STRATEGIC VISION

for Taiwan Security

Learning From Ukraine, Taiwan Must Prepare for Drone-Centric Nature of Modern War

Tobias Burgers ‘Precise Mass’ Drone Warfare

Multi-Domain Denial

Hui-Chen Lai & Yin-Hsin Chien

Beijing’s ‘Lawfare’ Tactics

Cebile Amanda Maphosa

Decentralized ‘Mission Command’

Ho Pei-sung

Taiwan’s Failed Recall Vote

Pei-shan Lee

STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan Security

Pei-sung

Hui-Chen Lai & Yin-Hsin Chien

Cebile Amanda Maphosa

Pei-shan Lee

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision. Once accepted for publication, manuscripts become the intellectual property of Strategic Vision. Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for reprints should be made with the editor. The editors are responsible for the selection and acceptance of articles; responsibility for opinions expressed and accuracy of facts in articles published rests solely with individual authors. The editors are not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; unaccepted manuscripts will be returned if accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. Strategic Vision remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Digitally enhanced cover photograph of a Ukrainian soldier with drones is courtesy of the National Guard of Ukraine.

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Editor-at-Large

Dean Karalekas

Editorial Board

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Richard Hu, NCCU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Hon-Min Yau, NDU

Ruei-lin Yu, NDU

Osama Kubbar, QAFSSC

Rashed Hamad Al-Nuaimi, QAFSSC

Chang-Ching Tu, NDU

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security (ISSN 2227-3646) Volume 14, Number 63, October, 2025, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Taiwan Center for Security Studies. No. 64, Wanshou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Associate Editor directly via email at: xiongmu@gmail.com. Or by telephone at: +886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: https://taiwancss.org/ strategic-vision/

© Copyright 2025 by the Taiwan Center for Security Studies.

Articles in this periodical do not necessarily represent the views of either the TCSS, NDU, or the editors

From The Editor

As global tensions continue to mount, this month’s issue of Strategic Vision offers critical insights into Taiwan’s evolving security landscape.

We begin with Tobias Burgers’ compelling argument that modern warfare is becoming increasingly dronecentric. Drawing lessons from the conflict in Ukraine, he advocates for a shift towards “precise mass”—leveraging large numbers of affordable drones for enhanced asymmetric defense. Burgers urges Taiwan to prioritize expendable, semi-autonomous systems and adapt its training and recruitment strategies accordingly.

Next, Ho Pei-sung delves into the concept of “mission command,” a decentralized command philosophy crucial for enhancing combat effectiveness. Ho highlights the challenges the ROC military faces in adopting this approach, including hierarchical cultural norms and limited trust in subordinates, and offers recommendations for effective implementation.

Lai Hui-Chen and Chien Yin-Hsin emphasize the importance of both external resistance and internal sustainability for Taiwan’s security. They propose a comprehensive framework, including a National Resilience Command Center and a Strategic Societal Resilience Index, to bolster societal resilience and counter hybrid threats.

Cebile Amanda Maphosa examines Beijing’s use of “lawfare” to constrain Taiwan’s role in international organizations. Through a WHO/WHA case study, Maphosa illustrates how political obstruction undermines global cooperation and public health, and offers recommendations for Taiwan to navigate these challenges.

Finally, Pei-shan Lee explores Taiwan’s tripartite politics and in the wake of a failed recall vote against several KMT legislators, and what effect this might have for closer cross-strait ties.

We trust that this issue will provide valuable perspectives on the multifaceted security challenges facing Taiwan and the broader region. n

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor

Strategic Vision

Strategic Vision vol. 14, no. 63 (October, 2025)

The Drone Age

Taiwan must prioritize unmanned systems into its defensive architecture

Tobias Burgers

The Russo-Ukrainian war has illustrated that the longer-term development of everincreasing technological integration into military conduct has now reached a point at which we observe a fundamental shift in the nature of war: Namely, a new reality is emerging in which humans are no longer at the center of actual combat, but have been replaced on, near, above, below and around the battlefield by drones. It is now these machines that are the standard tools for ISR missions in all domains of warfare, operating in logistic roles, even taking prisoners, but more importantly, they do the bulk of the actual killing. By some estimates, drones inflict 70 percent of all casualties. As Franz-Stefan Gady

observed in Foreign Policy, drones “help decide the outcome of the entire conflict.”

Moreover, the world is taking notice: North Korea seems to have embarked on the unmanned pathway, and the United States, generally a leader in military technological advancement and Revolutions in Military Affairs, is seeking to catch up urgently. Eastern European countries such as Latvia, frightened by an increasingly aggressive Russian posture, are building military drones to stop any possible Russian invasion. Finally, drones have prevailed in all the current conflicts in the Middle East. Observing this change in dynamics, it is evident that the future of warfare will be drone-centric.

Dr. Tobias Burgers is an assistant professor at the Social Studies faculty, Fulbright University Vietnam and a fellow at the Cyber Civilization Research Center, Keio University.

An ROC Military representative introduces the latest drone technology at the 2025 Taipei Aerospace & Defense Technology Exhibition.

Photo: ROC Presidential Office

This change in warfare will have significant implications for Taiwan’s security and defense posture, and Taipei must adapt to this new reality as it presents its defensive establishment with new, asymmetric opportunities that would allow it to increase its defensive posture. These benefits can be found in both the military domain and the economic and military-industrial realm. It is therefore imperative that Taiwan start learning the lessons of Ukraine and begin preparations to enter this new world of drone wars.

For much of the late 20th-century, Western military doctrines centered around the concept of precision strikes: Using new technological communication tools, armed forces turned their offensive and defensive capabilities into high-precision strike assets. It has created what Thomas Mahnken of the US Naval War College refers to as the “Precision Strike Regime” (PSR). This regime is facilitated by highly technical and sophisticated military machinery and staffing, allowing for precision warfare. The variables in this doctrine, according to Michael Horowitz and

Joshua Schwartz, are accuracy and precision. In other words, quality is the variable that delivers military strike power, not quantity. The PSR strategy follows established logic and is a clear evolution from the mass scale attacks that were the standard for much of military history.

“A

future defense force should be oneinwhichamannedarmyremains, yet most strike capabilities are outsourcedtounmannedsystems.”

The age of drones is testing the validity of this strategy, however. Precision (to wit: quality) will remain key, but the introduction of drones is changing the quantity calculations. Cheap to build, relatively easy to operate, and not requiring an extensive defense industry, drones can be used en masse across multiple domains. As a result, a new military strategy is emerging which fuses old-meets-new and ancient and novel military lessons. Put another way: it is one

Photo: Adam Craft

The Los Angeles-Class fast attack submarine USS Springfield (SSN-761) pulls into Busan Harbor, South Korea.

in which both quality (precision) and quantity (mass) are present. Horowitz refers to this doctrine as “precise mass.” This new strategy enables military forces to apply the ancient logic of mass as the variable to victory, but then combines this with the variable of precision. In the future, battles will, once again, be characterized by mass, but wielded in a way that is precise, accurate, and reliable.

Embracing innovation

It is precisely the type of strategy that can favor an asymmetric battlefield, as the crucible of the Ukrainian-Russian war has demonstrated. Through innovative new tactics, such as “precise mass” applied to drone warfare, Ukraine has been able to withstand a much more powerful enemy, and despite losing parts of its territory, has been able to withstand far better than expected since Russia launched its fullfledged invasion in February 2022.

It would therefore be worthwhile for the Taiwanese defense establishment to consider further how to engage in drone warfare with more focus on the precise

mass concept, as Taiwan’s defense establishment has also embarked on its unmanned path for national defense. The precise mass concept, however, is still not being considered significantly enough. Indeed, as Hong-Lun Tiunn writes in The Diplomat, the first objective of Taiwan’s drone strategy focuses on “integrating autonomous systems into a layered, survivable defense posture.” While this autonomous integration should be lauded, the notion of survivability remains subject to debate. As Ukraine has illustrated, losing 10,000 drones per month is common. It is therefore likely that Taiwan, facing an adversary significantly more powerful and more technologically adept than Russia, would face similar, if not worse, battlefield conditions. As such, mere survivability might not be the best-suited approach.

Furthermore, it would not entirely align with the precise mass strategy that emphasizes mass as a means to overwhelm and overpower—even if that means a considerable part of the mass will be sacrificed to achieve its target. Further indications are somewhat hopeful, but also not ideal: the ROC Ministry of Defense recently put out a tender notice

Members of the ROC Army’s 257th Infantry Brigade prepare to train with drones.

Photo: ROC Presidential Office

through its Government e-Procurement System seeking around 50,000 drones. While the number would indicate that precise mass might be possible, these drones are expected to be procured over the course of two years. As noted—and as can be expected in the case of a severe attack against its main island— Taiwan can lose that amount of drones in a period of five days, if not less.

Therefore, a larger emphasis on mass is needed. Unfortunately, a further dive into Taiwan’s defensive procurements in recent years, such as the M109A6 Paladin and the F-16V jets, as well as domestic projects such as the Indigenous Defense Submarine program and surface vessels, indicates that Taiwan buys its new military tools largely with the idea of PSR in mind. Taiwan’s defensive establishment should consider further integrating the concept of precise mass into its defensive strategies and aim to find a fusion between existing defense strategies and this new one. It will still require tanks, howitzers, and fighter jets in its arsenal, but these should not be the predominant concern.

A future defense force should be one in which a manned army remains, yet most strike capabilities

are outsourced to unmanned systems. Such an effort centered around drone-precise mass carries several strategic and tactical benefits that are well suited to Taiwan’s defensive posture, in which a conflict will be primarily naval, near-shore, and landing shore, aiming to prevent amphibious assault or the establishment of a beachhead. In a possible conflict scenario like this, the concept of precise mass would be suitable.

First, since these are unmanned systems, they are consumable systems. They can be lost. As Ukraine has illustrated, losing up to 10,000 drones monthly is not uncommon. Due to their relatively low price tag, losing drones is significantly preferable over expensive weapon systems or, worse, human lives.

Second, they can replace humans in the 3D missions: Dangerous, dull, or dirty. In particular, and once again as illustrated on the Ukrainian battlefield and across Russia, unmanned systems are ideally suited for one-way missions. This also means that more aggressive kamikaze-style tactics can be pursued.

Third, drones require less military infrastructure to operate. For one, protecting them would not require a significant infrastructure, which would be neces-

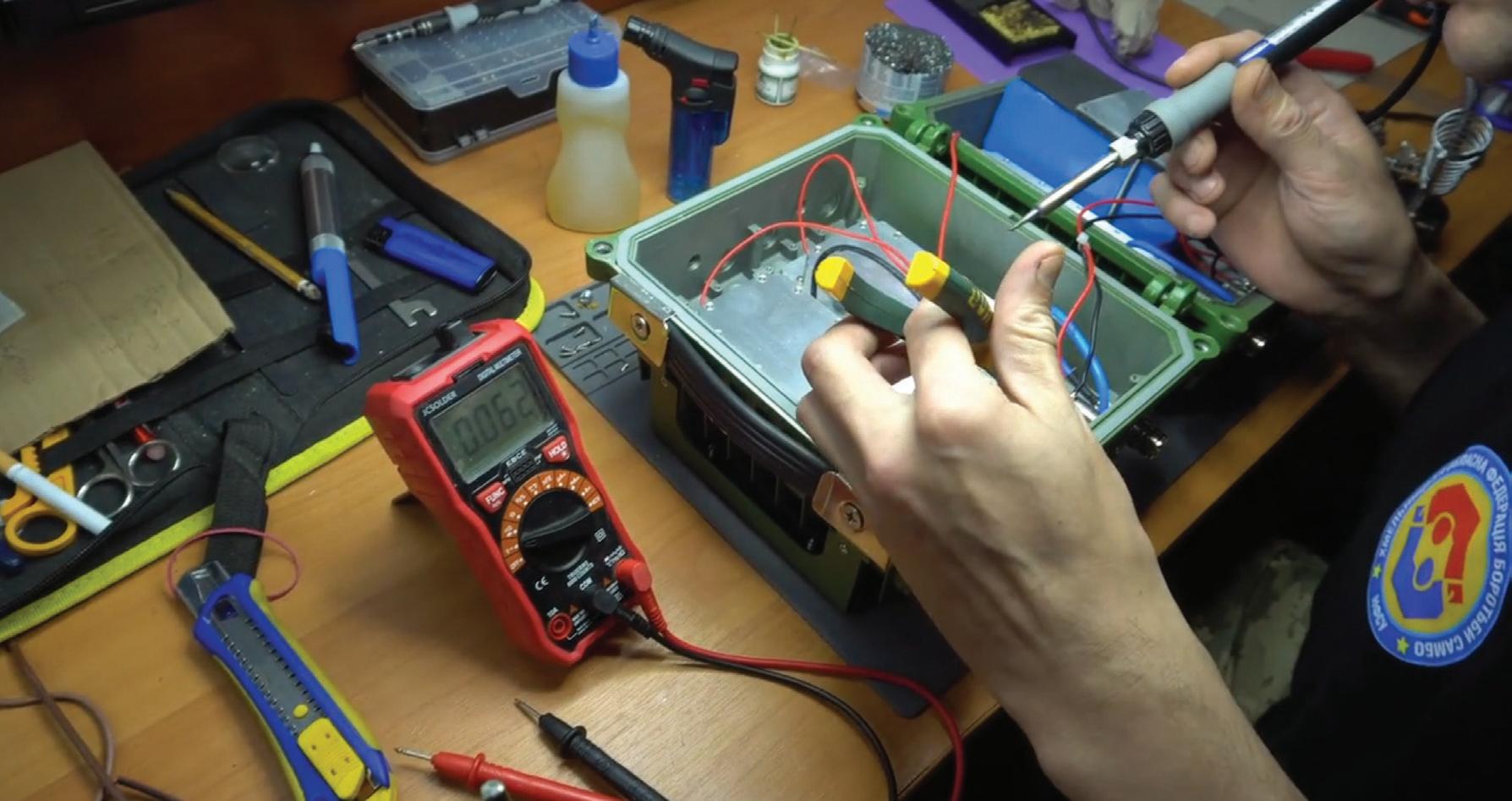

A technician with the Ukrainian military repairs components of a damaged drone so that it can be quickly redeployed to the battlefield.

photo: Dean Karalekas

sary in cases of more sophisticated, high-end (and expensive) military material such as fighter jets. One can move these smaller systems and hide them in forests, caves, office buildings, and other locations that offer a degree of protection and concealment.

Fourth, the military infrastructure necessary to operate these systems requires fewer resources. There is no need for military airports, large harbors, and other military infrastructure.

Fifth, and related, operating such systems would not require significant training compared to more conventional systems. This means that its armed forces can utilize its soldiers more effectively. This would be particularly advantageous in an era, and a society, in which many of the young recruits are more proficient in the digital environment than in the forest.

Sixth, unmanned systems—particularly those with a degree of autonomy—require less staffing than manned systems. A recent article by Tereza Pultarova in IEEE Spectrum magazine illustrated that even smaller, hobby-grade drones will have software that allows them to operate (semi) independently in their respective target areas. Software integration like this would make the concept of swarming or mesh net-

work operations considerably easier, while equally decreasing the necessity for one operator per drone.

Offering alternatives

For a defense force that struggles with recruitment, a precise mass drone strategy offers a viable alternative to increasing recruitment. In a society in which many young Taiwanese, of all genders, are savvier in operating handheld digital devices than they are in dealing with kilos of ammunition, precise mass drone warfare could well resonate and be better suited to the skills and expertise of the younger Taiwanese generation. The question then arises, how such a strategy of precise mass drone warfare could be best initiated. Indeed, it would require retraining existing forces, adopting new tactical and strategic plans, and changing the focus of recruitment efforts. Given that such a force must operate across multiple domains—air, sea, and land—it would seem best suited to the formation of a new joint command to oversee precise mass drone operations: a command that can develop plans, enable operations in this domain, and train and retrain new and existing forces. n

The Shahed 136 is a loitering munition in the Iranian-made line of Shahed drones favored by Russia in its strikes against Ukraine.

photo: Tasnim News Agency, CC BY 4.0

Strategic Vision vol. 14, no. 63 (October, 2025)

Mission Command

Adopting ‘mission command’ doctrine would hone the ROC military’s lethality Pei-sung Ho

The concept of “Mission Command” originated in the Prussian military of the 19th century, and has since been adopted by many countries due to its operational effectiveness. It stresses the importance of such factors as developing a shared understanding of the mission; the clear expression of the commander’s intent; and training subordinates to take the initiative. The Republic of China (ROC) military has begun promoting mission command at all echelons. Although there has been some progress, there are still some unique challenges that remain. These include such factors as Taiwan’s obedience culture, the excessive focus placed on the

officer class, and an ingrained tendency to limit the trust placed in one’s subordinates. It is recommended that the ROC military emphasize improved education, planning, and empowering the ranks of noncommissioned officers (NCOs).

Mission command was developed by Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke, who eagerly wanted to resolve problems caused by unreliable communications between headquarters and subordinate units, wherein detailed orders and instructions could not be clearly conveyed. The idea was to empower subordinate unit leaders to make decisions whenever necessary, based on the com-

Colonel Pei-sung Ho is a professor at the ROC National Defense University. He can be reached for comment at owpho123@gmail.com

Members of the ROC Army’s 257th Infantry Brigade train with the Kestrel anti-armor missile system.

photo: ROC Presidential Office

mander’s intent, when the commander himself was either unavailable or unreachable. Although there are many practical reasons for adopting mission command as a doctrine, its purpose can be summarized as giving subordinate units the maximum degree of freedom to carry out their missions by telling them only what to do, without micromanaging how to do it, so as to expedite the Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA) decision cycle and get ahead of the enemy. Swift, decisive action can often determine the difference between victory and defeat, and between life and death, on a highly dynamic, volatile, and fluid battlefield.

According to US joint doctrine, mission command is the conduct of military operations through decentralized execution based upon mission-type orders. Successful mission command practices can usually be attributed to the following seven characteristics: competent and well-trained personnel; a team with a high level of mutual trust and respect; a shared understanding of the mission; a clear and well-understood commander’s intent; well-planned missiontype orders; disciplined initiatives exercised by lead-

ers at all echelons; and tolerance for calculated and reasonable risks.

Defining objectieves

When a unit receives its operational orders, the commander and his staff first have to conduct a mission analysis and an overall situation assessment (called the intelligence preparation of the operational environment). This will help everyone to see clearly what results have to be accomplished, i.e., the specific tasks, the implied tasks, and the critical tasks, plus many other important factors such as the critical requirements, capabilities, and vulnerabilities of both sides. The point is to ensure there is a shared understanding of the mission among everyone involved.

The commander should then provide the necessary guidance and very clearly state the commander’s intent (specifying what end states should be achieved) for the staff to start the planning process, which in turn will generate several courses of action (COAs) that assign specific missions to each subordinate unit. After carefully evaluating different COAs, the offi-

The USS Chancellorsville (CG-62), a Ticonderoga-class guided-missile class cruiser, transits the Taiwan Strait.

photo: Justin Stack

cer in charge and his command staff (subordinate unit leaders may also be present) would then decide which COA is selected to become the official plan to be implemented as the mission-type orders for all subordinate units, and its quality is determined by the competence of the personnel involved.

Though every participant in the process described above would definitely do their best to anticipate all possibilities, there would still be information gaps and unknown facts, each of which may evolve into either a risk to be mitigated beforehand or a risk to be accepted along the way. Furthermore, the leaders of all subordinate units have to be confident that the commander and staff have done their best to create a plan with the highest probability of success. The commander would also have to be confident that the subordinate leaders would do their best to accomplish their assigned missions, and thus demonstrate the importance of mutual trust in the team.

Finally, during the execution phase, many things will not go as planned. This is usually the case in com-

bat. When this happens, there is a decision cycle that has to be carried out as soon as possible to minimize the negative impact of the specific unplanned-for contingency. However, if all of the above characteristics of mission command have been present, the

“A

military force’s ability to improvise, adapt, and overcome obstacles isnecessarywhenfacingamuchmore powerfulenemy.”

subordinate unit leaders should have the discipline and the initiative to be able to decide for themselves how to proceed, without the need to first ask the commander for permission. This increases the proficiency of the team, and the efficiency of the mission execution, which is paramount in getting ahead of the enemy.

The United States military has been promoting the concept of mission command since 2011, partially due to a rising demand for decentralized command-

A USAF B-2 bomber is being readied for flight. Mission command is a key leadership philosophy instilled in the US Air Force.

photo: Joshua Hastings

and-control and distributed execution while facing modern-day adversaries. The Pentagon, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, all service branches, and most of their education and training organizations have published various mission command-related white papers, focus papers, course materials, doctrines, and so on, to aid in this effort. The results have been positive. Nowadays, the practice of mission command is included in almost every exercise, training

“The broad application of mission commandwouldhelpnurtureanROC militarythatisfarmorecapable,better prepared, and more resilient to fight againstanumericallyandtechnologicallysuperiorfoe.”

activity, and leadership development course conducted by the US military, and overall proficiency has consistently improved, though not without a few difficulties and challenges encountered from time to time.

The idea of mission command was introduced to the armed forces of the ROC by the US military through official exchange channels in recent years, and it has been promoted diligently throughout all echelons. There are several reasons that mission command has gained so much attention in the ROC military. First of all, the US military has provided a very good example of the successful adoption and application of mission command in real-world operations, and the published statistics and outstanding results speak for themselves. Secondly, the ROC military’s comprehensive application of mission command would be extremely useful in the event of an invasion by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), during which most, if not all, key command centers, communication nodes, and fixed radar sites will definitely be attacked repeatedly, devastating the ROC military’s command and control capabilities.

The successful adoption of the mission command ethos would, under these circumstances, allow the majority of the ROC armed forces to continue to fight with efficiency and resilience, and continue to cause damage to the PLA, thereby maintaining a meaningful resistance for much longer. Lastly, a military force’s ability to improvise, adapt, and overcome obstacles is necessary when facing a much more powerful enemy, as is the case for the ROC. Such mindsets and initiatives are all included in the practice of mission command, and they are therefore valued highly by tacticians and stressed often in military publications.

In short, the broad application of mission command would help nurture an ROC military that is far more capable, better prepared, and more resilient to fight against a numerically and technologically superior foe for a longer time. This is the most important factor in Taiwan being able to summon international assistance and allied intervention, while aiding in the prevention of a Chinese invasion.

Every reform or modernization effort experiences resistance and challenges. This is especially true when attempting to change the command culture of such a conservative institution as the military. In adopting a mission command ethos, the ROC armed forces will face many if not all of the same challenges encountered by the US military: there were difficulties in building mutual trust, in direct higher-level interventions made possible by modern technologies, in focusing on short-term gains rather than long-term cultural change, and the usual tendency among war planners to avoid risk. Most of these challenges have been addressed and resolved in the American forces, and learning from these lessons will make it relatively easier to the ROC military to deal with a similar organizational transformation.

There will, however, be some additional challenges, unique to the ROC military, which means an extra effort will have to be put forth if the project is to be successful. First, ROC officers tend to have a nega-

tive view of their subordinates’ ability to take the initiative. Much of this tendency is a result of Chinese culture and Confucian tradition, which reinforces the rigidity of hierarchy and reflexive deference to authority. As a result, there an ingrained practice to do precisely the opposite of what mission command advocates: namely, to exhibit unconditional obedience to leaders. It is considered a virtue to always wait for guidance and orders from the commander, and subordinates who take the initiative to act on their own are frequently seen as impertinent, impatient, and insubordinate, and this is unsatisfactory to officers trained in the traditional methods of leadership. As a result, fostering subordinate initiative will be especially difficult in Taiwan, because both leaders—as well as those being led—will need to change their very relationship.

Second, most in the ROC officer class tend to bear excessive responsibilities. This is another side effect of traditional Chinese military culture, wherein an officer is held responsible for everyone and everything under his command, and is supposed to exude an aura of omniscience and omnipotence. Therefore, it is the commander’s duty not only to plan and supervise everything, but also to instruct, direct, and even demand how everything is to be done.

Third, the typical commander trusts very few of his subordinates. Since there are indeed many officers who behave in the manner described above, they leave their subordinates very little space to take risks, to make mistakes, or to learn, grow, and prove themselves capable in their officer’s eyes.

Maintaining focus

For the reasons mentioned above, it is necessary to continue promoting mission command as a doctrine in the ROC military. Additional attention should also be given to the following challenges. First, leadership training among the junior ranks is

the key to success. In order to speed up the adoption process and minimize transitional resistance, everyone in uniform needs to know mission command in order to carry out their respective duties. It is especially important that the traditional concepts of respect and obedience, while laudable, be tempered to give NCOs more room for initiative and feedback.

Second, the correct execution and implementation of the military planning process must be emphasized. In most cases, the planning processes for joint commands and all service branches are very similar in essence, and they all require meaningful and active participation of the commander, staff members, as well as subordinate unit leaders. They have to work together to form a shared understanding of the mission, as well as a clear idea of the commander’s intent during the initial steps. The commander and his subordinates will also get to know each other much better through COA development and the phases of comparison and war gaming. In addition, they have to work as a team to evaluate and decide on the best COA, and then to turn it into the mission-type orders that would be given to all units. Mutual trust will be earned during this process.

Third, NCOs must be empowered with more authority and responsibility. In the US military, there is a clear separation of responsibilities for officers and those for NCOs. The officers usually give orders and decide what to do, while it is the NCOs that actually get things done. As stated above, the officer class in the ROC armed forces have been burdened with too much responsibility. If well-trained and experienced NCOs could be given more authority and responsibility, they would be of great value to the officer as well as the unit. They could help share the commander’s burden, thus giving commanders more time to work with staff to come up with the best plan and ensure mission success, using mission command skills. n

Strategic Vision vol. 14, no. 63 (October, 2025)

Building Resilience

Societal resilience as important as military in ensuring Taiwan’s wartime survival

Hui-chen Lai & Yin-hsin Chien

The current international security environment faces systemic challenges, with gray zone incursions, hybrid warfare, and cognitive warfare becoming increasingly common. In today’s world, national defense is no longer the exclusive domain of the military but a shared responsibility and collective undertaking of the entire society. As a geostrategic frontline state, Taiwan must transform its national security orientation from the traditional military-centered defense approach to a comprehensive community-wide system of resistance against the enemy. Central to this evolution is the integration of such approaches as Multi-Domain Denial and Wholeof-Society Defense Resilience, ensuring both a robust deterrence on the battlefield and sustained societal functioning during crises.

While multi-domain deterrence aims to complicate the adversary’s ability to achieve its objectives across the land, maritime, air, space, electromagnetic, and cognitive domains, its effectiveness is intrinsically linked to the strength of societal resilience. Without resilient communities, robust institutions, and public psychological fortitude, even successful military actions risk being undermined by internal collapse. Therefore, these concepts shouldn’t be treated separately; instead, they should be viewed as complementary pillars supporting a credible and sustainable national security strategy.

ROC President Lai Ching-te stated at the opening ceremony of the Resilient Taiwan for Sustainable Democracy International Forum on September 20, 2025, that Taiwan had implemented concrete actions across five key areas: civilian training, material logistics, energy security, medical evacuation, and cyberfinancial protection.

Fostering integration

The declaration of July as National Solidarity Month is aimed at promoting military-civilian integration capabilities. However, significant departmental silos persist across agencies, resulting in joint exercises yielding limited substantive integration. Their impact remains largely symbolic in nature. This underscores a critical perspective: while multi-domain denial centers on battlefield resistance capabilities, its long-term effectiveness ultimately depends on the resilience of society as a whole.

This article argues that while multi-domain denial primarily focuses on battlefield resistance against the enemy, its long-term effectiveness requires the support of societal resilience. If domestic society collapses due to psychological, economic, or critical service system failures, even successful military denial would struggle to translate into a national strategic advantage. Therefore, this article attempts to explore the com-

Commander Hui-chen Lai is an instructor at the Naval Command and Staff College, National Defense University, ROC. She can be reached at laihuichen@gmail.com

Commander Yin-hsin Chien is an instructor at the Military Common Curriculum Center of the National Defense University, ROC. He can be reached at chienyunhsin@gmail.com

plementary relationship between these two concepts and offer recommendations at both theoretical and policy levels to strengthen Taiwan’s overall national defense system.

The strategic logic of multi-domain denial originates from denial-based deterrence theory, which aims not to annihilate the enemy but to make it difficult for them to achieve their objectives. It emphasizes integrating operational capabilities across ground, maritime, air, space, electromagnetic, and cognitive domains to disrupt, weaken, and delay the opponent’s actions, forcing their operational costs to exceed expected gains. In Taiwan’s defense framework, this concept has been gradually reflected in policy measures such as asymmetric warfare, dispersed deployment, and force preservation. Taiwan’s approach aims to disrupt and delay an adversary’s plans, exploiting terrain and extending conflict timelines to strain enemy resources and morale.

In parallel, societal resilience theory emphasizes a system’s ability to survive and recover from shocks. Works in this emerging field by scholars such as Arjen Boin, Louise Comfort, and Chris Demchak increas-

ing call for Resilience Governance. National security policy relies not only on physical strength but also on the societal system’s capacity to withstand pressure and recover from shocks to the system. Resilience is seen to be operating on three levels: institutional resilience, which ensures that governance structures remain capable of crisis management and decision-making under stress; infrastructure resilience, which maintains the continuity of critical services like energy, communications, and transport; and cultural and psychological resilience, which bolsters social cohesion, trust, and the public’s will to resist manipulation and fear.

These layers are mutually reinforcing. If military deterrence succeeds but society crumbles due to panic, disinformation, or economic breakdown, strategic objectives will remain unmet. Conversely, a resilient society lacking credible defense capabilities may still succumb to full-scale invasion or coercion. Therefore, these are crucial for multi-domain denial to translate into long-term national security outcomes.

Multi-domain denial and whole-of-society defense resilience are not independent concepts, but rather

Vice President Hsiao Bhi-kim speaks at the Presidential Office’s International Forum on Whole-of-Society Defense.

Photo: ROC Presidential Office

two major pillars of national security strategy, jointly forming a dual-axis system, with external resistance at one end and internal sustainability at the other. Military denial alone, without the backing of societal resilience, may significantly reduce its long-term effectiveness. Conversely, a resilient society without effective military denial would also struggle to resist a full-scale invasion.

Wider threats

First of all, to deal with hybrid warfare and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) doctrine of Three Warfares—namely, public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare—it must be understood that modern conflicts are no longer limited to traditional military engagements but combine multiple means such as information, cyber, economic, and psychological warfare. These non-military threats can no longer be dealt with by purely military means. For example, the Three Warfares strategy aims to erode societal trust; if society lacks defense awareness and psychological literacy, it is prone to panic and division. Countries like Ukraine and Finland demonstrate that

a prepared, psychologically resilient public can limit the impact of cognitive operations and strengthen collective resolve.

Second, it is important to ensure the conversion of the strategic advantage: Even if military denial is successful, if domestic society collapses due to psychological, economic, or critical service system failures, it will be difficult to translate military gains into national strategic advantage. In addition, the collapse of societal systems will also reduce the feasibility and effectiveness of international assistance. In the case of Taiwan, if critical supply chains, governance systems, or communications remain functional during crises, Taiwan can maintain economic activity, deliver essential services, and coordinate international assistance more effectively. This enhances the credibility of allied support and reassures partners that aid will be used effectively.

Third, the goal of all-out defense and societal mobilization rests on this integration: Effective national security strategies rely on the participation of the entire population. Only by combining military denial capabilities with societal resilience can a stable system of allout defense and societal mobilization truly be formed,

An F/A-18F Super Hornet and an F/A-18E Super Hornet conduct airborne refueling during an all-domain joint exercise.

Photo: US Navy

ensuring that national security is not merely a military victory, but something that requires the support of societal resilience, psychological fortitude, and cultural consensus. An army alone cannot secure a nation’s freedom if the population is unprepared or divided. Fostering civil preparedness, local defense networks, and shared narratives of resistance transforms each community into an active node of national resilience.

Energy resilience

Finally, ensuring the resilience of Taiwan’s energy and food supplies is of paramount importance. According to Taiwan’s Energy Administration, natural gas power generation accounted for approximately 42.4 percent of Taiwan’s electricity mix in 2024, whereas coal-fired power generation accounted for 39.2 percent, and renewable energy made up just 11.7 percent. The first two sources combined constitute 80 percent of thermal

power generation. If this is disrupted during wartime or blockade, as is widely expected to happen, energy shortages would directly impact the life of every civilian, with effects felt in industrial operations and military functionality.

Furthermore, the latest data from the Ministry of Agriculture indicates that Taiwan’s food self-sufficiency rate (calculated by caloric value) reached a recent low of 30.4 percent in 2023. Overall rice self-sufficiency has been declining annually, with substantial reliance on imported grains like wheat, corn, and soybeans. Within this context, disruptions to the food supply chain would trigger social unrest and psychological stress in Taiwan. These facts support the argument that Taiwan needs to establish a strategic integration framework encompassing three levels: institutional, operational, and cultural.

The current Central Disaster Prevention and Response Council and the Executive Yuan’s Office of Disaster

An F/A-18E prepares to launch from the flight deck of the USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76), a Nimitz-class nuclear-powered supercarrier commissioned in 2003.

photo: Heather McGee

Management serve as the core bodies responsible for the formulation of disaster prevention policy in Taiwan. Enhancement efforts could focus on strengthening the existing Office of Disaster Management at the Executive Yuan level (e.g., establishing a National Resilience Command Center). This would grant it cross-ministerial coordination authority spanning defense, economy, energy, and communications to protect critical infrastructure—its mandate extending beyond mere natural disaster coordination. Its core responsibility lies in ensuring the integration of national defense and public welfare from peacetime onward.

Second, it is necessary to formulate a Strategic Societal Resilience Index. Taiwan should regularly assess its societal resilience across various domains, including infrastructure redundancy, cyber protection, supply chain robustness, and civic engagement. This can be done through a comprehensive, objective indicator system that integrates both quantitative and qualitative metrics. The resulting resilience index will serve a dual purpose: to inform the National Defense Report and to guide policy adjustments and budget prioritization, all while being integrated into overall readiness exercises. For resource-constrained nations like Taiwan, this not only helps identify weaknesses but also provides a basis for more effective policy adjustments and resource allocation.

“Ensuring the resilience of Taiwan’s energyandfoodsuppliesisofparamountimportance.”

According to President Lai, Taiwan’s defense budget will reach 3.32 percent of GDP in 2026, with a target of increasing it to 5 percent by 2030. An additional NT$150 billion will be allocated to strengthen homeland security and enhance societal defense resilience. By increasing the budget, societal resilience and military readiness can be enhanced simultaneously, ensuring strategies translate into concrete actions. This un-

derscores the government’s resolve to defend Taiwan’s freedom, democracy, and social stability.

Dispersed backup infrastructure

Taiwan also needs better redundancy to weather a potential crisis. It is necessary to build dispersed backup infrastructure, which would include not only military facilities but also energy reserve stations (e.g., microgrids, distributed energy storage), backup communication nodes (e.g., satellite communication, low-Earth orbit satellites, alternative communication pathways), and mobile medical units (rapidly deployable field hospitals or medical teams). These facilities should possess high flexibility and anti-strike capabilities to ensure continued operation during wartime.

It is also important to develop local autonomous defense organizations and resilient supply node networks. The civil defense should be combined with township-level fundamental governance mechanisms to train residents in basic emergency response, rescue, and logistical support capabilities.

Concurrently, wartime reserves and redistribution capabilities should be developed for important materials such as medicine, food, and fuel. This would consist of resilient supply chains, incorporating a sound logistics and warehousing system and the participation of enterprises to ensure that materials can be effectively delivered to those in need during wartime. This requires a robust logistics and warehousing system, as well as the participation of private enterprises.

It is also important to educate Taiwan’s society about defense issues to increase public resilience. National resilience education courses should also be integrated into public education. From elementary schools to universities, disaster prevention, media literacy (especially the ability to discern disinformation), and national defense knowledge should be integrated into regular curricula. This would not only enhance response capabilities but also cultivate national security awareness

and civic responsibility from an early age.

It is also important to foster a historical consciousness of past conflicts. A historically contextualized allout defense narrative platform should be established through the joint efforts of the government, media, and civil society to transform Taiwan’s historical memories, war experiences (such as local memories of the August 23rd Artillery Battle), and cultural sentiments into resources for a resistance narrative. This would help to consolidate national identity and strengthen the will and consensus for collective defense.

Taiwan should also establish community psychological resilience training and counseling mechanisms and develop a stable of civic mental resilience instructors who could offer psychological support and training at the local community level to help the public cope with wartime stress, anxiety, and trauma. Civilian instructors with expertise in psychological counseling should be trained and sent into communities to provide emotional support and build psychological resilience among the public.

Taiwan’s defense strategy is shifting from a traditional military-oriented approach to a whole-of-society resistance system. Multi-domain denial provides the techniques and an operational framework for resisting aggression on the battlefield, while whole-of-society defense resilience offers the nation enduring internal support and recovery capabilities. The integration of these two not only allows the armed forces to build a robust battlefield defense line but also ensures that society maintains its essential functions and national psychological stability amidst shocks.

Looking ahead, Taiwan’s ability to preserve its way of life and its democracy will depend on whether it can institutionalize this dual-axis model—simultaneously strengthening external resistance and internal sustainability. Only then can the nation transform security from the domain of a few, such as the military, into a shared collective responsibility that is rooted in civic duty and cultural identity. In this era of uncertainty, resilience is not just a policy goal; it is a way of life. n

Societal resilience has seen an uptick in interest of late as civilians have independently sought training in such skills as combat first aid.

photo: Kuma Academy

Vision vol. 14, no. 63 (October, 2025)

One China Prevarication

An analysis of China’s lawfare challenge to Taiwan’s international participation

Cebile Amanda Maphosa

The persistent claim of sovereignty by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan presents a multifaceted challenge to Taiwan’s international status and participation. This challenge is intensified with 1971’s United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758, which, despite not addressing Taiwan’s status, has been used and distorted by the PRC to justify Taiwan’s exclusion from the UN system and associated international organizations. The PRC’s campaign to exclude Taiwan from the international system constitutes a strategic employment of lawfare, poses a threat to the rulesbased international order, obstructs global coopera-

tion, and corrodes democratic values.

The employment of lawfare is a misuse of international law that is otherwise integral to international politics, providing order and predictability. Thus, states strategically use international law to preserve the existing order according to their interests. Charles Dunlap Jr. argued in 2001 that lawfare is the logical extension of this instrumental use; it is commonly defined as the strategic use of law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve a warfighting objective. In this case, the PRC employs a multilayered strategy to enforce Taiwan’s isolation within the international system.

Cebile

is pursuing a masters degree in International Relations and Security at the Graduate Institute of International Security at Taiwan’s National Defense University. She can be reached for comment at cebyphosas@gmail.com

Amanda Maphosa

PRC’s Wang Guangya addresses the assembly following the decision to exclude from the agenda an application by Taiwan to join the United Nations.

UN Photo/Ryan Brown

The PRC’s denial of accreditation to NGOs, and its pressure on other international entities to label Taiwan as “Taiwan, Province of China” or “Chinese Taipei” is a tactic in Beijing’s campaign to isolate Taiwan. This acts as an intentional effort to enforce the One China Principle and undermine any appearance of Taiwan’s international identity. In essence, the One China Principle is what the PRC demands and believes, while the One China Policy is something another nation can adopt in an effort to navigate this complex issue in their foreign relations, often involving a degree of strategic ambiguity. However, the PRC conditions access on the adoption of this interpretation and seeks to normalize its sovereignty claim and limit Taiwan’s independent participation and voice in international forums, extending its political influence into civil society.

Similarly, the PRC’s practice of influencing UN documents is an indirect tactic in its broader strategy to advance its political agenda within the international

system. It has been noted that the PRC actively works to ensure UN documents align with its preferred terminology and interpretations, mainly concerning Taiwan and the One China Principle. The PRC aims to legitimize its claims and control the international narrative by undermining alternative viewpoints. Since UN documents serve as authoritative references, the PRC’s efforts to shape their content have significant implications for how member states and the international community understand issues related to Taiwan.

Attack on visibility

Furthermore, the PRC’s practice of barring Taiwanese nationals from attending international conferences and technical meetings associated with UN agencies represents an attack on Taiwan’s international visibility and contributions. The PRC aims to diminish Taiwan’s presence and silence valuable Taiwanese

Photo: ROC Government

ROC military personnel aid in sterilization efforts after a natural disaster in Hualien in eastern Taiwan.

voices and expertise on global issues by influencing international organizations. For instance, leading Taiwanese medical professionals with crucial insights into pandemic preparedness gained from Taiwan’s experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), have routinely been denied access to World Health Organization (WHO) technical meetings despite advocacy from other member states recognizing their expertise. This exclusion deprives international discussions of unique perspectives and knowledge sharing, and hinders professional and academic exchanges. These actions discourage Taiwanese engagement with UN agencies and obstruct international cooperation and progress in specialized fields where Taiwan has much to offer.

regarding its pressure on Taiwan and legitimize its actions as upholding fundamental UN principles. Concurrently, this weakens the rules-based international order which often prioritizes the rights and agency of democratic entities.

Taiwan’s exclusion from groups such as the International Civil Aviation Organization and the WHO illustrates how China’s political agenda, which is rooted in its sovereignty claims, undermines global health and safety cooperation. Taiwan’s observer sta-

While the UN Charter emphasizes the principle of self-determination, the PRC strategically links this universally accepted concept with its particularistic claim of sovereignty over Taiwan, arguing that any move by Taiwan towards greater international recognition is a violation of its territorial integrity and thus contrary to the spirit of the UN Charter. This tactic aims to shield the PRC from criticism

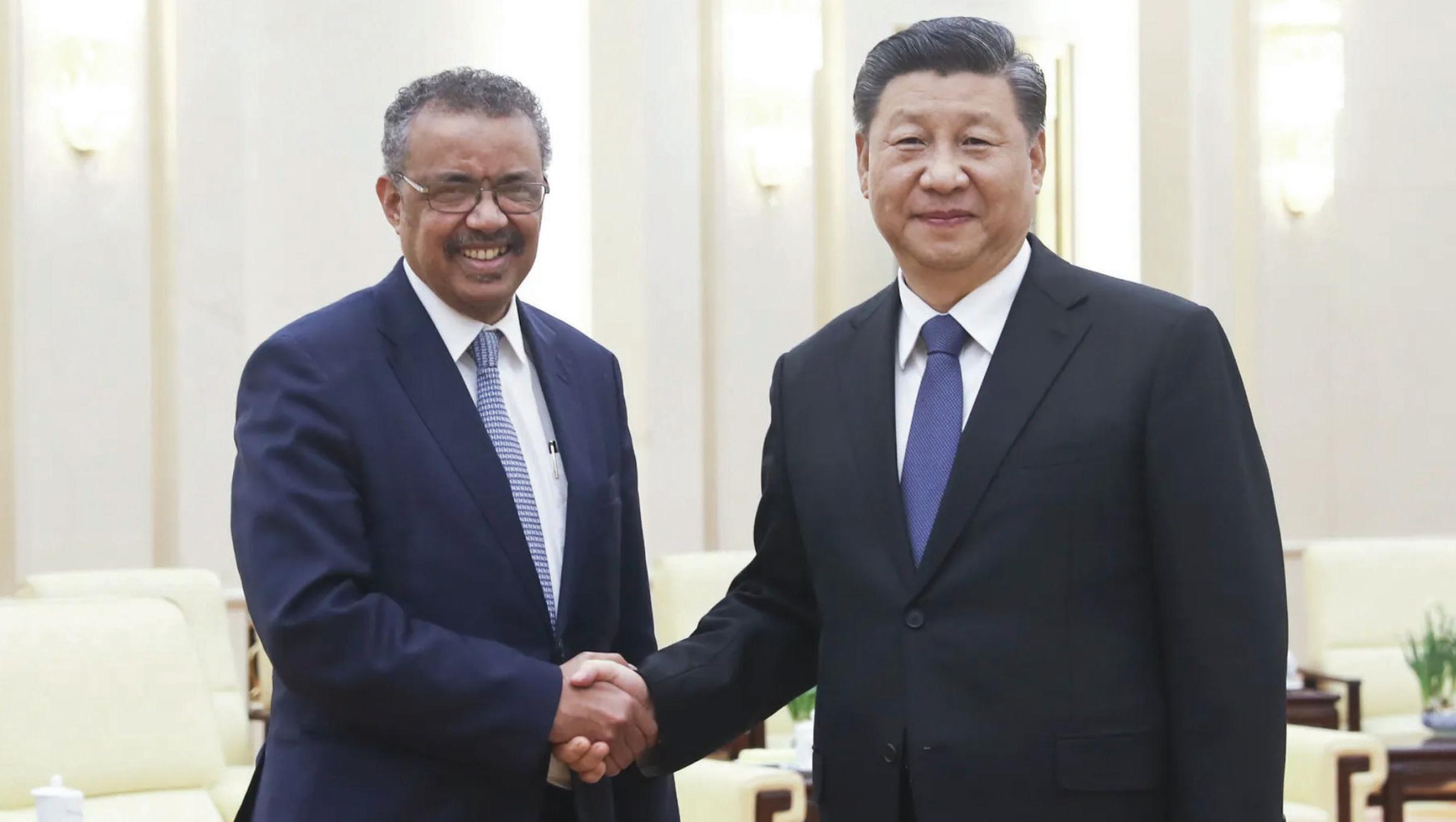

tus at the World Health Assembly (WHA) from 2009 to 2016 under the designation Chinese Taipei ended abruptly when Republic of China (ROC) President Tsai Ing-wen won the presidency, as her administration’s stance was perceived by the PRC as leaning towards independence. Since then, China’s obstruction of Taiwan’s participation, despite widespread international support, underscores PRC’s priority of political objectives over global health.

Similarly, the secret 2005 memorandum of understanding between the WHO Secretariat and the PRC, alongside internal WHO memos dictating the belittling “Taiwan, Province of China” moniker and

The United Nations General Assembly meet in New York City to elect menbers of the body’s Human Rights Council in 2025.

UN Photo/Manuel Elias

Taiwan’s exclusion from the International Health Regulations, reveals the extent of China’s influence and the administrative obstacles erected to marginalize Taiwan. The consequences of this political exclusion are evident in past health crises. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, Taiwan’s isolation hampered its access to crucial information and prevented the timely sharing of its experience. Similarly, in the COVID-19 pandemic, Taiwan faced alleged obstruction from China in its attempts to directly procure vaccines.

Global health security

Despite these politically motivated barriers, Taiwan’s public health record and proactive international health cooperation demonstrate its significant potential contributions to global health security. The exclusion of Taiwan, whose expertise is widely acknowledged as being valuable, represents a tangible loss for the international community. This underscores how China’s strategic lawfare and pursuit of sovereignty claims suppress the health rights of Taiwanese and

hinder essential global collaboration in addressing shared health challenges, prioritizing political objectives over the well-being of people throughout the world.

“Byemployingcoercivetacticsandlawfare, the PRC seeks to reshape global governanceinitsfavor,impactingglobal cooperation, challenging the international order, and undermining human rightsanddemocraticvalues.”

Taiwan’s exclusion from vital platforms like the WHO deprives the international community of its valuable expertise and contributions in areas that are essential for global well-being and security. This situation signals a dangerous precedent where a single nation can unilaterally obstruct the participation of a capable and willing partner based on its political agenda. Also, the PRC’s assertive manipulation of international organizations, such as the distortion of UN Resolution 2758 and attempts to impose its

World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing on January 28, 2020.

photo: Ju Peng

own interpretations of international norms, poses a challenge to the existing liberal world order and the foundational principles of multilateralism. This behavior raises profound concerns about the erosion of the rules-based system that could occur if powerful actors are consistently allowed to prioritize their particularistic claims over the collective interests of the international community. The weakening of human rights and democratic values is a potential consequence, as the PRC’s actions demonstrate a willingness to suppress the agency and voice of a democratic entity.

Taiwan’s persistent yet pragmatic international engagement is crucial, requiring a strategic focus on issue-oriented contributions in international forums where its technical expertise is highly valuable. This approach prioritizes tangible contributions over pursuing symbolic recognition, demonstrating Taiwan’s commitment and capabilities to the global community. Complementing this is active public outreach through digital diplomacy, tourism, international media engagement, and public forums. This in turn highlights Taiwan’s democratic values, and its successful handling of global challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic, thus building international awareness and support for its meaningful participation.

Crucial partnerships

Accordingly, Taiwan’s strategic partnerships and democratic solidarity are crucial, necessitating deepened collaborations with its remaining allies and likeminded democracies through strengthened official and unofficial engagements. Advocating for Taiwan’s inclusion in international organizations should be considered, with more emphasis on strengthening the global order through the participation of capable entities. Addressing the PRC’s exploitation of the ambiguity surrounding the One China terminology is crucial. Consistently affirming the distinction be-

tween a country’s individual One China policy and the PRC’s One China Principle, while also actively calling out and raising international awareness of China’s coercive actions that pressure nations and

“The PRC’s exclusion of Taiwan from the UN system and specialized agenciesrepresentsastrategicchallengethat extends beyond the issue of Taiwan’s status.”

organizations to adhere to its principle, as seen, for example, in instances where airlines are pressured to change Taiwan’s designation, is vital.

Lastly, for specific international organizations like the WHO, sustained international advocacy for Taiwan’s meaningful and dignified participation is essential, involving consistent lobbying for its inclusion, actively opposing discriminatory terminology like “Taiwan, Province of China,” and persistently pushing for expanded access beyond observer status to ensure applicable involvement in technical meetings and decision-making processes, as Taiwan has valuable contributions to make in the realm of global health security.

The PRC’s exclusion of Taiwan from the UN system and specialized agencies represents a strategic challenge that extends beyond the issue of Taiwan’s status. By employing coercive tactics and lawfare, the PRC seeks to reshape global governance in its favor, impacting global cooperation, challenging the international order, and undermining human rights and democratic values. A comprehensive strategy involving Taiwan’s self-strengthening, pragmatic engagement, strong democratic partnerships, and active resistance to China’s distortion of international norms is essential to counter this challenge and ensure Taiwan can contribute to and benefit from the international community for the advancement of global health and other shared objectives. n

Strategic Vision vol. 14, no. 63 (October, 2025)

Domestic Disturbance

Taiwan’s failed recall vote: implications for party politics and cross-strait ties

Pei-shan Lee

Taiwan voters recently went to the polls for two rounds of a massive recall vote in the country’s Legislative Yuan. The first wave of recall voting, held on July 26, targeted 24 legislators who are members of the opposition party, the Kuomintang (KMT). On August 23 the second round saw seven KMT legislators on the ballot. The largescale recall cast on all regional seats held by KMT legislators was initiated by so-called independent civilsociety groups in the name of removing pro-China legislators. The ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), initially kept its distance from the recall campaign, however, Republic of China (ROC)

President Lai Ching-te plunged headlong into the political movement in the final stages of the campaign.

Lai put forth a discourse on the theme of unifying the country, by giving a series of public lectures to boost the movement. Of the 10 lectures that were originally planned, four lectures were delivered, and they revealed disturbing messages, further dividing Taiwan society. The remaining lectures were cancelled with no explanation given. Embroiled in the year-long recall mobilization, Taiwanese turned more divided and hostile against each other. Widespread hatred and distrust permeate the daily life of Taiwan society.

All of the 31 KMT legislators who were targeted

Professor Pei-shan Lee lectures in the Department of Political Science at Taiwan’s National Chung Cheng University.

Protestors take to the streets in Taiwan to call attention to the issue of the recall vote.

photo: rafm0913/ CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

survived the recall and retained their seats in the Legislative Yuan. The DPP suffered an alarming setback in this failure to remove any KMT legislators and its ongoing effort to overturn its minority status in the legislature. As DPP chairman, President Lai has had a compelling anti-China stance since becoming president in 2024. The alliance of the nation’s two opposition parties has declared an emergency in the need to scale back Lai’s “Anti-Communist China, Safeguarding Taiwan” movement. The timing of the prosecution and detention of the chairman of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), Ko Wen-je, who was indicted on bribery and other corruption charges in December 2024 relating to a property development project during his time as mayor of Taipei, has raised concerns about the politicization of the justice system.

The result seemed to take international society by surprise. For a long time, the international media has bought into the DPP’s national narrative as the only legitimate voice for the Taiwanese. Reports from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan on the eve of the first recall vote appeared positive and opti-

mistic about the likelihood that the DPP could achieve a majority in the legislature. The subtle wishful thinking echoed the DPP’s riding on anti-China sentiment for international support. Since 2016, former President Tsai Ing-wen walked a precarious tightrope, by pushing forward Taiwanese identity and leaning into the de facto independence of the island, while trying to avoid irritating the People’s Republic of China (PRC) head on. During her tenure, however, the ROC was essentially renamed “Republic of China (Taiwan)” in the nation’s passports and official diplomatic announcements.

The results of the recall effort delivered a strong yet unexpected message from the electorate to President Lai’s mandate, and anti-DPP sentiment, rather than anti-China, is paradoxically transforming the political climate. After the failed recalls, the DPP’s support base dwindled to 29.4 percent, compared with the KMT’s 20.1 percent and the TPP’s 15.2 percent. Swing voters—around 29.8 percent of the electorate—were siding with the opposition parties in this recall.

Voters were driven by various forms of discontent

Kuomintang supporters echo a call by KMT Chairman Eric Chu to defeat the recall efforts at the polls.

photo: Kokuyo

with the current situation, which sparked the antirecall sentiment—including dissatisfaction with inadequate and slow relief efforts after a recent typhoon; frustration over government incompetence in dealing with the Trump administration’s tariff wars and TSMC; aversion to the excessively radicalized recall movement; and opposition criticism of an analogy used in a speech by Lai, in which the president likened the defense of democracy to forging a sword by hammering out impurities in the iron. All these factors combined led to a collective rebuke of the DPP’s radicalization of the anti-China movement.

CCP collaborators

Compared to the Tsai administration’s stance on China, Lai is more concerned about identifying collaborators (or proxies) of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) operating in Taiwan. In addition to restricting cross-strait exchanges and warning about the political risks of traveling to China, the Lai ad-

ministration has launched investigations into Chinese spouses found to have been retaining their PRC household registration, rather than renouncing it as naturalized citizens are required to do by law. Those found hewing to their PRC household registration may have their political rights in the ROC revoked. The focus of resistance against China has thus shifted toward rooting out internal enemies—a political course that the opposition has criticized as authoritarian; even dictatorial.

The DPP backed the large-scale recall campaign behind the scenes in the hopes of returning to a majority status in the Legislative Yuan, as was the case during Tsai’s first term as president. The DPP was able to pass controversial legislation including pension reform for retired military, civil servants, and public school teachers, as well as same-sex marriage legalization—both of which were swiftly passed into law despite continued opposition to them.

The results of the 2024 presidential election demonstrated that the TPP has siphoned off a significant

KMT supporters storm the Prosecutors Office after it raided KMT offices over allegations of forging signatures on petitions to recall DPP lawmakers.

photo: Kokuyo

portion of the DPP’s young votes, reducing the DPP’s support to 40 percent, while the KMT and TPP together hold a stable 60 percent of electoral support. The DPP still stands a considerable chance of winning future presidential elections by a simple plurality—as long as the KMT and the TPP fail to unite, as was demonstrated in 2024. But Lai’s is destined to remain a minority presidency. In the legislature, it will be difficult for the DPP to secure a majority on its own, resulting in a scenario where none of the three major parties holds more than half the seats. The party structure absolutely requires inter-party compromise, if not a coalition government.

The DPP’s judicial actions against the chairman of the TPP have strengthened the TPP’s unity and empowered Huang Kuo-chang, who succeeded Ko for the party leadership, to rally more public support—particularly among young voters disillusioned with the political establishment. Huang, a veteran street activ-

ist and former leader of the Sunflower Movement that opposed the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement, has paradoxically become the driver fostering cooperation with the KMT. The TPP has in effect turned itself into a critical minority within the tripartite political landscape.

Taiwan’s domestic political configuration is an important intervening variable, which is particularly salient when China is sticking to its discourse of wanting a peaceful reunification with Taiwan. If political reconciliation, and eventually peace talks across the Taiwan Strait, are inevitable for the near future, then the newly emerged tripartite politics is likely to crack up a peace route, however rocky, to reverse the dangerous escalation of hostility between Taiwan and China.

The crystallization of the tripartite politics of the DPP, KMT, and TPP, in which no single political party can command a governing majority, minimizes the chance of reckless acts by the pro-independence re-

Protestors rally against KMT lawmakers whom they accuse of legislative maneuvers designed to undermine democratic values and suppress dissent.

photo: Kokuyo

gime. Even if a DPP candidate wins presidential office in the future, it is destined to be a minority presidency, with little chance of securing a legislative majority. The three-party structure might cool down the anti-China fever and be conducive to peace. Whether it leads to the continuation of the status quo, rather than an improvement in cross-strait relations, will hinge on two exogenous factors. First, how various political forces and the general public in Taiwan watch and interpret the outcome of the war in Ukraine. If arming Taiwan to counter China—as Ukraine was armed to defend against Russia—comes to be perceived as a doomed endeavor, then a consensus in favor of peace efforts may emerge, to avoid the tragedy of war. Second, how the United States and China might reach compromise on Taiwan deserves close attention. The CCP has demonstrated its resolve to risk war with the United States, yet it has thus far restrained itself from directly attacking Taiwan. The September 3, 2025, military parade in Beijing demonstrated how the People’s Liberation Army is growing, narrowing the power gap with the United States. How Washington evaluates the con-

sequences of a war with great uncertainty and huge costs—and a potentially fatal blow to American hegemonic status—will shape possible compromise solutions regarding Taiwan. Seeking compromise and placing the Taiwan issue on the track of the peace process may no longer be such a far-fetched idea. Great power competition might prefer and help sustain a peace-oriented political equilibrium in Taiwan to prevent this island from moving toward outright disaster.

Undetermined status

The issue of Taiwan’s so-called undetermined status was recently brought up again. A September 2025 poll conducted by Formosa e-Paper showed that 76.4 percent of respondents in Taiwan believe that Taiwan’s sovereignty belongs to the Republic of China, with just 15.2 percent supporting the “undetermined status” theory—a theory which holds that WWII-era documents such as the Cairo Declaration and the San Francisco Peace Treaty cannot be used to determine Taiwan’s political status. Despite it being a legal

Soldiers practice for the September 3, 2025, parade in Beijing showing off the enhanced lethality of the PLA. The PRC has vowed to annex Taiwan.

photo: Kremlin.ru

basis often cited by advocates supporting Taiwan’s de facto independence, the theory has not gained widespread acceptance.

The results of the massive recall have kindled hope for those who worry whether Taiwan can avoid the catastrophe of war. The failure of the mass recall campaign signified that the radicalization of anti-China mobilization is not supported by the majority of voters. The return to political moderation and de-politicization of national security may be the path forward for a minority president to lift himself out of a governance limbo.

On October 19, Cheng Li-wun was elected Chairwoman of the KMT with 50.15 percent of the party vote. Her victory not only marks a major strategic shift for the KMT but also injects new potential for changes of Taiwan’s tripartite politics. During her campaign, Cheng publicly declared herself a “Chinese” and emphasized that the KMT’s historical legacy cannot be separated from the word “China.” She insisted on restoring an institutionalized channel of dialogue with the PRC based on the 1992 Consensus. Following her election, she immediately received a congratulatory message from Xi Jinping, who mentioned jointly advancing “national unification.”

Cheng’s elevation to the KMT leadership will have striking security implications. First, she highlights the party’s Chinese identity, seeking to overturn the KMT’s previous approach of downplaying its Chinese connotation. Second, she stated during her campaign that it is no longer viable to maintain the status quo, arguing that the KMT must lead Taiwan in preventing a war by pursuing “cooperation and dialogue with the mainland.” Her attempt to reshape public opinion carries great uncertainty, however. Assuming that the supporters of the TPP will continue to favor maintaining the status quo, they are likely to balk at Cheng’s Chinaleaning stance, and perceive her as too explicitly pro-

China. This could give rise to a divergence between the KMT and the TPP, and put any future electoral collaboration between the parties at risk. Third, Cheng explicitly opposed the increase of Taiwan’s defense budget to 3.3 percent of GDP for next year. Her proposed strategic re-orientation has raised concerns in Washington.

On the eve of the highly anticipated Trump-Xi meeting in Busan, Time Magazine published an article by Lyle Goldstein criticizing President Lai as a brash leader lurching toward formal independence, and warning against allowing Taiwan to drag the United States into a war with a nuclear-armed China. Goldstein suggested that Washington should rein in Lai to preserve the status quo, criticizing moves toward formal independence. Goldstein’s is just the latest of several such articles in the “abandon Taiwan” camp that have appeared in the Western media, perhaps reflecting anxiety about Trump’s unpredictability and a desire for stability among the superpowers. In the end, these worries proved unfounded, as the topic of Taiwan never even came up in the TrumpXi meeting.

Meanwhile, in Taiwan, a poll was conducted by My Formosa News in late October to gauge opinions on the issue of war or peace with China. Sixty percent of respondents do not believe that war with China is inevitable, with 53.2 percent of respondents not willing to sacrifice their lives for Taiwan. Moreover, 58.3 percent of respondents favored cross-strait talks and exchanges to avoid a war with the PRC, compared to just 28.2 percent supporting an increase in the annual budget for weapons purchases to strengthen national defense. This poll revealed that public opinion has turned around and a prevailing consensus on seeking cross-strait peace is on the rise. It remains to be seen how this political shift will affect the DPP government and how it fares in future elections. n

KMT Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun

Visit our website:

https://taiwancss.org/strategic-vision/