Introduced by Zadie Smith

Introduced by Zadie Smith

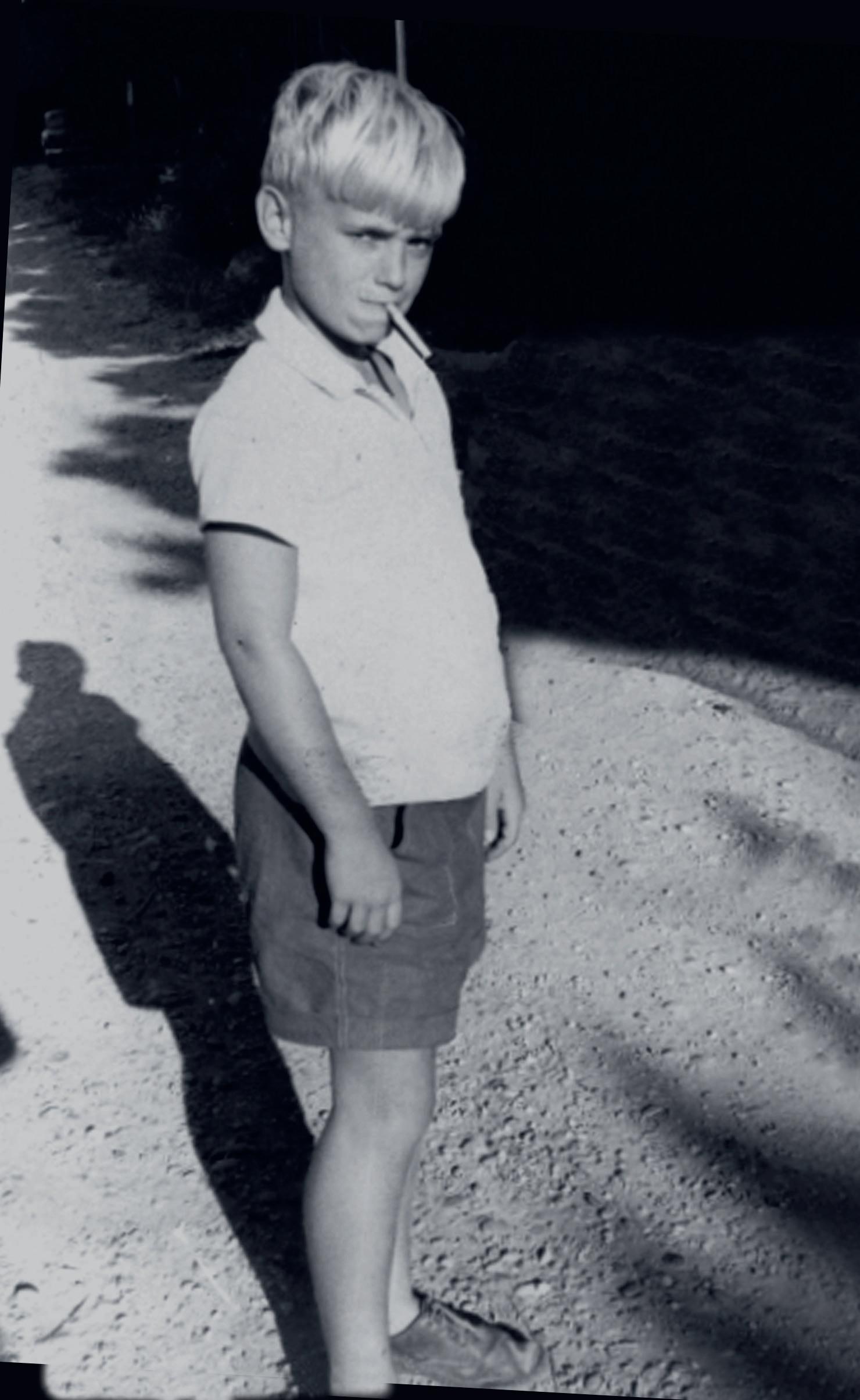

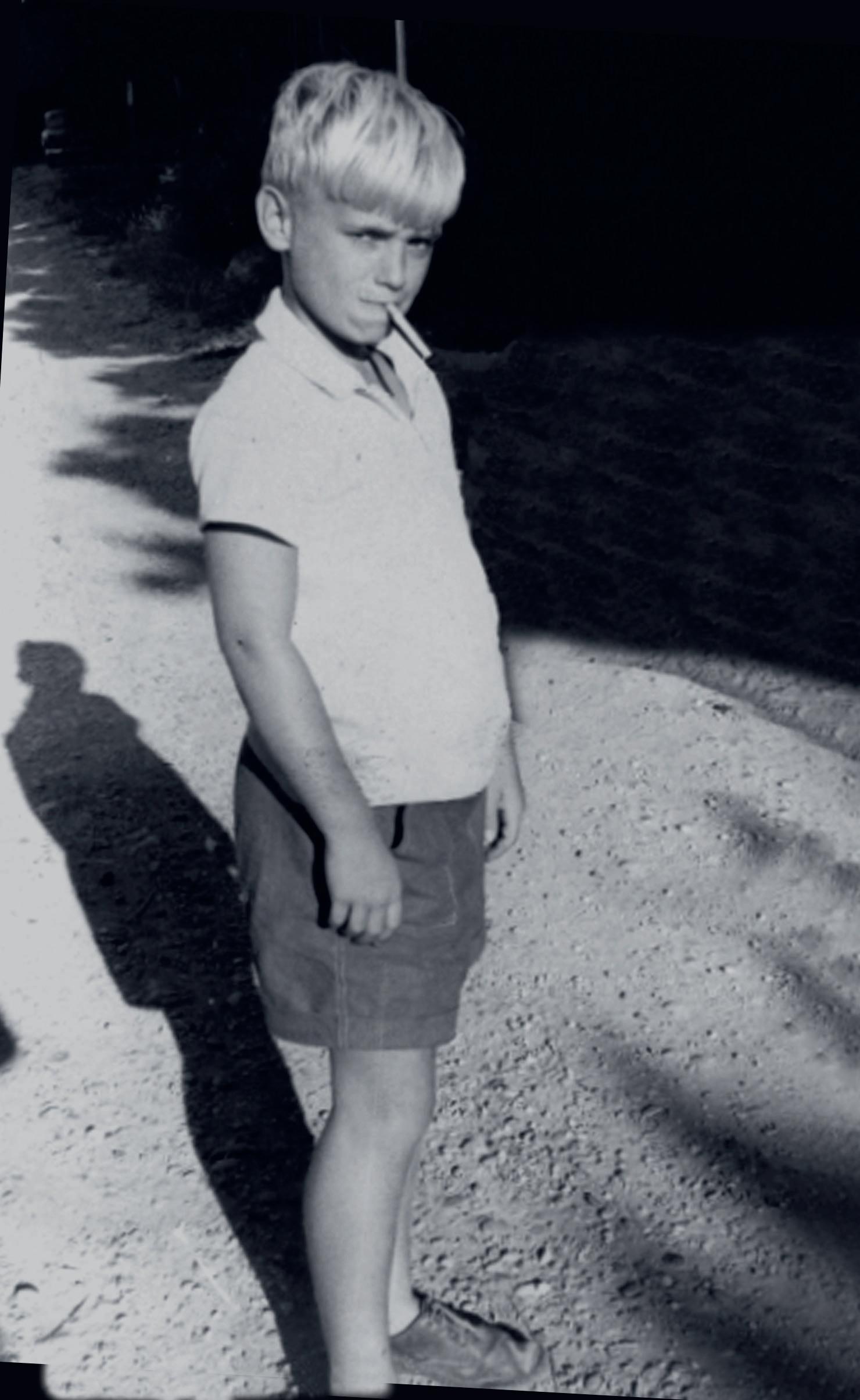

Martin Amis was twenty-three when he wrote his first novel, The Rachel Papers (1973). Over the next half century – in fifteen novels, two collections of short stories, eight works of literary criticism and reportage, and his acclaimed memoir, Experience – he established himself as the most distinctive and influential prose stylist of his generation. His books, which have been translated into thirty-eight languages, provide an indelible portrait and critique of late-capitalist society at the turn of the twenty-first century. For many of his readers, Amis is simply the funniest writer of his era. Amis was born in Oxford in 1949 and died in Florida in 2023.

f I c TION

The Rachel Papers

Dead Babies

Success

Other People

Money

London Fields

Time’s Arrow

The Information

Night Train

Yellow Dog

House of Meetings

The Pregnant Widow

Lionel Asbo

The Zone of Interest

Inside Story

S h ORT STORI e S

Einstein’s Monsters

Heavy Water and Other Stories

NON -f I c TION

Invasion of the Space Invaders

The Moronic Inferno: And Other Visits to America

Visiting Mrs Nabokov: And Other Excursions

The War Against Cliché: Essays and Reviews 1971–2000

Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million

The Second Plane

The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump. Essays and Reportage, 1986–2016

w IT h AN INTRO duc TION BY Zadie Smith

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London S w 11 7B w

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Martin Amis 2000

Introduction copyright © Zadie Smith 2025

Martin Amis has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape in 2000 This paperback first published in Vintage Classics in 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529952681

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 0 2 Y h 68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

I was turning twenty-five but how very young I was, how really terribly young. And how long it lasts, youth, that time of constant imposture, when you have to pretend to understand everything while understanding nothing at all. You understand nothing about time.

This piece of Martinian wisdom – generally applicable – in fact refers to an excruciating particular: the 1973 disappearance of Martin’s cousin, Lucy Partington. Lucy’s mother is confessing to her young literary nephew that not a minute goes by without the thought of Lucy – without wondering where she might be:

I ducked my head and I thought: Poor Miggy! She thinks about Lucy every minute, and it’s been . . . nine months.

Nine months?

Back when Experience was first published, I was twenty-five, and likewise knew nothing about time. The ‘pain schedule’ described and coined by Saul Bellow* – which mid-life Martin was busy filling in – was still mere abstraction to me. Parental death, loss, grief, relationship breakdowns, lost children, broken friendships, mid-life crises, public shame, private shame, professional failure, health emergencies, dental misery – I read about it all with a keen anthropological and vocational interest, but with no sense that any such schedule would ever be filled out by me . . . Then came experience. I’ve always loved this book but it is a quite different book to me now. It used to make me laugh and frown. Now it makes me cry, too. And there are other discombobulating shifts: generational,

* In More Die of Heartbreak : ‘A long schedule like a federal document, only it’s your pain schedule. Endless categories.’

[vii]

political. Re-reading it, I find myself occasionally as exasperated by Martin’s opinions as Martin was about Kingsley’s . . . But I still love this book. (I no more read a novelist for their opinions than I read Paradise Lost for its theology.) In Martin what I love is his humour, his language, his ethical clarity, his soulful innocence, and yes, his experience, which manifests in this particular book as a persistent, hard-won wisdom. Especially when it comes to the life of a writer. Twenty-five years later, I can see how much this book affected me. How much I borrowed and reused. I can feel Dad’s thumb upon the scale. For years I have been judging dull or didactic fiction by this yardstick, without remembering it is Martin’s yardstick for measuring Kingsley. (Specifically, the post-divorce misogyny to be found in the novels Jake’s Thing and Stanley and the Women.) When I accused a friend or a colleague of being a ‘leaf in the wind of trend’, I’d almost come to believe that this comic indictment was original to me. (It’s Kingsley measuring Martin.) And when I think about writing as a controlling art rather than a creative one, once again I am unconsciously plagiarising:

But there was another world, one I felt I could control and order – which was fiction. And I have always been in love with that.

Me, too, Martin. Me, too. For years, while teaching aspiring writers, I would try to honestly describe the basic non-glamour of a writing life by reusing your copy:

And I still felt like a student. The TLS felt like a library, the sessions with the literary editors felt like tutorials, and my articles felt like weekly essays.*

* It still feels like that, sometimes. Just last night in fact, moments after enquiring whether the children might consider helping clear the table after dinner, I was met with a screaming chorus of BUT I HAVE HOMEWORK ! And I thought of you, Martin, and this very introduction that I knew I was going to have to start sometime after I had cleaned the kitchen, sometime after the children had gone to bed, and I felt like screaming right back at them: ME TOO!

[viii]

In Experience, one of the things Martin reveals is that writing isn’t some distant summit that can be finally and absolutely scaled, but rather a task that is endlessly regenerated and freshly assigned, although by the time you reach your thirties, the person doing the assigning, generally speaking, is you. It probably doesn’t look like a real job to anyone looking on – but it is one. And it has its peculiarities and its vagaries, like any vocation. Alcohol sits in worryingly close relation to it, for example, and cigarettes, and ambition, and vanity, and self-absorption, and the desire for control . . . but also innocence, love, awe, and gratitude for the simple fact of existence. In this book Martin exalts writing, as a practice, but is also clear-eyed about its limits. ‘Its imitation of nature’, he reminds us, ‘cannot prepare you for the main events.’* Experience is largely an account of those events. One of the ways you can tell this memoir is written by a novelist and not, say, a politician, is that his life has taught him, is teaching him, that existence is both comedy and tragedy, simultaneously, and all the time. Anyone who has this writerly vision of life will not be able to write a memoir in the conventional chronological mode. Such a structure requires faith in the ultimate authority of calendars, clocks, decades, eras and so on. The pain schedule, by contrast, is intimate and obeys only subjective laws. Theme unites with theme across the barrier of years. People ‘go under’; daughters go missing; fathers real and symbolic must die. ‘My organisational principles, therefore, derive from an inner urgency’. Yes, exactly that. The unique rhythms of this book – the way the chapters swing in and out of view, in response to this ‘inner urgency’, as dancers respond to music – this is a part of its beauty. In 2000 it seemed a whole new way to write a life. Not when something happened, or even what happened – but how it felt.

The point of a writer, in my view, is not that they have remarkable lives or even unusual feelings but that whatever they do experience, they can articulate. This was true for Martin from the molehills of daily life to the mountain of a brutal murder. Let’s start from the top down. ‘Cursing and sobbing and thinking of the dead’ is what we do when a human being isn’t just gone but rather stolen from us. And when we are watching our

* And there’s another thing I didn’t know, aged twenty-five.

grubby true crime documentaries, and wishing there was a little less screen time given to the murderer and a lot more to the victims, well, in that case, our inarticulate guts are intuiting what Martin precisely and eloquently states: ‘The murderer, in a sense, presides over this little universe, with all its points and circles, but of course there is no place for him within it. He caused it but he is not of it.’ He caused it but he is not of it. Later in that grim process, the deaths the murderer has caused will require funerals, some of them atheistic, where people will struggle to find a language with which to clothe their grief. And if you ever find yourself in that situation, here is the plain-speaking Anglo-Saxon version of Martin to accompany you: ‘This is where we really go when we die: into the hearts of those who remember us.’ And here is his far more elaborate – but equally unforgettable – one-sentence judgment on Fred West, the man who added so monstrously to the pain schedule of so many: ‘A sordid inadequate who was trained by his childhood to addict himself to the moment when impotence became prepotence.’ People sometimes talk about stylists like Martin as if style in a sentence were mere decoration. But look at that sentence! In it are condensed several lengthy judicial, spiritual and ethical arguments regarding the nature of crime and/or mental illness and/or evil. And I notice that although it seems a thunderingly dark appraisal, deep within it persists a tiny crack of light. It is a sentence that retains the possibility of a comprehension that need not simultaneously serve as an excuse nor, necessarily, compel us to forgive . . .

Because of Martin’s murdered cousin, because of his chaotic friend Rob who went to jail and perhaps also because of Martin’s peripatetic and unstable childhood, his parents’ divorce and his own perilous class position* – I think the sum of all these varied experiences meant Martin was always keenly aware of how quickly and suddenly things can turn bad. As he puts it: ‘Going under [. . .] lives very close to what I write.’ One other consequence of this knowledge was that it made him sensitive to human frailty – sympathetic to it. To put it another way, he got the lesson about human fuckery close up and all

* ‘Dad, what class are we?’ asks Louis Amis, at one point.

[x]

the time, and it made him capable of looking at people in the round. His father, for example, was at one and the same time a drunk, a bully, a sometimes woman-hater and anti-Semite, as well as a studentcommunist turned professional right-wing contrarian. He was also a vulnerable, anxious man, terrified of the dark, who couldn’t sleep in a house alone, a man who had to be ‘Dad-sat’. Also the bitter patriarch who would greet your arrival at his deathbed with the words: FUCK OFF . And yet:

When the time came for me to go he didn’t plead with me. He only said, as I hugged him,

– Little hug.

I straightened up. He said, – One little more hug. And I hugged him again.

Experience purports to be Martin’s memoir, but really it’s a double-hander: a father and son two-for-one. And because Martin was first and foremost a comic novelist with a gift for character, it makes sense that Kingsley should come out of it on top in terms of outline and definition. Martin is the consciousness behind it all but Kingsley is the character. And what a character! Most of us, if pressed to describe a dead and difficult parent, would struggle to find the story, the anecdote, the language with which to bring that person fully to life. Martin delivers us Kingsley whole. Every few years I remember the tale about the dog that said FUCK OFF to Kingsley (page 304) and I just start laughing again. And am freshly amazed at myself, so amused by an anecdote delivered by a dead man I never met, who also appears to have believed that Nelson Mandela was a terrorist. But that’s what writing is, according to Martin: ‘not communication but a means of communion.’ Now, not all of me communes with Kingsley, by any means, but that bit of me that delights in anthropomorphic canines?

Martin inherited his father’s comic gifts and expanded upon them. Salman Rushdie looking ‘like a falcon staring through a venetian blind’. Or a friends and family visit to the cinema: ‘My father once told Christopher

[xi]

Hitchens and me to fuck off after we took him to Leicester Square to see Beverley Hills Cop. No: he liked it and we didn’t.’ Sometimes the comedy comes out of the transformations of Time itself. People change so much. It is comic – and nigh impossible – to imagine James Fenton and ‘The Hitch’ selling the Socialist Worker on ‘Kilburn High Street’.* Meanwhile, teenage Martin’s dating technique squeezes laughs out of the ever mysterious recent past:

you wrote out visiting-cards, with your name and number, and distributed them, by the tens of thousands, to every girl you could find on the London Underground; then you hurried home to wait, often in vain, for your one or two calls.

And imagine the fourth estate these days having sufficient interest in the private life of a novelist – or sufficient funds – to send a journo to Ecuador to interview your ‘secret’ daughter!

Experience finds the humour in time’s transformations, but never evades the pain. Here is a book that knows mid-life crises are hilarious until you have one, and old age a sort of personal failure of other people – until it’s your turn to ‘have a fall’. Threshold experiences – by which I mean the moments when you’re teetering on the edge of transformation – are particularly well described, from the dentist’s chair to the delivery room, to the offices of divorce lawyers: ‘Really, I was saying goodbye to myself. I would be different hereafter. How different, I didn’t know. But different: a changed proposition.’ And though I agree with Martin that writing can never prepare you for such main events, I think reading can. Reading provides the hypotheticals. You read and in this way try out concepts, ideas, beliefs and see if you can use them. For example, that line of Kingsley’s, about identifying the beloved, which Martin quotes so affectionately: Is it now? Is it you? That’s definitely one worth taking for a test drive, out in the real world. Or how about this? ‘Stopping being married to someone is an incredibly violent thing to

* Martin, one posthumous note: nobody calls it Kilburn High Street. Kilburn High Road!

[xii]

happen to you, not easy to take in completely, ever.’* I imagine many readers nodding their rueful heads to that one. Novels are never instruction manuals on experience – at least, they shouldn’t be. But they can certainly offer you a few hypothetical scenarios, to be noted, to be considered, when experience happens to you . . .

I treasure the experience in Martin – and the innocence. Both. Experience is what allows him to recognise, when thinking ‘with his blood’ – that is, when he is being irrational on political or personal questions – that this is what he is doing. (Plenty of people think with their blood while believing themselves to be perfectly rational.) Experience tells him that no matter how vital the political or professional issue appears, it’s probably not worth losing a really good friend over. But one of the most important lessons of experience, to Martin, concerned the importance of protecting innocence itself. Wherever and whenever it appears. Your own and other people’s. He understood that one of the most valuable things a novelist has is access to their innocence, in the form of the unprettified, uncommodified and unregulated content of their own unconscious. ‘Because that’s what novels are (among other things): not almanacs of your waking life but messages from your unconscious history. They come from the back of your mind, not from its forefront.’ I claim that a writer is three things: literary being, innocent, everyman. This is Martin doing the claiming. Everyman? The life of Martin Amis – lurid, banal, sometimes privileged, sometimes not, geographically uncertain, wildly particular, passionate, romantic, occasionally bizarre and continually surprising – this life would not seem, on the surface, to be the life of an Everyman (to say nothing of an Everywoman). But Martin explicitly believed that, to be a writer, you had to be under the delusion that you are an example of a general case. That the universal lurks in all of us. And if you know how to read between the lines, there it is. The ageing, impossible parent whom you both adore and occasionally dread. The children who can appear wiser than you are. The siblings and friends you don’t know how to help. The times when you can’t help yourself – or when you hurt others. The mid-life catastrophes. The thinking with the blood.

* Found in this book but borrowed by Martin from Kingsley’s.

[xiii]

The search for home. The threat of violence. The fear of poverty. Of ‘going under’. The loss, drink, joy, birth, comedy, sex, death, gratitude and fury. Against all the odds of demographics, history and personality, so much in Experience makes me laugh and cry in painful recognition. But here I have to qualify that term ‘Everyman’, again. I do agree with Martin: becoming a writer involves cultivating the necessary delusion of the universal. But I think it is even more important to acknowledge and sustain the true intimation that you belong in one sense to a giant, unruly family: literature. In which clan you will find dozens of difficult, frustrating parents, untold quantities of annoying brothers and sisters, many or even most of whom you could easily go ten rounds with over any hot topic, and yet they would still, despite it all, remain, in some sense ‘your people’. Your people being: writers. Martin’s fellow feeling for writers across great gulfs of time and sensibility was exemplary. He thought of literature as one task, done by many hands across the generations, like a single lake fed by many tributaries. His reading fed his writing and then his writing fed the lake. Speaking of bodies of water, here is Martin describing a trip to Iceland: There I saw a rainbow entire, bandily bestriding a fjord in austere isolation. That’s Martin in show-off mode, obviously, but it’s also Martin communing with his extended family. The rhythms of British poetry embedded in that line! Faint echoes of centuries of verse, contained and reproduced in Martin. And a few of Martin’s faint echoes are contained and reproduced in me. And larger and deeper grows the lake. Even if these many tributaries come from different countries, tongues, mindsets and traditions there will always be some fellow feeling between the people who contribute to the lake, and of course the people who swim in it – readers. But Martin describes reading best, too: ‘Frowning, nodding, withholding, qualifying, objecting, conceding and smiling, first with reluctant admiration, then smiling with unreluctant admiration.’ And here he is, at it again, describing my experience with this book exactly: Frequently I wiped my eyes, from laughter, and from the opposite of laughter.

Zadie Smith, 2025

[xiv]