can be used in the document review to assesses construction documents’ quality.

The first tier that the author’s firm uses consists of the baseline criteria of proficiency, efficiency, and legibility that can be applied to any set of documents.

Proficiency measures whether all needed content is present and technically correct, if every area of the project is documented, and if the firm’s standards are utilized.

• Has the project been thoroughly documented?

• Has the team used the firm’s standard elements where appropriate (e.g. sheet numbering, set organization, tags, symbols)?

• Do detail components have an appropriate level of complexity (e.g. no overly complex graphics of manufactured items, like curtain wall extrusions)?

• Are details technically sound and constructible?

• Are drawings annotated and dimensioned appropriately? Efficiency measures whether the documents are organized in a clear, concise manner and if the content and number of drawings match the project’s scope and complexity.

• Is the amount of content sufficient to convey design intent and no more?

• Has sheet real estate been used intelligently?

• Are plans scaled appropriately for efficient presentation without unnecessary enlargements?

• Is ‘SIM’ used effectively to identify details that are largely the same?

• Is information duplicated at multiple scales or in multiple drawings?

• Is information in the drawings that is, or should be, in the specifications?

Legibility assesses whether the set is easy to navigate, if information is easy to find and read, and if the sheets are laid out logically.

• Is the flow and navigation of the set intuitive?

• Are drawing sheets organized in a logical way?

• Does the general graphic quality make the set easy to read?

Tier 2

Tier 2 is applied at the beginning of the assessment program’s second

year and has just one criterion: continuous improvement.

Continuous Improvement—During each review period, reviewers should identify “Start” (elements that all drawing sets should employ) and “Stop” (elements that should not be used in the future) practices. These will depend entirely on the firm’s processes, standards, and priorities.

After the first review period has been completed and the Start and Stop elements are broadcast to all design staff, adherence can then become a review criterion going forward.

The final step in determining the efficacy of a Quality Program is to compare review results with adoption rates of individual QA and QC components. This can be done broadly or narrowly.

Broadly, the combined scores of all assessment criteria can be compared to the overall adoption rate of all QA and QC processes by a project team, practice area, or office. This can be useful in surfacing broad trends across the firm.

More narrowly, individual criterion scores can be correlated with individual QA and QC processes to better understand their effectiveness. For instance, Efficiency scores can be compared to the frequency of projects doing cartoon sets to see if the cartooning process is improving productivity.

A combination of broad and granular assessments is likely to provide the best and most complete evaluation of whether a Quality Program and its individual components is working well, and it can also surface areas for improvement. Engaging in this process on a regular cycle will help demonstrate the Quality Program’s value and allow the firm to adjust that program to be most effective.

The work of architects, engineers, and designers is variable, constantly changing, and often difficult to evaluate objectively. A rigorous and repeating system of evaluating a firm’s work and correlating the results with the QA and QC process is one way to bring some order to the process, help firm leadership understand strengths and weaknesses, and improve project outcomes. ■

Mark Walsh is an architect with 30 years of experience in design and coordination for all phases of project design and delivery, from programming and pre-design through construction contract administration. As Perkins&Will’s Firmwide Director of Technical Design, Walsh focuses on developing a culture that delivers design and technical excellence while embracing innovative delivery and construction techniques and seeking to improve efficiency across all aspects of the firm’s work.

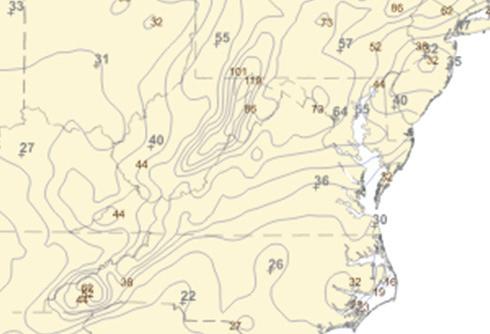

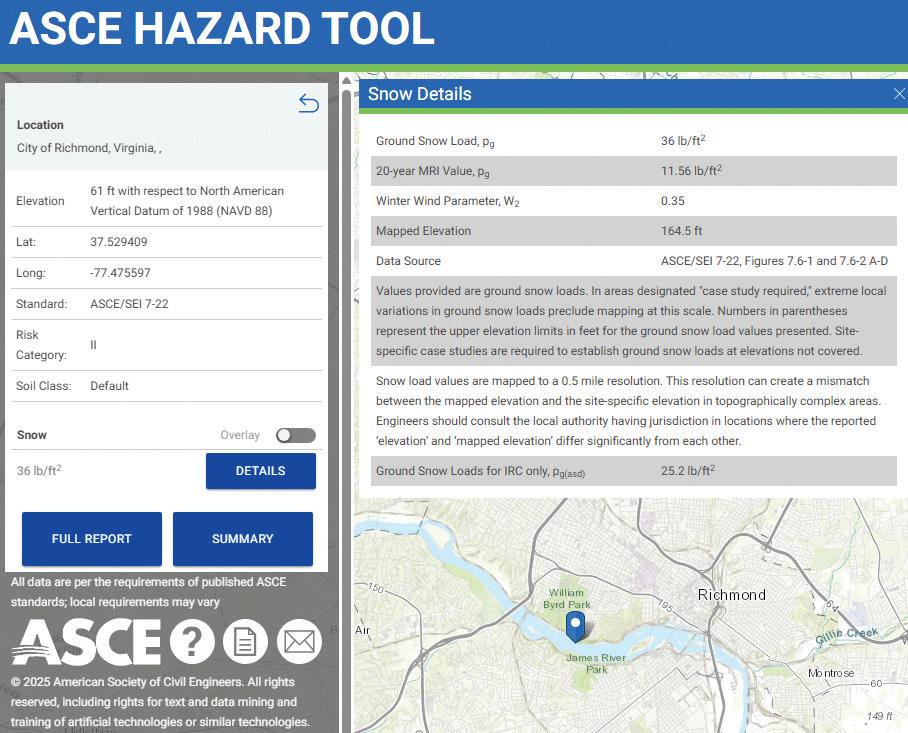

Recommendations for a new direction for residential buildings in high-risk areas include using masonry or concrete in construction and adding a sprinkler system to the roof.

By Dilip Khatri, PhD, SE, PE

The recent disaster in Pacific Palisades, Malibu, and Altadena areas of Los Angeles County, California has brought the issues of fire damage to the forefront of a national conversation. The Los Angeles fire disaster is estimated to exceed $50 billion in damages, most of this will be underinsured or not insured. Recently, the Grand Canyon North Rim Lodge burned to the ground from the Dragon Bravo Fire. These recent events again bring up the topic of rebuilding homes with “fire-safe” materials to avoid such future catastrophes.

As a country, the United States has the highest proportion of wood-framed buildings in the world. In 2020, residential woodframe construction accounted for 64% of the fire deaths in 2020. Approximately 70-80% of residential buildings are wood-framed buildings. The five types of construction recognized by the building code are:

• Type I: Noncombustible construction, office, commercial, hospitals, schools, police stations, fire stations.

• Type II: Noncombustible construction; shopping malls, warehouses, schools.

• Type III: Noncombustible exterior, combustible interior, older warehouses, apartments, mini-malls.

• Type IV: Heavy timber construction, combustible cross laminated timber (CLT).

• Type VA/B: Combustible woodframed building.

Combustible wood-framed buildings are classified as Type V construction structures which have zero-fire resistance. Commercial buildings, retail structures, churches, schools, police stations, fire stations, and government offices are not Type V construction buildings but are Type I construction buildings with maximum fire protection and that also can resist earthquakes, wind forces, and storm effects with greater resiliency.

Then why are homes built out of wood-frame construction?

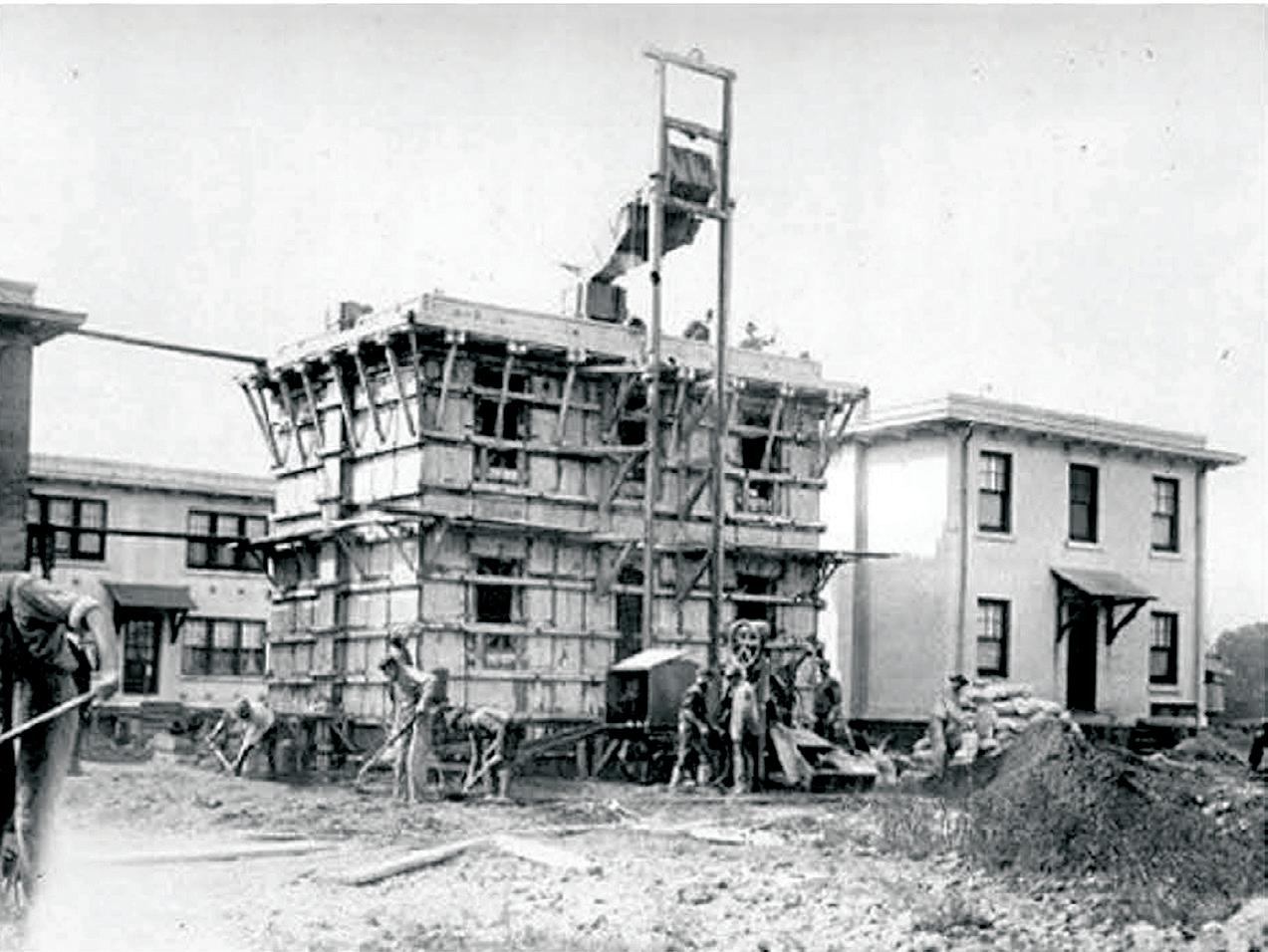

Wood-frame construction

has been the primary building type in the U.S. for over 200 years. The main reason for this is cost and availability of materials. Woodframe construction is termed, “Light-Frame Construction” by the building code because it is easy to work with. Wood can be cut and placed by carpenters with simple tooling. No heavy machinery is required, and changes can be handled during the construction phase.

The downsides of wood-framed buildings are:

• Poor resistance to fire

• Poor resistance to termites

• Prone to dry rot

• Good resistance to earthquakes only for buildings up to 2 stories, but questionable beyond 3 stories.

• Poor resistance to wind, tornado, and hurricane forces

The risk factors for wood-framed buildings include:

• Wood houses burns.

• Interior content is flammable.

• Storage of flammable/combustible materials.

• Garages used for incorrect storage.

• “Homemade” electrical solutions.

• Electrical overload.

• Smoking.

• Kitchen fires responsible for 50%+ cause and origin.

Given this track record and known risk factors, this author proposes a new direction for residential buildings.

The number one building system for protection is Type I construction which is specified for shelter structures and “critical facilities” such as police stations, command centers, government offices, military stations, embassies, hospitals, telecommunications facilities, power stations, etc. Facilities that are “must have” are never built as Type V construction. The code and

regulations will not allow this because wood-framed buildings have the highest risk of destruction from fire.

In 2008, the author wrote an article recommending the residential home building industry move away from Type V construction, especially in areas of high fire risk [i.e., California].

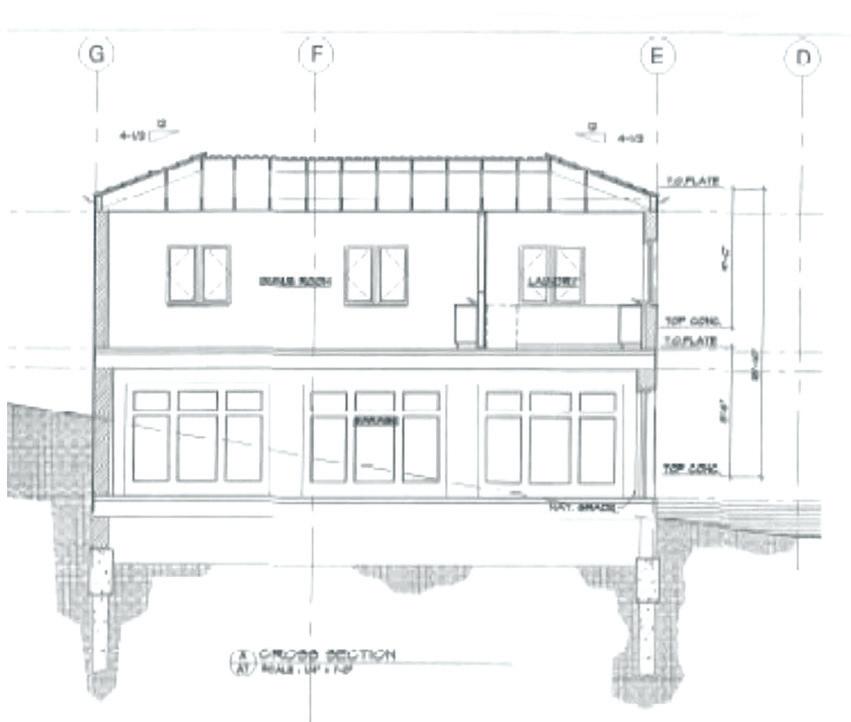

This author built two prototype buildings of custom home design (Figs. 1-3) The first one was approximately 6,000 square feet located in Monterey, California, in a private development. The second house was approximately 12,500 square feet located in Bell Canyon, California. Both homes have survived for the past 20 years, with several fire threats in the area.

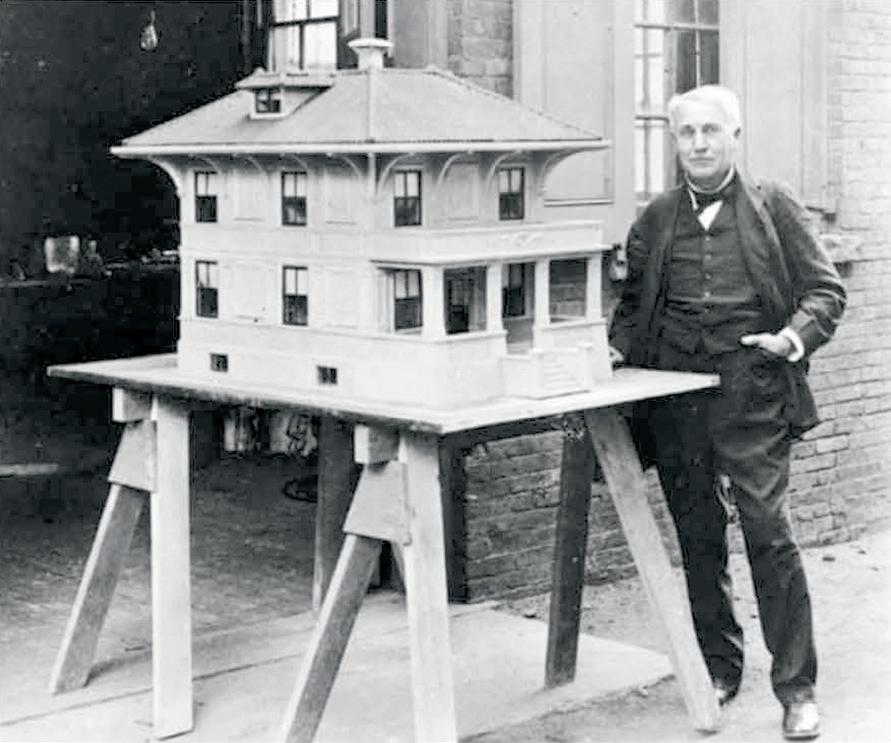

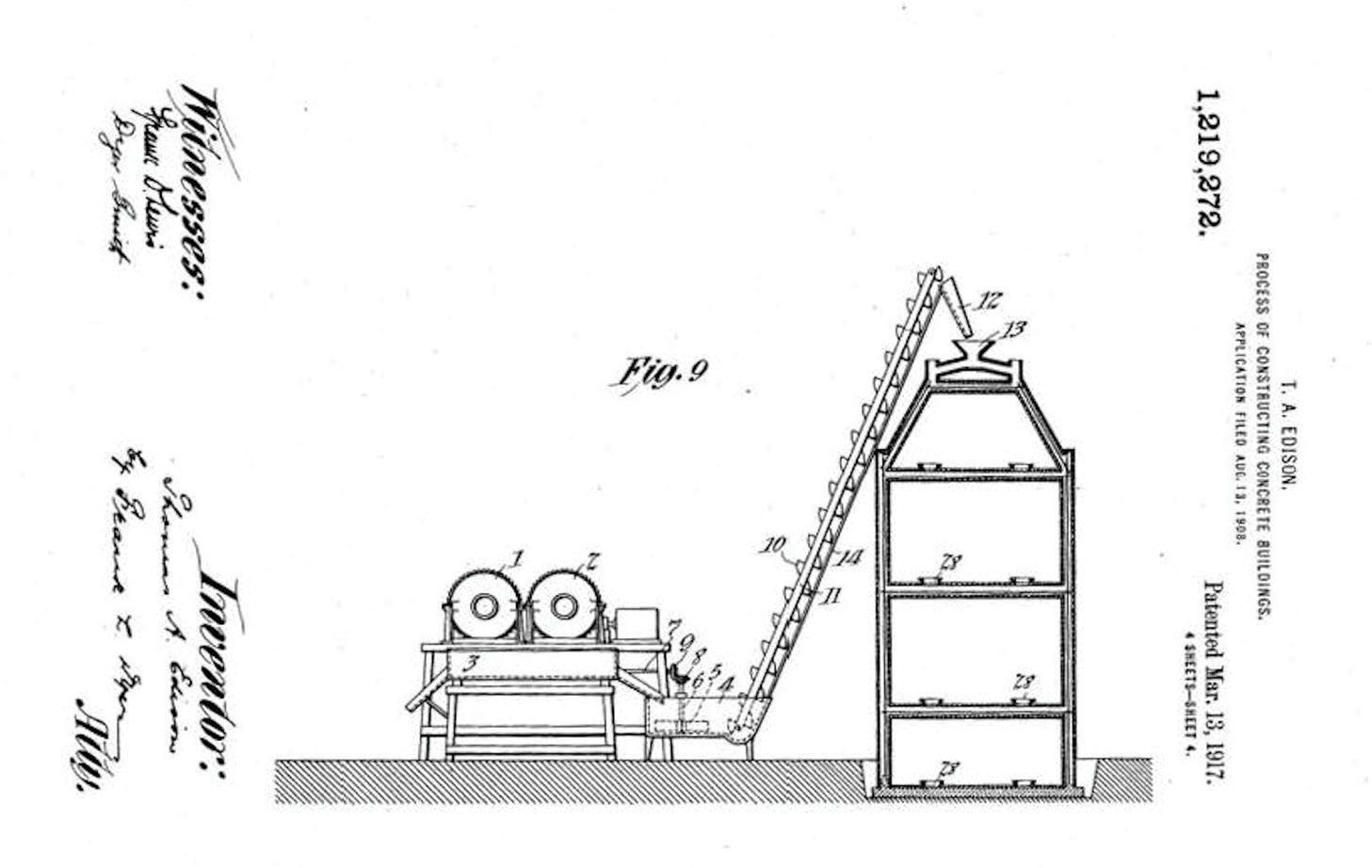

This is not an original idea. Thomas Edison built the first concrete

house in 1908 in New Jersey and patented the concept of building mass housing out of concrete with a single pour (Figs. 4-5).

The use of reinforced masonry and/or precast, prestressed hollow core concrete floor planks (e.g. Spancrete) are the best materials for resisting fire because they are noncombustible, eliminating many of the risk factors associated with Type V construction buildings. The advantages of building with masonry and concrete are:

1. Best fire-resistant material.

2. No termite infestation.

3. No dry rot.

4. Excellent earthquake resistance for larger floor spans and taller structures.

5. High resistance to wind, tornado, and hurricane forces.

Cost is a significant concern as there is an increased structural cost in materials and labor using reinforced masonry and precast, prestressed hollow core concrete floor planks. The interior improvements, finishes, and mechanical systems will be the same as a Type V building using interior drywall/finished surfaces because they are not changed.

The author recommends adding a sprinkler system for the rooftop framing system powered by a gas generator that draws water from a backyard pool or water tank. This will provide a primary fire protection system to prevent flame spread from the outside through windows that could enter the structure. The cost of this system would be added to the overall structure cost.

The final cost of Type I construction depends on many factors, but industry estimates indicate this should not exceed 15% of the wood-frame system. Each floor plan and design will dictate a different cost profile, so this is not a guarantee, but an educated estimate. The important advantages are clear, and long-term sustainability will add a lifelong security for the home. Also, insurance risk is far less. Survivability of the Type I construction residential structure will match that of other critical facilities like police and fire stations. This Type I construction residential home will be a fortress, and its life equity will remain protected.

forces, projectile impact, and earthquake resistance and are well suited for tornadoes, hurricanes, and fire zones.

D. It is advised to consider additional fire protection measures for new/existing homes: (a) Adding metal shutters to all windows; (b) Roof sprinkler system; (c) perimeter fire protection sprinklers linked to a pool/water tank with temporary power generation.

This Type I construction residential home will be a fortress, and its life equity will remain protected.

For example, in Palisades the projected replacement cost estimates for residential properties are in the range of $600-$850/square foot. This estimate is for higher-end residential rebuilds and depends on interior improvements. The structure’s cost is approximately 50% of the replacement cost or $300-$425/square foot for a two-story woodframed building of approximately 4,000 square feet, [foundation not included]. Three major areas where reinforced masonry wall and concrete floor systems will reduce costs are:

A. Reinforced masonry shear wall strength is approximately 3,000 pounds per linear foot (plf) vs. approximately 1,500 plf maximum for wood shear walls. This system makes every masonry wall a shear wall and therefore the installation of hold downs, straps, etc. are reduced/eliminated because the diaphragms are precast, prestressed hollow core concrete floor planks.

B. Precast, prestressed hollow core concrete floor planks can be designed for longer spans, upwards to 40 feet with no interior columns/walls. This gives the architect great flexibility in design options.

C. Reinforced masonry walls and precast, prestressed hollow core concrete floors provide excellent resistance for wind

Certainly, there are disadvantages. Wall and diaphragm designs must be precisely dimensioned and cut to fit perfectly with tight tolerances. One cannot make adjustments in the field to “move a wall” or cut an opening arbitrarily. But this could be an advantage because it forces the design team and owner to reconcile their designs before construction begins and not allow for inordinate change orders during the construction phase.

Final cost estimates of the masonry and concrete Type I construction are emerging to be approximately 15-20% above the wood-frame Type V construction, with reduced insurance risk and long-term sustainability. This is arguably a negligible increase considering the life safety advantages.

The biggest advantage is the reduced risk for total loss. Given the insurance industry crises in California and fire prone states, for many communities in hillside/high fire risk areas this may not be an option, but the only way to build in the future. ■

SE, PE, Ph.D., is a professional structural and civil engineer with 42 years of experience and licensed in 48 United States, four Canadian Provinces, and Australia. He has published over 200 technical papers/symposiums/presentations. (dkhatri2006@gmail.com, Khatriinternational.com)

Photo by Nicholas Venezia.

The Frick Collection recently reopened after a yearslong renovation to the century-old museum. Simpson Gumpertz & Heger was tasked with engineering the unique solutions that addressed the archaic systems and complex structural limitations of this historic landmark.

By Filippo Masetti, PE, David Ribbans, PE, Lauren Feinstein, PE, and Kevin Poulin, PE

This is the second of a two-part series discussing the renovation of The Frick Collection in New York City. Part 1 was published in the July 2025 issue of STRUCTURE Magazine and discusses design challenges in modifying archaic gravity systems.

Nestled into half a city block on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, just steps from the tranquil green expanses of Central Park, The Frick Collection is a world-class art museum and research center specializing in fine and decorative arts from the Renaissance to the late 19th century. The collection was initially enjoyed by Henry Clay Frick and family in their 1914 Gilded Age Mansion, which became a public museum 90 years ago in 1935. The property has expanded over the course of more than a century to consist of five separate buildings and three historic gardens (two outside and one inside). With an evergrowing collection attracting an increasing number of first-time and returning visitors with each passing year, The Frick Collection commenced a renovation project in 2016 to expand publicly accessible gallery spaces within, improve circulation and amenities, modernize back-of-house facilities, and improve energy efficiency. Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (SGH) was the Engineer of Record for this challenging project that included the repair and strengthening of numerous archaic structural systems throughout the historic buildings.

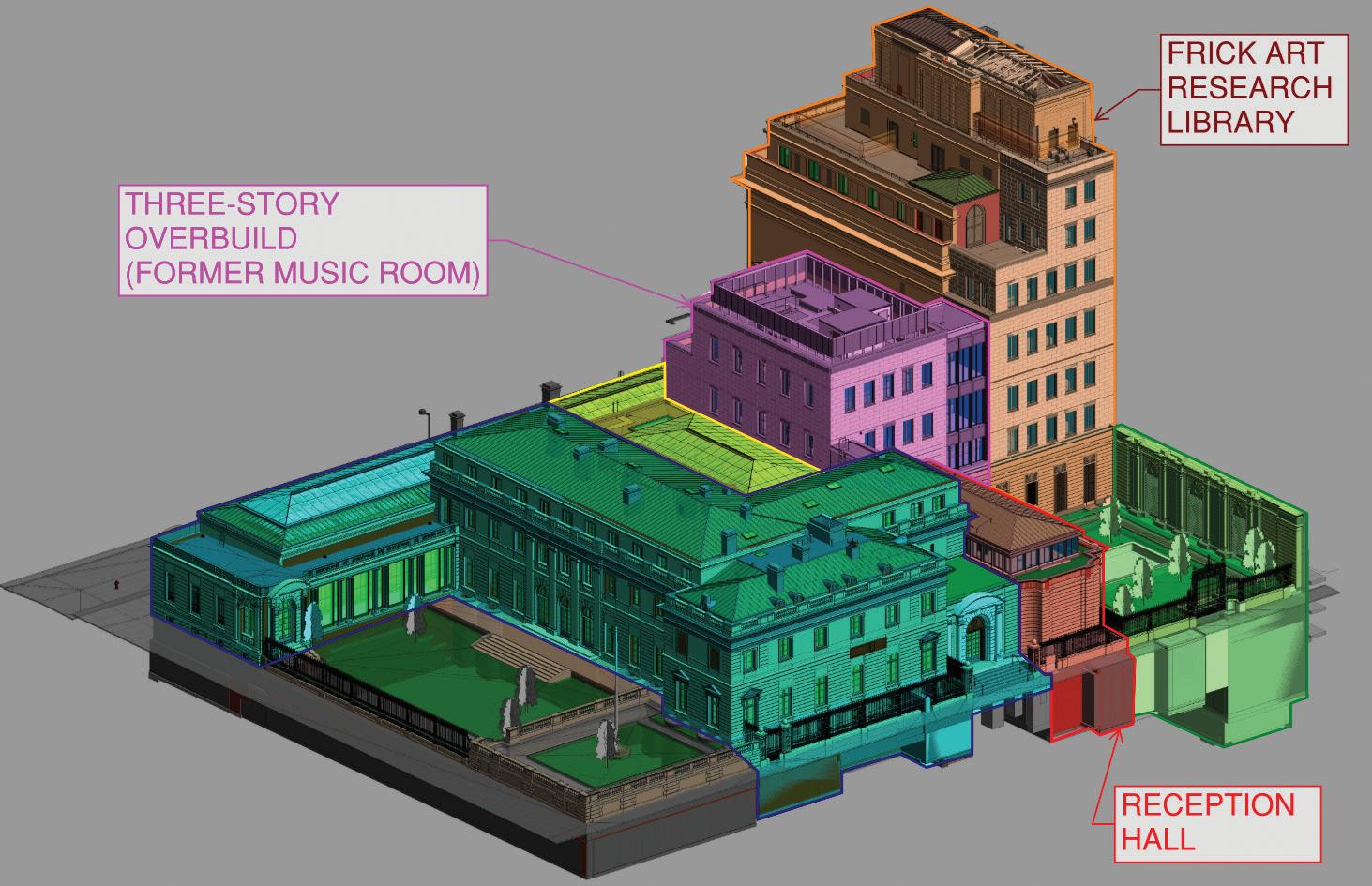

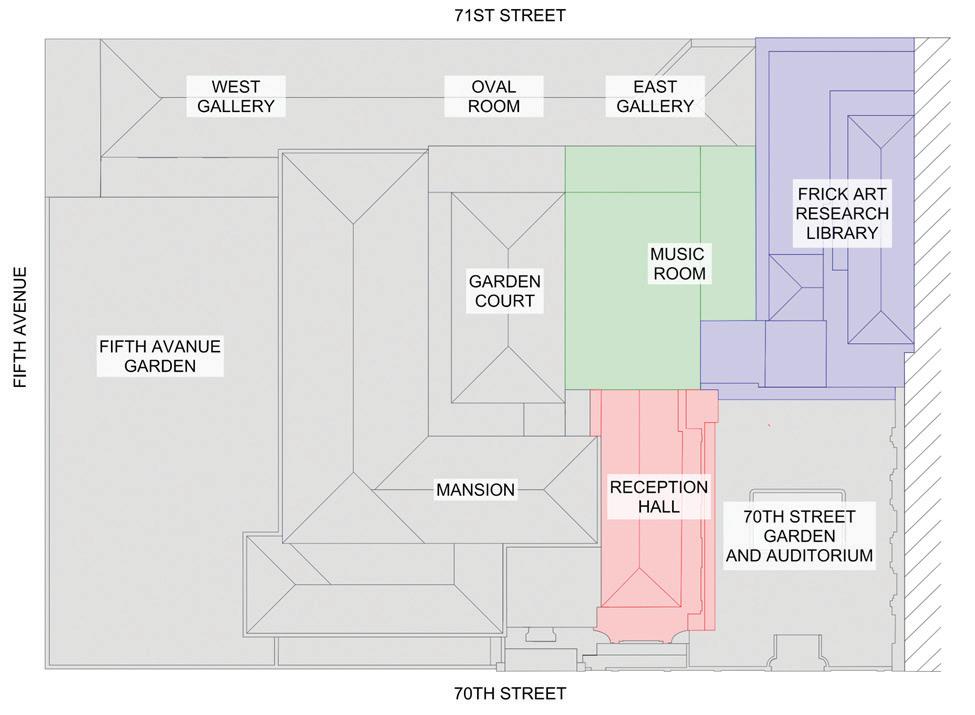

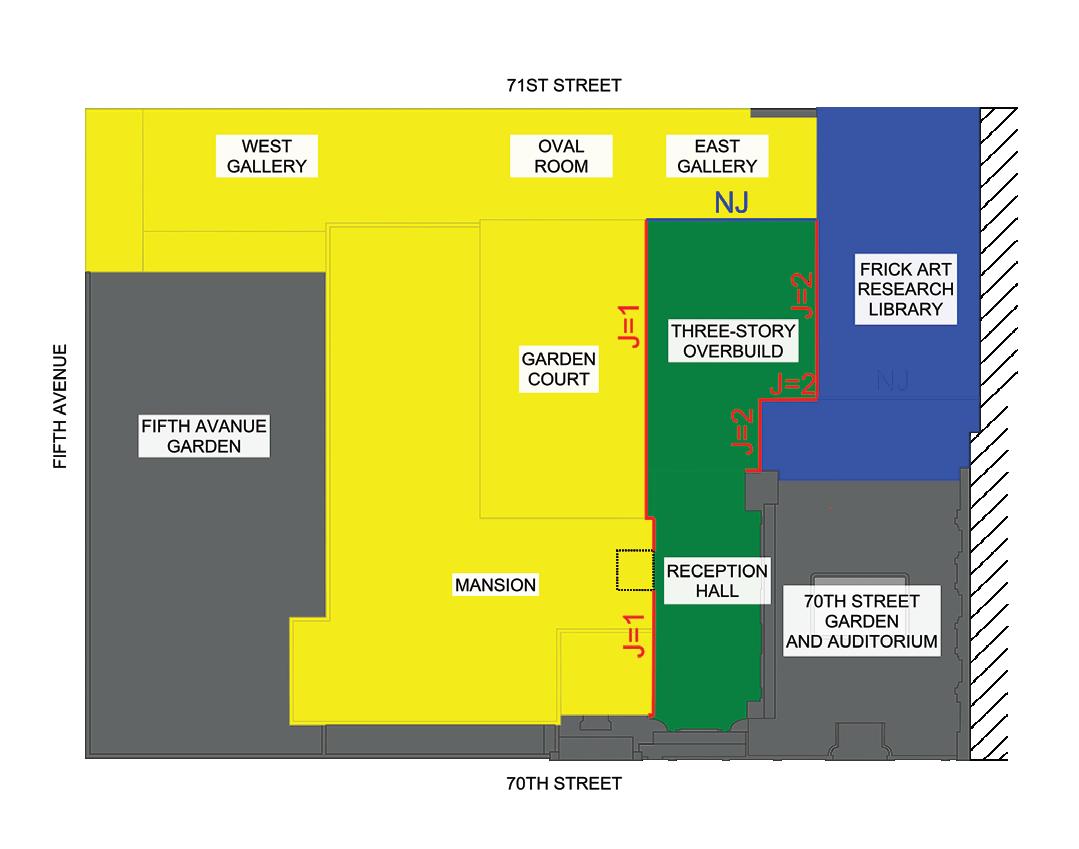

While renovations occurred in all of the institution’s buildings (Fig. 1), it was the three buildings with additions (Fig. 2) that required new lateral-load-resisting (lateral) systems and strengthening of existing lateral systems: the Frick Art Research Library (FARL), a 1935 extension, originally called the Music Room, and the reception hall. The additions provided more space for a new conservation studio, educational programming, and additional galleries, and they provided an interconnection of all buildings for the very first time. This trio of structures is now clad with a panelized facade system (a thin-stone system supported by metal backup framing) that harmoniously complements the original limestone cladding of the adjacent buildings. Although the impact of this new system is primarily aesthetic, it significantly affected the renovation’s structural design and presented some unique challenges for the SGH engineering team.

Fig. 1. The three buildings with additions are shown in this Revit model: the Frick Art Research Library, reception hall, and 1935 extension (former Music Room).

Fig. 2. The Music Room, Frick Art Research Library, and reception hall required new lateral load resisting systems and strengthening of existing lateral systems.

New construction architecture requires special consideration for the inevitability of future upgrades. That’s why modern construction projects need hanging solutions that are built for speed, versatility, and adaptability to ensure quick and seamless renovations.

To help meet that challenge, Vulcraft-Verco has developed the PinTail™ Anchor, an innovative hanging solution that works exclusively with our Next Generation Dovetail Floor Deck, and are specifically designed to futureproof today’s construction projects for tomorrow’s renovations.

To provide more space for the museum, the project team designed a narrow, nine-story addition to the FARL (horizontal enlargement), a three-story “overbuild” (vertical enlargement) at the 1935 extension, and a one-story overbuild at the reception hall.

The FARL’s nine-story transitional masonry structure (the exterior steel frame is embedded in masonry) has two below-grade levels, and, as discussed in Part I of this series, the floor structure varies from the proprietary “stack-slab” system in the library stacks to draped-mesh cinder concrete slabs and slagblok (waffle) slabs. Large openings in the floor diaphragms were needed for a new egress stair and elevator at the south end of the building, adjacent to the steel framing for the new addition.

The 1935 extension was a two-story transitional masonry structure with two below-grade levels and floors that featured draped-mesh cinder concrete slabs spanning between steel framing. The recently-completed project included demolishing the upper floors and roof while keeping the perimeter steel columns, first-floor structure, and below-grade construction to allow for a new three-story overbuild above the first floor, reaching a full height of four stories. To provide a connection with the nearby reception hall, the building was also expanded south beyond the original footprint.

In 1975, The Frick Collection demolished existing townhouses east of the mansion and constructed the reception hall and 70th Street Garden on top of remnant brick masonry foundation walls. The reception hall included two original below-grade levels and featured a steel-framed roof. The structure abutted, but was separate from, the mansion’s masonry walls. The recently-completed renovation included the demolition of the roof framing, interior floors, and a portion of the north masonry wall. For the new construction, SGH designed an opening in the west masonry wall for access to new elevators located within the mansion, a one-story overbuild featuring glass curtain walls, a concrete core for a monumental stair, and the replacement of the east masonry foundation wall with a new corbeled concrete shear wall.

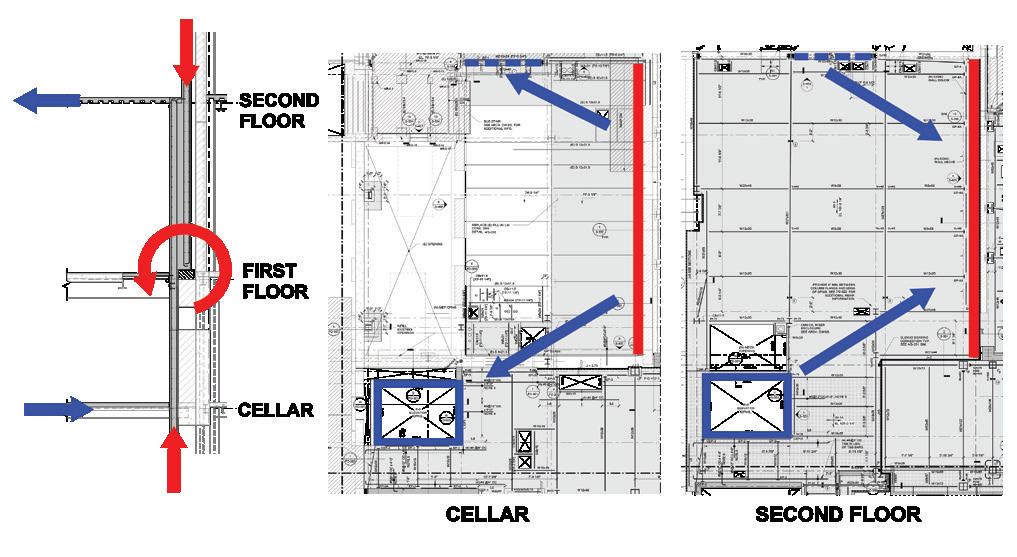

Given all the modifications over several decades, SGH had to decide whether to structurally connect the buildings or keep them separated. Unfortunately, there was no catch-all solution, as each building presented different existing conditions and constraints dictated by the architectural vision for the project. The team’s design followed the 2014 New York City Building Code (NYCBC), which included provisions for structural separations. They also relied on “Technical Policy and Procedure Notice 4/99” (TPPN 4/99) issued by the New York City Department of Buildings, which provides guidelines on the interpretation of seismic design requirements when renovating existing buildings. In this provision, a seismic retrofit of an existing building is not required if there is a seismic joint isolating it from the new construction. A seismic retrofit can also be avoided if the increase in seismic forces is less than 20 percent, even if the existing building is not isolated.

The first step was to understand whether the existing buildings were connected and, if so, how. Above grade, the FARL was separated from the adjacent 1935 extension (without a distinguishable joint), and both the 1935 extension and reception hall were connected to the adjacent portions of the mansion. Below grade, all of the buildings were not generally connected.

SGH decided to connect the FARL and its addition because the increase in seismic forces was below the 20 percent threshold, but the FARL was kept separated from the 1935 extension, above grade. The

1935 extension and reception hall were connected to one another, but the team disconnected them from the mansion as much as possible. However, in some locations, the columns of the 1935 extension were integrated with the bearing walls of the mansion and could not be separated (Fig. 3). Remaining below the 20 percent threshold avoided a costly seismic retrofit of the mansion. Per TPPN 4/99, the new superstructure at the FARL addition, three-story overbuild, and reception hall were designed for both the seismic and wind requirements of the NYCBC.

Next, SGH had to determine the required joint sizes between the above-grade separated portions of these buildings. This required a delicate balance between meeting the code-required minimum structural separations, while reducing the size of the joints in architectural finishes and limiting the movement of deflection-sensitive facades under lateral loads. The final design required substantial effort and coordination between SGH and the facade consultant. The spandrel beams needed to be iteratively designed to limit the facade joints considering the combination of lateral drift of the buildings under wind and seismic loading, along with the gravity deflections. After the facade consultant established the deflection criteria of the spandrel framing, SGH designed them, determined lateral drifts under wind and seismic loading, calculated resulting joint sizes and spandrel deflections, and repeated the process (typically by upsizing or downsizing the lateral and spandrel structural systems) until the results were satisfactory. In general terms, the controlling scenarios were the minimum inter-building joint size under ultimate limit-state seismic loading and the square root of the sum of the squares of the lateral drifts of adjacent buildings under service-level wind loads (MRI=50 years).

Because of the elevational difference of the foundations, the first floor was the lowest level to connect the three buildings via the 70th Street Garden slab, and SGH designed the new first-floor framing and slab diaphragms to withstand significant lateral force transfers. On upper floors, there were also pinch points in the diaphragms. For the FARL, it was near the new elevator and stair openings on every floor. At these locations, the engineering team added slab reinforcing or in-plane bracing at the concrete-on-metal-deck slab to withstand the forces. A similar pinch point existed between the elevator core of the three-story overbuild and the monumental stair of the reception hall on the first and second floors that generated high diaphragm forces. At the threestory overbuild and reception hall, SGH designed solid cast-in-place concrete slabs with heavy chord reinforcement that acted compositely with the steel floor framing.

Frick Art Research Library

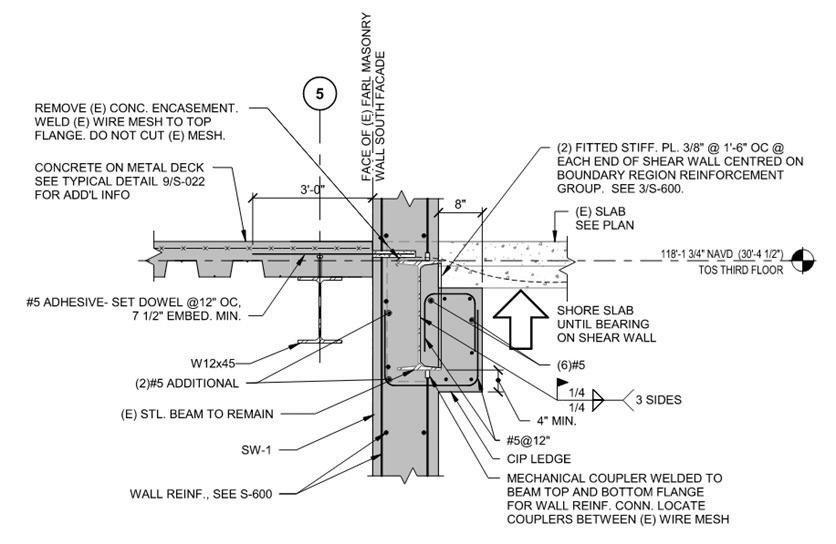

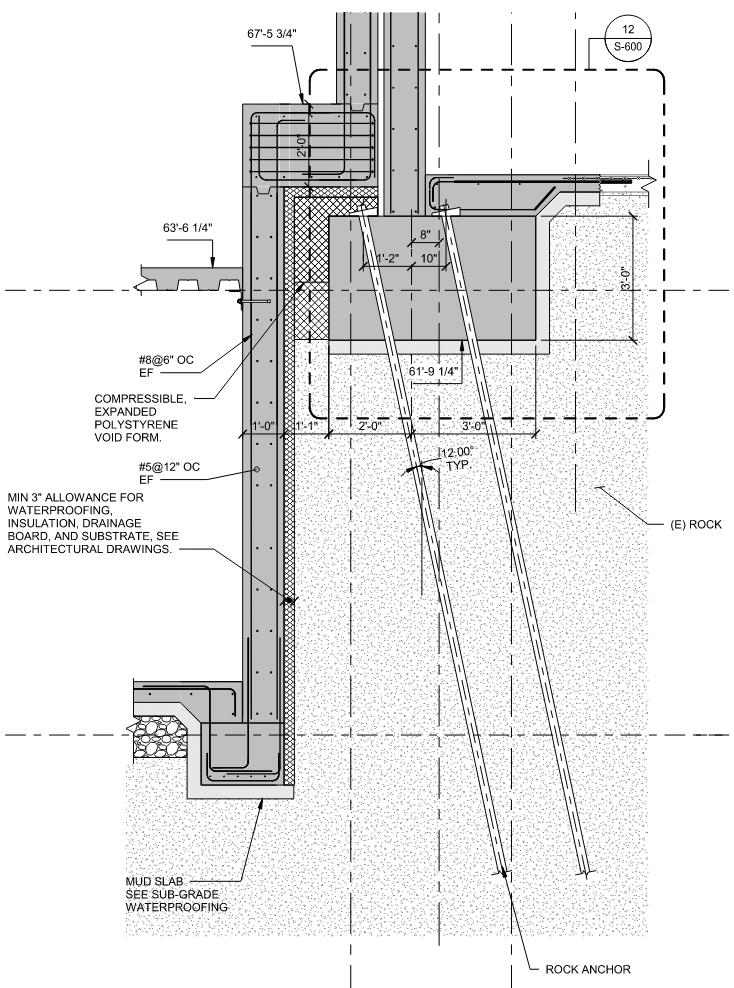

To provide access to the FARL addition, the western portion of the exterior masonry wall on the south elevation of the existing FARL was removed and replaced by a new reinforced concrete shear wall, in between and encasing two columns, and the eastern portion was removed to allow for circulation to and from the addition (Figs. 4 and 5). The new shear wall extends from the subcellar to the eighth floor and replaces the lateral capacity of the previous transitional masonry wall. The new shear wall is the stiffest lateral element of the FARL and its expansion. On top of the resulting significant lateral forces, the design of the shear wall was complicated by the detailing to connect existing diaphragms of the FARL and the new diaphragms of the addition. The existing columns and spandrels encased by the concrete shear wall are detailed with welded studs at the webs of the columns and couplers at the top and bottom flanges of the beams to transfer gravity and lateral forces to the shear wall, rather than into the columns and their existing foundations. The diaphragm was laterally connected to the shear wall while the associated gravity loads were re-supported (Fig. 6).

Because the shear wall extended between and encased the existing columns, openings for the door and window were needed, and the proximity of these openings to the existing columns required close coordination with the boundary-element reinforcement.

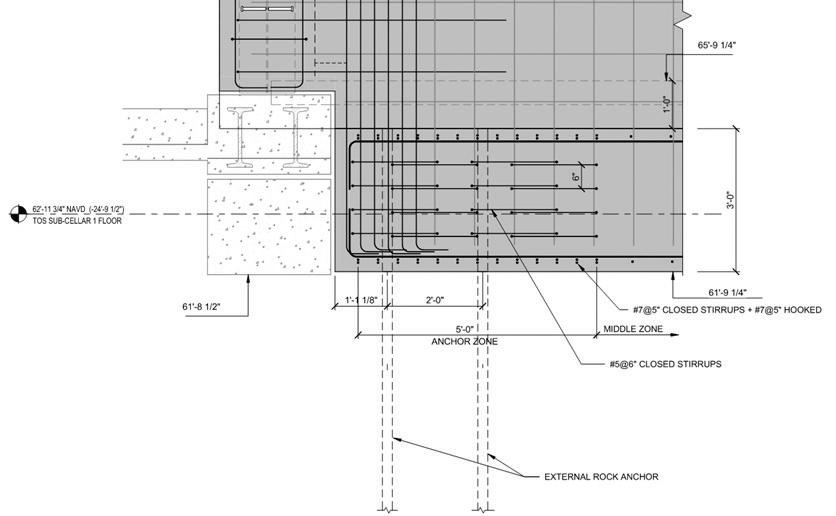

The foundation for the shear wall needed to be independent from the existing column footings because strengthening the existing footings would be both difficult and costly. South of the shear wall, the rock excavation continued down to Subcellar 2, approximately 10 feet below the bottom of the existing column footings, and thus the shear wall foundation, which

would also bear on rock, needed to be located away from the edge of excavation. Consequently, the new footing is eccentric with respect to the shear wall. It extends the full length of the shear wall but stops at the edge of the existing column footings and cantilevers over them (Fig. 7).

To resist uplift, rock anchors were required below the boundary element zones of the shear wall. Due to the proximity of the rock face as well as the shear wall eccentricity, the rock anchors were inclined. (Fig. 8).

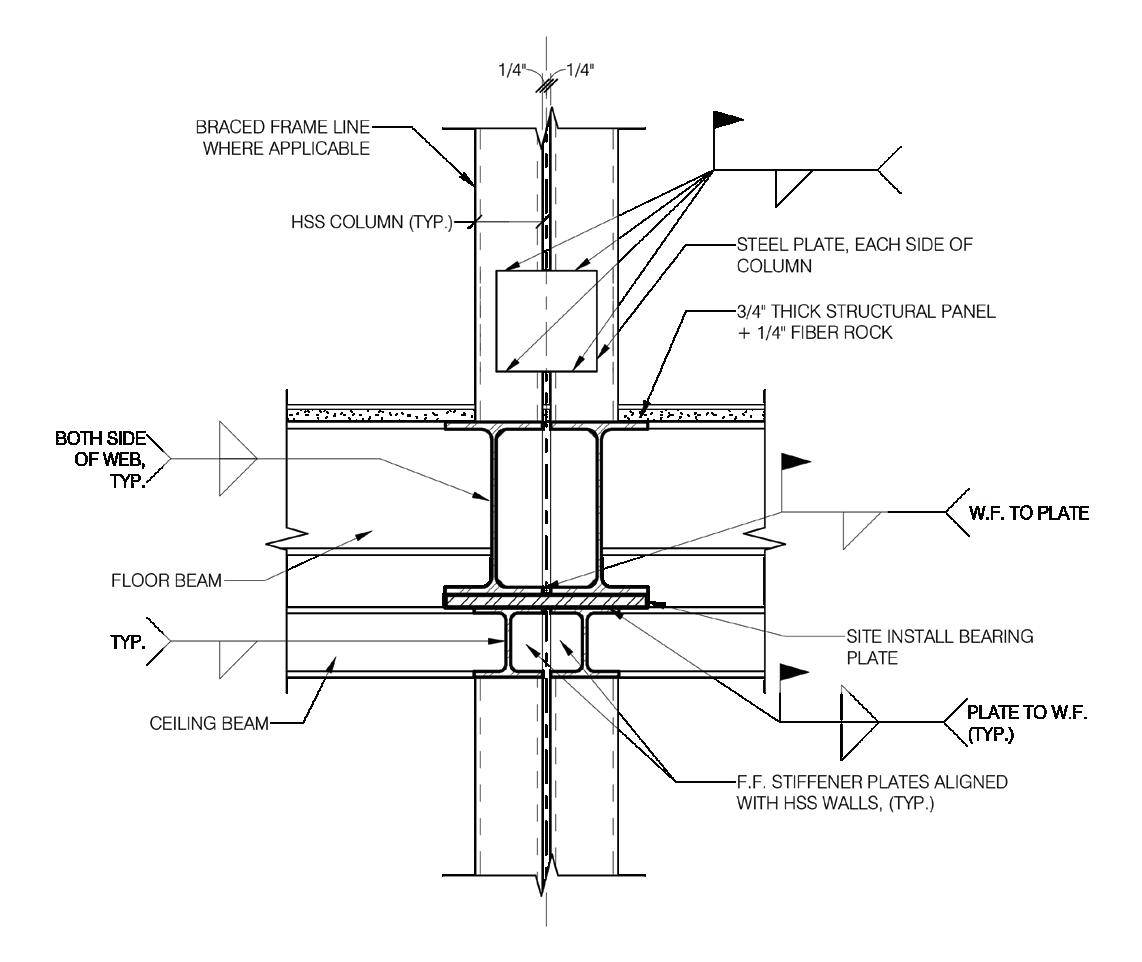

To accommodate new art galleries, offices, and a conservation studio, the museum added three stories to the 1935 Extension. As such, the three-story overbuild required a new lateral system that extended all the

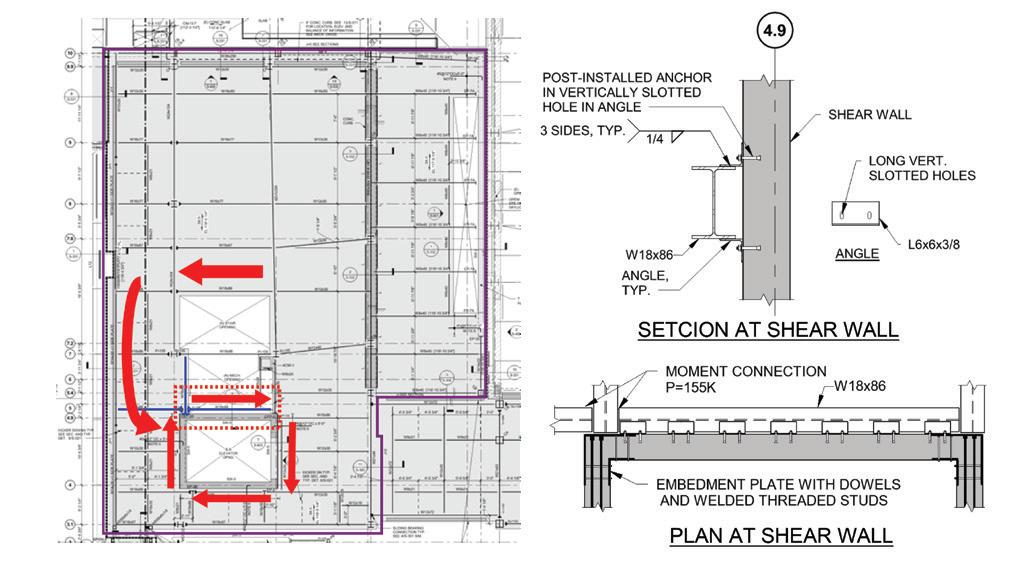

way down to the foundation. To maximize the use of the new space and minimize the size of the new structure, SGH designed an asymmetric lateral system comprising a reinforced concrete core at the south end of the building, a stepped reinforced concrete shear wall at the east end (adjacent to the FARL), and a horizontally offset steel frame at the north end. The steel frame features moment frames in the upper floors for large windows and braced frames on the lower floors at the solid masonry walls that separated the 1935 extension from the East Gallery.

The eccentric layout of the lateral system resulted in a large, concentrated transfer of lateral forces around the elevator’s concrete core. The programming of the new space also required stair and mechanical openings to be located adjacent to the core, exacerbating the lack of space to transfer forces. The design team utilized the shear studs of the composite steel framing around the openings to collect lateral forces, and a steel drag strut on the south edge of the opening connected to the concrete core through a series of angles and post-installed anchors (Fig. 9).

The team designed the below-grade portion of the east concrete shear wall as a liner wall inside the footprint of the existing foundation wall to avoid strengthening of the wall and its footing. Above the first floor, it “steps over” the top of the existing mass masonry foundation wall toward the FARL to maximize interior space. Between the first and second floors, the shear wall doubles in thickness to allow the formation of an inclined diagonal strut to transfer gravity and lateral forces to the lower portion of the wall at the step. The moment from the gravity eccentricity caused by the step was resolved by transferring the resulting force couple to the concrete diaphragms of the new second floor and the existing cellar floor (Fig. 10). At the cellar level, SGH specified the removal of the cement topping and cinder fill of the existing draped-mesh cinder-concrete slab and its replacement with a new structural concrete topping slab that was detailed to transfer the compression component of the force couple from the east shear wall to the concrete core and the braced frame. Transferring the tension component of the force couple to the new second-floor diaphragm was more straightforward, and it was detailed as a simple slab connection to the concrete wall and braced frame.

Several factors and constraints dictated the design of the new belowgrade concrete shear wall along the east side of the reception hall. First and foremost, the new concrete wall needed to re-support the landmarked masonry wall on the east facade, which is eccentric to the new concrete wall below. In addition, the new concrete wall required a large opening for an entrance to the new auditorium below the 70th Street Garden, and many smaller openings for mechanical ductwork. The new concrete wall also needed to laterally connect the first-floor diaphragm of the reception hall and the 70th Street Garden slab diaphragm.

The top of the concrete wall was designed with a heavily reinforced corbel to re-support the eccentric landmarked masonry wall and reinstalled limestone-clad concrete stairs. The new concrete wall continues slightly above the corbel to support the framing of the new first-floor slab and to laterally tie the diaphragm to the wall. The “closed ties” that are required across the height of the corbel were particularly difficult to install, as the contractor only had access from the exterior side to install the ties. Access from above and from the interior side, something generally available in ground-up construction projects, was restricted by the

construction sequence and the existing wall to be re-supported. As a workaround, SGH designed a series of hooked reinforcement and cross ties that could be installed from one side (Fig. 11).

Finally, SGH designed a horizontal steel truss to transfer lateral forces between the shear wall and the 70th Street Garden diaphragm. The truss, located just below the corbel base, is connected to the shear wall by cast-in-place steel plates embedded into the concrete wall and to the garden diaphragm by steel-plated connections welded to the long-span composite steel beams that support the garden slab.

Navigating the challenges of designing lateral systems for additions and overbuilds in historic buildings requires an in-depth knowledge of several archaic structural systems, an understanding of lateral load paths, some creative detailing, and extensive familiarity with relevant building codes and available literature. When all this takes place at an iconic, world-renowned museum like The Frick Collection, the journey becomes even more arduous.

After several years of seamlessly concealing structural systems behind lavish finishes, addressing unforeseen field conditions, and modifying the structural design to expedite construction, The Frick Collection finally reopened to the public in April 2025 to overwhelming acclaim and throngs of curious visitors (Fig. 12). Despite its array of complex challenges, the project proved to be a formative, unprecedented, and deeply rewarding experience—and one for which the authors remain profoundly grateful.■

Strong but narrow-profile steel frames offer visual continuity between fire-rated and non-rated assemblies within the

By Devin Bowman

Elevators are a near necessity in most publicly accessible buildings. They augment stairwells by dispersing traffic flow. They also support accessibility and provide additional means of egress. With advances in fire-rated glazing, designers have shifted from using strictly opaque materials to planning open, bright and code-compliant elevator shafts. However, unlike other elements of the built environment, elevators generally require larger load tolerances to accommodate full cars, machinery, and dynamic forces. These higher tolerances help maintain precise alignment of vertical elements.

These considerations can make designing and engineering modern and visually stunning elevators challenging, especially when taking into account visibility into and out of elevator cars. When an elevator design includes glass curtain walls or other glazing assemblies, project teams can utilize steel sub-frames to meet both fire-rated as well as dynamic and static load requirements. And when these sub-frames are roll-formed, they can be specified with narrower profiles to maximize the glazing area and allow the use of a variety of cover caps without significantly increasing framing width. This can support a cohesive design aesthetic between fire-rated and non-rated assemblies in a wide range of applications.

Steel sub-frames were used in two prominent elevator shafts in New York City: The Fulton Center Transit Hub and the Empire State Building. These projects exemplify how steel can be at the center of a successful elevator shaft design—literally and metaphorically. But before discussing them directly, it is important to detail what these structures may need to be safe and code-compliant.

First and foremost, as a vital component in a means of egress system, elevators shafts are often required to meet local building code requirements for fire and life safety. As these requirements can vary significantly between locations, project teams are encouraged to consult with local

fire- and life-safety codes and to clarify any ambiguities with an Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). That said, model building codes, like the International Building Code (IBC), provide an adequate baseline for the discussion of these structures.

According to Chapter 7 of the 2024 edition of the IBC, shaft enclosures must be constructed as fire barriers, which is a wall or other kind of continuous membrane designed and tested to limit the spread of fire—a full definition can be found in the National Fire Protection Association’s Life Safety Code (NFPA 101). Commonly, for elevator shafts that connect less than four stories, a fire-resistance rating of 60 minutes is required. Shafts larger than four stories will often need a 120-minute fire-resistance rating. To meet these requirements, structural components, including glazing and framing systems, will need to defend against fire, smoke, and radiant heat for the duration specified in the building codes for their size and occupancy.

In addition to meeting requirements for fire and life safety, as structural elements of the built environment, elevator shafts and their components must meet all applicable design loading criteria, including wind, flood, and seismic loads, as defined by local codes. Likewise, these structures must also have the strength to hold the machinery, elevator cars and their maximum load weight without deformation to ensure proper functioning. They must also meet requirements for vertical and lateral deflection tolerances. These requirements can vary significantly between projects based on local building codes, location of the elevator shaft within the building, its height, its motor and car, capacity, and other considerations—all found in Chapter 16 of the 2024 edition of the IBC. Although aluminum frames can meet these requirements, they may require more material, supplemental supports, and ancillary fire defense systems. Steel frames, on the other hand, can minimize the need for these additional systems. Steel frame systems can pass ASTM E330-97 test standards, demonstrating a resistance to damage from a uniform structural load of +/- 125 pounds per square foot (PSF). Additionally, there are systems ranked for use in hurricane zones that have been certified to multiple standards that determine

their resistance to wind loads, cyclic wind pressure, impact, design pressure, and more.

In terms of fire-resistance, two factors differentiate steel from aluminum: melting point and thermal conductivity. Depending on the alloy, steel generally has a melting point between 1,370C and 1,540C while aluminum’s is around 660C. Considering temperatures can reach up to 1,000C in typical commercial building fires, steel’s higher melting point helps reduce risk of deformation and melting, which is crucial for ensuring elevator components remain functional to help occupants evacuate during a fire emergency.

Steel also has a lower thermal conductivity than

aluminum—approximately 50-60 Watts per meter-Kelvin (W/mK) compared to 205-237 W/mK. This means steel transfers less heat over a given time range than aluminum. With a higher resistance to radiant heat, steel framing helps egress paths remain traversable as occupants evacuate and first responders arrive. Both the higher melting point and lower thermal conductivity of steel contribute to a full glazing system’s ability to meet ASTM E119 (Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials) and UL 263 (Fire-resistance Ratings) as required by fire- and life-safety building codes.

In addition to fire-resistance, steel also offers a modulus of elasticity of over 29 million pounds per square inch (PSI), nearly three times that of aluminum’s 10 million PSI. As a stiffer material, steel framing can accommodate design loading criteria, including both static and dynamic loads, as well as the extra weight of fire-rated glazing. And the material can do this without requiring larger framing profiles since it does not require any fire resistive interlayers or multiple bulky secondary