The Somerset Slade’s Ferry Design Guidelines would not have been possible without the support, input, and local knowledge provided by the town’s residents, professional staff, and leadership. The Town would like to acknowledge the following for their role in preparing these Urban Design Guidelines.

Mark Ulluci - Town Administrator

Amy Messier - Town Planner

Paul Cogley - Economic Development Committee Chair

Rick Peirce, Esq.

This document was prepared by the following agency and individuals:

Southeastern Regional Planning and Economic Development District (SRPEDD)

Danyel Kenis, Urban Design Planner

Robert Cabral, Director of Housing and Community Development

Lizeth Gonzalez, Director of Economic Development

Grant King, Comprehensive Planning Manager

Maria Jones, Senior Public Engagement and Communications Planner

Some of the elements in this document are Design Standards, which are binding and required. The rest are nonbinding Design Guidelines. Design standards will define measurable elements that are required for design approval, with exceptions available at the discretion of the Planning Board. Design Guidelines, on the other hand, will describe ‘Encouraged’ and ‘Discouraged,’ aspects of the built environment to help achieve the principles described in this document, support high quality design for the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District, and assist the Planning Board and developers during the review process. These guidelines; however, are not required.

The design guidelines section of this document contains three general concepts: Principles, Elements, and Strategies. Principles introduce the overall vision that each section supports. Strategies provide organizing mechanisms for the elements, helping define

what should be encouraged and discouraged on a site. Elements define the individual built, spatial, or programmatic components that support each principle and strategy; adding fidelity providing smaller, defined steps to achieve the defined aspirations in the Standards and Guidelines.

These Design Standards and Guidelines supplement the Town of Somerset Zoning Bylaw Section 9.5 “Slade’s Ferry Crossing District.” The Planning Board, at its sole discretion, can approve reasonable and justifiable deviations from the Design Standards and Guidelines if its members collectively opine that these deviations contribute to the goals articulated in Section II (Goals and Principles) more effectively. Adherence to any and all guidelines is not a substitute for, and does not exempt applicants from obtaining all required permits and complying with the applicable building codes, laws, and regulations in force.

The Design Guidelines and Standards contain 5 sections:

The Slade’s Ferry Crossing District serves as a waterfrontadjacent mixed-use district. Located in Southeastern Somerset, directly across from Fall River’s western riverfront, the district’s main thoroughfares maintain an axial relationship to the waterfront, with a large portion of land enjoying direct frontage along the Taunton River. These adjacencies provide the Slade’s Ferry Crossing district with unique juxtaposition to both the region’s natural coastal ecosystems and Fall River’s historic waterfront architecture.

The District sits directly south of a series of open spaces, that are highly flexible in use, and frequently serve as a site for outdoor activities, passive recreation, and open air markets. Slade’s Ferry Crossing also maintains a northern adjacency to a long-standing residential neighborhood.

These Design Guidelines aim to ensure that both current and future development reinforce a positive relationship to the site’s physical, social, and environmental context, while

serving as a vibrant, attractive, livable mixed-use destination for the surrounding area. To achieve this, the District contains within it three distinct, but related sub-districts: each designed to relate to its adjacent context.

Subdistrict A serves as the heart of Slade’s Ferry Crossing. In contrast to the District’s periphery, this subdistrict allows building heights of 4.5 stories (55 feet). To enable a more comfortable first floor commercial footprint, and to produce a walkable and vibrant environment this subdistrict also has a slightly lower rear setback (15 feet) and does not require side setbacks – creating the necessary conditions to produce and maintain a retail- andpublic realm-supportive street wall.

Subdistrict B buffers the area between Subdistrict A and adjacent residential properties, while still allowing smaller-scale development. Development within this subdistrict can achieve 2.5 stories at 35 feet (in contrast to the 4.5 allowed in the Core). Additionally, the rear setbacks of properties in

the transition zone are 25 feet, with 20 feet on each side providing increased physical distance between development parcels and neighboring properties.

The Waterfront Subdistrict allows for environmental and contextually sensitive development along the waterfront. The zoning language encourages development at the water, but also seeks to preserve a generous viewshed from all points within the District, and a general feeling of permeability between the accessible waterfront and the nearby Slade’s Ferry Crossing. To achieve this, Subdistrict C (like Subdistrict B) allows 2.5 stories of development at 35 feet. Additionally, development in this sub-zone must be 45% or less of each parcel’s lot area and must ensure 40% of the parcel will serve as public or green space.

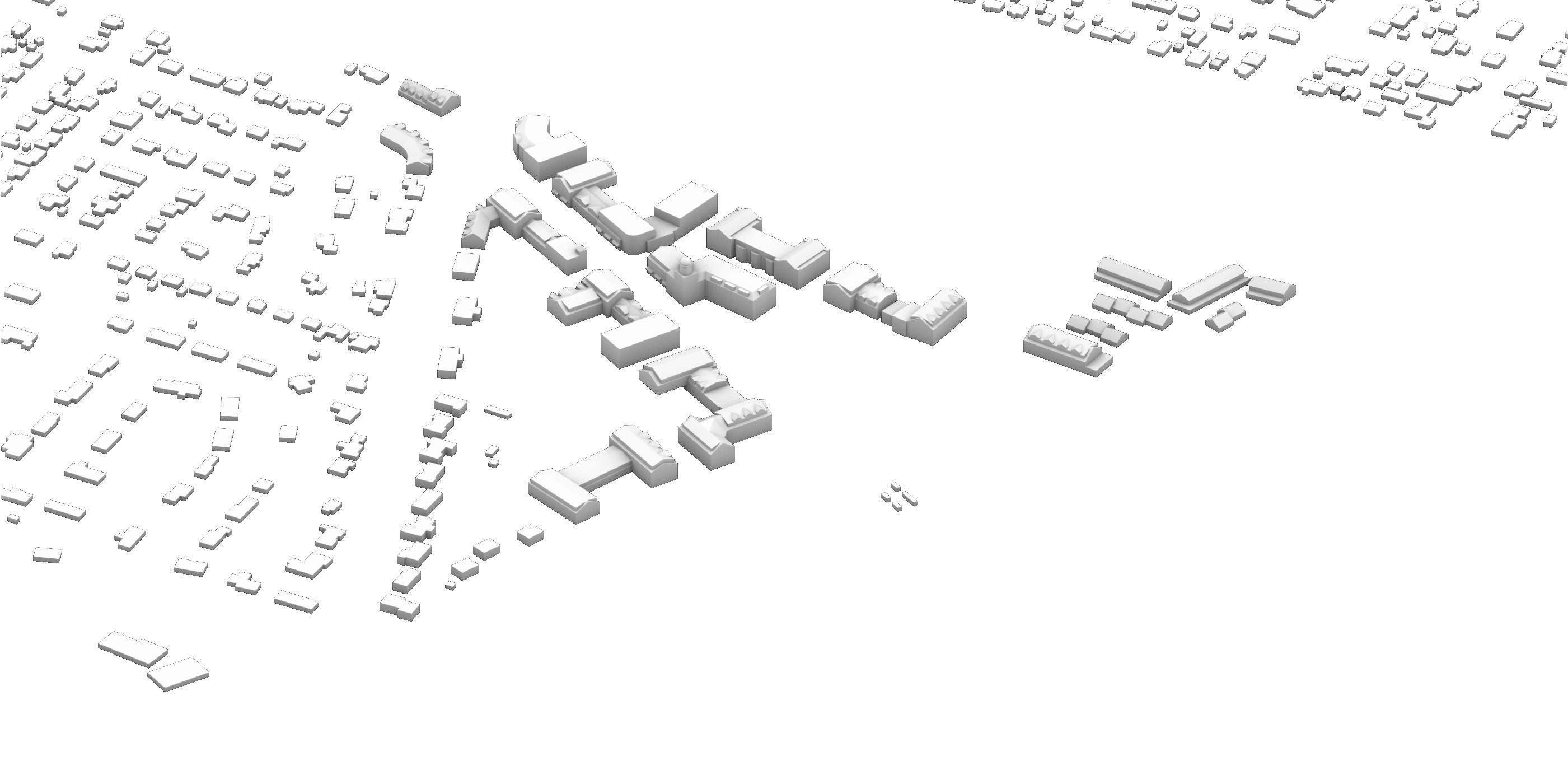

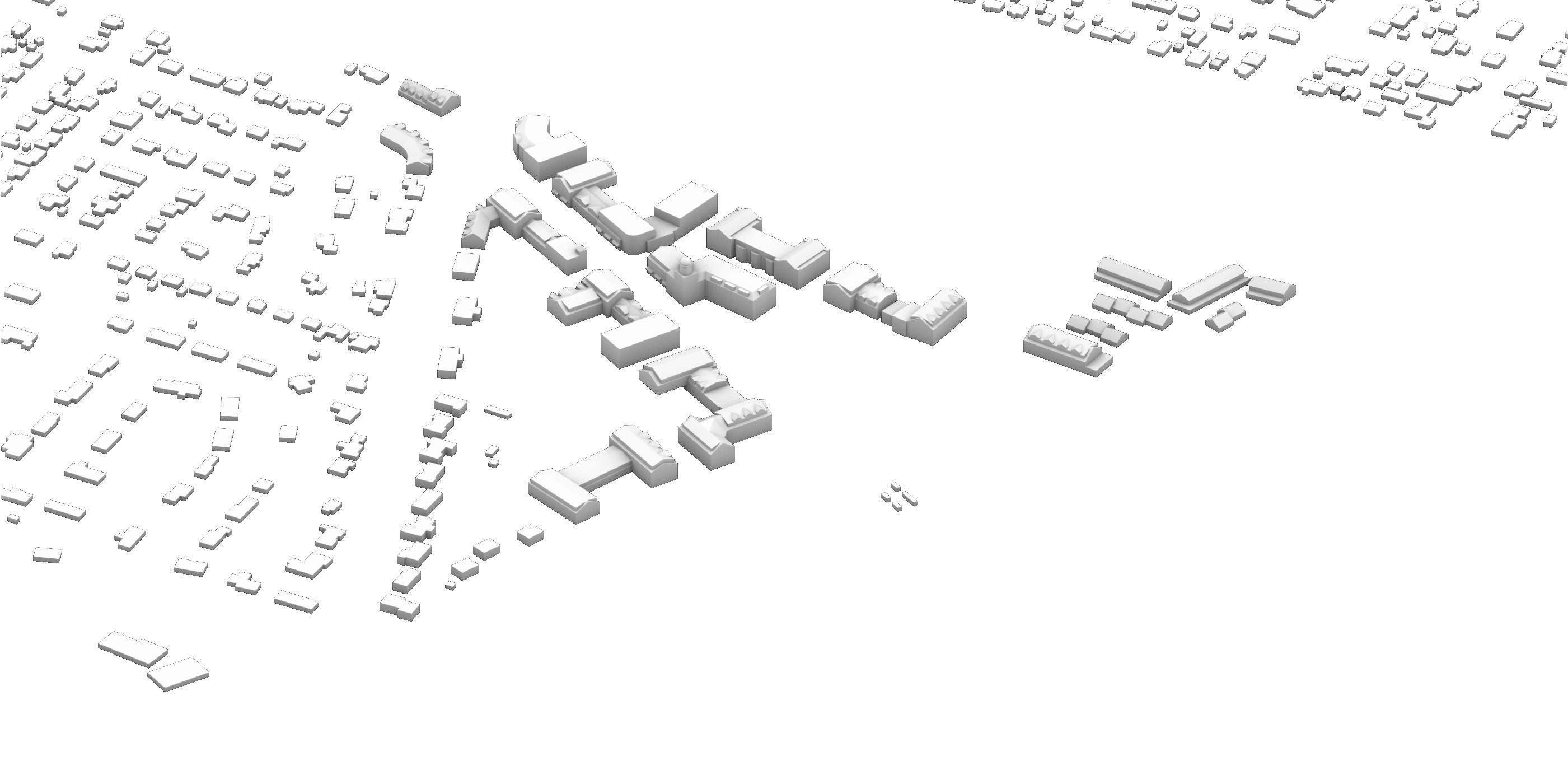

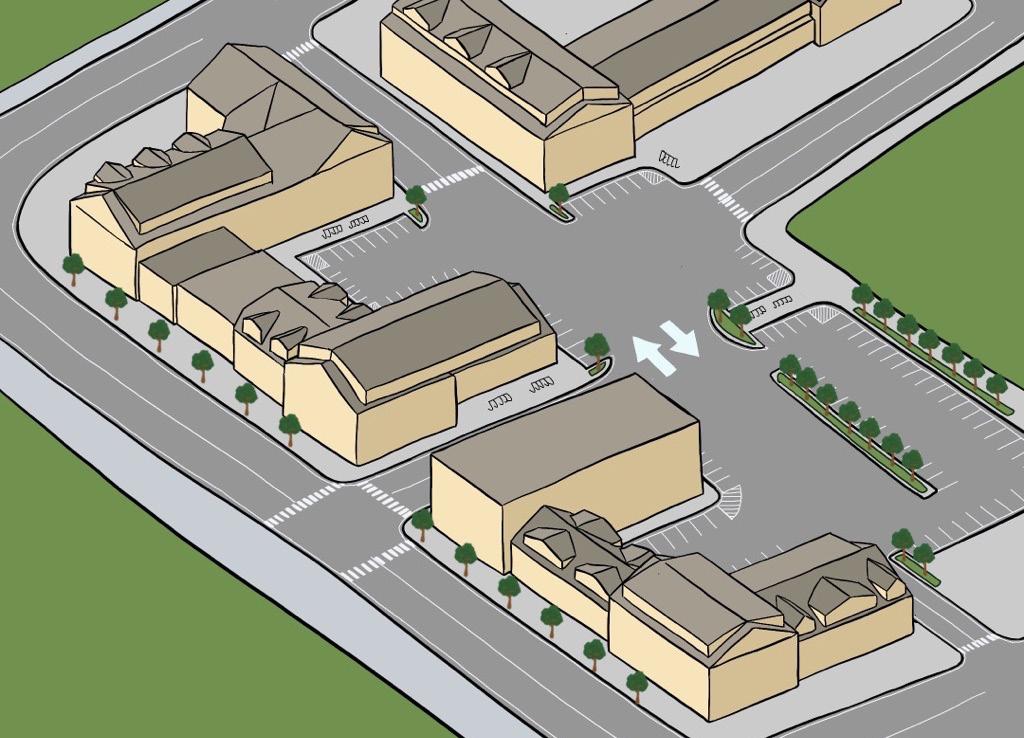

Above is a rendering of the current existing conditions in Slade’s Ferry. As you’ll see on the following page, we have also created renderings of potential development outcomes over the next ~20 years based on principles encouraged by the new zoning laws and in accordance with these design guidelines.

It is vital to reinforce the notion that this development will not be occuring overnight, or potentially even within the timeframe we have laid out, and that these drawings are not prescriptive.

The zoning in the associated guidelines outlines a blueprint that sets the parameters for many possible futures. Ideally this future is aligned with Somerset’s community values and aesthetics while remaining

reverent to the pre-existing neighborhood context.

The goal of these Design Guidelines and the updated Slade’s Ferry zoning is to both inspire and facilitate development in the site in order to make Slade’s Ferry should feel special, and these drawings display one potential idea of a Slade’s Ferry that is modern and active but takes care to not overwhelm surrounding neighborhoods.

New development often inspires further growth, which in this case is likely to begin along the site’s greatest asset, the waterfront. Development is likely to expand inward from the water, but should remain appropriately scaled as it approaches residential lots.

By virtue of its location, the Slade’s Ferry neighborhood has significant development potential. Waterfront access, a gentle slope that allows consistent vistas of the Taunton River, and immediate access to Route 6 all bode well for the site’s future. However, a shotgun-style approach to development is in neither a developer’s nor the community’s best interest.

These Design Guidelines will help new development to fit in the neighborhood context while improving the quality of life of new and existing residents.

The following are general goals inherent to “good” planning, specifically within the context of Slade’s Ferry and should be kept in mind throughout all phases of the planning and development process.

Encourage new mixed-use development that is inclusive to all and builds on the area’s existing vitality and community connections.

Create jobs and bring economic development opportunities to Somerset, including compatible waterfront, light industrial and commercial uses.

Create new walkable and bikeable connections that foster livable and vibrant streetscapes and encourage transit use.

Increase the supply of housing close to transit and at a range of price points, including affordable housing.

Create human-scaled neighborhoods with welcoming public spaces and green open spaces.

Encourage a positive relationship with the coastline while centering climate resilience at all scales of design; reducing carbon impact and mitigating the effects of sea level rise, heat island, and stormwater runoff.

It is imperative to create an active or welcoming ground floor on building street edges that aligns with the street type’s level of desired activity. Public space should be inviting, comfortable, and active. Developments should use green open space to play an active ecological, sustainable, stormwater management, and climate resilient role.

1. Ground Level Transparency

Large areas of glazing at ground level dissolve the visual barrier between the interior and exterior of a building, allowing the sidewalk to benefit from the adjacent activity.

2. Canopies and Awnings

Exterior overhangs and projections protect pedestrians from the elements, create a threshold at the entrances to shops and restaurants, and visually complete the “ceiling” of the public realm.

3. Public Spaces

Well designed, appropriately-scaled, and publicly accessible exterior spaces create an inviting public realm that becomes an integral part of the surrounding neighborhood and can be enjoyed by the widest range of users. These should be fully accessible for persons with disabilities.

Having frequent entrances along public ways creates a lively and more interesting pedestrian experience. Shops, cafés, restaurants, offices, and lobbies all create destinations that increase foot traffic. Include a minimum of one automated door for ease of access.

5. Street Trees and Vegetation

Street trees and other plantings help to visually soften the building, create a permeable barrier between the street and sidewalk, reduce solar gain, provide shade, and create a more appealing environment.

Creating porches, terraces, and balconies on the exterior of a building help to bring the activity within to the outside, increasing both the safety of the sidewalk as well as enlivening the building façade.

7. Paving Patterns

Varying the paving patterns through the use of colored concrete, pavers, and other materials can help to create a unique sense of place in front of a building and visually brand the location.

8. Street Furniture

Benches, trash receptacles, pedestrian lighting, and other types of street furniture make a welcoming pedestrian realm that invites people to linger.

9. Connectivity Support

Bicycle racks, bicycle lanes, and general support for alternate modes of transportation improves pedestrian sentiment towards the site. Adequate storage and safety for bicycles helps create a sense of community trust while promoting healthy physical activity.

Realm: While the size and shape of buildings receives significant scrutiny, we can apply similar standards to the public realm. Calibrating the sidewalk’s width to that of the adjacent road and height of buildings can create a comfortable and inviting public realm. Additionally, ‘carving out’ spaces in the building massing creates opportunities for comfortable public spaces –both breaking up the monotony of the façade and defining the entrance to buildings. Following this principle achieves the goal of making the setting read as a neighborhood and not a singular, oversized structure (or series of structures).

Design details can further reinforce these concepts. For example, using varied paving materials to define spaces, planting appropriately sized street trees, and providing ground level site features (such as benches) introduce human-scaled elements and reinforce a well considered hierarchy of spaces.

Circulation: Circulation in the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District should contribute to the area’s purpose as a local destination. This means providing a safe, pleasant,

and accessible environment for pedestrians; as well as organized circulation for bikes and motor vehicles. To achieve this, sidewalks should maintain a clear and generous pedestrian circulation zone. The portion of the sidewalk closer to the road should maintain space for trees, furnishings, and plantings. The spaces in front of buildings should serve as a frontage zone with café seating, planters, entry space, and other elements that support the use in the building.

It is important to create as few interruptions along the sidewalk as possible. To achieve this, development should limit the number and size of curb cuts on the primary (storefront-facing) street. Additionally, the road should contain enough space to provide safe and clearly marked bike lanes or multi-use paths that have sufficient separation from local traffic.

parks, plazas, outdoor seating spaces, and small green spaces play a critical role in generating a healthy public realm, mediating the space between the public right of way and the building. It is important to ensure that these spaces are visible, accessible,

and offer places for passive enjoyment (this often requires little more than a place to sit). These open spaces should relate to the broader public realm infrastructure, providing a variety of ways for residents and visitors to enjoy the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District.

Buildings and their associated open spaces serve as perfect locations for public art. Often, successful public art brings in voices from the local community.

There are several ways that a proposed development can encourage an active ground floor and public realm. Frequent building entrances alongside transparent façades introduce a rhythm to the public realm that reflects the scale of interior uses. Allowing buildings to directly front the sidewalk further activates these spaces. Additionally, it is important to limit building frontages to 300 feet, providing through-block connections for pedestrians. Through block connections are also an excellent place to display public art.

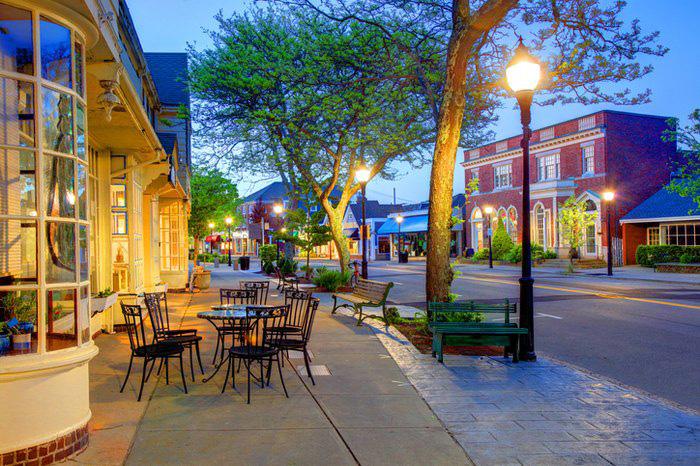

Falmouth, MA’s downtown was the most popular precedent option on the Visual Preference Survey boards shown to Somerset residents during the Slade’s Ferry Traveling Workshops. Residents emphasized their approval of its human scale, wide sidewalks, outdoor seating, lighting, and large windows. Each of those aspects blend together to create a distinctly “New England” feel that they’d like represented in Slade’s Ferry.

These three photos were also amongst the most popular Visual Preference Survey options, highlighting a desire amongst Somerset residents for active uses, greenery, and public art. Used tastefully, their contributions to placemaking/creating a distinct Slade’s Ferry site experience cannot be overstated.

Transparent retail ground floor with entrance alcoves and planters (Chicago Neighborhood Design Guidelines).

Integrated pocket parks turn otherwise unused alleyways into organic-feeling, welcoming public spaces.

or Inaccessible

“Public Spaces”: Public spaces, by their nature, should benefit all visitors. Public spaces can meet the requirements of the by-law, in terms of open space percentages, without providing the necessary and assumed public value. This occurs when these spaces are completely enclosed or inaccessible from public right of way; or when they are liminal in nature, providing no discernible benefit to their end users. Public spaces should ensure that they are visible, accessible, inviting, and of appropriate size to serve as a usable destination.

Multiple or Widened Curb Cuts on Primary Streets: When transportation circulation works as intended, the design can feel almost invisible. When circulation

is poorly planned, it generates noticeable conflicts. Frequent and wide curb cuts can serve as a significant source of these conflicts. Developments should funnel vehicular circulation, entry to rear parking lots, as well as delivery/service/operational traffic to secondary street entrances. Doing so avoids circumstances requiring multiple access points, wide curb cuts, and large radii for vehicles. This ultimately reduces conflict points between pedestrians and cars, enhancing public realm safety.

Appearance along the Ground Floor: Buildings should avoid appearing as a large, blank wall – particularly on the first or ground floor of a structure (except along service alleys, which should always be towards the

sides and back of the building). Architectural program such as parking entrances and loading docks should not abut the primary public realm sidewalk. Additionally, building façades should not appear as a large wall and should avoid high opacity, instead favoring transparent and glass storefronts.

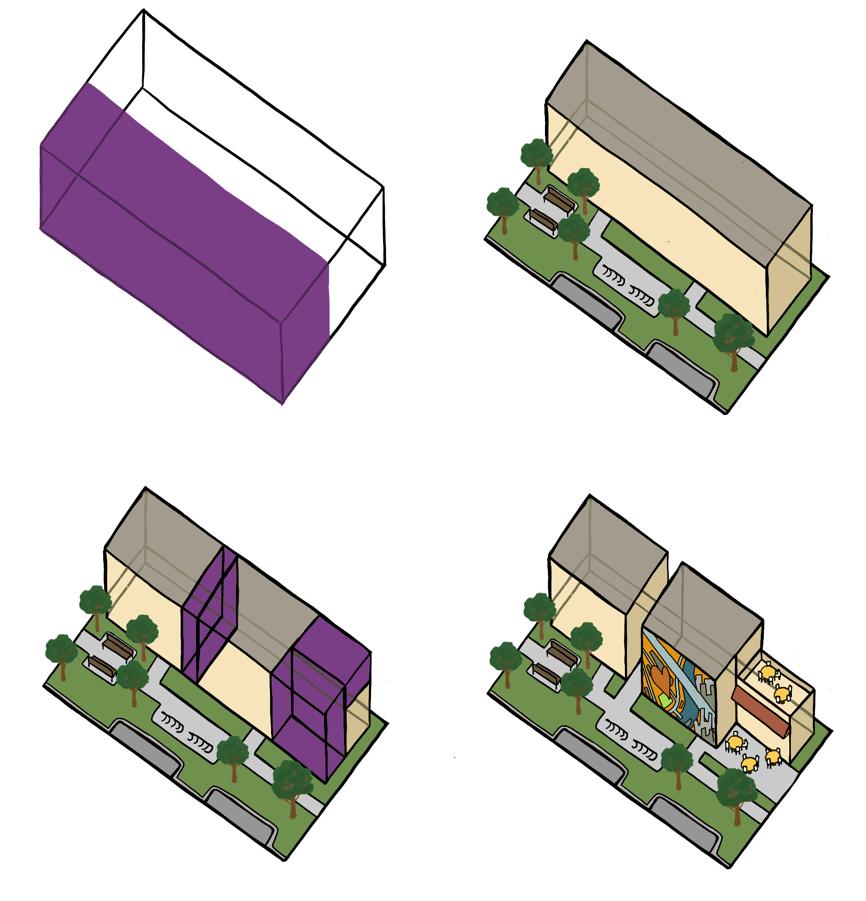

New developments should create new human-scaled blocks by breaking up large, monotonous structures. Portions of parcels should be left for public-use elements and placemaking. Intentional variations in height and shape can be used to create more interesting and engaging ground-level and human-scale experiences.

45-55% maximum lot coverage (and setbacks) depending on subdistrict.

Variation in building footprint can make for a more interesting site.

Rest of site should be used for streetscapes and interblock connections.

A portion of the site should be used for placemaking goals.

Context: The zoning for Slade’s Ferry Crossing requires a shorter building height of 2 ½ stories. It is important for properties that interface with this step-down requirement to manage any height difference in a way that feels organic and contextual to local surroundings. Further, these buildings should be architecturally referential to the surrounding neighborhood fabric. While it is not necessary to directly imitate local surroundings, new development should feel harmonious with its context. There are several tools to achieve this, including:

a) Introducing step-downs with the building design so an aggregated volume presents itself as a singular building, rather than appearing to step down within the same architectural volume.

b) Pitched roofs, dormers, and ½ stories can hide height in a building – particularly when adjacent to a residential area.

c) The development can align floor-to-floor heights with those in the adjacent neighborhood.

d) A building’s horizontal proportions can draw from the rhythm of adjacent buildings.

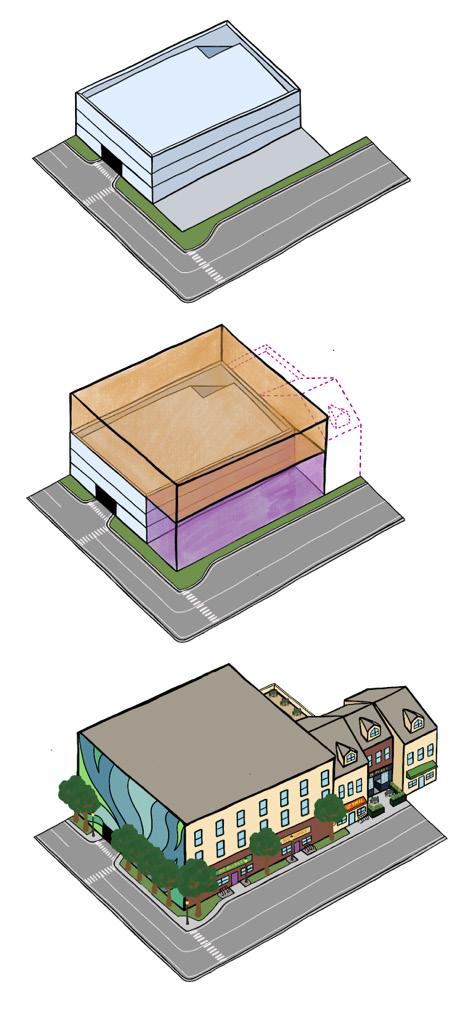

Massing: It is important for all buildings in the District to appear appropriately scaled to their context. Developments should ensure that the buildings manage their height, horizontal scale, and visual presence. It is also critical and that structures comfortably navigate differences between heights. The most successful projects break up a singular building massing into several smaller forms by manipulating its architectural volume. Methods to achieve this include:

a) Breaking up massing heights, roof types, floor-to-floor heights, and setbacks. This can help what would otherwise read as a monolithic structure read as integrated into the historic fabric of Town.

b) Strategically setting a structure back can make a building appear visually smaller.

c) Adding porches, dormers, and bays; or recessing volumes for porches and terraces can add visual interest.

important for the corners of a building massing to maintain a strong presence. Developments achieve this through maintaining building height at the corner volume. Providing vertical and impactful architectural elements can emphasize a corner lot’s importance. Corner lots can use subtractive elements to emphasize the public realm portion of this space, when appropriate. Regardless of approach, it is important that corner lots hold and maintain a strong presence.

In this case, each building is relatively similar in aesthetics, yet the visual monotony is broken up through variations in heights, additions of porches, color variation and roof styles (Open Gable roof on the left, Mansard roofs with Dormers on the furthest two buildings)

The building footprint on this site does not cover the entirety of the parcel and instead sacrifices some square footage for a public use element. This contributes to the positive public sentiment around the development while increasing both cultural and financial value.

The tower serves little functional purpose other than as a wayfinding landmark, yet when coupled with a dynamic, rounded first level creates a very strong and visually pleasing corner. Pedestrians are guided around the building in an arc, forced to engage with the building by virtue of its shape and tempted to gaze through one of its many windows. Despite containing nothing but a clothing store on the ground level, there is a gravitas to the corner that makes it feel more important than it is.

Large and Monotonous Building

Volumes: Volumes should not display a large and uniform looking, ‘canyon-like’ façade. It is critical to scale smaller volumes of the building.

Jarring or Abrupt Height

Differences: Avoid creating jarringly different height conditions when directly abutting significantly shorter buildings or height differences that look like they are occurring within the same architectural volume (with no relationship to the building program or structure).

Overuse of and Arbitrary Façade Differentiation:

Avoid haphazard differences in materials, massing volume, and façades. Breaking up a façade or massing with these elements, or introducing too much complexity in the form of overuse of bay windows and protruding elements like balconies can ultimately have the opposite effect of what a designer might intend – making a building seem boxier or more monolithic.

structures

When abutting shorter buildings, height changes should feel natural. One building should not “loom” over another.

Despite greenery and pedestrian elements, arbitrary material changes coupled with random colors and other chaotic design elements implemented for the sake of variation can be even less appealing.

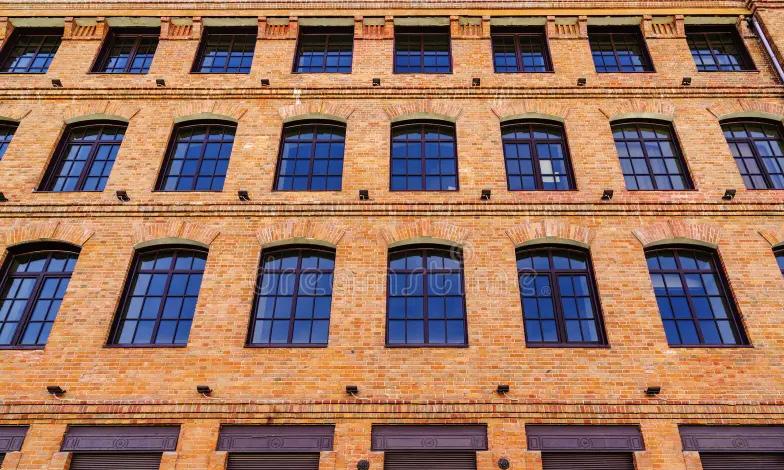

Use façade elements to define proportions of the massing and create distinct organization, such as street-level, upper-level, and roof. Entries and windows should be arranged to create a welcoming appearance for public entries and uses. Use materials to thoughtfully reinforce the organization of massing and façade elements. The ground floor should include welcoming entrances and views into the building’s activity. Other recommendations apply to larger industrial and smaller residential buildings. Ground

Buildings should be designed with transparency at the ground level. The success of a commercial or mixed-use district relies on an activated public realm with ground floor cafes, restaurants, and retail stores. Making the internal building program of the store visible through continuous glazing and connect the public realm to the first floor of the building –ultimately activating the public realm.

Combine horizontal elements (such as belt courses, projecting cornices, canopies, and step backs) with vertical elements (such as recesses, projecting bays, parapets and vertically aligned windows), to create façades that evoke the proportions and style of New England architecture typically found in and around Somerset. Building elements do not need to recreate historic architecture – modern and contemporary architecture are welcome in the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District; however when possible these buildings should relate to the scale, site, and context of the location.

Façade elements should continue around to all sides of buildings visible from the street and, as appropriate to all sides of buildings that face directly abutting residential uses. Elements can be simplified at the rear of buildings to clarify a front-back hierarchy. Include elements such as parapets to define the roof. Rooftop mechanical equipment should not be visible from the street or directly abutting residential properties. They should be set back and screened from view behind parapets or enclosed within architectural elements that integrate it into the building design. Screening elements should incorporate sound control devices or construction that mitigates equipment noises.

discouraged

Developments should avoid poor quality and non-contextual finishes; instead, these structures should favor natural or visually rich materials that add value and contextual sensitivity and to the development.

Buildings should not have monolithic facades, blank walls, or flat and uninterrupted elevations. Instead, developments should vary setbacks, consider glazing or permeability, break the structure into smaller architectural volumes, and enhance the public realm.

Off-street parking and loading facilities, such as parking lots or garages, should be located away from the primary street, as well as screened/de-emphasized. Multiple building footprints can share parking lots.

1. Shared Parking

Shared parking is a strategy where nearby or adjacent property owners allow combined access and utilization to their parking facilities in an effort to meet demand while also reducing the number of parking spaces necessary on their own properties. In most cases, successful shared parking strategies are for special events, weekends, or off-hours where participating properties contain land uses that have different peak hours of parking demand (e.g., a municipal facility vs. an apartment complex). Parking should be behind buildings, so as not to damage the aesthetics of the street-front.

2. Alternate Entrances and Exits

Alternate means of entry allow for fluid circulation and prevent traffic slowdowns. However, multiple entrances to parking one lot should not interrupt the same stretch of sidewalk.

3. Rear Parking Means Active Street Wall

Parking lots are away from street, hidden behind buildings. There should be no parking barrier between pedestrians and storefronts. This also mitigates chances of pedestrian/ vehicle collisions by reducing interaction.

4. Support Alternate Mobility

Offer safe and secure parking for bicycles and scooters. Place storage racks both behind and in front of buildings, allowing people to choose a more secure parking option if they are concerned about their belongings.

5. Street Trees and Vegetation

Street trees and other plantings help to visually soften the building, create a permeable barrier between the street and sidewalk, reduce solar gain, provide shade, and create a more appealing environment.

It’s ideal to place garage entrances along secondary streets, off of main corridors. Do not cover entire lots with parking,but instead reserve portions of site for more active uses.

“Wrap” parking garages with active uses along primary streets. Make sure to take height of attached/nearby structures into consideration in order to ensure cohesion with existing neighborhood aesthetics.

Use creative façades, public art, and greenery to “screen” exposed parking garage façades. Take inspiration from surrounding neighborhood aesthetics to taintain visual continuity with neighborhood. Widen sidewalks and promote active uses.

Parking should be located away from the primary street. In the case of the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District, primary streets include Slade’s Ferry Avenue and Slade’s Ferry Boulevard which should be reserved for building frontage with minimal setbacks.

New commercial developments should explore ways to share parking with adjacent businesses to reduce the total number of parking spaces required. Reviewers should make accommodations for commercial establishments who seek to reduce the amount of parking in lieu of pursuing a more productive use or providing quality of life and public realm enhancements.

The arrangement of parking entrances should be designed to limit curb cuts to the greatest extent possible, with a particular focus on eliminating curb cuts on primary streets. Developments should consider sharing entrances and coordinating the circulation within parking lots to encourage sharing of parking spaces. Pedestrian access to parking should be well-defined, safe, and separated from car circulation.

Attached, above-ground or below-grade parking structures should be integrated into the building design. Use building wrapping, screening, and facade design elements to mask parking.

Parking lots should be appropriately vegetated, with a planting design that provides stormwater management and shade for vehicles and pedestrians. Strategic use of planting can also visually shield parking areas from the public right of way and to define pedestrian circulation, providing safe separation from vehicles.

Non-rectangular lot with green elements

Permeable parking spots with EV chargers

discouraged:

Developments should not site off-street parking in front of buildings, or facing any primary streets. Pedestrians approaching building entrances should not have to cross the paths of any moving vehicles. This allows for a more consistent street wall, creating visual continuity between buildings and enhancing the feeling of a cohesive neighborhood.

Parking garages should not generate large, blank facades facing the street. Further, parking should not be the main focus of a building, and should not occupy the ground floor of a primary street.

wrapping is not allowed. The garage is also unscreened

Parking lot behind sidewalk but in front of building. No direct pedestrian access to front door, forcing them to cross lot

Enhance the pedestrian environment in parking areas by creating inviting rear entrances using signage, canopies or awnings, paved paths, display windows. Signage across the district should visually contribute to the neighborhood and provide way-finding. They should not add visual clutter. Signage should be integrated with the building’s architecture and not obstruct building cornice lines, windows, and architectural details.

All signage must follow Somerset’s standards outlined in 6.5.3 (residential), 6.5.4 (commercial), and 6.5.12 (Prohibited Signs), included in the Town of Somerset’s Zoning By-Law. These sections of the by-law define the size, height, allowable quantity, dimensional, and locational requirements for signage throughout Somerset

Signage should clearly identify residential and non-residential uses. The principal entrance(s) of each development should have a sign in an easily identifiable, related, and legible location –in the case of a ground-floor commercial use, it is best to place signage close to the storefront. Signs should include pertinent information, such as the address, name of business, and relevant branding.

The dimensions and location of signage should integrate seamlessly into the building façade with placements that respect building cornice lines, windows, and architectural details.

Signage in the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District should be readable and legible for pedestrians or slow-moving vehicular traffic. Consider the purpose and user of each sign, and whether the person will be standing still when reading the sign or passing by.

Signage should do its best to avoid creating visual clutter. While all signage can and should be distinct, reflect the personality of the business/tenant, and provide appropriate wayfinding; these signs should similarly be mindful of context. Business owners can achieve this by scaling signage to the pedestrian experience, projecting signage when it may be difficult to read as parallel to the building façade, and avoiding interference between signage and other public realm amenities (such as street trees, planters, light posts and street furniture).

discouraged:

Signage should not interfere with the architectural features of a building. While the Town Signage By-law prohibits certain conflicts between signage and structure, such as roof signs, business and developers should avoid placings signs in ways that visually interfere with a structure’s architectural features.

Signs should not be stand-alone in nature, as these are too auto centric for the design goals of the Slade’s Ferry Crossing District. This includes signs on large poles, or signage that is far-removed from a structure. In addition to encouraging an autocentric approach to the district, they are often out of scale with the public realm, discourage foot traffic, and do not integrate well with adjacent buildings.

sign catered towards cars, usually signifying a parking lot entrance

Somerset maintains strict standards around appropriate and acceptable signage. Please refer to section 6.5.12 (Prohibited Signs) of the Town of Somerset’s Zoning By-Law for the full list of prohibited signage types. Examples of restricted signage include, but are not limited to:

• Any sign which incorporates any flashing, moving, intermittent, animated or rotating lighting except those displaying only time and temperature on separate displays.

• Any sign which infringes upon the area necessary for visibility on corner lots as set forth in Section 6.8.

• Any portable sign, including any sign displayed on a unregistered vehicle, except by special permit.

• Any sign or sign structure involving the use of motion pictures or projected photographic scenes or images.

• Roof signs.

• Signs that will obstruct the visibility of another sign which has the required permits and is otherwise in compliance with this ordinance.

• Off-premise signs except as otherwise provided for herein.

• All inflatable signs except those permitted in writing by the Building Inspector.