Economy • Environment • Society

The Southeastern Massachusetts Metropolitan Planning Organization (SMMPO) through the Southeastern Regional Planning and Economic Development District (SRPEDD) operates its programs, services, and activities in compliance with federal nondiscrimination laws including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, and related statutes and regulations. Title VI prohibits discrimination in federally assisted programs and requires that no person in the United States of America shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin (including limited English proficiency), be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal assistance. Related federal nondiscrimination laws administrated by the Federal Highway Administration, the Federal Transit Administration, or both prohibit discrimination on the basis of age, sex, and disability. These protected categories are contemplated within SRPEDD’s Title VI Programs consistent with federal interpretation and administration. Additionally, SRPEDD provides meaningful access to its programs, services, and activities to individuals with limited English proficiency, in compliance with US Department of Transportation policy and guidance on federal Executive Order 13166.

Individuals seeking additional information or wishing to file a Title VI/Nondiscrimination complaint may contact the SRPEDD Title VI/Nondiscrimination Coordinator at the contact information here. All such complaints must be received, in writing, within 180 days of the alleged discriminatory occurrence. Assistance will be provided, upon request, to individuals unable to provide the complaint form in writing.

Title VI Coordinator - SRPEDD

88 Broadway, Taunton, MA 02780

Phone: 508 824-1367 or dial 711 to use MassRelay

Email: aduarte@srpedd.org

Massachusetts Public Accommodation Law (M.G.L. c 272 §§92a, 98, 98a) and Executive Order 526 section 4 also prohibit discrimination in public accommodations based on religion, creed, class, race, color, denomination, sex, sexual orientation, nationality, disability, gender identity and expression, and veteran’s status, and SRPEDD and the SMMPO assures compliance with these laws. Public Accommodation Law concerns can be brought to SRPEDD’s Title VI /Nondiscrimination Coordinator or to file a complaint alleging a violation of the state’s Public Accommodation Law, contact the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination within 300 days of the alleged discriminatory conduct.

The SMMPO is equally committed to implementing federal Executive Order 12898, entitled “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations” and Executive Order 13985 (2021) entitled “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.”

In this capacity, the SMMPO identifies and addresses disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on low-income and minority, including BIPOC, Asian or Pacific Islander populations, as well as religious minorities, LGBTQ+ persons, Limited English Proficient (LEP) persons or those who have a disability. The SMMPO carries out this responsibility by the consistent, fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, and by involving underserved individuals in the transportation process and considering their transportation needs in the development and review of the SMMPO’s transportation plans, programs and projects.

English: If this information is needed in another language, please contact the MPO Title VI Coordinator at 508-824-1367 ext. 235 or at aduarte@srpedd.org

Spanish: Si necesita esta información en otro idioma, por favor contacte al coordinador de MPO del Título VI al 508-824-1367 ext. 235 o en aduarte@srpedd.org .

Portuguese: Caso estas informações sejam necessárias em outro idioma, por favor, contate o Coordenador de Título VI da MPO pelo telefone 508-824-1367, Ramal 235 ou em aduarte@ srpedd.org .

Haitian Creole: Si yon moun bezwen enfòmasyon sa a nan yon lòt lang, tanpri kontakte Koòdonatè a Title VI MPO nan 508-824-1367 ext. 235.

Simplified Chinese: 如果需要其他语言的此信息,请致电 508-824-1367 分机联系 MPO Titl e VI 协调员。 235 或发送电子邮件至 aduarte@srpedd.org 。

Simplified Chinese: 如果需要其他语言的此信息,请致电 508-824-1367 分机联系 MPO Titl e VI 协调员。 235 或发送电子邮件至 aduarte@srpedd.org 。

Traditional Chinese: 如果需要其他語言的此信息,請致電 508-824-1367 分機聯繫 MPO Tit le VI 協調員。 235 或發送電子郵件至 aduarte@srpedd.org 。

Mon Khmer Cambodian (Khmer): ប្រសិនបើព័ត៌មាននេះត្រូវការជាភាសាផ្សេង សូម ទាក់ទងអ្នកសម្របសម្រួល MPO Title VI តាមរយៈលេខ 508-824-1367 ext ។ 235 ឬនៅ aduarte@srpedd.org ។

This report was made possible with funding from the following sources:

U.S. Economic Development Administration

Massachusetts Community Compact Cabinet

District Local Technical Assistance

Maps produced by SRPEDD are for the sole purpose of aiding regional planning decisions and are not warranted for any other use. This map is not intended for engineering, legal, or survey purposes.

This report was prepared by the Southeastern Regional Planning and Economic Development District (SRPEDD):

Jeffrey Walker, AICP; Executive Director

ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING

Danica Belknap, CC-P; Environmental Planning Manager

Michelle Tinger; Assistant Director of Environmental Planning

Karen Pettinelli; Principal Natural Resource Planner

Audrey Matthews; Senior Climate Planner

Lauren Lunetta; Environmental Planner

Cecelia Lagomarsino; Environmental Planner

Helen Zincavage, AICP; Environmental Planning Manager (former)

COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING

Grant King, AICP; Deputy Director/Comprehensive Planning Manager

Robert Cabral; Assistant Comprehensive Planning Manager

Lizeth Gonzalez; Director of Economic and Community Development

Taylor Perez; Director of Housing and Research Initiatives

Chris Welch; Principal Comprehensive Planner

Maria Jones; Senior Public Engagement and Communications Planner

Amber Davis; Senior Comprehensive Planner

Laura Tsang; Senior GIS and Data Planner

Danyel Kenis; Urban Design Planner

Aubrey Hoes; Comprehensive Planner

Kaitlin Whalen; Comprehensive Planner

Emily Duseau; Comprehensive Planning Intern (former)

HOMELAND SECURITY

Kevin Ham; Director of Homeland Security

Joseph Monet; Homeland Security Specialist/Comprehensive Planner

TRANSPORTATION PLANNING

Lisa Estrela-Pedro; Transportation Planning Manager

Jackie Jones, AICP; Assistant Director of Transportation Planning

Sean Hilton; Senior Transportation Planner

Noah Soutier; Public Health and Transportation Planner

Prosperity and continued growth depend in part on a region’s ability to predict, prevent, withstand, and recover from disruptions to its economic systems. While acknowledging that these disruptions often originate from larger market changes, regional, national, or even international industry downturns, and other external shocks, our region seeks to build lasting economic resilience by anticipating risks, evaluating their potential impact on economic assets, and building responsive capacity. In the context of the SRRP, economic resilience is defined in three categories of needs that address diversifying the economy, providing a sustainable future for utilities networks, and supporting resilient transportation models.

Best Practice #1: Upgrade existing public water infrastructure.

Best Practice #2: Provide resources and programming to increase awareness around water quality.

Best Practice #3: Increase awareness of water conservation tactics.

Best Practice #1: Upgrade existing wastewater infrastructure.

Best Practice #2: Implement Green Infrastructure.

Best Practice #3: Increase regional coordination.

Best Practice #1: Pursue and support municipal fiber networks.

Best Practice #2: Increase awareness of lifeline and the comcast internet essentials program.

Best Practice #1: Support the offshore wind industry and encourage new projects.

Best Practice #2: Increase awareness and accessibility to solar PV systems.

Best Practice #3: Plan for long-term electrification and natural gas transitioning.

Best Practice #4: Increase participation in statewide clean energy programs.

Most communities in the SRPEDD region have access to public water, though the extent of access varies widely. There are a fair number of inter-municipal agreements (IMAs) involving the exchange of water treatment and/or distribution for consumption. Almost all towns in the region, with the exception of Carver, Rehoboth, and Seekonk, have some form of an IMA that involves shared water resources.

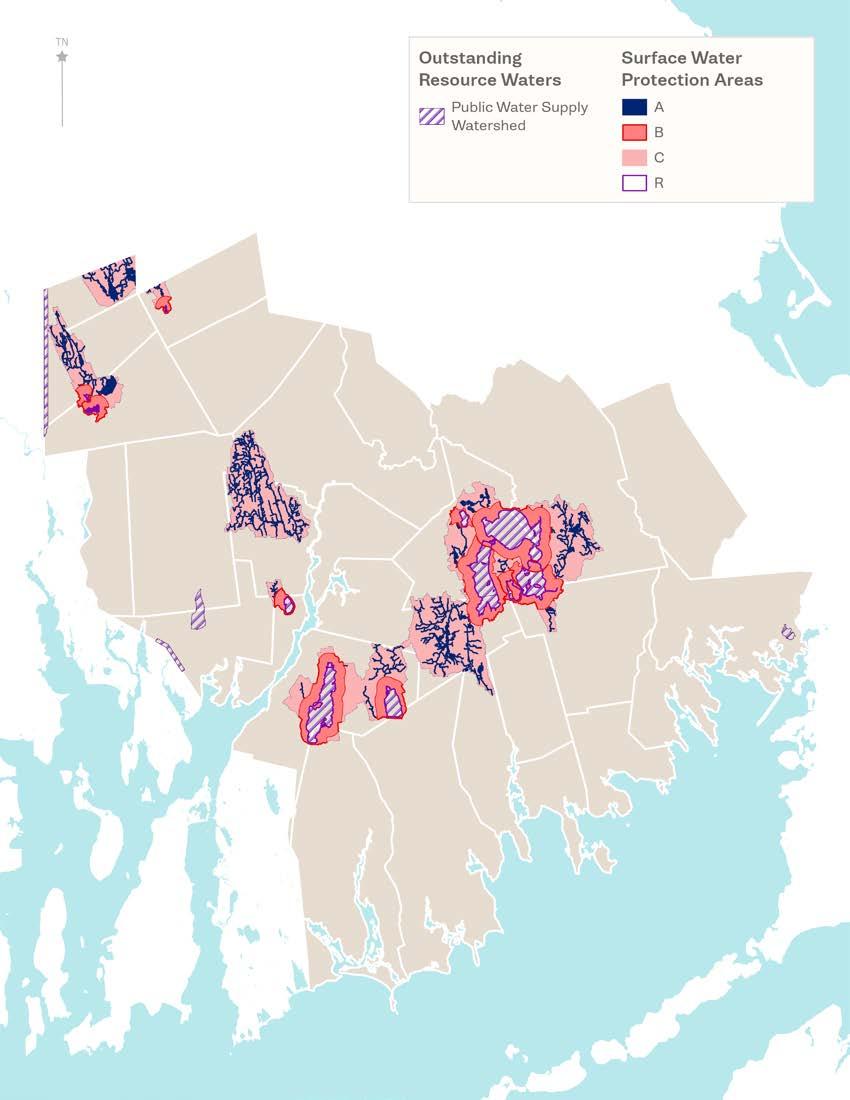

Some of the primary sources of water for the region are the Assawompset Pond Complex, the Mattapoisett River Valley, and the Taunton River Basin.

Increased flood events and precipitation are putting a strain on existing water infrastructure. Many wastewater treatment facilities in the region have been pushed over capacity from stormwater infiltration during heavy rains, leading to untreated effluent overflowing into nearby bodies of water or soil. Further, a significant and/or sudden increase in hydraulic load can induce stress on microorganisms essential for treating wastewater and breaking down certain hazardous materials. This added stress can kill off the microorganisms, effectively decreasing water quality exiting the treatment facility. Additionally, a lack of stormwater infrastructure can lead to increased presence of pesticides, insecticides, and other pollutants from runoff in local public water supplies and sensitive ecosystems. This can cause eutrophication, increase the risk of tick and mosquito-borne diseases, and endanger drinking water quality.

Additional contaminants can make their way into public water supplies from aging/failing septic systems. While soil can filter most bacteria and viruses in wastewater, it cannot remove all contaminants, including medicines, cleaning products, and other chemicals. When a septic system fails or is severely inundated during a flood event,1 untreated sewage may surface and can leach into surface waters or drinking wells via cracks or the well cap.2 Released nitrogen from septic systems can also accumulate to unsafe levels in drinking water and cause a number of environmental hazards.3

Another known concern in public water supplies is the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS have been used in manufacturing for years and are found in clothing, furniture, packaging, non-stick cooking surfaces, and many other products. These chemicals are man-made and do not break down in the environment. Since PFAS do not break down and can move through soils, they can accumulate in water and in wildlife.4 While research is still ongoing to determine the full list of effects of PFAS on humans, it is believed that these chemicals can affect fertility, fetal development, hormones, and the body’s immune system. They are also believed to increase the risk of certain cancers. Several communities in the region reported concerns about PFAS concentrations in the local water supply in their Water Management Plans, including Carver, Plainville, and Raynham, though the problem is widespread throughout the region and the state. This problem is discussed in detail in the Provide Drinking Water section of this report.

In addition to contaminants, the actual availability of potable water is a concern for many communities in the Southeast. Increased drought events, such as the ones that occurred in 2016-2017, 2020, and 2022,5 put pressure on local public water supplies and have led to communities needing to tap into emergency water supplies.6 Some communities, such as Swansea, have turned to alternative sources of water via desalination, though these alternative measures can be costly.

Source: Sierra Club.

1. Aging/Outdated Infrastructure: Much of the Southeast’s water infrastructure is aging. Aging infrastructure is more susceptible to infiltration and contamination during storm events. Additionally, lead present in old service lines can leach into drinking water.

2. Sensitive Infrastructure: Many communities rely on municipal wells or private wells for drinking water. Residents with private wells may lose access to their water supply during storm events if the power goes out. Wells can also dry out during drought events. Additionally, residents are responsible for maintaining the water quality of their wells, which can be contaminated by fertilizers, chemicals, and nearby septic systems.

3. High Costs: Water infrastructure, including wells and public water supplies, are costly to install and maintain.

4. Presence of Contaminants: Combined Sewer Overflow events endanger local drinking supplies and the ecosystems that support them. Additionally, the presence of PFAs, lead, nitrogen, bacteria, and other contaminants in drinking water poses public and ecological health risks.

A resilient water supply must be safe, accessible during extreme weather events, and affordable. For communities with limited public water, this means promoting emergency preparedness, maintaining municipal wells, and facilitating necessary upgrades to private wells. For communities with existing public water networks, this means ensuring safe drinking water at affordable rates.

T2-T6: Communities should prioritize and implement upgrades to aging water systems, develop and maintain emergency water plans, and utilize available funding programs (such as those through MassWorks or CDBG) to ensure water is affordable, safe, and accessible for all.

Like wastewater infrastructure, public water infrastructure is aging. Municipalities should prioritize upgrades in key areas to ensure residents and commercial users have access to safe drinking water.

There are numerous programs at the state and federal level designed to support infrastructure improvements, including programs specifically geared towards drinking water infrastructure. Communities can individually apply for these programs or work with SRPEDD, other public agencies, or private consultants to tap into these funds to support their infrastructure improvement needs. Many of these programs overlap with those addressed in the Wastewater section of this plan. These include (but are not limited to):

• Massachusetts State Revolving Fund Program (SRF): The State Revolving Fund (SRF) financial assistance program offers affordable financing options to cities, towns, and public water utilities to improve water infrastructure and drinking water safety. The program helps communities comply with federal and state water quality requirements of wastewater treatment plants and collection systems, evaluate issues related to watershed management priorities, stormwater management, green infrastructure, and provides financial assistance to communities to implement their community septic management programs that make available loans to homeowners with failed septic systems.

• MassWorks (One Stop for Growth Program): A competitive grant program that provides capital funds for public infrastructure projects that support growth.

• HousingWorks (One Stop for Growth Program): A competitive grant program that provides capital funds for infrastructure projects that support housing development.

• Sections 319 and 604b Grant Programs (MassDEP/EPA): Competitive grant programs that support planning for and implementing measures that protect water quality and target nonpoint source pollution.

• Planning Assistance Grants (EOEEA): A competitive grant program that supports planning for sustainable land use practices.

• Community Development Block Grants [CDBG] (EOHLC): A competitive grant program that distributes federal CDBG funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to support needs for housing, infrastructure, economic development, revitalization, and public social services.

• Lead Service Line Replacement Program (MA Clean Water Trust/ MassDEP): A program offering 0% interest construction loans and planning grants to support lead service line inventorying and replacement.

• Water & Environmental Programs (USDA Rural Development): A program that provides loans and grants for drinking water, sewer, and storm drainage facilities in rural areas and municipalities with a population of 10,000 people or less.

• Community Development Block Grants (HUD): A program that distributes funding to “Entitlement Communities” to provide livable housing and expanded economic opportunities for low- and moderate-income people.

Private well owners are responsible for maintaining the quality of their drinking water. Municipalities should work to ensure owners are aware of their options for testing, treatment, and maintenance of their wells. This can be accomplished through educational workshops, informational campaigns, and collaboration with local health departments or environmental groups. This can be further incentivized through public recognition programs that highlight communities with the highest clean water rates.

The Town of Middleborough has several wells with higher concentrations of PFAs than the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allows. Through coordinated outreach, the Town was able to work with a well-known resident group to educate the public and promote resources regarding PFAs in municipal drinking water sources, which has greatly aided their efforts to address ongoing water quality issues townwide.

T2-T6: To increase awareness around water quality and support private well owners, municipalities should host educational workshops, launch targeted informational campaigns, and collaborate with local health departments and environmental groups to provide accessible testing and treatment services. Additionally, they should create public recognition programs to incentivize high water quality standards, develop online resources, send annual reminders for testing and maintenance.

Given increasing rates of drought events, water conservation measures will be crucial to implement throughout the region. There are many ways communities can conserve water and prepare for drought events, from simple tactics such as water reuse to complex tactics such as creating a large-scale desalination plant. In most cases, communities should begin with the least intense interventions, namely stormwater capture and re-use (usually for non-potable purposes), increasing access to low-flow plumbing, and educational campaigns to teach household-level water conservation tips.

Some common water conservation methods for residential uses include:

• Identifying and fixing any water leaks;

• Installing low-flow plumbing, including faucets, showerheads, and toilets;

• Fully loading dishwashers and washing machines before running;

• Minimizing outdoor landscape watering; and

• Minimize draining pools in the summer and cover them when not in use.

It is important to note that, while residential reductions in water usage are important, water is primarily used for electricity generation and agriculture.7 Any concerted effort to reduce residential water consumption must also be mirrored by efforts to reduce commercial and industrial water consumption.

Plymouth is currently undergoing a period of rapid development. To accommodate for the town’s sole-source aquifer and water-dependent economic base, Plymouth has put a stronger emphasis on water conservation through a ‘Save Water’ campaign established by the Plymouth Water Conservation Committee.

Southeastern Massachusetts manages sewer systems collaboratively through regional initiatives and partnerships among municipalities. Key efforts include regional sewer districts such as the Greater New Bedford Regional Refuse Management District and the Upper Blackstone Water Pollution Abatement District, collaborative projects with organizations like the Buzzards Bay Coalition, regional sewer expansion projects, and stormwater management through Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4). The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) provides grants and assistance to support these efforts.

Across the region, sewer service areas are generally concentrated in urban and densely populated towns, while rural and suburban regions rely heavily on septic systems. Key sewer service areas include the Greater New Bedford Area, Fall River, and Wareham. In the surrounding suburban communities, the network is usually limited; in rural communities, it is often minimal or non-existent. Efforts are ongoing to expand sewer services and improve wastewater management, reducing the environmental impact of septic systems in vulnerable areas. High densities of septic systems in towns like Wareham, Westport, and Marion contribute to nitrogen pollution, affecting the health of coastal ecosystems and water quality in Buzzards Bay. Areas with extensive sewer service host their own wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs) or water pollution control facilities (WPCFs).

Several cities and towns treat neighboring communities’ wastewater through inter-municipal agreements (IMAs). Fall River hosts a regional WWTF, which processes flows from Freetown, Westport, and Tiverton. New Bedford, North Attleborough, Somerset, and Taunton also have IMAs with nearby communities. Additionally, the towns of Mansfield and Norton formed a regional wastewater district with Foxborough. The three towns’ wastewater is treated at the Nortonlocated MFN (Mansfield-Foxborough-Norton) Regional WPCF.

Table 1. Sewer availability by municipality.

Municipality

Sewer Availability

Wastewater Treatment Facility

Acushnet Extensive New Bedford WWTF

Attleboro Extensive Attleboro WWTF

Berkley None -

Carver None -

Dartmouth Extensive Dartmouth WPCF

Dighton Limited Taunton WWTF

Fairhaven Extensive Fairhaven WPCF

Fall River Extensive Fall River Regional WWTF

Freetown Limited Fall River Regional WWTF

Lakeville None -

Mansfield Extensive MFN Regional WPCF

Marion Extensive Marion WWTF

Mattapoisett Limited Fairhaven WPCF

Middleborough Extensive Middleborough WWTF

New Bedford Extensive New Bedford WWTF

North Attleborough Extensive North Attleborough WWTF

Norton Extensive MFN Regional WPCF

Plainville Limited North Attleborough WWTF

Raynham Extensive North Main St Treatment Facility John P. Lynn Treatment Facility

Nip Treatment Facility

Rehoboth No -

Rochester No

Seekonk No

Somerset Extensive Somerset WPCF

Swansea Limited Somerset WPCF

Taunton Extensive Taunton WWTF

Wareham Extensive Wareham WPCF

Westport Limited Fall River Regional WWTF

The state also focuses on water quality and management, utilizing detailed GIS mapping to delineate sewer service areas and wellhead protection zones. Wellhead protection areas are critical for safeguarding drinking water sources from contamination, especially in regions relying heavily on groundwater. This mapping is also crucial in areas that depend heavily on septic systems, highlighting regional disparities in sewer services and the resulting environmental impacts. These disparities are addressed through updated regulations, including new standards for contaminants like PFAS, which are essential for improving wastewater treatment and stormwater management.

Additionally, the management of Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4) plays a pivotal role in mitigating pollutant runoff into stormwater, which is vital for maintaining both environmental and public health. In southeastern Massachusetts, MS4 areas are primarily located in urbanized regions as defined by the U.S. Census. The MS4 permit applies to these urban areas and aims to manage stormwater to reduce pollution. The map above shows the automatically designated MS4 areas under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Phase II Stormwater Program, based on the 2000 and 2010 U.S. Census data (the most current analysis available). These areas are required to adopt comprehensive stormwater management practices to protect water quality and comply with federal and state regulations.

Climate change and aging infrastructure will continue to strain local sewer networks. Increasing rainfall has caused significant flash flooding across the Southeast region and the state. These flash flooding events can contribute to inflow and infiltration (I&I) issues and overwhelm combined sewer systems, causing a combined sewer overflow (CSO). During a CSO, systems can discharge sewage, often untreated, into local waterbodies. In 2023, there were 1,943 sewage overflow events statewide. Fall River and New Bedford experienced some of the highest instances of these events in the state between April and September 2023.8

Table 2. Top five overflow events statewide. (EOEEA)

These overflows pose significant environmental and public health hazards. Discharge can contain harmful chemicals, pathogens, and trash, which can affect the local ecosystem and endanger residents who may not be aware of sewage in the water. Furthermore, these discharge events often occur in urban areas near environmental justice populations.

Where sewer is not present or widely available, many residents and businesses rely on septic systems to capture and treat wastewater. On average, a new septic system costs $20,000 in Massachusetts, with more complex systems costing upwards of $50,000.9 These prices can fluctuate depending on the local soil conditions and environmental regulations, where more challenging soils and stricter regulations can result in higher costs for residents and developers. These costs can inhibit new housing and economic and community development opportunities, posing significant financial challenges for homeowners with fixed or low/moderate incomes and small businesses.

Finally, concerns about nitrogen loading in estuaries and embayments are an important consideration when looking at the future of septic systems in Southeastern Massachusetts. Changes to Title V regulations in regions such as Cape Cod10 to reduce nitrogen loading will likely serve as a model for areas in the South Coast as the environmental impacts of septic systems are further studied.

1. Aging/outdated infrastructure: Much of the Southeast region’s sewer infrastructure is aging. This aging infrastructure is more likely to contribute to environmental hazards.

2. Limited infrastructure: Sewer infrastructure is limited or non-existent in smaller suburban and rural communities. This can hinder development opportunities.

3. High costs: Replacing septic systems and acquiring new sewer infrastructure is costly. This can make addressing wastewater issues difficult to achieve.

Resilient wastewater systems should output high-quality, treated effluence; they should also be able to handle excess capacity during storm events while still outputting at the same level of quality. These quality systems should be supported by strong governance structures that prioritize regionalization and resource sharing.

T2-T3: Rural and semi-suburban communities with limited or no public wastewater infrastructure should evaluate which areas in their community would need new infrastructure to foster economic development, the creation of new housing opportunities, and environmental protection. Once these areas have been identified, these communities should pursue funding to begin design and engineering studies (many grant programs for construction require or recommend projects at greater than or equal to 25% design), likely in partnership with a neighboring municipality with existing infrastructure, alongside robust public engagement campaigns.

T4-T6: Dense suburban and urban communities with existing public wastewater infrastructure should work to evaluate capacity needs and prioritize the highest-impact upgrades. Upon determining which areas have the highest need, these communities should pursue funding to begin design and engineering studies and/or construction.

Funding Sources: Community One Stop for Growth (MassWorks, HousingWorks), USDA, EDA, EOEEA, HUD and MA CDBG grants.

Aging infrastructure across the region, state, and nationally has led to increased pollution and environmental hazards, posing risks for both humans and the ecosystems we live within. Municipalities can pursue upgrades to their existing wastewater systems, prioritizing key upgrades in areas with the most severe need.

The state and federal government have many programs that support critical infrastructure planning and improvements. These include (but are not limited to):

• Massachusetts State Revolving Fund Program (SRF): The State Revolving Fund (SRF) financial assistance program offers affordable financing options to cities, towns, and public water utilities to improve water infrastructure and drinking water safety. In addition, the program helps communities comply with federal and state water quality requirements of wastewater treatment plants and collection systems, evaluate issues related to watershed management priorities, stormwater management, green infrastructure, and provides financial assistance to communities to implement their community septic management programs that make available loans to homeowners with failed septic systems.

• MassWorks (One Stop for Growth Program): A competitive grant program that provides capital funds for public infrastructure projects that support growth.

• HousingWorks (One Stop for Growth Program): A competitive grant program that provides capital funds for infrastructure projects that support housing development.

• Sections 319 and 604b Grant Programs (MassDEP/EPA): Competitive grant programs that support planning for and implementing measures that protect water quality and target nonpoint source pollution.

• Planning Assistance Grants (EOEEA): A competitive grant program that supports planning for sustainable land use practices.

• Community Development Block Grants [CDBG] (EOHLC): A competitive grant program that distributes federal CDBG funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to support needs for housing, infrastructure, economic development, revitalization, and public social services.

• Water & Environmental Programs (USDA Rural Development): A program that provides loans and grants for drinking water, sewer, and storm drainage facilities in rural areas and municipalities with a population of 10,000 people or less.

• Community Development Block Grants (HUD): A program that distributes funding to “Entitlement Communities” to provide livable housing and expanded economic opportunities for low- and moderate-income people.

Communities can individually apply for these programs or work with SRPEDD, other public agencies, or private consultants to tap into these funds to support their infrastructure improvement needs.

T2-T4: Rural, semi-suburban, and suburban communities should explore opportunities to install small- and medium-scale green infrastructure in key areas, particularly those with large amounts of pavement/impervious surfaces and/or areas prone to flooding. Consider LID regulations an guidedance.

T5-T6: Urban communities should explore all forms of green infrastructure installation, focusing on differing areas of need and determining the appropriate best practice/scale. This can include limiting residential runoff by implementing small-scale green infrastructure programming to establishing community-wide tree planting programs for property owners.

Funding Sources: MassDEP 604b, SRF Program, MVP, and MS4 Municipal Assistance Grant Program; EPA UWSG and WIFIA; Rockefeller Foundation Environmental Impact Bond (EIB); NFWF and Wells Fargo Resilient Communities Program.

“Green infrastructure” is defined in the 2019 Water Infrastructure Improvement Act as “the range of measures that use plant or soil systems, permeable pavement or other permeable surfaces or substrates, stormwater harvest and reuse, or landscaping to store, infiltrate, or evapotranspiration stormwater and reduce flows to sewer systems or to surface waters.”11 Green infrastructure is the opposite of “gray infrastructure,” which refers to conventional stormwater management practices in place regionally and nationally, including gutters, pipes, and tunnels that move stormwater from the source to treatment facilities or water bodies. Green infrastructure is designed to mimic the natural water cycle, absorbing and filtering stormwater and runoff at the source.

There are varying scales of green infrastructure, ranging from small-scale solutions such as rain barrels for homeowners, to large-scale solutions such as constructed wetlands. Some common types of green infrastructure include:

• Small-scale Green Infrastructure: This includes downspout disconnection, rain barrels, and rain gardens. These small-scale solutions aim to collect stormwater at the source, allowing it either to filter through permeable surfaces (rather than flow into the drainage system or local water bodies) or to be re-used.

• Medium-scale Green Infrastructure: This includes streetside planter boxes, bioswales, and permeable pavement. Like small-scale green infrastructure, these solutions are designed to capture and filter stormwater at the source to prevent runoff. However, these solutions are usually incorporated in parking lots, along streets, and adjacent to larger developments. Since they incorporate landscaping elements, they can also be used to beautify areas.

• Large-scale Green Infrastructure: This includes green walls/roofs, maintaining tree canopy cover, land conservation, and constructed wetlands. These tactics are designed to manage stormwater runoff at a large scale and can be ideal in urban areas where space is limited.

Depending on the need, communities can work to implement these green infrastructure solutions into their local regulations for stormwater management (often known as “Low Impact Development” or LID standards), design standards, and programming. Doing so can limit the risks posed by untreated runoff and minimize the strain on wastewater systems during storm events.

The City of Watertown was awarded a grant from MassDEP’s 604b EPA pass-through to fund various green infrastructure projects.12 Using the funds, the City installed several rain gardens, bioswales, and tree trenches, helping to limit runoff that would otherwise end up flowing, untreated, into the Charles River.

T2-T6: Smaller communities should partner with larger communities to explore opportunities to regionalize their wastewater infrastructure, sharing capacity where appropriate and mutually finding ways to increase costsavings and efficiency.

For communities with limited staff capacity and resources, coordinating with neighboring municipalities may be the best solution to increasing wastewater infrastructure access. Many of SRPEDD’s communities are already participating in an Intermunicipal Agreement. Strengthening these partnerships through increased coordination will help foster better outcomes for all members. This can include mutually pursuing funding for improvements that expand capacity and upgrade facilities, as well as sharing leadership roles and jointly managing responsibilities.

The Mansfield Foxborough Norton (MFN) Wastewater District was formed through a partnership and agreement between the Towns of Mansfield, Foxborough, and Norton in July 2014, the first wastewater district created in Massachusetts in over 20 years. The MFN Wastewater District owns and operates the MFN Regional Wastewater Facility, which is located within the Town of Norton. The 4.14 million gallons-per-day facility treats wastewater and septage from the three member towns, as well as from Easton and Sharon. Treated effluent is discharged into the Three Mile River. The facility is governed by a seven-member commission with representatives from each of the three towns, and was last upgraded in 2018, which added a new chlorine contact tank and secondary clarifier, as well as primary clariflocculation and a four-state biological treatment process.13 The upgrade increased regional capacity by 1 million gallons-per-day, increasing the wastewater flow allotments for all three towns and mutually reducing costs.

Access to reliable and affordable internet is essential to everything from going to school, scheduling a doctor’s appointment, paying bills, and applying for jobs. The majority of households in the Southeast region have access to broadband internet in their home. Broadband is defined as internet that is 100/20 Mbps (a measure of upload/download speed) or faster, a standard set the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Currently, the average lowest price for broadband in the southeast region is $58 a month. Additionally, 71% of people in the southeast region who responded to the Massachusetts Broadband Institute’s (MBI) survey for the recent State Digital Equity Plan say that their monthly internet cost is either “very” or “somewhat” hard for them to afford. For 38% of households in southeastern Massachusetts, their internet bill is over $100 a month. In comparison to the rest of the state, residents in this area were more likely to say that the cost of an internet subscription prevents them from having an internet plan.14

One issue that people in the southeast note about their broadband service is the lack of choice when it comes to selecting an internet service provider. Many areas only have one prominent internet service provider, leading to a lack of choice and competition (often resulting in higher internet prices in these markets). In this region, the most common internet service providers are Comcast and Verizon. Other providers that operate in the area include Charter, the Taunton Municipal Lighting Plant (TMLP), and T-Mobile. TMLP operates a municipal fiber network that provides service to homes and businesses in parts of Taunton, Raynham, Berkley, Dighton, and Lakeville. Other towns in the region have municipal fiber networks that connect their municipal buildings, but not residential homes, including Acushnet and Seekonk. Additionally, the towns of Westport, Wareham, Middleborough, Mattapoisett, Lakeville, Fairhaven, Dighton, and Freetown have received Municipal Fiber Grant Funding between FY 2022 and FY 2024 to either create or expand a Municipal Fiber Network.15

The Cities of Taunton, Fall River, and New Bedford have the highest need for digital equity and broadband availability, access, and adoption in the SRPEDD region. In both Taunton and Fall River, 11% of households, and 10% of households in New Bedford, do not have internet access. In terms of current services, SRPEDD identified 138 digital equity assets in the region. This includes locations and organizations such as libraries that have free public wi-fi and hotspot lending programs, councils on aging that offer computer classes for seniors, and various nonprofits that provide digital skills training.

The Massachusetts Broadband Institute is currently funding a Municipal Digital Equity Planning Program which allows towns to create Municipal Digital Equity Plans at no cost to the town. These plans analyze the current state of internet use, access, service, and programs in a community. Based on these findings, the plan identifies implementation activities and projects to expand broadband service and digital equity in the community. In the SRPEDD region, Fairhaven, New Bedford, Wareham, Attleboro, Freetown, Swansea, Rochester, Marion, and Mattapoisett are enrolled.

Table 3. Broadband access by municipality. (ACS 2022)

1. High Costs: A large percentage of people in the Southeast region report that their monthly internet bill is hard for them to pay.

2. Lack of Options: Many households across the Southeast region only have one option for an internet service provider that is providing broadband speeds (100/20 Mbps).

A resilient broadband network provides high-quality internet for all residents at an affordable price. A resilient network should provide adequate internet coverage to all residents, regardless of whether they reside in a rural or urban area.

T2-T3: Rural and suburban communities should consider creating a Municipal Fiber Network to offer residents additional internet service providers and create competition in the market, lowering prices for residents of these areas.

Across the Southeast, a growing concern is the cost of internet being too high. In many communities, this often results from little to no competition with internet service providers. According to MBI, Fairhaven, New Bedford, Somerset, and Swansea have the least competition in the SRPEDD region, with no access to broadband internet speeds from two or more providers anywhere in the municipality. Creating a municipal fiber network would allow residents to have access to additional internet service providers.

Massachusetts awards Municipal Fiber Grants to communities looking to create or expand their fiber optic infrastructure. In the Southeastern region, Acushnet, Dighton, Fairhaven, Freetown, Lakeville, Mattapoisett, Middleborough, New Bedford, Raynham, Seekonk, Taunton, Wareham, and Westport have been awarded Municipal Fiber Grants to use for various projects.

• Community Development Block Grants: Federal funds that can be used to install wiring, cables, and other equipment necessary for a broadband network.

• EDA Public Works and Economic Adjustment Assistance Programs: Federal funds that can be used for construction or upgrades to public infrastructure.

• Department of the Treasury Capital Projects Fund: Federal funds that can be used to ensure that a community has access to high-quality modern infrastructure, including broadband.

The City of Taunton has been awarded two Municipal Fiber Grants, one in FY 2022 to expand the water department’s fiber optic infrastructure, and another in FY 2024 to expand the city’s existing fiber optic infrastructure. Currently, TMLP is offering 100 Mbps speeds for $49.95 a month for residential customers.

T2-T6: Communities should consider having dedicated days at local community anchor institutions, such as schools, libraries, or councils on aging to help people enroll in the Lifeline or Comcast Internet Essentials program.

T2-T6: Communities can explore the option of replicating the Affordable Connectivity Program on a local level. Using income-based or other qualifications, communities can implement a similar program that would provide a monthly discount on residents’ internet bill.

Because of the high cost of internet in the Southeast region, it is important that residents are aware of programs that can offset this cost. From December 2021 to May 2024, the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), a federal program, gave eligible households $30 off their internet bill, or $75 on tribal lands, as well as a one-time device credit.16 Many households in the region utilized this benefit.

While there is no substitute for the program, the Comcast Internet Essentials Program, as well as the federal Lifeline program can help with the cost of broadband and phone service. Lifeline provides a $9.25 monthly discount which can be used on either a phone or internet plan. To qualify you must either receive SNAP, or Medicaid benefits, or have an income that is lower than 135% of the federal poverty guidelines. The Comcast/Xfinity Internet Essentials program is an internet service option that offers a $9.95 a month internet plan option to qualified households. To qualify for this program, you must have either previously been enrolled in the Affordable Connectivity Program or participate in other government assistance programs, such as Medicaid, SNAP, or housing assistance.17

The state of New York recently passed the Affordable Broadband Act, which requires all internet service providers to provide low-income households with an affordable broadband option. Providers must offer a service plan of 25 Mbps for $15 a month or 200 Mbps for $20 per month.18

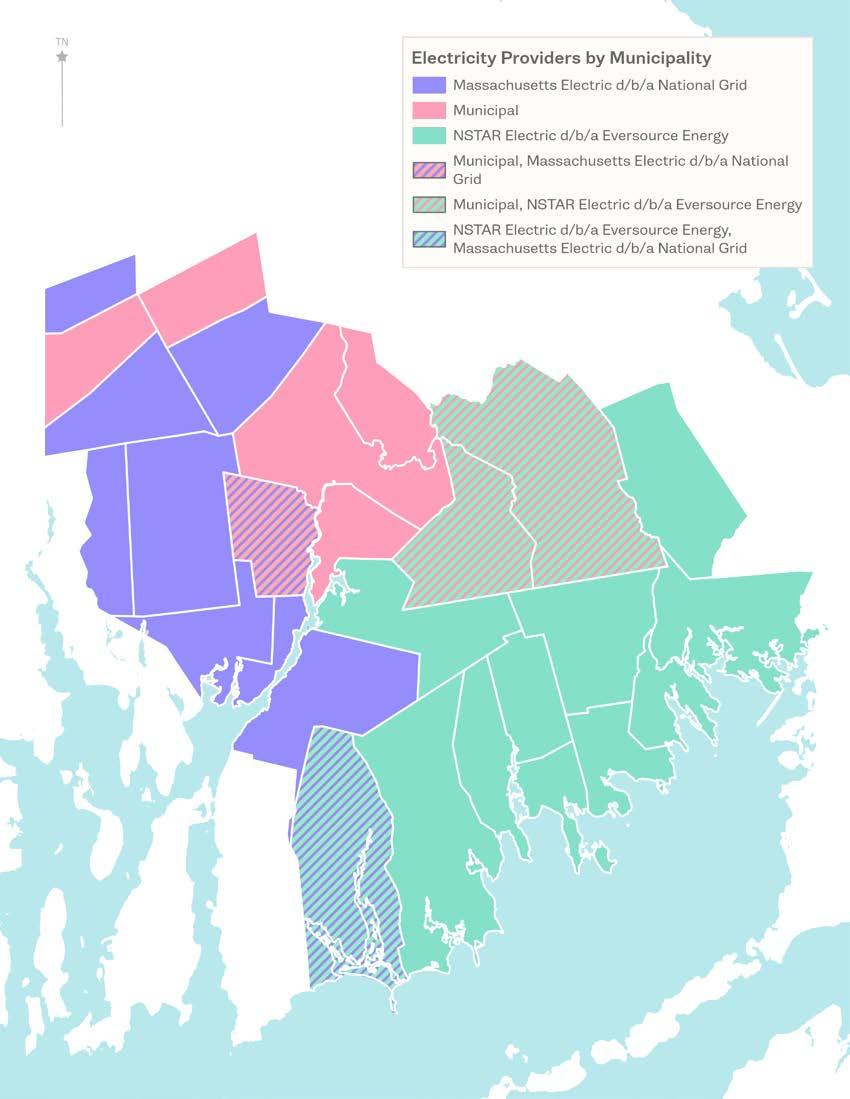

The region’s energy portfolio is currently serviced by three major suppliers: Massachusetts Electric (National Grid), NSTAR Electric (Eversource Energy), and municipal-run entities. Only four of the 27 communities in the region, however, offer multiple options for customers. The remaining 23 municipalities only offer one energy provider for the entire jurisdiction. NSTAR Electric has the largest service area in the region, with availability in over 13 municipalities; Massachusetts Electric is available in 11 municipalities; and municipal-run energy is available in eight municipalities.

The three different energy suppliers hold territory in different parts of the region. Massachusetts Electric dominates suburban/urban areas (T4-T6), while municipal energy and NSTAR Electric remain the principal providers for lesser developed (T2-T3) territory. Only Westport, Dighton, Lakeville, and Middleborough have access to both private and municipal service providers. Conversely, customers in highly developed areas such as Taunton, Fall River, New Bedford, and Attleboro only have singular options for energy service.

There is a distinct lack of competition across the jurisdictions in the region. With town/city-run energy service only available in eight of the region’s 27 towns and cities, many customers are left without competitive pricing options for their residential or commercial energy utilities. Given that National Grid and Eversource Energy – both of which are publicly traded companies – dominate the region, customers may be exposed to monopolistic pricing, a trend that is pervasive statewide, as noted in the Attorney General’s 2024 updated report on Competitive Electric Supply.19 As many of the jurisdictions in Bristol County and Plymouth County are managed by a single energy provider, it would be possible to note that the energy market in the region has characteristics of areas with true energy monopolies.

Table 4. Residential fixed price electricity rate by provider as of August 2024. (National Grid, Eversource, Towns of North Attleborough, Mansfield, and Middleborough, and City of Taunton)

A public monopoly situation can be detrimental to customers; without sufficient competition, utilities providers such as National Grid or Eversource could subject residential and commercial parties to increased prices and decreased service quality (i.e. frequent or long-lasting outages, lacking customer service, inadequate service network). However, the trajectory of a public monopoly is wholly dependent on the existing municipal, state, and federal regulations within the region or industry.

The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890, provides sweeping protections against monopolistic practices, including the utilities industry.20 Yet, as the Sherman Act has served as the landmark for antitrust regulation over the past 100 years, there still exist legislative gaps, even in the utilities industry. For example, ‘tie-ins’ can be a major concern within the energy sector. Tie-ins in the utilities industry occur when a service provider requires customers to purchase a proprietary product or service that a customer may have purchased or installed elsewhere.21 In application, a company like Eversource or National Grid could require the installation of proprietary service lines for customers wishing to integrate new residential or commercial developments. Though the Sherman Act does cover practices such as tie-ins, further enforcement is often necessary to police these issues.

Furthermore, 19 of SRPEDD’s member communities have created a Community Choice Electricity (CCE) program as of November 2021. Community Choice

Electricity programs, also known as municipal aggregation programs, are defined in UMass Ahmerst’s 2023 CCE Report as “[programs to] allow local governments to aggregate the electricity loads of residents, businesses, and municipal facilities to procure their supply of electricity (including renewable energy) in the competitive market.”22 The primary benefits of CCEs are reducing consumer electricity rates and increasing the percentage of renewables within a community’s energy mix. UMass Amherst’s report notes that 80% of municipalities surveyed had experienced savings by developing a CCE program, as well as achieving higher renewable energy levels. For additional guidance, the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources has a guide for advancing clean energy through CCEs. Municipalities can create their own CCE or participate in a regional CCE with other communities.

Communities in the region will need to further diversify their energy portfolios by incorporating more renewables. As of 2023, solar growth has been lagging statewide, exacerbated by supply chain issues throughout the COVID pandemic. Many solar projects in the Southeast have also been delayed while awaiting state approval for necessary grid upgrades, including projects in Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard.23 There is also concern among community members about the land use implications associated with large-scale ground-mounted solar arrays. According to Mass Audubon’s 2020 Losing Ground report, an estimated 6,000 acres of undeveloped land have been converted to solar arrays since 2012. A priority at both the state and regional level will be getting solar off the ground, instead encouraging installation on rooftops and over parking lots and other previously disturbed and impervious areas. Currently,17 of the region’s 27 municipalities include language pertaining to solar development. However, only Dighton, Marion, Taunton, and Westport have a full solar bylaw or ordinance, and only three of those include provisions for small-scale ground-mounted solar systems.

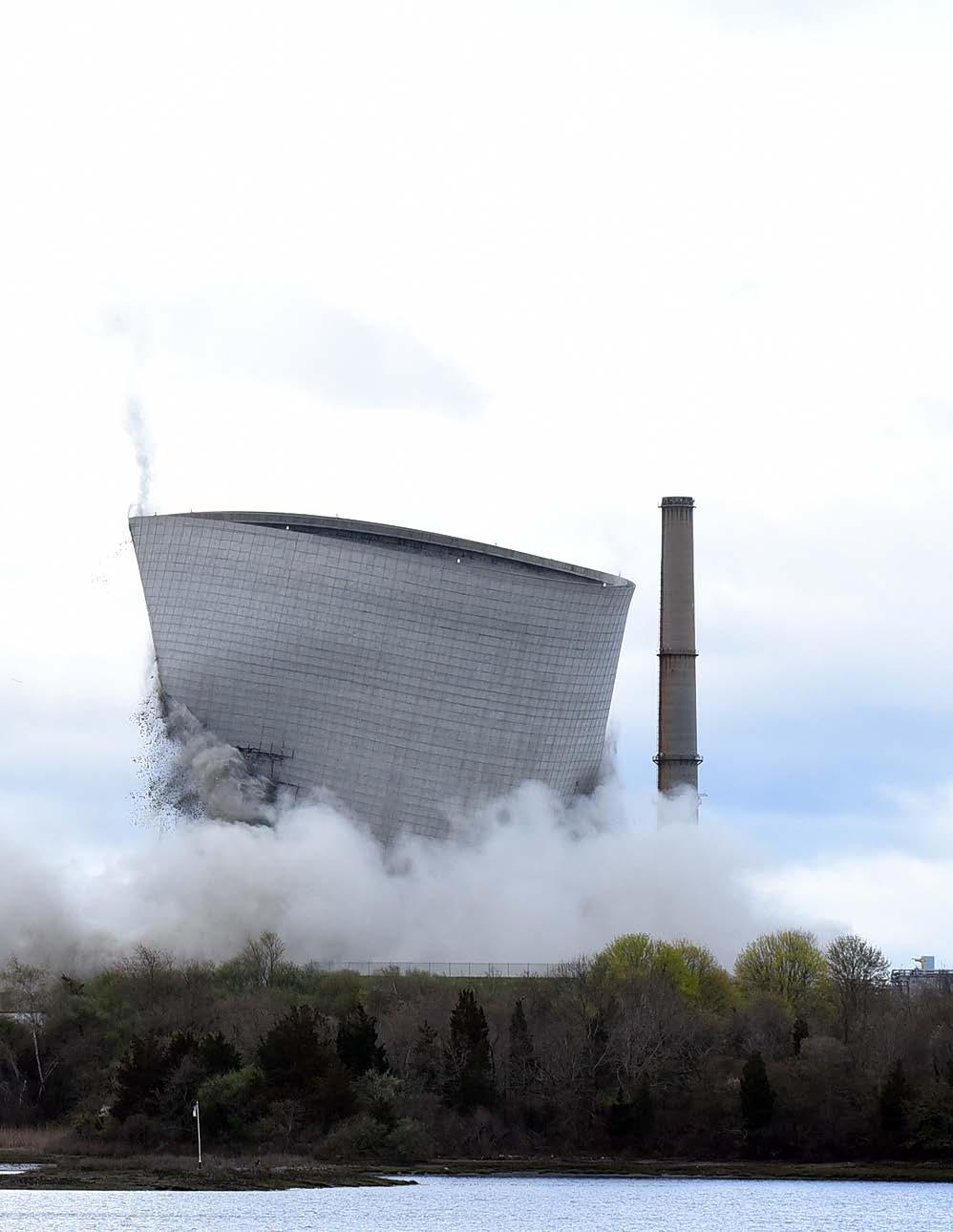

Wind energy potential is incredibly high in the region, as well, and several communities have existing or proposed wind projects. Several communities along the coast have deep-water ports, notably those in New Bedford and Somerset. One of the highest priorities for the region will be the realization of Italy-based Prysmian Group’s proposal to build an offshore wind manufacturing facility at Brayton Point, a former coal-fired power plant.

Massachusetts’ REPA (Regional Energy Planning Assistance Program) helps communities in the SRPEDD region develop energy plans that incorporate a mix of energy sources, including renewable energy. REPA often involves helping towns and cities apply for grants, such as the Green Communities designation, which encourages energy efficiency and renewable energy projects.

1. Limited Options: Most of SRPEDD’s region only has access to one electric utility provider. This can lead to monopolistic practices and high costs for consumers.

2. Aging Grid Networks: Renewable generation and long-term electrification will necessitate significant and costly grid upgrades. Additionally, it will leave fewer consumers utilizing natural gas infrastructure. The cost to repair aging infrastructure may end up being passed on to the most vulnerable residents, as more affluent communities move away from natural gas consumption.24

3. Local Perceptions and Skepticism: There is inherent skepticism about renewables/energy conservation measures, and the upfront costs associated with them. This skepticism makes it difficult to gain the local buy-in necessary to support new programs and investments.

For a resilient future, the SRPEDD region must focus on both diversifying supplier options and increasing renewables uptake to follow suit with the statewide goals to achieve Net Zero by 2050. A resilient energy portfolio will prioritize equitable energy outcomes, emphasizing transitioning from natural gas while ensuring the most vulnerable residents are not shouldering the burden. Additionally, a resilient energy portfolio will tap into the region’s most pertinent renewable energy resources, including offshore wind and rooftop solar.

T2-T6: Communities should update local zoning codes and streamline permitting processes, integrate these projects into economic development plans, and invest in relevant infrastructure and workforce training programs to facilitate offshore wind projects in the South Coast.

The region’s most recent 2023 Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) highlights offshore wind and ocean-based industry clusters as a notable strength. The Massachusetts Decarbonization Roadmap also highlights the New England coast as having access to world-class offshore wind resources. To prepare for decarbonization and to promote economic development and job creation SRPEDD’s coastal communities, especially those with deep water ports, should prioritize enabling new offshore wind projects (including manufacturing and installation) through local zoning and regulatory processes. These efforts can tie directly into education and workforce development opportunities to accomplish multiple resilience initiatives at once.

13. Offshore wind turbine blades on a cargo ship at the Port of New Bedford, MA. (Kevin Ham/SRPEDD)

T2-T6: Addressing common concerns by providing clear, unbiased information about solar benefits and educating on issues such as predatory sales practices and safety will strengthen awareness and accessibility of solar PV systems. Communities should also leverage resources from organizations like the Green Energy Consumers Alliance and DOER to streamline awareness and increase solar use in the region.

Another major component of decarbonization and energy diversification is increasing the uptake of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. As noted in the statewide Decarbonization Plan, offshore wind alone will not provide enough carbon-free electricity to meet the needs required to reach Net Zero by 2050. Increasing rooftop solar will allow users to access new energy sources outside of the limited network of existing options while also contributing to the state’s pathway to decarbonization.

Recent trends in the solar market have likely left many residents skeptical of the benefits of rooftop solar installation. Communities considering programming to increase solar uptake will need to address concerns about predatory sales practices, lacking returns on investment, and safety.25 Organizations such as the Green Energy Consumers Alliance offer resources to educate consumers on their options, and have notably highlighted some of these prominent issues in the solar industry in recent years.26 The Office of the Attorney General also has a resource page on frequently asked questions about solar products in Massachusetts, which describes how to handle predatory/aggressive sales tactics and how to choose between solar options.

There are a number of incentives and rebates available to consumers in Massachusetts, including:

• Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target Program (DOER): A state program that provides monthly incentives to small-scale solar developments producing no more than 5 MW electricity per parcel of land. Eligible solar PV systems must be integrated with the Massachusetts electricity grid.

• Federal Residential Solar Energy Credit (DOE): A tax credit provided to residents who have installed/plan to install a small-scale solar PV system. The apportioned tax credit is determined by the date of installation.

• Massachusetts Residential Energy Credit (DOR) (DOER): A tax credit allowing residents to receive 15% of the cost of a residential solar PV system, up to a maximum of $1,000.

• Massachusetts Property Tax Exemption (DOR) (DOER): A law, initially enacted in 1970, exempting property owners from property taxes for 20 years following the initial installation of a residential solar PV system. This exemption applies to both on and off-grid systems.

• Municipal Light Plants: Residents and commercial parties living or operating in a municipality managed by an MLP are eligible for various incentives and rebates, such as net metering, allowing for reimbursement of excess energy provided to the MLP.

T2-T6: Planning for long-term electrification will be possible by developing or utilizing state and federal programs that support low-to-moderate income households and businesses in transition. Communities should equip residential and small commercial buildings with the resources for longterm renewable use by promoting the adoption of rooftop solar, induction stovetops, and heat pumps.

There is an impending need to plan for increasing electricity loads to the grid as communities begin to transition to renewable energy sources.27 As discussed earlier, long-term electrification goals statewide and nationally will likely drive up maintenance costs for natural gas infrastructure, a burden that, without proper planning, may likely be passed on to the most vulnerable consumers.

Communities should plan to create new programs or tap into existing ones at the state and federal level to support low-to-moderate income households and businesses transition to all-electric appliances and home heating/cooling. For residential and small commercial buildings – and especially older buildings – this transition will primarily focus on the uptake of rooftop solar, induction stovetops, and heat pumps. Recent research is beginning to home in on “neighborhoodscale electrification” strategies, which aims to transition entire neighborhoods off natural gas at once.28 The State’s recent creation of the nation’s first Office of Energy Transformation29 is a strong indication that more statewide programming around natural gas transitioning is coming.

In the interim, communities should remain engaged with this new Office and begin exploring ways to work together regionally to coordinate transitioning and electrification. Long-term exploration of these efforts can also examine more advanced technologies, including microgrids and battery storage.

THE CALIFORNIA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION (CPUC)

The CPUC has been actively involved in creating policies and regulations that encourage the transition from natural gas to electrification in California. This includes building decarbonization efforts and incentives for all-electric homes. California’s Building Decarbonization program, which provides incentives for electric heat pumps and other electrification technologies, and the CPUC’s Long-Term Gas Planning Process are several initiatives that serve to enhance long-term electrification and the transition away from natural gas.

T2-T6: By engaging with DOER’s Green Communities Division, communities can access technical and financial support for adopting green energy alternatives. Additionally, utilizing MassCEC’s funding opportunities for green investments and promoting clean energy education can further enhance local clean energy initiatives.

The Commonwealth has various clean energy programs available to the public. The Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER) Green Communities Division provides both technical and financial assistance to adopt green energy alternatives. The Massachusetts Clean Energy Center (MassCEC) offers funding to green investment programs, while also promoting clean energy education across various disciplines.

Best Practice #1: Support job stability in healthcare and retail.

Best Practice #2: Enable innovation and support small businesses through modern and flexible zoning.

Best Practice #3: Ensure the longevity of agricultural activities by supporting related agrotourism activities.

Best Practice #4: Support competitive wages, especially among retailer workers.

Best Practice #1: Encourage students to pursue higher education in health sciences, biotechnology, and engineering.

Best Practice #2: Invest in partnerships and educational campaigns that connect the region’s students and workforce to education necessary in the Offshore Wind industry.

Best Practice #3: Create an ecosystem to attract and retain biotechnology firms to the region.

Best Practice #1: Encourage and adopt “high road management practices.”

Best Practice #2: Develop a framework to support small business development and entrepreneurship.

Best Practice #3: Invest in a revolving loan fund to support small business establishment and growth.

Best Practice #4: Support small businesses through support programs and flexible permitting and zoning.

Throughout the last 10 years, the region’s industries experienced a wide range of growth and decline. Most recent industry data shows that the region’s top industries include:

1. Healthcare & Social Assistance (17.26%)

2. Retail Trade (12.77%)

3. Educational Services (9.01%)

4. Accommodation & Food Services (8.89%)

5. Manufacturing (6.97%)

The region’s overall employment grew by 4% between 2013-2022; however, over half of the industries in the region saw a decrease in percent employment. The industries with the greatest decline in employment include Management of Companies and Enterprises (-28%), Utilities (-18%), and Manufacturing (-12%). Industries with the greatest employment growth were Construction (36%), Transportation and Warehousing (29%), and Administrative and Waste Services (9%). Most of region’s top industries declined, except for Health Care & Social Assistance which saw less than 1% of growth. Across the region, Healthcare and Social Assistance holds the largest share of employees, which is also reflected in the top employers in the region, which includes Partners Healthcare System Inc, St. Anne’s Hospital, Brockton VA Hospital Medical Center, and Good Samaritan Medical Center. The closure of Steward Hospitals threatened this industry in late 2024, and prompts the region to consider an economic landscape that supports heath care in the face of future challenges created by the private market.

Despite the modest growth in employment and mixed industry trends, wages grew across all industries. Wage growth can most likely be attributed to several different factors, the first of which is the increase of minimum wage from $11 to $15 per hour. The other major reason could be attributed to rising inflation, further exacerbated by trends due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The region should stabilize existing critical industries such as Healthcare and Retail, while also promoting growth in emerging industries. Between 1977-2007, big box stores and chains grew much faster than specialist retail chains.30 This is evident in the region’s major commercial corridors and business trends, where many businesses can be considered big box and chain stores. The preference for big box stores fluctuated over the years, with demands growing for more local and crafted products found most at specialty retailers. In fact, according to some sources, consumers are willing to spend more money at local shops to ensure they thrive.31 Studies also show that shopping local benefits the overall economy, with small businesses returning more than three times per dollar in sales to the local economy.32

Construction is among the fastest developing industries in the region due to its growth in wages and share of employment, mirroring trends in Transportation and Warehousing. These two industries, along with Professional and Technical Services and Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting were the only industries to have growth in both wages and employment share in all three of the region’s counties (Bristol, Norfolk, and Plymouth Counties) from 2013-2022. Though agriculture accounts for less than 1% of employment in the region, the New Bedford Port is the highest grossing port in the United States, which accounts for the significant growth in wages.33 However, with deep agricultural roots – and a distinct desire to preserve this history as part of the economic and physical landscape – the region has potential to capitalize on agritourism initiatives. The USDA touts agritourism as a means to generate revenue from recreational or educational activities, particularly in farms closer to urban centers, such as those in the Southcoast.34 Throughout the Commonwealth, 13% of farms participate in agritourism activities – a figure that grew 41% between 2017-2022. These activities account for upwards of $23 million worth of revenue.35

Sustainable growth requires careful consideration of future economic trends. For example, the rapid development of warehouses in the region occurred to meet high demand, elevated further during the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic tested local economies, particularly those that lean too heavily on the success of one industry; in response, communities should pursue any tools available to anticipate disruptions and diversify their economies to withstand them. A diversified, well-planned economy is the main way to combat changes in industry trends and survive future economic turbulence.

1. Low wages: Though the region has a moderate concentration of high-wage employment, our top 5 industries (in terms of share of employment) rank lower with an average high of $80,000 per year. Growth in these sectors is expected, and should be encouraged, though the region should consider industry diversification to make higher paying jobs available.

2. High Concentration of Healthcare and Retail jobs: Healthcare and Social Assistance and Retail Trade are the largest industries in the region. The region should work to diversify and grow new sectors.

3. Low employment in high-wage industries: The region’s share of employment in high-wage industries such as Agriculture, Utilities, and Transportation & Warehousing is growing. Though not as competitive compared to the top 5 industries, projections show the region should focus on growing employment in these sectors to diversify employment sectors.

The region’s economy is growing – and shifting – along with modern trends. In order to sustain employment in the region’s largest sectors, and create opportunities for new ones, municipalities need to proactively implement changes in close coordination with regional and state actors.

T4-T6: Communities within these typologies are often host to regional retail clusters and health care centers. Municipal officials – both elected and appointed – should maintain collaborative relationships with private sector representatives from these industries and institutions. These types of public-private partnerships are essential to ensuring sustained economic activity, navigating necessary changes, and preparing for and responding to market changes.

Recent troubles with the Steward Healthcare System and the COVID-19 pandemic show that private market disruptions and public health crises can significantly impact job stability in healthcare and retail. In collaboration with the state, the region should consider potential safety measures should private equity fail to meet the mission of public health.

T3-T6: Communities with greater densities have the consumer capacity, supportive infrastructure, and built landscape to support business innovation through zoning. Communities within these typologies may consider implementing modern zoning such as Innovation Districts, Village Districts, Transit Oriented Development Districts, Main Street and Downtown Districts, Technology and Lab Districts, and other zoning that removes unnecessary barriers to economic activity, both large and small.

Funding Opportunities: Community One Stop for Growth, Community Compact Cabinet, District Local Technical Assistance.

Communities throughout the region enable economic activity and influence small business growth through zoning, which establishes what uses are allowed, where they are allowed, and at what intensities (regulated through dimensional characteristics, such as minimum lot sizes and height restrictions). Municipalities can support small businesses and their longevity by enabling mixed use zoning and removing unnecessary regulations and procedures. Similarly, flexible (not overly prescriptive) zoning that is regularly updated based on market trends can proactively make space for new and emerging economic activities such as labs, flex spaces, and incubators in select places in each community

the longevity of agricultural activities by supporting related agrotourism activities.

T2-T3: Rural and select suburban communities with agricultural traditions and active farms are best suited to support agrotourism initiatives. Economies in these communities would benefit from the diversification of agricultural activities, insulating farms from closure and creating alternative paths for future development. Communities can ensure that their zoning and other bylaws (such as Right-to-Farm bylaws) enable ancillary activities such as those envisioned here.

Funding Opportunities: Community One Stop for Growth, Community Compact Cabinet, United States Department of Agriculture.

Many rural communities report uncertainty with regards to the future of farms in their communities. To support their longevity, municipalities should work with regional organizations, such as SEMAP, and the USDA to identify ways in which to diversify their activities to include paid experiences, weddings, and harvest events.

Best Practice

Support competitive wages, especially among retailer workers.

T3-T6: Local and state officials may choose to participate in a multisectoral collaborative dedicated to this issue, including the participation business owners, community members, and workers’ advocacy groups. They collaborative would ensure that wage-related advocacy is conducted lawfully, openly, and with accurate market data to support recommendations. The collaborative could raise public and executive-level awareness of the importance of equitable wage policies; it would also allow interested parties to launch a coordinated effort to lobby for improved workers’ rights through targeted advocacy campaigns, public forums, and direct engagement with policymakers.

Funding Opportunities: US Dept. of Labor Growth Opportunities Grant Program, HUD Community Development Block Grant Program, DOC Economic Development Administration PWEAA Program.

Minimum wages have increased significantly over the last decade; however, they struggle to keep pace with the rate of inflation. As the cost of living continues to rise, local representatives should support reasonable and lawful efforts to increase wages, especially for the region’s retail and service industry workers.

A modern economy can only be achieved by cultivating innovations in technology and aligning workforce development strategies with the skills necessary for rising industries. According to the MassTech Collaborative, Massachusetts is one of the leading states in the innovation economy that hinges on talent, research activity, and access to capital. In 2021, the MassTech Collaborative published The Annual Index of the Massachusetts Innovation Economy. From a statewide perspective, their research considered the factors that have made the state successful; MassTech also laid out the challenges the state contends with as it continues to grow.

Though the economic well-being of the state as a whole is on solid ground, the Southeastern region trails behind the Boston metro research and development corridor, which brings renowned biotechnology and life science firms to the Commonwealth. The StatsAmerica Innovation Intelligence Tool provides data that describe human capital, business dynamics, employment, and productivity to provide a more complete picture of the current state of the innovation economy in southeastern Massachusetts.36 For example, communities within the southeast region are in proximity of universities with high R&D spending in science and engineering. This should positively impact the average share of employees in high-tech industries, however, only 5%, are employed in these industries in Southeastern MA – compared to 9% at the state level and 16% in the nearby Boston Metro.37 Additionally, the tool compares the diversity of patents in the region against the U.S., showing the southeast region is more diverse.38

The region (and neighboring Rhode Island) host an emerging cluster of activity in the Offshore Wind sector, which is evident in projections that show Utilities as an industry is expected to grow across Bristol (27%), Greater New Bedford (33%), and the South Shore WDAs (79%) between 2020-2030.39 Offshore Wind is already creating demand for laborers with specialized skills obtained only through

training and certification. However, there is a clear gap between this demand and availability of a homegrown regional workforce with the skills necessary to secure well-paying jobs in this industry.

Additionally, other trends in the Southeast region impact innovation and workforce development, including education, training, and competition created by its proximity to the Boston research and development corridor. The region trails behind in educational attainment, particularly in higher education. Furthermore, Recent Graduate Surveys from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth highlight that most students graduate and remain in the state; however, only a fraction – an average of 14% over the last three yearsremain in the region.40 Recent Graduate Surveys also reveal Healthcare and Technical Occupations are among the most frequently cited occupations of recent graduates, with an average 15% in the last 5 years. Students pursuing graduate education also cited Engineering Technologies and Related Fields most frequently.41 Unfortunately, industry projections for the region’s workforce development areas (WDA) do not align with growth in these sectors. Though not part of the region’s critical industries, Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services are expected to grow in the South Shore and New Bedford WDAs. This industry cluster supports research and development locally, while also ensuring high-wage employment for individuals with a background in health sciences, engineering, and other modern technologies.

Further efforts to understand and influence these sometimes divergent trends would enable the region to have a more resilient, modern, and sustainable economy.

1. Educational attainment: The region’s ability to compete with neighboring regions that host robust research and development markets are directly hindered by the educational attainment of our workforce.

2. Training and certification in specialized industry skills: As the Offshore Wind industry grows in the region, necessary training and certification programs should be address skills gaps in the local workforce.

3. Retention of graduates in health sciences and biotechnology: Though the region produces skilled and educated workers in the fields of science and technology, few students stay in the region to pursue these careers.

4. Retention and attraction of research and development firms: Though the region excels in the production of patent technologies, low growth projections show that few research and development firms are settling or growing in the region.

An innovative economy and skilled workforce require investments in people. The South Coast is a prime location for research and development activities. It is central and strategically located; it boasts an increasingly educated population; and land values and development costs are lower compared to the Greater Boston Region. To create greater diversity in the local economy, the region and its municipalities should explore ways in which to encourage industry growth and align skills with local employment opportunities.

Education is one of the greatest barriers to entry for health sciences, biotechnology, and engineering. Trends show encouraging students to pursue degrees in these fields will also support the industrial growth in the region.

Best Practice 2: Invest in partnerships and educational campaigns that connect the region’s students and workforce to education necessary in the Offshore Wind industry.

T1-T6: Various technical schools and post-secondary institutions offer training programs that specialize in Offshore Wind operations. Partnering with these institutions, along with existing Offshore Wind industry leaders, would allow for the development of an educational pathway to directed, in-demand career opportunities in offshore wind. Offering flexible learning options, apprenticeship programs, subsidized transportation, or scholarships would reduce financial and logistical burdens and would incentivize residents of the region to participate in these educational programs.

Funding Opportunities: MassCEC.

Municipalities, regional workforce organizations, and institutions for higher education may coordinate efforts to connect local students and communities with training and certifications to enable entry into the specialized Offshore Wind workforce.

Create an ecosystem to attract and retain biotechnology firms to the region.

T1-T6: The development of a region-wide coalition, comprised of municipal representatives, industry members, chambers of commerce, and local business owners, would help to foster growth in the region’s biotechnology industry. This intersectional collaboration, through routine meetings, strategic planning, and private/public partnerships, would fulfill the interests of both municipalities and existing biotechnology firms. The coalition would serve to promote biotech-friendly development that would transform the region into a leading hub for innovation, helping to retain and attract firms within the region.

Funding Opportunities: DOC Economic Development Administration, EOLWD.

To support industry diversification through biotechnology and engineering, the region needs a prepared workforce to meet demand from local companies. This ecosystem needs to be cultivated by a variety of actors.

Mansfield Bio-Incubator is a non-profit organization whose mission is to facilitate and assist the creation, growth, and success of the next generation of biotech companies. The incubator supports nascent companies and nurtures entrepreneurship by providing affordable lab and office space to lease. Additionally, the Incubator provides services, training, mentoring, and a network of professional advisors. In late 2023, the Mansfield Bio-Incubator received funding from the EDA to cultivate an biotech ecosystem in the region to compete with the Boston corridor. Similar incubator success stories are available throughout the Commonwealth and the nation.