Thank you to all of the participants

Your hard work and dedication to the craft and skill of structural engineering is unmatched.

We are honored to be a part of your projects, and look forward to what the future holds for our industry.

Prize of the Public

Hannahville Indian Community Governmental & Health Services Building

Wilson, MI

Lead Engineer | Gregory Naghtin

Company | ISG

Architect | ISG

Contractor | Miron Construction

Software | RISA-3D | RISAFloor | RISAFoundation | RISAConnection

Scan to See All Winning Projects

— Gregory Naghtin, PE

Available Only at STRUCTUREmag.org

Publication of any article, image, or advertisement in STRUCTURE® magazine does not constitute endorsement by NCSEA, CASE, SEI, the Publisher, or the Editorial Board. Authors, contributors, and advertisers retain sole responsibility for the content of their submissions. STRUCTURE magazine is not a peer-reviewed publication. Readers are encouraged to do their due diligence through personal research on topics.

subscriptions@structuremag.org

Chair John A. Dal Pino, S.E. Claremont Engineers Inc., Oakland, CA chair@STRUCTUREmag.org

Kevin Adamson, PE Structural Focus, Gardena, CA

Marshall Carman, PE, SE Schaefer, Cincinnati, Ohio

Erin Conaway, PE AISC, Littleton, CO

Sarah Evans, PE Walter P Moore, Houston, TX

Linda M. Kaplan, PE Pennoni, Pittsburgh, PA

Nicholas Lang, PE Vice President Engineering & Advocacy, Masonry Concrete Masonry and Hardscapes Association (CMHA)

Jessica Mandrick, PE, SE, LEED AP Gilsanz Murray Steficek, LLP, New York, NY

Brian W. Miller

Cast Connex Corporation, Davis, CA

Evans Mountzouris, PE Retired, Milford, CT

Kenneth Ogorzalek, PE, SE KPFF Consulting Engineers, San Francisco, CA (WI)

John “Buddy” Showalter, PE International Code Council, Washington, DC

Eytan Solomon, PE, LEED AP Silman, New York, NY

Executive Editor Alfred Spada aspada@ncsea.com

Managing Editor Shannon Wetzel swetzel@structuremag.org

Production production@structuremag.org

Director for Sales, Marketing & Business Development

Monica Shripka Tel: 773-974-6561 monica.shripka@STRUCTUREmag.org

Sales Manager

Audrey Schmook Tel: 312-649-4600 Ext. 213 aschmook@ncsea.com

The National Council of Structural Engineers Associations (NCSEA) is pleased to share winners of the 2025 SEE Awards, which were recognized at the NCSEA Summit.

By Jessica Westermeyer, PE, SE

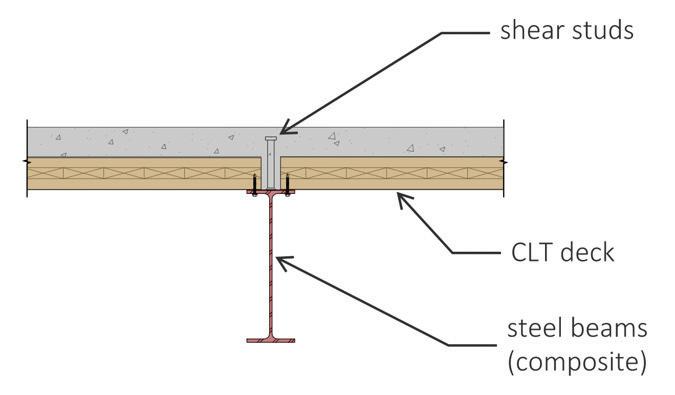

The four-story Health Sciences Education Building at the University of Washington represents a case study in hybrid mass timber.

SPEED-TO-MARKET

DEDICATED TEAM DESIGN FLEXIBILITY

SUSTAINABILITY

Technology evolves at warp speed, and the construction of your data centers needs to keep pace. Steel joist and deck solutions from New Millennium bring data centers to market quickly, so revenue flows faster.

By James Robert Harris, Ph.D, PE

Salmon, PE,

By Robert K. Dowell, Ph.D, PE and Althaf Shajihan, Ph.D

Silky Wong, Ph.D,

Aaron Kostrzewa,

By James Robert Harris, Ph.D, PE

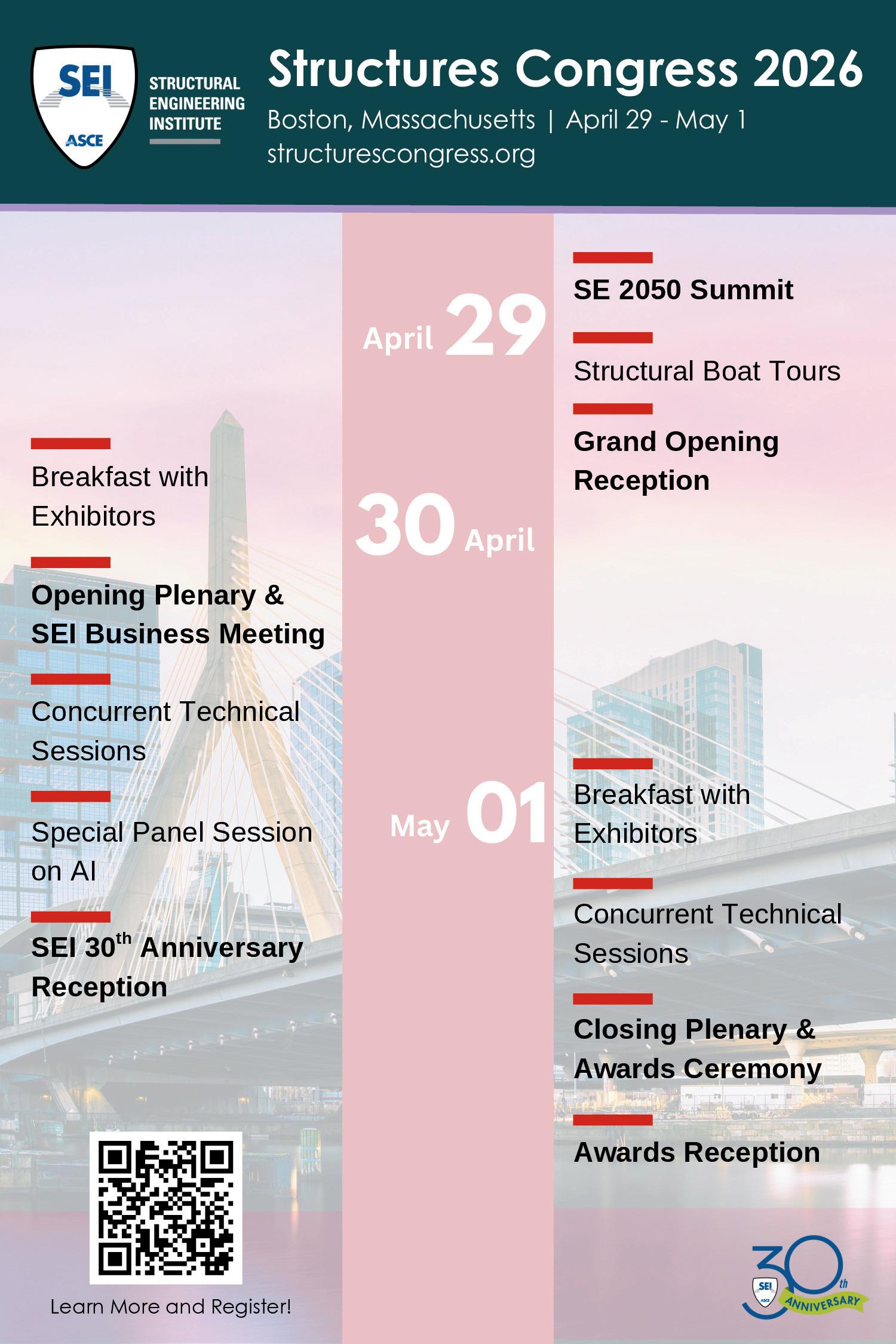

The SEI Futures Fund supports programs beyond the SEI operating budget—programs that inspire, educate, and connect the next generation of structural engineers while advancing the art, science, and practice of the profession.

Through the generous support of donors, the Fund invests in high-impact initiatives that align with SEI programs and vision for the future of structural engineering. I am proud of the programs the SEI Futures Fund has made possible in 2025, through the support of your donations.

120+ scholarships were awarded to students and young professionals to help them get involved at Structures Congress and the Electrical Transmission and Substation Structures Conference, including informal mentoring for further involvement in SEI. This was the largest group of scholarship recipients to date, with former scholarship recipients leading and serving at all levels—on the SEI Board, committees, and with local and grad student chapters.

The Fund provided support for 17 Young Professional SEI Standards Committee Leaders (Secretary, Balloter, or Historian), to participate in committee operations, realizing critical knowledge transfer to next generation leaders. Past recipients now serve in several Chair and Vice-Chair positions.

“Serving as the balloter for the ASCE 7 Wind Load Subcommittee has allowed me to actively participate in the Steering Committee and gain a comprehensive understanding of the entire code development process—from proposal generation, to voting, approval, and final inclusion in the next code. The Committee brings together professionals from diverse disciplines, including wind and structural engineering, as well as consultants and researchers. This experience has strengthened my relationships with industry leaders, opened the door to new professional connections, and sparked cross-disciplinary conversations—even beyond the scope of code development. This code cycle has been particularly exciting, as it includes impactful changes, and I was able to engage directly with the researchers whose work is driving these advancements.”—Juliana Rochester, PE, SE, M.ASCE

Going forward this will expand to other SEI standards and technical committees.

At the Towards Zero Carbon 2025: Summit and Symposium, support was provided for speakers, representatives from SE2050 signatory firms, and members of the organizing committee to participate. In 2026, support will align strategic Towards Zero Carbon activities to address growing needs: to offer the SE2050 Signatory Summit at Structures Congress as a pre-conference workshop, to continue to educate about the SEI Embodied Carbon Prestandard, and to support data analysis of the new SE2050 database, enabling insights on design parameters that influence lower carbon and resource efficient designs, to develop a roadmap to net zero.

Funding brought together leading experts in a workshop to plan implementation of performance-based design for wind, identify next steps in developing standard provisions and performance objectives for performance-based design procedures, and produce resources and educational activities to advance the use of performance-based design procedures in practice.

Small grant funding was provided for 12 local SEI Chapters and Grad Student Chapters to run innovative programs leveraging local partnerships to engage students and professionals and to foster continuous membership and involvement in SEI/ASCE. Efforts included technical/networking and career insight events, site or firm visit, training, etc.

The SEI Futures Fund has supported the following resources:

• SEI/ASCE webinar series on Client Value, Productivity, Entrepreneurship,

which will continue in 2026 with SEI Grad Student Chapters.

• ASCE/SEI 7 Student Primer.

• Prestandard for Assessing the Embodied Carbon of Structural Systems for Buildings in the ASCE Library.

Through your generous giving, the SEI Futures Fund Board has committed more than $300,000 to support SEI strategic initiatives in 2026.

Now more than ever we need your gift to continue growing and empowering the next generation of innovators, problem-solvers, and leaders who will define the future of structural engineering.

Our goals include supporting programs that:

• Invest in the future of the structural engineering profession.

• Promote student interest in structural engineering.

• Support younger member involvement in SEI.

• Enhance opportunities for professional development.

Give now to show your support and invest in the future of our profession. Your gift is taxdeductible and goes 100% toward programs, with no administrative fees.

Thank you to SEI Futures Fund Donors, and especially Thornton Tomasetti for their match up to $5,000! If you or your firm want to set up a matching gift challenge, contact me or any other member of the SEI Futures Fund Board (www.asce.org/SEIFuturesFund ). And by the way, if you have a great idea to further these goals and want to submit a proposal, contact the leaders of SEI chapters or national committees for guidance on how to gain their support for a proposal.

Thank you for your gift and have a wonderful holiday season! ■

Contractor involvement during design can help take the guesswork out of what may be most economical for building projects.

By Jeremy Salmon, PE, SE and Zak Pruitt, PE, SE

Design decisions are typically based on previous experience, engineering judgment, and code requirements. However, the project location, general contractor, trade partners, and local practices may impact the structural design and detailing. Contractor involvement during design can provide input on key decisions in the selection of structural systems, use of building materials, and more. Instead of value engineering after the project has been completed, early contractor input can avoid costly redesign efforts and schedule delays. Part 1 will discuss contractor input that affects the design of the structure. Part 2 will discuss contractor input that affects detailing, constructability issues, and construction sequencing.

Concrete elevated floor systems can be constructed using either structural lightweight or normal weight concrete. Structural lightweight concrete can reduce an elevated slab’s weight and thickness. Lightweight concrete weighs approximately 107 to 112 pounds per cubic foot (pcf) versus approximately 145 pcf to 150 pcf for normal

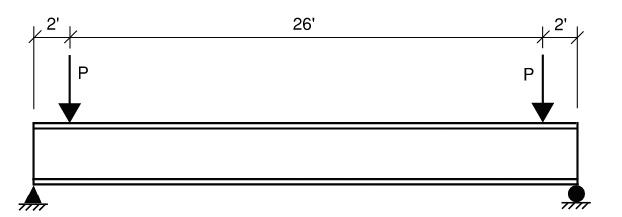

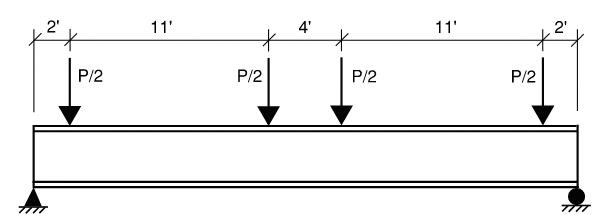

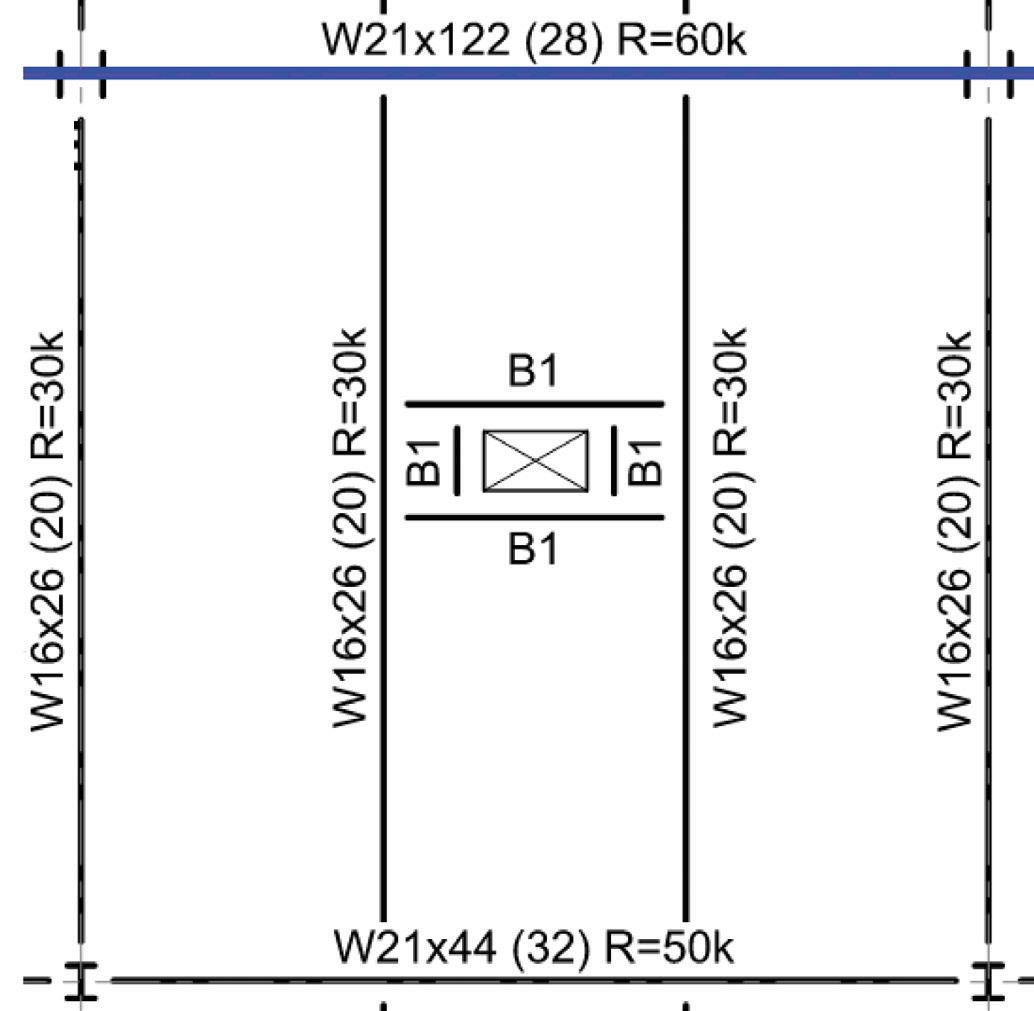

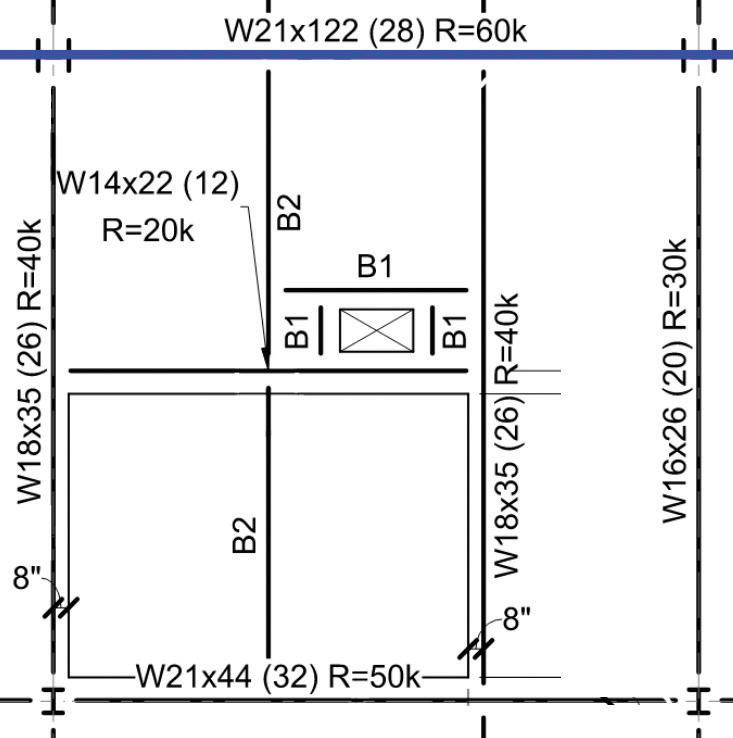

Precast Panel Loading at Ends of Beam Only:

Total Panel Weight Supported by Beam =2xP

Maximum Applied Moment =2xP

Moment of Inertia Required for L/480 =17.77xP

Precast Panel Loading at Ends of Beam and Mid-Span:

Total Panel Weight Supported by Beam =2xP

Maximum Applied Moment =7.5xP

Moment of Inertia Required for L/480 =52.44xP

Takeaway: While the total panel weight to be supported by the beam remains constant, the applied moment demand increases by 375% and the required moment of inertia increases 295% due to precast panel loading locations.

UL assembly D-925). The lighter floor system decreases dead load, which reduces the beam, column, and foundation member sizes. However, structural lightweight concrete may not prove to be the most economical choice for a project. The availability and source of lightweight aggregates must first be discussed with the contractor. It may be more common for normal weight concrete to be specified in some locations, such as Alaska, Idaho, and others. The same holds true for lightweight concrete masonry units (CMU). While lightweight CMU is easier to handle during construction, its availability may be limited in some locales.

weight concrete. Lightweight concrete also provides better fire rating properties. For example, to achieve a two-hour fire floor rating, only 3¼ inches of structural lightweight concrete is required compared with 4½ inches of normal weight concrete (per Underwriters Laboratories

Design of concrete structures is not limited to just one solution. A range of member sizes and material strengths are available for each structural component. Understanding the availability and cost associated with high strength concrete may help determine member designs. For example, a spread footing or pile cap may be adequate with a 2-foot thickness and a 28-day compressive strength (f’c) = 8 kips per square inch (ksi), or a 4-foot thickness and f’c = 4 ksi. Either option may be adequate structurally, but the cost difference in mix design, material quantities, excavation depth, formwork, etc. may not be obvious without contractor input. As another example, specifying various concrete column compressive strengths at various columns within a given floor could result in mix design savings, but the contractor may prefer to use the higher strength concrete for

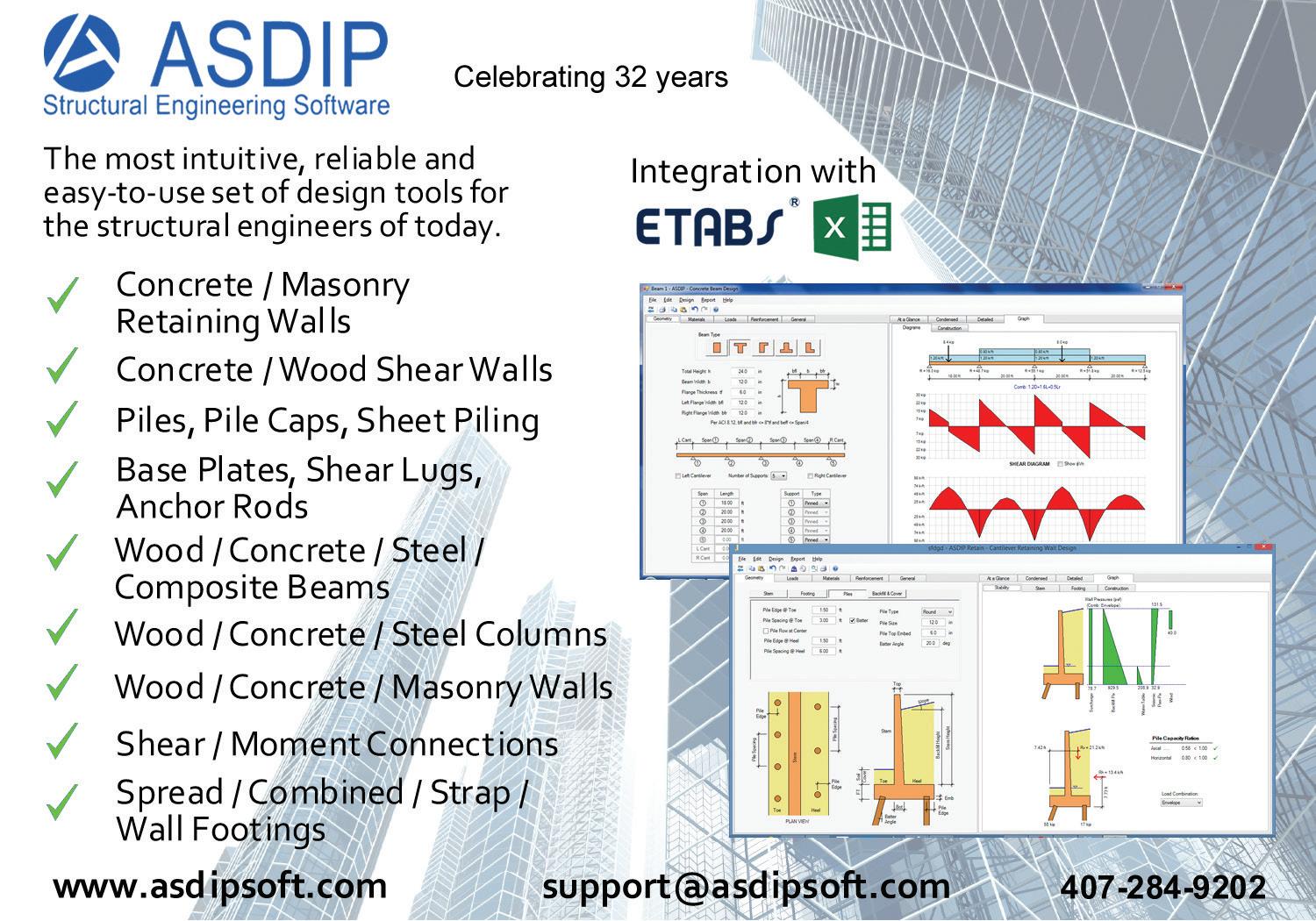

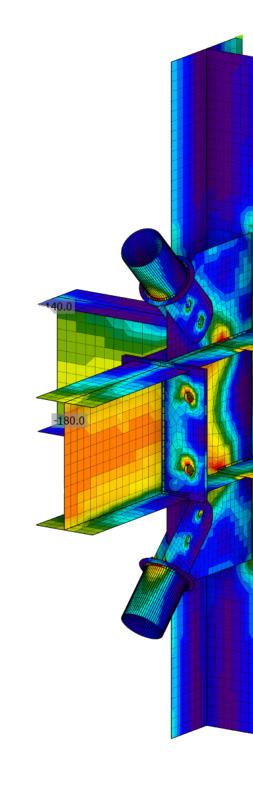

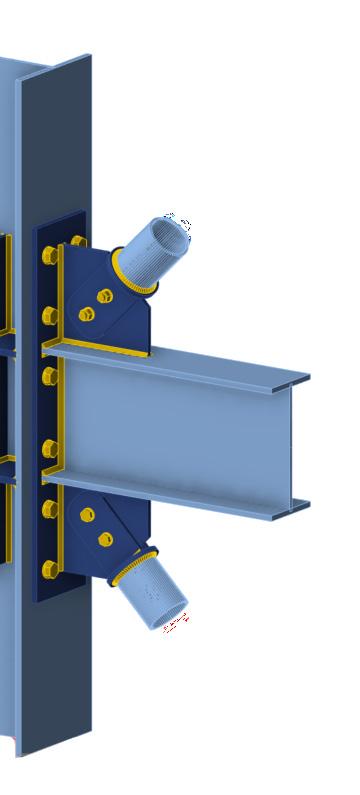

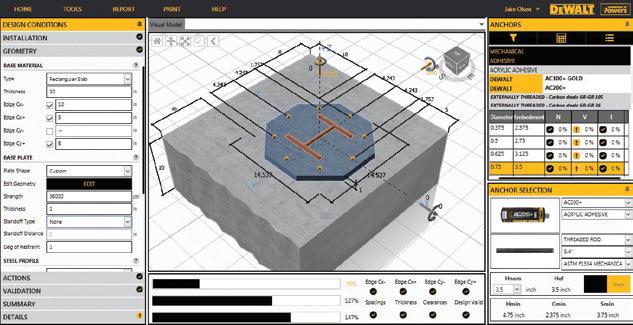

Save time and money with the world-leading structural design software.

Connection design at its best

Steel anchorage workflow

Supplement your strut and tie analysis

Any geometry, any loading, in minutes

Intergates with your software

Try the full version for 14 days for free

all columns to avoid concrete mixer trucks with different strengths of concrete to maintain simplicity on site.

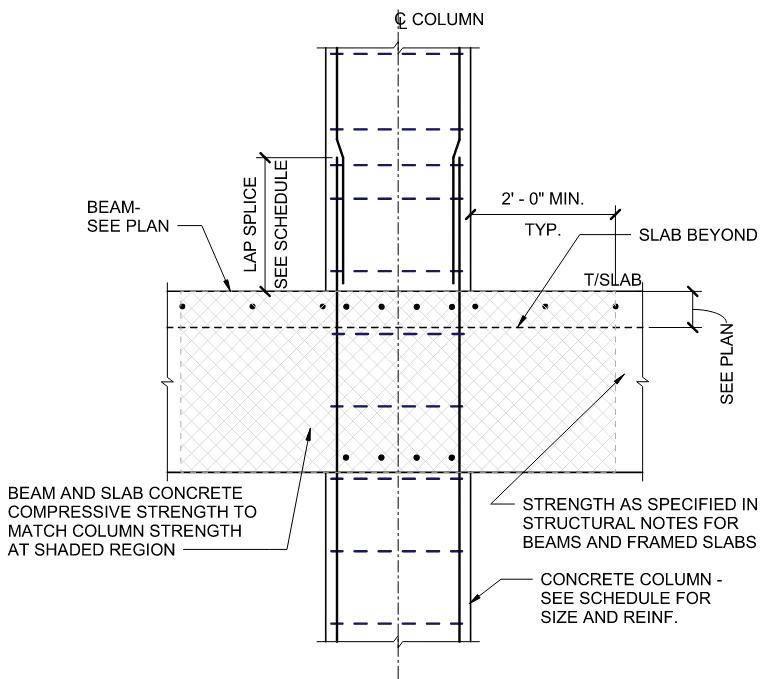

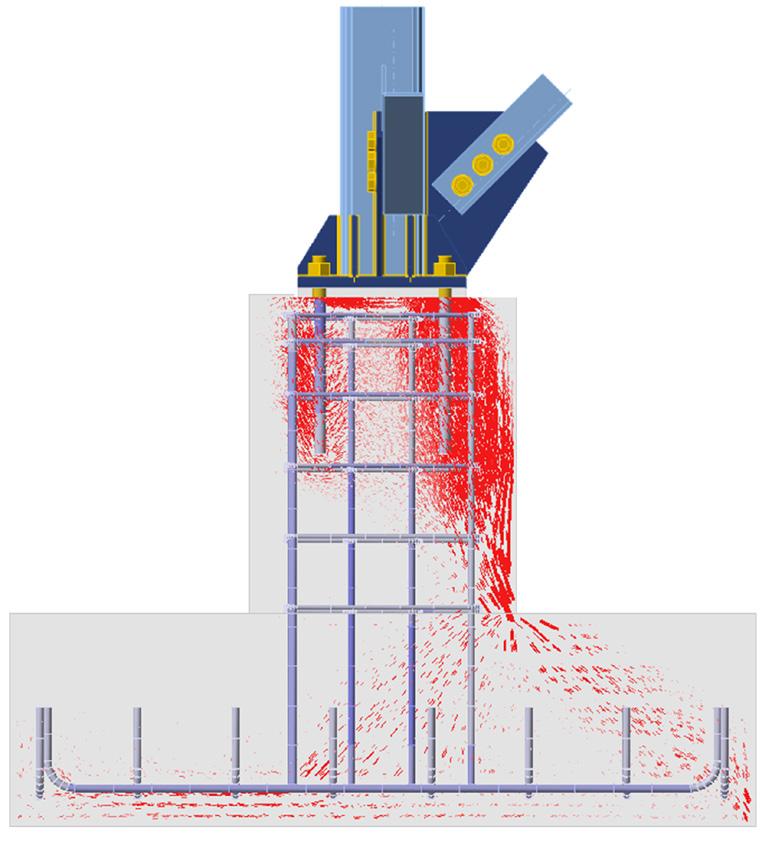

Another example is puddling at concrete columns which consists of placing higher strength concrete in the slab around a column before the rest of the slab is placed (Fig. 1). Discussion with the contractor may dictate if it is cheaper to puddle, increase the specified floor plate compressive strength, or increase the column size to reduce its required specified compressive strength.

There are more grades of reinforcement steel for concrete structures available now than ever before. High strength reinforcement, such as 75 ksi, 80 ksi, and 100 ksi are now options found in the American Concrete Institute’s ACI 318, Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete, and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) specifications. Specifying higher grade reinforcement can help mitigate congestion issues, but their longer development lengths and material availability should be considered. Providing options for contractor review will allow for an economical design and minimize the risk of specifying high strength reinforcement that may not be available or would require a cost premium.

Architectural precast panels can provide strength, durability, and energy efficiency to the building facade. A wide variety of custom

shapes and sizes are possible. Designing the structure for the weight of the precast panels successfully requires an understanding of the panel thickness, joint locations, and approximate locations of bearing/lateral connections. The floor heights, wind pressures, and building elevations will drive the panel thickness and connection locations. While it may be simplest to assume the precast panels can span between columns, bearing locations may be necessary on each side of the columns, or even at mid-span of the spandrel beams. The crane selection and site constraints may determine how the panels need to be broken up for erection purposes. Two possible precast loadings are shown in the sidebar. In one scenario the precast bearing connections are located two feet from the columns. In the second scenario, the precast panels are broken at mid-span adding additional point loads along the length of the beam. The total weight on the beam is the same, but the maximum moment and required moment of inertia are significantly different. Contractor and precast supplier involvement can provide input on the feasibility of complex precast shapes.

Design of the roof and floor framing may be affected by the need for the contractor to access the lower floors of the structure. Large items, e.g. construction materials or say prefabricated bathroom pods, may need to be dropped into place through the roof of the structure, which will require roof opening framing (Fig. 2). Similarly, if site constraints or crane reach limitations require the crane to be located within the building footprint, an opening at each floor and a required crane mat will affect the design of the structure and foundations.

Before proceeding with a proprietary system, the product should be reviewed with the contractor during the design phase. For example, SidePlate moment frame connections consisting of steel plates connected to the columns that are field bolted to plates and angles on the beams are widely used today. SidePlate eliminates complete penetration welds and ultrasonic testing. It is a best practice to ensure the contractor, fabricator, and erector are familiar with the proprietary system and licensing fee, and if not, get them connected.

Foundation types will vary between projects, but contractor input can assist in providing cost-effective and practical solutions.

• For auger cast piles, geotechnical engineers will typically provide multiple pile diameter options (e.g. 14 inch, 16 inch, or 18 inch) and varying embedment depths. The contractor may have a preference on fewer piles with bigger diameters/deeper pile tip elevations compared with more piles with smaller diameters/ shallower pile tip elevations. So for lightly loaded columns, is it better to switch pile diameters or keep the same pile diameter?

• Drilled pier diameters could range from 24 inch diameter to over 120 inch. The pier diameter could vary from column to column with a consistent embedment depth, or the pier diameter could be kept constant and vary the embedment depth. There also could be a maximum pier diameter that is feasible for the drill rig; in lieu of using a 120 inch diameter drilled pier, it could be better to use two 84 inch diameter piers with a concrete grade beam to support the building column.

• For additions adjacent to existing buildings, it is helpful to understand what drill rig will be used and how close a new drilled pier or auger cast pile can be installed next to an existing structure. If a building column with its drilled pier is located only a foot from an existing building, the drilled pier instead may be located say three feet away from the existing building with

a concrete grade beam designed to cantilever over the drilled pier to support the building column.

• Aggregate stone column foundations can be an effective intermediate foundation system and would allow for a high allowable bearing capacity (5 ksf to 8 ksf); however, the vibrations and noise from their installation should be considered. Sensitive equipment and occupant discomfort can be addressed with the contractor to determine if alternative ground improvement methods (e.g. rigid inclusions, compaction grouting) should be considered. Monitoring equipment may also be recommended for adjacent existing structures.

• Due to expansive soils or undocumented fill on a site, the geotechnical engineer may recommend removing a significant volume of existing soils or using a framed first floor over a crawl space. Contractor pricing can provide insights to the owner on the most economical approach.

Contractor involvement during design can help take the guesswork out of what may be preferred and considered most economical by the contractor. The design can be optimized to provide a cost-effective project and minimize potential design and drawing changes after construction documents are issued. Part 2 of this series will discuss contractor input that affects detailing, constructability issues, and construction sequencing. ■

at zakp@sdg-structure.com.

The traditional and novel computational methods are compared in various statically indeterminate structural engineering problems.

By Robert K. Dowell, Ph.D, PE and Althaf Shajihan, Ph.D

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has really taken off since the release of the initial version of ChatGPT in 2022 by OpenAI, and its use has accelerated with the many subsequent versions, having a significant impact in so many different areas of life. The newest open-to-public version from OpenAI is GPT-5, with more sophisticated capabilities for solving problems using the deeper reasoning model (GPT-5 Thinking) and GPT-5 Pro with research-grade intelligence. AI is rapidly growing and affecting our daily lives, both professionally and personally. So it is important to understand its benefits and limitations applied to structural engineering and how it can be used by the profession going forward. Until about 1980, structural analysis and structural design of buildings, bridges, and other structures, were still typically performed using hand calculations. However, since about 1980, most structures have been analyzed and designed using computers and dedicated, commercially available structural analysis software, from beam elements to sophisticated finite element solutions, including shell and solid elements. While hand calculations are still used by structural engineers, this is typically relegated to spot-checking the computer results.

In 2022, another potential option suddenly presented itself to solve structural analysis problems, including statically indeterminate structures, with the release of the first version of ChatGPT. Engineers now have three possible ways to solve structural engineering problems: (1) hand calculations, (2) developing a computer model of the structure and solving it on a computer with dedicated structural analysis software, and (3) using generative AI.

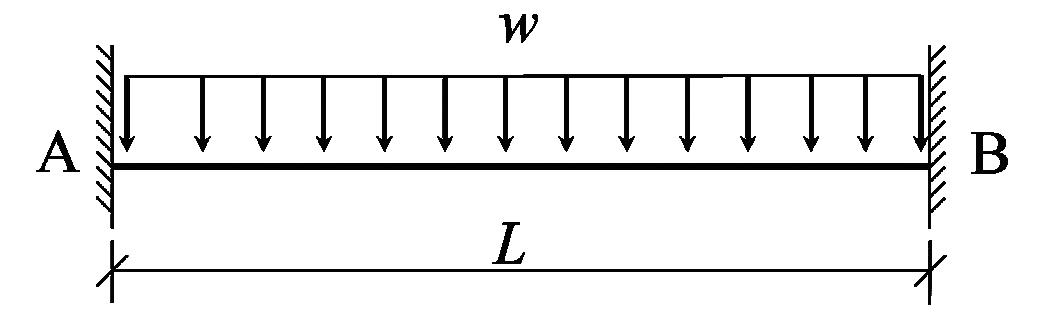

Since the first author has, for decades, been steeped in hand calculation methods and deriving unique closed-form solutions to complicated structural engineering problems, allowing these to be solved by hand, and the second author is an expert of AI applications in structural engineering, this article presents several examples of statically indeterminate structures and compares the AI results to those found from the relatively simple hand calculations. When ChatGPT and hand-calculated solutions did not match, another hand calculation method was used to verify the hand results. In the following, five different statically indeterminate problems are given, asking for either the numeric or symbolic solutions from ChatGPT, depending on the problem statement. Interestingly, a computer model is not required to solve these problems with ChatGPT, at least not a model developed by the user. For each problem, three independent trials were conducted. ChatGPT was provided with a screenshot of the problem statement and the corresponding structural image, along with the following prompt: “Think thoroughly, satisfy governing physics and compatibility requirements, and solve this.” Notably, even a simple hand sketch of the structure proved sufficient in place of a detailed engineering drawing, as ChatGPT is trained to interpret visual inputs through advanced visual-understanding capabilities.

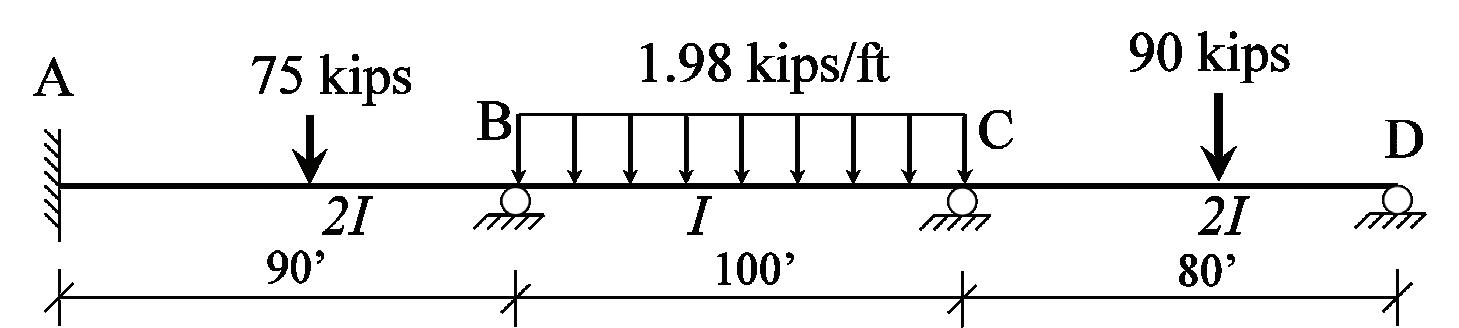

Problem 1. Find the final member-end-moments, symbolically, in terms of w and L, for the beam with fixed ends given below. Consider only flexural deformations (no shear deformations).

Solution: Attempt Model and Approach by AI Result Accuracy Comments

1 (GPT-5 Thinking) First principles, Euler-Bernoulli beam theory

2

3

Correct final member-endmoments of wL2/12; matched hand calculation from compatibility method.

Same as above ✅ NA: problem solved correctly in first trial.

Same as above ✅ NA: single attempt sufficient.

Summary: For this simple fixed-fixed beam, ChatGPT quickly produced the correct symbolic solution for final member-end-moments, matching the well-known closed-form hand-calculation result of wL2/12

Problem 2. Determine final member-end-moments, and draw shear and moment diagrams, for the three-span continuous beam shown. Consider only flexural deformations (no shear deformations). Provide results in kip and kip-ft units.

Solution:

Attempt Model and approach by AI

1 (GPT-5 Thinking) Moment Distribution

Stiffness Method

2 (GPT-5 Thinking) Slope Deflection Method

3 (GPT-5 Thinking) Moment Distribution

Correct results; AI wrote Python code; ~8 min to solve.

Incorrect; largest member-end-moment error over 600%; ~12 min to solve.

Correct results; consistent with Attempt 1 and hand calculations; ~13 min.

Summary: Three independent attempts using GPT-5 Thinking produced mixed results. ChatGPT selected a different fundamental method each time and independently wrote computer code to solve the structure. Two of the three attempts matched the hand calculations exactly, while one produced large errors. In the first attempt it switched part-way through from one method to another.

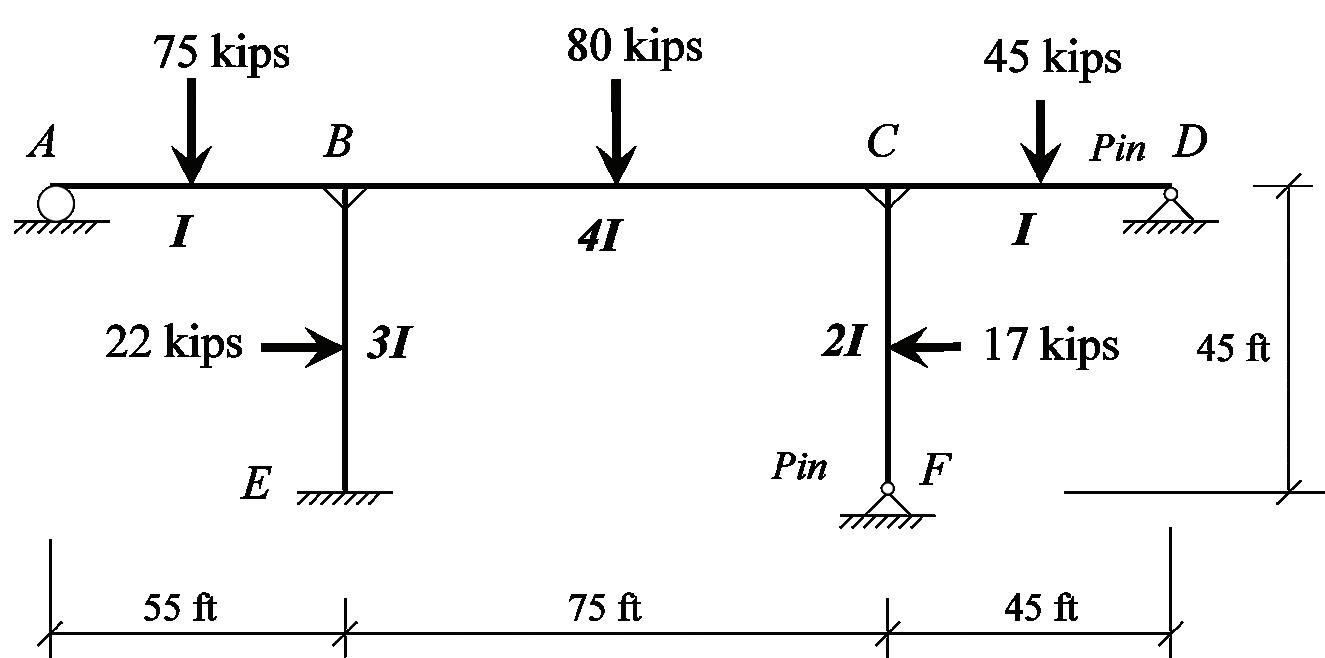

Problem 3. For the statically indeterminate frame structure given here, calculate final member-end-moments, and draw shear, moment and axial force diagrams. Consider only flexural deformations (no shear or axial deformations). Provide results in kip and kip-ft units.

Solution:

1 (GPT-5 Thinking) Slope Deflection Method

2 (GPT-5 Thinking) Stiffness Method

3 (GPT-5 Thinking) Stiffness Method

Maximum moment error in: Span ~12%; column error ~90%; AI wrote Python code.

Maximum moment error in: Span~10%; column error ~100% (factor of two).

Same as Attempt 2; results consistent with each other but incorrect compared to hand calculations.

Summary: Three independent GPT-5 Thinking attempts produced similar but incorrect results. ChatGPT used the Slope Deflection and Stiffness Methods, writing Python code in each case. Errors were verified by hand using the Closed-Form Method, confirming deviations of up to 100% in column member-end-moments.

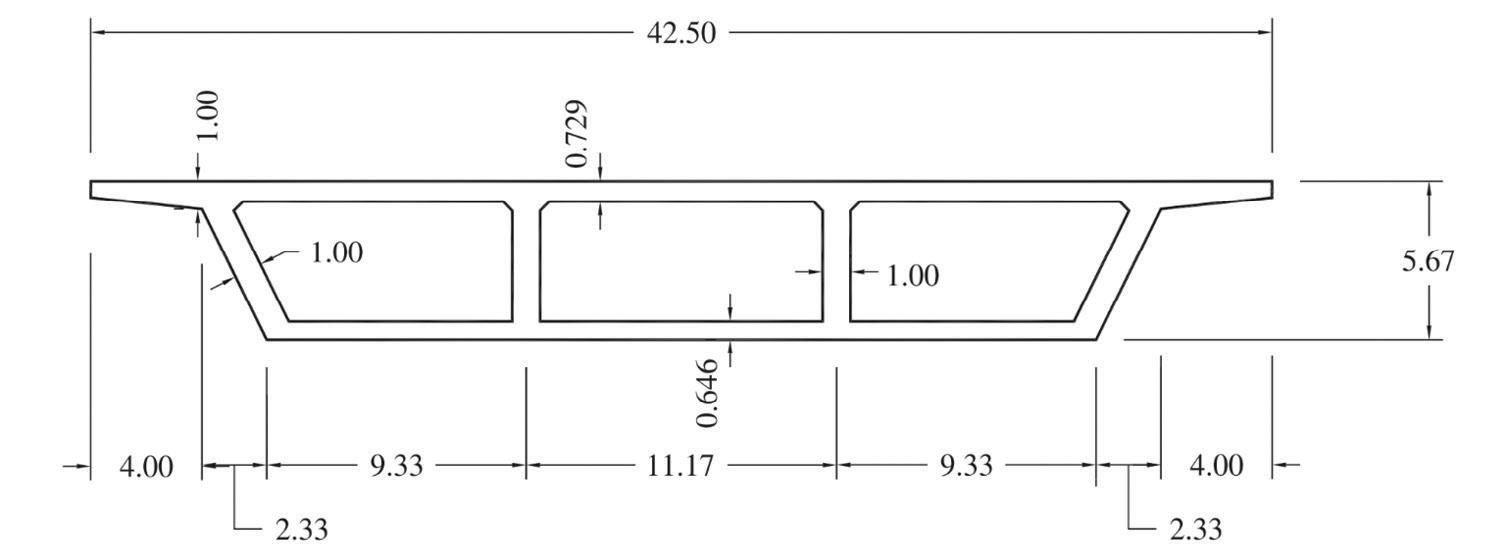

Problem 4. Find final shear flows on all walls for the box-girder bridge crosssection given here, with applied torsion of 20,000 kip-ft. The lengths in the figure below are in ft units. Ignore the cantilevers at the overhangs. Solve this as three cells of a multi-cell, statically indeterminate, cross-section. Provide shear flow results in units of kips/ft.

Solution:

Attempt Model and approach by AI

1 (GPT-5-Pro) Bredt-Batho model for multi-cell torsion

2 (GPT-5 Thinking) Bredt-Batho model

3 (GPT-5 Thinking) Bredt-Batho model

Comments

Approx. 10% error in shear flow; incorrect torsion area for exterior cells.

Same error; used simultaneous equations for torsion compatibility.

Same as above; consistent but incorrect.

Summary: All three ChatGPT attempts produced similar but incorrect shear-flow distributions. The error was traced to the AI’s use of the exterior surface instead of the girder centerline for calculating effective torsion areas in the end cells. Despite the mistake, ChatGPT correctly applied the Bredt-Batho compatibility equations and wrote Python code to solve the system.

Problem 5. For a continuous beam that is loaded with point load P at the center of one span, and has an infinite number of spans, all of length L, in each direction from this one loaded span, determine exact final member-end-moments for the loaded span in terms of P and L, as well as any span beyond this loaded span, considering only flexural deformations. The results to this infinitely-redundant problem are to be given exactly as a fraction, and not in decimal form.

Solution:

Attempt

1 (GPT-5-Pro) Slope Deflection Method, symbolic

2 (GPT-5-Pro) Slope Deflection Method, symbolic

3 (GPT-5-Pro) Slope Deflection Method, symbolic

Correct for non-loaded spans; incorrect for loaded span.

Same result; omitted fixed-end-moment for loaded span.

Repeated same oversight; otherwise, consistent symbolic reasoning.

Summary: This problem represents a significant challenge to solve exactly, since the Stiffness Method and the Moment Distribution Method require either an infinite number of equations to be solved or an infinite number of distribution cycles for convergence. Requiring the results in fractional form rather than in decimal form further increases the difficulty. An exact, hand-derived solution to this problem was published in Engineering Structures in 2009 by the first author, introducing the Closed-Form Method for continuous beams and frame structures. In three independent attempts using both GPT-5 Pro and GPT-5 Thinking, ChatGPT solved the problem symbolically with the Slope Deflection Method, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of the other techniques. It produced the correct symbolic fractional results for all non-loaded spans but made an error for the one loaded span by omitting the initial fixed-end-moments from the final solution. Since no initial fixed-end-moments exist in the non-loaded spans, the distributed moments from the single loaded span were otherwise correct and final.

AI is being used in all sorts of ways, including in structural engineering. This article considered state-of-the-art AI for public use, focusing on the most recent version from OpenAI, GPT-5, including the more advanced GPT-5-Thinking and GPT-5-Pro versions for their higher problem-solving capabilities. Five statically indeterminate problems were solved by hand calculations and then compared to the ChatGPT solution. In all cases, the input to ChatGPT was just a simple drawing of the problem and the statement that it needed to solve it by thinking. From the drawing, ChatGPT correctly interpreted the member lengths, point loads and distributed loads, boundary conditions, and the different moment of inertia values for the various members. It also understood when the point loads were applied at mid-span, based on the geometry of the drawing. To solve the problem, ChatGPT wrote its own computer program in Python and then ran it. Interestingly, it relied on classical methods of structural engineering, rather than inventing its own new technique, and then wrote the program to solve the problem once it had decided on a method to use - typically Moment Distribution, the Stiffness Method or the Slope Deflection Method. For one problem, it solved it three different ways in the three different attempts. When there was a difference between the ChatGPT and hand calculation results, another hand calculation method was used to verify the initial hand calculations. In addition, for all five problems the first author’s Closed-Form Method was applied by hand to verify the results. The AI approach is extremely simple and sometimes provides the correct results, but it often gives the wrong answers, even on

repeat attempts for the same problem that it got correct on another attempt. And sometimes the results were off by a lot. This variation in results is expected because large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT rely on probabilistic reasoning rather than deterministic computation. Each attempt follows a slightly different logical path, depending on how the model interprets the problem, leading to different intermediate steps and final answers. Note that for each attempt of the same problem, no information was given from one try to the other; they were all completely independent efforts. Also, after providing ChatGPT with the initial information for a given problem, there was no human involvement whatsoever. Clearly, had we guided ChatGPT along its path to a solution, better results could have been found and, perhaps, the correct solutions obtained more consistently. It seems that for structural engineering applications, especially for statically indeterminate structures, AI in its current state should be used as an assistant to the structural engineer, helping with given tasks, but not allowed to just move along on its own, from start to finish. Results from the five examples in this article clearly show that AI is powerful, but can be wrong, and for various reasons. To use AI, the structural engineer needs to verify key elements of the analysis and prod it to change direction if it gets lost. While the examples in this article demonstrate the remarkable capability of ChatGPT to interpret sketches and write its own computer code and reason to solve structural problems, this may not be the most effective use of AI for engineering work. The proper role of AI should be to assist in developing, validating, or automating components within established engineering workflows, rather than replacing them. At this stage, a more practical approach would be to use AI to generate or translate model inputs for established

Want to experiment yourself? Scan the QR code to download the Chat GPT prompts and hand calculations, and compare the results.

matrix-based analysis programs where materials, boundary conditions, and load combinations can be defined and verified by the engineer. In this way, AI could act as an intelligent interface—converting sketches or descriptions into preliminary models, plotting and visualizing the structure, or writing custom code to perform specific tasks—while leaving final analysis and design decisions under direct human control. Future implementations may evolve toward an agentic AI workflow which involve existing software/tool use, where AI systems interpret and help reason with the problem to complete the solution process collaboratively. These examples therefore highlight both the power and the current limitations of AI, emphasizing that its greatest potential lies in assisting the engineer to work more efficiently, not in performing complete tasks autonomously. Ultimately, the structural engineer, the human, is still responsible for the analysis and design of structures, and the proper use of AI, computer modeling and hand calculations. ■

Robert K. Dowell received his B.S. degree in Civil Engineering from San Diego State Univeristy (SDSU), and his M.S. and Ph.D degrees in Structural Engineering from the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). He is a licensed Civil Engineer (PE) and a Professor of Structural Engineering at SDSU.

Dr. Althaf Shajihan, Assistant Professor at San Diego State University, received his Ph.D. in Civil Engineering and M.S. in Computer Science from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His research bridges structural engineering and artificial intelligence to advance the structural assessment of civil infrastructure.

A framework based on past project experiences offers practical insights for engineers.

By Silky Wong, Ph.D, SE, PE, C.Eng, P.Eng. and Vigneshwar Natesan PE, P.Eng.

Dimensional control has emerged as a critical discipline in modular construction, particularly for energy infrastructure. The integration of dimensional control into early project phases ensures geometric fidelity—meaning that the construction of modules accurately matches the dimensions and spatial relationships as defined in the engineering model—across modules and mitigates risks associated with misalignment, settlement, and thermal expansion.

Dimensional control is a specialized form of surveying that focuses on precise measurements using techniques and methods designed to determine the three-dimensional spatial properties, dimensions, conformity, and interconnection of objects or structures through both simple and complex calculations. While it shares foundational principles with industrial metrology, dimensional control differs primarily in its broader scope and its application in more varied and often challenging field environments. As the design progresses, the Engineer of Record typically identifies the initial critical control points. These are then reviewed by the dimensional control surveying company. Upon client approval, the surveying company conducts the dimensional control survey and collects the necessary measurements to meet the module erection requirements.

The delayed engagement of dimensional control teams in modular construction projects can result in significant geometric discrepancies, misalignments, and costly rework. Dimensional control is not merely a verification step—it is a proactive quality assurance mechanism that should be embedded throughout the project lifecycle. Figure 1 shows an example of a misaligned pipe at the site when a dimensional control survey was not performed early during the fabrication at the

Without continuous oversight from dimensional control, control monuments and layout references are susceptible to settlement, thermal drift, and cumulative errors without being noticed. In one case, a project ran for 18 months with surveying lacking dimensional control requirements, resulting in misaligned bolt patterns across eight tank foundations. When the tank arrived, it could not align with the bolts. A dimensional control survey was subsequently conducted to enable trimming for fit-up. However, the tank holes were found to be deviated from the engineering design—an issue that early dimensional control verification at the fabrication yard could have identified and resolved.

Projects involving remote fabrication yards face compounded risks when dimensional control is not mobilized early. In a case involving a fabrication yard in the Gulf Coast region of the U.S., the absence of dimensional control jeopardized the single weld hookup strategy. The mitigation involved leaving one module end long and performing as-built surveys post-installation to guide trimming of subsequent modules. This adaptive strategy enabled successful single weld hook-up execution across multiple modules, but only after dimensional control was engaged midstream.

Late dimensional control mobilization (Fig. 2) also limits the ability to influence fabrication procedures. On a project involving mega modules, pile caps were bowed up vertically in the middle (~0.236 inches dome) due to welding-induced shrinkage. The deformation disrupted the use of tapered shim plate, requiring grinding of the cap centerline to achieve surface-to-surface contact. Had dimensional control been present during early welding operations, procedural adjustments could have mitigated the bowing effects at the pile caps.

Large-diameter piping systems, typically those exceeding 30 inches in diameter, pose distinct challenges in modular construction, particularly within the energy facilities including liquefied natural gas. The following project cases collectively highlight the necessity of early and continuous dimensional control engagement in modular construction. From nozzle alignment to thermal expansion, proactive surveying and verification

are essential to preventing costly errors and ensuring successful field fit-up of large-diameter piping systems.

Nozzle misalignments and spool fit-up are common large-diameter piping installation issues, as they are highly sensitive to small coordinate deviations at source points like tanks, absorbers, and compressors. In a recent project, the absence of early dimensional control support for the compressor piping fit-up resulted in multiple failed spool installations and seven piping cuts. Facing the challenge of excessive spool shortening, dimensional control surveyors were finally brought in, and the surveyed data from spools and hard points were used to guide a single corrective cut. In another case, delayed surveying allowed minor misalignments to compound into nearly a foot of deviation after module placement, causing substantial cost and schedule impacts.

Thermal expansion is another critical factor in large-diameter piping systems. Temperature differences between fabrication and installation environments can significantly affect pipe lengths due to the coefficient of thermal expansion in steel, potentially causing clashes or gaps. In a past project, modules fabricated in Louisiana (average temperature 69F) were installed in Alaska (average temperature 14F) without accounting for thermal differential.

A large-diameter pipe designed for single weld hook-up spanning all modules (highlighted in red in Figure 3) led to repeated positional offsets, eventually deviating from the pile foundations’ centerline. Structural engineers halted further offsets due to integrity concerns, leaving a substantial gap between modules. Additional piping was procured to bridge the misalignment, delaying startup and triggering penalties from the State of Alaska. The cost impact, though unreported, was substantial. While observed thermal different effects may be misinterpreted as a design error, qualified dimensional control teams can mitigate this risk by establishing temperature correction protocols and adjusting the spool lengths accordingly, often using multiple target temperatures based on schedule and location. This example illustrates that dimensional control teams are not merely surveying control points but are also

considering the broader project context to ensure successful completion of modular scope.

Dimensional control surveys conducted prior to taking ownership of structures and large diameter piping spools enable early detection of fabrication errors. In several cases, pre-fabricated spools were found to be dimensionally incorrect. Identifying these discrepancies in the shop environment prevents downstream installation issues and minimizes field modifications. Early verification not only improves installation efficiency but also enhances quality assurance across the project lifecycle.

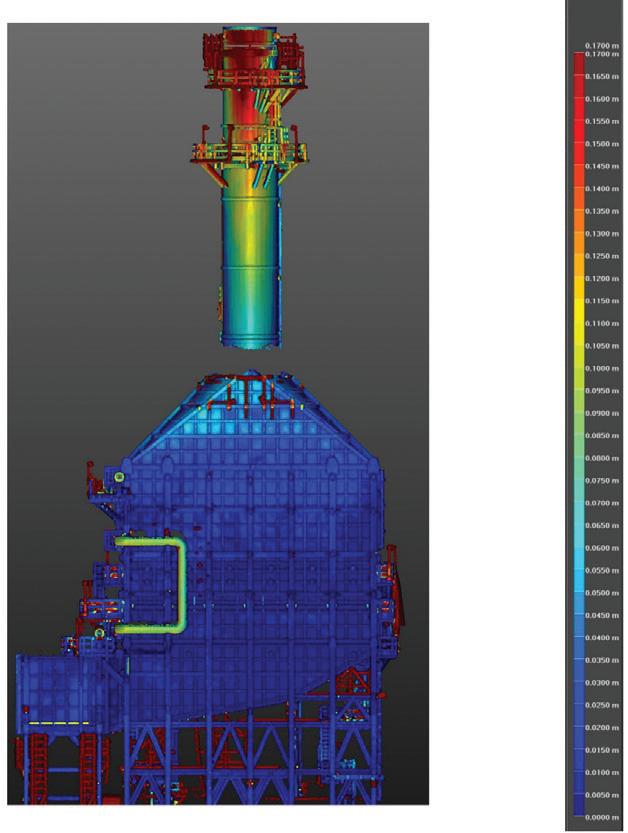

Although not traditionally categorized under dimensional control, modern structural QA/QC practices increasingly incorporate advanced surveying and visualization technologies to identify issues and verify tolerances. This is especially critical in large-scale modular construction projects, where conventional methods may be impractical due to access limitations or time constraints.

In one industrial facility, a tall flare tower was required to remain within a strict tolerance of ±50 mm. With limited access, 3D scanning proved to be effective in meeting this requirement. While laser scanning does not replace traditional dimensional control surveys, it enhances survey effectiveness by providing highresolution spatial data.

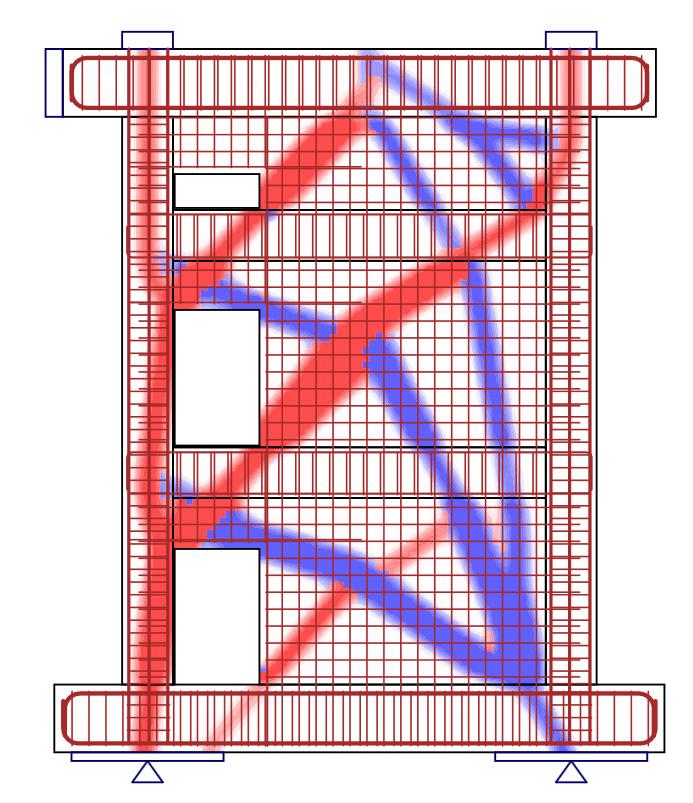

3D

Verification: Tools like 3D heat maps (Fig. 4), inspection point clouds, and automated reports allow engineers to visually assess the conformance of fabricated or installed structures to design tolerances. These deliverables provide accurate visualizations of deviations, enabling quick detection of out-ofspec conditions and timely corrections.

Geo-Referenced Model Alignment

To maximize inspection accuracy, the design model, typically in .ifc format, is geo-referenced to

the survey dataset using identifiable key connection points (such as bolt hole #1 at the base plate corner). This process begins with a full structure scan and simultaneous surveying of key locations. Aligning the model to these references eliminates control errors, instrument or setup inaccuracies, and ensures results reflect actual conditions.

By integrating high-precision instruments with intelligent model alignment workflows, teams can achieve more reliable QA/QC supporting both safety and performance goals, particularly for the following situations:

• Verticality assessments of tall or complex structures.

• Out-of-tolerance detection in prefabricated modules.

• Surveying in remote or constrained environments.

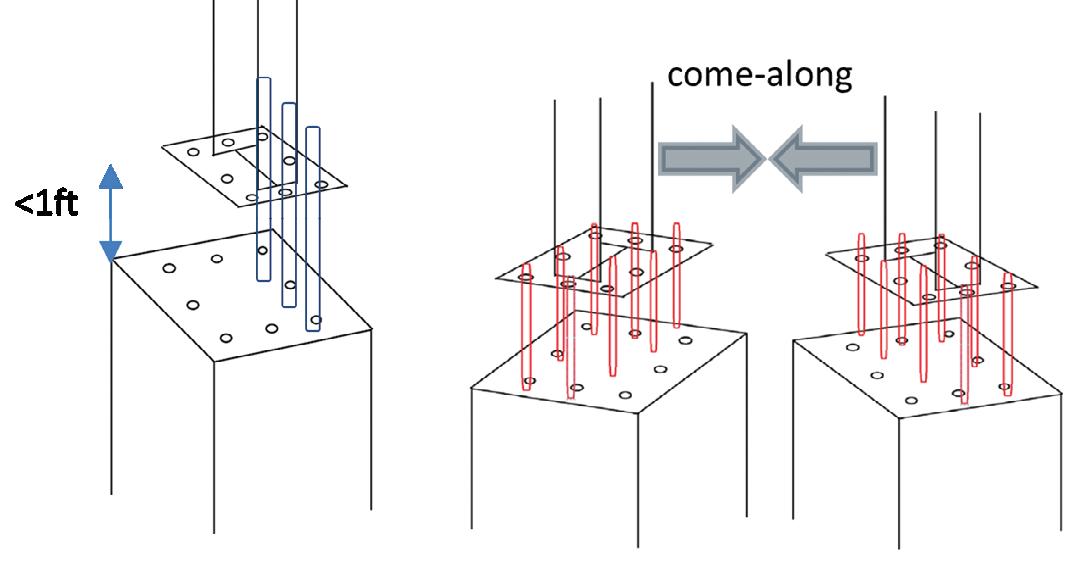

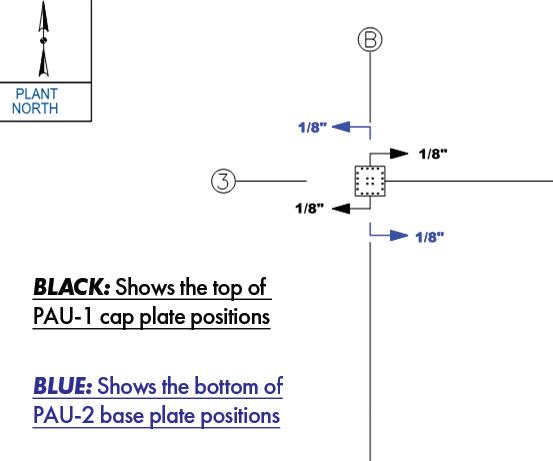

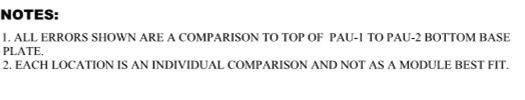

In this project, a structured interface management plan was established early among dimensional control teams, the owner’s construction group, precast manufacturer, structural steel fabricator, general mechanical contractor, and heavy-haul contractor to align expectations across stakeholders.

Design Provisions for Tolerance Control

During detailed design, provisions were incorporated to manage interface challenges. These included tighter tolerances for concrete pedestal pours with embedded anchor bolts and revised connection details (Fig. 5) at the top of precast columns to accommodate structural steel base plates. These measures helped reduce misalignment risks during construction.

Progressive Measurement and Verification

Critical interfaces, including anchor bolts in concrete pedestals, precast column bases, precast column-to-steel connections, and structural steel base plates (Fig. 6), were measured and checked for alignment by dimensional control survey team to provide unbiased data. Field measurements were continuously compared against design values, and any deviations were corrected before proceeding with the next installation step.

These proactive approaches prevented cumulative errors and significantly reduced the risk of costly rework during later phases.

The following dimensional control optimization framework is recommended to improve coordination, reduce rework, and prevent schedule delays:

1. Team Education for Establishing Full Dimensional Control Workflow: Promote awareness of dimensional control’s role in risk mitigation and encourage adherence to full workflows, from design and fabrication to field installation. Establishing appropriate fabrication tolerances and integrating dimensional control into QA/QC processes from the shop floor to the field further strengthens project delivery.

2. Early Mobilization: Engage dimensional control teams during initial layout and fabrication to monitor control points and minimize settlement-related alignment issues.

3. Design Provisions: Ensure engineering design supports dimensional control, for example, incorporate thermal expansion calculations into spool length specifications.

4. Pre-shipment Verification: Survey modules and spools at fabrication yards to ensure dimensional compliance before transport.

5. Field Monitoring: Integrate dimensional control into construction activities for alignment checks and corrections.

6. Advanced Surveying Tools: Where appropriate, utilize high precision surveying tools and scanning to improve measurement accuracy and data confidence.

As modular projects grow in complexity, adopting modern dimensional control practices is essential for improving precision and predictability in construction. Early deviation detection and strong stakeholder collaboration are key to minimizing risk and improving project outcomes.■

Full references are included in the online version of the article at STRUCTUREmag.org .

Silky Wong leads the Civil, Structural & Buildings Modularization Technical Solutions team at Dow Inc. She chairs the ASCE Energy division task committee on Wind Induced Forces and serves on its Onshore Heavy Industrial Modularization Guidelines Task Committee.

Vigneshwar Natesan is currently pursuing a Master of Science degree in energy management from University of Texas at Dallas and is a member of the ASCE Energy division task committee on Wind Induced Forces. He was Civil Engineer Manager at Dow Inc. with over 13 years of industry experience.

Successful design incorporates key considerations at the interfaces of the facade and primary structure.

By Aaron Kostrzewa, PE

Successful structural design relies on the harmonious integration of various elements. The primary building structure often comes to mind first when thinking of the structural integrity of a structure, but many other elements are critical to the design. The building facade is one such element, with curtainwall being a further subset.

The goal of the engineer is ultimately to protect the “health, safety, and welfare” of the public as dictated by the engineering code of ethics. While individually, one can complete a scope and achieve this goal, the greater goal of achieving this for a building is only satisfied when this is accomplished for all structural trades. It is at these crossroads where critical junctions occur, and proper coordination is essential for successful design.

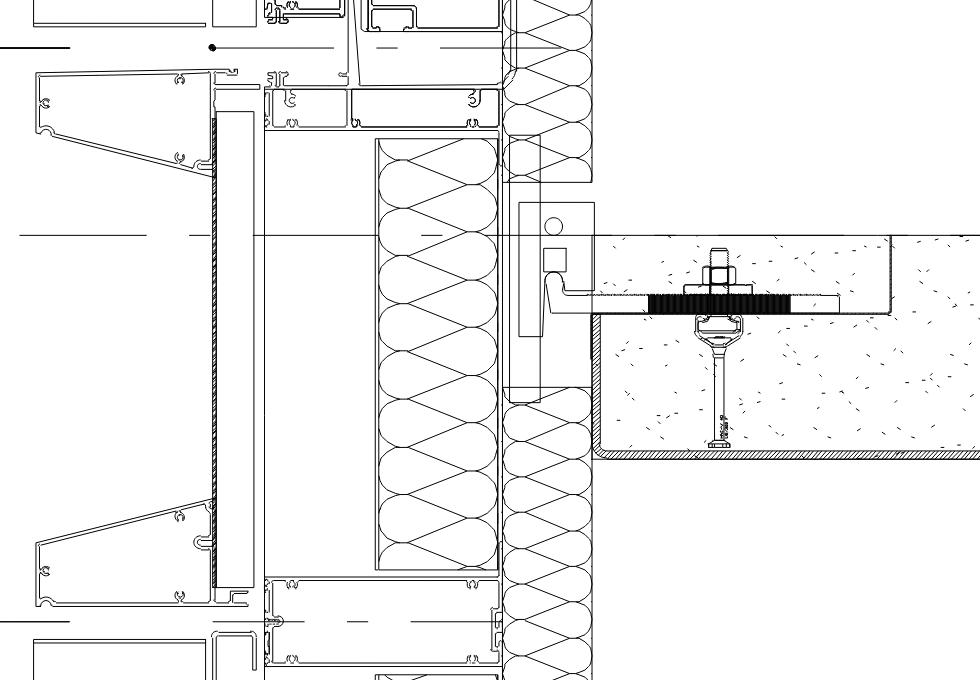

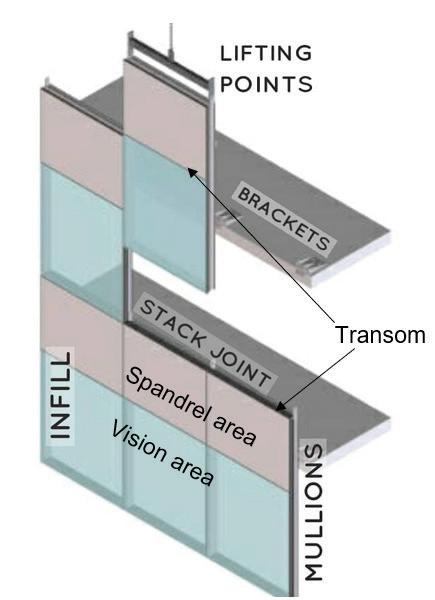

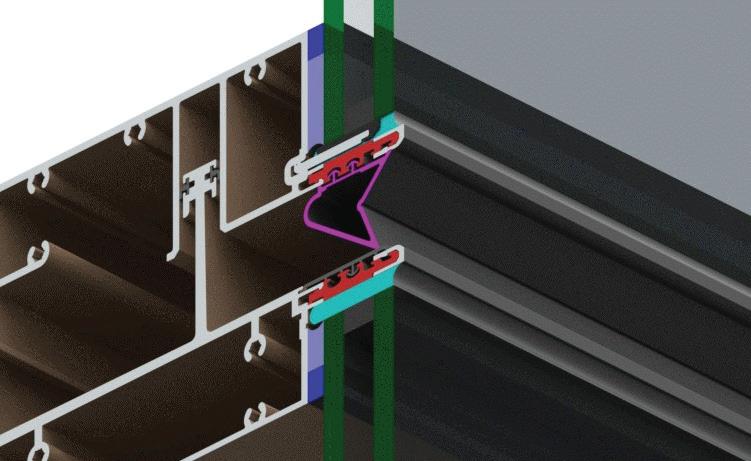

Curtainwall is a type of exterior building cladding commonly unitized to facilitate rapid installation on large projects. Modular sections, known as units, are prefabricated in a factory and shipped to the site for fast installation and better quality control. The units are lifted into place and hung from the structure with perimeter anchors (Fig. 1 and 3). The units interface with one another to provide a weather-tight seal via gasket engagement and minimal field-applied sealant.

A typical unit is rectangular with a transparent vision area and an opaque spandrel area, collectively known as the infill, but limitless geometric configurations exist. The vision area permits occupants to view the exterior while the spandrel area covers the slab and plenum space. Vertical framing components, known as mullions, interface with horizontal elements, called transoms (Fig. 4). The transoms frame into the mullions and the mullions engage with the units above and below for structural continuity.

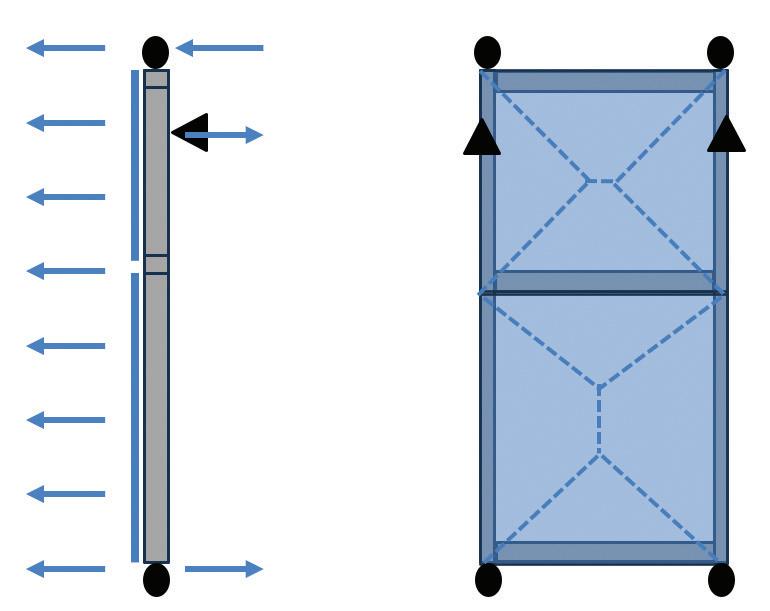

Curtainwall must resist all applicable loads as dictated by their use case, but common loads are self weight, wind pressure, loads induced from seismic acceleration, and live loads from building maintenance units (e.g. window washing platforms). The common standards governing the designs are the adopted

versions of ASCE 7 (loads), Aluminum Design Manual (ADM) (aluminum), ASTM E1300 (glass), AAMA TIR-A9 (fasteners), AISC-360 (steel) and ACI 318 (concrete anchorage), in addition to any unique materials used in the facade. Curtainwall is commonly still designed according to allowable stress design (ASD). Wind pressures are frequently the type of load governing the design of curtainwall. A typical unit will resist the resultant force of the building internal pressure and the external pressure imparted from wind events. Zone 4 (interior wall) and 5 (edge/corner wall) component and cladding wind pressures from ASCE 7 Chapter 30 are of interest, which consider the localized “hot spots” on a structure during a wind event. Negative wind pressures (suction) at the corners of the building often govern cladding design as they can be nearly double those of interior wall pressures. Wind pressures are resisted by the framing infill, commonly glass or metal panel, transferred to framing members, and then to anchorage into the primary structure. See Figure 5 for an example load path and free body diagram. For complex buildings, a wind tunnel study is frequently commissioned since the often lower-than-code-prescribed pressures can result in net savings.

The engineer of record will naturally have to make assumptions about the weight of the facade and loading imparted to the primary structure prior to the engagement of the facade

contractor. For critical interfaces or incipient design where conservative assumptions are warranted, one should take due care for the determination of loads. However, the following may be considered as general guidance: metal panel cladding typically does not exceed 10 psf; typical glass units, 15 psf; or extra thick glass, 30 psf. Facades with stone or other cementitious products can greatly exceed this value. One can determine an approximate facade weight by multiplying the thickness of the predominant infill material by the appropriate specific gravity. For the case of an all-glass facade unit, most of the weight is the glass, so an approximate determination can be carried out if the thickness of glass is known.

Unitized curtainwall designers often leverage the interface of the units by using the unit above and below for stability and load transfer, thus requiring two anchorage points to the structure per unit. The mullions are the primary wind load resisting members since the horizontals frame into them. If horizontal members (transoms) are beams, then mullions are girders. The mullion can be conservatively analyzed as a simple beam loaded based on its tributary width with determinate boundary reactions. Mullions of unitized curtainwall mate together as the units are installed and will share tributary out of plane load based on relative stiffness since they are constrained to deflect together. In addition to aluminum stress and buckling checks, mullions must be designed for deflection, which is commonly L/175 for spans less than 13 feet-6 inches and L/240 + ¼ inches for greater spans, where L is the clear span between supports. Framing members supporting glass must be limited to L/175 along the length of the glass infill for the edge to be considered firmly supported, which dictates which edges may be considered supported for glass analysis.

The wind load imparted to the primary structure at discrete anchorage points can accurately be determined by statics of an individual unit or approximated by the tributary wind of the adjacent unit on either side of the anchor multiplied by the tributary height. Reactions can exceed this simplification at the lower floor of a curtainwall run, the upper floors of a run, and at parapet conditions, and should be considered on a case by case basis accordingly.

Unitized curtainwall is commonly hung from the perimeter of the slab. The self weight of the unit is imparted at the slab edge, inducing eccentricity in the primary structure. A common note in structural drawings and specifications is that the facade shall not impart any torsion to the perimeter of the structure, which is not feasible. To be more accurate and avoid inherently impractical requirements, construction documents and specifications should state that “the facade engineer of record shall submit a diagrammatic representation of the loads imparted to the primary structure and associated eccentricities,” for proper consideration in the design of the structure. For unique or critical load coordination locations, the engineer of record should require that a loads-imposed coordination document be sealed by the facade engineer of record.

Coordinating loads imposed is almost always challenging due to the varying manner in which loads can be conveyed and engineers’ attention to detail on the providing and receiving end. The facade is most often designed based on allowable stress design, and the structure is likely designed according to Load Resistance and Factor Design (LRFD). A loads-imposed document could indicate factored ASD loads, unfactored loads, factored LRFD, and so on. The document must convey the loading category, factors to the loads, how load combinations are considered, and eccentricities. The facade engineer must discern how to concisely provide reactions at facade anchorage points in a document with sufficient accuracy. The document must encompass the varying conditions while striving for brevity to avoid providing loads for each individual anchorage condition. Additionally, he or she must also discern what buffer to incorporate into the loading to account for conservatism and the potential for the design to

Before Curtainwall Installation

Primary structure erection tolerance

During Curtainwall Installation

Deflection of structure from curtainwall weight

change that could alter the loading. The author encourages engineers of record to tell the facade engineer how to communicate loads, since they are the ultimate recipients of such information.

The facade engineer should provide curtainwall shop drawings and/or calculations that clearly convey the loads imposed. Elevation drawings should have graphics of wind load and dead load anchors of the facade, and calculations and/or detail drawings should convey facade anchor reactions to clarify how load is being imparted to the structure. The coordination of loads at the interface of engineering trades is one that requires careful consideration and communication

After Curtainwall Installation

Structure

- Column shortening

- Creep - Live load deflection

- Building drift

Curtainwall

- Thermal movement

- Fabrication tolerance

to avoid additional provisions for facade reactions that are higher than anticipated.

The final consideration for this article is the coordination of building and facade movements. The facade will move, and the building will move. Their movements must be compatible in order to avoid

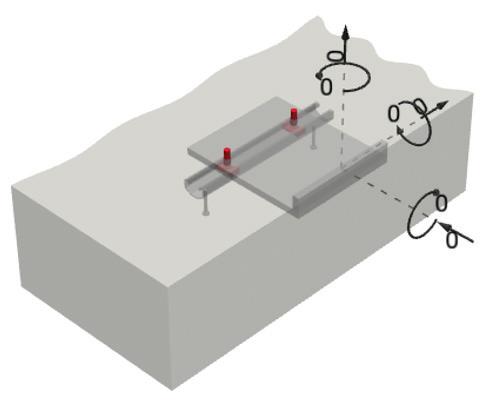

a clash. Any such clash will almost certainly result in a failure of the facade in the form of glass breakage, facade damage, and potentially dislodgement of the facade from the building. The impetus is on the facade engineer to facilitate the proper design of the facade for movement consideration; however, the engineer of record must also provide values of the primary structure movement for proper coordination. While the facade engineer must take due care in providing loads with adequate specificity and conservatism, so too must the engineer of record when providing building movements. Common structure movement considerations are structure creep, slab edge deflection prior to curtainwall installation, slab edge deflection due to curtainwall self weight, slab edge live load deflection after curtainwall installation, structure settlement, construction tolerances, and service/ultimate level drifts for wind and seismic building movements. Additional unique movements should be provided as needed. The facade is effectively always set in a theoretical position, regardless

of the position of the primary structure. This is required to ensure the aesthetic of the facade. Therefore, unitized curtainwall units must accommodate movements in several ways. Movements prior to the installation of the facade can be accommodated via 3-way adjustability of the facade anchorage. Thus, the magnitude of these movements needs to be understood for provisions in the anchorage design. Further, smaller erection tolerances will result in a more economical facade design and lower facade reaction eccentricities, which is worth considering when engaging various contractors.

by CTS Cement Manufacturing Corp

Movements of both the facade and the structure after installation need to be accommodated in the vertical and horizontal joints of the facade. Facade movement such as thermal, fabrication tolerances, and movements induced from vertical and horizontal building movements are all combined as appropriate to determine the opening and closing demand of the facade joints. The sidebar, “Movement Considerations” on page 23 notes where the various movements need to be considered in the design of the facade and its attachment to the structure. Adjustable anchors can adjust the unit attachment point to the nominal position while the movement joint between the units, known as the stack joint, accommodates movements after installation. The deflection of the structure due to the weight of the curtainwall can be accounted for in adjustment of the anchors or at the stack joint.

Your work shapes skylines. But staying ahead of changing codes, materials, and innovations can be a challenge.

CTS Cement’s AIA-accredited CE Courses offer learn on-demand or live training designed to meet today’s construction challenges and sustainability initiatives:

¾ Performance-driven concrete solutions you can specify with confidence.

¾ Latest standards, materials, and best practices for sustainable, durable designs.

¾ Innovative design options using Komponent shrinkage-compensating concrete.

¾ Case studies that solve real-world challenges.

Early coordination of facade gravity and lateral anchors along with anticipated facade movements is critical between the facade engineer, engineer of record, and the architect to ensure coordination, movement coordination and joint sizes. Curtainwall extrusions are often custom on elaborate projects. Any change resulting in a modification of the design curtainwall movements can have significant fees resulting from changing extrusions and undesirable aesthetics due to larger curtainwall joints.

Facade design is constantly evolving as architects push the boundary of creativity. Custom curtainwall warrants individualized considerations with the information presented as key considerations. Ensuring the resilience of the primary structure and accessory structures demands close coordination between the structural engineer of record and the facade engineer of record. Doing so will facilitate the conveyance of digestible information without undue conservatism. ■

Aaron J. Kostrzewa, PE, has served as the facade engineer of record for multiple projects and has designed curtainwall systems around the country. He serves as the managing member at Kosco Engineering Group and enjoys teaching structural concepts. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

The National Council of Structural Engineers Associations (NCSEA) is pleased to share winners of the 2025 Excellence in Structural Engineering (SEE) Awards, which were recognized at the SEE Awards Celebration on October 16, 2025, at the New York Hilton Midtown during the 2025 NCSEA Structural Engineering Summit. The winning projects can also be viewed throughout 2026 during the free, in-depth SEE Awards Webinar Series at www.ncsea.com.

Outstanding Projects were awarded in each of the following 10 categories:

• Bridge and Transportation

• Forensic/Retrofit/Rehabilitation

• Innovation in Materials

• Landmark Structures

• Non-Building Structures

• Performance Design for Resilience

• Renovation/Adaptive Reuse

• Residential/Single and Multi-Family Homes

• Social Impact

• Sustainable Design

For the first time in program history, two projects have been named Structure of the Year. The judges were so impressed by the ingenuity and technical achievement of both projects that they chose to honor the National Medal of Honor Museum in Arlington, Texas, by schlaich bergermann partner, and the Millennium Tower Perimeter Pile Upgrade in San Francisco, California, by Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, as this year’s top honorees.

The National Medal of Honor Museum by schlaich bergermann partner was chosen because of its unique structural challenges. With its sweeping stair and framing cantilevered from only five columns, it represents how structural engineering can enhance the design of a building.

Simpson Gumpertz & Heger’s Millennium Tower Perimeter Pile Upgrade was selected due to the immense creativity required to solve an extremely difficult problem at a fraction of the predicted cost while under intense public scrutiny.

The SEE Awards celebrate the most accomplished work in structural engineering, recognizing projects that demonstrate innovation, resilience, creativity, and more.

of the

SAN FRANCISCO, CA

Structural Design Firm

Simpson Gumpertz & Heger

General Contractor

Shimmick Construction

Approximate Construction Cost $100 million

The 58-story Millennium Tower in San Francisco, one of the city’s tallest residential buildings, was designed with a foundation of 990 pre-stressed precast concrete piles. By 2016, the building had settled 14 inches and was tilting. This led to a lawsuit from homeowners, who sought a $300 million foundation upgrade requiring 300 piles installed to rock through the existing 10-foot mat. SGH devised a new plan to install 55 piles drilled to rock along the north and west perimeters. New pile installation resulted in further settlement and tilting. Under public scrutiny, the project team determined the issue was due to the installation technique. They modified the procedure and reduced the number

of new piles to 18, with additional load jacked onto each. After 18 months of monitoring, the project has been deemed a success, with the building’s settlement arrested and gradual tilt recovery occurring. The project demonstrated the use of a minimalist approach and capacity design principles to solve a challenging problem in a safe and reliable manner. Notably, the project used existing underpinning technology, but at a scale not previously attempted. Despite substantive criticism in the local and national media, the project team persevered and completed the project successfully. Now that the work has completed, the building’s reputation and property values have been restored.

ARLINGTON, TX

Structural Design Firm schlaich bergermann partner

Architect Rafael Viñoly Architects

General Contractor Linbeck Group

Approximate Construction Cost

$140 million

The new museum by Rafael Viñoly Architects is dedicated to the legacy of the 3,500 recipients of the Medal of Honor. The design symbolically lifts their accomplishments with a 200 foot x 200 foot x 35 foot Exhibition Hall that appears to float 50 feet above the rotunda below. At the center of the Hall is a 20-foot diameter oculus that allows light to enter below. Additional education, conference and event spaces are housed in the museum’s lower levels, below an accessible green roof, overlooking Mark Holtz Lake. The primary Exhibition Hall is housed in a striking, aluminum-clad volume and is supported by five tapering precast mega-columns, each hollow to accommodate mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems routed through their cores. Atop each column sits a spherical bearing beneath a massive steel supernode that supports built-up box beams forming the floor and primary structural frame. The interior of the Exhibition Hall is entirely column-free, aside from five inner service-ring columns. The outer roof members are supported by a perimeter belt truss. Access to the elevated structure is provided by a pair of intertwining spiral staircases suspended from the floor above by seven tension rods at the inner edge of each stringer. Additional access is offered via hydraulic elevators enclosed in glass.

INDIANAPOLIS, IN

Structural Design Firm: schlaich bergermann partner

Architect: Practice for Architecture and Urbanism

General Contractor: Kokosing Construction Co.

The 16 Tech Innovation District Bridge spans 342 feet and creates a new multimodal connection between the 16 Tech Innovation District and Indianapolis’ research and medical corridor. The bridge reinterprets a classic suspension bridge by replacing the large vertical masts with a fan-type arrangement of multiple smaller masts. Likewise, elegant flat steel plates replace the traditional suspension cables as the main supports. The bridge’s tension element is allowed to follow the new mast arrangement, creating its signature wavelike form. The resulting shape promotes axial behavior, primarily utilizing tension and compression instead of bending. The bridge is designed as an integral structure, with the superstructure and substructure acting as a single monolithic unit. This eliminates expansion joints and bearings increasing long-term durability, reliability, and simplicity. With more than half of the 65-foot-wide deck devoted to non-vehicular use, the bridge promotes multimodal forms of transit to and from the Innovation District.

Newark Liberty International Airport’s new Terminal A replaced the existing terminal with a new 1-million-square-foot, 33-gate domestic terminal. The structural team was tasked with minimizing the number of columns in the terminal building to create a large, open space. With 150-foot-long roof spans using a diagrid system of tapered plate girders, the terminal features a sloping ceiling that expresses the structural members and allows natural light to enter. In addition to the terminal building, the project includes 1,000 feet of new bridge structures approaching the departures level, a 660-foot-long pedestrian bridge to a new car rental facility. The structural team designed a substructure utilizing over 3,000 De Waal drilled displacement piles.

CHICAGO | HOK

Finalist

O’Hare’s expansion consists of a new 300,000 square foot east concourse and expanded headhouse. The headhouse expansion sits atop the existing sub-grade customs facilities; the need for continuous operation drove the selection of framing that would not require modifications to the original building foundations. A unique parabolic clerestory is defined by the interstitial space between the low and high portions of a series of bent steel girders that span 67 feet across the concourse width. To rationalize the complex east concourse roof geometry, HOK’s engineers developed a Grasshopper parametric script that defined a series of intersecting planes and two singly-curved tilted barrel vaults to generate the appearance of a curving roof structure.

Balboa Botanical Building

SAN DIEGO, CA | DEGENKOLB ENGINEERS

SAN FRANCISCO, CA

Structural Design Firm: Simpson Gumpertz & Heger

General Contractor: Shimmick Construction

The 58-story Millennium Tower in San Francisco, one of the city’s tallest residential buildings, was designed with a foundation of 990 pre-stressed precast concrete piles. By 2016, the building had settled 14 inches and was tilting. This led to a lawsuit from homeowners, who sought a $300 million foundation upgrade requiring 300 piles installed to rock through the existing 10-foot mat. SGH devised a new plan to install 55 piles drilled to rock along the north and west perimeters. New pile installation resulted in further settlement and tilting. Under public scrutiny, the project team determined the issue was due to the installation technique. They modified the procedure and reduced the number of new piles to 18, with additional load jacked onto each. After 18 months of monitoring, the project has been deemed a success, with the building’s settlement arrested and gradual tilt recovery occurring.

SANTA MONICA, CA |TIPPING

The Balboa Botanical Building, originally constructed in 1915, is composed of exposed steel three-hinge arch trusses which support wood purlins and wood lath. In 2021, a design-build team embarked on a project to fully restore the building to its original historic character and repair decades of deterioration. The project included new solutions to repair and replace structural framing and reconstruction of the historic arcade that wraps the building. The existing truss hinge base which had previously been cast into concrete as a repair strategy was exposed, requiring shoring, removal, and replacement of the bottom 10 feet of the steel trusses. After nearly 4 years of design and construction, the project was completed at the end of 2024.

3130 Wilshire, a 1968 six-story office building in Santa Monica, was subject to the city’s Mandatory Nonductile Concrete Ordinance. The building’s lateral system does not resemble the layout or proportions common in modern buildings. However, the key to this project’s success lies in recognizing the original construction of repetitive exterior concrete fins actually creates a robust and ductile seismic system in need of only localized improvements. Using nonlinear analysis, Tipping developed a way to “harvest the strength and ductility” of the existing structure using six Buckling Restrained Brace frames at the perimeter of level one. The result was a significantly more resilient building for a fraction of the initial assessment, saving substantial costs over the conventional approach.

General Medical Center GOLDEN, CO

Structural Design Firm: Martin/Martin, Inc.

Architect: HDR

General Contractor: Barton Malow Builders + Haseldon Construction

Intermountain Health Lutheran Medical Center represents a new standard in fast-track healthcare construction, combining high-performance structural design, material innovation, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The seven-story, 660,000-square-foot facility was delivered on an accelerated schedule, moving from schematic design to completion in less than four years. Martin/Martin’s engineering team used innovative structural systems to cut four months from the construction schedule. The hallmark innovation was the use of shotcrete core walls supported by core wall frames. These frames housed leave-in-place formwork and allowed steel erection and core wall construction to proceed simultaneously. The result was quicker erection of the primary structure, improved safety, and fewer site coordination conflicts. Additional innovations included field-welded anchor systems, erection-optimized steel framing, and phase-sequenced steel packages. The completed hospital reflects a highly constructible, material-efficient solution delivered with speed and precision.

The University of San Francisco’s new Malloy Pavilion faced significant site challenges due to its location above a 1965 concrete parking garage. Given the site constraints, the project could not be designed as a conventional building using typical engineering solutions. To ensure that the parking garage was not affected by a new building above, only one steel frame and one stand-alone steel column penetrate through the garage levels below. The new Pavilion extends beyond the footprint of the existing parking garage, allowing robust perimeter steel frames to occur outside the garage structure. Minimal steel columns over micropile foundations provide vertical support, creating the appearance of a floating structure.

The three-story Arrupe Hall combines elegant architectural expression with complex structural coordination. Keast & Hood’s structural design uses a hybrid steel and wood system. A key challenge was integrating a lateral system within the open-plan layout. Load-bearing walls that stepped back along the facade utilized transfer beams and panelized shear walls. At the heart of the building, a three-story atrium features a monumental wood-and-steel stair with a flowing guardrail. The chapel’s brick screen wall stands as the project’s most innovative structural feature. Rising 30 feet, the curving and battered singlewythe wall is built with custom hollow-core bricks and reinforced with concealed stainless-steel rods. A hidden galvanized steel armature provides lateral support while allowing for thermal movement.

ARLINGTON, TX

Structural Design Firm: schlaich bergermann partner

Architect: Rafael Viñoly Architects

General Contractor: Linbeck Group

The new museum by Rafael Viñoly Architects is dedicated to the legacy of the 3,500 recipients of the Medal of Honor. The primary Exhibition Hall is housed in a striking, aluminum-clad volume, elevated 50 feet above the entry rotunda. The Exhibition Hall is supported by five tapering precast mega-columns, each hollow to accommodate mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems routed through their cores. Atop each column sits a spherical bearing beneath a massive steel supernode that supports built-up box beams forming the floor and primary structural frame. The interior of the Exhibition Hall is entirely column-free, aside from five inner service-ring columns. The outer roof members are supported by a perimeter belt truss. Access to the elevated structure is provided by a pair of intertwining spiral staircases suspended from the floor above by seven tension rods at the inner edge of each stringer.

BOSTON, MA |LEMESSURIER

The $2 billion Terminal Core Redevelopment project provides a completely rebuilt open concept terminal where 670 existing columns at tight grids were replaced with 34 new columns supporting a new 1,000 feet x 400 feet hybrid mass timber roof. A long-span, 1,000-feet by 400-feet (9-acre) hybrid mass timber roof was designed as a series of modules to cover the terminal, supported by 34 Y-shaped steel columns that provide both gravity and lateral support with seismic isolation bearings at the roof connection for seismic resilience. The remaining portion of the existing structure was seismically retrofitted. The design exceeds code requirements for seismic resilience, achieving Immediate Occupancy performance after a Magnitude 9 earthquake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

400 Summer Street is designed to rise above the complex underground infrastructure of the Central Artery Tunnel. Originally intended to support a five-story building, the site was reimagined decades later as a high-rise tower. The structural team designed a solution to prevent this 630,000 square foot tower from overloading the existing infrastructure and keep the asymmetric structure plumb as it was erected. Transfer girders were used to align the building grid with existing foundation. Sloping columns shed excessive tower loads away from the foundation elements. A multi-story Vierendeel truss transfers loads from the perimeter tower columns to the sloping columns. Lateral camber counterbalances the lurching effect of the asymmetrically positioned sloping columns.

SEATTLE, WA

Structural Design Firm: KPFF Consulting Engineers

Architects: Power Engineers (Substation Electrical Design and Prime Consultant) and NBBJ (Architect)

General Contractor: Walsh Construction

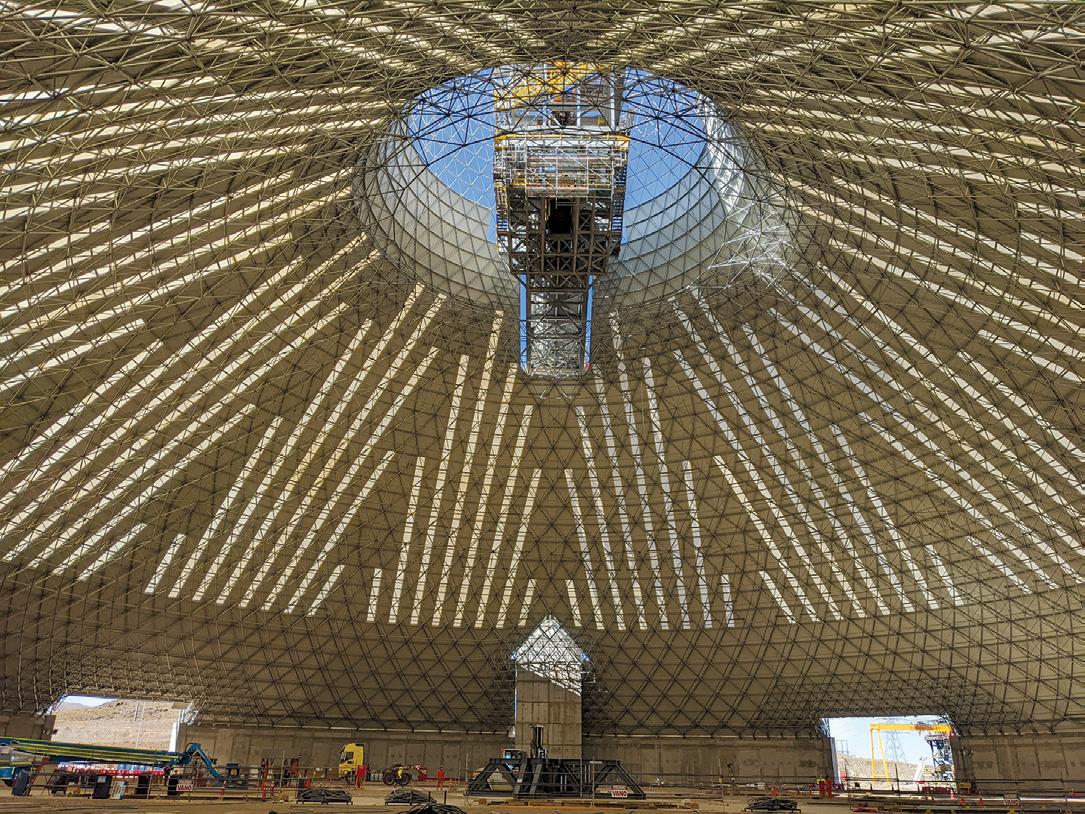

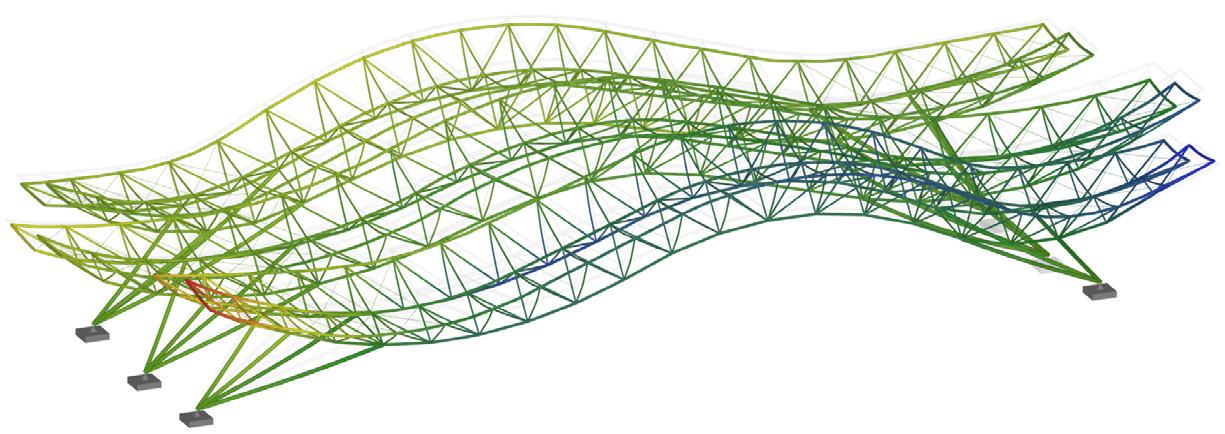

The dome, completed in 2022 for Teck’s Quebrada Blanca Phase 2, spans 124 meters and houses crushed copper ore and a conveyor at 4,300 meters elevation. Geometrica designed a hyperbolic doublelayer frame, assembled at grade and lifted using a single hydraulic tower to enhance safety and accelerate construction. The dome’s hyperbolic geometry naturally creates a “gazebo” at the dome’s apex, enclosing the feeding conveyor delivery point. The structure covers nearly 10,000 square meters without internal supports and was enclosed with corrosion-resistant cladding during assembly. The result is a durable, efficient enclosure—engineered for extreme weather and tailored to support critical operations at one of South America’s highest-altitude mines.

Seattle City Light’s Denny Substation sets a new urban substation standard with its intricate non-building structure. KPFF’s team designed a complex cantilevered screenwall to protect the public from high-voltage equipment while adding visual appeal. This structure features an elevated park and a 1/4-mile walkway supported by innovative box-truss towers. Advanced modeling software aided in designing prefabricated components. A deep foundation system coordinated below-grade utilities, incorporating temporary excavation shoring piles. The highly sensitive existing HPFF transmission line, over which the substation was built, had to remain energized during construction activities. KPFF designed an innovative temporary reverse-shoring system and supportive structures and considered how the permanent structure could be sequenced to protect the line throughout construction and

GEORGETOWN, WASHINGTON, DC | MCMULLAN & ASSOCIATES, INC.

The C&O Canal features four locks to transition barges between water levels. McMullan performed the structural engineering for two 1832 stone masonry locks between 30th and 31st Streets NW. Lock No. 3 was fully reconstructed due to wall tilting from a failing timber foundation; its wooden gates were removed, stone walls disassembled and stored, and a new concrete foundation was laid. The original stones were then reassembled. Lock No. 4 underwent repairs for water leakage and deteriorated timber gates, including stone replacement, repointing, and the replacement of wood gates and hardware.

LOMA LINDA, CA

Structural Design Firm: Arup Architect: NBBJ

General Contractor: McCarthy Building Companies

At 1,000,000 square feet and 260 feet tall, the Dennis and Carol Troesh Medical Campus is currently the tallest hospital in California. As the hospital is situated only 0.6 miles from the San Jacinto fault and 3.1 miles from the San Andreas fault, this critical care facility faces significant earthquake risk and the highest seismic demands of any hospital in California. To ensure the highest level of earthquake resilience and hospital safety, Arup implemented an integrated state-of-the-art structural system consisting of 126 triple-friction-pendulum isolators, 104 nonlinear fluid viscous dampers, buckling restrained braces and SidePlate moment frames. A nonlinear performance-based design, cloud-based digital tools and LS-Dyna software were used to analyze, design, and permit the hospital in a high seismic region under the stringent requirements of OSHPD/HCAI. The state-of-the-art facilities, improved services, earthquake-ready construction, and increased capacity for care will enable Loma Linda to serve the community better for generations to come.

VANCOUVER, BC, CANADA | FAST + EPP