STRATEGIC VISION for

Taiwan Security

US Forces Seize Maduro

Implications of the Venezuela Operation For the Indo-Pacific Region

Hon-min Yau

Taipei Eyes Defense Industrial Cooperation

Yen Ming Chen & Ru-Yen Zheng

South China Sea Increasingly Overcrowded

Rhomir Yanquiling

Building Maritime Domain Awareness

Hui-Chen Lai

PLA’s Justice Mission 2025 Drills

Dean Karalekas

Hon-min Yau Dean Karalekas Rhomir Yanquiling

Hui-Chen Lai

Yen Ming Chen & Ru-Yen Zheng

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools to author or substantially generate manuscript content is not permitted. Any use of AI tools (e.g., for language editing, proofreading, or formatting assistance) must be fully disclosed at the time of submission, including a brief description of the purpose and extent of such use. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision. Once accepted for publication, manuscripts become the intellectual property of Strategic Vision. Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for reprints should be made with the editor. The editors are responsible for the selection and acceptance of articles; responsibility for opinions expressed and accuracy of facts in articles published rests solely with individual authors. The editors are not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; unaccepted manuscripts will be returned if accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. Strategic Vision remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Digitally enhanced cover photograph of a US Air Force F-35A Lightning II immediately following military actions in Venezuela in support of Operation Absolute Resolve, taken Jan. 3, 2026, is courtesy of Katelynn Jackson.

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Editor-at-Large

Dean Karalekas

Editorial Board

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Richard Hu, NCCU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Hon-Min Yau, NDU

Ruei-lin Yu, NDU

Osama Kubbar, QAFSSC

Rashed Hamad Al-Nuaimi, QAFSSC Chang-Ching Tu, NDU

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security (ISSN 2227-3646) Volume 15, Number 64, February, 2026, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Taiwan Center for Security Studies. No. 64, Wanshou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Associate Editor directly via email at: xiongmu@gmail.com. Or by telephone at: +886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: https://taiwancss.org/ strategic-vision/

© Copyright 2026 by the Taiwan Center for Security Studies.

Articles in this periodical do not necessarily represent the views of either the TCSS, NDU, or the editors

From The Editor

Lunar New Year 2026 approaches, and the editors and staff of Strategic Vision would like to extend our warmest wishes to our readers at a time of continued uncertainty and transition across the Indo-Pacific. The region’s security environment remains fluid, shaped by intensifying great-power competition, gray-zone pressures, and shifting strategic alignments. We hope that students, scholars, and practitioners alike are able to keep pace with these developments, and in support of that effort, we are pleased to present this latest edition of Strategic Vision.

We open our first issue of the year with Dr. Hon-min Yau, who examines the implications for Taiwan of the 2025–2026 US military action against Venezuela. Dr. Yau is a professor of Strategic Studies at the ROC National Defense University.

Next, Dean Karalekas, Editor-at-Large for Strategic Vision and author of Civil-Military Relations in Taiwan: Identity and Transformation, analyzes how China tests regional red lines through its Justice Mission 2025 drills around Taiwan.

Rhomir Yanquiling, a Ministry of Foreign Affairs Research Fellow affiliated with the Taiwan Center for Security Studies, offers a long-term, data-driven analysis of maritime incidents in the South China Sea, introducing the concept of the region as a dynamic “maritimescape” where conflict and cooperation coexist.

Commander Hui-Chen Lai, an assistant professor at the Graduate Institute of International Security at the ROC National Defense University, examines Taiwan’s role in the Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness network and argues for strategies that turn political exclusion into strategic advantage.

Finally, Commander Yen Ming Chen, an instructor at the ROC National Defense University’s War College, and Commander Ru-Yen Zheng, a War College student, assess how the US–China trade war reshapes Taiwan’s defense posture and argue that defense industrial cooperation is essential to strengthening Taiwan’s long-term resilience.

We hope you enjoy this issue, and we look ahead to the coming year—the Year of the Fire Horse—with renewed drive and purpose, as we continue to bring our readers timely analysis and informed reporting on the security challenges shaping the Taiwan Strait and the wider Indo-Pacific region. n

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor Strategic Vision

Strategic Vision vol. 15, no. 64 (February, 2026)

The Donroe Doctrine

Implications for Taiwan of the 2025-2026 US military action against Venezuela

Hon-min Yau

The United States and Venezuela already had a troublesome relationship in the early 21st century, when the left-leaning Hugo Chávez had full control over Venezuela and overhauled the country’s foreign policy, directing it squarely against the United States. However, this tense relationship deteriorated dramatically, and eventually devolved from being merely troublesome toward being problematic by late 2025.

In September 2025, the disagreement between the

two countries first culminated in a US-led military operation in late 2025, and that development later resulted in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife on January 3, 2026. Official framing by the US government claimed that this military operation was a means to counter Venezuela’s use of narcotics for its terrorist policy toward the United States, a practiced termed “narco-terrorism” in America today. This operation marked the most significant US military intervention in Latin America

Dr. Hon-min Yau is a professor of Strategic Studies at the ROC National Defense University. He can be reached for comment at cf22517855@gmail.com

President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio monitor US military operations in Venezuela, from Mar-a-Lago in Florida on January 3, 2026.

Photo: Molly Riley

since the 1989 invasion of Panama. Beyond its immediate tactical objectives, the episode also carries profound strategic, legal, and geopolitical implications for US foreign policy, hemispheric order, and the future of international norms governing the use of force. As such, this article reviews this latest development and investigates what it means for the international community.

The antagonistic relationship between Washington and Caracas has deep historical roots. Venezuela’s late president Hugo Chávez, who first became the head of the state in 1999, pursued a strongly socialist and anti-American agenda that challenged US influence in Latin America. His rhetoric and policies, including the nationalization of energy assets and explicit personal attacks on George W. Bush, calling him “Donkey” in 2006, set the stage for a long period of mutual distrust between the two countries.

Following Chávez’s sudden death due to cancer in 2013, Nicolás Maduro inherited both power and conflict. Although he initially completed Chávez’s

“By 2025, roughly 80 percent of Venezuelanoilexportsweredirected toChinaasrepaymentforeconomic andinfrastructureassistance.”

remaining term (2013-2019) and served his second term (2019-2025), but his latest presidential election in 2024 for the third term (2025-2031) was widely criticized by the United States and other governments as fraudulent. Despite being sworn in for a third presidential term in January 2025, Maduro’s legitimacy remained internationally contested after allegations of widespread electoral irregularities, with Washington and other governments recognizing opposition leader Edmundo González as Venezuela’s rightful leader. These unresolved legitimacy disputes laid the political foundation for the US escalation. The turning point came after President Donald Trump returned to office in 2025. Although Trump was often perceived as being transactional and focus-

Photo: US Air Force

A Marine Corps pilot captain guides in an F-35B Lightning II following military actions in Venezuela in support of Operation Absolute Resolve, Jan. 3, 2026.

ing more on economic means, rather than the use of military force, his administration in fact articulated a foreign policy centered on America First, emphasizing national strength, economic security, and reduced tolerance for challenges within the Western Hemisphere. While Trump’s policies were often confrontational toward both rivals and allies, they were underpinned by a consistent belief that peace is best preserved through overwhelming strength.

National Security Strategy

The US National Security Strategy finally released in December 2025 highlights this worldview. It called for reduced overseas entanglements but simultaneously stressed the importance of securing US dominance in the Western Hemisphere. This updated code, later

referred to as the “Donroe Doctrine,” represented Donald Trumps’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. However, unlike its 19th-century predecessor, which focused on excluding European powers from the Americas, the Donroe Doctrine asserts US primacy against any external or ideological challenge, particularly from China and those China-friendly leftleaning regimes. As such, Venezuela emerged as a critical test case for this doctrine.

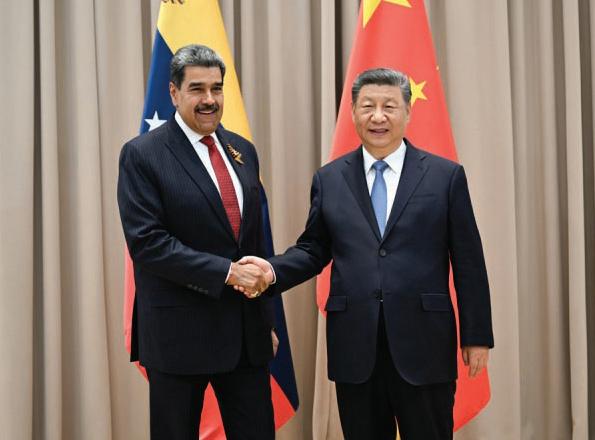

Venezuela’s growing alignment with China significantly intensified US concerns. Since 2018, Caracas had become a key participant in China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Latin America. By 2025, roughly 80 percent of Venezuelan oil exports were directed to China as repayment for economic and infrastructure assistance. From Washington’s perspective, this arrangement not only entrenched Chinese influence in the region but also

Xi Jinping meets with Nicolas Maduro in Moscow in 2025. China has pledged to be an all-weather strategic partner to Venezuela under Maduro.

Photo: PRC MOFA

threatened US energy and security interests.

Compounding these concerns was Venezuela’s long-standing practice of supplying subsidized oil to Cuba, thereby undermining US sanctions against Havana. US policymakers viewed these developments through a Cold War-style lens. Political leaders, such as Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is a descendent of Cuban family, is a vocal critic of communist influence in the Americas, and he feared a renewed “domino effect” in which leftist regimes across Latin America would gain confidence and support from extra-regional powers if Venezuela were allowed to persist unchecked.

The Trump administration eventually moved decisively in 2025. In February, it first designated Venezuelan drug trafficking organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and labeled Maduro himself a global terrorist leader. This designation provided a potential legal and rhetorical foundation for subsequent actions. In April, the United States imposed a 25 percent secondary tariff on countries importing Venezuelan oil and enforced an international embargo. By August, the US government had raised the bounty on Maduro’s head—initially set by the Biden administration at US$25 million—to US$50 million.

Military pressure followed economic coercion. In September 2025, US forces launched Operation Southern Spear in the Caribbean, ostensibly targeting unflagged vessels allegedly smuggling drugs in international waters. By December, these operations expanded into a comprehensive maritime quarantine (a de facto blockade), intercepting oil tankers suspected of violating US sanctions. The final escalation occurred on January 3, 2026, when US special forces, reportedly with CIA assistance, executed Operation Absolute Resolve, a surprise raid in Caracas that resulted in the capture of Maduro and his wife and their transfer to New York for trial on charges of narcoterrorism.

Legal debate

The operation immediately sparked intense legal debate. Critics argued that the US action violated Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, which prohibits the use of force in international relations, and failed to meet the requirements for collective authorization under Article 42 or self-defense under Article 51. From this perspective, the intervention represented a clear case of unlawful unilateral force.

Graphic: Chorchapu

Supporters of the US position advanced a different interpretation. Drawing on post-9/11 precedents, they cited UN Security Council Resolution 1368 (2001), which recognizes the right of self-defense against terrorist threats. By designating Venezuelan drug networks as terrorist organizations and alleging state sponsorship, the United States claimed that its actions fell within the scope of anticipatory self-defense.

Domestically, critics accused the Trump administration of bypassing Congress and violating constitutional war powers. In response, supporters argued that the initial maritime deployments constituted law enforcement or interdiction actions, while the Caracas raid was classified as a covert intelligence operation (a US Title 50 mission) rather than an act of war (a US Title 10 mission). This distinction, while controversial, reflects longstanding ambiguities in both US and international practice regarding covert action.

Reactions to the operation were mixed but largely critical. Venezuela’s constitutional court quickly in-

stalled Vice President Delcy Rodríguez as interim leader. While her initial statements denounced the US action as imperialist aggression and kidnapping, her tone quickly shifted toward cautious engagement, signaling a willingness to open dialogue with Washington.

Strong condemnation

China and Russia issued strong condemnations but stopped short of concrete countermeasures. The European Union called for restraint and adherence to international law, while reiterating its view that Maduro lacked democratic legitimacy. The UN Security Council convened an emergency session to discuss escalation risks, highlighting broader anxieties among smaller states that unilateral power might increasingly override established norms.

At a surface level, the US intervention can be interpreted as an effort to combat drug trafficking, stabilize migration flows, and secure energy interests. At a deeper level, however, it reflects a reassertion of

A photo released by the DEA shows captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro posing with agents after his arrival in New York under US custody.

photo: US DEA

US dominance in the Western Hemisphere under the Donroe Doctrine. The operation sent a clear signal not only to Venezuela but also to other socialistleaning governments in the region that alignment with US adversaries carries tangible risks.

More broadly, the episode underscores a shift in US strategic culture under Trump’s second term. When core national interests are perceived to be at stake, the administration appears willing to accept legal ambiguity and international criticism in exchange for decisive outcomes. This approach may deter some adversaries, but it also risks normalizing a world in which power increasingly defines legality rather than the reverse. The latest US military intervention unfortunately signified the beginning of the end of the rule-based international order.

The US 2025-2026 military action against Venezuela represents a watershed moment in contemporary hemispheric politics, and it is also the second time

during Trump’s second administration that he has been willing to use force upon another state actor. It highlights the resurgence of great-power competition in Latin America, the fragility of international legal norms, and the enduring tension between legitimacy and effectiveness in foreign policy. Whether viewed as a necessary act of enforcement or a troubling precedent, the operation illustrates how America First translates into action when strategic interests converge. Its long-term consequences could be damaging for regional stability, but it also signified the growing significance of the US-China rivalry, which facilitates more uncertainties and an undeniable shift toward international anarchy.

For Taiwan, this will unfortunately suggest that when the rules of international relations retreat to power politics, investing itself with more power, via either internal balancing or external balancing, sadly becomes the most important recipe for national survival. n

Photo: US Coast Guard

A US Coast Guard crew member observes the oil tanker Bella 1, which violated US sanctions and resisted initial boarding attempts off coastal Venezuela.

Vision vol. 15, no. 64 (February, 2026)

Injustice Mission

China tests regional red lines through Justice Mission 2025 drills around Taiwan

Dean Karalekas

In late December 2025, as many in the West were recovering from their Christmas celebrations and looking forward to ringing in the New Year, the forces of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), in conjunction with other paramilitary assets of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), were busy flexing their military muscle in the latest of the large-scale drills encircling Taiwan—drills that have become all but routine in recent years.

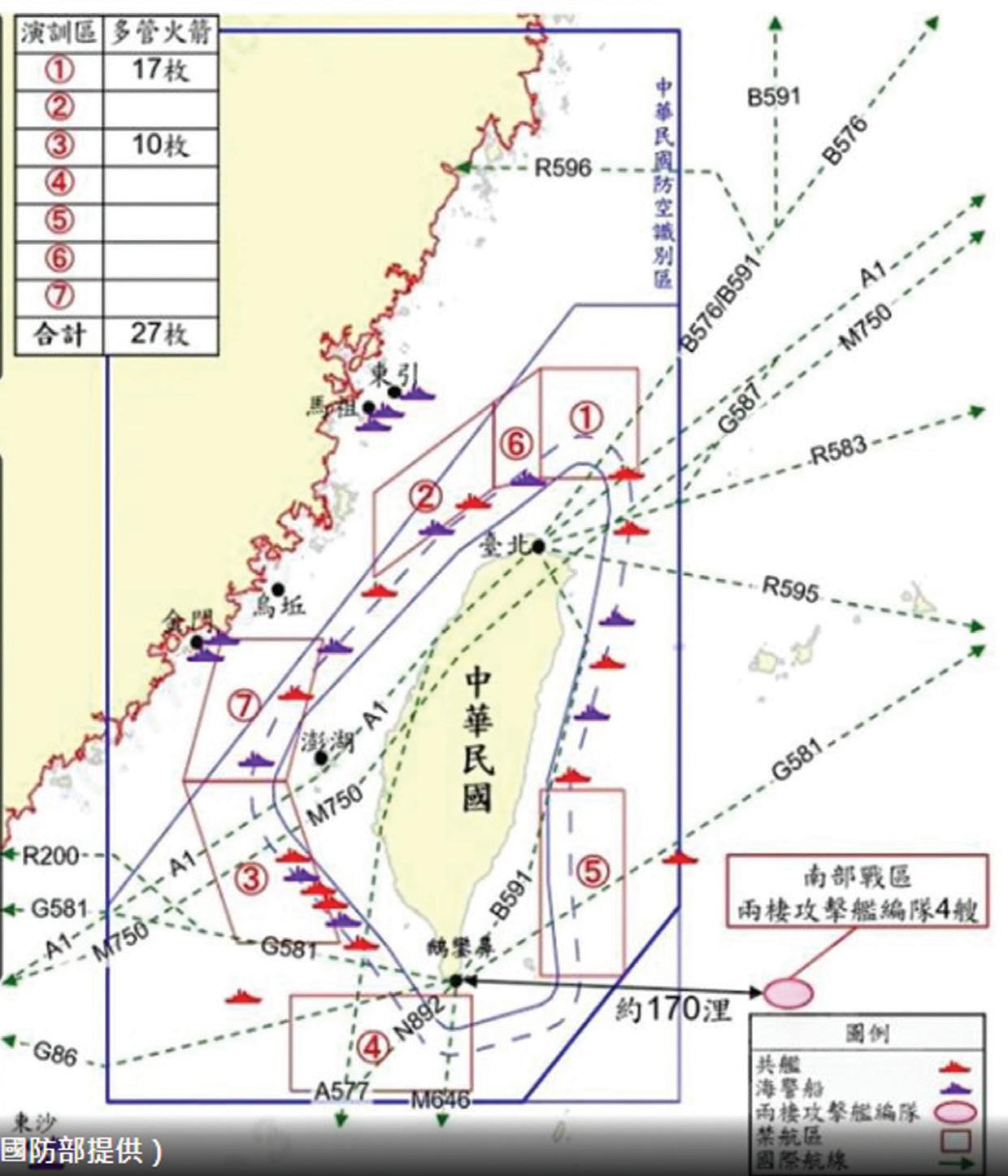

The latest exercise, dubbed Justice Mission 2025, was largely similar in scale and location to previous iterations. As PLA missiles splashed down in the waters to Taiwan’s north and south, military aircraft

practiced attacks on hypothetical foreign naval assets, and approximately 90 vessels of the PLA Navy (PLAN) erected two maritime blockades, one east of Taiwan and the other paralleling the First Island Chain. The area of operation (AO) consisted of seven established no-fly zones (surface ships were likewise barred from entry), allowing the PLA to simulate a blockade of key Taiwanese ports. It was reported by Taiwan’s Civil Aviation Administration that 857 international flights and 84 domestic flights were affected by the live-fire military drills.

Militarily, the purpose of the exercise was to assess the Eastern Theater Command’s ability to con-

Dean Karalekas is Editor-at-Large for Strategic Vision and the author of Civil-Military Relations in Taiwan: Identity and Transformation.

ROC Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo meets with high-level military leaders to manage the response to the PLA’s provocative drills.

photo: ROC MOD

duct joint operations under near-combat conditions, with an emphasis on joint firepower strikes, systemic blockade, and comprehensive domain control. Politically, it was purportedly motivated by Beijing’s displeasure with “foreign forces” and their attempts to embolden “Taiwan independence separatists and intensify cross-straits confrontation,” according to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpiece, Global Times. This may be a reference to the Trump administration’s recent announcement of a recordhigh US$11 billion arms sale to the island, or Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s now-infamous public acknowledgement that a Chinese attack on Taiwan would constitute “a survival-threatening situation” for Japan, requiring the use of defensive measures. Or, it may have been both: the official CCP wording was characteristically vague:

“We urge relevant countries to abandon the fantasy of ‘using Taiwan question to contain China,’ cease fanning the flames and stirring up trouble on the Taiwan question, and refrain from challenging China’s resolve and will to safeguard its core interests,” Chinese Defense Ministry spokesman Zhang Xiaogang was quoted in the Global Times as saying.

An assessment by Taiwan’s National Security Bureau later confirmed this view that the motivation behind the drills was primarily political. Domestically, the jingoistic messaging surrounding the military deployment was designed to divert the Chinese public’s attention away from worsening economic conditions in China. Internationally, the exercises were positioned as a response to growing international support for Taipei,

designed to send a message to the country’s democratic partners dissuading them from any attempt to aid in the island’s defense. Clearly, the aforementioned comments by Japan’s PM Takaichi struck a raw nerve in Beijing.

Similar scale

According to an analysis of the exercise by K. Tristan Tang, co-founder of the Taiwan Defense Studies Initiative, the scale of the exercise did not deviate from previous drills, and in fact may have been more subdued, as evidenced by a lack of participation by any of the PLAN’s aircraft carriers. In all, the Republic

PLA Eastern Theater Command poster, titled Arrow of Justice: Control and Denial.

of China (ROC) military tracked the participation of 17 PLA ships on December 30, a significant drop from the 27 detected during Joint Sword 2024A. Likewise, the number of PLA aircraft sorties detected did not reach the number seen during previous exercises such as Joint Sword-2024B.

Emerging patterns

While the scale of the Justice Mission 2025 did not break any records, there was much about the exercise that was new. As Tang points out, the timing of the exercise deviated from the norm in that December makes for a particularly challenging time for operations such as this one. For one thing, it falls at the end of the PLA’s training cycle, and is usually something

of a quiet period. Many analysts also argue that the least operationally challenging seasons for a kinetic engagement against Taiwan, and therefore the most likely time for a troop-crossing of the so-called Black Ditch, would be in either October or April, when the sea state in the Taiwan Strait is more amenable to the mass movement of troop transports and landing craft. The lighter winds and lower waves during these months would facilitate what is normally a hazardous crossing marked by monsoon winds and typhoon rains.

Moreover, judging by joint long-range firepower strikes conducted by the Army as part of an integrated, multi-service operation that included the PLAN, the Air Force (PLAAF), and the Rocket Force (PLARF), Justice Mission 2025 simulated for the first time the capture of the Penghu Islands, as well as the establishment of a beachhead on eastern Taiwan.

Unlike the live-fire PLA drills of August 4, 2022, no part of the Justice Mission 2025 AO overlapped with Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). In the 2022 drills, later dubbed the Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis, it was reported that five of the PLARF’s ballistic missiles splashed down in the East China Sea, inside Japan’s EEZ near Hateruma Island. That drill, which followed the visit to Taiwan of then-US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, was the largest-ever military exercise around the island to date, and served as a wake-up call to leaders in Tokyo. Indeed, it may have contributed to a hardening

of Japanese policy against Chinese aggression and led to the aforementioned statement by PM Takaichi.

No part of the exercise zone encroached into Japan’s EEZ this time, nor were any missiles fired into it. Indeed, writing in The Investigator, Gray Sergeant notes that a large gap was conspicuously observable in the map of the Chinese exercise zones, between Taiwan and Japan’s Yaeyama Islands. This may be an indication that the heated rhetoric coming out of Tokyo is having an effect on the CCP’s calculus on provoking Japan, or it may speak to more pragmatic considerations.

According to Kitsch Liao, associate director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, that gap in coverage may be more indicative of Chinese caution in the face of the recent Japanese deployment of Type 03 Chu-SAM mid-range air defense system on Yonaguni Island. According to Army Recognition Group, this mobile, networked air defense system features active radar-homing missiles, truck-mounted vertical launchers, and a phasedarray radar system that can track multiple targets simultaneously, and is designed to be integrated into Japan’s multi-layered air defense strategy. The placement of such a system on Yonaguni—just 68 miles from Taiwan, and visible on a clear day—is evidently a disincentive to the PLA and warplanners in Beijing, according to Liao, and is evidence that allied efforts to erect “a concrete deterrence against China’s anaconda strategy to normalize its coercion against Taiwan is indeed having a noticeable effect.”

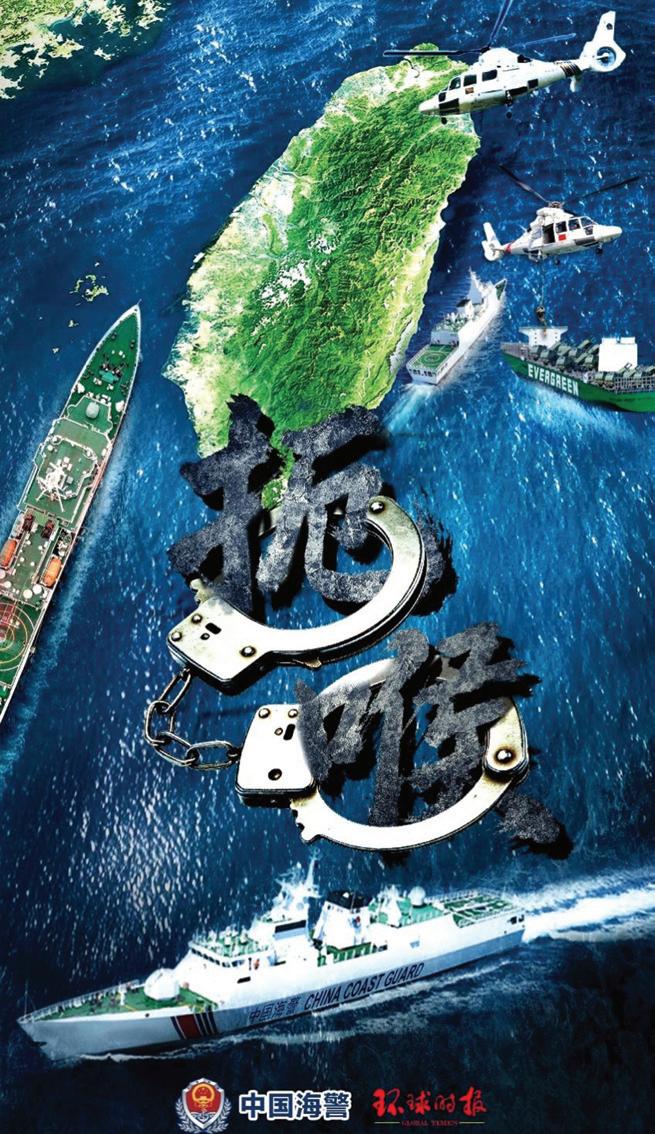

A variant of the PRC’s “Throat-choking” propaganda poster.

This deterrence effect was not replicated in Taiwan, however. Ten of the 27 rockets fired during the Justice

Mission 2025 exercise splashed down within the boundary of Taiwan’s contiguous zone (12-24 nautical miles from the coast), making it the closest-ever PLA live-fire exercise, according to Sergeant. Taiwan’s contiguous zone was breached by 11 PLAN warships and eight vessels of the China Coast Guard (CCG) on December 29, he points out, adding that the following day saw these same numbers repeated. In contrast, during April’s exercise Strait Thunder-2025A, only one CCG ship entered Taiwan’s contiguous zone.

The inclusion of the Coast Guard, which in other countries are considered a paramilitary force, continues a trend in the PRC’s use of law-enforcement and even civilian assets—as evidenced by China’s Maritime Militia, a government-deputized fleet of fishing vessels—to exercise national power through gray-zone coercion. Research by Julia Famularo of the Global Taiwan Institute suggests that warplanners in Beijing may believe that the deployment of CCG assets to impose a sea-based “quarantine”—rather than a full “blockade”—on Taiwan would force allied nations to conclude that the action remains under the threshold of war according to international law. Thus, in the absence of a legal casus belli, any third-party intervention would be effectively hampered.

This legal interpretation is moot, however, as Beijing in 2018 removed the CCG from civilian control and placed it under the People’s Armed Police, which itself is under the unified command of the Central Military Commission. Thus, for countries considering deploying military assets to help defend the Justice Mission 2025 b 13

island, there would seem to be little legal difference between a PLA-enforced blockade of Taiwan and a CCG-imposed quarantine.

PsyOps component

The purpose of Justice Mission 2025, as indeed with all of China’s drills surrounding Taiwan, was as much about achieving psychological objectives as military ones. This is in keeping with Beijing’s concept of systems-level warfare, in which PsyOps are integral to shaping the battlefield before and during conflict. The ROC military’s Political Warfare Bureau counted a reported 46 discrete items of disinformation geared toward undermining the public’s confidence in the ROC military and government. Over a five-day period, it was reported that the WuMao / 50 Cent Army posted approximately 19,000 so-called “controversial messages” on some 800 social media accounts, providing the military arm of the exercise with narrative support.

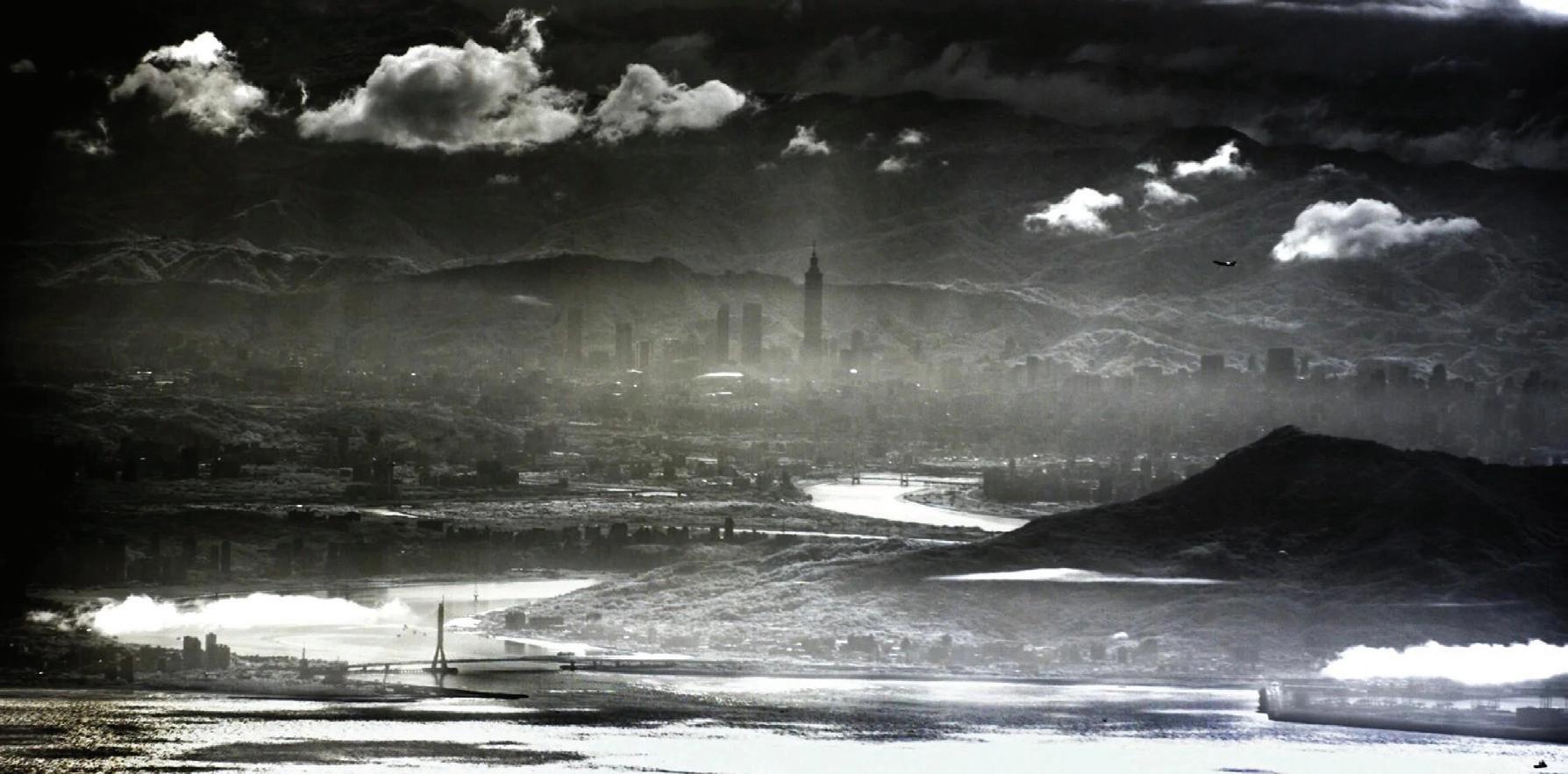

One such image making the rounds was the PRC’s “Throat-choking” poster of CCG assets boarding an Evergreen cargo vessel depicted carrying rocket launchers. In another widely-circulated piece of ag-

itprop, a blurry panoramic image of Taiwan’s capital with the iconic Taipei 101 skyscraper distinctly visible was ostensibly captured by a PLA drone during the exercises, with the caption “so close, so beautiful, ready to visit Taipei anytime.” The PLA claimed the image was taken on Monday, December 29 by a Chinese TB-001 medium-altitude, long-endurance

“The more these exercises normalize aPLApresenceinthewatersandairspacearoundTaiwan,themoreurgent itisthatTaiwansociety,atalllevels, remainonalertandvigilant.”

drone, which are equipped with advanced electrooptical pods and rumored to be capable of detecting targets from a distance of 37 miles. If true, this would indeed be chilling.

Taiwan’s defense ministry was quick to dismiss the image as nothing more than cognitive warfare, however. Speaking at a press briefing the following day, Taiwan’s assistant vice-minister for intelligence, Hsieh Jih-sheng, confirmed that while the ROC had monitored TB-001s operating near the island, none had breached the 24-nautical-mile contiguous zone.

Screencap from a PLA-released video purportedly showing a drone-captured view of central Taipei, circulated during the Justice Mission 2025 exercises.

Hsieh pointed out that the footage could have much more easily been digitally manipulated, or even AIgenerated.

Taiwan’s Response

In all, the Taiwanese response to Justice Mission 2025 was promising. The ROC government was effective in monitoring the activities of the PLA assets while pushing back against the narrative component of the exercise by taking control of the information environment. By holding regular press conferences and providing real-time situation updates, the Ministry of National Defense signaled maturity, readiness, and the need to deal as a society with the threat in a calm manner.

As reported by Jaime Ocon, the ROC Armed Forces were put on a high alert level, setting up an emergency operations center where government and military planners could monitor Chinese activity and determine appropriate rules of engagement should a kinetic confrontation erupt. It was reported, for example, that the PLAN’s Urumqi, a Type 052D guided-missile destroyer, was painted by Taiwanese fire-control radar from the frigate ROCS Pan Chao, though these

reports were officially denied. If accurate, this is precisely the type of response that signals to PLA personnel that military exercises may be tolerated, but there are real-world stakes to any escalation or wider conflagration, should they be so tempted.

All in all, Justice Mission 2025 fell squarely within the trendline of Beijing’s ongoing use of military exercises to both signal displeasure at some perceived slight, and to demoralize and destabilize Taiwan society. While the ROC government and military were effective in their defense against the latter effort, it is essential that Taiwan not fall into a sense of complacency. The more these exercises normalize a PLA presence in the waters and airspace around Taiwan, the more urgent it is that Taiwan society, at all levels, remain on alert and vigilant, without succumbing to burnout or despair. Finding that middle ground for managing both the military and psychological dimensions of gray-zone pressure will be crucial to ensuring continued deterrence in the Taiwan Strait— as the world saw in 2022 with the Russian attack on Ukraine: a large-scale military exercise can swiftly turn into a full-scale attack, merely on the whim of an autocratic leader. As the axiom goes, eternal vigilance is the price of liberty. n

ROCS Pan Chao (PFG-1108), a Cheng Kung–class frigate of the ROC Navy, based on the US Oliver Hazard Perry design with Taiwanese weapons and sensors.

photo: ROC MOD

Strategic Vision vol. 15, no. 64 (February, 2026)

Close Quarters

Managing risk and restraint in an increasingly overcrowded maritimescape Rhomir Yanquiling

On September 30, 2018, a US freedom of navigation operation (FONOPS) in the South China Sea nearly ended in disaster. As the guided-missile destroyer USS Decatur sailed near Gaven Reef in the Spratly Islands, the Chinese destroyer Lanzhou crossed the Decatur’s bow at a distance of just 45 yards, forcing the American ship to take evasive action to avoid a collision. Two years after this close-quarters situation, similar confrontations followed when the USS Barry and USS Bunker Hill were conducting FONOPS near the Paracels and Spratlys. Beijing claimed it had “expelled” these ships;

Washington disputed this characterization, pointing out that operations had continued as planned.

Maritime incidents like these are not confined to great power competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC); they increasingly spill into the everyday maritime lives of ordinary users at sea. For instance, on December 13, 2025, three Filipino fishermen were reportedly injured after Chinese law-enforcement vessels used high-pressure water cannons on them at Sabina Shoal. A year earlier in 2024, several Vietnamese fishermen were similarly injured in an encounter

Rhomir Yanquiling is a MOFA Research Fellow currently affiliated with the Taiwan Center for Security Studies. He can be reached for comment at yrhomir@gmail.com

The USS Bunker Hill (CG 52), front, and USS Barry (DDG 52) transit through the South China Sea on April 18, 2020.

Photo: Nicholas Huynh

with Chinese vessels. Between these incidents are frequent reports of ramming, unsafe laser illumination, and performing risky maneuvers.

None of this is full-blown conflict—yet. But each incident edges dangerously closer to a situation where a single miscalculation triggers something far more serious.

Over the past two years, maritime incidents in the South China Sea from 1947 to 2025 have been tracked and entered into a dataset of conflict and cooperation events. This long duree perspective reveals a dynamic and layered maritime space—a maritimescape— where geography, history, and geopolitics intersect.

Understanding the South China Sea as a maritimescape is essential for making sense of its recurring conflict-cooperation dynamics and for imagining more inclusive pathways toward regional stability.

Transboundary waters, such as seas and oceans, are viewed as a global public good and a shared heritage

of humanity. However, in a neo-liberal world, it can be treated as res publicae (public good) at the disposal of the state. Covering approximately 3.5 million square kilometers, the South China Sea (SCS) is one such transboundary waters. Claimant states include Malaysia, Vietnam, the PRC, the Philippines, Brunei, and the Republic of China (ROC). These countries, along with external powers such as the United States and its Indo-Pacific allies, are enmeshed in a complex web of SCS territorial disputes driven by overlapping geo-economic and geopolitical interests.

The South China Sea is often described as one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, host to trillions in untapped hydrocarbons, and home to fisheries that feed millions. A third of global shipping passes through these waters each year, while the region produces a significant share of the world’s marine catch that sustains livelihoods across Southeast Asia.

But the stakes today extend far beyond econom-

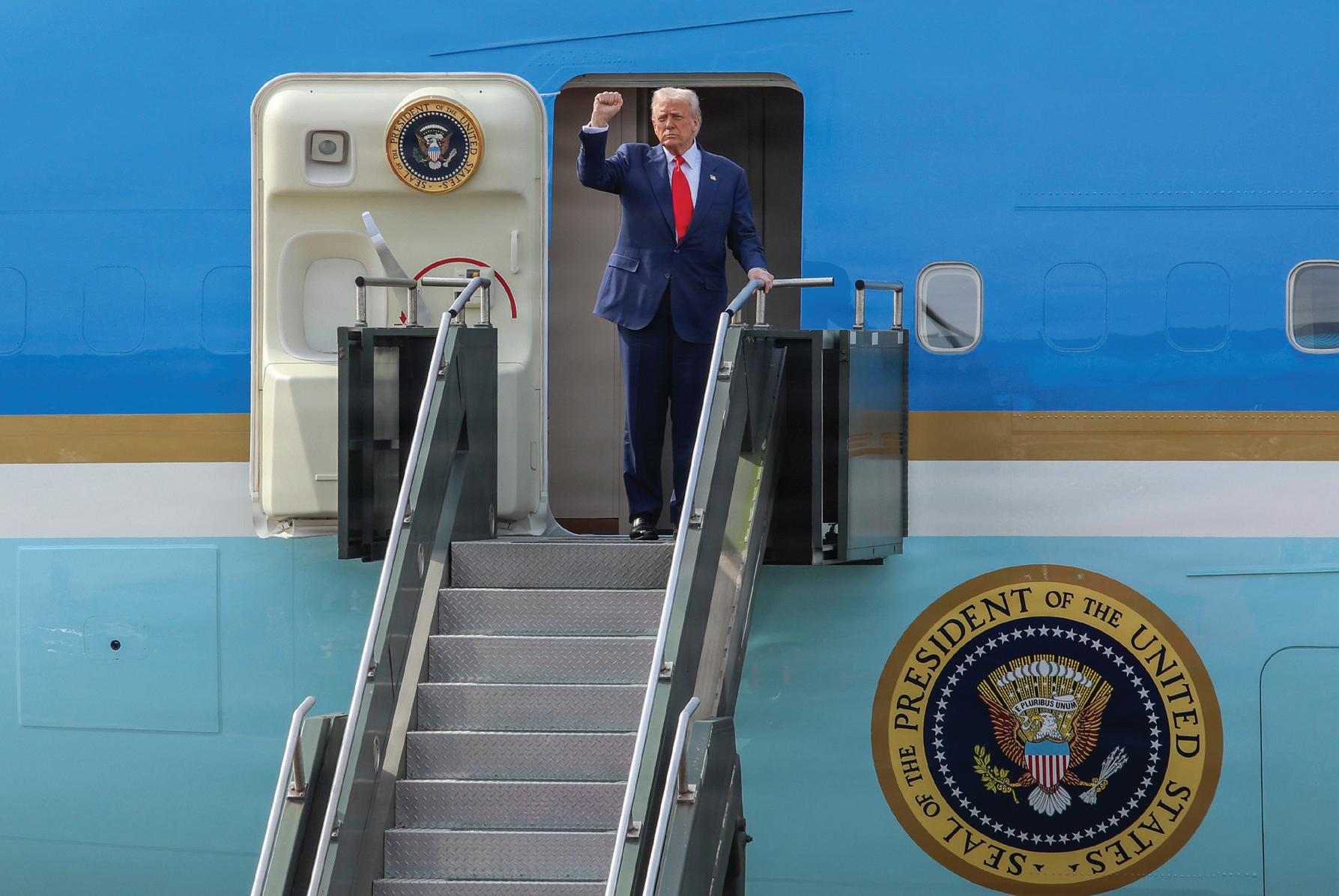

US President Donald J. Trump raises his fist as he departs Gimhae Airport, Busan, South Korea on Oct. 30, 2025.

photo: Daniela Lechuga Liggio

ics. Climate change, intensifying resource pressure, and deepening geopolitical realignments have transformed the SCS into a barometer of regional order and a crucible of competing strategic visions. For external major powers such as the United States and its NATO and Indo-Pacific allies, the need to maintain the SCS as mare liberum, or free sea, is consistent with its assertion of securing the seas as open and free, not only for global trade but also for navigation, overflight, and other rights in the high seas. In contrast, Beijing acting as a hydro-hegemon on the contested waters, increasingly presents such operations as interference in what it regards as a sovereign Chinese concern.

A defining role

The intensification of tensions in the South China Sea following the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling reinforces Philip Steinberg’s 1999 observation that, rather than serving merely as a backdrop to terrestrial politics, the sea has taken on a defining role in structuring contemporary social, environmental, and governance challenges. Given its vast resource endowments and

strategic importance in both economic and geopolitical terms, the South China Sea has increasingly become a focal point of regional and extra-regional contestation. Instability in these waters produces a butterfly effect that extends beyond claimant states and coastal communities to shape the broader security and economic calculations of actors well beyond the region.

The South China Sea is often described as a geopolitical chessboard—a fixed map of competing claims and strategic maneuvers. But this image misses much of what actually happens on the water. For the SCS, adoption of the maritimescape paradigm moves beyond what John Agnew calls the “territorial trap,” a land-centric conception of political space that, when applied to the maritime domain, treats the sea as empty space to be enclosed and territorialized by claimant littoral states. The maritimescape concept reconceptualizes the South China Sea as a living, dynamic, relational and fluid geography that shapes and is shaped by long histories of movement, empire, trade, and shifting forms of political power.

First, it draws attention to the sea’s historical and geographical character. For centuries, the South

The HNLMS Tromp conducts a Replenishment At Sea with USS Wally Schirra to secure the right of free passage for shipping in the Indo-Pacific.

Photo: Ronan Williams

China Sea has served as a corridor of commerce and migration, linking cultures and economies long before modern borders emerged. Its geography has always been fluid, shaped by tides, monsoons, trade winds, and the rhythms of human movement. This fluidity persists today, influencing everything from fisheries and migration to shipping routes and storm patterns. The sea therefore is not simply a battleground; it is a lived and governed space that supports millions of people and enables global trade and inter-continental relations. Reducing it to a theater of great-power rivalry between the United States and China or regional competition in the ASEAN region obscures the rich and nuanced nature of this sea lane.

Second, the maritimescape underpins the geopolitical pressures that now shape these waters. The sea has become a space where states project sovereignty, deploy coast guard and militia fleets, compete for the sea resources, and respond to marine environmental

changes. As demands on the maritime domain increase—from seabed exploration to blue-economy initiatives—territorialization intensifies. The result is a dynamic interplay between the sea’s inherent mobility and the political efforts to regulate, enclose, and control it.

Third, a maritimescape perspective encourages diplomatic approaches that build on interdependence rather than zero-sum rivalry. It shifts the focus from rigid territorial claims to shared problems such as climate change and maritime security. Despite episodes of conflict, claimant states in the SCS have repeatedly found ways to work together when functional needs demand it, whether in responding to typhoons, coordinating search-and-rescue operations, managing fisheries, or conducting scientific surveys. Seeing the sea as a corridor of cooperation opens pathways for joint conservation zones, coordinated fisheries management, incident-at-sea protocols, environmental

A landing craft approaches the well deck of USS Somerset (LPD 25) during Exercise Balikatan 24, held to promote US-Philippine military interoperability.

photo: Evan Diaz

monitoring, or even climate adaptation initiatives— all areas where cooperation can be expanded even amid disputes over sovereignty.

The longitudinal dataset of maritime incidents from 1947 to 2025 complicates the often reductionist narratives in the South China Sea as fundamentally conflictive.

One of the most striking patterns is that conflict and cooperation are not opposing conditions but often unfold simultaneously along a shared continuum. Periods marked by heightened standoffs or confrontations at sea frequently coincide with diplomatic initiatives, bilateral consultation mechanisms, and regional dialogues involving state and non-state actors. The 1990s, for instance, witnessed both maritime clashes and the early stages of regional norm-building through confidence-building measures and the 1992 ASEAN Declaration on the South China Sea. Similarly, the 2000s saw difficult fisheries and patrol incidents alongside cooperative

undertakings such as joint seismic surveys and the 2002 signing of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC). Even following the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff between the Philippines and China, states continued to pursue talks on fisheries, humanitarian coordination, and other confidence-building efforts. Cooperation thus persists not despite conflict, but alongside it, reflecting the enduring interdependence of states managing shared risks in a contested maritime space. Conflict and cooperation in the South China Sea are therefore not mutually exclusive but co-constitutive processes.

The dataset also reveals that the drivers of maritime incidents shift across historical periods. In the immediate postwar decades, many incidents reflected postcolonial state consolidation and Cold War maneuvering. This is illustrated by two developments in the early 1970s, namely reports of potential oil deposits in 1972 in the Paracels, and the Paris Peace Accords of January 1973 which ended US combat in

Secretary of War Pete Hegseth meets the ministers of defense from Malaysia, Thailand, and Cambodia at their 2025 ASEAN meeting in Kuala Lumpur.

photo: Madelyn Keech

Vietnam. From a largely political and administrative concern, the South China Sea has also emerged as an economic development issue. The Battle of the Paracel Islands was the first major clash in the South China Sea involving Chinese and South Vietnamese navies in January 1974.

From the 1980s onward, rising fishing pressure, offshore resource exploration, and naval modernization became more prominent drivers, mirroring broader economic and political transformations in the region. Following the Philippines’ filing of arbitration case against China in 2013, episodes of confrontation increased markedly—not only between China and the Philippines, but also between China and Vietnam. Triggers in this period expanded beyond hydrocarbons and fisheries to include legal enforcement of sovereignty claims through the growing use of grayzone tactics. All these happen in the context of intensifying geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China and the eventual 2016 Arbitral Ruling in

the Hague that ruled against Beijing’s excessive maritime claims. Maritime incidents during this phase increasingly featured not only naval and coast guard forces, but also China’s use of maritime militias, fishing fleets, and other ostensibly civilian vessels. Such shifts show that maritime tensions are not static; they evolve alongside regional geopolitics, historical antecedents, and the socio-economic and environmental changes in the region.

Strategic flashpoints

The dataset further reveals that maritime conflict in the South China Sea is spatially uneven and contingent. Although the Spratly Islands constitute the most enduring zone of contention, other sites—including Scarborough Shoal, Reed Bank, Luconia Shoals, and the Paracels—periodically rise in prominence as strategic flashpoints. Such spatial shifts reflect the interplay of resource discovery, evolving

A naval aircrewman observes the littoral combat ship USS Fort Worth (LCS 3) as it conducts routine patrols near the Spratly Islands.

photo: Conor Minto

patrol patterns, infrastructure expansion, and wider geopolitical developments. Maritime contention, therefore, unfolds as a series of spatially concentrated episodes rather than as a uniform basin-wide condition.

Finally, the range of actors involved in maritime incidents has also diversified over time. Whereas mid-twentieth-century encounters were dominated by naval forces, contemporary interactions increasingly involve coast guards, maritime militias, survey vessels, fishing fleets, and other civilian actors. External stakeholders exercising their rights of freedom of navigation and overflight also feature in the maritime landscape. This diversification expands the range of potential flashpoints, but it also introduces new avenues for engagement, coordination, and cooperation.

Looking at the South China Sea as a maritimescape makes one thing clear: approaches that focus only on sovereignty and territorial claims miss much of what is actually happening at sea. These waters are not just sites of strategic rivalry between the United States and China, or between China and other claimant states such as Vietnam, the Philippines, the ROC, Malaysia

and Brunei. They are also shared spaces that carry global shipping, sustain coastal livelihoods, support energy flows, and host fragile marine ecosystems.

This broader reality helps explain why the establishment of a South China Sea Code of Conduct (COC) is so important. While this may not conclusively put an end to the sovereignty disputes over the SCS, it provides a common framework for setting expectations about how claimant states should behave at sea and resolve issues diplomatically and peaceably. Its real value lies in encouraging restraint, transparency, and communication—practices that can prevent incidents from spiraling into crises.

For a COC to be inclusive and responsive, it needs to complement existing international law and remain connected to the wider range of actors operating in the region. There is a call to extend maritime diplomacy beyond claimant states to include non-ASEAN claimants such as the ROC; external stakeholders exercising high seas freedoms, including freedom of navigation and overflight; as well as non-state actors such as commercial shipping interests and ordinary maritime users—particularly fishermen pursuing their livelihoods—who experience maritime disrup-

A US sailor practices vessel boarding procedures with his counterpart from Thailand onboard US Coast Guard Cutter Munro (WMSL 755).

Photo: Brett Cote

tions most directly. Stability here depends not only on the actions of claimant states, but also on those of non-state, non-ASEAN, and external maritime stakeholders.

As maritime activities in the SCS have expanded due to a phenomenon scholars call “blue acceleration,” so too has the number of actors involved. Coast guards, maritime law-enforcement agencies, commercial fishing fleets, survey ships, and civilian vessels interact daily in close quarters. Clearer channels for communication, better procedures for managing unplanned encounters, and shared understandings about acceptable conduct can make these routine interactions less risky, even when political disagreements persist.

There is also room for cooperation that goes beyond managing crises. Sharing data on fisheries, environmental conditions, and maritime traffic can build confidence and reduce uncertainty. Some observ-

ers have suggested that the South China Sea could benefit from a basin-style arrangement—similar to river basin organizations—that focuses on technical coordination and joint governance of shared maritime concerns. Such an approach would not replace existing diplomatic efforts, but could sit alongside them, offering practical ways to manage common challenges.

Maritime diplomacy in the South China Sea is less about settling sovereignty disputes once and for all: it is about keeping relationships workable over time. It is about sustaining mutual respect, continuous engagement, open communication, and managing differences.

Seeing the South China Sea as a shared maritime commons helps move the conversation beyond rigid lines on maps and toward the everyday practices that make peace and stability possible, even in an uncertain and changing regional order. n

Marines watch as an MV-22 Osprey lands during evening flight operations aboard ship USS Tripoli (LHA 7) in the South China Sea on Dec. 12, 2025.

photo: Paul LeClair

Strategic Vision vol. 15, no. 64 (February, 2026)

Peripheral vision

Taiwan builds maritime domain awareness despite barriers in Indo-Pacific networks

Hui-Chen Lai

The emergence of the “Indo-Pacific” concept signified a shift in global strategic focus from the traditional “Asia-Pacific” conceptualization of the region to a broader perspective encompassing Indian Ocean nations along with those of the Pacific. This region serves not only as a vital corridor for global trade and energy transportation but also as a central arena for great power competition and geopolitical maneuvering. Within the Indo-Pacific, maritime security and freedom of navigation face increasingly severe challenges, particularly stemming from People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) military expansion, island construction activities in the South China Sea, hybrid tactics in the East China Sea and Taiwan Strait, and its normalized gray-zone operations. These actions, such as intrusions by China’s maritime militia and “threeno” vessels (no name, no flag, no home port), blur the lines between peace and conflict, posing a significant threat to regional stability.

In addressing these challenges, Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) has emerged as a core element within the Indo-Pacific security architecture. The United States and its allies, including Japan, Australia, and India—collectively known as the Quad— launched the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) initiative in 2022. It aims to enhance transparency and response capabilities among regional partner nations through technology and information sharing. Taiwan, strategically

positioned at a critical node within the First Island Chain, possesses irreplaceable value within the IndoPacific MDA network. Its surrounding waters serve as a vital transit corridor linking Northeast Asia and the Western Pacific. However, complex geopolitical factors hinder Taiwan’s formal participation in official multilateral mechanisms like IPMDA, making the exploration of its role and strategy all the more urgent.

Beyond technical surveillance

MDA is a complex process extending beyond mere technical surveillance. It involves collecting, integrating, analyzing, and sharing maritime information to support decision-making. The US Department of Defense defines MDA as the “effective understanding of all relevant entities, activities, and events within the maritime environment.” In the Indo-Pacific, MDA’s scope covers multiple security dimensions, including traditional and non-traditional security, environmental and humanitarian dimensions. The goal of MDA is to create a transparent, predictable maritime environment that enables nations to effectively address transnational threats, safeguard marine resources, and protect sovereign rights.

IPMDA stands as a flagship initiative in Indo-Pacific MDA cooperation, jointly advanced by Quad member states. It aims to leverage commercial satellite technology, radio frequency monitoring, and arti-

Commander Hui-Chen Lai is an assistant professor at the Graduate Institute of International Security, College of International and National Defense Affairs, National Defense University, ROC. She can be reached for comment at laihuichen@gmail.com

ficial intelligence (AI) to provide partner nations in the Indo-Pacific with near-real-time, integrated data on maritime activities. IPMDA focuses on enhancing regional transparency, particularly regarding activities of so-called dark vessels, whose officers shut off their identification systems, which are required by law. These vessels are often associated with fishing or gray-zone operations by Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated fishing vessels (IUU). Beyond IPMDA, the US-led Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative also assists partner nations in strengthening MDA capabilities by providing equipment, training, and services. Collectively, these mechanisms form a network centered on the United States and its allies, and are designed to counter China’s growing maritime influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Taiwan’s geographical location endows it with unique strategic value within the Indo-Pacific MDA network. The Taiwan Strait, the East China Sea, the Bashi Channel, and the waters east of Taiwan form

critical waterways connecting Northeast Asia with the South China Sea and the Western Pacific. Any attempt to control or influence these waterways would profoundly impact global supply chains and regional security. Therefore, Taiwan’s effective surveillance of its surrounding waters is not only a primary mission for safeguarding its own national security but also constitutes an intelligence contribution in the nature of a public good to the entire Indo-Pacific region.

Taiwan contribution

Taiwan’s development in the MDA domain has been primarily driven by the Navy and Coast Guard Administration, while leveraging private and academic resources to establish a solid technical foundation and intelligence-contribution capabilities.

Taiwan’s MDA capability is built upon a multitiered monitoring and information integration system: For coastal surveillance, assets include shore-

Photo: Lauren Kmiec

An F-15 Eagle receives fuel from a KC-135 Stratotanker off the coast of Hawaii.

based radar stations, electro-optical reconnaissance systems, and coast guard vessels. In terms of information integration, the system incorporates the Automatic Identification System (AIS), the Coast Guard Administration’s Command and Control System, and the Navy’s Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance System. In the remote and highaltitude domains, unmanned aerial vehicles, such as the MQ-9B procurement and evaluation, and autonomous satellite systems like the Formosat series expand monitoring coverage. For underwater surveillance, naval sonar systems and underwater sensors— particularly those designed for submarine cable security—monitor activities in the undersea domain. Taiwan’s intelligence contributions are anchored by its pivotal geographic position and sophisticated technical assets, providing a high-definition surveillance view of the First Island Chain. At the heart of this contribution is the Long-Range Early Warning Radar (EWR) at Leshan—a US-made PAVE PAWS (AN/FPS-115) system—which serves as a strategic intelligence multiplier that offers unparalleled sur-

veillance depth. Capable of tracking ballistic missiles as well as maritime and aerial movements deep into the mainland, the EWR provides regional partners with an invaluable early warning buffer. Its real-world value was proven in 2012, when it detected North Korea’s rocket launch faster than allied systems, and again in 2024, by providing high-fidelity trajectory data on Chinese missiles. By sharing these first-minute insights, Taiwan acts as a vital intelligence sentinel, significantly enhancing the collective Common Operational Picture (COP) and providing the critical seconds necessary for strategic response and regional stabilization across the Indo-Pacific.

Non-traditional security

Despite political constraints, Taiwan actively demonstrates its MDA capabilities and contributions through cooperation in non-traditional security domains such as combating IUU fishing, as well as maritime search and rescue (SAR) and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). For in-

Taiwan’s Thunderbolt 2000 multiple launch rocket system appears on display to the public.

Photo: ROC Presidential Office

stance, in combating IUU fishing, Taiwan not only engages in bilateral cooperation with the United States but also coordinates regionally with Japan, providing substantive assistance to Pacific Island nations. Simultaneously, by actively fulfilling its responsibilities within Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs), it plays a responsible role in global fisheries governance. In the realm of international cooperation concerning SAR/HADR, Taiwan has established key partnerships with the United States, Japan, and the Philippines. By focusing on humanitarian and apolitical issues as entry points, Taiwan demonstrates its contributions as a responsible regional member. For instance, the MDA systems of Taiwan’s Coast Guard and Navy could enable rapid location of distressed vessels, providing vital public safety services to the region.

Despite possessing robust MDA capabilities, Taiwan still faces multiple challenges in participating in the

Indo-Pacific MDA network. These challenges primarily stem from geopolitical exclusion and the complexity of emerging threats.

“China’s gray zone strategies have transformed Taiwan into a frontline “livinglaboratory,”yieldinguniqueoperationalinsightsfortheIndo-Pacific MDAnetwork.”

The China factor remains the primary obstacle to Taiwan’s participation in international MDA cooperation. Due to political pressure from China, Taiwan faces significant challenges in formally joining official multilateral mechanisms like the IPMDA, which are composed of sovereign states. This results in two major bottlenecks for Taiwan in MDA cooperation: First comes the bottleneck of information sharing, which makes it difficult for Taiwan to establish secure, insti-

Herring landing at a fishing port in Penghu Island, Taiwan.

photo: Chung Kevin

tutionalized real-time information exchange mechanisms with member states of MDA cooperation organizations, thereby confining its cooperation to unofficial channels. Moreover, there is the issue of fragmented technical standards. As Taiwan cannot participate in international decision-making processes, its MDA systems may prove incompatible with international data formats and transmission protocol standards, thereby hindering future integration efforts.

China’s gray zone strategies have transformed Taiwan into a frontline “living laboratory,” yielding unique operational insights for the Indo-Pacific MDA network. While dark ships and maritime militia deactivating their AIS pose severe challenges, Taiwan’s efforts to identify these irregular patterns yield critical behavioral data and operational playbooks for regional partners. Furthermore, the dilemma of balancing sovereignty with non-escalation has led Taiwan to develop refined situational assessment frameworks. Sharing these lessons offers other international defense cooperation members a vital reference for building asymmetric resilience and tactical foresight against similar maritime pressures, effectively turning Taiwan’s defensive experience into a collective security asset.

Multi-layered strategy

Facing geopolitical exclusion and a complex threat environment, Taiwan should adopt a multi-layered, pragmatic, and integrated strategy to maximize its value and contributions within the Indo-Pacific MDA network through the following three strategies. First, Taiwan must concentrate resources on enhancing its MDA technology and system integration capabilities to ensure it can independently address threats when immediate international support is unavailable. In this context, Taiwan should enhance its MDA capabilities through three key avenues: Firstly, substan-

tially investing in AI-assisted data analytics to utilize machine learning for automated identification of dark ships and anomalous behavior, while accelerating deployment of long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles for continuous surveillance. Secondly, an

“MDA

serves not only as a technicalframeworkbutalsoasapivotal instrumentfordeepeningTaiwan’s internationalengagement.”

efficient and secure tripartite information-sharing platform integrating Coast Guard, Navy, and intelligence must be established to forge a unified COP. Lastly, given the importance of submarine cables, underwater MDA capabilities should be bolstered through sensor deployment and patrols to effectively safeguard vital infrastructure.

Second, Taiwan should deepen non-official and functional cooperation. In non-traditional security domains with lower political sensitivity, Taiwan can pursue substantive functional cooperation with IPMDA member states as an entry point to break through diplomatic impasses. Accordingly, in terms of external cooperation, Taiwan should adopt a multi-tiered strategy to overcome diplomatic constraints. Firstly, by focusing on non-traditional security issues such as combating IUU fishing, marine environmental protection, and maritime search and rescue, proactively sharing MDA data to project an image of a responsible regional stakeholder. Secondly, to establish regular technical and intelligence exchanges with partner nations such as the United States, Japan, and Australia through Track II channels involving think tanks and academic institutions. Finally, Taiwan should leverage relations with Pacific Island countries to proactively offer assistance in building MDA capabilities, thereby indirectly aligning regional contributions with the objectives of international initiatives like the IPMDA. Finally, Taiwan should promote transparency, di-

plomacy, and international initiatives. In promoting transparency, Taiwan should proactively share its MDA findings and analyses with the international community, leveraging transparency as a diplomatic tool to secure international recognition and support through the following approaches. Taiwan should proactively share intelligence on gray-zone activities within its information and standards strategy, regularly publishing detailed reports on China’s operational patterns and intentions in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea. This will reinforce Taiwan’s strategic position as a democratic front line. Concurrently, Taiwan should also actively engage with relevant nongovernmental organizations and technical forums involved in international technical standard-setting to ensure its MDA systems maintain compatibility and interoperability with global networks.

Taiwan’s role within the Indo-Pacific MDA network demonstrates a multi-layered strategy integrating policy innovation, technological prowess, and pragmatic diplomacy. Through the threefold pathways of policy dialogue, gray-zone cooperation, and techno-

logical diplomacy, Taiwan is evolving from a passive recipient of security public goods to an active contributor. MDA serves not only as a technical framework but also as a pivotal instrument for deepening Taiwan’s international engagement and fortifying its strategic resilience.

Looking ahead, Taiwan stands poised to leverage its professional capabilities toward a free, open, and transparent Indo-Pacific. In short, Taiwan should adopt a pragmatic strategy—defined by prioritizing functional, non-political cooperation over formal diplomatic constraints—to navigate geopolitical marginalization. By pursuing a three-pronged approach of strengthening internal capabilities, expanding external functions, and actively promoting transparency, Taiwan can transform complex threats into opportunities, maximizing its substantive value and contribution within the regional security network. n

The USNS Tippecanoe (T-AO 199) replenishes the amphibious assault ship USS Tripoli in the South China Sea, Dec. 6, 2025.

photo: Paul LeClair

Editor’s note:

Generative AI tools were used in the preparation of this article for limited language editing and stylistic refinement. All analysis, interpretation, and conclusions are the sole responsibility of the author.

Strategic Vision vol. 15, no. 64 (February, 2026)

Beyond Tariffs

Taipei leverages US trade realignment to advance defense industrial cooperation

Yen Ming Chen & Ru-Yen Zheng

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has undergone decades of modernization efforts primarily focused on developing the capabilities needed to annex Taiwan. In 2025, a series of tariff policies were implemented after President Donald Trump’s inauguration to address various US problems, including drug trafficking, illegal immigration, revitalizing American manufacturing, reducing trade surpluses, and cutting fiscal deficits. Although

the tariff impact on Taiwan and US allies in East Asia was far less severe than on China, the uncertainty of this policy still harmed allies.

Many analysts believe the tariff war will damage Taiwan’s economy and even jeopardize its national defense security. Another perspective, however, challenges the conventional wisdom that tariffs are inherently harmful. An analysis of documents from the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for

Commander Yen Ming Chen is an instructor at the ROC National Defense University’s War College and a graduate of the US Navy War college. He can be reached at s0914712@gmail.com

Commander Ru-Yen Zheng is a student at the ROC National Defense University’s War College. He can be reached for comment at alwaysmiss1115@gmail.com

Navy Petty Officer Matthew Beck fires an MK 38 machine gun during an exercise aboard the USS Essex.

photo: Kenyatta Headley

fiscal years 2021 to 2026, as well as the report submitted to Congress, titled Taiwan: Defense and Military Issues, suggests that the temporal and spatial context of this tariff war differs significantly, and that Taiwan’s exports to the United States may actually benefit. This potential economic opportunity for Taiwan’s trade situation post-tariff war aligns with a broader shift in the US model of supporting Taiwan, which is moving beyond the previous narrow focus on arms sales and foreign military financing, and toward defense industrial cooperation. Taiwan’s future policy should therefore be oriented toward establishing complementary industrial chains with the United States to enhance Taiwan’s defense resilience.

The US-China trade war has been one of the defining geopolitical events of the past few years, characterized by punitive tariffs and high-tech sanctions targeted at the People’s Republic of China (PRC). These measures have significantly impacted Chinese industries, particularly in the high-tech and manufacturing sectors. However, the tariffs also have severe ramifications for the United States, which has relied

heavily on China for critical supplies, such as rare earth elements, which are indispensable for advanced technology manufacturing, including those crucial in military systems. In retaliation, China has leveraged its dominance in the global rare earth market, threatening to cut off supplies to the United States.

There are growing challenges for the Republic of China (ROC) in the realm of defense procurement.

The trade war has affected the US military-industrial complex, particularly in areas like arms production and shipbuilding, with delays in the delivery of advanced systems to the ROC military, such as the F-16 fighter jets . Although it cannot be directly proven that these rare earth restrictions are the main reason for the delayed delivery of weapons that Taiwan has procured from the United States, the increased demand for weapons due to the Ukraine war and the changes in the supply chain in recent years are indisputable facts.

With China’s manufacturing capacity and supply chains affected by the trade dispute, Taiwan has increasingly emerged as a critical alternative source of

US Air Force F-35s operate near Kadena Airbase, Japan.

photo: Amet Tamayo

supply, especially in high-tech industries. Taiwan’s exports to the United States have grown significantly, surpassing those of the PRC. While this presents an opportunity for the ROC to strengthen its economic position, it also introduces risks. Taiwan’s reliance on the United States for its export market has the potential to create a dependency, particularly as Taiwan’s role in the global supply chain deepens.

Navigating geopolitical tensions

Such a shift would underscore Taiwan’s delicate position within the US-China rivalry, forcing Taipei to carefully balance its economic interests with both countries. Taiwan’s strategic decisions could have lasting implications for its continued autonomy and economic stability as it navigates the geopolitical tensions exacerbated by the trade war. The restructuring of the industrial chain that could result from the current trade war demands that Taipei rethink the sources of its defensive weaponry and how to

leverage its strategic advantages to reshape its defense industry.

In addition to observing the trade war and economic aspects, changes in US Congressional and governmental policies should also be noted. In the United States, the congressional discourse surrounding Taiwan’s defense has undergone significant changes in recent years, particularly as the trade war has reshaped broader US-China relations. US Congressional documents, including the Taiwan Defense Issues for Congress reports for 2025 and 2026, highlight growing concerns about Taiwan’s defense capabilities. Issues such as insufficient military training, challenges in recruitment, and shortages of modern weaponry have been highlighted. These concerns reflect broader doubts about Taiwan’s ability to effectively defend itself when facing growing PLA military power and the increasingly strained US-China relations.

The US government has been largely supportive of Taiwan, but the shift toward a more sustainable and

US Army soldiers fire a surface-to-air missile during an exercise near Truppenübungsplatz Putlos, Germany.

photo: Yesenia Cadavic

collaborative approach to defense, as consistently outlined in the NDAA from 2021 to 2026, marks a notable change. The United States has moved away from purely military sales to Taiwan and has instead emphasized the importance of building Taiwan’s defense capabilities through training, education, and industrial cooperation. The Taiwan Enhanced Resilience Act (TERA) introduced to Congress, which was inspired by Ukraine war, aims to enhance Taiwan’s defense resilience by fostering long-term defense partnerships rather than relying solely on arms sales.

As an island nation, Taiwan faces logistical challenges that make sustaining defense efforts difficult in the event of a blockade. The US military sales model, on which Taiwan has relied for critical defense systems, is fraught with risks in this context. The shortage of spare parts and maintenance support, especially in a prolonged conflict or blockade, could severely hamper ROC defense capabilities. As Taiwan’s strategic position becomes even more critical, it is clear

that a robust, self-sustaining defense industry that complements the US deficiency will be essential for maintaining Taiwan’s security in the face of increasing external pressures.

In light of the evolving geopolitical environment, Taiwan must prioritize the strengthening of its defense resilience, with a focus on fostering strategic partnerships and developing self-sustaining defense capabilities. To achieve this, Taiwan should focus on the following areas.

Areas of focus

First, Taiwan should prioritize deepening collaboration with the United States in defense technology and industrial capabilities, similar to how South Korea and Japan have demonstrated a strong willingness to contribute to or compensate for America’s lackluster shipbuilding capacity. Taiwan can contribute high-volume production of drones and world-class

US soldiers construct a floating bridge during a wet gap-crossing exercise with South Korean personnel near the Namhan River, South Korea.

photo: Mark Bowman

semiconductor integration for the future AI industry. Reinvesting the profits from these sectors into US Treasuries to support the export market and stabilize the currency creates a strategic win-win scenario, reinforcing both regional security and economic interdependence between the two nations. This includes enhancing joint research and development in areas like advanced weaponry, cybersecurity, and intelligence systems, while ensuring that Taiwan’s industries play an active role in the production of critical defense components.

Second, Taiwan must invest in developing a more self-reliant defense infrastructure. This includes bolstering indigenous defense industries, particularly in areas such as unmanned aerial systems, energy production, and medical infrastructure, to ensure that Taiwan can maintain operational continuity even in times of crisis. In the case of Ukraine, they also decentralized the previously state-led military procurement, shifting it to be driven by battalion-level units, allowing for more flexible and tailored selection of equipment. By investing in the domestic production of key military technologies and supplies, Taiwan can reduce its reliance on foreign military sales and ensure its defense systems are less vulnerable to dis-

ruptions in global supply chains.

Third, given the concerns raised by the US Congress about Taiwan’s defense readiness, the ROC should focus on improving its military training programs and recruitment policies. This includes increasing investments in professional military education and training to ensure that Taiwan’s defense forces are prepared for the full spectrum of potential threats. Additionally, Taipei must explore increasing its defense budget to support military modernization, as well as offering incentives to attract highly skilled personnel into defense-related fields.

Fourth, Taiwan should continue to advocate for the implementation of the TERA, which focuses on building long-term partnerships with the United States and other like-minded allies. This law aims to enhance Taiwan’s defense capabilities through comprehensive defense cooperation, education, and technological collaboration. Taiwan should ensure that the Act is fully supported and that its provisions are leveraged to build a sustainable, resilient defense framework capable of countering the growing threat from China.

By focusing on these key areas, Taiwan can not only ensure its national security but also position

The US Coast Guard cutter Stratton (WMSL 753) departs Puerto Princesa, Philippines.

photo: William Kirk

itself as a critical and capable player in the global defense network.

Deep strategic competition

The current tariff war does not deliberately target Taiwan or other US allies; rather, it implicitly reflects the deep strategic competition between the United States and China. Japan and South Korea secured 15 percent tariff rates after committing to US investments. In contrast, US-China trade retains lingering room for negotiation. While Washington has imposed tariffs on various allies as a form of industrial protectionism, the measures directed at Beijing are designed to secure technological and industrial primacy. This is because resorting to force cannot resolve the competitive relationship between the two nations, and the Pyrrhic victories achieved through such means are not what either country de-

sires. Instead, technological prowess and industrial competitiveness are the critical factors in this USChina rivalry. Securing both undoubtedly positions a nation at the pinnacle of this contest.

Whether it be the US tariff war or strategic resource restrictions from China, these are merely strategic approaches to their end. The 2023 Foreign Military Financing was a one-time tranche, with subsequent Taiwan security assistance shifting primarily toward Presidential Drawdown Authority and the Taiwan Security Assistance Initiative, among other channels. The industrial resilience promoted by the ROC government in recent years is undoubtedly a priority for both the US Congress and the White House. With limited external support, the ability to demonstrate resilience and coexist with conflict, as has been seen in Ukraine, is arguably the most potent strategy for smaller nations confronting authoritarian expansion. n

Deputy Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter, second from right, meets with Taiwan’s Vice Minister of Defense Andrew Yang, left, on Oct. 2, 2012.

photo: Erin Kirk-Cuomo

Visit our website:

https://taiwancss.org/strategic-vision/